User login

Microbiome predicted response to high-fiber diet

Overweight individuals whose stool samples were abundant in Prevotella species lost about 2.3 kg more body fat on a 6-month high-fiber diet than individuals with a low ratio of Prevotella to Bacteroides, according to a randomized trial of 62 Danish adults.

The findings help explain why a high-fiber diet does not always produce meaningful weight loss, said Mads F. Hjorth, PhD, of the University of Copenhagen, and his associates. An “abundance of Prevotella” in the gut microbiome might underlie the “recent breakthrough in personalized nutrition,” they wrote in the International Journal of Obesity.

At the start of the study, 28 (45%) participants had a high (0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.11-7.5) ratio of Prevotella to Bacteroides and 34 (55%) had a much lower ratio (0.00007) but did not otherwise differ significantly by age, sex, body weight, or fasting insulin levels. After 26 weeks, the high-Prevotella group lost an average of 3.2 kg more fat on the high-fiber diet than the control diet (P less than .001). In contrast, the low-Prevotella group lost only 0.9 kg more fat with the high-fiber diet, a statistically insignificant difference from the control diet. Changes in waistline circumference reflected the findings – the high-fiber diet produced a 4.8-cm average reduction in the high-Prevotella group, compared with a 0.8-cm reduction in the low-Prevotella group.

Next, the researchers asked all 62 participants to follow the high-fiber diet, but did not provide them with food. After 1 year, the high-Prevotella group had maintained a 1.2-kg weight loss, compared with baseline, while the low-Prevotella group had regained 2.8 kg of body weight (P less than .001). Thus, baseline Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio explained a 4-kg difference in responsiveness to the high-fiber diet, the researchers concluded. The difference was even more marked when they excluded eight participants with undetectable levels of Prevotella.

Only two individuals switched from a low to a high Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio during the 6-month intervention period, which reflects prior findings that the intestinal microbiome is difficult to shift without “extreme changes, such as complete removal of carbohydrates from the diet,” the researchers wrote. Individual gut microbiome might affect energy absorption from different types of foods, the ability to utilize fiber, gut-brain signaling, or the secretion of hormones affecting appetite, they hypothesized. Thus, Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio “may serve as a biomarker to predict future weight loss success on specific diets.”

Gelesis provided funding. Dr. Hjorth and two coinvestigators reported having applied for a patent on the use of biomarkers to predict response to weight loss efforts. The remaining five researchers had no conflicts.

Overweight individuals whose stool samples were abundant in Prevotella species lost about 2.3 kg more body fat on a 6-month high-fiber diet than individuals with a low ratio of Prevotella to Bacteroides, according to a randomized trial of 62 Danish adults.

The findings help explain why a high-fiber diet does not always produce meaningful weight loss, said Mads F. Hjorth, PhD, of the University of Copenhagen, and his associates. An “abundance of Prevotella” in the gut microbiome might underlie the “recent breakthrough in personalized nutrition,” they wrote in the International Journal of Obesity.

At the start of the study, 28 (45%) participants had a high (0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.11-7.5) ratio of Prevotella to Bacteroides and 34 (55%) had a much lower ratio (0.00007) but did not otherwise differ significantly by age, sex, body weight, or fasting insulin levels. After 26 weeks, the high-Prevotella group lost an average of 3.2 kg more fat on the high-fiber diet than the control diet (P less than .001). In contrast, the low-Prevotella group lost only 0.9 kg more fat with the high-fiber diet, a statistically insignificant difference from the control diet. Changes in waistline circumference reflected the findings – the high-fiber diet produced a 4.8-cm average reduction in the high-Prevotella group, compared with a 0.8-cm reduction in the low-Prevotella group.

Next, the researchers asked all 62 participants to follow the high-fiber diet, but did not provide them with food. After 1 year, the high-Prevotella group had maintained a 1.2-kg weight loss, compared with baseline, while the low-Prevotella group had regained 2.8 kg of body weight (P less than .001). Thus, baseline Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio explained a 4-kg difference in responsiveness to the high-fiber diet, the researchers concluded. The difference was even more marked when they excluded eight participants with undetectable levels of Prevotella.

Only two individuals switched from a low to a high Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio during the 6-month intervention period, which reflects prior findings that the intestinal microbiome is difficult to shift without “extreme changes, such as complete removal of carbohydrates from the diet,” the researchers wrote. Individual gut microbiome might affect energy absorption from different types of foods, the ability to utilize fiber, gut-brain signaling, or the secretion of hormones affecting appetite, they hypothesized. Thus, Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio “may serve as a biomarker to predict future weight loss success on specific diets.”

Gelesis provided funding. Dr. Hjorth and two coinvestigators reported having applied for a patent on the use of biomarkers to predict response to weight loss efforts. The remaining five researchers had no conflicts.

Overweight individuals whose stool samples were abundant in Prevotella species lost about 2.3 kg more body fat on a 6-month high-fiber diet than individuals with a low ratio of Prevotella to Bacteroides, according to a randomized trial of 62 Danish adults.

The findings help explain why a high-fiber diet does not always produce meaningful weight loss, said Mads F. Hjorth, PhD, of the University of Copenhagen, and his associates. An “abundance of Prevotella” in the gut microbiome might underlie the “recent breakthrough in personalized nutrition,” they wrote in the International Journal of Obesity.

At the start of the study, 28 (45%) participants had a high (0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.11-7.5) ratio of Prevotella to Bacteroides and 34 (55%) had a much lower ratio (0.00007) but did not otherwise differ significantly by age, sex, body weight, or fasting insulin levels. After 26 weeks, the high-Prevotella group lost an average of 3.2 kg more fat on the high-fiber diet than the control diet (P less than .001). In contrast, the low-Prevotella group lost only 0.9 kg more fat with the high-fiber diet, a statistically insignificant difference from the control diet. Changes in waistline circumference reflected the findings – the high-fiber diet produced a 4.8-cm average reduction in the high-Prevotella group, compared with a 0.8-cm reduction in the low-Prevotella group.

Next, the researchers asked all 62 participants to follow the high-fiber diet, but did not provide them with food. After 1 year, the high-Prevotella group had maintained a 1.2-kg weight loss, compared with baseline, while the low-Prevotella group had regained 2.8 kg of body weight (P less than .001). Thus, baseline Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio explained a 4-kg difference in responsiveness to the high-fiber diet, the researchers concluded. The difference was even more marked when they excluded eight participants with undetectable levels of Prevotella.

Only two individuals switched from a low to a high Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio during the 6-month intervention period, which reflects prior findings that the intestinal microbiome is difficult to shift without “extreme changes, such as complete removal of carbohydrates from the diet,” the researchers wrote. Individual gut microbiome might affect energy absorption from different types of foods, the ability to utilize fiber, gut-brain signaling, or the secretion of hormones affecting appetite, they hypothesized. Thus, Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio “may serve as a biomarker to predict future weight loss success on specific diets.”

Gelesis provided funding. Dr. Hjorth and two coinvestigators reported having applied for a patent on the use of biomarkers to predict response to weight loss efforts. The remaining five researchers had no conflicts.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF OBESITY

Key clinical point: Fecal ratio of Prevotella to Bacteroides predicted amount of fat lost on a high-fiber diet.

Major finding: After 26 weeks, individuals with a high Prevotella-to-Bacteroides ratio lost an average of 2.3 kg more fat than individuals with a low ratio (P = .04).

Data source: A randomized prospective trial of 62 adults with increased waist circumference.

Disclosures: Gelesis provided funding. Dr. Hjorth and two coinvestigators reported that they have applied for a patent on the use of biomarkers to predict response to weight loss efforts. The remaining five researchers had no conflicts.

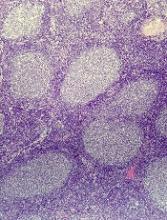

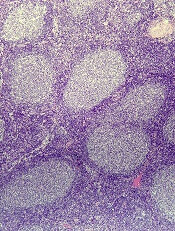

How APL cells evade the immune system

New research has revealed a way in which acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) cells evade destruction by the immune system.

The study showed how group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) are recruited by leukemic cells to suppress an essential anticancer immune response.

Researchers believe this newly discovered immunosuppressive axis likely holds sway in other cancers, and it might be disrupted by therapies already in use to treat other diseases.

Camilla Jandus, MD, PhD, of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research in Lausanne, Switzerland, and her colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

“ILCs are not very abundant in the body, but, when activated, they secrete large amounts of immune factors,” Dr Jandus said. “In this way, they can dictate whether a response will be pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory.”

ILC1, 2, and 3 have been shown to play a role in inflammation and autoimmune diseases. However, their role in cancer has remained unclear.

To address that question, Dr Jandus and her colleagues began with the observation that one subtype of the cells, ILC2s, are abnormally abundant and hyperactivated in patients with APL.

The researchers examined ILC2 immunology in patients with active APL and compared it to that of APL patients in remission.

“Our analyses suggest that, in patients with this leukemia, ILC2s are at the beginning of a novel immunosuppressive axis, one that is likely to be active in other types of cancer as well,” Dr Jandus said.

She and her colleagues found that APL cells secrete large quantities of PGD2 and express high levels of B7H6 on their surface. Both of these molecules bind to receptors on ILC2s—CRTH2 and NKp30, respectively—activating the ILC2s and prompting them to secrete interleukin-13 (IL-13).

The IL-13 switches on and expands the population of monocytic myeloid-derived immune cells (M-MDSCs). These cells suppress immune responses and allow leukemic cells to evade immune system attack.

The researchers tested these findings in a mouse model of APL. Like patients, mice with APL displayed abnormal activation of ILC2s and M-MDSCs.

However, interfering with all the signals of the immunosuppressive axis restored anti-cancer immunity and prolonged survival in the mice.

Treating mice with a PGD2 inhibitor, an NKp30-blocking antibody, and an anti-IL-13 antibody resulted in reduced APL cell engraftment and a decrease in PGD2, ILC2s, and M-MDSCs. These mice also had significantly longer survival than untreated control mice (P<0.05).

Dr Jandus and her colleagues noted that antibodies against IL-13 and inhibitors of PGD2 are already in clinical use for other diseases, and antibodies that interfere with NKp30-B7H6 binding are in clinical development.

“We also found that this immunosuppressive axis may be operating in other types of cancer; in particular, prostate cancer,” Dr Jandus said. “We believe that some ILCs, like ILC2s, might suppress immune responses, while others might stimulate them. That’s what we are investigating in other types of tumors now.”

This research was supported by the Novartis Foundation for Medical-Biological Research, Ludwig Cancer Research, the Swiss National Science Foundation, Fondazione San Salvatore, ProFemmes UNIL, Fondation Pierre Mercier pour la Science, the Swiss Cancer League, and the Foundation for the Fight against Cancer. ![]()

New research has revealed a way in which acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) cells evade destruction by the immune system.

The study showed how group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) are recruited by leukemic cells to suppress an essential anticancer immune response.

Researchers believe this newly discovered immunosuppressive axis likely holds sway in other cancers, and it might be disrupted by therapies already in use to treat other diseases.

Camilla Jandus, MD, PhD, of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research in Lausanne, Switzerland, and her colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

“ILCs are not very abundant in the body, but, when activated, they secrete large amounts of immune factors,” Dr Jandus said. “In this way, they can dictate whether a response will be pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory.”

ILC1, 2, and 3 have been shown to play a role in inflammation and autoimmune diseases. However, their role in cancer has remained unclear.

To address that question, Dr Jandus and her colleagues began with the observation that one subtype of the cells, ILC2s, are abnormally abundant and hyperactivated in patients with APL.

The researchers examined ILC2 immunology in patients with active APL and compared it to that of APL patients in remission.

“Our analyses suggest that, in patients with this leukemia, ILC2s are at the beginning of a novel immunosuppressive axis, one that is likely to be active in other types of cancer as well,” Dr Jandus said.

She and her colleagues found that APL cells secrete large quantities of PGD2 and express high levels of B7H6 on their surface. Both of these molecules bind to receptors on ILC2s—CRTH2 and NKp30, respectively—activating the ILC2s and prompting them to secrete interleukin-13 (IL-13).

The IL-13 switches on and expands the population of monocytic myeloid-derived immune cells (M-MDSCs). These cells suppress immune responses and allow leukemic cells to evade immune system attack.

The researchers tested these findings in a mouse model of APL. Like patients, mice with APL displayed abnormal activation of ILC2s and M-MDSCs.

However, interfering with all the signals of the immunosuppressive axis restored anti-cancer immunity and prolonged survival in the mice.

Treating mice with a PGD2 inhibitor, an NKp30-blocking antibody, and an anti-IL-13 antibody resulted in reduced APL cell engraftment and a decrease in PGD2, ILC2s, and M-MDSCs. These mice also had significantly longer survival than untreated control mice (P<0.05).

Dr Jandus and her colleagues noted that antibodies against IL-13 and inhibitors of PGD2 are already in clinical use for other diseases, and antibodies that interfere with NKp30-B7H6 binding are in clinical development.

“We also found that this immunosuppressive axis may be operating in other types of cancer; in particular, prostate cancer,” Dr Jandus said. “We believe that some ILCs, like ILC2s, might suppress immune responses, while others might stimulate them. That’s what we are investigating in other types of tumors now.”

This research was supported by the Novartis Foundation for Medical-Biological Research, Ludwig Cancer Research, the Swiss National Science Foundation, Fondazione San Salvatore, ProFemmes UNIL, Fondation Pierre Mercier pour la Science, the Swiss Cancer League, and the Foundation for the Fight against Cancer. ![]()

New research has revealed a way in which acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) cells evade destruction by the immune system.

The study showed how group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s) are recruited by leukemic cells to suppress an essential anticancer immune response.

Researchers believe this newly discovered immunosuppressive axis likely holds sway in other cancers, and it might be disrupted by therapies already in use to treat other diseases.

Camilla Jandus, MD, PhD, of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research in Lausanne, Switzerland, and her colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

“ILCs are not very abundant in the body, but, when activated, they secrete large amounts of immune factors,” Dr Jandus said. “In this way, they can dictate whether a response will be pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory.”

ILC1, 2, and 3 have been shown to play a role in inflammation and autoimmune diseases. However, their role in cancer has remained unclear.

To address that question, Dr Jandus and her colleagues began with the observation that one subtype of the cells, ILC2s, are abnormally abundant and hyperactivated in patients with APL.

The researchers examined ILC2 immunology in patients with active APL and compared it to that of APL patients in remission.

“Our analyses suggest that, in patients with this leukemia, ILC2s are at the beginning of a novel immunosuppressive axis, one that is likely to be active in other types of cancer as well,” Dr Jandus said.

She and her colleagues found that APL cells secrete large quantities of PGD2 and express high levels of B7H6 on their surface. Both of these molecules bind to receptors on ILC2s—CRTH2 and NKp30, respectively—activating the ILC2s and prompting them to secrete interleukin-13 (IL-13).

The IL-13 switches on and expands the population of monocytic myeloid-derived immune cells (M-MDSCs). These cells suppress immune responses and allow leukemic cells to evade immune system attack.

The researchers tested these findings in a mouse model of APL. Like patients, mice with APL displayed abnormal activation of ILC2s and M-MDSCs.

However, interfering with all the signals of the immunosuppressive axis restored anti-cancer immunity and prolonged survival in the mice.

Treating mice with a PGD2 inhibitor, an NKp30-blocking antibody, and an anti-IL-13 antibody resulted in reduced APL cell engraftment and a decrease in PGD2, ILC2s, and M-MDSCs. These mice also had significantly longer survival than untreated control mice (P<0.05).

Dr Jandus and her colleagues noted that antibodies against IL-13 and inhibitors of PGD2 are already in clinical use for other diseases, and antibodies that interfere with NKp30-B7H6 binding are in clinical development.

“We also found that this immunosuppressive axis may be operating in other types of cancer; in particular, prostate cancer,” Dr Jandus said. “We believe that some ILCs, like ILC2s, might suppress immune responses, while others might stimulate them. That’s what we are investigating in other types of tumors now.”

This research was supported by the Novartis Foundation for Medical-Biological Research, Ludwig Cancer Research, the Swiss National Science Foundation, Fondazione San Salvatore, ProFemmes UNIL, Fondation Pierre Mercier pour la Science, the Swiss Cancer League, and the Foundation for the Fight against Cancer. ![]()

‘Very daring study’ of neoadjuvant AI/CDKi combo in early BC is hypothesis generating

MADRID – For women with luminal breast cancer who are not initially candidates for breast-conserving surgery, neoadjuvant therapy with an aromatase inhibitor and a cyclin-dependent kinases 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitor offered a slightly higher residual cancer burden prior to surgery, but a significantly better safety profile than conventional chemotherapy with similar near-term safety outcomes, results of a phase 2 parallel group, noncomparative trial suggested.

Among 60 patients evaluable for response in an interim analysis of the UNICANCER NeoPAL trial, one patient (3.3%) treated with a combination of letrozole (Femara) and palbociclib (Ibrance) had a residual cancer burden (RCB) score of 0 (equivalent to a pathologic complete response; pCR), whereas three patients (10%) treated with FEC 100 chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide) had RCB 0 or I, reported Paul-Henri Cottu, MD, of the Institut Curie in Paris.

Following the interim analysis, the independent data monitoring committee for the NeoPAL trial recommended halting accrual; accrual was stopped in November 2016, after 106 patients had been randomized.

The IDMC also recommended that patients in the letrozole/palbociclib arm who did not have an RCB of 0 or I be offered adjuvant chemotherapy.

“Please note that 70% of those patients refused adjuvant chemotherapy,” Dr. Cottu said.

The investigators set out to test whether letrozole and palbociclib, which have been shown to have synergistic antiproliferative activity against advanced luminal breast cancer, could have similar benefits in the neoadjuvant setting.

They screened for women with luminal breast cancer who had newly diagnosed stage II or III breast cancer with biopsy-proven endocrine receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative tumors, using the Prosigna test, based on the PAM50 gene signature assay. Women with node-positive luminal A or luminal B disease were enrolled and randomized to receive either letrozole 2.5 mg and palbociclib 125 mg daily for 3 out of every 4 weeks over 19 weeks, or three cycles of FEC 100, followed by three cycles of docetaxel 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks, followed by surgery.

An interim analysis was planned after 30 patients were evaluable for RCB in the experimental arm, and, as prespecified, the trial was stopped for futility when fewer than five patients had an RCB of 0 or I.

The safety analysis, conducted with all 106 patients randomized, showed that letrozole/palbocilib was associated with more frequent grade 3 neutropenia (23% vs. 10% of patients with FEC), but less grade 4 neutropenia (1% vs. 11%, respectively), and no febrile neutropenia vs. 6% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 2 serious adverse events with the AI/CDK-inhibitor combination vs. 17 with chemotherapy. Dose reductions or interruptions were less frequent with letrozole/palbociclib (10 and 16), and only two patients in the experimental arm required premature cessation of therapy vs. seven in the chemotherapy arm.

The final response analysis in 103 patients showed that the rate of RCB 0 or I was 7.7% with letrozole/palbociclib and 15.7% with chemotherapy. Respective rates of RCB II-III were 92.3% and 84.3%.

Clinical response rates were similar in each study arm, with approximately 30% complete responses and 44% partial responses.

In each arm, slightly less than one-third of patients underwent mastectomy, and a little more than two-thirds were able to have breast-conserving surgery after neoadjuvant therapy.

The patients will be followed out to at least 3 years to see whether those patients in the letrozole/palbociclib arm who turned down subsequent chemotherapy will have worse survival than patients who decided to undergo it, Dr. Cottu said.

Invited discussant Nadia Harbeck, MD, PhD, of the University of Munich called the NeoPAL trial “a very daring study.”

“This is not a practice-changing trial, but it’s a very, very interesting hypothesis-generating trial,” she said.

She said that the choice of RCB was probably not the best endpoint in a trial of endocrine-based therapy vs. chemotherapy.

“I think the challenge remains to identify those patients with luminal early breast cancer for whom an endocrine-based approach – not endocrine, but endocrine-based – will improve outcome, either replacing chemotherapy in the intermediate-risk setting or as an add-on in high-risk disease,” she said.

The study was funded by Pfizer and Nanostring. Dr. Cottu disclosed advisory board participation and travel support from Pfizer and others, and research support from Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Harbeck disclosed advising and consulting fees from Pfizer, Nanostring, and other companies.

MADRID – For women with luminal breast cancer who are not initially candidates for breast-conserving surgery, neoadjuvant therapy with an aromatase inhibitor and a cyclin-dependent kinases 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitor offered a slightly higher residual cancer burden prior to surgery, but a significantly better safety profile than conventional chemotherapy with similar near-term safety outcomes, results of a phase 2 parallel group, noncomparative trial suggested.

Among 60 patients evaluable for response in an interim analysis of the UNICANCER NeoPAL trial, one patient (3.3%) treated with a combination of letrozole (Femara) and palbociclib (Ibrance) had a residual cancer burden (RCB) score of 0 (equivalent to a pathologic complete response; pCR), whereas three patients (10%) treated with FEC 100 chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide) had RCB 0 or I, reported Paul-Henri Cottu, MD, of the Institut Curie in Paris.

Following the interim analysis, the independent data monitoring committee for the NeoPAL trial recommended halting accrual; accrual was stopped in November 2016, after 106 patients had been randomized.

The IDMC also recommended that patients in the letrozole/palbociclib arm who did not have an RCB of 0 or I be offered adjuvant chemotherapy.

“Please note that 70% of those patients refused adjuvant chemotherapy,” Dr. Cottu said.

The investigators set out to test whether letrozole and palbociclib, which have been shown to have synergistic antiproliferative activity against advanced luminal breast cancer, could have similar benefits in the neoadjuvant setting.

They screened for women with luminal breast cancer who had newly diagnosed stage II or III breast cancer with biopsy-proven endocrine receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative tumors, using the Prosigna test, based on the PAM50 gene signature assay. Women with node-positive luminal A or luminal B disease were enrolled and randomized to receive either letrozole 2.5 mg and palbociclib 125 mg daily for 3 out of every 4 weeks over 19 weeks, or three cycles of FEC 100, followed by three cycles of docetaxel 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks, followed by surgery.

An interim analysis was planned after 30 patients were evaluable for RCB in the experimental arm, and, as prespecified, the trial was stopped for futility when fewer than five patients had an RCB of 0 or I.

The safety analysis, conducted with all 106 patients randomized, showed that letrozole/palbocilib was associated with more frequent grade 3 neutropenia (23% vs. 10% of patients with FEC), but less grade 4 neutropenia (1% vs. 11%, respectively), and no febrile neutropenia vs. 6% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 2 serious adverse events with the AI/CDK-inhibitor combination vs. 17 with chemotherapy. Dose reductions or interruptions were less frequent with letrozole/palbociclib (10 and 16), and only two patients in the experimental arm required premature cessation of therapy vs. seven in the chemotherapy arm.

The final response analysis in 103 patients showed that the rate of RCB 0 or I was 7.7% with letrozole/palbociclib and 15.7% with chemotherapy. Respective rates of RCB II-III were 92.3% and 84.3%.

Clinical response rates were similar in each study arm, with approximately 30% complete responses and 44% partial responses.

In each arm, slightly less than one-third of patients underwent mastectomy, and a little more than two-thirds were able to have breast-conserving surgery after neoadjuvant therapy.

The patients will be followed out to at least 3 years to see whether those patients in the letrozole/palbociclib arm who turned down subsequent chemotherapy will have worse survival than patients who decided to undergo it, Dr. Cottu said.

Invited discussant Nadia Harbeck, MD, PhD, of the University of Munich called the NeoPAL trial “a very daring study.”

“This is not a practice-changing trial, but it’s a very, very interesting hypothesis-generating trial,” she said.

She said that the choice of RCB was probably not the best endpoint in a trial of endocrine-based therapy vs. chemotherapy.

“I think the challenge remains to identify those patients with luminal early breast cancer for whom an endocrine-based approach – not endocrine, but endocrine-based – will improve outcome, either replacing chemotherapy in the intermediate-risk setting or as an add-on in high-risk disease,” she said.

The study was funded by Pfizer and Nanostring. Dr. Cottu disclosed advisory board participation and travel support from Pfizer and others, and research support from Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Harbeck disclosed advising and consulting fees from Pfizer, Nanostring, and other companies.

MADRID – For women with luminal breast cancer who are not initially candidates for breast-conserving surgery, neoadjuvant therapy with an aromatase inhibitor and a cyclin-dependent kinases 4/6 (CDK4/6) inhibitor offered a slightly higher residual cancer burden prior to surgery, but a significantly better safety profile than conventional chemotherapy with similar near-term safety outcomes, results of a phase 2 parallel group, noncomparative trial suggested.

Among 60 patients evaluable for response in an interim analysis of the UNICANCER NeoPAL trial, one patient (3.3%) treated with a combination of letrozole (Femara) and palbociclib (Ibrance) had a residual cancer burden (RCB) score of 0 (equivalent to a pathologic complete response; pCR), whereas three patients (10%) treated with FEC 100 chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide) had RCB 0 or I, reported Paul-Henri Cottu, MD, of the Institut Curie in Paris.

Following the interim analysis, the independent data monitoring committee for the NeoPAL trial recommended halting accrual; accrual was stopped in November 2016, after 106 patients had been randomized.

The IDMC also recommended that patients in the letrozole/palbociclib arm who did not have an RCB of 0 or I be offered adjuvant chemotherapy.

“Please note that 70% of those patients refused adjuvant chemotherapy,” Dr. Cottu said.

The investigators set out to test whether letrozole and palbociclib, which have been shown to have synergistic antiproliferative activity against advanced luminal breast cancer, could have similar benefits in the neoadjuvant setting.

They screened for women with luminal breast cancer who had newly diagnosed stage II or III breast cancer with biopsy-proven endocrine receptor–positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative tumors, using the Prosigna test, based on the PAM50 gene signature assay. Women with node-positive luminal A or luminal B disease were enrolled and randomized to receive either letrozole 2.5 mg and palbociclib 125 mg daily for 3 out of every 4 weeks over 19 weeks, or three cycles of FEC 100, followed by three cycles of docetaxel 100 mg/m2 every 3 weeks, followed by surgery.

An interim analysis was planned after 30 patients were evaluable for RCB in the experimental arm, and, as prespecified, the trial was stopped for futility when fewer than five patients had an RCB of 0 or I.

The safety analysis, conducted with all 106 patients randomized, showed that letrozole/palbocilib was associated with more frequent grade 3 neutropenia (23% vs. 10% of patients with FEC), but less grade 4 neutropenia (1% vs. 11%, respectively), and no febrile neutropenia vs. 6% in the chemotherapy arm.

There were 2 serious adverse events with the AI/CDK-inhibitor combination vs. 17 with chemotherapy. Dose reductions or interruptions were less frequent with letrozole/palbociclib (10 and 16), and only two patients in the experimental arm required premature cessation of therapy vs. seven in the chemotherapy arm.

The final response analysis in 103 patients showed that the rate of RCB 0 or I was 7.7% with letrozole/palbociclib and 15.7% with chemotherapy. Respective rates of RCB II-III were 92.3% and 84.3%.

Clinical response rates were similar in each study arm, with approximately 30% complete responses and 44% partial responses.

In each arm, slightly less than one-third of patients underwent mastectomy, and a little more than two-thirds were able to have breast-conserving surgery after neoadjuvant therapy.

The patients will be followed out to at least 3 years to see whether those patients in the letrozole/palbociclib arm who turned down subsequent chemotherapy will have worse survival than patients who decided to undergo it, Dr. Cottu said.

Invited discussant Nadia Harbeck, MD, PhD, of the University of Munich called the NeoPAL trial “a very daring study.”

“This is not a practice-changing trial, but it’s a very, very interesting hypothesis-generating trial,” she said.

She said that the choice of RCB was probably not the best endpoint in a trial of endocrine-based therapy vs. chemotherapy.

“I think the challenge remains to identify those patients with luminal early breast cancer for whom an endocrine-based approach – not endocrine, but endocrine-based – will improve outcome, either replacing chemotherapy in the intermediate-risk setting or as an add-on in high-risk disease,” she said.

The study was funded by Pfizer and Nanostring. Dr. Cottu disclosed advisory board participation and travel support from Pfizer and others, and research support from Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Harbeck disclosed advising and consulting fees from Pfizer, Nanostring, and other companies.

AT ESMO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: One patient (3.3%) assigned to letrozole/palbociclib had a residual cancer burden score of 0 or I, compared with three patients (10%) assigned to chemotherapy.

Data source: Interim analysis of a phase 2 parallel group trial with 60 patients evaluable for response and 106 evaluable for safety.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Pfizer and Nanostring. Dr. Cottu disclosed advisory board participation and travel support from Pfizer and others and research support from Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Harbeck disclosed advising and consulting fees from Pfizer, Nanostring, and other companies.

Picosecond lasers emerging as a go-to for tattoo removal

SAN DIEGO – When counseling patients about laser tattoo removal, resist the temptation to promise clearance in a certain number of treatments.

“You will regret it,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “If you say, ‘This looks like this is going to take 6-8 treatments, this looks very simple to me,’ you’ll find that you’ll have someone who requires 15-18 treatments. Further, partial clearing may be cosmetically inferior than nontreatment.”

“These target the microscopic tattoo particles located inside dermal phagocytic cells and scattered extracellularly throughout the dermis,” Dr. Avram explained. The Q-switched laser heats particles to more than 1,000º C within nanoseconds, or billionths of a second. “It produces extreme heat, cavitation, and cell rupture,” he said. “The clinical endpoint is immediate epidermal whitening of tattooed skin.” The process causes transdermal elimination; some of it flows into the lymphatic system, while the rest undergoes rephagocytosis by dermal scavenger cells.

Picosecond lasers are even faster than their Q-switched counterparts, delivering high energies in trillionths of a second. “A picosecond is to a second as 1 second is to 37,000 years,” Dr. Avram said. Commercially available picosecond (ps) lasers include devices with wavelengths of 532 nm, 755 nm, and 1,064 nm that deliver energy in a range of 300-750 ps. The Nd:YAG lasers work best for red and black ink, while Alexandrite lasers work best for green and blue ink.

In Dr. Avram’s experience, ps lasers are generally more effective for tattoo removal, compared with nanosecond lasers. “There’s some nonselective targeting of other pigments, and they’re particularly effective for faded tattoos,” he said. “Combining nanosecond and picosecond devices provides enhanced results, but picosecond lasers are more expensive.”

The clinical endpoint for ps lasers is the same as for nanosecond lasers: epidermal whitening. He said he schedules about 8 weeks between treatments. “If you don’t inform patients of the expectations, they’re going to be very disappointed with you,” Dr. Avram said. “You need to tell them that it’s going to take a lot of treatments and that it may not clear completely. You may be working with them for a year or 2.”

The checklist prior to the first treatment with any laser involves assessing the type of tattoo (amateur or professional), the color of the tattoo, patient skin type, and the duration of the tattoo. “You also want to palpate for an existing scar,” he said. “A lot of times, patients don’t recognize they have a scar on the treatment site. You don’t want to own a complication that has nothing to do with your treatments. Photographing the scar is also important.”

Hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation is a greater concern in darker skin types or tanned individuals, compared with fairer-skinned patients. “The 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser is the least likely to affect skin pigment,” said Dr. Avram, who is codirector of the Massachusetts General Hospital/Wellman Laser and Cosmetic Fellowship. “It’s safest for Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI but it’s not very effective for green, blue, and red tattoo ink colors. Some degree of dyspigmentation occurs in most patients regardless of skin type. Much of this is temporary and improves with time, but it may take months to years.”

Professional tattoos are the most difficult to treat because they often feature dense and deeply placed tattoo ink and require 6-20 or more treatments to improve, he said. On the other hand, amateur tattoos, traumatic tattoos, and radiation tattoos improve more rapidly and generally require fewer treatment to yield improvement.

“Color is key,” Dr. Avram said. “If you have different colors in one tattoo, it is going to be more difficult to clear.” Black and dark-blue tattoos respond best to laser, while light blue and green also respond well. Red responds well, but purple can be challenging. “Yellow and orange do not respond well, but they respond partially,” he said.

Researchers who conducted a large cohort trial of variables influencing the outcome of tattoos treated by Q-switched lasers found that 47% of tattoos were cleared after 10 treatment sessions, while 75% were cleared after 15 sessions (Arch Dermatol. 2012;148[12]:1364-9). Predictors of poor response included smoking, the presence of colors other than black and red, tattoo size larger than 30 cm2, location on the feet or legs, duration greater than 36 months, high color density, and treatment intervals of 8 weeks or less.

Dr. Avram cautioned against taking a “cookbook” approach to treating tattoos and underscored the importance of decreasing the fluence if tissue “splatter” occurs, as this may produce scarring. “The treating clinician should follow the treatment endpoint, not the laser fluences,” he said. “Do not use IPL [intense pulsed light therapy] for tattoos; that’s inappropriate and you may end up scarring your patient.”

Common adverse effects include erythema, blistering, hyper- and hypopigmentation, and scarring. Less common adverse effects include an allergic reaction, darkening of the cosmetic tattoo, an immune reaction, and chrysiasis, a dark-blue pigmentation caused by Q-switched laser treatment in patients with a history of gold-salt ingestion. “Any history of gold ingestion will produce this finding, even if they ingested 40 years ago,” he said. “This is very difficult to correct.”

The optimal interval between treatments continues to be explored. For example, the R20 method consists of four treatments separated by 20 minutes. The initial study found that this approach led to better outcomes, compared with conventional, single-pass laser treatment (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66[2]:271-7). A companion technology that is playing a role in such repeat treatments is a Food and Drug Administration–approved transparent silicone patch infused with perfluorodecalin that helps reduce scattering and improves efficacy.

“It also allows for performing consecutive repeat laser treatments at the same visit,” Dr. Avram said. In one study, 11 of 17 patients had more rapid clearance on the side treated with the perfluorodecalin patch, compared with the side that was treated without the patch (Laser Surg Med. 2015;47[8]:613-8).

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea.

[email protected]

SAN DIEGO – When counseling patients about laser tattoo removal, resist the temptation to promise clearance in a certain number of treatments.

“You will regret it,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “If you say, ‘This looks like this is going to take 6-8 treatments, this looks very simple to me,’ you’ll find that you’ll have someone who requires 15-18 treatments. Further, partial clearing may be cosmetically inferior than nontreatment.”

“These target the microscopic tattoo particles located inside dermal phagocytic cells and scattered extracellularly throughout the dermis,” Dr. Avram explained. The Q-switched laser heats particles to more than 1,000º C within nanoseconds, or billionths of a second. “It produces extreme heat, cavitation, and cell rupture,” he said. “The clinical endpoint is immediate epidermal whitening of tattooed skin.” The process causes transdermal elimination; some of it flows into the lymphatic system, while the rest undergoes rephagocytosis by dermal scavenger cells.

Picosecond lasers are even faster than their Q-switched counterparts, delivering high energies in trillionths of a second. “A picosecond is to a second as 1 second is to 37,000 years,” Dr. Avram said. Commercially available picosecond (ps) lasers include devices with wavelengths of 532 nm, 755 nm, and 1,064 nm that deliver energy in a range of 300-750 ps. The Nd:YAG lasers work best for red and black ink, while Alexandrite lasers work best for green and blue ink.

In Dr. Avram’s experience, ps lasers are generally more effective for tattoo removal, compared with nanosecond lasers. “There’s some nonselective targeting of other pigments, and they’re particularly effective for faded tattoos,” he said. “Combining nanosecond and picosecond devices provides enhanced results, but picosecond lasers are more expensive.”

The clinical endpoint for ps lasers is the same as for nanosecond lasers: epidermal whitening. He said he schedules about 8 weeks between treatments. “If you don’t inform patients of the expectations, they’re going to be very disappointed with you,” Dr. Avram said. “You need to tell them that it’s going to take a lot of treatments and that it may not clear completely. You may be working with them for a year or 2.”

The checklist prior to the first treatment with any laser involves assessing the type of tattoo (amateur or professional), the color of the tattoo, patient skin type, and the duration of the tattoo. “You also want to palpate for an existing scar,” he said. “A lot of times, patients don’t recognize they have a scar on the treatment site. You don’t want to own a complication that has nothing to do with your treatments. Photographing the scar is also important.”

Hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation is a greater concern in darker skin types or tanned individuals, compared with fairer-skinned patients. “The 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser is the least likely to affect skin pigment,” said Dr. Avram, who is codirector of the Massachusetts General Hospital/Wellman Laser and Cosmetic Fellowship. “It’s safest for Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI but it’s not very effective for green, blue, and red tattoo ink colors. Some degree of dyspigmentation occurs in most patients regardless of skin type. Much of this is temporary and improves with time, but it may take months to years.”

Professional tattoos are the most difficult to treat because they often feature dense and deeply placed tattoo ink and require 6-20 or more treatments to improve, he said. On the other hand, amateur tattoos, traumatic tattoos, and radiation tattoos improve more rapidly and generally require fewer treatment to yield improvement.

“Color is key,” Dr. Avram said. “If you have different colors in one tattoo, it is going to be more difficult to clear.” Black and dark-blue tattoos respond best to laser, while light blue and green also respond well. Red responds well, but purple can be challenging. “Yellow and orange do not respond well, but they respond partially,” he said.

Researchers who conducted a large cohort trial of variables influencing the outcome of tattoos treated by Q-switched lasers found that 47% of tattoos were cleared after 10 treatment sessions, while 75% were cleared after 15 sessions (Arch Dermatol. 2012;148[12]:1364-9). Predictors of poor response included smoking, the presence of colors other than black and red, tattoo size larger than 30 cm2, location on the feet or legs, duration greater than 36 months, high color density, and treatment intervals of 8 weeks or less.

Dr. Avram cautioned against taking a “cookbook” approach to treating tattoos and underscored the importance of decreasing the fluence if tissue “splatter” occurs, as this may produce scarring. “The treating clinician should follow the treatment endpoint, not the laser fluences,” he said. “Do not use IPL [intense pulsed light therapy] for tattoos; that’s inappropriate and you may end up scarring your patient.”

Common adverse effects include erythema, blistering, hyper- and hypopigmentation, and scarring. Less common adverse effects include an allergic reaction, darkening of the cosmetic tattoo, an immune reaction, and chrysiasis, a dark-blue pigmentation caused by Q-switched laser treatment in patients with a history of gold-salt ingestion. “Any history of gold ingestion will produce this finding, even if they ingested 40 years ago,” he said. “This is very difficult to correct.”

The optimal interval between treatments continues to be explored. For example, the R20 method consists of four treatments separated by 20 minutes. The initial study found that this approach led to better outcomes, compared with conventional, single-pass laser treatment (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66[2]:271-7). A companion technology that is playing a role in such repeat treatments is a Food and Drug Administration–approved transparent silicone patch infused with perfluorodecalin that helps reduce scattering and improves efficacy.

“It also allows for performing consecutive repeat laser treatments at the same visit,” Dr. Avram said. In one study, 11 of 17 patients had more rapid clearance on the side treated with the perfluorodecalin patch, compared with the side that was treated without the patch (Laser Surg Med. 2015;47[8]:613-8).

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea.

[email protected]

SAN DIEGO – When counseling patients about laser tattoo removal, resist the temptation to promise clearance in a certain number of treatments.

“You will regret it,” Mathew M. Avram, MD, JD, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “If you say, ‘This looks like this is going to take 6-8 treatments, this looks very simple to me,’ you’ll find that you’ll have someone who requires 15-18 treatments. Further, partial clearing may be cosmetically inferior than nontreatment.”

“These target the microscopic tattoo particles located inside dermal phagocytic cells and scattered extracellularly throughout the dermis,” Dr. Avram explained. The Q-switched laser heats particles to more than 1,000º C within nanoseconds, or billionths of a second. “It produces extreme heat, cavitation, and cell rupture,” he said. “The clinical endpoint is immediate epidermal whitening of tattooed skin.” The process causes transdermal elimination; some of it flows into the lymphatic system, while the rest undergoes rephagocytosis by dermal scavenger cells.

Picosecond lasers are even faster than their Q-switched counterparts, delivering high energies in trillionths of a second. “A picosecond is to a second as 1 second is to 37,000 years,” Dr. Avram said. Commercially available picosecond (ps) lasers include devices with wavelengths of 532 nm, 755 nm, and 1,064 nm that deliver energy in a range of 300-750 ps. The Nd:YAG lasers work best for red and black ink, while Alexandrite lasers work best for green and blue ink.

In Dr. Avram’s experience, ps lasers are generally more effective for tattoo removal, compared with nanosecond lasers. “There’s some nonselective targeting of other pigments, and they’re particularly effective for faded tattoos,” he said. “Combining nanosecond and picosecond devices provides enhanced results, but picosecond lasers are more expensive.”

The clinical endpoint for ps lasers is the same as for nanosecond lasers: epidermal whitening. He said he schedules about 8 weeks between treatments. “If you don’t inform patients of the expectations, they’re going to be very disappointed with you,” Dr. Avram said. “You need to tell them that it’s going to take a lot of treatments and that it may not clear completely. You may be working with them for a year or 2.”

The checklist prior to the first treatment with any laser involves assessing the type of tattoo (amateur or professional), the color of the tattoo, patient skin type, and the duration of the tattoo. “You also want to palpate for an existing scar,” he said. “A lot of times, patients don’t recognize they have a scar on the treatment site. You don’t want to own a complication that has nothing to do with your treatments. Photographing the scar is also important.”

Hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation is a greater concern in darker skin types or tanned individuals, compared with fairer-skinned patients. “The 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser is the least likely to affect skin pigment,” said Dr. Avram, who is codirector of the Massachusetts General Hospital/Wellman Laser and Cosmetic Fellowship. “It’s safest for Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI but it’s not very effective for green, blue, and red tattoo ink colors. Some degree of dyspigmentation occurs in most patients regardless of skin type. Much of this is temporary and improves with time, but it may take months to years.”

Professional tattoos are the most difficult to treat because they often feature dense and deeply placed tattoo ink and require 6-20 or more treatments to improve, he said. On the other hand, amateur tattoos, traumatic tattoos, and radiation tattoos improve more rapidly and generally require fewer treatment to yield improvement.

“Color is key,” Dr. Avram said. “If you have different colors in one tattoo, it is going to be more difficult to clear.” Black and dark-blue tattoos respond best to laser, while light blue and green also respond well. Red responds well, but purple can be challenging. “Yellow and orange do not respond well, but they respond partially,” he said.

Researchers who conducted a large cohort trial of variables influencing the outcome of tattoos treated by Q-switched lasers found that 47% of tattoos were cleared after 10 treatment sessions, while 75% were cleared after 15 sessions (Arch Dermatol. 2012;148[12]:1364-9). Predictors of poor response included smoking, the presence of colors other than black and red, tattoo size larger than 30 cm2, location on the feet or legs, duration greater than 36 months, high color density, and treatment intervals of 8 weeks or less.

Dr. Avram cautioned against taking a “cookbook” approach to treating tattoos and underscored the importance of decreasing the fluence if tissue “splatter” occurs, as this may produce scarring. “The treating clinician should follow the treatment endpoint, not the laser fluences,” he said. “Do not use IPL [intense pulsed light therapy] for tattoos; that’s inappropriate and you may end up scarring your patient.”

Common adverse effects include erythema, blistering, hyper- and hypopigmentation, and scarring. Less common adverse effects include an allergic reaction, darkening of the cosmetic tattoo, an immune reaction, and chrysiasis, a dark-blue pigmentation caused by Q-switched laser treatment in patients with a history of gold-salt ingestion. “Any history of gold ingestion will produce this finding, even if they ingested 40 years ago,” he said. “This is very difficult to correct.”

The optimal interval between treatments continues to be explored. For example, the R20 method consists of four treatments separated by 20 minutes. The initial study found that this approach led to better outcomes, compared with conventional, single-pass laser treatment (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66[2]:271-7). A companion technology that is playing a role in such repeat treatments is a Food and Drug Administration–approved transparent silicone patch infused with perfluorodecalin that helps reduce scattering and improves efficacy.

“It also allows for performing consecutive repeat laser treatments at the same visit,” Dr. Avram said. In one study, 11 of 17 patients had more rapid clearance on the side treated with the perfluorodecalin patch, compared with the side that was treated without the patch (Laser Surg Med. 2015;47[8]:613-8).

Dr. Avram disclosed that he has received consulting fees from Allergan, Merz, Sciton, Soliton, and Zalea. He also reported having ownership and/or shareholder interest in Cytrellis, Invasix, and Zalea.

[email protected]

AT MOAS 2017

RAS derangement linked to CVD risk in adolescents born preterm

SAN FRANCISCO – The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is out of balance in adolescents born prematurely, according to investigators from Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C.

Among other findings, the amount of circulating angiotensin 1-7, a vasodilator that counteracts the vasoconstrictive and other effects of angiotensin II, was lower relative to angiotensin II in 175 subjects born preterm and assessed at age 14 years, compared with 51 controls born at term.

The findings suggest a possible explanation for why people born prematurely have an increased risk for hypertension and cardiovascular disease, which has been a mystery. If the findings pan out with additional research, they also suggest potential therapeutic targets to attenuate the risk, namely upregulating angiotensin 1-7 and blocking angiotensin II, either at birth or later.

“If you could give medications to shift the balance in the RAS back to what it should be, then maybe you could prevent some of the changes that we see at age 14. With the current treatments, that’s difficult; ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers are (generally) not used in the neonatal period because they can precipitate acute kidney injury.” For older patients, “there’s no indication to use these medications in a subtle situation like we have here,” Dr. South said in an interview at a hypertension science meeting jointly sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension.

The direct manipulation of angiotensin 1-7 remains, for now, largely in the realm of clinical research.

The preterm subjects had lower plasma angiotensin II and lower angiotensin 1-7 concentrations, compared with their term peers, but an overall increase in the angiotensin II/angiotensin 1-7 ratio (4.2 vs. 2.4). Preterm subjects also had increased urinary excretion of angiotensin 1-7. The findings were statistically significant, and adjusted for potential confounders.

The differences were exaggerated in obese subjects, about a third in both groups. Obesity is known to be associated with increased angiotensin II activity.

The drop in angiotensin 1-7 was greater in preterm girls than in boys, which was curious because female sex is normally associated with decreased angiotensin II activity, and estrogen normally upregulates angiotensin 1-7; perhaps in prematurity, there’s a breakdown in the normal response to estrogen, Dr. South said.

Whatever the case, it’s possible the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease from preterm birth might be especially high in obese patients and women, he said.

The preterm group had a mean gestational age of 28 weeks, and a mean birth weight of 1.1 kg. The term group was born at a mean of 40 weeks, with a mean birth weight of 3.5 kg. At age 14 years, preterm subjects were shorter and weighed less than their peers.

Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures were higher in the preterm group, and 21 preterm subjects (12%) had blood pressures at or above 120/80 mm Hg, vs. one subject (2%) in the term group.

Maternal hypertension and smoking during pregnancy, and C-section delivery, were far more common in the preterm group, as was Medicaid use at age 14 years. There were slightly more girls than boys in both groups, and just over 40% of the subjects in each were black.

The Wake Forest team continues to follow their preterm subjects, who are now in their mid-twenties. “If we can correlate what we found at age 14 with” early development of disease, “it will give us more of an indication that this is actually true causation, not just an association,” Dr. South said.

The investigators had no industry disclosures. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

[email protected]

SAN FRANCISCO – The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is out of balance in adolescents born prematurely, according to investigators from Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C.

Among other findings, the amount of circulating angiotensin 1-7, a vasodilator that counteracts the vasoconstrictive and other effects of angiotensin II, was lower relative to angiotensin II in 175 subjects born preterm and assessed at age 14 years, compared with 51 controls born at term.

The findings suggest a possible explanation for why people born prematurely have an increased risk for hypertension and cardiovascular disease, which has been a mystery. If the findings pan out with additional research, they also suggest potential therapeutic targets to attenuate the risk, namely upregulating angiotensin 1-7 and blocking angiotensin II, either at birth or later.

“If you could give medications to shift the balance in the RAS back to what it should be, then maybe you could prevent some of the changes that we see at age 14. With the current treatments, that’s difficult; ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers are (generally) not used in the neonatal period because they can precipitate acute kidney injury.” For older patients, “there’s no indication to use these medications in a subtle situation like we have here,” Dr. South said in an interview at a hypertension science meeting jointly sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension.

The direct manipulation of angiotensin 1-7 remains, for now, largely in the realm of clinical research.

The preterm subjects had lower plasma angiotensin II and lower angiotensin 1-7 concentrations, compared with their term peers, but an overall increase in the angiotensin II/angiotensin 1-7 ratio (4.2 vs. 2.4). Preterm subjects also had increased urinary excretion of angiotensin 1-7. The findings were statistically significant, and adjusted for potential confounders.

The differences were exaggerated in obese subjects, about a third in both groups. Obesity is known to be associated with increased angiotensin II activity.

The drop in angiotensin 1-7 was greater in preterm girls than in boys, which was curious because female sex is normally associated with decreased angiotensin II activity, and estrogen normally upregulates angiotensin 1-7; perhaps in prematurity, there’s a breakdown in the normal response to estrogen, Dr. South said.

Whatever the case, it’s possible the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease from preterm birth might be especially high in obese patients and women, he said.

The preterm group had a mean gestational age of 28 weeks, and a mean birth weight of 1.1 kg. The term group was born at a mean of 40 weeks, with a mean birth weight of 3.5 kg. At age 14 years, preterm subjects were shorter and weighed less than their peers.

Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures were higher in the preterm group, and 21 preterm subjects (12%) had blood pressures at or above 120/80 mm Hg, vs. one subject (2%) in the term group.

Maternal hypertension and smoking during pregnancy, and C-section delivery, were far more common in the preterm group, as was Medicaid use at age 14 years. There were slightly more girls than boys in both groups, and just over 40% of the subjects in each were black.

The Wake Forest team continues to follow their preterm subjects, who are now in their mid-twenties. “If we can correlate what we found at age 14 with” early development of disease, “it will give us more of an indication that this is actually true causation, not just an association,” Dr. South said.

The investigators had no industry disclosures. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

[email protected]

SAN FRANCISCO – The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is out of balance in adolescents born prematurely, according to investigators from Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, N.C.

Among other findings, the amount of circulating angiotensin 1-7, a vasodilator that counteracts the vasoconstrictive and other effects of angiotensin II, was lower relative to angiotensin II in 175 subjects born preterm and assessed at age 14 years, compared with 51 controls born at term.

The findings suggest a possible explanation for why people born prematurely have an increased risk for hypertension and cardiovascular disease, which has been a mystery. If the findings pan out with additional research, they also suggest potential therapeutic targets to attenuate the risk, namely upregulating angiotensin 1-7 and blocking angiotensin II, either at birth or later.

“If you could give medications to shift the balance in the RAS back to what it should be, then maybe you could prevent some of the changes that we see at age 14. With the current treatments, that’s difficult; ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers are (generally) not used in the neonatal period because they can precipitate acute kidney injury.” For older patients, “there’s no indication to use these medications in a subtle situation like we have here,” Dr. South said in an interview at a hypertension science meeting jointly sponsored by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Hypertension.

The direct manipulation of angiotensin 1-7 remains, for now, largely in the realm of clinical research.

The preterm subjects had lower plasma angiotensin II and lower angiotensin 1-7 concentrations, compared with their term peers, but an overall increase in the angiotensin II/angiotensin 1-7 ratio (4.2 vs. 2.4). Preterm subjects also had increased urinary excretion of angiotensin 1-7. The findings were statistically significant, and adjusted for potential confounders.

The differences were exaggerated in obese subjects, about a third in both groups. Obesity is known to be associated with increased angiotensin II activity.

The drop in angiotensin 1-7 was greater in preterm girls than in boys, which was curious because female sex is normally associated with decreased angiotensin II activity, and estrogen normally upregulates angiotensin 1-7; perhaps in prematurity, there’s a breakdown in the normal response to estrogen, Dr. South said.

Whatever the case, it’s possible the risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease from preterm birth might be especially high in obese patients and women, he said.

The preterm group had a mean gestational age of 28 weeks, and a mean birth weight of 1.1 kg. The term group was born at a mean of 40 weeks, with a mean birth weight of 3.5 kg. At age 14 years, preterm subjects were shorter and weighed less than their peers.

Mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures were higher in the preterm group, and 21 preterm subjects (12%) had blood pressures at or above 120/80 mm Hg, vs. one subject (2%) in the term group.

Maternal hypertension and smoking during pregnancy, and C-section delivery, were far more common in the preterm group, as was Medicaid use at age 14 years. There were slightly more girls than boys in both groups, and just over 40% of the subjects in each were black.

The Wake Forest team continues to follow their preterm subjects, who are now in their mid-twenties. “If we can correlate what we found at age 14 with” early development of disease, “it will give us more of an indication that this is actually true causation, not just an association,” Dr. South said.

The investigators had no industry disclosures. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

[email protected]

AT THE AHA/ASH JOINT SCIENTIFIC HYPERTENSION MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The preterm subjects had lower plasma angiotensin II and lower angiotensin 1-7 concentrations, compared with their term peers, but an overall increase in the angiotensin II/angiotensin 1-7 ratio (4.2 vs. 2.4).

Data source: Comparison of 175 subjects born preterm to 51 controls born at term, assessed at age 14 years.

Disclosures: The investigators had no industry disclosures. The work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health.

Alternative therapies

Alternative therapies, from vitamins and supplements to meditation and acupuncture, have become increasingly popular treatments in the United States for many medical problems in the past few decades. In 2008, the National Institutes of Health reported that nearly 40% of adults and 12% of children had used “complementary or alternative medicine” (CAM) in the preceding year. Other surveys have suggested that closer to 30% of general pediatric patients and as many as 75% of adolescent patients have used CAM at least once. These treatments are especially popular for chronic conditions that are managed but not usually cured with current evidence-based treatments. Psychiatric conditions in childhood sometimes have a long course, and have effective but controversial treatments, as with stimulants for ADHD. Parents sometimes feel guilty about their child’s problem and want to use “natural” methods or deny the accepted understanding of their child’s illness. So it is not surprising that families may investigate alternative treatments, and such treatments have multiplied.

While there is evidence that parents and patients rarely discuss these treatments with their physicians, it is critical that you know what therapies your patients are using. You should focus on tolerance in the context of protecting the child from harm and improving the child’s functioning. If you have ever recommended chicken soup for a cold, then you have prescribed complementary medicine, so it is not a stretch for you to offer some input about the other alternative therapies your patients may be considering.

It is important to note that rigorous, case-controlled studies of efficacy of most alternative therapies are few in number and usually small in size (so any evidence of efficacy is weaker), and that the products themselves are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration or other public body. This means that the family (and you) will have to do some homework to ensure that the therapy they purchase comes from a reputable source and is what it purports to be.

Many of the alternative therapies patients are investigating will be herbs or supplements. Omega-3 fatty acids are critical to multiple essential body functions, and are taken in primarily via certain foods, primarily fish and certain seeds and nuts. A deficiency in certain omega-3 fatty acids can cause problems in infant neurological development and put one at risk for heart disease, rheumatologic illness, and depression. Supplementation with Omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] and docosahexaenoic acid [DHA], specifically) has a solid evidence base as an effective adjunctive treatment for depression and bipolar disorder in adults. In addition, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies have demonstrated efficacy in treatment of children with mild to moderate ADHD at doses of 1,200 mg/day. There are some studies that have demonstrated improvement in hyperactivity in children with autism with supplementation at similar doses. These supplements have very low risk of side effects. They are a reasonable recommendation to your patients whose children have mild to moderate ADHD, and they want to manage it without stimulants.

Families also may be considering physical or mechanical treatments. Acupuncture has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of fatigue and pain, migraines, and addiction, although there are very few studies in children and adolescents. There is some evidence for its efficacy in treatment of mild to moderate depression and anxiety in adults, but again no research has been done in youth. Hypnotherapy has shown modest efficacy in treatment of anticipatory anxiety symptoms, headache, chronic pain, nausea and vomiting, migraines, hair-pulling and skin picking as well as compulsive eating and smoking cessation in adults. There is some clinical evidence for its efficacy in children and adolescents, and its safety is well established. Massage therapy has shown value in improving mood and behavior in children with ADHD, but not efficacy as a first-line treatment for ADHD symptoms. Chiropractic care, which is among the most commonly used alternative therapies, claims to be effective for the treatment of anxiety, depression, ADHD, behavioral problems of autism and even schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, but there is no significant scientific evidence to support these claims. And neurofeedback, which is a variant of biofeedback in which patients practice calming themselves or improving focus while watching an EEG has shown modest efficacy in the treatment of ADHD in children in early studies. It is worth noting that all of these therapies may be costly and not covered by insurance.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

Additional readings

1. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013 Jul;22(3):375-80.

2. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(4):364-8.

3. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(10):991-1000.

4. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014 Jun; 53(6):658-66.

5. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;55(10):S168-9.

Alternative therapies, from vitamins and supplements to meditation and acupuncture, have become increasingly popular treatments in the United States for many medical problems in the past few decades. In 2008, the National Institutes of Health reported that nearly 40% of adults and 12% of children had used “complementary or alternative medicine” (CAM) in the preceding year. Other surveys have suggested that closer to 30% of general pediatric patients and as many as 75% of adolescent patients have used CAM at least once. These treatments are especially popular for chronic conditions that are managed but not usually cured with current evidence-based treatments. Psychiatric conditions in childhood sometimes have a long course, and have effective but controversial treatments, as with stimulants for ADHD. Parents sometimes feel guilty about their child’s problem and want to use “natural” methods or deny the accepted understanding of their child’s illness. So it is not surprising that families may investigate alternative treatments, and such treatments have multiplied.

While there is evidence that parents and patients rarely discuss these treatments with their physicians, it is critical that you know what therapies your patients are using. You should focus on tolerance in the context of protecting the child from harm and improving the child’s functioning. If you have ever recommended chicken soup for a cold, then you have prescribed complementary medicine, so it is not a stretch for you to offer some input about the other alternative therapies your patients may be considering.

It is important to note that rigorous, case-controlled studies of efficacy of most alternative therapies are few in number and usually small in size (so any evidence of efficacy is weaker), and that the products themselves are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration or other public body. This means that the family (and you) will have to do some homework to ensure that the therapy they purchase comes from a reputable source and is what it purports to be.

Many of the alternative therapies patients are investigating will be herbs or supplements. Omega-3 fatty acids are critical to multiple essential body functions, and are taken in primarily via certain foods, primarily fish and certain seeds and nuts. A deficiency in certain omega-3 fatty acids can cause problems in infant neurological development and put one at risk for heart disease, rheumatologic illness, and depression. Supplementation with Omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid [EPA] and docosahexaenoic acid [DHA], specifically) has a solid evidence base as an effective adjunctive treatment for depression and bipolar disorder in adults. In addition, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies have demonstrated efficacy in treatment of children with mild to moderate ADHD at doses of 1,200 mg/day. There are some studies that have demonstrated improvement in hyperactivity in children with autism with supplementation at similar doses. These supplements have very low risk of side effects. They are a reasonable recommendation to your patients whose children have mild to moderate ADHD, and they want to manage it without stimulants.

Families also may be considering physical or mechanical treatments. Acupuncture has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of fatigue and pain, migraines, and addiction, although there are very few studies in children and adolescents. There is some evidence for its efficacy in treatment of mild to moderate depression and anxiety in adults, but again no research has been done in youth. Hypnotherapy has shown modest efficacy in treatment of anticipatory anxiety symptoms, headache, chronic pain, nausea and vomiting, migraines, hair-pulling and skin picking as well as compulsive eating and smoking cessation in adults. There is some clinical evidence for its efficacy in children and adolescents, and its safety is well established. Massage therapy has shown value in improving mood and behavior in children with ADHD, but not efficacy as a first-line treatment for ADHD symptoms. Chiropractic care, which is among the most commonly used alternative therapies, claims to be effective for the treatment of anxiety, depression, ADHD, behavioral problems of autism and even schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, but there is no significant scientific evidence to support these claims. And neurofeedback, which is a variant of biofeedback in which patients practice calming themselves or improving focus while watching an EEG has shown modest efficacy in the treatment of ADHD in children in early studies. It is worth noting that all of these therapies may be costly and not covered by insurance.

Dr. Swick is an attending psychiatrist in the division of child psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and director of the Parenting at a Challenging Time (PACT) Program at the Vernon Cancer Center at Newton Wellesley Hospital, also in Boston. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

Additional readings

1. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2013 Jul;22(3):375-80.

2. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(4):364-8.

3. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(10):991-1000.

4. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014 Jun; 53(6):658-66.

5. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;55(10):S168-9.

Alternative therapies, from vitamins and supplements to meditation and acupuncture, have become increasingly popular treatments in the United States for many medical problems in the past few decades. In 2008, the National Institutes of Health reported that nearly 40% of adults and 12% of children had used “complementary or alternative medicine” (CAM) in the preceding year. Other surveys have suggested that closer to 30% of general pediatric patients and as many as 75% of adolescent patients have used CAM at least once. These treatments are especially popular for chronic conditions that are managed but not usually cured with current evidence-based treatments. Psychiatric conditions in childhood sometimes have a long course, and have effective but controversial treatments, as with stimulants for ADHD. Parents sometimes feel guilty about their child’s problem and want to use “natural” methods or deny the accepted understanding of their child’s illness. So it is not surprising that families may investigate alternative treatments, and such treatments have multiplied.

While there is evidence that parents and patients rarely discuss these treatments with their physicians, it is critical that you know what therapies your patients are using. You should focus on tolerance in the context of protecting the child from harm and improving the child’s functioning. If you have ever recommended chicken soup for a cold, then you have prescribed complementary medicine, so it is not a stretch for you to offer some input about the other alternative therapies your patients may be considering.