User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Obesity drugs overpriced, change needed to tackle issue

The lowest available national prices of drugs to treat obesity are up to 20 times higher than the estimated cost of profitable generic versions of the same agents, according to a new analysis.

The findings by Jacob Levi, MBBS, and colleagues were published in Obesity.

“Our study highlights the inequality in pricing that exists for effective antiobesity medications, which are largely unaffordable in most countries,” Dr. Levi, from Royal Free Hospital NHS Trust, London, said in a press release.

“We show that these drugs can actually be produced and sold profitably for low prices,” he summarized. “A public health approach that prioritizes improving access to medications should be adopted, instead of allowing companies to maximize profits,” Dr. Levi urged.

Dr. Levi and colleagues studied the oral agents orlistat, naltrexone/bupropion, topiramate/phentermine, and semaglutide, and subcutaneous liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide (all approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat obesity, except for oral semaglutide and subcutaneous tirzepatide, which are not yet approved to treat obesity in the absence of type 2 diabetes).

“Worldwide, more people are dying from diabetes and clinical obesity than HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria combined now,” senior author Andrew Hill, MD, department of pharmacology and therapeutics, University of Liverpool, England, pointed out.

We need to repeat the low-cost success story with obesity drugs

“Millions of lives have been saved by treating infectious diseases at low cost in poor countries,” Dr. Hill continued. “Now we need to repeat this medical success story, with mass treatment of diabetes and clinical obesity at low prices.”

However, in an accompanying editorial, Eric A. Finkelstein, MD, and Junxing Chay, PhD, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, maintain that “It would be great if everyone had affordable access to all medicines that might improve their health. Yet that is simply not possible, nor will it ever be.”

“What is truly needed is a better way to ration the health care dollars currently available in efforts to maximize population health. That is the challenge ahead not just for [antiobesity medications] but for all treatments,” they say.

“Greater use of cost-effectiveness analysis and direct negotiations, while maintaining the patent system, represents an appropriate approach for allocating scarce health care resources in the United States and beyond,” they continue.

Lowest current patented drug prices vs. estimated generic drug prices

New medications for obesity were highly effective in recent clinical trials, but high prices limit the ability of patients to get these medications, Dr. Levi and colleagues write.

They analyzed prices for obesity drugs in 16 low-, middle-, and high-income countries: Australia, Bangladesh, China, France, Germany, India, Kenya, Morocco, Norway, Peru, Pakistan, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Vietnam.

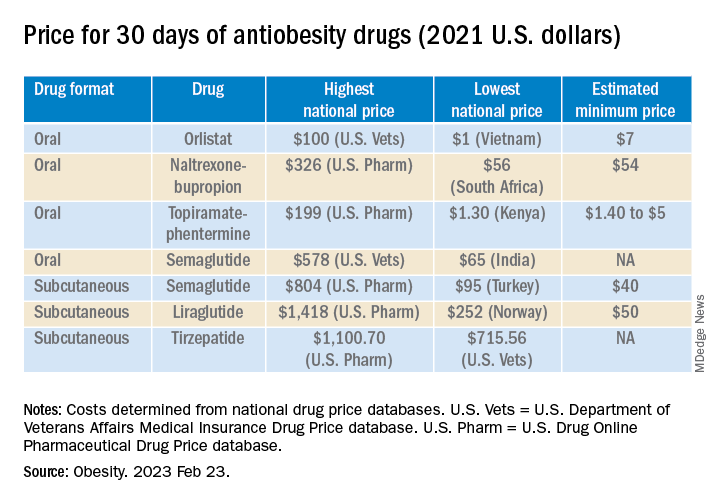

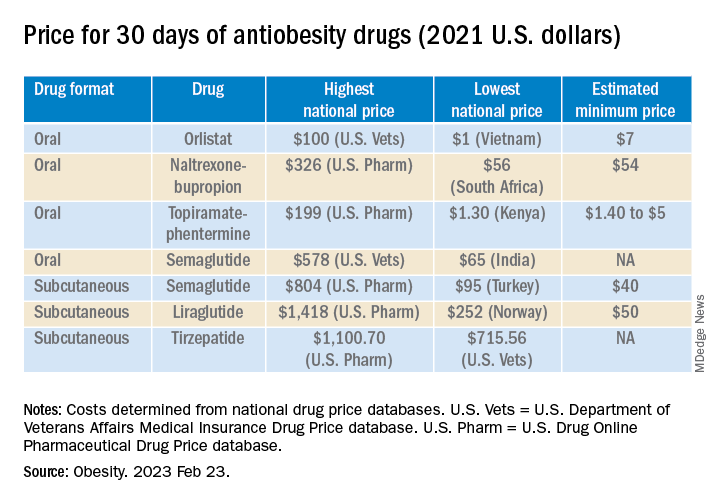

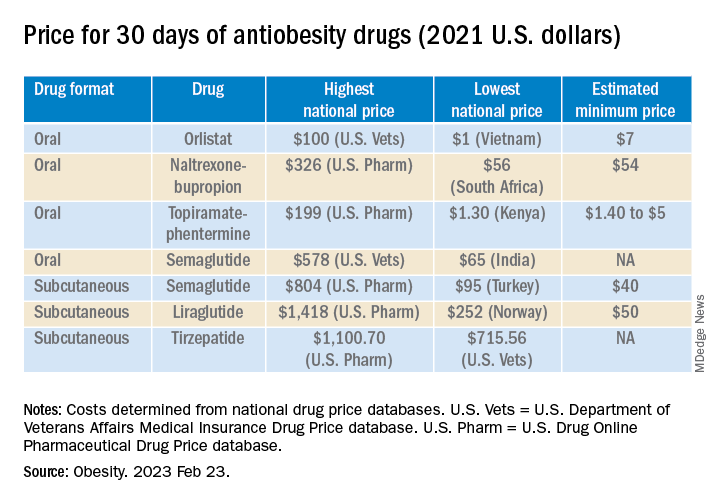

The researchers assessed the price of a 30-day supply of each of the studied branded drugs based on the lowest available price (in 2021 U.S. dollars) from multiple online national price databases.

Then they calculated the estimated minimum price of a 30-day supply of a potential generic version of these drugs, which included the cost of the active medicinal ingredients, the excipients (nonactive ingredients), the prefilled injectable device plus needles (for subcutaneous drugs), transportation, 10% profit, and 27% tax on profit.

The national prices of the branded medications for obesity were significantly higher than the estimated minimum prices of potential generic drugs (see Table).

The highest national price for a branded oral drug for obesity vs. the estimated minimum price for a potential generic version was $100 vs. $7 for orlistat, $199 vs. $5 for phentermine/topiramate, and $326 vs. $54 for naltrexone/bupropion, for a 30-day supply.

There was an even greater difference between highest national branded drug price vs. estimated minimum generic drug price for the newer subcutaneously injectable drugs for obesity.

For example, the price of a 30-day course of subcutaneous semaglutide ranged from $804 (United States) to $95 (Turkey), while the estimated minimum potential generic drug price was $40 (which is 20 times lower).

The study was funded by grants from the Make Medicines Affordable/International Treatment Preparedness Coalition and from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Coauthor Francois Venter has reported receiving support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, U.S. Agency for International Development, Unitaid, SA Medical Research Council, Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, Gilead, ViiV, Mylan, Merck, Adcock Ingram, Aspen, Abbott, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Virology Education, SA HIV Clinicians Society, and Dira Sengwe. The other authors and Dr. Chay have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Finkelstein has reported receiving support for serving on the WW scientific advisory board and an educational grant unrelated to the present work from Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The lowest available national prices of drugs to treat obesity are up to 20 times higher than the estimated cost of profitable generic versions of the same agents, according to a new analysis.

The findings by Jacob Levi, MBBS, and colleagues were published in Obesity.

“Our study highlights the inequality in pricing that exists for effective antiobesity medications, which are largely unaffordable in most countries,” Dr. Levi, from Royal Free Hospital NHS Trust, London, said in a press release.

“We show that these drugs can actually be produced and sold profitably for low prices,” he summarized. “A public health approach that prioritizes improving access to medications should be adopted, instead of allowing companies to maximize profits,” Dr. Levi urged.

Dr. Levi and colleagues studied the oral agents orlistat, naltrexone/bupropion, topiramate/phentermine, and semaglutide, and subcutaneous liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide (all approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat obesity, except for oral semaglutide and subcutaneous tirzepatide, which are not yet approved to treat obesity in the absence of type 2 diabetes).

“Worldwide, more people are dying from diabetes and clinical obesity than HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria combined now,” senior author Andrew Hill, MD, department of pharmacology and therapeutics, University of Liverpool, England, pointed out.

We need to repeat the low-cost success story with obesity drugs

“Millions of lives have been saved by treating infectious diseases at low cost in poor countries,” Dr. Hill continued. “Now we need to repeat this medical success story, with mass treatment of diabetes and clinical obesity at low prices.”

However, in an accompanying editorial, Eric A. Finkelstein, MD, and Junxing Chay, PhD, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, maintain that “It would be great if everyone had affordable access to all medicines that might improve their health. Yet that is simply not possible, nor will it ever be.”

“What is truly needed is a better way to ration the health care dollars currently available in efforts to maximize population health. That is the challenge ahead not just for [antiobesity medications] but for all treatments,” they say.

“Greater use of cost-effectiveness analysis and direct negotiations, while maintaining the patent system, represents an appropriate approach for allocating scarce health care resources in the United States and beyond,” they continue.

Lowest current patented drug prices vs. estimated generic drug prices

New medications for obesity were highly effective in recent clinical trials, but high prices limit the ability of patients to get these medications, Dr. Levi and colleagues write.

They analyzed prices for obesity drugs in 16 low-, middle-, and high-income countries: Australia, Bangladesh, China, France, Germany, India, Kenya, Morocco, Norway, Peru, Pakistan, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Vietnam.

The researchers assessed the price of a 30-day supply of each of the studied branded drugs based on the lowest available price (in 2021 U.S. dollars) from multiple online national price databases.

Then they calculated the estimated minimum price of a 30-day supply of a potential generic version of these drugs, which included the cost of the active medicinal ingredients, the excipients (nonactive ingredients), the prefilled injectable device plus needles (for subcutaneous drugs), transportation, 10% profit, and 27% tax on profit.

The national prices of the branded medications for obesity were significantly higher than the estimated minimum prices of potential generic drugs (see Table).

The highest national price for a branded oral drug for obesity vs. the estimated minimum price for a potential generic version was $100 vs. $7 for orlistat, $199 vs. $5 for phentermine/topiramate, and $326 vs. $54 for naltrexone/bupropion, for a 30-day supply.

There was an even greater difference between highest national branded drug price vs. estimated minimum generic drug price for the newer subcutaneously injectable drugs for obesity.

For example, the price of a 30-day course of subcutaneous semaglutide ranged from $804 (United States) to $95 (Turkey), while the estimated minimum potential generic drug price was $40 (which is 20 times lower).

The study was funded by grants from the Make Medicines Affordable/International Treatment Preparedness Coalition and from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Coauthor Francois Venter has reported receiving support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, U.S. Agency for International Development, Unitaid, SA Medical Research Council, Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, Gilead, ViiV, Mylan, Merck, Adcock Ingram, Aspen, Abbott, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Virology Education, SA HIV Clinicians Society, and Dira Sengwe. The other authors and Dr. Chay have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Finkelstein has reported receiving support for serving on the WW scientific advisory board and an educational grant unrelated to the present work from Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The lowest available national prices of drugs to treat obesity are up to 20 times higher than the estimated cost of profitable generic versions of the same agents, according to a new analysis.

The findings by Jacob Levi, MBBS, and colleagues were published in Obesity.

“Our study highlights the inequality in pricing that exists for effective antiobesity medications, which are largely unaffordable in most countries,” Dr. Levi, from Royal Free Hospital NHS Trust, London, said in a press release.

“We show that these drugs can actually be produced and sold profitably for low prices,” he summarized. “A public health approach that prioritizes improving access to medications should be adopted, instead of allowing companies to maximize profits,” Dr. Levi urged.

Dr. Levi and colleagues studied the oral agents orlistat, naltrexone/bupropion, topiramate/phentermine, and semaglutide, and subcutaneous liraglutide, semaglutide, and tirzepatide (all approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat obesity, except for oral semaglutide and subcutaneous tirzepatide, which are not yet approved to treat obesity in the absence of type 2 diabetes).

“Worldwide, more people are dying from diabetes and clinical obesity than HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria combined now,” senior author Andrew Hill, MD, department of pharmacology and therapeutics, University of Liverpool, England, pointed out.

We need to repeat the low-cost success story with obesity drugs

“Millions of lives have been saved by treating infectious diseases at low cost in poor countries,” Dr. Hill continued. “Now we need to repeat this medical success story, with mass treatment of diabetes and clinical obesity at low prices.”

However, in an accompanying editorial, Eric A. Finkelstein, MD, and Junxing Chay, PhD, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, maintain that “It would be great if everyone had affordable access to all medicines that might improve their health. Yet that is simply not possible, nor will it ever be.”

“What is truly needed is a better way to ration the health care dollars currently available in efforts to maximize population health. That is the challenge ahead not just for [antiobesity medications] but for all treatments,” they say.

“Greater use of cost-effectiveness analysis and direct negotiations, while maintaining the patent system, represents an appropriate approach for allocating scarce health care resources in the United States and beyond,” they continue.

Lowest current patented drug prices vs. estimated generic drug prices

New medications for obesity were highly effective in recent clinical trials, but high prices limit the ability of patients to get these medications, Dr. Levi and colleagues write.

They analyzed prices for obesity drugs in 16 low-, middle-, and high-income countries: Australia, Bangladesh, China, France, Germany, India, Kenya, Morocco, Norway, Peru, Pakistan, South Africa, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Vietnam.

The researchers assessed the price of a 30-day supply of each of the studied branded drugs based on the lowest available price (in 2021 U.S. dollars) from multiple online national price databases.

Then they calculated the estimated minimum price of a 30-day supply of a potential generic version of these drugs, which included the cost of the active medicinal ingredients, the excipients (nonactive ingredients), the prefilled injectable device plus needles (for subcutaneous drugs), transportation, 10% profit, and 27% tax on profit.

The national prices of the branded medications for obesity were significantly higher than the estimated minimum prices of potential generic drugs (see Table).

The highest national price for a branded oral drug for obesity vs. the estimated minimum price for a potential generic version was $100 vs. $7 for orlistat, $199 vs. $5 for phentermine/topiramate, and $326 vs. $54 for naltrexone/bupropion, for a 30-day supply.

There was an even greater difference between highest national branded drug price vs. estimated minimum generic drug price for the newer subcutaneously injectable drugs for obesity.

For example, the price of a 30-day course of subcutaneous semaglutide ranged from $804 (United States) to $95 (Turkey), while the estimated minimum potential generic drug price was $40 (which is 20 times lower).

The study was funded by grants from the Make Medicines Affordable/International Treatment Preparedness Coalition and from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Coauthor Francois Venter has reported receiving support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, U.S. Agency for International Development, Unitaid, SA Medical Research Council, Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, Gilead, ViiV, Mylan, Merck, Adcock Ingram, Aspen, Abbott, Roche, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Virology Education, SA HIV Clinicians Society, and Dira Sengwe. The other authors and Dr. Chay have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Finkelstein has reported receiving support for serving on the WW scientific advisory board and an educational grant unrelated to the present work from Novo Nordisk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Unawareness of memory slips could indicate risk for Alzheimer’s

Everyone’s memory fades to some extent as we age, but not everyone will develop Alzheimer’s disease. Screening the most likely people to develop Alzheimer’s remains an ongoing challenge, as some people present only unambiguous symptoms once their disease is advanced.

A new study in JAMA Network Open suggests that one early clue is found in people’s own self-perception of their memory skills. People who are more aware of their own declining memory capacity are less likely to develop Alzheimer’s, the study suggests.

“Some people are very aware of changes in their memory, but many people are unaware,” said study author Patrizia Vannini, PhD, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. There are gradations of unawareness of memory loss, Dr. Vannini said, from complete unawareness that anything is wrong, to a partial unawareness that memory is declining.

The study compared the records of 436 participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, an Alzheimer’s research institute housed at the University of Southern California. More than 90% of the participants were White, and generally had a college education. Their average age was 75 years, and 53% of participants were women.

Dr. Vannini and colleagues tracked people whose cognitive function was normal at the beginning of the study, based on the Clinical Dementia Rating. Throughout the course of the study, which included data from 2010 to 2021, 91 of the 436 participants experienced a sustained decline in their Clinical Dementia Rating scores, indicating a risk for eventual Alzheimer’s, whereas the other participants held steady.

The people who declined in cognitive function were less aware of slips in their memory, as assessed by discrepancies between people’s self-reports of their own memory skills and the perceptions of someone in their lives. For this part of the study, Dr. Vannini and colleagues used the Everyday Cognition Questionnaire, which evaluates memory tasks such as shopping without a grocery list or recalling conversations from a few days ago. Both the participant and the study partner rated their performance on such tasks compared to 10 years earlier. Those who were less aware of their memory slips were more likely to experience declines in the Clinical Dementia Rating, compared with people with a heightened concern about memory loss (as measured by being more concerned about memory decline than their study partners).

“Partial or complete unawareness is often related to delayed diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, because the patient is unaware they are having problems,” Dr. Vannini said, adding that this is associated with a poorer prognosis as well.

Implications for clinicians

Soo Borson, MD, professor of clinical family medicine at the University of Southern California and coleader of a CDC-funded early dementia detection center at New York University, pointed out that sometimes people are genuinely unaware that their memory is declining, while at other times they know it all too well but say everything is fine when a doctor asks about their current memory status. That may be because people fear the label of “Alzheimer’s,” Dr. Borson suggested, or simply because they don’t want to start a protracted diagnostic pathway that could involve lots of tests and time.

Dr. Borson, who was not involved in the study, noted that the population was predominantly White and well-educated, and by definition included people who were concerned enough about potential memory loss to become part of an Alzheimer’s research network. This limits the generalizability of this study’s results to other populations, Dr. Borson said.

Despite that limitation, in Dr. Borson’s view the study points to the continued importance of clinicians (ideally a primary care doctor who knows the patient well) engaging with patients about their brain health once they reach midlife. A doctor could ask if patients have noticed a decline in their thinking or memory over the last year, for example, or a more open-ended question about any memory concerns.

Although some patients may choose to withhold concerns about their memory, Dr. Borson acknowledged, the overall thrust of these questions is to provide a safe space for patients to air their concerns if they so choose. In some cases it would be appropriate to do a simple memory test on the spot, and then proceed accordingly – either for further tests if something of concern emerges, or to reassure the patient if the test doesn’t yield anything of note. In the latter case some patients will still want further tests for additional reassurance, and Dr. Borson thinks doctors should facilitate that request even if in their own judgment nothing is wrong.

“This is not like testing for impaired kidney function by doing a serum creatinine test,” Dr. Borson said. While the orientation of the health care system is toward quick and easy answers for everything, detecting possible dementia eludes such an approach.

Dr. Vannini reports funding from the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging. Dr. Borson reported no disclosures.

Everyone’s memory fades to some extent as we age, but not everyone will develop Alzheimer’s disease. Screening the most likely people to develop Alzheimer’s remains an ongoing challenge, as some people present only unambiguous symptoms once their disease is advanced.

A new study in JAMA Network Open suggests that one early clue is found in people’s own self-perception of their memory skills. People who are more aware of their own declining memory capacity are less likely to develop Alzheimer’s, the study suggests.

“Some people are very aware of changes in their memory, but many people are unaware,” said study author Patrizia Vannini, PhD, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. There are gradations of unawareness of memory loss, Dr. Vannini said, from complete unawareness that anything is wrong, to a partial unawareness that memory is declining.

The study compared the records of 436 participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, an Alzheimer’s research institute housed at the University of Southern California. More than 90% of the participants were White, and generally had a college education. Their average age was 75 years, and 53% of participants were women.

Dr. Vannini and colleagues tracked people whose cognitive function was normal at the beginning of the study, based on the Clinical Dementia Rating. Throughout the course of the study, which included data from 2010 to 2021, 91 of the 436 participants experienced a sustained decline in their Clinical Dementia Rating scores, indicating a risk for eventual Alzheimer’s, whereas the other participants held steady.

The people who declined in cognitive function were less aware of slips in their memory, as assessed by discrepancies between people’s self-reports of their own memory skills and the perceptions of someone in their lives. For this part of the study, Dr. Vannini and colleagues used the Everyday Cognition Questionnaire, which evaluates memory tasks such as shopping without a grocery list or recalling conversations from a few days ago. Both the participant and the study partner rated their performance on such tasks compared to 10 years earlier. Those who were less aware of their memory slips were more likely to experience declines in the Clinical Dementia Rating, compared with people with a heightened concern about memory loss (as measured by being more concerned about memory decline than their study partners).

“Partial or complete unawareness is often related to delayed diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, because the patient is unaware they are having problems,” Dr. Vannini said, adding that this is associated with a poorer prognosis as well.

Implications for clinicians

Soo Borson, MD, professor of clinical family medicine at the University of Southern California and coleader of a CDC-funded early dementia detection center at New York University, pointed out that sometimes people are genuinely unaware that their memory is declining, while at other times they know it all too well but say everything is fine when a doctor asks about their current memory status. That may be because people fear the label of “Alzheimer’s,” Dr. Borson suggested, or simply because they don’t want to start a protracted diagnostic pathway that could involve lots of tests and time.

Dr. Borson, who was not involved in the study, noted that the population was predominantly White and well-educated, and by definition included people who were concerned enough about potential memory loss to become part of an Alzheimer’s research network. This limits the generalizability of this study’s results to other populations, Dr. Borson said.

Despite that limitation, in Dr. Borson’s view the study points to the continued importance of clinicians (ideally a primary care doctor who knows the patient well) engaging with patients about their brain health once they reach midlife. A doctor could ask if patients have noticed a decline in their thinking or memory over the last year, for example, or a more open-ended question about any memory concerns.

Although some patients may choose to withhold concerns about their memory, Dr. Borson acknowledged, the overall thrust of these questions is to provide a safe space for patients to air their concerns if they so choose. In some cases it would be appropriate to do a simple memory test on the spot, and then proceed accordingly – either for further tests if something of concern emerges, or to reassure the patient if the test doesn’t yield anything of note. In the latter case some patients will still want further tests for additional reassurance, and Dr. Borson thinks doctors should facilitate that request even if in their own judgment nothing is wrong.

“This is not like testing for impaired kidney function by doing a serum creatinine test,” Dr. Borson said. While the orientation of the health care system is toward quick and easy answers for everything, detecting possible dementia eludes such an approach.

Dr. Vannini reports funding from the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging. Dr. Borson reported no disclosures.

Everyone’s memory fades to some extent as we age, but not everyone will develop Alzheimer’s disease. Screening the most likely people to develop Alzheimer’s remains an ongoing challenge, as some people present only unambiguous symptoms once their disease is advanced.

A new study in JAMA Network Open suggests that one early clue is found in people’s own self-perception of their memory skills. People who are more aware of their own declining memory capacity are less likely to develop Alzheimer’s, the study suggests.

“Some people are very aware of changes in their memory, but many people are unaware,” said study author Patrizia Vannini, PhD, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. There are gradations of unawareness of memory loss, Dr. Vannini said, from complete unawareness that anything is wrong, to a partial unawareness that memory is declining.

The study compared the records of 436 participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, an Alzheimer’s research institute housed at the University of Southern California. More than 90% of the participants were White, and generally had a college education. Their average age was 75 years, and 53% of participants were women.

Dr. Vannini and colleagues tracked people whose cognitive function was normal at the beginning of the study, based on the Clinical Dementia Rating. Throughout the course of the study, which included data from 2010 to 2021, 91 of the 436 participants experienced a sustained decline in their Clinical Dementia Rating scores, indicating a risk for eventual Alzheimer’s, whereas the other participants held steady.

The people who declined in cognitive function were less aware of slips in their memory, as assessed by discrepancies between people’s self-reports of their own memory skills and the perceptions of someone in their lives. For this part of the study, Dr. Vannini and colleagues used the Everyday Cognition Questionnaire, which evaluates memory tasks such as shopping without a grocery list or recalling conversations from a few days ago. Both the participant and the study partner rated their performance on such tasks compared to 10 years earlier. Those who were less aware of their memory slips were more likely to experience declines in the Clinical Dementia Rating, compared with people with a heightened concern about memory loss (as measured by being more concerned about memory decline than their study partners).

“Partial or complete unawareness is often related to delayed diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, because the patient is unaware they are having problems,” Dr. Vannini said, adding that this is associated with a poorer prognosis as well.

Implications for clinicians

Soo Borson, MD, professor of clinical family medicine at the University of Southern California and coleader of a CDC-funded early dementia detection center at New York University, pointed out that sometimes people are genuinely unaware that their memory is declining, while at other times they know it all too well but say everything is fine when a doctor asks about their current memory status. That may be because people fear the label of “Alzheimer’s,” Dr. Borson suggested, or simply because they don’t want to start a protracted diagnostic pathway that could involve lots of tests and time.

Dr. Borson, who was not involved in the study, noted that the population was predominantly White and well-educated, and by definition included people who were concerned enough about potential memory loss to become part of an Alzheimer’s research network. This limits the generalizability of this study’s results to other populations, Dr. Borson said.

Despite that limitation, in Dr. Borson’s view the study points to the continued importance of clinicians (ideally a primary care doctor who knows the patient well) engaging with patients about their brain health once they reach midlife. A doctor could ask if patients have noticed a decline in their thinking or memory over the last year, for example, or a more open-ended question about any memory concerns.

Although some patients may choose to withhold concerns about their memory, Dr. Borson acknowledged, the overall thrust of these questions is to provide a safe space for patients to air their concerns if they so choose. In some cases it would be appropriate to do a simple memory test on the spot, and then proceed accordingly – either for further tests if something of concern emerges, or to reassure the patient if the test doesn’t yield anything of note. In the latter case some patients will still want further tests for additional reassurance, and Dr. Borson thinks doctors should facilitate that request even if in their own judgment nothing is wrong.

“This is not like testing for impaired kidney function by doing a serum creatinine test,” Dr. Borson said. While the orientation of the health care system is toward quick and easy answers for everything, detecting possible dementia eludes such an approach.

Dr. Vannini reports funding from the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging. Dr. Borson reported no disclosures.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Drive, chip, and putt your way to osteoarthritis relief

Taking a swing against arthritis

Osteoarthritis is a tough disease to manage. Exercise helps ease the stiffness and pain of the joints, but at the same time, the disease makes it difficult to do that beneficial exercise. Even a relatively simple activity like jogging can hurt more than it helps. If only there were a low-impact exercise that was incredibly popular among the generally older population who are likely to have arthritis.

We love a good golf study here at LOTME, and a group of Australian and U.K. researchers have provided. Osteoarthritis affects 2 million people in the land down under, making it the most common source of disability there. In that population, only 64% reported their physical health to be good, very good, or excellent. Among the 459 golfers with OA that the study authors surveyed, however, the percentage reporting good health rose to more than 90%.

A similar story emerged when they looked at mental health. Nearly a quarter of nongolfers with OA reported high or very high levels of psychological distress, compared with just 8% of golfers. This pattern of improved physical and mental health remained when the researchers looked at the general, non-OA population.

This isn’t the first time golf’s been connected with improved health, and previous studies have shown golf to reduce the risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity, among other things. Just walking one 18-hole round significantly exceeds the CDC’s recommended 150 minutes of physical activity per week. Go out multiple times a week – leaving the cart and beer at home, American golfers – and you’ll be fit for a lifetime.

The golfers on our staff, however, are still waiting for those mental health benefits to kick in. Because when we’re adding up our scorecard after that string of four double bogeys to end the round, we’re most definitely thinking: “Yes, this sport is reducing my psychological distress. I am having fun right now.”

Battle of the sexes’ intestines

There are, we’re sure you’ve noticed, some differences between males and females. Females, for one thing, have longer small intestines than males. Everybody knows that, right? You didn’t know? Really? … Really?

Well, then, we’re guessing you haven’t read “Hidden diversity: Comparative functional morphology of humans and other species” by Erin A. McKenney, PhD, of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, and associates, which just appeared in PeerJ. We couldn’t put it down, even in the shower – a real page-turner/scroller. (It’s a great way to clean a phone, for those who also like to scroll, text, or talk on the toilet.)

The researchers got out their rulers, calipers, and string and took many measurements of the digestive systems of 45 human cadavers (21 female and 24 male), which were compared with data from 10 rats, 10 pigs, and 10 bullfrogs, which had been collected (the measurements, not the animals) by undergraduate students enrolled in a comparative anatomy laboratory course at the university.

There was little intestinal-length variation among the four-legged subjects, but when it comes to humans, females have “consistently and significantly longer small intestines than males,” the investigators noted.

The women’s small intestines, almost 14 feet long on average, were about a foot longer than the men’s, which suggests that women are better able to extract nutrients from food and “supports the canalization hypothesis, which posits that women are better able to survive during periods of stress,” coauthor Amanda Hale said in a written statement from the school. The way to a man’s heart may be through his stomach, but the way to a woman’s heart is through her duodenum, it seems.

Fascinating stuff, to be sure, but the thing that really caught our eye in the PeerJ article was the authors’ suggestion “that organs behave independently of one another, both within and across species.” Organs behaving independently? A somewhat ominous concept, no doubt, but it does explain a lot of the sounds we hear coming from our guts, which can get pretty frightening, especially on chili night.

Dog walking is dangerous business

Yes, you did read that right. A lot of strange things can send you to the emergency department. Go ahead and add dog walking onto that list.

Investigators from Johns Hopkins University estimate that over 422,000 adults presented to U.S. emergency departments with leash-dependent dog walking-related injuries between 2001 and 2020.

With almost 53% of U.S. households owning at least one dog in 2021-2022 in the wake of the COVID pet boom, this kind of occurrence is becoming more common than you think. The annual number of dog-walking injuries more than quadrupled from 7,300 to 32,000 over the course of the study, and the researchers link that spike to the promotion of dog walking for fitness, along with the boost of ownership itself.

The most common injuries listed in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database were finger fracture, traumatic brain injury, and shoulder sprain or strain. These mostly involved falls from being pulled, tripped, or tangled up in the leash while walking. For those aged 65 years and older, traumatic brain injury and hip fracture were the most common.

Women were 50% more likely to sustain a fracture than were men, and dog owners aged 65 and older were three times as likely to fall, twice as likely to get a fracture, and 60% more likely to have brain injury than were younger people. Now, that’s not to say younger people don’t also get hurt. After all, dogs aren’t ageists. The researchers have that data but it’s coming out later.

Meanwhile, the pitfalls involved with just trying to get our daily steps in while letting Muffin do her business have us on the lookout for random squirrels.

Taking a swing against arthritis

Osteoarthritis is a tough disease to manage. Exercise helps ease the stiffness and pain of the joints, but at the same time, the disease makes it difficult to do that beneficial exercise. Even a relatively simple activity like jogging can hurt more than it helps. If only there were a low-impact exercise that was incredibly popular among the generally older population who are likely to have arthritis.

We love a good golf study here at LOTME, and a group of Australian and U.K. researchers have provided. Osteoarthritis affects 2 million people in the land down under, making it the most common source of disability there. In that population, only 64% reported their physical health to be good, very good, or excellent. Among the 459 golfers with OA that the study authors surveyed, however, the percentage reporting good health rose to more than 90%.

A similar story emerged when they looked at mental health. Nearly a quarter of nongolfers with OA reported high or very high levels of psychological distress, compared with just 8% of golfers. This pattern of improved physical and mental health remained when the researchers looked at the general, non-OA population.

This isn’t the first time golf’s been connected with improved health, and previous studies have shown golf to reduce the risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity, among other things. Just walking one 18-hole round significantly exceeds the CDC’s recommended 150 minutes of physical activity per week. Go out multiple times a week – leaving the cart and beer at home, American golfers – and you’ll be fit for a lifetime.

The golfers on our staff, however, are still waiting for those mental health benefits to kick in. Because when we’re adding up our scorecard after that string of four double bogeys to end the round, we’re most definitely thinking: “Yes, this sport is reducing my psychological distress. I am having fun right now.”

Battle of the sexes’ intestines

There are, we’re sure you’ve noticed, some differences between males and females. Females, for one thing, have longer small intestines than males. Everybody knows that, right? You didn’t know? Really? … Really?

Well, then, we’re guessing you haven’t read “Hidden diversity: Comparative functional morphology of humans and other species” by Erin A. McKenney, PhD, of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, and associates, which just appeared in PeerJ. We couldn’t put it down, even in the shower – a real page-turner/scroller. (It’s a great way to clean a phone, for those who also like to scroll, text, or talk on the toilet.)

The researchers got out their rulers, calipers, and string and took many measurements of the digestive systems of 45 human cadavers (21 female and 24 male), which were compared with data from 10 rats, 10 pigs, and 10 bullfrogs, which had been collected (the measurements, not the animals) by undergraduate students enrolled in a comparative anatomy laboratory course at the university.

There was little intestinal-length variation among the four-legged subjects, but when it comes to humans, females have “consistently and significantly longer small intestines than males,” the investigators noted.

The women’s small intestines, almost 14 feet long on average, were about a foot longer than the men’s, which suggests that women are better able to extract nutrients from food and “supports the canalization hypothesis, which posits that women are better able to survive during periods of stress,” coauthor Amanda Hale said in a written statement from the school. The way to a man’s heart may be through his stomach, but the way to a woman’s heart is through her duodenum, it seems.

Fascinating stuff, to be sure, but the thing that really caught our eye in the PeerJ article was the authors’ suggestion “that organs behave independently of one another, both within and across species.” Organs behaving independently? A somewhat ominous concept, no doubt, but it does explain a lot of the sounds we hear coming from our guts, which can get pretty frightening, especially on chili night.

Dog walking is dangerous business

Yes, you did read that right. A lot of strange things can send you to the emergency department. Go ahead and add dog walking onto that list.

Investigators from Johns Hopkins University estimate that over 422,000 adults presented to U.S. emergency departments with leash-dependent dog walking-related injuries between 2001 and 2020.

With almost 53% of U.S. households owning at least one dog in 2021-2022 in the wake of the COVID pet boom, this kind of occurrence is becoming more common than you think. The annual number of dog-walking injuries more than quadrupled from 7,300 to 32,000 over the course of the study, and the researchers link that spike to the promotion of dog walking for fitness, along with the boost of ownership itself.

The most common injuries listed in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database were finger fracture, traumatic brain injury, and shoulder sprain or strain. These mostly involved falls from being pulled, tripped, or tangled up in the leash while walking. For those aged 65 years and older, traumatic brain injury and hip fracture were the most common.

Women were 50% more likely to sustain a fracture than were men, and dog owners aged 65 and older were three times as likely to fall, twice as likely to get a fracture, and 60% more likely to have brain injury than were younger people. Now, that’s not to say younger people don’t also get hurt. After all, dogs aren’t ageists. The researchers have that data but it’s coming out later.

Meanwhile, the pitfalls involved with just trying to get our daily steps in while letting Muffin do her business have us on the lookout for random squirrels.

Taking a swing against arthritis

Osteoarthritis is a tough disease to manage. Exercise helps ease the stiffness and pain of the joints, but at the same time, the disease makes it difficult to do that beneficial exercise. Even a relatively simple activity like jogging can hurt more than it helps. If only there were a low-impact exercise that was incredibly popular among the generally older population who are likely to have arthritis.

We love a good golf study here at LOTME, and a group of Australian and U.K. researchers have provided. Osteoarthritis affects 2 million people in the land down under, making it the most common source of disability there. In that population, only 64% reported their physical health to be good, very good, or excellent. Among the 459 golfers with OA that the study authors surveyed, however, the percentage reporting good health rose to more than 90%.

A similar story emerged when they looked at mental health. Nearly a quarter of nongolfers with OA reported high or very high levels of psychological distress, compared with just 8% of golfers. This pattern of improved physical and mental health remained when the researchers looked at the general, non-OA population.

This isn’t the first time golf’s been connected with improved health, and previous studies have shown golf to reduce the risks of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and obesity, among other things. Just walking one 18-hole round significantly exceeds the CDC’s recommended 150 minutes of physical activity per week. Go out multiple times a week – leaving the cart and beer at home, American golfers – and you’ll be fit for a lifetime.

The golfers on our staff, however, are still waiting for those mental health benefits to kick in. Because when we’re adding up our scorecard after that string of four double bogeys to end the round, we’re most definitely thinking: “Yes, this sport is reducing my psychological distress. I am having fun right now.”

Battle of the sexes’ intestines

There are, we’re sure you’ve noticed, some differences between males and females. Females, for one thing, have longer small intestines than males. Everybody knows that, right? You didn’t know? Really? … Really?

Well, then, we’re guessing you haven’t read “Hidden diversity: Comparative functional morphology of humans and other species” by Erin A. McKenney, PhD, of North Carolina State University, Raleigh, and associates, which just appeared in PeerJ. We couldn’t put it down, even in the shower – a real page-turner/scroller. (It’s a great way to clean a phone, for those who also like to scroll, text, or talk on the toilet.)

The researchers got out their rulers, calipers, and string and took many measurements of the digestive systems of 45 human cadavers (21 female and 24 male), which were compared with data from 10 rats, 10 pigs, and 10 bullfrogs, which had been collected (the measurements, not the animals) by undergraduate students enrolled in a comparative anatomy laboratory course at the university.

There was little intestinal-length variation among the four-legged subjects, but when it comes to humans, females have “consistently and significantly longer small intestines than males,” the investigators noted.

The women’s small intestines, almost 14 feet long on average, were about a foot longer than the men’s, which suggests that women are better able to extract nutrients from food and “supports the canalization hypothesis, which posits that women are better able to survive during periods of stress,” coauthor Amanda Hale said in a written statement from the school. The way to a man’s heart may be through his stomach, but the way to a woman’s heart is through her duodenum, it seems.

Fascinating stuff, to be sure, but the thing that really caught our eye in the PeerJ article was the authors’ suggestion “that organs behave independently of one another, both within and across species.” Organs behaving independently? A somewhat ominous concept, no doubt, but it does explain a lot of the sounds we hear coming from our guts, which can get pretty frightening, especially on chili night.

Dog walking is dangerous business

Yes, you did read that right. A lot of strange things can send you to the emergency department. Go ahead and add dog walking onto that list.

Investigators from Johns Hopkins University estimate that over 422,000 adults presented to U.S. emergency departments with leash-dependent dog walking-related injuries between 2001 and 2020.

With almost 53% of U.S. households owning at least one dog in 2021-2022 in the wake of the COVID pet boom, this kind of occurrence is becoming more common than you think. The annual number of dog-walking injuries more than quadrupled from 7,300 to 32,000 over the course of the study, and the researchers link that spike to the promotion of dog walking for fitness, along with the boost of ownership itself.

The most common injuries listed in the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database were finger fracture, traumatic brain injury, and shoulder sprain or strain. These mostly involved falls from being pulled, tripped, or tangled up in the leash while walking. For those aged 65 years and older, traumatic brain injury and hip fracture were the most common.

Women were 50% more likely to sustain a fracture than were men, and dog owners aged 65 and older were three times as likely to fall, twice as likely to get a fracture, and 60% more likely to have brain injury than were younger people. Now, that’s not to say younger people don’t also get hurt. After all, dogs aren’t ageists. The researchers have that data but it’s coming out later.

Meanwhile, the pitfalls involved with just trying to get our daily steps in while letting Muffin do her business have us on the lookout for random squirrels.

New ABIM fees to stay listed as ‘board certified’ irk physicians

Abdul Moiz Hafiz, MD, was flabbergasted when he received a phone call from his institution’s credentialing office telling him that he was not certified for interventional cardiology – even though he had passed that exam in 2016.

Dr. Hafiz, who directs the Advanced Structural Heart Disease Program at Southern Illinois University, phoned the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), where he learned that to restore his credentials, he would need to pay $1,225 in maintenance of certification (MOC) fees.

Like Dr. Hafiz,

Even doctors who are participating in mandatory continuing education outside the ABIM’s auspices are finding themselves listed as “not certified.” Some physicians learned of the policy change only after applying for hospital privileges or for jobs that require ABIM certification.

Now that increasing numbers of physicians are employed by hospitals and health care organizations that require ABIM certification, many doctors have no option but to pony up the fees if they want to continue to practice medicine.

“We have no say in the matter,” said Dr. Hafiz, “and there’s no appeal process.”

The change affects nearly 330,000 physicians. Responses to the policy on Twitter included accusations of extortion and denunciations of the ABIM’s “money grab policies.”

Sunil Rao, MD, director of interventional cardiology at NYU Langone Health and president of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), has heard from many SCAI members who had experiences similar to Dr. Hafiz’s. While Dr. Rao describes some of the Twitter outrage as “emotional,” he does acknowledge that the ABIM’s moves appear to be financially motivated.

“The issue here was that as soon as they paid the fee, all of a sudden, ABIM flipped the switch and said they were certified,” he said. “It certainly sounds like a purely financial kind of structure.”

Richard Baron, MD, president and CEO of the ABIM, said doctors are misunderstanding the policy change.

“No doctor loses certification solely for failure to pay fees,” Dr. Baron told this news organization. “What caused them to be reported as not certified was that we didn’t have evidence that they had met program requirements. They could say, ‘But I did meet program requirements, you just didn’t know it.’ To which our answer would be, for us to know it, we have to process them. And our policy is that we don’t process them unless you are current on your fees.”

This is not the first time ABIM policies have alienated physicians.

Last year, the ABIM raised its MOC fees from $165 to $220. That also prompted a wave of outrage. Other grievances go further back. At one time, being board certified was a lifetime credential. However, in 1990 the ABIM made periodic recertification mandatory.

The process, which came to be known as “maintenance of certification,” had to be completed every 10 years, and fees were charged for each certification. At that point, said Dr. Baron, the relationship between the ABIM and physicians changed from a one-time interaction to a career-long relationship. He advises doctors to check in periodically on their portal page at the ABIM or download the app so they will always know their status.

Many physicians would prefer not to be bound to a lifetime relationship with the ABIM. There is an alternative licensing board, the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons (NBPAS), but it is accepted by only a limited number of hospitals.

“Until the NBPAS gains wide recognition,” said Dr. Hafiz, “the ABIM is going to continue to have basically a monopoly over the market.”

The value of MOC itself has been called into question. “There are no direct data supporting the value of the MOC process in either improving care, making patient care safer, or making patient care higher quality,” said Dr. Rao. This feeds frustration in a clinical community already dealing with onerous training requirements and expensive board certification exams and adds to the perception that it is a purely financial transaction, he said. (Studies examining whether the MOC system improves patient care have shown mixed results.)

The true value of the ABIM to physicians, Dr. Baron contends, is that the organization is an independent third party that differentiates those doctors from people who don’t have their skills, training, and expertise. “In these days, where anyone can be an ‘expert’ on the Internet, that’s more valuable than ever before,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Abdul Moiz Hafiz, MD, was flabbergasted when he received a phone call from his institution’s credentialing office telling him that he was not certified for interventional cardiology – even though he had passed that exam in 2016.

Dr. Hafiz, who directs the Advanced Structural Heart Disease Program at Southern Illinois University, phoned the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), where he learned that to restore his credentials, he would need to pay $1,225 in maintenance of certification (MOC) fees.

Like Dr. Hafiz,

Even doctors who are participating in mandatory continuing education outside the ABIM’s auspices are finding themselves listed as “not certified.” Some physicians learned of the policy change only after applying for hospital privileges or for jobs that require ABIM certification.

Now that increasing numbers of physicians are employed by hospitals and health care organizations that require ABIM certification, many doctors have no option but to pony up the fees if they want to continue to practice medicine.

“We have no say in the matter,” said Dr. Hafiz, “and there’s no appeal process.”

The change affects nearly 330,000 physicians. Responses to the policy on Twitter included accusations of extortion and denunciations of the ABIM’s “money grab policies.”

Sunil Rao, MD, director of interventional cardiology at NYU Langone Health and president of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), has heard from many SCAI members who had experiences similar to Dr. Hafiz’s. While Dr. Rao describes some of the Twitter outrage as “emotional,” he does acknowledge that the ABIM’s moves appear to be financially motivated.

“The issue here was that as soon as they paid the fee, all of a sudden, ABIM flipped the switch and said they were certified,” he said. “It certainly sounds like a purely financial kind of structure.”

Richard Baron, MD, president and CEO of the ABIM, said doctors are misunderstanding the policy change.

“No doctor loses certification solely for failure to pay fees,” Dr. Baron told this news organization. “What caused them to be reported as not certified was that we didn’t have evidence that they had met program requirements. They could say, ‘But I did meet program requirements, you just didn’t know it.’ To which our answer would be, for us to know it, we have to process them. And our policy is that we don’t process them unless you are current on your fees.”

This is not the first time ABIM policies have alienated physicians.

Last year, the ABIM raised its MOC fees from $165 to $220. That also prompted a wave of outrage. Other grievances go further back. At one time, being board certified was a lifetime credential. However, in 1990 the ABIM made periodic recertification mandatory.

The process, which came to be known as “maintenance of certification,” had to be completed every 10 years, and fees were charged for each certification. At that point, said Dr. Baron, the relationship between the ABIM and physicians changed from a one-time interaction to a career-long relationship. He advises doctors to check in periodically on their portal page at the ABIM or download the app so they will always know their status.

Many physicians would prefer not to be bound to a lifetime relationship with the ABIM. There is an alternative licensing board, the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons (NBPAS), but it is accepted by only a limited number of hospitals.

“Until the NBPAS gains wide recognition,” said Dr. Hafiz, “the ABIM is going to continue to have basically a monopoly over the market.”

The value of MOC itself has been called into question. “There are no direct data supporting the value of the MOC process in either improving care, making patient care safer, or making patient care higher quality,” said Dr. Rao. This feeds frustration in a clinical community already dealing with onerous training requirements and expensive board certification exams and adds to the perception that it is a purely financial transaction, he said. (Studies examining whether the MOC system improves patient care have shown mixed results.)

The true value of the ABIM to physicians, Dr. Baron contends, is that the organization is an independent third party that differentiates those doctors from people who don’t have their skills, training, and expertise. “In these days, where anyone can be an ‘expert’ on the Internet, that’s more valuable than ever before,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Abdul Moiz Hafiz, MD, was flabbergasted when he received a phone call from his institution’s credentialing office telling him that he was not certified for interventional cardiology – even though he had passed that exam in 2016.

Dr. Hafiz, who directs the Advanced Structural Heart Disease Program at Southern Illinois University, phoned the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), where he learned that to restore his credentials, he would need to pay $1,225 in maintenance of certification (MOC) fees.

Like Dr. Hafiz,

Even doctors who are participating in mandatory continuing education outside the ABIM’s auspices are finding themselves listed as “not certified.” Some physicians learned of the policy change only after applying for hospital privileges or for jobs that require ABIM certification.

Now that increasing numbers of physicians are employed by hospitals and health care organizations that require ABIM certification, many doctors have no option but to pony up the fees if they want to continue to practice medicine.

“We have no say in the matter,” said Dr. Hafiz, “and there’s no appeal process.”

The change affects nearly 330,000 physicians. Responses to the policy on Twitter included accusations of extortion and denunciations of the ABIM’s “money grab policies.”

Sunil Rao, MD, director of interventional cardiology at NYU Langone Health and president of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI), has heard from many SCAI members who had experiences similar to Dr. Hafiz’s. While Dr. Rao describes some of the Twitter outrage as “emotional,” he does acknowledge that the ABIM’s moves appear to be financially motivated.

“The issue here was that as soon as they paid the fee, all of a sudden, ABIM flipped the switch and said they were certified,” he said. “It certainly sounds like a purely financial kind of structure.”

Richard Baron, MD, president and CEO of the ABIM, said doctors are misunderstanding the policy change.

“No doctor loses certification solely for failure to pay fees,” Dr. Baron told this news organization. “What caused them to be reported as not certified was that we didn’t have evidence that they had met program requirements. They could say, ‘But I did meet program requirements, you just didn’t know it.’ To which our answer would be, for us to know it, we have to process them. And our policy is that we don’t process them unless you are current on your fees.”

This is not the first time ABIM policies have alienated physicians.

Last year, the ABIM raised its MOC fees from $165 to $220. That also prompted a wave of outrage. Other grievances go further back. At one time, being board certified was a lifetime credential. However, in 1990 the ABIM made periodic recertification mandatory.

The process, which came to be known as “maintenance of certification,” had to be completed every 10 years, and fees were charged for each certification. At that point, said Dr. Baron, the relationship between the ABIM and physicians changed from a one-time interaction to a career-long relationship. He advises doctors to check in periodically on their portal page at the ABIM or download the app so they will always know their status.

Many physicians would prefer not to be bound to a lifetime relationship with the ABIM. There is an alternative licensing board, the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons (NBPAS), but it is accepted by only a limited number of hospitals.

“Until the NBPAS gains wide recognition,” said Dr. Hafiz, “the ABIM is going to continue to have basically a monopoly over the market.”

The value of MOC itself has been called into question. “There are no direct data supporting the value of the MOC process in either improving care, making patient care safer, or making patient care higher quality,” said Dr. Rao. This feeds frustration in a clinical community already dealing with onerous training requirements and expensive board certification exams and adds to the perception that it is a purely financial transaction, he said. (Studies examining whether the MOC system improves patient care have shown mixed results.)

The true value of the ABIM to physicians, Dr. Baron contends, is that the organization is an independent third party that differentiates those doctors from people who don’t have their skills, training, and expertise. “In these days, where anyone can be an ‘expert’ on the Internet, that’s more valuable than ever before,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

BMI is a flawed measure of obesity. What are alternatives?

“BMI is trash. Full stop.” This controversial tweet, which received thousands of likes and retweets, was cited in a recent article by one doctor on when physicians might stop using body mass index (BMI) to diagnose obesity.

BMI has for years been the consensus default method for assessing whether a person is overweight or has obesity, and is still widely used as the gatekeeper metric for treatment eligibility for certain weight-loss agents and bariatric surgery.

an important determinant of the cardiometabolic consequences of fat.

Alternative metrics include waist circumference and/or waist-to-height ratio (WHtR); imaging methods such as CT, MRI, and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA); and bioelectrical impedance to assess fat volume and location. All have made some inroads on the tight grip BMI has had on obesity assessment.

Chances are, however, that BMI will not fade away anytime soon given how entrenched it has become in clinical practice and for insurance coverage, as well as its relative simplicity and precision.

“BMI is embedded in a wide range of guidelines on the use of medications and surgery. It’s embedded in Food and Drug Administration regulations and for billing and insurance coverage. It would take extremely strong data and years of work to undo the infrastructure built around BMI and replace it with something else. I don’t see that happening [anytime soon],” commented Daniel H. Bessesen, MD, a professor at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and chief of endocrinology for Denver Health.

“It would be almost impossible to replace all the studies that have used BMI with investigations using some other measure,” he said.

BMI Is ‘imperfect’

The entrenched position of BMI as the go-to metric doesn’t keep detractors from weighing in. As noted in a commentary on current clinical challenges surrounding obesity recently published in Annals of Internal Medicine, the journal’s editor-in-chief, Christine Laine, MD, and senior deputy editor Christina C. Wee, MD, listed six top issues clinicians must deal with, one of which, they say, is the need for a better measure of obesity than BMI.

“Unfortunately, BMI is an imperfect measure of body composition that differs with ethnicity, sex, body frame, and muscle mass,” noted Dr. Laine and Dr. Wee.

BMI is based on a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of their height in meters. A “healthy” BMI is between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2, overweight is 25-29.9, and 30 or greater is considered to represent obesity. However, certain ethnic groups have lower cutoffs for overweight or obesity because of evidence that such individuals can be at higher risk of obesity-related comorbidities at lower BMIs.

“BMI was chosen as the initial screening tool [for obesity] not because anyone thought it was perfect or the best measure but because of its simplicity. All you need is height, weight, and a calculator,” Dr. Wee said in an interview.

Numerous online calculators are available, including one from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention where height in feet and inches and weight in pounds can be entered to generate the BMI.

BMI is also inherently limited by being “a proxy for adiposity” and not a direct measure, added Dr. Wee, who is also director of the Obesity Research Program of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

As such, BMI can’t distinguish between fat and muscle because it relies on weight only to gauge adiposity, noted Tiffany Powell-Wiley, MD, an obesity researcher at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Md. Another shortcoming of BMI is that it “is good for distinguishing population-level risk for cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases, but it does not help as much for distinguishing risk at an individual level,” she said in an interview.

These and other drawbacks have prompted researchers to look for other useful metrics. WHtR, for example, has recently made headway as a potential BMI alternative or complement.

The case for WHtR

Concern about overreliance on BMI despite its limitations is not new. In 2015, an American Heart Association scientific statement from the group’s Obesity Committee concluded that “BMI alone, even with lower thresholds, is a useful but not an ideal tool for identification of obesity or assessment of cardiovascular risk,” especially for people from Asian, Black, Hispanic, and Pacific Islander populations.

The writing panel also recommended that clinicians measure waist circumference annually and use that information along with BMI “to better gauge cardiovascular risk in diverse populations.”

Momentum for moving beyond BMI alone has continued to build following the AHA statement.

In September 2022, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, which sets policies for the United Kingdom’s National Health Service, revised its guidancefor assessment and management of people with obesity. The updated guidance recommends that when clinicians assess “adults with BMI below 35 kg/m2, measure and use their WHtR, as well as their BMI, as a practical estimate of central adiposity and use these measurements to help to assess and predict health risks.”

NICE released an extensive literature review with the revision, and based on the evidence, said that “using waist-to-height ratio as well as BMI would help give a practical estimate of central adiposity in adults with BMI under 35 kg/m2. This would in turn help professionals assess and predict health risks.”

However, the review added that, “because people with a BMI over 35 kg/m2 are always likely to have a high WHtR, the committee recognized that it may not be a useful addition for predicting health risks in this group.” The 2022 NICE review also said that it is “important to estimate central adiposity when assessing future health risks, including for people whose BMI is in the healthy-weight category.”

This new emphasis by NICE on measuring and using WHtR as part of obesity assessment “represents an important change in population health policy,” commented Dr. Powell-Wiley. “I expect more professional organizations will endorse use of waist circumference or waist-to-height ratio now that NICE has taken this step,” she predicted.

Waist circumference and WHtR may become standard measures of adiposity in clinical practice over the next 5-10 years.

The recent move by NICE to highlight a complementary role for WHtR “is another acknowledgment that BMI is an imperfect tool for stratifying cardiometabolic risk in a diverse population, especially in people with lower BMIs” because of its variability, commented Jamie Almandoz, MD, medical director of the weight wellness program at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

WHtR vs. BMI

Another recent step forward for WHtR came with the publication of a post hoc analysis of data collected in the PARADIGM-HF trial, a study that had the primary purpose of comparing two medications for improving outcomes in more than 8,000 patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

The new analysis showed that “two indices that incorporate waist circumference and height, but not weight, showed a clearer association between greater adiposity and a higher risk of heart failure hospitalization,” compared with BMI.

WHtR was one of the two indices identified as being a better correlate for the adverse effect of excess adiposity compared with BMI.

The authors of the post hoc analysis did not design their analysis to compare WHtR with BMI. Instead, their goal was to better understand what’s known as the “obesity paradox” in people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: The recurring observation that, when these patients with heart failure have lower BMIs they fare worse, with higher rates of mortality and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, compared with patients with higher BMIs.

The new analysis showed that this paradox disappeared when WHtR was substituted for BMI as the obesity metric.

This “provides meaningful data about the superiority of WHtR, compared with BMI, for predicting heart failure outcomes,” said Dr. Powell-Wiley, although she cautioned that the analysis was limited by scant data in diverse populations and did not look at other important cardiovascular disease outcomes. While Dr. Powell-Wiley does not think that WHtR needs assessment in a prospective, controlled trial, she called for analysis of pooled prospective studies with more diverse populations to better document the advantages of WHtR over BMI.

The PARADIGM-HF post hoc analysis shows again how flawed BMI is for health assessment and the relative importance of an individualized understanding of a person’s body composition, Dr. Almandoz said in an interview. “As we collect more data, there is increasing awareness of how imperfect BMI is.”

Measuring waist circumference is tricky

Although WHtR looks promising as a substitute for or add-on to BMI, it has its own limitations, particularly the challenge of accurately measuring waist circumference.

Measuring waist circumference “not only takes more time but requires the assessor to be well trained about where to put the tape measure and making sure it’s measured at the same place each time,” even when different people take serial measurements from individual patients, noted Dr. Wee. Determining waist circumference can also be technically difficult when done on larger people, she added, and collectively these challenges make waist circumference “less reproducible from measurement to measurement.”

“It’s relatively clear how to standardize measurement of weight and height, but there is a huge amount of variability when the waist is measured,” agreed Dr. Almandoz. “And waist circumference also differs by ethnicity, race, sex, and body frame. There are significant differences in waist circumference levels that associate with increased health risks” between, for example, White and South Asian people.

Another limitation of waist circumference and WHtR is that they “cannot differentiate between visceral and abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue, which are vastly different regarding cardiometabolic risk, commented Ian Neeland, MD, director of cardiovascular prevention at the University Hospitals Harrington Heart & Vascular Institute, Cleveland.

The imaging option

“Waist-to-height ratio is not the ultimate answer,” Dr. Neeland said in an interview. He instead endorsed “advanced imaging for body fat distribution,” such as CT or MRI scans, as his pick for what should be the standard obesity metric, “given that it is much more specific and actionable for both risk assessment and response to therapy. I expect slow but steady advancements that move away from BMI cutoffs, for example for bariatric surgery, given that BMI is an imprecise and crude tool.”

But although imaging with methods like CT and MRI may provide the best accuracy and precision for tracking the volume of a person’s cardiometabolically dangerous fat, they are also hampered by relatively high cost and, for CT and DXA, the issue of radiation exposure.

“CT, MRI, and DXA scans give more in-depth assessment of body composition, but should we expose people to the radiation and the cost?” Dr. Almandoz wondered.

“Height, weight, and waist circumference cost nothing to obtain,” creating a big relative disadvantage for imaging, said Naveed Sattar, MD, professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow.

“Data would need to show that imaging gives clinicians substantially more information about future risk” to justify its price, Dr. Sattar emphasized.

BMI’s limits mean adding on

Regardless of whichever alternatives to BMI end up getting used most, experts generally agree that BMI alone is looking increasingly inadequate.

“Over the next 5 years, BMI will come to be seen as a screening tool that categorizes people into general risk groups” that also needs “other metrics and variables, such as age, race, ethnicity, family history, blood glucose, and blood pressure to better describe health risk in an individual,” predicted Dr. Bessesen.

The endorsement of WHtR by NICE “will lead to more research into how to incorporate WHtR into routine practice. We need more evidence to translate what NICE said into practice,” said Dr. Sattar. “I don’t think we’ll see a shift away from BMI, but we’ll add alternative measures that are particularly useful in certain patients.”

“Because we live in diverse societies, we need to individualize risk assessment and couple that with technology that makes analysis of body composition more accessible,” agreed Dr. Almandoz. He noted that the UT Southwestern weight wellness program where he practices has, for about the past decade, routinely collected waist circumference and bioelectrical impedance data as well as BMI on all people seen in the practice for obesity concerns. Making these additional measurements on a routine basis also helps strengthen patient engagement.

“We get into trouble when we make rigid health policy and clinical decisions based on BMI alone without looking at the patient holistically,” said Dr. Wee. “Patients are more than arbitrary numbers, and clinicians should make clinical decisions based on the totality of evidence for each individual patient.”

Dr. Bessesen, Dr. Wee, Dr. Powell-Wiley, and Dr. Almandoz reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Neeland has reported being a consultant for Merck. Dr. Sattar has reported being a consultant or speaker for Abbott Laboratories, Afimmune, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Hanmi Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche Diagnostics, and Sanofi.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

“BMI is trash. Full stop.” This controversial tweet, which received thousands of likes and retweets, was cited in a recent article by one doctor on when physicians might stop using body mass index (BMI) to diagnose obesity.

BMI has for years been the consensus default method for assessing whether a person is overweight or has obesity, and is still widely used as the gatekeeper metric for treatment eligibility for certain weight-loss agents and bariatric surgery.

an important determinant of the cardiometabolic consequences of fat.

Alternative metrics include waist circumference and/or waist-to-height ratio (WHtR); imaging methods such as CT, MRI, and dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA); and bioelectrical impedance to assess fat volume and location. All have made some inroads on the tight grip BMI has had on obesity assessment.

Chances are, however, that BMI will not fade away anytime soon given how entrenched it has become in clinical practice and for insurance coverage, as well as its relative simplicity and precision.

“BMI is embedded in a wide range of guidelines on the use of medications and surgery. It’s embedded in Food and Drug Administration regulations and for billing and insurance coverage. It would take extremely strong data and years of work to undo the infrastructure built around BMI and replace it with something else. I don’t see that happening [anytime soon],” commented Daniel H. Bessesen, MD, a professor at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and chief of endocrinology for Denver Health.

“It would be almost impossible to replace all the studies that have used BMI with investigations using some other measure,” he said.

BMI Is ‘imperfect’