User login

Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM): Annual Meeting

Head bath promising for primary headaches

DALLAS – A 30-minute cold-water head bath shows promise as a nonpharmacologic treatment for acute migraine or tension headache.

The key to this approach is that the water starts out lukewarm, cooling slowly to cold over the course of the first 15 minutes. It makes for a very different experience than abrupt immersion in an ice bath or placement of an ice pack against the head, which can actually worsen pain; indeed, many pain studies use a cold-water bath as the standardized pain stimulus, Dr. James R. Miner noted at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

He presented a prospective, observational, proof-of-concept study involving 18 adults who presented to an emergency department with a primary headache – that is, either migraine, migrainous headache not meeting full diagnostic criteria for migraine, or tension headache. Their mean age was 29 years, and all were free from known vascular disease. These were patients whose headaches were sufficiently severe that ED physicians had slated them for treatment with opioids, triptans, antiemetics, or other medications widely used to treat acute primary headache in the ED.

Instead, participants were placed in what Dr. Miner termed his migraine head box for 60 minutes. The jury-rigged box looks much like the sort of porcelain sink used for hair washing in salons. An icepack is placed at the bottom of the sink of lukewarm water, and the patient then lies back and submerges his or her head in the gradually chilling water to a level just below the ears.

The subjects’ median baseline self-rated pain score on a 0- to 100-mm visual analog scale was 78 mm. Ten patients described their head pain as severe and eight as moderate.

After 30 minutes in the migraine head box, patients reported a median 19.5-mm drop in their pain score, and nine patients now rated their headache as mild. And 60 minutes in the head box brought a modest additional median 2-mm reduction in pain scores, and one additional patient who rated the pain as mild, according to Dr. Miner of Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis.

Seven of the 18 patients received rescue medications. In a follow-up phone call at 72 hours, one-third of subjects reported experiencing a rebound headache after leaving the ED, a rate Dr. Miner found surprisingly high.

He stressed that these are early days for the migraine head box. Planned future studies will include controls given a sham intervention, as well as measurement of water temperatures to learn if outcomes are optimized at a certain temperature. Efforts will also be made to identify the mechanism of benefit.

"I don’t think the cold water therapy has anything to do with an anti-inflammatory effect," Dr. Miner speculated. "Most likely, the low-level innocuous stimulation is causing an afferent decrease in pain at the thalamic level."

He noted that the etiology of primary headaches remains elusive.

"You can go to a lot of different meetings and hear a lot of different theories. I can say that over the course of my career the leading contender for what causes these headaches has changed almost every 3 or 4 years. But I think there’s pretty good agreement that a lot of the pain is thalamically mediated hyperesthesia, although whether this is a result of vasospasm or spreading cortical depression immediately prior to the headache is a subject of conjecture," Dr. Miner commented.

"I think one of the reasons that we struggle with so many different drug classes that are all similarly effective for these headaches is that we don’t know what’s truly causing the headache," he added.

Audience members applauded his effort to develop a fast-acting nonpharmacologic treatment for what is a very common diagnosis in the ED. As one physician noted, "I suspect ED physicians, because of the greatly increased concern about prescribing opiates, are going to be told they need to be using other forms of treatment."

Dr. Miner reported receiving grants for acute pain research from the National Institute of Justice and Taser International.

DALLAS – A 30-minute cold-water head bath shows promise as a nonpharmacologic treatment for acute migraine or tension headache.

The key to this approach is that the water starts out lukewarm, cooling slowly to cold over the course of the first 15 minutes. It makes for a very different experience than abrupt immersion in an ice bath or placement of an ice pack against the head, which can actually worsen pain; indeed, many pain studies use a cold-water bath as the standardized pain stimulus, Dr. James R. Miner noted at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

He presented a prospective, observational, proof-of-concept study involving 18 adults who presented to an emergency department with a primary headache – that is, either migraine, migrainous headache not meeting full diagnostic criteria for migraine, or tension headache. Their mean age was 29 years, and all were free from known vascular disease. These were patients whose headaches were sufficiently severe that ED physicians had slated them for treatment with opioids, triptans, antiemetics, or other medications widely used to treat acute primary headache in the ED.

Instead, participants were placed in what Dr. Miner termed his migraine head box for 60 minutes. The jury-rigged box looks much like the sort of porcelain sink used for hair washing in salons. An icepack is placed at the bottom of the sink of lukewarm water, and the patient then lies back and submerges his or her head in the gradually chilling water to a level just below the ears.

The subjects’ median baseline self-rated pain score on a 0- to 100-mm visual analog scale was 78 mm. Ten patients described their head pain as severe and eight as moderate.

After 30 minutes in the migraine head box, patients reported a median 19.5-mm drop in their pain score, and nine patients now rated their headache as mild. And 60 minutes in the head box brought a modest additional median 2-mm reduction in pain scores, and one additional patient who rated the pain as mild, according to Dr. Miner of Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis.

Seven of the 18 patients received rescue medications. In a follow-up phone call at 72 hours, one-third of subjects reported experiencing a rebound headache after leaving the ED, a rate Dr. Miner found surprisingly high.

He stressed that these are early days for the migraine head box. Planned future studies will include controls given a sham intervention, as well as measurement of water temperatures to learn if outcomes are optimized at a certain temperature. Efforts will also be made to identify the mechanism of benefit.

"I don’t think the cold water therapy has anything to do with an anti-inflammatory effect," Dr. Miner speculated. "Most likely, the low-level innocuous stimulation is causing an afferent decrease in pain at the thalamic level."

He noted that the etiology of primary headaches remains elusive.

"You can go to a lot of different meetings and hear a lot of different theories. I can say that over the course of my career the leading contender for what causes these headaches has changed almost every 3 or 4 years. But I think there’s pretty good agreement that a lot of the pain is thalamically mediated hyperesthesia, although whether this is a result of vasospasm or spreading cortical depression immediately prior to the headache is a subject of conjecture," Dr. Miner commented.

"I think one of the reasons that we struggle with so many different drug classes that are all similarly effective for these headaches is that we don’t know what’s truly causing the headache," he added.

Audience members applauded his effort to develop a fast-acting nonpharmacologic treatment for what is a very common diagnosis in the ED. As one physician noted, "I suspect ED physicians, because of the greatly increased concern about prescribing opiates, are going to be told they need to be using other forms of treatment."

Dr. Miner reported receiving grants for acute pain research from the National Institute of Justice and Taser International.

DALLAS – A 30-minute cold-water head bath shows promise as a nonpharmacologic treatment for acute migraine or tension headache.

The key to this approach is that the water starts out lukewarm, cooling slowly to cold over the course of the first 15 minutes. It makes for a very different experience than abrupt immersion in an ice bath or placement of an ice pack against the head, which can actually worsen pain; indeed, many pain studies use a cold-water bath as the standardized pain stimulus, Dr. James R. Miner noted at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

He presented a prospective, observational, proof-of-concept study involving 18 adults who presented to an emergency department with a primary headache – that is, either migraine, migrainous headache not meeting full diagnostic criteria for migraine, or tension headache. Their mean age was 29 years, and all were free from known vascular disease. These were patients whose headaches were sufficiently severe that ED physicians had slated them for treatment with opioids, triptans, antiemetics, or other medications widely used to treat acute primary headache in the ED.

Instead, participants were placed in what Dr. Miner termed his migraine head box for 60 minutes. The jury-rigged box looks much like the sort of porcelain sink used for hair washing in salons. An icepack is placed at the bottom of the sink of lukewarm water, and the patient then lies back and submerges his or her head in the gradually chilling water to a level just below the ears.

The subjects’ median baseline self-rated pain score on a 0- to 100-mm visual analog scale was 78 mm. Ten patients described their head pain as severe and eight as moderate.

After 30 minutes in the migraine head box, patients reported a median 19.5-mm drop in their pain score, and nine patients now rated their headache as mild. And 60 minutes in the head box brought a modest additional median 2-mm reduction in pain scores, and one additional patient who rated the pain as mild, according to Dr. Miner of Hennepin County Medical Center, Minneapolis.

Seven of the 18 patients received rescue medications. In a follow-up phone call at 72 hours, one-third of subjects reported experiencing a rebound headache after leaving the ED, a rate Dr. Miner found surprisingly high.

He stressed that these are early days for the migraine head box. Planned future studies will include controls given a sham intervention, as well as measurement of water temperatures to learn if outcomes are optimized at a certain temperature. Efforts will also be made to identify the mechanism of benefit.

"I don’t think the cold water therapy has anything to do with an anti-inflammatory effect," Dr. Miner speculated. "Most likely, the low-level innocuous stimulation is causing an afferent decrease in pain at the thalamic level."

He noted that the etiology of primary headaches remains elusive.

"You can go to a lot of different meetings and hear a lot of different theories. I can say that over the course of my career the leading contender for what causes these headaches has changed almost every 3 or 4 years. But I think there’s pretty good agreement that a lot of the pain is thalamically mediated hyperesthesia, although whether this is a result of vasospasm or spreading cortical depression immediately prior to the headache is a subject of conjecture," Dr. Miner commented.

"I think one of the reasons that we struggle with so many different drug classes that are all similarly effective for these headaches is that we don’t know what’s truly causing the headache," he added.

Audience members applauded his effort to develop a fast-acting nonpharmacologic treatment for what is a very common diagnosis in the ED. As one physician noted, "I suspect ED physicians, because of the greatly increased concern about prescribing opiates, are going to be told they need to be using other forms of treatment."

Dr. Miner reported receiving grants for acute pain research from the National Institute of Justice and Taser International.

AT THE SAEM ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Reasonably effective treatment for primary headaches via placement of the back of a patient’s head in a slowly cooling water bath warrants further studies.

Major finding: Median self-rated head pain severity dropped from 78 on a 0-100 scale to 58.5 after 30 minutes in a migraine head box.

Data source: This was a prospective, observational, pilot study involving 18 adults who presented to an emergency department with moderate or severe migraine or tension headache.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts with regard to this study.

Emergency Physicians May Be Overprescribing PPIs

DALLAS – The frequency at which U.S. emergency department physicians prescribed proton pump inhibitors more than doubled during 2001-2010, despite mounting safety concerns surrounding this class of medications.

"More education may be needed to ensure ED providers are familiar with the appropriate indications for PPI use. The big thing that I’m hoping will be taken away from this study is that because of the increase in prescribing PPIs [proton pump inhibitors] and the concerns about safety, that we’re going to be more vigilant in educating ourselves and each other about appropriate use of these medications," Dr. Maryann Mazer-Amirshahi said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

Overprescribing of PPIs has been well documented in primary care offices, gastroenterology clinics, and inpatient settings. Up until now, however, prescribing patterns in the ED haven’t been well documented. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s annual National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey provided an opportunity to do so via a weighted nationally representative sample of ED visits, explained Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi of Children’s National Medical Center, Washington.

She presented a retrospective analysis of survey data for the years 2001-2010, during which the annual number of adult ED visits climbed from 20.1 million to 28.3 million. Meanwhile, PPI prescribing increased from 3% of adult patients in 2001 to 7.2% in 2010.

"I think that’s pretty significant when you’re talking about more than 7% of 28 million ED visits every year," she commented.

While PPI prescribing more than doubled during the study years, the use of alternative medications declined. Histamine2 blocker use dropped from 6.8% in 2001 to 5.7% in 2010, while the use of antacids decreased from 7.2% to 5.5%.

PPI prescribing rose in EDs in hospitals of all types: nonprofit, for-profit, and government. It increased in all regions of the country and across all payer types, including self-payment. Of note, the number of ED prescriptions increased to a greater extent in teaching hospitals, with a 276% increase, as compared with a 118% increase in nonteaching hospitals. Prescribing of PPIs by attending ED physicians climbed by 122%, by 185% by emergency medicine residents, and by 345% by mid-level providers.

In 2001, 3.3% of ED patients aged 65 years or older received a PPI. By 2010, this figure had climbed to 6.8%, a 104% increase. This trend is of particular concern because the elderly are the group at highest risk of PPI-related adverse events, including osteoporotic fractures, hypomagnesemia, drug-drug interactions, stent thrombosis, Clostridium difficile colitis, and community acquired pneumonia, Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi noted.

Roughly half of patients who got a PPI in the ED during the study years did not have a clear gastrointestinal complaint as the primary reason for their visit, suggesting that much of the ED prescribing of PPIs was not for an approved indication, she continued.

Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi observed that PPI prescribing has received special attention in the Choosing Wisely Program sponsored by the American Board of Internal Medicine, which recommends conducting a drug regimen review before prescribing a PPI in order to avoid drug-drug interactions. It’s also important to know whether a patient has osteoporosis before prescribing a PPI for longer than a few weeks. And there are additional reasons to think twice before prescribing a PPI in the ED.

"In the ED, we generally want to give our patients rapid symptom relief. PPIs have a delayed onset of action. They take 12-24 hours to take effect, so in many situations we might be better off giving an H2 blocker, which acts faster and is less costly," she said.

Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

DALLAS – The frequency at which U.S. emergency department physicians prescribed proton pump inhibitors more than doubled during 2001-2010, despite mounting safety concerns surrounding this class of medications.

"More education may be needed to ensure ED providers are familiar with the appropriate indications for PPI use. The big thing that I’m hoping will be taken away from this study is that because of the increase in prescribing PPIs [proton pump inhibitors] and the concerns about safety, that we’re going to be more vigilant in educating ourselves and each other about appropriate use of these medications," Dr. Maryann Mazer-Amirshahi said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

Overprescribing of PPIs has been well documented in primary care offices, gastroenterology clinics, and inpatient settings. Up until now, however, prescribing patterns in the ED haven’t been well documented. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s annual National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey provided an opportunity to do so via a weighted nationally representative sample of ED visits, explained Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi of Children’s National Medical Center, Washington.

She presented a retrospective analysis of survey data for the years 2001-2010, during which the annual number of adult ED visits climbed from 20.1 million to 28.3 million. Meanwhile, PPI prescribing increased from 3% of adult patients in 2001 to 7.2% in 2010.

"I think that’s pretty significant when you’re talking about more than 7% of 28 million ED visits every year," she commented.

While PPI prescribing more than doubled during the study years, the use of alternative medications declined. Histamine2 blocker use dropped from 6.8% in 2001 to 5.7% in 2010, while the use of antacids decreased from 7.2% to 5.5%.

PPI prescribing rose in EDs in hospitals of all types: nonprofit, for-profit, and government. It increased in all regions of the country and across all payer types, including self-payment. Of note, the number of ED prescriptions increased to a greater extent in teaching hospitals, with a 276% increase, as compared with a 118% increase in nonteaching hospitals. Prescribing of PPIs by attending ED physicians climbed by 122%, by 185% by emergency medicine residents, and by 345% by mid-level providers.

In 2001, 3.3% of ED patients aged 65 years or older received a PPI. By 2010, this figure had climbed to 6.8%, a 104% increase. This trend is of particular concern because the elderly are the group at highest risk of PPI-related adverse events, including osteoporotic fractures, hypomagnesemia, drug-drug interactions, stent thrombosis, Clostridium difficile colitis, and community acquired pneumonia, Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi noted.

Roughly half of patients who got a PPI in the ED during the study years did not have a clear gastrointestinal complaint as the primary reason for their visit, suggesting that much of the ED prescribing of PPIs was not for an approved indication, she continued.

Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi observed that PPI prescribing has received special attention in the Choosing Wisely Program sponsored by the American Board of Internal Medicine, which recommends conducting a drug regimen review before prescribing a PPI in order to avoid drug-drug interactions. It’s also important to know whether a patient has osteoporosis before prescribing a PPI for longer than a few weeks. And there are additional reasons to think twice before prescribing a PPI in the ED.

"In the ED, we generally want to give our patients rapid symptom relief. PPIs have a delayed onset of action. They take 12-24 hours to take effect, so in many situations we might be better off giving an H2 blocker, which acts faster and is less costly," she said.

Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

DALLAS – The frequency at which U.S. emergency department physicians prescribed proton pump inhibitors more than doubled during 2001-2010, despite mounting safety concerns surrounding this class of medications.

"More education may be needed to ensure ED providers are familiar with the appropriate indications for PPI use. The big thing that I’m hoping will be taken away from this study is that because of the increase in prescribing PPIs [proton pump inhibitors] and the concerns about safety, that we’re going to be more vigilant in educating ourselves and each other about appropriate use of these medications," Dr. Maryann Mazer-Amirshahi said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

Overprescribing of PPIs has been well documented in primary care offices, gastroenterology clinics, and inpatient settings. Up until now, however, prescribing patterns in the ED haven’t been well documented. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s annual National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey provided an opportunity to do so via a weighted nationally representative sample of ED visits, explained Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi of Children’s National Medical Center, Washington.

She presented a retrospective analysis of survey data for the years 2001-2010, during which the annual number of adult ED visits climbed from 20.1 million to 28.3 million. Meanwhile, PPI prescribing increased from 3% of adult patients in 2001 to 7.2% in 2010.

"I think that’s pretty significant when you’re talking about more than 7% of 28 million ED visits every year," she commented.

While PPI prescribing more than doubled during the study years, the use of alternative medications declined. Histamine2 blocker use dropped from 6.8% in 2001 to 5.7% in 2010, while the use of antacids decreased from 7.2% to 5.5%.

PPI prescribing rose in EDs in hospitals of all types: nonprofit, for-profit, and government. It increased in all regions of the country and across all payer types, including self-payment. Of note, the number of ED prescriptions increased to a greater extent in teaching hospitals, with a 276% increase, as compared with a 118% increase in nonteaching hospitals. Prescribing of PPIs by attending ED physicians climbed by 122%, by 185% by emergency medicine residents, and by 345% by mid-level providers.

In 2001, 3.3% of ED patients aged 65 years or older received a PPI. By 2010, this figure had climbed to 6.8%, a 104% increase. This trend is of particular concern because the elderly are the group at highest risk of PPI-related adverse events, including osteoporotic fractures, hypomagnesemia, drug-drug interactions, stent thrombosis, Clostridium difficile colitis, and community acquired pneumonia, Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi noted.

Roughly half of patients who got a PPI in the ED during the study years did not have a clear gastrointestinal complaint as the primary reason for their visit, suggesting that much of the ED prescribing of PPIs was not for an approved indication, she continued.

Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi observed that PPI prescribing has received special attention in the Choosing Wisely Program sponsored by the American Board of Internal Medicine, which recommends conducting a drug regimen review before prescribing a PPI in order to avoid drug-drug interactions. It’s also important to know whether a patient has osteoporosis before prescribing a PPI for longer than a few weeks. And there are additional reasons to think twice before prescribing a PPI in the ED.

"In the ED, we generally want to give our patients rapid symptom relief. PPIs have a delayed onset of action. They take 12-24 hours to take effect, so in many situations we might be better off giving an H2 blocker, which acts faster and is less costly," she said.

Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

AT SAEM 2014

Big gains shown in ED pediatric readiness

DALLAS – Emergency departments have substantially improved their readiness to receive pediatric patients since a 2009 multispecialty call to action was triggered by documented major deficiencies in preparedness, the results of a comprehensive new survey indicate.

"We’ve seen significant improvement in all ED patient volume classes in terms of median pediatric readiness scores. The data are pretty exciting. It says we’re moving in the right direction," Dr. Marianne Gausche-Hill said in presenting the survey findings at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The key outcome measure in the national survey was a weighted ED pediatric readiness score based upon the extent to which an ED was compliant with the major recommendations of the 2009 joint American Academy of Pediatrics/American College of Emergency Physicians/Emergency Nurses Association guidelines for the care of children in EDs (Pediatrics 2009;124:1233-44.

The guidelines lay out in concrete terms what ED pediatric readiness entails in terms of specialized equipment, medications, policies and protocols, safety issues, staff, and professional education.

Lack of recommended equipment needed to handle pediatric emergencies, such as laryngeal mask airways for children, was a major problem identified in the first survey. Indeed, at that time only 6% of EDs had all the recommended equipment and supplies. In contrast, the new survey showed that today EDs have a median of 91% of all recommended equipment; in higher-volume EDs that figure rises to virtually 100%, according to Dr. Gausche-Hill.

Overall, the median ED pediatric readiness score in the new survey was 69 on a 0-100 scale, up sharply from a median of 55 in an earlier nationwide survey, conducted in 2003 and published in 2007, for which Dr. Gausche-Hill also was the lead author (Pediatrics 2007;120:1229-37).

A test score of 55 gets a big red F in any classroom not grading on the curve. So this disappointing performance was an impetus for the 2009 joint guidelines, of which Dr. Gausche-Hill was a lead coauthor. The guidelines were endorsed by nearly two dozen organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Surgeons.

A theme emphasized in the joint guidelines is that all EDs need to be prepared to meet the unique needs of pediatric patients; 90% of all ED visits by patients under age 15 are to nonchildren’s hospitals, and roughly one-third of these visits are to EDs in rural and remote areas, which generally scored poorly in the initial national survey.

Another impetus for issuing the guidelines was recognition that pediatric ED visits are increasing even as the number of EDs nationwide is declining, worsening overcrowding, explained Dr. Gausche-Hill, professor of emergency medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of emergency medical services at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

She and her coinvestigators in the large coalition known as the National Pediatric Readiness Project sent the survey to more than 5,000 U.S. EDs. The response rate was an impressive 83%, despite the fact that the 55-question survey addressed 189 items and took a full hour to complete. Dr. Gausche-Hill attributed this remarkable response rate to on-site advocates’ passion for improved ED pediatric preparedness. Another factor: survey respondents received immediate feedback about how their hospital’s ED score compared with the average score of other hospitals with similar patient volume, as well as information about the top three things their hospital needs to do to reach a preparedness score of at least 80, which is the coalition’s short-term goal.

In analyzing the ED scores, the single most effective way most hospitals can improve their ED pediatric readiness score is for the hospital ED medical director to appoint a physician and/or a nurse pediatric emergency care coordinator. Hospitals with a coordinator scored higher, and the 42% of hospitals with both a physician and a nurse pediatric emergency care coordinator scored highest of all. Hospitals with at least one pediatric emergency care coordinator were more than fivefold more likely to have a quality improvement plan in place for ED pediatric patients, as recommended in a 2006 Institute of Medicine report that described the nation’s ED pediatric readiness as uneven.

In the new survey, 82% of EDs reported one or more barriers to compliance with the pediatric readiness guidelines. These barriers will be the focus of future quality improvement initiatives.

What’s next? Dr. Gausche-Hill said the coalition is reaching out to health care corporate groups in an effort to convince them to make changes in their hospitals.

"We’ve seen the Hospital Corporation of America make a huge initiative and change their average readiness score from 66 to 91 in the intervention hospitals. Also, Kaiser Permanente has initiated a readiness initiative," she said.

The plan is to keep the survey’s internet portal open so that hospitals can enter updated data and show continuous quality improvement. In addition, the coalition’s website – www.pediatricreadiness.org – includes tools to improve readiness.

Dr. Gausche-Hill reported having no financial conflicts regarding this project.

DALLAS – Emergency departments have substantially improved their readiness to receive pediatric patients since a 2009 multispecialty call to action was triggered by documented major deficiencies in preparedness, the results of a comprehensive new survey indicate.

"We’ve seen significant improvement in all ED patient volume classes in terms of median pediatric readiness scores. The data are pretty exciting. It says we’re moving in the right direction," Dr. Marianne Gausche-Hill said in presenting the survey findings at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The key outcome measure in the national survey was a weighted ED pediatric readiness score based upon the extent to which an ED was compliant with the major recommendations of the 2009 joint American Academy of Pediatrics/American College of Emergency Physicians/Emergency Nurses Association guidelines for the care of children in EDs (Pediatrics 2009;124:1233-44.

The guidelines lay out in concrete terms what ED pediatric readiness entails in terms of specialized equipment, medications, policies and protocols, safety issues, staff, and professional education.

Lack of recommended equipment needed to handle pediatric emergencies, such as laryngeal mask airways for children, was a major problem identified in the first survey. Indeed, at that time only 6% of EDs had all the recommended equipment and supplies. In contrast, the new survey showed that today EDs have a median of 91% of all recommended equipment; in higher-volume EDs that figure rises to virtually 100%, according to Dr. Gausche-Hill.

Overall, the median ED pediatric readiness score in the new survey was 69 on a 0-100 scale, up sharply from a median of 55 in an earlier nationwide survey, conducted in 2003 and published in 2007, for which Dr. Gausche-Hill also was the lead author (Pediatrics 2007;120:1229-37).

A test score of 55 gets a big red F in any classroom not grading on the curve. So this disappointing performance was an impetus for the 2009 joint guidelines, of which Dr. Gausche-Hill was a lead coauthor. The guidelines were endorsed by nearly two dozen organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Surgeons.

A theme emphasized in the joint guidelines is that all EDs need to be prepared to meet the unique needs of pediatric patients; 90% of all ED visits by patients under age 15 are to nonchildren’s hospitals, and roughly one-third of these visits are to EDs in rural and remote areas, which generally scored poorly in the initial national survey.

Another impetus for issuing the guidelines was recognition that pediatric ED visits are increasing even as the number of EDs nationwide is declining, worsening overcrowding, explained Dr. Gausche-Hill, professor of emergency medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of emergency medical services at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

She and her coinvestigators in the large coalition known as the National Pediatric Readiness Project sent the survey to more than 5,000 U.S. EDs. The response rate was an impressive 83%, despite the fact that the 55-question survey addressed 189 items and took a full hour to complete. Dr. Gausche-Hill attributed this remarkable response rate to on-site advocates’ passion for improved ED pediatric preparedness. Another factor: survey respondents received immediate feedback about how their hospital’s ED score compared with the average score of other hospitals with similar patient volume, as well as information about the top three things their hospital needs to do to reach a preparedness score of at least 80, which is the coalition’s short-term goal.

In analyzing the ED scores, the single most effective way most hospitals can improve their ED pediatric readiness score is for the hospital ED medical director to appoint a physician and/or a nurse pediatric emergency care coordinator. Hospitals with a coordinator scored higher, and the 42% of hospitals with both a physician and a nurse pediatric emergency care coordinator scored highest of all. Hospitals with at least one pediatric emergency care coordinator were more than fivefold more likely to have a quality improvement plan in place for ED pediatric patients, as recommended in a 2006 Institute of Medicine report that described the nation’s ED pediatric readiness as uneven.

In the new survey, 82% of EDs reported one or more barriers to compliance with the pediatric readiness guidelines. These barriers will be the focus of future quality improvement initiatives.

What’s next? Dr. Gausche-Hill said the coalition is reaching out to health care corporate groups in an effort to convince them to make changes in their hospitals.

"We’ve seen the Hospital Corporation of America make a huge initiative and change their average readiness score from 66 to 91 in the intervention hospitals. Also, Kaiser Permanente has initiated a readiness initiative," she said.

The plan is to keep the survey’s internet portal open so that hospitals can enter updated data and show continuous quality improvement. In addition, the coalition’s website – www.pediatricreadiness.org – includes tools to improve readiness.

Dr. Gausche-Hill reported having no financial conflicts regarding this project.

DALLAS – Emergency departments have substantially improved their readiness to receive pediatric patients since a 2009 multispecialty call to action was triggered by documented major deficiencies in preparedness, the results of a comprehensive new survey indicate.

"We’ve seen significant improvement in all ED patient volume classes in terms of median pediatric readiness scores. The data are pretty exciting. It says we’re moving in the right direction," Dr. Marianne Gausche-Hill said in presenting the survey findings at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The key outcome measure in the national survey was a weighted ED pediatric readiness score based upon the extent to which an ED was compliant with the major recommendations of the 2009 joint American Academy of Pediatrics/American College of Emergency Physicians/Emergency Nurses Association guidelines for the care of children in EDs (Pediatrics 2009;124:1233-44.

The guidelines lay out in concrete terms what ED pediatric readiness entails in terms of specialized equipment, medications, policies and protocols, safety issues, staff, and professional education.

Lack of recommended equipment needed to handle pediatric emergencies, such as laryngeal mask airways for children, was a major problem identified in the first survey. Indeed, at that time only 6% of EDs had all the recommended equipment and supplies. In contrast, the new survey showed that today EDs have a median of 91% of all recommended equipment; in higher-volume EDs that figure rises to virtually 100%, according to Dr. Gausche-Hill.

Overall, the median ED pediatric readiness score in the new survey was 69 on a 0-100 scale, up sharply from a median of 55 in an earlier nationwide survey, conducted in 2003 and published in 2007, for which Dr. Gausche-Hill also was the lead author (Pediatrics 2007;120:1229-37).

A test score of 55 gets a big red F in any classroom not grading on the curve. So this disappointing performance was an impetus for the 2009 joint guidelines, of which Dr. Gausche-Hill was a lead coauthor. The guidelines were endorsed by nearly two dozen organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American College of Surgeons.

A theme emphasized in the joint guidelines is that all EDs need to be prepared to meet the unique needs of pediatric patients; 90% of all ED visits by patients under age 15 are to nonchildren’s hospitals, and roughly one-third of these visits are to EDs in rural and remote areas, which generally scored poorly in the initial national survey.

Another impetus for issuing the guidelines was recognition that pediatric ED visits are increasing even as the number of EDs nationwide is declining, worsening overcrowding, explained Dr. Gausche-Hill, professor of emergency medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of emergency medical services at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

She and her coinvestigators in the large coalition known as the National Pediatric Readiness Project sent the survey to more than 5,000 U.S. EDs. The response rate was an impressive 83%, despite the fact that the 55-question survey addressed 189 items and took a full hour to complete. Dr. Gausche-Hill attributed this remarkable response rate to on-site advocates’ passion for improved ED pediatric preparedness. Another factor: survey respondents received immediate feedback about how their hospital’s ED score compared with the average score of other hospitals with similar patient volume, as well as information about the top three things their hospital needs to do to reach a preparedness score of at least 80, which is the coalition’s short-term goal.

In analyzing the ED scores, the single most effective way most hospitals can improve their ED pediatric readiness score is for the hospital ED medical director to appoint a physician and/or a nurse pediatric emergency care coordinator. Hospitals with a coordinator scored higher, and the 42% of hospitals with both a physician and a nurse pediatric emergency care coordinator scored highest of all. Hospitals with at least one pediatric emergency care coordinator were more than fivefold more likely to have a quality improvement plan in place for ED pediatric patients, as recommended in a 2006 Institute of Medicine report that described the nation’s ED pediatric readiness as uneven.

In the new survey, 82% of EDs reported one or more barriers to compliance with the pediatric readiness guidelines. These barriers will be the focus of future quality improvement initiatives.

What’s next? Dr. Gausche-Hill said the coalition is reaching out to health care corporate groups in an effort to convince them to make changes in their hospitals.

"We’ve seen the Hospital Corporation of America make a huge initiative and change their average readiness score from 66 to 91 in the intervention hospitals. Also, Kaiser Permanente has initiated a readiness initiative," she said.

The plan is to keep the survey’s internet portal open so that hospitals can enter updated data and show continuous quality improvement. In addition, the coalition’s website – www.pediatricreadiness.org – includes tools to improve readiness.

Dr. Gausche-Hill reported having no financial conflicts regarding this project.

AT SAEM 2014

Key clinical point: The nation’s hospital emergency departments are markedly better prepared to treat pediatric patients than they were 7 years ago.

Major finding: The median ED pediatric readiness score in a new national survey was 69 on a 0-100 scale, as compared to 55 in a survey published 7 years ago.

Data source: This detailed survey was sent to all of the more than 5,000 EDs in the U.S. and its territories. The response rate was 83%.

Disclosures: The National Pediatric Readiness Project is supported primarily by funding from federal agencies. The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Rhythm control protocol succeeds in recent onset atrial fibrillation

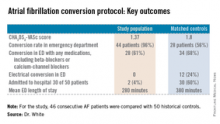

DALLAS – It’s not the rate; it’s the rhythm control that matters most for a selected subgroup of patients who present to the emergency department with recent onset atrial fibrillation.

The rhythm control approach, essentially the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol, uses intravenous procainamide as first-line therapy and, if the pharmacologic conversion is unsuccessful, subsequent electrical cardioversion by ED physicians. Patients converted to sinus rhythm are discharged home.

In a single-center prospective study, the rhythm control protocol proved safe, and 96% of recent-onset AF patients were converted in the ED. Among the historical controls, 56% were converted. Moreover, the rhythm control protocol cut ED lengths of stay, reduced hospital admissions, and proved highly popular with patients, who were returned to sinus rhythm and discharged home, noted Dr. Jennifer L. White, who presented the study results at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

"Is this study practice changing? It was for us. It’s our ED protocol now," said Dr. White, an emergency physician at Doylestown (Pa.) Hospital.

The Doylestown study included 46 consecutive patients who presented to the ED with atrial fibrillation (AF) of less than 48 hours duration. They were compared with 50 historical controls who met the same inclusion criteria and were treated before the ED rhythm protocol was implemented.

Dr. White said it took nearly 2 years to develop an ED protocol for AF conversion that was acceptable to cardiologists, nurses, and hospital administrators. The cardiologists dictated the exclusion criteria: No patients received the protocol if they had coronary artery disease, fever, concurrent ischemia, used medication that prolongs the QT interval, ejection fractions below 35%, hospital admission within the prior 3 months, and use of any antiarrhythmic agent within the past 72 hours. Patients with a history of TIA had to be on an oral anticoagulant. The baseline QTc could not exceed 460 msec.

Follow-up interviews conducted at 30 days showed no strokes or other serious adverse events, and a mean patient satisfaction score of 9.6 out of a possible 10. AF recurred in 4 of 46 patients during the 30-day period; 96% of patients were seen by a cardiologist within 14 days after ED discharge, as recommended by the ED staff.

The protocol put to the test in the ED in Doylestown entailed giving selected patients with recent-onset AF 1 g of procainamide intravenously. If patients converted to sinus rhythm, they were discharged. If not they were offered electrical cardioversion with moderate sedation using propofol, a procedure performed by two ED physicians. Patients who converted were sent home; for those who didn’t, cardiology was called in, and hospital admission usually followed.

"It took a while, honestly, to develop a protocol everyone felt comfortable with. We developed ED order sets for the nurses. There was a lot of education. But now when we say we’re going to cardiovert someone in the ED, no one seems to get uptight and upset about it," according to Dr. White.

The Ottawa Aggressive Protocol has been successfully used in Canada where "they’ve been converting patients in the ED and discharging them home with no bad outcomes. So why, then, are we in the United States admitting these patients for rate control?" Dr. White asked.

The protocol is in the process of being modified in response to the release of the 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines for the management of patients with AF (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014 [doi:10.1016/j.acc.2014.03.022]).

Those guidelines recommend that all patients with AF and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more be placed on an oral anticoagulant before or immediately following cardioversion.

Dr. White remarked that "personally, I would love to see this happen because I think our exclusion criteria are complicated and not reproducible. My thought is we should (instead) ask these three questions:

• Is the atrial fibrillation of recent onset and the primary diagnosis?

• Is the patient at CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1 without any significant valvular disease?

• Is the QTc interval less than 460 msec with no other arrhythmia?

If the answer to all three questions is ‘yes,’ then we use ED rhythm control. If not, we consult cardiology," she said.

Dr. White reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

DALLAS – It’s not the rate; it’s the rhythm control that matters most for a selected subgroup of patients who present to the emergency department with recent onset atrial fibrillation.

The rhythm control approach, essentially the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol, uses intravenous procainamide as first-line therapy and, if the pharmacologic conversion is unsuccessful, subsequent electrical cardioversion by ED physicians. Patients converted to sinus rhythm are discharged home.

In a single-center prospective study, the rhythm control protocol proved safe, and 96% of recent-onset AF patients were converted in the ED. Among the historical controls, 56% were converted. Moreover, the rhythm control protocol cut ED lengths of stay, reduced hospital admissions, and proved highly popular with patients, who were returned to sinus rhythm and discharged home, noted Dr. Jennifer L. White, who presented the study results at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

"Is this study practice changing? It was for us. It’s our ED protocol now," said Dr. White, an emergency physician at Doylestown (Pa.) Hospital.

The Doylestown study included 46 consecutive patients who presented to the ED with atrial fibrillation (AF) of less than 48 hours duration. They were compared with 50 historical controls who met the same inclusion criteria and were treated before the ED rhythm protocol was implemented.

Dr. White said it took nearly 2 years to develop an ED protocol for AF conversion that was acceptable to cardiologists, nurses, and hospital administrators. The cardiologists dictated the exclusion criteria: No patients received the protocol if they had coronary artery disease, fever, concurrent ischemia, used medication that prolongs the QT interval, ejection fractions below 35%, hospital admission within the prior 3 months, and use of any antiarrhythmic agent within the past 72 hours. Patients with a history of TIA had to be on an oral anticoagulant. The baseline QTc could not exceed 460 msec.

Follow-up interviews conducted at 30 days showed no strokes or other serious adverse events, and a mean patient satisfaction score of 9.6 out of a possible 10. AF recurred in 4 of 46 patients during the 30-day period; 96% of patients were seen by a cardiologist within 14 days after ED discharge, as recommended by the ED staff.

The protocol put to the test in the ED in Doylestown entailed giving selected patients with recent-onset AF 1 g of procainamide intravenously. If patients converted to sinus rhythm, they were discharged. If not they were offered electrical cardioversion with moderate sedation using propofol, a procedure performed by two ED physicians. Patients who converted were sent home; for those who didn’t, cardiology was called in, and hospital admission usually followed.

"It took a while, honestly, to develop a protocol everyone felt comfortable with. We developed ED order sets for the nurses. There was a lot of education. But now when we say we’re going to cardiovert someone in the ED, no one seems to get uptight and upset about it," according to Dr. White.

The Ottawa Aggressive Protocol has been successfully used in Canada where "they’ve been converting patients in the ED and discharging them home with no bad outcomes. So why, then, are we in the United States admitting these patients for rate control?" Dr. White asked.

The protocol is in the process of being modified in response to the release of the 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines for the management of patients with AF (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014 [doi:10.1016/j.acc.2014.03.022]).

Those guidelines recommend that all patients with AF and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more be placed on an oral anticoagulant before or immediately following cardioversion.

Dr. White remarked that "personally, I would love to see this happen because I think our exclusion criteria are complicated and not reproducible. My thought is we should (instead) ask these three questions:

• Is the atrial fibrillation of recent onset and the primary diagnosis?

• Is the patient at CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1 without any significant valvular disease?

• Is the QTc interval less than 460 msec with no other arrhythmia?

If the answer to all three questions is ‘yes,’ then we use ED rhythm control. If not, we consult cardiology," she said.

Dr. White reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

DALLAS – It’s not the rate; it’s the rhythm control that matters most for a selected subgroup of patients who present to the emergency department with recent onset atrial fibrillation.

The rhythm control approach, essentially the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol, uses intravenous procainamide as first-line therapy and, if the pharmacologic conversion is unsuccessful, subsequent electrical cardioversion by ED physicians. Patients converted to sinus rhythm are discharged home.

In a single-center prospective study, the rhythm control protocol proved safe, and 96% of recent-onset AF patients were converted in the ED. Among the historical controls, 56% were converted. Moreover, the rhythm control protocol cut ED lengths of stay, reduced hospital admissions, and proved highly popular with patients, who were returned to sinus rhythm and discharged home, noted Dr. Jennifer L. White, who presented the study results at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

"Is this study practice changing? It was for us. It’s our ED protocol now," said Dr. White, an emergency physician at Doylestown (Pa.) Hospital.

The Doylestown study included 46 consecutive patients who presented to the ED with atrial fibrillation (AF) of less than 48 hours duration. They were compared with 50 historical controls who met the same inclusion criteria and were treated before the ED rhythm protocol was implemented.

Dr. White said it took nearly 2 years to develop an ED protocol for AF conversion that was acceptable to cardiologists, nurses, and hospital administrators. The cardiologists dictated the exclusion criteria: No patients received the protocol if they had coronary artery disease, fever, concurrent ischemia, used medication that prolongs the QT interval, ejection fractions below 35%, hospital admission within the prior 3 months, and use of any antiarrhythmic agent within the past 72 hours. Patients with a history of TIA had to be on an oral anticoagulant. The baseline QTc could not exceed 460 msec.

Follow-up interviews conducted at 30 days showed no strokes or other serious adverse events, and a mean patient satisfaction score of 9.6 out of a possible 10. AF recurred in 4 of 46 patients during the 30-day period; 96% of patients were seen by a cardiologist within 14 days after ED discharge, as recommended by the ED staff.

The protocol put to the test in the ED in Doylestown entailed giving selected patients with recent-onset AF 1 g of procainamide intravenously. If patients converted to sinus rhythm, they were discharged. If not they were offered electrical cardioversion with moderate sedation using propofol, a procedure performed by two ED physicians. Patients who converted were sent home; for those who didn’t, cardiology was called in, and hospital admission usually followed.

"It took a while, honestly, to develop a protocol everyone felt comfortable with. We developed ED order sets for the nurses. There was a lot of education. But now when we say we’re going to cardiovert someone in the ED, no one seems to get uptight and upset about it," according to Dr. White.

The Ottawa Aggressive Protocol has been successfully used in Canada where "they’ve been converting patients in the ED and discharging them home with no bad outcomes. So why, then, are we in the United States admitting these patients for rate control?" Dr. White asked.

The protocol is in the process of being modified in response to the release of the 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines for the management of patients with AF (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014 [doi:10.1016/j.acc.2014.03.022]).

Those guidelines recommend that all patients with AF and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more be placed on an oral anticoagulant before or immediately following cardioversion.

Dr. White remarked that "personally, I would love to see this happen because I think our exclusion criteria are complicated and not reproducible. My thought is we should (instead) ask these three questions:

• Is the atrial fibrillation of recent onset and the primary diagnosis?

• Is the patient at CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1 without any significant valvular disease?

• Is the QTc interval less than 460 msec with no other arrhythmia?

If the answer to all three questions is ‘yes,’ then we use ED rhythm control. If not, we consult cardiology," she said.

Dr. White reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

AT SAEM 2014

Key clinical point: Select patients with recent-onset AF were safely and effectively converted to sinus rhythm in the ED using the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol.

Major finding: Of patients with AF of less than 48 hours duration, 4% of those managed using intravenous procainamide as first-line therapy with subsequent electrical cardioversion were admitted to the hospital. Of those managed according to the standard protocol, 60% were admitted.

Data source: The single-center, prospective study included 46 consecutive patients with recent-onset AF who presented to the ED and met study inclusion criteria and 50 matched historical controls.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted with institutional funds.

Five factors predict biphasic reactions in children with anaphylaxis

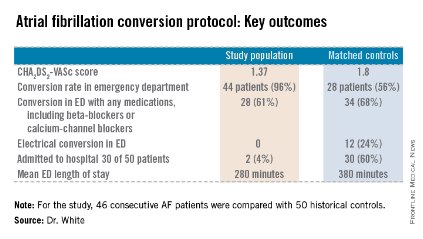

DALLAS – Five newly recognized clinical predictors are useful in identifying which children with anaphylaxis are at increased risk for a biphasic reaction.

"Children who match none of the five criteria can actually be discharged sooner from the ED [emergency department]. These predictors can potentially improve the efficiency and quality of care in the ED," Dr. Waleed Alqurashi said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The five risk factors are age of 6-9 years, a wide pulse pressure at triage, treatment of initial reaction requiring more than one dose of epinephrine, time from onset of initial anaphylactic reaction to ED presentation, and treatment with inhaled salbutamol in the ED (see graphic).

The other key – and surprising – finding was that prophylactic administration of systemic corticosteroids was ineffective in preventing biphasic reactions. The result is at odds with classic teaching regarding the benefit of prophylactic steroids in patients with anaphylaxis. "This is the largest study to date of biphasic reactions in children, and we found no association. Also, there’s no biologic plausibility for systemic steroids to prevent anaphylaxis," asserted Dr. Alqurashi of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa.

He presented a multicenter, retrospective cohort study of 484 children who presented with anaphylaxis to an ED during 2010. Biphasic reaction – the recurrence of anaphylactic symptoms at least 1 hour after initial resolution despite no additional exposure to the antigen – occurred in 71 (14.7%).

These biphasic events can be potentially fatal, he said. The 2010 guidelines on anaphylaxis from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases underscore the fact that significant knowledge gaps exist regarding the incidence, predictors, and treatment of biphasic reactions (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010;126:S1-58).

In the Canadian study, 49% of biphasic reactions were sufficiently severe as to require treatment with epinephrine. Three-quarters of these children developed their biphasic reaction prior to ED discharge, at a median of 4.7 hours following onset of the initial reaction. Onset in those whose biphasic reaction occurred after ED discharge was a median of 18.5 hours after onset of the first anaphylactic reaction.

No validated anaphylaxis severity score exists, Dr. Alqurashi remarked, so it wasn’t possible to analyze the relationship between initial reaction severity and likelihood of a subsequent biphasic event. However, several of the clinical predictors identified in this study via multivariate logistic regression analysis are clearly proxies for a more severe reaction.

"If a patient had a severe biphasic reaction, it was more likely to occur within 6 hours. So those with a mild initial anaphylactic reaction, if they don’t match any of these five criteria, can be sent home early. The majority of biphasic reactions occurring after ED discharge did not require epinephrine therapy," he observed.

Anaphylaxis is no longer a rare event, according to Dr. Alqurashi. During the last decade, rates for food-induced anaphylaxis have climbed 350% and for non–food-induced anaphylaxis 230%.

Dr. Marianne Gausche-Hill rose from the audience to comment that she gleaned a slightly different lesson.

"My take-home message from this study is if [patients] didn’t have any of the risk factors, maybe you could discharge them in 6 hours because they’re really unlikely to get into trouble. But if they have any risk factor, it’s probably best just to admit them overnight, which is our standard practice," said Dr. Gausche-Hill, professor of emergency medicine and director of the division of pediatric emergency medicine at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles.

Dr. Alqurashi reported having no financial conflicts of interest with regard to his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

DALLAS – Five newly recognized clinical predictors are useful in identifying which children with anaphylaxis are at increased risk for a biphasic reaction.

"Children who match none of the five criteria can actually be discharged sooner from the ED [emergency department]. These predictors can potentially improve the efficiency and quality of care in the ED," Dr. Waleed Alqurashi said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The five risk factors are age of 6-9 years, a wide pulse pressure at triage, treatment of initial reaction requiring more than one dose of epinephrine, time from onset of initial anaphylactic reaction to ED presentation, and treatment with inhaled salbutamol in the ED (see graphic).

The other key – and surprising – finding was that prophylactic administration of systemic corticosteroids was ineffective in preventing biphasic reactions. The result is at odds with classic teaching regarding the benefit of prophylactic steroids in patients with anaphylaxis. "This is the largest study to date of biphasic reactions in children, and we found no association. Also, there’s no biologic plausibility for systemic steroids to prevent anaphylaxis," asserted Dr. Alqurashi of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa.

He presented a multicenter, retrospective cohort study of 484 children who presented with anaphylaxis to an ED during 2010. Biphasic reaction – the recurrence of anaphylactic symptoms at least 1 hour after initial resolution despite no additional exposure to the antigen – occurred in 71 (14.7%).

These biphasic events can be potentially fatal, he said. The 2010 guidelines on anaphylaxis from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases underscore the fact that significant knowledge gaps exist regarding the incidence, predictors, and treatment of biphasic reactions (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010;126:S1-58).

In the Canadian study, 49% of biphasic reactions were sufficiently severe as to require treatment with epinephrine. Three-quarters of these children developed their biphasic reaction prior to ED discharge, at a median of 4.7 hours following onset of the initial reaction. Onset in those whose biphasic reaction occurred after ED discharge was a median of 18.5 hours after onset of the first anaphylactic reaction.

No validated anaphylaxis severity score exists, Dr. Alqurashi remarked, so it wasn’t possible to analyze the relationship between initial reaction severity and likelihood of a subsequent biphasic event. However, several of the clinical predictors identified in this study via multivariate logistic regression analysis are clearly proxies for a more severe reaction.

"If a patient had a severe biphasic reaction, it was more likely to occur within 6 hours. So those with a mild initial anaphylactic reaction, if they don’t match any of these five criteria, can be sent home early. The majority of biphasic reactions occurring after ED discharge did not require epinephrine therapy," he observed.

Anaphylaxis is no longer a rare event, according to Dr. Alqurashi. During the last decade, rates for food-induced anaphylaxis have climbed 350% and for non–food-induced anaphylaxis 230%.

Dr. Marianne Gausche-Hill rose from the audience to comment that she gleaned a slightly different lesson.

"My take-home message from this study is if [patients] didn’t have any of the risk factors, maybe you could discharge them in 6 hours because they’re really unlikely to get into trouble. But if they have any risk factor, it’s probably best just to admit them overnight, which is our standard practice," said Dr. Gausche-Hill, professor of emergency medicine and director of the division of pediatric emergency medicine at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles.

Dr. Alqurashi reported having no financial conflicts of interest with regard to his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

DALLAS – Five newly recognized clinical predictors are useful in identifying which children with anaphylaxis are at increased risk for a biphasic reaction.

"Children who match none of the five criteria can actually be discharged sooner from the ED [emergency department]. These predictors can potentially improve the efficiency and quality of care in the ED," Dr. Waleed Alqurashi said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The five risk factors are age of 6-9 years, a wide pulse pressure at triage, treatment of initial reaction requiring more than one dose of epinephrine, time from onset of initial anaphylactic reaction to ED presentation, and treatment with inhaled salbutamol in the ED (see graphic).

The other key – and surprising – finding was that prophylactic administration of systemic corticosteroids was ineffective in preventing biphasic reactions. The result is at odds with classic teaching regarding the benefit of prophylactic steroids in patients with anaphylaxis. "This is the largest study to date of biphasic reactions in children, and we found no association. Also, there’s no biologic plausibility for systemic steroids to prevent anaphylaxis," asserted Dr. Alqurashi of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa.

He presented a multicenter, retrospective cohort study of 484 children who presented with anaphylaxis to an ED during 2010. Biphasic reaction – the recurrence of anaphylactic symptoms at least 1 hour after initial resolution despite no additional exposure to the antigen – occurred in 71 (14.7%).

These biphasic events can be potentially fatal, he said. The 2010 guidelines on anaphylaxis from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases underscore the fact that significant knowledge gaps exist regarding the incidence, predictors, and treatment of biphasic reactions (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010;126:S1-58).

In the Canadian study, 49% of biphasic reactions were sufficiently severe as to require treatment with epinephrine. Three-quarters of these children developed their biphasic reaction prior to ED discharge, at a median of 4.7 hours following onset of the initial reaction. Onset in those whose biphasic reaction occurred after ED discharge was a median of 18.5 hours after onset of the first anaphylactic reaction.

No validated anaphylaxis severity score exists, Dr. Alqurashi remarked, so it wasn’t possible to analyze the relationship between initial reaction severity and likelihood of a subsequent biphasic event. However, several of the clinical predictors identified in this study via multivariate logistic regression analysis are clearly proxies for a more severe reaction.

"If a patient had a severe biphasic reaction, it was more likely to occur within 6 hours. So those with a mild initial anaphylactic reaction, if they don’t match any of these five criteria, can be sent home early. The majority of biphasic reactions occurring after ED discharge did not require epinephrine therapy," he observed.

Anaphylaxis is no longer a rare event, according to Dr. Alqurashi. During the last decade, rates for food-induced anaphylaxis have climbed 350% and for non–food-induced anaphylaxis 230%.

Dr. Marianne Gausche-Hill rose from the audience to comment that she gleaned a slightly different lesson.

"My take-home message from this study is if [patients] didn’t have any of the risk factors, maybe you could discharge them in 6 hours because they’re really unlikely to get into trouble. But if they have any risk factor, it’s probably best just to admit them overnight, which is our standard practice," said Dr. Gausche-Hill, professor of emergency medicine and director of the division of pediatric emergency medicine at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles.

Dr. Alqurashi reported having no financial conflicts of interest with regard to his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT SAEM 2014

Key clinical point: Children with anaphylaxis may reasonably be discharged from the ED at 6 hours provided they don’t have any of five newly identified clinical predictors of increased risk for a biphasic reaction.

Major finding: In children presenting to the ED with anaphylaxis, 75% of biphasic reactions occurred within 6 hours after the onset of the initial reaction. Biphasic reactions occurring after more than 6 hours were seldom severe.

Data source: This was a multicenter, retrospective cohort study of 484 children who presented to EDs with anaphylaxis during 2010.

Disclosures: Dr. Alqurashi reported having no financial conflicts of interest with regard to his study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Emergency physicians may be overprescribing PPIs

DALLAS – The frequency at which U.S. emergency department physicians prescribed proton pump inhibitors more than doubled during 2001-2010, despite mounting safety concerns surrounding this class of medications.

"More education may be needed to ensure ED providers are familiar with the appropriate indications for PPI use. The big thing that I’m hoping will be taken away from this study is that because of the increase in prescribing PPIs [proton pump inhibitors] and the concerns about safety, that we’re going to be more vigilant in educating ourselves and each other about appropriate use of these medications," Dr. Maryann Mazer-Amirshahi said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

Overprescribing of PPIs has been well documented in primary care offices, gastroenterology clinics, and inpatient settings. Up until now, however, prescribing patterns in the ED haven’t been well documented. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s annual National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey provided an opportunity to do so via a weighted nationally representative sample of ED visits, explained Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi of Children’s National Medical Center, Washington.

She presented a retrospective analysis of survey data for the years 2001-2010, during which the annual number of adult ED visits climbed from 20.1 million to 28.3 million. Meanwhile, PPI prescribing increased from 3% of adult patients in 2001 to 7.2% in 2010.

"I think that’s pretty significant when you’re talking about more than 7% of 28 million ED visits every year," she commented.

While PPI prescribing more than doubled during the study years, the use of alternative medications declined. Histamine2 blocker use dropped from 6.8% in 2001 to 5.7% in 2010, while the use of antacids decreased from 7.2% to 5.5%.

PPI prescribing rose in EDs in hospitals of all types: nonprofit, for-profit, and government. It increased in all regions of the country and across all payer types, including self-payment. Of note, the number of ED prescriptions increased to a greater extent in teaching hospitals, with a 276% increase, as compared with a 118% increase in nonteaching hospitals. Prescribing of PPIs by attending ED physicians climbed by 122%, by 185% by emergency medicine residents, and by 345% by mid-level providers.

In 2001, 3.3% of ED patients aged 65 years or older received a PPI. By 2010, this figure had climbed to 6.8%, a 104% increase. This trend is of particular concern because the elderly are the group at highest risk of PPI-related adverse events, including osteoporotic fractures, hypomagnesemia, drug-drug interactions, stent thrombosis, Clostridium difficile colitis, and community acquired pneumonia, Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi noted.

Roughly half of patients who got a PPI in the ED during the study years did not have a clear gastrointestinal complaint as the primary reason for their visit, suggesting that much of the ED prescribing of PPIs was not for an approved indication, she continued.

Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi observed that PPI prescribing has received special attention in the Choosing Wisely Program sponsored by the American Board of Internal Medicine, which recommends conducting a drug regimen review before prescribing a PPI in order to avoid drug-drug interactions. It’s also important to know whether a patient has osteoporosis before prescribing a PPI for longer than a few weeks. And there are additional reasons to think twice before prescribing a PPI in the ED.

"In the ED, we generally want to give our patients rapid symptom relief. PPIs have a delayed onset of action. They take 12-24 hours to take effect, so in many situations we might be better off giving an H2 blocker, which acts faster and is less costly," she said.

Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

DALLAS – The frequency at which U.S. emergency department physicians prescribed proton pump inhibitors more than doubled during 2001-2010, despite mounting safety concerns surrounding this class of medications.

"More education may be needed to ensure ED providers are familiar with the appropriate indications for PPI use. The big thing that I’m hoping will be taken away from this study is that because of the increase in prescribing PPIs [proton pump inhibitors] and the concerns about safety, that we’re going to be more vigilant in educating ourselves and each other about appropriate use of these medications," Dr. Maryann Mazer-Amirshahi said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

Overprescribing of PPIs has been well documented in primary care offices, gastroenterology clinics, and inpatient settings. Up until now, however, prescribing patterns in the ED haven’t been well documented. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s annual National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey provided an opportunity to do so via a weighted nationally representative sample of ED visits, explained Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi of Children’s National Medical Center, Washington.

She presented a retrospective analysis of survey data for the years 2001-2010, during which the annual number of adult ED visits climbed from 20.1 million to 28.3 million. Meanwhile, PPI prescribing increased from 3% of adult patients in 2001 to 7.2% in 2010.

"I think that’s pretty significant when you’re talking about more than 7% of 28 million ED visits every year," she commented.

While PPI prescribing more than doubled during the study years, the use of alternative medications declined. Histamine2 blocker use dropped from 6.8% in 2001 to 5.7% in 2010, while the use of antacids decreased from 7.2% to 5.5%.

PPI prescribing rose in EDs in hospitals of all types: nonprofit, for-profit, and government. It increased in all regions of the country and across all payer types, including self-payment. Of note, the number of ED prescriptions increased to a greater extent in teaching hospitals, with a 276% increase, as compared with a 118% increase in nonteaching hospitals. Prescribing of PPIs by attending ED physicians climbed by 122%, by 185% by emergency medicine residents, and by 345% by mid-level providers.

In 2001, 3.3% of ED patients aged 65 years or older received a PPI. By 2010, this figure had climbed to 6.8%, a 104% increase. This trend is of particular concern because the elderly are the group at highest risk of PPI-related adverse events, including osteoporotic fractures, hypomagnesemia, drug-drug interactions, stent thrombosis, Clostridium difficile colitis, and community acquired pneumonia, Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi noted.

Roughly half of patients who got a PPI in the ED during the study years did not have a clear gastrointestinal complaint as the primary reason for their visit, suggesting that much of the ED prescribing of PPIs was not for an approved indication, she continued.

Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi observed that PPI prescribing has received special attention in the Choosing Wisely Program sponsored by the American Board of Internal Medicine, which recommends conducting a drug regimen review before prescribing a PPI in order to avoid drug-drug interactions. It’s also important to know whether a patient has osteoporosis before prescribing a PPI for longer than a few weeks. And there are additional reasons to think twice before prescribing a PPI in the ED.

"In the ED, we generally want to give our patients rapid symptom relief. PPIs have a delayed onset of action. They take 12-24 hours to take effect, so in many situations we might be better off giving an H2 blocker, which acts faster and is less costly," she said.

Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

DALLAS – The frequency at which U.S. emergency department physicians prescribed proton pump inhibitors more than doubled during 2001-2010, despite mounting safety concerns surrounding this class of medications.

"More education may be needed to ensure ED providers are familiar with the appropriate indications for PPI use. The big thing that I’m hoping will be taken away from this study is that because of the increase in prescribing PPIs [proton pump inhibitors] and the concerns about safety, that we’re going to be more vigilant in educating ourselves and each other about appropriate use of these medications," Dr. Maryann Mazer-Amirshahi said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

Overprescribing of PPIs has been well documented in primary care offices, gastroenterology clinics, and inpatient settings. Up until now, however, prescribing patterns in the ED haven’t been well documented. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s annual National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey provided an opportunity to do so via a weighted nationally representative sample of ED visits, explained Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi of Children’s National Medical Center, Washington.

She presented a retrospective analysis of survey data for the years 2001-2010, during which the annual number of adult ED visits climbed from 20.1 million to 28.3 million. Meanwhile, PPI prescribing increased from 3% of adult patients in 2001 to 7.2% in 2010.

"I think that’s pretty significant when you’re talking about more than 7% of 28 million ED visits every year," she commented.

While PPI prescribing more than doubled during the study years, the use of alternative medications declined. Histamine2 blocker use dropped from 6.8% in 2001 to 5.7% in 2010, while the use of antacids decreased from 7.2% to 5.5%.

PPI prescribing rose in EDs in hospitals of all types: nonprofit, for-profit, and government. It increased in all regions of the country and across all payer types, including self-payment. Of note, the number of ED prescriptions increased to a greater extent in teaching hospitals, with a 276% increase, as compared with a 118% increase in nonteaching hospitals. Prescribing of PPIs by attending ED physicians climbed by 122%, by 185% by emergency medicine residents, and by 345% by mid-level providers.

In 2001, 3.3% of ED patients aged 65 years or older received a PPI. By 2010, this figure had climbed to 6.8%, a 104% increase. This trend is of particular concern because the elderly are the group at highest risk of PPI-related adverse events, including osteoporotic fractures, hypomagnesemia, drug-drug interactions, stent thrombosis, Clostridium difficile colitis, and community acquired pneumonia, Dr. Mazer-Amirshahi noted.