User login

DALLAS – Emergency departments across the United States vary widely in their admission rates for the 15 most common medical and surgical conditions resulting in hospitalization.

The variability is important from a cost perspective because ED admission is increasingly the dominant route by which patients enter the hospital, Dr. Keith E. Kocher observed at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. "We’re talking about potentially billions of dollars that may be in play if we narrow these differences." The 15 conditions collectively account for more than $266 billion/year in hospital charges to payers.

Dr. Kocher, an emergency medicine physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample for 2010. This database, maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), contains extensive records on the millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Their analysis adjusted for the severity of case mix by incorporating demographics, comorbid conditions, primary payer, median income, and patient zip code. The researchers then determined risk-standardized admission rates – the number of predicted admissions for each ED given the institutional case mix, divided by the number of expected admissions had those patients been treated at the average ED, multiplied by the mean admission rate for the sample.

The five disorders with the least variation in admission rates among the 15 most commonly admitted conditions were heart failure, stroke, acute renal failure, acute MI, and sepsis. All are characterized by relatively high inpatient mortality.

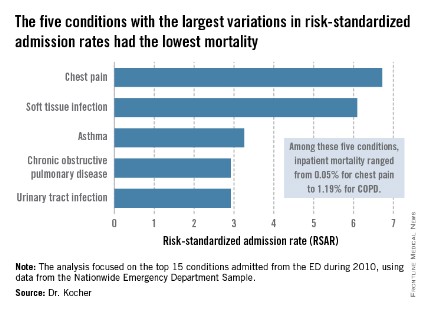

The five with the greatest variation in admission rates were chest pain, soft tissue infection, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and urinary tract infection. Importantly, these conditions were among those with the lowest inpatient mortality, ranging from 0.05% for patients admitted from the ED for chest pain to a high of 1.19% for those admitted for COPD.

"High-mortality/low-variation diagnoses like sepsis and MI provide little opportunity to realize meaningful spending reductions. Instead, the Big-5 high-variation/low-mortality conditions represent the greatest source of potential savings," Dr. Kocher said.

The ED could become "a workshop for developing innovative strategies for care coordination and alternatives to acute hospitalization, particularly around a select group of high-variation/low-mortality conditions" with the goal of reducing health costs, he said.

If EDs with high risk-standardized admission rates above the median reduced admissions for the five high-variation/low-mortality conditions to the median rate, it would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges and $5.1 billion in costs per year.Another option might be to set incentives to induce EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates in the top quartile to reduce admissions to the 75th percentile; the resulting saving would be $7 billion less in charges and $2.1 billion less in costs per year.

Incentivizing top quartile and bottom quartile EDs to meet the median rate would yield an estimated $2.8 billion reduction in charges and a $0.8 billion decrease in costs per year.

The in-hospital mortality implications of moving admission rates toward the median are not known, Dr. Kocher acknowledged. "We’re not implying that we know the optimal rate of admission. In fact, it probably varies from condition to condition."

Further, a formal economic analysis of net expenditures would need to incorporate the increased outpatient expenditures of shifting care to ambulatory settings, he said.

The study was supported by AHRQ. Dr. Kocher reported having no financial conflicts.

Dr. Daniel Ouellette, FCCP, comments: Health care professionals are beginning to appreciate the maxim that those in technology and industry sectors have known for years: Reduction in variance leads to improvement in quality. When this maxim is applied to the subject of hospital admission after an encounter in the ED, we find that a "good news/bad news" scenario exists.

A recent study examining admission rates after an ED visit for the 15 most common diagnoses finds a low variance in admission rates across the country for those diagnoses with a high mortality. On the other hand, those diagnoses with a low mortality had a high variance in admission rates. Can we improve quality and cost by reducing variance in admission rates for these disorders? The authors of this study suggest that costs will be improved substantially by reducing variance. I suspect that this will only happen (and should only happen!) if the optimal admission rates for quality care are low ones.

Dr. Daniel Ouellette, FCCP, comments: Health care professionals are beginning to appreciate the maxim that those in technology and industry sectors have known for years: Reduction in variance leads to improvement in quality. When this maxim is applied to the subject of hospital admission after an encounter in the ED, we find that a "good news/bad news" scenario exists.

A recent study examining admission rates after an ED visit for the 15 most common diagnoses finds a low variance in admission rates across the country for those diagnoses with a high mortality. On the other hand, those diagnoses with a low mortality had a high variance in admission rates. Can we improve quality and cost by reducing variance in admission rates for these disorders? The authors of this study suggest that costs will be improved substantially by reducing variance. I suspect that this will only happen (and should only happen!) if the optimal admission rates for quality care are low ones.

Dr. Daniel Ouellette, FCCP, comments: Health care professionals are beginning to appreciate the maxim that those in technology and industry sectors have known for years: Reduction in variance leads to improvement in quality. When this maxim is applied to the subject of hospital admission after an encounter in the ED, we find that a "good news/bad news" scenario exists.

A recent study examining admission rates after an ED visit for the 15 most common diagnoses finds a low variance in admission rates across the country for those diagnoses with a high mortality. On the other hand, those diagnoses with a low mortality had a high variance in admission rates. Can we improve quality and cost by reducing variance in admission rates for these disorders? The authors of this study suggest that costs will be improved substantially by reducing variance. I suspect that this will only happen (and should only happen!) if the optimal admission rates for quality care are low ones.

DALLAS – Emergency departments across the United States vary widely in their admission rates for the 15 most common medical and surgical conditions resulting in hospitalization.

The variability is important from a cost perspective because ED admission is increasingly the dominant route by which patients enter the hospital, Dr. Keith E. Kocher observed at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. "We’re talking about potentially billions of dollars that may be in play if we narrow these differences." The 15 conditions collectively account for more than $266 billion/year in hospital charges to payers.

Dr. Kocher, an emergency medicine physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample for 2010. This database, maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), contains extensive records on the millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Their analysis adjusted for the severity of case mix by incorporating demographics, comorbid conditions, primary payer, median income, and patient zip code. The researchers then determined risk-standardized admission rates – the number of predicted admissions for each ED given the institutional case mix, divided by the number of expected admissions had those patients been treated at the average ED, multiplied by the mean admission rate for the sample.

The five disorders with the least variation in admission rates among the 15 most commonly admitted conditions were heart failure, stroke, acute renal failure, acute MI, and sepsis. All are characterized by relatively high inpatient mortality.

The five with the greatest variation in admission rates were chest pain, soft tissue infection, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and urinary tract infection. Importantly, these conditions were among those with the lowest inpatient mortality, ranging from 0.05% for patients admitted from the ED for chest pain to a high of 1.19% for those admitted for COPD.

"High-mortality/low-variation diagnoses like sepsis and MI provide little opportunity to realize meaningful spending reductions. Instead, the Big-5 high-variation/low-mortality conditions represent the greatest source of potential savings," Dr. Kocher said.

The ED could become "a workshop for developing innovative strategies for care coordination and alternatives to acute hospitalization, particularly around a select group of high-variation/low-mortality conditions" with the goal of reducing health costs, he said.

If EDs with high risk-standardized admission rates above the median reduced admissions for the five high-variation/low-mortality conditions to the median rate, it would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges and $5.1 billion in costs per year.Another option might be to set incentives to induce EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates in the top quartile to reduce admissions to the 75th percentile; the resulting saving would be $7 billion less in charges and $2.1 billion less in costs per year.

Incentivizing top quartile and bottom quartile EDs to meet the median rate would yield an estimated $2.8 billion reduction in charges and a $0.8 billion decrease in costs per year.

The in-hospital mortality implications of moving admission rates toward the median are not known, Dr. Kocher acknowledged. "We’re not implying that we know the optimal rate of admission. In fact, it probably varies from condition to condition."

Further, a formal economic analysis of net expenditures would need to incorporate the increased outpatient expenditures of shifting care to ambulatory settings, he said.

The study was supported by AHRQ. Dr. Kocher reported having no financial conflicts.

DALLAS – Emergency departments across the United States vary widely in their admission rates for the 15 most common medical and surgical conditions resulting in hospitalization.

The variability is important from a cost perspective because ED admission is increasingly the dominant route by which patients enter the hospital, Dr. Keith E. Kocher observed at the annual meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. "We’re talking about potentially billions of dollars that may be in play if we narrow these differences." The 15 conditions collectively account for more than $266 billion/year in hospital charges to payers.

Dr. Kocher, an emergency medicine physician at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective analysis of the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample for 2010. This database, maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), contains extensive records on the millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Their analysis adjusted for the severity of case mix by incorporating demographics, comorbid conditions, primary payer, median income, and patient zip code. The researchers then determined risk-standardized admission rates – the number of predicted admissions for each ED given the institutional case mix, divided by the number of expected admissions had those patients been treated at the average ED, multiplied by the mean admission rate for the sample.

The five disorders with the least variation in admission rates among the 15 most commonly admitted conditions were heart failure, stroke, acute renal failure, acute MI, and sepsis. All are characterized by relatively high inpatient mortality.

The five with the greatest variation in admission rates were chest pain, soft tissue infection, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and urinary tract infection. Importantly, these conditions were among those with the lowest inpatient mortality, ranging from 0.05% for patients admitted from the ED for chest pain to a high of 1.19% for those admitted for COPD.

"High-mortality/low-variation diagnoses like sepsis and MI provide little opportunity to realize meaningful spending reductions. Instead, the Big-5 high-variation/low-mortality conditions represent the greatest source of potential savings," Dr. Kocher said.

The ED could become "a workshop for developing innovative strategies for care coordination and alternatives to acute hospitalization, particularly around a select group of high-variation/low-mortality conditions" with the goal of reducing health costs, he said.

If EDs with high risk-standardized admission rates above the median reduced admissions for the five high-variation/low-mortality conditions to the median rate, it would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges and $5.1 billion in costs per year.Another option might be to set incentives to induce EDs with high-risk–standardized admission rates in the top quartile to reduce admissions to the 75th percentile; the resulting saving would be $7 billion less in charges and $2.1 billion less in costs per year.

Incentivizing top quartile and bottom quartile EDs to meet the median rate would yield an estimated $2.8 billion reduction in charges and a $0.8 billion decrease in costs per year.

The in-hospital mortality implications of moving admission rates toward the median are not known, Dr. Kocher acknowledged. "We’re not implying that we know the optimal rate of admission. In fact, it probably varies from condition to condition."

Further, a formal economic analysis of net expenditures would need to incorporate the increased outpatient expenditures of shifting care to ambulatory settings, he said.

The study was supported by AHRQ. Dr. Kocher reported having no financial conflicts.

Key clinical point: Reducing variation in admission rates from EDs for selected common conditions with low inpatient mortality rates could save billions of dollars in health care expenditures annually.

Major finding: If EDs with hospital admission rates above the national median for five target conditions were to reduce those rates to the median, payers would save an estimated $16.9 billion in charges annually.

Data source: This was a retrospective analysis of the 2010 Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, which contains detailed records on millions of ED visits at nearly 1,000 hospitals in 28 states.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the AHRQ. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.