User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

What do I have? How to tell patients you’re not sure

Physicians often struggle with telling patients when they are unsure about a diagnosis. In the absence of clarity, doctors may fear losing a patient’s trust by appearing unsure.

Yet diagnostic uncertainty is an inevitable part of medicine.

“It’s often uncertain what is really going on. People have lots of unspecific symptoms,” said Gordon D. Schiff, MD, a patient safety researcher at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

By one estimate, more than one-third of patients are discharged from an emergency department without a clear diagnosis. Physicians may order more tests to try to resolve uncertainty, but this method is not foolproof and may lead to increased health care costs. Physicians can use an uncertain diagnosis as an opportunity to improve conversations with patients, Dr. Schiff said.

“How do you talk to patients about that? How do you convey that?” Dr. Schiff asked.

To begin to answer these questions, The scenarios included an enlarged lymph node in a patient in remission for lymphoma, which could suggest recurrence of the disease but not necessarily; a patient with a new-onset headache; and another patient with an unexplained fever and a respiratory tract infection.

For each vignette, the researchers also asked patient advocates – many of whom had experienced receiving an incorrect diagnosis – for their thoughts on how the conversation should go.

Almost 70 people were consulted (24 primary care physicians, 40 patients, and five experts in informatics and quality and safety). Dr. Schiff and his colleagues produced six standardized elements that should be part of a conversation whenever a diagnosis is unclear.

- The most likely diagnosis, along with any alternatives if this isn’t certain, with phrases such as, “Sometimes we don’t have the answers, but we will keep trying to figure out what is going on.”

- Next steps – lab tests, return visits, etc.

- Expected time frame for patient’s improvement and recovery.

- Full disclosure of the limitations of the physical examination or any lab tests.

- Ways to contact the physician going forward.

- Patient insights on their experience and reaction to what they just heard.

The researchers, who published their findings in JAMA Network Open, recommend that the conversation be transcribed in real time using voice recognition software and a microphone, and then printed for the patient to take home. The physician should make eye contact with the patient during the conversation, they suggested.

“Patients felt it was a conversation, that they actually understood what was said. Most patients felt like they were partners during the encounter,” said Maram Khazen, PhD, a coauthor of the paper, who studies communication dynamics. Dr. Khazen was a visiting postdoctoral fellow with Dr. Schiff during the study, and is now a lecturer at the Max Stern Yezreel Valley College in Israel.

Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH, a patient safety researcher at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, called the new work “a great start,” but said that the complexity of the field warrants more research into the tool. Dr. Singh was not involved in the study.

Dr. Singh pointed out that many of the patient voices came from spokespeople for advocacy groups, and that these participants are not necessarily representative of actual people with unclear diagnoses.

“The choice of words really matters,” said Dr. Singh, who led a 2018 study that showed that people reacted more negatively when physicians bluntly acknowledged uncertainty than when they walked patients through different possible diagnoses. Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen’s framework offers good principles for discussing uncertainty, he added, but further research is needed on the optimal language to use during conversations.

“It’s really encouraging that we’re seeing high-quality research like this, that leverages patient engagement principles,” said Dimitrios Papanagnou, MD, MPH, an emergency medicine physician and vice dean of medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Dr. Papanagnou, who was not part of the study, called for diverse patients to be part of conversations about diagnostic uncertainty.

“Are we having patients from diverse experiences, from underrepresented groups, participate in this kind of work?” Dr. Papanagnou asked. Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen said they agree that the tool needs to be tested in larger samples of diverse patients.

Some common themes about how to communicate diagnostic uncertainty are emerging in multiple areas of medicine. Dr. Papanagnou helped develop an uncertainty communication checklist for discharging patients from an emergency department to home, with principles similar to those that Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen recommend for primary care providers.

The study was funded by Harvard Hospitals’ malpractice insurer, the Controlled Risk Insurance Company. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians often struggle with telling patients when they are unsure about a diagnosis. In the absence of clarity, doctors may fear losing a patient’s trust by appearing unsure.

Yet diagnostic uncertainty is an inevitable part of medicine.

“It’s often uncertain what is really going on. People have lots of unspecific symptoms,” said Gordon D. Schiff, MD, a patient safety researcher at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

By one estimate, more than one-third of patients are discharged from an emergency department without a clear diagnosis. Physicians may order more tests to try to resolve uncertainty, but this method is not foolproof and may lead to increased health care costs. Physicians can use an uncertain diagnosis as an opportunity to improve conversations with patients, Dr. Schiff said.

“How do you talk to patients about that? How do you convey that?” Dr. Schiff asked.

To begin to answer these questions, The scenarios included an enlarged lymph node in a patient in remission for lymphoma, which could suggest recurrence of the disease but not necessarily; a patient with a new-onset headache; and another patient with an unexplained fever and a respiratory tract infection.

For each vignette, the researchers also asked patient advocates – many of whom had experienced receiving an incorrect diagnosis – for their thoughts on how the conversation should go.

Almost 70 people were consulted (24 primary care physicians, 40 patients, and five experts in informatics and quality and safety). Dr. Schiff and his colleagues produced six standardized elements that should be part of a conversation whenever a diagnosis is unclear.

- The most likely diagnosis, along with any alternatives if this isn’t certain, with phrases such as, “Sometimes we don’t have the answers, but we will keep trying to figure out what is going on.”

- Next steps – lab tests, return visits, etc.

- Expected time frame for patient’s improvement and recovery.

- Full disclosure of the limitations of the physical examination or any lab tests.

- Ways to contact the physician going forward.

- Patient insights on their experience and reaction to what they just heard.

The researchers, who published their findings in JAMA Network Open, recommend that the conversation be transcribed in real time using voice recognition software and a microphone, and then printed for the patient to take home. The physician should make eye contact with the patient during the conversation, they suggested.

“Patients felt it was a conversation, that they actually understood what was said. Most patients felt like they were partners during the encounter,” said Maram Khazen, PhD, a coauthor of the paper, who studies communication dynamics. Dr. Khazen was a visiting postdoctoral fellow with Dr. Schiff during the study, and is now a lecturer at the Max Stern Yezreel Valley College in Israel.

Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH, a patient safety researcher at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, called the new work “a great start,” but said that the complexity of the field warrants more research into the tool. Dr. Singh was not involved in the study.

Dr. Singh pointed out that many of the patient voices came from spokespeople for advocacy groups, and that these participants are not necessarily representative of actual people with unclear diagnoses.

“The choice of words really matters,” said Dr. Singh, who led a 2018 study that showed that people reacted more negatively when physicians bluntly acknowledged uncertainty than when they walked patients through different possible diagnoses. Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen’s framework offers good principles for discussing uncertainty, he added, but further research is needed on the optimal language to use during conversations.

“It’s really encouraging that we’re seeing high-quality research like this, that leverages patient engagement principles,” said Dimitrios Papanagnou, MD, MPH, an emergency medicine physician and vice dean of medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Dr. Papanagnou, who was not part of the study, called for diverse patients to be part of conversations about diagnostic uncertainty.

“Are we having patients from diverse experiences, from underrepresented groups, participate in this kind of work?” Dr. Papanagnou asked. Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen said they agree that the tool needs to be tested in larger samples of diverse patients.

Some common themes about how to communicate diagnostic uncertainty are emerging in multiple areas of medicine. Dr. Papanagnou helped develop an uncertainty communication checklist for discharging patients from an emergency department to home, with principles similar to those that Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen recommend for primary care providers.

The study was funded by Harvard Hospitals’ malpractice insurer, the Controlled Risk Insurance Company. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians often struggle with telling patients when they are unsure about a diagnosis. In the absence of clarity, doctors may fear losing a patient’s trust by appearing unsure.

Yet diagnostic uncertainty is an inevitable part of medicine.

“It’s often uncertain what is really going on. People have lots of unspecific symptoms,” said Gordon D. Schiff, MD, a patient safety researcher at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

By one estimate, more than one-third of patients are discharged from an emergency department without a clear diagnosis. Physicians may order more tests to try to resolve uncertainty, but this method is not foolproof and may lead to increased health care costs. Physicians can use an uncertain diagnosis as an opportunity to improve conversations with patients, Dr. Schiff said.

“How do you talk to patients about that? How do you convey that?” Dr. Schiff asked.

To begin to answer these questions, The scenarios included an enlarged lymph node in a patient in remission for lymphoma, which could suggest recurrence of the disease but not necessarily; a patient with a new-onset headache; and another patient with an unexplained fever and a respiratory tract infection.

For each vignette, the researchers also asked patient advocates – many of whom had experienced receiving an incorrect diagnosis – for their thoughts on how the conversation should go.

Almost 70 people were consulted (24 primary care physicians, 40 patients, and five experts in informatics and quality and safety). Dr. Schiff and his colleagues produced six standardized elements that should be part of a conversation whenever a diagnosis is unclear.

- The most likely diagnosis, along with any alternatives if this isn’t certain, with phrases such as, “Sometimes we don’t have the answers, but we will keep trying to figure out what is going on.”

- Next steps – lab tests, return visits, etc.

- Expected time frame for patient’s improvement and recovery.

- Full disclosure of the limitations of the physical examination or any lab tests.

- Ways to contact the physician going forward.

- Patient insights on their experience and reaction to what they just heard.

The researchers, who published their findings in JAMA Network Open, recommend that the conversation be transcribed in real time using voice recognition software and a microphone, and then printed for the patient to take home. The physician should make eye contact with the patient during the conversation, they suggested.

“Patients felt it was a conversation, that they actually understood what was said. Most patients felt like they were partners during the encounter,” said Maram Khazen, PhD, a coauthor of the paper, who studies communication dynamics. Dr. Khazen was a visiting postdoctoral fellow with Dr. Schiff during the study, and is now a lecturer at the Max Stern Yezreel Valley College in Israel.

Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH, a patient safety researcher at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, called the new work “a great start,” but said that the complexity of the field warrants more research into the tool. Dr. Singh was not involved in the study.

Dr. Singh pointed out that many of the patient voices came from spokespeople for advocacy groups, and that these participants are not necessarily representative of actual people with unclear diagnoses.

“The choice of words really matters,” said Dr. Singh, who led a 2018 study that showed that people reacted more negatively when physicians bluntly acknowledged uncertainty than when they walked patients through different possible diagnoses. Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen’s framework offers good principles for discussing uncertainty, he added, but further research is needed on the optimal language to use during conversations.

“It’s really encouraging that we’re seeing high-quality research like this, that leverages patient engagement principles,” said Dimitrios Papanagnou, MD, MPH, an emergency medicine physician and vice dean of medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Dr. Papanagnou, who was not part of the study, called for diverse patients to be part of conversations about diagnostic uncertainty.

“Are we having patients from diverse experiences, from underrepresented groups, participate in this kind of work?” Dr. Papanagnou asked. Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen said they agree that the tool needs to be tested in larger samples of diverse patients.

Some common themes about how to communicate diagnostic uncertainty are emerging in multiple areas of medicine. Dr. Papanagnou helped develop an uncertainty communication checklist for discharging patients from an emergency department to home, with principles similar to those that Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen recommend for primary care providers.

The study was funded by Harvard Hospitals’ malpractice insurer, the Controlled Risk Insurance Company. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Children and COVID: A look back as the fourth year begins

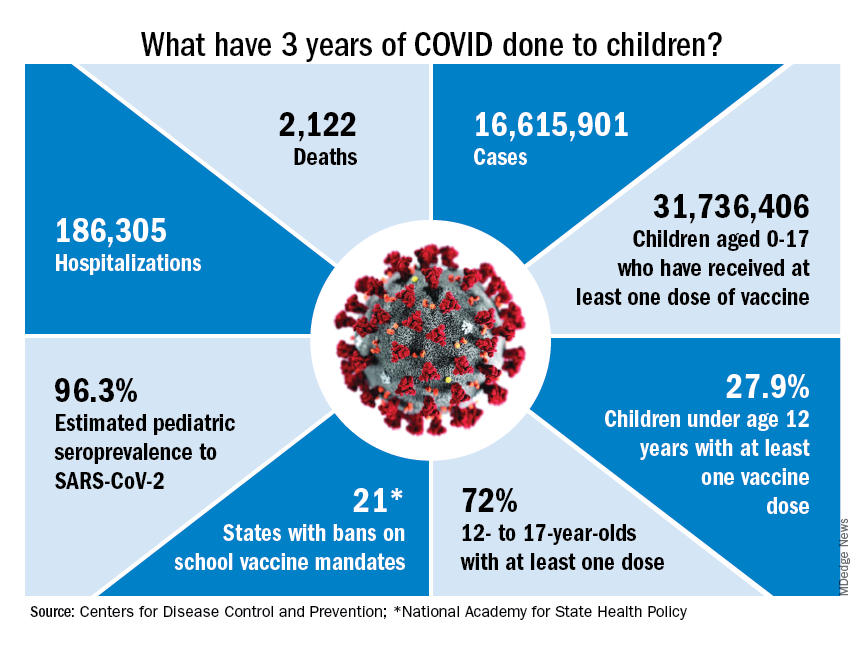

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

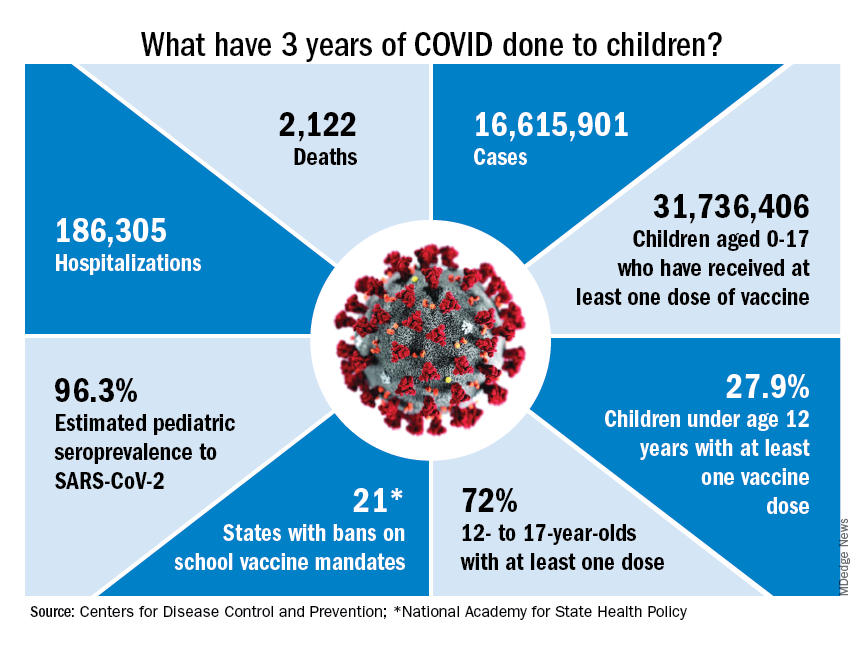

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

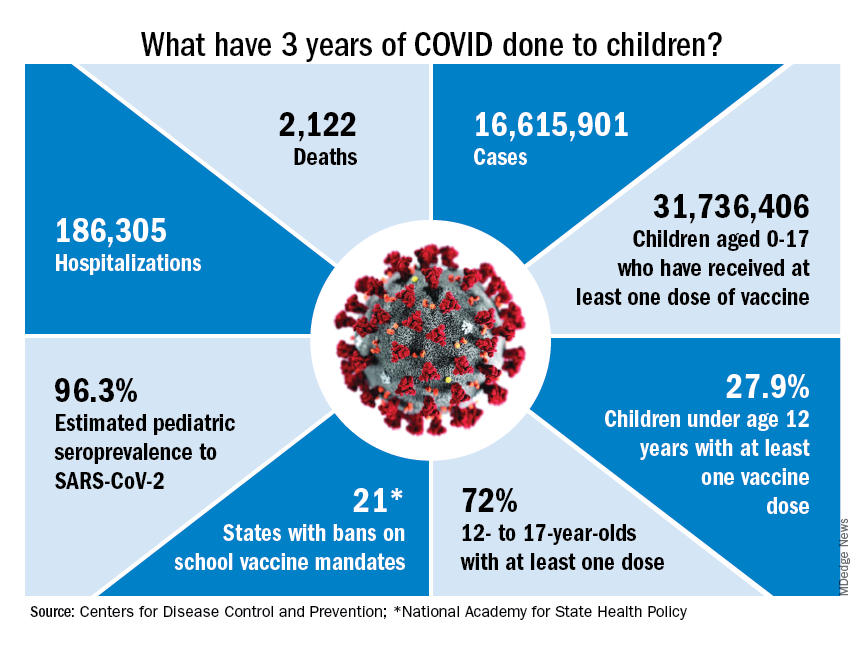

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

Factors linked with increased VTE risk in COVID outpatients

Though VTE risk is well studied and significant in those hospitalized with COVID, little is known about the risk in the outpatient setting, said the authors of the new research published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted at two integrated health care delivery systems in northern and southern California. Data were gathered from the Kaiser Permanente Virtual Data Warehouse and electronic health records.

Nearly 400,000 patients studied

Researchers, led by Margaret Fang, MD, with the division of hospital medicine, University of California, San Francisco, identified 398,530 outpatients with COVID-19 from Jan. 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2021.

VTE risk was low overall for ambulatory COVID patients.

“It is a reassuring study,” Dr. Fang said in an interview.

The researchers found that the risk is highest in the first 30 days after COVID-19 diagnosis (unadjusted rate, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.51-0.67 per 100 person-years vs. 0.09; 95% CI, 0.08-0.11 per 100 person-years after 30 days).

Factors linked with high VTE risk

They also found that several factors were linked with a higher risk of blood clots in the study population, including being at least 55 years old; being male; having a history of blood clots or thrombophilia; and a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2.

The authors write, “These findings may help identify subsets of patients with COVID-19 who could benefit from VTE preventive strategies and more intensive short-term surveillance.”

Are routine anticoagulants justified?

Previously, randomized clinical trials have found that hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19 may benefit from therapeutically dosed heparin anticoagulants but that therapeutic anticoagulation had no net benefit – and perhaps could even harm – patients who were critically ill with COVID.

“[M]uch less is known about the optimal thromboprophylaxis strategy for people with milder presentations of COVID-19 who do not require hospitalization,” they write.

Mild COVID VTE risk similar to general population

The authors note that rates of blood clots linked with COVID-19 are not much higher than the average blood clot rate in the general population, which is about 0.1-0.2 per 100 person-years.

Therefore, the results don’t justify routine administration of anticoagulation given the costs, inconvenience, and bleeding risks, they acknowledge.

Dr. Fang told this publication that it’s hard to know what to tell patients, given the overall low VTE risk. She said their study wasn’t designed to advise when to give prophylaxis.

Physicians should inform patients of their higher risk

“We should tell our patients who fall into these risk categories that blood clot is a concern after the development of COVID, especially in those first 30 days. And some people might benefit from increased surveillance,” Dr. Fang said.

”I think this study would support ongoing studies that look at whether selected patients benefit from VTE prophylaxis, for example low-dose anticoagulants,” she said.

Dr. Fang said the subgroup factors they found increased risk of blood clots for all patients, not just COVID-19 patients. It’s not clear why factors such as being male may increase blood clot risk, though that is consistent with previous literature, but higher risk with higher BMI might be related to a combination of inflammation or decreased mobility, she said.

Unanswered questions

Robert H. Hopkins Jr., MD, says the study helps answer a couple of important questions – that the VTE risk in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients is low and when and for which patients risk may be highest.

However, there are several unanswered questions that argue against routine initiation of anticoagulants, notes the professor of internal medicine and pediatrics chief, division of general internal medicine, at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

One is the change in the COVID variant landscape.

“We do not know whether rates of VTE are same or lower or higher with current circulating variants,” Dr. Hopkins said.

The authors acknowledge this as a limitation. Study data predate Omicron and subvariants, which appear to lower clinical severity, so it’s unclear whether VTE risk is different in this Omicron era.

Dr. Hopkins added another unknown: “We do not know whether vaccination affects rates of VTE in ambulatory breakthrough infection.”

Dr. Hopkins and the authors also note the lack of a control group in the study, to better compare risk.

Coauthor Dr. Prasad reports consultant fees from EpiExcellence LLC outside the submitted work. Coauthor Dr. Go reports grants paid to the division of research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, from CSL Behring, Novartis, Bristol Meyers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, and Janssen outside the submitted work.

The research was funded through Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Dr. Hopkins reports no relevant financial relationships.

Though VTE risk is well studied and significant in those hospitalized with COVID, little is known about the risk in the outpatient setting, said the authors of the new research published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted at two integrated health care delivery systems in northern and southern California. Data were gathered from the Kaiser Permanente Virtual Data Warehouse and electronic health records.

Nearly 400,000 patients studied

Researchers, led by Margaret Fang, MD, with the division of hospital medicine, University of California, San Francisco, identified 398,530 outpatients with COVID-19 from Jan. 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2021.

VTE risk was low overall for ambulatory COVID patients.

“It is a reassuring study,” Dr. Fang said in an interview.

The researchers found that the risk is highest in the first 30 days after COVID-19 diagnosis (unadjusted rate, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.51-0.67 per 100 person-years vs. 0.09; 95% CI, 0.08-0.11 per 100 person-years after 30 days).

Factors linked with high VTE risk

They also found that several factors were linked with a higher risk of blood clots in the study population, including being at least 55 years old; being male; having a history of blood clots or thrombophilia; and a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2.

The authors write, “These findings may help identify subsets of patients with COVID-19 who could benefit from VTE preventive strategies and more intensive short-term surveillance.”

Are routine anticoagulants justified?

Previously, randomized clinical trials have found that hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19 may benefit from therapeutically dosed heparin anticoagulants but that therapeutic anticoagulation had no net benefit – and perhaps could even harm – patients who were critically ill with COVID.

“[M]uch less is known about the optimal thromboprophylaxis strategy for people with milder presentations of COVID-19 who do not require hospitalization,” they write.

Mild COVID VTE risk similar to general population

The authors note that rates of blood clots linked with COVID-19 are not much higher than the average blood clot rate in the general population, which is about 0.1-0.2 per 100 person-years.

Therefore, the results don’t justify routine administration of anticoagulation given the costs, inconvenience, and bleeding risks, they acknowledge.

Dr. Fang told this publication that it’s hard to know what to tell patients, given the overall low VTE risk. She said their study wasn’t designed to advise when to give prophylaxis.

Physicians should inform patients of their higher risk

“We should tell our patients who fall into these risk categories that blood clot is a concern after the development of COVID, especially in those first 30 days. And some people might benefit from increased surveillance,” Dr. Fang said.

”I think this study would support ongoing studies that look at whether selected patients benefit from VTE prophylaxis, for example low-dose anticoagulants,” she said.

Dr. Fang said the subgroup factors they found increased risk of blood clots for all patients, not just COVID-19 patients. It’s not clear why factors such as being male may increase blood clot risk, though that is consistent with previous literature, but higher risk with higher BMI might be related to a combination of inflammation or decreased mobility, she said.

Unanswered questions

Robert H. Hopkins Jr., MD, says the study helps answer a couple of important questions – that the VTE risk in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients is low and when and for which patients risk may be highest.

However, there are several unanswered questions that argue against routine initiation of anticoagulants, notes the professor of internal medicine and pediatrics chief, division of general internal medicine, at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

One is the change in the COVID variant landscape.

“We do not know whether rates of VTE are same or lower or higher with current circulating variants,” Dr. Hopkins said.

The authors acknowledge this as a limitation. Study data predate Omicron and subvariants, which appear to lower clinical severity, so it’s unclear whether VTE risk is different in this Omicron era.

Dr. Hopkins added another unknown: “We do not know whether vaccination affects rates of VTE in ambulatory breakthrough infection.”

Dr. Hopkins and the authors also note the lack of a control group in the study, to better compare risk.

Coauthor Dr. Prasad reports consultant fees from EpiExcellence LLC outside the submitted work. Coauthor Dr. Go reports grants paid to the division of research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, from CSL Behring, Novartis, Bristol Meyers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, and Janssen outside the submitted work.

The research was funded through Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Dr. Hopkins reports no relevant financial relationships.

Though VTE risk is well studied and significant in those hospitalized with COVID, little is known about the risk in the outpatient setting, said the authors of the new research published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study was conducted at two integrated health care delivery systems in northern and southern California. Data were gathered from the Kaiser Permanente Virtual Data Warehouse and electronic health records.

Nearly 400,000 patients studied

Researchers, led by Margaret Fang, MD, with the division of hospital medicine, University of California, San Francisco, identified 398,530 outpatients with COVID-19 from Jan. 1, 2020, through Jan. 31, 2021.

VTE risk was low overall for ambulatory COVID patients.

“It is a reassuring study,” Dr. Fang said in an interview.

The researchers found that the risk is highest in the first 30 days after COVID-19 diagnosis (unadjusted rate, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.51-0.67 per 100 person-years vs. 0.09; 95% CI, 0.08-0.11 per 100 person-years after 30 days).

Factors linked with high VTE risk

They also found that several factors were linked with a higher risk of blood clots in the study population, including being at least 55 years old; being male; having a history of blood clots or thrombophilia; and a body mass index (BMI) of at least 30 kg/m2.

The authors write, “These findings may help identify subsets of patients with COVID-19 who could benefit from VTE preventive strategies and more intensive short-term surveillance.”

Are routine anticoagulants justified?

Previously, randomized clinical trials have found that hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19 may benefit from therapeutically dosed heparin anticoagulants but that therapeutic anticoagulation had no net benefit – and perhaps could even harm – patients who were critically ill with COVID.

“[M]uch less is known about the optimal thromboprophylaxis strategy for people with milder presentations of COVID-19 who do not require hospitalization,” they write.

Mild COVID VTE risk similar to general population

The authors note that rates of blood clots linked with COVID-19 are not much higher than the average blood clot rate in the general population, which is about 0.1-0.2 per 100 person-years.

Therefore, the results don’t justify routine administration of anticoagulation given the costs, inconvenience, and bleeding risks, they acknowledge.

Dr. Fang told this publication that it’s hard to know what to tell patients, given the overall low VTE risk. She said their study wasn’t designed to advise when to give prophylaxis.

Physicians should inform patients of their higher risk

“We should tell our patients who fall into these risk categories that blood clot is a concern after the development of COVID, especially in those first 30 days. And some people might benefit from increased surveillance,” Dr. Fang said.

”I think this study would support ongoing studies that look at whether selected patients benefit from VTE prophylaxis, for example low-dose anticoagulants,” she said.

Dr. Fang said the subgroup factors they found increased risk of blood clots for all patients, not just COVID-19 patients. It’s not clear why factors such as being male may increase blood clot risk, though that is consistent with previous literature, but higher risk with higher BMI might be related to a combination of inflammation or decreased mobility, she said.

Unanswered questions

Robert H. Hopkins Jr., MD, says the study helps answer a couple of important questions – that the VTE risk in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients is low and when and for which patients risk may be highest.

However, there are several unanswered questions that argue against routine initiation of anticoagulants, notes the professor of internal medicine and pediatrics chief, division of general internal medicine, at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock.

One is the change in the COVID variant landscape.

“We do not know whether rates of VTE are same or lower or higher with current circulating variants,” Dr. Hopkins said.

The authors acknowledge this as a limitation. Study data predate Omicron and subvariants, which appear to lower clinical severity, so it’s unclear whether VTE risk is different in this Omicron era.

Dr. Hopkins added another unknown: “We do not know whether vaccination affects rates of VTE in ambulatory breakthrough infection.”

Dr. Hopkins and the authors also note the lack of a control group in the study, to better compare risk.

Coauthor Dr. Prasad reports consultant fees from EpiExcellence LLC outside the submitted work. Coauthor Dr. Go reports grants paid to the division of research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, from CSL Behring, Novartis, Bristol Meyers Squibb/Pfizer Alliance, and Janssen outside the submitted work.

The research was funded through Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Dr. Hopkins reports no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Can particles in dairy and beef cause cancer and MS?

In Western diets, dairy and beef are ubiquitous: Milk goes with coffee, melted cheese with pizza, and chili with rice. But what if dairy products and beef contained a new kind of pathogen that could infect you as a child and trigger cancer or multiple sclerosis (MS) 40-70 years later?

However, in two joint statements, the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) and the Max Rubner Institute (MRI) have rejected such theories.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, DSc, received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his discovery that human papillomaviruses cause cervical cancer. His starting point was the observation that sexually abstinent women, such as nuns, rarely develop this cancer. So it was possible to draw the conclusion that pathogens are transmitted during sexual intercourse, explain Dr. zur Hausen and his wife Ethel-Michele de Villiers, PhD, both of DKFZ Heidelberg.

Papillomaviruses, as well as human herpes and Epstein-Barr viruses (EBV), polyomaviruses, and retroviruses, cause cancer in a direct way: by inserting their genes into the DNA of human cells. With a latency of a few years to a few decades, the proteins formed through expression stimulate malignant growth by altering the regulating host gene.

Acid radicals

However, viruses – just like bacteria and parasites – can also indirectly trigger cancer. One mechanism for this triggering is the disruption of immune defenses, as shown by the sometimes drastically increased tumor incidence with AIDS or with immunosuppressants after transplants. Chronic inflammation is a second mechanism that generates acid radicals and thereby causes random mutations in replicating cells. Examples include stomach cancer caused by Helicobacter pylori and liver cancer caused by Schistosoma, liver fluke, and hepatitis B and C viruses.

According to Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen, there are good reasons to believe that other pathogens could cause chronic inflammation and thereby lead to cancer. Epidemiologic data suggest that dairy and meat products from European cows (Bos taurus) are a potential source. This is because colon cancer and breast cancer commonly occur in places where these foods are heavily consumed (that is, in North America, Argentina, Europe, and Australia). In contrast, the rate is low in India, where cows are revered as holy animals. Also noteworthy is that women with a lactose intolerance rarely develop breast cancer.

Viral progeny

In fact, the researchers found single-stranded DNA rings that originated in viruses, which they named bovine meat and milk factors (BMMF), in the intestines of patients with colon cancer. They reported, “This new class of pathogen deserves, in our opinion at least, to become the focus of cancer development and further chronic diseases.” They also detected elevated levels of acid radicals in these areas (that is, oxidative stress), which is typical for chronic inflammation.

The researchers assume that infants, whose immune system is not yet fully matured, ingest the BMMF as soon as they have dairy. Therefore, there is no need for adults to avoid dairy or beef because everyone is infected anyway, said Dr. zur Hausen.

‘Breast milk is healthy’

Dr. De Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen outlined more evidence of cancer-triggering pathogens. Mothers who have breastfed are less likely, especially after multiple pregnancies, to develop tumors in various organs or to have MS and type 2 diabetes. The authors attribute the protective effect to oligosaccharides in breast milk, which begin to be formed midway through the pregnancy. They bind to lectin receptors and, in so doing, mask the terminal molecule onto which the viruses need to dock. As a result, their port of entry into the cells is blocked.

The oligosaccharides also protect the baby against life-threatening infections by blocking access by rotaviruses and noroviruses. In this way, especially if breastfeeding lasts a long time – around 1 year – the period of incomplete immunocompetence is bridged.

Colon cancer

To date, it has been assumed that around 20% of all cancerous diseases globally are caused by infections, said the researchers. But if the suspected BMMF cases are included, this figure rises to 50%, even to around 80%, for colon cancer. If the suspicion is confirmed, the consequences for prevention and therapy would be significant.

The voice of a Nobel prize winner undoubtedly carries weight, but at the time, Dr. zur Hausen still had to convince a host of skeptics with his discovery that a viral infection is a major cause of cervical cancer. Nonetheless, some indicators suggest that he and his wife have found a dead end this time.

Institutional skepticism

When his working group made the results public in February 2019, the DKFZ felt the need to give an all-clear signal in response to alarmed press reports. There is no reason to see dairy and meat consumption as something negative. Similarly, in their first joint statement, the BfR and the MRI judged the data to be insufficient and called for further studies. Multiple research teams began to focus on BMMF as a result. In what foods can they be found? Are they more common in patients with cancer than in healthy people? Are they infectious? Do they cause inflammation and cancer?

The findings presented in a second statement by the BfR and MRI at the end of November 2022 contradicted the claims made by the DKFZ scientists across the board. In no way do BMMF represent new pathogens. They are variants of already known DNA sequences. In addition, they are present in numerous animal-based and plant-based foods, including pork, fish, fruit, vegetables, and nuts.

BMMF do not possess the ability to infect human cells, the institutes said. The proof that they are damaging to one’s health was also absent. It is true that the incidence of intestinal tumors correlates positively with the consumption of red and processed meat – which in no way signifies causality – but dairy products are linked to a reduced risk. On the other hand, breast cancer cannot be associated with the consumption of beef or dairy.

Therefore, both institutes recommend continuing to use these products as supplementary diet for infants because of their micronutrients. They further stated that the products are safe for people of all ages.

Association with MS?

Unperturbed, Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen went one step further in their current article. They posited that MS is also associated with the consumption of dairy products and beef. Here too geographic distribution prompted the idea to look for BMMF in the brain lesions of patients with MS. The researchers isolated ring-shaped DNA molecules that proved to be closely related to BMMF from dairy and cattle blood. “The result was electrifying for us.”

However, there are several other factors to consider, such as vitamin D3 deficiency. This is because the incidence of MS decreases the further you travel from the poles toward the equator (that is, as solar radiation increases). Also, EBV clearly plays a role because patients with MS display increased titers of EBV antibodies. One study also showed that people in Antarctica excreted reactivated EBV in their saliva during winter and that vitamin D3 stopped the viral secretion.

Under these conditions, the researchers hypothesized that MS is caused by a double infection of brain cells by EBV and BMMF. EBV is reactivated by a lack of vitamin D3, and the BMMF multiply and are eventually converted into proteins. A focal immunoreaction causes the Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes to malfunction, which leads to the destruction of the myelin sheaths around the nerve fibers.

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

In Western diets, dairy and beef are ubiquitous: Milk goes with coffee, melted cheese with pizza, and chili with rice. But what if dairy products and beef contained a new kind of pathogen that could infect you as a child and trigger cancer or multiple sclerosis (MS) 40-70 years later?

However, in two joint statements, the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) and the Max Rubner Institute (MRI) have rejected such theories.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, DSc, received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his discovery that human papillomaviruses cause cervical cancer. His starting point was the observation that sexually abstinent women, such as nuns, rarely develop this cancer. So it was possible to draw the conclusion that pathogens are transmitted during sexual intercourse, explain Dr. zur Hausen and his wife Ethel-Michele de Villiers, PhD, both of DKFZ Heidelberg.

Papillomaviruses, as well as human herpes and Epstein-Barr viruses (EBV), polyomaviruses, and retroviruses, cause cancer in a direct way: by inserting their genes into the DNA of human cells. With a latency of a few years to a few decades, the proteins formed through expression stimulate malignant growth by altering the regulating host gene.

Acid radicals

However, viruses – just like bacteria and parasites – can also indirectly trigger cancer. One mechanism for this triggering is the disruption of immune defenses, as shown by the sometimes drastically increased tumor incidence with AIDS or with immunosuppressants after transplants. Chronic inflammation is a second mechanism that generates acid radicals and thereby causes random mutations in replicating cells. Examples include stomach cancer caused by Helicobacter pylori and liver cancer caused by Schistosoma, liver fluke, and hepatitis B and C viruses.

According to Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen, there are good reasons to believe that other pathogens could cause chronic inflammation and thereby lead to cancer. Epidemiologic data suggest that dairy and meat products from European cows (Bos taurus) are a potential source. This is because colon cancer and breast cancer commonly occur in places where these foods are heavily consumed (that is, in North America, Argentina, Europe, and Australia). In contrast, the rate is low in India, where cows are revered as holy animals. Also noteworthy is that women with a lactose intolerance rarely develop breast cancer.

Viral progeny

In fact, the researchers found single-stranded DNA rings that originated in viruses, which they named bovine meat and milk factors (BMMF), in the intestines of patients with colon cancer. They reported, “This new class of pathogen deserves, in our opinion at least, to become the focus of cancer development and further chronic diseases.” They also detected elevated levels of acid radicals in these areas (that is, oxidative stress), which is typical for chronic inflammation.

The researchers assume that infants, whose immune system is not yet fully matured, ingest the BMMF as soon as they have dairy. Therefore, there is no need for adults to avoid dairy or beef because everyone is infected anyway, said Dr. zur Hausen.

‘Breast milk is healthy’

Dr. De Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen outlined more evidence of cancer-triggering pathogens. Mothers who have breastfed are less likely, especially after multiple pregnancies, to develop tumors in various organs or to have MS and type 2 diabetes. The authors attribute the protective effect to oligosaccharides in breast milk, which begin to be formed midway through the pregnancy. They bind to lectin receptors and, in so doing, mask the terminal molecule onto which the viruses need to dock. As a result, their port of entry into the cells is blocked.

The oligosaccharides also protect the baby against life-threatening infections by blocking access by rotaviruses and noroviruses. In this way, especially if breastfeeding lasts a long time – around 1 year – the period of incomplete immunocompetence is bridged.

Colon cancer

To date, it has been assumed that around 20% of all cancerous diseases globally are caused by infections, said the researchers. But if the suspected BMMF cases are included, this figure rises to 50%, even to around 80%, for colon cancer. If the suspicion is confirmed, the consequences for prevention and therapy would be significant.

The voice of a Nobel prize winner undoubtedly carries weight, but at the time, Dr. zur Hausen still had to convince a host of skeptics with his discovery that a viral infection is a major cause of cervical cancer. Nonetheless, some indicators suggest that he and his wife have found a dead end this time.

Institutional skepticism

When his working group made the results public in February 2019, the DKFZ felt the need to give an all-clear signal in response to alarmed press reports. There is no reason to see dairy and meat consumption as something negative. Similarly, in their first joint statement, the BfR and the MRI judged the data to be insufficient and called for further studies. Multiple research teams began to focus on BMMF as a result. In what foods can they be found? Are they more common in patients with cancer than in healthy people? Are they infectious? Do they cause inflammation and cancer?

The findings presented in a second statement by the BfR and MRI at the end of November 2022 contradicted the claims made by the DKFZ scientists across the board. In no way do BMMF represent new pathogens. They are variants of already known DNA sequences. In addition, they are present in numerous animal-based and plant-based foods, including pork, fish, fruit, vegetables, and nuts.

BMMF do not possess the ability to infect human cells, the institutes said. The proof that they are damaging to one’s health was also absent. It is true that the incidence of intestinal tumors correlates positively with the consumption of red and processed meat – which in no way signifies causality – but dairy products are linked to a reduced risk. On the other hand, breast cancer cannot be associated with the consumption of beef or dairy.

Therefore, both institutes recommend continuing to use these products as supplementary diet for infants because of their micronutrients. They further stated that the products are safe for people of all ages.

Association with MS?

Unperturbed, Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen went one step further in their current article. They posited that MS is also associated with the consumption of dairy products and beef. Here too geographic distribution prompted the idea to look for BMMF in the brain lesions of patients with MS. The researchers isolated ring-shaped DNA molecules that proved to be closely related to BMMF from dairy and cattle blood. “The result was electrifying for us.”

However, there are several other factors to consider, such as vitamin D3 deficiency. This is because the incidence of MS decreases the further you travel from the poles toward the equator (that is, as solar radiation increases). Also, EBV clearly plays a role because patients with MS display increased titers of EBV antibodies. One study also showed that people in Antarctica excreted reactivated EBV in their saliva during winter and that vitamin D3 stopped the viral secretion.

Under these conditions, the researchers hypothesized that MS is caused by a double infection of brain cells by EBV and BMMF. EBV is reactivated by a lack of vitamin D3, and the BMMF multiply and are eventually converted into proteins. A focal immunoreaction causes the Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes to malfunction, which leads to the destruction of the myelin sheaths around the nerve fibers.

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

In Western diets, dairy and beef are ubiquitous: Milk goes with coffee, melted cheese with pizza, and chili with rice. But what if dairy products and beef contained a new kind of pathogen that could infect you as a child and trigger cancer or multiple sclerosis (MS) 40-70 years later?

However, in two joint statements, the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) and the Max Rubner Institute (MRI) have rejected such theories.

In 2008, Harald zur Hausen, MD, DSc, received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his discovery that human papillomaviruses cause cervical cancer. His starting point was the observation that sexually abstinent women, such as nuns, rarely develop this cancer. So it was possible to draw the conclusion that pathogens are transmitted during sexual intercourse, explain Dr. zur Hausen and his wife Ethel-Michele de Villiers, PhD, both of DKFZ Heidelberg.

Papillomaviruses, as well as human herpes and Epstein-Barr viruses (EBV), polyomaviruses, and retroviruses, cause cancer in a direct way: by inserting their genes into the DNA of human cells. With a latency of a few years to a few decades, the proteins formed through expression stimulate malignant growth by altering the regulating host gene.

Acid radicals

However, viruses – just like bacteria and parasites – can also indirectly trigger cancer. One mechanism for this triggering is the disruption of immune defenses, as shown by the sometimes drastically increased tumor incidence with AIDS or with immunosuppressants after transplants. Chronic inflammation is a second mechanism that generates acid radicals and thereby causes random mutations in replicating cells. Examples include stomach cancer caused by Helicobacter pylori and liver cancer caused by Schistosoma, liver fluke, and hepatitis B and C viruses.

According to Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen, there are good reasons to believe that other pathogens could cause chronic inflammation and thereby lead to cancer. Epidemiologic data suggest that dairy and meat products from European cows (Bos taurus) are a potential source. This is because colon cancer and breast cancer commonly occur in places where these foods are heavily consumed (that is, in North America, Argentina, Europe, and Australia). In contrast, the rate is low in India, where cows are revered as holy animals. Also noteworthy is that women with a lactose intolerance rarely develop breast cancer.

Viral progeny

In fact, the researchers found single-stranded DNA rings that originated in viruses, which they named bovine meat and milk factors (BMMF), in the intestines of patients with colon cancer. They reported, “This new class of pathogen deserves, in our opinion at least, to become the focus of cancer development and further chronic diseases.” They also detected elevated levels of acid radicals in these areas (that is, oxidative stress), which is typical for chronic inflammation.

The researchers assume that infants, whose immune system is not yet fully matured, ingest the BMMF as soon as they have dairy. Therefore, there is no need for adults to avoid dairy or beef because everyone is infected anyway, said Dr. zur Hausen.

‘Breast milk is healthy’

Dr. De Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen outlined more evidence of cancer-triggering pathogens. Mothers who have breastfed are less likely, especially after multiple pregnancies, to develop tumors in various organs or to have MS and type 2 diabetes. The authors attribute the protective effect to oligosaccharides in breast milk, which begin to be formed midway through the pregnancy. They bind to lectin receptors and, in so doing, mask the terminal molecule onto which the viruses need to dock. As a result, their port of entry into the cells is blocked.

The oligosaccharides also protect the baby against life-threatening infections by blocking access by rotaviruses and noroviruses. In this way, especially if breastfeeding lasts a long time – around 1 year – the period of incomplete immunocompetence is bridged.

Colon cancer

To date, it has been assumed that around 20% of all cancerous diseases globally are caused by infections, said the researchers. But if the suspected BMMF cases are included, this figure rises to 50%, even to around 80%, for colon cancer. If the suspicion is confirmed, the consequences for prevention and therapy would be significant.

The voice of a Nobel prize winner undoubtedly carries weight, but at the time, Dr. zur Hausen still had to convince a host of skeptics with his discovery that a viral infection is a major cause of cervical cancer. Nonetheless, some indicators suggest that he and his wife have found a dead end this time.

Institutional skepticism

When his working group made the results public in February 2019, the DKFZ felt the need to give an all-clear signal in response to alarmed press reports. There is no reason to see dairy and meat consumption as something negative. Similarly, in their first joint statement, the BfR and the MRI judged the data to be insufficient and called for further studies. Multiple research teams began to focus on BMMF as a result. In what foods can they be found? Are they more common in patients with cancer than in healthy people? Are they infectious? Do they cause inflammation and cancer?

The findings presented in a second statement by the BfR and MRI at the end of November 2022 contradicted the claims made by the DKFZ scientists across the board. In no way do BMMF represent new pathogens. They are variants of already known DNA sequences. In addition, they are present in numerous animal-based and plant-based foods, including pork, fish, fruit, vegetables, and nuts.

BMMF do not possess the ability to infect human cells, the institutes said. The proof that they are damaging to one’s health was also absent. It is true that the incidence of intestinal tumors correlates positively with the consumption of red and processed meat – which in no way signifies causality – but dairy products are linked to a reduced risk. On the other hand, breast cancer cannot be associated with the consumption of beef or dairy.

Therefore, both institutes recommend continuing to use these products as supplementary diet for infants because of their micronutrients. They further stated that the products are safe for people of all ages.

Association with MS?

Unperturbed, Dr. de Villiers and Dr. zur Hausen went one step further in their current article. They posited that MS is also associated with the consumption of dairy products and beef. Here too geographic distribution prompted the idea to look for BMMF in the brain lesions of patients with MS. The researchers isolated ring-shaped DNA molecules that proved to be closely related to BMMF from dairy and cattle blood. “The result was electrifying for us.”

However, there are several other factors to consider, such as vitamin D3 deficiency. This is because the incidence of MS decreases the further you travel from the poles toward the equator (that is, as solar radiation increases). Also, EBV clearly plays a role because patients with MS display increased titers of EBV antibodies. One study also showed that people in Antarctica excreted reactivated EBV in their saliva during winter and that vitamin D3 stopped the viral secretion.

Under these conditions, the researchers hypothesized that MS is caused by a double infection of brain cells by EBV and BMMF. EBV is reactivated by a lack of vitamin D3, and the BMMF multiply and are eventually converted into proteins. A focal immunoreaction causes the Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes to malfunction, which leads to the destruction of the myelin sheaths around the nerve fibers.

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

CDC recommends screening all adults for hepatitis B

This is the first update to HBV screening guidelines since 2008, the agency said.

“Risk-based testing alone has not identified most persons living with chronic HBV infection and is considered inefficient for providers to implement,” the authors wrote in the new guidance, published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “Universal screening of adults for HBV infection is cost-effective, compared with risk-based screening and averts liver disease and death. Although a curative treatment is not yet available, early diagnosis and treatment of chronic HBV infections reduces the risk for cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death.”

Howard Lee, MD, an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, agreed that risk-based screening has not been effective. A universal screening approach “is the way to go,” he said. With this new screening approach, patients can get tested without having to admit that they may be at risk for a chronic disease like HIV and HBV, which can be stigmatizing, said Dr. Lee, who was not involved with making these recommendations.

An estimated 580,000 to 2.4 million individuals are living with HBV infection in the United States, and two-thirds may be unaware they are infected, according to the CDC. The virus spreads through contact with blood, semen, and other body fluids of an infected person.

The guidance now recommends using the triple panel (HBsAg, anti-HBs, total anti-HBc) for initial screening.

“It can help identify persons who have an active HBV infection and could be linked to care; have resolved infection and might be susceptible to reactivation (for example, immunosuppressed persons); are susceptible and need vaccination; or are vaccinated,” the authors wrote.

Patients with previous HBV infection can have the infection reactivated with immunosuppressive treatments, Dr. Lee said, which is why detecting prior infection via the triple panel screening is important.

Women who are pregnant should be screened, ideally, in the first trimester of each pregnancy, regardless of vaccination status or testing history. If they have already received timely triple panel screening for hepatitis B and have no new HBV exposures, pregnant women only need HBsAg screening, the guidelines state.

The guidelines also specify that higher risk groups, specifically those incarcerated or formerly incarcerated, adults with current or past hepatitis C virus infection, and those with current or past sexually transmitted infections and multiple sex partners.

People who are susceptible for infection, refuse vaccination and are at higher risk for HBV should be screened periodically, but how often they should be screened should be based on shared decision-making between the provider and patient as well as individual risk and immune status.

Additional research into the optimal frequency of periodic testing is necessary, the authors say.

“Along with vaccination strategies, universal screening of adults and appropriate testing of persons at increased risk for HBV infection will improve health outcomes, reduce the prevalence of HBV infection in the United States, and advance viral hepatitis elimination goals,” the authors wrote.

The new recommendations now contrast with the 2020 screening guidelines issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) that recommend risk-based screening for hepatitis B.

“When that recommendation was published, the Task Force was aligned with several other organizations, including the CDC, in supporting screening for hepatitis B in high-risk populations — and importantly, we’re all still aligned in making sure that people get the care that they need,” said Michael Barry, MD, chair of the USPSTF, in an emailed statement. “The evidence on clinical preventive services is always changing, and the Task Force aims to keep all recommendations current, updating each recommendation approximately every 5 years.”

“In the meantime, we always encourage clinicians to use their judgment as they provide care for their patients — including those who may benefit from screening for hepatitis B — and to decide together with each patient which preventive services can best help them live a long and healthy life,” Dr. Barry said.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases is currently updating their HBV screening recommendations, Dr. Lee said, and he expects other professional societies to follow the CDC recommendations.

“It’s not uncommon that we see the CDC or societies making recommendations and the USPSTF following along, so hopefully that’s the case for hepatitis B as well,” he said.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This is the first update to HBV screening guidelines since 2008, the agency said.

“Risk-based testing alone has not identified most persons living with chronic HBV infection and is considered inefficient for providers to implement,” the authors wrote in the new guidance, published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “Universal screening of adults for HBV infection is cost-effective, compared with risk-based screening and averts liver disease and death. Although a curative treatment is not yet available, early diagnosis and treatment of chronic HBV infections reduces the risk for cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death.”

Howard Lee, MD, an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, agreed that risk-based screening has not been effective. A universal screening approach “is the way to go,” he said. With this new screening approach, patients can get tested without having to admit that they may be at risk for a chronic disease like HIV and HBV, which can be stigmatizing, said Dr. Lee, who was not involved with making these recommendations.

An estimated 580,000 to 2.4 million individuals are living with HBV infection in the United States, and two-thirds may be unaware they are infected, according to the CDC. The virus spreads through contact with blood, semen, and other body fluids of an infected person.

The guidance now recommends using the triple panel (HBsAg, anti-HBs, total anti-HBc) for initial screening.

“It can help identify persons who have an active HBV infection and could be linked to care; have resolved infection and might be susceptible to reactivation (for example, immunosuppressed persons); are susceptible and need vaccination; or are vaccinated,” the authors wrote.

Patients with previous HBV infection can have the infection reactivated with immunosuppressive treatments, Dr. Lee said, which is why detecting prior infection via the triple panel screening is important.

Women who are pregnant should be screened, ideally, in the first trimester of each pregnancy, regardless of vaccination status or testing history. If they have already received timely triple panel screening for hepatitis B and have no new HBV exposures, pregnant women only need HBsAg screening, the guidelines state.

The guidelines also specify that higher risk groups, specifically those incarcerated or formerly incarcerated, adults with current or past hepatitis C virus infection, and those with current or past sexually transmitted infections and multiple sex partners.

People who are susceptible for infection, refuse vaccination and are at higher risk for HBV should be screened periodically, but how often they should be screened should be based on shared decision-making between the provider and patient as well as individual risk and immune status.

Additional research into the optimal frequency of periodic testing is necessary, the authors say.

“Along with vaccination strategies, universal screening of adults and appropriate testing of persons at increased risk for HBV infection will improve health outcomes, reduce the prevalence of HBV infection in the United States, and advance viral hepatitis elimination goals,” the authors wrote.

The new recommendations now contrast with the 2020 screening guidelines issued by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) that recommend risk-based screening for hepatitis B.

“When that recommendation was published, the Task Force was aligned with several other organizations, including the CDC, in supporting screening for hepatitis B in high-risk populations — and importantly, we’re all still aligned in making sure that people get the care that they need,” said Michael Barry, MD, chair of the USPSTF, in an emailed statement. “The evidence on clinical preventive services is always changing, and the Task Force aims to keep all recommendations current, updating each recommendation approximately every 5 years.”

“In the meantime, we always encourage clinicians to use their judgment as they provide care for their patients — including those who may benefit from screening for hepatitis B — and to decide together with each patient which preventive services can best help them live a long and healthy life,” Dr. Barry said.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases is currently updating their HBV screening recommendations, Dr. Lee said, and he expects other professional societies to follow the CDC recommendations.

“It’s not uncommon that we see the CDC or societies making recommendations and the USPSTF following along, so hopefully that’s the case for hepatitis B as well,” he said.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This is the first update to HBV screening guidelines since 2008, the agency said.

“Risk-based testing alone has not identified most persons living with chronic HBV infection and is considered inefficient for providers to implement,” the authors wrote in the new guidance, published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “Universal screening of adults for HBV infection is cost-effective, compared with risk-based screening and averts liver disease and death. Although a curative treatment is not yet available, early diagnosis and treatment of chronic HBV infections reduces the risk for cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death.”

Howard Lee, MD, an assistant professor in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, agreed that risk-based screening has not been effective. A universal screening approach “is the way to go,” he said. With this new screening approach, patients can get tested without having to admit that they may be at risk for a chronic disease like HIV and HBV, which can be stigmatizing, said Dr. Lee, who was not involved with making these recommendations.

An estimated 580,000 to 2.4 million individuals are living with HBV infection in the United States, and two-thirds may be unaware they are infected, according to the CDC. The virus spreads through contact with blood, semen, and other body fluids of an infected person.

The guidance now recommends using the triple panel (HBsAg, anti-HBs, total anti-HBc) for initial screening.

“It can help identify persons who have an active HBV infection and could be linked to care; have resolved infection and might be susceptible to reactivation (for example, immunosuppressed persons); are susceptible and need vaccination; or are vaccinated,” the authors wrote.

Patients with previous HBV infection can have the infection reactivated with immunosuppressive treatments, Dr. Lee said, which is why detecting prior infection via the triple panel screening is important.

Women who are pregnant should be screened, ideally, in the first trimester of each pregnancy, regardless of vaccination status or testing history. If they have already received timely triple panel screening for hepatitis B and have no new HBV exposures, pregnant women only need HBsAg screening, the guidelines state.

The guidelines also specify that higher risk groups, specifically those incarcerated or formerly incarcerated, adults with current or past hepatitis C virus infection, and those with current or past sexually transmitted infections and multiple sex partners.

People who are susceptible for infection, refuse vaccination and are at higher risk for HBV should be screened periodically, but how often they should be screened should be based on shared decision-making between the provider and patient as well as individual risk and immune status.

Additional research into the optimal frequency of periodic testing is necessary, the authors say.