User login

Does fertility preservation in patients with breast cancer impact relapse rates and disease-specific mortality?

Marklund A, Lekberg T, Hedayati E, et al. Relapse rates and disease-specific mortality following procedures for fertility preservation at time of breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:1438-1446. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.3677.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Breast cancer is the most diagnosed cancer among US women after skin cancer.1 As of the end of 2020, 7.8 million women were alive who were diagnosed with breast cancer in the past 5 years, making it the world’s most prevalent cancer. Given the wide reach of breast cancer and the increase in its distant stage by more than 4% per year in women of reproductive age (20–39 years), clinicians are urged to address fertility preservation due to reproductive compromise of gonadotoxic therapies and gonadectomy.2 To predict the risk of infertility following chemotherapy, a Cyclophosphamide Equivalent Dose (CED) calculator can be used. A CED of 4,000 mg/m2 has been associated with a significant risk of infertility.3

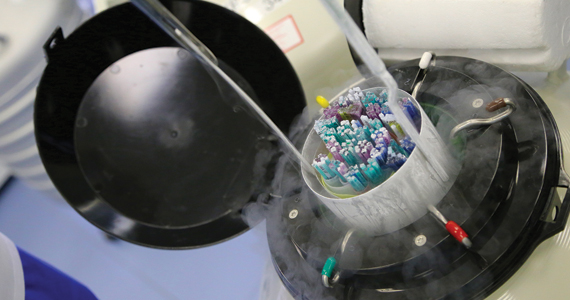

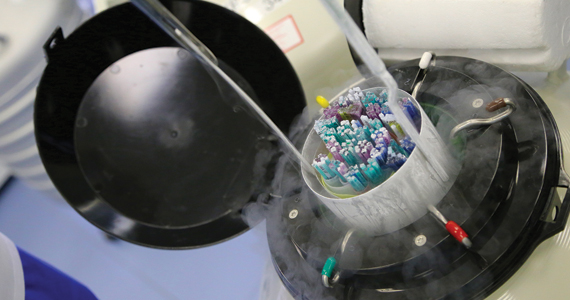

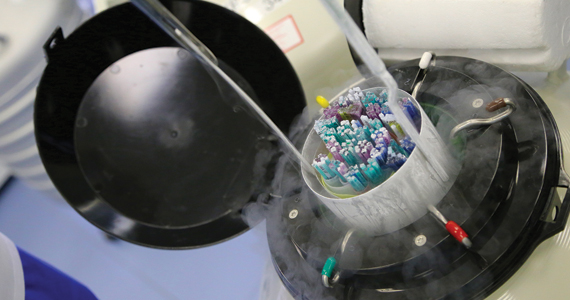

In 2012, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine removed the experimental label of oocyte cryopreservation then recently endorsed ovarian cryopreservation, thereby providing acceptable procedures for fertility preservation.4 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist use during chemotherapy, which is used to protect the ovary in premenopausal women against the effects of chemotherapy, has been shown to have inconsistent findings and should not replace the established modalities of oocyte/embryo/ovarian tissue cryopreservation.2,5

Details of the study

While studies have been reassuring that ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation in women with breast cancer does not worsen the prognosis, findings are limited by short-term follow-up.6

The recent study by Marklund and colleagues presented an analysis of breast cancer relapse and mortality following fertility preservation with and without hormonal stimulation. In their prospective cohort study of 425 Swedish women who underwent fertility preservation, the authors categorized patients into 2 groups: oocyte and embryo cryopreservation by ovarian hormonal stimulation and ovarian tissue cryopreservation without hormonal stimulation. The control group included 850 women with breast cancer who did not undergo fertility preservation. The cohort and the control groups were matched on age, calendar period of diagnosis, and region. Three Swedish registers for breast cancer were used to obtain the study cohort, and for each participant, 2 breast cancer patients who were unexposed to fertility preservation were used for comparison. The primary outcome was mortality while the secondary outcome was any event of death due to breast cancer or relapse.

Results. A total of 1,275 women were studied at the time of breast cancer diagnosis. After stratification, which included age, parity at diagnosis, tumor size, number of lymph node metastases, and estrogen receptor status, disease-specific mortality was similar in all categories of women, that is, hormonal fertility preservation, nonhormonal fertility preservation, and controls. In the subcohort of 723 women, the adjusted rate of relapse and disease-specific mortality remained the same among all groups.

Study strengths and limitations

This study prompts several areas of criticism. The follow-up of breast cancer patients was only 5 years, adding to the limitations of short-term monitoring seen in prior studies. The authors also considered a delay in pregnancy attempts following breast cancer treatment of hormonally sensitive cancers of 5 to 10 years. However, the long-term safety of pregnancy following breast cancer has shown a statistically significantly superior disease-free survival (DFS) in patients who became pregnant less than 2 years from diagnosis and no difference in those who became pregnant 2 or more years from diagnosis.7

Only 58 women in the nonhormonal fertility preservation group (ovarian tissue cryopreservation) were studied, which may limit an adequate evaluation although it is not expected to negatively impact breast cancer prognosis. Another area of potential bias was the use of only a subcohort to assess relapse-free survival as opposed to the entire cohort that was used to assess mortality.

Strengths of this study include obligatory reporting to the registry and equal access to anticancer treatment and fertility preservation in Sweden. Ovarian stimulating drugs were examined, as letrozole is often used in breast cancer patients to maintain lower estradiol levels due to aromatase inhibition. Nevertheless, this study did not demonstrate a difference in mortality with or without letrozole use. ●

Marklund and colleagues’ findings revealed no increase of breast cancer relapse and mortality following fertility preservation with or without hormonal stimulation. They also propose a “healthy user effect” whereby a woman who feels healthy may choose to undergo fertility preservation, thereby biasing the outcome by having a better survival.8

Future studies with longer follow-up are needed to address the hormonal impact of fertility preservation, if any, on breast cancer DFS and mortality, as well as to evaluate subsequent pregnancy outcomes, stratified for medication treatment type via the CED calculator. To date, evidence continues to support fertility preservation options that use hormonal ovarian stimulation in breast cancer patients as apparently safe for, at least, up to 5 years of follow-up.

MARK P. TROLICE, MD

- Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Miller KD, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:524-541. doi:10.3322/caac.21754.

- Oktay K, Harvey BE, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;1;36:1994-2001. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.78.1914.

- Fertility Preservation in Pittsburgh. CED calculator. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://fertilitypreservationpittsburgh.org/fertility-resources/fertility-risk-calculator/

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:1022-1033. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.09.013.

- Blumenfeld Z. Fertility preservation using GnRH agonists: rationale, possible mechanisms, and explanation of controversy. Clin Med Insights Reprod Health. 2019;13: 1179558119870163. doi:10.1177/1179558119870163.

- Beebeejaun Y, Athithan A, Copeland TP, et al. Risk of breast cancer in women treated with ovarian stimulation drugs for infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:198-207. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.01.044.

- Lambertini M, Kroman N, Ameye L, et al. Long-term safety of pregnancy following breast cancer according to estrogen receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:426-429. doi:10.1093/jnci/djx206.

- Marklund A, Lundberg FE, Eloranta S, et al. Reproductive outcomes after breast cancer in women with vs without fertility preservation. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:86-91. doi:10.1001/ jamaoncol.2020.5957.

Marklund A, Lekberg T, Hedayati E, et al. Relapse rates and disease-specific mortality following procedures for fertility preservation at time of breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:1438-1446. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.3677.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Breast cancer is the most diagnosed cancer among US women after skin cancer.1 As of the end of 2020, 7.8 million women were alive who were diagnosed with breast cancer in the past 5 years, making it the world’s most prevalent cancer. Given the wide reach of breast cancer and the increase in its distant stage by more than 4% per year in women of reproductive age (20–39 years), clinicians are urged to address fertility preservation due to reproductive compromise of gonadotoxic therapies and gonadectomy.2 To predict the risk of infertility following chemotherapy, a Cyclophosphamide Equivalent Dose (CED) calculator can be used. A CED of 4,000 mg/m2 has been associated with a significant risk of infertility.3

In 2012, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine removed the experimental label of oocyte cryopreservation then recently endorsed ovarian cryopreservation, thereby providing acceptable procedures for fertility preservation.4 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist use during chemotherapy, which is used to protect the ovary in premenopausal women against the effects of chemotherapy, has been shown to have inconsistent findings and should not replace the established modalities of oocyte/embryo/ovarian tissue cryopreservation.2,5

Details of the study

While studies have been reassuring that ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation in women with breast cancer does not worsen the prognosis, findings are limited by short-term follow-up.6

The recent study by Marklund and colleagues presented an analysis of breast cancer relapse and mortality following fertility preservation with and without hormonal stimulation. In their prospective cohort study of 425 Swedish women who underwent fertility preservation, the authors categorized patients into 2 groups: oocyte and embryo cryopreservation by ovarian hormonal stimulation and ovarian tissue cryopreservation without hormonal stimulation. The control group included 850 women with breast cancer who did not undergo fertility preservation. The cohort and the control groups were matched on age, calendar period of diagnosis, and region. Three Swedish registers for breast cancer were used to obtain the study cohort, and for each participant, 2 breast cancer patients who were unexposed to fertility preservation were used for comparison. The primary outcome was mortality while the secondary outcome was any event of death due to breast cancer or relapse.

Results. A total of 1,275 women were studied at the time of breast cancer diagnosis. After stratification, which included age, parity at diagnosis, tumor size, number of lymph node metastases, and estrogen receptor status, disease-specific mortality was similar in all categories of women, that is, hormonal fertility preservation, nonhormonal fertility preservation, and controls. In the subcohort of 723 women, the adjusted rate of relapse and disease-specific mortality remained the same among all groups.

Study strengths and limitations

This study prompts several areas of criticism. The follow-up of breast cancer patients was only 5 years, adding to the limitations of short-term monitoring seen in prior studies. The authors also considered a delay in pregnancy attempts following breast cancer treatment of hormonally sensitive cancers of 5 to 10 years. However, the long-term safety of pregnancy following breast cancer has shown a statistically significantly superior disease-free survival (DFS) in patients who became pregnant less than 2 years from diagnosis and no difference in those who became pregnant 2 or more years from diagnosis.7

Only 58 women in the nonhormonal fertility preservation group (ovarian tissue cryopreservation) were studied, which may limit an adequate evaluation although it is not expected to negatively impact breast cancer prognosis. Another area of potential bias was the use of only a subcohort to assess relapse-free survival as opposed to the entire cohort that was used to assess mortality.

Strengths of this study include obligatory reporting to the registry and equal access to anticancer treatment and fertility preservation in Sweden. Ovarian stimulating drugs were examined, as letrozole is often used in breast cancer patients to maintain lower estradiol levels due to aromatase inhibition. Nevertheless, this study did not demonstrate a difference in mortality with or without letrozole use. ●

Marklund and colleagues’ findings revealed no increase of breast cancer relapse and mortality following fertility preservation with or without hormonal stimulation. They also propose a “healthy user effect” whereby a woman who feels healthy may choose to undergo fertility preservation, thereby biasing the outcome by having a better survival.8

Future studies with longer follow-up are needed to address the hormonal impact of fertility preservation, if any, on breast cancer DFS and mortality, as well as to evaluate subsequent pregnancy outcomes, stratified for medication treatment type via the CED calculator. To date, evidence continues to support fertility preservation options that use hormonal ovarian stimulation in breast cancer patients as apparently safe for, at least, up to 5 years of follow-up.

MARK P. TROLICE, MD

Marklund A, Lekberg T, Hedayati E, et al. Relapse rates and disease-specific mortality following procedures for fertility preservation at time of breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8:1438-1446. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.3677.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Breast cancer is the most diagnosed cancer among US women after skin cancer.1 As of the end of 2020, 7.8 million women were alive who were diagnosed with breast cancer in the past 5 years, making it the world’s most prevalent cancer. Given the wide reach of breast cancer and the increase in its distant stage by more than 4% per year in women of reproductive age (20–39 years), clinicians are urged to address fertility preservation due to reproductive compromise of gonadotoxic therapies and gonadectomy.2 To predict the risk of infertility following chemotherapy, a Cyclophosphamide Equivalent Dose (CED) calculator can be used. A CED of 4,000 mg/m2 has been associated with a significant risk of infertility.3

In 2012, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine removed the experimental label of oocyte cryopreservation then recently endorsed ovarian cryopreservation, thereby providing acceptable procedures for fertility preservation.4 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist use during chemotherapy, which is used to protect the ovary in premenopausal women against the effects of chemotherapy, has been shown to have inconsistent findings and should not replace the established modalities of oocyte/embryo/ovarian tissue cryopreservation.2,5

Details of the study

While studies have been reassuring that ovarian stimulation for fertility preservation in women with breast cancer does not worsen the prognosis, findings are limited by short-term follow-up.6

The recent study by Marklund and colleagues presented an analysis of breast cancer relapse and mortality following fertility preservation with and without hormonal stimulation. In their prospective cohort study of 425 Swedish women who underwent fertility preservation, the authors categorized patients into 2 groups: oocyte and embryo cryopreservation by ovarian hormonal stimulation and ovarian tissue cryopreservation without hormonal stimulation. The control group included 850 women with breast cancer who did not undergo fertility preservation. The cohort and the control groups were matched on age, calendar period of diagnosis, and region. Three Swedish registers for breast cancer were used to obtain the study cohort, and for each participant, 2 breast cancer patients who were unexposed to fertility preservation were used for comparison. The primary outcome was mortality while the secondary outcome was any event of death due to breast cancer or relapse.

Results. A total of 1,275 women were studied at the time of breast cancer diagnosis. After stratification, which included age, parity at diagnosis, tumor size, number of lymph node metastases, and estrogen receptor status, disease-specific mortality was similar in all categories of women, that is, hormonal fertility preservation, nonhormonal fertility preservation, and controls. In the subcohort of 723 women, the adjusted rate of relapse and disease-specific mortality remained the same among all groups.

Study strengths and limitations

This study prompts several areas of criticism. The follow-up of breast cancer patients was only 5 years, adding to the limitations of short-term monitoring seen in prior studies. The authors also considered a delay in pregnancy attempts following breast cancer treatment of hormonally sensitive cancers of 5 to 10 years. However, the long-term safety of pregnancy following breast cancer has shown a statistically significantly superior disease-free survival (DFS) in patients who became pregnant less than 2 years from diagnosis and no difference in those who became pregnant 2 or more years from diagnosis.7

Only 58 women in the nonhormonal fertility preservation group (ovarian tissue cryopreservation) were studied, which may limit an adequate evaluation although it is not expected to negatively impact breast cancer prognosis. Another area of potential bias was the use of only a subcohort to assess relapse-free survival as opposed to the entire cohort that was used to assess mortality.

Strengths of this study include obligatory reporting to the registry and equal access to anticancer treatment and fertility preservation in Sweden. Ovarian stimulating drugs were examined, as letrozole is often used in breast cancer patients to maintain lower estradiol levels due to aromatase inhibition. Nevertheless, this study did not demonstrate a difference in mortality with or without letrozole use. ●

Marklund and colleagues’ findings revealed no increase of breast cancer relapse and mortality following fertility preservation with or without hormonal stimulation. They also propose a “healthy user effect” whereby a woman who feels healthy may choose to undergo fertility preservation, thereby biasing the outcome by having a better survival.8

Future studies with longer follow-up are needed to address the hormonal impact of fertility preservation, if any, on breast cancer DFS and mortality, as well as to evaluate subsequent pregnancy outcomes, stratified for medication treatment type via the CED calculator. To date, evidence continues to support fertility preservation options that use hormonal ovarian stimulation in breast cancer patients as apparently safe for, at least, up to 5 years of follow-up.

MARK P. TROLICE, MD

- Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Miller KD, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:524-541. doi:10.3322/caac.21754.

- Oktay K, Harvey BE, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;1;36:1994-2001. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.78.1914.

- Fertility Preservation in Pittsburgh. CED calculator. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://fertilitypreservationpittsburgh.org/fertility-resources/fertility-risk-calculator/

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:1022-1033. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.09.013.

- Blumenfeld Z. Fertility preservation using GnRH agonists: rationale, possible mechanisms, and explanation of controversy. Clin Med Insights Reprod Health. 2019;13: 1179558119870163. doi:10.1177/1179558119870163.

- Beebeejaun Y, Athithan A, Copeland TP, et al. Risk of breast cancer in women treated with ovarian stimulation drugs for infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:198-207. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.01.044.

- Lambertini M, Kroman N, Ameye L, et al. Long-term safety of pregnancy following breast cancer according to estrogen receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:426-429. doi:10.1093/jnci/djx206.

- Marklund A, Lundberg FE, Eloranta S, et al. Reproductive outcomes after breast cancer in women with vs without fertility preservation. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:86-91. doi:10.1001/ jamaoncol.2020.5957.

- Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Miller KD, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:524-541. doi:10.3322/caac.21754.

- Oktay K, Harvey BE, Partridge AH, et al. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;1;36:1994-2001. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.78.1914.

- Fertility Preservation in Pittsburgh. CED calculator. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://fertilitypreservationpittsburgh.org/fertility-resources/fertility-risk-calculator/

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:1022-1033. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.09.013.

- Blumenfeld Z. Fertility preservation using GnRH agonists: rationale, possible mechanisms, and explanation of controversy. Clin Med Insights Reprod Health. 2019;13: 1179558119870163. doi:10.1177/1179558119870163.

- Beebeejaun Y, Athithan A, Copeland TP, et al. Risk of breast cancer in women treated with ovarian stimulation drugs for infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2021;116:198-207. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.01.044.

- Lambertini M, Kroman N, Ameye L, et al. Long-term safety of pregnancy following breast cancer according to estrogen receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:426-429. doi:10.1093/jnci/djx206.

- Marklund A, Lundberg FE, Eloranta S, et al. Reproductive outcomes after breast cancer in women with vs without fertility preservation. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:86-91. doi:10.1001/ jamaoncol.2020.5957.

Breast conservation safe option in multisite breast cancer

SAN ANTONIO – Women with breast cancer at more than one site can undergo breast-conserving therapy and still have local recurrence rates well under the acceptable threshold of risk, suggest the results of first prospective study of this issue.

The ACOSOG-Z11102 trial involved more than 200 women with primarily endocrine receptor–positive (ER+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative (HER2-) breast cancer and up to three disease foci, all of whom underwent lumpectomy with nodal staging followed by whole-breast irradiation, then systemic therapy at the oncologist’s discretion.

After 5 years of follow-up, just 3% of women experienced a local recurrence, with none having a local or distant recurrence and one dying of the disease.

The new findings were presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium on Dec. 9.

“This study provides important information for clinicians to discuss with patients who have two or three foci of breast cancer in one breast, as it may allow more patients to consider breast-conserving therapy as an option,” said study presenter Judy C. Boughey, MD, chair of the division of breast and melanoma surgical oncology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“Lumpectomy with radiation therapy is often preferred to mastectomy, as it is a smaller operation with quicker recovery, resulting in better patient satisfaction and cosmetic outcomes,” Dr. Boughey said in a statement.

“We’ve all been anxiously awaiting the results of this trial,” Andrea V. Barrio, MD, associate attending surgeon, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, told this news organization. “We knew that in patients who have a single site tumor in the breast, that outcomes between lumpectomy and mastectomy are the same ... But none of those trials have enrolled women with multiple sites.”

“There were no prospective data out there telling us that doing two lumpectomies in the breast was safe, so a lot of times, women were getting mastectomy for these multiple tumors, even if women had two small tumors in the breast and could easily undergo a lumpectomy with a good cosmetic result,” she said.

“So this data provides very strong evidence that we can begin treating women with small tumors in the breast who can undergo lumpectomy with a good cosmetic results without needing a mastectomy,” Dr. Barrio continued. “From a long-term quality of life standpoint, this is a big deal for women moving forward who really want to keep their breasts.”

Dr. Barrio did highlight, however, that “not everybody routinely does MRI” in women with breast cancer, including her institution, although generally she feels that “our standard imaging has gotten better,” with screening ultrasound identifying more lesions than previously.

She also believes that the numbers of women in the study who did not receive MRI are too small to “draw any definitive conclusions.

“Personally, when I have a patient with multisite disease and I’m going to keep their breasts, that to me is one indication that I would consider an MRI, to make sure that I wasn’t missing intervening disease between the two sites – that there wasn’t something else that would change my mind about doing a two-site lumpectomy,” Dr. Barrio said.

Linda M. Pak, MD, a breast cancer surgeon and surgical oncologist at NYU Langone’s Breast Cancer Center, New York, who was not involved in the study, said that the new study provides “importation information regarding the oncologic safety” of lumpectomy.

These results are “exciting to see, as they provide important information that breast-conserving surgery is safe in these patients, and that we can now share the results of this study with patients when we discuss with them their surgical options.

“I hope this will make more breast surgeons and patients comfortable with this approach and that it will increase the use of breast conservation among these patients,” Dr. Pak said.

Study details

In recent years, there has been increased diagnosis of multiple foci of ipsilateral breast cancer, Dr. Boughey said in her presentation. “This is both as a result of improvements in screening imaging, as well as diagnostic imaging and an increased use of preoperative breast MRI.”

Although historical, retrospective studies have shown high rates of local regional recurrences with breast-conserving therapy in women with more than one foci of breast cancer, more recent analyses have indicated that the approach is associated with “acceptable” recurrence rates.

This, Dr. Boughey explained, is due not only to improvements in breast imaging but also to better pathologic margin assessment, and improved systematic and radiation therapy.

Nevertheless, “most patients who present with two or three sites of cancer in one breast are recommended to undergo a mastectomy,” she noted.

To examine the safety of breast-conserving therapy in such patients, the team conducted a single-arm, phase 2 trial in women at least 40 years of age who had two or three foci of breast cancer, of which at least one site was invasive disease.

“While a randomized trial design would have provided stronger data, we felt that accrual to such a design would be problematic, as many patients and surgeons would not be willing to randomize,” Dr. Boughey explained.

Participants were required to have at least 2 cm of normal tissue between the lesions and disease in no more than two quadrants of the breast. They could have node-negative or N1 disease.

Women were excluded if they had foci > 5 cm on imaging; had bilateral breast cancer; had known BRCA1/2 mutations; had had prior ipsilateral breast cancer; or had received neoadjuvant therapy.

All women in the trial underwent lumpectomy with nodal staging, with adjuvant chemotherapy at the physician’s discretion, followed by whole-breast irradiation, with regional nodal irradiation again at the physician’s discretion. This was followed by systemic therapy, at the discretion of the medical oncologist.

The women were then followed up every 6 months until 5 years after the completion of whole-breast irradiation.

Details of the results

Dr. Boughey said that previously presented data from this study revealed that 67.6% of women achieved a margin-negative excision in a single operation, whereas 7.1% converted to mastectomy. The cosmetic outcome was rated as good or excellent at 2 years by 70.6% of women.

For the current analysis, a total of 204 women were evaluable, who had a median age of 61.1 years. Just over half (59.3%) had T1 stage disease, and 95.6% were node-negative. The majority (83.5%) had ER+/HER2- breast cancer, whereas 5.0% had ER-/HER2- disease and 11.5% had HER2+ positive tumors.

Adjuvant chemotherapy was given to 28.9% of women, whereas 89.7% of those with ER+ disease received adjuvant endocrine therapy.

The primary outcome was local recurrence rate at 5 years, which had a prespecified acceptable rate of less than 8%.

Dr. Boughey showed that, in their series, the 5-year recurrence rate was just 3.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.3%-6.4%), which was “well below” the predefined “clinically significantly threshold.” This involved four cases in the ipsilateral breast, one in the skin, and one in the chest wall.

In addition to the six women with local regional recurrence, six developed contralateral breast cancer and four patients developed distant disease. There were no cases of local and distant recurrence. There were three non–breast cancer primary cancers: one gastric, one lung, and one ovarian.

Eight women died during follow-up; only one of the deaths was related to breast cancer.

Dr. Boughey explained that the small number of local recurrences was too small to identify predictive factors via multivariate analysis.

However, univariate analysis indicated that there were numerical but nonsignificant associations between local recurrence and pathologic stage T2-3 disease, pathologic nodal involvement, and surgical margins just under the negative threshold.

Among the 10 cases of ER–/HER2– breast cancer, there was one local recurrence, giving a 5-year rate of 10.0% vs. 2.6% for women with ER+/HER2– disease.

To examine the role of MRI, Dr. Boughey highlighted that although the imaging modality was initially a requirement for study entry, an amendment to the protocol in 2015 allowed 15 women who had not had MRI to take part.

The local recurrence rate in women who had undergone MRI was 1.7% vs. 22.6% in those who had not, for a hazard ratio of 13.5 (P = .002).

“While this was statistically significant, we need to bear in mind that this was a secondary unplanned analysis,” Dr. Boughey underlined.

Next, the team analyzed the impact of adjuvant endocrine therapy in the 195 women with at least one ER+ lesion, finding that it was associated with a 5-year recurrence rate of 1.9% vs. 12.5% in those who did not receive endocrine therapy, for a hazard ratio of 7.7 (P = .025).

Dr. Boughey highlighted that the study is limited by being single-arm and having only a small subset of patients without preoperative MRI, with HER2+ or ER–/HER2– disease, and with three foci of disease.

She also emphasized that “there is concern that the 5-year follow up on this protocol may be shorter than needed,” especially in women with ER+ disease.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Boughey declared relationships with Eli Lilly and Company, Symbiosis Pharma, CairnSurgical, UpToDate, and PeerView.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN ANTONIO – Women with breast cancer at more than one site can undergo breast-conserving therapy and still have local recurrence rates well under the acceptable threshold of risk, suggest the results of first prospective study of this issue.

The ACOSOG-Z11102 trial involved more than 200 women with primarily endocrine receptor–positive (ER+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative (HER2-) breast cancer and up to three disease foci, all of whom underwent lumpectomy with nodal staging followed by whole-breast irradiation, then systemic therapy at the oncologist’s discretion.

After 5 years of follow-up, just 3% of women experienced a local recurrence, with none having a local or distant recurrence and one dying of the disease.

The new findings were presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium on Dec. 9.

“This study provides important information for clinicians to discuss with patients who have two or three foci of breast cancer in one breast, as it may allow more patients to consider breast-conserving therapy as an option,” said study presenter Judy C. Boughey, MD, chair of the division of breast and melanoma surgical oncology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“Lumpectomy with radiation therapy is often preferred to mastectomy, as it is a smaller operation with quicker recovery, resulting in better patient satisfaction and cosmetic outcomes,” Dr. Boughey said in a statement.

“We’ve all been anxiously awaiting the results of this trial,” Andrea V. Barrio, MD, associate attending surgeon, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, told this news organization. “We knew that in patients who have a single site tumor in the breast, that outcomes between lumpectomy and mastectomy are the same ... But none of those trials have enrolled women with multiple sites.”

“There were no prospective data out there telling us that doing two lumpectomies in the breast was safe, so a lot of times, women were getting mastectomy for these multiple tumors, even if women had two small tumors in the breast and could easily undergo a lumpectomy with a good cosmetic result,” she said.

“So this data provides very strong evidence that we can begin treating women with small tumors in the breast who can undergo lumpectomy with a good cosmetic results without needing a mastectomy,” Dr. Barrio continued. “From a long-term quality of life standpoint, this is a big deal for women moving forward who really want to keep their breasts.”

Dr. Barrio did highlight, however, that “not everybody routinely does MRI” in women with breast cancer, including her institution, although generally she feels that “our standard imaging has gotten better,” with screening ultrasound identifying more lesions than previously.

She also believes that the numbers of women in the study who did not receive MRI are too small to “draw any definitive conclusions.

“Personally, when I have a patient with multisite disease and I’m going to keep their breasts, that to me is one indication that I would consider an MRI, to make sure that I wasn’t missing intervening disease between the two sites – that there wasn’t something else that would change my mind about doing a two-site lumpectomy,” Dr. Barrio said.

Linda M. Pak, MD, a breast cancer surgeon and surgical oncologist at NYU Langone’s Breast Cancer Center, New York, who was not involved in the study, said that the new study provides “importation information regarding the oncologic safety” of lumpectomy.

These results are “exciting to see, as they provide important information that breast-conserving surgery is safe in these patients, and that we can now share the results of this study with patients when we discuss with them their surgical options.

“I hope this will make more breast surgeons and patients comfortable with this approach and that it will increase the use of breast conservation among these patients,” Dr. Pak said.

Study details

In recent years, there has been increased diagnosis of multiple foci of ipsilateral breast cancer, Dr. Boughey said in her presentation. “This is both as a result of improvements in screening imaging, as well as diagnostic imaging and an increased use of preoperative breast MRI.”

Although historical, retrospective studies have shown high rates of local regional recurrences with breast-conserving therapy in women with more than one foci of breast cancer, more recent analyses have indicated that the approach is associated with “acceptable” recurrence rates.

This, Dr. Boughey explained, is due not only to improvements in breast imaging but also to better pathologic margin assessment, and improved systematic and radiation therapy.

Nevertheless, “most patients who present with two or three sites of cancer in one breast are recommended to undergo a mastectomy,” she noted.

To examine the safety of breast-conserving therapy in such patients, the team conducted a single-arm, phase 2 trial in women at least 40 years of age who had two or three foci of breast cancer, of which at least one site was invasive disease.

“While a randomized trial design would have provided stronger data, we felt that accrual to such a design would be problematic, as many patients and surgeons would not be willing to randomize,” Dr. Boughey explained.

Participants were required to have at least 2 cm of normal tissue between the lesions and disease in no more than two quadrants of the breast. They could have node-negative or N1 disease.

Women were excluded if they had foci > 5 cm on imaging; had bilateral breast cancer; had known BRCA1/2 mutations; had had prior ipsilateral breast cancer; or had received neoadjuvant therapy.

All women in the trial underwent lumpectomy with nodal staging, with adjuvant chemotherapy at the physician’s discretion, followed by whole-breast irradiation, with regional nodal irradiation again at the physician’s discretion. This was followed by systemic therapy, at the discretion of the medical oncologist.

The women were then followed up every 6 months until 5 years after the completion of whole-breast irradiation.

Details of the results

Dr. Boughey said that previously presented data from this study revealed that 67.6% of women achieved a margin-negative excision in a single operation, whereas 7.1% converted to mastectomy. The cosmetic outcome was rated as good or excellent at 2 years by 70.6% of women.

For the current analysis, a total of 204 women were evaluable, who had a median age of 61.1 years. Just over half (59.3%) had T1 stage disease, and 95.6% were node-negative. The majority (83.5%) had ER+/HER2- breast cancer, whereas 5.0% had ER-/HER2- disease and 11.5% had HER2+ positive tumors.

Adjuvant chemotherapy was given to 28.9% of women, whereas 89.7% of those with ER+ disease received adjuvant endocrine therapy.

The primary outcome was local recurrence rate at 5 years, which had a prespecified acceptable rate of less than 8%.

Dr. Boughey showed that, in their series, the 5-year recurrence rate was just 3.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.3%-6.4%), which was “well below” the predefined “clinically significantly threshold.” This involved four cases in the ipsilateral breast, one in the skin, and one in the chest wall.

In addition to the six women with local regional recurrence, six developed contralateral breast cancer and four patients developed distant disease. There were no cases of local and distant recurrence. There were three non–breast cancer primary cancers: one gastric, one lung, and one ovarian.

Eight women died during follow-up; only one of the deaths was related to breast cancer.

Dr. Boughey explained that the small number of local recurrences was too small to identify predictive factors via multivariate analysis.

However, univariate analysis indicated that there were numerical but nonsignificant associations between local recurrence and pathologic stage T2-3 disease, pathologic nodal involvement, and surgical margins just under the negative threshold.

Among the 10 cases of ER–/HER2– breast cancer, there was one local recurrence, giving a 5-year rate of 10.0% vs. 2.6% for women with ER+/HER2– disease.

To examine the role of MRI, Dr. Boughey highlighted that although the imaging modality was initially a requirement for study entry, an amendment to the protocol in 2015 allowed 15 women who had not had MRI to take part.

The local recurrence rate in women who had undergone MRI was 1.7% vs. 22.6% in those who had not, for a hazard ratio of 13.5 (P = .002).

“While this was statistically significant, we need to bear in mind that this was a secondary unplanned analysis,” Dr. Boughey underlined.

Next, the team analyzed the impact of adjuvant endocrine therapy in the 195 women with at least one ER+ lesion, finding that it was associated with a 5-year recurrence rate of 1.9% vs. 12.5% in those who did not receive endocrine therapy, for a hazard ratio of 7.7 (P = .025).

Dr. Boughey highlighted that the study is limited by being single-arm and having only a small subset of patients without preoperative MRI, with HER2+ or ER–/HER2– disease, and with three foci of disease.

She also emphasized that “there is concern that the 5-year follow up on this protocol may be shorter than needed,” especially in women with ER+ disease.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Boughey declared relationships with Eli Lilly and Company, Symbiosis Pharma, CairnSurgical, UpToDate, and PeerView.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN ANTONIO – Women with breast cancer at more than one site can undergo breast-conserving therapy and still have local recurrence rates well under the acceptable threshold of risk, suggest the results of first prospective study of this issue.

The ACOSOG-Z11102 trial involved more than 200 women with primarily endocrine receptor–positive (ER+), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative (HER2-) breast cancer and up to three disease foci, all of whom underwent lumpectomy with nodal staging followed by whole-breast irradiation, then systemic therapy at the oncologist’s discretion.

After 5 years of follow-up, just 3% of women experienced a local recurrence, with none having a local or distant recurrence and one dying of the disease.

The new findings were presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium on Dec. 9.

“This study provides important information for clinicians to discuss with patients who have two or three foci of breast cancer in one breast, as it may allow more patients to consider breast-conserving therapy as an option,” said study presenter Judy C. Boughey, MD, chair of the division of breast and melanoma surgical oncology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“Lumpectomy with radiation therapy is often preferred to mastectomy, as it is a smaller operation with quicker recovery, resulting in better patient satisfaction and cosmetic outcomes,” Dr. Boughey said in a statement.

“We’ve all been anxiously awaiting the results of this trial,” Andrea V. Barrio, MD, associate attending surgeon, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, told this news organization. “We knew that in patients who have a single site tumor in the breast, that outcomes between lumpectomy and mastectomy are the same ... But none of those trials have enrolled women with multiple sites.”

“There were no prospective data out there telling us that doing two lumpectomies in the breast was safe, so a lot of times, women were getting mastectomy for these multiple tumors, even if women had two small tumors in the breast and could easily undergo a lumpectomy with a good cosmetic result,” she said.

“So this data provides very strong evidence that we can begin treating women with small tumors in the breast who can undergo lumpectomy with a good cosmetic results without needing a mastectomy,” Dr. Barrio continued. “From a long-term quality of life standpoint, this is a big deal for women moving forward who really want to keep their breasts.”

Dr. Barrio did highlight, however, that “not everybody routinely does MRI” in women with breast cancer, including her institution, although generally she feels that “our standard imaging has gotten better,” with screening ultrasound identifying more lesions than previously.

She also believes that the numbers of women in the study who did not receive MRI are too small to “draw any definitive conclusions.

“Personally, when I have a patient with multisite disease and I’m going to keep their breasts, that to me is one indication that I would consider an MRI, to make sure that I wasn’t missing intervening disease between the two sites – that there wasn’t something else that would change my mind about doing a two-site lumpectomy,” Dr. Barrio said.

Linda M. Pak, MD, a breast cancer surgeon and surgical oncologist at NYU Langone’s Breast Cancer Center, New York, who was not involved in the study, said that the new study provides “importation information regarding the oncologic safety” of lumpectomy.

These results are “exciting to see, as they provide important information that breast-conserving surgery is safe in these patients, and that we can now share the results of this study with patients when we discuss with them their surgical options.

“I hope this will make more breast surgeons and patients comfortable with this approach and that it will increase the use of breast conservation among these patients,” Dr. Pak said.

Study details

In recent years, there has been increased diagnosis of multiple foci of ipsilateral breast cancer, Dr. Boughey said in her presentation. “This is both as a result of improvements in screening imaging, as well as diagnostic imaging and an increased use of preoperative breast MRI.”

Although historical, retrospective studies have shown high rates of local regional recurrences with breast-conserving therapy in women with more than one foci of breast cancer, more recent analyses have indicated that the approach is associated with “acceptable” recurrence rates.

This, Dr. Boughey explained, is due not only to improvements in breast imaging but also to better pathologic margin assessment, and improved systematic and radiation therapy.

Nevertheless, “most patients who present with two or three sites of cancer in one breast are recommended to undergo a mastectomy,” she noted.

To examine the safety of breast-conserving therapy in such patients, the team conducted a single-arm, phase 2 trial in women at least 40 years of age who had two or three foci of breast cancer, of which at least one site was invasive disease.

“While a randomized trial design would have provided stronger data, we felt that accrual to such a design would be problematic, as many patients and surgeons would not be willing to randomize,” Dr. Boughey explained.

Participants were required to have at least 2 cm of normal tissue between the lesions and disease in no more than two quadrants of the breast. They could have node-negative or N1 disease.

Women were excluded if they had foci > 5 cm on imaging; had bilateral breast cancer; had known BRCA1/2 mutations; had had prior ipsilateral breast cancer; or had received neoadjuvant therapy.

All women in the trial underwent lumpectomy with nodal staging, with adjuvant chemotherapy at the physician’s discretion, followed by whole-breast irradiation, with regional nodal irradiation again at the physician’s discretion. This was followed by systemic therapy, at the discretion of the medical oncologist.

The women were then followed up every 6 months until 5 years after the completion of whole-breast irradiation.

Details of the results

Dr. Boughey said that previously presented data from this study revealed that 67.6% of women achieved a margin-negative excision in a single operation, whereas 7.1% converted to mastectomy. The cosmetic outcome was rated as good or excellent at 2 years by 70.6% of women.

For the current analysis, a total of 204 women were evaluable, who had a median age of 61.1 years. Just over half (59.3%) had T1 stage disease, and 95.6% were node-negative. The majority (83.5%) had ER+/HER2- breast cancer, whereas 5.0% had ER-/HER2- disease and 11.5% had HER2+ positive tumors.

Adjuvant chemotherapy was given to 28.9% of women, whereas 89.7% of those with ER+ disease received adjuvant endocrine therapy.

The primary outcome was local recurrence rate at 5 years, which had a prespecified acceptable rate of less than 8%.

Dr. Boughey showed that, in their series, the 5-year recurrence rate was just 3.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.3%-6.4%), which was “well below” the predefined “clinically significantly threshold.” This involved four cases in the ipsilateral breast, one in the skin, and one in the chest wall.

In addition to the six women with local regional recurrence, six developed contralateral breast cancer and four patients developed distant disease. There were no cases of local and distant recurrence. There were three non–breast cancer primary cancers: one gastric, one lung, and one ovarian.

Eight women died during follow-up; only one of the deaths was related to breast cancer.

Dr. Boughey explained that the small number of local recurrences was too small to identify predictive factors via multivariate analysis.

However, univariate analysis indicated that there were numerical but nonsignificant associations between local recurrence and pathologic stage T2-3 disease, pathologic nodal involvement, and surgical margins just under the negative threshold.

Among the 10 cases of ER–/HER2– breast cancer, there was one local recurrence, giving a 5-year rate of 10.0% vs. 2.6% for women with ER+/HER2– disease.

To examine the role of MRI, Dr. Boughey highlighted that although the imaging modality was initially a requirement for study entry, an amendment to the protocol in 2015 allowed 15 women who had not had MRI to take part.

The local recurrence rate in women who had undergone MRI was 1.7% vs. 22.6% in those who had not, for a hazard ratio of 13.5 (P = .002).

“While this was statistically significant, we need to bear in mind that this was a secondary unplanned analysis,” Dr. Boughey underlined.

Next, the team analyzed the impact of adjuvant endocrine therapy in the 195 women with at least one ER+ lesion, finding that it was associated with a 5-year recurrence rate of 1.9% vs. 12.5% in those who did not receive endocrine therapy, for a hazard ratio of 7.7 (P = .025).

Dr. Boughey highlighted that the study is limited by being single-arm and having only a small subset of patients without preoperative MRI, with HER2+ or ER–/HER2– disease, and with three foci of disease.

She also emphasized that “there is concern that the 5-year follow up on this protocol may be shorter than needed,” especially in women with ER+ disease.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Boughey declared relationships with Eli Lilly and Company, Symbiosis Pharma, CairnSurgical, UpToDate, and PeerView.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT SABCS 2022

Mindfulness, exercise strike out in memory trial

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

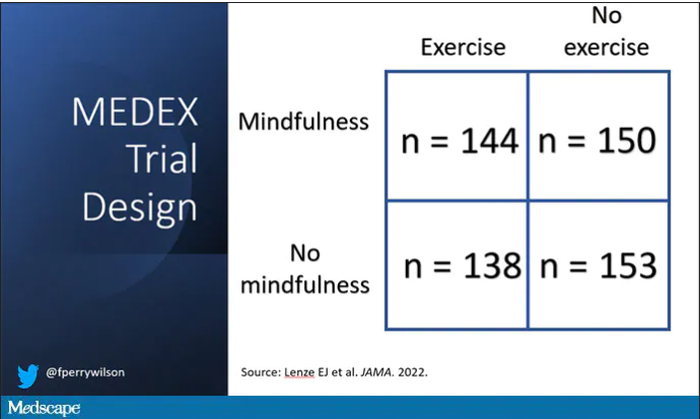

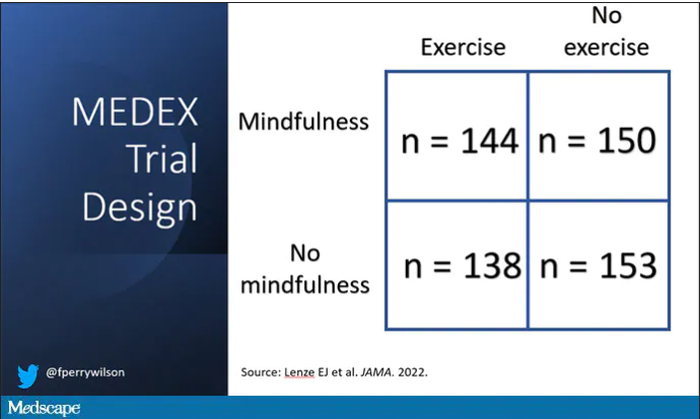

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

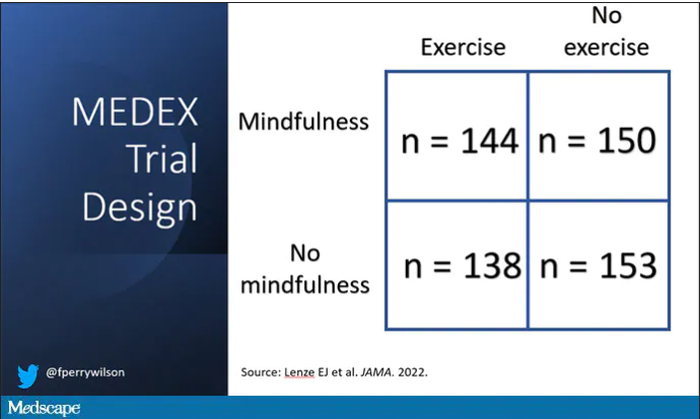

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

We are coming to the end of the year, which always makes me think about getting older. Much like the search for the fountain of youth, many promising leads have ultimately led to dead ends. And yet, I had high hopes for a trial that focused on two cornerstones of wellness – exercise and mindfulness – to address the subjective loss of memory that comes with aging. Alas, meditation and exercise do not appear to be the fountain of youth.

I’m talking about this study, appearing in JAMA, known as the MEDEX trial.

It’s a clever design: a 2 x 2 factorial randomized trial where participants could be randomized to a mindfulness intervention, an exercise intervention, both, or neither.

In this manner, you can test multiple hypotheses exploiting a shared control group. Or as a mentor of mine used to say, you get two trials for the price of one and a half.

The participants were older adults, aged 65-84, living in the community. They had to be relatively sedentary at baseline and not engaging in mindfulness practices. They had to subjectively report some memory or concentration issues but had to be cognitively intact, based on a standard dementia screening test. In other words, these are your average older people who are worried that they aren’t as sharp as they used to be.

The interventions themselves were fairly intense. The exercise group had instructor-led sessions for 90 minutes twice a week for the first 6 months of the study, once a week thereafter. And participants were encouraged to exercise at home such that they had a total of 300 minutes of weekly exercise.

The mindfulness program was characterized by eight weekly classes of 2.5 hours each as well as a half-day retreat to teach the tenets of mindfulness and meditation, with monthly refreshers thereafter. Participants were instructed to meditate for 60 minutes a day in addition to the classes.

For the 144 people who were randomized to both meditation and exercise, this trial amounted to something of a part-time job. So you might think that adherence to the interventions was low, but apparently that’s not the case. Attendance to the mindfulness classes was over 90%, and over 80% for the exercise classes. And diary-based reporting of home efforts was also pretty good.

The control group wasn’t left to their own devices. Recognizing that the community aspect of exercise or mindfulness classes might convey a benefit independent of the actual exercise or mindfulness, the control group met on a similar schedule to discuss health education, but no mention of exercise or mindfulness occurred in that setting.

The primary outcome was change in memory and executive function scores across a battery of neuropsychologic testing, but the story is told in just a few pictures.

Memory scores improved in all three groups – mindfulness, exercise, and health education – over time. Cognitive composite score improved in all three groups similarly. There was no synergistic effect of mindfulness and exercise either. Basically, everyone got a bit better.

But the study did way more than look at scores on tests. Researchers used MRI to measure brain anatomic outcomes as well. And the surprising thing is that virtually none of these outcomes were different between the groups either.

Hippocampal volume decreased a bit in all the groups. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex volume was flat. There was no change in scores measuring tasks of daily living.

When you see negative results like this, right away you worry that the intervention wasn’t properly delivered. Were these people really exercising and meditating? Well, the authors showed that individuals randomized to exercise, at least, had less sleep latency, greater aerobic fitness, and greater strength. So we know something was happening.

They then asked, would the people in the exercise group with the greatest changes in those physiologic parameters show some improvement in cognitive parameters? In other words, we know you were exercising because you got stronger and are sleeping better; is your memory better? The answer? Surprisingly, still no. Even in that honestly somewhat cherry-picked group, the interventions had no effect.

Could it be that the control was inappropriate, that the “health education” intervention was actually so helpful that it obscured the benefits of exercise and meditation? After all, cognitive scores did improve in all groups. The authors doubt it. They say they think the improvement in cognitive scores reflects the fact that patients had learned a bit about how to take the tests. This is pretty common in the neuropsychiatric literature.

So here we are and I just want to say, well, shoot. This is not the result I wanted. And I think the reason I’m so disappointed is because aging and the loss of cognitive faculties that comes with aging are just sort of scary. We are all looking for some control over that fear, and how nice it would be to be able to tell ourselves not to worry – that we won’t have those problems as we get older because we exercise, or meditate, or drink red wine, or don’t drink wine, or whatever. And while I have no doubt that staying healthier physically will keep you healthier mentally, it may take more than one simple thing to move the needle.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patient With Severe Headache After IV Immunoglobulin

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hypothyroidism and idiopathic small fiber autonomic and sensory neuropathy presented to the emergency department (ED) 48 hours after IV immunoglobulin (IG) infusion with a severe headache, nausea, neck stiffness, photophobia, and episodes of intense positional eye pressure. The patient reported previous episodes of headaches post-IVIG infusion but not nearly as severe. On ED arrival, the patient was afebrile with vital signs within normal limits. Initial laboratory results were notable for levels within reference range parameters: 5.9 × 109/L white blood cell (WBC) count, 13.3 g/dL hemoglobin, 38.7% hematocrit, and 279 × 109/L platelet count; there were no abnormal urinalysis findings, and she was negative for human chorionic gonadotropin.

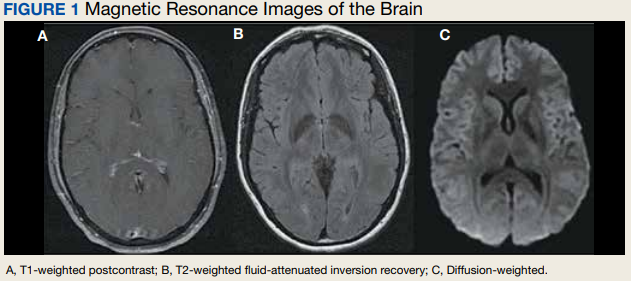

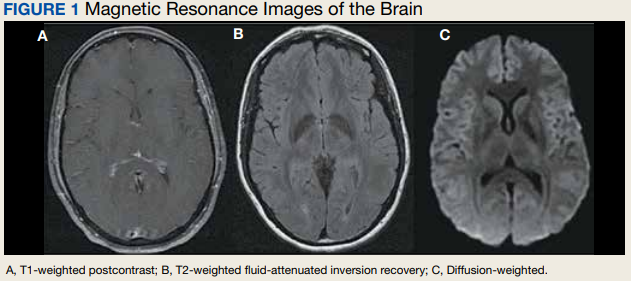

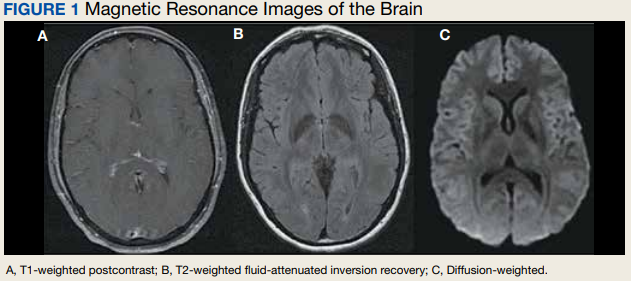

Due to the patient’s symptoms concerning for an acute intracranial process, a brain computed tomography (CT) without contrast was ordered. The CT demonstrated no intracranial abnormalities, but the patient’s symptoms continued to worsen. The patient was started on IV fluids and 1 g IV acetaminophen and underwent a lumbar puncture (LP). Her opening pressure was elevated at 29 cm H2O (reference range, 6-20 cm), and the fluid was notably clear. During the LP, 25 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected for laboratory analysis to include a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel and cultures, and a closing pressure of 12 cm H2O was recorded at the end of the procedure with the patient reporting some relief of pressure. The patient was admitted to the medicine ward for further workup and observations.The patient’s meningitis/encephalitis PCR panel detected no pathogens in the CSF, but her WBC count was 84 × 109/L (reference range, 4-11) with 30 segmented neutrophils (reference range, 0-6) and red blood cell count of 24 (reference range, 0-1); her normal glucose at 60 mg/dL (reference range, 40-70) and protein of 33 mg/dL (reference range, 15-45) were within normal parameters. Brain magnetic resonance images with and without contrast was inconsistent with any acute intracranial pathology to include subarachnoid hemorrhage or central nervous system neoplasm (Figure 1). Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Discussion

Aseptic meningitis presents with a typical clinical picture of meningitis to include headache, stiffened neck, and photophobia. In the event of negative CSF bacterial and fungal cultures and negative viral PCR, a diagnosis of aseptic meningitis is considered.1 Though the differential for aseptic meningitis is broad, in the immunocompetent patient, the most common etiology of aseptic meningitis in the United States is by far viral, and specifically, enterovirus (50.9%). It is less commonly caused by herpes simplex virus (8.3%), varicella zoster virus, and finally, the mosquito-borne St. Louis encephalitis and West Nile viruses typically acquired in the summer or early fall months. Other infectious agents that can present with aseptic meningitis are spirochetes (Lyme disease and syphilis), tuberculous meningitis, fungal infections (cryptococcal meningitis), and other bacterial infections that have a negative culture.

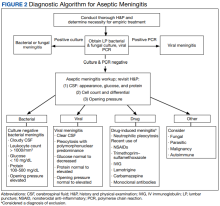

The patient’s history, physical examination, vital signs, imaging, and lumbar puncture findings were most concerning for drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM) secondary to her recent IVIG infusion. An algorithm can be used to work through the diagnostic approach (Figure 2).3,4

Immediate and delayed adverse reactions to IVIG are known risks for IVIG therapy. About 1% to 15% of patients who receive IVIG will experience mild immediate reactions to the infusion.6 These immediate reactions include fever (78.6%), acrocyanosis (71.4%), rash (64.3%), headache (57.1%), shortness of breath (42.8%), hypotension (35.7%), and chest pain (21.4%).

IVIG is an increasingly used biologic pharmacologic agent used for a variety of medical conditions. This can be attributed to its multifaceted properties and ability to fight infection when given as replacement therapy and provide immunomodulation in conjunction with its more well-known anti-inflammatory properties.8 The number of conditions that can potentially benefit from IVIG is so vast that the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology had to divide the indication for IVIG therapy into definitely beneficial, probably beneficial, may provide benefit, and unlikely to provide benefit categories.8

Conclusions

We encourage heightened clinical suspicion of DIAM in patients who have recently undergone IVIG infusion and present with meningeal signs (stiff neck, headache, photophobia, and ear/eye pressure) without any evidence of infection on physical examination or laboratory results. With such, we hope to improve clinician suspicion, detection, as well as patient education and outcomes in cases of DIAM.

1. Kareva L, Mironska K, Stavric K, Hasani A. Adverse reactions to intravenous immunoglobulins—our experience. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(12):2359-2362. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2018.513

2. Mount HR, Boyle SD. Aseptic and bacterial meningitis: evaluation, treatment, and prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(5):314-322.

3. Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(6):1103-1108.

4. Connolly KJ, Hammer SM. The acute aseptic meningitis syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1990;4(4):599-622.

5. Jolles S, Sewell WA, Leighton C. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: diagnosis and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22(3):215-226. doi:10.2165/00002018-200022030-00005

6. Yelehe-Okouma M, Czmil-Garon J, Pape E, Petitpain N, Gillet P. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis: a mini-review. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2018;32(3):252-260. doi:10.1111/fcp.12349

7. Kepa L, Oczko-Grzesik B, Stolarz W, Sobala-Szczygiel B. Drug-induced aseptic meningitis in suspected central nervous system infections. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12(5):562-564. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2004.08.024

8. Perez EE, Orange JS, Bonilla F, et al. Update on the use of immunoglobulin in human disease: a review of evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3S):S1-S46. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.09.023

9. Kaarthigeyan K, Burli VV. Aseptic meningitis following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy of common variable immunodeficiency. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2011;6(2):160-161. doi:10.4103/1817-1745.92858

A 35-year-old woman with a history of hypothyroidism and idiopathic small fiber autonomic and sensory neuropathy presented to the emergency department (ED) 48 hours after IV immunoglobulin (IG) infusion with a severe headache, nausea, neck stiffness, photophobia, and episodes of intense positional eye pressure. The patient reported previous episodes of headaches post-IVIG infusion but not nearly as severe. On ED arrival, the patient was afebrile with vital signs within normal limits. Initial laboratory results were notable for levels within reference range parameters: 5.9 × 109/L white blood cell (WBC) count, 13.3 g/dL hemoglobin, 38.7% hematocrit, and 279 × 109/L platelet count; there were no abnormal urinalysis findings, and she was negative for human chorionic gonadotropin.

Due to the patient’s symptoms concerning for an acute intracranial process, a brain computed tomography (CT) without contrast was ordered. The CT demonstrated no intracranial abnormalities, but the patient’s symptoms continued to worsen. The patient was started on IV fluids and 1 g IV acetaminophen and underwent a lumbar puncture (LP). Her opening pressure was elevated at 29 cm H2O (reference range, 6-20 cm), and the fluid was notably clear. During the LP, 25 mL of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected for laboratory analysis to include a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panel and cultures, and a closing pressure of 12 cm H2O was recorded at the end of the procedure with the patient reporting some relief of pressure. The patient was admitted to the medicine ward for further workup and observations.The patient’s meningitis/encephalitis PCR panel detected no pathogens in the CSF, but her WBC count was 84 × 109/L (reference range, 4-11) with 30 segmented neutrophils (reference range, 0-6) and red blood cell count of 24 (reference range, 0-1); her normal glucose at 60 mg/dL (reference range, 40-70) and protein of 33 mg/dL (reference range, 15-45) were within normal parameters. Brain magnetic resonance images with and without contrast was inconsistent with any acute intracranial pathology to include subarachnoid hemorrhage or central nervous system neoplasm (Figure 1). Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Discussion

Aseptic meningitis presents with a typical clinical picture of meningitis to include headache, stiffened neck, and photophobia. In the event of negative CSF bacterial and fungal cultures and negative viral PCR, a diagnosis of aseptic meningitis is considered.1 Though the differential for aseptic meningitis is broad, in the immunocompetent patient, the most common etiology of aseptic meningitis in the United States is by far viral, and specifically, enterovirus (50.9%). It is less commonly caused by herpes simplex virus (8.3%), varicella zoster virus, and finally, the mosquito-borne St. Louis encephalitis and West Nile viruses typically acquired in the summer or early fall months. Other infectious agents that can present with aseptic meningitis are spirochetes (Lyme disease and syphilis), tuberculous meningitis, fungal infections (cryptococcal meningitis), and other bacterial infections that have a negative culture.

The patient’s history, physical examination, vital signs, imaging, and lumbar puncture findings were most concerning for drug-induced aseptic meningitis (DIAM) secondary to her recent IVIG infusion. An algorithm can be used to work through the diagnostic approach (Figure 2).3,4

Immediate and delayed adverse reactions to IVIG are known risks for IVIG therapy. About 1% to 15% of patients who receive IVIG will experience mild immediate reactions to the infusion.6 These immediate reactions include fever (78.6%), acrocyanosis (71.4%), rash (64.3%), headache (57.1%), shortness of breath (42.8%), hypotension (35.7%), and chest pain (21.4%).

IVIG is an increasingly used biologic pharmacologic agent used for a variety of medical conditions. This can be attributed to its multifaceted properties and ability to fight infection when given as replacement therapy and provide immunomodulation in conjunction with its more well-known anti-inflammatory properties.8 The number of conditions that can potentially benefit from IVIG is so vast that the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology had to divide the indication for IVIG therapy into definitely beneficial, probably beneficial, may provide benefit, and unlikely to provide benefit categories.8

Conclusions

We encourage heightened clinical suspicion of DIAM in patients who have recently undergone IVIG infusion and present with meningeal signs (stiff neck, headache, photophobia, and ear/eye pressure) without any evidence of infection on physical examination or laboratory results. With such, we hope to improve clinician suspicion, detection, as well as patient education and outcomes in cases of DIAM.