User login

Take-home test strips allow drug users to detect fentanyl

Illicit drug users seem to overwhelmingly appreciate being able to use take-home test strips to detect the extremely common presence of dangerous fentanyl in opioids and other drugs, a new study finds. More than 95% said they’d use the inexpensive strips again.

said study lead author addiction medicine specialist Sukhpreet Klaire, MD, of the British Columbia Center on Substance Use in Vancouver, in an interview.

Dr. Klaire presented the study findings at the virtual annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

Researchers in Vancouver distributed take-home fentanyl test strip kits at 10 sites that allow users to test their illicit drugs. The 218 participants performed 1,680 tests, mainly (73%) for opioids, over 3 months in 2019. Of the participants, 61% were male, and the average age was 36 (interquartile range, 29-47). About 30% described themselves as indigenous Canadians (First Nations).

About 90% of the opioid samples tested at home were positive for fentanyl, about the same level as samples tested at clinics. Fentanyl is very potent and linked to the huge rise in overdose deaths in the United States.

Fentanyl test strips aren’t new. According to the Harm Reduction Coalition, they originally were developed to detect fentanyl in urine samples but were jury-rigged in Vancouver to work on samples of illicit drugs. “We literally just repurposed it,” Dr. Klaire said. “It’s the same strip.”

Users test their drugs by dissolving a small sample in water. Then then dip the test strip, which provides readings similar to those in a pregnancy test. If a sample turns up positive for fentanyl, Dr. Klaire said, users may discard the drug or “be more careful with it.”

When asked what they would do if a sample turned up positive, 27% said they’d make a “positive change,” such as using less or using more slowly (n = 45) or making sure that someone else is present in case of an overdose (n = 26). But most, 71%, reported no change in behavior.

Previously, researchers in Rhode Island and North Carolina also found that some users adopted safer behaviors – such as throwing out their drugs or using less often – after testing their drugs with the strips.

The strips cost about 75 cents, Dr. Klaire said.

Harm-reduction strategies are controversial, and fentanyl test strips aren’t any exemption. “The entire approach is based on the premise that a drug user poised to use a drug is making rational choices, is weighing pros and cons, and is thinking completely logically about his or her drug use. Based on my clinical experience, I know this could not be further from the truth,” wrote Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, assistant secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use with the Department of Health & Human Services, in a 2018 blog post.

But Dr. Klaire said the patients in the new study are highly dependent on opioids. “The drug supply is heavily contaminated [with fentanyl],” he said, “but even when people know it’s contaminated, they still need to go ahead and use it.”

In an interview, epidemiologist Brandon Marshall, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., who has conducted fentanyl test strip research, called the study results “compelling.”

“The researchers found that the fentanyl test strips had a very high level of acceptability – over 95% said they would use the strips again – which is remarkably similar to what we found in our work here in Rhode Island,” he said. “Taken together, these studies show that take-home test strips are a feasible, acceptable, and effective strategy for people who use drugs to reduce their risk of fentanyl overdose.”

He added that “fentanyl test strips help people make more informed decisions about their drug use and reducing their risk of overdose.”

However, he said, “one of important limitations of the strips is that they do not detect all contaminants that put persons at risk of overdose. Just because a test result is negative does not mean that the drug is 100% safe.”

Kimberly Sue, MD, PhD, medical director of the National Harm Reduction Coalition, said in an interview that the research is “important,” but noted that many drug users already have been using fentanyl test strips on their own. “We should be focusing on investing in variety of other interventions that could keep more people safe against nonfatal and fatal opioid overdoses, including structural interventions such as safe supply, housing and community with appropriate supports, low barrier access to medication for opioid use disorder, and safe consumption spaces,” she said.

No study funding was reported. Dr. Klaire disclosed participating in a research fellowship and a research in addiction medical scholars program, both funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Dr. Sue reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Marshall reported that he has collaborated frequently with one of the coauthors of the Vancouver study.

Illicit drug users seem to overwhelmingly appreciate being able to use take-home test strips to detect the extremely common presence of dangerous fentanyl in opioids and other drugs, a new study finds. More than 95% said they’d use the inexpensive strips again.

said study lead author addiction medicine specialist Sukhpreet Klaire, MD, of the British Columbia Center on Substance Use in Vancouver, in an interview.

Dr. Klaire presented the study findings at the virtual annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

Researchers in Vancouver distributed take-home fentanyl test strip kits at 10 sites that allow users to test their illicit drugs. The 218 participants performed 1,680 tests, mainly (73%) for opioids, over 3 months in 2019. Of the participants, 61% were male, and the average age was 36 (interquartile range, 29-47). About 30% described themselves as indigenous Canadians (First Nations).

About 90% of the opioid samples tested at home were positive for fentanyl, about the same level as samples tested at clinics. Fentanyl is very potent and linked to the huge rise in overdose deaths in the United States.

Fentanyl test strips aren’t new. According to the Harm Reduction Coalition, they originally were developed to detect fentanyl in urine samples but were jury-rigged in Vancouver to work on samples of illicit drugs. “We literally just repurposed it,” Dr. Klaire said. “It’s the same strip.”

Users test their drugs by dissolving a small sample in water. Then then dip the test strip, which provides readings similar to those in a pregnancy test. If a sample turns up positive for fentanyl, Dr. Klaire said, users may discard the drug or “be more careful with it.”

When asked what they would do if a sample turned up positive, 27% said they’d make a “positive change,” such as using less or using more slowly (n = 45) or making sure that someone else is present in case of an overdose (n = 26). But most, 71%, reported no change in behavior.

Previously, researchers in Rhode Island and North Carolina also found that some users adopted safer behaviors – such as throwing out their drugs or using less often – after testing their drugs with the strips.

The strips cost about 75 cents, Dr. Klaire said.

Harm-reduction strategies are controversial, and fentanyl test strips aren’t any exemption. “The entire approach is based on the premise that a drug user poised to use a drug is making rational choices, is weighing pros and cons, and is thinking completely logically about his or her drug use. Based on my clinical experience, I know this could not be further from the truth,” wrote Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, assistant secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use with the Department of Health & Human Services, in a 2018 blog post.

But Dr. Klaire said the patients in the new study are highly dependent on opioids. “The drug supply is heavily contaminated [with fentanyl],” he said, “but even when people know it’s contaminated, they still need to go ahead and use it.”

In an interview, epidemiologist Brandon Marshall, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., who has conducted fentanyl test strip research, called the study results “compelling.”

“The researchers found that the fentanyl test strips had a very high level of acceptability – over 95% said they would use the strips again – which is remarkably similar to what we found in our work here in Rhode Island,” he said. “Taken together, these studies show that take-home test strips are a feasible, acceptable, and effective strategy for people who use drugs to reduce their risk of fentanyl overdose.”

He added that “fentanyl test strips help people make more informed decisions about their drug use and reducing their risk of overdose.”

However, he said, “one of important limitations of the strips is that they do not detect all contaminants that put persons at risk of overdose. Just because a test result is negative does not mean that the drug is 100% safe.”

Kimberly Sue, MD, PhD, medical director of the National Harm Reduction Coalition, said in an interview that the research is “important,” but noted that many drug users already have been using fentanyl test strips on their own. “We should be focusing on investing in variety of other interventions that could keep more people safe against nonfatal and fatal opioid overdoses, including structural interventions such as safe supply, housing and community with appropriate supports, low barrier access to medication for opioid use disorder, and safe consumption spaces,” she said.

No study funding was reported. Dr. Klaire disclosed participating in a research fellowship and a research in addiction medical scholars program, both funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Dr. Sue reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Marshall reported that he has collaborated frequently with one of the coauthors of the Vancouver study.

Illicit drug users seem to overwhelmingly appreciate being able to use take-home test strips to detect the extremely common presence of dangerous fentanyl in opioids and other drugs, a new study finds. More than 95% said they’d use the inexpensive strips again.

said study lead author addiction medicine specialist Sukhpreet Klaire, MD, of the British Columbia Center on Substance Use in Vancouver, in an interview.

Dr. Klaire presented the study findings at the virtual annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

Researchers in Vancouver distributed take-home fentanyl test strip kits at 10 sites that allow users to test their illicit drugs. The 218 participants performed 1,680 tests, mainly (73%) for opioids, over 3 months in 2019. Of the participants, 61% were male, and the average age was 36 (interquartile range, 29-47). About 30% described themselves as indigenous Canadians (First Nations).

About 90% of the opioid samples tested at home were positive for fentanyl, about the same level as samples tested at clinics. Fentanyl is very potent and linked to the huge rise in overdose deaths in the United States.

Fentanyl test strips aren’t new. According to the Harm Reduction Coalition, they originally were developed to detect fentanyl in urine samples but were jury-rigged in Vancouver to work on samples of illicit drugs. “We literally just repurposed it,” Dr. Klaire said. “It’s the same strip.”

Users test their drugs by dissolving a small sample in water. Then then dip the test strip, which provides readings similar to those in a pregnancy test. If a sample turns up positive for fentanyl, Dr. Klaire said, users may discard the drug or “be more careful with it.”

When asked what they would do if a sample turned up positive, 27% said they’d make a “positive change,” such as using less or using more slowly (n = 45) or making sure that someone else is present in case of an overdose (n = 26). But most, 71%, reported no change in behavior.

Previously, researchers in Rhode Island and North Carolina also found that some users adopted safer behaviors – such as throwing out their drugs or using less often – after testing their drugs with the strips.

The strips cost about 75 cents, Dr. Klaire said.

Harm-reduction strategies are controversial, and fentanyl test strips aren’t any exemption. “The entire approach is based on the premise that a drug user poised to use a drug is making rational choices, is weighing pros and cons, and is thinking completely logically about his or her drug use. Based on my clinical experience, I know this could not be further from the truth,” wrote Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, assistant secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use with the Department of Health & Human Services, in a 2018 blog post.

But Dr. Klaire said the patients in the new study are highly dependent on opioids. “The drug supply is heavily contaminated [with fentanyl],” he said, “but even when people know it’s contaminated, they still need to go ahead and use it.”

In an interview, epidemiologist Brandon Marshall, PhD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., who has conducted fentanyl test strip research, called the study results “compelling.”

“The researchers found that the fentanyl test strips had a very high level of acceptability – over 95% said they would use the strips again – which is remarkably similar to what we found in our work here in Rhode Island,” he said. “Taken together, these studies show that take-home test strips are a feasible, acceptable, and effective strategy for people who use drugs to reduce their risk of fentanyl overdose.”

He added that “fentanyl test strips help people make more informed decisions about their drug use and reducing their risk of overdose.”

However, he said, “one of important limitations of the strips is that they do not detect all contaminants that put persons at risk of overdose. Just because a test result is negative does not mean that the drug is 100% safe.”

Kimberly Sue, MD, PhD, medical director of the National Harm Reduction Coalition, said in an interview that the research is “important,” but noted that many drug users already have been using fentanyl test strips on their own. “We should be focusing on investing in variety of other interventions that could keep more people safe against nonfatal and fatal opioid overdoses, including structural interventions such as safe supply, housing and community with appropriate supports, low barrier access to medication for opioid use disorder, and safe consumption spaces,” she said.

No study funding was reported. Dr. Klaire disclosed participating in a research fellowship and a research in addiction medical scholars program, both funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Dr. Sue reported no relevant disclosures. Dr. Marshall reported that he has collaborated frequently with one of the coauthors of the Vancouver study.

FROM CPDD 2020

Cushing’s and COVID-19: Nontraditional symptoms keys to assessment, treatments

Do not rely on more traditional signs and symptoms of COVID-19 like fever and dyspnea when assessing patients with Cushing’s syndrome for the novel coronavirus, Rosario Pivonello, MD, PhD, and colleagues urged.

Physicians evaluating patients with Cushing’s syndrome for COVID-19 “should be suspicious of any change in health status of their patients with Cushing’s syndrome, rather than relying on fever and [dyspnea] as typical features,” Dr. Pivonello, an endocrinologist with the University of Naples (Italy) Federico II, and colleagues wrote in a commentary published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

COVID-19 symptoms are a unique concern among patients with Cushing’s syndrome because many of the cardiometabolic and immune impairments that place someone at higher risk of more severe disease or mortality for the novel coronavirus – such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and immunodeficiency syndromes – are also shared with Cushing’s syndrome.

Increased cardiovascular risk factors and susceptibility to severe infection are “two leading causes of death” for patients with Cushing’s syndrome, Dr. Pivonello and colleagues noted.

The immunocompromised state of patients with Cushing’s syndrome may make detection of COVID-19 infection difficult, the authors say. For example, fever is a common symptom of patients with COVID-19, but in patients with active Cushing’s syndrome, “low-grade chronic inflammation and the poor immune response might limit febrile response in the early phase of infection,” Dr. Pivonello and colleagues wrote.

In other cases, because Cushing’s syndrome and COVID-19 have overlapping symptoms, it may be difficult to attribute a particular symptom to either disease. Dyspnea is a common symptom of COVID-19, but may present in Cushing’s syndrome because of “cardiac insufficiency or weakness of respiratory muscles,” the authors wrote. Instead, physicians should look to other COVID-19 symptoms, such as cough, dysgeusia, anosmia, and diarrhea, for signs of the disease.

Patients with Cushing’s syndrome may also be predisposed to a more severe course of COVID-19 because of the prevalence of obesity, hypertension, or diabetes in these patients, which have been identified as comorbidities that increase the likelihood of severe COVID-19 and progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). “However, a key element in the development of ARDS during COVID-19 is the exaggerated cellular response induced by the cytokine increase, leading to massive alveolar–capillary wall damage and a decline in gas exchange,” Dr. Pivonello and colleagues wrote. “Because patients with Cushing’s syndrome might not mount a normal cytokine response, these patients might [paradoxically] be less prone to develop severe ARDS with COVID-19.”

As both Cushing’s syndrome and COVID-19 are associated with hypercoagulability, the authors “strongly advise” using low-molecular-weight heparin in hospitalized patients with active Cushing’s syndrome who develop COVID-19. In both diseases, there is also a risk of longer duration of viral infections and opportunistic infections such as atypical bacterial and invasive fungal infections. For this reason, the authors also recommended patients with Cushing’s syndrome who have COVID-19 be placed on prolonged antiviral and broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment as a prophylactic measure.

During the pandemic, avoiding surgery for Cushing’s syndrome should be considered to reduce the likelihood of acquiring COVID-19 in a hospital setting, the authors wrote. Medical therapy can be temporarily used where appropriate, such as using ketoconazole, metyrapone, osilodrostat, and etomidate to lower cortisol levels. They acknowledge that some cases of malignant Cushing’s syndrome may require “expeditious definitive diagnosis and proper surgical resolution.”

After remission, while infection risk should be significantly lowered, other comorbidities like obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and thromboembolic diathesis may remain. “Because these are features associated with an increased death risk in patients with COVID-19, patients with Cushing’s syndrome in remission should be considered a high-risk population and consequently adopt adequate self-protection strategies to [minimize] contagion risk,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Pivonello reported relationships with Novartis, Strongbridge Biopharma, HRA Pharma, Ipsen, Shire, and Pfizer, Corcept Therapeutics, IBSA Farmaceutici, Ferring, and Italfarmaco in the form of receiving grants and/or personal fees. One coauthor reported receiving grants and/or nonfinancial support from Takeda, Ipsen, Shire, Pfizer, and Corcept Therapeutics. One coauthor reported receiving grants and personal fees from Novartis and Strongbridge, and grants from Millendo Therapeutics. Another coauthor reported receiving grants and/or personal fees from Novartis, Ipsen, Shire, Pfizer, Italfarmaco, Lilly, Merck, and Novo Nordisk. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pivonello R et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 Jun 9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30215-1.

Do not rely on more traditional signs and symptoms of COVID-19 like fever and dyspnea when assessing patients with Cushing’s syndrome for the novel coronavirus, Rosario Pivonello, MD, PhD, and colleagues urged.

Physicians evaluating patients with Cushing’s syndrome for COVID-19 “should be suspicious of any change in health status of their patients with Cushing’s syndrome, rather than relying on fever and [dyspnea] as typical features,” Dr. Pivonello, an endocrinologist with the University of Naples (Italy) Federico II, and colleagues wrote in a commentary published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

COVID-19 symptoms are a unique concern among patients with Cushing’s syndrome because many of the cardiometabolic and immune impairments that place someone at higher risk of more severe disease or mortality for the novel coronavirus – such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and immunodeficiency syndromes – are also shared with Cushing’s syndrome.

Increased cardiovascular risk factors and susceptibility to severe infection are “two leading causes of death” for patients with Cushing’s syndrome, Dr. Pivonello and colleagues noted.

The immunocompromised state of patients with Cushing’s syndrome may make detection of COVID-19 infection difficult, the authors say. For example, fever is a common symptom of patients with COVID-19, but in patients with active Cushing’s syndrome, “low-grade chronic inflammation and the poor immune response might limit febrile response in the early phase of infection,” Dr. Pivonello and colleagues wrote.

In other cases, because Cushing’s syndrome and COVID-19 have overlapping symptoms, it may be difficult to attribute a particular symptom to either disease. Dyspnea is a common symptom of COVID-19, but may present in Cushing’s syndrome because of “cardiac insufficiency or weakness of respiratory muscles,” the authors wrote. Instead, physicians should look to other COVID-19 symptoms, such as cough, dysgeusia, anosmia, and diarrhea, for signs of the disease.

Patients with Cushing’s syndrome may also be predisposed to a more severe course of COVID-19 because of the prevalence of obesity, hypertension, or diabetes in these patients, which have been identified as comorbidities that increase the likelihood of severe COVID-19 and progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). “However, a key element in the development of ARDS during COVID-19 is the exaggerated cellular response induced by the cytokine increase, leading to massive alveolar–capillary wall damage and a decline in gas exchange,” Dr. Pivonello and colleagues wrote. “Because patients with Cushing’s syndrome might not mount a normal cytokine response, these patients might [paradoxically] be less prone to develop severe ARDS with COVID-19.”

As both Cushing’s syndrome and COVID-19 are associated with hypercoagulability, the authors “strongly advise” using low-molecular-weight heparin in hospitalized patients with active Cushing’s syndrome who develop COVID-19. In both diseases, there is also a risk of longer duration of viral infections and opportunistic infections such as atypical bacterial and invasive fungal infections. For this reason, the authors also recommended patients with Cushing’s syndrome who have COVID-19 be placed on prolonged antiviral and broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment as a prophylactic measure.

During the pandemic, avoiding surgery for Cushing’s syndrome should be considered to reduce the likelihood of acquiring COVID-19 in a hospital setting, the authors wrote. Medical therapy can be temporarily used where appropriate, such as using ketoconazole, metyrapone, osilodrostat, and etomidate to lower cortisol levels. They acknowledge that some cases of malignant Cushing’s syndrome may require “expeditious definitive diagnosis and proper surgical resolution.”

After remission, while infection risk should be significantly lowered, other comorbidities like obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and thromboembolic diathesis may remain. “Because these are features associated with an increased death risk in patients with COVID-19, patients with Cushing’s syndrome in remission should be considered a high-risk population and consequently adopt adequate self-protection strategies to [minimize] contagion risk,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Pivonello reported relationships with Novartis, Strongbridge Biopharma, HRA Pharma, Ipsen, Shire, and Pfizer, Corcept Therapeutics, IBSA Farmaceutici, Ferring, and Italfarmaco in the form of receiving grants and/or personal fees. One coauthor reported receiving grants and/or nonfinancial support from Takeda, Ipsen, Shire, Pfizer, and Corcept Therapeutics. One coauthor reported receiving grants and personal fees from Novartis and Strongbridge, and grants from Millendo Therapeutics. Another coauthor reported receiving grants and/or personal fees from Novartis, Ipsen, Shire, Pfizer, Italfarmaco, Lilly, Merck, and Novo Nordisk. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pivonello R et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 Jun 9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30215-1.

Do not rely on more traditional signs and symptoms of COVID-19 like fever and dyspnea when assessing patients with Cushing’s syndrome for the novel coronavirus, Rosario Pivonello, MD, PhD, and colleagues urged.

Physicians evaluating patients with Cushing’s syndrome for COVID-19 “should be suspicious of any change in health status of their patients with Cushing’s syndrome, rather than relying on fever and [dyspnea] as typical features,” Dr. Pivonello, an endocrinologist with the University of Naples (Italy) Federico II, and colleagues wrote in a commentary published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

COVID-19 symptoms are a unique concern among patients with Cushing’s syndrome because many of the cardiometabolic and immune impairments that place someone at higher risk of more severe disease or mortality for the novel coronavirus – such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and immunodeficiency syndromes – are also shared with Cushing’s syndrome.

Increased cardiovascular risk factors and susceptibility to severe infection are “two leading causes of death” for patients with Cushing’s syndrome, Dr. Pivonello and colleagues noted.

The immunocompromised state of patients with Cushing’s syndrome may make detection of COVID-19 infection difficult, the authors say. For example, fever is a common symptom of patients with COVID-19, but in patients with active Cushing’s syndrome, “low-grade chronic inflammation and the poor immune response might limit febrile response in the early phase of infection,” Dr. Pivonello and colleagues wrote.

In other cases, because Cushing’s syndrome and COVID-19 have overlapping symptoms, it may be difficult to attribute a particular symptom to either disease. Dyspnea is a common symptom of COVID-19, but may present in Cushing’s syndrome because of “cardiac insufficiency or weakness of respiratory muscles,” the authors wrote. Instead, physicians should look to other COVID-19 symptoms, such as cough, dysgeusia, anosmia, and diarrhea, for signs of the disease.

Patients with Cushing’s syndrome may also be predisposed to a more severe course of COVID-19 because of the prevalence of obesity, hypertension, or diabetes in these patients, which have been identified as comorbidities that increase the likelihood of severe COVID-19 and progression to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). “However, a key element in the development of ARDS during COVID-19 is the exaggerated cellular response induced by the cytokine increase, leading to massive alveolar–capillary wall damage and a decline in gas exchange,” Dr. Pivonello and colleagues wrote. “Because patients with Cushing’s syndrome might not mount a normal cytokine response, these patients might [paradoxically] be less prone to develop severe ARDS with COVID-19.”

As both Cushing’s syndrome and COVID-19 are associated with hypercoagulability, the authors “strongly advise” using low-molecular-weight heparin in hospitalized patients with active Cushing’s syndrome who develop COVID-19. In both diseases, there is also a risk of longer duration of viral infections and opportunistic infections such as atypical bacterial and invasive fungal infections. For this reason, the authors also recommended patients with Cushing’s syndrome who have COVID-19 be placed on prolonged antiviral and broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment as a prophylactic measure.

During the pandemic, avoiding surgery for Cushing’s syndrome should be considered to reduce the likelihood of acquiring COVID-19 in a hospital setting, the authors wrote. Medical therapy can be temporarily used where appropriate, such as using ketoconazole, metyrapone, osilodrostat, and etomidate to lower cortisol levels. They acknowledge that some cases of malignant Cushing’s syndrome may require “expeditious definitive diagnosis and proper surgical resolution.”

After remission, while infection risk should be significantly lowered, other comorbidities like obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and thromboembolic diathesis may remain. “Because these are features associated with an increased death risk in patients with COVID-19, patients with Cushing’s syndrome in remission should be considered a high-risk population and consequently adopt adequate self-protection strategies to [minimize] contagion risk,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Pivonello reported relationships with Novartis, Strongbridge Biopharma, HRA Pharma, Ipsen, Shire, and Pfizer, Corcept Therapeutics, IBSA Farmaceutici, Ferring, and Italfarmaco in the form of receiving grants and/or personal fees. One coauthor reported receiving grants and/or nonfinancial support from Takeda, Ipsen, Shire, Pfizer, and Corcept Therapeutics. One coauthor reported receiving grants and personal fees from Novartis and Strongbridge, and grants from Millendo Therapeutics. Another coauthor reported receiving grants and/or personal fees from Novartis, Ipsen, Shire, Pfizer, Italfarmaco, Lilly, Merck, and Novo Nordisk. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Pivonello R et al. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 Jun 9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30215-1.

FROM THE LANCET DIABETES & ENDOCRINOLOGY

Community programs improve psychosis outcomes

Community-based services that tap into local environments not only reduce the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) but also provide improved long-term outcomes for patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP), results of two new studies show.

In the first study, investigators led by Vinod Srihari, MD, director of specialized treatment early in psychosis at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., developed a program to reduce DUP to complement their first-episode service (FES).

Through a combination of mass media and social media campaigns, outreach events with local professionals, and rapid triage, the team was able to nearly halve the time from diagnosis to initiation of antipsychotic treatment.

In the second study, a team led by Delbert G. Robinson, MD, of Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., conducted a 5-year follow-up of RAISE-ETP, the first U.S. randomized trial to compare a 2-year comprehensive early intervention service (EIS) with usual care.

These trial results showed that, among more than 400 FEP patients, the EIS significantly improved both symptoms and quality of life and reduced inpatient days in comparison with standard care.

The research was scheduled to be presented at the Congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society (SIRS) 2020, but the meeting was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Norwegian model

Dr. Srihari and colleagues note that a specialized treatment early in psychosis (STEP), which delivers a specialty team–based FES, was established at their institution in 2006.

However, in a bid to reduce DUP, in 2015 they launched MindMap, a 4-year early-detection campaign based on the Scandinavian TIPS Early Detection in Psychosis Study.

Dr. Srihari said in an interview that they visited the team that developed the TIPS program in Norway “to try to understand what elements of their approach had resulted in a successful reduction of DUP.”

He pointed out that the health care system in Norway has “more reliable pathways to care, with an ability to route people in more predictable ways from primary care to secondary care, and so on.”

In the United States, “there’s no expectation that people will go through a primary care provider,” he said. He noted that patients “make their way to specialty care in many different ways.”

Dr. Srihari said, “The other change we realized we’d have to make was that, since TIPS had been completed many years back, the media environment had changed substantially.

“At the time that TIPS was done, there was no such thing as social media, whereas when we began to think about designing our campaign, we thought social media would be a very efficient and also cost-effective way to target young people.”

MindMap, which covered a 10-town catchment area that has a population of 400,000, targeted both demand- and supply-side aspects of DUP. The former focused on delays in identifying illness and help-seeking, and the latter concentrated on referral and treatment access delays.

The researchers used a combination of mass media and social media messaging, professional detailing, and the rapid triage of referrals.

The media campaign included Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms that allowed the team to “target individuals in a somewhat more fine-grained way than mass media allows,” Dr. Srihari said. They focused on individuals in a particular age range and geographic location.

The professional detailing encompassed mental health agencies, emergency departments, and inpatient units, as well as colleges, college counseling centers, high schools, and police departments. The team hosted meetings, “often at local restaurants, where we provided a meal and provided some general education about what our mission was,” said Dr. Srihari. The researchers followed up these meetings with more in-person visits.

“The third arm was finding ways to basically eliminate any kind of a waiting time at our front door, such as ensuring that transportation issues were circumvented, in addition to cutting through any ambivalence they might have about finally making the leap to come to the center.”

More rapid treatment

Over the course of the baseline year and the 4 years of the MindMap program, almost 1,500 individuals were assessed. Of these, approximately 200 were eligible, and almost all were enrolled.

The researchers measured DUP at two time points from the onset of psychosis – the initiation of antipsychotic treatment (DUP1) and the initiation of FES care. Across the study period, they found that DUP1 fell significantly between the pre- and postprogram assessments, from 329 days to 185 days (P = .03). By contrast, there was no change over the same period for the Prevention and Recovery in Early Psychosis FES program in Boston, which served as a comparator.

There was also a cumulative effect on DUP, with each year of the 4-year program associated with a 46-day reduction in DUP1. However, the significant reduction was restricted to the third quintile of DUP1 and was not found in the other quintiles of DUP1 or for DUP2, despite all measures showing a consistent trend for reduction over time.

Dr. Srihari acknowledges that the team was “disappointed” that DUP2 did not fall significantly in their study. He suggested, “It might take longer for agencies to change their workloads and refer patients to STEP, which is what ended up resulting in the DUP2 not dropping as quickly.”

To see whether there was indeed a time lag in changes to practice, the team conducted an analysis in which they cut out the first year from the results and analyzed only the last 3 years. Then “we do see a decline in DUP2,” he said.

The study’s full results are currently being prepared for publication, and the investigators are considering relaunching the initiative.

“The question we are having now is how to resource the campaign without the research funds and which parts of it we think we can launch sustainably so we can continue the reduction of DUP,” Dr. Srihari said.

Plans may include developing partnerships with local businesses to help fund the media costs and working with the state government to build a learning health care network, which would make it easier for mental health agencies to consult with the team on problematic cases.

“We’re trying to reduce DUP referrals on the supply side by providing this kind of learning health collaborative ... that we also think might be fiscally a more sustainable way to do this vs. what we did in MindMap,” which would be “very expensive” to implement on a statewide basis, Dr. Srihari added.

Long-term benefit

In the second study, Dr. Robinson and colleagues highlight that EISs have been implemented worldwide for FEP patients and have been associated with improved outcomes.

However, these services typically provide care for a limited period, and cross-sectional follow-up studies have identified few advantages in comparison with standard care.

To provide a more robust longitudinal assessment of the ongoing effects of an EIS, the team conducted a 5-year follow-up of the first U.S.-based, multicenter, randomized clinical trial comparing an EIS, NAVIGATE, with usual clinical care in FEP.

RAISE-ETP was conducted at 34 sites across the United States. Seventeen sites provided NAVIGATE to 223 individuals with FEP, and the remaining 17 sites provided usual care to 181 patients.

NAVIGATE, which continued for 2 years, consisted of treatments and services delivered by a coordinated team of providers. Those services included the following:

- Education on schizophrenia and its treatment for patients and their families.

- Symptom and relapse prevention medication, using a computerized decision support system.

- Strategies for illness management building personal resilience.

- A supported employment/education model.

Patients were assessed every 6 months for up to 60 months via a video link using the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QLS) and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

The average age of the participants was 23 years; 78% of those who received NAVIGATE and 66% of those who received usual care were male. The opportunity for each participant to engage in NAVIGATE treatment lasted an average of 33.8 months. The longest was 44.4 months.

Over 5 years, NAVIGATE was associated with a significant improvement over usual care in QLS scores by an average of 13.14 units (P < .001). PANSS scores improved by an average of 7.73 units (P < .002). QLS scores were not affected either by the length of opportunity to participate in NAVIGATE or by DUP, the team reports. Patients who received NAVIGATE also had an average of 2.5 fewer inpatient days, compared with those on usual care (P = .02).

The investigators note that the study “provides compelling evidence of a substantial long-term benefit for FEP treatment with the NAVIGATE EIS, compared with standard care.”

A ‘great message’

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Ragy R. Girgis, MD, associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute, said

Dr. Girgis, who was not involved in either study, said that the research is “a great message.” He noted that it is “really important for people to know and it’s really important that we’re still doing research in those areas.”

However, he noted that psychosocial interventions such as these “sometimes take a lot of work.” Dr. Girgis said that it is “so easy to just give people a medication” but that approach has its own disadvantages, including adverse effects and sometimes a lack of efficacy.

“Psychosocial interventions, on the other hand, are very well tolerated by people. They are very effective, but they may require a lot more manpower, and in some ways they can also be more expensive.

“So this is a dialectic that we oftentimes have to deal with when we figure out the right balance between psychosocial vs. medication types of treatments,” he said.

STEP has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation. RAISE-ETP was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health as part of the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) Project. Dr. Gopal is an employee of Janssen Research & Development, and owns stock/equity in Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Girgis has received research support from Genentech, BioAdvantex, Allegran/Forest, and Otsuka, and royalties from Wipf and Stock and Routledge/Taylor and Francis.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Community-based services that tap into local environments not only reduce the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) but also provide improved long-term outcomes for patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP), results of two new studies show.

In the first study, investigators led by Vinod Srihari, MD, director of specialized treatment early in psychosis at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., developed a program to reduce DUP to complement their first-episode service (FES).

Through a combination of mass media and social media campaigns, outreach events with local professionals, and rapid triage, the team was able to nearly halve the time from diagnosis to initiation of antipsychotic treatment.

In the second study, a team led by Delbert G. Robinson, MD, of Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., conducted a 5-year follow-up of RAISE-ETP, the first U.S. randomized trial to compare a 2-year comprehensive early intervention service (EIS) with usual care.

These trial results showed that, among more than 400 FEP patients, the EIS significantly improved both symptoms and quality of life and reduced inpatient days in comparison with standard care.

The research was scheduled to be presented at the Congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society (SIRS) 2020, but the meeting was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Norwegian model

Dr. Srihari and colleagues note that a specialized treatment early in psychosis (STEP), which delivers a specialty team–based FES, was established at their institution in 2006.

However, in a bid to reduce DUP, in 2015 they launched MindMap, a 4-year early-detection campaign based on the Scandinavian TIPS Early Detection in Psychosis Study.

Dr. Srihari said in an interview that they visited the team that developed the TIPS program in Norway “to try to understand what elements of their approach had resulted in a successful reduction of DUP.”

He pointed out that the health care system in Norway has “more reliable pathways to care, with an ability to route people in more predictable ways from primary care to secondary care, and so on.”

In the United States, “there’s no expectation that people will go through a primary care provider,” he said. He noted that patients “make their way to specialty care in many different ways.”

Dr. Srihari said, “The other change we realized we’d have to make was that, since TIPS had been completed many years back, the media environment had changed substantially.

“At the time that TIPS was done, there was no such thing as social media, whereas when we began to think about designing our campaign, we thought social media would be a very efficient and also cost-effective way to target young people.”

MindMap, which covered a 10-town catchment area that has a population of 400,000, targeted both demand- and supply-side aspects of DUP. The former focused on delays in identifying illness and help-seeking, and the latter concentrated on referral and treatment access delays.

The researchers used a combination of mass media and social media messaging, professional detailing, and the rapid triage of referrals.

The media campaign included Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms that allowed the team to “target individuals in a somewhat more fine-grained way than mass media allows,” Dr. Srihari said. They focused on individuals in a particular age range and geographic location.

The professional detailing encompassed mental health agencies, emergency departments, and inpatient units, as well as colleges, college counseling centers, high schools, and police departments. The team hosted meetings, “often at local restaurants, where we provided a meal and provided some general education about what our mission was,” said Dr. Srihari. The researchers followed up these meetings with more in-person visits.

“The third arm was finding ways to basically eliminate any kind of a waiting time at our front door, such as ensuring that transportation issues were circumvented, in addition to cutting through any ambivalence they might have about finally making the leap to come to the center.”

More rapid treatment

Over the course of the baseline year and the 4 years of the MindMap program, almost 1,500 individuals were assessed. Of these, approximately 200 were eligible, and almost all were enrolled.

The researchers measured DUP at two time points from the onset of psychosis – the initiation of antipsychotic treatment (DUP1) and the initiation of FES care. Across the study period, they found that DUP1 fell significantly between the pre- and postprogram assessments, from 329 days to 185 days (P = .03). By contrast, there was no change over the same period for the Prevention and Recovery in Early Psychosis FES program in Boston, which served as a comparator.

There was also a cumulative effect on DUP, with each year of the 4-year program associated with a 46-day reduction in DUP1. However, the significant reduction was restricted to the third quintile of DUP1 and was not found in the other quintiles of DUP1 or for DUP2, despite all measures showing a consistent trend for reduction over time.

Dr. Srihari acknowledges that the team was “disappointed” that DUP2 did not fall significantly in their study. He suggested, “It might take longer for agencies to change their workloads and refer patients to STEP, which is what ended up resulting in the DUP2 not dropping as quickly.”

To see whether there was indeed a time lag in changes to practice, the team conducted an analysis in which they cut out the first year from the results and analyzed only the last 3 years. Then “we do see a decline in DUP2,” he said.

The study’s full results are currently being prepared for publication, and the investigators are considering relaunching the initiative.

“The question we are having now is how to resource the campaign without the research funds and which parts of it we think we can launch sustainably so we can continue the reduction of DUP,” Dr. Srihari said.

Plans may include developing partnerships with local businesses to help fund the media costs and working with the state government to build a learning health care network, which would make it easier for mental health agencies to consult with the team on problematic cases.

“We’re trying to reduce DUP referrals on the supply side by providing this kind of learning health collaborative ... that we also think might be fiscally a more sustainable way to do this vs. what we did in MindMap,” which would be “very expensive” to implement on a statewide basis, Dr. Srihari added.

Long-term benefit

In the second study, Dr. Robinson and colleagues highlight that EISs have been implemented worldwide for FEP patients and have been associated with improved outcomes.

However, these services typically provide care for a limited period, and cross-sectional follow-up studies have identified few advantages in comparison with standard care.

To provide a more robust longitudinal assessment of the ongoing effects of an EIS, the team conducted a 5-year follow-up of the first U.S.-based, multicenter, randomized clinical trial comparing an EIS, NAVIGATE, with usual clinical care in FEP.

RAISE-ETP was conducted at 34 sites across the United States. Seventeen sites provided NAVIGATE to 223 individuals with FEP, and the remaining 17 sites provided usual care to 181 patients.

NAVIGATE, which continued for 2 years, consisted of treatments and services delivered by a coordinated team of providers. Those services included the following:

- Education on schizophrenia and its treatment for patients and their families.

- Symptom and relapse prevention medication, using a computerized decision support system.

- Strategies for illness management building personal resilience.

- A supported employment/education model.

Patients were assessed every 6 months for up to 60 months via a video link using the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QLS) and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

The average age of the participants was 23 years; 78% of those who received NAVIGATE and 66% of those who received usual care were male. The opportunity for each participant to engage in NAVIGATE treatment lasted an average of 33.8 months. The longest was 44.4 months.

Over 5 years, NAVIGATE was associated with a significant improvement over usual care in QLS scores by an average of 13.14 units (P < .001). PANSS scores improved by an average of 7.73 units (P < .002). QLS scores were not affected either by the length of opportunity to participate in NAVIGATE or by DUP, the team reports. Patients who received NAVIGATE also had an average of 2.5 fewer inpatient days, compared with those on usual care (P = .02).

The investigators note that the study “provides compelling evidence of a substantial long-term benefit for FEP treatment with the NAVIGATE EIS, compared with standard care.”

A ‘great message’

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Ragy R. Girgis, MD, associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute, said

Dr. Girgis, who was not involved in either study, said that the research is “a great message.” He noted that it is “really important for people to know and it’s really important that we’re still doing research in those areas.”

However, he noted that psychosocial interventions such as these “sometimes take a lot of work.” Dr. Girgis said that it is “so easy to just give people a medication” but that approach has its own disadvantages, including adverse effects and sometimes a lack of efficacy.

“Psychosocial interventions, on the other hand, are very well tolerated by people. They are very effective, but they may require a lot more manpower, and in some ways they can also be more expensive.

“So this is a dialectic that we oftentimes have to deal with when we figure out the right balance between psychosocial vs. medication types of treatments,” he said.

STEP has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation. RAISE-ETP was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health as part of the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) Project. Dr. Gopal is an employee of Janssen Research & Development, and owns stock/equity in Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Girgis has received research support from Genentech, BioAdvantex, Allegran/Forest, and Otsuka, and royalties from Wipf and Stock and Routledge/Taylor and Francis.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Community-based services that tap into local environments not only reduce the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) but also provide improved long-term outcomes for patients with first-episode psychosis (FEP), results of two new studies show.

In the first study, investigators led by Vinod Srihari, MD, director of specialized treatment early in psychosis at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., developed a program to reduce DUP to complement their first-episode service (FES).

Through a combination of mass media and social media campaigns, outreach events with local professionals, and rapid triage, the team was able to nearly halve the time from diagnosis to initiation of antipsychotic treatment.

In the second study, a team led by Delbert G. Robinson, MD, of Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y., conducted a 5-year follow-up of RAISE-ETP, the first U.S. randomized trial to compare a 2-year comprehensive early intervention service (EIS) with usual care.

These trial results showed that, among more than 400 FEP patients, the EIS significantly improved both symptoms and quality of life and reduced inpatient days in comparison with standard care.

The research was scheduled to be presented at the Congress of the Schizophrenia International Research Society (SIRS) 2020, but the meeting was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic.

Norwegian model

Dr. Srihari and colleagues note that a specialized treatment early in psychosis (STEP), which delivers a specialty team–based FES, was established at their institution in 2006.

However, in a bid to reduce DUP, in 2015 they launched MindMap, a 4-year early-detection campaign based on the Scandinavian TIPS Early Detection in Psychosis Study.

Dr. Srihari said in an interview that they visited the team that developed the TIPS program in Norway “to try to understand what elements of their approach had resulted in a successful reduction of DUP.”

He pointed out that the health care system in Norway has “more reliable pathways to care, with an ability to route people in more predictable ways from primary care to secondary care, and so on.”

In the United States, “there’s no expectation that people will go through a primary care provider,” he said. He noted that patients “make their way to specialty care in many different ways.”

Dr. Srihari said, “The other change we realized we’d have to make was that, since TIPS had been completed many years back, the media environment had changed substantially.

“At the time that TIPS was done, there was no such thing as social media, whereas when we began to think about designing our campaign, we thought social media would be a very efficient and also cost-effective way to target young people.”

MindMap, which covered a 10-town catchment area that has a population of 400,000, targeted both demand- and supply-side aspects of DUP. The former focused on delays in identifying illness and help-seeking, and the latter concentrated on referral and treatment access delays.

The researchers used a combination of mass media and social media messaging, professional detailing, and the rapid triage of referrals.

The media campaign included Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms that allowed the team to “target individuals in a somewhat more fine-grained way than mass media allows,” Dr. Srihari said. They focused on individuals in a particular age range and geographic location.

The professional detailing encompassed mental health agencies, emergency departments, and inpatient units, as well as colleges, college counseling centers, high schools, and police departments. The team hosted meetings, “often at local restaurants, where we provided a meal and provided some general education about what our mission was,” said Dr. Srihari. The researchers followed up these meetings with more in-person visits.

“The third arm was finding ways to basically eliminate any kind of a waiting time at our front door, such as ensuring that transportation issues were circumvented, in addition to cutting through any ambivalence they might have about finally making the leap to come to the center.”

More rapid treatment

Over the course of the baseline year and the 4 years of the MindMap program, almost 1,500 individuals were assessed. Of these, approximately 200 were eligible, and almost all were enrolled.

The researchers measured DUP at two time points from the onset of psychosis – the initiation of antipsychotic treatment (DUP1) and the initiation of FES care. Across the study period, they found that DUP1 fell significantly between the pre- and postprogram assessments, from 329 days to 185 days (P = .03). By contrast, there was no change over the same period for the Prevention and Recovery in Early Psychosis FES program in Boston, which served as a comparator.

There was also a cumulative effect on DUP, with each year of the 4-year program associated with a 46-day reduction in DUP1. However, the significant reduction was restricted to the third quintile of DUP1 and was not found in the other quintiles of DUP1 or for DUP2, despite all measures showing a consistent trend for reduction over time.

Dr. Srihari acknowledges that the team was “disappointed” that DUP2 did not fall significantly in their study. He suggested, “It might take longer for agencies to change their workloads and refer patients to STEP, which is what ended up resulting in the DUP2 not dropping as quickly.”

To see whether there was indeed a time lag in changes to practice, the team conducted an analysis in which they cut out the first year from the results and analyzed only the last 3 years. Then “we do see a decline in DUP2,” he said.

The study’s full results are currently being prepared for publication, and the investigators are considering relaunching the initiative.

“The question we are having now is how to resource the campaign without the research funds and which parts of it we think we can launch sustainably so we can continue the reduction of DUP,” Dr. Srihari said.

Plans may include developing partnerships with local businesses to help fund the media costs and working with the state government to build a learning health care network, which would make it easier for mental health agencies to consult with the team on problematic cases.

“We’re trying to reduce DUP referrals on the supply side by providing this kind of learning health collaborative ... that we also think might be fiscally a more sustainable way to do this vs. what we did in MindMap,” which would be “very expensive” to implement on a statewide basis, Dr. Srihari added.

Long-term benefit

In the second study, Dr. Robinson and colleagues highlight that EISs have been implemented worldwide for FEP patients and have been associated with improved outcomes.

However, these services typically provide care for a limited period, and cross-sectional follow-up studies have identified few advantages in comparison with standard care.

To provide a more robust longitudinal assessment of the ongoing effects of an EIS, the team conducted a 5-year follow-up of the first U.S.-based, multicenter, randomized clinical trial comparing an EIS, NAVIGATE, with usual clinical care in FEP.

RAISE-ETP was conducted at 34 sites across the United States. Seventeen sites provided NAVIGATE to 223 individuals with FEP, and the remaining 17 sites provided usual care to 181 patients.

NAVIGATE, which continued for 2 years, consisted of treatments and services delivered by a coordinated team of providers. Those services included the following:

- Education on schizophrenia and its treatment for patients and their families.

- Symptom and relapse prevention medication, using a computerized decision support system.

- Strategies for illness management building personal resilience.

- A supported employment/education model.

Patients were assessed every 6 months for up to 60 months via a video link using the Heinrichs-Carpenter Quality of Life Scale (QLS) and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).

The average age of the participants was 23 years; 78% of those who received NAVIGATE and 66% of those who received usual care were male. The opportunity for each participant to engage in NAVIGATE treatment lasted an average of 33.8 months. The longest was 44.4 months.

Over 5 years, NAVIGATE was associated with a significant improvement over usual care in QLS scores by an average of 13.14 units (P < .001). PANSS scores improved by an average of 7.73 units (P < .002). QLS scores were not affected either by the length of opportunity to participate in NAVIGATE or by DUP, the team reports. Patients who received NAVIGATE also had an average of 2.5 fewer inpatient days, compared with those on usual care (P = .02).

The investigators note that the study “provides compelling evidence of a substantial long-term benefit for FEP treatment with the NAVIGATE EIS, compared with standard care.”

A ‘great message’

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Ragy R. Girgis, MD, associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, and the New York State Psychiatric Institute, said

Dr. Girgis, who was not involved in either study, said that the research is “a great message.” He noted that it is “really important for people to know and it’s really important that we’re still doing research in those areas.”

However, he noted that psychosocial interventions such as these “sometimes take a lot of work.” Dr. Girgis said that it is “so easy to just give people a medication” but that approach has its own disadvantages, including adverse effects and sometimes a lack of efficacy.

“Psychosocial interventions, on the other hand, are very well tolerated by people. They are very effective, but they may require a lot more manpower, and in some ways they can also be more expensive.

“So this is a dialectic that we oftentimes have to deal with when we figure out the right balance between psychosocial vs. medication types of treatments,” he said.

STEP has received research funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation. RAISE-ETP was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health as part of the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) Project. Dr. Gopal is an employee of Janssen Research & Development, and owns stock/equity in Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Girgis has received research support from Genentech, BioAdvantex, Allegran/Forest, and Otsuka, and royalties from Wipf and Stock and Routledge/Taylor and Francis.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Lifestyle changes may explain skin lesions in pandemic-era patients

such as lockdown conditions, which may be clarified with additional research.

Lindy P. Fox, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not an author of either study, urged caution in interpreting these results. Data from the American Academy of Dermatology and a recent paper from the British Journal of Dermatology suggest a real association exists, at in least some patients. “It’s going to be true that most patients with toe lesions are PCR [polymerase chain reaction]-negative because it tends to be a late phenomenon when patients are no longer shedding virus,” Dr. Fox said in an interview.

Reports about chickenpox-like vesicles, urticaria, and other skin lesions in SARS-CoV-2 patients have circulated in the clinical literature and the media. Acute acro-ischemia has been cited as a potential sign of infection in adolescents and children.

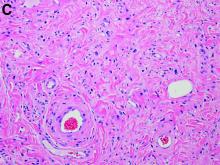

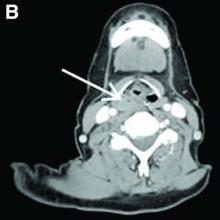

One of the European studies, which was published in JAMA Dermatology, explored this association in 20 patients aged 1-18 years (mean age, 12.3 years), who presented with new-onset acral inflammatory lesions in their hands and feet at La Fe University Hospital, in Valencia, during the country’s peak quarantine period in April. Investigators conducted blood tests and reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR) for SARS-CoV-2, and six patients had skin biopsies.

Juncal Roca-Ginés, MD, of the department of dermatology, at the Hospital Universitario y Politécnico in La Fe, and coauthors, identified acral erythema in 6 (30%) of the cases, dactylitis in 4 (20%), purpuric maculopapules in 7 (35%), and a mixed pattern in 3 (15%). Serologic and viral testing yielded no positive results for SARS-CoV-2 or other viruses, and none of the patients exhibited COVID-19 symptoms such as fever, dry cough, sore throat, myalgia, or taste or smell disorders. In other findings, 45% of the patients had a history of vascular reactive disease of the hands, and 75% reported walking barefoot in their homes while staying at home. Only two patients reported taking medications.

In the six patients who had a biopsy, the findings were characteristic of chillblains, “confirming the clinical impression,” the authors wrote. Concluding that they could not show a relationship between acute acral skin changes and COVID-19, they noted that “other studies with improved microbiologic tests or molecular techniques aimed at demonstrating the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the skin may help to clarify this problem.”

The other case series, which was also published in JAMA Dermatology and included 31 adults at a hospital in Brussels, who had recently developed chillblains, also looked for a connection between SARS-CoV-2 and chilblains, in April. Most of the participants were in their teens or 20s. Lesions had appeared on hands, feet, or on both extremities within 1-30 days of consultation, presenting as erythematous or purplish erythematous macules, occasionally with central vesicular or bullous lesions or necrotic areas. Patients reported pain, burning, and itching.

Skin biopsies were obtained in 22 patients and confirmed the diagnosis of chilblains; of the 15 with immunofluorescence analyses, 7 patients were found to have vasculitis of small-diameter vessels.

Of the 31 patients, 20 (64%) reported mild symptoms consistent with SARS-CoV-2, yet none of the RT-PCR or serologic test results showed signs of the virus in all 31 patients. “Because some patients had experienced chilblains for more than 15 days [under 30 days or less] at the time of inclusion, we can reasonably exclude the possibility that serologic testing was done too soon,” observed the authors. They also didn’t find eosinopenia, lymphopenia, and hyperferritinemia, which have been associated with COVID-19, they added.

Changes in lifestyle conditions during the pandemic may explain the appearance of these lesions, according to the authors of both studies, who mentioned that walking around in socks or bare feet and reduced physical activity could have indirectly led to the development of skin lesions.

It’s also possible that young people have less severe disease and a delayed reaction to the virus, Ignacio Torres-Navarro, MD, a dermatologist with La Fe University and the Spanish study’s corresponding author, said in an interview. Their feet may lack maturity in neurovascular regulation and/or the eccrine glands, which can happen in other diseases such as neutrophilic idiopathic eccrine hidradenitis. “In this context, perhaps there was an observational bias of the parents to the children when this manifestation was reported in the media. However, nothing has been demonstrated,” he said.

In an accompanying editor’s note, Claudia Hernandez, MD, of the departments of dermatology and pediatrics, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, and Anna L. Bruckner, MD, of the departments of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Aurora, wrote that “it is still unclear whether a viral cytopathic process vs a viral reaction pattern or other mechanism is responsible for ‘COVID toes.’ ” Lack of confirmatory testing and reliance on indirect evidence of infection complicates this further, they noted, adding that “dermatologists must be aware of the protean cutaneous findings that are possibly associated with COVID-19, even if our understanding of their origins remains incomplete.”

In an interview, Dr. Fox, a member of the AAD’s’s COVID-19 Registry task force, offered other possible reasons for the negative antibody tests in the studies. The assay might not have been testing the correct antigen, or the timing of the test might not have been optimal. “More studies will help this become less controversial,” she said.

The authors of the two case series acknowledged potential limitations of their studies. Neither was large in scope: Both took place over a week’s time and included small cohorts. The Belgian study had no control group or long-term follow-up. Little is still known about the clinical manifestations and detection methods for SARS-CoV-2, noted the authors of the Spanish study.

The Spanish study received funding La Fe University Hospital’s department of dermatology, and the authors had no disclosures. The Belgian study received support from the Fondation Saint-Luc, which provided academic funding for its lead author, Marie Baeck, MD, PhD. Another author of this study received personal fees from the Fondation Saint-Luc and personal fees and nonfinancial support from Bioderma. The authors of the editor’s note had no disclosures.

SOURCES: Roca-Ginés J et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jun 25. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2340; Herman A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jun 25. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2368.

such as lockdown conditions, which may be clarified with additional research.

Lindy P. Fox, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not an author of either study, urged caution in interpreting these results. Data from the American Academy of Dermatology and a recent paper from the British Journal of Dermatology suggest a real association exists, at in least some patients. “It’s going to be true that most patients with toe lesions are PCR [polymerase chain reaction]-negative because it tends to be a late phenomenon when patients are no longer shedding virus,” Dr. Fox said in an interview.

Reports about chickenpox-like vesicles, urticaria, and other skin lesions in SARS-CoV-2 patients have circulated in the clinical literature and the media. Acute acro-ischemia has been cited as a potential sign of infection in adolescents and children.

One of the European studies, which was published in JAMA Dermatology, explored this association in 20 patients aged 1-18 years (mean age, 12.3 years), who presented with new-onset acral inflammatory lesions in their hands and feet at La Fe University Hospital, in Valencia, during the country’s peak quarantine period in April. Investigators conducted blood tests and reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR) for SARS-CoV-2, and six patients had skin biopsies.

Juncal Roca-Ginés, MD, of the department of dermatology, at the Hospital Universitario y Politécnico in La Fe, and coauthors, identified acral erythema in 6 (30%) of the cases, dactylitis in 4 (20%), purpuric maculopapules in 7 (35%), and a mixed pattern in 3 (15%). Serologic and viral testing yielded no positive results for SARS-CoV-2 or other viruses, and none of the patients exhibited COVID-19 symptoms such as fever, dry cough, sore throat, myalgia, or taste or smell disorders. In other findings, 45% of the patients had a history of vascular reactive disease of the hands, and 75% reported walking barefoot in their homes while staying at home. Only two patients reported taking medications.

In the six patients who had a biopsy, the findings were characteristic of chillblains, “confirming the clinical impression,” the authors wrote. Concluding that they could not show a relationship between acute acral skin changes and COVID-19, they noted that “other studies with improved microbiologic tests or molecular techniques aimed at demonstrating the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the skin may help to clarify this problem.”

The other case series, which was also published in JAMA Dermatology and included 31 adults at a hospital in Brussels, who had recently developed chillblains, also looked for a connection between SARS-CoV-2 and chilblains, in April. Most of the participants were in their teens or 20s. Lesions had appeared on hands, feet, or on both extremities within 1-30 days of consultation, presenting as erythematous or purplish erythematous macules, occasionally with central vesicular or bullous lesions or necrotic areas. Patients reported pain, burning, and itching.

Skin biopsies were obtained in 22 patients and confirmed the diagnosis of chilblains; of the 15 with immunofluorescence analyses, 7 patients were found to have vasculitis of small-diameter vessels.

Of the 31 patients, 20 (64%) reported mild symptoms consistent with SARS-CoV-2, yet none of the RT-PCR or serologic test results showed signs of the virus in all 31 patients. “Because some patients had experienced chilblains for more than 15 days [under 30 days or less] at the time of inclusion, we can reasonably exclude the possibility that serologic testing was done too soon,” observed the authors. They also didn’t find eosinopenia, lymphopenia, and hyperferritinemia, which have been associated with COVID-19, they added.

Changes in lifestyle conditions during the pandemic may explain the appearance of these lesions, according to the authors of both studies, who mentioned that walking around in socks or bare feet and reduced physical activity could have indirectly led to the development of skin lesions.

It’s also possible that young people have less severe disease and a delayed reaction to the virus, Ignacio Torres-Navarro, MD, a dermatologist with La Fe University and the Spanish study’s corresponding author, said in an interview. Their feet may lack maturity in neurovascular regulation and/or the eccrine glands, which can happen in other diseases such as neutrophilic idiopathic eccrine hidradenitis. “In this context, perhaps there was an observational bias of the parents to the children when this manifestation was reported in the media. However, nothing has been demonstrated,” he said.

In an accompanying editor’s note, Claudia Hernandez, MD, of the departments of dermatology and pediatrics, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, and Anna L. Bruckner, MD, of the departments of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Aurora, wrote that “it is still unclear whether a viral cytopathic process vs a viral reaction pattern or other mechanism is responsible for ‘COVID toes.’ ” Lack of confirmatory testing and reliance on indirect evidence of infection complicates this further, they noted, adding that “dermatologists must be aware of the protean cutaneous findings that are possibly associated with COVID-19, even if our understanding of their origins remains incomplete.”

In an interview, Dr. Fox, a member of the AAD’s’s COVID-19 Registry task force, offered other possible reasons for the negative antibody tests in the studies. The assay might not have been testing the correct antigen, or the timing of the test might not have been optimal. “More studies will help this become less controversial,” she said.

The authors of the two case series acknowledged potential limitations of their studies. Neither was large in scope: Both took place over a week’s time and included small cohorts. The Belgian study had no control group or long-term follow-up. Little is still known about the clinical manifestations and detection methods for SARS-CoV-2, noted the authors of the Spanish study.

The Spanish study received funding La Fe University Hospital’s department of dermatology, and the authors had no disclosures. The Belgian study received support from the Fondation Saint-Luc, which provided academic funding for its lead author, Marie Baeck, MD, PhD. Another author of this study received personal fees from the Fondation Saint-Luc and personal fees and nonfinancial support from Bioderma. The authors of the editor’s note had no disclosures.

SOURCES: Roca-Ginés J et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jun 25. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2340; Herman A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jun 25. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2368.

such as lockdown conditions, which may be clarified with additional research.

Lindy P. Fox, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not an author of either study, urged caution in interpreting these results. Data from the American Academy of Dermatology and a recent paper from the British Journal of Dermatology suggest a real association exists, at in least some patients. “It’s going to be true that most patients with toe lesions are PCR [polymerase chain reaction]-negative because it tends to be a late phenomenon when patients are no longer shedding virus,” Dr. Fox said in an interview.

Reports about chickenpox-like vesicles, urticaria, and other skin lesions in SARS-CoV-2 patients have circulated in the clinical literature and the media. Acute acro-ischemia has been cited as a potential sign of infection in adolescents and children.

One of the European studies, which was published in JAMA Dermatology, explored this association in 20 patients aged 1-18 years (mean age, 12.3 years), who presented with new-onset acral inflammatory lesions in their hands and feet at La Fe University Hospital, in Valencia, during the country’s peak quarantine period in April. Investigators conducted blood tests and reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR) for SARS-CoV-2, and six patients had skin biopsies.

Juncal Roca-Ginés, MD, of the department of dermatology, at the Hospital Universitario y Politécnico in La Fe, and coauthors, identified acral erythema in 6 (30%) of the cases, dactylitis in 4 (20%), purpuric maculopapules in 7 (35%), and a mixed pattern in 3 (15%). Serologic and viral testing yielded no positive results for SARS-CoV-2 or other viruses, and none of the patients exhibited COVID-19 symptoms such as fever, dry cough, sore throat, myalgia, or taste or smell disorders. In other findings, 45% of the patients had a history of vascular reactive disease of the hands, and 75% reported walking barefoot in their homes while staying at home. Only two patients reported taking medications.

In the six patients who had a biopsy, the findings were characteristic of chillblains, “confirming the clinical impression,” the authors wrote. Concluding that they could not show a relationship between acute acral skin changes and COVID-19, they noted that “other studies with improved microbiologic tests or molecular techniques aimed at demonstrating the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the skin may help to clarify this problem.”