User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Kaposi Varicelliform Eruption of Mpox in a Peeling Sunburn

To the Editor:

The recent global mpox (monkeypox) outbreak that started in May 2022 has distinctive risk factors, clinical features, and patient attributes that can portend dissemination of infection. We report a case of Kaposi varicelliform eruption (KVE) over a peeling sunburn after mpox infection. Dermatologists should recognize cutaneous risk factors for dissemination of mpox.

A 35-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with a papulopustular eruption that began on the shoulders in an area that had been sunburned 24 to 48 hours earlier. He experienced fever (temperature, 38.6 °C)[101.5 °F]), chills, malaise, and the appearance of a painful penile ulcer. He reported a recent male sexual partner a week prior to the eruption during travel to eastern Asia and a subsequent male partner in the United States 5 days prior to eruption. Physical examination revealed a peeling sunburn with sharp clothing demarcation. Locations with the most notable desquamation—the superior shoulders, dorsal arms, upper chest, and ventral thighs—positively correlated with the highest density of scattered, discrete, erythematous-based pustules and pink papules, some with crusted umbilication (Figures 1 and 2). Lesions spared sun-protected locations except a punctate painful ulcer on the buccal mucosa and a tender well-demarcated ulcer with elevated borders on the ventral penile shaft. HIV antigen/antibody testing was negative; syphilis antibody testing was positive due to a prior infection 1 year earlier with titers down to 1:1. A penile ulcer swab did not detect herpes simplex virus types 1/2 DNA. Pharyngeal, penile, and rectal swabs were negative for chlamydia or gonorrhea DNA. A polymerase chain reaction assay of a pustule was positive for orthopoxvirus, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed Monkeypox virus. On day 12, a penile ulcer biopsy was nonspecific with dense mixed inflammation; immunohistochemical stains for Treponema pallidum and herpes simplex virus types 1/2 were negative. Consideration was given to starting antiviral treatment with tecovirimat, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for smallpox caused by variola virus, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expanded access protocol, but the patient’s symptoms and lesions cleared quickly without intervention. The patient’s recent sexual contact in the United States later tested positive for mpox. Given that the density of our patient’s mpox lesions positively correlated with areas of peeling sunburn with rapid spread during the period of desquamation, he was diagnosed with KVE due to mpox in the setting of a peeling sunburn.

The recent mpox outbreak began in May 2022, and within 3 months there were more than 31,000 confirmed mpox cases worldwide, with more than 11,000 of those cases within the United States across 49 states and Puerto Rico.1 Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men have constituted the majority of cases. Although prior outbreaks have exhibited cases of classic mpox lesions, the current cases are clinically distinctive from classic mpox due to prevalent orogenital involvement and generalized symptoms that often are mild, nonexistent, or can occur after the cutaneous lesions.2

Although most current cases of mpox have been mildly symptomatic, several patients have been ill enough to require hospital admission, including patients with severe anogenital ulcerative lesions or bacterial superinfection.3 Antiviral treatment with tecovirimat may be warranted for patients with severe disease or those at risk of becoming severe due to immunosuppression, pregnancy/breastfeeding, complications (as determined by the provider), younger age (ie, pediatric patients), or skin barrier disruption. Dermatologists play a particularly important role in identifying cutaneous risk factors that may indicate progression of infection (eg, atopic dermatitis, severe acne, intertrigo, Darier disease). Kaposi varicelliform eruption is the phenomenon where a more typically localized vesicular infection is disseminated to areas with a defective skin barrier.2 Eczema herpeticum refers to the most common type of KVE due to herpes simplex virus, but other known etiologies of KVE include coxsackievirus A16, vaccinia virus, varicella-zoster virus, and smallpox.2 Although classic mpox previously had only the theoretical potential to lead to a secondary KVE, we expect the literature to evolve as cases spread, with one recent report of eczema monkeypoxicum in the setting of atopic dermatitis.4

At the time of publication, mpox cases have notably dropped globally due to public health interventions; however, mpox infections are ongoing in areas previously identified as nonendemic. Given the distinctive risk factors and clinical presentations of this most recent outbreak, clinicians will need to be adept at identifying not only infection but also risk for dissemination, including skin barrier disruption.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 US map & case count. Updated February 15, 2023. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/us-map.html

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls. Updated September 12, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432

- Girometti N, Byrne R, Bracchi M, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in individuals attending a sexual health centre in London, UK: an observational analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;S1473-3099(22)00411-X. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00411-X

- Xia J, Huang CL, Chu P, et al. Eczema monkeypoxicum: report of monkeypox transmission in patients with atopic dermatitis. JAAD Case Reports. 2022;29:95-99.

To the Editor:

The recent global mpox (monkeypox) outbreak that started in May 2022 has distinctive risk factors, clinical features, and patient attributes that can portend dissemination of infection. We report a case of Kaposi varicelliform eruption (KVE) over a peeling sunburn after mpox infection. Dermatologists should recognize cutaneous risk factors for dissemination of mpox.

A 35-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with a papulopustular eruption that began on the shoulders in an area that had been sunburned 24 to 48 hours earlier. He experienced fever (temperature, 38.6 °C)[101.5 °F]), chills, malaise, and the appearance of a painful penile ulcer. He reported a recent male sexual partner a week prior to the eruption during travel to eastern Asia and a subsequent male partner in the United States 5 days prior to eruption. Physical examination revealed a peeling sunburn with sharp clothing demarcation. Locations with the most notable desquamation—the superior shoulders, dorsal arms, upper chest, and ventral thighs—positively correlated with the highest density of scattered, discrete, erythematous-based pustules and pink papules, some with crusted umbilication (Figures 1 and 2). Lesions spared sun-protected locations except a punctate painful ulcer on the buccal mucosa and a tender well-demarcated ulcer with elevated borders on the ventral penile shaft. HIV antigen/antibody testing was negative; syphilis antibody testing was positive due to a prior infection 1 year earlier with titers down to 1:1. A penile ulcer swab did not detect herpes simplex virus types 1/2 DNA. Pharyngeal, penile, and rectal swabs were negative for chlamydia or gonorrhea DNA. A polymerase chain reaction assay of a pustule was positive for orthopoxvirus, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed Monkeypox virus. On day 12, a penile ulcer biopsy was nonspecific with dense mixed inflammation; immunohistochemical stains for Treponema pallidum and herpes simplex virus types 1/2 were negative. Consideration was given to starting antiviral treatment with tecovirimat, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for smallpox caused by variola virus, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expanded access protocol, but the patient’s symptoms and lesions cleared quickly without intervention. The patient’s recent sexual contact in the United States later tested positive for mpox. Given that the density of our patient’s mpox lesions positively correlated with areas of peeling sunburn with rapid spread during the period of desquamation, he was diagnosed with KVE due to mpox in the setting of a peeling sunburn.

The recent mpox outbreak began in May 2022, and within 3 months there were more than 31,000 confirmed mpox cases worldwide, with more than 11,000 of those cases within the United States across 49 states and Puerto Rico.1 Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men have constituted the majority of cases. Although prior outbreaks have exhibited cases of classic mpox lesions, the current cases are clinically distinctive from classic mpox due to prevalent orogenital involvement and generalized symptoms that often are mild, nonexistent, or can occur after the cutaneous lesions.2

Although most current cases of mpox have been mildly symptomatic, several patients have been ill enough to require hospital admission, including patients with severe anogenital ulcerative lesions or bacterial superinfection.3 Antiviral treatment with tecovirimat may be warranted for patients with severe disease or those at risk of becoming severe due to immunosuppression, pregnancy/breastfeeding, complications (as determined by the provider), younger age (ie, pediatric patients), or skin barrier disruption. Dermatologists play a particularly important role in identifying cutaneous risk factors that may indicate progression of infection (eg, atopic dermatitis, severe acne, intertrigo, Darier disease). Kaposi varicelliform eruption is the phenomenon where a more typically localized vesicular infection is disseminated to areas with a defective skin barrier.2 Eczema herpeticum refers to the most common type of KVE due to herpes simplex virus, but other known etiologies of KVE include coxsackievirus A16, vaccinia virus, varicella-zoster virus, and smallpox.2 Although classic mpox previously had only the theoretical potential to lead to a secondary KVE, we expect the literature to evolve as cases spread, with one recent report of eczema monkeypoxicum in the setting of atopic dermatitis.4

At the time of publication, mpox cases have notably dropped globally due to public health interventions; however, mpox infections are ongoing in areas previously identified as nonendemic. Given the distinctive risk factors and clinical presentations of this most recent outbreak, clinicians will need to be adept at identifying not only infection but also risk for dissemination, including skin barrier disruption.

To the Editor:

The recent global mpox (monkeypox) outbreak that started in May 2022 has distinctive risk factors, clinical features, and patient attributes that can portend dissemination of infection. We report a case of Kaposi varicelliform eruption (KVE) over a peeling sunburn after mpox infection. Dermatologists should recognize cutaneous risk factors for dissemination of mpox.

A 35-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with a papulopustular eruption that began on the shoulders in an area that had been sunburned 24 to 48 hours earlier. He experienced fever (temperature, 38.6 °C)[101.5 °F]), chills, malaise, and the appearance of a painful penile ulcer. He reported a recent male sexual partner a week prior to the eruption during travel to eastern Asia and a subsequent male partner in the United States 5 days prior to eruption. Physical examination revealed a peeling sunburn with sharp clothing demarcation. Locations with the most notable desquamation—the superior shoulders, dorsal arms, upper chest, and ventral thighs—positively correlated with the highest density of scattered, discrete, erythematous-based pustules and pink papules, some with crusted umbilication (Figures 1 and 2). Lesions spared sun-protected locations except a punctate painful ulcer on the buccal mucosa and a tender well-demarcated ulcer with elevated borders on the ventral penile shaft. HIV antigen/antibody testing was negative; syphilis antibody testing was positive due to a prior infection 1 year earlier with titers down to 1:1. A penile ulcer swab did not detect herpes simplex virus types 1/2 DNA. Pharyngeal, penile, and rectal swabs were negative for chlamydia or gonorrhea DNA. A polymerase chain reaction assay of a pustule was positive for orthopoxvirus, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed Monkeypox virus. On day 12, a penile ulcer biopsy was nonspecific with dense mixed inflammation; immunohistochemical stains for Treponema pallidum and herpes simplex virus types 1/2 were negative. Consideration was given to starting antiviral treatment with tecovirimat, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for smallpox caused by variola virus, through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expanded access protocol, but the patient’s symptoms and lesions cleared quickly without intervention. The patient’s recent sexual contact in the United States later tested positive for mpox. Given that the density of our patient’s mpox lesions positively correlated with areas of peeling sunburn with rapid spread during the period of desquamation, he was diagnosed with KVE due to mpox in the setting of a peeling sunburn.

The recent mpox outbreak began in May 2022, and within 3 months there were more than 31,000 confirmed mpox cases worldwide, with more than 11,000 of those cases within the United States across 49 states and Puerto Rico.1 Gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men have constituted the majority of cases. Although prior outbreaks have exhibited cases of classic mpox lesions, the current cases are clinically distinctive from classic mpox due to prevalent orogenital involvement and generalized symptoms that often are mild, nonexistent, or can occur after the cutaneous lesions.2

Although most current cases of mpox have been mildly symptomatic, several patients have been ill enough to require hospital admission, including patients with severe anogenital ulcerative lesions or bacterial superinfection.3 Antiviral treatment with tecovirimat may be warranted for patients with severe disease or those at risk of becoming severe due to immunosuppression, pregnancy/breastfeeding, complications (as determined by the provider), younger age (ie, pediatric patients), or skin barrier disruption. Dermatologists play a particularly important role in identifying cutaneous risk factors that may indicate progression of infection (eg, atopic dermatitis, severe acne, intertrigo, Darier disease). Kaposi varicelliform eruption is the phenomenon where a more typically localized vesicular infection is disseminated to areas with a defective skin barrier.2 Eczema herpeticum refers to the most common type of KVE due to herpes simplex virus, but other known etiologies of KVE include coxsackievirus A16, vaccinia virus, varicella-zoster virus, and smallpox.2 Although classic mpox previously had only the theoretical potential to lead to a secondary KVE, we expect the literature to evolve as cases spread, with one recent report of eczema monkeypoxicum in the setting of atopic dermatitis.4

At the time of publication, mpox cases have notably dropped globally due to public health interventions; however, mpox infections are ongoing in areas previously identified as nonendemic. Given the distinctive risk factors and clinical presentations of this most recent outbreak, clinicians will need to be adept at identifying not only infection but also risk for dissemination, including skin barrier disruption.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 US map & case count. Updated February 15, 2023. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/us-map.html

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls. Updated September 12, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432

- Girometti N, Byrne R, Bracchi M, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in individuals attending a sexual health centre in London, UK: an observational analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;S1473-3099(22)00411-X. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00411-X

- Xia J, Huang CL, Chu P, et al. Eczema monkeypoxicum: report of monkeypox transmission in patients with atopic dermatitis. JAAD Case Reports. 2022;29:95-99.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mpox: 2022 US map & case count. Updated February 15, 2023. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/us-map.html

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls. Updated September 12, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432

- Girometti N, Byrne R, Bracchi M, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of confirmed human monkeypox virus cases in individuals attending a sexual health centre in London, UK: an observational analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;S1473-3099(22)00411-X. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00411-X

- Xia J, Huang CL, Chu P, et al. Eczema monkeypoxicum: report of monkeypox transmission in patients with atopic dermatitis. JAAD Case Reports. 2022;29:95-99.

Practice Points

- Desquamation can be associated with dissemination and higher severity course in the setting of mpox (monkeypox) viral infection.

- Antiviral treatment with tecovirimat is warranted in those with severe mpox infection or those at risk of severe infection including skin barrier disruption.

- Kaposi varicelliform–like eruptions can happen in the setting of barrier disruption from peeling sunburns, atopic dermatitis, severe acne, and other dermatologic conditions.

Protuberant, Pink, Irritated Growth on the Buttocks

The Diagnosis: Superficial Angiomyxoma

Superficial angiomyxoma is a rare, benign, cutaneous tumor of a myxoid matrix and blood vessels that was first described in association with Carney complex.1 Tumors may be solitary or multiple. A recent review of cases in the literature revealed a roughly equal distribution of superficial angiomyxomas in males and females occurring most frequently on the head and neck, extremities, and trunk or back. The peak incidence is between the fourth and fifth decades of life.2 Superficial angiomyxomas can occur sporadically or in association with Carney complex, an autosomal-dominant condition with germline inactivating mutations in protein kinase A, PRKAR1A. Interestingly, sporadic cases of superficial angiomyxoma also have shown loss of PRKAR1A expression on immunohistochemistry (IHC).3

Common histologic mimics of superficial angiomyxoma include aggressive angiomyxoma and angiomyofibroblastoma.4 It is thought that these 3 distinct tumor entities may arise from a common pluripotent cell of origin located near connective tissue vasculature, which may contribute to the similarities observed between them.5 For example, aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas also demonstrate a similar myxoid background and vascular proliferation that can closely mimic superficial angiomyxomas clinically. However, the vessels of superficial angiomyxomas tend to be long and thin walled, while aggressive angiomyxomas are characterized by large and thick-walled vessels and angiomyofibroblastomas by abundant smaller vessels. Additionally, unlike superficial angiomyxomas, both aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas typically occur in the genital tract of young to middle-aged women.6

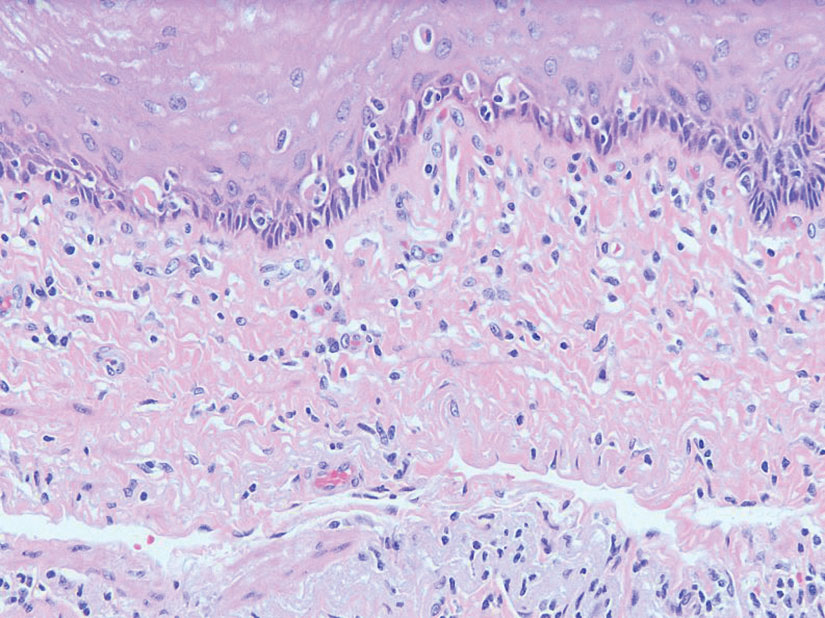

Histopathologic examination is imperative for differentiating between superficial angiomyxoma and more aggressive histologic mimics. Superficial angiomyxomas typically consist of a rich myxoid stroma, thin-walled or arborizing blood vessels, and spindled to stellate fibroblastlike cells (quiz image 2).3 Although not prominent in our case, superficial angiomyxomas also frequently present with stromal neutrophils and epithelial components, including keratinous cysts, basaloid buds, and strands of squamous epithelium.7 Minimal cellular atypia, mitotic activity, and nuclear pleomorphism often are seen, with IHC negative for desmin, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor; positive for CD34 and smooth muscle actin; and variable for S-100 and muscle-specific actin. Although IHC has limited utility in the diagnosis of superficial angiomyxomas, it may be useful to rule out other differential diagnoses.2,3 Superficial angiomyxomas usually show fibroblastic stromal cells, proteoglycan matrix, and collagen fibers on electron microscopy.8 Importantly, histopathologic examination of aggressive angiomyxoma will comparatively present with more invasive, infiltrative, and less well-circumscribed tumors.9 Other differential diagnoses on histology may include neurofibroma, focal cutaneous mucinosis, spindle cell lipoma, and myxofibrosarcoma. Additional considerations include fibroepithelial polyp, nevus lipomatosis, angiomyxolipoma, and anetoderma.

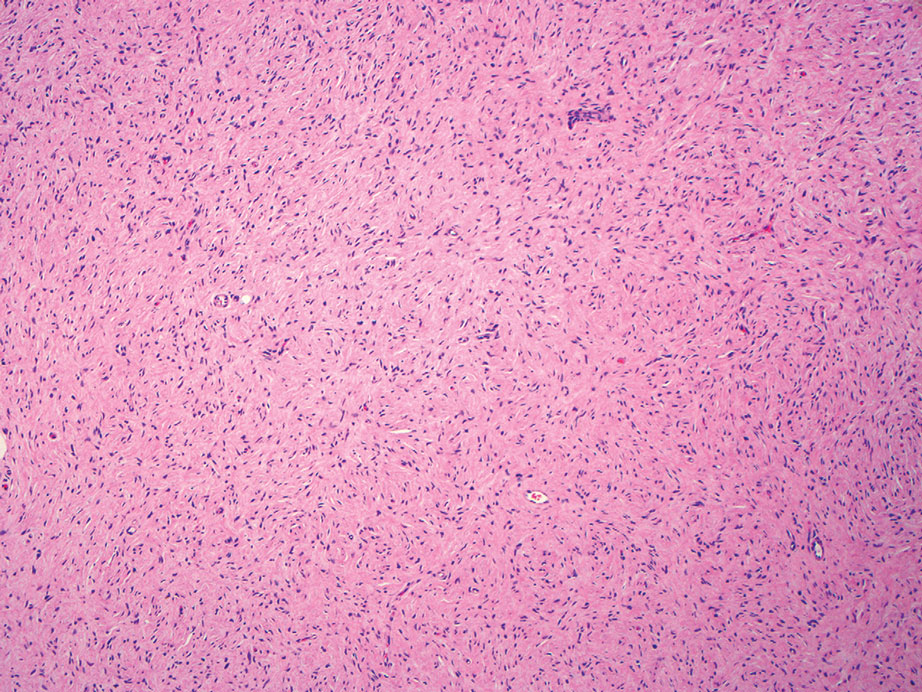

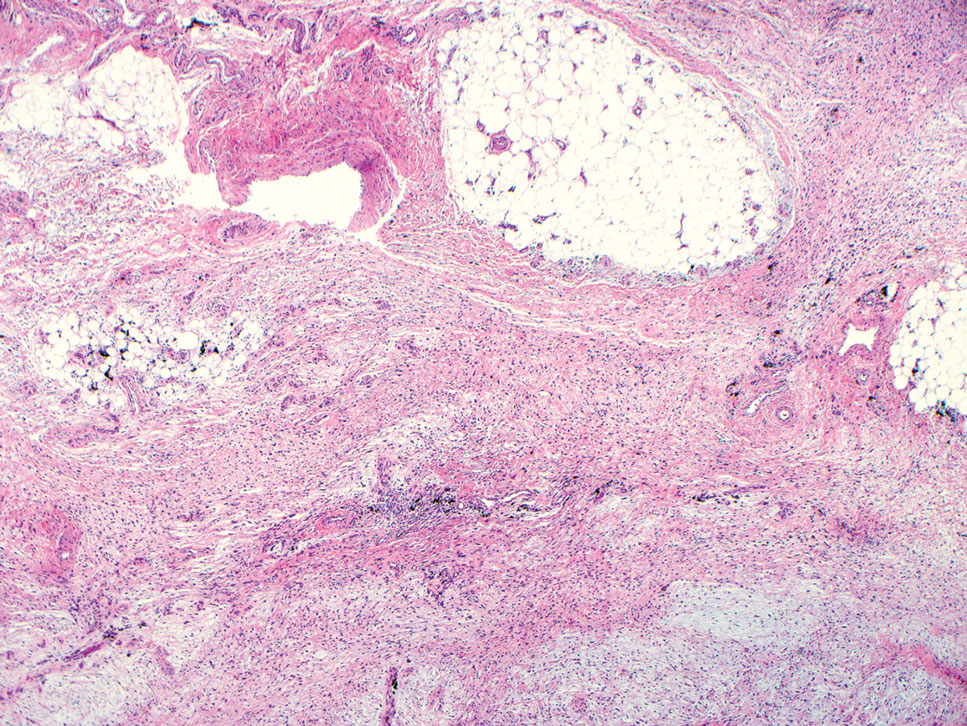

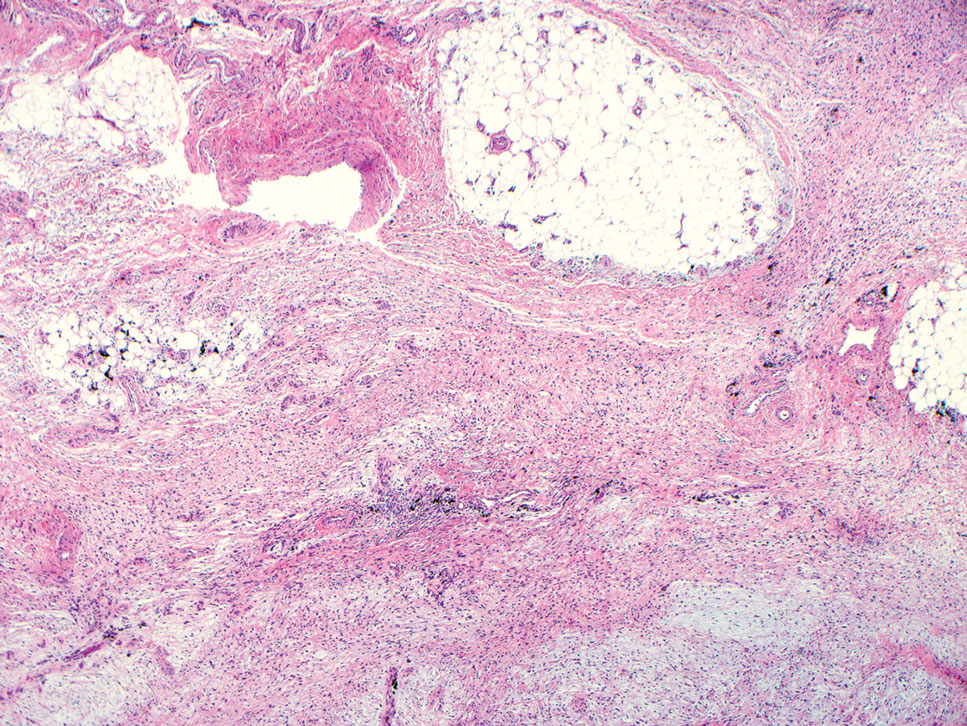

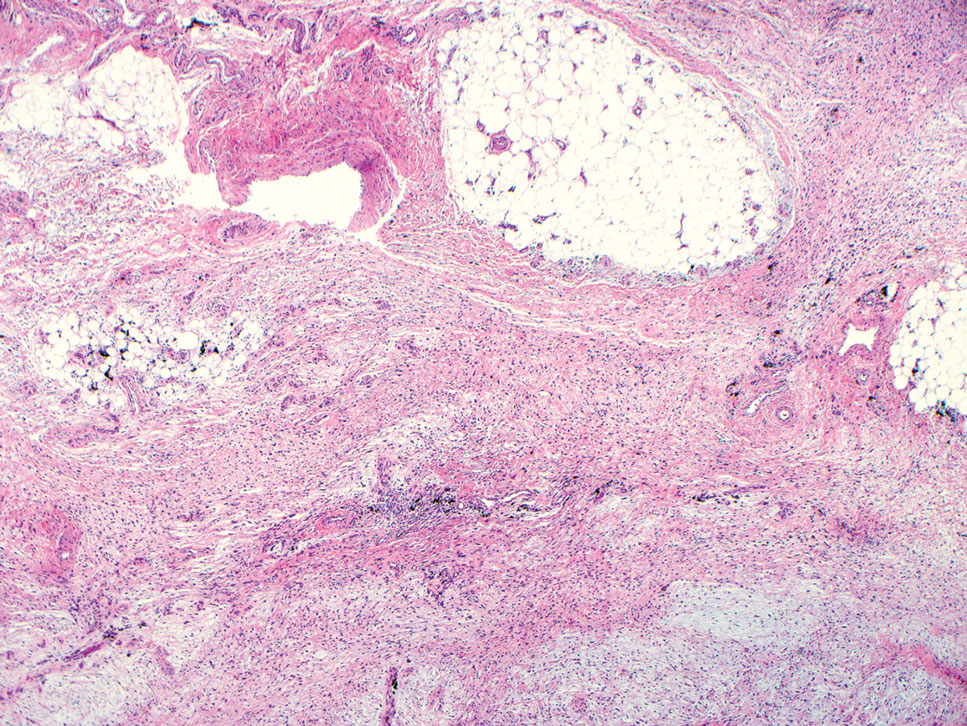

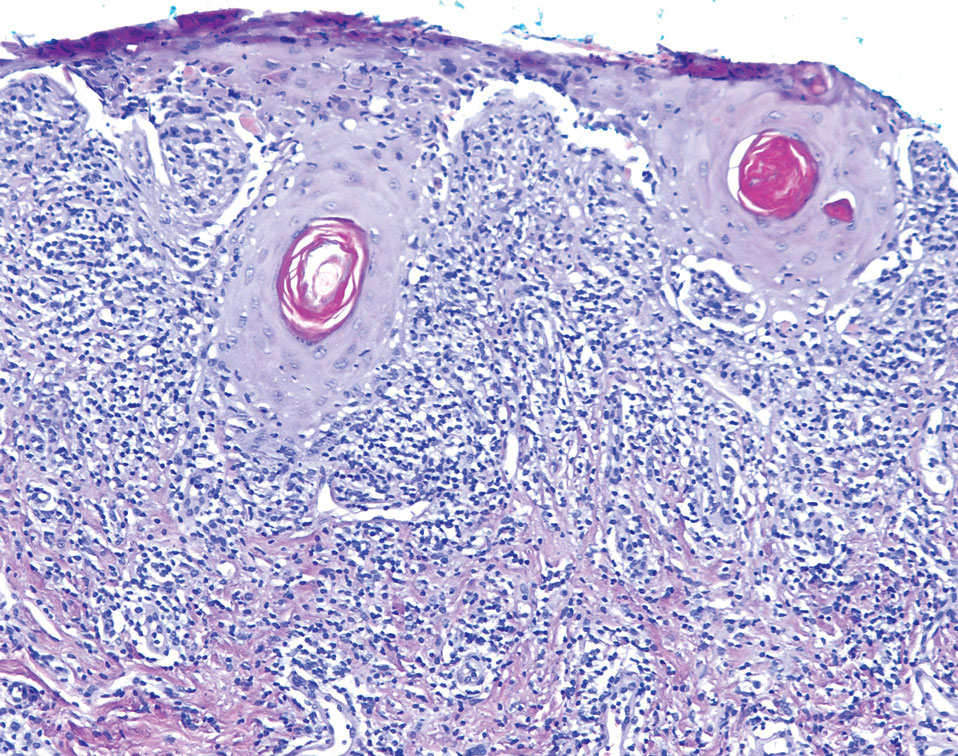

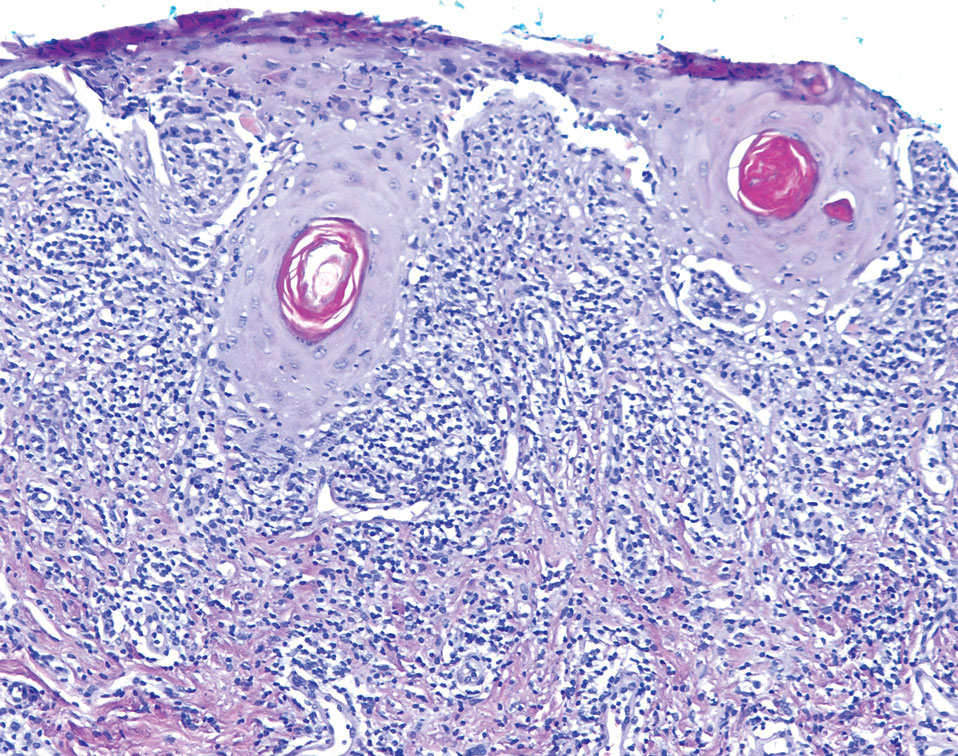

An important differential diagnosis in the evaluation of superficial angiomyxoma is neurofibroma, a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor that presents as a smooth, flesh-colored, and painless papule or nodule commonly associated with the buttonhole sign. Histopathology of neurofibroma features elongated spindle cells with comma-shaped or buckled wavy nuclei and variably sized collagen bundles described as “shredded carrots” (Figure 1).10 Occasional mast cells also can be seen. Immunohistochemistry targeting elements of peripheral nerve sheaths may assist in the diagnosis of neurofibromas, including positive S-100 and SOX10 in Schwann cells, epithelial membrane antigen in perineural cells, and fingerprint positivity for CD34 in fibroblasts.10

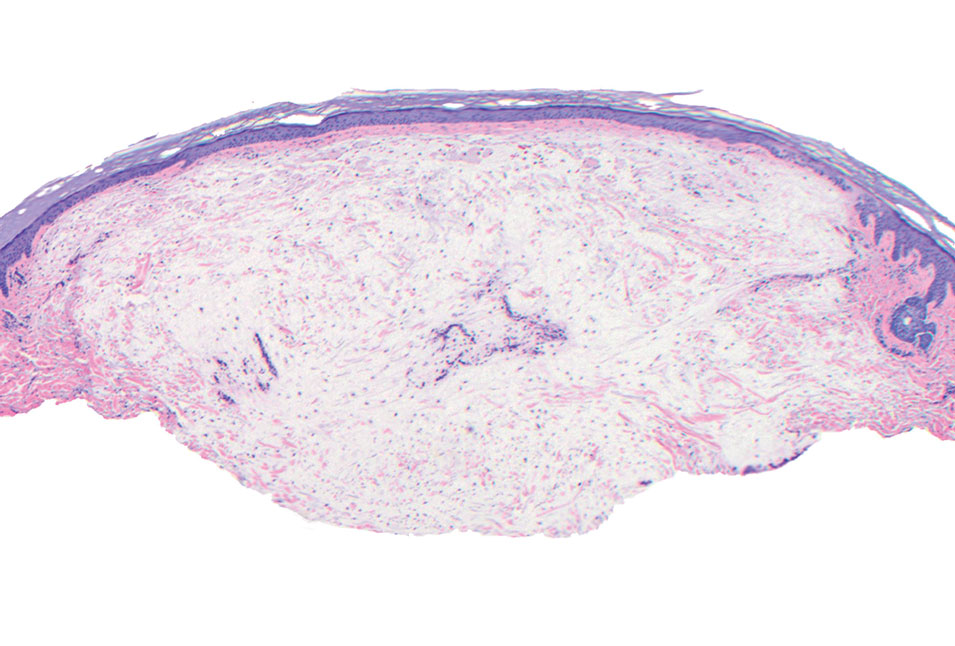

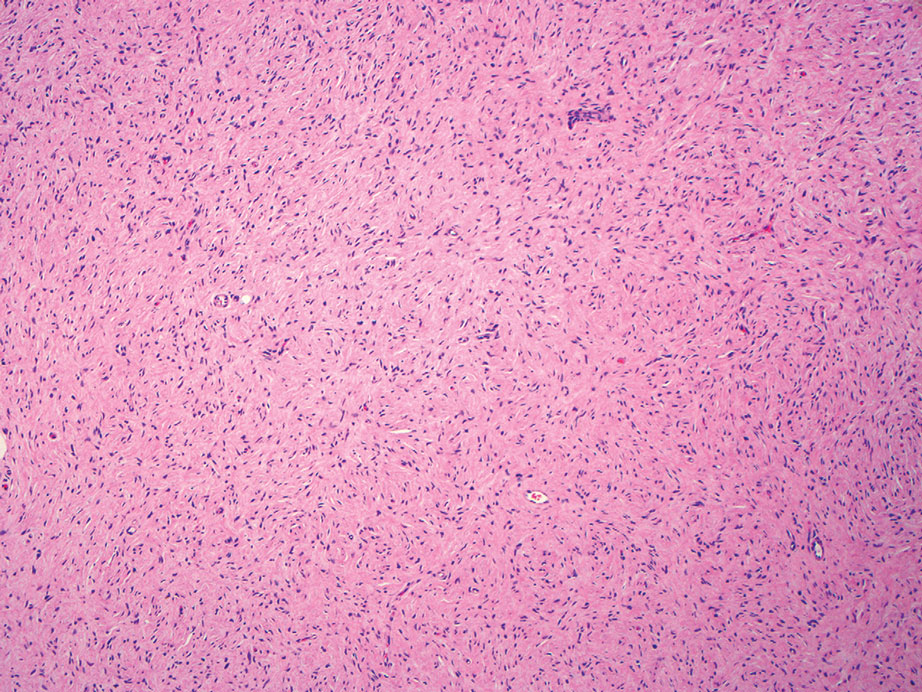

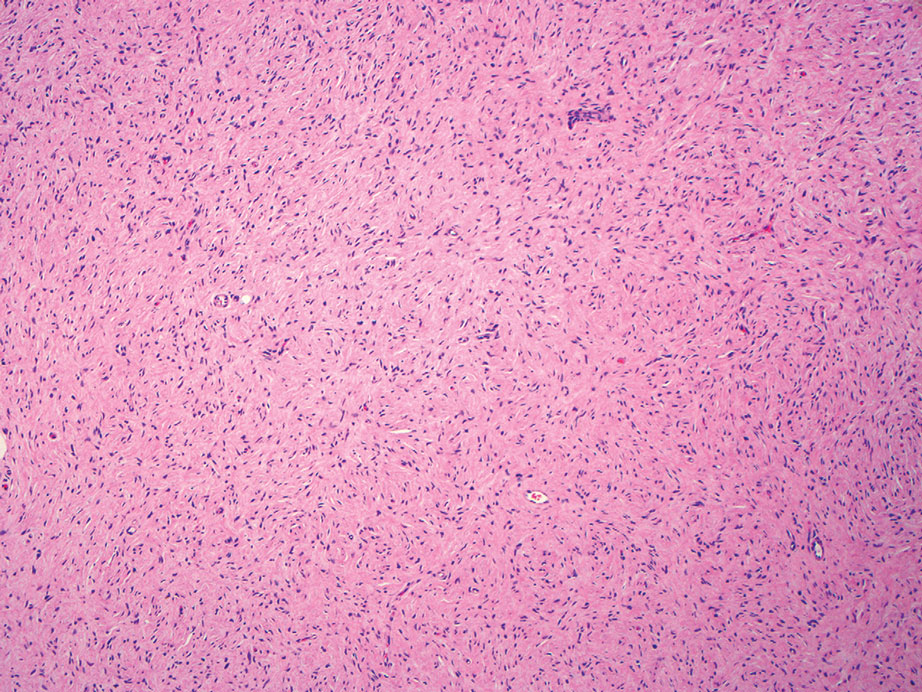

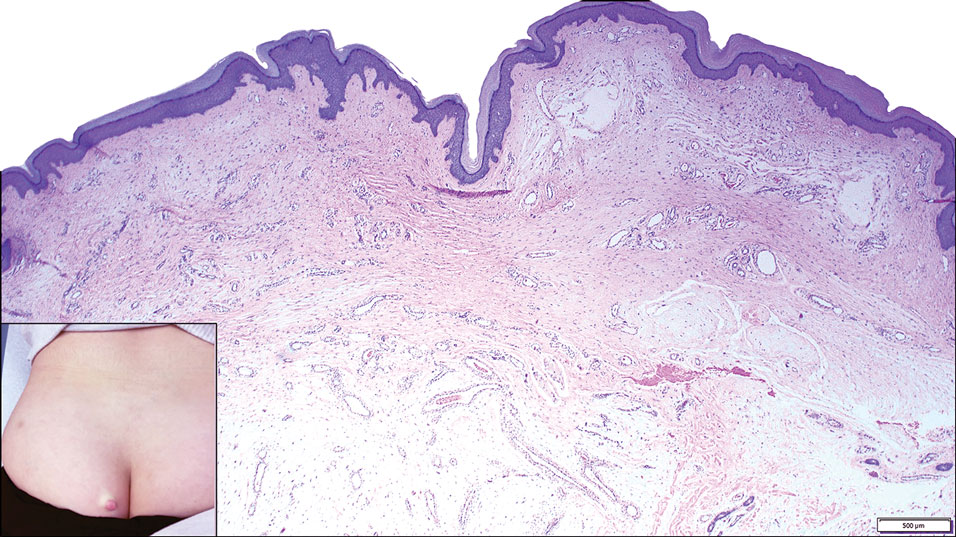

Cutaneous mucinoses encompass a diverse group of connective tissue disorders characterized by accumulation of mucin in the skin. Solitary focal cutaneous mucinoses (FCMs) are individual isolated lesions of mucin deposits that are unassociated with systemic conditions.11 Conversely, multiple FCMs presenting with multiple cutaneous lesions also have been described in association with systemic diseases such as scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and thyroid disease.12 Solitary FCM typically presents as an asymptomatic, flesh-colored papule or nodule on the extremities. It often arises in mid to late adulthood with a slightly increased frequency among males.12 Histopathology of solitary FCM commonly demonstrates a dome-shaped pool of basophilic mucin in the upper dermis sparing involvement of the underlying subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2).13 Notably, FCM often lacks the vascularity as well as stromal neutrophils and epithelial elements that are seen in superficial angiomyxomas. Although hematoxylin and eosin stains can be sufficient for diagnosis of solitary FCM, additional stains for mucin such as Alcian blue, colloidal iron, or toluidine blue also may be considered to support the diagnosis.12

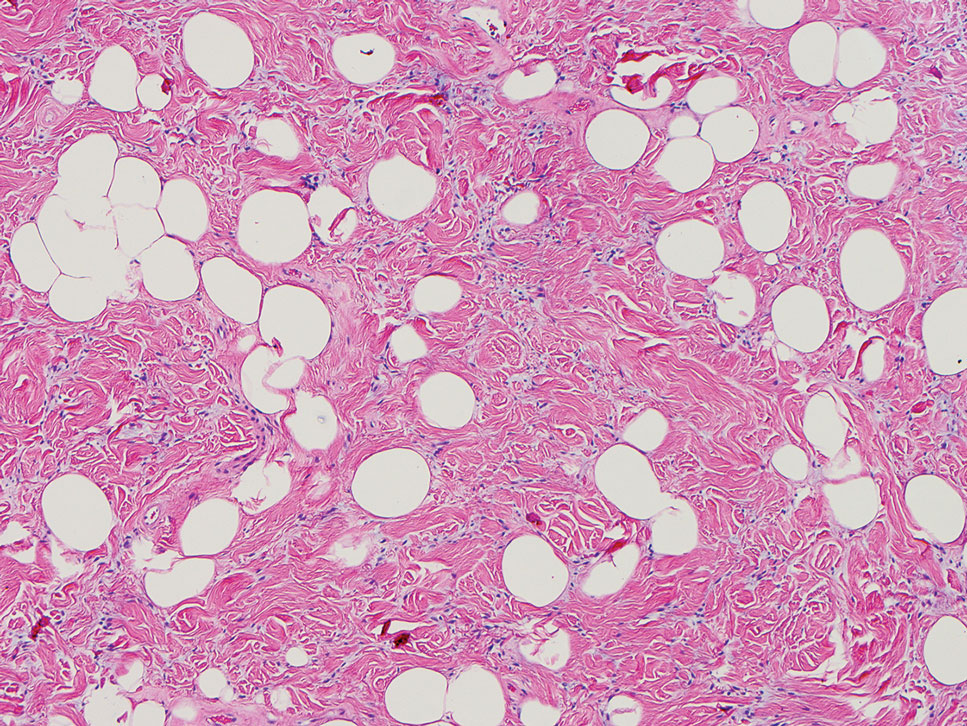

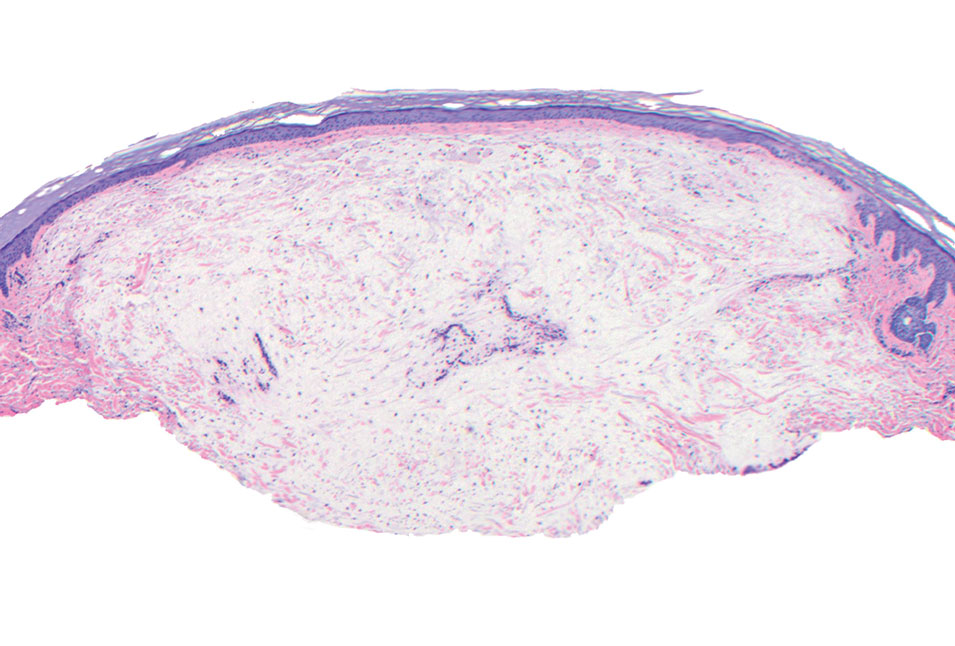

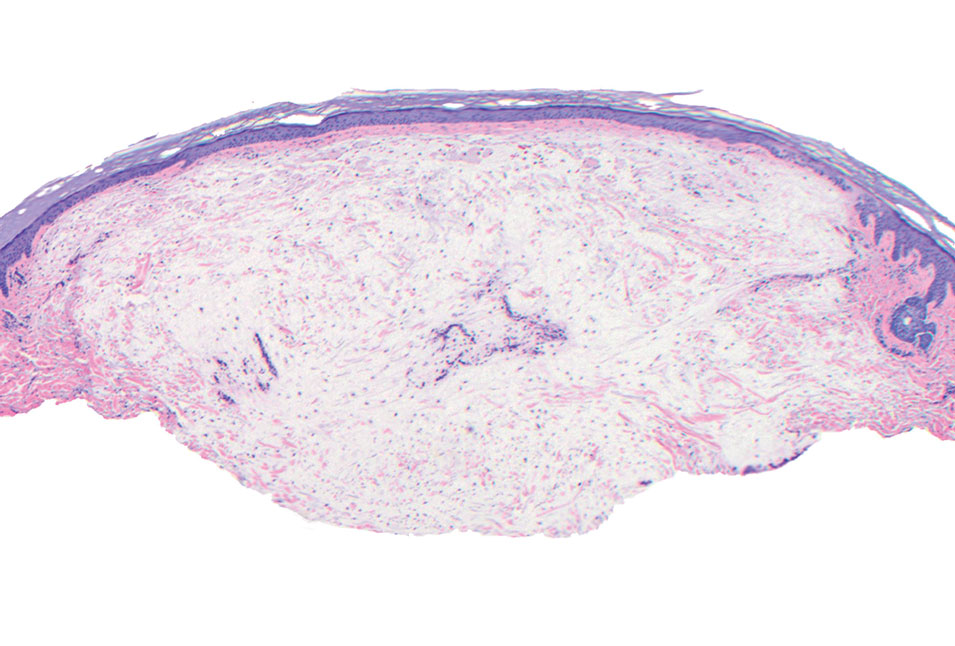

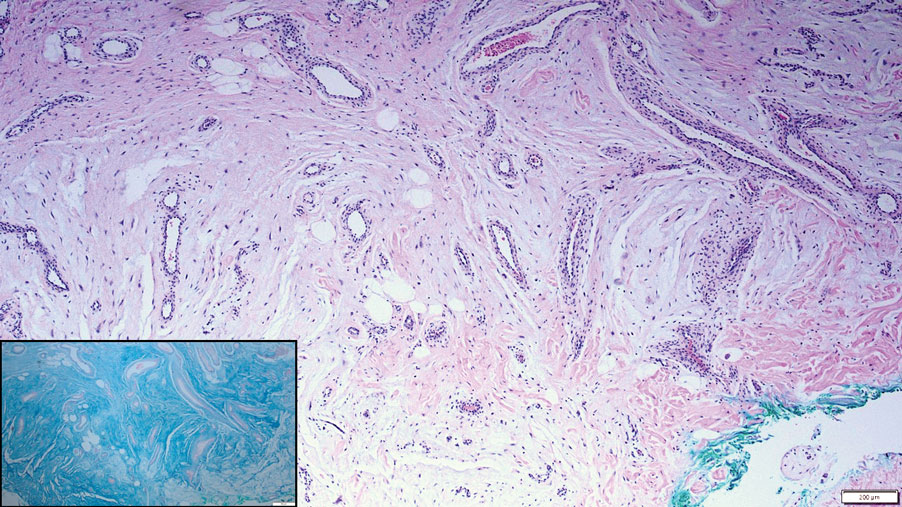

Spindle cell lipomas (SCLs) are rare, benign, subcutaneous, adipocytic tumors that arise on the upper back, posterior neck, or shoulders of middle-aged or elderly adult males.14 The clinical presentation often is an asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile subcutaneous mass that is firmer than a common lipoma. Histologically, SCLs are characterized by mature adipocytes, spindle cells, and wire or ropelike collagen fibers in a myxoid background (Figure 3). The spindle cells usually are bland with a notable bipolar shape and blunted ends. Infiltrative growth patterns or mitotic figures are uncommon. Diagnosis can be supported by IHC, as SCLs stain diffusely positive for CD34 with loss of the retinoblastoma protein.7

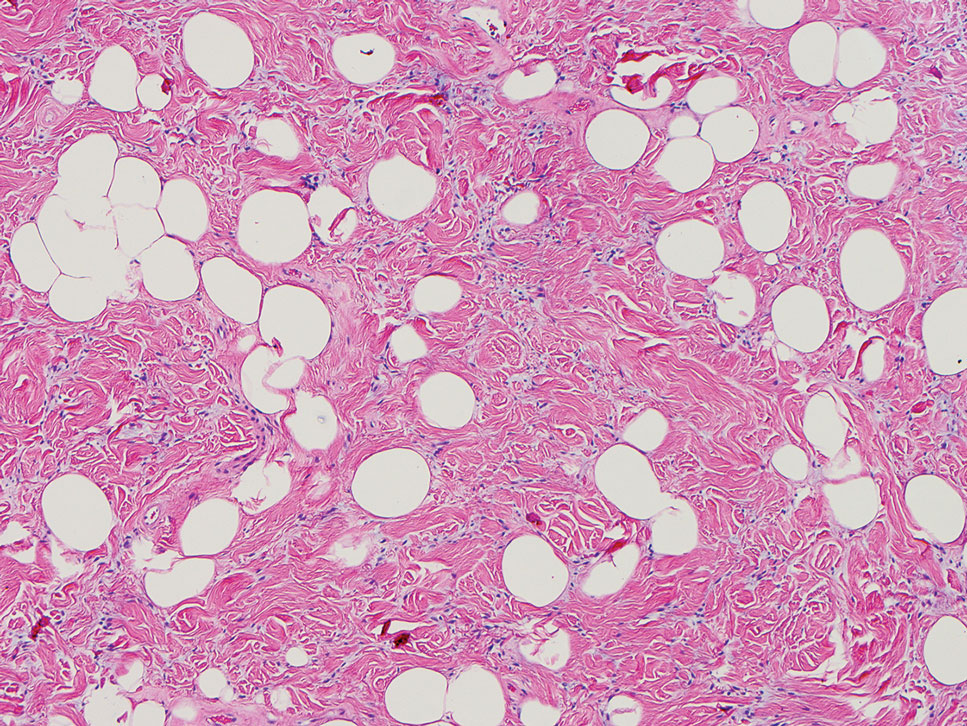

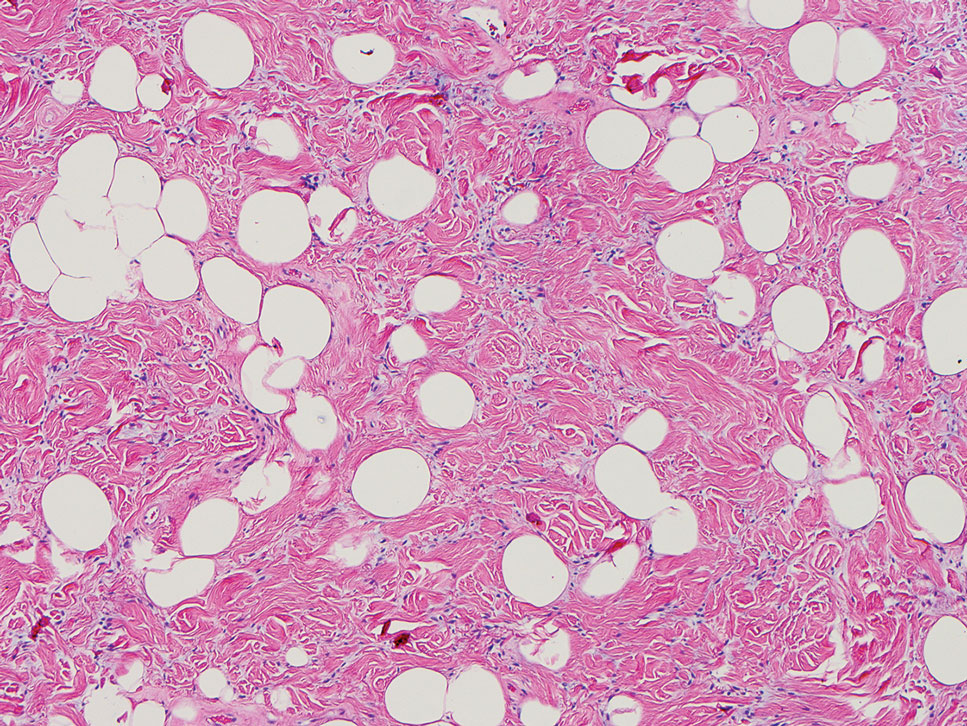

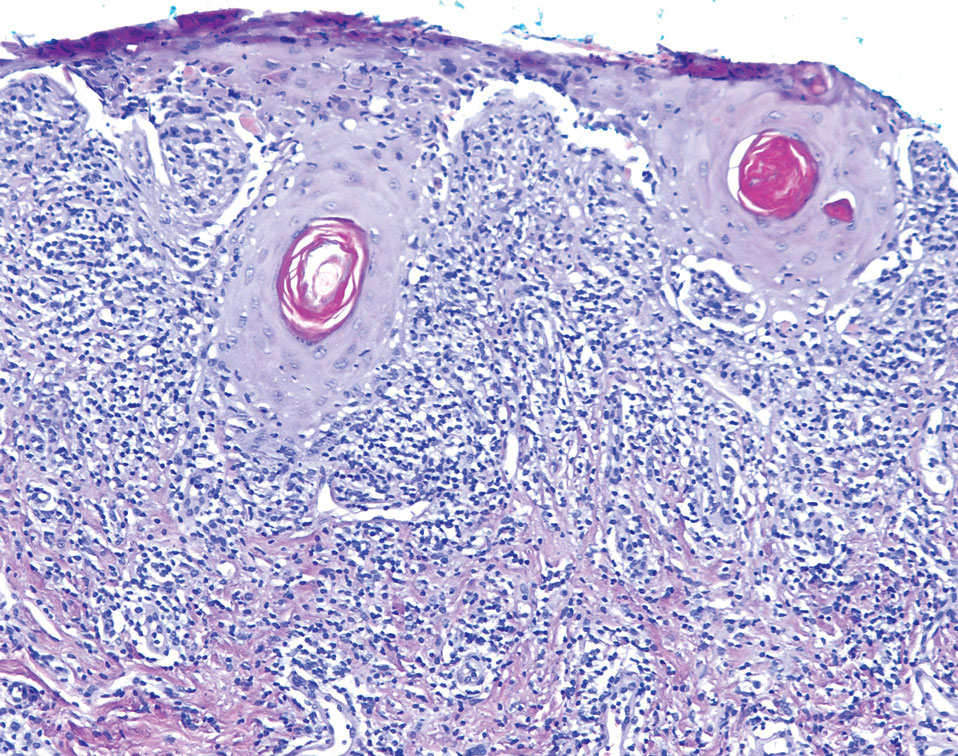

Another important differential diagnosis to consider is myxofibrosarcoma, a rare and malignant myxoid cutaneous tumor. Clinically, it presents asymptomatically as an indolent, slow-growing nodule on the limbs and limb girdles.7 Histopathologic features demonstrate a multilobular tumor composed of a mixture of hypocellular and hypercellular regions with incomplete fibrous septae (Figure 4). The presence of curvilinear vasculature is characteristic. Multinucleated giant cells and cellular atypia with nuclear pleomorphism also can be seen. Although IHC findings generally are not specific, they can be used to rule out other potential diagnoses. Myxofibrosarcomas stain positive for vimentin and occasionally smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and CD34.7

Superficial angiomyxomas are benign; however, excision is recommended to distinguish between mimics. Local recurrence after excision is common in 30% to 40% of patients.15 Mohs micrographic surgery has been considered, especially if the following are present: tumor characteristics (eg, poorly circumscribed), location (eg, head and neck or other cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas), and likelihood of recurrence (high for superficial angiomyxomas). 16 This case otherwise highlights a rare example of superficial angiomyxomas involving the buttocks.

- Allen PW, Dymock RB, MacCormac LB. Superficial angiomyxomas with and without epithelial components. report of 30 tumors in 28 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:519-530. doi:10.1097 /00000478-198807000-00003

- Sharma A, Khaitan N, Ko JS, et al. A clinicopathologic analysis of 54 cases of cutaneous myxoma. Hum Pathol. 2021:S0046-8177(21) 00201-X. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2021.12.003

- Hafeez F, Krakowski AC, Lian CG, et al. Sporadic superficial angiomyxomas demonstrate loss of PRKAR1A expression [published online March 17, 2022]. Histopathology. 2022;80:1001-1003. doi:10.1111/his.14568

- Mehrotra K, Bhandari M, Khullar G, et al. Large superficial angiomyxoma of the vulva: report of two cases with varied clinical presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:605-607. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_489_20

- Alameda F, Munné A, Baró T, et al. Vulvar angiomyxoma, aggressive angiomyxoma, and angiomyofibroblastoma: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2006;30:193-205. doi:10.1080/01913120500520911

- Haroon S, Irshad L, Zia S, et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma, angiomyofibroblastoma, and cellular angiofibroma of the lower female genital tract: related entities with different outcomes. Cureus. 2022;14:E29250. doi:10.7759/cureus.29250

- Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-918. doi:10.1111/cup.12749

- Allen PW. Myxoma is not a single entity: a review of the concept of myxoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2000;4:99-123. doi:10.1016 /s1092-9134(00)90019-4

- Lee C-C, Chen Y-L, Liau J-Y, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma on the vulva of an adolescent. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53:104-106. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2013.08.001

- Magro G, Amico P, Vecchio GM, et al. Multinucleated floret-like giant cells in sporadic and NF1-associated neurofibromas: a clinicopathologic study of 94 cases. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:71-76. doi:10.1007/s00428-009-0859-y

- Kuo KL, Lee LY, Kuo TT. Solitary cutaneous focal mucinosis: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases of soft fibroma-like cutaneous mucinous lesions. J Dermatol. 2017;44:335-338. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13523

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C, Calame A, et al. Solitary cutaneous focal mucinosis. Cureus. 2021;13:E18618. doi:10.7759/cureus.18618

- Biondo G, Sola S, Pastorino C, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic, and histologic aspects of two cases of cutaneous focal mucinosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:334-336. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198381

- Chen S, Huang H, He S, et al. Spindle cell lipoma: clinicopathologic characterization of 40 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:2613-2621.

- Bembem K, Jaiswal A, Singh M, et al. Cyto-histo correlation of a very rare tumor: superficial angiomyxoma. J Cytol. 2017;34:230-232. doi:10.4103/0970-9371.216119

- Aberdein G, Veitch D, Perrett C. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of superficial angiomyxoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42: 1014-1016. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000782

The Diagnosis: Superficial Angiomyxoma

Superficial angiomyxoma is a rare, benign, cutaneous tumor of a myxoid matrix and blood vessels that was first described in association with Carney complex.1 Tumors may be solitary or multiple. A recent review of cases in the literature revealed a roughly equal distribution of superficial angiomyxomas in males and females occurring most frequently on the head and neck, extremities, and trunk or back. The peak incidence is between the fourth and fifth decades of life.2 Superficial angiomyxomas can occur sporadically or in association with Carney complex, an autosomal-dominant condition with germline inactivating mutations in protein kinase A, PRKAR1A. Interestingly, sporadic cases of superficial angiomyxoma also have shown loss of PRKAR1A expression on immunohistochemistry (IHC).3

Common histologic mimics of superficial angiomyxoma include aggressive angiomyxoma and angiomyofibroblastoma.4 It is thought that these 3 distinct tumor entities may arise from a common pluripotent cell of origin located near connective tissue vasculature, which may contribute to the similarities observed between them.5 For example, aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas also demonstrate a similar myxoid background and vascular proliferation that can closely mimic superficial angiomyxomas clinically. However, the vessels of superficial angiomyxomas tend to be long and thin walled, while aggressive angiomyxomas are characterized by large and thick-walled vessels and angiomyofibroblastomas by abundant smaller vessels. Additionally, unlike superficial angiomyxomas, both aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas typically occur in the genital tract of young to middle-aged women.6

Histopathologic examination is imperative for differentiating between superficial angiomyxoma and more aggressive histologic mimics. Superficial angiomyxomas typically consist of a rich myxoid stroma, thin-walled or arborizing blood vessels, and spindled to stellate fibroblastlike cells (quiz image 2).3 Although not prominent in our case, superficial angiomyxomas also frequently present with stromal neutrophils and epithelial components, including keratinous cysts, basaloid buds, and strands of squamous epithelium.7 Minimal cellular atypia, mitotic activity, and nuclear pleomorphism often are seen, with IHC negative for desmin, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor; positive for CD34 and smooth muscle actin; and variable for S-100 and muscle-specific actin. Although IHC has limited utility in the diagnosis of superficial angiomyxomas, it may be useful to rule out other differential diagnoses.2,3 Superficial angiomyxomas usually show fibroblastic stromal cells, proteoglycan matrix, and collagen fibers on electron microscopy.8 Importantly, histopathologic examination of aggressive angiomyxoma will comparatively present with more invasive, infiltrative, and less well-circumscribed tumors.9 Other differential diagnoses on histology may include neurofibroma, focal cutaneous mucinosis, spindle cell lipoma, and myxofibrosarcoma. Additional considerations include fibroepithelial polyp, nevus lipomatosis, angiomyxolipoma, and anetoderma.

An important differential diagnosis in the evaluation of superficial angiomyxoma is neurofibroma, a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor that presents as a smooth, flesh-colored, and painless papule or nodule commonly associated with the buttonhole sign. Histopathology of neurofibroma features elongated spindle cells with comma-shaped or buckled wavy nuclei and variably sized collagen bundles described as “shredded carrots” (Figure 1).10 Occasional mast cells also can be seen. Immunohistochemistry targeting elements of peripheral nerve sheaths may assist in the diagnosis of neurofibromas, including positive S-100 and SOX10 in Schwann cells, epithelial membrane antigen in perineural cells, and fingerprint positivity for CD34 in fibroblasts.10

Cutaneous mucinoses encompass a diverse group of connective tissue disorders characterized by accumulation of mucin in the skin. Solitary focal cutaneous mucinoses (FCMs) are individual isolated lesions of mucin deposits that are unassociated with systemic conditions.11 Conversely, multiple FCMs presenting with multiple cutaneous lesions also have been described in association with systemic diseases such as scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and thyroid disease.12 Solitary FCM typically presents as an asymptomatic, flesh-colored papule or nodule on the extremities. It often arises in mid to late adulthood with a slightly increased frequency among males.12 Histopathology of solitary FCM commonly demonstrates a dome-shaped pool of basophilic mucin in the upper dermis sparing involvement of the underlying subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2).13 Notably, FCM often lacks the vascularity as well as stromal neutrophils and epithelial elements that are seen in superficial angiomyxomas. Although hematoxylin and eosin stains can be sufficient for diagnosis of solitary FCM, additional stains for mucin such as Alcian blue, colloidal iron, or toluidine blue also may be considered to support the diagnosis.12

Spindle cell lipomas (SCLs) are rare, benign, subcutaneous, adipocytic tumors that arise on the upper back, posterior neck, or shoulders of middle-aged or elderly adult males.14 The clinical presentation often is an asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile subcutaneous mass that is firmer than a common lipoma. Histologically, SCLs are characterized by mature adipocytes, spindle cells, and wire or ropelike collagen fibers in a myxoid background (Figure 3). The spindle cells usually are bland with a notable bipolar shape and blunted ends. Infiltrative growth patterns or mitotic figures are uncommon. Diagnosis can be supported by IHC, as SCLs stain diffusely positive for CD34 with loss of the retinoblastoma protein.7

Another important differential diagnosis to consider is myxofibrosarcoma, a rare and malignant myxoid cutaneous tumor. Clinically, it presents asymptomatically as an indolent, slow-growing nodule on the limbs and limb girdles.7 Histopathologic features demonstrate a multilobular tumor composed of a mixture of hypocellular and hypercellular regions with incomplete fibrous septae (Figure 4). The presence of curvilinear vasculature is characteristic. Multinucleated giant cells and cellular atypia with nuclear pleomorphism also can be seen. Although IHC findings generally are not specific, they can be used to rule out other potential diagnoses. Myxofibrosarcomas stain positive for vimentin and occasionally smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and CD34.7

Superficial angiomyxomas are benign; however, excision is recommended to distinguish between mimics. Local recurrence after excision is common in 30% to 40% of patients.15 Mohs micrographic surgery has been considered, especially if the following are present: tumor characteristics (eg, poorly circumscribed), location (eg, head and neck or other cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas), and likelihood of recurrence (high for superficial angiomyxomas). 16 This case otherwise highlights a rare example of superficial angiomyxomas involving the buttocks.

The Diagnosis: Superficial Angiomyxoma

Superficial angiomyxoma is a rare, benign, cutaneous tumor of a myxoid matrix and blood vessels that was first described in association with Carney complex.1 Tumors may be solitary or multiple. A recent review of cases in the literature revealed a roughly equal distribution of superficial angiomyxomas in males and females occurring most frequently on the head and neck, extremities, and trunk or back. The peak incidence is between the fourth and fifth decades of life.2 Superficial angiomyxomas can occur sporadically or in association with Carney complex, an autosomal-dominant condition with germline inactivating mutations in protein kinase A, PRKAR1A. Interestingly, sporadic cases of superficial angiomyxoma also have shown loss of PRKAR1A expression on immunohistochemistry (IHC).3

Common histologic mimics of superficial angiomyxoma include aggressive angiomyxoma and angiomyofibroblastoma.4 It is thought that these 3 distinct tumor entities may arise from a common pluripotent cell of origin located near connective tissue vasculature, which may contribute to the similarities observed between them.5 For example, aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas also demonstrate a similar myxoid background and vascular proliferation that can closely mimic superficial angiomyxomas clinically. However, the vessels of superficial angiomyxomas tend to be long and thin walled, while aggressive angiomyxomas are characterized by large and thick-walled vessels and angiomyofibroblastomas by abundant smaller vessels. Additionally, unlike superficial angiomyxomas, both aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas typically occur in the genital tract of young to middle-aged women.6

Histopathologic examination is imperative for differentiating between superficial angiomyxoma and more aggressive histologic mimics. Superficial angiomyxomas typically consist of a rich myxoid stroma, thin-walled or arborizing blood vessels, and spindled to stellate fibroblastlike cells (quiz image 2).3 Although not prominent in our case, superficial angiomyxomas also frequently present with stromal neutrophils and epithelial components, including keratinous cysts, basaloid buds, and strands of squamous epithelium.7 Minimal cellular atypia, mitotic activity, and nuclear pleomorphism often are seen, with IHC negative for desmin, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor; positive for CD34 and smooth muscle actin; and variable for S-100 and muscle-specific actin. Although IHC has limited utility in the diagnosis of superficial angiomyxomas, it may be useful to rule out other differential diagnoses.2,3 Superficial angiomyxomas usually show fibroblastic stromal cells, proteoglycan matrix, and collagen fibers on electron microscopy.8 Importantly, histopathologic examination of aggressive angiomyxoma will comparatively present with more invasive, infiltrative, and less well-circumscribed tumors.9 Other differential diagnoses on histology may include neurofibroma, focal cutaneous mucinosis, spindle cell lipoma, and myxofibrosarcoma. Additional considerations include fibroepithelial polyp, nevus lipomatosis, angiomyxolipoma, and anetoderma.

An important differential diagnosis in the evaluation of superficial angiomyxoma is neurofibroma, a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor that presents as a smooth, flesh-colored, and painless papule or nodule commonly associated with the buttonhole sign. Histopathology of neurofibroma features elongated spindle cells with comma-shaped or buckled wavy nuclei and variably sized collagen bundles described as “shredded carrots” (Figure 1).10 Occasional mast cells also can be seen. Immunohistochemistry targeting elements of peripheral nerve sheaths may assist in the diagnosis of neurofibromas, including positive S-100 and SOX10 in Schwann cells, epithelial membrane antigen in perineural cells, and fingerprint positivity for CD34 in fibroblasts.10

Cutaneous mucinoses encompass a diverse group of connective tissue disorders characterized by accumulation of mucin in the skin. Solitary focal cutaneous mucinoses (FCMs) are individual isolated lesions of mucin deposits that are unassociated with systemic conditions.11 Conversely, multiple FCMs presenting with multiple cutaneous lesions also have been described in association with systemic diseases such as scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and thyroid disease.12 Solitary FCM typically presents as an asymptomatic, flesh-colored papule or nodule on the extremities. It often arises in mid to late adulthood with a slightly increased frequency among males.12 Histopathology of solitary FCM commonly demonstrates a dome-shaped pool of basophilic mucin in the upper dermis sparing involvement of the underlying subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2).13 Notably, FCM often lacks the vascularity as well as stromal neutrophils and epithelial elements that are seen in superficial angiomyxomas. Although hematoxylin and eosin stains can be sufficient for diagnosis of solitary FCM, additional stains for mucin such as Alcian blue, colloidal iron, or toluidine blue also may be considered to support the diagnosis.12

Spindle cell lipomas (SCLs) are rare, benign, subcutaneous, adipocytic tumors that arise on the upper back, posterior neck, or shoulders of middle-aged or elderly adult males.14 The clinical presentation often is an asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile subcutaneous mass that is firmer than a common lipoma. Histologically, SCLs are characterized by mature adipocytes, spindle cells, and wire or ropelike collagen fibers in a myxoid background (Figure 3). The spindle cells usually are bland with a notable bipolar shape and blunted ends. Infiltrative growth patterns or mitotic figures are uncommon. Diagnosis can be supported by IHC, as SCLs stain diffusely positive for CD34 with loss of the retinoblastoma protein.7

Another important differential diagnosis to consider is myxofibrosarcoma, a rare and malignant myxoid cutaneous tumor. Clinically, it presents asymptomatically as an indolent, slow-growing nodule on the limbs and limb girdles.7 Histopathologic features demonstrate a multilobular tumor composed of a mixture of hypocellular and hypercellular regions with incomplete fibrous septae (Figure 4). The presence of curvilinear vasculature is characteristic. Multinucleated giant cells and cellular atypia with nuclear pleomorphism also can be seen. Although IHC findings generally are not specific, they can be used to rule out other potential diagnoses. Myxofibrosarcomas stain positive for vimentin and occasionally smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and CD34.7

Superficial angiomyxomas are benign; however, excision is recommended to distinguish between mimics. Local recurrence after excision is common in 30% to 40% of patients.15 Mohs micrographic surgery has been considered, especially if the following are present: tumor characteristics (eg, poorly circumscribed), location (eg, head and neck or other cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas), and likelihood of recurrence (high for superficial angiomyxomas). 16 This case otherwise highlights a rare example of superficial angiomyxomas involving the buttocks.

- Allen PW, Dymock RB, MacCormac LB. Superficial angiomyxomas with and without epithelial components. report of 30 tumors in 28 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:519-530. doi:10.1097 /00000478-198807000-00003

- Sharma A, Khaitan N, Ko JS, et al. A clinicopathologic analysis of 54 cases of cutaneous myxoma. Hum Pathol. 2021:S0046-8177(21) 00201-X. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2021.12.003

- Hafeez F, Krakowski AC, Lian CG, et al. Sporadic superficial angiomyxomas demonstrate loss of PRKAR1A expression [published online March 17, 2022]. Histopathology. 2022;80:1001-1003. doi:10.1111/his.14568

- Mehrotra K, Bhandari M, Khullar G, et al. Large superficial angiomyxoma of the vulva: report of two cases with varied clinical presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:605-607. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_489_20

- Alameda F, Munné A, Baró T, et al. Vulvar angiomyxoma, aggressive angiomyxoma, and angiomyofibroblastoma: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2006;30:193-205. doi:10.1080/01913120500520911

- Haroon S, Irshad L, Zia S, et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma, angiomyofibroblastoma, and cellular angiofibroma of the lower female genital tract: related entities with different outcomes. Cureus. 2022;14:E29250. doi:10.7759/cureus.29250

- Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-918. doi:10.1111/cup.12749

- Allen PW. Myxoma is not a single entity: a review of the concept of myxoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2000;4:99-123. doi:10.1016 /s1092-9134(00)90019-4

- Lee C-C, Chen Y-L, Liau J-Y, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma on the vulva of an adolescent. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53:104-106. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2013.08.001

- Magro G, Amico P, Vecchio GM, et al. Multinucleated floret-like giant cells in sporadic and NF1-associated neurofibromas: a clinicopathologic study of 94 cases. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:71-76. doi:10.1007/s00428-009-0859-y

- Kuo KL, Lee LY, Kuo TT. Solitary cutaneous focal mucinosis: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases of soft fibroma-like cutaneous mucinous lesions. J Dermatol. 2017;44:335-338. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13523

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C, Calame A, et al. Solitary cutaneous focal mucinosis. Cureus. 2021;13:E18618. doi:10.7759/cureus.18618

- Biondo G, Sola S, Pastorino C, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic, and histologic aspects of two cases of cutaneous focal mucinosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:334-336. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198381

- Chen S, Huang H, He S, et al. Spindle cell lipoma: clinicopathologic characterization of 40 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:2613-2621.

- Bembem K, Jaiswal A, Singh M, et al. Cyto-histo correlation of a very rare tumor: superficial angiomyxoma. J Cytol. 2017;34:230-232. doi:10.4103/0970-9371.216119

- Aberdein G, Veitch D, Perrett C. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of superficial angiomyxoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42: 1014-1016. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000782

- Allen PW, Dymock RB, MacCormac LB. Superficial angiomyxomas with and without epithelial components. report of 30 tumors in 28 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:519-530. doi:10.1097 /00000478-198807000-00003

- Sharma A, Khaitan N, Ko JS, et al. A clinicopathologic analysis of 54 cases of cutaneous myxoma. Hum Pathol. 2021:S0046-8177(21) 00201-X. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2021.12.003

- Hafeez F, Krakowski AC, Lian CG, et al. Sporadic superficial angiomyxomas demonstrate loss of PRKAR1A expression [published online March 17, 2022]. Histopathology. 2022;80:1001-1003. doi:10.1111/his.14568

- Mehrotra K, Bhandari M, Khullar G, et al. Large superficial angiomyxoma of the vulva: report of two cases with varied clinical presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:605-607. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_489_20

- Alameda F, Munné A, Baró T, et al. Vulvar angiomyxoma, aggressive angiomyxoma, and angiomyofibroblastoma: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2006;30:193-205. doi:10.1080/01913120500520911

- Haroon S, Irshad L, Zia S, et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma, angiomyofibroblastoma, and cellular angiofibroma of the lower female genital tract: related entities with different outcomes. Cureus. 2022;14:E29250. doi:10.7759/cureus.29250

- Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-918. doi:10.1111/cup.12749

- Allen PW. Myxoma is not a single entity: a review of the concept of myxoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2000;4:99-123. doi:10.1016 /s1092-9134(00)90019-4

- Lee C-C, Chen Y-L, Liau J-Y, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma on the vulva of an adolescent. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53:104-106. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2013.08.001

- Magro G, Amico P, Vecchio GM, et al. Multinucleated floret-like giant cells in sporadic and NF1-associated neurofibromas: a clinicopathologic study of 94 cases. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:71-76. doi:10.1007/s00428-009-0859-y

- Kuo KL, Lee LY, Kuo TT. Solitary cutaneous focal mucinosis: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases of soft fibroma-like cutaneous mucinous lesions. J Dermatol. 2017;44:335-338. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13523

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C, Calame A, et al. Solitary cutaneous focal mucinosis. Cureus. 2021;13:E18618. doi:10.7759/cureus.18618

- Biondo G, Sola S, Pastorino C, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic, and histologic aspects of two cases of cutaneous focal mucinosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:334-336. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198381

- Chen S, Huang H, He S, et al. Spindle cell lipoma: clinicopathologic characterization of 40 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:2613-2621.

- Bembem K, Jaiswal A, Singh M, et al. Cyto-histo correlation of a very rare tumor: superficial angiomyxoma. J Cytol. 2017;34:230-232. doi:10.4103/0970-9371.216119

- Aberdein G, Veitch D, Perrett C. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of superficial angiomyxoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42: 1014-1016. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000782

A 25-year-old woman presented with an irritated growth on the left buttock of 6 months’ duration. The lesion had grown slowly over time and became irritated because of the constant rubbing on her clothing due to its location. Physical examination revealed a 1-cm, pink, protuberant, soft, dome-shaped nodule on the left upper medial buttock (inset). A biopsy was performed for diagnostic purposes.

Dermatologic Implications of Sleep Deprivation in the US Military

Sleep deprivation can increase emotional distress and mood disorders; reduce quality of life; and lead to cognitive, memory, and performance deficits.1 Military service predisposes members to disordered sleep due to the rigors of deployments and field training, such as long shifts, shift changes, stressful work environments, and time zone changes. Evidence shows that sleep deprivation is associated with cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, and some cancers.2 We explore multiple mechanisms by which sleep deprivation may affect the skin. We also review the potential impacts of sleep deprivation on specific topics in dermatology, including atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical attractiveness, wound healing, and skin cancer.

Sleep and Military Service

Approximately 35.2% of Americans experience short sleep duration, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines as sleeping fewer than 7 hours per 24-hour period.3 Short sleep duration is even more common among individuals working in protective services and the military (50.4%).4 United States military service members experience multiple contributors to disordered sleep, including combat operations, shift work, psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injury.5 Bramoweth and Germain6 described the case of a 27-year-old man who served 2 combat tours as an infantryman in Afghanistan, during which time he routinely remained awake for more than 24 hours at a time due to night missions and extended operations. Even when he was not directly involved in combat operations, he was rarely able to keep a regular sleep schedule.6 Service members returning from deployment also report decreased sleep. In one study (N=2717), 43% of respondents reported short sleep duration (<7 hours of sleep per night) and 29% reported very short sleep duration (<6 hours of sleep per night).7 Even stateside, service members experience acute sleep deprivation during training.8

Sleep and Skin

The idea that skin conditions can affect quality of sleep is not controversial. Pruritus, pain, and emotional distress associated with different dermatologic conditions have all been implicated in adversely affecting sleep.9 Given the effects of sleep deprivation on other organ systems, it also can affect the skin. Possible mechanisms of action include negative effects of sleep deprivation on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, cutaneous barrier function, and immune function. First, the HPA axis activity follows a circadian rhythm.10 Activation outside of the bounds of this normal rhythm can have adverse effects on sleep. Alternatively, sleep deprivation and decreased sleep quality can negatively affect the HPA axis.10 These changes can adversely affect cutaneous barrier and immune function.11 Cutaneous barrier function is vitally important in the context of inflammatory dermatologic conditions. Transepidermal water loss, a measurement used to estimate cutaneous barrier function, is increased by sleep deprivation.12 Finally, the cutaneous immune system is an important component of inflammatory dermatologic conditions, cancer immune surveillance, and wound healing, and it also is negatively impacted by sleep deprivation.13 This framework of sleep deprivation affecting the HPA axis, cutaneous barrier function, and cutaneous immune function will help to guide the following discussion on the effects of decreased sleep on specific dermatologic conditions.

Atopic Dermatitis—Individuals with AD are at higher odds of having insomnia, fatigue, and overall poorer health status, including more sick days and increased visits to a physician.14 Additionally, it is possible that the relationship between AD and sleep is not unidirectional. Chang and Chiang15 discussed the possibility of sleep disturbances contributing to AD flares and listed 3 possible mechanisms by which sleep disturbance could potentially flare AD: exacerbation of the itch-scratch cycle; changes in the immune system, including a possible shift to helper T cell (TH2) dominance; and worsening of chronic stress in patients with AD. These changes may lead to a vicious cycle of impaired sleep and AD exacerbations. It may be helpful to view sleep impairment and AD as comorbid conditions requiring co-management for optimal outcomes. This perspective has military relevance because even without considering sleep deprivation, deployment and field conditions are known to increase the risk for AD flares.16

Psoriasis—Psoriasis also may have a bidirectional relationship with sleep. A study utilizing data from the Nurses’ Health Study showed that working a night shift increased the risk for psoriasis.17 Importantly, this connection is associative and not causative. It is possible that other factors in those who worked night shifts such as probable decreased UV exposure or reported increased body mass index played a role. Studies using psoriasis mice models have shown increased inflammation with sleep deprivation.18 Another possible connection is the effect of sleep deprivation on the gut microbiome. Sleep dysfunction is associated with altered gut bacteria ratios, and similar gut bacteria ratios were found in patients with psoriasis, which may indicate an association between sleep deprivation and psoriasis disease progression.19 There also is an increased association of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with psoriasis compared to the general population.20 Fortunately, the rate of consultations for psoriasis in deployed soldiers in the last several conflicts has been quite low, making up only 2.1% of diagnosed dermatologic conditions,21 which is because service members with moderate to severe psoriasis likely will not be deployed.

Alopecia Areata—Alopecia areata also may be associated with sleep deprivation. A large retrospective cohort study looking at the risk for alopecia in patients with sleep disorders showed that a sleep disorder was an independent risk factor for alopecia areata.22 The impact of sleep on the HPA axis portrays a possible mechanism for the negative effects of sleep deprivation on the immune system. Interestingly, in this study, the association was strongest for the 0- to 24-year-old age group. According to the 2020 demographics profile of the military community, 45% of active-duty personnel are 25 years or younger.23 Fortunately, although alopecia areata can be a distressing condition, it should not have much effect on military readiness, as most individuals with this diagnosis are still deployable.

Physical Appearance—

Wound Healing—Wound healing is of particular importance to the health of military members. Research is suggestive but not definitive of the relationship between sleep and wound healing. One intriguing study looked at the healing of blisters induced via suction in well-rested and sleep-deprived individuals. The results showed a difference, with the sleep-deprived individuals taking approximately 1 day longer to heal.13 This has some specific relevance to the military, as friction blisters can be common.30 A cross-sectional survey looking at a group of service members deployed in Iraq showed a prevalence of foot friction blisters of 33%, with 11% of individuals requiring medical care.31 Although this is an interesting example, it is not necessarily applicable to full-thickness wounds. A study utilizing rat models did not identify any differences between sleep-deprived and well-rested models in the healing of punch biopsy sites.32

Skin Cancer—Altered circadian rhythms resulting in changes in melatonin levels, changes in circadian rhythm–related gene pathways, and immunologic changes have been proposed as possible contributing mechanisms for the observed increased risk for skin cancers in military and civilian pilots.33,34 One study showed that UV-related erythema resolved quicker in well-rested individuals compared with those with short sleep duration, which could represent more efficient DNA repair given the relationship between UV-associated erythema and DNA damage and repair.35 Another study looking at circadian changes in the repair of UV-related DNA damage showed that mice exposed to UV radiation in the early morning had higher rates of squamous cell carcinoma than those exposed in the afternoon.36 However, a large cohort study using data from the Nurses’ Health Study II did not support a positive connection between short sleep duration and skin cancer; rather, it showed that a short sleep duration was associated with a decreased risk for melanoma and basal cell carcinoma, with no effect noted for squamous cell carcinoma.37 This does not support a positive association between short sleep duration and skin cancer and in some cases actually suggests a negative association.

Final Thoughts

Although more research is needed, there is evidence that sleep deprivation can negatively affect the skin. Randomized controlled trials looking at groups of individuals with specific dermatologic conditions with a very short sleep duration group (<6 hours of sleep per night), short sleep duration group (<7 hours of sleep per night), and a well-rested group (>7 hours of sleep per night) could be very helpful in this endeavor. Possible mechanisms include the HPA axis, immune system, and skin barrier function that are associated with sleep deprivation. Specific dermatologic conditions that may be affected by sleep deprivation include AD, psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical appearance, wound healing, and skin cancer. The impact of sleep deprivation on dermatologic conditions is particularly relevant to the military, as service members are at an increased risk for short sleep duration. It is possible that improving sleep may lead to better disease control for many dermatologic conditions.

- Carskadon M, Dement WC. Cumulative effects of sleep restriction on daytime sleepiness. Psychophysiology. 1981;18:107-113.

- Medic G, Wille M, Hemels ME. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat Sci Sleep. 2017;19;9:151-161.

- Sleep and sleep disorders. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Reviewed September 12, 2022. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/data_statistics.html

- Khubchandani J, Price JH. Short sleep duration in working American adults, 2010-2018. J Community Health. 2020;45:219-227.

- Good CH, Brager AJ, Capaldi VF, et al. Sleep in the United States military. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:176-191.

- Bramoweth AD, Germain A. Deployment-related insomnia in military personnel and veterans. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15:401.

- Luxton DD, Greenburg D, Ryan J, et al. Prevalence and impact of short sleep duration in redeployed OIF soldiers. Sleep. 2011;34:1189-1195.

- Crowley SK, Wilkinson LL, Burroughs EL, et al. Sleep during basic combat training: a qualitative study. Mil Med. 2012;177:823-828.

- Spindler M, Przybyłowicz K, Hawro M, et al. Sleep disturbance in adult dermatologic patients: a cross-sectional study on prevalence, burden, and associated factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:910-922.

- Guyon A, Balbo M, Morselli LL, et al. Adverse effects of two nights of sleep restriction on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:2861-2868.

- Lin TK, Zhong L, Santiago JL. Association between stress and the HPA axis in the atopic dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2131.

- Pinnagoda J, Tupker RA, Agner T, et al. Guidelines for transepidermal water loss (TEWL) measurement. a report from theStandardization Group of the European Society of Contact Dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 1990;22:164-178.

- Smith TJ, Wilson MA, Karl JP, et al. Impact of sleep restriction on local immune response and skin barrier restoration with and without “multinutrient” nutrition intervention. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2018;124:190-200.

- Silverberg JI, Garg NK, Paller AS, et al. Sleep disturbances in adults with eczema are associated with impaired overall health: a US population-based study. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:56-66.

- Chang YS, Chiang BL. Sleep disorders and atopic dermatitis: a 2-way street? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:1033-1040.

- Riegleman KL, Farnsworth GS, Wong EB. Atopic dermatitis in the US military. Cutis. 2019;104:144-147.

- Li WQ, Qureshi AA, Schernhammer ES, et al. Rotating night-shift work and risk of psoriasis in US women. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:565-567.

- Hirotsu C, Rydlewski M, Araújo MS, et al. Sleep loss and cytokines levels in an experimental model of psoriasis. PLoS One. 2012;7:E51183.

- Myers B, Vidhatha R, Nicholas B, et al. Sleep and the gut microbiome in psoriasis: clinical implications for disease progression and the development of cardiometabolic comorbidities. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2021;6:27-37.

- Gupta MA, Simpson FC, Gupta AK. Psoriasis and sleep disorders: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2016;29:63-75.

- Gelman AB, Norton SA, Valdes-Rodriguez R, et al. A review of skin conditions in modern warfare and peacekeeping operations. Mil Med. 2015;180:32-37.

- Seo HM, Kim TL, Kim JS. The risk of alopecia areata and other related autoimmune diseases in patients with sleep disorders: a Korean population-based retrospective cohort study. Sleep. 2018;41:10.1093/sleep/zsy111.

- Department of Defense. 2020 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community. Military One Source website. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2020-demographics-report.pdf

- Sundelin T, Lekander M, Kecklund G, et al. Cues of fatigue: effects of sleep deprivation on facial appearance. Sleep. 2013;36:1355-1360.

- Sundelin T, Lekander M, Sorjonen K, et a. Negative effects of restricted sleep on facial appearance and social appeal. R Soc Open Sci. 2017;4:160918.

- Holding BC, Sundelin T, Cairns P, et al. The effect of sleep deprivation on objective and subjective measures of facial appearance. J Sleep Res. 2019;28:E12860.

- Léger D, Gauriau C, Etzi C, et al. “You look sleepy…” the impact of sleep restriction on skin parameters and facial appearance of 24 women. Sleep Med. 2022;89:97-103.

- Talamas SN, Mavor KI, Perrett DI. Blinded by beauty: attractiveness bias and accurate perceptions of academic performance. PLoS One. 2016;11:E0148284.

- Department of the Army. Enlisted Promotions and Reductions. Army Publishing Directorate website. Published May 16, 2019. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/ARN17424_R600_8_19_Admin_FINAL.pdf

- Levy PD, Hile DC, Hile LM, et al. A prospective analysis of the treatment of friction blisters with 2-octylcyanoacrylate. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:232-237.

- Brennan FH Jr, Jackson CR, Olsen C, et al. Blisters on the battlefield: the prevalence of and factors associated with foot friction blisters during Operation Iraqi Freedom I. Mil Med. 2012;177:157-162.

- Mostaghimi L, Obermeyer WH, Ballamudi B, et al. Effects of sleep deprivation on wound healing. J Sleep Res. 2005;14:213-219.

- Wilkison BD, Wong EB. Skin cancer in military pilots: a special population with special risk factors. Cutis. 2017;100:218-220.

- IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Painting, Firefighting, and Shiftwork. World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. Accessed February 20, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326814/

- Oyetakin-White P, Suggs A, Koo B, et al. Does poor sleep quality affect skin ageing? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:17-22.

- Gaddameedhi S, Selby CP, Kaufmann WK, et al. Control of skin cancer by the circadian rhythm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18790-18795.

- Heckman CJ, Kloss JD, Feskanich D, et al. Associations among rotating night shift work, sleep and skin cancer in Nurses’ Health Study II participants. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74:169-175.

Sleep deprivation can increase emotional distress and mood disorders; reduce quality of life; and lead to cognitive, memory, and performance deficits.1 Military service predisposes members to disordered sleep due to the rigors of deployments and field training, such as long shifts, shift changes, stressful work environments, and time zone changes. Evidence shows that sleep deprivation is associated with cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, and some cancers.2 We explore multiple mechanisms by which sleep deprivation may affect the skin. We also review the potential impacts of sleep deprivation on specific topics in dermatology, including atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical attractiveness, wound healing, and skin cancer.

Sleep and Military Service

Approximately 35.2% of Americans experience short sleep duration, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines as sleeping fewer than 7 hours per 24-hour period.3 Short sleep duration is even more common among individuals working in protective services and the military (50.4%).4 United States military service members experience multiple contributors to disordered sleep, including combat operations, shift work, psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injury.5 Bramoweth and Germain6 described the case of a 27-year-old man who served 2 combat tours as an infantryman in Afghanistan, during which time he routinely remained awake for more than 24 hours at a time due to night missions and extended operations. Even when he was not directly involved in combat operations, he was rarely able to keep a regular sleep schedule.6 Service members returning from deployment also report decreased sleep. In one study (N=2717), 43% of respondents reported short sleep duration (<7 hours of sleep per night) and 29% reported very short sleep duration (<6 hours of sleep per night).7 Even stateside, service members experience acute sleep deprivation during training.8

Sleep and Skin

The idea that skin conditions can affect quality of sleep is not controversial. Pruritus, pain, and emotional distress associated with different dermatologic conditions have all been implicated in adversely affecting sleep.9 Given the effects of sleep deprivation on other organ systems, it also can affect the skin. Possible mechanisms of action include negative effects of sleep deprivation on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, cutaneous barrier function, and immune function. First, the HPA axis activity follows a circadian rhythm.10 Activation outside of the bounds of this normal rhythm can have adverse effects on sleep. Alternatively, sleep deprivation and decreased sleep quality can negatively affect the HPA axis.10 These changes can adversely affect cutaneous barrier and immune function.11 Cutaneous barrier function is vitally important in the context of inflammatory dermatologic conditions. Transepidermal water loss, a measurement used to estimate cutaneous barrier function, is increased by sleep deprivation.12 Finally, the cutaneous immune system is an important component of inflammatory dermatologic conditions, cancer immune surveillance, and wound healing, and it also is negatively impacted by sleep deprivation.13 This framework of sleep deprivation affecting the HPA axis, cutaneous barrier function, and cutaneous immune function will help to guide the following discussion on the effects of decreased sleep on specific dermatologic conditions.

Atopic Dermatitis—Individuals with AD are at higher odds of having insomnia, fatigue, and overall poorer health status, including more sick days and increased visits to a physician.14 Additionally, it is possible that the relationship between AD and sleep is not unidirectional. Chang and Chiang15 discussed the possibility of sleep disturbances contributing to AD flares and listed 3 possible mechanisms by which sleep disturbance could potentially flare AD: exacerbation of the itch-scratch cycle; changes in the immune system, including a possible shift to helper T cell (TH2) dominance; and worsening of chronic stress in patients with AD. These changes may lead to a vicious cycle of impaired sleep and AD exacerbations. It may be helpful to view sleep impairment and AD as comorbid conditions requiring co-management for optimal outcomes. This perspective has military relevance because even without considering sleep deprivation, deployment and field conditions are known to increase the risk for AD flares.16

Psoriasis—Psoriasis also may have a bidirectional relationship with sleep. A study utilizing data from the Nurses’ Health Study showed that working a night shift increased the risk for psoriasis.17 Importantly, this connection is associative and not causative. It is possible that other factors in those who worked night shifts such as probable decreased UV exposure or reported increased body mass index played a role. Studies using psoriasis mice models have shown increased inflammation with sleep deprivation.18 Another possible connection is the effect of sleep deprivation on the gut microbiome. Sleep dysfunction is associated with altered gut bacteria ratios, and similar gut bacteria ratios were found in patients with psoriasis, which may indicate an association between sleep deprivation and psoriasis disease progression.19 There also is an increased association of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with psoriasis compared to the general population.20 Fortunately, the rate of consultations for psoriasis in deployed soldiers in the last several conflicts has been quite low, making up only 2.1% of diagnosed dermatologic conditions,21 which is because service members with moderate to severe psoriasis likely will not be deployed.

Alopecia Areata—Alopecia areata also may be associated with sleep deprivation. A large retrospective cohort study looking at the risk for alopecia in patients with sleep disorders showed that a sleep disorder was an independent risk factor for alopecia areata.22 The impact of sleep on the HPA axis portrays a possible mechanism for the negative effects of sleep deprivation on the immune system. Interestingly, in this study, the association was strongest for the 0- to 24-year-old age group. According to the 2020 demographics profile of the military community, 45% of active-duty personnel are 25 years or younger.23 Fortunately, although alopecia areata can be a distressing condition, it should not have much effect on military readiness, as most individuals with this diagnosis are still deployable.

Physical Appearance—

Wound Healing—Wound healing is of particular importance to the health of military members. Research is suggestive but not definitive of the relationship between sleep and wound healing. One intriguing study looked at the healing of blisters induced via suction in well-rested and sleep-deprived individuals. The results showed a difference, with the sleep-deprived individuals taking approximately 1 day longer to heal.13 This has some specific relevance to the military, as friction blisters can be common.30 A cross-sectional survey looking at a group of service members deployed in Iraq showed a prevalence of foot friction blisters of 33%, with 11% of individuals requiring medical care.31 Although this is an interesting example, it is not necessarily applicable to full-thickness wounds. A study utilizing rat models did not identify any differences between sleep-deprived and well-rested models in the healing of punch biopsy sites.32

Skin Cancer—Altered circadian rhythms resulting in changes in melatonin levels, changes in circadian rhythm–related gene pathways, and immunologic changes have been proposed as possible contributing mechanisms for the observed increased risk for skin cancers in military and civilian pilots.33,34 One study showed that UV-related erythema resolved quicker in well-rested individuals compared with those with short sleep duration, which could represent more efficient DNA repair given the relationship between UV-associated erythema and DNA damage and repair.35 Another study looking at circadian changes in the repair of UV-related DNA damage showed that mice exposed to UV radiation in the early morning had higher rates of squamous cell carcinoma than those exposed in the afternoon.36 However, a large cohort study using data from the Nurses’ Health Study II did not support a positive connection between short sleep duration and skin cancer; rather, it showed that a short sleep duration was associated with a decreased risk for melanoma and basal cell carcinoma, with no effect noted for squamous cell carcinoma.37 This does not support a positive association between short sleep duration and skin cancer and in some cases actually suggests a negative association.

Final Thoughts

Although more research is needed, there is evidence that sleep deprivation can negatively affect the skin. Randomized controlled trials looking at groups of individuals with specific dermatologic conditions with a very short sleep duration group (<6 hours of sleep per night), short sleep duration group (<7 hours of sleep per night), and a well-rested group (>7 hours of sleep per night) could be very helpful in this endeavor. Possible mechanisms include the HPA axis, immune system, and skin barrier function that are associated with sleep deprivation. Specific dermatologic conditions that may be affected by sleep deprivation include AD, psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical appearance, wound healing, and skin cancer. The impact of sleep deprivation on dermatologic conditions is particularly relevant to the military, as service members are at an increased risk for short sleep duration. It is possible that improving sleep may lead to better disease control for many dermatologic conditions.

Sleep deprivation can increase emotional distress and mood disorders; reduce quality of life; and lead to cognitive, memory, and performance deficits.1 Military service predisposes members to disordered sleep due to the rigors of deployments and field training, such as long shifts, shift changes, stressful work environments, and time zone changes. Evidence shows that sleep deprivation is associated with cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal disease, and some cancers.2 We explore multiple mechanisms by which sleep deprivation may affect the skin. We also review the potential impacts of sleep deprivation on specific topics in dermatology, including atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, alopecia areata, physical attractiveness, wound healing, and skin cancer.

Sleep and Military Service

Approximately 35.2% of Americans experience short sleep duration, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines as sleeping fewer than 7 hours per 24-hour period.3 Short sleep duration is even more common among individuals working in protective services and the military (50.4%).4 United States military service members experience multiple contributors to disordered sleep, including combat operations, shift work, psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injury.5 Bramoweth and Germain6 described the case of a 27-year-old man who served 2 combat tours as an infantryman in Afghanistan, during which time he routinely remained awake for more than 24 hours at a time due to night missions and extended operations. Even when he was not directly involved in combat operations, he was rarely able to keep a regular sleep schedule.6 Service members returning from deployment also report decreased sleep. In one study (N=2717), 43% of respondents reported short sleep duration (<7 hours of sleep per night) and 29% reported very short sleep duration (<6 hours of sleep per night).7 Even stateside, service members experience acute sleep deprivation during training.8

Sleep and Skin