User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Tinted Sunscreens: Consumer Preferences Based on Light, Medium, and Dark Skin Tones

Sunscreen formulations typically protect from UV radiation (290–400 nm), as this is a well-established cause of photodamage, photoaging, and skin cancer.1 However, sunlight also consists of visible (400–700 nm) and infrared (>700 nm) radiation.2 In fact, UV radiation only comprises 5% to 7% of the solar radiation that reaches the surface of the earth, while visible and infrared lights comprise 44% and 53%, respectively.3 Visible light (VL) is the only portion of the solar spectrum visible to the human eye; it penetrates the skin to a depth range of 90 to 750 µm compared to 1.5 to 90 µm for UV radiation.4 Visible light also may come from artificial sources such as light bulbs and digital screens. The rapidly increasing use of smartphones, tablets, laptops, and other digital screens that emit high levels of short-wavelength VL has increased concerns about the safety of these devices. Although blue light exposure from screens is small compared with the amount of exposure from the sun, there is concern about the long-term effects of excessive screen time. Recent studies have demonstrated that exposure to light emitted from electronic devices, even for as little as 1 hour, may cause reactive oxygen species generation, apoptosis, collagen degradation, and necrosis of skin cells.5 Visible light increases tyrosinase activity and induces immediate erythema in light-skinned individuals and long-lasting pigmentation in dark-skinned individuals.4,6

Sunscreens consist of chemical and mineral active ingredients that contain UV filters designed to absorb, scatter, and reflect UV photons with wavelengths up to 380 nm. Historically, traditional options do not protect against the effects induced by VL, as these sunscreens use nanosized particles that help to reduce the white appearance and result in transparency of the product.7 To block VL, the topical agent must be visible. Tinted sunscreens (TSs) are products that combine UV and VL filters. They give a colored base coverage that is achieved by incorporating a blend of black, red, and yellow iron oxides (IOs) and/or pigmentary titanium dioxide (PTD)(ie, titanium dioxide [TD] that is not nanosized). Because TSs offer an instant glow and protect the skin from both sun and artificial light, they have become increasingly popular and have been incorporated into makeup and skin care products to facilitate daily convenient use.

The purpose of this analysis was to study current available options and product factors that may influence consumer preference when choosing a TS based on the reviewer characteristics.

Methods

The keyword sunscreen was searched in the broader category of skin care products on an online supplier of sunscreens (www.sephora.com). This supplier was chosen because, unlike other sources, specific reviewer characteristics regarding underlying skin tone also were available. The search produced 161 results. For the purpose of this analysis, only facial TSs containing IO and/or PTD were included. Each sunscreen was checked by the authors, and 58 sunscreens that met the inclusion criteria were identified and further reviewed. Descriptive data, including formulation, sun protection factor (SPF), ingredient type (chemical or physical), pigments used, shades available, additional benefits, price range, rating, and user reviews, were gathered. The authors extracted these data from the product information on the website, manufacturer claims, ratings, and reviewer comments on each of the listed sunscreens.

For each product, the content of the top 10 most helpful positive and negative reviews as voted by consumers (1160 total reviews, consisting of 1 or more comments) was analyzed. Two authors (H.D.L.G. and P.V.) coded consumer-reported comments for positive and negative descriptors into the categories of cosmetic elegance, performance, skin compatibility and tolerance, tone compatibility, and affordability. Cosmetic elegance was defined as any feature associated with skin sensation (eg, greasy), color (eg, white cast), scent, ability to blend, and overall appearance of the product on the skin. Product performance included SPF, effectiveness in preventing sunburn, coverage, and finish claims (ie, matte, glow, invisible). Skin compatibility and tolerance were represented in the reviewers’ comments and reflected how the product performed in association with underlying dermatologic conditions, skin type, and if there were any side effects such as irritation or allergic reactions. Tone compatibility referred to TS color similarity with users’ skin and shades available for individual products. Affordability reflected consumers’ perceptions of the product price. Comments may be included in multiple categories (eg, a product was noted to blend well on the skin but did not provide enough coverage). Of entries, 10% (116/1160 reviews) were coded by first author (H.D.L.G.) to ensure internal validity. Reviewer characteristics were consistently available and were used to determine the top 5 recommended products for light-, medium-, and dark-skinned individuals based on the number of 5-star ratings in each group. Porcelain, fair, and light were considered light skin tones. Medium, tan, and olive were considered medium skin tones. Deep, dark, and ebony were considered dark skin tones.

Results

Sunscreen Characteristics—Among the 161 screened products, 58 met the inclusion criteria. Four types of formulations were included: lotion, cream, liquid, and powder. Twenty-nine (50%) were creams, followed by lotions (19%), liquids (28%), and powders (3%). More than 79% (46/58) of products had a reported SPF of 30 or higher. Sunscreens with an active physical ingredient—the minerals TD and/or zinc oxide (ZO)—were most common (33/58 [57%]), followed by the chemical sunscreens avobenzone, octinoxate, oxybenzone, homosalate, octisalate, and/or octocrylene active ingredients (14/58 [24%]), and a combination of chemical and physical sunscreens (11/58 [19%]). Nearly all products (55/58 [95%]) contained pigmentary IO (red, CI 77491; yellow, CI 77492; black, CI 77499). Notably, only 38% (22/58) of products had more than 1 shade. All products had additional claims associated with being hydrating, having antiaging effects, smoothing texture, minimizing the appearance of pores, softening lines, and/or promoting even skin tone. Traditional physical sunscreens (those containing TD and/or ZO) were more expensive than chemical sunscreens, with a median price of $30. The median review rating was 4.5 of 5 stars, with a median of 2300 customer reviews per product. Findings are summarized in Table 1.

Positive Features of Sunscreens—Based on an analysis of total reviews (N=1160), cosmetic elegance was the most cited positive feature associated with TS products (31%), followed by product performance (10%). Skin compatibility and tolerance (7%), tone compatibility (7%), and affordability (7%) were cited less commonly as positive features. When negative features were cited, consumers mostly noted tone incompatibility (16%) and cosmetic elegance concerns (14%). Product performance (13%) was comparatively cited as a negative feature (Table 1). Exemplary positive comments categorized in cosmetic elegance included the subthemes of rubs in well and natural glow. Exemplary negative comments in cosmetic elegance and tone compatibility categories included the subthemes patchy/dry finish and color mismatch. Table 1 illustrates these findings.

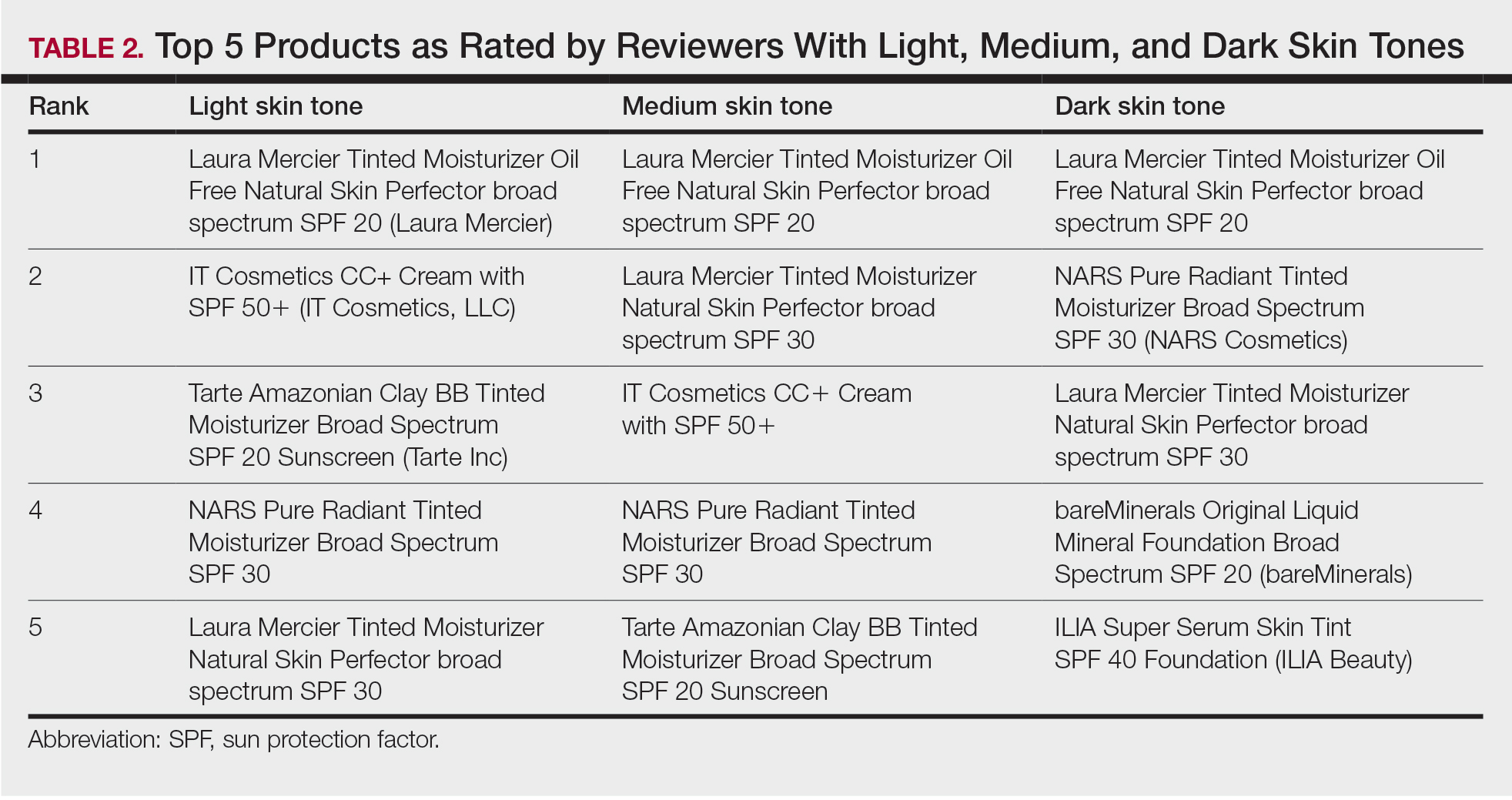

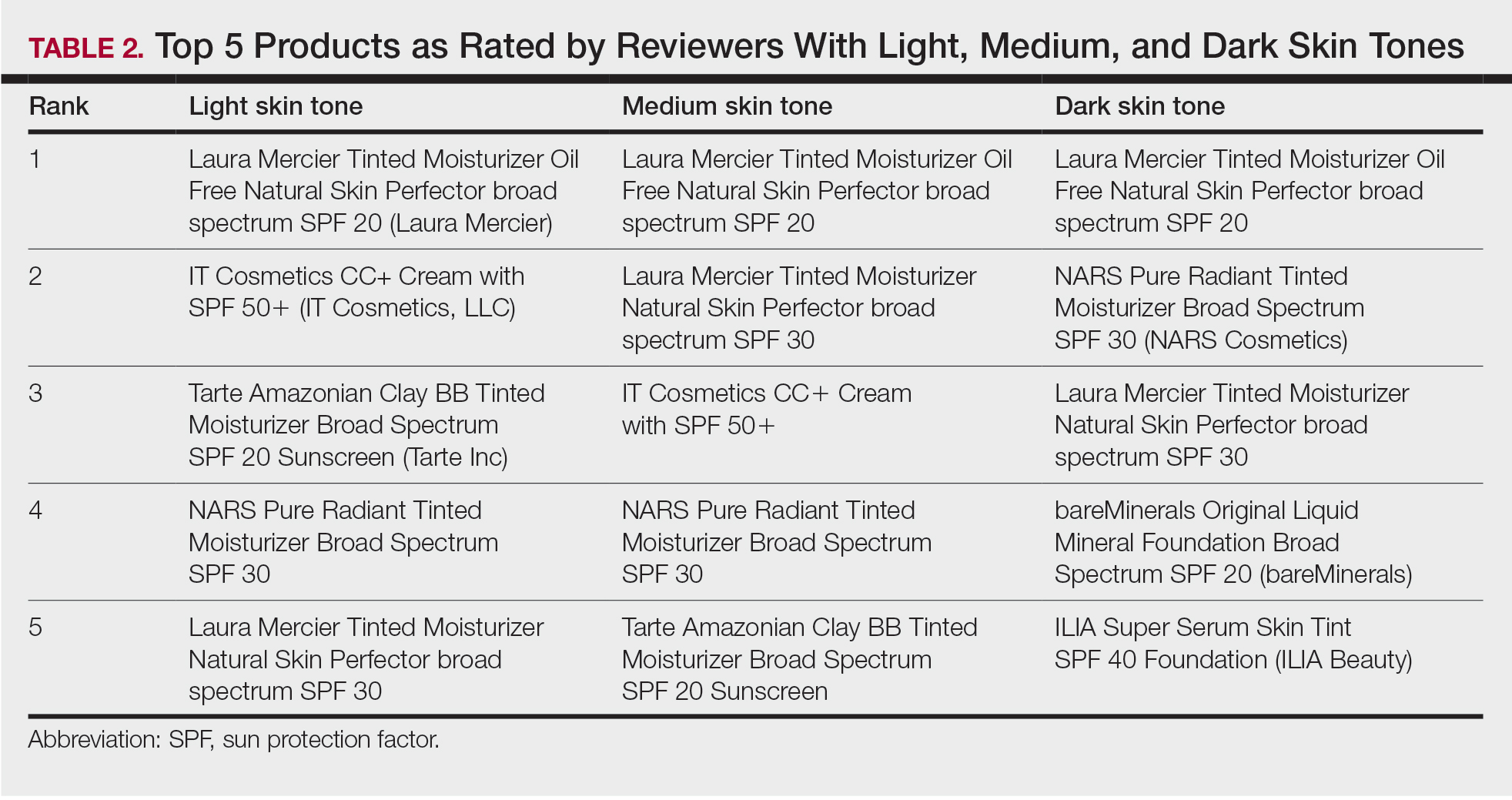

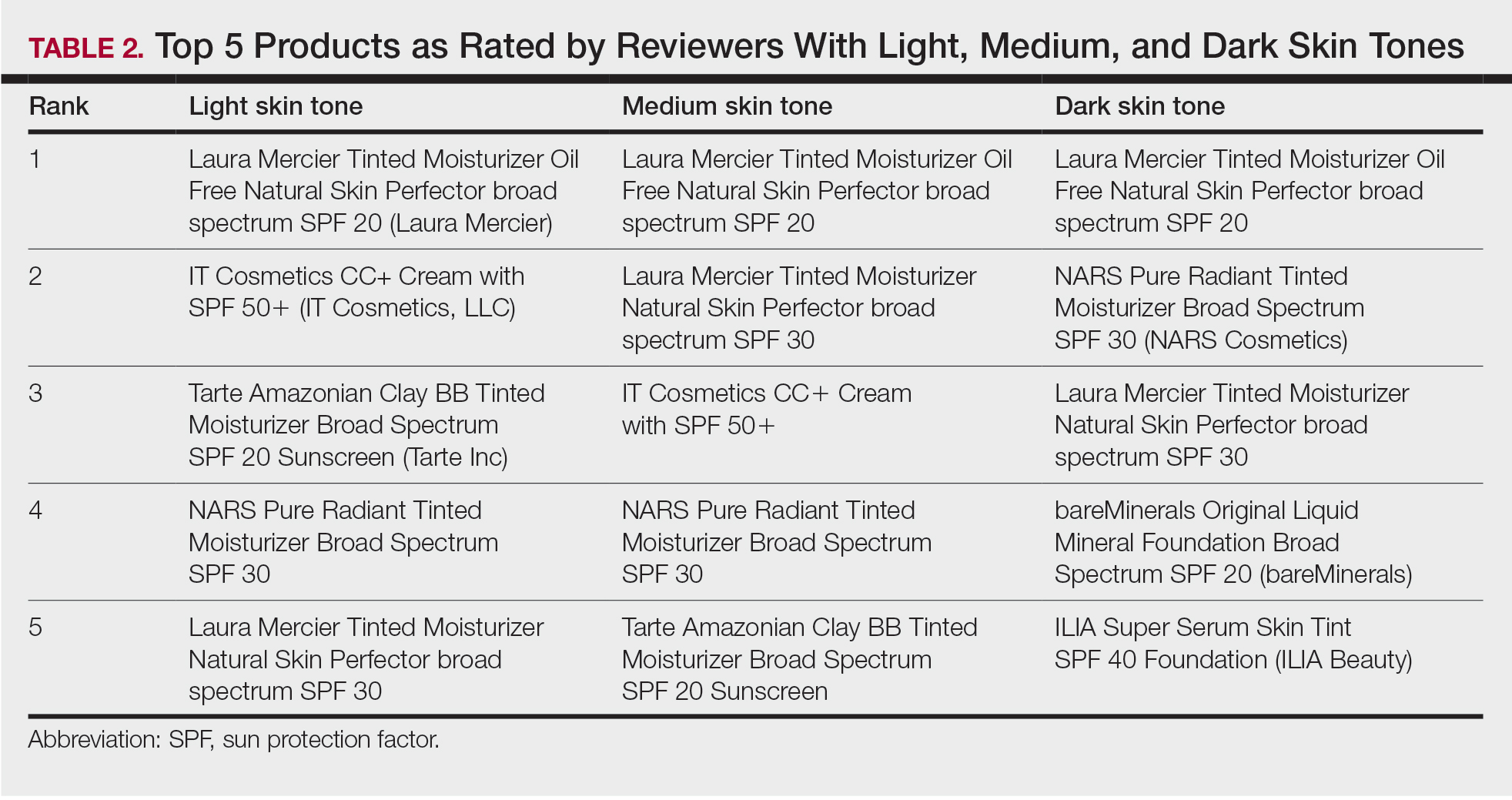

Product Recommendations—The top 5 recommendations of the best TS for each skin tone are listed in Table 2. The mean price of the recommended products was $42 for 1 to 1.9 oz. Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20 (Laura Mercier) was the top product for all 3 groups. Similarly, of 58 products available, the same 5 products—Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20, IT Cosmetics CC+ Cream with SPF 50 (IT Cosmetics, LLC), Tarte Amazonian Clay BB Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 20 (Tarte Cosmetics), NARS Pure Radiant Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 30 (NARS Cosmetics), and Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 30—were considered the best among consumers of all skin tones, with the addition of 2 different products (bareMinerals Original Liquid Mineral Foundation Broad Spectrum SPF 20 [bareMinerals] and ILIA Super Serum Skin Tint SPF 40 Foundation [ILIA Beauty]) in the dark skin group. Notably, these products were the only ones on Sephora’s website that offered up to 30 (22 on average) different shades.

Comment

Tone Compatibility—Tinted sunscreens were created to extend the range of photoprotection into the VL spectrum. The goal of TSs is to incorporate pigments that blend in with the natural skin tone, produce a glow, and have an aesthetically pleasing appearance. To accommodate a variety of skin colors, different shades can be obtained by mixing different amounts of yellow, red, and black IO with or without PTD. The pigments and reflective compounds provide color, opacity, and a natural coverage. Our qualitative analysis provides information on the lack of diversity among shades available for TS, especially for darker skin tones. Of the 58 products evaluated, 62% (32/58) only had 1 shade. In our cohort, tone compatibility was the most commonly cited negative feature. Of note, 89% of these comments were from consumers with dark skin tones, and there was a disproportional number of reviews by darker-skinned individuals compared to users with light and medium skin tones. This is of particular importance, as TSs have been shown to protect against dermatoses that disproportionally affect individuals with skin of color. When comparing sunscreen formulations containing IO with regular mineral sunscreens, Dumbuya et al3 found that IO-containing formulations significantly protected against VL-induced pigmentation compared with untreated skin or mineral sunscreen with SPF 50 or higher in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin type IV (P<.001). Similarly, Bernstein et al8 found that exposing patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV to blue-violet light resulted in marked hyperpigmentation that lasted up to 3 months. Visible light elicits immediate and persistent pigment darkening in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin phototype III and above via the photo-oxidation of pre-existing melanin and de novo melanogenesis.9 Tinted sunscreens formulated with IO have been shown to aid in the treatment of melasma and prevent hyperpigmentation in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.10 Patients with darker skin tones with dermatoses aggravated or induced by VL, such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, may seek photoprotection provided by TS but find the lack of matching shades unappealing. The dearth of shade diversity that matches all skin tones can lead to inequities and disproportionally affect those with darker skin.

Performance—Tinted sunscreen formulations containing IO have been proven effective in protecting against high-energy VL, especially when combined synergistically with ZO.11 Kaye et al12 found that TSs containing IO and the inorganic filters TD or ZO reduced transmittance of VL more effectively than nontinted sunscreens containing TD or ZO alone or products containing organic filters. The decreased VL transmittance in the former is due to synergistic effects of the VL-scattering properties of the TD and the VL absorption properties of the IO. Similarly, Sayre et al13 demonstrated that IO was superior to TD and ZO in attenuating the transmission of VL. Bernstein et al14 found that darker shades containing higher percentages of IO increased the attenuation of VL to 98% compared with lighter shades attenuating 93%. This correlates with the results of prior studies highlighting the potential of TSs in protecting individuals with skin of color.3 In our cohort, comments regarding product performance and protection were mostly positive, claiming that consistent use reduced hyperpigmentation on the skin surface, giving the appearance of a more even skin tone.

Tolerability—Iron oxides are minerals known to be safe, gentle, and nontoxic on the surface of the skin.15 Two case reports of contact dermatitis due to IO have been reported.16,17 Within our cohort, only a few of the comments (6%) described negative product tolerance or compatibility with their skin type. However, it is more likely that these incompatibilities were due to other ingredients in the product or the individuals’ underlying dermatologic conditions.

Cosmetic Elegance—Most of the sunscreens available on the market today contain micronized forms of TD and ZO particles because they have better cosmetic acceptability.18 However, their reduced size compromises the protection provided against VL whereby the addition of IO is of vital importance. According to the RealSelf Sun Safety Report, only 11% of Americans wear sunscreen daily, and 46% never wear sunscreen.19 The most common reasons consumers reported for not wearing sunscreen included not liking how it looks on the skin, forgetting to apply it, and/or believing that application is inconvenient and time-consuming. Currently, TSs have been incorporated into daily-life products such as makeup, moisturizers, and serums, making application for users easy and convenient, decreasing the necessity of using multiple products, and offering the opportunity to choose from different presentations to make decisions for convenience and/or diverse occasions. Products containing IO blend in with the natural skin tone and have an aesthetically pleasing cosmetic appearance. In our cohort, comments regarding cosmetic elegance were highly valued and were present in multiple reviews (45%), with 69% being positive.

Affordability—In our cohort, product price was not predominantly mentioned in consumers’ reviews. However, negative comments regarding affordability were slightly higher than the positive (56% vs 44%). Notably, the mean price of our top recommendations was $42. Higher price was associated with products with a wider range of shades available. Prior studies have found similar results demonstrating that websites with recommendations on sunscreens for patients with skin of color compared with sunscreens for white or fair skin were more likely to recommend more expensive products (median, $14/oz vs $11.3/oz) despite the lower SPF level.20 According to Schneider,21 daily use of the cheapest sunscreen on the head/neck region recommended for white/pale skin ($2/oz) would lead to an annual cost of $61 compared to $182 for darker skin ($6/oz). This showcases the considerable variation in sunscreen prices for both populations that could potentiate disparities and vulnerability in the latter group.

Conclusion

Tinted sunscreens provide both functional and cosmetic benefits and are a safe, effective, and convenient way to protect against high-energy VL. This study suggests that patients with skin of color encounter difficulties in finding matching shades in TS products. These difficulties may stem from the lack of knowledge regarding dark complexions and undertones and the lack of representation of black and brown skin that has persisted in dermatology research journals and textbooks for decades.22 Our study provides important insights to help dermatologists improve their familiarity with the brands and characteristics of TSs geared to patients with all skin tones, including skin of color. Limitations include single-retailer information and inclusion of both highly and poorly rated comments with subjective data, limiting generalizability. The limited selection of shades for darker skin poses a roadblock to proper treatment and prevention. These data represent an area for improvement within the beauty industry and the dermatologic field to deliver culturally sensitive care by being knowledgeable about darker skin tones and TS formulations tailored to people with skin of color.

- McDaniel D, Farris P, Valacchi G. Atmospheric skin aging-contributors and inhibitors. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:124-137.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Dumbuya H, Grimes PE, Lynch S, et al. Impact of iron-oxide containing formulations against visible light-induced skin pigmentation in skin of color individuals. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:712-717.

- Lyons AB, Trullas C, Kohli I, et al. Photoprotection beyond ultraviolet radiation: a review of tinted sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1393-1397.

- Austin E, Huang A, Adar T, et al. Electronic device generated light increases reactive oxygen species in human fibroblasts [published online February 5, 2018]. Lasers Surg Med. doi:10.1002/lsm.22794

- Randhawa M, Seo I, Liebel F, et al. Visible light induces melanogenesis in human skin through a photoadaptive response. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130949.

- Yeager DG, Lim HW. What’s new in photoprotection: a review of new concepts and controversies. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:149-157.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P. Iron oxides in novel skin care formulations attenuate blue light for enhanced protection against skin damage. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:532-537.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Ruvolo E, Fair M, Hutson A, et al. Photoprotection against visible light-induced pigmentation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:589-595.

- Cohen L, Brodsky MA, Zubair R, et al. Cutaneous interaction with visible light: what do we know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;S0190-9622(20)30551-X.

- Kaye ET, Levin JA, Blank IH, et al. Efficiency of opaque photoprotective agents in the visible light range. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:351-355.

- Sayre RM, Kollias N, Roberts RL, et al. Physical sunscreens. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1990;41:103-109.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P, et al. Beyond sun protection factor: an approach to environmental protection with novel mineral coatings in a vehicle containing a blend of skincare ingredients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:407-415.

- MacLeman E. Why are iron oxides used? Deep Science website. February 10, 2022. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://thedermreview.com/iron-oxides-ci-77491-ci-77492-ci-77499/

- Zugerman C. Contact dermatitis to yellow iron oxide. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:107-109.

- Saxena M, Warshaw E, Ahmed DD. Eyelid allergic contact dermatitis to black iron oxide. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:38-39.

- Smijs TG, Pavel S. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: focus on their safety and effectiveness. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2011;4:95-112.

- 2020 RealSelf Sun Safety Report: majority of Americans don’t use sunscreen daily. Practical Dermatology. May 6, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://practicaldermatology.com/news/realself-sun-safety-report-majority-of-americans-dont-use-sunscreen-daily

- Song H, Beckles A, Salian P, et al. Sunscreen recommendations for patients with skin of color in the popular press and in the dermatology clinic. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:165-170.

- Schneider J. The teaspoon rule of applying sunscreen. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:838-839.

- Nelson B. How dermatology is failing melanoma patients with skin of color: unanswered questions on risk and eye-opening disparities in outcomes are weighing heavily on melanoma patients with darker skin. in this article, part 1 of a 2-part series, we explore the deadly consequences of racism and inequality in cancer care. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;128:7-8.

Sunscreen formulations typically protect from UV radiation (290–400 nm), as this is a well-established cause of photodamage, photoaging, and skin cancer.1 However, sunlight also consists of visible (400–700 nm) and infrared (>700 nm) radiation.2 In fact, UV radiation only comprises 5% to 7% of the solar radiation that reaches the surface of the earth, while visible and infrared lights comprise 44% and 53%, respectively.3 Visible light (VL) is the only portion of the solar spectrum visible to the human eye; it penetrates the skin to a depth range of 90 to 750 µm compared to 1.5 to 90 µm for UV radiation.4 Visible light also may come from artificial sources such as light bulbs and digital screens. The rapidly increasing use of smartphones, tablets, laptops, and other digital screens that emit high levels of short-wavelength VL has increased concerns about the safety of these devices. Although blue light exposure from screens is small compared with the amount of exposure from the sun, there is concern about the long-term effects of excessive screen time. Recent studies have demonstrated that exposure to light emitted from electronic devices, even for as little as 1 hour, may cause reactive oxygen species generation, apoptosis, collagen degradation, and necrosis of skin cells.5 Visible light increases tyrosinase activity and induces immediate erythema in light-skinned individuals and long-lasting pigmentation in dark-skinned individuals.4,6

Sunscreens consist of chemical and mineral active ingredients that contain UV filters designed to absorb, scatter, and reflect UV photons with wavelengths up to 380 nm. Historically, traditional options do not protect against the effects induced by VL, as these sunscreens use nanosized particles that help to reduce the white appearance and result in transparency of the product.7 To block VL, the topical agent must be visible. Tinted sunscreens (TSs) are products that combine UV and VL filters. They give a colored base coverage that is achieved by incorporating a blend of black, red, and yellow iron oxides (IOs) and/or pigmentary titanium dioxide (PTD)(ie, titanium dioxide [TD] that is not nanosized). Because TSs offer an instant glow and protect the skin from both sun and artificial light, they have become increasingly popular and have been incorporated into makeup and skin care products to facilitate daily convenient use.

The purpose of this analysis was to study current available options and product factors that may influence consumer preference when choosing a TS based on the reviewer characteristics.

Methods

The keyword sunscreen was searched in the broader category of skin care products on an online supplier of sunscreens (www.sephora.com). This supplier was chosen because, unlike other sources, specific reviewer characteristics regarding underlying skin tone also were available. The search produced 161 results. For the purpose of this analysis, only facial TSs containing IO and/or PTD were included. Each sunscreen was checked by the authors, and 58 sunscreens that met the inclusion criteria were identified and further reviewed. Descriptive data, including formulation, sun protection factor (SPF), ingredient type (chemical or physical), pigments used, shades available, additional benefits, price range, rating, and user reviews, were gathered. The authors extracted these data from the product information on the website, manufacturer claims, ratings, and reviewer comments on each of the listed sunscreens.

For each product, the content of the top 10 most helpful positive and negative reviews as voted by consumers (1160 total reviews, consisting of 1 or more comments) was analyzed. Two authors (H.D.L.G. and P.V.) coded consumer-reported comments for positive and negative descriptors into the categories of cosmetic elegance, performance, skin compatibility and tolerance, tone compatibility, and affordability. Cosmetic elegance was defined as any feature associated with skin sensation (eg, greasy), color (eg, white cast), scent, ability to blend, and overall appearance of the product on the skin. Product performance included SPF, effectiveness in preventing sunburn, coverage, and finish claims (ie, matte, glow, invisible). Skin compatibility and tolerance were represented in the reviewers’ comments and reflected how the product performed in association with underlying dermatologic conditions, skin type, and if there were any side effects such as irritation or allergic reactions. Tone compatibility referred to TS color similarity with users’ skin and shades available for individual products. Affordability reflected consumers’ perceptions of the product price. Comments may be included in multiple categories (eg, a product was noted to blend well on the skin but did not provide enough coverage). Of entries, 10% (116/1160 reviews) were coded by first author (H.D.L.G.) to ensure internal validity. Reviewer characteristics were consistently available and were used to determine the top 5 recommended products for light-, medium-, and dark-skinned individuals based on the number of 5-star ratings in each group. Porcelain, fair, and light were considered light skin tones. Medium, tan, and olive were considered medium skin tones. Deep, dark, and ebony were considered dark skin tones.

Results

Sunscreen Characteristics—Among the 161 screened products, 58 met the inclusion criteria. Four types of formulations were included: lotion, cream, liquid, and powder. Twenty-nine (50%) were creams, followed by lotions (19%), liquids (28%), and powders (3%). More than 79% (46/58) of products had a reported SPF of 30 or higher. Sunscreens with an active physical ingredient—the minerals TD and/or zinc oxide (ZO)—were most common (33/58 [57%]), followed by the chemical sunscreens avobenzone, octinoxate, oxybenzone, homosalate, octisalate, and/or octocrylene active ingredients (14/58 [24%]), and a combination of chemical and physical sunscreens (11/58 [19%]). Nearly all products (55/58 [95%]) contained pigmentary IO (red, CI 77491; yellow, CI 77492; black, CI 77499). Notably, only 38% (22/58) of products had more than 1 shade. All products had additional claims associated with being hydrating, having antiaging effects, smoothing texture, minimizing the appearance of pores, softening lines, and/or promoting even skin tone. Traditional physical sunscreens (those containing TD and/or ZO) were more expensive than chemical sunscreens, with a median price of $30. The median review rating was 4.5 of 5 stars, with a median of 2300 customer reviews per product. Findings are summarized in Table 1.

Positive Features of Sunscreens—Based on an analysis of total reviews (N=1160), cosmetic elegance was the most cited positive feature associated with TS products (31%), followed by product performance (10%). Skin compatibility and tolerance (7%), tone compatibility (7%), and affordability (7%) were cited less commonly as positive features. When negative features were cited, consumers mostly noted tone incompatibility (16%) and cosmetic elegance concerns (14%). Product performance (13%) was comparatively cited as a negative feature (Table 1). Exemplary positive comments categorized in cosmetic elegance included the subthemes of rubs in well and natural glow. Exemplary negative comments in cosmetic elegance and tone compatibility categories included the subthemes patchy/dry finish and color mismatch. Table 1 illustrates these findings.

Product Recommendations—The top 5 recommendations of the best TS for each skin tone are listed in Table 2. The mean price of the recommended products was $42 for 1 to 1.9 oz. Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20 (Laura Mercier) was the top product for all 3 groups. Similarly, of 58 products available, the same 5 products—Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20, IT Cosmetics CC+ Cream with SPF 50 (IT Cosmetics, LLC), Tarte Amazonian Clay BB Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 20 (Tarte Cosmetics), NARS Pure Radiant Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 30 (NARS Cosmetics), and Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 30—were considered the best among consumers of all skin tones, with the addition of 2 different products (bareMinerals Original Liquid Mineral Foundation Broad Spectrum SPF 20 [bareMinerals] and ILIA Super Serum Skin Tint SPF 40 Foundation [ILIA Beauty]) in the dark skin group. Notably, these products were the only ones on Sephora’s website that offered up to 30 (22 on average) different shades.

Comment

Tone Compatibility—Tinted sunscreens were created to extend the range of photoprotection into the VL spectrum. The goal of TSs is to incorporate pigments that blend in with the natural skin tone, produce a glow, and have an aesthetically pleasing appearance. To accommodate a variety of skin colors, different shades can be obtained by mixing different amounts of yellow, red, and black IO with or without PTD. The pigments and reflective compounds provide color, opacity, and a natural coverage. Our qualitative analysis provides information on the lack of diversity among shades available for TS, especially for darker skin tones. Of the 58 products evaluated, 62% (32/58) only had 1 shade. In our cohort, tone compatibility was the most commonly cited negative feature. Of note, 89% of these comments were from consumers with dark skin tones, and there was a disproportional number of reviews by darker-skinned individuals compared to users with light and medium skin tones. This is of particular importance, as TSs have been shown to protect against dermatoses that disproportionally affect individuals with skin of color. When comparing sunscreen formulations containing IO with regular mineral sunscreens, Dumbuya et al3 found that IO-containing formulations significantly protected against VL-induced pigmentation compared with untreated skin or mineral sunscreen with SPF 50 or higher in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin type IV (P<.001). Similarly, Bernstein et al8 found that exposing patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV to blue-violet light resulted in marked hyperpigmentation that lasted up to 3 months. Visible light elicits immediate and persistent pigment darkening in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin phototype III and above via the photo-oxidation of pre-existing melanin and de novo melanogenesis.9 Tinted sunscreens formulated with IO have been shown to aid in the treatment of melasma and prevent hyperpigmentation in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.10 Patients with darker skin tones with dermatoses aggravated or induced by VL, such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, may seek photoprotection provided by TS but find the lack of matching shades unappealing. The dearth of shade diversity that matches all skin tones can lead to inequities and disproportionally affect those with darker skin.

Performance—Tinted sunscreen formulations containing IO have been proven effective in protecting against high-energy VL, especially when combined synergistically with ZO.11 Kaye et al12 found that TSs containing IO and the inorganic filters TD or ZO reduced transmittance of VL more effectively than nontinted sunscreens containing TD or ZO alone or products containing organic filters. The decreased VL transmittance in the former is due to synergistic effects of the VL-scattering properties of the TD and the VL absorption properties of the IO. Similarly, Sayre et al13 demonstrated that IO was superior to TD and ZO in attenuating the transmission of VL. Bernstein et al14 found that darker shades containing higher percentages of IO increased the attenuation of VL to 98% compared with lighter shades attenuating 93%. This correlates with the results of prior studies highlighting the potential of TSs in protecting individuals with skin of color.3 In our cohort, comments regarding product performance and protection were mostly positive, claiming that consistent use reduced hyperpigmentation on the skin surface, giving the appearance of a more even skin tone.

Tolerability—Iron oxides are minerals known to be safe, gentle, and nontoxic on the surface of the skin.15 Two case reports of contact dermatitis due to IO have been reported.16,17 Within our cohort, only a few of the comments (6%) described negative product tolerance or compatibility with their skin type. However, it is more likely that these incompatibilities were due to other ingredients in the product or the individuals’ underlying dermatologic conditions.

Cosmetic Elegance—Most of the sunscreens available on the market today contain micronized forms of TD and ZO particles because they have better cosmetic acceptability.18 However, their reduced size compromises the protection provided against VL whereby the addition of IO is of vital importance. According to the RealSelf Sun Safety Report, only 11% of Americans wear sunscreen daily, and 46% never wear sunscreen.19 The most common reasons consumers reported for not wearing sunscreen included not liking how it looks on the skin, forgetting to apply it, and/or believing that application is inconvenient and time-consuming. Currently, TSs have been incorporated into daily-life products such as makeup, moisturizers, and serums, making application for users easy and convenient, decreasing the necessity of using multiple products, and offering the opportunity to choose from different presentations to make decisions for convenience and/or diverse occasions. Products containing IO blend in with the natural skin tone and have an aesthetically pleasing cosmetic appearance. In our cohort, comments regarding cosmetic elegance were highly valued and were present in multiple reviews (45%), with 69% being positive.

Affordability—In our cohort, product price was not predominantly mentioned in consumers’ reviews. However, negative comments regarding affordability were slightly higher than the positive (56% vs 44%). Notably, the mean price of our top recommendations was $42. Higher price was associated with products with a wider range of shades available. Prior studies have found similar results demonstrating that websites with recommendations on sunscreens for patients with skin of color compared with sunscreens for white or fair skin were more likely to recommend more expensive products (median, $14/oz vs $11.3/oz) despite the lower SPF level.20 According to Schneider,21 daily use of the cheapest sunscreen on the head/neck region recommended for white/pale skin ($2/oz) would lead to an annual cost of $61 compared to $182 for darker skin ($6/oz). This showcases the considerable variation in sunscreen prices for both populations that could potentiate disparities and vulnerability in the latter group.

Conclusion

Tinted sunscreens provide both functional and cosmetic benefits and are a safe, effective, and convenient way to protect against high-energy VL. This study suggests that patients with skin of color encounter difficulties in finding matching shades in TS products. These difficulties may stem from the lack of knowledge regarding dark complexions and undertones and the lack of representation of black and brown skin that has persisted in dermatology research journals and textbooks for decades.22 Our study provides important insights to help dermatologists improve their familiarity with the brands and characteristics of TSs geared to patients with all skin tones, including skin of color. Limitations include single-retailer information and inclusion of both highly and poorly rated comments with subjective data, limiting generalizability. The limited selection of shades for darker skin poses a roadblock to proper treatment and prevention. These data represent an area for improvement within the beauty industry and the dermatologic field to deliver culturally sensitive care by being knowledgeable about darker skin tones and TS formulations tailored to people with skin of color.

Sunscreen formulations typically protect from UV radiation (290–400 nm), as this is a well-established cause of photodamage, photoaging, and skin cancer.1 However, sunlight also consists of visible (400–700 nm) and infrared (>700 nm) radiation.2 In fact, UV radiation only comprises 5% to 7% of the solar radiation that reaches the surface of the earth, while visible and infrared lights comprise 44% and 53%, respectively.3 Visible light (VL) is the only portion of the solar spectrum visible to the human eye; it penetrates the skin to a depth range of 90 to 750 µm compared to 1.5 to 90 µm for UV radiation.4 Visible light also may come from artificial sources such as light bulbs and digital screens. The rapidly increasing use of smartphones, tablets, laptops, and other digital screens that emit high levels of short-wavelength VL has increased concerns about the safety of these devices. Although blue light exposure from screens is small compared with the amount of exposure from the sun, there is concern about the long-term effects of excessive screen time. Recent studies have demonstrated that exposure to light emitted from electronic devices, even for as little as 1 hour, may cause reactive oxygen species generation, apoptosis, collagen degradation, and necrosis of skin cells.5 Visible light increases tyrosinase activity and induces immediate erythema in light-skinned individuals and long-lasting pigmentation in dark-skinned individuals.4,6

Sunscreens consist of chemical and mineral active ingredients that contain UV filters designed to absorb, scatter, and reflect UV photons with wavelengths up to 380 nm. Historically, traditional options do not protect against the effects induced by VL, as these sunscreens use nanosized particles that help to reduce the white appearance and result in transparency of the product.7 To block VL, the topical agent must be visible. Tinted sunscreens (TSs) are products that combine UV and VL filters. They give a colored base coverage that is achieved by incorporating a blend of black, red, and yellow iron oxides (IOs) and/or pigmentary titanium dioxide (PTD)(ie, titanium dioxide [TD] that is not nanosized). Because TSs offer an instant glow and protect the skin from both sun and artificial light, they have become increasingly popular and have been incorporated into makeup and skin care products to facilitate daily convenient use.

The purpose of this analysis was to study current available options and product factors that may influence consumer preference when choosing a TS based on the reviewer characteristics.

Methods

The keyword sunscreen was searched in the broader category of skin care products on an online supplier of sunscreens (www.sephora.com). This supplier was chosen because, unlike other sources, specific reviewer characteristics regarding underlying skin tone also were available. The search produced 161 results. For the purpose of this analysis, only facial TSs containing IO and/or PTD were included. Each sunscreen was checked by the authors, and 58 sunscreens that met the inclusion criteria were identified and further reviewed. Descriptive data, including formulation, sun protection factor (SPF), ingredient type (chemical or physical), pigments used, shades available, additional benefits, price range, rating, and user reviews, were gathered. The authors extracted these data from the product information on the website, manufacturer claims, ratings, and reviewer comments on each of the listed sunscreens.

For each product, the content of the top 10 most helpful positive and negative reviews as voted by consumers (1160 total reviews, consisting of 1 or more comments) was analyzed. Two authors (H.D.L.G. and P.V.) coded consumer-reported comments for positive and negative descriptors into the categories of cosmetic elegance, performance, skin compatibility and tolerance, tone compatibility, and affordability. Cosmetic elegance was defined as any feature associated with skin sensation (eg, greasy), color (eg, white cast), scent, ability to blend, and overall appearance of the product on the skin. Product performance included SPF, effectiveness in preventing sunburn, coverage, and finish claims (ie, matte, glow, invisible). Skin compatibility and tolerance were represented in the reviewers’ comments and reflected how the product performed in association with underlying dermatologic conditions, skin type, and if there were any side effects such as irritation or allergic reactions. Tone compatibility referred to TS color similarity with users’ skin and shades available for individual products. Affordability reflected consumers’ perceptions of the product price. Comments may be included in multiple categories (eg, a product was noted to blend well on the skin but did not provide enough coverage). Of entries, 10% (116/1160 reviews) were coded by first author (H.D.L.G.) to ensure internal validity. Reviewer characteristics were consistently available and were used to determine the top 5 recommended products for light-, medium-, and dark-skinned individuals based on the number of 5-star ratings in each group. Porcelain, fair, and light were considered light skin tones. Medium, tan, and olive were considered medium skin tones. Deep, dark, and ebony were considered dark skin tones.

Results

Sunscreen Characteristics—Among the 161 screened products, 58 met the inclusion criteria. Four types of formulations were included: lotion, cream, liquid, and powder. Twenty-nine (50%) were creams, followed by lotions (19%), liquids (28%), and powders (3%). More than 79% (46/58) of products had a reported SPF of 30 or higher. Sunscreens with an active physical ingredient—the minerals TD and/or zinc oxide (ZO)—were most common (33/58 [57%]), followed by the chemical sunscreens avobenzone, octinoxate, oxybenzone, homosalate, octisalate, and/or octocrylene active ingredients (14/58 [24%]), and a combination of chemical and physical sunscreens (11/58 [19%]). Nearly all products (55/58 [95%]) contained pigmentary IO (red, CI 77491; yellow, CI 77492; black, CI 77499). Notably, only 38% (22/58) of products had more than 1 shade. All products had additional claims associated with being hydrating, having antiaging effects, smoothing texture, minimizing the appearance of pores, softening lines, and/or promoting even skin tone. Traditional physical sunscreens (those containing TD and/or ZO) were more expensive than chemical sunscreens, with a median price of $30. The median review rating was 4.5 of 5 stars, with a median of 2300 customer reviews per product. Findings are summarized in Table 1.

Positive Features of Sunscreens—Based on an analysis of total reviews (N=1160), cosmetic elegance was the most cited positive feature associated with TS products (31%), followed by product performance (10%). Skin compatibility and tolerance (7%), tone compatibility (7%), and affordability (7%) were cited less commonly as positive features. When negative features were cited, consumers mostly noted tone incompatibility (16%) and cosmetic elegance concerns (14%). Product performance (13%) was comparatively cited as a negative feature (Table 1). Exemplary positive comments categorized in cosmetic elegance included the subthemes of rubs in well and natural glow. Exemplary negative comments in cosmetic elegance and tone compatibility categories included the subthemes patchy/dry finish and color mismatch. Table 1 illustrates these findings.

Product Recommendations—The top 5 recommendations of the best TS for each skin tone are listed in Table 2. The mean price of the recommended products was $42 for 1 to 1.9 oz. Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20 (Laura Mercier) was the top product for all 3 groups. Similarly, of 58 products available, the same 5 products—Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20, IT Cosmetics CC+ Cream with SPF 50 (IT Cosmetics, LLC), Tarte Amazonian Clay BB Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 20 (Tarte Cosmetics), NARS Pure Radiant Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 30 (NARS Cosmetics), and Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 30—were considered the best among consumers of all skin tones, with the addition of 2 different products (bareMinerals Original Liquid Mineral Foundation Broad Spectrum SPF 20 [bareMinerals] and ILIA Super Serum Skin Tint SPF 40 Foundation [ILIA Beauty]) in the dark skin group. Notably, these products were the only ones on Sephora’s website that offered up to 30 (22 on average) different shades.

Comment

Tone Compatibility—Tinted sunscreens were created to extend the range of photoprotection into the VL spectrum. The goal of TSs is to incorporate pigments that blend in with the natural skin tone, produce a glow, and have an aesthetically pleasing appearance. To accommodate a variety of skin colors, different shades can be obtained by mixing different amounts of yellow, red, and black IO with or without PTD. The pigments and reflective compounds provide color, opacity, and a natural coverage. Our qualitative analysis provides information on the lack of diversity among shades available for TS, especially for darker skin tones. Of the 58 products evaluated, 62% (32/58) only had 1 shade. In our cohort, tone compatibility was the most commonly cited negative feature. Of note, 89% of these comments were from consumers with dark skin tones, and there was a disproportional number of reviews by darker-skinned individuals compared to users with light and medium skin tones. This is of particular importance, as TSs have been shown to protect against dermatoses that disproportionally affect individuals with skin of color. When comparing sunscreen formulations containing IO with regular mineral sunscreens, Dumbuya et al3 found that IO-containing formulations significantly protected against VL-induced pigmentation compared with untreated skin or mineral sunscreen with SPF 50 or higher in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin type IV (P<.001). Similarly, Bernstein et al8 found that exposing patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV to blue-violet light resulted in marked hyperpigmentation that lasted up to 3 months. Visible light elicits immediate and persistent pigment darkening in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin phototype III and above via the photo-oxidation of pre-existing melanin and de novo melanogenesis.9 Tinted sunscreens formulated with IO have been shown to aid in the treatment of melasma and prevent hyperpigmentation in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.10 Patients with darker skin tones with dermatoses aggravated or induced by VL, such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, may seek photoprotection provided by TS but find the lack of matching shades unappealing. The dearth of shade diversity that matches all skin tones can lead to inequities and disproportionally affect those with darker skin.

Performance—Tinted sunscreen formulations containing IO have been proven effective in protecting against high-energy VL, especially when combined synergistically with ZO.11 Kaye et al12 found that TSs containing IO and the inorganic filters TD or ZO reduced transmittance of VL more effectively than nontinted sunscreens containing TD or ZO alone or products containing organic filters. The decreased VL transmittance in the former is due to synergistic effects of the VL-scattering properties of the TD and the VL absorption properties of the IO. Similarly, Sayre et al13 demonstrated that IO was superior to TD and ZO in attenuating the transmission of VL. Bernstein et al14 found that darker shades containing higher percentages of IO increased the attenuation of VL to 98% compared with lighter shades attenuating 93%. This correlates with the results of prior studies highlighting the potential of TSs in protecting individuals with skin of color.3 In our cohort, comments regarding product performance and protection were mostly positive, claiming that consistent use reduced hyperpigmentation on the skin surface, giving the appearance of a more even skin tone.

Tolerability—Iron oxides are minerals known to be safe, gentle, and nontoxic on the surface of the skin.15 Two case reports of contact dermatitis due to IO have been reported.16,17 Within our cohort, only a few of the comments (6%) described negative product tolerance or compatibility with their skin type. However, it is more likely that these incompatibilities were due to other ingredients in the product or the individuals’ underlying dermatologic conditions.

Cosmetic Elegance—Most of the sunscreens available on the market today contain micronized forms of TD and ZO particles because they have better cosmetic acceptability.18 However, their reduced size compromises the protection provided against VL whereby the addition of IO is of vital importance. According to the RealSelf Sun Safety Report, only 11% of Americans wear sunscreen daily, and 46% never wear sunscreen.19 The most common reasons consumers reported for not wearing sunscreen included not liking how it looks on the skin, forgetting to apply it, and/or believing that application is inconvenient and time-consuming. Currently, TSs have been incorporated into daily-life products such as makeup, moisturizers, and serums, making application for users easy and convenient, decreasing the necessity of using multiple products, and offering the opportunity to choose from different presentations to make decisions for convenience and/or diverse occasions. Products containing IO blend in with the natural skin tone and have an aesthetically pleasing cosmetic appearance. In our cohort, comments regarding cosmetic elegance were highly valued and were present in multiple reviews (45%), with 69% being positive.

Affordability—In our cohort, product price was not predominantly mentioned in consumers’ reviews. However, negative comments regarding affordability were slightly higher than the positive (56% vs 44%). Notably, the mean price of our top recommendations was $42. Higher price was associated with products with a wider range of shades available. Prior studies have found similar results demonstrating that websites with recommendations on sunscreens for patients with skin of color compared with sunscreens for white or fair skin were more likely to recommend more expensive products (median, $14/oz vs $11.3/oz) despite the lower SPF level.20 According to Schneider,21 daily use of the cheapest sunscreen on the head/neck region recommended for white/pale skin ($2/oz) would lead to an annual cost of $61 compared to $182 for darker skin ($6/oz). This showcases the considerable variation in sunscreen prices for both populations that could potentiate disparities and vulnerability in the latter group.

Conclusion

Tinted sunscreens provide both functional and cosmetic benefits and are a safe, effective, and convenient way to protect against high-energy VL. This study suggests that patients with skin of color encounter difficulties in finding matching shades in TS products. These difficulties may stem from the lack of knowledge regarding dark complexions and undertones and the lack of representation of black and brown skin that has persisted in dermatology research journals and textbooks for decades.22 Our study provides important insights to help dermatologists improve their familiarity with the brands and characteristics of TSs geared to patients with all skin tones, including skin of color. Limitations include single-retailer information and inclusion of both highly and poorly rated comments with subjective data, limiting generalizability. The limited selection of shades for darker skin poses a roadblock to proper treatment and prevention. These data represent an area for improvement within the beauty industry and the dermatologic field to deliver culturally sensitive care by being knowledgeable about darker skin tones and TS formulations tailored to people with skin of color.

- McDaniel D, Farris P, Valacchi G. Atmospheric skin aging-contributors and inhibitors. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:124-137.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Dumbuya H, Grimes PE, Lynch S, et al. Impact of iron-oxide containing formulations against visible light-induced skin pigmentation in skin of color individuals. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:712-717.

- Lyons AB, Trullas C, Kohli I, et al. Photoprotection beyond ultraviolet radiation: a review of tinted sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1393-1397.

- Austin E, Huang A, Adar T, et al. Electronic device generated light increases reactive oxygen species in human fibroblasts [published online February 5, 2018]. Lasers Surg Med. doi:10.1002/lsm.22794

- Randhawa M, Seo I, Liebel F, et al. Visible light induces melanogenesis in human skin through a photoadaptive response. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130949.

- Yeager DG, Lim HW. What’s new in photoprotection: a review of new concepts and controversies. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:149-157.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P. Iron oxides in novel skin care formulations attenuate blue light for enhanced protection against skin damage. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:532-537.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Ruvolo E, Fair M, Hutson A, et al. Photoprotection against visible light-induced pigmentation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:589-595.

- Cohen L, Brodsky MA, Zubair R, et al. Cutaneous interaction with visible light: what do we know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;S0190-9622(20)30551-X.

- Kaye ET, Levin JA, Blank IH, et al. Efficiency of opaque photoprotective agents in the visible light range. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:351-355.

- Sayre RM, Kollias N, Roberts RL, et al. Physical sunscreens. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1990;41:103-109.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P, et al. Beyond sun protection factor: an approach to environmental protection with novel mineral coatings in a vehicle containing a blend of skincare ingredients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:407-415.

- MacLeman E. Why are iron oxides used? Deep Science website. February 10, 2022. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://thedermreview.com/iron-oxides-ci-77491-ci-77492-ci-77499/

- Zugerman C. Contact dermatitis to yellow iron oxide. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:107-109.

- Saxena M, Warshaw E, Ahmed DD. Eyelid allergic contact dermatitis to black iron oxide. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:38-39.

- Smijs TG, Pavel S. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: focus on their safety and effectiveness. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2011;4:95-112.

- 2020 RealSelf Sun Safety Report: majority of Americans don’t use sunscreen daily. Practical Dermatology. May 6, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://practicaldermatology.com/news/realself-sun-safety-report-majority-of-americans-dont-use-sunscreen-daily

- Song H, Beckles A, Salian P, et al. Sunscreen recommendations for patients with skin of color in the popular press and in the dermatology clinic. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:165-170.

- Schneider J. The teaspoon rule of applying sunscreen. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:838-839.

- Nelson B. How dermatology is failing melanoma patients with skin of color: unanswered questions on risk and eye-opening disparities in outcomes are weighing heavily on melanoma patients with darker skin. in this article, part 1 of a 2-part series, we explore the deadly consequences of racism and inequality in cancer care. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;128:7-8.

- McDaniel D, Farris P, Valacchi G. Atmospheric skin aging-contributors and inhibitors. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:124-137.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Dumbuya H, Grimes PE, Lynch S, et al. Impact of iron-oxide containing formulations against visible light-induced skin pigmentation in skin of color individuals. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:712-717.

- Lyons AB, Trullas C, Kohli I, et al. Photoprotection beyond ultraviolet radiation: a review of tinted sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1393-1397.

- Austin E, Huang A, Adar T, et al. Electronic device generated light increases reactive oxygen species in human fibroblasts [published online February 5, 2018]. Lasers Surg Med. doi:10.1002/lsm.22794

- Randhawa M, Seo I, Liebel F, et al. Visible light induces melanogenesis in human skin through a photoadaptive response. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130949.

- Yeager DG, Lim HW. What’s new in photoprotection: a review of new concepts and controversies. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:149-157.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P. Iron oxides in novel skin care formulations attenuate blue light for enhanced protection against skin damage. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:532-537.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Ruvolo E, Fair M, Hutson A, et al. Photoprotection against visible light-induced pigmentation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:589-595.

- Cohen L, Brodsky MA, Zubair R, et al. Cutaneous interaction with visible light: what do we know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;S0190-9622(20)30551-X.

- Kaye ET, Levin JA, Blank IH, et al. Efficiency of opaque photoprotective agents in the visible light range. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:351-355.

- Sayre RM, Kollias N, Roberts RL, et al. Physical sunscreens. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1990;41:103-109.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P, et al. Beyond sun protection factor: an approach to environmental protection with novel mineral coatings in a vehicle containing a blend of skincare ingredients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:407-415.

- MacLeman E. Why are iron oxides used? Deep Science website. February 10, 2022. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://thedermreview.com/iron-oxides-ci-77491-ci-77492-ci-77499/

- Zugerman C. Contact dermatitis to yellow iron oxide. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:107-109.

- Saxena M, Warshaw E, Ahmed DD. Eyelid allergic contact dermatitis to black iron oxide. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:38-39.

- Smijs TG, Pavel S. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: focus on their safety and effectiveness. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2011;4:95-112.

- 2020 RealSelf Sun Safety Report: majority of Americans don’t use sunscreen daily. Practical Dermatology. May 6, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://practicaldermatology.com/news/realself-sun-safety-report-majority-of-americans-dont-use-sunscreen-daily

- Song H, Beckles A, Salian P, et al. Sunscreen recommendations for patients with skin of color in the popular press and in the dermatology clinic. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:165-170.

- Schneider J. The teaspoon rule of applying sunscreen. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:838-839.

- Nelson B. How dermatology is failing melanoma patients with skin of color: unanswered questions on risk and eye-opening disparities in outcomes are weighing heavily on melanoma patients with darker skin. in this article, part 1 of a 2-part series, we explore the deadly consequences of racism and inequality in cancer care. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;128:7-8.

Practice Points

- Visible light has been shown to increase tyrosinase activity and induce immediate erythema in light-skinned individuals and long-lasting pigmentation in dark-skinned individuals.

- The formulation of sunscreens with iron oxides and pigmentary titanium dioxide are a safe and effective way to protect against high-energy visible light, especially when combined with zinc oxide.

- Physicians should be aware of sunscreen characteristics that patients like and dislike to tailor recommendations that are appropriate for each individual to enhance adherence.

- Cosmetic elegance and tone compatibility are the most important criteria for individuals seeking tinted sunscreens.

The Molting Man: Anasarca-Induced Full-Body Desquamation

Edema blisters are a common but often underreported entity most commonly seen on the lower extremities in the setting of acute edema. 1 Reported risk factors and associations include chronic venous insufficiency, congestive heart failure, hereditary angioedema, and medications (eg, amlodipine). 1,2 We report a newly described variant that we have termed anasarca-induced desquamation in which a patient sloughed the entire cutaneous surface of the body after gaining almost 40 pounds over 5 days.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man without a home was found minimally responsive in a yard. His core body temperature was 25.5 °C. He was profoundly acidotic (pH, <6.733 [reference range, 7.35–7.45]; lactic acid, 20.5 mmol/L [reference range, 0.5–2.2 mmol/L]) at admission. His medical history was notable for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, alcohol abuse, and pulmonary embolism. The patient was resuscitated with rewarming and intravenous fluids in the setting of acute renal insufficiency. By day 5 of the hospital stay, he had a net positive intake of 21.8 L and an 18-kg (39.7-lb) weight gain.

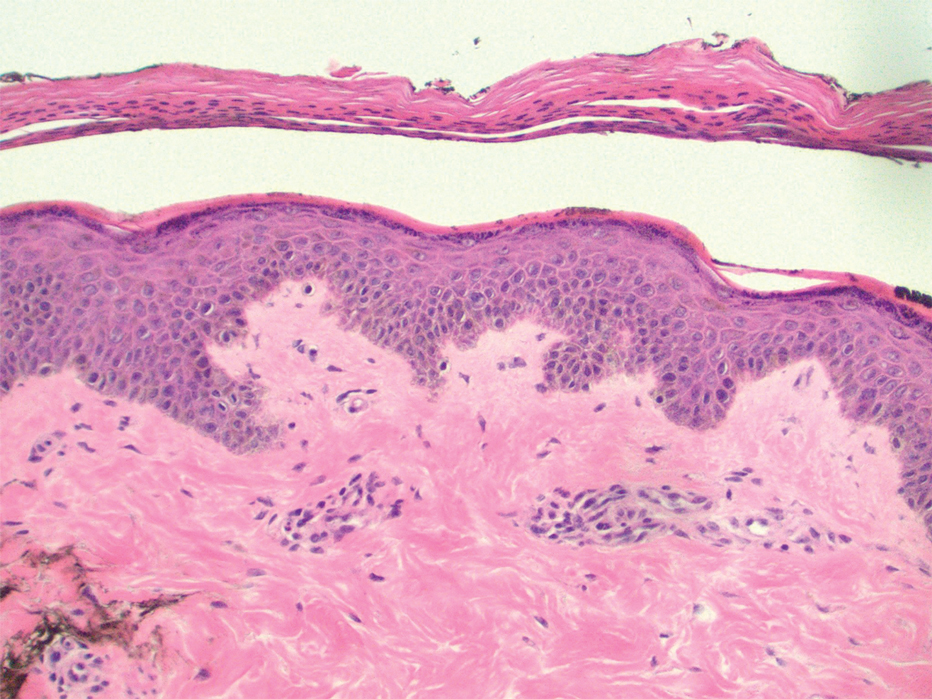

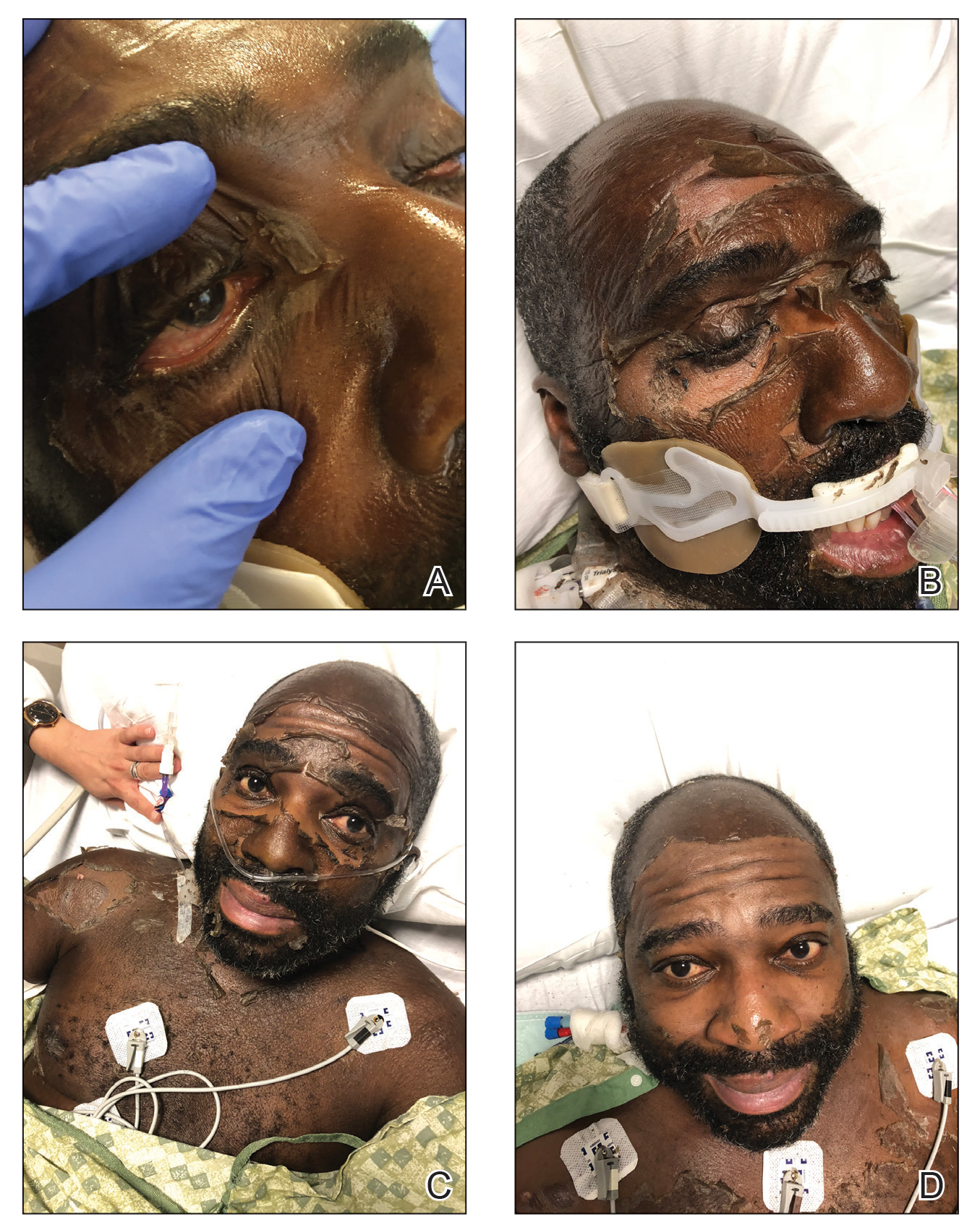

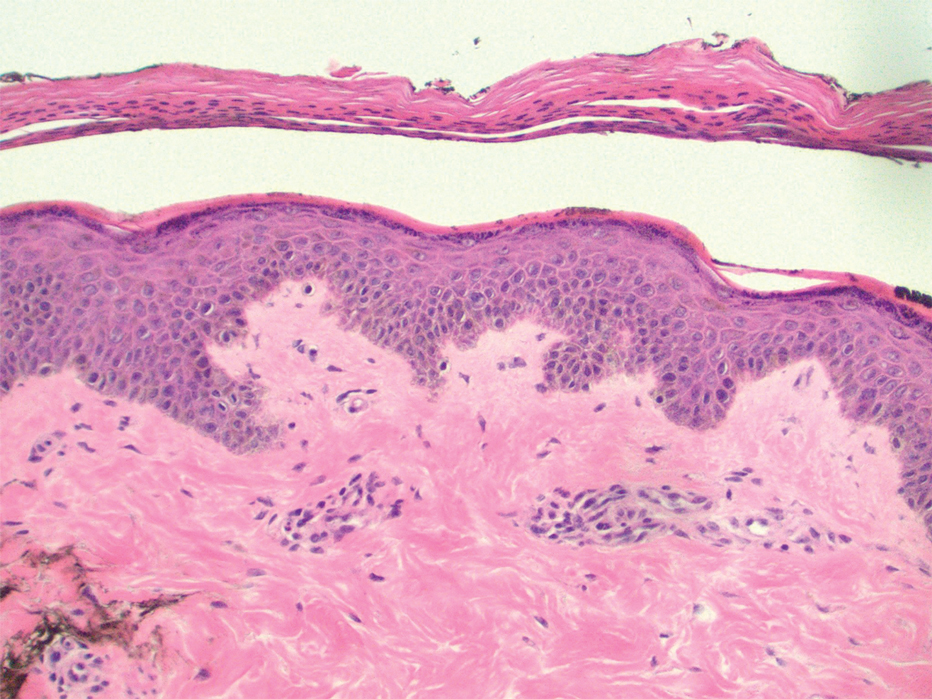

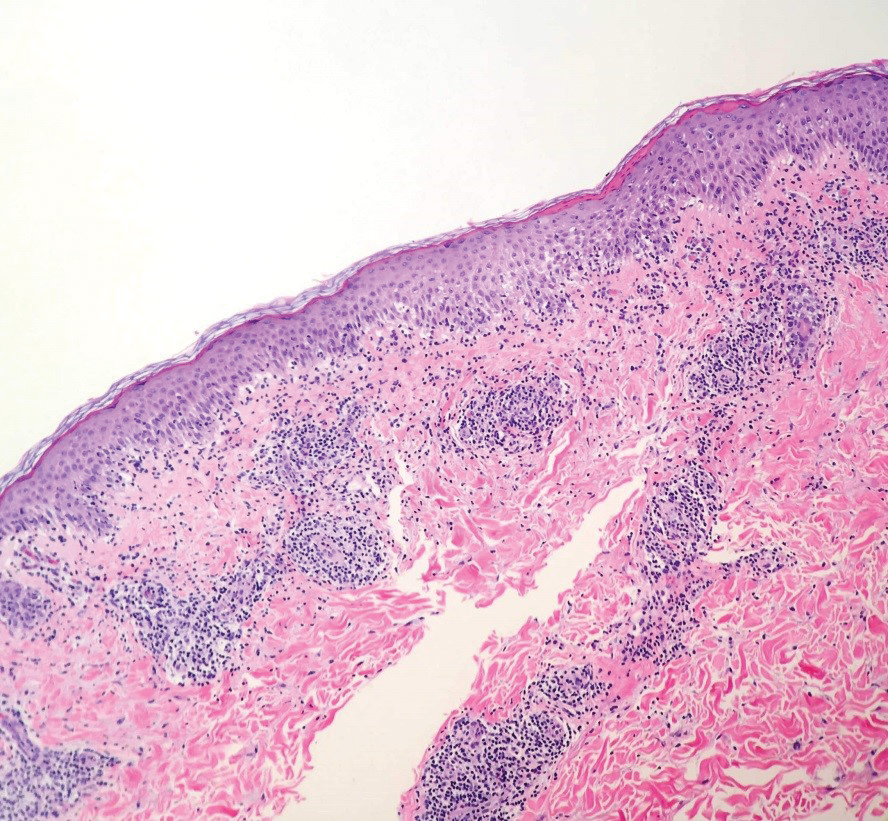

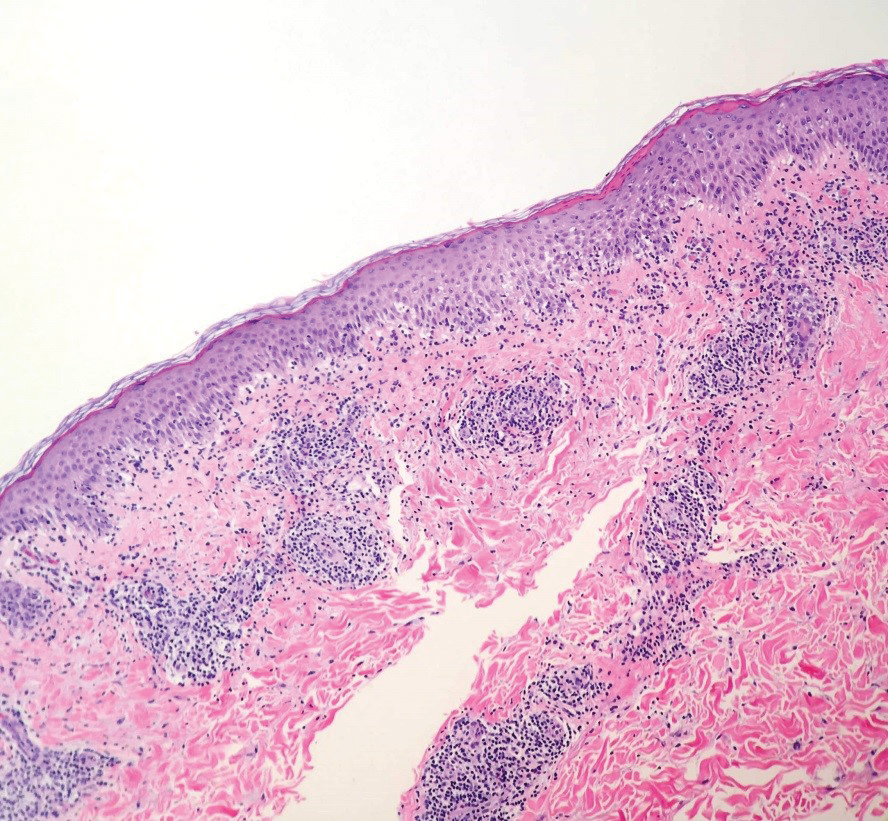

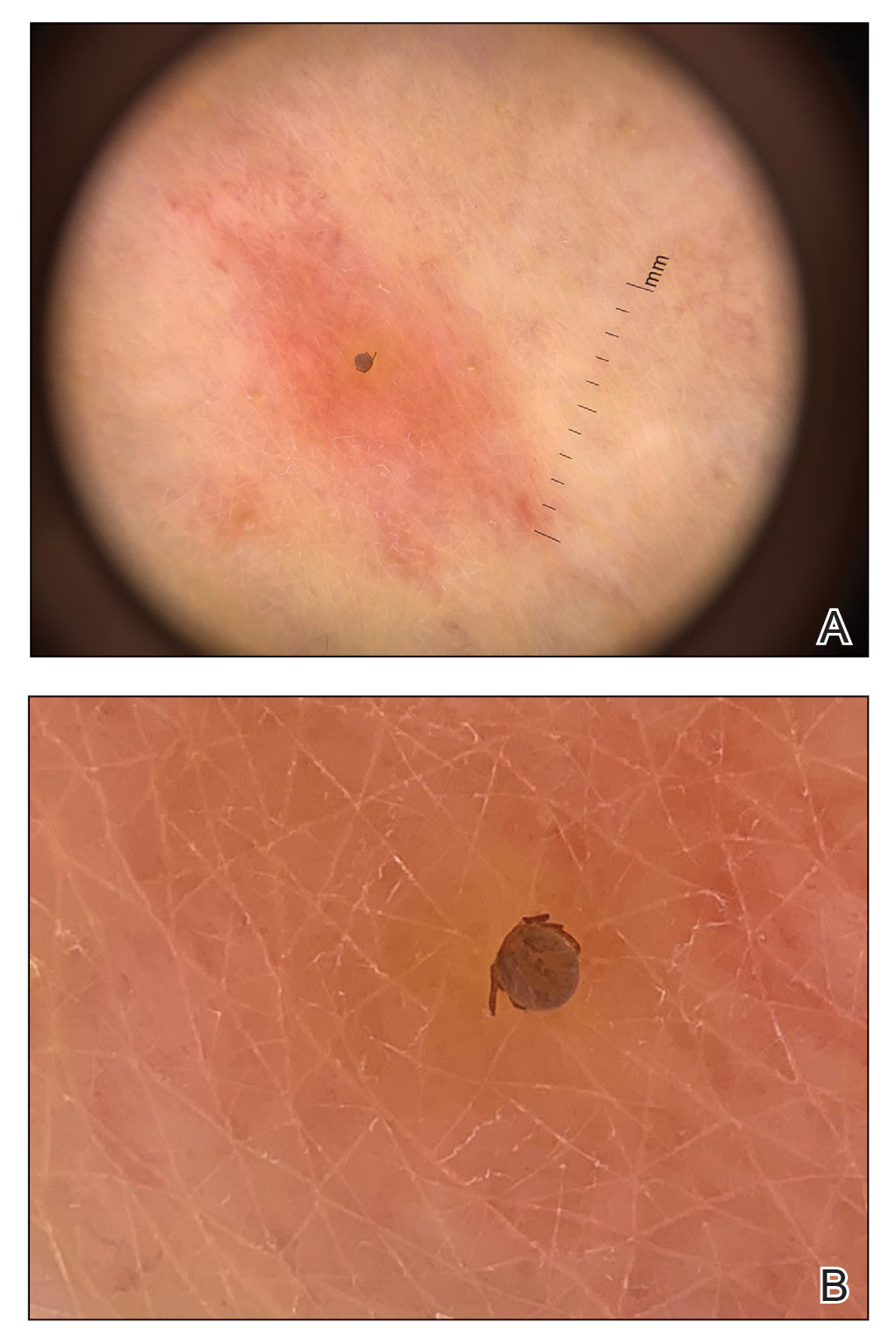

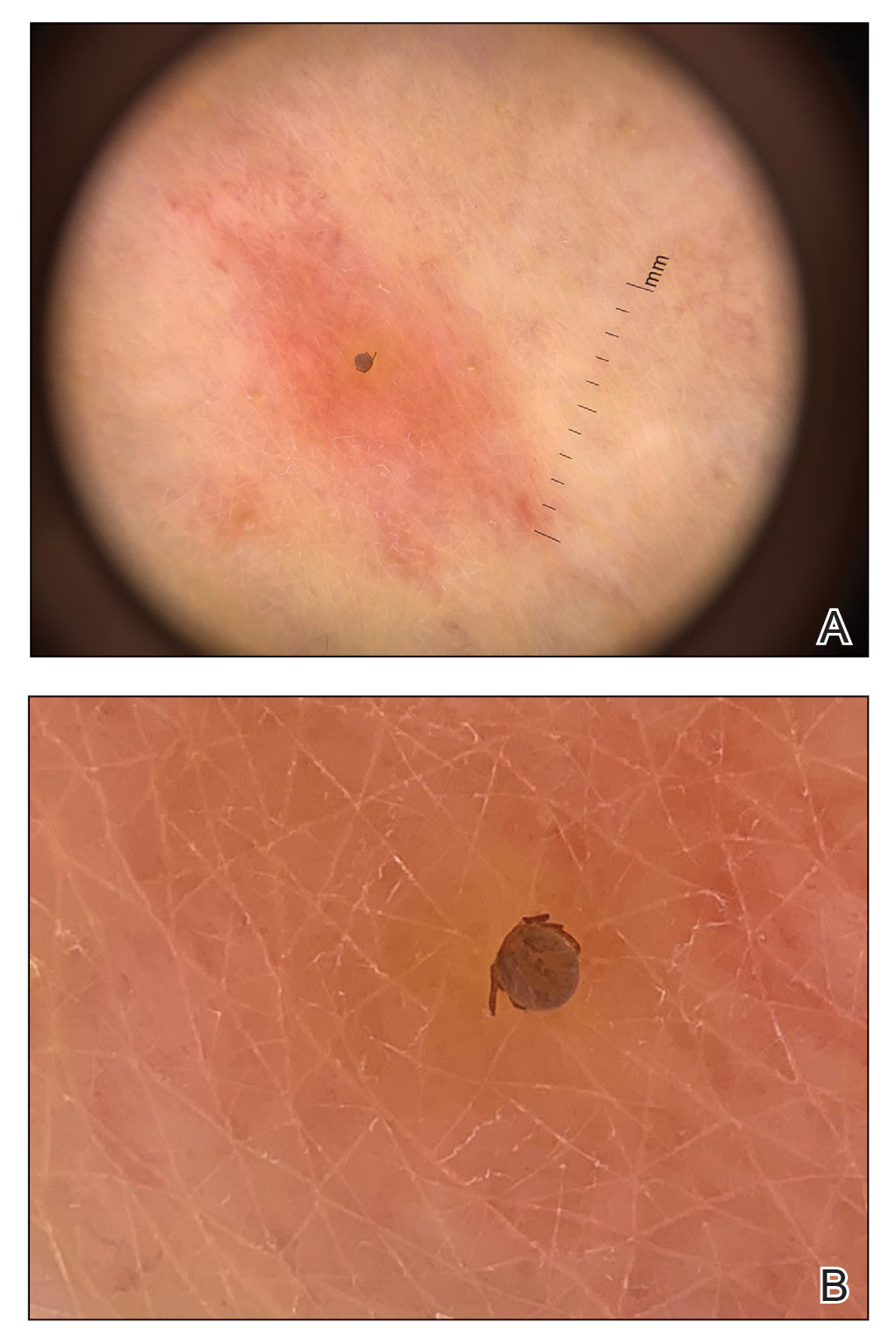

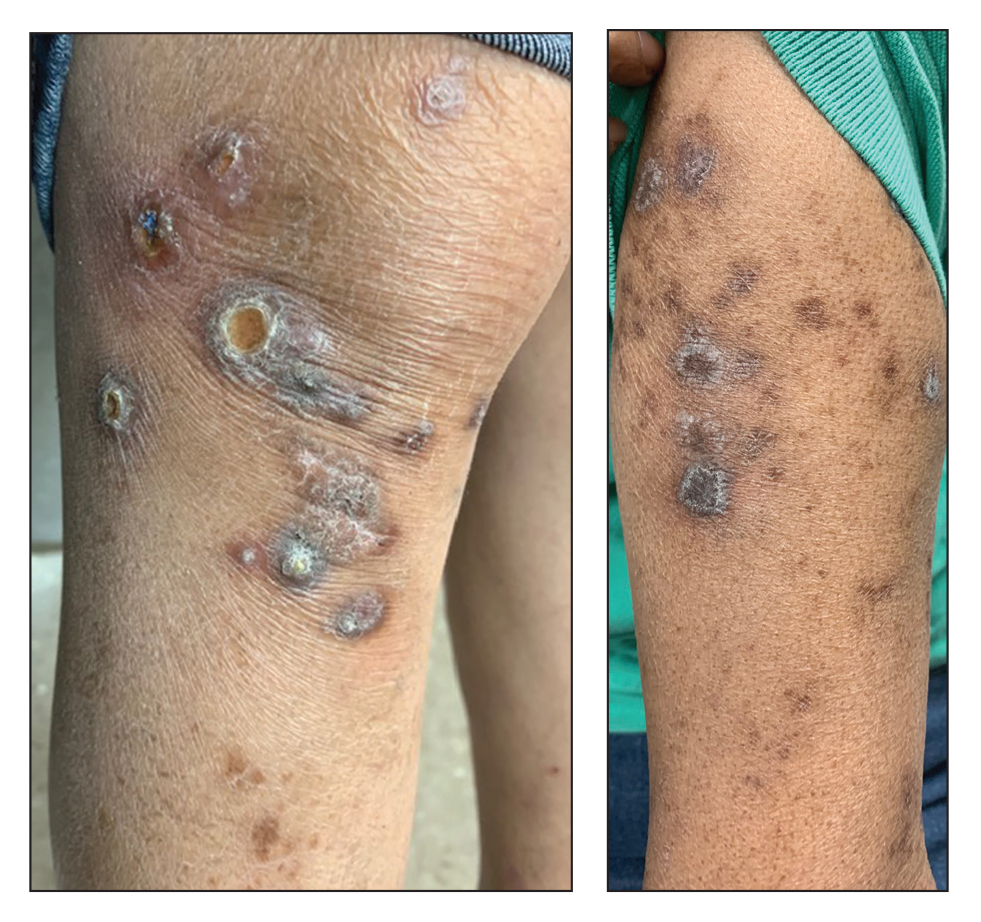

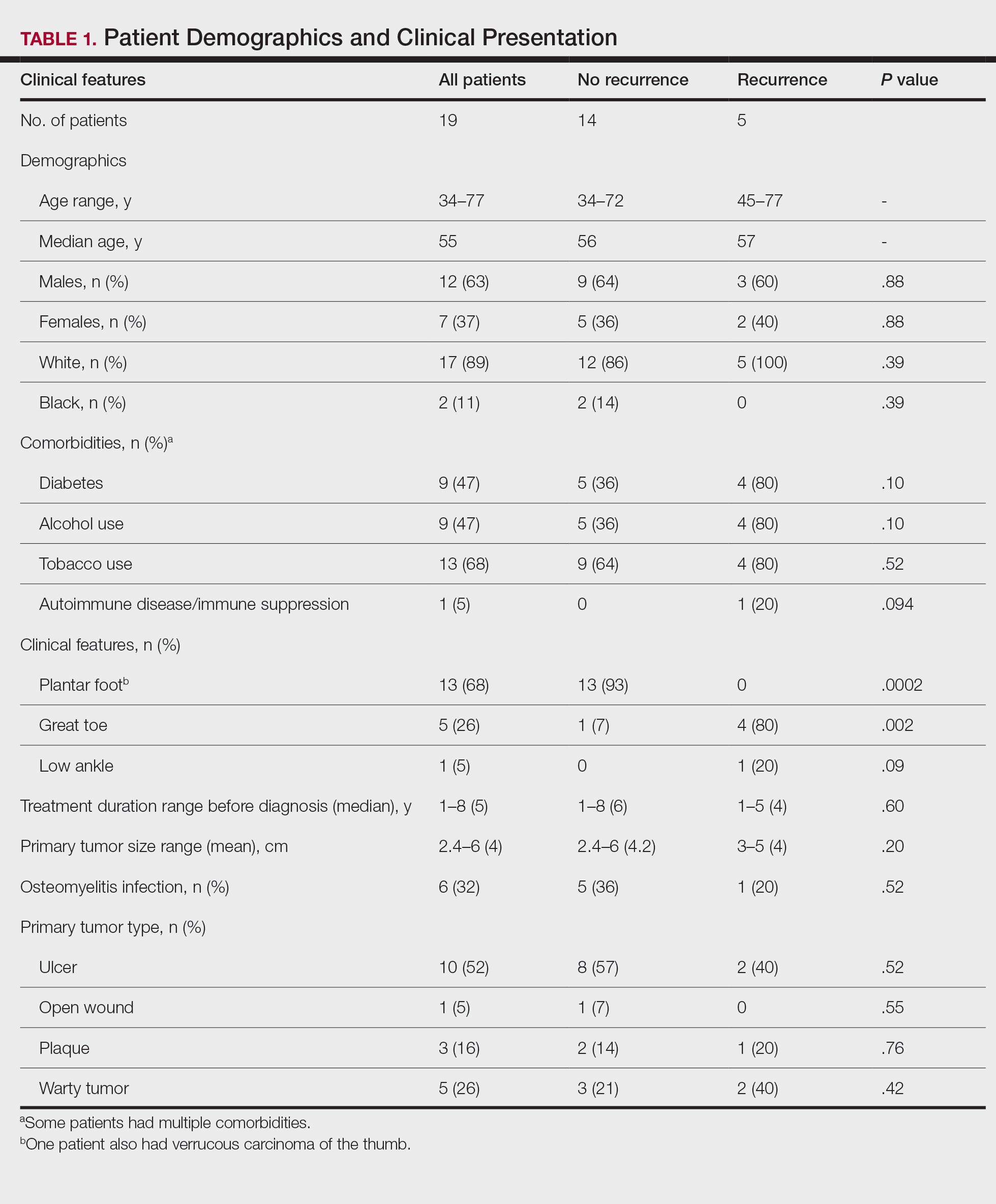

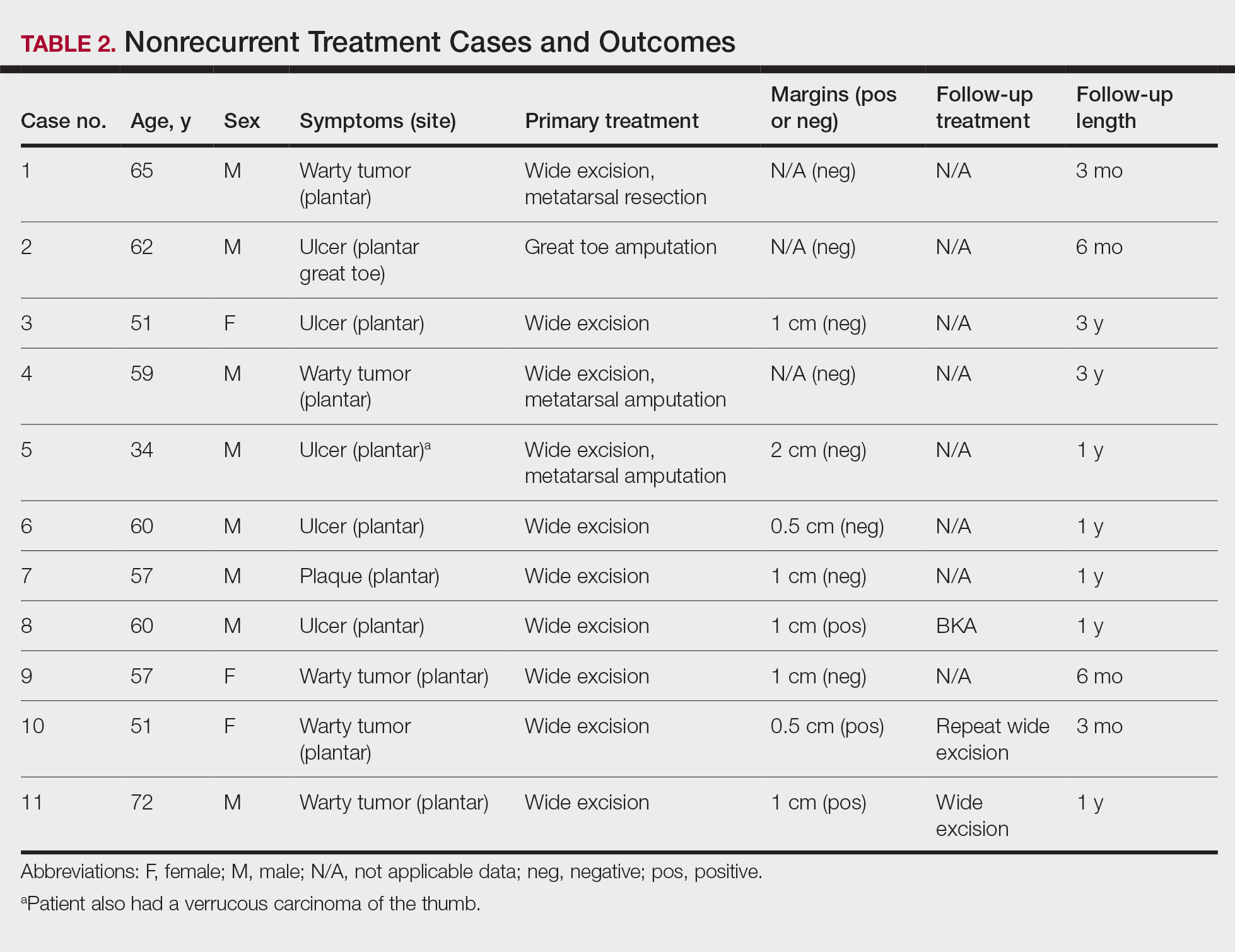

Dermatology was consulted for skin sloughing. Physical examination revealed nonpainful desquamation of the vermilion lip, periorbital skin, right shoulder, and hips without notable mucosal changes. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the shoulder revealed an intracorneal split with desquamation of the stratum corneum and a mild dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, consistent with exfoliation secondary to edema or staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (Figure 1). No staphylococcal growth was noted on blood, urine, nasal, wound, and ocular cultures throughout the hospital stay.

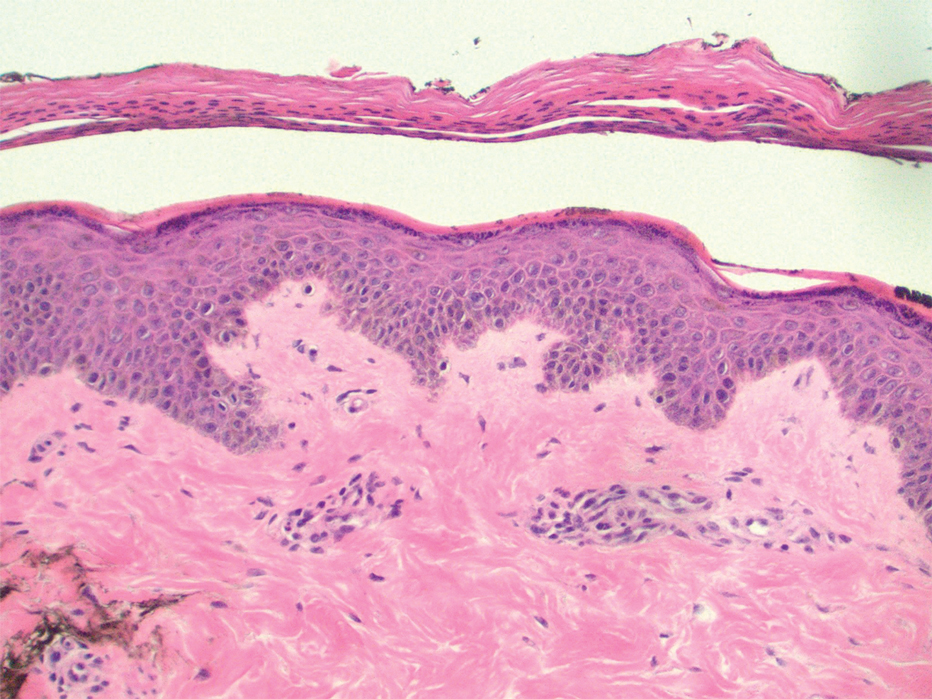

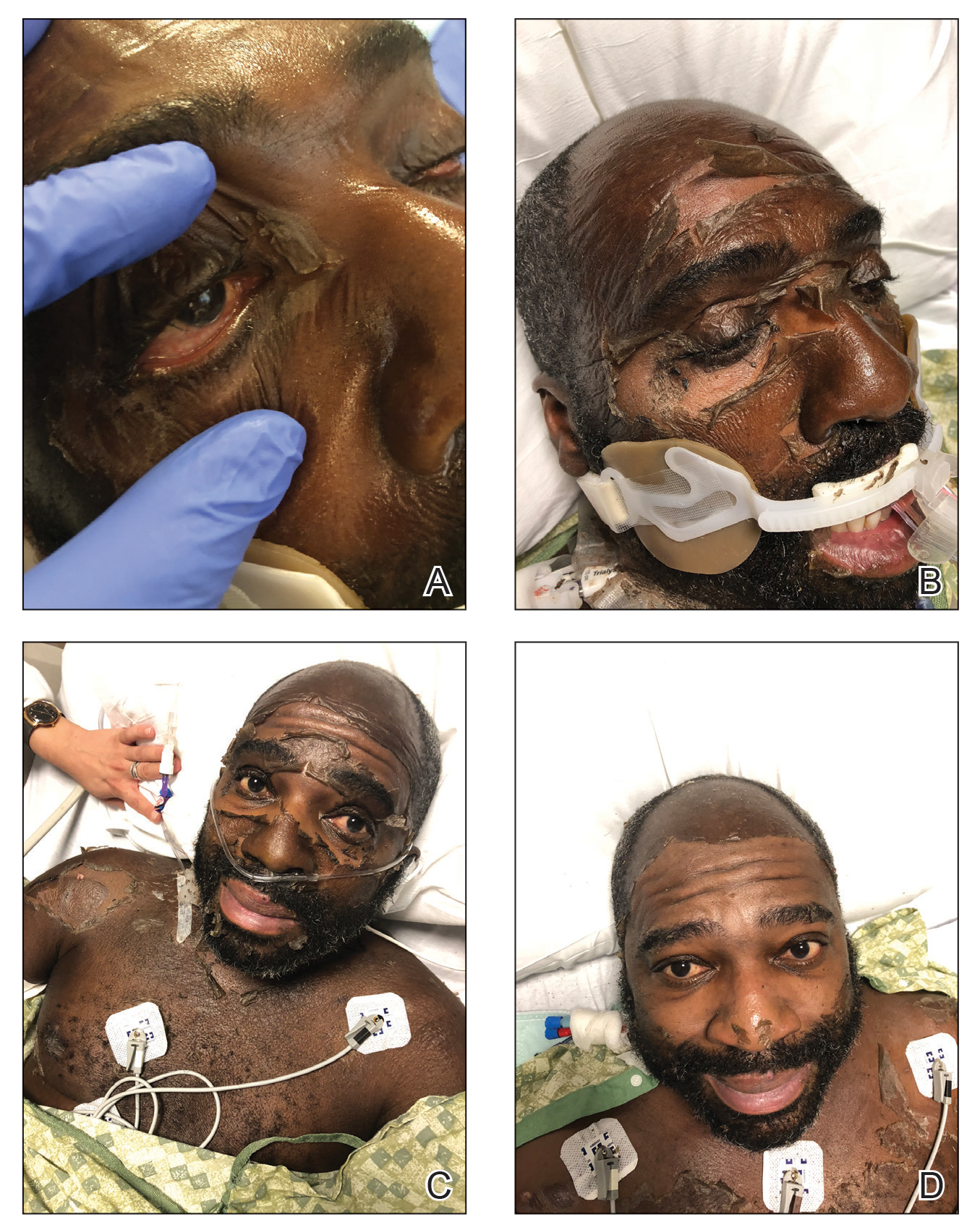

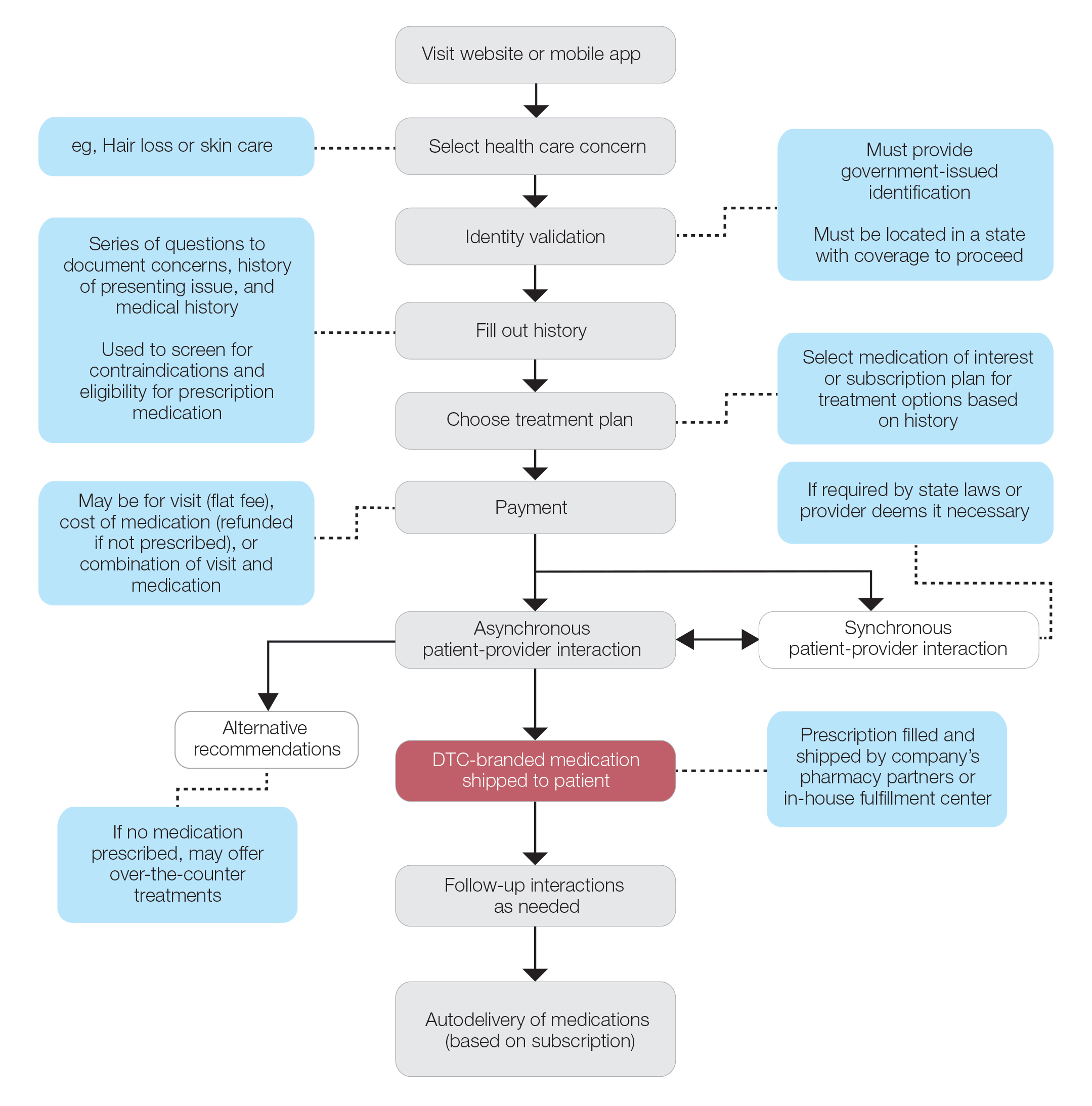

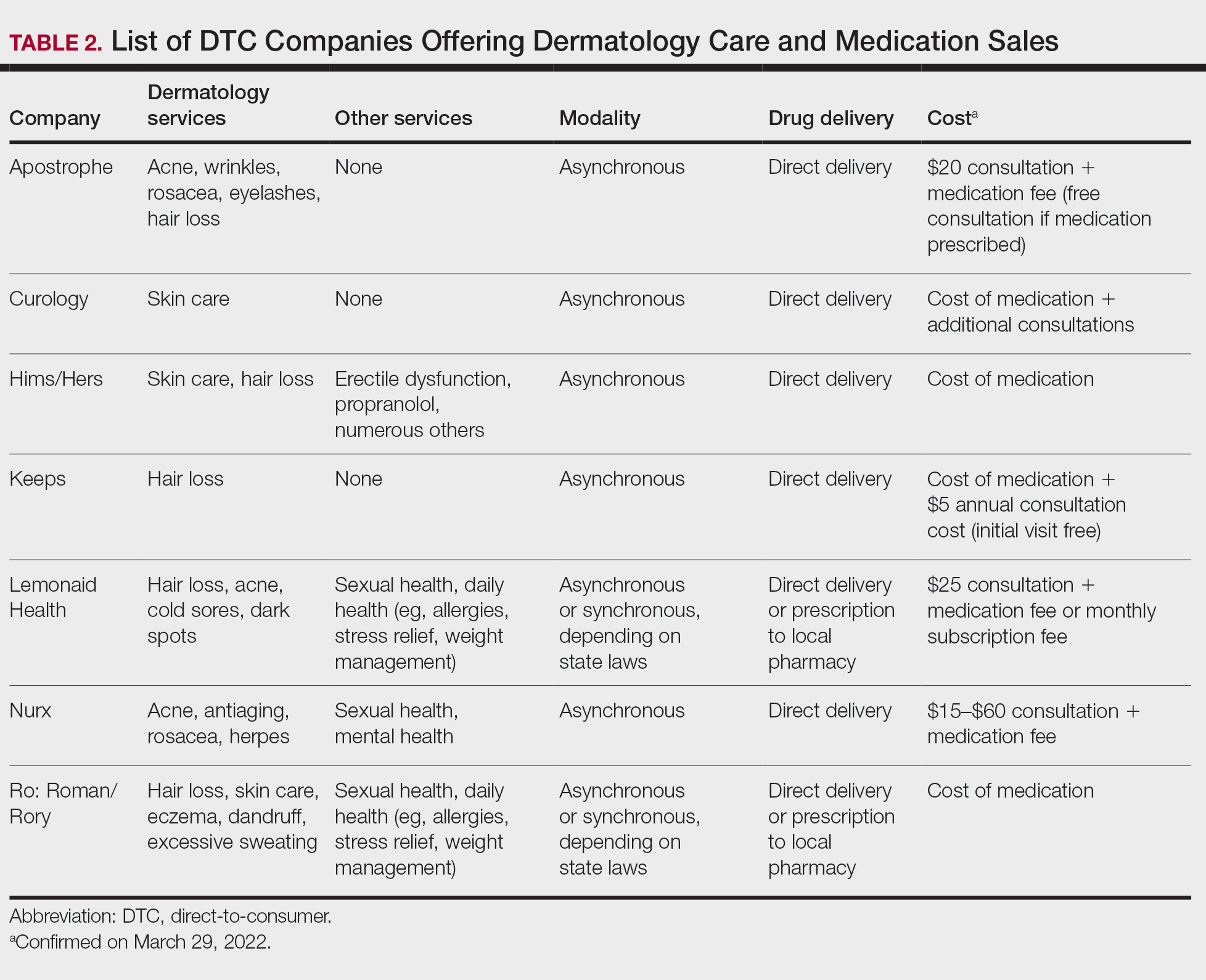

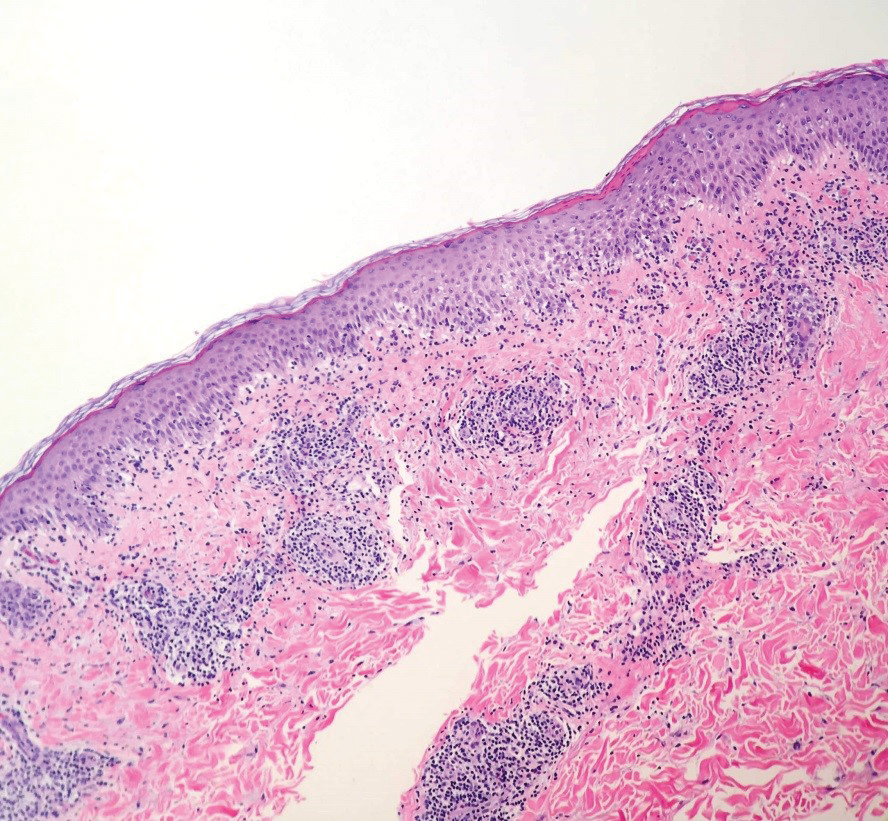

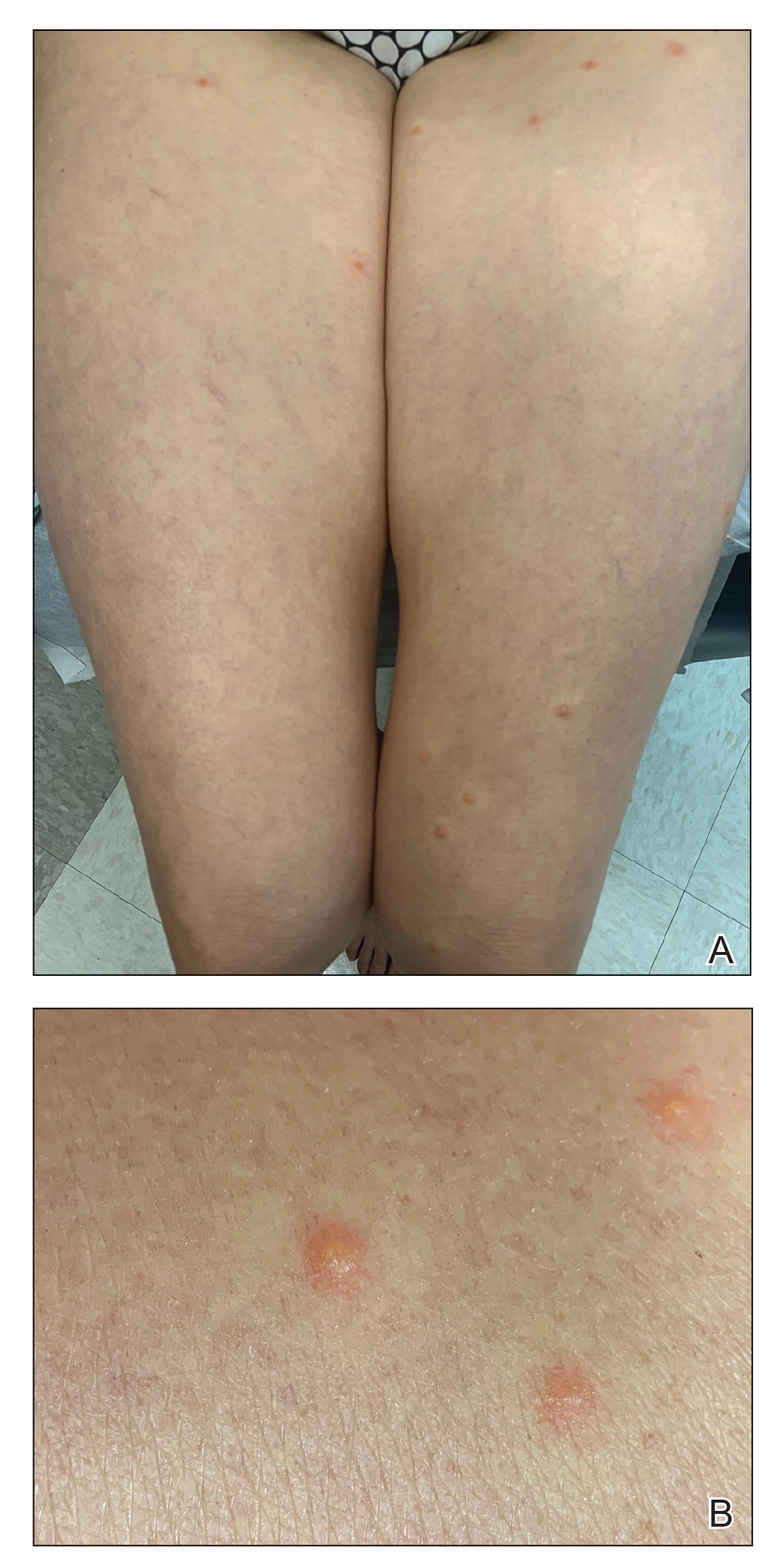

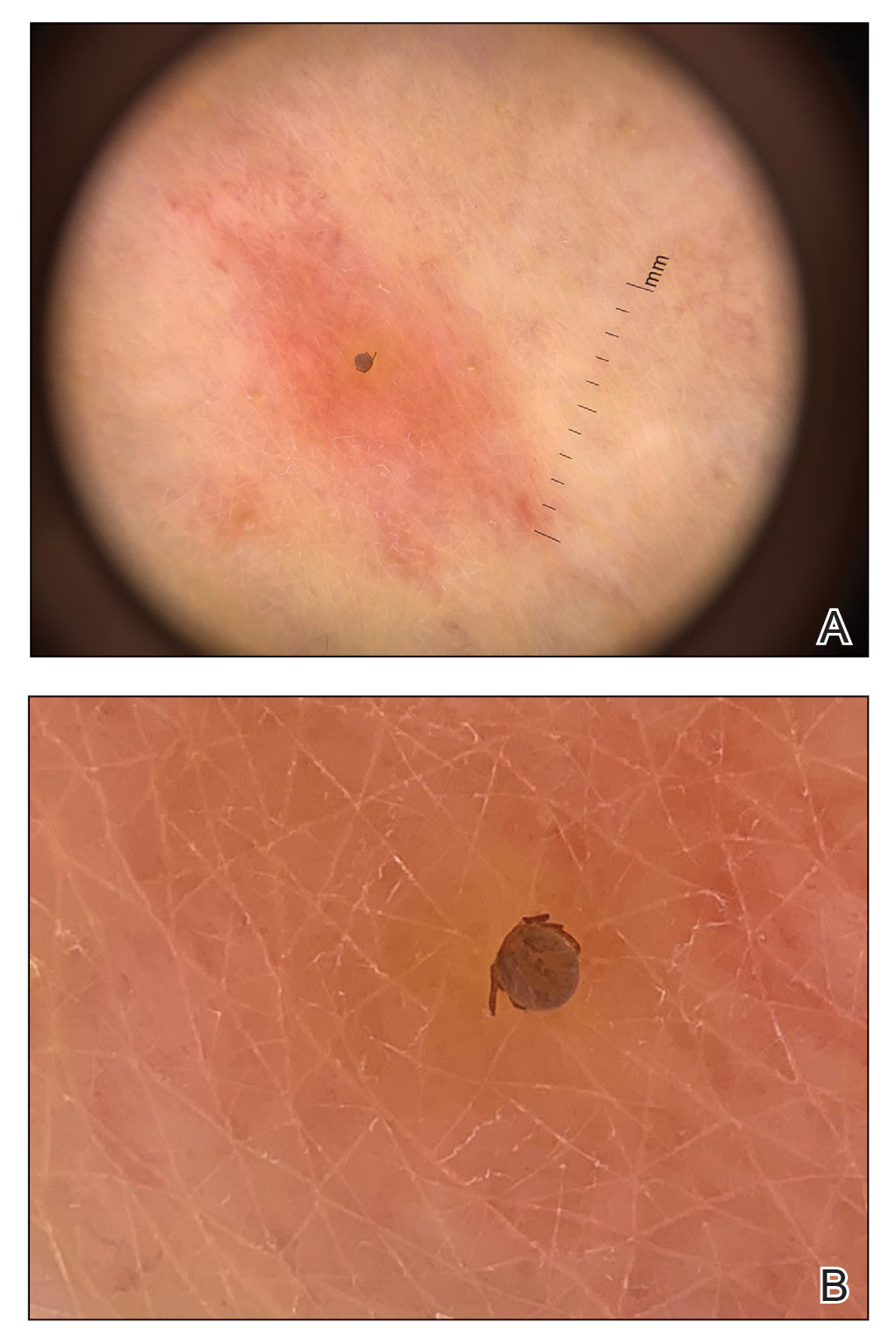

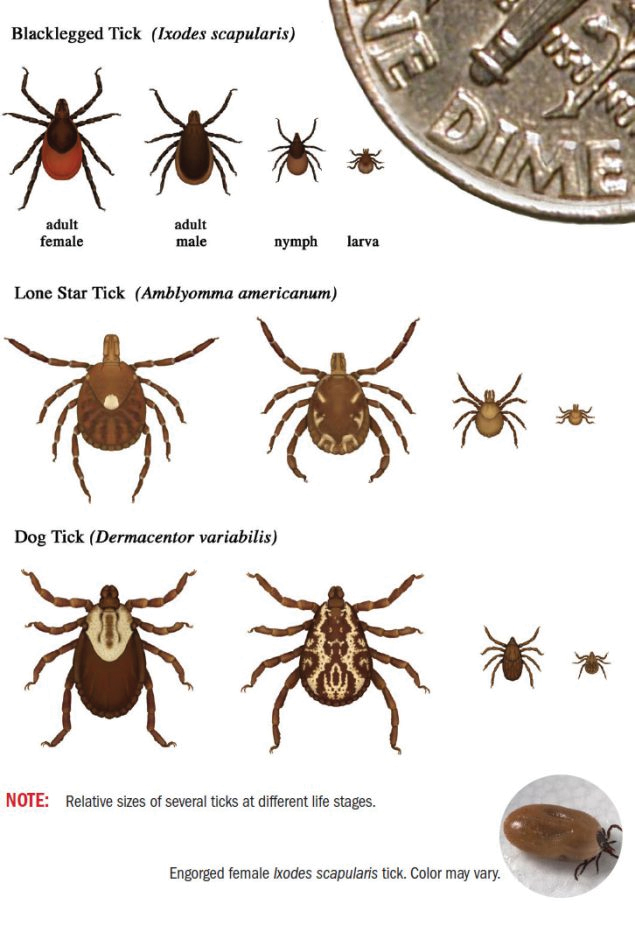

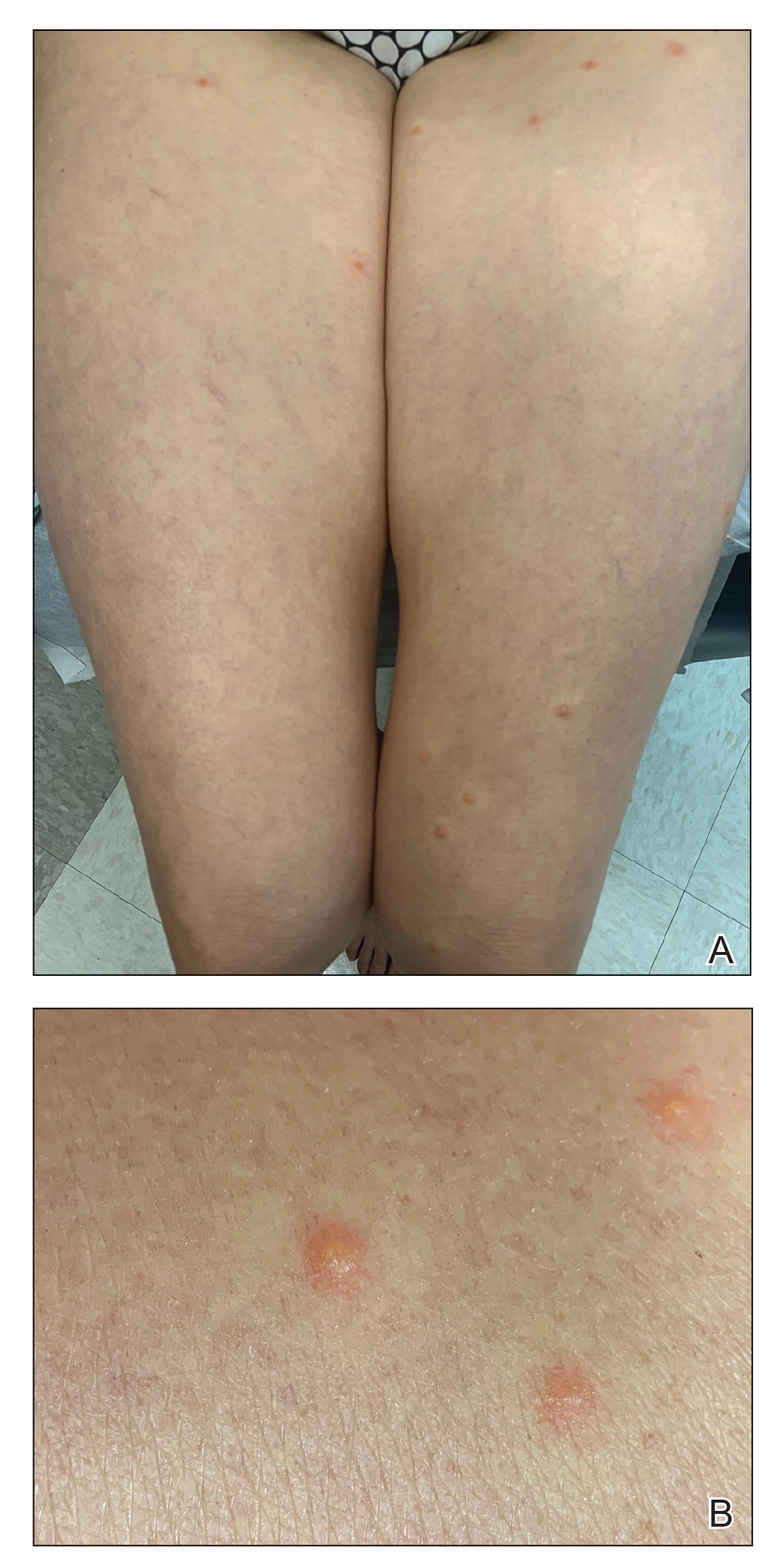

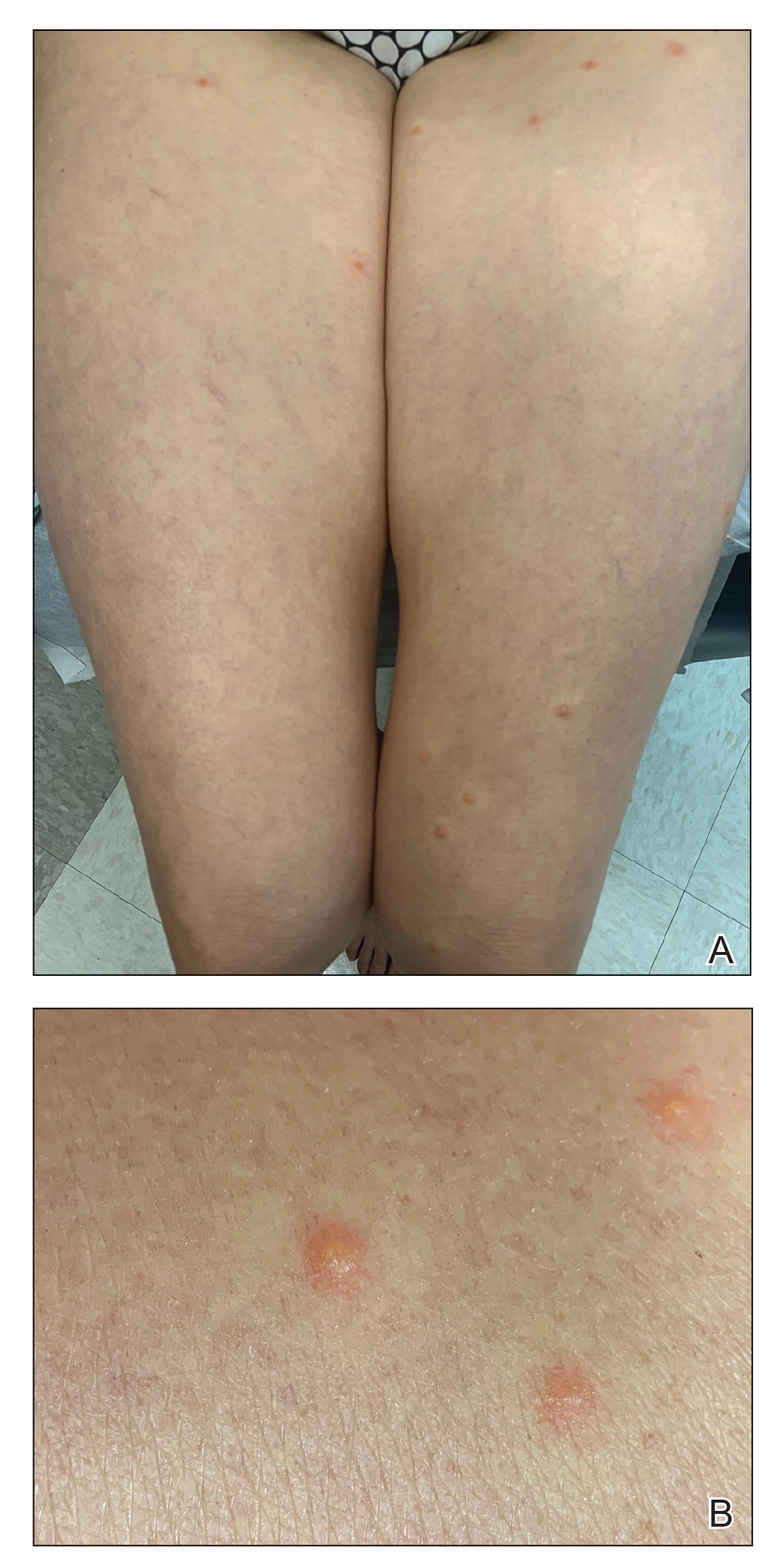

As the patient’s anasarca improved with diuretics and continuous renal replacement therapy, the entire cutaneous surface—head to toe—underwent desquamation, including the palms and soles. He was managed with supportive skin care. The anasarca healed completely with residual hypopigmentation (Figures 2 and 3).

Comment

Anasarca-induced desquamation represents a more diffuse form of a known entity: edema blisters. Occurring most commonly in the setting of acute exacerbation of chronic venous insufficiency, edema blisters can mimic other vesiculobullous conditions, such as bullous pemphigoid and herpes zoster.3

Pathogenesis of Edema Blisters—Edema develops in the skin when the capillary filtration rate, determined by the hydrostatic and oncotic pressures of the capillaries and interstitium, exceeds venous and lymphatic drainage. The appearance of edema blisters in the acute setting likely is related to the speed at which edema develops in skin.1 Although edema blisters often are described as tense, there is a paucity of histologic data at the anatomical level of split in the skin.In our patient, desquamation was within the stratum corneum and likely multifactorial. His weight gain of nearly 40 lb, the result of intravenous instillation of fluids and low urine output, was undeniably a contributing factor. The anasarca was aggravated by hypoalbuminemia (2.1 g/dL) in the setting of known liver disease. Other possible contributing factors were hypotension, which required vasopressor therapy that led to hypoperfusion of the skin, and treatment of hypothermia, with resulting reactive vasodilation and capillary leak.

Management—Treatment of acute edema blisters is focused on the underlying cause of the edema. In a study of 13 patients with edema blisters, all had blisters on the legs that resolved with treatment, such as diuretics or compression therapy.1

Anasarca-induced desquamation is an inherently benign condition that mimics potentially fatal disorders, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and toxic shock syndrome. Therefore, patients presenting with diffuse superficial desquamation should be assessed for the mucosal changes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and a history of acute edema in the affected areas to avoid potentially harmful empiric treatments, such as corticosteroids and intravenous antibiotics.

Conclusion

Anasarca-induced desquamation represents a more diffuse form of edema blisters. This desquamation can mimic a potentially fatal rash, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

- Bhushan M, Chalmers RJ, Cox NH. Acute oedema blisters: a report of 13 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:580-582. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04087.x

- Fabiani J, Bork K. Acute edema blisters on a skin swelling: an unusual manifestation of hereditary angioedema. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:556-557. doi:10.2340/00015555-2252

- Chen SX, Cohen PR. Edema bullae mimicking disseminated herpes zoster. Cureus. 2017;9:E1780. doi:10.7759/cureus.1780

Edema blisters are a common but often underreported entity most commonly seen on the lower extremities in the setting of acute edema. 1 Reported risk factors and associations include chronic venous insufficiency, congestive heart failure, hereditary angioedema, and medications (eg, amlodipine). 1,2 We report a newly described variant that we have termed anasarca-induced desquamation in which a patient sloughed the entire cutaneous surface of the body after gaining almost 40 pounds over 5 days.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man without a home was found minimally responsive in a yard. His core body temperature was 25.5 °C. He was profoundly acidotic (pH, <6.733 [reference range, 7.35–7.45]; lactic acid, 20.5 mmol/L [reference range, 0.5–2.2 mmol/L]) at admission. His medical history was notable for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, alcohol abuse, and pulmonary embolism. The patient was resuscitated with rewarming and intravenous fluids in the setting of acute renal insufficiency. By day 5 of the hospital stay, he had a net positive intake of 21.8 L and an 18-kg (39.7-lb) weight gain.

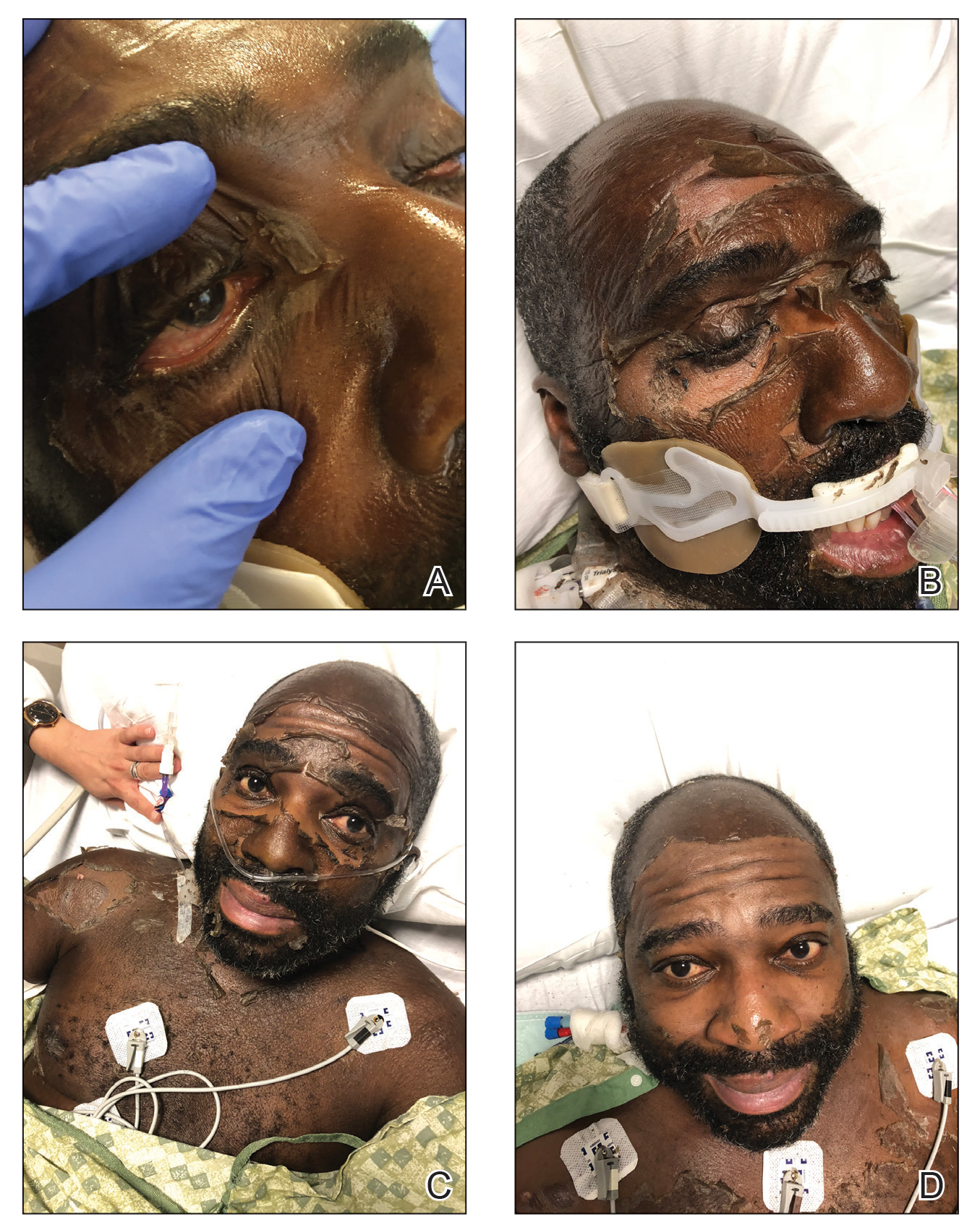

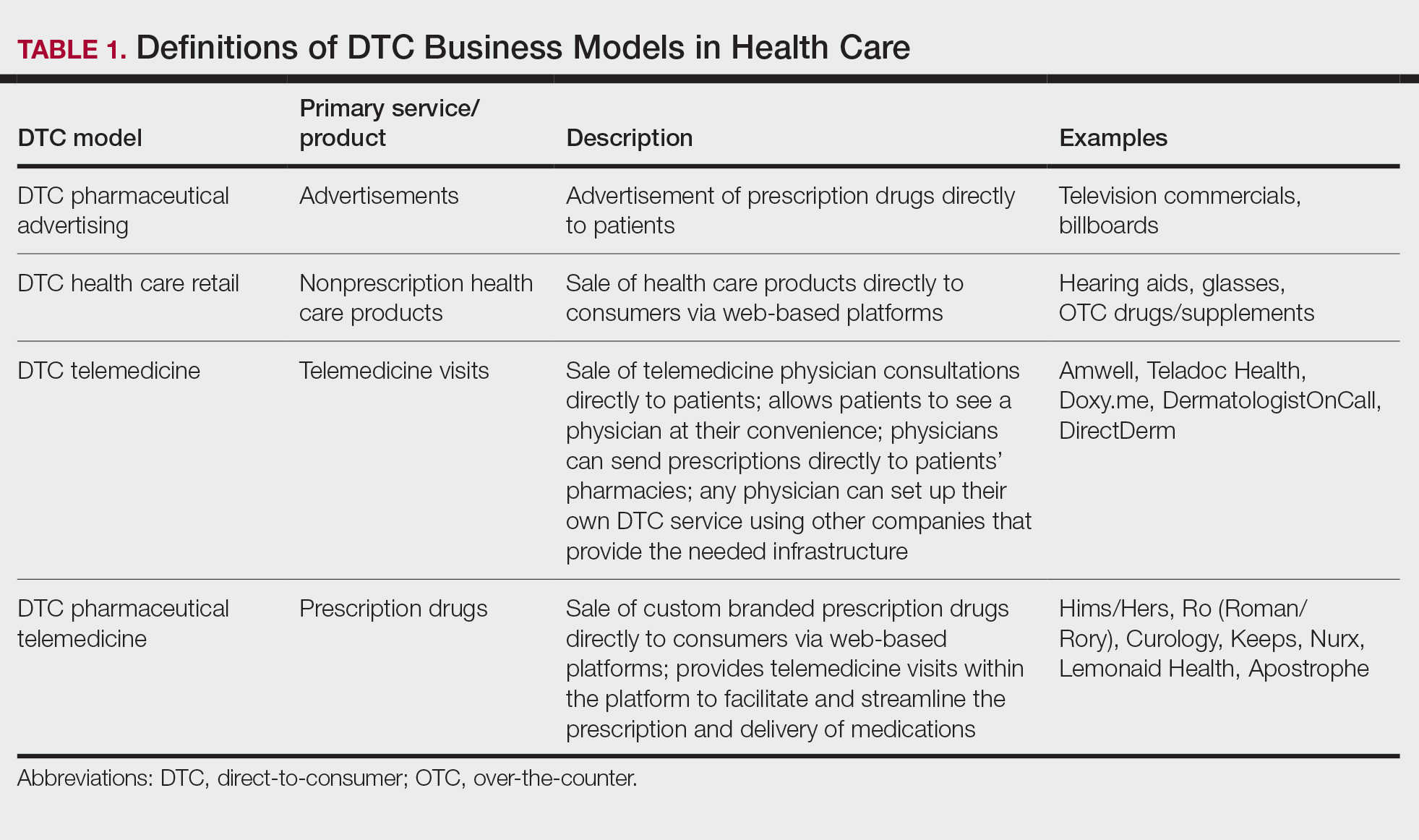

Dermatology was consulted for skin sloughing. Physical examination revealed nonpainful desquamation of the vermilion lip, periorbital skin, right shoulder, and hips without notable mucosal changes. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the shoulder revealed an intracorneal split with desquamation of the stratum corneum and a mild dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, consistent with exfoliation secondary to edema or staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (Figure 1). No staphylococcal growth was noted on blood, urine, nasal, wound, and ocular cultures throughout the hospital stay.

As the patient’s anasarca improved with diuretics and continuous renal replacement therapy, the entire cutaneous surface—head to toe—underwent desquamation, including the palms and soles. He was managed with supportive skin care. The anasarca healed completely with residual hypopigmentation (Figures 2 and 3).

Comment

Anasarca-induced desquamation represents a more diffuse form of a known entity: edema blisters. Occurring most commonly in the setting of acute exacerbation of chronic venous insufficiency, edema blisters can mimic other vesiculobullous conditions, such as bullous pemphigoid and herpes zoster.3

Pathogenesis of Edema Blisters—Edema develops in the skin when the capillary filtration rate, determined by the hydrostatic and oncotic pressures of the capillaries and interstitium, exceeds venous and lymphatic drainage. The appearance of edema blisters in the acute setting likely is related to the speed at which edema develops in skin.1 Although edema blisters often are described as tense, there is a paucity of histologic data at the anatomical level of split in the skin.In our patient, desquamation was within the stratum corneum and likely multifactorial. His weight gain of nearly 40 lb, the result of intravenous instillation of fluids and low urine output, was undeniably a contributing factor. The anasarca was aggravated by hypoalbuminemia (2.1 g/dL) in the setting of known liver disease. Other possible contributing factors were hypotension, which required vasopressor therapy that led to hypoperfusion of the skin, and treatment of hypothermia, with resulting reactive vasodilation and capillary leak.

Management—Treatment of acute edema blisters is focused on the underlying cause of the edema. In a study of 13 patients with edema blisters, all had blisters on the legs that resolved with treatment, such as diuretics or compression therapy.1

Anasarca-induced desquamation is an inherently benign condition that mimics potentially fatal disorders, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and toxic shock syndrome. Therefore, patients presenting with diffuse superficial desquamation should be assessed for the mucosal changes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and a history of acute edema in the affected areas to avoid potentially harmful empiric treatments, such as corticosteroids and intravenous antibiotics.

Conclusion

Anasarca-induced desquamation represents a more diffuse form of edema blisters. This desquamation can mimic a potentially fatal rash, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

Edema blisters are a common but often underreported entity most commonly seen on the lower extremities in the setting of acute edema. 1 Reported risk factors and associations include chronic venous insufficiency, congestive heart failure, hereditary angioedema, and medications (eg, amlodipine). 1,2 We report a newly described variant that we have termed anasarca-induced desquamation in which a patient sloughed the entire cutaneous surface of the body after gaining almost 40 pounds over 5 days.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man without a home was found minimally responsive in a yard. His core body temperature was 25.5 °C. He was profoundly acidotic (pH, <6.733 [reference range, 7.35–7.45]; lactic acid, 20.5 mmol/L [reference range, 0.5–2.2 mmol/L]) at admission. His medical history was notable for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, alcohol abuse, and pulmonary embolism. The patient was resuscitated with rewarming and intravenous fluids in the setting of acute renal insufficiency. By day 5 of the hospital stay, he had a net positive intake of 21.8 L and an 18-kg (39.7-lb) weight gain.

Dermatology was consulted for skin sloughing. Physical examination revealed nonpainful desquamation of the vermilion lip, periorbital skin, right shoulder, and hips without notable mucosal changes. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the shoulder revealed an intracorneal split with desquamation of the stratum corneum and a mild dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, consistent with exfoliation secondary to edema or staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (Figure 1). No staphylococcal growth was noted on blood, urine, nasal, wound, and ocular cultures throughout the hospital stay.

As the patient’s anasarca improved with diuretics and continuous renal replacement therapy, the entire cutaneous surface—head to toe—underwent desquamation, including the palms and soles. He was managed with supportive skin care. The anasarca healed completely with residual hypopigmentation (Figures 2 and 3).

Comment

Anasarca-induced desquamation represents a more diffuse form of a known entity: edema blisters. Occurring most commonly in the setting of acute exacerbation of chronic venous insufficiency, edema blisters can mimic other vesiculobullous conditions, such as bullous pemphigoid and herpes zoster.3

Pathogenesis of Edema Blisters—Edema develops in the skin when the capillary filtration rate, determined by the hydrostatic and oncotic pressures of the capillaries and interstitium, exceeds venous and lymphatic drainage. The appearance of edema blisters in the acute setting likely is related to the speed at which edema develops in skin.1 Although edema blisters often are described as tense, there is a paucity of histologic data at the anatomical level of split in the skin.In our patient, desquamation was within the stratum corneum and likely multifactorial. His weight gain of nearly 40 lb, the result of intravenous instillation of fluids and low urine output, was undeniably a contributing factor. The anasarca was aggravated by hypoalbuminemia (2.1 g/dL) in the setting of known liver disease. Other possible contributing factors were hypotension, which required vasopressor therapy that led to hypoperfusion of the skin, and treatment of hypothermia, with resulting reactive vasodilation and capillary leak.

Management—Treatment of acute edema blisters is focused on the underlying cause of the edema. In a study of 13 patients with edema blisters, all had blisters on the legs that resolved with treatment, such as diuretics or compression therapy.1

Anasarca-induced desquamation is an inherently benign condition that mimics potentially fatal disorders, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and toxic shock syndrome. Therefore, patients presenting with diffuse superficial desquamation should be assessed for the mucosal changes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and a history of acute edema in the affected areas to avoid potentially harmful empiric treatments, such as corticosteroids and intravenous antibiotics.

Conclusion

Anasarca-induced desquamation represents a more diffuse form of edema blisters. This desquamation can mimic a potentially fatal rash, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome.

- Bhushan M, Chalmers RJ, Cox NH. Acute oedema blisters: a report of 13 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:580-582. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04087.x

- Fabiani J, Bork K. Acute edema blisters on a skin swelling: an unusual manifestation of hereditary angioedema. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:556-557. doi:10.2340/00015555-2252

- Chen SX, Cohen PR. Edema bullae mimicking disseminated herpes zoster. Cureus. 2017;9:E1780. doi:10.7759/cureus.1780

- Bhushan M, Chalmers RJ, Cox NH. Acute oedema blisters: a report of 13 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:580-582. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04087.x

- Fabiani J, Bork K. Acute edema blisters on a skin swelling: an unusual manifestation of hereditary angioedema. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:556-557. doi:10.2340/00015555-2252

- Chen SX, Cohen PR. Edema bullae mimicking disseminated herpes zoster. Cureus. 2017;9:E1780. doi:10.7759/cureus.1780

Practice Points

- The appearance of anasarca-induced desquamation can be similar to staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

- Histopathologic evaluation of this condition shows desquamation localized to the stratum corneum without epidermal necrosis.

- Careful evaluation, including bacterial culture, is required to rule out an infectious cause.

- Early diagnosis of anasarca-induced desquamation reduces the potential for providing harmful empiric treatment, such as systemic steroids and intravenous antibiotics, especially in patients known to have comorbidities.

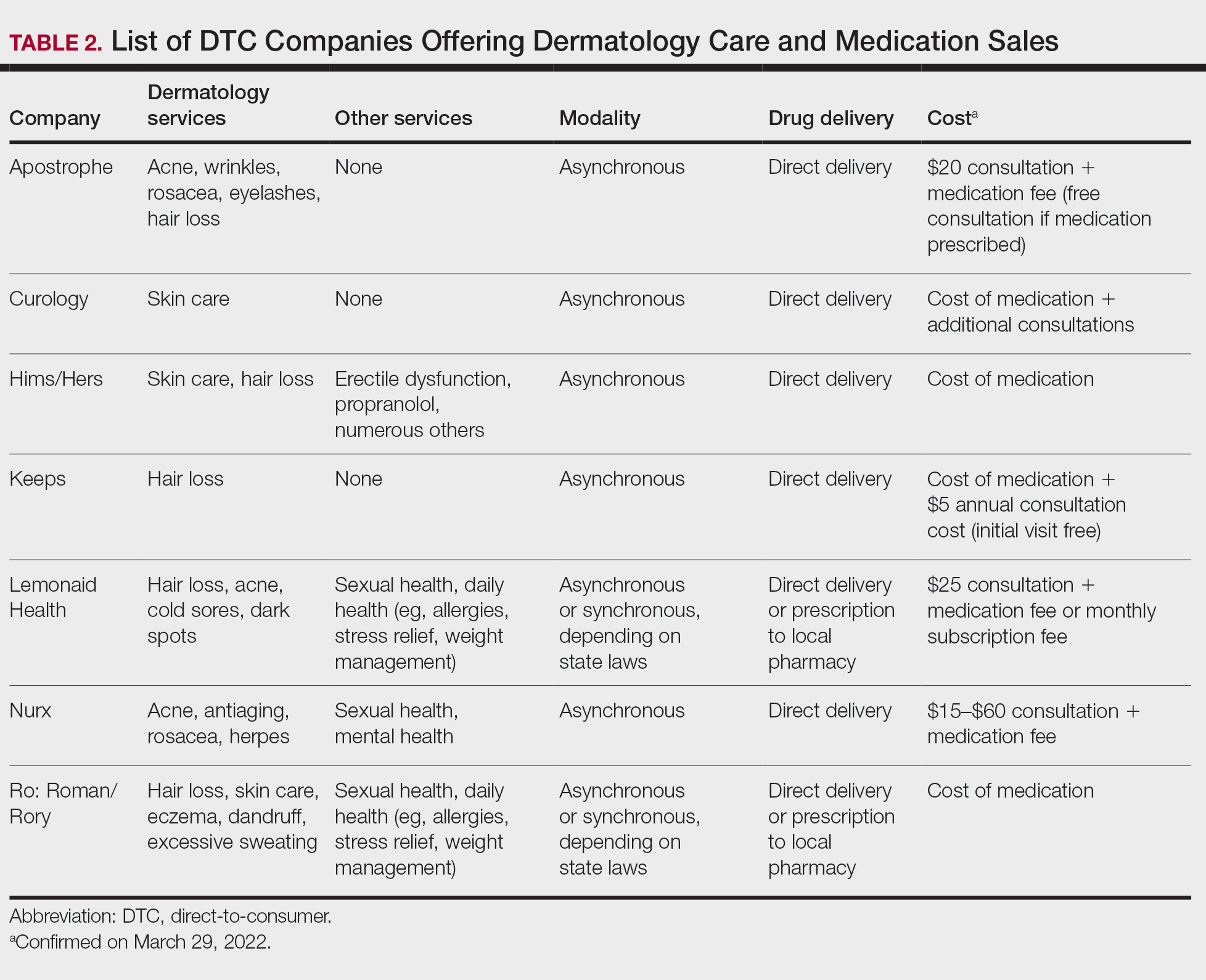

Direct-to-Consumer Teledermatology Growth: A Review and Outlook for the Future

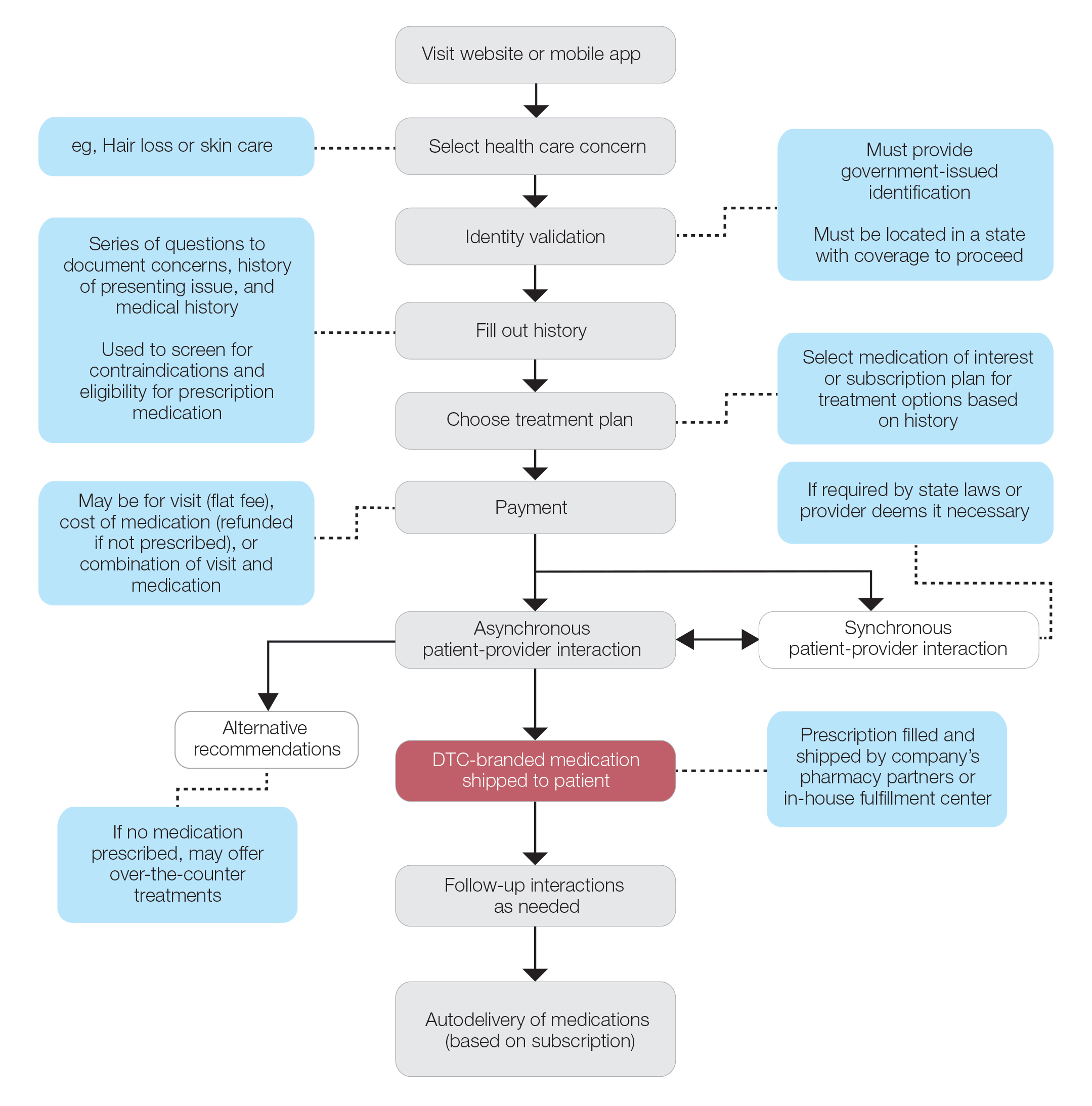

In recent years, direct-to-consumer (DTC) teledermatology platforms have gained popularity as telehealth business models, allowing patients to directly initiate visits with physicians and purchase medications from single platforms. A shortage of dermatologists, improved technology, drug patent expirations, and rising health care costs accelerated the growth of DTC dermatology.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, teledermatology adoption surged due to the need to provide care while social distancing and minimizing viral exposure. These needs prompted additional federal funding and loosened regulatory provisions.2 As the userbase of these companies has grown, so have their valuations.3 Although the DTC model has attracted the attention of patients and investors, its rise provokes many questions about patients acting as consumers in health care. Indeed, DTC telemedicine offers greater autonomy and convenience for patients, but it may impact the quality of care and the nature of physician-patient relationships, perhaps making them more transactional.

Evolution of DTC in Health Care

The DTC model emphasizes individual choice and accessible health care. Although the definition has evolved, the core idea is not new.4 Over decades, pharmaceutical companies have spent billions of dollars on DTC advertising, circumventing physicians by directly reaching patients with campaigns on prescription drugs and laboratory tests and shaping public definitions of diseases.5

The DTC model of care is fundamentally different from traditional care models in that it changes the roles of the patient and physician. Whereas early telehealth models required a health care provider to initiate teleconsultations with specialists, DTC telemedicine bypasses this step (eg, the patient can consult a dermatologist without needing a primary care provider’s input first). This care can then be provided by dermatologists with whom patients may or may not have pre-established relationships.4,6