User login

Targeted strategies better for birth cohort HCV testing

Targeted birth cohort testing for the hepatitis C virus is effective at identifying infections in primary care, particularly if a strategy of repeated mailings is used to reach out to patients about testing, according to new research.

Writing in the Sept. 23 online edition of Hepatology, researchers reported the results of three independent, randomized, controlled trials in three large academic primary care medical centers, each of which compared a different method of testing the 1945-1965 birth cohort – as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force – with usual care (2017. doi: 10.1002/hep.29548).

The results revealed a significant, eightfold greater likelihood of diagnosing hepatitis C in the intervention arm, compared with the control arm, with a 0.27% adjusted probability of a positive test in the intervention arm, compared with a 0.03% probability in the control arm.

The second center investigated a strategy of electronic medical record–integrated “Best Practice Alerts” that first targeted the medical assistant and then automatically implemented an order for testing to be included in the physician’s list of orders, including information about birth cohort testing recommendations.

“Targeting the medical assistant with the BPA first was designed to address alert fatigue commonly reported in studies of EMR-embedded alerts,” wrote Anthony K. Yartel, MPH, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his coauthors in their report about these studies.

This cluster-randomized trial, which included 14,475 eligible patients, found the intervention was 2.6 times more likely to identify patients with anti-HCV antibodies, compared with a control approach of usual care (95% confidence interval, 1.1-6.4). The adjusted probability of picking up a positive infection was 0.29% in the intervention arm compared to 0.11% in the usual care arm.

In the third center, 8,873 patients across four clinics participated in a cluster-randomized, cluster-crossover trial that compared a strategy of direct solicitation of eligible patients after an outpatient visit with a control strategy of usual care.

This approach achieved a fivefold higher rate of hepatitis C diagnoses than the control arm (95% CI, 2.3-12.3). The adjusted probability of a diagnosis was 0.68% in the intervention arm and 0.13% in the usual care arm.

“A key rationale for BC [birth cohort] testing is the premise that usual care is ineffective in identifying HCV infections since nearly half of adults (including those born in 1945-1965) do not report exposure to risk factors,” the authors wrote. “Our results are consistent with this rationale and bolster current public health recommendations for targeted HCV testing among persons born during 1945-1965.”

This study was funded by the CDC Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Targeted birth cohort testing for the hepatitis C virus is effective at identifying infections in primary care, particularly if a strategy of repeated mailings is used to reach out to patients about testing, according to new research.

Writing in the Sept. 23 online edition of Hepatology, researchers reported the results of three independent, randomized, controlled trials in three large academic primary care medical centers, each of which compared a different method of testing the 1945-1965 birth cohort – as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force – with usual care (2017. doi: 10.1002/hep.29548).

The results revealed a significant, eightfold greater likelihood of diagnosing hepatitis C in the intervention arm, compared with the control arm, with a 0.27% adjusted probability of a positive test in the intervention arm, compared with a 0.03% probability in the control arm.

The second center investigated a strategy of electronic medical record–integrated “Best Practice Alerts” that first targeted the medical assistant and then automatically implemented an order for testing to be included in the physician’s list of orders, including information about birth cohort testing recommendations.

“Targeting the medical assistant with the BPA first was designed to address alert fatigue commonly reported in studies of EMR-embedded alerts,” wrote Anthony K. Yartel, MPH, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his coauthors in their report about these studies.

This cluster-randomized trial, which included 14,475 eligible patients, found the intervention was 2.6 times more likely to identify patients with anti-HCV antibodies, compared with a control approach of usual care (95% confidence interval, 1.1-6.4). The adjusted probability of picking up a positive infection was 0.29% in the intervention arm compared to 0.11% in the usual care arm.

In the third center, 8,873 patients across four clinics participated in a cluster-randomized, cluster-crossover trial that compared a strategy of direct solicitation of eligible patients after an outpatient visit with a control strategy of usual care.

This approach achieved a fivefold higher rate of hepatitis C diagnoses than the control arm (95% CI, 2.3-12.3). The adjusted probability of a diagnosis was 0.68% in the intervention arm and 0.13% in the usual care arm.

“A key rationale for BC [birth cohort] testing is the premise that usual care is ineffective in identifying HCV infections since nearly half of adults (including those born in 1945-1965) do not report exposure to risk factors,” the authors wrote. “Our results are consistent with this rationale and bolster current public health recommendations for targeted HCV testing among persons born during 1945-1965.”

This study was funded by the CDC Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Targeted birth cohort testing for the hepatitis C virus is effective at identifying infections in primary care, particularly if a strategy of repeated mailings is used to reach out to patients about testing, according to new research.

Writing in the Sept. 23 online edition of Hepatology, researchers reported the results of three independent, randomized, controlled trials in three large academic primary care medical centers, each of which compared a different method of testing the 1945-1965 birth cohort – as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force – with usual care (2017. doi: 10.1002/hep.29548).

The results revealed a significant, eightfold greater likelihood of diagnosing hepatitis C in the intervention arm, compared with the control arm, with a 0.27% adjusted probability of a positive test in the intervention arm, compared with a 0.03% probability in the control arm.

The second center investigated a strategy of electronic medical record–integrated “Best Practice Alerts” that first targeted the medical assistant and then automatically implemented an order for testing to be included in the physician’s list of orders, including information about birth cohort testing recommendations.

“Targeting the medical assistant with the BPA first was designed to address alert fatigue commonly reported in studies of EMR-embedded alerts,” wrote Anthony K. Yartel, MPH, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and his coauthors in their report about these studies.

This cluster-randomized trial, which included 14,475 eligible patients, found the intervention was 2.6 times more likely to identify patients with anti-HCV antibodies, compared with a control approach of usual care (95% confidence interval, 1.1-6.4). The adjusted probability of picking up a positive infection was 0.29% in the intervention arm compared to 0.11% in the usual care arm.

In the third center, 8,873 patients across four clinics participated in a cluster-randomized, cluster-crossover trial that compared a strategy of direct solicitation of eligible patients after an outpatient visit with a control strategy of usual care.

This approach achieved a fivefold higher rate of hepatitis C diagnoses than the control arm (95% CI, 2.3-12.3). The adjusted probability of a diagnosis was 0.68% in the intervention arm and 0.13% in the usual care arm.

“A key rationale for BC [birth cohort] testing is the premise that usual care is ineffective in identifying HCV infections since nearly half of adults (including those born in 1945-1965) do not report exposure to risk factors,” the authors wrote. “Our results are consistent with this rationale and bolster current public health recommendations for targeted HCV testing among persons born during 1945-1965.”

This study was funded by the CDC Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Birth cohort testing for HCV is successful in primary care if targeted strategies are used to identify and recruit eligible patients for testing.

Major finding: Targeted birth cohort testing strategies for hepatitis C, such as repeat mailings and direct solicitation, significantly increase the uptake of testing and identification of positive cases.

Data source: Three independent, randomized, controlled trials of three different targeted birth cohort testing approaches in primary care.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the CDC Foundation. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Intensified approach reduces long-term heart failure risk in T2DM

LISBON – A 70% reduction in the risk of hospitalization for heart failure was achieved in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) given an intensified, multifactorial intervention versus conventional treatment in a long-term follow up of the STENO-2 study.

Over 21 years, 34 (21%) of 160 study subjects developed heart failure; 24 (30%) had initially been treated conventionally, and 10 (13%) had initially received intensive treatment. The annualized rates of heart failure were calculated as a respective 2.4% and 0.8% (hazard ratio, 0.30; P less than .002), Jens Øllgaard, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Furthermore, after adjustment was made for subject age, gender, prohormone brain natriuretic peptide levels, and ejection fraction at recruitment, there was a 76% relative risk reduction in heart failure with the intensified strategy versus conventional treatment.

“Heart failure in diabetes is frequent, fatal, and at least until very recently, quite forgotten,” said Dr. Øllgaard, who presented the research performed while he was at the STENO Diabetes Center in Copenhagen.

Dr. Øllgaard, who now works for Novo Nordisk, noted that heart failure was four times more likely to occur in patients with T2DM who had microalbuminuria than in those with normal albumin levels in the urine, and the median survival was around 3.5 years. While there is no regulatory requirement at present to stipulate that heart failure should be assessed in trials looking at the cardiovascular safety of T2DM treatments, recording such information is something that the STENO-2 investigators would recommend.

STENO-2 was an open, parallel group study initiated in 1993 to compare conventional multifactorial treatment of T2DM with an intensified approach over an 8-year period. After the primary composite cardiovascular endpoint was assessed, the trial continued as an observational study, with all patients given the intensified, multifactorial treatment that consisted of lifestyle measures and medications targeting hyperglycemia, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and hypercoagulation.

The primary endpoint of the long-term follow-up study was the difference in median survival time between the original treatment groups with and without incident cardiovascular disease. The results showed a 48% relative reduction in the risk of death; those initially given the intensified treatment had an increased lifespan of 7.9 years and an 8.1-year increased survival without cardiovascular disease versus those who had initially received conventional treatment (Diabetologica 2016;59:2298-307).

Dr. Øllgaard presented data on heart failure outcomes obtained from a post-hoc analysis of prospectively collected and externally adjudicated patient records.

In addition to the reductions in the primary outcome of time to heart failure, the secondary outcomes of time to heart failure or cardiovascular mortality (HR, 0.38; P = .006) and heart failure or all-cause mortality (relative risk reduction, 49%; P = .001) also favored initial intensive treatment versus conventional treatment.

The number of patients who would need to be treated for 1 year to prevent one heart failure event was 63. The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent heart failure or cardiovascular death was 48, and the NNT or heart failure or all-cause death was 37.

“Intensified, multifactorial intervention reduces the risk of heart failure and underlines the need for early, intensive treatment in these patients,” Dr. Øllgaard said. “Diabetologists should be aware of this increased risk and the early clinical signs and biomarkers of heart failure.” He added the study “also emphasizes the need for close collaboration, locally and globally, between endocrinologists and cardiologists.”

The STENO-2 long-term follow-up analysis was sponsored by an unrestricted grant from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Øllgaard disclosed being employed by Novo Nordisk after the submission of the abstract for presentation at the EASD meeting.

LISBON – A 70% reduction in the risk of hospitalization for heart failure was achieved in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) given an intensified, multifactorial intervention versus conventional treatment in a long-term follow up of the STENO-2 study.

Over 21 years, 34 (21%) of 160 study subjects developed heart failure; 24 (30%) had initially been treated conventionally, and 10 (13%) had initially received intensive treatment. The annualized rates of heart failure were calculated as a respective 2.4% and 0.8% (hazard ratio, 0.30; P less than .002), Jens Øllgaard, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Furthermore, after adjustment was made for subject age, gender, prohormone brain natriuretic peptide levels, and ejection fraction at recruitment, there was a 76% relative risk reduction in heart failure with the intensified strategy versus conventional treatment.

“Heart failure in diabetes is frequent, fatal, and at least until very recently, quite forgotten,” said Dr. Øllgaard, who presented the research performed while he was at the STENO Diabetes Center in Copenhagen.

Dr. Øllgaard, who now works for Novo Nordisk, noted that heart failure was four times more likely to occur in patients with T2DM who had microalbuminuria than in those with normal albumin levels in the urine, and the median survival was around 3.5 years. While there is no regulatory requirement at present to stipulate that heart failure should be assessed in trials looking at the cardiovascular safety of T2DM treatments, recording such information is something that the STENO-2 investigators would recommend.

STENO-2 was an open, parallel group study initiated in 1993 to compare conventional multifactorial treatment of T2DM with an intensified approach over an 8-year period. After the primary composite cardiovascular endpoint was assessed, the trial continued as an observational study, with all patients given the intensified, multifactorial treatment that consisted of lifestyle measures and medications targeting hyperglycemia, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and hypercoagulation.

The primary endpoint of the long-term follow-up study was the difference in median survival time between the original treatment groups with and without incident cardiovascular disease. The results showed a 48% relative reduction in the risk of death; those initially given the intensified treatment had an increased lifespan of 7.9 years and an 8.1-year increased survival without cardiovascular disease versus those who had initially received conventional treatment (Diabetologica 2016;59:2298-307).

Dr. Øllgaard presented data on heart failure outcomes obtained from a post-hoc analysis of prospectively collected and externally adjudicated patient records.

In addition to the reductions in the primary outcome of time to heart failure, the secondary outcomes of time to heart failure or cardiovascular mortality (HR, 0.38; P = .006) and heart failure or all-cause mortality (relative risk reduction, 49%; P = .001) also favored initial intensive treatment versus conventional treatment.

The number of patients who would need to be treated for 1 year to prevent one heart failure event was 63. The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent heart failure or cardiovascular death was 48, and the NNT or heart failure or all-cause death was 37.

“Intensified, multifactorial intervention reduces the risk of heart failure and underlines the need for early, intensive treatment in these patients,” Dr. Øllgaard said. “Diabetologists should be aware of this increased risk and the early clinical signs and biomarkers of heart failure.” He added the study “also emphasizes the need for close collaboration, locally and globally, between endocrinologists and cardiologists.”

The STENO-2 long-term follow-up analysis was sponsored by an unrestricted grant from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Øllgaard disclosed being employed by Novo Nordisk after the submission of the abstract for presentation at the EASD meeting.

LISBON – A 70% reduction in the risk of hospitalization for heart failure was achieved in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) given an intensified, multifactorial intervention versus conventional treatment in a long-term follow up of the STENO-2 study.

Over 21 years, 34 (21%) of 160 study subjects developed heart failure; 24 (30%) had initially been treated conventionally, and 10 (13%) had initially received intensive treatment. The annualized rates of heart failure were calculated as a respective 2.4% and 0.8% (hazard ratio, 0.30; P less than .002), Jens Øllgaard, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

Furthermore, after adjustment was made for subject age, gender, prohormone brain natriuretic peptide levels, and ejection fraction at recruitment, there was a 76% relative risk reduction in heart failure with the intensified strategy versus conventional treatment.

“Heart failure in diabetes is frequent, fatal, and at least until very recently, quite forgotten,” said Dr. Øllgaard, who presented the research performed while he was at the STENO Diabetes Center in Copenhagen.

Dr. Øllgaard, who now works for Novo Nordisk, noted that heart failure was four times more likely to occur in patients with T2DM who had microalbuminuria than in those with normal albumin levels in the urine, and the median survival was around 3.5 years. While there is no regulatory requirement at present to stipulate that heart failure should be assessed in trials looking at the cardiovascular safety of T2DM treatments, recording such information is something that the STENO-2 investigators would recommend.

STENO-2 was an open, parallel group study initiated in 1993 to compare conventional multifactorial treatment of T2DM with an intensified approach over an 8-year period. After the primary composite cardiovascular endpoint was assessed, the trial continued as an observational study, with all patients given the intensified, multifactorial treatment that consisted of lifestyle measures and medications targeting hyperglycemia, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and hypercoagulation.

The primary endpoint of the long-term follow-up study was the difference in median survival time between the original treatment groups with and without incident cardiovascular disease. The results showed a 48% relative reduction in the risk of death; those initially given the intensified treatment had an increased lifespan of 7.9 years and an 8.1-year increased survival without cardiovascular disease versus those who had initially received conventional treatment (Diabetologica 2016;59:2298-307).

Dr. Øllgaard presented data on heart failure outcomes obtained from a post-hoc analysis of prospectively collected and externally adjudicated patient records.

In addition to the reductions in the primary outcome of time to heart failure, the secondary outcomes of time to heart failure or cardiovascular mortality (HR, 0.38; P = .006) and heart failure or all-cause mortality (relative risk reduction, 49%; P = .001) also favored initial intensive treatment versus conventional treatment.

The number of patients who would need to be treated for 1 year to prevent one heart failure event was 63. The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent heart failure or cardiovascular death was 48, and the NNT or heart failure or all-cause death was 37.

“Intensified, multifactorial intervention reduces the risk of heart failure and underlines the need for early, intensive treatment in these patients,” Dr. Øllgaard said. “Diabetologists should be aware of this increased risk and the early clinical signs and biomarkers of heart failure.” He added the study “also emphasizes the need for close collaboration, locally and globally, between endocrinologists and cardiologists.”

The STENO-2 long-term follow-up analysis was sponsored by an unrestricted grant from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Øllgaard disclosed being employed by Novo Nordisk after the submission of the abstract for presentation at the EASD meeting.

AT EASD 2017

Key clinical point: Intensified, multifactorial treatment reduces the risk of heart failure in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus versus a conventional treatment approach.

Major finding: The risk of heart failure was reduced by 70% (P = .002).

Data source: Post hoc analysis from 21 years follow-up on the Steno-2 randomized trial conducted in 160 patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria who were randomized to an intensive or conventional treatment arm.

Disclosures: The STENO-2 long-term follow-up analysis was sponsored by an unrestricted grant from Novo Nordisk. Dr. Øllgaard disclosed being employed by Novo Nordisk after the submission of the abstract for presentation at the EASD meeting.

AML capsules

Detecting hereditary MDS/AML

Unexplained cytopenias or failure to mobilize stem cells in related donors of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) – important clues for the detection of a hereditary MDS/AML syndrome – should prompt efforts to obtain germ line tissue sources for collaborative research, Jane E. Churpek, MD, of the Hereditary Hematologic Malignancies Program at The University of Chicago Medicine, wrote.

Partnering with families to obtain germ line tissue sources uncontaminated by tumor cells from large numbers of patients with MDS/AML, and international collaboration to determine the mechanisms and multi-step processes from the carrier state to overt disease, have enormous potential to improve the outcomes of patients with both familial and sporadic forms of MDS/AML. Incorporating collection of ideal germ line tissue along with family histories to the already robust international MDS/AML registries and data sharing are all essential to future progress in this field, she wrote in a recent article published onlne in Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology.

Prophylactic granulocyte transfusions

Giving prophylactic granulocyte transfusions to AML patients during the induction phase of therapy is feasible and safe, but assuring an adequate donor pool and patient continuation of the transfusions are another matter.

In a phase 2 trial of 45 neutropenic patients with AML or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome undergoing induction or first-salvage therapy, non-irradiated allogeneic granulocyte transfusions were to be given every 3-4 days until sustained ANC recovery, initiation of new therapy, or completion of 6 weeks on study. But logistical problems limited the success of the protocol: 5 patients never received a granulocyte transfusion due to donor screening failure or donor unavailability and the other 40 received a median of 3 (range 1-9) granulocyte transfusions.

“We anticipated approximately 8 GTs per patient ... only 11 received 6 or more GTs,” Fleur M. Aung, MD, and colleagues at The MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, wrote in the Journal of Blood Disorders and Transfusion (DOI 10.4172/2155-9864.1000376).

The authors concluded that while the process is feasible, ex vivo expanded neutrophils, produced from multiple donors and cryopreserved to provide an “off the shelf” myeloid progenitor product, will likely prove more reliable for treating patients with prolonged neutropenia.

From ONC201 to ONC212

Oncoceutics has expanded its research collaboration agreement with The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, to include the clinical development of a second novel imipridone called ONC212.

Oncoceutics and MD Anderson are already collaborating on the clinical development of another imipridone, ONC201. Both drugs have the same chemical core that interacts with G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs). ONC212 targets GPR132, which influences the growth of acute leukemias and has not previously been successfully targeted by a small molecule.

This alliance between MD Anderson and Oncoceutics will support Phase I and Phase II clinical trials of ONC212 in patients with refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to Oncoceutics. The alliance provides for a sharing of risk and rewards from potential commercialization of ONC212.

Top risk factor miRNA

The miRNA hsa-mir-425 was identified as the top risk factor miRNA of AML survival and CD44 was identified as one of the top three risk factor target-genes associated with AML survival, based on a miRNA-mRNA interaction network.

Chunmei Zhang, MD, of the department of hematology at Taian City Central Hospital, Taian, Shandong, China, and colleagues used The Cancer Genome Atlas database to obtain miRNA and mRNA expression profiles from AML patients. Of 14 miRNAs associated with AML survival, 3 were associated with risk – hsa-mir-425, hsa-mir-1201, and hsa-mir-1978. GTSF1, RTN4R, and CD44 were the top risk factor target-genes associated with AML survival. Med Sci Monit 2017; 23:4705-14 (DOI: 10.12659/MSM.903989)

Detecting hereditary MDS/AML

Unexplained cytopenias or failure to mobilize stem cells in related donors of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) – important clues for the detection of a hereditary MDS/AML syndrome – should prompt efforts to obtain germ line tissue sources for collaborative research, Jane E. Churpek, MD, of the Hereditary Hematologic Malignancies Program at The University of Chicago Medicine, wrote.

Partnering with families to obtain germ line tissue sources uncontaminated by tumor cells from large numbers of patients with MDS/AML, and international collaboration to determine the mechanisms and multi-step processes from the carrier state to overt disease, have enormous potential to improve the outcomes of patients with both familial and sporadic forms of MDS/AML. Incorporating collection of ideal germ line tissue along with family histories to the already robust international MDS/AML registries and data sharing are all essential to future progress in this field, she wrote in a recent article published onlne in Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology.

Prophylactic granulocyte transfusions

Giving prophylactic granulocyte transfusions to AML patients during the induction phase of therapy is feasible and safe, but assuring an adequate donor pool and patient continuation of the transfusions are another matter.

In a phase 2 trial of 45 neutropenic patients with AML or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome undergoing induction or first-salvage therapy, non-irradiated allogeneic granulocyte transfusions were to be given every 3-4 days until sustained ANC recovery, initiation of new therapy, or completion of 6 weeks on study. But logistical problems limited the success of the protocol: 5 patients never received a granulocyte transfusion due to donor screening failure or donor unavailability and the other 40 received a median of 3 (range 1-9) granulocyte transfusions.

“We anticipated approximately 8 GTs per patient ... only 11 received 6 or more GTs,” Fleur M. Aung, MD, and colleagues at The MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, wrote in the Journal of Blood Disorders and Transfusion (DOI 10.4172/2155-9864.1000376).

The authors concluded that while the process is feasible, ex vivo expanded neutrophils, produced from multiple donors and cryopreserved to provide an “off the shelf” myeloid progenitor product, will likely prove more reliable for treating patients with prolonged neutropenia.

From ONC201 to ONC212

Oncoceutics has expanded its research collaboration agreement with The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, to include the clinical development of a second novel imipridone called ONC212.

Oncoceutics and MD Anderson are already collaborating on the clinical development of another imipridone, ONC201. Both drugs have the same chemical core that interacts with G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs). ONC212 targets GPR132, which influences the growth of acute leukemias and has not previously been successfully targeted by a small molecule.

This alliance between MD Anderson and Oncoceutics will support Phase I and Phase II clinical trials of ONC212 in patients with refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to Oncoceutics. The alliance provides for a sharing of risk and rewards from potential commercialization of ONC212.

Top risk factor miRNA

The miRNA hsa-mir-425 was identified as the top risk factor miRNA of AML survival and CD44 was identified as one of the top three risk factor target-genes associated with AML survival, based on a miRNA-mRNA interaction network.

Chunmei Zhang, MD, of the department of hematology at Taian City Central Hospital, Taian, Shandong, China, and colleagues used The Cancer Genome Atlas database to obtain miRNA and mRNA expression profiles from AML patients. Of 14 miRNAs associated with AML survival, 3 were associated with risk – hsa-mir-425, hsa-mir-1201, and hsa-mir-1978. GTSF1, RTN4R, and CD44 were the top risk factor target-genes associated with AML survival. Med Sci Monit 2017; 23:4705-14 (DOI: 10.12659/MSM.903989)

Detecting hereditary MDS/AML

Unexplained cytopenias or failure to mobilize stem cells in related donors of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) – important clues for the detection of a hereditary MDS/AML syndrome – should prompt efforts to obtain germ line tissue sources for collaborative research, Jane E. Churpek, MD, of the Hereditary Hematologic Malignancies Program at The University of Chicago Medicine, wrote.

Partnering with families to obtain germ line tissue sources uncontaminated by tumor cells from large numbers of patients with MDS/AML, and international collaboration to determine the mechanisms and multi-step processes from the carrier state to overt disease, have enormous potential to improve the outcomes of patients with both familial and sporadic forms of MDS/AML. Incorporating collection of ideal germ line tissue along with family histories to the already robust international MDS/AML registries and data sharing are all essential to future progress in this field, she wrote in a recent article published onlne in Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology.

Prophylactic granulocyte transfusions

Giving prophylactic granulocyte transfusions to AML patients during the induction phase of therapy is feasible and safe, but assuring an adequate donor pool and patient continuation of the transfusions are another matter.

In a phase 2 trial of 45 neutropenic patients with AML or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome undergoing induction or first-salvage therapy, non-irradiated allogeneic granulocyte transfusions were to be given every 3-4 days until sustained ANC recovery, initiation of new therapy, or completion of 6 weeks on study. But logistical problems limited the success of the protocol: 5 patients never received a granulocyte transfusion due to donor screening failure or donor unavailability and the other 40 received a median of 3 (range 1-9) granulocyte transfusions.

“We anticipated approximately 8 GTs per patient ... only 11 received 6 or more GTs,” Fleur M. Aung, MD, and colleagues at The MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, wrote in the Journal of Blood Disorders and Transfusion (DOI 10.4172/2155-9864.1000376).

The authors concluded that while the process is feasible, ex vivo expanded neutrophils, produced from multiple donors and cryopreserved to provide an “off the shelf” myeloid progenitor product, will likely prove more reliable for treating patients with prolonged neutropenia.

From ONC201 to ONC212

Oncoceutics has expanded its research collaboration agreement with The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, to include the clinical development of a second novel imipridone called ONC212.

Oncoceutics and MD Anderson are already collaborating on the clinical development of another imipridone, ONC201. Both drugs have the same chemical core that interacts with G-Protein Coupled Receptors (GPCRs). ONC212 targets GPR132, which influences the growth of acute leukemias and has not previously been successfully targeted by a small molecule.

This alliance between MD Anderson and Oncoceutics will support Phase I and Phase II clinical trials of ONC212 in patients with refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to Oncoceutics. The alliance provides for a sharing of risk and rewards from potential commercialization of ONC212.

Top risk factor miRNA

The miRNA hsa-mir-425 was identified as the top risk factor miRNA of AML survival and CD44 was identified as one of the top three risk factor target-genes associated with AML survival, based on a miRNA-mRNA interaction network.

Chunmei Zhang, MD, of the department of hematology at Taian City Central Hospital, Taian, Shandong, China, and colleagues used The Cancer Genome Atlas database to obtain miRNA and mRNA expression profiles from AML patients. Of 14 miRNAs associated with AML survival, 3 were associated with risk – hsa-mir-425, hsa-mir-1201, and hsa-mir-1978. GTSF1, RTN4R, and CD44 were the top risk factor target-genes associated with AML survival. Med Sci Monit 2017; 23:4705-14 (DOI: 10.12659/MSM.903989)

Poverty affects lupus mortality through damage accumulation

The extent of damage caused by lupus appears to be one of the strongest factors that contributes to the higher mortality observed in lupus patients who live in poverty, according to the results of a longitudinal cohort study of patients.

The findings from this analysis of participants in the Lupus Outcomes Study could potentially lead to solutions to reduce mortality of poor patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) through understanding why they have higher levels of disease damage, said first author Edward Yelin, PhD, of the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues at the university (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Oct 3. doi: 10.1002/acr.23428).

Previous studies by the researchers have shown that concurrent and persistent poverty are associated with increased damage accumulation, and permanently exiting poverty reduces the level of accumulated damage. Studies by other groups have also revealed that some measures of low socioeconomic status contribute to elevated mortality in patients with SLE. But few studies have explored how poverty leads to increased mortality in SLE patients.

About two-thirds of the patients recruited for the Lupus Outcomes Study, which began in 2003, joined the study through nonclinical sources, such as public service announcements, patient support groups, and word of mouth; the remainder were recruited from academic and community clinical practices. The patients came from 37 states and from urban and rural areas. The investigators contacted participants in annual structured phone interviews that lasted about 45 minutes. The investigators defined poverty as household income at or below 125% of the federal poverty level because most participants were from high-cost urban areas.

The investigators had full information available for 807 of 814 who completed the annual survey in 2009, and these individuals made up the baseline sample for the mortality analysis through 2015. These 807 patients had a mean age of about 50 years and a disease duration of about 17 years; 93% were women, more than one-third were members of racial and ethnic minorities, and 14% met the study’s definition of poverty.

Poor individuals were more likely to be from a racial or ethnic minority (54% vs. 33%), to have a history of smoking (47% vs. 37%, to have a high school education or less (37% vs. 14%), to have never been married (36% vs. 15%), and to have a higher baseline level of disease damage as measured by score on the Brief Index of Lupus Damage (BILD; 2.8 vs. 2.2).

Overall, more poor individuals died during 2009-2015 (12.1% vs. 8.3%), but the difference was not significant. However, the poor died at a mean age of about 50, compared with 64 for individuals who were not poor. Adjustments for age showed that poverty, disease duration, BILD damage score, and having less than a high school education were all associated with higher mortality. But in a full multivariable analysis, only female gender (hazard ratio, 0.43; 95% confidence interval, 0.19-0.94), BILD damage score (1.17/point on 0-18 scale; 95% CI, 1.07-1.29), and physical health status (0.96/point; 95% CI, 0.94-0.98) were significant predictors of subsequent mortality risk, and poverty was no longer a significant predictor of mortality.

While poverty adjusted for age more than doubled the mortality risk (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.18-3.88), much of the association could be attributed to the level of disease damage because once that variable was added to the analysis, poverty was no longer associated with an elevated mortality risk (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 0.91-3.10). Furthermore, once the investigators took physical and mental health status into account, the risk of mortality associated with poverty was even smaller (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.61-2.36).

“The present analysis indicates that prevention of accumulated damage will attenuate the mortality risk associated with poverty. We know that to achieve the goal of reduced damage requires good medical care in SLE, but that alone is insufficient since medical care accounts for only a small portion of the variance in damage accumulation between the poor and non-poor,” the investigators wrote. “Strategies to reduce disease damage must take into account the provision of high-quality care for the condition as well as the stress associated with poverty and living in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty.”

The research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Investigator in Health Policy Award and grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

The extent of damage caused by lupus appears to be one of the strongest factors that contributes to the higher mortality observed in lupus patients who live in poverty, according to the results of a longitudinal cohort study of patients.

The findings from this analysis of participants in the Lupus Outcomes Study could potentially lead to solutions to reduce mortality of poor patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) through understanding why they have higher levels of disease damage, said first author Edward Yelin, PhD, of the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues at the university (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Oct 3. doi: 10.1002/acr.23428).

Previous studies by the researchers have shown that concurrent and persistent poverty are associated with increased damage accumulation, and permanently exiting poverty reduces the level of accumulated damage. Studies by other groups have also revealed that some measures of low socioeconomic status contribute to elevated mortality in patients with SLE. But few studies have explored how poverty leads to increased mortality in SLE patients.

About two-thirds of the patients recruited for the Lupus Outcomes Study, which began in 2003, joined the study through nonclinical sources, such as public service announcements, patient support groups, and word of mouth; the remainder were recruited from academic and community clinical practices. The patients came from 37 states and from urban and rural areas. The investigators contacted participants in annual structured phone interviews that lasted about 45 minutes. The investigators defined poverty as household income at or below 125% of the federal poverty level because most participants were from high-cost urban areas.

The investigators had full information available for 807 of 814 who completed the annual survey in 2009, and these individuals made up the baseline sample for the mortality analysis through 2015. These 807 patients had a mean age of about 50 years and a disease duration of about 17 years; 93% were women, more than one-third were members of racial and ethnic minorities, and 14% met the study’s definition of poverty.

Poor individuals were more likely to be from a racial or ethnic minority (54% vs. 33%), to have a history of smoking (47% vs. 37%, to have a high school education or less (37% vs. 14%), to have never been married (36% vs. 15%), and to have a higher baseline level of disease damage as measured by score on the Brief Index of Lupus Damage (BILD; 2.8 vs. 2.2).

Overall, more poor individuals died during 2009-2015 (12.1% vs. 8.3%), but the difference was not significant. However, the poor died at a mean age of about 50, compared with 64 for individuals who were not poor. Adjustments for age showed that poverty, disease duration, BILD damage score, and having less than a high school education were all associated with higher mortality. But in a full multivariable analysis, only female gender (hazard ratio, 0.43; 95% confidence interval, 0.19-0.94), BILD damage score (1.17/point on 0-18 scale; 95% CI, 1.07-1.29), and physical health status (0.96/point; 95% CI, 0.94-0.98) were significant predictors of subsequent mortality risk, and poverty was no longer a significant predictor of mortality.

While poverty adjusted for age more than doubled the mortality risk (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.18-3.88), much of the association could be attributed to the level of disease damage because once that variable was added to the analysis, poverty was no longer associated with an elevated mortality risk (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 0.91-3.10). Furthermore, once the investigators took physical and mental health status into account, the risk of mortality associated with poverty was even smaller (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.61-2.36).

“The present analysis indicates that prevention of accumulated damage will attenuate the mortality risk associated with poverty. We know that to achieve the goal of reduced damage requires good medical care in SLE, but that alone is insufficient since medical care accounts for only a small portion of the variance in damage accumulation between the poor and non-poor,” the investigators wrote. “Strategies to reduce disease damage must take into account the provision of high-quality care for the condition as well as the stress associated with poverty and living in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty.”

The research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Investigator in Health Policy Award and grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

The extent of damage caused by lupus appears to be one of the strongest factors that contributes to the higher mortality observed in lupus patients who live in poverty, according to the results of a longitudinal cohort study of patients.

The findings from this analysis of participants in the Lupus Outcomes Study could potentially lead to solutions to reduce mortality of poor patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) through understanding why they have higher levels of disease damage, said first author Edward Yelin, PhD, of the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues at the university (Arthritis Care Res. 2017 Oct 3. doi: 10.1002/acr.23428).

Previous studies by the researchers have shown that concurrent and persistent poverty are associated with increased damage accumulation, and permanently exiting poverty reduces the level of accumulated damage. Studies by other groups have also revealed that some measures of low socioeconomic status contribute to elevated mortality in patients with SLE. But few studies have explored how poverty leads to increased mortality in SLE patients.

About two-thirds of the patients recruited for the Lupus Outcomes Study, which began in 2003, joined the study through nonclinical sources, such as public service announcements, patient support groups, and word of mouth; the remainder were recruited from academic and community clinical practices. The patients came from 37 states and from urban and rural areas. The investigators contacted participants in annual structured phone interviews that lasted about 45 minutes. The investigators defined poverty as household income at or below 125% of the federal poverty level because most participants were from high-cost urban areas.

The investigators had full information available for 807 of 814 who completed the annual survey in 2009, and these individuals made up the baseline sample for the mortality analysis through 2015. These 807 patients had a mean age of about 50 years and a disease duration of about 17 years; 93% were women, more than one-third were members of racial and ethnic minorities, and 14% met the study’s definition of poverty.

Poor individuals were more likely to be from a racial or ethnic minority (54% vs. 33%), to have a history of smoking (47% vs. 37%, to have a high school education or less (37% vs. 14%), to have never been married (36% vs. 15%), and to have a higher baseline level of disease damage as measured by score on the Brief Index of Lupus Damage (BILD; 2.8 vs. 2.2).

Overall, more poor individuals died during 2009-2015 (12.1% vs. 8.3%), but the difference was not significant. However, the poor died at a mean age of about 50, compared with 64 for individuals who were not poor. Adjustments for age showed that poverty, disease duration, BILD damage score, and having less than a high school education were all associated with higher mortality. But in a full multivariable analysis, only female gender (hazard ratio, 0.43; 95% confidence interval, 0.19-0.94), BILD damage score (1.17/point on 0-18 scale; 95% CI, 1.07-1.29), and physical health status (0.96/point; 95% CI, 0.94-0.98) were significant predictors of subsequent mortality risk, and poverty was no longer a significant predictor of mortality.

While poverty adjusted for age more than doubled the mortality risk (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.18-3.88), much of the association could be attributed to the level of disease damage because once that variable was added to the analysis, poverty was no longer associated with an elevated mortality risk (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 0.91-3.10). Furthermore, once the investigators took physical and mental health status into account, the risk of mortality associated with poverty was even smaller (HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.61-2.36).

“The present analysis indicates that prevention of accumulated damage will attenuate the mortality risk associated with poverty. We know that to achieve the goal of reduced damage requires good medical care in SLE, but that alone is insufficient since medical care accounts for only a small portion of the variance in damage accumulation between the poor and non-poor,” the investigators wrote. “Strategies to reduce disease damage must take into account the provision of high-quality care for the condition as well as the stress associated with poverty and living in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty.”

The research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Investigator in Health Policy Award and grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Poverty adjusted for age more than doubled the mortality risk (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.18-3.88), but poverty was no longer associated with an elevated mortality risk when level of damage was added (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 0.91-3.10).

Data source: A total of 807 participants in the Lupus Outcomes Study.

Disclosures: The research was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Investigator in Health Policy Award and grants from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

W. Curt LaFrance Jr, MD

Use of Intravenous Tranexamic Acid Improves Early Ambulation After Total Knee Arthroplasty and Anterior and Posterior Total Hip Arthroplasty

Take-Home Points

- IV-TXA significantly reduces intraoperative blood loss following TJA.

- Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of postoperative complications.

- IV-TXA minimizes postoperative anemia, facilitating improved early ambulation following TJA.

- IV-TXA significantly reduces the need for postoperative transfusions.

- IV-TXA is safe to use with no adverse events noted.

By the year 2020, use of primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the United States will increase an estimated 110%, to 1.375 million procedures annually, and use of primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) will increase an estimated 75%, to more than 500,000 procedures.1 Minimizing perioperative blood loss and improving early postoperative ambulation both correlate with reduced postoperative morbidity, allowing patients to return to their daily lives expeditiously.

Tranexamic acid (TXA), a fibrinolytic inhibitor, competitively blocks lysine receptor binding sites of plasminogen, sustaining and stabilizing the fibrin architecture.2 TXA must be present to occupy binding sites before plasminogen binds to fibrin, validating the need for preoperative administration so the drug is available early in the fibrinolytic cascade.3 Intravenous (IV) TXA diffuses rapidly into joint fluid and the synovial membrane.4 Drug concentration and elimination half-life in joint fluid are equivalent to those in serum. Elimination of TXA occurs by glomerular filtration, with about 30% of a 10-mg/kg dose removed in 1 hour, 55% over the first 3 hours, and 90% within 24 hours of IV administration.5

The efficacy of IV-TXA in minimizing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) perioperative blood loss has been proved in small studies and meta-analyses.6-9 TXA-induced blood conservation decreases or eliminates the need for postoperative transfusion, which can impede valuable, early ambulation.10 In addition, the positive clinical safety profile of TXA supports routine use of TXA in TJA.6,11-15

The benefits of early ambulation after TJA are well established. Getting patients to walk on the day of surgery is a key part of effective and rapid postoperative rehabilitation. Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of venous thrombosis and postoperative complications.16 In contrast to bed rest, sitting and standing promotes oxygen saturation, which improves tissue healing and minimizes adverse pulmonary events. Oxygen saturation also preserves muscle strength and blood flow, reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism and ulcers. Muscle strength must be maintained so normal gait can be regained.17 Compared with rehabilitation initiated 48 to 72 hours after TKA, rehabilitation initiated within 24 hours reduced the number of sessions needed to achieve independence and normal gait; in addition, early mobilization improved patient reports of pain after surgery.18 An evaluation of Denmark registry data revealed that mobilization to walking and use of crutches or canes was achieved earlier when ambulation was initiated on day of surgery.19 Finally, mobilization on day of surgery and during the immediate postoperative period improved long-term quality of life after TJA.20

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine if use of IV-TXA improves early ambulation and reduces blood loss after TKA and anterior and posterior THA. We hypothesized that IV-TXA use would reduce postoperative anemia and improve early ambulation and outcomes without producing adverse events during the immediate postoperative period. TXA reduces bleeding, and reduced incidence of hemarthrosis, wound swelling, and anemia could facilitate ambulation, reduce complications, and shorten recovery in patients who undergo TJA.

Patients and Methods

In February 2014, this retrospective cohort study received Institutional Review Board approval to compare the safety and efficacy of IV-TXA (vs no TXA) in patients who underwent TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA.

In March 2012, multidisciplinary protocols were standardized to ensure a uniform hospital course for patients at our institution. All patients underwent preoperative testing and evaluation by a nurse practitioner and an anesthesiologist. In March 2013, IV-TXA became our standard of care. TXA use was contraindicated in patients with thromboembolic disease or with hypersensitivity to TXA. Patients without a contraindication were given two 10-mg/kg IV-TXA doses, each administered over 15 to 30 minutes; the first dose was administered before incision, and the second was infused at case close and/or at least 60 minutes after the first dose. Most TKA patients received regional (femoral) anesthesia and analgesia, and most THA patients received spinal or epidural anesthesia and analgesia. In a small percentage of cases, IV analgesia was patient-controlled, as determined by the pain service. There were no significant differences in anesthesia/analgesia modality between the 2 study groups—patients who received TXA and those who did not. Patients were then transitioned to oral opioids for pain management, unless otherwise contraindicated, and were ambulated 4 hours after end of surgery, unless medically unstable. Hematology and chemistry laboratory values were monitored daily during admission.

Patients underwent physical therapy (PT) after surgery and until hospital discharge. Physical therapists blinded to patients’ intraoperative use or no use of TXA measured ambulation. After initial evaluation on postoperative day 0 (POD-0), patients were ambulated twice daily. The daily ambulation distance used for the study was the larger of the 2 daily PT distances (occasionally, patients were unable to participate fully in both sessions). Patients received either enoxaparin or rivaroxaban for postoperative thromboprophylaxis (the anticoagulant used was based on surgeon preference). Enoxaparin was subcutaneously administered at 30 mg every 12 hours for TKA, 40 mg once daily for THA, 30 mg once daily for calculated creatinine clearance under 30 mL/min, or 40 mg every 12 hours for body mass index (BMI) 40 or above. With enoxaparin, therapy duration was 14 days. Oral rivaroxaban was administered at 10 mg once daily for 12 days for TKA and 35 days for THA unless contraindicated.

The primary outcome variables were ambulation measured on POD-1 and POD-2 and intraoperative blood loss. In addition, hemoglobin and hematocrit were measured on POD-0, POD-1, and POD-2. Ambulation was defined as number of feet walked during postoperative hospitalization. To calculate intraoperative blood loss, the anesthesiologist subtracted any saline irrigation volume from the total volume in the suction canister. Also noted were postoperative transfusions and any diagnosis of postoperative venous thromboembolism—specifically, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the TXA and no-TXA groups were compared using either 2-sample t test (for continuous variables) or χ2 test (for categorical variables).

The ambulation outcome was log-transformed to meet standard assumptions of Gaussian residuals and equality of variance. Means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated on the log scale and were anti-logged so the results could be presented in their original units.

A linear mixed model was used to model intraoperative blood loss as a function of group (TXA, no TXA), procedure (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA), and potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time).

Linear mixed models for repeated measures were used to compare outcomes (hemoglobin, hematocrit) between groups (TXA, no TXA) and procedures (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA) and to compare changes in outcomes over time. Group, procedure, and operative time interactions were explored. Potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time) were included in the model as well.

A χ2 test was used to compare the groups (TXA, no TXA) on postoperative blood transfusion (yes, no). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used. Need for transfusion was clinically assessed case by case. Symptomatic anemia (dyspnea on exertion, headaches, tachycardia) was used as the primary indication for transfusion once hemoglobin fell below 8 g/dL or hematocrit below 24%. Number of patients with a postoperative thrombus formation was minimal. Therefore, this outcome was described with summary statistics and was not formally analyzed.

Results

Of the 477 patients who underwent TJAs (275 TKAs, 98 anterior THAs, 104 posterior THAs; all unilateral), 111 did not receive TXA (June 2012-February 2013), and 366 received TXA (March 2013-January 2014). Other than for the addition of IV-TXA, the same standardized protocols instituted in March 2012 continued throughout the study period. The difference in sample size between the TXA and no-TXA groups was not statistically significant and did not influence the outcome measures.

Ambulation

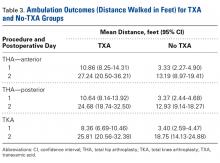

There was a significant (P = .0066) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P < .0001), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .8308). Regarding TKA, mean ambulation was higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-1 (8.36 vs 3.40 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (25.81 vs 18.75 feet; P = .0054). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (10.86 vs 3.33 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (27.24 vs 13.19 feet; P < .0001) and posterior THA at POD-1 (10.64 vs 3.37 feet; P < .0001) and POD-2 (24.68 vs 12.93 feet; P = .0002). See Table 3.

Intraoperative Blood Loss

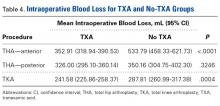

There was a significant 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure (P < .0053), and operative time (P < .0001) after adjusting for age (P < .6136), sex (P = .1147), and BMI (P = .6180). Regarding TKA, mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly lower for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group (241.58 vs 287.81 mL; P = .0004). The same was true for anterior THA (352.91 vs 533.79 mL; P < .0001). Regarding posterior THA, there was no significant difference between the TXA and no-TXA groups (326.00 vs 350.16 mL; P = .3246). See Table 4.

Hemoglobin

There was a significant (P = .0008) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .0174), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P = .0007), and operative time (P = .0002). Regarding TKA, postoperative hemoglobin levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (12.10 vs 11.68 g/dL; P = .0135), POD-1 (11.62 vs 10.67 g/dL; P < .0001), and POD-2 (11.02 vs 10.11 g/dL; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (11.03 vs 10.19 g/dL; P = .0034) and POD-2 (10.57 vs 9.64 g/dL; P = .0009) and posterior THA at POD-2 (11.04 vs 10.16 g/dL; P = .0003). See Table 5.

Hematocrit

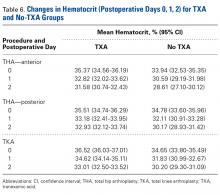

There was a significant (P < .0006) 3-way interaction of TXA, procedure, and operative time after adjusting for age (P = .1597), sex (P < .0001), BMI (P < .0001), and operative time (P = .0003). Regarding TKA, postoperative hematocrit levels were higher for the TXA group than for the no-TXA group at POD-0 (36.52% vs 34.65%; P < .0001), POD-1 (34.62% vs 31.83%; P < .0001), and POD-2 (33.01% vs 30.20%; P < .0001). The same was true for anterior THA at POD-1 (32.82% vs 30.59%; P = .0037) and POD-2 (31.58% vs 28.61%; P = .0004) and posterior THA at POD-2 (32.93% vs 30.17%; P < .0001). See Table 6.

Postoperative Transfusions

Of the 477 patients, 25 (5.24%) required a postoperative transfusion. Postoperative transfusions were less likely (P < .0001) required in the TXA group (1.64%, 6/366) than in the no-TXA group (17.12%, 19/111). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used, and the different procedures were not evaluated separately.

Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

Of the 477 patients, 2 developed a DVT, and 5 developed a PE. Both DVTs occurred in the TXA group (2/366, 0.55%; 95% CI, 0.07%-1.96%). Of the 5 PEs, 4 occurred in the TXA group (4/366, 1.09%; 95% CI, 0.30%-2.77%), and 1 occurred in the no-TXA group (1/111, 0.90%; 95% CI, 0.02%-4.92%). Given the exceedingly small number of events, no statistical significance was noted between groups.

Discussion

Orthopedic surgeons carefully balance patient expectations, societal needs, and regulatory mandates while providing excellent care and working under payers’ financial restrictions. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced that, starting in 2016, TJAs will be reimbursed in total as a single bundled payment, adding to the need to provide optimal care in a fiscally responsible manner.21 Standardized protocols implementing multimodal therapies are pivotal in achieving favorable postoperative outcomes.

Our study results showed that IV-TXA use minimized hemoglobin and hematocrit reductions after TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. Postoperative anemia correlates with decreased ambulation ability and performance during the early postoperative period. In general, higher postoperative hemoglobin and hematocrit levels result in improved motor performance and shorter recovery.22 In addition, early ambulation is a validated predictor of favorable TJA outcomes. In our study, for TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA, ambulation on POD-1 and POD-2 was significantly better for patients who received TXA than for patients who did not.

Transfusion rates were markedly lower for our TXA group than for our no-TXA group (1.64% vs 17.12%), confirming the findings of numerous other studies on outcomes of TJA with TXA.2,3,6-12,14,15 Transfusions impede physical therapy and affect hospitalization costs.

Although potential thrombosis-related adverse events remain an endpoint in studies involving TXA, we found a comparably low incidence of postoperative venous thrombosis in our TXA and no-TXA groups (1.09% and 0.90%, respectively). In addition, no patient in either group developed a postoperative arterial thrombosis.

This is the largest single-center study of TXA use in TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA. The effect of TXA use on postoperative ambulation was not previously found with TJA.

This study had its limitations. First, it was not prospective, randomized, or double-blinded. However, the physical therapists who mobilized patients and recorded ambulation data were blinded to the study and its hypothesis and followed a standardized protocol for all patients. In addition, intraoperative blood loss was recorded by an anesthesiologist using a standardized protocol, and patients received TXA per orthopedic protocol and surgeon preference, without selection bias. Another limitation was that ambulation data were captured only for POD-1 and POD-2 (most patients were discharged by POD-3). However, a goal of the study was to capture immediate postoperative data in order to determine the efficacy of intraoperative TXA. Subsequent studies can determine if this early benefit leads to long-term clinical outcome improvements.

In reducing blood loss and transfusion rates, intra-articular TXA is as efficacious as IV-TXA.23-25 We anticipate that the improved clinical outcomes found with IV-TXA in our study will be similar with intra-articular TXA, but more study is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Conclusion

This retrospective cohort study found that use of IV-TXA in TJA improved early ambulation and clinical outcomes (reduced anemia, fewer transfusions) in the initial postoperative period, without producing adverse events.

1. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630.

2. Jansen AJ, Andreica S, Claeys M, D’Haese J, Camu F, Jochmans K. Use of tranexamic acid for an effective blood conservation strategy after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83(4):596-601.

3. Benoni G, Fredin H, Knebel R, Nilsson P. Blood conservation with tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(5):442-448.

4. Tanaka N, Sakahashi, H, Sato E, Hirose K, Ishima T, Ishii S. Timing of the administration of tranexamic acid for maximum reduction in blood loss in arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(5):702-705.

5. Nilsson IM. Clinical pharmacology of aminocaproic and tranexamic acids. J Clin Pathol Suppl (R Coll Pathol). 1980;14:41-47.

6. George DA, Sarraf KM, Nwaboku H. Single perioperative dose of tranexamic acid in primary hip and knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(1):129-133.

7. Vigna-Taglianti F, Basso L, Rolfo P, et al. Tranexamic acid for reducing blood transfusions in arthroplasty interventions: a cost-effective practice. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(4):545-551.

8. Ho KM, Ismail H. Use of intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31(5):529-537.

9. Poeran J, Rasul R, Suzuki S, et al. Tranexamic acid use and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing total hip or knee arthroplasty in the United States: retrospective analysis of effectiveness and safety. BMJ. 2014;349:g4829.

10. Sculco PK, Pagnano MW. Perioperative solutions for rapid recovery joint arthroplasty: get ahead and stay ahead. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(4):518-520.

11. Lozano M, Basora M, Peidro L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid administration during total knee arthroplasty. Vox Sang. 2008;95(1):39-44.

12. Rajesparan K, Biant LC, Ahmad M, Field RE. The effect of an intravenous bolus of tranexamic acid on blood loss in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(6):776-783.

13. Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M, Nargol A, Blenkinsopp J, Mason JM. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(12):1577-1585.

14. Charoencholvanich K, Siriwattanasakul P. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(10):2874-2880.

15. Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):39-46.

16. Stowers M, Lemanu DP, Coleman B, Hill AG, Munro JT. Review article: perioperative care in enhanced recovery for total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2014;22(3):383-392.

17. Larsen K, Hansen TB, Søballe K. Hip arthroplasty patients benefit from accelerated perioperative care and rehabilitation. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(5):624-630.

18. Labraca NS, Castro-Sánchez AM, Matarán-Peñarrocha GA, Arroyo-Morales M, Sánchez-Joya Mdel M, Moreno-Lorenzo C. Benefits of starting rehabilitation within 24 hours of primary total knee arthroplasty: randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(6):557-566.

19. Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, et al. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130(2):263-268.

20. Husted H. Fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty: clinical and organizational aspects. Acta Orthop Suppl. 2012;83(346):1-39.

21. Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model. CMS.gov. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/cjr. Updated October 5, 2017.

22. Wang X, Rintala DH, Garber SL, Henson H. Association of hemoglobin levels, acute hemoglobin decrease, age, and co-morbidities with rehabilitation outcomes after total knee replacement. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(6):451-456.

23. Gomez-Barrena E, Ortega-Andreu M, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, Pérez-Chrzanowska H, Figueredo-Zalve R. Topical intra-articular compared with intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary total knee replacement: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, noninferiority clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):1937-1944.

24. Martin JG, Cassatt KB, Kincaid-Cinnamon KA, Westendorf DS, Garton AS, Lemke JH. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):889-894.

25. Alshryda S, Mason J, Sarda P, et al. Topical (intra-articular) tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and transfusion rates following total hip replacement: a randomized controlled trial (TRANX-H). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):1969-1974.

Take-Home Points

- IV-TXA significantly reduces intraoperative blood loss following TJA.

- Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of postoperative complications.

- IV-TXA minimizes postoperative anemia, facilitating improved early ambulation following TJA.

- IV-TXA significantly reduces the need for postoperative transfusions.

- IV-TXA is safe to use with no adverse events noted.

By the year 2020, use of primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the United States will increase an estimated 110%, to 1.375 million procedures annually, and use of primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) will increase an estimated 75%, to more than 500,000 procedures.1 Minimizing perioperative blood loss and improving early postoperative ambulation both correlate with reduced postoperative morbidity, allowing patients to return to their daily lives expeditiously.

Tranexamic acid (TXA), a fibrinolytic inhibitor, competitively blocks lysine receptor binding sites of plasminogen, sustaining and stabilizing the fibrin architecture.2 TXA must be present to occupy binding sites before plasminogen binds to fibrin, validating the need for preoperative administration so the drug is available early in the fibrinolytic cascade.3 Intravenous (IV) TXA diffuses rapidly into joint fluid and the synovial membrane.4 Drug concentration and elimination half-life in joint fluid are equivalent to those in serum. Elimination of TXA occurs by glomerular filtration, with about 30% of a 10-mg/kg dose removed in 1 hour, 55% over the first 3 hours, and 90% within 24 hours of IV administration.5

The efficacy of IV-TXA in minimizing total joint arthroplasty (TJA) perioperative blood loss has been proved in small studies and meta-analyses.6-9 TXA-induced blood conservation decreases or eliminates the need for postoperative transfusion, which can impede valuable, early ambulation.10 In addition, the positive clinical safety profile of TXA supports routine use of TXA in TJA.6,11-15

The benefits of early ambulation after TJA are well established. Getting patients to walk on the day of surgery is a key part of effective and rapid postoperative rehabilitation. Early mobilization correlates with reduced incidence of venous thrombosis and postoperative complications.16 In contrast to bed rest, sitting and standing promotes oxygen saturation, which improves tissue healing and minimizes adverse pulmonary events. Oxygen saturation also preserves muscle strength and blood flow, reducing the risk of venous thromboembolism and ulcers. Muscle strength must be maintained so normal gait can be regained.17 Compared with rehabilitation initiated 48 to 72 hours after TKA, rehabilitation initiated within 24 hours reduced the number of sessions needed to achieve independence and normal gait; in addition, early mobilization improved patient reports of pain after surgery.18 An evaluation of Denmark registry data revealed that mobilization to walking and use of crutches or canes was achieved earlier when ambulation was initiated on day of surgery.19 Finally, mobilization on day of surgery and during the immediate postoperative period improved long-term quality of life after TJA.20

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to determine if use of IV-TXA improves early ambulation and reduces blood loss after TKA and anterior and posterior THA. We hypothesized that IV-TXA use would reduce postoperative anemia and improve early ambulation and outcomes without producing adverse events during the immediate postoperative period. TXA reduces bleeding, and reduced incidence of hemarthrosis, wound swelling, and anemia could facilitate ambulation, reduce complications, and shorten recovery in patients who undergo TJA.

Patients and Methods

In February 2014, this retrospective cohort study received Institutional Review Board approval to compare the safety and efficacy of IV-TXA (vs no TXA) in patients who underwent TKA, anterior THA, and posterior THA.

In March 2012, multidisciplinary protocols were standardized to ensure a uniform hospital course for patients at our institution. All patients underwent preoperative testing and evaluation by a nurse practitioner and an anesthesiologist. In March 2013, IV-TXA became our standard of care. TXA use was contraindicated in patients with thromboembolic disease or with hypersensitivity to TXA. Patients without a contraindication were given two 10-mg/kg IV-TXA doses, each administered over 15 to 30 minutes; the first dose was administered before incision, and the second was infused at case close and/or at least 60 minutes after the first dose. Most TKA patients received regional (femoral) anesthesia and analgesia, and most THA patients received spinal or epidural anesthesia and analgesia. In a small percentage of cases, IV analgesia was patient-controlled, as determined by the pain service. There were no significant differences in anesthesia/analgesia modality between the 2 study groups—patients who received TXA and those who did not. Patients were then transitioned to oral opioids for pain management, unless otherwise contraindicated, and were ambulated 4 hours after end of surgery, unless medically unstable. Hematology and chemistry laboratory values were monitored daily during admission.

Patients underwent physical therapy (PT) after surgery and until hospital discharge. Physical therapists blinded to patients’ intraoperative use or no use of TXA measured ambulation. After initial evaluation on postoperative day 0 (POD-0), patients were ambulated twice daily. The daily ambulation distance used for the study was the larger of the 2 daily PT distances (occasionally, patients were unable to participate fully in both sessions). Patients received either enoxaparin or rivaroxaban for postoperative thromboprophylaxis (the anticoagulant used was based on surgeon preference). Enoxaparin was subcutaneously administered at 30 mg every 12 hours for TKA, 40 mg once daily for THA, 30 mg once daily for calculated creatinine clearance under 30 mL/min, or 40 mg every 12 hours for body mass index (BMI) 40 or above. With enoxaparin, therapy duration was 14 days. Oral rivaroxaban was administered at 10 mg once daily for 12 days for TKA and 35 days for THA unless contraindicated.

The primary outcome variables were ambulation measured on POD-1 and POD-2 and intraoperative blood loss. In addition, hemoglobin and hematocrit were measured on POD-0, POD-1, and POD-2. Ambulation was defined as number of feet walked during postoperative hospitalization. To calculate intraoperative blood loss, the anesthesiologist subtracted any saline irrigation volume from the total volume in the suction canister. Also noted were postoperative transfusions and any diagnosis of postoperative venous thromboembolism—specifically, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the TXA and no-TXA groups were compared using either 2-sample t test (for continuous variables) or χ2 test (for categorical variables).

The ambulation outcome was log-transformed to meet standard assumptions of Gaussian residuals and equality of variance. Means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated on the log scale and were anti-logged so the results could be presented in their original units.

A linear mixed model was used to model intraoperative blood loss as a function of group (TXA, no TXA), procedure (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA), and potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time).

Linear mixed models for repeated measures were used to compare outcomes (hemoglobin, hematocrit) between groups (TXA, no TXA) and procedures (TKA, anterior THA, posterior THA) and to compare changes in outcomes over time. Group, procedure, and operative time interactions were explored. Potential confounders (age, sex, BMI, operative time) were included in the model as well.

A χ2 test was used to compare the groups (TXA, no TXA) on postoperative blood transfusion (yes, no). Given the smaller number of events, a more complex model accounting for clustered data and potential confounders was not used. Need for transfusion was clinically assessed case by case. Symptomatic anemia (dyspnea on exertion, headaches, tachycardia) was used as the primary indication for transfusion once hemoglobin fell below 8 g/dL or hematocrit below 24%. Number of patients with a postoperative thrombus formation was minimal. Therefore, this outcome was described with summary statistics and was not formally analyzed.

Results

Of the 477 patients who underwent TJAs (275 TKAs, 98 anterior THAs, 104 posterior THAs; all unilateral), 111 did not receive TXA (June 2012-February 2013), and 366 received TXA (March 2013-January 2014). Other than for the addition of IV-TXA, the same standardized protocols instituted in March 2012 continued throughout the study period. The difference in sample size between the TXA and no-TXA groups was not statistically significant and did not influence the outcome measures.

Ambulation