User login

Physical inactivity in youth is an independent risk factor for schizophrenia

PARIS – Low physical activity in childhood and adolescence was independently associated with later development of schizophrenia and other nonaffective psychotic disorders in the large, prospective, population-based Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns cohort study, Jarmo Hietala, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The key question now: Is this risk factor remediable? That is, will a pediatric exercise intervention that results in improved physical fitness also reduce the risk of later nonaffective psychosis? Given that there are really no downsides to physical activity, the Finnish data make a strong case for including exercise and physical activity interventions in investigational psychosis prevention programs targeting high-risk youth, according to Dr. Hietala, professor of psychiatry at the University of Turku (Finland).

Dr. Hietala and his coinvestigators tapped into comprehensive national registries in order to identify all study participants with a psychiatric diagnosis of sufficient severity to have resulted in hospitalization up to 2012. Forty-one patients were hospitalized for schizophrenia spectrum disorders, 47 for other forms of nonaffective psychosis, 43 for personality disorders, 111 for affective disorders, and 49 with alcohol and other substance use disorders.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for sex, age, body mass index, birth weight, non-preterm birth, and maternal mental disorders, each 1-point decrement in the pediatric physical activity index was associated with a 26% increase in the risk of developing any nonaffective psychosis and, more specifically, a 43% increased risk of schizophrenia.

Moreover, nonparticipation in organized sports competitions was independently associated with a 2.58-fold increased risk of any nonaffective psychosis and a 4.88-fold increased risk of schizophrenia. And social isolation as reflected in spending less time in common activities with friends during leisure time was associated with a 71% increased risk of nonaffective psychosis and a 76% increased risk of schizophrenia.

Of note, schizophrenia was the only psychiatric disorder associated with low physical activity in childhood and adolescence. Sedentary youths were not at increased risk of later hospitalization for affective disorders or other forms of mental illness.

“Our results have relevance for preemptive psychiatry and provide rationale for including exercise in early interventions for psychosis,” the psychiatrist said.

Current programs aimed at preventing schizophrenia in youth at high risk because of family history typically emphasize avoidance of street drugs, the importance of seeking out constructive social interactions, stress reduction techniques, and cognitive-behavioral therapy aimed at promoting a positive world view.

Formal evaluation of physical activity as part of a preventive approach has a sound theoretic basis, according to Dr. Hietala. He cited an influential essay called “Rethinking Schizophrenia” by the then-director of the National Institute of Mental Health, Thomas R. Insel, MD. In that article, Dr. Insel highlights the past half-century of largely unsatisfactory results with pharmacotherapy and goes on to make the case for considering schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disorder in which, he argues, “psychosis is a late, potentially preventable stage of the illness” (Nature. 2010 Nov 11;468[7321]:187-93).

This view of schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disorder has quickly come to dominate thinking within the field. Dr. Hietala noted that the schizophrenia spectrum chapter in the DSM-5 includes a greater focus on abnormal behavior and catatonia as a core domain alongside classic features, such as delusions, hallucinations, negative symptoms, and disorganized speech.

“My view of schizophrenia is that the psychotic symptoms are a secondary phenomenon, a complication of the disease that has been going on for a while. It’s a pity that we focus so much on the psychotic symptoms rather than the cognitive or negative or affective symptoms,” he said.

The hope is that a long-term physical activity intervention in at-risk youth will stimulate neurodevelopmental catch-up, thereby thwarting their predisposition to schizophrenia.

“Human development is not a linear process; it happens in spurts of rapid growth followed by consolidation periods,” Dr. Hietala said.

However, even if it turns out that an early physical activity intervention does not reduce the risk of developing schizophrenia, it might favorably alter its course in important ways, according to Dr. Hietala.

Individuals with schizophrenia are known to be at increased risk for metabolic syndrome and premature death tied to cardiovascular disease. A recent meta-analysis of 16 prospective cohort studies totaling more than 1 million men and women found that mortality during follow-up was 59% greater in those who sat for more than 8 hours per day and were in the lowest quartile of physical activity, compared with those sitting for less than 4 hours per day who were in the top quartile of physical activity, at more than 35.5 metabolic equivalent hours per week.

But there was no increased risk of mortality among those who sat for more than 8 hours per day and were also in the highest quartile of physical activity. The implication is that high levels of moderate-intensity physical activity eliminates the increased risk of death associated with high sitting time (Lancet. 2016 Sep 24;388[10051]:1302-10). That’s a finding that could be applicable to patients with schizophrenia.

Dr. Hietala reported having no financial conflicts regarding the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns study, which is supported by the Academy of Finland, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, and grants from nonprofit foundations.

PARIS – Low physical activity in childhood and adolescence was independently associated with later development of schizophrenia and other nonaffective psychotic disorders in the large, prospective, population-based Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns cohort study, Jarmo Hietala, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The key question now: Is this risk factor remediable? That is, will a pediatric exercise intervention that results in improved physical fitness also reduce the risk of later nonaffective psychosis? Given that there are really no downsides to physical activity, the Finnish data make a strong case for including exercise and physical activity interventions in investigational psychosis prevention programs targeting high-risk youth, according to Dr. Hietala, professor of psychiatry at the University of Turku (Finland).

Dr. Hietala and his coinvestigators tapped into comprehensive national registries in order to identify all study participants with a psychiatric diagnosis of sufficient severity to have resulted in hospitalization up to 2012. Forty-one patients were hospitalized for schizophrenia spectrum disorders, 47 for other forms of nonaffective psychosis, 43 for personality disorders, 111 for affective disorders, and 49 with alcohol and other substance use disorders.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for sex, age, body mass index, birth weight, non-preterm birth, and maternal mental disorders, each 1-point decrement in the pediatric physical activity index was associated with a 26% increase in the risk of developing any nonaffective psychosis and, more specifically, a 43% increased risk of schizophrenia.

Moreover, nonparticipation in organized sports competitions was independently associated with a 2.58-fold increased risk of any nonaffective psychosis and a 4.88-fold increased risk of schizophrenia. And social isolation as reflected in spending less time in common activities with friends during leisure time was associated with a 71% increased risk of nonaffective psychosis and a 76% increased risk of schizophrenia.

Of note, schizophrenia was the only psychiatric disorder associated with low physical activity in childhood and adolescence. Sedentary youths were not at increased risk of later hospitalization for affective disorders or other forms of mental illness.

“Our results have relevance for preemptive psychiatry and provide rationale for including exercise in early interventions for psychosis,” the psychiatrist said.

Current programs aimed at preventing schizophrenia in youth at high risk because of family history typically emphasize avoidance of street drugs, the importance of seeking out constructive social interactions, stress reduction techniques, and cognitive-behavioral therapy aimed at promoting a positive world view.

Formal evaluation of physical activity as part of a preventive approach has a sound theoretic basis, according to Dr. Hietala. He cited an influential essay called “Rethinking Schizophrenia” by the then-director of the National Institute of Mental Health, Thomas R. Insel, MD. In that article, Dr. Insel highlights the past half-century of largely unsatisfactory results with pharmacotherapy and goes on to make the case for considering schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disorder in which, he argues, “psychosis is a late, potentially preventable stage of the illness” (Nature. 2010 Nov 11;468[7321]:187-93).

This view of schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disorder has quickly come to dominate thinking within the field. Dr. Hietala noted that the schizophrenia spectrum chapter in the DSM-5 includes a greater focus on abnormal behavior and catatonia as a core domain alongside classic features, such as delusions, hallucinations, negative symptoms, and disorganized speech.

“My view of schizophrenia is that the psychotic symptoms are a secondary phenomenon, a complication of the disease that has been going on for a while. It’s a pity that we focus so much on the psychotic symptoms rather than the cognitive or negative or affective symptoms,” he said.

The hope is that a long-term physical activity intervention in at-risk youth will stimulate neurodevelopmental catch-up, thereby thwarting their predisposition to schizophrenia.

“Human development is not a linear process; it happens in spurts of rapid growth followed by consolidation periods,” Dr. Hietala said.

However, even if it turns out that an early physical activity intervention does not reduce the risk of developing schizophrenia, it might favorably alter its course in important ways, according to Dr. Hietala.

Individuals with schizophrenia are known to be at increased risk for metabolic syndrome and premature death tied to cardiovascular disease. A recent meta-analysis of 16 prospective cohort studies totaling more than 1 million men and women found that mortality during follow-up was 59% greater in those who sat for more than 8 hours per day and were in the lowest quartile of physical activity, compared with those sitting for less than 4 hours per day who were in the top quartile of physical activity, at more than 35.5 metabolic equivalent hours per week.

But there was no increased risk of mortality among those who sat for more than 8 hours per day and were also in the highest quartile of physical activity. The implication is that high levels of moderate-intensity physical activity eliminates the increased risk of death associated with high sitting time (Lancet. 2016 Sep 24;388[10051]:1302-10). That’s a finding that could be applicable to patients with schizophrenia.

Dr. Hietala reported having no financial conflicts regarding the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns study, which is supported by the Academy of Finland, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, and grants from nonprofit foundations.

PARIS – Low physical activity in childhood and adolescence was independently associated with later development of schizophrenia and other nonaffective psychotic disorders in the large, prospective, population-based Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns cohort study, Jarmo Hietala, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

The key question now: Is this risk factor remediable? That is, will a pediatric exercise intervention that results in improved physical fitness also reduce the risk of later nonaffective psychosis? Given that there are really no downsides to physical activity, the Finnish data make a strong case for including exercise and physical activity interventions in investigational psychosis prevention programs targeting high-risk youth, according to Dr. Hietala, professor of psychiatry at the University of Turku (Finland).

Dr. Hietala and his coinvestigators tapped into comprehensive national registries in order to identify all study participants with a psychiatric diagnosis of sufficient severity to have resulted in hospitalization up to 2012. Forty-one patients were hospitalized for schizophrenia spectrum disorders, 47 for other forms of nonaffective psychosis, 43 for personality disorders, 111 for affective disorders, and 49 with alcohol and other substance use disorders.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for sex, age, body mass index, birth weight, non-preterm birth, and maternal mental disorders, each 1-point decrement in the pediatric physical activity index was associated with a 26% increase in the risk of developing any nonaffective psychosis and, more specifically, a 43% increased risk of schizophrenia.

Moreover, nonparticipation in organized sports competitions was independently associated with a 2.58-fold increased risk of any nonaffective psychosis and a 4.88-fold increased risk of schizophrenia. And social isolation as reflected in spending less time in common activities with friends during leisure time was associated with a 71% increased risk of nonaffective psychosis and a 76% increased risk of schizophrenia.

Of note, schizophrenia was the only psychiatric disorder associated with low physical activity in childhood and adolescence. Sedentary youths were not at increased risk of later hospitalization for affective disorders or other forms of mental illness.

“Our results have relevance for preemptive psychiatry and provide rationale for including exercise in early interventions for psychosis,” the psychiatrist said.

Current programs aimed at preventing schizophrenia in youth at high risk because of family history typically emphasize avoidance of street drugs, the importance of seeking out constructive social interactions, stress reduction techniques, and cognitive-behavioral therapy aimed at promoting a positive world view.

Formal evaluation of physical activity as part of a preventive approach has a sound theoretic basis, according to Dr. Hietala. He cited an influential essay called “Rethinking Schizophrenia” by the then-director of the National Institute of Mental Health, Thomas R. Insel, MD. In that article, Dr. Insel highlights the past half-century of largely unsatisfactory results with pharmacotherapy and goes on to make the case for considering schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disorder in which, he argues, “psychosis is a late, potentially preventable stage of the illness” (Nature. 2010 Nov 11;468[7321]:187-93).

This view of schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disorder has quickly come to dominate thinking within the field. Dr. Hietala noted that the schizophrenia spectrum chapter in the DSM-5 includes a greater focus on abnormal behavior and catatonia as a core domain alongside classic features, such as delusions, hallucinations, negative symptoms, and disorganized speech.

“My view of schizophrenia is that the psychotic symptoms are a secondary phenomenon, a complication of the disease that has been going on for a while. It’s a pity that we focus so much on the psychotic symptoms rather than the cognitive or negative or affective symptoms,” he said.

The hope is that a long-term physical activity intervention in at-risk youth will stimulate neurodevelopmental catch-up, thereby thwarting their predisposition to schizophrenia.

“Human development is not a linear process; it happens in spurts of rapid growth followed by consolidation periods,” Dr. Hietala said.

However, even if it turns out that an early physical activity intervention does not reduce the risk of developing schizophrenia, it might favorably alter its course in important ways, according to Dr. Hietala.

Individuals with schizophrenia are known to be at increased risk for metabolic syndrome and premature death tied to cardiovascular disease. A recent meta-analysis of 16 prospective cohort studies totaling more than 1 million men and women found that mortality during follow-up was 59% greater in those who sat for more than 8 hours per day and were in the lowest quartile of physical activity, compared with those sitting for less than 4 hours per day who were in the top quartile of physical activity, at more than 35.5 metabolic equivalent hours per week.

But there was no increased risk of mortality among those who sat for more than 8 hours per day and were also in the highest quartile of physical activity. The implication is that high levels of moderate-intensity physical activity eliminates the increased risk of death associated with high sitting time (Lancet. 2016 Sep 24;388[10051]:1302-10). That’s a finding that could be applicable to patients with schizophrenia.

Dr. Hietala reported having no financial conflicts regarding the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns study, which is supported by the Academy of Finland, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, and grants from nonprofit foundations.

AT THE ECNP CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Each 1-point decrement on a physical activity score recorded during childhood and adolescence was independently associated with a 43% increased risk of later development of schizophrenia.

Data source: The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns study is an ongoing prospective, population-based study of nearly 3,600 Finns who were aged 3-18 years old when the study began in 1980.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which is supported by the Academy of Finland, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, and grants from nonprofit foundations.

Contraception coverage rollback is discriminatory

On Oct. 6, the Trump administration rolled back a crucial piece of the Affordable Care Act so that any employer can now claim a moral or religious objection to providing contraception coverage, thus denying their employees access to critical health care – contraception.

Nearly all women – 99% – who have had sex have used some form of contraception at some point during their reproductive lives, regardless of faith or religion (National health statistics reports. 2013 Feb 14[62]). Most women spend the majority of their fertile life span, approximately 35-40 years, avoiding pregnancy, and only a few years actively trying to become pregnant. A desired pregnancy is a gift, but unplanned pregnancies may have a negative impact on women, families, and society.

In the United States, our rising maternal mortality ratio is currently at 26.4 per 100,000 live births (Lancet. 2016 Oct 8;388[10053]:1775-812). Given the risks of pregnancy, especially to those with medical conditions that make pregnancy more dangerous, women need access to methods to avoid pregnancy until they actively seek it. If employers of for-profit businesses now choose to claim a moral or religious objection to providing coverage for contraception, millions of women could become unable to access affordable, effective contraception.

Since the Affordable Care Act mandate that provided coverage for contraceptive methods with no cost-sharing, thousands of women have had improved access to contraception, including IUDs and contraceptive implants, the most effective and longest-lasting reversible methods available. Since President Trump took office, many women have presented to clinics across the country to get long-acting contraception, like an IUD or implant, before the Trump administration could pull the plug on the contraceptive mandate. That scenario has now occurred, leaving millions of women up in the air about the future of their contraceptive coverage.

By allowing employers to deny coverage of contraception, the Trump administration is demonstrating its lack of concern for women’s health and its denial of the most fundamental principles of public health.

Rolling back the contraceptive mandate is rolling back on vital women’s preventive health services. It is counter to society’s interest in public health and is discriminatory against women.

Dr. Prager is associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington, Seattle. She is also the director of the family planning division and family planning fellowship. Dr. Prager is an unpaid trainer for Nexplanon (Merck). Dr. Espey is professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Espey reported having no relevant disclosures.

On Oct. 6, the Trump administration rolled back a crucial piece of the Affordable Care Act so that any employer can now claim a moral or religious objection to providing contraception coverage, thus denying their employees access to critical health care – contraception.

Nearly all women – 99% – who have had sex have used some form of contraception at some point during their reproductive lives, regardless of faith or religion (National health statistics reports. 2013 Feb 14[62]). Most women spend the majority of their fertile life span, approximately 35-40 years, avoiding pregnancy, and only a few years actively trying to become pregnant. A desired pregnancy is a gift, but unplanned pregnancies may have a negative impact on women, families, and society.

In the United States, our rising maternal mortality ratio is currently at 26.4 per 100,000 live births (Lancet. 2016 Oct 8;388[10053]:1775-812). Given the risks of pregnancy, especially to those with medical conditions that make pregnancy more dangerous, women need access to methods to avoid pregnancy until they actively seek it. If employers of for-profit businesses now choose to claim a moral or religious objection to providing coverage for contraception, millions of women could become unable to access affordable, effective contraception.

Since the Affordable Care Act mandate that provided coverage for contraceptive methods with no cost-sharing, thousands of women have had improved access to contraception, including IUDs and contraceptive implants, the most effective and longest-lasting reversible methods available. Since President Trump took office, many women have presented to clinics across the country to get long-acting contraception, like an IUD or implant, before the Trump administration could pull the plug on the contraceptive mandate. That scenario has now occurred, leaving millions of women up in the air about the future of their contraceptive coverage.

By allowing employers to deny coverage of contraception, the Trump administration is demonstrating its lack of concern for women’s health and its denial of the most fundamental principles of public health.

Rolling back the contraceptive mandate is rolling back on vital women’s preventive health services. It is counter to society’s interest in public health and is discriminatory against women.

Dr. Prager is associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington, Seattle. She is also the director of the family planning division and family planning fellowship. Dr. Prager is an unpaid trainer for Nexplanon (Merck). Dr. Espey is professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Espey reported having no relevant disclosures.

On Oct. 6, the Trump administration rolled back a crucial piece of the Affordable Care Act so that any employer can now claim a moral or religious objection to providing contraception coverage, thus denying their employees access to critical health care – contraception.

Nearly all women – 99% – who have had sex have used some form of contraception at some point during their reproductive lives, regardless of faith or religion (National health statistics reports. 2013 Feb 14[62]). Most women spend the majority of their fertile life span, approximately 35-40 years, avoiding pregnancy, and only a few years actively trying to become pregnant. A desired pregnancy is a gift, but unplanned pregnancies may have a negative impact on women, families, and society.

In the United States, our rising maternal mortality ratio is currently at 26.4 per 100,000 live births (Lancet. 2016 Oct 8;388[10053]:1775-812). Given the risks of pregnancy, especially to those with medical conditions that make pregnancy more dangerous, women need access to methods to avoid pregnancy until they actively seek it. If employers of for-profit businesses now choose to claim a moral or religious objection to providing coverage for contraception, millions of women could become unable to access affordable, effective contraception.

Since the Affordable Care Act mandate that provided coverage for contraceptive methods with no cost-sharing, thousands of women have had improved access to contraception, including IUDs and contraceptive implants, the most effective and longest-lasting reversible methods available. Since President Trump took office, many women have presented to clinics across the country to get long-acting contraception, like an IUD or implant, before the Trump administration could pull the plug on the contraceptive mandate. That scenario has now occurred, leaving millions of women up in the air about the future of their contraceptive coverage.

By allowing employers to deny coverage of contraception, the Trump administration is demonstrating its lack of concern for women’s health and its denial of the most fundamental principles of public health.

Rolling back the contraceptive mandate is rolling back on vital women’s preventive health services. It is counter to society’s interest in public health and is discriminatory against women.

Dr. Prager is associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Washington, Seattle. She is also the director of the family planning division and family planning fellowship. Dr. Prager is an unpaid trainer for Nexplanon (Merck). Dr. Espey is professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. Dr. Espey reported having no relevant disclosures.

New antiviral combination for HCV infection in kidney disease

The combination of glecaprevir and pibrentasvir has been found to be both safe and effective as a treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in patients with end-stage kidney disease, according to a paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

There are few treatment options available for these patients, as ribavirin can accumulate systemically in patients with severe renal impairment with serious adverse consequences such as hemolytic anemia and pruritus, and interferon has a negative side-effect profile in this population.

In this open-label phase 3 trial, 104 patients with hepatitis C infection and either compensated liver disease with severe renal impairment, dependence on dialysis, or both received 300 mg glecaprevir and 120 mg pibrentasvir daily for 12 weeks (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704053).

The treatment was associated with a sustained virologic response in 102 patients (98%) at 12 weeks and 100 patients (96%) at 24 weeks, with no cases of virologic failure.

Of the two patients who did not have a sustained virologic response at 12 weeks, one was undergoing hemodialysis at baseline and had both compensated cirrhosis and underlying hypertension, while the other had a history of gastrointestinal tract telangiectasia and discontinued after a nonserious adverse event of diarrhea.

One-quarter of patients experienced serious adverse events, but none were deemed drug related, and there were no reports of liver decompensation. Five patients reported grade 3 hemoglobin abnormalities, but none showed abnormalities in alanine aminotransferase of grade 2 or higher.

The most common adverse events were pruritus, fatigue, and nausea, which were each reported in more than 10% of patients. The authors described this as an acceptable safety profile in a population of patients with numerous coexisting conditions. However, they noted that the absence of a placebo control group made it difficult to compare treatment-related adverse events with the underlying adverse event profile of this group of patients.

“Glecaprevir–pibrentasvir may fulfill an important unmet need; the absence of ribavirin as part of the treatment regimen minimizes the risks of treatment discontinuation and of adverse events due to anemia, which represents a considerable benefit for patients with severe renal insufficiency, since they are at increased risk for life-threatening anemia and cardiac events,” they wrote.

The study was supported by AbbVie. Twelve authors declared speakers bureau, advisory board positions, grants, or other support from AbbVie, as well as grants and funding from other pharmaceutical companies outside this work. Five authors were employees and stockholders of AbbVie.

The combination of glecaprevir and pibrentasvir has been found to be both safe and effective as a treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in patients with end-stage kidney disease, according to a paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

There are few treatment options available for these patients, as ribavirin can accumulate systemically in patients with severe renal impairment with serious adverse consequences such as hemolytic anemia and pruritus, and interferon has a negative side-effect profile in this population.

In this open-label phase 3 trial, 104 patients with hepatitis C infection and either compensated liver disease with severe renal impairment, dependence on dialysis, or both received 300 mg glecaprevir and 120 mg pibrentasvir daily for 12 weeks (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704053).

The treatment was associated with a sustained virologic response in 102 patients (98%) at 12 weeks and 100 patients (96%) at 24 weeks, with no cases of virologic failure.

Of the two patients who did not have a sustained virologic response at 12 weeks, one was undergoing hemodialysis at baseline and had both compensated cirrhosis and underlying hypertension, while the other had a history of gastrointestinal tract telangiectasia and discontinued after a nonserious adverse event of diarrhea.

One-quarter of patients experienced serious adverse events, but none were deemed drug related, and there were no reports of liver decompensation. Five patients reported grade 3 hemoglobin abnormalities, but none showed abnormalities in alanine aminotransferase of grade 2 or higher.

The most common adverse events were pruritus, fatigue, and nausea, which were each reported in more than 10% of patients. The authors described this as an acceptable safety profile in a population of patients with numerous coexisting conditions. However, they noted that the absence of a placebo control group made it difficult to compare treatment-related adverse events with the underlying adverse event profile of this group of patients.

“Glecaprevir–pibrentasvir may fulfill an important unmet need; the absence of ribavirin as part of the treatment regimen minimizes the risks of treatment discontinuation and of adverse events due to anemia, which represents a considerable benefit for patients with severe renal insufficiency, since they are at increased risk for life-threatening anemia and cardiac events,” they wrote.

The study was supported by AbbVie. Twelve authors declared speakers bureau, advisory board positions, grants, or other support from AbbVie, as well as grants and funding from other pharmaceutical companies outside this work. Five authors were employees and stockholders of AbbVie.

The combination of glecaprevir and pibrentasvir has been found to be both safe and effective as a treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in patients with end-stage kidney disease, according to a paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

There are few treatment options available for these patients, as ribavirin can accumulate systemically in patients with severe renal impairment with serious adverse consequences such as hemolytic anemia and pruritus, and interferon has a negative side-effect profile in this population.

In this open-label phase 3 trial, 104 patients with hepatitis C infection and either compensated liver disease with severe renal impairment, dependence on dialysis, or both received 300 mg glecaprevir and 120 mg pibrentasvir daily for 12 weeks (N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704053).

The treatment was associated with a sustained virologic response in 102 patients (98%) at 12 weeks and 100 patients (96%) at 24 weeks, with no cases of virologic failure.

Of the two patients who did not have a sustained virologic response at 12 weeks, one was undergoing hemodialysis at baseline and had both compensated cirrhosis and underlying hypertension, while the other had a history of gastrointestinal tract telangiectasia and discontinued after a nonserious adverse event of diarrhea.

One-quarter of patients experienced serious adverse events, but none were deemed drug related, and there were no reports of liver decompensation. Five patients reported grade 3 hemoglobin abnormalities, but none showed abnormalities in alanine aminotransferase of grade 2 or higher.

The most common adverse events were pruritus, fatigue, and nausea, which were each reported in more than 10% of patients. The authors described this as an acceptable safety profile in a population of patients with numerous coexisting conditions. However, they noted that the absence of a placebo control group made it difficult to compare treatment-related adverse events with the underlying adverse event profile of this group of patients.

“Glecaprevir–pibrentasvir may fulfill an important unmet need; the absence of ribavirin as part of the treatment regimen minimizes the risks of treatment discontinuation and of adverse events due to anemia, which represents a considerable benefit for patients with severe renal insufficiency, since they are at increased risk for life-threatening anemia and cardiac events,” they wrote.

The study was supported by AbbVie. Twelve authors declared speakers bureau, advisory board positions, grants, or other support from AbbVie, as well as grants and funding from other pharmaceutical companies outside this work. Five authors were employees and stockholders of AbbVie.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The combination of glecaprevir and pibrentasvir has been found to be both safe and effective as a treatment for hepatitis C infection in patients with end-stage kidney disease.

Major finding:

Data source: Open-label phase 3 trial in 104 patients with hepatitis C infection and renal failure.

Disclosures: The study was supported by AbbVie. Twelve authors declared speakers bureau, advisory board positions, grants, or other support from AbbVie, as well as grants and funding from other pharmaceutical companies outside this work. Five authors were employees and stockholders of AbbVie.

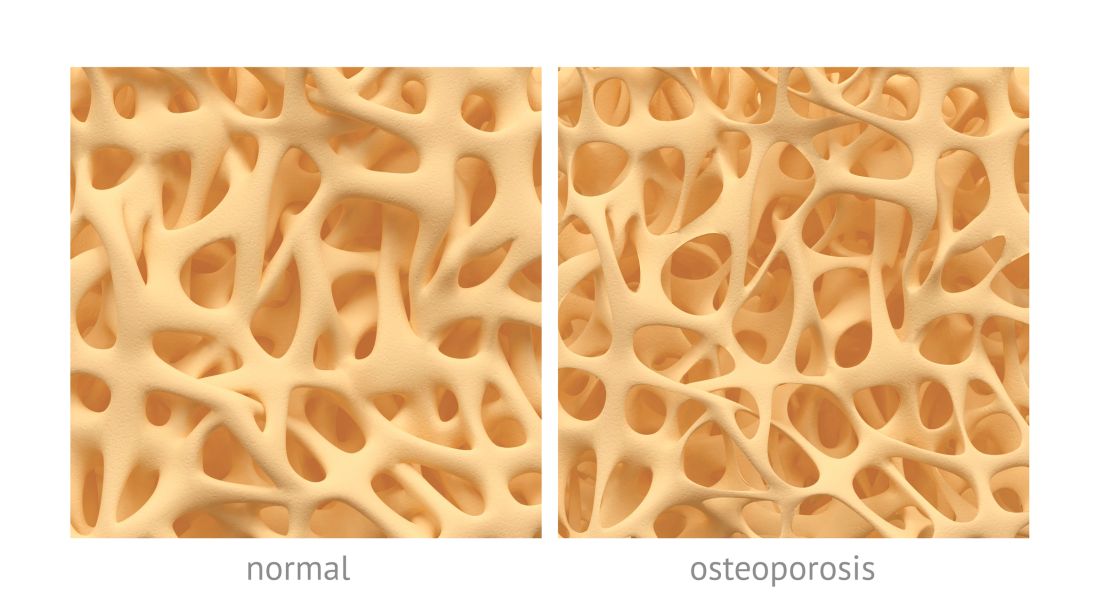

PBC linked to low BMD, increased risk of osteoporosis

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) have lower lumbar spine and hip bone mineral density (BMD) and are at an increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture, according to Junyu Fan, MD, and associates.

In a meta-analysis of 210 potentially relevant articles, only 8 met the study’s criteria. Of those, five studies were pooled and the overall relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk was assessed. Results found a significant association between PBC (n = 504) and the prevalence of osteoporosis (P = .01), compared with the control group (n = 2,052).

The study additionally examined possible connection between PBC and bone fractures; more fracture events were reported in PBC patients (n = 929) than in controls (n = 8,699; P less than .00001). It is noted that there was no publication bias (P = .476).

“Further clinical management, follow-up, and surveillance issues should be addressed with caution,” researchers concluded. “Given the limited number of studies included, more high-quality studies will be required to determine the mechanisms underpinning the relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk.”

Find the full study in Clinical Rheumatology (2017. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3844-x).

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) have lower lumbar spine and hip bone mineral density (BMD) and are at an increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture, according to Junyu Fan, MD, and associates.

In a meta-analysis of 210 potentially relevant articles, only 8 met the study’s criteria. Of those, five studies were pooled and the overall relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk was assessed. Results found a significant association between PBC (n = 504) and the prevalence of osteoporosis (P = .01), compared with the control group (n = 2,052).

The study additionally examined possible connection between PBC and bone fractures; more fracture events were reported in PBC patients (n = 929) than in controls (n = 8,699; P less than .00001). It is noted that there was no publication bias (P = .476).

“Further clinical management, follow-up, and surveillance issues should be addressed with caution,” researchers concluded. “Given the limited number of studies included, more high-quality studies will be required to determine the mechanisms underpinning the relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk.”

Find the full study in Clinical Rheumatology (2017. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3844-x).

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) have lower lumbar spine and hip bone mineral density (BMD) and are at an increased risk of osteoporosis and fracture, according to Junyu Fan, MD, and associates.

In a meta-analysis of 210 potentially relevant articles, only 8 met the study’s criteria. Of those, five studies were pooled and the overall relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk was assessed. Results found a significant association between PBC (n = 504) and the prevalence of osteoporosis (P = .01), compared with the control group (n = 2,052).

The study additionally examined possible connection between PBC and bone fractures; more fracture events were reported in PBC patients (n = 929) than in controls (n = 8,699; P less than .00001). It is noted that there was no publication bias (P = .476).

“Further clinical management, follow-up, and surveillance issues should be addressed with caution,” researchers concluded. “Given the limited number of studies included, more high-quality studies will be required to determine the mechanisms underpinning the relationship between PBC and osteoporosis risk.”

Find the full study in Clinical Rheumatology (2017. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3844-x).

FROM CLINICAL RHEUMATOLOGY

Minimal residual disease measures not yet impactful for AML patients

SAN FRANCISCO – Routine testing for minimal residual disease is probably not of value in acute myeloid leukemia, as there is no evidence that changing treatment based on MRD status currently makes a difference in patient outcomes, experts said at the annual congress on Hematologic Malignancies held by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“If we find minimal residual disease, we don’t always have a better therapy to offer our patients,” Jessica Altman, MD, associate professor of hematology and oncology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, said.

Beyond that therapeutic reality, there are no clear guidelines and standards for MRD testing. The optimal timing for MRD testing and a standard threshold for an MRD classification are not yet established, she said.

“Having MRD is bad, not having it is better,” Richard Stone, MD, PhD, clinical director of the adult leukemia program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, said. The problem in AML, he said, is, “So?” There is no reliable “MRD eraser” in AML, he said. Until then, there is not much point in knowing whether a patient is MRD positive or not.

A recent survey conducted by researchers at Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, addressed MRD testing at 13 major cancer centers. While most centers reported that they test for MRD, many physicians said that they are unsure about what to do with the results.

A 2013 study by the HOVON group found that patients who were in complete remission but MRD positive after their first course of therapy, subsequently became MRD negative after their second course of therapy. But the second regimen would not have been different based on knowledge of MRD status, according to the HOVON/SAKK AML 42A study (J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:3889-97).

The AML community is awaiting guidelines on MRD use from the NCCN and other groups, Dr. Altman said. An option for using NPM1 mutations to assess MRD should be available soon, and could be an improvement on existing options (N Engl J Med 2016; 374:422-33).

Given the treatment limitations, knowing about MRD status can have a negative mental toll on patients, Dr. Stone said. “I would not underplay the psychological burden.” Nevertheless, MRD should be measured in clinical trials, and it could be a valuable surrogate marker by which to compare drug efficacy.

One of the biggest hopes is that MRD status could eventually be useful in determining the need for allogeneic stem cell transplant in patients deemed intermediate risk, Dr. Altman said. “I think we are finally on the brink of this being actionable.”

Dr. Altman reports financial relationships with Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Novartis, and Syros. Dr. Stone reports financial relationships with AbbVie, Actinium, Agios, Amgen and many other companies.

SAN FRANCISCO – Routine testing for minimal residual disease is probably not of value in acute myeloid leukemia, as there is no evidence that changing treatment based on MRD status currently makes a difference in patient outcomes, experts said at the annual congress on Hematologic Malignancies held by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“If we find minimal residual disease, we don’t always have a better therapy to offer our patients,” Jessica Altman, MD, associate professor of hematology and oncology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, said.

Beyond that therapeutic reality, there are no clear guidelines and standards for MRD testing. The optimal timing for MRD testing and a standard threshold for an MRD classification are not yet established, she said.

“Having MRD is bad, not having it is better,” Richard Stone, MD, PhD, clinical director of the adult leukemia program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, said. The problem in AML, he said, is, “So?” There is no reliable “MRD eraser” in AML, he said. Until then, there is not much point in knowing whether a patient is MRD positive or not.

A recent survey conducted by researchers at Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, addressed MRD testing at 13 major cancer centers. While most centers reported that they test for MRD, many physicians said that they are unsure about what to do with the results.

A 2013 study by the HOVON group found that patients who were in complete remission but MRD positive after their first course of therapy, subsequently became MRD negative after their second course of therapy. But the second regimen would not have been different based on knowledge of MRD status, according to the HOVON/SAKK AML 42A study (J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:3889-97).

The AML community is awaiting guidelines on MRD use from the NCCN and other groups, Dr. Altman said. An option for using NPM1 mutations to assess MRD should be available soon, and could be an improvement on existing options (N Engl J Med 2016; 374:422-33).

Given the treatment limitations, knowing about MRD status can have a negative mental toll on patients, Dr. Stone said. “I would not underplay the psychological burden.” Nevertheless, MRD should be measured in clinical trials, and it could be a valuable surrogate marker by which to compare drug efficacy.

One of the biggest hopes is that MRD status could eventually be useful in determining the need for allogeneic stem cell transplant in patients deemed intermediate risk, Dr. Altman said. “I think we are finally on the brink of this being actionable.”

Dr. Altman reports financial relationships with Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Novartis, and Syros. Dr. Stone reports financial relationships with AbbVie, Actinium, Agios, Amgen and many other companies.

SAN FRANCISCO – Routine testing for minimal residual disease is probably not of value in acute myeloid leukemia, as there is no evidence that changing treatment based on MRD status currently makes a difference in patient outcomes, experts said at the annual congress on Hematologic Malignancies held by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“If we find minimal residual disease, we don’t always have a better therapy to offer our patients,” Jessica Altman, MD, associate professor of hematology and oncology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, said.

Beyond that therapeutic reality, there are no clear guidelines and standards for MRD testing. The optimal timing for MRD testing and a standard threshold for an MRD classification are not yet established, she said.

“Having MRD is bad, not having it is better,” Richard Stone, MD, PhD, clinical director of the adult leukemia program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, said. The problem in AML, he said, is, “So?” There is no reliable “MRD eraser” in AML, he said. Until then, there is not much point in knowing whether a patient is MRD positive or not.

A recent survey conducted by researchers at Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, addressed MRD testing at 13 major cancer centers. While most centers reported that they test for MRD, many physicians said that they are unsure about what to do with the results.

A 2013 study by the HOVON group found that patients who were in complete remission but MRD positive after their first course of therapy, subsequently became MRD negative after their second course of therapy. But the second regimen would not have been different based on knowledge of MRD status, according to the HOVON/SAKK AML 42A study (J Clin Oncol. 2013; 31:3889-97).

The AML community is awaiting guidelines on MRD use from the NCCN and other groups, Dr. Altman said. An option for using NPM1 mutations to assess MRD should be available soon, and could be an improvement on existing options (N Engl J Med 2016; 374:422-33).

Given the treatment limitations, knowing about MRD status can have a negative mental toll on patients, Dr. Stone said. “I would not underplay the psychological burden.” Nevertheless, MRD should be measured in clinical trials, and it could be a valuable surrogate marker by which to compare drug efficacy.

One of the biggest hopes is that MRD status could eventually be useful in determining the need for allogeneic stem cell transplant in patients deemed intermediate risk, Dr. Altman said. “I think we are finally on the brink of this being actionable.”

Dr. Altman reports financial relationships with Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Novartis, and Syros. Dr. Stone reports financial relationships with AbbVie, Actinium, Agios, Amgen and many other companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT NCCN HEMATOLOGIC MALIGNANCIES CONGRESS

Venography for stenting led to good results for patients with May-Thurner syndrome

Stenting of the left common iliac vein of patients with May-Thurner syndrome provided good short-term results as compared with nonstenting, according to the results of a retrospective, single-center registry study.

When to treat patients with May-Thurner syndrome (MTS) who have mild symptoms and what degree of compression should trigger intervention are in considerable question. Approximately 50% of the general population has some degree of left common iliac vein (LCIV) compression as detected using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and axial imaging, according to Johnathon C. Rollo, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and his colleagues at the University of California, Los Angeles. They performed their study in order to address the debate over what were the optimal IVUS and venography criteria for stent implantation in these patients.

Of 102 patients in a registry, 63 had clear evidence of LCIV compression by the overlying right common iliac artery by IVUS assessment or venography. Nonthrombotic MTS patients who presented with chronic leg swelling or venous claudication underwent duplex ultrasound to rule out deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) were placed in compression therapy, and venography was performed to assess for iliac vein involvement

Iliac vein stenting was offered to those patients who met the following criteria:

• Sufficiently severe symptoms of swelling, venous claudication, or pain to affect their quality of life despite compression therapy.

• Diagnostic venogram imaging showing evidence of physiologically significant MTS compression, including contrast stagnation within the proximal left common and external iliac vein, contralateral cross-filling to the right iliac venous • circulation via hypogastric collateral networks, and/or significant retroperitoneal collateralization.

• IVUS assessment demonstrating greater than 50% luminal narrowing of the LCIV or extensive intravascular webs.

Patients who did not meet one of these criteria (generally the venogram findings) were treated with continued conservative management, which consisted of compression therapy, weight loss and exercise programs, and other conservative measures (J Vasc Surg: Venous Lymphatic Disorders. 2017;5:667-76).

Of the 63 patients in the final study group, a total of 44 were treated with iliofemoral stents, with or without thrombolysis, and 19 conservatively managed patients who were not treated with stents served as controls. The mean age of the patients was 46 years, and 76% of them were women. With regard to comorbidities, 63% had a patient-reported history of DVT, and 22% had a patient-reported history of pulmonary embolism. Of the 63 patients, 32 had nonthrombotic MTS.

Stent diameter was based on IVUS measurement, with the goal of achieving normal vein diameter, and undersizing was avoided. Stenting was performed under local anesthesia.

A total of 44 patients (70%) underwent primary stenting (70%) or thrombolysis and stenting (30%), whereas 19 patients were not stented. Of these latter, 14 were nonthrombotic and were treated conservatively with compression therapy alone; the remaining 5 patients with thrombotic MTS were treated with lysis or angioplasty alone. Technical success was achieved in 100% of patients who had an intervention.

Primary and secondary patency rates in the stented thrombotic population were 87% and 93% at 24 months, respectively, by Kaplan-Meier analysis and were not significantly different from the results of the nonthrombotic stented patients.

Clinical improvement was significantly more likely in stented patients, compared with those managed without stenting (95% vs. 58%, respectively; P less than .001), Complete clinical resolution, defined as an absence of swelling or any other venous symptoms, was three times more likely in stented patients than in nonstented patients (64% vs. 21%, respectively; P less than .001), according to the researchers.

“MTS patients are typically young and relatively healthy. Whereas several series have demonstrated good intermediate-term results out to 7-10 years, the durability of these stents 20-30 years or more after implantation is unknown. For this reason, our group has been conservative in offering stent implantation to nonthrombotic patients,” Dr. Rollo and his colleagues stated.

“Regardless of the differential in clinical outcomes between stented and nonstented patients, this selective approach to stenting is reasonable in that those believed to be best managed with conservative therapy can be re-evaluated at regular intervals for clinical deterioration,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

Most vascular specialists, including our group in New York, have relied heavily on intravascular ultrasound demonstrating greater than 50% stenosis to decide whether or not stenting is indicated. Dr. Rollo and his associates emphasized the importance of using venography-guided findings (contrast stagnation within the external iliac vein, contralateral cross-filling to the right iliac system, and/or significant retroperitoneal collateralization) to decide on stent indication. They did, however, use IVUS to guide in stent sizing and placement.

Todd Berland, MD , is the director, outpatient vascular interventions, NYU Langone Health, New York, N.Y. He had no relevant financial disclosures.

Most vascular specialists, including our group in New York, have relied heavily on intravascular ultrasound demonstrating greater than 50% stenosis to decide whether or not stenting is indicated. Dr. Rollo and his associates emphasized the importance of using venography-guided findings (contrast stagnation within the external iliac vein, contralateral cross-filling to the right iliac system, and/or significant retroperitoneal collateralization) to decide on stent indication. They did, however, use IVUS to guide in stent sizing and placement.

Todd Berland, MD , is the director, outpatient vascular interventions, NYU Langone Health, New York, N.Y. He had no relevant financial disclosures.

Most vascular specialists, including our group in New York, have relied heavily on intravascular ultrasound demonstrating greater than 50% stenosis to decide whether or not stenting is indicated. Dr. Rollo and his associates emphasized the importance of using venography-guided findings (contrast stagnation within the external iliac vein, contralateral cross-filling to the right iliac system, and/or significant retroperitoneal collateralization) to decide on stent indication. They did, however, use IVUS to guide in stent sizing and placement.

Todd Berland, MD , is the director, outpatient vascular interventions, NYU Langone Health, New York, N.Y. He had no relevant financial disclosures.

Stenting of the left common iliac vein of patients with May-Thurner syndrome provided good short-term results as compared with nonstenting, according to the results of a retrospective, single-center registry study.

When to treat patients with May-Thurner syndrome (MTS) who have mild symptoms and what degree of compression should trigger intervention are in considerable question. Approximately 50% of the general population has some degree of left common iliac vein (LCIV) compression as detected using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and axial imaging, according to Johnathon C. Rollo, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and his colleagues at the University of California, Los Angeles. They performed their study in order to address the debate over what were the optimal IVUS and venography criteria for stent implantation in these patients.

Of 102 patients in a registry, 63 had clear evidence of LCIV compression by the overlying right common iliac artery by IVUS assessment or venography. Nonthrombotic MTS patients who presented with chronic leg swelling or venous claudication underwent duplex ultrasound to rule out deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) were placed in compression therapy, and venography was performed to assess for iliac vein involvement

Iliac vein stenting was offered to those patients who met the following criteria:

• Sufficiently severe symptoms of swelling, venous claudication, or pain to affect their quality of life despite compression therapy.

• Diagnostic venogram imaging showing evidence of physiologically significant MTS compression, including contrast stagnation within the proximal left common and external iliac vein, contralateral cross-filling to the right iliac venous • circulation via hypogastric collateral networks, and/or significant retroperitoneal collateralization.

• IVUS assessment demonstrating greater than 50% luminal narrowing of the LCIV or extensive intravascular webs.

Patients who did not meet one of these criteria (generally the venogram findings) were treated with continued conservative management, which consisted of compression therapy, weight loss and exercise programs, and other conservative measures (J Vasc Surg: Venous Lymphatic Disorders. 2017;5:667-76).

Of the 63 patients in the final study group, a total of 44 were treated with iliofemoral stents, with or without thrombolysis, and 19 conservatively managed patients who were not treated with stents served as controls. The mean age of the patients was 46 years, and 76% of them were women. With regard to comorbidities, 63% had a patient-reported history of DVT, and 22% had a patient-reported history of pulmonary embolism. Of the 63 patients, 32 had nonthrombotic MTS.

Stent diameter was based on IVUS measurement, with the goal of achieving normal vein diameter, and undersizing was avoided. Stenting was performed under local anesthesia.

A total of 44 patients (70%) underwent primary stenting (70%) or thrombolysis and stenting (30%), whereas 19 patients were not stented. Of these latter, 14 were nonthrombotic and were treated conservatively with compression therapy alone; the remaining 5 patients with thrombotic MTS were treated with lysis or angioplasty alone. Technical success was achieved in 100% of patients who had an intervention.

Primary and secondary patency rates in the stented thrombotic population were 87% and 93% at 24 months, respectively, by Kaplan-Meier analysis and were not significantly different from the results of the nonthrombotic stented patients.

Clinical improvement was significantly more likely in stented patients, compared with those managed without stenting (95% vs. 58%, respectively; P less than .001), Complete clinical resolution, defined as an absence of swelling or any other venous symptoms, was three times more likely in stented patients than in nonstented patients (64% vs. 21%, respectively; P less than .001), according to the researchers.

“MTS patients are typically young and relatively healthy. Whereas several series have demonstrated good intermediate-term results out to 7-10 years, the durability of these stents 20-30 years or more after implantation is unknown. For this reason, our group has been conservative in offering stent implantation to nonthrombotic patients,” Dr. Rollo and his colleagues stated.

“Regardless of the differential in clinical outcomes between stented and nonstented patients, this selective approach to stenting is reasonable in that those believed to be best managed with conservative therapy can be re-evaluated at regular intervals for clinical deterioration,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

Stenting of the left common iliac vein of patients with May-Thurner syndrome provided good short-term results as compared with nonstenting, according to the results of a retrospective, single-center registry study.

When to treat patients with May-Thurner syndrome (MTS) who have mild symptoms and what degree of compression should trigger intervention are in considerable question. Approximately 50% of the general population has some degree of left common iliac vein (LCIV) compression as detected using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and axial imaging, according to Johnathon C. Rollo, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and his colleagues at the University of California, Los Angeles. They performed their study in order to address the debate over what were the optimal IVUS and venography criteria for stent implantation in these patients.

Of 102 patients in a registry, 63 had clear evidence of LCIV compression by the overlying right common iliac artery by IVUS assessment or venography. Nonthrombotic MTS patients who presented with chronic leg swelling or venous claudication underwent duplex ultrasound to rule out deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) were placed in compression therapy, and venography was performed to assess for iliac vein involvement

Iliac vein stenting was offered to those patients who met the following criteria:

• Sufficiently severe symptoms of swelling, venous claudication, or pain to affect their quality of life despite compression therapy.

• Diagnostic venogram imaging showing evidence of physiologically significant MTS compression, including contrast stagnation within the proximal left common and external iliac vein, contralateral cross-filling to the right iliac venous • circulation via hypogastric collateral networks, and/or significant retroperitoneal collateralization.

• IVUS assessment demonstrating greater than 50% luminal narrowing of the LCIV or extensive intravascular webs.

Patients who did not meet one of these criteria (generally the venogram findings) were treated with continued conservative management, which consisted of compression therapy, weight loss and exercise programs, and other conservative measures (J Vasc Surg: Venous Lymphatic Disorders. 2017;5:667-76).

Of the 63 patients in the final study group, a total of 44 were treated with iliofemoral stents, with or without thrombolysis, and 19 conservatively managed patients who were not treated with stents served as controls. The mean age of the patients was 46 years, and 76% of them were women. With regard to comorbidities, 63% had a patient-reported history of DVT, and 22% had a patient-reported history of pulmonary embolism. Of the 63 patients, 32 had nonthrombotic MTS.

Stent diameter was based on IVUS measurement, with the goal of achieving normal vein diameter, and undersizing was avoided. Stenting was performed under local anesthesia.

A total of 44 patients (70%) underwent primary stenting (70%) or thrombolysis and stenting (30%), whereas 19 patients were not stented. Of these latter, 14 were nonthrombotic and were treated conservatively with compression therapy alone; the remaining 5 patients with thrombotic MTS were treated with lysis or angioplasty alone. Technical success was achieved in 100% of patients who had an intervention.

Primary and secondary patency rates in the stented thrombotic population were 87% and 93% at 24 months, respectively, by Kaplan-Meier analysis and were not significantly different from the results of the nonthrombotic stented patients.

Clinical improvement was significantly more likely in stented patients, compared with those managed without stenting (95% vs. 58%, respectively; P less than .001), Complete clinical resolution, defined as an absence of swelling or any other venous symptoms, was three times more likely in stented patients than in nonstented patients (64% vs. 21%, respectively; P less than .001), according to the researchers.

“MTS patients are typically young and relatively healthy. Whereas several series have demonstrated good intermediate-term results out to 7-10 years, the durability of these stents 20-30 years or more after implantation is unknown. For this reason, our group has been conservative in offering stent implantation to nonthrombotic patients,” Dr. Rollo and his colleagues stated.

“Regardless of the differential in clinical outcomes between stented and nonstented patients, this selective approach to stenting is reasonable in that those believed to be best managed with conservative therapy can be re-evaluated at regular intervals for clinical deterioration,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF VASCULAR SURGERY: VENOUS AND LYMPHATIC DISORDERS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: May-Thurner patients treated with iliofemoral stents had significantly better (95%) clinical improvement than 21 patients not treated with stents (58%).

Data source: Retrospective analysis of a single-center registry of 65 patients with May-Thurner syndrome.

Disclosures: The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

Adaptive pneumatic compression device found comparable to compression stockings

The use of an adaptive pneumatic compression device showed comparable results to compression stockings in a two-arm, randomized multicenter pilot study of previously noncompliant patients with chronic venous disease.

In addition, patient satisfaction regarding ease of use was higher in for the device, compared with the stockings, according to Fedor Lurie, MD, PhD, of the Jobst Vascular Institute, Toledo, Ohio, and his colleague.

A total of 89 subjects with unilateral or bilateral chronic venous insufficiency were randomized and included in the final analysis of the study. The patients comprised 44% women, with a median age of nearly 63 years, the majority (53%) of whom had bilateral chronic venous insufficiency (J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017 Sep;5[5]:699-706).

Significantly more patients found the ACTitouch device easy to apply (71%) versus the compression stockings (37.5%; P = .0001) and easy to remove (89% vs. 59%; P = .0001). However, compliance and average time of use were not significantly different between the two treatment groups.

In terms of limb volume reduction, the device group demonstrated a significant volume reduction (44%), compared with the standard compression garment use (17%) in obese patients (P = .019) but not in nonobese patients.

The device was easy to put on and remove and was considered comfortable, according to the researchers. “These are characteristics usually associated with good potential for long-term acceptance by patients. The observed trend that suggested an associated benefit in achieving limb volume reduction (magnified in obese patients) was greater with the AT device than with [compression stockings],” the researchers concluded.

Tactile Medical, which manufactures the device, was the study sponsor and provided funding for the study costs. The authors received no specific funding for their work.

The use of an adaptive pneumatic compression device showed comparable results to compression stockings in a two-arm, randomized multicenter pilot study of previously noncompliant patients with chronic venous disease.

In addition, patient satisfaction regarding ease of use was higher in for the device, compared with the stockings, according to Fedor Lurie, MD, PhD, of the Jobst Vascular Institute, Toledo, Ohio, and his colleague.

A total of 89 subjects with unilateral or bilateral chronic venous insufficiency were randomized and included in the final analysis of the study. The patients comprised 44% women, with a median age of nearly 63 years, the majority (53%) of whom had bilateral chronic venous insufficiency (J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017 Sep;5[5]:699-706).

Significantly more patients found the ACTitouch device easy to apply (71%) versus the compression stockings (37.5%; P = .0001) and easy to remove (89% vs. 59%; P = .0001). However, compliance and average time of use were not significantly different between the two treatment groups.

In terms of limb volume reduction, the device group demonstrated a significant volume reduction (44%), compared with the standard compression garment use (17%) in obese patients (P = .019) but not in nonobese patients.

The device was easy to put on and remove and was considered comfortable, according to the researchers. “These are characteristics usually associated with good potential for long-term acceptance by patients. The observed trend that suggested an associated benefit in achieving limb volume reduction (magnified in obese patients) was greater with the AT device than with [compression stockings],” the researchers concluded.

Tactile Medical, which manufactures the device, was the study sponsor and provided funding for the study costs. The authors received no specific funding for their work.

The use of an adaptive pneumatic compression device showed comparable results to compression stockings in a two-arm, randomized multicenter pilot study of previously noncompliant patients with chronic venous disease.

In addition, patient satisfaction regarding ease of use was higher in for the device, compared with the stockings, according to Fedor Lurie, MD, PhD, of the Jobst Vascular Institute, Toledo, Ohio, and his colleague.

A total of 89 subjects with unilateral or bilateral chronic venous insufficiency were randomized and included in the final analysis of the study. The patients comprised 44% women, with a median age of nearly 63 years, the majority (53%) of whom had bilateral chronic venous insufficiency (J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2017 Sep;5[5]:699-706).

Significantly more patients found the ACTitouch device easy to apply (71%) versus the compression stockings (37.5%; P = .0001) and easy to remove (89% vs. 59%; P = .0001). However, compliance and average time of use were not significantly different between the two treatment groups.

In terms of limb volume reduction, the device group demonstrated a significant volume reduction (44%), compared with the standard compression garment use (17%) in obese patients (P = .019) but not in nonobese patients.

The device was easy to put on and remove and was considered comfortable, according to the researchers. “These are characteristics usually associated with good potential for long-term acceptance by patients. The observed trend that suggested an associated benefit in achieving limb volume reduction (magnified in obese patients) was greater with the AT device than with [compression stockings],” the researchers concluded.

Tactile Medical, which manufactures the device, was the study sponsor and provided funding for the study costs. The authors received no specific funding for their work.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF VASCULAR SURGERY: VENOUS AND LYMPHATIC DISORDERS

Vascular surgery trainees perceive weakness in venous education, case volumes

Venous training during vascular residency programs is perceived to be lacking in both case volume and didactic education, based on the results of a national survey of vascular trainees.

The majority of respondents (82%) believed that treating venous disease is part of a standard vascular practice, and 75% indicated a desire for increased venous training, according to article in press published online in the Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders.

In terms of case loads, the responders reported the following:

- 63% had performed fewer than 10 inferior vena cava stents.

- 64% had performed fewer than 10 vein stripping/ligation procedures.

- 50% had performed fewer than 10 iliac stents.

- 92% had performed fewer than 10 venous bypasses.

In contrast, 74% of responders reported having performed as many as 20 cases of endothermal ablation.

Currently, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education does not demand a minimum number of venous cases before graduation from a vascular training program, Dr. Hicks and her colleagues wrote.

Although integrated and traditional vascular surgery trainees showed no overall differences in reported venous procedure volumes (P less than or equal to .28), integrated students reported receiving significantly more didactic education than their traditionally trained peers (P less than or equal to .01).

Both integrated and traditional vascular surgery trainees recognized a need for a more comprehensive educational curriculum in venous disease in terms of both didactic education and case exposure, the authors reported.

“Our data suggest that expansion of the venous training curriculum with clear training standards is warranted and that trainees would welcome such a change,” wrote Dr. Hicks and her colleagues.

“Further study will be required to determine if the perceived deficits affect recent graduates’ experiences with venous disease in their developing practice and if increasing training in venous disease during vascular residency will increase the venous work performed by practicing vascular surgeons,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Venous training during vascular residency programs is perceived to be lacking in both case volume and didactic education, based on the results of a national survey of vascular trainees.

The majority of respondents (82%) believed that treating venous disease is part of a standard vascular practice, and 75% indicated a desire for increased venous training, according to article in press published online in the Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders.

In terms of case loads, the responders reported the following:

- 63% had performed fewer than 10 inferior vena cava stents.

- 64% had performed fewer than 10 vein stripping/ligation procedures.

- 50% had performed fewer than 10 iliac stents.

- 92% had performed fewer than 10 venous bypasses.

In contrast, 74% of responders reported having performed as many as 20 cases of endothermal ablation.

Currently, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education does not demand a minimum number of venous cases before graduation from a vascular training program, Dr. Hicks and her colleagues wrote.

Although integrated and traditional vascular surgery trainees showed no overall differences in reported venous procedure volumes (P less than or equal to .28), integrated students reported receiving significantly more didactic education than their traditionally trained peers (P less than or equal to .01).

Both integrated and traditional vascular surgery trainees recognized a need for a more comprehensive educational curriculum in venous disease in terms of both didactic education and case exposure, the authors reported.

“Our data suggest that expansion of the venous training curriculum with clear training standards is warranted and that trainees would welcome such a change,” wrote Dr. Hicks and her colleagues.

“Further study will be required to determine if the perceived deficits affect recent graduates’ experiences with venous disease in their developing practice and if increasing training in venous disease during vascular residency will increase the venous work performed by practicing vascular surgeons,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Venous training during vascular residency programs is perceived to be lacking in both case volume and didactic education, based on the results of a national survey of vascular trainees.

The majority of respondents (82%) believed that treating venous disease is part of a standard vascular practice, and 75% indicated a desire for increased venous training, according to article in press published online in the Journal of Vascular Surgery: Venous and Lymphatic Disorders.

In terms of case loads, the responders reported the following:

- 63% had performed fewer than 10 inferior vena cava stents.

- 64% had performed fewer than 10 vein stripping/ligation procedures.

- 50% had performed fewer than 10 iliac stents.

- 92% had performed fewer than 10 venous bypasses.

In contrast, 74% of responders reported having performed as many as 20 cases of endothermal ablation.

Currently, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education does not demand a minimum number of venous cases before graduation from a vascular training program, Dr. Hicks and her colleagues wrote.

Although integrated and traditional vascular surgery trainees showed no overall differences in reported venous procedure volumes (P less than or equal to .28), integrated students reported receiving significantly more didactic education than their traditionally trained peers (P less than or equal to .01).

Both integrated and traditional vascular surgery trainees recognized a need for a more comprehensive educational curriculum in venous disease in terms of both didactic education and case exposure, the authors reported.

“Our data suggest that expansion of the venous training curriculum with clear training standards is warranted and that trainees would welcome such a change,” wrote Dr. Hicks and her colleagues.

“Further study will be required to determine if the perceived deficits affect recent graduates’ experiences with venous disease in their developing practice and if increasing training in venous disease during vascular residency will increase the venous work performed by practicing vascular surgeons,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF VASCULAR SURGERY: VENOUS AND LYMPHATIC DISORDERS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of the of vascular trainees who responded to the survey, 75% reported a desire for increased venous training.

Data source: Nationwide U.S. survey of vascular trainees resulting in a 104/464 (22%) response rate.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Watch for our breaking news coverage

GI & Hepatology News will be in Orlando next week at the Orange County Convention Center reporting the latest news from the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017. Studies slated for presentation will detail new findings in every area of clinical concern to the gastroenterologist.

Our onsite reporters will cover new drugs and treatment regimens in inflammatory bowel disease, endoscopic advances for treatment along the GI tract, and novel tests and biomarkers for various disease states.

Highly anticipated presentations include:

- Risk of metachronous high-risk adenomas and large (greater than or equal to 1 cm) serrated polyps in individuals with serrated polyps on index colonoscopy: Longitudinal data from the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry.

- Enhanced recovery in acute pancreatitis (RAPTor): A randomized controlled trial.

- A prospective validation of deep learning for polyp autodetection during colonoscopy.