User login

FDA approves pembrolizumab/lenvatinib combo for advanced endometrial carcinoma

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to a pembrolizumab (Keytruda) plus lenvatinib (Lenvima) combination for the treatment of patients with advanced endometrial carcinoma that is not microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair deficient, and who have disease progression following prior systemic therapy but are not candidates for curative surgery or radiation.

The approval was based on results of KEYNOTE-146, a single-arm, multicenter, open-label, multicohort trial with 108 patients with metastatic endometrial carcinoma; 94 of these were not microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair deficient. The objective response rate in those 94 patients was 38.3% (95% confidence interval, 29%-49%), with 10 complete responses and 26 partial responses. The median duration of response was not reached over the trial period, and 69% of those who responded had a response duration of at least 6 months.

The most common adverse events reported during the trial were fatigue, hypertension, musculoskeletal pain, diarrhea, decreased appetite, hypothyroidism, nausea, stomatitis, vomiting, decreased weight, abdominal pain, headache, constipation, urinary tract infection, dysphonia, hemorrhagic events, hypomagnesemia, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, dyspnea, cough, and rash.

The recommended dosage is lenvatinib 20 mg orally once daily with pembrolizumab 200 mg administered as an intravenous infusion over 30 minutes every 3 weeks, according to the FDA.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to a pembrolizumab (Keytruda) plus lenvatinib (Lenvima) combination for the treatment of patients with advanced endometrial carcinoma that is not microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair deficient, and who have disease progression following prior systemic therapy but are not candidates for curative surgery or radiation.

The approval was based on results of KEYNOTE-146, a single-arm, multicenter, open-label, multicohort trial with 108 patients with metastatic endometrial carcinoma; 94 of these were not microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair deficient. The objective response rate in those 94 patients was 38.3% (95% confidence interval, 29%-49%), with 10 complete responses and 26 partial responses. The median duration of response was not reached over the trial period, and 69% of those who responded had a response duration of at least 6 months.

The most common adverse events reported during the trial were fatigue, hypertension, musculoskeletal pain, diarrhea, decreased appetite, hypothyroidism, nausea, stomatitis, vomiting, decreased weight, abdominal pain, headache, constipation, urinary tract infection, dysphonia, hemorrhagic events, hypomagnesemia, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, dyspnea, cough, and rash.

The recommended dosage is lenvatinib 20 mg orally once daily with pembrolizumab 200 mg administered as an intravenous infusion over 30 minutes every 3 weeks, according to the FDA.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted accelerated approval to a pembrolizumab (Keytruda) plus lenvatinib (Lenvima) combination for the treatment of patients with advanced endometrial carcinoma that is not microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair deficient, and who have disease progression following prior systemic therapy but are not candidates for curative surgery or radiation.

The approval was based on results of KEYNOTE-146, a single-arm, multicenter, open-label, multicohort trial with 108 patients with metastatic endometrial carcinoma; 94 of these were not microsatellite instability high or mismatch repair deficient. The objective response rate in those 94 patients was 38.3% (95% confidence interval, 29%-49%), with 10 complete responses and 26 partial responses. The median duration of response was not reached over the trial period, and 69% of those who responded had a response duration of at least 6 months.

The most common adverse events reported during the trial were fatigue, hypertension, musculoskeletal pain, diarrhea, decreased appetite, hypothyroidism, nausea, stomatitis, vomiting, decreased weight, abdominal pain, headache, constipation, urinary tract infection, dysphonia, hemorrhagic events, hypomagnesemia, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, dyspnea, cough, and rash.

The recommended dosage is lenvatinib 20 mg orally once daily with pembrolizumab 200 mg administered as an intravenous infusion over 30 minutes every 3 weeks, according to the FDA.

Rivaroxaban bests combo therapy in post-PCI AFib

PARIS – Rivaroxaban monotherapy bested combination therapy with rivaroxaban and an antiplatelet agent for patients with atrial fibrillation and stable coronary artery disease, with significantly more deaths and bleeding events seen with combination therapy.

The pronounced imbalance in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (the hazard ratio favoring rivaroxaban monotherapy was 9.72) came as a surprise, and led to early cessation of the multisite Japanese trial, lead investigator Satoshi Yasuda, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Several previous clinical trials had studied a reduced antithrombotic regimen for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), said Dr. Yasuda, professor of medicine at Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan. Current guidelines recommend triple therapy with an oral anticoagulant plus aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor for the shortest duration possible, with combination therapy of an anticoagulant plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for up to 12 months. Once the 1-year post-PCI mark is reached, current European and American guidelines or consensus documents recommend monotherapy with an oral anticoagulant if AFib persists and the patient has stable coronary artery disease (CAD), explained Dr. Yasuda. “However, this approach has yet to be supported by evidence from randomized, controlled trials,” he said, adding “substantial numbers of patients in this situation continue to be treated with combination therapy, which indicates a gap between guidelines and clinical practice.”

The Atrial Fibrillation and Ischemic events with Rivaroxaban in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease Study (AFIRE), he said, was designed to address this practice gap, randomizing 2,200 individuals to receive monotherapy with rivaroxaban or combination therapy. A total of 1,973 patients completed follow-up.

Patients were included in the randomized, open-label, parallel-group trial if they had AFib and stable CAD and were more than 1 year out from revascularization, or if they had angiographically confirmed CAD that did not need revascularization. All 294 AFIRE study sites were in Japan.

The study’s primary endpoint for efficacy was a composite of stroke, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularization, and all-cause death.

Most of the patients (79%) were male, and the mean age was 74 years. About 70% of patients in each treatment arm had received prior PCI, and 11% had undergone previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

The monotherapy arm received rivaroxaban 10 or 15 mg once daily depending on renal status. Patients in the combination therapy arm received rivaroxaban, plus a single antiplatelet drug. This could be 81 or 100 mg aspirin daily, clopidogrel at 50 or 75 mg/day, or prasugrel at 2.5 or 3.5 mg/day.

On the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring committee, the trial was terminated about 3 months early because significantly more all-cause deaths were being seen in the combination therapy group, said Dr. Yasuda. In the end, patients were treated under the study protocol for a median 23 months and followed up for a median 24.1 months.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for the first occurrence of the composite efficacy endpoint showed that monotherapy had a rate of 4.14% per patient-year, while combination therapy had a rate of occurrence for the efficacy endpoint of 5.75% per patient-year.

These figures yielded a statistically significant hazard ratio (HR) of 9.72 favoring monotherapy (P less than .001) for the prespecified noninferiority endpoint. In a post hoc analysis, rivaroxaban monotherapy achieved superiority over dual therapy (P = .02).

Breaking down the composite efficacy endpoint into its constituents, deaths by any cause and cardiovascular deaths primarily drove the difference in treatment arms. Seventy-three patients in the combo therapy arm and 41 in the rivaroxaban arm died of any cause, and the cause of death was cardiovascular for 43 combination therapy patients and 26 monotherapy patients. This yielded HRs favoring rivaroxaban of 0.55 for all-cause mortality and 0.59 for cardiovascular deaths.

Hazard ratios for individual cardiovascular events were not statistically significantly different between treatment arms, except for hemorrhagic stroke, which was seen in 13 patients receiving dual therapy and 4 receiving rivaroxaban alone, for a hazard ratio of 0.30.

Rivaroxaban monotherapy also bested dual therapy in safety: The HR was 0.59 for the incidence of a major bleed on rivaroxaban versus combination therapy, using International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis–established criteria for major bleeding. In the dual therapy arm, 58 individuals experienced major bleeding – the study’s primary safety endpoint – compared with 35 in the monotherapy arm, for a hazard ratio of 0.59; nonmajor bleeding occurred in 198 dual therapy patients and 121 monotherapy patients, yielding a hazard ratio of 0.58.

The Kaplan-Meier estimate for major bleeding on monotherapy was 1.62% per patient-year, compared with 2.76% per patient-year for those on combination therapy. These findings, said Dr. Yasuda, were “generally” consistent across prespecified subgroups that included participant stratification by age, sex, and bleeding risk, among others.

Dr. Yasuda acknowledged the many limitations of the trial. First, early termination introduced the possibility of overestimating the benefit of rivaroxaban monotherapy. Indeed, said Dr. Yasuda, “the reductions in rate of ischemic events and death from any cause with rivaroxaban monotherapy were unanticipated and are difficult to explain.”

Furthermore, the open-label trial design could be a source of bias and the use of both aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors for antiplatelet therapy “makes it uncertain whether the benefit of rivaroxaban monotherapy applies equally to the two combination regimens,” said Dr. Yasuda.

Rivaroxaban dosing in AFIRE was tailored to the Japanese study population, noted Dr. Yasuda. This means that the study is not immediately generalizable to non-Asian populations, needing replication before fully closing the knowledge gap about best long-term management of patients with AFib and stable CAD in the United States and Western Europe.

However, Dr. Yasuda pointed out, serum rivaroxaban levels in Japanese patients taking the 10- or 15-mg dose are generally similar to those seen in white patients taking a 20-mg rivaroxaban dose.

Freek Verheugt, MD, of Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis Hospital, Amsterdam, was the discussant for the presentation. He raised an additional concern: “East Asian patients are poor metabolizers of clopidogrel, which may have resulted also in underestimation of bleeding.” He cautioned that the AFIRE results may not be applicable to patients on a novel anticoagulant other than clopidogrel, or on vitamin K antagonists.

In his detailed critique of the AFIRE results, Dr. Verheugt cited the OAC ALONE trial, which used a similar study design and was also conducted in Japan. For OAC ALONE, Dr. Verheugt pointed out that “You can see ... that it was not harmful in this 700-patient study to stop aspirin therapy 1 year after an intervention.” However, he said, “the net clinical benefit is not very different, either” between treatment arms in the OAC ALONE trial. “Given the low number of patients and the low number of events, this trial was not conclusive whatsoever” he added, so AFIRE’s findings were needed.

The safety data from AFIRE, with a study population triple that of OAC ALONE, makes the safety argument for monotherapy “a very easy winner,” said Dr. Verheugt.

Dr. Verheugt was not mystified by the lower all-cause and cardiovascular death rate in the monotherapy group. “What are the mechanisms that if you stop antiplatelet therapy you have a better ischemic outcome? How come?” asked Dr. Verheugt.

“Very likely, it is the bleeding ... that you prevent if you stop antiplatelet therapy,” he said, adding that it’s known from previous studies in individuals with acute coronary syndromes and AFib that “bleeding is correlated with mortality, and that’s also proven here.”

Though Dr. Verheugt joined Dr. Yasuda in calling for replication of the results in a non-Asian population, he concurred that the AFIRE results validate current practice for anticoagulation in AFib with stable CAD. “Stopping at 1 year is safer than continuation and, most of all, it saves lives,” he said.

Full results of AFIRE were published online at the time of Dr. Yasuda’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904143).

The study was funded by the Japanese Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Dr. Yasuda reported financial relationships with Abbott, Bristol-Myers, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Takeda. Dr. Verheugt reported financial relationships with BayerHealthcare, BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Daiichi-Sankyo.

SOURCE: Yasuda S. et al. ESC 2019, Hot Line Session 3, Abstract 3175.

PARIS – Rivaroxaban monotherapy bested combination therapy with rivaroxaban and an antiplatelet agent for patients with atrial fibrillation and stable coronary artery disease, with significantly more deaths and bleeding events seen with combination therapy.

The pronounced imbalance in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (the hazard ratio favoring rivaroxaban monotherapy was 9.72) came as a surprise, and led to early cessation of the multisite Japanese trial, lead investigator Satoshi Yasuda, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Several previous clinical trials had studied a reduced antithrombotic regimen for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), said Dr. Yasuda, professor of medicine at Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan. Current guidelines recommend triple therapy with an oral anticoagulant plus aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor for the shortest duration possible, with combination therapy of an anticoagulant plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for up to 12 months. Once the 1-year post-PCI mark is reached, current European and American guidelines or consensus documents recommend monotherapy with an oral anticoagulant if AFib persists and the patient has stable coronary artery disease (CAD), explained Dr. Yasuda. “However, this approach has yet to be supported by evidence from randomized, controlled trials,” he said, adding “substantial numbers of patients in this situation continue to be treated with combination therapy, which indicates a gap between guidelines and clinical practice.”

The Atrial Fibrillation and Ischemic events with Rivaroxaban in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease Study (AFIRE), he said, was designed to address this practice gap, randomizing 2,200 individuals to receive monotherapy with rivaroxaban or combination therapy. A total of 1,973 patients completed follow-up.

Patients were included in the randomized, open-label, parallel-group trial if they had AFib and stable CAD and were more than 1 year out from revascularization, or if they had angiographically confirmed CAD that did not need revascularization. All 294 AFIRE study sites were in Japan.

The study’s primary endpoint for efficacy was a composite of stroke, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularization, and all-cause death.

Most of the patients (79%) were male, and the mean age was 74 years. About 70% of patients in each treatment arm had received prior PCI, and 11% had undergone previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

The monotherapy arm received rivaroxaban 10 or 15 mg once daily depending on renal status. Patients in the combination therapy arm received rivaroxaban, plus a single antiplatelet drug. This could be 81 or 100 mg aspirin daily, clopidogrel at 50 or 75 mg/day, or prasugrel at 2.5 or 3.5 mg/day.

On the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring committee, the trial was terminated about 3 months early because significantly more all-cause deaths were being seen in the combination therapy group, said Dr. Yasuda. In the end, patients were treated under the study protocol for a median 23 months and followed up for a median 24.1 months.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for the first occurrence of the composite efficacy endpoint showed that monotherapy had a rate of 4.14% per patient-year, while combination therapy had a rate of occurrence for the efficacy endpoint of 5.75% per patient-year.

These figures yielded a statistically significant hazard ratio (HR) of 9.72 favoring monotherapy (P less than .001) for the prespecified noninferiority endpoint. In a post hoc analysis, rivaroxaban monotherapy achieved superiority over dual therapy (P = .02).

Breaking down the composite efficacy endpoint into its constituents, deaths by any cause and cardiovascular deaths primarily drove the difference in treatment arms. Seventy-three patients in the combo therapy arm and 41 in the rivaroxaban arm died of any cause, and the cause of death was cardiovascular for 43 combination therapy patients and 26 monotherapy patients. This yielded HRs favoring rivaroxaban of 0.55 for all-cause mortality and 0.59 for cardiovascular deaths.

Hazard ratios for individual cardiovascular events were not statistically significantly different between treatment arms, except for hemorrhagic stroke, which was seen in 13 patients receiving dual therapy and 4 receiving rivaroxaban alone, for a hazard ratio of 0.30.

Rivaroxaban monotherapy also bested dual therapy in safety: The HR was 0.59 for the incidence of a major bleed on rivaroxaban versus combination therapy, using International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis–established criteria for major bleeding. In the dual therapy arm, 58 individuals experienced major bleeding – the study’s primary safety endpoint – compared with 35 in the monotherapy arm, for a hazard ratio of 0.59; nonmajor bleeding occurred in 198 dual therapy patients and 121 monotherapy patients, yielding a hazard ratio of 0.58.

The Kaplan-Meier estimate for major bleeding on monotherapy was 1.62% per patient-year, compared with 2.76% per patient-year for those on combination therapy. These findings, said Dr. Yasuda, were “generally” consistent across prespecified subgroups that included participant stratification by age, sex, and bleeding risk, among others.

Dr. Yasuda acknowledged the many limitations of the trial. First, early termination introduced the possibility of overestimating the benefit of rivaroxaban monotherapy. Indeed, said Dr. Yasuda, “the reductions in rate of ischemic events and death from any cause with rivaroxaban monotherapy were unanticipated and are difficult to explain.”

Furthermore, the open-label trial design could be a source of bias and the use of both aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors for antiplatelet therapy “makes it uncertain whether the benefit of rivaroxaban monotherapy applies equally to the two combination regimens,” said Dr. Yasuda.

Rivaroxaban dosing in AFIRE was tailored to the Japanese study population, noted Dr. Yasuda. This means that the study is not immediately generalizable to non-Asian populations, needing replication before fully closing the knowledge gap about best long-term management of patients with AFib and stable CAD in the United States and Western Europe.

However, Dr. Yasuda pointed out, serum rivaroxaban levels in Japanese patients taking the 10- or 15-mg dose are generally similar to those seen in white patients taking a 20-mg rivaroxaban dose.

Freek Verheugt, MD, of Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis Hospital, Amsterdam, was the discussant for the presentation. He raised an additional concern: “East Asian patients are poor metabolizers of clopidogrel, which may have resulted also in underestimation of bleeding.” He cautioned that the AFIRE results may not be applicable to patients on a novel anticoagulant other than clopidogrel, or on vitamin K antagonists.

In his detailed critique of the AFIRE results, Dr. Verheugt cited the OAC ALONE trial, which used a similar study design and was also conducted in Japan. For OAC ALONE, Dr. Verheugt pointed out that “You can see ... that it was not harmful in this 700-patient study to stop aspirin therapy 1 year after an intervention.” However, he said, “the net clinical benefit is not very different, either” between treatment arms in the OAC ALONE trial. “Given the low number of patients and the low number of events, this trial was not conclusive whatsoever” he added, so AFIRE’s findings were needed.

The safety data from AFIRE, with a study population triple that of OAC ALONE, makes the safety argument for monotherapy “a very easy winner,” said Dr. Verheugt.

Dr. Verheugt was not mystified by the lower all-cause and cardiovascular death rate in the monotherapy group. “What are the mechanisms that if you stop antiplatelet therapy you have a better ischemic outcome? How come?” asked Dr. Verheugt.

“Very likely, it is the bleeding ... that you prevent if you stop antiplatelet therapy,” he said, adding that it’s known from previous studies in individuals with acute coronary syndromes and AFib that “bleeding is correlated with mortality, and that’s also proven here.”

Though Dr. Verheugt joined Dr. Yasuda in calling for replication of the results in a non-Asian population, he concurred that the AFIRE results validate current practice for anticoagulation in AFib with stable CAD. “Stopping at 1 year is safer than continuation and, most of all, it saves lives,” he said.

Full results of AFIRE were published online at the time of Dr. Yasuda’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904143).

The study was funded by the Japanese Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Dr. Yasuda reported financial relationships with Abbott, Bristol-Myers, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Takeda. Dr. Verheugt reported financial relationships with BayerHealthcare, BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Daiichi-Sankyo.

SOURCE: Yasuda S. et al. ESC 2019, Hot Line Session 3, Abstract 3175.

PARIS – Rivaroxaban monotherapy bested combination therapy with rivaroxaban and an antiplatelet agent for patients with atrial fibrillation and stable coronary artery disease, with significantly more deaths and bleeding events seen with combination therapy.

The pronounced imbalance in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (the hazard ratio favoring rivaroxaban monotherapy was 9.72) came as a surprise, and led to early cessation of the multisite Japanese trial, lead investigator Satoshi Yasuda, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Several previous clinical trials had studied a reduced antithrombotic regimen for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), said Dr. Yasuda, professor of medicine at Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan. Current guidelines recommend triple therapy with an oral anticoagulant plus aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor for the shortest duration possible, with combination therapy of an anticoagulant plus a P2Y12 inhibitor for up to 12 months. Once the 1-year post-PCI mark is reached, current European and American guidelines or consensus documents recommend monotherapy with an oral anticoagulant if AFib persists and the patient has stable coronary artery disease (CAD), explained Dr. Yasuda. “However, this approach has yet to be supported by evidence from randomized, controlled trials,” he said, adding “substantial numbers of patients in this situation continue to be treated with combination therapy, which indicates a gap between guidelines and clinical practice.”

The Atrial Fibrillation and Ischemic events with Rivaroxaban in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease Study (AFIRE), he said, was designed to address this practice gap, randomizing 2,200 individuals to receive monotherapy with rivaroxaban or combination therapy. A total of 1,973 patients completed follow-up.

Patients were included in the randomized, open-label, parallel-group trial if they had AFib and stable CAD and were more than 1 year out from revascularization, or if they had angiographically confirmed CAD that did not need revascularization. All 294 AFIRE study sites were in Japan.

The study’s primary endpoint for efficacy was a composite of stroke, systemic embolism, myocardial infarction, unstable angina requiring revascularization, and all-cause death.

Most of the patients (79%) were male, and the mean age was 74 years. About 70% of patients in each treatment arm had received prior PCI, and 11% had undergone previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

The monotherapy arm received rivaroxaban 10 or 15 mg once daily depending on renal status. Patients in the combination therapy arm received rivaroxaban, plus a single antiplatelet drug. This could be 81 or 100 mg aspirin daily, clopidogrel at 50 or 75 mg/day, or prasugrel at 2.5 or 3.5 mg/day.

On the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring committee, the trial was terminated about 3 months early because significantly more all-cause deaths were being seen in the combination therapy group, said Dr. Yasuda. In the end, patients were treated under the study protocol for a median 23 months and followed up for a median 24.1 months.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for the first occurrence of the composite efficacy endpoint showed that monotherapy had a rate of 4.14% per patient-year, while combination therapy had a rate of occurrence for the efficacy endpoint of 5.75% per patient-year.

These figures yielded a statistically significant hazard ratio (HR) of 9.72 favoring monotherapy (P less than .001) for the prespecified noninferiority endpoint. In a post hoc analysis, rivaroxaban monotherapy achieved superiority over dual therapy (P = .02).

Breaking down the composite efficacy endpoint into its constituents, deaths by any cause and cardiovascular deaths primarily drove the difference in treatment arms. Seventy-three patients in the combo therapy arm and 41 in the rivaroxaban arm died of any cause, and the cause of death was cardiovascular for 43 combination therapy patients and 26 monotherapy patients. This yielded HRs favoring rivaroxaban of 0.55 for all-cause mortality and 0.59 for cardiovascular deaths.

Hazard ratios for individual cardiovascular events were not statistically significantly different between treatment arms, except for hemorrhagic stroke, which was seen in 13 patients receiving dual therapy and 4 receiving rivaroxaban alone, for a hazard ratio of 0.30.

Rivaroxaban monotherapy also bested dual therapy in safety: The HR was 0.59 for the incidence of a major bleed on rivaroxaban versus combination therapy, using International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis–established criteria for major bleeding. In the dual therapy arm, 58 individuals experienced major bleeding – the study’s primary safety endpoint – compared with 35 in the monotherapy arm, for a hazard ratio of 0.59; nonmajor bleeding occurred in 198 dual therapy patients and 121 monotherapy patients, yielding a hazard ratio of 0.58.

The Kaplan-Meier estimate for major bleeding on monotherapy was 1.62% per patient-year, compared with 2.76% per patient-year for those on combination therapy. These findings, said Dr. Yasuda, were “generally” consistent across prespecified subgroups that included participant stratification by age, sex, and bleeding risk, among others.

Dr. Yasuda acknowledged the many limitations of the trial. First, early termination introduced the possibility of overestimating the benefit of rivaroxaban monotherapy. Indeed, said Dr. Yasuda, “the reductions in rate of ischemic events and death from any cause with rivaroxaban monotherapy were unanticipated and are difficult to explain.”

Furthermore, the open-label trial design could be a source of bias and the use of both aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors for antiplatelet therapy “makes it uncertain whether the benefit of rivaroxaban monotherapy applies equally to the two combination regimens,” said Dr. Yasuda.

Rivaroxaban dosing in AFIRE was tailored to the Japanese study population, noted Dr. Yasuda. This means that the study is not immediately generalizable to non-Asian populations, needing replication before fully closing the knowledge gap about best long-term management of patients with AFib and stable CAD in the United States and Western Europe.

However, Dr. Yasuda pointed out, serum rivaroxaban levels in Japanese patients taking the 10- or 15-mg dose are generally similar to those seen in white patients taking a 20-mg rivaroxaban dose.

Freek Verheugt, MD, of Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis Hospital, Amsterdam, was the discussant for the presentation. He raised an additional concern: “East Asian patients are poor metabolizers of clopidogrel, which may have resulted also in underestimation of bleeding.” He cautioned that the AFIRE results may not be applicable to patients on a novel anticoagulant other than clopidogrel, or on vitamin K antagonists.

In his detailed critique of the AFIRE results, Dr. Verheugt cited the OAC ALONE trial, which used a similar study design and was also conducted in Japan. For OAC ALONE, Dr. Verheugt pointed out that “You can see ... that it was not harmful in this 700-patient study to stop aspirin therapy 1 year after an intervention.” However, he said, “the net clinical benefit is not very different, either” between treatment arms in the OAC ALONE trial. “Given the low number of patients and the low number of events, this trial was not conclusive whatsoever” he added, so AFIRE’s findings were needed.

The safety data from AFIRE, with a study population triple that of OAC ALONE, makes the safety argument for monotherapy “a very easy winner,” said Dr. Verheugt.

Dr. Verheugt was not mystified by the lower all-cause and cardiovascular death rate in the monotherapy group. “What are the mechanisms that if you stop antiplatelet therapy you have a better ischemic outcome? How come?” asked Dr. Verheugt.

“Very likely, it is the bleeding ... that you prevent if you stop antiplatelet therapy,” he said, adding that it’s known from previous studies in individuals with acute coronary syndromes and AFib that “bleeding is correlated with mortality, and that’s also proven here.”

Though Dr. Verheugt joined Dr. Yasuda in calling for replication of the results in a non-Asian population, he concurred that the AFIRE results validate current practice for anticoagulation in AFib with stable CAD. “Stopping at 1 year is safer than continuation and, most of all, it saves lives,” he said.

Full results of AFIRE were published online at the time of Dr. Yasuda’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904143).

The study was funded by the Japanese Cardiovascular Research Foundation. Dr. Yasuda reported financial relationships with Abbott, Bristol-Myers, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Takeda. Dr. Verheugt reported financial relationships with BayerHealthcare, BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Daiichi-Sankyo.

SOURCE: Yasuda S. et al. ESC 2019, Hot Line Session 3, Abstract 3175.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

ISAR-REACT 5: Prasugrel superior to ticagrelor in ACS

PARIS – Prasugrel proved superior to ticagrelor in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in what was hailed as “a landmark study” presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The results of ISAR-REACT 5 (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment 5) were unequivocal: “In ACS patients with or without ST-segment elevation, treatment with prasugrel as compared with ticagrelor significantly reduced the composite rate of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke at 1 year without an increase in major bleeding,” declared first author Stephanie Schuepke, MD, a cardiologist at the German Heart Center in Munich.

The study outcome was totally unexpected. Indeed, the result didn’t merely turn heads, it no doubt caused numerous wrenched necks caused by strenuous double-takes on the part of interventional cardiologists at the congress. That’s because, even though both ticagrelor and prasugrel enjoy a class I recommendation for use in ACS in the ESC guidelines, it has been widely assumed – based on previous evidence plus the fact that ticagrelor is the more potent platelet inhibitor – that ticagrelor is the superior drug in this setting. It turns out, however, that those earlier studies weren’t germane to the issue directly addressed in ISAR-REACT 5, the first-ever direct head-to-head comparison of the two potent P2Y12 inhibitors in the setting of ACS with a planned invasive strategy.

“Obviously, very surprising results,” commented Roxana Mehran, MD, professor of medicine and director of interventional cardiology research and clinical trials at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, who cochaired a press conference where Dr. Schuepke shared the study findings.

“We were surprised as well,” confessed Dr. Schuepke. “We assumed that ticagrelor is superior to prasugrel in terms of clinical outcomes in patients with ACS with a planned invasive strategy. But the results show us that the opposite is true.”

ISAR-REACT 5 was an open-label, investigator-initiated randomized trial conducted at 23 centers in Germany and Italy. It included 4,018 participants with ST-elevation segment MI (STEMI), without STEMI, or with unstable angina, all with scheduled coronary angiography. Participants were randomized to ticagrelor or prasugrel and were expected to remain on their assigned potent antiplatelet agent plus aspirin for 1 year of dual-antiplatelet therapy.

The primary outcome was the composite of death, MI, or stroke at 1 year of follow-up. This endpoint occurred in 9.3% of the ticagrelor group and 6.9% of patients in the prasugrel group, for a highly significant 36% increased relative risk in the ticagrelor-treated patients. Prasugrel had a numeric advantage in each of the individual components of the endpoint: the 1-year rate of all-cause mortality was 4.5% with ticagrelor versus 3.7% with prasugrel; for MI, the incidence was 4.8% with ticagrelor and 3.0% with prasugrel, a statistically significant difference; and for stroke, 1.1% versus 1.0%.

Major bleeding as defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium scale occurred in 5.4% of patients in the ticagrelor arm, and was similar at 4.8% in the prasugrel group, Dr. Schuepke continued.

Definite or probable stent thrombosis occurred in 1.3% of the ticagrelor group and 1.0% of patients assigned to prasugrel.

The mechanism for prasugrel’s superior results is unclear, she said. Possibilities include the fact that it’s a once-daily drug, compared with twice-daily ticagrelor, which could affect adherence; a differential profile in terms of drug interactions; and prasugrel’s reversibility of action and capacity for step-down dosing in patients at high bleeding risk.

Discussant Gilles Montalescot, MD, PhD, called ISAR-REACT 5 a “fascinating” study. He elaborated: “It is a pragmatic study to answer a pragmatic question. It’s not a drug trial; really, it’s more a strategy trial, with a comparison of two drugs and two strategies.”

In ISAR-REACT 5, ticagrelor was utilized in standard fashion: Patients, regardless of their ACS type, received a 180-mg loading dose as soon as possible after randomization, typically about 3 hours after presentation. That was also the protocol in the prasugrel arm, but only in patients with STEMI, who quickly got a 60-mg loading dose. In contrast, patients without STEMI or with unstable angina didn’t get a loading dose of prasugrel until they’d undergone coronary angiography and their coronary anatomy was known. That was the ISAR-REACT 5 strategy in light of an earlier study, which concluded that giving prasugrel prior to angiography in such patients led to increased bleeding without any improvement in clinical outcomes.

The essence of ISAR-REACT 5 lies in that difference in treatment strategies and the impact it had on outcomes. “The one-size-fits-all strategy – here, with ticagrelor – was inferior to an individualized strategy, here with prasugrel,” observed Dr. Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris VI and director of the cardiac care unit at Paris-Salpetriere Hospital.

The study results were notably consistent, favoring prasugrel over ticagrelor numerically across the board regardless of whether a patient presented with STEMI, without STEMI, or with unstable angina. Particularly noteworthy was the finding that this was also true in terms of the individual components of the 1-year composite endpoint. Dr. Montalescot drew special attention to the large subset of patients who had presented with STEMI and thus received the same treatment strategy involving a loading dose of their assigned P2Y12 inhibitor prior to angiography. This allowed for a direct head-to-head comparison of the clinical efficacy of the two antiplatelet agents in STEMI patients. The clear winner here was prasugrel, as the composite event rate was 10.1% in the ticagrelor group, compared with 7.9% in the prasugrel group.

“ISAR-REACT 5 is a landmark study which is going to impact our practice and the next set of guidelines to come in 2020,” the interventional cardiologist predicted.

Dr. Schuepke reported having no financial conflicts regarding the ISAR-REACT 5 study, sponsored by the German Heart Center and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research.

Simultaneous with her presentation of ISAR-REACT 5, the study results were published online (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908973).

PARIS – Prasugrel proved superior to ticagrelor in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in what was hailed as “a landmark study” presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The results of ISAR-REACT 5 (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment 5) were unequivocal: “In ACS patients with or without ST-segment elevation, treatment with prasugrel as compared with ticagrelor significantly reduced the composite rate of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke at 1 year without an increase in major bleeding,” declared first author Stephanie Schuepke, MD, a cardiologist at the German Heart Center in Munich.

The study outcome was totally unexpected. Indeed, the result didn’t merely turn heads, it no doubt caused numerous wrenched necks caused by strenuous double-takes on the part of interventional cardiologists at the congress. That’s because, even though both ticagrelor and prasugrel enjoy a class I recommendation for use in ACS in the ESC guidelines, it has been widely assumed – based on previous evidence plus the fact that ticagrelor is the more potent platelet inhibitor – that ticagrelor is the superior drug in this setting. It turns out, however, that those earlier studies weren’t germane to the issue directly addressed in ISAR-REACT 5, the first-ever direct head-to-head comparison of the two potent P2Y12 inhibitors in the setting of ACS with a planned invasive strategy.

“Obviously, very surprising results,” commented Roxana Mehran, MD, professor of medicine and director of interventional cardiology research and clinical trials at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, who cochaired a press conference where Dr. Schuepke shared the study findings.

“We were surprised as well,” confessed Dr. Schuepke. “We assumed that ticagrelor is superior to prasugrel in terms of clinical outcomes in patients with ACS with a planned invasive strategy. But the results show us that the opposite is true.”

ISAR-REACT 5 was an open-label, investigator-initiated randomized trial conducted at 23 centers in Germany and Italy. It included 4,018 participants with ST-elevation segment MI (STEMI), without STEMI, or with unstable angina, all with scheduled coronary angiography. Participants were randomized to ticagrelor or prasugrel and were expected to remain on their assigned potent antiplatelet agent plus aspirin for 1 year of dual-antiplatelet therapy.

The primary outcome was the composite of death, MI, or stroke at 1 year of follow-up. This endpoint occurred in 9.3% of the ticagrelor group and 6.9% of patients in the prasugrel group, for a highly significant 36% increased relative risk in the ticagrelor-treated patients. Prasugrel had a numeric advantage in each of the individual components of the endpoint: the 1-year rate of all-cause mortality was 4.5% with ticagrelor versus 3.7% with prasugrel; for MI, the incidence was 4.8% with ticagrelor and 3.0% with prasugrel, a statistically significant difference; and for stroke, 1.1% versus 1.0%.

Major bleeding as defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium scale occurred in 5.4% of patients in the ticagrelor arm, and was similar at 4.8% in the prasugrel group, Dr. Schuepke continued.

Definite or probable stent thrombosis occurred in 1.3% of the ticagrelor group and 1.0% of patients assigned to prasugrel.

The mechanism for prasugrel’s superior results is unclear, she said. Possibilities include the fact that it’s a once-daily drug, compared with twice-daily ticagrelor, which could affect adherence; a differential profile in terms of drug interactions; and prasugrel’s reversibility of action and capacity for step-down dosing in patients at high bleeding risk.

Discussant Gilles Montalescot, MD, PhD, called ISAR-REACT 5 a “fascinating” study. He elaborated: “It is a pragmatic study to answer a pragmatic question. It’s not a drug trial; really, it’s more a strategy trial, with a comparison of two drugs and two strategies.”

In ISAR-REACT 5, ticagrelor was utilized in standard fashion: Patients, regardless of their ACS type, received a 180-mg loading dose as soon as possible after randomization, typically about 3 hours after presentation. That was also the protocol in the prasugrel arm, but only in patients with STEMI, who quickly got a 60-mg loading dose. In contrast, patients without STEMI or with unstable angina didn’t get a loading dose of prasugrel until they’d undergone coronary angiography and their coronary anatomy was known. That was the ISAR-REACT 5 strategy in light of an earlier study, which concluded that giving prasugrel prior to angiography in such patients led to increased bleeding without any improvement in clinical outcomes.

The essence of ISAR-REACT 5 lies in that difference in treatment strategies and the impact it had on outcomes. “The one-size-fits-all strategy – here, with ticagrelor – was inferior to an individualized strategy, here with prasugrel,” observed Dr. Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris VI and director of the cardiac care unit at Paris-Salpetriere Hospital.

The study results were notably consistent, favoring prasugrel over ticagrelor numerically across the board regardless of whether a patient presented with STEMI, without STEMI, or with unstable angina. Particularly noteworthy was the finding that this was also true in terms of the individual components of the 1-year composite endpoint. Dr. Montalescot drew special attention to the large subset of patients who had presented with STEMI and thus received the same treatment strategy involving a loading dose of their assigned P2Y12 inhibitor prior to angiography. This allowed for a direct head-to-head comparison of the clinical efficacy of the two antiplatelet agents in STEMI patients. The clear winner here was prasugrel, as the composite event rate was 10.1% in the ticagrelor group, compared with 7.9% in the prasugrel group.

“ISAR-REACT 5 is a landmark study which is going to impact our practice and the next set of guidelines to come in 2020,” the interventional cardiologist predicted.

Dr. Schuepke reported having no financial conflicts regarding the ISAR-REACT 5 study, sponsored by the German Heart Center and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research.

Simultaneous with her presentation of ISAR-REACT 5, the study results were published online (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908973).

PARIS – Prasugrel proved superior to ticagrelor in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in what was hailed as “a landmark study” presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The results of ISAR-REACT 5 (Intracoronary Stenting and Antithrombotic Regimen: Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment 5) were unequivocal: “In ACS patients with or without ST-segment elevation, treatment with prasugrel as compared with ticagrelor significantly reduced the composite rate of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke at 1 year without an increase in major bleeding,” declared first author Stephanie Schuepke, MD, a cardiologist at the German Heart Center in Munich.

The study outcome was totally unexpected. Indeed, the result didn’t merely turn heads, it no doubt caused numerous wrenched necks caused by strenuous double-takes on the part of interventional cardiologists at the congress. That’s because, even though both ticagrelor and prasugrel enjoy a class I recommendation for use in ACS in the ESC guidelines, it has been widely assumed – based on previous evidence plus the fact that ticagrelor is the more potent platelet inhibitor – that ticagrelor is the superior drug in this setting. It turns out, however, that those earlier studies weren’t germane to the issue directly addressed in ISAR-REACT 5, the first-ever direct head-to-head comparison of the two potent P2Y12 inhibitors in the setting of ACS with a planned invasive strategy.

“Obviously, very surprising results,” commented Roxana Mehran, MD, professor of medicine and director of interventional cardiology research and clinical trials at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, who cochaired a press conference where Dr. Schuepke shared the study findings.

“We were surprised as well,” confessed Dr. Schuepke. “We assumed that ticagrelor is superior to prasugrel in terms of clinical outcomes in patients with ACS with a planned invasive strategy. But the results show us that the opposite is true.”

ISAR-REACT 5 was an open-label, investigator-initiated randomized trial conducted at 23 centers in Germany and Italy. It included 4,018 participants with ST-elevation segment MI (STEMI), without STEMI, or with unstable angina, all with scheduled coronary angiography. Participants were randomized to ticagrelor or prasugrel and were expected to remain on their assigned potent antiplatelet agent plus aspirin for 1 year of dual-antiplatelet therapy.

The primary outcome was the composite of death, MI, or stroke at 1 year of follow-up. This endpoint occurred in 9.3% of the ticagrelor group and 6.9% of patients in the prasugrel group, for a highly significant 36% increased relative risk in the ticagrelor-treated patients. Prasugrel had a numeric advantage in each of the individual components of the endpoint: the 1-year rate of all-cause mortality was 4.5% with ticagrelor versus 3.7% with prasugrel; for MI, the incidence was 4.8% with ticagrelor and 3.0% with prasugrel, a statistically significant difference; and for stroke, 1.1% versus 1.0%.

Major bleeding as defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium scale occurred in 5.4% of patients in the ticagrelor arm, and was similar at 4.8% in the prasugrel group, Dr. Schuepke continued.

Definite or probable stent thrombosis occurred in 1.3% of the ticagrelor group and 1.0% of patients assigned to prasugrel.

The mechanism for prasugrel’s superior results is unclear, she said. Possibilities include the fact that it’s a once-daily drug, compared with twice-daily ticagrelor, which could affect adherence; a differential profile in terms of drug interactions; and prasugrel’s reversibility of action and capacity for step-down dosing in patients at high bleeding risk.

Discussant Gilles Montalescot, MD, PhD, called ISAR-REACT 5 a “fascinating” study. He elaborated: “It is a pragmatic study to answer a pragmatic question. It’s not a drug trial; really, it’s more a strategy trial, with a comparison of two drugs and two strategies.”

In ISAR-REACT 5, ticagrelor was utilized in standard fashion: Patients, regardless of their ACS type, received a 180-mg loading dose as soon as possible after randomization, typically about 3 hours after presentation. That was also the protocol in the prasugrel arm, but only in patients with STEMI, who quickly got a 60-mg loading dose. In contrast, patients without STEMI or with unstable angina didn’t get a loading dose of prasugrel until they’d undergone coronary angiography and their coronary anatomy was known. That was the ISAR-REACT 5 strategy in light of an earlier study, which concluded that giving prasugrel prior to angiography in such patients led to increased bleeding without any improvement in clinical outcomes.

The essence of ISAR-REACT 5 lies in that difference in treatment strategies and the impact it had on outcomes. “The one-size-fits-all strategy – here, with ticagrelor – was inferior to an individualized strategy, here with prasugrel,” observed Dr. Montalescot, professor of cardiology at the University of Paris VI and director of the cardiac care unit at Paris-Salpetriere Hospital.

The study results were notably consistent, favoring prasugrel over ticagrelor numerically across the board regardless of whether a patient presented with STEMI, without STEMI, or with unstable angina. Particularly noteworthy was the finding that this was also true in terms of the individual components of the 1-year composite endpoint. Dr. Montalescot drew special attention to the large subset of patients who had presented with STEMI and thus received the same treatment strategy involving a loading dose of their assigned P2Y12 inhibitor prior to angiography. This allowed for a direct head-to-head comparison of the clinical efficacy of the two antiplatelet agents in STEMI patients. The clear winner here was prasugrel, as the composite event rate was 10.1% in the ticagrelor group, compared with 7.9% in the prasugrel group.

“ISAR-REACT 5 is a landmark study which is going to impact our practice and the next set of guidelines to come in 2020,” the interventional cardiologist predicted.

Dr. Schuepke reported having no financial conflicts regarding the ISAR-REACT 5 study, sponsored by the German Heart Center and the German Center for Cardiovascular Research.

Simultaneous with her presentation of ISAR-REACT 5, the study results were published online (N Engl J Med. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908973).

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

Adolescent and young adult (AYA) survival trends

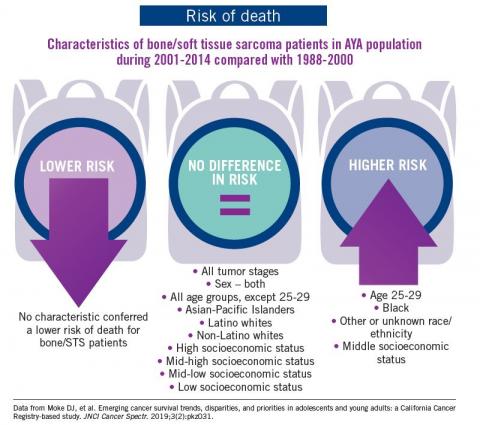

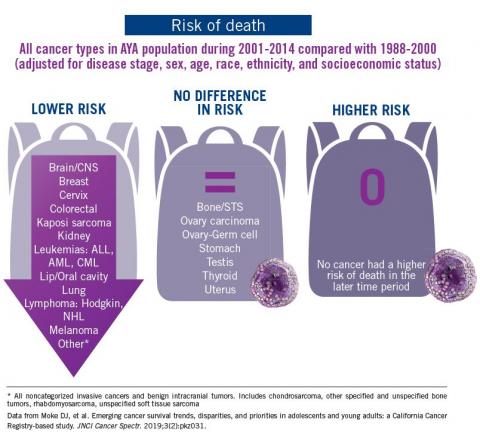

The good news: AYA survival improvement was at least as large as in younger children and older adults comparing deaths in two time periods, 1988-2000 and 2001-2014, in a California Cancer Registry.

The bad news: There was no statistically significant difference in survival between time periods for patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma.

The good news: AYA survival improvement was at least as large as in younger children and older adults comparing deaths in two time periods, 1988-2000 and 2001-2014, in a California Cancer Registry.

The bad news: There was no statistically significant difference in survival between time periods for patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma.

The good news: AYA survival improvement was at least as large as in younger children and older adults comparing deaths in two time periods, 1988-2000 and 2001-2014, in a California Cancer Registry.

The bad news: There was no statistically significant difference in survival between time periods for patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma.

Observation versus inpatient status

A dilemma for hospitalists and patients

A federal effort to reduce health care expenditures has left many older Medicare recipients experiencing the sticker shock of “observation status.” Patients who are not sick enough to meet inpatient admission criteria, however, still require hospitalization, and may be placed under Medicare observation care.

Seniors can get frustrated, confused, and anxious as their status can be changed while they are in the hospital, and they may receive large medical bills after they are discharged. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ “3-day rule” mandates that Medicare will not pay for skilled nursing facility care unless the patient is admitted as an “inpatient” for at least 3 days. Observation days do not count towards this 3-day hospital stay.

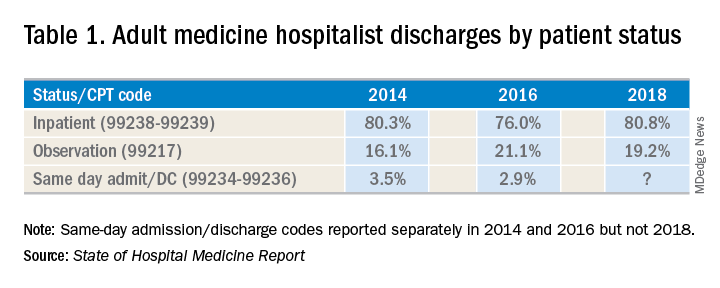

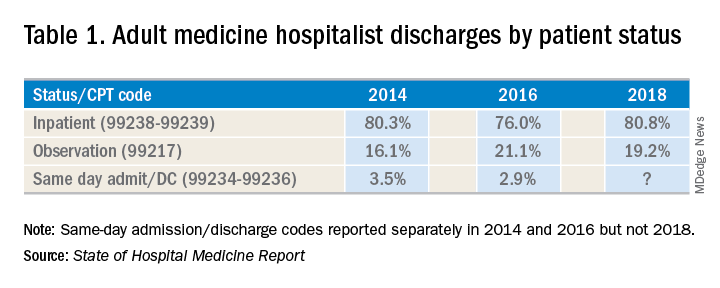

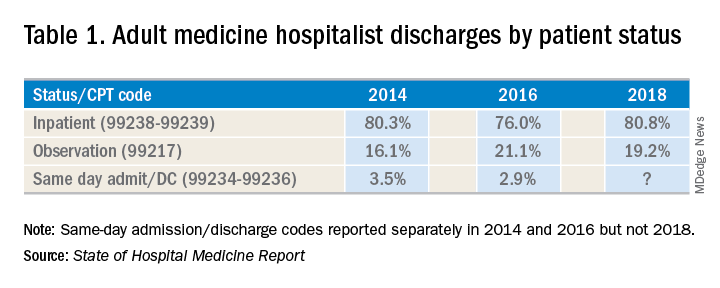

There has been an increase in outpatient services over the years since 2006. The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) highlights the percentage of discharges based on hospitalists’ billed Current Procedural Terminology codes. Codes 99217 (observation discharge) and 99238-99239 (inpatient discharge) were used to calculate the percentages. 80.7% of adult medicine hospitalist discharges were coded using inpatient discharge codes, while 19.3% of patients were discharged with observation discharge codes.

In the 2016 SoHM report, the ratio was 76.0% inpatient and 21.1% observation codes and in the 2014 report we saw 80.3% inpatient and 16.1% observation discharges (see table 1). But in both of those surveys, same-day admission/discharge codes were also separately reported, which did not occur in 2018. That makes year-over-year comparison of the data challenging.

Interestingly, the 2017 CMS data on Evaluation and Management Codes by Specialty for the first time included separate data for hospitalists, based on hospitalists who credentialed with Medicare using the new C6 specialty code. Based on that data, when looking only at inpatient (99238-99239) and observation (99217) codes, 83% of the discharges were inpatient and 17% were observation.

Physicians feel the pressure of strained patient-physician relationships as a consequence of patients feeling the brunt of the financing gap related to observation status. Patients often feel they were not warned adequately about the financial ramifications of observation status. Even if Medicare beneficiaries have received the Medicare Outpatient Observation Notice, outlined by the Notice of Observation Treatment and Implication for Care Eligibility Act, they have no rights to appeal.

Currently Medicare beneficiaries admitted as inpatients only incur a Part A deductible; they are not liable for tests, procedures, and nursing care. On the other hand, in observation status all services are billed separately. For Medicare Part B services (which covers observation care) patients must pay 20% of services after the Part B deductible, which could result in a huge financial burden. Costs for skilled nursing facilities, when they are not covered by Medicare Part A, because of the 3-day rule, can easily go up to $20,000 or more. Medicare beneficiaries have no cap on costs for an observation stay. In some cases, hospitals have to apply a condition code 44 and retroactively change the stay to observation status.

I attended the 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference in Washington. Hospitalists from all parts of the country advocated on Capitol Hill against the “observation bill,” and “meet and greets” with congressional representatives increased their opposition to the bill. These efforts may work in favor of protecting patients from surprise medical bills. Hospital medicine physicians are on the front lines for providing health care in the hospital setting; they have demanded a fix to this legislative loophole which brings high out of pocket costs to our nation’s most vulnerable seniors. The observation status “2-midnight rule” utilized by CMS has increased financial barriers and decreased access to postacute care, affecting the provision of high-quality care for patients.

My hospital has a utilization review committee which reviews all cases to determine the appropriateness of an inpatient versus an observation designation. (An interesting question is whether the financial resources used to support this additional staff could be better assigned to provide high-quality care.) Distribution of these patients is determined on very specific criteria as outlined by Medicare. Observation is basically considered a billing method implemented by payers to decrease dollars paid to acute care hospitals for inpatient care. It pertains to admission status, not to the level of care provided in the hospital. Unfortunately, it is felt that no two payers define observation the same way. A few examples of common observation diagnoses are chest pain, abdominal pain, syncope, and migraine headache; in other words, patients with diagnoses where it is suspected that a less than 24-hour stay in the hospital could be sufficient.

Observation care is increasing and can sometimes contribute to work flow impediments and frustrations in hospitalists; thus, hospitalists are demanding reform. It has been proposed that observation could be eliminated altogether by creating a payment blend of inpatient/outpatient rates. Another option could be to assign lower Diagnosis Related Group coding to lower acuity disease processes, instead of separate observation reimbursement.

Patients and doctors lament that “Once you are in the hospital, you are admitted!” I don’t know the right answer that would solve the observation versus inpatient dilemma, but it is intriguing to consider changes in policy that might focus on the complete elimination of observation status.

Dr. Puri is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

A dilemma for hospitalists and patients

A dilemma for hospitalists and patients

A federal effort to reduce health care expenditures has left many older Medicare recipients experiencing the sticker shock of “observation status.” Patients who are not sick enough to meet inpatient admission criteria, however, still require hospitalization, and may be placed under Medicare observation care.

Seniors can get frustrated, confused, and anxious as their status can be changed while they are in the hospital, and they may receive large medical bills after they are discharged. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ “3-day rule” mandates that Medicare will not pay for skilled nursing facility care unless the patient is admitted as an “inpatient” for at least 3 days. Observation days do not count towards this 3-day hospital stay.

There has been an increase in outpatient services over the years since 2006. The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) highlights the percentage of discharges based on hospitalists’ billed Current Procedural Terminology codes. Codes 99217 (observation discharge) and 99238-99239 (inpatient discharge) were used to calculate the percentages. 80.7% of adult medicine hospitalist discharges were coded using inpatient discharge codes, while 19.3% of patients were discharged with observation discharge codes.

In the 2016 SoHM report, the ratio was 76.0% inpatient and 21.1% observation codes and in the 2014 report we saw 80.3% inpatient and 16.1% observation discharges (see table 1). But in both of those surveys, same-day admission/discharge codes were also separately reported, which did not occur in 2018. That makes year-over-year comparison of the data challenging.

Interestingly, the 2017 CMS data on Evaluation and Management Codes by Specialty for the first time included separate data for hospitalists, based on hospitalists who credentialed with Medicare using the new C6 specialty code. Based on that data, when looking only at inpatient (99238-99239) and observation (99217) codes, 83% of the discharges were inpatient and 17% were observation.

Physicians feel the pressure of strained patient-physician relationships as a consequence of patients feeling the brunt of the financing gap related to observation status. Patients often feel they were not warned adequately about the financial ramifications of observation status. Even if Medicare beneficiaries have received the Medicare Outpatient Observation Notice, outlined by the Notice of Observation Treatment and Implication for Care Eligibility Act, they have no rights to appeal.

Currently Medicare beneficiaries admitted as inpatients only incur a Part A deductible; they are not liable for tests, procedures, and nursing care. On the other hand, in observation status all services are billed separately. For Medicare Part B services (which covers observation care) patients must pay 20% of services after the Part B deductible, which could result in a huge financial burden. Costs for skilled nursing facilities, when they are not covered by Medicare Part A, because of the 3-day rule, can easily go up to $20,000 or more. Medicare beneficiaries have no cap on costs for an observation stay. In some cases, hospitals have to apply a condition code 44 and retroactively change the stay to observation status.

I attended the 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference in Washington. Hospitalists from all parts of the country advocated on Capitol Hill against the “observation bill,” and “meet and greets” with congressional representatives increased their opposition to the bill. These efforts may work in favor of protecting patients from surprise medical bills. Hospital medicine physicians are on the front lines for providing health care in the hospital setting; they have demanded a fix to this legislative loophole which brings high out of pocket costs to our nation’s most vulnerable seniors. The observation status “2-midnight rule” utilized by CMS has increased financial barriers and decreased access to postacute care, affecting the provision of high-quality care for patients.

My hospital has a utilization review committee which reviews all cases to determine the appropriateness of an inpatient versus an observation designation. (An interesting question is whether the financial resources used to support this additional staff could be better assigned to provide high-quality care.) Distribution of these patients is determined on very specific criteria as outlined by Medicare. Observation is basically considered a billing method implemented by payers to decrease dollars paid to acute care hospitals for inpatient care. It pertains to admission status, not to the level of care provided in the hospital. Unfortunately, it is felt that no two payers define observation the same way. A few examples of common observation diagnoses are chest pain, abdominal pain, syncope, and migraine headache; in other words, patients with diagnoses where it is suspected that a less than 24-hour stay in the hospital could be sufficient.

Observation care is increasing and can sometimes contribute to work flow impediments and frustrations in hospitalists; thus, hospitalists are demanding reform. It has been proposed that observation could be eliminated altogether by creating a payment blend of inpatient/outpatient rates. Another option could be to assign lower Diagnosis Related Group coding to lower acuity disease processes, instead of separate observation reimbursement.

Patients and doctors lament that “Once you are in the hospital, you are admitted!” I don’t know the right answer that would solve the observation versus inpatient dilemma, but it is intriguing to consider changes in policy that might focus on the complete elimination of observation status.

Dr. Puri is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

A federal effort to reduce health care expenditures has left many older Medicare recipients experiencing the sticker shock of “observation status.” Patients who are not sick enough to meet inpatient admission criteria, however, still require hospitalization, and may be placed under Medicare observation care.

Seniors can get frustrated, confused, and anxious as their status can be changed while they are in the hospital, and they may receive large medical bills after they are discharged. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ “3-day rule” mandates that Medicare will not pay for skilled nursing facility care unless the patient is admitted as an “inpatient” for at least 3 days. Observation days do not count towards this 3-day hospital stay.

There has been an increase in outpatient services over the years since 2006. The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report (SoHM) highlights the percentage of discharges based on hospitalists’ billed Current Procedural Terminology codes. Codes 99217 (observation discharge) and 99238-99239 (inpatient discharge) were used to calculate the percentages. 80.7% of adult medicine hospitalist discharges were coded using inpatient discharge codes, while 19.3% of patients were discharged with observation discharge codes.

In the 2016 SoHM report, the ratio was 76.0% inpatient and 21.1% observation codes and in the 2014 report we saw 80.3% inpatient and 16.1% observation discharges (see table 1). But in both of those surveys, same-day admission/discharge codes were also separately reported, which did not occur in 2018. That makes year-over-year comparison of the data challenging.

Interestingly, the 2017 CMS data on Evaluation and Management Codes by Specialty for the first time included separate data for hospitalists, based on hospitalists who credentialed with Medicare using the new C6 specialty code. Based on that data, when looking only at inpatient (99238-99239) and observation (99217) codes, 83% of the discharges were inpatient and 17% were observation.

Physicians feel the pressure of strained patient-physician relationships as a consequence of patients feeling the brunt of the financing gap related to observation status. Patients often feel they were not warned adequately about the financial ramifications of observation status. Even if Medicare beneficiaries have received the Medicare Outpatient Observation Notice, outlined by the Notice of Observation Treatment and Implication for Care Eligibility Act, they have no rights to appeal.

Currently Medicare beneficiaries admitted as inpatients only incur a Part A deductible; they are not liable for tests, procedures, and nursing care. On the other hand, in observation status all services are billed separately. For Medicare Part B services (which covers observation care) patients must pay 20% of services after the Part B deductible, which could result in a huge financial burden. Costs for skilled nursing facilities, when they are not covered by Medicare Part A, because of the 3-day rule, can easily go up to $20,000 or more. Medicare beneficiaries have no cap on costs for an observation stay. In some cases, hospitals have to apply a condition code 44 and retroactively change the stay to observation status.

I attended the 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference in Washington. Hospitalists from all parts of the country advocated on Capitol Hill against the “observation bill,” and “meet and greets” with congressional representatives increased their opposition to the bill. These efforts may work in favor of protecting patients from surprise medical bills. Hospital medicine physicians are on the front lines for providing health care in the hospital setting; they have demanded a fix to this legislative loophole which brings high out of pocket costs to our nation’s most vulnerable seniors. The observation status “2-midnight rule” utilized by CMS has increased financial barriers and decreased access to postacute care, affecting the provision of high-quality care for patients.

My hospital has a utilization review committee which reviews all cases to determine the appropriateness of an inpatient versus an observation designation. (An interesting question is whether the financial resources used to support this additional staff could be better assigned to provide high-quality care.) Distribution of these patients is determined on very specific criteria as outlined by Medicare. Observation is basically considered a billing method implemented by payers to decrease dollars paid to acute care hospitals for inpatient care. It pertains to admission status, not to the level of care provided in the hospital. Unfortunately, it is felt that no two payers define observation the same way. A few examples of common observation diagnoses are chest pain, abdominal pain, syncope, and migraine headache; in other words, patients with diagnoses where it is suspected that a less than 24-hour stay in the hospital could be sufficient.

Observation care is increasing and can sometimes contribute to work flow impediments and frustrations in hospitalists; thus, hospitalists are demanding reform. It has been proposed that observation could be eliminated altogether by creating a payment blend of inpatient/outpatient rates. Another option could be to assign lower Diagnosis Related Group coding to lower acuity disease processes, instead of separate observation reimbursement.

Patients and doctors lament that “Once you are in the hospital, you are admitted!” I don’t know the right answer that would solve the observation versus inpatient dilemma, but it is intriguing to consider changes in policy that might focus on the complete elimination of observation status.

Dr. Puri is a hospitalist at Lahey Hospital and Medical Center in Burlington, Mass.

My patient tells me that they are transgender – now what?

I am privileged to work in a university hospital system where I have access to colleagues with expertise in LGBT health; however, medical providers in the community may not enjoy such resources. Many transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) youth now are seeking help from their community primary care providers to affirm their gender identity, but many community primary care providers do not have the luxury of referring these patients to an expert in gender-affirming care when their TGD patients express the desire to affirm their gender through medical and surgical means. This is even more difficult if the nearest referral center is hundreds of miles away. Nevertheless,

If a TGD youth discloses their gender identity to you, it is critical that you make the patient feel safe and supported. Showing support is important in maintaining rapport between you and the patient. Furthermore, you may be one of the very few adults in the child’s life whom they can trust.

First of all, thank them. For many TGD patients, disclosing their gender identity to a health care provider can be a herculean task. They may have spent many hours trying to find the right words to say to disclose an important aspect of themselves to you. They also probably spent a fair amount of time worrying about whether or not you would react positively to this disclosure. This fear is reasonable. About one-fifth of transgender people have reported being kicked out of a medical practice because of their disclosure of their gender identity.1

Secondly, assure the TGD patient that your treatment would be no different from the care provided for other patients. Discrimination from a health care provider has frequently been reported by TGD patients1 and is expected from this population.2 By emphasizing this, you have signaled to them that you are committed to treating them with dignity and respect. Furthermore, signal your commitment to this treatment by making the clinic a safe and welcoming place for LGBT youth. Several resources exist that can help with this. The American Medical Association provides a good example on how to draft a nondiscrimination statement that can be posted in waiting areas;3 the Fenway Institute has a good example of an intake form that is LGBT friendly.4

In addition, a good way to help affirm their gender identity is to tell them that being transgender or gender-diverse is normal and healthy. Many times, TGD youth will hear narratives that gender diversity is pathological or aberrant; however, hearing that they are healthy and normal, especially from a health care provider, can make a powerful impact on feeling supported and affirmed.

Furthermore, inform your TGD youth of their right to confidentiality. Many TGD youth may not be out to their parents, and you may be the first person to whom they disclosed their gender identity. This is especially helpful if you describe their right to and the limits of confidentiality (e.g., suicidality) at the beginning of the visit. Assurance of confidentiality is a vital reason adolescents and young adults seek health care from a medical provider,5 and the same can be said of TGD youth; however, keep in mind that if they do desire to transition using cross-sex hormones or surgery, parental permission is required.

If they are not out to their parents and they are planning to come out to their parents, offer to be there when they do. Having someone to support the child – someone who is a medical provider – can add to the sense of legitimacy that what the child is experiencing is normal and healthy. Providing guidance on how parents can support their TGD child is essential for successful affirmation, and some suggestions can be found in an LGBT Youth Consult column I wrote titled, “Guidance for parents of LGBT youth.”

If you practice in a location where the nearest expert in gender-affirming care can be hundreds of miles away, educate yourself on gender-affirming care. Several guidelines are available. The World Professional Society for Transgender Standards of Care (SOC) focuses on the mental health aspects of gender-affirming care. The SOC recommends, but no longer requires, letters from a mental health therapist to start gender-affirming medical treatments and does allow for a discussion between you and the patient on the risks, benefits, alternatives, unknowns, limitations of treatment, and risks of not treating (i.e., obtaining informed consent) as the threshold for hormone therapy.6 This approach, known as the “informed consent model,” can be helpful in expanding health care access for TGD youth. Furthermore, there’s the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines7 and the University of California, San Francisco, Guidelines,8 which focus on the medical aspects of gender-affirming care, such as when to start pubertal blockers and dosing for cross-sex hormones. Finally, there are resources that allow providers to consult an expert remotely for more complicated cases. Transline is a transgender medical consultation service staffed by medical providers with expertise in gender-affirming care. Providers can learn more about this valuable service on the website: http://project-health.org/transline/.

Working in a major medical center is not necessary in providing gender-affirming care to TGD youth. Being respectful, supportive, and having the willingness to learn are the minimal requirements. Resources are available to help guide you on the more technical aspects of gender-affirming care. Maintaining a supportive environment and using these resources will help you expand health care access for this population.

Dr. Montano is an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh and an adolescent medicine physician at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Injustice at every turn: A report of the national transgender discrimination survey (National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011).

2. Psychol Bull. 2003 Sep;129(5):674-97.

3. “Creating an LGBTQ-friendly practice,” American Medical Association.

4. Fenway Health Client Registration Form.

5. JAMA. 1993 Mar 17;269(11):1404-7.

6. Int J Transgenderism 2012;13:165-232.

7. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Nov 1;102(11):3869-903.

8. “Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People,” 2nd edition (San Francisco, CA: University of California, San Francisco, June 17, 2016).

I am privileged to work in a university hospital system where I have access to colleagues with expertise in LGBT health; however, medical providers in the community may not enjoy such resources. Many transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) youth now are seeking help from their community primary care providers to affirm their gender identity, but many community primary care providers do not have the luxury of referring these patients to an expert in gender-affirming care when their TGD patients express the desire to affirm their gender through medical and surgical means. This is even more difficult if the nearest referral center is hundreds of miles away. Nevertheless,

If a TGD youth discloses their gender identity to you, it is critical that you make the patient feel safe and supported. Showing support is important in maintaining rapport between you and the patient. Furthermore, you may be one of the very few adults in the child’s life whom they can trust.

First of all, thank them. For many TGD patients, disclosing their gender identity to a health care provider can be a herculean task. They may have spent many hours trying to find the right words to say to disclose an important aspect of themselves to you. They also probably spent a fair amount of time worrying about whether or not you would react positively to this disclosure. This fear is reasonable. About one-fifth of transgender people have reported being kicked out of a medical practice because of their disclosure of their gender identity.1

Secondly, assure the TGD patient that your treatment would be no different from the care provided for other patients. Discrimination from a health care provider has frequently been reported by TGD patients1 and is expected from this population.2 By emphasizing this, you have signaled to them that you are committed to treating them with dignity and respect. Furthermore, signal your commitment to this treatment by making the clinic a safe and welcoming place for LGBT youth. Several resources exist that can help with this. The American Medical Association provides a good example on how to draft a nondiscrimination statement that can be posted in waiting areas;3 the Fenway Institute has a good example of an intake form that is LGBT friendly.4