User login

Complete PCI beats culprit-lesion-only PCI in STEMI patients with multivessel CAD

Background: Previous trials have shown a reduction in composite outcomes if STEMI patients undergo staged PCI of nonculprit lesions discovered incidentally at the time of primary PCI for STEMI. However, no randomized trial has had the power to assess if staged PCI of nonculprit lesions reduces cardiovascular death or MI.

Study design: Prospective randomized clinical trial.

Setting: PCI-capable centers in 31 countries.

Synopsis: In this study, if multivessel disease was identified during primary PCI for STEMI, patients were randomized to either culprit-lesion-only PCI or complete revascularization with staged PCI of all suitable nonculprit lesions (either during the index hospitalization or up to 45 days after randomization).

Overall, 4,041 patients from 140 centers were randomized with median 3-year follow-up. The complete revascularization group had lower rates of the primary composite outcome of death from cardiovascular disease or new MI (absolute reduction, 2.7%; 7.8% vs. 10.5%; number needed to treat, 37; hazard ratio, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.91; P = .004). This finding was driven by lower incidence of new MI in the complete revascularization group – the incidence of death was similar between the groups. A coprimary composite outcome of death from cardiovascular causes, new MI, or ischemia-driven revascularization also favored complete revascularization, with an absolute risk reduction of 7.8% (8.9% vs. 16.7%; NNT, 13; HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.43-0.61; P less than .001). No statistically significant differences between groups were noted for the safety outcomes of major bleeding, stroke, stent thrombosis, or contrast-induced kidney injury.

Bottom line: Patients with STEMI who have multivessel disease incidentally discovered during primary PCI have a lower incidence of new MI and ischemia-driven revascularization when they undergo complete revascularization of all suitable lesions, as opposed to PCI of only their culprit lesion.

Citation: Mehta SR et al. Complete revascularization with multivessel PCI for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 10;381:1411-21.

Dr. Porter is chief quality and safety resident at the Rocky Mountain Veterans Affairs Regional Medical Center, Aurora, Colo.

Background: Previous trials have shown a reduction in composite outcomes if STEMI patients undergo staged PCI of nonculprit lesions discovered incidentally at the time of primary PCI for STEMI. However, no randomized trial has had the power to assess if staged PCI of nonculprit lesions reduces cardiovascular death or MI.

Study design: Prospective randomized clinical trial.

Setting: PCI-capable centers in 31 countries.

Synopsis: In this study, if multivessel disease was identified during primary PCI for STEMI, patients were randomized to either culprit-lesion-only PCI or complete revascularization with staged PCI of all suitable nonculprit lesions (either during the index hospitalization or up to 45 days after randomization).

Overall, 4,041 patients from 140 centers were randomized with median 3-year follow-up. The complete revascularization group had lower rates of the primary composite outcome of death from cardiovascular disease or new MI (absolute reduction, 2.7%; 7.8% vs. 10.5%; number needed to treat, 37; hazard ratio, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.91; P = .004). This finding was driven by lower incidence of new MI in the complete revascularization group – the incidence of death was similar between the groups. A coprimary composite outcome of death from cardiovascular causes, new MI, or ischemia-driven revascularization also favored complete revascularization, with an absolute risk reduction of 7.8% (8.9% vs. 16.7%; NNT, 13; HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.43-0.61; P less than .001). No statistically significant differences between groups were noted for the safety outcomes of major bleeding, stroke, stent thrombosis, or contrast-induced kidney injury.

Bottom line: Patients with STEMI who have multivessel disease incidentally discovered during primary PCI have a lower incidence of new MI and ischemia-driven revascularization when they undergo complete revascularization of all suitable lesions, as opposed to PCI of only their culprit lesion.

Citation: Mehta SR et al. Complete revascularization with multivessel PCI for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 10;381:1411-21.

Dr. Porter is chief quality and safety resident at the Rocky Mountain Veterans Affairs Regional Medical Center, Aurora, Colo.

Background: Previous trials have shown a reduction in composite outcomes if STEMI patients undergo staged PCI of nonculprit lesions discovered incidentally at the time of primary PCI for STEMI. However, no randomized trial has had the power to assess if staged PCI of nonculprit lesions reduces cardiovascular death or MI.

Study design: Prospective randomized clinical trial.

Setting: PCI-capable centers in 31 countries.

Synopsis: In this study, if multivessel disease was identified during primary PCI for STEMI, patients were randomized to either culprit-lesion-only PCI or complete revascularization with staged PCI of all suitable nonculprit lesions (either during the index hospitalization or up to 45 days after randomization).

Overall, 4,041 patients from 140 centers were randomized with median 3-year follow-up. The complete revascularization group had lower rates of the primary composite outcome of death from cardiovascular disease or new MI (absolute reduction, 2.7%; 7.8% vs. 10.5%; number needed to treat, 37; hazard ratio, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.91; P = .004). This finding was driven by lower incidence of new MI in the complete revascularization group – the incidence of death was similar between the groups. A coprimary composite outcome of death from cardiovascular causes, new MI, or ischemia-driven revascularization also favored complete revascularization, with an absolute risk reduction of 7.8% (8.9% vs. 16.7%; NNT, 13; HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.43-0.61; P less than .001). No statistically significant differences between groups were noted for the safety outcomes of major bleeding, stroke, stent thrombosis, or contrast-induced kidney injury.

Bottom line: Patients with STEMI who have multivessel disease incidentally discovered during primary PCI have a lower incidence of new MI and ischemia-driven revascularization when they undergo complete revascularization of all suitable lesions, as opposed to PCI of only their culprit lesion.

Citation: Mehta SR et al. Complete revascularization with multivessel PCI for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 10;381:1411-21.

Dr. Porter is chief quality and safety resident at the Rocky Mountain Veterans Affairs Regional Medical Center, Aurora, Colo.

Hair Follicle Bulb Region: A Potential Nidus for the Formation of Osteoma Cutis

The term osteoma cutis (OC) is defined as the ossification or bone formation either in the dermis or hypodermis. 1 It is heterotopic in nature, referring to extraneous bone formation in soft tissue. Osteoma cutis was first described in 1858 2,3 ; in 1868, the multiple miliary form on the face was described. 4 Cutaneous ossification can take many forms, ranging from occurrence in a nevus (nevus of Nanta) to its association with rare genetic disorders, such as fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva and Albright hereditary osteodystrophy.

Some of these ossifications are classified as primary; others are secondary, depending on the presence of a preexisting lesion (eg, pilomatricoma, basal cell carcinoma). However, certain conditions, such as multiple miliary osteoma of the face, can be difficult to classify due to the presence or absence of a history of acne or dermabrasion, or both. The secondary forms more commonly are encountered due to their incidental association with an excised lesion, such as pilomatricoma.

A precursor of OC has been neglected in the literature despite its common occurrence. It may have been peripherally alluded to in the literature in reference to the miliary form of OC.5,6 The cases reported here demonstrate small round nodules of calcification or ossification, or both, in punch biopsies and excision specimens from hair-bearing areas of skin, especially from the head and neck. These lesions are mainly observed in the peripilar location or more specifically in the approximate location of the hair bulb.

This article reviews a possible mechanism of formation of these osteocalcific micronodules. These often-encountered micronodules are small osteocalcific lesions without typical bone or well-formed OC, such as trabeculae formation or fatty marrow, and may represent earliest stages in the formation of OC.

Clinical Observations

During routine dermatopathologic practice, I observed incidental small osteocalcific micronodules in close proximity to the lower part of the hair follicle in multiple cases. These nodules were not related to the main lesion in the specimen and were not the reason for the biopsy or excision. Most of the time, these micronodules were noted in excision or re-excision specimens or in a punch biopsy.

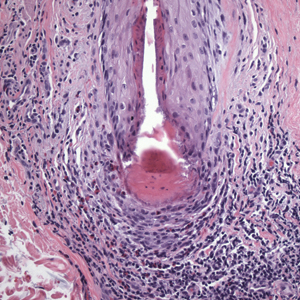

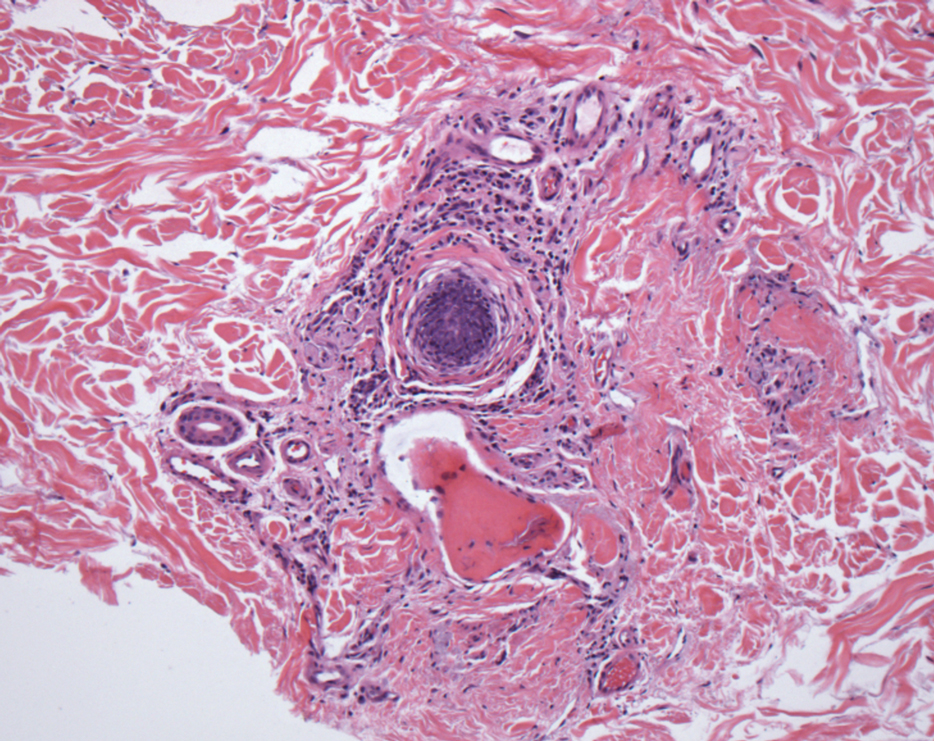

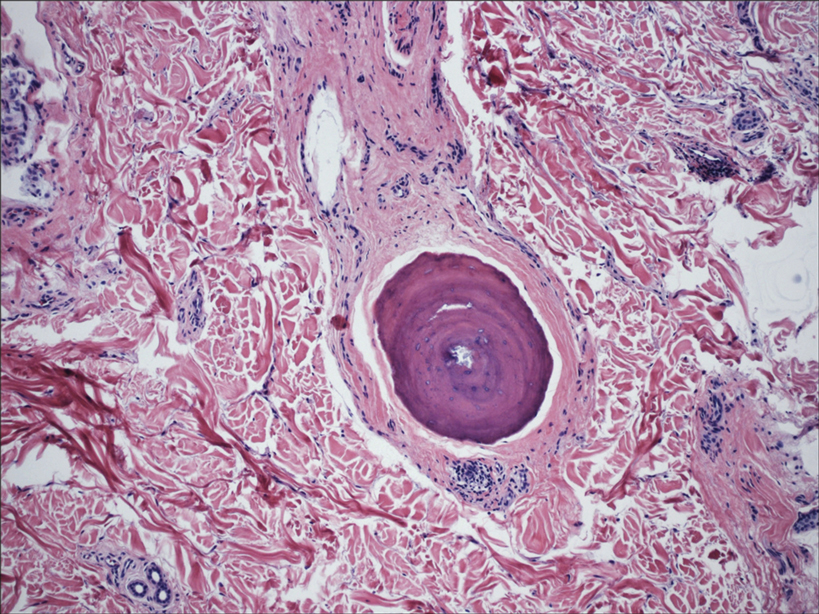

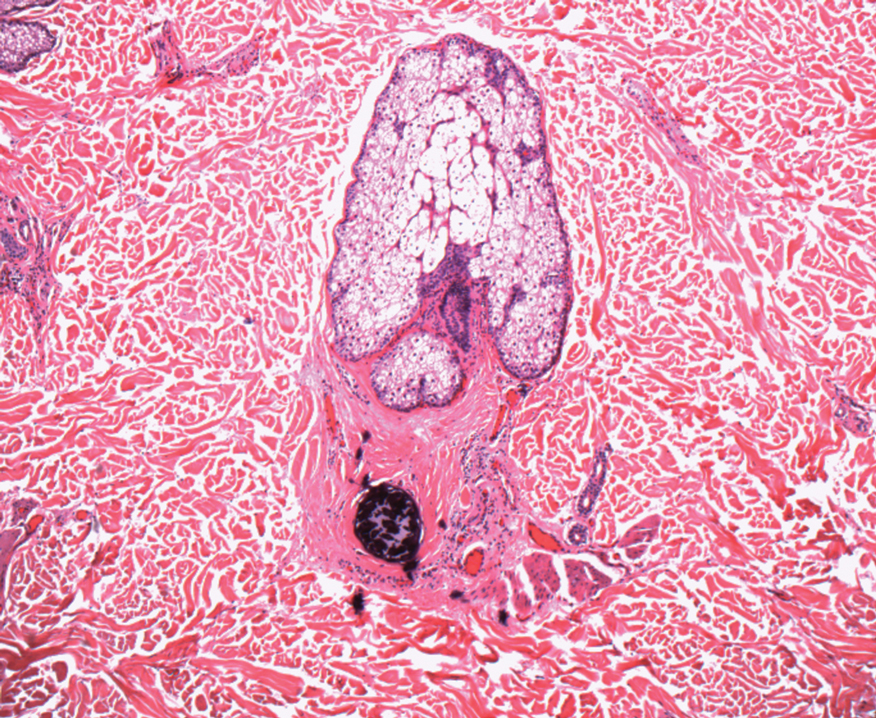

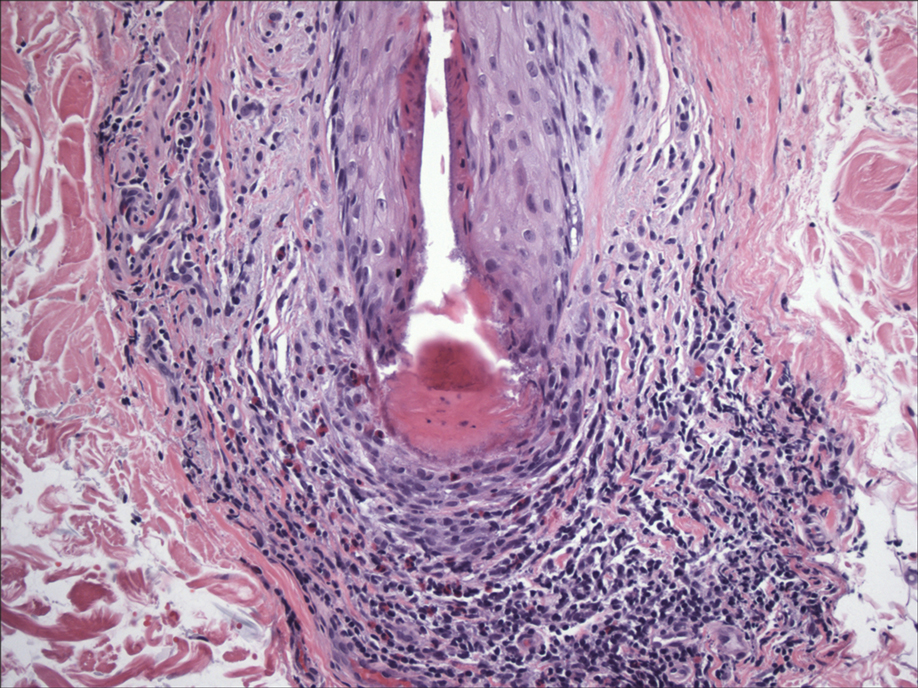

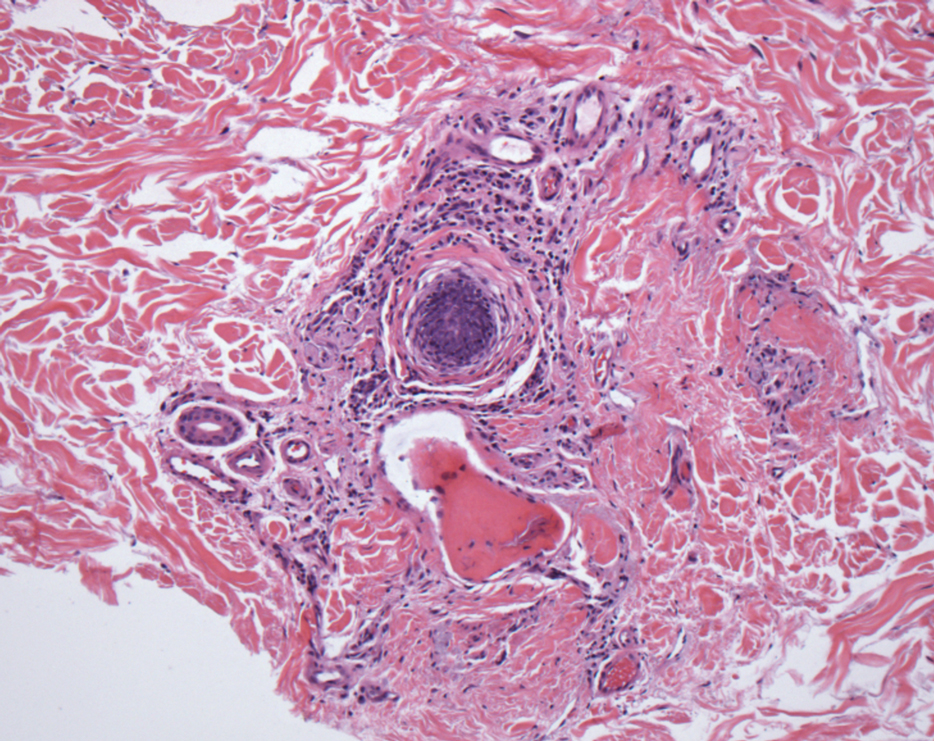

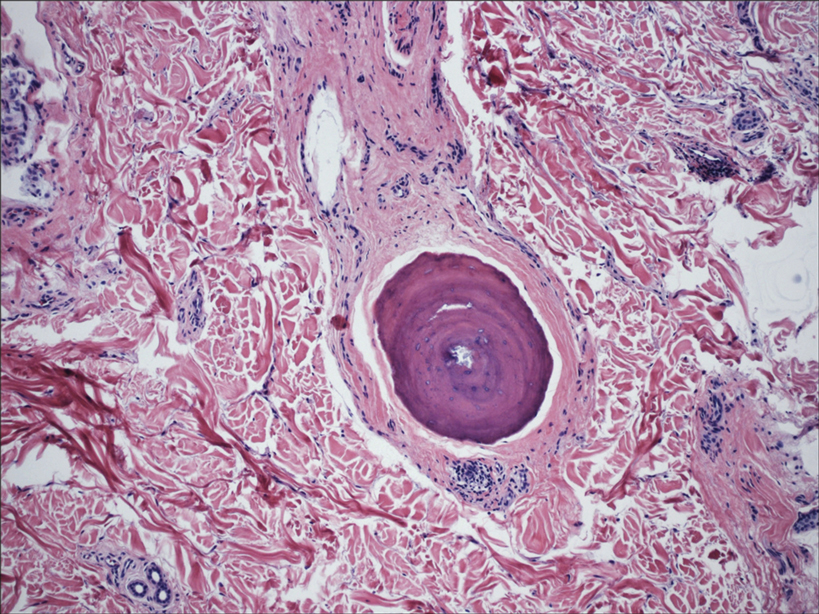

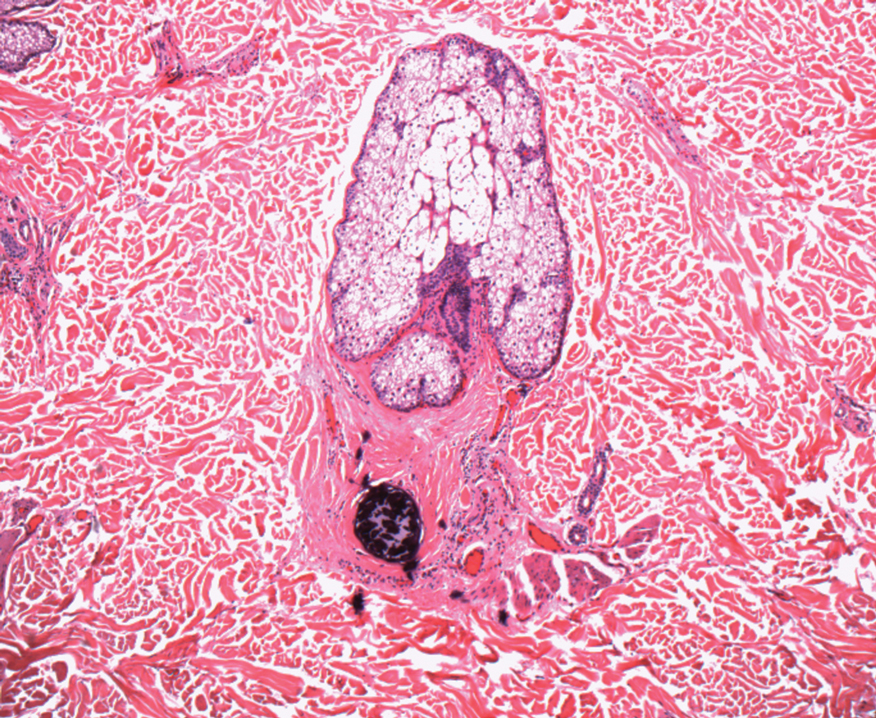

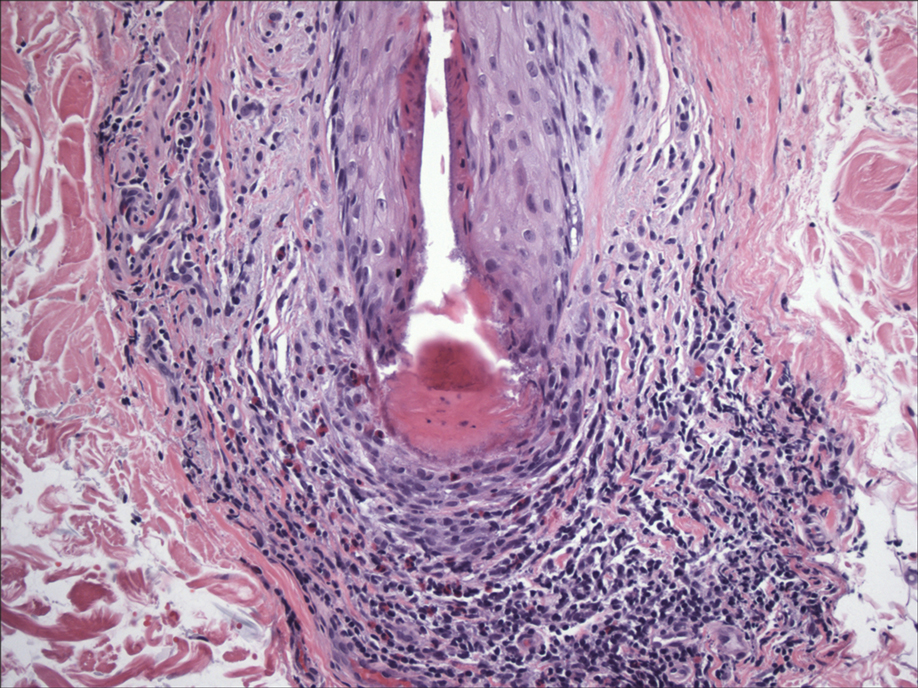

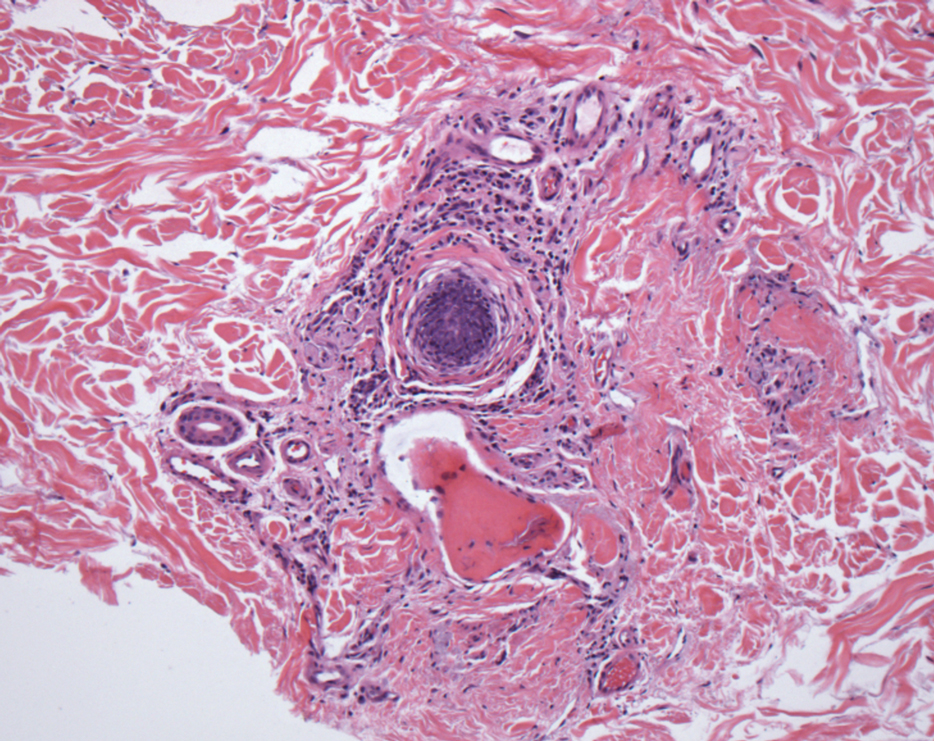

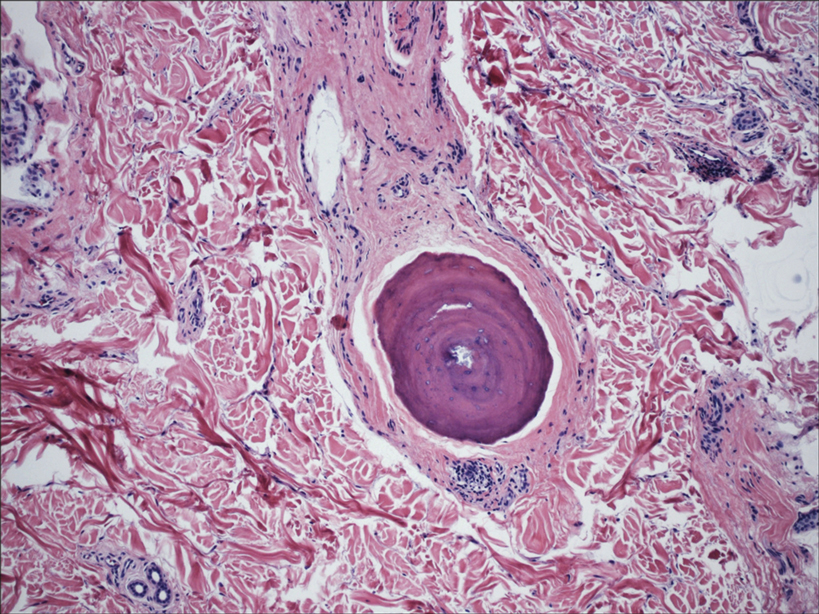

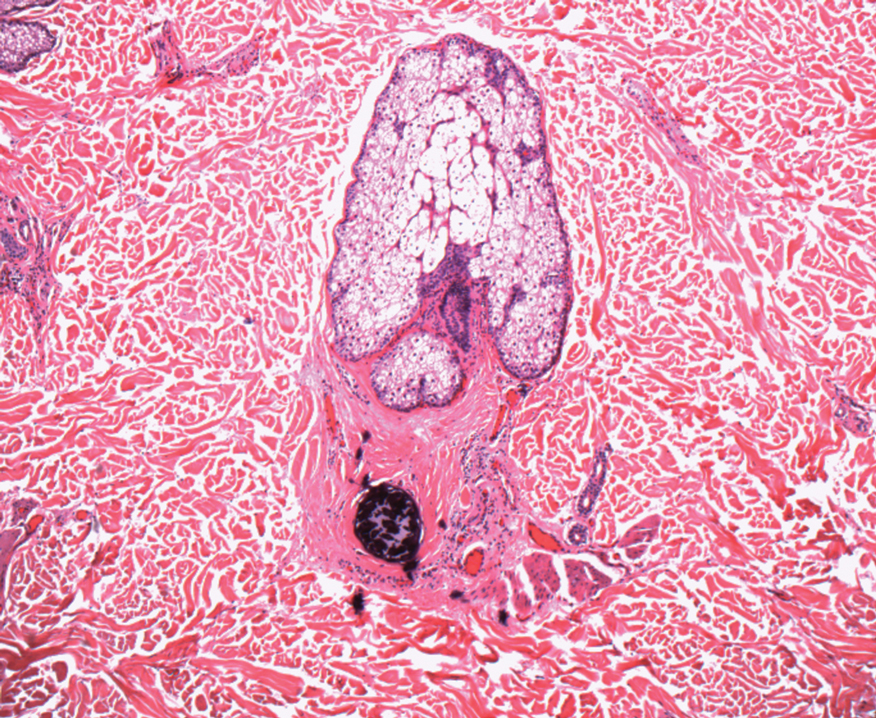

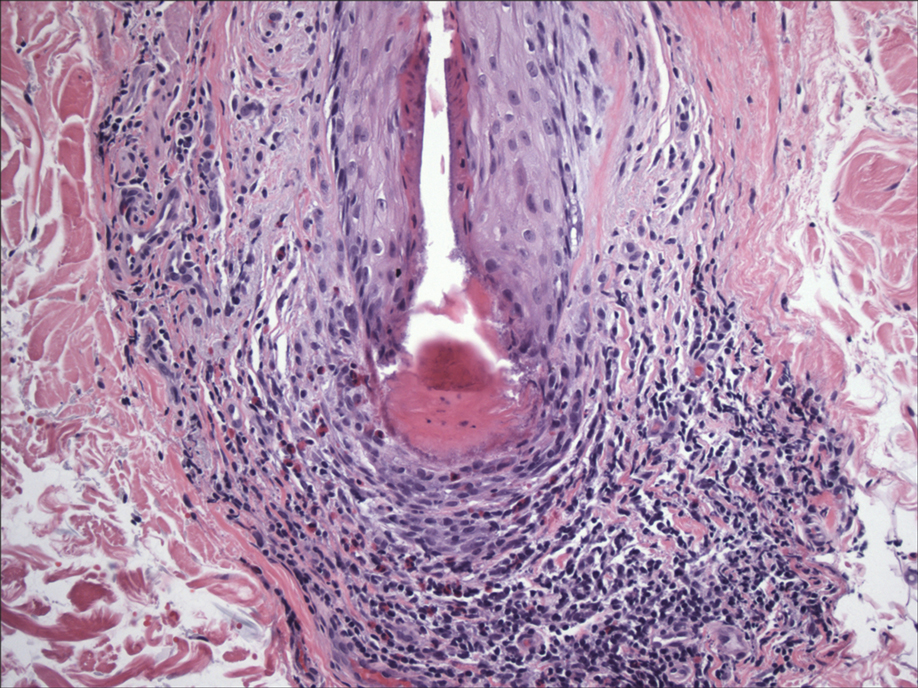

In my review of multiple unrelated cases over time, incidental osteocalcific micronodules were observed occasionally in punch biopsies and excision specimens during routine practice. These micronodules were mainly located in the vicinity of a hair bulb (Figure 1). If the hair bulb was not present in the sections, these micronodules were noted near or within the fibrous tract (Figure 2) or beneath a sebaceous lobule (Figure 3). In an exceptional case, a small round deposit of osteoid was seen forming just above the dermal papilla of the hair bulb (Figure 4).

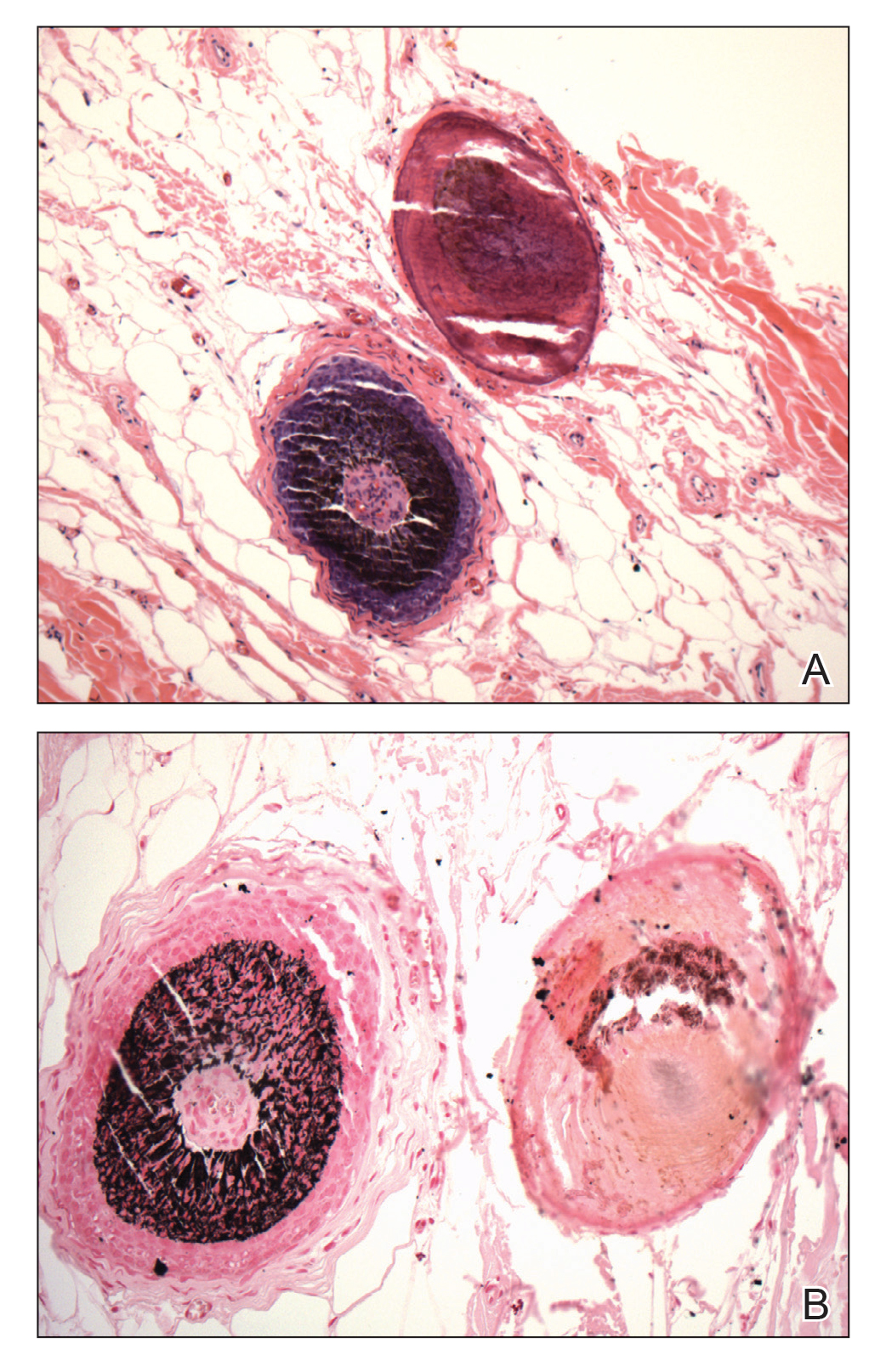

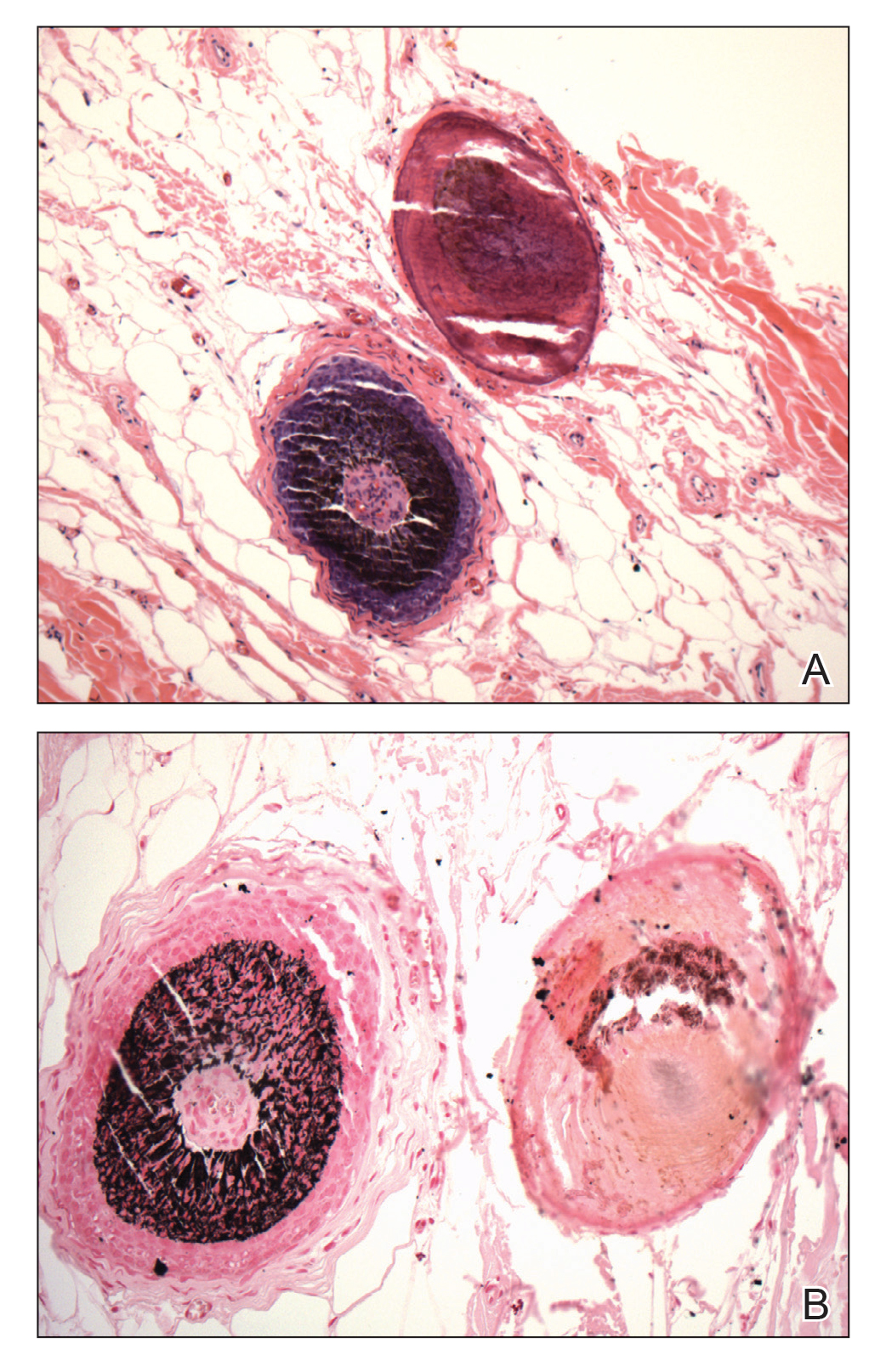

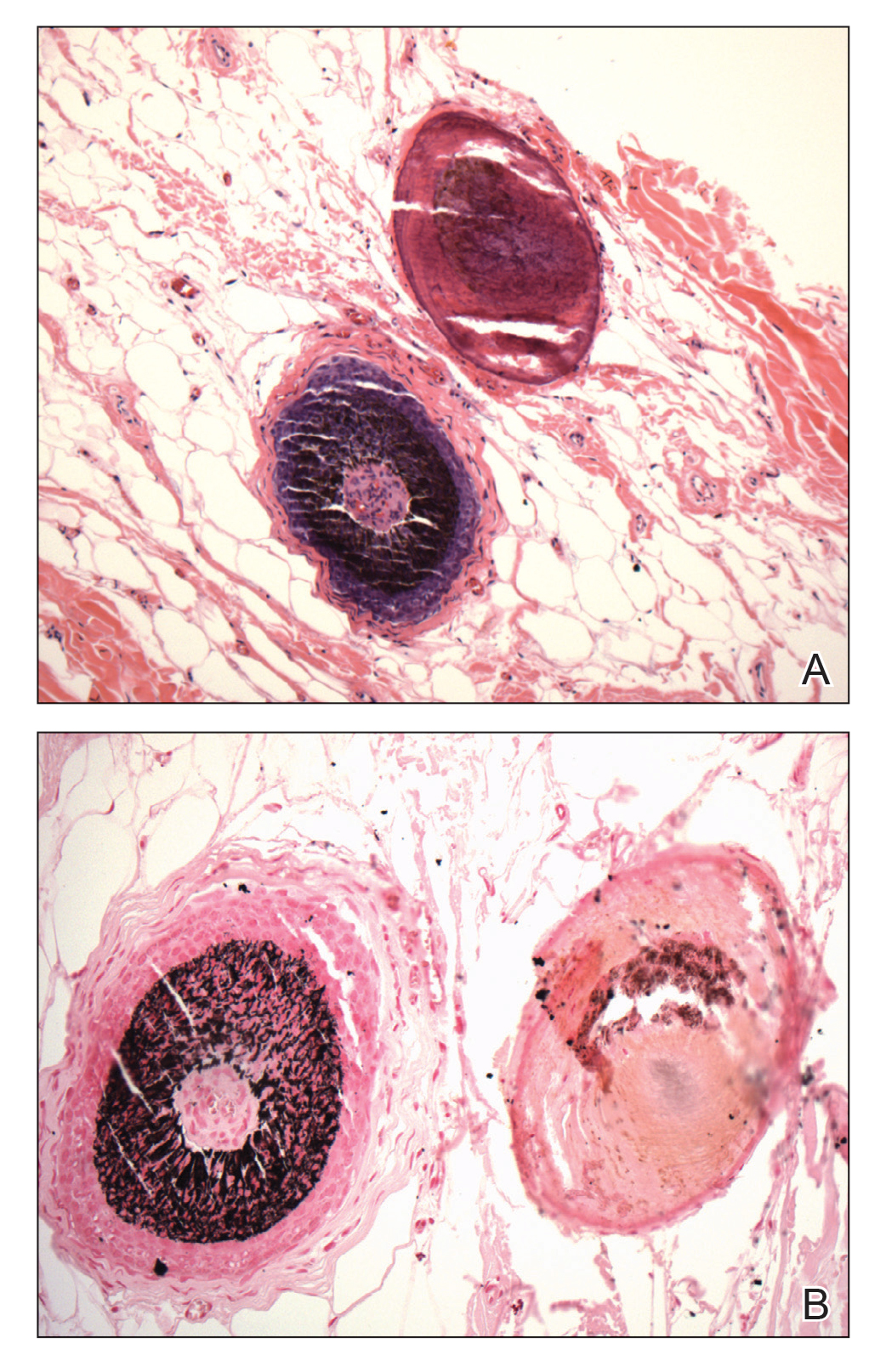

Multiple osteocalcific micronodules were identified in a case of cicatricial alopecia. These micronodules were observed in sections taken at the levels of hair bulbs, and more or less corresponded to the size of the bulb (Figure 5A). Fortuitously, the patient was dark-skinned; the remnants of melanin within the micronodules provided evidence that the micronodules were formed within hair bulbs. Melanin staining confirmed the presence of melanin within some of the micronodules (Figure 5B).

Comment

Skeletogenesis in humans takes place by 2 methods: endochondral ossification and intramembranous ossification. In contrast to endochondral ossification, intramembranous ossification does not require a preexisting cartilaginous template. Instead, there is condensation of mesenchymal cells, which differentiate into osteoblasts and lay down osteoid, thus forming an ossification center. Little is known about the mechanism of formation of OC or the nidus of formation of the primary form.

Incidental micronodules of calcification and ossification are routinely encountered during histopathologic review of specimens from hair-bearing areas of the skin in dermatopathology practice. A review of the literature, however, does not reveal any specific dermatopathologic term ascribed to this phenomenon. These lesions might be similar to those described by Hopkins5 in 1928 in the setting of miliary OC of the face secondary to acne. Rossman and Freeman6 also described the same lesions when referring to facial OC as a “stage of pre-osseous calcification.”

When these osteocalcific micronodules are encountered, it usually is in close proximity to a hair follicle bulb. When a hair bulb is not seen in the sections, the micronodules are noted near fibrous tracts, arrector pili muscles, or sebaceous lobules, suggesting a close peripilar or peribulbar location. The micronodules are approximately 0.5 mm in diameter—roughly the size of a hair bulb. Due to the close anatomic association of micronodules and the hair bulb, these lesions can be called pilar osteocalcific nodules (PONs).

The role of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in the maintenance of the hair cycle is well established. Bone morphogenetic proteins are extracellular cytokines that belong to the transforming growth factor β family. The hair bulb microenvironment is rich in BMPs

As the name implies, BMPs were discovered in relation to their important role in osteogenesis and tissue homeostasis. More than 20 BMPs have been identified, many of which promote bone formation and repair of bone fracture. Osteoinductive BMPs include BMP-2 and BMP-4 through BMP-10; BMP-2 and BMP-4 are expressed in the hair matrix and BMP-4 and BMP-6 are expressed in the FDP.8,9 All bone-inducing BMPs can cause mesenchymal stem cells to differentiate into osteoblasts in vitro.10

Overactive BMP signaling has been shown to cause heterotopic ossification in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva.8 Immunohistochemical expression of BMP-2 has been demonstrated in shadow cells of pilomatricoma.11 Calcification and ossification are seen in as many as 20% of pilomatricomas. Both BMP-2 and BMP-4 have been shown to induce osteogenic differentiation of mouse skin−derived fibroblasts and FDP cells.12

Myllylä et al13 described 4 cases of multiple miliary osteoma cutis (MMOC). They also found 47 reported cases of MMOC, in which there was a history of acne in 55% (26/47). Only 15% (7/47) of these cases were extrafacial on the neck, chest, back, and arms. Osteomas in these cases were not associated with folliculosebaceous units or other adnexal structures, which may have been due to replacement by acne scarring, as all 4 patients had a history of acne vulgaris. The authors postulated a role for the GNAS gene mutation in the morphogenesis of MMOC; however, no supporting evidence was found for this claim. They also postulated a role for BMPs in the formation of MMOC.13

Some disturbance or imbalance in hair bulb homeostasis leads to overactivity of BMP signaling, causing osteoinduction in the hair bulb region and formation of PONs. The cause of the disturbance could be a traumatic or inflammatory injury to the hair follicle, as in the case of the secondary form of MMOC in association with chronic acne. In the primary form of osteoma cutis, the trigger could be more subtle or subclinical.

Trauma and inflammation are the main initiating factors involved in ossification in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva due to ectopic activity of BMPs.9 The primary form of ossification appears to be similar to the mechanism by which intramembranous ossification is laid down (ie, by differentiation of mesenchymal cells into osteoblasts). In the proposed scenario, the cells of FDP, under the influence of BMPs, differentiate into osteoblasts and lay down osteoid, forming a limited-capacity “ossification center” or pilar osteocalcific nodule.

It is difficult to know the exact relationship of PONs or OC to the hair bulb due to the 2-dimensional nature of histologic sections. However, considering the finding of a rare case of osteoid forming within the bulb and in another the presence of melanin within the osteocalcific nodule, it is likely that these lesions are formed within the hair bulb or in situations in which the conditions replicate the biochemical characteristics of the hair bulb (eg, pilomatricoma).

The formation of PONs might act as a terminal phase in the hair cycle that is rarely induced to provide an exit for damaged hair follicles from cyclical perpetuity. An unspecified event or injury might render a hair follicle unable to continue its cyclical growth and cause BMPs to induce premature calcification in or around the hair bulb, which would probably be the only known quasiphysiological mechanism for a damaged hair follicle to exit the hair cycle.

Another interesting aspect of osteoma formation in human skin is the similarity to osteoderms or the integumentary skeleton of vertebrates.14 Early in evolution, the dermal skeleton was the predominant skeletal system in some lineages. Phylogenetically, osteoderms are not uniformly distributed, and show a latent ability to manifest in some groups or lay dormant or disappear in others. The occurrence of primary osteomas in the human integument might be a vestigial manifestation of deep homology,15 a latent ability to form structures that have been lost. The embryologic formation of osteoderms in the dermis of vertebrates is thought to depend on the interaction or cross-talk between ectomesenchymal cells of neural crest origin and cells of the stratum basalis of epidermis, which is somewhat similar to the formation of the hair follicles.

Conclusion

Under certain conditions, the bulb region of a hair follicle might provide a nidus for the formation of OC. The hair bulb region contains both the precursor cellular element (mesenchymal cells of FDP) and the trigger cytokine (BMP) for the induction of osteogenic metaplasia.

- Burgdorf W, Nasemann T. Cutaneous osteomas: a clinical and histopathologic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 1977;260:121-135.

- Essing M. Osteoma cutis of the forehead. HNO. 1985;33:548-550.

- Bouraoui S, Mlika M, Kort R, et al. Miliary osteoma cutis of the face. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:77-81.

- Virchow R. Die krankhaften Geschwülste. Vol 2. Hirschwald; 1864.

- Hopkins JG. Multiple miliary osteomas of the skin: report of a case. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1928;18:706-715.

- Rossman RE, Freeman RG. Osteoma cutis, a stage of preosseous calcification. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:68-73.

- Guha U, Mecklenburg L, Cowin P, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling regulates postnatal hair follicle differentiation and cycling. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:729-740.

- Rendl M, Polak L, Fuchs E. BMP signaling in dermal papilla cells is required for their hair follicle-inductive properties. Genes Dev. 2008;22:543-557.

- Shi S, de Gorter DJJ, Hoogaars WMH, et al. Overactive bone morphogenetic protein signaling in heterotopic ossification and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:407-423.

- Miyazono K, Kamiya Y, Morikawa M. Bone morphogenetic protein receptors and signal transduction. J Biochem. 2010;147:35-51.

- Kurokawa I, Kusumoto K, Bessho K. Immunohistochemical expression of bone morphogenetic protein-2 in pilomatricoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:754-758.

- Myllylä RM, Haapasaari K-M, Lehenkari P, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins 4 and 2/7 induce osteogenic differentiation of mouse skin derived fibroblast and dermal papilla cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;355:463-470.

- Myllylä RM, Haapasaari KM, Palatsi R, et al. Multiple miliary osteoma cutis is a distinct disease entity: four case reports and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:544-552.

- Vickaryous MK, Sire J-Y. The integumentary skeleton of tetrapods: origin, evolution, and development. J Anat. 2009;214:441-464.

- Vickaryous MK, Hall BK. Development of the dermal skeleton in Alligator mississippiensis (Archosauria, Crocodylia) with comments on the homology of osteoderms. J Morphol. 2008;269:398-422.

The term osteoma cutis (OC) is defined as the ossification or bone formation either in the dermis or hypodermis. 1 It is heterotopic in nature, referring to extraneous bone formation in soft tissue. Osteoma cutis was first described in 1858 2,3 ; in 1868, the multiple miliary form on the face was described. 4 Cutaneous ossification can take many forms, ranging from occurrence in a nevus (nevus of Nanta) to its association with rare genetic disorders, such as fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva and Albright hereditary osteodystrophy.

Some of these ossifications are classified as primary; others are secondary, depending on the presence of a preexisting lesion (eg, pilomatricoma, basal cell carcinoma). However, certain conditions, such as multiple miliary osteoma of the face, can be difficult to classify due to the presence or absence of a history of acne or dermabrasion, or both. The secondary forms more commonly are encountered due to their incidental association with an excised lesion, such as pilomatricoma.

A precursor of OC has been neglected in the literature despite its common occurrence. It may have been peripherally alluded to in the literature in reference to the miliary form of OC.5,6 The cases reported here demonstrate small round nodules of calcification or ossification, or both, in punch biopsies and excision specimens from hair-bearing areas of skin, especially from the head and neck. These lesions are mainly observed in the peripilar location or more specifically in the approximate location of the hair bulb.

This article reviews a possible mechanism of formation of these osteocalcific micronodules. These often-encountered micronodules are small osteocalcific lesions without typical bone or well-formed OC, such as trabeculae formation or fatty marrow, and may represent earliest stages in the formation of OC.

Clinical Observations

During routine dermatopathologic practice, I observed incidental small osteocalcific micronodules in close proximity to the lower part of the hair follicle in multiple cases. These nodules were not related to the main lesion in the specimen and were not the reason for the biopsy or excision. Most of the time, these micronodules were noted in excision or re-excision specimens or in a punch biopsy.

In my review of multiple unrelated cases over time, incidental osteocalcific micronodules were observed occasionally in punch biopsies and excision specimens during routine practice. These micronodules were mainly located in the vicinity of a hair bulb (Figure 1). If the hair bulb was not present in the sections, these micronodules were noted near or within the fibrous tract (Figure 2) or beneath a sebaceous lobule (Figure 3). In an exceptional case, a small round deposit of osteoid was seen forming just above the dermal papilla of the hair bulb (Figure 4).

Multiple osteocalcific micronodules were identified in a case of cicatricial alopecia. These micronodules were observed in sections taken at the levels of hair bulbs, and more or less corresponded to the size of the bulb (Figure 5A). Fortuitously, the patient was dark-skinned; the remnants of melanin within the micronodules provided evidence that the micronodules were formed within hair bulbs. Melanin staining confirmed the presence of melanin within some of the micronodules (Figure 5B).

Comment

Skeletogenesis in humans takes place by 2 methods: endochondral ossification and intramembranous ossification. In contrast to endochondral ossification, intramembranous ossification does not require a preexisting cartilaginous template. Instead, there is condensation of mesenchymal cells, which differentiate into osteoblasts and lay down osteoid, thus forming an ossification center. Little is known about the mechanism of formation of OC or the nidus of formation of the primary form.

Incidental micronodules of calcification and ossification are routinely encountered during histopathologic review of specimens from hair-bearing areas of the skin in dermatopathology practice. A review of the literature, however, does not reveal any specific dermatopathologic term ascribed to this phenomenon. These lesions might be similar to those described by Hopkins5 in 1928 in the setting of miliary OC of the face secondary to acne. Rossman and Freeman6 also described the same lesions when referring to facial OC as a “stage of pre-osseous calcification.”

When these osteocalcific micronodules are encountered, it usually is in close proximity to a hair follicle bulb. When a hair bulb is not seen in the sections, the micronodules are noted near fibrous tracts, arrector pili muscles, or sebaceous lobules, suggesting a close peripilar or peribulbar location. The micronodules are approximately 0.5 mm in diameter—roughly the size of a hair bulb. Due to the close anatomic association of micronodules and the hair bulb, these lesions can be called pilar osteocalcific nodules (PONs).

The role of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in the maintenance of the hair cycle is well established. Bone morphogenetic proteins are extracellular cytokines that belong to the transforming growth factor β family. The hair bulb microenvironment is rich in BMPs

As the name implies, BMPs were discovered in relation to their important role in osteogenesis and tissue homeostasis. More than 20 BMPs have been identified, many of which promote bone formation and repair of bone fracture. Osteoinductive BMPs include BMP-2 and BMP-4 through BMP-10; BMP-2 and BMP-4 are expressed in the hair matrix and BMP-4 and BMP-6 are expressed in the FDP.8,9 All bone-inducing BMPs can cause mesenchymal stem cells to differentiate into osteoblasts in vitro.10

Overactive BMP signaling has been shown to cause heterotopic ossification in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva.8 Immunohistochemical expression of BMP-2 has been demonstrated in shadow cells of pilomatricoma.11 Calcification and ossification are seen in as many as 20% of pilomatricomas. Both BMP-2 and BMP-4 have been shown to induce osteogenic differentiation of mouse skin−derived fibroblasts and FDP cells.12

Myllylä et al13 described 4 cases of multiple miliary osteoma cutis (MMOC). They also found 47 reported cases of MMOC, in which there was a history of acne in 55% (26/47). Only 15% (7/47) of these cases were extrafacial on the neck, chest, back, and arms. Osteomas in these cases were not associated with folliculosebaceous units or other adnexal structures, which may have been due to replacement by acne scarring, as all 4 patients had a history of acne vulgaris. The authors postulated a role for the GNAS gene mutation in the morphogenesis of MMOC; however, no supporting evidence was found for this claim. They also postulated a role for BMPs in the formation of MMOC.13

Some disturbance or imbalance in hair bulb homeostasis leads to overactivity of BMP signaling, causing osteoinduction in the hair bulb region and formation of PONs. The cause of the disturbance could be a traumatic or inflammatory injury to the hair follicle, as in the case of the secondary form of MMOC in association with chronic acne. In the primary form of osteoma cutis, the trigger could be more subtle or subclinical.

Trauma and inflammation are the main initiating factors involved in ossification in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva due to ectopic activity of BMPs.9 The primary form of ossification appears to be similar to the mechanism by which intramembranous ossification is laid down (ie, by differentiation of mesenchymal cells into osteoblasts). In the proposed scenario, the cells of FDP, under the influence of BMPs, differentiate into osteoblasts and lay down osteoid, forming a limited-capacity “ossification center” or pilar osteocalcific nodule.

It is difficult to know the exact relationship of PONs or OC to the hair bulb due to the 2-dimensional nature of histologic sections. However, considering the finding of a rare case of osteoid forming within the bulb and in another the presence of melanin within the osteocalcific nodule, it is likely that these lesions are formed within the hair bulb or in situations in which the conditions replicate the biochemical characteristics of the hair bulb (eg, pilomatricoma).

The formation of PONs might act as a terminal phase in the hair cycle that is rarely induced to provide an exit for damaged hair follicles from cyclical perpetuity. An unspecified event or injury might render a hair follicle unable to continue its cyclical growth and cause BMPs to induce premature calcification in or around the hair bulb, which would probably be the only known quasiphysiological mechanism for a damaged hair follicle to exit the hair cycle.

Another interesting aspect of osteoma formation in human skin is the similarity to osteoderms or the integumentary skeleton of vertebrates.14 Early in evolution, the dermal skeleton was the predominant skeletal system in some lineages. Phylogenetically, osteoderms are not uniformly distributed, and show a latent ability to manifest in some groups or lay dormant or disappear in others. The occurrence of primary osteomas in the human integument might be a vestigial manifestation of deep homology,15 a latent ability to form structures that have been lost. The embryologic formation of osteoderms in the dermis of vertebrates is thought to depend on the interaction or cross-talk between ectomesenchymal cells of neural crest origin and cells of the stratum basalis of epidermis, which is somewhat similar to the formation of the hair follicles.

Conclusion

Under certain conditions, the bulb region of a hair follicle might provide a nidus for the formation of OC. The hair bulb region contains both the precursor cellular element (mesenchymal cells of FDP) and the trigger cytokine (BMP) for the induction of osteogenic metaplasia.

The term osteoma cutis (OC) is defined as the ossification or bone formation either in the dermis or hypodermis. 1 It is heterotopic in nature, referring to extraneous bone formation in soft tissue. Osteoma cutis was first described in 1858 2,3 ; in 1868, the multiple miliary form on the face was described. 4 Cutaneous ossification can take many forms, ranging from occurrence in a nevus (nevus of Nanta) to its association with rare genetic disorders, such as fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva and Albright hereditary osteodystrophy.

Some of these ossifications are classified as primary; others are secondary, depending on the presence of a preexisting lesion (eg, pilomatricoma, basal cell carcinoma). However, certain conditions, such as multiple miliary osteoma of the face, can be difficult to classify due to the presence or absence of a history of acne or dermabrasion, or both. The secondary forms more commonly are encountered due to their incidental association with an excised lesion, such as pilomatricoma.

A precursor of OC has been neglected in the literature despite its common occurrence. It may have been peripherally alluded to in the literature in reference to the miliary form of OC.5,6 The cases reported here demonstrate small round nodules of calcification or ossification, or both, in punch biopsies and excision specimens from hair-bearing areas of skin, especially from the head and neck. These lesions are mainly observed in the peripilar location or more specifically in the approximate location of the hair bulb.

This article reviews a possible mechanism of formation of these osteocalcific micronodules. These often-encountered micronodules are small osteocalcific lesions without typical bone or well-formed OC, such as trabeculae formation or fatty marrow, and may represent earliest stages in the formation of OC.

Clinical Observations

During routine dermatopathologic practice, I observed incidental small osteocalcific micronodules in close proximity to the lower part of the hair follicle in multiple cases. These nodules were not related to the main lesion in the specimen and were not the reason for the biopsy or excision. Most of the time, these micronodules were noted in excision or re-excision specimens or in a punch biopsy.

In my review of multiple unrelated cases over time, incidental osteocalcific micronodules were observed occasionally in punch biopsies and excision specimens during routine practice. These micronodules were mainly located in the vicinity of a hair bulb (Figure 1). If the hair bulb was not present in the sections, these micronodules were noted near or within the fibrous tract (Figure 2) or beneath a sebaceous lobule (Figure 3). In an exceptional case, a small round deposit of osteoid was seen forming just above the dermal papilla of the hair bulb (Figure 4).

Multiple osteocalcific micronodules were identified in a case of cicatricial alopecia. These micronodules were observed in sections taken at the levels of hair bulbs, and more or less corresponded to the size of the bulb (Figure 5A). Fortuitously, the patient was dark-skinned; the remnants of melanin within the micronodules provided evidence that the micronodules were formed within hair bulbs. Melanin staining confirmed the presence of melanin within some of the micronodules (Figure 5B).

Comment

Skeletogenesis in humans takes place by 2 methods: endochondral ossification and intramembranous ossification. In contrast to endochondral ossification, intramembranous ossification does not require a preexisting cartilaginous template. Instead, there is condensation of mesenchymal cells, which differentiate into osteoblasts and lay down osteoid, thus forming an ossification center. Little is known about the mechanism of formation of OC or the nidus of formation of the primary form.

Incidental micronodules of calcification and ossification are routinely encountered during histopathologic review of specimens from hair-bearing areas of the skin in dermatopathology practice. A review of the literature, however, does not reveal any specific dermatopathologic term ascribed to this phenomenon. These lesions might be similar to those described by Hopkins5 in 1928 in the setting of miliary OC of the face secondary to acne. Rossman and Freeman6 also described the same lesions when referring to facial OC as a “stage of pre-osseous calcification.”

When these osteocalcific micronodules are encountered, it usually is in close proximity to a hair follicle bulb. When a hair bulb is not seen in the sections, the micronodules are noted near fibrous tracts, arrector pili muscles, or sebaceous lobules, suggesting a close peripilar or peribulbar location. The micronodules are approximately 0.5 mm in diameter—roughly the size of a hair bulb. Due to the close anatomic association of micronodules and the hair bulb, these lesions can be called pilar osteocalcific nodules (PONs).

The role of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling in the maintenance of the hair cycle is well established. Bone morphogenetic proteins are extracellular cytokines that belong to the transforming growth factor β family. The hair bulb microenvironment is rich in BMPs

As the name implies, BMPs were discovered in relation to their important role in osteogenesis and tissue homeostasis. More than 20 BMPs have been identified, many of which promote bone formation and repair of bone fracture. Osteoinductive BMPs include BMP-2 and BMP-4 through BMP-10; BMP-2 and BMP-4 are expressed in the hair matrix and BMP-4 and BMP-6 are expressed in the FDP.8,9 All bone-inducing BMPs can cause mesenchymal stem cells to differentiate into osteoblasts in vitro.10

Overactive BMP signaling has been shown to cause heterotopic ossification in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva.8 Immunohistochemical expression of BMP-2 has been demonstrated in shadow cells of pilomatricoma.11 Calcification and ossification are seen in as many as 20% of pilomatricomas. Both BMP-2 and BMP-4 have been shown to induce osteogenic differentiation of mouse skin−derived fibroblasts and FDP cells.12

Myllylä et al13 described 4 cases of multiple miliary osteoma cutis (MMOC). They also found 47 reported cases of MMOC, in which there was a history of acne in 55% (26/47). Only 15% (7/47) of these cases were extrafacial on the neck, chest, back, and arms. Osteomas in these cases were not associated with folliculosebaceous units or other adnexal structures, which may have been due to replacement by acne scarring, as all 4 patients had a history of acne vulgaris. The authors postulated a role for the GNAS gene mutation in the morphogenesis of MMOC; however, no supporting evidence was found for this claim. They also postulated a role for BMPs in the formation of MMOC.13

Some disturbance or imbalance in hair bulb homeostasis leads to overactivity of BMP signaling, causing osteoinduction in the hair bulb region and formation of PONs. The cause of the disturbance could be a traumatic or inflammatory injury to the hair follicle, as in the case of the secondary form of MMOC in association with chronic acne. In the primary form of osteoma cutis, the trigger could be more subtle or subclinical.

Trauma and inflammation are the main initiating factors involved in ossification in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva due to ectopic activity of BMPs.9 The primary form of ossification appears to be similar to the mechanism by which intramembranous ossification is laid down (ie, by differentiation of mesenchymal cells into osteoblasts). In the proposed scenario, the cells of FDP, under the influence of BMPs, differentiate into osteoblasts and lay down osteoid, forming a limited-capacity “ossification center” or pilar osteocalcific nodule.

It is difficult to know the exact relationship of PONs or OC to the hair bulb due to the 2-dimensional nature of histologic sections. However, considering the finding of a rare case of osteoid forming within the bulb and in another the presence of melanin within the osteocalcific nodule, it is likely that these lesions are formed within the hair bulb or in situations in which the conditions replicate the biochemical characteristics of the hair bulb (eg, pilomatricoma).

The formation of PONs might act as a terminal phase in the hair cycle that is rarely induced to provide an exit for damaged hair follicles from cyclical perpetuity. An unspecified event or injury might render a hair follicle unable to continue its cyclical growth and cause BMPs to induce premature calcification in or around the hair bulb, which would probably be the only known quasiphysiological mechanism for a damaged hair follicle to exit the hair cycle.

Another interesting aspect of osteoma formation in human skin is the similarity to osteoderms or the integumentary skeleton of vertebrates.14 Early in evolution, the dermal skeleton was the predominant skeletal system in some lineages. Phylogenetically, osteoderms are not uniformly distributed, and show a latent ability to manifest in some groups or lay dormant or disappear in others. The occurrence of primary osteomas in the human integument might be a vestigial manifestation of deep homology,15 a latent ability to form structures that have been lost. The embryologic formation of osteoderms in the dermis of vertebrates is thought to depend on the interaction or cross-talk between ectomesenchymal cells of neural crest origin and cells of the stratum basalis of epidermis, which is somewhat similar to the formation of the hair follicles.

Conclusion

Under certain conditions, the bulb region of a hair follicle might provide a nidus for the formation of OC. The hair bulb region contains both the precursor cellular element (mesenchymal cells of FDP) and the trigger cytokine (BMP) for the induction of osteogenic metaplasia.

- Burgdorf W, Nasemann T. Cutaneous osteomas: a clinical and histopathologic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 1977;260:121-135.

- Essing M. Osteoma cutis of the forehead. HNO. 1985;33:548-550.

- Bouraoui S, Mlika M, Kort R, et al. Miliary osteoma cutis of the face. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:77-81.

- Virchow R. Die krankhaften Geschwülste. Vol 2. Hirschwald; 1864.

- Hopkins JG. Multiple miliary osteomas of the skin: report of a case. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1928;18:706-715.

- Rossman RE, Freeman RG. Osteoma cutis, a stage of preosseous calcification. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:68-73.

- Guha U, Mecklenburg L, Cowin P, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling regulates postnatal hair follicle differentiation and cycling. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:729-740.

- Rendl M, Polak L, Fuchs E. BMP signaling in dermal papilla cells is required for their hair follicle-inductive properties. Genes Dev. 2008;22:543-557.

- Shi S, de Gorter DJJ, Hoogaars WMH, et al. Overactive bone morphogenetic protein signaling in heterotopic ossification and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:407-423.

- Miyazono K, Kamiya Y, Morikawa M. Bone morphogenetic protein receptors and signal transduction. J Biochem. 2010;147:35-51.

- Kurokawa I, Kusumoto K, Bessho K. Immunohistochemical expression of bone morphogenetic protein-2 in pilomatricoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:754-758.

- Myllylä RM, Haapasaari K-M, Lehenkari P, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins 4 and 2/7 induce osteogenic differentiation of mouse skin derived fibroblast and dermal papilla cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;355:463-470.

- Myllylä RM, Haapasaari KM, Palatsi R, et al. Multiple miliary osteoma cutis is a distinct disease entity: four case reports and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:544-552.

- Vickaryous MK, Sire J-Y. The integumentary skeleton of tetrapods: origin, evolution, and development. J Anat. 2009;214:441-464.

- Vickaryous MK, Hall BK. Development of the dermal skeleton in Alligator mississippiensis (Archosauria, Crocodylia) with comments on the homology of osteoderms. J Morphol. 2008;269:398-422.

- Burgdorf W, Nasemann T. Cutaneous osteomas: a clinical and histopathologic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 1977;260:121-135.

- Essing M. Osteoma cutis of the forehead. HNO. 1985;33:548-550.

- Bouraoui S, Mlika M, Kort R, et al. Miliary osteoma cutis of the face. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2011;5:77-81.

- Virchow R. Die krankhaften Geschwülste. Vol 2. Hirschwald; 1864.

- Hopkins JG. Multiple miliary osteomas of the skin: report of a case. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1928;18:706-715.

- Rossman RE, Freeman RG. Osteoma cutis, a stage of preosseous calcification. Arch Dermatol. 1964;89:68-73.

- Guha U, Mecklenburg L, Cowin P, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling regulates postnatal hair follicle differentiation and cycling. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:729-740.

- Rendl M, Polak L, Fuchs E. BMP signaling in dermal papilla cells is required for their hair follicle-inductive properties. Genes Dev. 2008;22:543-557.

- Shi S, de Gorter DJJ, Hoogaars WMH, et al. Overactive bone morphogenetic protein signaling in heterotopic ossification and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:407-423.

- Miyazono K, Kamiya Y, Morikawa M. Bone morphogenetic protein receptors and signal transduction. J Biochem. 2010;147:35-51.

- Kurokawa I, Kusumoto K, Bessho K. Immunohistochemical expression of bone morphogenetic protein-2 in pilomatricoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:754-758.

- Myllylä RM, Haapasaari K-M, Lehenkari P, et al. Bone morphogenetic proteins 4 and 2/7 induce osteogenic differentiation of mouse skin derived fibroblast and dermal papilla cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;355:463-470.

- Myllylä RM, Haapasaari KM, Palatsi R, et al. Multiple miliary osteoma cutis is a distinct disease entity: four case reports and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:544-552.

- Vickaryous MK, Sire J-Y. The integumentary skeleton of tetrapods: origin, evolution, and development. J Anat. 2009;214:441-464.

- Vickaryous MK, Hall BK. Development of the dermal skeleton in Alligator mississippiensis (Archosauria, Crocodylia) with comments on the homology of osteoderms. J Morphol. 2008;269:398-422.

Practice Points

- Understanding the pathogenesis of osteoma cutis (OC) can help physicians devise management of these disfiguring lesions.

- Small osteocalcific nodules in close proximity to the lower aspect of the hair bulb may be an important precursor to OC.

Few outcome differences for younger adolescents after bariatric surgery

Younger adolescents who underwent metabolic and bariatric surgery had outcomes similar to those of older adolescents undergoing the same procedure, according to recent research in Pediatrics.

Five years after metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS), adolescents between ages 13 and 15 years had similar outcomes with regard to reduction in body mass index percentage, hypertension and dyslipidemia, and improved quality of life, compared with adolescents between ages 16 and 19 years, according to Sarah B. Ogle, DO, MS, of Children’s Hospital Colorado at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues.

“These results appear promising for the treatment of severe obesity in young patients,” Dr. Ogle and colleagues wrote, “however, further controlled studies are needed to fully evaluate the timing of surgery and extended long-term durability.”

The researchers analyzed the outcomes of adolescents enrolled in the Teen–Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery who were aged 19 years or younger and underwent MBS between March 2007 and December 2011 at five U.S. centers. In the group of younger adolescents (66 participants), the mean age at surgery was 15.1 years, while the group of older adolescents (162 participants) had a mean age of 17.7 years at the time of surgery. Both groups consisted mostly of White (71.6%-72.7%) girls (72.7%-75.9%) who were morbidly obese (mean BMI, 52.4-53.1 kg/m2). With regard to baseline comorbidities, about three-quarters of participants in the younger (72.4%) and older (77.0%) adolescent groups had dyslipidemia. More than one-quarter of younger adolescents had hypertension (27.3%) compared with more than one-third of older adolescents (37.1%). The prevalence of type 2 diabetes was 10.6% in the younger adolescent group and 13.6% among older adolescents.

At 5-year follow-up, there was a similar BMI reduction maintained from baseline in the younger adolescent group (–22.2%; 95% confidence interval, –26.2% to –18.2%) and the older adolescent group (–24.6%; 95% CI, –27.7% to –22.5%; P = .59). There was a similar number of participants who had remission of dyslipidemia at 5 years in the younger adolescent group (61%; 95% CI, 46.3%-81.1%) and older adolescent group (58%; 95% CI, 48.0%-68.9%; P = .74). In participants with hypertension, 77% of younger adolescents (95% CI, 57.1%-100.0%) and 67% of older adolescents (95% CI, 54.5%-81.5%) achieved remission at 5 years after MBS, which showed no significant differences after adjustment (P = .84). For participants with type 2 diabetes at baseline, 83% of younger adolescents (6 participants) and 87% of older adolescents (15 participants) experienced remission by 5 years after surgery. Participants in both younger and older adolescent groups had similar quality of life scores at 5 years after surgery. When analyzing nutritional abnormalities, the researchers found younger adolescents in the group were less at risk for elevated transferrin levels (prevalence ratio, 0.52; P = .048) as well as less likely to have low vitamin D levels (prevalence ratio, 0.8; P = .034).

Pediatricians still concerned about safety

In an interview, Kelly A. Curran, MD, MA, assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Oklahoma Children’s Hospital in Oklahoma City, said that the findings by Dr. Ogle and colleagues add to a “growing body of literature about the importance of bariatric surgery for both younger and older adolescents.

“While many often see bariatric surgery as a ‘last resort,’ this study shows good outcomes in resolving obesity-related health conditions in both young and older teens over time – and something that should be considered more frequently than it is currently being used,” she said.

Guidelines from the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery removed a restriction for younger age before a patient undergoes MBS, and a policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics encouraged increased use and access to MBS for younger adolescents. However, Dr. Curran noted that many pediatricians are still concerned about performing MBS on younger adolescents.

“Despite growing evidence of safety, I think many pediatricians worry about the potential for unintended consequences and potential impact on adolescent development or for lifelong micronutrition deficiencies – especially as there are no longitudinal studies over a lifetime,” she said.

“[W]ith the growing obesity epidemic and the long-term consequences of obesity on health and quality of life – the potential to help impact adolescents’ lives – for now and for the future – is impressive,” Dr. Curran said, acknowledging the ethical challenges involved with performing MBS on a patient who may be too young to understand the full risks and benefits of surgery.

“There are always inherent ethical challenges in providing surgery for patients too young to understand – we are asking parents to act in their child’s best interests, which may be murky to elucidate,” she explained. “While there is [a] growing body of literature around the safety and efficacy in bariatric surgery for children and adolescents, there are still many unanswered questions that remain – especially for parents. Parents can feel trapped in between these two choices – have children undergo surgery or stick with potentially less effective medical management.”

The limitations of the study include its observational nature, small sample size of some comorbidities, and a lack of diversity among participants, most of whom were White and female. In addition, “long-term studies examining the impact of bariatric surgery during adolescence would be important to give more perspective and guidance on the risks and benefits for teens,” Dr. Curran said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases as well as grants from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The authors and Dr. Curran reported no conflicts of interest.

Younger adolescents who underwent metabolic and bariatric surgery had outcomes similar to those of older adolescents undergoing the same procedure, according to recent research in Pediatrics.

Five years after metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS), adolescents between ages 13 and 15 years had similar outcomes with regard to reduction in body mass index percentage, hypertension and dyslipidemia, and improved quality of life, compared with adolescents between ages 16 and 19 years, according to Sarah B. Ogle, DO, MS, of Children’s Hospital Colorado at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues.

“These results appear promising for the treatment of severe obesity in young patients,” Dr. Ogle and colleagues wrote, “however, further controlled studies are needed to fully evaluate the timing of surgery and extended long-term durability.”

The researchers analyzed the outcomes of adolescents enrolled in the Teen–Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery who were aged 19 years or younger and underwent MBS between March 2007 and December 2011 at five U.S. centers. In the group of younger adolescents (66 participants), the mean age at surgery was 15.1 years, while the group of older adolescents (162 participants) had a mean age of 17.7 years at the time of surgery. Both groups consisted mostly of White (71.6%-72.7%) girls (72.7%-75.9%) who were morbidly obese (mean BMI, 52.4-53.1 kg/m2). With regard to baseline comorbidities, about three-quarters of participants in the younger (72.4%) and older (77.0%) adolescent groups had dyslipidemia. More than one-quarter of younger adolescents had hypertension (27.3%) compared with more than one-third of older adolescents (37.1%). The prevalence of type 2 diabetes was 10.6% in the younger adolescent group and 13.6% among older adolescents.

At 5-year follow-up, there was a similar BMI reduction maintained from baseline in the younger adolescent group (–22.2%; 95% confidence interval, –26.2% to –18.2%) and the older adolescent group (–24.6%; 95% CI, –27.7% to –22.5%; P = .59). There was a similar number of participants who had remission of dyslipidemia at 5 years in the younger adolescent group (61%; 95% CI, 46.3%-81.1%) and older adolescent group (58%; 95% CI, 48.0%-68.9%; P = .74). In participants with hypertension, 77% of younger adolescents (95% CI, 57.1%-100.0%) and 67% of older adolescents (95% CI, 54.5%-81.5%) achieved remission at 5 years after MBS, which showed no significant differences after adjustment (P = .84). For participants with type 2 diabetes at baseline, 83% of younger adolescents (6 participants) and 87% of older adolescents (15 participants) experienced remission by 5 years after surgery. Participants in both younger and older adolescent groups had similar quality of life scores at 5 years after surgery. When analyzing nutritional abnormalities, the researchers found younger adolescents in the group were less at risk for elevated transferrin levels (prevalence ratio, 0.52; P = .048) as well as less likely to have low vitamin D levels (prevalence ratio, 0.8; P = .034).

Pediatricians still concerned about safety

In an interview, Kelly A. Curran, MD, MA, assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Oklahoma Children’s Hospital in Oklahoma City, said that the findings by Dr. Ogle and colleagues add to a “growing body of literature about the importance of bariatric surgery for both younger and older adolescents.

“While many often see bariatric surgery as a ‘last resort,’ this study shows good outcomes in resolving obesity-related health conditions in both young and older teens over time – and something that should be considered more frequently than it is currently being used,” she said.

Guidelines from the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery removed a restriction for younger age before a patient undergoes MBS, and a policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics encouraged increased use and access to MBS for younger adolescents. However, Dr. Curran noted that many pediatricians are still concerned about performing MBS on younger adolescents.

“Despite growing evidence of safety, I think many pediatricians worry about the potential for unintended consequences and potential impact on adolescent development or for lifelong micronutrition deficiencies – especially as there are no longitudinal studies over a lifetime,” she said.

“[W]ith the growing obesity epidemic and the long-term consequences of obesity on health and quality of life – the potential to help impact adolescents’ lives – for now and for the future – is impressive,” Dr. Curran said, acknowledging the ethical challenges involved with performing MBS on a patient who may be too young to understand the full risks and benefits of surgery.

“There are always inherent ethical challenges in providing surgery for patients too young to understand – we are asking parents to act in their child’s best interests, which may be murky to elucidate,” she explained. “While there is [a] growing body of literature around the safety and efficacy in bariatric surgery for children and adolescents, there are still many unanswered questions that remain – especially for parents. Parents can feel trapped in between these two choices – have children undergo surgery or stick with potentially less effective medical management.”

The limitations of the study include its observational nature, small sample size of some comorbidities, and a lack of diversity among participants, most of whom were White and female. In addition, “long-term studies examining the impact of bariatric surgery during adolescence would be important to give more perspective and guidance on the risks and benefits for teens,” Dr. Curran said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases as well as grants from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The authors and Dr. Curran reported no conflicts of interest.

Younger adolescents who underwent metabolic and bariatric surgery had outcomes similar to those of older adolescents undergoing the same procedure, according to recent research in Pediatrics.

Five years after metabolic and bariatric surgery (MBS), adolescents between ages 13 and 15 years had similar outcomes with regard to reduction in body mass index percentage, hypertension and dyslipidemia, and improved quality of life, compared with adolescents between ages 16 and 19 years, according to Sarah B. Ogle, DO, MS, of Children’s Hospital Colorado at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and colleagues.

“These results appear promising for the treatment of severe obesity in young patients,” Dr. Ogle and colleagues wrote, “however, further controlled studies are needed to fully evaluate the timing of surgery and extended long-term durability.”

The researchers analyzed the outcomes of adolescents enrolled in the Teen–Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery who were aged 19 years or younger and underwent MBS between March 2007 and December 2011 at five U.S. centers. In the group of younger adolescents (66 participants), the mean age at surgery was 15.1 years, while the group of older adolescents (162 participants) had a mean age of 17.7 years at the time of surgery. Both groups consisted mostly of White (71.6%-72.7%) girls (72.7%-75.9%) who were morbidly obese (mean BMI, 52.4-53.1 kg/m2). With regard to baseline comorbidities, about three-quarters of participants in the younger (72.4%) and older (77.0%) adolescent groups had dyslipidemia. More than one-quarter of younger adolescents had hypertension (27.3%) compared with more than one-third of older adolescents (37.1%). The prevalence of type 2 diabetes was 10.6% in the younger adolescent group and 13.6% among older adolescents.

At 5-year follow-up, there was a similar BMI reduction maintained from baseline in the younger adolescent group (–22.2%; 95% confidence interval, –26.2% to –18.2%) and the older adolescent group (–24.6%; 95% CI, –27.7% to –22.5%; P = .59). There was a similar number of participants who had remission of dyslipidemia at 5 years in the younger adolescent group (61%; 95% CI, 46.3%-81.1%) and older adolescent group (58%; 95% CI, 48.0%-68.9%; P = .74). In participants with hypertension, 77% of younger adolescents (95% CI, 57.1%-100.0%) and 67% of older adolescents (95% CI, 54.5%-81.5%) achieved remission at 5 years after MBS, which showed no significant differences after adjustment (P = .84). For participants with type 2 diabetes at baseline, 83% of younger adolescents (6 participants) and 87% of older adolescents (15 participants) experienced remission by 5 years after surgery. Participants in both younger and older adolescent groups had similar quality of life scores at 5 years after surgery. When analyzing nutritional abnormalities, the researchers found younger adolescents in the group were less at risk for elevated transferrin levels (prevalence ratio, 0.52; P = .048) as well as less likely to have low vitamin D levels (prevalence ratio, 0.8; P = .034).

Pediatricians still concerned about safety

In an interview, Kelly A. Curran, MD, MA, assistant professor of pediatrics at University of Oklahoma Children’s Hospital in Oklahoma City, said that the findings by Dr. Ogle and colleagues add to a “growing body of literature about the importance of bariatric surgery for both younger and older adolescents.

“While many often see bariatric surgery as a ‘last resort,’ this study shows good outcomes in resolving obesity-related health conditions in both young and older teens over time – and something that should be considered more frequently than it is currently being used,” she said.

Guidelines from the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery removed a restriction for younger age before a patient undergoes MBS, and a policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics encouraged increased use and access to MBS for younger adolescents. However, Dr. Curran noted that many pediatricians are still concerned about performing MBS on younger adolescents.

“Despite growing evidence of safety, I think many pediatricians worry about the potential for unintended consequences and potential impact on adolescent development or for lifelong micronutrition deficiencies – especially as there are no longitudinal studies over a lifetime,” she said.

“[W]ith the growing obesity epidemic and the long-term consequences of obesity on health and quality of life – the potential to help impact adolescents’ lives – for now and for the future – is impressive,” Dr. Curran said, acknowledging the ethical challenges involved with performing MBS on a patient who may be too young to understand the full risks and benefits of surgery.

“There are always inherent ethical challenges in providing surgery for patients too young to understand – we are asking parents to act in their child’s best interests, which may be murky to elucidate,” she explained. “While there is [a] growing body of literature around the safety and efficacy in bariatric surgery for children and adolescents, there are still many unanswered questions that remain – especially for parents. Parents can feel trapped in between these two choices – have children undergo surgery or stick with potentially less effective medical management.”

The limitations of the study include its observational nature, small sample size of some comorbidities, and a lack of diversity among participants, most of whom were White and female. In addition, “long-term studies examining the impact of bariatric surgery during adolescence would be important to give more perspective and guidance on the risks and benefits for teens,” Dr. Curran said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases as well as grants from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The authors and Dr. Curran reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Expert shares hyperhidrosis treatment pearls

Even though over-the-counter topical antiperspirants are a common go-to treatment for primary axillary hyperhidrosis, a large survey commissioned by the International Hyperhidrosis Society showed that, while OTC aluminum products are the most recommended, they offer the least satisfaction to patients.

Of the 1,985 survey respondents who self-identified as having excessive sweating, those who received treatment were most satisfied with injections and least satisfied with prescription and OTC antiperspirants and liposuction. “It’s important to recognize that, while these are not invasive, they’re simple, you need to keep up with it, and they’re really not that effective for primary hyperhidrosis,” Adam Friedman, MD, said during the virtual Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

A major development came in 2018, when the Food and Drug Administration approved topical glycopyrronium tosylate for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis in adults and in children as young as age 9. It marked the first topical anticholinergic approved for the condition. Results from the pivotal phase 2 ATMOS-1 and ATMOS-2 randomized, controlled trials found that, after 4 weeks of daily use, 53%-66% of patients reported a 4-point improvement or greater on the ASDD item 2, which is defined as the worst sweating they experienced in a 24-hour period on an 11-point scale.

“Patients want to know: How quickly am I going to see improvement? The answer to this can be central to treatment compliance,” said Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at the George Washington University, Washington. “We have data showing that 23%-29% of patients using glycopyrronium tosylate met that primary outcome within 1 week of use. So, you can tell patients: ‘Help is on the way. You may see a response relatively soon.’ ”

The most common adverse events in the two trials were dry mouth, which affected 24% of patients, followed by mydriasis (7%), and oropharyngeal pain (6%). He advises patients to apply it once at night. “I tell my patients make this the last thing you do during your nighttime routine,” said Dr. Friedman, who coauthored a case-based clinical algorithm for approaching primary hyperhidrosis patients.

“Open it up, one swipe to the right [underarm], flip it over, one wipe of the left [underarm], toss the towelette, and wash your hands thoroughly. You don’t need to remove axillary hair or occlude the area. I tell them they may find some improvement within one week of daily use, but I give realistic expectations, usually 2-3 weeks. Tell them about the potential for side effects, which certainly can happen,” he said.

Investigators are evaluating how this product could be delivered to other body sites. Dr. Friedman said that he uses glycopyrronium tosylate off label for palmar and plantar hyperhidrosis. He advises patients to rub their hands or feet the cloth until it dries, toss the towelette, apply an occlusive agent like Aquaphor followed by gloves/socks for at least an hour, and then wash their hands or feet. “If they can keep the gloves or socks on overnight, that’s fine, but that’s very rare,” Dr. Friedman added.

“Typically, an hour or 2 of occlusive covering will get the product in where it needs to be. The upside of this product is that it’s noninvasive, there’s minimal irritation, it’s effective, and FDA approved. On the downside, it’s a long-term therapy. This is forever, so cost can be an issue, and you have to think about the anticholinergic effects as well.”

Iontophoresis is a first-line treatment for moderate to severe palmar and plantar hyperhidrosis. It’s also effective for mild hyperhidrosis with limited side effects, but it’s cumbersome, he said, requiring thrice-weekly treatment of each palm or sole for approximately 30 minutes to a controlled electric current at 15-20 mA with tap water.

There are no systemic agents approved for hyperhidrosis, only case reports or small case series. For now, the two commonly used anticholinergics are glycopyrrolate and oxybutynin. Glycopyrrolate comes in 1- and 2-mg capsules. “You can break the tablets easily and it’s pretty cheap, with an estimated cost of 2 mg/day at $756 per year,” Dr. Friedman said. “I typically start patients on 1 mg twice per day for a week, then ask how they’re doing. If they notice improvement, have minimal side effects but think they can do better, then I increase it by 1 mg and reassess. I give them autonomy, and at most, want them to max out at 6 mg per day. There is an oral solution for kids, which can make this a little more accessible.”

He prescribes oxybutynin infrequently but considers it effective. “Most patients respond to 5- to 10-mg/day dosing, but doses up to 15 or 20 mg daily may be required,” he noted.

For persistent flushing with hyperhidrosis, Dr. Friedman typically recommends treatment with clonidine. “I start patients pretty low, sometimes 0.05 mg twice per day.”

For patients who sweat because of social phobias and performance anxiety, he typically recommends treatment with a beta-adrenergic blocker. “These are highly lipophilic, so I advise patients not to take them with food,” he said. “The peak concentration is 1-1.5 hours. Usually, I start at 10 mg and I have people do a test run at home. I also take a baseline blood pressure in the office to make sure they’re not hypotensive.” The use of beta-adrenergic blockers is contraindicated in patients with bradycardia, atrioventricular block, and asthma. They can also exacerbate psoriasis.

On Sept. 20, 2020, Brickell Biotech announced the approval of sofpironium bromide gel, 5%, in Japan for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis. Sofpironium bromide is an analog of glycopyrrolate “that gets metabolized very quickly in order to limit systemic absorption of the active agent and therefore mitigate side effects,” Dr. Friedman said.

A recently published Japanese study found that 54% of patients with primary axillary hyperhidrosis who received sofpironium bromide experienced a 1- or 2-point improvement on the Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale and a 50% or greater reduction in gravimetric sweat production from baseline to week 6 of treatment, compared with 36% of patients in the control group (P = .003). According to Dr. Friedman, a 15% formulation of this product is being studied in the United States, “but the experience in Japan with the 5% formulation should give us some real-world information about this product,” he said. “Out of the gate, we’re going to know something about how it’s being used.”

Dr. Friedman reported that he serves as a consultant and/or advisor to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including some that produce cannabinoids. He is also a speaker for Regeneron, Abbvie, Novartis, LRP, Dermira, and Brickel Biotech, and has received grants from Pfizer, the Dermatology Foundation, Almirall, and Janssen.

Even though over-the-counter topical antiperspirants are a common go-to treatment for primary axillary hyperhidrosis, a large survey commissioned by the International Hyperhidrosis Society showed that, while OTC aluminum products are the most recommended, they offer the least satisfaction to patients.

Of the 1,985 survey respondents who self-identified as having excessive sweating, those who received treatment were most satisfied with injections and least satisfied with prescription and OTC antiperspirants and liposuction. “It’s important to recognize that, while these are not invasive, they’re simple, you need to keep up with it, and they’re really not that effective for primary hyperhidrosis,” Adam Friedman, MD, said during the virtual Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

A major development came in 2018, when the Food and Drug Administration approved topical glycopyrronium tosylate for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis in adults and in children as young as age 9. It marked the first topical anticholinergic approved for the condition. Results from the pivotal phase 2 ATMOS-1 and ATMOS-2 randomized, controlled trials found that, after 4 weeks of daily use, 53%-66% of patients reported a 4-point improvement or greater on the ASDD item 2, which is defined as the worst sweating they experienced in a 24-hour period on an 11-point scale.

“Patients want to know: How quickly am I going to see improvement? The answer to this can be central to treatment compliance,” said Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at the George Washington University, Washington. “We have data showing that 23%-29% of patients using glycopyrronium tosylate met that primary outcome within 1 week of use. So, you can tell patients: ‘Help is on the way. You may see a response relatively soon.’ ”

The most common adverse events in the two trials were dry mouth, which affected 24% of patients, followed by mydriasis (7%), and oropharyngeal pain (6%). He advises patients to apply it once at night. “I tell my patients make this the last thing you do during your nighttime routine,” said Dr. Friedman, who coauthored a case-based clinical algorithm for approaching primary hyperhidrosis patients.

“Open it up, one swipe to the right [underarm], flip it over, one wipe of the left [underarm], toss the towelette, and wash your hands thoroughly. You don’t need to remove axillary hair or occlude the area. I tell them they may find some improvement within one week of daily use, but I give realistic expectations, usually 2-3 weeks. Tell them about the potential for side effects, which certainly can happen,” he said.

Investigators are evaluating how this product could be delivered to other body sites. Dr. Friedman said that he uses glycopyrronium tosylate off label for palmar and plantar hyperhidrosis. He advises patients to rub their hands or feet the cloth until it dries, toss the towelette, apply an occlusive agent like Aquaphor followed by gloves/socks for at least an hour, and then wash their hands or feet. “If they can keep the gloves or socks on overnight, that’s fine, but that’s very rare,” Dr. Friedman added.

“Typically, an hour or 2 of occlusive covering will get the product in where it needs to be. The upside of this product is that it’s noninvasive, there’s minimal irritation, it’s effective, and FDA approved. On the downside, it’s a long-term therapy. This is forever, so cost can be an issue, and you have to think about the anticholinergic effects as well.”

Iontophoresis is a first-line treatment for moderate to severe palmar and plantar hyperhidrosis. It’s also effective for mild hyperhidrosis with limited side effects, but it’s cumbersome, he said, requiring thrice-weekly treatment of each palm or sole for approximately 30 minutes to a controlled electric current at 15-20 mA with tap water.

There are no systemic agents approved for hyperhidrosis, only case reports or small case series. For now, the two commonly used anticholinergics are glycopyrrolate and oxybutynin. Glycopyrrolate comes in 1- and 2-mg capsules. “You can break the tablets easily and it’s pretty cheap, with an estimated cost of 2 mg/day at $756 per year,” Dr. Friedman said. “I typically start patients on 1 mg twice per day for a week, then ask how they’re doing. If they notice improvement, have minimal side effects but think they can do better, then I increase it by 1 mg and reassess. I give them autonomy, and at most, want them to max out at 6 mg per day. There is an oral solution for kids, which can make this a little more accessible.”

He prescribes oxybutynin infrequently but considers it effective. “Most patients respond to 5- to 10-mg/day dosing, but doses up to 15 or 20 mg daily may be required,” he noted.

For persistent flushing with hyperhidrosis, Dr. Friedman typically recommends treatment with clonidine. “I start patients pretty low, sometimes 0.05 mg twice per day.”

For patients who sweat because of social phobias and performance anxiety, he typically recommends treatment with a beta-adrenergic blocker. “These are highly lipophilic, so I advise patients not to take them with food,” he said. “The peak concentration is 1-1.5 hours. Usually, I start at 10 mg and I have people do a test run at home. I also take a baseline blood pressure in the office to make sure they’re not hypotensive.” The use of beta-adrenergic blockers is contraindicated in patients with bradycardia, atrioventricular block, and asthma. They can also exacerbate psoriasis.

On Sept. 20, 2020, Brickell Biotech announced the approval of sofpironium bromide gel, 5%, in Japan for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis. Sofpironium bromide is an analog of glycopyrrolate “that gets metabolized very quickly in order to limit systemic absorption of the active agent and therefore mitigate side effects,” Dr. Friedman said.

A recently published Japanese study found that 54% of patients with primary axillary hyperhidrosis who received sofpironium bromide experienced a 1- or 2-point improvement on the Hyperhidrosis Disease Severity Scale and a 50% or greater reduction in gravimetric sweat production from baseline to week 6 of treatment, compared with 36% of patients in the control group (P = .003). According to Dr. Friedman, a 15% formulation of this product is being studied in the United States, “but the experience in Japan with the 5% formulation should give us some real-world information about this product,” he said. “Out of the gate, we’re going to know something about how it’s being used.”

Dr. Friedman reported that he serves as a consultant and/or advisor to numerous pharmaceutical companies, including some that produce cannabinoids. He is also a speaker for Regeneron, Abbvie, Novartis, LRP, Dermira, and Brickel Biotech, and has received grants from Pfizer, the Dermatology Foundation, Almirall, and Janssen.

Even though over-the-counter topical antiperspirants are a common go-to treatment for primary axillary hyperhidrosis, a large survey commissioned by the International Hyperhidrosis Society showed that, while OTC aluminum products are the most recommended, they offer the least satisfaction to patients.

Of the 1,985 survey respondents who self-identified as having excessive sweating, those who received treatment were most satisfied with injections and least satisfied with prescription and OTC antiperspirants and liposuction. “It’s important to recognize that, while these are not invasive, they’re simple, you need to keep up with it, and they’re really not that effective for primary hyperhidrosis,” Adam Friedman, MD, said during the virtual Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic and Clinical Conference.

A major development came in 2018, when the Food and Drug Administration approved topical glycopyrronium tosylate for the treatment of primary axillary hyperhidrosis in adults and in children as young as age 9. It marked the first topical anticholinergic approved for the condition. Results from the pivotal phase 2 ATMOS-1 and ATMOS-2 randomized, controlled trials found that, after 4 weeks of daily use, 53%-66% of patients reported a 4-point improvement or greater on the ASDD item 2, which is defined as the worst sweating they experienced in a 24-hour period on an 11-point scale.

“Patients want to know: How quickly am I going to see improvement? The answer to this can be central to treatment compliance,” said Dr. Friedman, professor and interim chair of dermatology at the George Washington University, Washington. “We have data showing that 23%-29% of patients using glycopyrronium tosylate met that primary outcome within 1 week of use. So, you can tell patients: ‘Help is on the way. You may see a response relatively soon.’ ”

The most common adverse events in the two trials were dry mouth, which affected 24% of patients, followed by mydriasis (7%), and oropharyngeal pain (6%). He advises patients to apply it once at night. “I tell my patients make this the last thing you do during your nighttime routine,” said Dr. Friedman, who coauthored a case-based clinical algorithm for approaching primary hyperhidrosis patients.

“Open it up, one swipe to the right [underarm], flip it over, one wipe of the left [underarm], toss the towelette, and wash your hands thoroughly. You don’t need to remove axillary hair or occlude the area. I tell them they may find some improvement within one week of daily use, but I give realistic expectations, usually 2-3 weeks. Tell them about the potential for side effects, which certainly can happen,” he said.

Investigators are evaluating how this product could be delivered to other body sites. Dr. Friedman said that he uses glycopyrronium tosylate off label for palmar and plantar hyperhidrosis. He advises patients to rub their hands or feet the cloth until it dries, toss the towelette, apply an occlusive agent like Aquaphor followed by gloves/socks for at least an hour, and then wash their hands or feet. “If they can keep the gloves or socks on overnight, that’s fine, but that’s very rare,” Dr. Friedman added.