User login

In Case You Missed It: COVID

Decline in weekly child COVID-19 cases has almost stopped

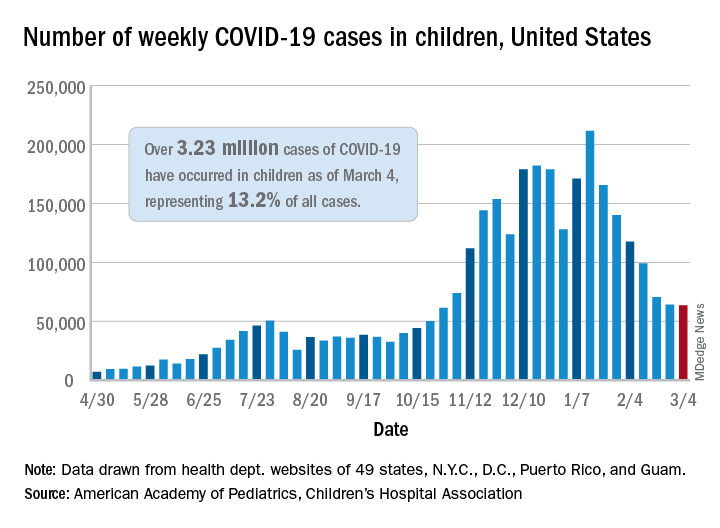

A third COVID-19 vaccine is now in circulation and states are starting to drop mask mandates, but the latest decline in weekly child cases barely registers as a decline, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That’s only 702 cases – a drop of just 1.1% – the smallest by far since weekly cases peaked in mid-January, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. Since that peak, the last 7 weeks of declines have looked like this: 21.7%, 15.3%, 16.2%, 15.7%, 28.7%, 9.0%, and 1.1%.

Meanwhile, children’s share of the COVID-19 burden increased to its highest point ever: 18.0% of all new cases occurred in children during the week ending March 4, climbing from 15.7% the week before and eclipsing the previous high of 16.9%. Cumulatively, the 3.23 million cases in children represent 13.2% of all COVID-19 cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

At the state level, the new leader in cumulative share of cases is Vermont at 19.4%, which just edged past Wyoming’s 19.3% as of the week ending March 4. The other states above 18% are Alaska (19.2%) and South Carolina (18.2%). The lowest rates can be found in Florida (8.1%), New Jersey (10.2%), Iowa (10.4%), and Utah (10.5%), the AAP and CHA said.

The overall rate of COVID-19 cases nationwide was 4,294 cases per 100,000 children as of March 4, up from 4,209 per 100,000 the week before. That measure had doubled between Dec. 3 (1,941 per 100,000) and Feb. 4 (3,899) but has only risen about 10% in the last month, the AAP/CHA data show.

Perhaps the most surprising news of the week involves the number of COVID-19 deaths in children, which went from 256 the previous week to 253 after Ohio made a downward revision of its mortality data. So far, children represent just 0.06% of all coronavirus-related deaths, a figure that has held steady since last summer in the 43 states (along with New York City and Guam) that are reporting mortality data by age, the AAP and CHA said.

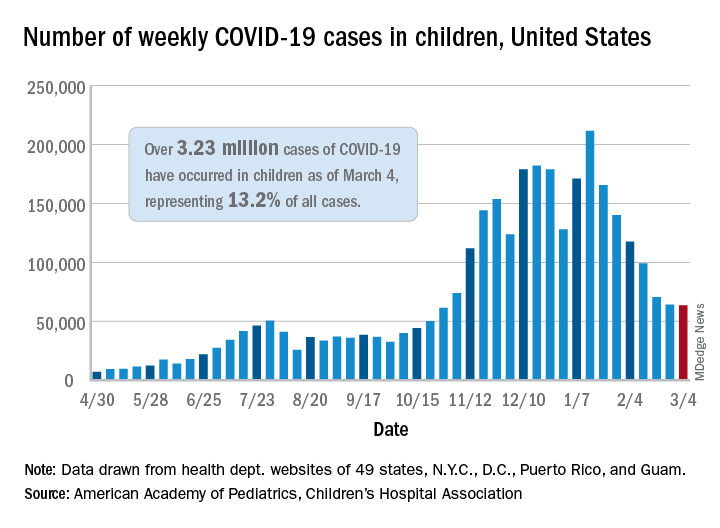

A third COVID-19 vaccine is now in circulation and states are starting to drop mask mandates, but the latest decline in weekly child cases barely registers as a decline, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That’s only 702 cases – a drop of just 1.1% – the smallest by far since weekly cases peaked in mid-January, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. Since that peak, the last 7 weeks of declines have looked like this: 21.7%, 15.3%, 16.2%, 15.7%, 28.7%, 9.0%, and 1.1%.

Meanwhile, children’s share of the COVID-19 burden increased to its highest point ever: 18.0% of all new cases occurred in children during the week ending March 4, climbing from 15.7% the week before and eclipsing the previous high of 16.9%. Cumulatively, the 3.23 million cases in children represent 13.2% of all COVID-19 cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

At the state level, the new leader in cumulative share of cases is Vermont at 19.4%, which just edged past Wyoming’s 19.3% as of the week ending March 4. The other states above 18% are Alaska (19.2%) and South Carolina (18.2%). The lowest rates can be found in Florida (8.1%), New Jersey (10.2%), Iowa (10.4%), and Utah (10.5%), the AAP and CHA said.

The overall rate of COVID-19 cases nationwide was 4,294 cases per 100,000 children as of March 4, up from 4,209 per 100,000 the week before. That measure had doubled between Dec. 3 (1,941 per 100,000) and Feb. 4 (3,899) but has only risen about 10% in the last month, the AAP/CHA data show.

Perhaps the most surprising news of the week involves the number of COVID-19 deaths in children, which went from 256 the previous week to 253 after Ohio made a downward revision of its mortality data. So far, children represent just 0.06% of all coronavirus-related deaths, a figure that has held steady since last summer in the 43 states (along with New York City and Guam) that are reporting mortality data by age, the AAP and CHA said.

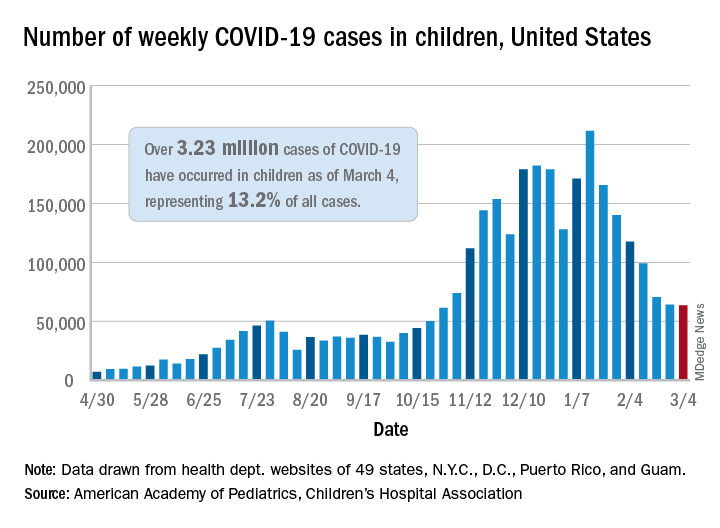

A third COVID-19 vaccine is now in circulation and states are starting to drop mask mandates, but the latest decline in weekly child cases barely registers as a decline, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That’s only 702 cases – a drop of just 1.1% – the smallest by far since weekly cases peaked in mid-January, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. Since that peak, the last 7 weeks of declines have looked like this: 21.7%, 15.3%, 16.2%, 15.7%, 28.7%, 9.0%, and 1.1%.

Meanwhile, children’s share of the COVID-19 burden increased to its highest point ever: 18.0% of all new cases occurred in children during the week ending March 4, climbing from 15.7% the week before and eclipsing the previous high of 16.9%. Cumulatively, the 3.23 million cases in children represent 13.2% of all COVID-19 cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

At the state level, the new leader in cumulative share of cases is Vermont at 19.4%, which just edged past Wyoming’s 19.3% as of the week ending March 4. The other states above 18% are Alaska (19.2%) and South Carolina (18.2%). The lowest rates can be found in Florida (8.1%), New Jersey (10.2%), Iowa (10.4%), and Utah (10.5%), the AAP and CHA said.

The overall rate of COVID-19 cases nationwide was 4,294 cases per 100,000 children as of March 4, up from 4,209 per 100,000 the week before. That measure had doubled between Dec. 3 (1,941 per 100,000) and Feb. 4 (3,899) but has only risen about 10% in the last month, the AAP/CHA data show.

Perhaps the most surprising news of the week involves the number of COVID-19 deaths in children, which went from 256 the previous week to 253 after Ohio made a downward revision of its mortality data. So far, children represent just 0.06% of all coronavirus-related deaths, a figure that has held steady since last summer in the 43 states (along with New York City and Guam) that are reporting mortality data by age, the AAP and CHA said.

Call to action on obesity amid COVID-19 pandemic

Hundreds of thousands of deaths worldwide from COVID-19 could have been avoided if obesity rates were lower, a new report says.

An analysis by the World Obesity Federation found that of the 2.5 million COVID-19 deaths reported by the end of February 2021, almost 90% (2.2 million) were in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

The report, released to coincide with World Obesity Day, calls for obesity to be recognized as a disease in its own right around the world, and for people with obesity to be included in priority lists for COVID-19 testing and vaccination.

“Overweight is a highly significant predictor of developing complications from COVID-19, including the need for hospitalization, for intensive care and for mechanical ventilation,” the WOF notes in the report.

It adds that in countries where less than half the adult population is classified as overweight (body mass index > 25 mg/kg2), for example, Vietnam, the likelihood of death from COVID-19 is a small fraction – around one-tenth – of the level seen in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

And while it acknowledges that figures for COVID-19 deaths are affected by the age structure of national populations and a country’s relative wealth and reporting capacity, “our findings appear to be independent of these contributory factors. Furthermore, other studies have found that overweight remains a highly significant predictor of the need for COVID-19 health care after accounting for these other influences.”

As an example, based on the U.K. experience, where an estimated 36% of COVID-19 hospitalizations have been attributed to lack of physical activity and excess body weight, it can be suggested that up to a third of the costs – between $6 trillion and $7 trillion over the longer period – might be attributable to these predisposing risks.

The report said the prevalence of obesity in the United Kingdom is expected to rise from 27.8% in 2016 to more than 35% by 2025.

Rachel Batterham, lead adviser on obesity at the Royal College of Physicians, commented: “The link between high levels of obesity and deaths from COVID-19 in the U.K. is indisputable, as is the urgent need to address the factors that lead so many people to be living with obesity.

“With 30% of COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.K. directly attributed to overweight and obesity, and three-quarters of all critically ill patients having overweight or obesity, the human and financial costs are high.”

Window of opportunity to prioritize obesity as a disease

WOF says that evolving evidence on the close association between COVID-19 and underlying obesity “provides a new urgency … for political and collective action.”

“Obesity is a disease that does not receive prioritization commensurate with its prevalence and impact, which is rising fastest in emerging economies. It is a gateway to many other noncommunicable diseases and mental-health illness and is now a major factor in COVID-19 complications and mortality.”

The WOF also shows that COVID-19 is not a special case, noting that several other respiratory viruses lead to more severe consequences in people living with excess bodyweight, giving good reasons to expect the next pandemic to have similar effects. “For these reasons we need to recognize overweight as a major risk factor for infectious diseases including respiratory viruses.”

“To prevent pandemic health crises in future requires action now: we call on all readers to support the World Obesity Federation’s call for stronger, more resilient economies that prioritize investment in people’s health.”

There is, it stresses, “a window of opportunity to advocate for, fund and implement these actions in all countries to ensure better, more resilient and sustainable health for all, “now and in our postCOVID-19 future.”

It proposes a ROOTS approach:

- Recognize that obesity is a disease in its own right.

- Obesity monitoring and surveillance must be enhanced.

- Obesity prevention strategies must be developed.

- Treatment of obesity.

- Systems-based approaches should be applied.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hundreds of thousands of deaths worldwide from COVID-19 could have been avoided if obesity rates were lower, a new report says.

An analysis by the World Obesity Federation found that of the 2.5 million COVID-19 deaths reported by the end of February 2021, almost 90% (2.2 million) were in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

The report, released to coincide with World Obesity Day, calls for obesity to be recognized as a disease in its own right around the world, and for people with obesity to be included in priority lists for COVID-19 testing and vaccination.

“Overweight is a highly significant predictor of developing complications from COVID-19, including the need for hospitalization, for intensive care and for mechanical ventilation,” the WOF notes in the report.

It adds that in countries where less than half the adult population is classified as overweight (body mass index > 25 mg/kg2), for example, Vietnam, the likelihood of death from COVID-19 is a small fraction – around one-tenth – of the level seen in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

And while it acknowledges that figures for COVID-19 deaths are affected by the age structure of national populations and a country’s relative wealth and reporting capacity, “our findings appear to be independent of these contributory factors. Furthermore, other studies have found that overweight remains a highly significant predictor of the need for COVID-19 health care after accounting for these other influences.”

As an example, based on the U.K. experience, where an estimated 36% of COVID-19 hospitalizations have been attributed to lack of physical activity and excess body weight, it can be suggested that up to a third of the costs – between $6 trillion and $7 trillion over the longer period – might be attributable to these predisposing risks.

The report said the prevalence of obesity in the United Kingdom is expected to rise from 27.8% in 2016 to more than 35% by 2025.

Rachel Batterham, lead adviser on obesity at the Royal College of Physicians, commented: “The link between high levels of obesity and deaths from COVID-19 in the U.K. is indisputable, as is the urgent need to address the factors that lead so many people to be living with obesity.

“With 30% of COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.K. directly attributed to overweight and obesity, and three-quarters of all critically ill patients having overweight or obesity, the human and financial costs are high.”

Window of opportunity to prioritize obesity as a disease

WOF says that evolving evidence on the close association between COVID-19 and underlying obesity “provides a new urgency … for political and collective action.”

“Obesity is a disease that does not receive prioritization commensurate with its prevalence and impact, which is rising fastest in emerging economies. It is a gateway to many other noncommunicable diseases and mental-health illness and is now a major factor in COVID-19 complications and mortality.”

The WOF also shows that COVID-19 is not a special case, noting that several other respiratory viruses lead to more severe consequences in people living with excess bodyweight, giving good reasons to expect the next pandemic to have similar effects. “For these reasons we need to recognize overweight as a major risk factor for infectious diseases including respiratory viruses.”

“To prevent pandemic health crises in future requires action now: we call on all readers to support the World Obesity Federation’s call for stronger, more resilient economies that prioritize investment in people’s health.”

There is, it stresses, “a window of opportunity to advocate for, fund and implement these actions in all countries to ensure better, more resilient and sustainable health for all, “now and in our postCOVID-19 future.”

It proposes a ROOTS approach:

- Recognize that obesity is a disease in its own right.

- Obesity monitoring and surveillance must be enhanced.

- Obesity prevention strategies must be developed.

- Treatment of obesity.

- Systems-based approaches should be applied.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hundreds of thousands of deaths worldwide from COVID-19 could have been avoided if obesity rates were lower, a new report says.

An analysis by the World Obesity Federation found that of the 2.5 million COVID-19 deaths reported by the end of February 2021, almost 90% (2.2 million) were in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

The report, released to coincide with World Obesity Day, calls for obesity to be recognized as a disease in its own right around the world, and for people with obesity to be included in priority lists for COVID-19 testing and vaccination.

“Overweight is a highly significant predictor of developing complications from COVID-19, including the need for hospitalization, for intensive care and for mechanical ventilation,” the WOF notes in the report.

It adds that in countries where less than half the adult population is classified as overweight (body mass index > 25 mg/kg2), for example, Vietnam, the likelihood of death from COVID-19 is a small fraction – around one-tenth – of the level seen in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

And while it acknowledges that figures for COVID-19 deaths are affected by the age structure of national populations and a country’s relative wealth and reporting capacity, “our findings appear to be independent of these contributory factors. Furthermore, other studies have found that overweight remains a highly significant predictor of the need for COVID-19 health care after accounting for these other influences.”

As an example, based on the U.K. experience, where an estimated 36% of COVID-19 hospitalizations have been attributed to lack of physical activity and excess body weight, it can be suggested that up to a third of the costs – between $6 trillion and $7 trillion over the longer period – might be attributable to these predisposing risks.

The report said the prevalence of obesity in the United Kingdom is expected to rise from 27.8% in 2016 to more than 35% by 2025.

Rachel Batterham, lead adviser on obesity at the Royal College of Physicians, commented: “The link between high levels of obesity and deaths from COVID-19 in the U.K. is indisputable, as is the urgent need to address the factors that lead so many people to be living with obesity.

“With 30% of COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.K. directly attributed to overweight and obesity, and three-quarters of all critically ill patients having overweight or obesity, the human and financial costs are high.”

Window of opportunity to prioritize obesity as a disease

WOF says that evolving evidence on the close association between COVID-19 and underlying obesity “provides a new urgency … for political and collective action.”

“Obesity is a disease that does not receive prioritization commensurate with its prevalence and impact, which is rising fastest in emerging economies. It is a gateway to many other noncommunicable diseases and mental-health illness and is now a major factor in COVID-19 complications and mortality.”

The WOF also shows that COVID-19 is not a special case, noting that several other respiratory viruses lead to more severe consequences in people living with excess bodyweight, giving good reasons to expect the next pandemic to have similar effects. “For these reasons we need to recognize overweight as a major risk factor for infectious diseases including respiratory viruses.”

“To prevent pandemic health crises in future requires action now: we call on all readers to support the World Obesity Federation’s call for stronger, more resilient economies that prioritize investment in people’s health.”

There is, it stresses, “a window of opportunity to advocate for, fund and implement these actions in all countries to ensure better, more resilient and sustainable health for all, “now and in our postCOVID-19 future.”

It proposes a ROOTS approach:

- Recognize that obesity is a disease in its own right.

- Obesity monitoring and surveillance must be enhanced.

- Obesity prevention strategies must be developed.

- Treatment of obesity.

- Systems-based approaches should be applied.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Federal Government Ramps Up COVID-19 Vaccination Programs

The Biden Administration launched the first phase of the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Program for COVID-19 Vaccination. Beginning February 15, FQHCs (including centers in the Urban Indian Health Program) began directly receiving vaccines.

The announcement coincided with a boost in vaccine supply for states, Tribes, and territories. In early February, the Biden Administration announced it would expand vaccine supply to 11 million doses nationwide, a 28% increase since January 20, when President Biden took office. According to a White House fact sheet, “The Administration is committing to maintaining this as the minimum supply level for the next three weeks, and we will continue to work with manufacturers in their efforts to ramp up supply.”

In February, President Biden and Vice President Harris travelled to Arizona and toured a vaccination site at State Farm Stadium in Glendale. Arizona, one of the first states to reach out for federal help from the new administration, has 15 counties and 22 Tribes with sovereign lands in the state. Those 37 entities work collaboratively with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), said Major General Michael McGuire, head of the Arizona National Guard.

In his remarks during the tour, President Biden addressed equity, saying, “[I]t really does matter that we have access to the people who are most in need [and are] most affected by the COVID crisis, dying at faster rates, getting sick at faster rates, …but not being able to get into the mix. …Equity is a big thing.”

To that end, one of the programs under way is to stand up four vaccination centers for the Navajo Nation. Tammy Littrell, Acting Regional Administrator for FEMA, said the centers will help increase tribal members’ access to vaccination, as well as take the burden off from having to drive in “austere winter conditions.”

In addition to more vaccines, Indian Health Services (IHS) is allocating $1 billion it received to help with COVID-19 response. Of the $1 billion, $790 million will go to testing, contact tracing, containment, and mitigation, among other things. Another $210 million will support IHS, tribal, and urban Indian health programs for vaccine-related activities to ensure broad-based distribution, access, and vaccine coverage. The money is part of the fifth round of supplemental COVID-19 funding from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act. The funds transferred so far amount to nearly $3 billion.

According to IHS, the money can be used to scale up testing by public health, academic, commercial, and hospital laboratories, as well as community-based testing sites, mobile testing units, healthcare facilities, and other entities engaged in COVID-19 testing. The funds are also legally available to lease or purchase non-federally owned facilities to improve COVID-19 preparedness and response capability.

The Biden Administration launched the first phase of the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Program for COVID-19 Vaccination. Beginning February 15, FQHCs (including centers in the Urban Indian Health Program) began directly receiving vaccines.

The announcement coincided with a boost in vaccine supply for states, Tribes, and territories. In early February, the Biden Administration announced it would expand vaccine supply to 11 million doses nationwide, a 28% increase since January 20, when President Biden took office. According to a White House fact sheet, “The Administration is committing to maintaining this as the minimum supply level for the next three weeks, and we will continue to work with manufacturers in their efforts to ramp up supply.”

In February, President Biden and Vice President Harris travelled to Arizona and toured a vaccination site at State Farm Stadium in Glendale. Arizona, one of the first states to reach out for federal help from the new administration, has 15 counties and 22 Tribes with sovereign lands in the state. Those 37 entities work collaboratively with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), said Major General Michael McGuire, head of the Arizona National Guard.

In his remarks during the tour, President Biden addressed equity, saying, “[I]t really does matter that we have access to the people who are most in need [and are] most affected by the COVID crisis, dying at faster rates, getting sick at faster rates, …but not being able to get into the mix. …Equity is a big thing.”

To that end, one of the programs under way is to stand up four vaccination centers for the Navajo Nation. Tammy Littrell, Acting Regional Administrator for FEMA, said the centers will help increase tribal members’ access to vaccination, as well as take the burden off from having to drive in “austere winter conditions.”

In addition to more vaccines, Indian Health Services (IHS) is allocating $1 billion it received to help with COVID-19 response. Of the $1 billion, $790 million will go to testing, contact tracing, containment, and mitigation, among other things. Another $210 million will support IHS, tribal, and urban Indian health programs for vaccine-related activities to ensure broad-based distribution, access, and vaccine coverage. The money is part of the fifth round of supplemental COVID-19 funding from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act. The funds transferred so far amount to nearly $3 billion.

According to IHS, the money can be used to scale up testing by public health, academic, commercial, and hospital laboratories, as well as community-based testing sites, mobile testing units, healthcare facilities, and other entities engaged in COVID-19 testing. The funds are also legally available to lease or purchase non-federally owned facilities to improve COVID-19 preparedness and response capability.

The Biden Administration launched the first phase of the Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) Program for COVID-19 Vaccination. Beginning February 15, FQHCs (including centers in the Urban Indian Health Program) began directly receiving vaccines.

The announcement coincided with a boost in vaccine supply for states, Tribes, and territories. In early February, the Biden Administration announced it would expand vaccine supply to 11 million doses nationwide, a 28% increase since January 20, when President Biden took office. According to a White House fact sheet, “The Administration is committing to maintaining this as the minimum supply level for the next three weeks, and we will continue to work with manufacturers in their efforts to ramp up supply.”

In February, President Biden and Vice President Harris travelled to Arizona and toured a vaccination site at State Farm Stadium in Glendale. Arizona, one of the first states to reach out for federal help from the new administration, has 15 counties and 22 Tribes with sovereign lands in the state. Those 37 entities work collaboratively with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), said Major General Michael McGuire, head of the Arizona National Guard.

In his remarks during the tour, President Biden addressed equity, saying, “[I]t really does matter that we have access to the people who are most in need [and are] most affected by the COVID crisis, dying at faster rates, getting sick at faster rates, …but not being able to get into the mix. …Equity is a big thing.”

To that end, one of the programs under way is to stand up four vaccination centers for the Navajo Nation. Tammy Littrell, Acting Regional Administrator for FEMA, said the centers will help increase tribal members’ access to vaccination, as well as take the burden off from having to drive in “austere winter conditions.”

In addition to more vaccines, Indian Health Services (IHS) is allocating $1 billion it received to help with COVID-19 response. Of the $1 billion, $790 million will go to testing, contact tracing, containment, and mitigation, among other things. Another $210 million will support IHS, tribal, and urban Indian health programs for vaccine-related activities to ensure broad-based distribution, access, and vaccine coverage. The money is part of the fifth round of supplemental COVID-19 funding from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act. The funds transferred so far amount to nearly $3 billion.

According to IHS, the money can be used to scale up testing by public health, academic, commercial, and hospital laboratories, as well as community-based testing sites, mobile testing units, healthcare facilities, and other entities engaged in COVID-19 testing. The funds are also legally available to lease or purchase non-federally owned facilities to improve COVID-19 preparedness and response capability.

Who do you call in those late, quiet hours, when all seems lost?

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygeia and Panacea and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant.

On my desk sits a bust of Hygeia, a mask from Venice, next to a small sculpture and a figurine of the plague doctor. Nearby, there is a Klimt closeup of Hygeia, a postcard portraying Asclepius, St. Sebastian paintings, and quotes from Maimonides. They whisper secrets and nod to the challenges of the past. These medical specters, ancient voices of the past, keep me grounded. They speak, listen, and elevate me, too. They bring life into my otherwise quiet room.

We all began our careers swearing to Apollo, Asclepius, Hygeia, and Panacea when we recited the Hippocratic Oath. I call upon them, and other gods and totems, and saints and ancient healers, now more than ever. As an atheist, I don’t appeal to them as prayers, but as Hippocrates intended. I look to their supernatural healing powers as a source of strength and as revealers of the natural and observable phenomena.

Apollo was one of the Twelve Olympians, a God of medicine, father of Asclepius. He was a healer, though his arrows also bore the plagues of the Gods.

For centuries, Apollo was found floating above the marble dissection table in the Bologna anatomical theater, guiding students who dove into the secrets of the human body.

Asclepius, son of Apollo, was hailed as a god of medicine. He healed many from plagues at his temples throughout the Ancient Greek and Roman empires. He was mentored in the healing arts by the centaur, Chiron. His many daughters and sons represent various aspects of medicine including cures, healing, recovery, sanitation, and beauty. To Asclepius, temples were places of healing, an ancient ancestor to modern hospitals.

Two of his daughters, Panacea and Hygeia, gave us the healing words of panacea and hygiene. Today, these acts of hygiene, handwashing, mask-wearing, and sanitation are discussed across the world louder than ever. While we’re all wishing for a panacea, we know it will take all the attributes of medicine to get us through this pandemic.

Hospitalists are part of the frontline teams facing this pandemic head-on. Gowning up for MRSA isolation seems quaint nowadays.

My attendings spoke of their fears, up against the unknown while on service in the 1980s, when HIV appeared. 2014 brought the Ebola biocontainment units. Now, this generation works daily against a modern plague, where every day is a risk of exposure. When every patient is in isolation, the garb begins to reflect the PPE that emerged during a 17th-century plague epidemics, the plague doctor outfit.

Godfather II fans recall the famous portrayal of the August 16th festival to San Rocco play out in the streets of New York. For those stricken with COVID-19 and recovered, you emulate San Rocco, in your continued return to service.

The Scuola Grande di San Rocco, in Venice, is the epitome of healing and greatness in one building. Tintoretto, the great Venetian painter, assembled the story of healing through art and portraits of San Rocco. The scuola, a confraternity, was a community of healers, gathered in one place to look after the less fortunate.

Hospitalists march into the hospital risking their lives. We always wear PPE for MRSA, ESBL, or C. diff. And enter reverse isolation rooms wearing N95s for possible TB cases. But those don’t elevate to the volume, to the same fear, as gowning up for COVID-19.

Hospitalists, frontline health care workers, embody the story of San Sebastian, another plague saint who absorbed the arrows, the symbolic plagues, onto his own shoulders so no one else had to bear them. San Sebastian was a Christian persecuted by a Roman emperor once his beliefs were discovered. He is often laden with arrows in spots where buboes would have appeared: the armpits and the groin. His sacrifice for others’ recovery became a symbol of absorbing the plague, the wounds, and the impact of the arrows.

This sacrifice epitomizes the daily work the frontline nurses, ER docs, intensivists, hospitalists, and the entire hospital staff perform daily, bearing the slung arrows of coronavirus.

One of the images I think of frequently during this time lies atop Castel San Angelo in Rome. Built in 161 AD, it has served as a mausoleum, prison, papal residence, and is currently a museum. Atop San’Angelo stands St. Michael, the destroyer of the dragon. He is sheathing his sword in representation of the end of the plague in 590.

The arrows flow, yet the sword will be sheathed. Evil will be halted. The stories of these ancient totems and strength can give us strength as they remind us of the work that was done for centuries: pestilence, famine, war. The great killers never go away completely.

Fast forward to today

These medical specters serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so inspiring: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories, we spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day. These specters encourage us to defeat any and all of the scourges that come our way.

I hear and read stories about the frontline heroes, the vaccine makers, the PPE creators, the health care workers, grocery store clerks, and teachers. I’m honored to hear of these stories and your sacrifices. I’m inspired to continue upholding your essence, your fight, and your stories. In keeping with ancient empire metaphors, you are taking the slings of the diseased arrows flying to our brethren as you try to keep yourself and others safe.

The sheathing of this sword will come. These arrows will be silenced. But until then, I lean on these pictures, these stories, and these saints, to give us all the strength to wake up each morning and continue healing.

They serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so great: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day and defeat any and all scourges that come our way.

So, who do you call in those late, quiet hours, when all seems lost?

Dr. Messler is the executive director, quality initiatives at Glytec and works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. This essay appeared initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygeia and Panacea and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant.

On my desk sits a bust of Hygeia, a mask from Venice, next to a small sculpture and a figurine of the plague doctor. Nearby, there is a Klimt closeup of Hygeia, a postcard portraying Asclepius, St. Sebastian paintings, and quotes from Maimonides. They whisper secrets and nod to the challenges of the past. These medical specters, ancient voices of the past, keep me grounded. They speak, listen, and elevate me, too. They bring life into my otherwise quiet room.

We all began our careers swearing to Apollo, Asclepius, Hygeia, and Panacea when we recited the Hippocratic Oath. I call upon them, and other gods and totems, and saints and ancient healers, now more than ever. As an atheist, I don’t appeal to them as prayers, but as Hippocrates intended. I look to their supernatural healing powers as a source of strength and as revealers of the natural and observable phenomena.

Apollo was one of the Twelve Olympians, a God of medicine, father of Asclepius. He was a healer, though his arrows also bore the plagues of the Gods.

For centuries, Apollo was found floating above the marble dissection table in the Bologna anatomical theater, guiding students who dove into the secrets of the human body.

Asclepius, son of Apollo, was hailed as a god of medicine. He healed many from plagues at his temples throughout the Ancient Greek and Roman empires. He was mentored in the healing arts by the centaur, Chiron. His many daughters and sons represent various aspects of medicine including cures, healing, recovery, sanitation, and beauty. To Asclepius, temples were places of healing, an ancient ancestor to modern hospitals.

Two of his daughters, Panacea and Hygeia, gave us the healing words of panacea and hygiene. Today, these acts of hygiene, handwashing, mask-wearing, and sanitation are discussed across the world louder than ever. While we’re all wishing for a panacea, we know it will take all the attributes of medicine to get us through this pandemic.

Hospitalists are part of the frontline teams facing this pandemic head-on. Gowning up for MRSA isolation seems quaint nowadays.

My attendings spoke of their fears, up against the unknown while on service in the 1980s, when HIV appeared. 2014 brought the Ebola biocontainment units. Now, this generation works daily against a modern plague, where every day is a risk of exposure. When every patient is in isolation, the garb begins to reflect the PPE that emerged during a 17th-century plague epidemics, the plague doctor outfit.

Godfather II fans recall the famous portrayal of the August 16th festival to San Rocco play out in the streets of New York. For those stricken with COVID-19 and recovered, you emulate San Rocco, in your continued return to service.

The Scuola Grande di San Rocco, in Venice, is the epitome of healing and greatness in one building. Tintoretto, the great Venetian painter, assembled the story of healing through art and portraits of San Rocco. The scuola, a confraternity, was a community of healers, gathered in one place to look after the less fortunate.

Hospitalists march into the hospital risking their lives. We always wear PPE for MRSA, ESBL, or C. diff. And enter reverse isolation rooms wearing N95s for possible TB cases. But those don’t elevate to the volume, to the same fear, as gowning up for COVID-19.

Hospitalists, frontline health care workers, embody the story of San Sebastian, another plague saint who absorbed the arrows, the symbolic plagues, onto his own shoulders so no one else had to bear them. San Sebastian was a Christian persecuted by a Roman emperor once his beliefs were discovered. He is often laden with arrows in spots where buboes would have appeared: the armpits and the groin. His sacrifice for others’ recovery became a symbol of absorbing the plague, the wounds, and the impact of the arrows.

This sacrifice epitomizes the daily work the frontline nurses, ER docs, intensivists, hospitalists, and the entire hospital staff perform daily, bearing the slung arrows of coronavirus.

One of the images I think of frequently during this time lies atop Castel San Angelo in Rome. Built in 161 AD, it has served as a mausoleum, prison, papal residence, and is currently a museum. Atop San’Angelo stands St. Michael, the destroyer of the dragon. He is sheathing his sword in representation of the end of the plague in 590.

The arrows flow, yet the sword will be sheathed. Evil will be halted. The stories of these ancient totems and strength can give us strength as they remind us of the work that was done for centuries: pestilence, famine, war. The great killers never go away completely.

Fast forward to today

These medical specters serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so inspiring: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories, we spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day. These specters encourage us to defeat any and all of the scourges that come our way.

I hear and read stories about the frontline heroes, the vaccine makers, the PPE creators, the health care workers, grocery store clerks, and teachers. I’m honored to hear of these stories and your sacrifices. I’m inspired to continue upholding your essence, your fight, and your stories. In keeping with ancient empire metaphors, you are taking the slings of the diseased arrows flying to our brethren as you try to keep yourself and others safe.

The sheathing of this sword will come. These arrows will be silenced. But until then, I lean on these pictures, these stories, and these saints, to give us all the strength to wake up each morning and continue healing.

They serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so great: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day and defeat any and all scourges that come our way.

So, who do you call in those late, quiet hours, when all seems lost?

Dr. Messler is the executive director, quality initiatives at Glytec and works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. This essay appeared initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygeia and Panacea and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant.

On my desk sits a bust of Hygeia, a mask from Venice, next to a small sculpture and a figurine of the plague doctor. Nearby, there is a Klimt closeup of Hygeia, a postcard portraying Asclepius, St. Sebastian paintings, and quotes from Maimonides. They whisper secrets and nod to the challenges of the past. These medical specters, ancient voices of the past, keep me grounded. They speak, listen, and elevate me, too. They bring life into my otherwise quiet room.

We all began our careers swearing to Apollo, Asclepius, Hygeia, and Panacea when we recited the Hippocratic Oath. I call upon them, and other gods and totems, and saints and ancient healers, now more than ever. As an atheist, I don’t appeal to them as prayers, but as Hippocrates intended. I look to their supernatural healing powers as a source of strength and as revealers of the natural and observable phenomena.

Apollo was one of the Twelve Olympians, a God of medicine, father of Asclepius. He was a healer, though his arrows also bore the plagues of the Gods.

For centuries, Apollo was found floating above the marble dissection table in the Bologna anatomical theater, guiding students who dove into the secrets of the human body.

Asclepius, son of Apollo, was hailed as a god of medicine. He healed many from plagues at his temples throughout the Ancient Greek and Roman empires. He was mentored in the healing arts by the centaur, Chiron. His many daughters and sons represent various aspects of medicine including cures, healing, recovery, sanitation, and beauty. To Asclepius, temples were places of healing, an ancient ancestor to modern hospitals.

Two of his daughters, Panacea and Hygeia, gave us the healing words of panacea and hygiene. Today, these acts of hygiene, handwashing, mask-wearing, and sanitation are discussed across the world louder than ever. While we’re all wishing for a panacea, we know it will take all the attributes of medicine to get us through this pandemic.

Hospitalists are part of the frontline teams facing this pandemic head-on. Gowning up for MRSA isolation seems quaint nowadays.

My attendings spoke of their fears, up against the unknown while on service in the 1980s, when HIV appeared. 2014 brought the Ebola biocontainment units. Now, this generation works daily against a modern plague, where every day is a risk of exposure. When every patient is in isolation, the garb begins to reflect the PPE that emerged during a 17th-century plague epidemics, the plague doctor outfit.

Godfather II fans recall the famous portrayal of the August 16th festival to San Rocco play out in the streets of New York. For those stricken with COVID-19 and recovered, you emulate San Rocco, in your continued return to service.

The Scuola Grande di San Rocco, in Venice, is the epitome of healing and greatness in one building. Tintoretto, the great Venetian painter, assembled the story of healing through art and portraits of San Rocco. The scuola, a confraternity, was a community of healers, gathered in one place to look after the less fortunate.

Hospitalists march into the hospital risking their lives. We always wear PPE for MRSA, ESBL, or C. diff. And enter reverse isolation rooms wearing N95s for possible TB cases. But those don’t elevate to the volume, to the same fear, as gowning up for COVID-19.

Hospitalists, frontline health care workers, embody the story of San Sebastian, another plague saint who absorbed the arrows, the symbolic plagues, onto his own shoulders so no one else had to bear them. San Sebastian was a Christian persecuted by a Roman emperor once his beliefs were discovered. He is often laden with arrows in spots where buboes would have appeared: the armpits and the groin. His sacrifice for others’ recovery became a symbol of absorbing the plague, the wounds, and the impact of the arrows.

This sacrifice epitomizes the daily work the frontline nurses, ER docs, intensivists, hospitalists, and the entire hospital staff perform daily, bearing the slung arrows of coronavirus.

One of the images I think of frequently during this time lies atop Castel San Angelo in Rome. Built in 161 AD, it has served as a mausoleum, prison, papal residence, and is currently a museum. Atop San’Angelo stands St. Michael, the destroyer of the dragon. He is sheathing his sword in representation of the end of the plague in 590.

The arrows flow, yet the sword will be sheathed. Evil will be halted. The stories of these ancient totems and strength can give us strength as they remind us of the work that was done for centuries: pestilence, famine, war. The great killers never go away completely.

Fast forward to today

These medical specters serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so inspiring: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories, we spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day. These specters encourage us to defeat any and all of the scourges that come our way.

I hear and read stories about the frontline heroes, the vaccine makers, the PPE creators, the health care workers, grocery store clerks, and teachers. I’m honored to hear of these stories and your sacrifices. I’m inspired to continue upholding your essence, your fight, and your stories. In keeping with ancient empire metaphors, you are taking the slings of the diseased arrows flying to our brethren as you try to keep yourself and others safe.

The sheathing of this sword will come. These arrows will be silenced. But until then, I lean on these pictures, these stories, and these saints, to give us all the strength to wake up each morning and continue healing.

They serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so great: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day and defeat any and all scourges that come our way.

So, who do you call in those late, quiet hours, when all seems lost?

Dr. Messler is the executive director, quality initiatives at Glytec and works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. This essay appeared initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Potential COVID-19 variant surge looms over U.S.

Another coronavirus surge may be on the way in the United States as daily COVID-19 cases continue to plateau around 60,000, states begin to lift restrictions, and people embark on spring break trips this week, according to CNN.

Outbreaks will likely stem from the B.1.1.7 variant, which was first identified in the United Kingdom, and gain momentum during the next 6-14 weeks.

“Four weeks ago, the B.1.1.7 variant made up about 1%-4% of the virus that we were seeing in communities across the country. Today it’s up to 30%-40%,” Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told NBC’s Meet the Press on March 7.

Dr. Osterholm compared the current situation with the “eye of the hurricane,” where the skies appear clear but more storms are on the way. Across Europe, 27 countries are seeing significant B.1.1.7 case increases, and 10 are getting hit hard, he said.

“What we’ve seen in Europe, when we hit that 50% mark, you see cases surge,” he said. “So right now, we do have to keep America as safe as we can from this virus by not letting up on any of the public health measures we’ve taken.”

In January, the CDC warned that B.1.1.7 variant cases would increase in 2021 and become the dominant variant in the country by this month. The United States has now reported more than 3,000 cases across 46 states, according to the latest CDC tally updated on March 7. More than 600 cases have been found in Florida, followed by more than 400 in Michigan.

The CDC has said the tally doesn’t represent the total number of B.1.1.7 cases in the United States, only the ones that have been identified by analyzing samples through genomic sequencing.

“Where it has hit in the U.K. and now elsewhere in Europe, it has been catastrophic,” Celine Gounder, MD, an infectious disease specialist with New York University Langone Health, told CNN on March 7.

The variant is more transmissible than the original novel coronavirus, and the cases in the United States are “increasing exponentially,” she said.

“It has driven up rates of hospitalizations and deaths and it’s very difficult to control,” Dr. Gounder said.

Vaccination numbers aren’t yet high enough to stop the predicted surge, she added. The United States has shipped more than 116 million vaccine doses, according to the latest CDC update on March 7. Nearly 59 million people have received at least one dose, and 30.6 million people have received two vaccine doses. About 9% of the U.S. population has been fully vaccinated.

States shouldn’t ease restrictions until the vaccination numbers are much higher and daily COVID-19 cases fall below 10,000 – and maybe “considerably less than that,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNN on March 4.

Several states have already begun to lift COVID-19 safety protocols, with Texas and Mississippi removing mask mandates last week. Businesses in Texas will be able to reopen at full capacity on March 10. For now, public health officials are urging Americans to continue to wear masks, avoid crowds, and follow social distancing guidelines as vaccines roll out across the country.

“This is sort of like we’ve been running this really long marathon, and we’re 100 yards from the finish line and we sit down and we give up,” Dr. Gounder told CNN on Sunday. ‘We’re almost there, we just need to give ourselves a bit more time to get a larger proportion of the population covered with vaccines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Another coronavirus surge may be on the way in the United States as daily COVID-19 cases continue to plateau around 60,000, states begin to lift restrictions, and people embark on spring break trips this week, according to CNN.

Outbreaks will likely stem from the B.1.1.7 variant, which was first identified in the United Kingdom, and gain momentum during the next 6-14 weeks.

“Four weeks ago, the B.1.1.7 variant made up about 1%-4% of the virus that we were seeing in communities across the country. Today it’s up to 30%-40%,” Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told NBC’s Meet the Press on March 7.

Dr. Osterholm compared the current situation with the “eye of the hurricane,” where the skies appear clear but more storms are on the way. Across Europe, 27 countries are seeing significant B.1.1.7 case increases, and 10 are getting hit hard, he said.

“What we’ve seen in Europe, when we hit that 50% mark, you see cases surge,” he said. “So right now, we do have to keep America as safe as we can from this virus by not letting up on any of the public health measures we’ve taken.”

In January, the CDC warned that B.1.1.7 variant cases would increase in 2021 and become the dominant variant in the country by this month. The United States has now reported more than 3,000 cases across 46 states, according to the latest CDC tally updated on March 7. More than 600 cases have been found in Florida, followed by more than 400 in Michigan.

The CDC has said the tally doesn’t represent the total number of B.1.1.7 cases in the United States, only the ones that have been identified by analyzing samples through genomic sequencing.

“Where it has hit in the U.K. and now elsewhere in Europe, it has been catastrophic,” Celine Gounder, MD, an infectious disease specialist with New York University Langone Health, told CNN on March 7.

The variant is more transmissible than the original novel coronavirus, and the cases in the United States are “increasing exponentially,” she said.

“It has driven up rates of hospitalizations and deaths and it’s very difficult to control,” Dr. Gounder said.

Vaccination numbers aren’t yet high enough to stop the predicted surge, she added. The United States has shipped more than 116 million vaccine doses, according to the latest CDC update on March 7. Nearly 59 million people have received at least one dose, and 30.6 million people have received two vaccine doses. About 9% of the U.S. population has been fully vaccinated.

States shouldn’t ease restrictions until the vaccination numbers are much higher and daily COVID-19 cases fall below 10,000 – and maybe “considerably less than that,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNN on March 4.

Several states have already begun to lift COVID-19 safety protocols, with Texas and Mississippi removing mask mandates last week. Businesses in Texas will be able to reopen at full capacity on March 10. For now, public health officials are urging Americans to continue to wear masks, avoid crowds, and follow social distancing guidelines as vaccines roll out across the country.

“This is sort of like we’ve been running this really long marathon, and we’re 100 yards from the finish line and we sit down and we give up,” Dr. Gounder told CNN on Sunday. ‘We’re almost there, we just need to give ourselves a bit more time to get a larger proportion of the population covered with vaccines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Another coronavirus surge may be on the way in the United States as daily COVID-19 cases continue to plateau around 60,000, states begin to lift restrictions, and people embark on spring break trips this week, according to CNN.

Outbreaks will likely stem from the B.1.1.7 variant, which was first identified in the United Kingdom, and gain momentum during the next 6-14 weeks.

“Four weeks ago, the B.1.1.7 variant made up about 1%-4% of the virus that we were seeing in communities across the country. Today it’s up to 30%-40%,” Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told NBC’s Meet the Press on March 7.

Dr. Osterholm compared the current situation with the “eye of the hurricane,” where the skies appear clear but more storms are on the way. Across Europe, 27 countries are seeing significant B.1.1.7 case increases, and 10 are getting hit hard, he said.

“What we’ve seen in Europe, when we hit that 50% mark, you see cases surge,” he said. “So right now, we do have to keep America as safe as we can from this virus by not letting up on any of the public health measures we’ve taken.”

In January, the CDC warned that B.1.1.7 variant cases would increase in 2021 and become the dominant variant in the country by this month. The United States has now reported more than 3,000 cases across 46 states, according to the latest CDC tally updated on March 7. More than 600 cases have been found in Florida, followed by more than 400 in Michigan.

The CDC has said the tally doesn’t represent the total number of B.1.1.7 cases in the United States, only the ones that have been identified by analyzing samples through genomic sequencing.

“Where it has hit in the U.K. and now elsewhere in Europe, it has been catastrophic,” Celine Gounder, MD, an infectious disease specialist with New York University Langone Health, told CNN on March 7.

The variant is more transmissible than the original novel coronavirus, and the cases in the United States are “increasing exponentially,” she said.

“It has driven up rates of hospitalizations and deaths and it’s very difficult to control,” Dr. Gounder said.

Vaccination numbers aren’t yet high enough to stop the predicted surge, she added. The United States has shipped more than 116 million vaccine doses, according to the latest CDC update on March 7. Nearly 59 million people have received at least one dose, and 30.6 million people have received two vaccine doses. About 9% of the U.S. population has been fully vaccinated.

States shouldn’t ease restrictions until the vaccination numbers are much higher and daily COVID-19 cases fall below 10,000 – and maybe “considerably less than that,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNN on March 4.

Several states have already begun to lift COVID-19 safety protocols, with Texas and Mississippi removing mask mandates last week. Businesses in Texas will be able to reopen at full capacity on March 10. For now, public health officials are urging Americans to continue to wear masks, avoid crowds, and follow social distancing guidelines as vaccines roll out across the country.

“This is sort of like we’ve been running this really long marathon, and we’re 100 yards from the finish line and we sit down and we give up,” Dr. Gounder told CNN on Sunday. ‘We’re almost there, we just need to give ourselves a bit more time to get a larger proportion of the population covered with vaccines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Five-day course of oral antiviral appears to stop SARS-CoV-2 in its tracks

A single pill of the investigational drug molnupiravir taken twice a day for 5 days eliminated SARS-CoV-2 from the nasopharynx of 49 participants.

That led Carlos del Rio, MD, distinguished professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, to suggest a future in which a drug like molnupiravir could be taken in the first few days of symptoms to prevent severe disease, similar to Tamiflu for influenza.

“I think it’s critically important,” he said of the data. Emory University was involved in the trial of molnupiravir but Dr. del Rio was not part of that team. “This drug offers the first antiviral oral drug that then could be used in an outpatient setting.”

Still, Dr. del Rio said it’s too soon to call this particular drug the breakthrough clinicians need to keep people out of the ICU. “It has the potential to be practice changing; it’s not practice changing at the moment.”

Wendy Painter, MD, of Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, who presented the data at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, agreed. While the data are promising, “We will need to see if people get better from actual illness” to assess the real value of the drug in clinical care.

“That’s a phase 3 objective we’ll need to prove,” she said in an interview.

Phase 2/3 efficacy and safety studies of the drug are now underway in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients.

In a brief prerecorded presentation of the data, Dr. Painter laid out what researchers know so far: Preclinical studies suggest that molnupiravir is effective against a number of viruses, including coronaviruses and specifically SARS-CoV-2. It prevents a virus from replicating by inducing viral error catastrophe (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Oct 15;99[21]:13374-6) – essentially overloading the virus with replication and mutation until the virus burns itself out and can’t produce replicable copies.

In this phase 2a, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial, researchers recruited 202 adults who were treated at an outpatient clinic with fever or other symptoms of a respiratory virus and confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by day 4. Participants were randomly assigned to three different groups: 200 mg of molnupiravir, 400 mg, or 800 mg. The 200-mg arm was matched 1:1 with a placebo-controlled group, and the other two groups had three participants in the active group for every one control.

Participants took the pills twice daily for 5 days, and then were followed for a total of 28 days to monitor for complications or adverse events. At days 3, 5, 7, 14, and 28, researchers also took nasopharyngeal swabs for polymerase chain reaction tests, to sequence the virus, and to grow cultures of SARS-CoV-2 to see if the virus that’s present is actually capable of infecting others.

Notably, the pills do not have to be refrigerated at any point in the process, alleviating the cold-chain challenges that have plagued vaccines.

“There’s an urgent need for an easily produced, transported, stored, and administered antiviral drug against SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Painter said.

Of the 202 people recruited, 182 had swabs that could be evaluated, of which 78 showed infection at baseline. The results are based on labs of those 78 participants.

By day 3, 28% of patients in the placebo arm had SARS-CoV-2 in their nasopharynx, compared with 20.4% of patients receiving any dose of molnupiravir. But by day 5, none of the participants receiving the active drug had evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in their nasopharynx. In comparison, 24% of people in the placebo arm still had detectable virus.

Halfway through the treatment course, differences in the presence of infectious virus were already evident. By day 3 of the 5-day course, 36.4% of participants in the 200-mg group had detectable virus in the nasopharynx, compared with 21% in the 400-mg group and just 12.5% in the 800-mg group. And although the reduction in SARS-CoV-2 was noticeable in the 200-mg and the 400-mg arms, it was only statistically significant in the 800-mg arm.

In contrast, by the end of the 5 days in the placebo groups, infectious virus varied from 18.2% in the 200-mg placebo group to 30% in the 800-mg group. This points out the variability of the disease course of SARS-CoV-2.

“You just don’t know” which infections will lead to serious disease, Dr. Painter said in an interview. “And don’t you wish we did?”

Seven participants discontinued treatment, though only four experienced adverse events. Three of those discontinued the trial because of adverse events. The study is still blinded, so it’s unclear what those events were, but Dr. Painter said that they were not thought to be related to the study drug.

The bottom line, said Dr. Painter, was that people treated with molnupiravir had starkly different outcomes in lab measures during the study.

“An average of 10 days after symptom onset, 24% of placebo patients remained culture positive” for SARS-CoV-2 – meaning there wasn’t just virus in the nasopharynx, but it was capable of replicating, Dr. Painter said. “In contrast, no infectious virus could be recovered at study day 5 in any molnupiravir-treated patients.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A single pill of the investigational drug molnupiravir taken twice a day for 5 days eliminated SARS-CoV-2 from the nasopharynx of 49 participants.

That led Carlos del Rio, MD, distinguished professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, to suggest a future in which a drug like molnupiravir could be taken in the first few days of symptoms to prevent severe disease, similar to Tamiflu for influenza.

“I think it’s critically important,” he said of the data. Emory University was involved in the trial of molnupiravir but Dr. del Rio was not part of that team. “This drug offers the first antiviral oral drug that then could be used in an outpatient setting.”

Still, Dr. del Rio said it’s too soon to call this particular drug the breakthrough clinicians need to keep people out of the ICU. “It has the potential to be practice changing; it’s not practice changing at the moment.”

Wendy Painter, MD, of Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, who presented the data at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, agreed. While the data are promising, “We will need to see if people get better from actual illness” to assess the real value of the drug in clinical care.

“That’s a phase 3 objective we’ll need to prove,” she said in an interview.

Phase 2/3 efficacy and safety studies of the drug are now underway in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients.

In a brief prerecorded presentation of the data, Dr. Painter laid out what researchers know so far: Preclinical studies suggest that molnupiravir is effective against a number of viruses, including coronaviruses and specifically SARS-CoV-2. It prevents a virus from replicating by inducing viral error catastrophe (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Oct 15;99[21]:13374-6) – essentially overloading the virus with replication and mutation until the virus burns itself out and can’t produce replicable copies.

In this phase 2a, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial, researchers recruited 202 adults who were treated at an outpatient clinic with fever or other symptoms of a respiratory virus and confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by day 4. Participants were randomly assigned to three different groups: 200 mg of molnupiravir, 400 mg, or 800 mg. The 200-mg arm was matched 1:1 with a placebo-controlled group, and the other two groups had three participants in the active group for every one control.

Participants took the pills twice daily for 5 days, and then were followed for a total of 28 days to monitor for complications or adverse events. At days 3, 5, 7, 14, and 28, researchers also took nasopharyngeal swabs for polymerase chain reaction tests, to sequence the virus, and to grow cultures of SARS-CoV-2 to see if the virus that’s present is actually capable of infecting others.

Notably, the pills do not have to be refrigerated at any point in the process, alleviating the cold-chain challenges that have plagued vaccines.

“There’s an urgent need for an easily produced, transported, stored, and administered antiviral drug against SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Painter said.

Of the 202 people recruited, 182 had swabs that could be evaluated, of which 78 showed infection at baseline. The results are based on labs of those 78 participants.

By day 3, 28% of patients in the placebo arm had SARS-CoV-2 in their nasopharynx, compared with 20.4% of patients receiving any dose of molnupiravir. But by day 5, none of the participants receiving the active drug had evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in their nasopharynx. In comparison, 24% of people in the placebo arm still had detectable virus.

Halfway through the treatment course, differences in the presence of infectious virus were already evident. By day 3 of the 5-day course, 36.4% of participants in the 200-mg group had detectable virus in the nasopharynx, compared with 21% in the 400-mg group and just 12.5% in the 800-mg group. And although the reduction in SARS-CoV-2 was noticeable in the 200-mg and the 400-mg arms, it was only statistically significant in the 800-mg arm.

In contrast, by the end of the 5 days in the placebo groups, infectious virus varied from 18.2% in the 200-mg placebo group to 30% in the 800-mg group. This points out the variability of the disease course of SARS-CoV-2.

“You just don’t know” which infections will lead to serious disease, Dr. Painter said in an interview. “And don’t you wish we did?”

Seven participants discontinued treatment, though only four experienced adverse events. Three of those discontinued the trial because of adverse events. The study is still blinded, so it’s unclear what those events were, but Dr. Painter said that they were not thought to be related to the study drug.

The bottom line, said Dr. Painter, was that people treated with molnupiravir had starkly different outcomes in lab measures during the study.

“An average of 10 days after symptom onset, 24% of placebo patients remained culture positive” for SARS-CoV-2 – meaning there wasn’t just virus in the nasopharynx, but it was capable of replicating, Dr. Painter said. “In contrast, no infectious virus could be recovered at study day 5 in any molnupiravir-treated patients.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A single pill of the investigational drug molnupiravir taken twice a day for 5 days eliminated SARS-CoV-2 from the nasopharynx of 49 participants.

That led Carlos del Rio, MD, distinguished professor of medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, to suggest a future in which a drug like molnupiravir could be taken in the first few days of symptoms to prevent severe disease, similar to Tamiflu for influenza.

“I think it’s critically important,” he said of the data. Emory University was involved in the trial of molnupiravir but Dr. del Rio was not part of that team. “This drug offers the first antiviral oral drug that then could be used in an outpatient setting.”

Still, Dr. del Rio said it’s too soon to call this particular drug the breakthrough clinicians need to keep people out of the ICU. “It has the potential to be practice changing; it’s not practice changing at the moment.”

Wendy Painter, MD, of Ridgeback Biotherapeutics, who presented the data at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, agreed. While the data are promising, “We will need to see if people get better from actual illness” to assess the real value of the drug in clinical care.

“That’s a phase 3 objective we’ll need to prove,” she said in an interview.

Phase 2/3 efficacy and safety studies of the drug are now underway in hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients.

In a brief prerecorded presentation of the data, Dr. Painter laid out what researchers know so far: Preclinical studies suggest that molnupiravir is effective against a number of viruses, including coronaviruses and specifically SARS-CoV-2. It prevents a virus from replicating by inducing viral error catastrophe (Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Oct 15;99[21]:13374-6) – essentially overloading the virus with replication and mutation until the virus burns itself out and can’t produce replicable copies.

In this phase 2a, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial, researchers recruited 202 adults who were treated at an outpatient clinic with fever or other symptoms of a respiratory virus and confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection by day 4. Participants were randomly assigned to three different groups: 200 mg of molnupiravir, 400 mg, or 800 mg. The 200-mg arm was matched 1:1 with a placebo-controlled group, and the other two groups had three participants in the active group for every one control.

Participants took the pills twice daily for 5 days, and then were followed for a total of 28 days to monitor for complications or adverse events. At days 3, 5, 7, 14, and 28, researchers also took nasopharyngeal swabs for polymerase chain reaction tests, to sequence the virus, and to grow cultures of SARS-CoV-2 to see if the virus that’s present is actually capable of infecting others.

Notably, the pills do not have to be refrigerated at any point in the process, alleviating the cold-chain challenges that have plagued vaccines.

“There’s an urgent need for an easily produced, transported, stored, and administered antiviral drug against SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Painter said.

Of the 202 people recruited, 182 had swabs that could be evaluated, of which 78 showed infection at baseline. The results are based on labs of those 78 participants.

By day 3, 28% of patients in the placebo arm had SARS-CoV-2 in their nasopharynx, compared with 20.4% of patients receiving any dose of molnupiravir. But by day 5, none of the participants receiving the active drug had evidence of SARS-CoV-2 in their nasopharynx. In comparison, 24% of people in the placebo arm still had detectable virus.

Halfway through the treatment course, differences in the presence of infectious virus were already evident. By day 3 of the 5-day course, 36.4% of participants in the 200-mg group had detectable virus in the nasopharynx, compared with 21% in the 400-mg group and just 12.5% in the 800-mg group. And although the reduction in SARS-CoV-2 was noticeable in the 200-mg and the 400-mg arms, it was only statistically significant in the 800-mg arm.

In contrast, by the end of the 5 days in the placebo groups, infectious virus varied from 18.2% in the 200-mg placebo group to 30% in the 800-mg group. This points out the variability of the disease course of SARS-CoV-2.

“You just don’t know” which infections will lead to serious disease, Dr. Painter said in an interview. “And don’t you wish we did?”

Seven participants discontinued treatment, though only four experienced adverse events. Three of those discontinued the trial because of adverse events. The study is still blinded, so it’s unclear what those events were, but Dr. Painter said that they were not thought to be related to the study drug.

The bottom line, said Dr. Painter, was that people treated with molnupiravir had starkly different outcomes in lab measures during the study.

“An average of 10 days after symptom onset, 24% of placebo patients remained culture positive” for SARS-CoV-2 – meaning there wasn’t just virus in the nasopharynx, but it was capable of replicating, Dr. Painter said. “In contrast, no infectious virus could be recovered at study day 5 in any molnupiravir-treated patients.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Management of a Child vs an Adult Presenting With Acral Lesions During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Practical Review

There has been a rise in the prevalence of perniolike lesions—erythematous to violaceous, edematous papules or nodules on the fingers or toes—during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. These lesions are referred to as “COVID toes.” Although several studies have suggested an association with these lesions and COVID-19, and coronavirus particles have been identified in endothelial cells of biopsies of pernio lesions, questions remain on the management, pathophysiology, and implications of these lesions.1 We provide a practical review for primary care clinicians and dermatologists on the current management, recommendations, and remaining questions, with particular attention to the distinctions for children vs adults presenting with pernio lesions.

Hypothetical Case of a Child Presenting With Acral Lesions

A 7-year-old boy presents with acute-onset, violaceous, mildly painful and pruritic macules on the distal toes that began 3 days earlier and have progressed to involve more toes and appear more purpuric. A review of symptoms reveals no fever, cough, fatigue, or viral symptoms. He has been staying at home for the last few weeks with his brother, mother, and father. His father is working in delivery services and is social distancing at work but not at home. His mother is concerned about the lesions, if they could be COVID toes, and if testing is needed for the patient or family. In your assessment and management of this patient, you consider the following questions.

What Is the Relationship Between These Clinical Findings and COVID-19?

Despite negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests reported in cases of chilblains during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the possibility that these lesions are an indirect result of environmental factors or behavioral changes during quarantine, the majority of studies favor an association between these chilblains lesions and COVID-19 infection.2,3 Most compellingly, COVID-19 viral particles have been identified by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy in the endothelial cells of biopsies of these lesions.1 Additionally, there is evidence for possible associations of other viruses, including Epstein-Barr virus and parvovirus B19, with chilblains lesions.4,5 In sum, with the lack of any large prospective study, the weight of current evidence suggests that these perniolike skin lesions are not specific markers of infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).6

Published studies differ in reporting the coincidence of perniolike lesions with typical COVID-19 symptoms, including fever, dyspnea, cough, fatigue, myalgia, headache, and anosmia, among others. Some studies have reported that up to 63% of patients with reported perniolike lesions developed typical COVID-19 symptoms, but other studies found that no patients with these lesions developed symptoms.6-11 Studies with younger cohorts tended to report lower prevalence of COVID-19 symptoms, and within cohorts, younger patients tended to have less severe symptoms. For example, 78.8% of patients in a cohort (n=58) with an average age of 14 years did not experience COVID-19–related symptoms.6 Based on these data, it has been hypothesized that patients with chilblainslike lesions may represent a subpopulation who will have a robust interferon response that is protective from more symptomatic and severe COVID-19.12-14

Current evidence suggests that these lesions are most likely to occur between 9 days and 2 months after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms.4,9,10 Most cases have been only mildly symptomatic, with an overall favorable prognosis of both lesions and any viral symptoms.8,10 The lesions typically resolve without treatment within a few days of initial onset.15,16

What Should Be the Workup and Management of These Lesions?