User login

Get triage plans in place before COVID-19 surge hits, critical care experts say

, according to authors of recent reports that offer advice on how to prepare for surges in demand.

Even modest numbers of critically ill COVID-19 patients have already rapidly overwhelmed existing hospital capacity in hard-hit areas including Italy, Spain, and New York City, said authors of an expert panel report released in CHEST.

“The ethical burden this places on hospitals, health systems, and society is enormous,” said Ryan C. Maves, MD, FCCP, of the Naval Medical Center in San Diego, lead author of the expert panel report from the Task Force for Mass Critical Care and the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

Triage decisions could be especially daunting for resource-intensive therapies such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), as physicians may be forced to decide when and if to offer such support after demand outstrips a hospital’s ability to provide it.

“ECMO requires a lot of specialized capability to initiate on a patient, and then, it requires a lot of specialized capability to maintain and do safely,” said Steven P. Keller, MD, of the division of emergency critical care medicine in the department of emergency medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Those resource requirements can present a challenge to health care systems already overtaxed by COVID-19, according to Dr. Keller, coauthor of a guidance document in Annals of the American Thoracic Society. The guidance suggests a pandemic approach to ECMO response that’s tiered depending on the intensity of the surge over usual hospital volumes.

Mild surges call for a focus on increasing ECMO capacity, while a moderate surge may indicate a need to focus on allocating scarce resources, and a major surge may signal the need to limit or defer use of scarce resources, according to the guidance.

“If your health care system is stretched from a resource standpoint, at what point do you say, ‘we don’t even have the capability to even safely do ECMO, and so, perhaps we should not even be offering the support’?” Dr. Keller said in an interview. “That’s what we tried to get at in the paper – helping institutions think about how to prepare for that pandemic, and then when to make decisions on when it should and should not be offered.”

Critical care guidance for COVID-19

The guidance from the Task Force for Mass Critical Care and CHEST offers nine specific actions that authors suggest as part of a framework for communities to establish the infrastructure needed to triage critical care resources and “equitably” meet the needs of the largest number of COVID-19 patients.

“It is the goal of the task force to minimize the need for allocation of scarce resources as much as possible,” the authors stated.

The framework starts with surge planning that includes an inventory of intensive care unit resources such as ventilators, beds, supplies, and staff that could be marshaled to meet a surge in demand, followed by establishing “identification triggers” for triage initiation by a regional authority, should clinical demand reach a crisis stage.

The next step is preparing the triage system, which includes creating a committee at the regional level, identifying members of tertiary triage teams and the support structures they will need, and preparing and distributing training materials.

Agreeing on a triage protocol is important to ensure equitable targeting of resources, and how to allocate limited life-sustaining measures needs to be considered, according to the panel of experts. They also recommend adaptations to the standards of care such as modification of end-of-life care policies, support for health care workers, family, and the public, and consideration of pediatric issues including transport, concentration of care at specific centers, and potential increases in age thresholds to accommodate surges.

Barriers to triage?

When asked about potential barriers to rolling out a triage plan, Dr. Maves said the first is acknowledging the possible need for such a plan: “It is a difficult concept for most in critical care to accept – the idea that we may not be able to provide an individual patient with interventions that we consider routine,” he said.

Beyond acknowledging need, other potential barriers to successful implementation include the limited evidence base to support development of these protocols, as well as the need to address public trust.

“If a triage system is perceived as unjust or biased, or if people think that triage favors or excludes certain groups unfairly, it will undermine any system,” Dr. Maves said. “Making sure the public both understands and has input into system development is critical if we are going to be able to make this work.”

Dr. Maves and coauthors reported that some of the authors of their guidance are United States government employees or military service members, and that their opinions and assertions do not reflect the official views or position of those institutions. Dr. Keller reported no disclosures related to the ECMO guidance.

SOURCES: Maves RC et al. Chest. 2020 Apr 11. pii: S0012-3692(20)30691-7. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.063; Seethara R and Keller SP. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020 Apr 15. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-233PS.

, according to authors of recent reports that offer advice on how to prepare for surges in demand.

Even modest numbers of critically ill COVID-19 patients have already rapidly overwhelmed existing hospital capacity in hard-hit areas including Italy, Spain, and New York City, said authors of an expert panel report released in CHEST.

“The ethical burden this places on hospitals, health systems, and society is enormous,” said Ryan C. Maves, MD, FCCP, of the Naval Medical Center in San Diego, lead author of the expert panel report from the Task Force for Mass Critical Care and the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

Triage decisions could be especially daunting for resource-intensive therapies such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), as physicians may be forced to decide when and if to offer such support after demand outstrips a hospital’s ability to provide it.

“ECMO requires a lot of specialized capability to initiate on a patient, and then, it requires a lot of specialized capability to maintain and do safely,” said Steven P. Keller, MD, of the division of emergency critical care medicine in the department of emergency medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Those resource requirements can present a challenge to health care systems already overtaxed by COVID-19, according to Dr. Keller, coauthor of a guidance document in Annals of the American Thoracic Society. The guidance suggests a pandemic approach to ECMO response that’s tiered depending on the intensity of the surge over usual hospital volumes.

Mild surges call for a focus on increasing ECMO capacity, while a moderate surge may indicate a need to focus on allocating scarce resources, and a major surge may signal the need to limit or defer use of scarce resources, according to the guidance.

“If your health care system is stretched from a resource standpoint, at what point do you say, ‘we don’t even have the capability to even safely do ECMO, and so, perhaps we should not even be offering the support’?” Dr. Keller said in an interview. “That’s what we tried to get at in the paper – helping institutions think about how to prepare for that pandemic, and then when to make decisions on when it should and should not be offered.”

Critical care guidance for COVID-19

The guidance from the Task Force for Mass Critical Care and CHEST offers nine specific actions that authors suggest as part of a framework for communities to establish the infrastructure needed to triage critical care resources and “equitably” meet the needs of the largest number of COVID-19 patients.

“It is the goal of the task force to minimize the need for allocation of scarce resources as much as possible,” the authors stated.

The framework starts with surge planning that includes an inventory of intensive care unit resources such as ventilators, beds, supplies, and staff that could be marshaled to meet a surge in demand, followed by establishing “identification triggers” for triage initiation by a regional authority, should clinical demand reach a crisis stage.

The next step is preparing the triage system, which includes creating a committee at the regional level, identifying members of tertiary triage teams and the support structures they will need, and preparing and distributing training materials.

Agreeing on a triage protocol is important to ensure equitable targeting of resources, and how to allocate limited life-sustaining measures needs to be considered, according to the panel of experts. They also recommend adaptations to the standards of care such as modification of end-of-life care policies, support for health care workers, family, and the public, and consideration of pediatric issues including transport, concentration of care at specific centers, and potential increases in age thresholds to accommodate surges.

Barriers to triage?

When asked about potential barriers to rolling out a triage plan, Dr. Maves said the first is acknowledging the possible need for such a plan: “It is a difficult concept for most in critical care to accept – the idea that we may not be able to provide an individual patient with interventions that we consider routine,” he said.

Beyond acknowledging need, other potential barriers to successful implementation include the limited evidence base to support development of these protocols, as well as the need to address public trust.

“If a triage system is perceived as unjust or biased, or if people think that triage favors or excludes certain groups unfairly, it will undermine any system,” Dr. Maves said. “Making sure the public both understands and has input into system development is critical if we are going to be able to make this work.”

Dr. Maves and coauthors reported that some of the authors of their guidance are United States government employees or military service members, and that their opinions and assertions do not reflect the official views or position of those institutions. Dr. Keller reported no disclosures related to the ECMO guidance.

SOURCES: Maves RC et al. Chest. 2020 Apr 11. pii: S0012-3692(20)30691-7. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.063; Seethara R and Keller SP. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020 Apr 15. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-233PS.

, according to authors of recent reports that offer advice on how to prepare for surges in demand.

Even modest numbers of critically ill COVID-19 patients have already rapidly overwhelmed existing hospital capacity in hard-hit areas including Italy, Spain, and New York City, said authors of an expert panel report released in CHEST.

“The ethical burden this places on hospitals, health systems, and society is enormous,” said Ryan C. Maves, MD, FCCP, of the Naval Medical Center in San Diego, lead author of the expert panel report from the Task Force for Mass Critical Care and the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST).

Triage decisions could be especially daunting for resource-intensive therapies such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), as physicians may be forced to decide when and if to offer such support after demand outstrips a hospital’s ability to provide it.

“ECMO requires a lot of specialized capability to initiate on a patient, and then, it requires a lot of specialized capability to maintain and do safely,” said Steven P. Keller, MD, of the division of emergency critical care medicine in the department of emergency medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

Those resource requirements can present a challenge to health care systems already overtaxed by COVID-19, according to Dr. Keller, coauthor of a guidance document in Annals of the American Thoracic Society. The guidance suggests a pandemic approach to ECMO response that’s tiered depending on the intensity of the surge over usual hospital volumes.

Mild surges call for a focus on increasing ECMO capacity, while a moderate surge may indicate a need to focus on allocating scarce resources, and a major surge may signal the need to limit or defer use of scarce resources, according to the guidance.

“If your health care system is stretched from a resource standpoint, at what point do you say, ‘we don’t even have the capability to even safely do ECMO, and so, perhaps we should not even be offering the support’?” Dr. Keller said in an interview. “That’s what we tried to get at in the paper – helping institutions think about how to prepare for that pandemic, and then when to make decisions on when it should and should not be offered.”

Critical care guidance for COVID-19

The guidance from the Task Force for Mass Critical Care and CHEST offers nine specific actions that authors suggest as part of a framework for communities to establish the infrastructure needed to triage critical care resources and “equitably” meet the needs of the largest number of COVID-19 patients.

“It is the goal of the task force to minimize the need for allocation of scarce resources as much as possible,” the authors stated.

The framework starts with surge planning that includes an inventory of intensive care unit resources such as ventilators, beds, supplies, and staff that could be marshaled to meet a surge in demand, followed by establishing “identification triggers” for triage initiation by a regional authority, should clinical demand reach a crisis stage.

The next step is preparing the triage system, which includes creating a committee at the regional level, identifying members of tertiary triage teams and the support structures they will need, and preparing and distributing training materials.

Agreeing on a triage protocol is important to ensure equitable targeting of resources, and how to allocate limited life-sustaining measures needs to be considered, according to the panel of experts. They also recommend adaptations to the standards of care such as modification of end-of-life care policies, support for health care workers, family, and the public, and consideration of pediatric issues including transport, concentration of care at specific centers, and potential increases in age thresholds to accommodate surges.

Barriers to triage?

When asked about potential barriers to rolling out a triage plan, Dr. Maves said the first is acknowledging the possible need for such a plan: “It is a difficult concept for most in critical care to accept – the idea that we may not be able to provide an individual patient with interventions that we consider routine,” he said.

Beyond acknowledging need, other potential barriers to successful implementation include the limited evidence base to support development of these protocols, as well as the need to address public trust.

“If a triage system is perceived as unjust or biased, or if people think that triage favors or excludes certain groups unfairly, it will undermine any system,” Dr. Maves said. “Making sure the public both understands and has input into system development is critical if we are going to be able to make this work.”

Dr. Maves and coauthors reported that some of the authors of their guidance are United States government employees or military service members, and that their opinions and assertions do not reflect the official views or position of those institutions. Dr. Keller reported no disclosures related to the ECMO guidance.

SOURCES: Maves RC et al. Chest. 2020 Apr 11. pii: S0012-3692(20)30691-7. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.063; Seethara R and Keller SP. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020 Apr 15. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202003-233PS.

FROM CHEST AND ANNALS OF THE AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY

EU panel review supports decision to pull Picato from market

Picato was cleared for marketing in the European Union in November 2012. The European Commission requested a safety review of the drug in September 2019 after data suggested a higher number of skin cancer cases, including cases of squamous cell carcinoma, in patients using it, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

In January 2020, use of Picato was suspended as a precaution while the PRAC review was underway. One month later, marketing authorization was withdrawn at the request of Leo Laboratories Ltd, which marketed the medicine.

The PRAC has now concluded its review of all available data on the risk for skin cancer in patients using Picato, including results of a study that compared Picato with imiquimod.

The review found “a higher occurrence of skin cancers, especially squamous cell carcinoma, in areas of skin treated with Picato than in areas treated with imiquimod,” the EMA said Friday in a news release.

“The committee also considered that Picato’s effectiveness is not maintained over time and noted that other treatment options are available for actinic keratosis,” the EMA said.

The agency recommends that patients who have used Picato watch for unusual skin changes or growths, which may occur weeks to months after use, and seek medical advice if any occur.

Picato continues to be available in the United States, although the US Food and Drug Administration is also looking into its safety and risks.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Picato was cleared for marketing in the European Union in November 2012. The European Commission requested a safety review of the drug in September 2019 after data suggested a higher number of skin cancer cases, including cases of squamous cell carcinoma, in patients using it, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

In January 2020, use of Picato was suspended as a precaution while the PRAC review was underway. One month later, marketing authorization was withdrawn at the request of Leo Laboratories Ltd, which marketed the medicine.

The PRAC has now concluded its review of all available data on the risk for skin cancer in patients using Picato, including results of a study that compared Picato with imiquimod.

The review found “a higher occurrence of skin cancers, especially squamous cell carcinoma, in areas of skin treated with Picato than in areas treated with imiquimod,” the EMA said Friday in a news release.

“The committee also considered that Picato’s effectiveness is not maintained over time and noted that other treatment options are available for actinic keratosis,” the EMA said.

The agency recommends that patients who have used Picato watch for unusual skin changes or growths, which may occur weeks to months after use, and seek medical advice if any occur.

Picato continues to be available in the United States, although the US Food and Drug Administration is also looking into its safety and risks.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Picato was cleared for marketing in the European Union in November 2012. The European Commission requested a safety review of the drug in September 2019 after data suggested a higher number of skin cancer cases, including cases of squamous cell carcinoma, in patients using it, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

In January 2020, use of Picato was suspended as a precaution while the PRAC review was underway. One month later, marketing authorization was withdrawn at the request of Leo Laboratories Ltd, which marketed the medicine.

The PRAC has now concluded its review of all available data on the risk for skin cancer in patients using Picato, including results of a study that compared Picato with imiquimod.

The review found “a higher occurrence of skin cancers, especially squamous cell carcinoma, in areas of skin treated with Picato than in areas treated with imiquimod,” the EMA said Friday in a news release.

“The committee also considered that Picato’s effectiveness is not maintained over time and noted that other treatment options are available for actinic keratosis,” the EMA said.

The agency recommends that patients who have used Picato watch for unusual skin changes or growths, which may occur weeks to months after use, and seek medical advice if any occur.

Picato continues to be available in the United States, although the US Food and Drug Administration is also looking into its safety and risks.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Boxing helps knock out nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease

new research suggests. In the study, patients with Parkinson’s disease who participated in a noncontact boxing program experienced improvement in nonmotor symptoms such as fatigue, depression, and anxiety, and had significantly better quality of life compared with their counterparts who did not engage in this type of exercise.

“We know we should be prescribing exercise for our Parkinson’s disease patients because more and more research shows it can delay the progression of the disease, but it can be overwhelming to know what type of exercise to prescribe to patients,” study investigator Danielle Larson, MD, a neurologist and movement disorders fellow at Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, told Medscape Medical News.

On a daily basis, patients at Dr. Larson’s clinic who have taken Rock Steady Boxing (RSB) classes “really endorse” this exercise, she said.

The findings were released March 4 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The AAN canceled the meeting and released abstracts and access to presenters for press coverage.

Global program

A form of noncontact boxing, RSB was created in 2006 for patients with Parkinson’s disease. A typical 90-minute class starts with stretching and cardiovascular exercises, then foot movements and stepping over obstacles.

“Parkinson’s disease patients are slowed down and have difficulty navigating around obstacles,” Dr. Larson noted.

The class also includes “speed training,” such as fast walking or running. In the boxing part of the class, participants use suspended punching bags.

Dr. Larson said the RSB program caters to all patients with Parkinson’s disease, “even those who need a walker for assistance.” Most RSB sites require a release from a physician to ensure patient safety, she said.

There are now about 43,500 participants at 871 RSB sites around the world.

Adults with Parkinson’s disease who were aware of RSB completed a 20-minute anonymous survey, distributed via email and social media by RSB Inc and the Parkinson Foundation.

Of 2,054 survey respondents, 1,709 were eligible for analysis. Of these, 1,333 were currently participating in RSB, 166 had previously participated, and 210 had never participated in the program.

For all three groups, researchers gathered demographic information, such as age, gender, and income, and asked respondents how long they had the condition, who takes care of their illness, etc.

Current and previous RSB participants were asked about the exercise. For example, they were asked how many classes on average they would take per week and whether specific symptoms had improved or not changed with their participation.

RSB participants had a mean age of 69 years, 59% were male, and 96% were white. Demographics were similar for the other groups, although Dr. Larson noted that the group that had never participated was relatively small.

There was no difference between the groups in terms of years since Parkinson’ disease diagnosis or use of a movement disorders specialist.

Less fatigue

Compared with nonparticipants, a higher percentage of participants were retired (76% vs. 65%, P < .01) and married/had a partner (85% vs. 80%, P = .03).

The symptoms for which participants reported at least a 50% improvement were mostly nonmotor symptoms. For example, participants had improvements in social life (70%), fatigue (63%), fear of falling (62%), depression (60%), and anxiety (59%).

More than 50% of respondents in the previous participant group also reported improvement in these symptoms, “just not to the same degree as the current participants,” Dr. Larson said.

“Those symptoms are difficult to treat in Parkinson’s disease,” she noted. “We really don’t have any good medications for those symptoms; so to report, for example, a 63% improvement in fatigue is pretty substantial.”

The survey included the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire–39 (PDQ-39). The questionnaire assesses factors associated with daily living, including relationships and the impact of Parkinson’s disease on functioning and well-being.

Compared with nonparticipants, current participants had better mean scores on the PDQ-39 (25 vs. 32, P < .01), which indicates better quality of life, Dr. Larson said. Previous participants had a higher (or worse) score than current participants, she added.

Largest study to date

Researchers also examined likelihood of exercising even with certain barriers, such as distance to the gym, bad weather, or fatigue using the Self Efficacy for Exercise (SEE) Scale. Current participants had better SEE scores compared with nonparticipants (54 vs. 48, P < .01).

“We can’t prove causality. We can’t say it was the RSB that improved their quality of life or their exercise self-efficacy, but at least there’s a correlation,” Dr. Larson said.

For the SEE, again, the previous participants had lower scores than current participants, she noted.

“An interpretation of this is that individuals who previously participated but stopped did so because they had lower exercise self-efficacy – which is the ability to self-motivate and stick with an exercise – to begin with,” she said.

As for Parkinson’s disease–related motor symptoms, the survey found some improvements. “People did report between 20% and 40% improvement on various motor symptoms,” but not more than 50% of respondents.

Dr. Larson noted that some motor symptoms such as tremor would not be expected to improve with exercise.

This study, the largest to date of RSB in patients with Parkinson’s disease, illustrates the benefits of this type of exercise intervention for these patients, she said.

“It’s a step in the right direction in showing that RSB, or noncontact boxing classes, can be a really good option for patients who have previously not been motivated to exercise, or maybe haven’t stuck with an exercise class, or maybe fatigue or anxiety or depression is a barrier for them to exercise.”

Patients who have experienced RSB praise its unique approach, in addition to generating friendships and promoting a sense of camaraderie and team spirit, Dr. Larson said.

“It’s almost like a support group inside an exercise class,” she noted. “We also see that people are really committed to the classes, whereas with other exercises it can be hard to get people to be motivated.”

Some 99% of current and 94% of previous participants indicated they would recommend RSB to others with Parkinson’s disease.

Interpret with caution

Commenting on the research, Michael S. Okun, MD, professor and chair of neurology, University of Florida Health, Gainesville, and medical director at the Parkinson’s Foundation, said many patients with Parkinson’s disease attend RSB classes and report that the regimen has a beneficial effect on symptoms and quality of life.

“The data from this study support these types of observations,” he said.

But Dr. Okun noted that caution is in order. “We should be careful not to overinterpret the results given that the methodology was survey-based,” he said.

To some extent, the results aren’t surprising, as multiple studies have already shown that exercise improves Parkinson’s disease symptoms and quality of life, Dr. Okun said. “We have no reason to believe that Rock Steady Boxing would not result in similar improvements.”

He stressed that a follow-up study will be necessary to better understand the potential benefits, both nonmotor and motor.

Also commenting, movement disorders specialist Anna DePold Hohler, MD, professor of neurology at Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, and chair of neurology at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton, Massachusetts, said the new results “provide an added incentive” for patients to participate in RSB programs.

Such programs “should be started early and maintained,” Dr. Hohler added.

The study received no outside funding. The study authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Drs. Okun and Hohler have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests. In the study, patients with Parkinson’s disease who participated in a noncontact boxing program experienced improvement in nonmotor symptoms such as fatigue, depression, and anxiety, and had significantly better quality of life compared with their counterparts who did not engage in this type of exercise.

“We know we should be prescribing exercise for our Parkinson’s disease patients because more and more research shows it can delay the progression of the disease, but it can be overwhelming to know what type of exercise to prescribe to patients,” study investigator Danielle Larson, MD, a neurologist and movement disorders fellow at Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, told Medscape Medical News.

On a daily basis, patients at Dr. Larson’s clinic who have taken Rock Steady Boxing (RSB) classes “really endorse” this exercise, she said.

The findings were released March 4 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The AAN canceled the meeting and released abstracts and access to presenters for press coverage.

Global program

A form of noncontact boxing, RSB was created in 2006 for patients with Parkinson’s disease. A typical 90-minute class starts with stretching and cardiovascular exercises, then foot movements and stepping over obstacles.

“Parkinson’s disease patients are slowed down and have difficulty navigating around obstacles,” Dr. Larson noted.

The class also includes “speed training,” such as fast walking or running. In the boxing part of the class, participants use suspended punching bags.

Dr. Larson said the RSB program caters to all patients with Parkinson’s disease, “even those who need a walker for assistance.” Most RSB sites require a release from a physician to ensure patient safety, she said.

There are now about 43,500 participants at 871 RSB sites around the world.

Adults with Parkinson’s disease who were aware of RSB completed a 20-minute anonymous survey, distributed via email and social media by RSB Inc and the Parkinson Foundation.

Of 2,054 survey respondents, 1,709 were eligible for analysis. Of these, 1,333 were currently participating in RSB, 166 had previously participated, and 210 had never participated in the program.

For all three groups, researchers gathered demographic information, such as age, gender, and income, and asked respondents how long they had the condition, who takes care of their illness, etc.

Current and previous RSB participants were asked about the exercise. For example, they were asked how many classes on average they would take per week and whether specific symptoms had improved or not changed with their participation.

RSB participants had a mean age of 69 years, 59% were male, and 96% were white. Demographics were similar for the other groups, although Dr. Larson noted that the group that had never participated was relatively small.

There was no difference between the groups in terms of years since Parkinson’ disease diagnosis or use of a movement disorders specialist.

Less fatigue

Compared with nonparticipants, a higher percentage of participants were retired (76% vs. 65%, P < .01) and married/had a partner (85% vs. 80%, P = .03).

The symptoms for which participants reported at least a 50% improvement were mostly nonmotor symptoms. For example, participants had improvements in social life (70%), fatigue (63%), fear of falling (62%), depression (60%), and anxiety (59%).

More than 50% of respondents in the previous participant group also reported improvement in these symptoms, “just not to the same degree as the current participants,” Dr. Larson said.

“Those symptoms are difficult to treat in Parkinson’s disease,” she noted. “We really don’t have any good medications for those symptoms; so to report, for example, a 63% improvement in fatigue is pretty substantial.”

The survey included the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire–39 (PDQ-39). The questionnaire assesses factors associated with daily living, including relationships and the impact of Parkinson’s disease on functioning and well-being.

Compared with nonparticipants, current participants had better mean scores on the PDQ-39 (25 vs. 32, P < .01), which indicates better quality of life, Dr. Larson said. Previous participants had a higher (or worse) score than current participants, she added.

Largest study to date

Researchers also examined likelihood of exercising even with certain barriers, such as distance to the gym, bad weather, or fatigue using the Self Efficacy for Exercise (SEE) Scale. Current participants had better SEE scores compared with nonparticipants (54 vs. 48, P < .01).

“We can’t prove causality. We can’t say it was the RSB that improved their quality of life or their exercise self-efficacy, but at least there’s a correlation,” Dr. Larson said.

For the SEE, again, the previous participants had lower scores than current participants, she noted.

“An interpretation of this is that individuals who previously participated but stopped did so because they had lower exercise self-efficacy – which is the ability to self-motivate and stick with an exercise – to begin with,” she said.

As for Parkinson’s disease–related motor symptoms, the survey found some improvements. “People did report between 20% and 40% improvement on various motor symptoms,” but not more than 50% of respondents.

Dr. Larson noted that some motor symptoms such as tremor would not be expected to improve with exercise.

This study, the largest to date of RSB in patients with Parkinson’s disease, illustrates the benefits of this type of exercise intervention for these patients, she said.

“It’s a step in the right direction in showing that RSB, or noncontact boxing classes, can be a really good option for patients who have previously not been motivated to exercise, or maybe haven’t stuck with an exercise class, or maybe fatigue or anxiety or depression is a barrier for them to exercise.”

Patients who have experienced RSB praise its unique approach, in addition to generating friendships and promoting a sense of camaraderie and team spirit, Dr. Larson said.

“It’s almost like a support group inside an exercise class,” she noted. “We also see that people are really committed to the classes, whereas with other exercises it can be hard to get people to be motivated.”

Some 99% of current and 94% of previous participants indicated they would recommend RSB to others with Parkinson’s disease.

Interpret with caution

Commenting on the research, Michael S. Okun, MD, professor and chair of neurology, University of Florida Health, Gainesville, and medical director at the Parkinson’s Foundation, said many patients with Parkinson’s disease attend RSB classes and report that the regimen has a beneficial effect on symptoms and quality of life.

“The data from this study support these types of observations,” he said.

But Dr. Okun noted that caution is in order. “We should be careful not to overinterpret the results given that the methodology was survey-based,” he said.

To some extent, the results aren’t surprising, as multiple studies have already shown that exercise improves Parkinson’s disease symptoms and quality of life, Dr. Okun said. “We have no reason to believe that Rock Steady Boxing would not result in similar improvements.”

He stressed that a follow-up study will be necessary to better understand the potential benefits, both nonmotor and motor.

Also commenting, movement disorders specialist Anna DePold Hohler, MD, professor of neurology at Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, and chair of neurology at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton, Massachusetts, said the new results “provide an added incentive” for patients to participate in RSB programs.

Such programs “should be started early and maintained,” Dr. Hohler added.

The study received no outside funding. The study authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Drs. Okun and Hohler have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests. In the study, patients with Parkinson’s disease who participated in a noncontact boxing program experienced improvement in nonmotor symptoms such as fatigue, depression, and anxiety, and had significantly better quality of life compared with their counterparts who did not engage in this type of exercise.

“We know we should be prescribing exercise for our Parkinson’s disease patients because more and more research shows it can delay the progression of the disease, but it can be overwhelming to know what type of exercise to prescribe to patients,” study investigator Danielle Larson, MD, a neurologist and movement disorders fellow at Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois, told Medscape Medical News.

On a daily basis, patients at Dr. Larson’s clinic who have taken Rock Steady Boxing (RSB) classes “really endorse” this exercise, she said.

The findings were released March 4 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The AAN canceled the meeting and released abstracts and access to presenters for press coverage.

Global program

A form of noncontact boxing, RSB was created in 2006 for patients with Parkinson’s disease. A typical 90-minute class starts with stretching and cardiovascular exercises, then foot movements and stepping over obstacles.

“Parkinson’s disease patients are slowed down and have difficulty navigating around obstacles,” Dr. Larson noted.

The class also includes “speed training,” such as fast walking or running. In the boxing part of the class, participants use suspended punching bags.

Dr. Larson said the RSB program caters to all patients with Parkinson’s disease, “even those who need a walker for assistance.” Most RSB sites require a release from a physician to ensure patient safety, she said.

There are now about 43,500 participants at 871 RSB sites around the world.

Adults with Parkinson’s disease who were aware of RSB completed a 20-minute anonymous survey, distributed via email and social media by RSB Inc and the Parkinson Foundation.

Of 2,054 survey respondents, 1,709 were eligible for analysis. Of these, 1,333 were currently participating in RSB, 166 had previously participated, and 210 had never participated in the program.

For all three groups, researchers gathered demographic information, such as age, gender, and income, and asked respondents how long they had the condition, who takes care of their illness, etc.

Current and previous RSB participants were asked about the exercise. For example, they were asked how many classes on average they would take per week and whether specific symptoms had improved or not changed with their participation.

RSB participants had a mean age of 69 years, 59% were male, and 96% were white. Demographics were similar for the other groups, although Dr. Larson noted that the group that had never participated was relatively small.

There was no difference between the groups in terms of years since Parkinson’ disease diagnosis or use of a movement disorders specialist.

Less fatigue

Compared with nonparticipants, a higher percentage of participants were retired (76% vs. 65%, P < .01) and married/had a partner (85% vs. 80%, P = .03).

The symptoms for which participants reported at least a 50% improvement were mostly nonmotor symptoms. For example, participants had improvements in social life (70%), fatigue (63%), fear of falling (62%), depression (60%), and anxiety (59%).

More than 50% of respondents in the previous participant group also reported improvement in these symptoms, “just not to the same degree as the current participants,” Dr. Larson said.

“Those symptoms are difficult to treat in Parkinson’s disease,” she noted. “We really don’t have any good medications for those symptoms; so to report, for example, a 63% improvement in fatigue is pretty substantial.”

The survey included the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire–39 (PDQ-39). The questionnaire assesses factors associated with daily living, including relationships and the impact of Parkinson’s disease on functioning and well-being.

Compared with nonparticipants, current participants had better mean scores on the PDQ-39 (25 vs. 32, P < .01), which indicates better quality of life, Dr. Larson said. Previous participants had a higher (or worse) score than current participants, she added.

Largest study to date

Researchers also examined likelihood of exercising even with certain barriers, such as distance to the gym, bad weather, or fatigue using the Self Efficacy for Exercise (SEE) Scale. Current participants had better SEE scores compared with nonparticipants (54 vs. 48, P < .01).

“We can’t prove causality. We can’t say it was the RSB that improved their quality of life or their exercise self-efficacy, but at least there’s a correlation,” Dr. Larson said.

For the SEE, again, the previous participants had lower scores than current participants, she noted.

“An interpretation of this is that individuals who previously participated but stopped did so because they had lower exercise self-efficacy – which is the ability to self-motivate and stick with an exercise – to begin with,” she said.

As for Parkinson’s disease–related motor symptoms, the survey found some improvements. “People did report between 20% and 40% improvement on various motor symptoms,” but not more than 50% of respondents.

Dr. Larson noted that some motor symptoms such as tremor would not be expected to improve with exercise.

This study, the largest to date of RSB in patients with Parkinson’s disease, illustrates the benefits of this type of exercise intervention for these patients, she said.

“It’s a step in the right direction in showing that RSB, or noncontact boxing classes, can be a really good option for patients who have previously not been motivated to exercise, or maybe haven’t stuck with an exercise class, or maybe fatigue or anxiety or depression is a barrier for them to exercise.”

Patients who have experienced RSB praise its unique approach, in addition to generating friendships and promoting a sense of camaraderie and team spirit, Dr. Larson said.

“It’s almost like a support group inside an exercise class,” she noted. “We also see that people are really committed to the classes, whereas with other exercises it can be hard to get people to be motivated.”

Some 99% of current and 94% of previous participants indicated they would recommend RSB to others with Parkinson’s disease.

Interpret with caution

Commenting on the research, Michael S. Okun, MD, professor and chair of neurology, University of Florida Health, Gainesville, and medical director at the Parkinson’s Foundation, said many patients with Parkinson’s disease attend RSB classes and report that the regimen has a beneficial effect on symptoms and quality of life.

“The data from this study support these types of observations,” he said.

But Dr. Okun noted that caution is in order. “We should be careful not to overinterpret the results given that the methodology was survey-based,” he said.

To some extent, the results aren’t surprising, as multiple studies have already shown that exercise improves Parkinson’s disease symptoms and quality of life, Dr. Okun said. “We have no reason to believe that Rock Steady Boxing would not result in similar improvements.”

He stressed that a follow-up study will be necessary to better understand the potential benefits, both nonmotor and motor.

Also commenting, movement disorders specialist Anna DePold Hohler, MD, professor of neurology at Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, and chair of neurology at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton, Massachusetts, said the new results “provide an added incentive” for patients to participate in RSB programs.

Such programs “should be started early and maintained,” Dr. Hohler added.

The study received no outside funding. The study authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Drs. Okun and Hohler have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Five prognostic indexes come up short for planning early CLL treatment

Prognostic indexes have been developed recently to assess time to first treatment in early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients. However, none of five indexes evaluated in a study showed more than a moderate prognostic value or were precise enough to permit clinical decisions to be made, according to a report by Spanish researchers.

Their study, published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia, examined the comparative prognostic value of five prognostic indexes – the CLL-IPI, the Barcelona-Brno, the IPS-A, the CLL-01, and the Tailored approach – on evaluating 428 Binet A CLL patients from a multicenter Spanish database which contained the relevant necessary clinical and biological information. The predictive value of the scores was assessed with Harrell´s C index and receiver operating characteristic curve (area under the curve, AUC).

The researchers found a significant association between time to first treatment and risk subgroups for all the indexes used. The most accurate index was the IPS-A (Harrell´s C, 0.72; AUC, 0.76), followed by the CLL-01 (Harrell´s C, 0.69; AUC, 0.70), the CLL-IPI (Harrell´s C, .69; AUC, 0.69), the Barcelona-Brno (Harrell´s C: 0.67, AUC, 0.69) and the Tailored approach (Harrell´s C, 0.61 and 0.58, AUCs, 0.58 and 0.54).

However, the concordance between four of the five indexes (the Tailored approach was not included for technical reasons) compared was low (44%): 146 cases were classified as low risk with all four indexes tested, 36 as intermediate risk, and 4 as high risk. In the remaining 242 patients (56%) at least one discrepancy was detected in the allocation among prognostic subgroups between the indexes. However, only 12 patients (3%) were allocated as low and high risk at the same time with different indexes, showing the extremes of the discordance.

These data suggest that, although all of these indexes “significantly improve clinical staging and help physicians in routine clinical practice, it is necessary to harmonize larger cohorts of patients in order to define the best index for treatment decision making in the real world,” the authors stated.

“All the models had a moderate prognostic value to predict time to first therapy. ... None of them was precise enough to allow clinical decisions based exclusively on it,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the Spanish government and a variety of nonprofit institutions. The authors reported no commercial disclosures.

SOURCE: Gascon y Marín IG et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Apr 13. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.03.003.

Prognostic indexes have been developed recently to assess time to first treatment in early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients. However, none of five indexes evaluated in a study showed more than a moderate prognostic value or were precise enough to permit clinical decisions to be made, according to a report by Spanish researchers.

Their study, published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia, examined the comparative prognostic value of five prognostic indexes – the CLL-IPI, the Barcelona-Brno, the IPS-A, the CLL-01, and the Tailored approach – on evaluating 428 Binet A CLL patients from a multicenter Spanish database which contained the relevant necessary clinical and biological information. The predictive value of the scores was assessed with Harrell´s C index and receiver operating characteristic curve (area under the curve, AUC).

The researchers found a significant association between time to first treatment and risk subgroups for all the indexes used. The most accurate index was the IPS-A (Harrell´s C, 0.72; AUC, 0.76), followed by the CLL-01 (Harrell´s C, 0.69; AUC, 0.70), the CLL-IPI (Harrell´s C, .69; AUC, 0.69), the Barcelona-Brno (Harrell´s C: 0.67, AUC, 0.69) and the Tailored approach (Harrell´s C, 0.61 and 0.58, AUCs, 0.58 and 0.54).

However, the concordance between four of the five indexes (the Tailored approach was not included for technical reasons) compared was low (44%): 146 cases were classified as low risk with all four indexes tested, 36 as intermediate risk, and 4 as high risk. In the remaining 242 patients (56%) at least one discrepancy was detected in the allocation among prognostic subgroups between the indexes. However, only 12 patients (3%) were allocated as low and high risk at the same time with different indexes, showing the extremes of the discordance.

These data suggest that, although all of these indexes “significantly improve clinical staging and help physicians in routine clinical practice, it is necessary to harmonize larger cohorts of patients in order to define the best index for treatment decision making in the real world,” the authors stated.

“All the models had a moderate prognostic value to predict time to first therapy. ... None of them was precise enough to allow clinical decisions based exclusively on it,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the Spanish government and a variety of nonprofit institutions. The authors reported no commercial disclosures.

SOURCE: Gascon y Marín IG et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Apr 13. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.03.003.

Prognostic indexes have been developed recently to assess time to first treatment in early-stage chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients. However, none of five indexes evaluated in a study showed more than a moderate prognostic value or were precise enough to permit clinical decisions to be made, according to a report by Spanish researchers.

Their study, published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia, examined the comparative prognostic value of five prognostic indexes – the CLL-IPI, the Barcelona-Brno, the IPS-A, the CLL-01, and the Tailored approach – on evaluating 428 Binet A CLL patients from a multicenter Spanish database which contained the relevant necessary clinical and biological information. The predictive value of the scores was assessed with Harrell´s C index and receiver operating characteristic curve (area under the curve, AUC).

The researchers found a significant association between time to first treatment and risk subgroups for all the indexes used. The most accurate index was the IPS-A (Harrell´s C, 0.72; AUC, 0.76), followed by the CLL-01 (Harrell´s C, 0.69; AUC, 0.70), the CLL-IPI (Harrell´s C, .69; AUC, 0.69), the Barcelona-Brno (Harrell´s C: 0.67, AUC, 0.69) and the Tailored approach (Harrell´s C, 0.61 and 0.58, AUCs, 0.58 and 0.54).

However, the concordance between four of the five indexes (the Tailored approach was not included for technical reasons) compared was low (44%): 146 cases were classified as low risk with all four indexes tested, 36 as intermediate risk, and 4 as high risk. In the remaining 242 patients (56%) at least one discrepancy was detected in the allocation among prognostic subgroups between the indexes. However, only 12 patients (3%) were allocated as low and high risk at the same time with different indexes, showing the extremes of the discordance.

These data suggest that, although all of these indexes “significantly improve clinical staging and help physicians in routine clinical practice, it is necessary to harmonize larger cohorts of patients in order to define the best index for treatment decision making in the real world,” the authors stated.

“All the models had a moderate prognostic value to predict time to first therapy. ... None of them was precise enough to allow clinical decisions based exclusively on it,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the Spanish government and a variety of nonprofit institutions. The authors reported no commercial disclosures.

SOURCE: Gascon y Marín IG et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Apr 13. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.03.003.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA AND LEUKEMIA

Ping-pong may improve motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease

new research suggests. The results of a small pilot study show that table ping-pong is a safe and effective rehabilitative intervention for patients with Parkinson’s disease that can be easily introduced, study investigator Shinsuke Fujioka, MD, Department of Neurology, Fukuoka University, Japan, told Medscape Medical News.

He emphasized that any rehabilitation for patients with Parkinson’s disease could be beneficial, especially during the early stages of their illness. “The most important thing is that patients have fun when doing rehabilitation.”

The findings were released February 25 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The AAN canceled the meeting and released abstracts and access to presenters for press coverage.

All exercise beneficial

The idea of studying ping-pong as a therapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease originated when Dr. Fujioka heard about a patient who used a cane but no longer needed it after taking up the exercise as a weekly rehabilitation therapy.

“It’s apparent that the exercise can improve motor function of Parkinson’s disease. However, to date, the effects of the sport have not been well investigated for this patient population, so our study aimed to disclose the effects that table tennis can bring to patients with Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Fujioka.

The study included 12 patients with Parkinson’s disease – 10 women and two men. Mean age at disease onset was 67 years, and mean disease duration was 7 years. Mean stage on the Hoehn & Yahr scale, which assesses severity of Parkinson’s disease symptoms, was three, so most patients had balance problems.

Study participants played ping-pong at once-weekly 5-hour sessions that included rest breaks whenever they felt it was necessary.

Researchers assessed participants using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) part I-IV. Parts II and III assess motor function whereas parts I and IV evaluate nonmotor function and motor complications, respectively.

The main motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease include bradykinesia and muscle rigidity, tremor, and postural instability.

Researchers also assessed participants using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), and Apathy scale.

Results showed that UPDRS part II significantly improved at 3 and 6 months (both P < 0.001), as did UPDRS part III (P = 0.002 at 3 months; P < 0.001 at 6 months).

Dr. Fujioka speculated, “twisting axial muscles when hitting a ping-pong ball may be the most efficacious for patients, especially for bradykinesia and balance problems.”

Significant improvement

Such findings may not be that surprising. Dr. Fujioka pointed to other rehabilitation therapies such as tai chi or tango that may also improve Parkinson’s disease motor symptoms.

For UPDRS part II, subscores of speech, saliva and drooling, dressing, handwriting, doing hobbies and other activities, getting out of bed, a car, or a deep chair, and walking and balance, significantly improved.

In addition, for UPDRS part III, subscores of facial expression, rigidity, postural stability, posture, bradykinesia, and kinetic tremor of the hands also significantly improved.

As for nonmotor symptoms such as mood, anxiety, depression, and apathy assessed in UPDRS part I, scores did not significantly change, which was also the case for part IV.

However, Dr. Fujioka pointed out that patient scores didn’t worsen. “Given the nature of disease, not worsening of nonmotor features can potentially be a good effect of the sport.” MoCA, FAB, SDS, and Apathy scale scores also did not change.

Dr. Fujioka noted that all participants enjoyed the table tennis rehabilitation, and “gradually smiled more during the study period.” All study participants continued the table tennis rehabilitation after the 6-month program.

Dr. Fujioka noted that although patients with Parkinson’s disease often have difficulty moving in a front-to-back direction, they can move relatively easily in a lateral direction.

“In that sense, table tennis is suitable for them,” he said. However, he added, court tennis, handball, and badminton may not be suitable for most patients with Parkinson’s disease.

One patient suffered a fall and another backache. Dr. Fujioka cautioned that more frequent ping-pong playing might increase the risk of adverse events.

He also suggests patients with Parkinson’s disease have their bone density checked before starting regular rehabilitation exercise as they are at increased risk for osteoporosis.

The investigators are currently organizing a prospective, multicenter randomized study to compare the effectiveness of table tennis with conventional rehabilitation and the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment, which is designed to increase vocal intensity in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Fun, engaging

Commenting on the findings, Cynthia Comella, MD, professor emeritus, Neurological Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, New Philadelphia, Ohio, said ping-pong is a “fun and engaging” exercise for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Comella noted prior studies have shown many types of exercise are beneficial for patients with Parkinson’s disease “provided that they continue” with it.

In that regard, these new results are “promising,” she said. “It may be that this type of community generating, fun exercise would lead to a continuation of the exercise after a study is completed.”

A controlled trial that includes a post-study follow-up to evaluate compliance and continued benefit is needed, she said.

Purchase of equipment, including tables, rackets, and balls, was possible through funds donated by Hisako Kobayashi-Levin, which provides Murakami Karindoh Hospital with an annual fund to improve the quality of their rehabilitation program. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests. The results of a small pilot study show that table ping-pong is a safe and effective rehabilitative intervention for patients with Parkinson’s disease that can be easily introduced, study investigator Shinsuke Fujioka, MD, Department of Neurology, Fukuoka University, Japan, told Medscape Medical News.

He emphasized that any rehabilitation for patients with Parkinson’s disease could be beneficial, especially during the early stages of their illness. “The most important thing is that patients have fun when doing rehabilitation.”

The findings were released February 25 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The AAN canceled the meeting and released abstracts and access to presenters for press coverage.

All exercise beneficial

The idea of studying ping-pong as a therapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease originated when Dr. Fujioka heard about a patient who used a cane but no longer needed it after taking up the exercise as a weekly rehabilitation therapy.

“It’s apparent that the exercise can improve motor function of Parkinson’s disease. However, to date, the effects of the sport have not been well investigated for this patient population, so our study aimed to disclose the effects that table tennis can bring to patients with Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Fujioka.

The study included 12 patients with Parkinson’s disease – 10 women and two men. Mean age at disease onset was 67 years, and mean disease duration was 7 years. Mean stage on the Hoehn & Yahr scale, which assesses severity of Parkinson’s disease symptoms, was three, so most patients had balance problems.

Study participants played ping-pong at once-weekly 5-hour sessions that included rest breaks whenever they felt it was necessary.

Researchers assessed participants using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) part I-IV. Parts II and III assess motor function whereas parts I and IV evaluate nonmotor function and motor complications, respectively.

The main motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease include bradykinesia and muscle rigidity, tremor, and postural instability.

Researchers also assessed participants using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), and Apathy scale.

Results showed that UPDRS part II significantly improved at 3 and 6 months (both P < 0.001), as did UPDRS part III (P = 0.002 at 3 months; P < 0.001 at 6 months).

Dr. Fujioka speculated, “twisting axial muscles when hitting a ping-pong ball may be the most efficacious for patients, especially for bradykinesia and balance problems.”

Significant improvement

Such findings may not be that surprising. Dr. Fujioka pointed to other rehabilitation therapies such as tai chi or tango that may also improve Parkinson’s disease motor symptoms.

For UPDRS part II, subscores of speech, saliva and drooling, dressing, handwriting, doing hobbies and other activities, getting out of bed, a car, or a deep chair, and walking and balance, significantly improved.

In addition, for UPDRS part III, subscores of facial expression, rigidity, postural stability, posture, bradykinesia, and kinetic tremor of the hands also significantly improved.

As for nonmotor symptoms such as mood, anxiety, depression, and apathy assessed in UPDRS part I, scores did not significantly change, which was also the case for part IV.

However, Dr. Fujioka pointed out that patient scores didn’t worsen. “Given the nature of disease, not worsening of nonmotor features can potentially be a good effect of the sport.” MoCA, FAB, SDS, and Apathy scale scores also did not change.

Dr. Fujioka noted that all participants enjoyed the table tennis rehabilitation, and “gradually smiled more during the study period.” All study participants continued the table tennis rehabilitation after the 6-month program.

Dr. Fujioka noted that although patients with Parkinson’s disease often have difficulty moving in a front-to-back direction, they can move relatively easily in a lateral direction.

“In that sense, table tennis is suitable for them,” he said. However, he added, court tennis, handball, and badminton may not be suitable for most patients with Parkinson’s disease.

One patient suffered a fall and another backache. Dr. Fujioka cautioned that more frequent ping-pong playing might increase the risk of adverse events.

He also suggests patients with Parkinson’s disease have their bone density checked before starting regular rehabilitation exercise as they are at increased risk for osteoporosis.

The investigators are currently organizing a prospective, multicenter randomized study to compare the effectiveness of table tennis with conventional rehabilitation and the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment, which is designed to increase vocal intensity in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Fun, engaging

Commenting on the findings, Cynthia Comella, MD, professor emeritus, Neurological Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, New Philadelphia, Ohio, said ping-pong is a “fun and engaging” exercise for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Comella noted prior studies have shown many types of exercise are beneficial for patients with Parkinson’s disease “provided that they continue” with it.

In that regard, these new results are “promising,” she said. “It may be that this type of community generating, fun exercise would lead to a continuation of the exercise after a study is completed.”

A controlled trial that includes a post-study follow-up to evaluate compliance and continued benefit is needed, she said.

Purchase of equipment, including tables, rackets, and balls, was possible through funds donated by Hisako Kobayashi-Levin, which provides Murakami Karindoh Hospital with an annual fund to improve the quality of their rehabilitation program. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests. The results of a small pilot study show that table ping-pong is a safe and effective rehabilitative intervention for patients with Parkinson’s disease that can be easily introduced, study investigator Shinsuke Fujioka, MD, Department of Neurology, Fukuoka University, Japan, told Medscape Medical News.

He emphasized that any rehabilitation for patients with Parkinson’s disease could be beneficial, especially during the early stages of their illness. “The most important thing is that patients have fun when doing rehabilitation.”

The findings were released February 25 ahead of the study’s scheduled presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology. The AAN canceled the meeting and released abstracts and access to presenters for press coverage.

All exercise beneficial

The idea of studying ping-pong as a therapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease originated when Dr. Fujioka heard about a patient who used a cane but no longer needed it after taking up the exercise as a weekly rehabilitation therapy.

“It’s apparent that the exercise can improve motor function of Parkinson’s disease. However, to date, the effects of the sport have not been well investigated for this patient population, so our study aimed to disclose the effects that table tennis can bring to patients with Parkinson’s disease,” said Dr. Fujioka.

The study included 12 patients with Parkinson’s disease – 10 women and two men. Mean age at disease onset was 67 years, and mean disease duration was 7 years. Mean stage on the Hoehn & Yahr scale, which assesses severity of Parkinson’s disease symptoms, was three, so most patients had balance problems.

Study participants played ping-pong at once-weekly 5-hour sessions that included rest breaks whenever they felt it was necessary.

Researchers assessed participants using the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) part I-IV. Parts II and III assess motor function whereas parts I and IV evaluate nonmotor function and motor complications, respectively.

The main motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease include bradykinesia and muscle rigidity, tremor, and postural instability.

Researchers also assessed participants using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), and Apathy scale.

Results showed that UPDRS part II significantly improved at 3 and 6 months (both P < 0.001), as did UPDRS part III (P = 0.002 at 3 months; P < 0.001 at 6 months).

Dr. Fujioka speculated, “twisting axial muscles when hitting a ping-pong ball may be the most efficacious for patients, especially for bradykinesia and balance problems.”

Significant improvement

Such findings may not be that surprising. Dr. Fujioka pointed to other rehabilitation therapies such as tai chi or tango that may also improve Parkinson’s disease motor symptoms.

For UPDRS part II, subscores of speech, saliva and drooling, dressing, handwriting, doing hobbies and other activities, getting out of bed, a car, or a deep chair, and walking and balance, significantly improved.

In addition, for UPDRS part III, subscores of facial expression, rigidity, postural stability, posture, bradykinesia, and kinetic tremor of the hands also significantly improved.

As for nonmotor symptoms such as mood, anxiety, depression, and apathy assessed in UPDRS part I, scores did not significantly change, which was also the case for part IV.

However, Dr. Fujioka pointed out that patient scores didn’t worsen. “Given the nature of disease, not worsening of nonmotor features can potentially be a good effect of the sport.” MoCA, FAB, SDS, and Apathy scale scores also did not change.

Dr. Fujioka noted that all participants enjoyed the table tennis rehabilitation, and “gradually smiled more during the study period.” All study participants continued the table tennis rehabilitation after the 6-month program.

Dr. Fujioka noted that although patients with Parkinson’s disease often have difficulty moving in a front-to-back direction, they can move relatively easily in a lateral direction.

“In that sense, table tennis is suitable for them,” he said. However, he added, court tennis, handball, and badminton may not be suitable for most patients with Parkinson’s disease.

One patient suffered a fall and another backache. Dr. Fujioka cautioned that more frequent ping-pong playing might increase the risk of adverse events.

He also suggests patients with Parkinson’s disease have their bone density checked before starting regular rehabilitation exercise as they are at increased risk for osteoporosis.

The investigators are currently organizing a prospective, multicenter randomized study to compare the effectiveness of table tennis with conventional rehabilitation and the Lee Silverman Voice Treatment, which is designed to increase vocal intensity in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Fun, engaging

Commenting on the findings, Cynthia Comella, MD, professor emeritus, Neurological Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, New Philadelphia, Ohio, said ping-pong is a “fun and engaging” exercise for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Comella noted prior studies have shown many types of exercise are beneficial for patients with Parkinson’s disease “provided that they continue” with it.

In that regard, these new results are “promising,” she said. “It may be that this type of community generating, fun exercise would lead to a continuation of the exercise after a study is completed.”

A controlled trial that includes a post-study follow-up to evaluate compliance and continued benefit is needed, she said.

Purchase of equipment, including tables, rackets, and balls, was possible through funds donated by Hisako Kobayashi-Levin, which provides Murakami Karindoh Hospital with an annual fund to improve the quality of their rehabilitation program. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Steps to leadership during the COVID-19 era and beyond

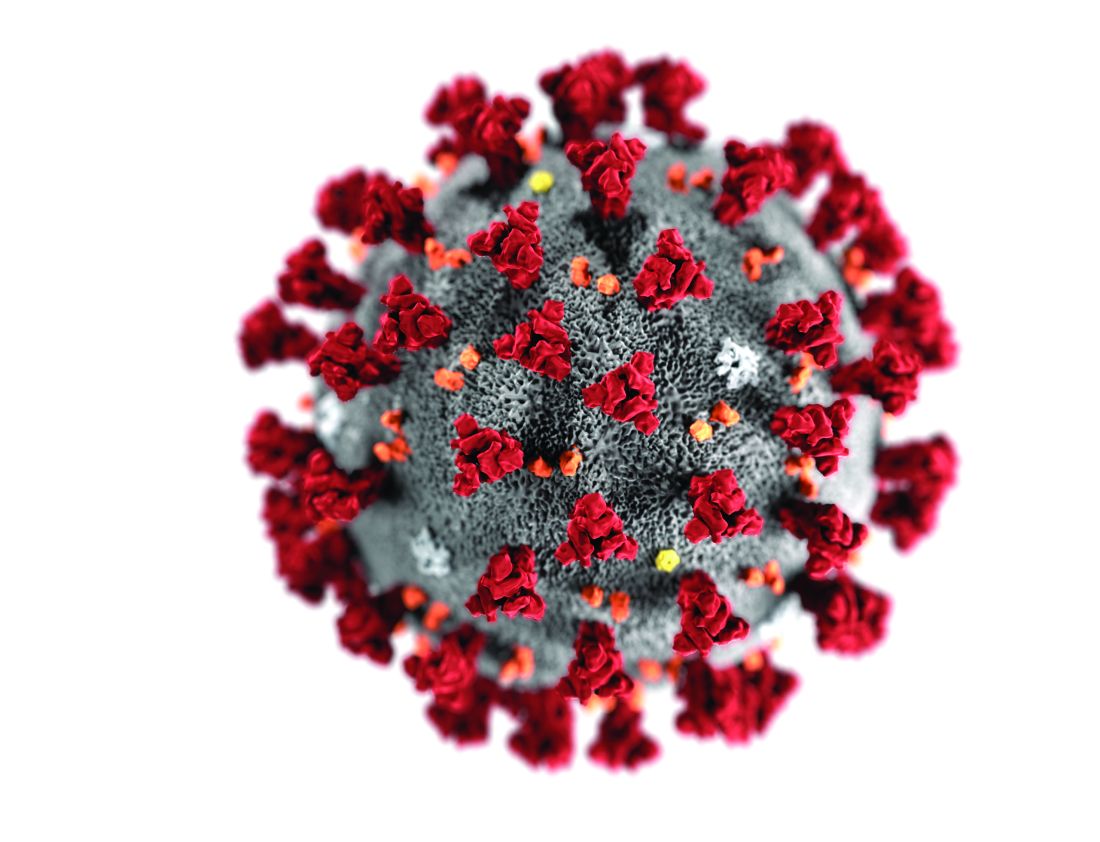

SARS CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome corona-

virus 2) has challenged us all and will continue to do so for at least the next several months. This novel virus has uncovered our medical hubris and our collective failure to acknowledge our vulnerability in the face of biological threats. As government, public health, health systems, medical professionals, and individuals struggle to grasp its enormous impact, we must recognize and seize the opportunities for leadership that the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic presents to us as physicians.

For too long we have abdicated responsibility for driving change in the US health system to politicians, administrators, and those not on the front line of care delivery. We can, however, reclaim our voice and position of influence in 2 primary spheres: first, as ObGyns we have the specific clinical knowledge and experience required to help guide our institutions in the care of our patients under new and ever-changing circumstances; second, beyond our clinical role as ObGyns, we are servant leaders to whom the public, the government, our trainees, and our clinical teams turn for guidance.

Foundations for policy development

Disaster planning in hospitals and public health systems rarely includes consideration for pregnant and delivering patients. As ObGyns, we must create policies and procedures using the best available evidence—which is slim—and, in the absence of evidence, use our clinical and scientific expertise both to optimize patient care and to minimize risk to the health care team.

At this point in time there is much we do not know, such as whether viral particles in blood are contagious, amniotic fluid contains infectious droplets, or newborns are in danger if they room-in with an infected mother. What we do know is that the evidence will evolve and that our policies and procedures must be fluid and allow for rapid change. Here are some guiding principles for such policies.

Maximize telemedicine and remote monitoring

Labor and delivery (L&D) is an emergency department in which people are triaged from the outside. Systems should incorporate the best guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists while reducing infection exposure to staff, laboring patients, and newborns. One way to limit traffic in the triage area is to have a seasoned clinician perform phone triage for women who think they need evaluation for labor.

Maintain universal caution and precautions

All people entering L&D should be presumed to be COVID-19 positive, according to early evidence reported from Columbia University in New York City.1 After remote or off-site phone triage determines that evaluation is needed in L&D, a transporter could ensure that all people escorted to L&D undergo a rapid COVID-19 test, wear a mask, and wash their hands. Until point-of-care testing is available, we must adopt safety precautions, since current data suggest that asymptomatic people may shed the infectious virus.

Both vaginal and cesarean deliveries expose everyone in the room to respiratory droplets. Common sense tells us that the laboring patient and her support person should wear a mask and that caregivers should be protected with N95 masks as well as face shields. If this were standard for every laboring patient, exposure during emergency situations might be minimized.

Continue to: Maximize support during labor...

Maximize support during labor

We should not need to ban partners and support people. Solid evidence demonstrates that support in labor improves outcomes, reduces the need for cesarean delivery, and increases patient satisfaction. We can and should protect staff and patients by requiring everyone to wear a mask.

Symptomatic patients, of course, require additional measures and personal protective equipment (PPE) to reduce the risk of infection among the health care team. These should be identical to the measures the hospital infectious disease experts have implemented in the intensive care unit.

Champion continuous quality improvement

It is our responsibility to implement continuous quality improvement processes so that we can respond to data that become available, and this begins with collecting our own local data.

We have sparse data on the risks of miscarriage, congenital anomalies, and preterm birth, but there have been anecdotal reports of both early miscarriage and premature labor. Given the known increased risk for severe disease with influenza during pregnancy, we understandably are concerned about how our pregnant patients will fare. There are also unknowns with respect to fetal exposure risk. During this pandemic we must capture such data within our own systems and share aggregated, de-identified data broadly and swiftly if real signals indicate a need for change in procedures or policy.

In the meantime, we can apply our expertise and best judgment to work within teams that include all stakeholders—administrators, nurses, engineers, pediatricians, infectious disease experts, and public members—to establish policies that respond to the best current evidence.

Protect vulnerable team members

SARS CoV-2 is highly contagious. Thus far, data do not suggest that pregnant women are at higher risk for severe disease, but we must assume that working in the hospital environment among many COVID-19 patients increases the risk for exposure. With so many current unknowns, it may be prudent to keep pregnant health care workers out of clinical areas in the hospital and reassign them to other duties when feasible. Medical students nationwide similarly have been removed from clinical rotations to minimize their exposure risk as well as to preserve scarce PPE.

These decisions are difficult for all involved, and shared decision making between administrators, clinical leaders, and pregnant staff that promotes transparency, honesty, and openness is key. Since the risk is unknown and financial consequences may result for both the hospital and the staff member, open discussion and thoughtful policies that can be revised as new information is obtained will help achieve the best possible resolution to a difficult situation.

Continue to: ObGyns as servant leaders...

ObGyns as servant leaders

COVID-19 challenges us to balance individual and public health considerations while also considering the economic and social consequences of actions. The emergence of this novel pathogen and its rapid global spread are frightening both to an uninformed public and to our skeptical government officials. Beyond our immediate clinical responsibilities, how should we as knowledgeable professionals respond?

Servant leaders commit to service and support and mentor those around them with empathy and collaboration. Servant leaders have the strategic vision to continuously grow, change, and improve at all times, but especially during a crisis. COVID-19 challenges us to be those servant leaders. To do so we must:

Promote and exhibit transparency by speaking truth to power and communicating with empathy for patients, staff, and those on the front lines who daily place themselves and their families at risk to ensure that we have essential services. Amplifying the needs and concerns of the frontline workers can drive those in power to develop practical and useful solutions.