User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

Obesity can shift severe COVID-19 to younger age groups

published in The Lancet.

“By itself, obesity seems to be a sufficient risk factor to start seeing younger people landing in the ICU,” said the study’s lead author, David Kass, MD, a professor of cardiology and medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“In that sense, there’s a simple message: If you’re very, very overweight, don’t think that if you’re 35 you’re that much safer [from severe COVID-19] than your mother or grandparents or others in their 60s or 70s,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

The findings, which Kass describes as a “2-week snapshot” of 265 patients (58% male) in late March and early April at a handful of university hospitals in the United States reinforces other recent research indicating that obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease, particularly among younger patients. In addition, a large British study showed that, after adjusting for comorbidities, obesity was a significant factor associated with in-hospital death in COVID-19.

But this new analysis stands out as the only dataset to date that specifically “asks the question relative to age” of whether severe COVID-19 disease correlates to ICU treatment, he said.

The mean age of his study population of ICU patients was 55, Kass said, “and that was young, not what we were expecting.”

“Even with the first 20 patients, we were already seeing younger people and they definitely were heavier, with plenty of patients with a BMI over 35 kg/m2,” he added. “The relationship was pretty tight, pretty quick.”

“Just don’t make the assumption that any of us are too young to be vulnerable if, in fact, this is an aspect of our bodies,” he said.

Steven Heymsfield, MD, past president and a spokesperson for the Obesity Society, agrees with Kass’ conclusions.

“One thing we’ve had on our minds is that the prototype of a person with this disease is older...but now if we get [a patient] who’s symptomatic and 40 and obese, we shouldn’t assume they have some other disease,” Heymsfield told Medscape Medical News.

“We should think of them as a susceptible population.”

Kass and colleagues agree. “Public messaging to younger adults, reducing the threshold for virus testing in obese individuals, and maintaining greater vigilance for this at-risk population should reduce the prevalence of severe COVID-19 disease [among those with obesity],” they state.

“I think it’s a mental adjustment from a health care standpoint, which might hopefully help target the folks who are at higher risk before they get into trouble,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

Trio of mechanisms explain obesity’s extra COVID-19 risks

Kass and coauthors write that, in analyzing their data, they anticipated similar results to the largest study of 1591 ICU patients from Italy in which only 203 were younger than 51 years. Common comorbidities among those patients included hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes, with similar data reported from China.

When the COVID-19 epidemic accelerated in the United States, older age was also identified as a risk factor. Obesity had not yet been added to this list, Kass noted. But following informal discussions with colleagues in other ICUs around the country, he decided to investigate further as to whether it was an underappreciated risk factor.

Kass and colleagues did a quick evaluation of the link between BMI and age of patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICUs at Johns Hopkins, University of Cincinnati, New York University, University of Washington, Florida Health, and University of Pennsylvania.

The “significant inverse correlation between age and BMI” showed younger ICU patients were more likely to be obese, with no difference by gender.

Median BMI among study participants was 29.3 kg/m2, with only a quarter having a BMI lower than 26 kg/m2 and another 25% having a BMI higher than 34.7 kg/m2.

Kass acknowledged that it wasn’t possible with this simple dataset to account for any other potential confounders, but he told Medscape Medical News that, “while diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension, for example, can occur with obesity, this is generally less so in younger populations as it takes time for the other comorbidities to develop.”

He said several mechanisms could explain why obesity predisposes patients with COVID-19 to severe disease.

For one, obesity places extra pressure on the diaphragm while lying on the back, restricting breathing.

“Morbid obesity itself is sort of proinflammatory,” he continued.

“Here we’ve got a viral infection where the early reports suggest that cytokine storms and immune mishandling of the virus are why it’s so much more severe than other forms of coronavirus we’ve seen before. So if you have someone with an already underlying proinflammatory state, this could be a reason there’s higher risk.”

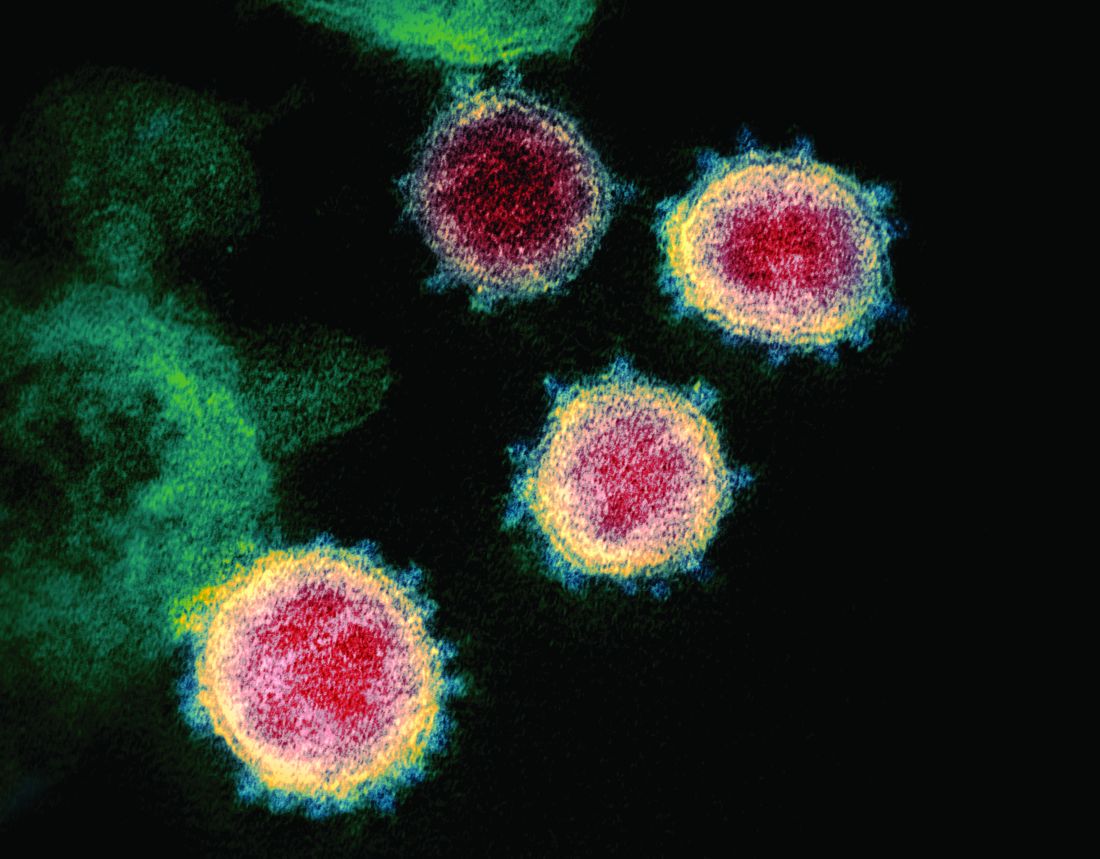

Additionally, the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor to which the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 attaches is expressed in higher amounts in adipose tissue than the lungs, Kass noted.

“This could turn into kind of a viral replication depot,” he explained. “You may well be brewing more virus as a component of obesity.”

Sensitivity needed in public messaging about risks, but test sooner

With an obesity rate of about 40% in the United States, the results are particularly relevant for Americans, Kass and Heymsfield say, noting that the country’s “obesity belt” runs through the South.

Heymsfield, who wasn’t part of the new analysis, notes that public messaging around severe COVID-19 risks to younger adults with obesity is “tricky,” especially because the virus is “still pretty common in nonobese people.”

Kass agrees, noting, “it’s difficult to turn to 40% of the population and say: ‘You guys have to watch it.’ ”

But the mounting research findings necessitate linking obesity with severe COVID-19 disease and perhaps testing patients in this category for the virus sooner before symptoms become severe.

And of note, since shortness of breath is common among people with obesity regardless of illness, similar COVID-19 symptoms might catch these individuals unaware, pointed out Heymsfield, who is also a professor in the Metabolism and Body Composition Lab at Pennington Biomedical Research Center at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

“They may find themselves literally unable to breathe, and the concern would be that they wait much too long to come in” for treatment, he said. Typically, people can deteriorate between day 7 and 10 of the COVID-19 infection.

Individuals with obesity “need to be educated to recognize the serious complications of COVID-19 often appear suddenly, although the virus has sometimes been working its way through the body for a long time,” he concluded.

Kass and Heymsfield have declared no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published in The Lancet.

“By itself, obesity seems to be a sufficient risk factor to start seeing younger people landing in the ICU,” said the study’s lead author, David Kass, MD, a professor of cardiology and medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“In that sense, there’s a simple message: If you’re very, very overweight, don’t think that if you’re 35 you’re that much safer [from severe COVID-19] than your mother or grandparents or others in their 60s or 70s,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

The findings, which Kass describes as a “2-week snapshot” of 265 patients (58% male) in late March and early April at a handful of university hospitals in the United States reinforces other recent research indicating that obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease, particularly among younger patients. In addition, a large British study showed that, after adjusting for comorbidities, obesity was a significant factor associated with in-hospital death in COVID-19.

But this new analysis stands out as the only dataset to date that specifically “asks the question relative to age” of whether severe COVID-19 disease correlates to ICU treatment, he said.

The mean age of his study population of ICU patients was 55, Kass said, “and that was young, not what we were expecting.”

“Even with the first 20 patients, we were already seeing younger people and they definitely were heavier, with plenty of patients with a BMI over 35 kg/m2,” he added. “The relationship was pretty tight, pretty quick.”

“Just don’t make the assumption that any of us are too young to be vulnerable if, in fact, this is an aspect of our bodies,” he said.

Steven Heymsfield, MD, past president and a spokesperson for the Obesity Society, agrees with Kass’ conclusions.

“One thing we’ve had on our minds is that the prototype of a person with this disease is older...but now if we get [a patient] who’s symptomatic and 40 and obese, we shouldn’t assume they have some other disease,” Heymsfield told Medscape Medical News.

“We should think of them as a susceptible population.”

Kass and colleagues agree. “Public messaging to younger adults, reducing the threshold for virus testing in obese individuals, and maintaining greater vigilance for this at-risk population should reduce the prevalence of severe COVID-19 disease [among those with obesity],” they state.

“I think it’s a mental adjustment from a health care standpoint, which might hopefully help target the folks who are at higher risk before they get into trouble,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

Trio of mechanisms explain obesity’s extra COVID-19 risks

Kass and coauthors write that, in analyzing their data, they anticipated similar results to the largest study of 1591 ICU patients from Italy in which only 203 were younger than 51 years. Common comorbidities among those patients included hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes, with similar data reported from China.

When the COVID-19 epidemic accelerated in the United States, older age was also identified as a risk factor. Obesity had not yet been added to this list, Kass noted. But following informal discussions with colleagues in other ICUs around the country, he decided to investigate further as to whether it was an underappreciated risk factor.

Kass and colleagues did a quick evaluation of the link between BMI and age of patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICUs at Johns Hopkins, University of Cincinnati, New York University, University of Washington, Florida Health, and University of Pennsylvania.

The “significant inverse correlation between age and BMI” showed younger ICU patients were more likely to be obese, with no difference by gender.

Median BMI among study participants was 29.3 kg/m2, with only a quarter having a BMI lower than 26 kg/m2 and another 25% having a BMI higher than 34.7 kg/m2.

Kass acknowledged that it wasn’t possible with this simple dataset to account for any other potential confounders, but he told Medscape Medical News that, “while diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension, for example, can occur with obesity, this is generally less so in younger populations as it takes time for the other comorbidities to develop.”

He said several mechanisms could explain why obesity predisposes patients with COVID-19 to severe disease.

For one, obesity places extra pressure on the diaphragm while lying on the back, restricting breathing.

“Morbid obesity itself is sort of proinflammatory,” he continued.

“Here we’ve got a viral infection where the early reports suggest that cytokine storms and immune mishandling of the virus are why it’s so much more severe than other forms of coronavirus we’ve seen before. So if you have someone with an already underlying proinflammatory state, this could be a reason there’s higher risk.”

Additionally, the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor to which the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 attaches is expressed in higher amounts in adipose tissue than the lungs, Kass noted.

“This could turn into kind of a viral replication depot,” he explained. “You may well be brewing more virus as a component of obesity.”

Sensitivity needed in public messaging about risks, but test sooner

With an obesity rate of about 40% in the United States, the results are particularly relevant for Americans, Kass and Heymsfield say, noting that the country’s “obesity belt” runs through the South.

Heymsfield, who wasn’t part of the new analysis, notes that public messaging around severe COVID-19 risks to younger adults with obesity is “tricky,” especially because the virus is “still pretty common in nonobese people.”

Kass agrees, noting, “it’s difficult to turn to 40% of the population and say: ‘You guys have to watch it.’ ”

But the mounting research findings necessitate linking obesity with severe COVID-19 disease and perhaps testing patients in this category for the virus sooner before symptoms become severe.

And of note, since shortness of breath is common among people with obesity regardless of illness, similar COVID-19 symptoms might catch these individuals unaware, pointed out Heymsfield, who is also a professor in the Metabolism and Body Composition Lab at Pennington Biomedical Research Center at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

“They may find themselves literally unable to breathe, and the concern would be that they wait much too long to come in” for treatment, he said. Typically, people can deteriorate between day 7 and 10 of the COVID-19 infection.

Individuals with obesity “need to be educated to recognize the serious complications of COVID-19 often appear suddenly, although the virus has sometimes been working its way through the body for a long time,” he concluded.

Kass and Heymsfield have declared no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published in The Lancet.

“By itself, obesity seems to be a sufficient risk factor to start seeing younger people landing in the ICU,” said the study’s lead author, David Kass, MD, a professor of cardiology and medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“In that sense, there’s a simple message: If you’re very, very overweight, don’t think that if you’re 35 you’re that much safer [from severe COVID-19] than your mother or grandparents or others in their 60s or 70s,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

The findings, which Kass describes as a “2-week snapshot” of 265 patients (58% male) in late March and early April at a handful of university hospitals in the United States reinforces other recent research indicating that obesity is one of the biggest risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease, particularly among younger patients. In addition, a large British study showed that, after adjusting for comorbidities, obesity was a significant factor associated with in-hospital death in COVID-19.

But this new analysis stands out as the only dataset to date that specifically “asks the question relative to age” of whether severe COVID-19 disease correlates to ICU treatment, he said.

The mean age of his study population of ICU patients was 55, Kass said, “and that was young, not what we were expecting.”

“Even with the first 20 patients, we were already seeing younger people and they definitely were heavier, with plenty of patients with a BMI over 35 kg/m2,” he added. “The relationship was pretty tight, pretty quick.”

“Just don’t make the assumption that any of us are too young to be vulnerable if, in fact, this is an aspect of our bodies,” he said.

Steven Heymsfield, MD, past president and a spokesperson for the Obesity Society, agrees with Kass’ conclusions.

“One thing we’ve had on our minds is that the prototype of a person with this disease is older...but now if we get [a patient] who’s symptomatic and 40 and obese, we shouldn’t assume they have some other disease,” Heymsfield told Medscape Medical News.

“We should think of them as a susceptible population.”

Kass and colleagues agree. “Public messaging to younger adults, reducing the threshold for virus testing in obese individuals, and maintaining greater vigilance for this at-risk population should reduce the prevalence of severe COVID-19 disease [among those with obesity],” they state.

“I think it’s a mental adjustment from a health care standpoint, which might hopefully help target the folks who are at higher risk before they get into trouble,” Kass told Medscape Medical News.

Trio of mechanisms explain obesity’s extra COVID-19 risks

Kass and coauthors write that, in analyzing their data, they anticipated similar results to the largest study of 1591 ICU patients from Italy in which only 203 were younger than 51 years. Common comorbidities among those patients included hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes, with similar data reported from China.

When the COVID-19 epidemic accelerated in the United States, older age was also identified as a risk factor. Obesity had not yet been added to this list, Kass noted. But following informal discussions with colleagues in other ICUs around the country, he decided to investigate further as to whether it was an underappreciated risk factor.

Kass and colleagues did a quick evaluation of the link between BMI and age of patients with COVID-19 admitted to ICUs at Johns Hopkins, University of Cincinnati, New York University, University of Washington, Florida Health, and University of Pennsylvania.

The “significant inverse correlation between age and BMI” showed younger ICU patients were more likely to be obese, with no difference by gender.

Median BMI among study participants was 29.3 kg/m2, with only a quarter having a BMI lower than 26 kg/m2 and another 25% having a BMI higher than 34.7 kg/m2.

Kass acknowledged that it wasn’t possible with this simple dataset to account for any other potential confounders, but he told Medscape Medical News that, “while diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hypertension, for example, can occur with obesity, this is generally less so in younger populations as it takes time for the other comorbidities to develop.”

He said several mechanisms could explain why obesity predisposes patients with COVID-19 to severe disease.

For one, obesity places extra pressure on the diaphragm while lying on the back, restricting breathing.

“Morbid obesity itself is sort of proinflammatory,” he continued.

“Here we’ve got a viral infection where the early reports suggest that cytokine storms and immune mishandling of the virus are why it’s so much more severe than other forms of coronavirus we’ve seen before. So if you have someone with an already underlying proinflammatory state, this could be a reason there’s higher risk.”

Additionally, the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor to which the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 attaches is expressed in higher amounts in adipose tissue than the lungs, Kass noted.

“This could turn into kind of a viral replication depot,” he explained. “You may well be brewing more virus as a component of obesity.”

Sensitivity needed in public messaging about risks, but test sooner

With an obesity rate of about 40% in the United States, the results are particularly relevant for Americans, Kass and Heymsfield say, noting that the country’s “obesity belt” runs through the South.

Heymsfield, who wasn’t part of the new analysis, notes that public messaging around severe COVID-19 risks to younger adults with obesity is “tricky,” especially because the virus is “still pretty common in nonobese people.”

Kass agrees, noting, “it’s difficult to turn to 40% of the population and say: ‘You guys have to watch it.’ ”

But the mounting research findings necessitate linking obesity with severe COVID-19 disease and perhaps testing patients in this category for the virus sooner before symptoms become severe.

And of note, since shortness of breath is common among people with obesity regardless of illness, similar COVID-19 symptoms might catch these individuals unaware, pointed out Heymsfield, who is also a professor in the Metabolism and Body Composition Lab at Pennington Biomedical Research Center at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

“They may find themselves literally unable to breathe, and the concern would be that they wait much too long to come in” for treatment, he said. Typically, people can deteriorate between day 7 and 10 of the COVID-19 infection.

Individuals with obesity “need to be educated to recognize the serious complications of COVID-19 often appear suddenly, although the virus has sometimes been working its way through the body for a long time,” he concluded.

Kass and Heymsfield have declared no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Triple-antiviral combo speeds COVID-19 recovery

A triple-antiviral therapy regimen of interferon-beta1, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin shortened median time to COVID-19 viral negativity by 5 days in a small trial from Hong Kong.

In an open-label, randomized phase 2 trial in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 infections, the median time to viral negativity by nasopharyngeal swab was 7 days for 86 patients assigned to receive a 14-day course of lopinavir 400 mg and ritonavir 100 mg every 12 hours, ribavirin 400 mg every 12 hours, and three doses of 8 million international units of interferon beta-1b on alternate days, compared with a median time to negativity of 12 days for patients treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone (P = .0010), wrote Ivan Fan-Ngai Hung, MD, from Gleaneagles Hospital in Hong Kong, and colleagues.

“Triple-antiviral therapy with interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin were safe and superior to lopinavir/ritonavir alone in shortening virus shedding, alleviating symptoms, and facilitating discharge of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19,” they wrote in a study published online in The Lancet.

Patients who received the combination also had significantly shorter time to complete alleviation of symptoms as assessed by a National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2, a system for detecting clinical deterioration in patients with acute illnesses) score of 0 (4 vs. 8 days, respectively; hazard ratio 3.92, P < .0001), and to a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of 0 (3 vs. 8 days, HR 1.89, P = .041).

The median hospital stay was 9 days for patients treated with the combination, compared with 14.5 days for controls (HR 2.72, P = .016).

In most patients treated with the combination, SARS-CoV-2 viral load was effectively suppressed in all clinical specimens, including nasopharyngeal swabs, throat and posterior oropharyngeal saliva, and stool.

In addition, serum levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6) – an inflammatory cytokine implicated in the cytokine storm frequently seen in patients with severe COVID-19 infections – were significantly lower on treatment days 2, 6, and 8 in patients treated with the combination, compared with those treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone.

“Our trial demonstrates that early treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 with a triple combination of antiviral drugs may rapidly suppress the amount of virus in a patient’s body, relieve symptoms, and reduce the risk to health care workers by reducing the duration and quantity of viral shedding (when the virus is detectable and potentially transmissible). Furthermore, the treatment combination appeared safe and well tolerated by patients,” said lead investigator Professor Kwok-Yung Yuen from the University of Hong Kong, in a statement.

“Despite these encouraging findings,” he continued, “we must confirm in larger phase 3 trials that interferon beta-1b alone or in combination with other drugs is effective in patients with more severe illness (in whom the virus has had more time to replicate).”

Plausible rationale

Benjamin Medoff, MD, chief of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that the biologic rationale for the combination is plausible.

“I think this is a promising study that suggests that a regimen of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin can shorten the duration of infection and improve symptoms in COVID-19 patients especially if started early in disease, in less than 7 days of symptom onset,” he said in reply to a request for expert analysis.

“The open-label nature and small size of the study limits the broad use of the regimen as noted by the authors, and it’s important to emphasize that the subjects enrolled did not have very severe disease (not in the ICU). However, the study does suggest that a larger truly randomized study is warranted,” he said.

AIDS drugs repurposed

Lopinavir/ritonavir is commonly used to treat HIV/AIDS throughout the world, and the investigators had previously reported that the antiviral agents combined with ribavirin reduced deaths and the need for intensive ventilator support among patients with SARS-CoV, the betacoronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and antivirals have shown in vitro activity against both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, the closely related pathogen that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome.

“ However the viral load of SARS and MERS peaks at around day 7-10 after symptom onset, whereas the viral load of COVID-19 peaks at the time of presentation, similar to influenza. Experience from the treatment of patients with influenza who are admitted to hospital suggested that a combination of multiple antiviral drugs is more effective than single-drug treatments in this setting of patients with a high viral load at presentation,” the investigators wrote.

To test this, they enrolled adults patients admitted to one of six Hong Kong Hospitals for virologically confirmed COVID-19 infections from Feb. 10 through March 20, 2020.

A total of 86 patients were randomly assigned to the combination and 41 to lopinavir/ritonavir alone as controls, at doses described above.

Patients who entered the trial within less than 7 days of symptom onset received the triple combination, with interferon dosing adjusted according to the day that treatment started. Patients recruited 1 or 2 days after symptom onset received three doses of interferon, patients started on day 3 or 4 received two doses, and those started on days 5 or 6 received one interferon dose. Patients recruited 7 days or later from symptom onset did not receive interferon beta-1b because of its proinflammatory effects.

In post-hoc analysis by day of treatment initiation, clinical and virological outcomes (except stool samples) were superior in patients admitted less than 7 days after symptom onset for the 52 patients who received a least one interferon dose plus lopinavir/ritonavir and ribavirin, compared with 24 patients randomized to the control arm (lopinavir/ritonavir only). In contrast, among patients admitted and started on treatment at day 7 or later after symptom onset, there were no differences between those who received lopinavir/ritonavir alone or combined with ribavirin.

Adverse events were reported in 41 of 86 patients in the combination group and 20 of 41 patients in the control arm. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, occurring in 52 of all 127 patients, fever in 48, nausea in 43, and elevated alanine transaminase level in 18. The side effects generally resolved within 3 days of the start of treatments.

There were no serious adverse events reported in the combination group. One patient in the control group had impaired hepatic enzymes requiring discontinuation of treatment. No patients died during the study.

The study was funded by the Shaw Foundation, Richard and Carol Yu, May Tam Mak Mei Yin, and Sanming Project of Medicine. The authors and Dr. Medoff declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Hung IFN et al. Lancet. 2020 May 8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31101-6.

A triple-antiviral therapy regimen of interferon-beta1, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin shortened median time to COVID-19 viral negativity by 5 days in a small trial from Hong Kong.

In an open-label, randomized phase 2 trial in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 infections, the median time to viral negativity by nasopharyngeal swab was 7 days for 86 patients assigned to receive a 14-day course of lopinavir 400 mg and ritonavir 100 mg every 12 hours, ribavirin 400 mg every 12 hours, and three doses of 8 million international units of interferon beta-1b on alternate days, compared with a median time to negativity of 12 days for patients treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone (P = .0010), wrote Ivan Fan-Ngai Hung, MD, from Gleaneagles Hospital in Hong Kong, and colleagues.

“Triple-antiviral therapy with interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin were safe and superior to lopinavir/ritonavir alone in shortening virus shedding, alleviating symptoms, and facilitating discharge of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19,” they wrote in a study published online in The Lancet.

Patients who received the combination also had significantly shorter time to complete alleviation of symptoms as assessed by a National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2, a system for detecting clinical deterioration in patients with acute illnesses) score of 0 (4 vs. 8 days, respectively; hazard ratio 3.92, P < .0001), and to a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of 0 (3 vs. 8 days, HR 1.89, P = .041).

The median hospital stay was 9 days for patients treated with the combination, compared with 14.5 days for controls (HR 2.72, P = .016).

In most patients treated with the combination, SARS-CoV-2 viral load was effectively suppressed in all clinical specimens, including nasopharyngeal swabs, throat and posterior oropharyngeal saliva, and stool.

In addition, serum levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6) – an inflammatory cytokine implicated in the cytokine storm frequently seen in patients with severe COVID-19 infections – were significantly lower on treatment days 2, 6, and 8 in patients treated with the combination, compared with those treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone.

“Our trial demonstrates that early treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 with a triple combination of antiviral drugs may rapidly suppress the amount of virus in a patient’s body, relieve symptoms, and reduce the risk to health care workers by reducing the duration and quantity of viral shedding (when the virus is detectable and potentially transmissible). Furthermore, the treatment combination appeared safe and well tolerated by patients,” said lead investigator Professor Kwok-Yung Yuen from the University of Hong Kong, in a statement.

“Despite these encouraging findings,” he continued, “we must confirm in larger phase 3 trials that interferon beta-1b alone or in combination with other drugs is effective in patients with more severe illness (in whom the virus has had more time to replicate).”

Plausible rationale

Benjamin Medoff, MD, chief of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that the biologic rationale for the combination is plausible.

“I think this is a promising study that suggests that a regimen of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin can shorten the duration of infection and improve symptoms in COVID-19 patients especially if started early in disease, in less than 7 days of symptom onset,” he said in reply to a request for expert analysis.

“The open-label nature and small size of the study limits the broad use of the regimen as noted by the authors, and it’s important to emphasize that the subjects enrolled did not have very severe disease (not in the ICU). However, the study does suggest that a larger truly randomized study is warranted,” he said.

AIDS drugs repurposed

Lopinavir/ritonavir is commonly used to treat HIV/AIDS throughout the world, and the investigators had previously reported that the antiviral agents combined with ribavirin reduced deaths and the need for intensive ventilator support among patients with SARS-CoV, the betacoronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and antivirals have shown in vitro activity against both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, the closely related pathogen that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome.

“ However the viral load of SARS and MERS peaks at around day 7-10 after symptom onset, whereas the viral load of COVID-19 peaks at the time of presentation, similar to influenza. Experience from the treatment of patients with influenza who are admitted to hospital suggested that a combination of multiple antiviral drugs is more effective than single-drug treatments in this setting of patients with a high viral load at presentation,” the investigators wrote.

To test this, they enrolled adults patients admitted to one of six Hong Kong Hospitals for virologically confirmed COVID-19 infections from Feb. 10 through March 20, 2020.

A total of 86 patients were randomly assigned to the combination and 41 to lopinavir/ritonavir alone as controls, at doses described above.

Patients who entered the trial within less than 7 days of symptom onset received the triple combination, with interferon dosing adjusted according to the day that treatment started. Patients recruited 1 or 2 days after symptom onset received three doses of interferon, patients started on day 3 or 4 received two doses, and those started on days 5 or 6 received one interferon dose. Patients recruited 7 days or later from symptom onset did not receive interferon beta-1b because of its proinflammatory effects.

In post-hoc analysis by day of treatment initiation, clinical and virological outcomes (except stool samples) were superior in patients admitted less than 7 days after symptom onset for the 52 patients who received a least one interferon dose plus lopinavir/ritonavir and ribavirin, compared with 24 patients randomized to the control arm (lopinavir/ritonavir only). In contrast, among patients admitted and started on treatment at day 7 or later after symptom onset, there were no differences between those who received lopinavir/ritonavir alone or combined with ribavirin.

Adverse events were reported in 41 of 86 patients in the combination group and 20 of 41 patients in the control arm. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, occurring in 52 of all 127 patients, fever in 48, nausea in 43, and elevated alanine transaminase level in 18. The side effects generally resolved within 3 days of the start of treatments.

There were no serious adverse events reported in the combination group. One patient in the control group had impaired hepatic enzymes requiring discontinuation of treatment. No patients died during the study.

The study was funded by the Shaw Foundation, Richard and Carol Yu, May Tam Mak Mei Yin, and Sanming Project of Medicine. The authors and Dr. Medoff declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Hung IFN et al. Lancet. 2020 May 8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31101-6.

A triple-antiviral therapy regimen of interferon-beta1, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin shortened median time to COVID-19 viral negativity by 5 days in a small trial from Hong Kong.

In an open-label, randomized phase 2 trial in patients with mild or moderate COVID-19 infections, the median time to viral negativity by nasopharyngeal swab was 7 days for 86 patients assigned to receive a 14-day course of lopinavir 400 mg and ritonavir 100 mg every 12 hours, ribavirin 400 mg every 12 hours, and three doses of 8 million international units of interferon beta-1b on alternate days, compared with a median time to negativity of 12 days for patients treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone (P = .0010), wrote Ivan Fan-Ngai Hung, MD, from Gleaneagles Hospital in Hong Kong, and colleagues.

“Triple-antiviral therapy with interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin were safe and superior to lopinavir/ritonavir alone in shortening virus shedding, alleviating symptoms, and facilitating discharge of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19,” they wrote in a study published online in The Lancet.

Patients who received the combination also had significantly shorter time to complete alleviation of symptoms as assessed by a National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2, a system for detecting clinical deterioration in patients with acute illnesses) score of 0 (4 vs. 8 days, respectively; hazard ratio 3.92, P < .0001), and to a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of 0 (3 vs. 8 days, HR 1.89, P = .041).

The median hospital stay was 9 days for patients treated with the combination, compared with 14.5 days for controls (HR 2.72, P = .016).

In most patients treated with the combination, SARS-CoV-2 viral load was effectively suppressed in all clinical specimens, including nasopharyngeal swabs, throat and posterior oropharyngeal saliva, and stool.

In addition, serum levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6) – an inflammatory cytokine implicated in the cytokine storm frequently seen in patients with severe COVID-19 infections – were significantly lower on treatment days 2, 6, and 8 in patients treated with the combination, compared with those treated with lopinavir/ritonavir alone.

“Our trial demonstrates that early treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 with a triple combination of antiviral drugs may rapidly suppress the amount of virus in a patient’s body, relieve symptoms, and reduce the risk to health care workers by reducing the duration and quantity of viral shedding (when the virus is detectable and potentially transmissible). Furthermore, the treatment combination appeared safe and well tolerated by patients,” said lead investigator Professor Kwok-Yung Yuen from the University of Hong Kong, in a statement.

“Despite these encouraging findings,” he continued, “we must confirm in larger phase 3 trials that interferon beta-1b alone or in combination with other drugs is effective in patients with more severe illness (in whom the virus has had more time to replicate).”

Plausible rationale

Benjamin Medoff, MD, chief of the division of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview that the biologic rationale for the combination is plausible.

“I think this is a promising study that suggests that a regimen of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir/ritonavir, and ribavirin can shorten the duration of infection and improve symptoms in COVID-19 patients especially if started early in disease, in less than 7 days of symptom onset,” he said in reply to a request for expert analysis.

“The open-label nature and small size of the study limits the broad use of the regimen as noted by the authors, and it’s important to emphasize that the subjects enrolled did not have very severe disease (not in the ICU). However, the study does suggest that a larger truly randomized study is warranted,” he said.

AIDS drugs repurposed

Lopinavir/ritonavir is commonly used to treat HIV/AIDS throughout the world, and the investigators had previously reported that the antiviral agents combined with ribavirin reduced deaths and the need for intensive ventilator support among patients with SARS-CoV, the betacoronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and antivirals have shown in vitro activity against both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, the closely related pathogen that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome.

“ However the viral load of SARS and MERS peaks at around day 7-10 after symptom onset, whereas the viral load of COVID-19 peaks at the time of presentation, similar to influenza. Experience from the treatment of patients with influenza who are admitted to hospital suggested that a combination of multiple antiviral drugs is more effective than single-drug treatments in this setting of patients with a high viral load at presentation,” the investigators wrote.

To test this, they enrolled adults patients admitted to one of six Hong Kong Hospitals for virologically confirmed COVID-19 infections from Feb. 10 through March 20, 2020.

A total of 86 patients were randomly assigned to the combination and 41 to lopinavir/ritonavir alone as controls, at doses described above.

Patients who entered the trial within less than 7 days of symptom onset received the triple combination, with interferon dosing adjusted according to the day that treatment started. Patients recruited 1 or 2 days after symptom onset received three doses of interferon, patients started on day 3 or 4 received two doses, and those started on days 5 or 6 received one interferon dose. Patients recruited 7 days or later from symptom onset did not receive interferon beta-1b because of its proinflammatory effects.

In post-hoc analysis by day of treatment initiation, clinical and virological outcomes (except stool samples) were superior in patients admitted less than 7 days after symptom onset for the 52 patients who received a least one interferon dose plus lopinavir/ritonavir and ribavirin, compared with 24 patients randomized to the control arm (lopinavir/ritonavir only). In contrast, among patients admitted and started on treatment at day 7 or later after symptom onset, there were no differences between those who received lopinavir/ritonavir alone or combined with ribavirin.

Adverse events were reported in 41 of 86 patients in the combination group and 20 of 41 patients in the control arm. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, occurring in 52 of all 127 patients, fever in 48, nausea in 43, and elevated alanine transaminase level in 18. The side effects generally resolved within 3 days of the start of treatments.

There were no serious adverse events reported in the combination group. One patient in the control group had impaired hepatic enzymes requiring discontinuation of treatment. No patients died during the study.

The study was funded by the Shaw Foundation, Richard and Carol Yu, May Tam Mak Mei Yin, and Sanming Project of Medicine. The authors and Dr. Medoff declared no competing interests.

SOURCE: Hung IFN et al. Lancet. 2020 May 8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31101-6.

FROM THE LANCET

Evolocumab safe, well-tolerated in HIV+ patients

Evolocumab proved effective, well tolerated, and safe for the treatment of refractory dyslipidemia in persons living with HIV in the phase 3, randomized, double-blind BEIJERINCK study.

At 24 weeks, nearly three-quarters of patients randomized to evolocumab (Repatha) achieved at least a 50% reduction in LDL cholesterol while on maximally tolerated background lipid lowering with a statin and/or other drugs. This was accompanied by significant reductions in other atherogenic lipids, Franck Boccara, MD, PhD, reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Evolocumab thus shows the potential to help fill a major unmet need for more effective treatment of dyslipidemia in HIV-positive patients, who number an estimated 38 million worldwide, including 1.1 million in the United States. Access to highly active antiretroviral therapies has transformed HIV infection into a chronic manageable disease, but this major advance has been accompanied by a rate of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease that’s nearly twice that of the general population, observed Dr. Boccara, a cardiologist at Sorbonne University, Paris.

The BEIJERINCK study included 464 HIV-infected patients in the United States and 14 other countries on five continents. Participants had a mean baseline LDL cholesterol of 133 mg/dL and triglycerides of about 190 mg/dL while on maximally tolerated lipid-lowering therapy. They had been diagnosed with HIV an average of 18 years earlier. One-third of them had known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. More than one-quarter of participants were cigarette smokers. Patients were randomized 2:1 to 24 weeks of double-blind subcutaneous evolocumab at 420 mg once monthly or placebo, then an additional 24 weeks of open-label evolocumab for all.

The primary endpoint was change in LDL from baseline to week 24: a 56.2% reduction in the evolocumab group and a 0.7% increase with placebo. About 73% of patients on evolocumab achieved at least a 50% reduction in LDL cholesterol, as did less than 1% of controls. Likewise, 73% of the evolocumab group got their LDL cholesterol below 70 mg/dL, compared with 7.9% with placebo.

The evolocumab group also experienced favorable placebo-subtracted differences from baseline of 23% in triglycerides, 27% in lipoprotein(a), and 22% in very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

As was the case in the earlier, much larger landmark clinical trials, evolocumab was well tolerated in BEIJERINCK, with a side effect profile similar to placebo. Notably, there was no increase in liver abnormalities in evolocumab-treated patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy, and no one developed evolocumab neutralizing antibodies.

Dr. Boccara reported receiving a research grant from Amgen, the study sponsor, as well as lecture fees from several other pharmaceutical companies.

Simultaneous with the presentation at ACC 2020, the primary results of the BEIJERINCK study were published online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Mar 19. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.025).

Evolocumab proved effective, well tolerated, and safe for the treatment of refractory dyslipidemia in persons living with HIV in the phase 3, randomized, double-blind BEIJERINCK study.

At 24 weeks, nearly three-quarters of patients randomized to evolocumab (Repatha) achieved at least a 50% reduction in LDL cholesterol while on maximally tolerated background lipid lowering with a statin and/or other drugs. This was accompanied by significant reductions in other atherogenic lipids, Franck Boccara, MD, PhD, reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Evolocumab thus shows the potential to help fill a major unmet need for more effective treatment of dyslipidemia in HIV-positive patients, who number an estimated 38 million worldwide, including 1.1 million in the United States. Access to highly active antiretroviral therapies has transformed HIV infection into a chronic manageable disease, but this major advance has been accompanied by a rate of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease that’s nearly twice that of the general population, observed Dr. Boccara, a cardiologist at Sorbonne University, Paris.

The BEIJERINCK study included 464 HIV-infected patients in the United States and 14 other countries on five continents. Participants had a mean baseline LDL cholesterol of 133 mg/dL and triglycerides of about 190 mg/dL while on maximally tolerated lipid-lowering therapy. They had been diagnosed with HIV an average of 18 years earlier. One-third of them had known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. More than one-quarter of participants were cigarette smokers. Patients were randomized 2:1 to 24 weeks of double-blind subcutaneous evolocumab at 420 mg once monthly or placebo, then an additional 24 weeks of open-label evolocumab for all.

The primary endpoint was change in LDL from baseline to week 24: a 56.2% reduction in the evolocumab group and a 0.7% increase with placebo. About 73% of patients on evolocumab achieved at least a 50% reduction in LDL cholesterol, as did less than 1% of controls. Likewise, 73% of the evolocumab group got their LDL cholesterol below 70 mg/dL, compared with 7.9% with placebo.

The evolocumab group also experienced favorable placebo-subtracted differences from baseline of 23% in triglycerides, 27% in lipoprotein(a), and 22% in very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

As was the case in the earlier, much larger landmark clinical trials, evolocumab was well tolerated in BEIJERINCK, with a side effect profile similar to placebo. Notably, there was no increase in liver abnormalities in evolocumab-treated patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy, and no one developed evolocumab neutralizing antibodies.

Dr. Boccara reported receiving a research grant from Amgen, the study sponsor, as well as lecture fees from several other pharmaceutical companies.

Simultaneous with the presentation at ACC 2020, the primary results of the BEIJERINCK study were published online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Mar 19. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.025).

Evolocumab proved effective, well tolerated, and safe for the treatment of refractory dyslipidemia in persons living with HIV in the phase 3, randomized, double-blind BEIJERINCK study.

At 24 weeks, nearly three-quarters of patients randomized to evolocumab (Repatha) achieved at least a 50% reduction in LDL cholesterol while on maximally tolerated background lipid lowering with a statin and/or other drugs. This was accompanied by significant reductions in other atherogenic lipids, Franck Boccara, MD, PhD, reported at the joint scientific sessions of the American College of Cardiology and the World Heart Federation. The meeting was conducted online after its cancellation because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Evolocumab thus shows the potential to help fill a major unmet need for more effective treatment of dyslipidemia in HIV-positive patients, who number an estimated 38 million worldwide, including 1.1 million in the United States. Access to highly active antiretroviral therapies has transformed HIV infection into a chronic manageable disease, but this major advance has been accompanied by a rate of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease that’s nearly twice that of the general population, observed Dr. Boccara, a cardiologist at Sorbonne University, Paris.

The BEIJERINCK study included 464 HIV-infected patients in the United States and 14 other countries on five continents. Participants had a mean baseline LDL cholesterol of 133 mg/dL and triglycerides of about 190 mg/dL while on maximally tolerated lipid-lowering therapy. They had been diagnosed with HIV an average of 18 years earlier. One-third of them had known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. More than one-quarter of participants were cigarette smokers. Patients were randomized 2:1 to 24 weeks of double-blind subcutaneous evolocumab at 420 mg once monthly or placebo, then an additional 24 weeks of open-label evolocumab for all.

The primary endpoint was change in LDL from baseline to week 24: a 56.2% reduction in the evolocumab group and a 0.7% increase with placebo. About 73% of patients on evolocumab achieved at least a 50% reduction in LDL cholesterol, as did less than 1% of controls. Likewise, 73% of the evolocumab group got their LDL cholesterol below 70 mg/dL, compared with 7.9% with placebo.

The evolocumab group also experienced favorable placebo-subtracted differences from baseline of 23% in triglycerides, 27% in lipoprotein(a), and 22% in very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

As was the case in the earlier, much larger landmark clinical trials, evolocumab was well tolerated in BEIJERINCK, with a side effect profile similar to placebo. Notably, there was no increase in liver abnormalities in evolocumab-treated patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy, and no one developed evolocumab neutralizing antibodies.

Dr. Boccara reported receiving a research grant from Amgen, the study sponsor, as well as lecture fees from several other pharmaceutical companies.

Simultaneous with the presentation at ACC 2020, the primary results of the BEIJERINCK study were published online (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Mar 19. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.025).

FROM ACC 2020

How to expand the APP role in a crisis

An opportunity to better appreciate the value of PAs, NPs

Advanced practice providers – physician assistants and nurse practitioners – at the 733-bed Emory University Hospital in Atlanta are playing an expanded role in the admission of patients into the hospital, particularly those suspected of having COVID-19.

Before the pandemic crisis, evaluation visits by the APP would have been reviewed on the same day by the supervising physician through an in-person encounter with the patient. The new protocol is not outside of scope-of-practice regulations for APPs in Georgia or of the hospital’s bylaws. But it offers a way to help limit the overall exposure of hospital staff to patients suspected of COVID-19 infection, and the total amount of time providers spend in such patients’ room. Just one provider now needs to meet the patient during the admissions process, while the attending physician can fulfill a requirement for seeing the patient within 24 hours during rounds the following day. Emergency encounters would still be done as needed.

These protocols point toward future conversations about the limits to APPs’ scope of practice, and whether more expansive approaches could be widely adopted once the current crisis is over, say advocates for the APPs’ role.

“Our APPs are primarily doing the admissions to the hospital of COVID patients and of non-COVID patients, as we’ve always done. But with COVID-infected or -suspected patients, we’re trying to minimize exposure for our providers,” explained Susan Ortiz, a certified PA, lead APP at Emory University Hospital. “In this way, we can also see more patients more efficiently.” Ms. Ortiz said she finds in talking to other APP leads in the Emory system that “each facility has its own culture and way of doing things. But for the most part, they’re all trying to do something to limit providers’ time in patients’ rooms.”

In response to the rapidly moving crisis, tactics to limit personnel in COVID patients’ rooms to the “absolutely essential” include gathering much of the needed history and other information requested from the patient by telephone, Ms. Ortiz said. This can be done either over the patient’s own cell phone or a phone placed in the room by hospital staff. Family members may be called to supplement this information, with the patient’s consent.

Once vital sign monitoring equipment is hooked up, it is possible to monitor the patient’s vital signs remotely without making frequent trips into the room. That way, in-person vital sign monitoring doesn’t need to happen routinely – at least not as often. One observation by clinicians on Ms. Ortiz’s team: listening for lung sounds with a stethoscope has not been shown to alter treatment for these patients. Once a chest X-ray shows structural changes in a patient’s lung, all lung exams are going to sound bad.

The admitting provider still needs to meet the patient in person for part of the admission visit and physical exam, but the amount of time spent in close personal contact with the patient can be much shorter, Ms. Ortiz said. For patients who are admitted, if there is a question about difficulty swallowing, they will see a speech pathologist, and if evidence of malnutrition, a nutritionist. “But we have to be extremely thoughtful about when people go into the room. So we are not ordering these ancillary services as routinely as we do during non-COVID times,” she said.

Appropriate levels of fear

Emory’s hospitalists are communicating daily about a rapidly changing situation. “We get a note by email every day, and we have a Dropbox account for downloading more information,” Ms. Ortiz said. A joint on-call system is used to provide backup coverage of APPs at the seven Emory hospitals. When replacement shifts need filling in a hurry, practitioners are able to obtain emergency credentials at any of the other hospitals. “It’s a voluntary process to sign up to be on-call,” Ms. Ortiz said. So far, that has been sufficient.

All staff have their own level of “appropriate fear” of this infection, Ms. Ortiz noted. “We have an extremely supportive group here to back up those of us who, for good reason, don’t want to be admitting the COVID patients.” Ms. Ortiz opted out of doing COVID admissions because her husband’s health places him at particular risk. “But with the cross-coverage we have, sometimes I’ll provide assistance when needed if a patient is suspected of being infected.” APPs are critical to Emory’s hospital medicine group – not ancillaries. “Everyone here feels that way. So we want to give them a lot of support. We’re all pitching in, doing it together,” she said.

“We said when we started with this, a couple of weeks before the surge started, that you could volunteer to see COVID patients,” said Emory hospitalist Jessica Nave, MD. “As we came to realize that the demand would be greater, we said you would need to opt out of seeing these patients, rather than opt in, and have a reason for doing so.” An example is pregnant staff, of which there seems to be a lot at Emory right now, Dr. Nave said, or those who are immunocompromised for other reasons. Those who don’t opt out are seeing the majority of the COVID patients, depending on actual need.

Dr. Nave is married to another hospitalist at Emory. “We can’t isolate from each other or our children. He and I have a regimented protocol for how we handle the risk, which includes taking off our shoes and clothes in the garage, showering and wiping down every place we might have touched. But those steps are not guarantees.” Other staff at Emory are isolating from their families for weeks at a time. Emory has a conference hotel offering discounted rates to staff. Nine physicians at Emory have been tested for the infection based on presenting symptoms, but at press time none had tested positive.

Streamlining code blue

Another area in which Emory has revised its policies in response to COVID-19 is for in-hospital cardiac arrest code response. Codes are inherently unpredictable, and crowd control has always been an issue for them, Dr. Nave said. “Historically, you could have 15 or more people show up when a code was called. Now, more than ever, we need to limit the number of people involved, for the same reason, avoiding unnecessary patient contact.”

The hospital’s Resuscitation Committee took the lead on developing a new policy, approved by the its Critical Care Committee and COVID Task Force, to limit the number of professionals in the room when running a code to an essential six: two doing chest compression, two managing airways, a code leader, and a critical care nurse. Outside the patient’s door, wearing the same personal protective equipment (PPE), are a pharmacist, recorder, and runner. “If you’re not one of those nine, you don’t need to be involved and should leave the area,” Dr. Nave said.

Staff have been instructed that they need to don appropriate PPE, including gown, mask, and eye wear, before entering the room for a code – even if that delays the start of intervention. “We’ve also made a code kit for each unit with quickly accessible gowns and masks. It should be used only for code blues.”

Increasing flexibility for the team

PAs and NPs in other locations are also exploring opportunities for gearing up to play larger roles in hospital care in the current crisis situation. The American Association of Physician Assistants has urged all U.S. governors to issue executive orders to waive state-specific licensing requirements for physician supervision or collaboration during the crisis, in order to increase flexibility of health care teams to deploy APPs.

AAPA believes the supervisory requirement is the biggest current barrier to mobilizing PAs and NPs. That includes those who have been furloughed from outpatient or other settings but are limited in their ability to contribute to the COVID crisis by the need to sign a supervision agreement with a physician at a new hospital.

The crisis is creating an opportunity to better appreciate the value PAs and NPs bring to health care, said Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM, vice president for advanced practice providers at Sound Physicians, a national hospitalist company based in Tacoma, Wash. The company recently sent a memo to the leadership of hospital sites at which it has contracts, requesting suspension of the hospitals’ requirements for a daily physician supervisory visit for APPs – which can be a hurdle when trying to leverage all hands on deck in the crisis.

NPs and PAs are stepping up and volunteering for COVID patients, Ms. Cardin said. Some have even taken leaves from their jobs to go to New York to help out at the epicenter of the U.S. crisis. “They want to make a difference. We’ve been deploying nonhospital medicine APPs from surgery, primary care, and elsewhere, embedding them on the hospital medicine team.”

Before the crisis, APPs at Sound Physicians weren’t always able to practice at the top of their licenses, depending on the hospital setting, added Alicia Scheffer, CNP, the company’s Great Lakes regional director for APPs. “Then COVID-19 showed up and really expedited conversations about how to maximize caseloads using APPs and about the fear of failing patients due to lack of capacity.”

In several locales, Sound Physicians is using quarantined providers to do telephone triage, or staffing ICUs with APPs backed up by telemedicine. “In APP-led ICUs, where the nurses are leading, they are intubating patients, placing central lines, things we weren’t allowed to do before,” Ms. Scheffer said.

A spirit of improvisation

There is a lot of tension at Emory University Hospital these days, reflecting the fears and uncertainties about the crisis, Dr. Nave said. “But there’s also a strangely powerful camaraderie like I’ve never seen before. When you walk onto the COVID units, you feel immediately bonded to the nurses, the techs, the phlebotomists. And you feel like you could talk about anything.”

Changes such as those made at Emory, have been talked about for a while, for example when hospitalists are having a busy night, she said. “But because this is a big cultural change, some physicians resisted it. We trust our APPs. But if the doctor’s name is on a patient chart, they want to see the patient – just for their own comfort level.”

Ms. Ortiz thinks the experience with the COVID crisis could help to advance the conversation about the appropriate role for APPs and their scope of practice in hospital medicine, once the current crisis has passed. “People were used to always doing things a certain way. This experience, hopefully, will get us to the point where attending physicians have more comfort with the APP’s ability to act autonomously,” she said.

“We’ve also talked about piloting telemedicine examinations using Zoom,” Dr. Nave added. “It’s making us think a lot of remote cross-coverage could be done that way. We’ve talked about using the hospital’s iPads with patients. This crisis really makes you think you want to innovate, in a spirit of improvisation,” she said. “Now is the time to try some of these things.”

Editors note: During the COVID-19 pandemic, many hospitals are seeing unprecedented volumes of patients requiring hospital medicine groups to stretch their current resources and recruit providers from outside their groups to bolster their inpatient services. The Society of Hospital Medicine has put together the following stepwise guide for onboarding traditional outpatient and subspecialty-based providers to work on general medicine wards: COVID-19 nonhospitalist onboarding resources.

An opportunity to better appreciate the value of PAs, NPs

An opportunity to better appreciate the value of PAs, NPs

Advanced practice providers – physician assistants and nurse practitioners – at the 733-bed Emory University Hospital in Atlanta are playing an expanded role in the admission of patients into the hospital, particularly those suspected of having COVID-19.

Before the pandemic crisis, evaluation visits by the APP would have been reviewed on the same day by the supervising physician through an in-person encounter with the patient. The new protocol is not outside of scope-of-practice regulations for APPs in Georgia or of the hospital’s bylaws. But it offers a way to help limit the overall exposure of hospital staff to patients suspected of COVID-19 infection, and the total amount of time providers spend in such patients’ room. Just one provider now needs to meet the patient during the admissions process, while the attending physician can fulfill a requirement for seeing the patient within 24 hours during rounds the following day. Emergency encounters would still be done as needed.

These protocols point toward future conversations about the limits to APPs’ scope of practice, and whether more expansive approaches could be widely adopted once the current crisis is over, say advocates for the APPs’ role.

“Our APPs are primarily doing the admissions to the hospital of COVID patients and of non-COVID patients, as we’ve always done. But with COVID-infected or -suspected patients, we’re trying to minimize exposure for our providers,” explained Susan Ortiz, a certified PA, lead APP at Emory University Hospital. “In this way, we can also see more patients more efficiently.” Ms. Ortiz said she finds in talking to other APP leads in the Emory system that “each facility has its own culture and way of doing things. But for the most part, they’re all trying to do something to limit providers’ time in patients’ rooms.”

In response to the rapidly moving crisis, tactics to limit personnel in COVID patients’ rooms to the “absolutely essential” include gathering much of the needed history and other information requested from the patient by telephone, Ms. Ortiz said. This can be done either over the patient’s own cell phone or a phone placed in the room by hospital staff. Family members may be called to supplement this information, with the patient’s consent.

Once vital sign monitoring equipment is hooked up, it is possible to monitor the patient’s vital signs remotely without making frequent trips into the room. That way, in-person vital sign monitoring doesn’t need to happen routinely – at least not as often. One observation by clinicians on Ms. Ortiz’s team: listening for lung sounds with a stethoscope has not been shown to alter treatment for these patients. Once a chest X-ray shows structural changes in a patient’s lung, all lung exams are going to sound bad.

The admitting provider still needs to meet the patient in person for part of the admission visit and physical exam, but the amount of time spent in close personal contact with the patient can be much shorter, Ms. Ortiz said. For patients who are admitted, if there is a question about difficulty swallowing, they will see a speech pathologist, and if evidence of malnutrition, a nutritionist. “But we have to be extremely thoughtful about when people go into the room. So we are not ordering these ancillary services as routinely as we do during non-COVID times,” she said.

Appropriate levels of fear

Emory’s hospitalists are communicating daily about a rapidly changing situation. “We get a note by email every day, and we have a Dropbox account for downloading more information,” Ms. Ortiz said. A joint on-call system is used to provide backup coverage of APPs at the seven Emory hospitals. When replacement shifts need filling in a hurry, practitioners are able to obtain emergency credentials at any of the other hospitals. “It’s a voluntary process to sign up to be on-call,” Ms. Ortiz said. So far, that has been sufficient.

All staff have their own level of “appropriate fear” of this infection, Ms. Ortiz noted. “We have an extremely supportive group here to back up those of us who, for good reason, don’t want to be admitting the COVID patients.” Ms. Ortiz opted out of doing COVID admissions because her husband’s health places him at particular risk. “But with the cross-coverage we have, sometimes I’ll provide assistance when needed if a patient is suspected of being infected.” APPs are critical to Emory’s hospital medicine group – not ancillaries. “Everyone here feels that way. So we want to give them a lot of support. We’re all pitching in, doing it together,” she said.

“We said when we started with this, a couple of weeks before the surge started, that you could volunteer to see COVID patients,” said Emory hospitalist Jessica Nave, MD. “As we came to realize that the demand would be greater, we said you would need to opt out of seeing these patients, rather than opt in, and have a reason for doing so.” An example is pregnant staff, of which there seems to be a lot at Emory right now, Dr. Nave said, or those who are immunocompromised for other reasons. Those who don’t opt out are seeing the majority of the COVID patients, depending on actual need.

Dr. Nave is married to another hospitalist at Emory. “We can’t isolate from each other or our children. He and I have a regimented protocol for how we handle the risk, which includes taking off our shoes and clothes in the garage, showering and wiping down every place we might have touched. But those steps are not guarantees.” Other staff at Emory are isolating from their families for weeks at a time. Emory has a conference hotel offering discounted rates to staff. Nine physicians at Emory have been tested for the infection based on presenting symptoms, but at press time none had tested positive.

Streamlining code blue

Another area in which Emory has revised its policies in response to COVID-19 is for in-hospital cardiac arrest code response. Codes are inherently unpredictable, and crowd control has always been an issue for them, Dr. Nave said. “Historically, you could have 15 or more people show up when a code was called. Now, more than ever, we need to limit the number of people involved, for the same reason, avoiding unnecessary patient contact.”

The hospital’s Resuscitation Committee took the lead on developing a new policy, approved by the its Critical Care Committee and COVID Task Force, to limit the number of professionals in the room when running a code to an essential six: two doing chest compression, two managing airways, a code leader, and a critical care nurse. Outside the patient’s door, wearing the same personal protective equipment (PPE), are a pharmacist, recorder, and runner. “If you’re not one of those nine, you don’t need to be involved and should leave the area,” Dr. Nave said.

Staff have been instructed that they need to don appropriate PPE, including gown, mask, and eye wear, before entering the room for a code – even if that delays the start of intervention. “We’ve also made a code kit for each unit with quickly accessible gowns and masks. It should be used only for code blues.”

Increasing flexibility for the team

PAs and NPs in other locations are also exploring opportunities for gearing up to play larger roles in hospital care in the current crisis situation. The American Association of Physician Assistants has urged all U.S. governors to issue executive orders to waive state-specific licensing requirements for physician supervision or collaboration during the crisis, in order to increase flexibility of health care teams to deploy APPs.

AAPA believes the supervisory requirement is the biggest current barrier to mobilizing PAs and NPs. That includes those who have been furloughed from outpatient or other settings but are limited in their ability to contribute to the COVID crisis by the need to sign a supervision agreement with a physician at a new hospital.

The crisis is creating an opportunity to better appreciate the value PAs and NPs bring to health care, said Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM, vice president for advanced practice providers at Sound Physicians, a national hospitalist company based in Tacoma, Wash. The company recently sent a memo to the leadership of hospital sites at which it has contracts, requesting suspension of the hospitals’ requirements for a daily physician supervisory visit for APPs – which can be a hurdle when trying to leverage all hands on deck in the crisis.

NPs and PAs are stepping up and volunteering for COVID patients, Ms. Cardin said. Some have even taken leaves from their jobs to go to New York to help out at the epicenter of the U.S. crisis. “They want to make a difference. We’ve been deploying nonhospital medicine APPs from surgery, primary care, and elsewhere, embedding them on the hospital medicine team.”

Before the crisis, APPs at Sound Physicians weren’t always able to practice at the top of their licenses, depending on the hospital setting, added Alicia Scheffer, CNP, the company’s Great Lakes regional director for APPs. “Then COVID-19 showed up and really expedited conversations about how to maximize caseloads using APPs and about the fear of failing patients due to lack of capacity.”

In several locales, Sound Physicians is using quarantined providers to do telephone triage, or staffing ICUs with APPs backed up by telemedicine. “In APP-led ICUs, where the nurses are leading, they are intubating patients, placing central lines, things we weren’t allowed to do before,” Ms. Scheffer said.

A spirit of improvisation

There is a lot of tension at Emory University Hospital these days, reflecting the fears and uncertainties about the crisis, Dr. Nave said. “But there’s also a strangely powerful camaraderie like I’ve never seen before. When you walk onto the COVID units, you feel immediately bonded to the nurses, the techs, the phlebotomists. And you feel like you could talk about anything.”

Changes such as those made at Emory, have been talked about for a while, for example when hospitalists are having a busy night, she said. “But because this is a big cultural change, some physicians resisted it. We trust our APPs. But if the doctor’s name is on a patient chart, they want to see the patient – just for their own comfort level.”

Ms. Ortiz thinks the experience with the COVID crisis could help to advance the conversation about the appropriate role for APPs and their scope of practice in hospital medicine, once the current crisis has passed. “People were used to always doing things a certain way. This experience, hopefully, will get us to the point where attending physicians have more comfort with the APP’s ability to act autonomously,” she said.

“We’ve also talked about piloting telemedicine examinations using Zoom,” Dr. Nave added. “It’s making us think a lot of remote cross-coverage could be done that way. We’ve talked about using the hospital’s iPads with patients. This crisis really makes you think you want to innovate, in a spirit of improvisation,” she said. “Now is the time to try some of these things.”

Editors note: During the COVID-19 pandemic, many hospitals are seeing unprecedented volumes of patients requiring hospital medicine groups to stretch their current resources and recruit providers from outside their groups to bolster their inpatient services. The Society of Hospital Medicine has put together the following stepwise guide for onboarding traditional outpatient and subspecialty-based providers to work on general medicine wards: COVID-19 nonhospitalist onboarding resources.

Advanced practice providers – physician assistants and nurse practitioners – at the 733-bed Emory University Hospital in Atlanta are playing an expanded role in the admission of patients into the hospital, particularly those suspected of having COVID-19.

Before the pandemic crisis, evaluation visits by the APP would have been reviewed on the same day by the supervising physician through an in-person encounter with the patient. The new protocol is not outside of scope-of-practice regulations for APPs in Georgia or of the hospital’s bylaws. But it offers a way to help limit the overall exposure of hospital staff to patients suspected of COVID-19 infection, and the total amount of time providers spend in such patients’ room. Just one provider now needs to meet the patient during the admissions process, while the attending physician can fulfill a requirement for seeing the patient within 24 hours during rounds the following day. Emergency encounters would still be done as needed.

These protocols point toward future conversations about the limits to APPs’ scope of practice, and whether more expansive approaches could be widely adopted once the current crisis is over, say advocates for the APPs’ role.

“Our APPs are primarily doing the admissions to the hospital of COVID patients and of non-COVID patients, as we’ve always done. But with COVID-infected or -suspected patients, we’re trying to minimize exposure for our providers,” explained Susan Ortiz, a certified PA, lead APP at Emory University Hospital. “In this way, we can also see more patients more efficiently.” Ms. Ortiz said she finds in talking to other APP leads in the Emory system that “each facility has its own culture and way of doing things. But for the most part, they’re all trying to do something to limit providers’ time in patients’ rooms.”

In response to the rapidly moving crisis, tactics to limit personnel in COVID patients’ rooms to the “absolutely essential” include gathering much of the needed history and other information requested from the patient by telephone, Ms. Ortiz said. This can be done either over the patient’s own cell phone or a phone placed in the room by hospital staff. Family members may be called to supplement this information, with the patient’s consent.