User login

Online Information About Hydroquinone: An Assessment of Accuracy and Readability

To the Editor:

The internet is a popular resource for patients seeking information about dermatologic treatments. Hydroquinone (HQ) cream 4% is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for skin hyperpigmentation.1 The agency enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform on September 25, 2020, to restrict distribution of OTC HQ.2 Exogenous ochronosis is listed as a potential adverse effect in the prescribing information for HQ.1

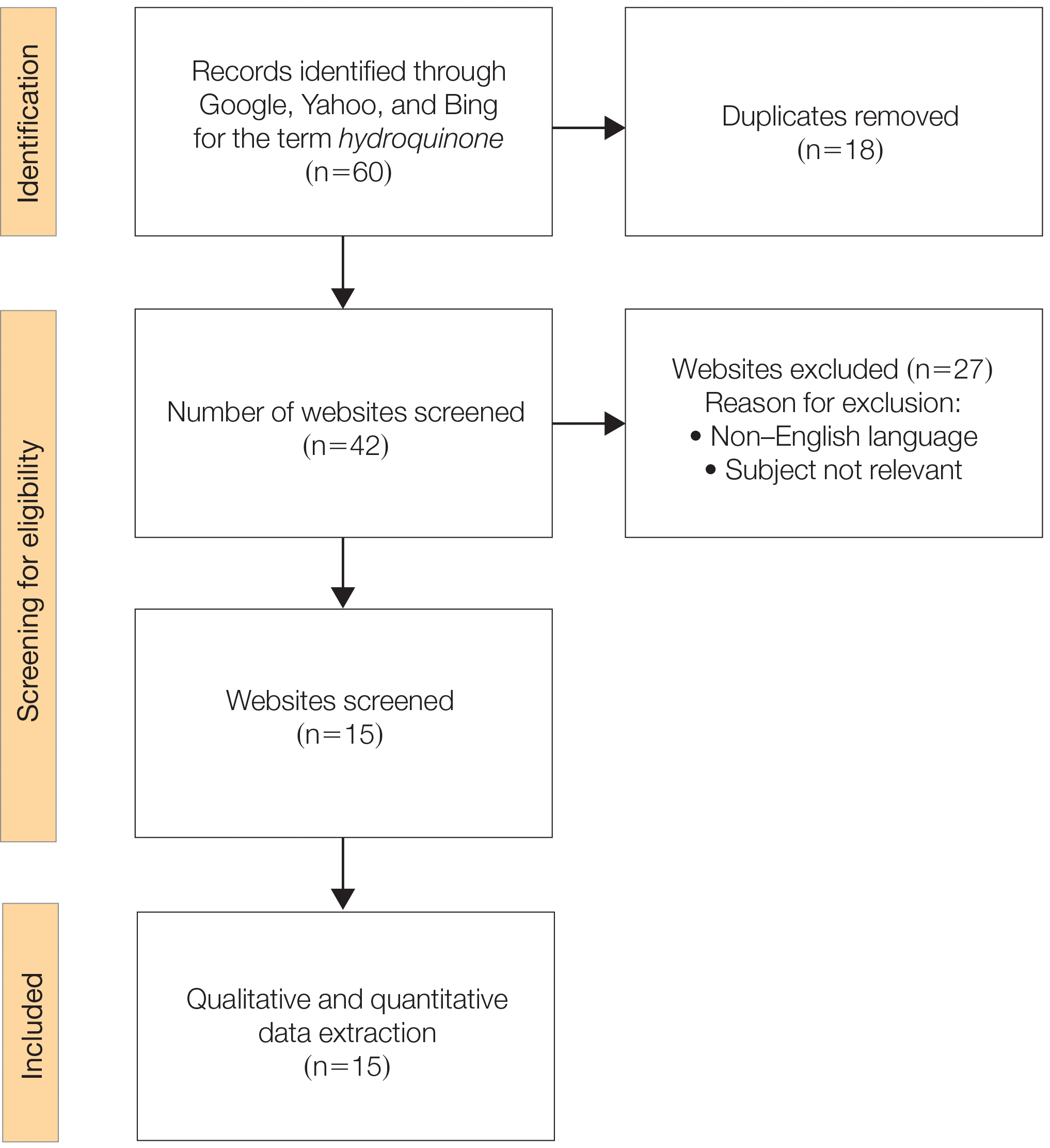

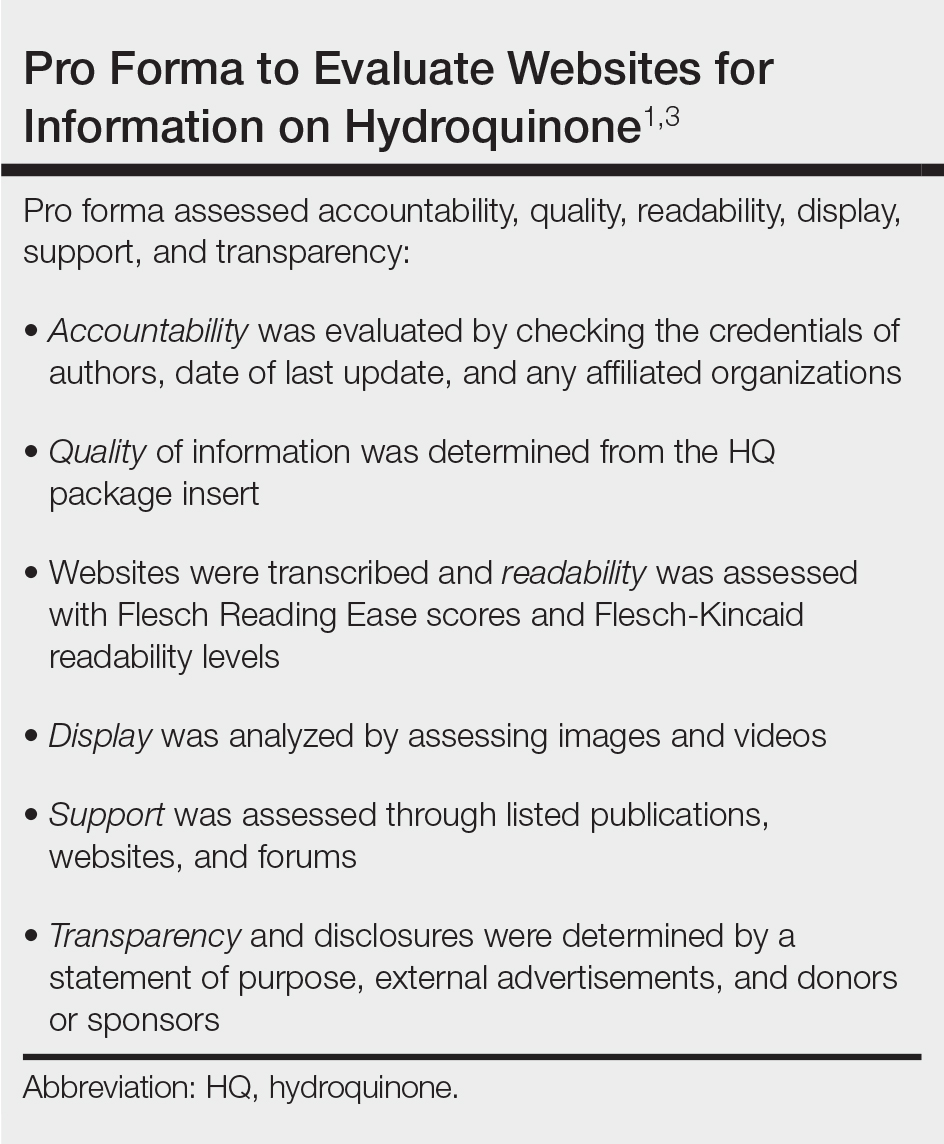

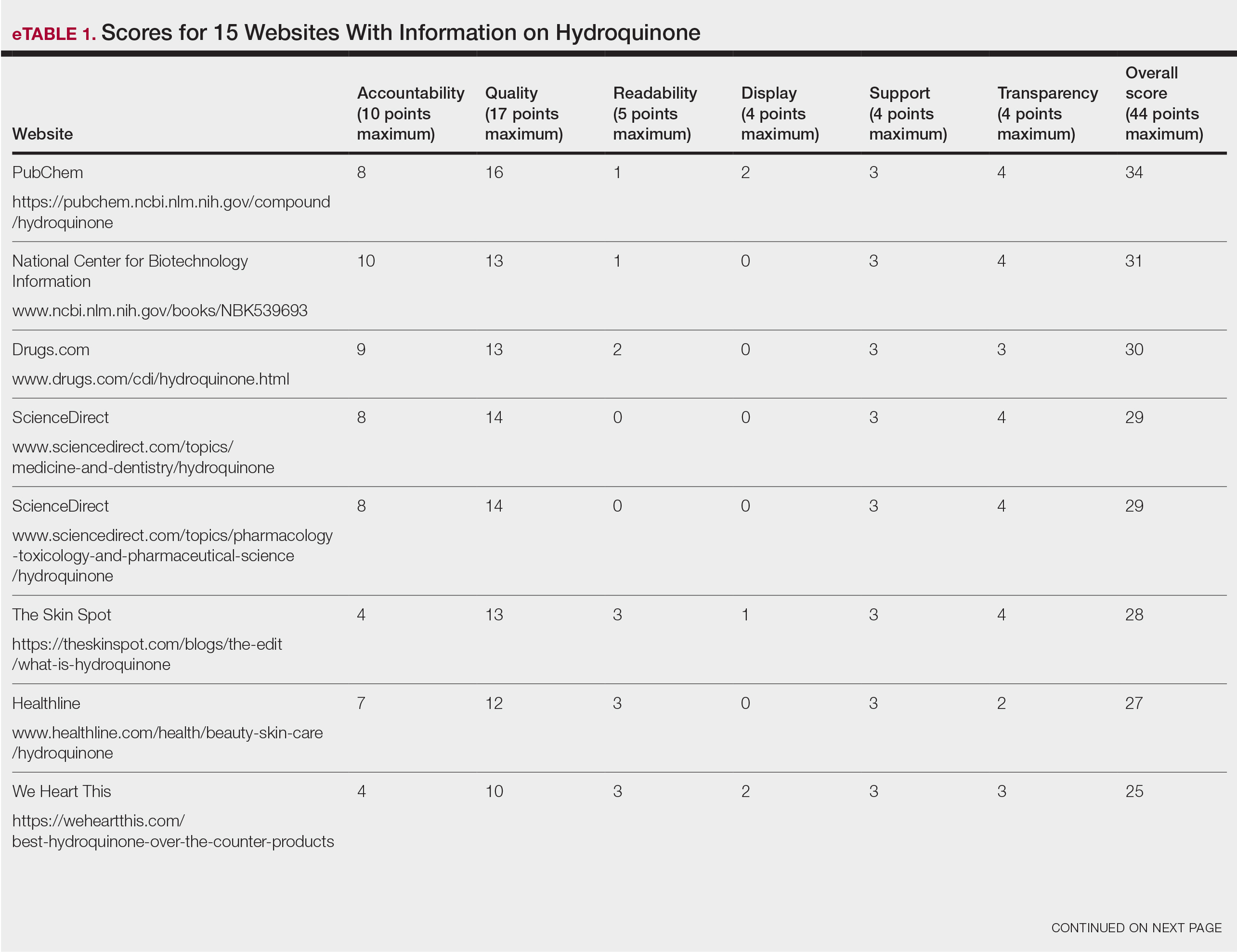

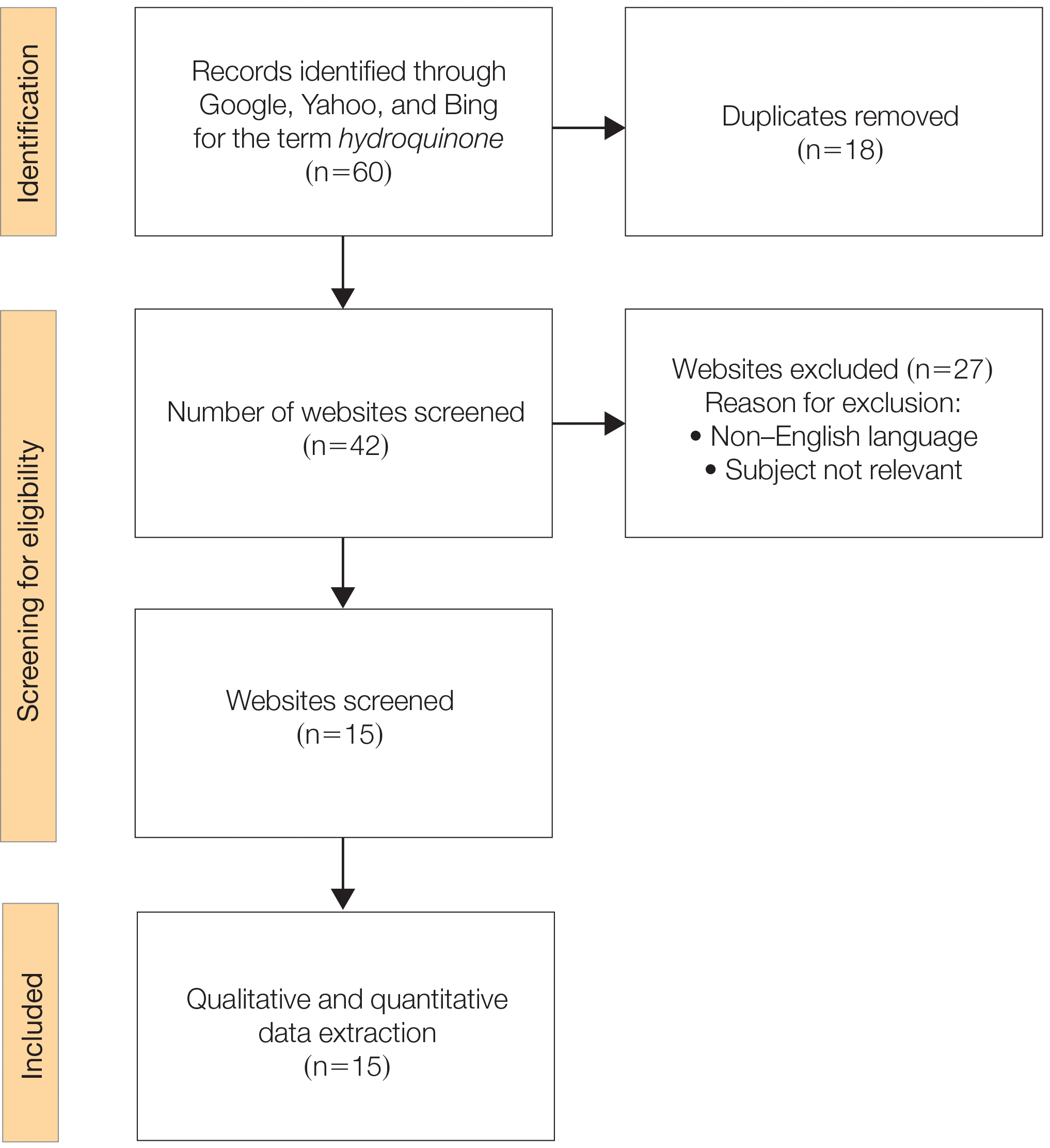

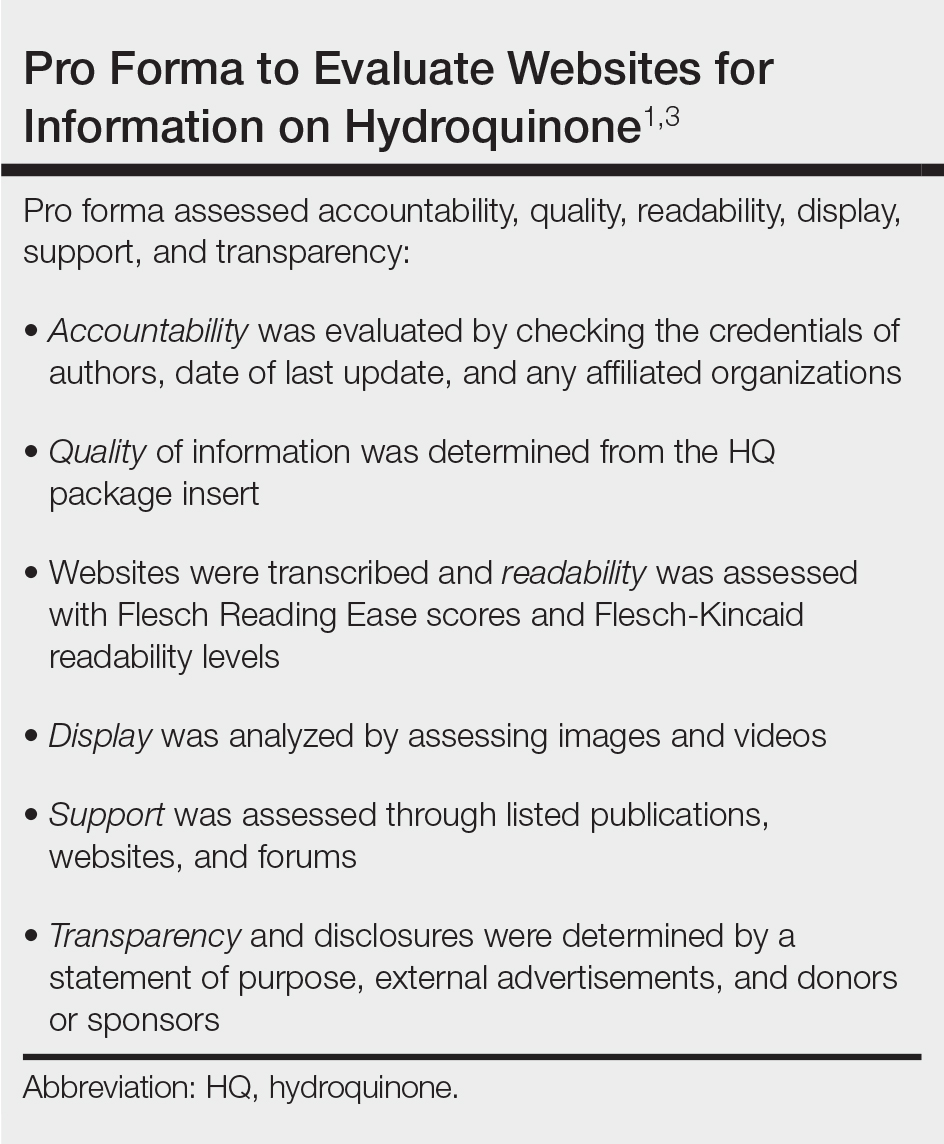

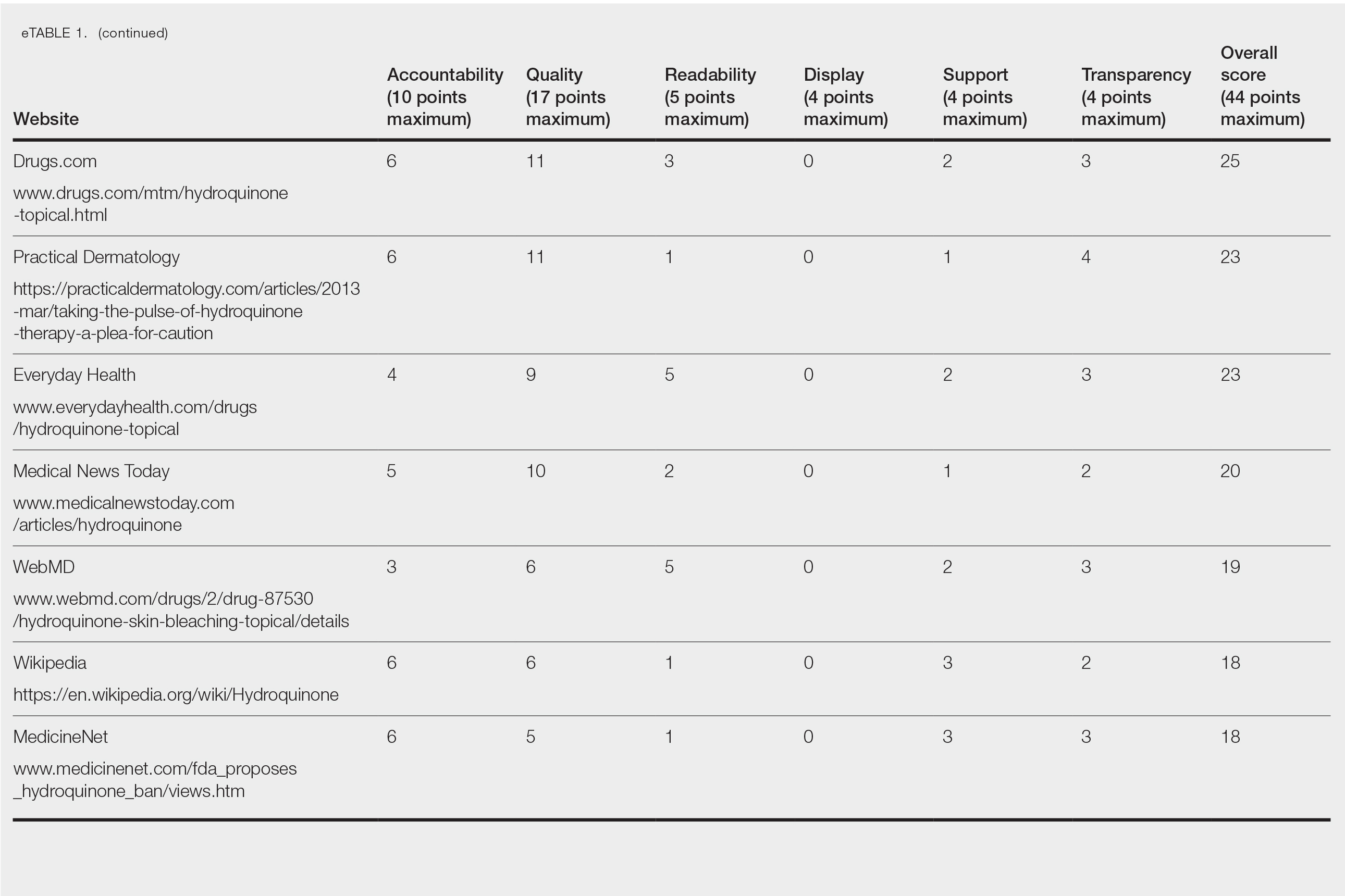

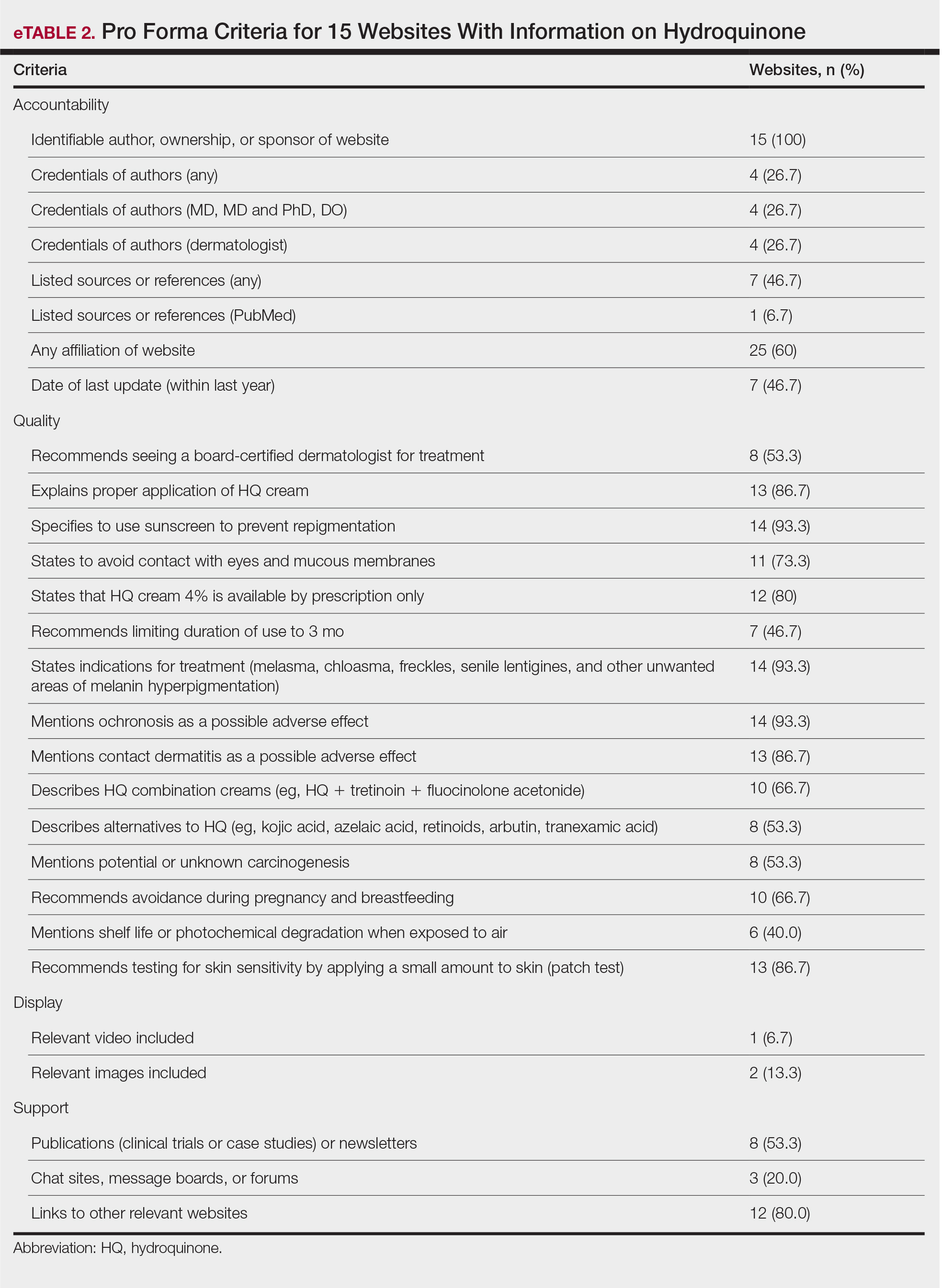

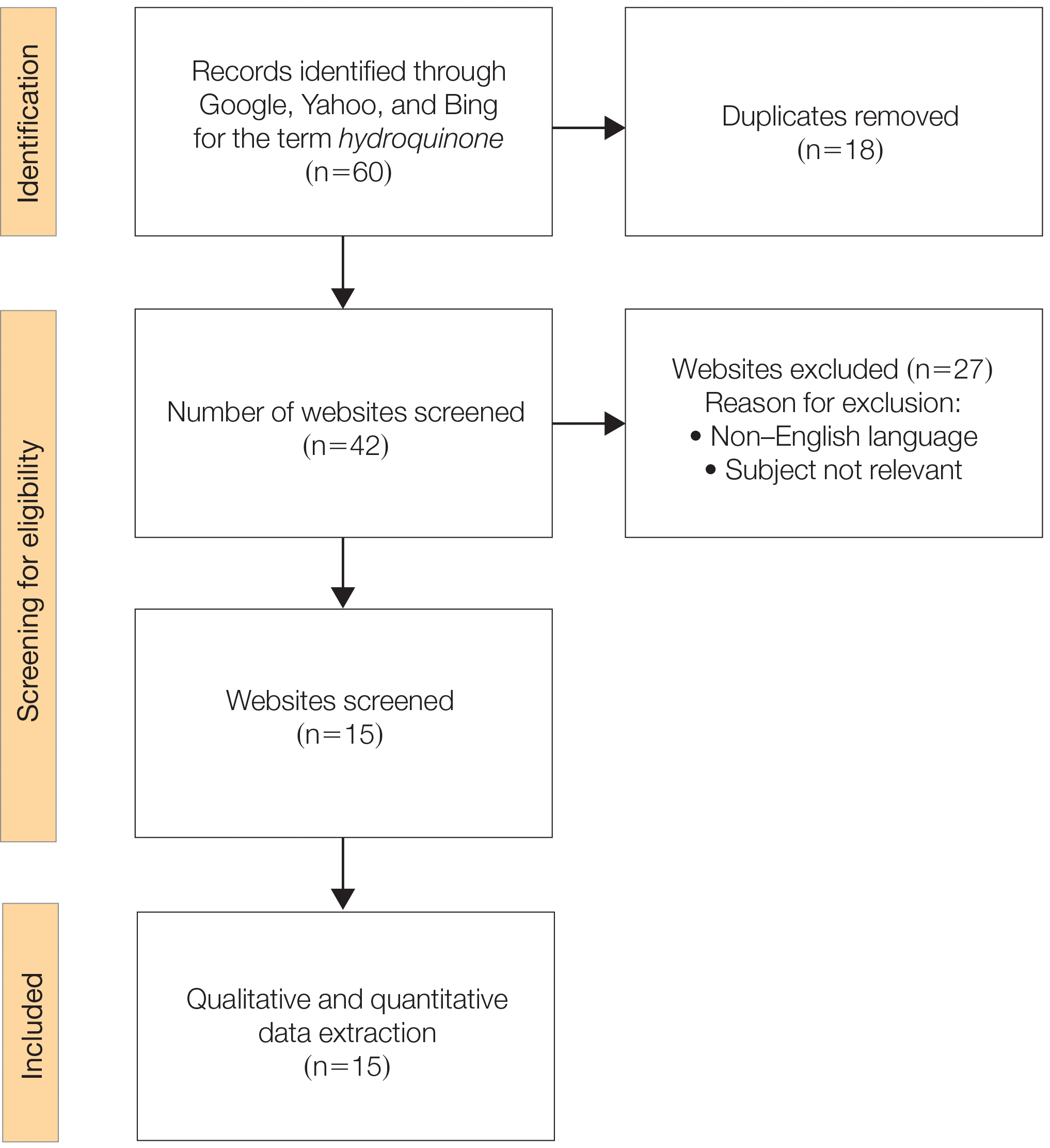

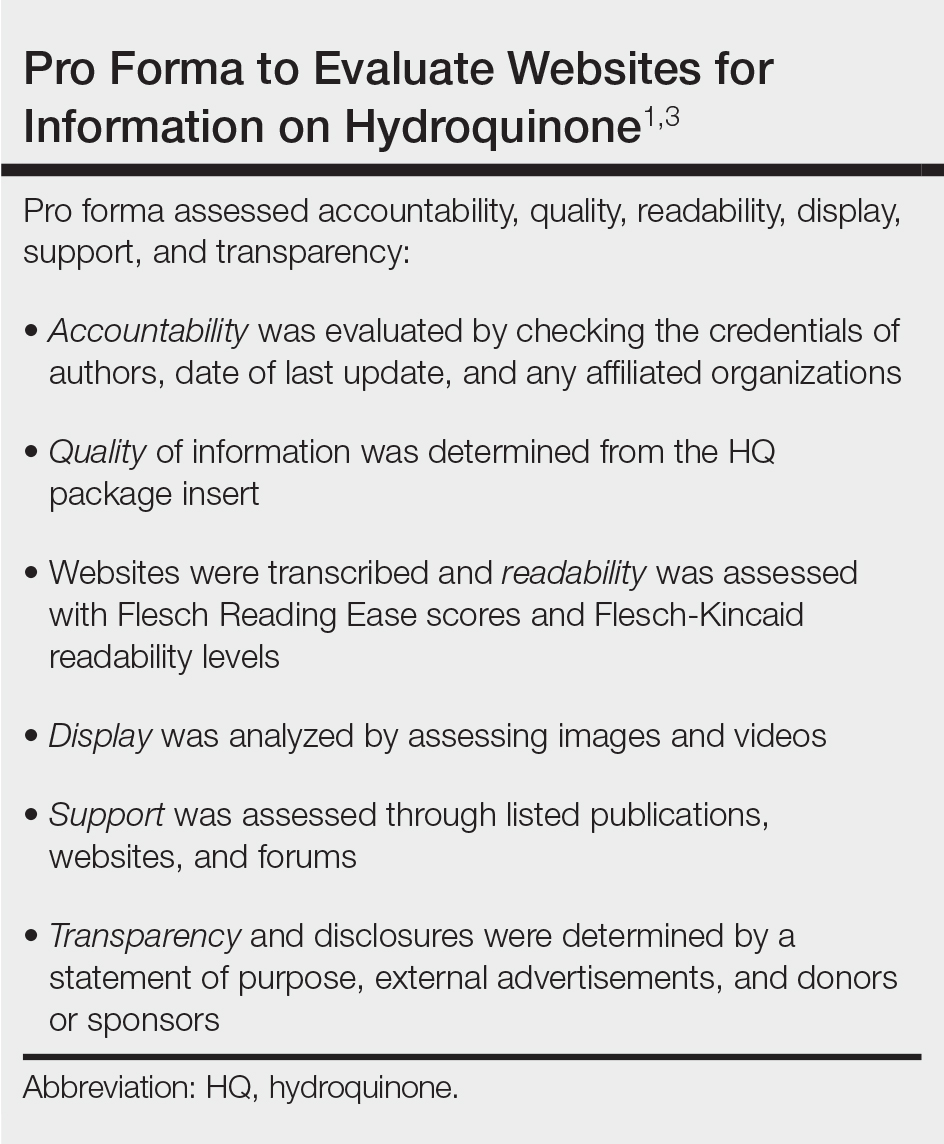

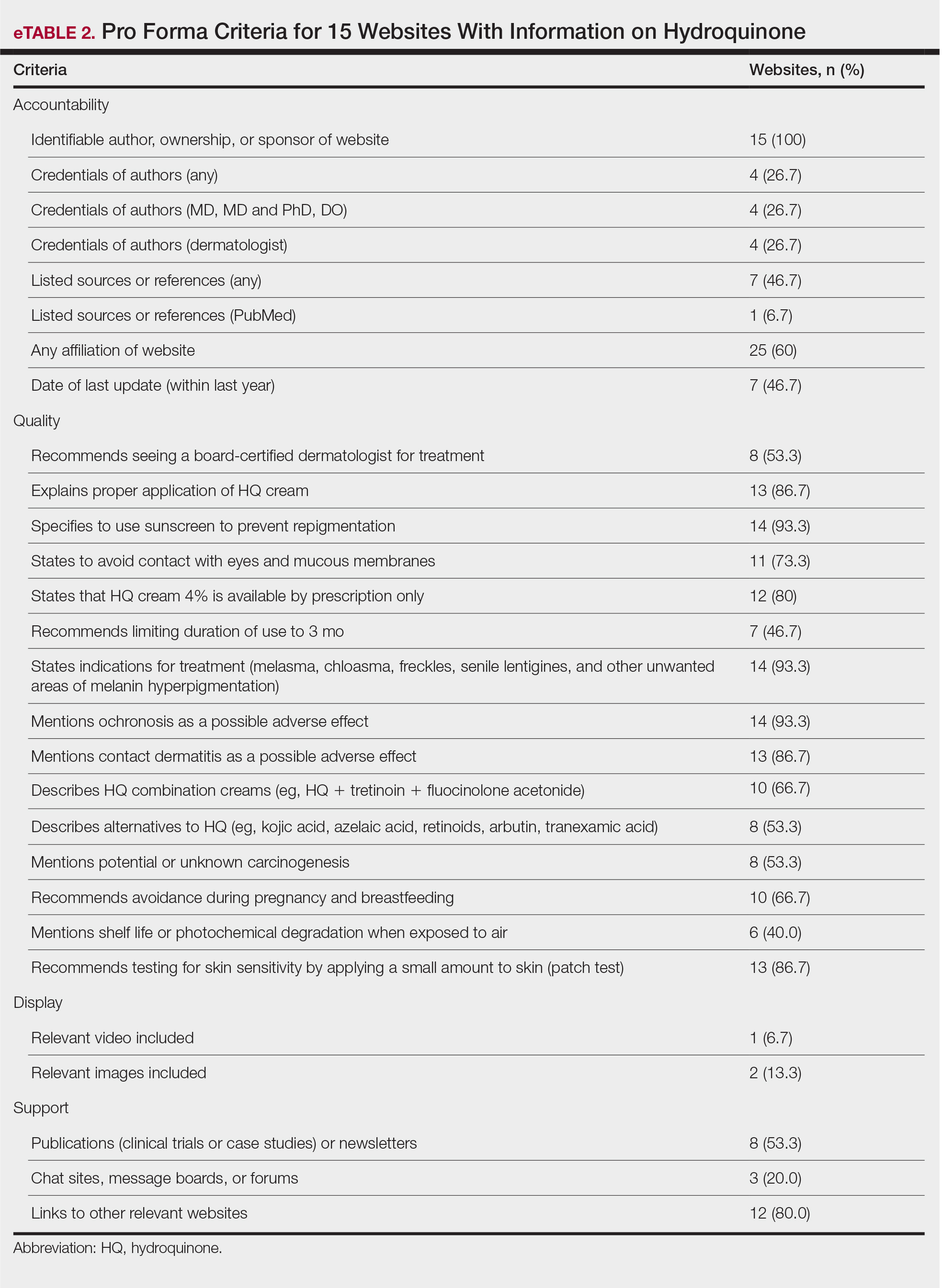

We sought to assess online resources on HQ for accuracy of information, including the recent OTC ban, as well as readability. The word hydroquinone was searched on 3 internet search engines—Google, Yahoo, and Bing—on December 12, 2020, each for the first 20 URLs (ie, websites)(total of 60 URLs). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)(Figure) reporting guidelines were used to assess a list of relevant websites to include in the final analysis. Website data were reviewed by both authors. Eighteen duplicates and 27 irrelevant and non–English-language URLs were excluded. The remaining 15 websites were analyzed. Based on a previously published and validated tool, a pro forma was designed to evaluate information on HQ for each website based on accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency (Table).1,3

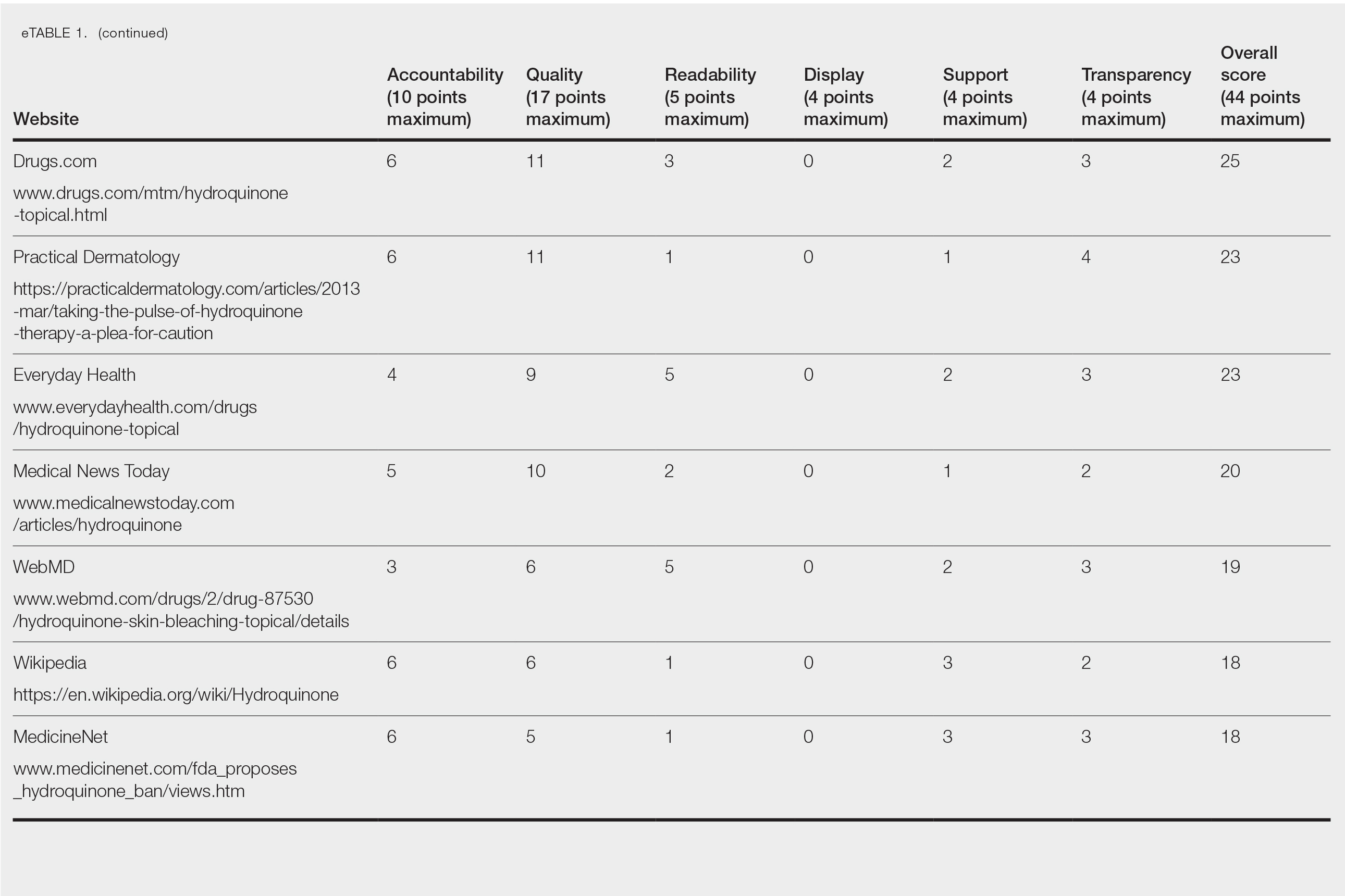

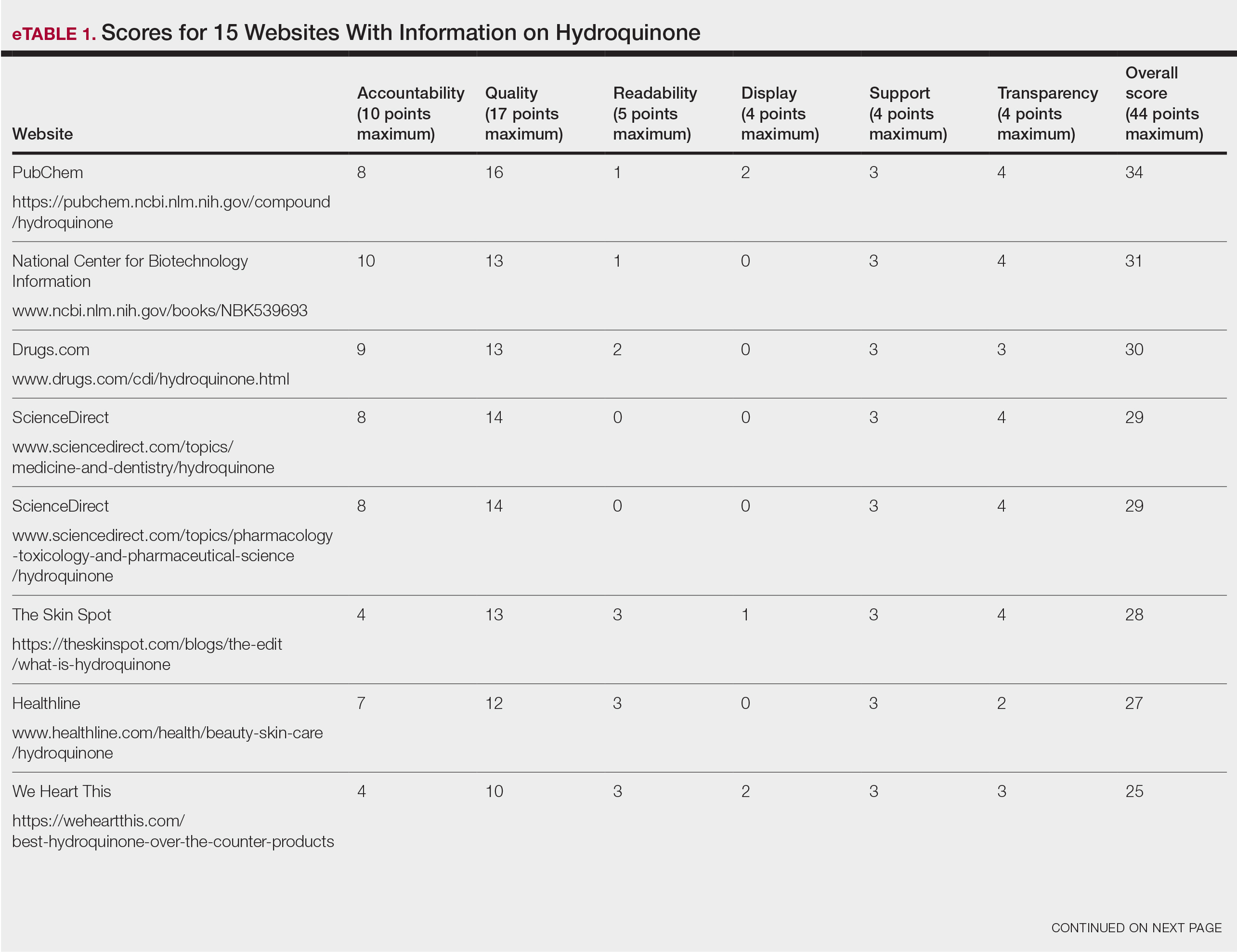

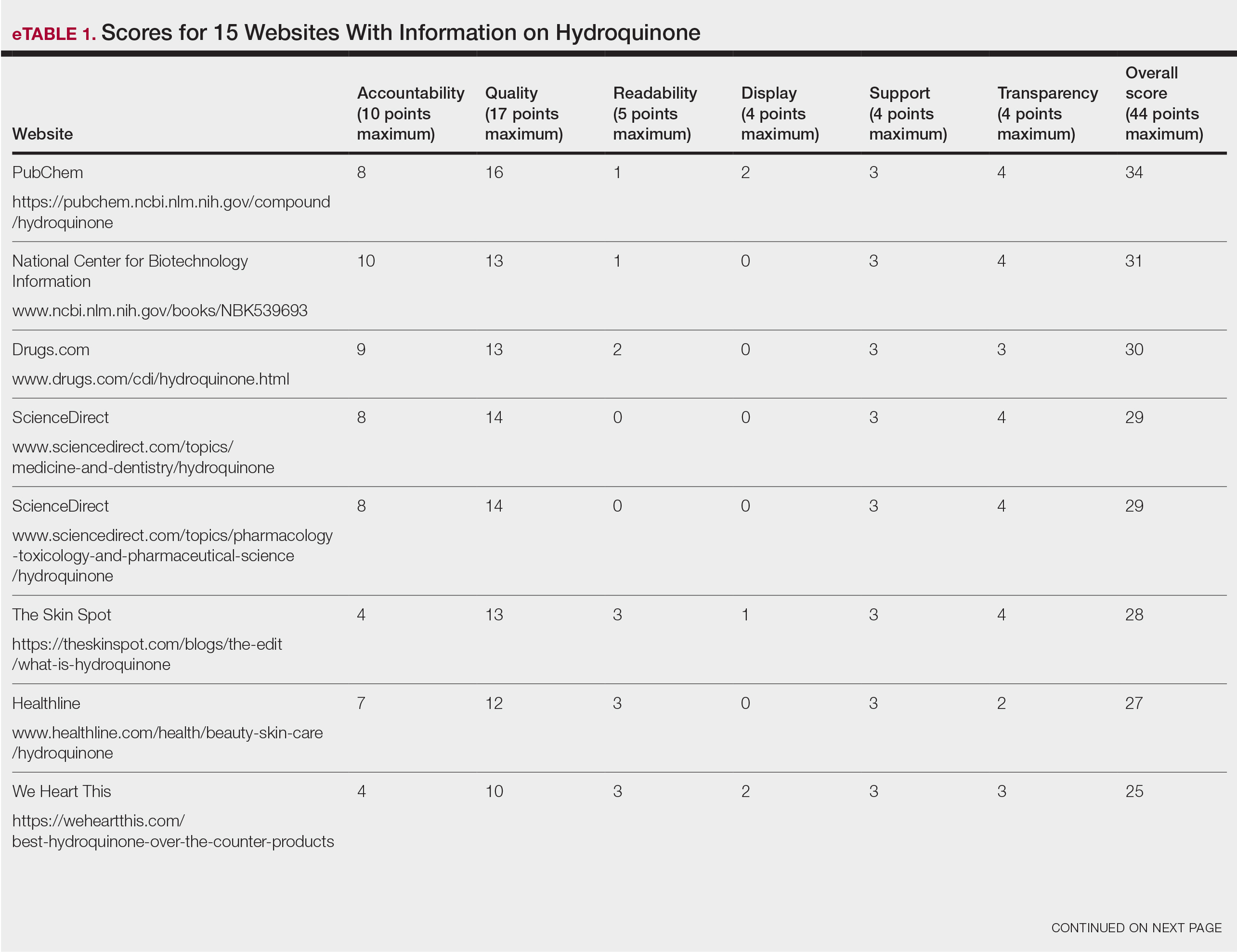

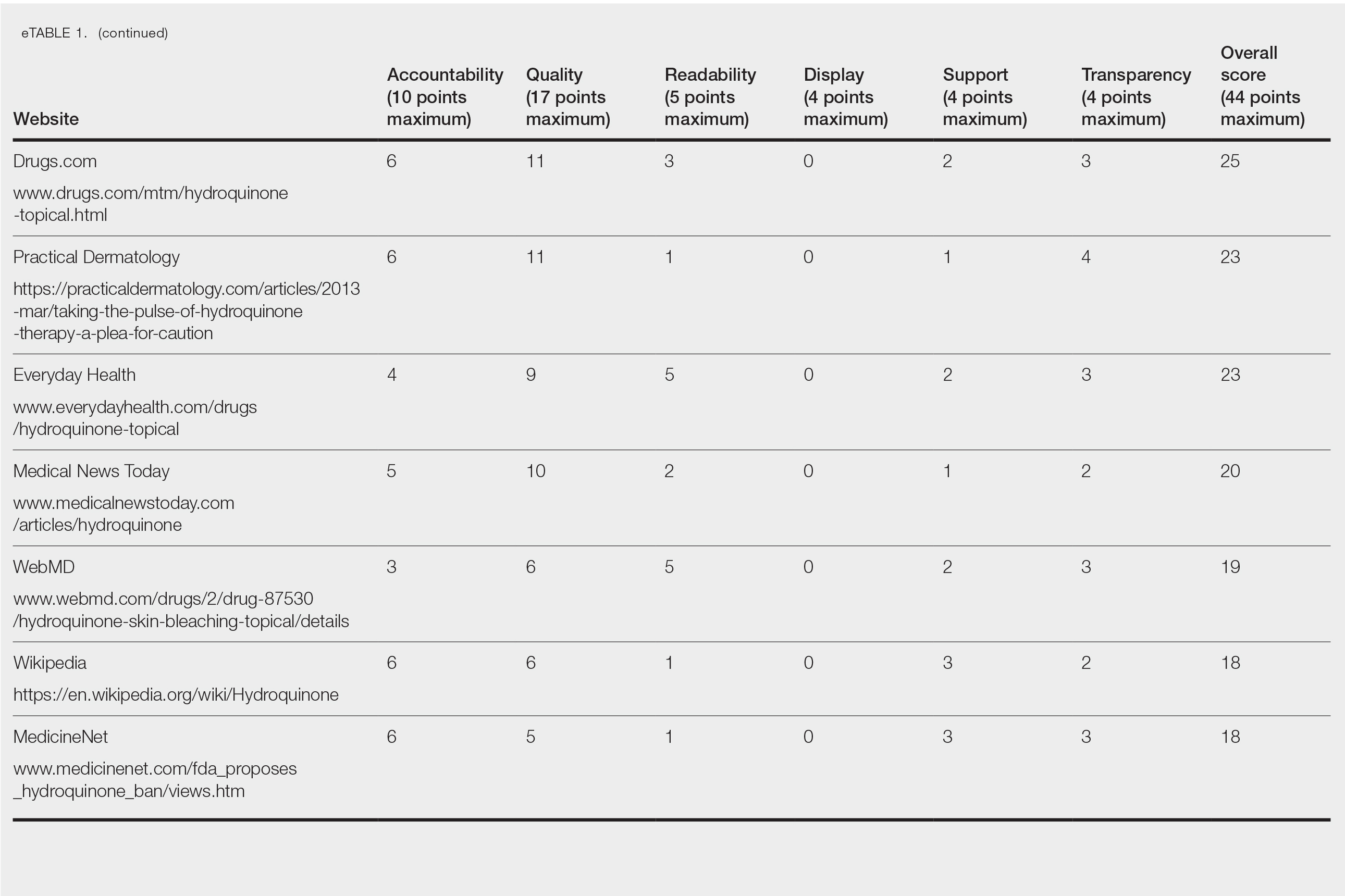

Scores for all 15 websites are listed in eTable 1. The mean overall (total) score was

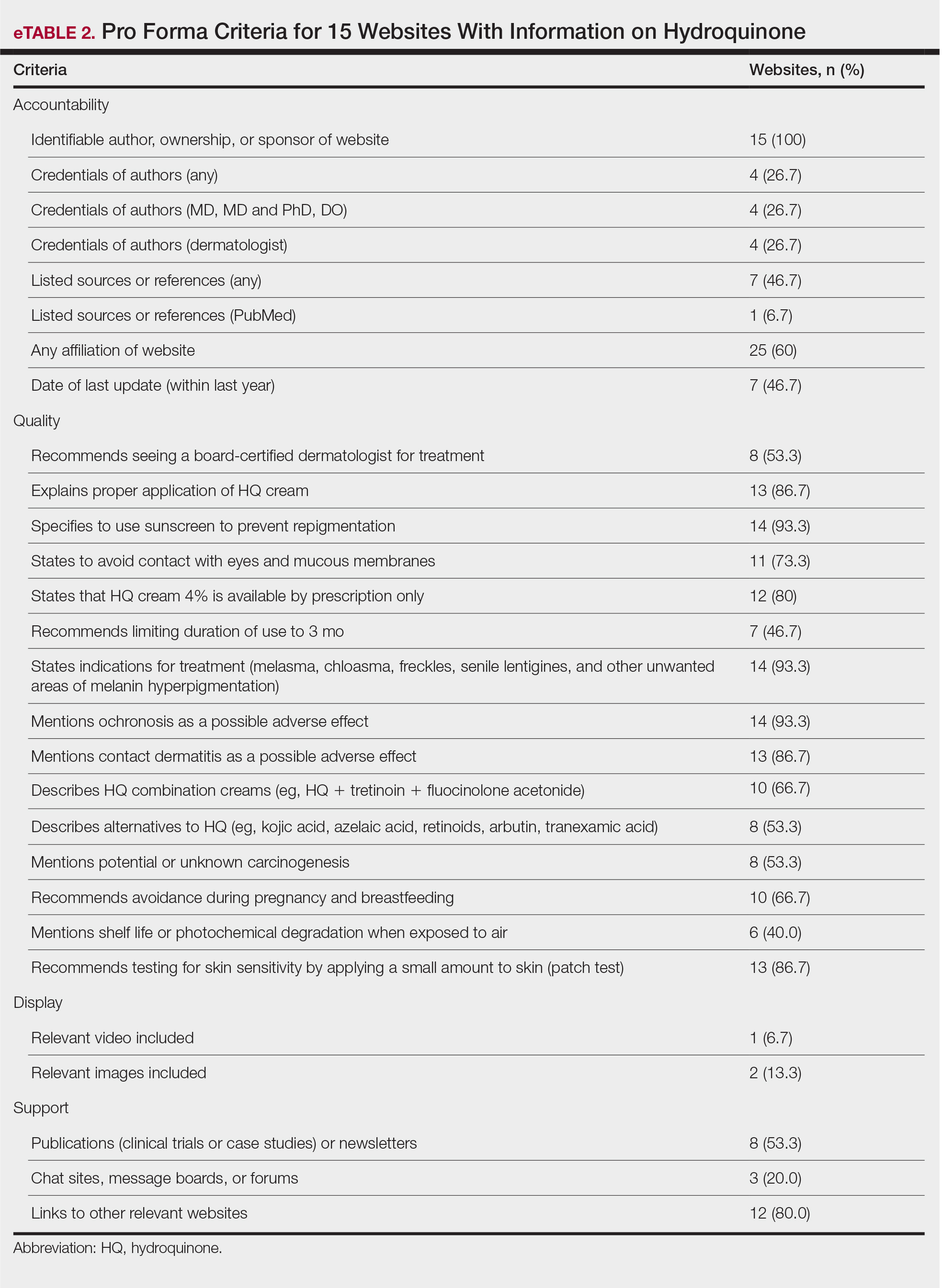

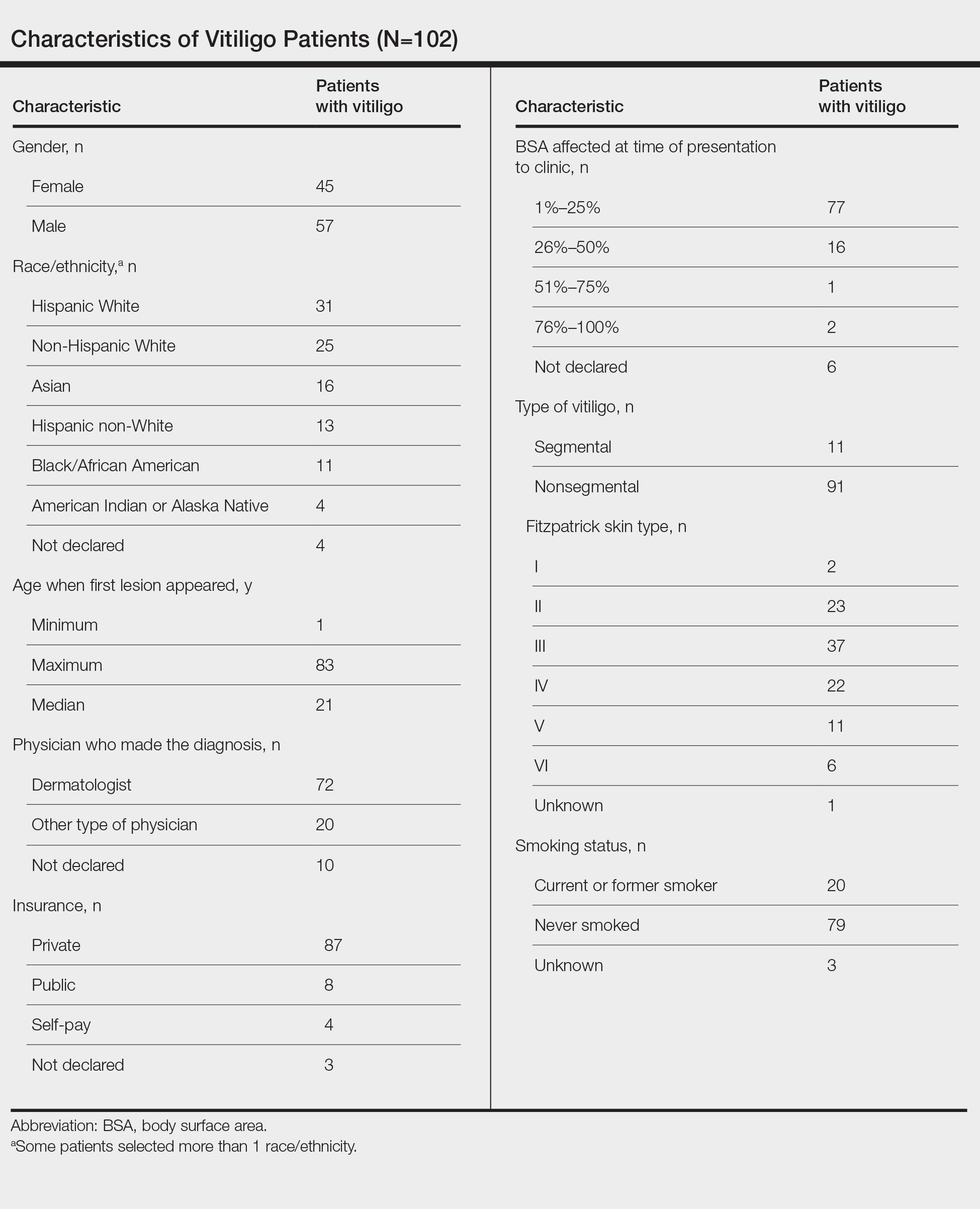

The mean display score was 0.3 (of a possible 4; range, 0–2); 66.7% of websites (10/15) had advertisements or irrelevant material. Only 6.7% and 13.3% of websites included relevant videos or images, respectively, on applying HQ (eTable 2). We identified only 3 photographs—across all 15 websites—that depicted skin, all of which were Fitzpatrick skin types II or III. Therefore, none of the websites included a diversity of images to indicate broad ethnic relatability.

The average support score was 2.5 (of a possible 4; range, 1–3); 20% (3/15) of URLs included chat sites, message boards, or forums, and approximately half (8/15 [53.3%]) included references. Only 7 URLs (46.7%) had been updated in the last 12 months. Only 4 (26.7%) were written by a board-certified dermatologist (eTable 2). Most (60%) websites contained advertising, though none were sponsored by a pharmaceutical company that manufactures HQ.

Only 46.7% (7/15) of websites recommended limiting a course of HQ treatment to 3 months; only 40% (6/15) mentioned shelf life or photochemical degradation when exposed to air. Although 93.3% (14/15) of URLs mentioned ochronosis, a clinical description of the condition was provided in only 33.3% (5/15)—none with images.

Only 2 sites (13.3%; Everyday Health and WebMD) met the accepted 7th-grade reading level for online patient education material; those sites scored lower on quality (9 of 17 and 6 of 17, respectively) than sites with higher overall scores.

None of the 15 websites studied, therefore, demonstrated optimal features on combined measures of accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency regarding HQ. Notably, the American Academy of Dermatology website (www.aad.org) was not among the 15 websites studied; the AAD website mentions HQ in a section on melasma, but only minimal detail is provided.

Limitations of this study include the small number of websites analyzed and possible selection bias because only 3 internet search engines were used to identify websites for study and analysis.

Previously, we analyzed content about HQ on the video-sharing and social media platform YouTube.4 The most viewed YouTube videos on HQ had poor-quality information (ie, only 20% mentioned ochronosis and only 28.6% recommended sunscreen [N=70]). However, average reading level of these videos was 7th grade.4,5 Therefore, YouTube HQ content, though comprehensible, generally is of poor quality.

By conducting a search for website content about HQ, we found that the most popular URLs had either accurate information with poor readability or lower-quality educational material that was more comprehensible. We conclude that there is a need to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality, up-to-date medical information; have been written by board-certified dermatologists; are comprehensible (ie, no more than approximately 1200 words and written at a 7th-grade reading level); and contain relevant clinical images and references. We encourage dermatologists to recognize the limitations of online patient education resources on HQ and educate patients on the proper use of the drug as well as its potential adverse effects

- US National Library of Medicine. Label: hydroquinone cream. DailyMed website. Updated November 24, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=dc72c0b2-4505-4dcf-8a69-889cd9f41693

- US Congress. H.R.748 - CARES Act. 116th Congress (2019-2020). Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text?fbclid=IwAR3ZxGP6AKUl6ce-dlWSU6D5MfCLD576nWNBV5YTE7R2a0IdLY4Usw4oOv4

- Kang R, Lipner S. Evaluation of onychomycosis information on the internet. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:484-487.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Assessing the impact and educational value of YouTube as a source of information on hydroquinone: a content-quality and readability analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1-3. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782318

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003. Accessed May 19, 2022. http://lib.ncfh.org/pdfs/6617.pdf

To the Editor:

The internet is a popular resource for patients seeking information about dermatologic treatments. Hydroquinone (HQ) cream 4% is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for skin hyperpigmentation.1 The agency enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform on September 25, 2020, to restrict distribution of OTC HQ.2 Exogenous ochronosis is listed as a potential adverse effect in the prescribing information for HQ.1

We sought to assess online resources on HQ for accuracy of information, including the recent OTC ban, as well as readability. The word hydroquinone was searched on 3 internet search engines—Google, Yahoo, and Bing—on December 12, 2020, each for the first 20 URLs (ie, websites)(total of 60 URLs). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)(Figure) reporting guidelines were used to assess a list of relevant websites to include in the final analysis. Website data were reviewed by both authors. Eighteen duplicates and 27 irrelevant and non–English-language URLs were excluded. The remaining 15 websites were analyzed. Based on a previously published and validated tool, a pro forma was designed to evaluate information on HQ for each website based on accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency (Table).1,3

Scores for all 15 websites are listed in eTable 1. The mean overall (total) score was

The mean display score was 0.3 (of a possible 4; range, 0–2); 66.7% of websites (10/15) had advertisements or irrelevant material. Only 6.7% and 13.3% of websites included relevant videos or images, respectively, on applying HQ (eTable 2). We identified only 3 photographs—across all 15 websites—that depicted skin, all of which were Fitzpatrick skin types II or III. Therefore, none of the websites included a diversity of images to indicate broad ethnic relatability.

The average support score was 2.5 (of a possible 4; range, 1–3); 20% (3/15) of URLs included chat sites, message boards, or forums, and approximately half (8/15 [53.3%]) included references. Only 7 URLs (46.7%) had been updated in the last 12 months. Only 4 (26.7%) were written by a board-certified dermatologist (eTable 2). Most (60%) websites contained advertising, though none were sponsored by a pharmaceutical company that manufactures HQ.

Only 46.7% (7/15) of websites recommended limiting a course of HQ treatment to 3 months; only 40% (6/15) mentioned shelf life or photochemical degradation when exposed to air. Although 93.3% (14/15) of URLs mentioned ochronosis, a clinical description of the condition was provided in only 33.3% (5/15)—none with images.

Only 2 sites (13.3%; Everyday Health and WebMD) met the accepted 7th-grade reading level for online patient education material; those sites scored lower on quality (9 of 17 and 6 of 17, respectively) than sites with higher overall scores.

None of the 15 websites studied, therefore, demonstrated optimal features on combined measures of accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency regarding HQ. Notably, the American Academy of Dermatology website (www.aad.org) was not among the 15 websites studied; the AAD website mentions HQ in a section on melasma, but only minimal detail is provided.

Limitations of this study include the small number of websites analyzed and possible selection bias because only 3 internet search engines were used to identify websites for study and analysis.

Previously, we analyzed content about HQ on the video-sharing and social media platform YouTube.4 The most viewed YouTube videos on HQ had poor-quality information (ie, only 20% mentioned ochronosis and only 28.6% recommended sunscreen [N=70]). However, average reading level of these videos was 7th grade.4,5 Therefore, YouTube HQ content, though comprehensible, generally is of poor quality.

By conducting a search for website content about HQ, we found that the most popular URLs had either accurate information with poor readability or lower-quality educational material that was more comprehensible. We conclude that there is a need to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality, up-to-date medical information; have been written by board-certified dermatologists; are comprehensible (ie, no more than approximately 1200 words and written at a 7th-grade reading level); and contain relevant clinical images and references. We encourage dermatologists to recognize the limitations of online patient education resources on HQ and educate patients on the proper use of the drug as well as its potential adverse effects

To the Editor:

The internet is a popular resource for patients seeking information about dermatologic treatments. Hydroquinone (HQ) cream 4% is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for skin hyperpigmentation.1 The agency enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform on September 25, 2020, to restrict distribution of OTC HQ.2 Exogenous ochronosis is listed as a potential adverse effect in the prescribing information for HQ.1

We sought to assess online resources on HQ for accuracy of information, including the recent OTC ban, as well as readability. The word hydroquinone was searched on 3 internet search engines—Google, Yahoo, and Bing—on December 12, 2020, each for the first 20 URLs (ie, websites)(total of 60 URLs). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA)(Figure) reporting guidelines were used to assess a list of relevant websites to include in the final analysis. Website data were reviewed by both authors. Eighteen duplicates and 27 irrelevant and non–English-language URLs were excluded. The remaining 15 websites were analyzed. Based on a previously published and validated tool, a pro forma was designed to evaluate information on HQ for each website based on accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency (Table).1,3

Scores for all 15 websites are listed in eTable 1. The mean overall (total) score was

The mean display score was 0.3 (of a possible 4; range, 0–2); 66.7% of websites (10/15) had advertisements or irrelevant material. Only 6.7% and 13.3% of websites included relevant videos or images, respectively, on applying HQ (eTable 2). We identified only 3 photographs—across all 15 websites—that depicted skin, all of which were Fitzpatrick skin types II or III. Therefore, none of the websites included a diversity of images to indicate broad ethnic relatability.

The average support score was 2.5 (of a possible 4; range, 1–3); 20% (3/15) of URLs included chat sites, message boards, or forums, and approximately half (8/15 [53.3%]) included references. Only 7 URLs (46.7%) had been updated in the last 12 months. Only 4 (26.7%) were written by a board-certified dermatologist (eTable 2). Most (60%) websites contained advertising, though none were sponsored by a pharmaceutical company that manufactures HQ.

Only 46.7% (7/15) of websites recommended limiting a course of HQ treatment to 3 months; only 40% (6/15) mentioned shelf life or photochemical degradation when exposed to air. Although 93.3% (14/15) of URLs mentioned ochronosis, a clinical description of the condition was provided in only 33.3% (5/15)—none with images.

Only 2 sites (13.3%; Everyday Health and WebMD) met the accepted 7th-grade reading level for online patient education material; those sites scored lower on quality (9 of 17 and 6 of 17, respectively) than sites with higher overall scores.

None of the 15 websites studied, therefore, demonstrated optimal features on combined measures of accountability, quality, readability, display, support, and transparency regarding HQ. Notably, the American Academy of Dermatology website (www.aad.org) was not among the 15 websites studied; the AAD website mentions HQ in a section on melasma, but only minimal detail is provided.

Limitations of this study include the small number of websites analyzed and possible selection bias because only 3 internet search engines were used to identify websites for study and analysis.

Previously, we analyzed content about HQ on the video-sharing and social media platform YouTube.4 The most viewed YouTube videos on HQ had poor-quality information (ie, only 20% mentioned ochronosis and only 28.6% recommended sunscreen [N=70]). However, average reading level of these videos was 7th grade.4,5 Therefore, YouTube HQ content, though comprehensible, generally is of poor quality.

By conducting a search for website content about HQ, we found that the most popular URLs had either accurate information with poor readability or lower-quality educational material that was more comprehensible. We conclude that there is a need to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality, up-to-date medical information; have been written by board-certified dermatologists; are comprehensible (ie, no more than approximately 1200 words and written at a 7th-grade reading level); and contain relevant clinical images and references. We encourage dermatologists to recognize the limitations of online patient education resources on HQ and educate patients on the proper use of the drug as well as its potential adverse effects

- US National Library of Medicine. Label: hydroquinone cream. DailyMed website. Updated November 24, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=dc72c0b2-4505-4dcf-8a69-889cd9f41693

- US Congress. H.R.748 - CARES Act. 116th Congress (2019-2020). Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text?fbclid=IwAR3ZxGP6AKUl6ce-dlWSU6D5MfCLD576nWNBV5YTE7R2a0IdLY4Usw4oOv4

- Kang R, Lipner S. Evaluation of onychomycosis information on the internet. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:484-487.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Assessing the impact and educational value of YouTube as a source of information on hydroquinone: a content-quality and readability analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1-3. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782318

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003. Accessed May 19, 2022. http://lib.ncfh.org/pdfs/6617.pdf

- US National Library of Medicine. Label: hydroquinone cream. DailyMed website. Updated November 24, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=dc72c0b2-4505-4dcf-8a69-889cd9f41693

- US Congress. H.R.748 - CARES Act. 116th Congress (2019-2020). Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/748/text?fbclid=IwAR3ZxGP6AKUl6ce-dlWSU6D5MfCLD576nWNBV5YTE7R2a0IdLY4Usw4oOv4

- Kang R, Lipner S. Evaluation of onychomycosis information on the internet. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:484-487.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Assessing the impact and educational value of YouTube as a source of information on hydroquinone: a content-quality and readability analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020:1-3. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1782318

- Weiss BD. Health Literacy: A Manual for Clinicians. American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003. Accessed May 19, 2022. http://lib.ncfh.org/pdfs/6617.pdf

Practice Points

- Hydroquinone (HQ) 4% is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for skin hyperpigmentation including melasma.

- In September 2020, the FDA enforced the CARES (Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security) Act and OTC (over-the-counter) Monograph Reform, announcing that HQ is not classified as Category II/not generally recognized as safe and effective, thus prohibiting the distribution of OTC HQ products.

- Exogenous ochronosis is a potential side effect associated with HQ.

- There is a need for dermatologists to develop online patient education materials on HQ that are characterized by high-quality and up-to-date medical information.

California doctor to pay $9.5 million in Medicare, Medi-Cal fraud scheme

Part of the payment was a settlement in a civil case in which Minas Kochumian, MD, an internist who ran a solo practice in Northridge, Calif., was accused of submitting claims to Medicare and Medi-Cal for procedures, services, and tests that were never performed. The procedures he falsely billed for included injecting a medication for treating osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, draining tailbone cysts, and removal of various growths.

As part of the settlement, Dr. Kochumian admitted that he intentionally submitted false claims with the intent to deceive the United States and the State of California. The damages and penalties were possible under the federal False Claims Act and the California False Claims Act.

According to the Medical Board of California, Dr. Kochumian’s license is current and set to expire next July.

The allegations against Dr. Kochumian were first brought to the attention of authorities in a whistleblower lawsuit filed by Elize Oganesyan, Dr. Kochumian’s former medical assistant, and Damon Davies, former information technology consultant for the practice. Among her other duties, Ms. Oganesyan was responsible for verifying insurance eligibility and obtaining authorization for drugs, procedures, services, and tests.

The medical assistant first realized that something was amiss when a patient brought her a Medicare Explanation of Benefits document that included charges for an injection the practice had not administered, according to court records. Ms. Oganesyan then realized the clinic was filing claims for other services that were never provided. She stated in the original complaint that the clinic did not even have the necessary equipment for providing some of these tests — skin allergy tests, for example.

The False Claims Act permits private parties to sue on behalf of the government for false claims for government funds and to receive a share of any recovery. Ms. Oganesyan and Davies will receive more than $1.75 million as their share of the recovery. The whistleblowers’ claims for attorneys’ fees are not resolved by this settlement, according to a statement from the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Eastern District of California.

The $9.5 million payment includes $5.4 million owed by Dr. Kochumian as criminal restitution following his guilty plea to one count of healthcare fraud in a separate criminal case filed in the Central District of California. In addition to the fine, Dr. Kochumian was sentenced to 41 months in prison, according to a statement by California Attorney General Rob Bonta.

“When doctors misuse the state’s Medi-Cal funds, they violate their Hippocratic Oath by harming a program which exists to help California’s Medi-Cal population, including the elderly, the sick, and the vulnerable,” said Mr. Bonta. “Dr. Kochumian’s alleged misconduct violated the trust of the patients in his care, and he selfishly pocketed funds that would otherwise have gone toward critical publicly funded healthcare services.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Part of the payment was a settlement in a civil case in which Minas Kochumian, MD, an internist who ran a solo practice in Northridge, Calif., was accused of submitting claims to Medicare and Medi-Cal for procedures, services, and tests that were never performed. The procedures he falsely billed for included injecting a medication for treating osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, draining tailbone cysts, and removal of various growths.

As part of the settlement, Dr. Kochumian admitted that he intentionally submitted false claims with the intent to deceive the United States and the State of California. The damages and penalties were possible under the federal False Claims Act and the California False Claims Act.

According to the Medical Board of California, Dr. Kochumian’s license is current and set to expire next July.

The allegations against Dr. Kochumian were first brought to the attention of authorities in a whistleblower lawsuit filed by Elize Oganesyan, Dr. Kochumian’s former medical assistant, and Damon Davies, former information technology consultant for the practice. Among her other duties, Ms. Oganesyan was responsible for verifying insurance eligibility and obtaining authorization for drugs, procedures, services, and tests.

The medical assistant first realized that something was amiss when a patient brought her a Medicare Explanation of Benefits document that included charges for an injection the practice had not administered, according to court records. Ms. Oganesyan then realized the clinic was filing claims for other services that were never provided. She stated in the original complaint that the clinic did not even have the necessary equipment for providing some of these tests — skin allergy tests, for example.

The False Claims Act permits private parties to sue on behalf of the government for false claims for government funds and to receive a share of any recovery. Ms. Oganesyan and Davies will receive more than $1.75 million as their share of the recovery. The whistleblowers’ claims for attorneys’ fees are not resolved by this settlement, according to a statement from the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Eastern District of California.

The $9.5 million payment includes $5.4 million owed by Dr. Kochumian as criminal restitution following his guilty plea to one count of healthcare fraud in a separate criminal case filed in the Central District of California. In addition to the fine, Dr. Kochumian was sentenced to 41 months in prison, according to a statement by California Attorney General Rob Bonta.

“When doctors misuse the state’s Medi-Cal funds, they violate their Hippocratic Oath by harming a program which exists to help California’s Medi-Cal population, including the elderly, the sick, and the vulnerable,” said Mr. Bonta. “Dr. Kochumian’s alleged misconduct violated the trust of the patients in his care, and he selfishly pocketed funds that would otherwise have gone toward critical publicly funded healthcare services.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Part of the payment was a settlement in a civil case in which Minas Kochumian, MD, an internist who ran a solo practice in Northridge, Calif., was accused of submitting claims to Medicare and Medi-Cal for procedures, services, and tests that were never performed. The procedures he falsely billed for included injecting a medication for treating osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, draining tailbone cysts, and removal of various growths.

As part of the settlement, Dr. Kochumian admitted that he intentionally submitted false claims with the intent to deceive the United States and the State of California. The damages and penalties were possible under the federal False Claims Act and the California False Claims Act.

According to the Medical Board of California, Dr. Kochumian’s license is current and set to expire next July.

The allegations against Dr. Kochumian were first brought to the attention of authorities in a whistleblower lawsuit filed by Elize Oganesyan, Dr. Kochumian’s former medical assistant, and Damon Davies, former information technology consultant for the practice. Among her other duties, Ms. Oganesyan was responsible for verifying insurance eligibility and obtaining authorization for drugs, procedures, services, and tests.

The medical assistant first realized that something was amiss when a patient brought her a Medicare Explanation of Benefits document that included charges for an injection the practice had not administered, according to court records. Ms. Oganesyan then realized the clinic was filing claims for other services that were never provided. She stated in the original complaint that the clinic did not even have the necessary equipment for providing some of these tests — skin allergy tests, for example.

The False Claims Act permits private parties to sue on behalf of the government for false claims for government funds and to receive a share of any recovery. Ms. Oganesyan and Davies will receive more than $1.75 million as their share of the recovery. The whistleblowers’ claims for attorneys’ fees are not resolved by this settlement, according to a statement from the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Eastern District of California.

The $9.5 million payment includes $5.4 million owed by Dr. Kochumian as criminal restitution following his guilty plea to one count of healthcare fraud in a separate criminal case filed in the Central District of California. In addition to the fine, Dr. Kochumian was sentenced to 41 months in prison, according to a statement by California Attorney General Rob Bonta.

“When doctors misuse the state’s Medi-Cal funds, they violate their Hippocratic Oath by harming a program which exists to help California’s Medi-Cal population, including the elderly, the sick, and the vulnerable,” said Mr. Bonta. “Dr. Kochumian’s alleged misconduct violated the trust of the patients in his care, and he selfishly pocketed funds that would otherwise have gone toward critical publicly funded healthcare services.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Severe ipsilateral headache

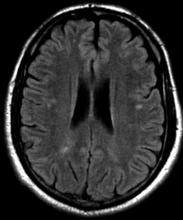

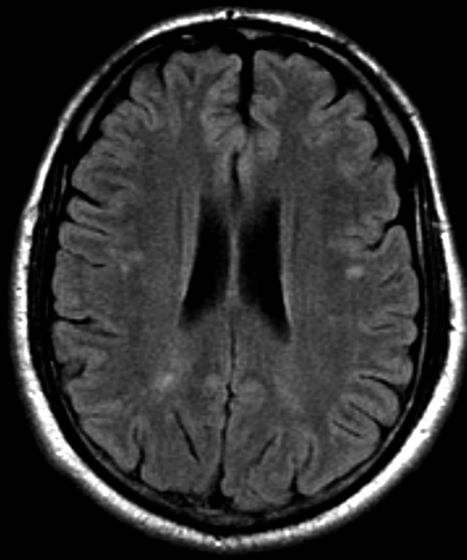

On the basis of the patient's presentation, family history, and personal history of headache, she seems to be presenting with hemiplegic migraine, an uncommon migraine subtype characterized by recurrent headaches associated with temporary unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia. The hemiparesis may resolve before the headache, as seen in the present case, or it may persist for days to weeks. These episodes are sometimes accompanied by ipsilateral numbness, tingling, or paresthesia, with or without a speech disturbance. Visual defects (ie, scintillating scotoma and hemianopia) and aphasia may occur.

Hemiplegic migraine can be sporadic or familial. Familial hemiplegic migraine is the only migraine subtype for which an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance has been identified. The onset is generally in adolescence between 12 and 17 years of age, with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%. Female patients are more likely to have these types of migraines.

Diagnosis of hemiplegic migraine is centered on exclusion of other possible causes of headache with motor weakness. When a patient presents with motor deficit, these symptoms can also be the result of a secondary headache rather than a primary headache disorder. Because of this neurologic aspect of presentation, the differential diagnosis is broad and should span other migraine subtypes, inflammatory or metabolic disorders, and mitochondrial diseases, as well as any condition that shows neurologic deficits without radiologic alterations. Pediatric patients with hemiplegic migraine are often misdiagnosed with epilepsy. Compared with hemiplegic migraine, seizures are much more brief, and any associated hemiparesis is usually characterized by limb jerking, head turning, and loss of consciousness. Of note, up to 7% of patients with familial hemiplegic migraine do eventually develop epilepsy. Although there are no telltale pathognomonic clinical, laboratory, or radiologic findings of hemiplegic migraine, electroencephalography may show asymmetric slow-wave activity contralateral to the hemiparesis.

In hemiplegic migraine, acute treatment options include antiemetics, NSAIDs, and nonnarcotic pain relievers; triptans and ergotamine preparations are contraindicated in this setting because of their potential vasoconstrictive effects. Even if episode frequency is low, the American Headache Society advises that prophylactic treatment should also be considered in the management of uncommon migraine subtypes such as this one.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation, family history, and personal history of headache, she seems to be presenting with hemiplegic migraine, an uncommon migraine subtype characterized by recurrent headaches associated with temporary unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia. The hemiparesis may resolve before the headache, as seen in the present case, or it may persist for days to weeks. These episodes are sometimes accompanied by ipsilateral numbness, tingling, or paresthesia, with or without a speech disturbance. Visual defects (ie, scintillating scotoma and hemianopia) and aphasia may occur.

Hemiplegic migraine can be sporadic or familial. Familial hemiplegic migraine is the only migraine subtype for which an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance has been identified. The onset is generally in adolescence between 12 and 17 years of age, with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%. Female patients are more likely to have these types of migraines.

Diagnosis of hemiplegic migraine is centered on exclusion of other possible causes of headache with motor weakness. When a patient presents with motor deficit, these symptoms can also be the result of a secondary headache rather than a primary headache disorder. Because of this neurologic aspect of presentation, the differential diagnosis is broad and should span other migraine subtypes, inflammatory or metabolic disorders, and mitochondrial diseases, as well as any condition that shows neurologic deficits without radiologic alterations. Pediatric patients with hemiplegic migraine are often misdiagnosed with epilepsy. Compared with hemiplegic migraine, seizures are much more brief, and any associated hemiparesis is usually characterized by limb jerking, head turning, and loss of consciousness. Of note, up to 7% of patients with familial hemiplegic migraine do eventually develop epilepsy. Although there are no telltale pathognomonic clinical, laboratory, or radiologic findings of hemiplegic migraine, electroencephalography may show asymmetric slow-wave activity contralateral to the hemiparesis.

In hemiplegic migraine, acute treatment options include antiemetics, NSAIDs, and nonnarcotic pain relievers; triptans and ergotamine preparations are contraindicated in this setting because of their potential vasoconstrictive effects. Even if episode frequency is low, the American Headache Society advises that prophylactic treatment should also be considered in the management of uncommon migraine subtypes such as this one.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

On the basis of the patient's presentation, family history, and personal history of headache, she seems to be presenting with hemiplegic migraine, an uncommon migraine subtype characterized by recurrent headaches associated with temporary unilateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia. The hemiparesis may resolve before the headache, as seen in the present case, or it may persist for days to weeks. These episodes are sometimes accompanied by ipsilateral numbness, tingling, or paresthesia, with or without a speech disturbance. Visual defects (ie, scintillating scotoma and hemianopia) and aphasia may occur.

Hemiplegic migraine can be sporadic or familial. Familial hemiplegic migraine is the only migraine subtype for which an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance has been identified. The onset is generally in adolescence between 12 and 17 years of age, with an estimated prevalence of 0.01%. Female patients are more likely to have these types of migraines.

Diagnosis of hemiplegic migraine is centered on exclusion of other possible causes of headache with motor weakness. When a patient presents with motor deficit, these symptoms can also be the result of a secondary headache rather than a primary headache disorder. Because of this neurologic aspect of presentation, the differential diagnosis is broad and should span other migraine subtypes, inflammatory or metabolic disorders, and mitochondrial diseases, as well as any condition that shows neurologic deficits without radiologic alterations. Pediatric patients with hemiplegic migraine are often misdiagnosed with epilepsy. Compared with hemiplegic migraine, seizures are much more brief, and any associated hemiparesis is usually characterized by limb jerking, head turning, and loss of consciousness. Of note, up to 7% of patients with familial hemiplegic migraine do eventually develop epilepsy. Although there are no telltale pathognomonic clinical, laboratory, or radiologic findings of hemiplegic migraine, electroencephalography may show asymmetric slow-wave activity contralateral to the hemiparesis.

In hemiplegic migraine, acute treatment options include antiemetics, NSAIDs, and nonnarcotic pain relievers; triptans and ergotamine preparations are contraindicated in this setting because of their potential vasoconstrictive effects. Even if episode frequency is low, the American Headache Society advises that prophylactic treatment should also be considered in the management of uncommon migraine subtypes such as this one.

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, Headache Fellow, Department of Neurology, Harvard University, John R. Graham Headache Center, Mass General Brigham, Boston, MA

Jasmin Harpe, MD, MPH, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 16-year-old female patient presents with a severe ipsilateral headache. She describes that before the onset of head pain, she felt like she could not control her facial muscles on one side, and she was unable to speak in full sentences. She reports that these symptoms probably lasted an hour or so, and she was worried that she was experiencing an allergic reaction, though she reports no known allergies. In terms of family history, the patient explains that she does not have a close relationship with her father, but she recalls that he experienced similar episodes. She notes a history of frequent and recurrent headaches, varying in severity, for which she usually takes a high dose of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Cutaneous Body Image: How the Mental Health Benefits of Treating Dermatologic Disease Support Military Readiness in Service Members

According to the US Department of Defense, the term readiness refers to the ability to recruit, train, deploy, and sustain military forces that will be ready to “fight tonight” and succeed in combat. Readiness is a top priority for military medicine, which functions to diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate service members so that they can return to the fight. This central concept drives programs across the military—from operational training events to the establishment of medical and dental standards. Readiness is tracked and scrutinized constantly, and although it is a shared responsibility, efforts to increase and sustain readiness often fall on support staff and military medical providers.

In recent years, there has been a greater awareness of the negative effects of mental illness, low morale, and suicidality on military readiness. In 2013, suicide accounted for 28.1% of all deaths that occurred in the US Armed Forces.1 Put frankly, suicide was one of the leading causes of death among military members.

The most recent Marine Corps Order regarding the Marine Corps Suicide Prevention Program stated that “suicidal behaviors are a barrier to readiness that have lasting effects on Marines and Service Members attached to Marine Commands. . .Families, and the Marine Corps.” It goes on to say that “[e]ffective suicide prevention requires coordinated efforts within a prevention framework dedicated to promoting mental, physical, spiritual, and social fitness. . .[and] mitigating stressors that interfere with mission readiness.”2 This statement supports the notion that preventing suicide is not just about treating mental illness; it also involves maximizing physical, spiritual, and social fitness. Although it is well established that various mental health disorders are associated with an increased risk for suicide, it is worth noting that, in one study, only half of individuals who died by suicide had a mental health disorder diagnosed prior to their death.3 These statistics translate to the military. The 2015 Department of Defense Suicide Event Report noted that only 28% of service members who died by suicide and 22% of members with attempted suicide had been documented as having sought mental health care and disclosed their potential for self-harm prior to the event.1,4 In 2018, a study published by Ursano et al5 showed that 36.3% of US soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (N=9650) had no prior mental health diagnoses.

Expanding the scope to include mental health issues in general, only 29% of service members who reported experiencing a mental health problem actually sought mental health care in that same period. Overall, approximately 40% of service members with a reported perceived need for mental health care actually sought care over their entire course of service time,1 which raises concern for a large population of undiagnosed and undertreated mental illnesses across the military. In response to these statistics, Reger et al3 posited that it is “essential that suicide prevention efforts move outside the silo of mental health.” The authors went on to challenge health care providers across all specialties and civilians alike to take responsibility in understanding, recognizing, and mitigating risk factors for suicide in the general population.3 Although treating a service member’s acne or offering to stand duty for a service member who has been under a great deal of stress in their personal life may appear to be indirect ways of reducing suicide in the US military, they actually may be the most critical means of prevention in a culture that emphasizes resilience and self-reliance, where seeking help for mental health struggles could be perceived as weakness.1

In this review article, we discuss the concept of cutaneous body image (CBI) and its associated outcomes on health, satisfaction, and quality of life in military service members. We then examine the intersections between common dermatologic conditions, CBI, and mental health and explore the ability and role of the military dermatologist to serve as a positive influence on military readiness.

What is cutaneous body image?

Cutaneous body image is “the individual’s mental perception of his or her skin and its appendages (ie, hair, nails).”6 It is measured objectively using the Cutaneous Body Image Scale, a questionnaire that includes 7 items related to the overall satisfaction with the appearance of skin, color of skin, skin of the face, complexion of the face, hair, fingernails, and toenails. Each question is rated using a 10-point Likert scale (0=not at all; 10=very markedly).6

Some degree of CBI dissatisfaction is expected and has been shown in the general population at large; for example, more than 56% of women older than 30 years report some degree of dissatisfaction with their skin. Similarly, data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that while 10.9 million cosmetic procedures were performed in 2006, 9.1 million of them involved minimally invasive procedures such as botulinum toxin type A injections with the purpose of skin rejuvenation and improvement of facial appearance.7 However, lower than average CBI can contribute to considerable psychosocial morbidity. Dissatisfaction with CBI is associated with self-consciousness, feelings of inferiority, and social exclusion. These symptoms can be grouped into a construct called interpersonal sensitivity (IS). A 2013 study by Gupta and Gupta6 investigated the relationship between CBI, IS, and suicidal ideation among 312 consenting nonclinical participants in Canada. The study found that greater dissatisfaction with an individual’s CBI correlated to increased IS and increased rates of suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury.6

Cutaneous body image is particularly relevant to dermatologists, as many common dermatoses can cause cosmetically disfiguring skin conditions; for example, acne and rosacea have the propensity to cause notable disfigurement to the facial unit. Other common conditions such as atopic dermatitis or psoriasis can flare with stress and thereby throw patients into a vicious cycle of physical and psychosocial stress caused by social stigma, cosmetic disfigurement, and reduced CBI, in turn leading to worsening of the disease at hand. Dermatologists need to be aware that common dermatoses can impact a patient’s mental health via poor CBI.8 Similarly, dermatologists may be empowered by the awareness that treating common dermatoses, especially those associated with poor cosmesis, have 2-fold benefits—on the skin condition itself and on the patient’s mental health.

How are common dermatoses associated with mental health?

Acne—Acne is one of the most common skin diseases, so much so that in many cases acne has become an accepted and expected part of adolescence and young adulthood. Studies estimate that 85% of the US population aged 12 to 25 years have acne.9 For some adults, acne persists even longer, with 1% to 5% of adults reporting to have active lesions at 40 years of age.10 Acne is a multifactorial skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit that results in the development of inflammatory papules, pustules, and cysts. These lesions are most common on the face but can extend to other areas of the body, such as the chest and back.11 Although the active lesions can be painful and disfiguring, if left untreated, acne may lead to permanent disfigurement and scarring, which can have long-lasting psychosocial impacts.

Individuals with acne have an increased likelihood of self-consciousness, social isolation, depression, and suicidal ideation. This relationship has been well established for decades. In the 1990s, a small study reported that 7 of 16 (43.8%) cases of completed suicide in dermatology patients were in patients with acne.12 In a recent meta-analysis including 2,276,798 participants across 5 separate studies, researchers found that suicide was positively associated with acne, carrying an odds ratio of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.09-2.06).13

Rosacea—Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by facial erythema, telangiectasia, phymatous changes, papules, pustules, and ocular irritation. The estimated worldwide prevalence is 5.5%.14 In addition to discomfort and irritation of the skin and eyes, rosacea often carries a higher risk of psychological and psychosocial distress due to its potentially disfiguring nature. Rosacea patients are at greater risk for having anxiety disorders and depression,15 and a 2018 study by Alinia et al16 showed that there is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and the actual level of depression.Although disease improvement certainly leads to improvements in quality of life and psychosocial status, Alinia et al16 noted that depression often is associated with poor treatment adherence due to poor motivation and hopelessness. It is critical that dermatologists are aware of these associations and maintain close follow-up with patients, even when the condition is not life-threatening, such as rosacea.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit that is characterized by the development of painful, malodorous, draining abscesses, fistulas, sinus tracts, and scars in sensitive areas such as the axillae, breasts, groin, and perineum.17 In severe cases, surgery may be required to excise affected areas. Compared to other cutaneous disease, HS is considered one of the most life-impacting disorders.18 The physical symptoms themselves often are debilitating, and patients often report considerable psychosocial and psychological impairment with decreased quality of life. Major depression frequently is noted, with 1 in 4 adults with HS also being depressed. In a large cross-sectional analysis of 38,140 adults and 1162 pediatric patients with HS, Wright et al17 reported the prevalence of depression among adults with HS as 30.0% compared to 16.9% in healthy controls. In children, the prevalence of depression was 11.7% compared to 4.1% in the general population.17 Similarly, 1 out of every 5 patients with HS experiences anxiety.18

In the military population, HS often can be duty limiting. The disease requires constant attention to wound care and frequent medical visits. For many service members operating in field training or combat environments, opportunities for and access to showers and basic hygiene is limited. Uniforms and additional necessary combat gear often are thick and occlusive. Taken as a whole, these factors may contribute to worsening of the disease and in severe cases are simply not conducive to the successful management of the condition. However, given the most commonly involved body areas and the nature of the disease, many service members with HS may feel embarrassed to disclose their condition. In uniform, the disease is not easily visible, and for unaware persons, the frequency of medical visits and limited duty status may seem unnecessary. This perception of a service member’s lack of productivity due to an unseen disease may further add to the psychosocial stress they experience.

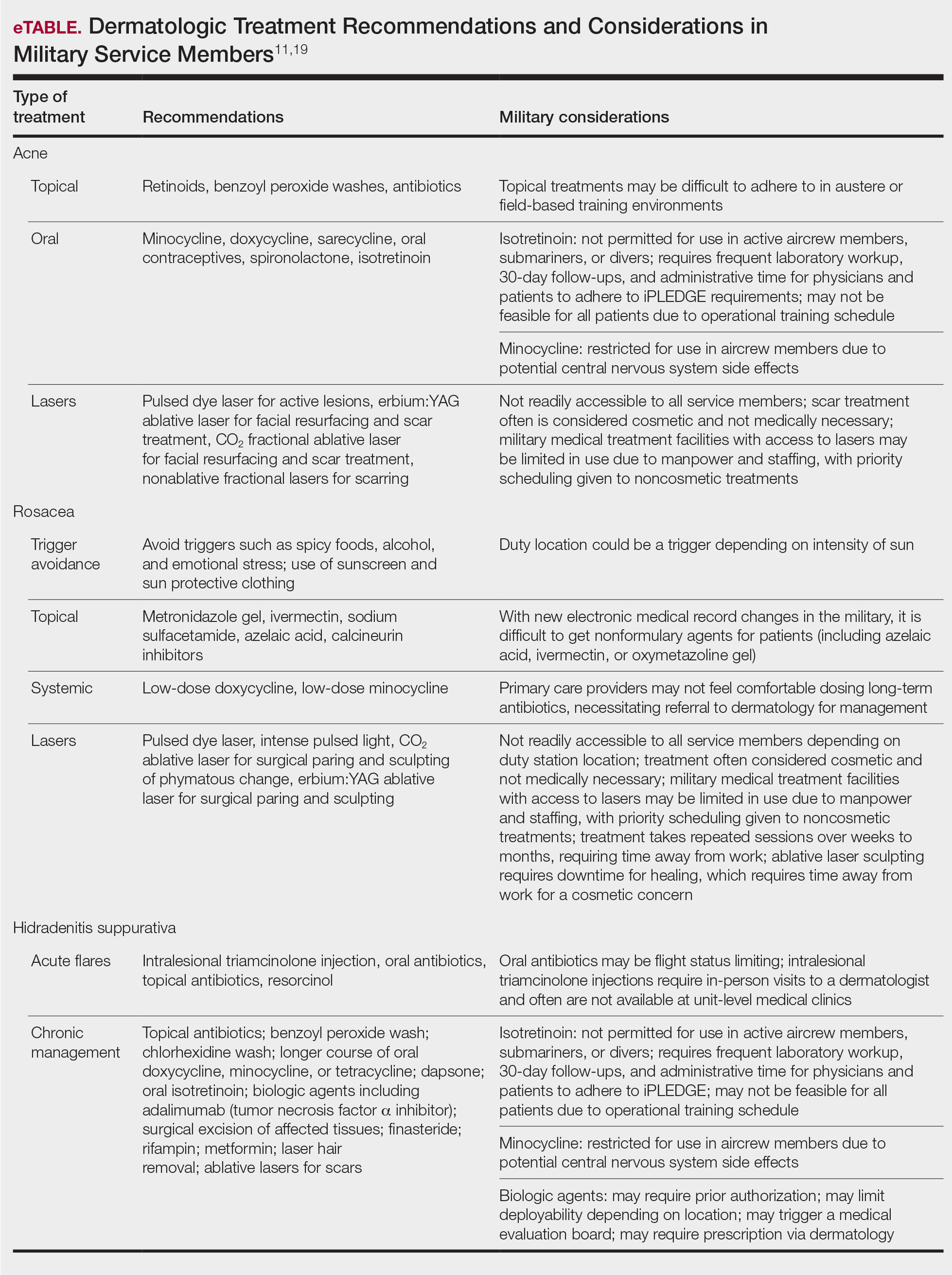

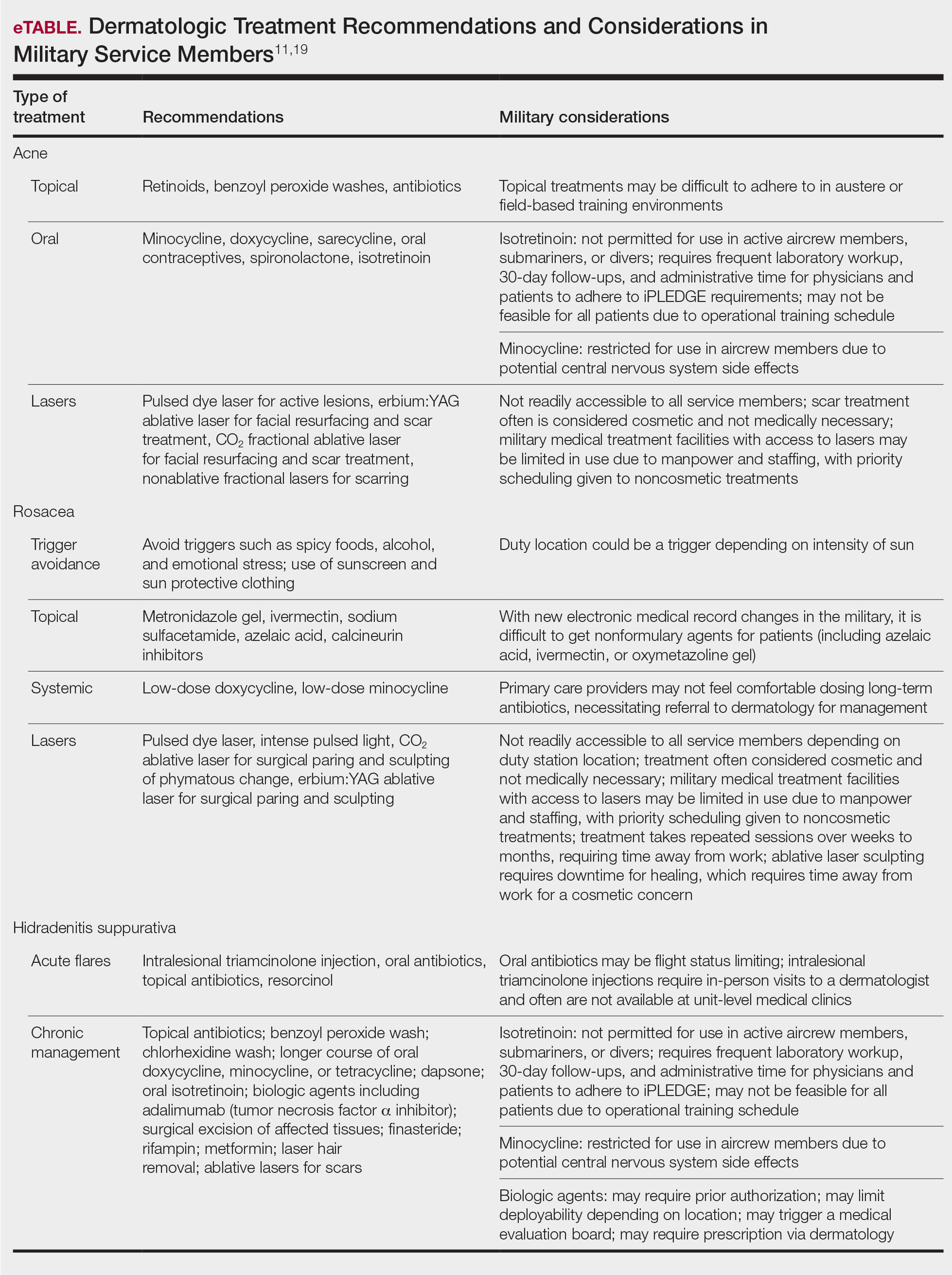

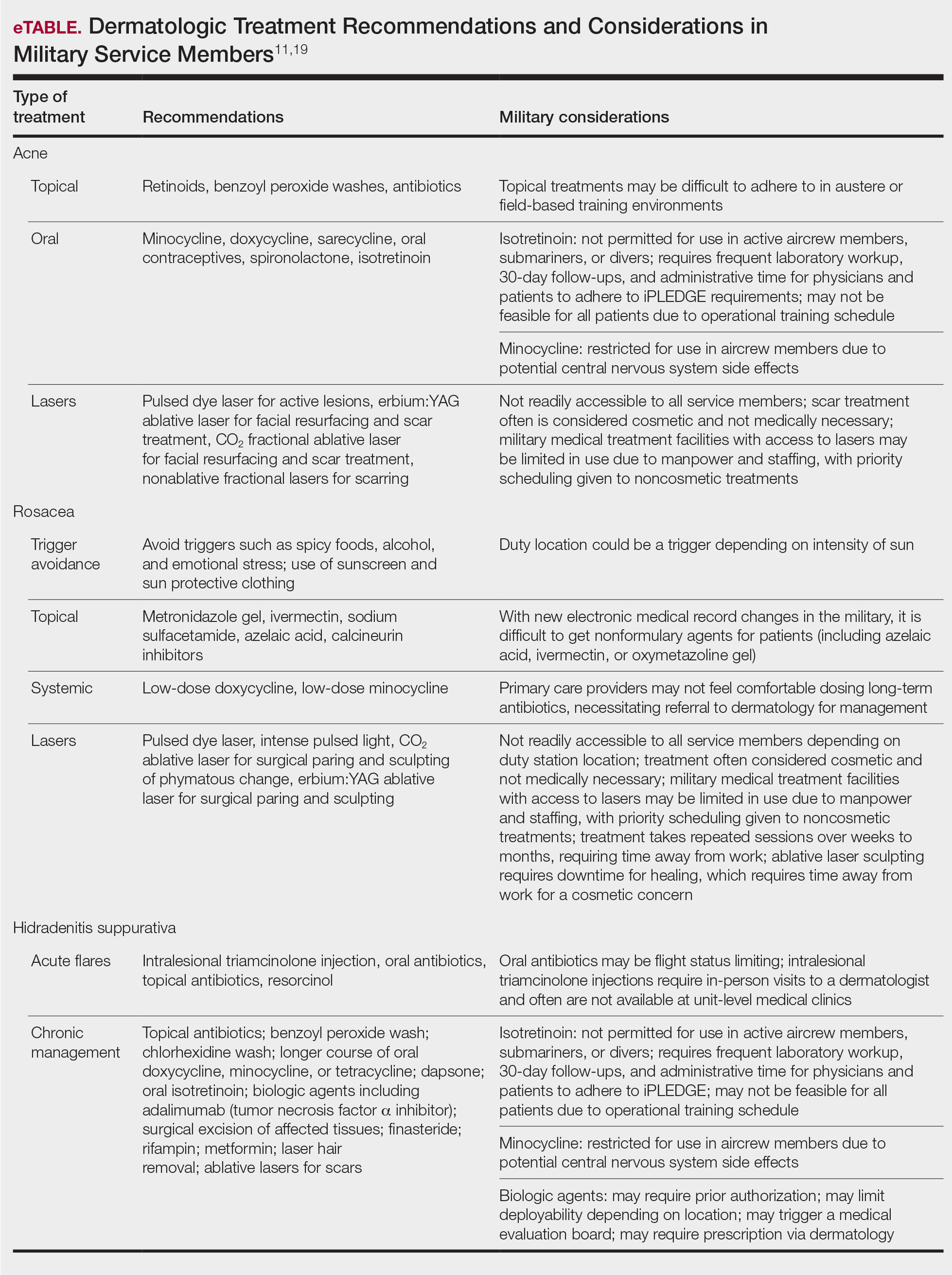

The treatments for acne, rosacea, and HS are outlined in the eTable.11,19 Also noted are specific considerations when managing an active-duty service member due to various operational duty restrictions and constraints.

Final Thoughts

Maintaining readiness in the military is essential to the ability to not only “fight tonight” but also to win tonight in whatever operational or combat mission a service member may be. Although many factors impact readiness, the rates of suicide within the armed forces cannot be ignored. Suicide not only eliminates the readiness of the deceased service member but has lasting ripple effects on the overall readiness of their unit and command at large. Most suicides in the military occur in personnel with no prior documented mental health diagnoses or treatment. Therefore, it is the responsibility of all service members to recognize and mitigate stressors and risk factors that may lead to mental health distress and suicidality. In the medical corps, this translates to a responsibility of all medical specialists to recognize and understand unique risk factors for suicidality and to do as much as they can to reduce these risks. For military dermatologists and for civilian physicians treating military service members, it is imperative to predict and understand the relationship between common dermatoses; reduced satisfaction with CBI; and increased risk for mental health illness, self-harm, and suicide. Military dermatologists, as well as other specialists, may be limited in the care they are able to provide due to manpower, staffing, demand, and institutional guidelines; however, to better serve those who serve in a holistic manner, consideration must be given to rethink what is “medically essential” and “cosmetic” and leverage the available skills, techniques, and equipment to increase the readiness of the force.

- Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, LaCroix JM, Koss K, et al. Outpatient mental health treatment utilization and military career impact in the United States Marine Corps. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:828. doi:10.3390/ijerph15040828

- Ottignon DA. Marine Corps Suicide Prevention System (MCSPS). Marine Corps Order 1720.2A. 2021. Headquarters United States Marine Corps. Published August 2, 2021. Accessed May 25, 2022. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/MCO%201720.2A.pdf?ver=QPxZ_qMS-X-d037B65N9Tg%3d%3d

- Reger MA, Smolenski DJ, Carter SP. Suicide prevention in the US Army: a mission for more than mental health clinicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:991-992. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2042

- Pruitt LD, Smolenski DJ, Bush NE, et al. Department of Defense Suicide Event Report Calendar Year 2015 Annual Report. National Center for Telehealth & Technology (T2); 2016. Accessed May 20, 2022. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Centers-of-Excellence/Psychological-Health-Center-of-Excellence/Department-of-Defense-Suicide-Event-Report

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Naifeh JA, et al. Risk factors associated with attempted suicide among US Army soldiers without a history of mental health diagnosis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:1022-1032. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2069

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Cutaneous body image dissatisfaction and suicidal ideation: mediation by interpersonal sensitivity. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:55-59. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.01.015

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Evaluation of cutaneous body image dissatisfaction in the dermatology patient. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:72-79. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.11.010

- Hinkley SB, Holub SC, Menter A. The validity of cutaneous body image as a construct and as a mediator of the relationship between cutaneous disease and mental health. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:203-211. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00351-5

- Stamu-O’Brien C, Jafferany M, Carniciu S, et al. Psychodermatology of acne: psychological aspects and effects of acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:1080-1083. doi:10.1111/jocd.13765

- Sood S, Jafferany M, Vinaya Kumar S. Depression, psychiatric comorbidities, and psychosocial implications associated with acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:3177-3182. doi:10.1111/jocd.13753

- Brahe C, Peters K. Fighting acne for the fighting forces. Cutis. 2020;106:18-20, 22. doi:10.12788/cutis.0057

- Cotterill JA, Cunliffe WJ. Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:246-250.

- Xu S, Zhu Y, Hu H, et al. The analysis of acne increasing suicide risk. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:E26035. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000026035

- Chen M, Deng Z, Huang Y, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of anxiety and depression in rosacea patients: a cross-sectional study in China [published online June 16, 2021]. Front Psychiatry. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.659171

- Incel Uysal P, Akdogan N, Hayran Y, et al. Rosacea associated with increased risk of generalized anxiety disorder: a case-control study of prevalence and risk of anxiety in patients with rosacea. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:704-709. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.03.002

- Alinia H, Cardwell LA, Tuchayi SM, et al. Screening for depression in rosacea patients. Cutis. 2018;102:36-38.

- Wright S, Strunk A, Garg A. Prevalence of depression among children, adolescents, and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa [published online June 16, 2021]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.843

- Misitzis A, Goldust M, Jafferany M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13541. doi:10.1111/dth.13541

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017.

According to the US Department of Defense, the term readiness refers to the ability to recruit, train, deploy, and sustain military forces that will be ready to “fight tonight” and succeed in combat. Readiness is a top priority for military medicine, which functions to diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate service members so that they can return to the fight. This central concept drives programs across the military—from operational training events to the establishment of medical and dental standards. Readiness is tracked and scrutinized constantly, and although it is a shared responsibility, efforts to increase and sustain readiness often fall on support staff and military medical providers.

In recent years, there has been a greater awareness of the negative effects of mental illness, low morale, and suicidality on military readiness. In 2013, suicide accounted for 28.1% of all deaths that occurred in the US Armed Forces.1 Put frankly, suicide was one of the leading causes of death among military members.

The most recent Marine Corps Order regarding the Marine Corps Suicide Prevention Program stated that “suicidal behaviors are a barrier to readiness that have lasting effects on Marines and Service Members attached to Marine Commands. . .Families, and the Marine Corps.” It goes on to say that “[e]ffective suicide prevention requires coordinated efforts within a prevention framework dedicated to promoting mental, physical, spiritual, and social fitness. . .[and] mitigating stressors that interfere with mission readiness.”2 This statement supports the notion that preventing suicide is not just about treating mental illness; it also involves maximizing physical, spiritual, and social fitness. Although it is well established that various mental health disorders are associated with an increased risk for suicide, it is worth noting that, in one study, only half of individuals who died by suicide had a mental health disorder diagnosed prior to their death.3 These statistics translate to the military. The 2015 Department of Defense Suicide Event Report noted that only 28% of service members who died by suicide and 22% of members with attempted suicide had been documented as having sought mental health care and disclosed their potential for self-harm prior to the event.1,4 In 2018, a study published by Ursano et al5 showed that 36.3% of US soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (N=9650) had no prior mental health diagnoses.

Expanding the scope to include mental health issues in general, only 29% of service members who reported experiencing a mental health problem actually sought mental health care in that same period. Overall, approximately 40% of service members with a reported perceived need for mental health care actually sought care over their entire course of service time,1 which raises concern for a large population of undiagnosed and undertreated mental illnesses across the military. In response to these statistics, Reger et al3 posited that it is “essential that suicide prevention efforts move outside the silo of mental health.” The authors went on to challenge health care providers across all specialties and civilians alike to take responsibility in understanding, recognizing, and mitigating risk factors for suicide in the general population.3 Although treating a service member’s acne or offering to stand duty for a service member who has been under a great deal of stress in their personal life may appear to be indirect ways of reducing suicide in the US military, they actually may be the most critical means of prevention in a culture that emphasizes resilience and self-reliance, where seeking help for mental health struggles could be perceived as weakness.1

In this review article, we discuss the concept of cutaneous body image (CBI) and its associated outcomes on health, satisfaction, and quality of life in military service members. We then examine the intersections between common dermatologic conditions, CBI, and mental health and explore the ability and role of the military dermatologist to serve as a positive influence on military readiness.

What is cutaneous body image?

Cutaneous body image is “the individual’s mental perception of his or her skin and its appendages (ie, hair, nails).”6 It is measured objectively using the Cutaneous Body Image Scale, a questionnaire that includes 7 items related to the overall satisfaction with the appearance of skin, color of skin, skin of the face, complexion of the face, hair, fingernails, and toenails. Each question is rated using a 10-point Likert scale (0=not at all; 10=very markedly).6

Some degree of CBI dissatisfaction is expected and has been shown in the general population at large; for example, more than 56% of women older than 30 years report some degree of dissatisfaction with their skin. Similarly, data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that while 10.9 million cosmetic procedures were performed in 2006, 9.1 million of them involved minimally invasive procedures such as botulinum toxin type A injections with the purpose of skin rejuvenation and improvement of facial appearance.7 However, lower than average CBI can contribute to considerable psychosocial morbidity. Dissatisfaction with CBI is associated with self-consciousness, feelings of inferiority, and social exclusion. These symptoms can be grouped into a construct called interpersonal sensitivity (IS). A 2013 study by Gupta and Gupta6 investigated the relationship between CBI, IS, and suicidal ideation among 312 consenting nonclinical participants in Canada. The study found that greater dissatisfaction with an individual’s CBI correlated to increased IS and increased rates of suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury.6

Cutaneous body image is particularly relevant to dermatologists, as many common dermatoses can cause cosmetically disfiguring skin conditions; for example, acne and rosacea have the propensity to cause notable disfigurement to the facial unit. Other common conditions such as atopic dermatitis or psoriasis can flare with stress and thereby throw patients into a vicious cycle of physical and psychosocial stress caused by social stigma, cosmetic disfigurement, and reduced CBI, in turn leading to worsening of the disease at hand. Dermatologists need to be aware that common dermatoses can impact a patient’s mental health via poor CBI.8 Similarly, dermatologists may be empowered by the awareness that treating common dermatoses, especially those associated with poor cosmesis, have 2-fold benefits—on the skin condition itself and on the patient’s mental health.

How are common dermatoses associated with mental health?

Acne—Acne is one of the most common skin diseases, so much so that in many cases acne has become an accepted and expected part of adolescence and young adulthood. Studies estimate that 85% of the US population aged 12 to 25 years have acne.9 For some adults, acne persists even longer, with 1% to 5% of adults reporting to have active lesions at 40 years of age.10 Acne is a multifactorial skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit that results in the development of inflammatory papules, pustules, and cysts. These lesions are most common on the face but can extend to other areas of the body, such as the chest and back.11 Although the active lesions can be painful and disfiguring, if left untreated, acne may lead to permanent disfigurement and scarring, which can have long-lasting psychosocial impacts.

Individuals with acne have an increased likelihood of self-consciousness, social isolation, depression, and suicidal ideation. This relationship has been well established for decades. In the 1990s, a small study reported that 7 of 16 (43.8%) cases of completed suicide in dermatology patients were in patients with acne.12 In a recent meta-analysis including 2,276,798 participants across 5 separate studies, researchers found that suicide was positively associated with acne, carrying an odds ratio of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.09-2.06).13

Rosacea—Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by facial erythema, telangiectasia, phymatous changes, papules, pustules, and ocular irritation. The estimated worldwide prevalence is 5.5%.14 In addition to discomfort and irritation of the skin and eyes, rosacea often carries a higher risk of psychological and psychosocial distress due to its potentially disfiguring nature. Rosacea patients are at greater risk for having anxiety disorders and depression,15 and a 2018 study by Alinia et al16 showed that there is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and the actual level of depression.Although disease improvement certainly leads to improvements in quality of life and psychosocial status, Alinia et al16 noted that depression often is associated with poor treatment adherence due to poor motivation and hopelessness. It is critical that dermatologists are aware of these associations and maintain close follow-up with patients, even when the condition is not life-threatening, such as rosacea.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit that is characterized by the development of painful, malodorous, draining abscesses, fistulas, sinus tracts, and scars in sensitive areas such as the axillae, breasts, groin, and perineum.17 In severe cases, surgery may be required to excise affected areas. Compared to other cutaneous disease, HS is considered one of the most life-impacting disorders.18 The physical symptoms themselves often are debilitating, and patients often report considerable psychosocial and psychological impairment with decreased quality of life. Major depression frequently is noted, with 1 in 4 adults with HS also being depressed. In a large cross-sectional analysis of 38,140 adults and 1162 pediatric patients with HS, Wright et al17 reported the prevalence of depression among adults with HS as 30.0% compared to 16.9% in healthy controls. In children, the prevalence of depression was 11.7% compared to 4.1% in the general population.17 Similarly, 1 out of every 5 patients with HS experiences anxiety.18

In the military population, HS often can be duty limiting. The disease requires constant attention to wound care and frequent medical visits. For many service members operating in field training or combat environments, opportunities for and access to showers and basic hygiene is limited. Uniforms and additional necessary combat gear often are thick and occlusive. Taken as a whole, these factors may contribute to worsening of the disease and in severe cases are simply not conducive to the successful management of the condition. However, given the most commonly involved body areas and the nature of the disease, many service members with HS may feel embarrassed to disclose their condition. In uniform, the disease is not easily visible, and for unaware persons, the frequency of medical visits and limited duty status may seem unnecessary. This perception of a service member’s lack of productivity due to an unseen disease may further add to the psychosocial stress they experience.

The treatments for acne, rosacea, and HS are outlined in the eTable.11,19 Also noted are specific considerations when managing an active-duty service member due to various operational duty restrictions and constraints.

Final Thoughts

Maintaining readiness in the military is essential to the ability to not only “fight tonight” but also to win tonight in whatever operational or combat mission a service member may be. Although many factors impact readiness, the rates of suicide within the armed forces cannot be ignored. Suicide not only eliminates the readiness of the deceased service member but has lasting ripple effects on the overall readiness of their unit and command at large. Most suicides in the military occur in personnel with no prior documented mental health diagnoses or treatment. Therefore, it is the responsibility of all service members to recognize and mitigate stressors and risk factors that may lead to mental health distress and suicidality. In the medical corps, this translates to a responsibility of all medical specialists to recognize and understand unique risk factors for suicidality and to do as much as they can to reduce these risks. For military dermatologists and for civilian physicians treating military service members, it is imperative to predict and understand the relationship between common dermatoses; reduced satisfaction with CBI; and increased risk for mental health illness, self-harm, and suicide. Military dermatologists, as well as other specialists, may be limited in the care they are able to provide due to manpower, staffing, demand, and institutional guidelines; however, to better serve those who serve in a holistic manner, consideration must be given to rethink what is “medically essential” and “cosmetic” and leverage the available skills, techniques, and equipment to increase the readiness of the force.

According to the US Department of Defense, the term readiness refers to the ability to recruit, train, deploy, and sustain military forces that will be ready to “fight tonight” and succeed in combat. Readiness is a top priority for military medicine, which functions to diagnose, treat, and rehabilitate service members so that they can return to the fight. This central concept drives programs across the military—from operational training events to the establishment of medical and dental standards. Readiness is tracked and scrutinized constantly, and although it is a shared responsibility, efforts to increase and sustain readiness often fall on support staff and military medical providers.

In recent years, there has been a greater awareness of the negative effects of mental illness, low morale, and suicidality on military readiness. In 2013, suicide accounted for 28.1% of all deaths that occurred in the US Armed Forces.1 Put frankly, suicide was one of the leading causes of death among military members.

The most recent Marine Corps Order regarding the Marine Corps Suicide Prevention Program stated that “suicidal behaviors are a barrier to readiness that have lasting effects on Marines and Service Members attached to Marine Commands. . .Families, and the Marine Corps.” It goes on to say that “[e]ffective suicide prevention requires coordinated efforts within a prevention framework dedicated to promoting mental, physical, spiritual, and social fitness. . .[and] mitigating stressors that interfere with mission readiness.”2 This statement supports the notion that preventing suicide is not just about treating mental illness; it also involves maximizing physical, spiritual, and social fitness. Although it is well established that various mental health disorders are associated with an increased risk for suicide, it is worth noting that, in one study, only half of individuals who died by suicide had a mental health disorder diagnosed prior to their death.3 These statistics translate to the military. The 2015 Department of Defense Suicide Event Report noted that only 28% of service members who died by suicide and 22% of members with attempted suicide had been documented as having sought mental health care and disclosed their potential for self-harm prior to the event.1,4 In 2018, a study published by Ursano et al5 showed that 36.3% of US soldiers with a documented suicide attempt (N=9650) had no prior mental health diagnoses.

Expanding the scope to include mental health issues in general, only 29% of service members who reported experiencing a mental health problem actually sought mental health care in that same period. Overall, approximately 40% of service members with a reported perceived need for mental health care actually sought care over their entire course of service time,1 which raises concern for a large population of undiagnosed and undertreated mental illnesses across the military. In response to these statistics, Reger et al3 posited that it is “essential that suicide prevention efforts move outside the silo of mental health.” The authors went on to challenge health care providers across all specialties and civilians alike to take responsibility in understanding, recognizing, and mitigating risk factors for suicide in the general population.3 Although treating a service member’s acne or offering to stand duty for a service member who has been under a great deal of stress in their personal life may appear to be indirect ways of reducing suicide in the US military, they actually may be the most critical means of prevention in a culture that emphasizes resilience and self-reliance, where seeking help for mental health struggles could be perceived as weakness.1

In this review article, we discuss the concept of cutaneous body image (CBI) and its associated outcomes on health, satisfaction, and quality of life in military service members. We then examine the intersections between common dermatologic conditions, CBI, and mental health and explore the ability and role of the military dermatologist to serve as a positive influence on military readiness.

What is cutaneous body image?

Cutaneous body image is “the individual’s mental perception of his or her skin and its appendages (ie, hair, nails).”6 It is measured objectively using the Cutaneous Body Image Scale, a questionnaire that includes 7 items related to the overall satisfaction with the appearance of skin, color of skin, skin of the face, complexion of the face, hair, fingernails, and toenails. Each question is rated using a 10-point Likert scale (0=not at all; 10=very markedly).6

Some degree of CBI dissatisfaction is expected and has been shown in the general population at large; for example, more than 56% of women older than 30 years report some degree of dissatisfaction with their skin. Similarly, data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons showed that while 10.9 million cosmetic procedures were performed in 2006, 9.1 million of them involved minimally invasive procedures such as botulinum toxin type A injections with the purpose of skin rejuvenation and improvement of facial appearance.7 However, lower than average CBI can contribute to considerable psychosocial morbidity. Dissatisfaction with CBI is associated with self-consciousness, feelings of inferiority, and social exclusion. These symptoms can be grouped into a construct called interpersonal sensitivity (IS). A 2013 study by Gupta and Gupta6 investigated the relationship between CBI, IS, and suicidal ideation among 312 consenting nonclinical participants in Canada. The study found that greater dissatisfaction with an individual’s CBI correlated to increased IS and increased rates of suicidal ideation and intentional self-injury.6

Cutaneous body image is particularly relevant to dermatologists, as many common dermatoses can cause cosmetically disfiguring skin conditions; for example, acne and rosacea have the propensity to cause notable disfigurement to the facial unit. Other common conditions such as atopic dermatitis or psoriasis can flare with stress and thereby throw patients into a vicious cycle of physical and psychosocial stress caused by social stigma, cosmetic disfigurement, and reduced CBI, in turn leading to worsening of the disease at hand. Dermatologists need to be aware that common dermatoses can impact a patient’s mental health via poor CBI.8 Similarly, dermatologists may be empowered by the awareness that treating common dermatoses, especially those associated with poor cosmesis, have 2-fold benefits—on the skin condition itself and on the patient’s mental health.

How are common dermatoses associated with mental health?

Acne—Acne is one of the most common skin diseases, so much so that in many cases acne has become an accepted and expected part of adolescence and young adulthood. Studies estimate that 85% of the US population aged 12 to 25 years have acne.9 For some adults, acne persists even longer, with 1% to 5% of adults reporting to have active lesions at 40 years of age.10 Acne is a multifactorial skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit that results in the development of inflammatory papules, pustules, and cysts. These lesions are most common on the face but can extend to other areas of the body, such as the chest and back.11 Although the active lesions can be painful and disfiguring, if left untreated, acne may lead to permanent disfigurement and scarring, which can have long-lasting psychosocial impacts.

Individuals with acne have an increased likelihood of self-consciousness, social isolation, depression, and suicidal ideation. This relationship has been well established for decades. In the 1990s, a small study reported that 7 of 16 (43.8%) cases of completed suicide in dermatology patients were in patients with acne.12 In a recent meta-analysis including 2,276,798 participants across 5 separate studies, researchers found that suicide was positively associated with acne, carrying an odds ratio of 1.50 (95% CI, 1.09-2.06).13

Rosacea—Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by facial erythema, telangiectasia, phymatous changes, papules, pustules, and ocular irritation. The estimated worldwide prevalence is 5.5%.14 In addition to discomfort and irritation of the skin and eyes, rosacea often carries a higher risk of psychological and psychosocial distress due to its potentially disfiguring nature. Rosacea patients are at greater risk for having anxiety disorders and depression,15 and a 2018 study by Alinia et al16 showed that there is a direct relationship between rosacea severity and the actual level of depression.Although disease improvement certainly leads to improvements in quality of life and psychosocial status, Alinia et al16 noted that depression often is associated with poor treatment adherence due to poor motivation and hopelessness. It is critical that dermatologists are aware of these associations and maintain close follow-up with patients, even when the condition is not life-threatening, such as rosacea.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit that is characterized by the development of painful, malodorous, draining abscesses, fistulas, sinus tracts, and scars in sensitive areas such as the axillae, breasts, groin, and perineum.17 In severe cases, surgery may be required to excise affected areas. Compared to other cutaneous disease, HS is considered one of the most life-impacting disorders.18 The physical symptoms themselves often are debilitating, and patients often report considerable psychosocial and psychological impairment with decreased quality of life. Major depression frequently is noted, with 1 in 4 adults with HS also being depressed. In a large cross-sectional analysis of 38,140 adults and 1162 pediatric patients with HS, Wright et al17 reported the prevalence of depression among adults with HS as 30.0% compared to 16.9% in healthy controls. In children, the prevalence of depression was 11.7% compared to 4.1% in the general population.17 Similarly, 1 out of every 5 patients with HS experiences anxiety.18

In the military population, HS often can be duty limiting. The disease requires constant attention to wound care and frequent medical visits. For many service members operating in field training or combat environments, opportunities for and access to showers and basic hygiene is limited. Uniforms and additional necessary combat gear often are thick and occlusive. Taken as a whole, these factors may contribute to worsening of the disease and in severe cases are simply not conducive to the successful management of the condition. However, given the most commonly involved body areas and the nature of the disease, many service members with HS may feel embarrassed to disclose their condition. In uniform, the disease is not easily visible, and for unaware persons, the frequency of medical visits and limited duty status may seem unnecessary. This perception of a service member’s lack of productivity due to an unseen disease may further add to the psychosocial stress they experience.

The treatments for acne, rosacea, and HS are outlined in the eTable.11,19 Also noted are specific considerations when managing an active-duty service member due to various operational duty restrictions and constraints.

Final Thoughts