User login

Newer cholesterol-lowering agents: What you must know

Over the past 3 decades, age-adjusted mortality for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the United States has dropped by more than 50%.1 While multiple factors have contributed to this remarkable decline, the introduction and widespread use of statin therapy is unquestionably one key factor. Despite nearly overwhelming evidence that statins effectively lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and predictably reduce cardiovascular events, less than half of patients with clinical coronary heart disease receive high-intensity statin therapy, leaving this population at increased risk for future events.2

Statins: Latest evidence on risks and benefits

Statins aren’t perfect. Not every patient is able to achieve the desired LDL-C lowering with statin therapy, and some patients develop adverse effects such as myopathy, new-onset diabetes, and occasionally hemorrhagic stroke. A recent report puts the risks of statin therapy in perspective, estimating that the treatment of 10,000 patients for 5 years would cause one case of rhabdomyolysis, 5 cases of myopathy, 75 new cases of diabetes, and 7 hemorrhagic strokes.3 The same treatment would avert approximately 1000 CVD events among those with preexisting disease, and approximately 500 CVD events among those with elevated risk, but no preexisting disease.3

In blinded randomized controlled trials, statin therapy is associated with relatively few adverse events (AEs). In open-label observational studies, however, substantially more AEs are reported. During the blinded phase of one recent study, muscle-related AEs and erectile dysfunction were reported at a similar rate by participants randomly assigned to receive atorvastatin or placebo. During the nonblinded nonrandomized phase, complaints of muscle-related AEs were 41% more likely in participants taking statins compared with those who were not.4

Statin therapy offers predictable CVD risk reduction. The evidence report accompanying the 2016 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines on statins for the prevention of CVD states that the use of low- or moderate-dose statin therapy was associated with an approximately 30% relative risk reduction (RRR) in CVD events and in CVD deaths, and a 10% to 15% RRR in all-cause mortality.5 Those with greater baseline CVD risk will have greater absolute risk reduction (ARR) than those with low baseline risk.5

How effective are non-statin therapies?

Multiple studies have demonstrated that some drugs can favorably modify lipid levels but not improve patient outcomes—eg, niacin, fibrates, and omega-3 fatty acids. The therapies that do improve outcomes are those that act via upregulation of LDL-receptor expression: statins, ezetimibe, bile acid sequestrants, dietary interventions, and ileal bypass surgery.

A recent meta-analysis found that with a 38.7-mg/dL (1-mmol/L) reduction in LDL-C level, the relative risk for major vascular events was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.71-0.84) for statins and 0.75 (95% CI, 0.66-0.86) for monotherapy with non-statin interventions that upregulate LDL-receptor expression.6

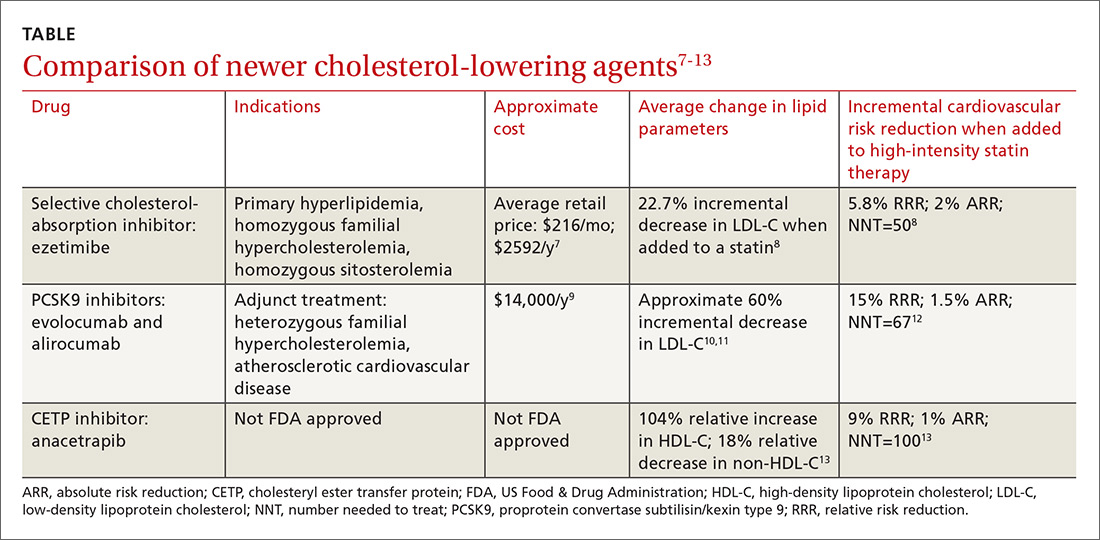

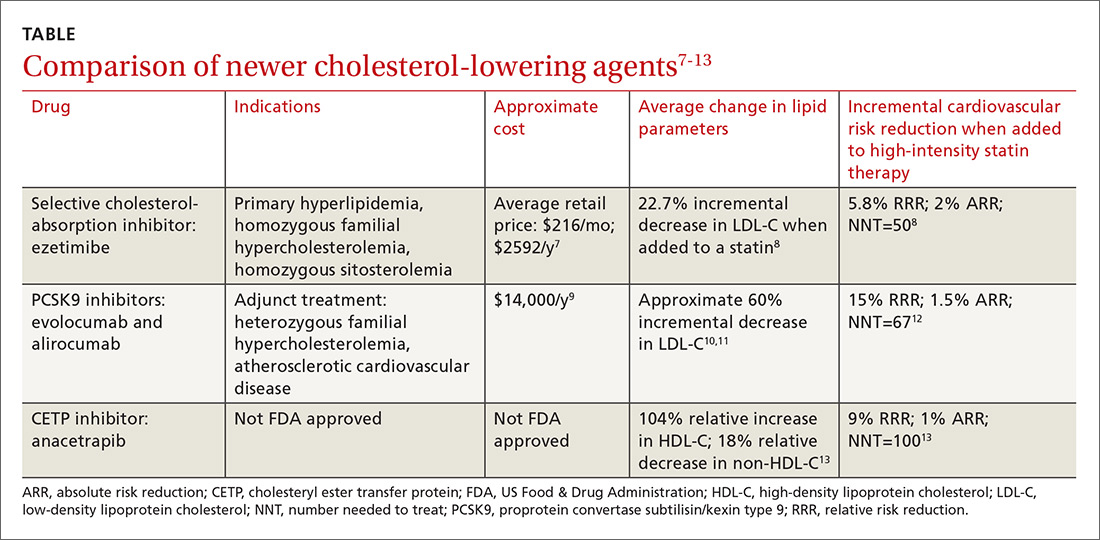

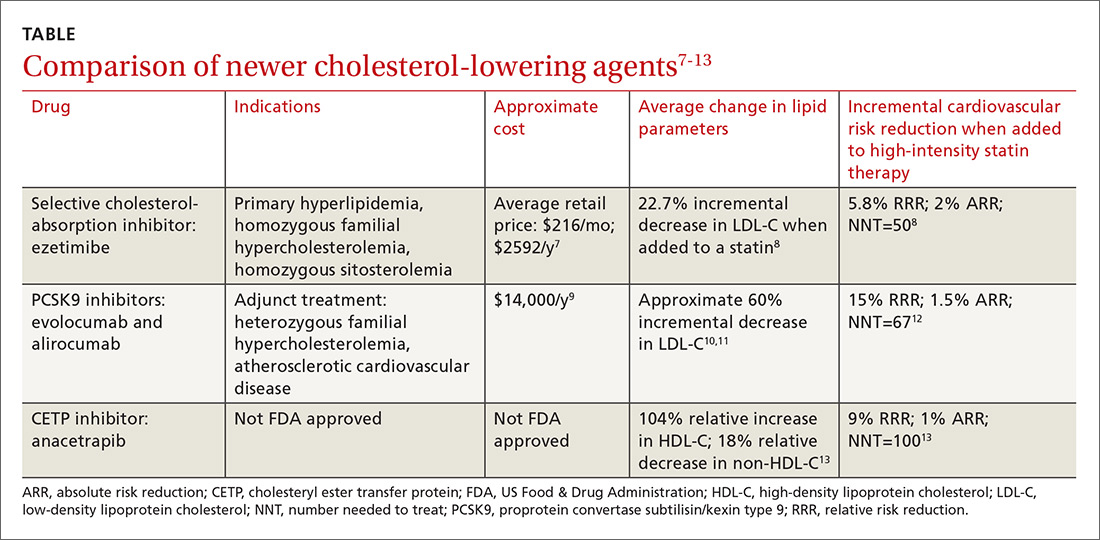

Ezetimibe. Less impressive is the incremental benefit of adding some non-statin therapies to effective statin therapy. The IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT) reported that adding ezetimibe to effective statin therapy in stable patients with previous acute coronary syndrome reduced the LDL-C level from 69.5 mg/dL to 53.7 mg/dL (TABLE7-13).8 After 7 years of treatment, relative risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) outcomes decreased by 5.8%; absolute decrease in risk was 2%: from 34.7% to 32.7% (number needed to treat [NNT]=50).8 Consider adding ezetimibe to maximally-tolerated statin therapy for patients not meeting LDL-C goals with a statin alone.

Continue to: A new class to lower LDL-C: PCSK9 inhibitors

A new class to lower LDL-C: PCSK9 inhibitors

It is clear that additional approaches to LDL-C reduction are needed. A new drug class that effectively lowers LDL-C levels is monoclonal antibodies that inhibit PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9). PCSK9 activity is directly proportional to the circulating LDL-C level: gene mutations that increase PCSK9 function are one cause of elevated LDL-C and CVD risk in familial hypercholesterolemia (FH),14 whereas mutations that decrease PCSK9 activity are associated with a decrease in LDL-C levels and risk of ASCVD.15

Circulating PCSK9 initiates LDL-receptor clearance by binding to the LDL receptor; the complex is then taken into the hepatocyte, where it undergoes degradation, and the receptor is not recycled to the cell’s surface. The resultant decreased level of cholesterol within the hepatocyte upregulates HMG-CoA reductase (the enzyme that controls the rate-limiting step in cholesterol production and is targeted by statin therapy) and LDL-receptor activity to increase the available cholesterol in the hepatocyte. Unfortunately, statins promote the upregulation of both the LDL receptor and PCSK9, thereby limiting their LDL-C-lowering potency. Combined inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase with statins and PCSK9 with monoclonal antibodies exerts additive reductions in LDL-C.16

Evolocumab and alirocumab—monoclonal antibodies that prevent circulating PCSK9 from binding to the LDL receptor—have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as adjuncts to diet and maximally-tolerated statin therapy in adults who have heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) or clinical ASCVD and who must further lower LDL-C levels. The addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor to statin therapy consistently results in an incremental decrease in LDL-C of around 60%.10,11 Much of the data supporting the use of PCSK9 inhibitors are disease-oriented. Among patients with angiographic coronary disease treated with statins, the addition of evolocumab resulted in regression of atherosclerotic plaque measured by intravascular ultrasound after 18 months of treatment.10

Continue to: PCSK9 inhibitors reduce adverse CVD events when added to a statin

PCSK9 inhibitors reduce adverse CVD events when added to a statin. In a study designed to evaluate AEs and LDL-C lowering with evolocumab, a prespecified exploratory outcome was the incidence of adjudicated CVD events. After one year of therapy, the rate of events was reduced from 2.18% in the standard-therapy group to 0.95% in the evolocumab group—a relative decrease of 53%, but an absolute decrease of 1.23% (NNT=81).17

A similar reduction in the rate of major adverse CVD events was found in adding alirocumab to ongoing statin therapy. In a post hoc analysis of patients who received either adjunctive alirocumab or placebo, CVD events (death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction [MI], fatal or nonfatal ischemic stroke, or unstable angina requiring hospitalization) were 1.7% vs 3.3% (hazard ratio=0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.90).11

FOURIER, the first major trial designed to evaluate cardiovascular outcomes with PCSK9 therapy, showed that adding evolocumab to effective statin therapy reduced the average LDL-C level from 92 mg/dL to 30 mg/dL.12 Evolocumab decreased the composite CVD outcome (cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization) over 2.2 years from 11.3% to 9.8%—a 15% RRR and a 1.5% ARR (NNT=67). Most of the participants were receiving high-intensity statin therapy at study entry. AEs were similar between the study groups.12

A prespecified analysis of FOURIER data found that evolocumab did not increase the risk of new-onset diabetes in patients without diabetes or prediabetes at baseline. Fasting plasma glucose and hemoglobin A1c levels in the evolocumab and placebo groups remained similar throughout the trial in patients with diabetes, prediabetes, or normoglycemia.18 Additionally, a randomized trial involving patients who received either evolocumab or placebo in addition to statin therapy found no significant difference in cognitive function between the groups over a median of 19 months.19

Continue to: Effective, but expensive

Effective, but expensive. At its current list price of approximately $14,000 per year,9 evolocumab, added to standard therapy in patients with ASCVD, exceeds the generally accepted cost-effectiveness threshold of $150,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) achieved.20 Similar analysis in patients with HeFH estimated a cost of $503,000 per QALY achieved with evolocumab.21 The outcomes of cost-effectiveness analyses hinge on the event rate in the study population and the threshold for initiating therapy. For the FOURIER trial participants, with an annual event rate of 4.2 per 100 patient-years, a net annual price of approximately $6700 would be necessary to meet a $150,000 per QALY threshold.22

At 2015 prices, the addition of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy for all eligible patients would reduce cardiovascular care costs by an estimated $29 billion over 5 years but would also increase drug costs by an estimated $592 billion, representing a 38% increase over 2015 prescription drug expenditures.21 Treatment of less than 20 million US adults with evolocumab at the cost of this single drug would match the entire cost for all other prescription pharmaceuticals for all diseases in the United States combined.23

In 2012, 27.9% of US adults ages 40 years and older were taking prescribed lipid-lowering treatment; 23.2% were taking only statins.24 If the

Until the cost of PCSK9 inhibitors decreases to a justifiable level and outcomes of longer term studies are available, consider prescribing other adjunctive treatments for patients who have not achieved LDL-C goals with statin therapy alone. Generally, reserve use of PCSK9 inhibitors for the highest-risk adults: those with HeFH or clinical ASCVD who must further lower LDL-C levels. Some insurers, including Medicare, are covering PCSK9 inhibitors, but many patients have difficulty obtaining coverage.27

Continue to: CETP inhibitors: Not FDA approved

CETP inhibitors: Not FDA approved

In a recent trial of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitor evacetrapib, the drug had favorable effects on lipid biomarkers but did not improve cardiovascular outcomes.28 More recently, the CETP inhibitor anacetrapib was shown to decrease the composite outcome of coronary death, MI, or coronary revascularization in adults with established ASCVD who were receiving high-intensity atorvastatin therapy.13 At the trial midpoint, mean high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels increased by 43 mg/dL in the anacetrapib group compared with that of the placebo group (a relative difference of 104%); mean non-HDL cholesterol decreased by 17 mg/dL, a relative difference of −18%. Over a median follow-up period of 4.1 years, the addition of anacetrapib was associated with a 9% RRR and a 1% absolute reduction in the composite outcome over a statin alone (NNT=100).13 At this point, the manufacturers of both agents have halted efforts to gain FDA approval.

Future directions

Newer strategies to inhibit PCSK9 function are under development. Small peptides that inhibit PCSK9 interaction with the LDL receptor offer the potential advantage of oral administration, as opposed to the currently available injectable anti-PCSK9 antibodies.29 A recent trial found that inhibition of PCSK9 messenger RNA (mRNA) synthesis with the small interfering RNA (siRNA) molecule inclisiran lowered LDL-C in patients with high cardiovascular risk and elevated LDL-C levels despite aggressive statin therapy.30 The effect of these strategies on cardiovascular outcomes remains unproven.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathon Firnhaber, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Brody School of Medicine, 101 Heart Drive, Mail Stop 654, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected].

1. Weir HK, Anderson RN, Coleman King SM, et al. Heart disease and cancer deaths — trends and projections in the United States, 1969-2020. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E157.

2. Rodriguez F, Harrington RA. Cholesterol, cardiovascular risk, statins, PCSK9 inhibitors, and the future of LDL-C lowering. JAMA. 2016;316:1967-1968.

3. Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet. 2016;388:2532-2561.

4. Gupta A, Thompson D, Whitehouse A, et al. Adverse events associated with unblinded, but not with blinded, statin therapy in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial—Lipid-Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial and its non-randomised non-blind extension phase. Lancet. 2017;389:2473-2481.

5. Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008-2024.

6. Silverman MG, Ference BA, Im K, et al. Association between lowering LDL-C and cardiovascular risk reduction among different therapeutic interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1289-1297.

7. GoodRx. Ezetimibe. Available at: https://www.goodrx.com/ezetimibe. Accessed May 2, 2018.

8. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387-2397.

9. American Journal of Managed Care. Outcomes-based pricing for PCSK9 inhibitors. Available at: http://www.ajmc.com/contributor/inmaculada-hernandez-pharmd/2017/09/outcomes-based-pricing-for-pcsk9-inhibitors. Accessed May 2, 2018.

10. Nicholls S, Puri R, Anderson T, et al. Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin-treated patients: the GLAGOV randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:2373-2384.

11. Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1489-1499.

12. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

13. HPS3/TIMI55-REVEAL Collaborative Group. Effects of anacetrapib in patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1217-1227.

14. Hunt SC, Hopkins PN, Bulka K, et al. Genetic localization to chromosome 1p32 of the third locus for familial hypercholesterolemia in a Utah kindred. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1089-1093.

15. Cohen J, Pertsemlidis A, Kotowski I, et al. Low LDL cholesterol in individuals of African descent resulting from frequent nonsense mutations in PCSK9. Nat Genet. 2005;37:161-165.

16. Dixon DL, Trankle C, Buckley L, et al. A review of PCSK9 inhibition and its effects beyond LDL receptors. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:1073-1080.

17. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, et al. Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1500-1509.

18. Sabatine MS, Leiter LA, Wiviott SD, et al. Cardiovascular safety and efficacy of the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab in patients with and without diabetes and the effect of evolocumab on glycaemia and risk of new-onset diabetes: a prespecified analysis of the FOURIER randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:941-950.

19. Giugliano RP, Mach F, Zavitz K, et al. Cognitive function in a randomized trial of evolocumab. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:633-643.

20. Anderson JL, Heidenreich PA, Barnett PG, et al. ACC/AHA statement on cost/value methodology in clinical practice guidelines and performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2304-2322.

21. Kazi DS, Moran AE, Coxson PG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2016;316:743-753.

22. Fonarow GC, Keech AC, Pedersen TR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of evolocumab therapy for reducing cardiovascular events in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1069-1078.

23. Ioannidis JPA. Inconsistent guideline recommendations for cardiovascular prevention and the debate about zeroing in on and zeroing LDL-C levels with PCSK9 inhibitors. JAMA. 2017;318:419-420.

24. Gu Q, Paulose-Ram R, Burt VL, et al. Prescription cholesterol-lowering medication use in adults aged 40 and over: United States, 2003-2012. NCHS data Brief. 2014;177:1-8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db177.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2018.

25. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(suppl 2):S1-S45.

26. Pagidipati NJ, Navar AM, Mulder H, et al. Comparison of recommended eligibility for primary prevention statin therapy based on the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations vs the ACC/AHA Guidelines. JAMA. 2017;317:1563-1567.

27

28. Lincoff AM, Nicholls SJ, Riesmeyer JS, et al. Evacetrapib and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1933-1942.

29. Dixon DL, Trankle C, Buckley L, et al. A review of PCSK9 inhibition and its effects beyond LDL receptors. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:1073-1080.

30. Ray KK, Landmesser U, Leiter LA, et al. Inclisiran in patients at high cardiovascular risk with elevated LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1430-1440.

Over the past 3 decades, age-adjusted mortality for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the United States has dropped by more than 50%.1 While multiple factors have contributed to this remarkable decline, the introduction and widespread use of statin therapy is unquestionably one key factor. Despite nearly overwhelming evidence that statins effectively lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and predictably reduce cardiovascular events, less than half of patients with clinical coronary heart disease receive high-intensity statin therapy, leaving this population at increased risk for future events.2

Statins: Latest evidence on risks and benefits

Statins aren’t perfect. Not every patient is able to achieve the desired LDL-C lowering with statin therapy, and some patients develop adverse effects such as myopathy, new-onset diabetes, and occasionally hemorrhagic stroke. A recent report puts the risks of statin therapy in perspective, estimating that the treatment of 10,000 patients for 5 years would cause one case of rhabdomyolysis, 5 cases of myopathy, 75 new cases of diabetes, and 7 hemorrhagic strokes.3 The same treatment would avert approximately 1000 CVD events among those with preexisting disease, and approximately 500 CVD events among those with elevated risk, but no preexisting disease.3

In blinded randomized controlled trials, statin therapy is associated with relatively few adverse events (AEs). In open-label observational studies, however, substantially more AEs are reported. During the blinded phase of one recent study, muscle-related AEs and erectile dysfunction were reported at a similar rate by participants randomly assigned to receive atorvastatin or placebo. During the nonblinded nonrandomized phase, complaints of muscle-related AEs were 41% more likely in participants taking statins compared with those who were not.4

Statin therapy offers predictable CVD risk reduction. The evidence report accompanying the 2016 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines on statins for the prevention of CVD states that the use of low- or moderate-dose statin therapy was associated with an approximately 30% relative risk reduction (RRR) in CVD events and in CVD deaths, and a 10% to 15% RRR in all-cause mortality.5 Those with greater baseline CVD risk will have greater absolute risk reduction (ARR) than those with low baseline risk.5

How effective are non-statin therapies?

Multiple studies have demonstrated that some drugs can favorably modify lipid levels but not improve patient outcomes—eg, niacin, fibrates, and omega-3 fatty acids. The therapies that do improve outcomes are those that act via upregulation of LDL-receptor expression: statins, ezetimibe, bile acid sequestrants, dietary interventions, and ileal bypass surgery.

A recent meta-analysis found that with a 38.7-mg/dL (1-mmol/L) reduction in LDL-C level, the relative risk for major vascular events was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.71-0.84) for statins and 0.75 (95% CI, 0.66-0.86) for monotherapy with non-statin interventions that upregulate LDL-receptor expression.6

Ezetimibe. Less impressive is the incremental benefit of adding some non-statin therapies to effective statin therapy. The IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT) reported that adding ezetimibe to effective statin therapy in stable patients with previous acute coronary syndrome reduced the LDL-C level from 69.5 mg/dL to 53.7 mg/dL (TABLE7-13).8 After 7 years of treatment, relative risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) outcomes decreased by 5.8%; absolute decrease in risk was 2%: from 34.7% to 32.7% (number needed to treat [NNT]=50).8 Consider adding ezetimibe to maximally-tolerated statin therapy for patients not meeting LDL-C goals with a statin alone.

Continue to: A new class to lower LDL-C: PCSK9 inhibitors

A new class to lower LDL-C: PCSK9 inhibitors

It is clear that additional approaches to LDL-C reduction are needed. A new drug class that effectively lowers LDL-C levels is monoclonal antibodies that inhibit PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9). PCSK9 activity is directly proportional to the circulating LDL-C level: gene mutations that increase PCSK9 function are one cause of elevated LDL-C and CVD risk in familial hypercholesterolemia (FH),14 whereas mutations that decrease PCSK9 activity are associated with a decrease in LDL-C levels and risk of ASCVD.15

Circulating PCSK9 initiates LDL-receptor clearance by binding to the LDL receptor; the complex is then taken into the hepatocyte, where it undergoes degradation, and the receptor is not recycled to the cell’s surface. The resultant decreased level of cholesterol within the hepatocyte upregulates HMG-CoA reductase (the enzyme that controls the rate-limiting step in cholesterol production and is targeted by statin therapy) and LDL-receptor activity to increase the available cholesterol in the hepatocyte. Unfortunately, statins promote the upregulation of both the LDL receptor and PCSK9, thereby limiting their LDL-C-lowering potency. Combined inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase with statins and PCSK9 with monoclonal antibodies exerts additive reductions in LDL-C.16

Evolocumab and alirocumab—monoclonal antibodies that prevent circulating PCSK9 from binding to the LDL receptor—have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as adjuncts to diet and maximally-tolerated statin therapy in adults who have heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) or clinical ASCVD and who must further lower LDL-C levels. The addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor to statin therapy consistently results in an incremental decrease in LDL-C of around 60%.10,11 Much of the data supporting the use of PCSK9 inhibitors are disease-oriented. Among patients with angiographic coronary disease treated with statins, the addition of evolocumab resulted in regression of atherosclerotic plaque measured by intravascular ultrasound after 18 months of treatment.10

Continue to: PCSK9 inhibitors reduce adverse CVD events when added to a statin

PCSK9 inhibitors reduce adverse CVD events when added to a statin. In a study designed to evaluate AEs and LDL-C lowering with evolocumab, a prespecified exploratory outcome was the incidence of adjudicated CVD events. After one year of therapy, the rate of events was reduced from 2.18% in the standard-therapy group to 0.95% in the evolocumab group—a relative decrease of 53%, but an absolute decrease of 1.23% (NNT=81).17

A similar reduction in the rate of major adverse CVD events was found in adding alirocumab to ongoing statin therapy. In a post hoc analysis of patients who received either adjunctive alirocumab or placebo, CVD events (death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction [MI], fatal or nonfatal ischemic stroke, or unstable angina requiring hospitalization) were 1.7% vs 3.3% (hazard ratio=0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.90).11

FOURIER, the first major trial designed to evaluate cardiovascular outcomes with PCSK9 therapy, showed that adding evolocumab to effective statin therapy reduced the average LDL-C level from 92 mg/dL to 30 mg/dL.12 Evolocumab decreased the composite CVD outcome (cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization) over 2.2 years from 11.3% to 9.8%—a 15% RRR and a 1.5% ARR (NNT=67). Most of the participants were receiving high-intensity statin therapy at study entry. AEs were similar between the study groups.12

A prespecified analysis of FOURIER data found that evolocumab did not increase the risk of new-onset diabetes in patients without diabetes or prediabetes at baseline. Fasting plasma glucose and hemoglobin A1c levels in the evolocumab and placebo groups remained similar throughout the trial in patients with diabetes, prediabetes, or normoglycemia.18 Additionally, a randomized trial involving patients who received either evolocumab or placebo in addition to statin therapy found no significant difference in cognitive function between the groups over a median of 19 months.19

Continue to: Effective, but expensive

Effective, but expensive. At its current list price of approximately $14,000 per year,9 evolocumab, added to standard therapy in patients with ASCVD, exceeds the generally accepted cost-effectiveness threshold of $150,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) achieved.20 Similar analysis in patients with HeFH estimated a cost of $503,000 per QALY achieved with evolocumab.21 The outcomes of cost-effectiveness analyses hinge on the event rate in the study population and the threshold for initiating therapy. For the FOURIER trial participants, with an annual event rate of 4.2 per 100 patient-years, a net annual price of approximately $6700 would be necessary to meet a $150,000 per QALY threshold.22

At 2015 prices, the addition of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy for all eligible patients would reduce cardiovascular care costs by an estimated $29 billion over 5 years but would also increase drug costs by an estimated $592 billion, representing a 38% increase over 2015 prescription drug expenditures.21 Treatment of less than 20 million US adults with evolocumab at the cost of this single drug would match the entire cost for all other prescription pharmaceuticals for all diseases in the United States combined.23

In 2012, 27.9% of US adults ages 40 years and older were taking prescribed lipid-lowering treatment; 23.2% were taking only statins.24 If the

Until the cost of PCSK9 inhibitors decreases to a justifiable level and outcomes of longer term studies are available, consider prescribing other adjunctive treatments for patients who have not achieved LDL-C goals with statin therapy alone. Generally, reserve use of PCSK9 inhibitors for the highest-risk adults: those with HeFH or clinical ASCVD who must further lower LDL-C levels. Some insurers, including Medicare, are covering PCSK9 inhibitors, but many patients have difficulty obtaining coverage.27

Continue to: CETP inhibitors: Not FDA approved

CETP inhibitors: Not FDA approved

In a recent trial of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitor evacetrapib, the drug had favorable effects on lipid biomarkers but did not improve cardiovascular outcomes.28 More recently, the CETP inhibitor anacetrapib was shown to decrease the composite outcome of coronary death, MI, or coronary revascularization in adults with established ASCVD who were receiving high-intensity atorvastatin therapy.13 At the trial midpoint, mean high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels increased by 43 mg/dL in the anacetrapib group compared with that of the placebo group (a relative difference of 104%); mean non-HDL cholesterol decreased by 17 mg/dL, a relative difference of −18%. Over a median follow-up period of 4.1 years, the addition of anacetrapib was associated with a 9% RRR and a 1% absolute reduction in the composite outcome over a statin alone (NNT=100).13 At this point, the manufacturers of both agents have halted efforts to gain FDA approval.

Future directions

Newer strategies to inhibit PCSK9 function are under development. Small peptides that inhibit PCSK9 interaction with the LDL receptor offer the potential advantage of oral administration, as opposed to the currently available injectable anti-PCSK9 antibodies.29 A recent trial found that inhibition of PCSK9 messenger RNA (mRNA) synthesis with the small interfering RNA (siRNA) molecule inclisiran lowered LDL-C in patients with high cardiovascular risk and elevated LDL-C levels despite aggressive statin therapy.30 The effect of these strategies on cardiovascular outcomes remains unproven.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathon Firnhaber, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Brody School of Medicine, 101 Heart Drive, Mail Stop 654, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected].

Over the past 3 decades, age-adjusted mortality for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in the United States has dropped by more than 50%.1 While multiple factors have contributed to this remarkable decline, the introduction and widespread use of statin therapy is unquestionably one key factor. Despite nearly overwhelming evidence that statins effectively lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and predictably reduce cardiovascular events, less than half of patients with clinical coronary heart disease receive high-intensity statin therapy, leaving this population at increased risk for future events.2

Statins: Latest evidence on risks and benefits

Statins aren’t perfect. Not every patient is able to achieve the desired LDL-C lowering with statin therapy, and some patients develop adverse effects such as myopathy, new-onset diabetes, and occasionally hemorrhagic stroke. A recent report puts the risks of statin therapy in perspective, estimating that the treatment of 10,000 patients for 5 years would cause one case of rhabdomyolysis, 5 cases of myopathy, 75 new cases of diabetes, and 7 hemorrhagic strokes.3 The same treatment would avert approximately 1000 CVD events among those with preexisting disease, and approximately 500 CVD events among those with elevated risk, but no preexisting disease.3

In blinded randomized controlled trials, statin therapy is associated with relatively few adverse events (AEs). In open-label observational studies, however, substantially more AEs are reported. During the blinded phase of one recent study, muscle-related AEs and erectile dysfunction were reported at a similar rate by participants randomly assigned to receive atorvastatin or placebo. During the nonblinded nonrandomized phase, complaints of muscle-related AEs were 41% more likely in participants taking statins compared with those who were not.4

Statin therapy offers predictable CVD risk reduction. The evidence report accompanying the 2016 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines on statins for the prevention of CVD states that the use of low- or moderate-dose statin therapy was associated with an approximately 30% relative risk reduction (RRR) in CVD events and in CVD deaths, and a 10% to 15% RRR in all-cause mortality.5 Those with greater baseline CVD risk will have greater absolute risk reduction (ARR) than those with low baseline risk.5

How effective are non-statin therapies?

Multiple studies have demonstrated that some drugs can favorably modify lipid levels but not improve patient outcomes—eg, niacin, fibrates, and omega-3 fatty acids. The therapies that do improve outcomes are those that act via upregulation of LDL-receptor expression: statins, ezetimibe, bile acid sequestrants, dietary interventions, and ileal bypass surgery.

A recent meta-analysis found that with a 38.7-mg/dL (1-mmol/L) reduction in LDL-C level, the relative risk for major vascular events was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.71-0.84) for statins and 0.75 (95% CI, 0.66-0.86) for monotherapy with non-statin interventions that upregulate LDL-receptor expression.6

Ezetimibe. Less impressive is the incremental benefit of adding some non-statin therapies to effective statin therapy. The IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT) reported that adding ezetimibe to effective statin therapy in stable patients with previous acute coronary syndrome reduced the LDL-C level from 69.5 mg/dL to 53.7 mg/dL (TABLE7-13).8 After 7 years of treatment, relative risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) outcomes decreased by 5.8%; absolute decrease in risk was 2%: from 34.7% to 32.7% (number needed to treat [NNT]=50).8 Consider adding ezetimibe to maximally-tolerated statin therapy for patients not meeting LDL-C goals with a statin alone.

Continue to: A new class to lower LDL-C: PCSK9 inhibitors

A new class to lower LDL-C: PCSK9 inhibitors

It is clear that additional approaches to LDL-C reduction are needed. A new drug class that effectively lowers LDL-C levels is monoclonal antibodies that inhibit PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9). PCSK9 activity is directly proportional to the circulating LDL-C level: gene mutations that increase PCSK9 function are one cause of elevated LDL-C and CVD risk in familial hypercholesterolemia (FH),14 whereas mutations that decrease PCSK9 activity are associated with a decrease in LDL-C levels and risk of ASCVD.15

Circulating PCSK9 initiates LDL-receptor clearance by binding to the LDL receptor; the complex is then taken into the hepatocyte, where it undergoes degradation, and the receptor is not recycled to the cell’s surface. The resultant decreased level of cholesterol within the hepatocyte upregulates HMG-CoA reductase (the enzyme that controls the rate-limiting step in cholesterol production and is targeted by statin therapy) and LDL-receptor activity to increase the available cholesterol in the hepatocyte. Unfortunately, statins promote the upregulation of both the LDL receptor and PCSK9, thereby limiting their LDL-C-lowering potency. Combined inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase with statins and PCSK9 with monoclonal antibodies exerts additive reductions in LDL-C.16

Evolocumab and alirocumab—monoclonal antibodies that prevent circulating PCSK9 from binding to the LDL receptor—have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as adjuncts to diet and maximally-tolerated statin therapy in adults who have heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HeFH) or clinical ASCVD and who must further lower LDL-C levels. The addition of a PCSK9 inhibitor to statin therapy consistently results in an incremental decrease in LDL-C of around 60%.10,11 Much of the data supporting the use of PCSK9 inhibitors are disease-oriented. Among patients with angiographic coronary disease treated with statins, the addition of evolocumab resulted in regression of atherosclerotic plaque measured by intravascular ultrasound after 18 months of treatment.10

Continue to: PCSK9 inhibitors reduce adverse CVD events when added to a statin

PCSK9 inhibitors reduce adverse CVD events when added to a statin. In a study designed to evaluate AEs and LDL-C lowering with evolocumab, a prespecified exploratory outcome was the incidence of adjudicated CVD events. After one year of therapy, the rate of events was reduced from 2.18% in the standard-therapy group to 0.95% in the evolocumab group—a relative decrease of 53%, but an absolute decrease of 1.23% (NNT=81).17

A similar reduction in the rate of major adverse CVD events was found in adding alirocumab to ongoing statin therapy. In a post hoc analysis of patients who received either adjunctive alirocumab or placebo, CVD events (death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal myocardial infarction [MI], fatal or nonfatal ischemic stroke, or unstable angina requiring hospitalization) were 1.7% vs 3.3% (hazard ratio=0.52; 95% confidence interval, 0.31-0.90).11

FOURIER, the first major trial designed to evaluate cardiovascular outcomes with PCSK9 therapy, showed that adding evolocumab to effective statin therapy reduced the average LDL-C level from 92 mg/dL to 30 mg/dL.12 Evolocumab decreased the composite CVD outcome (cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or coronary revascularization) over 2.2 years from 11.3% to 9.8%—a 15% RRR and a 1.5% ARR (NNT=67). Most of the participants were receiving high-intensity statin therapy at study entry. AEs were similar between the study groups.12

A prespecified analysis of FOURIER data found that evolocumab did not increase the risk of new-onset diabetes in patients without diabetes or prediabetes at baseline. Fasting plasma glucose and hemoglobin A1c levels in the evolocumab and placebo groups remained similar throughout the trial in patients with diabetes, prediabetes, or normoglycemia.18 Additionally, a randomized trial involving patients who received either evolocumab or placebo in addition to statin therapy found no significant difference in cognitive function between the groups over a median of 19 months.19

Continue to: Effective, but expensive

Effective, but expensive. At its current list price of approximately $14,000 per year,9 evolocumab, added to standard therapy in patients with ASCVD, exceeds the generally accepted cost-effectiveness threshold of $150,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) achieved.20 Similar analysis in patients with HeFH estimated a cost of $503,000 per QALY achieved with evolocumab.21 The outcomes of cost-effectiveness analyses hinge on the event rate in the study population and the threshold for initiating therapy. For the FOURIER trial participants, with an annual event rate of 4.2 per 100 patient-years, a net annual price of approximately $6700 would be necessary to meet a $150,000 per QALY threshold.22

At 2015 prices, the addition of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy for all eligible patients would reduce cardiovascular care costs by an estimated $29 billion over 5 years but would also increase drug costs by an estimated $592 billion, representing a 38% increase over 2015 prescription drug expenditures.21 Treatment of less than 20 million US adults with evolocumab at the cost of this single drug would match the entire cost for all other prescription pharmaceuticals for all diseases in the United States combined.23

In 2012, 27.9% of US adults ages 40 years and older were taking prescribed lipid-lowering treatment; 23.2% were taking only statins.24 If the

Until the cost of PCSK9 inhibitors decreases to a justifiable level and outcomes of longer term studies are available, consider prescribing other adjunctive treatments for patients who have not achieved LDL-C goals with statin therapy alone. Generally, reserve use of PCSK9 inhibitors for the highest-risk adults: those with HeFH or clinical ASCVD who must further lower LDL-C levels. Some insurers, including Medicare, are covering PCSK9 inhibitors, but many patients have difficulty obtaining coverage.27

Continue to: CETP inhibitors: Not FDA approved

CETP inhibitors: Not FDA approved

In a recent trial of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) inhibitor evacetrapib, the drug had favorable effects on lipid biomarkers but did not improve cardiovascular outcomes.28 More recently, the CETP inhibitor anacetrapib was shown to decrease the composite outcome of coronary death, MI, or coronary revascularization in adults with established ASCVD who were receiving high-intensity atorvastatin therapy.13 At the trial midpoint, mean high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels increased by 43 mg/dL in the anacetrapib group compared with that of the placebo group (a relative difference of 104%); mean non-HDL cholesterol decreased by 17 mg/dL, a relative difference of −18%. Over a median follow-up period of 4.1 years, the addition of anacetrapib was associated with a 9% RRR and a 1% absolute reduction in the composite outcome over a statin alone (NNT=100).13 At this point, the manufacturers of both agents have halted efforts to gain FDA approval.

Future directions

Newer strategies to inhibit PCSK9 function are under development. Small peptides that inhibit PCSK9 interaction with the LDL receptor offer the potential advantage of oral administration, as opposed to the currently available injectable anti-PCSK9 antibodies.29 A recent trial found that inhibition of PCSK9 messenger RNA (mRNA) synthesis with the small interfering RNA (siRNA) molecule inclisiran lowered LDL-C in patients with high cardiovascular risk and elevated LDL-C levels despite aggressive statin therapy.30 The effect of these strategies on cardiovascular outcomes remains unproven.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathon Firnhaber, MD, Department of Family Medicine, Brody School of Medicine, 101 Heart Drive, Mail Stop 654, Greenville, NC 27834; [email protected].

1. Weir HK, Anderson RN, Coleman King SM, et al. Heart disease and cancer deaths — trends and projections in the United States, 1969-2020. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E157.

2. Rodriguez F, Harrington RA. Cholesterol, cardiovascular risk, statins, PCSK9 inhibitors, and the future of LDL-C lowering. JAMA. 2016;316:1967-1968.

3. Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet. 2016;388:2532-2561.

4. Gupta A, Thompson D, Whitehouse A, et al. Adverse events associated with unblinded, but not with blinded, statin therapy in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial—Lipid-Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial and its non-randomised non-blind extension phase. Lancet. 2017;389:2473-2481.

5. Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008-2024.

6. Silverman MG, Ference BA, Im K, et al. Association between lowering LDL-C and cardiovascular risk reduction among different therapeutic interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1289-1297.

7. GoodRx. Ezetimibe. Available at: https://www.goodrx.com/ezetimibe. Accessed May 2, 2018.

8. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387-2397.

9. American Journal of Managed Care. Outcomes-based pricing for PCSK9 inhibitors. Available at: http://www.ajmc.com/contributor/inmaculada-hernandez-pharmd/2017/09/outcomes-based-pricing-for-pcsk9-inhibitors. Accessed May 2, 2018.

10. Nicholls S, Puri R, Anderson T, et al. Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin-treated patients: the GLAGOV randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:2373-2384.

11. Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1489-1499.

12. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

13. HPS3/TIMI55-REVEAL Collaborative Group. Effects of anacetrapib in patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1217-1227.

14. Hunt SC, Hopkins PN, Bulka K, et al. Genetic localization to chromosome 1p32 of the third locus for familial hypercholesterolemia in a Utah kindred. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1089-1093.

15. Cohen J, Pertsemlidis A, Kotowski I, et al. Low LDL cholesterol in individuals of African descent resulting from frequent nonsense mutations in PCSK9. Nat Genet. 2005;37:161-165.

16. Dixon DL, Trankle C, Buckley L, et al. A review of PCSK9 inhibition and its effects beyond LDL receptors. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:1073-1080.

17. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, et al. Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1500-1509.

18. Sabatine MS, Leiter LA, Wiviott SD, et al. Cardiovascular safety and efficacy of the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab in patients with and without diabetes and the effect of evolocumab on glycaemia and risk of new-onset diabetes: a prespecified analysis of the FOURIER randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:941-950.

19. Giugliano RP, Mach F, Zavitz K, et al. Cognitive function in a randomized trial of evolocumab. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:633-643.

20. Anderson JL, Heidenreich PA, Barnett PG, et al. ACC/AHA statement on cost/value methodology in clinical practice guidelines and performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2304-2322.

21. Kazi DS, Moran AE, Coxson PG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2016;316:743-753.

22. Fonarow GC, Keech AC, Pedersen TR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of evolocumab therapy for reducing cardiovascular events in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1069-1078.

23. Ioannidis JPA. Inconsistent guideline recommendations for cardiovascular prevention and the debate about zeroing in on and zeroing LDL-C levels with PCSK9 inhibitors. JAMA. 2017;318:419-420.

24. Gu Q, Paulose-Ram R, Burt VL, et al. Prescription cholesterol-lowering medication use in adults aged 40 and over: United States, 2003-2012. NCHS data Brief. 2014;177:1-8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db177.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2018.

25. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(suppl 2):S1-S45.

26. Pagidipati NJ, Navar AM, Mulder H, et al. Comparison of recommended eligibility for primary prevention statin therapy based on the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations vs the ACC/AHA Guidelines. JAMA. 2017;317:1563-1567.

27

28. Lincoff AM, Nicholls SJ, Riesmeyer JS, et al. Evacetrapib and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1933-1942.

29. Dixon DL, Trankle C, Buckley L, et al. A review of PCSK9 inhibition and its effects beyond LDL receptors. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:1073-1080.

30. Ray KK, Landmesser U, Leiter LA, et al. Inclisiran in patients at high cardiovascular risk with elevated LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1430-1440.

1. Weir HK, Anderson RN, Coleman King SM, et al. Heart disease and cancer deaths — trends and projections in the United States, 1969-2020. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E157.

2. Rodriguez F, Harrington RA. Cholesterol, cardiovascular risk, statins, PCSK9 inhibitors, and the future of LDL-C lowering. JAMA. 2016;316:1967-1968.

3. Collins R, Reith C, Emberson J, et al. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet. 2016;388:2532-2561.

4. Gupta A, Thompson D, Whitehouse A, et al. Adverse events associated with unblinded, but not with blinded, statin therapy in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial—Lipid-Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial and its non-randomised non-blind extension phase. Lancet. 2017;389:2473-2481.

5. Chou R, Dana T, Blazina I, et al. Statins for prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;316:2008-2024.

6. Silverman MG, Ference BA, Im K, et al. Association between lowering LDL-C and cardiovascular risk reduction among different therapeutic interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:1289-1297.

7. GoodRx. Ezetimibe. Available at: https://www.goodrx.com/ezetimibe. Accessed May 2, 2018.

8. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387-2397.

9. American Journal of Managed Care. Outcomes-based pricing for PCSK9 inhibitors. Available at: http://www.ajmc.com/contributor/inmaculada-hernandez-pharmd/2017/09/outcomes-based-pricing-for-pcsk9-inhibitors. Accessed May 2, 2018.

10. Nicholls S, Puri R, Anderson T, et al. Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin-treated patients: the GLAGOV randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:2373-2384.

11. Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1489-1499.

12. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

13. HPS3/TIMI55-REVEAL Collaborative Group. Effects of anacetrapib in patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1217-1227.

14. Hunt SC, Hopkins PN, Bulka K, et al. Genetic localization to chromosome 1p32 of the third locus for familial hypercholesterolemia in a Utah kindred. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1089-1093.

15. Cohen J, Pertsemlidis A, Kotowski I, et al. Low LDL cholesterol in individuals of African descent resulting from frequent nonsense mutations in PCSK9. Nat Genet. 2005;37:161-165.

16. Dixon DL, Trankle C, Buckley L, et al. A review of PCSK9 inhibition and its effects beyond LDL receptors. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:1073-1080.

17. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Wiviott SD, et al. Efficacy and safety of evolocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1500-1509.

18. Sabatine MS, Leiter LA, Wiviott SD, et al. Cardiovascular safety and efficacy of the PCSK9 inhibitor evolocumab in patients with and without diabetes and the effect of evolocumab on glycaemia and risk of new-onset diabetes: a prespecified analysis of the FOURIER randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:941-950.

19. Giugliano RP, Mach F, Zavitz K, et al. Cognitive function in a randomized trial of evolocumab. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:633-643.

20. Anderson JL, Heidenreich PA, Barnett PG, et al. ACC/AHA statement on cost/value methodology in clinical practice guidelines and performance measures: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures and Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2304-2322.

21. Kazi DS, Moran AE, Coxson PG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of PCSK9 inhibitor therapy in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2016;316:743-753.

22. Fonarow GC, Keech AC, Pedersen TR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of evolocumab therapy for reducing cardiovascular events in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:1069-1078.

23. Ioannidis JPA. Inconsistent guideline recommendations for cardiovascular prevention and the debate about zeroing in on and zeroing LDL-C levels with PCSK9 inhibitors. JAMA. 2017;318:419-420.

24. Gu Q, Paulose-Ram R, Burt VL, et al. Prescription cholesterol-lowering medication use in adults aged 40 and over: United States, 2003-2012. NCHS data Brief. 2014;177:1-8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db177.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2018.

25. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(suppl 2):S1-S45.

26. Pagidipati NJ, Navar AM, Mulder H, et al. Comparison of recommended eligibility for primary prevention statin therapy based on the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations vs the ACC/AHA Guidelines. JAMA. 2017;317:1563-1567.

27

28. Lincoff AM, Nicholls SJ, Riesmeyer JS, et al. Evacetrapib and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1933-1942.

29. Dixon DL, Trankle C, Buckley L, et al. A review of PCSK9 inhibition and its effects beyond LDL receptors. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10:1073-1080.

30. Ray KK, Landmesser U, Leiter LA, et al. Inclisiran in patients at high cardiovascular risk with elevated LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1430-1440.

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2018;67(6):339-341,344-345.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider adding ezetimibe to maximally tolerated statin therapy for patients not meeting low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) goals with a statin alone. B

› Limit consideration of PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) inhibitors to adults at highest risk: those with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia or clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease who must further lower LDL-C levels. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Letter from the Editor: A moment of grace

She was my 3:45 p.m. return visit. She had been a new patient with dyspepsia and I had found Helicobacter pylori–gastritis on endoscopy. She had marketplace-based coverage (silver, high-deductible plan), which was why she had to travel from her community to our university for care. That she did not look like me (older white male) was an understatement. She was so enthusiastic as she thanked me for helping her. Then she described how she, her husband (both hourly-wage, working adults) and their two young kids had gathered around the dinner table to discuss how they could reduce their food allowance for 2 months to have money for mom’s H. pylori medication. She said her entire family was grateful for the help to get her well. It was a moment of grace. She is why I keep fighting to make our health system great again.

Our cover articles this month discuss HCV treatment in patients with special risk factors or co-conditions. Fascinating information will emerge from studies like the article about artificial sweeteners. Scientists studied hunger-related enzyme levels and brain blood flow with functional MRI’s in obese and lean individuals after ingesting placebo and sucralose-containing solutions. Results might influence our weight loss advice to patients. Worried about malpractice? See our third front page article.

Additional articles discuss a reversal agent for one of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants and a hemospray for GI bleeding. Clinically impactful articles from the AGA journals are highlighted.

Finally, I would like to thank all of you who filled out the readership survey last fall. We are proud that you identified GI & Hepatology News as the best overall source for news information in gastroenterology.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

She was my 3:45 p.m. return visit. She had been a new patient with dyspepsia and I had found Helicobacter pylori–gastritis on endoscopy. She had marketplace-based coverage (silver, high-deductible plan), which was why she had to travel from her community to our university for care. That she did not look like me (older white male) was an understatement. She was so enthusiastic as she thanked me for helping her. Then she described how she, her husband (both hourly-wage, working adults) and their two young kids had gathered around the dinner table to discuss how they could reduce their food allowance for 2 months to have money for mom’s H. pylori medication. She said her entire family was grateful for the help to get her well. It was a moment of grace. She is why I keep fighting to make our health system great again.

Our cover articles this month discuss HCV treatment in patients with special risk factors or co-conditions. Fascinating information will emerge from studies like the article about artificial sweeteners. Scientists studied hunger-related enzyme levels and brain blood flow with functional MRI’s in obese and lean individuals after ingesting placebo and sucralose-containing solutions. Results might influence our weight loss advice to patients. Worried about malpractice? See our third front page article.

Additional articles discuss a reversal agent for one of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants and a hemospray for GI bleeding. Clinically impactful articles from the AGA journals are highlighted.

Finally, I would like to thank all of you who filled out the readership survey last fall. We are proud that you identified GI & Hepatology News as the best overall source for news information in gastroenterology.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

She was my 3:45 p.m. return visit. She had been a new patient with dyspepsia and I had found Helicobacter pylori–gastritis on endoscopy. She had marketplace-based coverage (silver, high-deductible plan), which was why she had to travel from her community to our university for care. That she did not look like me (older white male) was an understatement. She was so enthusiastic as she thanked me for helping her. Then she described how she, her husband (both hourly-wage, working adults) and their two young kids had gathered around the dinner table to discuss how they could reduce their food allowance for 2 months to have money for mom’s H. pylori medication. She said her entire family was grateful for the help to get her well. It was a moment of grace. She is why I keep fighting to make our health system great again.

Our cover articles this month discuss HCV treatment in patients with special risk factors or co-conditions. Fascinating information will emerge from studies like the article about artificial sweeteners. Scientists studied hunger-related enzyme levels and brain blood flow with functional MRI’s in obese and lean individuals after ingesting placebo and sucralose-containing solutions. Results might influence our weight loss advice to patients. Worried about malpractice? See our third front page article.

Additional articles discuss a reversal agent for one of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants and a hemospray for GI bleeding. Clinically impactful articles from the AGA journals are highlighted.

Finally, I would like to thank all of you who filled out the readership survey last fall. We are proud that you identified GI & Hepatology News as the best overall source for news information in gastroenterology.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Jump start immunizations in NICU

MALMO, SWEDEN – The neonatal intensive care unit often represents a lost opportunity to bring an infant fully up to date for recommended age-appropriate immunizations – but it needn’t be that way, Raymond C. Stetson, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“We were able to find that within our unit a small number of quality improvement measures enabled us to drastically increase our vaccination rate in this population. I think this shows that other units ought to be auditing their immunization rates, and if they find similar root causes of low rates our experience could be generalized to those units as well,” Dr. Stetson said.

It’s well established that premature infants are at increased risk for underimmunization. Dr. Stetson and his coinvestigators deemed the baseline 56% on-time immunization rate in their NICU patients to be unacceptable, because underimmunized infants are more vulnerable to vaccine-preventable illnesses after discharge. So using the quality improvement methodology known as DMAIC – for Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control – the investigators surveyed Mayo NICU physicians and nurses and identified three root causes of the quality gap: lack of staff knowledge of the routine immunization schedule, lack of awareness of when a NICU patient’s vaccines were actually due, and parental vaccine hesitancy.

Session chair Karina Butler, MD, was clearly impressed.

“You make it sound so easy to get such an increment. What were the barriers and obstacles you ran into?” asked Dr. Butler of Temple Street Children’s University Hospital, Dublin.

“Certain providers in our group were a bit more hesitant about giving vaccines,” Dr. Stetson replied. “There had to be a lot of provider education to get them to use the resources we’d created. And parental vaccine hesitancy was a barrier for us. Of that 6% of infants who weren’t fully up to date at discharge, the majority of those were due to parental vaccine hesitancy. I think that’s still a barrier that’s going to need more work.”

Dr. Stetson reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

MALMO, SWEDEN – The neonatal intensive care unit often represents a lost opportunity to bring an infant fully up to date for recommended age-appropriate immunizations – but it needn’t be that way, Raymond C. Stetson, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“We were able to find that within our unit a small number of quality improvement measures enabled us to drastically increase our vaccination rate in this population. I think this shows that other units ought to be auditing their immunization rates, and if they find similar root causes of low rates our experience could be generalized to those units as well,” Dr. Stetson said.

It’s well established that premature infants are at increased risk for underimmunization. Dr. Stetson and his coinvestigators deemed the baseline 56% on-time immunization rate in their NICU patients to be unacceptable, because underimmunized infants are more vulnerable to vaccine-preventable illnesses after discharge. So using the quality improvement methodology known as DMAIC – for Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control – the investigators surveyed Mayo NICU physicians and nurses and identified three root causes of the quality gap: lack of staff knowledge of the routine immunization schedule, lack of awareness of when a NICU patient’s vaccines were actually due, and parental vaccine hesitancy.

Session chair Karina Butler, MD, was clearly impressed.

“You make it sound so easy to get such an increment. What were the barriers and obstacles you ran into?” asked Dr. Butler of Temple Street Children’s University Hospital, Dublin.

“Certain providers in our group were a bit more hesitant about giving vaccines,” Dr. Stetson replied. “There had to be a lot of provider education to get them to use the resources we’d created. And parental vaccine hesitancy was a barrier for us. Of that 6% of infants who weren’t fully up to date at discharge, the majority of those were due to parental vaccine hesitancy. I think that’s still a barrier that’s going to need more work.”

Dr. Stetson reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

MALMO, SWEDEN – The neonatal intensive care unit often represents a lost opportunity to bring an infant fully up to date for recommended age-appropriate immunizations – but it needn’t be that way, Raymond C. Stetson, MD, declared at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“We were able to find that within our unit a small number of quality improvement measures enabled us to drastically increase our vaccination rate in this population. I think this shows that other units ought to be auditing their immunization rates, and if they find similar root causes of low rates our experience could be generalized to those units as well,” Dr. Stetson said.

It’s well established that premature infants are at increased risk for underimmunization. Dr. Stetson and his coinvestigators deemed the baseline 56% on-time immunization rate in their NICU patients to be unacceptable, because underimmunized infants are more vulnerable to vaccine-preventable illnesses after discharge. So using the quality improvement methodology known as DMAIC – for Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control – the investigators surveyed Mayo NICU physicians and nurses and identified three root causes of the quality gap: lack of staff knowledge of the routine immunization schedule, lack of awareness of when a NICU patient’s vaccines were actually due, and parental vaccine hesitancy.

Session chair Karina Butler, MD, was clearly impressed.

“You make it sound so easy to get such an increment. What were the barriers and obstacles you ran into?” asked Dr. Butler of Temple Street Children’s University Hospital, Dublin.

“Certain providers in our group were a bit more hesitant about giving vaccines,” Dr. Stetson replied. “There had to be a lot of provider education to get them to use the resources we’d created. And parental vaccine hesitancy was a barrier for us. Of that 6% of infants who weren’t fully up to date at discharge, the majority of those were due to parental vaccine hesitancy. I think that’s still a barrier that’s going to need more work.”

Dr. Stetson reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ESPID 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Only 56% of 754 NICU patients from 2015 through mid-2017 were up to date for the ACIP-recommended vaccinations at discharge or transfer. After an intervention, the on-time immunization rate rose to 94% in 155 patients discharged during the first 6 months.

Study details: A study comparing 754 NICU patients prior to intervention and 155 after intervention.

Disclosures: Dr. Stetson reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Stetson R. E-Poster Discussion Session 04.

Mesenteric adipose–derived stromal cell lactoferrin may mediate protective effects in Crohn’s disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and Crohn’s disease (CD), in particular, are characterized by an unusual ectopic extension of mesenteric adipose tissue. This intra-abdominal fat, also known as “creeping fat,” which wraps around the intestine during the onset of CD, is associated with inflammation and ulceration of the small or large intestine. The role of this fat in the development of CD, and whether it is protective or harmful, however, is not clear.

The current study demonstrates that adipose-derived stromal cells (ADSCs), the precursor cell population of adipose tissue, promote colonocyte proliferation and exhibit a differential gene expression profile in a disease-dependent manner. according to Jill M. Hoffman, MD, and her colleagues at the University of California, Los Angeles. Increased expression and release of lactoferrin by ADSCs – an iron-binding glycoprotein and antimicrobial peptide usually found in large quantities in breast milk – was shown to be a likely mediator that could regulate inflammatory responses during CD. These results were published in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.02.001).

Intestinal inflammation is primarily mediated by cytokine production, and targeted anticytokine therapy is the current standard for IBD treatment. The cytokine profile from CD patient–derived mesenteric ADSCs and fat tissue was significantly different from that of these patients’ disease-free counterparts. The authors hypothesized that mesenteric ADSCs release adipokines in response to disease-associated signals; this release of adipokines results from differential gene expression of mesenteric ADSCs in CD versus control patients. To test this hypothesis, conditioned media from CD patient–derived ADSCs was used to study gene expression in colonic intestinal epithelial cells in vitro and in mice with experimental colitis in vivo.

Using the Human LncRNA Expression Microarray V4.0, expression of 20,730 protein-coding mRNA targets was analysed, and 992 mRNA transcripts were found to be differentially (less than or equal to twofold change) expressed in CD patient–derived ADSCs, compared with control patient–derived ADSCs. Subsequent pathway analysis suggested activation of cellular growth and proliferation pathways with caspase 8 and p42/44 as top predicted networks that are differentially regulated in CD patient–derived ADSCs with respect to those of control patients.

The investigators treated intestinal epithelial cells – specifically, NCM460 – with conditioned 233 media from the same CD or control patient–derived ADSCs; subsequent microarray profiling using the GeneChip Human Gene ST Array showed increased expression of interleukin-17A, CCL23, and VEGFA. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis of mRNA expression indicated convergence in injury and inflammation pathways with the SERPINE1 gene, which suggests it’s the central regulator of the differential gene expression network.

In vivo, mice with active dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) colitis that were treated with daily injections of conditioned media from CD patients showed attenuation of colitis as compared with mice treated with vehicle or conditioned media from control patients. Furthermore, the mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines was reduced with increased proliferative response (as measured by Ki67 expression) in intestinal epithelial cells in the dextran sulfate sodium–treated mice receiving media from CD patients, compared with that in mice receiving media from control patients or vehicle-treated mice.

Cell proliferation was studied in real time (during a period of 120 hours) using the xCELLigence platform. The authors suggested that mesenteric adipose tissue–derived mediators may regulate proliferative responses in intestinal epithelial cells during intestinal inflammation, as observed by enhanced cell-doubling time in conditioned media from CD patient–derived ADSCs.

Levels of lactoferrin mRNA (validated by real time polymerase chain reaction; 92.70 ± 18.41 versus 28.98 ± 5.681; P less than .05) and protein (validated by ELISA; 142.2 ± 5.653 versus 120.1 ± 3.664; P less than .01) were increased in human mesenteric ADSCs and conditioned media from CD patients, respectively, compared with that from controls.

“Compared with mice receiving vehicle injections, mice receiving daily injections of lactoferrin had improved clinical scores (5.625 ± 0.565 versus 11.125 ± 0.743; n = 8) and colon length at day 7 (6.575 ± 0.1688 versus 5.613 ± 0.1445; n = 8). In addition, we found epithelial cell proliferation was increased in the colons of lactoferrin-treated mice with colitis, compared with vehicle-treated controls (3.548e7 ± 1.547e6 versus 1.184e7 ± 2.915e6; P less than .01),” said the authors.

Collectively, the presented data was suggestive of a protective role of mesenteric adipose tissue–derived mediators, such as lactoferrin, in the pathophysiology of CD.

The study was supported by the Broad Medical Research Program (IBD-0390), an NIDDK Q51856 Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Postdoctoral Fellowship 1857 (F32 DK102322), the Neuroendocrine Assay and Models of Gastrointestinal Function and Disease Cores (P50 DK 64539), an AGA-1858 Broad Student Research Fellowship, the Blinder Center for Crohn’s 1859 Disease Research, the Eli and Edythe Broad Chair, and NIH/NIDDK grant DK047343.

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hoffman J et al. Cell Molec Gastro Hepatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.02.001.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease, is a chronic inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract that is often associated with changes in adipose tissue. However, the pathophysiological significance of fat wrapping in Crohn’s disease remains largely elusive. A correlation of IBD with obesity has been established by a number of studies, which report 15%-40% of adults with IBD are obese. Obesity is found to have a negative effect on disease activity and progression to surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. In contrast, adipose-derived stromal or stem cells exhibit regenerative and anti-inflammatory function.

A recent study published in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology by Jill M. Hoffman and her colleagues highlighted the immune-modulatory function of adipose-derived stromal cells (ADSCs) in Crohn’s disease patients. They observed that patient-derived ADSCs promote colonocyte proliferation and exhibit distinct gene expression patterns, compared with healthy controls. The authors successfully identified ADSC-derived lactoferrin, an iron binding glycoprotein and an antimicrobial peptide, as a potential immunoregulatory molecule.

Amlan Biswas, PhD, is an instructor in pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and is affiliated with Boston Children’s Hospital in the division of gastroenterology and nutrition. He has no conflicts of interest

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease, is a chronic inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract that is often associated with changes in adipose tissue. However, the pathophysiological significance of fat wrapping in Crohn’s disease remains largely elusive. A correlation of IBD with obesity has been established by a number of studies, which report 15%-40% of adults with IBD are obese. Obesity is found to have a negative effect on disease activity and progression to surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. In contrast, adipose-derived stromal or stem cells exhibit regenerative and anti-inflammatory function.

A recent study published in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology by Jill M. Hoffman and her colleagues highlighted the immune-modulatory function of adipose-derived stromal cells (ADSCs) in Crohn’s disease patients. They observed that patient-derived ADSCs promote colonocyte proliferation and exhibit distinct gene expression patterns, compared with healthy controls. The authors successfully identified ADSC-derived lactoferrin, an iron binding glycoprotein and an antimicrobial peptide, as a potential immunoregulatory molecule.

Amlan Biswas, PhD, is an instructor in pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and is affiliated with Boston Children’s Hospital in the division of gastroenterology and nutrition. He has no conflicts of interest

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease, is a chronic inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract that is often associated with changes in adipose tissue. However, the pathophysiological significance of fat wrapping in Crohn’s disease remains largely elusive. A correlation of IBD with obesity has been established by a number of studies, which report 15%-40% of adults with IBD are obese. Obesity is found to have a negative effect on disease activity and progression to surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. In contrast, adipose-derived stromal or stem cells exhibit regenerative and anti-inflammatory function.

A recent study published in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology by Jill M. Hoffman and her colleagues highlighted the immune-modulatory function of adipose-derived stromal cells (ADSCs) in Crohn’s disease patients. They observed that patient-derived ADSCs promote colonocyte proliferation and exhibit distinct gene expression patterns, compared with healthy controls. The authors successfully identified ADSC-derived lactoferrin, an iron binding glycoprotein and an antimicrobial peptide, as a potential immunoregulatory molecule.

Amlan Biswas, PhD, is an instructor in pediatrics at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and is affiliated with Boston Children’s Hospital in the division of gastroenterology and nutrition. He has no conflicts of interest

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and Crohn’s disease (CD), in particular, are characterized by an unusual ectopic extension of mesenteric adipose tissue. This intra-abdominal fat, also known as “creeping fat,” which wraps around the intestine during the onset of CD, is associated with inflammation and ulceration of the small or large intestine. The role of this fat in the development of CD, and whether it is protective or harmful, however, is not clear.

The current study demonstrates that adipose-derived stromal cells (ADSCs), the precursor cell population of adipose tissue, promote colonocyte proliferation and exhibit a differential gene expression profile in a disease-dependent manner. according to Jill M. Hoffman, MD, and her colleagues at the University of California, Los Angeles. Increased expression and release of lactoferrin by ADSCs – an iron-binding glycoprotein and antimicrobial peptide usually found in large quantities in breast milk – was shown to be a likely mediator that could regulate inflammatory responses during CD. These results were published in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2018.02.001).

Intestinal inflammation is primarily mediated by cytokine production, and targeted anticytokine therapy is the current standard for IBD treatment. The cytokine profile from CD patient–derived mesenteric ADSCs and fat tissue was significantly different from that of these patients’ disease-free counterparts. The authors hypothesized that mesenteric ADSCs release adipokines in response to disease-associated signals; this release of adipokines results from differential gene expression of mesenteric ADSCs in CD versus control patients. To test this hypothesis, conditioned media from CD patient–derived ADSCs was used to study gene expression in colonic intestinal epithelial cells in vitro and in mice with experimental colitis in vivo.

Using the Human LncRNA Expression Microarray V4.0, expression of 20,730 protein-coding mRNA targets was analysed, and 992 mRNA transcripts were found to be differentially (less than or equal to twofold change) expressed in CD patient–derived ADSCs, compared with control patient–derived ADSCs. Subsequent pathway analysis suggested activation of cellular growth and proliferation pathways with caspase 8 and p42/44 as top predicted networks that are differentially regulated in CD patient–derived ADSCs with respect to those of control patients.