User login

Commentary: Multifocal Hepatocellular Carcinoma, November 2022

Orimo and colleagues addressed the use of liver resection in patients with more than one HCC in the liver. Patients with no or Child-Pugh A/B cirrhosis were included in this single-center retrospective study of 1088 patients who underwent hepatectomy for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0 (n = 88), A (n = 750), or B (n = 250) HCC, with stages A and B subcategorized into A1 (single nodule 2-5 cm or ≤ 3 nodules ≤ 3 cm), A2 (single nodule 5-10 cm), A3 (single nodule ≥ 10 cm), B1 (2-3 nodules > 3 cm), and B2 (≥ 4 nodules). The 5-year overall survival (OS) rates for stage 0, A1, A2, A3, B1, and B2 patients were 70.4%, 74.2%, 63.8%, 47.7%, 47.5%, and 31.9%, respectively (P < .0001). Significant differences in overall survival (OS) were found between stages A1 and A2 (P = .0118), A2 and A3 (P = .0013), and B1 and B2 (P = .0050), but not between stages A3 and B1 (P = .4742). In stage B1 patients, Child-Pugh B cirrhosis was the only independent prognostic factor for OS. The authors concluded that hepatectomy is beneficial in patients with three or fewer hepatocellular carcinomas and either no or Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis, with the long-term results being comparable to those in patients who underwent a resection of a single HCC. Therefore, resection of up to three HCC is safe and should be considered in clinically appropriate patients.

Many patients with multifocal HCC are not eligible for liver-directed therapies. The standard of care for first-line systemic therapy is the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab, as reported in the IMbrave150 clinical trial. Fulgenzi and colleagues published the results of a multicenter prospective observational study, AB-Real, that included 433 patients who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab in routine clinical practice. The investigators confirmed the efficacy of the combination and found that portal vein tumor thrombosis and worse albumin-bilirubin grade were independent prognostic factors for poor OS and were associated with an increased risk for hemorrhagic events. In addition, the authors reported that the overall response rate (ORR) predicted better outcomes, including longer OS. Therefore, atezolizumab and bevacizumab remains a safe and effective first-line treatment for many patients with unresectable HCC.

Finally, Finn and colleagues reported the results of an open-label, noncomparative cohort of the REACH-2 study of ramucirumab in 47 patients with advanced HCC and an alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level ≥ 400 ng/mL. These patients had previously received one to two lines of systemic therapy, excluding sorafenib or chemotherapy. Lenvatinib was the most common prior systemic therapy (n = 20; 43%). Others included immune checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) monotherapies (n = 11), CPI/antiangiogenic therapy (n = 14), or dual CPI therapy (n = 5). The ORR was 10.6% (95% CI 1.8-19.5) and disease control rate was 46.8% (95% CI 32.5-61.1), with a median duration of response of 8.3 months [95% CI 2.4 to not reached). The grade 3 or more adverse event rate was 57%, with hypertension (11%) being the most common, allowing the authors to conclude that ramucirumab offers clinically significant efficacy with no new safety signals in this setting. Therefore, ramucirumab remains as a safe and effective later-line treatment option for patients with unresectable HCC and an AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL.

Orimo and colleagues addressed the use of liver resection in patients with more than one HCC in the liver. Patients with no or Child-Pugh A/B cirrhosis were included in this single-center retrospective study of 1088 patients who underwent hepatectomy for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0 (n = 88), A (n = 750), or B (n = 250) HCC, with stages A and B subcategorized into A1 (single nodule 2-5 cm or ≤ 3 nodules ≤ 3 cm), A2 (single nodule 5-10 cm), A3 (single nodule ≥ 10 cm), B1 (2-3 nodules > 3 cm), and B2 (≥ 4 nodules). The 5-year overall survival (OS) rates for stage 0, A1, A2, A3, B1, and B2 patients were 70.4%, 74.2%, 63.8%, 47.7%, 47.5%, and 31.9%, respectively (P < .0001). Significant differences in overall survival (OS) were found between stages A1 and A2 (P = .0118), A2 and A3 (P = .0013), and B1 and B2 (P = .0050), but not between stages A3 and B1 (P = .4742). In stage B1 patients, Child-Pugh B cirrhosis was the only independent prognostic factor for OS. The authors concluded that hepatectomy is beneficial in patients with three or fewer hepatocellular carcinomas and either no or Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis, with the long-term results being comparable to those in patients who underwent a resection of a single HCC. Therefore, resection of up to three HCC is safe and should be considered in clinically appropriate patients.

Many patients with multifocal HCC are not eligible for liver-directed therapies. The standard of care for first-line systemic therapy is the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab, as reported in the IMbrave150 clinical trial. Fulgenzi and colleagues published the results of a multicenter prospective observational study, AB-Real, that included 433 patients who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab in routine clinical practice. The investigators confirmed the efficacy of the combination and found that portal vein tumor thrombosis and worse albumin-bilirubin grade were independent prognostic factors for poor OS and were associated with an increased risk for hemorrhagic events. In addition, the authors reported that the overall response rate (ORR) predicted better outcomes, including longer OS. Therefore, atezolizumab and bevacizumab remains a safe and effective first-line treatment for many patients with unresectable HCC.

Finally, Finn and colleagues reported the results of an open-label, noncomparative cohort of the REACH-2 study of ramucirumab in 47 patients with advanced HCC and an alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level ≥ 400 ng/mL. These patients had previously received one to two lines of systemic therapy, excluding sorafenib or chemotherapy. Lenvatinib was the most common prior systemic therapy (n = 20; 43%). Others included immune checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) monotherapies (n = 11), CPI/antiangiogenic therapy (n = 14), or dual CPI therapy (n = 5). The ORR was 10.6% (95% CI 1.8-19.5) and disease control rate was 46.8% (95% CI 32.5-61.1), with a median duration of response of 8.3 months [95% CI 2.4 to not reached). The grade 3 or more adverse event rate was 57%, with hypertension (11%) being the most common, allowing the authors to conclude that ramucirumab offers clinically significant efficacy with no new safety signals in this setting. Therefore, ramucirumab remains as a safe and effective later-line treatment option for patients with unresectable HCC and an AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL.

Orimo and colleagues addressed the use of liver resection in patients with more than one HCC in the liver. Patients with no or Child-Pugh A/B cirrhosis were included in this single-center retrospective study of 1088 patients who underwent hepatectomy for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0 (n = 88), A (n = 750), or B (n = 250) HCC, with stages A and B subcategorized into A1 (single nodule 2-5 cm or ≤ 3 nodules ≤ 3 cm), A2 (single nodule 5-10 cm), A3 (single nodule ≥ 10 cm), B1 (2-3 nodules > 3 cm), and B2 (≥ 4 nodules). The 5-year overall survival (OS) rates for stage 0, A1, A2, A3, B1, and B2 patients were 70.4%, 74.2%, 63.8%, 47.7%, 47.5%, and 31.9%, respectively (P < .0001). Significant differences in overall survival (OS) were found between stages A1 and A2 (P = .0118), A2 and A3 (P = .0013), and B1 and B2 (P = .0050), but not between stages A3 and B1 (P = .4742). In stage B1 patients, Child-Pugh B cirrhosis was the only independent prognostic factor for OS. The authors concluded that hepatectomy is beneficial in patients with three or fewer hepatocellular carcinomas and either no or Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis, with the long-term results being comparable to those in patients who underwent a resection of a single HCC. Therefore, resection of up to three HCC is safe and should be considered in clinically appropriate patients.

Many patients with multifocal HCC are not eligible for liver-directed therapies. The standard of care for first-line systemic therapy is the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab, as reported in the IMbrave150 clinical trial. Fulgenzi and colleagues published the results of a multicenter prospective observational study, AB-Real, that included 433 patients who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab in routine clinical practice. The investigators confirmed the efficacy of the combination and found that portal vein tumor thrombosis and worse albumin-bilirubin grade were independent prognostic factors for poor OS and were associated with an increased risk for hemorrhagic events. In addition, the authors reported that the overall response rate (ORR) predicted better outcomes, including longer OS. Therefore, atezolizumab and bevacizumab remains a safe and effective first-line treatment for many patients with unresectable HCC.

Finally, Finn and colleagues reported the results of an open-label, noncomparative cohort of the REACH-2 study of ramucirumab in 47 patients with advanced HCC and an alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level ≥ 400 ng/mL. These patients had previously received one to two lines of systemic therapy, excluding sorafenib or chemotherapy. Lenvatinib was the most common prior systemic therapy (n = 20; 43%). Others included immune checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) monotherapies (n = 11), CPI/antiangiogenic therapy (n = 14), or dual CPI therapy (n = 5). The ORR was 10.6% (95% CI 1.8-19.5) and disease control rate was 46.8% (95% CI 32.5-61.1), with a median duration of response of 8.3 months [95% CI 2.4 to not reached). The grade 3 or more adverse event rate was 57%, with hypertension (11%) being the most common, allowing the authors to conclude that ramucirumab offers clinically significant efficacy with no new safety signals in this setting. Therefore, ramucirumab remains as a safe and effective later-line treatment option for patients with unresectable HCC and an AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL.

Commentary: Multifocal Hepatocellular Carcinoma, November 2022

Orimo and colleagues addressed the use of liver resection in patients with more than one HCC in the liver. Patients with no or Child-Pugh A/B cirrhosis were included in this single-center retrospective study of 1088 patients who underwent hepatectomy for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0 (n = 88), A (n = 750), or B (n = 250) HCC, with stages A and B subcategorized into A1 (single nodule 2-5 cm or ≤ 3 nodules ≤ 3 cm), A2 (single nodule 5-10 cm), A3 (single nodule ≥ 10 cm), B1 (2-3 nodules > 3 cm), and B2 (≥ 4 nodules). The 5-year overall survival (OS) rates for stage 0, A1, A2, A3, B1, and B2 patients were 70.4%, 74.2%, 63.8%, 47.7%, 47.5%, and 31.9%, respectively (P < .0001). Significant differences in overall survival (OS) were found between stages A1 and A2 (P = .0118), A2 and A3 (P = .0013), and B1 and B2 (P = .0050), but not between stages A3 and B1 (P = .4742). In stage B1 patients, Child-Pugh B cirrhosis was the only independent prognostic factor for OS. The authors concluded that hepatectomy is beneficial in patients with three or fewer hepatocellular carcinomas and either no or Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis, with the long-term results being comparable to those in patients who underwent a resection of a single HCC. Therefore, resection of up to three HCC is safe and should be considered in clinically appropriate patients.

Many patients with multifocal HCC are not eligible for liver-directed therapies. The standard of care for first-line systemic therapy is the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab, as reported in the IMbrave150 clinical trial. Fulgenzi and colleagues published the results of a multicenter prospective observational study, AB-Real, that included 433 patients who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab in routine clinical practice. The investigators confirmed the efficacy of the combination and found that portal vein tumor thrombosis and worse albumin-bilirubin grade were independent prognostic factors for poor OS and were associated with an increased risk for hemorrhagic events. In addition, the authors reported that the overall response rate (ORR) predicted better outcomes, including longer OS. Therefore, atezolizumab and bevacizumab remains a safe and effective first-line treatment for many patients with unresectable HCC.

Finally, Finn and colleagues reported the results of an open-label, noncomparative cohort of the REACH-2 study of ramucirumab in 47 patients with advanced HCC and an alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level ≥ 400 ng/mL. These patients had previously received one to two lines of systemic therapy, excluding sorafenib or chemotherapy. Lenvatinib was the most common prior systemic therapy (n = 20; 43%). Others included immune checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) monotherapies (n = 11), CPI/antiangiogenic therapy (n = 14), or dual CPI therapy (n = 5). The ORR was 10.6% (95% CI 1.8-19.5) and disease control rate was 46.8% (95% CI 32.5-61.1), with a median duration of response of 8.3 months (95% CI 2.4 to not reached). The grade 3 or more adverse event rate was 57%, with hypertension (11%) being the most common, allowing the authors to conclude that ramucirumab offers clinically significant efficacy with no new safety signals in this setting. Therefore, ramucirumab remains as a safe and effective later-line treatment option for patients with unresectable HCC and an AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL.

Orimo and colleagues addressed the use of liver resection in patients with more than one HCC in the liver. Patients with no or Child-Pugh A/B cirrhosis were included in this single-center retrospective study of 1088 patients who underwent hepatectomy for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0 (n = 88), A (n = 750), or B (n = 250) HCC, with stages A and B subcategorized into A1 (single nodule 2-5 cm or ≤ 3 nodules ≤ 3 cm), A2 (single nodule 5-10 cm), A3 (single nodule ≥ 10 cm), B1 (2-3 nodules > 3 cm), and B2 (≥ 4 nodules). The 5-year overall survival (OS) rates for stage 0, A1, A2, A3, B1, and B2 patients were 70.4%, 74.2%, 63.8%, 47.7%, 47.5%, and 31.9%, respectively (P < .0001). Significant differences in overall survival (OS) were found between stages A1 and A2 (P = .0118), A2 and A3 (P = .0013), and B1 and B2 (P = .0050), but not between stages A3 and B1 (P = .4742). In stage B1 patients, Child-Pugh B cirrhosis was the only independent prognostic factor for OS. The authors concluded that hepatectomy is beneficial in patients with three or fewer hepatocellular carcinomas and either no or Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis, with the long-term results being comparable to those in patients who underwent a resection of a single HCC. Therefore, resection of up to three HCC is safe and should be considered in clinically appropriate patients.

Many patients with multifocal HCC are not eligible for liver-directed therapies. The standard of care for first-line systemic therapy is the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab, as reported in the IMbrave150 clinical trial. Fulgenzi and colleagues published the results of a multicenter prospective observational study, AB-Real, that included 433 patients who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab in routine clinical practice. The investigators confirmed the efficacy of the combination and found that portal vein tumor thrombosis and worse albumin-bilirubin grade were independent prognostic factors for poor OS and were associated with an increased risk for hemorrhagic events. In addition, the authors reported that the overall response rate (ORR) predicted better outcomes, including longer OS. Therefore, atezolizumab and bevacizumab remains a safe and effective first-line treatment for many patients with unresectable HCC.

Finally, Finn and colleagues reported the results of an open-label, noncomparative cohort of the REACH-2 study of ramucirumab in 47 patients with advanced HCC and an alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level ≥ 400 ng/mL. These patients had previously received one to two lines of systemic therapy, excluding sorafenib or chemotherapy. Lenvatinib was the most common prior systemic therapy (n = 20; 43%). Others included immune checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) monotherapies (n = 11), CPI/antiangiogenic therapy (n = 14), or dual CPI therapy (n = 5). The ORR was 10.6% (95% CI 1.8-19.5) and disease control rate was 46.8% (95% CI 32.5-61.1), with a median duration of response of 8.3 months (95% CI 2.4 to not reached). The grade 3 or more adverse event rate was 57%, with hypertension (11%) being the most common, allowing the authors to conclude that ramucirumab offers clinically significant efficacy with no new safety signals in this setting. Therefore, ramucirumab remains as a safe and effective later-line treatment option for patients with unresectable HCC and an AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL.

Orimo and colleagues addressed the use of liver resection in patients with more than one HCC in the liver. Patients with no or Child-Pugh A/B cirrhosis were included in this single-center retrospective study of 1088 patients who underwent hepatectomy for Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage 0 (n = 88), A (n = 750), or B (n = 250) HCC, with stages A and B subcategorized into A1 (single nodule 2-5 cm or ≤ 3 nodules ≤ 3 cm), A2 (single nodule 5-10 cm), A3 (single nodule ≥ 10 cm), B1 (2-3 nodules > 3 cm), and B2 (≥ 4 nodules). The 5-year overall survival (OS) rates for stage 0, A1, A2, A3, B1, and B2 patients were 70.4%, 74.2%, 63.8%, 47.7%, 47.5%, and 31.9%, respectively (P < .0001). Significant differences in overall survival (OS) were found between stages A1 and A2 (P = .0118), A2 and A3 (P = .0013), and B1 and B2 (P = .0050), but not between stages A3 and B1 (P = .4742). In stage B1 patients, Child-Pugh B cirrhosis was the only independent prognostic factor for OS. The authors concluded that hepatectomy is beneficial in patients with three or fewer hepatocellular carcinomas and either no or Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis, with the long-term results being comparable to those in patients who underwent a resection of a single HCC. Therefore, resection of up to three HCC is safe and should be considered in clinically appropriate patients.

Many patients with multifocal HCC are not eligible for liver-directed therapies. The standard of care for first-line systemic therapy is the combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab, as reported in the IMbrave150 clinical trial. Fulgenzi and colleagues published the results of a multicenter prospective observational study, AB-Real, that included 433 patients who received atezolizumab and bevacizumab in routine clinical practice. The investigators confirmed the efficacy of the combination and found that portal vein tumor thrombosis and worse albumin-bilirubin grade were independent prognostic factors for poor OS and were associated with an increased risk for hemorrhagic events. In addition, the authors reported that the overall response rate (ORR) predicted better outcomes, including longer OS. Therefore, atezolizumab and bevacizumab remains a safe and effective first-line treatment for many patients with unresectable HCC.

Finally, Finn and colleagues reported the results of an open-label, noncomparative cohort of the REACH-2 study of ramucirumab in 47 patients with advanced HCC and an alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level ≥ 400 ng/mL. These patients had previously received one to two lines of systemic therapy, excluding sorafenib or chemotherapy. Lenvatinib was the most common prior systemic therapy (n = 20; 43%). Others included immune checkpoint inhibitor (CPI) monotherapies (n = 11), CPI/antiangiogenic therapy (n = 14), or dual CPI therapy (n = 5). The ORR was 10.6% (95% CI 1.8-19.5) and disease control rate was 46.8% (95% CI 32.5-61.1), with a median duration of response of 8.3 months (95% CI 2.4 to not reached). The grade 3 or more adverse event rate was 57%, with hypertension (11%) being the most common, allowing the authors to conclude that ramucirumab offers clinically significant efficacy with no new safety signals in this setting. Therefore, ramucirumab remains as a safe and effective later-line treatment option for patients with unresectable HCC and an AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL.

Strategies to treat food allergy with oral immunotherapy

according to a new review.

In OIT, a patient who is allergic to a specific food consumes increasing amounts of the allergen over time to reduce their risk for allergic reaction.

“OIT is an elective, usually noncurative procedure with inherent risks that require families to function as amateur medical professionals. Preparing them for this role is essential to protect patients and ensure the long-term success of this life-changing procedure,” lead author Douglas P. Mack, MD, MSc, a pediatric allergy, asthma, and immunology specialist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., and colleagues write in Clinical & Experimental Allergy.

From strict avoidance to desensitization

Food allergy treatment has traditionally involved avoiding accidental exposure that may lead to anaphylaxis and providing rescue medication. In recent years, OIT “has been recommended by several guidelines as a primary option,” Dr. Mack and coauthors write. And with the “approval by European and USA regulators of [peanut allergen powder] Palforzia [Aimmune Therapeutics], there are now commercial and noncommercial forms of OIT available for use in several countries.”

They advise physicians to take a proactive, educational, supportive approach to patients and their families throughout the therapy.

“Ultimately, the decision to pursue OIT or continue avoidance strategies remains the responsibility of the family and the patients,” they write. “Some families may not be prepared for the role that they have to play in actively managing their child’s food allergy treatment.”

Strategies to overcome OIT challenges

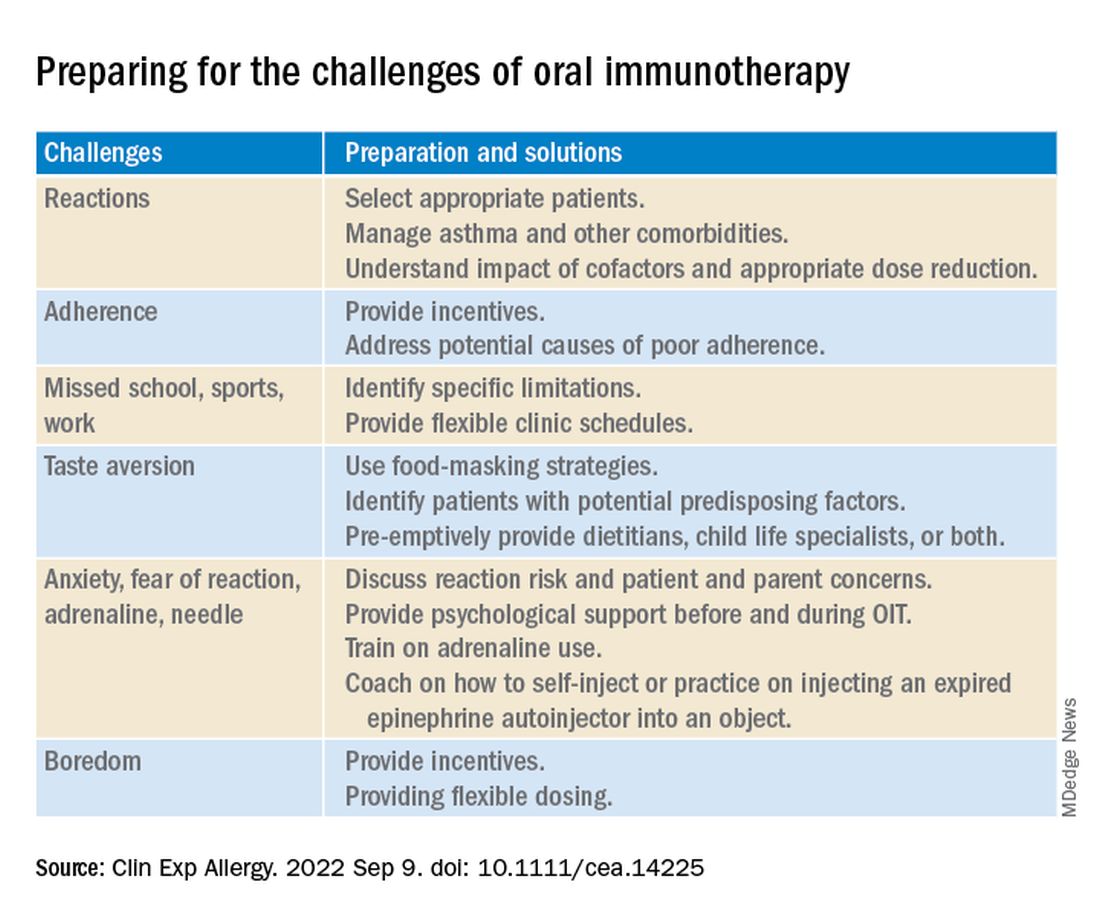

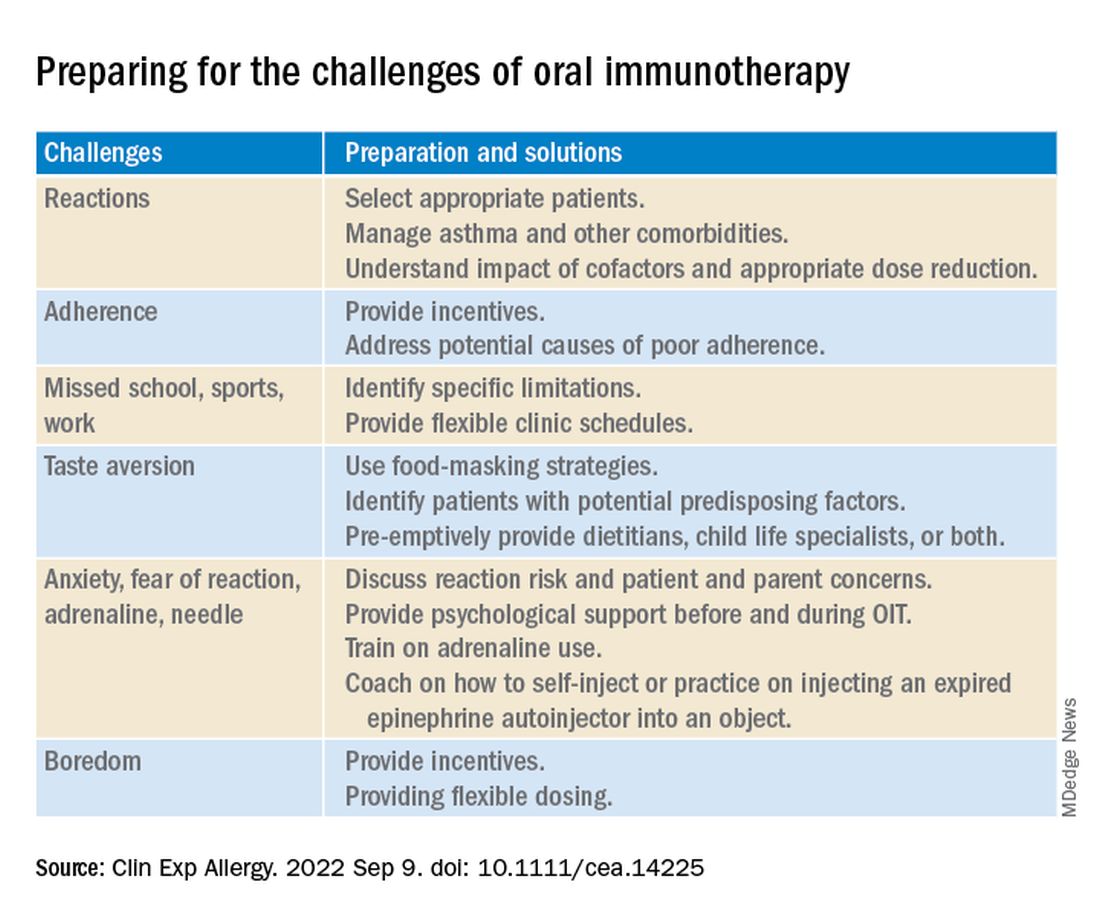

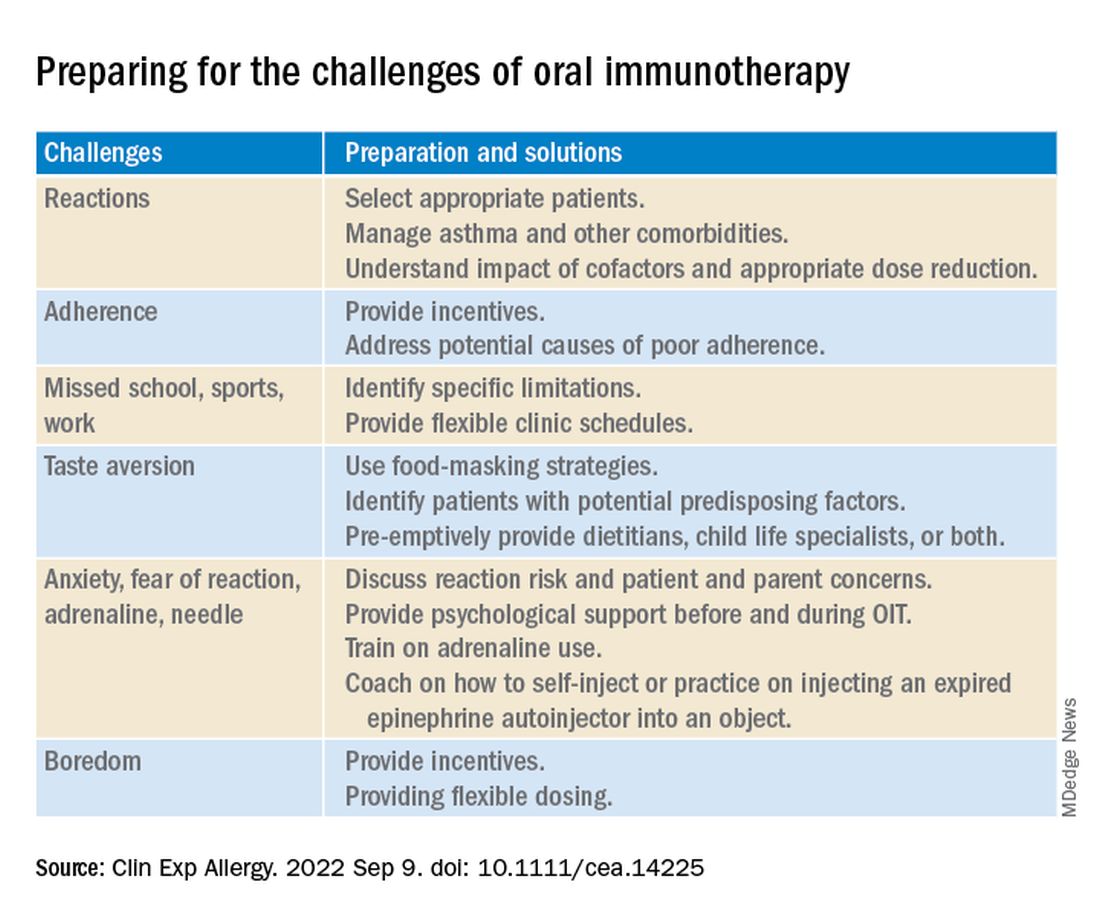

Reviewing the literature about OIT for food allergy, the authors suggest various strategies physicians can use to help OIT patients and their families prepare for and overcome common treatment-related challenges.

Two experts welcome the report

Rita Kachru, MD, a specialist in allergy and immunology and a codirector of the food allergy program at UCLA Health in Los Angeles, called this “an excellent report about a wonderful, individualized option in food allergy management.

“The authors did an excellent job delineating OIT terminology, outlining the goals, risks, and benefits of OIT, noting that it’s not a cure, and emphasizing the crucial importance of discussions with each family throughout the process,” Dr. Kachru, who was not involved in developing the report, told this news organization.

“I thoroughly agree with their assessment,” she added. “The more you do OIT research and clinical care, the more you realize the pitfalls, the benefits, and the importance of patient goals and family dynamics. Discussing the goals, risks, benefits, and alternatives to OIT in detail with the family is crucial so they fully understand the process.”

Basil M. Kahwash, MD, an allergy, pulmonary, and critical care medicine specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., said that providers in the immunology community have been discussing OIT for years and that he welcomes the well-written report that summarizes the evidence.

“It’s important to periodically summarize the evidence, as well as the consensus expert opinion about the evidence, so we may better inform our colleagues and patients,” said Dr. Kahwash, who was not involved in developing the report. “The authors are well-known experts in our field who have experience with OIT and with reviewing the evidence of food allergy.

“OIT can be a fantastic option for some patients, especially those who are very highly motivated and understand the process from start to finish. But OIT is not the best option for every child, and it’s not much of an option for adults,” he explained. “Patients need to be chosen carefully and understand the level of motivation required to safely follow through with the treatment.

“The report will hopefully affect patient care positively and allow patients to understand the limitations around OIT when they consider their candidacy for it,” he added. “In most cases, OIT patients will still need to avoid the allergen, but if a small amount accidentally gets into their food, they probably won’t have a very severe reaction to it.”

Dr. Kahwash would like to see data on patients who have seen long-term remission with OIT.

“Clearly, some patients benefit from OIT. What differentiates patients who benefit from OIT from those who do not?” he asked. “In the future, we need to consider possible biomarkers of patients who are and who aren’t good candidates for OIT.

“Regardless of OIT’s limitations, the potential for desensitization rather than strict avoidance represents a big step in the evolution of food allergy treatment,” Dr. Kahwash noted.

No funding details were provided. Dr. Mack and three coauthors report financial relationships with Aimmune. Aimmune Therapeutics is the manufacturer of Palforzia OIT (AR101 powder provided in capsules and sachets). Most coauthors also report financial relationships with other pharmaceutical companies. The full list can be found with the original article. Dr. Kachru was an investigator in the PALISADES clinical trial of AR101. Dr. Kahwash reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new review.

In OIT, a patient who is allergic to a specific food consumes increasing amounts of the allergen over time to reduce their risk for allergic reaction.

“OIT is an elective, usually noncurative procedure with inherent risks that require families to function as amateur medical professionals. Preparing them for this role is essential to protect patients and ensure the long-term success of this life-changing procedure,” lead author Douglas P. Mack, MD, MSc, a pediatric allergy, asthma, and immunology specialist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., and colleagues write in Clinical & Experimental Allergy.

From strict avoidance to desensitization

Food allergy treatment has traditionally involved avoiding accidental exposure that may lead to anaphylaxis and providing rescue medication. In recent years, OIT “has been recommended by several guidelines as a primary option,” Dr. Mack and coauthors write. And with the “approval by European and USA regulators of [peanut allergen powder] Palforzia [Aimmune Therapeutics], there are now commercial and noncommercial forms of OIT available for use in several countries.”

They advise physicians to take a proactive, educational, supportive approach to patients and their families throughout the therapy.

“Ultimately, the decision to pursue OIT or continue avoidance strategies remains the responsibility of the family and the patients,” they write. “Some families may not be prepared for the role that they have to play in actively managing their child’s food allergy treatment.”

Strategies to overcome OIT challenges

Reviewing the literature about OIT for food allergy, the authors suggest various strategies physicians can use to help OIT patients and their families prepare for and overcome common treatment-related challenges.

Two experts welcome the report

Rita Kachru, MD, a specialist in allergy and immunology and a codirector of the food allergy program at UCLA Health in Los Angeles, called this “an excellent report about a wonderful, individualized option in food allergy management.

“The authors did an excellent job delineating OIT terminology, outlining the goals, risks, and benefits of OIT, noting that it’s not a cure, and emphasizing the crucial importance of discussions with each family throughout the process,” Dr. Kachru, who was not involved in developing the report, told this news organization.

“I thoroughly agree with their assessment,” she added. “The more you do OIT research and clinical care, the more you realize the pitfalls, the benefits, and the importance of patient goals and family dynamics. Discussing the goals, risks, benefits, and alternatives to OIT in detail with the family is crucial so they fully understand the process.”

Basil M. Kahwash, MD, an allergy, pulmonary, and critical care medicine specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., said that providers in the immunology community have been discussing OIT for years and that he welcomes the well-written report that summarizes the evidence.

“It’s important to periodically summarize the evidence, as well as the consensus expert opinion about the evidence, so we may better inform our colleagues and patients,” said Dr. Kahwash, who was not involved in developing the report. “The authors are well-known experts in our field who have experience with OIT and with reviewing the evidence of food allergy.

“OIT can be a fantastic option for some patients, especially those who are very highly motivated and understand the process from start to finish. But OIT is not the best option for every child, and it’s not much of an option for adults,” he explained. “Patients need to be chosen carefully and understand the level of motivation required to safely follow through with the treatment.

“The report will hopefully affect patient care positively and allow patients to understand the limitations around OIT when they consider their candidacy for it,” he added. “In most cases, OIT patients will still need to avoid the allergen, but if a small amount accidentally gets into their food, they probably won’t have a very severe reaction to it.”

Dr. Kahwash would like to see data on patients who have seen long-term remission with OIT.

“Clearly, some patients benefit from OIT. What differentiates patients who benefit from OIT from those who do not?” he asked. “In the future, we need to consider possible biomarkers of patients who are and who aren’t good candidates for OIT.

“Regardless of OIT’s limitations, the potential for desensitization rather than strict avoidance represents a big step in the evolution of food allergy treatment,” Dr. Kahwash noted.

No funding details were provided. Dr. Mack and three coauthors report financial relationships with Aimmune. Aimmune Therapeutics is the manufacturer of Palforzia OIT (AR101 powder provided in capsules and sachets). Most coauthors also report financial relationships with other pharmaceutical companies. The full list can be found with the original article. Dr. Kachru was an investigator in the PALISADES clinical trial of AR101. Dr. Kahwash reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to a new review.

In OIT, a patient who is allergic to a specific food consumes increasing amounts of the allergen over time to reduce their risk for allergic reaction.

“OIT is an elective, usually noncurative procedure with inherent risks that require families to function as amateur medical professionals. Preparing them for this role is essential to protect patients and ensure the long-term success of this life-changing procedure,” lead author Douglas P. Mack, MD, MSc, a pediatric allergy, asthma, and immunology specialist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., and colleagues write in Clinical & Experimental Allergy.

From strict avoidance to desensitization

Food allergy treatment has traditionally involved avoiding accidental exposure that may lead to anaphylaxis and providing rescue medication. In recent years, OIT “has been recommended by several guidelines as a primary option,” Dr. Mack and coauthors write. And with the “approval by European and USA regulators of [peanut allergen powder] Palforzia [Aimmune Therapeutics], there are now commercial and noncommercial forms of OIT available for use in several countries.”

They advise physicians to take a proactive, educational, supportive approach to patients and their families throughout the therapy.

“Ultimately, the decision to pursue OIT or continue avoidance strategies remains the responsibility of the family and the patients,” they write. “Some families may not be prepared for the role that they have to play in actively managing their child’s food allergy treatment.”

Strategies to overcome OIT challenges

Reviewing the literature about OIT for food allergy, the authors suggest various strategies physicians can use to help OIT patients and their families prepare for and overcome common treatment-related challenges.

Two experts welcome the report

Rita Kachru, MD, a specialist in allergy and immunology and a codirector of the food allergy program at UCLA Health in Los Angeles, called this “an excellent report about a wonderful, individualized option in food allergy management.

“The authors did an excellent job delineating OIT terminology, outlining the goals, risks, and benefits of OIT, noting that it’s not a cure, and emphasizing the crucial importance of discussions with each family throughout the process,” Dr. Kachru, who was not involved in developing the report, told this news organization.

“I thoroughly agree with their assessment,” she added. “The more you do OIT research and clinical care, the more you realize the pitfalls, the benefits, and the importance of patient goals and family dynamics. Discussing the goals, risks, benefits, and alternatives to OIT in detail with the family is crucial so they fully understand the process.”

Basil M. Kahwash, MD, an allergy, pulmonary, and critical care medicine specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., said that providers in the immunology community have been discussing OIT for years and that he welcomes the well-written report that summarizes the evidence.

“It’s important to periodically summarize the evidence, as well as the consensus expert opinion about the evidence, so we may better inform our colleagues and patients,” said Dr. Kahwash, who was not involved in developing the report. “The authors are well-known experts in our field who have experience with OIT and with reviewing the evidence of food allergy.

“OIT can be a fantastic option for some patients, especially those who are very highly motivated and understand the process from start to finish. But OIT is not the best option for every child, and it’s not much of an option for adults,” he explained. “Patients need to be chosen carefully and understand the level of motivation required to safely follow through with the treatment.

“The report will hopefully affect patient care positively and allow patients to understand the limitations around OIT when they consider their candidacy for it,” he added. “In most cases, OIT patients will still need to avoid the allergen, but if a small amount accidentally gets into their food, they probably won’t have a very severe reaction to it.”

Dr. Kahwash would like to see data on patients who have seen long-term remission with OIT.

“Clearly, some patients benefit from OIT. What differentiates patients who benefit from OIT from those who do not?” he asked. “In the future, we need to consider possible biomarkers of patients who are and who aren’t good candidates for OIT.

“Regardless of OIT’s limitations, the potential for desensitization rather than strict avoidance represents a big step in the evolution of food allergy treatment,” Dr. Kahwash noted.

No funding details were provided. Dr. Mack and three coauthors report financial relationships with Aimmune. Aimmune Therapeutics is the manufacturer of Palforzia OIT (AR101 powder provided in capsules and sachets). Most coauthors also report financial relationships with other pharmaceutical companies. The full list can be found with the original article. Dr. Kachru was an investigator in the PALISADES clinical trial of AR101. Dr. Kahwash reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CLINICAL & EXPERIMENTAL ALLERGY

Legal and malpractice risks when taking call

Taking call is one of the more challenging - and annoying - aspects of the job for many physicians. Calls may wake them up in the middle of the night and can interfere with their at-home activities. In Medscape’s Employed Physicians Report, 37% of respondents said they have from 1 to 5 hours of call per month; 19% said they have 6 to 10 hours; and 12% have 11 hours or more.

“Even if you don’t have to come in to the ED, you can get calls in the middle of the night, and you may get paid very little, if anything,” said Robert Bitterman MD, JD, an emergency physician and attorney in Harbor Springs, Mich.

And responding to the calls is not optional. Dr. Bitterman said

On-call activities are regulated by the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA). Dr. Bitterman said it’s rare for the federal government to prosecute on-call physicians for violating EMTALA. Instead, it’s more likely that the hospital will be fined for EMTALA violations committed by on-call physicians.

However, the hospital passes the on-call obligation on to individual physicians through medical staff bylaws. Physicians who violate the bylaws may have their privileges restricted or removed, Dr. Bitterman said. Physicians could also be sued for malpractice, even if they never treated the patient, he added.

After-hours call duty in physicians’ practices

A very different type of call duty is having to respond to calls from one’s own patients after regular hours. Unlike doctors on ED call, who usually deal with patients they have never met, these physicians deal with their established patients or those of a colleague in their practice.

Courts have established that physicians have to provide an answering service or other means for their patients to contact them after hours, and the doctor must respond to these calls in a timely manner.

In a 2015 Louisiana ruling, a cardiologist was found liable for malpractice because he didn’t respond to an after-hours call from his patient. The patient tried several times to contact the cardiologist but got no reply.

Physicians may also be responsible if their answering service does not send critical messages to them immediately, if it fails to make appropriate documentation, or if it sends inaccurate data to the doctor.

Cases when on-call doctors didn’t respond

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of the U.S. Health and Human Services Administration oversees federal EMTALA violations and regularly reports them.

In 2018, the OIG fined a hospital in Waterloo, Iowa, $90,000 when an on-call cardiologist failed to implant a pacemaker for an ED patient. According to the OIG’s report, the patient arrived at the hospital with heart problems. Reached by phone, the cardiologist directed the ED physician to begin transcutaneous pacing but asked that the patient be transferred to another hospital for placement of the pacemaker. The patient died after transfer.

The OIG found that the original cardiologist could have placed the pacemaker, but, as often happens, it only fined the hospital, not the on-call physician for the EMTALA violation.

EMTALA requires that hospitals provide on-call specialists to assist emergency physicians with care of patients who arrive in the ED. In specialties for which there are few doctors to choose from, the on-call specialist may be on duty every third night and every third weekend. This can be daunting, especially for specialists who’ve had a grueling day of work.

Occasionally, on-call physicians, fearful they could make a medical error, request that the patient be transferred to another hospital for treatment. This is what a neurosurgeon who was on call at a Topeka, Kan., hospital did in 2001. Transferred to another hospital, the patient underwent an operation but lost sensation in his lower extremities. The patient sued the on-call neurosurgeon for negligence.

During the trial, the on-call neurosurgeon testified that he was “feeling run-down because he had been an on-call physician every third night for more than 10 years.” He also said this was the first time he had refused to see a patient because of fatigue, and he had decided that the patient “would be better off at a trauma center that had a trauma team and a fresher surgeon.”

The neurosurgeon successfully defended the malpractice suit, but Dr. Bitterman said he might have lost had there not been some unusual circumstances in the case. The court ruled that the hospital had not clearly defined the duties of on-call physicians, and the lawsuit didn’t cite the neurosurgeon’s EMTALA duty.

On-call duties defined by EMTALA

EMTALA sets the overall rules for on-call duties, which each hospital is expected to fine-tune on the basis of its own particular circumstances. Here are some of those rules, issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the OIG.

Only an individual physician can be on call. The hospital’s on-call schedule cannot name a physician practice.

Call applies to all ED patients. Physicians cannot limit their on-call responsibilities to their own patients, to patients in their insurance network, or to paying patients.

There may be some gaps in the call schedule. The OIG is not specific as to how many gaps are allowed, said Nick Healey, an attorney in Cheyenne, Wyo., who has written about on-call duties. Among other things, adequate coverage depends on the number of available physicians and the demand for their services. Mr. Healey added that states may require more extensive availability of on-call physicians at high-level trauma centers.

Hospitals must have made arrangements for transfer. Whenever there is a gap in the schedule, hospitals need to have a designated hospital to send the patient to. Hospitals that unnecessarily transfer patients will be penalized.

The ED physician calls the shots. The emergency physician handling the case decides if the on-call doctor has to come in and treat the patient firsthand.

The on-call physician may delegate the work to others. On-call physicians may designate a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, but the on-call physician is ultimately responsible. The ED doctor may require the physician to come in anyway, according to Todd B. Taylor, MD, an emergency physician in Phoenix, who has written about on-call duties. Dr. Bitterman noted that the physician may designate a colleague to take their call, but the substitute has to have privileges at the hospital.

Physicians may do their own work while on call. Physicians can perform elective surgery while on call, provided they have made arrangements if they then become unavailable for duty, Dr. Taylor said. He added that physicians can also have simultaneous call at other hospitals, provided they make arrangements.

The hospital fine-tunes call obligations

The hospital is expected to further define the federal rules. For instance, the CMS says physicians should respond to calls within a “reasonable period of time” and requires hospitals to specify response times, which may be 15-30 minutes for responding to phone calls and traveling to the ED, Dr. Bitterman said.

The CMS says older physicians can be exempted from call. The hospital determines the age at which physicians can be exempted. “Hospitals typically exempt physicians over age 65 or 70, or when they have certain medical conditions,” said Lowell Brown, a Los Angeles attorney who deals with on-call duties.

The hospital also sets the call schedule, which may result in uncovered periods in specialties in which there are few physicians to draw from, according to Mr. Healey. He said many hospitals still use a simple rule of thumb, even though it has been dismissed by the CMS. Under this so-called “rule of three,” hospitals that have three doctors or fewer in a specialty do not have to provide constant call coverage.

On-call rules are part of the medical staff bylaws, and they have to be approved by the medical staff. This may require delicate negotiations between the staff’s leadership and administrators, Dr. Bitterman said.

It is often up to the emergency physician on duty to enforce the hospital’s on-call rules, Dr. Taylor said. “If the ED physician is having trouble, he or she may contact the on-call physician’s department chairman or, if necessary, the chief of the medical staff and ask that person to deal with the physician,” Dr. Taylor said.

The ED physician has to determine whether the patient needs to be transferred to another hospital. Dr. Taylor said the ED physician must fill out a transfer form and obtain consent from the receiving hospital.

If a patient has to be transferred because an on-call physician failed to appear, the originating hospital has to report this to the CMS, and the physician and the hospital can be cited for an inappropriate transfer and fined, Mr. Brown said. “The possibility of being identified in this way should be a powerful incentive to accept call duty,” he added.

Malpractice exposure of on-call physicians

When on-call doctors provide medical advice regarding an ED patient, that advice may be subject to malpractice litigation, Dr. Taylor said. “Even if you only give the ED doctor advice over the phone, that may establish a patient-physician relationship and a duty that patient can cite in a malpractice case,” he noted.

Refusing to take call may also be grounds for a malpractice lawsuit, Dr. Bitterman said. Refusing to see a patient would not be considered medical negligence, he continued, because no medical decision is made. Rather, it involves general negligence, which occurs when physicians fail to carry out duties expected of them.

Dr. Bitterman cited a 2006 malpractice judgment in which an on-call neurosurgeon in Missouri was found to be generally negligent. The neurosurgeon had arranged for a colleague in his practice to take his call, but the colleague did not have privileges at the hospital.

A patient with a brain bleed came in and the substitute was on duty. The patient had to be transferred to another hospital, where the patient died. The court ordered that the on-call doctor and the originating hospital had to split a fine of $400,800.

On-call physicians can be charged with abandonment

Dr. Bitterman said that if on-call physicians do not provide expected follow-up treatment for an ED patient, they could be charged with abandonment, which is a matter of state law and involves filing a malpractice lawsuit.

Abandonment involves unilaterally terminating the patient relationship without providing notice. There must be an established relationship, which, in the case of call, is formed when the doctor comes to the ED to examine or admit the patient, Dr. Bitterman said. He added that the on-call doctor’s obligation applies only to the medical condition the patient came in for.

Even when an on-call doctor does not see a patient, a relationship can be established if the hospital requires its on-call doctors to make follow-up visits for ED patients, Dr. Taylor said. At some hospitals, he said, on-call doctors have blanket agreements to provide follow-up care in return for not having to arrive in the middle of the night during the ED visit.

Dr. Taylor gave an example of the on-call doctor’s obligation: “The ED doctor puts a splint on the patient’s ankle fracture, and the orthopedic surgeon on call agrees to follow up with the patient within the next few days. If the orthopedic surgeon refuses to follow up without making a reasonable accommodation, it may become an issue of patient abandonment.”

Now everyone has a good grasp of the rules

Fifteen years ago, many doctors were in open revolt against on-call duties, but they are more accepting now and understand the rules better, Mr. Healey said.

“Many hospitals have begun paying some specialists for call and designating hospitalists and surgicalists to do at least some of the work that used to be expected of on-call doctors,” he said.

According to Dr. Taylor, today’s on-call doctors often have less to do than in the past. “For example,” he said, “the hospitalist may admit an orthopedic patient at night, and then the orthopedic surgeon does the operation the next day. We’ve had EMTALA for 36 years now, and hospitals and doctors know how call works.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Taking call is one of the more challenging - and annoying - aspects of the job for many physicians. Calls may wake them up in the middle of the night and can interfere with their at-home activities. In Medscape’s Employed Physicians Report, 37% of respondents said they have from 1 to 5 hours of call per month; 19% said they have 6 to 10 hours; and 12% have 11 hours or more.

“Even if you don’t have to come in to the ED, you can get calls in the middle of the night, and you may get paid very little, if anything,” said Robert Bitterman MD, JD, an emergency physician and attorney in Harbor Springs, Mich.

And responding to the calls is not optional. Dr. Bitterman said

On-call activities are regulated by the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA). Dr. Bitterman said it’s rare for the federal government to prosecute on-call physicians for violating EMTALA. Instead, it’s more likely that the hospital will be fined for EMTALA violations committed by on-call physicians.

However, the hospital passes the on-call obligation on to individual physicians through medical staff bylaws. Physicians who violate the bylaws may have their privileges restricted or removed, Dr. Bitterman said. Physicians could also be sued for malpractice, even if they never treated the patient, he added.

After-hours call duty in physicians’ practices

A very different type of call duty is having to respond to calls from one’s own patients after regular hours. Unlike doctors on ED call, who usually deal with patients they have never met, these physicians deal with their established patients or those of a colleague in their practice.

Courts have established that physicians have to provide an answering service or other means for their patients to contact them after hours, and the doctor must respond to these calls in a timely manner.

In a 2015 Louisiana ruling, a cardiologist was found liable for malpractice because he didn’t respond to an after-hours call from his patient. The patient tried several times to contact the cardiologist but got no reply.

Physicians may also be responsible if their answering service does not send critical messages to them immediately, if it fails to make appropriate documentation, or if it sends inaccurate data to the doctor.

Cases when on-call doctors didn’t respond

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of the U.S. Health and Human Services Administration oversees federal EMTALA violations and regularly reports them.

In 2018, the OIG fined a hospital in Waterloo, Iowa, $90,000 when an on-call cardiologist failed to implant a pacemaker for an ED patient. According to the OIG’s report, the patient arrived at the hospital with heart problems. Reached by phone, the cardiologist directed the ED physician to begin transcutaneous pacing but asked that the patient be transferred to another hospital for placement of the pacemaker. The patient died after transfer.

The OIG found that the original cardiologist could have placed the pacemaker, but, as often happens, it only fined the hospital, not the on-call physician for the EMTALA violation.

EMTALA requires that hospitals provide on-call specialists to assist emergency physicians with care of patients who arrive in the ED. In specialties for which there are few doctors to choose from, the on-call specialist may be on duty every third night and every third weekend. This can be daunting, especially for specialists who’ve had a grueling day of work.

Occasionally, on-call physicians, fearful they could make a medical error, request that the patient be transferred to another hospital for treatment. This is what a neurosurgeon who was on call at a Topeka, Kan., hospital did in 2001. Transferred to another hospital, the patient underwent an operation but lost sensation in his lower extremities. The patient sued the on-call neurosurgeon for negligence.

During the trial, the on-call neurosurgeon testified that he was “feeling run-down because he had been an on-call physician every third night for more than 10 years.” He also said this was the first time he had refused to see a patient because of fatigue, and he had decided that the patient “would be better off at a trauma center that had a trauma team and a fresher surgeon.”

The neurosurgeon successfully defended the malpractice suit, but Dr. Bitterman said he might have lost had there not been some unusual circumstances in the case. The court ruled that the hospital had not clearly defined the duties of on-call physicians, and the lawsuit didn’t cite the neurosurgeon’s EMTALA duty.

On-call duties defined by EMTALA

EMTALA sets the overall rules for on-call duties, which each hospital is expected to fine-tune on the basis of its own particular circumstances. Here are some of those rules, issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the OIG.

Only an individual physician can be on call. The hospital’s on-call schedule cannot name a physician practice.

Call applies to all ED patients. Physicians cannot limit their on-call responsibilities to their own patients, to patients in their insurance network, or to paying patients.

There may be some gaps in the call schedule. The OIG is not specific as to how many gaps are allowed, said Nick Healey, an attorney in Cheyenne, Wyo., who has written about on-call duties. Among other things, adequate coverage depends on the number of available physicians and the demand for their services. Mr. Healey added that states may require more extensive availability of on-call physicians at high-level trauma centers.

Hospitals must have made arrangements for transfer. Whenever there is a gap in the schedule, hospitals need to have a designated hospital to send the patient to. Hospitals that unnecessarily transfer patients will be penalized.

The ED physician calls the shots. The emergency physician handling the case decides if the on-call doctor has to come in and treat the patient firsthand.

The on-call physician may delegate the work to others. On-call physicians may designate a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, but the on-call physician is ultimately responsible. The ED doctor may require the physician to come in anyway, according to Todd B. Taylor, MD, an emergency physician in Phoenix, who has written about on-call duties. Dr. Bitterman noted that the physician may designate a colleague to take their call, but the substitute has to have privileges at the hospital.

Physicians may do their own work while on call. Physicians can perform elective surgery while on call, provided they have made arrangements if they then become unavailable for duty, Dr. Taylor said. He added that physicians can also have simultaneous call at other hospitals, provided they make arrangements.

The hospital fine-tunes call obligations

The hospital is expected to further define the federal rules. For instance, the CMS says physicians should respond to calls within a “reasonable period of time” and requires hospitals to specify response times, which may be 15-30 minutes for responding to phone calls and traveling to the ED, Dr. Bitterman said.

The CMS says older physicians can be exempted from call. The hospital determines the age at which physicians can be exempted. “Hospitals typically exempt physicians over age 65 or 70, or when they have certain medical conditions,” said Lowell Brown, a Los Angeles attorney who deals with on-call duties.

The hospital also sets the call schedule, which may result in uncovered periods in specialties in which there are few physicians to draw from, according to Mr. Healey. He said many hospitals still use a simple rule of thumb, even though it has been dismissed by the CMS. Under this so-called “rule of three,” hospitals that have three doctors or fewer in a specialty do not have to provide constant call coverage.

On-call rules are part of the medical staff bylaws, and they have to be approved by the medical staff. This may require delicate negotiations between the staff’s leadership and administrators, Dr. Bitterman said.

It is often up to the emergency physician on duty to enforce the hospital’s on-call rules, Dr. Taylor said. “If the ED physician is having trouble, he or she may contact the on-call physician’s department chairman or, if necessary, the chief of the medical staff and ask that person to deal with the physician,” Dr. Taylor said.

The ED physician has to determine whether the patient needs to be transferred to another hospital. Dr. Taylor said the ED physician must fill out a transfer form and obtain consent from the receiving hospital.

If a patient has to be transferred because an on-call physician failed to appear, the originating hospital has to report this to the CMS, and the physician and the hospital can be cited for an inappropriate transfer and fined, Mr. Brown said. “The possibility of being identified in this way should be a powerful incentive to accept call duty,” he added.

Malpractice exposure of on-call physicians

When on-call doctors provide medical advice regarding an ED patient, that advice may be subject to malpractice litigation, Dr. Taylor said. “Even if you only give the ED doctor advice over the phone, that may establish a patient-physician relationship and a duty that patient can cite in a malpractice case,” he noted.

Refusing to take call may also be grounds for a malpractice lawsuit, Dr. Bitterman said. Refusing to see a patient would not be considered medical negligence, he continued, because no medical decision is made. Rather, it involves general negligence, which occurs when physicians fail to carry out duties expected of them.

Dr. Bitterman cited a 2006 malpractice judgment in which an on-call neurosurgeon in Missouri was found to be generally negligent. The neurosurgeon had arranged for a colleague in his practice to take his call, but the colleague did not have privileges at the hospital.

A patient with a brain bleed came in and the substitute was on duty. The patient had to be transferred to another hospital, where the patient died. The court ordered that the on-call doctor and the originating hospital had to split a fine of $400,800.

On-call physicians can be charged with abandonment

Dr. Bitterman said that if on-call physicians do not provide expected follow-up treatment for an ED patient, they could be charged with abandonment, which is a matter of state law and involves filing a malpractice lawsuit.

Abandonment involves unilaterally terminating the patient relationship without providing notice. There must be an established relationship, which, in the case of call, is formed when the doctor comes to the ED to examine or admit the patient, Dr. Bitterman said. He added that the on-call doctor’s obligation applies only to the medical condition the patient came in for.

Even when an on-call doctor does not see a patient, a relationship can be established if the hospital requires its on-call doctors to make follow-up visits for ED patients, Dr. Taylor said. At some hospitals, he said, on-call doctors have blanket agreements to provide follow-up care in return for not having to arrive in the middle of the night during the ED visit.

Dr. Taylor gave an example of the on-call doctor’s obligation: “The ED doctor puts a splint on the patient’s ankle fracture, and the orthopedic surgeon on call agrees to follow up with the patient within the next few days. If the orthopedic surgeon refuses to follow up without making a reasonable accommodation, it may become an issue of patient abandonment.”

Now everyone has a good grasp of the rules

Fifteen years ago, many doctors were in open revolt against on-call duties, but they are more accepting now and understand the rules better, Mr. Healey said.

“Many hospitals have begun paying some specialists for call and designating hospitalists and surgicalists to do at least some of the work that used to be expected of on-call doctors,” he said.

According to Dr. Taylor, today’s on-call doctors often have less to do than in the past. “For example,” he said, “the hospitalist may admit an orthopedic patient at night, and then the orthopedic surgeon does the operation the next day. We’ve had EMTALA for 36 years now, and hospitals and doctors know how call works.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Taking call is one of the more challenging - and annoying - aspects of the job for many physicians. Calls may wake them up in the middle of the night and can interfere with their at-home activities. In Medscape’s Employed Physicians Report, 37% of respondents said they have from 1 to 5 hours of call per month; 19% said they have 6 to 10 hours; and 12% have 11 hours or more.

“Even if you don’t have to come in to the ED, you can get calls in the middle of the night, and you may get paid very little, if anything,” said Robert Bitterman MD, JD, an emergency physician and attorney in Harbor Springs, Mich.

And responding to the calls is not optional. Dr. Bitterman said

On-call activities are regulated by the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA). Dr. Bitterman said it’s rare for the federal government to prosecute on-call physicians for violating EMTALA. Instead, it’s more likely that the hospital will be fined for EMTALA violations committed by on-call physicians.

However, the hospital passes the on-call obligation on to individual physicians through medical staff bylaws. Physicians who violate the bylaws may have their privileges restricted or removed, Dr. Bitterman said. Physicians could also be sued for malpractice, even if they never treated the patient, he added.

After-hours call duty in physicians’ practices

A very different type of call duty is having to respond to calls from one’s own patients after regular hours. Unlike doctors on ED call, who usually deal with patients they have never met, these physicians deal with their established patients or those of a colleague in their practice.

Courts have established that physicians have to provide an answering service or other means for their patients to contact them after hours, and the doctor must respond to these calls in a timely manner.

In a 2015 Louisiana ruling, a cardiologist was found liable for malpractice because he didn’t respond to an after-hours call from his patient. The patient tried several times to contact the cardiologist but got no reply.

Physicians may also be responsible if their answering service does not send critical messages to them immediately, if it fails to make appropriate documentation, or if it sends inaccurate data to the doctor.

Cases when on-call doctors didn’t respond

The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) of the U.S. Health and Human Services Administration oversees federal EMTALA violations and regularly reports them.

In 2018, the OIG fined a hospital in Waterloo, Iowa, $90,000 when an on-call cardiologist failed to implant a pacemaker for an ED patient. According to the OIG’s report, the patient arrived at the hospital with heart problems. Reached by phone, the cardiologist directed the ED physician to begin transcutaneous pacing but asked that the patient be transferred to another hospital for placement of the pacemaker. The patient died after transfer.

The OIG found that the original cardiologist could have placed the pacemaker, but, as often happens, it only fined the hospital, not the on-call physician for the EMTALA violation.

EMTALA requires that hospitals provide on-call specialists to assist emergency physicians with care of patients who arrive in the ED. In specialties for which there are few doctors to choose from, the on-call specialist may be on duty every third night and every third weekend. This can be daunting, especially for specialists who’ve had a grueling day of work.

Occasionally, on-call physicians, fearful they could make a medical error, request that the patient be transferred to another hospital for treatment. This is what a neurosurgeon who was on call at a Topeka, Kan., hospital did in 2001. Transferred to another hospital, the patient underwent an operation but lost sensation in his lower extremities. The patient sued the on-call neurosurgeon for negligence.

During the trial, the on-call neurosurgeon testified that he was “feeling run-down because he had been an on-call physician every third night for more than 10 years.” He also said this was the first time he had refused to see a patient because of fatigue, and he had decided that the patient “would be better off at a trauma center that had a trauma team and a fresher surgeon.”

The neurosurgeon successfully defended the malpractice suit, but Dr. Bitterman said he might have lost had there not been some unusual circumstances in the case. The court ruled that the hospital had not clearly defined the duties of on-call physicians, and the lawsuit didn’t cite the neurosurgeon’s EMTALA duty.

On-call duties defined by EMTALA

EMTALA sets the overall rules for on-call duties, which each hospital is expected to fine-tune on the basis of its own particular circumstances. Here are some of those rules, issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the OIG.

Only an individual physician can be on call. The hospital’s on-call schedule cannot name a physician practice.

Call applies to all ED patients. Physicians cannot limit their on-call responsibilities to their own patients, to patients in their insurance network, or to paying patients.

There may be some gaps in the call schedule. The OIG is not specific as to how many gaps are allowed, said Nick Healey, an attorney in Cheyenne, Wyo., who has written about on-call duties. Among other things, adequate coverage depends on the number of available physicians and the demand for their services. Mr. Healey added that states may require more extensive availability of on-call physicians at high-level trauma centers.

Hospitals must have made arrangements for transfer. Whenever there is a gap in the schedule, hospitals need to have a designated hospital to send the patient to. Hospitals that unnecessarily transfer patients will be penalized.

The ED physician calls the shots. The emergency physician handling the case decides if the on-call doctor has to come in and treat the patient firsthand.

The on-call physician may delegate the work to others. On-call physicians may designate a nurse practitioner or physician assistant, but the on-call physician is ultimately responsible. The ED doctor may require the physician to come in anyway, according to Todd B. Taylor, MD, an emergency physician in Phoenix, who has written about on-call duties. Dr. Bitterman noted that the physician may designate a colleague to take their call, but the substitute has to have privileges at the hospital.

Physicians may do their own work while on call. Physicians can perform elective surgery while on call, provided they have made arrangements if they then become unavailable for duty, Dr. Taylor said. He added that physicians can also have simultaneous call at other hospitals, provided they make arrangements.

The hospital fine-tunes call obligations

The hospital is expected to further define the federal rules. For instance, the CMS says physicians should respond to calls within a “reasonable period of time” and requires hospitals to specify response times, which may be 15-30 minutes for responding to phone calls and traveling to the ED, Dr. Bitterman said.

The CMS says older physicians can be exempted from call. The hospital determines the age at which physicians can be exempted. “Hospitals typically exempt physicians over age 65 or 70, or when they have certain medical conditions,” said Lowell Brown, a Los Angeles attorney who deals with on-call duties.

The hospital also sets the call schedule, which may result in uncovered periods in specialties in which there are few physicians to draw from, according to Mr. Healey. He said many hospitals still use a simple rule of thumb, even though it has been dismissed by the CMS. Under this so-called “rule of three,” hospitals that have three doctors or fewer in a specialty do not have to provide constant call coverage.

On-call rules are part of the medical staff bylaws, and they have to be approved by the medical staff. This may require delicate negotiations between the staff’s leadership and administrators, Dr. Bitterman said.

It is often up to the emergency physician on duty to enforce the hospital’s on-call rules, Dr. Taylor said. “If the ED physician is having trouble, he or she may contact the on-call physician’s department chairman or, if necessary, the chief of the medical staff and ask that person to deal with the physician,” Dr. Taylor said.

The ED physician has to determine whether the patient needs to be transferred to another hospital. Dr. Taylor said the ED physician must fill out a transfer form and obtain consent from the receiving hospital.

If a patient has to be transferred because an on-call physician failed to appear, the originating hospital has to report this to the CMS, and the physician and the hospital can be cited for an inappropriate transfer and fined, Mr. Brown said. “The possibility of being identified in this way should be a powerful incentive to accept call duty,” he added.

Malpractice exposure of on-call physicians

When on-call doctors provide medical advice regarding an ED patient, that advice may be subject to malpractice litigation, Dr. Taylor said. “Even if you only give the ED doctor advice over the phone, that may establish a patient-physician relationship and a duty that patient can cite in a malpractice case,” he noted.

Refusing to take call may also be grounds for a malpractice lawsuit, Dr. Bitterman said. Refusing to see a patient would not be considered medical negligence, he continued, because no medical decision is made. Rather, it involves general negligence, which occurs when physicians fail to carry out duties expected of them.

Dr. Bitterman cited a 2006 malpractice judgment in which an on-call neurosurgeon in Missouri was found to be generally negligent. The neurosurgeon had arranged for a colleague in his practice to take his call, but the colleague did not have privileges at the hospital.

A patient with a brain bleed came in and the substitute was on duty. The patient had to be transferred to another hospital, where the patient died. The court ordered that the on-call doctor and the originating hospital had to split a fine of $400,800.

On-call physicians can be charged with abandonment

Dr. Bitterman said that if on-call physicians do not provide expected follow-up treatment for an ED patient, they could be charged with abandonment, which is a matter of state law and involves filing a malpractice lawsuit.

Abandonment involves unilaterally terminating the patient relationship without providing notice. There must be an established relationship, which, in the case of call, is formed when the doctor comes to the ED to examine or admit the patient, Dr. Bitterman said. He added that the on-call doctor’s obligation applies only to the medical condition the patient came in for.

Even when an on-call doctor does not see a patient, a relationship can be established if the hospital requires its on-call doctors to make follow-up visits for ED patients, Dr. Taylor said. At some hospitals, he said, on-call doctors have blanket agreements to provide follow-up care in return for not having to arrive in the middle of the night during the ED visit.

Dr. Taylor gave an example of the on-call doctor’s obligation: “The ED doctor puts a splint on the patient’s ankle fracture, and the orthopedic surgeon on call agrees to follow up with the patient within the next few days. If the orthopedic surgeon refuses to follow up without making a reasonable accommodation, it may become an issue of patient abandonment.”

Now everyone has a good grasp of the rules

Fifteen years ago, many doctors were in open revolt against on-call duties, but they are more accepting now and understand the rules better, Mr. Healey said.

“Many hospitals have begun paying some specialists for call and designating hospitalists and surgicalists to do at least some of the work that used to be expected of on-call doctors,” he said.

According to Dr. Taylor, today’s on-call doctors often have less to do than in the past. “For example,” he said, “the hospitalist may admit an orthopedic patient at night, and then the orthopedic surgeon does the operation the next day. We’ve had EMTALA for 36 years now, and hospitals and doctors know how call works.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Collateral flow flags stroke patients for late thrombectomy

Patients with acute ischemic stroke presenting late at the hospital can be selected for endovascular thrombectomy by the presence of collateral flow on CT angiography (CTA), a new study shows.

The MR CLEAN-LATE trial found that patients selected for thrombectomy in this way had a greater chance of a better functional outcome than patients who did not receive endovascular therapy.

The study was presented at the 14th World Stroke Congress in Singapore by study investigator Susanne Olthuis, MD, of Maastricht (the Netherlands) University Medical Center.

Patients in the intervention group were more likely to show a benefit on the primary endpoint of modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score at 90 days with a significant common odds ratio of 1.68, a finding that received applause from attendees of the plenary WSC session at which the study was presented.

“This means that patients treated with endovascular therapy in this trial had about a 1.7 times higher chance of achieving a better functional outcome at 90 days,” Dr. Olthuis said.

“Selection based on collateral flow identifies an additional group of patients eligible for late-window endovascular therapy in addition to those eligible based on perfusion and clinical criteria,” Dr. Olthuis concluded.

“We recommend implementation of collateral selection in routine clinical practice as it is time efficient. The CTA is already available, and it involves a low-complexity assessment. The only distinction that needs to be made is whether or not there are any collaterals visible on CTA. If collaterals are absent or there is any doubt, then CT perfusion [CTP] imaging can still be used,” she added.

Co–principal investigator Wim H. van Zwam, MD, interventional radiologist at Maastricht, said in a comment:“My take-home message is that now in the late window we can select patients based on the presence of collaterals on CT angiography, which makes selection easier and faster and more widely available.

“If any collaterals are seen – and that is easily done just by looking at the CTA scan – then the patient can be selected for endovascular treatment,” Dr. van Zwam added. “We don’t need to wait for calculations of core and penumbra volumes from the CTP scan. There will also be additional patients who can benefit from endovascular therapy who do not fulfill the CTP criteria but do have visible collaterals.”

Explaining the background to the study, Dr. Olthuis noted that endovascular thrombectomy for large vessel occlusion stroke is safe and effective if performed within 6 hours and the effect then diminishes over time. In the original trial of endovascular treatment, MR CLEAN, patients with higher collateral grades had more treatment benefit, leading to the hypothesis that the assessment of collateral blood flow could help identify patients who would still benefit in the late time window.

The current MR CLEAN-LATE trial therefore set out to compare safety and efficacy of endovascular therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke in the anterior circulation presenting within 6-24 hours from symptom onset with patients selected based on the presence of collateral flow on CTA.

At the time the trial was starting, the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials reported showing benefit of endovascular therapy in patients presenting in the late window who had been selected for endovascular treatment based on a combination of perfusion imaging and clinical criteria, so patients who fitted these criteria were also excluded from MR CLEAN-LATE as they would now be eligible for endovascular therapy under the latest clinical guidelines.

But the study continued, as “we believed collateral selection may still be able to identify an additional group of patients that may benefit from endovascular therapy in the late window,” Dr. Olthuis said.

The trial randomly assigned 502 such patients with a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of at least 2 and with collateral flow grades of 1-3 to receive endovascular therapy (intervention) or control.

Safety data showed a slightly but nonsignificantly higher mortality rate at 90 days in the control group (30%) versus 24% in the intervention group.

The rate of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was higher in the intervention group (6.7%) versus 1.6% in the control group, but Dr. Olthuis pointed out that the rate of sICH in the intervention group was similar to that in the endovascular groups of the DAWN and DEFUSE 3 trials.

The primary endpoint – mRS score at 90 days – showed a shift toward better outcome in the intervention group, with an adjusted common OR of 1.68 (95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.33).

The median mRS score in the intervention group was 3 (95% CI, 2-5) versus 4 (95% CI, 2-6) in the control group.

Secondary outcomes also showed benefits for the intervention group for the endpoints of mRS score 0-1 versus 2-6 (OR, 1.63); mRS 0-2 versus 3-6 (OR 1.54); and mRS 0-3 versus 4-6 (OR, 1.74).

In addition, NIHSS score was reduced by 17% at 24 hours and by 27% by 5-7 days or discharge in the intervention group. Recanalization at 24 hours was also improved in the intervention group (81% vs. 52%) and infarct size was reduced by 32%.

Dr. Olthuis explained that collateral grade was defined as the amount of collateral flow in the affected hemisphere as a percentage of the contralateral site, with grade 0 correlating to an absence of collaterals (and these were the only patients excluded).