User login

CHEST Keynote: Reflections of a Lifetime Practicing Chest Medicine

Dr. Richard Irwin, the Editor in Chief for the journal CHEST, and Chair of UMass Memorial Medical Center’s Department of Critical Care, has observed the way patient-focused care has evolved through the years. He will be speaking on this topic at the CHEST 2018 opening session on Sunday, October 7.

During Dr. Irwin’s early years at UMass Memorial, the then chairman of Medicine, Dr. James Dalen, a longtime CHEST member who was about to begin his term as CHEST President, strongly encouraged Dr. Irwin to join the organization. By joining the college, Dr. Irwin was able to form strong connections with other influential chest medicine professionals, such as Dr. Jack Weg, a former CHEST President, and Dr. Alfred Soffer – who was the Editor in Chief of CHEST.

While Dr. Irwin was not yet a member of the CHEST community, the college became instrumental in focusing Dr. Irwin’s academic career because of a manuscript that he and colleagues had been working on, titled Cough. A Comprehensive Review. After submitting the early version of his manuscript to ten different journals and being rejected by each one, Dr. Irwin contacted Dr. Soffer and asked him, if he had the time, could he please read it and offer advice. Dr. Soffer, who had a reputation of being a mentor with endless generosity of his time, reviewed the manuscript and worked with Dr. Irwin on the article, leading to its publication in the Archives of Internal Medicine in 1977. Dr. Soffer’s kindness would lead to the start of Dr. Irwin’s 40-year career of studying cough.

Dr. Irwin has been very influential within the CHEST organization throughout his career. In addition to his years as the Editor in Chief of CHEST, he also served on every major CHEST committee and held the office of CHEST President in 2003-2004. “If you want to join a society that has a family-feel to it and focuses on clinical care and education, then CHEST is the place to be.”

Throughout his years as a physician, Dr. Irwin has been interested in the way physicians learn. During his formative years, he says the way he learned was to “see one, do one, teach one.” He gives the example of the flexible fiber-optic bronchoscope, which was developed in Japan in the late 1960s, arriving in the US in 1970. It was a new way of performing bronchoscopy, which led to physicians reading about it, and then putting what they read into action. Now – there are high fidelity simulation instruments and models and a lot of experiential learning prefacing the use of new technologies for patients. We have CHEST to thank for being a leader in experiential learning and an international resource for simulation training.

Dr. Richard Irwin, the Editor in Chief for the journal CHEST, and Chair of UMass Memorial Medical Center’s Department of Critical Care, has observed the way patient-focused care has evolved through the years. He will be speaking on this topic at the CHEST 2018 opening session on Sunday, October 7.

During Dr. Irwin’s early years at UMass Memorial, the then chairman of Medicine, Dr. James Dalen, a longtime CHEST member who was about to begin his term as CHEST President, strongly encouraged Dr. Irwin to join the organization. By joining the college, Dr. Irwin was able to form strong connections with other influential chest medicine professionals, such as Dr. Jack Weg, a former CHEST President, and Dr. Alfred Soffer – who was the Editor in Chief of CHEST.

While Dr. Irwin was not yet a member of the CHEST community, the college became instrumental in focusing Dr. Irwin’s academic career because of a manuscript that he and colleagues had been working on, titled Cough. A Comprehensive Review. After submitting the early version of his manuscript to ten different journals and being rejected by each one, Dr. Irwin contacted Dr. Soffer and asked him, if he had the time, could he please read it and offer advice. Dr. Soffer, who had a reputation of being a mentor with endless generosity of his time, reviewed the manuscript and worked with Dr. Irwin on the article, leading to its publication in the Archives of Internal Medicine in 1977. Dr. Soffer’s kindness would lead to the start of Dr. Irwin’s 40-year career of studying cough.

Dr. Irwin has been very influential within the CHEST organization throughout his career. In addition to his years as the Editor in Chief of CHEST, he also served on every major CHEST committee and held the office of CHEST President in 2003-2004. “If you want to join a society that has a family-feel to it and focuses on clinical care and education, then CHEST is the place to be.”

Throughout his years as a physician, Dr. Irwin has been interested in the way physicians learn. During his formative years, he says the way he learned was to “see one, do one, teach one.” He gives the example of the flexible fiber-optic bronchoscope, which was developed in Japan in the late 1960s, arriving in the US in 1970. It was a new way of performing bronchoscopy, which led to physicians reading about it, and then putting what they read into action. Now – there are high fidelity simulation instruments and models and a lot of experiential learning prefacing the use of new technologies for patients. We have CHEST to thank for being a leader in experiential learning and an international resource for simulation training.

Dr. Richard Irwin, the Editor in Chief for the journal CHEST, and Chair of UMass Memorial Medical Center’s Department of Critical Care, has observed the way patient-focused care has evolved through the years. He will be speaking on this topic at the CHEST 2018 opening session on Sunday, October 7.

During Dr. Irwin’s early years at UMass Memorial, the then chairman of Medicine, Dr. James Dalen, a longtime CHEST member who was about to begin his term as CHEST President, strongly encouraged Dr. Irwin to join the organization. By joining the college, Dr. Irwin was able to form strong connections with other influential chest medicine professionals, such as Dr. Jack Weg, a former CHEST President, and Dr. Alfred Soffer – who was the Editor in Chief of CHEST.

While Dr. Irwin was not yet a member of the CHEST community, the college became instrumental in focusing Dr. Irwin’s academic career because of a manuscript that he and colleagues had been working on, titled Cough. A Comprehensive Review. After submitting the early version of his manuscript to ten different journals and being rejected by each one, Dr. Irwin contacted Dr. Soffer and asked him, if he had the time, could he please read it and offer advice. Dr. Soffer, who had a reputation of being a mentor with endless generosity of his time, reviewed the manuscript and worked with Dr. Irwin on the article, leading to its publication in the Archives of Internal Medicine in 1977. Dr. Soffer’s kindness would lead to the start of Dr. Irwin’s 40-year career of studying cough.

Dr. Irwin has been very influential within the CHEST organization throughout his career. In addition to his years as the Editor in Chief of CHEST, he also served on every major CHEST committee and held the office of CHEST President in 2003-2004. “If you want to join a society that has a family-feel to it and focuses on clinical care and education, then CHEST is the place to be.”

Throughout his years as a physician, Dr. Irwin has been interested in the way physicians learn. During his formative years, he says the way he learned was to “see one, do one, teach one.” He gives the example of the flexible fiber-optic bronchoscope, which was developed in Japan in the late 1960s, arriving in the US in 1970. It was a new way of performing bronchoscopy, which led to physicians reading about it, and then putting what they read into action. Now – there are high fidelity simulation instruments and models and a lot of experiential learning prefacing the use of new technologies for patients. We have CHEST to thank for being a leader in experiential learning and an international resource for simulation training.

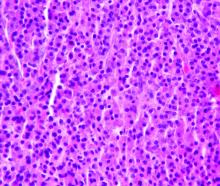

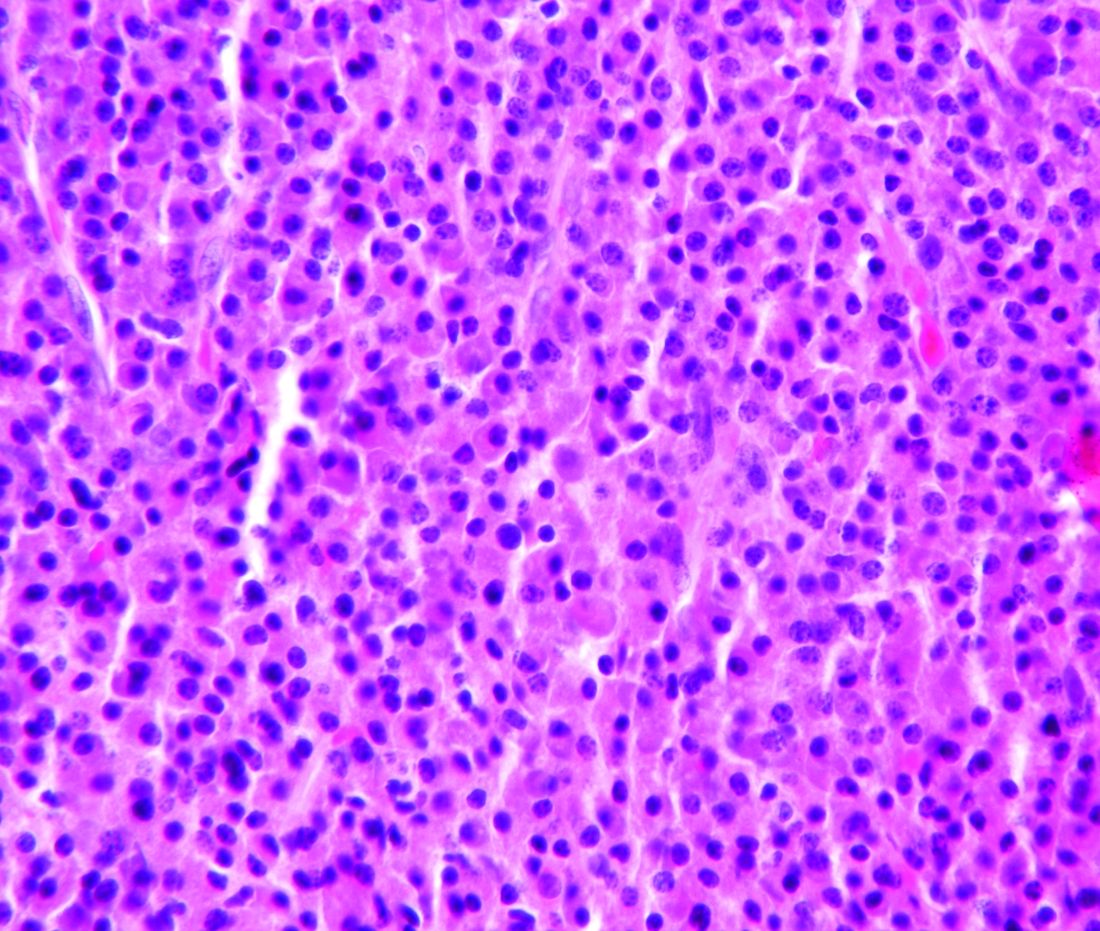

Doc reports ‘very encouraging’ results in penta-refractory MM

HOUSTON—Treatment with selinexor and low-dose dexamethasone can provide a “meaningful clinical benefit” in patients with penta-refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to the principal investigator of the STORM trial.

Updated results from this phase 2 trial showed that selinexor and low-dose dexamethasone produced an overall response rate of 26.2% and a clinical benefit rate of 39.3%.

The median progression-free survival was 3.7 months, and the median overall survival was 8.6 months.

The trial’s principal investigator, Sundar Jagannath, MBBS, of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, N.Y., presented these results at the Society of Hematologic Oncology (SOHO) 2018 Annual Meeting as abstract MM-255.*

“The additional phase 2b clinical results ... are very encouraging for the patients suffering from penta-refractory multiple myeloma and their families,” Dr. Jagannath said.

“Of particular significance, for the nearly 40% of patients who had a minimal response or better, the median survival was 15.6 months, which provided the opportunity for a meaningful clinical benefit for patients on the STORM study.”

The study (NCT02336815) included 122 patients with penta-refractory MM. They had previously received bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, daratumumab, alkylating agents, and glucocorticoids. Their disease was refractory to glucocorticoids, at least one proteasome inhibitor, at least one immunomodulatory drug, daratumumab, and their most recent therapy.

The patients had received a median of 7 (range, 3-18) prior treatment regimens. Their median age was 65 (range, 40-86), 58% were male, and 53% had high-risk cytogenetics.

Patients received oral selinexor at 80 mg twice weekly plus dexamethasone at 20 mg twice weekly until disease progression.

Response and survival

Two patients (1.6%) achieved stringent complete responses. They also had minimal residual disease negativity, one at the level of 1 x 10-6 and one at 1 x 10-4.

Six patients (4.9%) had very good partial responses, 24 (19.7%) had partial responses (PRs), 16 (13.1%) had minimal responses (MRs), and 48 (39.3%) had stable disease (SD).

Sixteen patients (13.1%) had progressive disease (PD), and 10 (8.2%) were not evaluable for response.

The overall response rate (PR or better) was 26.2% (n=32), the clinical benefit rate (MR or better) was 39.3% (n=48), and the disease control rate (SD or better) was 78.7% (n=98).

The median duration of response was 4.4 months (range, <1 to 12.2 months).

The median progression-free survival was 3.7 months overall, 4.6 months in patients with an MR or better, and 1.1 months in patients who had PD or were not evaluable.

The median overall survival was 8.6 months for the entire cohort. It was 15.6 months in patients with an MR or better and 1.7 months in patients who had PD or were not evaluable (P<0.0001).

Safety

The most common non-hematologic treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were fatigue/asthenia (69.9%), nausea (69.1%), anorexia (52.0%), weight loss (47.2%), vomiting (35.0%), diarrhea (33.3%), and hyponatremia (30.9%).

Hematologic treatment-related AEs included thrombocytopenia (67.5%), anemia (48.0%), neutropenia (35.8%), leukopenia (29.3%), and lymphopenia (13.8%).

The “most important” grade 3/4 AEs, according to Dr. Jagannath, were thrombocytopenia (53.7%), anemia (29.3%), fatigue (22.8%), hyponatremia (16.3%), nausea (9.8%), diarrhea (6.5%), anorexia (3.3%), and emesis (3.3%).

Twenty-three patients (19.5%) discontinued treatment due to a related AE.

This study was sponsored by Karyopharm Therapeutics. Dr. Jagannath reported relationships with Karyopharm, Janssen, Celgene, Amgen, and GSK.

*Information in the abstract differs from the presentation.

HOUSTON—Treatment with selinexor and low-dose dexamethasone can provide a “meaningful clinical benefit” in patients with penta-refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to the principal investigator of the STORM trial.

Updated results from this phase 2 trial showed that selinexor and low-dose dexamethasone produced an overall response rate of 26.2% and a clinical benefit rate of 39.3%.

The median progression-free survival was 3.7 months, and the median overall survival was 8.6 months.

The trial’s principal investigator, Sundar Jagannath, MBBS, of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, N.Y., presented these results at the Society of Hematologic Oncology (SOHO) 2018 Annual Meeting as abstract MM-255.*

“The additional phase 2b clinical results ... are very encouraging for the patients suffering from penta-refractory multiple myeloma and their families,” Dr. Jagannath said.

“Of particular significance, for the nearly 40% of patients who had a minimal response or better, the median survival was 15.6 months, which provided the opportunity for a meaningful clinical benefit for patients on the STORM study.”

The study (NCT02336815) included 122 patients with penta-refractory MM. They had previously received bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, daratumumab, alkylating agents, and glucocorticoids. Their disease was refractory to glucocorticoids, at least one proteasome inhibitor, at least one immunomodulatory drug, daratumumab, and their most recent therapy.

The patients had received a median of 7 (range, 3-18) prior treatment regimens. Their median age was 65 (range, 40-86), 58% were male, and 53% had high-risk cytogenetics.

Patients received oral selinexor at 80 mg twice weekly plus dexamethasone at 20 mg twice weekly until disease progression.

Response and survival

Two patients (1.6%) achieved stringent complete responses. They also had minimal residual disease negativity, one at the level of 1 x 10-6 and one at 1 x 10-4.

Six patients (4.9%) had very good partial responses, 24 (19.7%) had partial responses (PRs), 16 (13.1%) had minimal responses (MRs), and 48 (39.3%) had stable disease (SD).

Sixteen patients (13.1%) had progressive disease (PD), and 10 (8.2%) were not evaluable for response.

The overall response rate (PR or better) was 26.2% (n=32), the clinical benefit rate (MR or better) was 39.3% (n=48), and the disease control rate (SD or better) was 78.7% (n=98).

The median duration of response was 4.4 months (range, <1 to 12.2 months).

The median progression-free survival was 3.7 months overall, 4.6 months in patients with an MR or better, and 1.1 months in patients who had PD or were not evaluable.

The median overall survival was 8.6 months for the entire cohort. It was 15.6 months in patients with an MR or better and 1.7 months in patients who had PD or were not evaluable (P<0.0001).

Safety

The most common non-hematologic treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were fatigue/asthenia (69.9%), nausea (69.1%), anorexia (52.0%), weight loss (47.2%), vomiting (35.0%), diarrhea (33.3%), and hyponatremia (30.9%).

Hematologic treatment-related AEs included thrombocytopenia (67.5%), anemia (48.0%), neutropenia (35.8%), leukopenia (29.3%), and lymphopenia (13.8%).

The “most important” grade 3/4 AEs, according to Dr. Jagannath, were thrombocytopenia (53.7%), anemia (29.3%), fatigue (22.8%), hyponatremia (16.3%), nausea (9.8%), diarrhea (6.5%), anorexia (3.3%), and emesis (3.3%).

Twenty-three patients (19.5%) discontinued treatment due to a related AE.

This study was sponsored by Karyopharm Therapeutics. Dr. Jagannath reported relationships with Karyopharm, Janssen, Celgene, Amgen, and GSK.

*Information in the abstract differs from the presentation.

HOUSTON—Treatment with selinexor and low-dose dexamethasone can provide a “meaningful clinical benefit” in patients with penta-refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to the principal investigator of the STORM trial.

Updated results from this phase 2 trial showed that selinexor and low-dose dexamethasone produced an overall response rate of 26.2% and a clinical benefit rate of 39.3%.

The median progression-free survival was 3.7 months, and the median overall survival was 8.6 months.

The trial’s principal investigator, Sundar Jagannath, MBBS, of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, N.Y., presented these results at the Society of Hematologic Oncology (SOHO) 2018 Annual Meeting as abstract MM-255.*

“The additional phase 2b clinical results ... are very encouraging for the patients suffering from penta-refractory multiple myeloma and their families,” Dr. Jagannath said.

“Of particular significance, for the nearly 40% of patients who had a minimal response or better, the median survival was 15.6 months, which provided the opportunity for a meaningful clinical benefit for patients on the STORM study.”

The study (NCT02336815) included 122 patients with penta-refractory MM. They had previously received bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, daratumumab, alkylating agents, and glucocorticoids. Their disease was refractory to glucocorticoids, at least one proteasome inhibitor, at least one immunomodulatory drug, daratumumab, and their most recent therapy.

The patients had received a median of 7 (range, 3-18) prior treatment regimens. Their median age was 65 (range, 40-86), 58% were male, and 53% had high-risk cytogenetics.

Patients received oral selinexor at 80 mg twice weekly plus dexamethasone at 20 mg twice weekly until disease progression.

Response and survival

Two patients (1.6%) achieved stringent complete responses. They also had minimal residual disease negativity, one at the level of 1 x 10-6 and one at 1 x 10-4.

Six patients (4.9%) had very good partial responses, 24 (19.7%) had partial responses (PRs), 16 (13.1%) had minimal responses (MRs), and 48 (39.3%) had stable disease (SD).

Sixteen patients (13.1%) had progressive disease (PD), and 10 (8.2%) were not evaluable for response.

The overall response rate (PR or better) was 26.2% (n=32), the clinical benefit rate (MR or better) was 39.3% (n=48), and the disease control rate (SD or better) was 78.7% (n=98).

The median duration of response was 4.4 months (range, <1 to 12.2 months).

The median progression-free survival was 3.7 months overall, 4.6 months in patients with an MR or better, and 1.1 months in patients who had PD or were not evaluable.

The median overall survival was 8.6 months for the entire cohort. It was 15.6 months in patients with an MR or better and 1.7 months in patients who had PD or were not evaluable (P<0.0001).

Safety

The most common non-hematologic treatment-related adverse events (AEs) were fatigue/asthenia (69.9%), nausea (69.1%), anorexia (52.0%), weight loss (47.2%), vomiting (35.0%), diarrhea (33.3%), and hyponatremia (30.9%).

Hematologic treatment-related AEs included thrombocytopenia (67.5%), anemia (48.0%), neutropenia (35.8%), leukopenia (29.3%), and lymphopenia (13.8%).

The “most important” grade 3/4 AEs, according to Dr. Jagannath, were thrombocytopenia (53.7%), anemia (29.3%), fatigue (22.8%), hyponatremia (16.3%), nausea (9.8%), diarrhea (6.5%), anorexia (3.3%), and emesis (3.3%).

Twenty-three patients (19.5%) discontinued treatment due to a related AE.

This study was sponsored by Karyopharm Therapeutics. Dr. Jagannath reported relationships with Karyopharm, Janssen, Celgene, Amgen, and GSK.

*Information in the abstract differs from the presentation.

Pediatricians fall short on transition to adult care

Many adolescent patients, both with and without special health care needs, are not receiving guidance from their physicians about transitioning to adult care, according to recent findings published in Pediatrics.

Lydie A. Lebrun-Harris, PhD, of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau at the Health Resources and Services Administration, and her colleagues examined data from 20,708 youth aged 12-17 years with and without special health care needs obtained from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. The aim was to determine the current level of transition planning to adult care from a pediatric or other health care provider (HCP).

Parents and caregivers were asked whether a doctor or HCP had spent time alone with the adolescent during the last year, had discussed the transition to adult care, and had actively helped the adolescent “gain self-care skills or understand changes in health care” when they reached the age of 18 years.

Overall, 17% of youth with special health care needs and 14% of youth without met all three transition elements.

The figures were higher for individual measures. For instance, 44% of youth with special health care needs spent time alone with an HCP within the past year, 41% discussed transition to an adult provider, and 69% reported an HCP had worked with them to understand health care changes and gain self-care skills.

Youth without special health care needs were more likely to discus the shift to adult care with HCPs than those with special needs, but special needs youth were more likely to have met the other two transition measurements (P less than .001).

Being older (aged 15-17 years) were associated with an increased prevalence of meeting the overall transition measure and the individual elements among both youth with and without special health care needs.

“Findings from this study underscore the urgent need for HCPs to work with youth independently and in collaboration with their parents and/or caregivers throughout the adolescent years to improve transition planning,” Dr. Lebrun-Harris and her colleagues wrote.

The study was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health. The authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lebrun-Harris LA et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0194.

While researchers and clinicians have been discussing how to improve the poor health outcomes seen in the transition from pediatric to adult care for youth with special health care needs for decades, there has been little improvement, Megumi J. Okumura, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In 2016, 41% of youth with special health care needs had a discussion about the transition from pediatric to adult care, a figure that is “largely unchanged from 2010,” she noted.

One hurdle is the lack of a gold standard for measuring an ideal transition. Is it successful scheduling of an appointment with adult provider or having a job and being able to manage one’s own disease?

“Until our health system supports pediatric providers in offering adequate transition planning, it will be difficult to expect any uptick in these measures. In addition, we still need to understand why some adolescents fail in their transition and transfer and how to develop the appropriate interventions to improve health outcomes for these patients,” Dr. Okumura wrote.

Dr. Okumura is with the division of general pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2245). She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

While researchers and clinicians have been discussing how to improve the poor health outcomes seen in the transition from pediatric to adult care for youth with special health care needs for decades, there has been little improvement, Megumi J. Okumura, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In 2016, 41% of youth with special health care needs had a discussion about the transition from pediatric to adult care, a figure that is “largely unchanged from 2010,” she noted.

One hurdle is the lack of a gold standard for measuring an ideal transition. Is it successful scheduling of an appointment with adult provider or having a job and being able to manage one’s own disease?

“Until our health system supports pediatric providers in offering adequate transition planning, it will be difficult to expect any uptick in these measures. In addition, we still need to understand why some adolescents fail in their transition and transfer and how to develop the appropriate interventions to improve health outcomes for these patients,” Dr. Okumura wrote.

Dr. Okumura is with the division of general pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2245). She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

While researchers and clinicians have been discussing how to improve the poor health outcomes seen in the transition from pediatric to adult care for youth with special health care needs for decades, there has been little improvement, Megumi J. Okumura, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In 2016, 41% of youth with special health care needs had a discussion about the transition from pediatric to adult care, a figure that is “largely unchanged from 2010,” she noted.

One hurdle is the lack of a gold standard for measuring an ideal transition. Is it successful scheduling of an appointment with adult provider or having a job and being able to manage one’s own disease?

“Until our health system supports pediatric providers in offering adequate transition planning, it will be difficult to expect any uptick in these measures. In addition, we still need to understand why some adolescents fail in their transition and transfer and how to develop the appropriate interventions to improve health outcomes for these patients,” Dr. Okumura wrote.

Dr. Okumura is with the division of general pediatrics at the University of California, San Francisco. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2245). She reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Many adolescent patients, both with and without special health care needs, are not receiving guidance from their physicians about transitioning to adult care, according to recent findings published in Pediatrics.

Lydie A. Lebrun-Harris, PhD, of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau at the Health Resources and Services Administration, and her colleagues examined data from 20,708 youth aged 12-17 years with and without special health care needs obtained from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. The aim was to determine the current level of transition planning to adult care from a pediatric or other health care provider (HCP).

Parents and caregivers were asked whether a doctor or HCP had spent time alone with the adolescent during the last year, had discussed the transition to adult care, and had actively helped the adolescent “gain self-care skills or understand changes in health care” when they reached the age of 18 years.

Overall, 17% of youth with special health care needs and 14% of youth without met all three transition elements.

The figures were higher for individual measures. For instance, 44% of youth with special health care needs spent time alone with an HCP within the past year, 41% discussed transition to an adult provider, and 69% reported an HCP had worked with them to understand health care changes and gain self-care skills.

Youth without special health care needs were more likely to discus the shift to adult care with HCPs than those with special needs, but special needs youth were more likely to have met the other two transition measurements (P less than .001).

Being older (aged 15-17 years) were associated with an increased prevalence of meeting the overall transition measure and the individual elements among both youth with and without special health care needs.

“Findings from this study underscore the urgent need for HCPs to work with youth independently and in collaboration with their parents and/or caregivers throughout the adolescent years to improve transition planning,” Dr. Lebrun-Harris and her colleagues wrote.

The study was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health. The authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lebrun-Harris LA et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0194.

Many adolescent patients, both with and without special health care needs, are not receiving guidance from their physicians about transitioning to adult care, according to recent findings published in Pediatrics.

Lydie A. Lebrun-Harris, PhD, of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau at the Health Resources and Services Administration, and her colleagues examined data from 20,708 youth aged 12-17 years with and without special health care needs obtained from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. The aim was to determine the current level of transition planning to adult care from a pediatric or other health care provider (HCP).

Parents and caregivers were asked whether a doctor or HCP had spent time alone with the adolescent during the last year, had discussed the transition to adult care, and had actively helped the adolescent “gain self-care skills or understand changes in health care” when they reached the age of 18 years.

Overall, 17% of youth with special health care needs and 14% of youth without met all three transition elements.

The figures were higher for individual measures. For instance, 44% of youth with special health care needs spent time alone with an HCP within the past year, 41% discussed transition to an adult provider, and 69% reported an HCP had worked with them to understand health care changes and gain self-care skills.

Youth without special health care needs were more likely to discus the shift to adult care with HCPs than those with special needs, but special needs youth were more likely to have met the other two transition measurements (P less than .001).

Being older (aged 15-17 years) were associated with an increased prevalence of meeting the overall transition measure and the individual elements among both youth with and without special health care needs.

“Findings from this study underscore the urgent need for HCPs to work with youth independently and in collaboration with their parents and/or caregivers throughout the adolescent years to improve transition planning,” Dr. Lebrun-Harris and her colleagues wrote.

The study was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health. The authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lebrun-Harris LA et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0194.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In total, 17% of youth with special health care needs and 14% of youth without received support for the transition to adult care.

Study details: A nationally representative exploratory analysis of transition planning from pediatric to adult health care for 20,708 adolescents from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health. The authors reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Lebrun-Harris LA et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0194.

AAP guidelines emphasize gender-affirmative care

according to an American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement published in Pediatrics.

The policy statement defines the gender-affirmative care model as one that provide “developmentally appropriate care that is oriented toward understanding and appreciating the youth’s gender experience,” wrote Jason Rafferty, MD, of the department of pediatrics at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., and the department of child psychiatryf at Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital, East Providence, R.I. Dr. Rafferty serves on the AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. The AAP Committee on Adolescence, Section on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness also participated in writing this policy statement.

The model emphasizes four main points, according to the statement:

- Transgender and gender-diverse identities are not mental disorders.

- Variations in gender identity are “normal aspects of human diversity.”

- Gender identity “evolves as a result of the interaction between biology, development, socialization, and culture.”

- Any mental health issue “most often stems from stigma and negative experiences” rather than being “intrinsic” to the child.

In the gender-affirmative approach, a supportive, nonjudgmental partnership between you, the patient, and the patient’s family is encouraged to “facilitate exploration of complicated emotions and gender-diverse expressions while allowing questions and concerns to be raised,” Dr. Rafferty said. This contrasts with “reparative” or “conversion” treatment, which seeks to change rather than accept the patient’s gender identity.

The AAP statement also recommends accessibility of family therapy, addressing the emotional and mental health needs not only of the patient, but also the parents, caregivers, and siblings.

The policy statement provides definitions for common terminology and distinguishes between “sex” as assigned at birth, based on anatomy, and “gender identity,” described as one’s internal sense of self. It also emphasizes that gender identity is not synonymous with sexual orientation, although the two may be interrelated. “The Gender Book” website is a resource that explains these terms and concepts.

A 2015 study revealed that 25% of transgender adults avoided a necessary doctor appointment because they feared mistreatment. Creating an environment at your office where TGD patients feel safe is key. This can be done by displaying posters or having flyers about lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) issues and having a gender-neutral bathroom. Educate staff by having diversity training that makes them sensitive to the needs of LGBTQ youth and their families. Patient-asserted names and pronouns should be used by staff and reflected in the EHR. “Explaining and maintaining confidentiality procedures promotes openness and trust, particularly with youth who identify as LGBTQ,” according to the statement. “Maintaining a safe clinical space can provide at least one consistent, protective refuge for patients and families, allowing authentic gender expression and exploration that builds resiliency.”

Barriers to care cited in the report include fear of discrimination by providers, lack of access to physical and sexual health services, inadequate mental health resources, and lack of provider continuity. The AAP recommends that EHRs respect the gender identity of the patient. Further research into health disparities, as well as establishment of standards of care, also are needed, the author notes.

The stigma and discrimination often experienced by TGD youth lead to feelings of rejection and isolation. Prior research has shown that transgender adolescents and adults have high rates of depression, anxiety, eating disorders, self-harm, and suicide, the report noted. One retrospective study found that 56% of transgender youth reported previous suicidal ideation, compared with 20% of those who identified as cisgender, and 31% reported a prior suicide attempt, compared with 11% cisgender youth. TGD youth also experience high rates of homelessness, violence, substance abuse, and high-risk sexual behaviors, studies have shown.

The statement also addresses issues such as medical interventions for pubertal suppression, surgical affirmation, difficulties with obtaining insurance coverage because of being transgender, family acceptance, safety in schools and communities, and medical education.

No disclosures or funding sources were reported.

SOURCE: Rafferty J et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20182162.

The AAP policy offers a more detailed overview of the health care needs of transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) youth than was previously available, with data to support these recommendations.

Future efforts should focus on expanding the definition and components of gender-affirmative care, as well as training providers to be more competent in providing this care by introducing these concepts earlier in medical training so that pediatricians feel comfortable with implementation.

The new guidelines “emphasize that care for TGD youth is a rapidly evolving field,” and that “continued support is needed for research, education, and advocacy in this arena so we can provide the best level of evidence-based care to TGD youth.”

Gayathri Chelvakumar, MD, is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She was asked to comment on the AAP guidelines.

The AAP policy offers a more detailed overview of the health care needs of transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) youth than was previously available, with data to support these recommendations.

Future efforts should focus on expanding the definition and components of gender-affirmative care, as well as training providers to be more competent in providing this care by introducing these concepts earlier in medical training so that pediatricians feel comfortable with implementation.

The new guidelines “emphasize that care for TGD youth is a rapidly evolving field,” and that “continued support is needed for research, education, and advocacy in this arena so we can provide the best level of evidence-based care to TGD youth.”

Gayathri Chelvakumar, MD, is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She was asked to comment on the AAP guidelines.

The AAP policy offers a more detailed overview of the health care needs of transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) youth than was previously available, with data to support these recommendations.

Future efforts should focus on expanding the definition and components of gender-affirmative care, as well as training providers to be more competent in providing this care by introducing these concepts earlier in medical training so that pediatricians feel comfortable with implementation.

The new guidelines “emphasize that care for TGD youth is a rapidly evolving field,” and that “continued support is needed for research, education, and advocacy in this arena so we can provide the best level of evidence-based care to TGD youth.”

Gayathri Chelvakumar, MD, is an attending physician in the division of adolescent medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and an assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Ohio State University, both in Columbus. She was asked to comment on the AAP guidelines.

according to an American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement published in Pediatrics.

The policy statement defines the gender-affirmative care model as one that provide “developmentally appropriate care that is oriented toward understanding and appreciating the youth’s gender experience,” wrote Jason Rafferty, MD, of the department of pediatrics at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., and the department of child psychiatryf at Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital, East Providence, R.I. Dr. Rafferty serves on the AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. The AAP Committee on Adolescence, Section on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness also participated in writing this policy statement.

The model emphasizes four main points, according to the statement:

- Transgender and gender-diverse identities are not mental disorders.

- Variations in gender identity are “normal aspects of human diversity.”

- Gender identity “evolves as a result of the interaction between biology, development, socialization, and culture.”

- Any mental health issue “most often stems from stigma and negative experiences” rather than being “intrinsic” to the child.

In the gender-affirmative approach, a supportive, nonjudgmental partnership between you, the patient, and the patient’s family is encouraged to “facilitate exploration of complicated emotions and gender-diverse expressions while allowing questions and concerns to be raised,” Dr. Rafferty said. This contrasts with “reparative” or “conversion” treatment, which seeks to change rather than accept the patient’s gender identity.

The AAP statement also recommends accessibility of family therapy, addressing the emotional and mental health needs not only of the patient, but also the parents, caregivers, and siblings.

The policy statement provides definitions for common terminology and distinguishes between “sex” as assigned at birth, based on anatomy, and “gender identity,” described as one’s internal sense of self. It also emphasizes that gender identity is not synonymous with sexual orientation, although the two may be interrelated. “The Gender Book” website is a resource that explains these terms and concepts.

A 2015 study revealed that 25% of transgender adults avoided a necessary doctor appointment because they feared mistreatment. Creating an environment at your office where TGD patients feel safe is key. This can be done by displaying posters or having flyers about lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) issues and having a gender-neutral bathroom. Educate staff by having diversity training that makes them sensitive to the needs of LGBTQ youth and their families. Patient-asserted names and pronouns should be used by staff and reflected in the EHR. “Explaining and maintaining confidentiality procedures promotes openness and trust, particularly with youth who identify as LGBTQ,” according to the statement. “Maintaining a safe clinical space can provide at least one consistent, protective refuge for patients and families, allowing authentic gender expression and exploration that builds resiliency.”

Barriers to care cited in the report include fear of discrimination by providers, lack of access to physical and sexual health services, inadequate mental health resources, and lack of provider continuity. The AAP recommends that EHRs respect the gender identity of the patient. Further research into health disparities, as well as establishment of standards of care, also are needed, the author notes.

The stigma and discrimination often experienced by TGD youth lead to feelings of rejection and isolation. Prior research has shown that transgender adolescents and adults have high rates of depression, anxiety, eating disorders, self-harm, and suicide, the report noted. One retrospective study found that 56% of transgender youth reported previous suicidal ideation, compared with 20% of those who identified as cisgender, and 31% reported a prior suicide attempt, compared with 11% cisgender youth. TGD youth also experience high rates of homelessness, violence, substance abuse, and high-risk sexual behaviors, studies have shown.

The statement also addresses issues such as medical interventions for pubertal suppression, surgical affirmation, difficulties with obtaining insurance coverage because of being transgender, family acceptance, safety in schools and communities, and medical education.

No disclosures or funding sources were reported.

SOURCE: Rafferty J et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20182162.

according to an American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement published in Pediatrics.

The policy statement defines the gender-affirmative care model as one that provide “developmentally appropriate care that is oriented toward understanding and appreciating the youth’s gender experience,” wrote Jason Rafferty, MD, of the department of pediatrics at Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., and the department of child psychiatryf at Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital, East Providence, R.I. Dr. Rafferty serves on the AAP Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. The AAP Committee on Adolescence, Section on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness also participated in writing this policy statement.

The model emphasizes four main points, according to the statement:

- Transgender and gender-diverse identities are not mental disorders.

- Variations in gender identity are “normal aspects of human diversity.”

- Gender identity “evolves as a result of the interaction between biology, development, socialization, and culture.”

- Any mental health issue “most often stems from stigma and negative experiences” rather than being “intrinsic” to the child.

In the gender-affirmative approach, a supportive, nonjudgmental partnership between you, the patient, and the patient’s family is encouraged to “facilitate exploration of complicated emotions and gender-diverse expressions while allowing questions and concerns to be raised,” Dr. Rafferty said. This contrasts with “reparative” or “conversion” treatment, which seeks to change rather than accept the patient’s gender identity.

The AAP statement also recommends accessibility of family therapy, addressing the emotional and mental health needs not only of the patient, but also the parents, caregivers, and siblings.

The policy statement provides definitions for common terminology and distinguishes between “sex” as assigned at birth, based on anatomy, and “gender identity,” described as one’s internal sense of self. It also emphasizes that gender identity is not synonymous with sexual orientation, although the two may be interrelated. “The Gender Book” website is a resource that explains these terms and concepts.

A 2015 study revealed that 25% of transgender adults avoided a necessary doctor appointment because they feared mistreatment. Creating an environment at your office where TGD patients feel safe is key. This can be done by displaying posters or having flyers about lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) issues and having a gender-neutral bathroom. Educate staff by having diversity training that makes them sensitive to the needs of LGBTQ youth and their families. Patient-asserted names and pronouns should be used by staff and reflected in the EHR. “Explaining and maintaining confidentiality procedures promotes openness and trust, particularly with youth who identify as LGBTQ,” according to the statement. “Maintaining a safe clinical space can provide at least one consistent, protective refuge for patients and families, allowing authentic gender expression and exploration that builds resiliency.”

Barriers to care cited in the report include fear of discrimination by providers, lack of access to physical and sexual health services, inadequate mental health resources, and lack of provider continuity. The AAP recommends that EHRs respect the gender identity of the patient. Further research into health disparities, as well as establishment of standards of care, also are needed, the author notes.

The stigma and discrimination often experienced by TGD youth lead to feelings of rejection and isolation. Prior research has shown that transgender adolescents and adults have high rates of depression, anxiety, eating disorders, self-harm, and suicide, the report noted. One retrospective study found that 56% of transgender youth reported previous suicidal ideation, compared with 20% of those who identified as cisgender, and 31% reported a prior suicide attempt, compared with 11% cisgender youth. TGD youth also experience high rates of homelessness, violence, substance abuse, and high-risk sexual behaviors, studies have shown.

The statement also addresses issues such as medical interventions for pubertal suppression, surgical affirmation, difficulties with obtaining insurance coverage because of being transgender, family acceptance, safety in schools and communities, and medical education.

No disclosures or funding sources were reported.

SOURCE: Rafferty J et al. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20182162.

FROM PEDATRICS

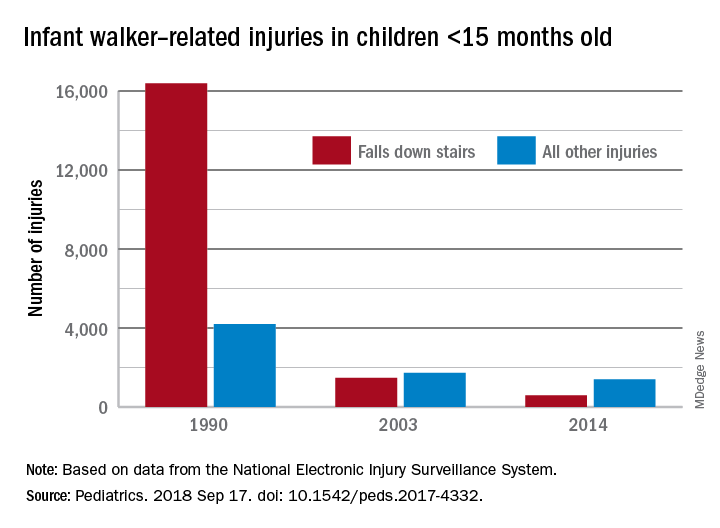

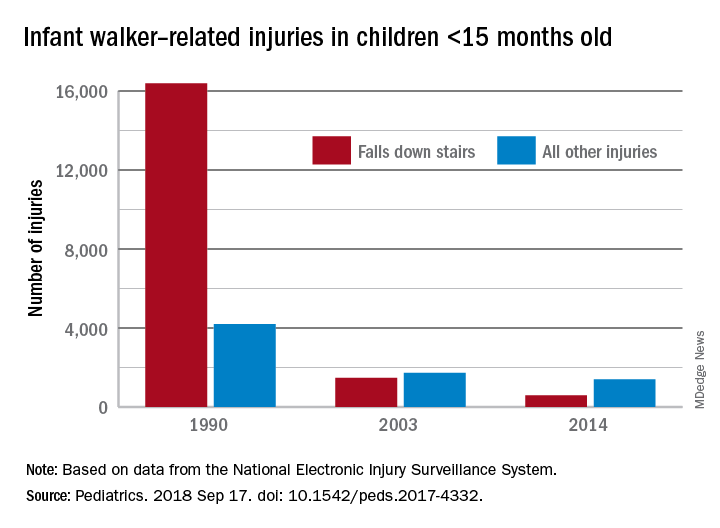

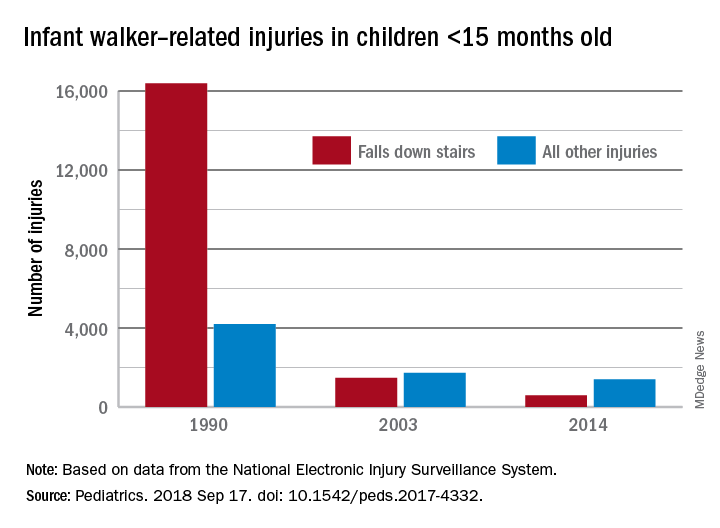

Decline of infant walker–related injuries continues

but most of that drop occurred before the federal mandatory safety standard went into effect in 2010, according to an analysis of a federal injury database.

In 1990, there were 20,650 walker-related injuries among children younger than 15 months, and by 2003 that number was down to 3,201 – a significant decline of 85%. In 2014, the last year for which data were available, there were 1,995 such injuries, which translates to a nonsignificant decrease of 38% from 2003 to 2014, Ariel Sims, MS, and her associates at the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, wrote in Pediatrics.

During the study period from 1990 to 2014, a total of 230,676 children aged less than 15 months received treatment in emergency departments after walker-related injuries, with the majority (74%) caused by falls down stairs. That percentage did go down over time, though, with falls down stairs representing more than 80% of all such injuries during 1990-1996, 66% during 1997-2009, and 41% during 2010-2014, Ms. Sims and her associates reported based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System.

As for the 2010 federal safety standard, the annual average injury total went from 2,801 for the previous 4 years (2006-2009) to 2,165 for the 4 years after (2010-2014) – a decline of 23% (P = .019), they noted.

The federal standard may have contributed to the overall decline, Ms. Sims and her associates suggested, but the “reduction is most likely attributable to … an increase in public awareness of infant walker–related injury risks when advocacy groups petitioned the [Consumer Product Safety Commission] in 1992 to ban infant walker sales in the United States, the increasing use of stationary activity centers as an alternative to infant walkers, and improvements in the voluntary infant walker safety standard.”

In a September 2001 policy statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended a ban on the manufacture and sale of mobile infant walkers (Pediatrics. 2001 Sep. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.790). This policy has been reaffirmed every 5 years in accordance with AAP policy.

Ms. Sims received a research stipend from the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Child Injury Prevention Alliance. The other investigators said that they have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sims A et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4332.

but most of that drop occurred before the federal mandatory safety standard went into effect in 2010, according to an analysis of a federal injury database.

In 1990, there were 20,650 walker-related injuries among children younger than 15 months, and by 2003 that number was down to 3,201 – a significant decline of 85%. In 2014, the last year for which data were available, there were 1,995 such injuries, which translates to a nonsignificant decrease of 38% from 2003 to 2014, Ariel Sims, MS, and her associates at the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, wrote in Pediatrics.

During the study period from 1990 to 2014, a total of 230,676 children aged less than 15 months received treatment in emergency departments after walker-related injuries, with the majority (74%) caused by falls down stairs. That percentage did go down over time, though, with falls down stairs representing more than 80% of all such injuries during 1990-1996, 66% during 1997-2009, and 41% during 2010-2014, Ms. Sims and her associates reported based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System.

As for the 2010 federal safety standard, the annual average injury total went from 2,801 for the previous 4 years (2006-2009) to 2,165 for the 4 years after (2010-2014) – a decline of 23% (P = .019), they noted.

The federal standard may have contributed to the overall decline, Ms. Sims and her associates suggested, but the “reduction is most likely attributable to … an increase in public awareness of infant walker–related injury risks when advocacy groups petitioned the [Consumer Product Safety Commission] in 1992 to ban infant walker sales in the United States, the increasing use of stationary activity centers as an alternative to infant walkers, and improvements in the voluntary infant walker safety standard.”

In a September 2001 policy statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended a ban on the manufacture and sale of mobile infant walkers (Pediatrics. 2001 Sep. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.790). This policy has been reaffirmed every 5 years in accordance with AAP policy.

Ms. Sims received a research stipend from the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Child Injury Prevention Alliance. The other investigators said that they have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sims A et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4332.

but most of that drop occurred before the federal mandatory safety standard went into effect in 2010, according to an analysis of a federal injury database.

In 1990, there were 20,650 walker-related injuries among children younger than 15 months, and by 2003 that number was down to 3,201 – a significant decline of 85%. In 2014, the last year for which data were available, there were 1,995 such injuries, which translates to a nonsignificant decrease of 38% from 2003 to 2014, Ariel Sims, MS, and her associates at the Center for Injury Research and Policy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, wrote in Pediatrics.

During the study period from 1990 to 2014, a total of 230,676 children aged less than 15 months received treatment in emergency departments after walker-related injuries, with the majority (74%) caused by falls down stairs. That percentage did go down over time, though, with falls down stairs representing more than 80% of all such injuries during 1990-1996, 66% during 1997-2009, and 41% during 2010-2014, Ms. Sims and her associates reported based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System.

As for the 2010 federal safety standard, the annual average injury total went from 2,801 for the previous 4 years (2006-2009) to 2,165 for the 4 years after (2010-2014) – a decline of 23% (P = .019), they noted.

The federal standard may have contributed to the overall decline, Ms. Sims and her associates suggested, but the “reduction is most likely attributable to … an increase in public awareness of infant walker–related injury risks when advocacy groups petitioned the [Consumer Product Safety Commission] in 1992 to ban infant walker sales in the United States, the increasing use of stationary activity centers as an alternative to infant walkers, and improvements in the voluntary infant walker safety standard.”

In a September 2001 policy statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended a ban on the manufacture and sale of mobile infant walkers (Pediatrics. 2001 Sep. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.790). This policy has been reaffirmed every 5 years in accordance with AAP policy.

Ms. Sims received a research stipend from the Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital and was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Child Injury Prevention Alliance. The other investigators said that they have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Sims A et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sep 17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4332.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Embracing therapeutic silence: A resident’s perspective on learning psychotherapy

There is a tendency among young psychiatric residents, including me, to experience significant anxiety when providing outpatient psychotherapy for the first time. This anxiety often leads to rigid adherence to structured sessions aimed at a specific therapeutic target. Unfortunately, as patients begin to stray from the mold, this model breaks down and leaves the resident with little direction.

As a resident with an engineering background, I felt a strong affinity for this targeted approach, and have struggled for direction with patients whose symptoms or willingness to engage therapeutically did not match this method. I have slowly come to appreciate a more nimble approach that balances elements of both a structured method (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) with more free-flowing psychoanalytic techniques. This approach is based on several principles, including relinquishing a desire for a grand therapeutic arc, gaining comfort with silence, and, finally, allowing the patient to do the work.

Perhaps the most difficult part of this evolving realization is learning to resist the desire for an overarching path from session to session. As a novice therapist, I struggled with the apparent disconnect from session to session, and attempted to force this need for a therapeutic arc on each subsequent visit. This meant that rather than meeting the patient in his or her current state, I was forever reaching to the past, attempting to create a link between what was discussed previously to the topic of today’s session. While some patients readily identified with the concepts of CBT—where maladaptive cognitions are identified and challenged via reflection on past progress—there was another subset of patients who seemed unwilling to do so.

In his Notes On Memory and Desire,1 psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion proclaimed, “Do not remember past sessions.” As I discussed this concept in psychotherapy supervision, I began to understand the value of a less directed approach, and to try it with patients. I soon discovered interactions were more rewarding, and I gained a deeper understanding than I had before. Without a formulaic approach, patients were free to give voice to any issue, whether or not it conformed to their perceived “chief complaint.” It was refreshing to see the work progress over time as we began to slowly integrate the seemingly disparate themes of each session.

In addition to the naive idea of forcing a formulaic arc on the therapeutic process, I felt a strong desire for tangible results. Perhaps it was my engineering side yearning for the quantifiable, but nonetheless, I fell into the trap of trying to push patients to gain insights they may have not been ready to make. This led to dissatisfaction on both sides. I was reminded of another directive from Bion: “Desires for results, cure, or even understanding must not be allowed to proliferate.”1 It was interesting: the less I focused on results, the more patients began to open up and explore. By using their present experiences to examine patterns of behavior, we were able to slowly reach new levels of understanding.

The corollary to gaining comfort with relinquishing my desire for results was gaining comfort with silence and learning to meet patients where they are. The concept of using nonverbal cues to communicate is not a novel one. However, the idea that one might communicate by doing nothing at all is somewhat profound. I began to explore the use of silence with my patients, and have found an unknown richness that was previously hidden by my own tendency to interject. Psychotherapist Mark Epstein wrote, “When a therapist can sit with a patient without an agenda, without trying to force an experience, without thinking that she knows what is going to happen or who this person is…when he falls silent…the possibility of some real, spontaneous, unscripted communication exists.”2 Sitting in silence and allowing my patients to grow in their own insight has given them a sense of empowerment and mastery, and has greatly enriched our sessions.

Psychotherapy is not an easy thing for most embryonic psychiatrists or therapists, and many cling to formulaic methods because such methods are an easy approach. Initially, I, too, clung to this rigid approach, but it ultimately left me unfulfilled. I have learned to be more nimble, embrace silence, and relinquish my desire for results. I was initially uncomfortable with this unstructured model of psychotherapeutic interaction, preferring the more concrete thinking I had come to expect from engineering. It is likely that few residents will share this unique background, and thus may not struggle as I have, but I believe that the process of adaptation and change is relevant to all. As a young psychiatrist, I have gained much joy from being able to work with patients in psychotherapy. It is my hope that other young trainees, regardless of background, will learn to let go of their preconceived ideas and embrace change, for it is only through change that we grow.

1. Bion WR. Wilfred R. Bion: notes on memory and desire. In: Aguayo J, Malin B, eds. Wilfred Bion: Los Angeles seminars and supervision. London, UK: Karnac; 2013:136-138.

2. Epstein M. Remembering. In: Thoughts without a thinker. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1995:187-189.

There is a tendency among young psychiatric residents, including me, to experience significant anxiety when providing outpatient psychotherapy for the first time. This anxiety often leads to rigid adherence to structured sessions aimed at a specific therapeutic target. Unfortunately, as patients begin to stray from the mold, this model breaks down and leaves the resident with little direction.

As a resident with an engineering background, I felt a strong affinity for this targeted approach, and have struggled for direction with patients whose symptoms or willingness to engage therapeutically did not match this method. I have slowly come to appreciate a more nimble approach that balances elements of both a structured method (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) with more free-flowing psychoanalytic techniques. This approach is based on several principles, including relinquishing a desire for a grand therapeutic arc, gaining comfort with silence, and, finally, allowing the patient to do the work.

Perhaps the most difficult part of this evolving realization is learning to resist the desire for an overarching path from session to session. As a novice therapist, I struggled with the apparent disconnect from session to session, and attempted to force this need for a therapeutic arc on each subsequent visit. This meant that rather than meeting the patient in his or her current state, I was forever reaching to the past, attempting to create a link between what was discussed previously to the topic of today’s session. While some patients readily identified with the concepts of CBT—where maladaptive cognitions are identified and challenged via reflection on past progress—there was another subset of patients who seemed unwilling to do so.

In his Notes On Memory and Desire,1 psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion proclaimed, “Do not remember past sessions.” As I discussed this concept in psychotherapy supervision, I began to understand the value of a less directed approach, and to try it with patients. I soon discovered interactions were more rewarding, and I gained a deeper understanding than I had before. Without a formulaic approach, patients were free to give voice to any issue, whether or not it conformed to their perceived “chief complaint.” It was refreshing to see the work progress over time as we began to slowly integrate the seemingly disparate themes of each session.

In addition to the naive idea of forcing a formulaic arc on the therapeutic process, I felt a strong desire for tangible results. Perhaps it was my engineering side yearning for the quantifiable, but nonetheless, I fell into the trap of trying to push patients to gain insights they may have not been ready to make. This led to dissatisfaction on both sides. I was reminded of another directive from Bion: “Desires for results, cure, or even understanding must not be allowed to proliferate.”1 It was interesting: the less I focused on results, the more patients began to open up and explore. By using their present experiences to examine patterns of behavior, we were able to slowly reach new levels of understanding.

The corollary to gaining comfort with relinquishing my desire for results was gaining comfort with silence and learning to meet patients where they are. The concept of using nonverbal cues to communicate is not a novel one. However, the idea that one might communicate by doing nothing at all is somewhat profound. I began to explore the use of silence with my patients, and have found an unknown richness that was previously hidden by my own tendency to interject. Psychotherapist Mark Epstein wrote, “When a therapist can sit with a patient without an agenda, without trying to force an experience, without thinking that she knows what is going to happen or who this person is…when he falls silent…the possibility of some real, spontaneous, unscripted communication exists.”2 Sitting in silence and allowing my patients to grow in their own insight has given them a sense of empowerment and mastery, and has greatly enriched our sessions.

Psychotherapy is not an easy thing for most embryonic psychiatrists or therapists, and many cling to formulaic methods because such methods are an easy approach. Initially, I, too, clung to this rigid approach, but it ultimately left me unfulfilled. I have learned to be more nimble, embrace silence, and relinquish my desire for results. I was initially uncomfortable with this unstructured model of psychotherapeutic interaction, preferring the more concrete thinking I had come to expect from engineering. It is likely that few residents will share this unique background, and thus may not struggle as I have, but I believe that the process of adaptation and change is relevant to all. As a young psychiatrist, I have gained much joy from being able to work with patients in psychotherapy. It is my hope that other young trainees, regardless of background, will learn to let go of their preconceived ideas and embrace change, for it is only through change that we grow.

There is a tendency among young psychiatric residents, including me, to experience significant anxiety when providing outpatient psychotherapy for the first time. This anxiety often leads to rigid adherence to structured sessions aimed at a specific therapeutic target. Unfortunately, as patients begin to stray from the mold, this model breaks down and leaves the resident with little direction.

As a resident with an engineering background, I felt a strong affinity for this targeted approach, and have struggled for direction with patients whose symptoms or willingness to engage therapeutically did not match this method. I have slowly come to appreciate a more nimble approach that balances elements of both a structured method (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) with more free-flowing psychoanalytic techniques. This approach is based on several principles, including relinquishing a desire for a grand therapeutic arc, gaining comfort with silence, and, finally, allowing the patient to do the work.

Perhaps the most difficult part of this evolving realization is learning to resist the desire for an overarching path from session to session. As a novice therapist, I struggled with the apparent disconnect from session to session, and attempted to force this need for a therapeutic arc on each subsequent visit. This meant that rather than meeting the patient in his or her current state, I was forever reaching to the past, attempting to create a link between what was discussed previously to the topic of today’s session. While some patients readily identified with the concepts of CBT—where maladaptive cognitions are identified and challenged via reflection on past progress—there was another subset of patients who seemed unwilling to do so.

In his Notes On Memory and Desire,1 psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion proclaimed, “Do not remember past sessions.” As I discussed this concept in psychotherapy supervision, I began to understand the value of a less directed approach, and to try it with patients. I soon discovered interactions were more rewarding, and I gained a deeper understanding than I had before. Without a formulaic approach, patients were free to give voice to any issue, whether or not it conformed to their perceived “chief complaint.” It was refreshing to see the work progress over time as we began to slowly integrate the seemingly disparate themes of each session.

In addition to the naive idea of forcing a formulaic arc on the therapeutic process, I felt a strong desire for tangible results. Perhaps it was my engineering side yearning for the quantifiable, but nonetheless, I fell into the trap of trying to push patients to gain insights they may have not been ready to make. This led to dissatisfaction on both sides. I was reminded of another directive from Bion: “Desires for results, cure, or even understanding must not be allowed to proliferate.”1 It was interesting: the less I focused on results, the more patients began to open up and explore. By using their present experiences to examine patterns of behavior, we were able to slowly reach new levels of understanding.

The corollary to gaining comfort with relinquishing my desire for results was gaining comfort with silence and learning to meet patients where they are. The concept of using nonverbal cues to communicate is not a novel one. However, the idea that one might communicate by doing nothing at all is somewhat profound. I began to explore the use of silence with my patients, and have found an unknown richness that was previously hidden by my own tendency to interject. Psychotherapist Mark Epstein wrote, “When a therapist can sit with a patient without an agenda, without trying to force an experience, without thinking that she knows what is going to happen or who this person is…when he falls silent…the possibility of some real, spontaneous, unscripted communication exists.”2 Sitting in silence and allowing my patients to grow in their own insight has given them a sense of empowerment and mastery, and has greatly enriched our sessions.

Psychotherapy is not an easy thing for most embryonic psychiatrists or therapists, and many cling to formulaic methods because such methods are an easy approach. Initially, I, too, clung to this rigid approach, but it ultimately left me unfulfilled. I have learned to be more nimble, embrace silence, and relinquish my desire for results. I was initially uncomfortable with this unstructured model of psychotherapeutic interaction, preferring the more concrete thinking I had come to expect from engineering. It is likely that few residents will share this unique background, and thus may not struggle as I have, but I believe that the process of adaptation and change is relevant to all. As a young psychiatrist, I have gained much joy from being able to work with patients in psychotherapy. It is my hope that other young trainees, regardless of background, will learn to let go of their preconceived ideas and embrace change, for it is only through change that we grow.

1. Bion WR. Wilfred R. Bion: notes on memory and desire. In: Aguayo J, Malin B, eds. Wilfred Bion: Los Angeles seminars and supervision. London, UK: Karnac; 2013:136-138.

2. Epstein M. Remembering. In: Thoughts without a thinker. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1995:187-189.

1. Bion WR. Wilfred R. Bion: notes on memory and desire. In: Aguayo J, Malin B, eds. Wilfred Bion: Los Angeles seminars and supervision. London, UK: Karnac; 2013:136-138.

2. Epstein M. Remembering. In: Thoughts without a thinker. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1995:187-189.

Rural Surgery - A View From the Front Lines: “I need to transfer this patient”

Nobody is happy when a patient needs to be transferred. A patient transfer is an unplanned event for all parties involved: the patient, the family, the surgeon requesting a transfer, and the accepting surgeon or physician.

It’s a fact of life that a rural surgeon will, at times, need to transfer patients to a larger center. The reasons should come as no surprise to any surgeon. Sometimes there are simply not enough ICU beds, ICU nurses, ventilators, or respiratory therapists to care for patients. At times, very complicated surgical patients will present through the ED and sometimes a work-up on a hospitalized patient may reveal a complex surgical problem. Despite the best efforts of a rural surgeon, surgical complications will occur and a transfer can be the wisest choice. Trauma patients, especially those with a neurologic injury, will often need to be transferred. And then there is the exhaustion factor: A long stretch of on-call duty, or a series of difficult, time-consuming patients can deplete the mental and physical resources of a rural surgeon and the next patient who comes in the door with a complicated surgical issue will be transferred.

The transferring of patients from a rural hospital to a larger medical center with higher-level technology on hand is becoming more common. An example of this would be a patient with a blunt splenic injury. In years past, this patient could be carefully followed in a rural hospital, and a splenectomy could be done if necessary. With the ability of interventional radiologists to control splenic bleeding by embolization techniques, some of these patients do better if transferred to a larger center. Some rural hospitals used to operate on patients with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, but now many of these cases are transferred so that the patient can be treated with endovascular techniques. Some patients with GI bleeding are now transferred for possible treatment with embolization techniques.

In many ways, it has gotten easier in recent years to transfer a patient from a rural hospital. Almost all tertiary hospitals now have a transfer team or transfer coordinator that will determine bed availability, and arrange for a conference call between the rural surgeon and the accepting surgeon and other physicians at the larger hospital. Cell phones have allowed for much quicker communication between physicians. Many rural hospitals are now owned or affiliated with a larger medical center, which can allow for a quick transfer. As a result of Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act laws, a patient’s medical insurance status should not be a determining factor in a transfer.

Although transfers are easier than they once were, it should be noted that a transfer is not the easy or preferred option for most rural surgeons. Many rural surgeons inwardly groan when they realize that a patient needs to be transferred. Most surgeons can’t help having a feeling of defeat when a transfer is needed. Transfers can be very time-consuming, partly because there is usually no transfer team at a rural hospital and the surgeon has to be involved in making the arrangements and speaking with physicians at the larger center.

Because of the time commitment required for a transfer, it’s very important for the patient and his or her family to make a quick and definite decision about where they’d prefer the patient to be transferred to. Occasionally, after investing time to arrange for a transfer to a larger center, the rural surgeon is told that the accepting hospital will accept the patient, but that there are no open beds, which can mean that the patient can be waiting for several days for the transfer to occur, or that the rural surgeon needs to start the transfer process over again with another center. All this means can mean a further investment of time by the rural surgeon.

Ambulance transfer, whether by ground or air, is another complicating factor in transferring a patient. Medicare will pay the base rate and mileage for a medically necessary ambulance transport to the nearest facility that can care for the patient. Private insurance companies follow suit on this issue. If a patient and the family choose to go to a hospital that’s further away than the closest available facility, the patient will be required to pay for the extra mileage involved in the transfer. During a surgical emergency, patients and their families may have a difficult time with this concept, and it can fall to the surgeon to walk them through the decision and its financial implications. More time devoted to the transfer.

Since the rural surgeon best understands the reasons for the transfer, the rural surgeon should be the one making the phone calls to the larger center, and participating in the conference calls with the accepting physicians. This process should not be delegated to the hospitalist or anyone else. The rural surgeon should also take great care to ensure a complete record is sent with the patient and that pertinent x-ray studies are sent on a CD. The rural surgeon should make it clear to the accepting physicians that he/she will do whatever they can to help care for the patient once the patient returns home.

After the transfer has occurred, the rural surgeon should communicate with the accepting physician periodically to follow the patient’s progress. If the rural hospital and the accepting hospital have the same EHR system, the rural surgeon should follow the progress of the patient and communicate with the accepting physician through the EHR email system or some other means. It’s also very helpful to obtain a cell phone number of the patient, or of a key family member, so that the rural surgeon can communicate with the family after the transfer to monitor the patient’s progress.

There are several important principles regarding transferring patients. First and foremost, accepting physicians at larger hospitals should be treated like gold. A wise rural surgeon keeps a list of accepting physicians that he/she has worked with in the past, as well as their cell phone numbers and email addresses. A good reputation as a surgeon requesting a transfer is very helpful, and part of that is never looking to “dump a patient.” A rural surgeon also must work hard at “networking” to get to know personally as many surgeons and physicians at accepting hospitals as possible. This takes effort, but can be accomplished by being active in the state American College of Surgeons Chapter, regional surgical societies, or state medical society. Personally visiting accepting hospitals, and meeting the surgeons and specialists there, is another great way to develop personal contacts. Every experienced rural surgeon knows that personal connections can pay off in many ways, and in particular, making transfers much easier.