User login

Experts publish imaging recommendations for pediatric COVID-19

A team of pulmonologists has synthesized the clinical and imaging characteristics of COVID-19 in children, and has devised recommendations for ordering imaging studies in suspected cases of the infection.

The review also included useful radiographic findings to help in the differential diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia from other respiratory infections. Alexandra M. Foust, DO, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and colleagues reported the summary of findings and recommendations in Pediatric Pulmonology.

“Pediatricians face numerous challenges created by increasing reports of severe COVID-19 related findings in affected children,” said Mary Cataletto, MD, of NYU Langone Health in Mineola, N.Y. “[The current review] represents a multinational collaboration to provide up to date information and key imaging findings to guide chest physicians caring for children with pneumonia symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Clinical presentation in children

In general, pediatric patients infected with the virus show milder symptoms compared with adults, and based on the limited evidence reported to date, the most common clinical symptoms of COVID-19 in children are rhinorrhea and/or nasal congestion, fever and cough with sore throat, fatigue or dyspnea, and diarrhea.

As with other viral pneumonias in children, the laboratory parameters are usually nonspecific; however, while the complete blood count (CBC) is often normal, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia have been reported in some cases of pediatric COVID-19, the authors noted.

The current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendation for initial diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 is obtaining a nasopharyngeal swab, followed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, they explained.

Role of imaging in diagnosis

The researchers reported that current recommendations from the American College of Radiology (ACR) do not include chest computed tomography (CT) or chest radiography (CXR) as a upfront test to diagnose pediatric COVID-19, but they may still have a role in clinical monitoring, especially in patients with a moderate to severe disease course.

The potential benefits of utilizing radiologic evaluation, such as establishing a baseline for monitoring disease progression, must be balanced with potential drawbacks, which include radiation exposure, and reduced availability of imaging resources owing to necessary cleaning and air turnover time.

Recommendations for ordering imaging studies

Based on the most recent international guidelines for pediatric COVID-19 patient management, the authors developed an algorithm for performing imaging studies in suspected cases of COVID-19 pneumonia.

The purpose of the tool is to support clinical decision-making around the utilization of CXR and CT to evaluate pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia.

“The step by step algorithm addresses the selection, sequence and timing of imaging studies with multiple images illustrating key findings of COVID-19 pneumonia in the pediatric age group,” said Dr. Cataletto. “By synthesizing the available imaging case series and guidelines, this primer provides a useful tool for the practicing pulmonologist,” she explained.

Key recommendations: CXR

“For pediatric patients with suspected or known COVID-19 infection with moderate to severe clinical symptoms requiring hospitalization (i.e., hypoxia, moderate or severe dyspnea, signs of sepsis, shock, cardiovascular compromise, altered mentation), CXR is usually indicated to establish an imaging baseline and to assess for an alternative diagnosis,” they recommended.

“Sequential CXRs may be helpful to assess pediatric patients with COVID-19 who demonstrate worsening clinical symptoms or to assess response to supportive therapy,” they wrote.

Key recommendations: CT

“Due to the increased radiation sensitivity of pediatric patients, chest CT is not recommended as an initial diagnostic test for pediatric patients with known or suspected COVID-19 pneumonia,” they explained.

The guide also included several considerations around the differential diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia from other pediatric lung disorders, including immune-related conditions, infectious etiologies, hematological dyscrasias, and inhalation-related lung injury.

As best practice recommendations for COVID-19 continue to evolve, the availability of practical clinical decision-making tools becomes essential to ensure optimal patient care.

No funding sources or financial disclosures were reported in the manuscript.

SOURCE: Foust AM et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 May 28. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24870.

A team of pulmonologists has synthesized the clinical and imaging characteristics of COVID-19 in children, and has devised recommendations for ordering imaging studies in suspected cases of the infection.

The review also included useful radiographic findings to help in the differential diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia from other respiratory infections. Alexandra M. Foust, DO, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and colleagues reported the summary of findings and recommendations in Pediatric Pulmonology.

“Pediatricians face numerous challenges created by increasing reports of severe COVID-19 related findings in affected children,” said Mary Cataletto, MD, of NYU Langone Health in Mineola, N.Y. “[The current review] represents a multinational collaboration to provide up to date information and key imaging findings to guide chest physicians caring for children with pneumonia symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Clinical presentation in children

In general, pediatric patients infected with the virus show milder symptoms compared with adults, and based on the limited evidence reported to date, the most common clinical symptoms of COVID-19 in children are rhinorrhea and/or nasal congestion, fever and cough with sore throat, fatigue or dyspnea, and diarrhea.

As with other viral pneumonias in children, the laboratory parameters are usually nonspecific; however, while the complete blood count (CBC) is often normal, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia have been reported in some cases of pediatric COVID-19, the authors noted.

The current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendation for initial diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 is obtaining a nasopharyngeal swab, followed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, they explained.

Role of imaging in diagnosis

The researchers reported that current recommendations from the American College of Radiology (ACR) do not include chest computed tomography (CT) or chest radiography (CXR) as a upfront test to diagnose pediatric COVID-19, but they may still have a role in clinical monitoring, especially in patients with a moderate to severe disease course.

The potential benefits of utilizing radiologic evaluation, such as establishing a baseline for monitoring disease progression, must be balanced with potential drawbacks, which include radiation exposure, and reduced availability of imaging resources owing to necessary cleaning and air turnover time.

Recommendations for ordering imaging studies

Based on the most recent international guidelines for pediatric COVID-19 patient management, the authors developed an algorithm for performing imaging studies in suspected cases of COVID-19 pneumonia.

The purpose of the tool is to support clinical decision-making around the utilization of CXR and CT to evaluate pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia.

“The step by step algorithm addresses the selection, sequence and timing of imaging studies with multiple images illustrating key findings of COVID-19 pneumonia in the pediatric age group,” said Dr. Cataletto. “By synthesizing the available imaging case series and guidelines, this primer provides a useful tool for the practicing pulmonologist,” she explained.

Key recommendations: CXR

“For pediatric patients with suspected or known COVID-19 infection with moderate to severe clinical symptoms requiring hospitalization (i.e., hypoxia, moderate or severe dyspnea, signs of sepsis, shock, cardiovascular compromise, altered mentation), CXR is usually indicated to establish an imaging baseline and to assess for an alternative diagnosis,” they recommended.

“Sequential CXRs may be helpful to assess pediatric patients with COVID-19 who demonstrate worsening clinical symptoms or to assess response to supportive therapy,” they wrote.

Key recommendations: CT

“Due to the increased radiation sensitivity of pediatric patients, chest CT is not recommended as an initial diagnostic test for pediatric patients with known or suspected COVID-19 pneumonia,” they explained.

The guide also included several considerations around the differential diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia from other pediatric lung disorders, including immune-related conditions, infectious etiologies, hematological dyscrasias, and inhalation-related lung injury.

As best practice recommendations for COVID-19 continue to evolve, the availability of practical clinical decision-making tools becomes essential to ensure optimal patient care.

No funding sources or financial disclosures were reported in the manuscript.

SOURCE: Foust AM et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 May 28. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24870.

A team of pulmonologists has synthesized the clinical and imaging characteristics of COVID-19 in children, and has devised recommendations for ordering imaging studies in suspected cases of the infection.

The review also included useful radiographic findings to help in the differential diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia from other respiratory infections. Alexandra M. Foust, DO, of Boston Children’s Hospital, and colleagues reported the summary of findings and recommendations in Pediatric Pulmonology.

“Pediatricians face numerous challenges created by increasing reports of severe COVID-19 related findings in affected children,” said Mary Cataletto, MD, of NYU Langone Health in Mineola, N.Y. “[The current review] represents a multinational collaboration to provide up to date information and key imaging findings to guide chest physicians caring for children with pneumonia symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Clinical presentation in children

In general, pediatric patients infected with the virus show milder symptoms compared with adults, and based on the limited evidence reported to date, the most common clinical symptoms of COVID-19 in children are rhinorrhea and/or nasal congestion, fever and cough with sore throat, fatigue or dyspnea, and diarrhea.

As with other viral pneumonias in children, the laboratory parameters are usually nonspecific; however, while the complete blood count (CBC) is often normal, lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia have been reported in some cases of pediatric COVID-19, the authors noted.

The current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendation for initial diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 is obtaining a nasopharyngeal swab, followed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, they explained.

Role of imaging in diagnosis

The researchers reported that current recommendations from the American College of Radiology (ACR) do not include chest computed tomography (CT) or chest radiography (CXR) as a upfront test to diagnose pediatric COVID-19, but they may still have a role in clinical monitoring, especially in patients with a moderate to severe disease course.

The potential benefits of utilizing radiologic evaluation, such as establishing a baseline for monitoring disease progression, must be balanced with potential drawbacks, which include radiation exposure, and reduced availability of imaging resources owing to necessary cleaning and air turnover time.

Recommendations for ordering imaging studies

Based on the most recent international guidelines for pediatric COVID-19 patient management, the authors developed an algorithm for performing imaging studies in suspected cases of COVID-19 pneumonia.

The purpose of the tool is to support clinical decision-making around the utilization of CXR and CT to evaluate pediatric COVID-19 pneumonia.

“The step by step algorithm addresses the selection, sequence and timing of imaging studies with multiple images illustrating key findings of COVID-19 pneumonia in the pediatric age group,” said Dr. Cataletto. “By synthesizing the available imaging case series and guidelines, this primer provides a useful tool for the practicing pulmonologist,” she explained.

Key recommendations: CXR

“For pediatric patients with suspected or known COVID-19 infection with moderate to severe clinical symptoms requiring hospitalization (i.e., hypoxia, moderate or severe dyspnea, signs of sepsis, shock, cardiovascular compromise, altered mentation), CXR is usually indicated to establish an imaging baseline and to assess for an alternative diagnosis,” they recommended.

“Sequential CXRs may be helpful to assess pediatric patients with COVID-19 who demonstrate worsening clinical symptoms or to assess response to supportive therapy,” they wrote.

Key recommendations: CT

“Due to the increased radiation sensitivity of pediatric patients, chest CT is not recommended as an initial diagnostic test for pediatric patients with known or suspected COVID-19 pneumonia,” they explained.

The guide also included several considerations around the differential diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia from other pediatric lung disorders, including immune-related conditions, infectious etiologies, hematological dyscrasias, and inhalation-related lung injury.

As best practice recommendations for COVID-19 continue to evolve, the availability of practical clinical decision-making tools becomes essential to ensure optimal patient care.

No funding sources or financial disclosures were reported in the manuscript.

SOURCE: Foust AM et al. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020 May 28. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24870.

FROM PEDIATRIC PULMONOLOGY

Trifarotene sails through 52-week acne trial

James Q. Del Rosso, MD, reported at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The study is noteworthy because, even though roughly half of patients with facial acne also have truncal acne, there is actually very little clinical trial data on the treatment of truncal acne other than this new long-term study and the two earlier pivotal phase 3, 12-week trials which led to the October 2019 approval of trifarotene 50 mcg/g cream (Aklief) as the first novel retinoid for acne to reach the market in 20 years, observed Dr. Del Rosso, research director at JDR Research in Las Vegas and a member of the dermatology faculty at Touro University in Henderson, Nev.

The 52-week study, known as SATISFY, began with 454 patients with moderate facial and truncal acne who treated themselves with trifarotene once daily. Among the 348 patients who completed the full year, 67% achieved a score of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear – with at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline by Investigator’s Global Assessment on their facial acne, and 65% met the same measure of success on the trunk. Moreover, 58% of patients met that standard at both acne sites.

The IGA success rate rose throughout the study period without ever reaching a plateau. However, it should be noted that 23% of participants dropped out of the study over the course of the year.

Mean tolerability scores reflecting redness, scaling, stinging or burning, and skin dryness remained well below the threshold for mild severity, peaking at weeks 2-4 of the study. The most common treatment-related adverse events were mild to moderate itching and irritation, each occurring in less than 5% of subjects.

Trifarotene is a first-in-class retinoid that specifically targets the retinoic acid receptor gamma, the most common cutaneous retinoic acid receptor.

Dr. Del Rosso reported serving as an investigator and consultant for Galderma, which sponsored the study and markets trifarotene cream.

James Q. Del Rosso, MD, reported at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The study is noteworthy because, even though roughly half of patients with facial acne also have truncal acne, there is actually very little clinical trial data on the treatment of truncal acne other than this new long-term study and the two earlier pivotal phase 3, 12-week trials which led to the October 2019 approval of trifarotene 50 mcg/g cream (Aklief) as the first novel retinoid for acne to reach the market in 20 years, observed Dr. Del Rosso, research director at JDR Research in Las Vegas and a member of the dermatology faculty at Touro University in Henderson, Nev.

The 52-week study, known as SATISFY, began with 454 patients with moderate facial and truncal acne who treated themselves with trifarotene once daily. Among the 348 patients who completed the full year, 67% achieved a score of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear – with at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline by Investigator’s Global Assessment on their facial acne, and 65% met the same measure of success on the trunk. Moreover, 58% of patients met that standard at both acne sites.

The IGA success rate rose throughout the study period without ever reaching a plateau. However, it should be noted that 23% of participants dropped out of the study over the course of the year.

Mean tolerability scores reflecting redness, scaling, stinging or burning, and skin dryness remained well below the threshold for mild severity, peaking at weeks 2-4 of the study. The most common treatment-related adverse events were mild to moderate itching and irritation, each occurring in less than 5% of subjects.

Trifarotene is a first-in-class retinoid that specifically targets the retinoic acid receptor gamma, the most common cutaneous retinoic acid receptor.

Dr. Del Rosso reported serving as an investigator and consultant for Galderma, which sponsored the study and markets trifarotene cream.

James Q. Del Rosso, MD, reported at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The study is noteworthy because, even though roughly half of patients with facial acne also have truncal acne, there is actually very little clinical trial data on the treatment of truncal acne other than this new long-term study and the two earlier pivotal phase 3, 12-week trials which led to the October 2019 approval of trifarotene 50 mcg/g cream (Aklief) as the first novel retinoid for acne to reach the market in 20 years, observed Dr. Del Rosso, research director at JDR Research in Las Vegas and a member of the dermatology faculty at Touro University in Henderson, Nev.

The 52-week study, known as SATISFY, began with 454 patients with moderate facial and truncal acne who treated themselves with trifarotene once daily. Among the 348 patients who completed the full year, 67% achieved a score of 0 or 1 – clear or almost clear – with at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline by Investigator’s Global Assessment on their facial acne, and 65% met the same measure of success on the trunk. Moreover, 58% of patients met that standard at both acne sites.

The IGA success rate rose throughout the study period without ever reaching a plateau. However, it should be noted that 23% of participants dropped out of the study over the course of the year.

Mean tolerability scores reflecting redness, scaling, stinging or burning, and skin dryness remained well below the threshold for mild severity, peaking at weeks 2-4 of the study. The most common treatment-related adverse events were mild to moderate itching and irritation, each occurring in less than 5% of subjects.

Trifarotene is a first-in-class retinoid that specifically targets the retinoic acid receptor gamma, the most common cutaneous retinoic acid receptor.

Dr. Del Rosso reported serving as an investigator and consultant for Galderma, which sponsored the study and markets trifarotene cream.

FROM AAD 2020

ED visits for life-threatening conditions declined early in COVID-19 pandemic

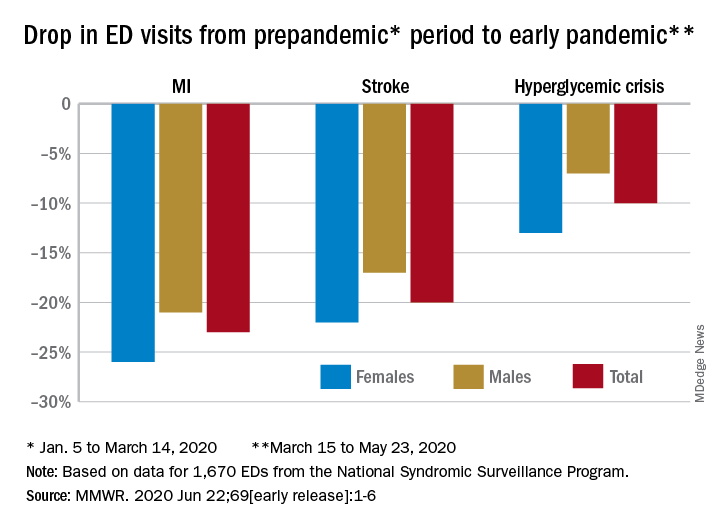

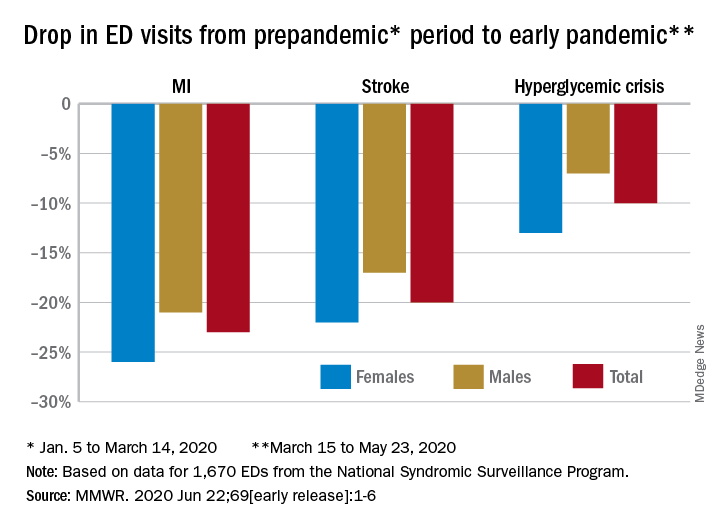

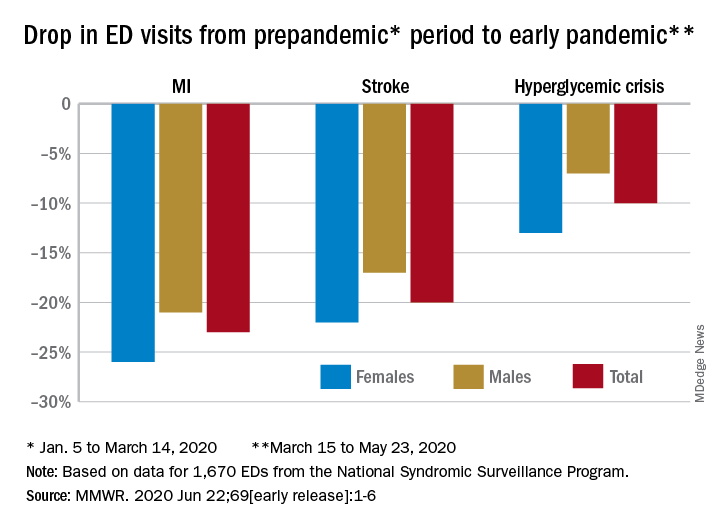

ED visits for myocardial infarction, stroke, and hyperglycemic crisis dropped substantially in the 10 weeks after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Compared with the 10-week period from Jan. 5 to March 14, ED visits were down by 23% for MI, 20% for stroke, and 10% for hyperglycemic crisis from March 15 to May 23, Samantha J. Lange, MPH, and associates at the CDC reported June 22 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“A short-term decline of this magnitude … is biologically implausible for MI and stroke, especially for older adults, and unlikely for hyperglycemic crisis, and the finding suggests that patients with these conditions either could not access care or were delaying or avoiding seeking care during the early pandemic period,” they wrote.

The largest decreases in the actual number of visits for MI occurred among both men (down by 2,114, –24%) and women (down by 1,459, –25%) aged 65-74 years. For stroke, men aged 65-74 years had 1,406 (–19%) fewer visits to the ED and women 75-84 years had 1,642 (–23%) fewer visits, the CDC researchers said.

For hypoglycemic crisis, the largest declines during the early pandemic period occurred among younger adults: ED visits for men and women aged 18-44 years were down, respectively, by 419 (–8%) and 775 (–16%), they reported based on data from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program.

“Decreases in ED visits for hyperglycemic crisis might be less striking because patient recognition of this crisis is typically augmented by home glucose monitoring and not reliant upon symptoms alone, as is the case for MI and stroke,” Ms. Lange and her associates noted.

Charting weekly visit numbers showed that the drop for all three conditions actually started the week before the emergency was declared and reached its nadir the week after (March 22) for MI and 2 weeks later (March 29) for stroke and hypoglycemic crisis.

Visits for hypoglycemic crisis have largely returned to normal since those low points, but MI and stroke visits “remain below prepandemic levels” despite gradual increases through April and May, they said.

It has been reported that “deaths not associated with confirmed or probable COVID-19 might have been directly or indirectly attributed to the pandemic. The striking decline in ED visits for acute life-threatening conditions might partially explain observed excess mortality not associated with COVID-19,” the investigators wrote.

ED visits for myocardial infarction, stroke, and hyperglycemic crisis dropped substantially in the 10 weeks after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Compared with the 10-week period from Jan. 5 to March 14, ED visits were down by 23% for MI, 20% for stroke, and 10% for hyperglycemic crisis from March 15 to May 23, Samantha J. Lange, MPH, and associates at the CDC reported June 22 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“A short-term decline of this magnitude … is biologically implausible for MI and stroke, especially for older adults, and unlikely for hyperglycemic crisis, and the finding suggests that patients with these conditions either could not access care or were delaying or avoiding seeking care during the early pandemic period,” they wrote.

The largest decreases in the actual number of visits for MI occurred among both men (down by 2,114, –24%) and women (down by 1,459, –25%) aged 65-74 years. For stroke, men aged 65-74 years had 1,406 (–19%) fewer visits to the ED and women 75-84 years had 1,642 (–23%) fewer visits, the CDC researchers said.

For hypoglycemic crisis, the largest declines during the early pandemic period occurred among younger adults: ED visits for men and women aged 18-44 years were down, respectively, by 419 (–8%) and 775 (–16%), they reported based on data from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program.

“Decreases in ED visits for hyperglycemic crisis might be less striking because patient recognition of this crisis is typically augmented by home glucose monitoring and not reliant upon symptoms alone, as is the case for MI and stroke,” Ms. Lange and her associates noted.

Charting weekly visit numbers showed that the drop for all three conditions actually started the week before the emergency was declared and reached its nadir the week after (March 22) for MI and 2 weeks later (March 29) for stroke and hypoglycemic crisis.

Visits for hypoglycemic crisis have largely returned to normal since those low points, but MI and stroke visits “remain below prepandemic levels” despite gradual increases through April and May, they said.

It has been reported that “deaths not associated with confirmed or probable COVID-19 might have been directly or indirectly attributed to the pandemic. The striking decline in ED visits for acute life-threatening conditions might partially explain observed excess mortality not associated with COVID-19,” the investigators wrote.

ED visits for myocardial infarction, stroke, and hyperglycemic crisis dropped substantially in the 10 weeks after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Compared with the 10-week period from Jan. 5 to March 14, ED visits were down by 23% for MI, 20% for stroke, and 10% for hyperglycemic crisis from March 15 to May 23, Samantha J. Lange, MPH, and associates at the CDC reported June 22 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“A short-term decline of this magnitude … is biologically implausible for MI and stroke, especially for older adults, and unlikely for hyperglycemic crisis, and the finding suggests that patients with these conditions either could not access care or were delaying or avoiding seeking care during the early pandemic period,” they wrote.

The largest decreases in the actual number of visits for MI occurred among both men (down by 2,114, –24%) and women (down by 1,459, –25%) aged 65-74 years. For stroke, men aged 65-74 years had 1,406 (–19%) fewer visits to the ED and women 75-84 years had 1,642 (–23%) fewer visits, the CDC researchers said.

For hypoglycemic crisis, the largest declines during the early pandemic period occurred among younger adults: ED visits for men and women aged 18-44 years were down, respectively, by 419 (–8%) and 775 (–16%), they reported based on data from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program.

“Decreases in ED visits for hyperglycemic crisis might be less striking because patient recognition of this crisis is typically augmented by home glucose monitoring and not reliant upon symptoms alone, as is the case for MI and stroke,” Ms. Lange and her associates noted.

Charting weekly visit numbers showed that the drop for all three conditions actually started the week before the emergency was declared and reached its nadir the week after (March 22) for MI and 2 weeks later (March 29) for stroke and hypoglycemic crisis.

Visits for hypoglycemic crisis have largely returned to normal since those low points, but MI and stroke visits “remain below prepandemic levels” despite gradual increases through April and May, they said.

It has been reported that “deaths not associated with confirmed or probable COVID-19 might have been directly or indirectly attributed to the pandemic. The striking decline in ED visits for acute life-threatening conditions might partially explain observed excess mortality not associated with COVID-19,” the investigators wrote.

FROM MMWR

Ibrutinib-venetoclax produces high MRD-negative rates in CLL/SLL

In patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), a once-daily oral regimen of ibrutinib and venetoclax was associated with deep molecular remissions in both bone marrow and peripheral blood, including in patients with high-risk disease, according to investigators in the phase 2 CAPTIVATE MRD trial.

An intention-to-treat analysis of 164 patients with CLL/SLL treated with the combination of ibrutinib (Imbruvica) and venetoclax (Venclexta) showed a 75% rate of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity in peripheral blood, and a 68% rate of MRD negativity in bone marrow among patients who received up to 12 cycles of the combination, reported Tanya Siddiqi, MD, of City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, Calif., and colleagues.

“This phase 2 study supports synergistic antitumor activity of the combination with notable deep responses across multiple compartments,” she said in an oral presentation during the virtual annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

Not ready to change practice

A hematologist/oncologist who was not involved in the study said that the data from CAPTIVATE MRD look good, but it’s still not known whether concurrent or sequential administration of the agents is optimal, and whether other regimens may be more effective in the first line.

“I think this is promising, but the informative and practice-changing study would be to compare this combination to ibrutinib monotherapy or to venetoclax and obinutuzumab, and that’s actually the subject of the next large German cooperative group study, CLL17,” said Catherine C. Coombs, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina, and the UNC Lineberger Cancer Center, Chapel Hill.

She noted that the combination of venetoclax and obinutuzumab (Gazyva) is also associated with high rates of MRD negativity in the first-line setting, and that use of this regimen allows clinicians to reserve ibrutinib or acalabrutinib (Calquence) for patients in the relapsed setting.

Prerandomization results

Dr. Siddiqi presented prerandomization results from the MRD cohort of the CAPTIVATE trial (NCT02910583), which is evaluating the combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax for depth of MRD response. Following 12 cycles of the combinations, patients in this cohort are then randomized based on confirmed MRD status, with patients who are MRD negative randomized to maintenance with either ibrutinib or placebo, and patients with residual disease (MRD positive) randomized to maintenance with either ibrutinib alone or with venetoclax.

A total of 164 patients with previously untreated CLL/SLL and active disease requiring treatment who were under age 70 and had good performance status were enrolled. Following an ibrutinib lead-in period with the drug given at 420 mg once daily for three cycles of 28 days, the patients were continued on ibrutinib, and were started on venetoclax with a ramp up to 400 mg once daily, for 12 additional cycles.

As planned, patients were assessed after 15 cycles for tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) risk assessment, MRD, and hematologic, clinical, imaging, and bone marrow exams for response.

The median patient age was 58, with poor-risk features such as deletion 17p seen in 16%, complex karyotype in 19%, and unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) in 59%.

A total of 152 patients (90%) completed all 12 cycles of the combined agents, with a median treatment duration of 14.7 months on ibrutinib and 12 months on venetoclax. Eight patients had adverse events leading to discontinuation, but there were no treatment-related deaths.

A majority of patients had reductions in lymph node burden after the three-cycle ibrutinib lead in. TLS risk also decreased during the lead-in period, with 90% of patients who had a high baseline TLS risk shifting to medium or low-risk categories, and no patients moved into the high-risk category.

“Hospitalization because of this was no longer required in 66% of at-risk patients after three cycles of ibrutinib lead in, and 82% of patients initiated venetoclax ramp up without the need for hospitalization,” Dr. Siddiqi said.

The best response of undetectable MRD was seen in peripheral blood of 75% of 163 evaluable patients, and in bone marrow of 72% of 155 patients. As noted before, the respective rates of MRD negativity in the intention-to-treat population were 75% and 68%. The proportion of patients with undetectable MRD in peripheral blood increased over time, from 57% after six cycles of the combination, she said.

The overall response rate was 97%, including 51% complete responses (CR) or CR with incomplete bone marrow recovery (CRi), and 46% partial (PR) or nodular PR (nPR). Among patients with CR/CRi, 85% had undetectable MRD in peripheral blood and 80% were MRD negative in bone marrow. In patients with PR/nPR, the respective rates were 69% and 59%. The high rates of undetectable MRD were seen irrespective of baseline disease characteristics, including bulky disease, cytogenetic risk category, del(17p) or TP53 mutation, and complex karyotype.

The most common adverse events with the combination were grade 1 or 2 diarrhea, arthralgia, fatigue, headache, and nausea. Grade 3 neutropenia was seen in 17% of patients, and grade 4 neutropenia was seen in 16%. Grade 3 febrile neutropenia and laboratory confirmed TLS occurred in 2 patients each (1%), and there were no grade 4 instances of either adverse event.

Postrandomization follow-up and analyses are currently being conducted, and results will be reported at a future meeting, real or virtual. An analysis of data on a separate cohort of 159 patients treated with the ibrutinib-venetoclax combination for a fixed duration is currently ongoing.

Dr. Siddiqi disclosed research funding and speakers bureau activity for Pharmacyclics, which sponsored the study, and others, as well as consulting/advising for several companies. Dr. Coombs disclosed consulting for AbbVie.

SOURCE: Siddiqi T et al. EHA25. Abstract S158.

In patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), a once-daily oral regimen of ibrutinib and venetoclax was associated with deep molecular remissions in both bone marrow and peripheral blood, including in patients with high-risk disease, according to investigators in the phase 2 CAPTIVATE MRD trial.

An intention-to-treat analysis of 164 patients with CLL/SLL treated with the combination of ibrutinib (Imbruvica) and venetoclax (Venclexta) showed a 75% rate of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity in peripheral blood, and a 68% rate of MRD negativity in bone marrow among patients who received up to 12 cycles of the combination, reported Tanya Siddiqi, MD, of City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, Calif., and colleagues.

“This phase 2 study supports synergistic antitumor activity of the combination with notable deep responses across multiple compartments,” she said in an oral presentation during the virtual annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

Not ready to change practice

A hematologist/oncologist who was not involved in the study said that the data from CAPTIVATE MRD look good, but it’s still not known whether concurrent or sequential administration of the agents is optimal, and whether other regimens may be more effective in the first line.

“I think this is promising, but the informative and practice-changing study would be to compare this combination to ibrutinib monotherapy or to venetoclax and obinutuzumab, and that’s actually the subject of the next large German cooperative group study, CLL17,” said Catherine C. Coombs, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina, and the UNC Lineberger Cancer Center, Chapel Hill.

She noted that the combination of venetoclax and obinutuzumab (Gazyva) is also associated with high rates of MRD negativity in the first-line setting, and that use of this regimen allows clinicians to reserve ibrutinib or acalabrutinib (Calquence) for patients in the relapsed setting.

Prerandomization results

Dr. Siddiqi presented prerandomization results from the MRD cohort of the CAPTIVATE trial (NCT02910583), which is evaluating the combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax for depth of MRD response. Following 12 cycles of the combinations, patients in this cohort are then randomized based on confirmed MRD status, with patients who are MRD negative randomized to maintenance with either ibrutinib or placebo, and patients with residual disease (MRD positive) randomized to maintenance with either ibrutinib alone or with venetoclax.

A total of 164 patients with previously untreated CLL/SLL and active disease requiring treatment who were under age 70 and had good performance status were enrolled. Following an ibrutinib lead-in period with the drug given at 420 mg once daily for three cycles of 28 days, the patients were continued on ibrutinib, and were started on venetoclax with a ramp up to 400 mg once daily, for 12 additional cycles.

As planned, patients were assessed after 15 cycles for tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) risk assessment, MRD, and hematologic, clinical, imaging, and bone marrow exams for response.

The median patient age was 58, with poor-risk features such as deletion 17p seen in 16%, complex karyotype in 19%, and unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) in 59%.

A total of 152 patients (90%) completed all 12 cycles of the combined agents, with a median treatment duration of 14.7 months on ibrutinib and 12 months on venetoclax. Eight patients had adverse events leading to discontinuation, but there were no treatment-related deaths.

A majority of patients had reductions in lymph node burden after the three-cycle ibrutinib lead in. TLS risk also decreased during the lead-in period, with 90% of patients who had a high baseline TLS risk shifting to medium or low-risk categories, and no patients moved into the high-risk category.

“Hospitalization because of this was no longer required in 66% of at-risk patients after three cycles of ibrutinib lead in, and 82% of patients initiated venetoclax ramp up without the need for hospitalization,” Dr. Siddiqi said.

The best response of undetectable MRD was seen in peripheral blood of 75% of 163 evaluable patients, and in bone marrow of 72% of 155 patients. As noted before, the respective rates of MRD negativity in the intention-to-treat population were 75% and 68%. The proportion of patients with undetectable MRD in peripheral blood increased over time, from 57% after six cycles of the combination, she said.

The overall response rate was 97%, including 51% complete responses (CR) or CR with incomplete bone marrow recovery (CRi), and 46% partial (PR) or nodular PR (nPR). Among patients with CR/CRi, 85% had undetectable MRD in peripheral blood and 80% were MRD negative in bone marrow. In patients with PR/nPR, the respective rates were 69% and 59%. The high rates of undetectable MRD were seen irrespective of baseline disease characteristics, including bulky disease, cytogenetic risk category, del(17p) or TP53 mutation, and complex karyotype.

The most common adverse events with the combination were grade 1 or 2 diarrhea, arthralgia, fatigue, headache, and nausea. Grade 3 neutropenia was seen in 17% of patients, and grade 4 neutropenia was seen in 16%. Grade 3 febrile neutropenia and laboratory confirmed TLS occurred in 2 patients each (1%), and there were no grade 4 instances of either adverse event.

Postrandomization follow-up and analyses are currently being conducted, and results will be reported at a future meeting, real or virtual. An analysis of data on a separate cohort of 159 patients treated with the ibrutinib-venetoclax combination for a fixed duration is currently ongoing.

Dr. Siddiqi disclosed research funding and speakers bureau activity for Pharmacyclics, which sponsored the study, and others, as well as consulting/advising for several companies. Dr. Coombs disclosed consulting for AbbVie.

SOURCE: Siddiqi T et al. EHA25. Abstract S158.

In patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), a once-daily oral regimen of ibrutinib and venetoclax was associated with deep molecular remissions in both bone marrow and peripheral blood, including in patients with high-risk disease, according to investigators in the phase 2 CAPTIVATE MRD trial.

An intention-to-treat analysis of 164 patients with CLL/SLL treated with the combination of ibrutinib (Imbruvica) and venetoclax (Venclexta) showed a 75% rate of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity in peripheral blood, and a 68% rate of MRD negativity in bone marrow among patients who received up to 12 cycles of the combination, reported Tanya Siddiqi, MD, of City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, Calif., and colleagues.

“This phase 2 study supports synergistic antitumor activity of the combination with notable deep responses across multiple compartments,” she said in an oral presentation during the virtual annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

Not ready to change practice

A hematologist/oncologist who was not involved in the study said that the data from CAPTIVATE MRD look good, but it’s still not known whether concurrent or sequential administration of the agents is optimal, and whether other regimens may be more effective in the first line.

“I think this is promising, but the informative and practice-changing study would be to compare this combination to ibrutinib monotherapy or to venetoclax and obinutuzumab, and that’s actually the subject of the next large German cooperative group study, CLL17,” said Catherine C. Coombs, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina, and the UNC Lineberger Cancer Center, Chapel Hill.

She noted that the combination of venetoclax and obinutuzumab (Gazyva) is also associated with high rates of MRD negativity in the first-line setting, and that use of this regimen allows clinicians to reserve ibrutinib or acalabrutinib (Calquence) for patients in the relapsed setting.

Prerandomization results

Dr. Siddiqi presented prerandomization results from the MRD cohort of the CAPTIVATE trial (NCT02910583), which is evaluating the combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax for depth of MRD response. Following 12 cycles of the combinations, patients in this cohort are then randomized based on confirmed MRD status, with patients who are MRD negative randomized to maintenance with either ibrutinib or placebo, and patients with residual disease (MRD positive) randomized to maintenance with either ibrutinib alone or with venetoclax.

A total of 164 patients with previously untreated CLL/SLL and active disease requiring treatment who were under age 70 and had good performance status were enrolled. Following an ibrutinib lead-in period with the drug given at 420 mg once daily for three cycles of 28 days, the patients were continued on ibrutinib, and were started on venetoclax with a ramp up to 400 mg once daily, for 12 additional cycles.

As planned, patients were assessed after 15 cycles for tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) risk assessment, MRD, and hematologic, clinical, imaging, and bone marrow exams for response.

The median patient age was 58, with poor-risk features such as deletion 17p seen in 16%, complex karyotype in 19%, and unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) in 59%.

A total of 152 patients (90%) completed all 12 cycles of the combined agents, with a median treatment duration of 14.7 months on ibrutinib and 12 months on venetoclax. Eight patients had adverse events leading to discontinuation, but there were no treatment-related deaths.

A majority of patients had reductions in lymph node burden after the three-cycle ibrutinib lead in. TLS risk also decreased during the lead-in period, with 90% of patients who had a high baseline TLS risk shifting to medium or low-risk categories, and no patients moved into the high-risk category.

“Hospitalization because of this was no longer required in 66% of at-risk patients after three cycles of ibrutinib lead in, and 82% of patients initiated venetoclax ramp up without the need for hospitalization,” Dr. Siddiqi said.

The best response of undetectable MRD was seen in peripheral blood of 75% of 163 evaluable patients, and in bone marrow of 72% of 155 patients. As noted before, the respective rates of MRD negativity in the intention-to-treat population were 75% and 68%. The proportion of patients with undetectable MRD in peripheral blood increased over time, from 57% after six cycles of the combination, she said.

The overall response rate was 97%, including 51% complete responses (CR) or CR with incomplete bone marrow recovery (CRi), and 46% partial (PR) or nodular PR (nPR). Among patients with CR/CRi, 85% had undetectable MRD in peripheral blood and 80% were MRD negative in bone marrow. In patients with PR/nPR, the respective rates were 69% and 59%. The high rates of undetectable MRD were seen irrespective of baseline disease characteristics, including bulky disease, cytogenetic risk category, del(17p) or TP53 mutation, and complex karyotype.

The most common adverse events with the combination were grade 1 or 2 diarrhea, arthralgia, fatigue, headache, and nausea. Grade 3 neutropenia was seen in 17% of patients, and grade 4 neutropenia was seen in 16%. Grade 3 febrile neutropenia and laboratory confirmed TLS occurred in 2 patients each (1%), and there were no grade 4 instances of either adverse event.

Postrandomization follow-up and analyses are currently being conducted, and results will be reported at a future meeting, real or virtual. An analysis of data on a separate cohort of 159 patients treated with the ibrutinib-venetoclax combination for a fixed duration is currently ongoing.

Dr. Siddiqi disclosed research funding and speakers bureau activity for Pharmacyclics, which sponsored the study, and others, as well as consulting/advising for several companies. Dr. Coombs disclosed consulting for AbbVie.

SOURCE: Siddiqi T et al. EHA25. Abstract S158.

FROM EHA 2020

What’s pushing cannabis use in first-episode psychosis?

The desire to feel better is a major driver for patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) to turn to cannabis, new research shows.

An analysis of more than 1,300 individuals from six European countries showed patients with FEP were four times more likely than their healthy peers to start smoking cannabis in order to make themselves feel better.

The results also revealed that initiating cannabis use to feel better was associated with a more than tripled risk of being a daily user.

as well as offer an opportunity for psychoeducation – particularly as the reasons for starting cannabis appear to influence frequency of use, study investigator Edoardo Spinazzola, MD, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience at King’s College London, said in an interview.

Patients who start smoking cannabis because their friends or family partakes may benefit from therapies that encourage more “assertiveness” and being “socially comfortable without the substance,” Dr. Spinazzola said, noting that it might also be beneficial to identify the specific cause of the psychological discomfort driving cannabis use, such as depression, and specifically treat that issue.

The results were scheduled to be presented at the Congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society 2020, but the meeting was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Answering the skeptics

Previous studies suggest that cannabis use can increase risk for psychosis up to 290%, with both frequency of use and potency playing a role, the researchers noted.

However, they added that “skeptics” argue the association could be caused by individuals with psychosis using cannabis as a form of self-medication, the comorbid effect of other psychogenic drugs, or a common genetic vulnerability between cannabis use and psychosis.

The reasons for starting cannabis use remain “largely unexplored,” so the researchers examined records from the European network of national schizophrenia networks studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) database, which includes patients with FEP and healthy individuals acting as controls from France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, United Kingdom, and Brazil.

The analysis included 1,347 individuals, of whom 446 had a diagnosis of nonaffective psychosis, 89 had bipolar disorder, and 58 had psychotic depression.

Reasons to start smoking cannabis and patterns of use were determined using the modified version of the Cannabis Experiences Questionnaire.

Results showed that participants who started cannabis to feel better were significantly more likely to be younger, have fewer years of education, to be black or of mixed ethnicity, to be single, or to not be living independently than those who started it because their friends or family were using it (P < .001 for all comparisons).

In addition, 68% of the patients with FEP and 85% of the healthy controls started using cannabis because friends or family were using it. In contrast, 18% of those with FEP versus 5% of controls starting using cannabis to feel better; 13% versus 10%, respectively, started using for “other reasons.”

After taking into account gender, age, ethnicity, and study site, the patients with FEP were significantly more likely than their healthy peers to have started using cannabis to feel better (relative risk ratio, 4.67; P < .001).

Starting to smoke cannabis to feel better versus any other reason was associated with an increased frequency of use in both those with and without FEP, with an RRR of 2.9 for using the drug more than once a week (P = .001) and an RRR of 3.13 for daily use (P < .001). However, the association was stronger in the healthy controls than in those with FEP, with an RRR for daily use of 4.45 versus 3.11, respectively.

The investigators also examined whether there was a link between reasons to start smoking and an individual’s polygenic risk score (PRS) for developing schizophrenia.

Multinomial regression indicated that PRS was not associated with starting cannabis to feel better or because friends were using it. However, there was an association between PRS score and starting the drug because family members were using it (RRR, 0.68; P < .05).

Complex association

Gabriella Gobbi, MD, PhD, professor in the neurobiological psychiatry unit, department of psychiatry, at McGill University, Montreal, said the data confirm “what we already know about cannabis.”

She noted that one of the “major causes” of young people starting cannabis is the social environment, while the desire to use the drug to feel better is linked to “the fact that cannabis, in a lot of cases, is used as a self-medication” in order to be calmer and as a relief from anxiety.

There is a “very complex” association between using cannabis to feel better and the self-medication seen with cigarette smoking and alcohol in patients with schizophrenia, said Dr. Gobbi, who was not involved with the research.

“When we talk about [patients using] cannabis, alcohol, and cigarettes, actually we’re talking about the same group of people,” she said.

Although “it is true they say that people look to cigarettes, tobacco, and alcohol to feel happier because they are depressed, the risk of psychosis is only for cannabis,” she added. “It is very low for alcohol and tobacco.”

As a result, Dr. Gobbi said she and her colleagues are “very worried” about the consequences for mental health of the legalization of cannabis consumption in Canada in October 2018 with the passing of the Cannabis Act.

Although there are no firm statistics yet, she has observed that since the law was passed, cannabis use has stabilized at a lower level among adolescents. “But now we have another population of people aged 34 and older that consume cannabis,” she said.

Particularly when considering the impact of higher strength cannabis on psychosis risk, Dr. Gobbi believes the increase in consumption in this age group will result in a “more elevated” risk for mental health issues.

Dr. Spinazzola and Dr. Gobbi have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The desire to feel better is a major driver for patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) to turn to cannabis, new research shows.

An analysis of more than 1,300 individuals from six European countries showed patients with FEP were four times more likely than their healthy peers to start smoking cannabis in order to make themselves feel better.

The results also revealed that initiating cannabis use to feel better was associated with a more than tripled risk of being a daily user.

as well as offer an opportunity for psychoeducation – particularly as the reasons for starting cannabis appear to influence frequency of use, study investigator Edoardo Spinazzola, MD, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience at King’s College London, said in an interview.

Patients who start smoking cannabis because their friends or family partakes may benefit from therapies that encourage more “assertiveness” and being “socially comfortable without the substance,” Dr. Spinazzola said, noting that it might also be beneficial to identify the specific cause of the psychological discomfort driving cannabis use, such as depression, and specifically treat that issue.

The results were scheduled to be presented at the Congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society 2020, but the meeting was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Answering the skeptics

Previous studies suggest that cannabis use can increase risk for psychosis up to 290%, with both frequency of use and potency playing a role, the researchers noted.

However, they added that “skeptics” argue the association could be caused by individuals with psychosis using cannabis as a form of self-medication, the comorbid effect of other psychogenic drugs, or a common genetic vulnerability between cannabis use and psychosis.

The reasons for starting cannabis use remain “largely unexplored,” so the researchers examined records from the European network of national schizophrenia networks studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) database, which includes patients with FEP and healthy individuals acting as controls from France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, United Kingdom, and Brazil.

The analysis included 1,347 individuals, of whom 446 had a diagnosis of nonaffective psychosis, 89 had bipolar disorder, and 58 had psychotic depression.

Reasons to start smoking cannabis and patterns of use were determined using the modified version of the Cannabis Experiences Questionnaire.

Results showed that participants who started cannabis to feel better were significantly more likely to be younger, have fewer years of education, to be black or of mixed ethnicity, to be single, or to not be living independently than those who started it because their friends or family were using it (P < .001 for all comparisons).

In addition, 68% of the patients with FEP and 85% of the healthy controls started using cannabis because friends or family were using it. In contrast, 18% of those with FEP versus 5% of controls starting using cannabis to feel better; 13% versus 10%, respectively, started using for “other reasons.”

After taking into account gender, age, ethnicity, and study site, the patients with FEP were significantly more likely than their healthy peers to have started using cannabis to feel better (relative risk ratio, 4.67; P < .001).

Starting to smoke cannabis to feel better versus any other reason was associated with an increased frequency of use in both those with and without FEP, with an RRR of 2.9 for using the drug more than once a week (P = .001) and an RRR of 3.13 for daily use (P < .001). However, the association was stronger in the healthy controls than in those with FEP, with an RRR for daily use of 4.45 versus 3.11, respectively.

The investigators also examined whether there was a link between reasons to start smoking and an individual’s polygenic risk score (PRS) for developing schizophrenia.

Multinomial regression indicated that PRS was not associated with starting cannabis to feel better or because friends were using it. However, there was an association between PRS score and starting the drug because family members were using it (RRR, 0.68; P < .05).

Complex association

Gabriella Gobbi, MD, PhD, professor in the neurobiological psychiatry unit, department of psychiatry, at McGill University, Montreal, said the data confirm “what we already know about cannabis.”

She noted that one of the “major causes” of young people starting cannabis is the social environment, while the desire to use the drug to feel better is linked to “the fact that cannabis, in a lot of cases, is used as a self-medication” in order to be calmer and as a relief from anxiety.

There is a “very complex” association between using cannabis to feel better and the self-medication seen with cigarette smoking and alcohol in patients with schizophrenia, said Dr. Gobbi, who was not involved with the research.

“When we talk about [patients using] cannabis, alcohol, and cigarettes, actually we’re talking about the same group of people,” she said.

Although “it is true they say that people look to cigarettes, tobacco, and alcohol to feel happier because they are depressed, the risk of psychosis is only for cannabis,” she added. “It is very low for alcohol and tobacco.”

As a result, Dr. Gobbi said she and her colleagues are “very worried” about the consequences for mental health of the legalization of cannabis consumption in Canada in October 2018 with the passing of the Cannabis Act.

Although there are no firm statistics yet, she has observed that since the law was passed, cannabis use has stabilized at a lower level among adolescents. “But now we have another population of people aged 34 and older that consume cannabis,” she said.

Particularly when considering the impact of higher strength cannabis on psychosis risk, Dr. Gobbi believes the increase in consumption in this age group will result in a “more elevated” risk for mental health issues.

Dr. Spinazzola and Dr. Gobbi have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The desire to feel better is a major driver for patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP) to turn to cannabis, new research shows.

An analysis of more than 1,300 individuals from six European countries showed patients with FEP were four times more likely than their healthy peers to start smoking cannabis in order to make themselves feel better.

The results also revealed that initiating cannabis use to feel better was associated with a more than tripled risk of being a daily user.

as well as offer an opportunity for psychoeducation – particularly as the reasons for starting cannabis appear to influence frequency of use, study investigator Edoardo Spinazzola, MD, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience at King’s College London, said in an interview.

Patients who start smoking cannabis because their friends or family partakes may benefit from therapies that encourage more “assertiveness” and being “socially comfortable without the substance,” Dr. Spinazzola said, noting that it might also be beneficial to identify the specific cause of the psychological discomfort driving cannabis use, such as depression, and specifically treat that issue.

The results were scheduled to be presented at the Congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society 2020, but the meeting was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Answering the skeptics

Previous studies suggest that cannabis use can increase risk for psychosis up to 290%, with both frequency of use and potency playing a role, the researchers noted.

However, they added that “skeptics” argue the association could be caused by individuals with psychosis using cannabis as a form of self-medication, the comorbid effect of other psychogenic drugs, or a common genetic vulnerability between cannabis use and psychosis.

The reasons for starting cannabis use remain “largely unexplored,” so the researchers examined records from the European network of national schizophrenia networks studying Gene-Environment Interactions (EU-GEI) database, which includes patients with FEP and healthy individuals acting as controls from France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, United Kingdom, and Brazil.

The analysis included 1,347 individuals, of whom 446 had a diagnosis of nonaffective psychosis, 89 had bipolar disorder, and 58 had psychotic depression.

Reasons to start smoking cannabis and patterns of use were determined using the modified version of the Cannabis Experiences Questionnaire.

Results showed that participants who started cannabis to feel better were significantly more likely to be younger, have fewer years of education, to be black or of mixed ethnicity, to be single, or to not be living independently than those who started it because their friends or family were using it (P < .001 for all comparisons).

In addition, 68% of the patients with FEP and 85% of the healthy controls started using cannabis because friends or family were using it. In contrast, 18% of those with FEP versus 5% of controls starting using cannabis to feel better; 13% versus 10%, respectively, started using for “other reasons.”

After taking into account gender, age, ethnicity, and study site, the patients with FEP were significantly more likely than their healthy peers to have started using cannabis to feel better (relative risk ratio, 4.67; P < .001).

Starting to smoke cannabis to feel better versus any other reason was associated with an increased frequency of use in both those with and without FEP, with an RRR of 2.9 for using the drug more than once a week (P = .001) and an RRR of 3.13 for daily use (P < .001). However, the association was stronger in the healthy controls than in those with FEP, with an RRR for daily use of 4.45 versus 3.11, respectively.

The investigators also examined whether there was a link between reasons to start smoking and an individual’s polygenic risk score (PRS) for developing schizophrenia.

Multinomial regression indicated that PRS was not associated with starting cannabis to feel better or because friends were using it. However, there was an association between PRS score and starting the drug because family members were using it (RRR, 0.68; P < .05).

Complex association

Gabriella Gobbi, MD, PhD, professor in the neurobiological psychiatry unit, department of psychiatry, at McGill University, Montreal, said the data confirm “what we already know about cannabis.”

She noted that one of the “major causes” of young people starting cannabis is the social environment, while the desire to use the drug to feel better is linked to “the fact that cannabis, in a lot of cases, is used as a self-medication” in order to be calmer and as a relief from anxiety.

There is a “very complex” association between using cannabis to feel better and the self-medication seen with cigarette smoking and alcohol in patients with schizophrenia, said Dr. Gobbi, who was not involved with the research.

“When we talk about [patients using] cannabis, alcohol, and cigarettes, actually we’re talking about the same group of people,” she said.

Although “it is true they say that people look to cigarettes, tobacco, and alcohol to feel happier because they are depressed, the risk of psychosis is only for cannabis,” she added. “It is very low for alcohol and tobacco.”

As a result, Dr. Gobbi said she and her colleagues are “very worried” about the consequences for mental health of the legalization of cannabis consumption in Canada in October 2018 with the passing of the Cannabis Act.

Although there are no firm statistics yet, she has observed that since the law was passed, cannabis use has stabilized at a lower level among adolescents. “But now we have another population of people aged 34 and older that consume cannabis,” she said.

Particularly when considering the impact of higher strength cannabis on psychosis risk, Dr. Gobbi believes the increase in consumption in this age group will result in a “more elevated” risk for mental health issues.

Dr. Spinazzola and Dr. Gobbi have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SIRS 2020

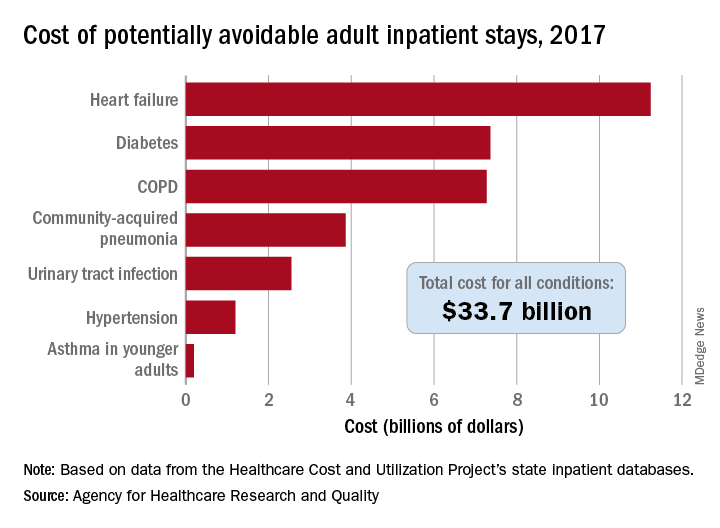

T2D plus heart failure packs a deadly punch

It’s bad news for patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes when they then develop heart failure during the next few years.

Patients with incident type 2 diabetes (T2D) who soon after also had heart failure appear faced a dramatically elevated mortality risk, higher than the incremental risk from any other cardiovascular or renal comorbidity that appeared following diabetes onset, in an analysis of more than 150,000 Danish patients with incident type 2 diabetes during 1998-2015.

The 5-year risk of death in patients who developed heart failure during the first 5 years following an initial diagnosis of T2D was about 48%, about threefold higher than in patients with newly diagnosed T2D who remained free of heart failure or any of the other studied comorbidities, Bochra Zareini, MD, and associates reported in a study published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. The studied patients had no known cardiovascular or renal disease at the time of their first T2D diagnosis.

“Our study reports not only on the absolute 5-year risk” of mortality, “but also takes into consideration when patients developed” a comorbidity. “What is surprising and worrying is the very high risk of death following heart failure and the potential life years lost when compared to T2D patients who do not develop heart failure,” said Dr. Zareini, a cardiologist at Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital in Copenhagen. “The implications of our study are to create awareness and highlight the importance of early detection of heart failure development in patients with T2D.” The results also showed that “heart failure is a common cardiovascular disease” in patients with newly diagnosed T2D, she added in an interview.

The data she and her associates reported came from a retrospective analysis of 153,403 Danish citizens in national health records who received a prescription for an antidiabetes drug for the first time during 1998-2015, excluding patients with a prior diagnosis of heart failure, ischemic heart disease (IHD), stroke, peripheral artery disease (PAD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), or gestational diabetes. They followed these patients for a median of just under 10 years, during which time 45% of the cohort had an incident diagnosis of at least one of these cardiovascular and renal conditions, based on medical-record entries from hospitalization discharges or ambulatory contacts.

Nearly two-thirds of the T2D patients with an incident comorbidity during follow-up had a single new diagnosis, a quarter had two new comorbidities appear during follow-up, and 13% developed at least three new comorbidities.

Heart failure, least common but deadliest comorbidity

The most common of the tracked comorbidities was IHD, which appeared in 8% of the T2D patients within 5 years and in 13% after 10 years. Next most common was stroke, affecting 3% of patients after 5 years and 5% after 10 years. CKD occurred in 2.2% after 5 years and in 4.0% after 10 years, PAD occurred in 2.1% after 5 years and in 3.0% at 10 years, and heart failure occurred in 1.6% at 5 years and in 2.2% after 10 years.

But despite being the least common of the studied comorbidities, heart failure was by far the most deadly, roughly tripling the 5-year mortality rate, compared with T2D patients with no comorbidities, regardless of exactly when it first appeared during the first 5 years after the initial T2D diagnosis. The next most deadly comorbidities were stroke and PAD, which each roughly doubled mortality, compared with the patients who remained free of any studied comorbidity. CKD boosted mortality by 70%-110%, depending on exactly when it appeared during the first 5 years of follow-up, and IHD, while the most frequent comorbidity was also the most benign, increasing mortality by about 30%.

The most deadly combinations of two comorbidities were when heart failure appeared with either CKD or with PAD; each of these combinations boosted mortality by 300%-400% when it occurred during the first few years after a T2D diagnosis.

The findings came from “a very big and unselected patient group of patients, making our results highly generalizable in terms of assessing the prognostic consequences of heart failure,” Dr. Zareini stressed.

Management implications

The dangerous combination of T2D and heart failure has been documented for several years, and prompted a focused statement in 2019 about best practices for managing these patients (Circulation. 2019 Aug 3;140[7]:e294-324). “Heart failure has been known for some time to predict poorer outcomes in patients with T2D. Not much surprising” in the new findings reported by Dr. Zareini and associates, commented Robert H. Eckel, MD, a cardiovascular endocrinologist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Heart failure “rarely acts alone, but in combination with other forms of heart or renal disease,” he noted in an interview.

Earlier studies may have “overlooked” heart failure’s importance compared with other comorbidities because they often “only investigated one cardiovascular disease in patients with T2D,” Dr. Zareini noted. In recent years the importance of heart failure occurring in patients with T2D also gained heightened significance because of the growing role of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor drug class in treating patients with T2D and the documented ability of these drugs to significantly reduce hospitalizations for heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 28;75[16]:1956-74). Dr. Zareini and associates put it this way in their report: “Heart failure has in recent years been recognized as an important clinical endpoint ... in patients with T2D, in particular, after the results from randomized, controlled trials of SGLT2 inhibitors showed benefit on cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalizations.”

Despite this, the new findings “do not address treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with T2D, nor can we use our data to address which patients should not be treated,” with this drug class, which instead should rely on “current evidence and expert consensus,” she said.

“Guidelines favor SGLT2 inhibitors or [glucagonlike peptide–1] receptor agonists in patients with a history of or high risk for major adverse coronary events,” and SGLT2 inhibitors are also “preferable in patients with renal disease,” Dr. Eckel noted.

Other avenues also exist for minimizing the onset of heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases in patients with T2D, Dr. Zareini said, citing modifiable risks that lead to heart failure that include hypertension, “diabetic cardiomyopathy,” and ISD. “Clinicians must treat all modifiable risk factors in patients with T2D in order to improve prognosis and limit development of cardiovascular and renal disease.”

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Zareini and Dr. Eckel had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zareini B et al. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020 Jun 23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006260.

It’s bad news for patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes when they then develop heart failure during the next few years.

Patients with incident type 2 diabetes (T2D) who soon after also had heart failure appear faced a dramatically elevated mortality risk, higher than the incremental risk from any other cardiovascular or renal comorbidity that appeared following diabetes onset, in an analysis of more than 150,000 Danish patients with incident type 2 diabetes during 1998-2015.

The 5-year risk of death in patients who developed heart failure during the first 5 years following an initial diagnosis of T2D was about 48%, about threefold higher than in patients with newly diagnosed T2D who remained free of heart failure or any of the other studied comorbidities, Bochra Zareini, MD, and associates reported in a study published in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. The studied patients had no known cardiovascular or renal disease at the time of their first T2D diagnosis.

“Our study reports not only on the absolute 5-year risk” of mortality, “but also takes into consideration when patients developed” a comorbidity. “What is surprising and worrying is the very high risk of death following heart failure and the potential life years lost when compared to T2D patients who do not develop heart failure,” said Dr. Zareini, a cardiologist at Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital in Copenhagen. “The implications of our study are to create awareness and highlight the importance of early detection of heart failure development in patients with T2D.” The results also showed that “heart failure is a common cardiovascular disease” in patients with newly diagnosed T2D, she added in an interview.

The data she and her associates reported came from a retrospective analysis of 153,403 Danish citizens in national health records who received a prescription for an antidiabetes drug for the first time during 1998-2015, excluding patients with a prior diagnosis of heart failure, ischemic heart disease (IHD), stroke, peripheral artery disease (PAD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), or gestational diabetes. They followed these patients for a median of just under 10 years, during which time 45% of the cohort had an incident diagnosis of at least one of these cardiovascular and renal conditions, based on medical-record entries from hospitalization discharges or ambulatory contacts.

Nearly two-thirds of the T2D patients with an incident comorbidity during follow-up had a single new diagnosis, a quarter had two new comorbidities appear during follow-up, and 13% developed at least three new comorbidities.

Heart failure, least common but deadliest comorbidity

The most common of the tracked comorbidities was IHD, which appeared in 8% of the T2D patients within 5 years and in 13% after 10 years. Next most common was stroke, affecting 3% of patients after 5 years and 5% after 10 years. CKD occurred in 2.2% after 5 years and in 4.0% after 10 years, PAD occurred in 2.1% after 5 years and in 3.0% at 10 years, and heart failure occurred in 1.6% at 5 years and in 2.2% after 10 years.

But despite being the least common of the studied comorbidities, heart failure was by far the most deadly, roughly tripling the 5-year mortality rate, compared with T2D patients with no comorbidities, regardless of exactly when it first appeared during the first 5 years after the initial T2D diagnosis. The next most deadly comorbidities were stroke and PAD, which each roughly doubled mortality, compared with the patients who remained free of any studied comorbidity. CKD boosted mortality by 70%-110%, depending on exactly when it appeared during the first 5 years of follow-up, and IHD, while the most frequent comorbidity was also the most benign, increasing mortality by about 30%.

The most deadly combinations of two comorbidities were when heart failure appeared with either CKD or with PAD; each of these combinations boosted mortality by 300%-400% when it occurred during the first few years after a T2D diagnosis.

The findings came from “a very big and unselected patient group of patients, making our results highly generalizable in terms of assessing the prognostic consequences of heart failure,” Dr. Zareini stressed.

Management implications

The dangerous combination of T2D and heart failure has been documented for several years, and prompted a focused statement in 2019 about best practices for managing these patients (Circulation. 2019 Aug 3;140[7]:e294-324). “Heart failure has been known for some time to predict poorer outcomes in patients with T2D. Not much surprising” in the new findings reported by Dr. Zareini and associates, commented Robert H. Eckel, MD, a cardiovascular endocrinologist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Heart failure “rarely acts alone, but in combination with other forms of heart or renal disease,” he noted in an interview.

Earlier studies may have “overlooked” heart failure’s importance compared with other comorbidities because they often “only investigated one cardiovascular disease in patients with T2D,” Dr. Zareini noted. In recent years the importance of heart failure occurring in patients with T2D also gained heightened significance because of the growing role of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor drug class in treating patients with T2D and the documented ability of these drugs to significantly reduce hospitalizations for heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 28;75[16]:1956-74). Dr. Zareini and associates put it this way in their report: “Heart failure has in recent years been recognized as an important clinical endpoint ... in patients with T2D, in particular, after the results from randomized, controlled trials of SGLT2 inhibitors showed benefit on cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalizations.”

Despite this, the new findings “do not address treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with T2D, nor can we use our data to address which patients should not be treated,” with this drug class, which instead should rely on “current evidence and expert consensus,” she said.

“Guidelines favor SGLT2 inhibitors or [glucagonlike peptide–1] receptor agonists in patients with a history of or high risk for major adverse coronary events,” and SGLT2 inhibitors are also “preferable in patients with renal disease,” Dr. Eckel noted.

Other avenues also exist for minimizing the onset of heart failure and other cardiovascular diseases in patients with T2D, Dr. Zareini said, citing modifiable risks that lead to heart failure that include hypertension, “diabetic cardiomyopathy,” and ISD. “Clinicians must treat all modifiable risk factors in patients with T2D in order to improve prognosis and limit development of cardiovascular and renal disease.”

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Zareini and Dr. Eckel had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Zareini B et al. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020 Jun 23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006260.