User login

EMERGENCY MEDICINE is a practical, peer-reviewed monthly publication and Web site that meets the educational needs of emergency clinicians and urgent care clinicians for their practice.

Candida Esophagitis Associated With Adalimumab for Hidradenitis Suppurativa

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the development of painful abscesses, fistulous tracts, and scars. It most commonly affects the apocrine gland–bearing areas of the body such as the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions. With a prevalence of approximately 1%, HS can lead to notable morbidity.1 The pathogenesis is thought to be due to occlusion of terminal hair follicles that subsequently stimulates release of proinflammatory cytokines from nearby keratinocytes. The mechanism of initial occlusion is not well understood but may be due to friction or trauma. An inflammatory mechanism of disease also has been hypothesized; however, the exact cytokine profile is not known. Treatment of HS consists of several different modalities, including oral retinoids, antibiotics, antiandrogenic therapy, and surgery.1,2 Adalimumab is a well-known biologic that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS.

Adalimumab is a human monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α and is thought to improve HS by several mechanisms. Inhibition of TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines found in inflammatory lesions and apocrine glands directly decreases the severity of lesion size and the frequency of recurrence.3 Adalimumab also is thought to downregulate expression of keratin 6 and prevent the hyperkeratinization seen in HS.4 Additionally, TNF-α inhibition decreases production of IL-1, which has been shown to cause hypercornification of follicles and perpetuate HS pathogenesis.5

A 41-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, adenomyosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, interstitial cystitis, asthma, fibromyalgia, depression, and Hashimoto thyroiditis presented to our dermatology clinic with active draining lesions and sinus tracts in the perivaginal area that were consistent with HS, which initially was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. She experienced minimal improvement of the HS lesions at 2-month follow-up.

Due to disease severity, adalimumab was started. The patient received a loading dose of 4 injections totaling 160 mg and 80 mg on day 15, followed by a maintenance dose of 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly. The patient reported substantial improvement of pain, and complete resolution of active lesions was noted on physical examination after 4 weeks of treatment with adalimumab.

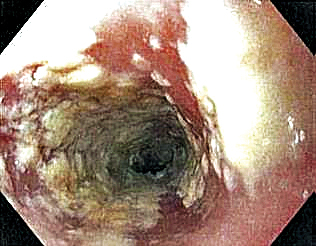

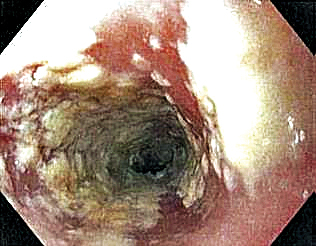

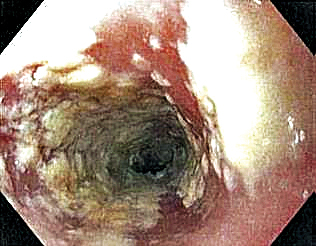

Six weeks after adalimumab was started, the patient developed severe dysphagia. She was evaluated by a gastroenterologist and underwent endoscopy (Figure), which led to a diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis. Adalimumab was discontinued immediately thereafter. The patient started treatment with nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily and oral fluconazole 200 mg daily. The candidiasis resolved within 2 weeks; however, she experienced recurrence of HS with draining lesions in the perivaginal area approximately 8 weeks after discontinuation of adalimumab. The patient requested to restart adalimumab treatment despite the recent history of esophagitis. Adalimumab 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly was restarted along with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice weekly and nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily. This regimen resulted in complete resolution of HS symptoms within 6 weeks with no recurrence of esophageal candidiasis during 6 months of follow-up.

Although the side effect of Candida esophagitis associated with adalimumab treatment in our patient may be logical given the medication’s mechanism of action and side-effect profile, this case warrants additional attention. An increase in fungal infections occurs from treatment with adalimumab because TNF-α is involved in many immune regulatory steps that counteract infection. Candida typically activates the innate immune system through macrophages via pathogen-associated molecular pattern stimulation, subsequently stimulating the release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. The cellular immune system also is activated. Helper T cells (TH1) release TNF-α along with other proinflammatory cytokines to increase phagocytosis in polymorphonuclear cells and macrophages.6 Thus, inhibition of TNF-α compromises innate and cellular immunity, thereby increasing susceptibility to fungal organisms.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Candida, candidiasis, esophageal, adalimumab, anti-TNF, and TNF revealed no reports of esophageal candidiasis in patients receiving adalimumab or any of the TNF inhibitors. Candida laryngitis was reported in a patient receiving adalimumab for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.7 Other studies have demonstrated an incidence of mucocutaneous candidiasis, most notably oropharyngeal and vaginal candidiasis.8-10 One study found that anti-TNF medications were associated with an increased risk for candidiasis by a hazard ratio of 2.7 in patients with Crohn disease.8 Other studies have shown that the highest incidence of fungal infection is seen with the use of infliximab, while adalimumab is associated with lower rates of fungal infection.9,10 Although it is known that anti-TNF therapy predisposes patients to fungal infection, the dose of medication known to preclude the highest risk has not been studied. Furthermore, most studies assess rates of Candida infection in individuals receiving anti-TNF therapy in addition to several other immunosuppressant agents (ie, corticosteroids), which confounds the interpretation of results. Additional studies assessing rates of Candida and other opportunistic infections associated with use of adalimumab alone are needed to better guide clinical practices in dermatology.

Patients receiving adalimumab for dermatologic or other conditions should be closely monitored for opportunistic infections. Although immunomodulatory medications offer promising therapeutic benefits in patients with HS, larger studies regarding treatment with anti-TNF agents in HS are warranted to prevent complications from treatment and promote long-term efficacy and safety.

- Kurayev A, Ashkar H, Saraiya A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: review of the pathogenesis and treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1107-1022.

- Rambhatla PV, Lim HW, Hamzavi I. A systematic review of treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:439-446.

- van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, van den Broecke DG, et al. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1292-1298.

- Shuja F, Chan CS, Rosen T. Biologic drugs for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: an evidence-based review. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:511-521, 523-514.

- Kutsch CL, Norris DA, Arend WP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist production by cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:79-85.

- Senet JM. Risk factors and physiopathology of candidiasis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1997;14:6-13.

- Kobak S, Yilmaz H, Guclu O, et al. Severe candida laryngitis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. Eur J Rheumatol. 2014;1:167-169.

- Marehbian J, Arrighi HM, Hass S, et al. Adverse events associated with common therapy regimens for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2524-2533.

- Tsiodras S, Samonis G, Boumpas DT, et al. Fungal infections complicating tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:181-194.

- Aikawa NE, Rosa DT, Del Negro GM, et al. Systemic and localized infection by Candida species in patients with rheumatic diseases receiving anti-TNF therapy [in Portuguese]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.03.010

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the development of painful abscesses, fistulous tracts, and scars. It most commonly affects the apocrine gland–bearing areas of the body such as the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions. With a prevalence of approximately 1%, HS can lead to notable morbidity.1 The pathogenesis is thought to be due to occlusion of terminal hair follicles that subsequently stimulates release of proinflammatory cytokines from nearby keratinocytes. The mechanism of initial occlusion is not well understood but may be due to friction or trauma. An inflammatory mechanism of disease also has been hypothesized; however, the exact cytokine profile is not known. Treatment of HS consists of several different modalities, including oral retinoids, antibiotics, antiandrogenic therapy, and surgery.1,2 Adalimumab is a well-known biologic that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS.

Adalimumab is a human monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α and is thought to improve HS by several mechanisms. Inhibition of TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines found in inflammatory lesions and apocrine glands directly decreases the severity of lesion size and the frequency of recurrence.3 Adalimumab also is thought to downregulate expression of keratin 6 and prevent the hyperkeratinization seen in HS.4 Additionally, TNF-α inhibition decreases production of IL-1, which has been shown to cause hypercornification of follicles and perpetuate HS pathogenesis.5

A 41-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, adenomyosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, interstitial cystitis, asthma, fibromyalgia, depression, and Hashimoto thyroiditis presented to our dermatology clinic with active draining lesions and sinus tracts in the perivaginal area that were consistent with HS, which initially was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. She experienced minimal improvement of the HS lesions at 2-month follow-up.

Due to disease severity, adalimumab was started. The patient received a loading dose of 4 injections totaling 160 mg and 80 mg on day 15, followed by a maintenance dose of 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly. The patient reported substantial improvement of pain, and complete resolution of active lesions was noted on physical examination after 4 weeks of treatment with adalimumab.

Six weeks after adalimumab was started, the patient developed severe dysphagia. She was evaluated by a gastroenterologist and underwent endoscopy (Figure), which led to a diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis. Adalimumab was discontinued immediately thereafter. The patient started treatment with nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily and oral fluconazole 200 mg daily. The candidiasis resolved within 2 weeks; however, she experienced recurrence of HS with draining lesions in the perivaginal area approximately 8 weeks after discontinuation of adalimumab. The patient requested to restart adalimumab treatment despite the recent history of esophagitis. Adalimumab 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly was restarted along with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice weekly and nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily. This regimen resulted in complete resolution of HS symptoms within 6 weeks with no recurrence of esophageal candidiasis during 6 months of follow-up.

Although the side effect of Candida esophagitis associated with adalimumab treatment in our patient may be logical given the medication’s mechanism of action and side-effect profile, this case warrants additional attention. An increase in fungal infections occurs from treatment with adalimumab because TNF-α is involved in many immune regulatory steps that counteract infection. Candida typically activates the innate immune system through macrophages via pathogen-associated molecular pattern stimulation, subsequently stimulating the release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. The cellular immune system also is activated. Helper T cells (TH1) release TNF-α along with other proinflammatory cytokines to increase phagocytosis in polymorphonuclear cells and macrophages.6 Thus, inhibition of TNF-α compromises innate and cellular immunity, thereby increasing susceptibility to fungal organisms.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Candida, candidiasis, esophageal, adalimumab, anti-TNF, and TNF revealed no reports of esophageal candidiasis in patients receiving adalimumab or any of the TNF inhibitors. Candida laryngitis was reported in a patient receiving adalimumab for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.7 Other studies have demonstrated an incidence of mucocutaneous candidiasis, most notably oropharyngeal and vaginal candidiasis.8-10 One study found that anti-TNF medications were associated with an increased risk for candidiasis by a hazard ratio of 2.7 in patients with Crohn disease.8 Other studies have shown that the highest incidence of fungal infection is seen with the use of infliximab, while adalimumab is associated with lower rates of fungal infection.9,10 Although it is known that anti-TNF therapy predisposes patients to fungal infection, the dose of medication known to preclude the highest risk has not been studied. Furthermore, most studies assess rates of Candida infection in individuals receiving anti-TNF therapy in addition to several other immunosuppressant agents (ie, corticosteroids), which confounds the interpretation of results. Additional studies assessing rates of Candida and other opportunistic infections associated with use of adalimumab alone are needed to better guide clinical practices in dermatology.

Patients receiving adalimumab for dermatologic or other conditions should be closely monitored for opportunistic infections. Although immunomodulatory medications offer promising therapeutic benefits in patients with HS, larger studies regarding treatment with anti-TNF agents in HS are warranted to prevent complications from treatment and promote long-term efficacy and safety.

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the development of painful abscesses, fistulous tracts, and scars. It most commonly affects the apocrine gland–bearing areas of the body such as the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions. With a prevalence of approximately 1%, HS can lead to notable morbidity.1 The pathogenesis is thought to be due to occlusion of terminal hair follicles that subsequently stimulates release of proinflammatory cytokines from nearby keratinocytes. The mechanism of initial occlusion is not well understood but may be due to friction or trauma. An inflammatory mechanism of disease also has been hypothesized; however, the exact cytokine profile is not known. Treatment of HS consists of several different modalities, including oral retinoids, antibiotics, antiandrogenic therapy, and surgery.1,2 Adalimumab is a well-known biologic that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS.

Adalimumab is a human monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α and is thought to improve HS by several mechanisms. Inhibition of TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines found in inflammatory lesions and apocrine glands directly decreases the severity of lesion size and the frequency of recurrence.3 Adalimumab also is thought to downregulate expression of keratin 6 and prevent the hyperkeratinization seen in HS.4 Additionally, TNF-α inhibition decreases production of IL-1, which has been shown to cause hypercornification of follicles and perpetuate HS pathogenesis.5

A 41-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, adenomyosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, interstitial cystitis, asthma, fibromyalgia, depression, and Hashimoto thyroiditis presented to our dermatology clinic with active draining lesions and sinus tracts in the perivaginal area that were consistent with HS, which initially was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. She experienced minimal improvement of the HS lesions at 2-month follow-up.

Due to disease severity, adalimumab was started. The patient received a loading dose of 4 injections totaling 160 mg and 80 mg on day 15, followed by a maintenance dose of 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly. The patient reported substantial improvement of pain, and complete resolution of active lesions was noted on physical examination after 4 weeks of treatment with adalimumab.

Six weeks after adalimumab was started, the patient developed severe dysphagia. She was evaluated by a gastroenterologist and underwent endoscopy (Figure), which led to a diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis. Adalimumab was discontinued immediately thereafter. The patient started treatment with nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily and oral fluconazole 200 mg daily. The candidiasis resolved within 2 weeks; however, she experienced recurrence of HS with draining lesions in the perivaginal area approximately 8 weeks after discontinuation of adalimumab. The patient requested to restart adalimumab treatment despite the recent history of esophagitis. Adalimumab 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly was restarted along with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice weekly and nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily. This regimen resulted in complete resolution of HS symptoms within 6 weeks with no recurrence of esophageal candidiasis during 6 months of follow-up.

Although the side effect of Candida esophagitis associated with adalimumab treatment in our patient may be logical given the medication’s mechanism of action and side-effect profile, this case warrants additional attention. An increase in fungal infections occurs from treatment with adalimumab because TNF-α is involved in many immune regulatory steps that counteract infection. Candida typically activates the innate immune system through macrophages via pathogen-associated molecular pattern stimulation, subsequently stimulating the release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. The cellular immune system also is activated. Helper T cells (TH1) release TNF-α along with other proinflammatory cytokines to increase phagocytosis in polymorphonuclear cells and macrophages.6 Thus, inhibition of TNF-α compromises innate and cellular immunity, thereby increasing susceptibility to fungal organisms.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Candida, candidiasis, esophageal, adalimumab, anti-TNF, and TNF revealed no reports of esophageal candidiasis in patients receiving adalimumab or any of the TNF inhibitors. Candida laryngitis was reported in a patient receiving adalimumab for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.7 Other studies have demonstrated an incidence of mucocutaneous candidiasis, most notably oropharyngeal and vaginal candidiasis.8-10 One study found that anti-TNF medications were associated with an increased risk for candidiasis by a hazard ratio of 2.7 in patients with Crohn disease.8 Other studies have shown that the highest incidence of fungal infection is seen with the use of infliximab, while adalimumab is associated with lower rates of fungal infection.9,10 Although it is known that anti-TNF therapy predisposes patients to fungal infection, the dose of medication known to preclude the highest risk has not been studied. Furthermore, most studies assess rates of Candida infection in individuals receiving anti-TNF therapy in addition to several other immunosuppressant agents (ie, corticosteroids), which confounds the interpretation of results. Additional studies assessing rates of Candida and other opportunistic infections associated with use of adalimumab alone are needed to better guide clinical practices in dermatology.

Patients receiving adalimumab for dermatologic or other conditions should be closely monitored for opportunistic infections. Although immunomodulatory medications offer promising therapeutic benefits in patients with HS, larger studies regarding treatment with anti-TNF agents in HS are warranted to prevent complications from treatment and promote long-term efficacy and safety.

- Kurayev A, Ashkar H, Saraiya A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: review of the pathogenesis and treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1107-1022.

- Rambhatla PV, Lim HW, Hamzavi I. A systematic review of treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:439-446.

- van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, van den Broecke DG, et al. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1292-1298.

- Shuja F, Chan CS, Rosen T. Biologic drugs for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: an evidence-based review. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:511-521, 523-514.

- Kutsch CL, Norris DA, Arend WP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist production by cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:79-85.

- Senet JM. Risk factors and physiopathology of candidiasis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1997;14:6-13.

- Kobak S, Yilmaz H, Guclu O, et al. Severe candida laryngitis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. Eur J Rheumatol. 2014;1:167-169.

- Marehbian J, Arrighi HM, Hass S, et al. Adverse events associated with common therapy regimens for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2524-2533.

- Tsiodras S, Samonis G, Boumpas DT, et al. Fungal infections complicating tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:181-194.

- Aikawa NE, Rosa DT, Del Negro GM, et al. Systemic and localized infection by Candida species in patients with rheumatic diseases receiving anti-TNF therapy [in Portuguese]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.03.010

- Kurayev A, Ashkar H, Saraiya A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: review of the pathogenesis and treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1107-1022.

- Rambhatla PV, Lim HW, Hamzavi I. A systematic review of treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:439-446.

- van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, van den Broecke DG, et al. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1292-1298.

- Shuja F, Chan CS, Rosen T. Biologic drugs for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: an evidence-based review. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:511-521, 523-514.

- Kutsch CL, Norris DA, Arend WP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist production by cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:79-85.

- Senet JM. Risk factors and physiopathology of candidiasis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1997;14:6-13.

- Kobak S, Yilmaz H, Guclu O, et al. Severe candida laryngitis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. Eur J Rheumatol. 2014;1:167-169.

- Marehbian J, Arrighi HM, Hass S, et al. Adverse events associated with common therapy regimens for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2524-2533.

- Tsiodras S, Samonis G, Boumpas DT, et al. Fungal infections complicating tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:181-194.

- Aikawa NE, Rosa DT, Del Negro GM, et al. Systemic and localized infection by Candida species in patients with rheumatic diseases receiving anti-TNF therapy [in Portuguese]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.03.010

Practice Points

- Adalimumab is an effective treatment for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

- There is risk for opportunistic infections with adalimumab, and patients should be monitored closely.

We’re all vaccinated: Can we go back to the office (unmasked) now?

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

Congratulations, you’ve been vaccinated!

It’s been a year like no other, and outpatient psychiatrists turned to Zoom and other telemental health platforms to provide treatment for our patients. Offices sit empty as the dust lands and the plants wilt. Perhaps a few patients are seen in person, masked and carefully distanced, after health screening and temperature checks, with surfaces sanitized between visits, all in accordance with health department regulations. But now the vaccine offers both safety and the promise of a return to a new normal, one that is certain to look different from the normal that was left behind.

I have been vaccinated and many of my patients have also been vaccinated. I began to wonder if it was safe to start seeing patients in person; could I see fully vaccinated patients, unmasked and without temperature checks and sanitizing? I started asking this question in February, and the response I got then was that it was too soon to tell; we did not have any data on whether vaccinated people could transmit the novel coronavirus. Two vaccinated people might be at risk of transmitting the virus and then infecting others, and the question of whether the vaccines would protect against illness caused by variants remained. Preliminary data out of Israel indicated that the vaccine did reduce transmission, but no one was saying that it was fine to see patients without masks, and video-conferencing remained the safest option.

On Monday, March 8, 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released long-awaited interim public health guidelines for fully vaccinated people. The guidelines allowed for two vaccinated people to be in a room together unmasked, and for a fully-vaccinated person to be in a room unmasked with an unvaccinated person who did not have risk factors for becoming severely ill with COVID. Was this the green light that psychiatrists were waiting for? Was there new data about transmission, or was this part of the CDC’s effort to make vaccines more desirable?

Michael Chang, MD, is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We spoke 2 days after the CDC interim guidelines were released. Dr. Chang was optimistic.

“, including data about variants and about transmission. At some point, however, the risk is low enough, and we should probably start thinking about going back to in-person visits,” Dr. Chang said. He said he personally would feel safe meeting unmasked with a vaccinated patient, but noted that his institution still requires doctors to wear masks. “Most vaccinations reduce transmission of illness,” Dr. Chang said, “but SARS-CoV-2 continues to surprise us in many ways.”

Katelyn Jetelina, PhD, MPH, an epidemiologist at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Dallas, distributes a newsletter, “Your Local Epidemiologist,” where she discusses data pertaining to the pandemic. In her newsletter dated March 14, 2021, Dr. Jetelina wrote, “There are now 7 sub-studies/press releases that confirm a 50-95% reduced transmission after vaccination. This is a big range, which is typical for such drastically different scientific studies. Variability is likely due to different sample sizes, locations, vaccines, genetics, cultures, etc. It will be a while until we know the ‘true’ percentage for each vaccine.”

Leslie Walker, MD, is a fully vaccinated psychiatrist in private practice in Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has recently started seeing fully vaccinated patients in person.

“So far it’s only 1 or 2 patients a day. I’m leaving it up to the patient. If they prefer masks, we stay masked. I may reverse course, depending on what information comes out.” She went on to note, “There are benefits to being able to see someone’s full facial expressions and whether they match someone’s words and body language, so the benefit of “unmasking” extends beyond comfort and convenience and must be balanced against the theoretical risk of COVID exposure in the room.”

While the CDC has now said it is safe to meet, the state health departments also have guidelines for medical practices, and everyone is still worried about vulnerable people in their households and potential spread to the community at large.

In Maryland, where I work, Aliya Jones, MD, MBA, is the head of the Behavioral Health Administration (BHA) for the Maryland Department of Health. “It remains risky to not wear masks, however, the risk is low when both individuals are vaccinated,” Dr. Jones wrote. “BHA is not recommending that providers see clients without both parties wearing a mask. All of our general practice recommendations for infection control are unchanged. People should be screened before entering clinical practices and persons who are symptomatic, whether vaccinated or not, should not be seen face-to-face, except in cases of an emergency, in which case additional precautions should be taken.”

So is it safe for a fully-vaccinated psychiatrist to have a session with a fully-vaccinated patient sitting 8 feet apart without masks? I’m left with the idea that it is for those two people, but when it comes to unvaccinated people in their households, we want more certainty than we currently have. The messaging remains unclear. The CDC’s interim guidelines offer hope for a future, but the science is still catching up, and to feel safe enough, we may want to wait a little longer for more definitive data – or herd immunity – before we reveal our smiles.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She has a private practice and is assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, both in Baltimore.

‘Major update’ of BP guidance for kidney disease; treat to 120 mm Hg

The new 2021 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guideline for blood pressure management for adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who are not receiving dialysis advises treating to a target systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg, provided measurements are “standardized” and that blood pressure is “measured properly.”

This blood pressure target – largely based on evidence from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) – represents “a major update” from the 2012 KDIGO guideline, which advised clinicians to treat to a target blood pressure of less than or equal to 130/80 mm Hg for patients with albuminuria or less than or equal to 140/90 mm Hg for patients without albuminuria.

The new goal is also lower than the less than 130/80 mm Hg target in the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline.

In a study of the public health implications of the guideline, Kathryn Foti, PhD, and colleagues determined that 70% of U.S. adults with CKD would now be eligible for treatment to lower blood pressure, as opposed to 50% under the previous KDIGO guideline and 56% under the ACC/AHA guideline.

“This is a major update of an influential set of guidelines for chronic kidney disease patients” at a time when blood pressure control is worsening in the United States, Dr. Foti, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, said in a statement from her institution.

The 2021 KDIGO blood pressure guideline and executive summary and the public health implications study are published online in Kidney International.

First, ‘take blood pressure well’

The cochair of the new KDIGO guidelines, Alfred K. Cheung, MD, from the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said in an interview that the guideline has “two important points.”

First, “take that blood pressure well,” he said. “That has a lot to do with patient preparation rather than any fancy instrument,” he emphasized.

Second, the guideline proposes a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg for most people with CKD not receiving dialysis, except for children and kidney transplant recipients. This target is “contingent on ‘standardized’ blood pressure measurement.”

The document provides a checklist for obtaining a standardized blood pressure measurement, adapted from the 2017 ACC/AHA blood pressure guidelines. It starts with the patient relaxed and sitting on a chair for more than 5 minutes.

In contrast to this measurement, a “routine” or “casual” office blood pressure measurement could be off by plus or minus 10 mm Hg, Dr. Cheung noted.

In a typical scenario, he continued, a patient cannot find a place to park, rushes into the clinic, and has his or her blood pressure checked right away, which would provide a “totally unreliable” reading. Adding a “fudge factor” (correction factor) would not provide an accurate reading.

Clinicians “would not settle for a potassium measurement that is 5.0 mmol/L plus or minus a few decimal points” to guide treatment, he pointed out.

Second, target 120, properly measured

“The very first chapter of the guidelines is devoted to blood pressure measurement, because we recognize if we’re going to do 120 [mm Hg] – the emphasis is on 120 measured properly – so we try to drive that point home,” Tara I. Chang, MD, guideline second author and a coauthor of the public health implications study, pointed out in an interview.

“There are a lot of other things that we base clinical decisions on where we really require some degree of precision, and blood pressure is important enough that to us it’s kind of in the same boat,” said Dr. Chang, from Stanford (Calif.) University.

“In SPRINT, people were randomized to less than less than 120 vs. less than 140 (they weren’t randomized to <130),” she noted.

“The recommendation should be widely adopted in clinical practice,” the guideline authors write, “since accurate measurements will ensure that proper guidance is being applied to the management of BP, as it is to the management of other risk factors.”

Still need individual treatment

Nevertheless, patients still need individualized treatment, the document stresses. “Not every patient with CKD will be appropriate to target to less than 120,” Dr. Chang said. However, “we want people to at least consider less than 120,” she added, to avoid therapeutic inertia.

“If you take the blood pressure in a standardized manner – such as in the ACCORD trial and in the SPRINT trial – even patients over 75 years old, or people over 80 years old, they have very little side effects,” Dr. Cheung noted.

“In the overall cohort,” he continued, “they do not have a significant increase in serious adverse events, do not have adverse events of postural hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, injurious falls – so people are worried about it, but it’s not borne out by the data.

“That said, I have two cautions,” Dr. Cheung noted. “One. If you drop somebody’s blood pressure rapidly over a week, you may be more likely to get in trouble. If you drop the blood pressure gradually over several weeks, several months, you’re much less likely to get into trouble.”

“Two. If the patient is old, you know the patient has carotid stenosis and already has postural dizziness, you may not want to try on that patient – but just because the patient is old is not the reason not to target 120.”

ACE inhibitors and ARBs beneficial in albuminuria, underused

“How do you get to less than 120? The short answer is, use whatever medications you need to – there is no necessarily right cocktail,” Dr. Chang said.

“We’ve known that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and ARBs [angiotensin II receptor blockers] are beneficial in patients with CKD and in particular those with heavier albuminuria,” she continued. “We’ve known this for over 20 years.”

Yet, the study identified underutilization – “a persistent gap, just like blood pressure control and awareness,” she noted. “We’re just not making much headway.

“We are not recommending ACE inhibitors or ARBs for all the patients,” Dr. Cheung clarified. “If you are diabetic and have heavy proteinuria, that’s when the use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs are most indicated.”

Public health implications

SPRINT showed that treating to a systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg vs. less than 140 mm Hg reduced the risk for cardiovascular disease by 25% and all-cause mortality by 27% for participants with and those without CKD, Dr. Foti and colleagues stress.

They aimed to estimate how the new guideline would affect (1) the number of U.S. patients with CKD who would be eligible for blood pressure lowering treatment, and (2) the proportion of those with albuminuria who would be eligible for an ACE inhibitor or an ARB.

The researchers analyzed data from 1,699 adults with CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate, 15-59 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio of ≥30 mg/g) who participated in the 2015-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Both the 2021 and 2012 KDIGO guidelines recommend that patients with albuminuria and blood pressure higher than the target value who are not kidney transplant recipients should be treated with an ACE inhibitor or an ARB.

On the basis of the new target, 78% of patients with CKD and albuminuria were eligible for ACE inhibitor/ARB treatment by the 2021 KDIGO guideline, compared with 71% by the 2012 KDIGO guideline. However, only 39% were taking one of these drugs.

These findings show that “with the new guideline and with the lower blood pressure target, you potentially have an even larger pool of people who have blood pressure that’s not under control, and a potential larger group of people who may benefit from ACE inhibitors and ARBs,” Dr. Chang said.

“Our paper is not the only one to show that we haven’t made a whole lot of progress,” she said, “and now that the bar has been lowered, there [have] to be some renewed efforts on controlling blood pressure, because we know that blood pressure control is such an important risk factor for cardiovascular outcomes.”

Dr. Foti is supported by an NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant. Dr. Cheung has received consultancy fees from Amgen, Bard, Boehringer Ingelheim, Calliditas, Tricida, and UpToDate, and grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health for SPRINT (monies paid to institution). Dr. Chang has received consultancy fees from Bayer, Gilead, Janssen Research and Development, Novo Nordisk, Tricida, and Vascular Dynamics; grant/research support from AstraZeneca and Satellite Healthcare (monies paid to institution), the NIH, and the American Heart Association; is on advisory boards for AstraZeneca and Fresenius Medical Care Renal Therapies Group; and has received workshop honoraria from Fresenius. Disclosures of relevant financial relationships of the other authors are listed in the original articles.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The new 2021 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guideline for blood pressure management for adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who are not receiving dialysis advises treating to a target systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg, provided measurements are “standardized” and that blood pressure is “measured properly.”

This blood pressure target – largely based on evidence from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) – represents “a major update” from the 2012 KDIGO guideline, which advised clinicians to treat to a target blood pressure of less than or equal to 130/80 mm Hg for patients with albuminuria or less than or equal to 140/90 mm Hg for patients without albuminuria.

The new goal is also lower than the less than 130/80 mm Hg target in the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline.

In a study of the public health implications of the guideline, Kathryn Foti, PhD, and colleagues determined that 70% of U.S. adults with CKD would now be eligible for treatment to lower blood pressure, as opposed to 50% under the previous KDIGO guideline and 56% under the ACC/AHA guideline.

“This is a major update of an influential set of guidelines for chronic kidney disease patients” at a time when blood pressure control is worsening in the United States, Dr. Foti, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, said in a statement from her institution.

The 2021 KDIGO blood pressure guideline and executive summary and the public health implications study are published online in Kidney International.

First, ‘take blood pressure well’

The cochair of the new KDIGO guidelines, Alfred K. Cheung, MD, from the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said in an interview that the guideline has “two important points.”

First, “take that blood pressure well,” he said. “That has a lot to do with patient preparation rather than any fancy instrument,” he emphasized.

Second, the guideline proposes a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg for most people with CKD not receiving dialysis, except for children and kidney transplant recipients. This target is “contingent on ‘standardized’ blood pressure measurement.”

The document provides a checklist for obtaining a standardized blood pressure measurement, adapted from the 2017 ACC/AHA blood pressure guidelines. It starts with the patient relaxed and sitting on a chair for more than 5 minutes.

In contrast to this measurement, a “routine” or “casual” office blood pressure measurement could be off by plus or minus 10 mm Hg, Dr. Cheung noted.

In a typical scenario, he continued, a patient cannot find a place to park, rushes into the clinic, and has his or her blood pressure checked right away, which would provide a “totally unreliable” reading. Adding a “fudge factor” (correction factor) would not provide an accurate reading.

Clinicians “would not settle for a potassium measurement that is 5.0 mmol/L plus or minus a few decimal points” to guide treatment, he pointed out.

Second, target 120, properly measured

“The very first chapter of the guidelines is devoted to blood pressure measurement, because we recognize if we’re going to do 120 [mm Hg] – the emphasis is on 120 measured properly – so we try to drive that point home,” Tara I. Chang, MD, guideline second author and a coauthor of the public health implications study, pointed out in an interview.

“There are a lot of other things that we base clinical decisions on where we really require some degree of precision, and blood pressure is important enough that to us it’s kind of in the same boat,” said Dr. Chang, from Stanford (Calif.) University.

“In SPRINT, people were randomized to less than less than 120 vs. less than 140 (they weren’t randomized to <130),” she noted.

“The recommendation should be widely adopted in clinical practice,” the guideline authors write, “since accurate measurements will ensure that proper guidance is being applied to the management of BP, as it is to the management of other risk factors.”

Still need individual treatment

Nevertheless, patients still need individualized treatment, the document stresses. “Not every patient with CKD will be appropriate to target to less than 120,” Dr. Chang said. However, “we want people to at least consider less than 120,” she added, to avoid therapeutic inertia.

“If you take the blood pressure in a standardized manner – such as in the ACCORD trial and in the SPRINT trial – even patients over 75 years old, or people over 80 years old, they have very little side effects,” Dr. Cheung noted.

“In the overall cohort,” he continued, “they do not have a significant increase in serious adverse events, do not have adverse events of postural hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, injurious falls – so people are worried about it, but it’s not borne out by the data.

“That said, I have two cautions,” Dr. Cheung noted. “One. If you drop somebody’s blood pressure rapidly over a week, you may be more likely to get in trouble. If you drop the blood pressure gradually over several weeks, several months, you’re much less likely to get into trouble.”

“Two. If the patient is old, you know the patient has carotid stenosis and already has postural dizziness, you may not want to try on that patient – but just because the patient is old is not the reason not to target 120.”

ACE inhibitors and ARBs beneficial in albuminuria, underused

“How do you get to less than 120? The short answer is, use whatever medications you need to – there is no necessarily right cocktail,” Dr. Chang said.

“We’ve known that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and ARBs [angiotensin II receptor blockers] are beneficial in patients with CKD and in particular those with heavier albuminuria,” she continued. “We’ve known this for over 20 years.”

Yet, the study identified underutilization – “a persistent gap, just like blood pressure control and awareness,” she noted. “We’re just not making much headway.

“We are not recommending ACE inhibitors or ARBs for all the patients,” Dr. Cheung clarified. “If you are diabetic and have heavy proteinuria, that’s when the use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs are most indicated.”

Public health implications

SPRINT showed that treating to a systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg vs. less than 140 mm Hg reduced the risk for cardiovascular disease by 25% and all-cause mortality by 27% for participants with and those without CKD, Dr. Foti and colleagues stress.

They aimed to estimate how the new guideline would affect (1) the number of U.S. patients with CKD who would be eligible for blood pressure lowering treatment, and (2) the proportion of those with albuminuria who would be eligible for an ACE inhibitor or an ARB.

The researchers analyzed data from 1,699 adults with CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate, 15-59 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio of ≥30 mg/g) who participated in the 2015-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Both the 2021 and 2012 KDIGO guidelines recommend that patients with albuminuria and blood pressure higher than the target value who are not kidney transplant recipients should be treated with an ACE inhibitor or an ARB.

On the basis of the new target, 78% of patients with CKD and albuminuria were eligible for ACE inhibitor/ARB treatment by the 2021 KDIGO guideline, compared with 71% by the 2012 KDIGO guideline. However, only 39% were taking one of these drugs.

These findings show that “with the new guideline and with the lower blood pressure target, you potentially have an even larger pool of people who have blood pressure that’s not under control, and a potential larger group of people who may benefit from ACE inhibitors and ARBs,” Dr. Chang said.

“Our paper is not the only one to show that we haven’t made a whole lot of progress,” she said, “and now that the bar has been lowered, there [have] to be some renewed efforts on controlling blood pressure, because we know that blood pressure control is such an important risk factor for cardiovascular outcomes.”

Dr. Foti is supported by an NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant. Dr. Cheung has received consultancy fees from Amgen, Bard, Boehringer Ingelheim, Calliditas, Tricida, and UpToDate, and grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health for SPRINT (monies paid to institution). Dr. Chang has received consultancy fees from Bayer, Gilead, Janssen Research and Development, Novo Nordisk, Tricida, and Vascular Dynamics; grant/research support from AstraZeneca and Satellite Healthcare (monies paid to institution), the NIH, and the American Heart Association; is on advisory boards for AstraZeneca and Fresenius Medical Care Renal Therapies Group; and has received workshop honoraria from Fresenius. Disclosures of relevant financial relationships of the other authors are listed in the original articles.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The new 2021 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guideline for blood pressure management for adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who are not receiving dialysis advises treating to a target systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg, provided measurements are “standardized” and that blood pressure is “measured properly.”

This blood pressure target – largely based on evidence from the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) – represents “a major update” from the 2012 KDIGO guideline, which advised clinicians to treat to a target blood pressure of less than or equal to 130/80 mm Hg for patients with albuminuria or less than or equal to 140/90 mm Hg for patients without albuminuria.

The new goal is also lower than the less than 130/80 mm Hg target in the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline.

In a study of the public health implications of the guideline, Kathryn Foti, PhD, and colleagues determined that 70% of U.S. adults with CKD would now be eligible for treatment to lower blood pressure, as opposed to 50% under the previous KDIGO guideline and 56% under the ACC/AHA guideline.

“This is a major update of an influential set of guidelines for chronic kidney disease patients” at a time when blood pressure control is worsening in the United States, Dr. Foti, a postdoctoral researcher in the department of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, said in a statement from her institution.

The 2021 KDIGO blood pressure guideline and executive summary and the public health implications study are published online in Kidney International.

First, ‘take blood pressure well’

The cochair of the new KDIGO guidelines, Alfred K. Cheung, MD, from the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, said in an interview that the guideline has “two important points.”

First, “take that blood pressure well,” he said. “That has a lot to do with patient preparation rather than any fancy instrument,” he emphasized.

Second, the guideline proposes a systolic blood pressure target of less than 120 mm Hg for most people with CKD not receiving dialysis, except for children and kidney transplant recipients. This target is “contingent on ‘standardized’ blood pressure measurement.”

The document provides a checklist for obtaining a standardized blood pressure measurement, adapted from the 2017 ACC/AHA blood pressure guidelines. It starts with the patient relaxed and sitting on a chair for more than 5 minutes.

In contrast to this measurement, a “routine” or “casual” office blood pressure measurement could be off by plus or minus 10 mm Hg, Dr. Cheung noted.

In a typical scenario, he continued, a patient cannot find a place to park, rushes into the clinic, and has his or her blood pressure checked right away, which would provide a “totally unreliable” reading. Adding a “fudge factor” (correction factor) would not provide an accurate reading.

Clinicians “would not settle for a potassium measurement that is 5.0 mmol/L plus or minus a few decimal points” to guide treatment, he pointed out.

Second, target 120, properly measured

“The very first chapter of the guidelines is devoted to blood pressure measurement, because we recognize if we’re going to do 120 [mm Hg] – the emphasis is on 120 measured properly – so we try to drive that point home,” Tara I. Chang, MD, guideline second author and a coauthor of the public health implications study, pointed out in an interview.

“There are a lot of other things that we base clinical decisions on where we really require some degree of precision, and blood pressure is important enough that to us it’s kind of in the same boat,” said Dr. Chang, from Stanford (Calif.) University.

“In SPRINT, people were randomized to less than less than 120 vs. less than 140 (they weren’t randomized to <130),” she noted.

“The recommendation should be widely adopted in clinical practice,” the guideline authors write, “since accurate measurements will ensure that proper guidance is being applied to the management of BP, as it is to the management of other risk factors.”

Still need individual treatment

Nevertheless, patients still need individualized treatment, the document stresses. “Not every patient with CKD will be appropriate to target to less than 120,” Dr. Chang said. However, “we want people to at least consider less than 120,” she added, to avoid therapeutic inertia.

“If you take the blood pressure in a standardized manner – such as in the ACCORD trial and in the SPRINT trial – even patients over 75 years old, or people over 80 years old, they have very little side effects,” Dr. Cheung noted.

“In the overall cohort,” he continued, “they do not have a significant increase in serious adverse events, do not have adverse events of postural hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, injurious falls – so people are worried about it, but it’s not borne out by the data.

“That said, I have two cautions,” Dr. Cheung noted. “One. If you drop somebody’s blood pressure rapidly over a week, you may be more likely to get in trouble. If you drop the blood pressure gradually over several weeks, several months, you’re much less likely to get into trouble.”

“Two. If the patient is old, you know the patient has carotid stenosis and already has postural dizziness, you may not want to try on that patient – but just because the patient is old is not the reason not to target 120.”

ACE inhibitors and ARBs beneficial in albuminuria, underused

“How do you get to less than 120? The short answer is, use whatever medications you need to – there is no necessarily right cocktail,” Dr. Chang said.

“We’ve known that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and ARBs [angiotensin II receptor blockers] are beneficial in patients with CKD and in particular those with heavier albuminuria,” she continued. “We’ve known this for over 20 years.”

Yet, the study identified underutilization – “a persistent gap, just like blood pressure control and awareness,” she noted. “We’re just not making much headway.

“We are not recommending ACE inhibitors or ARBs for all the patients,” Dr. Cheung clarified. “If you are diabetic and have heavy proteinuria, that’s when the use of ACE inhibitors and ARBs are most indicated.”

Public health implications

SPRINT showed that treating to a systolic blood pressure of less than 120 mm Hg vs. less than 140 mm Hg reduced the risk for cardiovascular disease by 25% and all-cause mortality by 27% for participants with and those without CKD, Dr. Foti and colleagues stress.

They aimed to estimate how the new guideline would affect (1) the number of U.S. patients with CKD who would be eligible for blood pressure lowering treatment, and (2) the proportion of those with albuminuria who would be eligible for an ACE inhibitor or an ARB.

The researchers analyzed data from 1,699 adults with CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate, 15-59 mL/min/1.73 m2 or a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio of ≥30 mg/g) who participated in the 2015-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Both the 2021 and 2012 KDIGO guidelines recommend that patients with albuminuria and blood pressure higher than the target value who are not kidney transplant recipients should be treated with an ACE inhibitor or an ARB.

On the basis of the new target, 78% of patients with CKD and albuminuria were eligible for ACE inhibitor/ARB treatment by the 2021 KDIGO guideline, compared with 71% by the 2012 KDIGO guideline. However, only 39% were taking one of these drugs.

These findings show that “with the new guideline and with the lower blood pressure target, you potentially have an even larger pool of people who have blood pressure that’s not under control, and a potential larger group of people who may benefit from ACE inhibitors and ARBs,” Dr. Chang said.

“Our paper is not the only one to show that we haven’t made a whole lot of progress,” she said, “and now that the bar has been lowered, there [have] to be some renewed efforts on controlling blood pressure, because we know that blood pressure control is such an important risk factor for cardiovascular outcomes.”

Dr. Foti is supported by an NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant. Dr. Cheung has received consultancy fees from Amgen, Bard, Boehringer Ingelheim, Calliditas, Tricida, and UpToDate, and grant/research support from the National Institutes of Health for SPRINT (monies paid to institution). Dr. Chang has received consultancy fees from Bayer, Gilead, Janssen Research and Development, Novo Nordisk, Tricida, and Vascular Dynamics; grant/research support from AstraZeneca and Satellite Healthcare (monies paid to institution), the NIH, and the American Heart Association; is on advisory boards for AstraZeneca and Fresenius Medical Care Renal Therapies Group; and has received workshop honoraria from Fresenius. Disclosures of relevant financial relationships of the other authors are listed in the original articles.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

JAMA editor resigns over controversial podcast

JAMA editor in chief Howard Bauchner, MD, apologized to JAMA staff and stakeholders and asked for and received Dr. Livingston’s resignation, according to a statement from AMA CEO James Madara.

More than 2,000 people have signed a petition on Change.org calling for an investigation at JAMA over the podcast, called “Structural Racism for Doctors: What Is It?”

It appears they are now getting their wish. Dr. Bauchner announced that the journal’s oversight committee is investigating how the podcast and a tweet promoting the episode were developed, reviewed, and ultimately posted.

“This investigation and report of its findings will be thorough and completed rapidly,” Dr. Bauchner said.

Dr. Livingston, the host of the podcast, has been heavily criticized across social media. During the podcast, Dr. Livingston, who is White, said: “Structural racism is an unfortunate term. Personally, I think taking racism out of the conversation will help. Many of us are offended by the concept that we are racist.”

The audio of the podcast has been deleted from JAMA’s website. In its place is audio of a statement from Dr. Bauchner. In his statement, which he released last week, he said the comments in the podcast, which also featured Mitch Katz, MD, were “inaccurate, offensive, hurtful, and inconsistent with the standards of JAMA.”

Dr. Katz is an editor at JAMA Internal Medicine and CEO of NYC Health + Hospitals in New York.

Also deleted was a JAMA tweet promoting the podcast episode. The tweet said: “No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care? An explanation of the idea by doctors for doctors in this user-friendly podcast.”

The incident was met with anger and confusion in the medical community.

Herbert C. Smitherman, MD, vice dean of diversity and community affairs at Wayne State University, Detroit, noted after hearing the podcast that it was a symptom of a much larger problem.

“At its core, this podcast had racist tendencies. Those attitudes are why you don’t have as many articles by Black and Brown people in JAMA,” he said. “People’s attitudes, whether conscious or unconscious, are what drive the policies and practices which create the structural racism.”

Dr. Katz responded to the backlash last week with the following statement: “Systemic racism exists in our country. The disparate effects of the pandemic have made this painfully clear in New York City and across the country.

“As clinicians, we must understand how these structures and policies have a direct impact on the health outcomes of the patients and communities we serve. It is woefully naive to say that no physician is a racist just because the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbade it, or that we should avoid the term ‘systematic racism’ because it makes people uncomfortable. We must and can do better.”

JAMA, an independent arm of the AMA, is taking other steps to address concerns. Its executive publisher, Thomas Easley, held an employee town hall this week, and said JAMA acknowledges that “structural racism is real, pernicious, and pervasive in health care.” The journal is also starting an “end-to-end review” of all editorial processes across all JAMA publications. Finally, the journal will also create a new associate editor’s position who will provide “insight and counsel” on racism and structural racism in health care.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

JAMA editor in chief Howard Bauchner, MD, apologized to JAMA staff and stakeholders and asked for and received Dr. Livingston’s resignation, according to a statement from AMA CEO James Madara.

More than 2,000 people have signed a petition on Change.org calling for an investigation at JAMA over the podcast, called “Structural Racism for Doctors: What Is It?”

It appears they are now getting their wish. Dr. Bauchner announced that the journal’s oversight committee is investigating how the podcast and a tweet promoting the episode were developed, reviewed, and ultimately posted.

“This investigation and report of its findings will be thorough and completed rapidly,” Dr. Bauchner said.

Dr. Livingston, the host of the podcast, has been heavily criticized across social media. During the podcast, Dr. Livingston, who is White, said: “Structural racism is an unfortunate term. Personally, I think taking racism out of the conversation will help. Many of us are offended by the concept that we are racist.”

The audio of the podcast has been deleted from JAMA’s website. In its place is audio of a statement from Dr. Bauchner. In his statement, which he released last week, he said the comments in the podcast, which also featured Mitch Katz, MD, were “inaccurate, offensive, hurtful, and inconsistent with the standards of JAMA.”

Dr. Katz is an editor at JAMA Internal Medicine and CEO of NYC Health + Hospitals in New York.

Also deleted was a JAMA tweet promoting the podcast episode. The tweet said: “No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care? An explanation of the idea by doctors for doctors in this user-friendly podcast.”

The incident was met with anger and confusion in the medical community.

Herbert C. Smitherman, MD, vice dean of diversity and community affairs at Wayne State University, Detroit, noted after hearing the podcast that it was a symptom of a much larger problem.

“At its core, this podcast had racist tendencies. Those attitudes are why you don’t have as many articles by Black and Brown people in JAMA,” he said. “People’s attitudes, whether conscious or unconscious, are what drive the policies and practices which create the structural racism.”

Dr. Katz responded to the backlash last week with the following statement: “Systemic racism exists in our country. The disparate effects of the pandemic have made this painfully clear in New York City and across the country.

“As clinicians, we must understand how these structures and policies have a direct impact on the health outcomes of the patients and communities we serve. It is woefully naive to say that no physician is a racist just because the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbade it, or that we should avoid the term ‘systematic racism’ because it makes people uncomfortable. We must and can do better.”

JAMA, an independent arm of the AMA, is taking other steps to address concerns. Its executive publisher, Thomas Easley, held an employee town hall this week, and said JAMA acknowledges that “structural racism is real, pernicious, and pervasive in health care.” The journal is also starting an “end-to-end review” of all editorial processes across all JAMA publications. Finally, the journal will also create a new associate editor’s position who will provide “insight and counsel” on racism and structural racism in health care.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

JAMA editor in chief Howard Bauchner, MD, apologized to JAMA staff and stakeholders and asked for and received Dr. Livingston’s resignation, according to a statement from AMA CEO James Madara.

More than 2,000 people have signed a petition on Change.org calling for an investigation at JAMA over the podcast, called “Structural Racism for Doctors: What Is It?”

It appears they are now getting their wish. Dr. Bauchner announced that the journal’s oversight committee is investigating how the podcast and a tweet promoting the episode were developed, reviewed, and ultimately posted.

“This investigation and report of its findings will be thorough and completed rapidly,” Dr. Bauchner said.

Dr. Livingston, the host of the podcast, has been heavily criticized across social media. During the podcast, Dr. Livingston, who is White, said: “Structural racism is an unfortunate term. Personally, I think taking racism out of the conversation will help. Many of us are offended by the concept that we are racist.”

The audio of the podcast has been deleted from JAMA’s website. In its place is audio of a statement from Dr. Bauchner. In his statement, which he released last week, he said the comments in the podcast, which also featured Mitch Katz, MD, were “inaccurate, offensive, hurtful, and inconsistent with the standards of JAMA.”

Dr. Katz is an editor at JAMA Internal Medicine and CEO of NYC Health + Hospitals in New York.

Also deleted was a JAMA tweet promoting the podcast episode. The tweet said: “No physician is racist, so how can there be structural racism in health care? An explanation of the idea by doctors for doctors in this user-friendly podcast.”

The incident was met with anger and confusion in the medical community.

Herbert C. Smitherman, MD, vice dean of diversity and community affairs at Wayne State University, Detroit, noted after hearing the podcast that it was a symptom of a much larger problem.

“At its core, this podcast had racist tendencies. Those attitudes are why you don’t have as many articles by Black and Brown people in JAMA,” he said. “People’s attitudes, whether conscious or unconscious, are what drive the policies and practices which create the structural racism.”

Dr. Katz responded to the backlash last week with the following statement: “Systemic racism exists in our country. The disparate effects of the pandemic have made this painfully clear in New York City and across the country.

“As clinicians, we must understand how these structures and policies have a direct impact on the health outcomes of the patients and communities we serve. It is woefully naive to say that no physician is a racist just because the Civil Rights Act of 1964 forbade it, or that we should avoid the term ‘systematic racism’ because it makes people uncomfortable. We must and can do better.”

JAMA, an independent arm of the AMA, is taking other steps to address concerns. Its executive publisher, Thomas Easley, held an employee town hall this week, and said JAMA acknowledges that “structural racism is real, pernicious, and pervasive in health care.” The journal is also starting an “end-to-end review” of all editorial processes across all JAMA publications. Finally, the journal will also create a new associate editor’s position who will provide “insight and counsel” on racism and structural racism in health care.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .