User login

Expert advice for immediate postpartum LARC insertion

Evidence-based education about long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) for women in the postpartum period can result in the increased continuation of and satisfaction with LARC.1 However, nearly 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit.2 And up to 57% of women report having unprotected intercourse before the 6-week postpartum visit, which increases the risk of unplanned pregnancy.3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports immediate postpartum LARC insertion as best practice,3 and clinicians providing care for women during the peripartum period can counsel women regarding informed contraceptive decisions and provide guidance regarding both short-acting contraception and LARC.1

Immediate postpartum LARC, using intrauterine devices (IUDs) in particular, has been used around the world for a long time, says Lisa Hofler, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief in the Division of Family Planning at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. “Much of our initial data came from other countries, but eventually people in the United States said, ‘This is a great option, why aren't we doing this?’" In addition, although women considering immediate postpartum LARC should be counseled about the theoretical risk of reduced duration of breastfeeding, the evidence overwhelmingly has not shown a negative effect on actual breastfeeding outcomes according to ACOG.3 OBG MANAGEMENT recently met up with Dr. Hofler to ask her which patients are ideal for postpartum LARC, how to troubleshoot common pitfalls, and how to implement the practice within one’s own institution.

OBG Management: Who do you consider to be the ideal patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Lisa Hofler, MD: The great thing about immediate postpartum LARC (including IUDs and implants) is that any woman is an ideal candidate. We are simply talking about the timing of when a woman chooses to get an IUD or an implant after the birth of her child. There is no one perfect woman; it is the person who chooses the method and wants to use that method immediately after birth. When a woman chooses a LARC, she can be assured that after the birth of her child she will be protected against pregnancy. If she chooses an IUD as her LARC method, she will be comfortable at insertion because the cervix is already dilated when it is inserted.

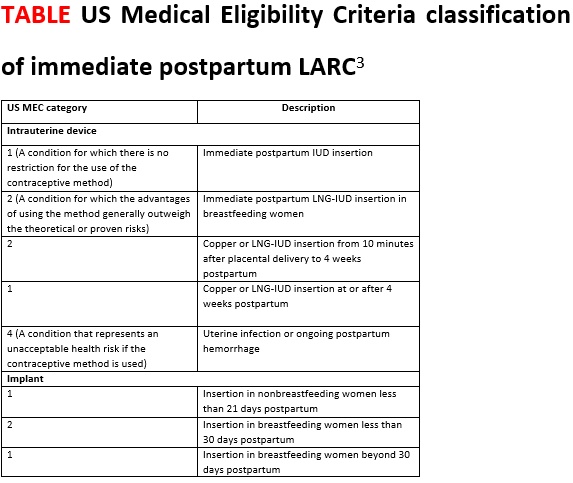

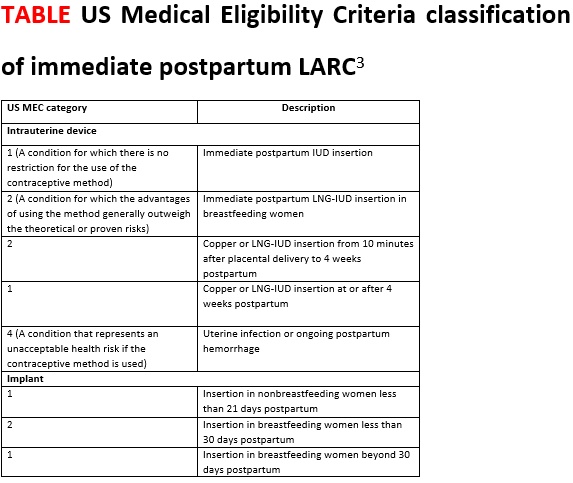

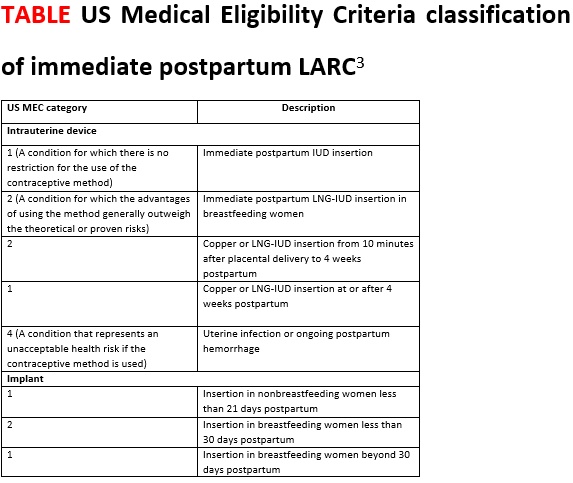

For the implant, the contraindications are the same as in the outpatient setting. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use covers many medical conditions and whether or not a person might be a candidate for different birth control methods.4 Those same considerations apply for the implant postpartum (TABLE).3

For the IUD, similarly, anyone who would not be a candidate for the IUD in the outpatient setting is not a candidate for immediate postpartum IUD. For instance, if the person has an intrauterine infection, you should not place an IUD. Also, if a patient is hemorrhaging and you are managing the hemorrhage (say she has retained placenta or membranes or she has uterine atony), you are not going to put an IUD in, as you need to attend to her bleeding.

OBG Management: What is your approach to counseling a patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Dr. Hofler: The ideal time to counsel about postbirth contraception is in the prenatal period, when the patient is making decisions about what method she wants to use after the birth. Once she chooses her preferred method, address timing if appropriate. It is less ideal to talk to a woman about the option of immediate postpartum LARC when she comes to labor and delivery, especially if that is the first time she has heard about it. Certainly, the time to talk about postpartum LARC options is not immediately after the baby is born. Approaching your patient with, "What do you want for birth control? Do you want this IUD? I can put it in right now," can feel coercive. This approach does not put the woman in a position in which she has enough decision-making time or time to ask questions.

OBG Management: What problems do clinicians run into when placing an immediate postpartum IUD, and can you offer solutions?

Dr. Hofler: When placing an immediate postpartum IUD, people might run into a few problems. The first relates to preplacement counseling. Perhaps when making the plan for the postpartum IUD the clinician did not counsel the woman that there are certain conditions that could preclude IUD placement—such as intrauterine infection or postpartum hemorrhage. When dealing with those types of issues, a patient is not eligible for an IUD, and she should be mentally prepared for this type of situation. Let her know during the counseling before the birth that immediately postpartum is a great time and opportunity for effective contraception placement. Tell her that hopefully IUD placement will be possible but that occasionally it is not, and make a back-up plan in case the IUD cannot be placed immediately postpartum.

The second unique area for counseling with immediate postpartum IUDs is a slightly increased risk of expulsion of an IUD placed immediately postpartum compared with in the office. The risk of expulsion varies by type of delivery. For instance, cesarean delivery births have a lower expulsion rate than vaginal births. The expulsion rate seems to vary by type of IUD as well. Copper IUDs seem to have a slightly lower expulsion rate than hormonal IUDs. (See “Levonorgestrel vs copper IUD expulsion rates after immediate postpartum insertion.”) This consideration should be talked about ahead of time, too. Provider training in IUD placement does impact the likelihood of expulsion, and if you place the IUD at the fundus, it is less likely to expel. (See “Inserting the immediate postpartum IUD after vaginal and cesarean birth step by step.”)

A third issue that clinicians run into is actually the systems of care—making sure that the IUD or implant is available when you need it, making sure that documentation happens the way it should, and ensuring that the follow-up billing and revenue cycle happens so that the woman gets the device that she wants and the providers get paid for having provided it. These issues require a multidisciplinary team to work through in order to ensure that postpartum LARC placement is a sustainable process in the long run.

Often, when people think of immediate postpartum LARC they think of postplacental IUDs. However, an implant also is an option, and that too is immediate postpartum LARC. Placing an implant is often a lot easier to do after the birth than placing an IUD. As clinicians work toward bringing an immediate postpartum LARC program to their hospital system, starting with implants is a smart thing to do because clinicians do not have to learn or teach new clinical skills. Because of that, immediate postpartum implants are a good troubleshooting mechanism for opening up the conversation about immediate postpartum LARC at your institution.

OBG MANAGEMENT: What advice do you have for administrators or physicians looking to implement an immediate postpartum LARC program into a hospital setting?

Dr. Hofler: Probably the best single resource is the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Postpartum Contraception Access Initiative (PCAI). They have a dedicated website and offer a lot of support and resources that include site-specific training at the hospital or the institution; clinician training on implants and IUDs; and administrator training on some of the systems of care, the billing process, the stocking process, and pharmacy education. They also provide information on all the things that should be included beyond the clinical aspects. I strongly recommend looking at what they offer.

Also, because many hospitals say, "We love this idea. We would support immediate postpartum LARC, we just want to make sure we get paid," the ACOG LARC Program website includes state-specific guidance for how Medicaid pays for LARC devices. There is state-specific guidance about how the device payment can be separated from the global payment for delivery—specific things for each institution to do to get reimbursed.

A 2017 prospective cohort study was the first to directly compare expulsion rates of the levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) and the copper IUD placed postplacentally (within 10 minutes of placental delivery). The study investigators found that, among 96 women at 12 weeks, 38% of the LNG-IUD users and 20% of the copper IUD users experienced IUD expulsion (odds ratio, 2.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.99-6.55; P = .05). Women were aged 18 to 40 and had a singleton vaginal delivery at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation.1 The two study groups were similar except that more copper IUD users were Hispanic (66% vs 38%) and fewer were primiparous (16% vs 31%). The study authors found the only independent predictor of device expulsion to be IUD type.

In a 2019 prospective cohort study, Hinz and colleagues compared the 6-month expulsion rate of IUDs inserted in the immediate postpartum period (within 10 to 15 minutes of placental delivery) after vaginal or cesarean delivery.2 Women were aged 18 to 45 years and selected a LNG 52-mg IUD (75 women) or copper IUD (58 women) for postpartum contraception. They completed a survey from weeks 0 to 5 and on weeks 12 and 24 postpartum regarding IUD expulsion, IUD removal, vaginal bleeding, and breastfeeding. A total of 58 women had a vaginal delivery, and 56 had a cesarean delivery.

At 6 months, the expulsion rates were similar in the two groups: 26.7% of the LNG IUDs expelled, compared with 20.5% of the copper IUDs (P = .38). The study groups were similar, point out the study investigators, except that the copper IUD users had a higher median parity (3 vs. 2; P = .03). In addition, the copper IUDs were inserted by more senior than junior residents (46.2% vs 22.7%, P = .02).

A 2018 systematic review pooled absolute rates of IUD expulsion and estimated adjusted relative risk (RR) for IUD type. A total of 48 studies (rated level I to II-3 of poor to good quality) were included in the analysis, and results indicated that the LNG-IUD was associated with a higher risk of expulsion at less than 4 weeks postpartum than the copper IUD (adjusted RR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.50-2.43).3

References

1. Goldthwaite LM, Sheeder J, Hyer J, et al. Postplacental intrauterine device expulsion by 12 weeks: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:674.e1-674.e8.

2. Hinz EK, Murthy A, Wang B, Ryan N, Ades V. A prospective cohort study comparing expulsion after postplacental insertion: the levonorgestrel versus the copper intrauterine device. Contraception. May 17, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.04.011.

3. Jatlaoui TC, Whiteman MK, Jeng G, et al. Intrauterine device expulsion after postpartum placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2018:895-905.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after vaginal birth

1. Bring supplies for intrauterine device (IUD) insertion: the IUD, posterior blade of a speculum or retractor for posterior vagina, ring forceps, curved Kelly placenta forceps, and scissors.

2. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta. Any perineal lacerations should be repaired after IUD placement.

3. Break down the bed to facilitate placement. If the perineum or vagina is soiled with stool or meconium then consider povodine-iodine prep.

4. Place the posterior blade of the speculum into the vagina and grasp the anterior cervix with the ring forceps.

5. Set up the IUD for insertion: Change into new sterile gloves. Remove the IUD from the inserter. For levonorgestrel IUDs, cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm; copper IUDs do not need strings trimmed. Hold one arm of the IUD with the long Kelly placenta forceps so that the stem of the IUD is approximately parallel to the shaft of the forceps.

6. Insert the IUD: Guide the IUD into the lower uterine segment with the left hand on the cervix ring forceps and the right hand on the IUD forceps. After passing the IUD through the cervix, move the left hand to the abdomen and press the fundus posterior and caudad to straighten the endometrial canal and to feel the IUD at the fundus. With the right hand, guide the IUD to the fundus; this often entails dropping the hand significantly and guiding the IUD much more anteriorly than first expected.

7. Release the IUD with forceps wide open, sweeping the forceps to one side to avoid pulling the IUD out with the forceps. 8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

Troubleshooting tips:

- If you are unable to visualize the anterior cervix, try to place the ring forceps by palpation.

- If you are unable to grasp the cervix with ring forceps by palpation, you may try to place the IUD manually. Hold the IUD between the first and second fingers of the right hand and place the IUD at the fundus. Release the IUD with the fingers wide open and remove the hand without removing the IUD.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after cesarean birth

1. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta.

2. For levonorgestrel IUDs: Remove the IUD from the inserter. Cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm. Place the IUD at the fundus with a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

3. For copper IUDs: String trimming is not necessary. Place the IUD at the fundus with the IUD inserter or a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

4. Repair the hysterotomy as usual.

1. Dole DM, Martin J. What nurses need to know about immediate postpartum initiation of long-acting reversible contraception. Nurs Womens Health. 2017;21:186-195.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Work Group. Practice Bulletin no. 186: long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-e269.

4. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-104.

Evidence-based education about long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) for women in the postpartum period can result in the increased continuation of and satisfaction with LARC.1 However, nearly 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit.2 And up to 57% of women report having unprotected intercourse before the 6-week postpartum visit, which increases the risk of unplanned pregnancy.3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports immediate postpartum LARC insertion as best practice,3 and clinicians providing care for women during the peripartum period can counsel women regarding informed contraceptive decisions and provide guidance regarding both short-acting contraception and LARC.1

Immediate postpartum LARC, using intrauterine devices (IUDs) in particular, has been used around the world for a long time, says Lisa Hofler, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief in the Division of Family Planning at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. “Much of our initial data came from other countries, but eventually people in the United States said, ‘This is a great option, why aren't we doing this?’" In addition, although women considering immediate postpartum LARC should be counseled about the theoretical risk of reduced duration of breastfeeding, the evidence overwhelmingly has not shown a negative effect on actual breastfeeding outcomes according to ACOG.3 OBG MANAGEMENT recently met up with Dr. Hofler to ask her which patients are ideal for postpartum LARC, how to troubleshoot common pitfalls, and how to implement the practice within one’s own institution.

OBG Management: Who do you consider to be the ideal patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Lisa Hofler, MD: The great thing about immediate postpartum LARC (including IUDs and implants) is that any woman is an ideal candidate. We are simply talking about the timing of when a woman chooses to get an IUD or an implant after the birth of her child. There is no one perfect woman; it is the person who chooses the method and wants to use that method immediately after birth. When a woman chooses a LARC, she can be assured that after the birth of her child she will be protected against pregnancy. If she chooses an IUD as her LARC method, she will be comfortable at insertion because the cervix is already dilated when it is inserted.

For the implant, the contraindications are the same as in the outpatient setting. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use covers many medical conditions and whether or not a person might be a candidate for different birth control methods.4 Those same considerations apply for the implant postpartum (TABLE).3

For the IUD, similarly, anyone who would not be a candidate for the IUD in the outpatient setting is not a candidate for immediate postpartum IUD. For instance, if the person has an intrauterine infection, you should not place an IUD. Also, if a patient is hemorrhaging and you are managing the hemorrhage (say she has retained placenta or membranes or she has uterine atony), you are not going to put an IUD in, as you need to attend to her bleeding.

OBG Management: What is your approach to counseling a patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Dr. Hofler: The ideal time to counsel about postbirth contraception is in the prenatal period, when the patient is making decisions about what method she wants to use after the birth. Once she chooses her preferred method, address timing if appropriate. It is less ideal to talk to a woman about the option of immediate postpartum LARC when she comes to labor and delivery, especially if that is the first time she has heard about it. Certainly, the time to talk about postpartum LARC options is not immediately after the baby is born. Approaching your patient with, "What do you want for birth control? Do you want this IUD? I can put it in right now," can feel coercive. This approach does not put the woman in a position in which she has enough decision-making time or time to ask questions.

OBG Management: What problems do clinicians run into when placing an immediate postpartum IUD, and can you offer solutions?

Dr. Hofler: When placing an immediate postpartum IUD, people might run into a few problems. The first relates to preplacement counseling. Perhaps when making the plan for the postpartum IUD the clinician did not counsel the woman that there are certain conditions that could preclude IUD placement—such as intrauterine infection or postpartum hemorrhage. When dealing with those types of issues, a patient is not eligible for an IUD, and she should be mentally prepared for this type of situation. Let her know during the counseling before the birth that immediately postpartum is a great time and opportunity for effective contraception placement. Tell her that hopefully IUD placement will be possible but that occasionally it is not, and make a back-up plan in case the IUD cannot be placed immediately postpartum.

The second unique area for counseling with immediate postpartum IUDs is a slightly increased risk of expulsion of an IUD placed immediately postpartum compared with in the office. The risk of expulsion varies by type of delivery. For instance, cesarean delivery births have a lower expulsion rate than vaginal births. The expulsion rate seems to vary by type of IUD as well. Copper IUDs seem to have a slightly lower expulsion rate than hormonal IUDs. (See “Levonorgestrel vs copper IUD expulsion rates after immediate postpartum insertion.”) This consideration should be talked about ahead of time, too. Provider training in IUD placement does impact the likelihood of expulsion, and if you place the IUD at the fundus, it is less likely to expel. (See “Inserting the immediate postpartum IUD after vaginal and cesarean birth step by step.”)

A third issue that clinicians run into is actually the systems of care—making sure that the IUD or implant is available when you need it, making sure that documentation happens the way it should, and ensuring that the follow-up billing and revenue cycle happens so that the woman gets the device that she wants and the providers get paid for having provided it. These issues require a multidisciplinary team to work through in order to ensure that postpartum LARC placement is a sustainable process in the long run.

Often, when people think of immediate postpartum LARC they think of postplacental IUDs. However, an implant also is an option, and that too is immediate postpartum LARC. Placing an implant is often a lot easier to do after the birth than placing an IUD. As clinicians work toward bringing an immediate postpartum LARC program to their hospital system, starting with implants is a smart thing to do because clinicians do not have to learn or teach new clinical skills. Because of that, immediate postpartum implants are a good troubleshooting mechanism for opening up the conversation about immediate postpartum LARC at your institution.

OBG MANAGEMENT: What advice do you have for administrators or physicians looking to implement an immediate postpartum LARC program into a hospital setting?

Dr. Hofler: Probably the best single resource is the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Postpartum Contraception Access Initiative (PCAI). They have a dedicated website and offer a lot of support and resources that include site-specific training at the hospital or the institution; clinician training on implants and IUDs; and administrator training on some of the systems of care, the billing process, the stocking process, and pharmacy education. They also provide information on all the things that should be included beyond the clinical aspects. I strongly recommend looking at what they offer.

Also, because many hospitals say, "We love this idea. We would support immediate postpartum LARC, we just want to make sure we get paid," the ACOG LARC Program website includes state-specific guidance for how Medicaid pays for LARC devices. There is state-specific guidance about how the device payment can be separated from the global payment for delivery—specific things for each institution to do to get reimbursed.

A 2017 prospective cohort study was the first to directly compare expulsion rates of the levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) and the copper IUD placed postplacentally (within 10 minutes of placental delivery). The study investigators found that, among 96 women at 12 weeks, 38% of the LNG-IUD users and 20% of the copper IUD users experienced IUD expulsion (odds ratio, 2.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.99-6.55; P = .05). Women were aged 18 to 40 and had a singleton vaginal delivery at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation.1 The two study groups were similar except that more copper IUD users were Hispanic (66% vs 38%) and fewer were primiparous (16% vs 31%). The study authors found the only independent predictor of device expulsion to be IUD type.

In a 2019 prospective cohort study, Hinz and colleagues compared the 6-month expulsion rate of IUDs inserted in the immediate postpartum period (within 10 to 15 minutes of placental delivery) after vaginal or cesarean delivery.2 Women were aged 18 to 45 years and selected a LNG 52-mg IUD (75 women) or copper IUD (58 women) for postpartum contraception. They completed a survey from weeks 0 to 5 and on weeks 12 and 24 postpartum regarding IUD expulsion, IUD removal, vaginal bleeding, and breastfeeding. A total of 58 women had a vaginal delivery, and 56 had a cesarean delivery.

At 6 months, the expulsion rates were similar in the two groups: 26.7% of the LNG IUDs expelled, compared with 20.5% of the copper IUDs (P = .38). The study groups were similar, point out the study investigators, except that the copper IUD users had a higher median parity (3 vs. 2; P = .03). In addition, the copper IUDs were inserted by more senior than junior residents (46.2% vs 22.7%, P = .02).

A 2018 systematic review pooled absolute rates of IUD expulsion and estimated adjusted relative risk (RR) for IUD type. A total of 48 studies (rated level I to II-3 of poor to good quality) were included in the analysis, and results indicated that the LNG-IUD was associated with a higher risk of expulsion at less than 4 weeks postpartum than the copper IUD (adjusted RR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.50-2.43).3

References

1. Goldthwaite LM, Sheeder J, Hyer J, et al. Postplacental intrauterine device expulsion by 12 weeks: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:674.e1-674.e8.

2. Hinz EK, Murthy A, Wang B, Ryan N, Ades V. A prospective cohort study comparing expulsion after postplacental insertion: the levonorgestrel versus the copper intrauterine device. Contraception. May 17, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.04.011.

3. Jatlaoui TC, Whiteman MK, Jeng G, et al. Intrauterine device expulsion after postpartum placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2018:895-905.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after vaginal birth

1. Bring supplies for intrauterine device (IUD) insertion: the IUD, posterior blade of a speculum or retractor for posterior vagina, ring forceps, curved Kelly placenta forceps, and scissors.

2. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta. Any perineal lacerations should be repaired after IUD placement.

3. Break down the bed to facilitate placement. If the perineum or vagina is soiled with stool or meconium then consider povodine-iodine prep.

4. Place the posterior blade of the speculum into the vagina and grasp the anterior cervix with the ring forceps.

5. Set up the IUD for insertion: Change into new sterile gloves. Remove the IUD from the inserter. For levonorgestrel IUDs, cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm; copper IUDs do not need strings trimmed. Hold one arm of the IUD with the long Kelly placenta forceps so that the stem of the IUD is approximately parallel to the shaft of the forceps.

6. Insert the IUD: Guide the IUD into the lower uterine segment with the left hand on the cervix ring forceps and the right hand on the IUD forceps. After passing the IUD through the cervix, move the left hand to the abdomen and press the fundus posterior and caudad to straighten the endometrial canal and to feel the IUD at the fundus. With the right hand, guide the IUD to the fundus; this often entails dropping the hand significantly and guiding the IUD much more anteriorly than first expected.

7. Release the IUD with forceps wide open, sweeping the forceps to one side to avoid pulling the IUD out with the forceps. 8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

Troubleshooting tips:

- If you are unable to visualize the anterior cervix, try to place the ring forceps by palpation.

- If you are unable to grasp the cervix with ring forceps by palpation, you may try to place the IUD manually. Hold the IUD between the first and second fingers of the right hand and place the IUD at the fundus. Release the IUD with the fingers wide open and remove the hand without removing the IUD.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after cesarean birth

1. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta.

2. For levonorgestrel IUDs: Remove the IUD from the inserter. Cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm. Place the IUD at the fundus with a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

3. For copper IUDs: String trimming is not necessary. Place the IUD at the fundus with the IUD inserter or a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

4. Repair the hysterotomy as usual.

Evidence-based education about long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) for women in the postpartum period can result in the increased continuation of and satisfaction with LARC.1 However, nearly 40% of women do not attend a postpartum visit.2 And up to 57% of women report having unprotected intercourse before the 6-week postpartum visit, which increases the risk of unplanned pregnancy.3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) supports immediate postpartum LARC insertion as best practice,3 and clinicians providing care for women during the peripartum period can counsel women regarding informed contraceptive decisions and provide guidance regarding both short-acting contraception and LARC.1

Immediate postpartum LARC, using intrauterine devices (IUDs) in particular, has been used around the world for a long time, says Lisa Hofler, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief in the Division of Family Planning at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque. “Much of our initial data came from other countries, but eventually people in the United States said, ‘This is a great option, why aren't we doing this?’" In addition, although women considering immediate postpartum LARC should be counseled about the theoretical risk of reduced duration of breastfeeding, the evidence overwhelmingly has not shown a negative effect on actual breastfeeding outcomes according to ACOG.3 OBG MANAGEMENT recently met up with Dr. Hofler to ask her which patients are ideal for postpartum LARC, how to troubleshoot common pitfalls, and how to implement the practice within one’s own institution.

OBG Management: Who do you consider to be the ideal patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Lisa Hofler, MD: The great thing about immediate postpartum LARC (including IUDs and implants) is that any woman is an ideal candidate. We are simply talking about the timing of when a woman chooses to get an IUD or an implant after the birth of her child. There is no one perfect woman; it is the person who chooses the method and wants to use that method immediately after birth. When a woman chooses a LARC, she can be assured that after the birth of her child she will be protected against pregnancy. If she chooses an IUD as her LARC method, she will be comfortable at insertion because the cervix is already dilated when it is inserted.

For the implant, the contraindications are the same as in the outpatient setting. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use covers many medical conditions and whether or not a person might be a candidate for different birth control methods.4 Those same considerations apply for the implant postpartum (TABLE).3

For the IUD, similarly, anyone who would not be a candidate for the IUD in the outpatient setting is not a candidate for immediate postpartum IUD. For instance, if the person has an intrauterine infection, you should not place an IUD. Also, if a patient is hemorrhaging and you are managing the hemorrhage (say she has retained placenta or membranes or she has uterine atony), you are not going to put an IUD in, as you need to attend to her bleeding.

OBG Management: What is your approach to counseling a patient for immediate postpartum LARC?

Dr. Hofler: The ideal time to counsel about postbirth contraception is in the prenatal period, when the patient is making decisions about what method she wants to use after the birth. Once she chooses her preferred method, address timing if appropriate. It is less ideal to talk to a woman about the option of immediate postpartum LARC when she comes to labor and delivery, especially if that is the first time she has heard about it. Certainly, the time to talk about postpartum LARC options is not immediately after the baby is born. Approaching your patient with, "What do you want for birth control? Do you want this IUD? I can put it in right now," can feel coercive. This approach does not put the woman in a position in which she has enough decision-making time or time to ask questions.

OBG Management: What problems do clinicians run into when placing an immediate postpartum IUD, and can you offer solutions?

Dr. Hofler: When placing an immediate postpartum IUD, people might run into a few problems. The first relates to preplacement counseling. Perhaps when making the plan for the postpartum IUD the clinician did not counsel the woman that there are certain conditions that could preclude IUD placement—such as intrauterine infection or postpartum hemorrhage. When dealing with those types of issues, a patient is not eligible for an IUD, and she should be mentally prepared for this type of situation. Let her know during the counseling before the birth that immediately postpartum is a great time and opportunity for effective contraception placement. Tell her that hopefully IUD placement will be possible but that occasionally it is not, and make a back-up plan in case the IUD cannot be placed immediately postpartum.

The second unique area for counseling with immediate postpartum IUDs is a slightly increased risk of expulsion of an IUD placed immediately postpartum compared with in the office. The risk of expulsion varies by type of delivery. For instance, cesarean delivery births have a lower expulsion rate than vaginal births. The expulsion rate seems to vary by type of IUD as well. Copper IUDs seem to have a slightly lower expulsion rate than hormonal IUDs. (See “Levonorgestrel vs copper IUD expulsion rates after immediate postpartum insertion.”) This consideration should be talked about ahead of time, too. Provider training in IUD placement does impact the likelihood of expulsion, and if you place the IUD at the fundus, it is less likely to expel. (See “Inserting the immediate postpartum IUD after vaginal and cesarean birth step by step.”)

A third issue that clinicians run into is actually the systems of care—making sure that the IUD or implant is available when you need it, making sure that documentation happens the way it should, and ensuring that the follow-up billing and revenue cycle happens so that the woman gets the device that she wants and the providers get paid for having provided it. These issues require a multidisciplinary team to work through in order to ensure that postpartum LARC placement is a sustainable process in the long run.

Often, when people think of immediate postpartum LARC they think of postplacental IUDs. However, an implant also is an option, and that too is immediate postpartum LARC. Placing an implant is often a lot easier to do after the birth than placing an IUD. As clinicians work toward bringing an immediate postpartum LARC program to their hospital system, starting with implants is a smart thing to do because clinicians do not have to learn or teach new clinical skills. Because of that, immediate postpartum implants are a good troubleshooting mechanism for opening up the conversation about immediate postpartum LARC at your institution.

OBG MANAGEMENT: What advice do you have for administrators or physicians looking to implement an immediate postpartum LARC program into a hospital setting?

Dr. Hofler: Probably the best single resource is the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Postpartum Contraception Access Initiative (PCAI). They have a dedicated website and offer a lot of support and resources that include site-specific training at the hospital or the institution; clinician training on implants and IUDs; and administrator training on some of the systems of care, the billing process, the stocking process, and pharmacy education. They also provide information on all the things that should be included beyond the clinical aspects. I strongly recommend looking at what they offer.

Also, because many hospitals say, "We love this idea. We would support immediate postpartum LARC, we just want to make sure we get paid," the ACOG LARC Program website includes state-specific guidance for how Medicaid pays for LARC devices. There is state-specific guidance about how the device payment can be separated from the global payment for delivery—specific things for each institution to do to get reimbursed.

A 2017 prospective cohort study was the first to directly compare expulsion rates of the levonorgestrel (LNG) intrauterine device (IUD) and the copper IUD placed postplacentally (within 10 minutes of placental delivery). The study investigators found that, among 96 women at 12 weeks, 38% of the LNG-IUD users and 20% of the copper IUD users experienced IUD expulsion (odds ratio, 2.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.99-6.55; P = .05). Women were aged 18 to 40 and had a singleton vaginal delivery at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation.1 The two study groups were similar except that more copper IUD users were Hispanic (66% vs 38%) and fewer were primiparous (16% vs 31%). The study authors found the only independent predictor of device expulsion to be IUD type.

In a 2019 prospective cohort study, Hinz and colleagues compared the 6-month expulsion rate of IUDs inserted in the immediate postpartum period (within 10 to 15 minutes of placental delivery) after vaginal or cesarean delivery.2 Women were aged 18 to 45 years and selected a LNG 52-mg IUD (75 women) or copper IUD (58 women) for postpartum contraception. They completed a survey from weeks 0 to 5 and on weeks 12 and 24 postpartum regarding IUD expulsion, IUD removal, vaginal bleeding, and breastfeeding. A total of 58 women had a vaginal delivery, and 56 had a cesarean delivery.

At 6 months, the expulsion rates were similar in the two groups: 26.7% of the LNG IUDs expelled, compared with 20.5% of the copper IUDs (P = .38). The study groups were similar, point out the study investigators, except that the copper IUD users had a higher median parity (3 vs. 2; P = .03). In addition, the copper IUDs were inserted by more senior than junior residents (46.2% vs 22.7%, P = .02).

A 2018 systematic review pooled absolute rates of IUD expulsion and estimated adjusted relative risk (RR) for IUD type. A total of 48 studies (rated level I to II-3 of poor to good quality) were included in the analysis, and results indicated that the LNG-IUD was associated with a higher risk of expulsion at less than 4 weeks postpartum than the copper IUD (adjusted RR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.50-2.43).3

References

1. Goldthwaite LM, Sheeder J, Hyer J, et al. Postplacental intrauterine device expulsion by 12 weeks: a prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217:674.e1-674.e8.

2. Hinz EK, Murthy A, Wang B, Ryan N, Ades V. A prospective cohort study comparing expulsion after postplacental insertion: the levonorgestrel versus the copper intrauterine device. Contraception. May 17, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2019.04.011.

3. Jatlaoui TC, Whiteman MK, Jeng G, et al. Intrauterine device expulsion after postpartum placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2018:895-905.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after vaginal birth

1. Bring supplies for intrauterine device (IUD) insertion: the IUD, posterior blade of a speculum or retractor for posterior vagina, ring forceps, curved Kelly placenta forceps, and scissors.

2. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta. Any perineal lacerations should be repaired after IUD placement.

3. Break down the bed to facilitate placement. If the perineum or vagina is soiled with stool or meconium then consider povodine-iodine prep.

4. Place the posterior blade of the speculum into the vagina and grasp the anterior cervix with the ring forceps.

5. Set up the IUD for insertion: Change into new sterile gloves. Remove the IUD from the inserter. For levonorgestrel IUDs, cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm; copper IUDs do not need strings trimmed. Hold one arm of the IUD with the long Kelly placenta forceps so that the stem of the IUD is approximately parallel to the shaft of the forceps.

6. Insert the IUD: Guide the IUD into the lower uterine segment with the left hand on the cervix ring forceps and the right hand on the IUD forceps. After passing the IUD through the cervix, move the left hand to the abdomen and press the fundus posterior and caudad to straighten the endometrial canal and to feel the IUD at the fundus. With the right hand, guide the IUD to the fundus; this often entails dropping the hand significantly and guiding the IUD much more anteriorly than first expected.

7. Release the IUD with forceps wide open, sweeping the forceps to one side to avoid pulling the IUD out with the forceps. 8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

8. Consider use of ultrasound guidance and ultrasound verification of fundal location, especially when first performing postplacental IUD placements.

Troubleshooting tips:

- If you are unable to visualize the anterior cervix, try to place the ring forceps by palpation.

- If you are unable to grasp the cervix with ring forceps by palpation, you may try to place the IUD manually. Hold the IUD between the first and second fingers of the right hand and place the IUD at the fundus. Release the IUD with the fingers wide open and remove the hand without removing the IUD.

Technique for placing an IUD immediately after cesarean birth

1. Determine that the patient still wants the IUD and is still medically eligible for the IUD. Place the IUD as soon as possible following placenta delivery; in most studies IUD placement occurred within 10 minutes of the placenta.

2. For levonorgestrel IUDs: Remove the IUD from the inserter. Cut the strings so that the length of the IUD and strings together is approximately 10 to 12 cm. Place the IUD at the fundus with a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

3. For copper IUDs: String trimming is not necessary. Place the IUD at the fundus with the IUD inserter or a ring forceps and tuck the strings toward the cervix. It is not necessary to open the cervix or to place the strings through the cervix.

4. Repair the hysterotomy as usual.

1. Dole DM, Martin J. What nurses need to know about immediate postpartum initiation of long-acting reversible contraception. Nurs Womens Health. 2017;21:186-195.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Work Group. Practice Bulletin no. 186: long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-e269.

4. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-104.

1. Dole DM, Martin J. What nurses need to know about immediate postpartum initiation of long-acting reversible contraception. Nurs Womens Health. 2017;21:186-195.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 736: optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:e140-e150.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Work Group. Practice Bulletin no. 186: long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e251-e269.

4. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-104.

First-time fathers at risk of postnatal depressive symptoms

First-time fathers may be at risk of experiencing depressive symptoms as they transition to parenthood – especially if risk factors such as poor sleep are present, results of a prospective study of more than 600 new fathers show.

“Strategies to promote better sleep, mobilize social support, and strengthen the couple relationship may be important to address in innovative interventions tailored to new fathers at risk for depression during the perinatal period,” wrote Deborah Da Costa, PhD, of McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues. The study was published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

To determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms in first-time fathers and identify notable risk factors, the researchers surveyed 622 Canadian men during their partner’s third trimester. The same group was surveyed again at 2 and 6 months postpartum. Depression was assessed via the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), and additional variables such as sleep quality, social support, and stress were gathered as well.

Of the initial 622 men surveyed, 487 (78.3%) and 375 (60.3%) completed the questionnaires at 2 and 6 months postpartum, respectively. The prevalence of paternal depressive symptoms was 13.76% (95% confidence interval, 10.70-16.82) at 2 months and 13.6% (95% CI, 10.13-17.07) at 6 months. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 2 months postpartum, 40.3% also experienced symptoms during the third trimester. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 6 months postpartum, 24% experienced symptoms during the third trimester and after 2 months.

At 2 months, the risk of depressive symptoms increased for men with worse sleep quality (odds ratio, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.10-1.42), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99), and higher parenting stress (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.11). At 6 months, there was a significant association between paternal depressive symptoms and unemployment (OR, 3.75; 95% CI, 1.00-13.72), poorer sleep quality (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16-1.65), lower social support (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.84-1.00), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-0.98), and higher financial stress (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.04-1.42).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a middling response rate that could affect the accuracy of prevalence estimates and a well-educated, largely middle-class sample that could limit generalizability. In addition, they assessed depressive symptoms by self-report and not diagnostic clinical interviews. However, they also noted that “the EPDS is the most widely used tool to assess depressive symptoms in parents during the perinatal period and was validated in expectant and new fathers.”

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Da Costa D et al. J Affect Disord. 2019 Apr 15;249:371-7.

First-time fathers may be at risk of experiencing depressive symptoms as they transition to parenthood – especially if risk factors such as poor sleep are present, results of a prospective study of more than 600 new fathers show.

“Strategies to promote better sleep, mobilize social support, and strengthen the couple relationship may be important to address in innovative interventions tailored to new fathers at risk for depression during the perinatal period,” wrote Deborah Da Costa, PhD, of McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues. The study was published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

To determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms in first-time fathers and identify notable risk factors, the researchers surveyed 622 Canadian men during their partner’s third trimester. The same group was surveyed again at 2 and 6 months postpartum. Depression was assessed via the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), and additional variables such as sleep quality, social support, and stress were gathered as well.

Of the initial 622 men surveyed, 487 (78.3%) and 375 (60.3%) completed the questionnaires at 2 and 6 months postpartum, respectively. The prevalence of paternal depressive symptoms was 13.76% (95% confidence interval, 10.70-16.82) at 2 months and 13.6% (95% CI, 10.13-17.07) at 6 months. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 2 months postpartum, 40.3% also experienced symptoms during the third trimester. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 6 months postpartum, 24% experienced symptoms during the third trimester and after 2 months.

At 2 months, the risk of depressive symptoms increased for men with worse sleep quality (odds ratio, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.10-1.42), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99), and higher parenting stress (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.11). At 6 months, there was a significant association between paternal depressive symptoms and unemployment (OR, 3.75; 95% CI, 1.00-13.72), poorer sleep quality (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16-1.65), lower social support (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.84-1.00), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-0.98), and higher financial stress (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.04-1.42).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a middling response rate that could affect the accuracy of prevalence estimates and a well-educated, largely middle-class sample that could limit generalizability. In addition, they assessed depressive symptoms by self-report and not diagnostic clinical interviews. However, they also noted that “the EPDS is the most widely used tool to assess depressive symptoms in parents during the perinatal period and was validated in expectant and new fathers.”

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Da Costa D et al. J Affect Disord. 2019 Apr 15;249:371-7.

First-time fathers may be at risk of experiencing depressive symptoms as they transition to parenthood – especially if risk factors such as poor sleep are present, results of a prospective study of more than 600 new fathers show.

“Strategies to promote better sleep, mobilize social support, and strengthen the couple relationship may be important to address in innovative interventions tailored to new fathers at risk for depression during the perinatal period,” wrote Deborah Da Costa, PhD, of McGill University, Montreal, and colleagues. The study was published in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

To determine the prevalence of depressive symptoms in first-time fathers and identify notable risk factors, the researchers surveyed 622 Canadian men during their partner’s third trimester. The same group was surveyed again at 2 and 6 months postpartum. Depression was assessed via the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), and additional variables such as sleep quality, social support, and stress were gathered as well.

Of the initial 622 men surveyed, 487 (78.3%) and 375 (60.3%) completed the questionnaires at 2 and 6 months postpartum, respectively. The prevalence of paternal depressive symptoms was 13.76% (95% confidence interval, 10.70-16.82) at 2 months and 13.6% (95% CI, 10.13-17.07) at 6 months. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 2 months postpartum, 40.3% also experienced symptoms during the third trimester. Of the men who reported depressive symptoms at 6 months postpartum, 24% experienced symptoms during the third trimester and after 2 months.

At 2 months, the risk of depressive symptoms increased for men with worse sleep quality (odds ratio, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.10-1.42), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.94-0.99), and higher parenting stress (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02-1.11). At 6 months, there was a significant association between paternal depressive symptoms and unemployment (OR, 3.75; 95% CI, 1.00-13.72), poorer sleep quality (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16-1.65), lower social support (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.84-1.00), poorer couple relationship adjustment (OR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.92-0.98), and higher financial stress (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.04-1.42).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a middling response rate that could affect the accuracy of prevalence estimates and a well-educated, largely middle-class sample that could limit generalizability. In addition, they assessed depressive symptoms by self-report and not diagnostic clinical interviews. However, they also noted that “the EPDS is the most widely used tool to assess depressive symptoms in parents during the perinatal period and was validated in expectant and new fathers.”

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Da Costa D et al. J Affect Disord. 2019 Apr 15;249:371-7.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

FDA approves Gadavist for evaluation of supra-aortic, renal artery disease

The Food and Drug Administration has approved gadobutrol (Gadavist) injections, for use in conjunction with magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), to evaluate known or suspected supra-aortic or renal artery disease in adult and pediatric patients.

Approval was based on a pair of open-label, phase 3 studies in which the efficacy of gadobutrol was assessed, based on visualization and performance for distinguishing between normal and abnormal anatomy. MRA with gadobutrol improved visualization by 88%-98%, compared with unenhanced MRA, in which visualization was improved by 24%-82%. Sensitivity and specificity were noninferior to unenhanced MRA.

Gadobutrol was previously indicated for use in diagnostic MRI in both adults and children to detect areas with disrupted blood-brain barrier and/or abnormal vascularity of the central nervous system, and for MRI of the breast to assess the presence and extent of malignant breast disease. The safety profile in the two current trials matched data previously gathered, with the most common adverse events including headache, nausea, and dizziness.

“Until now, no contrast agents were FDA approved for use with MRA of the supra-aortic arteries. With FDA’s action, radiologists now have an approved MRA contrast agent to help visualize supra-aortic arteries in patients with known or suspected supra-aortic arterial disease, including conditions such as prior stroke or transient ischemic attack,” Elias Melhem, MD, chair of the department of diagnostic radiology and nuclear medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, said in the press release.

Find the full release on the Bayer website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved gadobutrol (Gadavist) injections, for use in conjunction with magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), to evaluate known or suspected supra-aortic or renal artery disease in adult and pediatric patients.

Approval was based on a pair of open-label, phase 3 studies in which the efficacy of gadobutrol was assessed, based on visualization and performance for distinguishing between normal and abnormal anatomy. MRA with gadobutrol improved visualization by 88%-98%, compared with unenhanced MRA, in which visualization was improved by 24%-82%. Sensitivity and specificity were noninferior to unenhanced MRA.

Gadobutrol was previously indicated for use in diagnostic MRI in both adults and children to detect areas with disrupted blood-brain barrier and/or abnormal vascularity of the central nervous system, and for MRI of the breast to assess the presence and extent of malignant breast disease. The safety profile in the two current trials matched data previously gathered, with the most common adverse events including headache, nausea, and dizziness.

“Until now, no contrast agents were FDA approved for use with MRA of the supra-aortic arteries. With FDA’s action, radiologists now have an approved MRA contrast agent to help visualize supra-aortic arteries in patients with known or suspected supra-aortic arterial disease, including conditions such as prior stroke or transient ischemic attack,” Elias Melhem, MD, chair of the department of diagnostic radiology and nuclear medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, said in the press release.

Find the full release on the Bayer website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved gadobutrol (Gadavist) injections, for use in conjunction with magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), to evaluate known or suspected supra-aortic or renal artery disease in adult and pediatric patients.

Approval was based on a pair of open-label, phase 3 studies in which the efficacy of gadobutrol was assessed, based on visualization and performance for distinguishing between normal and abnormal anatomy. MRA with gadobutrol improved visualization by 88%-98%, compared with unenhanced MRA, in which visualization was improved by 24%-82%. Sensitivity and specificity were noninferior to unenhanced MRA.

Gadobutrol was previously indicated for use in diagnostic MRI in both adults and children to detect areas with disrupted blood-brain barrier and/or abnormal vascularity of the central nervous system, and for MRI of the breast to assess the presence and extent of malignant breast disease. The safety profile in the two current trials matched data previously gathered, with the most common adverse events including headache, nausea, and dizziness.

“Until now, no contrast agents were FDA approved for use with MRA of the supra-aortic arteries. With FDA’s action, radiologists now have an approved MRA contrast agent to help visualize supra-aortic arteries in patients with known or suspected supra-aortic arterial disease, including conditions such as prior stroke or transient ischemic attack,” Elias Melhem, MD, chair of the department of diagnostic radiology and nuclear medicine at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, said in the press release.

Find the full release on the Bayer website.

Periodontal Inflammation in Patients with Migraine

Periodontal inflammation is associated with increased circulating levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in patients with chronic migraine, a new study found. The cohort included 102 chronic migraineurs and 77 age- and sex-matched individuals free of headache/migraine. Full-mouth periodontal parameters were recorded and the periodontal inflamed surface area (PISA) was calculated to quantify the periodontal inflammatory status for each participant. Researchers found:

- In the chronic migraine group, patients with periodontitis had greater levels of serum CGRP and IL-6, while nonsignificant differences were observed with IL-10 concentrations vs those without periodontitis.

- PISA was independently associated with CGRP in patients with chronic migraine.

Leira Y, et al. Periodontal inflammation is related to increased serum calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) levels in patients with chronic migraine. [Published online ahead of print May 9, 2019]. J Periodontol. doi: 10.1002/JPER.19-0051.

Periodontal inflammation is associated with increased circulating levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in patients with chronic migraine, a new study found. The cohort included 102 chronic migraineurs and 77 age- and sex-matched individuals free of headache/migraine. Full-mouth periodontal parameters were recorded and the periodontal inflamed surface area (PISA) was calculated to quantify the periodontal inflammatory status for each participant. Researchers found:

- In the chronic migraine group, patients with periodontitis had greater levels of serum CGRP and IL-6, while nonsignificant differences were observed with IL-10 concentrations vs those without periodontitis.

- PISA was independently associated with CGRP in patients with chronic migraine.

Leira Y, et al. Periodontal inflammation is related to increased serum calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) levels in patients with chronic migraine. [Published online ahead of print May 9, 2019]. J Periodontol. doi: 10.1002/JPER.19-0051.

Periodontal inflammation is associated with increased circulating levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in patients with chronic migraine, a new study found. The cohort included 102 chronic migraineurs and 77 age- and sex-matched individuals free of headache/migraine. Full-mouth periodontal parameters were recorded and the periodontal inflamed surface area (PISA) was calculated to quantify the periodontal inflammatory status for each participant. Researchers found:

- In the chronic migraine group, patients with periodontitis had greater levels of serum CGRP and IL-6, while nonsignificant differences were observed with IL-10 concentrations vs those without periodontitis.

- PISA was independently associated with CGRP in patients with chronic migraine.

Leira Y, et al. Periodontal inflammation is related to increased serum calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) levels in patients with chronic migraine. [Published online ahead of print May 9, 2019]. J Periodontol. doi: 10.1002/JPER.19-0051.

Dry Eye Symptoms in Individuals with Migraine

Individuals with migraine demonstrated a different dry eye (DE) symptom, yet a similar DE sign profile when compared with those without migraine, a new study found. The prospective cross-sectional study of individuals with DE symptoms evaluated symptoms and signs of DE, including symptoms suggestive of nerve dysfunction. Among the details:

- Of 250 individuals, 31 met International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria for migraine based on a validated screen.

- Those with migraine were significantly younger and more likely to be female vs controls.

- Individuals with migraine had more severe DE symptoms and ocular pain vs controls.

- DE symptoms in those with migraine may be driven by nerve dysfunction as opposed to ocular surface abnormalities.

Farhangi M, et al. Individuals with migraine have a different dry eye symptom profile than individuals without migraine. [Published online ahead of print April 30, 2019]. Br J Opthalmol. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313471.

Individuals with migraine demonstrated a different dry eye (DE) symptom, yet a similar DE sign profile when compared with those without migraine, a new study found. The prospective cross-sectional study of individuals with DE symptoms evaluated symptoms and signs of DE, including symptoms suggestive of nerve dysfunction. Among the details:

- Of 250 individuals, 31 met International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria for migraine based on a validated screen.

- Those with migraine were significantly younger and more likely to be female vs controls.

- Individuals with migraine had more severe DE symptoms and ocular pain vs controls.

- DE symptoms in those with migraine may be driven by nerve dysfunction as opposed to ocular surface abnormalities.

Farhangi M, et al. Individuals with migraine have a different dry eye symptom profile than individuals without migraine. [Published online ahead of print April 30, 2019]. Br J Opthalmol. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313471.

Individuals with migraine demonstrated a different dry eye (DE) symptom, yet a similar DE sign profile when compared with those without migraine, a new study found. The prospective cross-sectional study of individuals with DE symptoms evaluated symptoms and signs of DE, including symptoms suggestive of nerve dysfunction. Among the details:

- Of 250 individuals, 31 met International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria for migraine based on a validated screen.

- Those with migraine were significantly younger and more likely to be female vs controls.

- Individuals with migraine had more severe DE symptoms and ocular pain vs controls.

- DE symptoms in those with migraine may be driven by nerve dysfunction as opposed to ocular surface abnormalities.

Farhangi M, et al. Individuals with migraine have a different dry eye symptom profile than individuals without migraine. [Published online ahead of print April 30, 2019]. Br J Opthalmol. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313471.

Atypical Interactions of Cortical Networks in Chronic Migraine

Atypical Interactions of Cortical Networks in Chronic Migraine

The severity of headache is associated with opposite connectivity patterns in frontal executive and dorsal attentional networks in patients with chronic migraine, a new study found. Twenty patients with chronic migraine (CM) without preventive therapy, or acute medication overuse underwent 3T MRI scans and were compared to a group of 20 healthy controls (HC). Researchers used MRI to collect resting-state data in 3 selected networks, identified using group independent component analysis (ICA): the default mode network (DMN), the executive control network (ECN), and the dorsal attention system (DAS). They found:

- Compared to HC, patients with CM had significantly reduced functional connectivity between the DMN and the ECN.

- The DAS showed significantly stronger functional connectivity (FC) with the DMN and weaker FC with the ECN.

- The higher the severity of the headache, the increased strength of DAD connectivity, and the lower the strength of the ECN connectivity.

Coppola G, et al. Aberrant interactions of cortical networks in chronic migraine: A resting-state fMRI study. [Published online ahead of print May 28, 2019]. Neurology. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007577.

Atypical Interactions of Cortical Networks in Chronic Migraine

The severity of headache is associated with opposite connectivity patterns in frontal executive and dorsal attentional networks in patients with chronic migraine, a new study found. Twenty patients with chronic migraine (CM) without preventive therapy, or acute medication overuse underwent 3T MRI scans and were compared to a group of 20 healthy controls (HC). Researchers used MRI to collect resting-state data in 3 selected networks, identified using group independent component analysis (ICA): the default mode network (DMN), the executive control network (ECN), and the dorsal attention system (DAS). They found:

- Compared to HC, patients with CM had significantly reduced functional connectivity between the DMN and the ECN.

- The DAS showed significantly stronger functional connectivity (FC) with the DMN and weaker FC with the ECN.

- The higher the severity of the headache, the increased strength of DAD connectivity, and the lower the strength of the ECN connectivity.

Coppola G, et al. Aberrant interactions of cortical networks in chronic migraine: A resting-state fMRI study. [Published online ahead of print May 28, 2019]. Neurology. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007577.

Atypical Interactions of Cortical Networks in Chronic Migraine

The severity of headache is associated with opposite connectivity patterns in frontal executive and dorsal attentional networks in patients with chronic migraine, a new study found. Twenty patients with chronic migraine (CM) without preventive therapy, or acute medication overuse underwent 3T MRI scans and were compared to a group of 20 healthy controls (HC). Researchers used MRI to collect resting-state data in 3 selected networks, identified using group independent component analysis (ICA): the default mode network (DMN), the executive control network (ECN), and the dorsal attention system (DAS). They found:

- Compared to HC, patients with CM had significantly reduced functional connectivity between the DMN and the ECN.

- The DAS showed significantly stronger functional connectivity (FC) with the DMN and weaker FC with the ECN.

- The higher the severity of the headache, the increased strength of DAD connectivity, and the lower the strength of the ECN connectivity.

Coppola G, et al. Aberrant interactions of cortical networks in chronic migraine: A resting-state fMRI study. [Published online ahead of print May 28, 2019]. Neurology. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007577.

The expert trap

When you fly as a physician, there’s always a chance you’ll get a free drink. It’s not free, of course. For at least a few minutes, you worked. “Is there a physician onboard? – Ah, just how badly do you want that vodka tonic?

I ring my call button, as I’m sure you do. (It’s worth it to see the flight attendant’s face when I reply: “I’m a dermatologist.”) Last time it was for a 68-year-old man who was vomiting. There was no rash.

I responded along with a pediatrician and an ER nurse – gratitude is an ER nurse at 38,000 feet. The patient had chemotherapy-induced nausea. We three managed to get him well enough to finish the flight. Our ER nurse team member ran the show; she was excellent. She asked all the right questions and helped us all make good decisions. Unlike in clinic, I wasn’t an expert here despite my MD.

Several weeks ago, I saw a patient in the office with severe psoriasis. She stood before me erythrodermic. As I was adjusting her orders, I stepped out of the office to call one of my partners for her opinion. She examined the patient and declared: “I don’t think it’s psoriasis. Despite that biopsy, I think this is chronic eczema.” Brilliant.

In contrast to the former story, I was an expert in my office. And yet, success depended in both instances on my recognizing a cognitive bias: I don’t know everything, and worse, I sometimes don’t realize what I don’t know.

. It’s a common mistake and manifests as overconfidence in our own abilities. For example, what decade did Hawaii join the union? Who is on the 20-dollar bill? Which is the farthest planet? You might be 90% confident of your answers, but most of us are more confident than we ought to be. Chances are you’ll be wrong on one. Recognizing this is hard. And yet, it’s what separates the good from the great clinicians.

Short of having your medical assistant whisper in your ear each day “Memento stultus” (remember you’re stupid), avoiding this bias is difficult. Signs that you might be trapped in an expert mindset are: 1. You believe your patients’ failure to improve is due to lack of adherence to your plan. 2. You cannot recall the last time you tried a new treatment. 3. You never ask others for second opinions. 4. Your colleagues stop asking for your opinion. 5. A flight attendant asks if you would mind returning to your seat rather than help with a medical situation.

If you want to be a better doctor, try working on your sense of self-importance. Remember your limitations and those of medicine. Be methodical in questioning your assumptions. Could you be wrong? Could the data you have be misleading? What are you missing? Ask a colleague to review some of your charts or spend time with you during procedures. Join (or start!) a journal club. Share your difficult cases with others and take note of how their advice differs from your approach.

By recognizing when you might be wrong and humbly stepping aside or taking the time to learn, you might just earn that free drink.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

When you fly as a physician, there’s always a chance you’ll get a free drink. It’s not free, of course. For at least a few minutes, you worked. “Is there a physician onboard? – Ah, just how badly do you want that vodka tonic?

I ring my call button, as I’m sure you do. (It’s worth it to see the flight attendant’s face when I reply: “I’m a dermatologist.”) Last time it was for a 68-year-old man who was vomiting. There was no rash.

I responded along with a pediatrician and an ER nurse – gratitude is an ER nurse at 38,000 feet. The patient had chemotherapy-induced nausea. We three managed to get him well enough to finish the flight. Our ER nurse team member ran the show; she was excellent. She asked all the right questions and helped us all make good decisions. Unlike in clinic, I wasn’t an expert here despite my MD.

Several weeks ago, I saw a patient in the office with severe psoriasis. She stood before me erythrodermic. As I was adjusting her orders, I stepped out of the office to call one of my partners for her opinion. She examined the patient and declared: “I don’t think it’s psoriasis. Despite that biopsy, I think this is chronic eczema.” Brilliant.

In contrast to the former story, I was an expert in my office. And yet, success depended in both instances on my recognizing a cognitive bias: I don’t know everything, and worse, I sometimes don’t realize what I don’t know.

. It’s a common mistake and manifests as overconfidence in our own abilities. For example, what decade did Hawaii join the union? Who is on the 20-dollar bill? Which is the farthest planet? You might be 90% confident of your answers, but most of us are more confident than we ought to be. Chances are you’ll be wrong on one. Recognizing this is hard. And yet, it’s what separates the good from the great clinicians.

Short of having your medical assistant whisper in your ear each day “Memento stultus” (remember you’re stupid), avoiding this bias is difficult. Signs that you might be trapped in an expert mindset are: 1. You believe your patients’ failure to improve is due to lack of adherence to your plan. 2. You cannot recall the last time you tried a new treatment. 3. You never ask others for second opinions. 4. Your colleagues stop asking for your opinion. 5. A flight attendant asks if you would mind returning to your seat rather than help with a medical situation.

If you want to be a better doctor, try working on your sense of self-importance. Remember your limitations and those of medicine. Be methodical in questioning your assumptions. Could you be wrong? Could the data you have be misleading? What are you missing? Ask a colleague to review some of your charts or spend time with you during procedures. Join (or start!) a journal club. Share your difficult cases with others and take note of how their advice differs from your approach.

By recognizing when you might be wrong and humbly stepping aside or taking the time to learn, you might just earn that free drink.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected].

When you fly as a physician, there’s always a chance you’ll get a free drink. It’s not free, of course. For at least a few minutes, you worked. “Is there a physician onboard? – Ah, just how badly do you want that vodka tonic?

I ring my call button, as I’m sure you do. (It’s worth it to see the flight attendant’s face when I reply: “I’m a dermatologist.”) Last time it was for a 68-year-old man who was vomiting. There was no rash.

I responded along with a pediatrician and an ER nurse – gratitude is an ER nurse at 38,000 feet. The patient had chemotherapy-induced nausea. We three managed to get him well enough to finish the flight. Our ER nurse team member ran the show; she was excellent. She asked all the right questions and helped us all make good decisions. Unlike in clinic, I wasn’t an expert here despite my MD.

Several weeks ago, I saw a patient in the office with severe psoriasis. She stood before me erythrodermic. As I was adjusting her orders, I stepped out of the office to call one of my partners for her opinion. She examined the patient and declared: “I don’t think it’s psoriasis. Despite that biopsy, I think this is chronic eczema.” Brilliant.

In contrast to the former story, I was an expert in my office. And yet, success depended in both instances on my recognizing a cognitive bias: I don’t know everything, and worse, I sometimes don’t realize what I don’t know.

. It’s a common mistake and manifests as overconfidence in our own abilities. For example, what decade did Hawaii join the union? Who is on the 20-dollar bill? Which is the farthest planet? You might be 90% confident of your answers, but most of us are more confident than we ought to be. Chances are you’ll be wrong on one. Recognizing this is hard. And yet, it’s what separates the good from the great clinicians.

Short of having your medical assistant whisper in your ear each day “Memento stultus” (remember you’re stupid), avoiding this bias is difficult. Signs that you might be trapped in an expert mindset are: 1. You believe your patients’ failure to improve is due to lack of adherence to your plan. 2. You cannot recall the last time you tried a new treatment. 3. You never ask others for second opinions. 4. Your colleagues stop asking for your opinion. 5. A flight attendant asks if you would mind returning to your seat rather than help with a medical situation.

If you want to be a better doctor, try working on your sense of self-importance. Remember your limitations and those of medicine. Be methodical in questioning your assumptions. Could you be wrong? Could the data you have be misleading? What are you missing? Ask a colleague to review some of your charts or spend time with you during procedures. Join (or start!) a journal club. Share your difficult cases with others and take note of how their advice differs from your approach.