User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

When you see something ...

Over the last several decades science has fallen off this country’s radar screen. Yes, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) has recently had a brief moment in the spotlight as a buzzword de jour. But the critical importance of careful and systematic investigation into the world around us using observation and trial and error is a tough sell to a large segment of our population.

The COVID-19 pandemic is providing an excellent opportunity for science and medicine to showcase their star qualities. Of course some people in leadership positions persist in disregarding the value of scientific investigation. But I get the feeling that the fear generated by the pandemic is creating some converts among many previous science skeptics. This gathering enthusiasm among the general population is a predictably slow process because that’s the way science works. It often doesn’t provide quick answers. And it is difficult for the nonscientist to see the beauty in the reality that the things we thought were true 2 months ago are likely to be proven wrong today as more observations accumulate.

A recent New York Times article examines the career of one such unscrupulous physician/scientist whose recent exploits threaten to undo much of the positive image the pandemic has cast on science (“The Doctor Behind the Disputed Covid Data,” by Ellen Gabler and Roni Caryn Rabin, The New York Times, July 27, 2020). The subject of the article is the physician who was responsible for providing some of the large data sets on which several papers were published about the apparent ineffectiveness and danger of using hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 patients. The authenticity of the data sets recently has been seriously questioned, and the articles have been retracted by the journals in which they had appeared.

Based on numerous interviews with coworkers, the Times reporters present a strong case that this individual’s long history of unreliability make his association with allegedly fraudulent data set not surprising but maybe even predictable. At one point in his training, there appears to have been serious questions about advancing the physician to the next level. Despite these concerns, he was allowed to continue and complete his specialty training. It is of note that in his last year of clinical practice, the physician became the subject of three serious malpractice claims that question his competence.

I suspect that some of you have crossed paths with physicians whose competence and/or moral character you found concerning. Were they peers? Were you the individual’s supervisor or was he or she your mentor? How did you respond? Did anyone respond at all?

There has been a lot written and said in recent months about how and when to respond to respond to sexual harassment in the workplace. But I don’t recall reading any articles that discuss how one should respond to incompetence. Of course competency can be a relative term, but in most cases significant incompetence is hard to miss because it tends to be repeated.

It is easy for the airports and subway systems to post signs that say “If you see something say something.” It’s a different story for hospitals and medical schools that may have systems in place for reporting and following up on poor practice. But my sense is that there are too many cases that slip through the cracks.

This is another example of a problem for which I don’t have a solution. However, if this column prompts just one of you who sees something to say something then I have had a good day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Over the last several decades science has fallen off this country’s radar screen. Yes, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) has recently had a brief moment in the spotlight as a buzzword de jour. But the critical importance of careful and systematic investigation into the world around us using observation and trial and error is a tough sell to a large segment of our population.

The COVID-19 pandemic is providing an excellent opportunity for science and medicine to showcase their star qualities. Of course some people in leadership positions persist in disregarding the value of scientific investigation. But I get the feeling that the fear generated by the pandemic is creating some converts among many previous science skeptics. This gathering enthusiasm among the general population is a predictably slow process because that’s the way science works. It often doesn’t provide quick answers. And it is difficult for the nonscientist to see the beauty in the reality that the things we thought were true 2 months ago are likely to be proven wrong today as more observations accumulate.

A recent New York Times article examines the career of one such unscrupulous physician/scientist whose recent exploits threaten to undo much of the positive image the pandemic has cast on science (“The Doctor Behind the Disputed Covid Data,” by Ellen Gabler and Roni Caryn Rabin, The New York Times, July 27, 2020). The subject of the article is the physician who was responsible for providing some of the large data sets on which several papers were published about the apparent ineffectiveness and danger of using hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 patients. The authenticity of the data sets recently has been seriously questioned, and the articles have been retracted by the journals in which they had appeared.

Based on numerous interviews with coworkers, the Times reporters present a strong case that this individual’s long history of unreliability make his association with allegedly fraudulent data set not surprising but maybe even predictable. At one point in his training, there appears to have been serious questions about advancing the physician to the next level. Despite these concerns, he was allowed to continue and complete his specialty training. It is of note that in his last year of clinical practice, the physician became the subject of three serious malpractice claims that question his competence.

I suspect that some of you have crossed paths with physicians whose competence and/or moral character you found concerning. Were they peers? Were you the individual’s supervisor or was he or she your mentor? How did you respond? Did anyone respond at all?

There has been a lot written and said in recent months about how and when to respond to respond to sexual harassment in the workplace. But I don’t recall reading any articles that discuss how one should respond to incompetence. Of course competency can be a relative term, but in most cases significant incompetence is hard to miss because it tends to be repeated.

It is easy for the airports and subway systems to post signs that say “If you see something say something.” It’s a different story for hospitals and medical schools that may have systems in place for reporting and following up on poor practice. But my sense is that there are too many cases that slip through the cracks.

This is another example of a problem for which I don’t have a solution. However, if this column prompts just one of you who sees something to say something then I have had a good day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Over the last several decades science has fallen off this country’s radar screen. Yes, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) has recently had a brief moment in the spotlight as a buzzword de jour. But the critical importance of careful and systematic investigation into the world around us using observation and trial and error is a tough sell to a large segment of our population.

The COVID-19 pandemic is providing an excellent opportunity for science and medicine to showcase their star qualities. Of course some people in leadership positions persist in disregarding the value of scientific investigation. But I get the feeling that the fear generated by the pandemic is creating some converts among many previous science skeptics. This gathering enthusiasm among the general population is a predictably slow process because that’s the way science works. It often doesn’t provide quick answers. And it is difficult for the nonscientist to see the beauty in the reality that the things we thought were true 2 months ago are likely to be proven wrong today as more observations accumulate.

A recent New York Times article examines the career of one such unscrupulous physician/scientist whose recent exploits threaten to undo much of the positive image the pandemic has cast on science (“The Doctor Behind the Disputed Covid Data,” by Ellen Gabler and Roni Caryn Rabin, The New York Times, July 27, 2020). The subject of the article is the physician who was responsible for providing some of the large data sets on which several papers were published about the apparent ineffectiveness and danger of using hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19 patients. The authenticity of the data sets recently has been seriously questioned, and the articles have been retracted by the journals in which they had appeared.

Based on numerous interviews with coworkers, the Times reporters present a strong case that this individual’s long history of unreliability make his association with allegedly fraudulent data set not surprising but maybe even predictable. At one point in his training, there appears to have been serious questions about advancing the physician to the next level. Despite these concerns, he was allowed to continue and complete his specialty training. It is of note that in his last year of clinical practice, the physician became the subject of three serious malpractice claims that question his competence.

I suspect that some of you have crossed paths with physicians whose competence and/or moral character you found concerning. Were they peers? Were you the individual’s supervisor or was he or she your mentor? How did you respond? Did anyone respond at all?

There has been a lot written and said in recent months about how and when to respond to respond to sexual harassment in the workplace. But I don’t recall reading any articles that discuss how one should respond to incompetence. Of course competency can be a relative term, but in most cases significant incompetence is hard to miss because it tends to be repeated.

It is easy for the airports and subway systems to post signs that say “If you see something say something.” It’s a different story for hospitals and medical schools that may have systems in place for reporting and following up on poor practice. But my sense is that there are too many cases that slip through the cracks.

This is another example of a problem for which I don’t have a solution. However, if this column prompts just one of you who sees something to say something then I have had a good day.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Medicare sticks with E/M pay plan over some groups’ objections

The Trump administration is sticking with a plan to boost certain Medicare pay for many primary care and other specialties focused heavily on office visits while lowering that for other groups to balance these increased costs.

On Aug. 4, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services posted on the Federal Register draft versions of two of its major annual payment measures: the physician fee schedule and the payment rule for hospital outpatient services. On Aug. 3, the CMS informally posted a copy of the physician fee schedule on its own website, allowing medical groups to begin reading the more than 1,300-page rule.

Federal officials normally use annual Medicare payment rules to make many revisions to policies as well as adjust reimbursement.

The draft 2021 physician fee schedule, for example, calls for broadening the authority of clinicians other than physicians to authorize testing of people enrolled in Medicare.

The CMS intends to allow nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and certain other health care professionals to more widely supervise diagnostic psychological and neuropsychological tests, in keeping with applicable state laws.

The draft 2021 hospital outpatient rule proposes a gradual changeover to allow more procedures to be performed on an outpatient basis. This shift could save money for Medicare as well as for the people enrolled in the giant federal health program who need these services, the CMS explained.

Medicare would begin with a change in status for almost 300 musculoskeletal-related services, making them eligible for payment in the hospital outpatient setting when appropriate, CMS wrote in a fact sheet.

The initial reaction to Medicare’s proposed 2021 rules centered on its planned redistribution of funds among medical specialties. The CMS had outlined this plan last year. It is part of longstanding efforts to boost pay for primary care specialists and other physicians whose practice centers more around office visits than procedures.

There is broad support in health policy circles for raising pay for these specialties, but there also are strong objections to the cuts the CMS plans to offset the cost of rising pay for some fields.

Susan R. Bailey, MD, president of the American Medical Association, addressed both of these ideas in an AMA news release on the proposed 2021 physician fee schedule. The increase in pay for office visits, covered under evaluation and management services (E/M), stems from recommendations on resource costs from the AMA/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee, Dr. Bailey said.

“Unfortunately, these office visit payment increases, and a multitude of other new CMS proposed payment increases, are required by statute to be offset by payment reductions to other services, through an unsustainable reduction of nearly 11% to the Medicare conversion factor,” Dr. Bailey explained.

In the news release, Dr. Bailey asked Congress to waive Medicare’s budget-neutrality requirements to allow increases without the cuts.

“Physicians are already experiencing substantial economic hardships due to COVID-19, so these pay cuts could not come at a worse time,” she said.

Winners and losers

The CMS details the possible winners and losers in its payment reshuffle in Table 90 of the proposed 2021 physician fee schedule. In the proposed rule, CMS notes in the draft that these figures are based upon estimates of aggregate allowed charges across all services furnished by physicians and other clinicians.

“Therefore, they are averages, and may not necessarily be representative of what is happening to the particular services furnished by a single practitioner within any given specialty,” the CMS said.

Specialties in line for increases under the 2021 draft rule include allergy/immunology (9%), endocrinology (17%), family practice (13%), general practice (8%), geriatrics (4%), hematology/oncology (14%), internal medicine (4%), nephrology (6%), physician assistants (8%), psychiatry (8%), rheumatology (16%), and urology (8%).

In line for cuts would be anesthesiology (–8%), cardiac surgery (–9%), emergency medicine (–6%), general surgery (–7%), infectious disease (–4%), neurosurgery (–7%), physical/occupational therapy (–9%), plastic surgery (–7%), radiology (–11%), and thoracic surgery (–8%).

An umbrella group, the Surgical Care Coalition, on Aug. 3 had a quick statement ready about the CMS proposal. Writing on behalf of the group was David B. Hoyt, MD, executive director of the American College of Surgeons.

“Today’s proposed rule ignores both patients and the surgeons who care for them. The middle of a pandemic is no time for cuts to any form of health care, but today’s announcement moves ahead as if nothing has changed,” Hoyt said in the statement. “The Surgical Care Coalition believes no physician should see payment cuts that will reduce patients’ access to care.”

The Surgical Care Coalition already has been asking Congress to waive budget-neutrality requirements. Making a similar request Aug. 4 in a unified statement were the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA).

“Our organizations call on Congress and CMS to advance well-reasoned fee schedule payment policies and waive budget neutrality,” the groups said. “While APTA, AOTA, and ASHA do not oppose payment increases for primary care physicians, we believe these increases can be implemented without imposing payment reductions on other providers.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Trump administration is sticking with a plan to boost certain Medicare pay for many primary care and other specialties focused heavily on office visits while lowering that for other groups to balance these increased costs.

On Aug. 4, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services posted on the Federal Register draft versions of two of its major annual payment measures: the physician fee schedule and the payment rule for hospital outpatient services. On Aug. 3, the CMS informally posted a copy of the physician fee schedule on its own website, allowing medical groups to begin reading the more than 1,300-page rule.

Federal officials normally use annual Medicare payment rules to make many revisions to policies as well as adjust reimbursement.

The draft 2021 physician fee schedule, for example, calls for broadening the authority of clinicians other than physicians to authorize testing of people enrolled in Medicare.

The CMS intends to allow nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and certain other health care professionals to more widely supervise diagnostic psychological and neuropsychological tests, in keeping with applicable state laws.

The draft 2021 hospital outpatient rule proposes a gradual changeover to allow more procedures to be performed on an outpatient basis. This shift could save money for Medicare as well as for the people enrolled in the giant federal health program who need these services, the CMS explained.

Medicare would begin with a change in status for almost 300 musculoskeletal-related services, making them eligible for payment in the hospital outpatient setting when appropriate, CMS wrote in a fact sheet.

The initial reaction to Medicare’s proposed 2021 rules centered on its planned redistribution of funds among medical specialties. The CMS had outlined this plan last year. It is part of longstanding efforts to boost pay for primary care specialists and other physicians whose practice centers more around office visits than procedures.

There is broad support in health policy circles for raising pay for these specialties, but there also are strong objections to the cuts the CMS plans to offset the cost of rising pay for some fields.

Susan R. Bailey, MD, president of the American Medical Association, addressed both of these ideas in an AMA news release on the proposed 2021 physician fee schedule. The increase in pay for office visits, covered under evaluation and management services (E/M), stems from recommendations on resource costs from the AMA/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee, Dr. Bailey said.

“Unfortunately, these office visit payment increases, and a multitude of other new CMS proposed payment increases, are required by statute to be offset by payment reductions to other services, through an unsustainable reduction of nearly 11% to the Medicare conversion factor,” Dr. Bailey explained.

In the news release, Dr. Bailey asked Congress to waive Medicare’s budget-neutrality requirements to allow increases without the cuts.

“Physicians are already experiencing substantial economic hardships due to COVID-19, so these pay cuts could not come at a worse time,” she said.

Winners and losers

The CMS details the possible winners and losers in its payment reshuffle in Table 90 of the proposed 2021 physician fee schedule. In the proposed rule, CMS notes in the draft that these figures are based upon estimates of aggregate allowed charges across all services furnished by physicians and other clinicians.

“Therefore, they are averages, and may not necessarily be representative of what is happening to the particular services furnished by a single practitioner within any given specialty,” the CMS said.

Specialties in line for increases under the 2021 draft rule include allergy/immunology (9%), endocrinology (17%), family practice (13%), general practice (8%), geriatrics (4%), hematology/oncology (14%), internal medicine (4%), nephrology (6%), physician assistants (8%), psychiatry (8%), rheumatology (16%), and urology (8%).

In line for cuts would be anesthesiology (–8%), cardiac surgery (–9%), emergency medicine (–6%), general surgery (–7%), infectious disease (–4%), neurosurgery (–7%), physical/occupational therapy (–9%), plastic surgery (–7%), radiology (–11%), and thoracic surgery (–8%).

An umbrella group, the Surgical Care Coalition, on Aug. 3 had a quick statement ready about the CMS proposal. Writing on behalf of the group was David B. Hoyt, MD, executive director of the American College of Surgeons.

“Today’s proposed rule ignores both patients and the surgeons who care for them. The middle of a pandemic is no time for cuts to any form of health care, but today’s announcement moves ahead as if nothing has changed,” Hoyt said in the statement. “The Surgical Care Coalition believes no physician should see payment cuts that will reduce patients’ access to care.”

The Surgical Care Coalition already has been asking Congress to waive budget-neutrality requirements. Making a similar request Aug. 4 in a unified statement were the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA).

“Our organizations call on Congress and CMS to advance well-reasoned fee schedule payment policies and waive budget neutrality,” the groups said. “While APTA, AOTA, and ASHA do not oppose payment increases for primary care physicians, we believe these increases can be implemented without imposing payment reductions on other providers.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Trump administration is sticking with a plan to boost certain Medicare pay for many primary care and other specialties focused heavily on office visits while lowering that for other groups to balance these increased costs.

On Aug. 4, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services posted on the Federal Register draft versions of two of its major annual payment measures: the physician fee schedule and the payment rule for hospital outpatient services. On Aug. 3, the CMS informally posted a copy of the physician fee schedule on its own website, allowing medical groups to begin reading the more than 1,300-page rule.

Federal officials normally use annual Medicare payment rules to make many revisions to policies as well as adjust reimbursement.

The draft 2021 physician fee schedule, for example, calls for broadening the authority of clinicians other than physicians to authorize testing of people enrolled in Medicare.

The CMS intends to allow nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and certain other health care professionals to more widely supervise diagnostic psychological and neuropsychological tests, in keeping with applicable state laws.

The draft 2021 hospital outpatient rule proposes a gradual changeover to allow more procedures to be performed on an outpatient basis. This shift could save money for Medicare as well as for the people enrolled in the giant federal health program who need these services, the CMS explained.

Medicare would begin with a change in status for almost 300 musculoskeletal-related services, making them eligible for payment in the hospital outpatient setting when appropriate, CMS wrote in a fact sheet.

The initial reaction to Medicare’s proposed 2021 rules centered on its planned redistribution of funds among medical specialties. The CMS had outlined this plan last year. It is part of longstanding efforts to boost pay for primary care specialists and other physicians whose practice centers more around office visits than procedures.

There is broad support in health policy circles for raising pay for these specialties, but there also are strong objections to the cuts the CMS plans to offset the cost of rising pay for some fields.

Susan R. Bailey, MD, president of the American Medical Association, addressed both of these ideas in an AMA news release on the proposed 2021 physician fee schedule. The increase in pay for office visits, covered under evaluation and management services (E/M), stems from recommendations on resource costs from the AMA/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee, Dr. Bailey said.

“Unfortunately, these office visit payment increases, and a multitude of other new CMS proposed payment increases, are required by statute to be offset by payment reductions to other services, through an unsustainable reduction of nearly 11% to the Medicare conversion factor,” Dr. Bailey explained.

In the news release, Dr. Bailey asked Congress to waive Medicare’s budget-neutrality requirements to allow increases without the cuts.

“Physicians are already experiencing substantial economic hardships due to COVID-19, so these pay cuts could not come at a worse time,” she said.

Winners and losers

The CMS details the possible winners and losers in its payment reshuffle in Table 90 of the proposed 2021 physician fee schedule. In the proposed rule, CMS notes in the draft that these figures are based upon estimates of aggregate allowed charges across all services furnished by physicians and other clinicians.

“Therefore, they are averages, and may not necessarily be representative of what is happening to the particular services furnished by a single practitioner within any given specialty,” the CMS said.

Specialties in line for increases under the 2021 draft rule include allergy/immunology (9%), endocrinology (17%), family practice (13%), general practice (8%), geriatrics (4%), hematology/oncology (14%), internal medicine (4%), nephrology (6%), physician assistants (8%), psychiatry (8%), rheumatology (16%), and urology (8%).

In line for cuts would be anesthesiology (–8%), cardiac surgery (–9%), emergency medicine (–6%), general surgery (–7%), infectious disease (–4%), neurosurgery (–7%), physical/occupational therapy (–9%), plastic surgery (–7%), radiology (–11%), and thoracic surgery (–8%).

An umbrella group, the Surgical Care Coalition, on Aug. 3 had a quick statement ready about the CMS proposal. Writing on behalf of the group was David B. Hoyt, MD, executive director of the American College of Surgeons.

“Today’s proposed rule ignores both patients and the surgeons who care for them. The middle of a pandemic is no time for cuts to any form of health care, but today’s announcement moves ahead as if nothing has changed,” Hoyt said in the statement. “The Surgical Care Coalition believes no physician should see payment cuts that will reduce patients’ access to care.”

The Surgical Care Coalition already has been asking Congress to waive budget-neutrality requirements. Making a similar request Aug. 4 in a unified statement were the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA).

“Our organizations call on Congress and CMS to advance well-reasoned fee schedule payment policies and waive budget neutrality,” the groups said. “While APTA, AOTA, and ASHA do not oppose payment increases for primary care physicians, we believe these increases can be implemented without imposing payment reductions on other providers.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

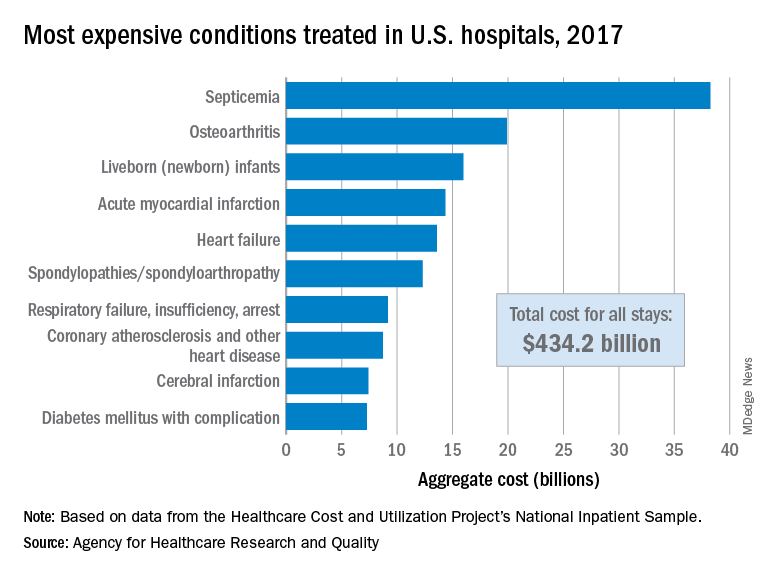

Septicemia first among hospital inpatient costs

according to a recent analysis from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The single most expensive inpatient condition that year, representing about 8.8% of all hospital costs, was septicemia at $38.2 billion, nearly double the $19.9 billion spent on the next most expensive condition, osteoarthritis, Lan Liang, PhD, of the AHRQ, and associates said in a statistical brief.

These figures “represent the hospital’s costs to produce the services – not the amount paid for services by payers – and they do not include separately billed physician fees associated with the hospitalization,” they noted.

Third in overall cost for 2017 but first in total number of stays were live-born infants, with 3.7 million admissions costing just under $16 billion. Hospital costs for acute myocardial infarction ($14.3 billion) made it the fourth most expensive condition, with heart failure fifth at $13.6 billion, based on data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample.

The 20 most expensive conditions, which also included coronary atherosclerosis, pneumonia, renal failure, and lower-limb fracture, accounted for close to 47% of all hospital costs and over 43% of all stays in 2017. The total amount spent by hospitals that year, $1.1 trillion, constituted nearly a third of all health care expenditures and was 4.7% higher than in 2016, Dr. Liang and associates reported.

“Although this growth represented deceleration, compared with the 5.8% increase between 2014 and 2015, the consistent year-to-year rise in hospital-related expenses remains a central concern among policymakers,” they wrote.

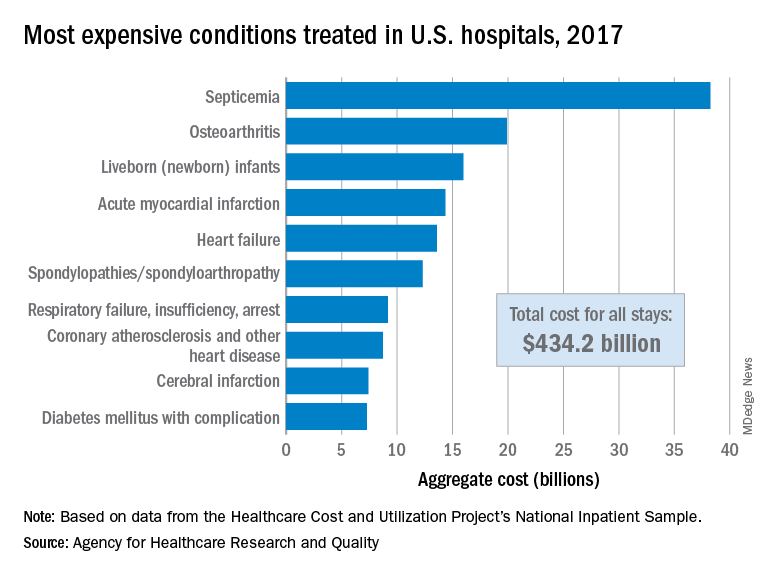

according to a recent analysis from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The single most expensive inpatient condition that year, representing about 8.8% of all hospital costs, was septicemia at $38.2 billion, nearly double the $19.9 billion spent on the next most expensive condition, osteoarthritis, Lan Liang, PhD, of the AHRQ, and associates said in a statistical brief.

These figures “represent the hospital’s costs to produce the services – not the amount paid for services by payers – and they do not include separately billed physician fees associated with the hospitalization,” they noted.

Third in overall cost for 2017 but first in total number of stays were live-born infants, with 3.7 million admissions costing just under $16 billion. Hospital costs for acute myocardial infarction ($14.3 billion) made it the fourth most expensive condition, with heart failure fifth at $13.6 billion, based on data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample.

The 20 most expensive conditions, which also included coronary atherosclerosis, pneumonia, renal failure, and lower-limb fracture, accounted for close to 47% of all hospital costs and over 43% of all stays in 2017. The total amount spent by hospitals that year, $1.1 trillion, constituted nearly a third of all health care expenditures and was 4.7% higher than in 2016, Dr. Liang and associates reported.

“Although this growth represented deceleration, compared with the 5.8% increase between 2014 and 2015, the consistent year-to-year rise in hospital-related expenses remains a central concern among policymakers,” they wrote.

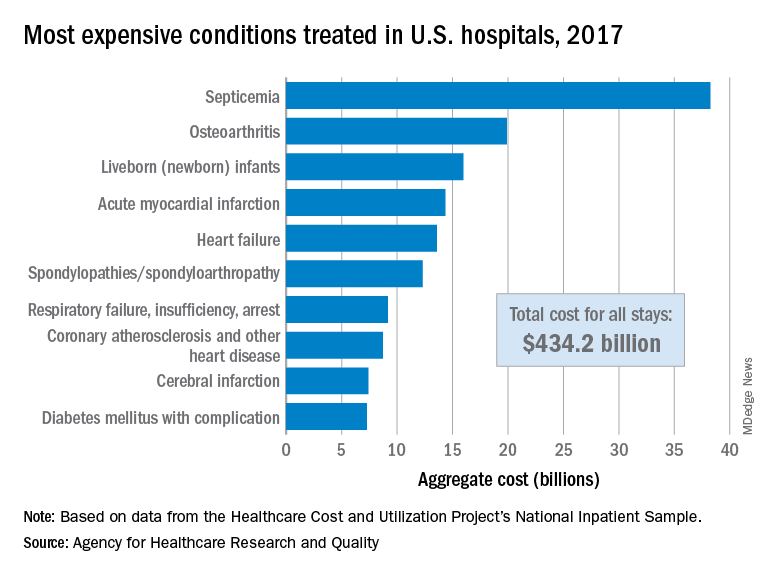

according to a recent analysis from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

The single most expensive inpatient condition that year, representing about 8.8% of all hospital costs, was septicemia at $38.2 billion, nearly double the $19.9 billion spent on the next most expensive condition, osteoarthritis, Lan Liang, PhD, of the AHRQ, and associates said in a statistical brief.

These figures “represent the hospital’s costs to produce the services – not the amount paid for services by payers – and they do not include separately billed physician fees associated with the hospitalization,” they noted.

Third in overall cost for 2017 but first in total number of stays were live-born infants, with 3.7 million admissions costing just under $16 billion. Hospital costs for acute myocardial infarction ($14.3 billion) made it the fourth most expensive condition, with heart failure fifth at $13.6 billion, based on data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project’s National Inpatient Sample.

The 20 most expensive conditions, which also included coronary atherosclerosis, pneumonia, renal failure, and lower-limb fracture, accounted for close to 47% of all hospital costs and over 43% of all stays in 2017. The total amount spent by hospitals that year, $1.1 trillion, constituted nearly a third of all health care expenditures and was 4.7% higher than in 2016, Dr. Liang and associates reported.

“Although this growth represented deceleration, compared with the 5.8% increase between 2014 and 2015, the consistent year-to-year rise in hospital-related expenses remains a central concern among policymakers,” they wrote.

Cardiorespiratory fitness may alter AFib ablation outcomes

Higher baseline cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) is associated with better outcomes after atrial fibrillation (AFib) ablation, according to new research.

In a single-center, retrospective cohort study, patients with the highest level of baseline CRF had significantly lower rates of arrhythmia recurrence and death than did patients with lower levels of CRF.

“It is stunning how just a simple measure, in this case walking on a treadmill, can predict whether atrial fibrillation ablation will be a successful endeavor or if it will fail,” senior author Wael A. Jaber, MD, professor of medicine, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“We found that ablation was not successful in most patients who had poor functional class and, conversely, that it was successful in most patients who were in tip-top shape when they walked on the treadmill. Our results can help clinicians inform patients about what they can expect after the procedure, depending on the baseline fitness level,” Dr. Jaber said.

The study was published online Aug. 2 in Heart Rhythm.

Several studies have shown a reduction in AFib incidence among individuals who report a physically active lifestyle, but the extent to which baseline CRF influences arrhythmia rates after AFib ablation is unknown, the authors note.

For the study, Dr. Jaber and colleagues analyzed results in 591 consecutive patients (mean age, 66.5 years; 75% male) with symptomatic paroxysmal or persistent AFib who underwent de novo AFib ablation at their institution. Only patients who had undergone an exercise stress test in the 12 months before AFib ablation (average, 4.5 months) were included.

Age- and sex-specific predicted metabolic equivalents (METs) were calculated using the St. James model for women and the Veterans Affairs referral model for men. The number of METs achieved was then divided by the predicted METs, and the patients were categorized into low (<85% predicted; n = 152), adequate (85%-100% predicted; n = 115), and high (>100% predicted; n = 324) CRF groups. Functional capacity was characterized as poor in 56 patients (9.5%), fair in 94 (16.0%), average in 225 (38.1%), good in 169 (28.6%), and high in 47 (8.0%).

During a mean follow-up of 32 months, arrhythmia recurrence was observed in 79% of patients in the low-CRF group, 54% of patients in the adequate-CRF group, and 27.5% of patients in the high-CRF group (P < .0001). Rates of repeat arrhythmia-related hospitalization, repeat rhythm-control procedures, and the need for ongoing antiarrhythmic therapy (ATT) were significantly lower in the high-CRF group. Specifically, ATT was stopped in 56% of patients in the high-CRF group, compared with 24% in the adequate-CRF group and 11% in the low-CRF group (P < .0001). Rehospitalization for arrhythmia was required in 18.5%, 38.0%, and 60.5% of cases, respectively, and repeat direct-current cardioversion or ablation was performed in 26.0%, 49.0%, and 65.0%, respectively (P < .0001 for both).

Death occurred in 11% of the low-CRF group, compared with 4% in the adequate-CRF group and 2.5% in the high-CRF group. Most (70%) of the deaths were caused by cardiovascular events, including heart failure, cardiac arrest, and coronary artery disease. The most common cause of noncardiac death was respiratory failure (13%), followed by sepsis (10%), malignancy (3%), and complications of Parkinson’s disease (3%).

“Although there was a statistically significant association between higher CRF and lower mortality in this cohort, the findings are to be viewed through the prism of a small sample size and relatively low death rate,” the authors wrote.

Don’t “overpromise” results

“The important message for clinicians is that when, you are discussing what to expect after atrial fibrillation ablation with your patients, do not overpromise the results. You can inform them that the success of the procedure depends more on how they perform on the baseline exercise test, and less on the ablation itself,” Dr. Jaber said.

Clinicians might want to consider advising their patients to become more active and increase their fitness level before undergoing the procedure, but whether doing so will improve outcomes is still unknown.

“This is what we don’t know. It makes sense. Hopefully, our results will encourage people to be more active before they arrive here for the procedure,” he said. “Our study is retrospective and is hypothesis generating, but we are planning a prospective study where patients will be referred to cardiac rehab prior to having ablation to try to improve their functional class to see if this will improve outcomes.”

Survival of the fittest

In an accompanying editorial commentary, Eric Black-Maier, MD, and Jonathan P. Piccini Sr, MD, from Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., wrote that the findings have “important implications for clinical practice and raise important additional questions.”

They note that catheter ablation as a first-line rhythm-control strategy, per current recommendations, “seems reasonable” in individuals with high baseline cardiorespiratory fitness, but that the benefit is less clear for patients with poor baseline CRF and uncontrolled risk factors.

“Significant limitations in functional status may be at least partially attributable to uncontrolled [AFib], and patients with limited exercise capacity may stand to gain most from successful catheter ablation,” the editorialists wrote.

“Furthermore, because shorter time from [AFib] diagnosis to catheter ablation has been associated with improved outcomes, the decision to postpone ablation in favor of lifestyle modification is not without potential adverse consequences,” they added.

Dr. Black-Maier and Dr. Piccini agree with the need for additional prospective randomized clinical trials to confirm that exercise training to improve cardiorespiratory fitness before AFib ablation is practical and effective for reducing arrhythmia recurrence.

“Over the past 50-plus years, our understanding of cardiorespiratory fitness, exercise capacity, and arrhythmia occurrence in patients with [AFib] continues to evolve,” the editorialists concluded. Data from the study “clearly demonstrate that arrhythmia-free survival is indeed survival of the fittest. Time will tell if exercise training and improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness can change outcomes after ablation.”

The study was sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Jaber and Dr. Black-Maier report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Piccini receives grants for clinical research from Abbott, the American Heart Association, the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, Bayer, Boston Scientific, and Philips and serves as a consultant to Abbott, Allergan, ARCA Biopharma, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, LivaNova, Medtronic, Milestone, MyoKardia, Sanofi, Philips, and UpToDate.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Higher baseline cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) is associated with better outcomes after atrial fibrillation (AFib) ablation, according to new research.

In a single-center, retrospective cohort study, patients with the highest level of baseline CRF had significantly lower rates of arrhythmia recurrence and death than did patients with lower levels of CRF.

“It is stunning how just a simple measure, in this case walking on a treadmill, can predict whether atrial fibrillation ablation will be a successful endeavor or if it will fail,” senior author Wael A. Jaber, MD, professor of medicine, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“We found that ablation was not successful in most patients who had poor functional class and, conversely, that it was successful in most patients who were in tip-top shape when they walked on the treadmill. Our results can help clinicians inform patients about what they can expect after the procedure, depending on the baseline fitness level,” Dr. Jaber said.

The study was published online Aug. 2 in Heart Rhythm.

Several studies have shown a reduction in AFib incidence among individuals who report a physically active lifestyle, but the extent to which baseline CRF influences arrhythmia rates after AFib ablation is unknown, the authors note.

For the study, Dr. Jaber and colleagues analyzed results in 591 consecutive patients (mean age, 66.5 years; 75% male) with symptomatic paroxysmal or persistent AFib who underwent de novo AFib ablation at their institution. Only patients who had undergone an exercise stress test in the 12 months before AFib ablation (average, 4.5 months) were included.

Age- and sex-specific predicted metabolic equivalents (METs) were calculated using the St. James model for women and the Veterans Affairs referral model for men. The number of METs achieved was then divided by the predicted METs, and the patients were categorized into low (<85% predicted; n = 152), adequate (85%-100% predicted; n = 115), and high (>100% predicted; n = 324) CRF groups. Functional capacity was characterized as poor in 56 patients (9.5%), fair in 94 (16.0%), average in 225 (38.1%), good in 169 (28.6%), and high in 47 (8.0%).

During a mean follow-up of 32 months, arrhythmia recurrence was observed in 79% of patients in the low-CRF group, 54% of patients in the adequate-CRF group, and 27.5% of patients in the high-CRF group (P < .0001). Rates of repeat arrhythmia-related hospitalization, repeat rhythm-control procedures, and the need for ongoing antiarrhythmic therapy (ATT) were significantly lower in the high-CRF group. Specifically, ATT was stopped in 56% of patients in the high-CRF group, compared with 24% in the adequate-CRF group and 11% in the low-CRF group (P < .0001). Rehospitalization for arrhythmia was required in 18.5%, 38.0%, and 60.5% of cases, respectively, and repeat direct-current cardioversion or ablation was performed in 26.0%, 49.0%, and 65.0%, respectively (P < .0001 for both).

Death occurred in 11% of the low-CRF group, compared with 4% in the adequate-CRF group and 2.5% in the high-CRF group. Most (70%) of the deaths were caused by cardiovascular events, including heart failure, cardiac arrest, and coronary artery disease. The most common cause of noncardiac death was respiratory failure (13%), followed by sepsis (10%), malignancy (3%), and complications of Parkinson’s disease (3%).

“Although there was a statistically significant association between higher CRF and lower mortality in this cohort, the findings are to be viewed through the prism of a small sample size and relatively low death rate,” the authors wrote.

Don’t “overpromise” results

“The important message for clinicians is that when, you are discussing what to expect after atrial fibrillation ablation with your patients, do not overpromise the results. You can inform them that the success of the procedure depends more on how they perform on the baseline exercise test, and less on the ablation itself,” Dr. Jaber said.

Clinicians might want to consider advising their patients to become more active and increase their fitness level before undergoing the procedure, but whether doing so will improve outcomes is still unknown.

“This is what we don’t know. It makes sense. Hopefully, our results will encourage people to be more active before they arrive here for the procedure,” he said. “Our study is retrospective and is hypothesis generating, but we are planning a prospective study where patients will be referred to cardiac rehab prior to having ablation to try to improve their functional class to see if this will improve outcomes.”

Survival of the fittest

In an accompanying editorial commentary, Eric Black-Maier, MD, and Jonathan P. Piccini Sr, MD, from Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., wrote that the findings have “important implications for clinical practice and raise important additional questions.”

They note that catheter ablation as a first-line rhythm-control strategy, per current recommendations, “seems reasonable” in individuals with high baseline cardiorespiratory fitness, but that the benefit is less clear for patients with poor baseline CRF and uncontrolled risk factors.

“Significant limitations in functional status may be at least partially attributable to uncontrolled [AFib], and patients with limited exercise capacity may stand to gain most from successful catheter ablation,” the editorialists wrote.

“Furthermore, because shorter time from [AFib] diagnosis to catheter ablation has been associated with improved outcomes, the decision to postpone ablation in favor of lifestyle modification is not without potential adverse consequences,” they added.

Dr. Black-Maier and Dr. Piccini agree with the need for additional prospective randomized clinical trials to confirm that exercise training to improve cardiorespiratory fitness before AFib ablation is practical and effective for reducing arrhythmia recurrence.

“Over the past 50-plus years, our understanding of cardiorespiratory fitness, exercise capacity, and arrhythmia occurrence in patients with [AFib] continues to evolve,” the editorialists concluded. Data from the study “clearly demonstrate that arrhythmia-free survival is indeed survival of the fittest. Time will tell if exercise training and improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness can change outcomes after ablation.”

The study was sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Jaber and Dr. Black-Maier report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Piccini receives grants for clinical research from Abbott, the American Heart Association, the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, Bayer, Boston Scientific, and Philips and serves as a consultant to Abbott, Allergan, ARCA Biopharma, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, LivaNova, Medtronic, Milestone, MyoKardia, Sanofi, Philips, and UpToDate.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Higher baseline cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) is associated with better outcomes after atrial fibrillation (AFib) ablation, according to new research.

In a single-center, retrospective cohort study, patients with the highest level of baseline CRF had significantly lower rates of arrhythmia recurrence and death than did patients with lower levels of CRF.

“It is stunning how just a simple measure, in this case walking on a treadmill, can predict whether atrial fibrillation ablation will be a successful endeavor or if it will fail,” senior author Wael A. Jaber, MD, professor of medicine, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“We found that ablation was not successful in most patients who had poor functional class and, conversely, that it was successful in most patients who were in tip-top shape when they walked on the treadmill. Our results can help clinicians inform patients about what they can expect after the procedure, depending on the baseline fitness level,” Dr. Jaber said.

The study was published online Aug. 2 in Heart Rhythm.

Several studies have shown a reduction in AFib incidence among individuals who report a physically active lifestyle, but the extent to which baseline CRF influences arrhythmia rates after AFib ablation is unknown, the authors note.

For the study, Dr. Jaber and colleagues analyzed results in 591 consecutive patients (mean age, 66.5 years; 75% male) with symptomatic paroxysmal or persistent AFib who underwent de novo AFib ablation at their institution. Only patients who had undergone an exercise stress test in the 12 months before AFib ablation (average, 4.5 months) were included.

Age- and sex-specific predicted metabolic equivalents (METs) were calculated using the St. James model for women and the Veterans Affairs referral model for men. The number of METs achieved was then divided by the predicted METs, and the patients were categorized into low (<85% predicted; n = 152), adequate (85%-100% predicted; n = 115), and high (>100% predicted; n = 324) CRF groups. Functional capacity was characterized as poor in 56 patients (9.5%), fair in 94 (16.0%), average in 225 (38.1%), good in 169 (28.6%), and high in 47 (8.0%).

During a mean follow-up of 32 months, arrhythmia recurrence was observed in 79% of patients in the low-CRF group, 54% of patients in the adequate-CRF group, and 27.5% of patients in the high-CRF group (P < .0001). Rates of repeat arrhythmia-related hospitalization, repeat rhythm-control procedures, and the need for ongoing antiarrhythmic therapy (ATT) were significantly lower in the high-CRF group. Specifically, ATT was stopped in 56% of patients in the high-CRF group, compared with 24% in the adequate-CRF group and 11% in the low-CRF group (P < .0001). Rehospitalization for arrhythmia was required in 18.5%, 38.0%, and 60.5% of cases, respectively, and repeat direct-current cardioversion or ablation was performed in 26.0%, 49.0%, and 65.0%, respectively (P < .0001 for both).

Death occurred in 11% of the low-CRF group, compared with 4% in the adequate-CRF group and 2.5% in the high-CRF group. Most (70%) of the deaths were caused by cardiovascular events, including heart failure, cardiac arrest, and coronary artery disease. The most common cause of noncardiac death was respiratory failure (13%), followed by sepsis (10%), malignancy (3%), and complications of Parkinson’s disease (3%).

“Although there was a statistically significant association between higher CRF and lower mortality in this cohort, the findings are to be viewed through the prism of a small sample size and relatively low death rate,” the authors wrote.

Don’t “overpromise” results

“The important message for clinicians is that when, you are discussing what to expect after atrial fibrillation ablation with your patients, do not overpromise the results. You can inform them that the success of the procedure depends more on how they perform on the baseline exercise test, and less on the ablation itself,” Dr. Jaber said.

Clinicians might want to consider advising their patients to become more active and increase their fitness level before undergoing the procedure, but whether doing so will improve outcomes is still unknown.

“This is what we don’t know. It makes sense. Hopefully, our results will encourage people to be more active before they arrive here for the procedure,” he said. “Our study is retrospective and is hypothesis generating, but we are planning a prospective study where patients will be referred to cardiac rehab prior to having ablation to try to improve their functional class to see if this will improve outcomes.”

Survival of the fittest

In an accompanying editorial commentary, Eric Black-Maier, MD, and Jonathan P. Piccini Sr, MD, from Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., wrote that the findings have “important implications for clinical practice and raise important additional questions.”

They note that catheter ablation as a first-line rhythm-control strategy, per current recommendations, “seems reasonable” in individuals with high baseline cardiorespiratory fitness, but that the benefit is less clear for patients with poor baseline CRF and uncontrolled risk factors.

“Significant limitations in functional status may be at least partially attributable to uncontrolled [AFib], and patients with limited exercise capacity may stand to gain most from successful catheter ablation,” the editorialists wrote.

“Furthermore, because shorter time from [AFib] diagnosis to catheter ablation has been associated with improved outcomes, the decision to postpone ablation in favor of lifestyle modification is not without potential adverse consequences,” they added.

Dr. Black-Maier and Dr. Piccini agree with the need for additional prospective randomized clinical trials to confirm that exercise training to improve cardiorespiratory fitness before AFib ablation is practical and effective for reducing arrhythmia recurrence.

“Over the past 50-plus years, our understanding of cardiorespiratory fitness, exercise capacity, and arrhythmia occurrence in patients with [AFib] continues to evolve,” the editorialists concluded. Data from the study “clearly demonstrate that arrhythmia-free survival is indeed survival of the fittest. Time will tell if exercise training and improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness can change outcomes after ablation.”

The study was sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Jaber and Dr. Black-Maier report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Piccini receives grants for clinical research from Abbott, the American Heart Association, the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, Bayer, Boston Scientific, and Philips and serves as a consultant to Abbott, Allergan, ARCA Biopharma, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, LivaNova, Medtronic, Milestone, MyoKardia, Sanofi, Philips, and UpToDate.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

SGLT2 inhibitors have a breakout year

The benefits from sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor drugs proven during the past year for cutting heart failure hospitalization rates substantially in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and slowing progression of chronic kidney disease, all regardless of diabetes status, have thrust this drug class into the top tier of agents for potentially treating millions of patients with cardiac or renal disease.

The sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, first licensed for U.S. marketing in 2013 purely for glycemic control, have, during the 5 years since the first cardiovascular outcome trial results for the class came out, shown benefits in a range of patients reminiscent of what’s been established for ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

The wide-reaching benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors have recently become even more relevant by showing clinically meaningful effects in patients without type 2 diabetes (T2D). And in an uncanny coincidence, the SGLT2 inhibitors appear to act in complementary harmony with the ACE inhibitors and ARBs for preserving heart and renal function. These properties have made the SGLT2 inhibitors especially attractive as a new weapon for controlling the ascendant disorder of cardiorenal syndrome.

“SGLT2 inhibitors have a relatively greater impact on cardiovascular outcomes, compared with ACE inhibitors and ARBs, but the effects [of the two classes] are synergistic and ideally patients receive both,” said Peter McCullough, MD, a specialist in treating cardiorenal syndrome and other cardiovascular and renal disorders at Baylor, Scott, and White Heart and Vascular Hospital in Dallas. The SGLT2 inhibitors are among the drugs best suited to both treating and preventing cardiorenal syndrome by targeting both ends of the disorder, said Dr. McCullough, who chaired an American Heart Association panel that last year issued a scientific statement on cardiorenal syndrome (Circulation. 2019 Apr 16;139[16]:e840-78).

Although data on the SGLT2 inhibitors “are evolving,” the drug class is “going in the direction” of being “reasonably compared” with the ACE inhibitors and ARBs, said Javed Butler, MD, professor and chair of medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson. “There are certainly complementary benefits that we see for both cardiovascular and renal outcomes.”

“We’ll think more and more about the SGLT2 inhibitors like renin-angiotensin system [RAS] inhibitors,” said David Z. Cherney, MD, referring to the drug class that includes ACE inhibitors and ARBs. “We should start to approach SGLT2 inhibitors like RAS inhibitors, with pleiotropic effects that go beyond glucose,” said Dr. Cherney, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, during the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association in June 2020.

Working together in the nephron

One of the clearest complementary interactions between the SGLT2 inhibitors and the RAS inhibitors is their ability to reduce intraglomerular pressure, a key mechanism that slows nephron loss and progression of chronic kidney disease. SGLT2 inhibitors reduce sodium absorption in the proximal tubule that causes, through tubuloglomerular feedback, afferent arteriole constriction that lowers intraglomerular pressure, while the RAS inhibitors inhibit efferent arteriole constriction mediated by angiotensin II, also cutting intraglomerular pressure. Together, “they almost work in tandem,” explained Janani Rangaswami, MD, a nephrologist at Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, vice chair of the Kidney Council of the AHA, and first author of the 2019 cardiorenal syndrome AHA statement.

“Many had worried that if we target both the afferent and efferent arterioles simultaneously, it might increase the risk for acute kidney injury. What has been reassuring in both the recent data from the DAPA-HF trial and in recent meta-analysis was no evidence of increased risk for acute kidney injury with use of the SGLT2 inhibitor,” Dr. Rangaswami said in an interview. For example, a recent report on more than 39,000 Canadian patients with T2D who were at least 66 years old and newly begun on either an SGLT2 inhibitor or a different oral diabetes drug (a dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitor), found a statistically significant 21% lower rate of acute kidney injury during the first 90 days on treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor in a propensity score–matched analysis (CMAJ. 2020 Apr 6;192: e351-60).

Much of the concern about possible acute kidney injury stemmed from a property that the SGLT2 inhibitors share with RAS inhibitors: They cause an initial, reversible decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), followed by longer-term nephron preservation, a pattern attributable to reduced intraglomerular pressure. The question early on was: “ ‘Does this harm the kidney?’ But what we’ve seen is that patients do better over time, even with this initial hit. Whenever you offload the glomerulus you cut barotrauma and protect renal function,” explained Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center.

Dr. Inzucchi cautioned, however, that a small number of patients starting treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor may have their GFR drop too sharply, especially if their GFR was low to start with. “You need to be careful, especially at the lower end of the GFR range. I recheck renal function after 1 month” after a patient starts an SGLT2. Patients whose level falls too low may need to discontinue. He added that it’s hard to set a uniform threshold for alarm, and instead assess patients on a case-by-case basis, but “you need some threshold in mind, where you will stop” treatment.

A smarter diuretic

One of the most intriguing renal effects of SGLT2 inhibitors is their diuretic action. During a talk at the virtual ADA scientific sessions, cardiologist Jeffrey Testani, MD, called them “smart” diuretics, because their effect on diuresis is relatively modest but comes without the neurohormonal price paid when patients take conventional loop diuretics.

”Loop diuretics are particularly bad,” causing neurohormonal activation that includes norepinephrine, renin, and vasopressin, said Dr. Testani, director of heart failure research at Yale. They also fail to produce a meaningful drop in blood volume despite causing substantial natriuresis.

In contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors cause “moderate” natriuresis while producing a significant cut in blood volume. “The body seems content with this lower plasma volume without activating catecholamines or renin, and that’s how the SGLT2 inhibitors differ from other diuretics,” said Dr. Inzucchi.

The class also maintains serum levels of potassium and magnesium, produces significant improvements in serum uric acid levels, and avoids the electrolyte abnormalities, volume depletion, and acute kidney injury that can occur with conventional distal diuretics, Dr. Testani said.

In short, the SGLT2 inhibitors “are safe and easy-to-use diuretics,” which allows them to fill a “huge unmet need for patients with heart failure.” As evidence accumulates for the benefits of the drug class in patients with heart failure and renal disease, “uptake will be extensive,” Dr. Testani predicted, driven in part by how easy it is to add the class to existing cardiorenal drug regimens.

Other standard therapies for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) risk electrolyte abnormalities, renal dysfunction, significantly lower blood pressure, often make patients feel worse, and involve a slow and laborious titration process, Dr. Testani noted. The SGLT2 inhibitor agents avoid these issues, a property that has played out in quality of life assessments of patients with HFrEF who received a drug from this class.

Outcomes met in trial after trial

In the DAPA-HF trial, with 4,443 patients with HFrEF and divided roughly equally between those with or without T2D, treatment with dapagliflozin (Farxiga) linked with significant improvements in health status and quality of life measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (Circulation. 2020 Jan 14;141[2]:90-9). “Not all treatments for HFrEF improve symptoms,” but in this study the SGTL2 inhibitor dapagliflozin did, boosting the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire score by about the same magnitude as treatment with a cardiac resynchronization device in patients with HFrEF, said Mikhail N. Kosiborod, MD, director of Cardiometabolic Research at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City, Mo., speaking at the virtual ADA scientific sessions.

Two more recent renal observations have further solidified the growing role of these drugs for kidney protection. Results from the CREDENCE trial that looked at canagliflozin (Invokana) treatment in 4,401 patients with T2D and albuminuria and chronic kidney disease showed canagliflozin treatment cut the primary, composite renal endpoint by a statistically significant 30%, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380[24]:2295-306). The study stopped earlier than planned because of how effective canagliflozin appeared.

“Never before has a renal protection clinical trial stopped for overwhelming efficacy,” noted nephrologist Katherine R. Tuttle, MD, executive director for research at Providence Health Care in Spokane, Wash. “It’s very exciting to have a treatment that works on both the heart and kidney, given their interrelationship,” she said during the ADA sessions. Dr. Tuttle called the cardiorenal effects from the SGLT2 inhibitors “amazing.”

Just as the DAPA-HF trial’s primary outcome showed the ability of at least one drug from the class, dapagliflozin, to improve outcomes in HFrEF patients without T2D, topline results recently reported from the DAPA-CDK trial showed for the first time renal protection by an SGLT2 inhibitor in patients with chronic kidney disease but no T2D, in a study with about 4,300 patients.

Although detailed results from DAPA-CKD are not yet available, so far the outcomes seem consistent with the CREDENCE findings, and the cumulative renal findings for the class show the SGLT2 inhibitors have “potential for a profound impact on the patients we see in every nephrology clinic, and with dual cardiorenal disease,” said Dr. Rangaswami. The class is now established as “standard of care for patients with chronic kidney disease. The CREDENCE results made that clear.”

The DAPA-CKD findings in patients with chronic kidney disease regardless of their diabetes status “are very important. We really have not had any advances in this space for some time, and chronic kidney disease patients have very poor outcomes, both cardiovascular and renal,” commented Dr. Butler. The advantage from using this drug class in these patients “is huge.”

The DAPA-CKD findings are a “major advance,” agreed Dr. McCullough.

SGLT2 inhibitor use needs to grow

Experts lament that although the evidence favoring the class has been very bullish, prescribing uptake has been slow, perhaps partly explained by the retail U.S. cost for most of these agents, generally about $17/day.

Cost is, unfortunately, an issue right now for these drugs, said Dr. Butler. Generic formulations are imminent, “but we cannot accept waiting. Providing this therapy when insurance coverage is available,” is essential.

The FDA has already granted tentative approval to some generic formulations, although resolution of patent issues can delay generics actually reaching the market. “Generic dapagliflozin will have a major impact; the marketplace for these drugs will shift very quickly,” predicted Dr. McCullough.

But price may not be the sole barrier, cautioned Dr. Rangaswami. “I don’t think it’s just a cost issue. Several factors explain the slow uptake,” of the SGLT2 inhibitors. “The biggest barrier is that this is a new drug class, and understanding how to use the class is not yet where it needs to be in the physician community.” One of the biggest problems is that the SGLT2 inhibitors are still primarily regarded as drugs to treat hyperglycemia.

Physicians who treat patients with heart or renal disease “need to wrap their head around the idea that a drug with antihyperglycemic effects is now in their practice territory, and something they need to prescribe,” she noted. Currently “there is a reluctance to prescribe these drugs given the perception that they are antihyperglycemic agents, and usually get deferred to primary care physicians or endocrinologists. This results in huge missed opportunities by cardiologists and nephrologists in initiating these agents that have major cardiorenal risk reduction effects.”

The key role that cardiologists need to play in prescribing the SGLT2 inhibitors was brought home in a recent study of two representative U.S. health systems that showed patients with T2D were far more likely to see a cardiologist than an endocrinologist (Cardiovasc Endocrinol Metab. 2020 Jun;9[2]:56-9).

“The SGLT2 inhibitors are definitely a game-changing drug class,” summed up Dr. Rangaswami. “We’re going to see a lot of use in patients with heart and kidney disease.”

Dr. Cherney has been a consultant to or has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, and Sanofi. Dr. Butler has had financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies. Dr. McCullough and Dr. Rangaswami had no disclosures. Dr. Inzucchi has been a consultant to or helped run trials for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi/Lexicon, and vTv Therapeutics. Dr. Testani has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, cardionomic, FIRE1 Magenta Med, Novartis, Reprieve, Sanofi, and W.L. Gore. Dr. Kosiborod has been a consultant to or led trials for Amarin, Amgen, Applied Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Glytec, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Vifor. Dr. Tuttle has been a consultant to AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, Goldfinch Bio, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk.

The benefits from sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor drugs proven during the past year for cutting heart failure hospitalization rates substantially in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and slowing progression of chronic kidney disease, all regardless of diabetes status, have thrust this drug class into the top tier of agents for potentially treating millions of patients with cardiac or renal disease.

The sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, first licensed for U.S. marketing in 2013 purely for glycemic control, have, during the 5 years since the first cardiovascular outcome trial results for the class came out, shown benefits in a range of patients reminiscent of what’s been established for ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

The wide-reaching benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors have recently become even more relevant by showing clinically meaningful effects in patients without type 2 diabetes (T2D). And in an uncanny coincidence, the SGLT2 inhibitors appear to act in complementary harmony with the ACE inhibitors and ARBs for preserving heart and renal function. These properties have made the SGLT2 inhibitors especially attractive as a new weapon for controlling the ascendant disorder of cardiorenal syndrome.

“SGLT2 inhibitors have a relatively greater impact on cardiovascular outcomes, compared with ACE inhibitors and ARBs, but the effects [of the two classes] are synergistic and ideally patients receive both,” said Peter McCullough, MD, a specialist in treating cardiorenal syndrome and other cardiovascular and renal disorders at Baylor, Scott, and White Heart and Vascular Hospital in Dallas. The SGLT2 inhibitors are among the drugs best suited to both treating and preventing cardiorenal syndrome by targeting both ends of the disorder, said Dr. McCullough, who chaired an American Heart Association panel that last year issued a scientific statement on cardiorenal syndrome (Circulation. 2019 Apr 16;139[16]:e840-78).

Although data on the SGLT2 inhibitors “are evolving,” the drug class is “going in the direction” of being “reasonably compared” with the ACE inhibitors and ARBs, said Javed Butler, MD, professor and chair of medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson. “There are certainly complementary benefits that we see for both cardiovascular and renal outcomes.”

“We’ll think more and more about the SGLT2 inhibitors like renin-angiotensin system [RAS] inhibitors,” said David Z. Cherney, MD, referring to the drug class that includes ACE inhibitors and ARBs. “We should start to approach SGLT2 inhibitors like RAS inhibitors, with pleiotropic effects that go beyond glucose,” said Dr. Cherney, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, during the virtual annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association in June 2020.

Working together in the nephron

One of the clearest complementary interactions between the SGLT2 inhibitors and the RAS inhibitors is their ability to reduce intraglomerular pressure, a key mechanism that slows nephron loss and progression of chronic kidney disease. SGLT2 inhibitors reduce sodium absorption in the proximal tubule that causes, through tubuloglomerular feedback, afferent arteriole constriction that lowers intraglomerular pressure, while the RAS inhibitors inhibit efferent arteriole constriction mediated by angiotensin II, also cutting intraglomerular pressure. Together, “they almost work in tandem,” explained Janani Rangaswami, MD, a nephrologist at Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, vice chair of the Kidney Council of the AHA, and first author of the 2019 cardiorenal syndrome AHA statement.

“Many had worried that if we target both the afferent and efferent arterioles simultaneously, it might increase the risk for acute kidney injury. What has been reassuring in both the recent data from the DAPA-HF trial and in recent meta-analysis was no evidence of increased risk for acute kidney injury with use of the SGLT2 inhibitor,” Dr. Rangaswami said in an interview. For example, a recent report on more than 39,000 Canadian patients with T2D who were at least 66 years old and newly begun on either an SGLT2 inhibitor or a different oral diabetes drug (a dipeptidyl peptidase–4 inhibitor), found a statistically significant 21% lower rate of acute kidney injury during the first 90 days on treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor in a propensity score–matched analysis (CMAJ. 2020 Apr 6;192: e351-60).

Much of the concern about possible acute kidney injury stemmed from a property that the SGLT2 inhibitors share with RAS inhibitors: They cause an initial, reversible decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR), followed by longer-term nephron preservation, a pattern attributable to reduced intraglomerular pressure. The question early on was: “ ‘Does this harm the kidney?’ But what we’ve seen is that patients do better over time, even with this initial hit. Whenever you offload the glomerulus you cut barotrauma and protect renal function,” explained Silvio E. Inzucchi, MD, professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and director of the Yale Medicine Diabetes Center.

Dr. Inzucchi cautioned, however, that a small number of patients starting treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor may have their GFR drop too sharply, especially if their GFR was low to start with. “You need to be careful, especially at the lower end of the GFR range. I recheck renal function after 1 month” after a patient starts an SGLT2. Patients whose level falls too low may need to discontinue. He added that it’s hard to set a uniform threshold for alarm, and instead assess patients on a case-by-case basis, but “you need some threshold in mind, where you will stop” treatment.

A smarter diuretic

One of the most intriguing renal effects of SGLT2 inhibitors is their diuretic action. During a talk at the virtual ADA scientific sessions, cardiologist Jeffrey Testani, MD, called them “smart” diuretics, because their effect on diuresis is relatively modest but comes without the neurohormonal price paid when patients take conventional loop diuretics.

”Loop diuretics are particularly bad,” causing neurohormonal activation that includes norepinephrine, renin, and vasopressin, said Dr. Testani, director of heart failure research at Yale. They also fail to produce a meaningful drop in blood volume despite causing substantial natriuresis.

In contrast, SGLT2 inhibitors cause “moderate” natriuresis while producing a significant cut in blood volume. “The body seems content with this lower plasma volume without activating catecholamines or renin, and that’s how the SGLT2 inhibitors differ from other diuretics,” said Dr. Inzucchi.

The class also maintains serum levels of potassium and magnesium, produces significant improvements in serum uric acid levels, and avoids the electrolyte abnormalities, volume depletion, and acute kidney injury that can occur with conventional distal diuretics, Dr. Testani said.

In short, the SGLT2 inhibitors “are safe and easy-to-use diuretics,” which allows them to fill a “huge unmet need for patients with heart failure.” As evidence accumulates for the benefits of the drug class in patients with heart failure and renal disease, “uptake will be extensive,” Dr. Testani predicted, driven in part by how easy it is to add the class to existing cardiorenal drug regimens.

Other standard therapies for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) risk electrolyte abnormalities, renal dysfunction, significantly lower blood pressure, often make patients feel worse, and involve a slow and laborious titration process, Dr. Testani noted. The SGLT2 inhibitor agents avoid these issues, a property that has played out in quality of life assessments of patients with HFrEF who received a drug from this class.

Outcomes met in trial after trial

In the DAPA-HF trial, with 4,443 patients with HFrEF and divided roughly equally between those with or without T2D, treatment with dapagliflozin (Farxiga) linked with significant improvements in health status and quality of life measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (Circulation. 2020 Jan 14;141[2]:90-9). “Not all treatments for HFrEF improve symptoms,” but in this study the SGTL2 inhibitor dapagliflozin did, boosting the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire score by about the same magnitude as treatment with a cardiac resynchronization device in patients with HFrEF, said Mikhail N. Kosiborod, MD, director of Cardiometabolic Research at Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City, Mo., speaking at the virtual ADA scientific sessions.

Two more recent renal observations have further solidified the growing role of these drugs for kidney protection. Results from the CREDENCE trial that looked at canagliflozin (Invokana) treatment in 4,401 patients with T2D and albuminuria and chronic kidney disease showed canagliflozin treatment cut the primary, composite renal endpoint by a statistically significant 30%, compared with placebo (N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380[24]:2295-306). The study stopped earlier than planned because of how effective canagliflozin appeared.

“Never before has a renal protection clinical trial stopped for overwhelming efficacy,” noted nephrologist Katherine R. Tuttle, MD, executive director for research at Providence Health Care in Spokane, Wash. “It’s very exciting to have a treatment that works on both the heart and kidney, given their interrelationship,” she said during the ADA sessions. Dr. Tuttle called the cardiorenal effects from the SGLT2 inhibitors “amazing.”