User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

ZUMA-5: Axi-cel yields high response rate in indolent NHL

, according to phase 2 study results presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, held virtually this year.

The overall response rate exceeded 90% in the ZUMA-5 study, which included patients with multiply relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL) or marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) who were treated with this anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy.

“Although longer follow-up is needed, these responses appear to be durable,” said investigator Caron Jacobson, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

Complete responses (CRs) after axi-cel treatment were seen in about three-quarters of patients, and most of those patients were still in response with a median follow-up that approached 1.5 years as of this report at the ASH meeting.

In her presentation, Dr. Jacobson said the safety profile of axi-cel in ZUMA-5 was manageable and “at least similar” to what was previously seen in aggressive relapsed lymphomas, referring to the ZUMA-1 study that led to 2017 approval by the Food and Drug Administration of the treatment for relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

The FL patient cohort in ZUMA-5 appeared to have lower rates of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and high-grade neurotoxicity, compared with the MZL cohort in the study, she added.

Catherine Bollard, MD, of Children’s National Research Institute in Washington, said these results suggest axi-cel may be a “viable treatment option” for some patients with indolent lymphomas who have not responded to other therapies.

“What the field does need is long-term follow-up in the real-world setting to see what the true progression-free and disease-free survival is for these patients,” said Dr. Bollard, who moderated a media briefing that included the ZUMA-5 study.

“It’s really exciting to see this data in the [indolent] lymphoma setting, and I actually would like to see it moved further up in the treatment of patients, earlier in their disease process, if that’s going to be possible,” she added.

Promising results

The report on ZUMA-5, presented by Dr. Jacobson, involved 146 patients with relapsed/refractory indolent NHL: 124 patients with FL and an exploratory cohort of 22 patients with MZL. All patients had received at least two prior lines of therapy.

Following a fludarabine/cyclophosphamide conditioning regimen, patients received axi-cel at the FDA-approved dose of 2 x 106 CAR-positive T cells per kg of body weight. The primary endpoint of the study was overall response rate (ORR).

For 104 patients evaluable for efficacy, the ORR was 92% (96 patients), including CR in 76% (79 patients), data show. Among 84 FL patients evaluable for efficacy, ORR and CR were 94% (79 patients) and 80% (67 patients), respectively, while among 20 evaluable patients in the exploratory MZL cohort, ORR and CR were 60% (12 patients) and 25% (5 patients), respectively.

Sixty-four percent of patients with FL had an ongoing response at a median follow-up of 17.5 months, according to Dr. Jacobson, who added that median duration of response (DOR) had not been reached, while the 12-month DOR rate approached 72%.

The 12-month progression-free survival and overall survival rates were 73.7% and 92.9%, respectively, with medians not yet reached for either survival outcome, according to reported data.

Adverse effects

The incidence of grade 3 or greater neurologic events was lower in FL patients (15%), compared with MZL patients (41%), according to Dr. Jacobson.

While CRS occurred in 82% of patients, rates of grade 3 or greater CRS occurred in just 6% of FL patients and 9% of MZL patients, the investigator said.

There were no grade 5 neurologic events, and one grade 5 CRS was observed, she noted in her presentation.

The median time to onset of CRS was 4 days, compared with 2 days in the ZUMA-1 trial. “This may have implications for the possibility of outpatient therapy,” she said.

A study is planned to look at outpatient administration of axi-cel in patients with indolent NHL, she added.

Dr. Jacobson said she had no conflicts of interest to declare. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Kite, a Gilead Company; Genentech; Epizyme; Verastem; Novartis; and Pfizer, among others.

Correction, 12/7/20: An earlier version of this article misattributed some aspects of the ZUMA-5 trial to ZUMA-1.

SOURCE: Jacobson CA et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 700.

, according to phase 2 study results presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, held virtually this year.

The overall response rate exceeded 90% in the ZUMA-5 study, which included patients with multiply relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL) or marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) who were treated with this anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy.

“Although longer follow-up is needed, these responses appear to be durable,” said investigator Caron Jacobson, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

Complete responses (CRs) after axi-cel treatment were seen in about three-quarters of patients, and most of those patients were still in response with a median follow-up that approached 1.5 years as of this report at the ASH meeting.

In her presentation, Dr. Jacobson said the safety profile of axi-cel in ZUMA-5 was manageable and “at least similar” to what was previously seen in aggressive relapsed lymphomas, referring to the ZUMA-1 study that led to 2017 approval by the Food and Drug Administration of the treatment for relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

The FL patient cohort in ZUMA-5 appeared to have lower rates of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and high-grade neurotoxicity, compared with the MZL cohort in the study, she added.

Catherine Bollard, MD, of Children’s National Research Institute in Washington, said these results suggest axi-cel may be a “viable treatment option” for some patients with indolent lymphomas who have not responded to other therapies.

“What the field does need is long-term follow-up in the real-world setting to see what the true progression-free and disease-free survival is for these patients,” said Dr. Bollard, who moderated a media briefing that included the ZUMA-5 study.

“It’s really exciting to see this data in the [indolent] lymphoma setting, and I actually would like to see it moved further up in the treatment of patients, earlier in their disease process, if that’s going to be possible,” she added.

Promising results

The report on ZUMA-5, presented by Dr. Jacobson, involved 146 patients with relapsed/refractory indolent NHL: 124 patients with FL and an exploratory cohort of 22 patients with MZL. All patients had received at least two prior lines of therapy.

Following a fludarabine/cyclophosphamide conditioning regimen, patients received axi-cel at the FDA-approved dose of 2 x 106 CAR-positive T cells per kg of body weight. The primary endpoint of the study was overall response rate (ORR).

For 104 patients evaluable for efficacy, the ORR was 92% (96 patients), including CR in 76% (79 patients), data show. Among 84 FL patients evaluable for efficacy, ORR and CR were 94% (79 patients) and 80% (67 patients), respectively, while among 20 evaluable patients in the exploratory MZL cohort, ORR and CR were 60% (12 patients) and 25% (5 patients), respectively.

Sixty-four percent of patients with FL had an ongoing response at a median follow-up of 17.5 months, according to Dr. Jacobson, who added that median duration of response (DOR) had not been reached, while the 12-month DOR rate approached 72%.

The 12-month progression-free survival and overall survival rates were 73.7% and 92.9%, respectively, with medians not yet reached for either survival outcome, according to reported data.

Adverse effects

The incidence of grade 3 or greater neurologic events was lower in FL patients (15%), compared with MZL patients (41%), according to Dr. Jacobson.

While CRS occurred in 82% of patients, rates of grade 3 or greater CRS occurred in just 6% of FL patients and 9% of MZL patients, the investigator said.

There were no grade 5 neurologic events, and one grade 5 CRS was observed, she noted in her presentation.

The median time to onset of CRS was 4 days, compared with 2 days in the ZUMA-1 trial. “This may have implications for the possibility of outpatient therapy,” she said.

A study is planned to look at outpatient administration of axi-cel in patients with indolent NHL, she added.

Dr. Jacobson said she had no conflicts of interest to declare. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Kite, a Gilead Company; Genentech; Epizyme; Verastem; Novartis; and Pfizer, among others.

Correction, 12/7/20: An earlier version of this article misattributed some aspects of the ZUMA-5 trial to ZUMA-1.

SOURCE: Jacobson CA et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 700.

, according to phase 2 study results presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, held virtually this year.

The overall response rate exceeded 90% in the ZUMA-5 study, which included patients with multiply relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL) or marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) who were treated with this anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy.

“Although longer follow-up is needed, these responses appear to be durable,” said investigator Caron Jacobson, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

Complete responses (CRs) after axi-cel treatment were seen in about three-quarters of patients, and most of those patients were still in response with a median follow-up that approached 1.5 years as of this report at the ASH meeting.

In her presentation, Dr. Jacobson said the safety profile of axi-cel in ZUMA-5 was manageable and “at least similar” to what was previously seen in aggressive relapsed lymphomas, referring to the ZUMA-1 study that led to 2017 approval by the Food and Drug Administration of the treatment for relapsed or refractory large B-cell lymphoma after two or more lines of systemic therapy.

The FL patient cohort in ZUMA-5 appeared to have lower rates of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and high-grade neurotoxicity, compared with the MZL cohort in the study, she added.

Catherine Bollard, MD, of Children’s National Research Institute in Washington, said these results suggest axi-cel may be a “viable treatment option” for some patients with indolent lymphomas who have not responded to other therapies.

“What the field does need is long-term follow-up in the real-world setting to see what the true progression-free and disease-free survival is for these patients,” said Dr. Bollard, who moderated a media briefing that included the ZUMA-5 study.

“It’s really exciting to see this data in the [indolent] lymphoma setting, and I actually would like to see it moved further up in the treatment of patients, earlier in their disease process, if that’s going to be possible,” she added.

Promising results

The report on ZUMA-5, presented by Dr. Jacobson, involved 146 patients with relapsed/refractory indolent NHL: 124 patients with FL and an exploratory cohort of 22 patients with MZL. All patients had received at least two prior lines of therapy.

Following a fludarabine/cyclophosphamide conditioning regimen, patients received axi-cel at the FDA-approved dose of 2 x 106 CAR-positive T cells per kg of body weight. The primary endpoint of the study was overall response rate (ORR).

For 104 patients evaluable for efficacy, the ORR was 92% (96 patients), including CR in 76% (79 patients), data show. Among 84 FL patients evaluable for efficacy, ORR and CR were 94% (79 patients) and 80% (67 patients), respectively, while among 20 evaluable patients in the exploratory MZL cohort, ORR and CR were 60% (12 patients) and 25% (5 patients), respectively.

Sixty-four percent of patients with FL had an ongoing response at a median follow-up of 17.5 months, according to Dr. Jacobson, who added that median duration of response (DOR) had not been reached, while the 12-month DOR rate approached 72%.

The 12-month progression-free survival and overall survival rates were 73.7% and 92.9%, respectively, with medians not yet reached for either survival outcome, according to reported data.

Adverse effects

The incidence of grade 3 or greater neurologic events was lower in FL patients (15%), compared with MZL patients (41%), according to Dr. Jacobson.

While CRS occurred in 82% of patients, rates of grade 3 or greater CRS occurred in just 6% of FL patients and 9% of MZL patients, the investigator said.

There were no grade 5 neurologic events, and one grade 5 CRS was observed, she noted in her presentation.

The median time to onset of CRS was 4 days, compared with 2 days in the ZUMA-1 trial. “This may have implications for the possibility of outpatient therapy,” she said.

A study is planned to look at outpatient administration of axi-cel in patients with indolent NHL, she added.

Dr. Jacobson said she had no conflicts of interest to declare. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Kite, a Gilead Company; Genentech; Epizyme; Verastem; Novartis; and Pfizer, among others.

Correction, 12/7/20: An earlier version of this article misattributed some aspects of the ZUMA-5 trial to ZUMA-1.

SOURCE: Jacobson CA et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 700.

FROM ASH 2020

COVID-19–related outcomes poor for patients with hematologic disease in ASH registry

Patients with hematologic disease who develop COVID-19 may experience substantial morbidity and mortality related to SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to recent registry data reported at the all-virtual annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Overall mortality was 28% for the first 250 patients entered into the ASH Research Collaborative COVID-19 Registry for Hematology, researchers reported in an abstract of their study findings.

However, the burden of death and moderate-to-severe COVID-19 outcomes was highest in patients with poorer prognosis and those with relapsed/refractory hematological disease, they added.

The most commonly represented malignancies were acute leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and myeloma or amyloidosis, according to the report.

Taken together, the findings do support an “emerging consensus” that COVID-19 related morbidity and mortality is significant in these patients, authors said – however, the current findings may not be reason enough to support a change in treatment course for the underlying disease.

“We see no reason, based on our data, to withhold intensive therapies from patients with underlying hematologic malignancies and favorable prognoses, if aggressive supportive care is consistent with patient preferences,” wrote the researchers.

ASH President Stephanie Lee, MD, MPH, said these registry findings are important to better understand how SARS-CoV-2 is affecting not only patients with hematologic diseases, but also individuals who experience COVID-19-related hematologic complications.

However, the findings are limited due to the heterogeneity of diseases, symptoms, and treatments represented in the registry, said Dr. Lee, associate director of the clinical research division at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle.

“More data will be coming in, but I think this is an example of trying to harness real-world information to try to learn things until we get more controlled studies,” Dr. Lee said in a media briefing held in advance of the ASH meeting.

Comorbidities and more

Patients with blood cancers are often older and may have comorbidities such as diabetes or hypertension that have been linked to poor COVID-19 outcomes, according to the authors of the report, led by William A. Wood, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine with the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, N.C.

Moreover, these patients may have underlying immune dysfunction and may receive chemotherapy or immunotherapy that is “profoundly immunosuppressive,” Dr. Wood and coauthors said in their report.

To date, however, risks of morbidity and mortality related to SARS-CoV-2 infection have not been well defined in this patient population, authors said.

More data is emerging now from the ASH Research Collaborative COVID-19 Registry for Hematology, which includes data on patients positive for COVID-19 who have a past or present hematologic condition or have experienced a hematologic complication related to COVID-19.

All data from the registry is being made available through a dashboard on the ASH Research Collaborative website, which as of Dec. 1, 2020, included 693 complete cases.

The data cut in the ASH abstract includes the first 250 patients enrolled at 74 sites around the world, the authors said. The most common malignancies included acute leukemia in 33%, non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 27%, and myeloma or amyloidosis in 16%.

The most frequently reported symptoms included fever in 73%, cough in 67%, dyspnea in 50%, and fatigue in 40%, according to that report.

At the time of this data snapshot, treatment with COVID-19-directed therapies including hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin were common, reported in 76 and 59 patients, respectively, in the cohort.

Batch submissions from sites with high incidence of COVID-19 infection are ongoing. The registry has been expanded to include nonmalignant hematologic diseases, and the registry will continue to accumulate data as a resource for the hematology community.

Overall mortality was 28% at the time, according to the abstract, with nearly all of the deaths occurring in patients classified as having COVID-19 that was moderate (i.e., requiring hospitalization) or severe (i.e., requiring ICU admission).

“In some instances, death occurred after a decision was made to forgo ICU admission in favor of a palliative approach,” said Dr. Wood and coauthors in their report.

Dr. Wood reported research funding from Pfizer, consultancy with Teladoc/Best Doctors, and honoraria from the ASH Research Collaborative. Coauthors provided disclosures related to Celgene, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, Pharmacyclics, and Amgen, among others.

SOURCE: Wood WA et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 215.

Patients with hematologic disease who develop COVID-19 may experience substantial morbidity and mortality related to SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to recent registry data reported at the all-virtual annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Overall mortality was 28% for the first 250 patients entered into the ASH Research Collaborative COVID-19 Registry for Hematology, researchers reported in an abstract of their study findings.

However, the burden of death and moderate-to-severe COVID-19 outcomes was highest in patients with poorer prognosis and those with relapsed/refractory hematological disease, they added.

The most commonly represented malignancies were acute leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and myeloma or amyloidosis, according to the report.

Taken together, the findings do support an “emerging consensus” that COVID-19 related morbidity and mortality is significant in these patients, authors said – however, the current findings may not be reason enough to support a change in treatment course for the underlying disease.

“We see no reason, based on our data, to withhold intensive therapies from patients with underlying hematologic malignancies and favorable prognoses, if aggressive supportive care is consistent with patient preferences,” wrote the researchers.

ASH President Stephanie Lee, MD, MPH, said these registry findings are important to better understand how SARS-CoV-2 is affecting not only patients with hematologic diseases, but also individuals who experience COVID-19-related hematologic complications.

However, the findings are limited due to the heterogeneity of diseases, symptoms, and treatments represented in the registry, said Dr. Lee, associate director of the clinical research division at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle.

“More data will be coming in, but I think this is an example of trying to harness real-world information to try to learn things until we get more controlled studies,” Dr. Lee said in a media briefing held in advance of the ASH meeting.

Comorbidities and more

Patients with blood cancers are often older and may have comorbidities such as diabetes or hypertension that have been linked to poor COVID-19 outcomes, according to the authors of the report, led by William A. Wood, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine with the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, N.C.

Moreover, these patients may have underlying immune dysfunction and may receive chemotherapy or immunotherapy that is “profoundly immunosuppressive,” Dr. Wood and coauthors said in their report.

To date, however, risks of morbidity and mortality related to SARS-CoV-2 infection have not been well defined in this patient population, authors said.

More data is emerging now from the ASH Research Collaborative COVID-19 Registry for Hematology, which includes data on patients positive for COVID-19 who have a past or present hematologic condition or have experienced a hematologic complication related to COVID-19.

All data from the registry is being made available through a dashboard on the ASH Research Collaborative website, which as of Dec. 1, 2020, included 693 complete cases.

The data cut in the ASH abstract includes the first 250 patients enrolled at 74 sites around the world, the authors said. The most common malignancies included acute leukemia in 33%, non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 27%, and myeloma or amyloidosis in 16%.

The most frequently reported symptoms included fever in 73%, cough in 67%, dyspnea in 50%, and fatigue in 40%, according to that report.

At the time of this data snapshot, treatment with COVID-19-directed therapies including hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin were common, reported in 76 and 59 patients, respectively, in the cohort.

Batch submissions from sites with high incidence of COVID-19 infection are ongoing. The registry has been expanded to include nonmalignant hematologic diseases, and the registry will continue to accumulate data as a resource for the hematology community.

Overall mortality was 28% at the time, according to the abstract, with nearly all of the deaths occurring in patients classified as having COVID-19 that was moderate (i.e., requiring hospitalization) or severe (i.e., requiring ICU admission).

“In some instances, death occurred after a decision was made to forgo ICU admission in favor of a palliative approach,” said Dr. Wood and coauthors in their report.

Dr. Wood reported research funding from Pfizer, consultancy with Teladoc/Best Doctors, and honoraria from the ASH Research Collaborative. Coauthors provided disclosures related to Celgene, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, Pharmacyclics, and Amgen, among others.

SOURCE: Wood WA et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 215.

Patients with hematologic disease who develop COVID-19 may experience substantial morbidity and mortality related to SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to recent registry data reported at the all-virtual annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Overall mortality was 28% for the first 250 patients entered into the ASH Research Collaborative COVID-19 Registry for Hematology, researchers reported in an abstract of their study findings.

However, the burden of death and moderate-to-severe COVID-19 outcomes was highest in patients with poorer prognosis and those with relapsed/refractory hematological disease, they added.

The most commonly represented malignancies were acute leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and myeloma or amyloidosis, according to the report.

Taken together, the findings do support an “emerging consensus” that COVID-19 related morbidity and mortality is significant in these patients, authors said – however, the current findings may not be reason enough to support a change in treatment course for the underlying disease.

“We see no reason, based on our data, to withhold intensive therapies from patients with underlying hematologic malignancies and favorable prognoses, if aggressive supportive care is consistent with patient preferences,” wrote the researchers.

ASH President Stephanie Lee, MD, MPH, said these registry findings are important to better understand how SARS-CoV-2 is affecting not only patients with hematologic diseases, but also individuals who experience COVID-19-related hematologic complications.

However, the findings are limited due to the heterogeneity of diseases, symptoms, and treatments represented in the registry, said Dr. Lee, associate director of the clinical research division at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle.

“More data will be coming in, but I think this is an example of trying to harness real-world information to try to learn things until we get more controlled studies,” Dr. Lee said in a media briefing held in advance of the ASH meeting.

Comorbidities and more

Patients with blood cancers are often older and may have comorbidities such as diabetes or hypertension that have been linked to poor COVID-19 outcomes, according to the authors of the report, led by William A. Wood, MD, MPH, associate professor of medicine with the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill, N.C.

Moreover, these patients may have underlying immune dysfunction and may receive chemotherapy or immunotherapy that is “profoundly immunosuppressive,” Dr. Wood and coauthors said in their report.

To date, however, risks of morbidity and mortality related to SARS-CoV-2 infection have not been well defined in this patient population, authors said.

More data is emerging now from the ASH Research Collaborative COVID-19 Registry for Hematology, which includes data on patients positive for COVID-19 who have a past or present hematologic condition or have experienced a hematologic complication related to COVID-19.

All data from the registry is being made available through a dashboard on the ASH Research Collaborative website, which as of Dec. 1, 2020, included 693 complete cases.

The data cut in the ASH abstract includes the first 250 patients enrolled at 74 sites around the world, the authors said. The most common malignancies included acute leukemia in 33%, non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 27%, and myeloma or amyloidosis in 16%.

The most frequently reported symptoms included fever in 73%, cough in 67%, dyspnea in 50%, and fatigue in 40%, according to that report.

At the time of this data snapshot, treatment with COVID-19-directed therapies including hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin were common, reported in 76 and 59 patients, respectively, in the cohort.

Batch submissions from sites with high incidence of COVID-19 infection are ongoing. The registry has been expanded to include nonmalignant hematologic diseases, and the registry will continue to accumulate data as a resource for the hematology community.

Overall mortality was 28% at the time, according to the abstract, with nearly all of the deaths occurring in patients classified as having COVID-19 that was moderate (i.e., requiring hospitalization) or severe (i.e., requiring ICU admission).

“In some instances, death occurred after a decision was made to forgo ICU admission in favor of a palliative approach,” said Dr. Wood and coauthors in their report.

Dr. Wood reported research funding from Pfizer, consultancy with Teladoc/Best Doctors, and honoraria from the ASH Research Collaborative. Coauthors provided disclosures related to Celgene, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, Pharmacyclics, and Amgen, among others.

SOURCE: Wood WA et al. ASH 2020, Abstract 215.

FROM ASH 2020

Infant’s COVID-19–related myocardial injury reversed

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

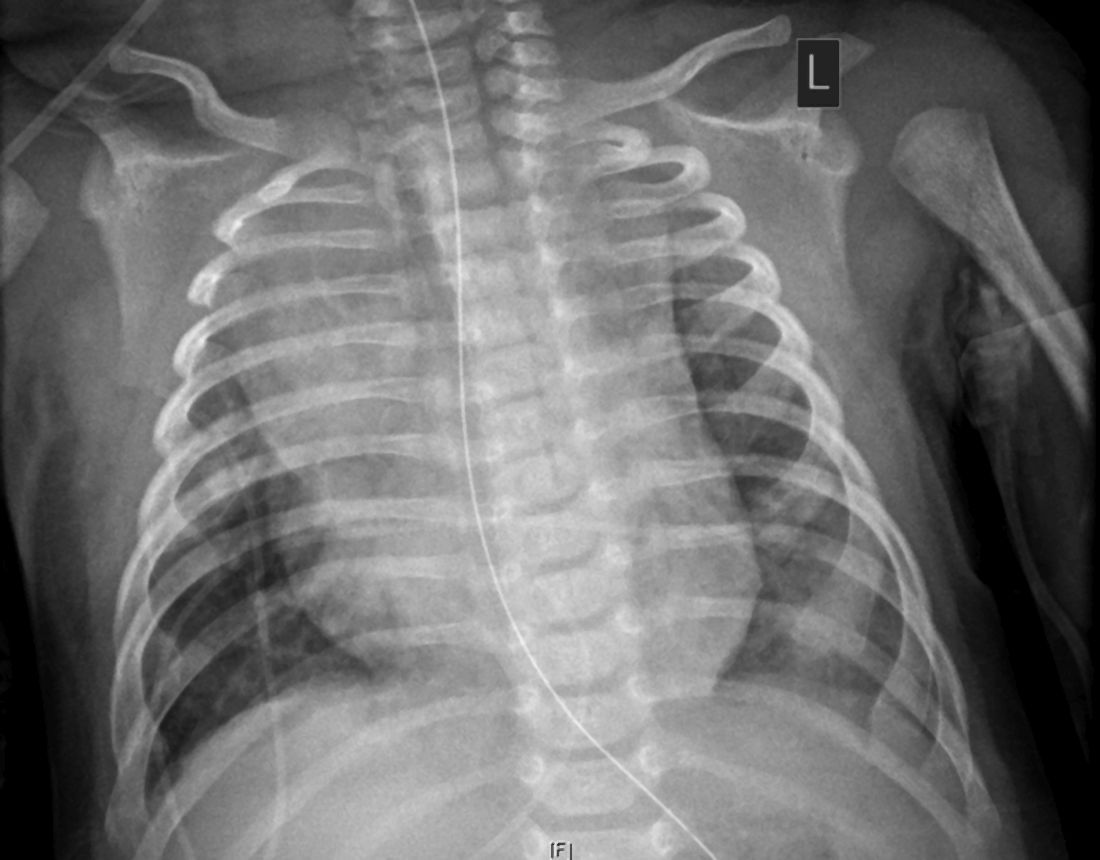

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

Reports of signs of heart failure in adults with COVID-19 have been rare – just four such cases have been published since the outbreak started in China – and now a team of pediatric cardiologists in New York have reported a case of acute but reversible myocardial injury in an infant with COVID-19.

and right upper lobe atelectasis.

The 2-month-old infant went home after more than 2 weeks in the hospital with no apparent lingering cardiac effects of the illness and not needing any oral heart failure medications, Madhu Sharma, MD, of the Children’s Hospital and Montefiore in New York and colleagues reported in JACC Case Reports. With close follow-up, the child’s left ventricle size and systolic function have remained normal and mitral regurgitation resolved. The case report didn’t mention the infant’s gender.

But before the straightforward postdischarge course emerged, the infant was in a precarious state, and Dr. Sharma and her team were challenged to diagnose the underlying causes.

The child, who was born about 7 weeks premature, first came to the hospital having turned blue after choking on food. Nonrebreather mask ventilation was initiated in the ED, and an examination detected a holosystolic murmur. A test for COVID-19 was negative, but a later test was positive, and a chest x-ray exhibited cardiomegaly and signs of fluid and inflammation in the lungs.

An electrocardiogram detected sinus tachycardia, ST-segment depression and other anomalies in cardiac function. Further investigation with a transthoracic ECG showed severely depressed left ventricle systolic function with an ejection fraction of 30%, severe mitral regurgitation, and normal right ventricular systolic function.

Treatment included remdesivir and intravenous antibiotics. Through the hospital course, the patient was extubated to noninvasive ventilation, reintubated, put on intravenous steroid (methylprednisolone) and low-molecular-weight heparin, extubated, and tested throughout for cardiac function.

By day 14, left ventricle size and function normalized, and while the mitral regurgitation remained severe, it improved later without HF therapies. Left ventricle ejection fraction had recovered to 60%, and key cardiac biomarkers had normalized. On day 16, milrinone was discontinued, and the care team determined the patient no longer needed oral heart failure therapies.

“Most children with COVID-19 are either asymptomatic or have mild symptoms, but our case shows the potential for reversible myocardial injury in infants with COVID-19,” said Dr. Sharma. “Testing for COVID-19 in children presenting with signs and symptoms of heart failure is very important as we learn more about the impact of this virus.”

Dr. Sharma and coauthors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

FROM JACC CASE REPORTS

Key clinical point: Children presenting with COVID-19 should be tested for heart failure.

Major finding: A 2-month-old infant with COVID-19 had acute but reversible myocardial injury.

Study details: Single case report.

Disclosures: Dr. Sharma, MD, has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Source: Sharma M et al. JACC Case Rep. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.031.

Cancer rates on the rise in adolescents and young adults

Rates of cancer increased by 30% from 1973 to 2015 in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) aged 15–39 years in the United States, according to a review of almost a half million cases in the National Institutes of Health’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database.

There was an annual increase of 0.537 new cases per 100,000 people, from 57.2 cases per 100,000 in 1973 to 74.2 in 2015.

Kidney carcinoma led with the highest rate increase. There were also marked increases in thyroid and colorectal carcinoma, germ cell and trophoblastic neoplasms, and melanoma, among others.

The report was published online December 1 in JAMA Network Open.

“Clinicians should be on the lookout for these cancers in their adolescent and young adult patients,” said senior investigator Nicholas Zaorsky, MD, an assistant professor of radiation oncology and public health sciences at the Penn State Cancer Institute, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

“Now that there is a better understanding of the types of cancer that are prevalent and rising in this age group, prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment protocols specifically targeted to this population should be developed,” he said in a press release.

The reasons for the increases are unclear, but environmental and dietary factors, increasing obesity, and changing screening practices are likely in play, the authors comment. In addition, “cancer screening and overdiagnosis are thought to account for much of the increasing rates of thyroid and kidney carcinoma, among others,” they add.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) recently found similar increases in thyroid, kidney, and colorectal cancer among AYAs, as well as an increase in uterine cancer.

It’s important to note, however, that “this phenomenon is largely driven by trends for thyroid cancer, which is thought to be a result of overdiagnosis,” said ACS surveillance researcher Kimberly Miller, MPH, when asked to comment on the new study.

“As such, it is extremely important to also consider trends in cancer mortality rates among this age group, which are declining overall but are increasing for colorectal and uterine cancers. The fact that both incidence and mortality rates are increasing for these two cancers suggests a true increase in disease burden and certainly requires further attention and research,” she said.

Historically, management of cancer in AYAs has fallen somewhere between pediatric and adult oncology, neither of which capture the distinct biological, social, and economic needs of AYAs. Research has also focused on childhood and adult cancers, leaving cancer in AYAs inadequately studied.

The new findings are “valuable to guide more targeted research and interventions specifically to AYAs,” Zaorsky and colleagues say in their report.

Among female patients ― 59.1% of the study population ― incidence increased for 15 cancers, including kidney carcinoma (annual percent change [APC], 3.632), thyroid carcinoma (APC, 3.456), and myeloma, mast cell, and miscellaneous lymphoreticular neoplasms not otherwise specified (APC, 2.805). Rates of five cancers declined, led by astrocytoma not otherwise specified (APC, –3.369) and carcinoma of the gonads (APC, –1.743).

Among male patients, incidence increased for 14 cancers, including kidney carcinoma (APC, 3.572), unspecified soft tissue sarcoma (APC 2.543), and thyroid carcinoma (APC, 2.273). Incidence fell for seven, led by astrocytoma not otherwise specified (APC, –3.759) and carcinoma of the trachea, bronchus, and lung (APC, –2.635).

Increased testicular cancer rates (APC, 1.246) could be related to greater prenatal exposure to estrogen and progesterone or through dairy consumption; increasing survival of premature infants; and greater exposure to cannabis, among other possibilities, the investigators say.

Increases in colorectal cancer might be related to fewer vegetables and more fat and processed meat in the diet; lack of exercise; and increasing obesity. Human papillomavirus infection has also been implicated.

Higher rates of melanoma could be related to tanning bed use.

Declines in some cancers could be related to greater use of oral contraceptives; laws reducing exposure to benzene and other chemicals; and fewer people smoking.

Although kidney carcinoma has increased at the greatest rate, it’s uncommon. Colorectal and thyroid carcinoma, melanoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and germ cell and trophoblastic neoplasms of the gonads contribute more to the overall increase in cancers among AYAs, the investigators note.

Almost 80% of the patients were White; 10.3% were Black.

The study was funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The investigators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rates of cancer increased by 30% from 1973 to 2015 in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) aged 15–39 years in the United States, according to a review of almost a half million cases in the National Institutes of Health’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database.

There was an annual increase of 0.537 new cases per 100,000 people, from 57.2 cases per 100,000 in 1973 to 74.2 in 2015.

Kidney carcinoma led with the highest rate increase. There were also marked increases in thyroid and colorectal carcinoma, germ cell and trophoblastic neoplasms, and melanoma, among others.

The report was published online December 1 in JAMA Network Open.

“Clinicians should be on the lookout for these cancers in their adolescent and young adult patients,” said senior investigator Nicholas Zaorsky, MD, an assistant professor of radiation oncology and public health sciences at the Penn State Cancer Institute, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

“Now that there is a better understanding of the types of cancer that are prevalent and rising in this age group, prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment protocols specifically targeted to this population should be developed,” he said in a press release.

The reasons for the increases are unclear, but environmental and dietary factors, increasing obesity, and changing screening practices are likely in play, the authors comment. In addition, “cancer screening and overdiagnosis are thought to account for much of the increasing rates of thyroid and kidney carcinoma, among others,” they add.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) recently found similar increases in thyroid, kidney, and colorectal cancer among AYAs, as well as an increase in uterine cancer.

It’s important to note, however, that “this phenomenon is largely driven by trends for thyroid cancer, which is thought to be a result of overdiagnosis,” said ACS surveillance researcher Kimberly Miller, MPH, when asked to comment on the new study.

“As such, it is extremely important to also consider trends in cancer mortality rates among this age group, which are declining overall but are increasing for colorectal and uterine cancers. The fact that both incidence and mortality rates are increasing for these two cancers suggests a true increase in disease burden and certainly requires further attention and research,” she said.

Historically, management of cancer in AYAs has fallen somewhere between pediatric and adult oncology, neither of which capture the distinct biological, social, and economic needs of AYAs. Research has also focused on childhood and adult cancers, leaving cancer in AYAs inadequately studied.

The new findings are “valuable to guide more targeted research and interventions specifically to AYAs,” Zaorsky and colleagues say in their report.

Among female patients ― 59.1% of the study population ― incidence increased for 15 cancers, including kidney carcinoma (annual percent change [APC], 3.632), thyroid carcinoma (APC, 3.456), and myeloma, mast cell, and miscellaneous lymphoreticular neoplasms not otherwise specified (APC, 2.805). Rates of five cancers declined, led by astrocytoma not otherwise specified (APC, –3.369) and carcinoma of the gonads (APC, –1.743).

Among male patients, incidence increased for 14 cancers, including kidney carcinoma (APC, 3.572), unspecified soft tissue sarcoma (APC 2.543), and thyroid carcinoma (APC, 2.273). Incidence fell for seven, led by astrocytoma not otherwise specified (APC, –3.759) and carcinoma of the trachea, bronchus, and lung (APC, –2.635).

Increased testicular cancer rates (APC, 1.246) could be related to greater prenatal exposure to estrogen and progesterone or through dairy consumption; increasing survival of premature infants; and greater exposure to cannabis, among other possibilities, the investigators say.

Increases in colorectal cancer might be related to fewer vegetables and more fat and processed meat in the diet; lack of exercise; and increasing obesity. Human papillomavirus infection has also been implicated.

Higher rates of melanoma could be related to tanning bed use.

Declines in some cancers could be related to greater use of oral contraceptives; laws reducing exposure to benzene and other chemicals; and fewer people smoking.

Although kidney carcinoma has increased at the greatest rate, it’s uncommon. Colorectal and thyroid carcinoma, melanoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and germ cell and trophoblastic neoplasms of the gonads contribute more to the overall increase in cancers among AYAs, the investigators note.

Almost 80% of the patients were White; 10.3% were Black.

The study was funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The investigators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rates of cancer increased by 30% from 1973 to 2015 in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) aged 15–39 years in the United States, according to a review of almost a half million cases in the National Institutes of Health’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database.

There was an annual increase of 0.537 new cases per 100,000 people, from 57.2 cases per 100,000 in 1973 to 74.2 in 2015.

Kidney carcinoma led with the highest rate increase. There were also marked increases in thyroid and colorectal carcinoma, germ cell and trophoblastic neoplasms, and melanoma, among others.

The report was published online December 1 in JAMA Network Open.

“Clinicians should be on the lookout for these cancers in their adolescent and young adult patients,” said senior investigator Nicholas Zaorsky, MD, an assistant professor of radiation oncology and public health sciences at the Penn State Cancer Institute, Hershey, Pennsylvania.

“Now that there is a better understanding of the types of cancer that are prevalent and rising in this age group, prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment protocols specifically targeted to this population should be developed,” he said in a press release.

The reasons for the increases are unclear, but environmental and dietary factors, increasing obesity, and changing screening practices are likely in play, the authors comment. In addition, “cancer screening and overdiagnosis are thought to account for much of the increasing rates of thyroid and kidney carcinoma, among others,” they add.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) recently found similar increases in thyroid, kidney, and colorectal cancer among AYAs, as well as an increase in uterine cancer.

It’s important to note, however, that “this phenomenon is largely driven by trends for thyroid cancer, which is thought to be a result of overdiagnosis,” said ACS surveillance researcher Kimberly Miller, MPH, when asked to comment on the new study.

“As such, it is extremely important to also consider trends in cancer mortality rates among this age group, which are declining overall but are increasing for colorectal and uterine cancers. The fact that both incidence and mortality rates are increasing for these two cancers suggests a true increase in disease burden and certainly requires further attention and research,” she said.

Historically, management of cancer in AYAs has fallen somewhere between pediatric and adult oncology, neither of which capture the distinct biological, social, and economic needs of AYAs. Research has also focused on childhood and adult cancers, leaving cancer in AYAs inadequately studied.

The new findings are “valuable to guide more targeted research and interventions specifically to AYAs,” Zaorsky and colleagues say in their report.

Among female patients ― 59.1% of the study population ― incidence increased for 15 cancers, including kidney carcinoma (annual percent change [APC], 3.632), thyroid carcinoma (APC, 3.456), and myeloma, mast cell, and miscellaneous lymphoreticular neoplasms not otherwise specified (APC, 2.805). Rates of five cancers declined, led by astrocytoma not otherwise specified (APC, –3.369) and carcinoma of the gonads (APC, –1.743).

Among male patients, incidence increased for 14 cancers, including kidney carcinoma (APC, 3.572), unspecified soft tissue sarcoma (APC 2.543), and thyroid carcinoma (APC, 2.273). Incidence fell for seven, led by astrocytoma not otherwise specified (APC, –3.759) and carcinoma of the trachea, bronchus, and lung (APC, –2.635).

Increased testicular cancer rates (APC, 1.246) could be related to greater prenatal exposure to estrogen and progesterone or through dairy consumption; increasing survival of premature infants; and greater exposure to cannabis, among other possibilities, the investigators say.

Increases in colorectal cancer might be related to fewer vegetables and more fat and processed meat in the diet; lack of exercise; and increasing obesity. Human papillomavirus infection has also been implicated.

Higher rates of melanoma could be related to tanning bed use.

Declines in some cancers could be related to greater use of oral contraceptives; laws reducing exposure to benzene and other chemicals; and fewer people smoking.

Although kidney carcinoma has increased at the greatest rate, it’s uncommon. Colorectal and thyroid carcinoma, melanoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and germ cell and trophoblastic neoplasms of the gonads contribute more to the overall increase in cancers among AYAs, the investigators note.

Almost 80% of the patients were White; 10.3% were Black.

The study was funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The investigators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA clears first drug for rare genetic causes of severe obesity

The Food and Drug Administration has approved setmelanotide (Imcivree, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals) for weight management in adults and children as young as 6 years with obesity because of proopiomelanocortin (POMC), proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 (PCSK1), or leptin receptor (LEPR) deficiency confirmed by genetic testing.

Individuals with these rare genetic causes of severe obesity have a normal weight at birth but develop persistent severe obesity within months because of insatiable hunger (hyperphagia).

Setmelanotide, a melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) agonist, is the first FDA-approved therapy for these disorders.

“Many patients and families who live with these diseases face an often-burdensome stigma associated with severe obesity. To manage this obesity and control disruptive food-seeking behavior, caregivers often lock cabinets and refrigerators and significantly limit social activities,” said Jennifer Miller, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist at University of Florida Health, Gainesville, in a press release issued by the company.

“This FDA approval marks an important turning point, providing a much needed therapy and supporting the use of genetic testing to identify and properly diagnose patients with these rare genetic diseases of obesity,” she noted.

David Meeker, MD, chair, president, and CEO of Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, added: “We are advancing a first-in-class, precision medicine that is designed to directly address the underlying cause of obesities driven by genetic deficits in the MC4R pathway.”

Setmelanotide was evaluated in two phase 3 clinical trials. In one trial, 80% of patients with obesity caused by POMC or PCSK1 deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss after 1 year of treatment.

In the other trial, 45.5% of patients with obesity caused by LEPR deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss with 1 year of treatment.

Results for the two trials were recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology and discussed at the ObesityWeek Interactive 2020 meeting.

Setmelanotide was generally well tolerated in both trials. The most common adverse events were injection-site reactions, skin hyperpigmentation, and nausea.

The drug label notes that disturbances in sexual arousal, depression, and suicidal ideation; skin pigmentation; and darkening of preexisting nevi may occur with setmelanotide treatment.

The drug label also notes a risk for serious adverse reactions because of benzyl alcohol preservative in neonates and low-birth-weight infants. Setmelanotide is not approved for use in neonates or infants.

The company expects the drug to be commercially available in the United States in the first quarter of 2021.

Setmelanotide for the treatment of obesity associated with rare genetic defects had FDA breakthrough therapy designation as well as orphan drug designation.

The company is also evaluating setmelanotide for reduction in hunger and body weight in a pivotal phase 3 trial in people living with Bardet-Biedl or Alström syndrome, and top-line data are due soon.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved setmelanotide (Imcivree, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals) for weight management in adults and children as young as 6 years with obesity because of proopiomelanocortin (POMC), proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 (PCSK1), or leptin receptor (LEPR) deficiency confirmed by genetic testing.

Individuals with these rare genetic causes of severe obesity have a normal weight at birth but develop persistent severe obesity within months because of insatiable hunger (hyperphagia).

Setmelanotide, a melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) agonist, is the first FDA-approved therapy for these disorders.

“Many patients and families who live with these diseases face an often-burdensome stigma associated with severe obesity. To manage this obesity and control disruptive food-seeking behavior, caregivers often lock cabinets and refrigerators and significantly limit social activities,” said Jennifer Miller, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist at University of Florida Health, Gainesville, in a press release issued by the company.

“This FDA approval marks an important turning point, providing a much needed therapy and supporting the use of genetic testing to identify and properly diagnose patients with these rare genetic diseases of obesity,” she noted.

David Meeker, MD, chair, president, and CEO of Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, added: “We are advancing a first-in-class, precision medicine that is designed to directly address the underlying cause of obesities driven by genetic deficits in the MC4R pathway.”

Setmelanotide was evaluated in two phase 3 clinical trials. In one trial, 80% of patients with obesity caused by POMC or PCSK1 deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss after 1 year of treatment.

In the other trial, 45.5% of patients with obesity caused by LEPR deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss with 1 year of treatment.

Results for the two trials were recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology and discussed at the ObesityWeek Interactive 2020 meeting.

Setmelanotide was generally well tolerated in both trials. The most common adverse events were injection-site reactions, skin hyperpigmentation, and nausea.

The drug label notes that disturbances in sexual arousal, depression, and suicidal ideation; skin pigmentation; and darkening of preexisting nevi may occur with setmelanotide treatment.

The drug label also notes a risk for serious adverse reactions because of benzyl alcohol preservative in neonates and low-birth-weight infants. Setmelanotide is not approved for use in neonates or infants.

The company expects the drug to be commercially available in the United States in the first quarter of 2021.

Setmelanotide for the treatment of obesity associated with rare genetic defects had FDA breakthrough therapy designation as well as orphan drug designation.

The company is also evaluating setmelanotide for reduction in hunger and body weight in a pivotal phase 3 trial in people living with Bardet-Biedl or Alström syndrome, and top-line data are due soon.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved setmelanotide (Imcivree, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals) for weight management in adults and children as young as 6 years with obesity because of proopiomelanocortin (POMC), proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 (PCSK1), or leptin receptor (LEPR) deficiency confirmed by genetic testing.

Individuals with these rare genetic causes of severe obesity have a normal weight at birth but develop persistent severe obesity within months because of insatiable hunger (hyperphagia).

Setmelanotide, a melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) agonist, is the first FDA-approved therapy for these disorders.

“Many patients and families who live with these diseases face an often-burdensome stigma associated with severe obesity. To manage this obesity and control disruptive food-seeking behavior, caregivers often lock cabinets and refrigerators and significantly limit social activities,” said Jennifer Miller, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist at University of Florida Health, Gainesville, in a press release issued by the company.

“This FDA approval marks an important turning point, providing a much needed therapy and supporting the use of genetic testing to identify and properly diagnose patients with these rare genetic diseases of obesity,” she noted.

David Meeker, MD, chair, president, and CEO of Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, added: “We are advancing a first-in-class, precision medicine that is designed to directly address the underlying cause of obesities driven by genetic deficits in the MC4R pathway.”

Setmelanotide was evaluated in two phase 3 clinical trials. In one trial, 80% of patients with obesity caused by POMC or PCSK1 deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss after 1 year of treatment.

In the other trial, 45.5% of patients with obesity caused by LEPR deficiency achieved greater than 10% weight loss with 1 year of treatment.

Results for the two trials were recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology and discussed at the ObesityWeek Interactive 2020 meeting.

Setmelanotide was generally well tolerated in both trials. The most common adverse events were injection-site reactions, skin hyperpigmentation, and nausea.

The drug label notes that disturbances in sexual arousal, depression, and suicidal ideation; skin pigmentation; and darkening of preexisting nevi may occur with setmelanotide treatment.

The drug label also notes a risk for serious adverse reactions because of benzyl alcohol preservative in neonates and low-birth-weight infants. Setmelanotide is not approved for use in neonates or infants.

The company expects the drug to be commercially available in the United States in the first quarter of 2021.

Setmelanotide for the treatment of obesity associated with rare genetic defects had FDA breakthrough therapy designation as well as orphan drug designation.

The company is also evaluating setmelanotide for reduction in hunger and body weight in a pivotal phase 3 trial in people living with Bardet-Biedl or Alström syndrome, and top-line data are due soon.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

VTE prophylaxis is feasible, effective in some high-risk cancer patients

Primary thromboprophylaxis is feasible and worth considering for high-risk ambulatory patients with cancer who are initiating systemic chemotherapy, according to Marc Carrier, MD.

Risk scores can identify patients at high risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE), and treatments that are effective and associated with low bleeding risk are available, Dr. Carrier explained at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America.

However, caution is advised in patients with certain types of cancer, including some gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancers, because of the possibility of increased major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding risk, he said.

VTE and cancer

VTE is relatively rare in the general population, occurring in about 1 or 2 per 1,000 people annually. The risk increases 4.1-fold in patients with cancer, and 6.5-fold in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy.

“So just putting these numbers together, we’re no longer talking about 1 in 1,000, but 1 in 200, so [this is] something that is very common among cancer patients,” said Dr. Carrier, a professor at the University of Ottawa and chief of the division of hematology at The Ottawa Hospital.

The mortality rate associated with cancer-associated thrombosis is about 9%, comparable to that associated with infection in the cancer outpatient setting, which underscores the importance of educating patients about the signs and symptoms of VTE so they can seek medical treatment quickly if necessary, he added.

It may also be useful to discuss prophylaxis or other ways to prevent venous thromboembolic complications with certain patients, he said, noting that in an observational cohort study of nearly 600 patients at the University of Ottawa, 25% of those initiating chemotherapy were identified as intermediate or high risk using the validated Khorana risk score, and thus would likely benefit from thromboprophylaxis.

Risk assessment

The Khorana risk score assesses VTE risk based on cancer site, blood counts, and body mass index. It is simple to use and has been validated in more than 20,000 people in multiple countries, Dr. Carrier said.

In a well-known validation study, Ay et al. showed a VTE complication rate of 10% in patients with a Khorana risk score of 2 or higher who were followed up to 6 months.

“This is huge,” Dr. Carrier stressed. “This is much higher than what we tolerate for all sorts of different populations for which we would recommend anticoagulation or thromboprophylaxis.”

The question is whether the risk score can be helpful in a real-world clinic setting, he said, adding: “I’d like to think the answer to that is yes.”

In the University of Ottawa cohort study, 11% of high-risk patients experienced a VTE complication, compared with 4% of those with lower risk, suggesting that the validation data for the Khorana risk score is not only accurate, it is “actually applicable in real-world practice, and you can use it in your own center,” he said.

Further, recent studies have demonstrated that treatment based on Khorana risk score assessment reduces VTE complications.

Prophylaxis options

Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) has been shown in several studies to be associated with a significant relative VTE risk reduction in patients with cancer initiating chemotherapy – with only a slight, nonsignificant increase in the risk of major bleeding.

However, the absolute benefit was small, and LMWH is “parenteral, relatively costly, and, based on that, although we showed relatively good risk-benefit ratio, it never really got translated to clinical practice,” Dr. Carrier said.

In fact, a 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines update recommended against routine thromboprophylaxis in this setting, but stated that it could be considered in select high-risk patients identified using a validated risk-assessment tool.

The guidelines noted that “individual risk factors such as biomarkers and cancer site don’t reliably identify high-risk patients.”

More recent data provide additional support for risk assessment and treatment based on Khorana risk score of 2 or higher.

The AVERT trial, for which Dr. Carrier was the first author, showed that the direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC) apixaban reduced VTE incidence, compared with placebo, in patients with Khorana score of 2 or higher (4.2% vs. 10.2%; hazard ratio, 0.41 overall, and 1.0 vs. 7.3; HR, 0.14 on treatment), and the CASSINI trial showed that another DOAC, rivaroxaban, reduced VTE incidence, compared with placebo, in those with Khorana score of 2 or higher (5.9 vs. 6.7; HR, 0.6 overall, and 2.6 vs. 6.4; HR, 0.40 on treatment). The differences in the on-treatment populations were statistically significant.

The two trials, which included a variety of tumor types, showed similar rates of major bleeding, with an absolute difference of about 1% between treatment and placebo, which was not statistically significant in the on-treatment analyses (HR, 1.89 in AVERT and HR, 1.96 in CASSINI).

A systematic review of these trials showed an overall significant decrease in VTE complication risk with treatment in high-risk patients, and a nonstatistically significant major bleeding risk increase.

Based on these findings, ASCO guidelines were updated in 2020 to state that “routine thromboprophylaxis should not be offered to all patients with cancer. ... However, high-risk outpatients with cancer may be offered thromboprophylaxis with apixaban, rivaroxaban or LMWH, providing there are no significant risk factors for bleeding or drug-drug interactions, and after having a full discussion with patients ... to make sure they understand the risk-benefit ratio and the rationale for that particular recommendation,” he said.

Real-world implementation

Implementing this approach in the clinic setting requires a practical model, such as the Venous Thromboembolism Prevention in the Ambulatory Cancer Clinic (VTEPACC) program, a prospective quality improvement research initiative developed in collaboration with the Jeffords Institute for Quality at the University of Vermont Medical Center and described in a recent report, Dr. Carrier said.

The “Vermont model” is “really a comprehensive model that includes identifying patients with the electronic medical records, gathering the formal education and insight from other health care providers like pharmacists and nurses in order to really come up with personalized care for your patients,” he explained.

In 918 outpatients with cancer who were included in the program, VTE awareness increased from less than 5% before VTEPACC to nearly 82% during the implementation phase and 94.7% after 2 years, with nearly 94% of high-risk patients receiving VTE prophylaxis at that time.

“So we can certainly do that in our own center.” he said. “It’s a matter of coming up with the model and making sure that the patients are seen at the right time.”

Given the high frequency of VTE in patients with cancer initiating chemotherapy, the usefulness of risk scores such as the Khorana risk score for identifying those at high risk, and the availability of safe and effective interventions for reducing risk, “we should probably use the data and incorporate them into clinical practice by implementation of programs for primary prevention,” he said.

A word of caution

Caution is warranted, however, when it comes to using DOACs in patients with higher-risk or potentially higher-risk tumor types, he added.

“It’s an important question we are facing as clinicians on a daily basis,” he said, responding to an attendee’s query, as shared by session moderator James Douketis, MD, professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., regarding possible bleeding risks in certain genitourinary cancers.

A recent meta-analysis published in Nature, for example, noted that, in the SELECT-D trial, rivaroxaban was associated with significantly higher incidence of clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, most often in bladder and colorectal cancers, and most often at genitourinary and gastrointestinal sites.

Both Dr. Carrier and fellow panelist Michael Streiff, MD, professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University and medical director at the Johns Hopkins Hospital Special Coagulation Laboratory, Baltimore, said they approach DOAC use cautiously, but don’t rule it out entirely, in patients with unresected genitourinary tumors that could pose a risk of bleeding.

“It’s worth mentioning and being cautious. In my own personal practice, I’m very careful with unresected urothelial-type tumors or, for example, bladder cancer, for the same reason as [with] unresected luminal GI tumors,” Dr. Carrier said, adding that he’s also mindful that patients with nephropathy were excluded from U.S. DOAC trials because of bleeding risk.

He said he sometimes tries a LMWH challenge first in higher-risk patients, and then might try a DOAC if no bleeding occurs.

“But it certainly is controversial,” he noted.

Dr. Streiff added that he also worries less with genitourinary cancers than with upper GI lesions because “the signals weren’t as big as in GI” cancers, but he noted that “the drugs are going out through the kidneys ... so I’m cautious in those populations.”

“So caution, but not complete exclusion, is the operative management,” Dr. Douketis said, summarizing the panelists’ consensus.

Dr. Carrier reported clinical trial or advisory board participation for Bayer, Pfizer, Servier, Leo Pharma, and/or BMS.

Primary thromboprophylaxis is feasible and worth considering for high-risk ambulatory patients with cancer who are initiating systemic chemotherapy, according to Marc Carrier, MD.

Risk scores can identify patients at high risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE), and treatments that are effective and associated with low bleeding risk are available, Dr. Carrier explained at the biennial summit of the Thrombosis & Hemostasis Societies of North America.

However, caution is advised in patients with certain types of cancer, including some gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancers, because of the possibility of increased major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding risk, he said.

VTE and cancer

VTE is relatively rare in the general population, occurring in about 1 or 2 per 1,000 people annually. The risk increases 4.1-fold in patients with cancer, and 6.5-fold in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy.

“So just putting these numbers together, we’re no longer talking about 1 in 1,000, but 1 in 200, so [this is] something that is very common among cancer patients,” said Dr. Carrier, a professor at the University of Ottawa and chief of the division of hematology at The Ottawa Hospital.

The mortality rate associated with cancer-associated thrombosis is about 9%, comparable to that associated with infection in the cancer outpatient setting, which underscores the importance of educating patients about the signs and symptoms of VTE so they can seek medical treatment quickly if necessary, he added.

It may also be useful to discuss prophylaxis or other ways to prevent venous thromboembolic complications with certain patients, he said, noting that in an observational cohort study of nearly 600 patients at the University of Ottawa, 25% of those initiating chemotherapy were identified as intermediate or high risk using the validated Khorana risk score, and thus would likely benefit from thromboprophylaxis.

Risk assessment

The Khorana risk score assesses VTE risk based on cancer site, blood counts, and body mass index. It is simple to use and has been validated in more than 20,000 people in multiple countries, Dr. Carrier said.

In a well-known validation study, Ay et al. showed a VTE complication rate of 10% in patients with a Khorana risk score of 2 or higher who were followed up to 6 months.

“This is huge,” Dr. Carrier stressed. “This is much higher than what we tolerate for all sorts of different populations for which we would recommend anticoagulation or thromboprophylaxis.”

The question is whether the risk score can be helpful in a real-world clinic setting, he said, adding: “I’d like to think the answer to that is yes.”

In the University of Ottawa cohort study, 11% of high-risk patients experienced a VTE complication, compared with 4% of those with lower risk, suggesting that the validation data for the Khorana risk score is not only accurate, it is “actually applicable in real-world practice, and you can use it in your own center,” he said.

Further, recent studies have demonstrated that treatment based on Khorana risk score assessment reduces VTE complications.

Prophylaxis options

Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) has been shown in several studies to be associated with a significant relative VTE risk reduction in patients with cancer initiating chemotherapy – with only a slight, nonsignificant increase in the risk of major bleeding.

However, the absolute benefit was small, and LMWH is “parenteral, relatively costly, and, based on that, although we showed relatively good risk-benefit ratio, it never really got translated to clinical practice,” Dr. Carrier said.

In fact, a 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines update recommended against routine thromboprophylaxis in this setting, but stated that it could be considered in select high-risk patients identified using a validated risk-assessment tool.

The guidelines noted that “individual risk factors such as biomarkers and cancer site don’t reliably identify high-risk patients.”

More recent data provide additional support for risk assessment and treatment based on Khorana risk score of 2 or higher.

The AVERT trial, for which Dr. Carrier was the first author, showed that the direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC) apixaban reduced VTE incidence, compared with placebo, in patients with Khorana score of 2 or higher (4.2% vs. 10.2%; hazard ratio, 0.41 overall, and 1.0 vs. 7.3; HR, 0.14 on treatment), and the CASSINI trial showed that another DOAC, rivaroxaban, reduced VTE incidence, compared with placebo, in those with Khorana score of 2 or higher (5.9 vs. 6.7; HR, 0.6 overall, and 2.6 vs. 6.4; HR, 0.40 on treatment). The differences in the on-treatment populations were statistically significant.

The two trials, which included a variety of tumor types, showed similar rates of major bleeding, with an absolute difference of about 1% between treatment and placebo, which was not statistically significant in the on-treatment analyses (HR, 1.89 in AVERT and HR, 1.96 in CASSINI).

A systematic review of these trials showed an overall significant decrease in VTE complication risk with treatment in high-risk patients, and a nonstatistically significant major bleeding risk increase.

Based on these findings, ASCO guidelines were updated in 2020 to state that “routine thromboprophylaxis should not be offered to all patients with cancer. ... However, high-risk outpatients with cancer may be offered thromboprophylaxis with apixaban, rivaroxaban or LMWH, providing there are no significant risk factors for bleeding or drug-drug interactions, and after having a full discussion with patients ... to make sure they understand the risk-benefit ratio and the rationale for that particular recommendation,” he said.

Real-world implementation

Implementing this approach in the clinic setting requires a practical model, such as the Venous Thromboembolism Prevention in the Ambulatory Cancer Clinic (VTEPACC) program, a prospective quality improvement research initiative developed in collaboration with the Jeffords Institute for Quality at the University of Vermont Medical Center and described in a recent report, Dr. Carrier said.

The “Vermont model” is “really a comprehensive model that includes identifying patients with the electronic medical records, gathering the formal education and insight from other health care providers like pharmacists and nurses in order to really come up with personalized care for your patients,” he explained.

In 918 outpatients with cancer who were included in the program, VTE awareness increased from less than 5% before VTEPACC to nearly 82% during the implementation phase and 94.7% after 2 years, with nearly 94% of high-risk patients receiving VTE prophylaxis at that time.

“So we can certainly do that in our own center.” he said. “It’s a matter of coming up with the model and making sure that the patients are seen at the right time.”