User login

Misconduct, Failures, and Miscommunication Contributed to Patient Suicide at Washington VAMC

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Inspector General (OIG) recently completed a highly critical investigation into allegations concerning the care of a suicidal patient in the Washington, DC, VA Medical Center Emergency Department (ED). The patient committed suicide by gunshot 6 days after an ED visit in which a VA provider reportedly commented, “[The patient] can go shoot [themself]. I do not care.”

In early 2019, the patient, who was in his 60s and had a history of panic attacks, painkiller addiction, and various injuries, came to the ED complaining of alprazolam and oxycodone withdrawal and insomnia. He asked to be admitted for detoxification. The ED resident physician documented that request and recommended outpatient psychiatry follow-up. The attending physician documented agreement with the assessment, and an ED social worker scheduled the patient for a same-day outpatient psychiatry evaluation. However, the patient, along with a family member, told a Veteran Experience Specialist he was dissatisfied with care, and again requested admission for inpatient detoxification. The specialist accompanied the patient and family member to the ED and informed a staff member of the patient’s preference for admission.

Following this, the patient presented to the outpatient psychiatry appointment, where a psychiatrist assessed his suicide risk as “moderate” and recommended admission. He was escorted back to the ED, where the psychiatrist reportedly handed him off both verbally and with an alert in the electronic health record to the attending physician. The family member told the OIG that the outpatient psychiatrist had indicated that the patient was going to be admitted to the detoxification of the psychiatry unit. The family member left, thinking the patient was being admitted.

A physician assistant documented the patient’s chief complaint as anxiety, documented the patient’s suicidal ideation, and placed a psychiatry consult to evaluate the patient for inpatient admission. The consulting psychiatry resident and attending psychiatrist deemed him at mild risk of suicide and didn’t meet the criterial for inpatient admission. They recommended outpatient care, and that the patient be discharged and sent home. The patient, though, refused to leave. A second ED attending physician documented that the patient was “clearly malingering” and “ranting.” Police were called to escort him out. At least 3 hospital staff members said they heard the physician say “I do not care,” if the patient committed suicide. A family member later called the facility’s medical advice line and told the on-call nurse that the patient had died at home 6 days after the ED visit.

The OIG found numerous preventable mix-ups, oversights, and outright misconduct throughout this patient’s health care experience. Notably, the patient navigated 2 transitions between the ED and outpatient Mental Health Clinic and saw 7 providers over the course of 12 hours. The lack of collaboration between the various health care providers, deficiencies in the hand-off process, and ED and inpatient mental health providers’ failure to read the outpatient psychiatrist’s notes led to a “compromised understanding” of the patient’s treatment needs and a failure to enact the outpatient psychiatrist’s recommended treatment plan.

For instance, 2 days after the patient presented to the ED, the outpatient psychiatrist entered a consult for the outpatient substance use treatment program indicating that the patient was informed of the appointment date and time (5 days after the ED visit); however, the OIG found no evidence that staff informed the patient of the appointment date and time. An outpatient nurse closed the consult and added a comment that the patient was to report to the treatment program 5 days after the ED visit. Contrary to Veterans Health Administration (VHA) policy, the OIG report says, the nurse explained that an appointment was not scheduled because it was not program procedure at the time. The nurse mistakenly thought the patient already was receiving outpatient treatment, and because the patient had no scheduled appointment, staff did not follow up when he missed it.

The OIG also found that the facility’s Suicide Prevention Coordinator had failed to complete the suicide behavior report following notification of the patient’s death by suicide, as required by VHA. In fact, the coordinator was unable to locate a suicide behavior report. Moreover, the OIG says, the ED failed to meet VHA’s requirements for a safe and secure evaluation area for patients seeking mental health services. A renovation project begun in 2009 to include 3 mental health examination rooms had been on hold.

Regarding the doctor who was heard making the callous statement, the OIG found that, despite the facility leaders’ awareness of the comment and of the doctor’s “prior pattern of misconduct,” they did not conduct a formal fact-finding or administrative investigation as required by the VA. Instead, they seemed to focus on the physician’s “overall positive clinical outcomes.”

The doctor “was never a VA employee, only worked on a contract basis and is no longer welcome at the facility,” said Dr. Michael Heimall, the center’s director, in a statement to The New York Times.

He added that the episode has prompted the hospital to change its policies. Among the changes: a “comprehensive education program” on employee misconduct and patient abuse has been instituted. Further, now only the Chief of Staff can reverse the outpatient mental health provider’s recommendation for a patient’s admission.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Inspector General (OIG) recently completed a highly critical investigation into allegations concerning the care of a suicidal patient in the Washington, DC, VA Medical Center Emergency Department (ED). The patient committed suicide by gunshot 6 days after an ED visit in which a VA provider reportedly commented, “[The patient] can go shoot [themself]. I do not care.”

In early 2019, the patient, who was in his 60s and had a history of panic attacks, painkiller addiction, and various injuries, came to the ED complaining of alprazolam and oxycodone withdrawal and insomnia. He asked to be admitted for detoxification. The ED resident physician documented that request and recommended outpatient psychiatry follow-up. The attending physician documented agreement with the assessment, and an ED social worker scheduled the patient for a same-day outpatient psychiatry evaluation. However, the patient, along with a family member, told a Veteran Experience Specialist he was dissatisfied with care, and again requested admission for inpatient detoxification. The specialist accompanied the patient and family member to the ED and informed a staff member of the patient’s preference for admission.

Following this, the patient presented to the outpatient psychiatry appointment, where a psychiatrist assessed his suicide risk as “moderate” and recommended admission. He was escorted back to the ED, where the psychiatrist reportedly handed him off both verbally and with an alert in the electronic health record to the attending physician. The family member told the OIG that the outpatient psychiatrist had indicated that the patient was going to be admitted to the detoxification of the psychiatry unit. The family member left, thinking the patient was being admitted.

A physician assistant documented the patient’s chief complaint as anxiety, documented the patient’s suicidal ideation, and placed a psychiatry consult to evaluate the patient for inpatient admission. The consulting psychiatry resident and attending psychiatrist deemed him at mild risk of suicide and didn’t meet the criterial for inpatient admission. They recommended outpatient care, and that the patient be discharged and sent home. The patient, though, refused to leave. A second ED attending physician documented that the patient was “clearly malingering” and “ranting.” Police were called to escort him out. At least 3 hospital staff members said they heard the physician say “I do not care,” if the patient committed suicide. A family member later called the facility’s medical advice line and told the on-call nurse that the patient had died at home 6 days after the ED visit.

The OIG found numerous preventable mix-ups, oversights, and outright misconduct throughout this patient’s health care experience. Notably, the patient navigated 2 transitions between the ED and outpatient Mental Health Clinic and saw 7 providers over the course of 12 hours. The lack of collaboration between the various health care providers, deficiencies in the hand-off process, and ED and inpatient mental health providers’ failure to read the outpatient psychiatrist’s notes led to a “compromised understanding” of the patient’s treatment needs and a failure to enact the outpatient psychiatrist’s recommended treatment plan.

For instance, 2 days after the patient presented to the ED, the outpatient psychiatrist entered a consult for the outpatient substance use treatment program indicating that the patient was informed of the appointment date and time (5 days after the ED visit); however, the OIG found no evidence that staff informed the patient of the appointment date and time. An outpatient nurse closed the consult and added a comment that the patient was to report to the treatment program 5 days after the ED visit. Contrary to Veterans Health Administration (VHA) policy, the OIG report says, the nurse explained that an appointment was not scheduled because it was not program procedure at the time. The nurse mistakenly thought the patient already was receiving outpatient treatment, and because the patient had no scheduled appointment, staff did not follow up when he missed it.

The OIG also found that the facility’s Suicide Prevention Coordinator had failed to complete the suicide behavior report following notification of the patient’s death by suicide, as required by VHA. In fact, the coordinator was unable to locate a suicide behavior report. Moreover, the OIG says, the ED failed to meet VHA’s requirements for a safe and secure evaluation area for patients seeking mental health services. A renovation project begun in 2009 to include 3 mental health examination rooms had been on hold.

Regarding the doctor who was heard making the callous statement, the OIG found that, despite the facility leaders’ awareness of the comment and of the doctor’s “prior pattern of misconduct,” they did not conduct a formal fact-finding or administrative investigation as required by the VA. Instead, they seemed to focus on the physician’s “overall positive clinical outcomes.”

The doctor “was never a VA employee, only worked on a contract basis and is no longer welcome at the facility,” said Dr. Michael Heimall, the center’s director, in a statement to The New York Times.

He added that the episode has prompted the hospital to change its policies. Among the changes: a “comprehensive education program” on employee misconduct and patient abuse has been instituted. Further, now only the Chief of Staff can reverse the outpatient mental health provider’s recommendation for a patient’s admission.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Inspector General (OIG) recently completed a highly critical investigation into allegations concerning the care of a suicidal patient in the Washington, DC, VA Medical Center Emergency Department (ED). The patient committed suicide by gunshot 6 days after an ED visit in which a VA provider reportedly commented, “[The patient] can go shoot [themself]. I do not care.”

In early 2019, the patient, who was in his 60s and had a history of panic attacks, painkiller addiction, and various injuries, came to the ED complaining of alprazolam and oxycodone withdrawal and insomnia. He asked to be admitted for detoxification. The ED resident physician documented that request and recommended outpatient psychiatry follow-up. The attending physician documented agreement with the assessment, and an ED social worker scheduled the patient for a same-day outpatient psychiatry evaluation. However, the patient, along with a family member, told a Veteran Experience Specialist he was dissatisfied with care, and again requested admission for inpatient detoxification. The specialist accompanied the patient and family member to the ED and informed a staff member of the patient’s preference for admission.

Following this, the patient presented to the outpatient psychiatry appointment, where a psychiatrist assessed his suicide risk as “moderate” and recommended admission. He was escorted back to the ED, where the psychiatrist reportedly handed him off both verbally and with an alert in the electronic health record to the attending physician. The family member told the OIG that the outpatient psychiatrist had indicated that the patient was going to be admitted to the detoxification of the psychiatry unit. The family member left, thinking the patient was being admitted.

A physician assistant documented the patient’s chief complaint as anxiety, documented the patient’s suicidal ideation, and placed a psychiatry consult to evaluate the patient for inpatient admission. The consulting psychiatry resident and attending psychiatrist deemed him at mild risk of suicide and didn’t meet the criterial for inpatient admission. They recommended outpatient care, and that the patient be discharged and sent home. The patient, though, refused to leave. A second ED attending physician documented that the patient was “clearly malingering” and “ranting.” Police were called to escort him out. At least 3 hospital staff members said they heard the physician say “I do not care,” if the patient committed suicide. A family member later called the facility’s medical advice line and told the on-call nurse that the patient had died at home 6 days after the ED visit.

The OIG found numerous preventable mix-ups, oversights, and outright misconduct throughout this patient’s health care experience. Notably, the patient navigated 2 transitions between the ED and outpatient Mental Health Clinic and saw 7 providers over the course of 12 hours. The lack of collaboration between the various health care providers, deficiencies in the hand-off process, and ED and inpatient mental health providers’ failure to read the outpatient psychiatrist’s notes led to a “compromised understanding” of the patient’s treatment needs and a failure to enact the outpatient psychiatrist’s recommended treatment plan.

For instance, 2 days after the patient presented to the ED, the outpatient psychiatrist entered a consult for the outpatient substance use treatment program indicating that the patient was informed of the appointment date and time (5 days after the ED visit); however, the OIG found no evidence that staff informed the patient of the appointment date and time. An outpatient nurse closed the consult and added a comment that the patient was to report to the treatment program 5 days after the ED visit. Contrary to Veterans Health Administration (VHA) policy, the OIG report says, the nurse explained that an appointment was not scheduled because it was not program procedure at the time. The nurse mistakenly thought the patient already was receiving outpatient treatment, and because the patient had no scheduled appointment, staff did not follow up when he missed it.

The OIG also found that the facility’s Suicide Prevention Coordinator had failed to complete the suicide behavior report following notification of the patient’s death by suicide, as required by VHA. In fact, the coordinator was unable to locate a suicide behavior report. Moreover, the OIG says, the ED failed to meet VHA’s requirements for a safe and secure evaluation area for patients seeking mental health services. A renovation project begun in 2009 to include 3 mental health examination rooms had been on hold.

Regarding the doctor who was heard making the callous statement, the OIG found that, despite the facility leaders’ awareness of the comment and of the doctor’s “prior pattern of misconduct,” they did not conduct a formal fact-finding or administrative investigation as required by the VA. Instead, they seemed to focus on the physician’s “overall positive clinical outcomes.”

The doctor “was never a VA employee, only worked on a contract basis and is no longer welcome at the facility,” said Dr. Michael Heimall, the center’s director, in a statement to The New York Times.

He added that the episode has prompted the hospital to change its policies. Among the changes: a “comprehensive education program” on employee misconduct and patient abuse has been instituted. Further, now only the Chief of Staff can reverse the outpatient mental health provider’s recommendation for a patient’s admission.

Study highlights potential advantages of tape strips over biopsy

for monitoring these and potentially other dermatologic diseases, according to the latest advances with this approach.

“Tape strips are not going to fully replace biopsies, but we think they will have an important role in diagnosing and monitoring response to therapy by avoiding the potential scarring and pain of biopsy,” reported Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and director of the laboratory inflammatory skin diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

The concept of using adhesive strips to remove surface skin cells for clinical study has been around for more than 20 years, but there has been recent progress. A newly published study, which compared skin from patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis with that of controls, was characterized as “the most comprehensive tape strip molecular profiling in any inflammatory skin disease to date and the first to fully characterize and compare AD to psoriasis,” wrote Dr. Guttman-Yassky, the senior author, and coauthors.

It also appears to be a leap forward. RNA sequencing detected thousands of differentially expressed genes reflecting immune and barrier biomarkers characteristic of the molecular phenotypes of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. These were not only found to be consistent with biopsy studies but identified additional unique genes and pathways relevant to their pathological signature.

“In the past, the success rate for transcriptome sequencing even for a more limited panel of proteins was approaching 50% when considering both lesional, nonlesional skin, and healthy skin, but we are now approaching 100% for sample recovery and for analysis of RNA and genes,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said in an interview.

Tissue samples were obtained with tape strips from lesional and nonlesional skin from 20 patients with AD and 20 patients with psoriasis. Compared with 20 tape strips from controls, they were evaluated with RNA sequencing followed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction of immune and barrier biomarkers.

The sample recovery rate was 96% overall and 95% or better regardless of whether the skin was lesional or nonlesional.

With RNA sequencing of more than 20,000 transcripts, including multiple cellular, immune, and barrier biomarkers, an enormous amount of data was generated, but the key finding is that these diseases are readily distinguished with profiling based on tape strips.

Although numerous biomarkers were shared, “tape strips completely discriminate between atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with a degree of reliability that is comparable to skin biopsy,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said.

One of the biomarkers, expression of nitric oxide synthase 2/inducible nitric oxide synthase, distinguished AD from psoriasis with 100% accuracy. As previously reported in biopsy studies, other biomarkers collectively associated AD with a profile related to a Th2-type inflammatory response and psoriasis with a Th17-type inflammatory response.

Tape strips also confirmed significant pathology in the nonlesional as well as the lesional skin of patients with AD or psoriasis. This included an increase in Th2-type products, such as interleukin-4 and IL-13, in nonlesional skin of atopic dermatitis and Th17-type products, such as IL-17, in nonlesional skin of psoriasis.

Some biomarkers of AD and psoriasis had an even greater differentiation in tape strips than previously reported from biopsy studies, according to Dr. Guttman-Yassky. In this study, tape strips also captured more differentially expressed genes than previously reported with biopsies.

One potential limitation of tape strips is that the RNA isolation process is time consuming, but this might be less of an issue in routine clinical use if there is a more refined number of biomarkers that are targeted or if technological improvements simplify processing, Dr. Guttman-Yassky pointed out.

To develop clinical utility for tape strips beyond AD and psoriasis, more work is needed to standardize the depth of sampling, which is variable with tape strips, she noted. Depth is relevant to the analysis of gene expression and mRNA activity of each dermatologic disease.

“Tape strips remain a research tool for now, but we do think that this technique can be refined and employed for clinical purposes, including diagnosis and monitoring response to treatment,” she said.

Relative to biopsy, the advantages are not difficult to envision. Dr. Guttman-Yassky, who recently published a study of tape strips for evaluating AD in children emphasized that tape strips are generally painless.

“Patients really do not mind tape strips,” she said. Although she believes that tape strips are providing unique insight into the pathology of inflammatory diseases not necessarily available with biopsy, she emphasized the practical value. Not least, “these could really help when the goal is to evaluate response to therapy over time.”

Another investigator who has conducted studies with tape strips, Maja-Lisa Clausen, MD, PhD, also thinks tape strips are likely to become routine clinical tools.

“Once the basis research, validation, and data are out, I think numerous companies will be ready to develop machines for more quick and easy processing, compared to the more labor intensive process that is used today for research,” explained Dr. Clausen, who is in the department of dermatology, Bispebjerb Hospital, University of Copenhagen.

She considers tape strips particularly promising for children, but she thinks the biomarker profiling made possible by these strips might be leading to personalized treatment programs for dermatologic diseases.

“What we need is further validation; which tape to use, how deep, and the importance of storage, which is a big issue in the clinic,” Dr. Clausen said in an interview.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky has financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, including those with therapies for psoriasis.

SOURCE: Guttman-Yassky E et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 Jul 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.048.

for monitoring these and potentially other dermatologic diseases, according to the latest advances with this approach.

“Tape strips are not going to fully replace biopsies, but we think they will have an important role in diagnosing and monitoring response to therapy by avoiding the potential scarring and pain of biopsy,” reported Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and director of the laboratory inflammatory skin diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

The concept of using adhesive strips to remove surface skin cells for clinical study has been around for more than 20 years, but there has been recent progress. A newly published study, which compared skin from patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis with that of controls, was characterized as “the most comprehensive tape strip molecular profiling in any inflammatory skin disease to date and the first to fully characterize and compare AD to psoriasis,” wrote Dr. Guttman-Yassky, the senior author, and coauthors.

It also appears to be a leap forward. RNA sequencing detected thousands of differentially expressed genes reflecting immune and barrier biomarkers characteristic of the molecular phenotypes of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. These were not only found to be consistent with biopsy studies but identified additional unique genes and pathways relevant to their pathological signature.

“In the past, the success rate for transcriptome sequencing even for a more limited panel of proteins was approaching 50% when considering both lesional, nonlesional skin, and healthy skin, but we are now approaching 100% for sample recovery and for analysis of RNA and genes,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said in an interview.

Tissue samples were obtained with tape strips from lesional and nonlesional skin from 20 patients with AD and 20 patients with psoriasis. Compared with 20 tape strips from controls, they were evaluated with RNA sequencing followed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction of immune and barrier biomarkers.

The sample recovery rate was 96% overall and 95% or better regardless of whether the skin was lesional or nonlesional.

With RNA sequencing of more than 20,000 transcripts, including multiple cellular, immune, and barrier biomarkers, an enormous amount of data was generated, but the key finding is that these diseases are readily distinguished with profiling based on tape strips.

Although numerous biomarkers were shared, “tape strips completely discriminate between atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with a degree of reliability that is comparable to skin biopsy,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said.

One of the biomarkers, expression of nitric oxide synthase 2/inducible nitric oxide synthase, distinguished AD from psoriasis with 100% accuracy. As previously reported in biopsy studies, other biomarkers collectively associated AD with a profile related to a Th2-type inflammatory response and psoriasis with a Th17-type inflammatory response.

Tape strips also confirmed significant pathology in the nonlesional as well as the lesional skin of patients with AD or psoriasis. This included an increase in Th2-type products, such as interleukin-4 and IL-13, in nonlesional skin of atopic dermatitis and Th17-type products, such as IL-17, in nonlesional skin of psoriasis.

Some biomarkers of AD and psoriasis had an even greater differentiation in tape strips than previously reported from biopsy studies, according to Dr. Guttman-Yassky. In this study, tape strips also captured more differentially expressed genes than previously reported with biopsies.

One potential limitation of tape strips is that the RNA isolation process is time consuming, but this might be less of an issue in routine clinical use if there is a more refined number of biomarkers that are targeted or if technological improvements simplify processing, Dr. Guttman-Yassky pointed out.

To develop clinical utility for tape strips beyond AD and psoriasis, more work is needed to standardize the depth of sampling, which is variable with tape strips, she noted. Depth is relevant to the analysis of gene expression and mRNA activity of each dermatologic disease.

“Tape strips remain a research tool for now, but we do think that this technique can be refined and employed for clinical purposes, including diagnosis and monitoring response to treatment,” she said.

Relative to biopsy, the advantages are not difficult to envision. Dr. Guttman-Yassky, who recently published a study of tape strips for evaluating AD in children emphasized that tape strips are generally painless.

“Patients really do not mind tape strips,” she said. Although she believes that tape strips are providing unique insight into the pathology of inflammatory diseases not necessarily available with biopsy, she emphasized the practical value. Not least, “these could really help when the goal is to evaluate response to therapy over time.”

Another investigator who has conducted studies with tape strips, Maja-Lisa Clausen, MD, PhD, also thinks tape strips are likely to become routine clinical tools.

“Once the basis research, validation, and data are out, I think numerous companies will be ready to develop machines for more quick and easy processing, compared to the more labor intensive process that is used today for research,” explained Dr. Clausen, who is in the department of dermatology, Bispebjerb Hospital, University of Copenhagen.

She considers tape strips particularly promising for children, but she thinks the biomarker profiling made possible by these strips might be leading to personalized treatment programs for dermatologic diseases.

“What we need is further validation; which tape to use, how deep, and the importance of storage, which is a big issue in the clinic,” Dr. Clausen said in an interview.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky has financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, including those with therapies for psoriasis.

SOURCE: Guttman-Yassky E et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 Jul 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.048.

for monitoring these and potentially other dermatologic diseases, according to the latest advances with this approach.

“Tape strips are not going to fully replace biopsies, but we think they will have an important role in diagnosing and monitoring response to therapy by avoiding the potential scarring and pain of biopsy,” reported Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology and director of the laboratory inflammatory skin diseases at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York.

The concept of using adhesive strips to remove surface skin cells for clinical study has been around for more than 20 years, but there has been recent progress. A newly published study, which compared skin from patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) or psoriasis with that of controls, was characterized as “the most comprehensive tape strip molecular profiling in any inflammatory skin disease to date and the first to fully characterize and compare AD to psoriasis,” wrote Dr. Guttman-Yassky, the senior author, and coauthors.

It also appears to be a leap forward. RNA sequencing detected thousands of differentially expressed genes reflecting immune and barrier biomarkers characteristic of the molecular phenotypes of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. These were not only found to be consistent with biopsy studies but identified additional unique genes and pathways relevant to their pathological signature.

“In the past, the success rate for transcriptome sequencing even for a more limited panel of proteins was approaching 50% when considering both lesional, nonlesional skin, and healthy skin, but we are now approaching 100% for sample recovery and for analysis of RNA and genes,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said in an interview.

Tissue samples were obtained with tape strips from lesional and nonlesional skin from 20 patients with AD and 20 patients with psoriasis. Compared with 20 tape strips from controls, they were evaluated with RNA sequencing followed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction of immune and barrier biomarkers.

The sample recovery rate was 96% overall and 95% or better regardless of whether the skin was lesional or nonlesional.

With RNA sequencing of more than 20,000 transcripts, including multiple cellular, immune, and barrier biomarkers, an enormous amount of data was generated, but the key finding is that these diseases are readily distinguished with profiling based on tape strips.

Although numerous biomarkers were shared, “tape strips completely discriminate between atopic dermatitis and psoriasis with a degree of reliability that is comparable to skin biopsy,” Dr. Guttman-Yassky said.

One of the biomarkers, expression of nitric oxide synthase 2/inducible nitric oxide synthase, distinguished AD from psoriasis with 100% accuracy. As previously reported in biopsy studies, other biomarkers collectively associated AD with a profile related to a Th2-type inflammatory response and psoriasis with a Th17-type inflammatory response.

Tape strips also confirmed significant pathology in the nonlesional as well as the lesional skin of patients with AD or psoriasis. This included an increase in Th2-type products, such as interleukin-4 and IL-13, in nonlesional skin of atopic dermatitis and Th17-type products, such as IL-17, in nonlesional skin of psoriasis.

Some biomarkers of AD and psoriasis had an even greater differentiation in tape strips than previously reported from biopsy studies, according to Dr. Guttman-Yassky. In this study, tape strips also captured more differentially expressed genes than previously reported with biopsies.

One potential limitation of tape strips is that the RNA isolation process is time consuming, but this might be less of an issue in routine clinical use if there is a more refined number of biomarkers that are targeted or if technological improvements simplify processing, Dr. Guttman-Yassky pointed out.

To develop clinical utility for tape strips beyond AD and psoriasis, more work is needed to standardize the depth of sampling, which is variable with tape strips, she noted. Depth is relevant to the analysis of gene expression and mRNA activity of each dermatologic disease.

“Tape strips remain a research tool for now, but we do think that this technique can be refined and employed for clinical purposes, including diagnosis and monitoring response to treatment,” she said.

Relative to biopsy, the advantages are not difficult to envision. Dr. Guttman-Yassky, who recently published a study of tape strips for evaluating AD in children emphasized that tape strips are generally painless.

“Patients really do not mind tape strips,” she said. Although she believes that tape strips are providing unique insight into the pathology of inflammatory diseases not necessarily available with biopsy, she emphasized the practical value. Not least, “these could really help when the goal is to evaluate response to therapy over time.”

Another investigator who has conducted studies with tape strips, Maja-Lisa Clausen, MD, PhD, also thinks tape strips are likely to become routine clinical tools.

“Once the basis research, validation, and data are out, I think numerous companies will be ready to develop machines for more quick and easy processing, compared to the more labor intensive process that is used today for research,” explained Dr. Clausen, who is in the department of dermatology, Bispebjerb Hospital, University of Copenhagen.

She considers tape strips particularly promising for children, but she thinks the biomarker profiling made possible by these strips might be leading to personalized treatment programs for dermatologic diseases.

“What we need is further validation; which tape to use, how deep, and the importance of storage, which is a big issue in the clinic,” Dr. Clausen said in an interview.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky has financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies, including those with therapies for psoriasis.

SOURCE: Guttman-Yassky E et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020 Jul 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.048.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY

Guidance covers glycemia in dexamethasone-treated COVID-19 patients

New guidance from the U.K. National Diabetes COVID-19 Response Group addresses glucose management in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving dexamethasone therapy.

Although there are already guidelines that address inpatient management of steroid-induced hyperglycemia, the authors of the new document wrote that this new expert opinion paper was needed “given the ‘triple insult’ of dexamethasone-induced–impaired glucose metabolism, COVID-19–induced insulin resistance, and COVID-19–impaired insulin production.”

RECOVERY trial spurs response

The document, which is the latest in a series from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists, was published online Aug. 2 in Diabetic Medicine. The group is chaired by Gerry Rayman, MD, consultant physician at the diabetes centre and diabetes research unit, East Suffolk (England) and North East NHS Foundation Trust.

The guidance was developed in response to the recent “breakthrough” Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, which showed that dexamethasone reduced deaths in patients with COVID-19 on ventilators or receiving oxygen therapy. The advice is not intended for critical care units but can be adapted for that use.

The dose used in RECOVERY – 6 mg daily for 10 days – is 400%-500% greater than the therapeutic glucocorticoid replacement dose. High glucocorticoid doses can exacerbate hyperglycemia in people with established diabetes, unmask undiagnosed diabetes, precipitate hyperglycemia or new-onset diabetes, and can also cause hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS), the authors explained.

They recommended a target glucose of 6.0-10.0 mmol/L (108-180 mg/dL), although they say up to 12 mmol/L (216 mg/dL) is “acceptable.” They then gave advice on frequency of monitoring for people with and without known diabetes, exclusion of diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS, correction of initial hyperglycemia and maintenance of glycemic control using subcutaneous insulin, and prevention of hypoglycemia at the end of dexamethasone therapy (day 10) with insulin down-titration, discharge, and follow-up.

The detailed insulin guidance covers dose escalation for both insulin-treated and insulin-naive patients. A table suggests increasing correction doses of rapid-acting insulin based on prior total daily dose or weight.

Use of once- or twice-daily NPH insulin is recommended for patients whose glucose has risen above 12 mmol/L, in some cases with the addition of a long-acting analog. A second chart gives dose adjustments for those insulins. Additional guidance addresses patients on insulin pumps.

Guidance useful for U.S. physicians

Francisco Pasquel, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of endocrinology at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview that he believes the guidance is “acceptable” for worldwide use, and that “it’s coherent and consistent with what we typically do.”

However, Dr. Pasquel, who founded COVID-in-Diabetes, an online repository of published guidance and shared experience – to which this new document has now been added – did take issue with one piece of advice. The guidance says that patients already taking premixed insulin formulations can continue using them while increasing the dose by 20%-40%. Given the risk of hypoglycemia associated with those formulations, Dr. Pasquel said he would switch those patients to NPH during the time that they’re on dexamethasone.

He also noted that the rapid-acting insulin dose range of 2-10 units provided in the first table, for correction of initial hyperglycemia, are more conservative than those used at his hospital, where correction doses of up to 14-16 units are sometimes necessary.

But Dr. Pasquel praised the group’s overall efforts since the pandemic began, noting that “they’re very organized and constantly updating their recommendations. They have a unified system in the [National Health Service], so it’s easier to standardize. They have a unique [electronic health record] which is far superior to what we do from a public health perspective.”

Dr. Rayman reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pasquel reported receiving research funding from Dexcom, Merck, and the National Institutes of Health, and consulting for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

New guidance from the U.K. National Diabetes COVID-19 Response Group addresses glucose management in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving dexamethasone therapy.

Although there are already guidelines that address inpatient management of steroid-induced hyperglycemia, the authors of the new document wrote that this new expert opinion paper was needed “given the ‘triple insult’ of dexamethasone-induced–impaired glucose metabolism, COVID-19–induced insulin resistance, and COVID-19–impaired insulin production.”

RECOVERY trial spurs response

The document, which is the latest in a series from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists, was published online Aug. 2 in Diabetic Medicine. The group is chaired by Gerry Rayman, MD, consultant physician at the diabetes centre and diabetes research unit, East Suffolk (England) and North East NHS Foundation Trust.

The guidance was developed in response to the recent “breakthrough” Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, which showed that dexamethasone reduced deaths in patients with COVID-19 on ventilators or receiving oxygen therapy. The advice is not intended for critical care units but can be adapted for that use.

The dose used in RECOVERY – 6 mg daily for 10 days – is 400%-500% greater than the therapeutic glucocorticoid replacement dose. High glucocorticoid doses can exacerbate hyperglycemia in people with established diabetes, unmask undiagnosed diabetes, precipitate hyperglycemia or new-onset diabetes, and can also cause hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS), the authors explained.

They recommended a target glucose of 6.0-10.0 mmol/L (108-180 mg/dL), although they say up to 12 mmol/L (216 mg/dL) is “acceptable.” They then gave advice on frequency of monitoring for people with and without known diabetes, exclusion of diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS, correction of initial hyperglycemia and maintenance of glycemic control using subcutaneous insulin, and prevention of hypoglycemia at the end of dexamethasone therapy (day 10) with insulin down-titration, discharge, and follow-up.

The detailed insulin guidance covers dose escalation for both insulin-treated and insulin-naive patients. A table suggests increasing correction doses of rapid-acting insulin based on prior total daily dose or weight.

Use of once- or twice-daily NPH insulin is recommended for patients whose glucose has risen above 12 mmol/L, in some cases with the addition of a long-acting analog. A second chart gives dose adjustments for those insulins. Additional guidance addresses patients on insulin pumps.

Guidance useful for U.S. physicians

Francisco Pasquel, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of endocrinology at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview that he believes the guidance is “acceptable” for worldwide use, and that “it’s coherent and consistent with what we typically do.”

However, Dr. Pasquel, who founded COVID-in-Diabetes, an online repository of published guidance and shared experience – to which this new document has now been added – did take issue with one piece of advice. The guidance says that patients already taking premixed insulin formulations can continue using them while increasing the dose by 20%-40%. Given the risk of hypoglycemia associated with those formulations, Dr. Pasquel said he would switch those patients to NPH during the time that they’re on dexamethasone.

He also noted that the rapid-acting insulin dose range of 2-10 units provided in the first table, for correction of initial hyperglycemia, are more conservative than those used at his hospital, where correction doses of up to 14-16 units are sometimes necessary.

But Dr. Pasquel praised the group’s overall efforts since the pandemic began, noting that “they’re very organized and constantly updating their recommendations. They have a unified system in the [National Health Service], so it’s easier to standardize. They have a unique [electronic health record] which is far superior to what we do from a public health perspective.”

Dr. Rayman reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pasquel reported receiving research funding from Dexcom, Merck, and the National Institutes of Health, and consulting for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

New guidance from the U.K. National Diabetes COVID-19 Response Group addresses glucose management in patients with COVID-19 who are receiving dexamethasone therapy.

Although there are already guidelines that address inpatient management of steroid-induced hyperglycemia, the authors of the new document wrote that this new expert opinion paper was needed “given the ‘triple insult’ of dexamethasone-induced–impaired glucose metabolism, COVID-19–induced insulin resistance, and COVID-19–impaired insulin production.”

RECOVERY trial spurs response

The document, which is the latest in a series from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists, was published online Aug. 2 in Diabetic Medicine. The group is chaired by Gerry Rayman, MD, consultant physician at the diabetes centre and diabetes research unit, East Suffolk (England) and North East NHS Foundation Trust.

The guidance was developed in response to the recent “breakthrough” Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, which showed that dexamethasone reduced deaths in patients with COVID-19 on ventilators or receiving oxygen therapy. The advice is not intended for critical care units but can be adapted for that use.

The dose used in RECOVERY – 6 mg daily for 10 days – is 400%-500% greater than the therapeutic glucocorticoid replacement dose. High glucocorticoid doses can exacerbate hyperglycemia in people with established diabetes, unmask undiagnosed diabetes, precipitate hyperglycemia or new-onset diabetes, and can also cause hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state (HHS), the authors explained.

They recommended a target glucose of 6.0-10.0 mmol/L (108-180 mg/dL), although they say up to 12 mmol/L (216 mg/dL) is “acceptable.” They then gave advice on frequency of monitoring for people with and without known diabetes, exclusion of diabetic ketoacidosis and HHS, correction of initial hyperglycemia and maintenance of glycemic control using subcutaneous insulin, and prevention of hypoglycemia at the end of dexamethasone therapy (day 10) with insulin down-titration, discharge, and follow-up.

The detailed insulin guidance covers dose escalation for both insulin-treated and insulin-naive patients. A table suggests increasing correction doses of rapid-acting insulin based on prior total daily dose or weight.

Use of once- or twice-daily NPH insulin is recommended for patients whose glucose has risen above 12 mmol/L, in some cases with the addition of a long-acting analog. A second chart gives dose adjustments for those insulins. Additional guidance addresses patients on insulin pumps.

Guidance useful for U.S. physicians

Francisco Pasquel, MD, assistant professor of medicine in the division of endocrinology at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview that he believes the guidance is “acceptable” for worldwide use, and that “it’s coherent and consistent with what we typically do.”

However, Dr. Pasquel, who founded COVID-in-Diabetes, an online repository of published guidance and shared experience – to which this new document has now been added – did take issue with one piece of advice. The guidance says that patients already taking premixed insulin formulations can continue using them while increasing the dose by 20%-40%. Given the risk of hypoglycemia associated with those formulations, Dr. Pasquel said he would switch those patients to NPH during the time that they’re on dexamethasone.

He also noted that the rapid-acting insulin dose range of 2-10 units provided in the first table, for correction of initial hyperglycemia, are more conservative than those used at his hospital, where correction doses of up to 14-16 units are sometimes necessary.

But Dr. Pasquel praised the group’s overall efforts since the pandemic began, noting that “they’re very organized and constantly updating their recommendations. They have a unified system in the [National Health Service], so it’s easier to standardize. They have a unique [electronic health record] which is far superior to what we do from a public health perspective.”

Dr. Rayman reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pasquel reported receiving research funding from Dexcom, Merck, and the National Institutes of Health, and consulting for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Antiaffirmative action paper blasted on Twitter now retracted

An article published in March in the Journal of the American Heart Association that raised a ruckus on #medtwitter this week has now been retracted.

It’s unclear what prompted the public explosion of anger, sadness, and recrimination that ultimately led to the retraction of this article – which flew almost completely under the radar when it first appeared online and in print – but it’s crystal clear why it might offend.

To many readers, the paper, written by Norman C. Wang, MD, MSc, an electrophysiologist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, is a “racist” rant that relies on half-truths (J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Mar 24. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.015959).

Officially, the article, “Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity: Evolution of Race and Ethnicity Considerations for the Cardiology Workforce in the United States of America From 1969 to 2019,” was retracted after the American Heart Association “became aware of serious concerns after publication. The author’s institution, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, has notified the Editor‐in‐Chief that the article contains many misconceptions and misquotes and that together those inaccuracies, misstatements, and selective misreading of source materials strip the paper of its scientific validity,” the retraction reads (J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Aug 6. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014602).

The journal will be publishing a detailed rebuttal, the notice adds: “This retraction notice will be updated with a link to the rebuttal when it publishes.”

“The Editor‐in‐Chief deeply regrets publishing the article and offers his apologies,” it further reads. “The American Heart Association and the Editor‐in‐Chief have determined that the best interest of the public and the research community will be served by issuing this notice of retraction. The author does not agree to the retraction.”

In the paper, Dr. Wang argues that affirmative action policies designed to increase minority representation in medical schools and cardiovascular training programs result in unqualified applicants being admitted, where they will struggle to succeed.

The article itself is a dense review of the topic of diversity, inclusion, and equity, aiming to “critically assess current paradigms, and to consider potential solutions to anticipated challenges,” according to its author. Supported by 108 references, Dr. Wang concludes with a lengthy quote from tennis great Arthur Ashe, an opponent of affirmative action who died in 1993.

Affirmative action, said Mr. Ashe, is “an insult to the people it intended to help.” Dr. Wang suggests that “racial and ethnic preferences for undergraduate and medical school admissions should be gradually rolled back with a target end year of 2028.”

He cites the $16 billion in federal funding that cardiovascular disease training programs receive every year to support graduate medical education in support of this contention.

#Medtwitter explodes

“My entire lived experience contradicts everything in that racist @JAHA_AHA article, as does the experience of so many others. So, I know it’s just a bad opinion piece passed off as ‘research’ that shouldn’t have been published. Still the damage has been done. We MUST do better,” tweeted Bryan A. Smith, MD, University of Chicago Medicine.

According to its Altmetric score, the article received very little attention back in March and April. There were three tweets referencing it, including one from JAHA announcing its publication. Since Aug. 2, an additional 390-odd Tweets from 347 Twitter users have been registered. None appear to be complimentary. Several days into the Twitter storm, the article was officially retracted.

“This article is shocking and makes me sad,” Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, said in an interview. “We are all working so hard to make cardiology more inclusive and diverse, and this takes us like 1,000 steps backwards.”

For her part, Dr. Gulati would have liked a retraction earlier in the week. “The analysis was selective and incorrect, and the statements made intimate that minority trainees were selected based on affirmative action rather than their merits,” she said. It also suggested that their presence was representative of a decline in standards in cardiology programs that take underrepresented minorities (URMs).

Standard arguments against affirmative action

According to Dr. Wang, who did not respond to a request to comment for this article, allowing minority students into medical school with academic records that are weaker than their classmates sets them up for failure.

“Many do not complete their intended programs or do not attain academic success to be attractive candidates for subsequent educational programs or employment,” he wrote.

This is a standard argument of opponents to affirmative action, said Quinn Capers IV, MD. Dr. Capers, a longtime advocate for diversity in medicine, acknowledges that, “on average,” test scores for Blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans tend to be lower than for White applicants for a wide range of reasons, many of which are related to systemic racism.

“This is the strongest weapon opponents to affirmative action have, and they keep coming back to it, but it’s out of step with how many in academic medicine feel,” said Dr. Capers, who is an interventional cardiologist and the vice dean for faculty affairs at Ohio State University, Columbus.

This is why, he added, most medical schools have embraced the Association of American Medical Colleges’ concept of “holistic review,” which judges potential physicians on their academic records, their personal experiences, and their individual attributes.

“Standardized tests and academic records are important, but so are the experiences one has gone through and the individual attributes they may have. How resilient are you? How compassionate? Our embrace of this more holistic approach, I believe, is helping many medical schools move toward having a more diverse class that is closer to reflecting the needs of our multicultural and multiracial society,” Dr. Capers said.

To be clear, Dr. Capers is not afraid of having a discussion on this topic and denies that the uproar against this article represents “cancel culture.”

“Hey, I love to debate and I’m not against hearing divisive voices, but then let’s have a debate and hear both sides. But there are several problems with the way they did this. No. 1, they called it a ‘white paper,’ which to most people means it reflects the views of the organization, not a specific individual, and, secondly, it’s more than an opinion piece in that he manipulates facts to make his points, with no chance for rebuttal.”

Several have also questioned how this paper, which is written by a nonexpert in the field, passed peer review.

The article contains some accurate historical references, said Dr. Capers, but intertwined with this history the author editorializes in a fashion that is “charged with racism.” In other places, Dr. Wang is just outright wrong, he added.

“I can also tell you that, in one place where he quotes me specifically, what he says is quite damaging and completely wrong. He quotes something we wrote but cuts off the final sentence, making it seem as though we acknowledged that we had to artificially rank minority applicants high, just so we could say we have a diverse fellowship program.

“It’s frankly very hard to believe that was an accident,” Dr. Capers added.

AHA backs away, promises investigation

The article has been disowned by all levels of the AHA leadership – past, present, and future.

In an Editor’s Note, Barry London, MD, PhD, the Editor in chief of the Journal of the American Heart Association, apologized for his role and the role of his staff in publishing the article.

“JAHA will support all efforts to correct this error, including but not limited to the publication of alternate viewpoints, which we solicited at the time of publication but have not yet been submitted to the journal. In addition, we will work to improve our peer review system to prevent future missteps of this type,” Dr. London wrote. “I can only hope that igniting a discussion around diversity in cardiology will ultimately fuel new ideas and lead to real advances.”

“I want to emphasize in the strongest possible terms that this paper does not represent the views of the AHA as an organization or its leadership. This paper should never have been published. A thorough investigation is rightly being conducted,” tweeted Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, MPhil, who took over the AHA presidency last month.

“Author’s views are racist and not consistent with my values nor AHA,” tweeted Robert Harrington, MD, immediate past president of the AHA. ‘Investigation is underway into how it made it through the editorial process. Like you, I want to know what happened. I am angry, frustrated and disappointed that this piece was published; expect review soon.’

“Agree with @HeartBobH. It is impossible not to hear and feel the hurt and pain out there on a very personal level, especially among our young colleagues. You are valued, and worthy. Please stay tuned and then help all of us work to be better,” tweeted Donald Lloyd-Jones, MD, president-elect of AHA.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

An article published in March in the Journal of the American Heart Association that raised a ruckus on #medtwitter this week has now been retracted.

It’s unclear what prompted the public explosion of anger, sadness, and recrimination that ultimately led to the retraction of this article – which flew almost completely under the radar when it first appeared online and in print – but it’s crystal clear why it might offend.

To many readers, the paper, written by Norman C. Wang, MD, MSc, an electrophysiologist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, is a “racist” rant that relies on half-truths (J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Mar 24. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.015959).

Officially, the article, “Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity: Evolution of Race and Ethnicity Considerations for the Cardiology Workforce in the United States of America From 1969 to 2019,” was retracted after the American Heart Association “became aware of serious concerns after publication. The author’s institution, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, has notified the Editor‐in‐Chief that the article contains many misconceptions and misquotes and that together those inaccuracies, misstatements, and selective misreading of source materials strip the paper of its scientific validity,” the retraction reads (J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Aug 6. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014602).

The journal will be publishing a detailed rebuttal, the notice adds: “This retraction notice will be updated with a link to the rebuttal when it publishes.”

“The Editor‐in‐Chief deeply regrets publishing the article and offers his apologies,” it further reads. “The American Heart Association and the Editor‐in‐Chief have determined that the best interest of the public and the research community will be served by issuing this notice of retraction. The author does not agree to the retraction.”

In the paper, Dr. Wang argues that affirmative action policies designed to increase minority representation in medical schools and cardiovascular training programs result in unqualified applicants being admitted, where they will struggle to succeed.

The article itself is a dense review of the topic of diversity, inclusion, and equity, aiming to “critically assess current paradigms, and to consider potential solutions to anticipated challenges,” according to its author. Supported by 108 references, Dr. Wang concludes with a lengthy quote from tennis great Arthur Ashe, an opponent of affirmative action who died in 1993.

Affirmative action, said Mr. Ashe, is “an insult to the people it intended to help.” Dr. Wang suggests that “racial and ethnic preferences for undergraduate and medical school admissions should be gradually rolled back with a target end year of 2028.”

He cites the $16 billion in federal funding that cardiovascular disease training programs receive every year to support graduate medical education in support of this contention.

#Medtwitter explodes

“My entire lived experience contradicts everything in that racist @JAHA_AHA article, as does the experience of so many others. So, I know it’s just a bad opinion piece passed off as ‘research’ that shouldn’t have been published. Still the damage has been done. We MUST do better,” tweeted Bryan A. Smith, MD, University of Chicago Medicine.

According to its Altmetric score, the article received very little attention back in March and April. There were three tweets referencing it, including one from JAHA announcing its publication. Since Aug. 2, an additional 390-odd Tweets from 347 Twitter users have been registered. None appear to be complimentary. Several days into the Twitter storm, the article was officially retracted.

“This article is shocking and makes me sad,” Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, said in an interview. “We are all working so hard to make cardiology more inclusive and diverse, and this takes us like 1,000 steps backwards.”

For her part, Dr. Gulati would have liked a retraction earlier in the week. “The analysis was selective and incorrect, and the statements made intimate that minority trainees were selected based on affirmative action rather than their merits,” she said. It also suggested that their presence was representative of a decline in standards in cardiology programs that take underrepresented minorities (URMs).

Standard arguments against affirmative action

According to Dr. Wang, who did not respond to a request to comment for this article, allowing minority students into medical school with academic records that are weaker than their classmates sets them up for failure.

“Many do not complete their intended programs or do not attain academic success to be attractive candidates for subsequent educational programs or employment,” he wrote.

This is a standard argument of opponents to affirmative action, said Quinn Capers IV, MD. Dr. Capers, a longtime advocate for diversity in medicine, acknowledges that, “on average,” test scores for Blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans tend to be lower than for White applicants for a wide range of reasons, many of which are related to systemic racism.

“This is the strongest weapon opponents to affirmative action have, and they keep coming back to it, but it’s out of step with how many in academic medicine feel,” said Dr. Capers, who is an interventional cardiologist and the vice dean for faculty affairs at Ohio State University, Columbus.

This is why, he added, most medical schools have embraced the Association of American Medical Colleges’ concept of “holistic review,” which judges potential physicians on their academic records, their personal experiences, and their individual attributes.

“Standardized tests and academic records are important, but so are the experiences one has gone through and the individual attributes they may have. How resilient are you? How compassionate? Our embrace of this more holistic approach, I believe, is helping many medical schools move toward having a more diverse class that is closer to reflecting the needs of our multicultural and multiracial society,” Dr. Capers said.

To be clear, Dr. Capers is not afraid of having a discussion on this topic and denies that the uproar against this article represents “cancel culture.”

“Hey, I love to debate and I’m not against hearing divisive voices, but then let’s have a debate and hear both sides. But there are several problems with the way they did this. No. 1, they called it a ‘white paper,’ which to most people means it reflects the views of the organization, not a specific individual, and, secondly, it’s more than an opinion piece in that he manipulates facts to make his points, with no chance for rebuttal.”

Several have also questioned how this paper, which is written by a nonexpert in the field, passed peer review.

The article contains some accurate historical references, said Dr. Capers, but intertwined with this history the author editorializes in a fashion that is “charged with racism.” In other places, Dr. Wang is just outright wrong, he added.

“I can also tell you that, in one place where he quotes me specifically, what he says is quite damaging and completely wrong. He quotes something we wrote but cuts off the final sentence, making it seem as though we acknowledged that we had to artificially rank minority applicants high, just so we could say we have a diverse fellowship program.

“It’s frankly very hard to believe that was an accident,” Dr. Capers added.

AHA backs away, promises investigation

The article has been disowned by all levels of the AHA leadership – past, present, and future.

In an Editor’s Note, Barry London, MD, PhD, the Editor in chief of the Journal of the American Heart Association, apologized for his role and the role of his staff in publishing the article.

“JAHA will support all efforts to correct this error, including but not limited to the publication of alternate viewpoints, which we solicited at the time of publication but have not yet been submitted to the journal. In addition, we will work to improve our peer review system to prevent future missteps of this type,” Dr. London wrote. “I can only hope that igniting a discussion around diversity in cardiology will ultimately fuel new ideas and lead to real advances.”

“I want to emphasize in the strongest possible terms that this paper does not represent the views of the AHA as an organization or its leadership. This paper should never have been published. A thorough investigation is rightly being conducted,” tweeted Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, MPhil, who took over the AHA presidency last month.

“Author’s views are racist and not consistent with my values nor AHA,” tweeted Robert Harrington, MD, immediate past president of the AHA. ‘Investigation is underway into how it made it through the editorial process. Like you, I want to know what happened. I am angry, frustrated and disappointed that this piece was published; expect review soon.’

“Agree with @HeartBobH. It is impossible not to hear and feel the hurt and pain out there on a very personal level, especially among our young colleagues. You are valued, and worthy. Please stay tuned and then help all of us work to be better,” tweeted Donald Lloyd-Jones, MD, president-elect of AHA.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

An article published in March in the Journal of the American Heart Association that raised a ruckus on #medtwitter this week has now been retracted.

It’s unclear what prompted the public explosion of anger, sadness, and recrimination that ultimately led to the retraction of this article – which flew almost completely under the radar when it first appeared online and in print – but it’s crystal clear why it might offend.

To many readers, the paper, written by Norman C. Wang, MD, MSc, an electrophysiologist at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, is a “racist” rant that relies on half-truths (J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Mar 24. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.015959).

Officially, the article, “Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity: Evolution of Race and Ethnicity Considerations for the Cardiology Workforce in the United States of America From 1969 to 2019,” was retracted after the American Heart Association “became aware of serious concerns after publication. The author’s institution, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, has notified the Editor‐in‐Chief that the article contains many misconceptions and misquotes and that together those inaccuracies, misstatements, and selective misreading of source materials strip the paper of its scientific validity,” the retraction reads (J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Aug 6. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.014602).

The journal will be publishing a detailed rebuttal, the notice adds: “This retraction notice will be updated with a link to the rebuttal when it publishes.”

“The Editor‐in‐Chief deeply regrets publishing the article and offers his apologies,” it further reads. “The American Heart Association and the Editor‐in‐Chief have determined that the best interest of the public and the research community will be served by issuing this notice of retraction. The author does not agree to the retraction.”

In the paper, Dr. Wang argues that affirmative action policies designed to increase minority representation in medical schools and cardiovascular training programs result in unqualified applicants being admitted, where they will struggle to succeed.

The article itself is a dense review of the topic of diversity, inclusion, and equity, aiming to “critically assess current paradigms, and to consider potential solutions to anticipated challenges,” according to its author. Supported by 108 references, Dr. Wang concludes with a lengthy quote from tennis great Arthur Ashe, an opponent of affirmative action who died in 1993.

Affirmative action, said Mr. Ashe, is “an insult to the people it intended to help.” Dr. Wang suggests that “racial and ethnic preferences for undergraduate and medical school admissions should be gradually rolled back with a target end year of 2028.”

He cites the $16 billion in federal funding that cardiovascular disease training programs receive every year to support graduate medical education in support of this contention.

#Medtwitter explodes

“My entire lived experience contradicts everything in that racist @JAHA_AHA article, as does the experience of so many others. So, I know it’s just a bad opinion piece passed off as ‘research’ that shouldn’t have been published. Still the damage has been done. We MUST do better,” tweeted Bryan A. Smith, MD, University of Chicago Medicine.

According to its Altmetric score, the article received very little attention back in March and April. There were three tweets referencing it, including one from JAHA announcing its publication. Since Aug. 2, an additional 390-odd Tweets from 347 Twitter users have been registered. None appear to be complimentary. Several days into the Twitter storm, the article was officially retracted.

“This article is shocking and makes me sad,” Martha Gulati, MD, University of Arizona, Phoenix, said in an interview. “We are all working so hard to make cardiology more inclusive and diverse, and this takes us like 1,000 steps backwards.”

For her part, Dr. Gulati would have liked a retraction earlier in the week. “The analysis was selective and incorrect, and the statements made intimate that minority trainees were selected based on affirmative action rather than their merits,” she said. It also suggested that their presence was representative of a decline in standards in cardiology programs that take underrepresented minorities (URMs).

Standard arguments against affirmative action

According to Dr. Wang, who did not respond to a request to comment for this article, allowing minority students into medical school with academic records that are weaker than their classmates sets them up for failure.

“Many do not complete their intended programs or do not attain academic success to be attractive candidates for subsequent educational programs or employment,” he wrote.

This is a standard argument of opponents to affirmative action, said Quinn Capers IV, MD. Dr. Capers, a longtime advocate for diversity in medicine, acknowledges that, “on average,” test scores for Blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans tend to be lower than for White applicants for a wide range of reasons, many of which are related to systemic racism.

“This is the strongest weapon opponents to affirmative action have, and they keep coming back to it, but it’s out of step with how many in academic medicine feel,” said Dr. Capers, who is an interventional cardiologist and the vice dean for faculty affairs at Ohio State University, Columbus.

This is why, he added, most medical schools have embraced the Association of American Medical Colleges’ concept of “holistic review,” which judges potential physicians on their academic records, their personal experiences, and their individual attributes.

“Standardized tests and academic records are important, but so are the experiences one has gone through and the individual attributes they may have. How resilient are you? How compassionate? Our embrace of this more holistic approach, I believe, is helping many medical schools move toward having a more diverse class that is closer to reflecting the needs of our multicultural and multiracial society,” Dr. Capers said.

To be clear, Dr. Capers is not afraid of having a discussion on this topic and denies that the uproar against this article represents “cancel culture.”

“Hey, I love to debate and I’m not against hearing divisive voices, but then let’s have a debate and hear both sides. But there are several problems with the way they did this. No. 1, they called it a ‘white paper,’ which to most people means it reflects the views of the organization, not a specific individual, and, secondly, it’s more than an opinion piece in that he manipulates facts to make his points, with no chance for rebuttal.”

Several have also questioned how this paper, which is written by a nonexpert in the field, passed peer review.

The article contains some accurate historical references, said Dr. Capers, but intertwined with this history the author editorializes in a fashion that is “charged with racism.” In other places, Dr. Wang is just outright wrong, he added.

“I can also tell you that, in one place where he quotes me specifically, what he says is quite damaging and completely wrong. He quotes something we wrote but cuts off the final sentence, making it seem as though we acknowledged that we had to artificially rank minority applicants high, just so we could say we have a diverse fellowship program.

“It’s frankly very hard to believe that was an accident,” Dr. Capers added.

AHA backs away, promises investigation

The article has been disowned by all levels of the AHA leadership – past, present, and future.

In an Editor’s Note, Barry London, MD, PhD, the Editor in chief of the Journal of the American Heart Association, apologized for his role and the role of his staff in publishing the article.

“JAHA will support all efforts to correct this error, including but not limited to the publication of alternate viewpoints, which we solicited at the time of publication but have not yet been submitted to the journal. In addition, we will work to improve our peer review system to prevent future missteps of this type,” Dr. London wrote. “I can only hope that igniting a discussion around diversity in cardiology will ultimately fuel new ideas and lead to real advances.”

“I want to emphasize in the strongest possible terms that this paper does not represent the views of the AHA as an organization or its leadership. This paper should never have been published. A thorough investigation is rightly being conducted,” tweeted Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, MPhil, who took over the AHA presidency last month.

“Author’s views are racist and not consistent with my values nor AHA,” tweeted Robert Harrington, MD, immediate past president of the AHA. ‘Investigation is underway into how it made it through the editorial process. Like you, I want to know what happened. I am angry, frustrated and disappointed that this piece was published; expect review soon.’

“Agree with @HeartBobH. It is impossible not to hear and feel the hurt and pain out there on a very personal level, especially among our young colleagues. You are valued, and worthy. Please stay tuned and then help all of us work to be better,” tweeted Donald Lloyd-Jones, MD, president-elect of AHA.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

ED visits for mental health, substance use doubled in 1 decade

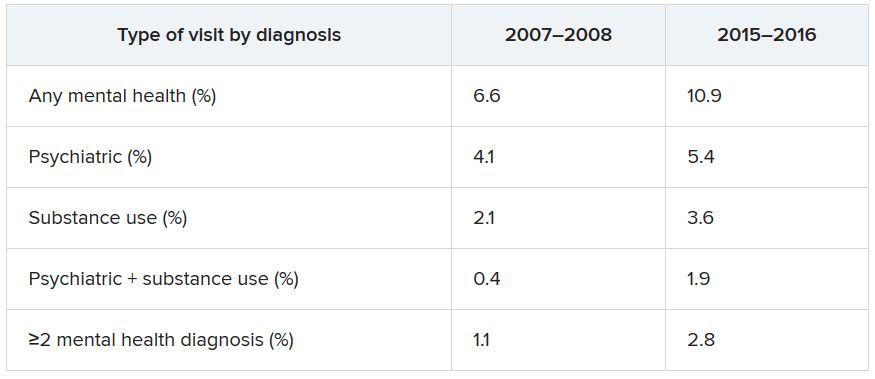

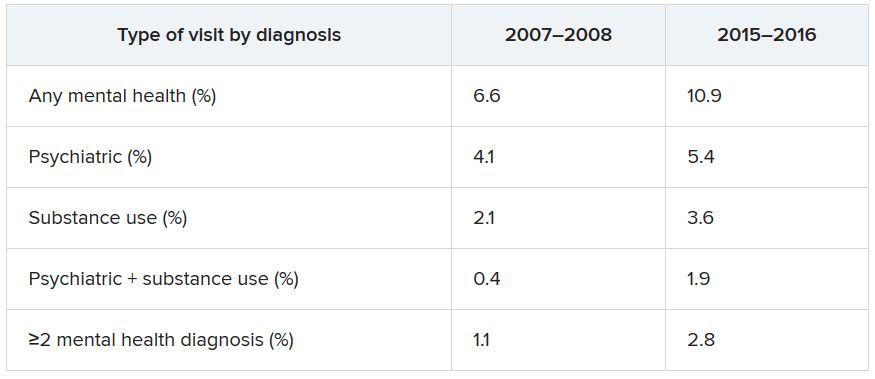

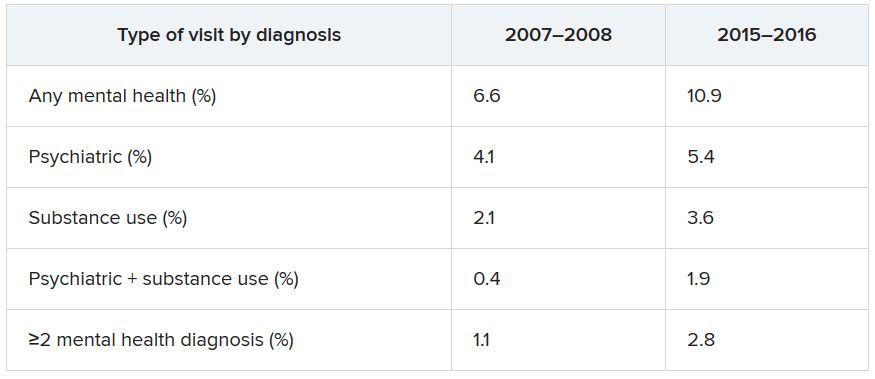

ED visits related to mental health conditions increased nearly twofold from 2007-2008 to 2015-2016, new research suggests.

Data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) showed that, over the 10-year study period, the proportion of ED visits for mental health diagnoses increased from 6.6% to 10.9%, with substance use accounting for much of the increase.

Although there have been policy efforts, such as expanding access to mental health care as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2011, the senior author Taeho Greg Rhee, PhD, MSW, said in an interview.

“Treating mental health conditions in EDs is often considered suboptimal” because of limited time for full psychiatric assessment, lack of trained providers, and limited privacy in EDs, said Dr. Rhee of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The findings were published online July 28 in The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

“Outdated” research

Roughly one-fifth of U.S. adults experience some type of mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder annually. Moreover, the suicide rate has been steadily increasing, and there continues to be a “raging opioid epidemic,” the researchers wrote.

Despite these alarming figures, 57.4% of adults with mental illness reported in 2017 that they had not received any mental health treatment in the past year, reported the investigators.

Previous research has suggested that many adults have difficulty seeking outpatient mental health treatment and may turn to EDs instead. However, most studies of mental health ED use “are by now outdated, as they used data from years prior to the full implementation of the ACA,” the researchers noted.

“More Americans are suffering from mental illness, and given the recent policy efforts of expanding access to mental health care, we were questioning if ED visits due to mental health has changed or not,” Dr. Rhee said.

To investigate the question, the researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from the NHAMCS, a publicly available dataset provided by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.