User login

Targetoid eruption

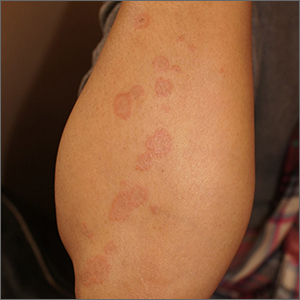

The clinical features of targetoid lesions occurring soon after herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection points to a diagnosis of erythema multiforme (EM), which was confirmed by punch biopsy. The differential diagnosis for targetoid small lesions includes granuloma annulare, pityriasis rosea, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Larger targetoid lesions would be more concerning for erythema migrans (Lyme disease), tumid lupus, and severe tinea corporis.

Erythema multiforme represents an immune reaction triggered most often by HSV. About 10% of cases are triggered by exposure to various other viruses, drugs, and bacteria—notably, Mycoplasma pneumonia.1 Symptoms vary from mildly uncomfortable crops of annular and targetoid plaques to widespread annular plaques and bullae.

In the past, EM was considered a clinical variant along a continuum with Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Although mucosal involvement may occur with EM, it never progresses to SJS or TEN. The latter 2 diagnoses are associated with significant skin pain, dusky confluent patches, and a positive Nikolsky sign—wherein skin pressure causes superficial separation of the epidermis. Additionally, SJS and TEN tend to involve the trunk, whereas EM typically involves acral surfaces.

EM is self-limited but may recur in patients with additional HSV flares. Patients with frequent recurrences benefit from long-term suppression of HSV with valacyclovir 500 mg bid. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cool compresses control mild pain. Itching may be relieved with topical, medium-potency steroids or oral antihistamines. Oral ulcers or lesions may be treated with lidocaine oral suspension. Systemic steroids are contraindicated for mild disease, but they have a somewhat controversial role in alleviating severe symptoms.

This patient had mild symptoms and tolerated topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid without recurrence at 6 months.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

The clinical features of targetoid lesions occurring soon after herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection points to a diagnosis of erythema multiforme (EM), which was confirmed by punch biopsy. The differential diagnosis for targetoid small lesions includes granuloma annulare, pityriasis rosea, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Larger targetoid lesions would be more concerning for erythema migrans (Lyme disease), tumid lupus, and severe tinea corporis.

Erythema multiforme represents an immune reaction triggered most often by HSV. About 10% of cases are triggered by exposure to various other viruses, drugs, and bacteria—notably, Mycoplasma pneumonia.1 Symptoms vary from mildly uncomfortable crops of annular and targetoid plaques to widespread annular plaques and bullae.

In the past, EM was considered a clinical variant along a continuum with Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Although mucosal involvement may occur with EM, it never progresses to SJS or TEN. The latter 2 diagnoses are associated with significant skin pain, dusky confluent patches, and a positive Nikolsky sign—wherein skin pressure causes superficial separation of the epidermis. Additionally, SJS and TEN tend to involve the trunk, whereas EM typically involves acral surfaces.

EM is self-limited but may recur in patients with additional HSV flares. Patients with frequent recurrences benefit from long-term suppression of HSV with valacyclovir 500 mg bid. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cool compresses control mild pain. Itching may be relieved with topical, medium-potency steroids or oral antihistamines. Oral ulcers or lesions may be treated with lidocaine oral suspension. Systemic steroids are contraindicated for mild disease, but they have a somewhat controversial role in alleviating severe symptoms.

This patient had mild symptoms and tolerated topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid without recurrence at 6 months.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The clinical features of targetoid lesions occurring soon after herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection points to a diagnosis of erythema multiforme (EM), which was confirmed by punch biopsy. The differential diagnosis for targetoid small lesions includes granuloma annulare, pityriasis rosea, and linear IgA bullous dermatosis. Larger targetoid lesions would be more concerning for erythema migrans (Lyme disease), tumid lupus, and severe tinea corporis.

Erythema multiforme represents an immune reaction triggered most often by HSV. About 10% of cases are triggered by exposure to various other viruses, drugs, and bacteria—notably, Mycoplasma pneumonia.1 Symptoms vary from mildly uncomfortable crops of annular and targetoid plaques to widespread annular plaques and bullae.

In the past, EM was considered a clinical variant along a continuum with Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Although mucosal involvement may occur with EM, it never progresses to SJS or TEN. The latter 2 diagnoses are associated with significant skin pain, dusky confluent patches, and a positive Nikolsky sign—wherein skin pressure causes superficial separation of the epidermis. Additionally, SJS and TEN tend to involve the trunk, whereas EM typically involves acral surfaces.

EM is self-limited but may recur in patients with additional HSV flares. Patients with frequent recurrences benefit from long-term suppression of HSV with valacyclovir 500 mg bid. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cool compresses control mild pain. Itching may be relieved with topical, medium-potency steroids or oral antihistamines. Oral ulcers or lesions may be treated with lidocaine oral suspension. Systemic steroids are contraindicated for mild disease, but they have a somewhat controversial role in alleviating severe symptoms.

This patient had mild symptoms and tolerated topical triamcinolone 0.1% cream bid without recurrence at 6 months.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

1. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:82-88.

Florida-based doctor arrested in Haiti president’s assassination

About two dozen people have been arrested as suspects, the newspaper reported, though police believe Christian Emmanuel Sanon, 63, was plotting to become president.

“He arrived by private plane in June with political objectives and contacted a private security firm to recruit the people who committed this act,” Léon Charles, Haiti’s national police chief, said during a news conference on July 11.

The firm, called CTU Security, is a Venezuelan company based in Miami, Mr. Charles said. During a raid at Mr. Sanon’s home in Port-au-Prince, police found six rifles, 20 boxes of bullets, 24 unused shooting targets, pistol holsters, and a hat with a U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency logo.

“This initial mission that was given to these assailants was to protect the individual named Emmanuel Sanon, but afterwards, the mission changed,” Mr. Charles said.

The new “mission” was to arrest President Moïse and install Mr. Sanon as president, The New York Times reported, though Mr. Charles didn’t explain when the mission changed to assassination or how Mr. Sanon could have taken control of the government.

President Moïse was shot to death on July 7 at his home in Port-au-Prince by a “team of commandos,” according to The Washington Post. On July 9, Haiti asked the U.S. to send troops to the country to protect its airport and key infrastructure.

The announcement of Mr. Sanon’s arrest came hours after FBI and Department of Homeland Security officials arrived in Haiti on July 11 to discuss how the U.S. can offer assistance, the newspaper reported.

Mr. Sanon has a YouTube channel with three political campaign videos from 2011, which include discussions about Haitian politics, according to Forbes. In one of the videos, titled “Dr. Christian Sanon – Leadership for Haiti,” Mr. Sanon talks about corruption in the country and presents himself as a potential leader.

Mr. Sanon lived in Florida for more than 20 years, ranging from the Tampa Bay area to South Florida, according to the Miami Herald. Public records show that he had more than a dozen businesses registered in the state, including medical services and real estate, though most are inactive.

Mr. Sanon is the third person with links to the U.S. who has been arrested in connection with the assassination, the Miami Herald reported. Two Haitian-Americans from southern Florida – James Solages, 35, and Joseph G. Vincent, 55 – were arrested by local police. They claimed they were working as translators for the assassins.

The first lady, Martine Moïse, was wounded in the attack and is now receiving treatment at a hospital in Miami, the newspaper reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

About two dozen people have been arrested as suspects, the newspaper reported, though police believe Christian Emmanuel Sanon, 63, was plotting to become president.

“He arrived by private plane in June with political objectives and contacted a private security firm to recruit the people who committed this act,” Léon Charles, Haiti’s national police chief, said during a news conference on July 11.

The firm, called CTU Security, is a Venezuelan company based in Miami, Mr. Charles said. During a raid at Mr. Sanon’s home in Port-au-Prince, police found six rifles, 20 boxes of bullets, 24 unused shooting targets, pistol holsters, and a hat with a U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency logo.

“This initial mission that was given to these assailants was to protect the individual named Emmanuel Sanon, but afterwards, the mission changed,” Mr. Charles said.

The new “mission” was to arrest President Moïse and install Mr. Sanon as president, The New York Times reported, though Mr. Charles didn’t explain when the mission changed to assassination or how Mr. Sanon could have taken control of the government.

President Moïse was shot to death on July 7 at his home in Port-au-Prince by a “team of commandos,” according to The Washington Post. On July 9, Haiti asked the U.S. to send troops to the country to protect its airport and key infrastructure.

The announcement of Mr. Sanon’s arrest came hours after FBI and Department of Homeland Security officials arrived in Haiti on July 11 to discuss how the U.S. can offer assistance, the newspaper reported.

Mr. Sanon has a YouTube channel with three political campaign videos from 2011, which include discussions about Haitian politics, according to Forbes. In one of the videos, titled “Dr. Christian Sanon – Leadership for Haiti,” Mr. Sanon talks about corruption in the country and presents himself as a potential leader.

Mr. Sanon lived in Florida for more than 20 years, ranging from the Tampa Bay area to South Florida, according to the Miami Herald. Public records show that he had more than a dozen businesses registered in the state, including medical services and real estate, though most are inactive.

Mr. Sanon is the third person with links to the U.S. who has been arrested in connection with the assassination, the Miami Herald reported. Two Haitian-Americans from southern Florida – James Solages, 35, and Joseph G. Vincent, 55 – were arrested by local police. They claimed they were working as translators for the assassins.

The first lady, Martine Moïse, was wounded in the attack and is now receiving treatment at a hospital in Miami, the newspaper reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

About two dozen people have been arrested as suspects, the newspaper reported, though police believe Christian Emmanuel Sanon, 63, was plotting to become president.

“He arrived by private plane in June with political objectives and contacted a private security firm to recruit the people who committed this act,” Léon Charles, Haiti’s national police chief, said during a news conference on July 11.

The firm, called CTU Security, is a Venezuelan company based in Miami, Mr. Charles said. During a raid at Mr. Sanon’s home in Port-au-Prince, police found six rifles, 20 boxes of bullets, 24 unused shooting targets, pistol holsters, and a hat with a U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency logo.

“This initial mission that was given to these assailants was to protect the individual named Emmanuel Sanon, but afterwards, the mission changed,” Mr. Charles said.

The new “mission” was to arrest President Moïse and install Mr. Sanon as president, The New York Times reported, though Mr. Charles didn’t explain when the mission changed to assassination or how Mr. Sanon could have taken control of the government.

President Moïse was shot to death on July 7 at his home in Port-au-Prince by a “team of commandos,” according to The Washington Post. On July 9, Haiti asked the U.S. to send troops to the country to protect its airport and key infrastructure.

The announcement of Mr. Sanon’s arrest came hours after FBI and Department of Homeland Security officials arrived in Haiti on July 11 to discuss how the U.S. can offer assistance, the newspaper reported.

Mr. Sanon has a YouTube channel with three political campaign videos from 2011, which include discussions about Haitian politics, according to Forbes. In one of the videos, titled “Dr. Christian Sanon – Leadership for Haiti,” Mr. Sanon talks about corruption in the country and presents himself as a potential leader.

Mr. Sanon lived in Florida for more than 20 years, ranging from the Tampa Bay area to South Florida, according to the Miami Herald. Public records show that he had more than a dozen businesses registered in the state, including medical services and real estate, though most are inactive.

Mr. Sanon is the third person with links to the U.S. who has been arrested in connection with the assassination, the Miami Herald reported. Two Haitian-Americans from southern Florida – James Solages, 35, and Joseph G. Vincent, 55 – were arrested by local police. They claimed they were working as translators for the assassins.

The first lady, Martine Moïse, was wounded in the attack and is now receiving treatment at a hospital in Miami, the newspaper reported.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Three new ACR guidelines recommend treatment for six forms of vasculitis

Three new guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology, in partnership with the Vasculitis Foundation, offer evidence-based recommendations for managing and treating six different forms of systemic vasculitis.

“It’s not unusual for many rheumatologists to have fairly limited experience caring for patients with vasculitis,” coauthor Sharon Chung, MD, director of the Vasculitis Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview. “And with limited experience comes anxiety and concerns about whether or not one is treating patients appropriately. First and foremost, these guidelines are to help rheumatologists who may not have experience treating patients with vasculitides, to provide them with a framework they can use.”

The guidelines – the first to be produced and endorsed by both the ACR and the Vasculitis Foundation – were published July 8 in both Arthritis & Rheumatology and Arthritis Care & Research.

To assess the recent expansion in diagnostic and treatment options for various forms of vasculitis, the ACR assembled a literature review team, an 11-person patient panel, and a voting panel – made up of 9 adult rheumatologists, 5 pediatric rheumatologists, and 2 patients – to evaluate evidence, provide feedback, and formulate and vote on recommendations, respectively. The guidelines cover six types of vasculitis: one focusing on giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu arteritis (TAK); one on polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), and another on three forms of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV): granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA).

As with other ACR guidelines, these three were developed via the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, which was used to rate the quality of the gathered evidence. For a recommendation to be published, it required 70% consensus or greater from the voting panel.

GCA and TAK guideline

Regarding the management and treatment of GCA and TAK, the guideline offers 42 recommendations and three ungraded position statements. Due to the low quality of evidence – “reflecting the paucity of randomized clinical trials in these diseases,” the authors noted – only one of the GCA recommendations and one of the TAK recommendations are strong; the rest are conditional.

For patients with GCA, the guideline strongly recommends long-term clinical monitoring over no clinical monitoring for anyone in apparent clinical remission. Other notable recommendations include favoring oral glucocorticoids (GCs) with tocilizumab (Actemra) over oral glucocorticoids alone in newly diagnosed GCA, adding a non-GC immunosuppressive agent to oral GCs for GCA patients with active extracranial large vessel involvement, and preferring temporary artery biopsy as their “diagnostic test of choice at this time.”

“The Europeans generally are more comfortable relying on temporal artery ultrasound,” Robert F. Spiera, MD, director of the vasculitis and scleroderma program at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said in an interview. “In this country, possibly in part due to less uniform expertise in performing these ultrasounds, we have not had as much success in terms of accuracy.

These ACR guidelines therefore recommended biopsy to establish the diagnosis in patients with cranial presentations, whereas in the EULAR guidelines, ultrasound was felt to be preferable to biopsy.”

“While we have temporal artery ultrasound available in the United States, we just don’t have the expertise at this point to perform or interpret that test like the European rheumatologists do,” Dr. Chung agreed. “But I think we’re all hopeful that experience with temporal artery ultrasound will improve in the future, so we can use that test instead of an invasive biopsy.”

Dr. Spiera, who was not a coauthor on any of the guidelines, also highlighted the conditional recommendation of noninvasive vascular imaging of the large vessels in patients with newly diagnosed GCA.

“It is well recognized that a substantial portion of patients with GCA have unrecognized evidence of large vessel involvement, and patients with GCA in general are at higher risk of aneurysms later in the disease course,” he said. “These guidelines suggest screening even patients with purely cranial presentations for large vessel involvement with imaging to possibly identify the patients at higher risk for those later complications.

“What they didn’t offer were recommendations on how to follow up on that imaging,” he added, “which is an important and as-yet-unanswered question.”

For patients with TAK, the guideline again strongly recommends long-term clinical monitoring over no clinical monitoring for anyone in apparent clinical remission. Other conditional recommendations include choosing a non-GC immunosuppressive agent such as methotrexate or a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor over tocilizumab as initial therapy because “the efficacy of tocilizumab in TAK is not established at this time.”

AAV guideline

Regarding the management and treatment of GPA, MPA, and EGPA, the guideline offers 41 recommendations and 10 ungraded position statements. All recommendations were conditional, and many address GPA and MPA together because, as the authors noted, “pivotal trials have enrolled both groups and presented results for these diseases together.”

One notable recommendation is their preference for rituximab over cyclophosphamide for remission induction and for rituximab over methotrexate or azathioprine for remission maintenance in patients with severe GPA or MPA. “I don’t think this is a surprise to people, but I think it reaffirms where our current practice is moving,” Dr. Chung said.

“The literature supports that in patients with relapsing disease, rituximab works better than cyclophosphamide for remission induction,” Dr. Spiera said. “But in these guidelines, even in new disease, rituximab is suggested as the agent of choice to induce remission. I would say that that is reasonable, but you could make an argument that it’s maybe beyond what the literature supports, particularly in patients with advanced renal insufficiency attributable to that initial vasculitis flare.”

Other recommendations include being against routinely adding plasma exchange to remission induction therapy in GPA or MPA patients with active glomerulonephritis – although they added that it should be considered in patients at high risk of end-stage kidney disease – as well as preferring cyclophosphamide or rituximab over mepolizumab for remission induction in patients with severe EGPA.

“We, to the surprise of many, were more supportive for the use of rituximab in EGPA than others were expecting, given the limited evidence,” Dr. Chung said. “One of the reasons for that is the wide experience we’ve had with rituximab in GPA and MPA, and our recognition that there is a population of patients with EGPA who are ANCA positive who do seem to benefit from rituximab therapy.”

And although the voting panel strongly favored treatment with methotrexate or azathioprine over trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for GPA patients in remission, they ultimately labeled the recommendation as conditional “due to the lack of sufficient high-quality evidence comparing the two treatments.”

“There has been progress in terms of well-done clinical trials to inform our decision-making, particularly for ANCA-associated vasculitis, both in terms of how to induce and maintain remission,” Dr. Spiera said. “Though the recommendations were conditional, I think there’s very strong data to support many of them.”

PAN guideline

Regarding the management and treatment of PAN, the guideline offers 16 recommendations – all but one are conditional – and one ungraded position statement. Their strong recommendation was for treatment with TNF inhibitors over GCs in patients with clinical manifestations of deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2, which they asked doctors to consider “in the setting of a PAN-like syndrome with strokes.” Other conditional recommendations include treating patients with newly diagnosed, severe PAN with cyclophosphamide and GCs, as well as the use of abdominal vascular imaging and/or a deep-skin biopsy to help establish a diagnosis.

According to the authors, a fourth guideline on treating and managing Kawasaki syndrome will be released in the coming weeks.

The guidelines were supported by the ACR and the Vasculitis Foundation. Several authors acknowledged potential conflicts of interest, including receiving speaking and consulting fees, research grants, and honoraria from various pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Spiera has received grant support or consulting fees from Roche-Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chemocentryx, Corbus, Formation Biologics, InflaRx, Kadmon, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, CSL Behring, Sanofi, and Janssen.

Three new guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology, in partnership with the Vasculitis Foundation, offer evidence-based recommendations for managing and treating six different forms of systemic vasculitis.

“It’s not unusual for many rheumatologists to have fairly limited experience caring for patients with vasculitis,” coauthor Sharon Chung, MD, director of the Vasculitis Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview. “And with limited experience comes anxiety and concerns about whether or not one is treating patients appropriately. First and foremost, these guidelines are to help rheumatologists who may not have experience treating patients with vasculitides, to provide them with a framework they can use.”

The guidelines – the first to be produced and endorsed by both the ACR and the Vasculitis Foundation – were published July 8 in both Arthritis & Rheumatology and Arthritis Care & Research.

To assess the recent expansion in diagnostic and treatment options for various forms of vasculitis, the ACR assembled a literature review team, an 11-person patient panel, and a voting panel – made up of 9 adult rheumatologists, 5 pediatric rheumatologists, and 2 patients – to evaluate evidence, provide feedback, and formulate and vote on recommendations, respectively. The guidelines cover six types of vasculitis: one focusing on giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu arteritis (TAK); one on polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), and another on three forms of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV): granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA).

As with other ACR guidelines, these three were developed via the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, which was used to rate the quality of the gathered evidence. For a recommendation to be published, it required 70% consensus or greater from the voting panel.

GCA and TAK guideline

Regarding the management and treatment of GCA and TAK, the guideline offers 42 recommendations and three ungraded position statements. Due to the low quality of evidence – “reflecting the paucity of randomized clinical trials in these diseases,” the authors noted – only one of the GCA recommendations and one of the TAK recommendations are strong; the rest are conditional.

For patients with GCA, the guideline strongly recommends long-term clinical monitoring over no clinical monitoring for anyone in apparent clinical remission. Other notable recommendations include favoring oral glucocorticoids (GCs) with tocilizumab (Actemra) over oral glucocorticoids alone in newly diagnosed GCA, adding a non-GC immunosuppressive agent to oral GCs for GCA patients with active extracranial large vessel involvement, and preferring temporary artery biopsy as their “diagnostic test of choice at this time.”

“The Europeans generally are more comfortable relying on temporal artery ultrasound,” Robert F. Spiera, MD, director of the vasculitis and scleroderma program at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said in an interview. “In this country, possibly in part due to less uniform expertise in performing these ultrasounds, we have not had as much success in terms of accuracy.

These ACR guidelines therefore recommended biopsy to establish the diagnosis in patients with cranial presentations, whereas in the EULAR guidelines, ultrasound was felt to be preferable to biopsy.”

“While we have temporal artery ultrasound available in the United States, we just don’t have the expertise at this point to perform or interpret that test like the European rheumatologists do,” Dr. Chung agreed. “But I think we’re all hopeful that experience with temporal artery ultrasound will improve in the future, so we can use that test instead of an invasive biopsy.”

Dr. Spiera, who was not a coauthor on any of the guidelines, also highlighted the conditional recommendation of noninvasive vascular imaging of the large vessels in patients with newly diagnosed GCA.

“It is well recognized that a substantial portion of patients with GCA have unrecognized evidence of large vessel involvement, and patients with GCA in general are at higher risk of aneurysms later in the disease course,” he said. “These guidelines suggest screening even patients with purely cranial presentations for large vessel involvement with imaging to possibly identify the patients at higher risk for those later complications.

“What they didn’t offer were recommendations on how to follow up on that imaging,” he added, “which is an important and as-yet-unanswered question.”

For patients with TAK, the guideline again strongly recommends long-term clinical monitoring over no clinical monitoring for anyone in apparent clinical remission. Other conditional recommendations include choosing a non-GC immunosuppressive agent such as methotrexate or a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor over tocilizumab as initial therapy because “the efficacy of tocilizumab in TAK is not established at this time.”

AAV guideline

Regarding the management and treatment of GPA, MPA, and EGPA, the guideline offers 41 recommendations and 10 ungraded position statements. All recommendations were conditional, and many address GPA and MPA together because, as the authors noted, “pivotal trials have enrolled both groups and presented results for these diseases together.”

One notable recommendation is their preference for rituximab over cyclophosphamide for remission induction and for rituximab over methotrexate or azathioprine for remission maintenance in patients with severe GPA or MPA. “I don’t think this is a surprise to people, but I think it reaffirms where our current practice is moving,” Dr. Chung said.

“The literature supports that in patients with relapsing disease, rituximab works better than cyclophosphamide for remission induction,” Dr. Spiera said. “But in these guidelines, even in new disease, rituximab is suggested as the agent of choice to induce remission. I would say that that is reasonable, but you could make an argument that it’s maybe beyond what the literature supports, particularly in patients with advanced renal insufficiency attributable to that initial vasculitis flare.”

Other recommendations include being against routinely adding plasma exchange to remission induction therapy in GPA or MPA patients with active glomerulonephritis – although they added that it should be considered in patients at high risk of end-stage kidney disease – as well as preferring cyclophosphamide or rituximab over mepolizumab for remission induction in patients with severe EGPA.

“We, to the surprise of many, were more supportive for the use of rituximab in EGPA than others were expecting, given the limited evidence,” Dr. Chung said. “One of the reasons for that is the wide experience we’ve had with rituximab in GPA and MPA, and our recognition that there is a population of patients with EGPA who are ANCA positive who do seem to benefit from rituximab therapy.”

And although the voting panel strongly favored treatment with methotrexate or azathioprine over trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for GPA patients in remission, they ultimately labeled the recommendation as conditional “due to the lack of sufficient high-quality evidence comparing the two treatments.”

“There has been progress in terms of well-done clinical trials to inform our decision-making, particularly for ANCA-associated vasculitis, both in terms of how to induce and maintain remission,” Dr. Spiera said. “Though the recommendations were conditional, I think there’s very strong data to support many of them.”

PAN guideline

Regarding the management and treatment of PAN, the guideline offers 16 recommendations – all but one are conditional – and one ungraded position statement. Their strong recommendation was for treatment with TNF inhibitors over GCs in patients with clinical manifestations of deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2, which they asked doctors to consider “in the setting of a PAN-like syndrome with strokes.” Other conditional recommendations include treating patients with newly diagnosed, severe PAN with cyclophosphamide and GCs, as well as the use of abdominal vascular imaging and/or a deep-skin biopsy to help establish a diagnosis.

According to the authors, a fourth guideline on treating and managing Kawasaki syndrome will be released in the coming weeks.

The guidelines were supported by the ACR and the Vasculitis Foundation. Several authors acknowledged potential conflicts of interest, including receiving speaking and consulting fees, research grants, and honoraria from various pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Spiera has received grant support or consulting fees from Roche-Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chemocentryx, Corbus, Formation Biologics, InflaRx, Kadmon, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, CSL Behring, Sanofi, and Janssen.

Three new guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology, in partnership with the Vasculitis Foundation, offer evidence-based recommendations for managing and treating six different forms of systemic vasculitis.

“It’s not unusual for many rheumatologists to have fairly limited experience caring for patients with vasculitis,” coauthor Sharon Chung, MD, director of the Vasculitis Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview. “And with limited experience comes anxiety and concerns about whether or not one is treating patients appropriately. First and foremost, these guidelines are to help rheumatologists who may not have experience treating patients with vasculitides, to provide them with a framework they can use.”

The guidelines – the first to be produced and endorsed by both the ACR and the Vasculitis Foundation – were published July 8 in both Arthritis & Rheumatology and Arthritis Care & Research.

To assess the recent expansion in diagnostic and treatment options for various forms of vasculitis, the ACR assembled a literature review team, an 11-person patient panel, and a voting panel – made up of 9 adult rheumatologists, 5 pediatric rheumatologists, and 2 patients – to evaluate evidence, provide feedback, and formulate and vote on recommendations, respectively. The guidelines cover six types of vasculitis: one focusing on giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu arteritis (TAK); one on polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), and another on three forms of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV): granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA).

As with other ACR guidelines, these three were developed via the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology, which was used to rate the quality of the gathered evidence. For a recommendation to be published, it required 70% consensus or greater from the voting panel.

GCA and TAK guideline

Regarding the management and treatment of GCA and TAK, the guideline offers 42 recommendations and three ungraded position statements. Due to the low quality of evidence – “reflecting the paucity of randomized clinical trials in these diseases,” the authors noted – only one of the GCA recommendations and one of the TAK recommendations are strong; the rest are conditional.

For patients with GCA, the guideline strongly recommends long-term clinical monitoring over no clinical monitoring for anyone in apparent clinical remission. Other notable recommendations include favoring oral glucocorticoids (GCs) with tocilizumab (Actemra) over oral glucocorticoids alone in newly diagnosed GCA, adding a non-GC immunosuppressive agent to oral GCs for GCA patients with active extracranial large vessel involvement, and preferring temporary artery biopsy as their “diagnostic test of choice at this time.”

“The Europeans generally are more comfortable relying on temporal artery ultrasound,” Robert F. Spiera, MD, director of the vasculitis and scleroderma program at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said in an interview. “In this country, possibly in part due to less uniform expertise in performing these ultrasounds, we have not had as much success in terms of accuracy.

These ACR guidelines therefore recommended biopsy to establish the diagnosis in patients with cranial presentations, whereas in the EULAR guidelines, ultrasound was felt to be preferable to biopsy.”

“While we have temporal artery ultrasound available in the United States, we just don’t have the expertise at this point to perform or interpret that test like the European rheumatologists do,” Dr. Chung agreed. “But I think we’re all hopeful that experience with temporal artery ultrasound will improve in the future, so we can use that test instead of an invasive biopsy.”

Dr. Spiera, who was not a coauthor on any of the guidelines, also highlighted the conditional recommendation of noninvasive vascular imaging of the large vessels in patients with newly diagnosed GCA.

“It is well recognized that a substantial portion of patients with GCA have unrecognized evidence of large vessel involvement, and patients with GCA in general are at higher risk of aneurysms later in the disease course,” he said. “These guidelines suggest screening even patients with purely cranial presentations for large vessel involvement with imaging to possibly identify the patients at higher risk for those later complications.

“What they didn’t offer were recommendations on how to follow up on that imaging,” he added, “which is an important and as-yet-unanswered question.”

For patients with TAK, the guideline again strongly recommends long-term clinical monitoring over no clinical monitoring for anyone in apparent clinical remission. Other conditional recommendations include choosing a non-GC immunosuppressive agent such as methotrexate or a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor over tocilizumab as initial therapy because “the efficacy of tocilizumab in TAK is not established at this time.”

AAV guideline

Regarding the management and treatment of GPA, MPA, and EGPA, the guideline offers 41 recommendations and 10 ungraded position statements. All recommendations were conditional, and many address GPA and MPA together because, as the authors noted, “pivotal trials have enrolled both groups and presented results for these diseases together.”

One notable recommendation is their preference for rituximab over cyclophosphamide for remission induction and for rituximab over methotrexate or azathioprine for remission maintenance in patients with severe GPA or MPA. “I don’t think this is a surprise to people, but I think it reaffirms where our current practice is moving,” Dr. Chung said.

“The literature supports that in patients with relapsing disease, rituximab works better than cyclophosphamide for remission induction,” Dr. Spiera said. “But in these guidelines, even in new disease, rituximab is suggested as the agent of choice to induce remission. I would say that that is reasonable, but you could make an argument that it’s maybe beyond what the literature supports, particularly in patients with advanced renal insufficiency attributable to that initial vasculitis flare.”

Other recommendations include being against routinely adding plasma exchange to remission induction therapy in GPA or MPA patients with active glomerulonephritis – although they added that it should be considered in patients at high risk of end-stage kidney disease – as well as preferring cyclophosphamide or rituximab over mepolizumab for remission induction in patients with severe EGPA.

“We, to the surprise of many, were more supportive for the use of rituximab in EGPA than others were expecting, given the limited evidence,” Dr. Chung said. “One of the reasons for that is the wide experience we’ve had with rituximab in GPA and MPA, and our recognition that there is a population of patients with EGPA who are ANCA positive who do seem to benefit from rituximab therapy.”

And although the voting panel strongly favored treatment with methotrexate or azathioprine over trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole for GPA patients in remission, they ultimately labeled the recommendation as conditional “due to the lack of sufficient high-quality evidence comparing the two treatments.”

“There has been progress in terms of well-done clinical trials to inform our decision-making, particularly for ANCA-associated vasculitis, both in terms of how to induce and maintain remission,” Dr. Spiera said. “Though the recommendations were conditional, I think there’s very strong data to support many of them.”

PAN guideline

Regarding the management and treatment of PAN, the guideline offers 16 recommendations – all but one are conditional – and one ungraded position statement. Their strong recommendation was for treatment with TNF inhibitors over GCs in patients with clinical manifestations of deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2, which they asked doctors to consider “in the setting of a PAN-like syndrome with strokes.” Other conditional recommendations include treating patients with newly diagnosed, severe PAN with cyclophosphamide and GCs, as well as the use of abdominal vascular imaging and/or a deep-skin biopsy to help establish a diagnosis.

According to the authors, a fourth guideline on treating and managing Kawasaki syndrome will be released in the coming weeks.

The guidelines were supported by the ACR and the Vasculitis Foundation. Several authors acknowledged potential conflicts of interest, including receiving speaking and consulting fees, research grants, and honoraria from various pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Spiera has received grant support or consulting fees from Roche-Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chemocentryx, Corbus, Formation Biologics, InflaRx, Kadmon, AstraZeneca, AbbVie, CSL Behring, Sanofi, and Janssen.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Talking about guns: Website helps physicians follow through on pledge

The group has developed a national resource for clinicians who wish to address the problem of gun violence deaths in the United States, which continue to mount by the day.

Signatures came quickly in 2018 after the Annals of Internal Medicine asked physicians to sign a formal pledge in which they commit to talking with their patients about firearms. To date, the list has grown to more than 3,600, and it remains open for additional signatories.

The effort built on data showing that before people commit violence with firearms, they often have notable risk factors that prompt them to see a physician.

At the time the pledge campaign was launched, frustration and despair had hit new highs after the school shooting of Feb. 14, 2018, in Parkland, Florida, in which 17 people were killed. That occurred just 4 months after the mass shooting in Las Vegas, Nevada, on Oct. 1, 2017, in which 58 people were gunned down.

An editorial by Garen J. Wintemute, MD, MPH, helped kick off the drive.

More deaths than WWII combat fatalities

Dr. Wintemute cited some grim statistics, writing that “nationwide in 2016, there was an average of 97 deaths from firearm violence per day: 35,476 altogether. In the 10 years ending with 2016, deaths of U.S. civilians from firearm violence exceeded American combat fatalities in World War II.”

Amy Barnhorst, MD, vice chair of psychiatry at UC Davis, who was one of the early signers of the pledge, told this news organization that data analyst Rocco Pallin, MPH, with the UC Davis Violence Prevention Research Program (VPRP), quickly started managing commitments to the pledge and developed a “What You Can Do” intervention for physicians looking for help on how to prevent firearm injury and death.

Those efforts snowballed, and a need arose for a centralized public resource. In 2019, the state of California gave $3.8 million to the VPRP, which helped launch the BulletPoints Project, which Dr. Barnhorst now directs.

The website provides clinicians with evidence-based direction on how to have the conversations with patients. It walks them through various scenarios and details what can be done if what they learn during a patient interview requires action.

Dr. Barnhorst said the team is working on formalized online educational courses for mental health professionals and medical clinicians that will be hosted through various national organizations.

Christine Laine, MD, editor-in-chief of the Annals of Internal Medicine, said in an interview that although almost 4,000 persons have made the pledge, that number should be higher. She notes that the American College of Physicians has about 165,000 members, and even that is only a fraction of all physicians and clinicians.

“Signing the pledge helps raise awareness that this is a public health issue and, within the realm of health care providers, that they should be counseling patients about reducing risk, the same way we counsel people to wear bike helmets and use seat belts,” she said.

Dr. Barnhorst says those who don’t want to sign the pledge usually cite time considerations and that they already talk with patients about a list of public health issues. They also say they don’t know how to have the conversations or what they should do if what they hear in the interviews requires action.

“We can’t do anything about the time, but we can do something about the resources,” Dr. Barnhorst said.

Some clinicians, she said, worry that patients will get angry if physicians ask about guns, or they believe it’s illegal to ask.

“But there’s no law preventing physicians from asking these questions,” she said.

Dr. Wintemute told this news organization that he is not discouraged that only about 4,000 have signed the pledge. Rather, he was encouraged that the signatures came so quickly. He also notes that the number of persons who are interested far exceeds the number who have made the pledge.

Boosting the pledge numbers will likely take a new push in the form of published articles, he added, and those are in the works.

Among the next steps is conducting pre- and post-tests to see whether BulletPoints is effectively conveying the information for users, he said.

Another is pushing for advances in petitioning for “extreme risk protection orders,” which would require a gun owner to temporarily relinquish any firearms and ammunition and not purchase additional firearms.

Dr. Wintemute said that currently, Maryland is the only state in which health care professionals can petition for extreme risk protection orders. In any state that has the law, a health care professional can contact law enforcement about “a person who is at very high risk for violence in the very near future” but who has not committed a crime and is not mentally ill and so cannot be legally detained.

For physicians to include gun counseling as a routine part of patient care will likely require hearing from peers who are finding the time to do this effectively and hearing that it matters, he said.

“It’s going to take that on-the-ground diffusion of information, just as it has with vaccine hesitancy,” he said.

He notes that data on how to stop firearm violence are sparse and approaches so far have extrapolated from information on how to stop other health threats, such as smoking and drinking.

But that is changing rapidly, he said: “There’s funding from the CDC for research into the kind of work we’re doing.”

Measuring the success of those efforts is difficult.

One sign of change in the past 3 years, Dr. Wintemute says, is that there’s recognition among health care professionals and the public that this fits into clinicians’ “lane.”

Mass shootings not the largest source of gun violence

Mass shootings continue to dominate news about fatal shootings, but Dr. Barnhorst notes that such shootings represent a very small part – reportedly 1% to 2% – of the firearm deaths in the United States. Almost two-thirds of the deaths are suicides. Domestic violence deaths make up another large sector.

But it’s the mass shootings that stick in the collective U.S. consciousness, and the rising and unrelenting numbers can lead to a sense of futility.

Dr. Barnhorst, Dr. Laine, and Dr. Wintemute acknowledge they don’t know to what degree physicians’ talking to patients about firearms can help. But they do not doubt it’s worthy of the effort.

Dr. Laine said that during the past year, COVID-19 overshadowed the focus on the pledge, but he notes the signup for the pledge remains open. Information on firearm injury is collected on the Annals website.

Dr. Barnhorst says there is no good answer to the question of how many lives need to be saved before talking with patients about firearms becomes worth the effort. “For me,” she said, “that number is very, very low.”

Dr. Laine puts the number at one.

“If a physician talking to their patients about firearms prevents one suicide, then the intervention is a success,” she said.

Dr. Laine, Dr. Barnhorst, and Dr. Wintemute report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The group has developed a national resource for clinicians who wish to address the problem of gun violence deaths in the United States, which continue to mount by the day.

Signatures came quickly in 2018 after the Annals of Internal Medicine asked physicians to sign a formal pledge in which they commit to talking with their patients about firearms. To date, the list has grown to more than 3,600, and it remains open for additional signatories.

The effort built on data showing that before people commit violence with firearms, they often have notable risk factors that prompt them to see a physician.

At the time the pledge campaign was launched, frustration and despair had hit new highs after the school shooting of Feb. 14, 2018, in Parkland, Florida, in which 17 people were killed. That occurred just 4 months after the mass shooting in Las Vegas, Nevada, on Oct. 1, 2017, in which 58 people were gunned down.

An editorial by Garen J. Wintemute, MD, MPH, helped kick off the drive.

More deaths than WWII combat fatalities

Dr. Wintemute cited some grim statistics, writing that “nationwide in 2016, there was an average of 97 deaths from firearm violence per day: 35,476 altogether. In the 10 years ending with 2016, deaths of U.S. civilians from firearm violence exceeded American combat fatalities in World War II.”

Amy Barnhorst, MD, vice chair of psychiatry at UC Davis, who was one of the early signers of the pledge, told this news organization that data analyst Rocco Pallin, MPH, with the UC Davis Violence Prevention Research Program (VPRP), quickly started managing commitments to the pledge and developed a “What You Can Do” intervention for physicians looking for help on how to prevent firearm injury and death.

Those efforts snowballed, and a need arose for a centralized public resource. In 2019, the state of California gave $3.8 million to the VPRP, which helped launch the BulletPoints Project, which Dr. Barnhorst now directs.

The website provides clinicians with evidence-based direction on how to have the conversations with patients. It walks them through various scenarios and details what can be done if what they learn during a patient interview requires action.

Dr. Barnhorst said the team is working on formalized online educational courses for mental health professionals and medical clinicians that will be hosted through various national organizations.

Christine Laine, MD, editor-in-chief of the Annals of Internal Medicine, said in an interview that although almost 4,000 persons have made the pledge, that number should be higher. She notes that the American College of Physicians has about 165,000 members, and even that is only a fraction of all physicians and clinicians.

“Signing the pledge helps raise awareness that this is a public health issue and, within the realm of health care providers, that they should be counseling patients about reducing risk, the same way we counsel people to wear bike helmets and use seat belts,” she said.

Dr. Barnhorst says those who don’t want to sign the pledge usually cite time considerations and that they already talk with patients about a list of public health issues. They also say they don’t know how to have the conversations or what they should do if what they hear in the interviews requires action.

“We can’t do anything about the time, but we can do something about the resources,” Dr. Barnhorst said.

Some clinicians, she said, worry that patients will get angry if physicians ask about guns, or they believe it’s illegal to ask.

“But there’s no law preventing physicians from asking these questions,” she said.

Dr. Wintemute told this news organization that he is not discouraged that only about 4,000 have signed the pledge. Rather, he was encouraged that the signatures came so quickly. He also notes that the number of persons who are interested far exceeds the number who have made the pledge.

Boosting the pledge numbers will likely take a new push in the form of published articles, he added, and those are in the works.

Among the next steps is conducting pre- and post-tests to see whether BulletPoints is effectively conveying the information for users, he said.

Another is pushing for advances in petitioning for “extreme risk protection orders,” which would require a gun owner to temporarily relinquish any firearms and ammunition and not purchase additional firearms.

Dr. Wintemute said that currently, Maryland is the only state in which health care professionals can petition for extreme risk protection orders. In any state that has the law, a health care professional can contact law enforcement about “a person who is at very high risk for violence in the very near future” but who has not committed a crime and is not mentally ill and so cannot be legally detained.

For physicians to include gun counseling as a routine part of patient care will likely require hearing from peers who are finding the time to do this effectively and hearing that it matters, he said.

“It’s going to take that on-the-ground diffusion of information, just as it has with vaccine hesitancy,” he said.

He notes that data on how to stop firearm violence are sparse and approaches so far have extrapolated from information on how to stop other health threats, such as smoking and drinking.

But that is changing rapidly, he said: “There’s funding from the CDC for research into the kind of work we’re doing.”

Measuring the success of those efforts is difficult.

One sign of change in the past 3 years, Dr. Wintemute says, is that there’s recognition among health care professionals and the public that this fits into clinicians’ “lane.”

Mass shootings not the largest source of gun violence

Mass shootings continue to dominate news about fatal shootings, but Dr. Barnhorst notes that such shootings represent a very small part – reportedly 1% to 2% – of the firearm deaths in the United States. Almost two-thirds of the deaths are suicides. Domestic violence deaths make up another large sector.

But it’s the mass shootings that stick in the collective U.S. consciousness, and the rising and unrelenting numbers can lead to a sense of futility.

Dr. Barnhorst, Dr. Laine, and Dr. Wintemute acknowledge they don’t know to what degree physicians’ talking to patients about firearms can help. But they do not doubt it’s worthy of the effort.

Dr. Laine said that during the past year, COVID-19 overshadowed the focus on the pledge, but he notes the signup for the pledge remains open. Information on firearm injury is collected on the Annals website.

Dr. Barnhorst says there is no good answer to the question of how many lives need to be saved before talking with patients about firearms becomes worth the effort. “For me,” she said, “that number is very, very low.”

Dr. Laine puts the number at one.

“If a physician talking to their patients about firearms prevents one suicide, then the intervention is a success,” she said.

Dr. Laine, Dr. Barnhorst, and Dr. Wintemute report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The group has developed a national resource for clinicians who wish to address the problem of gun violence deaths in the United States, which continue to mount by the day.

Signatures came quickly in 2018 after the Annals of Internal Medicine asked physicians to sign a formal pledge in which they commit to talking with their patients about firearms. To date, the list has grown to more than 3,600, and it remains open for additional signatories.

The effort built on data showing that before people commit violence with firearms, they often have notable risk factors that prompt them to see a physician.

At the time the pledge campaign was launched, frustration and despair had hit new highs after the school shooting of Feb. 14, 2018, in Parkland, Florida, in which 17 people were killed. That occurred just 4 months after the mass shooting in Las Vegas, Nevada, on Oct. 1, 2017, in which 58 people were gunned down.

An editorial by Garen J. Wintemute, MD, MPH, helped kick off the drive.

More deaths than WWII combat fatalities

Dr. Wintemute cited some grim statistics, writing that “nationwide in 2016, there was an average of 97 deaths from firearm violence per day: 35,476 altogether. In the 10 years ending with 2016, deaths of U.S. civilians from firearm violence exceeded American combat fatalities in World War II.”

Amy Barnhorst, MD, vice chair of psychiatry at UC Davis, who was one of the early signers of the pledge, told this news organization that data analyst Rocco Pallin, MPH, with the UC Davis Violence Prevention Research Program (VPRP), quickly started managing commitments to the pledge and developed a “What You Can Do” intervention for physicians looking for help on how to prevent firearm injury and death.

Those efforts snowballed, and a need arose for a centralized public resource. In 2019, the state of California gave $3.8 million to the VPRP, which helped launch the BulletPoints Project, which Dr. Barnhorst now directs.

The website provides clinicians with evidence-based direction on how to have the conversations with patients. It walks them through various scenarios and details what can be done if what they learn during a patient interview requires action.

Dr. Barnhorst said the team is working on formalized online educational courses for mental health professionals and medical clinicians that will be hosted through various national organizations.

Christine Laine, MD, editor-in-chief of the Annals of Internal Medicine, said in an interview that although almost 4,000 persons have made the pledge, that number should be higher. She notes that the American College of Physicians has about 165,000 members, and even that is only a fraction of all physicians and clinicians.

“Signing the pledge helps raise awareness that this is a public health issue and, within the realm of health care providers, that they should be counseling patients about reducing risk, the same way we counsel people to wear bike helmets and use seat belts,” she said.

Dr. Barnhorst says those who don’t want to sign the pledge usually cite time considerations and that they already talk with patients about a list of public health issues. They also say they don’t know how to have the conversations or what they should do if what they hear in the interviews requires action.

“We can’t do anything about the time, but we can do something about the resources,” Dr. Barnhorst said.

Some clinicians, she said, worry that patients will get angry if physicians ask about guns, or they believe it’s illegal to ask.

“But there’s no law preventing physicians from asking these questions,” she said.

Dr. Wintemute told this news organization that he is not discouraged that only about 4,000 have signed the pledge. Rather, he was encouraged that the signatures came so quickly. He also notes that the number of persons who are interested far exceeds the number who have made the pledge.

Boosting the pledge numbers will likely take a new push in the form of published articles, he added, and those are in the works.

Among the next steps is conducting pre- and post-tests to see whether BulletPoints is effectively conveying the information for users, he said.

Another is pushing for advances in petitioning for “extreme risk protection orders,” which would require a gun owner to temporarily relinquish any firearms and ammunition and not purchase additional firearms.

Dr. Wintemute said that currently, Maryland is the only state in which health care professionals can petition for extreme risk protection orders. In any state that has the law, a health care professional can contact law enforcement about “a person who is at very high risk for violence in the very near future” but who has not committed a crime and is not mentally ill and so cannot be legally detained.

For physicians to include gun counseling as a routine part of patient care will likely require hearing from peers who are finding the time to do this effectively and hearing that it matters, he said.

“It’s going to take that on-the-ground diffusion of information, just as it has with vaccine hesitancy,” he said.

He notes that data on how to stop firearm violence are sparse and approaches so far have extrapolated from information on how to stop other health threats, such as smoking and drinking.

But that is changing rapidly, he said: “There’s funding from the CDC for research into the kind of work we’re doing.”

Measuring the success of those efforts is difficult.

One sign of change in the past 3 years, Dr. Wintemute says, is that there’s recognition among health care professionals and the public that this fits into clinicians’ “lane.”

Mass shootings not the largest source of gun violence

Mass shootings continue to dominate news about fatal shootings, but Dr. Barnhorst notes that such shootings represent a very small part – reportedly 1% to 2% – of the firearm deaths in the United States. Almost two-thirds of the deaths are suicides. Domestic violence deaths make up another large sector.

But it’s the mass shootings that stick in the collective U.S. consciousness, and the rising and unrelenting numbers can lead to a sense of futility.

Dr. Barnhorst, Dr. Laine, and Dr. Wintemute acknowledge they don’t know to what degree physicians’ talking to patients about firearms can help. But they do not doubt it’s worthy of the effort.

Dr. Laine said that during the past year, COVID-19 overshadowed the focus on the pledge, but he notes the signup for the pledge remains open. Information on firearm injury is collected on the Annals website.

Dr. Barnhorst says there is no good answer to the question of how many lives need to be saved before talking with patients about firearms becomes worth the effort. “For me,” she said, “that number is very, very low.”

Dr. Laine puts the number at one.

“If a physician talking to their patients about firearms prevents one suicide, then the intervention is a success,” she said.

Dr. Laine, Dr. Barnhorst, and Dr. Wintemute report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

UV light linked to prevention of allergic disease in infants

Higher direct ultraviolet light exposure in the first 3 months of life was linked to lower incidence of proinflammatory immune markers and lower incidence of eczema in an early-stage double-blind, randomized controlled trial.

Kristina Rueter, MD, with the University of Western Australia, Perth, who presented her team’s findings on Sunday at the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Hybrid Congress 2021, said their study is the first to demonstrate the association.

“There has been a significant rise in allergic diseases, particularly within the last 20-30 years,” Dr. Rueter noted.

“Changes to the genetic pool take thousands of years to have an impact,” she said, “so the question is why do we have the significant, very recent rise of allergic diseases?”

Suboptimal vitamin D levels during infancy, lifestyle changes, nutritional changes, and living at higher latitudes have emerged as explanations.

In this study, 195 high-risk newborns were randomized to receive oral vitamin D supplements (400 IU/day) or placebo until 6 months of age.

Researchers found that UV light exposure appears more beneficial than vitamin D supplements as an allergy prevention strategy in the critical early years of immune system development.

The researchers used a novel approach of attaching a personal UV dosimeter to the infants’ clothing to measure direct UV light exposure (290-380 nm). Vitamin D levels were measured at 3, 6, 12, and 30 months of age. Immune function was assessed at 6 months of age, and food allergy, eczema, and wheeze were assessed at 6, 12, and 30 months of age.

At 3 (P < .01) and 6 (P = .02) months of age, vitamin D levels were greater in the children who received vitamin D supplements than those who received placebo, but there was no difference in eczema incidence between groups. The finding matched those of previous studies that compared the supplements with placebo, Dr. Rueter said.

However, infants with eczema were found to have had less UV light exposure compared to those without eczema (median interquartile range [IQR], 555 J/m2 vs. 998 J/m2; P = .023).

“We also found an inverse correlation between total UV light exposure and toll-like receptor cytokine production,” Dr. Rueter said.

“The more direct UV light exposure a child got, the less the chance to develop eczema,” she said.

Researchers then extended their analysis to see whether the effect of direct UV light exposure on reduced eczema would be maintained in the first 2.5 years of life, “and we could see again a significant difference, that the children who received higher UV light exposure had less eczema,” Dr. Rueter said.

Barbara Rogala, MD, PhD, professor at the Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland, told this news organization that, just as in studies on vitamin D in adult populations, there must be a balance in infant studies between potential benefit of a therapeutic strategy of vitamin D and sunlight and risk of side effects. (Dr. Rogala was not involved in Dr. Rueter’s study.)

Although vitamin D supplements are a standard part of infant care, exposure to sunlight can come with cancer risk, she noted.

Dr. Rueter agreed caution is necessary.

“You have to follow the cancer guidelines,” she said. “Sunlight may play a role in causing skin cancer, and lots of research needs to be done to find the right balance between what is a good amount which may influence the immune system in a positive way and what, on the other hand, might be too much.”

As for vitamin D supplements, Dr. Rueter said, toxic levels require “extremely high doses,” so with 400 IU/day used in the study, children are likely not being overtreated by combining sunlight and vitamin D supplements.

The study was supported by grants from Telethon–New Children’s Hospital Research Fund, Australia; Asthma Foundation of Western Australia; and the Princess Margaret Hospital Foundation, Australia. Dr. Rueter and Dr. Rogala have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Higher direct ultraviolet light exposure in the first 3 months of life was linked to lower incidence of proinflammatory immune markers and lower incidence of eczema in an early-stage double-blind, randomized controlled trial.

Kristina Rueter, MD, with the University of Western Australia, Perth, who presented her team’s findings on Sunday at the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Hybrid Congress 2021, said their study is the first to demonstrate the association.

“There has been a significant rise in allergic diseases, particularly within the last 20-30 years,” Dr. Rueter noted.

“Changes to the genetic pool take thousands of years to have an impact,” she said, “so the question is why do we have the significant, very recent rise of allergic diseases?”

Suboptimal vitamin D levels during infancy, lifestyle changes, nutritional changes, and living at higher latitudes have emerged as explanations.

In this study, 195 high-risk newborns were randomized to receive oral vitamin D supplements (400 IU/day) or placebo until 6 months of age.

Researchers found that UV light exposure appears more beneficial than vitamin D supplements as an allergy prevention strategy in the critical early years of immune system development.

The researchers used a novel approach of attaching a personal UV dosimeter to the infants’ clothing to measure direct UV light exposure (290-380 nm). Vitamin D levels were measured at 3, 6, 12, and 30 months of age. Immune function was assessed at 6 months of age, and food allergy, eczema, and wheeze were assessed at 6, 12, and 30 months of age.

At 3 (P < .01) and 6 (P = .02) months of age, vitamin D levels were greater in the children who received vitamin D supplements than those who received placebo, but there was no difference in eczema incidence between groups. The finding matched those of previous studies that compared the supplements with placebo, Dr. Rueter said.

However, infants with eczema were found to have had less UV light exposure compared to those without eczema (median interquartile range [IQR], 555 J/m2 vs. 998 J/m2; P = .023).

“We also found an inverse correlation between total UV light exposure and toll-like receptor cytokine production,” Dr. Rueter said.

“The more direct UV light exposure a child got, the less the chance to develop eczema,” she said.

Researchers then extended their analysis to see whether the effect of direct UV light exposure on reduced eczema would be maintained in the first 2.5 years of life, “and we could see again a significant difference, that the children who received higher UV light exposure had less eczema,” Dr. Rueter said.

Barbara Rogala, MD, PhD, professor at the Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland, told this news organization that, just as in studies on vitamin D in adult populations, there must be a balance in infant studies between potential benefit of a therapeutic strategy of vitamin D and sunlight and risk of side effects. (Dr. Rogala was not involved in Dr. Rueter’s study.)

Although vitamin D supplements are a standard part of infant care, exposure to sunlight can come with cancer risk, she noted.

Dr. Rueter agreed caution is necessary.

“You have to follow the cancer guidelines,” she said. “Sunlight may play a role in causing skin cancer, and lots of research needs to be done to find the right balance between what is a good amount which may influence the immune system in a positive way and what, on the other hand, might be too much.”

As for vitamin D supplements, Dr. Rueter said, toxic levels require “extremely high doses,” so with 400 IU/day used in the study, children are likely not being overtreated by combining sunlight and vitamin D supplements.

The study was supported by grants from Telethon–New Children’s Hospital Research Fund, Australia; Asthma Foundation of Western Australia; and the Princess Margaret Hospital Foundation, Australia. Dr. Rueter and Dr. Rogala have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Higher direct ultraviolet light exposure in the first 3 months of life was linked to lower incidence of proinflammatory immune markers and lower incidence of eczema in an early-stage double-blind, randomized controlled trial.

Kristina Rueter, MD, with the University of Western Australia, Perth, who presented her team’s findings on Sunday at the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Hybrid Congress 2021, said their study is the first to demonstrate the association.

“There has been a significant rise in allergic diseases, particularly within the last 20-30 years,” Dr. Rueter noted.

“Changes to the genetic pool take thousands of years to have an impact,” she said, “so the question is why do we have the significant, very recent rise of allergic diseases?”

Suboptimal vitamin D levels during infancy, lifestyle changes, nutritional changes, and living at higher latitudes have emerged as explanations.

In this study, 195 high-risk newborns were randomized to receive oral vitamin D supplements (400 IU/day) or placebo until 6 months of age.

Researchers found that UV light exposure appears more beneficial than vitamin D supplements as an allergy prevention strategy in the critical early years of immune system development.

The researchers used a novel approach of attaching a personal UV dosimeter to the infants’ clothing to measure direct UV light exposure (290-380 nm). Vitamin D levels were measured at 3, 6, 12, and 30 months of age. Immune function was assessed at 6 months of age, and food allergy, eczema, and wheeze were assessed at 6, 12, and 30 months of age.

At 3 (P < .01) and 6 (P = .02) months of age, vitamin D levels were greater in the children who received vitamin D supplements than those who received placebo, but there was no difference in eczema incidence between groups. The finding matched those of previous studies that compared the supplements with placebo, Dr. Rueter said.

However, infants with eczema were found to have had less UV light exposure compared to those without eczema (median interquartile range [IQR], 555 J/m2 vs. 998 J/m2; P = .023).

“We also found an inverse correlation between total UV light exposure and toll-like receptor cytokine production,” Dr. Rueter said.

“The more direct UV light exposure a child got, the less the chance to develop eczema,” she said.

Researchers then extended their analysis to see whether the effect of direct UV light exposure on reduced eczema would be maintained in the first 2.5 years of life, “and we could see again a significant difference, that the children who received higher UV light exposure had less eczema,” Dr. Rueter said.

Barbara Rogala, MD, PhD, professor at the Medical University of Silesia, Katowice, Poland, told this news organization that, just as in studies on vitamin D in adult populations, there must be a balance in infant studies between potential benefit of a therapeutic strategy of vitamin D and sunlight and risk of side effects. (Dr. Rogala was not involved in Dr. Rueter’s study.)

Although vitamin D supplements are a standard part of infant care, exposure to sunlight can come with cancer risk, she noted.

Dr. Rueter agreed caution is necessary.

“You have to follow the cancer guidelines,” she said. “Sunlight may play a role in causing skin cancer, and lots of research needs to be done to find the right balance between what is a good amount which may influence the immune system in a positive way and what, on the other hand, might be too much.”

As for vitamin D supplements, Dr. Rueter said, toxic levels require “extremely high doses,” so with 400 IU/day used in the study, children are likely not being overtreated by combining sunlight and vitamin D supplements.

The study was supported by grants from Telethon–New Children’s Hospital Research Fund, Australia; Asthma Foundation of Western Australia; and the Princess Margaret Hospital Foundation, Australia. Dr. Rueter and Dr. Rogala have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Subcutaneous Nodule on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Cystic Panfolliculoma

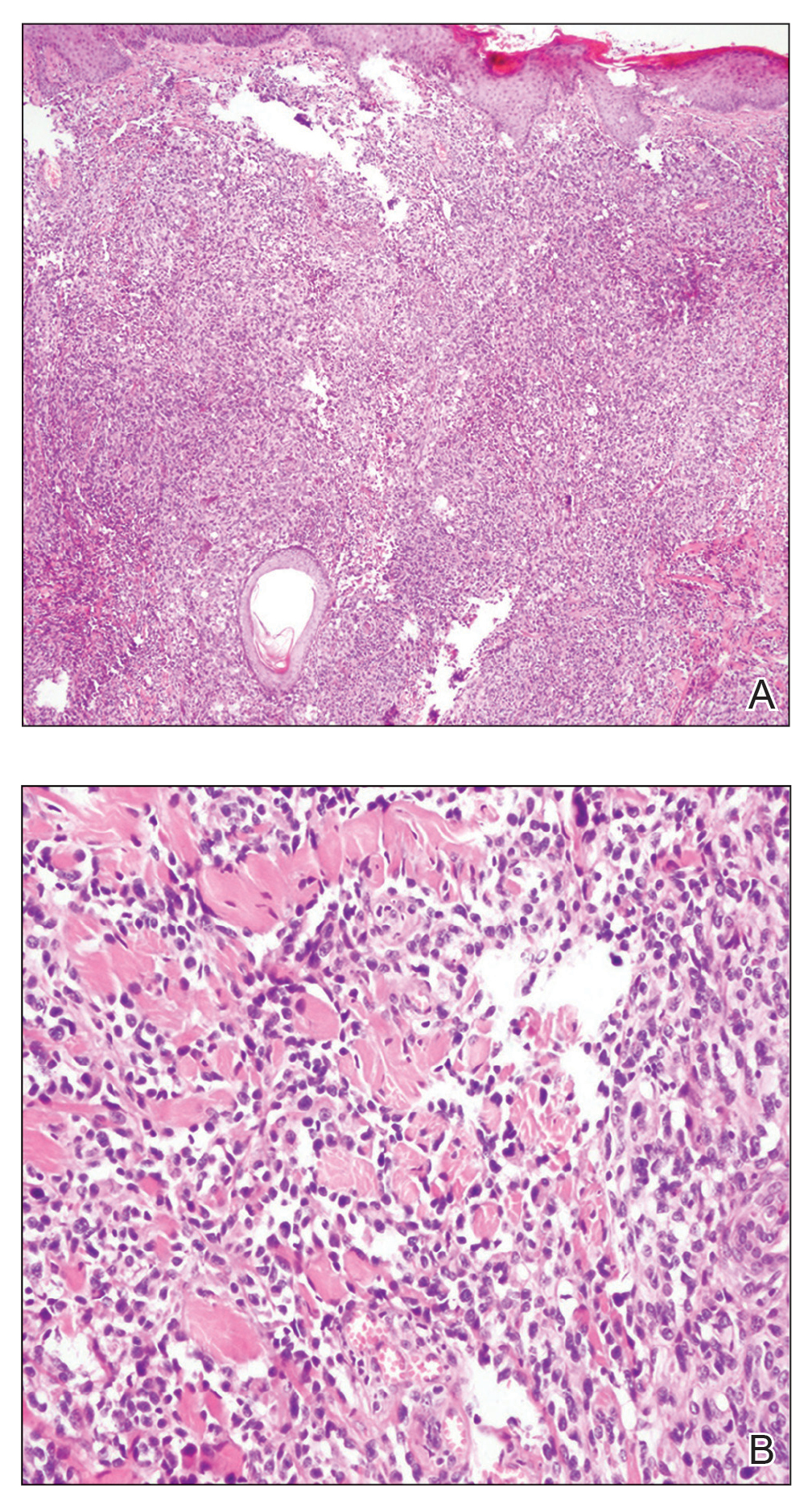

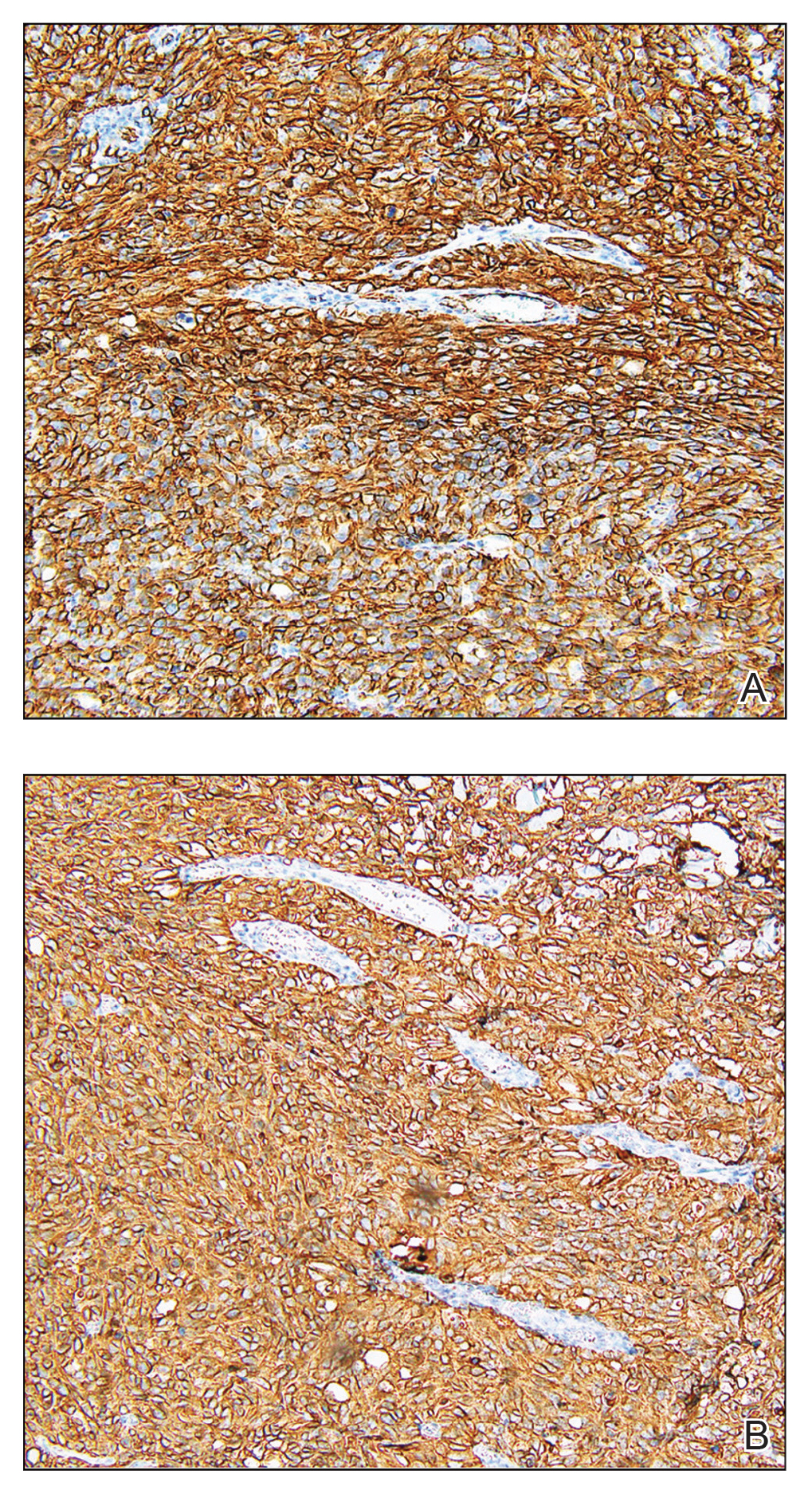

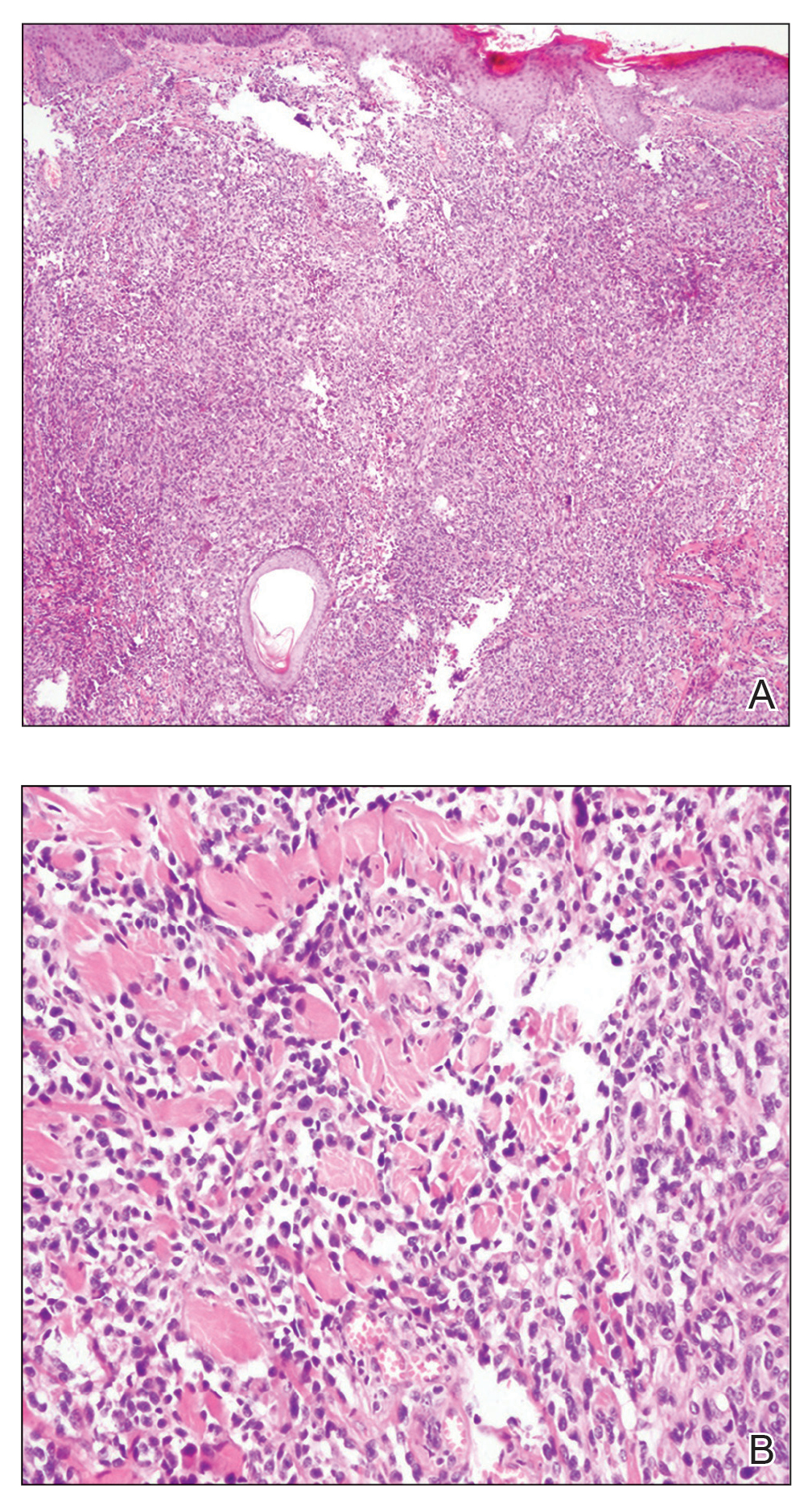

Panfolliculoma is a rare tumor of follicular origin.1 Clinical examination can reveal a papule, nodule, or tumor that typically is mistaken for an epidermal inclusion cyst, trichoepithelioma, or basal cell carcinoma (BCC).2 As with other benign follicular neoplasms, it often exhibits a protracted growth pattern.3,4 Most cases reported in the literature have been shown to occur in the head or neck region. One hypothesis is that separation into the various components of the hair follicle occurs at a higher frequency in areas with a higher hair density such as the face and scalp.4 The lesion typically presents in patients aged 20 to 70 years, as in our patient, with cases equally distributed among males and females.4,5 Neill et al1 reported a rare case of cystic panfolliculoma occurring on the right forearm of a 64-year-old woman.

As its name suggests, panfolliculoma is exceptional in that it displays features of all segments of the hair follicle, including the infundibulum, isthmus, stem, and bulb.6 Although not necessary for diagnosis, immunohistochemical staining can be utilized to identify each hair follicle component on histopathologic examination. Panfolliculoma stains positive for 34βE12 and cytokeratin 5/6, highlighting infundibular and isthmus keratinocytes and the outer root sheath, respectively. Additionally, Ber-EP4 labels germinative cells, while CD34 highlights contiguous fibrotic stroma and trichilemmal areas.3,4

In our patient, histopathology revealed a cystic structure that was lined by an infundibular epithelium with a prominent granular layer. Solid collections of basaloid germinative cells that demonstrated peripheral palisading were observed (quiz image [top]). Cells with trichohyalin granules, indicative of inner root sheath differentiation, were encased by matrical cells (quiz image [bottom]).

Historically, panfolliculomas characteristically have been known to reside in the dermis, with only focal connection to the epidermis, if at all present. Nevertheless, Harris et al7 detailed 2 cases that displayed predominant epidermal involvement, defined by the term epidermal panfolliculoma. In a study performed by Shan and Guo,2 an additional 9 cases (19 panfolliculomas) were found to have similar findings, for which the term superficial panfolliculoma was suggested. In cases that display a primary epidermal component, common mimickers include tumor of the follicular infundibulum and the reactive process of follicular induction.7