User login

DALLAS – It’s not the rate; it’s the rhythm control that matters most for a selected subgroup of patients who present to the emergency department with recent onset atrial fibrillation.

The rhythm control approach, essentially the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol, uses intravenous procainamide as first-line therapy and, if the pharmacologic conversion is unsuccessful, subsequent electrical cardioversion by ED physicians. Patients converted to sinus rhythm are discharged home.

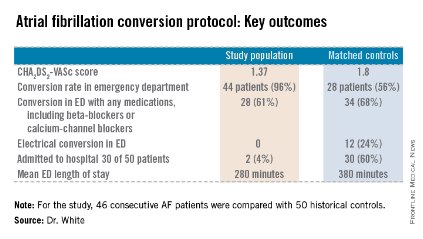

In a single-center prospective study, the rhythm control protocol proved safe, and 96% of recent-onset AF patients were converted in the ED. Among the historical controls, 56% were converted. Moreover, the rhythm control protocol cut ED lengths of stay, reduced hospital admissions, and proved highly popular with patients, who were returned to sinus rhythm and discharged home, noted Dr. Jennifer L. White, who presented the study results at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

"Is this study practice changing? It was for us. It’s our ED protocol now," said Dr. White, an emergency physician at Doylestown (Pa.) Hospital.

The Doylestown study included 46 consecutive patients who presented to the ED with atrial fibrillation (AF) of less than 48 hours duration. They were compared with 50 historical controls who met the same inclusion criteria and were treated before the ED rhythm protocol was implemented.

Dr. White said it took nearly 2 years to develop an ED protocol for AF conversion that was acceptable to cardiologists, nurses, and hospital administrators. The cardiologists dictated the exclusion criteria: No patients received the protocol if they had coronary artery disease, fever, concurrent ischemia, used medication that prolongs the QT interval, ejection fractions below 35%, hospital admission within the prior 3 months, and use of any antiarrhythmic agent within the past 72 hours. Patients with a history of TIA had to be on an oral anticoagulant. The baseline QTc could not exceed 460 msec.

Follow-up interviews conducted at 30 days showed no strokes or other serious adverse events, and a mean patient satisfaction score of 9.6 out of a possible 10. AF recurred in 4 of 46 patients during the 30-day period; 96% of patients were seen by a cardiologist within 14 days after ED discharge, as recommended by the ED staff.

The protocol put to the test in the ED in Doylestown entailed giving selected patients with recent-onset AF 1 g of procainamide intravenously. If patients converted to sinus rhythm, they were discharged. If not they were offered electrical cardioversion with moderate sedation using propofol, a procedure performed by two ED physicians. Patients who converted were sent home; for those who didn’t, cardiology was called in, and hospital admission usually followed.

"It took a while, honestly, to develop a protocol everyone felt comfortable with. We developed ED order sets for the nurses. There was a lot of education. But now when we say we’re going to cardiovert someone in the ED, no one seems to get uptight and upset about it," according to Dr. White.

The Ottawa Aggressive Protocol has been successfully used in Canada where "they’ve been converting patients in the ED and discharging them home with no bad outcomes. So why, then, are we in the United States admitting these patients for rate control?" Dr. White asked.

The protocol is in the process of being modified in response to the release of the 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines for the management of patients with AF (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014 [doi:10.1016/j.acc.2014.03.022]).

Those guidelines recommend that all patients with AF and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more be placed on an oral anticoagulant before or immediately following cardioversion.

Dr. White remarked that "personally, I would love to see this happen because I think our exclusion criteria are complicated and not reproducible. My thought is we should (instead) ask these three questions:

• Is the atrial fibrillation of recent onset and the primary diagnosis?

• Is the patient at CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1 without any significant valvular disease?

• Is the QTc interval less than 460 msec with no other arrhythmia?

If the answer to all three questions is ‘yes,’ then we use ED rhythm control. If not, we consult cardiology," she said.

Dr. White reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

DALLAS – It’s not the rate; it’s the rhythm control that matters most for a selected subgroup of patients who present to the emergency department with recent onset atrial fibrillation.

The rhythm control approach, essentially the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol, uses intravenous procainamide as first-line therapy and, if the pharmacologic conversion is unsuccessful, subsequent electrical cardioversion by ED physicians. Patients converted to sinus rhythm are discharged home.

In a single-center prospective study, the rhythm control protocol proved safe, and 96% of recent-onset AF patients were converted in the ED. Among the historical controls, 56% were converted. Moreover, the rhythm control protocol cut ED lengths of stay, reduced hospital admissions, and proved highly popular with patients, who were returned to sinus rhythm and discharged home, noted Dr. Jennifer L. White, who presented the study results at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

"Is this study practice changing? It was for us. It’s our ED protocol now," said Dr. White, an emergency physician at Doylestown (Pa.) Hospital.

The Doylestown study included 46 consecutive patients who presented to the ED with atrial fibrillation (AF) of less than 48 hours duration. They were compared with 50 historical controls who met the same inclusion criteria and were treated before the ED rhythm protocol was implemented.

Dr. White said it took nearly 2 years to develop an ED protocol for AF conversion that was acceptable to cardiologists, nurses, and hospital administrators. The cardiologists dictated the exclusion criteria: No patients received the protocol if they had coronary artery disease, fever, concurrent ischemia, used medication that prolongs the QT interval, ejection fractions below 35%, hospital admission within the prior 3 months, and use of any antiarrhythmic agent within the past 72 hours. Patients with a history of TIA had to be on an oral anticoagulant. The baseline QTc could not exceed 460 msec.

Follow-up interviews conducted at 30 days showed no strokes or other serious adverse events, and a mean patient satisfaction score of 9.6 out of a possible 10. AF recurred in 4 of 46 patients during the 30-day period; 96% of patients were seen by a cardiologist within 14 days after ED discharge, as recommended by the ED staff.

The protocol put to the test in the ED in Doylestown entailed giving selected patients with recent-onset AF 1 g of procainamide intravenously. If patients converted to sinus rhythm, they were discharged. If not they were offered electrical cardioversion with moderate sedation using propofol, a procedure performed by two ED physicians. Patients who converted were sent home; for those who didn’t, cardiology was called in, and hospital admission usually followed.

"It took a while, honestly, to develop a protocol everyone felt comfortable with. We developed ED order sets for the nurses. There was a lot of education. But now when we say we’re going to cardiovert someone in the ED, no one seems to get uptight and upset about it," according to Dr. White.

The Ottawa Aggressive Protocol has been successfully used in Canada where "they’ve been converting patients in the ED and discharging them home with no bad outcomes. So why, then, are we in the United States admitting these patients for rate control?" Dr. White asked.

The protocol is in the process of being modified in response to the release of the 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines for the management of patients with AF (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014 [doi:10.1016/j.acc.2014.03.022]).

Those guidelines recommend that all patients with AF and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more be placed on an oral anticoagulant before or immediately following cardioversion.

Dr. White remarked that "personally, I would love to see this happen because I think our exclusion criteria are complicated and not reproducible. My thought is we should (instead) ask these three questions:

• Is the atrial fibrillation of recent onset and the primary diagnosis?

• Is the patient at CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1 without any significant valvular disease?

• Is the QTc interval less than 460 msec with no other arrhythmia?

If the answer to all three questions is ‘yes,’ then we use ED rhythm control. If not, we consult cardiology," she said.

Dr. White reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

DALLAS – It’s not the rate; it’s the rhythm control that matters most for a selected subgroup of patients who present to the emergency department with recent onset atrial fibrillation.

The rhythm control approach, essentially the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol, uses intravenous procainamide as first-line therapy and, if the pharmacologic conversion is unsuccessful, subsequent electrical cardioversion by ED physicians. Patients converted to sinus rhythm are discharged home.

In a single-center prospective study, the rhythm control protocol proved safe, and 96% of recent-onset AF patients were converted in the ED. Among the historical controls, 56% were converted. Moreover, the rhythm control protocol cut ED lengths of stay, reduced hospital admissions, and proved highly popular with patients, who were returned to sinus rhythm and discharged home, noted Dr. Jennifer L. White, who presented the study results at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.

"Is this study practice changing? It was for us. It’s our ED protocol now," said Dr. White, an emergency physician at Doylestown (Pa.) Hospital.

The Doylestown study included 46 consecutive patients who presented to the ED with atrial fibrillation (AF) of less than 48 hours duration. They were compared with 50 historical controls who met the same inclusion criteria and were treated before the ED rhythm protocol was implemented.

Dr. White said it took nearly 2 years to develop an ED protocol for AF conversion that was acceptable to cardiologists, nurses, and hospital administrators. The cardiologists dictated the exclusion criteria: No patients received the protocol if they had coronary artery disease, fever, concurrent ischemia, used medication that prolongs the QT interval, ejection fractions below 35%, hospital admission within the prior 3 months, and use of any antiarrhythmic agent within the past 72 hours. Patients with a history of TIA had to be on an oral anticoagulant. The baseline QTc could not exceed 460 msec.

Follow-up interviews conducted at 30 days showed no strokes or other serious adverse events, and a mean patient satisfaction score of 9.6 out of a possible 10. AF recurred in 4 of 46 patients during the 30-day period; 96% of patients were seen by a cardiologist within 14 days after ED discharge, as recommended by the ED staff.

The protocol put to the test in the ED in Doylestown entailed giving selected patients with recent-onset AF 1 g of procainamide intravenously. If patients converted to sinus rhythm, they were discharged. If not they were offered electrical cardioversion with moderate sedation using propofol, a procedure performed by two ED physicians. Patients who converted were sent home; for those who didn’t, cardiology was called in, and hospital admission usually followed.

"It took a while, honestly, to develop a protocol everyone felt comfortable with. We developed ED order sets for the nurses. There was a lot of education. But now when we say we’re going to cardiovert someone in the ED, no one seems to get uptight and upset about it," according to Dr. White.

The Ottawa Aggressive Protocol has been successfully used in Canada where "they’ve been converting patients in the ED and discharging them home with no bad outcomes. So why, then, are we in the United States admitting these patients for rate control?" Dr. White asked.

The protocol is in the process of being modified in response to the release of the 2014 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines for the management of patients with AF (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014 [doi:10.1016/j.acc.2014.03.022]).

Those guidelines recommend that all patients with AF and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more be placed on an oral anticoagulant before or immediately following cardioversion.

Dr. White remarked that "personally, I would love to see this happen because I think our exclusion criteria are complicated and not reproducible. My thought is we should (instead) ask these three questions:

• Is the atrial fibrillation of recent onset and the primary diagnosis?

• Is the patient at CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1 without any significant valvular disease?

• Is the QTc interval less than 460 msec with no other arrhythmia?

If the answer to all three questions is ‘yes,’ then we use ED rhythm control. If not, we consult cardiology," she said.

Dr. White reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study.

AT SAEM 2014

Key clinical point: Select patients with recent-onset AF were safely and effectively converted to sinus rhythm in the ED using the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol.

Major finding: Of patients with AF of less than 48 hours duration, 4% of those managed using intravenous procainamide as first-line therapy with subsequent electrical cardioversion were admitted to the hospital. Of those managed according to the standard protocol, 60% were admitted.

Data source: The single-center, prospective study included 46 consecutive patients with recent-onset AF who presented to the ED and met study inclusion criteria and 50 matched historical controls.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted with institutional funds.