User login

AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines: Pharmacologic treatment of IBS

The American Gastroenterological Association has issued new guidelines for the medical treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

The guidelines, which are separated into one publication for IBS with constipation (IBS-C) and another for IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), are the first to advise clinicians in the usage of new, old, and over-the-counter drugs for IBS, according to a press release from the AGA.

“With more treatments available, physicians can tailor a personalized approach based on the symptoms a patient with IBS is experiencing,” AGA said.

Published simultaneously in Gastroenterology, the two guidelines describe a shared rationale for their creation, noting how the treatment landscape has changed since the AGA last issued IBS guidelines in 2014.

“New pharmacological treatments have become available and new evidence has accumulated about established treatments,” both guidelines stated. “The purpose of these guidelines is to provide evidence-based recommendations for the pharmacologic management” of individuals with IBS “based on a systematic and comprehensive synthesis of the literature.”

IBS-C

In the IBS-C guidelines, co–first authors Lin Chang, MD, AGAF, of the University of Los Angeles, and Shahnaz Sultan, MD, MHSc, AGAF, of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, noted that IBS-C accounts for “more than a third of IBS cases,” with patients frequently reporting “feeling self-conscious, avoiding sex, difficulty concentrating, [and] not feeling able to reach one’s full potential.”

They offered nine pharmacologic recommendations, eight of which are conditional, with certainty in evidence ranging from low to high.

The only strong recommendation with a high certainty in evidence is for linaclotide.

“Across four RCTs [randomized controlled trials], linaclotide improved global assessment of IBS-C symptoms (FDA responder), abdominal pain, complete spontaneous bowel movement response, as well as adequate global response,” Dr. Chang and colleagues wrote.

Conditional recommendations with moderate certainty in evidence are provided for tenapanor, plecanatide, tegaserod, and lubiprostone. Recommendations for polyethylene glycol laxatives, tricyclic antidepressants and antispasmodics are conditional and based on low-certainty evidence, as well as a conditional recommendation against selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, also based on low-certainty evidence.

IBS-D

The IBS-D guidelines, led by co–first authors Anthony Lembo, MD, AGAF, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and Dr. Sultan, includes eight conditional recommendations with certainty in evidence ranging from very low to moderate.

Drugs recommended based on moderate-certainty evidence include eluxadoline, alosetron, and rifaximin, with the added note that patients who respond to rifaximin but have recurrence should be treated again with rifaximin. Low-certainty evidence supported recommendations for tricyclic antidepressants, and antispasmodics. Very low–certainty evidence stands behind a recommendation for loperamide. Again, the panel made a conditional recommendation against SSRIs, also based on low-certainty evidence.

Shared decision-making

Both publications concluded with similar statements about the importance of shared decision-making, plus a practical mindset, in management of IBS.

“Acknowledging that multimodal treatments that include dietary and behavioral approaches in conjunction with drug therapy may provide maximal benefits and that treatment choices may be influenced by patient preferences, practitioners should engage in shared decision-making with patients when choosing the best therapy,” Dr. Lembo and colleagues wrote. “The importance of the patient-physician relationship is paramount in caring for individuals with IBS, and understanding patient preferences (for side-effect tolerability as well as cost) is valuable in choosing the right therapy.”

Both guidelines noted that some newer drugs for IBS have no generic alternative, and preauthorization may be required. Payer approval may depend on previous treatment failure with generic alternatives, they added.

The guidelines were commissioned and funded by the AGA Institute. The authors disclosed relationships with Ardelyx, Immunic, Protagonist, and others.

The American Gastroenterological Association has issued new guidelines for the medical treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

The guidelines, which are separated into one publication for IBS with constipation (IBS-C) and another for IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), are the first to advise clinicians in the usage of new, old, and over-the-counter drugs for IBS, according to a press release from the AGA.

“With more treatments available, physicians can tailor a personalized approach based on the symptoms a patient with IBS is experiencing,” AGA said.

Published simultaneously in Gastroenterology, the two guidelines describe a shared rationale for their creation, noting how the treatment landscape has changed since the AGA last issued IBS guidelines in 2014.

“New pharmacological treatments have become available and new evidence has accumulated about established treatments,” both guidelines stated. “The purpose of these guidelines is to provide evidence-based recommendations for the pharmacologic management” of individuals with IBS “based on a systematic and comprehensive synthesis of the literature.”

IBS-C

In the IBS-C guidelines, co–first authors Lin Chang, MD, AGAF, of the University of Los Angeles, and Shahnaz Sultan, MD, MHSc, AGAF, of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, noted that IBS-C accounts for “more than a third of IBS cases,” with patients frequently reporting “feeling self-conscious, avoiding sex, difficulty concentrating, [and] not feeling able to reach one’s full potential.”

They offered nine pharmacologic recommendations, eight of which are conditional, with certainty in evidence ranging from low to high.

The only strong recommendation with a high certainty in evidence is for linaclotide.

“Across four RCTs [randomized controlled trials], linaclotide improved global assessment of IBS-C symptoms (FDA responder), abdominal pain, complete spontaneous bowel movement response, as well as adequate global response,” Dr. Chang and colleagues wrote.

Conditional recommendations with moderate certainty in evidence are provided for tenapanor, plecanatide, tegaserod, and lubiprostone. Recommendations for polyethylene glycol laxatives, tricyclic antidepressants and antispasmodics are conditional and based on low-certainty evidence, as well as a conditional recommendation against selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, also based on low-certainty evidence.

IBS-D

The IBS-D guidelines, led by co–first authors Anthony Lembo, MD, AGAF, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and Dr. Sultan, includes eight conditional recommendations with certainty in evidence ranging from very low to moderate.

Drugs recommended based on moderate-certainty evidence include eluxadoline, alosetron, and rifaximin, with the added note that patients who respond to rifaximin but have recurrence should be treated again with rifaximin. Low-certainty evidence supported recommendations for tricyclic antidepressants, and antispasmodics. Very low–certainty evidence stands behind a recommendation for loperamide. Again, the panel made a conditional recommendation against SSRIs, also based on low-certainty evidence.

Shared decision-making

Both publications concluded with similar statements about the importance of shared decision-making, plus a practical mindset, in management of IBS.

“Acknowledging that multimodal treatments that include dietary and behavioral approaches in conjunction with drug therapy may provide maximal benefits and that treatment choices may be influenced by patient preferences, practitioners should engage in shared decision-making with patients when choosing the best therapy,” Dr. Lembo and colleagues wrote. “The importance of the patient-physician relationship is paramount in caring for individuals with IBS, and understanding patient preferences (for side-effect tolerability as well as cost) is valuable in choosing the right therapy.”

Both guidelines noted that some newer drugs for IBS have no generic alternative, and preauthorization may be required. Payer approval may depend on previous treatment failure with generic alternatives, they added.

The guidelines were commissioned and funded by the AGA Institute. The authors disclosed relationships with Ardelyx, Immunic, Protagonist, and others.

The American Gastroenterological Association has issued new guidelines for the medical treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

The guidelines, which are separated into one publication for IBS with constipation (IBS-C) and another for IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), are the first to advise clinicians in the usage of new, old, and over-the-counter drugs for IBS, according to a press release from the AGA.

“With more treatments available, physicians can tailor a personalized approach based on the symptoms a patient with IBS is experiencing,” AGA said.

Published simultaneously in Gastroenterology, the two guidelines describe a shared rationale for their creation, noting how the treatment landscape has changed since the AGA last issued IBS guidelines in 2014.

“New pharmacological treatments have become available and new evidence has accumulated about established treatments,” both guidelines stated. “The purpose of these guidelines is to provide evidence-based recommendations for the pharmacologic management” of individuals with IBS “based on a systematic and comprehensive synthesis of the literature.”

IBS-C

In the IBS-C guidelines, co–first authors Lin Chang, MD, AGAF, of the University of Los Angeles, and Shahnaz Sultan, MD, MHSc, AGAF, of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Healthcare System, noted that IBS-C accounts for “more than a third of IBS cases,” with patients frequently reporting “feeling self-conscious, avoiding sex, difficulty concentrating, [and] not feeling able to reach one’s full potential.”

They offered nine pharmacologic recommendations, eight of which are conditional, with certainty in evidence ranging from low to high.

The only strong recommendation with a high certainty in evidence is for linaclotide.

“Across four RCTs [randomized controlled trials], linaclotide improved global assessment of IBS-C symptoms (FDA responder), abdominal pain, complete spontaneous bowel movement response, as well as adequate global response,” Dr. Chang and colleagues wrote.

Conditional recommendations with moderate certainty in evidence are provided for tenapanor, plecanatide, tegaserod, and lubiprostone. Recommendations for polyethylene glycol laxatives, tricyclic antidepressants and antispasmodics are conditional and based on low-certainty evidence, as well as a conditional recommendation against selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, also based on low-certainty evidence.

IBS-D

The IBS-D guidelines, led by co–first authors Anthony Lembo, MD, AGAF, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and Dr. Sultan, includes eight conditional recommendations with certainty in evidence ranging from very low to moderate.

Drugs recommended based on moderate-certainty evidence include eluxadoline, alosetron, and rifaximin, with the added note that patients who respond to rifaximin but have recurrence should be treated again with rifaximin. Low-certainty evidence supported recommendations for tricyclic antidepressants, and antispasmodics. Very low–certainty evidence stands behind a recommendation for loperamide. Again, the panel made a conditional recommendation against SSRIs, also based on low-certainty evidence.

Shared decision-making

Both publications concluded with similar statements about the importance of shared decision-making, plus a practical mindset, in management of IBS.

“Acknowledging that multimodal treatments that include dietary and behavioral approaches in conjunction with drug therapy may provide maximal benefits and that treatment choices may be influenced by patient preferences, practitioners should engage in shared decision-making with patients when choosing the best therapy,” Dr. Lembo and colleagues wrote. “The importance of the patient-physician relationship is paramount in caring for individuals with IBS, and understanding patient preferences (for side-effect tolerability as well as cost) is valuable in choosing the right therapy.”

Both guidelines noted that some newer drugs for IBS have no generic alternative, and preauthorization may be required. Payer approval may depend on previous treatment failure with generic alternatives, they added.

The guidelines were commissioned and funded by the AGA Institute. The authors disclosed relationships with Ardelyx, Immunic, Protagonist, and others.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Long-term safety and efficacy of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Dupilumab showed an acceptable safety profile and sustained efficacy through 52 weeks in adolescents with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Rate of treatment emergent adverse events was 370.2 events/100 patient-years, with most being mild/moderate. At least 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index scores was achieved by 81.2% of patients receiving dupilumab at week 52 and 51.9% of patients who were uptitrated from every-4-week (q4w) to every-2-week (q2w) dosing regimen at week 48 after the first uptitration visit.

Study details: Findings are from an ongoing open-label extension study, LIBERTY AD PED-OLE, including 294 adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD who participated in previous dupilumab trials, received dupilumab q4w, and were uptitrated to the weight-tiered q2w dose regimen upon inadequate clinical response.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Eight authors declared being employees or shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals or Sanofi, and the other authors reported ties with various sources, including Sanofi and Regeneron.

Source: Blauvelt A et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results through week 52 from a phase III open-label extension trial (LIBERTY AD PED-OLE). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:365–383 (May 14). Doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00683-2

Key clinical point: Dupilumab showed an acceptable safety profile and sustained efficacy through 52 weeks in adolescents with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Rate of treatment emergent adverse events was 370.2 events/100 patient-years, with most being mild/moderate. At least 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index scores was achieved by 81.2% of patients receiving dupilumab at week 52 and 51.9% of patients who were uptitrated from every-4-week (q4w) to every-2-week (q2w) dosing regimen at week 48 after the first uptitration visit.

Study details: Findings are from an ongoing open-label extension study, LIBERTY AD PED-OLE, including 294 adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD who participated in previous dupilumab trials, received dupilumab q4w, and were uptitrated to the weight-tiered q2w dose regimen upon inadequate clinical response.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Eight authors declared being employees or shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals or Sanofi, and the other authors reported ties with various sources, including Sanofi and Regeneron.

Source: Blauvelt A et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results through week 52 from a phase III open-label extension trial (LIBERTY AD PED-OLE). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:365–383 (May 14). Doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00683-2

Key clinical point: Dupilumab showed an acceptable safety profile and sustained efficacy through 52 weeks in adolescents with inadequately controlled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: Rate of treatment emergent adverse events was 370.2 events/100 patient-years, with most being mild/moderate. At least 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index scores was achieved by 81.2% of patients receiving dupilumab at week 52 and 51.9% of patients who were uptitrated from every-4-week (q4w) to every-2-week (q2w) dosing regimen at week 48 after the first uptitration visit.

Study details: Findings are from an ongoing open-label extension study, LIBERTY AD PED-OLE, including 294 adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD who participated in previous dupilumab trials, received dupilumab q4w, and were uptitrated to the weight-tiered q2w dose regimen upon inadequate clinical response.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Eight authors declared being employees or shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals or Sanofi, and the other authors reported ties with various sources, including Sanofi and Regeneron.

Source: Blauvelt A et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results through week 52 from a phase III open-label extension trial (LIBERTY AD PED-OLE). Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:365–383 (May 14). Doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00683-2

Children and COVID: Vaccines now available to all ages

The COVID-19 prevention effort in children enters its next phase as June draws to a close, while new pediatric cases continued on a downward trend and hospitalizations continued to rise.

The COVID-19 vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna were approved for use in children as young as 6 months, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced on June 18.

“We know millions of parents and caregivers are eager to get their young children vaccinated. ... I encourage parents and caregivers with questions to talk to their doctor, nurse, or local pharmacist to learn more about the benefits of vaccinations,” CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, MPH, said in a written statement.

There are, however, indications that many parents are not that eager. Another 11% said “they will only do so if they are required,” Kaiser noted.

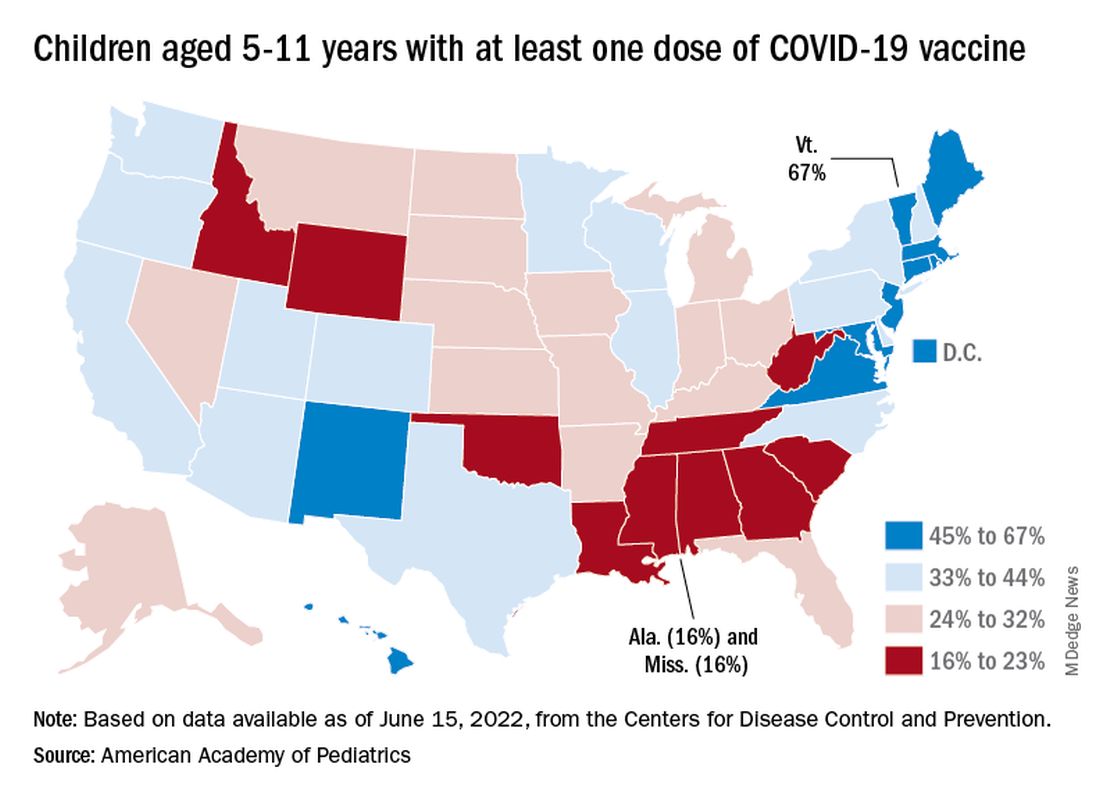

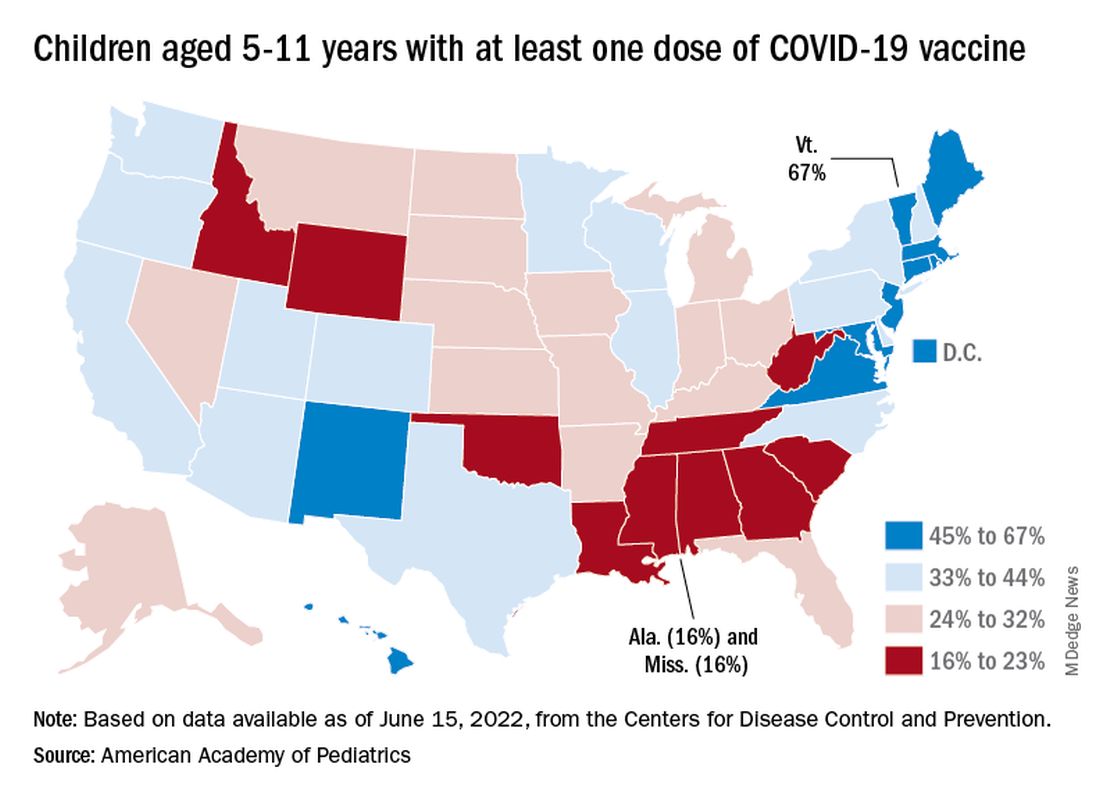

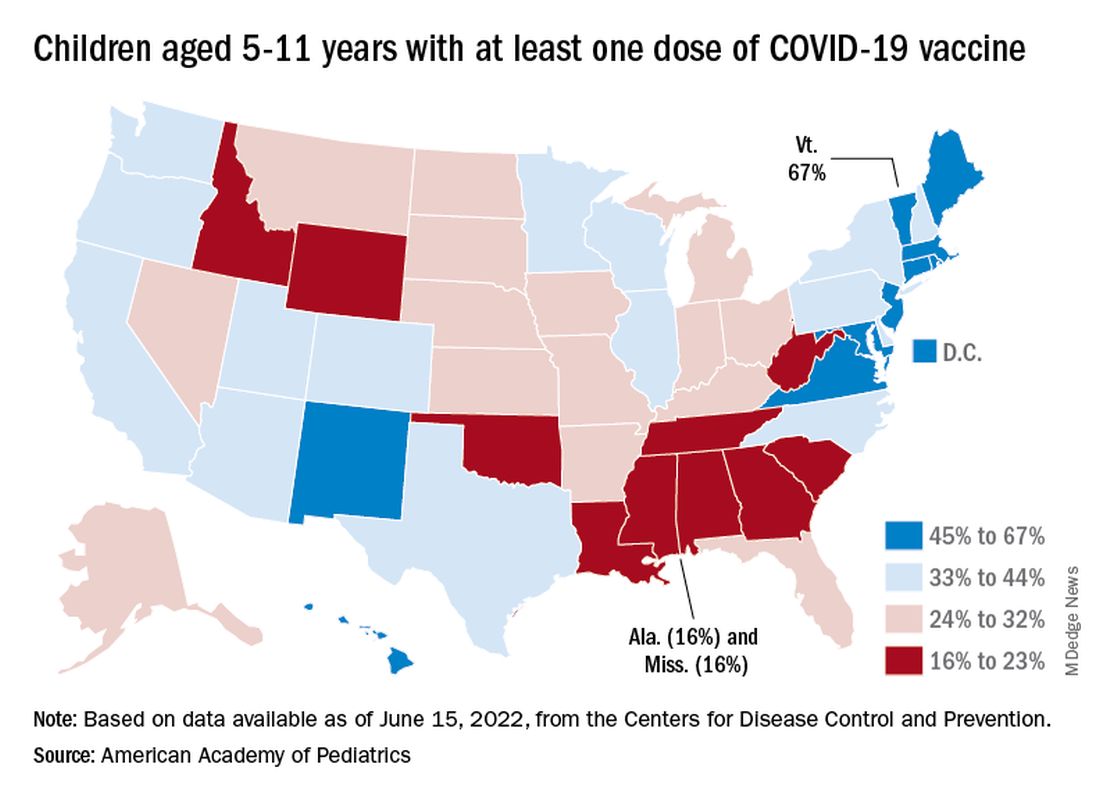

The vaccination experience with children aged 5-11 years seems to agree with those numbers. As of June 16, more than 7 months after the vaccine became available, just over 36% had received at least one dose and about 30% were fully vaccinated, CDC data show.

There are, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, still five states where less than 20% of eligible 5- to 11-year-olds have received an initial vaccination. Among children aged 12-17, uptake has been much higher: 70% have received at least one dose and 60% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

Trends for new cases, hospitalizations diverging

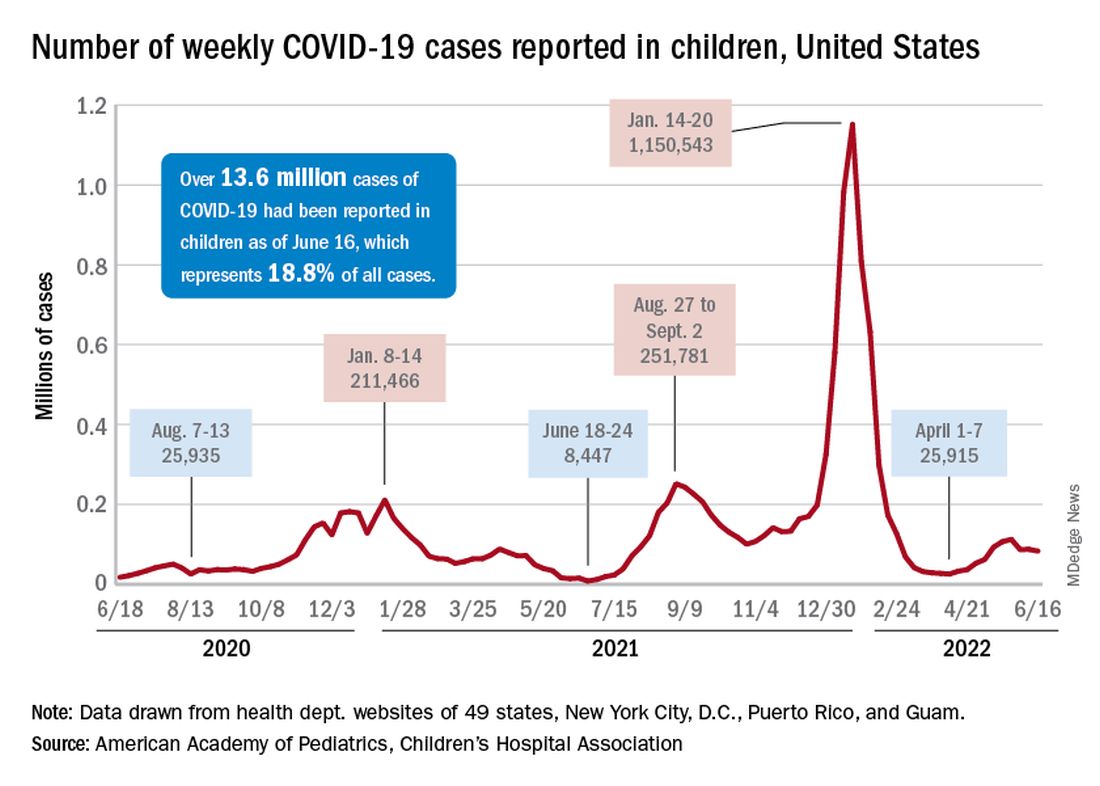

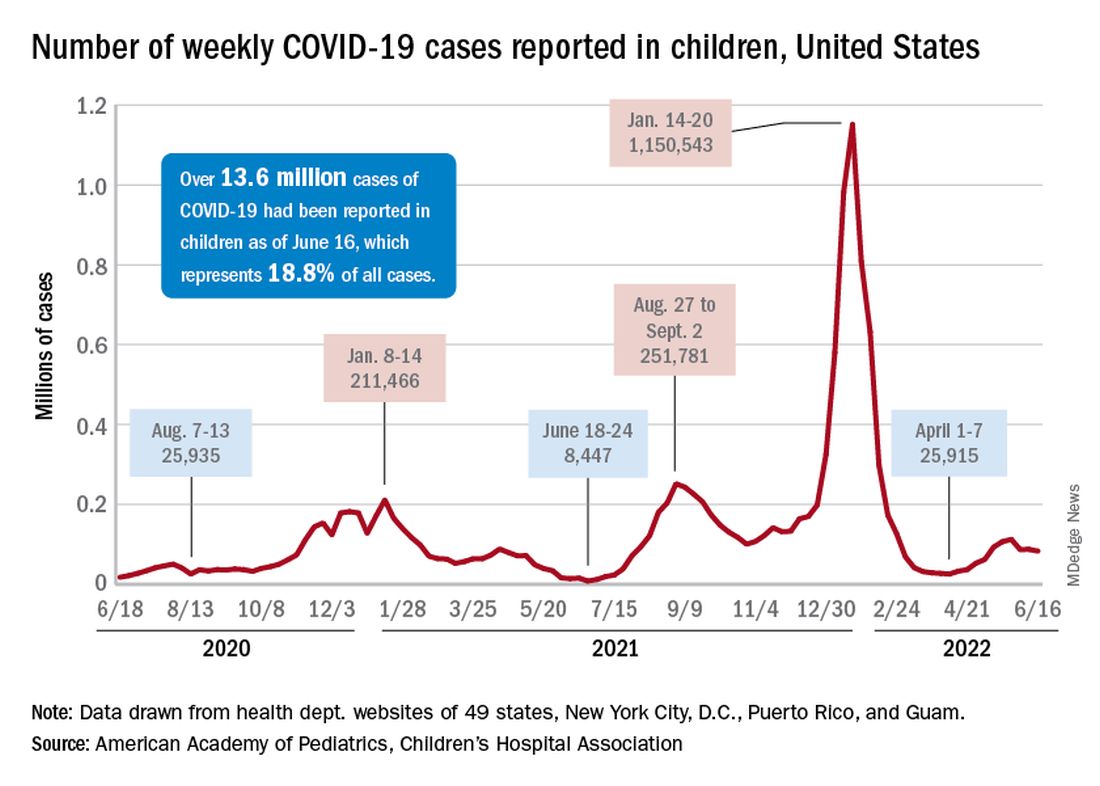

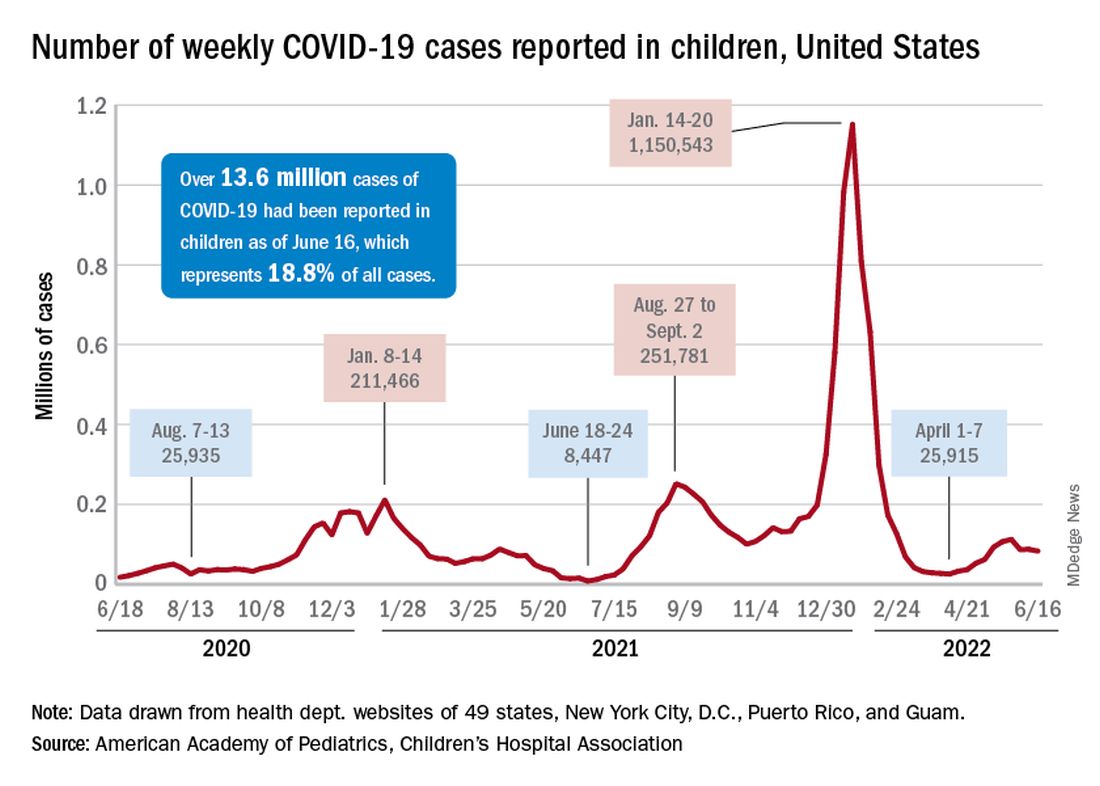

COVID incidence in children, meanwhile, dropped for the second time in 3 weeks. There were 83,000 new cases reported during June 10-16, a decline of 4.8% from the previous week, according to the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New cases had risen by a very slight 0.31% during the week of June 3-9 after dropping 22% the week before (May 27 to June 2). Total cases in children have surpassed 13.6 million, which represents 18.8% of cases in all ages since the start of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

New admissions of children with confirmed COVID-19, however, have continued to climb since early to mid April. On June 16, the rate for children aged 0-17 years was up to 0.31 per 100,000, compared with the 0.13 per 100,000 recorded as late as April 11, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The COVID-19 prevention effort in children enters its next phase as June draws to a close, while new pediatric cases continued on a downward trend and hospitalizations continued to rise.

The COVID-19 vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna were approved for use in children as young as 6 months, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced on June 18.

“We know millions of parents and caregivers are eager to get their young children vaccinated. ... I encourage parents and caregivers with questions to talk to their doctor, nurse, or local pharmacist to learn more about the benefits of vaccinations,” CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, MPH, said in a written statement.

There are, however, indications that many parents are not that eager. Another 11% said “they will only do so if they are required,” Kaiser noted.

The vaccination experience with children aged 5-11 years seems to agree with those numbers. As of June 16, more than 7 months after the vaccine became available, just over 36% had received at least one dose and about 30% were fully vaccinated, CDC data show.

There are, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, still five states where less than 20% of eligible 5- to 11-year-olds have received an initial vaccination. Among children aged 12-17, uptake has been much higher: 70% have received at least one dose and 60% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

Trends for new cases, hospitalizations diverging

COVID incidence in children, meanwhile, dropped for the second time in 3 weeks. There were 83,000 new cases reported during June 10-16, a decline of 4.8% from the previous week, according to the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New cases had risen by a very slight 0.31% during the week of June 3-9 after dropping 22% the week before (May 27 to June 2). Total cases in children have surpassed 13.6 million, which represents 18.8% of cases in all ages since the start of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

New admissions of children with confirmed COVID-19, however, have continued to climb since early to mid April. On June 16, the rate for children aged 0-17 years was up to 0.31 per 100,000, compared with the 0.13 per 100,000 recorded as late as April 11, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The COVID-19 prevention effort in children enters its next phase as June draws to a close, while new pediatric cases continued on a downward trend and hospitalizations continued to rise.

The COVID-19 vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna were approved for use in children as young as 6 months, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced on June 18.

“We know millions of parents and caregivers are eager to get their young children vaccinated. ... I encourage parents and caregivers with questions to talk to their doctor, nurse, or local pharmacist to learn more about the benefits of vaccinations,” CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky, MD, MPH, said in a written statement.

There are, however, indications that many parents are not that eager. Another 11% said “they will only do so if they are required,” Kaiser noted.

The vaccination experience with children aged 5-11 years seems to agree with those numbers. As of June 16, more than 7 months after the vaccine became available, just over 36% had received at least one dose and about 30% were fully vaccinated, CDC data show.

There are, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, still five states where less than 20% of eligible 5- to 11-year-olds have received an initial vaccination. Among children aged 12-17, uptake has been much higher: 70% have received at least one dose and 60% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

Trends for new cases, hospitalizations diverging

COVID incidence in children, meanwhile, dropped for the second time in 3 weeks. There were 83,000 new cases reported during June 10-16, a decline of 4.8% from the previous week, according to the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association.

New cases had risen by a very slight 0.31% during the week of June 3-9 after dropping 22% the week before (May 27 to June 2). Total cases in children have surpassed 13.6 million, which represents 18.8% of cases in all ages since the start of the pandemic, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

New admissions of children with confirmed COVID-19, however, have continued to climb since early to mid April. On June 16, the rate for children aged 0-17 years was up to 0.31 per 100,000, compared with the 0.13 per 100,000 recorded as late as April 11, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Baclofen shows limited role in GERD

A randomized clinical trial indicated that add-on baclofen may be of benefit to patients on adequate doses of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, the benefit was limited to a subset of patients with positive symptom association probability (SAP), which was calculated using 24-hour combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring (24h pH-MII).

“Empirical add-on therapy with baclofen in GERD patients with persisting typical symptoms in spite of double-dose PPI therapy does not seem justified. The use of baclofen should be limited to patients who display a positive SAP for typical reflux symptoms (heartburn and/or regurgitation) during PPI therapy,” researchers led by Ans Pauwels, PhD, MPharmSc, of the Catholic University of Leuven (Belgium) concluded in Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

Asked to comment, Philip Katz, MD, professor of medicine and director of GI Function Laboratories at Weill Cornell Medicine and a co-author of some recent GERD guidelines said, “What it tells me is that baclofen may be useful to a patient population that has an accurate diagnosis of reflux hypersensitivity. The difficulty with this study is that the patients you would expect to be helped by baclofen, which were patients who satisfied the criteria for true GERD, didn’t have any improvement.”

PPIs are effective at reducing acid reflux and promoting esophageal healing in GERD patients, but they have little effect on non-acid reflux. Heartburn is most often tied to acid reflux, but regurgitation occurs with similar frequency during both acid and non-acid episodes.

Up to 50% of patients still have reflux despite PPI treatment, and many of these patients will respond to higher PPI doses. However, those who don’t respond are left with few treatment choices.

Reflux events generally occur during transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLOSRs), and this mechanism is predominant in mild and moderate GERD. A gamma-aminobutyric acid type B receptor agonist, baclofen reduces TLOSRs and associated reflux episodes following meals. Few studies have examined the clinical potential of baclofen in refractory GERD, and it generally is only used after determining that ongoing weakly acidic reflux is responsible for symptoms, using 24h pH-MII.

The study included about 60 patients who underwent 24-hour monitoring while taking a PPI twice daily. Over a 2-week run-in period, participants filled out daily diaries and were randomized to placebo or baclofen 3 times daily over 4 weeks. The baclofen dose was 5 mg for the first week, then 10 mg for the next 3 weeks.

At the end of treatment, 24h pH-MII was repeated. The researchers found no significant decreases in non-acid reflux events after placebo treatment (corrected P = .74) and a trend towards a reduction following baclofen treatment (corrected P = .12).

Although the results won’t change his practice significantly, Dr. Katz congratulated the authors on the thoroughness of the study. However, he noted that wellbeing is a difficult endpoint to study: “The importance of this study to me is that it confirms that baclofen shouldn’t be used empirically, since there was no improvement in patients who were functional, and it was hard to find improvement in any group. This reinforces the need for a thorough work-up of the patient with GERD.”

The drug also had some tolerability issues: 16% of patients on baclofen discontinued its use because of adverse events such as drowsiness, dizziness, headache, and nausea.

An important limitation of the study is that the researchers recruited patients with persistent GERD symptoms despite use of PPIs. “Calling it refractory GERD is tricky because they didn’t prove they had GERD before they were enrolled in the study. That being said, the researchers did a very rigorous, very careful study to try and find potentially some place that baclofen might benefit patients,” said Dr. Katz.

The authors of the study and Dr. Katz have no relevant financial disclosures.

A randomized clinical trial indicated that add-on baclofen may be of benefit to patients on adequate doses of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, the benefit was limited to a subset of patients with positive symptom association probability (SAP), which was calculated using 24-hour combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring (24h pH-MII).

“Empirical add-on therapy with baclofen in GERD patients with persisting typical symptoms in spite of double-dose PPI therapy does not seem justified. The use of baclofen should be limited to patients who display a positive SAP for typical reflux symptoms (heartburn and/or regurgitation) during PPI therapy,” researchers led by Ans Pauwels, PhD, MPharmSc, of the Catholic University of Leuven (Belgium) concluded in Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

Asked to comment, Philip Katz, MD, professor of medicine and director of GI Function Laboratories at Weill Cornell Medicine and a co-author of some recent GERD guidelines said, “What it tells me is that baclofen may be useful to a patient population that has an accurate diagnosis of reflux hypersensitivity. The difficulty with this study is that the patients you would expect to be helped by baclofen, which were patients who satisfied the criteria for true GERD, didn’t have any improvement.”

PPIs are effective at reducing acid reflux and promoting esophageal healing in GERD patients, but they have little effect on non-acid reflux. Heartburn is most often tied to acid reflux, but regurgitation occurs with similar frequency during both acid and non-acid episodes.

Up to 50% of patients still have reflux despite PPI treatment, and many of these patients will respond to higher PPI doses. However, those who don’t respond are left with few treatment choices.

Reflux events generally occur during transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLOSRs), and this mechanism is predominant in mild and moderate GERD. A gamma-aminobutyric acid type B receptor agonist, baclofen reduces TLOSRs and associated reflux episodes following meals. Few studies have examined the clinical potential of baclofen in refractory GERD, and it generally is only used after determining that ongoing weakly acidic reflux is responsible for symptoms, using 24h pH-MII.

The study included about 60 patients who underwent 24-hour monitoring while taking a PPI twice daily. Over a 2-week run-in period, participants filled out daily diaries and were randomized to placebo or baclofen 3 times daily over 4 weeks. The baclofen dose was 5 mg for the first week, then 10 mg for the next 3 weeks.

At the end of treatment, 24h pH-MII was repeated. The researchers found no significant decreases in non-acid reflux events after placebo treatment (corrected P = .74) and a trend towards a reduction following baclofen treatment (corrected P = .12).

Although the results won’t change his practice significantly, Dr. Katz congratulated the authors on the thoroughness of the study. However, he noted that wellbeing is a difficult endpoint to study: “The importance of this study to me is that it confirms that baclofen shouldn’t be used empirically, since there was no improvement in patients who were functional, and it was hard to find improvement in any group. This reinforces the need for a thorough work-up of the patient with GERD.”

The drug also had some tolerability issues: 16% of patients on baclofen discontinued its use because of adverse events such as drowsiness, dizziness, headache, and nausea.

An important limitation of the study is that the researchers recruited patients with persistent GERD symptoms despite use of PPIs. “Calling it refractory GERD is tricky because they didn’t prove they had GERD before they were enrolled in the study. That being said, the researchers did a very rigorous, very careful study to try and find potentially some place that baclofen might benefit patients,” said Dr. Katz.

The authors of the study and Dr. Katz have no relevant financial disclosures.

A randomized clinical trial indicated that add-on baclofen may be of benefit to patients on adequate doses of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, the benefit was limited to a subset of patients with positive symptom association probability (SAP), which was calculated using 24-hour combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring (24h pH-MII).

“Empirical add-on therapy with baclofen in GERD patients with persisting typical symptoms in spite of double-dose PPI therapy does not seem justified. The use of baclofen should be limited to patients who display a positive SAP for typical reflux symptoms (heartburn and/or regurgitation) during PPI therapy,” researchers led by Ans Pauwels, PhD, MPharmSc, of the Catholic University of Leuven (Belgium) concluded in Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics.

Asked to comment, Philip Katz, MD, professor of medicine and director of GI Function Laboratories at Weill Cornell Medicine and a co-author of some recent GERD guidelines said, “What it tells me is that baclofen may be useful to a patient population that has an accurate diagnosis of reflux hypersensitivity. The difficulty with this study is that the patients you would expect to be helped by baclofen, which were patients who satisfied the criteria for true GERD, didn’t have any improvement.”

PPIs are effective at reducing acid reflux and promoting esophageal healing in GERD patients, but they have little effect on non-acid reflux. Heartburn is most often tied to acid reflux, but regurgitation occurs with similar frequency during both acid and non-acid episodes.

Up to 50% of patients still have reflux despite PPI treatment, and many of these patients will respond to higher PPI doses. However, those who don’t respond are left with few treatment choices.

Reflux events generally occur during transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLOSRs), and this mechanism is predominant in mild and moderate GERD. A gamma-aminobutyric acid type B receptor agonist, baclofen reduces TLOSRs and associated reflux episodes following meals. Few studies have examined the clinical potential of baclofen in refractory GERD, and it generally is only used after determining that ongoing weakly acidic reflux is responsible for symptoms, using 24h pH-MII.

The study included about 60 patients who underwent 24-hour monitoring while taking a PPI twice daily. Over a 2-week run-in period, participants filled out daily diaries and were randomized to placebo or baclofen 3 times daily over 4 weeks. The baclofen dose was 5 mg for the first week, then 10 mg for the next 3 weeks.

At the end of treatment, 24h pH-MII was repeated. The researchers found no significant decreases in non-acid reflux events after placebo treatment (corrected P = .74) and a trend towards a reduction following baclofen treatment (corrected P = .12).

Although the results won’t change his practice significantly, Dr. Katz congratulated the authors on the thoroughness of the study. However, he noted that wellbeing is a difficult endpoint to study: “The importance of this study to me is that it confirms that baclofen shouldn’t be used empirically, since there was no improvement in patients who were functional, and it was hard to find improvement in any group. This reinforces the need for a thorough work-up of the patient with GERD.”

The drug also had some tolerability issues: 16% of patients on baclofen discontinued its use because of adverse events such as drowsiness, dizziness, headache, and nausea.

An important limitation of the study is that the researchers recruited patients with persistent GERD symptoms despite use of PPIs. “Calling it refractory GERD is tricky because they didn’t prove they had GERD before they were enrolled in the study. That being said, the researchers did a very rigorous, very careful study to try and find potentially some place that baclofen might benefit patients,” said Dr. Katz.

The authors of the study and Dr. Katz have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM ALIMENTARY PHARMACOLOGY & THERAPEUTICS

Postherpetic Pink, Smooth, Annular Convalescing Plaques

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Annulare

A biopsy of a lesion on the right flank demonstrated granulomatous inflammation and interstitial mucin (Figure), characteristic of granuloma annulare (GA).1,2 Granuloma annulare is a relatively common skin disorder with an unknown etiology. It typically presents as smooth, annular, erythematous plaques.1 The most common variants of GA are localized, generalized, and subcutaneous. Our case demonstrated Wolf isotopic response, an unrelated skin disease that forms at the same location as a previously healed skin lesion.2 It is important to be aware of this phenomenon so that it is not confused with a recurrence of herpes zoster virus (HZV).

Although relatively infrequent, GA is the most common isotopic response following HZV infections.3-5 Other postherpetic isotopic eruptions include cutaneous malignancies, lichen planus, sarcoidosis, morphea, reactive perforating collagenosis, psoriasis, and infections, among others.3,5,6 The time between HZV infection and GA can be variable, ranging from a few weeks to many years apart.3

Oftentimes GA will spontaneously resolve within 2 years; however, recurrence is common.7-9 There currently are no standard treatment guidelines. The most promising treatment options include intralesional or topical glucocorticoids for localized GA as well as phototherapy or hydroxychloroquine for widespread disease.8,10

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (also called actinic granuloma) is a rare idiopathic inflammatory skin disease. It is characterized by erythematous annular papules or plaques mainly found on sun-exposed skin, such as the backs of the hands, forearms, or face.11,12 Therefore, based on the distribution of our patient’s lesions, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma was an unlikely diagnosis. Furthermore, it is not a known postherpetic isotopic reaction. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma can appear histologically similar to GA. Differentiating histologic features include a nonpalisading granuloma as well as the absence of mucin and necrobiosis.12

Annular lichen planus is a long-recognized but uncommon clinical variant of lichen planus that typically presents as pruritic, purple, annular plaques on the penis, scrotum, or intertriginous areas.13 The violaceous coloring is more characteristic of lichen planus. Histology is helpful in differentiating from GA.

Nummular eczema presents as scattered, welldefined, pruritic, erythematous, coin-shaped, coin-sized plaques in patients with diffusely dry skin.14 The scaling and serous crusting as well as more prominent pruritus help distinguish it from GA. The appearance of nummular eczema is quite characteristic; therefore, a biopsy typically is unnecessary for diagnosis. However, a potassium hydroxide wet mount examination of a skin scraping should be performed if tinea corporis also is suspected.

Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum classically presents as an annular or arciform pruritic lesion with an advancing outer erythematous edge with an inner rim of scale that most commonly occurs on the lower extremities. 15 The presence of pruritus and trailing scale helps distinguish this lesion from GA. Histologically, there are epidermal changes of hyperplasia, spongiosis, and parakeratosis, as well as lymphohistiocytic infiltrate surrounding the superficial dermal vessels.16

We report this case to highlight GA as the most common postherpetic isotopic response. It should be on the differential diagnosis when a patient presents with erythematous, smooth, annular plaques occurring in the distribution of a resolved case of HZV.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- . Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Kapoor R, Piris A, Saavedra AP, et al. Wolf isotopic response manifesting as postherpetic granuloma annulare: a case series. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:255-258.

- Ezra N, Ahdout J, Haley JC, et al. Granuloma annulare in a zoster scar of a patient with multiple myeloma. Cutis. 2011;87:240-244.

- Noh TW, Park SH, Kang YS, et al. Morphea developing at the site of healed herpes zoster. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:242-245.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpesvirus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Sparrow G, Abell E. Granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica treated by jet injector. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:85-89.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Thornsberry LA, English JC. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

- Rubin CB, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: a retrospective series of 133 patients. Cutis. 2019;103:102-106.

- Stein JA, Fangman B, Strober B. Actinic granuloma. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:19.

- Mistry AM, Patel R, Mistry M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cureus. 2020;12:E11456.

- Reich HL, Nguyen JT, James WD. Annular lichen planus: a case series of 20 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:595-599.

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Nummular eczema: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2020;14:146-155.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Coronel-Pérez IM, Morillo-Andújar M. Erythema annulare centrifugum responding to natural ultraviolet light [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:177-178.

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Annulare

A biopsy of a lesion on the right flank demonstrated granulomatous inflammation and interstitial mucin (Figure), characteristic of granuloma annulare (GA).1,2 Granuloma annulare is a relatively common skin disorder with an unknown etiology. It typically presents as smooth, annular, erythematous plaques.1 The most common variants of GA are localized, generalized, and subcutaneous. Our case demonstrated Wolf isotopic response, an unrelated skin disease that forms at the same location as a previously healed skin lesion.2 It is important to be aware of this phenomenon so that it is not confused with a recurrence of herpes zoster virus (HZV).

Although relatively infrequent, GA is the most common isotopic response following HZV infections.3-5 Other postherpetic isotopic eruptions include cutaneous malignancies, lichen planus, sarcoidosis, morphea, reactive perforating collagenosis, psoriasis, and infections, among others.3,5,6 The time between HZV infection and GA can be variable, ranging from a few weeks to many years apart.3

Oftentimes GA will spontaneously resolve within 2 years; however, recurrence is common.7-9 There currently are no standard treatment guidelines. The most promising treatment options include intralesional or topical glucocorticoids for localized GA as well as phototherapy or hydroxychloroquine for widespread disease.8,10

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (also called actinic granuloma) is a rare idiopathic inflammatory skin disease. It is characterized by erythematous annular papules or plaques mainly found on sun-exposed skin, such as the backs of the hands, forearms, or face.11,12 Therefore, based on the distribution of our patient’s lesions, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma was an unlikely diagnosis. Furthermore, it is not a known postherpetic isotopic reaction. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma can appear histologically similar to GA. Differentiating histologic features include a nonpalisading granuloma as well as the absence of mucin and necrobiosis.12

Annular lichen planus is a long-recognized but uncommon clinical variant of lichen planus that typically presents as pruritic, purple, annular plaques on the penis, scrotum, or intertriginous areas.13 The violaceous coloring is more characteristic of lichen planus. Histology is helpful in differentiating from GA.

Nummular eczema presents as scattered, welldefined, pruritic, erythematous, coin-shaped, coin-sized plaques in patients with diffusely dry skin.14 The scaling and serous crusting as well as more prominent pruritus help distinguish it from GA. The appearance of nummular eczema is quite characteristic; therefore, a biopsy typically is unnecessary for diagnosis. However, a potassium hydroxide wet mount examination of a skin scraping should be performed if tinea corporis also is suspected.

Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum classically presents as an annular or arciform pruritic lesion with an advancing outer erythematous edge with an inner rim of scale that most commonly occurs on the lower extremities. 15 The presence of pruritus and trailing scale helps distinguish this lesion from GA. Histologically, there are epidermal changes of hyperplasia, spongiosis, and parakeratosis, as well as lymphohistiocytic infiltrate surrounding the superficial dermal vessels.16

We report this case to highlight GA as the most common postherpetic isotopic response. It should be on the differential diagnosis when a patient presents with erythematous, smooth, annular plaques occurring in the distribution of a resolved case of HZV.

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Annulare

A biopsy of a lesion on the right flank demonstrated granulomatous inflammation and interstitial mucin (Figure), characteristic of granuloma annulare (GA).1,2 Granuloma annulare is a relatively common skin disorder with an unknown etiology. It typically presents as smooth, annular, erythematous plaques.1 The most common variants of GA are localized, generalized, and subcutaneous. Our case demonstrated Wolf isotopic response, an unrelated skin disease that forms at the same location as a previously healed skin lesion.2 It is important to be aware of this phenomenon so that it is not confused with a recurrence of herpes zoster virus (HZV).

Although relatively infrequent, GA is the most common isotopic response following HZV infections.3-5 Other postherpetic isotopic eruptions include cutaneous malignancies, lichen planus, sarcoidosis, morphea, reactive perforating collagenosis, psoriasis, and infections, among others.3,5,6 The time between HZV infection and GA can be variable, ranging from a few weeks to many years apart.3

Oftentimes GA will spontaneously resolve within 2 years; however, recurrence is common.7-9 There currently are no standard treatment guidelines. The most promising treatment options include intralesional or topical glucocorticoids for localized GA as well as phototherapy or hydroxychloroquine for widespread disease.8,10

Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma (also called actinic granuloma) is a rare idiopathic inflammatory skin disease. It is characterized by erythematous annular papules or plaques mainly found on sun-exposed skin, such as the backs of the hands, forearms, or face.11,12 Therefore, based on the distribution of our patient’s lesions, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma was an unlikely diagnosis. Furthermore, it is not a known postherpetic isotopic reaction. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma can appear histologically similar to GA. Differentiating histologic features include a nonpalisading granuloma as well as the absence of mucin and necrobiosis.12

Annular lichen planus is a long-recognized but uncommon clinical variant of lichen planus that typically presents as pruritic, purple, annular plaques on the penis, scrotum, or intertriginous areas.13 The violaceous coloring is more characteristic of lichen planus. Histology is helpful in differentiating from GA.

Nummular eczema presents as scattered, welldefined, pruritic, erythematous, coin-shaped, coin-sized plaques in patients with diffusely dry skin.14 The scaling and serous crusting as well as more prominent pruritus help distinguish it from GA. The appearance of nummular eczema is quite characteristic; therefore, a biopsy typically is unnecessary for diagnosis. However, a potassium hydroxide wet mount examination of a skin scraping should be performed if tinea corporis also is suspected.

Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum classically presents as an annular or arciform pruritic lesion with an advancing outer erythematous edge with an inner rim of scale that most commonly occurs on the lower extremities. 15 The presence of pruritus and trailing scale helps distinguish this lesion from GA. Histologically, there are epidermal changes of hyperplasia, spongiosis, and parakeratosis, as well as lymphohistiocytic infiltrate surrounding the superficial dermal vessels.16

We report this case to highlight GA as the most common postherpetic isotopic response. It should be on the differential diagnosis when a patient presents with erythematous, smooth, annular plaques occurring in the distribution of a resolved case of HZV.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- . Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Kapoor R, Piris A, Saavedra AP, et al. Wolf isotopic response manifesting as postherpetic granuloma annulare: a case series. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:255-258.

- Ezra N, Ahdout J, Haley JC, et al. Granuloma annulare in a zoster scar of a patient with multiple myeloma. Cutis. 2011;87:240-244.

- Noh TW, Park SH, Kang YS, et al. Morphea developing at the site of healed herpes zoster. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:242-245.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpesvirus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Sparrow G, Abell E. Granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica treated by jet injector. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:85-89.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Thornsberry LA, English JC. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

- Rubin CB, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: a retrospective series of 133 patients. Cutis. 2019;103:102-106.

- Stein JA, Fangman B, Strober B. Actinic granuloma. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:19.

- Mistry AM, Patel R, Mistry M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cureus. 2020;12:E11456.

- Reich HL, Nguyen JT, James WD. Annular lichen planus: a case series of 20 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:595-599.

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Nummular eczema: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2020;14:146-155.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Coronel-Pérez IM, Morillo-Andújar M. Erythema annulare centrifugum responding to natural ultraviolet light [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:177-178.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- . Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Kapoor R, Piris A, Saavedra AP, et al. Wolf isotopic response manifesting as postherpetic granuloma annulare: a case series. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:255-258.

- Ezra N, Ahdout J, Haley JC, et al. Granuloma annulare in a zoster scar of a patient with multiple myeloma. Cutis. 2011;87:240-244.

- Noh TW, Park SH, Kang YS, et al. Morphea developing at the site of healed herpes zoster. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:242-245.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Ghersetich I, et al. Isotopic response after herpesvirus infection: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:90-94.

- Sparrow G, Abell E. Granuloma annulare and necrobiosis lipoidica treated by jet injector. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:85-89.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479.

- Thornsberry LA, English JC. Etiology, diagnosis, and therapeutic management of granuloma annulare: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:279-290.

- Rubin CB, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: a retrospective series of 133 patients. Cutis. 2019;103:102-106.

- Stein JA, Fangman B, Strober B. Actinic granuloma. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:19.

- Mistry AM, Patel R, Mistry M, et al. Annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma. Cureus. 2020;12:E11456.

- Reich HL, Nguyen JT, James WD. Annular lichen planus: a case series of 20 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:595-599.

- Leung AKC, Lam JM, Leong KF, et al. Nummular eczema: an updated review. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2020;14:146-155.

- Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

- Coronel-Pérez IM, Morillo-Andújar M. Erythema annulare centrifugum responding to natural ultraviolet light [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:177-178.

An 82-year-old man presented with painful, pink, smooth, annular convalescing plaques on the right back, flank, and abdomen in a zosteriform distribution involving the T10/11 dermatome. He had a history of hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus, and 12 months prior to presentation he had an outbreak of herpes zoster virus in the same distribution that was treated with valacyclovir 1000 mg 3 times daily for 7 days. Over the following month he noticed a resolution of blisters and crusting as they morphed into the current lesions.

KRAS-mutated NSCLC: Adagrasib shows favorable efficacy

Key clinical point: Adagrasib shows favorable clinical efficacy without any new safety signals in patients with previously treated KRASG12C-mutated nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Among patients with measurable disease at baseline, 42.9% had a confirmed objective response. The median progression-free survival was 6.5 (95% CI 4.7-8.4) months. At a median follow-up of 15.6 months, the median overall survival was 12.6 (95% CI 9.2-19.2) months. The treatment-related adverse events of grade 1/2 and 3 occurred in 52.6% and 44.8% of patients, respectively.

Study details: This registrational phase 2 cohort study investigated adagrasib in 116 patients with KRASG12C-mutated NSCLC previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy with or without anti-programmed death 1 or programmed death ligand 1 therapy.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Mirati Therapeutics. The authors reported ties with one or more pharmaceutical companies, including employment or stock options in Mirati Therapeutics.

Source: Jänne PA et al. Adagrasib in non–small-cell lung cancer harboring a KRASG12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2022 (Jun 3). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204619

Key clinical point: Adagrasib shows favorable clinical efficacy without any new safety signals in patients with previously treated KRASG12C-mutated nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Among patients with measurable disease at baseline, 42.9% had a confirmed objective response. The median progression-free survival was 6.5 (95% CI 4.7-8.4) months. At a median follow-up of 15.6 months, the median overall survival was 12.6 (95% CI 9.2-19.2) months. The treatment-related adverse events of grade 1/2 and 3 occurred in 52.6% and 44.8% of patients, respectively.

Study details: This registrational phase 2 cohort study investigated adagrasib in 116 patients with KRASG12C-mutated NSCLC previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy with or without anti-programmed death 1 or programmed death ligand 1 therapy.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Mirati Therapeutics. The authors reported ties with one or more pharmaceutical companies, including employment or stock options in Mirati Therapeutics.

Source: Jänne PA et al. Adagrasib in non–small-cell lung cancer harboring a KRASG12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2022 (Jun 3). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204619

Key clinical point: Adagrasib shows favorable clinical efficacy without any new safety signals in patients with previously treated KRASG12C-mutated nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Among patients with measurable disease at baseline, 42.9% had a confirmed objective response. The median progression-free survival was 6.5 (95% CI 4.7-8.4) months. At a median follow-up of 15.6 months, the median overall survival was 12.6 (95% CI 9.2-19.2) months. The treatment-related adverse events of grade 1/2 and 3 occurred in 52.6% and 44.8% of patients, respectively.

Study details: This registrational phase 2 cohort study investigated adagrasib in 116 patients with KRASG12C-mutated NSCLC previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy with or without anti-programmed death 1 or programmed death ligand 1 therapy.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Mirati Therapeutics. The authors reported ties with one or more pharmaceutical companies, including employment or stock options in Mirati Therapeutics.

Source: Jänne PA et al. Adagrasib in non–small-cell lung cancer harboring a KRASG12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2022 (Jun 3). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204619

Most favorable immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment for NSCLC

Key clinical point: Cemiplimab appears to have the most favorable benefit-risk ratio among the analyzed immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) for the treatment of patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Cemiplimab was associated with the lowest hazard ratio (HR) for overall survival (OS) relative to chemotherapy (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0. 57-0.81), translating to the highest surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) value of 49.5%. Additionally, cemiplimab was associated with the lowest incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAE) relative to chemotherapy (odds ratio 0.17; 95% credible interval 0.06-0.45).

Study details: The data come from a network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials (n = 7795). The SUCRA values of all ICI (cemiplimab, avelumab, atezolizumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab) were determined for OS and TRAE.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Jiang M et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: A network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled studies. Front Oncol. 2022;12:827050 (May 10). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.827050

Key clinical point: Cemiplimab appears to have the most favorable benefit-risk ratio among the analyzed immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) for the treatment of patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Cemiplimab was associated with the lowest hazard ratio (HR) for overall survival (OS) relative to chemotherapy (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0. 57-0.81), translating to the highest surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) value of 49.5%. Additionally, cemiplimab was associated with the lowest incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAE) relative to chemotherapy (odds ratio 0.17; 95% credible interval 0.06-0.45).

Study details: The data come from a network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials (n = 7795). The SUCRA values of all ICI (cemiplimab, avelumab, atezolizumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab) were determined for OS and TRAE.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Jiang M et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: A network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled studies. Front Oncol. 2022;12:827050 (May 10). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.827050

Key clinical point: Cemiplimab appears to have the most favorable benefit-risk ratio among the analyzed immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) for the treatment of patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Cemiplimab was associated with the lowest hazard ratio (HR) for overall survival (OS) relative to chemotherapy (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0. 57-0.81), translating to the highest surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) value of 49.5%. Additionally, cemiplimab was associated with the lowest incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAE) relative to chemotherapy (odds ratio 0.17; 95% credible interval 0.06-0.45).

Study details: The data come from a network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials (n = 7795). The SUCRA values of all ICI (cemiplimab, avelumab, atezolizumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab) were determined for OS and TRAE.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Jiang M et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: A network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled studies. Front Oncol. 2022;12:827050 (May 10). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.827050

KRAS-mutated NSCLC: Adagrasib shows favorable efficacy

Key clinical point: Adagrasib shows favorable clinical efficacy without any new safety signals in patients with previously treated KRASG12C-mutated nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Among patients with measurable disease at baseline, 42.9% had a confirmed objective response. The median progression-free survival was 6.5 (95% CI 4.7-8.4) months. At a median follow-up of 15.6 months, the median overall survival was 12.6 (95% CI 9.2-19.2) months. The treatment-related adverse events of grade 1/2 and 3 occurred in 52.6% and 44.8% of patients, respectively.

Study details: This registrational phase 2 cohort study investigated adagrasib in 116 patients with KRASG12C-mutated NSCLC previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy with or without anti-programmed death 1 or programmed death ligand 1 therapy.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Mirati Therapeutics. The authors reported ties with one or more pharmaceutical companies, including employment or stock options in Mirati Therapeutics.

Source: Jänne PA et al. Adagrasib in non–small-cell lung cancer harboring a KRASG12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2022 (Jun 3). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204619

Key clinical point: Adagrasib shows favorable clinical efficacy without any new safety signals in patients with previously treated KRASG12C-mutated nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Among patients with measurable disease at baseline, 42.9% had a confirmed objective response. The median progression-free survival was 6.5 (95% CI 4.7-8.4) months. At a median follow-up of 15.6 months, the median overall survival was 12.6 (95% CI 9.2-19.2) months. The treatment-related adverse events of grade 1/2 and 3 occurred in 52.6% and 44.8% of patients, respectively.

Study details: This registrational phase 2 cohort study investigated adagrasib in 116 patients with KRASG12C-mutated NSCLC previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy with or without anti-programmed death 1 or programmed death ligand 1 therapy.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Mirati Therapeutics. The authors reported ties with one or more pharmaceutical companies, including employment or stock options in Mirati Therapeutics.

Source: Jänne PA et al. Adagrasib in non–small-cell lung cancer harboring a KRASG12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2022 (Jun 3). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204619

Key clinical point: Adagrasib shows favorable clinical efficacy without any new safety signals in patients with previously treated KRASG12C-mutated nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Among patients with measurable disease at baseline, 42.9% had a confirmed objective response. The median progression-free survival was 6.5 (95% CI 4.7-8.4) months. At a median follow-up of 15.6 months, the median overall survival was 12.6 (95% CI 9.2-19.2) months. The treatment-related adverse events of grade 1/2 and 3 occurred in 52.6% and 44.8% of patients, respectively.

Study details: This registrational phase 2 cohort study investigated adagrasib in 116 patients with KRASG12C-mutated NSCLC previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy with or without anti-programmed death 1 or programmed death ligand 1 therapy.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Mirati Therapeutics. The authors reported ties with one or more pharmaceutical companies, including employment or stock options in Mirati Therapeutics.

Source: Jänne PA et al. Adagrasib in non–small-cell lung cancer harboring a KRASG12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2022 (Jun 3). Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204619

Lung cancer screening using low-dose CT may be cost saving

Key clinical point: A modeling study suggests that the low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening of high-risk adults is likely to be cost saving by shifting lung cancer diagnosis to earlier stages.

Major finding: LDCT screening would lead to a stage shift toward earlier diagnosis, with 43% more patients being identified at stage I or II. The estimated screening costs, at $35.6 million, avoid $42 million in treating later stages of the disease, resulting in a cost saving of $6.65 million.

Study details: Canadian researchers used a decision analytic modeling technique to compare the benefits of earlier diagnosis of lung cancer with the costs of screening in current and former smokers aged 55-74 years.

Disclosures: The study did not receive any funding. A Tremblay and D Steward reported ties with one or more pharmaceutical companies or health organizations. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Thanh NX et al. Expected cost savings from low dose computed tomography scan screening for lung cancer in Alberta, Canada. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2022 (Jun 2). Doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2022.100350

Key clinical point: A modeling study suggests that the low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening of high-risk adults is likely to be cost saving by shifting lung cancer diagnosis to earlier stages.

Major finding: LDCT screening would lead to a stage shift toward earlier diagnosis, with 43% more patients being identified at stage I or II. The estimated screening costs, at $35.6 million, avoid $42 million in treating later stages of the disease, resulting in a cost saving of $6.65 million.

Study details: Canadian researchers used a decision analytic modeling technique to compare the benefits of earlier diagnosis of lung cancer with the costs of screening in current and former smokers aged 55-74 years.

Disclosures: The study did not receive any funding. A Tremblay and D Steward reported ties with one or more pharmaceutical companies or health organizations. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Thanh NX et al. Expected cost savings from low dose computed tomography scan screening for lung cancer in Alberta, Canada. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2022 (Jun 2). Doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2022.100350

Key clinical point: A modeling study suggests that the low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening of high-risk adults is likely to be cost saving by shifting lung cancer diagnosis to earlier stages.

Major finding: LDCT screening would lead to a stage shift toward earlier diagnosis, with 43% more patients being identified at stage I or II. The estimated screening costs, at $35.6 million, avoid $42 million in treating later stages of the disease, resulting in a cost saving of $6.65 million.

Study details: Canadian researchers used a decision analytic modeling technique to compare the benefits of earlier diagnosis of lung cancer with the costs of screening in current and former smokers aged 55-74 years.

Disclosures: The study did not receive any funding. A Tremblay and D Steward reported ties with one or more pharmaceutical companies or health organizations. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Thanh NX et al. Expected cost savings from low dose computed tomography scan screening for lung cancer in Alberta, Canada. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2022 (Jun 2). Doi: 10.1016/j.jtocrr.2022.100350

Most favorable immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment for NSCLC

Key clinical point: Cemiplimab appears to have the most favorable benefit-risk ratio among the analyzed immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) for the treatment of patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Cemiplimab was associated with the lowest hazard ratio (HR) for overall survival (OS) relative to chemotherapy (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0. 57-0.81), translating to the highest surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) value of 49.5%. Additionally, cemiplimab was associated with the lowest incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAE) relative to chemotherapy (odds ratio 0.17; 95% credible interval 0.06-0.45).

Study details: The data come from a network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials (n = 7795). The SUCRA values of all ICI (cemiplimab, avelumab, atezolizumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab) were determined for OS and TRAE.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Jiang M et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: A network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled studies. Front Oncol. 2022;12:827050 (May 10). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.827050

Key clinical point: Cemiplimab appears to have the most favorable benefit-risk ratio among the analyzed immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) for the treatment of patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Cemiplimab was associated with the lowest hazard ratio (HR) for overall survival (OS) relative to chemotherapy (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0. 57-0.81), translating to the highest surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) value of 49.5%. Additionally, cemiplimab was associated with the lowest incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAE) relative to chemotherapy (odds ratio 0.17; 95% credible interval 0.06-0.45).

Study details: The data come from a network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials (n = 7795). The SUCRA values of all ICI (cemiplimab, avelumab, atezolizumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab) were determined for OS and TRAE.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Jiang M et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: A network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled studies. Front Oncol. 2022;12:827050 (May 10). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.827050

Key clinical point: Cemiplimab appears to have the most favorable benefit-risk ratio among the analyzed immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) for the treatment of patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Major finding: Cemiplimab was associated with the lowest hazard ratio (HR) for overall survival (OS) relative to chemotherapy (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0. 57-0.81), translating to the highest surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) value of 49.5%. Additionally, cemiplimab was associated with the lowest incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAE) relative to chemotherapy (odds ratio 0.17; 95% credible interval 0.06-0.45).

Study details: The data come from a network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials (n = 7795). The SUCRA values of all ICI (cemiplimab, avelumab, atezolizumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab) were determined for OS and TRAE.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Jiang M et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: A network meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled studies. Front Oncol. 2022;12:827050 (May 10). Doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.827050