User login

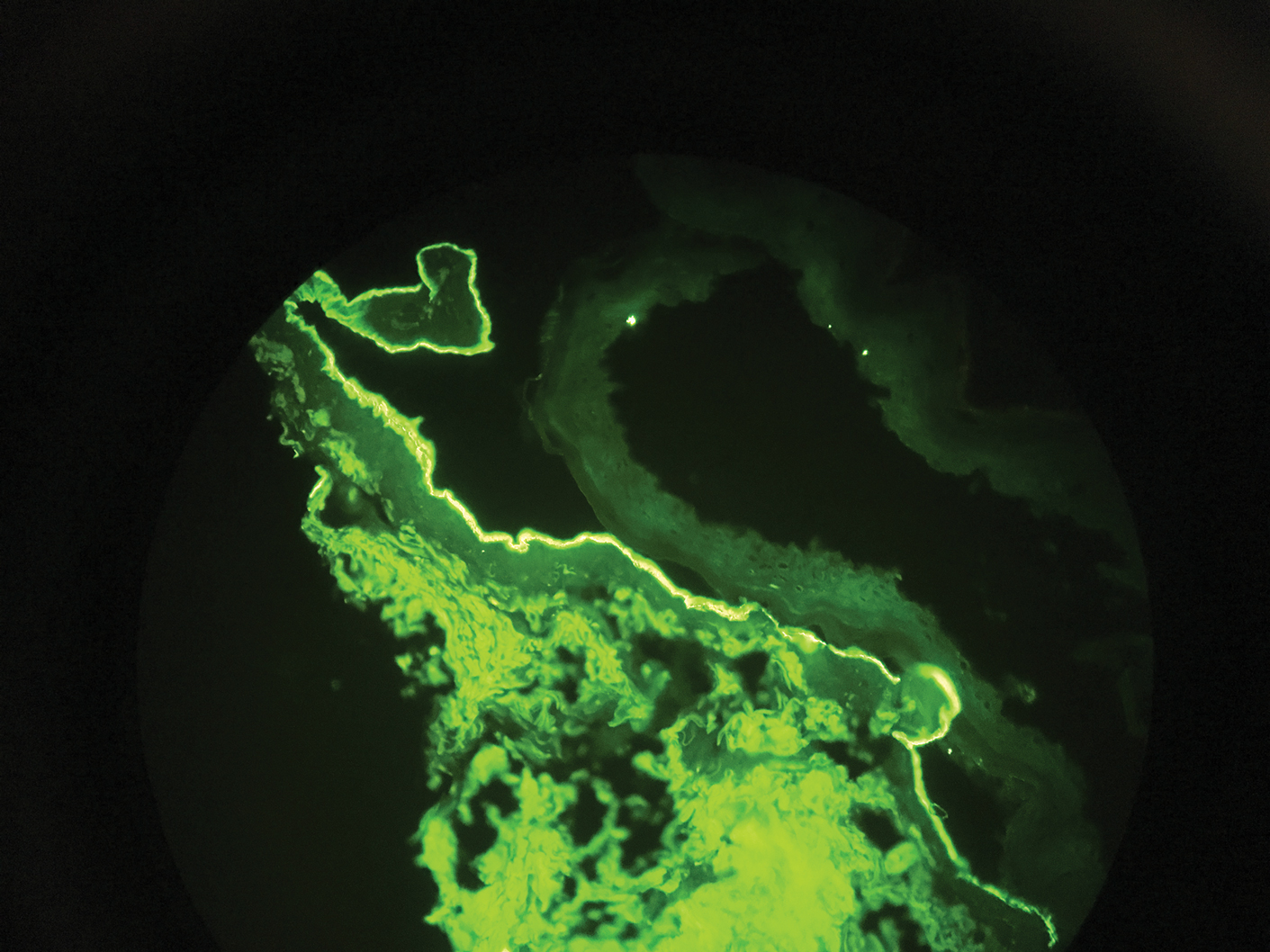

Responsible use of breast cancer screening

In this edition of “Applying research to practice,” I examine a study suggesting that annual screening mammography does not reduce the risk of death from breast cancer in women aged 75 years and older. I also highlight a related editorial noting that we should optimize treatment as well as screening for breast cancer.

Regular screening mammography in women aged 50-69 years prevents 21.3 breast cancer deaths among 10,000 women over a 10-year time period (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Feb 16;164[4]:244-55). However, in the published screening trials, few participants were older than 70 years of age.

More than half of women above age 74 receive annual mammograms (Health, United States, 2018. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus18.pdf). And more than a third of breast cancer deaths occur in women aged 70 years or older (CA Cancer J Clin. 2016 Mar-Apr;66[2]:96-114).

Do older women benefit from annual mammography to the same extent as younger women? Is there a point at which benefit ends?

To answer these questions, Xabier García-Albéniz, MD, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues studied 1,058,013 women enrolled in Medicare during 2000-2008 (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.7326/M18-1199).

The researchers examined data on patients aged 70-84 years who had a life expectancy of at least 10 years, at least one recent mammogram, and no history of breast cancer. The team emulated a prospective trial by examining deaths over an 8-year period for women aged 70 years and older who either continued or stopped screening mammography. The researchers conducted separate analyses for women aged 70-74 years and those aged 75-84 years.

Diagnoses of breast cancer were, not surprisingly, higher in the continued-screening group, but there were no major reductions in breast cancer–related deaths.

Among women aged 70-74 years, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer death was reduced for women who continued screening versus those who stopped it by one death per 1,000 women (hazard ratio, 0.78). Among women aged 75-84 years, the 8-year risk reduction was 0.07 deaths per 1,000 women (HR, 1.00).

The authors concluded that continuing mammographic screening past age 75 years resulted in no material difference in cancer-specific mortality over an 8-year time period, in comparison with stopping regular screening examinations.

Considering treatment as well as screening

For a variety of reasons (ethical, economic, methodologic), it is unreasonable to expect a randomized, clinical trial examining the value of mammography in older women. An informative alternative would be a well-designed, large-scale, population-based, observational study that takes into consideration potentially confounding variables of the binary strategies of continuing screening versus stopping it.

Although the 8-year risk of breast cancer in older women is not low among screened women – 5.5% in women aged 70-74 years and 5.8% in women aged 75-84 years – and mammography remains an effective screening tool, the effect of screening on breast cancer mortality appears to decline as women age.

In the editorial that accompanies the study by Dr. García-Albéniz and colleagues, Otis Brawley, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, highlighted the role of inadequate, ineffective, inconvenient, or poorly tolerated treatment in older women (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.7326/M20-0429).

Dr. Brawley illustrated that focusing too much on screening diverts attention from the major driver of cancer mortality in older women: suboptimal treatment. That certainly has been the case for the dramatic impact of improved lung cancer treatment on mortality, despite a statistically significant impact of screening on lung cancer mortality as well.

As with lung cancer screening, Dr. Brawley describes the goal of defining “personalized screening recommendations” in breast cancer, or screening that is targeted to the highest-risk women and those who stand a high chance of benefiting from treatment if they are diagnosed with breast cancer.

As our population ages and health care expenditures continue to rise, there can be little disagreement that responsible use of cancer diagnostics will be as vital as judicious application of treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations.

In this edition of “Applying research to practice,” I examine a study suggesting that annual screening mammography does not reduce the risk of death from breast cancer in women aged 75 years and older. I also highlight a related editorial noting that we should optimize treatment as well as screening for breast cancer.

Regular screening mammography in women aged 50-69 years prevents 21.3 breast cancer deaths among 10,000 women over a 10-year time period (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Feb 16;164[4]:244-55). However, in the published screening trials, few participants were older than 70 years of age.

More than half of women above age 74 receive annual mammograms (Health, United States, 2018. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus18.pdf). And more than a third of breast cancer deaths occur in women aged 70 years or older (CA Cancer J Clin. 2016 Mar-Apr;66[2]:96-114).

Do older women benefit from annual mammography to the same extent as younger women? Is there a point at which benefit ends?

To answer these questions, Xabier García-Albéniz, MD, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues studied 1,058,013 women enrolled in Medicare during 2000-2008 (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.7326/M18-1199).

The researchers examined data on patients aged 70-84 years who had a life expectancy of at least 10 years, at least one recent mammogram, and no history of breast cancer. The team emulated a prospective trial by examining deaths over an 8-year period for women aged 70 years and older who either continued or stopped screening mammography. The researchers conducted separate analyses for women aged 70-74 years and those aged 75-84 years.

Diagnoses of breast cancer were, not surprisingly, higher in the continued-screening group, but there were no major reductions in breast cancer–related deaths.

Among women aged 70-74 years, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer death was reduced for women who continued screening versus those who stopped it by one death per 1,000 women (hazard ratio, 0.78). Among women aged 75-84 years, the 8-year risk reduction was 0.07 deaths per 1,000 women (HR, 1.00).

The authors concluded that continuing mammographic screening past age 75 years resulted in no material difference in cancer-specific mortality over an 8-year time period, in comparison with stopping regular screening examinations.

Considering treatment as well as screening

For a variety of reasons (ethical, economic, methodologic), it is unreasonable to expect a randomized, clinical trial examining the value of mammography in older women. An informative alternative would be a well-designed, large-scale, population-based, observational study that takes into consideration potentially confounding variables of the binary strategies of continuing screening versus stopping it.

Although the 8-year risk of breast cancer in older women is not low among screened women – 5.5% in women aged 70-74 years and 5.8% in women aged 75-84 years – and mammography remains an effective screening tool, the effect of screening on breast cancer mortality appears to decline as women age.

In the editorial that accompanies the study by Dr. García-Albéniz and colleagues, Otis Brawley, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, highlighted the role of inadequate, ineffective, inconvenient, or poorly tolerated treatment in older women (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.7326/M20-0429).

Dr. Brawley illustrated that focusing too much on screening diverts attention from the major driver of cancer mortality in older women: suboptimal treatment. That certainly has been the case for the dramatic impact of improved lung cancer treatment on mortality, despite a statistically significant impact of screening on lung cancer mortality as well.

As with lung cancer screening, Dr. Brawley describes the goal of defining “personalized screening recommendations” in breast cancer, or screening that is targeted to the highest-risk women and those who stand a high chance of benefiting from treatment if they are diagnosed with breast cancer.

As our population ages and health care expenditures continue to rise, there can be little disagreement that responsible use of cancer diagnostics will be as vital as judicious application of treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations.

In this edition of “Applying research to practice,” I examine a study suggesting that annual screening mammography does not reduce the risk of death from breast cancer in women aged 75 years and older. I also highlight a related editorial noting that we should optimize treatment as well as screening for breast cancer.

Regular screening mammography in women aged 50-69 years prevents 21.3 breast cancer deaths among 10,000 women over a 10-year time period (Ann Intern Med. 2016 Feb 16;164[4]:244-55). However, in the published screening trials, few participants were older than 70 years of age.

More than half of women above age 74 receive annual mammograms (Health, United States, 2018. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus18.pdf). And more than a third of breast cancer deaths occur in women aged 70 years or older (CA Cancer J Clin. 2016 Mar-Apr;66[2]:96-114).

Do older women benefit from annual mammography to the same extent as younger women? Is there a point at which benefit ends?

To answer these questions, Xabier García-Albéniz, MD, PhD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues studied 1,058,013 women enrolled in Medicare during 2000-2008 (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.7326/M18-1199).

The researchers examined data on patients aged 70-84 years who had a life expectancy of at least 10 years, at least one recent mammogram, and no history of breast cancer. The team emulated a prospective trial by examining deaths over an 8-year period for women aged 70 years and older who either continued or stopped screening mammography. The researchers conducted separate analyses for women aged 70-74 years and those aged 75-84 years.

Diagnoses of breast cancer were, not surprisingly, higher in the continued-screening group, but there were no major reductions in breast cancer–related deaths.

Among women aged 70-74 years, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer death was reduced for women who continued screening versus those who stopped it by one death per 1,000 women (hazard ratio, 0.78). Among women aged 75-84 years, the 8-year risk reduction was 0.07 deaths per 1,000 women (HR, 1.00).

The authors concluded that continuing mammographic screening past age 75 years resulted in no material difference in cancer-specific mortality over an 8-year time period, in comparison with stopping regular screening examinations.

Considering treatment as well as screening

For a variety of reasons (ethical, economic, methodologic), it is unreasonable to expect a randomized, clinical trial examining the value of mammography in older women. An informative alternative would be a well-designed, large-scale, population-based, observational study that takes into consideration potentially confounding variables of the binary strategies of continuing screening versus stopping it.

Although the 8-year risk of breast cancer in older women is not low among screened women – 5.5% in women aged 70-74 years and 5.8% in women aged 75-84 years – and mammography remains an effective screening tool, the effect of screening on breast cancer mortality appears to decline as women age.

In the editorial that accompanies the study by Dr. García-Albéniz and colleagues, Otis Brawley, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, highlighted the role of inadequate, ineffective, inconvenient, or poorly tolerated treatment in older women (Ann Intern Med. 2020 Feb 25. doi: 10.7326/M20-0429).

Dr. Brawley illustrated that focusing too much on screening diverts attention from the major driver of cancer mortality in older women: suboptimal treatment. That certainly has been the case for the dramatic impact of improved lung cancer treatment on mortality, despite a statistically significant impact of screening on lung cancer mortality as well.

As with lung cancer screening, Dr. Brawley describes the goal of defining “personalized screening recommendations” in breast cancer, or screening that is targeted to the highest-risk women and those who stand a high chance of benefiting from treatment if they are diagnosed with breast cancer.

As our population ages and health care expenditures continue to rise, there can be little disagreement that responsible use of cancer diagnostics will be as vital as judicious application of treatment.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations.

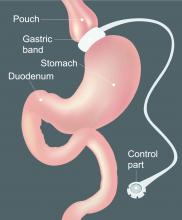

The hospitalized postbariatric surgery patient

What every hospitalist should know

With the prevalence of obesity worldwide topping 650 million people1 and nearly 40% of U.S. adults having obesity,2 bariatric surgery is increasingly used to treat this disease and its associated comorbidities.

The American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery estimates that 228,000 bariatric procedures were performed on Americans in 2017, up from 158,000 in 2011.3 Despite lowering the risks of diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer, and all-cause mortality,4 bariatric surgery is associated with increased health care use. Neovius et al. found that people who underwent bariatric surgery used 54 mean cumulative hospital days in the 20 years following their procedures, compared with just 40 inpatient days used by controls.5

Although hospitalists are caring for increasing numbers of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, many of us may not be aware of some of the things that can lead to hospitalization or otherwise affect inpatient medical care. Here are a few points to keep in mind the next time you care for an inpatient with prior bariatric surgery.

Pharmacokinetics change after surgery

Gastrointestinal anatomy necessarily changes after bariatric surgery and can affect the oral absorption of drugs. Because gastric motility may be impaired and the pH in the stomach is increased after bariatric surgery, the disintegration and dissolution of immediate-release solid pills or caps may be compromised.

It is therefore prudent to crush solid forms or switch to liquid or chewable formulations of immediate-release drugs for the first few weeks to months after surgery. Enteric-coated or long-acting drug formulations should not be crushed and should generally be avoided in patients who have undergone bypass procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS), as they can demonstrate either enhanced or diminished absorption (depending on the drug).

Reduced intestinal transit times and changes in intestinal pH can alter the absorption of certain drugs as well, and the expression of some drug transporter proteins and enzymes such as the CYP3A4 variant of cytochrome P450 – which is estimated to metabolize up to half of currently available drugs – varies between the upper and the lower small intestine, potentially leading to increased bioavailability of medications metabolized by this enzyme in patients who have undergone bypass surgeries.

Interestingly, longer-term studies have reexamined drug absorption in patients 2-4 years after RYGB and found that initially-increased drug plasma levels often return to preoperative levels or even lower over time,6 likely because of adaptive changes in the GI tract. Because research on the pharmacokinetics of individual drugs after bariatric surgery is lacking, the hospitalist should be aware that the bioavailability of oral drugs is often altered and should monitor patients for the desired therapeutic effect as well as potential toxicities for any drug administered to postbariatric surgery patients.

Finally, note that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and corticosteroids should be avoided after bariatric surgery unless the benefit clearly outweighs the risk, as they increase the risk of ulcers even in patients without underlying surgical disruptions to the gastric mucosa.

Micronutrient deficiencies are common and can occur at any time

While many clinicians recognize that vitamin deficiencies can occur after weight loss surgeries which bypass the duodenum, such as the RYGB or the BPD/DS, it is important to note that vitamin and mineral deficiencies occur commonly even in patients with intact intestinal absorption such as those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and even despite regained weight due to greater volumes of food (and micronutrient) intake over time.

The most common vitamin deficiencies include iron, vitamin B12, thiamine (vitamin B1), and vitamin D, but deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals may found as well. Anemia, bone fractures, heart failure, and encephalopathy can all be related to postoperative vitamin deficiencies. Most bariatric surgery patients should have micronutrient levels monitored on a yearly basis and should be taking at least a multivitamin with minerals (including zinc, copper, selenium and iron), a form of vitamin B12, and vitamin D with calcium supplementation. Additional supplements may be appropriate depending on the type of surgery the patient had or whether a deficiency is found.

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain after bariatric surgery is unique

While the usual suspects such as diverticulitis or gastritis should be considered in postbariatric surgery patients just as in others, a few specific complications can arise after weight loss surgery.

Marginal ulcerations (ulcers at the surgical anastomotic sites) have been reported in up to a third of patients complaining of abdominal pain or dysphagia after RYGB, with tobacco, alcohol, or NSAID use conferring even greater risk.7 Early upper endoscopy may be warranted in symptomatic patients.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) may occur due to surgical adhesions as in other patients, but catastrophic internal hernias with associated volvulus can occur due to specific anatomical defects that are created by the RYGB and BPD/DS procedures. CT imaging is insensitive and can miss up to 30% of these cases,8 and nasogastric tubes placed blindly for decompression of an SBO can lead to perforation of the end of the alimentary limb at the gastric pouch outlet, so post-RYGB or BPD/DS patients presenting with signs of small bowel obstruction should have an early surgical consult for expeditious surgical management rather than a trial of conservative medical management.9

Cholelithiasis is a very common postoperative complication, occurring in about 25% of SG patients and 32% of RYGB patients in the first year following surgery. The risk of gallstone formation can be significantly reduced with the postoperative use of ursodeoxycholic acid.10

Onset of abdominal cramping, nausea and diarrhea (sometimes accompanied by vasomotor symptoms) within 15-60 minutes of eating may be due to early dumping syndrome. Rapid delivery of food from the gastric pouch into the small intestine causes the release of gut peptides and an osmotic fluid shift into the intestinal lumen that can trigger these symptoms even in patients with a preserved pyloric sphincter, such as those who underwent SG. Simply eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet usually resolves the problem, and eliminating lactose can often be helpful as well.

Postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (“late dumping syndrome”) can develop years after surgery

Vasomotor symptoms such as flushing/sweating, shaking, tachycardia/palpitations, lightheadedness, or difficulty concentrating occurring 1-3 hours after a meal should prompt blood glucose testing, as delayed hypoglycemia can occur after a large insulin surge.

Most commonly seen after RYGB, late dumping syndrome, like early dumping syndrome, can often be managed by eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet. The onset of late dumping syndrome has been reported as late as 8 years after surgery,11 so the etiology of symptoms can be elusive. If the diagnosis is unclear, an oral glucose tolerance test may be helpful.

Alcohol use disorder is more prevalent after weight loss surgery

Changes to the gastrointestinal anatomy allow for more rapid absorption of ethanol into the bloodstream, making the drug more potent in postop patients. Simultaneously, many patients who undergo bariatric surgery have a history of using food to buffer negative emotions. Abruptly depriving them of that comfort in the context of the increased potency of alcohol could potentially leave bariatric surgery patients vulnerable to the development of alcohol use disorder, even when they did not misuse alcohol preoperatively.

Of note, alcohol misuse becomes more prevalent after the first postoperative year.12 Screening for alcohol misuse on admission to the hospital is wise in all cases, but perhaps even more so in the postbariatric surgery patient. If a patient does report excessive alcohol use, keep possible thiamine deficiency in mind.

The risk of suicide and self-harm increases after bariatric surgery

While all-cause mortality rates decrease after bariatric surgery compared with matched controls, the risk of suicide and nonfatal self-harm increases.

About half of bariatric surgery patients with nonfatal events have substance misuse.13 Notably, several studies have found reduced plasma levels of SSRIs in patients after RYGB,6 so pharmacotherapy for mood disorders could be less effective after bariatric surgery as well. The hospitalist could positively impact patients by screening for both substance misuse and depression and by having a low threshold for referral to a mental health professional.

As we see ever-increasing numbers of inpatients who have a history of bariatric surgery, being aware of these common and important complications can help today’s hospitalist provide the best care possible.

Dr. Kerns is a hospitalist and codirector of bariatric surgery at the Washington DC VA Medical Center.

References

1. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Published Feb 16, 2018.

2. Hales CM et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

3. Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2018. ASMBS.org. Published June 2018.

4. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013 Mar;273(3):219-34. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012.

5. Neovius M et al. Health care use during 20 years following bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Sep 19; 308(11):1132-41. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11792.

6. Azran C. et al. Oral drug therapy following bariatric surgery: An overview of fundamentals, literature and clinical recommendations. Obes Rev. 2016 Nov;17(11):1050-66. doi: 10.1111/obr.12434.

7. El-hayek KM et al. Marginal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: What have we really learned? Surg Endosc. 2012 Oct;26(10):2789-96. Epub 2012 Apr 28. (Abstract presented at Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons 2012 annual meeting, San Diego.) 8. Iannelli A et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1265-71. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663689.

9. Lim R et al. Early and late complications of bariatric operation. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018 Oct 9;3(1): e000219. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000219.

10. Coupaye M et al. Evaluation of incidence of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery in subjects treated or not treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):681-5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.11.022.

11. Eisenberg D et al. ASMBS position statement on postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Mar;13(3):371-8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.005.

12. King WC et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2516-25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147.

13. Neovius M et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: Results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Mar;6(3):197-207. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0.

What every hospitalist should know

What every hospitalist should know

With the prevalence of obesity worldwide topping 650 million people1 and nearly 40% of U.S. adults having obesity,2 bariatric surgery is increasingly used to treat this disease and its associated comorbidities.

The American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery estimates that 228,000 bariatric procedures were performed on Americans in 2017, up from 158,000 in 2011.3 Despite lowering the risks of diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer, and all-cause mortality,4 bariatric surgery is associated with increased health care use. Neovius et al. found that people who underwent bariatric surgery used 54 mean cumulative hospital days in the 20 years following their procedures, compared with just 40 inpatient days used by controls.5

Although hospitalists are caring for increasing numbers of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, many of us may not be aware of some of the things that can lead to hospitalization or otherwise affect inpatient medical care. Here are a few points to keep in mind the next time you care for an inpatient with prior bariatric surgery.

Pharmacokinetics change after surgery

Gastrointestinal anatomy necessarily changes after bariatric surgery and can affect the oral absorption of drugs. Because gastric motility may be impaired and the pH in the stomach is increased after bariatric surgery, the disintegration and dissolution of immediate-release solid pills or caps may be compromised.

It is therefore prudent to crush solid forms or switch to liquid or chewable formulations of immediate-release drugs for the first few weeks to months after surgery. Enteric-coated or long-acting drug formulations should not be crushed and should generally be avoided in patients who have undergone bypass procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS), as they can demonstrate either enhanced or diminished absorption (depending on the drug).

Reduced intestinal transit times and changes in intestinal pH can alter the absorption of certain drugs as well, and the expression of some drug transporter proteins and enzymes such as the CYP3A4 variant of cytochrome P450 – which is estimated to metabolize up to half of currently available drugs – varies between the upper and the lower small intestine, potentially leading to increased bioavailability of medications metabolized by this enzyme in patients who have undergone bypass surgeries.

Interestingly, longer-term studies have reexamined drug absorption in patients 2-4 years after RYGB and found that initially-increased drug plasma levels often return to preoperative levels or even lower over time,6 likely because of adaptive changes in the GI tract. Because research on the pharmacokinetics of individual drugs after bariatric surgery is lacking, the hospitalist should be aware that the bioavailability of oral drugs is often altered and should monitor patients for the desired therapeutic effect as well as potential toxicities for any drug administered to postbariatric surgery patients.

Finally, note that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and corticosteroids should be avoided after bariatric surgery unless the benefit clearly outweighs the risk, as they increase the risk of ulcers even in patients without underlying surgical disruptions to the gastric mucosa.

Micronutrient deficiencies are common and can occur at any time

While many clinicians recognize that vitamin deficiencies can occur after weight loss surgeries which bypass the duodenum, such as the RYGB or the BPD/DS, it is important to note that vitamin and mineral deficiencies occur commonly even in patients with intact intestinal absorption such as those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and even despite regained weight due to greater volumes of food (and micronutrient) intake over time.

The most common vitamin deficiencies include iron, vitamin B12, thiamine (vitamin B1), and vitamin D, but deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals may found as well. Anemia, bone fractures, heart failure, and encephalopathy can all be related to postoperative vitamin deficiencies. Most bariatric surgery patients should have micronutrient levels monitored on a yearly basis and should be taking at least a multivitamin with minerals (including zinc, copper, selenium and iron), a form of vitamin B12, and vitamin D with calcium supplementation. Additional supplements may be appropriate depending on the type of surgery the patient had or whether a deficiency is found.

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain after bariatric surgery is unique

While the usual suspects such as diverticulitis or gastritis should be considered in postbariatric surgery patients just as in others, a few specific complications can arise after weight loss surgery.

Marginal ulcerations (ulcers at the surgical anastomotic sites) have been reported in up to a third of patients complaining of abdominal pain or dysphagia after RYGB, with tobacco, alcohol, or NSAID use conferring even greater risk.7 Early upper endoscopy may be warranted in symptomatic patients.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) may occur due to surgical adhesions as in other patients, but catastrophic internal hernias with associated volvulus can occur due to specific anatomical defects that are created by the RYGB and BPD/DS procedures. CT imaging is insensitive and can miss up to 30% of these cases,8 and nasogastric tubes placed blindly for decompression of an SBO can lead to perforation of the end of the alimentary limb at the gastric pouch outlet, so post-RYGB or BPD/DS patients presenting with signs of small bowel obstruction should have an early surgical consult for expeditious surgical management rather than a trial of conservative medical management.9

Cholelithiasis is a very common postoperative complication, occurring in about 25% of SG patients and 32% of RYGB patients in the first year following surgery. The risk of gallstone formation can be significantly reduced with the postoperative use of ursodeoxycholic acid.10

Onset of abdominal cramping, nausea and diarrhea (sometimes accompanied by vasomotor symptoms) within 15-60 minutes of eating may be due to early dumping syndrome. Rapid delivery of food from the gastric pouch into the small intestine causes the release of gut peptides and an osmotic fluid shift into the intestinal lumen that can trigger these symptoms even in patients with a preserved pyloric sphincter, such as those who underwent SG. Simply eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet usually resolves the problem, and eliminating lactose can often be helpful as well.

Postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (“late dumping syndrome”) can develop years after surgery

Vasomotor symptoms such as flushing/sweating, shaking, tachycardia/palpitations, lightheadedness, or difficulty concentrating occurring 1-3 hours after a meal should prompt blood glucose testing, as delayed hypoglycemia can occur after a large insulin surge.

Most commonly seen after RYGB, late dumping syndrome, like early dumping syndrome, can often be managed by eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet. The onset of late dumping syndrome has been reported as late as 8 years after surgery,11 so the etiology of symptoms can be elusive. If the diagnosis is unclear, an oral glucose tolerance test may be helpful.

Alcohol use disorder is more prevalent after weight loss surgery

Changes to the gastrointestinal anatomy allow for more rapid absorption of ethanol into the bloodstream, making the drug more potent in postop patients. Simultaneously, many patients who undergo bariatric surgery have a history of using food to buffer negative emotions. Abruptly depriving them of that comfort in the context of the increased potency of alcohol could potentially leave bariatric surgery patients vulnerable to the development of alcohol use disorder, even when they did not misuse alcohol preoperatively.

Of note, alcohol misuse becomes more prevalent after the first postoperative year.12 Screening for alcohol misuse on admission to the hospital is wise in all cases, but perhaps even more so in the postbariatric surgery patient. If a patient does report excessive alcohol use, keep possible thiamine deficiency in mind.

The risk of suicide and self-harm increases after bariatric surgery

While all-cause mortality rates decrease after bariatric surgery compared with matched controls, the risk of suicide and nonfatal self-harm increases.

About half of bariatric surgery patients with nonfatal events have substance misuse.13 Notably, several studies have found reduced plasma levels of SSRIs in patients after RYGB,6 so pharmacotherapy for mood disorders could be less effective after bariatric surgery as well. The hospitalist could positively impact patients by screening for both substance misuse and depression and by having a low threshold for referral to a mental health professional.

As we see ever-increasing numbers of inpatients who have a history of bariatric surgery, being aware of these common and important complications can help today’s hospitalist provide the best care possible.

Dr. Kerns is a hospitalist and codirector of bariatric surgery at the Washington DC VA Medical Center.

References

1. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Published Feb 16, 2018.

2. Hales CM et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

3. Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2018. ASMBS.org. Published June 2018.

4. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013 Mar;273(3):219-34. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012.

5. Neovius M et al. Health care use during 20 years following bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Sep 19; 308(11):1132-41. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11792.

6. Azran C. et al. Oral drug therapy following bariatric surgery: An overview of fundamentals, literature and clinical recommendations. Obes Rev. 2016 Nov;17(11):1050-66. doi: 10.1111/obr.12434.

7. El-hayek KM et al. Marginal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: What have we really learned? Surg Endosc. 2012 Oct;26(10):2789-96. Epub 2012 Apr 28. (Abstract presented at Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons 2012 annual meeting, San Diego.) 8. Iannelli A et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1265-71. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663689.

9. Lim R et al. Early and late complications of bariatric operation. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018 Oct 9;3(1): e000219. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000219.

10. Coupaye M et al. Evaluation of incidence of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery in subjects treated or not treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):681-5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.11.022.

11. Eisenberg D et al. ASMBS position statement on postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Mar;13(3):371-8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.005.

12. King WC et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2516-25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147.

13. Neovius M et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: Results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Mar;6(3):197-207. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0.

With the prevalence of obesity worldwide topping 650 million people1 and nearly 40% of U.S. adults having obesity,2 bariatric surgery is increasingly used to treat this disease and its associated comorbidities.

The American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery estimates that 228,000 bariatric procedures were performed on Americans in 2017, up from 158,000 in 2011.3 Despite lowering the risks of diabetes, stroke, myocardial infarction, cancer, and all-cause mortality,4 bariatric surgery is associated with increased health care use. Neovius et al. found that people who underwent bariatric surgery used 54 mean cumulative hospital days in the 20 years following their procedures, compared with just 40 inpatient days used by controls.5

Although hospitalists are caring for increasing numbers of patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, many of us may not be aware of some of the things that can lead to hospitalization or otherwise affect inpatient medical care. Here are a few points to keep in mind the next time you care for an inpatient with prior bariatric surgery.

Pharmacokinetics change after surgery

Gastrointestinal anatomy necessarily changes after bariatric surgery and can affect the oral absorption of drugs. Because gastric motility may be impaired and the pH in the stomach is increased after bariatric surgery, the disintegration and dissolution of immediate-release solid pills or caps may be compromised.

It is therefore prudent to crush solid forms or switch to liquid or chewable formulations of immediate-release drugs for the first few weeks to months after surgery. Enteric-coated or long-acting drug formulations should not be crushed and should generally be avoided in patients who have undergone bypass procedures such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS), as they can demonstrate either enhanced or diminished absorption (depending on the drug).

Reduced intestinal transit times and changes in intestinal pH can alter the absorption of certain drugs as well, and the expression of some drug transporter proteins and enzymes such as the CYP3A4 variant of cytochrome P450 – which is estimated to metabolize up to half of currently available drugs – varies between the upper and the lower small intestine, potentially leading to increased bioavailability of medications metabolized by this enzyme in patients who have undergone bypass surgeries.

Interestingly, longer-term studies have reexamined drug absorption in patients 2-4 years after RYGB and found that initially-increased drug plasma levels often return to preoperative levels or even lower over time,6 likely because of adaptive changes in the GI tract. Because research on the pharmacokinetics of individual drugs after bariatric surgery is lacking, the hospitalist should be aware that the bioavailability of oral drugs is often altered and should monitor patients for the desired therapeutic effect as well as potential toxicities for any drug administered to postbariatric surgery patients.

Finally, note that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin, and corticosteroids should be avoided after bariatric surgery unless the benefit clearly outweighs the risk, as they increase the risk of ulcers even in patients without underlying surgical disruptions to the gastric mucosa.

Micronutrient deficiencies are common and can occur at any time

While many clinicians recognize that vitamin deficiencies can occur after weight loss surgeries which bypass the duodenum, such as the RYGB or the BPD/DS, it is important to note that vitamin and mineral deficiencies occur commonly even in patients with intact intestinal absorption such as those who underwent sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and even despite regained weight due to greater volumes of food (and micronutrient) intake over time.

The most common vitamin deficiencies include iron, vitamin B12, thiamine (vitamin B1), and vitamin D, but deficiencies in other vitamins and minerals may found as well. Anemia, bone fractures, heart failure, and encephalopathy can all be related to postoperative vitamin deficiencies. Most bariatric surgery patients should have micronutrient levels monitored on a yearly basis and should be taking at least a multivitamin with minerals (including zinc, copper, selenium and iron), a form of vitamin B12, and vitamin D with calcium supplementation. Additional supplements may be appropriate depending on the type of surgery the patient had or whether a deficiency is found.

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain after bariatric surgery is unique

While the usual suspects such as diverticulitis or gastritis should be considered in postbariatric surgery patients just as in others, a few specific complications can arise after weight loss surgery.

Marginal ulcerations (ulcers at the surgical anastomotic sites) have been reported in up to a third of patients complaining of abdominal pain or dysphagia after RYGB, with tobacco, alcohol, or NSAID use conferring even greater risk.7 Early upper endoscopy may be warranted in symptomatic patients.

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) may occur due to surgical adhesions as in other patients, but catastrophic internal hernias with associated volvulus can occur due to specific anatomical defects that are created by the RYGB and BPD/DS procedures. CT imaging is insensitive and can miss up to 30% of these cases,8 and nasogastric tubes placed blindly for decompression of an SBO can lead to perforation of the end of the alimentary limb at the gastric pouch outlet, so post-RYGB or BPD/DS patients presenting with signs of small bowel obstruction should have an early surgical consult for expeditious surgical management rather than a trial of conservative medical management.9

Cholelithiasis is a very common postoperative complication, occurring in about 25% of SG patients and 32% of RYGB patients in the first year following surgery. The risk of gallstone formation can be significantly reduced with the postoperative use of ursodeoxycholic acid.10

Onset of abdominal cramping, nausea and diarrhea (sometimes accompanied by vasomotor symptoms) within 15-60 minutes of eating may be due to early dumping syndrome. Rapid delivery of food from the gastric pouch into the small intestine causes the release of gut peptides and an osmotic fluid shift into the intestinal lumen that can trigger these symptoms even in patients with a preserved pyloric sphincter, such as those who underwent SG. Simply eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet usually resolves the problem, and eliminating lactose can often be helpful as well.

Postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia (“late dumping syndrome”) can develop years after surgery

Vasomotor symptoms such as flushing/sweating, shaking, tachycardia/palpitations, lightheadedness, or difficulty concentrating occurring 1-3 hours after a meal should prompt blood glucose testing, as delayed hypoglycemia can occur after a large insulin surge.

Most commonly seen after RYGB, late dumping syndrome, like early dumping syndrome, can often be managed by eliminating sugars and simple carbohydrates from the diet. The onset of late dumping syndrome has been reported as late as 8 years after surgery,11 so the etiology of symptoms can be elusive. If the diagnosis is unclear, an oral glucose tolerance test may be helpful.

Alcohol use disorder is more prevalent after weight loss surgery

Changes to the gastrointestinal anatomy allow for more rapid absorption of ethanol into the bloodstream, making the drug more potent in postop patients. Simultaneously, many patients who undergo bariatric surgery have a history of using food to buffer negative emotions. Abruptly depriving them of that comfort in the context of the increased potency of alcohol could potentially leave bariatric surgery patients vulnerable to the development of alcohol use disorder, even when they did not misuse alcohol preoperatively.

Of note, alcohol misuse becomes more prevalent after the first postoperative year.12 Screening for alcohol misuse on admission to the hospital is wise in all cases, but perhaps even more so in the postbariatric surgery patient. If a patient does report excessive alcohol use, keep possible thiamine deficiency in mind.

The risk of suicide and self-harm increases after bariatric surgery

While all-cause mortality rates decrease after bariatric surgery compared with matched controls, the risk of suicide and nonfatal self-harm increases.

About half of bariatric surgery patients with nonfatal events have substance misuse.13 Notably, several studies have found reduced plasma levels of SSRIs in patients after RYGB,6 so pharmacotherapy for mood disorders could be less effective after bariatric surgery as well. The hospitalist could positively impact patients by screening for both substance misuse and depression and by having a low threshold for referral to a mental health professional.

As we see ever-increasing numbers of inpatients who have a history of bariatric surgery, being aware of these common and important complications can help today’s hospitalist provide the best care possible.

Dr. Kerns is a hospitalist and codirector of bariatric surgery at the Washington DC VA Medical Center.

References

1. Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Published Feb 16, 2018.

2. Hales CM et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017.

3. Estimate of Bariatric Surgery Numbers, 2011-2018. ASMBS.org. Published June 2018.

4. Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial – a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013 Mar;273(3):219-34. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012.

5. Neovius M et al. Health care use during 20 years following bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Sep 19; 308(11):1132-41. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11792.

6. Azran C. et al. Oral drug therapy following bariatric surgery: An overview of fundamentals, literature and clinical recommendations. Obes Rev. 2016 Nov;17(11):1050-66. doi: 10.1111/obr.12434.

7. El-hayek KM et al. Marginal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: What have we really learned? Surg Endosc. 2012 Oct;26(10):2789-96. Epub 2012 Apr 28. (Abstract presented at Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons 2012 annual meeting, San Diego.) 8. Iannelli A et al. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1265-71. doi: 10.1381/096089206778663689.

9. Lim R et al. Early and late complications of bariatric operation. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018 Oct 9;3(1): e000219. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000219.

10. Coupaye M et al. Evaluation of incidence of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery in subjects treated or not treated with ursodeoxycholic acid. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):681-5. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.11.022.

11. Eisenberg D et al. ASMBS position statement on postprandial hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017 Mar;13(3):371-8. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.005.

12. King WC et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012 Jun 20;307(23):2516-25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147.

13. Neovius M et al. Risk of suicide and non-fatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: Results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018 Mar;6(3):197-207. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30437-0.

Disruptions in cancer care in the era of COVID-19

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

Even in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, cancer care must go on, but changes may need to be made in the way some care is delivered.

“We’re headed for a time when there will be significant disruptions in the care of patients with cancer,” said Len Lichtenfeld, MD, deputy chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society (ACS), in a statement. “For some it may be as straightforward as a delay in having elective surgery. For others it may be delaying preventive care or adjuvant chemotherapy that’s meant to keep cancer from returning or rescheduling appointments.”

Lichtenfeld emphasized that cancer care teams are going to do the best they can to deliver care to those most in need. However, even in those circumstances, it won’t be life as usual. “It will require patience on everyone’s part as we go through this pandemic,” he said.

“The way we treat cancer over the next few months will change enormously,” writes a British oncologist in an article published in the Guardian.

“As oncologists, we will have to find a tenuous balance between undertreating people with cancer, resulting in more deaths from the disease in the medium to long term, and increasing deaths from COVID-19 in a vulnerable patient population. Alongside our patients we will have to make difficult decisions regarding treatments, with only low-quality evidence to guide us,” writes Lucy Gossage, MD, consultant oncologist at Nottingham University Hospital, UK.

The evidence to date (from reports from China in Lancet Oncology) suggests that people with cancer have a significantly higher risk of severe illness resulting in intensive care admissions or death when infected with COVID-19, particularly if they recently had chemotherapy or surgery.

“Many of the oncology treatments we currently use, especially those given after surgery to reduce risk of cancer recurrence, have relatively small benefits,” she writes.

“In the current climate, the balance of offering these treatments may shift; a small reduction in risk of cancer recurrence over the next 5 years may be outweighed by the potential for a short-term increase in risk of death from COVID-19. In the long term, more people’s cancer will return if we aren’t able to offer these treatments,” she adds.

Postpone Routine Screening

One thing that can go on the back burner for now is routine cancer screening, which can be postponed for now in order to conserve health system resources and reduce contact with healthcare facilities, says the ACS.

“Patients seeking routine cancer screenings should delay those until further notice,” said Lichtenfeld. “While timely screening is important, the need to prevent the spread of coronavirus and to reduce the strain on the medical system is more important right now.”

But as soon as restrictions to slow the spread of COVID-19 are lifted and routine visits to health facilities are safe, regular screening tests should be rescheduled.

Guidance From ASCO

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has issued new guidance on caring for patients with cancer during the COVID-19 outbreak.

First and foremost, ASCO encourages providers, facilities, and anyone caring for patients with cancer to follow the existing guidelines from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention when possible.

ASCO highlights the CDC’s general recommendation for healthcare facilities that suggests “elective surgeries” at inpatient facilities be rescheduled if possible, which has also been recommended by the American College of Surgeons.

However, in many cases, cancer surgery is not elective but essential, it points out. So this is largely an individual determination that clinicians and patients will need to make, taking into account the potential harms of delaying needed cancer-related surgery.

Systemic treatments, including chemotherapy and immunotherapy, leave cancer patients vulnerable to infection, but ASCO says there is no direct evidence to support changes in regimens during the pandemic. Therefore, routinely stopping anticancer or immunosuppressive therapy is not recommended, as the balance of potential harms that may result from delaying or interrupting treatment versus the potential benefits of possibly preventing or delaying COVID-19 infection remains very unclear.

Clinical decisions must be individualized, ASCO emphasized, and suggested the following practice points be considered:

- For patients already in deep remission who are receiving maintenance therapy, stopping treatment may be an option.

- Some patients may be able to switch from IV to oral therapies, which would decrease the frequency of clinic visits.

- Decisions on modifying or withholding chemotherapy need to consider both the indication and goals of care, as well as where the patient is in the treatment regimen and tolerance to the therapy. As an example, the risk–benefit assessment for proceeding with chemotherapy in patients with untreated extensive small-cell lung cancer is quite different than proceeding with maintenance pemetrexed for metastatic non–small cell lung cancer.

- If local coronavirus transmission is an issue at a particular cancer center, reasonable options may include taking a 2-week treatment break or arranging treatment at a different facility.

- Evaluate if home infusion is medically and logistically feasible.

- In some settings, delaying or modifying adjuvant treatment presents a higher risk of compromised disease control and long-term survival than in others, but in cases where the absolute benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy may be quite small and other options are available, the risk of COVID-19 may be considered an additional factor when evaluating care.

Delay Stem Cell Transplants

For patients who are candidates for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, a delay may be reasonable if the patient is currently well controlled with conventional treatment, ASCO comments. It also directs clinicians to follow the recommendations provided by the American Society of Transplantation and Cellular Therapy and from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation regarding this issue.

Finally, there is also the question of prophylactic antiviral therapy: Should it be considered for cancer patients undergoing active therapy?

The answer to that question is currently unknown, says ASCO, but “this is an active area of research and evidence may be available at any time.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

Even in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, cancer care must go on, but changes may need to be made in the way some care is delivered.

“We’re headed for a time when there will be significant disruptions in the care of patients with cancer,” said Len Lichtenfeld, MD, deputy chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society (ACS), in a statement. “For some it may be as straightforward as a delay in having elective surgery. For others it may be delaying preventive care or adjuvant chemotherapy that’s meant to keep cancer from returning or rescheduling appointments.”

Lichtenfeld emphasized that cancer care teams are going to do the best they can to deliver care to those most in need. However, even in those circumstances, it won’t be life as usual. “It will require patience on everyone’s part as we go through this pandemic,” he said.

“The way we treat cancer over the next few months will change enormously,” writes a British oncologist in an article published in the Guardian.

“As oncologists, we will have to find a tenuous balance between undertreating people with cancer, resulting in more deaths from the disease in the medium to long term, and increasing deaths from COVID-19 in a vulnerable patient population. Alongside our patients we will have to make difficult decisions regarding treatments, with only low-quality evidence to guide us,” writes Lucy Gossage, MD, consultant oncologist at Nottingham University Hospital, UK.

The evidence to date (from reports from China in Lancet Oncology) suggests that people with cancer have a significantly higher risk of severe illness resulting in intensive care admissions or death when infected with COVID-19, particularly if they recently had chemotherapy or surgery.

“Many of the oncology treatments we currently use, especially those given after surgery to reduce risk of cancer recurrence, have relatively small benefits,” she writes.

“In the current climate, the balance of offering these treatments may shift; a small reduction in risk of cancer recurrence over the next 5 years may be outweighed by the potential for a short-term increase in risk of death from COVID-19. In the long term, more people’s cancer will return if we aren’t able to offer these treatments,” she adds.

Postpone Routine Screening

One thing that can go on the back burner for now is routine cancer screening, which can be postponed for now in order to conserve health system resources and reduce contact with healthcare facilities, says the ACS.

“Patients seeking routine cancer screenings should delay those until further notice,” said Lichtenfeld. “While timely screening is important, the need to prevent the spread of coronavirus and to reduce the strain on the medical system is more important right now.”

But as soon as restrictions to slow the spread of COVID-19 are lifted and routine visits to health facilities are safe, regular screening tests should be rescheduled.

Guidance From ASCO

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has issued new guidance on caring for patients with cancer during the COVID-19 outbreak.

First and foremost, ASCO encourages providers, facilities, and anyone caring for patients with cancer to follow the existing guidelines from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention when possible.

ASCO highlights the CDC’s general recommendation for healthcare facilities that suggests “elective surgeries” at inpatient facilities be rescheduled if possible, which has also been recommended by the American College of Surgeons.

However, in many cases, cancer surgery is not elective but essential, it points out. So this is largely an individual determination that clinicians and patients will need to make, taking into account the potential harms of delaying needed cancer-related surgery.

Systemic treatments, including chemotherapy and immunotherapy, leave cancer patients vulnerable to infection, but ASCO says there is no direct evidence to support changes in regimens during the pandemic. Therefore, routinely stopping anticancer or immunosuppressive therapy is not recommended, as the balance of potential harms that may result from delaying or interrupting treatment versus the potential benefits of possibly preventing or delaying COVID-19 infection remains very unclear.

Clinical decisions must be individualized, ASCO emphasized, and suggested the following practice points be considered:

- For patients already in deep remission who are receiving maintenance therapy, stopping treatment may be an option.

- Some patients may be able to switch from IV to oral therapies, which would decrease the frequency of clinic visits.

- Decisions on modifying or withholding chemotherapy need to consider both the indication and goals of care, as well as where the patient is in the treatment regimen and tolerance to the therapy. As an example, the risk–benefit assessment for proceeding with chemotherapy in patients with untreated extensive small-cell lung cancer is quite different than proceeding with maintenance pemetrexed for metastatic non–small cell lung cancer.

- If local coronavirus transmission is an issue at a particular cancer center, reasonable options may include taking a 2-week treatment break or arranging treatment at a different facility.

- Evaluate if home infusion is medically and logistically feasible.

- In some settings, delaying or modifying adjuvant treatment presents a higher risk of compromised disease control and long-term survival than in others, but in cases where the absolute benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy may be quite small and other options are available, the risk of COVID-19 may be considered an additional factor when evaluating care.

Delay Stem Cell Transplants

For patients who are candidates for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, a delay may be reasonable if the patient is currently well controlled with conventional treatment, ASCO comments. It also directs clinicians to follow the recommendations provided by the American Society of Transplantation and Cellular Therapy and from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation regarding this issue.

Finally, there is also the question of prophylactic antiviral therapy: Should it be considered for cancer patients undergoing active therapy?

The answer to that question is currently unknown, says ASCO, but “this is an active area of research and evidence may be available at any time.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

Even in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, cancer care must go on, but changes may need to be made in the way some care is delivered.

“We’re headed for a time when there will be significant disruptions in the care of patients with cancer,” said Len Lichtenfeld, MD, deputy chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society (ACS), in a statement. “For some it may be as straightforward as a delay in having elective surgery. For others it may be delaying preventive care or adjuvant chemotherapy that’s meant to keep cancer from returning or rescheduling appointments.”

Lichtenfeld emphasized that cancer care teams are going to do the best they can to deliver care to those most in need. However, even in those circumstances, it won’t be life as usual. “It will require patience on everyone’s part as we go through this pandemic,” he said.

“The way we treat cancer over the next few months will change enormously,” writes a British oncologist in an article published in the Guardian.

“As oncologists, we will have to find a tenuous balance between undertreating people with cancer, resulting in more deaths from the disease in the medium to long term, and increasing deaths from COVID-19 in a vulnerable patient population. Alongside our patients we will have to make difficult decisions regarding treatments, with only low-quality evidence to guide us,” writes Lucy Gossage, MD, consultant oncologist at Nottingham University Hospital, UK.

The evidence to date (from reports from China in Lancet Oncology) suggests that people with cancer have a significantly higher risk of severe illness resulting in intensive care admissions or death when infected with COVID-19, particularly if they recently had chemotherapy or surgery.

“Many of the oncology treatments we currently use, especially those given after surgery to reduce risk of cancer recurrence, have relatively small benefits,” she writes.

“In the current climate, the balance of offering these treatments may shift; a small reduction in risk of cancer recurrence over the next 5 years may be outweighed by the potential for a short-term increase in risk of death from COVID-19. In the long term, more people’s cancer will return if we aren’t able to offer these treatments,” she adds.

Postpone Routine Screening

One thing that can go on the back burner for now is routine cancer screening, which can be postponed for now in order to conserve health system resources and reduce contact with healthcare facilities, says the ACS.

“Patients seeking routine cancer screenings should delay those until further notice,” said Lichtenfeld. “While timely screening is important, the need to prevent the spread of coronavirus and to reduce the strain on the medical system is more important right now.”

But as soon as restrictions to slow the spread of COVID-19 are lifted and routine visits to health facilities are safe, regular screening tests should be rescheduled.

Guidance From ASCO

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has issued new guidance on caring for patients with cancer during the COVID-19 outbreak.

First and foremost, ASCO encourages providers, facilities, and anyone caring for patients with cancer to follow the existing guidelines from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention when possible.

ASCO highlights the CDC’s general recommendation for healthcare facilities that suggests “elective surgeries” at inpatient facilities be rescheduled if possible, which has also been recommended by the American College of Surgeons.

However, in many cases, cancer surgery is not elective but essential, it points out. So this is largely an individual determination that clinicians and patients will need to make, taking into account the potential harms of delaying needed cancer-related surgery.

Systemic treatments, including chemotherapy and immunotherapy, leave cancer patients vulnerable to infection, but ASCO says there is no direct evidence to support changes in regimens during the pandemic. Therefore, routinely stopping anticancer or immunosuppressive therapy is not recommended, as the balance of potential harms that may result from delaying or interrupting treatment versus the potential benefits of possibly preventing or delaying COVID-19 infection remains very unclear.

Clinical decisions must be individualized, ASCO emphasized, and suggested the following practice points be considered:

- For patients already in deep remission who are receiving maintenance therapy, stopping treatment may be an option.

- Some patients may be able to switch from IV to oral therapies, which would decrease the frequency of clinic visits.

- Decisions on modifying or withholding chemotherapy need to consider both the indication and goals of care, as well as where the patient is in the treatment regimen and tolerance to the therapy. As an example, the risk–benefit assessment for proceeding with chemotherapy in patients with untreated extensive small-cell lung cancer is quite different than proceeding with maintenance pemetrexed for metastatic non–small cell lung cancer.

- If local coronavirus transmission is an issue at a particular cancer center, reasonable options may include taking a 2-week treatment break or arranging treatment at a different facility.

- Evaluate if home infusion is medically and logistically feasible.

- In some settings, delaying or modifying adjuvant treatment presents a higher risk of compromised disease control and long-term survival than in others, but in cases where the absolute benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy may be quite small and other options are available, the risk of COVID-19 may be considered an additional factor when evaluating care.

Delay Stem Cell Transplants

For patients who are candidates for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, a delay may be reasonable if the patient is currently well controlled with conventional treatment, ASCO comments. It also directs clinicians to follow the recommendations provided by the American Society of Transplantation and Cellular Therapy and from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation regarding this issue.

Finally, there is also the question of prophylactic antiviral therapy: Should it be considered for cancer patients undergoing active therapy?

The answer to that question is currently unknown, says ASCO, but “this is an active area of research and evidence may be available at any time.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What to know about CFTR modulator therapy for cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators are bringing new hope to many patients with CF. But what do physicians and patients need to know about the latest CFTR modulator therapies?

Susan M. Millard, MD, is a pediatric pulmonologist at Helen DeVos Children's Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich. In an audio interview, Dr. Millard discusses the new Food and Drug Administration-approved combination therapy of elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor (Trikafta). It's a trio that could make a significant difference for the roughly 90% of patients with at least one F508del mutation.

Dr. Millard outlines which patients are candidates for the combination therapy, what physicians and patients can expect with Trikafta use, and how the drug affects patients' use of other CF therapies. She also explains the steps physicians should take before starting patients on the therapy, and what side effects to watch for during treatment.

Dr. Millard is the local principal investigator for CF research at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, including Mylan, Therapeutic Development Network, and Vertex clinical studies.

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators are bringing new hope to many patients with CF. But what do physicians and patients need to know about the latest CFTR modulator therapies?

Susan M. Millard, MD, is a pediatric pulmonologist at Helen DeVos Children's Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich. In an audio interview, Dr. Millard discusses the new Food and Drug Administration-approved combination therapy of elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor (Trikafta). It's a trio that could make a significant difference for the roughly 90% of patients with at least one F508del mutation.

Dr. Millard outlines which patients are candidates for the combination therapy, what physicians and patients can expect with Trikafta use, and how the drug affects patients' use of other CF therapies. She also explains the steps physicians should take before starting patients on the therapy, and what side effects to watch for during treatment.

Dr. Millard is the local principal investigator for CF research at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, including Mylan, Therapeutic Development Network, and Vertex clinical studies.

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators are bringing new hope to many patients with CF. But what do physicians and patients need to know about the latest CFTR modulator therapies?

Susan M. Millard, MD, is a pediatric pulmonologist at Helen DeVos Children's Hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich. In an audio interview, Dr. Millard discusses the new Food and Drug Administration-approved combination therapy of elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor (Trikafta). It's a trio that could make a significant difference for the roughly 90% of patients with at least one F508del mutation.

Dr. Millard outlines which patients are candidates for the combination therapy, what physicians and patients can expect with Trikafta use, and how the drug affects patients' use of other CF therapies. She also explains the steps physicians should take before starting patients on the therapy, and what side effects to watch for during treatment.

Dr. Millard is the local principal investigator for CF research at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, including Mylan, Therapeutic Development Network, and Vertex clinical studies.

TAVR for low-risk bicuspid aortic stenosis appears safe, effective

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD – Data presented at the 2020 CRT meeting, sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute, show that transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is safe and effective, at least in the short term, for low-risk patients with bicuspid aortic stenosis, which addresses a data gap.

In an investigator-driven prospective study, called LRT, there was no mortality, no myocardial infarctions (MI), and no disabling strokes 30 days after the procedure, according to Ronald Waksman, MD, associate director of cardiology at Medstar Heart Institute in Washington.

TAVR was approved in 2019 for low-risk patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis regardless of aortic valve morphology, but the pivotal industry-led trials only enrolled patients with tricuspid valves, excluding the bicuspid population, according to Dr. Waksman.

However, bicuspid patients were enrolled in the investigator-led LRT study. The 1-year results with tricuspid values have been published previously (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:901-7), but new data from this same study provides the first prospective evaluation in low-risk bicuspid patients.

The LRT enrollment criteria were the same for the bicuspid patients as they were for those enrolled with tricuspid valves. These included a low surgical risk, defined as a Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score of 3 or less; no high-risk criteria independent of STS score; and eligibility for a transfemoral percutaneous procedure. Patients were permitted to undergo TAVR with any commercially available device.

The 61 patients enrolled from August 2016 to September 2019 were compared at 30 days of follow-up with 211 low-risk bicuspid patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). Propensity matched, the two groups had generally similar baseline characteristics with some exceptions. Relative to the SAVR group, the TAVR group had an older median age (68.6 vs. 63.4 years) and a lower proportion of males (42.6% vs. 65.7%) and a lower proportion with New York Heart Association heart failure of class III or higher (15.8% vs. 24.6%).

For the primary outcome of all-cause mortality at 30 days, there were no deaths in the TAVR group versus one death in the SAVR group. TAVR was associated with a shorter length of stay (2.0 vs. 5.8 days) and a lower risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (1.6% vs. 42.6%). However, pacemaker implantations were more common in the TAVR group (11.5% vs. 5.6%). There was one stroke in the TAVR group, but it was not disabling.

Following TAVR, there was one case of paravalvular leak, but it was of moderate severity, according to Dr. Waksman. Leaflet thrombosis in the form of hypoattenuated leaflet thickening (HALT), which occurred in 10.2% of patients; reduced leaflet motion (RELM), which occurred in 6.9%; and hypoattenuation affecting motion (HAM), which also occurred in 6.9%, was observed at 30 days following TAVR, but these have not so far been associated with any clinical consequences.

At baseline, only 4.9% of the bicuspid patients met criteria for NYHA class I function and 23% were in NYHA class III or higher. By 30 days, the proportion in NYHA class I had risen to 78.3%, and no patient was in NYHA class III or higher. Dr. Waksman characterized the improvement in hemodynamics – measured by mean aortic valve gradient and aortic valve area – as “excellent” at 30 days.

Further follow-up of bicuspid patients in the LRT study is needed to confirm long-term safety and efficacy, but Dr. Waksman indicated that the 30-day results are encouraging, in part because they show no greater risk of periprocedural complications than that observed in the tricuspid population.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD – Data presented at the 2020 CRT meeting, sponsored by MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute, show that transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is safe and effective, at least in the short term, for low-risk patients with bicuspid aortic stenosis, which addresses a data gap.

In an investigator-driven prospective study, called LRT, there was no mortality, no myocardial infarctions (MI), and no disabling strokes 30 days after the procedure, according to Ronald Waksman, MD, associate director of cardiology at Medstar Heart Institute in Washington.

TAVR was approved in 2019 for low-risk patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis regardless of aortic valve morphology, but the pivotal industry-led trials only enrolled patients with tricuspid valves, excluding the bicuspid population, according to Dr. Waksman.

However, bicuspid patients were enrolled in the investigator-led LRT study. The 1-year results with tricuspid values have been published previously (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:901-7), but new data from this same study provides the first prospective evaluation in low-risk bicuspid patients.

The LRT enrollment criteria were the same for the bicuspid patients as they were for those enrolled with tricuspid valves. These included a low surgical risk, defined as a Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score of 3 or less; no high-risk criteria independent of STS score; and eligibility for a transfemoral percutaneous procedure. Patients were permitted to undergo TAVR with any commercially available device.

The 61 patients enrolled from August 2016 to September 2019 were compared at 30 days of follow-up with 211 low-risk bicuspid patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). Propensity matched, the two groups had generally similar baseline characteristics with some exceptions. Relative to the SAVR group, the TAVR group had an older median age (68.6 vs. 63.4 years) and a lower proportion of males (42.6% vs. 65.7%) and a lower proportion with New York Heart Association heart failure of class III or higher (15.8% vs. 24.6%).

For the primary outcome of all-cause mortality at 30 days, there were no deaths in the TAVR group versus one death in the SAVR group. TAVR was associated with a shorter length of stay (2.0 vs. 5.8 days) and a lower risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation (1.6% vs. 42.6%). However, pacemaker implantations were more common in the TAVR group (11.5% vs. 5.6%). There was one stroke in the TAVR group, but it was not disabling.