User login

Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM): Annual Meeting

Study: Excedrin ‘good choice’ as first-line therapy for migraine in ED

DALLAS – Acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine in combination – the tablet familiarly known as Excedrin – proved an attractive alternative to intravenous prochlorperazine as first-line therapy for uncomplicated acute migraine in the emergency department, in a randomized, prospective, double-blind clinical trial.

"Excedrin worked as well as prochlorperazine in this study and doesn’t require an IV. I think it’s a good choice for acute cephalgia without significant nausea and vomiting," Dr. Kenneth R. Deitch said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

In this 71-patient study, both therapies provided significant and comparable pain relief at 60 minutes. Restlessness and/or muscle spasms occurred within the first 120 minutes in 10 patients in the prochlorperazine group and in 3 on acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine (AAC). At follow-up 24 hours later, roughly 90% of patients in each study arm said they would use their study medication again, according to Dr. Deitch, an emergency medicine physician at Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia.

All study participants met International Headache Society criteria for migraine or probable migraine. They were randomized to receive 10 mg of prochlorperazine IV in a 2-minute push plus placebo, or two generic AAC tablets, each containing 250 mg of acetaminophen, 250 mg of aspirin, and 65 mg of caffeine, along with a placebo IV.

The primary endpoint was reduction in pain on a 0-100 visual analog scale at 60 minutes post treatment. The mean reduction was 47 points in the prochlorperazine group and 37 points with AAC; the difference was not statistically significant.

If patients reported inadequate pain relief after 60 minutes, the study code was broken and physicians prescribed a rescue medication of their choosing – most often an opiate. Ten patients in each study arm required the use of rescue medication after 60 minutes.

The study initially included an additional 10 patients – 6 in the prochlorperazine arm and 4 in the AAC arm – who demanded opiates or other drugs before the 60-minute mark. Those patients were excluded from the analysis.

Dr. Deitch noted that migraine or presumed migraine annually accounts for several million ED visits. Guidelines vary for treatment of migraine in the ED and don’t rely on a strong evidence base. Oral narcotics are the most frequently prescribed agents, but the International Headache Society does not recommend them as first-line therapy because of their major drawbacks, which include nausea, constipation, and the potential for abuse and overuse. Other guidelines advocate triptans, but they’re not popular with emergency medicine physicians because of the cardiovascular risk profile.

Prochlorperazine – the most commonly prescribed dopamine agonist for acute migraine in the ED – does not have a Food and Drug Administration indication for migraine. The drug’s off-label usage in this setting is well established, however. Randomized trials have demonstrated that prochlorperazine is as effective as are narcotics and may be more effective than sumatriptan. Akathisia and dystonia are common side effects with prochlorperazine, and those adverse effects are often sufficiently severe to require rescue diphenhydramine, which prolongs the ED stay.

AAC (Excedrin) is the only OTC medication with FDA approval for the treatment of migraine. Its side effect profile is better than that of prochlorperazine, yet AAC is rarely used as first-line therapy for acute migraine in the ED. In part, the evidence was lacking. But even with demonstrated efficacy in a randomized head-to-head comparison with prochlorperazine, "Excedrin is an oral medication. Physicians and patients have an expectation that if a headache is bad enough to bring someone into the ED, the patient expects an IV, and we expect to do that for them."

With fairly good evidence of efficacy even in patients with mild to moderate migraine with nausea, the situation may begin to change as the majority of patients who receive Excedrin have pain relief, he said.

Dr. Deitch reported having no financial conflicts of interest with regard to this study, conducted free of commercial support.

DALLAS – Acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine in combination – the tablet familiarly known as Excedrin – proved an attractive alternative to intravenous prochlorperazine as first-line therapy for uncomplicated acute migraine in the emergency department, in a randomized, prospective, double-blind clinical trial.

"Excedrin worked as well as prochlorperazine in this study and doesn’t require an IV. I think it’s a good choice for acute cephalgia without significant nausea and vomiting," Dr. Kenneth R. Deitch said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

In this 71-patient study, both therapies provided significant and comparable pain relief at 60 minutes. Restlessness and/or muscle spasms occurred within the first 120 minutes in 10 patients in the prochlorperazine group and in 3 on acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine (AAC). At follow-up 24 hours later, roughly 90% of patients in each study arm said they would use their study medication again, according to Dr. Deitch, an emergency medicine physician at Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia.

All study participants met International Headache Society criteria for migraine or probable migraine. They were randomized to receive 10 mg of prochlorperazine IV in a 2-minute push plus placebo, or two generic AAC tablets, each containing 250 mg of acetaminophen, 250 mg of aspirin, and 65 mg of caffeine, along with a placebo IV.

The primary endpoint was reduction in pain on a 0-100 visual analog scale at 60 minutes post treatment. The mean reduction was 47 points in the prochlorperazine group and 37 points with AAC; the difference was not statistically significant.

If patients reported inadequate pain relief after 60 minutes, the study code was broken and physicians prescribed a rescue medication of their choosing – most often an opiate. Ten patients in each study arm required the use of rescue medication after 60 minutes.

The study initially included an additional 10 patients – 6 in the prochlorperazine arm and 4 in the AAC arm – who demanded opiates or other drugs before the 60-minute mark. Those patients were excluded from the analysis.

Dr. Deitch noted that migraine or presumed migraine annually accounts for several million ED visits. Guidelines vary for treatment of migraine in the ED and don’t rely on a strong evidence base. Oral narcotics are the most frequently prescribed agents, but the International Headache Society does not recommend them as first-line therapy because of their major drawbacks, which include nausea, constipation, and the potential for abuse and overuse. Other guidelines advocate triptans, but they’re not popular with emergency medicine physicians because of the cardiovascular risk profile.

Prochlorperazine – the most commonly prescribed dopamine agonist for acute migraine in the ED – does not have a Food and Drug Administration indication for migraine. The drug’s off-label usage in this setting is well established, however. Randomized trials have demonstrated that prochlorperazine is as effective as are narcotics and may be more effective than sumatriptan. Akathisia and dystonia are common side effects with prochlorperazine, and those adverse effects are often sufficiently severe to require rescue diphenhydramine, which prolongs the ED stay.

AAC (Excedrin) is the only OTC medication with FDA approval for the treatment of migraine. Its side effect profile is better than that of prochlorperazine, yet AAC is rarely used as first-line therapy for acute migraine in the ED. In part, the evidence was lacking. But even with demonstrated efficacy in a randomized head-to-head comparison with prochlorperazine, "Excedrin is an oral medication. Physicians and patients have an expectation that if a headache is bad enough to bring someone into the ED, the patient expects an IV, and we expect to do that for them."

With fairly good evidence of efficacy even in patients with mild to moderate migraine with nausea, the situation may begin to change as the majority of patients who receive Excedrin have pain relief, he said.

Dr. Deitch reported having no financial conflicts of interest with regard to this study, conducted free of commercial support.

DALLAS – Acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine in combination – the tablet familiarly known as Excedrin – proved an attractive alternative to intravenous prochlorperazine as first-line therapy for uncomplicated acute migraine in the emergency department, in a randomized, prospective, double-blind clinical trial.

"Excedrin worked as well as prochlorperazine in this study and doesn’t require an IV. I think it’s a good choice for acute cephalgia without significant nausea and vomiting," Dr. Kenneth R. Deitch said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

In this 71-patient study, both therapies provided significant and comparable pain relief at 60 minutes. Restlessness and/or muscle spasms occurred within the first 120 minutes in 10 patients in the prochlorperazine group and in 3 on acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine (AAC). At follow-up 24 hours later, roughly 90% of patients in each study arm said they would use their study medication again, according to Dr. Deitch, an emergency medicine physician at Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia.

All study participants met International Headache Society criteria for migraine or probable migraine. They were randomized to receive 10 mg of prochlorperazine IV in a 2-minute push plus placebo, or two generic AAC tablets, each containing 250 mg of acetaminophen, 250 mg of aspirin, and 65 mg of caffeine, along with a placebo IV.

The primary endpoint was reduction in pain on a 0-100 visual analog scale at 60 minutes post treatment. The mean reduction was 47 points in the prochlorperazine group and 37 points with AAC; the difference was not statistically significant.

If patients reported inadequate pain relief after 60 minutes, the study code was broken and physicians prescribed a rescue medication of their choosing – most often an opiate. Ten patients in each study arm required the use of rescue medication after 60 minutes.

The study initially included an additional 10 patients – 6 in the prochlorperazine arm and 4 in the AAC arm – who demanded opiates or other drugs before the 60-minute mark. Those patients were excluded from the analysis.

Dr. Deitch noted that migraine or presumed migraine annually accounts for several million ED visits. Guidelines vary for treatment of migraine in the ED and don’t rely on a strong evidence base. Oral narcotics are the most frequently prescribed agents, but the International Headache Society does not recommend them as first-line therapy because of their major drawbacks, which include nausea, constipation, and the potential for abuse and overuse. Other guidelines advocate triptans, but they’re not popular with emergency medicine physicians because of the cardiovascular risk profile.

Prochlorperazine – the most commonly prescribed dopamine agonist for acute migraine in the ED – does not have a Food and Drug Administration indication for migraine. The drug’s off-label usage in this setting is well established, however. Randomized trials have demonstrated that prochlorperazine is as effective as are narcotics and may be more effective than sumatriptan. Akathisia and dystonia are common side effects with prochlorperazine, and those adverse effects are often sufficiently severe to require rescue diphenhydramine, which prolongs the ED stay.

AAC (Excedrin) is the only OTC medication with FDA approval for the treatment of migraine. Its side effect profile is better than that of prochlorperazine, yet AAC is rarely used as first-line therapy for acute migraine in the ED. In part, the evidence was lacking. But even with demonstrated efficacy in a randomized head-to-head comparison with prochlorperazine, "Excedrin is an oral medication. Physicians and patients have an expectation that if a headache is bad enough to bring someone into the ED, the patient expects an IV, and we expect to do that for them."

With fairly good evidence of efficacy even in patients with mild to moderate migraine with nausea, the situation may begin to change as the majority of patients who receive Excedrin have pain relief, he said.

Dr. Deitch reported having no financial conflicts of interest with regard to this study, conducted free of commercial support.

AT SAEM 2014

Major finding: Patients who present to the ED with acute migraine experience comparable pain relief at 60 minutes regardless of whether their treatment consists of Excedrin or the more cumbersome intravenous prochlorperazine.

Data source: A single-center, prospective, double-blind randomized trial of 71 ED patients with acute migraine or presumed migraine.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was free of commercial support.

Variation in Admission Rates From EDs Raising Eyebrows

DALLAS – Emergency departments across the United States vary widely in their admission rates for the 15 most common medical and surgical conditions resulting in hospitalization.

The variability is important from a cost perspective because ED admission is increasingly the dominant route by which patients enter the hospital, Dr. Keith E. Kocher observed at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. "We’re talking about potentially billions of dollars that may be in play if we narrow these differences." The 15 conditions collectively account for more than $266 billion/year in hospital charges to payers.

Dr. Kocher, an emergency medicine physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample for 2010. This database, maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, contains extensive records on the millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Their analysis adjusted for the severity of case mix by incorporating demographics, comorbid conditions, primary payer, median income, and patient zip code. The researchers then determined risk-standardized admission rates – the number of predicted admissions for each ED given the institutional case mix, divided by the number of expected admissions had those patients been treated at the average ED, multiplied by the mean admission rate for the sample.

The five disorders with the least variation in admission rates among the 15 most commonly admitted conditions were heart failure, stroke, acute renal failure, acute MI, and sepsis. All are characterized by relatively high inpatient mortality.

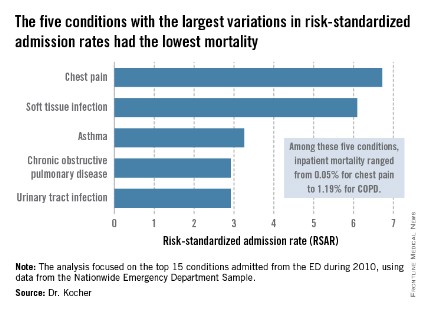

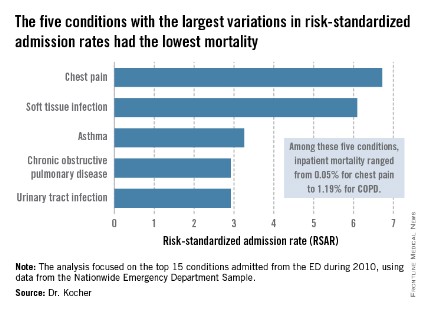

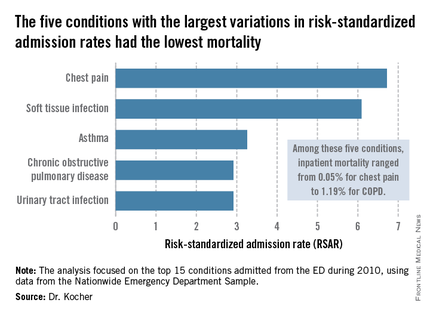

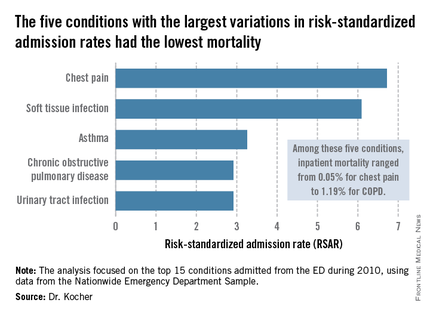

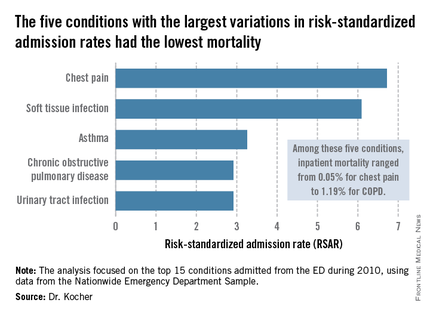

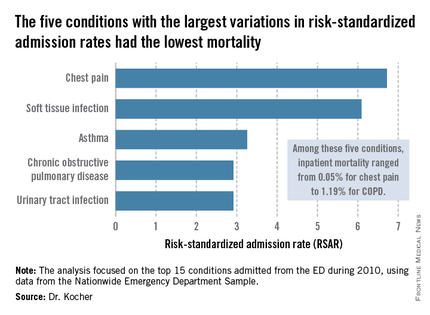

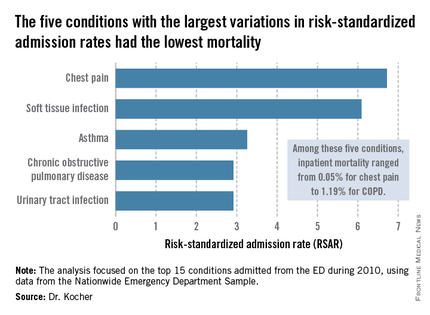

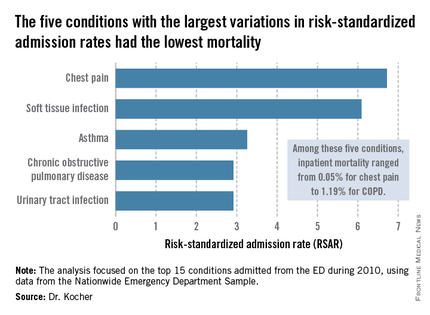

The five with the greatest variation in admission rates were chest pain, soft tissue infection, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and urinary tract infection. Importantly, these conditions were among those with the lowest inpatient mortality, ranging from 0.05% for patients admitted from the ED for chest pain to a high of 1.19% for those admitted for COPD.

"High-mortality/low-variation diagnoses like sepsis and MI provide little opportunity to realize meaningful spending reductions. Instead, the Big-5 high-variation/low-mortality conditions represent the greatest source of potential savings," Dr. Kocher said.

The ED could become "a workshop for developing innovative strategies for care coordination and alternatives to acute hospitalization, particularly around a select group of high-variation/low-mortality conditions" with the goal of reducing health costs, he said.

If EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates above the median reduced admissions for the five high-variation/low-mortality conditions to the median rate, it would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges and $5.1 billion in costs per year. Another option might be to set incentives to induce EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates in the top quartile to reduce admissions to the 75th percentile; the resulting saving would be $7 billion less in charges and $2.1 billion less in costs per year.

Incentivizing top quartile and bottom quartile EDs to meet the median rate would yield an estimated $2.8 billion reduction in charges and a $0.8 billion decrease in costs per year.

The in-hospital mortality implications of moving admission rates toward the median are not known, Dr. Kocher acknowledged. "We’re not implying that we know the optimal rate of admission. In fact, it probably varies from condition to condition."

Further, a formal economic analysis of net expenditures would need to incorporate the increased outpatient expenditures of shifting care to ambulatory settings, he said.

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Kocher reported having no financial conflicts.

DALLAS – Emergency departments across the United States vary widely in their admission rates for the 15 most common medical and surgical conditions resulting in hospitalization.

The variability is important from a cost perspective because ED admission is increasingly the dominant route by which patients enter the hospital, Dr. Keith E. Kocher observed at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. "We’re talking about potentially billions of dollars that may be in play if we narrow these differences." The 15 conditions collectively account for more than $266 billion/year in hospital charges to payers.

Dr. Kocher, an emergency medicine physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample for 2010. This database, maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, contains extensive records on the millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Their analysis adjusted for the severity of case mix by incorporating demographics, comorbid conditions, primary payer, median income, and patient zip code. The researchers then determined risk-standardized admission rates – the number of predicted admissions for each ED given the institutional case mix, divided by the number of expected admissions had those patients been treated at the average ED, multiplied by the mean admission rate for the sample.

The five disorders with the least variation in admission rates among the 15 most commonly admitted conditions were heart failure, stroke, acute renal failure, acute MI, and sepsis. All are characterized by relatively high inpatient mortality.

The five with the greatest variation in admission rates were chest pain, soft tissue infection, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and urinary tract infection. Importantly, these conditions were among those with the lowest inpatient mortality, ranging from 0.05% for patients admitted from the ED for chest pain to a high of 1.19% for those admitted for COPD.

"High-mortality/low-variation diagnoses like sepsis and MI provide little opportunity to realize meaningful spending reductions. Instead, the Big-5 high-variation/low-mortality conditions represent the greatest source of potential savings," Dr. Kocher said.

The ED could become "a workshop for developing innovative strategies for care coordination and alternatives to acute hospitalization, particularly around a select group of high-variation/low-mortality conditions" with the goal of reducing health costs, he said.

If EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates above the median reduced admissions for the five high-variation/low-mortality conditions to the median rate, it would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges and $5.1 billion in costs per year. Another option might be to set incentives to induce EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates in the top quartile to reduce admissions to the 75th percentile; the resulting saving would be $7 billion less in charges and $2.1 billion less in costs per year.

Incentivizing top quartile and bottom quartile EDs to meet the median rate would yield an estimated $2.8 billion reduction in charges and a $0.8 billion decrease in costs per year.

The in-hospital mortality implications of moving admission rates toward the median are not known, Dr. Kocher acknowledged. "We’re not implying that we know the optimal rate of admission. In fact, it probably varies from condition to condition."

Further, a formal economic analysis of net expenditures would need to incorporate the increased outpatient expenditures of shifting care to ambulatory settings, he said.

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Kocher reported having no financial conflicts.

DALLAS – Emergency departments across the United States vary widely in their admission rates for the 15 most common medical and surgical conditions resulting in hospitalization.

The variability is important from a cost perspective because ED admission is increasingly the dominant route by which patients enter the hospital, Dr. Keith E. Kocher observed at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. "We’re talking about potentially billions of dollars that may be in play if we narrow these differences." The 15 conditions collectively account for more than $266 billion/year in hospital charges to payers.

Dr. Kocher, an emergency medicine physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample for 2010. This database, maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, contains extensive records on the millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Their analysis adjusted for the severity of case mix by incorporating demographics, comorbid conditions, primary payer, median income, and patient zip code. The researchers then determined risk-standardized admission rates – the number of predicted admissions for each ED given the institutional case mix, divided by the number of expected admissions had those patients been treated at the average ED, multiplied by the mean admission rate for the sample.

The five disorders with the least variation in admission rates among the 15 most commonly admitted conditions were heart failure, stroke, acute renal failure, acute MI, and sepsis. All are characterized by relatively high inpatient mortality.

The five with the greatest variation in admission rates were chest pain, soft tissue infection, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and urinary tract infection. Importantly, these conditions were among those with the lowest inpatient mortality, ranging from 0.05% for patients admitted from the ED for chest pain to a high of 1.19% for those admitted for COPD.

"High-mortality/low-variation diagnoses like sepsis and MI provide little opportunity to realize meaningful spending reductions. Instead, the Big-5 high-variation/low-mortality conditions represent the greatest source of potential savings," Dr. Kocher said.

The ED could become "a workshop for developing innovative strategies for care coordination and alternatives to acute hospitalization, particularly around a select group of high-variation/low-mortality conditions" with the goal of reducing health costs, he said.

If EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates above the median reduced admissions for the five high-variation/low-mortality conditions to the median rate, it would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges and $5.1 billion in costs per year. Another option might be to set incentives to induce EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates in the top quartile to reduce admissions to the 75th percentile; the resulting saving would be $7 billion less in charges and $2.1 billion less in costs per year.

Incentivizing top quartile and bottom quartile EDs to meet the median rate would yield an estimated $2.8 billion reduction in charges and a $0.8 billion decrease in costs per year.

The in-hospital mortality implications of moving admission rates toward the median are not known, Dr. Kocher acknowledged. "We’re not implying that we know the optimal rate of admission. In fact, it probably varies from condition to condition."

Further, a formal economic analysis of net expenditures would need to incorporate the increased outpatient expenditures of shifting care to ambulatory settings, he said.

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Kocher reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SAEM 2014

Variation in admission rates from EDs raising eyebrows

DALLAS – Emergency departments across the United States vary widely in their admission rates for the 15 most common medical and surgical conditions resulting in hospitalization.

The variability is important from a cost perspective because ED admission is increasingly the dominant route by which patients enter the hospital, Dr. Keith E. Kocher observed at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. "We’re talking about potentially billions of dollars that may be in play if we narrow these differences." The 15 conditions collectively account for more than $266 billion/year in hospital charges to payers.

Dr. Kocher, an emergency medicine physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample for 2010. This database, maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, contains extensive records on the millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Their analysis adjusted for the severity of case mix by incorporating demographics, comorbid conditions, primary payer, median income, and patient zip code. The researchers then determined risk-standardized admission rates – the number of predicted admissions for each ED given the institutional case mix, divided by the number of expected admissions had those patients been treated at the average ED, multiplied by the mean admission rate for the sample.

The five disorders with the least variation in admission rates among the 15 most commonly admitted conditions were heart failure, stroke, acute renal failure, acute MI, and sepsis. All are characterized by relatively high inpatient mortality.

The five with the greatest variation in admission rates were chest pain, soft tissue infection, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and urinary tract infection. Importantly, these conditions were among those with the lowest inpatient mortality, ranging from 0.05% for patients admitted from the ED for chest pain to a high of 1.19% for those admitted for COPD.

"High-mortality/low-variation diagnoses like sepsis and MI provide little opportunity to realize meaningful spending reductions. Instead, the Big-5 high-variation/low-mortality conditions represent the greatest source of potential savings," Dr. Kocher said.

The ED could become "a workshop for developing innovative strategies for care coordination and alternatives to acute hospitalization, particularly around a select group of high-variation/low-mortality conditions" with the goal of reducing health costs, he said.

If EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates above the median reduced admissions for the five high-variation/low-mortality conditions to the median rate, it would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges and $5.1 billion in costs per year. Another option might be to set incentives to induce EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates in the top quartile to reduce admissions to the 75th percentile; the resulting saving would be $7 billion less in charges and $2.1 billion less in costs per year.

Incentivizing top quartile and bottom quartile EDs to meet the median rate would yield an estimated $2.8 billion reduction in charges and a $0.8 billion decrease in costs per year.

The in-hospital mortality implications of moving admission rates toward the median are not known, Dr. Kocher acknowledged. "We’re not implying that we know the optimal rate of admission. In fact, it probably varies from condition to condition."

Further, a formal economic analysis of net expenditures would need to incorporate the increased outpatient expenditures of shifting care to ambulatory settings, he said.

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Kocher reported having no financial conflicts.

DALLAS – Emergency departments across the United States vary widely in their admission rates for the 15 most common medical and surgical conditions resulting in hospitalization.

The variability is important from a cost perspective because ED admission is increasingly the dominant route by which patients enter the hospital, Dr. Keith E. Kocher observed at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. "We’re talking about potentially billions of dollars that may be in play if we narrow these differences." The 15 conditions collectively account for more than $266 billion/year in hospital charges to payers.

Dr. Kocher, an emergency medicine physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample for 2010. This database, maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, contains extensive records on the millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Their analysis adjusted for the severity of case mix by incorporating demographics, comorbid conditions, primary payer, median income, and patient zip code. The researchers then determined risk-standardized admission rates – the number of predicted admissions for each ED given the institutional case mix, divided by the number of expected admissions had those patients been treated at the average ED, multiplied by the mean admission rate for the sample.

The five disorders with the least variation in admission rates among the 15 most commonly admitted conditions were heart failure, stroke, acute renal failure, acute MI, and sepsis. All are characterized by relatively high inpatient mortality.

The five with the greatest variation in admission rates were chest pain, soft tissue infection, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and urinary tract infection. Importantly, these conditions were among those with the lowest inpatient mortality, ranging from 0.05% for patients admitted from the ED for chest pain to a high of 1.19% for those admitted for COPD.

"High-mortality/low-variation diagnoses like sepsis and MI provide little opportunity to realize meaningful spending reductions. Instead, the Big-5 high-variation/low-mortality conditions represent the greatest source of potential savings," Dr. Kocher said.

The ED could become "a workshop for developing innovative strategies for care coordination and alternatives to acute hospitalization, particularly around a select group of high-variation/low-mortality conditions" with the goal of reducing health costs, he said.

If EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates above the median reduced admissions for the five high-variation/low-mortality conditions to the median rate, it would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges and $5.1 billion in costs per year. Another option might be to set incentives to induce EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates in the top quartile to reduce admissions to the 75th percentile; the resulting saving would be $7 billion less in charges and $2.1 billion less in costs per year.

Incentivizing top quartile and bottom quartile EDs to meet the median rate would yield an estimated $2.8 billion reduction in charges and a $0.8 billion decrease in costs per year.

The in-hospital mortality implications of moving admission rates toward the median are not known, Dr. Kocher acknowledged. "We’re not implying that we know the optimal rate of admission. In fact, it probably varies from condition to condition."

Further, a formal economic analysis of net expenditures would need to incorporate the increased outpatient expenditures of shifting care to ambulatory settings, he said.

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Kocher reported having no financial conflicts.

DALLAS – Emergency departments across the United States vary widely in their admission rates for the 15 most common medical and surgical conditions resulting in hospitalization.

The variability is important from a cost perspective because ED admission is increasingly the dominant route by which patients enter the hospital, Dr. Keith E. Kocher observed at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. "We’re talking about potentially billions of dollars that may be in play if we narrow these differences." The 15 conditions collectively account for more than $266 billion/year in hospital charges to payers.

Dr. Kocher, an emergency medicine physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample for 2010. This database, maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, contains extensive records on the millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Their analysis adjusted for the severity of case mix by incorporating demographics, comorbid conditions, primary payer, median income, and patient zip code. The researchers then determined risk-standardized admission rates – the number of predicted admissions for each ED given the institutional case mix, divided by the number of expected admissions had those patients been treated at the average ED, multiplied by the mean admission rate for the sample.

The five disorders with the least variation in admission rates among the 15 most commonly admitted conditions were heart failure, stroke, acute renal failure, acute MI, and sepsis. All are characterized by relatively high inpatient mortality.

The five with the greatest variation in admission rates were chest pain, soft tissue infection, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and urinary tract infection. Importantly, these conditions were among those with the lowest inpatient mortality, ranging from 0.05% for patients admitted from the ED for chest pain to a high of 1.19% for those admitted for COPD.

"High-mortality/low-variation diagnoses like sepsis and MI provide little opportunity to realize meaningful spending reductions. Instead, the Big-5 high-variation/low-mortality conditions represent the greatest source of potential savings," Dr. Kocher said.

The ED could become "a workshop for developing innovative strategies for care coordination and alternatives to acute hospitalization, particularly around a select group of high-variation/low-mortality conditions" with the goal of reducing health costs, he said.

If EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates above the median reduced admissions for the five high-variation/low-mortality conditions to the median rate, it would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges and $5.1 billion in costs per year. Another option might be to set incentives to induce EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates in the top quartile to reduce admissions to the 75th percentile; the resulting saving would be $7 billion less in charges and $2.1 billion less in costs per year.

Incentivizing top quartile and bottom quartile EDs to meet the median rate would yield an estimated $2.8 billion reduction in charges and a $0.8 billion decrease in costs per year.

The in-hospital mortality implications of moving admission rates toward the median are not known, Dr. Kocher acknowledged. "We’re not implying that we know the optimal rate of admission. In fact, it probably varies from condition to condition."

Further, a formal economic analysis of net expenditures would need to incorporate the increased outpatient expenditures of shifting care to ambulatory settings, he said.

The study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Kocher reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SAEM 2014

Key clinical point: Reducing variation in admission rates from EDs for selected common conditions with low inpatient mortality rates could save billions of dollars in health care expenditures annually.

Major finding: If EDs with hospital admission rates above the national median for five target conditions were to reduce those rates to the median, payers would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges annually.

Data source: This was a retrospective analysis of the 2010 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, which contains detailed records on millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the AHRQ. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

ECG predictors of cardiac events mandate troponin level testing in drug overdoses

DALLAS – The initial ECG is invaluable in predicting which emergency department patients with acute drug overdose will have a major cardiovascular event during hospitalization, a prospective study indicates.

"Based on our data, ECG evidence of ischemia or infarction really mandates sending for a troponin level in ED patients with overdose," Dr. Alex F. Manini said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The findings are important as "we’re currently undergoing the worst epidemic of drug overdoses in our nation’s history," observed Dr. Manini of the department of emergency medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Poisoning is now the No. 1 cause of injury-related fatalities in the United States, and many patient series indicate 10%-15% of ED patients with an acute drug overdose experience a major cardiac event during their hospitalization.

Dr. Manini and his colleagues performed a study that validated the prognostic value of four high-risk features of the ED admission ECG in an acute drug overdose cohort: ectopy, a QTc interval of 500 msec or longer, non–sinus rhythm, and any evidence of ischemia or infarction.

Emergency physicians can readily identify those features without need for input from a cardiologist, he said.

In their study performed at two university EDs, 16% of 589 adults with acute drug overdoses experienced an acute MI, cardiogenic shock, dysrhythmia, or cardiac arrest during their hospitalization. The most common drug exposures were benzodiazepines, opioids, and acetaminophen.

Ectopy was associated with an 8.9-fold increased odds ratio for a major cardiovascular event. A QTc of 500 msec or longer was associated with an odds ratio of 11.2; a non–sinus rhythm, 8.9; and ischemia, 5.0.

The presence of one or more of these four ECG predictors was associated with 68% sensitivity and 69% specificity for a subsequent in-hospital cardiac event, with a negative predictive value of 91.9%. Dr. Manini called those sensitivity and specificity figures "modest." Thus, the ECG findings alone are not sufficient to exclude the likelihood of a cardiac event, although they certainly are useful in risk stratification. Future studies will seek to boost the predictive power by combining the ECG findings with other clinical tools, he said.

A QT dispersion of 50 msec or more also proved useful for prognosis, with an associated 2.2-fold increased risk of an in-hospital cardiac event. However, measuring QT dispersion is a fairly cumbersome process, and for this reason it needs further study before being introduced into clinical practice in busy EDs, Dr. Manini added.

In this study, any ECG evidence of ischemia or infarction – including ST depression or elevation, T wave inversion, or Q waves – had specificities of 91%-98% for an elevated troponin assay. In addition, ST depression was associated with a 6.4-fold increased odds ratio for in-hospital cardiac arrest.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Manini reported having no financial conflicts.

DALLAS – The initial ECG is invaluable in predicting which emergency department patients with acute drug overdose will have a major cardiovascular event during hospitalization, a prospective study indicates.

"Based on our data, ECG evidence of ischemia or infarction really mandates sending for a troponin level in ED patients with overdose," Dr. Alex F. Manini said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The findings are important as "we’re currently undergoing the worst epidemic of drug overdoses in our nation’s history," observed Dr. Manini of the department of emergency medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Poisoning is now the No. 1 cause of injury-related fatalities in the United States, and many patient series indicate 10%-15% of ED patients with an acute drug overdose experience a major cardiac event during their hospitalization.

Dr. Manini and his colleagues performed a study that validated the prognostic value of four high-risk features of the ED admission ECG in an acute drug overdose cohort: ectopy, a QTc interval of 500 msec or longer, non–sinus rhythm, and any evidence of ischemia or infarction.

Emergency physicians can readily identify those features without need for input from a cardiologist, he said.

In their study performed at two university EDs, 16% of 589 adults with acute drug overdoses experienced an acute MI, cardiogenic shock, dysrhythmia, or cardiac arrest during their hospitalization. The most common drug exposures were benzodiazepines, opioids, and acetaminophen.

Ectopy was associated with an 8.9-fold increased odds ratio for a major cardiovascular event. A QTc of 500 msec or longer was associated with an odds ratio of 11.2; a non–sinus rhythm, 8.9; and ischemia, 5.0.

The presence of one or more of these four ECG predictors was associated with 68% sensitivity and 69% specificity for a subsequent in-hospital cardiac event, with a negative predictive value of 91.9%. Dr. Manini called those sensitivity and specificity figures "modest." Thus, the ECG findings alone are not sufficient to exclude the likelihood of a cardiac event, although they certainly are useful in risk stratification. Future studies will seek to boost the predictive power by combining the ECG findings with other clinical tools, he said.

A QT dispersion of 50 msec or more also proved useful for prognosis, with an associated 2.2-fold increased risk of an in-hospital cardiac event. However, measuring QT dispersion is a fairly cumbersome process, and for this reason it needs further study before being introduced into clinical practice in busy EDs, Dr. Manini added.

In this study, any ECG evidence of ischemia or infarction – including ST depression or elevation, T wave inversion, or Q waves – had specificities of 91%-98% for an elevated troponin assay. In addition, ST depression was associated with a 6.4-fold increased odds ratio for in-hospital cardiac arrest.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Manini reported having no financial conflicts.

DALLAS – The initial ECG is invaluable in predicting which emergency department patients with acute drug overdose will have a major cardiovascular event during hospitalization, a prospective study indicates.

"Based on our data, ECG evidence of ischemia or infarction really mandates sending for a troponin level in ED patients with overdose," Dr. Alex F. Manini said at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

The findings are important as "we’re currently undergoing the worst epidemic of drug overdoses in our nation’s history," observed Dr. Manini of the department of emergency medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Poisoning is now the No. 1 cause of injury-related fatalities in the United States, and many patient series indicate 10%-15% of ED patients with an acute drug overdose experience a major cardiac event during their hospitalization.

Dr. Manini and his colleagues performed a study that validated the prognostic value of four high-risk features of the ED admission ECG in an acute drug overdose cohort: ectopy, a QTc interval of 500 msec or longer, non–sinus rhythm, and any evidence of ischemia or infarction.

Emergency physicians can readily identify those features without need for input from a cardiologist, he said.

In their study performed at two university EDs, 16% of 589 adults with acute drug overdoses experienced an acute MI, cardiogenic shock, dysrhythmia, or cardiac arrest during their hospitalization. The most common drug exposures were benzodiazepines, opioids, and acetaminophen.

Ectopy was associated with an 8.9-fold increased odds ratio for a major cardiovascular event. A QTc of 500 msec or longer was associated with an odds ratio of 11.2; a non–sinus rhythm, 8.9; and ischemia, 5.0.

The presence of one or more of these four ECG predictors was associated with 68% sensitivity and 69% specificity for a subsequent in-hospital cardiac event, with a negative predictive value of 91.9%. Dr. Manini called those sensitivity and specificity figures "modest." Thus, the ECG findings alone are not sufficient to exclude the likelihood of a cardiac event, although they certainly are useful in risk stratification. Future studies will seek to boost the predictive power by combining the ECG findings with other clinical tools, he said.

A QT dispersion of 50 msec or more also proved useful for prognosis, with an associated 2.2-fold increased risk of an in-hospital cardiac event. However, measuring QT dispersion is a fairly cumbersome process, and for this reason it needs further study before being introduced into clinical practice in busy EDs, Dr. Manini added.

In this study, any ECG evidence of ischemia or infarction – including ST depression or elevation, T wave inversion, or Q waves – had specificities of 91%-98% for an elevated troponin assay. In addition, ST depression was associated with a 6.4-fold increased odds ratio for in-hospital cardiac arrest.

The study was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Dr. Manini reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SAEM 2014

Key clinical point: Roughly 15% of adult ED patients with an acute drug overdose will experience a major cardiac event during their hospital stay. The ED admission ECG is helpful in risk stratification.

Major finding: Acute drug overdose patients with one or more of four key findings on their initial ECG in the ED – ectopy, a QTc interval of 500 msec or longer, non–sinus rhythm, or any evidence of ischemia or infarction – are at increased risk for a major cardiac event during their hospitalization.

Data source: This was a prospective study involving 589 adults with acute drug overdose in two university EDs.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

EHR stroke order-set in ED improves outcomes

DALLAS – The use of an electronic health record order-set with built-in clinical decision support for ischemic stroke patients in the emergency department was associated with markedly improved patient outcomes in a large observational study.

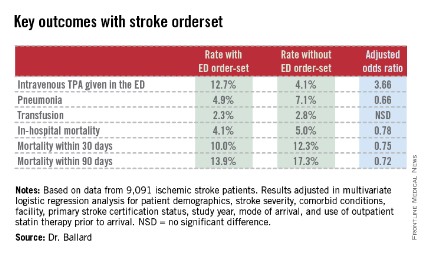

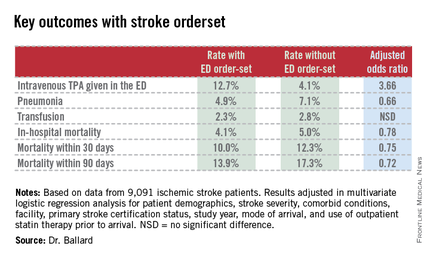

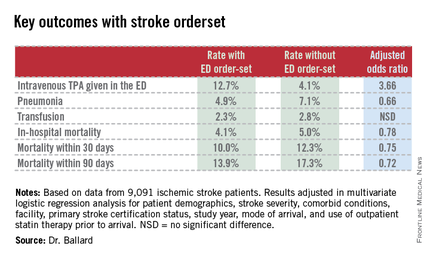

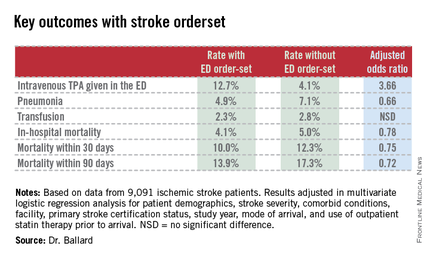

Where the order-set was used, stroke patients were significantly more likely to receive tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) therapy in the ED. They were also significantly less likely to develop pneumonia, including aspiration pneumonia. And they had significantly reduced in-hospital, 30- and 90-day mortality, compared with patients in EDs where the stroke order-set wasn’t yet available, Dr. Dustin W. Ballard reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

"The magnitude of the difference in outcomes was greater than we expected, for certain," commented Dr. Ballard, an emergency medicine physician at Kaiser Permanente San Rafael (Calif.) Medical Center.

This retrospective observational study took advantage of a natural experiment going on within the 21–medical center Kaiser Permanente of Northern California integrated health care delivery system. During 2007-2012, an electronic health record (EHR) with stroke order-set was introduced across the system in staggered fashion such that it was up and running in some of the 21 EDs, while in others, it wasn’t yet available. As a result, Dr. Ballard was able to report on 9,091 ischemic stroke patients who presented to Kaiser Permanente EDs during the study period, 53% of whom were managed with the assistance of the stroke order-set.

The order-set incorporates laboratory tests, neuroimaging orders, and other diagnostic options as well as inclusion and exclusion criteria for TPA therapy, TPA dosing recommendations, criteria for conducting a swallowing evaluation, and dysphagia orders.

"Where it was available for use, there was no mandate that ED physicians had to use it. It’s intended to be the first thing you open up when you see a patient who you think might have a stroke. I use the order-set in all patients I think might have stroke. It gives me back-up, regardless of whether I think I’m going to use TPA or not. But certainly if I were going to use TPA, I can scan through the inclusion/exclusion criteria really quickly, and the dosing recommendations are right there. There are certainly other ways to get that information, but the order-set just makes it much simpler and much easier. I think that’s the primary reason why we’re seeing much higher TPA utilization rates," Dr. Ballard explained.

Indeed, when the order-set was used, 12.7% of stroke patients received intravenous TPA in the ED. Where it wasn’t, the rate was 4.1%. And reassuringly, this nearly 3.7-fold greater use of TPA wasn’t accompanied by an increased rate of bleeding requiring transfusion (see chart).

Audience members who feel pressure to convince their hospital administrators that an ED provides good value to a medical center even if the ED isn’t a major profit center greeted the study results enthusiastically.

"This could be very exciting," one physician rose to comment. "Now we’ve not only got a checklist for stroke, but we’ve also got a mortality reduction in those patients it’s provided to."

Other audience members cautioned that confounding by indication is always a potential concern in a retrospective study such as this. That is, perhaps when ED physicians encountered a patient with a really severe stroke and low likelihood of successful recovery, they dispensed with the order-set. Dr. Ballard responded that patient stroke severity scores and overall comorbidity burden were similar in the groups with and without the order-set. And while secular trends in stroke diagnosis and treatment during 2007-2012 led to an overall reduction in stroke mortality at Kaiser Permanente during that period, "it was not anywhere near as dramatic as what we see with the order-set," he added.

Dr. Ballard noted that the Kaiser Permanente results add to a growing body of evidence that carefully designed order-sets for selected disorders leads to improved clinical outcomes. Most of those studies, however, involved paper order-sets rather than electronic aids.

The study was supported by the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research. Dr. Ballard is a Kaiser Permanente employee.

|

|

Physician apprehension of "cookbook" medicine should be relegated to a bygone era. The seamless use of standard work processes such as checklists or well constructed EMR order sets can support the delivery of consistent evidence-based care and let the clinician focus their time on communication and management decisions for the clinical outliers. The growing body of evidence supporting integration of standard work continues to expand–an ED based stroke order set in this study by Kaiser is just one more excellent example.

Dr. Robert Pendleton is codirector of University of Utah Hospitalist Program, director of University Healthcare Thrombosis Service, both in Salt Lake City, and an adviser to Hospitalist News.

|

|

Physician apprehension of "cookbook" medicine should be relegated to a bygone era. The seamless use of standard work processes such as checklists or well constructed EMR order sets can support the delivery of consistent evidence-based care and let the clinician focus their time on communication and management decisions for the clinical outliers. The growing body of evidence supporting integration of standard work continues to expand–an ED based stroke order set in this study by Kaiser is just one more excellent example.

Dr. Robert Pendleton is codirector of University of Utah Hospitalist Program, director of University Healthcare Thrombosis Service, both in Salt Lake City, and an adviser to Hospitalist News.

|

|

Physician apprehension of "cookbook" medicine should be relegated to a bygone era. The seamless use of standard work processes such as checklists or well constructed EMR order sets can support the delivery of consistent evidence-based care and let the clinician focus their time on communication and management decisions for the clinical outliers. The growing body of evidence supporting integration of standard work continues to expand–an ED based stroke order set in this study by Kaiser is just one more excellent example.

Dr. Robert Pendleton is codirector of University of Utah Hospitalist Program, director of University Healthcare Thrombosis Service, both in Salt Lake City, and an adviser to Hospitalist News.

DALLAS – The use of an electronic health record order-set with built-in clinical decision support for ischemic stroke patients in the emergency department was associated with markedly improved patient outcomes in a large observational study.

Where the order-set was used, stroke patients were significantly more likely to receive tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) therapy in the ED. They were also significantly less likely to develop pneumonia, including aspiration pneumonia. And they had significantly reduced in-hospital, 30- and 90-day mortality, compared with patients in EDs where the stroke order-set wasn’t yet available, Dr. Dustin W. Ballard reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

"The magnitude of the difference in outcomes was greater than we expected, for certain," commented Dr. Ballard, an emergency medicine physician at Kaiser Permanente San Rafael (Calif.) Medical Center.

This retrospective observational study took advantage of a natural experiment going on within the 21–medical center Kaiser Permanente of Northern California integrated health care delivery system. During 2007-2012, an electronic health record (EHR) with stroke order-set was introduced across the system in staggered fashion such that it was up and running in some of the 21 EDs, while in others, it wasn’t yet available. As a result, Dr. Ballard was able to report on 9,091 ischemic stroke patients who presented to Kaiser Permanente EDs during the study period, 53% of whom were managed with the assistance of the stroke order-set.

The order-set incorporates laboratory tests, neuroimaging orders, and other diagnostic options as well as inclusion and exclusion criteria for TPA therapy, TPA dosing recommendations, criteria for conducting a swallowing evaluation, and dysphagia orders.

"Where it was available for use, there was no mandate that ED physicians had to use it. It’s intended to be the first thing you open up when you see a patient who you think might have a stroke. I use the order-set in all patients I think might have stroke. It gives me back-up, regardless of whether I think I’m going to use TPA or not. But certainly if I were going to use TPA, I can scan through the inclusion/exclusion criteria really quickly, and the dosing recommendations are right there. There are certainly other ways to get that information, but the order-set just makes it much simpler and much easier. I think that’s the primary reason why we’re seeing much higher TPA utilization rates," Dr. Ballard explained.

Indeed, when the order-set was used, 12.7% of stroke patients received intravenous TPA in the ED. Where it wasn’t, the rate was 4.1%. And reassuringly, this nearly 3.7-fold greater use of TPA wasn’t accompanied by an increased rate of bleeding requiring transfusion (see chart).

Audience members who feel pressure to convince their hospital administrators that an ED provides good value to a medical center even if the ED isn’t a major profit center greeted the study results enthusiastically.

"This could be very exciting," one physician rose to comment. "Now we’ve not only got a checklist for stroke, but we’ve also got a mortality reduction in those patients it’s provided to."

Other audience members cautioned that confounding by indication is always a potential concern in a retrospective study such as this. That is, perhaps when ED physicians encountered a patient with a really severe stroke and low likelihood of successful recovery, they dispensed with the order-set. Dr. Ballard responded that patient stroke severity scores and overall comorbidity burden were similar in the groups with and without the order-set. And while secular trends in stroke diagnosis and treatment during 2007-2012 led to an overall reduction in stroke mortality at Kaiser Permanente during that period, "it was not anywhere near as dramatic as what we see with the order-set," he added.

Dr. Ballard noted that the Kaiser Permanente results add to a growing body of evidence that carefully designed order-sets for selected disorders leads to improved clinical outcomes. Most of those studies, however, involved paper order-sets rather than electronic aids.

The study was supported by the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research. Dr. Ballard is a Kaiser Permanente employee.

DALLAS – The use of an electronic health record order-set with built-in clinical decision support for ischemic stroke patients in the emergency department was associated with markedly improved patient outcomes in a large observational study.

Where the order-set was used, stroke patients were significantly more likely to receive tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) therapy in the ED. They were also significantly less likely to develop pneumonia, including aspiration pneumonia. And they had significantly reduced in-hospital, 30- and 90-day mortality, compared with patients in EDs where the stroke order-set wasn’t yet available, Dr. Dustin W. Ballard reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

"The magnitude of the difference in outcomes was greater than we expected, for certain," commented Dr. Ballard, an emergency medicine physician at Kaiser Permanente San Rafael (Calif.) Medical Center.

This retrospective observational study took advantage of a natural experiment going on within the 21–medical center Kaiser Permanente of Northern California integrated health care delivery system. During 2007-2012, an electronic health record (EHR) with stroke order-set was introduced across the system in staggered fashion such that it was up and running in some of the 21 EDs, while in others, it wasn’t yet available. As a result, Dr. Ballard was able to report on 9,091 ischemic stroke patients who presented to Kaiser Permanente EDs during the study period, 53% of whom were managed with the assistance of the stroke order-set.

The order-set incorporates laboratory tests, neuroimaging orders, and other diagnostic options as well as inclusion and exclusion criteria for TPA therapy, TPA dosing recommendations, criteria for conducting a swallowing evaluation, and dysphagia orders.

"Where it was available for use, there was no mandate that ED physicians had to use it. It’s intended to be the first thing you open up when you see a patient who you think might have a stroke. I use the order-set in all patients I think might have stroke. It gives me back-up, regardless of whether I think I’m going to use TPA or not. But certainly if I were going to use TPA, I can scan through the inclusion/exclusion criteria really quickly, and the dosing recommendations are right there. There are certainly other ways to get that information, but the order-set just makes it much simpler and much easier. I think that’s the primary reason why we’re seeing much higher TPA utilization rates," Dr. Ballard explained.

Indeed, when the order-set was used, 12.7% of stroke patients received intravenous TPA in the ED. Where it wasn’t, the rate was 4.1%. And reassuringly, this nearly 3.7-fold greater use of TPA wasn’t accompanied by an increased rate of bleeding requiring transfusion (see chart).

Audience members who feel pressure to convince their hospital administrators that an ED provides good value to a medical center even if the ED isn’t a major profit center greeted the study results enthusiastically.

"This could be very exciting," one physician rose to comment. "Now we’ve not only got a checklist for stroke, but we’ve also got a mortality reduction in those patients it’s provided to."

Other audience members cautioned that confounding by indication is always a potential concern in a retrospective study such as this. That is, perhaps when ED physicians encountered a patient with a really severe stroke and low likelihood of successful recovery, they dispensed with the order-set. Dr. Ballard responded that patient stroke severity scores and overall comorbidity burden were similar in the groups with and without the order-set. And while secular trends in stroke diagnosis and treatment during 2007-2012 led to an overall reduction in stroke mortality at Kaiser Permanente during that period, "it was not anywhere near as dramatic as what we see with the order-set," he added.

Dr. Ballard noted that the Kaiser Permanente results add to a growing body of evidence that carefully designed order-sets for selected disorders leads to improved clinical outcomes. Most of those studies, however, involved paper order-sets rather than electronic aids.

The study was supported by the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research. Dr. Ballard is a Kaiser Permanente employee.

AT SAEM 2014

Key clinical point: Embrace EHR stroke order-sets to improve clinical decision making.

Major finding: In-hospital mortality in patients who presented to the ED with ischemic stroke was 4.1% if ED physicians used an EHR stroke order-set and significantly worse at 5.0% if physicians didn’t yet have access to the electronic order-set.

Data source: This was a retrospective observational study of 9,091 patients who presented with ischemic stroke to 1 of 21 EDs in an integrated health system during 2007-2012. A total of 53% were managed with the assistance of an EHR stroke order-set for the ED.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Kaiser Permanente. The presenter is employed as an emergency medicine physician by the health system.

Surprise! Lorazepam, diazepam are similarly beneficial in pediatric status epilepticus

DALLAS – Contrary to expectation, lorazepam and diazepam displayed similar efficacy and safety for treatment of pediatric status epilepticus in a definitive head-to-head randomized controlled trial.

"Both medications are efficacious 70% of the time and both have rates of respiratory depression below 20%. These results contrast with retrospective studies which suggested lorazepam was more effective. The results of our trial suggest that logistic considerations such as need for refrigeration and medication availability rather than concerns about efficacy should influence the choice of benzodiazepine for pediatric status epilepticus," Dr. Jill M. Baren declared at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

Surveys show that 80% of neurologists have a preference for lorazepam over diazepam on the basis of single-center retrospective studies that reported lorazepam to be more effective in terminating convulsions, with less respiratory depression and a longer duration of action. On the downside, lorazepam, unlike diazepam, is not stable at room temperature. And it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for pediatric status epilepticus, so its use there is off label.

Because lorazepam hadn’t been well studied in children, Congress identified it as a high-priority drug in the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act. That was the impetus for Dr. Baren and her colleagues in the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network to conduct their randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial involving 273 children and adolescents who presented with convulsive status epilepticus at 14 U.S. and Canadian medical centers. They received either 0.1 mg/kg of IV lorazepam or 0.2 mg/kg of diazepam delivered over a 1-minute push. Half of the initial dose could be repeated at 5 minutes if necessary.

The primary efficacy outcome was cessation of status epilepticus by 10 minutes with no recurrence by 30 minutes. This was achieved in 72.1% of the diazepam group and 72.9% on lorazepam. The primary safety outcome – need for assisted ventilation within 4 hours of giving the study drug – occurred in 16% of the diazepam group and 17.6% of patients on lorazepam, reported Dr. Baren of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Rates of nearly all the prespecified secondary outcomes also were closely similar in the two groups. For example, 62% of patients were successfully treated with a single dose of diazepam, as were 60% on lorazepam. Generalized convulsions recurred within 60 minutes in 11% of the diazepam group and 10% on lorazepam. Response latency averaged 2.5 minutes with diazepam and 2.0 minutes with lorazepam.

Statistically significant differences were seen in only two secondary endpoints. Fifty percent of the diazepam group needed to be placed in deep sedation, compared with 67% of the lorazepam group. And sedation recovery time averaged 104 minutes in the diazepam group versus 120 minutes with lorazepam.

Dr. Baren said that the results of this study, considered together with the findings of the landmark Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior to Arrival Trial (RAMPART), which demonstrated that intramuscular midazolam was comparable in effectiveness to IV lorazepam for pediatric status epilepticus (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:591-600), provide persuasive evidence that any of the three benzodiazepines can be considered acceptable first-line therapy.

"Future research should focus on the development of agents for seizure control in patients with benzodiazepine-refractory seizures and high risk of respiratory failure," she concluded.

Roughly 10,000 children per year in the United States experience status epilepticus. Rapid control is key in order to avoid acute life-threatening complications along with permanent neuronal injury.

This randomized trial was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and carried out by the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network, which is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Baren reported having no financial conflicts.

DALLAS – Contrary to expectation, lorazepam and diazepam displayed similar efficacy and safety for treatment of pediatric status epilepticus in a definitive head-to-head randomized controlled trial.

"Both medications are efficacious 70% of the time and both have rates of respiratory depression below 20%. These results contrast with retrospective studies which suggested lorazepam was more effective. The results of our trial suggest that logistic considerations such as need for refrigeration and medication availability rather than concerns about efficacy should influence the choice of benzodiazepine for pediatric status epilepticus," Dr. Jill M. Baren declared at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

Surveys show that 80% of neurologists have a preference for lorazepam over diazepam on the basis of single-center retrospective studies that reported lorazepam to be more effective in terminating convulsions, with less respiratory depression and a longer duration of action. On the downside, lorazepam, unlike diazepam, is not stable at room temperature. And it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for pediatric status epilepticus, so its use there is off label.

Because lorazepam hadn’t been well studied in children, Congress identified it as a high-priority drug in the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act. That was the impetus for Dr. Baren and her colleagues in the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network to conduct their randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial involving 273 children and adolescents who presented with convulsive status epilepticus at 14 U.S. and Canadian medical centers. They received either 0.1 mg/kg of IV lorazepam or 0.2 mg/kg of diazepam delivered over a 1-minute push. Half of the initial dose could be repeated at 5 minutes if necessary.

The primary efficacy outcome was cessation of status epilepticus by 10 minutes with no recurrence by 30 minutes. This was achieved in 72.1% of the diazepam group and 72.9% on lorazepam. The primary safety outcome – need for assisted ventilation within 4 hours of giving the study drug – occurred in 16% of the diazepam group and 17.6% of patients on lorazepam, reported Dr. Baren of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Rates of nearly all the prespecified secondary outcomes also were closely similar in the two groups. For example, 62% of patients were successfully treated with a single dose of diazepam, as were 60% on lorazepam. Generalized convulsions recurred within 60 minutes in 11% of the diazepam group and 10% on lorazepam. Response latency averaged 2.5 minutes with diazepam and 2.0 minutes with lorazepam.

Statistically significant differences were seen in only two secondary endpoints. Fifty percent of the diazepam group needed to be placed in deep sedation, compared with 67% of the lorazepam group. And sedation recovery time averaged 104 minutes in the diazepam group versus 120 minutes with lorazepam.

Dr. Baren said that the results of this study, considered together with the findings of the landmark Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior to Arrival Trial (RAMPART), which demonstrated that intramuscular midazolam was comparable in effectiveness to IV lorazepam for pediatric status epilepticus (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:591-600), provide persuasive evidence that any of the three benzodiazepines can be considered acceptable first-line therapy.

"Future research should focus on the development of agents for seizure control in patients with benzodiazepine-refractory seizures and high risk of respiratory failure," she concluded.

Roughly 10,000 children per year in the United States experience status epilepticus. Rapid control is key in order to avoid acute life-threatening complications along with permanent neuronal injury.

This randomized trial was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and carried out by the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network, which is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Baren reported having no financial conflicts.

DALLAS – Contrary to expectation, lorazepam and diazepam displayed similar efficacy and safety for treatment of pediatric status epilepticus in a definitive head-to-head randomized controlled trial.

"Both medications are efficacious 70% of the time and both have rates of respiratory depression below 20%. These results contrast with retrospective studies which suggested lorazepam was more effective. The results of our trial suggest that logistic considerations such as need for refrigeration and medication availability rather than concerns about efficacy should influence the choice of benzodiazepine for pediatric status epilepticus," Dr. Jill M. Baren declared at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

Surveys show that 80% of neurologists have a preference for lorazepam over diazepam on the basis of single-center retrospective studies that reported lorazepam to be more effective in terminating convulsions, with less respiratory depression and a longer duration of action. On the downside, lorazepam, unlike diazepam, is not stable at room temperature. And it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for pediatric status epilepticus, so its use there is off label.

Because lorazepam hadn’t been well studied in children, Congress identified it as a high-priority drug in the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act. That was the impetus for Dr. Baren and her colleagues in the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network to conduct their randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial involving 273 children and adolescents who presented with convulsive status epilepticus at 14 U.S. and Canadian medical centers. They received either 0.1 mg/kg of IV lorazepam or 0.2 mg/kg of diazepam delivered over a 1-minute push. Half of the initial dose could be repeated at 5 minutes if necessary.

The primary efficacy outcome was cessation of status epilepticus by 10 minutes with no recurrence by 30 minutes. This was achieved in 72.1% of the diazepam group and 72.9% on lorazepam. The primary safety outcome – need for assisted ventilation within 4 hours of giving the study drug – occurred in 16% of the diazepam group and 17.6% of patients on lorazepam, reported Dr. Baren of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Rates of nearly all the prespecified secondary outcomes also were closely similar in the two groups. For example, 62% of patients were successfully treated with a single dose of diazepam, as were 60% on lorazepam. Generalized convulsions recurred within 60 minutes in 11% of the diazepam group and 10% on lorazepam. Response latency averaged 2.5 minutes with diazepam and 2.0 minutes with lorazepam.

Statistically significant differences were seen in only two secondary endpoints. Fifty percent of the diazepam group needed to be placed in deep sedation, compared with 67% of the lorazepam group. And sedation recovery time averaged 104 minutes in the diazepam group versus 120 minutes with lorazepam.

Dr. Baren said that the results of this study, considered together with the findings of the landmark Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior to Arrival Trial (RAMPART), which demonstrated that intramuscular midazolam was comparable in effectiveness to IV lorazepam for pediatric status epilepticus (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:591-600), provide persuasive evidence that any of the three benzodiazepines can be considered acceptable first-line therapy.

"Future research should focus on the development of agents for seizure control in patients with benzodiazepine-refractory seizures and high risk of respiratory failure," she concluded.

Roughly 10,000 children per year in the United States experience status epilepticus. Rapid control is key in order to avoid acute life-threatening complications along with permanent neuronal injury.

This randomized trial was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and carried out by the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network, which is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Baren reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SAEM 2014

Key clinical point: Intravenous lorazepam is not better than IV diazepam for status epilepticus in children, contrary to the conventional wisdom. The two benzodiazepines are similarly safe and effective.

Major finding: Cessation of pediatric status epilepticus within 10 minutes without recurrence by 30 minutes occurred in 72% of patients regardless of whether they received IV lorazepam or diazepam.

Data source: This was a randomized, double-blind, prospective, head-to-head comparative study conducted in 273 children and adolescents with status epilepticus at 14 U.S. and Canadian centers.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and carried out by the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Ottawa headache rule passes muster

DALLAS – The revised Ottawa Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Rule is now ready for prime-time use in EDs.

The final, tweaked version of the rule sailed through a large new prospective validation study, exhibiting 100% sensitivity and 14% specificity for the detection of this high-mortality headache, Dr. Jeffrey J. Perry reported at the annual meeting of the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine*.

"This tool provides a method to standardize who is investigated in an attempt to minimize the chances of missed diagnosis, given that we know from previous studies that 1 in 20 patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage are missed at the time of their first ED [emergency department] visit," explained Dr. Perry, an emergency physician at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute and the University of Ottawa.

"The Ottawa Rule will not result in a large reduction in investigations in Canada, but the investigations will be more standardized. I suspect perhaps in the United States, where there’s often a lower threshold to investigate, there may actually be some reduction in investigations, but that hasn’t been assessed," Dr. Perry observed.

An earlier version of the Ottawa Subarachnoid Headache Rule was previously tested in a study conducted at 10 Canadian tertiary-care EDs. In that study, published last year (JAMA 2013;310:1248-55), the rule showed 98.5% sensitivity and 27.5% specificity for subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Dr. Perry and his colleagues felt that 98.5% sensitivity just wasn’t good enough for a condition with 50% mortality and permanent neurologic deficits in 42% of survivors. So they added two additional elements to the rule: "thunderclap headache with instantly peaking pain," and "limited neck flexion on examination." But by changing the Ottawa SAH Rule, it became necessary to conduct a new prospective validation study of the revised rule in a new patient cohort. That’s the study that Dr. Perry presented at SAEM 2014.