User login

Safety and efficacy of biosimilar CT-P17 and adalimumab in RA

Key clinical point: Citrate-free adalimumab biosimilar (CT-P17) and European Union-approved adalimumab (EU-adalimumab) demonstrated equivalent efficacy and comparable safety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: At week 24, CT-P17 and EU-adalimumab groups showed similar 20% improvement by the American College of Rheumatology criteria response rate (82.7%). The 95% confidence interval (CI; −5.94 to 5.94) and 90% CI (−4.98 to 4.98) for estimated treatment difference were within predefined equivalence margin, demonstrating therapeutic equivalence. Overall, safety was similar between both treatment groups.

Study details: This was a randomized, double-blind phase 3 study of 648 patients with RA who were randomly allocated to receive 40 mg of either CT-P17 (n=324) or EU-adalimumab (n=324), every 2 weeks until week 48.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Celltrion, Inc. (Incheon, Republic of Korea). The authors reported receiving support, investigator fees, speaking fees, and/or consulting for various pharmaceutical companies including Celltrion, Inc. SJ Lee, YJ Bae, GE Yang, and JK Yoo reported being employees of Celltrion, Inc.

Source: Kay J et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021 Feb 5. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02394-7.

Key clinical point: Citrate-free adalimumab biosimilar (CT-P17) and European Union-approved adalimumab (EU-adalimumab) demonstrated equivalent efficacy and comparable safety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: At week 24, CT-P17 and EU-adalimumab groups showed similar 20% improvement by the American College of Rheumatology criteria response rate (82.7%). The 95% confidence interval (CI; −5.94 to 5.94) and 90% CI (−4.98 to 4.98) for estimated treatment difference were within predefined equivalence margin, demonstrating therapeutic equivalence. Overall, safety was similar between both treatment groups.

Study details: This was a randomized, double-blind phase 3 study of 648 patients with RA who were randomly allocated to receive 40 mg of either CT-P17 (n=324) or EU-adalimumab (n=324), every 2 weeks until week 48.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Celltrion, Inc. (Incheon, Republic of Korea). The authors reported receiving support, investigator fees, speaking fees, and/or consulting for various pharmaceutical companies including Celltrion, Inc. SJ Lee, YJ Bae, GE Yang, and JK Yoo reported being employees of Celltrion, Inc.

Source: Kay J et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021 Feb 5. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02394-7.

Key clinical point: Citrate-free adalimumab biosimilar (CT-P17) and European Union-approved adalimumab (EU-adalimumab) demonstrated equivalent efficacy and comparable safety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: At week 24, CT-P17 and EU-adalimumab groups showed similar 20% improvement by the American College of Rheumatology criteria response rate (82.7%). The 95% confidence interval (CI; −5.94 to 5.94) and 90% CI (−4.98 to 4.98) for estimated treatment difference were within predefined equivalence margin, demonstrating therapeutic equivalence. Overall, safety was similar between both treatment groups.

Study details: This was a randomized, double-blind phase 3 study of 648 patients with RA who were randomly allocated to receive 40 mg of either CT-P17 (n=324) or EU-adalimumab (n=324), every 2 weeks until week 48.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Celltrion, Inc. (Incheon, Republic of Korea). The authors reported receiving support, investigator fees, speaking fees, and/or consulting for various pharmaceutical companies including Celltrion, Inc. SJ Lee, YJ Bae, GE Yang, and JK Yoo reported being employees of Celltrion, Inc.

Source: Kay J et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021 Feb 5. doi: 10.1186/s13075-020-02394-7.

Anti-PAD3 positivity tied to higher disease activity and joint damage in RA

Key clinical point: Positivity for antipeptidyl-arginine deiminase type-3 (anti-PAD3) antibodies was associated with higher disease activity and joint damage scores in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: Patients positive vs. negative for anti-PAD3 had significantly higher 28-swollen joint count (7.1 vs. 4.3; P less than .0001), 28-joint disease activity score-erythrocyte sedimentation rate (4.2 vs. 3.7; P = .005), and radiographic damage (14.9 vs. 8.8; P = .02).

Study details: Findings are from the assessment of biomarkers in 851 patients with RA and 516 disease controls (axial spondyloarthritis, n=320; psoriatic arthritis, n=196) from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management registry.

Disclosures: This work was supported by the De Reuter Foundation. M Mahler, C Bentow, and L Martinez-Prat declared being current or former employees at Inova Diagnostics. All the other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lamacchia C et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab050.

Key clinical point: Positivity for antipeptidyl-arginine deiminase type-3 (anti-PAD3) antibodies was associated with higher disease activity and joint damage scores in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: Patients positive vs. negative for anti-PAD3 had significantly higher 28-swollen joint count (7.1 vs. 4.3; P less than .0001), 28-joint disease activity score-erythrocyte sedimentation rate (4.2 vs. 3.7; P = .005), and radiographic damage (14.9 vs. 8.8; P = .02).

Study details: Findings are from the assessment of biomarkers in 851 patients with RA and 516 disease controls (axial spondyloarthritis, n=320; psoriatic arthritis, n=196) from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management registry.

Disclosures: This work was supported by the De Reuter Foundation. M Mahler, C Bentow, and L Martinez-Prat declared being current or former employees at Inova Diagnostics. All the other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lamacchia C et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab050.

Key clinical point: Positivity for antipeptidyl-arginine deiminase type-3 (anti-PAD3) antibodies was associated with higher disease activity and joint damage scores in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: Patients positive vs. negative for anti-PAD3 had significantly higher 28-swollen joint count (7.1 vs. 4.3; P less than .0001), 28-joint disease activity score-erythrocyte sedimentation rate (4.2 vs. 3.7; P = .005), and radiographic damage (14.9 vs. 8.8; P = .02).

Study details: Findings are from the assessment of biomarkers in 851 patients with RA and 516 disease controls (axial spondyloarthritis, n=320; psoriatic arthritis, n=196) from the Swiss Clinical Quality Management registry.

Disclosures: This work was supported by the De Reuter Foundation. M Mahler, C Bentow, and L Martinez-Prat declared being current or former employees at Inova Diagnostics. All the other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Lamacchia C et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab050.

Filgotinib+MTX shows benefit in RA patients with inadequate response to MTX

Key clinical point: Treatment with filgotinib and methotrexate (MTX) reduced signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in patients with moderate-to-severe active RA and inadequate response to MTX.

Major finding: Proportion of patients achieving 20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology criteria at week 12 was significantly higher with filgotinib 200 mg (76.6%) and 100 mg (69.8%) vs. placebo (49.9%; P for all less than .001). Overall, both filgotinib doses were well tolerated.

Study details: Findings are from FINCH I phase 3 study including 1,755 patients with moderate-to-severe active RA and inadequate response to MTX. Patients were randomly assigned to once-daily oral filgotinib 200 mg or filgotinib 100 mg, subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg biweekly, or placebo, all with stable background MTX.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Gilead Sciences. Study investigators including the lead author reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies, including Gilead Sciences. MC Genovese, F Matzkies, B Bartok, L Ye, and Y Guo declared being employees and shareholders of Gilead Sciences. JS Sundy, A Jahreis, and N Mozaffarian declared being former employees of Gilead Sciences and may hold shares. C Tasset declared being an employee and shareholder of Galapagos NV. JA Simon, U Kumar U, and S-C Bae report no disclosures.

Source: Combe B et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219214.

Key clinical point: Treatment with filgotinib and methotrexate (MTX) reduced signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in patients with moderate-to-severe active RA and inadequate response to MTX.

Major finding: Proportion of patients achieving 20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology criteria at week 12 was significantly higher with filgotinib 200 mg (76.6%) and 100 mg (69.8%) vs. placebo (49.9%; P for all less than .001). Overall, both filgotinib doses were well tolerated.

Study details: Findings are from FINCH I phase 3 study including 1,755 patients with moderate-to-severe active RA and inadequate response to MTX. Patients were randomly assigned to once-daily oral filgotinib 200 mg or filgotinib 100 mg, subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg biweekly, or placebo, all with stable background MTX.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Gilead Sciences. Study investigators including the lead author reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies, including Gilead Sciences. MC Genovese, F Matzkies, B Bartok, L Ye, and Y Guo declared being employees and shareholders of Gilead Sciences. JS Sundy, A Jahreis, and N Mozaffarian declared being former employees of Gilead Sciences and may hold shares. C Tasset declared being an employee and shareholder of Galapagos NV. JA Simon, U Kumar U, and S-C Bae report no disclosures.

Source: Combe B et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219214.

Key clinical point: Treatment with filgotinib and methotrexate (MTX) reduced signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in patients with moderate-to-severe active RA and inadequate response to MTX.

Major finding: Proportion of patients achieving 20% improvement in American College of Rheumatology criteria at week 12 was significantly higher with filgotinib 200 mg (76.6%) and 100 mg (69.8%) vs. placebo (49.9%; P for all less than .001). Overall, both filgotinib doses were well tolerated.

Study details: Findings are from FINCH I phase 3 study including 1,755 patients with moderate-to-severe active RA and inadequate response to MTX. Patients were randomly assigned to once-daily oral filgotinib 200 mg or filgotinib 100 mg, subcutaneous adalimumab 40 mg biweekly, or placebo, all with stable background MTX.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Gilead Sciences. Study investigators including the lead author reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies, including Gilead Sciences. MC Genovese, F Matzkies, B Bartok, L Ye, and Y Guo declared being employees and shareholders of Gilead Sciences. JS Sundy, A Jahreis, and N Mozaffarian declared being former employees of Gilead Sciences and may hold shares. C Tasset declared being an employee and shareholder of Galapagos NV. JA Simon, U Kumar U, and S-C Bae report no disclosures.

Source: Combe B et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Jan 27. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219214.

Is board recertification worth it?

I passed the neurology boards, for the first time, in 1998. Then again in 2009, and most recently in 2019.

So I’m up again in 2029. Regrettably, I missed grandfathering in for life by a few years.

Some people don’t study for them, but I’m a little too compulsive not to. I’d guess I put 40-50 hours into doing so in the 3 months beforehand. I didn’t want to fail and have to pay a hefty fee to retake them (the test fee for once is enough as it is).

I’ll be 63 when my next certification is due.

So I wonder (if I’m still in practice) will it even be worthwhile to do it all again? I like what I do, but certainly don’t plan on practicing forever.

Board certification looks good on paper, but certainly isn’t a requirement to practice. One of the best cardiologists I know has never bothered to get his board certification and I don’t think any less of him for it. He also isn’t wanting for patients, and those he has think he’s awesome.

That said, there are things, like being involved in research and legal work, where board certification is strongly recommended, if not mandatory. Since I do both, I certainly wouldn’t want to do anything that might affect my participating in them – if I’m still doing this in 8 years.

By the same token, my office lease runs out when I’m 62. At that point I’ll have been in the same place for 17 years. I don’t consider that a bad thing. I like my current office, and will be perfectly happy to wrap up my career here.

It brings up the same question, though, with logistics that are an even bigger PIA. The last thing I want to do is move my office as my career is winding down. But a lease extension for a few years can be negotiated, a board certification can’t.

I can’t help but wonder: If I’ve already passed it three times, hopefully that means I know what I’m doing. One side will argue that it’s purely greed, as the people who run the boards need money and a way to justify their existence. On the other side are those who argue that maintenance of certification, while not perfect, is the only way we have of making sure practicing physicians are staying up to snuff.

The truth, as always, is somewhere in between.

But it still raises a question that I, fortunately, have another 8 years to think about. Because I’m not in a position to debate if it’s right or wrong, I just have to play by the rules.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I passed the neurology boards, for the first time, in 1998. Then again in 2009, and most recently in 2019.

So I’m up again in 2029. Regrettably, I missed grandfathering in for life by a few years.

Some people don’t study for them, but I’m a little too compulsive not to. I’d guess I put 40-50 hours into doing so in the 3 months beforehand. I didn’t want to fail and have to pay a hefty fee to retake them (the test fee for once is enough as it is).

I’ll be 63 when my next certification is due.

So I wonder (if I’m still in practice) will it even be worthwhile to do it all again? I like what I do, but certainly don’t plan on practicing forever.

Board certification looks good on paper, but certainly isn’t a requirement to practice. One of the best cardiologists I know has never bothered to get his board certification and I don’t think any less of him for it. He also isn’t wanting for patients, and those he has think he’s awesome.

That said, there are things, like being involved in research and legal work, where board certification is strongly recommended, if not mandatory. Since I do both, I certainly wouldn’t want to do anything that might affect my participating in them – if I’m still doing this in 8 years.

By the same token, my office lease runs out when I’m 62. At that point I’ll have been in the same place for 17 years. I don’t consider that a bad thing. I like my current office, and will be perfectly happy to wrap up my career here.

It brings up the same question, though, with logistics that are an even bigger PIA. The last thing I want to do is move my office as my career is winding down. But a lease extension for a few years can be negotiated, a board certification can’t.

I can’t help but wonder: If I’ve already passed it three times, hopefully that means I know what I’m doing. One side will argue that it’s purely greed, as the people who run the boards need money and a way to justify their existence. On the other side are those who argue that maintenance of certification, while not perfect, is the only way we have of making sure practicing physicians are staying up to snuff.

The truth, as always, is somewhere in between.

But it still raises a question that I, fortunately, have another 8 years to think about. Because I’m not in a position to debate if it’s right or wrong, I just have to play by the rules.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I passed the neurology boards, for the first time, in 1998. Then again in 2009, and most recently in 2019.

So I’m up again in 2029. Regrettably, I missed grandfathering in for life by a few years.

Some people don’t study for them, but I’m a little too compulsive not to. I’d guess I put 40-50 hours into doing so in the 3 months beforehand. I didn’t want to fail and have to pay a hefty fee to retake them (the test fee for once is enough as it is).

I’ll be 63 when my next certification is due.

So I wonder (if I’m still in practice) will it even be worthwhile to do it all again? I like what I do, but certainly don’t plan on practicing forever.

Board certification looks good on paper, but certainly isn’t a requirement to practice. One of the best cardiologists I know has never bothered to get his board certification and I don’t think any less of him for it. He also isn’t wanting for patients, and those he has think he’s awesome.

That said, there are things, like being involved in research and legal work, where board certification is strongly recommended, if not mandatory. Since I do both, I certainly wouldn’t want to do anything that might affect my participating in them – if I’m still doing this in 8 years.

By the same token, my office lease runs out when I’m 62. At that point I’ll have been in the same place for 17 years. I don’t consider that a bad thing. I like my current office, and will be perfectly happy to wrap up my career here.

It brings up the same question, though, with logistics that are an even bigger PIA. The last thing I want to do is move my office as my career is winding down. But a lease extension for a few years can be negotiated, a board certification can’t.

I can’t help but wonder: If I’ve already passed it three times, hopefully that means I know what I’m doing. One side will argue that it’s purely greed, as the people who run the boards need money and a way to justify their existence. On the other side are those who argue that maintenance of certification, while not perfect, is the only way we have of making sure practicing physicians are staying up to snuff.

The truth, as always, is somewhere in between.

But it still raises a question that I, fortunately, have another 8 years to think about. Because I’m not in a position to debate if it’s right or wrong, I just have to play by the rules.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The surgical approach to the obliterated anterior cul-de-sac

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

• A minimally invasive modification for fascia lata mid-urethral sling

• Retroperitoneal anatomy and parametrial dissection in robotic uterine artery-sparing radical trachelectomy

• Maintaining and reclaiming hemostasis in laparoscopic surgery

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

• A minimally invasive modification for fascia lata mid-urethral sling

• Retroperitoneal anatomy and parametrial dissection in robotic uterine artery-sparing radical trachelectomy

• Maintaining and reclaiming hemostasis in laparoscopic surgery

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

• A minimally invasive modification for fascia lata mid-urethral sling

• Retroperitoneal anatomy and parametrial dissection in robotic uterine artery-sparing radical trachelectomy

• Maintaining and reclaiming hemostasis in laparoscopic surgery

Minorities underrepresented on liver transplant waiting lists

Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients are underrepresented on many liver transplant waiting lists, whereas non-Hispanic White patients are often overrepresented, according to data from 109 centers.

While racial disparities “greatly diminished” after placement on a waiting list, which suggests recent progress in the field, pre–wait-listing disparities may be more challenging to overcome, reported lead author Curtis Warren, MPH, CPH, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and colleagues.

“In 2020, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network implemented a new allocation system for liver transplantation based on concentric circles of geographic proximity rather than somewhat arbitrarily delineated Donor Service Areas (DSAs),” the investigators wrote in Journal of the American College of Surgeons. “Although this was a step toward improving and equalizing access to lifesaving organs for those on the liver transplant wait list, the listing process determining which patients will be considered for transplantation has continued to be a significant hurdle.”

The process is “rife with impediments to equal access to listing,” according to Dr. Warren and colleagues; getting on a waiting list can be affected by factors such as inequitable access to primary care, lack of private health insurance, and subjective selection by transplant centers.

To better characterize these impediments, the investigators gathered center-specific data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients and the U.S. Census Bureau. The final dataset included 30,353 patients from treated at 109 transplant centers, each of which performed more than 250 transplants between January 2013 and December 2018. The investigators compared waiting list data for each center with demographics from its DSA. Primary variables included race/ethnicity, education level, poverty, and insurance coverage.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to compare expected waiting list demographics with observed waiting list demographics with the aid of observed/expected ratios for each race/ethnicity. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify significant predictors, including covariates such as age at listing, distance traveled to transplant center, and center type.

On an adjusted basis, the observed/expected ratios showed that non-Hispanic Black patients were underrepresented on waiting lists at 88 out of 109 centers (81%) and Hispanic patients were underrepresented at 68 centers (62%). In contrast, non-Hispanic White patients were overrepresented on waiting lists at 65 centers (58%). Non-Hispanic White patients were underrepresented on waiting lists at 49 centers, or 45%. Minority underrepresentation was further supported by mean MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) scores, which were significantly higher among non-Hispanic Black patients (20.2) and Hispanic patients (19.4), compared with non-Hispanic White patients (18.7) (P < .0001 for all) at the time of wait-listing.

Based on the multivariate model, underrepresentation among Black patients was most common in areas with a higher proportion of Black individuals in the population, longer travel distances to transplant centers, and a higher rate of private insurance among transplant recipients. For Hispanic patients, rates of private insurance alone predicted underrepresentation.

Once patients were listed, however, these disparities faded. Non-Hispanic Black patients accounted for 9.8% of all transplants across all hospitals, compared with 7.9% of wait-listed individuals (P < .0001). At approximately two out of three hospitals (65%), the transplanted percentage of Black patients exceeded the wait-listed percentage (P = .002).

“Data from this study show that the wait lists at many transplant centers in the United States underrepresent minority populations, compared with what would be expected based on their service areas,” the investigators concluded. “Future work will need to be devoted to increasing awareness of these trends to promote equitable access to listing for liver transplantation.”

Looking at social determinants of health

According to Lauren D. Nephew, MD, MSc, MAE, of Indiana University, Indianapolis, “The question of access to care is particularly important at this juncture as we examine the inequities that COVID-19 exposed in access to care for racial minorities, and as we prepare for potential changes to health insurance coverage with the new administration.”

Dr. Nephew noted that the reported racial disparities stem from social determinants of health, such as proximity to transplant centers and type of insurance coverage.

“Another striking finding was that the disparity in wait-listing non-Hispanic Black patients increased with the percentage of non-Hispanic Black patients living in the area, further highlighting barriers in access to care in majority Black neighborhoods,” she said. “Inequities such as these are unacceptable, given our mandate to distribute organs in a fair and equitable fashion, and they require prospective studies for further examination.”

Identifying discrimination

Lanla Conteh, MD, MPH, of the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, described how these inequities are magnified through bias in patient selection.

“Often times two very similar patients may present with the same medical profile and social circumstances; however, one is turned down,” she said. “Often the patient turned down is the non-Hispanic Black patient while the non-Hispanic White patient is given a pass.”

Dr. Conteh suggested that the first step in fixing this bias is recognizing that it is a problem and calling it by its proper name.

“As transplant centers, in order to address and change these significant disparities, we must first be willing to acknowledge that they do exist,” she said. “Only then can we move to the next step of developing awareness and methods to actively combat what we should label as systemic discrimination in medicine. Transplantation is a lifesaving treatment for many patients with decompensated liver disease or liver cancer. Ensuring equitable access for all patients and populations is of paramount importance.”

The study was supported by a Health Resources and Services Administration contract, as well as grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients are underrepresented on many liver transplant waiting lists, whereas non-Hispanic White patients are often overrepresented, according to data from 109 centers.

While racial disparities “greatly diminished” after placement on a waiting list, which suggests recent progress in the field, pre–wait-listing disparities may be more challenging to overcome, reported lead author Curtis Warren, MPH, CPH, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and colleagues.

“In 2020, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network implemented a new allocation system for liver transplantation based on concentric circles of geographic proximity rather than somewhat arbitrarily delineated Donor Service Areas (DSAs),” the investigators wrote in Journal of the American College of Surgeons. “Although this was a step toward improving and equalizing access to lifesaving organs for those on the liver transplant wait list, the listing process determining which patients will be considered for transplantation has continued to be a significant hurdle.”

The process is “rife with impediments to equal access to listing,” according to Dr. Warren and colleagues; getting on a waiting list can be affected by factors such as inequitable access to primary care, lack of private health insurance, and subjective selection by transplant centers.

To better characterize these impediments, the investigators gathered center-specific data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients and the U.S. Census Bureau. The final dataset included 30,353 patients from treated at 109 transplant centers, each of which performed more than 250 transplants between January 2013 and December 2018. The investigators compared waiting list data for each center with demographics from its DSA. Primary variables included race/ethnicity, education level, poverty, and insurance coverage.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to compare expected waiting list demographics with observed waiting list demographics with the aid of observed/expected ratios for each race/ethnicity. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify significant predictors, including covariates such as age at listing, distance traveled to transplant center, and center type.

On an adjusted basis, the observed/expected ratios showed that non-Hispanic Black patients were underrepresented on waiting lists at 88 out of 109 centers (81%) and Hispanic patients were underrepresented at 68 centers (62%). In contrast, non-Hispanic White patients were overrepresented on waiting lists at 65 centers (58%). Non-Hispanic White patients were underrepresented on waiting lists at 49 centers, or 45%. Minority underrepresentation was further supported by mean MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) scores, which were significantly higher among non-Hispanic Black patients (20.2) and Hispanic patients (19.4), compared with non-Hispanic White patients (18.7) (P < .0001 for all) at the time of wait-listing.

Based on the multivariate model, underrepresentation among Black patients was most common in areas with a higher proportion of Black individuals in the population, longer travel distances to transplant centers, and a higher rate of private insurance among transplant recipients. For Hispanic patients, rates of private insurance alone predicted underrepresentation.

Once patients were listed, however, these disparities faded. Non-Hispanic Black patients accounted for 9.8% of all transplants across all hospitals, compared with 7.9% of wait-listed individuals (P < .0001). At approximately two out of three hospitals (65%), the transplanted percentage of Black patients exceeded the wait-listed percentage (P = .002).

“Data from this study show that the wait lists at many transplant centers in the United States underrepresent minority populations, compared with what would be expected based on their service areas,” the investigators concluded. “Future work will need to be devoted to increasing awareness of these trends to promote equitable access to listing for liver transplantation.”

Looking at social determinants of health

According to Lauren D. Nephew, MD, MSc, MAE, of Indiana University, Indianapolis, “The question of access to care is particularly important at this juncture as we examine the inequities that COVID-19 exposed in access to care for racial minorities, and as we prepare for potential changes to health insurance coverage with the new administration.”

Dr. Nephew noted that the reported racial disparities stem from social determinants of health, such as proximity to transplant centers and type of insurance coverage.

“Another striking finding was that the disparity in wait-listing non-Hispanic Black patients increased with the percentage of non-Hispanic Black patients living in the area, further highlighting barriers in access to care in majority Black neighborhoods,” she said. “Inequities such as these are unacceptable, given our mandate to distribute organs in a fair and equitable fashion, and they require prospective studies for further examination.”

Identifying discrimination

Lanla Conteh, MD, MPH, of the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, described how these inequities are magnified through bias in patient selection.

“Often times two very similar patients may present with the same medical profile and social circumstances; however, one is turned down,” she said. “Often the patient turned down is the non-Hispanic Black patient while the non-Hispanic White patient is given a pass.”

Dr. Conteh suggested that the first step in fixing this bias is recognizing that it is a problem and calling it by its proper name.

“As transplant centers, in order to address and change these significant disparities, we must first be willing to acknowledge that they do exist,” she said. “Only then can we move to the next step of developing awareness and methods to actively combat what we should label as systemic discrimination in medicine. Transplantation is a lifesaving treatment for many patients with decompensated liver disease or liver cancer. Ensuring equitable access for all patients and populations is of paramount importance.”

The study was supported by a Health Resources and Services Administration contract, as well as grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients are underrepresented on many liver transplant waiting lists, whereas non-Hispanic White patients are often overrepresented, according to data from 109 centers.

While racial disparities “greatly diminished” after placement on a waiting list, which suggests recent progress in the field, pre–wait-listing disparities may be more challenging to overcome, reported lead author Curtis Warren, MPH, CPH, of the University of Florida, Gainesville, and colleagues.

“In 2020, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network implemented a new allocation system for liver transplantation based on concentric circles of geographic proximity rather than somewhat arbitrarily delineated Donor Service Areas (DSAs),” the investigators wrote in Journal of the American College of Surgeons. “Although this was a step toward improving and equalizing access to lifesaving organs for those on the liver transplant wait list, the listing process determining which patients will be considered for transplantation has continued to be a significant hurdle.”

The process is “rife with impediments to equal access to listing,” according to Dr. Warren and colleagues; getting on a waiting list can be affected by factors such as inequitable access to primary care, lack of private health insurance, and subjective selection by transplant centers.

To better characterize these impediments, the investigators gathered center-specific data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients and the U.S. Census Bureau. The final dataset included 30,353 patients from treated at 109 transplant centers, each of which performed more than 250 transplants between January 2013 and December 2018. The investigators compared waiting list data for each center with demographics from its DSA. Primary variables included race/ethnicity, education level, poverty, and insurance coverage.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to compare expected waiting list demographics with observed waiting list demographics with the aid of observed/expected ratios for each race/ethnicity. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify significant predictors, including covariates such as age at listing, distance traveled to transplant center, and center type.

On an adjusted basis, the observed/expected ratios showed that non-Hispanic Black patients were underrepresented on waiting lists at 88 out of 109 centers (81%) and Hispanic patients were underrepresented at 68 centers (62%). In contrast, non-Hispanic White patients were overrepresented on waiting lists at 65 centers (58%). Non-Hispanic White patients were underrepresented on waiting lists at 49 centers, or 45%. Minority underrepresentation was further supported by mean MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) scores, which were significantly higher among non-Hispanic Black patients (20.2) and Hispanic patients (19.4), compared with non-Hispanic White patients (18.7) (P < .0001 for all) at the time of wait-listing.

Based on the multivariate model, underrepresentation among Black patients was most common in areas with a higher proportion of Black individuals in the population, longer travel distances to transplant centers, and a higher rate of private insurance among transplant recipients. For Hispanic patients, rates of private insurance alone predicted underrepresentation.

Once patients were listed, however, these disparities faded. Non-Hispanic Black patients accounted for 9.8% of all transplants across all hospitals, compared with 7.9% of wait-listed individuals (P < .0001). At approximately two out of three hospitals (65%), the transplanted percentage of Black patients exceeded the wait-listed percentage (P = .002).

“Data from this study show that the wait lists at many transplant centers in the United States underrepresent minority populations, compared with what would be expected based on their service areas,” the investigators concluded. “Future work will need to be devoted to increasing awareness of these trends to promote equitable access to listing for liver transplantation.”

Looking at social determinants of health

According to Lauren D. Nephew, MD, MSc, MAE, of Indiana University, Indianapolis, “The question of access to care is particularly important at this juncture as we examine the inequities that COVID-19 exposed in access to care for racial minorities, and as we prepare for potential changes to health insurance coverage with the new administration.”

Dr. Nephew noted that the reported racial disparities stem from social determinants of health, such as proximity to transplant centers and type of insurance coverage.

“Another striking finding was that the disparity in wait-listing non-Hispanic Black patients increased with the percentage of non-Hispanic Black patients living in the area, further highlighting barriers in access to care in majority Black neighborhoods,” she said. “Inequities such as these are unacceptable, given our mandate to distribute organs in a fair and equitable fashion, and they require prospective studies for further examination.”

Identifying discrimination

Lanla Conteh, MD, MPH, of the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, described how these inequities are magnified through bias in patient selection.

“Often times two very similar patients may present with the same medical profile and social circumstances; however, one is turned down,” she said. “Often the patient turned down is the non-Hispanic Black patient while the non-Hispanic White patient is given a pass.”

Dr. Conteh suggested that the first step in fixing this bias is recognizing that it is a problem and calling it by its proper name.

“As transplant centers, in order to address and change these significant disparities, we must first be willing to acknowledge that they do exist,” she said. “Only then can we move to the next step of developing awareness and methods to actively combat what we should label as systemic discrimination in medicine. Transplantation is a lifesaving treatment for many patients with decompensated liver disease or liver cancer. Ensuring equitable access for all patients and populations is of paramount importance.”

The study was supported by a Health Resources and Services Administration contract, as well as grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The investigators and interviewees reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Anthracycline-free neoadjuvant regimen safe, effective for TNBC

The results come from a phase 2 trial that involved 100 women. The study was published online in February in Clinical Cancer Research.

The doublet provides a safe, effective alternative for patients who are not candidates for treatment with anthracyclines and should be explored further for neoadjuvant deescalation, according to investigators led by Priyanka Sharma, MD, TNBC specialist and professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Westwood.

The trial wasn’t powered to demonstrate noninferiority, so it “probably does not provide enough evidence to state that [taxane/platinum] should replace other regimens,” Dr. Sharma said in an interview.

A proper noninferiority trial would require more than 2,500 participants, she said, adding that such a trial is unlikely, because companies are focused on immunotherapies for neoadjuvant TNBC.

“Our study does, however, provide a very effective alternative for patients and providers who want to use or prefer an anthracycline-sparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen. We are very encouraged” by the findings, Dr. Sharma said.

This is “a provocative study that should make us pause and reevaluate our current approach. Further study of this approach in early-stage TNBC is warranted,” Melinda L. Telli, MD, associate professor of medicine and director of the breast cancer program at Stanford (Calif.) University, said when asked for comment.

Avoiding the risks associated with anthracycline “is great. I would be particularly enthusiastic using this regimen in patients with known increased risk of cardiac toxicity,” said Amy Tiersten, MD, a breast cancer specialist and professor at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Anthracycline-based regimens are the standard of care for neoadjuvant TNBC. They typically include a taxane with or without carboplatin plus an anthracycline/cyclophosphamide combination. The regimen is highly active, but there is a small but serious risk for cardiomyopathy and leukemia with anthracycline/cyclophosphamide. In the current trial, one woman in the anthracycline arm died of secondary acute myeloid leukemia.

Given its tolerability and effectiveness, a taxane/carboplatin doublet might serve as a good backbone for the addition of novel immunotherapies in trials. Dr. Sharma is the principal investigator in one such trial, a phase 2 trial of carboplatin/docetaxel plus pembrolizumab for stage I–III TNBC.

Study details

The Neoadjuvant Study of Two Platinum Regimens in Stage I–III Triple Negative Breast Cancer (NeoSTOP) involved 100 women with stage I–III TNBC.

In the experimental arm, 52 women received carboplatin AUC 6 plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 21 days for six cycles.

In the standard-of-care anthracycline arm, 48 women received carboplatin AUC 6 every 21 days for four cycles plus paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 weekly for 12 weeks, followed by doxorubicin 60 mg/m2 plus cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 every 2 weeks for four cycles.

Docetaxel and paclitaxel in the two regimens are interchangeable because they have shown equal efficacy in adjuvant trials, Dr. Sharma said.

At surgery, 54% of women in both arms had a breast/axilla pathologic complete response – the primary endpoint – and 67% in both arms had a residual cancer burden of 0-1. Event-free and overall survival (about 55% at 3 years for both) were similar with the two regimens.

Grade 3/4 adverse events were more common in the anthracycline arm. They included neutropenia, which occurred in 60% of women in the anthracycline arm, vs. 8% with the doublet; and febrile neutropenia, which occurred in 19% with anthracycline, vs. none with the doublet.

The toxicity profile of the anthracycline regimen was comparable to those in previous reports.

Ninety-two percent of the docetaxel/carboplatin group completed all six cycles; 72% of women in the anthracycline arm completed 10 or more doses of paclitaxel, and 85% completed all 4 carboplatin doses.

Mean costs of treatment, patient transportation, and lost productivity were $36,720 in the anthracycline arm, vs. $33,148 with the doublet.

The two arms were well balanced with respect to patient characteristics. The median age was 51 years, 30% of patients had axillary lymph node–positive disease, and 16% had ER/PgR expression of 1% to 10%. Of the study population, 17% carried deleterious BRCA1/2 mutations. Women were enrolled from July 2015 to May 2018. Median follow-up was 38 months.

Of the study population, 17% had stage I disease, so NeoSTOP included a lower-risk population than some neoadjuvant trials. However, there was no significant change in pathologic complete response rates in the two arms after exclusion of women with stage I disease (doublet, 50%; anthracycline, 54%).

The study was funded by the University of Kansas Cancer Center, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The investigators disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results come from a phase 2 trial that involved 100 women. The study was published online in February in Clinical Cancer Research.

The doublet provides a safe, effective alternative for patients who are not candidates for treatment with anthracyclines and should be explored further for neoadjuvant deescalation, according to investigators led by Priyanka Sharma, MD, TNBC specialist and professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Westwood.

The trial wasn’t powered to demonstrate noninferiority, so it “probably does not provide enough evidence to state that [taxane/platinum] should replace other regimens,” Dr. Sharma said in an interview.

A proper noninferiority trial would require more than 2,500 participants, she said, adding that such a trial is unlikely, because companies are focused on immunotherapies for neoadjuvant TNBC.

“Our study does, however, provide a very effective alternative for patients and providers who want to use or prefer an anthracycline-sparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen. We are very encouraged” by the findings, Dr. Sharma said.

This is “a provocative study that should make us pause and reevaluate our current approach. Further study of this approach in early-stage TNBC is warranted,” Melinda L. Telli, MD, associate professor of medicine and director of the breast cancer program at Stanford (Calif.) University, said when asked for comment.

Avoiding the risks associated with anthracycline “is great. I would be particularly enthusiastic using this regimen in patients with known increased risk of cardiac toxicity,” said Amy Tiersten, MD, a breast cancer specialist and professor at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Anthracycline-based regimens are the standard of care for neoadjuvant TNBC. They typically include a taxane with or without carboplatin plus an anthracycline/cyclophosphamide combination. The regimen is highly active, but there is a small but serious risk for cardiomyopathy and leukemia with anthracycline/cyclophosphamide. In the current trial, one woman in the anthracycline arm died of secondary acute myeloid leukemia.

Given its tolerability and effectiveness, a taxane/carboplatin doublet might serve as a good backbone for the addition of novel immunotherapies in trials. Dr. Sharma is the principal investigator in one such trial, a phase 2 trial of carboplatin/docetaxel plus pembrolizumab for stage I–III TNBC.

Study details

The Neoadjuvant Study of Two Platinum Regimens in Stage I–III Triple Negative Breast Cancer (NeoSTOP) involved 100 women with stage I–III TNBC.

In the experimental arm, 52 women received carboplatin AUC 6 plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 21 days for six cycles.

In the standard-of-care anthracycline arm, 48 women received carboplatin AUC 6 every 21 days for four cycles plus paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 weekly for 12 weeks, followed by doxorubicin 60 mg/m2 plus cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 every 2 weeks for four cycles.

Docetaxel and paclitaxel in the two regimens are interchangeable because they have shown equal efficacy in adjuvant trials, Dr. Sharma said.

At surgery, 54% of women in both arms had a breast/axilla pathologic complete response – the primary endpoint – and 67% in both arms had a residual cancer burden of 0-1. Event-free and overall survival (about 55% at 3 years for both) were similar with the two regimens.

Grade 3/4 adverse events were more common in the anthracycline arm. They included neutropenia, which occurred in 60% of women in the anthracycline arm, vs. 8% with the doublet; and febrile neutropenia, which occurred in 19% with anthracycline, vs. none with the doublet.

The toxicity profile of the anthracycline regimen was comparable to those in previous reports.

Ninety-two percent of the docetaxel/carboplatin group completed all six cycles; 72% of women in the anthracycline arm completed 10 or more doses of paclitaxel, and 85% completed all 4 carboplatin doses.

Mean costs of treatment, patient transportation, and lost productivity were $36,720 in the anthracycline arm, vs. $33,148 with the doublet.

The two arms were well balanced with respect to patient characteristics. The median age was 51 years, 30% of patients had axillary lymph node–positive disease, and 16% had ER/PgR expression of 1% to 10%. Of the study population, 17% carried deleterious BRCA1/2 mutations. Women were enrolled from July 2015 to May 2018. Median follow-up was 38 months.

Of the study population, 17% had stage I disease, so NeoSTOP included a lower-risk population than some neoadjuvant trials. However, there was no significant change in pathologic complete response rates in the two arms after exclusion of women with stage I disease (doublet, 50%; anthracycline, 54%).

The study was funded by the University of Kansas Cancer Center, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The investigators disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The results come from a phase 2 trial that involved 100 women. The study was published online in February in Clinical Cancer Research.

The doublet provides a safe, effective alternative for patients who are not candidates for treatment with anthracyclines and should be explored further for neoadjuvant deescalation, according to investigators led by Priyanka Sharma, MD, TNBC specialist and professor at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Westwood.

The trial wasn’t powered to demonstrate noninferiority, so it “probably does not provide enough evidence to state that [taxane/platinum] should replace other regimens,” Dr. Sharma said in an interview.

A proper noninferiority trial would require more than 2,500 participants, she said, adding that such a trial is unlikely, because companies are focused on immunotherapies for neoadjuvant TNBC.

“Our study does, however, provide a very effective alternative for patients and providers who want to use or prefer an anthracycline-sparing neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen. We are very encouraged” by the findings, Dr. Sharma said.

This is “a provocative study that should make us pause and reevaluate our current approach. Further study of this approach in early-stage TNBC is warranted,” Melinda L. Telli, MD, associate professor of medicine and director of the breast cancer program at Stanford (Calif.) University, said when asked for comment.

Avoiding the risks associated with anthracycline “is great. I would be particularly enthusiastic using this regimen in patients with known increased risk of cardiac toxicity,” said Amy Tiersten, MD, a breast cancer specialist and professor at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Anthracycline-based regimens are the standard of care for neoadjuvant TNBC. They typically include a taxane with or without carboplatin plus an anthracycline/cyclophosphamide combination. The regimen is highly active, but there is a small but serious risk for cardiomyopathy and leukemia with anthracycline/cyclophosphamide. In the current trial, one woman in the anthracycline arm died of secondary acute myeloid leukemia.

Given its tolerability and effectiveness, a taxane/carboplatin doublet might serve as a good backbone for the addition of novel immunotherapies in trials. Dr. Sharma is the principal investigator in one such trial, a phase 2 trial of carboplatin/docetaxel plus pembrolizumab for stage I–III TNBC.

Study details

The Neoadjuvant Study of Two Platinum Regimens in Stage I–III Triple Negative Breast Cancer (NeoSTOP) involved 100 women with stage I–III TNBC.

In the experimental arm, 52 women received carboplatin AUC 6 plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 21 days for six cycles.

In the standard-of-care anthracycline arm, 48 women received carboplatin AUC 6 every 21 days for four cycles plus paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 weekly for 12 weeks, followed by doxorubicin 60 mg/m2 plus cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 every 2 weeks for four cycles.

Docetaxel and paclitaxel in the two regimens are interchangeable because they have shown equal efficacy in adjuvant trials, Dr. Sharma said.

At surgery, 54% of women in both arms had a breast/axilla pathologic complete response – the primary endpoint – and 67% in both arms had a residual cancer burden of 0-1. Event-free and overall survival (about 55% at 3 years for both) were similar with the two regimens.

Grade 3/4 adverse events were more common in the anthracycline arm. They included neutropenia, which occurred in 60% of women in the anthracycline arm, vs. 8% with the doublet; and febrile neutropenia, which occurred in 19% with anthracycline, vs. none with the doublet.

The toxicity profile of the anthracycline regimen was comparable to those in previous reports.

Ninety-two percent of the docetaxel/carboplatin group completed all six cycles; 72% of women in the anthracycline arm completed 10 or more doses of paclitaxel, and 85% completed all 4 carboplatin doses.

Mean costs of treatment, patient transportation, and lost productivity were $36,720 in the anthracycline arm, vs. $33,148 with the doublet.

The two arms were well balanced with respect to patient characteristics. The median age was 51 years, 30% of patients had axillary lymph node–positive disease, and 16% had ER/PgR expression of 1% to 10%. Of the study population, 17% carried deleterious BRCA1/2 mutations. Women were enrolled from July 2015 to May 2018. Median follow-up was 38 months.

Of the study population, 17% had stage I disease, so NeoSTOP included a lower-risk population than some neoadjuvant trials. However, there was no significant change in pathologic complete response rates in the two arms after exclusion of women with stage I disease (doublet, 50%; anthracycline, 54%).

The study was funded by the University of Kansas Cancer Center, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The investigators disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cannabis vaping triggers respiratory symptoms in teens

, according to findings of a study based on a national sample of teens.

Most studies of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) use in teens have not addressed cannabis vaping, although e-cigarette– or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) has been predominately associated with cannabis products, wrote Carol J. Boyd, PhD, of the University of Michigan School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“At this time, relatively little is known about the population-level health consequences of adolescents’ use of ENDS, including use with cannabis and controlling for a history of asthma,” they said.

In a study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health, the researchers identified 14,798 adolescents aged 12-17 years using Wave 4 data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Of these, 17.6% had a baseline asthma diagnosis, 8.9% reported ever using cannabis in ENDS, and 4.7% reported any cannabis use. In addition, 4.2% reported current e-cigarette use, 3.1% reported current cigarette use, 51% were male, and 69.2% were white.

Any cannabis vaping makes impact

In a fully-adjusted model, teens who had ever vaped cannabis had higher odds of five respiratory symptoms in the past year, compared with those with no history of cannabis vaping: wheezing or whistling in the chest (adjusted odds ratio, 1.81); sleep disturbed by wheezing or whistling (AOR, 1.71); speech limited because of wheezing (AOR, 1.96); wheezy during and after exercise (AOR, 1.33), and a dry cough at night independent of a cold or chest infection (AOR, 1.26).

Neither e-cigarettes nor cigarettes were significantly associated with any of these five respiratory symptoms in the fully adjusted models. In addition, “past 30-day use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes and cannabis use were associated with some respiratory symptoms in bivariate analyses but not in the adjusted models,” the researchers noted. In addition, the associations of an asthma diagnosis and respiratory symptoms had greater magnitudes than either cigarette, e-cigarette, and cannabis use or vaping cannabis with ENDS.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inherent limitations of secondary database analysis, the researchers noted. “Another limitation is that co-use of cannabis and tobacco/nicotine was not assessed and, in the future, should be examined: Researchers have found that co-use is related to EVALI symptoms among young adults,” they said.

However, the study is the first known to include ENDS product use and respiratory symptoms while accounting for baseline asthma, and an asthma diagnosis was even more strongly associated with all five respiratory symptoms, the researchers said.

The results suggest that “the inhalation of cannabis via vaping is associated with some pulmonary irritation and symptoms of lung diseases (both known and unknown),” that may be predictive of later EVALI, they concluded.

Product details aid in diagnosis

“As we continue to see patients presenting with EVALI in pediatric hospitals, it is important for us to identify if there are specific products (or categories) that are more likely to cause it,” said Brandon Seay, MD, FCCP, a pediatric pulmonologist and sleep specialist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, in an interview. “When we are trying to diagnose EVALI, we should be asking appropriate questions about exposures to specific products to get the best answers. If we simply ask ‘Are you smoking e-cigarettes?’ the patient may not [equate] e-cigarette smoking to vaping cannabis products,” he said.

Dr. Seay said he was not surprised by the study findings. “A lot of the patients I see with EVALI have reported vaping THC products, and most of them also report that the products were mixed by a friend or an individual instead of being a commercially produced product,” he noted. “This is not surprising, as THC is still illegal in most states and there would not be any commercially available products,” he said. “The mixing of these products by individuals increases the risk of ingredients being more toxic or irritating to the lungs,” Dr. Seay added. “This does highlight the need for more regulation of vaping products. As more states legalize marijuana, more of these products will become available, which will provide an opportunity for increased regulation, he said.

The take-home message for clinicians is to seek specific details from their young patients, Dr. Seay emphasized. “When we are educating our patients on the dangers of vaping/e-cigarettes, we need to make sure we are asking specifically which products they are using and know the terminology,” he said. “The use of THC-containing products will be increasing across the country with more legalization, so we need to keep ourselves apprised of the different risks between THC- and nicotine-containing devices,” he added.

As for additional research, it would be interesting to know whether patients were asked where they had gotten their products (commercially available products vs. those mixed by individuals) and explore any difference between the two, said Dr. Seay. “Also, as these products are relatively new to the market, compared to cigarettes, data on the longitudinal effects of vaping (nicotine and THC) over a long period of time, compared to traditional combustible cigarettes, will be needed,” he said.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and National Cancer Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Seay had no financial disclosures, but serves as a member of the CHEST Physician editorial board.

, according to findings of a study based on a national sample of teens.

Most studies of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) use in teens have not addressed cannabis vaping, although e-cigarette– or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) has been predominately associated with cannabis products, wrote Carol J. Boyd, PhD, of the University of Michigan School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“At this time, relatively little is known about the population-level health consequences of adolescents’ use of ENDS, including use with cannabis and controlling for a history of asthma,” they said.

In a study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health, the researchers identified 14,798 adolescents aged 12-17 years using Wave 4 data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Of these, 17.6% had a baseline asthma diagnosis, 8.9% reported ever using cannabis in ENDS, and 4.7% reported any cannabis use. In addition, 4.2% reported current e-cigarette use, 3.1% reported current cigarette use, 51% were male, and 69.2% were white.

Any cannabis vaping makes impact

In a fully-adjusted model, teens who had ever vaped cannabis had higher odds of five respiratory symptoms in the past year, compared with those with no history of cannabis vaping: wheezing or whistling in the chest (adjusted odds ratio, 1.81); sleep disturbed by wheezing or whistling (AOR, 1.71); speech limited because of wheezing (AOR, 1.96); wheezy during and after exercise (AOR, 1.33), and a dry cough at night independent of a cold or chest infection (AOR, 1.26).

Neither e-cigarettes nor cigarettes were significantly associated with any of these five respiratory symptoms in the fully adjusted models. In addition, “past 30-day use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes and cannabis use were associated with some respiratory symptoms in bivariate analyses but not in the adjusted models,” the researchers noted. In addition, the associations of an asthma diagnosis and respiratory symptoms had greater magnitudes than either cigarette, e-cigarette, and cannabis use or vaping cannabis with ENDS.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inherent limitations of secondary database analysis, the researchers noted. “Another limitation is that co-use of cannabis and tobacco/nicotine was not assessed and, in the future, should be examined: Researchers have found that co-use is related to EVALI symptoms among young adults,” they said.

However, the study is the first known to include ENDS product use and respiratory symptoms while accounting for baseline asthma, and an asthma diagnosis was even more strongly associated with all five respiratory symptoms, the researchers said.

The results suggest that “the inhalation of cannabis via vaping is associated with some pulmonary irritation and symptoms of lung diseases (both known and unknown),” that may be predictive of later EVALI, they concluded.

Product details aid in diagnosis

“As we continue to see patients presenting with EVALI in pediatric hospitals, it is important for us to identify if there are specific products (or categories) that are more likely to cause it,” said Brandon Seay, MD, FCCP, a pediatric pulmonologist and sleep specialist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, in an interview. “When we are trying to diagnose EVALI, we should be asking appropriate questions about exposures to specific products to get the best answers. If we simply ask ‘Are you smoking e-cigarettes?’ the patient may not [equate] e-cigarette smoking to vaping cannabis products,” he said.

Dr. Seay said he was not surprised by the study findings. “A lot of the patients I see with EVALI have reported vaping THC products, and most of them also report that the products were mixed by a friend or an individual instead of being a commercially produced product,” he noted. “This is not surprising, as THC is still illegal in most states and there would not be any commercially available products,” he said. “The mixing of these products by individuals increases the risk of ingredients being more toxic or irritating to the lungs,” Dr. Seay added. “This does highlight the need for more regulation of vaping products. As more states legalize marijuana, more of these products will become available, which will provide an opportunity for increased regulation, he said.

The take-home message for clinicians is to seek specific details from their young patients, Dr. Seay emphasized. “When we are educating our patients on the dangers of vaping/e-cigarettes, we need to make sure we are asking specifically which products they are using and know the terminology,” he said. “The use of THC-containing products will be increasing across the country with more legalization, so we need to keep ourselves apprised of the different risks between THC- and nicotine-containing devices,” he added.

As for additional research, it would be interesting to know whether patients were asked where they had gotten their products (commercially available products vs. those mixed by individuals) and explore any difference between the two, said Dr. Seay. “Also, as these products are relatively new to the market, compared to cigarettes, data on the longitudinal effects of vaping (nicotine and THC) over a long period of time, compared to traditional combustible cigarettes, will be needed,” he said.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and National Cancer Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Seay had no financial disclosures, but serves as a member of the CHEST Physician editorial board.

, according to findings of a study based on a national sample of teens.

Most studies of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) use in teens have not addressed cannabis vaping, although e-cigarette– or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI) has been predominately associated with cannabis products, wrote Carol J. Boyd, PhD, of the University of Michigan School of Nursing, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“At this time, relatively little is known about the population-level health consequences of adolescents’ use of ENDS, including use with cannabis and controlling for a history of asthma,” they said.

In a study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health, the researchers identified 14,798 adolescents aged 12-17 years using Wave 4 data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Of these, 17.6% had a baseline asthma diagnosis, 8.9% reported ever using cannabis in ENDS, and 4.7% reported any cannabis use. In addition, 4.2% reported current e-cigarette use, 3.1% reported current cigarette use, 51% were male, and 69.2% were white.

Any cannabis vaping makes impact

In a fully-adjusted model, teens who had ever vaped cannabis had higher odds of five respiratory symptoms in the past year, compared with those with no history of cannabis vaping: wheezing or whistling in the chest (adjusted odds ratio, 1.81); sleep disturbed by wheezing or whistling (AOR, 1.71); speech limited because of wheezing (AOR, 1.96); wheezy during and after exercise (AOR, 1.33), and a dry cough at night independent of a cold or chest infection (AOR, 1.26).

Neither e-cigarettes nor cigarettes were significantly associated with any of these five respiratory symptoms in the fully adjusted models. In addition, “past 30-day use of cigarettes, e-cigarettes and cannabis use were associated with some respiratory symptoms in bivariate analyses but not in the adjusted models,” the researchers noted. In addition, the associations of an asthma diagnosis and respiratory symptoms had greater magnitudes than either cigarette, e-cigarette, and cannabis use or vaping cannabis with ENDS.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inherent limitations of secondary database analysis, the researchers noted. “Another limitation is that co-use of cannabis and tobacco/nicotine was not assessed and, in the future, should be examined: Researchers have found that co-use is related to EVALI symptoms among young adults,” they said.

However, the study is the first known to include ENDS product use and respiratory symptoms while accounting for baseline asthma, and an asthma diagnosis was even more strongly associated with all five respiratory symptoms, the researchers said.

The results suggest that “the inhalation of cannabis via vaping is associated with some pulmonary irritation and symptoms of lung diseases (both known and unknown),” that may be predictive of later EVALI, they concluded.

Product details aid in diagnosis

“As we continue to see patients presenting with EVALI in pediatric hospitals, it is important for us to identify if there are specific products (or categories) that are more likely to cause it,” said Brandon Seay, MD, FCCP, a pediatric pulmonologist and sleep specialist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, in an interview. “When we are trying to diagnose EVALI, we should be asking appropriate questions about exposures to specific products to get the best answers. If we simply ask ‘Are you smoking e-cigarettes?’ the patient may not [equate] e-cigarette smoking to vaping cannabis products,” he said.

Dr. Seay said he was not surprised by the study findings. “A lot of the patients I see with EVALI have reported vaping THC products, and most of them also report that the products were mixed by a friend or an individual instead of being a commercially produced product,” he noted. “This is not surprising, as THC is still illegal in most states and there would not be any commercially available products,” he said. “The mixing of these products by individuals increases the risk of ingredients being more toxic or irritating to the lungs,” Dr. Seay added. “This does highlight the need for more regulation of vaping products. As more states legalize marijuana, more of these products will become available, which will provide an opportunity for increased regulation, he said.

The take-home message for clinicians is to seek specific details from their young patients, Dr. Seay emphasized. “When we are educating our patients on the dangers of vaping/e-cigarettes, we need to make sure we are asking specifically which products they are using and know the terminology,” he said. “The use of THC-containing products will be increasing across the country with more legalization, so we need to keep ourselves apprised of the different risks between THC- and nicotine-containing devices,” he added.

As for additional research, it would be interesting to know whether patients were asked where they had gotten their products (commercially available products vs. those mixed by individuals) and explore any difference between the two, said Dr. Seay. “Also, as these products are relatively new to the market, compared to cigarettes, data on the longitudinal effects of vaping (nicotine and THC) over a long period of time, compared to traditional combustible cigarettes, will be needed,” he said.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and National Cancer Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Seay had no financial disclosures, but serves as a member of the CHEST Physician editorial board.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ADOLESCENT HEALTH

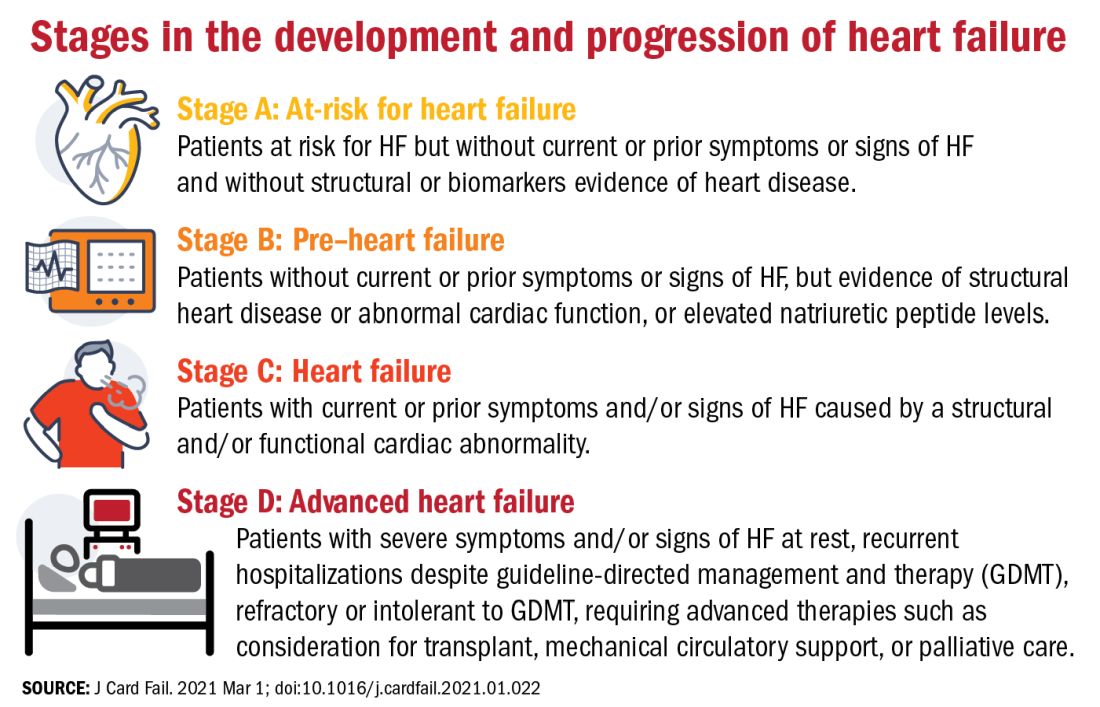

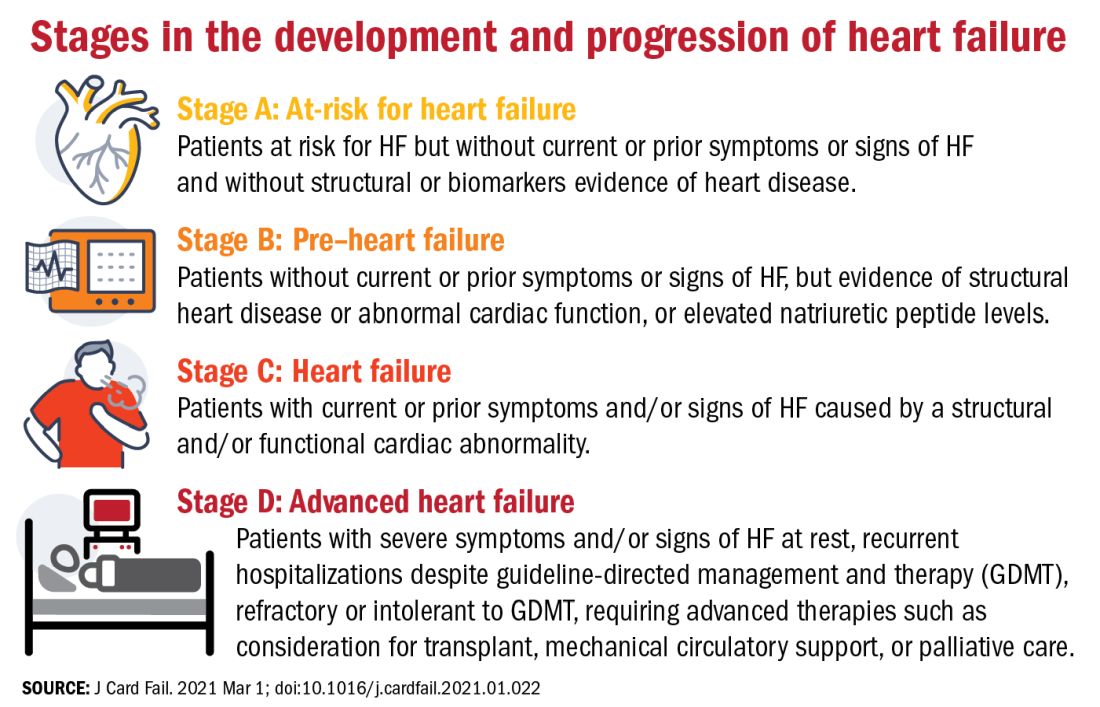

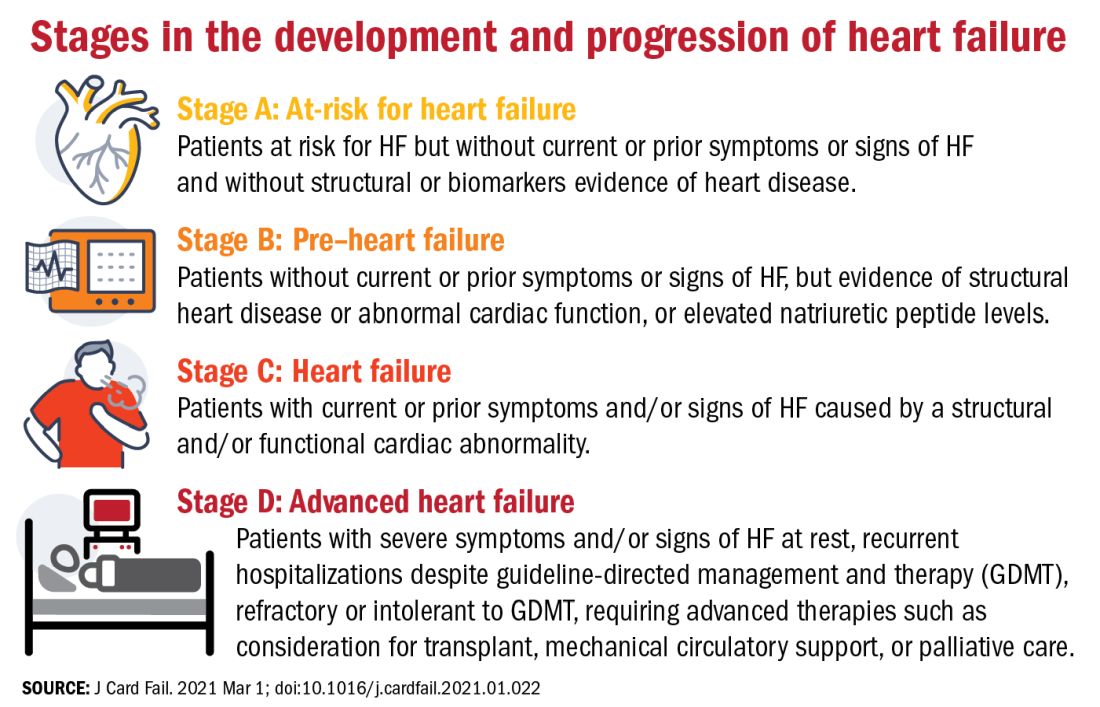

Heart failure redefined with new classifications, staging

The terminology and classification scheme for heart failure (HF) is changing in ways that experts hope will directly impact patient outcomes.

In a new consensus statement, a multisociety group of experts proposed a new universal definition of heart failure and made substantial revisions to the way in which the disease is staged and classified.

The authors of the statement, led by writing committee chair and immediate past president of the Heart Failure Society of America Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, hope their efforts will go far to improve standardization of terminology, but more importantly will facilitate better management of the disease in ways that keep pace with current knowledge and advances in the field.

“There is a great need for reframing and standardizing the terminology across societies and different stakeholders, and importantly for patients because a lot of the terminology we were using was understood by academicians, but were not being translated in important ways to ensure patients are being appropriately treated,” said Dr. Bozkurt, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The consensus statement was a group effort led by the HFSA, the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Japanese Heart Failure Society, with endorsements from the Canadian Heart Failure Society, the Heart Failure Association of India, the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and the Chinese Heart Failure Association.

The article was published March 1 in the Journal of Cardiac Failure and the European Journal of Heart Failure, authored by a writing committee of 38 individuals with domain expertise in HF, cardiomyopathy, and cardiovascular disease.

“This is a very thorough and very carefully written document that I think will be helpful for clinicians because they’ve tapped into important changes in the field that have occurred over the past 10 years and that now allow us to do more for patients than we could before,” Eugene Braunwald, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Braunwald and Elliott M. Antman, MD, both from TIMI Study Group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, wrote an editorial that accompanied the European Journal of Heart Failure article.

A new universal definition

“[Heart failure] is a clinical syndrome with symptoms and or signs caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality and corroborated by elevated natriuretic peptide levels and/or objective evidence of pulmonary or systemic congestion.”

This proposed definition, said the authors, is designed to be contemporary and simple “but conceptually comprehensive, with near universal applicability, prognostic and therapeutic viability, and acceptable sensitivity and specificity.”

Both left and right HF qualifies under this definition, said the authors, but conditions that result in marked volume overload, such as chronic kidney disease, which may present with signs and symptoms of HF, do not.

“Although some of these patients may have concomitant HF, these patients have a primary abnormality that may require a specific treatment beyond that for HF,” said the consensus statement authors.

For his part, Douglas L. Mann, MD, is happy to see what he considers a more accurate and practical definition for heart failure.

“We’ve had some wacky definitions in heart failure that haven’t made sense for 30 years, the principal of which is the definition of heart failure that says it’s the inability of the heart to meet the metabolic demands of the body,” Dr. Mann, of Washington University, St. Louis, said in an interview.

“I think this description was developed thinking about people with end-stage heart failure, but it makes no sense in clinical practice. Does it make sense to say about someone with New York Heart Association class I heart failure that their heart can’t meet the metabolic demands of the body?” said Dr. Mann, who was not involved with the writing of the consensus statement.

Proposed revised stages of the HF continuum

Overall, minimal changes have been made to the HF stages, with tweaks intended to enhance understanding and address the evolving role of biomarkers.

The authors proposed an approach to staging of HF:

- At-risk for HF (stage A), for patients at risk for HF but without current or prior symptoms or signs of HF and without structural or biomarkers evidence of heart disease.

- Pre-HF (stage B), for patients without current or prior symptoms or signs of HF, but evidence of structural heart disease or abnormal cardiac function, or elevated natriuretic peptide levels.

- HF (stage C), for patients with current or prior symptoms and/or signs of HF caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality.

- Advanced HF (stage D), for patients with severe symptoms and/or signs of HF at rest, recurrent hospitalizations despite guideline-directed management and therapy (GDMT), refractory or intolerant to GDMT, requiring advanced therapies such as consideration for transplant, mechanical circulatory support, or palliative care.

One notable change to the staging scheme is stage B, which the authors have reframed as “pre–heart failure.”

“Pre-cancer is a term widely understood and considered actionable and we wanted to tap into this successful messaging and embrace the pre–heart failure concept as something that is treatable and preventable,” said Dr. Bozkurt.

“We want patients and clinicians to understand that there are things we can do to prevent heart failure, strategies we didn’t have before, like SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with diabetes at risk for HF,” she added.

The revision also avoids the stigma of HF before the symptoms are manifest.

“Not calling it stage A and stage B heart failure you might say is semantics, but it’s important semantics,” said Dr. Braunwald. “When you’re talking to a patient or a relative and tell them they have stage A heart failure, it’s scares them unnecessarily. They don’t hear the stage A or B part, just the heart failure part.”

New classifications according to LVEF

And finally, in what some might consider the most obviously needed modification, the document proposes a new and revised classification of HF according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Most agree on how to classify heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), but although the middle range has long been understood to be a clinically relevant, it has no proper name or clear delineation.

“For standardization across practice guidelines, to recognize clinical trajectories in HF, and to facilitate the recognition of different heart failure entities in a sensitive and specific manner that can guide therapy, we want to formalize the heart failure categories according to ejection fraction,” said Dr. Bozkurt.