User login

Kid with glasses: Many children live far from pediatric eye care

More than 2,800 counties in the United States lack a practicing pediatric ophthalmologist, limiting easy access to specialized eye care, a new study found.

The review of public, online pediatric ophthalmology directories found 1,056 pediatric ophthalmologists registered. The majority of these doctors practiced in densely populated areas, leaving many poor and rural residents across the United States without a nearby doctor to visit, and with the burden of spending time and money to get care for their children.

Travel for that care may be out of reach for some, according to Hannah Walsh, a medical student at the University of Miami, who led the study published in JAMA Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh’s research found that the median income of families living in a county without a pediatric ophthalmologist was nearly $17,000 lower than that for families with access to such specialists (95% confidence interval, −$18,544 to −$14,389; P < .001). These families were also less likely to own a car.

“We found that counties that didn’t have access to ophthalmic care for pediatrics were already disproportionately affected by lower socioeconomic status,” she said.

Children often receive routine vision screenings through their primary care clinician, but children who fail a routine screening may need to visit a pediatric ophthalmologist for a full eye examination, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh and colleagues pulled data in March 2022 on the demographics of pediatric ophthalmologists from online directories hosted by the AAO and the American Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Ms. Walsh cautioned that the directories might include eye doctors who are no longer practicing, or there might be specialists who had not registered for the databases.

Yasmin Bradfield, MD, a pediatric ophthalmologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, noted that after the study published, pediatric ophthalmologists from Vermont and New Mexico notified study authors and AAPOS that they are practicing in the states.

Dr. Bradfield, a board member of AAPOS who also heads the organization’s recruitment task force, said the organization is aware of only one state – Wyoming – without a currently practicing pediatric ophthalmologist.

But based on the March 2022 data, Ms. Walsh and her colleagues found four states – New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Vermont – did not have any pediatric ophthalmologists listed in directories for the organizations. Meanwhile, the country’s most populous states – California, New York, Florida, and Texas – had the most pediatric ophthalmologists.

For every million people, the study identified 7.7 pediatric ophthalmologists nationwide.

Julius T. Oatts, MD, the lead author of an accompanying editorial, said the findings are “valuable and sobering.” Even in San Francisco, where Dr. Oatts practices, most pediatric eye specialists have 6-month wait lists, he said.

Not fixing the shortage of children’s eye doctors could carry lifetime consequences, Dr. Oatts and his colleagues warned.

“Vision and eye health represent an important health barrier to learning in children,” Dr. Oatts and his colleagues wrote. “Lack of access to pediatric vision screening and care also contributes to the academic achievement gap and educational disparities.”

Dr. Bradfield said that disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care could leave some children at risk for losing their vision or never being able to see 20/20. Parents living in areas without a specialist may decide to instead visit an optometrist, but they are not trained to treat serious cases, such as strabismus, and only test and diagnose vision changes, according to AAPOS.

“If we don’t get to the kids in time, they can lose vision permanently, even if it’s something as simple as they just need glasses as a toddler,” Dr. Bradfield said.

Dr. Bradfield said AAPOS is recruiting new pediatric ophthalmologists by offering fellowships for medical students to attend the association’s annual conference and creating shadowing opportunities for students. The society also will release a survey of pediatric ophthalmology salaries to dispel rumors that the specialty does not have lucrative wages.

Ms. Walsh said she was interested in looking at disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care, in part, because she was surprised by how few of her classmates attending medical school were interested in the field of study.

“I hope it encourages ophthalmologists to consider pediatric ophthalmology, or to consider volunteering their time, or going to underserved areas to provide care to families that really are in need,” she said.

Coauthor Jayanth Sridhar, MD, reported receiving personal fees from Alcon, Apellis, Allergan, Dutch Ophthalmic Research Center, Genentech, OcuTerra Therapeutics, and Regeneron outside the submitted work. The other authors and the editorialists report no relevant financial relationships.

*This article was updated on 2/2/2023.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than 2,800 counties in the United States lack a practicing pediatric ophthalmologist, limiting easy access to specialized eye care, a new study found.

The review of public, online pediatric ophthalmology directories found 1,056 pediatric ophthalmologists registered. The majority of these doctors practiced in densely populated areas, leaving many poor and rural residents across the United States without a nearby doctor to visit, and with the burden of spending time and money to get care for their children.

Travel for that care may be out of reach for some, according to Hannah Walsh, a medical student at the University of Miami, who led the study published in JAMA Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh’s research found that the median income of families living in a county without a pediatric ophthalmologist was nearly $17,000 lower than that for families with access to such specialists (95% confidence interval, −$18,544 to −$14,389; P < .001). These families were also less likely to own a car.

“We found that counties that didn’t have access to ophthalmic care for pediatrics were already disproportionately affected by lower socioeconomic status,” she said.

Children often receive routine vision screenings through their primary care clinician, but children who fail a routine screening may need to visit a pediatric ophthalmologist for a full eye examination, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh and colleagues pulled data in March 2022 on the demographics of pediatric ophthalmologists from online directories hosted by the AAO and the American Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Ms. Walsh cautioned that the directories might include eye doctors who are no longer practicing, or there might be specialists who had not registered for the databases.

Yasmin Bradfield, MD, a pediatric ophthalmologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, noted that after the study published, pediatric ophthalmologists from Vermont and New Mexico notified study authors and AAPOS that they are practicing in the states.

Dr. Bradfield, a board member of AAPOS who also heads the organization’s recruitment task force, said the organization is aware of only one state – Wyoming – without a currently practicing pediatric ophthalmologist.

But based on the March 2022 data, Ms. Walsh and her colleagues found four states – New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Vermont – did not have any pediatric ophthalmologists listed in directories for the organizations. Meanwhile, the country’s most populous states – California, New York, Florida, and Texas – had the most pediatric ophthalmologists.

For every million people, the study identified 7.7 pediatric ophthalmologists nationwide.

Julius T. Oatts, MD, the lead author of an accompanying editorial, said the findings are “valuable and sobering.” Even in San Francisco, where Dr. Oatts practices, most pediatric eye specialists have 6-month wait lists, he said.

Not fixing the shortage of children’s eye doctors could carry lifetime consequences, Dr. Oatts and his colleagues warned.

“Vision and eye health represent an important health barrier to learning in children,” Dr. Oatts and his colleagues wrote. “Lack of access to pediatric vision screening and care also contributes to the academic achievement gap and educational disparities.”

Dr. Bradfield said that disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care could leave some children at risk for losing their vision or never being able to see 20/20. Parents living in areas without a specialist may decide to instead visit an optometrist, but they are not trained to treat serious cases, such as strabismus, and only test and diagnose vision changes, according to AAPOS.

“If we don’t get to the kids in time, they can lose vision permanently, even if it’s something as simple as they just need glasses as a toddler,” Dr. Bradfield said.

Dr. Bradfield said AAPOS is recruiting new pediatric ophthalmologists by offering fellowships for medical students to attend the association’s annual conference and creating shadowing opportunities for students. The society also will release a survey of pediatric ophthalmology salaries to dispel rumors that the specialty does not have lucrative wages.

Ms. Walsh said she was interested in looking at disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care, in part, because she was surprised by how few of her classmates attending medical school were interested in the field of study.

“I hope it encourages ophthalmologists to consider pediatric ophthalmology, or to consider volunteering their time, or going to underserved areas to provide care to families that really are in need,” she said.

Coauthor Jayanth Sridhar, MD, reported receiving personal fees from Alcon, Apellis, Allergan, Dutch Ophthalmic Research Center, Genentech, OcuTerra Therapeutics, and Regeneron outside the submitted work. The other authors and the editorialists report no relevant financial relationships.

*This article was updated on 2/2/2023.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More than 2,800 counties in the United States lack a practicing pediatric ophthalmologist, limiting easy access to specialized eye care, a new study found.

The review of public, online pediatric ophthalmology directories found 1,056 pediatric ophthalmologists registered. The majority of these doctors practiced in densely populated areas, leaving many poor and rural residents across the United States without a nearby doctor to visit, and with the burden of spending time and money to get care for their children.

Travel for that care may be out of reach for some, according to Hannah Walsh, a medical student at the University of Miami, who led the study published in JAMA Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh’s research found that the median income of families living in a county without a pediatric ophthalmologist was nearly $17,000 lower than that for families with access to such specialists (95% confidence interval, −$18,544 to −$14,389; P < .001). These families were also less likely to own a car.

“We found that counties that didn’t have access to ophthalmic care for pediatrics were already disproportionately affected by lower socioeconomic status,” she said.

Children often receive routine vision screenings through their primary care clinician, but children who fail a routine screening may need to visit a pediatric ophthalmologist for a full eye examination, according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

Ms. Walsh and colleagues pulled data in March 2022 on the demographics of pediatric ophthalmologists from online directories hosted by the AAO and the American Association of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Ms. Walsh cautioned that the directories might include eye doctors who are no longer practicing, or there might be specialists who had not registered for the databases.

Yasmin Bradfield, MD, a pediatric ophthalmologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, noted that after the study published, pediatric ophthalmologists from Vermont and New Mexico notified study authors and AAPOS that they are practicing in the states.

Dr. Bradfield, a board member of AAPOS who also heads the organization’s recruitment task force, said the organization is aware of only one state – Wyoming – without a currently practicing pediatric ophthalmologist.

But based on the March 2022 data, Ms. Walsh and her colleagues found four states – New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Vermont – did not have any pediatric ophthalmologists listed in directories for the organizations. Meanwhile, the country’s most populous states – California, New York, Florida, and Texas – had the most pediatric ophthalmologists.

For every million people, the study identified 7.7 pediatric ophthalmologists nationwide.

Julius T. Oatts, MD, the lead author of an accompanying editorial, said the findings are “valuable and sobering.” Even in San Francisco, where Dr. Oatts practices, most pediatric eye specialists have 6-month wait lists, he said.

Not fixing the shortage of children’s eye doctors could carry lifetime consequences, Dr. Oatts and his colleagues warned.

“Vision and eye health represent an important health barrier to learning in children,” Dr. Oatts and his colleagues wrote. “Lack of access to pediatric vision screening and care also contributes to the academic achievement gap and educational disparities.”

Dr. Bradfield said that disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care could leave some children at risk for losing their vision or never being able to see 20/20. Parents living in areas without a specialist may decide to instead visit an optometrist, but they are not trained to treat serious cases, such as strabismus, and only test and diagnose vision changes, according to AAPOS.

“If we don’t get to the kids in time, they can lose vision permanently, even if it’s something as simple as they just need glasses as a toddler,” Dr. Bradfield said.

Dr. Bradfield said AAPOS is recruiting new pediatric ophthalmologists by offering fellowships for medical students to attend the association’s annual conference and creating shadowing opportunities for students. The society also will release a survey of pediatric ophthalmology salaries to dispel rumors that the specialty does not have lucrative wages.

Ms. Walsh said she was interested in looking at disparities in pediatric ophthalmology care, in part, because she was surprised by how few of her classmates attending medical school were interested in the field of study.

“I hope it encourages ophthalmologists to consider pediatric ophthalmology, or to consider volunteering their time, or going to underserved areas to provide care to families that really are in need,” she said.

Coauthor Jayanth Sridhar, MD, reported receiving personal fees from Alcon, Apellis, Allergan, Dutch Ophthalmic Research Center, Genentech, OcuTerra Therapeutics, and Regeneron outside the submitted work. The other authors and the editorialists report no relevant financial relationships.

*This article was updated on 2/2/2023.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Similar brain atrophy in obesity and Alzheimer’s disease

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Comparisons of MRI scans for more than 1,000 participants indicate correlations between the two conditions, especially in areas of gray matter thinning, suggesting that managing excess weight might slow cognitive decline and lower the risk for AD, according to the researchers.

However, brain maps of obesity did not correlate with maps of amyloid or tau protein accumulation.

“The fact that obesity-related brain atrophy did not correlate with the distribution of amyloid and tau proteins in AD was not what we expected,” study author Filip Morys, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University, Montreal, said in an interview. “But it might just show that the specific mechanisms underpinning obesity- and Alzheimer’s disease–related neurodegeneration are different. This remains to be confirmed.”

The study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Cortical Thinning

The current study was prompted by the team’s earlier study, which showed that obesity-related neurodegeneration patterns were visually similar to those of AD, said Dr. Morys. “It was known previously that obesity is a risk factor for AD, but we wanted to directly compare brain atrophy patterns in both, which is what we did in this new study.”

The researchers analyzed data from a pooled sample of more than 1,300 participants. From the ADNI database, the researchers selected participants with AD and age- and sex-matched cognitively healthy controls. From the UK Biobank, the researchers drew a sample of lean, overweight, and obese participants without neurologic disease.

To determine how the weight status of patients with AD affects the correspondence between AD and obesity maps, they categorized participants with AD and healthy controls from the ADNI database into lean, overweight, and obese subgroups.

Then, to investigate mechanisms that might drive the similarities between obesity-related brain atrophy and AD-related amyloid-beta accumulation, they looked for overlapping areas in PET brain maps between patients with these outcomes.

The investigations showed that obesity maps were highly correlated with AD maps, but not with amyloid-beta or tau protein maps. The researchers also found significant correlations between obesity and the lean individuals with AD.

Brain regions with the highest similarities between obesity and AD were located mainly in the left temporal and bilateral prefrontal cortices.

“Our research confirms that obesity-related gray matter atrophy resembles that of AD,” the authors concluded. “Excess weight management could lead to improved health outcomes, slow down cognitive decline in aging, and lower the risk for AD.”

Upcoming research “will focus on investigating how weight loss can affect the risk for AD, other dementias, and cognitive decline in general,” said Dr. Morys. “At this point, our study suggests that obesity prevention, weight loss, but also decreasing other metabolic risk factors related to obesity, such as type-2 diabetes or hypertension, might reduce the risk for AD and have beneficial effects on cognition.”

Lifestyle habits

Commenting on the findings, Claire Sexton, DPhil, vice president of scientific programs and outreach at the Alzheimer’s Association, cautioned that a single cross-sectional study isn’t conclusive. “Previous studies have illustrated that the relationship between obesity and dementia is complex. Growing evidence indicates that people can reduce their risk of cognitive decline by adopting key lifestyle habits, like regular exercise, a heart-healthy diet and staying socially and cognitively engaged.”

The Alzheimer’s Association is leading a 2-year clinical trial, U.S. Pointer, to study how targeting these risk factors in combination may reduce risk for cognitive decline in older adults.

The work was supported by a Foundation Scheme award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Morys received a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de Recherche du Quebec – Santé. Data collection and sharing were funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and multiple pharmaceutical companies and other private sector organizations. Dr. Morys and Dr. Sexton reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Expert gives tips on less-discussed dermatologic diseases

ORLANDO – , according to Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

These semi-forsaken diseases are important not to miss and can “also be quite challenging when we think about their management,” he said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference.

Dr. Friedman, also director of the GW dermatology residency program, reviewed several of these diseases – along with tips for management – during a session at the meeting.

. It does not always have the classic ring pattern for which it is best known, he said. And in patients with darker skin tones, it is characterized by more of a brown or black color, rather than the pink-red color.

Dr. Friedman said that despite a kind of “Pavlovian response” linking GA with diabetes, this link might not be as strong as the field has come to believe, since the studies on which this belief was based included a patient population with narrow demographics. “Maybe GA and type 1 diabetes aren’t necessarily connected,” he said.

Dyslipidemia, on the other hand, has a strong connection with GA, he said. The disease is also linked to thyroid disease and is linked with malignancy, especially in older patients with generalized or atypical presentations of GA, he said.

Spontaneous resolution of the disease is seen within 2 years for 50% to 75% of patients, so “no treatment may be the best treatment,” but antimalarials can be effective, Dr. Friedman said. “I use antimalarials frequently in my practice,” he said. “The key is, they take time to work (4-5 months),” which should be explained to patients.

Antibiotics, he said, can be “somewhat effective,” but in the case of doxycycline at least, the disease can resolve within weeks but then may return when treatment is stopped.

There is some evidence to support using biologics and more recently, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, off-label, to treat GA. Efficacy has been seen with the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker infliximab and with the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib, he said.

Lichen planus (LP). This is another common disease that can go off-script with its presentation. The disease is often described with the “six P’s” indicating the following characteristics: pruritic, polygonal, planar or flat-topped, purple papules, and plaques. But LP “didn’t read the textbook,” Dr. Friedman said.

“The clinical presentation of lichen planus can be quite broad,” he said. “The P’s aren’t always followed as there are a variety of colors and configurations which can be witnessed.”

With LP, there is a clear association with dyslipidemia and diabetes, so “asking the right questions is going to be important” when talking to the patient. There is also a higher risk of autoimmune diseases, especially of the thyroid type, associated with LP, he said.

No treatment has been Food and Drug Administration approved for LP, but some are expected in the future, he said.

For now, he emphasized creativity in the management of patients with LP. “I love oral retinoids for this,” he said. Antimalarials and methotrexate are also options.

In one case Dr. Friedman saw, nothing seemed to work: light therapy for a year; metronidazole; isotretinoin; halobetasol/tazarotene lotion; and the TNF-blocker adalimumab either weren’t effective or resulted in complications in the patient.

Knowing the recent implication of the interleukin (IL)-17 pathway in the pathophysiology of LP, he then tried the anti-IL17 antibody secukinumab. “This patient had a pretty robust response to treatment,” Dr. Friedman said. “He was very excited. The problem, as always, is access, especially for off-label therapies.”

Tumid lupus erythematosus. This disease is characterized by erythematous, edematous, nonscarring plaques on sun-exposed sites. For treatment, Dr. Friedman said antimalarials can be up to 90% effective, sometimes with rapid resolution of the lesions.

“You want to dose below that 5 mg per kg of true body weight to limit the small potential for ocular toxicity over time,” he said. And, he emphasized, “always combine treatment with good sun-protective measures.”

Dr. Friedman reported financial relationships with Sanova, Pfizer, Novartis, and other companies.

ORLANDO – , according to Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

These semi-forsaken diseases are important not to miss and can “also be quite challenging when we think about their management,” he said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference.

Dr. Friedman, also director of the GW dermatology residency program, reviewed several of these diseases – along with tips for management – during a session at the meeting.

. It does not always have the classic ring pattern for which it is best known, he said. And in patients with darker skin tones, it is characterized by more of a brown or black color, rather than the pink-red color.

Dr. Friedman said that despite a kind of “Pavlovian response” linking GA with diabetes, this link might not be as strong as the field has come to believe, since the studies on which this belief was based included a patient population with narrow demographics. “Maybe GA and type 1 diabetes aren’t necessarily connected,” he said.

Dyslipidemia, on the other hand, has a strong connection with GA, he said. The disease is also linked to thyroid disease and is linked with malignancy, especially in older patients with generalized or atypical presentations of GA, he said.

Spontaneous resolution of the disease is seen within 2 years for 50% to 75% of patients, so “no treatment may be the best treatment,” but antimalarials can be effective, Dr. Friedman said. “I use antimalarials frequently in my practice,” he said. “The key is, they take time to work (4-5 months),” which should be explained to patients.

Antibiotics, he said, can be “somewhat effective,” but in the case of doxycycline at least, the disease can resolve within weeks but then may return when treatment is stopped.

There is some evidence to support using biologics and more recently, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, off-label, to treat GA. Efficacy has been seen with the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker infliximab and with the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib, he said.

Lichen planus (LP). This is another common disease that can go off-script with its presentation. The disease is often described with the “six P’s” indicating the following characteristics: pruritic, polygonal, planar or flat-topped, purple papules, and plaques. But LP “didn’t read the textbook,” Dr. Friedman said.

“The clinical presentation of lichen planus can be quite broad,” he said. “The P’s aren’t always followed as there are a variety of colors and configurations which can be witnessed.”

With LP, there is a clear association with dyslipidemia and diabetes, so “asking the right questions is going to be important” when talking to the patient. There is also a higher risk of autoimmune diseases, especially of the thyroid type, associated with LP, he said.

No treatment has been Food and Drug Administration approved for LP, but some are expected in the future, he said.

For now, he emphasized creativity in the management of patients with LP. “I love oral retinoids for this,” he said. Antimalarials and methotrexate are also options.

In one case Dr. Friedman saw, nothing seemed to work: light therapy for a year; metronidazole; isotretinoin; halobetasol/tazarotene lotion; and the TNF-blocker adalimumab either weren’t effective or resulted in complications in the patient.

Knowing the recent implication of the interleukin (IL)-17 pathway in the pathophysiology of LP, he then tried the anti-IL17 antibody secukinumab. “This patient had a pretty robust response to treatment,” Dr. Friedman said. “He was very excited. The problem, as always, is access, especially for off-label therapies.”

Tumid lupus erythematosus. This disease is characterized by erythematous, edematous, nonscarring plaques on sun-exposed sites. For treatment, Dr. Friedman said antimalarials can be up to 90% effective, sometimes with rapid resolution of the lesions.

“You want to dose below that 5 mg per kg of true body weight to limit the small potential for ocular toxicity over time,” he said. And, he emphasized, “always combine treatment with good sun-protective measures.”

Dr. Friedman reported financial relationships with Sanova, Pfizer, Novartis, and other companies.

ORLANDO – , according to Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

These semi-forsaken diseases are important not to miss and can “also be quite challenging when we think about their management,” he said at the ODAC Dermatology, Aesthetic & Surgical Conference.

Dr. Friedman, also director of the GW dermatology residency program, reviewed several of these diseases – along with tips for management – during a session at the meeting.

. It does not always have the classic ring pattern for which it is best known, he said. And in patients with darker skin tones, it is characterized by more of a brown or black color, rather than the pink-red color.

Dr. Friedman said that despite a kind of “Pavlovian response” linking GA with diabetes, this link might not be as strong as the field has come to believe, since the studies on which this belief was based included a patient population with narrow demographics. “Maybe GA and type 1 diabetes aren’t necessarily connected,” he said.

Dyslipidemia, on the other hand, has a strong connection with GA, he said. The disease is also linked to thyroid disease and is linked with malignancy, especially in older patients with generalized or atypical presentations of GA, he said.

Spontaneous resolution of the disease is seen within 2 years for 50% to 75% of patients, so “no treatment may be the best treatment,” but antimalarials can be effective, Dr. Friedman said. “I use antimalarials frequently in my practice,” he said. “The key is, they take time to work (4-5 months),” which should be explained to patients.

Antibiotics, he said, can be “somewhat effective,” but in the case of doxycycline at least, the disease can resolve within weeks but then may return when treatment is stopped.

There is some evidence to support using biologics and more recently, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, off-label, to treat GA. Efficacy has been seen with the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker infliximab and with the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib, he said.

Lichen planus (LP). This is another common disease that can go off-script with its presentation. The disease is often described with the “six P’s” indicating the following characteristics: pruritic, polygonal, planar or flat-topped, purple papules, and plaques. But LP “didn’t read the textbook,” Dr. Friedman said.

“The clinical presentation of lichen planus can be quite broad,” he said. “The P’s aren’t always followed as there are a variety of colors and configurations which can be witnessed.”

With LP, there is a clear association with dyslipidemia and diabetes, so “asking the right questions is going to be important” when talking to the patient. There is also a higher risk of autoimmune diseases, especially of the thyroid type, associated with LP, he said.

No treatment has been Food and Drug Administration approved for LP, but some are expected in the future, he said.

For now, he emphasized creativity in the management of patients with LP. “I love oral retinoids for this,” he said. Antimalarials and methotrexate are also options.

In one case Dr. Friedman saw, nothing seemed to work: light therapy for a year; metronidazole; isotretinoin; halobetasol/tazarotene lotion; and the TNF-blocker adalimumab either weren’t effective or resulted in complications in the patient.

Knowing the recent implication of the interleukin (IL)-17 pathway in the pathophysiology of LP, he then tried the anti-IL17 antibody secukinumab. “This patient had a pretty robust response to treatment,” Dr. Friedman said. “He was very excited. The problem, as always, is access, especially for off-label therapies.”

Tumid lupus erythematosus. This disease is characterized by erythematous, edematous, nonscarring plaques on sun-exposed sites. For treatment, Dr. Friedman said antimalarials can be up to 90% effective, sometimes with rapid resolution of the lesions.

“You want to dose below that 5 mg per kg of true body weight to limit the small potential for ocular toxicity over time,” he said. And, he emphasized, “always combine treatment with good sun-protective measures.”

Dr. Friedman reported financial relationships with Sanova, Pfizer, Novartis, and other companies.

AT ODAC 2023

Long QT syndrome overdiagnosis persists

Five factors underlie the ongoing overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of long QT syndrome (LQTS), including temporary QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, a “pseudo”-positive genetic test result, family history of sudden cardiac death, transient QT prolongation, and misinterpretation of the QTc interval, a new study suggests.

Awareness of these characteristics, which led to a diagnostic reversal in 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients, could reduce the burden of overdiagnosis on the health care system and on patients and families, senior author Michael J. Ackerman, MD, PhD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conclude.

“The findings are a disturbing and disappointing sequel to the paper we published about LQTS overdiagnosis back in 2007, which showed that 2 out of every 5 patients who came to Mayo Clinic for a second opinion left without the diagnosis,” Dr. Ackerman told this news organization.

To date, Dr. Ackerman has reversed the diagnosis for 350 patients, he said.

The consequences of an LQTS diagnosis are “profound,” he noted, including years of unnecessary drug therapy, implantation of a cardioverter defibrillator, disqualification from competitive sports, and emotional stress to the individual and family.

By pointing out the five biggest mistakes his team has seen, he said, “we hope to equip the diagnostician with the means to challenge and assess the veracity of a LQTS diagnosis.”

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Time to do better

Dr. Ackerman and colleagues analyzed electronic medical records on 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients who presented with an outside diagnosis of LQTS but subsequently were dismissed as having normal findings. The mean age of these patients at their first Mayo Clinic evaluation was 22, 60% were female, and the mean QTc interval was 427 ±25 milliseconds.

Overall, 38% of misdiagnoses were the result of misinterpretation of clinical factors; 29%, to diagnostic test misinterpretations; 17%, to an apparently positive genetic test in the context of a weak or absent phenotype; and 16%, to a family history of false LQTS or of sudden cardiac or sudden unexplained death.

More specifically, the most common cause of an LQTS misdiagnosis was QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, which was misinterpreted as LQTS-attributed syncope.

The second most common cause was an apparently positive genetic test for an LQTS gene that turned out to be a benign or likely benign variant.

The third most common cause was an LQTS diagnosis based solely on a family history of sudden unexplained death (26 patients), QT prolongation (11 patients), or sudden cardiac arrest (9 patients).

The fourth most common cause was an isolated event of QT prolongation (44 patients). The transient QT prolongation was observed under myriad conditions unrelated to LQTS. Yet, 31 patients received a diagnosis based solely on the event.

The fifth most common cause was inclusion of the U-wave in the calculation of the QTc interval (40 patients), leading to an inaccurate interpretation of the electrocardiogram.

Dr. Ackerman noted that these LQTS diagnoses were given by heart-rhythm specialists, and most patients self-referred for a second opinion because a family member questioned the diagnosis after doing their own research.

“It’s time that we step up to the plate and do better,” Dr. Ackerman said. The team’s evaluation of the impact of the misdiagnosis on the patients’ lifestyle and quality of life showed that 45% had been restricted from competitive sports (and subsequently resumed sports activity with no adverse events); 80% had been started on beta-blockers (the drugs were discontinued in 84% as a result of the Mayo Clinic evaluation, whereas 16% opted to continue); and 10 of 22 patients (45%) who received an implanted cardioverter device underwent an extraction of the device without complications.

The authors conclude: “Although missing a patient who truly has LQTS can lead to a tragic outcome, the implications of overdiagnosed LQTS are not trivial and are potentially tragic as well.”

‘Tricky diagnosis’

LQTS specialist Peter Aziz, MD, director of pediatric electrophysiology at the Cleveland Clinic, agreed with these findings.

“Most of us ‘channelopathists’ who see LQTS for a living have a good grasp of the disease, but it can be elusive for others,” he said in an interview. “This is a tricky diagnosis. There are ends of the spectrum where people for sure don’t have it and people for sure do. Most clinicians are able to identify that.”

However, he added, “A lot of patients fall into that gray area where it may not be clear at first, even to an expert. But the expert knows how to do a comprehensive evaluation, examining episodes and symptoms and understanding whether they are relevant to LQTS or completely red herrings, and feeling confident about how they calculate the acute interval on an electrocardiogram.”

“All of these may seem mundane, but without the experience, clinicians are vulnerable to miscalculations,” he said. “That’s why our bias, as channelopathists, is that every patient who has a suspected diagnosis or is being treated for LQTS really should see an expert.”

Similarly, Arthur A.M. Wilde, MD, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam, and Peter J. Schwartz, MD, of IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan, write in a related editorial that it “has to be kept in mind that both diagnostic scores and risk scores are dynamic and can be modified by time and by appropriate therapy.

“Therefore, to make hasty diagnosis of a disease that requires life-long treatment is inappropriate, especially when this is done without the support of adequate, specific experience.”

No commercial funding or relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Five factors underlie the ongoing overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of long QT syndrome (LQTS), including temporary QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, a “pseudo”-positive genetic test result, family history of sudden cardiac death, transient QT prolongation, and misinterpretation of the QTc interval, a new study suggests.

Awareness of these characteristics, which led to a diagnostic reversal in 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients, could reduce the burden of overdiagnosis on the health care system and on patients and families, senior author Michael J. Ackerman, MD, PhD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conclude.

“The findings are a disturbing and disappointing sequel to the paper we published about LQTS overdiagnosis back in 2007, which showed that 2 out of every 5 patients who came to Mayo Clinic for a second opinion left without the diagnosis,” Dr. Ackerman told this news organization.

To date, Dr. Ackerman has reversed the diagnosis for 350 patients, he said.

The consequences of an LQTS diagnosis are “profound,” he noted, including years of unnecessary drug therapy, implantation of a cardioverter defibrillator, disqualification from competitive sports, and emotional stress to the individual and family.

By pointing out the five biggest mistakes his team has seen, he said, “we hope to equip the diagnostician with the means to challenge and assess the veracity of a LQTS diagnosis.”

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Time to do better

Dr. Ackerman and colleagues analyzed electronic medical records on 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients who presented with an outside diagnosis of LQTS but subsequently were dismissed as having normal findings. The mean age of these patients at their first Mayo Clinic evaluation was 22, 60% were female, and the mean QTc interval was 427 ±25 milliseconds.

Overall, 38% of misdiagnoses were the result of misinterpretation of clinical factors; 29%, to diagnostic test misinterpretations; 17%, to an apparently positive genetic test in the context of a weak or absent phenotype; and 16%, to a family history of false LQTS or of sudden cardiac or sudden unexplained death.

More specifically, the most common cause of an LQTS misdiagnosis was QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, which was misinterpreted as LQTS-attributed syncope.

The second most common cause was an apparently positive genetic test for an LQTS gene that turned out to be a benign or likely benign variant.

The third most common cause was an LQTS diagnosis based solely on a family history of sudden unexplained death (26 patients), QT prolongation (11 patients), or sudden cardiac arrest (9 patients).

The fourth most common cause was an isolated event of QT prolongation (44 patients). The transient QT prolongation was observed under myriad conditions unrelated to LQTS. Yet, 31 patients received a diagnosis based solely on the event.

The fifth most common cause was inclusion of the U-wave in the calculation of the QTc interval (40 patients), leading to an inaccurate interpretation of the electrocardiogram.

Dr. Ackerman noted that these LQTS diagnoses were given by heart-rhythm specialists, and most patients self-referred for a second opinion because a family member questioned the diagnosis after doing their own research.

“It’s time that we step up to the plate and do better,” Dr. Ackerman said. The team’s evaluation of the impact of the misdiagnosis on the patients’ lifestyle and quality of life showed that 45% had been restricted from competitive sports (and subsequently resumed sports activity with no adverse events); 80% had been started on beta-blockers (the drugs were discontinued in 84% as a result of the Mayo Clinic evaluation, whereas 16% opted to continue); and 10 of 22 patients (45%) who received an implanted cardioverter device underwent an extraction of the device without complications.

The authors conclude: “Although missing a patient who truly has LQTS can lead to a tragic outcome, the implications of overdiagnosed LQTS are not trivial and are potentially tragic as well.”

‘Tricky diagnosis’

LQTS specialist Peter Aziz, MD, director of pediatric electrophysiology at the Cleveland Clinic, agreed with these findings.

“Most of us ‘channelopathists’ who see LQTS for a living have a good grasp of the disease, but it can be elusive for others,” he said in an interview. “This is a tricky diagnosis. There are ends of the spectrum where people for sure don’t have it and people for sure do. Most clinicians are able to identify that.”

However, he added, “A lot of patients fall into that gray area where it may not be clear at first, even to an expert. But the expert knows how to do a comprehensive evaluation, examining episodes and symptoms and understanding whether they are relevant to LQTS or completely red herrings, and feeling confident about how they calculate the acute interval on an electrocardiogram.”

“All of these may seem mundane, but without the experience, clinicians are vulnerable to miscalculations,” he said. “That’s why our bias, as channelopathists, is that every patient who has a suspected diagnosis or is being treated for LQTS really should see an expert.”

Similarly, Arthur A.M. Wilde, MD, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam, and Peter J. Schwartz, MD, of IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan, write in a related editorial that it “has to be kept in mind that both diagnostic scores and risk scores are dynamic and can be modified by time and by appropriate therapy.

“Therefore, to make hasty diagnosis of a disease that requires life-long treatment is inappropriate, especially when this is done without the support of adequate, specific experience.”

No commercial funding or relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Five factors underlie the ongoing overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis of long QT syndrome (LQTS), including temporary QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, a “pseudo”-positive genetic test result, family history of sudden cardiac death, transient QT prolongation, and misinterpretation of the QTc interval, a new study suggests.

Awareness of these characteristics, which led to a diagnostic reversal in 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients, could reduce the burden of overdiagnosis on the health care system and on patients and families, senior author Michael J. Ackerman, MD, PhD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conclude.

“The findings are a disturbing and disappointing sequel to the paper we published about LQTS overdiagnosis back in 2007, which showed that 2 out of every 5 patients who came to Mayo Clinic for a second opinion left without the diagnosis,” Dr. Ackerman told this news organization.

To date, Dr. Ackerman has reversed the diagnosis for 350 patients, he said.

The consequences of an LQTS diagnosis are “profound,” he noted, including years of unnecessary drug therapy, implantation of a cardioverter defibrillator, disqualification from competitive sports, and emotional stress to the individual and family.

By pointing out the five biggest mistakes his team has seen, he said, “we hope to equip the diagnostician with the means to challenge and assess the veracity of a LQTS diagnosis.”

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Time to do better

Dr. Ackerman and colleagues analyzed electronic medical records on 290 of 1,841 (16%) patients who presented with an outside diagnosis of LQTS but subsequently were dismissed as having normal findings. The mean age of these patients at their first Mayo Clinic evaluation was 22, 60% were female, and the mean QTc interval was 427 ±25 milliseconds.

Overall, 38% of misdiagnoses were the result of misinterpretation of clinical factors; 29%, to diagnostic test misinterpretations; 17%, to an apparently positive genetic test in the context of a weak or absent phenotype; and 16%, to a family history of false LQTS or of sudden cardiac or sudden unexplained death.

More specifically, the most common cause of an LQTS misdiagnosis was QT prolongation following vasovagal syncope, which was misinterpreted as LQTS-attributed syncope.

The second most common cause was an apparently positive genetic test for an LQTS gene that turned out to be a benign or likely benign variant.

The third most common cause was an LQTS diagnosis based solely on a family history of sudden unexplained death (26 patients), QT prolongation (11 patients), or sudden cardiac arrest (9 patients).

The fourth most common cause was an isolated event of QT prolongation (44 patients). The transient QT prolongation was observed under myriad conditions unrelated to LQTS. Yet, 31 patients received a diagnosis based solely on the event.

The fifth most common cause was inclusion of the U-wave in the calculation of the QTc interval (40 patients), leading to an inaccurate interpretation of the electrocardiogram.

Dr. Ackerman noted that these LQTS diagnoses were given by heart-rhythm specialists, and most patients self-referred for a second opinion because a family member questioned the diagnosis after doing their own research.

“It’s time that we step up to the plate and do better,” Dr. Ackerman said. The team’s evaluation of the impact of the misdiagnosis on the patients’ lifestyle and quality of life showed that 45% had been restricted from competitive sports (and subsequently resumed sports activity with no adverse events); 80% had been started on beta-blockers (the drugs were discontinued in 84% as a result of the Mayo Clinic evaluation, whereas 16% opted to continue); and 10 of 22 patients (45%) who received an implanted cardioverter device underwent an extraction of the device without complications.

The authors conclude: “Although missing a patient who truly has LQTS can lead to a tragic outcome, the implications of overdiagnosed LQTS are not trivial and are potentially tragic as well.”

‘Tricky diagnosis’

LQTS specialist Peter Aziz, MD, director of pediatric electrophysiology at the Cleveland Clinic, agreed with these findings.

“Most of us ‘channelopathists’ who see LQTS for a living have a good grasp of the disease, but it can be elusive for others,” he said in an interview. “This is a tricky diagnosis. There are ends of the spectrum where people for sure don’t have it and people for sure do. Most clinicians are able to identify that.”

However, he added, “A lot of patients fall into that gray area where it may not be clear at first, even to an expert. But the expert knows how to do a comprehensive evaluation, examining episodes and symptoms and understanding whether they are relevant to LQTS or completely red herrings, and feeling confident about how they calculate the acute interval on an electrocardiogram.”

“All of these may seem mundane, but without the experience, clinicians are vulnerable to miscalculations,” he said. “That’s why our bias, as channelopathists, is that every patient who has a suspected diagnosis or is being treated for LQTS really should see an expert.”

Similarly, Arthur A.M. Wilde, MD, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam, and Peter J. Schwartz, MD, of IRCCS Istituto Auxologico Italiano, Milan, write in a related editorial that it “has to be kept in mind that both diagnostic scores and risk scores are dynamic and can be modified by time and by appropriate therapy.

“Therefore, to make hasty diagnosis of a disease that requires life-long treatment is inappropriate, especially when this is done without the support of adequate, specific experience.”

No commercial funding or relevant financial relationships were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Psychiatric illnesses share common brain network

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

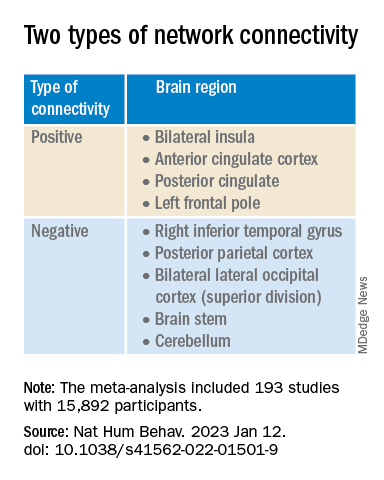

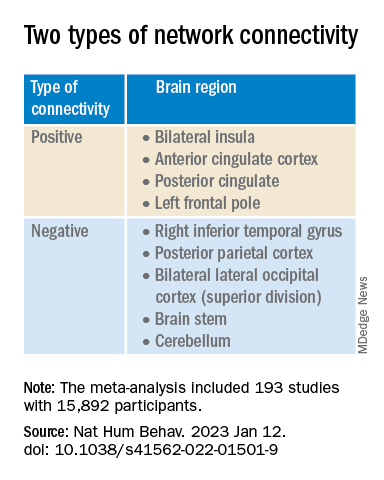

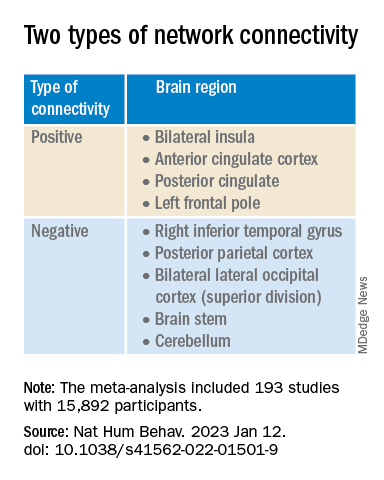

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.

When lesions from dataset 3 were overlaid onto the ALE map and the transdiagnostic network in order to evaluate whether damage to either map correlated with number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnosis, results showed no evidence of a correlation between psychiatric comorbidity and damage on the ALE map (Pearson r, 0.02; P = .766).

However, when the same approach was applied to the transdiagnostic network, a statistically significant correlation was found between psychiatric comorbidity and lesion damage (Pearson r, –0.21; P = .01). A multiple regression model showed that the transdiagnostic, but not the ALE, network “independently predicted the number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnoses” (P = .003 vs. P = .1), the investigators reported.

All four neurosurgical ablative targets for psychiatric disorders found on analysis of dataset 4 “intersected” and aligned with the transdiagnostic network.

“The study does not immediately impact clinical practice, but it would be helpful for practicing clinicians to know that psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur and might share common neurobiology and a convergent brain network,” Dr. Taylor said.

“Future work based on our findings could potentially influence clinical trials and clinical practice, especially in the area of brain stimulation,” he added.

‘Exciting new targets’

In a comment, Desmond Oathes, PhD, associate director, Center for Neuromodulation and Stress, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the “next step in the science is to combine individual brain imaging, aka, ‘individualized connectomes,’ with these promising group maps to determine something meaningful at the individual patient level.”

Dr. Oathes, who is also a faculty clinician at the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and was not involved with the study, noted that an open question is whether the brain volume abnormalities/atrophy “can be changed with treatment and in what direction.”

A “strong take-home message from this paper is that brain volume measures from single coordinates are noisy as measures of psychiatric abnormality, whereas network effects seem to be especially sensitive for capturing these effects,” Dr. Oathes said.

The “abnormal networks across these disorders do not fit easily into well-known networks from healthy participants. However, they map well onto other databases relevant to psychiatric disorders and offer exciting new potential targets for prospective treatment studies,” he added.

The investigators received no specific funding for this work. Dr. Taylor reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Oathes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.

When lesions from dataset 3 were overlaid onto the ALE map and the transdiagnostic network in order to evaluate whether damage to either map correlated with number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnosis, results showed no evidence of a correlation between psychiatric comorbidity and damage on the ALE map (Pearson r, 0.02; P = .766).

However, when the same approach was applied to the transdiagnostic network, a statistically significant correlation was found between psychiatric comorbidity and lesion damage (Pearson r, –0.21; P = .01). A multiple regression model showed that the transdiagnostic, but not the ALE, network “independently predicted the number of post-lesion psychiatric diagnoses” (P = .003 vs. P = .1), the investigators reported.

All four neurosurgical ablative targets for psychiatric disorders found on analysis of dataset 4 “intersected” and aligned with the transdiagnostic network.

“The study does not immediately impact clinical practice, but it would be helpful for practicing clinicians to know that psychiatric disorders commonly co-occur and might share common neurobiology and a convergent brain network,” Dr. Taylor said.

“Future work based on our findings could potentially influence clinical trials and clinical practice, especially in the area of brain stimulation,” he added.

‘Exciting new targets’

In a comment, Desmond Oathes, PhD, associate director, Center for Neuromodulation and Stress, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the “next step in the science is to combine individual brain imaging, aka, ‘individualized connectomes,’ with these promising group maps to determine something meaningful at the individual patient level.”

Dr. Oathes, who is also a faculty clinician at the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety and was not involved with the study, noted that an open question is whether the brain volume abnormalities/atrophy “can be changed with treatment and in what direction.”

A “strong take-home message from this paper is that brain volume measures from single coordinates are noisy as measures of psychiatric abnormality, whereas network effects seem to be especially sensitive for capturing these effects,” Dr. Oathes said.

The “abnormal networks across these disorders do not fit easily into well-known networks from healthy participants. However, they map well onto other databases relevant to psychiatric disorders and offer exciting new potential targets for prospective treatment studies,” he added.

The investigators received no specific funding for this work. Dr. Taylor reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Oathes reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators used coordinate and lesion network mapping to assess whether there was a shared brain network common to multiple psychiatric disorders. In a meta-analysis of almost 200 studies encompassing more than 15,000 individuals, they found that atrophy coordinates across these six psychiatric conditions all mapped to a common brain network.

Moreover, lesion damage to this network in patients with penetrating head trauma correlated with the number of psychiatric illnesses that the patients were diagnosed with post trauma.

The findings have “bigger-picture potential implications,” lead author Joseph Taylor, MD, PhD, medical director of transcranial magnetic stimulation at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics, Boston, told this news organization.

“In psychiatry, we talk about symptoms and define our disorders based on symptom checklists, which are fairly reliable but don’t have neurobiological underpinnings,” said Dr. Taylor, who is also an associate psychiatrist in Brigham’s department of psychiatry.

By contrast, “in neurology, we ask: ‘Where is the lesion?’ Studying brain networks could potentially help us diagnose and treat people with psychiatric illness more effectively, just as we treat neurological disorders,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Human Behavior.

Beyond symptom checklists

Dr. Taylor noted that, in the field of psychiatry, “we often study disorders in isolation,” such as generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

“But what see clinically is that half of patients meet the criteria for more than one psychiatric disorder,” he said. “It can be difficult to diagnose and treat these patients, and there are worse treatment outcomes.”

There is also a “discrepancy” between how these disorders are studied (one at a time) and how patients are treated in clinic, Dr. Taylor noted. And there is increasing evidence that psychiatric disorders may share a common neurobiology.

This “highlights the possibility of potentially developing transdiagnostic treatments based on common neurobiology, not just symptom checklists,” Dr. Taylor said.

Prior work “has attempted to map abnormalities to common brain regions rather than to a common brain network,” the investigators wrote. Moreover, “prior studies have rarely tested specificity by comparing psychiatric disorders to other brain disorders.”

In the current study, the researchers used “morphometric brain lesion datasets coupled with a wiring diagram of the human brain to derive a convergent brain network for psychiatric illness.”

They analyzed four large published datasets. Dataset 1 was sourced from an activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis (ALE) of whole-brain voxel-based studies that compared patients with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, BD, depression, addiction, OCD, and anxiety to healthy controls (n = 193 studies; 15,892 individuals in total).

Dataset 2 was drawn from published neuroimaging studies involving patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative conditions (n = 72 studies). They reported coordinates regarding which patients with these disorders had more atrophy compared with control persons.

Dataset 3 was sourced from the Vietnam Head Injury study, which followed veterans with and those without penetrating head injuries (n = 194 veterans with injuries). Dataset 4 was sourced from published neurosurgical ablation coordinates for depression.

Shared neurobiology

Upon analyzing dataset 1, the researchers found decreased gray matter in the bilateral anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, and parietal operculum – findings that are “consistent with prior work.”

However, fewer than 35% of the studies contributed to any single cluster; and no cluster was specific to psychiatric versus neurodegenerative coordinates (drawn from dataset 2).

On the other hand, coordinate network mapping yielded “more statistically robust” (P < .001) results, which were found in 85% of the studies. “Psychiatric atrophy coordinates were functionally connected to the same network of brain regions,” the researchers reported.

This network was defined by two types of connectivity, positive and negative.

“The topography of this transdiagnostic network was independent of the statistical threshold and specific to psychiatric (vs. neurodegenerative) disorders, with the strongest peak occurring in the posterior parietal cortex (Brodmann Area 7) near the intraparietal sulcus,” the investigators wrote.