User login

FDA approves nivolumab for metastatic CRC

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab for the treatment of patients with mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) and microsatellite instability high (MSI-H) metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) that has progressed following treatment with fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan.

The indication covers patients aged 12 years and older. Efficacy for adolescent patients with MSI-H or dMMR metastatic CRC is extrapolated from the results in the respective adult population, the FDA said in a statement.

Approval of nivolumab in the adult population was based on an objective response rate of 28% in CHECKMATE 142, an open-label, single-arm study of 53 patients with locally determined dMMR or MSI-H metastatic CRC who had disease progression during, after, or were intolerant to prior treatment with fluoropyrimidine-, oxaliplatin-, and irinotecan-based chemotherapy.

The most common adverse reactions to nivolumab, marketed as Opdivo by Bristol-Myers Squibb, include fatigue, rash, musculoskeletal pain, pruritus, diarrhea, nausea, asthenia, cough, dyspnea, constipation, decreased appetite, back pain, arthralgia, upper respiratory tract infection, and pyrexia, the FDA said.

The recommended nivolumab dose is 240 mg every 2 weeks.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab for the treatment of patients with mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) and microsatellite instability high (MSI-H) metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) that has progressed following treatment with fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan.

The indication covers patients aged 12 years and older. Efficacy for adolescent patients with MSI-H or dMMR metastatic CRC is extrapolated from the results in the respective adult population, the FDA said in a statement.

Approval of nivolumab in the adult population was based on an objective response rate of 28% in CHECKMATE 142, an open-label, single-arm study of 53 patients with locally determined dMMR or MSI-H metastatic CRC who had disease progression during, after, or were intolerant to prior treatment with fluoropyrimidine-, oxaliplatin-, and irinotecan-based chemotherapy.

The most common adverse reactions to nivolumab, marketed as Opdivo by Bristol-Myers Squibb, include fatigue, rash, musculoskeletal pain, pruritus, diarrhea, nausea, asthenia, cough, dyspnea, constipation, decreased appetite, back pain, arthralgia, upper respiratory tract infection, and pyrexia, the FDA said.

The recommended nivolumab dose is 240 mg every 2 weeks.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab for the treatment of patients with mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) and microsatellite instability high (MSI-H) metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) that has progressed following treatment with fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan.

The indication covers patients aged 12 years and older. Efficacy for adolescent patients with MSI-H or dMMR metastatic CRC is extrapolated from the results in the respective adult population, the FDA said in a statement.

Approval of nivolumab in the adult population was based on an objective response rate of 28% in CHECKMATE 142, an open-label, single-arm study of 53 patients with locally determined dMMR or MSI-H metastatic CRC who had disease progression during, after, or were intolerant to prior treatment with fluoropyrimidine-, oxaliplatin-, and irinotecan-based chemotherapy.

The most common adverse reactions to nivolumab, marketed as Opdivo by Bristol-Myers Squibb, include fatigue, rash, musculoskeletal pain, pruritus, diarrhea, nausea, asthenia, cough, dyspnea, constipation, decreased appetite, back pain, arthralgia, upper respiratory tract infection, and pyrexia, the FDA said.

The recommended nivolumab dose is 240 mg every 2 weeks.

Annular Atrophic Lichen Planus Responds to Hydroxychloroquine and Acitretin

Annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP) is a rare variant of lichen planus that was first described by Friedman and Hashimoto1 in 1991. Clinically, it combines the configuration and morphological features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus. It is a rare entity. We report a case of AALP in a 69-year-old black man. The clinical and histopathological presentation depicted the defining features of this entity with a characteristic loss of elastic fibers corresponding to central atrophy of active lesions.

Case Report

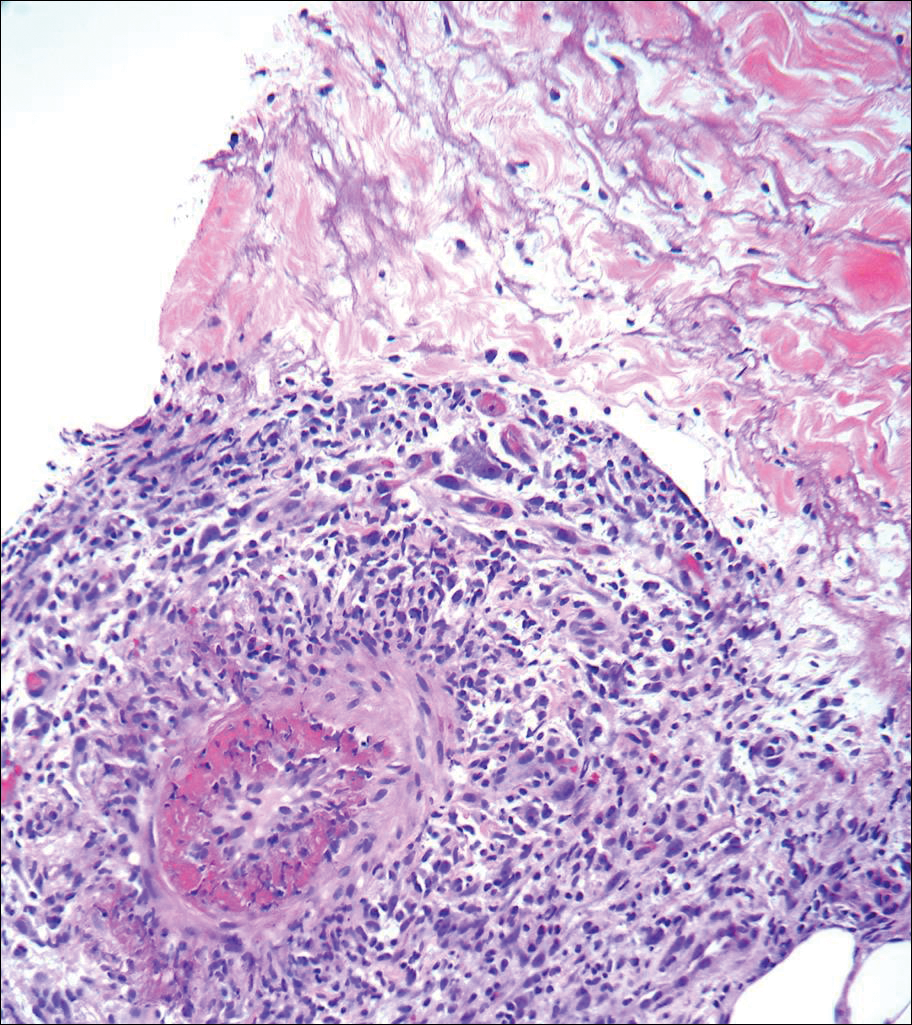

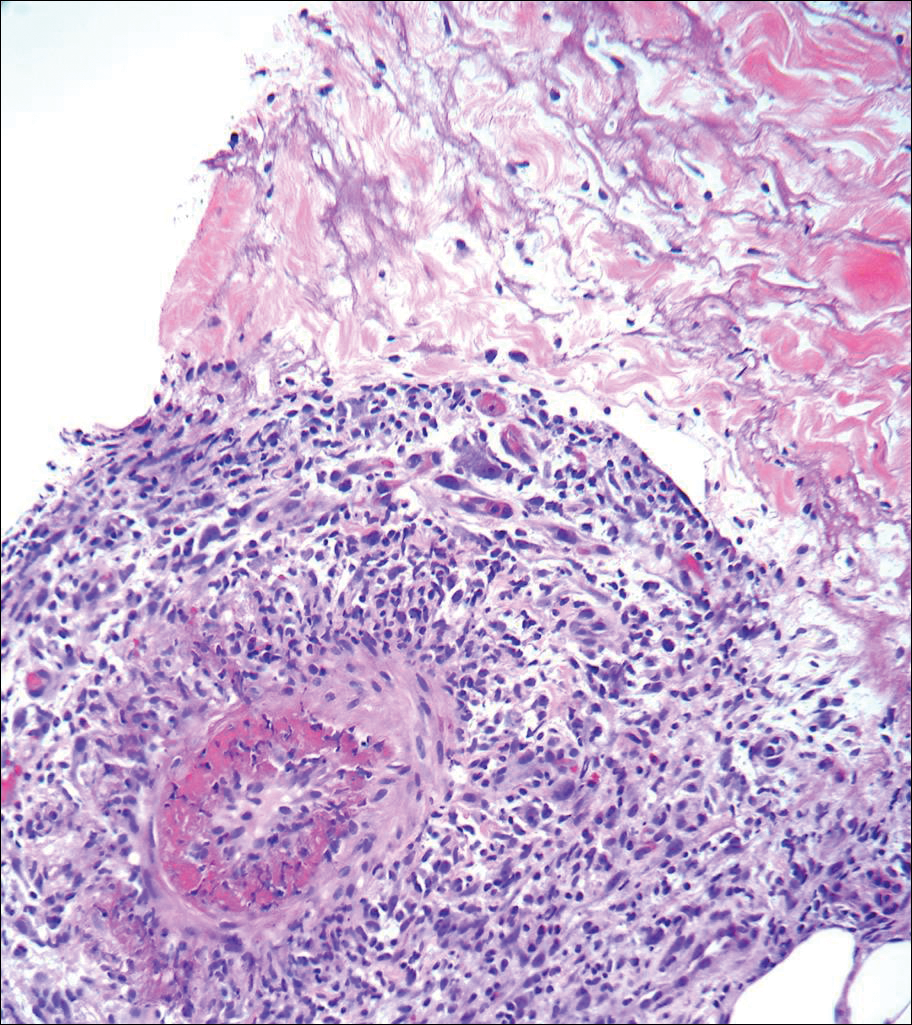

A 69-year-old black man with a history of hepatitis C virus infection and hypothyroidism presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic rash on the trunk, extremities, groin, and scalp of 4 months' duration. He denied any new medications, recent illnesses, or sick contacts. Physical examination demonstrated well-demarcated violaceous papules and plaques on the trunk, extensor aspect of the forearms, and thighs involving 10% of the body surface area (Figure 1A). The lesions were annular with raised borders and central depigmented atrophic scarring (Figure 1B). The examination also revealed several large hypopigmented atrophic patches and plaques in the right inguinal region and on the dorsal aspect of the penile shaft and buttocks as well as a single atrophic plaque on the scalp. No oral lesions were seen. An initial punch biopsy was consistent with a nonspecific lichenoid dermatitis (Figure 2), and the patient was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% for the trunk and extremities and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% for the groin and genital region.

The patient continued to develop new annular atrophic skin lesions over the next several months. Repeat punch biopsies of lesional and uninvolved perilesional skin from the trunk were obtained for histopathologic confirmation and special staining. Lichenoid dermatitis again was noted on the lesional biopsy, and no notable histopathologic changes were observed on the perilesional biopsy. Verhoeff-van Gieson staining for elastic fibers was performed on both biopsies, which revealed destruction of elastic fibers in the central papillary dermis and upper reticular dermis of the lesional biopsy (Figure 3A). The elastic fibers on the perilesional biopsy were preserved (Figure 3B).

The clinical presentation and histopathological findings confirmed a diagnosis of AALP. The patient was prescribed a short taper of oral prednisone, which halted further disease progression. The patient was then started on pentoxifylline and continued on tacrolimus ointment 0.1% with minimal improvement in existing lesions. These medications were discontinued after 3 months. Hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily was administered, which initially resulted in some thinning of the plaques on the trunk; however, further progression of the disease was noted after 3 months. Acitretin 25 mg once daily was added to his treatment regimen. Marked thinning of active lesions, hyperpigmentation, and residual scarring was noted after 2 months of combined therapy with acitretin and hydroxychloroquine (Figure 4), with continued improvement appreciable several months later.

Comment

Lichen planus is a common pruritic inflammatory disease of the skin, mucous membranes, hair follicles, and nails with a highly variable clinical pattern and disease course that typically affects the adult population.2 There are many clinical variants of lichen planus, which all demonstrate lichenoid dermatitis on histology. Annular lichen planus is an uncommon variant most commonly seen in men with asymptomatic lesions involving the axillae and groin.2 Atrophic lichen planus is another variant demonstrating atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.3 Annular atrophic lichen planus is the rarest variant of lichen planus, incorporating features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus.

The first case of AALP involved a 56-year-old black man with a 25-year history of annular atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.1 The second case reported by Requena et al4 in 1994 described a 65-year-old woman with characteristic lesions on the right elbow and left knee. Lipsker et al5 reported a third case in a 41-year-old man with a history of Sneddon syndrome who had lesions typical for AALP for 20 years. In all of these cases, histopathologic examination revealed a lichenoid infiltrate with thinning of the epidermis and loss of elastic fibers in the center of the active lesions.

In more recent cases of AALP, the characteristic findings primarily occurred on the trunk and extremities.6-10 Treatment with topical corticosteroids failed in most cases and some patients noted moderate improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. Sugashima and Yamamoto11 reported a unique case in 2012 of a 32-year-old woman with AALP on the lower lip. She had notable improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% after 6 months.11

All of the known cases of AALP to date have occurred in adults, both male and female, presenting with a limited number of annular plaques with slightly elevated borders and depressed atrophic centers.1,3-11 Disease duration of AALP has ranged from 2 months to 25 years.11 Histopathologic findings characteristically demonstrate a lichenoid dermatitis of the raised lesional border with a flattened epidermis, loss of rete ridges, and fibrosis of dermal papillae in the lesion center.7 The elastic fibers are destroyed in the papillary dermis of the lesion center, presumably due to elastolytic activity of inflammatory cells.1 Macrophages present in the lichenoid infiltrate of acute lesions release elastases contributing to this destruction.7 Furthermore, elastic fibers appear fragmented on electron microscopy.1

The clinical course of AALP has proven to be chronic in most cases and frequently is resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids, retinoids, phototherapy, and immunosuppressive agents.3 Treatment administered early in the disease course may provide a more favorable outcome.11 Lesions characteristically heal with scarring and hyperpigmentation. Our case displayed more extensive involvement than has previously been reported. Our patient showed minimal improvement with topical therapy; however, he demonstrated thinning and regression of active lesions after 2 months of combined treatment with hydroxychloroquine and acitretin. Our use of oral pentoxifylline, hydroxychloroquine, and acitretin has not been previously reported in the other cases of AALP we reviewed. Acitretin is the only systemic agent for lichen planus that has achieved level A evidence, as it previously was shown to be highly effective in a placebo-controlled, double-blind study of 65 patients.12

Conclusion

Annular atrophic lichen planus is a known variant of lichen planus characterized by a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of active lesions. Treatment with topical corticosteroids and phototherapy frequently is ineffective. To our knowledge, there are no studies to date regarding the efficacy of systemic therapy in treatment of AALP. Hydroxychloroquine and acitretin may prove to be beneficial treatment options for resistant AALP. Additional alternative treatments continue to be explored. We encourage reporting additional cases of AALP to further characterize its clinical presentation and response to treatments.

- Friedman DB, Hashimoto K. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:392-394.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Lichen planus and related conditions. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:213-215.

- Kim BS, Seo SH, Jang BS, et al. A case of annular atrophic lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:989-990.

- Requena L, Olivares M, Pique E, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 1994;189:95-98.

- Lipsker D, Piette JC, Laporte JL, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus and Sneddon's syndrome. Dermatology. 1997;105:402-403.

- Mseddi M, Bouassadi S, Marrakchi S, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 2003;207:208-209.

- Morales-Callaghan A Jr, Martinez G, Aragoneses H, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:906-908.

- Ponce-Olivera RM, Tirado-Sánchez A, Montes-de-Oca-Sánchez G, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:490-491.

- Kim JS, Kang MS, Sagong C, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus associated with hypertrophic lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:195-197.

- Li B, Li JH, Xiao T, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:842-843.

- Sugashima Y, Yamamoto T. Annular atrophic lichen planus of the lip. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:14.

- Manousaridis I, Manousaridis K, Peitsch WK, et al. Individualizing treatment and choice of medication in lichen planus: a step by step approach. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:981-991.

Annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP) is a rare variant of lichen planus that was first described by Friedman and Hashimoto1 in 1991. Clinically, it combines the configuration and morphological features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus. It is a rare entity. We report a case of AALP in a 69-year-old black man. The clinical and histopathological presentation depicted the defining features of this entity with a characteristic loss of elastic fibers corresponding to central atrophy of active lesions.

Case Report

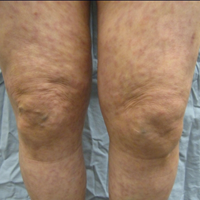

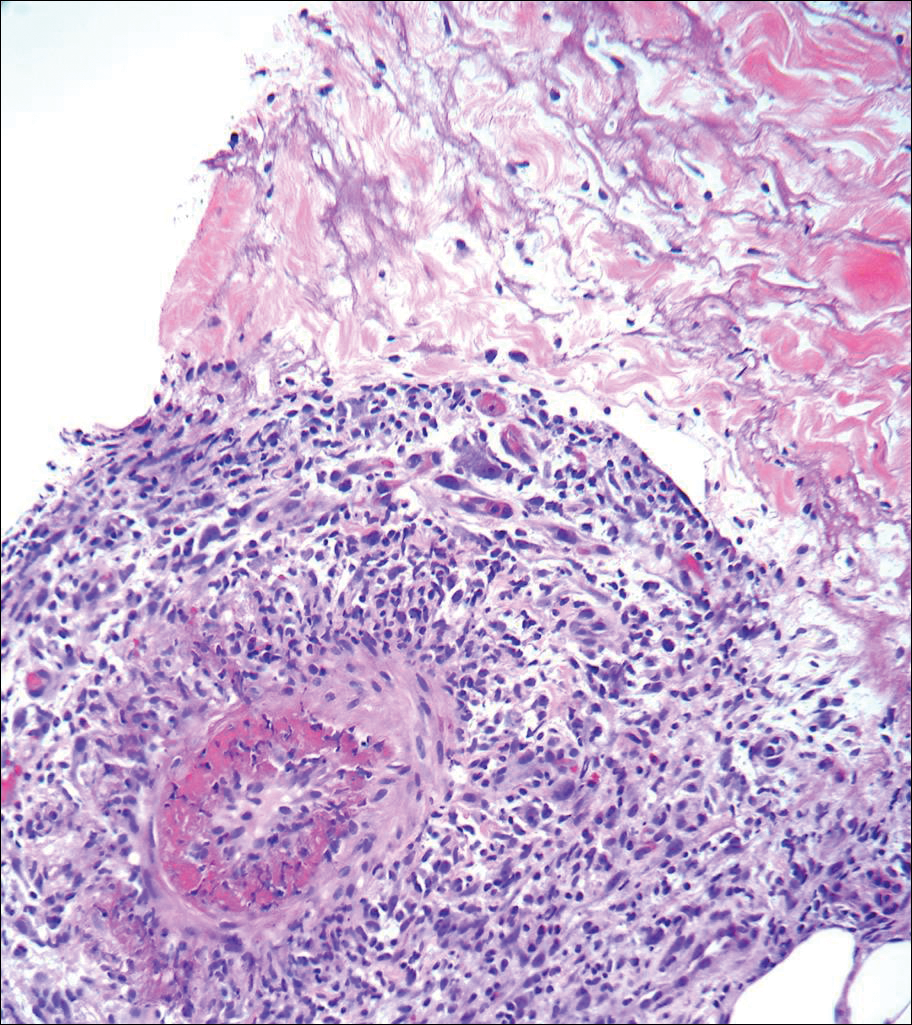

A 69-year-old black man with a history of hepatitis C virus infection and hypothyroidism presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic rash on the trunk, extremities, groin, and scalp of 4 months' duration. He denied any new medications, recent illnesses, or sick contacts. Physical examination demonstrated well-demarcated violaceous papules and plaques on the trunk, extensor aspect of the forearms, and thighs involving 10% of the body surface area (Figure 1A). The lesions were annular with raised borders and central depigmented atrophic scarring (Figure 1B). The examination also revealed several large hypopigmented atrophic patches and plaques in the right inguinal region and on the dorsal aspect of the penile shaft and buttocks as well as a single atrophic plaque on the scalp. No oral lesions were seen. An initial punch biopsy was consistent with a nonspecific lichenoid dermatitis (Figure 2), and the patient was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% for the trunk and extremities and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% for the groin and genital region.

The patient continued to develop new annular atrophic skin lesions over the next several months. Repeat punch biopsies of lesional and uninvolved perilesional skin from the trunk were obtained for histopathologic confirmation and special staining. Lichenoid dermatitis again was noted on the lesional biopsy, and no notable histopathologic changes were observed on the perilesional biopsy. Verhoeff-van Gieson staining for elastic fibers was performed on both biopsies, which revealed destruction of elastic fibers in the central papillary dermis and upper reticular dermis of the lesional biopsy (Figure 3A). The elastic fibers on the perilesional biopsy were preserved (Figure 3B).

The clinical presentation and histopathological findings confirmed a diagnosis of AALP. The patient was prescribed a short taper of oral prednisone, which halted further disease progression. The patient was then started on pentoxifylline and continued on tacrolimus ointment 0.1% with minimal improvement in existing lesions. These medications were discontinued after 3 months. Hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily was administered, which initially resulted in some thinning of the plaques on the trunk; however, further progression of the disease was noted after 3 months. Acitretin 25 mg once daily was added to his treatment regimen. Marked thinning of active lesions, hyperpigmentation, and residual scarring was noted after 2 months of combined therapy with acitretin and hydroxychloroquine (Figure 4), with continued improvement appreciable several months later.

Comment

Lichen planus is a common pruritic inflammatory disease of the skin, mucous membranes, hair follicles, and nails with a highly variable clinical pattern and disease course that typically affects the adult population.2 There are many clinical variants of lichen planus, which all demonstrate lichenoid dermatitis on histology. Annular lichen planus is an uncommon variant most commonly seen in men with asymptomatic lesions involving the axillae and groin.2 Atrophic lichen planus is another variant demonstrating atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.3 Annular atrophic lichen planus is the rarest variant of lichen planus, incorporating features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus.

The first case of AALP involved a 56-year-old black man with a 25-year history of annular atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.1 The second case reported by Requena et al4 in 1994 described a 65-year-old woman with characteristic lesions on the right elbow and left knee. Lipsker et al5 reported a third case in a 41-year-old man with a history of Sneddon syndrome who had lesions typical for AALP for 20 years. In all of these cases, histopathologic examination revealed a lichenoid infiltrate with thinning of the epidermis and loss of elastic fibers in the center of the active lesions.

In more recent cases of AALP, the characteristic findings primarily occurred on the trunk and extremities.6-10 Treatment with topical corticosteroids failed in most cases and some patients noted moderate improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. Sugashima and Yamamoto11 reported a unique case in 2012 of a 32-year-old woman with AALP on the lower lip. She had notable improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% after 6 months.11

All of the known cases of AALP to date have occurred in adults, both male and female, presenting with a limited number of annular plaques with slightly elevated borders and depressed atrophic centers.1,3-11 Disease duration of AALP has ranged from 2 months to 25 years.11 Histopathologic findings characteristically demonstrate a lichenoid dermatitis of the raised lesional border with a flattened epidermis, loss of rete ridges, and fibrosis of dermal papillae in the lesion center.7 The elastic fibers are destroyed in the papillary dermis of the lesion center, presumably due to elastolytic activity of inflammatory cells.1 Macrophages present in the lichenoid infiltrate of acute lesions release elastases contributing to this destruction.7 Furthermore, elastic fibers appear fragmented on electron microscopy.1

The clinical course of AALP has proven to be chronic in most cases and frequently is resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids, retinoids, phototherapy, and immunosuppressive agents.3 Treatment administered early in the disease course may provide a more favorable outcome.11 Lesions characteristically heal with scarring and hyperpigmentation. Our case displayed more extensive involvement than has previously been reported. Our patient showed minimal improvement with topical therapy; however, he demonstrated thinning and regression of active lesions after 2 months of combined treatment with hydroxychloroquine and acitretin. Our use of oral pentoxifylline, hydroxychloroquine, and acitretin has not been previously reported in the other cases of AALP we reviewed. Acitretin is the only systemic agent for lichen planus that has achieved level A evidence, as it previously was shown to be highly effective in a placebo-controlled, double-blind study of 65 patients.12

Conclusion

Annular atrophic lichen planus is a known variant of lichen planus characterized by a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of active lesions. Treatment with topical corticosteroids and phototherapy frequently is ineffective. To our knowledge, there are no studies to date regarding the efficacy of systemic therapy in treatment of AALP. Hydroxychloroquine and acitretin may prove to be beneficial treatment options for resistant AALP. Additional alternative treatments continue to be explored. We encourage reporting additional cases of AALP to further characterize its clinical presentation and response to treatments.

Annular atrophic lichen planus (AALP) is a rare variant of lichen planus that was first described by Friedman and Hashimoto1 in 1991. Clinically, it combines the configuration and morphological features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus. It is a rare entity. We report a case of AALP in a 69-year-old black man. The clinical and histopathological presentation depicted the defining features of this entity with a characteristic loss of elastic fibers corresponding to central atrophy of active lesions.

Case Report

A 69-year-old black man with a history of hepatitis C virus infection and hypothyroidism presented to the dermatology clinic with a pruritic rash on the trunk, extremities, groin, and scalp of 4 months' duration. He denied any new medications, recent illnesses, or sick contacts. Physical examination demonstrated well-demarcated violaceous papules and plaques on the trunk, extensor aspect of the forearms, and thighs involving 10% of the body surface area (Figure 1A). The lesions were annular with raised borders and central depigmented atrophic scarring (Figure 1B). The examination also revealed several large hypopigmented atrophic patches and plaques in the right inguinal region and on the dorsal aspect of the penile shaft and buttocks as well as a single atrophic plaque on the scalp. No oral lesions were seen. An initial punch biopsy was consistent with a nonspecific lichenoid dermatitis (Figure 2), and the patient was prescribed triamcinolone ointment 0.1% for the trunk and extremities and tacrolimus ointment 0.1% for the groin and genital region.

The patient continued to develop new annular atrophic skin lesions over the next several months. Repeat punch biopsies of lesional and uninvolved perilesional skin from the trunk were obtained for histopathologic confirmation and special staining. Lichenoid dermatitis again was noted on the lesional biopsy, and no notable histopathologic changes were observed on the perilesional biopsy. Verhoeff-van Gieson staining for elastic fibers was performed on both biopsies, which revealed destruction of elastic fibers in the central papillary dermis and upper reticular dermis of the lesional biopsy (Figure 3A). The elastic fibers on the perilesional biopsy were preserved (Figure 3B).

The clinical presentation and histopathological findings confirmed a diagnosis of AALP. The patient was prescribed a short taper of oral prednisone, which halted further disease progression. The patient was then started on pentoxifylline and continued on tacrolimus ointment 0.1% with minimal improvement in existing lesions. These medications were discontinued after 3 months. Hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily was administered, which initially resulted in some thinning of the plaques on the trunk; however, further progression of the disease was noted after 3 months. Acitretin 25 mg once daily was added to his treatment regimen. Marked thinning of active lesions, hyperpigmentation, and residual scarring was noted after 2 months of combined therapy with acitretin and hydroxychloroquine (Figure 4), with continued improvement appreciable several months later.

Comment

Lichen planus is a common pruritic inflammatory disease of the skin, mucous membranes, hair follicles, and nails with a highly variable clinical pattern and disease course that typically affects the adult population.2 There are many clinical variants of lichen planus, which all demonstrate lichenoid dermatitis on histology. Annular lichen planus is an uncommon variant most commonly seen in men with asymptomatic lesions involving the axillae and groin.2 Atrophic lichen planus is another variant demonstrating atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.3 Annular atrophic lichen planus is the rarest variant of lichen planus, incorporating features of both annular and atrophic lichen planus.

The first case of AALP involved a 56-year-old black man with a 25-year history of annular atrophic papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities.1 The second case reported by Requena et al4 in 1994 described a 65-year-old woman with characteristic lesions on the right elbow and left knee. Lipsker et al5 reported a third case in a 41-year-old man with a history of Sneddon syndrome who had lesions typical for AALP for 20 years. In all of these cases, histopathologic examination revealed a lichenoid infiltrate with thinning of the epidermis and loss of elastic fibers in the center of the active lesions.

In more recent cases of AALP, the characteristic findings primarily occurred on the trunk and extremities.6-10 Treatment with topical corticosteroids failed in most cases and some patients noted moderate improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1%. Sugashima and Yamamoto11 reported a unique case in 2012 of a 32-year-old woman with AALP on the lower lip. She had notable improvement with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% after 6 months.11

All of the known cases of AALP to date have occurred in adults, both male and female, presenting with a limited number of annular plaques with slightly elevated borders and depressed atrophic centers.1,3-11 Disease duration of AALP has ranged from 2 months to 25 years.11 Histopathologic findings characteristically demonstrate a lichenoid dermatitis of the raised lesional border with a flattened epidermis, loss of rete ridges, and fibrosis of dermal papillae in the lesion center.7 The elastic fibers are destroyed in the papillary dermis of the lesion center, presumably due to elastolytic activity of inflammatory cells.1 Macrophages present in the lichenoid infiltrate of acute lesions release elastases contributing to this destruction.7 Furthermore, elastic fibers appear fragmented on electron microscopy.1

The clinical course of AALP has proven to be chronic in most cases and frequently is resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids, retinoids, phototherapy, and immunosuppressive agents.3 Treatment administered early in the disease course may provide a more favorable outcome.11 Lesions characteristically heal with scarring and hyperpigmentation. Our case displayed more extensive involvement than has previously been reported. Our patient showed minimal improvement with topical therapy; however, he demonstrated thinning and regression of active lesions after 2 months of combined treatment with hydroxychloroquine and acitretin. Our use of oral pentoxifylline, hydroxychloroquine, and acitretin has not been previously reported in the other cases of AALP we reviewed. Acitretin is the only systemic agent for lichen planus that has achieved level A evidence, as it previously was shown to be highly effective in a placebo-controlled, double-blind study of 65 patients.12

Conclusion

Annular atrophic lichen planus is a known variant of lichen planus characterized by a loss of elastic fibers in the papillary dermis in the center of active lesions. Treatment with topical corticosteroids and phototherapy frequently is ineffective. To our knowledge, there are no studies to date regarding the efficacy of systemic therapy in treatment of AALP. Hydroxychloroquine and acitretin may prove to be beneficial treatment options for resistant AALP. Additional alternative treatments continue to be explored. We encourage reporting additional cases of AALP to further characterize its clinical presentation and response to treatments.

- Friedman DB, Hashimoto K. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:392-394.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Lichen planus and related conditions. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:213-215.

- Kim BS, Seo SH, Jang BS, et al. A case of annular atrophic lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:989-990.

- Requena L, Olivares M, Pique E, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 1994;189:95-98.

- Lipsker D, Piette JC, Laporte JL, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus and Sneddon's syndrome. Dermatology. 1997;105:402-403.

- Mseddi M, Bouassadi S, Marrakchi S, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 2003;207:208-209.

- Morales-Callaghan A Jr, Martinez G, Aragoneses H, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:906-908.

- Ponce-Olivera RM, Tirado-Sánchez A, Montes-de-Oca-Sánchez G, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:490-491.

- Kim JS, Kang MS, Sagong C, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus associated with hypertrophic lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:195-197.

- Li B, Li JH, Xiao T, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:842-843.

- Sugashima Y, Yamamoto T. Annular atrophic lichen planus of the lip. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:14.

- Manousaridis I, Manousaridis K, Peitsch WK, et al. Individualizing treatment and choice of medication in lichen planus: a step by step approach. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:981-991.

- Friedman DB, Hashimoto K. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:392-394.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Lichen planus and related conditions. In: James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:213-215.

- Kim BS, Seo SH, Jang BS, et al. A case of annular atrophic lichen planus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:989-990.

- Requena L, Olivares M, Pique E, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 1994;189:95-98.

- Lipsker D, Piette JC, Laporte JL, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus and Sneddon's syndrome. Dermatology. 1997;105:402-403.

- Mseddi M, Bouassadi S, Marrakchi S, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Dermatology. 2003;207:208-209.

- Morales-Callaghan A Jr, Martinez G, Aragoneses H, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:906-908.

- Ponce-Olivera RM, Tirado-Sánchez A, Montes-de-Oca-Sánchez G, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:490-491.

- Kim JS, Kang MS, Sagong C, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus associated with hypertrophic lichen planus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:195-197.

- Li B, Li JH, Xiao T, et al. Annular atrophic lichen planus. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:842-843.

- Sugashima Y, Yamamoto T. Annular atrophic lichen planus of the lip. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:14.

- Manousaridis I, Manousaridis K, Peitsch WK, et al. Individualizing treatment and choice of medication in lichen planus: a step by step approach. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:981-991.

FDA grants priority review of acalabrutinib for second-line treatment of MCL

The Food and Drug Administration has granted a priority review for acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who have received at least one prior therapy.

The new drug application is based on results from the phase 2 ACE-LY-004 trial, which evaluated the safety and efficacy of acalabrutinib in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL who had received at least one prior therapy.

[email protected]

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

The Food and Drug Administration has granted a priority review for acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who have received at least one prior therapy.

The new drug application is based on results from the phase 2 ACE-LY-004 trial, which evaluated the safety and efficacy of acalabrutinib in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL who had received at least one prior therapy.

[email protected]

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

The Food and Drug Administration has granted a priority review for acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) who have received at least one prior therapy.

The new drug application is based on results from the phase 2 ACE-LY-004 trial, which evaluated the safety and efficacy of acalabrutinib in patients with relapsed/refractory MCL who had received at least one prior therapy.

[email protected]

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

Ibrutinib becomes first FDA-approved treatment for chronic GVHD

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) added another notch on its indications belt with its Aug. 2 approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of adult patients with chronic graft versus host disease (cGVHD) after failure of one or more lines of systemic therapy.

The new indication makes ibrutinib the first FDA-approved therapy for the treatment of cGVHD, according to an FDA press release.

Ibrutinib’s other approved indications include chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma with 17p deletion, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, marginal zone lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma, according to a press release from the FDA.

The recommended dose of ibrutinib for cGVHD is 420 mg (three 140 mg capsules once daily). Prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

Imbruvica is manufactured by Pharmacyclics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) added another notch on its indications belt with its Aug. 2 approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of adult patients with chronic graft versus host disease (cGVHD) after failure of one or more lines of systemic therapy.

The new indication makes ibrutinib the first FDA-approved therapy for the treatment of cGVHD, according to an FDA press release.

Ibrutinib’s other approved indications include chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma with 17p deletion, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, marginal zone lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma, according to a press release from the FDA.

The recommended dose of ibrutinib for cGVHD is 420 mg (three 140 mg capsules once daily). Prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

Imbruvica is manufactured by Pharmacyclics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) added another notch on its indications belt with its Aug. 2 approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of adult patients with chronic graft versus host disease (cGVHD) after failure of one or more lines of systemic therapy.

The new indication makes ibrutinib the first FDA-approved therapy for the treatment of cGVHD, according to an FDA press release.

Ibrutinib’s other approved indications include chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma with 17p deletion, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, marginal zone lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma, according to a press release from the FDA.

The recommended dose of ibrutinib for cGVHD is 420 mg (three 140 mg capsules once daily). Prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

Imbruvica is manufactured by Pharmacyclics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryjodales

Care of infants with ichthyosis requires ‘all hands on deck’

CHICAGO – The neonatal period and early infancy are especially critical for patients with ichthyosis, because compromised barrier function increases risk for morbidity and mortality.

“There are minimal data presently to guide management of patients with ichthyosis, making it a time of uncertainty,” Brittany Craiglow, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “You’re going to want to get all hands on deck for the care of these patients. And don’t forget about the family – involve them in the care as much as possible. Reassure them; normalize their feelings, acknowledge them.”

There are six general phenotypes of ichthyosis that differ from the eventual “mature” phenotype and are associated with numerous genes: collodion baby, armor-like scale, exuberant vernix, erythroderma and scale, bullae and erosions, and generalized scale.

The collodion baby phenotype is characterized by a shiny parchment-like membrane that covers the baby’s body, ectropion, and fissures, and is commonly associated with autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis (ARCI). “About 10% of babies with ARCI are self healing, so they’ll go on to have largely normal skin,” Dr. Craiglow said. Guidelines for managing this phenotype can be found in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2012 Dec;67[6]:1362-74).

Armor-like scale is pathognomonic for harlequin ichthyosis. “This condition is associated with the highest mortality in the neonatal period,” she said. “In addition to the potential complications associated with other phenotypes, babies with harlequin ichthyosis can also have issues related to constriction of movement and flexibility and digital ischemia.” Tips for practical management of this phenotype were published online in the journal Pediatrics (2017 Jan;139[1]).

The exuberant vernix/cephalic hyperkeratosis phenotype generally appears in children with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (KID) and ichthyosis prematurity syndrome (IPS). Special considerations in KID include a hearing test and ophthalmology exam, while special considerations in IPS include respiratory compromise and atopic diathesis. Electron microscopy is diagnostic, characterized by curvilinear bodies in the granular layer.

The erythroderma and scale phenotype occurs most commonly in ARCI and Netherton syndrome. “Special considerations in Netherton syndrome include failure to thrive/growth failure,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Hair shaft abnormalities are usually present later, and nutritional support is really important.”

Bullae and erosions are hallmark signs of epidermolytic/superficial ichthyosis. On biopsy, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is diagnostic for this phenotype. At the same time, cases with normal skin or xerosis are suggestive of X-linked ichthyosis, ichthyosis vulgaris, erythrokeratodermas, and Sjögren-Larsson syndrome.

Genetic testing for ichthyosis is generally readily available, Dr. Craiglow said. She advised clinicians to obtain a sample soon after birth to confirm the clinical diagnosis, assist with assessing prognosis, and enable genetic counseling. “It’s important to help identify those at risk for systemic complications,” she said. “Obtaining insurance coverage may be easier when sent during hospital admission.”

Babies with moderate to severe congenital ichthyosis are typically cared for in the neonatal ICU of a tertiary care center by a multidisciplinary team consisting of neonatology, dermatology, nursing, nutrition, and genetics, as well as ophthalmology, otolaryngology, orthopedics, plastic surgery, and spiritual/religious services in many cases. “These babies often have impaired thermoregulation,” Dr. Craiglow said. “They need to be in an isolette, generally with humidity somewhere between 50% and 70% – you don’t want it too high, because they can overheat. It’s also important to get them out of the isolette and into an open crib when they’re ready. That can help with bonding and has been shown to decrease hospital stay.”

Infection is a common culprit for morbidity and mortality. “In general, there are not a lot of data to guide our management; but generally, we don’t recommend prophylactic antibiotics,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Some people do surveillance cultures just to know what microbes are there in case there are signs of infection. Look for level of alertness, because they’re not always going to have a fever. Look for hemodynamic instability, irritability, or poor feeding, and have a low threshold to do your cultures and treat if necessary.”

Pain control is an imperative aspect of pain management.

“Typical newborn pain parameters of facial expression and extremity tone may be hard to interpret,” she said. “Look at heart rate, blood pressure, crying, level of arousal, and have a low threshold to treat for pain, especially prior to changing dressings. Acetaminophen and NSAIDs and even opioids in some cases might be indicated. Families want to know that pain is being adequately controlled.”

Retinoids are generally used in patients with harlequin ichthyosis. “In the United States, we generally use acitretin, but there is no liquid formulation, so you have to enlist help from a compounding pharmacy to mix a formulation of 0.5-0.1 mg/kg per day,” Dr. Craiglow said. “You want to start as soon as you can. Topical retinoids such as tazarotene are also an option.”

Resources that she recommends for parents include the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types, the Ichthyosis Support Group, and the European Network for Ichthyosis.

Dr. Craiglow reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – The neonatal period and early infancy are especially critical for patients with ichthyosis, because compromised barrier function increases risk for morbidity and mortality.

“There are minimal data presently to guide management of patients with ichthyosis, making it a time of uncertainty,” Brittany Craiglow, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “You’re going to want to get all hands on deck for the care of these patients. And don’t forget about the family – involve them in the care as much as possible. Reassure them; normalize their feelings, acknowledge them.”

There are six general phenotypes of ichthyosis that differ from the eventual “mature” phenotype and are associated with numerous genes: collodion baby, armor-like scale, exuberant vernix, erythroderma and scale, bullae and erosions, and generalized scale.

The collodion baby phenotype is characterized by a shiny parchment-like membrane that covers the baby’s body, ectropion, and fissures, and is commonly associated with autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis (ARCI). “About 10% of babies with ARCI are self healing, so they’ll go on to have largely normal skin,” Dr. Craiglow said. Guidelines for managing this phenotype can be found in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2012 Dec;67[6]:1362-74).

Armor-like scale is pathognomonic for harlequin ichthyosis. “This condition is associated with the highest mortality in the neonatal period,” she said. “In addition to the potential complications associated with other phenotypes, babies with harlequin ichthyosis can also have issues related to constriction of movement and flexibility and digital ischemia.” Tips for practical management of this phenotype were published online in the journal Pediatrics (2017 Jan;139[1]).

The exuberant vernix/cephalic hyperkeratosis phenotype generally appears in children with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (KID) and ichthyosis prematurity syndrome (IPS). Special considerations in KID include a hearing test and ophthalmology exam, while special considerations in IPS include respiratory compromise and atopic diathesis. Electron microscopy is diagnostic, characterized by curvilinear bodies in the granular layer.

The erythroderma and scale phenotype occurs most commonly in ARCI and Netherton syndrome. “Special considerations in Netherton syndrome include failure to thrive/growth failure,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Hair shaft abnormalities are usually present later, and nutritional support is really important.”

Bullae and erosions are hallmark signs of epidermolytic/superficial ichthyosis. On biopsy, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is diagnostic for this phenotype. At the same time, cases with normal skin or xerosis are suggestive of X-linked ichthyosis, ichthyosis vulgaris, erythrokeratodermas, and Sjögren-Larsson syndrome.

Genetic testing for ichthyosis is generally readily available, Dr. Craiglow said. She advised clinicians to obtain a sample soon after birth to confirm the clinical diagnosis, assist with assessing prognosis, and enable genetic counseling. “It’s important to help identify those at risk for systemic complications,” she said. “Obtaining insurance coverage may be easier when sent during hospital admission.”

Babies with moderate to severe congenital ichthyosis are typically cared for in the neonatal ICU of a tertiary care center by a multidisciplinary team consisting of neonatology, dermatology, nursing, nutrition, and genetics, as well as ophthalmology, otolaryngology, orthopedics, plastic surgery, and spiritual/religious services in many cases. “These babies often have impaired thermoregulation,” Dr. Craiglow said. “They need to be in an isolette, generally with humidity somewhere between 50% and 70% – you don’t want it too high, because they can overheat. It’s also important to get them out of the isolette and into an open crib when they’re ready. That can help with bonding and has been shown to decrease hospital stay.”

Infection is a common culprit for morbidity and mortality. “In general, there are not a lot of data to guide our management; but generally, we don’t recommend prophylactic antibiotics,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Some people do surveillance cultures just to know what microbes are there in case there are signs of infection. Look for level of alertness, because they’re not always going to have a fever. Look for hemodynamic instability, irritability, or poor feeding, and have a low threshold to do your cultures and treat if necessary.”

Pain control is an imperative aspect of pain management.

“Typical newborn pain parameters of facial expression and extremity tone may be hard to interpret,” she said. “Look at heart rate, blood pressure, crying, level of arousal, and have a low threshold to treat for pain, especially prior to changing dressings. Acetaminophen and NSAIDs and even opioids in some cases might be indicated. Families want to know that pain is being adequately controlled.”

Retinoids are generally used in patients with harlequin ichthyosis. “In the United States, we generally use acitretin, but there is no liquid formulation, so you have to enlist help from a compounding pharmacy to mix a formulation of 0.5-0.1 mg/kg per day,” Dr. Craiglow said. “You want to start as soon as you can. Topical retinoids such as tazarotene are also an option.”

Resources that she recommends for parents include the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types, the Ichthyosis Support Group, and the European Network for Ichthyosis.

Dr. Craiglow reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – The neonatal period and early infancy are especially critical for patients with ichthyosis, because compromised barrier function increases risk for morbidity and mortality.

“There are minimal data presently to guide management of patients with ichthyosis, making it a time of uncertainty,” Brittany Craiglow, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “You’re going to want to get all hands on deck for the care of these patients. And don’t forget about the family – involve them in the care as much as possible. Reassure them; normalize their feelings, acknowledge them.”

There are six general phenotypes of ichthyosis that differ from the eventual “mature” phenotype and are associated with numerous genes: collodion baby, armor-like scale, exuberant vernix, erythroderma and scale, bullae and erosions, and generalized scale.

The collodion baby phenotype is characterized by a shiny parchment-like membrane that covers the baby’s body, ectropion, and fissures, and is commonly associated with autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis (ARCI). “About 10% of babies with ARCI are self healing, so they’ll go on to have largely normal skin,” Dr. Craiglow said. Guidelines for managing this phenotype can be found in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2012 Dec;67[6]:1362-74).

Armor-like scale is pathognomonic for harlequin ichthyosis. “This condition is associated with the highest mortality in the neonatal period,” she said. “In addition to the potential complications associated with other phenotypes, babies with harlequin ichthyosis can also have issues related to constriction of movement and flexibility and digital ischemia.” Tips for practical management of this phenotype were published online in the journal Pediatrics (2017 Jan;139[1]).

The exuberant vernix/cephalic hyperkeratosis phenotype generally appears in children with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome (KID) and ichthyosis prematurity syndrome (IPS). Special considerations in KID include a hearing test and ophthalmology exam, while special considerations in IPS include respiratory compromise and atopic diathesis. Electron microscopy is diagnostic, characterized by curvilinear bodies in the granular layer.

The erythroderma and scale phenotype occurs most commonly in ARCI and Netherton syndrome. “Special considerations in Netherton syndrome include failure to thrive/growth failure,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Hair shaft abnormalities are usually present later, and nutritional support is really important.”

Bullae and erosions are hallmark signs of epidermolytic/superficial ichthyosis. On biopsy, epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is diagnostic for this phenotype. At the same time, cases with normal skin or xerosis are suggestive of X-linked ichthyosis, ichthyosis vulgaris, erythrokeratodermas, and Sjögren-Larsson syndrome.

Genetic testing for ichthyosis is generally readily available, Dr. Craiglow said. She advised clinicians to obtain a sample soon after birth to confirm the clinical diagnosis, assist with assessing prognosis, and enable genetic counseling. “It’s important to help identify those at risk for systemic complications,” she said. “Obtaining insurance coverage may be easier when sent during hospital admission.”

Babies with moderate to severe congenital ichthyosis are typically cared for in the neonatal ICU of a tertiary care center by a multidisciplinary team consisting of neonatology, dermatology, nursing, nutrition, and genetics, as well as ophthalmology, otolaryngology, orthopedics, plastic surgery, and spiritual/religious services in many cases. “These babies often have impaired thermoregulation,” Dr. Craiglow said. “They need to be in an isolette, generally with humidity somewhere between 50% and 70% – you don’t want it too high, because they can overheat. It’s also important to get them out of the isolette and into an open crib when they’re ready. That can help with bonding and has been shown to decrease hospital stay.”

Infection is a common culprit for morbidity and mortality. “In general, there are not a lot of data to guide our management; but generally, we don’t recommend prophylactic antibiotics,” Dr. Craiglow said. “Some people do surveillance cultures just to know what microbes are there in case there are signs of infection. Look for level of alertness, because they’re not always going to have a fever. Look for hemodynamic instability, irritability, or poor feeding, and have a low threshold to do your cultures and treat if necessary.”

Pain control is an imperative aspect of pain management.

“Typical newborn pain parameters of facial expression and extremity tone may be hard to interpret,” she said. “Look at heart rate, blood pressure, crying, level of arousal, and have a low threshold to treat for pain, especially prior to changing dressings. Acetaminophen and NSAIDs and even opioids in some cases might be indicated. Families want to know that pain is being adequately controlled.”

Retinoids are generally used in patients with harlequin ichthyosis. “In the United States, we generally use acitretin, but there is no liquid formulation, so you have to enlist help from a compounding pharmacy to mix a formulation of 0.5-0.1 mg/kg per day,” Dr. Craiglow said. “You want to start as soon as you can. Topical retinoids such as tazarotene are also an option.”

Resources that she recommends for parents include the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types, the Ichthyosis Support Group, and the European Network for Ichthyosis.

Dr. Craiglow reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT WCPD 2017

Manage headache separately from idiopathic intracranial hypertension

Headache in idiopathic intracranial hypertension appears to be clinically independent of raised intracranial pressure and may require a different treatment approach than simply lowering intracranial pressure, say the authors of a study published online July 28 in Headache.

The researchers looked at data from 165 patients with untreated idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) and mild vision loss, who were randomized to weight loss plus acetazolamide or placebo as part of the Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial.

In the 139 patients who had headaches at baseline, the researchers saw no significant correlation between lumbar puncture opening pressure – which was measured at baseline and 6 months – and Headache Impact Test-6 scores, or with the presence or absence of headache (Headache. 2017 Jul 28. doi: 10.1111/head.13153).

The study also failed to show any significant difference in headache outcomes between the acetazolamide and placebo groups at 6 months, although headaches in both groups improved overall during the course of the study.

“A substantial proportion of participants had severe headaches at 6 months, stressing the importance of incorporating other headache treatments,” the authors wrote. “These data support the view that additional treatments beyond those used to lower intracranial pressure are needed to treat the headaches associated with IIH.”

At baseline, participants with headache reported taking a range of symptomatic headache treatments including acetaminophen, ibuprofen, naproxen, and combination medications. Some also reported taking hydrocodone, tramadol, or combination formulations containing codeine.

More than one-third (37%) of the participants were assessed as overusing symptomatic pain medications, and 15 of these met the criteria for overuse of opioids or combination medications. Researchers noted that the mean Headache Impact Test-6 scores were significantly higher in those who were overusing medications, compared with those who weren’t.

The most common headache phenotype was migraine (52%), followed by tension-type headache (22%), probable migraine (16%), and probable tension-type headache (4%), with 7% unclassified.

Patients with headache also experienced associated symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, vomiting, visual loss or obscurations, diplopia, and dizziness.

The study was funded by the National Eye Institute. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Headache in idiopathic intracranial hypertension appears to be clinically independent of raised intracranial pressure and may require a different treatment approach than simply lowering intracranial pressure, say the authors of a study published online July 28 in Headache.

The researchers looked at data from 165 patients with untreated idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) and mild vision loss, who were randomized to weight loss plus acetazolamide or placebo as part of the Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial.

In the 139 patients who had headaches at baseline, the researchers saw no significant correlation between lumbar puncture opening pressure – which was measured at baseline and 6 months – and Headache Impact Test-6 scores, or with the presence or absence of headache (Headache. 2017 Jul 28. doi: 10.1111/head.13153).

The study also failed to show any significant difference in headache outcomes between the acetazolamide and placebo groups at 6 months, although headaches in both groups improved overall during the course of the study.

“A substantial proportion of participants had severe headaches at 6 months, stressing the importance of incorporating other headache treatments,” the authors wrote. “These data support the view that additional treatments beyond those used to lower intracranial pressure are needed to treat the headaches associated with IIH.”

At baseline, participants with headache reported taking a range of symptomatic headache treatments including acetaminophen, ibuprofen, naproxen, and combination medications. Some also reported taking hydrocodone, tramadol, or combination formulations containing codeine.

More than one-third (37%) of the participants were assessed as overusing symptomatic pain medications, and 15 of these met the criteria for overuse of opioids or combination medications. Researchers noted that the mean Headache Impact Test-6 scores were significantly higher in those who were overusing medications, compared with those who weren’t.

The most common headache phenotype was migraine (52%), followed by tension-type headache (22%), probable migraine (16%), and probable tension-type headache (4%), with 7% unclassified.

Patients with headache also experienced associated symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, vomiting, visual loss or obscurations, diplopia, and dizziness.

The study was funded by the National Eye Institute. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Headache in idiopathic intracranial hypertension appears to be clinically independent of raised intracranial pressure and may require a different treatment approach than simply lowering intracranial pressure, say the authors of a study published online July 28 in Headache.

The researchers looked at data from 165 patients with untreated idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) and mild vision loss, who were randomized to weight loss plus acetazolamide or placebo as part of the Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial.

In the 139 patients who had headaches at baseline, the researchers saw no significant correlation between lumbar puncture opening pressure – which was measured at baseline and 6 months – and Headache Impact Test-6 scores, or with the presence or absence of headache (Headache. 2017 Jul 28. doi: 10.1111/head.13153).

The study also failed to show any significant difference in headache outcomes between the acetazolamide and placebo groups at 6 months, although headaches in both groups improved overall during the course of the study.

“A substantial proportion of participants had severe headaches at 6 months, stressing the importance of incorporating other headache treatments,” the authors wrote. “These data support the view that additional treatments beyond those used to lower intracranial pressure are needed to treat the headaches associated with IIH.”

At baseline, participants with headache reported taking a range of symptomatic headache treatments including acetaminophen, ibuprofen, naproxen, and combination medications. Some also reported taking hydrocodone, tramadol, or combination formulations containing codeine.

More than one-third (37%) of the participants were assessed as overusing symptomatic pain medications, and 15 of these met the criteria for overuse of opioids or combination medications. Researchers noted that the mean Headache Impact Test-6 scores were significantly higher in those who were overusing medications, compared with those who weren’t.

The most common headache phenotype was migraine (52%), followed by tension-type headache (22%), probable migraine (16%), and probable tension-type headache (4%), with 7% unclassified.

Patients with headache also experienced associated symptoms such as photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, vomiting, visual loss or obscurations, diplopia, and dizziness.

The study was funded by the National Eye Institute. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM HEADACHE

Key clinical point: and may require a different treatment approach.

Major finding: There were no significant differences in lumbar puncture opening pressure between patients with and without headache.

Data source: A subanalysis of 139 patients with headaches at baseline in addition to idiopathic intracranial hypertension and mild vision loss in the Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Eye Institute. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Precise cause of pityriasis rosea remains elusive

CHICAGO – Pityriasis rosea was recognized as early as 1798, yet its precise cause remains elusive.

“We still don’t have a lot of information on it, because it’s self limited and it resolves,” John C. Browning, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “There hasn’t been quite as much of a burning push for research into pityriasis rosea as there has been for pityriasis rubra pilaris, for instance.”

Classic pityriasis rosea (PR) is characterized by oval scaly, erythematous lesions on the trunk and extremities, sparing the face, scalp, palms, and soles, said Dr. Browning, a pediatric dermatologist who is chief of dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio, Texas. The hallmark sign is a so-called herald patch, an oval, slightly scaly patch with a pale center, which usually appears on the trunk and remains isolated for about 2 weeks before the generalized papulosquamous eruption begins. This typically lasts for about 45 days but can range from 2 weeks to 5 months.

Symptoms of PR may include malaise, nausea, loss of appetite, headache, difficulty concentrating, irritability, gastrointestinal upset, upper respiratory symptoms, joint pain, lymph node swelling, sore throat, and low-grade fever. Pruritus is variable, both in frequency and in intensity, and can be exacerbated by topical medications. Some studies have found a higher female-to-male ratio, while other studies have shown no such association.

“Only 6% of PR cases have been reported in children under 10 years of age,” Dr. Browning said. “PR in dark-skinned children tends to have more facial involvement and a scaly appearance, compared with lighter-skinned children.”

Human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and HHV 7, members of the Roseolovirus genus of HHVs, have been implicated in triggering PR. These viruses cause a primary infection and can establish latent infection with reactivation if altered immunity develops.

“That’s probably why we don’t see PR in younger children, because that’s when the primary infection is happening,” Dr. Browning said. “These viruses are commonly acquired during childhood, with adult seroprevalence in the range of 80%-90%. Latency occurs in monocytes, bone marrow progenitor cells, in salivary glands, the brain, and in the kidneys, so it’s pretty widespread.”

He added that controversy exists as to whether HHV 6 and 7 cause PR, because older diagnostic methods only detected the presence of HHV DNA, rather than viral load. “HHV reactivation, rather than primary infection, is more likely the cause of PR as supported by sporadic occurrence of PR, reduced contagiousness, age of PR onset, possible relapse during a limited span of time, and frequent occurrence after stress or immunosuppressive states such as pregnancy,” Dr. Browning said.

Classical presentations of PR are not clinically worrisome, but atypical cases could indicate other triggers, such as drug-induced PR. “This is typically more itchy, can have mucous membrane involvement, and you’re not going to see the herald patch,” he said. “It’s more likely to be confluent with no prodromal symptoms.” Agents that have been implicated in drug-induced PR include isotretinoin, terbinafine, and adalimumab.

Other conditions that can trigger PR include secondary syphilis (characterized by involvement of the palms and soles, lymphadenopathy, and greater lesional infiltration); seborrheic dermatitis (characterized by greater involvement of the scalp and other hairy parts of the body); nummular eczema (more pruritic); and pityriasis lichenoides chronica, which involves more chronic and relapsing lesions. Histology of PR reveals focal parakeratosis in the epidermis in mounds with exocytosis of lymphocytes, variable spongiosis, mild acanthosis, and a thinned granular layer.

Dr. Browning noted that PR is more common in pregnancy. One study of 38 pregnant women with PR found that 13% miscarried before 16 weeks, compared with a normal miscarriage rate of 10% (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 May; 58[5 Suppl 1]:S78-83). “Neonatal hypotonia, weal motility, and hyporeactivity have been reported,” he said. “And with immunocompromised patients, you might see a longer, protracted course of PR.”

Although no treatment is recommended for classical cases of PR, Dr. Browning said that topical steroids “are widely employed because we all want to do something, especially if there’s some pruritus.” According to a position statement on the management of patients with PR, erythromycin has been reported to shorten the duration of rash and pruritus, but it can cause gastrointestinal disturbance (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016 Oct;30[10]:1670-81). Acyclovir has been reported to hasten clearance of PR in one placebo-controlled study, but PR has also been reported in another patient taking low doses of acyclovir. Phototherapy has also been found to be beneficial.

Dr. Browning reported having no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Pityriasis rosea was recognized as early as 1798, yet its precise cause remains elusive.

“We still don’t have a lot of information on it, because it’s self limited and it resolves,” John C. Browning, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “There hasn’t been quite as much of a burning push for research into pityriasis rosea as there has been for pityriasis rubra pilaris, for instance.”

Classic pityriasis rosea (PR) is characterized by oval scaly, erythematous lesions on the trunk and extremities, sparing the face, scalp, palms, and soles, said Dr. Browning, a pediatric dermatologist who is chief of dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio, Texas. The hallmark sign is a so-called herald patch, an oval, slightly scaly patch with a pale center, which usually appears on the trunk and remains isolated for about 2 weeks before the generalized papulosquamous eruption begins. This typically lasts for about 45 days but can range from 2 weeks to 5 months.

Symptoms of PR may include malaise, nausea, loss of appetite, headache, difficulty concentrating, irritability, gastrointestinal upset, upper respiratory symptoms, joint pain, lymph node swelling, sore throat, and low-grade fever. Pruritus is variable, both in frequency and in intensity, and can be exacerbated by topical medications. Some studies have found a higher female-to-male ratio, while other studies have shown no such association.

“Only 6% of PR cases have been reported in children under 10 years of age,” Dr. Browning said. “PR in dark-skinned children tends to have more facial involvement and a scaly appearance, compared with lighter-skinned children.”

Human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and HHV 7, members of the Roseolovirus genus of HHVs, have been implicated in triggering PR. These viruses cause a primary infection and can establish latent infection with reactivation if altered immunity develops.

“That’s probably why we don’t see PR in younger children, because that’s when the primary infection is happening,” Dr. Browning said. “These viruses are commonly acquired during childhood, with adult seroprevalence in the range of 80%-90%. Latency occurs in monocytes, bone marrow progenitor cells, in salivary glands, the brain, and in the kidneys, so it’s pretty widespread.”

He added that controversy exists as to whether HHV 6 and 7 cause PR, because older diagnostic methods only detected the presence of HHV DNA, rather than viral load. “HHV reactivation, rather than primary infection, is more likely the cause of PR as supported by sporadic occurrence of PR, reduced contagiousness, age of PR onset, possible relapse during a limited span of time, and frequent occurrence after stress or immunosuppressive states such as pregnancy,” Dr. Browning said.

Classical presentations of PR are not clinically worrisome, but atypical cases could indicate other triggers, such as drug-induced PR. “This is typically more itchy, can have mucous membrane involvement, and you’re not going to see the herald patch,” he said. “It’s more likely to be confluent with no prodromal symptoms.” Agents that have been implicated in drug-induced PR include isotretinoin, terbinafine, and adalimumab.

Other conditions that can trigger PR include secondary syphilis (characterized by involvement of the palms and soles, lymphadenopathy, and greater lesional infiltration); seborrheic dermatitis (characterized by greater involvement of the scalp and other hairy parts of the body); nummular eczema (more pruritic); and pityriasis lichenoides chronica, which involves more chronic and relapsing lesions. Histology of PR reveals focal parakeratosis in the epidermis in mounds with exocytosis of lymphocytes, variable spongiosis, mild acanthosis, and a thinned granular layer.

Dr. Browning noted that PR is more common in pregnancy. One study of 38 pregnant women with PR found that 13% miscarried before 16 weeks, compared with a normal miscarriage rate of 10% (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 May; 58[5 Suppl 1]:S78-83). “Neonatal hypotonia, weal motility, and hyporeactivity have been reported,” he said. “And with immunocompromised patients, you might see a longer, protracted course of PR.”

Although no treatment is recommended for classical cases of PR, Dr. Browning said that topical steroids “are widely employed because we all want to do something, especially if there’s some pruritus.” According to a position statement on the management of patients with PR, erythromycin has been reported to shorten the duration of rash and pruritus, but it can cause gastrointestinal disturbance (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016 Oct;30[10]:1670-81). Acyclovir has been reported to hasten clearance of PR in one placebo-controlled study, but PR has also been reported in another patient taking low doses of acyclovir. Phototherapy has also been found to be beneficial.

Dr. Browning reported having no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Pityriasis rosea was recognized as early as 1798, yet its precise cause remains elusive.

“We still don’t have a lot of information on it, because it’s self limited and it resolves,” John C. Browning, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Dermatology. “There hasn’t been quite as much of a burning push for research into pityriasis rosea as there has been for pityriasis rubra pilaris, for instance.”

Classic pityriasis rosea (PR) is characterized by oval scaly, erythematous lesions on the trunk and extremities, sparing the face, scalp, palms, and soles, said Dr. Browning, a pediatric dermatologist who is chief of dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio, Texas. The hallmark sign is a so-called herald patch, an oval, slightly scaly patch with a pale center, which usually appears on the trunk and remains isolated for about 2 weeks before the generalized papulosquamous eruption begins. This typically lasts for about 45 days but can range from 2 weeks to 5 months.

Symptoms of PR may include malaise, nausea, loss of appetite, headache, difficulty concentrating, irritability, gastrointestinal upset, upper respiratory symptoms, joint pain, lymph node swelling, sore throat, and low-grade fever. Pruritus is variable, both in frequency and in intensity, and can be exacerbated by topical medications. Some studies have found a higher female-to-male ratio, while other studies have shown no such association.

“Only 6% of PR cases have been reported in children under 10 years of age,” Dr. Browning said. “PR in dark-skinned children tends to have more facial involvement and a scaly appearance, compared with lighter-skinned children.”

Human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and HHV 7, members of the Roseolovirus genus of HHVs, have been implicated in triggering PR. These viruses cause a primary infection and can establish latent infection with reactivation if altered immunity develops.

“That’s probably why we don’t see PR in younger children, because that’s when the primary infection is happening,” Dr. Browning said. “These viruses are commonly acquired during childhood, with adult seroprevalence in the range of 80%-90%. Latency occurs in monocytes, bone marrow progenitor cells, in salivary glands, the brain, and in the kidneys, so it’s pretty widespread.”

He added that controversy exists as to whether HHV 6 and 7 cause PR, because older diagnostic methods only detected the presence of HHV DNA, rather than viral load. “HHV reactivation, rather than primary infection, is more likely the cause of PR as supported by sporadic occurrence of PR, reduced contagiousness, age of PR onset, possible relapse during a limited span of time, and frequent occurrence after stress or immunosuppressive states such as pregnancy,” Dr. Browning said.

Classical presentations of PR are not clinically worrisome, but atypical cases could indicate other triggers, such as drug-induced PR. “This is typically more itchy, can have mucous membrane involvement, and you’re not going to see the herald patch,” he said. “It’s more likely to be confluent with no prodromal symptoms.” Agents that have been implicated in drug-induced PR include isotretinoin, terbinafine, and adalimumab.

Other conditions that can trigger PR include secondary syphilis (characterized by involvement of the palms and soles, lymphadenopathy, and greater lesional infiltration); seborrheic dermatitis (characterized by greater involvement of the scalp and other hairy parts of the body); nummular eczema (more pruritic); and pityriasis lichenoides chronica, which involves more chronic and relapsing lesions. Histology of PR reveals focal parakeratosis in the epidermis in mounds with exocytosis of lymphocytes, variable spongiosis, mild acanthosis, and a thinned granular layer.

Dr. Browning noted that PR is more common in pregnancy. One study of 38 pregnant women with PR found that 13% miscarried before 16 weeks, compared with a normal miscarriage rate of 10% (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 May; 58[5 Suppl 1]:S78-83). “Neonatal hypotonia, weal motility, and hyporeactivity have been reported,” he said. “And with immunocompromised patients, you might see a longer, protracted course of PR.”

Although no treatment is recommended for classical cases of PR, Dr. Browning said that topical steroids “are widely employed because we all want to do something, especially if there’s some pruritus.” According to a position statement on the management of patients with PR, erythromycin has been reported to shorten the duration of rash and pruritus, but it can cause gastrointestinal disturbance (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016 Oct;30[10]:1670-81). Acyclovir has been reported to hasten clearance of PR in one placebo-controlled study, but PR has also been reported in another patient taking low doses of acyclovir. Phototherapy has also been found to be beneficial.

Dr. Browning reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCPD 2017

How Can Neurologists Help Manage Symptoms in Patients With ALS?

Prognosis and Multidisciplinary Care

ALS is a rare degenerative disorder of motor neurons of the cerebral cortex, brainstem, and spinal cord that results in progressive wasting and paralysis of voluntary muscles. The median age of onset is 55, and the disease has a slight male predominance. Fifty percent of patients with ALS die within three years of symptoms onset; 90% of patients die within five years. Patients with bulbar-onset ALS are more likely to die sooner. Riluzole is the only FDA-approved disease-modifying therapy for patients with ALS. Studies have indicated that this drug extends median survival by two to three months.

In addition, data suggest that multidisciplinary care improves quality of life and survival in patients with ALS. Traynor et al found that survival increased by 7.5 months among all patients in multidisciplinary clinics; patients with bulbar onset lived 9.5 months longer.

Managing Muscle Cramps

Recent studies suggest that muscle cramps occur in 85% of patients with ALS. Cramps can vary in severity and can be debilitating, said Dr. Weiss. Some patients can have as many as 50 cramps per day. Few efficacious treatments for managing this symptom of ALS are available. A recent trial showed that patients who received either 300 mg or 900 mg of mexiletine experienced significant declines in cramping.

Spasticity

It is common for patients with ALS to develop spasticity. Several therapies that may reduce spasticity include baclofen, tizanidine, diazepam, and botulinum toxin injections. The baclofen pump might be more helpful than these therapies for patients who have upper motor neuron dominance.

Sialorrhea

Sialorrhea occurs when patients are unable to clear extra saliva due to weakness in the oropharyngeal muscles. Doses of 600 mg to 1,200 mg of guaifenesin twice per day may be beneficial in managing sialorrhea. Other drying agents such as atropine drops and glycopyrrolate may also be efficacious. These drying agents may cause urinary retention in older patients, Dr. Weiss cautioned.

Amitriptyline can also help manage sialorrhea. It also improves sleep and reduces depression. Hyoscyamine, the transdermal scopolamine patch, and botulinum toxin injections into the submandibular glands may also be beneficial for patients. A suction machine or a mechanical in-exsufflator can also help manage this symptom of ALS.

Emotional Incontinence and Depression

Pseudobulbar affect, also known as emotional incontinence, affects as much as 50% of patients with ALS and is more common in bulbar ALS. This condition causes patients to have uncontrollable episodes of laughing and crying that are inconsistent with the patients’ mood. A randomized controlled trial found that dextromethorphan–quinidine was beneficial in managing these emotional symptoms. Other treatments include tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Reactive clinical depression occurs in 9% to 11% of patients with ALS. Once the ALS diagnosis is confirmed, patients should be counseled about their prognosis; their spouses and family members should also be offered counseling. Antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors should be offered to all patients. These drugs may help to elevate mood, stimulate appetite, and improve sleep.

Respiratory Insufficiency and Falls