User login

When is catheter ablation a sound option for your patient with A-fib?

CASE

Jack Z, a 75-year-old man with well-controlled hypertension, diabetes controlled by diet, and atrial fibrillation (AF) presents to the family medicine clinic to establish care with you after moving to the community from out of town.

The patient describes a 1-year history of AF. He provides you with an echocardiography report from 6 months ago that shows no evidence of structural heart disease. He takes lisinopril, to control blood pressure; an anticoagulant; a beta-blocker; and amiodarone for rhythm control. Initially, he took flecainide, which was ineffective for rhythm control, before being switched to amiodarone. He had 2 cardioversion procedures, each time after episodes of symptoms. He does not smoke or drink alcohol.

Mr. Z describes worsening palpitations and shortness of breath over the past 9 months. Symptoms now include episodes of exertional fatigue, even when he is not having palpitations. Prior to the episodes of worsening symptoms, he tells you that he lived a “fairly active” life, golfing twice a week.

The patient’s previous primary care physician had encouraged him to talk to his cardiologist about “other options” for managing AF, because levels of his liver enzymes had started to rise (a known adverse effect of amiodarone1) when measured 3 months ago. He did not undertake that conversation, but asks you now about other treatments for AF.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, characterized by discordant electrical activation of the atria due to structural or electrophysiological abnormalities, or both. The disorder is associated with an increased rate of stroke and heart failure and is independently associated with a 1.5- to 2-fold risk of all-cause mortality.2

In this article, we review the pathophysiology of AF; management, including the role of, and indications for, catheter ablation; and patient- and disease-related factors associated with ablation (including odds of success, complications, risk of recurrence, and continuing need for thromboprophylaxis) that family physicians should consider when contemplating referral to a cardiologist or electrophysiologist for catheter ablation for AF.

What provokes AF?

AF is thought to occur as a result of an interaction among 3 phenomena:

- enhanced automaticity of abnormal atrial tissue

- triggered activity of ectopic foci within 1 or more pulmonary veins, lying within the left atrium

- re-entry, in which there is propagation of electrical impulses from an ectopic beat through another pathway.

Continue to: In patients who progress...

In patients who progress from paroxysmal to persistent AF (see “Subtypes,” below), 2 distinct pathways, facilitated by the presence of abnormal tissue, continuously activate one another, thus maintaining the arrhythmia. Myocardial tissue in the pulmonary veins is responsible for most ectopic electrical impulses in patients with drug-refractory AF (see “Rhythm control”).

Subtypes. For the purpose of planning treatment, AF is classified as:

- Paroxysmal. Terminates spontaneously or with intervention ≤ 7 days after onset.

- Persistent. Continuous and sustained for > 7 days.

- Longstanding persistent. Continuous for > 12 months.

- Permanent. The patient and physician accept that there will be no further attempt to restore or maintain sinus rhythm.

Goals of treatment

Primary management goals in patients with AF are 2-fold: control of symptoms and prevention of thromboembolism. A patient with new-onset AF who presents acutely with inadequate rate control and hemodynamic compromise requires urgent assessment to determine the cause of the arrhythmia and need for cardioversion.3 A symptomatic patient with AF who does not have high-risk features (eg, valvular heart disease, mechanical valves) might be a candidate for rhythm control in addition to rate control.3,4

Rate control. After evaluation in the hospital, a patient who has a rapid ventricular response but remains hemodynamically stable, without evidence of heart failure, should be initiated on a rate-controlling medication, such as a beta-blocker or nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker. A resting heart rate goal of < 80 beats per minute (bpm) is recommended for a symptomatic patient with AF. The heart rate goal can be relaxed, to < 110 bpm, in an asymptomatic patient with preserved left ventricular function.5,6

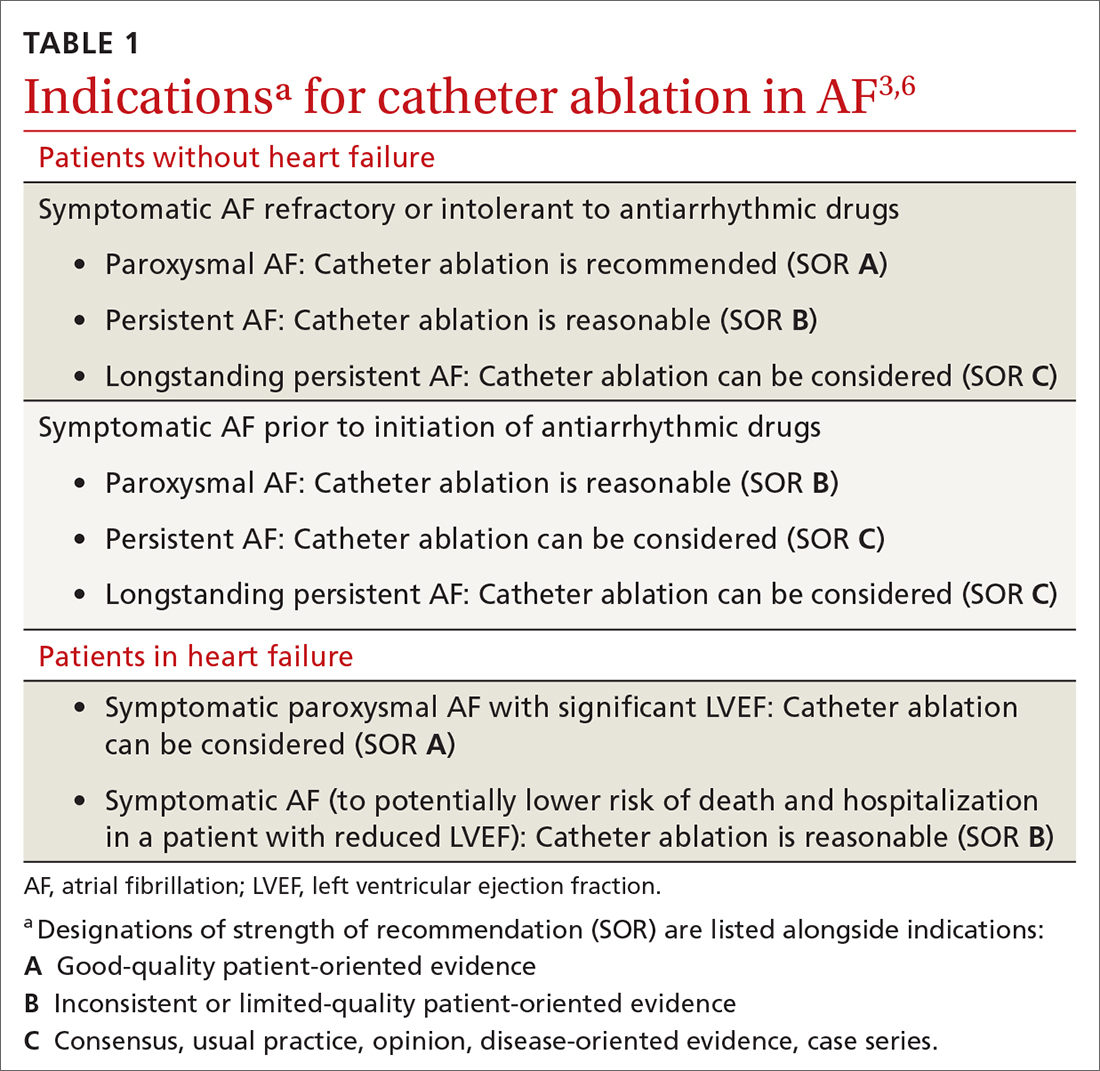

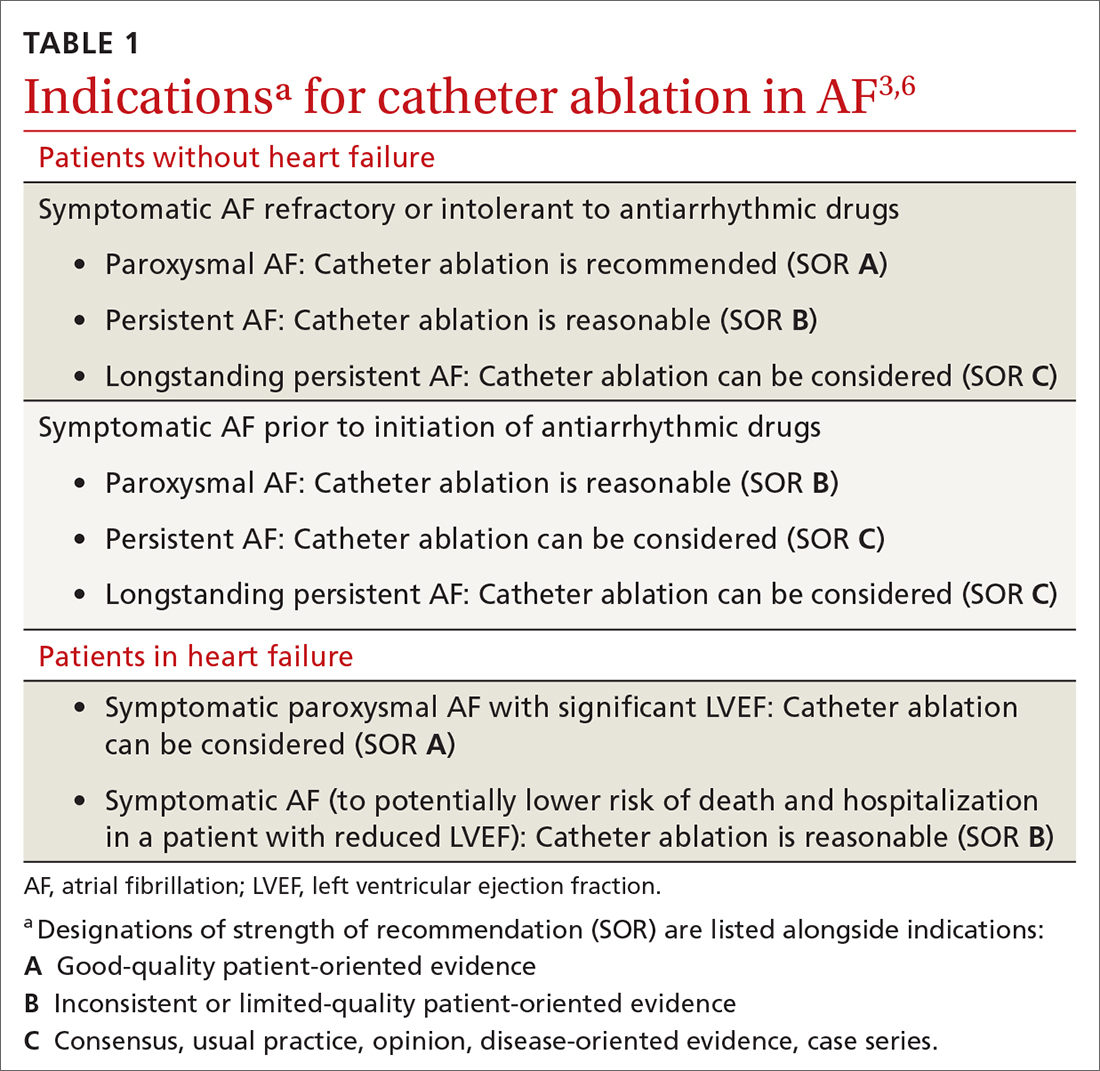

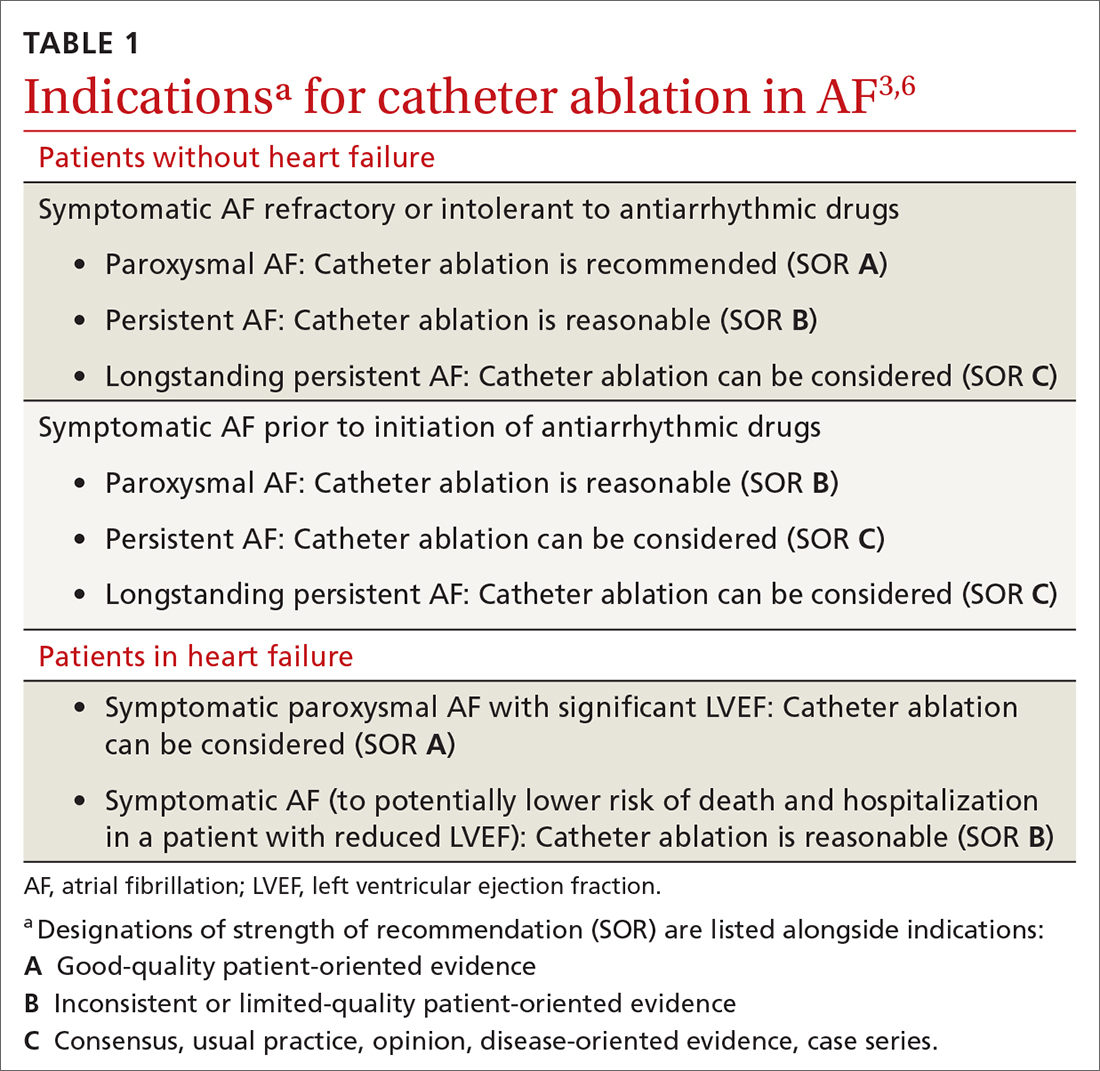

Rhythm control, indicated in patients who remain symptomatic on rate-controlling medication, can be achieved either with an antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) or by catheter ablation.4,5 In stable patients, rhythm control should be considered only after a thorough work-up for a reversible cause of AF, and can be achieved with an oral AAD or, in select patients, through catheter ablation (TABLE 13,6). Other indications for chronic rhythm control include treatment of patients with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.5

A major study that documented the benefit of early rhythm control evaluated long-term outcomes in 2789 patients with AF who were undergoing catheter ablation.7 Patients were randomized to early rhythm control (catheter ablation or AAD) or “usual care”—ie, in this study, rhythm control limited to symptomatic patients. Primary outcomes were death from cardiovascular causes, stroke, and hospitalization with worsening heart failure or acute coronary syndrome. A first primary outcome event occurred in 249 patients (3.9/100 person-years) assigned to early rhythm control, compared to 316 (5.0 per 100 person-years) in the group assigned to usual care.

The study was terminated early (after 5.1 years) because of overwhelming evidence of efficacy (number need to treat = 7). Although early rhythm control was obtained through both catheter ablation and AAD (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.79; 96% CI, 0.66-0.94; P = .005), success was attributed to the use of catheter ablation for a rhythm-control strategy and its use among patients whose AF was present for < 1 year. Most patients in both treatment groups continued to receive anticoagulation, rate control, and optimization of cardiovascular risk.7

Continue to: Notably, direct studies...

Notably, direct studies comparing ablation and AAD have not confirmed the benefit of ablation over AAD in outcomes of all-cause mortality, bleeding, stroke, or cardiac arrest over a 5-year period.8

Adverse effects and mortality outcomes with AAD. Concern over using AAD for rhythm control is based mostly on adverse effects and long-term (1-year) mortality outcomes. Long-term AAD therapy has been shown to decrease the recurrence of AF—but without evidence to suggest other mortality benefits.

A meta-analysis of 59 randomized controlled trials reviewed 20,981 patients receiving AAD (including quinidine, disopyramide, propafenone, flecainide, metoprolol, amiodarone, dofetilide, dronedarone, and sotalol) for long-term effects on death, stroke, adverse reactions, and recurrence of AF.9 Findings at 10 months suggest that:

- Compared to placebo, amiodarone and sotalol increased the risk of all-cause mortality during the study period.

- There was minimal difference in mortality among patients taking dofetilide or dronedarone, compared to placebo.

- There were insufficient data to draw conclusions about the effect of disopyramide, flecainide, and propafenone on mortality.

Before starting a patient on AAD, the risk of arrhythmias and the potential for these agents to cause toxicity and adverse events should always be discussed.

CASE

You tell Mr. Z that you need to know the status of his comorbidities to make a recommendation about “other” management options, and proceed to take a detailed history.

Recent history. Mr. Z reveals that “today is a good day”: He has had “only 1” episode of palpitations, which resolved on its own. The previous episode, he explains, was 3 days ago, when palpitations were associated with lightheadedness and shortness of breath. He denies chest pains or swelling of the legs.

Physical exam. The patient appears spry, comfortable, and in no acute distress. Vital signs are within normal limits. A body mass index of 28.4 puts him in the “overweight” category. His blood pressure is 118/75 mm Hg.

Continue to: Cardiac examination...

Cardiac examination is significant for an irregular rhythm without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. His lungs are clear bilaterally; his abdomen is soft and nondistended. His extremities show no edema.

Testing. You obtain an electrocardiogram, which demonstrates a controlled ventricular rate of 88 bpm and AF. You order a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, tests of hemoglobin A1C and thyroid-stimulating hormone, lipid panel, echocardiogram, and a chest radiograph.

Results. The chest radiograph is negative for an acute cardiopulmonary process; cardiac size is normal. Aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels are higher than twice the normal limit. The echocardiogram reveals an estimated left ventricular ejection fraction of 55% to 60%; no structural abnormalities are noted.

In which AF patients is catheter ablation indicated?

Ablation is recommended for select patients (TABLE 13,6) with symptomatic paroxysmal AF that is refractory to AAD or who are intolerant of AAD.3,6 It is a reasonable first-line therapy for high-performing athletes in whom AAD would affect athletic performance.3,10 It is also a reasonable option in select patients > 75 years and as an alternative to AAD therapy.3 Finally, catheter ablation should be considered in symptomatic patients with longstanding persistent AF and congestive heart failure, with or without reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.3

CASE

You inform Mr. Z that his symptoms are likely a result of symptomatic paroxysmal AF, which was refractory to flecainide and amiodarone, and that his abnormal liver function test results preclude continued use of amiodarone. You propose Holter monitoring to correlate timing of symptoms with the arrhythmia, but he reports this has been done, and the correlation confirmed, by his previous physician.

You explain that, because the diagnosis of symptomatic paroxysmal AF refractory to AADs has been confirmed, he is categorized as a patient who might benefit from catheter ablation, based on:

- the type of AF (ie, paroxysmal AF is associated with better ablation outcomes)

- persistent symptoms that are refractory to AADs

- his intolerance of AAD

- the length of time since onset of symptoms.

Mr. Z agrees to consider your recommendation.

Continue to: What are the benefits of catheter ablation?

What are the benefits of catheter ablation?

Ablation can be achieved through radiofrequency (RF) ablation, cryoablation, or newer, laser-based balloon ablation. Primary outcomes used to determine the success of any options for performing ablation include mortality, stroke, and hospitalization. Other endpoints include maintenance of sinus rhythm, freedom from AF, reduction in AF burden (estimated through patients’ report of symptoms, recurrence rate, need for a second ablation procedure, and serial long-term monitoring through an implantable cardiac monitoring device), quality of life, and prevention of AF progression.3

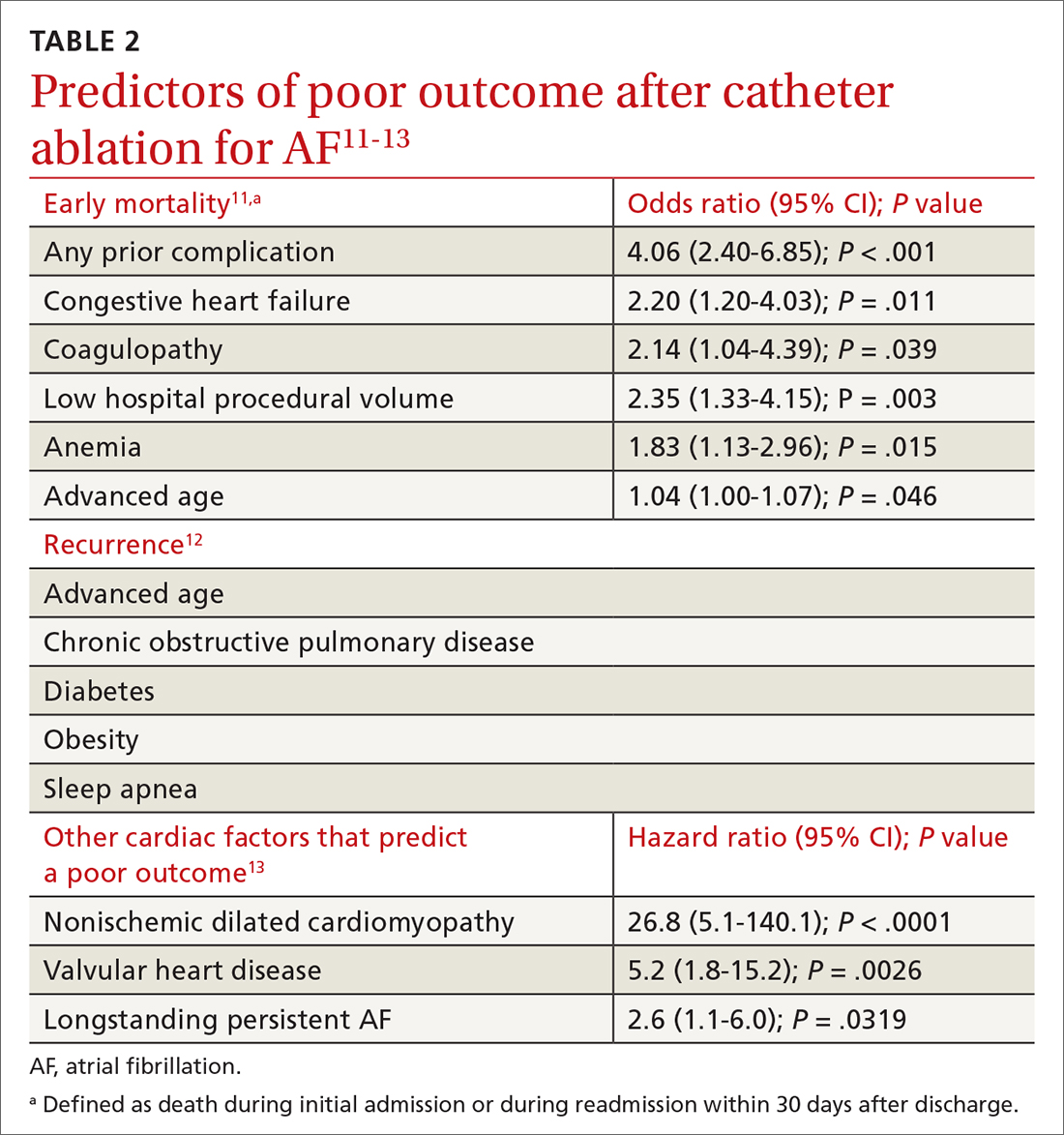

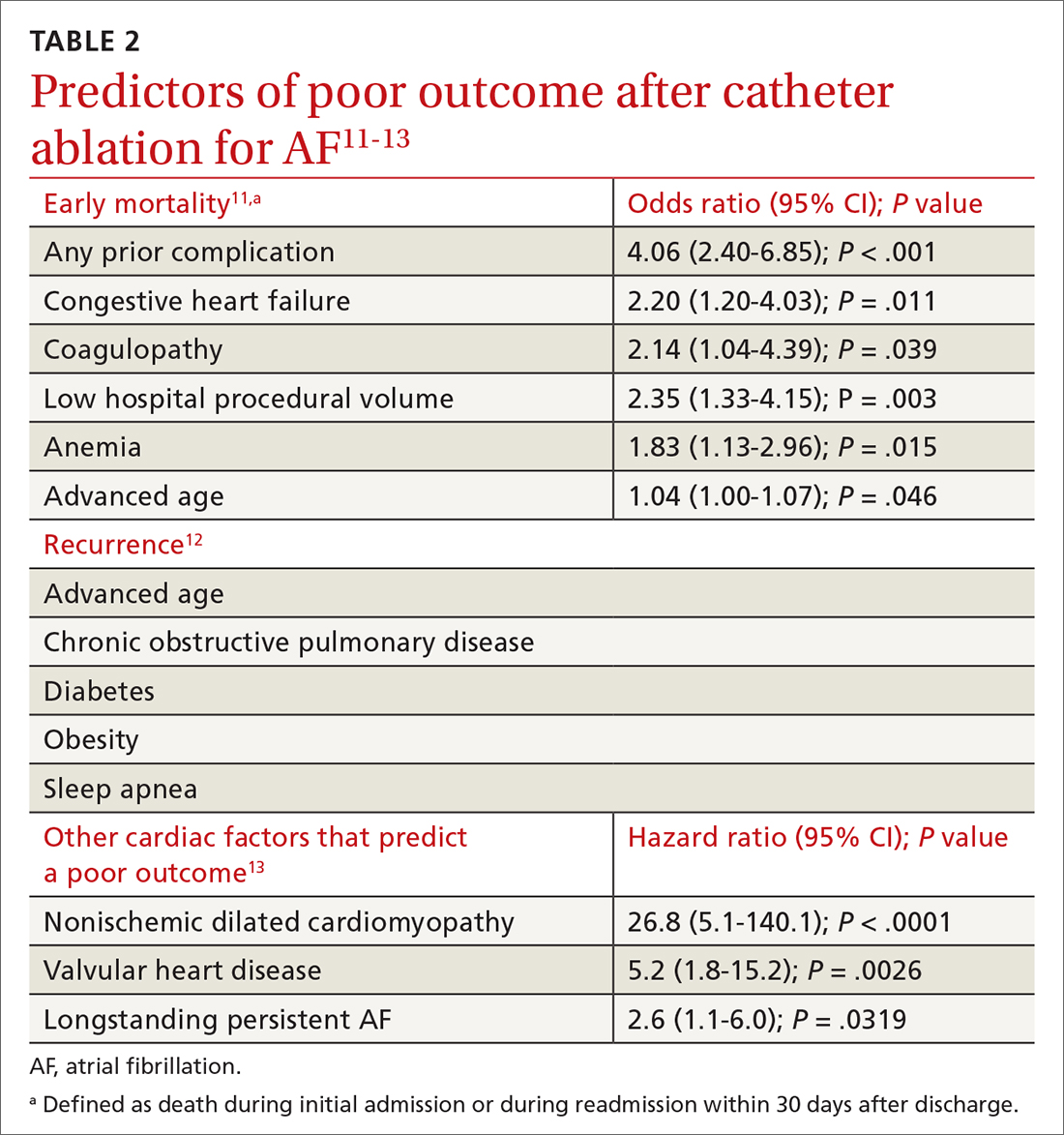

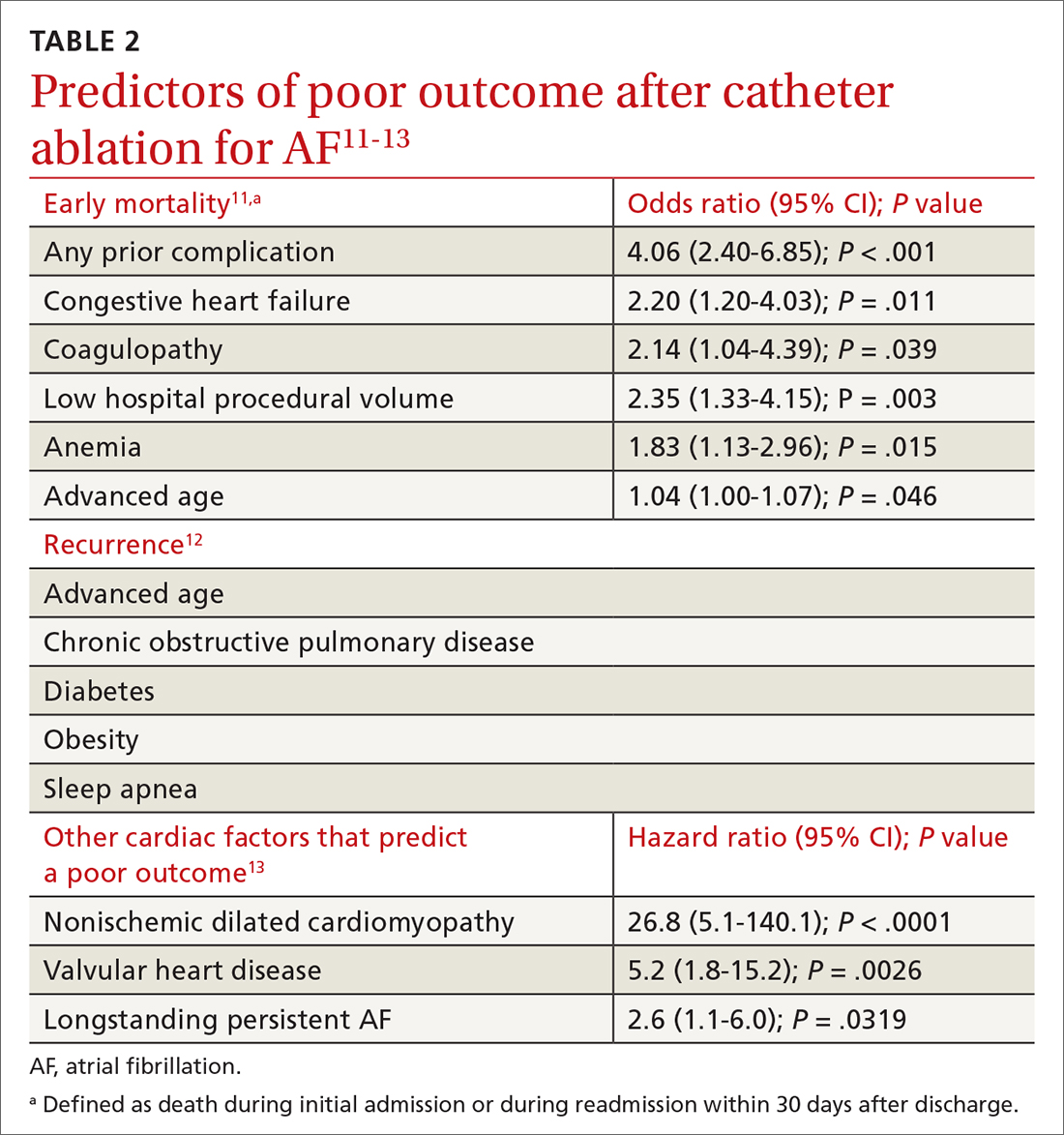

Patient and disease variables (TABLE 211-13). The success rate of catheter ablation, defined as freedom from either symptomatic or asymptomatic episodes of AF, is dependent on several factors,3,14 including:

- type of AF (paroxysmal or persistent)

- duration and degree of symptoms

- age

- sex

- comorbidities, including heart failure and structural heart or lung disease.

Overall, in patients with paroxysmal AF, an estimated 75% are symptom free 1 year after ablation.15 Patients with persistent and longstanding persistent AF experience a lower success rate.

RF catheter ablation has demonstrated superiority to AAD in reducing the need for cardioversion (relative risk [RR] = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.47-0.82) and cardiac-related hospitalization (RR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.10-0.72;) at 12 months in patients with nonparoxysmal AF (persistent or longstanding persistent).16

Effect on mortality. Among patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, long-term studies of cardiovascular outcomes 5 years post ablation concluded that ablation is associated with a decrease in all-cause mortality (RR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54-0.88; P = .003) and a reduction in hospitalization (RR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.47-0.82; P = .0006); younger (< 65 years) and male patients derive greater benefit.6,17 Indications for ablation in patients with heart failure are similar to those in patients without heart failure; ablation can therefore be considered for select heart failure patients who remain symptomatic or for whom AAD has failed.3

Older patients. Ablation can be considered for patients > 75 years with symptomatic paroxysmal AF refractory to AAD or who are intolerant of AAD.3 A study that assessed the benefit of catheter ablation reviewed 587 older (> 75 years) patients with AF, of whom 324 were eligible for ablation. Endpoints were maintenance of sinus rhythm, stroke, death, and major bleeding. Return to normal sinus rhythm was an independent factor, associated with a decrease in the risk of mortality among all patient groups that underwent ablation (HR = 0.36; 95% CI, 0.2-0.63; P = .0005). Age > 75 years (HR = 1.09; 95% CI, 1.01-1.16; P > .02) and depressed ejection fraction < 40% (HR = 2.38; 95% CI, 1.28-4.4; P = .006) were determined to be unfavorable parameters for survival.18

Complications and risks

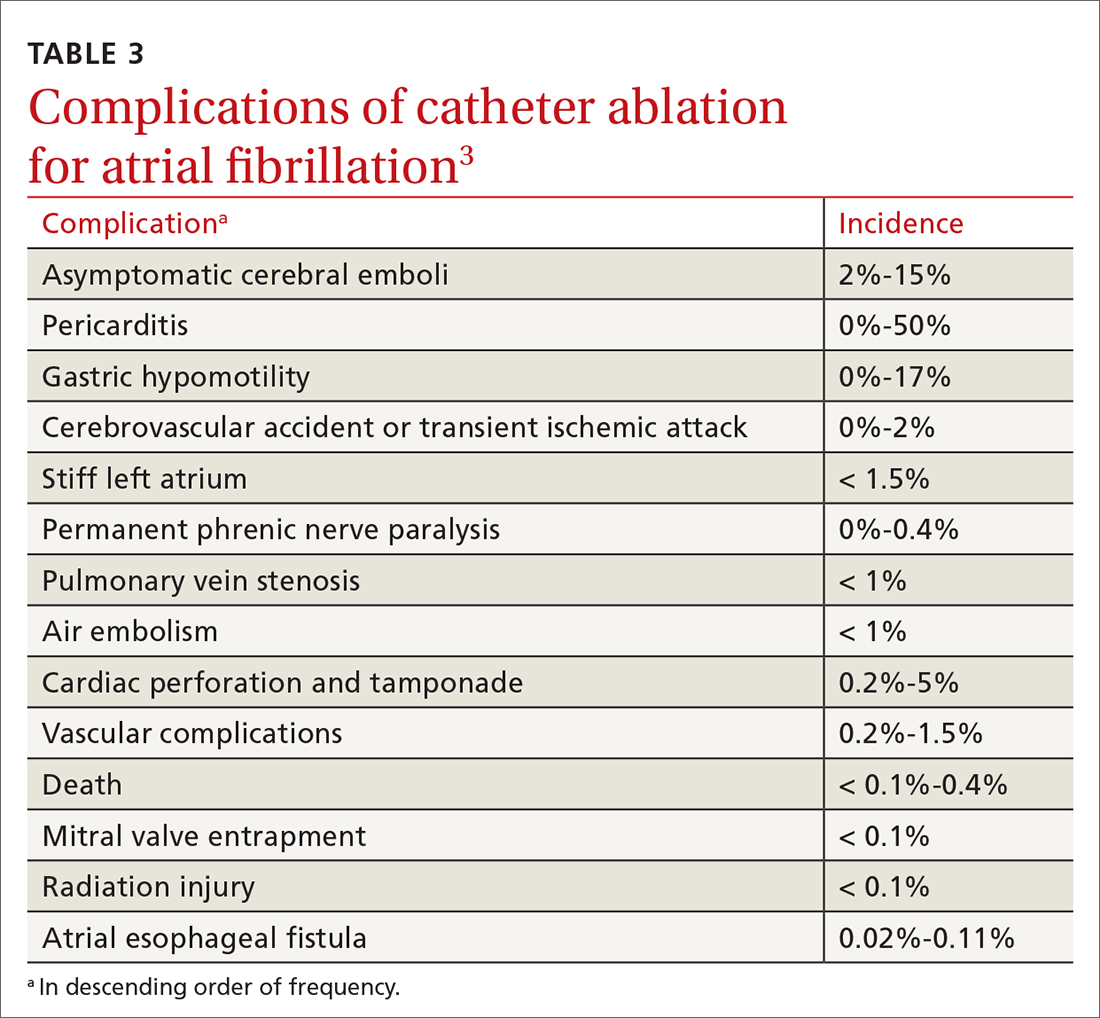

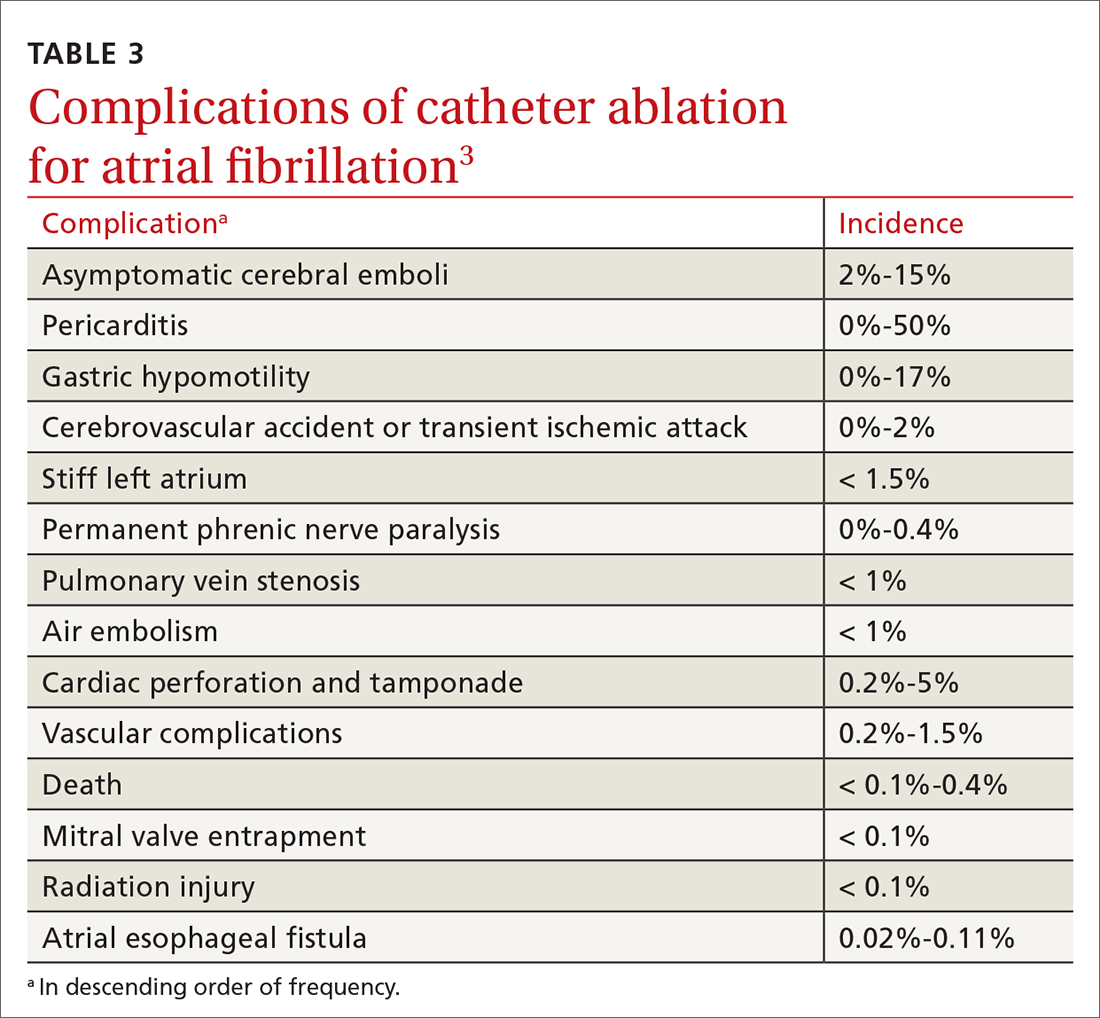

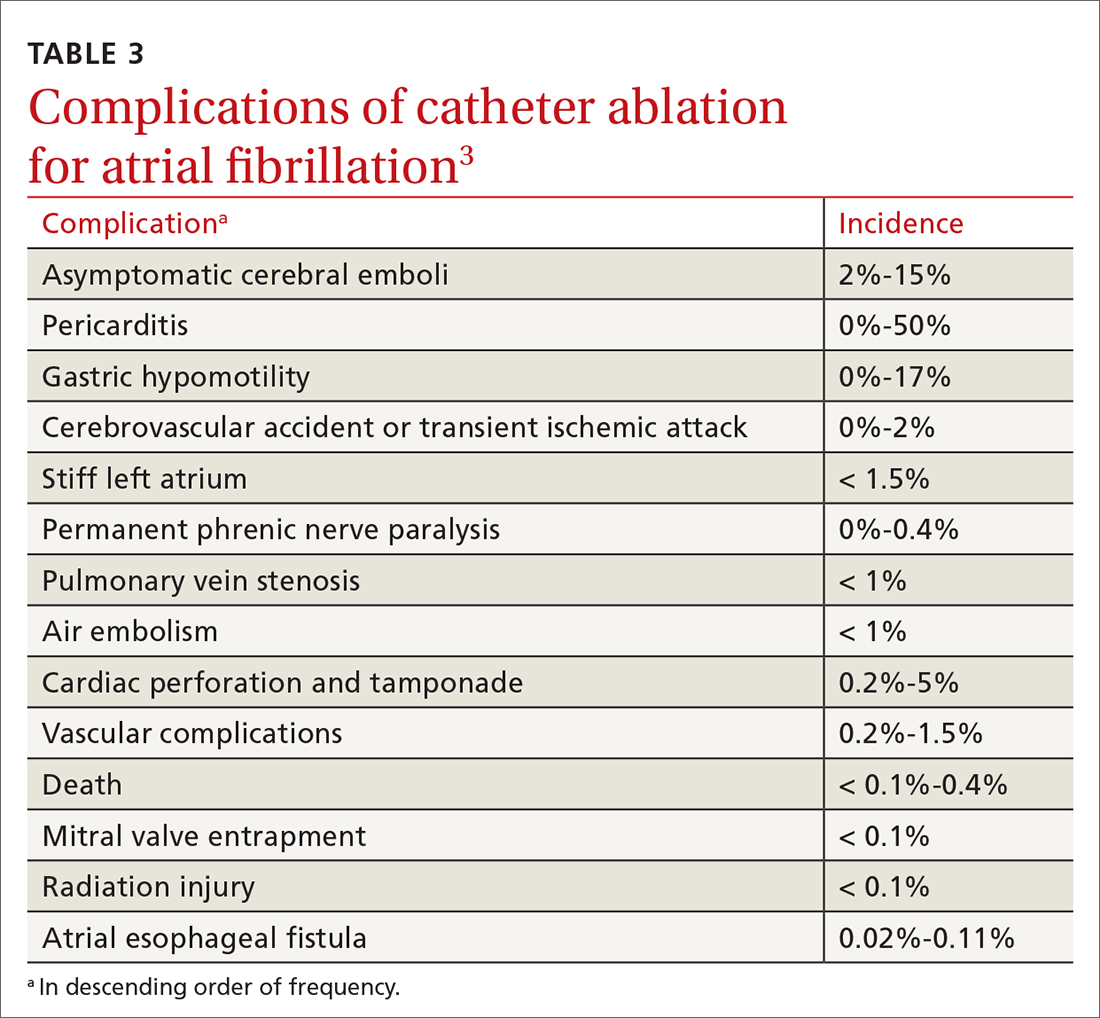

Complications of catheter ablation for AF, although infrequent, can be severe (TABLE 33). Early mortality, defined as death during initial admission or 30-day readmission, occurs in approximately 0.5% of cases; half of deaths take place during readmission.11

Continue to: Complications vary...

Complications vary, based on the type and site of ablation.19,20 Cardiac tamponade or perforation, the most life-threatening complications, taken together occur in an estimated 1.9% of patients (odds ratio [OR] = 2.98; 95% CI, 1.36-6.56; P = .007).11 Other in-hospital complications independently predictive of death include any cardiac complications (OR = 12.8; 95% CI, 6.86 to 23.8; P < .001) and neurologic complications (cerebrovascular accident and transient ischemic attack) (OR = 8.72; 95% CI, 2.71-28.1; P < .001).

Other complications that do not cause death but might prolong the hospital stay include pericarditis without effusion, anesthesia-related complications, and vascular-access complications. Patients whose ablation is performed at an institution where the volume of ablations is low are also at higher risk of early mortality (OR = 2.35; 95% CI, 1.33-4.15; P = .003).16

Recurrence is common (TABLE 211-13). Risk of recurrence following ablation is significant; early (within 3 months after ablation) recurrence is seen in 50% of patients.21,22 However, this is a so-called "blanking period"—ie, a temporary period of inflammatory and proarrhythmic changes that are not predictors of later recurrence. The 5-year post-ablation recurrence rate is approximately 25.5%; longstanding persistent and persistent AF and the presence of comorbidities are major risk factors for recurrence.13,23

Recurrence is also associated with the type of procedure; pulmonary vein isolation, alone or in combination with another type of procedure, results in higher long-term success.21,23

Other variables affect outcome (TABLE 211-13). Following AF ablation, patients with nonparoxysmal AF at baseline, advanced age, sleep apnea and obesity, left atrial enlargement, and any structural heart disease tend to have a poorer long-term (5-year) outcome (ie, freedom from extended episodes of AF).3,13,23,24

Patients who undergo repeat procedures have higher arrhythmia-free survival; the highest ablation success rate is for patients with paroxysmal AF.13,23

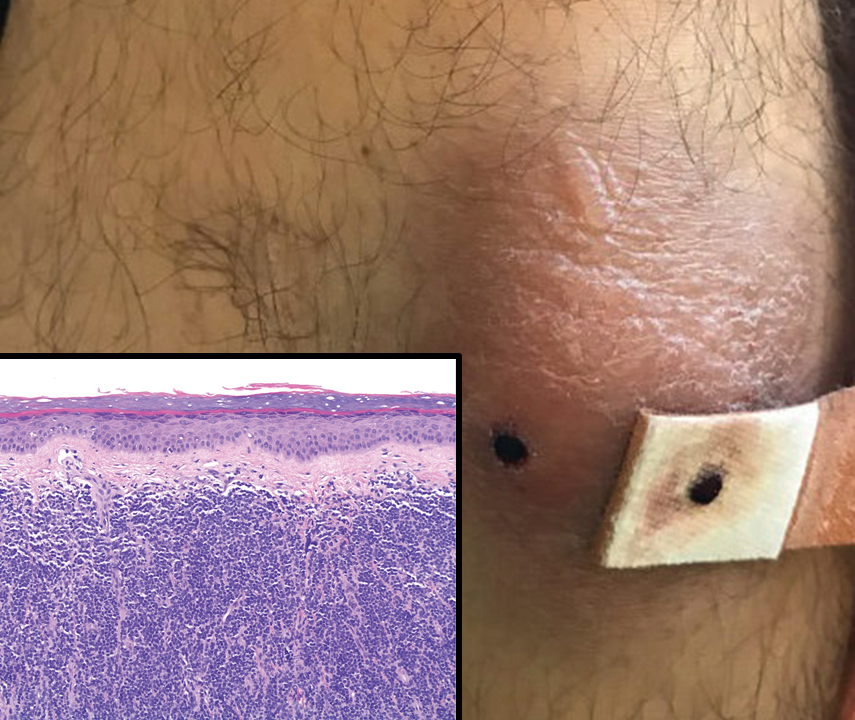

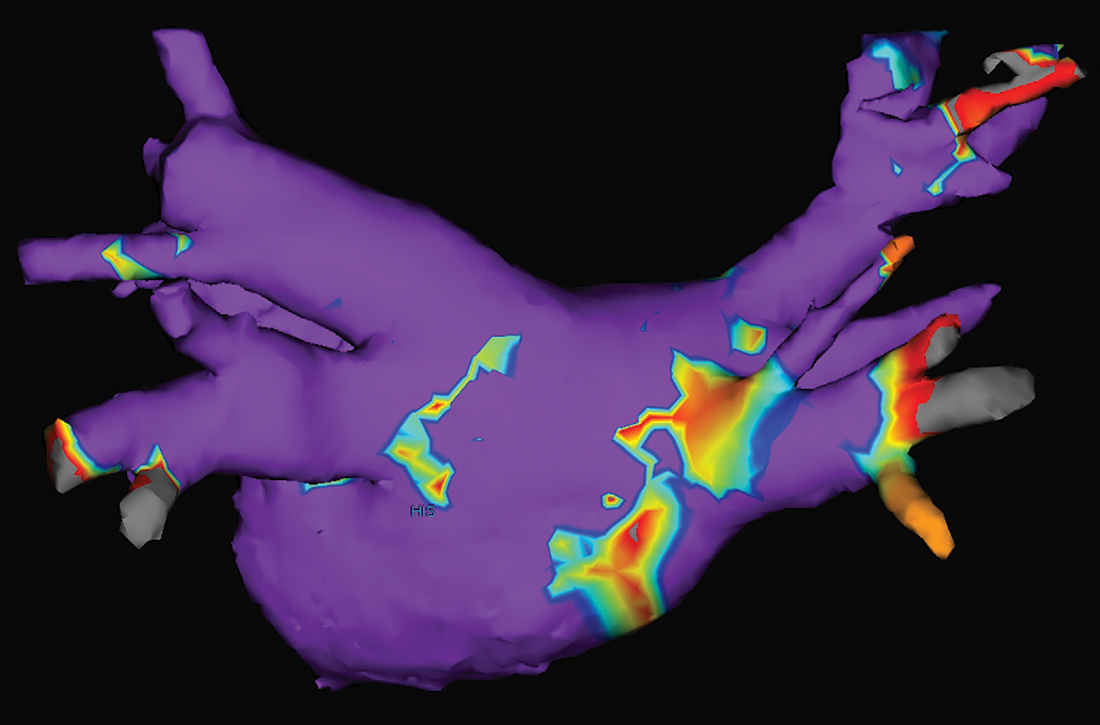

Exposure to ionizing radiation. Fluoroscopy is required for multiple components of atrial mapping and ablation during RF ablation, including navigation, visualization, and monitoring of catheter placement. Patients undergoing this particular procedure therefore receive significant exposure to ionizing radiation. A reduction in, even complete elimination of, fluoroscopy has been achieved with:

- nonfluoroscopic 3-dimensional mapping systems25

- intracardiac echocardiography, which utilizes ultrasonographic imaging as the primary visual mode for tracking and manipulating the catheter

- robotic guided navigation.26-28

Continue to: CASE

CASE

At his return visit, Mr. Z says that he is concerned about, first, undergoing catheter ablation at his age and, second, the risks associated with the procedure. You explain that it is true that ablation is ideal in younger patients who have minimal comorbidities and that the risk of complications increases with age—but that there is no cutoff or absolute age contraindication to ablation.

You tell Mr. Z that you will work with him on risk-factor modification in anticipation of ablation. You also assure him that the decision whether to ablate must be a joint one—between him and a cardiologist experienced both in electrophysiology and in performing this highly technical procedure. And you explain that a highly practiced specialist can identify Mr. Z’s risk factors that might make ablation more difficult to perform and affect the long-term outcome.

With Mr. Z’s agreement, you screen for sleep apnea and start him on a lifestyle modification plan to achieve a more ideal weight, explaining that the risk of recurrence of AF after catheter ablation is increased by obesity and sleep apnea, in addition to age. You explain that, based on his CHA2DS2–VASc (congestive heart failure; hypertension; age, ≥ 75 years; diabetes; prior stroke, transient ischemic attack, or thromboembolism; vascular disease; age, 65 to 74 years; sex category) score of 3, he will remain on anticoagulation whether or not he has the ablation.

You refer the patient to the nearest high-volume cardiac ablation center.

Last, you caution Mr. Z that, based on his lipid levels, his 10-year risk of heart disease or stroke is elevated. You recommend treatment with a statin agent while he continues his other medications.

Delivering energy to myocardium

Myocardial tissue in pulmonary veins is responsible for most ectopic electrical impulses in patients with drug-refractory AF. The goal of catheter ablation in AF is destruction (scarring) of tissue that is the source of abnormal vein potentials.15

How RF ablation works. Ablation is most commonly performed using RF energy, a high-frequency form of electrical energy. Electrophysiology studies are carried out at the time of ablation by percutaneous, fluoroscopically guided insertion of 2 to 5 catheters, usually through the femoral or internal jugular vein, which are then positioned within several areas of the heart—usually, the right atrium, bundle of His, right ventricle, and coronary sinus.

Continue to: Electrical current...

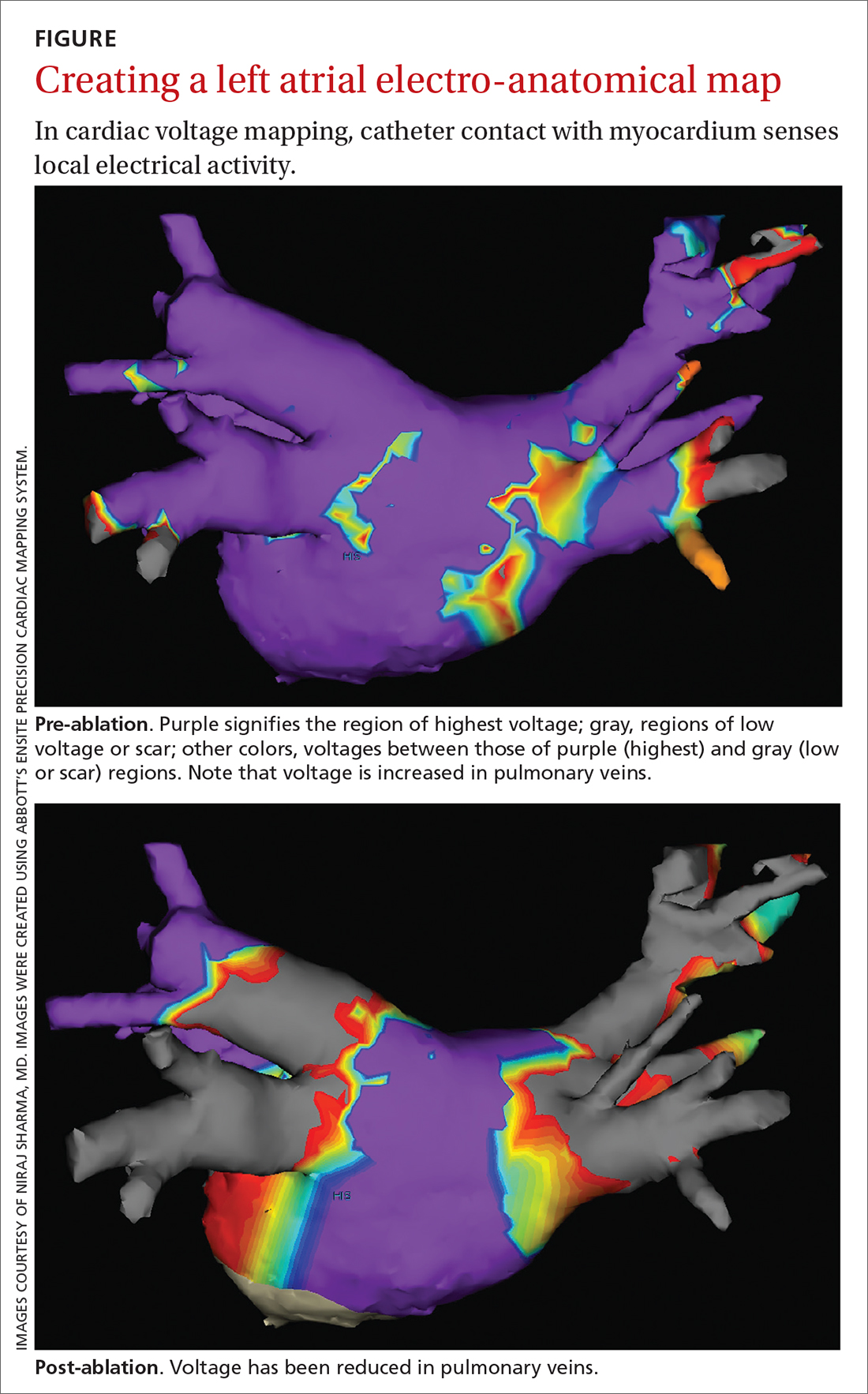

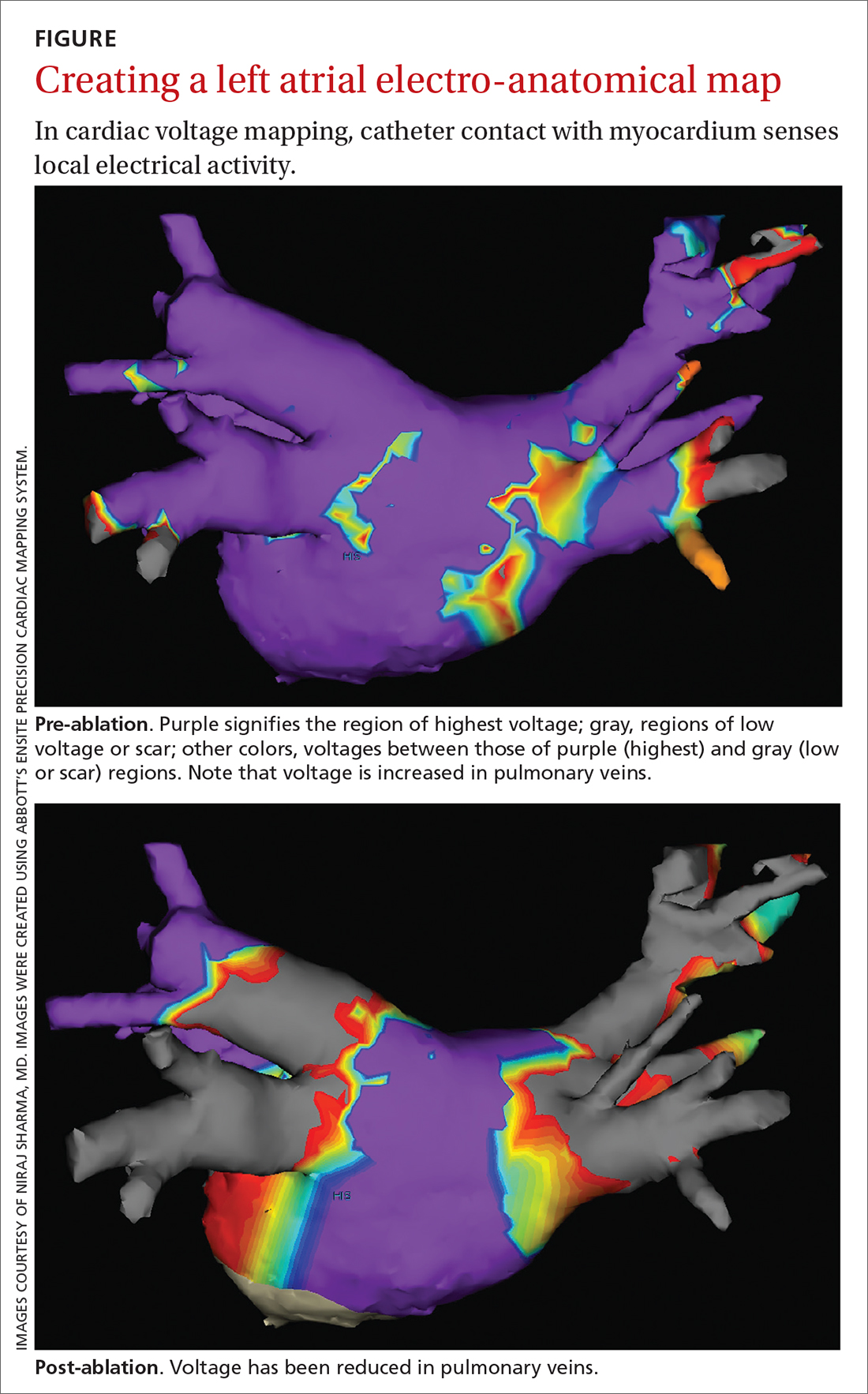

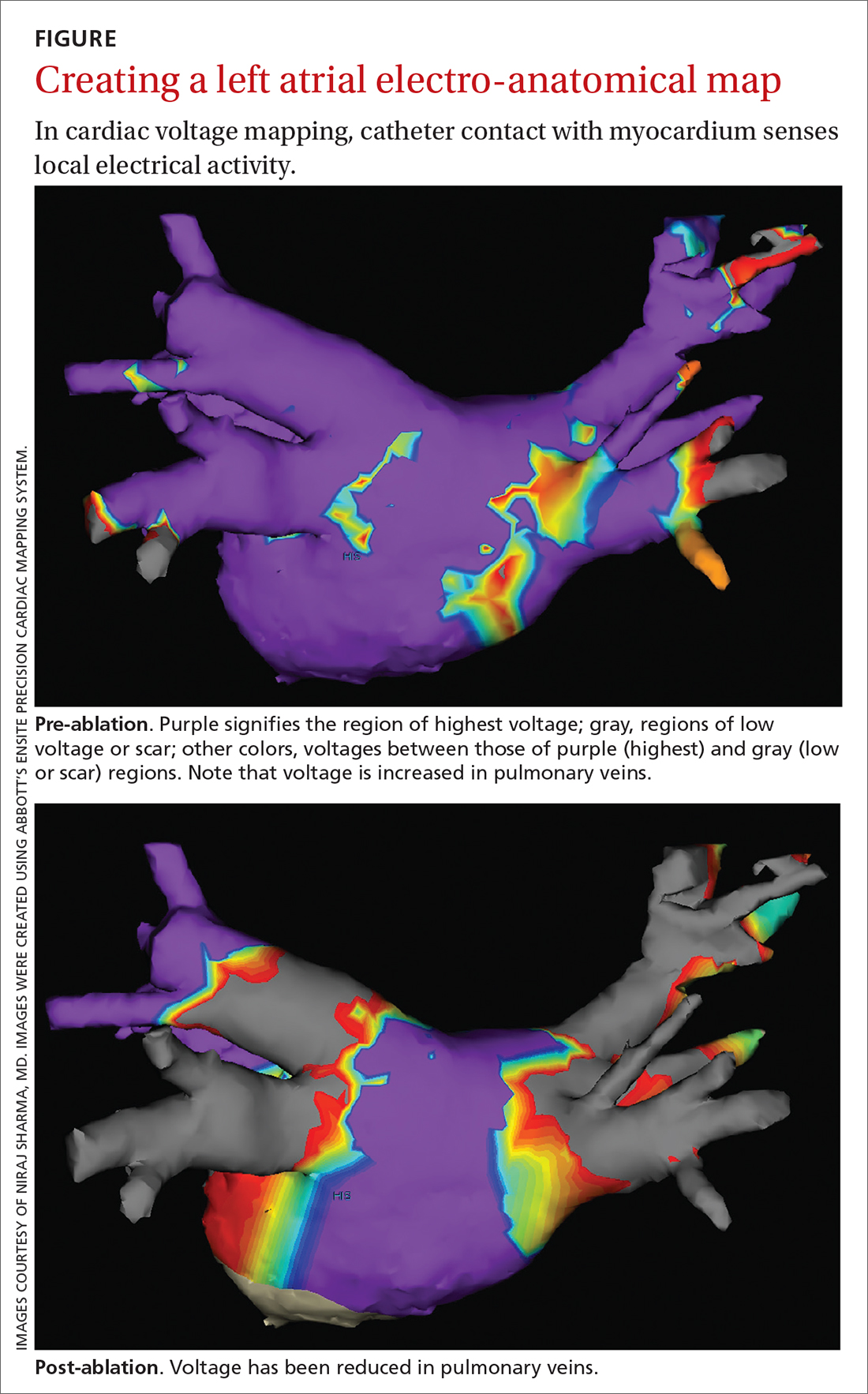

Electrical current is applied through the catheters from an external generator to stimulate the myocardium and thus determine its electrophysiologic properties. The anatomic and electrical activity of the left atrium and pulmonary veins is then identified, a technique known as electro-anatomical mapping (FIGURE). After arrhythmogenic myocardial tissue is mapped, ablation is carried out with RF energy through the catheter to the pathogenic myocardium from which arrhythmias are initiated or conducted. The result is thermal destruction of tissue and creation of small, shallow lesions that vary in size with the type of catheter and the force of contact pressure applied.3,29

Other energy sources used in catheter ablation include cryothermal energy, which utilizes liquid nitrous oxide under pressure through a cryocatheter or cryoballoon catheter. Application of cryothermal energy freezes tissue and disrupts cell membranes and any electrical activity. Cryoballoon ablation has been shown to be similarly safe and efficacious as RF ablation in patients with paroxysmal AF.30,31

Newer laser-based balloon ablations are performed under ultrasonographic guidance and utilize arcs of laser energy delivered to the pathogenic myocardium.3

Thromboembolism prophylaxis

Oral anticoagulation to decrease the risk of stroke is initiated in all patients with AF, based on a thromboembolic risk profile determined by their CHA2DS2–VASc score, with anticoagulation recommended when the score is ≥ 2 in men and ≥ 3 in women. Options for anticoagulation include warfarin and one of the novel oral anticoagulants dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban.4 Recommendations are as follows3:

- For patients with a CHA2DS2–VASc score of ≥ 2 (men) or ≥ 3 (women), anticoagulation should be continued indefinitely, regardless of how successful the ablation procedure is.

- When patients choose to discontinue anticoagulation, they should be counseled in detail about the risk of doing so. The continued need for frequent arrhythmia monitoring should be emphasized.

The route from primary careto catheter ablation

Perform a thorough evaluation. Patients who present to you with palpitations should first undergo a routine workup for AF, followed by confirmation of the diagnosis. Exclude structural heart disease with echocardiography. Undertake monitoring, which is essential to determine whether symptoms are a reflection of the arrhythmia, using noncontinuous or continuous electrocardiographic (EKG) monitoring. Noncontinuous detection devices include:

- scheduled or symptom-initiated EKG

- a Holter monitor, worn for at least 24 hours and as long as 7 days

- trans-telephonic recordings and patient- or automatically activated devices

- an external loop recorder.32

Continuous EKG monitoring is more permanent (≥ 12 months). This is usually achieved through an implantable loop powered by a battery that lasts as long as 3 years.3

Ablation: Yes or no? Ablation is not recommended to avoid anticoagulation or when anticoagulation is contraindicated.5 With regard to specific patient criteria, the ideal patient:

- is symptomatic

- has failed AAD therapy

- does not have pulmonary disease

- has a normal or mildly dilated left atrium or normal or mildly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.5

Continue to: There is no absolute age...

There is no absolute age or comorbidity contraindication to ablation. The patient should be referred to a cardiologist who has received appropriate training in electrophysiology, to identify comorbidities that (1) increase the technical difficulty of the procedure and baseline risk and (2) affect long-term outcome,12 and who performs the procedure in a center that has considerable experience with catheter ablation.33

Once the decision is made to perform ablation, you can provide strategies that optimize the outcome (freedom from AF episodes). Those tactics include weight loss and screening evaluation and, if indicated, treatment for sleep apnea.3

Protocol. Prior to the procedure, the patient fasts overnight; they might be asked to taper or discontinue cardiac medications that have electrophysiologic effects. Studies suggest a low risk of bleeding associated with catheter ablation; anticoagulation should therefore continue uninterrupted for patients undergoing catheter ablation for AF3,4,34,35; however, this practice varies with the cardiologist or electrophysiologist performing ablation.

Because of the length and complexity of the procedure, electro-anatomical mapping and ablation are conducted with the patient under general anesthesia.3 The patient is kept supine, and remains so for 2 to 4 hours afterward to allow for hemostasis at puncture sites.3

Patients might be monitored overnight, although same-day catheter ablation has been shown to be safe and cost-effective in select patients.36,37 Post ablation, patients follow up with the cardiologist and electrophysiologist. Long-term arrhythmia monitoring is required.3 Anticoagulation is continued for at least 2 months, and is discontinued based on the patient’s risk for stroke, utilizing their CHA2DS2–VASc score.3,4

CASE

At Mr. Z’s 6-month primary care follow-up, he confirms what has been reported to you as the referring physician: He had a successful catheter ablation and continues to have regular follow-up monitoring with the cardiologist. He is no longer taking amiodarone.

At this visit, he reports no recurrence of AF-associated symptoms or detectable AF on cardiac monitoring. He has lost 8 lbs. You counsel to him to continue to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

CORRESPONDENCE

Amimi S. Osayande MD, FAAFP, Northside-Gwinnett Family Medicine Residency Program, Strickland Family Medicine Center, 665 Duluth Highway, Suite 501, Lawrenceville, GA 30046; [email protected]

1. Amiodarone hydrochloride (marketed as Cordarone and Pacerone) information. Silver Spring, Md.: US Food & Drug Administration. Reviewed March 23, 2015. Accessed January 16, 2022. www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/amiodarone-hydrochloride-marketed-cordarone-and-pacerone-information

2. Gómez-Outes A, Suárez-Gea ML,García-Pinilla JM. Causes of death in atrial fibrillation: challenges and opportunities. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2017;27:494-503. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.05.002

3. Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, et al. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/ APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: executive summary. J Arrhythm. 2017;33:369-409. doi: 10.1016/j.joa.2017.08.001

4. Camm AJ, Lip GYH, De Caterina R, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines-CPG; Document Reviewers. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation—developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2012;14:1385-1413. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus305

5. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130:2071-2104. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000040

6. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al; Writing Group Members. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/ HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:e66-e93. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.01.024

7. Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, et al; EAST-AFNET 4 Trial Investigators. Early rhythm-control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1305-1316. doi: 10.1056/ NEJMoa2019422

8. Packer DL, Mark DB, Robb RA, et al; CABANA Investigators. Effect of catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug therapy on mortality, stroke, bleeding, and cardiac arrest among patients with atrial fibrillation: the CABANA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:1261-1274. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0693

9. Valembois L, Audureau E, Takeda A, et al. Antiarrhythmics for maintaining sinus rhythm after cardioversion of atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9:CD005049. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005049

10. Koopman P, Nuyens D, Garweg C, et al. Efficacy of radiofrequency catheter ablation in athletes with atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2011;13:1386-1393. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur142

11. Hakalahti A, Biancari F, Nielsen JC, et al. Radiofrequency ablation vs. antiarrhythmic drug therapy as first line treatment of symptomatic atrial fibrillation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2015;17:370-378. doi: 10.1093/europace/euu376

12. Nyong J, Amit G, Adler AJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of ablation for people with non-paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD012088. doi: 10.1002/14651858. CD012088.pub2

13. Andrade JG, Champagne J, Dubuc M, et al; CIRCA-DOSE Study Investigators. Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation assessed by continuous monitoring: a randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2019;140:1779-1788. doi: 10.1161/ CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042622

14. Asad ZUA, Yousif A, Khan MS, et al. Catheter ablation versus medical therapy for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019;12:e007414. doi: 10.1161/ CIRCEP.119.007414

15. Nademanee K, Amnueypol M, Lee F, et al. Benefits and risks of catheter ablation in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:44-51. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.09.049

16. Cheng EP, Liu CF, Yeo I, et al. Risk of mortality following catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74: 2254-2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.1036

17. Brugada J, Katritsis DG, Arbelo E, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia. The Task Force for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:655-720. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz467

18. Hosseini SM, Rozen G, Saleh A, et al. Catheter ablation for cardiac arrhythmias: utilization and in-hospital complications, 2000 to 2013. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2017;3:1240-1248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2017.05.005

19. Andrade JG, Macle L, Khairy P, et al. Incidence and significance of early recurrences associated with different ablation strategies for AF: a STAR-AF substudy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23:1295-1301. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2012.02399.x

20. Joshi S, Choi AD, Kamath GS, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and prognosis of atrial fibrillation early after pulmonary vein isolation: findings from 3 months of continuous automatic ECG loop recordings. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:1089-1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01506.x

21. Weerasooriya R, Khairy P, Litalien J, et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: are results maintained at 5 years of follow-up? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:160-166. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.061

22. Ouyang F, Tilz R, Chun J, et al. Long-term results of catheter ablation in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: lessons from a 5-year follow-up. Circulation. 2010;122:2368-2377. doi: 10.1161/ CIRCULATIONAHA.110.946806

23. Tilz RR, Rillig A, Thum A-M, et al. Catheter ablation of long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation: 5-year outcomes of the Hamburg Sequential Ablation Strategy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60: 1921-1929. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.060

24. Forkmann M, Schwab C, Busch S. [Catheter ablation of supraventricular tachycardia]. Herzschrittmacherther Elektrophysiol. 2019;30:336-342. doi: 10.1007/s00399-019-00654-x

25. Bulava A, Hanis J, Eisenberger M. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation using zero-fluoroscopy technique: a randomized trial. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;38:797-806. doi: 10.1111/pace.12634

26. Haegeli LM, Stutz L, Mohsen M, et al. Feasibility of zero or near zero fluoroscopy during catheter ablation procedures. Cardiol J. 2019;26:226-232. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2018.0029

27. Steven D, Servatius H, Rostock T, et al. Reduced fluoroscopy during atrial fibrillation ablation: benefits of robotic guided navigation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:6-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01592.x

28. General therapy for cardiac arrhythmias. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, et al. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2019.

29. Kuck K-H, Brugada J, Albenque J-P. Cryoballoon or radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2016;375: 1100-1101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1609160

30. Chen Y-H, Lu Z-Y, Xiang Y, et al. Cryoablation vs. radiofrequency ablation for treatment of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2017;19:784-794. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw330

31. Locati ET, Vecchi AM, Vargiu S, et al. Role of extended external loop recorders for the diagnosis of unexplained syncope, presyncope, and sustained palpitations. Europace. 2014;16:914-922. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut337

32. Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, et al; Heart Rhythm Society Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design: a report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:632-696.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.12.016

33. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Europace. 2016;18:1609-1678. doi: 10.1093/ europace/euw295

34. Nairooz R, Sardar P, Payne J, et al. Meta-analysis of major bleeding with uninterrupted warfarin compared to interrupted warfarin and heparin bridging in ablation of atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2015;187:426-429. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.376

35. Romero J, Cerrud-Rodriguez RC, Diaz JC, et al. Uninterrupted direct oral anticoagulants vs. uninterrupted vitamin K antagonists during catheter ablation of non-valvular atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Europace. 2018;20:1612-1620. doi: 10.1093/europace/euy133

36. Deyell MW, Leather RA, Macle L, et al. Efficacy and safety of same-day discharge for atrial fibrillation ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;6:609-619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.02.009

37. Theodoreson MD, Chohan BC, McAloon CJ, et al. Same-day cardiac catheter ablation is safe and cost-effective: experience from a UK tertiary center. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1756-1761. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.05.006

CASE

Jack Z, a 75-year-old man with well-controlled hypertension, diabetes controlled by diet, and atrial fibrillation (AF) presents to the family medicine clinic to establish care with you after moving to the community from out of town.

The patient describes a 1-year history of AF. He provides you with an echocardiography report from 6 months ago that shows no evidence of structural heart disease. He takes lisinopril, to control blood pressure; an anticoagulant; a beta-blocker; and amiodarone for rhythm control. Initially, he took flecainide, which was ineffective for rhythm control, before being switched to amiodarone. He had 2 cardioversion procedures, each time after episodes of symptoms. He does not smoke or drink alcohol.

Mr. Z describes worsening palpitations and shortness of breath over the past 9 months. Symptoms now include episodes of exertional fatigue, even when he is not having palpitations. Prior to the episodes of worsening symptoms, he tells you that he lived a “fairly active” life, golfing twice a week.

The patient’s previous primary care physician had encouraged him to talk to his cardiologist about “other options” for managing AF, because levels of his liver enzymes had started to rise (a known adverse effect of amiodarone1) when measured 3 months ago. He did not undertake that conversation, but asks you now about other treatments for AF.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, characterized by discordant electrical activation of the atria due to structural or electrophysiological abnormalities, or both. The disorder is associated with an increased rate of stroke and heart failure and is independently associated with a 1.5- to 2-fold risk of all-cause mortality.2

In this article, we review the pathophysiology of AF; management, including the role of, and indications for, catheter ablation; and patient- and disease-related factors associated with ablation (including odds of success, complications, risk of recurrence, and continuing need for thromboprophylaxis) that family physicians should consider when contemplating referral to a cardiologist or electrophysiologist for catheter ablation for AF.

What provokes AF?

AF is thought to occur as a result of an interaction among 3 phenomena:

- enhanced automaticity of abnormal atrial tissue

- triggered activity of ectopic foci within 1 or more pulmonary veins, lying within the left atrium

- re-entry, in which there is propagation of electrical impulses from an ectopic beat through another pathway.

Continue to: In patients who progress...

In patients who progress from paroxysmal to persistent AF (see “Subtypes,” below), 2 distinct pathways, facilitated by the presence of abnormal tissue, continuously activate one another, thus maintaining the arrhythmia. Myocardial tissue in the pulmonary veins is responsible for most ectopic electrical impulses in patients with drug-refractory AF (see “Rhythm control”).

Subtypes. For the purpose of planning treatment, AF is classified as:

- Paroxysmal. Terminates spontaneously or with intervention ≤ 7 days after onset.

- Persistent. Continuous and sustained for > 7 days.

- Longstanding persistent. Continuous for > 12 months.

- Permanent. The patient and physician accept that there will be no further attempt to restore or maintain sinus rhythm.

Goals of treatment

Primary management goals in patients with AF are 2-fold: control of symptoms and prevention of thromboembolism. A patient with new-onset AF who presents acutely with inadequate rate control and hemodynamic compromise requires urgent assessment to determine the cause of the arrhythmia and need for cardioversion.3 A symptomatic patient with AF who does not have high-risk features (eg, valvular heart disease, mechanical valves) might be a candidate for rhythm control in addition to rate control.3,4

Rate control. After evaluation in the hospital, a patient who has a rapid ventricular response but remains hemodynamically stable, without evidence of heart failure, should be initiated on a rate-controlling medication, such as a beta-blocker or nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker. A resting heart rate goal of < 80 beats per minute (bpm) is recommended for a symptomatic patient with AF. The heart rate goal can be relaxed, to < 110 bpm, in an asymptomatic patient with preserved left ventricular function.5,6

Rhythm control, indicated in patients who remain symptomatic on rate-controlling medication, can be achieved either with an antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) or by catheter ablation.4,5 In stable patients, rhythm control should be considered only after a thorough work-up for a reversible cause of AF, and can be achieved with an oral AAD or, in select patients, through catheter ablation (TABLE 13,6). Other indications for chronic rhythm control include treatment of patients with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.5

A major study that documented the benefit of early rhythm control evaluated long-term outcomes in 2789 patients with AF who were undergoing catheter ablation.7 Patients were randomized to early rhythm control (catheter ablation or AAD) or “usual care”—ie, in this study, rhythm control limited to symptomatic patients. Primary outcomes were death from cardiovascular causes, stroke, and hospitalization with worsening heart failure or acute coronary syndrome. A first primary outcome event occurred in 249 patients (3.9/100 person-years) assigned to early rhythm control, compared to 316 (5.0 per 100 person-years) in the group assigned to usual care.

The study was terminated early (after 5.1 years) because of overwhelming evidence of efficacy (number need to treat = 7). Although early rhythm control was obtained through both catheter ablation and AAD (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.79; 96% CI, 0.66-0.94; P = .005), success was attributed to the use of catheter ablation for a rhythm-control strategy and its use among patients whose AF was present for < 1 year. Most patients in both treatment groups continued to receive anticoagulation, rate control, and optimization of cardiovascular risk.7

Continue to: Notably, direct studies...

Notably, direct studies comparing ablation and AAD have not confirmed the benefit of ablation over AAD in outcomes of all-cause mortality, bleeding, stroke, or cardiac arrest over a 5-year period.8

Adverse effects and mortality outcomes with AAD. Concern over using AAD for rhythm control is based mostly on adverse effects and long-term (1-year) mortality outcomes. Long-term AAD therapy has been shown to decrease the recurrence of AF—but without evidence to suggest other mortality benefits.

A meta-analysis of 59 randomized controlled trials reviewed 20,981 patients receiving AAD (including quinidine, disopyramide, propafenone, flecainide, metoprolol, amiodarone, dofetilide, dronedarone, and sotalol) for long-term effects on death, stroke, adverse reactions, and recurrence of AF.9 Findings at 10 months suggest that:

- Compared to placebo, amiodarone and sotalol increased the risk of all-cause mortality during the study period.

- There was minimal difference in mortality among patients taking dofetilide or dronedarone, compared to placebo.

- There were insufficient data to draw conclusions about the effect of disopyramide, flecainide, and propafenone on mortality.

Before starting a patient on AAD, the risk of arrhythmias and the potential for these agents to cause toxicity and adverse events should always be discussed.

CASE

You tell Mr. Z that you need to know the status of his comorbidities to make a recommendation about “other” management options, and proceed to take a detailed history.

Recent history. Mr. Z reveals that “today is a good day”: He has had “only 1” episode of palpitations, which resolved on its own. The previous episode, he explains, was 3 days ago, when palpitations were associated with lightheadedness and shortness of breath. He denies chest pains or swelling of the legs.

Physical exam. The patient appears spry, comfortable, and in no acute distress. Vital signs are within normal limits. A body mass index of 28.4 puts him in the “overweight” category. His blood pressure is 118/75 mm Hg.

Continue to: Cardiac examination...

Cardiac examination is significant for an irregular rhythm without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. His lungs are clear bilaterally; his abdomen is soft and nondistended. His extremities show no edema.

Testing. You obtain an electrocardiogram, which demonstrates a controlled ventricular rate of 88 bpm and AF. You order a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, tests of hemoglobin A1C and thyroid-stimulating hormone, lipid panel, echocardiogram, and a chest radiograph.

Results. The chest radiograph is negative for an acute cardiopulmonary process; cardiac size is normal. Aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels are higher than twice the normal limit. The echocardiogram reveals an estimated left ventricular ejection fraction of 55% to 60%; no structural abnormalities are noted.

In which AF patients is catheter ablation indicated?

Ablation is recommended for select patients (TABLE 13,6) with symptomatic paroxysmal AF that is refractory to AAD or who are intolerant of AAD.3,6 It is a reasonable first-line therapy for high-performing athletes in whom AAD would affect athletic performance.3,10 It is also a reasonable option in select patients > 75 years and as an alternative to AAD therapy.3 Finally, catheter ablation should be considered in symptomatic patients with longstanding persistent AF and congestive heart failure, with or without reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.3

CASE

You inform Mr. Z that his symptoms are likely a result of symptomatic paroxysmal AF, which was refractory to flecainide and amiodarone, and that his abnormal liver function test results preclude continued use of amiodarone. You propose Holter monitoring to correlate timing of symptoms with the arrhythmia, but he reports this has been done, and the correlation confirmed, by his previous physician.

You explain that, because the diagnosis of symptomatic paroxysmal AF refractory to AADs has been confirmed, he is categorized as a patient who might benefit from catheter ablation, based on:

- the type of AF (ie, paroxysmal AF is associated with better ablation outcomes)

- persistent symptoms that are refractory to AADs

- his intolerance of AAD

- the length of time since onset of symptoms.

Mr. Z agrees to consider your recommendation.

Continue to: What are the benefits of catheter ablation?

What are the benefits of catheter ablation?

Ablation can be achieved through radiofrequency (RF) ablation, cryoablation, or newer, laser-based balloon ablation. Primary outcomes used to determine the success of any options for performing ablation include mortality, stroke, and hospitalization. Other endpoints include maintenance of sinus rhythm, freedom from AF, reduction in AF burden (estimated through patients’ report of symptoms, recurrence rate, need for a second ablation procedure, and serial long-term monitoring through an implantable cardiac monitoring device), quality of life, and prevention of AF progression.3

Patient and disease variables (TABLE 211-13). The success rate of catheter ablation, defined as freedom from either symptomatic or asymptomatic episodes of AF, is dependent on several factors,3,14 including:

- type of AF (paroxysmal or persistent)

- duration and degree of symptoms

- age

- sex

- comorbidities, including heart failure and structural heart or lung disease.

Overall, in patients with paroxysmal AF, an estimated 75% are symptom free 1 year after ablation.15 Patients with persistent and longstanding persistent AF experience a lower success rate.

RF catheter ablation has demonstrated superiority to AAD in reducing the need for cardioversion (relative risk [RR] = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.47-0.82) and cardiac-related hospitalization (RR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.10-0.72;) at 12 months in patients with nonparoxysmal AF (persistent or longstanding persistent).16

Effect on mortality. Among patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, long-term studies of cardiovascular outcomes 5 years post ablation concluded that ablation is associated with a decrease in all-cause mortality (RR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54-0.88; P = .003) and a reduction in hospitalization (RR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.47-0.82; P = .0006); younger (< 65 years) and male patients derive greater benefit.6,17 Indications for ablation in patients with heart failure are similar to those in patients without heart failure; ablation can therefore be considered for select heart failure patients who remain symptomatic or for whom AAD has failed.3

Older patients. Ablation can be considered for patients > 75 years with symptomatic paroxysmal AF refractory to AAD or who are intolerant of AAD.3 A study that assessed the benefit of catheter ablation reviewed 587 older (> 75 years) patients with AF, of whom 324 were eligible for ablation. Endpoints were maintenance of sinus rhythm, stroke, death, and major bleeding. Return to normal sinus rhythm was an independent factor, associated with a decrease in the risk of mortality among all patient groups that underwent ablation (HR = 0.36; 95% CI, 0.2-0.63; P = .0005). Age > 75 years (HR = 1.09; 95% CI, 1.01-1.16; P > .02) and depressed ejection fraction < 40% (HR = 2.38; 95% CI, 1.28-4.4; P = .006) were determined to be unfavorable parameters for survival.18

Complications and risks

Complications of catheter ablation for AF, although infrequent, can be severe (TABLE 33). Early mortality, defined as death during initial admission or 30-day readmission, occurs in approximately 0.5% of cases; half of deaths take place during readmission.11

Continue to: Complications vary...

Complications vary, based on the type and site of ablation.19,20 Cardiac tamponade or perforation, the most life-threatening complications, taken together occur in an estimated 1.9% of patients (odds ratio [OR] = 2.98; 95% CI, 1.36-6.56; P = .007).11 Other in-hospital complications independently predictive of death include any cardiac complications (OR = 12.8; 95% CI, 6.86 to 23.8; P < .001) and neurologic complications (cerebrovascular accident and transient ischemic attack) (OR = 8.72; 95% CI, 2.71-28.1; P < .001).

Other complications that do not cause death but might prolong the hospital stay include pericarditis without effusion, anesthesia-related complications, and vascular-access complications. Patients whose ablation is performed at an institution where the volume of ablations is low are also at higher risk of early mortality (OR = 2.35; 95% CI, 1.33-4.15; P = .003).16

Recurrence is common (TABLE 211-13). Risk of recurrence following ablation is significant; early (within 3 months after ablation) recurrence is seen in 50% of patients.21,22 However, this is a so-called "blanking period"—ie, a temporary period of inflammatory and proarrhythmic changes that are not predictors of later recurrence. The 5-year post-ablation recurrence rate is approximately 25.5%; longstanding persistent and persistent AF and the presence of comorbidities are major risk factors for recurrence.13,23

Recurrence is also associated with the type of procedure; pulmonary vein isolation, alone or in combination with another type of procedure, results in higher long-term success.21,23

Other variables affect outcome (TABLE 211-13). Following AF ablation, patients with nonparoxysmal AF at baseline, advanced age, sleep apnea and obesity, left atrial enlargement, and any structural heart disease tend to have a poorer long-term (5-year) outcome (ie, freedom from extended episodes of AF).3,13,23,24

Patients who undergo repeat procedures have higher arrhythmia-free survival; the highest ablation success rate is for patients with paroxysmal AF.13,23

Exposure to ionizing radiation. Fluoroscopy is required for multiple components of atrial mapping and ablation during RF ablation, including navigation, visualization, and monitoring of catheter placement. Patients undergoing this particular procedure therefore receive significant exposure to ionizing radiation. A reduction in, even complete elimination of, fluoroscopy has been achieved with:

- nonfluoroscopic 3-dimensional mapping systems25

- intracardiac echocardiography, which utilizes ultrasonographic imaging as the primary visual mode for tracking and manipulating the catheter

- robotic guided navigation.26-28

Continue to: CASE

CASE

At his return visit, Mr. Z says that he is concerned about, first, undergoing catheter ablation at his age and, second, the risks associated with the procedure. You explain that it is true that ablation is ideal in younger patients who have minimal comorbidities and that the risk of complications increases with age—but that there is no cutoff or absolute age contraindication to ablation.

You tell Mr. Z that you will work with him on risk-factor modification in anticipation of ablation. You also assure him that the decision whether to ablate must be a joint one—between him and a cardiologist experienced both in electrophysiology and in performing this highly technical procedure. And you explain that a highly practiced specialist can identify Mr. Z’s risk factors that might make ablation more difficult to perform and affect the long-term outcome.

With Mr. Z’s agreement, you screen for sleep apnea and start him on a lifestyle modification plan to achieve a more ideal weight, explaining that the risk of recurrence of AF after catheter ablation is increased by obesity and sleep apnea, in addition to age. You explain that, based on his CHA2DS2–VASc (congestive heart failure; hypertension; age, ≥ 75 years; diabetes; prior stroke, transient ischemic attack, or thromboembolism; vascular disease; age, 65 to 74 years; sex category) score of 3, he will remain on anticoagulation whether or not he has the ablation.

You refer the patient to the nearest high-volume cardiac ablation center.

Last, you caution Mr. Z that, based on his lipid levels, his 10-year risk of heart disease or stroke is elevated. You recommend treatment with a statin agent while he continues his other medications.

Delivering energy to myocardium

Myocardial tissue in pulmonary veins is responsible for most ectopic electrical impulses in patients with drug-refractory AF. The goal of catheter ablation in AF is destruction (scarring) of tissue that is the source of abnormal vein potentials.15

How RF ablation works. Ablation is most commonly performed using RF energy, a high-frequency form of electrical energy. Electrophysiology studies are carried out at the time of ablation by percutaneous, fluoroscopically guided insertion of 2 to 5 catheters, usually through the femoral or internal jugular vein, which are then positioned within several areas of the heart—usually, the right atrium, bundle of His, right ventricle, and coronary sinus.

Continue to: Electrical current...

Electrical current is applied through the catheters from an external generator to stimulate the myocardium and thus determine its electrophysiologic properties. The anatomic and electrical activity of the left atrium and pulmonary veins is then identified, a technique known as electro-anatomical mapping (FIGURE). After arrhythmogenic myocardial tissue is mapped, ablation is carried out with RF energy through the catheter to the pathogenic myocardium from which arrhythmias are initiated or conducted. The result is thermal destruction of tissue and creation of small, shallow lesions that vary in size with the type of catheter and the force of contact pressure applied.3,29

Other energy sources used in catheter ablation include cryothermal energy, which utilizes liquid nitrous oxide under pressure through a cryocatheter or cryoballoon catheter. Application of cryothermal energy freezes tissue and disrupts cell membranes and any electrical activity. Cryoballoon ablation has been shown to be similarly safe and efficacious as RF ablation in patients with paroxysmal AF.30,31

Newer laser-based balloon ablations are performed under ultrasonographic guidance and utilize arcs of laser energy delivered to the pathogenic myocardium.3

Thromboembolism prophylaxis

Oral anticoagulation to decrease the risk of stroke is initiated in all patients with AF, based on a thromboembolic risk profile determined by their CHA2DS2–VASc score, with anticoagulation recommended when the score is ≥ 2 in men and ≥ 3 in women. Options for anticoagulation include warfarin and one of the novel oral anticoagulants dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban.4 Recommendations are as follows3:

- For patients with a CHA2DS2–VASc score of ≥ 2 (men) or ≥ 3 (women), anticoagulation should be continued indefinitely, regardless of how successful the ablation procedure is.

- When patients choose to discontinue anticoagulation, they should be counseled in detail about the risk of doing so. The continued need for frequent arrhythmia monitoring should be emphasized.

The route from primary careto catheter ablation

Perform a thorough evaluation. Patients who present to you with palpitations should first undergo a routine workup for AF, followed by confirmation of the diagnosis. Exclude structural heart disease with echocardiography. Undertake monitoring, which is essential to determine whether symptoms are a reflection of the arrhythmia, using noncontinuous or continuous electrocardiographic (EKG) monitoring. Noncontinuous detection devices include:

- scheduled or symptom-initiated EKG

- a Holter monitor, worn for at least 24 hours and as long as 7 days

- trans-telephonic recordings and patient- or automatically activated devices

- an external loop recorder.32

Continuous EKG monitoring is more permanent (≥ 12 months). This is usually achieved through an implantable loop powered by a battery that lasts as long as 3 years.3

Ablation: Yes or no? Ablation is not recommended to avoid anticoagulation or when anticoagulation is contraindicated.5 With regard to specific patient criteria, the ideal patient:

- is symptomatic

- has failed AAD therapy

- does not have pulmonary disease

- has a normal or mildly dilated left atrium or normal or mildly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.5

Continue to: There is no absolute age...

There is no absolute age or comorbidity contraindication to ablation. The patient should be referred to a cardiologist who has received appropriate training in electrophysiology, to identify comorbidities that (1) increase the technical difficulty of the procedure and baseline risk and (2) affect long-term outcome,12 and who performs the procedure in a center that has considerable experience with catheter ablation.33

Once the decision is made to perform ablation, you can provide strategies that optimize the outcome (freedom from AF episodes). Those tactics include weight loss and screening evaluation and, if indicated, treatment for sleep apnea.3

Protocol. Prior to the procedure, the patient fasts overnight; they might be asked to taper or discontinue cardiac medications that have electrophysiologic effects. Studies suggest a low risk of bleeding associated with catheter ablation; anticoagulation should therefore continue uninterrupted for patients undergoing catheter ablation for AF3,4,34,35; however, this practice varies with the cardiologist or electrophysiologist performing ablation.

Because of the length and complexity of the procedure, electro-anatomical mapping and ablation are conducted with the patient under general anesthesia.3 The patient is kept supine, and remains so for 2 to 4 hours afterward to allow for hemostasis at puncture sites.3

Patients might be monitored overnight, although same-day catheter ablation has been shown to be safe and cost-effective in select patients.36,37 Post ablation, patients follow up with the cardiologist and electrophysiologist. Long-term arrhythmia monitoring is required.3 Anticoagulation is continued for at least 2 months, and is discontinued based on the patient’s risk for stroke, utilizing their CHA2DS2–VASc score.3,4

CASE

At Mr. Z’s 6-month primary care follow-up, he confirms what has been reported to you as the referring physician: He had a successful catheter ablation and continues to have regular follow-up monitoring with the cardiologist. He is no longer taking amiodarone.

At this visit, he reports no recurrence of AF-associated symptoms or detectable AF on cardiac monitoring. He has lost 8 lbs. You counsel to him to continue to maintain a healthy lifestyle.

CORRESPONDENCE

Amimi S. Osayande MD, FAAFP, Northside-Gwinnett Family Medicine Residency Program, Strickland Family Medicine Center, 665 Duluth Highway, Suite 501, Lawrenceville, GA 30046; [email protected]

CASE

Jack Z, a 75-year-old man with well-controlled hypertension, diabetes controlled by diet, and atrial fibrillation (AF) presents to the family medicine clinic to establish care with you after moving to the community from out of town.

The patient describes a 1-year history of AF. He provides you with an echocardiography report from 6 months ago that shows no evidence of structural heart disease. He takes lisinopril, to control blood pressure; an anticoagulant; a beta-blocker; and amiodarone for rhythm control. Initially, he took flecainide, which was ineffective for rhythm control, before being switched to amiodarone. He had 2 cardioversion procedures, each time after episodes of symptoms. He does not smoke or drink alcohol.

Mr. Z describes worsening palpitations and shortness of breath over the past 9 months. Symptoms now include episodes of exertional fatigue, even when he is not having palpitations. Prior to the episodes of worsening symptoms, he tells you that he lived a “fairly active” life, golfing twice a week.

The patient’s previous primary care physician had encouraged him to talk to his cardiologist about “other options” for managing AF, because levels of his liver enzymes had started to rise (a known adverse effect of amiodarone1) when measured 3 months ago. He did not undertake that conversation, but asks you now about other treatments for AF.

Atrial fibrillation is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, characterized by discordant electrical activation of the atria due to structural or electrophysiological abnormalities, or both. The disorder is associated with an increased rate of stroke and heart failure and is independently associated with a 1.5- to 2-fold risk of all-cause mortality.2

In this article, we review the pathophysiology of AF; management, including the role of, and indications for, catheter ablation; and patient- and disease-related factors associated with ablation (including odds of success, complications, risk of recurrence, and continuing need for thromboprophylaxis) that family physicians should consider when contemplating referral to a cardiologist or electrophysiologist for catheter ablation for AF.

What provokes AF?

AF is thought to occur as a result of an interaction among 3 phenomena:

- enhanced automaticity of abnormal atrial tissue

- triggered activity of ectopic foci within 1 or more pulmonary veins, lying within the left atrium

- re-entry, in which there is propagation of electrical impulses from an ectopic beat through another pathway.

Continue to: In patients who progress...

In patients who progress from paroxysmal to persistent AF (see “Subtypes,” below), 2 distinct pathways, facilitated by the presence of abnormal tissue, continuously activate one another, thus maintaining the arrhythmia. Myocardial tissue in the pulmonary veins is responsible for most ectopic electrical impulses in patients with drug-refractory AF (see “Rhythm control”).

Subtypes. For the purpose of planning treatment, AF is classified as:

- Paroxysmal. Terminates spontaneously or with intervention ≤ 7 days after onset.

- Persistent. Continuous and sustained for > 7 days.

- Longstanding persistent. Continuous for > 12 months.

- Permanent. The patient and physician accept that there will be no further attempt to restore or maintain sinus rhythm.

Goals of treatment

Primary management goals in patients with AF are 2-fold: control of symptoms and prevention of thromboembolism. A patient with new-onset AF who presents acutely with inadequate rate control and hemodynamic compromise requires urgent assessment to determine the cause of the arrhythmia and need for cardioversion.3 A symptomatic patient with AF who does not have high-risk features (eg, valvular heart disease, mechanical valves) might be a candidate for rhythm control in addition to rate control.3,4

Rate control. After evaluation in the hospital, a patient who has a rapid ventricular response but remains hemodynamically stable, without evidence of heart failure, should be initiated on a rate-controlling medication, such as a beta-blocker or nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker. A resting heart rate goal of < 80 beats per minute (bpm) is recommended for a symptomatic patient with AF. The heart rate goal can be relaxed, to < 110 bpm, in an asymptomatic patient with preserved left ventricular function.5,6

Rhythm control, indicated in patients who remain symptomatic on rate-controlling medication, can be achieved either with an antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) or by catheter ablation.4,5 In stable patients, rhythm control should be considered only after a thorough work-up for a reversible cause of AF, and can be achieved with an oral AAD or, in select patients, through catheter ablation (TABLE 13,6). Other indications for chronic rhythm control include treatment of patients with tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy.5

A major study that documented the benefit of early rhythm control evaluated long-term outcomes in 2789 patients with AF who were undergoing catheter ablation.7 Patients were randomized to early rhythm control (catheter ablation or AAD) or “usual care”—ie, in this study, rhythm control limited to symptomatic patients. Primary outcomes were death from cardiovascular causes, stroke, and hospitalization with worsening heart failure or acute coronary syndrome. A first primary outcome event occurred in 249 patients (3.9/100 person-years) assigned to early rhythm control, compared to 316 (5.0 per 100 person-years) in the group assigned to usual care.

The study was terminated early (after 5.1 years) because of overwhelming evidence of efficacy (number need to treat = 7). Although early rhythm control was obtained through both catheter ablation and AAD (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.79; 96% CI, 0.66-0.94; P = .005), success was attributed to the use of catheter ablation for a rhythm-control strategy and its use among patients whose AF was present for < 1 year. Most patients in both treatment groups continued to receive anticoagulation, rate control, and optimization of cardiovascular risk.7

Continue to: Notably, direct studies...

Notably, direct studies comparing ablation and AAD have not confirmed the benefit of ablation over AAD in outcomes of all-cause mortality, bleeding, stroke, or cardiac arrest over a 5-year period.8

Adverse effects and mortality outcomes with AAD. Concern over using AAD for rhythm control is based mostly on adverse effects and long-term (1-year) mortality outcomes. Long-term AAD therapy has been shown to decrease the recurrence of AF—but without evidence to suggest other mortality benefits.

A meta-analysis of 59 randomized controlled trials reviewed 20,981 patients receiving AAD (including quinidine, disopyramide, propafenone, flecainide, metoprolol, amiodarone, dofetilide, dronedarone, and sotalol) for long-term effects on death, stroke, adverse reactions, and recurrence of AF.9 Findings at 10 months suggest that:

- Compared to placebo, amiodarone and sotalol increased the risk of all-cause mortality during the study period.

- There was minimal difference in mortality among patients taking dofetilide or dronedarone, compared to placebo.

- There were insufficient data to draw conclusions about the effect of disopyramide, flecainide, and propafenone on mortality.

Before starting a patient on AAD, the risk of arrhythmias and the potential for these agents to cause toxicity and adverse events should always be discussed.

CASE

You tell Mr. Z that you need to know the status of his comorbidities to make a recommendation about “other” management options, and proceed to take a detailed history.

Recent history. Mr. Z reveals that “today is a good day”: He has had “only 1” episode of palpitations, which resolved on its own. The previous episode, he explains, was 3 days ago, when palpitations were associated with lightheadedness and shortness of breath. He denies chest pains or swelling of the legs.

Physical exam. The patient appears spry, comfortable, and in no acute distress. Vital signs are within normal limits. A body mass index of 28.4 puts him in the “overweight” category. His blood pressure is 118/75 mm Hg.

Continue to: Cardiac examination...

Cardiac examination is significant for an irregular rhythm without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. His lungs are clear bilaterally; his abdomen is soft and nondistended. His extremities show no edema.

Testing. You obtain an electrocardiogram, which demonstrates a controlled ventricular rate of 88 bpm and AF. You order a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, tests of hemoglobin A1C and thyroid-stimulating hormone, lipid panel, echocardiogram, and a chest radiograph.

Results. The chest radiograph is negative for an acute cardiopulmonary process; cardiac size is normal. Aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels are higher than twice the normal limit. The echocardiogram reveals an estimated left ventricular ejection fraction of 55% to 60%; no structural abnormalities are noted.

In which AF patients is catheter ablation indicated?

Ablation is recommended for select patients (TABLE 13,6) with symptomatic paroxysmal AF that is refractory to AAD or who are intolerant of AAD.3,6 It is a reasonable first-line therapy for high-performing athletes in whom AAD would affect athletic performance.3,10 It is also a reasonable option in select patients > 75 years and as an alternative to AAD therapy.3 Finally, catheter ablation should be considered in symptomatic patients with longstanding persistent AF and congestive heart failure, with or without reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.3

CASE

You inform Mr. Z that his symptoms are likely a result of symptomatic paroxysmal AF, which was refractory to flecainide and amiodarone, and that his abnormal liver function test results preclude continued use of amiodarone. You propose Holter monitoring to correlate timing of symptoms with the arrhythmia, but he reports this has been done, and the correlation confirmed, by his previous physician.

You explain that, because the diagnosis of symptomatic paroxysmal AF refractory to AADs has been confirmed, he is categorized as a patient who might benefit from catheter ablation, based on:

- the type of AF (ie, paroxysmal AF is associated with better ablation outcomes)

- persistent symptoms that are refractory to AADs

- his intolerance of AAD

- the length of time since onset of symptoms.

Mr. Z agrees to consider your recommendation.

Continue to: What are the benefits of catheter ablation?

What are the benefits of catheter ablation?

Ablation can be achieved through radiofrequency (RF) ablation, cryoablation, or newer, laser-based balloon ablation. Primary outcomes used to determine the success of any options for performing ablation include mortality, stroke, and hospitalization. Other endpoints include maintenance of sinus rhythm, freedom from AF, reduction in AF burden (estimated through patients’ report of symptoms, recurrence rate, need for a second ablation procedure, and serial long-term monitoring through an implantable cardiac monitoring device), quality of life, and prevention of AF progression.3

Patient and disease variables (TABLE 211-13). The success rate of catheter ablation, defined as freedom from either symptomatic or asymptomatic episodes of AF, is dependent on several factors,3,14 including:

- type of AF (paroxysmal or persistent)

- duration and degree of symptoms

- age

- sex

- comorbidities, including heart failure and structural heart or lung disease.

Overall, in patients with paroxysmal AF, an estimated 75% are symptom free 1 year after ablation.15 Patients with persistent and longstanding persistent AF experience a lower success rate.

RF catheter ablation has demonstrated superiority to AAD in reducing the need for cardioversion (relative risk [RR] = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.47-0.82) and cardiac-related hospitalization (RR = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.10-0.72;) at 12 months in patients with nonparoxysmal AF (persistent or longstanding persistent).16

Effect on mortality. Among patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, long-term studies of cardiovascular outcomes 5 years post ablation concluded that ablation is associated with a decrease in all-cause mortality (RR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54-0.88; P = .003) and a reduction in hospitalization (RR = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.47-0.82; P = .0006); younger (< 65 years) and male patients derive greater benefit.6,17 Indications for ablation in patients with heart failure are similar to those in patients without heart failure; ablation can therefore be considered for select heart failure patients who remain symptomatic or for whom AAD has failed.3

Older patients. Ablation can be considered for patients > 75 years with symptomatic paroxysmal AF refractory to AAD or who are intolerant of AAD.3 A study that assessed the benefit of catheter ablation reviewed 587 older (> 75 years) patients with AF, of whom 324 were eligible for ablation. Endpoints were maintenance of sinus rhythm, stroke, death, and major bleeding. Return to normal sinus rhythm was an independent factor, associated with a decrease in the risk of mortality among all patient groups that underwent ablation (HR = 0.36; 95% CI, 0.2-0.63; P = .0005). Age > 75 years (HR = 1.09; 95% CI, 1.01-1.16; P > .02) and depressed ejection fraction < 40% (HR = 2.38; 95% CI, 1.28-4.4; P = .006) were determined to be unfavorable parameters for survival.18

Complications and risks

Complications of catheter ablation for AF, although infrequent, can be severe (TABLE 33). Early mortality, defined as death during initial admission or 30-day readmission, occurs in approximately 0.5% of cases; half of deaths take place during readmission.11

Continue to: Complications vary...

Complications vary, based on the type and site of ablation.19,20 Cardiac tamponade or perforation, the most life-threatening complications, taken together occur in an estimated 1.9% of patients (odds ratio [OR] = 2.98; 95% CI, 1.36-6.56; P = .007).11 Other in-hospital complications independently predictive of death include any cardiac complications (OR = 12.8; 95% CI, 6.86 to 23.8; P < .001) and neurologic complications (cerebrovascular accident and transient ischemic attack) (OR = 8.72; 95% CI, 2.71-28.1; P < .001).

Other complications that do not cause death but might prolong the hospital stay include pericarditis without effusion, anesthesia-related complications, and vascular-access complications. Patients whose ablation is performed at an institution where the volume of ablations is low are also at higher risk of early mortality (OR = 2.35; 95% CI, 1.33-4.15; P = .003).16

Recurrence is common (TABLE 211-13). Risk of recurrence following ablation is significant; early (within 3 months after ablation) recurrence is seen in 50% of patients.21,22 However, this is a so-called "blanking period"—ie, a temporary period of inflammatory and proarrhythmic changes that are not predictors of later recurrence. The 5-year post-ablation recurrence rate is approximately 25.5%; longstanding persistent and persistent AF and the presence of comorbidities are major risk factors for recurrence.13,23

Recurrence is also associated with the type of procedure; pulmonary vein isolation, alone or in combination with another type of procedure, results in higher long-term success.21,23

Other variables affect outcome (TABLE 211-13). Following AF ablation, patients with nonparoxysmal AF at baseline, advanced age, sleep apnea and obesity, left atrial enlargement, and any structural heart disease tend to have a poorer long-term (5-year) outcome (ie, freedom from extended episodes of AF).3,13,23,24

Patients who undergo repeat procedures have higher arrhythmia-free survival; the highest ablation success rate is for patients with paroxysmal AF.13,23

Exposure to ionizing radiation. Fluoroscopy is required for multiple components of atrial mapping and ablation during RF ablation, including navigation, visualization, and monitoring of catheter placement. Patients undergoing this particular procedure therefore receive significant exposure to ionizing radiation. A reduction in, even complete elimination of, fluoroscopy has been achieved with:

- nonfluoroscopic 3-dimensional mapping systems25

- intracardiac echocardiography, which utilizes ultrasonographic imaging as the primary visual mode for tracking and manipulating the catheter

- robotic guided navigation.26-28

Continue to: CASE

CASE

At his return visit, Mr. Z says that he is concerned about, first, undergoing catheter ablation at his age and, second, the risks associated with the procedure. You explain that it is true that ablation is ideal in younger patients who have minimal comorbidities and that the risk of complications increases with age—but that there is no cutoff or absolute age contraindication to ablation.

You tell Mr. Z that you will work with him on risk-factor modification in anticipation of ablation. You also assure him that the decision whether to ablate must be a joint one—between him and a cardiologist experienced both in electrophysiology and in performing this highly technical procedure. And you explain that a highly practiced specialist can identify Mr. Z’s risk factors that might make ablation more difficult to perform and affect the long-term outcome.

With Mr. Z’s agreement, you screen for sleep apnea and start him on a lifestyle modification plan to achieve a more ideal weight, explaining that the risk of recurrence of AF after catheter ablation is increased by obesity and sleep apnea, in addition to age. You explain that, based on his CHA2DS2–VASc (congestive heart failure; hypertension; age, ≥ 75 years; diabetes; prior stroke, transient ischemic attack, or thromboembolism; vascular disease; age, 65 to 74 years; sex category) score of 3, he will remain on anticoagulation whether or not he has the ablation.

You refer the patient to the nearest high-volume cardiac ablation center.

Last, you caution Mr. Z that, based on his lipid levels, his 10-year risk of heart disease or stroke is elevated. You recommend treatment with a statin agent while he continues his other medications.

Delivering energy to myocardium

Myocardial tissue in pulmonary veins is responsible for most ectopic electrical impulses in patients with drug-refractory AF. The goal of catheter ablation in AF is destruction (scarring) of tissue that is the source of abnormal vein potentials.15

How RF ablation works. Ablation is most commonly performed using RF energy, a high-frequency form of electrical energy. Electrophysiology studies are carried out at the time of ablation by percutaneous, fluoroscopically guided insertion of 2 to 5 catheters, usually through the femoral or internal jugular vein, which are then positioned within several areas of the heart—usually, the right atrium, bundle of His, right ventricle, and coronary sinus.

Continue to: Electrical current...