User login

Psychotic symptoms predict persistent problems in adolescents

BERLIN – Teens who reported psychotic symptoms – especially hallucinations – on a baseline mental health screening were twice as likely to develop persistent psychiatric symptoms over the next year as were those without such experiences.

Hallucinations in particular predicted a persistent course, nearly tripling the risk (odds ratio, 2.74), Saliha El-Bouhaddani said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

“This is quite informative and quite clinically relevant,” said Ms. El-Bouhaddani, a doctoral student in psychology at the Parnassia Group, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Because mental health symptoms in young people may be self-limiting, it’s not easy to identify which teens are at high risk for developing persistent problems that can predispose them to a full-blown mental disorder. “But we can see here that psychotic experiences may be very useful in detecting which adolescents may have persistency of symptoms. I believe that screening tools for teenagers should involve questions about psychotic symptoms, because the answer may help us discriminate who will have a self-limiting course and who will have a persistent course.”

Ms. El-Bouhaddani described MasterMind, a longitudinal cohort study of adolescents drawn from the general population. Each teen completed self-report questionnaires on psychotic experiences and psychosocial problems at two time points over a 2-year period. The study was divided into two phases: a 1-year observational period, followed by an intervention for those at risk, and then a 1-year treatment and follow-up period. She reported only the results of the observational phase.

The study enrolled 1,827 young people, who completed four questionnaires: the Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire, and questionnaires about psychotic experiences, trauma, and self-esteem. One year later, 1,521 of the participants returned and completed the same surveys.

Ms. El-Bouhaddani constructed four potential pathways from baseline to follow-up: no psychiatric symptoms, remitting symptoms (baseline psychosocial symptoms that remitted by 1 year), incident symptoms (symptoms that appeared only at 1 year), and persistent symptoms (symptoms at both baseline and 1 year). Her goal was to identify any baseline characteristics that might predict a persistent course.

At the 1-year point, the cohort was a mean of 13.5 years old. Most subjects (1,134) had no symptoms at either time point. Incident symptoms were present in 151, remitting symptoms in 181, and persistent symptoms in 46.

Several baseline characteristics significantly separated the group with remitting symptoms from all other groups: They were significantly more likely to have a low education level (61%), to have divorced parents (38%), to report frequent household moves (22%), to have repeated a grade (31%), to report low self-esteem (15%), and to have somatic symptoms (3%). Teens with persistent symptoms also reported more somatic symptoms (3%), but they were significantly more likely than any of the other groups to report having had at least one traumatic event (45%).

At follow-up, psychotic incidents were significantly more common in the remitting and persistent groups (40% and 62%, respectively) than in the nonsymptomatic and incident groups (10% and 11%).

Ms. El-Bouhaddani then broke psychotic experiences down into hallucinations and delusions, and examined their relationships to symptom course. Hallucinations were significantly more common than delusions among those with a persistent course (58% vs. 42%).

She conducted a logistic regression analysis, which determined that any psychotic experience nearly doubled the risk of a persistent course of psychiatric symptoms (OR, 1.92). Hallucinations nearly tripled the risk (OR, 2.74), as did traumatic experiences (OR, 3.0). Delusions increased the risk by close to 60% (OR, 1.59).

The SDQ does not contain questions about psychotic experiences or trauma – the two most powerful predictors of persistent symptoms. It’s time to change this, Ms. El-Bouhaddani said.

“From these results it seems as though we should be asking adolescents about psychotic experiences and trauma. Perhaps it’s time for a new version of the SDQ.”

She had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

SOURCE: El-Bouhaddani S et al. WPA 2017 Abstract S-023 002.

BERLIN – Teens who reported psychotic symptoms – especially hallucinations – on a baseline mental health screening were twice as likely to develop persistent psychiatric symptoms over the next year as were those without such experiences.

Hallucinations in particular predicted a persistent course, nearly tripling the risk (odds ratio, 2.74), Saliha El-Bouhaddani said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

“This is quite informative and quite clinically relevant,” said Ms. El-Bouhaddani, a doctoral student in psychology at the Parnassia Group, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Because mental health symptoms in young people may be self-limiting, it’s not easy to identify which teens are at high risk for developing persistent problems that can predispose them to a full-blown mental disorder. “But we can see here that psychotic experiences may be very useful in detecting which adolescents may have persistency of symptoms. I believe that screening tools for teenagers should involve questions about psychotic symptoms, because the answer may help us discriminate who will have a self-limiting course and who will have a persistent course.”

Ms. El-Bouhaddani described MasterMind, a longitudinal cohort study of adolescents drawn from the general population. Each teen completed self-report questionnaires on psychotic experiences and psychosocial problems at two time points over a 2-year period. The study was divided into two phases: a 1-year observational period, followed by an intervention for those at risk, and then a 1-year treatment and follow-up period. She reported only the results of the observational phase.

The study enrolled 1,827 young people, who completed four questionnaires: the Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire, and questionnaires about psychotic experiences, trauma, and self-esteem. One year later, 1,521 of the participants returned and completed the same surveys.

Ms. El-Bouhaddani constructed four potential pathways from baseline to follow-up: no psychiatric symptoms, remitting symptoms (baseline psychosocial symptoms that remitted by 1 year), incident symptoms (symptoms that appeared only at 1 year), and persistent symptoms (symptoms at both baseline and 1 year). Her goal was to identify any baseline characteristics that might predict a persistent course.

At the 1-year point, the cohort was a mean of 13.5 years old. Most subjects (1,134) had no symptoms at either time point. Incident symptoms were present in 151, remitting symptoms in 181, and persistent symptoms in 46.

Several baseline characteristics significantly separated the group with remitting symptoms from all other groups: They were significantly more likely to have a low education level (61%), to have divorced parents (38%), to report frequent household moves (22%), to have repeated a grade (31%), to report low self-esteem (15%), and to have somatic symptoms (3%). Teens with persistent symptoms also reported more somatic symptoms (3%), but they were significantly more likely than any of the other groups to report having had at least one traumatic event (45%).

At follow-up, psychotic incidents were significantly more common in the remitting and persistent groups (40% and 62%, respectively) than in the nonsymptomatic and incident groups (10% and 11%).

Ms. El-Bouhaddani then broke psychotic experiences down into hallucinations and delusions, and examined their relationships to symptom course. Hallucinations were significantly more common than delusions among those with a persistent course (58% vs. 42%).

She conducted a logistic regression analysis, which determined that any psychotic experience nearly doubled the risk of a persistent course of psychiatric symptoms (OR, 1.92). Hallucinations nearly tripled the risk (OR, 2.74), as did traumatic experiences (OR, 3.0). Delusions increased the risk by close to 60% (OR, 1.59).

The SDQ does not contain questions about psychotic experiences or trauma – the two most powerful predictors of persistent symptoms. It’s time to change this, Ms. El-Bouhaddani said.

“From these results it seems as though we should be asking adolescents about psychotic experiences and trauma. Perhaps it’s time for a new version of the SDQ.”

She had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

SOURCE: El-Bouhaddani S et al. WPA 2017 Abstract S-023 002.

BERLIN – Teens who reported psychotic symptoms – especially hallucinations – on a baseline mental health screening were twice as likely to develop persistent psychiatric symptoms over the next year as were those without such experiences.

Hallucinations in particular predicted a persistent course, nearly tripling the risk (odds ratio, 2.74), Saliha El-Bouhaddani said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

“This is quite informative and quite clinically relevant,” said Ms. El-Bouhaddani, a doctoral student in psychology at the Parnassia Group, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Because mental health symptoms in young people may be self-limiting, it’s not easy to identify which teens are at high risk for developing persistent problems that can predispose them to a full-blown mental disorder. “But we can see here that psychotic experiences may be very useful in detecting which adolescents may have persistency of symptoms. I believe that screening tools for teenagers should involve questions about psychotic symptoms, because the answer may help us discriminate who will have a self-limiting course and who will have a persistent course.”

Ms. El-Bouhaddani described MasterMind, a longitudinal cohort study of adolescents drawn from the general population. Each teen completed self-report questionnaires on psychotic experiences and psychosocial problems at two time points over a 2-year period. The study was divided into two phases: a 1-year observational period, followed by an intervention for those at risk, and then a 1-year treatment and follow-up period. She reported only the results of the observational phase.

The study enrolled 1,827 young people, who completed four questionnaires: the Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire, and questionnaires about psychotic experiences, trauma, and self-esteem. One year later, 1,521 of the participants returned and completed the same surveys.

Ms. El-Bouhaddani constructed four potential pathways from baseline to follow-up: no psychiatric symptoms, remitting symptoms (baseline psychosocial symptoms that remitted by 1 year), incident symptoms (symptoms that appeared only at 1 year), and persistent symptoms (symptoms at both baseline and 1 year). Her goal was to identify any baseline characteristics that might predict a persistent course.

At the 1-year point, the cohort was a mean of 13.5 years old. Most subjects (1,134) had no symptoms at either time point. Incident symptoms were present in 151, remitting symptoms in 181, and persistent symptoms in 46.

Several baseline characteristics significantly separated the group with remitting symptoms from all other groups: They were significantly more likely to have a low education level (61%), to have divorced parents (38%), to report frequent household moves (22%), to have repeated a grade (31%), to report low self-esteem (15%), and to have somatic symptoms (3%). Teens with persistent symptoms also reported more somatic symptoms (3%), but they were significantly more likely than any of the other groups to report having had at least one traumatic event (45%).

At follow-up, psychotic incidents were significantly more common in the remitting and persistent groups (40% and 62%, respectively) than in the nonsymptomatic and incident groups (10% and 11%).

Ms. El-Bouhaddani then broke psychotic experiences down into hallucinations and delusions, and examined their relationships to symptom course. Hallucinations were significantly more common than delusions among those with a persistent course (58% vs. 42%).

She conducted a logistic regression analysis, which determined that any psychotic experience nearly doubled the risk of a persistent course of psychiatric symptoms (OR, 1.92). Hallucinations nearly tripled the risk (OR, 2.74), as did traumatic experiences (OR, 3.0). Delusions increased the risk by close to 60% (OR, 1.59).

The SDQ does not contain questions about psychotic experiences or trauma – the two most powerful predictors of persistent symptoms. It’s time to change this, Ms. El-Bouhaddani said.

“From these results it seems as though we should be asking adolescents about psychotic experiences and trauma. Perhaps it’s time for a new version of the SDQ.”

She had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

SOURCE: El-Bouhaddani S et al. WPA 2017 Abstract S-023 002.

REPORTING FROM WPA 2017

Key clinical point: Among teens, psychotic symptoms predicted a persistent course of psychosocial problems.

Major finding: Psychotic experiences at baseline doubled the risk of a persistent course of psychosocial problems (odds ratio, 1.94).

Study details: A prospective longitudinal cohort study of 1,521 teens.

Disclosures: Ms. El-Bouhaddani had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: El-Bouhaddani S et al. WPA 2017 Abstract S-023 002.

Psychiatric illness, low IQ often co-occur among male inmates

BERLIN – Among inmates in a Mexican federal prison, psychiatric disorders went hand-in-hand with low or extremely low IQ scores, a study showed.

About 86% of the inmates with a mental illness also had an IQ of 67-69. These men were likely to have multiple psychiatric diagnoses compounded by traumatic brain injury and substance dependence. They also were lowest in the hierarchy of organized crime, Isaac S. Carlos, MD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

Outside prison, this combination of mental illness and low intelligence set these men up for manipulation by more intelligent criminals, who used them most frequently as drug mules or henchmen, Dr. Carlos said. Inside, they were still extremely vulnerable to manipulation and abuse by more intelligent inmates who retain their intellectual dominance in the prison social structure.

Dr. Carlos is an attending psychiatrist in a large, maximum security federal prison that houses thousands of men convicted mostly in organized crime rings associated with drug trafficking. About 45% of the country’s federal inmate population overall has been diagnosed with some kind of mental disorder and requires treatment, but there are few options, he said. In Dr. Carlos’s institution, with one psychiatrist, one criminologist, and 20 psychologists to serve more than 5,000 prisoners, there are few opportunities to do rehabilitative therapy, counseling, or any behavioral interventions. Medication is about the best treatment offered, Dr. Carlos said.

He said he is actively trying to establish an integrative care system there. As part of the project, Dr. Carlos and his colleagues looked at the co-occurrence of psychiatric diagnoses and IQ level.

His group comprised 400 inmates who were sent for psychiatric assessment, which included the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition. Each inmate also received a ranking for his role in organized crime: intellectual (administrative leaders and organizers at the top of the hierarchy), technical (responsible for transportation and transactions), or material (executers of the criminal commands from above).

Of the 400 inmates referred, 300 had at least one ICD-10 mental illness diagnosis. These men were a mean of 30 years old with a mean of 10 years of education. About a third of the group had a triple diagnosis of psychosis, dependence on multiple substances, and dissocial personality disorder (which is comparable to antisocial personality disorder in the DSM-5). These inmates also had the lowest IQ measurements.

Other diagnostic combinations included schizoaffective plus dissocial disorder; substance abuse plus psychosis; dependent personality disorder plus dissocial disorder; traumatic brain injury or posttraumatic stress disorder with psychosis; dependent personality plus dissocial disorder; bipolar disorder plus either dissocial disorder or dependent personality; depression plus borderline personality disorder; depression plus narcissistic disorder; depression plus both personality disorder and dependent personality disorder; adjustment disorder plus dissocial disorder; anxiety plus both dependent and personality disorder, with or without narcissistic disorder; and dependent disorder plus either narcissism or borderline personality disorder.

Only one inmate had a high IQ score. This man had a dual diagnosis of depression and narcissism, and an IQ of 129. He was considered an intellectual offender.

The next highest IQ was 77 – the upper limit of a large group of scores in the 70s. Diagnoses included adjustment disorder plus dissocial disorder; posttraumatic stress disorder plus dissocial disorder; bipolar plus dissocial disorder; and depression plus borderline personality disorder. These men largely fell into the “technical” offender category – the middlemen of organized crime.

At the lower end of the IQ scale were the men categorized as “material” offenders. With IQs ranging from 67 to 69, these men frequently had multiple mental illnesses complicated by brain damage and substance abuse. When psychosis occurred, it was always in conjunction with these lower IQ scores. Low scores were common, Dr. Carlos said: In fact, 45% of the cohort had an IQ of 67; 22%, an IQ of 68; and 19%, an IQ of 69.

“It is necessary to understand the psychiatric comorbidities as well as the IQ in order to get better treatment responses,” Dr. Carlos said. “In some other prisons, this is already understood and a part of therapeutic treatment, but we just don’t have this (in the federal prison system). We have to make the people who run these prisons understand this.”

He had no relevant financial disclosure.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – Among inmates in a Mexican federal prison, psychiatric disorders went hand-in-hand with low or extremely low IQ scores, a study showed.

About 86% of the inmates with a mental illness also had an IQ of 67-69. These men were likely to have multiple psychiatric diagnoses compounded by traumatic brain injury and substance dependence. They also were lowest in the hierarchy of organized crime, Isaac S. Carlos, MD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

Outside prison, this combination of mental illness and low intelligence set these men up for manipulation by more intelligent criminals, who used them most frequently as drug mules or henchmen, Dr. Carlos said. Inside, they were still extremely vulnerable to manipulation and abuse by more intelligent inmates who retain their intellectual dominance in the prison social structure.

Dr. Carlos is an attending psychiatrist in a large, maximum security federal prison that houses thousands of men convicted mostly in organized crime rings associated with drug trafficking. About 45% of the country’s federal inmate population overall has been diagnosed with some kind of mental disorder and requires treatment, but there are few options, he said. In Dr. Carlos’s institution, with one psychiatrist, one criminologist, and 20 psychologists to serve more than 5,000 prisoners, there are few opportunities to do rehabilitative therapy, counseling, or any behavioral interventions. Medication is about the best treatment offered, Dr. Carlos said.

He said he is actively trying to establish an integrative care system there. As part of the project, Dr. Carlos and his colleagues looked at the co-occurrence of psychiatric diagnoses and IQ level.

His group comprised 400 inmates who were sent for psychiatric assessment, which included the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition. Each inmate also received a ranking for his role in organized crime: intellectual (administrative leaders and organizers at the top of the hierarchy), technical (responsible for transportation and transactions), or material (executers of the criminal commands from above).

Of the 400 inmates referred, 300 had at least one ICD-10 mental illness diagnosis. These men were a mean of 30 years old with a mean of 10 years of education. About a third of the group had a triple diagnosis of psychosis, dependence on multiple substances, and dissocial personality disorder (which is comparable to antisocial personality disorder in the DSM-5). These inmates also had the lowest IQ measurements.

Other diagnostic combinations included schizoaffective plus dissocial disorder; substance abuse plus psychosis; dependent personality disorder plus dissocial disorder; traumatic brain injury or posttraumatic stress disorder with psychosis; dependent personality plus dissocial disorder; bipolar disorder plus either dissocial disorder or dependent personality; depression plus borderline personality disorder; depression plus narcissistic disorder; depression plus both personality disorder and dependent personality disorder; adjustment disorder plus dissocial disorder; anxiety plus both dependent and personality disorder, with or without narcissistic disorder; and dependent disorder plus either narcissism or borderline personality disorder.

Only one inmate had a high IQ score. This man had a dual diagnosis of depression and narcissism, and an IQ of 129. He was considered an intellectual offender.

The next highest IQ was 77 – the upper limit of a large group of scores in the 70s. Diagnoses included adjustment disorder plus dissocial disorder; posttraumatic stress disorder plus dissocial disorder; bipolar plus dissocial disorder; and depression plus borderline personality disorder. These men largely fell into the “technical” offender category – the middlemen of organized crime.

At the lower end of the IQ scale were the men categorized as “material” offenders. With IQs ranging from 67 to 69, these men frequently had multiple mental illnesses complicated by brain damage and substance abuse. When psychosis occurred, it was always in conjunction with these lower IQ scores. Low scores were common, Dr. Carlos said: In fact, 45% of the cohort had an IQ of 67; 22%, an IQ of 68; and 19%, an IQ of 69.

“It is necessary to understand the psychiatric comorbidities as well as the IQ in order to get better treatment responses,” Dr. Carlos said. “In some other prisons, this is already understood and a part of therapeutic treatment, but we just don’t have this (in the federal prison system). We have to make the people who run these prisons understand this.”

He had no relevant financial disclosure.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – Among inmates in a Mexican federal prison, psychiatric disorders went hand-in-hand with low or extremely low IQ scores, a study showed.

About 86% of the inmates with a mental illness also had an IQ of 67-69. These men were likely to have multiple psychiatric diagnoses compounded by traumatic brain injury and substance dependence. They also were lowest in the hierarchy of organized crime, Isaac S. Carlos, MD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

Outside prison, this combination of mental illness and low intelligence set these men up for manipulation by more intelligent criminals, who used them most frequently as drug mules or henchmen, Dr. Carlos said. Inside, they were still extremely vulnerable to manipulation and abuse by more intelligent inmates who retain their intellectual dominance in the prison social structure.

Dr. Carlos is an attending psychiatrist in a large, maximum security federal prison that houses thousands of men convicted mostly in organized crime rings associated with drug trafficking. About 45% of the country’s federal inmate population overall has been diagnosed with some kind of mental disorder and requires treatment, but there are few options, he said. In Dr. Carlos’s institution, with one psychiatrist, one criminologist, and 20 psychologists to serve more than 5,000 prisoners, there are few opportunities to do rehabilitative therapy, counseling, or any behavioral interventions. Medication is about the best treatment offered, Dr. Carlos said.

He said he is actively trying to establish an integrative care system there. As part of the project, Dr. Carlos and his colleagues looked at the co-occurrence of psychiatric diagnoses and IQ level.

His group comprised 400 inmates who were sent for psychiatric assessment, which included the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition. Each inmate also received a ranking for his role in organized crime: intellectual (administrative leaders and organizers at the top of the hierarchy), technical (responsible for transportation and transactions), or material (executers of the criminal commands from above).

Of the 400 inmates referred, 300 had at least one ICD-10 mental illness diagnosis. These men were a mean of 30 years old with a mean of 10 years of education. About a third of the group had a triple diagnosis of psychosis, dependence on multiple substances, and dissocial personality disorder (which is comparable to antisocial personality disorder in the DSM-5). These inmates also had the lowest IQ measurements.

Other diagnostic combinations included schizoaffective plus dissocial disorder; substance abuse plus psychosis; dependent personality disorder plus dissocial disorder; traumatic brain injury or posttraumatic stress disorder with psychosis; dependent personality plus dissocial disorder; bipolar disorder plus either dissocial disorder or dependent personality; depression plus borderline personality disorder; depression plus narcissistic disorder; depression plus both personality disorder and dependent personality disorder; adjustment disorder plus dissocial disorder; anxiety plus both dependent and personality disorder, with or without narcissistic disorder; and dependent disorder plus either narcissism or borderline personality disorder.

Only one inmate had a high IQ score. This man had a dual diagnosis of depression and narcissism, and an IQ of 129. He was considered an intellectual offender.

The next highest IQ was 77 – the upper limit of a large group of scores in the 70s. Diagnoses included adjustment disorder plus dissocial disorder; posttraumatic stress disorder plus dissocial disorder; bipolar plus dissocial disorder; and depression plus borderline personality disorder. These men largely fell into the “technical” offender category – the middlemen of organized crime.

At the lower end of the IQ scale were the men categorized as “material” offenders. With IQs ranging from 67 to 69, these men frequently had multiple mental illnesses complicated by brain damage and substance abuse. When psychosis occurred, it was always in conjunction with these lower IQ scores. Low scores were common, Dr. Carlos said: In fact, 45% of the cohort had an IQ of 67; 22%, an IQ of 68; and 19%, an IQ of 69.

“It is necessary to understand the psychiatric comorbidities as well as the IQ in order to get better treatment responses,” Dr. Carlos said. “In some other prisons, this is already understood and a part of therapeutic treatment, but we just don’t have this (in the federal prison system). We have to make the people who run these prisons understand this.”

He had no relevant financial disclosure.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT WPA 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Almost 90% of inmates in a Mexican federal prison with a mental disorder also had a low or extremely low IQ.

Data source: A prospective study of 400 men; 300 had at least one ICD-10 mental health diagnosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Carlos had no relevant financial disclosures.

In high-risk patients, methylation strikes genes before psychosis hits

BERLIN – Researchers are honing in on several sets of genes that, when altered by as-yet-unknown factors, may signal conversion to full-blown psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk for the disorder.

If confirmed, these candidate markers might have potential as blood-based biomarkers to predict conversion risk and assist in clinical staging, Marie-Odile Krebs, MD, PhD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

The genes modulate three biologic pathways that also have been implicated in schizophrenia: glutathione metabolism, axonal targeting, and inflammation, said Dr. Krebs of Saint-Anne Hospital, Paris. “Knowing this may even help us to target some drugs that work in those pathways,” she said.

Several blood-based analyte screens have been investigated with mixed results, Dr. Krebs noted.

In 2015, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, created a 15-analyte plasma panel that performed well in the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPL-S) cohort. The project is a multisite endeavor that aims to better understand predictors and mechanisms for the development of psychosis. The panel separated 35 unaffected controls from 32 with high-risk symptoms who converted to psychosis and from 40 who did not, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.91 (Schizophr Bull. 2015 Mar;41[2]:419-28).

Selected from an initial group of 185 analytes, the candidate markers were inflammatory cytokines, proteins modulating blood-brain barrier inflammation, and hormones related to the hypothalamic-pituitary axes. Several also were involved in reacting to oxidative stress.

Earlier this year, members of that same group identified a set of nine microRNAs related to cortical thinning in patients who converted to psychosis. These microRNAs also have been implicated in brain development, synaptic plasticity, immune function, and schizophrenia (Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017 Feb 10. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.34).

Although these studies are helpful signposts, Dr. Krebs said they do not reflect the dynamic interaction of disease risk, which includes not only the intrinsic factors of genetics, enzymes, and proteins, but the extrinsic risks imposed by other factors: stress, trauma, cannabis use, and other completely individual experiences. “This is a dynamic process, and we need a dynamic assessment,” she said.

To that end, Dr. Krebs and her colleagues decided to look at methylomic changes in a small group of 39 patients at ultrahigh risk for psychosis conversion. All of these patients (mean age, 22 years) were seen at Saint-Anne Hospital from 2009 to 2013. Using whole blood, Dr. Krebs performed a genomewide DNA methylation study to determine what genes – if any – were differently methylated between the converters and nonconverters. The mean follow-up was 1 year (Mol Psychiatry. 2017 Apr;22[4]:512-8).

Although no significant difference was found in global methylation associated with conversion, Dr. Krebs did find longitudinal changes associated with conversion in three regions.

A cluster of five genes in the glutathione S-transferase family was differently methylated between the converters and nonconverters. Two were related to the GSTM5 promoter gene, which encodes for cytosolic and membrane-bound glutathione S-transferase – an important antioxidant enzyme, the downregulation of which has been implicated in schizophrenia. These two regions appeared to be stable over time, suggesting that methylation occurred before conversion, Dr. Krebs said.

Oxidative stress has been implicated in schizophrenia, and GSTM5 is expressed in the brain, Dr. Krebs noted. Some researchers suggest the gene is involved in dopamine metabolism. It’s also underexpressed in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia patients.

Three other regions in the GST family changed with conversion: two on the glutathione S-transferase theta 1 gene and one on the glutathione S-transferase P gene. Since all of these have to do with production of the innate antioxidant glutathione, “these findings suggest a potential use for antioxidant drugs,” Dr. Krebs said.

She found two other differently methylated regions as well.

One was a cluster of eight genes that are all involved in axon guidance – the process by which axons branch out to their correct targets. The second cluster comprised seven genes, all of which are involved in regulating interleukin-17 signaling. This cytokine has been implicated in autoimmune disorders.

Finally, Dr. Krebs performed a transcriptome analysis looking at the brain-expressed messenger RNA in the samples. “The methylome seemed less dynamic than the transcriptome,” she said. “Some methylomic changes may have occurred several months before the conversion, whereas transcriptomic analysis may reflect more rapid changes.”

There was only a 22% concordance between the two analyses. However, the GSTM5 gene and the neuropilin 1 gene – one of those involved in axon guidance – were both methylated and downregulated in the converters. The transcriptome analysis also found significantly decreased expression (although not methylation) of another gene, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A. This is a key enzyme in oxidizing long-chain fatty acids and transporting them into the mitochondria.

Adapting these observed differences in gene expression into a useful clinical tool will be challenging, Dr. Krebs said. In addition to large-group validation, any risk prediction model would have to take into account the many other factors that influence psychosis conversion: cerebral and sexual maturation during adolescence, cannabis use, and stress and other completely individual life experiences.

Nevertheless, she concluded, “longitudinal ‘multi-omics’ may be a step toward a future of personalized molecular psychiatry.”

Dr. Krebs had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – Researchers are honing in on several sets of genes that, when altered by as-yet-unknown factors, may signal conversion to full-blown psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk for the disorder.

If confirmed, these candidate markers might have potential as blood-based biomarkers to predict conversion risk and assist in clinical staging, Marie-Odile Krebs, MD, PhD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

The genes modulate three biologic pathways that also have been implicated in schizophrenia: glutathione metabolism, axonal targeting, and inflammation, said Dr. Krebs of Saint-Anne Hospital, Paris. “Knowing this may even help us to target some drugs that work in those pathways,” she said.

Several blood-based analyte screens have been investigated with mixed results, Dr. Krebs noted.

In 2015, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, created a 15-analyte plasma panel that performed well in the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPL-S) cohort. The project is a multisite endeavor that aims to better understand predictors and mechanisms for the development of psychosis. The panel separated 35 unaffected controls from 32 with high-risk symptoms who converted to psychosis and from 40 who did not, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.91 (Schizophr Bull. 2015 Mar;41[2]:419-28).

Selected from an initial group of 185 analytes, the candidate markers were inflammatory cytokines, proteins modulating blood-brain barrier inflammation, and hormones related to the hypothalamic-pituitary axes. Several also were involved in reacting to oxidative stress.

Earlier this year, members of that same group identified a set of nine microRNAs related to cortical thinning in patients who converted to psychosis. These microRNAs also have been implicated in brain development, synaptic plasticity, immune function, and schizophrenia (Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017 Feb 10. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.34).

Although these studies are helpful signposts, Dr. Krebs said they do not reflect the dynamic interaction of disease risk, which includes not only the intrinsic factors of genetics, enzymes, and proteins, but the extrinsic risks imposed by other factors: stress, trauma, cannabis use, and other completely individual experiences. “This is a dynamic process, and we need a dynamic assessment,” she said.

To that end, Dr. Krebs and her colleagues decided to look at methylomic changes in a small group of 39 patients at ultrahigh risk for psychosis conversion. All of these patients (mean age, 22 years) were seen at Saint-Anne Hospital from 2009 to 2013. Using whole blood, Dr. Krebs performed a genomewide DNA methylation study to determine what genes – if any – were differently methylated between the converters and nonconverters. The mean follow-up was 1 year (Mol Psychiatry. 2017 Apr;22[4]:512-8).

Although no significant difference was found in global methylation associated with conversion, Dr. Krebs did find longitudinal changes associated with conversion in three regions.

A cluster of five genes in the glutathione S-transferase family was differently methylated between the converters and nonconverters. Two were related to the GSTM5 promoter gene, which encodes for cytosolic and membrane-bound glutathione S-transferase – an important antioxidant enzyme, the downregulation of which has been implicated in schizophrenia. These two regions appeared to be stable over time, suggesting that methylation occurred before conversion, Dr. Krebs said.

Oxidative stress has been implicated in schizophrenia, and GSTM5 is expressed in the brain, Dr. Krebs noted. Some researchers suggest the gene is involved in dopamine metabolism. It’s also underexpressed in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia patients.

Three other regions in the GST family changed with conversion: two on the glutathione S-transferase theta 1 gene and one on the glutathione S-transferase P gene. Since all of these have to do with production of the innate antioxidant glutathione, “these findings suggest a potential use for antioxidant drugs,” Dr. Krebs said.

She found two other differently methylated regions as well.

One was a cluster of eight genes that are all involved in axon guidance – the process by which axons branch out to their correct targets. The second cluster comprised seven genes, all of which are involved in regulating interleukin-17 signaling. This cytokine has been implicated in autoimmune disorders.

Finally, Dr. Krebs performed a transcriptome analysis looking at the brain-expressed messenger RNA in the samples. “The methylome seemed less dynamic than the transcriptome,” she said. “Some methylomic changes may have occurred several months before the conversion, whereas transcriptomic analysis may reflect more rapid changes.”

There was only a 22% concordance between the two analyses. However, the GSTM5 gene and the neuropilin 1 gene – one of those involved in axon guidance – were both methylated and downregulated in the converters. The transcriptome analysis also found significantly decreased expression (although not methylation) of another gene, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A. This is a key enzyme in oxidizing long-chain fatty acids and transporting them into the mitochondria.

Adapting these observed differences in gene expression into a useful clinical tool will be challenging, Dr. Krebs said. In addition to large-group validation, any risk prediction model would have to take into account the many other factors that influence psychosis conversion: cerebral and sexual maturation during adolescence, cannabis use, and stress and other completely individual life experiences.

Nevertheless, she concluded, “longitudinal ‘multi-omics’ may be a step toward a future of personalized molecular psychiatry.”

Dr. Krebs had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – Researchers are honing in on several sets of genes that, when altered by as-yet-unknown factors, may signal conversion to full-blown psychosis in people at ultrahigh risk for the disorder.

If confirmed, these candidate markers might have potential as blood-based biomarkers to predict conversion risk and assist in clinical staging, Marie-Odile Krebs, MD, PhD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

The genes modulate three biologic pathways that also have been implicated in schizophrenia: glutathione metabolism, axonal targeting, and inflammation, said Dr. Krebs of Saint-Anne Hospital, Paris. “Knowing this may even help us to target some drugs that work in those pathways,” she said.

Several blood-based analyte screens have been investigated with mixed results, Dr. Krebs noted.

In 2015, researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, created a 15-analyte plasma panel that performed well in the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPL-S) cohort. The project is a multisite endeavor that aims to better understand predictors and mechanisms for the development of psychosis. The panel separated 35 unaffected controls from 32 with high-risk symptoms who converted to psychosis and from 40 who did not, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.91 (Schizophr Bull. 2015 Mar;41[2]:419-28).

Selected from an initial group of 185 analytes, the candidate markers were inflammatory cytokines, proteins modulating blood-brain barrier inflammation, and hormones related to the hypothalamic-pituitary axes. Several also were involved in reacting to oxidative stress.

Earlier this year, members of that same group identified a set of nine microRNAs related to cortical thinning in patients who converted to psychosis. These microRNAs also have been implicated in brain development, synaptic plasticity, immune function, and schizophrenia (Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017 Feb 10. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.34).

Although these studies are helpful signposts, Dr. Krebs said they do not reflect the dynamic interaction of disease risk, which includes not only the intrinsic factors of genetics, enzymes, and proteins, but the extrinsic risks imposed by other factors: stress, trauma, cannabis use, and other completely individual experiences. “This is a dynamic process, and we need a dynamic assessment,” she said.

To that end, Dr. Krebs and her colleagues decided to look at methylomic changes in a small group of 39 patients at ultrahigh risk for psychosis conversion. All of these patients (mean age, 22 years) were seen at Saint-Anne Hospital from 2009 to 2013. Using whole blood, Dr. Krebs performed a genomewide DNA methylation study to determine what genes – if any – were differently methylated between the converters and nonconverters. The mean follow-up was 1 year (Mol Psychiatry. 2017 Apr;22[4]:512-8).

Although no significant difference was found in global methylation associated with conversion, Dr. Krebs did find longitudinal changes associated with conversion in three regions.

A cluster of five genes in the glutathione S-transferase family was differently methylated between the converters and nonconverters. Two were related to the GSTM5 promoter gene, which encodes for cytosolic and membrane-bound glutathione S-transferase – an important antioxidant enzyme, the downregulation of which has been implicated in schizophrenia. These two regions appeared to be stable over time, suggesting that methylation occurred before conversion, Dr. Krebs said.

Oxidative stress has been implicated in schizophrenia, and GSTM5 is expressed in the brain, Dr. Krebs noted. Some researchers suggest the gene is involved in dopamine metabolism. It’s also underexpressed in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia patients.

Three other regions in the GST family changed with conversion: two on the glutathione S-transferase theta 1 gene and one on the glutathione S-transferase P gene. Since all of these have to do with production of the innate antioxidant glutathione, “these findings suggest a potential use for antioxidant drugs,” Dr. Krebs said.

She found two other differently methylated regions as well.

One was a cluster of eight genes that are all involved in axon guidance – the process by which axons branch out to their correct targets. The second cluster comprised seven genes, all of which are involved in regulating interleukin-17 signaling. This cytokine has been implicated in autoimmune disorders.

Finally, Dr. Krebs performed a transcriptome analysis looking at the brain-expressed messenger RNA in the samples. “The methylome seemed less dynamic than the transcriptome,” she said. “Some methylomic changes may have occurred several months before the conversion, whereas transcriptomic analysis may reflect more rapid changes.”

There was only a 22% concordance between the two analyses. However, the GSTM5 gene and the neuropilin 1 gene – one of those involved in axon guidance – were both methylated and downregulated in the converters. The transcriptome analysis also found significantly decreased expression (although not methylation) of another gene, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A. This is a key enzyme in oxidizing long-chain fatty acids and transporting them into the mitochondria.

Adapting these observed differences in gene expression into a useful clinical tool will be challenging, Dr. Krebs said. In addition to large-group validation, any risk prediction model would have to take into account the many other factors that influence psychosis conversion: cerebral and sexual maturation during adolescence, cannabis use, and stress and other completely individual life experiences.

Nevertheless, she concluded, “longitudinal ‘multi-omics’ may be a step toward a future of personalized molecular psychiatry.”

Dr. Krebs had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WPA 2017

As nations advance economically, mental illnesses exact greater burdens

BERLIN – A vision perceived during America’s Great Depression has come to fruition across the globe, putting mental illness at the center of a devastating web of personal and economic costs.

In the 1930s, the Rockefeller Foundation’s director of medical science, Alan Gregg, MD, distilled an important notion from his decades of travel providing health care and advice to developing nations. As poor countries became richer, infectious diseases that had long ravaged their populations came under control. As people lived longer, however, they became subject to other disorders: chronic age-related illnesses for the old and, for the young, mental illnesses.

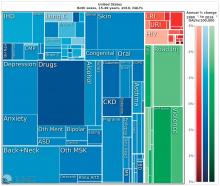

“We have a very, very low rate of infectious disease now, much as the Rockefeller Foundation predicted,” said Dr. Summergrad, the Dr. Frances S. Arkin Professor and chair of psychiatry at Tufts University, Boston. “But, in 2010, the biggest causes of morbidity and disability for U.S. residents aged 15-49 years old were major depressive disorder, dysthymia, drug and alcohol use, schizophrenia, and anxiety. These dwarf the impact of every other illness during that age period. …. They are the burdens of disease of the modern world.”

This shift from infectious disease to mental illness as a primary cause of disability has profound downstream health implications as well, Dr. Summergrad said. Mental disorders that emerge in adolescent and young adulthood are inextricably linked to the chronic diseases that develop in older people.

“Mental and behavioral disturbances are important risk factors for medical conditions that also exact a heavy burden,” he said, referring to a study in JAMA (2013 Aug 14;310[6]:591-608). The report, “The state of U.S. health, 1990-2010: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors,” found that more than half of the of the Top 17 risk factors for morbidity and mortality were directly or indirectly related to mental or behavioral disorders. These included direct causes like alcohol and drug use, and indirect causes that are highly correlated with mental illnesses: physical inactivity, tobacco use, glycemic abnormalities, hypertension, and obesity.

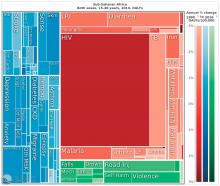

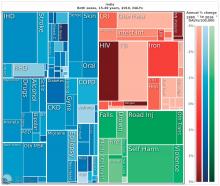

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle, illustrated these global trends in September, with a report published in the Lancet (2017;390:1423-59). Produced in collaboration with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the report focused on the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, measured 37 of the 50 health-related SDG indicators from 1990-2016 in 188 countries, and projected the indicators to 2030.

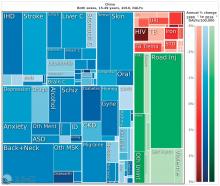

China, on the other hand, looked very much like North America. The proportion of infectious diseases was much smaller than in sub-Saharan Africa or India, a finding Dr. Summergrad attributed to the Chinese government’s post–World War II determination to eradicate communicable diseases.

Unfortunately, Dr. Summergrad said, most countries are ill equipped to handle this shift in the burden of illness. Even in the United States, there are limited mental health hospital beds and a dearth of psychiatrists to handle the burgeoning patient load. And the shift toward higher rates of mental illness will likely continue, at a shocking financial cost.

A Harvard School of Public Health policy report, issued in 2011, paints a stark picture. In 2010, mental illness cost high-income countries about $5.5 trillion in lost income and productivity, narrowly beating out the burden imposed by cardivoascular disease ($5.4 trillion). By 2030, lost wages and productivity tied to mental illiness is expected to cost the United States $7.3 trillion.

“Globally, by 2030, we can expect the direct economic impact of mental illnesses to reach $16 trillion,” Dr. Summergrad said. “We have a limited workforce, limited outpatient facilities, limited hospital beds, and limited money, even here in the U.S. All of this is almost nonexistent in much of the world. The integration of care and workforce and facilities will be a huge challenge as we move forward. We need to think about long-term investment here, much in the same way that the Rockefeller Foundation thought about this in the 1930s.”

Dr. Summergrad had no relevant financial disclosures.

BERLIN – A vision perceived during America’s Great Depression has come to fruition across the globe, putting mental illness at the center of a devastating web of personal and economic costs.

In the 1930s, the Rockefeller Foundation’s director of medical science, Alan Gregg, MD, distilled an important notion from his decades of travel providing health care and advice to developing nations. As poor countries became richer, infectious diseases that had long ravaged their populations came under control. As people lived longer, however, they became subject to other disorders: chronic age-related illnesses for the old and, for the young, mental illnesses.

“We have a very, very low rate of infectious disease now, much as the Rockefeller Foundation predicted,” said Dr. Summergrad, the Dr. Frances S. Arkin Professor and chair of psychiatry at Tufts University, Boston. “But, in 2010, the biggest causes of morbidity and disability for U.S. residents aged 15-49 years old were major depressive disorder, dysthymia, drug and alcohol use, schizophrenia, and anxiety. These dwarf the impact of every other illness during that age period. …. They are the burdens of disease of the modern world.”

This shift from infectious disease to mental illness as a primary cause of disability has profound downstream health implications as well, Dr. Summergrad said. Mental disorders that emerge in adolescent and young adulthood are inextricably linked to the chronic diseases that develop in older people.

“Mental and behavioral disturbances are important risk factors for medical conditions that also exact a heavy burden,” he said, referring to a study in JAMA (2013 Aug 14;310[6]:591-608). The report, “The state of U.S. health, 1990-2010: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors,” found that more than half of the of the Top 17 risk factors for morbidity and mortality were directly or indirectly related to mental or behavioral disorders. These included direct causes like alcohol and drug use, and indirect causes that are highly correlated with mental illnesses: physical inactivity, tobacco use, glycemic abnormalities, hypertension, and obesity.

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle, illustrated these global trends in September, with a report published in the Lancet (2017;390:1423-59). Produced in collaboration with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the report focused on the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, measured 37 of the 50 health-related SDG indicators from 1990-2016 in 188 countries, and projected the indicators to 2030.

China, on the other hand, looked very much like North America. The proportion of infectious diseases was much smaller than in sub-Saharan Africa or India, a finding Dr. Summergrad attributed to the Chinese government’s post–World War II determination to eradicate communicable diseases.

Unfortunately, Dr. Summergrad said, most countries are ill equipped to handle this shift in the burden of illness. Even in the United States, there are limited mental health hospital beds and a dearth of psychiatrists to handle the burgeoning patient load. And the shift toward higher rates of mental illness will likely continue, at a shocking financial cost.

A Harvard School of Public Health policy report, issued in 2011, paints a stark picture. In 2010, mental illness cost high-income countries about $5.5 trillion in lost income and productivity, narrowly beating out the burden imposed by cardivoascular disease ($5.4 trillion). By 2030, lost wages and productivity tied to mental illiness is expected to cost the United States $7.3 trillion.

“Globally, by 2030, we can expect the direct economic impact of mental illnesses to reach $16 trillion,” Dr. Summergrad said. “We have a limited workforce, limited outpatient facilities, limited hospital beds, and limited money, even here in the U.S. All of this is almost nonexistent in much of the world. The integration of care and workforce and facilities will be a huge challenge as we move forward. We need to think about long-term investment here, much in the same way that the Rockefeller Foundation thought about this in the 1930s.”

Dr. Summergrad had no relevant financial disclosures.

BERLIN – A vision perceived during America’s Great Depression has come to fruition across the globe, putting mental illness at the center of a devastating web of personal and economic costs.

In the 1930s, the Rockefeller Foundation’s director of medical science, Alan Gregg, MD, distilled an important notion from his decades of travel providing health care and advice to developing nations. As poor countries became richer, infectious diseases that had long ravaged their populations came under control. As people lived longer, however, they became subject to other disorders: chronic age-related illnesses for the old and, for the young, mental illnesses.

“We have a very, very low rate of infectious disease now, much as the Rockefeller Foundation predicted,” said Dr. Summergrad, the Dr. Frances S. Arkin Professor and chair of psychiatry at Tufts University, Boston. “But, in 2010, the biggest causes of morbidity and disability for U.S. residents aged 15-49 years old were major depressive disorder, dysthymia, drug and alcohol use, schizophrenia, and anxiety. These dwarf the impact of every other illness during that age period. …. They are the burdens of disease of the modern world.”

This shift from infectious disease to mental illness as a primary cause of disability has profound downstream health implications as well, Dr. Summergrad said. Mental disorders that emerge in adolescent and young adulthood are inextricably linked to the chronic diseases that develop in older people.

“Mental and behavioral disturbances are important risk factors for medical conditions that also exact a heavy burden,” he said, referring to a study in JAMA (2013 Aug 14;310[6]:591-608). The report, “The state of U.S. health, 1990-2010: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors,” found that more than half of the of the Top 17 risk factors for morbidity and mortality were directly or indirectly related to mental or behavioral disorders. These included direct causes like alcohol and drug use, and indirect causes that are highly correlated with mental illnesses: physical inactivity, tobacco use, glycemic abnormalities, hypertension, and obesity.

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle, illustrated these global trends in September, with a report published in the Lancet (2017;390:1423-59). Produced in collaboration with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the report focused on the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, measured 37 of the 50 health-related SDG indicators from 1990-2016 in 188 countries, and projected the indicators to 2030.

China, on the other hand, looked very much like North America. The proportion of infectious diseases was much smaller than in sub-Saharan Africa or India, a finding Dr. Summergrad attributed to the Chinese government’s post–World War II determination to eradicate communicable diseases.

Unfortunately, Dr. Summergrad said, most countries are ill equipped to handle this shift in the burden of illness. Even in the United States, there are limited mental health hospital beds and a dearth of psychiatrists to handle the burgeoning patient load. And the shift toward higher rates of mental illness will likely continue, at a shocking financial cost.

A Harvard School of Public Health policy report, issued in 2011, paints a stark picture. In 2010, mental illness cost high-income countries about $5.5 trillion in lost income and productivity, narrowly beating out the burden imposed by cardivoascular disease ($5.4 trillion). By 2030, lost wages and productivity tied to mental illiness is expected to cost the United States $7.3 trillion.

“Globally, by 2030, we can expect the direct economic impact of mental illnesses to reach $16 trillion,” Dr. Summergrad said. “We have a limited workforce, limited outpatient facilities, limited hospital beds, and limited money, even here in the U.S. All of this is almost nonexistent in much of the world. The integration of care and workforce and facilities will be a huge challenge as we move forward. We need to think about long-term investment here, much in the same way that the Rockefeller Foundation thought about this in the 1930s.”

Dr. Summergrad had no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WPA 2017

From cells to socioeconomics, meth worsens HIV outcomes

BERLIN – From cellular pathology to socioeconomics, methamphetamine and HIV are a devastating combination.

Either one is enough to ruin a life on its own. But together they can become a fatal ouroboros, Jordi Blanch, MD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Congress. The drug sparks dangerous sexual behavior that ups HIV risk. It increases HIV-vulnerable receptors on immune cells, priming them for viral invasion. It interferes with the metabolism of antiretroviral drugs and grinds medication adherence into the dust.

And even when faced with the facts about these interactions with a serious disease, meth users find it almost impossible to leave the drug behind.

Methamphetamine was once almost exclusively a North American problem, said Dr. Blanch of the University of Barcelona. But in the last decade, the drug has jumped the pond, storming the beaches of Western Europe. Bolstered by imports from Asia, it’s now spreading eastward and down into Africa. Meth is challenging and surpassing alcohol as the drug of choice for HIV high-risk groups (particularly men who have sex with men). Like alcohol, it’s cheap and easy to find. Unlike alcohol, it delivers an incredibly potent, nearly instantaneous brain hit that amps up sexual desire and capacity while decreasing inhibition and executive function.

“When we look at the use of meth in the context of sexual relationships, it’s not hard to understand how it leads to all kinds of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV,” Dr. Blanch said.

A potent dopamine agonist, meth not only increases the neurotransmitter’s release, it blocks reuptake. It reduces the expression of dopamine transporters on the cell surface. At the same time, meth inhibits monoamine oxidase, normally a prime metabolizer. It even creates more dopamine: Methamphetamine increases the activity of tyrosine hydroxylase, the enzyme that catalyzes tyrosine into the dopamine precursor, l-dopa.

The neurologic response to smoking crystal meth – still the most popular way of ingesting the drug – is practically instantaneous. “It’s a very fast and intense euphoric high that, as we know, can have a lot of really bad side effects, like anxiety, restlessness, and even psychosis,” Dr. Blanch said. Its other side effects, though, are what make meth such a potent driver of risky sexual behavior.

“Men who have sex with men use it because it dramatically facilitates sexual functioning. It allows them to have sex for much longer. It decreases pain sensation, so this makes it easier to engage in anal sex, which is likely to be unprotected,” Dr. Blanch said. At the same time, the drug decreases higher-order thinking and increases impulsivity, driving even more behaviors that increase the risk of HIV, including group sex and the use of alcohol and injectable drugs together.

It is not just a cognitive-behavioral problem, though. Animal studies have found some intriguing pathophysiologic links between HIV viral activity and meth.

“Meth actually facilitates the infection,” Dr. Blanch said. “The risk of getting it is much higher, and the risk of it progressing with a high viral load is much higher.”

A 2015 review paper by Ryan Colby Passaro and his associates touches on some of these animal models (J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015 Sep;10[3]:477-86). One of the most intriguing is a mouse study, which found that methamphetamine upregulated the HIV-1 coreceptors, CXCR4 and CCR5, not only on CD4+ T cells, but on monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and, to some extent, astrocytes.

Cat and rhesus monkey data implicated this meth-related effect on CXCR4 and CCR5 as well. But the drug also was implicated in other cellular pathways – all of which serve to make immune cells more vulnerable to HIV attack. These findings support the observation that methamphetamine users with the disease frequently have higher viral loads than nonusers.

After a diagnosis, users may continue to use as a way of avoiding confronting their illness, or even to combat the accompanying physical fatigue, Dr. Blanch said. Like many illicit drug users, meth users often show poor compliance with medical follow-up and poor medication adherence. But even if they do take their antiretroviral medications, methamphetamine still has a way of exerting its power. Ritonavir and cobicistat both inhibit the metabolic pathway that breaks down methamphetamine; using meth with either of those drugs can increase meth concentrations by up to 10-fold, a combination that has killed many patients.

Unfortunately, Dr. Blanch said, it’s terribly difficult for users to give up meth, even in the face of contracting such a serious illness.

“In the beginning, after a diagnosis, they may stop using for a while. But then many start again,” he said. “We see this in study after study. But we have not so many studies on how to treat these patients.”

Trials of antidepressants and antipsychotics, and of replacement therapy with amphetamines or methylphenidate, have had mixed results.

“In my own clinic, we try to explain these problems of the interaction of meth and HIV. We have tried even to motivate our patients to use just on the weekend, for example, but they didn’t accept that,” he said. “Usually, we end up trying to make an agreement that the patient will use as little as possible and let them know how much it interferes with their treatment. But in my clinical experience, it’s not so easy. It’s hard to make any change. … very difficult.”

Dr. Blanch had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – From cellular pathology to socioeconomics, methamphetamine and HIV are a devastating combination.

Either one is enough to ruin a life on its own. But together they can become a fatal ouroboros, Jordi Blanch, MD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Congress. The drug sparks dangerous sexual behavior that ups HIV risk. It increases HIV-vulnerable receptors on immune cells, priming them for viral invasion. It interferes with the metabolism of antiretroviral drugs and grinds medication adherence into the dust.

And even when faced with the facts about these interactions with a serious disease, meth users find it almost impossible to leave the drug behind.

Methamphetamine was once almost exclusively a North American problem, said Dr. Blanch of the University of Barcelona. But in the last decade, the drug has jumped the pond, storming the beaches of Western Europe. Bolstered by imports from Asia, it’s now spreading eastward and down into Africa. Meth is challenging and surpassing alcohol as the drug of choice for HIV high-risk groups (particularly men who have sex with men). Like alcohol, it’s cheap and easy to find. Unlike alcohol, it delivers an incredibly potent, nearly instantaneous brain hit that amps up sexual desire and capacity while decreasing inhibition and executive function.

“When we look at the use of meth in the context of sexual relationships, it’s not hard to understand how it leads to all kinds of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV,” Dr. Blanch said.

A potent dopamine agonist, meth not only increases the neurotransmitter’s release, it blocks reuptake. It reduces the expression of dopamine transporters on the cell surface. At the same time, meth inhibits monoamine oxidase, normally a prime metabolizer. It even creates more dopamine: Methamphetamine increases the activity of tyrosine hydroxylase, the enzyme that catalyzes tyrosine into the dopamine precursor, l-dopa.

The neurologic response to smoking crystal meth – still the most popular way of ingesting the drug – is practically instantaneous. “It’s a very fast and intense euphoric high that, as we know, can have a lot of really bad side effects, like anxiety, restlessness, and even psychosis,” Dr. Blanch said. Its other side effects, though, are what make meth such a potent driver of risky sexual behavior.

“Men who have sex with men use it because it dramatically facilitates sexual functioning. It allows them to have sex for much longer. It decreases pain sensation, so this makes it easier to engage in anal sex, which is likely to be unprotected,” Dr. Blanch said. At the same time, the drug decreases higher-order thinking and increases impulsivity, driving even more behaviors that increase the risk of HIV, including group sex and the use of alcohol and injectable drugs together.

It is not just a cognitive-behavioral problem, though. Animal studies have found some intriguing pathophysiologic links between HIV viral activity and meth.

“Meth actually facilitates the infection,” Dr. Blanch said. “The risk of getting it is much higher, and the risk of it progressing with a high viral load is much higher.”

A 2015 review paper by Ryan Colby Passaro and his associates touches on some of these animal models (J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015 Sep;10[3]:477-86). One of the most intriguing is a mouse study, which found that methamphetamine upregulated the HIV-1 coreceptors, CXCR4 and CCR5, not only on CD4+ T cells, but on monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and, to some extent, astrocytes.

Cat and rhesus monkey data implicated this meth-related effect on CXCR4 and CCR5 as well. But the drug also was implicated in other cellular pathways – all of which serve to make immune cells more vulnerable to HIV attack. These findings support the observation that methamphetamine users with the disease frequently have higher viral loads than nonusers.

After a diagnosis, users may continue to use as a way of avoiding confronting their illness, or even to combat the accompanying physical fatigue, Dr. Blanch said. Like many illicit drug users, meth users often show poor compliance with medical follow-up and poor medication adherence. But even if they do take their antiretroviral medications, methamphetamine still has a way of exerting its power. Ritonavir and cobicistat both inhibit the metabolic pathway that breaks down methamphetamine; using meth with either of those drugs can increase meth concentrations by up to 10-fold, a combination that has killed many patients.

Unfortunately, Dr. Blanch said, it’s terribly difficult for users to give up meth, even in the face of contracting such a serious illness.

“In the beginning, after a diagnosis, they may stop using for a while. But then many start again,” he said. “We see this in study after study. But we have not so many studies on how to treat these patients.”

Trials of antidepressants and antipsychotics, and of replacement therapy with amphetamines or methylphenidate, have had mixed results.

“In my own clinic, we try to explain these problems of the interaction of meth and HIV. We have tried even to motivate our patients to use just on the weekend, for example, but they didn’t accept that,” he said. “Usually, we end up trying to make an agreement that the patient will use as little as possible and let them know how much it interferes with their treatment. But in my clinical experience, it’s not so easy. It’s hard to make any change. … very difficult.”

Dr. Blanch had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

BERLIN – From cellular pathology to socioeconomics, methamphetamine and HIV are a devastating combination.

Either one is enough to ruin a life on its own. But together they can become a fatal ouroboros, Jordi Blanch, MD, said at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Congress. The drug sparks dangerous sexual behavior that ups HIV risk. It increases HIV-vulnerable receptors on immune cells, priming them for viral invasion. It interferes with the metabolism of antiretroviral drugs and grinds medication adherence into the dust.

And even when faced with the facts about these interactions with a serious disease, meth users find it almost impossible to leave the drug behind.

Methamphetamine was once almost exclusively a North American problem, said Dr. Blanch of the University of Barcelona. But in the last decade, the drug has jumped the pond, storming the beaches of Western Europe. Bolstered by imports from Asia, it’s now spreading eastward and down into Africa. Meth is challenging and surpassing alcohol as the drug of choice for HIV high-risk groups (particularly men who have sex with men). Like alcohol, it’s cheap and easy to find. Unlike alcohol, it delivers an incredibly potent, nearly instantaneous brain hit that amps up sexual desire and capacity while decreasing inhibition and executive function.

“When we look at the use of meth in the context of sexual relationships, it’s not hard to understand how it leads to all kinds of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV,” Dr. Blanch said.

A potent dopamine agonist, meth not only increases the neurotransmitter’s release, it blocks reuptake. It reduces the expression of dopamine transporters on the cell surface. At the same time, meth inhibits monoamine oxidase, normally a prime metabolizer. It even creates more dopamine: Methamphetamine increases the activity of tyrosine hydroxylase, the enzyme that catalyzes tyrosine into the dopamine precursor, l-dopa.

The neurologic response to smoking crystal meth – still the most popular way of ingesting the drug – is practically instantaneous. “It’s a very fast and intense euphoric high that, as we know, can have a lot of really bad side effects, like anxiety, restlessness, and even psychosis,” Dr. Blanch said. Its other side effects, though, are what make meth such a potent driver of risky sexual behavior.

“Men who have sex with men use it because it dramatically facilitates sexual functioning. It allows them to have sex for much longer. It decreases pain sensation, so this makes it easier to engage in anal sex, which is likely to be unprotected,” Dr. Blanch said. At the same time, the drug decreases higher-order thinking and increases impulsivity, driving even more behaviors that increase the risk of HIV, including group sex and the use of alcohol and injectable drugs together.

It is not just a cognitive-behavioral problem, though. Animal studies have found some intriguing pathophysiologic links between HIV viral activity and meth.

“Meth actually facilitates the infection,” Dr. Blanch said. “The risk of getting it is much higher, and the risk of it progressing with a high viral load is much higher.”

A 2015 review paper by Ryan Colby Passaro and his associates touches on some of these animal models (J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2015 Sep;10[3]:477-86). One of the most intriguing is a mouse study, which found that methamphetamine upregulated the HIV-1 coreceptors, CXCR4 and CCR5, not only on CD4+ T cells, but on monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and, to some extent, astrocytes.

Cat and rhesus monkey data implicated this meth-related effect on CXCR4 and CCR5 as well. But the drug also was implicated in other cellular pathways – all of which serve to make immune cells more vulnerable to HIV attack. These findings support the observation that methamphetamine users with the disease frequently have higher viral loads than nonusers.

After a diagnosis, users may continue to use as a way of avoiding confronting their illness, or even to combat the accompanying physical fatigue, Dr. Blanch said. Like many illicit drug users, meth users often show poor compliance with medical follow-up and poor medication adherence. But even if they do take their antiretroviral medications, methamphetamine still has a way of exerting its power. Ritonavir and cobicistat both inhibit the metabolic pathway that breaks down methamphetamine; using meth with either of those drugs can increase meth concentrations by up to 10-fold, a combination that has killed many patients.

Unfortunately, Dr. Blanch said, it’s terribly difficult for users to give up meth, even in the face of contracting such a serious illness.

“In the beginning, after a diagnosis, they may stop using for a while. But then many start again,” he said. “We see this in study after study. But we have not so many studies on how to treat these patients.”

Trials of antidepressants and antipsychotics, and of replacement therapy with amphetamines or methylphenidate, have had mixed results.

“In my own clinic, we try to explain these problems of the interaction of meth and HIV. We have tried even to motivate our patients to use just on the weekend, for example, but they didn’t accept that,” he said. “Usually, we end up trying to make an agreement that the patient will use as little as possible and let them know how much it interferes with their treatment. But in my clinical experience, it’s not so easy. It’s hard to make any change. … very difficult.”

Dr. Blanch had no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WPA 2017

Early births stress dads too

BERLIN – The anxiety of a preterm birth affects fathers just as much as it does mothers, significantly increasing depression rates both before and after the baby arrives.

More than one-third of fathers developed depression after their partners were admitted to a hospital with signs of impending preterm labor – similar to the percentage of mothers who experienced depression during that time, Sally Schulze reported at the meeting of the World Psychiatric Association.

The increased prevalence of depression lingered, too, she said. Even at 6 months after the birth, the rate of depression among these men was 2.5 times higher than in the general population.

Ms. Schulze and her colleagues prospectively followed 69 couples in which the woman was admitted to the hospital at high risk of preterm birth. These women had a mean gestational age of 30 weeks and had symptoms of imminent preterm birth: shortening of the cervix, premature rupture of membranes, or active preterm labor. Ms. Schulze compared this group to 49 control couples with no signs of preterm labor, who had come to the hospital to register for a birth at a mean of 35 weeks’ gestation.

The majority of the pregnancies were singletons; there were two twin pregnancies, but no high-order multiples. Couples whose infant died were later excluded from the study.

Both mothers and fathers completed the Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale at baseline, and at 6 weeks and 6 months after the birth. The survey has been validated for perinatal use. A score of 10 or higher is considered positive for depression.

She divided the preterm birth risk group into two subgroups: couples whose infant was born preterm (26) and couples who made it to term, either by staying in the hospital for treatment and observation, or after being stabilized and released home (27).

Upon admission to the hospital, 35% of the fathers in the preterm birth risk group scored positive for depression, compared with 8% of the fathers in the control group – a significant between-group difference.

“This is especially meaningful when we consider that the background rate of depression among men in Germany is 6%,” Ms. Schulze said. “So our control group fathers were right in line with that, but depression in the preterm birth fathers was significantly elevated.”

At 6 weeks’ postpartum, men in the preterm birth risk group still were experiencing significantly elevated rates of depression, compared with both the control group and the general population. The increase was apparent whether the infant had indeed been born early, or whether it made it to full term (12% and 15%, respectively). Both were significantly higher than the 5% rate among the control group fathers.