User login

COVID-19 may damage blood vessels in the brain

Until now, the neurological manifestations of COVID-19 have been believed to be a result of direct damage to nerve cells. However, a new study suggests that the virus might actually damage the brain’s small blood vessels rather than nerve cells themselves.

The findings add further weight to previous research into neurological complications from COVID-19, according to Anna Cervantes, MD. Dr. Cervantes is assistant professor of neurology at the Boston University and has been studying the neurological effects of COVID-19, though she was not involved in this study. “I can tell from my personal experience, and things we’ve published on and the literature that’s out there – there are patients that are having complications like stroke that aren’t even critically ill from COVID. We’re seeing that not in just the acute setting, but also in a delayed fashion. Even though most of the coagulopathy is largely venous and probably microvascular, this does affect the brain through a myriad of ways,” Dr. Cervantes said.

The research was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Myoung‑Hwa Lee, PhD, was the lead author.

The study included high resolution magnetic resonance imaging and histopathological examination of 13 individuals with a median age of 50 years. Among 10 patients with brain alterations, the researchers conducted further studies in 5 individuals using multiplex fluorescence imaging and chromogenic immunostaining in all 10.

The team conducted conventional histopathology on the brains of 18 individuals. Fourteen had a history of chronic illness, including diabetes, and hypertension, and 11 had died unexpectedly or been found dead. Magnetic resonance microscopy revealed punctuate hypo-intensities in nine subjects, indicating microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage. Histopathology using fluorescence imaging showed the same features. Collagen IV immunostaining showed thinning of the basal lamina of the endothelial cells in five patients. Ten patients had congested blood vessels and surrounding fibrinogen leakage, but comparatively intact vasculature. The researchers interpreted linear hypo-intensities as micro-hemorrhages.

The researchers found little perivascular inflammation, and no vascular occlusion. Thirteen subjects had perivascular-activated microglia, macrophage infiltrates, and hypertrophic astrocytes. Eight had CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in the perivascular spaces and in lumens next to endothelial cells, which could help explain vascular injury.

The researchers found no evidence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself, despite efforts using polymerase chain reaction with multiple primer sets, RNA sequencing within the brain, or RNA in situ hybridization and immunostaining. Subjects may have cleared the virus by the time they died, or viral copy numbers could have been below the detection limit of the assays.

The researchers also obtained a convenience sample of subjects who had died from COVID-19. Magnetic resonance microscopy, histopathology, and immunohistochemical analysis of sections revealed microvascular injury in the brain and olfactory bulb, despite no evidence of viral infection. The authors stressed that they could not draw conclusions about the neurological features of COVID-19 because of a lack of clinical information.

Dr. Cervantes noted that limitation: “We’re seeing a lot of patients with encephalopathy or alterations in their mental status. A lot of things can cause that, and some are common in patients who are critically ill, like medications and metabolic derangement.”

Still, the findings could help to inform future medical management. “There’s going to be a large number of patients who don’t have really bad pulmonary disease but still may have encephalopathy. So if there is small vessel involvement because of inflammation that we might not necessarily catch in a lumbar puncture or routine imaging, there’s still somebody we can make better (using) steroids. Having more information on what’s happening on a pathophysiologic level and on pathology is really helpful.”

The study was supported by internal funds from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Cervantes has no relevant financial disclosures.

Until now, the neurological manifestations of COVID-19 have been believed to be a result of direct damage to nerve cells. However, a new study suggests that the virus might actually damage the brain’s small blood vessels rather than nerve cells themselves.

The findings add further weight to previous research into neurological complications from COVID-19, according to Anna Cervantes, MD. Dr. Cervantes is assistant professor of neurology at the Boston University and has been studying the neurological effects of COVID-19, though she was not involved in this study. “I can tell from my personal experience, and things we’ve published on and the literature that’s out there – there are patients that are having complications like stroke that aren’t even critically ill from COVID. We’re seeing that not in just the acute setting, but also in a delayed fashion. Even though most of the coagulopathy is largely venous and probably microvascular, this does affect the brain through a myriad of ways,” Dr. Cervantes said.

The research was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Myoung‑Hwa Lee, PhD, was the lead author.

The study included high resolution magnetic resonance imaging and histopathological examination of 13 individuals with a median age of 50 years. Among 10 patients with brain alterations, the researchers conducted further studies in 5 individuals using multiplex fluorescence imaging and chromogenic immunostaining in all 10.

The team conducted conventional histopathology on the brains of 18 individuals. Fourteen had a history of chronic illness, including diabetes, and hypertension, and 11 had died unexpectedly or been found dead. Magnetic resonance microscopy revealed punctuate hypo-intensities in nine subjects, indicating microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage. Histopathology using fluorescence imaging showed the same features. Collagen IV immunostaining showed thinning of the basal lamina of the endothelial cells in five patients. Ten patients had congested blood vessels and surrounding fibrinogen leakage, but comparatively intact vasculature. The researchers interpreted linear hypo-intensities as micro-hemorrhages.

The researchers found little perivascular inflammation, and no vascular occlusion. Thirteen subjects had perivascular-activated microglia, macrophage infiltrates, and hypertrophic astrocytes. Eight had CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in the perivascular spaces and in lumens next to endothelial cells, which could help explain vascular injury.

The researchers found no evidence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself, despite efforts using polymerase chain reaction with multiple primer sets, RNA sequencing within the brain, or RNA in situ hybridization and immunostaining. Subjects may have cleared the virus by the time they died, or viral copy numbers could have been below the detection limit of the assays.

The researchers also obtained a convenience sample of subjects who had died from COVID-19. Magnetic resonance microscopy, histopathology, and immunohistochemical analysis of sections revealed microvascular injury in the brain and olfactory bulb, despite no evidence of viral infection. The authors stressed that they could not draw conclusions about the neurological features of COVID-19 because of a lack of clinical information.

Dr. Cervantes noted that limitation: “We’re seeing a lot of patients with encephalopathy or alterations in their mental status. A lot of things can cause that, and some are common in patients who are critically ill, like medications and metabolic derangement.”

Still, the findings could help to inform future medical management. “There’s going to be a large number of patients who don’t have really bad pulmonary disease but still may have encephalopathy. So if there is small vessel involvement because of inflammation that we might not necessarily catch in a lumbar puncture or routine imaging, there’s still somebody we can make better (using) steroids. Having more information on what’s happening on a pathophysiologic level and on pathology is really helpful.”

The study was supported by internal funds from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Cervantes has no relevant financial disclosures.

Until now, the neurological manifestations of COVID-19 have been believed to be a result of direct damage to nerve cells. However, a new study suggests that the virus might actually damage the brain’s small blood vessels rather than nerve cells themselves.

The findings add further weight to previous research into neurological complications from COVID-19, according to Anna Cervantes, MD. Dr. Cervantes is assistant professor of neurology at the Boston University and has been studying the neurological effects of COVID-19, though she was not involved in this study. “I can tell from my personal experience, and things we’ve published on and the literature that’s out there – there are patients that are having complications like stroke that aren’t even critically ill from COVID. We’re seeing that not in just the acute setting, but also in a delayed fashion. Even though most of the coagulopathy is largely venous and probably microvascular, this does affect the brain through a myriad of ways,” Dr. Cervantes said.

The research was published online Jan. 12 in the New England Journal of Medicine. Myoung‑Hwa Lee, PhD, was the lead author.

The study included high resolution magnetic resonance imaging and histopathological examination of 13 individuals with a median age of 50 years. Among 10 patients with brain alterations, the researchers conducted further studies in 5 individuals using multiplex fluorescence imaging and chromogenic immunostaining in all 10.

The team conducted conventional histopathology on the brains of 18 individuals. Fourteen had a history of chronic illness, including diabetes, and hypertension, and 11 had died unexpectedly or been found dead. Magnetic resonance microscopy revealed punctuate hypo-intensities in nine subjects, indicating microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage. Histopathology using fluorescence imaging showed the same features. Collagen IV immunostaining showed thinning of the basal lamina of the endothelial cells in five patients. Ten patients had congested blood vessels and surrounding fibrinogen leakage, but comparatively intact vasculature. The researchers interpreted linear hypo-intensities as micro-hemorrhages.

The researchers found little perivascular inflammation, and no vascular occlusion. Thirteen subjects had perivascular-activated microglia, macrophage infiltrates, and hypertrophic astrocytes. Eight had CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in the perivascular spaces and in lumens next to endothelial cells, which could help explain vascular injury.

The researchers found no evidence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself, despite efforts using polymerase chain reaction with multiple primer sets, RNA sequencing within the brain, or RNA in situ hybridization and immunostaining. Subjects may have cleared the virus by the time they died, or viral copy numbers could have been below the detection limit of the assays.

The researchers also obtained a convenience sample of subjects who had died from COVID-19. Magnetic resonance microscopy, histopathology, and immunohistochemical analysis of sections revealed microvascular injury in the brain and olfactory bulb, despite no evidence of viral infection. The authors stressed that they could not draw conclusions about the neurological features of COVID-19 because of a lack of clinical information.

Dr. Cervantes noted that limitation: “We’re seeing a lot of patients with encephalopathy or alterations in their mental status. A lot of things can cause that, and some are common in patients who are critically ill, like medications and metabolic derangement.”

Still, the findings could help to inform future medical management. “There’s going to be a large number of patients who don’t have really bad pulmonary disease but still may have encephalopathy. So if there is small vessel involvement because of inflammation that we might not necessarily catch in a lumbar puncture or routine imaging, there’s still somebody we can make better (using) steroids. Having more information on what’s happening on a pathophysiologic level and on pathology is really helpful.”

The study was supported by internal funds from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Cervantes has no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Patients fend for themselves to access highly touted COVID antibody treatments

By the time he tested positive for COVID-19 on Jan. 12, Gary Herritz was feeling pretty sick. He suspects he was infected a week earlier, during a medical appointment in which he saw health workers who were wearing masks beneath their noses or who had removed them entirely.

His scratchy throat had turned to a dry cough, headache, joint pain, and fever – all warning signs to Mr. Herritz, who underwent liver transplant surgery in 2012, followed by a rejection scare in 2018. He knew his compromised immune system left him especially vulnerable to a potentially deadly case of COVID.

“The thing with transplant patients is we can crash in a heartbeat,” said Mr. Herritz, 39. “The outcome for transplant patients [with COVID] is not good.”

On Twitter, Mr. Herritz had read about monoclonal antibody therapy, the treatment famously given to President Donald Trump and other high-profile politicians and authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use in high-risk COVID patients. But as his symptoms worsened, Mr. Herritz found himself very much on his own as he scrambled for access.

His primary care doctor wasn’t sure he qualified for treatment. His transplant team in Wisconsin, where he’d had the liver surgery, wasn’t calling back. No one was sure exactly where he should go to get it. From bed in Pascagoula, Miss., he spent 2 days punching in phone numbers, reaching out to health officials in four states, before he finally landed an appointment to receive a treatment aimed at keeping patients like him out of the hospital – and, perhaps, the morgue.

“I am not rich, I am not special, I am not a political figure,” Mr. Herritz, a former community service officer, wrote on Twitter. “I just called until someone would listen.”

Months after Mr. Trump emphatically credited an experimental antibody therapy for his quick recovery from covid and even as drugmakers ramp up supplies, only a trickle of the product has found its way into regular people. While hundreds of thousands of vials sit unused, sick patients who, research indicates, could benefit from early treatment – available for free – have largely been fending for themselves.

Federal officials have allocated more than 785,000 doses of two antibody treatments authorized for emergency use during the pandemic, and more than 550,000 doses have been delivered to sites across the nation. The federal government has contracted for nearly 2.5 million doses of the products from drugmakers Eli Lilly and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals at a cost of more than $4.4 billion.

So far, however, only about 30% of the available doses have been administered to patients, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services officials said.

Scores of high-risk COVID patients who are eligible remain unaware or have not been offered the option. Research has shown the therapy is most effective if given early in the illness, within 10 days of a positive COVID test. But many would-be recipients have missed this crucial window because of a patchwork system in the United States that can delay testing and diagnosis.

“The bottleneck here in the funnel is administration, not availability of the product,” said Dr. Janet Woodcock, a veteran FDA official in charge of therapeutics for the federal Operation Warp Speed effort.

Among the daunting hurdles: Until this week, there has been no nationwide system to tell people where they could obtain the drugs, which are delivered through IV infusions that require hours to administer and monitor. Finding space to keep COVID-infected patients separate from others has been difficult in some health centers slammed by the pandemic.

“The health care system is crashing,” Dr. Woodcock told reporters. “What we’ve heard around the country is the No. 1 barrier is staffing.”

At the same time, many hospitals have refused to offer the therapy because doctors were unimpressed with the research federal officials used to justify its use.

Monoclonal antibodies are lab-produced molecules that act as substitutes for the body’s own antibodies that fight infection. The COVID treatments are designed to block the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes infection from attaching to and entering human cells. Such treatments are usually prohibitively expensive, but for the time being the federal government is footing the bulk of the bill, though patients likely will be charged administrative fees.

Nationwide, nearly 4,000 sites offer the infusion therapies. But for patients and families of people most at risk – those 65 and older or with underlying health conditions – finding the sites and gaining access has been almost impossible, said Brian Nyquist, chief executive officer of the National Infusion Center Association, which is tracking supplies of the antibody products. Like Mr. Herritz, many seeking information about monoclonals find themselves on a lone crusade.

“If they’re not hammering the phones and advocating for access for their loved ones, others often won’t,” he said. “Tenacity is critical.”

Regeneron officials said they’re fielding calls about COVID treatments daily to the company’s medical information line. More than 3,500 people have flooded Eli Lilly’s COVID hotline with questions about access.

As of this week, all states are required to list on a federal locator map sites that have received the monoclonal antibody products, HHS officials said. The updated map shows wide distribution, but a listing doesn’t guarantee availability or access; patients still need to check. It’s best to confer with a primary care provider before reaching out to the centers. For best results, treatment should occur as soon as possible after a positive COVID test.

Some health systems have refused to offer the monoclonal antibody therapies because of doubts about the data used to authorize them. Early studies suggested that Lilly’s therapy, bamlanivimab, reduced the need for hospitalization or emergency treatment in outpatient COVID cases by about 70%, while Regeneron’s antibody cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab reduced the need by about 50%.

But those studies were small, just a few hundred subjects, and the results were limited. “A lot of doctors, actually, they’re not impressed with the data,” said Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease expert at Columbia University who cohosts the podcast “This Week in Virology.” “There really is still that question of, ‘Does this stuff really work?’ ”

As more patients are treated, however, there’s growing evidence that the therapies can keep high-risk patients out of the hospital, not only easing their recovery but also decreasing the burden on health systems struggling with record numbers of patients.

Dr. Raymund Razonable, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, said he has treated more than 2,500 COVID patients with monoclonal antibody therapy with promising results. “It’s looking good,” he said, declining to provide details because they’re embargoed for publication. “We are seeing reductions in hospitalizations; we’re seeing reductions in ICU care; we’re also seeing reductions in mortality.”

Banking on observations from Mayo experts and others, federal officials have been pushing for wider use of antibody therapies. HHS officials have partnered with hospitals in three hard-hit states – California, Arizona, and Nevada – to set up infusion centers that are treating dozens of COVID patients each day.

One of those sites went up in late December at El Centro Regional Medical Center in California’s Imperial County, an impoverished farming region on the state’s southern border that has recorded among the highest COVID infection rates in the state. For months, the medical center strained to absorb the overwhelming influx of patients, but chief executive Dr. Adolphe Edward said a new walk-up infusion site has already put a dent in the COVID load.

More than 130 people have been treated, all patients who were able to get the 2-hour infusions and then recuperate at home. “If those folks would not have had the treatment, they would have come through the emergency department and we would have had to admit the lion’s share of them,” he said.

It’s important to make sure people in high-risk groups know to seek out the therapy and to get it early, Dr. Edward said. He and his staff have been working with area doctors’ offices and nonprofit groups and relying on word of mouth.

“On multiple levels, we’re saying, ‘If you’ve tested positive for the virus, come and let us see if you are eligible,’ ” Dr. Edward said.

Greater awareness is a goal of the HHS effort, said Dr. John Redd, chief medical officer for the assistant secretary for preparedness and response. “These antibodies are meant for everyone,” he said. “Everyone across the country should have equal access to these products.”

For now, patients like Mr. Herritz, the Mississippi liver transplant recipient, say reality is falling well short of that goal. If he hadn’t continued to call in search of a referral, he wouldn’t have been treated. And without the therapy, Mr. Herritz believes, he was just days away from hospitalization.

“I think it’s horrible that if I didn’t have Twitter, I wouldn’t know anything about this,” he said. “I think about all the people who have died not knowing this was an option for high-risk individuals.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

By the time he tested positive for COVID-19 on Jan. 12, Gary Herritz was feeling pretty sick. He suspects he was infected a week earlier, during a medical appointment in which he saw health workers who were wearing masks beneath their noses or who had removed them entirely.

His scratchy throat had turned to a dry cough, headache, joint pain, and fever – all warning signs to Mr. Herritz, who underwent liver transplant surgery in 2012, followed by a rejection scare in 2018. He knew his compromised immune system left him especially vulnerable to a potentially deadly case of COVID.

“The thing with transplant patients is we can crash in a heartbeat,” said Mr. Herritz, 39. “The outcome for transplant patients [with COVID] is not good.”

On Twitter, Mr. Herritz had read about monoclonal antibody therapy, the treatment famously given to President Donald Trump and other high-profile politicians and authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use in high-risk COVID patients. But as his symptoms worsened, Mr. Herritz found himself very much on his own as he scrambled for access.

His primary care doctor wasn’t sure he qualified for treatment. His transplant team in Wisconsin, where he’d had the liver surgery, wasn’t calling back. No one was sure exactly where he should go to get it. From bed in Pascagoula, Miss., he spent 2 days punching in phone numbers, reaching out to health officials in four states, before he finally landed an appointment to receive a treatment aimed at keeping patients like him out of the hospital – and, perhaps, the morgue.

“I am not rich, I am not special, I am not a political figure,” Mr. Herritz, a former community service officer, wrote on Twitter. “I just called until someone would listen.”

Months after Mr. Trump emphatically credited an experimental antibody therapy for his quick recovery from covid and even as drugmakers ramp up supplies, only a trickle of the product has found its way into regular people. While hundreds of thousands of vials sit unused, sick patients who, research indicates, could benefit from early treatment – available for free – have largely been fending for themselves.

Federal officials have allocated more than 785,000 doses of two antibody treatments authorized for emergency use during the pandemic, and more than 550,000 doses have been delivered to sites across the nation. The federal government has contracted for nearly 2.5 million doses of the products from drugmakers Eli Lilly and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals at a cost of more than $4.4 billion.

So far, however, only about 30% of the available doses have been administered to patients, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services officials said.

Scores of high-risk COVID patients who are eligible remain unaware or have not been offered the option. Research has shown the therapy is most effective if given early in the illness, within 10 days of a positive COVID test. But many would-be recipients have missed this crucial window because of a patchwork system in the United States that can delay testing and diagnosis.

“The bottleneck here in the funnel is administration, not availability of the product,” said Dr. Janet Woodcock, a veteran FDA official in charge of therapeutics for the federal Operation Warp Speed effort.

Among the daunting hurdles: Until this week, there has been no nationwide system to tell people where they could obtain the drugs, which are delivered through IV infusions that require hours to administer and monitor. Finding space to keep COVID-infected patients separate from others has been difficult in some health centers slammed by the pandemic.

“The health care system is crashing,” Dr. Woodcock told reporters. “What we’ve heard around the country is the No. 1 barrier is staffing.”

At the same time, many hospitals have refused to offer the therapy because doctors were unimpressed with the research federal officials used to justify its use.

Monoclonal antibodies are lab-produced molecules that act as substitutes for the body’s own antibodies that fight infection. The COVID treatments are designed to block the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes infection from attaching to and entering human cells. Such treatments are usually prohibitively expensive, but for the time being the federal government is footing the bulk of the bill, though patients likely will be charged administrative fees.

Nationwide, nearly 4,000 sites offer the infusion therapies. But for patients and families of people most at risk – those 65 and older or with underlying health conditions – finding the sites and gaining access has been almost impossible, said Brian Nyquist, chief executive officer of the National Infusion Center Association, which is tracking supplies of the antibody products. Like Mr. Herritz, many seeking information about monoclonals find themselves on a lone crusade.

“If they’re not hammering the phones and advocating for access for their loved ones, others often won’t,” he said. “Tenacity is critical.”

Regeneron officials said they’re fielding calls about COVID treatments daily to the company’s medical information line. More than 3,500 people have flooded Eli Lilly’s COVID hotline with questions about access.

As of this week, all states are required to list on a federal locator map sites that have received the monoclonal antibody products, HHS officials said. The updated map shows wide distribution, but a listing doesn’t guarantee availability or access; patients still need to check. It’s best to confer with a primary care provider before reaching out to the centers. For best results, treatment should occur as soon as possible after a positive COVID test.

Some health systems have refused to offer the monoclonal antibody therapies because of doubts about the data used to authorize them. Early studies suggested that Lilly’s therapy, bamlanivimab, reduced the need for hospitalization or emergency treatment in outpatient COVID cases by about 70%, while Regeneron’s antibody cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab reduced the need by about 50%.

But those studies were small, just a few hundred subjects, and the results were limited. “A lot of doctors, actually, they’re not impressed with the data,” said Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease expert at Columbia University who cohosts the podcast “This Week in Virology.” “There really is still that question of, ‘Does this stuff really work?’ ”

As more patients are treated, however, there’s growing evidence that the therapies can keep high-risk patients out of the hospital, not only easing their recovery but also decreasing the burden on health systems struggling with record numbers of patients.

Dr. Raymund Razonable, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, said he has treated more than 2,500 COVID patients with monoclonal antibody therapy with promising results. “It’s looking good,” he said, declining to provide details because they’re embargoed for publication. “We are seeing reductions in hospitalizations; we’re seeing reductions in ICU care; we’re also seeing reductions in mortality.”

Banking on observations from Mayo experts and others, federal officials have been pushing for wider use of antibody therapies. HHS officials have partnered with hospitals in three hard-hit states – California, Arizona, and Nevada – to set up infusion centers that are treating dozens of COVID patients each day.

One of those sites went up in late December at El Centro Regional Medical Center in California’s Imperial County, an impoverished farming region on the state’s southern border that has recorded among the highest COVID infection rates in the state. For months, the medical center strained to absorb the overwhelming influx of patients, but chief executive Dr. Adolphe Edward said a new walk-up infusion site has already put a dent in the COVID load.

More than 130 people have been treated, all patients who were able to get the 2-hour infusions and then recuperate at home. “If those folks would not have had the treatment, they would have come through the emergency department and we would have had to admit the lion’s share of them,” he said.

It’s important to make sure people in high-risk groups know to seek out the therapy and to get it early, Dr. Edward said. He and his staff have been working with area doctors’ offices and nonprofit groups and relying on word of mouth.

“On multiple levels, we’re saying, ‘If you’ve tested positive for the virus, come and let us see if you are eligible,’ ” Dr. Edward said.

Greater awareness is a goal of the HHS effort, said Dr. John Redd, chief medical officer for the assistant secretary for preparedness and response. “These antibodies are meant for everyone,” he said. “Everyone across the country should have equal access to these products.”

For now, patients like Mr. Herritz, the Mississippi liver transplant recipient, say reality is falling well short of that goal. If he hadn’t continued to call in search of a referral, he wouldn’t have been treated. And without the therapy, Mr. Herritz believes, he was just days away from hospitalization.

“I think it’s horrible that if I didn’t have Twitter, I wouldn’t know anything about this,” he said. “I think about all the people who have died not knowing this was an option for high-risk individuals.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

By the time he tested positive for COVID-19 on Jan. 12, Gary Herritz was feeling pretty sick. He suspects he was infected a week earlier, during a medical appointment in which he saw health workers who were wearing masks beneath their noses or who had removed them entirely.

His scratchy throat had turned to a dry cough, headache, joint pain, and fever – all warning signs to Mr. Herritz, who underwent liver transplant surgery in 2012, followed by a rejection scare in 2018. He knew his compromised immune system left him especially vulnerable to a potentially deadly case of COVID.

“The thing with transplant patients is we can crash in a heartbeat,” said Mr. Herritz, 39. “The outcome for transplant patients [with COVID] is not good.”

On Twitter, Mr. Herritz had read about monoclonal antibody therapy, the treatment famously given to President Donald Trump and other high-profile politicians and authorized by the Food and Drug Administration for emergency use in high-risk COVID patients. But as his symptoms worsened, Mr. Herritz found himself very much on his own as he scrambled for access.

His primary care doctor wasn’t sure he qualified for treatment. His transplant team in Wisconsin, where he’d had the liver surgery, wasn’t calling back. No one was sure exactly where he should go to get it. From bed in Pascagoula, Miss., he spent 2 days punching in phone numbers, reaching out to health officials in four states, before he finally landed an appointment to receive a treatment aimed at keeping patients like him out of the hospital – and, perhaps, the morgue.

“I am not rich, I am not special, I am not a political figure,” Mr. Herritz, a former community service officer, wrote on Twitter. “I just called until someone would listen.”

Months after Mr. Trump emphatically credited an experimental antibody therapy for his quick recovery from covid and even as drugmakers ramp up supplies, only a trickle of the product has found its way into regular people. While hundreds of thousands of vials sit unused, sick patients who, research indicates, could benefit from early treatment – available for free – have largely been fending for themselves.

Federal officials have allocated more than 785,000 doses of two antibody treatments authorized for emergency use during the pandemic, and more than 550,000 doses have been delivered to sites across the nation. The federal government has contracted for nearly 2.5 million doses of the products from drugmakers Eli Lilly and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals at a cost of more than $4.4 billion.

So far, however, only about 30% of the available doses have been administered to patients, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services officials said.

Scores of high-risk COVID patients who are eligible remain unaware or have not been offered the option. Research has shown the therapy is most effective if given early in the illness, within 10 days of a positive COVID test. But many would-be recipients have missed this crucial window because of a patchwork system in the United States that can delay testing and diagnosis.

“The bottleneck here in the funnel is administration, not availability of the product,” said Dr. Janet Woodcock, a veteran FDA official in charge of therapeutics for the federal Operation Warp Speed effort.

Among the daunting hurdles: Until this week, there has been no nationwide system to tell people where they could obtain the drugs, which are delivered through IV infusions that require hours to administer and monitor. Finding space to keep COVID-infected patients separate from others has been difficult in some health centers slammed by the pandemic.

“The health care system is crashing,” Dr. Woodcock told reporters. “What we’ve heard around the country is the No. 1 barrier is staffing.”

At the same time, many hospitals have refused to offer the therapy because doctors were unimpressed with the research federal officials used to justify its use.

Monoclonal antibodies are lab-produced molecules that act as substitutes for the body’s own antibodies that fight infection. The COVID treatments are designed to block the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes infection from attaching to and entering human cells. Such treatments are usually prohibitively expensive, but for the time being the federal government is footing the bulk of the bill, though patients likely will be charged administrative fees.

Nationwide, nearly 4,000 sites offer the infusion therapies. But for patients and families of people most at risk – those 65 and older or with underlying health conditions – finding the sites and gaining access has been almost impossible, said Brian Nyquist, chief executive officer of the National Infusion Center Association, which is tracking supplies of the antibody products. Like Mr. Herritz, many seeking information about monoclonals find themselves on a lone crusade.

“If they’re not hammering the phones and advocating for access for their loved ones, others often won’t,” he said. “Tenacity is critical.”

Regeneron officials said they’re fielding calls about COVID treatments daily to the company’s medical information line. More than 3,500 people have flooded Eli Lilly’s COVID hotline with questions about access.

As of this week, all states are required to list on a federal locator map sites that have received the monoclonal antibody products, HHS officials said. The updated map shows wide distribution, but a listing doesn’t guarantee availability or access; patients still need to check. It’s best to confer with a primary care provider before reaching out to the centers. For best results, treatment should occur as soon as possible after a positive COVID test.

Some health systems have refused to offer the monoclonal antibody therapies because of doubts about the data used to authorize them. Early studies suggested that Lilly’s therapy, bamlanivimab, reduced the need for hospitalization or emergency treatment in outpatient COVID cases by about 70%, while Regeneron’s antibody cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab reduced the need by about 50%.

But those studies were small, just a few hundred subjects, and the results were limited. “A lot of doctors, actually, they’re not impressed with the data,” said Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease expert at Columbia University who cohosts the podcast “This Week in Virology.” “There really is still that question of, ‘Does this stuff really work?’ ”

As more patients are treated, however, there’s growing evidence that the therapies can keep high-risk patients out of the hospital, not only easing their recovery but also decreasing the burden on health systems struggling with record numbers of patients.

Dr. Raymund Razonable, an infectious disease expert at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, said he has treated more than 2,500 COVID patients with monoclonal antibody therapy with promising results. “It’s looking good,” he said, declining to provide details because they’re embargoed for publication. “We are seeing reductions in hospitalizations; we’re seeing reductions in ICU care; we’re also seeing reductions in mortality.”

Banking on observations from Mayo experts and others, federal officials have been pushing for wider use of antibody therapies. HHS officials have partnered with hospitals in three hard-hit states – California, Arizona, and Nevada – to set up infusion centers that are treating dozens of COVID patients each day.

One of those sites went up in late December at El Centro Regional Medical Center in California’s Imperial County, an impoverished farming region on the state’s southern border that has recorded among the highest COVID infection rates in the state. For months, the medical center strained to absorb the overwhelming influx of patients, but chief executive Dr. Adolphe Edward said a new walk-up infusion site has already put a dent in the COVID load.

More than 130 people have been treated, all patients who were able to get the 2-hour infusions and then recuperate at home. “If those folks would not have had the treatment, they would have come through the emergency department and we would have had to admit the lion’s share of them,” he said.

It’s important to make sure people in high-risk groups know to seek out the therapy and to get it early, Dr. Edward said. He and his staff have been working with area doctors’ offices and nonprofit groups and relying on word of mouth.

“On multiple levels, we’re saying, ‘If you’ve tested positive for the virus, come and let us see if you are eligible,’ ” Dr. Edward said.

Greater awareness is a goal of the HHS effort, said Dr. John Redd, chief medical officer for the assistant secretary for preparedness and response. “These antibodies are meant for everyone,” he said. “Everyone across the country should have equal access to these products.”

For now, patients like Mr. Herritz, the Mississippi liver transplant recipient, say reality is falling well short of that goal. If he hadn’t continued to call in search of a referral, he wouldn’t have been treated. And without the therapy, Mr. Herritz believes, he was just days away from hospitalization.

“I think it’s horrible that if I didn’t have Twitter, I wouldn’t know anything about this,” he said. “I think about all the people who have died not knowing this was an option for high-risk individuals.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

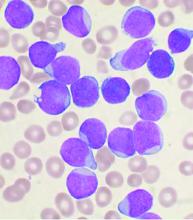

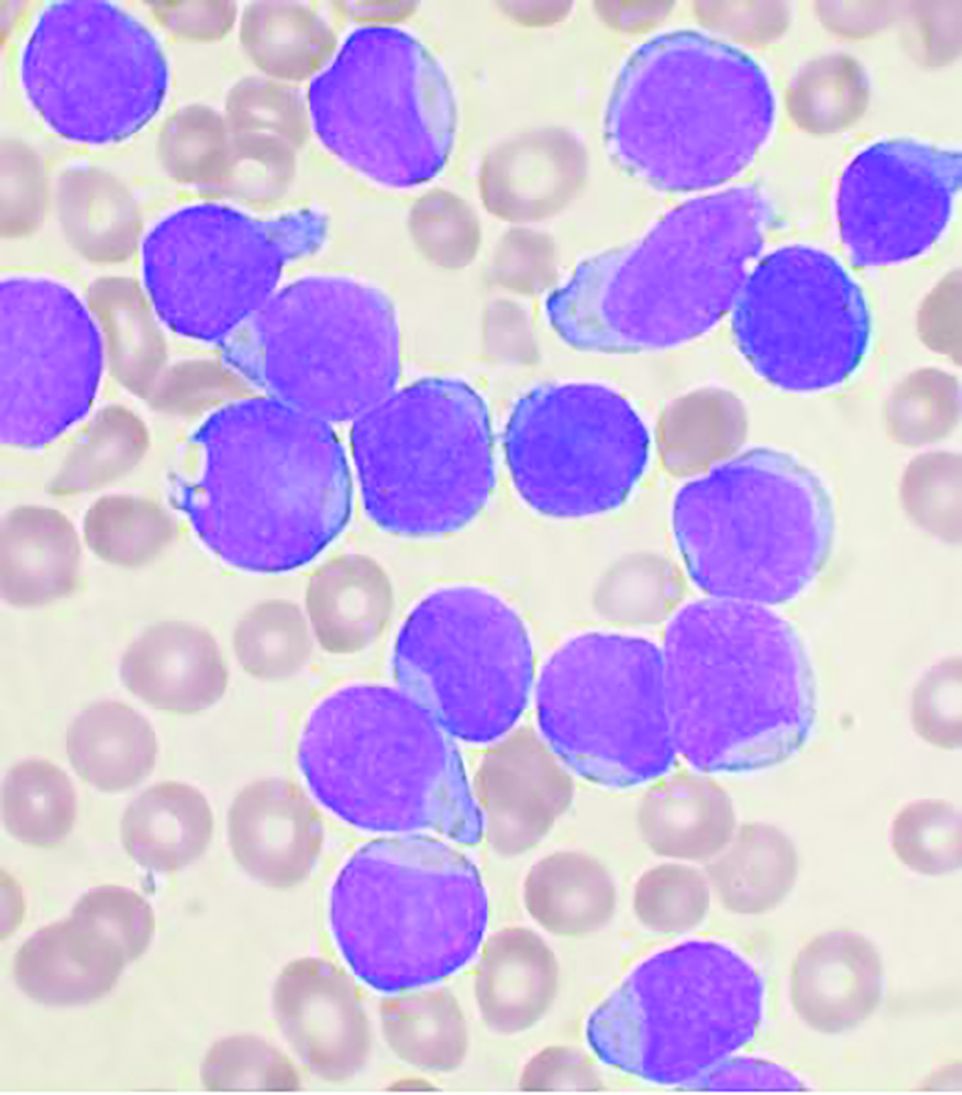

Allo-HSCT improves disease-free, but not overall survival in adults with ALL, compared with ped-inspired chemo

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (AHSCT) improved disease-free survival (DFS), compared with pediatric-inspired Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (BFM-95) chemotherapy in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to the results of retrospective study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia. However, overall survival (OS) was not significantly different between the two groups, as reported by Elifcan Aladag, MD, of the Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey, and colleagues.

Despite this, “AHSCT is recommended for all patients with suitable donors, but the risk of transplant-related mortality should be kept in mind,” according to the researchers.

The multicenter study compared two different treatment approaches (BFM-95 chemotherapy regimen and AHSCT). The BFM-95 chemotherapy group comprised 47 newly diagnosed ALL patients. The transplant cohort comprised 83 patients with ALL in first complete remission who received AHSCT from fully matched human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical siblings. Thirty-five of the AHSCT patients (42.1%) received chemotherapy at least until the M stage of the BFM-95 protocol.

The primary endpoints of the study were OS and duration of DFS. OS was defined from the day of starting BFM-95 chemotherapy until death from any cause, and DFS was calculated from the date of complete remission until the date of first relapse or death from any cause, whichever occurred first, according to the authors.

Study results

The median OS was 68 months in patients who underwent AHSCT and 46 months in patients treated only with BFM-95 (P = .3). Two- and 5-year OS rates were 78% and 60% , respectively, in the AHSCT group, and 69% and 64% in the BFM-95 group (P = .06 and .13, respectively).

The median DFS was 36.6 months in patients who underwent AHSCT and 28 months in patients treated with BFM-95 (P = .033). Two- and 5-year DFS rates were 68.5% and 57%, respectively, in the AHSCT group, and 63% and 38% respectively, in the BFM-95 group (P = .12 and .029, respectively).

Mortality in the BFM-95 group was the result of sepsis due to infections (fungal infection in two patients, resistant bacterial infections in four patients). In the AHSCT group, respectively, three and seven patients died of graft-versus-host disease and bacterial infections (with fungal infections in four patients and resistant bacterial infections in three patients), according to the researchers.

“In our study, no 2-year OS and DFS difference was observed in any treatment group; however, a significant difference occurred in 5-year DFS in favor of AHSCT. This may be due to transplant-related mortality in the first 2 years, which led to no statistically significant difference,” the authors stated.

“In order to further elucidate the role of AHSCT when pediatric-derived regimens are used for the treatment of adult lymphoblastic leukemia, higher-powered randomized prospective studies are needed,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (AHSCT) improved disease-free survival (DFS), compared with pediatric-inspired Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (BFM-95) chemotherapy in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to the results of retrospective study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia. However, overall survival (OS) was not significantly different between the two groups, as reported by Elifcan Aladag, MD, of the Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey, and colleagues.

Despite this, “AHSCT is recommended for all patients with suitable donors, but the risk of transplant-related mortality should be kept in mind,” according to the researchers.

The multicenter study compared two different treatment approaches (BFM-95 chemotherapy regimen and AHSCT). The BFM-95 chemotherapy group comprised 47 newly diagnosed ALL patients. The transplant cohort comprised 83 patients with ALL in first complete remission who received AHSCT from fully matched human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical siblings. Thirty-five of the AHSCT patients (42.1%) received chemotherapy at least until the M stage of the BFM-95 protocol.

The primary endpoints of the study were OS and duration of DFS. OS was defined from the day of starting BFM-95 chemotherapy until death from any cause, and DFS was calculated from the date of complete remission until the date of first relapse or death from any cause, whichever occurred first, according to the authors.

Study results

The median OS was 68 months in patients who underwent AHSCT and 46 months in patients treated only with BFM-95 (P = .3). Two- and 5-year OS rates were 78% and 60% , respectively, in the AHSCT group, and 69% and 64% in the BFM-95 group (P = .06 and .13, respectively).

The median DFS was 36.6 months in patients who underwent AHSCT and 28 months in patients treated with BFM-95 (P = .033). Two- and 5-year DFS rates were 68.5% and 57%, respectively, in the AHSCT group, and 63% and 38% respectively, in the BFM-95 group (P = .12 and .029, respectively).

Mortality in the BFM-95 group was the result of sepsis due to infections (fungal infection in two patients, resistant bacterial infections in four patients). In the AHSCT group, respectively, three and seven patients died of graft-versus-host disease and bacterial infections (with fungal infections in four patients and resistant bacterial infections in three patients), according to the researchers.

“In our study, no 2-year OS and DFS difference was observed in any treatment group; however, a significant difference occurred in 5-year DFS in favor of AHSCT. This may be due to transplant-related mortality in the first 2 years, which led to no statistically significant difference,” the authors stated.

“In order to further elucidate the role of AHSCT when pediatric-derived regimens are used for the treatment of adult lymphoblastic leukemia, higher-powered randomized prospective studies are needed,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (AHSCT) improved disease-free survival (DFS), compared with pediatric-inspired Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (BFM-95) chemotherapy in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), according to the results of retrospective study published in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia. However, overall survival (OS) was not significantly different between the two groups, as reported by Elifcan Aladag, MD, of the Hacettepe University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey, and colleagues.

Despite this, “AHSCT is recommended for all patients with suitable donors, but the risk of transplant-related mortality should be kept in mind,” according to the researchers.

The multicenter study compared two different treatment approaches (BFM-95 chemotherapy regimen and AHSCT). The BFM-95 chemotherapy group comprised 47 newly diagnosed ALL patients. The transplant cohort comprised 83 patients with ALL in first complete remission who received AHSCT from fully matched human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical siblings. Thirty-five of the AHSCT patients (42.1%) received chemotherapy at least until the M stage of the BFM-95 protocol.

The primary endpoints of the study were OS and duration of DFS. OS was defined from the day of starting BFM-95 chemotherapy until death from any cause, and DFS was calculated from the date of complete remission until the date of first relapse or death from any cause, whichever occurred first, according to the authors.

Study results

The median OS was 68 months in patients who underwent AHSCT and 46 months in patients treated only with BFM-95 (P = .3). Two- and 5-year OS rates were 78% and 60% , respectively, in the AHSCT group, and 69% and 64% in the BFM-95 group (P = .06 and .13, respectively).

The median DFS was 36.6 months in patients who underwent AHSCT and 28 months in patients treated with BFM-95 (P = .033). Two- and 5-year DFS rates were 68.5% and 57%, respectively, in the AHSCT group, and 63% and 38% respectively, in the BFM-95 group (P = .12 and .029, respectively).

Mortality in the BFM-95 group was the result of sepsis due to infections (fungal infection in two patients, resistant bacterial infections in four patients). In the AHSCT group, respectively, three and seven patients died of graft-versus-host disease and bacterial infections (with fungal infections in four patients and resistant bacterial infections in three patients), according to the researchers.

“In our study, no 2-year OS and DFS difference was observed in any treatment group; however, a significant difference occurred in 5-year DFS in favor of AHSCT. This may be due to transplant-related mortality in the first 2 years, which led to no statistically significant difference,” the authors stated.

“In order to further elucidate the role of AHSCT when pediatric-derived regimens are used for the treatment of adult lymphoblastic leukemia, higher-powered randomized prospective studies are needed,” they concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA & LEUKEMIA

Higher intensity therapy doesn’t increase surgical risk in esophageal cancer

The trial included patients with clinical stage IB, II, or III (non-T4) thoracic esophageal cancer randomly assigned to cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil (CF), CF plus radiotherapy (CF-RT), or docetaxel plus CF (DCF) prior to surgery.

Results showed the type of therapy did not significantly affect risk for either perioperative complications or deaths. There was also evidence to suggest that a lower risk of postoperative complications with DCF compared with CF might translate into improved prognosis with the addition of docetaxel, said Kazuo Koyanagi, MD, PhD, of National Cancer Center Hospital in Tokyo.

Dr. Koyanagi presented these results at the 2021 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

“Based on these results, we could say that preoperative chemotherapy with DCF and CF-RT didn’t increase the risk of postoperative complications when compared with standard CF, and whether the decrease in the risk in the DCF would be reflected in the improvement of prognosis should be examined in the future,” Dr. Koyanagi said.

Trial details

The JCOG1109 trial is a three-arm, phase 3 trial designed to see whether adding docetaxel or radiation to CF could improve outcomes. In the analysis presented here, the investigators examined whether the choice of regimen could affect the safety of esophagectomy, and they looked for risk factors for postoperative complications.

Patients with histologically proven squamous cell, adenosquamous, or basaloid carcinoma with locally advanced lesions in the thoracic esophagus were eligible.

The patients had to have good performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 0 or 1) and could not have had chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormonal therapy for any cancer, or prior therapy for esophageal cancer except for complete endoscopic mucosal or submucosal dissection.

A total of 601 patients were enrolled and randomized to receive one of the following treatments:

- CF, with cisplatin at a dose of 80 mg/m2 on day 1 and 5-fluorouracil at 800 mg/m2 on days 1-5 every 3 weeks for two cycles (199 assigned; 185 had surgery)

- DCF, with cisplatin at 70 mg/m2 on day 1, 5-fluorouracil at 750 mg/m2 on days 1-5, and docetaxel at 70 mg/m2 on day 1 every 3 weeks for three cycles (202 assigned; 183 had surgery)

- CF-RT, with cisplatin at 75 mg/m2 on day 1, 5-fluorouracil at 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1-4 every 4 weeks for two cycles, plus 1.8 Gy radiation divided into 23 fractions for a total of 41.4 Gy (200 assigned; 178 had surgery).

Patient age, body mass index, tumor location, clinical stage and node status were comparable among the treatment groups.

Operative characteristics (duration, blood loss, approach, extent of lymph node dissection) were generally similar between the arms as well, except that significantly fewer lymph nodes were harvested with CF-RT compared with either CF or DCF (median of 49, 58, and 59, respectively).

Results

Incidence rates of major postoperative complications – pneumonia, leakage, and recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis – were generally similar among the groups.

The cumulative rate of grade 2 or greater postoperative complications was significantly lower for DCF than for CF (P = .02), but not for DCF compared with CF-RT (P = .11). The rates were 43.7% with DCF, 47.8% with CF-RT, and 56.2% with CF.

The rate of grade 2 or greater chylothorax (leakage of lymphatics into the pleural space) was significantly higher with CF-RT than CF (5.1% vs. 1.1%, P = .03) but not with DCF vs. CF (3.8% vs. 1.1%, P = .10)

In multivariable analysis controlling for demographic, clinical, and operative characteristics, factors associated with lower risk for complications included:

- Middle esophageal tumor location vs. upper esophageal tumors (relative risk [RR], 0.79; P = .03)

- DCF (RR, 0.79; P = .02)

- A thoracoscopic vs. open approach (RR, 0.77; P = .002).

The only factor associated with higher risk was operative time longer than 492 minutes (RR, 1.26; P = .008).

Dr. Koyanagi said the reasons for the lower lymph node yield and more frequent chylothorax with CF-RT are unclear but may be related to tissue fibrosis from radiation exposure.

CROSS talk

“As a North American surgeon, I generally look to CROSS induction chemotherapy for the majority of my patients for both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus,” said invited discussant Jonathan Yeung, MD, PhD, of the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto.

The CROSS regimen consists of carboplatin titrated to an area under the curve of 2 mg/mL per minute and paclitaxel at 50 mg/m2 for 5 weeks with concurrent radiotherapy to a total dose of 41.4 Gy delivered in 23 fractions, 5 days per week.

Dr. Yeung noted that, of the eligible patients in JCOG1109, 92% of those assigned to DCF actually underwent surgery, and 90% of those assigned to CF-RT went on to surgery, compared with 98% of patients who had surgery in the CROSS trial, suggesting that the DCF and CF-RT regimens may be more toxic.

He also noted that the lower lymph node harvest seen with CF-RT was seen in other studies.

“I must say I’m always impressed by the lymph node yields that our Japanese colleagues can obtain at surgery, but this lower lymph node yield is also borne out in the CROSS data, where there are less lymph nodes harvested following chemoradiotherapy,” he said.

A higher rate of chylothorax with CF-RT was also seen in patients in the CROSS trial who were randomized to receive radiation compared with those who received chemotherapy alone.

“I await the final results to see if there is ultimately better survival,” Dr. Yeung said.

JCOG1109 was supported by grants from the National Cancer Center Research and Development Funds and Agency for Medical Research and Development of Japan. Dr. Koyanagi and Dr. Yeung reported no conflicts of interest.

The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

The trial included patients with clinical stage IB, II, or III (non-T4) thoracic esophageal cancer randomly assigned to cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil (CF), CF plus radiotherapy (CF-RT), or docetaxel plus CF (DCF) prior to surgery.

Results showed the type of therapy did not significantly affect risk for either perioperative complications or deaths. There was also evidence to suggest that a lower risk of postoperative complications with DCF compared with CF might translate into improved prognosis with the addition of docetaxel, said Kazuo Koyanagi, MD, PhD, of National Cancer Center Hospital in Tokyo.

Dr. Koyanagi presented these results at the 2021 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

“Based on these results, we could say that preoperative chemotherapy with DCF and CF-RT didn’t increase the risk of postoperative complications when compared with standard CF, and whether the decrease in the risk in the DCF would be reflected in the improvement of prognosis should be examined in the future,” Dr. Koyanagi said.

Trial details

The JCOG1109 trial is a three-arm, phase 3 trial designed to see whether adding docetaxel or radiation to CF could improve outcomes. In the analysis presented here, the investigators examined whether the choice of regimen could affect the safety of esophagectomy, and they looked for risk factors for postoperative complications.

Patients with histologically proven squamous cell, adenosquamous, or basaloid carcinoma with locally advanced lesions in the thoracic esophagus were eligible.

The patients had to have good performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 0 or 1) and could not have had chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormonal therapy for any cancer, or prior therapy for esophageal cancer except for complete endoscopic mucosal or submucosal dissection.

A total of 601 patients were enrolled and randomized to receive one of the following treatments:

- CF, with cisplatin at a dose of 80 mg/m2 on day 1 and 5-fluorouracil at 800 mg/m2 on days 1-5 every 3 weeks for two cycles (199 assigned; 185 had surgery)

- DCF, with cisplatin at 70 mg/m2 on day 1, 5-fluorouracil at 750 mg/m2 on days 1-5, and docetaxel at 70 mg/m2 on day 1 every 3 weeks for three cycles (202 assigned; 183 had surgery)

- CF-RT, with cisplatin at 75 mg/m2 on day 1, 5-fluorouracil at 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1-4 every 4 weeks for two cycles, plus 1.8 Gy radiation divided into 23 fractions for a total of 41.4 Gy (200 assigned; 178 had surgery).

Patient age, body mass index, tumor location, clinical stage and node status were comparable among the treatment groups.

Operative characteristics (duration, blood loss, approach, extent of lymph node dissection) were generally similar between the arms as well, except that significantly fewer lymph nodes were harvested with CF-RT compared with either CF or DCF (median of 49, 58, and 59, respectively).

Results

Incidence rates of major postoperative complications – pneumonia, leakage, and recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis – were generally similar among the groups.

The cumulative rate of grade 2 or greater postoperative complications was significantly lower for DCF than for CF (P = .02), but not for DCF compared with CF-RT (P = .11). The rates were 43.7% with DCF, 47.8% with CF-RT, and 56.2% with CF.

The rate of grade 2 or greater chylothorax (leakage of lymphatics into the pleural space) was significantly higher with CF-RT than CF (5.1% vs. 1.1%, P = .03) but not with DCF vs. CF (3.8% vs. 1.1%, P = .10)

In multivariable analysis controlling for demographic, clinical, and operative characteristics, factors associated with lower risk for complications included:

- Middle esophageal tumor location vs. upper esophageal tumors (relative risk [RR], 0.79; P = .03)

- DCF (RR, 0.79; P = .02)

- A thoracoscopic vs. open approach (RR, 0.77; P = .002).

The only factor associated with higher risk was operative time longer than 492 minutes (RR, 1.26; P = .008).

Dr. Koyanagi said the reasons for the lower lymph node yield and more frequent chylothorax with CF-RT are unclear but may be related to tissue fibrosis from radiation exposure.

CROSS talk

“As a North American surgeon, I generally look to CROSS induction chemotherapy for the majority of my patients for both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus,” said invited discussant Jonathan Yeung, MD, PhD, of the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto.

The CROSS regimen consists of carboplatin titrated to an area under the curve of 2 mg/mL per minute and paclitaxel at 50 mg/m2 for 5 weeks with concurrent radiotherapy to a total dose of 41.4 Gy delivered in 23 fractions, 5 days per week.

Dr. Yeung noted that, of the eligible patients in JCOG1109, 92% of those assigned to DCF actually underwent surgery, and 90% of those assigned to CF-RT went on to surgery, compared with 98% of patients who had surgery in the CROSS trial, suggesting that the DCF and CF-RT regimens may be more toxic.

He also noted that the lower lymph node harvest seen with CF-RT was seen in other studies.

“I must say I’m always impressed by the lymph node yields that our Japanese colleagues can obtain at surgery, but this lower lymph node yield is also borne out in the CROSS data, where there are less lymph nodes harvested following chemoradiotherapy,” he said.

A higher rate of chylothorax with CF-RT was also seen in patients in the CROSS trial who were randomized to receive radiation compared with those who received chemotherapy alone.

“I await the final results to see if there is ultimately better survival,” Dr. Yeung said.

JCOG1109 was supported by grants from the National Cancer Center Research and Development Funds and Agency for Medical Research and Development of Japan. Dr. Koyanagi and Dr. Yeung reported no conflicts of interest.

The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

The trial included patients with clinical stage IB, II, or III (non-T4) thoracic esophageal cancer randomly assigned to cisplatin plus 5-fluorouracil (CF), CF plus radiotherapy (CF-RT), or docetaxel plus CF (DCF) prior to surgery.

Results showed the type of therapy did not significantly affect risk for either perioperative complications or deaths. There was also evidence to suggest that a lower risk of postoperative complications with DCF compared with CF might translate into improved prognosis with the addition of docetaxel, said Kazuo Koyanagi, MD, PhD, of National Cancer Center Hospital in Tokyo.

Dr. Koyanagi presented these results at the 2021 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium.

“Based on these results, we could say that preoperative chemotherapy with DCF and CF-RT didn’t increase the risk of postoperative complications when compared with standard CF, and whether the decrease in the risk in the DCF would be reflected in the improvement of prognosis should be examined in the future,” Dr. Koyanagi said.

Trial details

The JCOG1109 trial is a three-arm, phase 3 trial designed to see whether adding docetaxel or radiation to CF could improve outcomes. In the analysis presented here, the investigators examined whether the choice of regimen could affect the safety of esophagectomy, and they looked for risk factors for postoperative complications.

Patients with histologically proven squamous cell, adenosquamous, or basaloid carcinoma with locally advanced lesions in the thoracic esophagus were eligible.

The patients had to have good performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 0 or 1) and could not have had chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormonal therapy for any cancer, or prior therapy for esophageal cancer except for complete endoscopic mucosal or submucosal dissection.

A total of 601 patients were enrolled and randomized to receive one of the following treatments:

- CF, with cisplatin at a dose of 80 mg/m2 on day 1 and 5-fluorouracil at 800 mg/m2 on days 1-5 every 3 weeks for two cycles (199 assigned; 185 had surgery)

- DCF, with cisplatin at 70 mg/m2 on day 1, 5-fluorouracil at 750 mg/m2 on days 1-5, and docetaxel at 70 mg/m2 on day 1 every 3 weeks for three cycles (202 assigned; 183 had surgery)

- CF-RT, with cisplatin at 75 mg/m2 on day 1, 5-fluorouracil at 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1-4 every 4 weeks for two cycles, plus 1.8 Gy radiation divided into 23 fractions for a total of 41.4 Gy (200 assigned; 178 had surgery).

Patient age, body mass index, tumor location, clinical stage and node status were comparable among the treatment groups.

Operative characteristics (duration, blood loss, approach, extent of lymph node dissection) were generally similar between the arms as well, except that significantly fewer lymph nodes were harvested with CF-RT compared with either CF or DCF (median of 49, 58, and 59, respectively).

Results

Incidence rates of major postoperative complications – pneumonia, leakage, and recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis – were generally similar among the groups.

The cumulative rate of grade 2 or greater postoperative complications was significantly lower for DCF than for CF (P = .02), but not for DCF compared with CF-RT (P = .11). The rates were 43.7% with DCF, 47.8% with CF-RT, and 56.2% with CF.

The rate of grade 2 or greater chylothorax (leakage of lymphatics into the pleural space) was significantly higher with CF-RT than CF (5.1% vs. 1.1%, P = .03) but not with DCF vs. CF (3.8% vs. 1.1%, P = .10)

In multivariable analysis controlling for demographic, clinical, and operative characteristics, factors associated with lower risk for complications included:

- Middle esophageal tumor location vs. upper esophageal tumors (relative risk [RR], 0.79; P = .03)

- DCF (RR, 0.79; P = .02)

- A thoracoscopic vs. open approach (RR, 0.77; P = .002).

The only factor associated with higher risk was operative time longer than 492 minutes (RR, 1.26; P = .008).

Dr. Koyanagi said the reasons for the lower lymph node yield and more frequent chylothorax with CF-RT are unclear but may be related to tissue fibrosis from radiation exposure.

CROSS talk

“As a North American surgeon, I generally look to CROSS induction chemotherapy for the majority of my patients for both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus,” said invited discussant Jonathan Yeung, MD, PhD, of the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto.

The CROSS regimen consists of carboplatin titrated to an area under the curve of 2 mg/mL per minute and paclitaxel at 50 mg/m2 for 5 weeks with concurrent radiotherapy to a total dose of 41.4 Gy delivered in 23 fractions, 5 days per week.

Dr. Yeung noted that, of the eligible patients in JCOG1109, 92% of those assigned to DCF actually underwent surgery, and 90% of those assigned to CF-RT went on to surgery, compared with 98% of patients who had surgery in the CROSS trial, suggesting that the DCF and CF-RT regimens may be more toxic.

He also noted that the lower lymph node harvest seen with CF-RT was seen in other studies.

“I must say I’m always impressed by the lymph node yields that our Japanese colleagues can obtain at surgery, but this lower lymph node yield is also borne out in the CROSS data, where there are less lymph nodes harvested following chemoradiotherapy,” he said.

A higher rate of chylothorax with CF-RT was also seen in patients in the CROSS trial who were randomized to receive radiation compared with those who received chemotherapy alone.

“I await the final results to see if there is ultimately better survival,” Dr. Yeung said.

JCOG1109 was supported by grants from the National Cancer Center Research and Development Funds and Agency for Medical Research and Development of Japan. Dr. Koyanagi and Dr. Yeung reported no conflicts of interest.

The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

FROM GI Cancers Symposium 2021

No benefit seen with radiotherapy in borderline resectable pancreatic cancer

Patients with borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) are often treated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both before undergoing surgery, but the optimal regimen in this setting is controversial.

Results from the Alliance A021501 study suggest the reference regimen should be neoadjuvant therapy with modified FOLFIRINOX (oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, irinotecan 180 mg/m2, leucovorin 400 mg/m2, and infusional 5-fluorouracil 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours), according to Matthew Katz, MD, FACS, chief of the pancreatic surgery service at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

This regimen improved survival for patients with PDAC, relative to historical data. For patients who received mFOLFIRINOX, the overall 18-month survival rate was 66.4%. However, when this regimen was combined with hypofractionated radiotherapy, the survival benefit was significantly lower, at 47.3%.

These findings were presented at the 2021 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium (GICS), which was held online this year.

“ASCO guidelines recommend that preoperative therapy be administered to patients with localized pancreatic adenocarcinoma who have tumors that have a significant radiographic interface with the major mesenteric blood vessels, as these patients are at high risk for a margin-positive operation and short survival when pancreatectomy is performed de novo,” Dr. Katz explained.

Although both chemotherapy and radiotherapy are used in these patients, there is no consensus as to the best approach, he commented.

The goal of Alliance A021501 “was to define a reference preoperative regimen for future trials of preoperative therapy,” he said.

The cohort included 126 patients who were randomly assigned to receive either mFOLFIRINOX (arm A) or mFOLFIRINOX plus radiotherapy (arm B).

Patients in arm A received eight cycles of neoadjuvant mFOLFIRINOX. Patients in arm B received seven cycles of mFOLFIRINOX followed by 5 days of hypofractionated radiotherapy with either stereotactic body radiotherapy or hypofractionated image-guided radiotherapy.

In either arm, patients who did not experience disease progression underwent pancreatectomy followed by four cycles of adjuvant mFOLFOX6 (oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, leucovorin 400 mg/m2, and infusional 5-fluorouracil 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours).

The study’s primary endpoint was 18-month overall survival in comparison to a historical control of 50%. “An interim futility analysis was scheduled to be conducted following treatment of 30 patients on each arm,” Dr. Katz said. “Either arm in which 11 or fewer patients underwent [curative] R0 resection on protocol was to be declared futile and closed to further enrollment.

“With 62 evaluable patients in each arm, the final efficacy analysis was powered to detect an improvement in 18-month overall survival of 13% over the historical rate of 50%,” said Dr. Katz. “The two arms would be compared only if both were declared efficacious.”

At the interim analysis, 57% of the first 30 patients in arm A had undergone a resection, vs. 33% in arm B. Therefore, arm B was considered futile and was closed to accrual.

The median overall survival in arm A was 29.8 months. The median event-free survival was 15 months. Nearly half (49%) of patients proceeded to pancreatectomy following neoadjuvant therapy. The R0 resection rate was 88%, the pathologic complete response rate was 0%, and the 18-month overall survival rate was 93.1%.

For the patients in arm B, which had been closed to accrual, the median overall survival was 17.1 months, and the median event-free survival was 10.2 months. About one-third (35%) of patients were able to proceed to pancreatectomy. The R0 resection rate was 74%, the pathologic complete response rate was 11%, and the 18-month overall survival rate was 78.9%.

“Preoperative mFOLFIRINOX was associated with favorable overall survival relative to historical criteria in patients with borderline resectable PDAC, and mFOLFIRINOX with radiation therapy met the predefined futility boundary for R0 resection at interim analysis,” Dr. Katz concluded. “Therefore, mFOLFIRINOX represents a reference perioperative regimen for patients with borderline resectable PDAC.”

Further investigation needed

The paper’s discussant, Rebecca A. Snyder, MD, MPH, of the Brody School of Medicine, East Carolina University, Greenville, N.C., emphasized that this study was not designed or powered to directly compare chemotherapy alone with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy in the neoadjuvant setting.

She noted that it is surprising that the radiotherapy arm was closed early. She said the reasons for this remain unclear, although a few possible reasons can be speculated.

“Based on multiple studies in both the adjuvant and neoadjuvant setting, including the Alliance [A021501] trial presented today, there is no convincing randomized data that radiation therapy prolongs survival in any population of unselected patients with pancreatic cancer,” said Dr. Snyder.

“Certainly, follow-up questions still remain, specifically regarding the role for non-SBRT radiation in the preoperative setting, which may be answered by the ongoing PREOPANC-2 and PRODIGE 44 trials,” she said.

She added that the “addition of SBRT in the preoperative setting does not appear to be justified.”

The role of radiotherapy for subsets of patients remains unknown, and future investigation should focus on patient-centered endpoints, such as symptomatic local control rates, Dr. Snyder concluded.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Katz has had a consulting or advisory role for AbbVie and Alcresta Therapeutics. Dr. Snyder has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium is sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with borderline resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) are often treated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both before undergoing surgery, but the optimal regimen in this setting is controversial.

Results from the Alliance A021501 study suggest the reference regimen should be neoadjuvant therapy with modified FOLFIRINOX (oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, irinotecan 180 mg/m2, leucovorin 400 mg/m2, and infusional 5-fluorouracil 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours), according to Matthew Katz, MD, FACS, chief of the pancreatic surgery service at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

This regimen improved survival for patients with PDAC, relative to historical data. For patients who received mFOLFIRINOX, the overall 18-month survival rate was 66.4%. However, when this regimen was combined with hypofractionated radiotherapy, the survival benefit was significantly lower, at 47.3%.

These findings were presented at the 2021 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium (GICS), which was held online this year.

“ASCO guidelines recommend that preoperative therapy be administered to patients with localized pancreatic adenocarcinoma who have tumors that have a significant radiographic interface with the major mesenteric blood vessels, as these patients are at high risk for a margin-positive operation and short survival when pancreatectomy is performed de novo,” Dr. Katz explained.

Although both chemotherapy and radiotherapy are used in these patients, there is no consensus as to the best approach, he commented.

The goal of Alliance A021501 “was to define a reference preoperative regimen for future trials of preoperative therapy,” he said.

The cohort included 126 patients who were randomly assigned to receive either mFOLFIRINOX (arm A) or mFOLFIRINOX plus radiotherapy (arm B).

Patients in arm A received eight cycles of neoadjuvant mFOLFIRINOX. Patients in arm B received seven cycles of mFOLFIRINOX followed by 5 days of hypofractionated radiotherapy with either stereotactic body radiotherapy or hypofractionated image-guided radiotherapy.

In either arm, patients who did not experience disease progression underwent pancreatectomy followed by four cycles of adjuvant mFOLFOX6 (oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, leucovorin 400 mg/m2, and infusional 5-fluorouracil 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours).

The study’s primary endpoint was 18-month overall survival in comparison to a historical control of 50%. “An interim futility analysis was scheduled to be conducted following treatment of 30 patients on each arm,” Dr. Katz said. “Either arm in which 11 or fewer patients underwent [curative] R0 resection on protocol was to be declared futile and closed to further enrollment.

“With 62 evaluable patients in each arm, the final efficacy analysis was powered to detect an improvement in 18-month overall survival of 13% over the historical rate of 50%,” said Dr. Katz. “The two arms would be compared only if both were declared efficacious.”

At the interim analysis, 57% of the first 30 patients in arm A had undergone a resection, vs. 33% in arm B. Therefore, arm B was considered futile and was closed to accrual.