User login

Who Receives Care in VA Medical Foster Homes?

New models are needed for delivering long-term care (LTC) that are home-based, cost-effective, and appropriate for older adults with a range of care needs.1,2 In fiscal year (FY) 2015, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) spent $7.4 billion on LTC, accounting for 13% of total VA health care spending. Overall, 71% of LTC spending in FY 2015 was allocated to institutional care.3 Beyond cost, 95% of older adults prefer to remain in community rather than institutional LTC settings, such as nursing homes.4 The COVID-19 pandemic created additional concerns related to the spread of infectious disease, with > 37% of COVID-19 deaths in the United States occurring in nursing homes irrespective of facility quality.5,6

One community-based LTC alternative developed within the VA is the Medical Foster Home (MFH) program. The MFH program is an adult foster care program in which veterans who are unable to live independently receive round-the-clock care in the home of a community-based caregiver.7 MFH caregivers usually have previous experience caring for family, working in a nursing home, or working as a caregiver in another capacity. These caregivers are responsible for providing 24-hour supervision and support to residents in their MFH and can care for up to 3 adults. In the MFH program, VA home-based primary care (HBPC) teams composed of physicians, registered nurses, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, pharmacists, dieticians, and psychologists, provide primary care for MFH veterans and oversee care in the caregiver’s home.

The goal of the VA HBPC program is to improve veterans’ access to medical care and shift LTC services from institutional to noninstitutional settings by providing in-home care for those who are too sick or disabled to go to a clinic for care. On average, veterans pay the MFH caregiver $2,500 out-of-pocket per month for their care.8 In 2016, there were 992 veterans residing in MFHs across the country.9 Since MFH program implementation expanded nationwide in 2008, more than 4,000 veterans have resided in MFHs in 45 states and territories.10

The VA is required to pay for nursing home care for veterans who have a qualifying VA service-connected disability or who meet a specific threshold of disability.11 Currently, the VA is not authorized to pay for MFH care for veterans who meet the eligibility criteria for VA-paid nursing home care. Over the past decade, the VA has introduced and expanded several initiatives and programs to help veterans who require LTC remain in their homes and communities. These include but are not limited to the Veteran Directed Care program, the Choose Home Initiative, and the Caregiver Support Program.12-14 Additionally, attempts have been made to pass legislation to authorize the VA to pay for MFH for veterans’ care whose military benefits include coverage for nursing home care.15 This legislation and VA initiatives are clear signs that the VA is committed to supporting programs such as the MFH program. Given this commitment, demand for the MFH program will likely increase.

Therefore, VA practitioners need to better identify which veterans are currently in the MFH program. While veterans are expected to need nursing home level care to qualify for MFH enrollment, little has been published about the physical and mental health care needs of veterans currently receiving MFH care. One previous study compared the demographics, diagnostic characteristics, and care utilization of MFH veterans with that of veterans receiving LTC in VA community living centers (CLCs), and found that veterans in MFHs had similar levels of frailty and comorbidity and had a higher mean age when compared with veterans in CLCs.16

Our study assessed a sample of veterans living in MFHs and describes these veterans’ clinical and functional characteristics. We used the Minimum Data Set 3.0 (MDS) to complete the assessments to allow comparisons with other populations residing in long-term care.17,18 While MDS assessments are required for Medicare/Medicaid-certified nursing home residents and for residents in VA CLCs, this study was the first attempt to perform in-home MDS data assessments in MFHs. This collection of descriptive clinical data is an important first step in providing VA practitioners with information about the characteristics of veterans currently cared for in MFHs and policymakers with data to think critically about which veterans are willing to pay for the MFH program.

Methods

This study was part of a larger research project assessing the impact of the MFH program on veterans’ outcomes and health care spending as well as factors influencing program growth.7,9,10,16,19-23 We report on the characteristics of veterans staying in MFHs, using data from the MDS, including a clinical assessment of patients’ cognitive, function, and health care–related needs, collected from participants recruited for this study.

Five research nurses were trained to administer the MDS assessment to veterans in MFHs. Data were collected between April 2014 and December 2015 from veterans at MFH sites associated with 4 urban VA medical centers in 4 different Veterans Integrated Service Networks (58 total homes). While the VA medical centers (VAMCs)were urban, many of the MFHs were in rural areas, given that MFHs can be up to 50 miles from the associated VAMC. We selected MFH sites for this study based on MFH program veteran census. Specifically, we identified MFH sites with high veteran enrollment to ensure we would have a sufficiently large sample for participant recruitment.

Veterans who had resided in an MFH for at least 90 days were eligible to participate. Of the 155 veterans mailed a letter of invitation to participate, 92 (59%) completed the in-home MDS assessment. Reasons for not participating included: 13 veterans died prior to data collection, 18 veterans declined to participate, 18 family members or legal guardians of cognitively impaired veterans did not want the veteran to participate, and 14 veterans left the MFH program or were hospitalized at the time of data collection.

Family members and legal guardians who declined participation on behalf of a veteran reported that they felt the veteran was too frail to participate or that participating would be an added burden on the veteran. Based on the census of veterans residing in all MFHs nationally in November 2015 (N = 972), 9.5% of MFH veterans were included in this study.7This study was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB #12–31), in addition to the local VA research and development review boards where MFH MDS assessments were collected.

Assessment Instrument and Variables

The MDS 3.0 assesses numerous aspects of clinical and functional status. Several resident-level characteristics from the MDS 3.0 were included in this study. The Cognitive Function Scale (CFS) was used to categorize cognitive function. The CFS is a categorical variable that is created from MDS 3.0 data. The CFS integrates self- and staff-reported data to classify individuals as cognitively intact, mildly impaired, moderately impaired, or severely impaired based on respondents’ Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS) assessment or staff-reported cognitive function collected as part of the MDS 3.0.24 We explored depression by calculating a mean summary severity score for all respondents from the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 item interview (PHQ-9).25 PHQ-9 summary scores range from 0 to 27, with mean scores of ≤ 4 indicating no or minimal depression, and higher scores corresponding to more severe depression as scores increase. For respondents who were unable to complete the PHQ-9, we calculated mean PHQ Observational Version (PHQ-9-OV) scores.

We included 2 variables to characterize behaviors: wandering frequency and presence and frequency of aggressive behaviors. We summarized aggressive behaviors using the Aggressive and Reactive Behavior Scale, which characterizes whether a resident has none, mild, moderate, or severe behavioral symptoms based on the presence and frequency of physical and verbal behaviors and resistance to care.26,27 We included items that described pain, number of falls since admission or prior assessment, degree of urinary and bowel continence (always continent vs not always continent) and mobility device use to describe respondents’ health conditions and functional status. To characterize pain, we used veteran’s self-reported frequency and intensity of pain experienced in the prior 5 days and classified the experienced pain as none, mild, moderate, or severe. Finally, demographic characteristics included age and gender.

To determine functional status, we included measures of needing help to perform activities of daily living (ADLs). The MDS allows us to understand functional status ranging from ADLs lost early in the trajectory of functional decline (ie, bathing, hygiene) to those lost in the middle (ie, walking, dressing, toileting, transferring) to those lost late in the trajectory of functional decline (ie, bed mobility and eating).28,29 To assess MFH veterans’ independence in mobility, we considered the veteran’s ability to walk without supervision or assistance in the hallway outside of their room, ability to move between their room and hallway, and ability to move throughout the house. Mobility includes use of an assistive device such as a cane, walker, or wheelchair if the veteran can use it without assistance. We summarized dependency in ADLs, using a combined score of dependence in bed mobility, transfer, locomotion on unit, dressing, eating, toilet use, and personal hygiene that ranges from 0 (independent) to 28 (completely dependent).30 Additionally, we created 3-category variables to indicate the degree of dependence in performing ADLs (independent, supervision or assistance, and completely dependent).

Finally, we included diagnoses identified as active to explore differences in neurologic, mood, psychiatric, and chronic disease morbidity. In the MDS 3.0 assessment, an active diagnosis is defined as a diagnosis documented by a licensed independent practitioner in the prior 60 days that has affected the resident or their care in the prior 7 days.

Analysis

We conducted statistical analyses using Stata MP version 15.1 (StataCorp). We summarized demographic characteristics, cognitive function scores, depression scores, pain status, behavioral symptoms, incidence of falls, degree of continence, functional status, and comorbidities, using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables.

Results

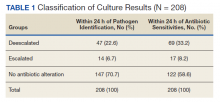

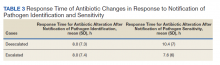

Of the 92 MFH veterans in our sample, 85% were male and 83% were aged ≥ 65 years (Table 1). Veterans had an average length of stay of 927 days at the time of MDS assessment. More than half (55%) of MFH veterans had cognitive impairment (ranging from mild to severe). The mean (SD) depression score was 3.3 (3.9), indicating minimal depression. For veterans who could not complete the depression questionnaire, the mean (SD) staff-assessed depression score was 5.9 (5.5), suggesting mild depression. Overall, 22% of the sample had aggressive behaviors but only 7 were noted to be severe. Few residents had caregiver-reported wandering. Self-reported pain intensity indicated that 45% of the sample had mild, moderate, or severe pain. While more than half the cohort had complete bowel continence (53%), only 36% had complete urinary continence. Use of mobility devices was common, with 56% of residents using a wheelchair, 42% using a walker, and 14% using a cane. One-fourth of veterans had fallen at least once since admission to the MFH.

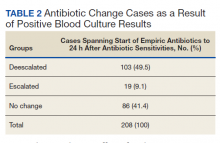

Of the 11 ADLs assessed, the percentage of MFH veterans requiring assistance with early and mid-loss ADLs ranged from 63% for transferring to 84% for bathing (Table 2). Even for the late-loss ADL of eating, 57% of the MFH cohort required assistance. Overall, MFH veterans had an average ADL dependency score of 11.

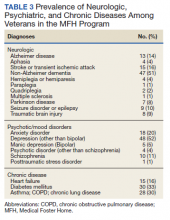

Physicians documented a diagnosis of either Alzheimer disease or non-Alzheimer dementia comorbidity for 65% of the cohort and traumatic brain injury for 9% (Table 3). Based on psychiatric comorbidities recorded in veterans’ health records, over half of MFH residents had depression (52%). Additionally, 1 in 5 MFH veterans had an anxiety disorder diagnosis. Chronic diseases were prevalent among veterans in MFHs, with 33% diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, 30% with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or chronic lung disease, and 16% with heart failure.

Discussion

In this study, we describe the characteristics of veterans receiving LTC in a sample of MFHs. This is the first study to assess veteran health and function across a group of MFHs. To help provide context for the description of MFH residents, we compared demographic characteristics, cognitive impairment, depression, pain, behaviors, functional status, and morbidity of veterans in the MFH program to long-stay residents in community nursing homes (eAppendix 1-3 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0102). A comparison with this reference population suggests that these MFH and nursing home cohorts are similar in terms of age, wandering behavior, incidence of falls, and prevalence of neurologic, psychiatric, and chronic diseases. Compared with nursing home residents, veterans in the MFH cohort had slightly higher mood symptom scores, were more likely to display aggressive behavior, and were more likely to report experiencing moderate and severe pain.

Additionally, MFH veterans displayed a lower level of cognitive impairment, fewer functional impairments, measured by the ADL dependency score, and were less likely to be bowel or bladder incontinent. Despite an overall lower ADL dependency score, a similar proportion of MFH veterans and nursing home residents were totally dependent in performing 7 of 11 ADLs and a higher proportion of MFH veterans were completely dependent for toileting (22% long-stay nursing home vs 31% MFH). The only ADLs for which there was a higher proportion of long-stay nursing home residents who were totally dependent compared with MFH residents were walking in room (54% long-stay nursing home vs 38% MFH), walking in the corridor (57% long-stay nursing home vs 33% MFH), and locomotion off the unit (36% long-stay nursing home vs 22% MFH).

While the rates of total ADL dependence among veterans in MFHs suggest that MFHs are providing care to a subset of veterans with high levels of functional impairment and care needs, MFHs are also providing care to veterans who are more independent in performing ADLs and who resemble low-care nursing home residents. A low-care nursing home resident is broadly defined as an one who does not need assistance performing late-loss ADLs (bed mobility, transferring, toileting, and eating) and who does not have the Resource Utilization Group classification of special rehab or clinically complex.31,32 Due to their overall higher functional capacity, low-care residents, even those with chronic medical care needs, may be more appropriately cared for in less intensive care settings than in nursing homes. About 5% to 30% of long-stay nursing home residents can be classified as low care.31,33-37 Additionally, a majority of newly admitted nursing home patients report a preference for or support community discharge rather than long-stay nursing home care, suggesting that many nursing home residents have the potential and desire to transition to a community-based setting.33

Based on the prevalence of veterans in our sample who are similar to low-care nursing home residents and the national focus on shifting LTC to community-based settings, MFHs may be an ideal setting for both low-care nursing home residents and those seeking community-based alternatives to traditional, institutionalized LTC. Additionally, given that we observed greater behavioral and pain needs and similar rates of comorbidities in MFH veterans relative to long-stay nursing home residents, our results indicate that MFHs also have the capacity to care for veterans with higher care needs who desire community-based LTC.

Previous research identified barriers to program MFH growth that may contribute to referral of veterans with fewer ADL dependencies compared with long-stay nursing home residents. A key barrier to MFH referral is that nursing home referral requires selection of a home, whereas MFH referral involves matching veterans with appropriate caregivers, which requires time to align the veteran’s needs with the right caregiver in the right home.7 Given the rigors of finding a match, VA staff who refer veterans may preferentially refer veterans with greater ADL impairments to nursing homes, assuming that higher levels of care needs will complicate the matching process and reserve MFH referral for only the highest functioning candidates.19 However, the ADL data presented here indicate that many MFH residents with significant levels of ADL dependence are living in MFHs. Meeting the care needs of those who have higher ADL dependencies is possible because MFH coordinators and HBPC providers deliver individual, ongoing education to MFH caregivers about caring for MFH veterans and provide available resources needed to safely care for MFH veterans across the spectrum of ADL dependency.7

Veterans with higher levels of functional dependence may also be referred to nursing homes rather than to MFHs because of payment issues. Independent of the VA, veterans or their families negotiate a contract with their caregiver to pay out-of-pocket for MFH caregiving as well as room and board. Particularly for veterans who have military benefits to cover nursing home care costs, the out-of-pocket payment for veterans with high degrees of functional dependence increase as needs increase. These out-of-pocket payments may serve as a barrier to MFH enrollment. The proposed Long-Term Care Veterans Choice Act, which would allow the VA to pay for MFH care for eligible veterans may address this barrier.15

Another possible explanation for the higher rates of functional independence in the MFH cohort is that veterans with functional impairment are not being referred to MFHs. A previous study of the MFH program found that health care providers were often unaware of the program and as a result did not refer eligible veterans to this alternative LTC option.7 The changes proposed by the Long-Term Care Veterans Choice Act may result in an increase in demand in MFH care and thus increase awareness of the program among VA physicians.15

Limitations

There are several potential limitations in this study. First, there are limits to the generalizability of the MFH sample given that the sample of veterans was not randomly selected and that weights were not applied to account for nonresponse bias. Second, charting requirements in MFHs are less intensive compared with nursing home tracking. While the training for research nurses on how to conduct MDS assessments in MFHs was designed to simulate the process in nursing homes, MDS data were likely impacted by differences in charting practices. In addition, MFH caregivers may report certain items, such as aggressive behaviors, more often because they observe MFH veterans round-the-clock compared with NH caregivers who work in shifts and have a lower caregiver to resident ratio. The current data suggest differences in prevalence of behavioral symptoms.

Future studies should examine whether this reflects differences in the populations served or differences in how MFH caregivers track and manage behavioral symptoms. Third, this study was conducted at only MFH sites associated with 4 VAMCs, thus our findings may not be generalizable to veterans in other areas. Finally, there may be differences in the veterans who agreed to participate in the study compared with those who declined to participate. For example, it is possible that the eligible MFH veterans who declined to participate in this study were more functionally impaired than those who did participate. More than one-third (39%) of the family members of cognitively impaired MFH veterans who did not participate cited concerns about the veteran’s frailty as a primary reason for declining to participate. Consequently, the high level of functional status among veterans included in this study compared to nursing home residents may be in part a result of selection bias from more ADL-impaired veterans declining to participate in the study.

Conclusions

Although the MFH program has provided LTC nationally to veterans for nearly 2 decades, this study is the first to administer in-home MDS assessments to veterans in MFHs, allowing for a detailed description of cognitive, functional, and behavioral characteristics of MFH residents. In this study, we found that veterans currently receiving care in MFHs have a wide range of care needs. Our findings indicate that MFHs are caring for some veterans with high functional impairment as well as those who are completely independent in performing ADLs.

Moreover, these results are a preliminary attempt to assist VA health care providers in determining which veterans can be cared for in an MFH such that they can make informed referrals to this alternative LTC setting. To improve the generalizability of these findings, future studies should collect MDS 3.0 assessments longitudinally from a representative sample of veterans in MFHs. Further research is needed to explore how VA providers make the decision to refer a veteran to an MFH compared to a nursing home. Additionally, the percentage of veterans in this study who reported experiencing pain may indicate the need to identify innovative, integrated pain management programs for home settings.

1. Rowe JW, Fulmer T, Fried L. Preparing for better health and health care for an aging population. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1643. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.12335

2. Reaves E, Musumeci M. Medicaid and long-term services and supports: a primer. kaiser family foundation. Published December 15, 2015. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-long-term-services-and-supports-a-primer

3. Collelo KJ, Panangala SV. Long-term care services for veterans. Congressional Research Service Report No. R44697. Published February 14, 2017. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44697.pdf

4. American Association of Retired Persons. Beyond 50.05: a report to the nation on livable communities creating environments for successful aging. Published online 2005. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/beyond_50_communities.pdf

5. Kaiser Family Foundation. State data and policy actions to address coronavirus. Updated February 11, 2021. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/state-data-and-policy-actions-to-address-coronavirus/

6. Abrams HR, Loomer L, Gandhi A, Grabowski DC. Characteristics of U.S. nursing homes with COVID-19 Cases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1653-1656. doi:10.1111/jgs.16661

7. Haverhals LM, Manheim CE, Jones J, Levy C. Launching medical foster home programs: key components to growing this alternative to nursing home placement. J Hous Elderly. 2017;31(1):14-33. doi:10.1080/01634372.2016.1268556

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Medical Foster Home Program Procedures- VHA Directive 1141.02(1). Published August 9, 2017. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=5447.

9. Haverhals LM, Manheim CE, Gilman CV, Jones J, Levy C. Caregivers create a veteran-centric community in VHA medical foster homes. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2016;59(6):441-457. doi:10.1080/01634372.2016.1231730

10. Jones J, Haverhals LM, Manheim CE, Levy C. Fostering excellence: an examination of high-enrollment VHA Medical Foster Home programs. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2017;30(1):16-22. doi:10.1177/1084822317736795

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration. Veterans Health Benefits Handbook. Published 2017. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www. va.gov/healthbenefits/vhbh/publications/vhbh_sample_handb ook_2014.pdf

12. Duan-Porter W, Ullman K, Rosebush C, McKenzie L, et al; Evidence Synthesis Program. Risk factors and interventions to prevent or delay long term nursing home placement for adults with impairments. Published May 2019. Accessed March 2, 2021. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/nursing-home-delay.pdf

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Caregiver Support Program- VHA NOTICE 2020-31. Published October 1, 2020. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=9048

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Geriatrics and extended care. Published June 10, 2020. Accessed February 22, 2021. https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/pages/Veteran-Directed_Care.asp

15. HR 1527, 116th Cong (2019). Accessed March 1, 2021. congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1527

16. Levy C, Whitfield EA. Medical foster homes: can the adult foster care model substitute for nursing home care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2585-2592. doi:10.1111/jgs.14517

17. Saliba D, Buchanan J. Making the investment count: revision of the Minimum Data Set for nursing homes, MDS 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):602-610. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2012.06.002

18. Saliba D, Jones M, Streim J, Ouslander J, Berlowitz D, Buchanan J. Overview of significant changes in the Minimum Data Set for nursing homes version 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):595-601. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2012.06.001

19. Gilman C, Haverhals L, Manheim C, Levy C. A qualitative exploration of veteran and family perspectives on medical foster homes. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2018;37(1):1-24. doi:10.1080/01621424.2017.1419156

20. Levy CR, Alemi F, Williams AE, et al. Shared homes as an alternative to nursing home care: impact of VA’s Medical Foster Home program on hospitalization. Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):62-71. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv092

21. Levy CR, Jones J, Haverhals LM, Nowels CT. A qualitative evaluation of a new community living model: medical foster home placement. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2013;4(1):p162. doi:10.5430/jnep.v4n1p162

22. Levy C, Whitfield EA, Gutman R. Medical foster home is less costly than traditional nursing home care. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(6):1346-1356. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13195

23. Manheim CE, Haverhals LM, Jones J, Levy CR. Allowing family to be family: end-of-life care in Veterans Affairs medical foster homes. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2016;12(1-2):104-125. doi:10.1080/15524256.2016.1156603

24. Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V. The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Med Care. 2017;55(9):e68-e72. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000334

25. Saliba D, DiFilippo S, Edelen MO, Kroenke K, Buchanan J, Streim J. Testing the PHQ-9 interview and observational versions (PHQ-9 OV) for MDS 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):618-625. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2012.06.003

26. Perlman CM, Hirdes JP. The aggressive behavior scale: a new scale to measure aggression based on the minimum data set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2298-2303. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02048.x

27. McCreedy E, Ogarek JA, Thomas KS, Mor V. The minimum data set agitated and reactive behavior scale: measuring behaviors in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(12):1548-1552. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.030

28. Levy CR, Zargoush M, Williams AE, et al. Sequence of functional loss and recovery in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):52-61. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv099

29. Wysocki A, Thomas KS, Mor V. Functional improvement among short-stay nursing home residents in the MDS 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(6):470-474. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2014.11.018

30. Morris JN, Pries B, Morris’ S. Scaling ADLs Within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(11):M546-M553. doi:10.1093/gerona/54.11.m546

31. Mor V, Zinn J, Gozalo P, Feng Z, Intrator O, Grabowski DC. Prospects for transferring nursing home residents to the community. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(6):1762-1771. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1762

32. Ikegami N, Morris JN, Fries BE. Low-care cases in long-term care settings: variation among nations. Age Ageing. 1997;26(suppl 2):67-71. doi:10.1093/ageing/26.suppl_2.67

33. Arling G, Kane RL, Cooke V, Lewis T. Targeting residents for transitions from nursing home to community. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(3):691-711. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01105.x

34. Castle NG. Low-care residents in nursing homes: the impact of market characteristics. J Health Soc Policy. 2002;14(3):41-58. doi:10.1300/J045v14n03_03

35. Grando VT, Rantz MJ, Petroski GF, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of nursing homes residents requiring light-care. Res Nurs Health. 2005;28(3):210-219. doi:10.1002/nur.20079

36. Hahn EA, Thomas KS, Hyer K, Andel R, Meng H. Predictors of low-care prevalence in Florida nursing homes: the role of Medicaid waiver programs. Gerontologist. 2011;51(4):495-503. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr020

37. Thomas KS. The relationship between older Americans act in-home services and low-care residents in nursing homes. J Aging Health. 2014;26(2):250-260. doi:10.1177/0898264313513611

New models are needed for delivering long-term care (LTC) that are home-based, cost-effective, and appropriate for older adults with a range of care needs.1,2 In fiscal year (FY) 2015, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) spent $7.4 billion on LTC, accounting for 13% of total VA health care spending. Overall, 71% of LTC spending in FY 2015 was allocated to institutional care.3 Beyond cost, 95% of older adults prefer to remain in community rather than institutional LTC settings, such as nursing homes.4 The COVID-19 pandemic created additional concerns related to the spread of infectious disease, with > 37% of COVID-19 deaths in the United States occurring in nursing homes irrespective of facility quality.5,6

One community-based LTC alternative developed within the VA is the Medical Foster Home (MFH) program. The MFH program is an adult foster care program in which veterans who are unable to live independently receive round-the-clock care in the home of a community-based caregiver.7 MFH caregivers usually have previous experience caring for family, working in a nursing home, or working as a caregiver in another capacity. These caregivers are responsible for providing 24-hour supervision and support to residents in their MFH and can care for up to 3 adults. In the MFH program, VA home-based primary care (HBPC) teams composed of physicians, registered nurses, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, pharmacists, dieticians, and psychologists, provide primary care for MFH veterans and oversee care in the caregiver’s home.

The goal of the VA HBPC program is to improve veterans’ access to medical care and shift LTC services from institutional to noninstitutional settings by providing in-home care for those who are too sick or disabled to go to a clinic for care. On average, veterans pay the MFH caregiver $2,500 out-of-pocket per month for their care.8 In 2016, there were 992 veterans residing in MFHs across the country.9 Since MFH program implementation expanded nationwide in 2008, more than 4,000 veterans have resided in MFHs in 45 states and territories.10

The VA is required to pay for nursing home care for veterans who have a qualifying VA service-connected disability or who meet a specific threshold of disability.11 Currently, the VA is not authorized to pay for MFH care for veterans who meet the eligibility criteria for VA-paid nursing home care. Over the past decade, the VA has introduced and expanded several initiatives and programs to help veterans who require LTC remain in their homes and communities. These include but are not limited to the Veteran Directed Care program, the Choose Home Initiative, and the Caregiver Support Program.12-14 Additionally, attempts have been made to pass legislation to authorize the VA to pay for MFH for veterans’ care whose military benefits include coverage for nursing home care.15 This legislation and VA initiatives are clear signs that the VA is committed to supporting programs such as the MFH program. Given this commitment, demand for the MFH program will likely increase.

Therefore, VA practitioners need to better identify which veterans are currently in the MFH program. While veterans are expected to need nursing home level care to qualify for MFH enrollment, little has been published about the physical and mental health care needs of veterans currently receiving MFH care. One previous study compared the demographics, diagnostic characteristics, and care utilization of MFH veterans with that of veterans receiving LTC in VA community living centers (CLCs), and found that veterans in MFHs had similar levels of frailty and comorbidity and had a higher mean age when compared with veterans in CLCs.16

Our study assessed a sample of veterans living in MFHs and describes these veterans’ clinical and functional characteristics. We used the Minimum Data Set 3.0 (MDS) to complete the assessments to allow comparisons with other populations residing in long-term care.17,18 While MDS assessments are required for Medicare/Medicaid-certified nursing home residents and for residents in VA CLCs, this study was the first attempt to perform in-home MDS data assessments in MFHs. This collection of descriptive clinical data is an important first step in providing VA practitioners with information about the characteristics of veterans currently cared for in MFHs and policymakers with data to think critically about which veterans are willing to pay for the MFH program.

Methods

This study was part of a larger research project assessing the impact of the MFH program on veterans’ outcomes and health care spending as well as factors influencing program growth.7,9,10,16,19-23 We report on the characteristics of veterans staying in MFHs, using data from the MDS, including a clinical assessment of patients’ cognitive, function, and health care–related needs, collected from participants recruited for this study.

Five research nurses were trained to administer the MDS assessment to veterans in MFHs. Data were collected between April 2014 and December 2015 from veterans at MFH sites associated with 4 urban VA medical centers in 4 different Veterans Integrated Service Networks (58 total homes). While the VA medical centers (VAMCs)were urban, many of the MFHs were in rural areas, given that MFHs can be up to 50 miles from the associated VAMC. We selected MFH sites for this study based on MFH program veteran census. Specifically, we identified MFH sites with high veteran enrollment to ensure we would have a sufficiently large sample for participant recruitment.

Veterans who had resided in an MFH for at least 90 days were eligible to participate. Of the 155 veterans mailed a letter of invitation to participate, 92 (59%) completed the in-home MDS assessment. Reasons for not participating included: 13 veterans died prior to data collection, 18 veterans declined to participate, 18 family members or legal guardians of cognitively impaired veterans did not want the veteran to participate, and 14 veterans left the MFH program or were hospitalized at the time of data collection.

Family members and legal guardians who declined participation on behalf of a veteran reported that they felt the veteran was too frail to participate or that participating would be an added burden on the veteran. Based on the census of veterans residing in all MFHs nationally in November 2015 (N = 972), 9.5% of MFH veterans were included in this study.7This study was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB #12–31), in addition to the local VA research and development review boards where MFH MDS assessments were collected.

Assessment Instrument and Variables

The MDS 3.0 assesses numerous aspects of clinical and functional status. Several resident-level characteristics from the MDS 3.0 were included in this study. The Cognitive Function Scale (CFS) was used to categorize cognitive function. The CFS is a categorical variable that is created from MDS 3.0 data. The CFS integrates self- and staff-reported data to classify individuals as cognitively intact, mildly impaired, moderately impaired, or severely impaired based on respondents’ Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS) assessment or staff-reported cognitive function collected as part of the MDS 3.0.24 We explored depression by calculating a mean summary severity score for all respondents from the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 item interview (PHQ-9).25 PHQ-9 summary scores range from 0 to 27, with mean scores of ≤ 4 indicating no or minimal depression, and higher scores corresponding to more severe depression as scores increase. For respondents who were unable to complete the PHQ-9, we calculated mean PHQ Observational Version (PHQ-9-OV) scores.

We included 2 variables to characterize behaviors: wandering frequency and presence and frequency of aggressive behaviors. We summarized aggressive behaviors using the Aggressive and Reactive Behavior Scale, which characterizes whether a resident has none, mild, moderate, or severe behavioral symptoms based on the presence and frequency of physical and verbal behaviors and resistance to care.26,27 We included items that described pain, number of falls since admission or prior assessment, degree of urinary and bowel continence (always continent vs not always continent) and mobility device use to describe respondents’ health conditions and functional status. To characterize pain, we used veteran’s self-reported frequency and intensity of pain experienced in the prior 5 days and classified the experienced pain as none, mild, moderate, or severe. Finally, demographic characteristics included age and gender.

To determine functional status, we included measures of needing help to perform activities of daily living (ADLs). The MDS allows us to understand functional status ranging from ADLs lost early in the trajectory of functional decline (ie, bathing, hygiene) to those lost in the middle (ie, walking, dressing, toileting, transferring) to those lost late in the trajectory of functional decline (ie, bed mobility and eating).28,29 To assess MFH veterans’ independence in mobility, we considered the veteran’s ability to walk without supervision or assistance in the hallway outside of their room, ability to move between their room and hallway, and ability to move throughout the house. Mobility includes use of an assistive device such as a cane, walker, or wheelchair if the veteran can use it without assistance. We summarized dependency in ADLs, using a combined score of dependence in bed mobility, transfer, locomotion on unit, dressing, eating, toilet use, and personal hygiene that ranges from 0 (independent) to 28 (completely dependent).30 Additionally, we created 3-category variables to indicate the degree of dependence in performing ADLs (independent, supervision or assistance, and completely dependent).

Finally, we included diagnoses identified as active to explore differences in neurologic, mood, psychiatric, and chronic disease morbidity. In the MDS 3.0 assessment, an active diagnosis is defined as a diagnosis documented by a licensed independent practitioner in the prior 60 days that has affected the resident or their care in the prior 7 days.

Analysis

We conducted statistical analyses using Stata MP version 15.1 (StataCorp). We summarized demographic characteristics, cognitive function scores, depression scores, pain status, behavioral symptoms, incidence of falls, degree of continence, functional status, and comorbidities, using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables.

Results

Of the 92 MFH veterans in our sample, 85% were male and 83% were aged ≥ 65 years (Table 1). Veterans had an average length of stay of 927 days at the time of MDS assessment. More than half (55%) of MFH veterans had cognitive impairment (ranging from mild to severe). The mean (SD) depression score was 3.3 (3.9), indicating minimal depression. For veterans who could not complete the depression questionnaire, the mean (SD) staff-assessed depression score was 5.9 (5.5), suggesting mild depression. Overall, 22% of the sample had aggressive behaviors but only 7 were noted to be severe. Few residents had caregiver-reported wandering. Self-reported pain intensity indicated that 45% of the sample had mild, moderate, or severe pain. While more than half the cohort had complete bowel continence (53%), only 36% had complete urinary continence. Use of mobility devices was common, with 56% of residents using a wheelchair, 42% using a walker, and 14% using a cane. One-fourth of veterans had fallen at least once since admission to the MFH.

Of the 11 ADLs assessed, the percentage of MFH veterans requiring assistance with early and mid-loss ADLs ranged from 63% for transferring to 84% for bathing (Table 2). Even for the late-loss ADL of eating, 57% of the MFH cohort required assistance. Overall, MFH veterans had an average ADL dependency score of 11.

Physicians documented a diagnosis of either Alzheimer disease or non-Alzheimer dementia comorbidity for 65% of the cohort and traumatic brain injury for 9% (Table 3). Based on psychiatric comorbidities recorded in veterans’ health records, over half of MFH residents had depression (52%). Additionally, 1 in 5 MFH veterans had an anxiety disorder diagnosis. Chronic diseases were prevalent among veterans in MFHs, with 33% diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, 30% with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or chronic lung disease, and 16% with heart failure.

Discussion

In this study, we describe the characteristics of veterans receiving LTC in a sample of MFHs. This is the first study to assess veteran health and function across a group of MFHs. To help provide context for the description of MFH residents, we compared demographic characteristics, cognitive impairment, depression, pain, behaviors, functional status, and morbidity of veterans in the MFH program to long-stay residents in community nursing homes (eAppendix 1-3 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0102). A comparison with this reference population suggests that these MFH and nursing home cohorts are similar in terms of age, wandering behavior, incidence of falls, and prevalence of neurologic, psychiatric, and chronic diseases. Compared with nursing home residents, veterans in the MFH cohort had slightly higher mood symptom scores, were more likely to display aggressive behavior, and were more likely to report experiencing moderate and severe pain.

Additionally, MFH veterans displayed a lower level of cognitive impairment, fewer functional impairments, measured by the ADL dependency score, and were less likely to be bowel or bladder incontinent. Despite an overall lower ADL dependency score, a similar proportion of MFH veterans and nursing home residents were totally dependent in performing 7 of 11 ADLs and a higher proportion of MFH veterans were completely dependent for toileting (22% long-stay nursing home vs 31% MFH). The only ADLs for which there was a higher proportion of long-stay nursing home residents who were totally dependent compared with MFH residents were walking in room (54% long-stay nursing home vs 38% MFH), walking in the corridor (57% long-stay nursing home vs 33% MFH), and locomotion off the unit (36% long-stay nursing home vs 22% MFH).

While the rates of total ADL dependence among veterans in MFHs suggest that MFHs are providing care to a subset of veterans with high levels of functional impairment and care needs, MFHs are also providing care to veterans who are more independent in performing ADLs and who resemble low-care nursing home residents. A low-care nursing home resident is broadly defined as an one who does not need assistance performing late-loss ADLs (bed mobility, transferring, toileting, and eating) and who does not have the Resource Utilization Group classification of special rehab or clinically complex.31,32 Due to their overall higher functional capacity, low-care residents, even those with chronic medical care needs, may be more appropriately cared for in less intensive care settings than in nursing homes. About 5% to 30% of long-stay nursing home residents can be classified as low care.31,33-37 Additionally, a majority of newly admitted nursing home patients report a preference for or support community discharge rather than long-stay nursing home care, suggesting that many nursing home residents have the potential and desire to transition to a community-based setting.33

Based on the prevalence of veterans in our sample who are similar to low-care nursing home residents and the national focus on shifting LTC to community-based settings, MFHs may be an ideal setting for both low-care nursing home residents and those seeking community-based alternatives to traditional, institutionalized LTC. Additionally, given that we observed greater behavioral and pain needs and similar rates of comorbidities in MFH veterans relative to long-stay nursing home residents, our results indicate that MFHs also have the capacity to care for veterans with higher care needs who desire community-based LTC.

Previous research identified barriers to program MFH growth that may contribute to referral of veterans with fewer ADL dependencies compared with long-stay nursing home residents. A key barrier to MFH referral is that nursing home referral requires selection of a home, whereas MFH referral involves matching veterans with appropriate caregivers, which requires time to align the veteran’s needs with the right caregiver in the right home.7 Given the rigors of finding a match, VA staff who refer veterans may preferentially refer veterans with greater ADL impairments to nursing homes, assuming that higher levels of care needs will complicate the matching process and reserve MFH referral for only the highest functioning candidates.19 However, the ADL data presented here indicate that many MFH residents with significant levels of ADL dependence are living in MFHs. Meeting the care needs of those who have higher ADL dependencies is possible because MFH coordinators and HBPC providers deliver individual, ongoing education to MFH caregivers about caring for MFH veterans and provide available resources needed to safely care for MFH veterans across the spectrum of ADL dependency.7

Veterans with higher levels of functional dependence may also be referred to nursing homes rather than to MFHs because of payment issues. Independent of the VA, veterans or their families negotiate a contract with their caregiver to pay out-of-pocket for MFH caregiving as well as room and board. Particularly for veterans who have military benefits to cover nursing home care costs, the out-of-pocket payment for veterans with high degrees of functional dependence increase as needs increase. These out-of-pocket payments may serve as a barrier to MFH enrollment. The proposed Long-Term Care Veterans Choice Act, which would allow the VA to pay for MFH care for eligible veterans may address this barrier.15

Another possible explanation for the higher rates of functional independence in the MFH cohort is that veterans with functional impairment are not being referred to MFHs. A previous study of the MFH program found that health care providers were often unaware of the program and as a result did not refer eligible veterans to this alternative LTC option.7 The changes proposed by the Long-Term Care Veterans Choice Act may result in an increase in demand in MFH care and thus increase awareness of the program among VA physicians.15

Limitations

There are several potential limitations in this study. First, there are limits to the generalizability of the MFH sample given that the sample of veterans was not randomly selected and that weights were not applied to account for nonresponse bias. Second, charting requirements in MFHs are less intensive compared with nursing home tracking. While the training for research nurses on how to conduct MDS assessments in MFHs was designed to simulate the process in nursing homes, MDS data were likely impacted by differences in charting practices. In addition, MFH caregivers may report certain items, such as aggressive behaviors, more often because they observe MFH veterans round-the-clock compared with NH caregivers who work in shifts and have a lower caregiver to resident ratio. The current data suggest differences in prevalence of behavioral symptoms.

Future studies should examine whether this reflects differences in the populations served or differences in how MFH caregivers track and manage behavioral symptoms. Third, this study was conducted at only MFH sites associated with 4 VAMCs, thus our findings may not be generalizable to veterans in other areas. Finally, there may be differences in the veterans who agreed to participate in the study compared with those who declined to participate. For example, it is possible that the eligible MFH veterans who declined to participate in this study were more functionally impaired than those who did participate. More than one-third (39%) of the family members of cognitively impaired MFH veterans who did not participate cited concerns about the veteran’s frailty as a primary reason for declining to participate. Consequently, the high level of functional status among veterans included in this study compared to nursing home residents may be in part a result of selection bias from more ADL-impaired veterans declining to participate in the study.

Conclusions

Although the MFH program has provided LTC nationally to veterans for nearly 2 decades, this study is the first to administer in-home MDS assessments to veterans in MFHs, allowing for a detailed description of cognitive, functional, and behavioral characteristics of MFH residents. In this study, we found that veterans currently receiving care in MFHs have a wide range of care needs. Our findings indicate that MFHs are caring for some veterans with high functional impairment as well as those who are completely independent in performing ADLs.

Moreover, these results are a preliminary attempt to assist VA health care providers in determining which veterans can be cared for in an MFH such that they can make informed referrals to this alternative LTC setting. To improve the generalizability of these findings, future studies should collect MDS 3.0 assessments longitudinally from a representative sample of veterans in MFHs. Further research is needed to explore how VA providers make the decision to refer a veteran to an MFH compared to a nursing home. Additionally, the percentage of veterans in this study who reported experiencing pain may indicate the need to identify innovative, integrated pain management programs for home settings.

New models are needed for delivering long-term care (LTC) that are home-based, cost-effective, and appropriate for older adults with a range of care needs.1,2 In fiscal year (FY) 2015, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) spent $7.4 billion on LTC, accounting for 13% of total VA health care spending. Overall, 71% of LTC spending in FY 2015 was allocated to institutional care.3 Beyond cost, 95% of older adults prefer to remain in community rather than institutional LTC settings, such as nursing homes.4 The COVID-19 pandemic created additional concerns related to the spread of infectious disease, with > 37% of COVID-19 deaths in the United States occurring in nursing homes irrespective of facility quality.5,6

One community-based LTC alternative developed within the VA is the Medical Foster Home (MFH) program. The MFH program is an adult foster care program in which veterans who are unable to live independently receive round-the-clock care in the home of a community-based caregiver.7 MFH caregivers usually have previous experience caring for family, working in a nursing home, or working as a caregiver in another capacity. These caregivers are responsible for providing 24-hour supervision and support to residents in their MFH and can care for up to 3 adults. In the MFH program, VA home-based primary care (HBPC) teams composed of physicians, registered nurses, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, pharmacists, dieticians, and psychologists, provide primary care for MFH veterans and oversee care in the caregiver’s home.

The goal of the VA HBPC program is to improve veterans’ access to medical care and shift LTC services from institutional to noninstitutional settings by providing in-home care for those who are too sick or disabled to go to a clinic for care. On average, veterans pay the MFH caregiver $2,500 out-of-pocket per month for their care.8 In 2016, there were 992 veterans residing in MFHs across the country.9 Since MFH program implementation expanded nationwide in 2008, more than 4,000 veterans have resided in MFHs in 45 states and territories.10

The VA is required to pay for nursing home care for veterans who have a qualifying VA service-connected disability or who meet a specific threshold of disability.11 Currently, the VA is not authorized to pay for MFH care for veterans who meet the eligibility criteria for VA-paid nursing home care. Over the past decade, the VA has introduced and expanded several initiatives and programs to help veterans who require LTC remain in their homes and communities. These include but are not limited to the Veteran Directed Care program, the Choose Home Initiative, and the Caregiver Support Program.12-14 Additionally, attempts have been made to pass legislation to authorize the VA to pay for MFH for veterans’ care whose military benefits include coverage for nursing home care.15 This legislation and VA initiatives are clear signs that the VA is committed to supporting programs such as the MFH program. Given this commitment, demand for the MFH program will likely increase.

Therefore, VA practitioners need to better identify which veterans are currently in the MFH program. While veterans are expected to need nursing home level care to qualify for MFH enrollment, little has been published about the physical and mental health care needs of veterans currently receiving MFH care. One previous study compared the demographics, diagnostic characteristics, and care utilization of MFH veterans with that of veterans receiving LTC in VA community living centers (CLCs), and found that veterans in MFHs had similar levels of frailty and comorbidity and had a higher mean age when compared with veterans in CLCs.16

Our study assessed a sample of veterans living in MFHs and describes these veterans’ clinical and functional characteristics. We used the Minimum Data Set 3.0 (MDS) to complete the assessments to allow comparisons with other populations residing in long-term care.17,18 While MDS assessments are required for Medicare/Medicaid-certified nursing home residents and for residents in VA CLCs, this study was the first attempt to perform in-home MDS data assessments in MFHs. This collection of descriptive clinical data is an important first step in providing VA practitioners with information about the characteristics of veterans currently cared for in MFHs and policymakers with data to think critically about which veterans are willing to pay for the MFH program.

Methods

This study was part of a larger research project assessing the impact of the MFH program on veterans’ outcomes and health care spending as well as factors influencing program growth.7,9,10,16,19-23 We report on the characteristics of veterans staying in MFHs, using data from the MDS, including a clinical assessment of patients’ cognitive, function, and health care–related needs, collected from participants recruited for this study.

Five research nurses were trained to administer the MDS assessment to veterans in MFHs. Data were collected between April 2014 and December 2015 from veterans at MFH sites associated with 4 urban VA medical centers in 4 different Veterans Integrated Service Networks (58 total homes). While the VA medical centers (VAMCs)were urban, many of the MFHs were in rural areas, given that MFHs can be up to 50 miles from the associated VAMC. We selected MFH sites for this study based on MFH program veteran census. Specifically, we identified MFH sites with high veteran enrollment to ensure we would have a sufficiently large sample for participant recruitment.

Veterans who had resided in an MFH for at least 90 days were eligible to participate. Of the 155 veterans mailed a letter of invitation to participate, 92 (59%) completed the in-home MDS assessment. Reasons for not participating included: 13 veterans died prior to data collection, 18 veterans declined to participate, 18 family members or legal guardians of cognitively impaired veterans did not want the veteran to participate, and 14 veterans left the MFH program or were hospitalized at the time of data collection.

Family members and legal guardians who declined participation on behalf of a veteran reported that they felt the veteran was too frail to participate or that participating would be an added burden on the veteran. Based on the census of veterans residing in all MFHs nationally in November 2015 (N = 972), 9.5% of MFH veterans were included in this study.7This study was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB #12–31), in addition to the local VA research and development review boards where MFH MDS assessments were collected.

Assessment Instrument and Variables

The MDS 3.0 assesses numerous aspects of clinical and functional status. Several resident-level characteristics from the MDS 3.0 were included in this study. The Cognitive Function Scale (CFS) was used to categorize cognitive function. The CFS is a categorical variable that is created from MDS 3.0 data. The CFS integrates self- and staff-reported data to classify individuals as cognitively intact, mildly impaired, moderately impaired, or severely impaired based on respondents’ Brief Interview for Mental Status (BIMS) assessment or staff-reported cognitive function collected as part of the MDS 3.0.24 We explored depression by calculating a mean summary severity score for all respondents from the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 item interview (PHQ-9).25 PHQ-9 summary scores range from 0 to 27, with mean scores of ≤ 4 indicating no or minimal depression, and higher scores corresponding to more severe depression as scores increase. For respondents who were unable to complete the PHQ-9, we calculated mean PHQ Observational Version (PHQ-9-OV) scores.

We included 2 variables to characterize behaviors: wandering frequency and presence and frequency of aggressive behaviors. We summarized aggressive behaviors using the Aggressive and Reactive Behavior Scale, which characterizes whether a resident has none, mild, moderate, or severe behavioral symptoms based on the presence and frequency of physical and verbal behaviors and resistance to care.26,27 We included items that described pain, number of falls since admission or prior assessment, degree of urinary and bowel continence (always continent vs not always continent) and mobility device use to describe respondents’ health conditions and functional status. To characterize pain, we used veteran’s self-reported frequency and intensity of pain experienced in the prior 5 days and classified the experienced pain as none, mild, moderate, or severe. Finally, demographic characteristics included age and gender.

To determine functional status, we included measures of needing help to perform activities of daily living (ADLs). The MDS allows us to understand functional status ranging from ADLs lost early in the trajectory of functional decline (ie, bathing, hygiene) to those lost in the middle (ie, walking, dressing, toileting, transferring) to those lost late in the trajectory of functional decline (ie, bed mobility and eating).28,29 To assess MFH veterans’ independence in mobility, we considered the veteran’s ability to walk without supervision or assistance in the hallway outside of their room, ability to move between their room and hallway, and ability to move throughout the house. Mobility includes use of an assistive device such as a cane, walker, or wheelchair if the veteran can use it without assistance. We summarized dependency in ADLs, using a combined score of dependence in bed mobility, transfer, locomotion on unit, dressing, eating, toilet use, and personal hygiene that ranges from 0 (independent) to 28 (completely dependent).30 Additionally, we created 3-category variables to indicate the degree of dependence in performing ADLs (independent, supervision or assistance, and completely dependent).

Finally, we included diagnoses identified as active to explore differences in neurologic, mood, psychiatric, and chronic disease morbidity. In the MDS 3.0 assessment, an active diagnosis is defined as a diagnosis documented by a licensed independent practitioner in the prior 60 days that has affected the resident or their care in the prior 7 days.

Analysis

We conducted statistical analyses using Stata MP version 15.1 (StataCorp). We summarized demographic characteristics, cognitive function scores, depression scores, pain status, behavioral symptoms, incidence of falls, degree of continence, functional status, and comorbidities, using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables.

Results

Of the 92 MFH veterans in our sample, 85% were male and 83% were aged ≥ 65 years (Table 1). Veterans had an average length of stay of 927 days at the time of MDS assessment. More than half (55%) of MFH veterans had cognitive impairment (ranging from mild to severe). The mean (SD) depression score was 3.3 (3.9), indicating minimal depression. For veterans who could not complete the depression questionnaire, the mean (SD) staff-assessed depression score was 5.9 (5.5), suggesting mild depression. Overall, 22% of the sample had aggressive behaviors but only 7 were noted to be severe. Few residents had caregiver-reported wandering. Self-reported pain intensity indicated that 45% of the sample had mild, moderate, or severe pain. While more than half the cohort had complete bowel continence (53%), only 36% had complete urinary continence. Use of mobility devices was common, with 56% of residents using a wheelchair, 42% using a walker, and 14% using a cane. One-fourth of veterans had fallen at least once since admission to the MFH.

Of the 11 ADLs assessed, the percentage of MFH veterans requiring assistance with early and mid-loss ADLs ranged from 63% for transferring to 84% for bathing (Table 2). Even for the late-loss ADL of eating, 57% of the MFH cohort required assistance. Overall, MFH veterans had an average ADL dependency score of 11.

Physicians documented a diagnosis of either Alzheimer disease or non-Alzheimer dementia comorbidity for 65% of the cohort and traumatic brain injury for 9% (Table 3). Based on psychiatric comorbidities recorded in veterans’ health records, over half of MFH residents had depression (52%). Additionally, 1 in 5 MFH veterans had an anxiety disorder diagnosis. Chronic diseases were prevalent among veterans in MFHs, with 33% diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, 30% with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or chronic lung disease, and 16% with heart failure.

Discussion

In this study, we describe the characteristics of veterans receiving LTC in a sample of MFHs. This is the first study to assess veteran health and function across a group of MFHs. To help provide context for the description of MFH residents, we compared demographic characteristics, cognitive impairment, depression, pain, behaviors, functional status, and morbidity of veterans in the MFH program to long-stay residents in community nursing homes (eAppendix 1-3 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0102). A comparison with this reference population suggests that these MFH and nursing home cohorts are similar in terms of age, wandering behavior, incidence of falls, and prevalence of neurologic, psychiatric, and chronic diseases. Compared with nursing home residents, veterans in the MFH cohort had slightly higher mood symptom scores, were more likely to display aggressive behavior, and were more likely to report experiencing moderate and severe pain.

Additionally, MFH veterans displayed a lower level of cognitive impairment, fewer functional impairments, measured by the ADL dependency score, and were less likely to be bowel or bladder incontinent. Despite an overall lower ADL dependency score, a similar proportion of MFH veterans and nursing home residents were totally dependent in performing 7 of 11 ADLs and a higher proportion of MFH veterans were completely dependent for toileting (22% long-stay nursing home vs 31% MFH). The only ADLs for which there was a higher proportion of long-stay nursing home residents who were totally dependent compared with MFH residents were walking in room (54% long-stay nursing home vs 38% MFH), walking in the corridor (57% long-stay nursing home vs 33% MFH), and locomotion off the unit (36% long-stay nursing home vs 22% MFH).

While the rates of total ADL dependence among veterans in MFHs suggest that MFHs are providing care to a subset of veterans with high levels of functional impairment and care needs, MFHs are also providing care to veterans who are more independent in performing ADLs and who resemble low-care nursing home residents. A low-care nursing home resident is broadly defined as an one who does not need assistance performing late-loss ADLs (bed mobility, transferring, toileting, and eating) and who does not have the Resource Utilization Group classification of special rehab or clinically complex.31,32 Due to their overall higher functional capacity, low-care residents, even those with chronic medical care needs, may be more appropriately cared for in less intensive care settings than in nursing homes. About 5% to 30% of long-stay nursing home residents can be classified as low care.31,33-37 Additionally, a majority of newly admitted nursing home patients report a preference for or support community discharge rather than long-stay nursing home care, suggesting that many nursing home residents have the potential and desire to transition to a community-based setting.33

Based on the prevalence of veterans in our sample who are similar to low-care nursing home residents and the national focus on shifting LTC to community-based settings, MFHs may be an ideal setting for both low-care nursing home residents and those seeking community-based alternatives to traditional, institutionalized LTC. Additionally, given that we observed greater behavioral and pain needs and similar rates of comorbidities in MFH veterans relative to long-stay nursing home residents, our results indicate that MFHs also have the capacity to care for veterans with higher care needs who desire community-based LTC.

Previous research identified barriers to program MFH growth that may contribute to referral of veterans with fewer ADL dependencies compared with long-stay nursing home residents. A key barrier to MFH referral is that nursing home referral requires selection of a home, whereas MFH referral involves matching veterans with appropriate caregivers, which requires time to align the veteran’s needs with the right caregiver in the right home.7 Given the rigors of finding a match, VA staff who refer veterans may preferentially refer veterans with greater ADL impairments to nursing homes, assuming that higher levels of care needs will complicate the matching process and reserve MFH referral for only the highest functioning candidates.19 However, the ADL data presented here indicate that many MFH residents with significant levels of ADL dependence are living in MFHs. Meeting the care needs of those who have higher ADL dependencies is possible because MFH coordinators and HBPC providers deliver individual, ongoing education to MFH caregivers about caring for MFH veterans and provide available resources needed to safely care for MFH veterans across the spectrum of ADL dependency.7

Veterans with higher levels of functional dependence may also be referred to nursing homes rather than to MFHs because of payment issues. Independent of the VA, veterans or their families negotiate a contract with their caregiver to pay out-of-pocket for MFH caregiving as well as room and board. Particularly for veterans who have military benefits to cover nursing home care costs, the out-of-pocket payment for veterans with high degrees of functional dependence increase as needs increase. These out-of-pocket payments may serve as a barrier to MFH enrollment. The proposed Long-Term Care Veterans Choice Act, which would allow the VA to pay for MFH care for eligible veterans may address this barrier.15

Another possible explanation for the higher rates of functional independence in the MFH cohort is that veterans with functional impairment are not being referred to MFHs. A previous study of the MFH program found that health care providers were often unaware of the program and as a result did not refer eligible veterans to this alternative LTC option.7 The changes proposed by the Long-Term Care Veterans Choice Act may result in an increase in demand in MFH care and thus increase awareness of the program among VA physicians.15

Limitations

There are several potential limitations in this study. First, there are limits to the generalizability of the MFH sample given that the sample of veterans was not randomly selected and that weights were not applied to account for nonresponse bias. Second, charting requirements in MFHs are less intensive compared with nursing home tracking. While the training for research nurses on how to conduct MDS assessments in MFHs was designed to simulate the process in nursing homes, MDS data were likely impacted by differences in charting practices. In addition, MFH caregivers may report certain items, such as aggressive behaviors, more often because they observe MFH veterans round-the-clock compared with NH caregivers who work in shifts and have a lower caregiver to resident ratio. The current data suggest differences in prevalence of behavioral symptoms.

Future studies should examine whether this reflects differences in the populations served or differences in how MFH caregivers track and manage behavioral symptoms. Third, this study was conducted at only MFH sites associated with 4 VAMCs, thus our findings may not be generalizable to veterans in other areas. Finally, there may be differences in the veterans who agreed to participate in the study compared with those who declined to participate. For example, it is possible that the eligible MFH veterans who declined to participate in this study were more functionally impaired than those who did participate. More than one-third (39%) of the family members of cognitively impaired MFH veterans who did not participate cited concerns about the veteran’s frailty as a primary reason for declining to participate. Consequently, the high level of functional status among veterans included in this study compared to nursing home residents may be in part a result of selection bias from more ADL-impaired veterans declining to participate in the study.

Conclusions

Although the MFH program has provided LTC nationally to veterans for nearly 2 decades, this study is the first to administer in-home MDS assessments to veterans in MFHs, allowing for a detailed description of cognitive, functional, and behavioral characteristics of MFH residents. In this study, we found that veterans currently receiving care in MFHs have a wide range of care needs. Our findings indicate that MFHs are caring for some veterans with high functional impairment as well as those who are completely independent in performing ADLs.

Moreover, these results are a preliminary attempt to assist VA health care providers in determining which veterans can be cared for in an MFH such that they can make informed referrals to this alternative LTC setting. To improve the generalizability of these findings, future studies should collect MDS 3.0 assessments longitudinally from a representative sample of veterans in MFHs. Further research is needed to explore how VA providers make the decision to refer a veteran to an MFH compared to a nursing home. Additionally, the percentage of veterans in this study who reported experiencing pain may indicate the need to identify innovative, integrated pain management programs for home settings.

1. Rowe JW, Fulmer T, Fried L. Preparing for better health and health care for an aging population. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1643. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.12335

2. Reaves E, Musumeci M. Medicaid and long-term services and supports: a primer. kaiser family foundation. Published December 15, 2015. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-long-term-services-and-supports-a-primer

3. Collelo KJ, Panangala SV. Long-term care services for veterans. Congressional Research Service Report No. R44697. Published February 14, 2017. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44697.pdf

4. American Association of Retired Persons. Beyond 50.05: a report to the nation on livable communities creating environments for successful aging. Published online 2005. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/beyond_50_communities.pdf

5. Kaiser Family Foundation. State data and policy actions to address coronavirus. Updated February 11, 2021. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/state-data-and-policy-actions-to-address-coronavirus/

6. Abrams HR, Loomer L, Gandhi A, Grabowski DC. Characteristics of U.S. nursing homes with COVID-19 Cases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8):1653-1656. doi:10.1111/jgs.16661

7. Haverhals LM, Manheim CE, Jones J, Levy C. Launching medical foster home programs: key components to growing this alternative to nursing home placement. J Hous Elderly. 2017;31(1):14-33. doi:10.1080/01634372.2016.1268556

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Medical Foster Home Program Procedures- VHA Directive 1141.02(1). Published August 9, 2017. Accessed February 12, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=5447.

9. Haverhals LM, Manheim CE, Gilman CV, Jones J, Levy C. Caregivers create a veteran-centric community in VHA medical foster homes. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2016;59(6):441-457. doi:10.1080/01634372.2016.1231730

10. Jones J, Haverhals LM, Manheim CE, Levy C. Fostering excellence: an examination of high-enrollment VHA Medical Foster Home programs. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2017;30(1):16-22. doi:10.1177/1084822317736795

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Health Administration. Veterans Health Benefits Handbook. Published 2017. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www. va.gov/healthbenefits/vhbh/publications/vhbh_sample_handb ook_2014.pdf

12. Duan-Porter W, Ullman K, Rosebush C, McKenzie L, et al; Evidence Synthesis Program. Risk factors and interventions to prevent or delay long term nursing home placement for adults with impairments. Published May 2019. Accessed March 2, 2021. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/nursing-home-delay.pdf

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Caregiver Support Program- VHA NOTICE 2020-31. Published October 1, 2020. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.va.gov/VHApublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=9048

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Geriatrics and extended care. Published June 10, 2020. Accessed February 22, 2021. https://www.va.gov/geriatrics/pages/Veteran-Directed_Care.asp

15. HR 1527, 116th Cong (2019). Accessed March 1, 2021. congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1527

16. Levy C, Whitfield EA. Medical foster homes: can the adult foster care model substitute for nursing home care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2585-2592. doi:10.1111/jgs.14517

17. Saliba D, Buchanan J. Making the investment count: revision of the Minimum Data Set for nursing homes, MDS 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):602-610. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2012.06.002

18. Saliba D, Jones M, Streim J, Ouslander J, Berlowitz D, Buchanan J. Overview of significant changes in the Minimum Data Set for nursing homes version 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):595-601. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2012.06.001

19. Gilman C, Haverhals L, Manheim C, Levy C. A qualitative exploration of veteran and family perspectives on medical foster homes. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2018;37(1):1-24. doi:10.1080/01621424.2017.1419156

20. Levy CR, Alemi F, Williams AE, et al. Shared homes as an alternative to nursing home care: impact of VA’s Medical Foster Home program on hospitalization. Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):62-71. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv092

21. Levy CR, Jones J, Haverhals LM, Nowels CT. A qualitative evaluation of a new community living model: medical foster home placement. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2013;4(1):p162. doi:10.5430/jnep.v4n1p162

22. Levy C, Whitfield EA, Gutman R. Medical foster home is less costly than traditional nursing home care. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(6):1346-1356. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13195

23. Manheim CE, Haverhals LM, Jones J, Levy CR. Allowing family to be family: end-of-life care in Veterans Affairs medical foster homes. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2016;12(1-2):104-125. doi:10.1080/15524256.2016.1156603

24. Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V. The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Med Care. 2017;55(9):e68-e72. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000334

25. Saliba D, DiFilippo S, Edelen MO, Kroenke K, Buchanan J, Streim J. Testing the PHQ-9 interview and observational versions (PHQ-9 OV) for MDS 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):618-625. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2012.06.003

26. Perlman CM, Hirdes JP. The aggressive behavior scale: a new scale to measure aggression based on the minimum data set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2298-2303. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02048.x

27. McCreedy E, Ogarek JA, Thomas KS, Mor V. The minimum data set agitated and reactive behavior scale: measuring behaviors in nursing home residents with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(12):1548-1552. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2019.08.030

28. Levy CR, Zargoush M, Williams AE, et al. Sequence of functional loss and recovery in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2016;56(1):52-61. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv099

29. Wysocki A, Thomas KS, Mor V. Functional improvement among short-stay nursing home residents in the MDS 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(6):470-474. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2014.11.018

30. Morris JN, Pries B, Morris’ S. Scaling ADLs Within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(11):M546-M553. doi:10.1093/gerona/54.11.m546