User login

Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management of typical and atypical bronchopulmonary carcinoid

Carcinoid lung tumors represent the most indolent form of a spectrum of bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) that includes small-cell carcinoma as its most malignant member, as well as several other forms of intermediately aggressive tumors, such as atypical carcinoid.1 Carcinoids represent 1.2% of all primary lung malignancies. Their incidence in the United States has increased rapidly over the last 30 years and is currently about 6% a year. Lung carcinoids are more prevalent in whites compared with blacks, and in Asians compared with non-Asians. They are less common in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics.1 Typical carcinoids represent 80%-90% of all lung carcinoids and occur more frequently in the fifth and sixth decades of life. They can, however, occur at any age, and are the most common lung tumor in childhood.1

Etiology and risk factors

Unlike carcinoma of the lung, no external environmental toxin or other stimulus has been identified as a causative agent for the development of pulmonary carcinoid tumors. It is not clear if there is an association between bronchial NETs and smoking.1 Nearly all bronchial NETs are sporadic; however, they can rarely occur in the setting of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1.1

Presentation

About 60% of the patients with bronchial carcinoids are symptomatic at presentation. The most common clinical findings are those associated with bronchial obstruction, such as persistent cough, hemoptysis, and recurrent or obstructive pneumonitis. Wheezing, chest pain, and dyspnea also may be noted.2 Various endocrine or neuroendocrine syndromes can be initial clinical manifestations of either typical or atypical pulmonary carcinoid tumors, but that is not common Cushing syndrome (ectopic production and secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH]) may occur in about 2% of lung carcinoid.3 In cases of malignancy, the presence of metastatic disease can produce weight loss, weakness, and a general feeling of ill health.

Diagnostic work-up

Biochemical test

There is no biochemical study that can be used as a screening test to determine the presence of a carcinoid tumor or to diagnose a known pulmonary mass as a carcinoid tumor. Neuroendocrine cells produce biologically active amines and peptides that can be detected in serum and urine. Although the syndromes associated with lung carcinoids are seen in about 1%-2% of the patients, assays of specific hormones or other circulating neuroendocrine substances, such as ACTH, melanocyte-stimulating hormone, or growth hormone may establish the existence of a clinically suspected syndrome.

Chest radiography

An abnormal finding on chest radiography is present in about 75% of patients with a pulmonary carcinoid tumor.1 Findings include either the presence of the tumor mass itself or indirect evidence of its presence observed as parenchymal changes associated with bronchial obstruction from the mass.

Computed-tomography imaging

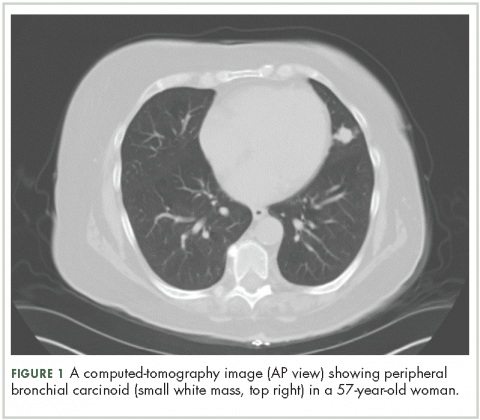

High-resolution computed-tomography (CT) imaging is the one of the best types of CT examination for evaluation of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor.4 A CT scan provides excellent resolution of tumor extent, location, and the presence or absence of mediastinal adenopathy. It also aids in morphologic characterization of peripheral (Figure 1) and especially centrally located carcinoids, which may be purely intraluminal (polypoid configuration), exclusively extra luminal, or more frequently, a mixture of intraluminal and extraluminal components.

CT scans may also be helpful for differentiating tumor from postobstructive atelectasis or bronchial obstruction-related mucoid impaction. Intravenous contrast in CT imaging can be useful in differentiating malignant from benign lesions. Because carcinoid tumors are highly vascular, they show greater enhancement on contrast CT than do benign lesions. The sensitivity of CT for detecting metastatic hilar or mediastinal nodes is high, but specificity is as low as 45%.4

Typical carcinoid is rarely metastatic so most patients do not need CT or MRI imaging to evaluate for liver involvement. Liver imaging is appropriate in patients with evidence of mediastinal involvement, relatively high mitotic rate, or clinical evidence of the carcinoid syndrome.8 To evaluate for metastatic spread to the liver, multiphase contrast-enhanced liver CT scans should be performed with arterial and portal-venous phases because carcinoid liver metastases are often hypervascular and appear isodense relative to the liver parenchyma after contrast administration.4 An MRI is often preferred the modality to evaluate for metastatic spread to the liver because of its higher sensitivity.5

Positron-emission tomography

Although carcinoid tumors of the lung are highly vascular, they do not show increased metabolic activity on positron-emission tomography (PET) and would be incorrectly designated as benign lesions on the basis of findings from a PET scan. Fludeoxyglucose F-18 PET has shown utility as a radiologic marker for atypical carcinoids, particularly for those with a higher proliferation index with Ki-67 index of 10%-20%.6

Radionucleotide studies

Somatostatin receptors (SSRs) are present in many tumors of neuroendocrine origin, including carcinoid tumors. These receptors interact with each other and undergo dimerization and internalization. SSTR subtypes (SSTRs) overexpressed in NETs are related to the type, origin, and grade of differentiation of tumor. The overexpression of an SSTR is a characteristic feature of bronchial NETs, which can be used to localize the primary tumor and its metastases by imaging with the radiolabeled SST analogues. Radionucleotide imaging modalities commonly used include single-photon–emission tomography and positron-emission tomography.

With regard to SSR scintigraphy testing, PET using Ga–DOTATATE/TOC is preferable to Octreoscan if it is available, because offers better spatial resolution and has a shorter scanning time. It has sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 92% and hence is preferable over Octreoscan in highly aggressive, atypical bronchial NETs. It also provides an estimate of receptor density and evidence of the functionality of receptors, which helps with selection of suitable treatments that act on these receptors.7

Tumor markers

Serum levels of chromogranin A in bronchial NETs are expressed at a lower rate than are other sites of carcinoid tumors, so its measurement is of limited utility in following disease activity in bronchial NETs.4,8

Bronchoscopy

About 75% of pulmonary carcinoids are visible on bronchoscopy. The bronchoscopic appearance may be characteristic but it is preferable that brushings or biopsy be performed to confirm the diagnosis. For central tumors endobronchial; and for peripheral tumors, CT-guided percutaneous biopsy is the accepted diagnostic approach. Cytologic study of bronchial brushings is more sensitive than sputum cytology, but the diagnostic yield of brushing is low overall (about 40%) and hence fine-needle biopsy is preferred. 8

A negative finding on biopsy should not produce a false sense of confidence. If a suspicion of malignancy exists despite a negative finding on transthoracic biopsy, surgical excision of the nodule and pathologic analysis should be undertaken.

Histological findings

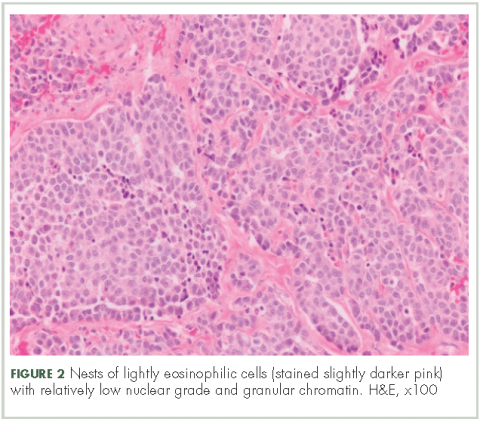

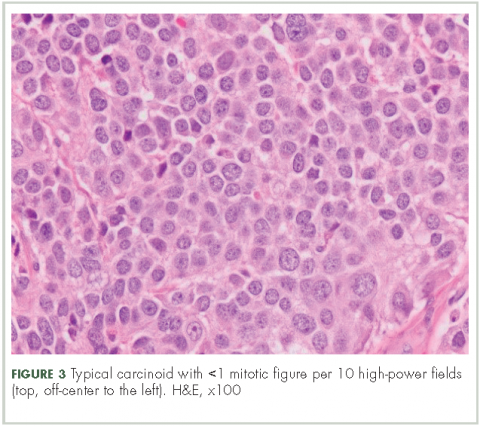

In typical carcinoid tumors, cells tend to group in nests, cords, or broad sheets. Arrangement is orderly, with groups of cells separated by highly vascular septa of connective tissue.9Individual cell features include small and polygonal cells with finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2). Nuclei are small and round. Mitoses are infrequent (Figure 3).

On electron microscopy, well-formed desmosomes and abundant neurosecretory granules are seen. Many pulmonary carcinoid tumors stain positive for a variety of neuroendocrine markers. Electron microscopy is of historical interest but is not used for tissue diagnosis for bronchial carcinoid patients.

Typical vs atypical tumors

In all, 10% of the carcinoid tumors are atypical in nature. They are generally larger than typical carcinoids and are located in the periphery of the lung in about 50% of cases. They have more aggressive behavior and tend to metastasize more commonly.2 Neither location nor size are distinguishing features. The distinction is based on histology and includes one or all of the following features:8,9

n Increased mitotic activity in a tumor with an identifiable carcinoid cellular arrangement with 2-10 mitotic figures per high-power field.9

n Pleomorphism and irregular nuclei with hyperchromatism and prominent nucleoli.

n Areas of increased cellularity with loss of the regular, organized architecture observed in typical carcinoid.

n Areas of necrosis within the tumor.

Ki-67 cell proliferation labeling index can be used to distinguish between high-grade lung NETs (>40%) and carcinoids (<20%), particularly in crushed biopsy specimens in which carcinoids may be mistaken for small-cell lung cancers. However, given overlap in the distribution of Ki-67 labeling index between typical carcinoids (≤5%) and atypical carcinoids (≤20%), Ki-67 expression does not reliably distinguish between well-differentiated lung carcinoids. The utility of Ki-67 to differentiate between typical and atypical carcinoids has yet to be established, and it is not presently recommended.9 Hence, the number of mitotic figures per high-power field of viable tumor area and presence or absence of necrosis continue to be the salient features distinguishing typical and atypical bronchial NETs.

Staging10

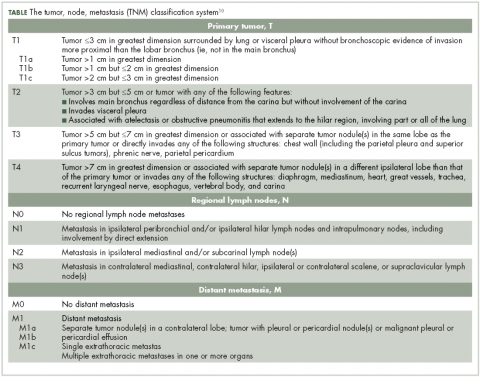

Lung NETs are staged using the same tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) that is used for bronchogenic lung carcinomas (Table).

Typical bronchial NETs most commonly present as stage I tumors, whereas more than one-half of atypical tumors are stage II (bronchopulmonary nodal involvement) or III (mediastinal nodal involvement) at presentation.

Treatment

Localized or nonmetastatic and rescetable disease

Surgical treatment. As with other non–small-cell lung cancers (NSCLCs), surgical resection is the treatment of choice for early-stage carcinoid. The long-term prognosis is typically excellent, with a 10-year disease-free survival of 77%-94%.11, 12 The extent of resection is determined by the tumor size, histology, and location. For NSCLC, the standard surgical approach is the minimal anatomic resection (lobectomy, sleeve lobectomy, bilobectomy, or pneumonectomy) needed to get microscopically negative margins, with an associated mediastinal and hilar lymph node dissection for staging.13

Given the indolent nature of typical carcinoids, there has been extensive research to evaluate whether a sublobar resection is oncologically appropriate for these tumors. Although there are no comprehensive randomized studies comparing sublobar resection with lobectomy for typical carcinoids, findings from numerous database reviews and single-center studies suggest that sublobar resections are noninferior.14-17 Due to the higher nodal metastatic rate and the overall poorer prognosis associated with atypical carcinoids, formal anatomic resection is still recommended with atypical histology.18

An adaptive approach must be taken for patients who undergo wedge resection of pulmonary lesions without a known diagnosis. If intraoperative frozen section is consistent with carcinoid and the margins are negative, mediastinal lymph node dissection should be performed. If the patient is node negative, then completion lobectomy is not required. In node-positive patients with adequate pulmonary reserve, lobectomy should be performed regardless of histology. If atypical features are found during pathologic evaluation, then interval completion lobectomy may be patients with adequate pulmonary reserve.19,20

As with other pulmonary malignancies, clinical or radiographic suspicion of mediastinal lymph node involvement requires invasive staging before pulmonary resection is considered. If the patient is proven to have mediastinal metastatic disease, then multimodality treatment should be considered.20

Adjuvant therapy. Postoperative adjuvant therapy for most resected bronchial NETs, even in the setting of positive lymph nodes, is generally not recommended.7 In clinical practice, adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy (RT) is a reasonable option for patients with histologically aggressive-appearing or poorly differentiated stage III atypical bronchial NETs, although there is only limited evidence to support this. RT is a reasonable option for atypical bronchial NETs if gross residual disease remains after surgery, although it has not been proven that this improves outcomes.7

Nonmetastatic and unresectable disease

For inoperable patients and for those with surgically unresectable but nonmetastatic disease, options for local control of tumor growth include RT with or without concurrent chemotherapy and palliative endobronchial resection of obstructing tumor.21

Metastatic and unresectable disease

Everolimus. In February 2016, everolimus was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as first-line therapy for progressive, well-differentiated, nonfunctional NETs of lung origin that are unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic. The aApproval was based on the RADIANT-4 trial, in which median progression-free survival was 11 months in the 205 patients allocated to receive everolimus (10 mg/day) and 3.9 months in the 97 patients who received placebo. Everolimus was associated with a 52% reduction in the estimated risk of progression or death.22

Somastatin analogues (SSA). There is lack of comprehensive data on the role of SSA compared with everolimus in lung carcinoid. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines on NETs and SCLCs recommend the consideration of octreotide or lanreotide as first-line therapies for select patients with symptoms of carcinoid syndrome or octreotide-positive scans.21 Guidelines from the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS)19 also recommend the use of SSAs as a first-line option in patients with: lung carcinoids exhibiting hormone-related symptoms or slowly progressive typical or atypical carcinoid with a low proliferative index (preferably Ki-67 <10%), provided there is a strongly positive SSTR status.

In cases in which metastatic lung NETs are associated with the carcinoid syndrome, initiation of long-acting SSA therapy in combination with everolimus is recommended.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy. According to the NCCN guidelines, cisplatin-etoposide or other cytotoxic regimens (eg, those that are temozolomide based) are recommended for advanced typical and atypical carcinoids, with cisplatin-etoposide being the preferred first-line systemic regimen in stage IV atypical carcinoid.22 ENETS guidelines stipulate that systemic chemotherapy is generally restricted to atypical carcinoid after failure of first-line therapies and only under certain conditions (Ki-67 >15%, rapidly progressive disease, and SSTR-negative disease).19 Based on a summary of NCCN and ENET guidelines:

n For patients with highly aggressive atypical bronchial NETs, a combination of platinum- and etoposide-based regimens such as those used for small-cell lung cancer has shown better response rate and overall survival data.

n For patients with typical or atypical bronchial NETs, temozolomide can be used as monotherapy or combination with capecitabine, although there are no findings from large randomized controlled trials to support this. Capecitabine-temozolomide has recently shown moderate activity in a small, single-institution study of patients with advanced lung carcinoids (N = 19), with 11 of 17 assessable patients (65%) demonstrating stable disease or partial response.23

n The following regimens can also be used for advanced disease after failure of somastatin analogues, although there are limited data for objective responses:24,25fluorouracil plus dacarbazine; epirubicin, capecitabine plus oxaliplatin; and capecitabine plus liposomal doxorubicin.

Participation in a clinical trial should be encouraged for patients with progressive bronchial NETs during any line of therapy. For patients who have a limited, potentially resectable liver-isolated metastatic NET, surgical resection should be pursued. For more extensive unresectable liver-dominant metastatic disease, treatment options include embolization, radiofrequency ablation, and cryoablation.20,22

Posttreatment surveillance

Posttreatment surveillance after resection of node-positive typical bronchial NETs and for all atypical tumors.26 Patients with lymph-node–negative typical bronchial NETs are very unlikely to benefit from postoperative surveillance because of the very low risk of recurrence. CT imaging (including the thorax and abdomen) every 6 months for 2 years, followed by annual scans for a total of 5-10 years are a reasonable surveillance schedule.

Prognosis 18,27

Typical bronchial NETs have an excellent prognosis after surgical resection. Reported 5-year survival rates are 87%-100%; the corresponding rates at 10 years are 82%-87%. Features associated with negative prognostic significance include lymph-node involvement and incomplete resection.

Atypical bronchial NETs have a worse prognosis than do typical tumors. Five-year survival rates range widely, from 30%-95%; the corresponding rates at 10 years are 35%-56%. Atypical tumors have a greater tendency to metastasize (16%-23%) and recur locally (3%-25%). Distant metastases to the liver or bone are more common than local recurrence. Adverse influence of nodal metastases on prognosis is more profound than for typical tumors. Survival rates by stage for patients who underwent surgical resection (including typical and atypical carcinoid27) are: stage I, 93%; stage II, 85%; stage III, 75%; and stage IV, 57%.

1. Hauso O, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, et al. Neuroendocrine tumor epidemiology: contrasting Norway and North America. Cancer. 2008;113(10):2655-2664.

2. Fink G, Krelbaum T, Yellin A, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid: presentation, diagnosis, and outcome in 142 cases in Israel and review of 640 cases from the literature. Chest. 2001;119(6):1647-1651.

3. Limper AH, Carpenter PC, Scheithauer B, Staats BA. The Cushing syndrome induced by bronchial carcinoid tumors. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(3):209-214.

4. Meisinger QC, Klein JS, Butnor KJ, Gentchos G, Leavitt BJ. CT features of peripheral pulmonary carcinoid tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197(5):1073-1080.

5. Guckel C, Schnabel K, Deimling M, Steinbrich W. Solitary pulmonary nodules: MR evaluation of enhancement patterns with contrast-enhanced dynamic snapshot gradient-echo imaging. Radiology. 1996;200(3):681-686.

6. Jindal T, Kumar A, Venkitaraman B, et al. Evaluation of the role of [18F]FDG-PET/CT and [68Ga]DOTATOC-PET/CT in differentiating typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Cancer Imaging. 2011;11:70-75.

7. Caplin ME, Baudin E, Ferolla P, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors: European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society expert consensus and recommendations for best practice for typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(8):1604-1620.

8. Travis WD. Pathology and diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors: lung neuroendocrine. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24(3):257-266.

9. Warren WH, Memoli VA, Gould VE. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis of bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms. II. Well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1984;7(2-3):185-199.

10. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(1):39-51.

11. McCaughan BC, Martini N, Bains MS. Bronchial carcinoids. Review of 124 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;89(1):8-17.

12. Hurt R, Bates M. Carcinoid tumours of the bronchus: a 33-year experience. Thorax. 1984;39(8):617-623.

13. Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Akerley W, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2014;12(12):1738-1761.

14. Ferguson MK, Landreneau RJ, Hazelrigg SR, et al. Long-term outcome after resection for bronchial carcinoid tumors. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;18(2):156-161.

15. Lucchi M, Melfi F, Ribechini A, et al. Sleeve and wedge parenchyma-sparing bronchial resections in low-grade neoplasms of the bronchial airway. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134(2):373-377.

16. Yendamuri S, Gold D, Jayaprakash V, Dexter E, Nwogu C, Demmy T. Is sublobar resection sufficient for carcinoid tumors? Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(5):1774-1778; discussion 8-9.

17. Fox M, Van Berkel V, Bousamra M II, Sloan S, Martin RC II. Surgical management of pulmonary carcinoid tumors: sublobar resection versus lobectomy. Am J Surg. 2013;205(2):200-208.

18. Cardillo G, Sera F, Di Martino M, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumors: nodal status and long-term survival after resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(5):1781-1785.

19. Oberg K, Hellman P, Ferolla P, Papotti M; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Neuroendocrine bronchial and thymic tumors: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 7:vii120-3).

20. Filosso PL, Ferolla P, Guerrera F, et al. Multidisciplinary management of advanced lung neuroendocrine tumors. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(Suppl 2):S163-171.

21. Kulke MH, Shah MH, Benson AB III, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2015;13(1):78-108.

22. Yao JC, Fazio N, Singh S, et al. Everolimus for the treatment of advanced, non-functional neuroendocrine tumours of the lung or gastrointestinal tract (RADIANT-4): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):968-977.

23. Ramirez RA, Beyer DT, Chauhan A, Boudreaux JP, Wang YZ, Woltering EA. The role of capecitabine/temozolomide in metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Oncologist. 2016;21(6):671-675.

24. Bajetta E, Rimassa L, Carnaghi C, et al. 5-Fluorouracil, dacarbazine, and epirubicin in the treatment of patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 1998;83(2):372-378.

25. Masi G, Fornaro L, Cupini S, et al. Refractory neuroendocrine tumor-response to liposomal doxorubicin and capecitabine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(11):670-674.

26. Lou F, Sarkaria I, Pietanza C, et al. Recurrence of pulmonary carcinoid tumors after resection: implications for postoperative surveillance. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(4):1156-1162.

27. Beasley MB, Thunnissen FB, Brambilla E, et al. Pulmonary atypical carcinoid: predictors of survival in 106 cases. Human Pathol. 2000;31(10):1255-1265.

Carcinoid lung tumors represent the most indolent form of a spectrum of bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) that includes small-cell carcinoma as its most malignant member, as well as several other forms of intermediately aggressive tumors, such as atypical carcinoid.1 Carcinoids represent 1.2% of all primary lung malignancies. Their incidence in the United States has increased rapidly over the last 30 years and is currently about 6% a year. Lung carcinoids are more prevalent in whites compared with blacks, and in Asians compared with non-Asians. They are less common in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics.1 Typical carcinoids represent 80%-90% of all lung carcinoids and occur more frequently in the fifth and sixth decades of life. They can, however, occur at any age, and are the most common lung tumor in childhood.1

Etiology and risk factors

Unlike carcinoma of the lung, no external environmental toxin or other stimulus has been identified as a causative agent for the development of pulmonary carcinoid tumors. It is not clear if there is an association between bronchial NETs and smoking.1 Nearly all bronchial NETs are sporadic; however, they can rarely occur in the setting of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1.1

Presentation

About 60% of the patients with bronchial carcinoids are symptomatic at presentation. The most common clinical findings are those associated with bronchial obstruction, such as persistent cough, hemoptysis, and recurrent or obstructive pneumonitis. Wheezing, chest pain, and dyspnea also may be noted.2 Various endocrine or neuroendocrine syndromes can be initial clinical manifestations of either typical or atypical pulmonary carcinoid tumors, but that is not common Cushing syndrome (ectopic production and secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH]) may occur in about 2% of lung carcinoid.3 In cases of malignancy, the presence of metastatic disease can produce weight loss, weakness, and a general feeling of ill health.

Diagnostic work-up

Biochemical test

There is no biochemical study that can be used as a screening test to determine the presence of a carcinoid tumor or to diagnose a known pulmonary mass as a carcinoid tumor. Neuroendocrine cells produce biologically active amines and peptides that can be detected in serum and urine. Although the syndromes associated with lung carcinoids are seen in about 1%-2% of the patients, assays of specific hormones or other circulating neuroendocrine substances, such as ACTH, melanocyte-stimulating hormone, or growth hormone may establish the existence of a clinically suspected syndrome.

Chest radiography

An abnormal finding on chest radiography is present in about 75% of patients with a pulmonary carcinoid tumor.1 Findings include either the presence of the tumor mass itself or indirect evidence of its presence observed as parenchymal changes associated with bronchial obstruction from the mass.

Computed-tomography imaging

High-resolution computed-tomography (CT) imaging is the one of the best types of CT examination for evaluation of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor.4 A CT scan provides excellent resolution of tumor extent, location, and the presence or absence of mediastinal adenopathy. It also aids in morphologic characterization of peripheral (Figure 1) and especially centrally located carcinoids, which may be purely intraluminal (polypoid configuration), exclusively extra luminal, or more frequently, a mixture of intraluminal and extraluminal components.

CT scans may also be helpful for differentiating tumor from postobstructive atelectasis or bronchial obstruction-related mucoid impaction. Intravenous contrast in CT imaging can be useful in differentiating malignant from benign lesions. Because carcinoid tumors are highly vascular, they show greater enhancement on contrast CT than do benign lesions. The sensitivity of CT for detecting metastatic hilar or mediastinal nodes is high, but specificity is as low as 45%.4

Typical carcinoid is rarely metastatic so most patients do not need CT or MRI imaging to evaluate for liver involvement. Liver imaging is appropriate in patients with evidence of mediastinal involvement, relatively high mitotic rate, or clinical evidence of the carcinoid syndrome.8 To evaluate for metastatic spread to the liver, multiphase contrast-enhanced liver CT scans should be performed with arterial and portal-venous phases because carcinoid liver metastases are often hypervascular and appear isodense relative to the liver parenchyma after contrast administration.4 An MRI is often preferred the modality to evaluate for metastatic spread to the liver because of its higher sensitivity.5

Positron-emission tomography

Although carcinoid tumors of the lung are highly vascular, they do not show increased metabolic activity on positron-emission tomography (PET) and would be incorrectly designated as benign lesions on the basis of findings from a PET scan. Fludeoxyglucose F-18 PET has shown utility as a radiologic marker for atypical carcinoids, particularly for those with a higher proliferation index with Ki-67 index of 10%-20%.6

Radionucleotide studies

Somatostatin receptors (SSRs) are present in many tumors of neuroendocrine origin, including carcinoid tumors. These receptors interact with each other and undergo dimerization and internalization. SSTR subtypes (SSTRs) overexpressed in NETs are related to the type, origin, and grade of differentiation of tumor. The overexpression of an SSTR is a characteristic feature of bronchial NETs, which can be used to localize the primary tumor and its metastases by imaging with the radiolabeled SST analogues. Radionucleotide imaging modalities commonly used include single-photon–emission tomography and positron-emission tomography.

With regard to SSR scintigraphy testing, PET using Ga–DOTATATE/TOC is preferable to Octreoscan if it is available, because offers better spatial resolution and has a shorter scanning time. It has sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 92% and hence is preferable over Octreoscan in highly aggressive, atypical bronchial NETs. It also provides an estimate of receptor density and evidence of the functionality of receptors, which helps with selection of suitable treatments that act on these receptors.7

Tumor markers

Serum levels of chromogranin A in bronchial NETs are expressed at a lower rate than are other sites of carcinoid tumors, so its measurement is of limited utility in following disease activity in bronchial NETs.4,8

Bronchoscopy

About 75% of pulmonary carcinoids are visible on bronchoscopy. The bronchoscopic appearance may be characteristic but it is preferable that brushings or biopsy be performed to confirm the diagnosis. For central tumors endobronchial; and for peripheral tumors, CT-guided percutaneous biopsy is the accepted diagnostic approach. Cytologic study of bronchial brushings is more sensitive than sputum cytology, but the diagnostic yield of brushing is low overall (about 40%) and hence fine-needle biopsy is preferred. 8

A negative finding on biopsy should not produce a false sense of confidence. If a suspicion of malignancy exists despite a negative finding on transthoracic biopsy, surgical excision of the nodule and pathologic analysis should be undertaken.

Histological findings

In typical carcinoid tumors, cells tend to group in nests, cords, or broad sheets. Arrangement is orderly, with groups of cells separated by highly vascular septa of connective tissue.9Individual cell features include small and polygonal cells with finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2). Nuclei are small and round. Mitoses are infrequent (Figure 3).

On electron microscopy, well-formed desmosomes and abundant neurosecretory granules are seen. Many pulmonary carcinoid tumors stain positive for a variety of neuroendocrine markers. Electron microscopy is of historical interest but is not used for tissue diagnosis for bronchial carcinoid patients.

Typical vs atypical tumors

In all, 10% of the carcinoid tumors are atypical in nature. They are generally larger than typical carcinoids and are located in the periphery of the lung in about 50% of cases. They have more aggressive behavior and tend to metastasize more commonly.2 Neither location nor size are distinguishing features. The distinction is based on histology and includes one or all of the following features:8,9

n Increased mitotic activity in a tumor with an identifiable carcinoid cellular arrangement with 2-10 mitotic figures per high-power field.9

n Pleomorphism and irregular nuclei with hyperchromatism and prominent nucleoli.

n Areas of increased cellularity with loss of the regular, organized architecture observed in typical carcinoid.

n Areas of necrosis within the tumor.

Ki-67 cell proliferation labeling index can be used to distinguish between high-grade lung NETs (>40%) and carcinoids (<20%), particularly in crushed biopsy specimens in which carcinoids may be mistaken for small-cell lung cancers. However, given overlap in the distribution of Ki-67 labeling index between typical carcinoids (≤5%) and atypical carcinoids (≤20%), Ki-67 expression does not reliably distinguish between well-differentiated lung carcinoids. The utility of Ki-67 to differentiate between typical and atypical carcinoids has yet to be established, and it is not presently recommended.9 Hence, the number of mitotic figures per high-power field of viable tumor area and presence or absence of necrosis continue to be the salient features distinguishing typical and atypical bronchial NETs.

Staging10

Lung NETs are staged using the same tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) that is used for bronchogenic lung carcinomas (Table).

Typical bronchial NETs most commonly present as stage I tumors, whereas more than one-half of atypical tumors are stage II (bronchopulmonary nodal involvement) or III (mediastinal nodal involvement) at presentation.

Treatment

Localized or nonmetastatic and rescetable disease

Surgical treatment. As with other non–small-cell lung cancers (NSCLCs), surgical resection is the treatment of choice for early-stage carcinoid. The long-term prognosis is typically excellent, with a 10-year disease-free survival of 77%-94%.11, 12 The extent of resection is determined by the tumor size, histology, and location. For NSCLC, the standard surgical approach is the minimal anatomic resection (lobectomy, sleeve lobectomy, bilobectomy, or pneumonectomy) needed to get microscopically negative margins, with an associated mediastinal and hilar lymph node dissection for staging.13

Given the indolent nature of typical carcinoids, there has been extensive research to evaluate whether a sublobar resection is oncologically appropriate for these tumors. Although there are no comprehensive randomized studies comparing sublobar resection with lobectomy for typical carcinoids, findings from numerous database reviews and single-center studies suggest that sublobar resections are noninferior.14-17 Due to the higher nodal metastatic rate and the overall poorer prognosis associated with atypical carcinoids, formal anatomic resection is still recommended with atypical histology.18

An adaptive approach must be taken for patients who undergo wedge resection of pulmonary lesions without a known diagnosis. If intraoperative frozen section is consistent with carcinoid and the margins are negative, mediastinal lymph node dissection should be performed. If the patient is node negative, then completion lobectomy is not required. In node-positive patients with adequate pulmonary reserve, lobectomy should be performed regardless of histology. If atypical features are found during pathologic evaluation, then interval completion lobectomy may be patients with adequate pulmonary reserve.19,20

As with other pulmonary malignancies, clinical or radiographic suspicion of mediastinal lymph node involvement requires invasive staging before pulmonary resection is considered. If the patient is proven to have mediastinal metastatic disease, then multimodality treatment should be considered.20

Adjuvant therapy. Postoperative adjuvant therapy for most resected bronchial NETs, even in the setting of positive lymph nodes, is generally not recommended.7 In clinical practice, adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy (RT) is a reasonable option for patients with histologically aggressive-appearing or poorly differentiated stage III atypical bronchial NETs, although there is only limited evidence to support this. RT is a reasonable option for atypical bronchial NETs if gross residual disease remains after surgery, although it has not been proven that this improves outcomes.7

Nonmetastatic and unresectable disease

For inoperable patients and for those with surgically unresectable but nonmetastatic disease, options for local control of tumor growth include RT with or without concurrent chemotherapy and palliative endobronchial resection of obstructing tumor.21

Metastatic and unresectable disease

Everolimus. In February 2016, everolimus was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as first-line therapy for progressive, well-differentiated, nonfunctional NETs of lung origin that are unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic. The aApproval was based on the RADIANT-4 trial, in which median progression-free survival was 11 months in the 205 patients allocated to receive everolimus (10 mg/day) and 3.9 months in the 97 patients who received placebo. Everolimus was associated with a 52% reduction in the estimated risk of progression or death.22

Somastatin analogues (SSA). There is lack of comprehensive data on the role of SSA compared with everolimus in lung carcinoid. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines on NETs and SCLCs recommend the consideration of octreotide or lanreotide as first-line therapies for select patients with symptoms of carcinoid syndrome or octreotide-positive scans.21 Guidelines from the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS)19 also recommend the use of SSAs as a first-line option in patients with: lung carcinoids exhibiting hormone-related symptoms or slowly progressive typical or atypical carcinoid with a low proliferative index (preferably Ki-67 <10%), provided there is a strongly positive SSTR status.

In cases in which metastatic lung NETs are associated with the carcinoid syndrome, initiation of long-acting SSA therapy in combination with everolimus is recommended.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy. According to the NCCN guidelines, cisplatin-etoposide or other cytotoxic regimens (eg, those that are temozolomide based) are recommended for advanced typical and atypical carcinoids, with cisplatin-etoposide being the preferred first-line systemic regimen in stage IV atypical carcinoid.22 ENETS guidelines stipulate that systemic chemotherapy is generally restricted to atypical carcinoid after failure of first-line therapies and only under certain conditions (Ki-67 >15%, rapidly progressive disease, and SSTR-negative disease).19 Based on a summary of NCCN and ENET guidelines:

n For patients with highly aggressive atypical bronchial NETs, a combination of platinum- and etoposide-based regimens such as those used for small-cell lung cancer has shown better response rate and overall survival data.

n For patients with typical or atypical bronchial NETs, temozolomide can be used as monotherapy or combination with capecitabine, although there are no findings from large randomized controlled trials to support this. Capecitabine-temozolomide has recently shown moderate activity in a small, single-institution study of patients with advanced lung carcinoids (N = 19), with 11 of 17 assessable patients (65%) demonstrating stable disease or partial response.23

n The following regimens can also be used for advanced disease after failure of somastatin analogues, although there are limited data for objective responses:24,25fluorouracil plus dacarbazine; epirubicin, capecitabine plus oxaliplatin; and capecitabine plus liposomal doxorubicin.

Participation in a clinical trial should be encouraged for patients with progressive bronchial NETs during any line of therapy. For patients who have a limited, potentially resectable liver-isolated metastatic NET, surgical resection should be pursued. For more extensive unresectable liver-dominant metastatic disease, treatment options include embolization, radiofrequency ablation, and cryoablation.20,22

Posttreatment surveillance

Posttreatment surveillance after resection of node-positive typical bronchial NETs and for all atypical tumors.26 Patients with lymph-node–negative typical bronchial NETs are very unlikely to benefit from postoperative surveillance because of the very low risk of recurrence. CT imaging (including the thorax and abdomen) every 6 months for 2 years, followed by annual scans for a total of 5-10 years are a reasonable surveillance schedule.

Prognosis 18,27

Typical bronchial NETs have an excellent prognosis after surgical resection. Reported 5-year survival rates are 87%-100%; the corresponding rates at 10 years are 82%-87%. Features associated with negative prognostic significance include lymph-node involvement and incomplete resection.

Atypical bronchial NETs have a worse prognosis than do typical tumors. Five-year survival rates range widely, from 30%-95%; the corresponding rates at 10 years are 35%-56%. Atypical tumors have a greater tendency to metastasize (16%-23%) and recur locally (3%-25%). Distant metastases to the liver or bone are more common than local recurrence. Adverse influence of nodal metastases on prognosis is more profound than for typical tumors. Survival rates by stage for patients who underwent surgical resection (including typical and atypical carcinoid27) are: stage I, 93%; stage II, 85%; stage III, 75%; and stage IV, 57%.

Carcinoid lung tumors represent the most indolent form of a spectrum of bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) that includes small-cell carcinoma as its most malignant member, as well as several other forms of intermediately aggressive tumors, such as atypical carcinoid.1 Carcinoids represent 1.2% of all primary lung malignancies. Their incidence in the United States has increased rapidly over the last 30 years and is currently about 6% a year. Lung carcinoids are more prevalent in whites compared with blacks, and in Asians compared with non-Asians. They are less common in Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics.1 Typical carcinoids represent 80%-90% of all lung carcinoids and occur more frequently in the fifth and sixth decades of life. They can, however, occur at any age, and are the most common lung tumor in childhood.1

Etiology and risk factors

Unlike carcinoma of the lung, no external environmental toxin or other stimulus has been identified as a causative agent for the development of pulmonary carcinoid tumors. It is not clear if there is an association between bronchial NETs and smoking.1 Nearly all bronchial NETs are sporadic; however, they can rarely occur in the setting of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1.1

Presentation

About 60% of the patients with bronchial carcinoids are symptomatic at presentation. The most common clinical findings are those associated with bronchial obstruction, such as persistent cough, hemoptysis, and recurrent or obstructive pneumonitis. Wheezing, chest pain, and dyspnea also may be noted.2 Various endocrine or neuroendocrine syndromes can be initial clinical manifestations of either typical or atypical pulmonary carcinoid tumors, but that is not common Cushing syndrome (ectopic production and secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH]) may occur in about 2% of lung carcinoid.3 In cases of malignancy, the presence of metastatic disease can produce weight loss, weakness, and a general feeling of ill health.

Diagnostic work-up

Biochemical test

There is no biochemical study that can be used as a screening test to determine the presence of a carcinoid tumor or to diagnose a known pulmonary mass as a carcinoid tumor. Neuroendocrine cells produce biologically active amines and peptides that can be detected in serum and urine. Although the syndromes associated with lung carcinoids are seen in about 1%-2% of the patients, assays of specific hormones or other circulating neuroendocrine substances, such as ACTH, melanocyte-stimulating hormone, or growth hormone may establish the existence of a clinically suspected syndrome.

Chest radiography

An abnormal finding on chest radiography is present in about 75% of patients with a pulmonary carcinoid tumor.1 Findings include either the presence of the tumor mass itself or indirect evidence of its presence observed as parenchymal changes associated with bronchial obstruction from the mass.

Computed-tomography imaging

High-resolution computed-tomography (CT) imaging is the one of the best types of CT examination for evaluation of a pulmonary carcinoid tumor.4 A CT scan provides excellent resolution of tumor extent, location, and the presence or absence of mediastinal adenopathy. It also aids in morphologic characterization of peripheral (Figure 1) and especially centrally located carcinoids, which may be purely intraluminal (polypoid configuration), exclusively extra luminal, or more frequently, a mixture of intraluminal and extraluminal components.

CT scans may also be helpful for differentiating tumor from postobstructive atelectasis or bronchial obstruction-related mucoid impaction. Intravenous contrast in CT imaging can be useful in differentiating malignant from benign lesions. Because carcinoid tumors are highly vascular, they show greater enhancement on contrast CT than do benign lesions. The sensitivity of CT for detecting metastatic hilar or mediastinal nodes is high, but specificity is as low as 45%.4

Typical carcinoid is rarely metastatic so most patients do not need CT or MRI imaging to evaluate for liver involvement. Liver imaging is appropriate in patients with evidence of mediastinal involvement, relatively high mitotic rate, or clinical evidence of the carcinoid syndrome.8 To evaluate for metastatic spread to the liver, multiphase contrast-enhanced liver CT scans should be performed with arterial and portal-venous phases because carcinoid liver metastases are often hypervascular and appear isodense relative to the liver parenchyma after contrast administration.4 An MRI is often preferred the modality to evaluate for metastatic spread to the liver because of its higher sensitivity.5

Positron-emission tomography

Although carcinoid tumors of the lung are highly vascular, they do not show increased metabolic activity on positron-emission tomography (PET) and would be incorrectly designated as benign lesions on the basis of findings from a PET scan. Fludeoxyglucose F-18 PET has shown utility as a radiologic marker for atypical carcinoids, particularly for those with a higher proliferation index with Ki-67 index of 10%-20%.6

Radionucleotide studies

Somatostatin receptors (SSRs) are present in many tumors of neuroendocrine origin, including carcinoid tumors. These receptors interact with each other and undergo dimerization and internalization. SSTR subtypes (SSTRs) overexpressed in NETs are related to the type, origin, and grade of differentiation of tumor. The overexpression of an SSTR is a characteristic feature of bronchial NETs, which can be used to localize the primary tumor and its metastases by imaging with the radiolabeled SST analogues. Radionucleotide imaging modalities commonly used include single-photon–emission tomography and positron-emission tomography.

With regard to SSR scintigraphy testing, PET using Ga–DOTATATE/TOC is preferable to Octreoscan if it is available, because offers better spatial resolution and has a shorter scanning time. It has sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 92% and hence is preferable over Octreoscan in highly aggressive, atypical bronchial NETs. It also provides an estimate of receptor density and evidence of the functionality of receptors, which helps with selection of suitable treatments that act on these receptors.7

Tumor markers

Serum levels of chromogranin A in bronchial NETs are expressed at a lower rate than are other sites of carcinoid tumors, so its measurement is of limited utility in following disease activity in bronchial NETs.4,8

Bronchoscopy

About 75% of pulmonary carcinoids are visible on bronchoscopy. The bronchoscopic appearance may be characteristic but it is preferable that brushings or biopsy be performed to confirm the diagnosis. For central tumors endobronchial; and for peripheral tumors, CT-guided percutaneous biopsy is the accepted diagnostic approach. Cytologic study of bronchial brushings is more sensitive than sputum cytology, but the diagnostic yield of brushing is low overall (about 40%) and hence fine-needle biopsy is preferred. 8

A negative finding on biopsy should not produce a false sense of confidence. If a suspicion of malignancy exists despite a negative finding on transthoracic biopsy, surgical excision of the nodule and pathologic analysis should be undertaken.

Histological findings

In typical carcinoid tumors, cells tend to group in nests, cords, or broad sheets. Arrangement is orderly, with groups of cells separated by highly vascular septa of connective tissue.9Individual cell features include small and polygonal cells with finely granular eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2). Nuclei are small and round. Mitoses are infrequent (Figure 3).

On electron microscopy, well-formed desmosomes and abundant neurosecretory granules are seen. Many pulmonary carcinoid tumors stain positive for a variety of neuroendocrine markers. Electron microscopy is of historical interest but is not used for tissue diagnosis for bronchial carcinoid patients.

Typical vs atypical tumors

In all, 10% of the carcinoid tumors are atypical in nature. They are generally larger than typical carcinoids and are located in the periphery of the lung in about 50% of cases. They have more aggressive behavior and tend to metastasize more commonly.2 Neither location nor size are distinguishing features. The distinction is based on histology and includes one or all of the following features:8,9

n Increased mitotic activity in a tumor with an identifiable carcinoid cellular arrangement with 2-10 mitotic figures per high-power field.9

n Pleomorphism and irregular nuclei with hyperchromatism and prominent nucleoli.

n Areas of increased cellularity with loss of the regular, organized architecture observed in typical carcinoid.

n Areas of necrosis within the tumor.

Ki-67 cell proliferation labeling index can be used to distinguish between high-grade lung NETs (>40%) and carcinoids (<20%), particularly in crushed biopsy specimens in which carcinoids may be mistaken for small-cell lung cancers. However, given overlap in the distribution of Ki-67 labeling index between typical carcinoids (≤5%) and atypical carcinoids (≤20%), Ki-67 expression does not reliably distinguish between well-differentiated lung carcinoids. The utility of Ki-67 to differentiate between typical and atypical carcinoids has yet to be established, and it is not presently recommended.9 Hence, the number of mitotic figures per high-power field of viable tumor area and presence or absence of necrosis continue to be the salient features distinguishing typical and atypical bronchial NETs.

Staging10

Lung NETs are staged using the same tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) classification from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) that is used for bronchogenic lung carcinomas (Table).

Typical bronchial NETs most commonly present as stage I tumors, whereas more than one-half of atypical tumors are stage II (bronchopulmonary nodal involvement) or III (mediastinal nodal involvement) at presentation.

Treatment

Localized or nonmetastatic and rescetable disease

Surgical treatment. As with other non–small-cell lung cancers (NSCLCs), surgical resection is the treatment of choice for early-stage carcinoid. The long-term prognosis is typically excellent, with a 10-year disease-free survival of 77%-94%.11, 12 The extent of resection is determined by the tumor size, histology, and location. For NSCLC, the standard surgical approach is the minimal anatomic resection (lobectomy, sleeve lobectomy, bilobectomy, or pneumonectomy) needed to get microscopically negative margins, with an associated mediastinal and hilar lymph node dissection for staging.13

Given the indolent nature of typical carcinoids, there has been extensive research to evaluate whether a sublobar resection is oncologically appropriate for these tumors. Although there are no comprehensive randomized studies comparing sublobar resection with lobectomy for typical carcinoids, findings from numerous database reviews and single-center studies suggest that sublobar resections are noninferior.14-17 Due to the higher nodal metastatic rate and the overall poorer prognosis associated with atypical carcinoids, formal anatomic resection is still recommended with atypical histology.18

An adaptive approach must be taken for patients who undergo wedge resection of pulmonary lesions without a known diagnosis. If intraoperative frozen section is consistent with carcinoid and the margins are negative, mediastinal lymph node dissection should be performed. If the patient is node negative, then completion lobectomy is not required. In node-positive patients with adequate pulmonary reserve, lobectomy should be performed regardless of histology. If atypical features are found during pathologic evaluation, then interval completion lobectomy may be patients with adequate pulmonary reserve.19,20

As with other pulmonary malignancies, clinical or radiographic suspicion of mediastinal lymph node involvement requires invasive staging before pulmonary resection is considered. If the patient is proven to have mediastinal metastatic disease, then multimodality treatment should be considered.20

Adjuvant therapy. Postoperative adjuvant therapy for most resected bronchial NETs, even in the setting of positive lymph nodes, is generally not recommended.7 In clinical practice, adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy (RT) is a reasonable option for patients with histologically aggressive-appearing or poorly differentiated stage III atypical bronchial NETs, although there is only limited evidence to support this. RT is a reasonable option for atypical bronchial NETs if gross residual disease remains after surgery, although it has not been proven that this improves outcomes.7

Nonmetastatic and unresectable disease

For inoperable patients and for those with surgically unresectable but nonmetastatic disease, options for local control of tumor growth include RT with or without concurrent chemotherapy and palliative endobronchial resection of obstructing tumor.21

Metastatic and unresectable disease

Everolimus. In February 2016, everolimus was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as first-line therapy for progressive, well-differentiated, nonfunctional NETs of lung origin that are unresectable, locally advanced, or metastatic. The aApproval was based on the RADIANT-4 trial, in which median progression-free survival was 11 months in the 205 patients allocated to receive everolimus (10 mg/day) and 3.9 months in the 97 patients who received placebo. Everolimus was associated with a 52% reduction in the estimated risk of progression or death.22

Somastatin analogues (SSA). There is lack of comprehensive data on the role of SSA compared with everolimus in lung carcinoid. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines on NETs and SCLCs recommend the consideration of octreotide or lanreotide as first-line therapies for select patients with symptoms of carcinoid syndrome or octreotide-positive scans.21 Guidelines from the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS)19 also recommend the use of SSAs as a first-line option in patients with: lung carcinoids exhibiting hormone-related symptoms or slowly progressive typical or atypical carcinoid with a low proliferative index (preferably Ki-67 <10%), provided there is a strongly positive SSTR status.

In cases in which metastatic lung NETs are associated with the carcinoid syndrome, initiation of long-acting SSA therapy in combination with everolimus is recommended.

Cytotoxic chemotherapy. According to the NCCN guidelines, cisplatin-etoposide or other cytotoxic regimens (eg, those that are temozolomide based) are recommended for advanced typical and atypical carcinoids, with cisplatin-etoposide being the preferred first-line systemic regimen in stage IV atypical carcinoid.22 ENETS guidelines stipulate that systemic chemotherapy is generally restricted to atypical carcinoid after failure of first-line therapies and only under certain conditions (Ki-67 >15%, rapidly progressive disease, and SSTR-negative disease).19 Based on a summary of NCCN and ENET guidelines:

n For patients with highly aggressive atypical bronchial NETs, a combination of platinum- and etoposide-based regimens such as those used for small-cell lung cancer has shown better response rate and overall survival data.

n For patients with typical or atypical bronchial NETs, temozolomide can be used as monotherapy or combination with capecitabine, although there are no findings from large randomized controlled trials to support this. Capecitabine-temozolomide has recently shown moderate activity in a small, single-institution study of patients with advanced lung carcinoids (N = 19), with 11 of 17 assessable patients (65%) demonstrating stable disease or partial response.23

n The following regimens can also be used for advanced disease after failure of somastatin analogues, although there are limited data for objective responses:24,25fluorouracil plus dacarbazine; epirubicin, capecitabine plus oxaliplatin; and capecitabine plus liposomal doxorubicin.

Participation in a clinical trial should be encouraged for patients with progressive bronchial NETs during any line of therapy. For patients who have a limited, potentially resectable liver-isolated metastatic NET, surgical resection should be pursued. For more extensive unresectable liver-dominant metastatic disease, treatment options include embolization, radiofrequency ablation, and cryoablation.20,22

Posttreatment surveillance

Posttreatment surveillance after resection of node-positive typical bronchial NETs and for all atypical tumors.26 Patients with lymph-node–negative typical bronchial NETs are very unlikely to benefit from postoperative surveillance because of the very low risk of recurrence. CT imaging (including the thorax and abdomen) every 6 months for 2 years, followed by annual scans for a total of 5-10 years are a reasonable surveillance schedule.

Prognosis 18,27

Typical bronchial NETs have an excellent prognosis after surgical resection. Reported 5-year survival rates are 87%-100%; the corresponding rates at 10 years are 82%-87%. Features associated with negative prognostic significance include lymph-node involvement and incomplete resection.

Atypical bronchial NETs have a worse prognosis than do typical tumors. Five-year survival rates range widely, from 30%-95%; the corresponding rates at 10 years are 35%-56%. Atypical tumors have a greater tendency to metastasize (16%-23%) and recur locally (3%-25%). Distant metastases to the liver or bone are more common than local recurrence. Adverse influence of nodal metastases on prognosis is more profound than for typical tumors. Survival rates by stage for patients who underwent surgical resection (including typical and atypical carcinoid27) are: stage I, 93%; stage II, 85%; stage III, 75%; and stage IV, 57%.

1. Hauso O, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, et al. Neuroendocrine tumor epidemiology: contrasting Norway and North America. Cancer. 2008;113(10):2655-2664.

2. Fink G, Krelbaum T, Yellin A, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid: presentation, diagnosis, and outcome in 142 cases in Israel and review of 640 cases from the literature. Chest. 2001;119(6):1647-1651.

3. Limper AH, Carpenter PC, Scheithauer B, Staats BA. The Cushing syndrome induced by bronchial carcinoid tumors. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(3):209-214.

4. Meisinger QC, Klein JS, Butnor KJ, Gentchos G, Leavitt BJ. CT features of peripheral pulmonary carcinoid tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197(5):1073-1080.

5. Guckel C, Schnabel K, Deimling M, Steinbrich W. Solitary pulmonary nodules: MR evaluation of enhancement patterns with contrast-enhanced dynamic snapshot gradient-echo imaging. Radiology. 1996;200(3):681-686.

6. Jindal T, Kumar A, Venkitaraman B, et al. Evaluation of the role of [18F]FDG-PET/CT and [68Ga]DOTATOC-PET/CT in differentiating typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Cancer Imaging. 2011;11:70-75.

7. Caplin ME, Baudin E, Ferolla P, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors: European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society expert consensus and recommendations for best practice for typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(8):1604-1620.

8. Travis WD. Pathology and diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors: lung neuroendocrine. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24(3):257-266.

9. Warren WH, Memoli VA, Gould VE. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis of bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms. II. Well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1984;7(2-3):185-199.

10. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(1):39-51.

11. McCaughan BC, Martini N, Bains MS. Bronchial carcinoids. Review of 124 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;89(1):8-17.

12. Hurt R, Bates M. Carcinoid tumours of the bronchus: a 33-year experience. Thorax. 1984;39(8):617-623.

13. Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Akerley W, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2014;12(12):1738-1761.

14. Ferguson MK, Landreneau RJ, Hazelrigg SR, et al. Long-term outcome after resection for bronchial carcinoid tumors. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;18(2):156-161.

15. Lucchi M, Melfi F, Ribechini A, et al. Sleeve and wedge parenchyma-sparing bronchial resections in low-grade neoplasms of the bronchial airway. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134(2):373-377.

16. Yendamuri S, Gold D, Jayaprakash V, Dexter E, Nwogu C, Demmy T. Is sublobar resection sufficient for carcinoid tumors? Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(5):1774-1778; discussion 8-9.

17. Fox M, Van Berkel V, Bousamra M II, Sloan S, Martin RC II. Surgical management of pulmonary carcinoid tumors: sublobar resection versus lobectomy. Am J Surg. 2013;205(2):200-208.

18. Cardillo G, Sera F, Di Martino M, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumors: nodal status and long-term survival after resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(5):1781-1785.

19. Oberg K, Hellman P, Ferolla P, Papotti M; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Neuroendocrine bronchial and thymic tumors: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 7:vii120-3).

20. Filosso PL, Ferolla P, Guerrera F, et al. Multidisciplinary management of advanced lung neuroendocrine tumors. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(Suppl 2):S163-171.

21. Kulke MH, Shah MH, Benson AB III, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2015;13(1):78-108.

22. Yao JC, Fazio N, Singh S, et al. Everolimus for the treatment of advanced, non-functional neuroendocrine tumours of the lung or gastrointestinal tract (RADIANT-4): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):968-977.

23. Ramirez RA, Beyer DT, Chauhan A, Boudreaux JP, Wang YZ, Woltering EA. The role of capecitabine/temozolomide in metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Oncologist. 2016;21(6):671-675.

24. Bajetta E, Rimassa L, Carnaghi C, et al. 5-Fluorouracil, dacarbazine, and epirubicin in the treatment of patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 1998;83(2):372-378.

25. Masi G, Fornaro L, Cupini S, et al. Refractory neuroendocrine tumor-response to liposomal doxorubicin and capecitabine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(11):670-674.

26. Lou F, Sarkaria I, Pietanza C, et al. Recurrence of pulmonary carcinoid tumors after resection: implications for postoperative surveillance. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(4):1156-1162.

27. Beasley MB, Thunnissen FB, Brambilla E, et al. Pulmonary atypical carcinoid: predictors of survival in 106 cases. Human Pathol. 2000;31(10):1255-1265.

1. Hauso O, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, et al. Neuroendocrine tumor epidemiology: contrasting Norway and North America. Cancer. 2008;113(10):2655-2664.

2. Fink G, Krelbaum T, Yellin A, et al. Pulmonary carcinoid: presentation, diagnosis, and outcome in 142 cases in Israel and review of 640 cases from the literature. Chest. 2001;119(6):1647-1651.

3. Limper AH, Carpenter PC, Scheithauer B, Staats BA. The Cushing syndrome induced by bronchial carcinoid tumors. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(3):209-214.

4. Meisinger QC, Klein JS, Butnor KJ, Gentchos G, Leavitt BJ. CT features of peripheral pulmonary carcinoid tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197(5):1073-1080.

5. Guckel C, Schnabel K, Deimling M, Steinbrich W. Solitary pulmonary nodules: MR evaluation of enhancement patterns with contrast-enhanced dynamic snapshot gradient-echo imaging. Radiology. 1996;200(3):681-686.

6. Jindal T, Kumar A, Venkitaraman B, et al. Evaluation of the role of [18F]FDG-PET/CT and [68Ga]DOTATOC-PET/CT in differentiating typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Cancer Imaging. 2011;11:70-75.

7. Caplin ME, Baudin E, Ferolla P, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors: European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society expert consensus and recommendations for best practice for typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(8):1604-1620.

8. Travis WD. Pathology and diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors: lung neuroendocrine. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24(3):257-266.

9. Warren WH, Memoli VA, Gould VE. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis of bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms. II. Well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1984;7(2-3):185-199.

10. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(1):39-51.

11. McCaughan BC, Martini N, Bains MS. Bronchial carcinoids. Review of 124 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;89(1):8-17.

12. Hurt R, Bates M. Carcinoid tumours of the bronchus: a 33-year experience. Thorax. 1984;39(8):617-623.

13. Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Akerley W, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2014;12(12):1738-1761.

14. Ferguson MK, Landreneau RJ, Hazelrigg SR, et al. Long-term outcome after resection for bronchial carcinoid tumors. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;18(2):156-161.

15. Lucchi M, Melfi F, Ribechini A, et al. Sleeve and wedge parenchyma-sparing bronchial resections in low-grade neoplasms of the bronchial airway. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134(2):373-377.

16. Yendamuri S, Gold D, Jayaprakash V, Dexter E, Nwogu C, Demmy T. Is sublobar resection sufficient for carcinoid tumors? Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(5):1774-1778; discussion 8-9.

17. Fox M, Van Berkel V, Bousamra M II, Sloan S, Martin RC II. Surgical management of pulmonary carcinoid tumors: sublobar resection versus lobectomy. Am J Surg. 2013;205(2):200-208.

18. Cardillo G, Sera F, Di Martino M, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumors: nodal status and long-term survival after resection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(5):1781-1785.

19. Oberg K, Hellman P, Ferolla P, Papotti M; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Neuroendocrine bronchial and thymic tumors: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 7:vii120-3).

20. Filosso PL, Ferolla P, Guerrera F, et al. Multidisciplinary management of advanced lung neuroendocrine tumors. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(Suppl 2):S163-171.

21. Kulke MH, Shah MH, Benson AB III, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2015;13(1):78-108.

22. Yao JC, Fazio N, Singh S, et al. Everolimus for the treatment of advanced, non-functional neuroendocrine tumours of the lung or gastrointestinal tract (RADIANT-4): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2016;387(10022):968-977.

23. Ramirez RA, Beyer DT, Chauhan A, Boudreaux JP, Wang YZ, Woltering EA. The role of capecitabine/temozolomide in metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Oncologist. 2016;21(6):671-675.

24. Bajetta E, Rimassa L, Carnaghi C, et al. 5-Fluorouracil, dacarbazine, and epirubicin in the treatment of patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 1998;83(2):372-378.

25. Masi G, Fornaro L, Cupini S, et al. Refractory neuroendocrine tumor-response to liposomal doxorubicin and capecitabine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(11):670-674.

26. Lou F, Sarkaria I, Pietanza C, et al. Recurrence of pulmonary carcinoid tumors after resection: implications for postoperative surveillance. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(4):1156-1162.

27. Beasley MB, Thunnissen FB, Brambilla E, et al. Pulmonary atypical carcinoid: predictors of survival in 106 cases. Human Pathol. 2000;31(10):1255-1265.

Gene variants associated with high-risk pediatric ALL

New research has revealed germline variations associated with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in children.

Researchers sequenced the TP53 tumor suppressor gene in nearly 4000 children with ALL and identified 22 pathogenic germline variants.

These variants were associated with inferior survival and an increased risk of developing second malignancies.

Jun J. Yang, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and his colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The researchers performed targeted sequencing of TP53 coding regions in 3801 children with ALL who were enrolled in 2 Children’s Oncology Group trials (AALL0232 and P9900).

The sequencing revealed 49 unique TP53 coding variants, which were found in 77 children. Twenty-two of the variants were pathogenic, and they were found in 26 children.

The researchers also analyzed data from 60,706 control subjects without ALL and found the 22 pathogenic variants were more likely to be found in the ALL patients than controls. The odds ratio was 5.2 (P<0.001).

Among the ALL patients, those who had the pathogenic variants were significantly older at diagnosis than those without the variants, with median ages of 15.5 years and 7.3 years, respectively (P<0.001).

The pathogenic variants were most common in patients with hypodiploid ALL. About 65% of patients who carried the pathogenic variants had hypodiploid ALL, as did 1.2% of children with wild-type genotype (P<0.001).

The pathogenic variants were associated with inferior event-free survival and overall survival as well. The hazard ratios were 4.2 (P<0.001) and 3.9 (P=0.001), respectively.

And the pathogenic variants were associated with a higher risk of second cancers. The 5-year cumulative incidence of second malignancies was 25.1% among patients with the pathogenic variants and 0.7% among patients without the variants (P<0.001).

“These germline variations are a double whammy for carriers,” Dr Yang said. “Not only is their risk of developing leukemia very high, they are also more likely to relapse or develop a second cancer.”

The association between the pathogenic variants and second cancers has prompted Dr Yang and his colleagues to explore ways to help patients manage their risk.

“Maybe these patients should avoid certain ALL therapies in order to reduce their risk of developing another cancer,” Dr Yang said. “I believe this finding may change treatment and follow-up for these high-risk patients.”

Dr Yang and his colleagues also noted that inherited variations in TP53 are a hallmark of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. And the syndrome might partially explain the high rate of second cancers in ALL patients with the pathogenic TP53 variants.

“The ALL treatment might have added to that risk,” Dr Yang said, “but we do not know for sure.” ![]()

New research has revealed germline variations associated with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in children.

Researchers sequenced the TP53 tumor suppressor gene in nearly 4000 children with ALL and identified 22 pathogenic germline variants.

These variants were associated with inferior survival and an increased risk of developing second malignancies.

Jun J. Yang, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and his colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The researchers performed targeted sequencing of TP53 coding regions in 3801 children with ALL who were enrolled in 2 Children’s Oncology Group trials (AALL0232 and P9900).

The sequencing revealed 49 unique TP53 coding variants, which were found in 77 children. Twenty-two of the variants were pathogenic, and they were found in 26 children.

The researchers also analyzed data from 60,706 control subjects without ALL and found the 22 pathogenic variants were more likely to be found in the ALL patients than controls. The odds ratio was 5.2 (P<0.001).

Among the ALL patients, those who had the pathogenic variants were significantly older at diagnosis than those without the variants, with median ages of 15.5 years and 7.3 years, respectively (P<0.001).

The pathogenic variants were most common in patients with hypodiploid ALL. About 65% of patients who carried the pathogenic variants had hypodiploid ALL, as did 1.2% of children with wild-type genotype (P<0.001).

The pathogenic variants were associated with inferior event-free survival and overall survival as well. The hazard ratios were 4.2 (P<0.001) and 3.9 (P=0.001), respectively.

And the pathogenic variants were associated with a higher risk of second cancers. The 5-year cumulative incidence of second malignancies was 25.1% among patients with the pathogenic variants and 0.7% among patients without the variants (P<0.001).

“These germline variations are a double whammy for carriers,” Dr Yang said. “Not only is their risk of developing leukemia very high, they are also more likely to relapse or develop a second cancer.”

The association between the pathogenic variants and second cancers has prompted Dr Yang and his colleagues to explore ways to help patients manage their risk.

“Maybe these patients should avoid certain ALL therapies in order to reduce their risk of developing another cancer,” Dr Yang said. “I believe this finding may change treatment and follow-up for these high-risk patients.”

Dr Yang and his colleagues also noted that inherited variations in TP53 are a hallmark of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. And the syndrome might partially explain the high rate of second cancers in ALL patients with the pathogenic TP53 variants.

“The ALL treatment might have added to that risk,” Dr Yang said, “but we do not know for sure.” ![]()

New research has revealed germline variations associated with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in children.

Researchers sequenced the TP53 tumor suppressor gene in nearly 4000 children with ALL and identified 22 pathogenic germline variants.

These variants were associated with inferior survival and an increased risk of developing second malignancies.

Jun J. Yang, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and his colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The researchers performed targeted sequencing of TP53 coding regions in 3801 children with ALL who were enrolled in 2 Children’s Oncology Group trials (AALL0232 and P9900).

The sequencing revealed 49 unique TP53 coding variants, which were found in 77 children. Twenty-two of the variants were pathogenic, and they were found in 26 children.

The researchers also analyzed data from 60,706 control subjects without ALL and found the 22 pathogenic variants were more likely to be found in the ALL patients than controls. The odds ratio was 5.2 (P<0.001).

Among the ALL patients, those who had the pathogenic variants were significantly older at diagnosis than those without the variants, with median ages of 15.5 years and 7.3 years, respectively (P<0.001).

The pathogenic variants were most common in patients with hypodiploid ALL. About 65% of patients who carried the pathogenic variants had hypodiploid ALL, as did 1.2% of children with wild-type genotype (P<0.001).

The pathogenic variants were associated with inferior event-free survival and overall survival as well. The hazard ratios were 4.2 (P<0.001) and 3.9 (P=0.001), respectively.

And the pathogenic variants were associated with a higher risk of second cancers. The 5-year cumulative incidence of second malignancies was 25.1% among patients with the pathogenic variants and 0.7% among patients without the variants (P<0.001).

“These germline variations are a double whammy for carriers,” Dr Yang said. “Not only is their risk of developing leukemia very high, they are also more likely to relapse or develop a second cancer.”

The association between the pathogenic variants and second cancers has prompted Dr Yang and his colleagues to explore ways to help patients manage their risk.

“Maybe these patients should avoid certain ALL therapies in order to reduce their risk of developing another cancer,” Dr Yang said. “I believe this finding may change treatment and follow-up for these high-risk patients.”

Dr Yang and his colleagues also noted that inherited variations in TP53 are a hallmark of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. And the syndrome might partially explain the high rate of second cancers in ALL patients with the pathogenic TP53 variants.

“The ALL treatment might have added to that risk,” Dr Yang said, “but we do not know for sure.” ![]()

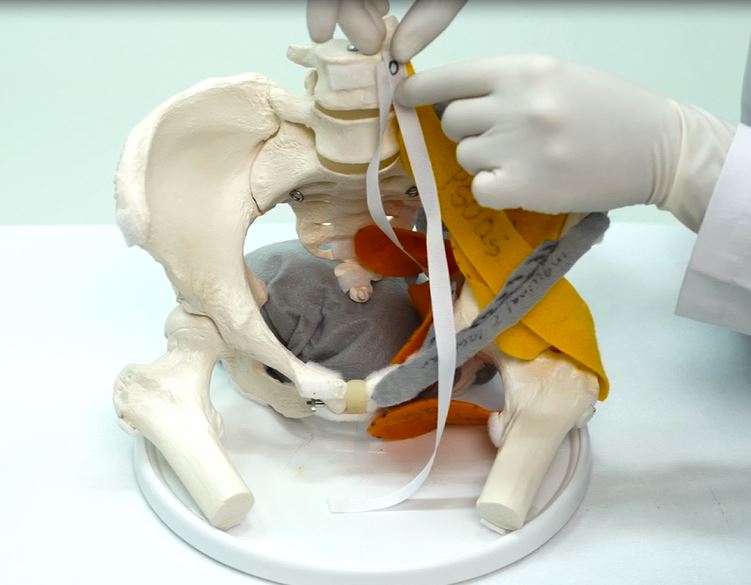

Method prolongs lifespan of blood samples

A new blood stabilization method significantly prolongs the lifespan of blood samples for microfluidic sorting and transcriptome profiling of rare circulating tumor cells (CTCs), according to researchers.

The method involves reducing the storage temperature to 4° C to reversibly slow down cellular processes while also counteracting the platelet activation that can occur because of the low temperature.

The researchers said this work overcomes a significant barrier to the translation of liquid biopsy technologies for precision oncology and other applications.

Keith Wong, PhD, of the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Engineering in Medicine (MGH-CEM), and his colleagues described this work in Nature Communications.

When isolating CTCs from fresh, unprocessed blood, timing is everything. Even minor changes in the quality of a blood sample—such as the breakdown of red cells, leukocyte activation, or clot formation— can greatly affect cell-sorting mechanisms and the quality of the biomolecules isolated for cancer detection.

According to published studies, factors such as the total number of CTCs in a sample and the number with high-quality RNA decrease by around 50% within the first 4 to 5 hours after the sample is collected.