User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

The evidence is not clear: Rheumatic diseases, drugs, and COVID-19

“We are faced by the worldwide spread of a disease that was nonexistent less than a year ago,” Féline P.B. Kroon, MD, and associates said in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. “To date, no robust evidence is available to allow strong conclusions on the effects of COVID-19 in patients with RMDs or whether RMDs or [their] treatment impact incidence of infection or outcomes.”

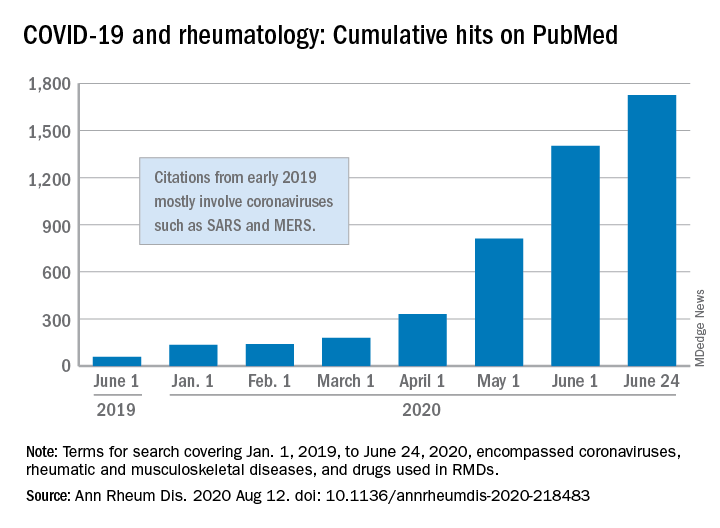

When it comes to quantity of evidence, “the exponential increase in publications over time is evident,” they said. From Jan. 1, 2019 to June 24, 2020, there were 1,725 hits on PubMed for published reports combining COVID-19 with RMDs and drugs used in RMDs. At the beginning of the year, there were only 135 such publications.

The early start of the search, well before identification of the novel coronavirus in China, was meant to ensure that nothing was missed, so “citations that came up in the first months of 2019 mostly encompass papers about other coronaviruses, such as SARS and MERS,” said Dr. Kroon of Zuyderland Medical Center, Heerlen, the Netherlands, when asked for clarification.

The quality of that evidence, however, is another matter. A majority of publications (60%) are “viewpoints or (narrative) literature reviews, and only a small proportion actually presents original data in the form of case reports or case series (15%), observational cohort studies (10%), or clinical trials (<1%),” the investigators explained.

Very few of the published studies, about 10%, specifically involve COVID-19 and RMDs. Even well-regarded sources such as systematic literature reviews or meta-analyses, “which will undoubtedly appear more frequently in the next few months in response to requests by users who feel overwhelmed by a multitude of data, will not eliminate the internal bias present in individual studies,” Dr. Kroon and associates wrote.

The lack of evidence also brings into question one particular form of guidance: recommendations “issued by groups of the so-called experts and (inter)national societies, such as, among others, American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism,” the investigators said.

“The rapid increase in research on COVID-19 is encouraging,” but at the same time it “also poses risks of ‘information overload’ or ‘fake news,’ ” they said. “As researchers and clinicians, it is our responsibility to carefully interpret study results that emerge, even more so in this ‘digital era,’ in which published data can quickly have a large societal impact.”

SOURCE: Kroon FPB et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Aug 12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218483.

“We are faced by the worldwide spread of a disease that was nonexistent less than a year ago,” Féline P.B. Kroon, MD, and associates said in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. “To date, no robust evidence is available to allow strong conclusions on the effects of COVID-19 in patients with RMDs or whether RMDs or [their] treatment impact incidence of infection or outcomes.”

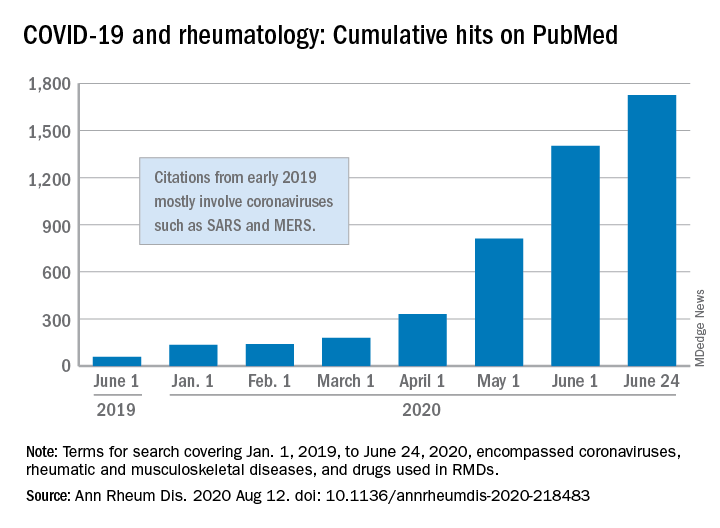

When it comes to quantity of evidence, “the exponential increase in publications over time is evident,” they said. From Jan. 1, 2019 to June 24, 2020, there were 1,725 hits on PubMed for published reports combining COVID-19 with RMDs and drugs used in RMDs. At the beginning of the year, there were only 135 such publications.

The early start of the search, well before identification of the novel coronavirus in China, was meant to ensure that nothing was missed, so “citations that came up in the first months of 2019 mostly encompass papers about other coronaviruses, such as SARS and MERS,” said Dr. Kroon of Zuyderland Medical Center, Heerlen, the Netherlands, when asked for clarification.

The quality of that evidence, however, is another matter. A majority of publications (60%) are “viewpoints or (narrative) literature reviews, and only a small proportion actually presents original data in the form of case reports or case series (15%), observational cohort studies (10%), or clinical trials (<1%),” the investigators explained.

Very few of the published studies, about 10%, specifically involve COVID-19 and RMDs. Even well-regarded sources such as systematic literature reviews or meta-analyses, “which will undoubtedly appear more frequently in the next few months in response to requests by users who feel overwhelmed by a multitude of data, will not eliminate the internal bias present in individual studies,” Dr. Kroon and associates wrote.

The lack of evidence also brings into question one particular form of guidance: recommendations “issued by groups of the so-called experts and (inter)national societies, such as, among others, American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism,” the investigators said.

“The rapid increase in research on COVID-19 is encouraging,” but at the same time it “also poses risks of ‘information overload’ or ‘fake news,’ ” they said. “As researchers and clinicians, it is our responsibility to carefully interpret study results that emerge, even more so in this ‘digital era,’ in which published data can quickly have a large societal impact.”

SOURCE: Kroon FPB et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Aug 12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218483.

“We are faced by the worldwide spread of a disease that was nonexistent less than a year ago,” Féline P.B. Kroon, MD, and associates said in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. “To date, no robust evidence is available to allow strong conclusions on the effects of COVID-19 in patients with RMDs or whether RMDs or [their] treatment impact incidence of infection or outcomes.”

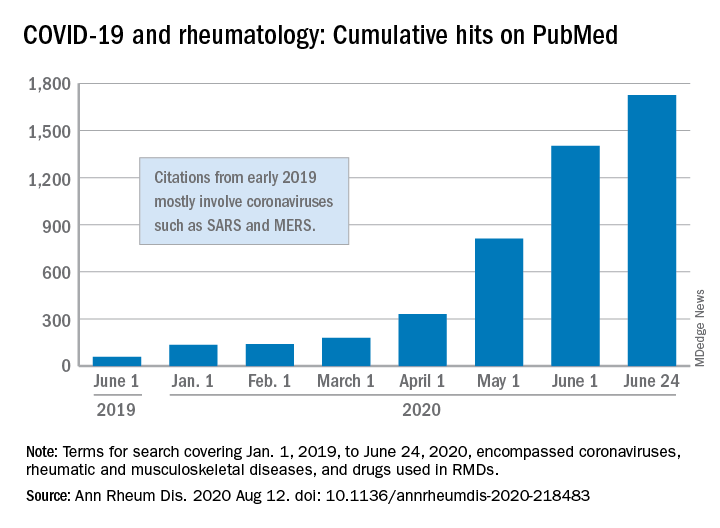

When it comes to quantity of evidence, “the exponential increase in publications over time is evident,” they said. From Jan. 1, 2019 to June 24, 2020, there were 1,725 hits on PubMed for published reports combining COVID-19 with RMDs and drugs used in RMDs. At the beginning of the year, there were only 135 such publications.

The early start of the search, well before identification of the novel coronavirus in China, was meant to ensure that nothing was missed, so “citations that came up in the first months of 2019 mostly encompass papers about other coronaviruses, such as SARS and MERS,” said Dr. Kroon of Zuyderland Medical Center, Heerlen, the Netherlands, when asked for clarification.

The quality of that evidence, however, is another matter. A majority of publications (60%) are “viewpoints or (narrative) literature reviews, and only a small proportion actually presents original data in the form of case reports or case series (15%), observational cohort studies (10%), or clinical trials (<1%),” the investigators explained.

Very few of the published studies, about 10%, specifically involve COVID-19 and RMDs. Even well-regarded sources such as systematic literature reviews or meta-analyses, “which will undoubtedly appear more frequently in the next few months in response to requests by users who feel overwhelmed by a multitude of data, will not eliminate the internal bias present in individual studies,” Dr. Kroon and associates wrote.

The lack of evidence also brings into question one particular form of guidance: recommendations “issued by groups of the so-called experts and (inter)national societies, such as, among others, American College of Rheumatology and European League Against Rheumatism,” the investigators said.

“The rapid increase in research on COVID-19 is encouraging,” but at the same time it “also poses risks of ‘information overload’ or ‘fake news,’ ” they said. “As researchers and clinicians, it is our responsibility to carefully interpret study results that emerge, even more so in this ‘digital era,’ in which published data can quickly have a large societal impact.”

SOURCE: Kroon FPB et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Aug 12. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218483.

FROM ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Pooled COVID-19 testing feasible, greatly reduces supply use

‘Straightforward, cost effective, and efficient’

Combining specimens from several low-risk inpatients in a single test for SARS-CoV-2 infection allowed hospital staff to stretch testing supplies and provide test results quickly for many more patients than they might have otherwise, researchers found.

“We believe this strategy conserved [personal protective equipment (PPE)], led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care,” wrote David Mastrianni, MD, and colleagues from Saratoga Hospital in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. “Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community.”

The researchers published their findings July 20 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“What was really important about this study was they were actually able to implement pooled testing after communication with the [Food and Drug Administration],” Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, SFHM, the journal’s editor-in-chief, said in an interview.

“Pooled testing combines samples from multiple people within a single test. The benefit is, if the test is negative [you know that] everyone whose sample was combined … is negative. So you’ve effectively tested anywhere from three to five people with the resources required for only one test,” Dr. Shah continued.

The challenge is that, if the test is positive, everyone in that testing group must be retested individually because one or more of them has the infection, said Dr. Shah, director of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Mastrianni said early in the pandemic they started getting the “New York surge” at their hospital, located approximately 3 hours from New York City. They wanted to test all of the inpatients at their hospital for COVID-19 and they had a rapid in-house test that worked well, “but we just didn’t have enough cartridges, and we couldn’t get deliveries, and we started pooling.” In fact, they ran out of testing supplies at one point during the study but were able to replenish their supply in about a day, he noted.

For the current study, all patients admitted to the hospital, including those admitted for observation, underwent testing for SARS-CoV-2. Staff in the emergency department designated patients as low risk if they had no symptoms or other clinical evidence of COVID-19; those patients underwent pooled testing.

Patients with clinical evidence of COVID-19, such as respiratory symptoms or laboratory or radiographic findings consistent with infection, were considered high risk and were tested on an individual basis and thus excluded from the current analysis.

The pooled testing strategy required some patients to be held in the emergency department until there were three available for pooled testing. On several occasions when this was not practical, specimens from two patients were pooled.

Between April 17 and May 11, clinicians tested 530 patients via pooled testing using 179 cartridges (172 with swabs from three patients and 7 with swabs from two patients). There were four positive pooled tests, which necessitated the use of an additional 11 cartridges. Overall, the testing used 190 cartridges, which is 340 fewer than would have been used if all patients had been tested individually.

Among the low-risk patients, the positive rate was 0.8% (4/530). No patients from pools that were negative tested positive later during their hospitalization or developed evidence of the infection.

Team effort, flexibility needed

Dr. Mastrianni said he expected their study to find that pooled testing saved testing resources, but he “was surprised by the complexity of the logistics in the hospital, and how it really required getting everybody to work together. …There were a lot of details, and it really took a lot of teamwork.”

The nursing supervisor in the emergency department was in charge of the batch and coordinated with the laboratory, he explained. There were many moving parts to manage, including monitoring how many patients were being admitted, what their conditions were, whether they were high or low risk, and where they would house those patients as the emergency department became increasingly busy. “It’s a lot for them, but they’ve adapted really well,” Dr. Mastrianni said.

Pooling tests seems to work best for three to five patients at a time; larger batches increase the chance of having a positive test, and thus identifying the sick individual(s) becomes more challenging and expensive, Dr. Shah said.

“It’s a fine line between having a pool large enough that you save on testing supplies and testing costs but not having the pool so large that you dramatically increase your likelihood of having a positive test,” Dr. Shah said.

Hospitals will likely need to be flexible and adapt as the local positivity rate changes and supply levels vary, according to the authors.

“Pooled testing is mainly dependent on the COVID-19 positive rate in the population of interest in addition to the sensitivity of the [reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)] method used for COVID-19 testing,” said Baha Abdalhamid, MD, PhD, of the department of pathology and microbiology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha.

“Each laboratory and hospital needs to do their own validation testing because it is dependent on the positive rate of COVID-19,” added Dr. Abdalhamid, who was not involved in the current study.

It’s important for clinicians to “do a good history to find who’s high risk and who’s low risk,” Dr. Mastrianni said. Clinicians also need to remember that, although a patient may test negative initially, they may still have COVID-19, he warned. That test reflects a single point in time, and a patient could be infected and not yet be ill, so clinicians need to be alert to a change in the patient’s status.

Best for settings with low-risk individuals

“Pooled COVID-19 testing is a straightforward, cost-effective, and efficient approach,” Dr. Abdalhamid said. He and his colleagues found pooled testing could increase testing capability by 69% or more when the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection is 10% or lower.

He said the approach would be helpful in other settings “as long as the positive rate is equal to or less than 10%. Asymptomatic population or surveillance groups such as students, athletes, and military service members are [an] interesting population to test using pooling testing because we expect these populations to have low positive rates, which makes pooled testing ideal.”

Benefit outweighs risk

“There is risk of missing specimens with low concentration of the virus,” Dr. Abdalhamid cautioned. “These specimens might be missed due to the dilution factor of pooling [false-negative specimens]. We did not have a single false-negative specimen in our proof-of-concept study. In addition, there are practical approaches to deal with false-negative pooled specimens.

“The benefit definitely outweighs the risk of false-negative specimens because false-negative results rarely occur, if any. In addition, there is significant saving of time, reagents, and supplies in [a] pooled specimens approach as well as expansion of the test for higher number of patients,” Dr. Abdalhamid continued.

Dr. Mastrianni’s hospital currently has enough testing cartridges, but they are continuing to conduct pooled testing to conserve resources for the benefit of their own hospital and for the nation as a whole, he said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abdalhamid and Dr. Shah have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Straightforward, cost effective, and efficient’

‘Straightforward, cost effective, and efficient’

Combining specimens from several low-risk inpatients in a single test for SARS-CoV-2 infection allowed hospital staff to stretch testing supplies and provide test results quickly for many more patients than they might have otherwise, researchers found.

“We believe this strategy conserved [personal protective equipment (PPE)], led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care,” wrote David Mastrianni, MD, and colleagues from Saratoga Hospital in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. “Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community.”

The researchers published their findings July 20 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“What was really important about this study was they were actually able to implement pooled testing after communication with the [Food and Drug Administration],” Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, SFHM, the journal’s editor-in-chief, said in an interview.

“Pooled testing combines samples from multiple people within a single test. The benefit is, if the test is negative [you know that] everyone whose sample was combined … is negative. So you’ve effectively tested anywhere from three to five people with the resources required for only one test,” Dr. Shah continued.

The challenge is that, if the test is positive, everyone in that testing group must be retested individually because one or more of them has the infection, said Dr. Shah, director of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Mastrianni said early in the pandemic they started getting the “New York surge” at their hospital, located approximately 3 hours from New York City. They wanted to test all of the inpatients at their hospital for COVID-19 and they had a rapid in-house test that worked well, “but we just didn’t have enough cartridges, and we couldn’t get deliveries, and we started pooling.” In fact, they ran out of testing supplies at one point during the study but were able to replenish their supply in about a day, he noted.

For the current study, all patients admitted to the hospital, including those admitted for observation, underwent testing for SARS-CoV-2. Staff in the emergency department designated patients as low risk if they had no symptoms or other clinical evidence of COVID-19; those patients underwent pooled testing.

Patients with clinical evidence of COVID-19, such as respiratory symptoms or laboratory or radiographic findings consistent with infection, were considered high risk and were tested on an individual basis and thus excluded from the current analysis.

The pooled testing strategy required some patients to be held in the emergency department until there were three available for pooled testing. On several occasions when this was not practical, specimens from two patients were pooled.

Between April 17 and May 11, clinicians tested 530 patients via pooled testing using 179 cartridges (172 with swabs from three patients and 7 with swabs from two patients). There were four positive pooled tests, which necessitated the use of an additional 11 cartridges. Overall, the testing used 190 cartridges, which is 340 fewer than would have been used if all patients had been tested individually.

Among the low-risk patients, the positive rate was 0.8% (4/530). No patients from pools that were negative tested positive later during their hospitalization or developed evidence of the infection.

Team effort, flexibility needed

Dr. Mastrianni said he expected their study to find that pooled testing saved testing resources, but he “was surprised by the complexity of the logistics in the hospital, and how it really required getting everybody to work together. …There were a lot of details, and it really took a lot of teamwork.”

The nursing supervisor in the emergency department was in charge of the batch and coordinated with the laboratory, he explained. There were many moving parts to manage, including monitoring how many patients were being admitted, what their conditions were, whether they were high or low risk, and where they would house those patients as the emergency department became increasingly busy. “It’s a lot for them, but they’ve adapted really well,” Dr. Mastrianni said.

Pooling tests seems to work best for three to five patients at a time; larger batches increase the chance of having a positive test, and thus identifying the sick individual(s) becomes more challenging and expensive, Dr. Shah said.

“It’s a fine line between having a pool large enough that you save on testing supplies and testing costs but not having the pool so large that you dramatically increase your likelihood of having a positive test,” Dr. Shah said.

Hospitals will likely need to be flexible and adapt as the local positivity rate changes and supply levels vary, according to the authors.

“Pooled testing is mainly dependent on the COVID-19 positive rate in the population of interest in addition to the sensitivity of the [reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)] method used for COVID-19 testing,” said Baha Abdalhamid, MD, PhD, of the department of pathology and microbiology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha.

“Each laboratory and hospital needs to do their own validation testing because it is dependent on the positive rate of COVID-19,” added Dr. Abdalhamid, who was not involved in the current study.

It’s important for clinicians to “do a good history to find who’s high risk and who’s low risk,” Dr. Mastrianni said. Clinicians also need to remember that, although a patient may test negative initially, they may still have COVID-19, he warned. That test reflects a single point in time, and a patient could be infected and not yet be ill, so clinicians need to be alert to a change in the patient’s status.

Best for settings with low-risk individuals

“Pooled COVID-19 testing is a straightforward, cost-effective, and efficient approach,” Dr. Abdalhamid said. He and his colleagues found pooled testing could increase testing capability by 69% or more when the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection is 10% or lower.

He said the approach would be helpful in other settings “as long as the positive rate is equal to or less than 10%. Asymptomatic population or surveillance groups such as students, athletes, and military service members are [an] interesting population to test using pooling testing because we expect these populations to have low positive rates, which makes pooled testing ideal.”

Benefit outweighs risk

“There is risk of missing specimens with low concentration of the virus,” Dr. Abdalhamid cautioned. “These specimens might be missed due to the dilution factor of pooling [false-negative specimens]. We did not have a single false-negative specimen in our proof-of-concept study. In addition, there are practical approaches to deal with false-negative pooled specimens.

“The benefit definitely outweighs the risk of false-negative specimens because false-negative results rarely occur, if any. In addition, there is significant saving of time, reagents, and supplies in [a] pooled specimens approach as well as expansion of the test for higher number of patients,” Dr. Abdalhamid continued.

Dr. Mastrianni’s hospital currently has enough testing cartridges, but they are continuing to conduct pooled testing to conserve resources for the benefit of their own hospital and for the nation as a whole, he said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abdalhamid and Dr. Shah have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Combining specimens from several low-risk inpatients in a single test for SARS-CoV-2 infection allowed hospital staff to stretch testing supplies and provide test results quickly for many more patients than they might have otherwise, researchers found.

“We believe this strategy conserved [personal protective equipment (PPE)], led to a marked reduction in staff and patient anxiety, and improved patient care,” wrote David Mastrianni, MD, and colleagues from Saratoga Hospital in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. “Our impression is that testing all admitted patients has also been reassuring to our community.”

The researchers published their findings July 20 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

“What was really important about this study was they were actually able to implement pooled testing after communication with the [Food and Drug Administration],” Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, SFHM, the journal’s editor-in-chief, said in an interview.

“Pooled testing combines samples from multiple people within a single test. The benefit is, if the test is negative [you know that] everyone whose sample was combined … is negative. So you’ve effectively tested anywhere from three to five people with the resources required for only one test,” Dr. Shah continued.

The challenge is that, if the test is positive, everyone in that testing group must be retested individually because one or more of them has the infection, said Dr. Shah, director of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Dr. Mastrianni said early in the pandemic they started getting the “New York surge” at their hospital, located approximately 3 hours from New York City. They wanted to test all of the inpatients at their hospital for COVID-19 and they had a rapid in-house test that worked well, “but we just didn’t have enough cartridges, and we couldn’t get deliveries, and we started pooling.” In fact, they ran out of testing supplies at one point during the study but were able to replenish their supply in about a day, he noted.

For the current study, all patients admitted to the hospital, including those admitted for observation, underwent testing for SARS-CoV-2. Staff in the emergency department designated patients as low risk if they had no symptoms or other clinical evidence of COVID-19; those patients underwent pooled testing.

Patients with clinical evidence of COVID-19, such as respiratory symptoms or laboratory or radiographic findings consistent with infection, were considered high risk and were tested on an individual basis and thus excluded from the current analysis.

The pooled testing strategy required some patients to be held in the emergency department until there were three available for pooled testing. On several occasions when this was not practical, specimens from two patients were pooled.

Between April 17 and May 11, clinicians tested 530 patients via pooled testing using 179 cartridges (172 with swabs from three patients and 7 with swabs from two patients). There were four positive pooled tests, which necessitated the use of an additional 11 cartridges. Overall, the testing used 190 cartridges, which is 340 fewer than would have been used if all patients had been tested individually.

Among the low-risk patients, the positive rate was 0.8% (4/530). No patients from pools that were negative tested positive later during their hospitalization or developed evidence of the infection.

Team effort, flexibility needed

Dr. Mastrianni said he expected their study to find that pooled testing saved testing resources, but he “was surprised by the complexity of the logistics in the hospital, and how it really required getting everybody to work together. …There were a lot of details, and it really took a lot of teamwork.”

The nursing supervisor in the emergency department was in charge of the batch and coordinated with the laboratory, he explained. There were many moving parts to manage, including monitoring how many patients were being admitted, what their conditions were, whether they were high or low risk, and where they would house those patients as the emergency department became increasingly busy. “It’s a lot for them, but they’ve adapted really well,” Dr. Mastrianni said.

Pooling tests seems to work best for three to five patients at a time; larger batches increase the chance of having a positive test, and thus identifying the sick individual(s) becomes more challenging and expensive, Dr. Shah said.

“It’s a fine line between having a pool large enough that you save on testing supplies and testing costs but not having the pool so large that you dramatically increase your likelihood of having a positive test,” Dr. Shah said.

Hospitals will likely need to be flexible and adapt as the local positivity rate changes and supply levels vary, according to the authors.

“Pooled testing is mainly dependent on the COVID-19 positive rate in the population of interest in addition to the sensitivity of the [reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)] method used for COVID-19 testing,” said Baha Abdalhamid, MD, PhD, of the department of pathology and microbiology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha.

“Each laboratory and hospital needs to do their own validation testing because it is dependent on the positive rate of COVID-19,” added Dr. Abdalhamid, who was not involved in the current study.

It’s important for clinicians to “do a good history to find who’s high risk and who’s low risk,” Dr. Mastrianni said. Clinicians also need to remember that, although a patient may test negative initially, they may still have COVID-19, he warned. That test reflects a single point in time, and a patient could be infected and not yet be ill, so clinicians need to be alert to a change in the patient’s status.

Best for settings with low-risk individuals

“Pooled COVID-19 testing is a straightforward, cost-effective, and efficient approach,” Dr. Abdalhamid said. He and his colleagues found pooled testing could increase testing capability by 69% or more when the incidence rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection is 10% or lower.

He said the approach would be helpful in other settings “as long as the positive rate is equal to or less than 10%. Asymptomatic population or surveillance groups such as students, athletes, and military service members are [an] interesting population to test using pooling testing because we expect these populations to have low positive rates, which makes pooled testing ideal.”

Benefit outweighs risk

“There is risk of missing specimens with low concentration of the virus,” Dr. Abdalhamid cautioned. “These specimens might be missed due to the dilution factor of pooling [false-negative specimens]. We did not have a single false-negative specimen in our proof-of-concept study. In addition, there are practical approaches to deal with false-negative pooled specimens.

“The benefit definitely outweighs the risk of false-negative specimens because false-negative results rarely occur, if any. In addition, there is significant saving of time, reagents, and supplies in [a] pooled specimens approach as well as expansion of the test for higher number of patients,” Dr. Abdalhamid continued.

Dr. Mastrianni’s hospital currently has enough testing cartridges, but they are continuing to conduct pooled testing to conserve resources for the benefit of their own hospital and for the nation as a whole, he said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Abdalhamid and Dr. Shah have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 and the myth of the super doctor

Let us begin with a thought exercise. Close your eyes and picture the word, “hero.” What comes to mind? A relative, a teacher, a fictional character wielding a hammer or flying gracefully through the air?

Several months ago, our country was introduced to a foe that brought us to our knees. Before that time, the idea of a hero had fluctuated with circumstance and had been guided by aging and maturity; however, since the moment COVID-19 struck, a new image has emerged. Not all heroes wear capes, but some wield stethoscopes.

Over these past months the phrase, “Health Care Heroes” has spread throughout our collective consciousness, highlighted everywhere from talk shows and news media to billboards and journals. Doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals are lauded for their strength, dedication, resilience, and compassion. Citizens line up to clap, honk horns, and shower praise in recognition of those who have risked their health, sacrificed their personal lives, and committed themselves to the greater good. Yet, what does it mean to be a hero, and what is the cost of hero worship?

The focus of medical training has gradually shifted to include the physical as well as mental well-being of future physicians, but the remnants of traditional doctrine linger. Hours of focused training through study and direct clinical interaction reinforce dedication to patient care. Rewards are given for time spent and compassion lent, and research is lauded, but family time is rarely applauded. We are encouraged to do our greatest, work our hardest, be the best, rise and defeat every test. Failure (or the perception thereof) is not an option.

According to Rikinkumar S. Patel, MD, MPH, and associates, physicians have nearly twice the burnout rate of other professionals (Behav Sci. [Basel]. 2018 Nov;8[11]:98). The dedication to our craft propels excellence as well as sacrifice. When COVID-19 entered our lives, many of my colleagues did not hesitate to heed to the call for action. They immersed themselves in the ICU, led triage units, and extended work hours in the service of the sick and dying. Several were years removed from emergency/intensive care, while others were allocated from their chosen residency programs and voluntarily thrust into an environment they had never before traversed.

These individuals are praised as “brave,” “dedicated,” “selfless.” A few even provided insight into their experiences through various publications highlighting their appreciation and gratitude toward such a treacherous, albeit, tremendous experience. Even though their words are an honest perspective of life through one of the worst health care crises in 100 years, in effect, they perpetuate the noble hero; the myth of the super doctor.

In a profession that has borne witness to multiple suicides over the past few months, why do we not encourage open dialogue of our victories as well as our defeats? Our wins as much as our losses? Why does an esteemed veteran physician feel guilt over declining to provide emergency services to patients whom they have long forgotten how to manage? What drives the guilt and the self-doubt? Are we ashamed of what others will think? Is it that the fear of not living up to our cherished medical oath outweighs our own boundaries and acknowledgment of our limitations?

A hero is an entity, a person encompassing a state of being, yet health care professionals are bestowed this title and this burden on a near-daily basis. We are perfectly imperfect. The more in tune we are to vulnerability, the more honest we can become with ourselves and one another.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

Let us begin with a thought exercise. Close your eyes and picture the word, “hero.” What comes to mind? A relative, a teacher, a fictional character wielding a hammer or flying gracefully through the air?

Several months ago, our country was introduced to a foe that brought us to our knees. Before that time, the idea of a hero had fluctuated with circumstance and had been guided by aging and maturity; however, since the moment COVID-19 struck, a new image has emerged. Not all heroes wear capes, but some wield stethoscopes.

Over these past months the phrase, “Health Care Heroes” has spread throughout our collective consciousness, highlighted everywhere from talk shows and news media to billboards and journals. Doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals are lauded for their strength, dedication, resilience, and compassion. Citizens line up to clap, honk horns, and shower praise in recognition of those who have risked their health, sacrificed their personal lives, and committed themselves to the greater good. Yet, what does it mean to be a hero, and what is the cost of hero worship?

The focus of medical training has gradually shifted to include the physical as well as mental well-being of future physicians, but the remnants of traditional doctrine linger. Hours of focused training through study and direct clinical interaction reinforce dedication to patient care. Rewards are given for time spent and compassion lent, and research is lauded, but family time is rarely applauded. We are encouraged to do our greatest, work our hardest, be the best, rise and defeat every test. Failure (or the perception thereof) is not an option.

According to Rikinkumar S. Patel, MD, MPH, and associates, physicians have nearly twice the burnout rate of other professionals (Behav Sci. [Basel]. 2018 Nov;8[11]:98). The dedication to our craft propels excellence as well as sacrifice. When COVID-19 entered our lives, many of my colleagues did not hesitate to heed to the call for action. They immersed themselves in the ICU, led triage units, and extended work hours in the service of the sick and dying. Several were years removed from emergency/intensive care, while others were allocated from their chosen residency programs and voluntarily thrust into an environment they had never before traversed.

These individuals are praised as “brave,” “dedicated,” “selfless.” A few even provided insight into their experiences through various publications highlighting their appreciation and gratitude toward such a treacherous, albeit, tremendous experience. Even though their words are an honest perspective of life through one of the worst health care crises in 100 years, in effect, they perpetuate the noble hero; the myth of the super doctor.

In a profession that has borne witness to multiple suicides over the past few months, why do we not encourage open dialogue of our victories as well as our defeats? Our wins as much as our losses? Why does an esteemed veteran physician feel guilt over declining to provide emergency services to patients whom they have long forgotten how to manage? What drives the guilt and the self-doubt? Are we ashamed of what others will think? Is it that the fear of not living up to our cherished medical oath outweighs our own boundaries and acknowledgment of our limitations?

A hero is an entity, a person encompassing a state of being, yet health care professionals are bestowed this title and this burden on a near-daily basis. We are perfectly imperfect. The more in tune we are to vulnerability, the more honest we can become with ourselves and one another.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

Let us begin with a thought exercise. Close your eyes and picture the word, “hero.” What comes to mind? A relative, a teacher, a fictional character wielding a hammer or flying gracefully through the air?

Several months ago, our country was introduced to a foe that brought us to our knees. Before that time, the idea of a hero had fluctuated with circumstance and had been guided by aging and maturity; however, since the moment COVID-19 struck, a new image has emerged. Not all heroes wear capes, but some wield stethoscopes.

Over these past months the phrase, “Health Care Heroes” has spread throughout our collective consciousness, highlighted everywhere from talk shows and news media to billboards and journals. Doctors, nurses, and other health care professionals are lauded for their strength, dedication, resilience, and compassion. Citizens line up to clap, honk horns, and shower praise in recognition of those who have risked their health, sacrificed their personal lives, and committed themselves to the greater good. Yet, what does it mean to be a hero, and what is the cost of hero worship?

The focus of medical training has gradually shifted to include the physical as well as mental well-being of future physicians, but the remnants of traditional doctrine linger. Hours of focused training through study and direct clinical interaction reinforce dedication to patient care. Rewards are given for time spent and compassion lent, and research is lauded, but family time is rarely applauded. We are encouraged to do our greatest, work our hardest, be the best, rise and defeat every test. Failure (or the perception thereof) is not an option.

According to Rikinkumar S. Patel, MD, MPH, and associates, physicians have nearly twice the burnout rate of other professionals (Behav Sci. [Basel]. 2018 Nov;8[11]:98). The dedication to our craft propels excellence as well as sacrifice. When COVID-19 entered our lives, many of my colleagues did not hesitate to heed to the call for action. They immersed themselves in the ICU, led triage units, and extended work hours in the service of the sick and dying. Several were years removed from emergency/intensive care, while others were allocated from their chosen residency programs and voluntarily thrust into an environment they had never before traversed.

These individuals are praised as “brave,” “dedicated,” “selfless.” A few even provided insight into their experiences through various publications highlighting their appreciation and gratitude toward such a treacherous, albeit, tremendous experience. Even though their words are an honest perspective of life through one of the worst health care crises in 100 years, in effect, they perpetuate the noble hero; the myth of the super doctor.

In a profession that has borne witness to multiple suicides over the past few months, why do we not encourage open dialogue of our victories as well as our defeats? Our wins as much as our losses? Why does an esteemed veteran physician feel guilt over declining to provide emergency services to patients whom they have long forgotten how to manage? What drives the guilt and the self-doubt? Are we ashamed of what others will think? Is it that the fear of not living up to our cherished medical oath outweighs our own boundaries and acknowledgment of our limitations?

A hero is an entity, a person encompassing a state of being, yet health care professionals are bestowed this title and this burden on a near-daily basis. We are perfectly imperfect. The more in tune we are to vulnerability, the more honest we can become with ourselves and one another.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with an interest in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. She has no conflicts of interest.

Does metformin reduce risk for death in COVID-19?

Accumulating observational data suggest that metformin use in patients with type 2 diabetes might reduce the risk for death from COVID-19, but the randomized trials needed to prove this are unlikely to be carried out, according to experts.

The latest results, which are not yet peer reviewed, were published online July 31. The study was conducted by Andrew B. Crouse, PhD, of the Hugh Kaul Precision Medicine Institute, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues.

The researchers found that among more than 600 patients with diabetes and COVID-19, use of metformin was associated with a nearly 70% reduction in mortality after adjustment for multiple confounders.

Data from four previous studies that also show a reduction in mortality among metformin users compared to nonusers were summarized in a “mini review” by André J. Scheen, MD, PhD, published Aug. 1 in Diabetes and Metabolism.

Dr. Scheen, of the division of diabetes, nutrition, and metabolic disorders and the division of clinical pharmacology at Liège (Belgium) University, discussed possible mechanisms behind this observation.

“Because metformin exerts various effects beyond its glucose-lowering action, among which are anti-inflammatory effects, it may be speculated that this biguanide might positively influence the prognosis of patients with [type 2 diabetes] hospitalized for COVID-19,” he said.

“However, given the potential confounders inherently found in observational studies, caution is required before drawing any firm conclusions in the absence of randomized controlled trials,” Dr. Scheen wrote.

Indeed, when asked to comment, endocrinologist Kasia Lipska, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview: “Metformin users tend to do better in many different settings with respect to many different outcomes. To me, it is still unclear whether metformin is truly a miracle drug or whether it is simply used more often among people who are healthier and who do not have contraindications to its use.”

She added, “I don’t think we have enough data to suggest metformin use for COVID-19 mitigation at this point.”

Alabama authors say confounding effects ‘unlikely’

In the retrospective analysis of electronic health records from their institution, Dr. Crouse and colleagues reviewed data from 604 patients who were confirmed to have tested positive for COVID-19 between Feb. 25 and June 22, 2020. Of those individuals, 40% had diabetes.

Death occurred in 11% (n = 67); the odds ratio (OR) for death among those with, vs. without, diabetes was 3.62 (P < .0001).

Individuals with diabetes accounted for >60% of all deaths. In multiple logistic regression, age 50-70 vs. <50, male sex, and diabetes emerged as independent predictors of death.

Of the 42 patients with diabetes who died, 8 (19%) had used metformin, and 34 (81%) had not*, a significant difference (OR, 0.38; P = .0221). Insulin use, on the other hand, had no effect on mortality (P = .5728).

“In fact, with 11% [being] the mortality of metformin users, [this] was comparable to that of the general COVID-19-positive population and dramatically lower than the 23% mortality observed in subjects with diabetes and not on metformin,” the authors said.

The survival benefit observed with metformin remained after exclusion of patients with classic metformin contraindications, such as chronic kidney disease and heart failure (OR, 0.17; P = .0231).

“This makes any potential confounding effects from skewing metformin users toward healthier subjects without these additional comorbidities very unlikely,” Dr. Crouse and colleagues contended.

After further analysis that controlled for other covariates (age, sex, obesity status, and hypertension), age, sex, and metformin use remained independent predictors of mortality.

For metformin, the odds ratio was 0.33 (P = .0210).

But, Dr. Lipska pointed out, “Observational studies can take into account confounders that are measured. However, unmeasured confounders may still affect the conclusions of these studies ... Propensity score matching to account for the likelihood of use of metformin could be used to better account for differences between metformin users and nonusers.”

If metformin does reduce COVID-19 deaths, multiple mechanisms likely

In his article, Dr. Scheen noted that several mechanisms have been proposed for the possible beneficial effect of metformin on COVID-19 outcomes, including direct improvements in glucose control, body weight, and insulin resistance; reduction in inflammation; inhibition of virus penetration via phosphorylation of ACE2; inhibition of an immune hyperactivation pathway; and neutrophil reduction. All remain theoretical, he emphasized.

He noted that some authors have raised concerns about possible harms from the use of metformin by patients with type 2 diabetes who are hospitalized for COVID-19, particularly because of the potential risk for lactic acidosis in cases of multiple organ failure.

In totality, four studies suggest 25% death reduction with metformin

Taken together, the four observational studies that Dr. Scheen reviewed showed that metformin had a positive effect, with an overall 25% reduction in death (P < .00001), albeit with relatively high heterogeneity (I² = 61%).

The largest of these, from the United States, included 6,256 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and involved propensity matching. A significant reduction in mortality with metformin use was seen in women but not men (odds ratio, 0.759).

The French Coronavirus-SARS-CoV-2 and Diabetes Outcomes (CORONADO) study of 1,317 patients with diabetes and confirmed COVID-19 who were admitted to 53 French hospitals also showed a significant survival benefit for metformin, although the study wasn’t designed to address that issue.

In that study, the odds ratio for death on day 7 in prior metformin users compared to nonusers was 0.59. This finding lost significance but remained a trend after full adjustments (0.80).

Two smaller observational studies produced similar trends toward survival benefit with metformin.

Nonetheless, Dr. Scheen cautioned: “Firm conclusions about the impact of metformin therapy can only be drawn from double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and such trials are almost impossible in the context of COVID-19.”

He added: “Because metformin is out of patent and very inexpensive, no pharmaceutical company is likely to be interested in planning a study to demonstrate the benefits of metformin on COVID-19-related clinical outcomes.”

Dr. Lipska agreed: “RCTs are unlikely to be conducted to settle these issues. In their absence, metformin use should be based on its safety and effectiveness profile.”

Dr. Scheen concluded, however, that “there are at least no negative safety indications, so there is no reason to stop metformin therapy during COVID-19 infection except in cases of severe gastrointestinal symptoms, hypoxia and/or multiple organ failure.”

Dr. Lipska has received grants from the National Institutes of Health and works under contract for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop publicly reported quality measures. Dr. Scheen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

*A previous version reversed these two outcomes in error.

Accumulating observational data suggest that metformin use in patients with type 2 diabetes might reduce the risk for death from COVID-19, but the randomized trials needed to prove this are unlikely to be carried out, according to experts.

The latest results, which are not yet peer reviewed, were published online July 31. The study was conducted by Andrew B. Crouse, PhD, of the Hugh Kaul Precision Medicine Institute, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues.

The researchers found that among more than 600 patients with diabetes and COVID-19, use of metformin was associated with a nearly 70% reduction in mortality after adjustment for multiple confounders.

Data from four previous studies that also show a reduction in mortality among metformin users compared to nonusers were summarized in a “mini review” by André J. Scheen, MD, PhD, published Aug. 1 in Diabetes and Metabolism.

Dr. Scheen, of the division of diabetes, nutrition, and metabolic disorders and the division of clinical pharmacology at Liège (Belgium) University, discussed possible mechanisms behind this observation.

“Because metformin exerts various effects beyond its glucose-lowering action, among which are anti-inflammatory effects, it may be speculated that this biguanide might positively influence the prognosis of patients with [type 2 diabetes] hospitalized for COVID-19,” he said.

“However, given the potential confounders inherently found in observational studies, caution is required before drawing any firm conclusions in the absence of randomized controlled trials,” Dr. Scheen wrote.

Indeed, when asked to comment, endocrinologist Kasia Lipska, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview: “Metformin users tend to do better in many different settings with respect to many different outcomes. To me, it is still unclear whether metformin is truly a miracle drug or whether it is simply used more often among people who are healthier and who do not have contraindications to its use.”

She added, “I don’t think we have enough data to suggest metformin use for COVID-19 mitigation at this point.”

Alabama authors say confounding effects ‘unlikely’

In the retrospective analysis of electronic health records from their institution, Dr. Crouse and colleagues reviewed data from 604 patients who were confirmed to have tested positive for COVID-19 between Feb. 25 and June 22, 2020. Of those individuals, 40% had diabetes.

Death occurred in 11% (n = 67); the odds ratio (OR) for death among those with, vs. without, diabetes was 3.62 (P < .0001).

Individuals with diabetes accounted for >60% of all deaths. In multiple logistic regression, age 50-70 vs. <50, male sex, and diabetes emerged as independent predictors of death.

Of the 42 patients with diabetes who died, 8 (19%) had used metformin, and 34 (81%) had not*, a significant difference (OR, 0.38; P = .0221). Insulin use, on the other hand, had no effect on mortality (P = .5728).

“In fact, with 11% [being] the mortality of metformin users, [this] was comparable to that of the general COVID-19-positive population and dramatically lower than the 23% mortality observed in subjects with diabetes and not on metformin,” the authors said.

The survival benefit observed with metformin remained after exclusion of patients with classic metformin contraindications, such as chronic kidney disease and heart failure (OR, 0.17; P = .0231).

“This makes any potential confounding effects from skewing metformin users toward healthier subjects without these additional comorbidities very unlikely,” Dr. Crouse and colleagues contended.

After further analysis that controlled for other covariates (age, sex, obesity status, and hypertension), age, sex, and metformin use remained independent predictors of mortality.

For metformin, the odds ratio was 0.33 (P = .0210).

But, Dr. Lipska pointed out, “Observational studies can take into account confounders that are measured. However, unmeasured confounders may still affect the conclusions of these studies ... Propensity score matching to account for the likelihood of use of metformin could be used to better account for differences between metformin users and nonusers.”

If metformin does reduce COVID-19 deaths, multiple mechanisms likely

In his article, Dr. Scheen noted that several mechanisms have been proposed for the possible beneficial effect of metformin on COVID-19 outcomes, including direct improvements in glucose control, body weight, and insulin resistance; reduction in inflammation; inhibition of virus penetration via phosphorylation of ACE2; inhibition of an immune hyperactivation pathway; and neutrophil reduction. All remain theoretical, he emphasized.

He noted that some authors have raised concerns about possible harms from the use of metformin by patients with type 2 diabetes who are hospitalized for COVID-19, particularly because of the potential risk for lactic acidosis in cases of multiple organ failure.

In totality, four studies suggest 25% death reduction with metformin

Taken together, the four observational studies that Dr. Scheen reviewed showed that metformin had a positive effect, with an overall 25% reduction in death (P < .00001), albeit with relatively high heterogeneity (I² = 61%).

The largest of these, from the United States, included 6,256 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and involved propensity matching. A significant reduction in mortality with metformin use was seen in women but not men (odds ratio, 0.759).

The French Coronavirus-SARS-CoV-2 and Diabetes Outcomes (CORONADO) study of 1,317 patients with diabetes and confirmed COVID-19 who were admitted to 53 French hospitals also showed a significant survival benefit for metformin, although the study wasn’t designed to address that issue.

In that study, the odds ratio for death on day 7 in prior metformin users compared to nonusers was 0.59. This finding lost significance but remained a trend after full adjustments (0.80).

Two smaller observational studies produced similar trends toward survival benefit with metformin.

Nonetheless, Dr. Scheen cautioned: “Firm conclusions about the impact of metformin therapy can only be drawn from double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and such trials are almost impossible in the context of COVID-19.”

He added: “Because metformin is out of patent and very inexpensive, no pharmaceutical company is likely to be interested in planning a study to demonstrate the benefits of metformin on COVID-19-related clinical outcomes.”

Dr. Lipska agreed: “RCTs are unlikely to be conducted to settle these issues. In their absence, metformin use should be based on its safety and effectiveness profile.”

Dr. Scheen concluded, however, that “there are at least no negative safety indications, so there is no reason to stop metformin therapy during COVID-19 infection except in cases of severe gastrointestinal symptoms, hypoxia and/or multiple organ failure.”

Dr. Lipska has received grants from the National Institutes of Health and works under contract for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop publicly reported quality measures. Dr. Scheen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

*A previous version reversed these two outcomes in error.

Accumulating observational data suggest that metformin use in patients with type 2 diabetes might reduce the risk for death from COVID-19, but the randomized trials needed to prove this are unlikely to be carried out, according to experts.

The latest results, which are not yet peer reviewed, were published online July 31. The study was conducted by Andrew B. Crouse, PhD, of the Hugh Kaul Precision Medicine Institute, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and colleagues.

The researchers found that among more than 600 patients with diabetes and COVID-19, use of metformin was associated with a nearly 70% reduction in mortality after adjustment for multiple confounders.

Data from four previous studies that also show a reduction in mortality among metformin users compared to nonusers were summarized in a “mini review” by André J. Scheen, MD, PhD, published Aug. 1 in Diabetes and Metabolism.

Dr. Scheen, of the division of diabetes, nutrition, and metabolic disorders and the division of clinical pharmacology at Liège (Belgium) University, discussed possible mechanisms behind this observation.

“Because metformin exerts various effects beyond its glucose-lowering action, among which are anti-inflammatory effects, it may be speculated that this biguanide might positively influence the prognosis of patients with [type 2 diabetes] hospitalized for COVID-19,” he said.

“However, given the potential confounders inherently found in observational studies, caution is required before drawing any firm conclusions in the absence of randomized controlled trials,” Dr. Scheen wrote.

Indeed, when asked to comment, endocrinologist Kasia Lipska, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview: “Metformin users tend to do better in many different settings with respect to many different outcomes. To me, it is still unclear whether metformin is truly a miracle drug or whether it is simply used more often among people who are healthier and who do not have contraindications to its use.”

She added, “I don’t think we have enough data to suggest metformin use for COVID-19 mitigation at this point.”

Alabama authors say confounding effects ‘unlikely’

In the retrospective analysis of electronic health records from their institution, Dr. Crouse and colleagues reviewed data from 604 patients who were confirmed to have tested positive for COVID-19 between Feb. 25 and June 22, 2020. Of those individuals, 40% had diabetes.

Death occurred in 11% (n = 67); the odds ratio (OR) for death among those with, vs. without, diabetes was 3.62 (P < .0001).

Individuals with diabetes accounted for >60% of all deaths. In multiple logistic regression, age 50-70 vs. <50, male sex, and diabetes emerged as independent predictors of death.

Of the 42 patients with diabetes who died, 8 (19%) had used metformin, and 34 (81%) had not*, a significant difference (OR, 0.38; P = .0221). Insulin use, on the other hand, had no effect on mortality (P = .5728).

“In fact, with 11% [being] the mortality of metformin users, [this] was comparable to that of the general COVID-19-positive population and dramatically lower than the 23% mortality observed in subjects with diabetes and not on metformin,” the authors said.

The survival benefit observed with metformin remained after exclusion of patients with classic metformin contraindications, such as chronic kidney disease and heart failure (OR, 0.17; P = .0231).

“This makes any potential confounding effects from skewing metformin users toward healthier subjects without these additional comorbidities very unlikely,” Dr. Crouse and colleagues contended.

After further analysis that controlled for other covariates (age, sex, obesity status, and hypertension), age, sex, and metformin use remained independent predictors of mortality.

For metformin, the odds ratio was 0.33 (P = .0210).

But, Dr. Lipska pointed out, “Observational studies can take into account confounders that are measured. However, unmeasured confounders may still affect the conclusions of these studies ... Propensity score matching to account for the likelihood of use of metformin could be used to better account for differences between metformin users and nonusers.”

If metformin does reduce COVID-19 deaths, multiple mechanisms likely

In his article, Dr. Scheen noted that several mechanisms have been proposed for the possible beneficial effect of metformin on COVID-19 outcomes, including direct improvements in glucose control, body weight, and insulin resistance; reduction in inflammation; inhibition of virus penetration via phosphorylation of ACE2; inhibition of an immune hyperactivation pathway; and neutrophil reduction. All remain theoretical, he emphasized.

He noted that some authors have raised concerns about possible harms from the use of metformin by patients with type 2 diabetes who are hospitalized for COVID-19, particularly because of the potential risk for lactic acidosis in cases of multiple organ failure.

In totality, four studies suggest 25% death reduction with metformin

Taken together, the four observational studies that Dr. Scheen reviewed showed that metformin had a positive effect, with an overall 25% reduction in death (P < .00001), albeit with relatively high heterogeneity (I² = 61%).

The largest of these, from the United States, included 6,256 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and involved propensity matching. A significant reduction in mortality with metformin use was seen in women but not men (odds ratio, 0.759).

The French Coronavirus-SARS-CoV-2 and Diabetes Outcomes (CORONADO) study of 1,317 patients with diabetes and confirmed COVID-19 who were admitted to 53 French hospitals also showed a significant survival benefit for metformin, although the study wasn’t designed to address that issue.

In that study, the odds ratio for death on day 7 in prior metformin users compared to nonusers was 0.59. This finding lost significance but remained a trend after full adjustments (0.80).

Two smaller observational studies produced similar trends toward survival benefit with metformin.

Nonetheless, Dr. Scheen cautioned: “Firm conclusions about the impact of metformin therapy can only be drawn from double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and such trials are almost impossible in the context of COVID-19.”

He added: “Because metformin is out of patent and very inexpensive, no pharmaceutical company is likely to be interested in planning a study to demonstrate the benefits of metformin on COVID-19-related clinical outcomes.”

Dr. Lipska agreed: “RCTs are unlikely to be conducted to settle these issues. In their absence, metformin use should be based on its safety and effectiveness profile.”

Dr. Scheen concluded, however, that “there are at least no negative safety indications, so there is no reason to stop metformin therapy during COVID-19 infection except in cases of severe gastrointestinal symptoms, hypoxia and/or multiple organ failure.”

Dr. Lipska has received grants from the National Institutes of Health and works under contract for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to develop publicly reported quality measures. Dr. Scheen has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

*A previous version reversed these two outcomes in error.

COVID-19 and masks: Doctor, may I be excused?

In the last 2 months, at least 10 patients have asked Constantine George, MD, for a written medical exemption so they won’t have to wear a mask in public. Dr. George, the chief medical officer of Vedius, an app for a travelers’ concierge medical service in Las Vegas, turned them all down.

Elena Christofides, MD, an endocrinologist in Columbus, Ohio, has also refused patients’ requests for exemptions.

“It’s very rare for someone to need an exemption,” says Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer for the American Lung Association and a lung specialist at ChristianaCare Health System in Newark, Del.

The opposition is sometimes strong. Recently, a video of Lenka Koloma of Laguna Niguel, Calif., who founded the antimask Freedom to Breathe Agency, went viral. She was in a California supermarket, maskless, telling an employee she was breaking the law by requiring patrons to wear masks.

“People need oxygen,” she said. “That alone is a medical condition.” Her webpage has a “Face Mask Exempt Card” that cites the Americans with Disabilities Act and posts a Department of Justice ADA violation reporting number. The DOJ issued a statement calling the cards fraudulent.

Figuring out if a patient’s request to opt out of wearing a mask is legitimate is a ‘’new frontier” for doctors, says Mical Raz, MD, a professor in public policy and health at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and a hospitalist at the university medical center.

Should some people skip masks?

Experts say there are very few medical reasons for people to skip masks. “If you look at the research, patients with COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder], those with reactive airway, even those can breathe through a mask,” Dr. George said. Requests for exemptions due to medical reasons are usually without basis. “Obviously, if someone is incapacitated, for example, with mental health issues, that’s case by case.”

Dr. Christofides said one of her patients cited anxiety and the other cited headaches as reasons not to wear a mask. “I told the one who asked for anxiety [reasons] that she could wear ones that were less tight.” The patient with headaches told Dr. Christofides that she had a buildup of carbon dioxide in the mask because of industrial exposure. Baloney, Dr. Christofides told her.

Dr. Rizzo says one rare example of someone who can’t wear a mask might be a patient with an advanced lung condition so severe, they need extra oxygen. “These are the extreme patients where any change in oxygen and carbon dioxide could make a difference,” he said. But “that’s also the population that shouldn’t be going out in the first place.”

Dr. Raz cowrote a commentary about mask exemptions, saying doctors are faced with difficult decisions and must keep a delicate balance between public health and individual disability needs. “Inappropriate medical exemptions may inadvertently hasten viral spread and threaten public health,” she wrote.

In an interview, she says that some people do have a hard time tolerating a mask. “Probably the most common reasons are mental health issues, such as anxiety, panic and PTSD, and children with sensory processing disorders (making them oversensitive to their environment). I think there are very few pulmonary reasons.”

CDC, professional organization guidelines

The CDC says people should wear masks in public and when around people who don’t live in the same household. Beyond that, it simply says masks should not be worn by children under age 2, “or anyone who has trouble breathing, is unconscious, incapacitated, or otherwise unable to remove the mask without assistance.”

In mid-July, four professional organizations released a statement in response to the CDC recommendation for facial coverings. Jointly issued by the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Lung Association, the American Thoracic Society and the COPD Foundation, it states in part that people with normal lungs and “even many individuals with underlying chronic lung disease should be able to wear a non-N95 facial covering without affecting their oxygen or carbon dioxide levels.”

It acknowledges that some people will seek an exemption and doctors must weigh the patient’s concerns against the need to stop the spread of the virus. “In some instances, physician reassurance regarding the safety of the facial coverings may be all that is needed,” it states.

Addressing the excuses

Here are some of the common medical reasons people give for not being able to tolerate a mask:

Claustrophobia or anxiety. Dr. Raz and others suggests a “desensitizing” period, wearing the mask for longer and longer periods of time to get used to it. Parents could suggest kids wear a mask when doing something they like, such as watching television, so they equate it with something pleasant. Switching to a different kind of mask or one that fits better could also help.

Masks cause Legionnaires’ disease. Not true, experts say. Legionnaires’ is a severe form of pneumonia, the result of inhaling tiny water droplets with legionella bacteria.

It’s difficult to read lips. People can buy masks with a clear window that makes their mouth and lips visible.

Trouble breathing. Brief periods of mask use won’t have a bad effect on oxygen levels for most people.

“There is not an inherent right to be out in a pandemic with an unmasked face,” Dr. Raz says. But “you are entitled to an accommodation.” That might be using curbside pickup for food and medication. That requires much less time wearing a mask than entering a store would.

There are no “boilerplate” cards or letters to excuse people provided by the four organizations that addressed the issue, Dr. Rizzo said. If he were to write a letter asking for an exemption, he would personalize it for an individual patient’s medical condition. As to whether a state would honor it, he cannot say. The states have a patchwork of recommendations, making it difficult to say.

Dr. Rizzo tells lung disease patients who are able to go out that wearing a mask for 15-20 minutes to do an errand won’t harm their oxygen levels. And he reminds them that having an exemption, in the form of a doctor’s letter, may bring more problems. “Even with an exemption, someone may confront them” for their lack of a face covering. People with COPD have a higher risk of getting a severe illness from COVID-19, according to the CDC.

This article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In the last 2 months, at least 10 patients have asked Constantine George, MD, for a written medical exemption so they won’t have to wear a mask in public. Dr. George, the chief medical officer of Vedius, an app for a travelers’ concierge medical service in Las Vegas, turned them all down.

Elena Christofides, MD, an endocrinologist in Columbus, Ohio, has also refused patients’ requests for exemptions.

“It’s very rare for someone to need an exemption,” says Albert Rizzo, MD, chief medical officer for the American Lung Association and a lung specialist at ChristianaCare Health System in Newark, Del.

The opposition is sometimes strong. Recently, a video of Lenka Koloma of Laguna Niguel, Calif., who founded the antimask Freedom to Breathe Agency, went viral. She was in a California supermarket, maskless, telling an employee she was breaking the law by requiring patrons to wear masks.

“People need oxygen,” she said. “That alone is a medical condition.” Her webpage has a “Face Mask Exempt Card” that cites the Americans with Disabilities Act and posts a Department of Justice ADA violation reporting number. The DOJ issued a statement calling the cards fraudulent.

Figuring out if a patient’s request to opt out of wearing a mask is legitimate is a ‘’new frontier” for doctors, says Mical Raz, MD, a professor in public policy and health at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), and a hospitalist at the university medical center.

Should some people skip masks?

Experts say there are very few medical reasons for people to skip masks. “If you look at the research, patients with COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder], those with reactive airway, even those can breathe through a mask,” Dr. George said. Requests for exemptions due to medical reasons are usually without basis. “Obviously, if someone is incapacitated, for example, with mental health issues, that’s case by case.”

Dr. Christofides said one of her patients cited anxiety and the other cited headaches as reasons not to wear a mask. “I told the one who asked for anxiety [reasons] that she could wear ones that were less tight.” The patient with headaches told Dr. Christofides that she had a buildup of carbon dioxide in the mask because of industrial exposure. Baloney, Dr. Christofides told her.

Dr. Rizzo says one rare example of someone who can’t wear a mask might be a patient with an advanced lung condition so severe, they need extra oxygen. “These are the extreme patients where any change in oxygen and carbon dioxide could make a difference,” he said. But “that’s also the population that shouldn’t be going out in the first place.”

Dr. Raz cowrote a commentary about mask exemptions, saying doctors are faced with difficult decisions and must keep a delicate balance between public health and individual disability needs. “Inappropriate medical exemptions may inadvertently hasten viral spread and threaten public health,” she wrote.

In an interview, she says that some people do have a hard time tolerating a mask. “Probably the most common reasons are mental health issues, such as anxiety, panic and PTSD, and children with sensory processing disorders (making them oversensitive to their environment). I think there are very few pulmonary reasons.”

CDC, professional organization guidelines

The CDC says people should wear masks in public and when around people who don’t live in the same household. Beyond that, it simply says masks should not be worn by children under age 2, “or anyone who has trouble breathing, is unconscious, incapacitated, or otherwise unable to remove the mask without assistance.”

In mid-July, four professional organizations released a statement in response to the CDC recommendation for facial coverings. Jointly issued by the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Lung Association, the American Thoracic Society and the COPD Foundation, it states in part that people with normal lungs and “even many individuals with underlying chronic lung disease should be able to wear a non-N95 facial covering without affecting their oxygen or carbon dioxide levels.”

It acknowledges that some people will seek an exemption and doctors must weigh the patient’s concerns against the need to stop the spread of the virus. “In some instances, physician reassurance regarding the safety of the facial coverings may be all that is needed,” it states.

Addressing the excuses

Here are some of the common medical reasons people give for not being able to tolerate a mask:

Claustrophobia or anxiety. Dr. Raz and others suggests a “desensitizing” period, wearing the mask for longer and longer periods of time to get used to it. Parents could suggest kids wear a mask when doing something they like, such as watching television, so they equate it with something pleasant. Switching to a different kind of mask or one that fits better could also help.

Masks cause Legionnaires’ disease. Not true, experts say. Legionnaires’ is a severe form of pneumonia, the result of inhaling tiny water droplets with legionella bacteria.

It’s difficult to read lips. People can buy masks with a clear window that makes their mouth and lips visible.

Trouble breathing. Brief periods of mask use won’t have a bad effect on oxygen levels for most people.

“There is not an inherent right to be out in a pandemic with an unmasked face,” Dr. Raz says. But “you are entitled to an accommodation.” That might be using curbside pickup for food and medication. That requires much less time wearing a mask than entering a store would.

There are no “boilerplate” cards or letters to excuse people provided by the four organizations that addressed the issue, Dr. Rizzo said. If he were to write a letter asking for an exemption, he would personalize it for an individual patient’s medical condition. As to whether a state would honor it, he cannot say. The states have a patchwork of recommendations, making it difficult to say.

Dr. Rizzo tells lung disease patients who are able to go out that wearing a mask for 15-20 minutes to do an errand won’t harm their oxygen levels. And he reminds them that having an exemption, in the form of a doctor’s letter, may bring more problems. “Even with an exemption, someone may confront them” for their lack of a face covering. People with COPD have a higher risk of getting a severe illness from COVID-19, according to the CDC.

This article first appeared on WebMD.com.