User login

Platelet-rich plasma treatment for hair loss continues to be refined

SAN DIEGO – There is currently no standard protocol for injecting autologous platelet-rich plasma to stimulate hair growth, but the technique appears to be about 50% effective, according to Marc R. Avram, MD.

“I tell patients that this is not FDA [Food and Drug Administration] approved, but we think it to be safe,” said Dr. Avram, clinical professor of dermatology at the Cornell University, New York, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “We don’t know how well it’s going to work. There are a lot of published data on it, but none of [them are] randomized or controlled long-term.”

In Dr. Avram’s experience, he has found that PRP is a good option for patients with difficult hair loss, such as those who had extensive hair loss after chemotherapy but the hair never grew back in the same fashion, or patients who have failed treatment with finasteride and minoxidil.

Currently, there is no standard protocol for using PRP to stimulate hair growth, but the approach Dr. Avram follows is modeled on his experience of injecting thousands of patients with triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) for hair loss every 4-6 weeks. After drawing 20 ccs-30 ccs of blood from the patient, the vial is placed in a centrifuge for 10 minutes, a process that separates PRP from red blood cells. Next, the clinician injects PRP into the deep dermis/superficial subcutaneous tissue of the desired treatment area. An average of 4 ccs-8 ccs is injected during each session.

After three monthly treatments, patients follow up at 3 and 6 months after the last treatment to evaluate efficacy. “All patients are told if there is regrowth or thickening of terminal hair, maintenance treatments will be needed every 6-9 months,” he said.

Published clinical trials of PRP include a follow-up period of 3-12 months and most demonstrate an efficacy in the range of 50%-70%. “It seems to be more effective for earlier stages of hair loss, and there are no known side effects to date,” said Dr. Avram, who has authored five textbooks on hair and cosmetic dermatology. “I had one patient call up to say he thought he had an increase in hair loss 2-3 weeks after treatment, but that’s one patient in a couple hundred. This may be similar to the effect minoxidil has on some patients. I’ve had no other issues with side effects.”

In his opinion, future challenges in the use of PRP for restoring hair loss include better defining optimal candidates for the procedure and establishing a better treatment protocol. “How often should maintenance be done?” he asked. “Is this going to be helpful for alopecia areata and scarring alopecia? Also, we need to determine if finasteride, minoxidil, low-level light laser therapy, or any other medications can enhance PRP efficacy in combination. What’s the optimal combination for patients? We don’t know yet. But I think in the future we will.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he is a consultant for Restoration Robotics.

SAN DIEGO – There is currently no standard protocol for injecting autologous platelet-rich plasma to stimulate hair growth, but the technique appears to be about 50% effective, according to Marc R. Avram, MD.

“I tell patients that this is not FDA [Food and Drug Administration] approved, but we think it to be safe,” said Dr. Avram, clinical professor of dermatology at the Cornell University, New York, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “We don’t know how well it’s going to work. There are a lot of published data on it, but none of [them are] randomized or controlled long-term.”

In Dr. Avram’s experience, he has found that PRP is a good option for patients with difficult hair loss, such as those who had extensive hair loss after chemotherapy but the hair never grew back in the same fashion, or patients who have failed treatment with finasteride and minoxidil.

Currently, there is no standard protocol for using PRP to stimulate hair growth, but the approach Dr. Avram follows is modeled on his experience of injecting thousands of patients with triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) for hair loss every 4-6 weeks. After drawing 20 ccs-30 ccs of blood from the patient, the vial is placed in a centrifuge for 10 minutes, a process that separates PRP from red blood cells. Next, the clinician injects PRP into the deep dermis/superficial subcutaneous tissue of the desired treatment area. An average of 4 ccs-8 ccs is injected during each session.

After three monthly treatments, patients follow up at 3 and 6 months after the last treatment to evaluate efficacy. “All patients are told if there is regrowth or thickening of terminal hair, maintenance treatments will be needed every 6-9 months,” he said.

Published clinical trials of PRP include a follow-up period of 3-12 months and most demonstrate an efficacy in the range of 50%-70%. “It seems to be more effective for earlier stages of hair loss, and there are no known side effects to date,” said Dr. Avram, who has authored five textbooks on hair and cosmetic dermatology. “I had one patient call up to say he thought he had an increase in hair loss 2-3 weeks after treatment, but that’s one patient in a couple hundred. This may be similar to the effect minoxidil has on some patients. I’ve had no other issues with side effects.”

In his opinion, future challenges in the use of PRP for restoring hair loss include better defining optimal candidates for the procedure and establishing a better treatment protocol. “How often should maintenance be done?” he asked. “Is this going to be helpful for alopecia areata and scarring alopecia? Also, we need to determine if finasteride, minoxidil, low-level light laser therapy, or any other medications can enhance PRP efficacy in combination. What’s the optimal combination for patients? We don’t know yet. But I think in the future we will.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he is a consultant for Restoration Robotics.

SAN DIEGO – There is currently no standard protocol for injecting autologous platelet-rich plasma to stimulate hair growth, but the technique appears to be about 50% effective, according to Marc R. Avram, MD.

“I tell patients that this is not FDA [Food and Drug Administration] approved, but we think it to be safe,” said Dr. Avram, clinical professor of dermatology at the Cornell University, New York, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “We don’t know how well it’s going to work. There are a lot of published data on it, but none of [them are] randomized or controlled long-term.”

In Dr. Avram’s experience, he has found that PRP is a good option for patients with difficult hair loss, such as those who had extensive hair loss after chemotherapy but the hair never grew back in the same fashion, or patients who have failed treatment with finasteride and minoxidil.

Currently, there is no standard protocol for using PRP to stimulate hair growth, but the approach Dr. Avram follows is modeled on his experience of injecting thousands of patients with triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) for hair loss every 4-6 weeks. After drawing 20 ccs-30 ccs of blood from the patient, the vial is placed in a centrifuge for 10 minutes, a process that separates PRP from red blood cells. Next, the clinician injects PRP into the deep dermis/superficial subcutaneous tissue of the desired treatment area. An average of 4 ccs-8 ccs is injected during each session.

After three monthly treatments, patients follow up at 3 and 6 months after the last treatment to evaluate efficacy. “All patients are told if there is regrowth or thickening of terminal hair, maintenance treatments will be needed every 6-9 months,” he said.

Published clinical trials of PRP include a follow-up period of 3-12 months and most demonstrate an efficacy in the range of 50%-70%. “It seems to be more effective for earlier stages of hair loss, and there are no known side effects to date,” said Dr. Avram, who has authored five textbooks on hair and cosmetic dermatology. “I had one patient call up to say he thought he had an increase in hair loss 2-3 weeks after treatment, but that’s one patient in a couple hundred. This may be similar to the effect minoxidil has on some patients. I’ve had no other issues with side effects.”

In his opinion, future challenges in the use of PRP for restoring hair loss include better defining optimal candidates for the procedure and establishing a better treatment protocol. “How often should maintenance be done?” he asked. “Is this going to be helpful for alopecia areata and scarring alopecia? Also, we need to determine if finasteride, minoxidil, low-level light laser therapy, or any other medications can enhance PRP efficacy in combination. What’s the optimal combination for patients? We don’t know yet. But I think in the future we will.”

Dr. Avram disclosed that he is a consultant for Restoration Robotics.

AT MOAS 2017

Sharing drug paraphernalia alone didn’t transmit HCV

nevertheless, according to researchers at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

That makes sharing paraphernalia a “surrogate” for HCV transmission “resulting from sharing drugs,” the investigators said, but it should not be a primary focus of harm-reduction and education programs.

“Water was introduced into the barrel of a contaminated ‘input’ syringe and expelled into a ‘cooker,’ and the water was drawn up into a ‘receptive’ syringe through a cotton filter,” the study authors explained. “The ‘input’ syringe, ‘cooker,’ and filter were rinsed with tissue culture medium and introduced into the microculture assay. The water drawn into the second syringe was combined with an equal volume of double-strength medium and introduced into the microculture assay” (J Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix427).

The researchers tested syringes (with fixed or detachable needles), cookers, and filters (single or pooled). They were significantly more likely to recover HCV from detachable-needle syringes than from fixed-needle syringes. In the input syringes, they recovered no HCV from 70 fixed-needle syringes while they did recover HCV from 96 of 130 (73.8%) detachable-needle syringes. HCV passed to both types of syringes in the experiment’s receptive syringes but at a much higher rate for those with detachable needles than for those with fixed needles (93.8% vs. 45.7%, respectively).

No HCV was recovered from any of the cookers, regardless of syringe type. Some was recovered from filters, at higher rates with detachable needles than with fixed (27.1% vs. 1.4%).

“Money spent on ‘cookers’ and filters would be better spent on giving away more syringes,” Dr. Heimer and his coauthors concluded. “Because HCV and HIV transmission are more likely if the syringe has a detachable rather than a fixed needle, efforts should focus on providing more syringes with fixed needles.”

nevertheless, according to researchers at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

That makes sharing paraphernalia a “surrogate” for HCV transmission “resulting from sharing drugs,” the investigators said, but it should not be a primary focus of harm-reduction and education programs.

“Water was introduced into the barrel of a contaminated ‘input’ syringe and expelled into a ‘cooker,’ and the water was drawn up into a ‘receptive’ syringe through a cotton filter,” the study authors explained. “The ‘input’ syringe, ‘cooker,’ and filter were rinsed with tissue culture medium and introduced into the microculture assay. The water drawn into the second syringe was combined with an equal volume of double-strength medium and introduced into the microculture assay” (J Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix427).

The researchers tested syringes (with fixed or detachable needles), cookers, and filters (single or pooled). They were significantly more likely to recover HCV from detachable-needle syringes than from fixed-needle syringes. In the input syringes, they recovered no HCV from 70 fixed-needle syringes while they did recover HCV from 96 of 130 (73.8%) detachable-needle syringes. HCV passed to both types of syringes in the experiment’s receptive syringes but at a much higher rate for those with detachable needles than for those with fixed needles (93.8% vs. 45.7%, respectively).

No HCV was recovered from any of the cookers, regardless of syringe type. Some was recovered from filters, at higher rates with detachable needles than with fixed (27.1% vs. 1.4%).

“Money spent on ‘cookers’ and filters would be better spent on giving away more syringes,” Dr. Heimer and his coauthors concluded. “Because HCV and HIV transmission are more likely if the syringe has a detachable rather than a fixed needle, efforts should focus on providing more syringes with fixed needles.”

nevertheless, according to researchers at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

That makes sharing paraphernalia a “surrogate” for HCV transmission “resulting from sharing drugs,” the investigators said, but it should not be a primary focus of harm-reduction and education programs.

“Water was introduced into the barrel of a contaminated ‘input’ syringe and expelled into a ‘cooker,’ and the water was drawn up into a ‘receptive’ syringe through a cotton filter,” the study authors explained. “The ‘input’ syringe, ‘cooker,’ and filter were rinsed with tissue culture medium and introduced into the microculture assay. The water drawn into the second syringe was combined with an equal volume of double-strength medium and introduced into the microculture assay” (J Infect Dis. 2017. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix427).

The researchers tested syringes (with fixed or detachable needles), cookers, and filters (single or pooled). They were significantly more likely to recover HCV from detachable-needle syringes than from fixed-needle syringes. In the input syringes, they recovered no HCV from 70 fixed-needle syringes while they did recover HCV from 96 of 130 (73.8%) detachable-needle syringes. HCV passed to both types of syringes in the experiment’s receptive syringes but at a much higher rate for those with detachable needles than for those with fixed needles (93.8% vs. 45.7%, respectively).

No HCV was recovered from any of the cookers, regardless of syringe type. Some was recovered from filters, at higher rates with detachable needles than with fixed (27.1% vs. 1.4%).

“Money spent on ‘cookers’ and filters would be better spent on giving away more syringes,” Dr. Heimer and his coauthors concluded. “Because HCV and HIV transmission are more likely if the syringe has a detachable rather than a fixed needle, efforts should focus on providing more syringes with fixed needles.”

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES

With inpatient flu shots, providers’ attitude problem may outweigh parents’

reported Suchitra Rao, MD, of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and her colleagues.

Surveys assessing attitudes toward inpatient influenza vaccination were given to parents/caregivers of general pediatric inpatients and to inpatient physicians, residents, nurses, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora between October 2014 and March 2015. Response rates were 95% of the 1,053 parents/caregivers and 58% of the 339 providers.

The parents agreed that the flu is a serious disease (92%), that flu vaccines work (58%), that flu vaccines are safe (76%), and that the vaccines are needed annually (76%), the Dr. Rao and her colleagues found.

The providers thought the most common barriers to vaccination were parental refusal because of child illness (80%) and family misconceptions about the vaccine (74%). Also, 54% of providers forgot to ask about flu vaccination status and 46% forgot to order flu vaccines.

When asked what interventions might increase flu vaccination rates in the inpatient setting, 73% of providers agreed that personal reminders might help increase vaccination rates, but only 48% thought that provider education might help do so.

Read more in the journal Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses (2017 Sep 5. doi: 10.1111/irv.12482.)

reported Suchitra Rao, MD, of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and her colleagues.

Surveys assessing attitudes toward inpatient influenza vaccination were given to parents/caregivers of general pediatric inpatients and to inpatient physicians, residents, nurses, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora between October 2014 and March 2015. Response rates were 95% of the 1,053 parents/caregivers and 58% of the 339 providers.

The parents agreed that the flu is a serious disease (92%), that flu vaccines work (58%), that flu vaccines are safe (76%), and that the vaccines are needed annually (76%), the Dr. Rao and her colleagues found.

The providers thought the most common barriers to vaccination were parental refusal because of child illness (80%) and family misconceptions about the vaccine (74%). Also, 54% of providers forgot to ask about flu vaccination status and 46% forgot to order flu vaccines.

When asked what interventions might increase flu vaccination rates in the inpatient setting, 73% of providers agreed that personal reminders might help increase vaccination rates, but only 48% thought that provider education might help do so.

Read more in the journal Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses (2017 Sep 5. doi: 10.1111/irv.12482.)

reported Suchitra Rao, MD, of the University of Colorado, Aurora, and her colleagues.

Surveys assessing attitudes toward inpatient influenza vaccination were given to parents/caregivers of general pediatric inpatients and to inpatient physicians, residents, nurses, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora between October 2014 and March 2015. Response rates were 95% of the 1,053 parents/caregivers and 58% of the 339 providers.

The parents agreed that the flu is a serious disease (92%), that flu vaccines work (58%), that flu vaccines are safe (76%), and that the vaccines are needed annually (76%), the Dr. Rao and her colleagues found.

The providers thought the most common barriers to vaccination were parental refusal because of child illness (80%) and family misconceptions about the vaccine (74%). Also, 54% of providers forgot to ask about flu vaccination status and 46% forgot to order flu vaccines.

When asked what interventions might increase flu vaccination rates in the inpatient setting, 73% of providers agreed that personal reminders might help increase vaccination rates, but only 48% thought that provider education might help do so.

Read more in the journal Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses (2017 Sep 5. doi: 10.1111/irv.12482.)

Can arterial switch operation impact cognitive deficits?

With dramatic advances of neonatal repair of complex cardiac disease, the population of adults with congenital heart disease (CHD) has increased dramatically, and while studies have shown an increased risk of neurodevelopmental and psychological disorders in these patients, few studies have evaluated their cognitive and psychosocial outcomes. Now, a review of young adults who had an arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries in France has found that they have almost twice the rate of cognitive difficulties and more than triple the rate of cognitive impairment as healthy peers.

“Despite satisfactory outcomes in most adults with transposition of the great arteries (TGA), a substantial proportion has cognitive or psychologic difficulties that may reduce their academic success and quality of life,” said lead author David Kalfa, MD, PhD, of Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of New York-Presbyterian, Columbia University Medical Center and coauthors in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;154:1028-35).

The study involved a review of 67 adults aged 18 and older born with TGA between 1984 and 1985 who had an arterial switch operation (ASO) at two hospitals in France: Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris and Marie Lannelongue Hospital in Le Plessis-Robinson. The researchers performed a matched analysis with 43 healthy subjects for age, gender, and education level.

The researchers found that 69% of the TGA patients had an intelligence quotient in the normal range of 85-115. The TGA patients had lower quotients for mean full-scale (94.9 plus or minus 15.3 vs. 103.4 plus or minus 12.3 in healthy subjects; P = 0.003), verbal (96.8 plus or minus 16.2 vs. 102.5 plus or minus 11.5; P =.033) and performance intelligence (93.7 plus or minus 14.6 vs. 103.8 plus or minus 14.3; P less than .001).

The TGA patients also had higher rates of cognitive difficulties, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –1 standard deviation, and cognitive impairment, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –2 standard deviation; 31% vs. 16% (P = .001) for the former and 6% vs. 2% (P = .030) for the latter.

TGA patients with cognitive difficulties had lower educational levels and were also more likely to repeat grades in school, Dr. Kalfa and coauthors noted. “Patients reported an overall satisfactory health-related quality of life,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said of the TGA group; “however, those with cognitive or psychologic difficulties reported poorer quality of life.” The researchers identified three predictors of worse outcomes: lower parental socioeconomic and educational status; older age at surgery; and longer hospital stays.

“Our findings suggest that the cognitive morbidities commonly reported in children and adolescents with complex CHD persist into adulthood in individuals with TGA after the ASO,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said. Future research should evaluate specific cognitive domains such as attention, memory, and executive functions. “This consideration is important for evaluation of the whole [adult] CHD population because specific cognitive impairments are increasingly documented into adolescence but remain rarely investigated in adulthood,” the researchers said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

The findings by Dr. Kalfa and coauthors may point the way to improve cognitive outcomes in children who have the arterial switch operation, said Ryan R. Davies, MD, of A.I duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1036-7.) “Modifiable factors may exist both during the perioperative stage (perfusion strategies, intensive care management) and over the longer term (early neurocognitive assessments and interventions,” Dr. Davies said.

That parental socioeconomic status is associated with cognitive performance suggests early intervention and education “may pay long-term dividends,” Dr. Davies said. Future studies should focus on the impact of specific interventions and identify modifiable developmental factors, he said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors have provided an “important start” in that direction, Dr. Davies said. “They have shown that the neurodevelopmental deficits seen early in children with CHD persist into adulthood,” he said. “There are also hints here as to where interventions may be effective in ameliorating those deficits.”

Dr. Davies reported having no financial disclosures.

The findings by Dr. Kalfa and coauthors may point the way to improve cognitive outcomes in children who have the arterial switch operation, said Ryan R. Davies, MD, of A.I duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1036-7.) “Modifiable factors may exist both during the perioperative stage (perfusion strategies, intensive care management) and over the longer term (early neurocognitive assessments and interventions,” Dr. Davies said.

That parental socioeconomic status is associated with cognitive performance suggests early intervention and education “may pay long-term dividends,” Dr. Davies said. Future studies should focus on the impact of specific interventions and identify modifiable developmental factors, he said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors have provided an “important start” in that direction, Dr. Davies said. “They have shown that the neurodevelopmental deficits seen early in children with CHD persist into adulthood,” he said. “There are also hints here as to where interventions may be effective in ameliorating those deficits.”

Dr. Davies reported having no financial disclosures.

The findings by Dr. Kalfa and coauthors may point the way to improve cognitive outcomes in children who have the arterial switch operation, said Ryan R. Davies, MD, of A.I duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1036-7.) “Modifiable factors may exist both during the perioperative stage (perfusion strategies, intensive care management) and over the longer term (early neurocognitive assessments and interventions,” Dr. Davies said.

That parental socioeconomic status is associated with cognitive performance suggests early intervention and education “may pay long-term dividends,” Dr. Davies said. Future studies should focus on the impact of specific interventions and identify modifiable developmental factors, he said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors have provided an “important start” in that direction, Dr. Davies said. “They have shown that the neurodevelopmental deficits seen early in children with CHD persist into adulthood,” he said. “There are also hints here as to where interventions may be effective in ameliorating those deficits.”

Dr. Davies reported having no financial disclosures.

With dramatic advances of neonatal repair of complex cardiac disease, the population of adults with congenital heart disease (CHD) has increased dramatically, and while studies have shown an increased risk of neurodevelopmental and psychological disorders in these patients, few studies have evaluated their cognitive and psychosocial outcomes. Now, a review of young adults who had an arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries in France has found that they have almost twice the rate of cognitive difficulties and more than triple the rate of cognitive impairment as healthy peers.

“Despite satisfactory outcomes in most adults with transposition of the great arteries (TGA), a substantial proportion has cognitive or psychologic difficulties that may reduce their academic success and quality of life,” said lead author David Kalfa, MD, PhD, of Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of New York-Presbyterian, Columbia University Medical Center and coauthors in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;154:1028-35).

The study involved a review of 67 adults aged 18 and older born with TGA between 1984 and 1985 who had an arterial switch operation (ASO) at two hospitals in France: Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris and Marie Lannelongue Hospital in Le Plessis-Robinson. The researchers performed a matched analysis with 43 healthy subjects for age, gender, and education level.

The researchers found that 69% of the TGA patients had an intelligence quotient in the normal range of 85-115. The TGA patients had lower quotients for mean full-scale (94.9 plus or minus 15.3 vs. 103.4 plus or minus 12.3 in healthy subjects; P = 0.003), verbal (96.8 plus or minus 16.2 vs. 102.5 plus or minus 11.5; P =.033) and performance intelligence (93.7 plus or minus 14.6 vs. 103.8 plus or minus 14.3; P less than .001).

The TGA patients also had higher rates of cognitive difficulties, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –1 standard deviation, and cognitive impairment, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –2 standard deviation; 31% vs. 16% (P = .001) for the former and 6% vs. 2% (P = .030) for the latter.

TGA patients with cognitive difficulties had lower educational levels and were also more likely to repeat grades in school, Dr. Kalfa and coauthors noted. “Patients reported an overall satisfactory health-related quality of life,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said of the TGA group; “however, those with cognitive or psychologic difficulties reported poorer quality of life.” The researchers identified three predictors of worse outcomes: lower parental socioeconomic and educational status; older age at surgery; and longer hospital stays.

“Our findings suggest that the cognitive morbidities commonly reported in children and adolescents with complex CHD persist into adulthood in individuals with TGA after the ASO,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said. Future research should evaluate specific cognitive domains such as attention, memory, and executive functions. “This consideration is important for evaluation of the whole [adult] CHD population because specific cognitive impairments are increasingly documented into adolescence but remain rarely investigated in adulthood,” the researchers said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

With dramatic advances of neonatal repair of complex cardiac disease, the population of adults with congenital heart disease (CHD) has increased dramatically, and while studies have shown an increased risk of neurodevelopmental and psychological disorders in these patients, few studies have evaluated their cognitive and psychosocial outcomes. Now, a review of young adults who had an arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries in France has found that they have almost twice the rate of cognitive difficulties and more than triple the rate of cognitive impairment as healthy peers.

“Despite satisfactory outcomes in most adults with transposition of the great arteries (TGA), a substantial proportion has cognitive or psychologic difficulties that may reduce their academic success and quality of life,” said lead author David Kalfa, MD, PhD, of Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of New York-Presbyterian, Columbia University Medical Center and coauthors in the September issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;154:1028-35).

The study involved a review of 67 adults aged 18 and older born with TGA between 1984 and 1985 who had an arterial switch operation (ASO) at two hospitals in France: Necker Children’s Hospital in Paris and Marie Lannelongue Hospital in Le Plessis-Robinson. The researchers performed a matched analysis with 43 healthy subjects for age, gender, and education level.

The researchers found that 69% of the TGA patients had an intelligence quotient in the normal range of 85-115. The TGA patients had lower quotients for mean full-scale (94.9 plus or minus 15.3 vs. 103.4 plus or minus 12.3 in healthy subjects; P = 0.003), verbal (96.8 plus or minus 16.2 vs. 102.5 plus or minus 11.5; P =.033) and performance intelligence (93.7 plus or minus 14.6 vs. 103.8 plus or minus 14.3; P less than .001).

The TGA patients also had higher rates of cognitive difficulties, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –1 standard deviation, and cognitive impairment, measured as intelligence quotient less than or equal to –2 standard deviation; 31% vs. 16% (P = .001) for the former and 6% vs. 2% (P = .030) for the latter.

TGA patients with cognitive difficulties had lower educational levels and were also more likely to repeat grades in school, Dr. Kalfa and coauthors noted. “Patients reported an overall satisfactory health-related quality of life,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said of the TGA group; “however, those with cognitive or psychologic difficulties reported poorer quality of life.” The researchers identified three predictors of worse outcomes: lower parental socioeconomic and educational status; older age at surgery; and longer hospital stays.

“Our findings suggest that the cognitive morbidities commonly reported in children and adolescents with complex CHD persist into adulthood in individuals with TGA after the ASO,” Dr. Kalfa and coauthors said. Future research should evaluate specific cognitive domains such as attention, memory, and executive functions. “This consideration is important for evaluation of the whole [adult] CHD population because specific cognitive impairments are increasingly documented into adolescence but remain rarely investigated in adulthood,” the researchers said.

Dr. Kalfa and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: A substantial proportion of young adults who had transposition of the great arteries have cognitive or psychological difficulties.

Major finding: Cognitive difficulties were significantly more frequent in the study population than the general population, 31% vs. 16%.

Data source: Age-, gender-, and education level–matched population of 67 young adults with transposition of the great arteries and 43 healthy subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Kalfa and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

Diagnostic laparoscopy pinpoints postop abdominal pain in bariatric patients

The etiology of chronic pain after bariatric surgery can be difficult to pinpoint, but diagnostic laparoscopy can detect causes in about half of patients, findings from a small study have shown.

In an investigation conducted by Mohammed Alsulaimy, MD, a surgeon at the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic, and his colleagues, 35 patients underwent diagnostic laparoscopy (DL) to identify the causes of their chronic abdominal pain after bariatric surgery. Patients included in the study had a history of abdominal pain lasting longer than 30 days after their bariatric procedure, a negative CT scan of their abdomen and pelvis, a gallstone-negative abdominal ultrasound, and an upper GI endoscopy with no abnormalities. Researchers collected patient data including age, gender, body, weight, and body mass index, type of previous bariatric procedure, and time between surgery and onset of pain.

The results of DL were either positive (presence detected of pathology or injury) or negative (no disease or injury detected).

Twenty patients (57%) had positive findings on DL including the presence of adhesions, chronic cholecystitis, mesenteric defect, internal hernia, and necrotic omentum, and of this group, 43% had treatment that led to improvement of pain symptoms. Only 1 of the 15 patients with negative DL findings had eventual improvement of their pain symptoms. Most patients with negative DL findings had persistent abdominal pain, possibly because of nonorganic causes and were referred to the chronic pain management service, the investigators wrote.

“About 40% of patients who undergo DL and 70% of patients with positive findings on DL experience significant symptom improvement,” the investigators said. “This study highlights the importance of offering DL as both a diagnostic and therapeutic tool in post–bariatric surgery patients with chronic abdominal of unknown etiology.”

The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

The etiology of chronic pain after bariatric surgery can be difficult to pinpoint, but diagnostic laparoscopy can detect causes in about half of patients, findings from a small study have shown.

In an investigation conducted by Mohammed Alsulaimy, MD, a surgeon at the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic, and his colleagues, 35 patients underwent diagnostic laparoscopy (DL) to identify the causes of their chronic abdominal pain after bariatric surgery. Patients included in the study had a history of abdominal pain lasting longer than 30 days after their bariatric procedure, a negative CT scan of their abdomen and pelvis, a gallstone-negative abdominal ultrasound, and an upper GI endoscopy with no abnormalities. Researchers collected patient data including age, gender, body, weight, and body mass index, type of previous bariatric procedure, and time between surgery and onset of pain.

The results of DL were either positive (presence detected of pathology or injury) or negative (no disease or injury detected).

Twenty patients (57%) had positive findings on DL including the presence of adhesions, chronic cholecystitis, mesenteric defect, internal hernia, and necrotic omentum, and of this group, 43% had treatment that led to improvement of pain symptoms. Only 1 of the 15 patients with negative DL findings had eventual improvement of their pain symptoms. Most patients with negative DL findings had persistent abdominal pain, possibly because of nonorganic causes and were referred to the chronic pain management service, the investigators wrote.

“About 40% of patients who undergo DL and 70% of patients with positive findings on DL experience significant symptom improvement,” the investigators said. “This study highlights the importance of offering DL as both a diagnostic and therapeutic tool in post–bariatric surgery patients with chronic abdominal of unknown etiology.”

The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

The etiology of chronic pain after bariatric surgery can be difficult to pinpoint, but diagnostic laparoscopy can detect causes in about half of patients, findings from a small study have shown.

In an investigation conducted by Mohammed Alsulaimy, MD, a surgeon at the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at the Cleveland Clinic, and his colleagues, 35 patients underwent diagnostic laparoscopy (DL) to identify the causes of their chronic abdominal pain after bariatric surgery. Patients included in the study had a history of abdominal pain lasting longer than 30 days after their bariatric procedure, a negative CT scan of their abdomen and pelvis, a gallstone-negative abdominal ultrasound, and an upper GI endoscopy with no abnormalities. Researchers collected patient data including age, gender, body, weight, and body mass index, type of previous bariatric procedure, and time between surgery and onset of pain.

The results of DL were either positive (presence detected of pathology or injury) or negative (no disease or injury detected).

Twenty patients (57%) had positive findings on DL including the presence of adhesions, chronic cholecystitis, mesenteric defect, internal hernia, and necrotic omentum, and of this group, 43% had treatment that led to improvement of pain symptoms. Only 1 of the 15 patients with negative DL findings had eventual improvement of their pain symptoms. Most patients with negative DL findings had persistent abdominal pain, possibly because of nonorganic causes and were referred to the chronic pain management service, the investigators wrote.

“About 40% of patients who undergo DL and 70% of patients with positive findings on DL experience significant symptom improvement,” the investigators said. “This study highlights the importance of offering DL as both a diagnostic and therapeutic tool in post–bariatric surgery patients with chronic abdominal of unknown etiology.”

The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

FROM OBESITY SURGERY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In the study group, 57% of patients had a positive diagnostic laparoscopy results identifying the source of their chronic abdominal pain.

Data source: Retrospective review of post–bariatric surgery patients who underwent diagnostic laparoscopy (DL) during 2003-2015.

Disclosures: The investigators had no relevant financial disclosures to report.

Nature versus nurture: 50 years of a popular debate

This basic question has been debated at settings ranging from scientific conferences to dinner tables for many decades. The media also has covered it in forms ranging from documentaries to the popular comedy movie “Trading Places” (1983). Yet, despite so much attention and so much research devoted to resolving this timeless debate, the arguments continue to this day.

A lack of a clear answer, however, by no means implies that we have not made major advances in our understanding. This short review takes a look at the progression of this seemingly eternal question by categorizing the development of the nature versus nurture question into three main stages. While such a partitioning is somewhat oversimplified with regard to what the various positions on this issue have been at different times, it does illustrate the way that the debate has gradually evolved.

Part 1: Nature versus nurture

The origins of the nature versus nurture debate date back far beyond the past 50 years. The ancient Greek philosopher Galen postulated that personality traits were driven by the relative concentrations of four bodily fluids or “humours.” In 1874, Sir Francis Galton published “English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture,” in which he advanced his ideas about the dominance of hereditary factors in intelligence and character at the beginning of the eugenics movement.1 These ideas were in stark opposition to the perspective of earlier scholars, such as the philosopher John Locke, who popularized the theory that children are born a “blank slate” and from there develop their traits and intellectual abilities through their environment and experiences.

The other primary school of thought in the mid-1960s was psychoanalysis, which was based on the ideas of Sigmund Freud, MD. Psychoanalysis maintains that the way that unconscious sexual and aggressive drives were channeled through various defense mechanisms was of primary importance to the understanding of both psychopathology and typical human behavior.

While these two perspectives were often very much in opposition to each other, they shared in common the view that the environment and a person’s individual experiences, i.e. nurture, were the prevailing forces in development. In the background, more biologically oriented research and clinical work was slowly beginning to work its way into the field, especially at certain institutions, such as Washington University in St. Louis. Several medications of various types were then available, including chlorpromazine, imipramine, and diazepam.

Overall, however, it is probably fair to say that, 50 years ago, it was the nurture perspective that held the most sway since psychodynamic treatment and behaviorist research dominated, while the emerging fields of genetics and neuroscience were only beginning to take hold.

Part 2: Nature and nurture

From the 1970s to the end of the 20th century, a noticeable shift occurred as knowledge of the brain and genetics – supported by remarkable advances in research techniques – began to swing the pendulum back toward an increased appreciation of nature as a critical influence on a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior.

Researchers Stella Chess, MD, and Alexander Thomas, MD, for example, conducted the New York Longitudinal Study, in which they closely observed a group of young children over many years. Their studies compelled them to argue for the significance of more innate temperament traits as critical aspects of a youth’s overall adjustment.2 The Human Genome Project was launched in 1990, and the entire decade was designated as the “Decade of the Brain.” During this time, neuroscience research exploded as techniques, such as MRI and PET, allowed scientists to view the living brain like never before.

The type of research investigation that perhaps was most directly relevant to the nature-nurture debate and that became quite popular during this time was the twin study. By comparing the relative similarities among monozygotic and dizygotic twins raised in the same household, it became possible to calculate directly the degree to which a variable of interest (intelligence, height, aggressive behavior) could be attributed to genetic versus environmental factors. When it came to behavioral variables, a repeated finding that emerged was that both genetic and environmental influences are important, often at close to a 50/50 split in terms of magnitude.3,4 These studies were complemented by molecular genetic studies, which were beginning to be able to identify specific genes that conveyed usually small amounts of risk for a wide range of psychiatric disorders.

Yet, while twin studies and many other lines of research made it increasingly difficult to argue for the overwhelming supremacy of either nature or nurture, the two domains generally were treated as being independent of each other. Specific traits or symptoms in an individual often were thought of as being the result of either psychological (nurture) or biological (nature) causes. Terms such as “endogenous depression,” for example, were used to distinguish those who had symptoms that were thought generally to be out of reach for “psychological” treatments, such as psychotherapy. Looking back, it might be fair to say that one of the principle flaws in this perspective was the commonly held belief that, if something was brain based or biological, then it therefore implied a kind of automatic “wiring” of the brain that was generally driven by genes and beyond the influence of environmental factors.

Part 3: Nature is nurture (and vice versa)

As the science progressed, it became increasingly clear that the nature and nurture domains were hopelessly intertwined with one another. From early PET-scan studies showing that both medications and psychotherapy not only changed the brain but also did so in ways similar to behavioral-genetic studies showing how genetically influenced behaviors actually cause certain environmental events to be more likely to occur, research continued to demonstrate the bidirectional influences of genetic and environmental factors on development.5,6 This appreciation rose to even greater heights with advances in the field of epigenetics, which was able to document some of the specific mechanisms through which environmental factors cause genes involved in regulating the plasticity of the brain to turn on and off.7

In thinking through some of this complexity, however, it is important to remember the hopeful message that is contained in this rich understanding. All of these complicated, interacting genetic and environmental factors give us many avenues for positive intervention. Now we understand that not only might a medication help strengthen some of the brain connections needed to reduce and cope with that child’s anxiety, but so could mindfulness, exercise, and addressing his parents’ symptoms. When the families ask me whether their child’s struggles are behavioral or psychological, the answer I tend to give them is “yes.”

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

Email him at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @pedipsych.

References

1. “English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture” (London: MacMillan & Co., 1874)

2. “Temperament: Theory and Practice” (New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1996)

3. “Nature and Nurture during Infancy and Early Childhood” (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988)

4. Nat Genet. 2015;47(7):702-9.

5. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(9):681-9.

6. Dev Psychopathol. 1997 Spring;9(2):335-64.

7. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):551-2.

This basic question has been debated at settings ranging from scientific conferences to dinner tables for many decades. The media also has covered it in forms ranging from documentaries to the popular comedy movie “Trading Places” (1983). Yet, despite so much attention and so much research devoted to resolving this timeless debate, the arguments continue to this day.

A lack of a clear answer, however, by no means implies that we have not made major advances in our understanding. This short review takes a look at the progression of this seemingly eternal question by categorizing the development of the nature versus nurture question into three main stages. While such a partitioning is somewhat oversimplified with regard to what the various positions on this issue have been at different times, it does illustrate the way that the debate has gradually evolved.

Part 1: Nature versus nurture

The origins of the nature versus nurture debate date back far beyond the past 50 years. The ancient Greek philosopher Galen postulated that personality traits were driven by the relative concentrations of four bodily fluids or “humours.” In 1874, Sir Francis Galton published “English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture,” in which he advanced his ideas about the dominance of hereditary factors in intelligence and character at the beginning of the eugenics movement.1 These ideas were in stark opposition to the perspective of earlier scholars, such as the philosopher John Locke, who popularized the theory that children are born a “blank slate” and from there develop their traits and intellectual abilities through their environment and experiences.

The other primary school of thought in the mid-1960s was psychoanalysis, which was based on the ideas of Sigmund Freud, MD. Psychoanalysis maintains that the way that unconscious sexual and aggressive drives were channeled through various defense mechanisms was of primary importance to the understanding of both psychopathology and typical human behavior.

While these two perspectives were often very much in opposition to each other, they shared in common the view that the environment and a person’s individual experiences, i.e. nurture, were the prevailing forces in development. In the background, more biologically oriented research and clinical work was slowly beginning to work its way into the field, especially at certain institutions, such as Washington University in St. Louis. Several medications of various types were then available, including chlorpromazine, imipramine, and diazepam.

Overall, however, it is probably fair to say that, 50 years ago, it was the nurture perspective that held the most sway since psychodynamic treatment and behaviorist research dominated, while the emerging fields of genetics and neuroscience were only beginning to take hold.

Part 2: Nature and nurture

From the 1970s to the end of the 20th century, a noticeable shift occurred as knowledge of the brain and genetics – supported by remarkable advances in research techniques – began to swing the pendulum back toward an increased appreciation of nature as a critical influence on a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior.

Researchers Stella Chess, MD, and Alexander Thomas, MD, for example, conducted the New York Longitudinal Study, in which they closely observed a group of young children over many years. Their studies compelled them to argue for the significance of more innate temperament traits as critical aspects of a youth’s overall adjustment.2 The Human Genome Project was launched in 1990, and the entire decade was designated as the “Decade of the Brain.” During this time, neuroscience research exploded as techniques, such as MRI and PET, allowed scientists to view the living brain like never before.

The type of research investigation that perhaps was most directly relevant to the nature-nurture debate and that became quite popular during this time was the twin study. By comparing the relative similarities among monozygotic and dizygotic twins raised in the same household, it became possible to calculate directly the degree to which a variable of interest (intelligence, height, aggressive behavior) could be attributed to genetic versus environmental factors. When it came to behavioral variables, a repeated finding that emerged was that both genetic and environmental influences are important, often at close to a 50/50 split in terms of magnitude.3,4 These studies were complemented by molecular genetic studies, which were beginning to be able to identify specific genes that conveyed usually small amounts of risk for a wide range of psychiatric disorders.

Yet, while twin studies and many other lines of research made it increasingly difficult to argue for the overwhelming supremacy of either nature or nurture, the two domains generally were treated as being independent of each other. Specific traits or symptoms in an individual often were thought of as being the result of either psychological (nurture) or biological (nature) causes. Terms such as “endogenous depression,” for example, were used to distinguish those who had symptoms that were thought generally to be out of reach for “psychological” treatments, such as psychotherapy. Looking back, it might be fair to say that one of the principle flaws in this perspective was the commonly held belief that, if something was brain based or biological, then it therefore implied a kind of automatic “wiring” of the brain that was generally driven by genes and beyond the influence of environmental factors.

Part 3: Nature is nurture (and vice versa)

As the science progressed, it became increasingly clear that the nature and nurture domains were hopelessly intertwined with one another. From early PET-scan studies showing that both medications and psychotherapy not only changed the brain but also did so in ways similar to behavioral-genetic studies showing how genetically influenced behaviors actually cause certain environmental events to be more likely to occur, research continued to demonstrate the bidirectional influences of genetic and environmental factors on development.5,6 This appreciation rose to even greater heights with advances in the field of epigenetics, which was able to document some of the specific mechanisms through which environmental factors cause genes involved in regulating the plasticity of the brain to turn on and off.7

In thinking through some of this complexity, however, it is important to remember the hopeful message that is contained in this rich understanding. All of these complicated, interacting genetic and environmental factors give us many avenues for positive intervention. Now we understand that not only might a medication help strengthen some of the brain connections needed to reduce and cope with that child’s anxiety, but so could mindfulness, exercise, and addressing his parents’ symptoms. When the families ask me whether their child’s struggles are behavioral or psychological, the answer I tend to give them is “yes.”

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

Email him at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @pedipsych.

References

1. “English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture” (London: MacMillan & Co., 1874)

2. “Temperament: Theory and Practice” (New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1996)

3. “Nature and Nurture during Infancy and Early Childhood” (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988)

4. Nat Genet. 2015;47(7):702-9.

5. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(9):681-9.

6. Dev Psychopathol. 1997 Spring;9(2):335-64.

7. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):551-2.

This basic question has been debated at settings ranging from scientific conferences to dinner tables for many decades. The media also has covered it in forms ranging from documentaries to the popular comedy movie “Trading Places” (1983). Yet, despite so much attention and so much research devoted to resolving this timeless debate, the arguments continue to this day.

A lack of a clear answer, however, by no means implies that we have not made major advances in our understanding. This short review takes a look at the progression of this seemingly eternal question by categorizing the development of the nature versus nurture question into three main stages. While such a partitioning is somewhat oversimplified with regard to what the various positions on this issue have been at different times, it does illustrate the way that the debate has gradually evolved.

Part 1: Nature versus nurture

The origins of the nature versus nurture debate date back far beyond the past 50 years. The ancient Greek philosopher Galen postulated that personality traits were driven by the relative concentrations of four bodily fluids or “humours.” In 1874, Sir Francis Galton published “English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture,” in which he advanced his ideas about the dominance of hereditary factors in intelligence and character at the beginning of the eugenics movement.1 These ideas were in stark opposition to the perspective of earlier scholars, such as the philosopher John Locke, who popularized the theory that children are born a “blank slate” and from there develop their traits and intellectual abilities through their environment and experiences.

The other primary school of thought in the mid-1960s was psychoanalysis, which was based on the ideas of Sigmund Freud, MD. Psychoanalysis maintains that the way that unconscious sexual and aggressive drives were channeled through various defense mechanisms was of primary importance to the understanding of both psychopathology and typical human behavior.

While these two perspectives were often very much in opposition to each other, they shared in common the view that the environment and a person’s individual experiences, i.e. nurture, were the prevailing forces in development. In the background, more biologically oriented research and clinical work was slowly beginning to work its way into the field, especially at certain institutions, such as Washington University in St. Louis. Several medications of various types were then available, including chlorpromazine, imipramine, and diazepam.

Overall, however, it is probably fair to say that, 50 years ago, it was the nurture perspective that held the most sway since psychodynamic treatment and behaviorist research dominated, while the emerging fields of genetics and neuroscience were only beginning to take hold.

Part 2: Nature and nurture

From the 1970s to the end of the 20th century, a noticeable shift occurred as knowledge of the brain and genetics – supported by remarkable advances in research techniques – began to swing the pendulum back toward an increased appreciation of nature as a critical influence on a person’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior.

Researchers Stella Chess, MD, and Alexander Thomas, MD, for example, conducted the New York Longitudinal Study, in which they closely observed a group of young children over many years. Their studies compelled them to argue for the significance of more innate temperament traits as critical aspects of a youth’s overall adjustment.2 The Human Genome Project was launched in 1990, and the entire decade was designated as the “Decade of the Brain.” During this time, neuroscience research exploded as techniques, such as MRI and PET, allowed scientists to view the living brain like never before.

The type of research investigation that perhaps was most directly relevant to the nature-nurture debate and that became quite popular during this time was the twin study. By comparing the relative similarities among monozygotic and dizygotic twins raised in the same household, it became possible to calculate directly the degree to which a variable of interest (intelligence, height, aggressive behavior) could be attributed to genetic versus environmental factors. When it came to behavioral variables, a repeated finding that emerged was that both genetic and environmental influences are important, often at close to a 50/50 split in terms of magnitude.3,4 These studies were complemented by molecular genetic studies, which were beginning to be able to identify specific genes that conveyed usually small amounts of risk for a wide range of psychiatric disorders.

Yet, while twin studies and many other lines of research made it increasingly difficult to argue for the overwhelming supremacy of either nature or nurture, the two domains generally were treated as being independent of each other. Specific traits or symptoms in an individual often were thought of as being the result of either psychological (nurture) or biological (nature) causes. Terms such as “endogenous depression,” for example, were used to distinguish those who had symptoms that were thought generally to be out of reach for “psychological” treatments, such as psychotherapy. Looking back, it might be fair to say that one of the principle flaws in this perspective was the commonly held belief that, if something was brain based or biological, then it therefore implied a kind of automatic “wiring” of the brain that was generally driven by genes and beyond the influence of environmental factors.

Part 3: Nature is nurture (and vice versa)

As the science progressed, it became increasingly clear that the nature and nurture domains were hopelessly intertwined with one another. From early PET-scan studies showing that both medications and psychotherapy not only changed the brain but also did so in ways similar to behavioral-genetic studies showing how genetically influenced behaviors actually cause certain environmental events to be more likely to occur, research continued to demonstrate the bidirectional influences of genetic and environmental factors on development.5,6 This appreciation rose to even greater heights with advances in the field of epigenetics, which was able to document some of the specific mechanisms through which environmental factors cause genes involved in regulating the plasticity of the brain to turn on and off.7

In thinking through some of this complexity, however, it is important to remember the hopeful message that is contained in this rich understanding. All of these complicated, interacting genetic and environmental factors give us many avenues for positive intervention. Now we understand that not only might a medication help strengthen some of the brain connections needed to reduce and cope with that child’s anxiety, but so could mindfulness, exercise, and addressing his parents’ symptoms. When the families ask me whether their child’s struggles are behavioral or psychological, the answer I tend to give them is “yes.”

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington.

Email him at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter @pedipsych.

References

1. “English Men of Science: Their Nature and Nurture” (London: MacMillan & Co., 1874)

2. “Temperament: Theory and Practice” (New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1996)

3. “Nature and Nurture during Infancy and Early Childhood” (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988)

4. Nat Genet. 2015;47(7):702-9.

5. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(9):681-9.

6. Dev Psychopathol. 1997 Spring;9(2):335-64.

7. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):551-2.

Recalcitrant Ulcer on the Lower Leg

The Diagnosis: Nonuremic Calciphylaxis

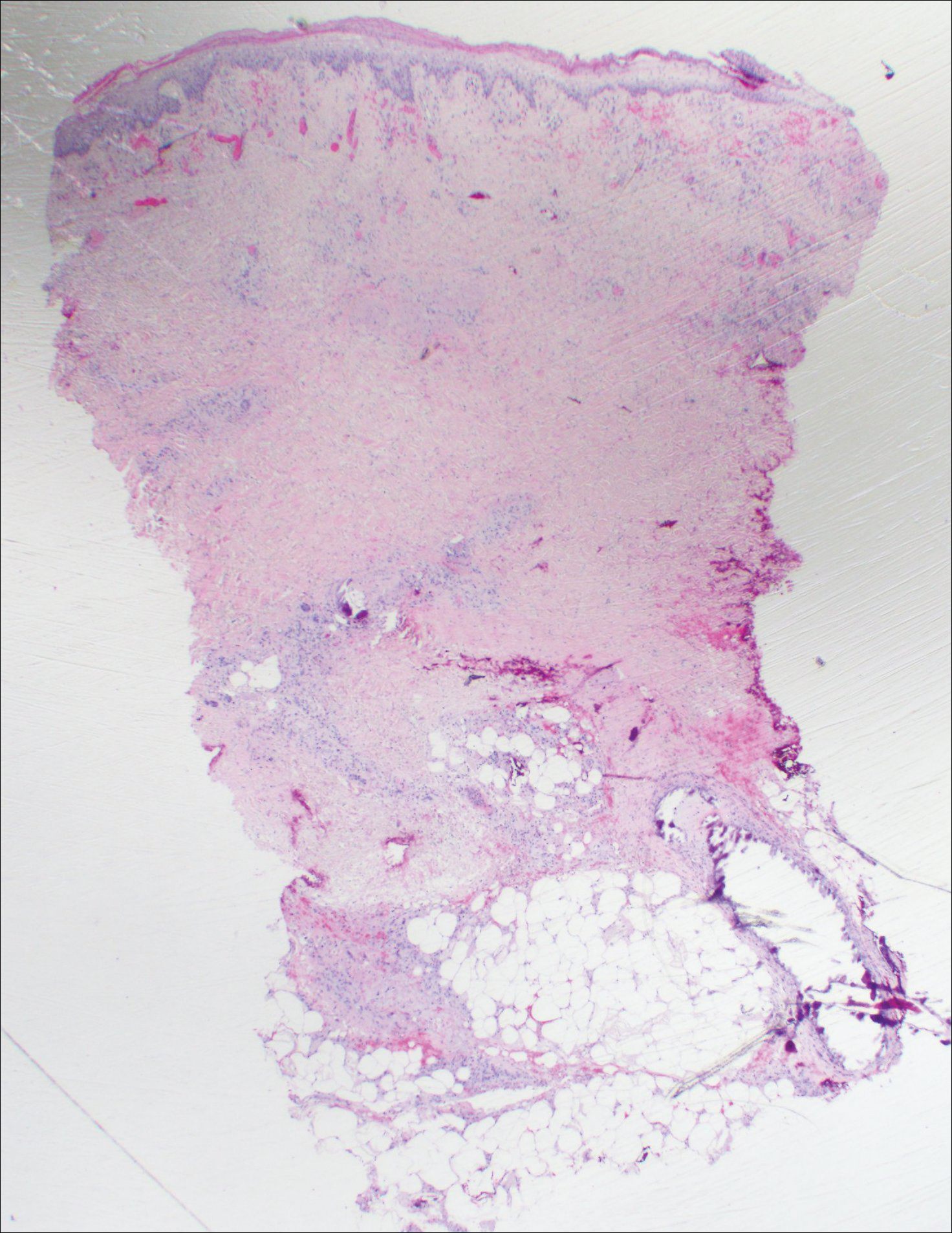

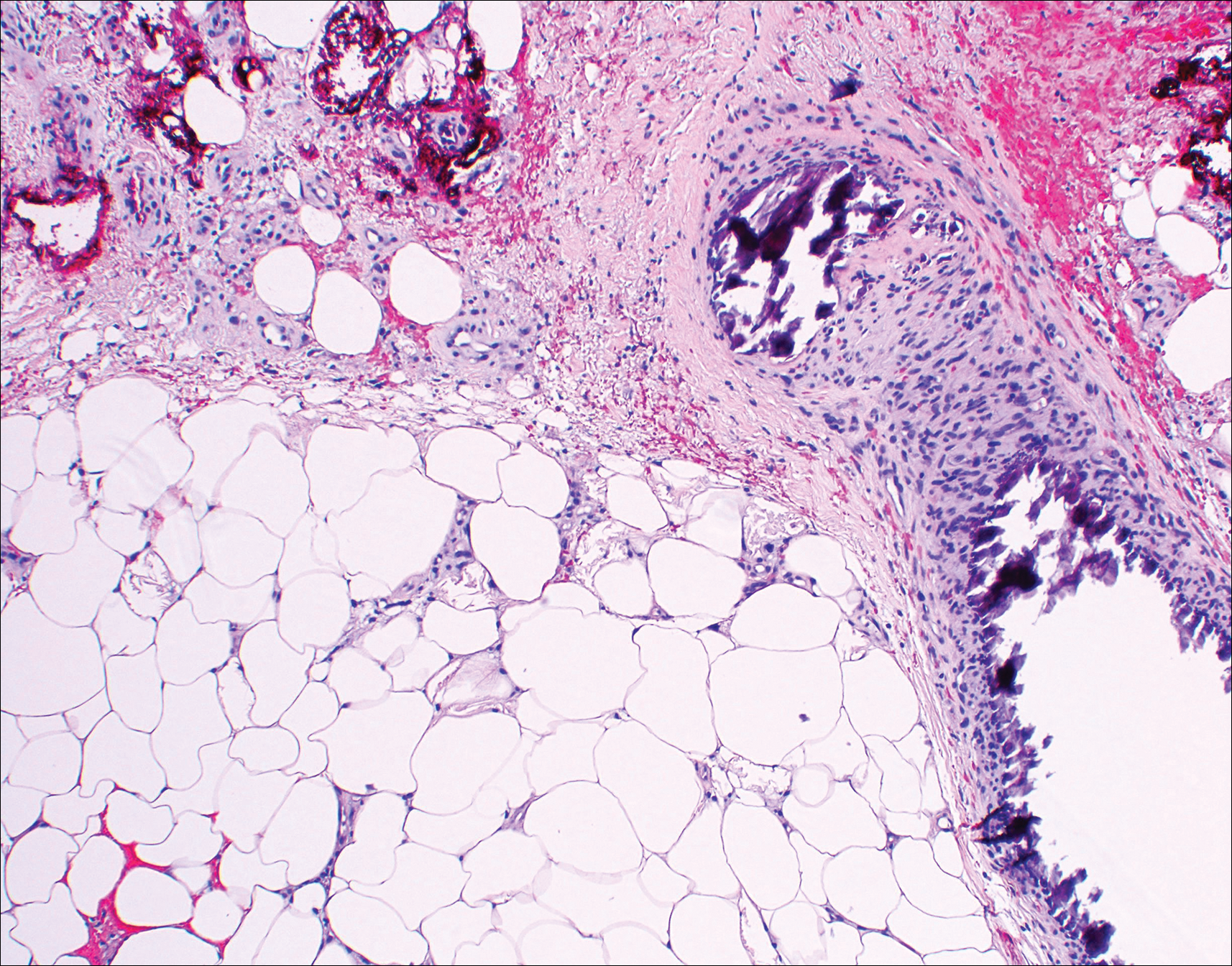

Histopathologic findings revealed ischemic necrosis and a subepidermal blister (Figure 1) with arteriosclerotic changes and fat necrosis. Foci of calcification were noted within the fat lobules. Arterioles within the deeper dermis and subcutis showed thickened hyalinized walls, narrowed lumina, and medial calcification (Figure 2). Multiple sections did not reveal any granulomatous inflammation. Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains were negative for fungal and bacterial elements, respectively. No dense neutrophilic infiltrate was seen. Multifocal calcific deposits within fat lobules and vessel walls (endothelium highlighted by the CD31 stain) suggested calciphylaxis.

Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count, international normalized ratio level of 4 (on warfarin), and an elevated sedimentation rate at 72 mm/h (reference range, 0-20 mm/h). Serum creatinine was 1.1 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6-1.2 mg/dL) and the calcium-phosphorous product was 40.8 mg2/dL (reference range, <55 mg2/dL). Hemoglobin A1C (glycated hemoglobin) was 8.2% (reference range, 4%-7%). Wound cultures grew Proteus mirabilis sensitive to cefazolin. Acid-fast bacilli and fungal cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the left lower leg without contrast showed no evidence of osteomyelitis. Of note, the popliteal arteries and distal vessels showed moderate vascular calcification.

Histopathology findings as well as a clinical picture of painful ulceration on the distal extremities and uncontrolled diabetes with normal renal function favored a diagnosis of nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC). The patient was treated with intravenous infusions of sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and oral cefazolin for superadded bacterial infection. Local wound care included collagenase dressings with light compression. Warfarin was discontinued, as it can worsen calciphylaxis. Complete reepithelialization of the ulcer along with substantial reduction in pain was noted within 4 weeks.

Ulceration of the lower legs is a relatively common condition in the Western world, the prevalence of which increases up to 5% in patients older than 65 years.1 Of the myriad of causes that lead to ulceration of the distal aspect of the leg, NUC is a rare but known phenomenon. The pathogenesis of NUC is complicated based on theories of derangement of receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ, receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ ligand, and osteoprotegerin, leading to calcium deposits in the media of the arteries.2 This deposition precipitates vascular occlusion coupled with ischemic necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue and skin.3 Some of the more common causes of NUC are primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancy, and rheumatoid arthritis. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a less common cause but often is found in association with NUC, as noted by Nigwekar et al.2 According to their study, the laboratory parameters commonly found in NUC included a calcium-phosphorous product greater than 50 mg2/dL and serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL or less.2

Our patient displayed these laboratory findings. However, distinguishing NUC from other atypical lower extremity ulcers such as Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer, pyoderma gangrenosum, and warfarin necrosis can pose a challenge to the dermatologist. Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer is excruciatingly painful and occurs more frequently near the Achilles tendon, responding well to surgical debridement. Histopathologically, medial calcinosis and arteriosclerosis are seen.4

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis wherein the classical ulcerative variant is painful. It occurs mostly on the pretibial area and worsens after debridement.5 Clinically and histopathologically, it is a diagnosis of exclusion in which a dense neutrophilic to mixed lymphocytic infiltrate is seen with necrosis of dermal vessels.6

Warfarin necrosis is extremely rare, affecting 0.01% to 0.1% of patients on warfarin-derived anticoagulant therapy.7 Necrosis occurs mostly on fat-bearing areas such as the breasts, abdomen, and thighs 3 to 5 days after initiating treatment. Histologically, fibrin deposits occlude dermal vessels without perivascular inflammation.8

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare cutaneous entity seen in 0.3% of diabetic patients.9 The exact pathogenesis is unknown; however, microangiopathy in collaboration with cross-linking of abnormal collagen fibers play a role. These lesions appear as erythematous plaques with a slightly depressed to atrophic center, ultimately taking on a waxy porcelain appearance. Although most of these lesions either resolve or become chronically persistent, approximately 15% undergo ulceration, which can be painful. Histologically, with hematoxylin and eosin staining, areas of necrobiosis are seen surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate comprised mainly of histiocytes along with lymphocytes and plasma cells.9

Nonuremic calciphylaxis can mimic the aforementioned conditions to a greater extent in female patients with obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. However, microscopic calcium deposition in the media of dermal arterioles, extravascular calcification within fat lobules, and cutaneous necrosis, along with remarkable response to intravenous sodium thiosulfate, confirmed a diagnosis of NUC in our patient. Sodium thiosulfate scavenges reactive oxygen species and promotes nitric oxygen generation, thereby reducing endothelial damage.10 Although there are no randomized controlled trials to support its use, sodium thiosulfate has been successfully used to treat established cases of NUC.11

- Spentzouris G, Labropoulos N. The evaluation of lower-extremity ulcers. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:286-295.

- Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, et al. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143.

- Bardin T. Musculoskeletal manifestations of chronic renal failure. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:48-54.

- Hafner J, Nobbe S, Partsch H, et al. Martorell hypertensive ischemic leg ulcer: a model of ischemic subcutaneous arteriolosclerosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:961-968.

- Sedda S, Caruso R, Marafini I, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum in refractory celiac disease: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:162.

- Su WP, Davis MD, Weenig RH, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:790-800.

- Breakey W, Hall C, Vann Jones S, et al. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis progressing to calciphylaxis. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:244-246.

- Kakagia DD, Papanas N, Karadimas E, et al. Warfarin-induced skin necrosis. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:96-98.

- Kota SK, Jammula S, Kota SK, et al. Necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum: a case-based review of literature. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:614-620.

- Hayden MR, Goldsmith DJ. Sodium thiosulfate: new hope for the treatment of calciphylaxis. Semin Dial. 2010;23:258-262.

- Ning MS, Dahir KM, Castellanos EH, et al. Sodium thiosulfate in the treatment of non-uremic calciphylaxis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:649-652.

The Diagnosis: Nonuremic Calciphylaxis

Histopathologic findings revealed ischemic necrosis and a subepidermal blister (Figure 1) with arteriosclerotic changes and fat necrosis. Foci of calcification were noted within the fat lobules. Arterioles within the deeper dermis and subcutis showed thickened hyalinized walls, narrowed lumina, and medial calcification (Figure 2). Multiple sections did not reveal any granulomatous inflammation. Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains were negative for fungal and bacterial elements, respectively. No dense neutrophilic infiltrate was seen. Multifocal calcific deposits within fat lobules and vessel walls (endothelium highlighted by the CD31 stain) suggested calciphylaxis.

Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count, international normalized ratio level of 4 (on warfarin), and an elevated sedimentation rate at 72 mm/h (reference range, 0-20 mm/h). Serum creatinine was 1.1 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6-1.2 mg/dL) and the calcium-phosphorous product was 40.8 mg2/dL (reference range, <55 mg2/dL). Hemoglobin A1C (glycated hemoglobin) was 8.2% (reference range, 4%-7%). Wound cultures grew Proteus mirabilis sensitive to cefazolin. Acid-fast bacilli and fungal cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the left lower leg without contrast showed no evidence of osteomyelitis. Of note, the popliteal arteries and distal vessels showed moderate vascular calcification.

Histopathology findings as well as a clinical picture of painful ulceration on the distal extremities and uncontrolled diabetes with normal renal function favored a diagnosis of nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC). The patient was treated with intravenous infusions of sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and oral cefazolin for superadded bacterial infection. Local wound care included collagenase dressings with light compression. Warfarin was discontinued, as it can worsen calciphylaxis. Complete reepithelialization of the ulcer along with substantial reduction in pain was noted within 4 weeks.

Ulceration of the lower legs is a relatively common condition in the Western world, the prevalence of which increases up to 5% in patients older than 65 years.1 Of the myriad of causes that lead to ulceration of the distal aspect of the leg, NUC is a rare but known phenomenon. The pathogenesis of NUC is complicated based on theories of derangement of receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ, receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ ligand, and osteoprotegerin, leading to calcium deposits in the media of the arteries.2 This deposition precipitates vascular occlusion coupled with ischemic necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue and skin.3 Some of the more common causes of NUC are primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancy, and rheumatoid arthritis. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a less common cause but often is found in association with NUC, as noted by Nigwekar et al.2 According to their study, the laboratory parameters commonly found in NUC included a calcium-phosphorous product greater than 50 mg2/dL and serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL or less.2

Our patient displayed these laboratory findings. However, distinguishing NUC from other atypical lower extremity ulcers such as Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer, pyoderma gangrenosum, and warfarin necrosis can pose a challenge to the dermatologist. Martorell hypertensive ischemic ulcer is excruciatingly painful and occurs more frequently near the Achilles tendon, responding well to surgical debridement. Histopathologically, medial calcinosis and arteriosclerosis are seen.4

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis wherein the classical ulcerative variant is painful. It occurs mostly on the pretibial area and worsens after debridement.5 Clinically and histopathologically, it is a diagnosis of exclusion in which a dense neutrophilic to mixed lymphocytic infiltrate is seen with necrosis of dermal vessels.6

Warfarin necrosis is extremely rare, affecting 0.01% to 0.1% of patients on warfarin-derived anticoagulant therapy.7 Necrosis occurs mostly on fat-bearing areas such as the breasts, abdomen, and thighs 3 to 5 days after initiating treatment. Histologically, fibrin deposits occlude dermal vessels without perivascular inflammation.8

Necrobiosis lipoidica is a rare cutaneous entity seen in 0.3% of diabetic patients.9 The exact pathogenesis is unknown; however, microangiopathy in collaboration with cross-linking of abnormal collagen fibers play a role. These lesions appear as erythematous plaques with a slightly depressed to atrophic center, ultimately taking on a waxy porcelain appearance. Although most of these lesions either resolve or become chronically persistent, approximately 15% undergo ulceration, which can be painful. Histologically, with hematoxylin and eosin staining, areas of necrobiosis are seen surrounded by an inflammatory infiltrate comprised mainly of histiocytes along with lymphocytes and plasma cells.9

Nonuremic calciphylaxis can mimic the aforementioned conditions to a greater extent in female patients with obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. However, microscopic calcium deposition in the media of dermal arterioles, extravascular calcification within fat lobules, and cutaneous necrosis, along with remarkable response to intravenous sodium thiosulfate, confirmed a diagnosis of NUC in our patient. Sodium thiosulfate scavenges reactive oxygen species and promotes nitric oxygen generation, thereby reducing endothelial damage.10 Although there are no randomized controlled trials to support its use, sodium thiosulfate has been successfully used to treat established cases of NUC.11

The Diagnosis: Nonuremic Calciphylaxis

Histopathologic findings revealed ischemic necrosis and a subepidermal blister (Figure 1) with arteriosclerotic changes and fat necrosis. Foci of calcification were noted within the fat lobules. Arterioles within the deeper dermis and subcutis showed thickened hyalinized walls, narrowed lumina, and medial calcification (Figure 2). Multiple sections did not reveal any granulomatous inflammation. Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains were negative for fungal and bacterial elements, respectively. No dense neutrophilic infiltrate was seen. Multifocal calcific deposits within fat lobules and vessel walls (endothelium highlighted by the CD31 stain) suggested calciphylaxis.

Laboratory test results revealed a normal white blood cell count, international normalized ratio level of 4 (on warfarin), and an elevated sedimentation rate at 72 mm/h (reference range, 0-20 mm/h). Serum creatinine was 1.1 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6-1.2 mg/dL) and the calcium-phosphorous product was 40.8 mg2/dL (reference range, <55 mg2/dL). Hemoglobin A1C (glycated hemoglobin) was 8.2% (reference range, 4%-7%). Wound cultures grew Proteus mirabilis sensitive to cefazolin. Acid-fast bacilli and fungal cultures were negative. Computed tomography of the left lower leg without contrast showed no evidence of osteomyelitis. Of note, the popliteal arteries and distal vessels showed moderate vascular calcification.

Histopathology findings as well as a clinical picture of painful ulceration on the distal extremities and uncontrolled diabetes with normal renal function favored a diagnosis of nonuremic calciphylaxis (NUC). The patient was treated with intravenous infusions of sodium thiosulfate 25 mg 3 times weekly and oral cefazolin for superadded bacterial infection. Local wound care included collagenase dressings with light compression. Warfarin was discontinued, as it can worsen calciphylaxis. Complete reepithelialization of the ulcer along with substantial reduction in pain was noted within 4 weeks.

Ulceration of the lower legs is a relatively common condition in the Western world, the prevalence of which increases up to 5% in patients older than 65 years.1 Of the myriad of causes that lead to ulceration of the distal aspect of the leg, NUC is a rare but known phenomenon. The pathogenesis of NUC is complicated based on theories of derangement of receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ, receptor activator of nuclear factor κβ ligand, and osteoprotegerin, leading to calcium deposits in the media of the arteries.2 This deposition precipitates vascular occlusion coupled with ischemic necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue and skin.3 Some of the more common causes of NUC are primary hyperparathyroidism, malignancy, and rheumatoid arthritis. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a less common cause but often is found in association with NUC, as noted by Nigwekar et al.2 According to their study, the laboratory parameters commonly found in NUC included a calcium-phosphorous product greater than 50 mg2/dL and serum creatinine of 1.2 mg/dL or less.2