User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Clustered Vesicles on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

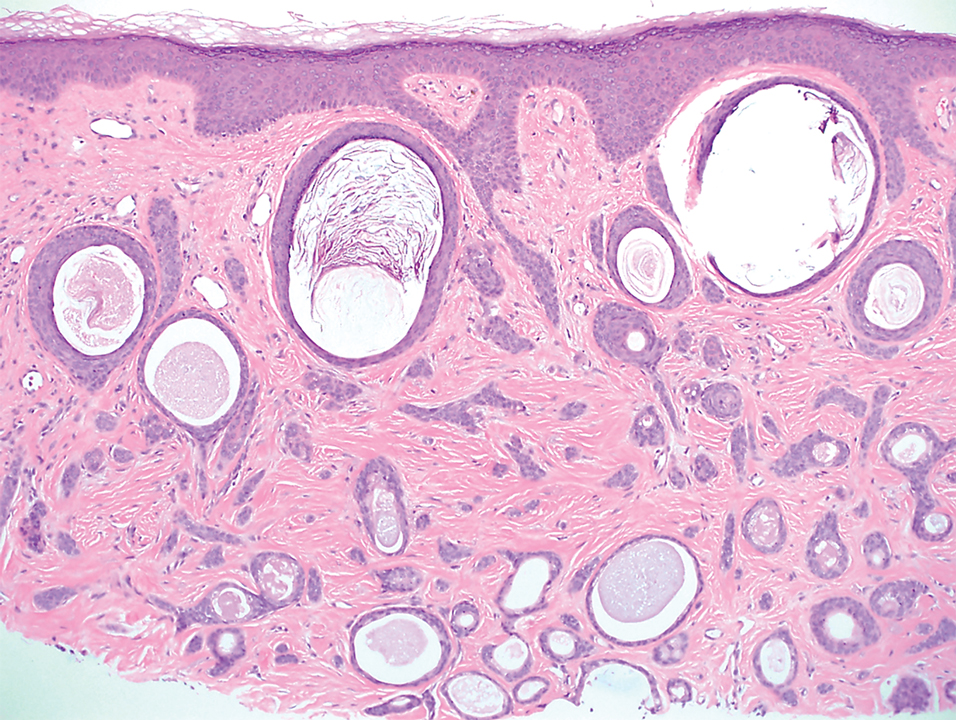

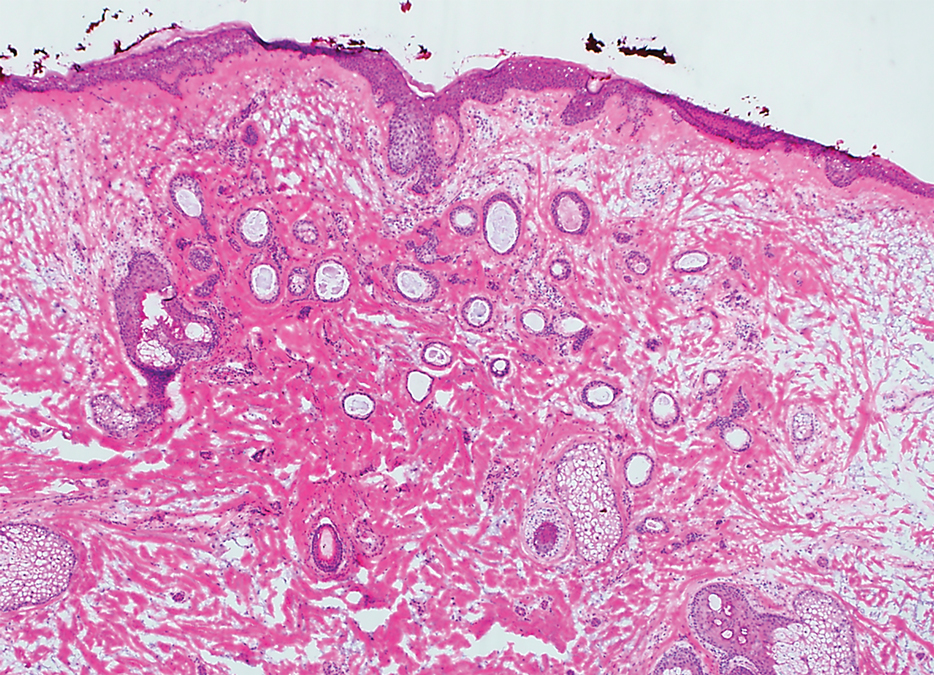

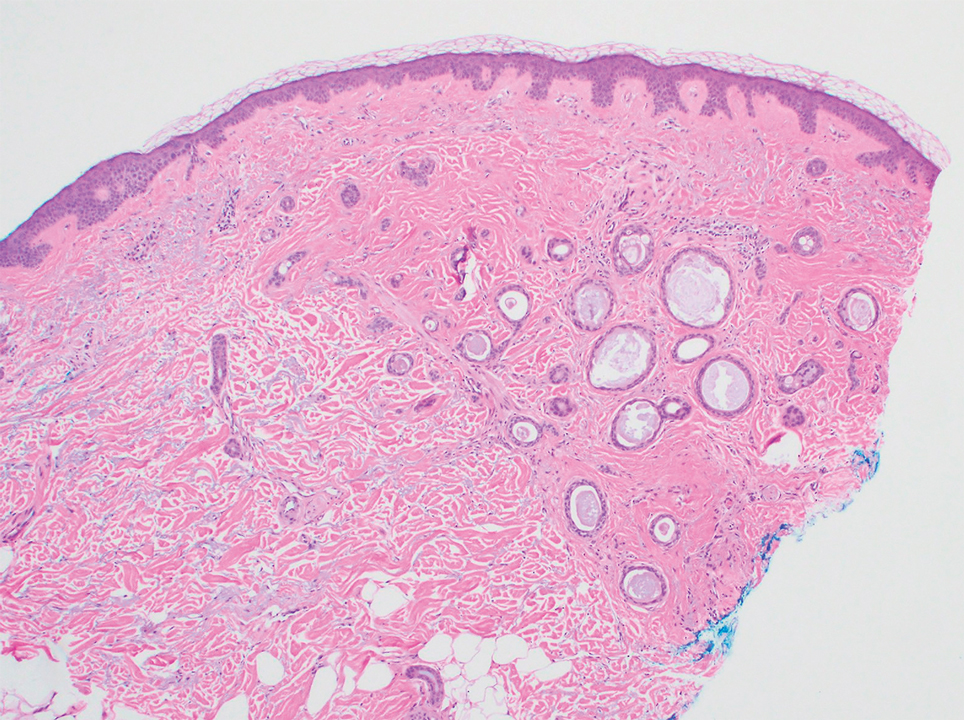

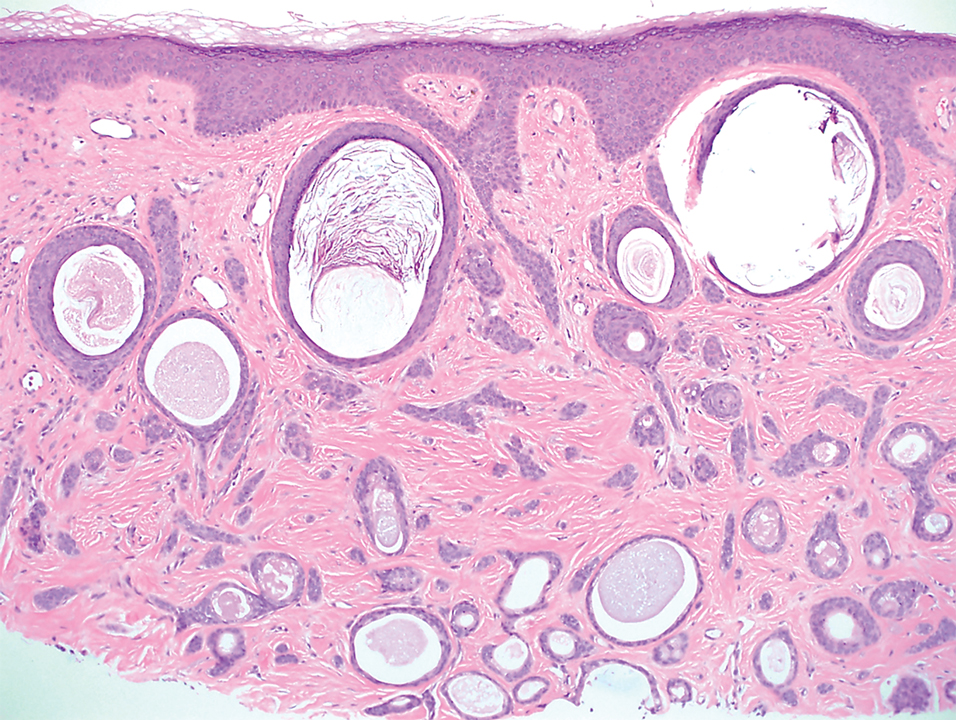

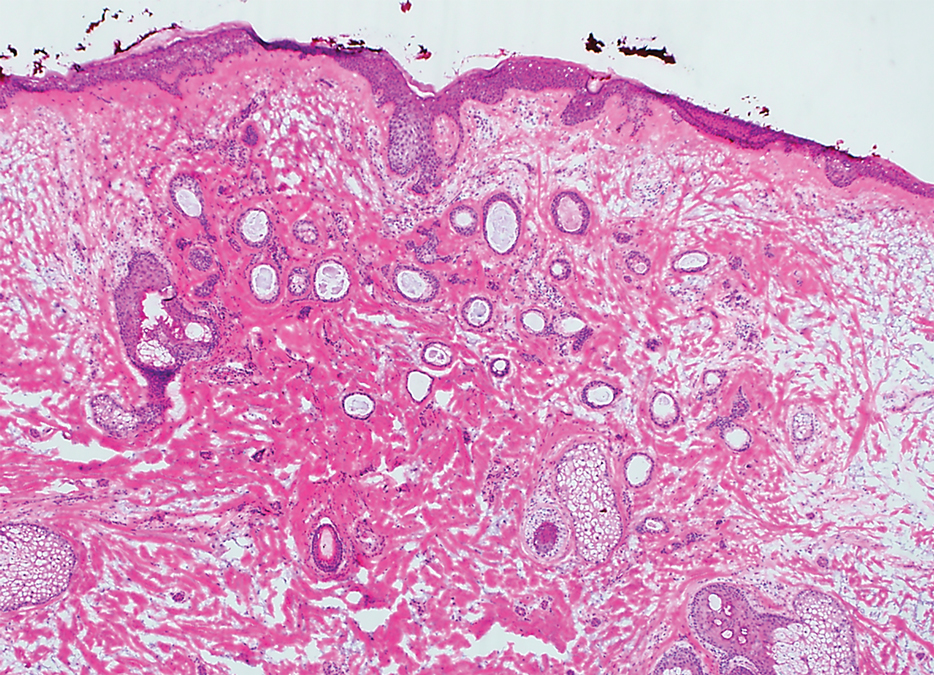

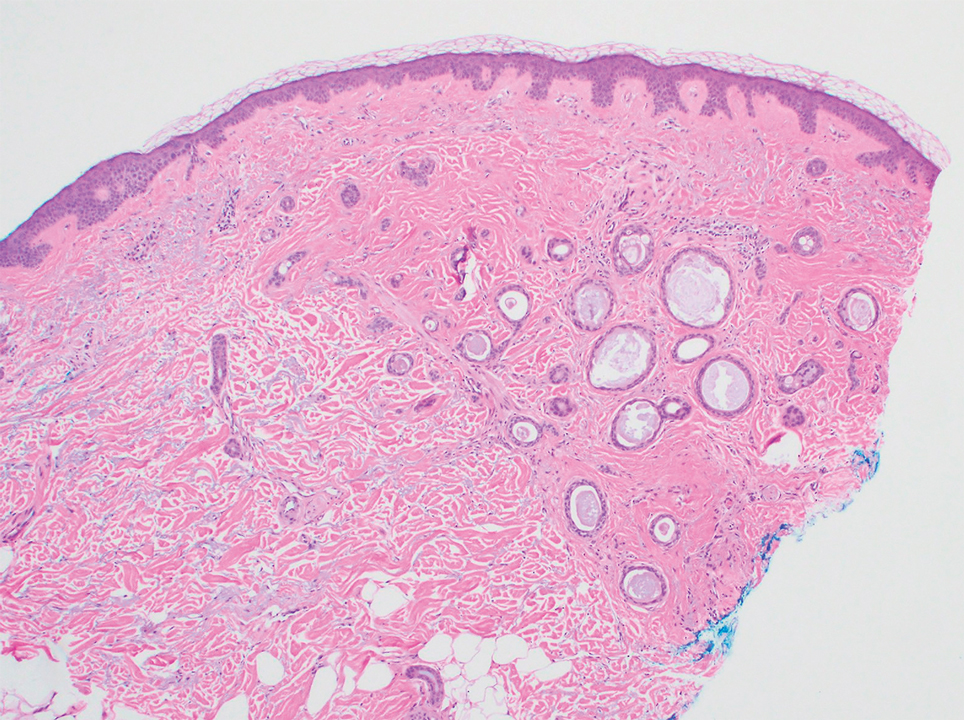

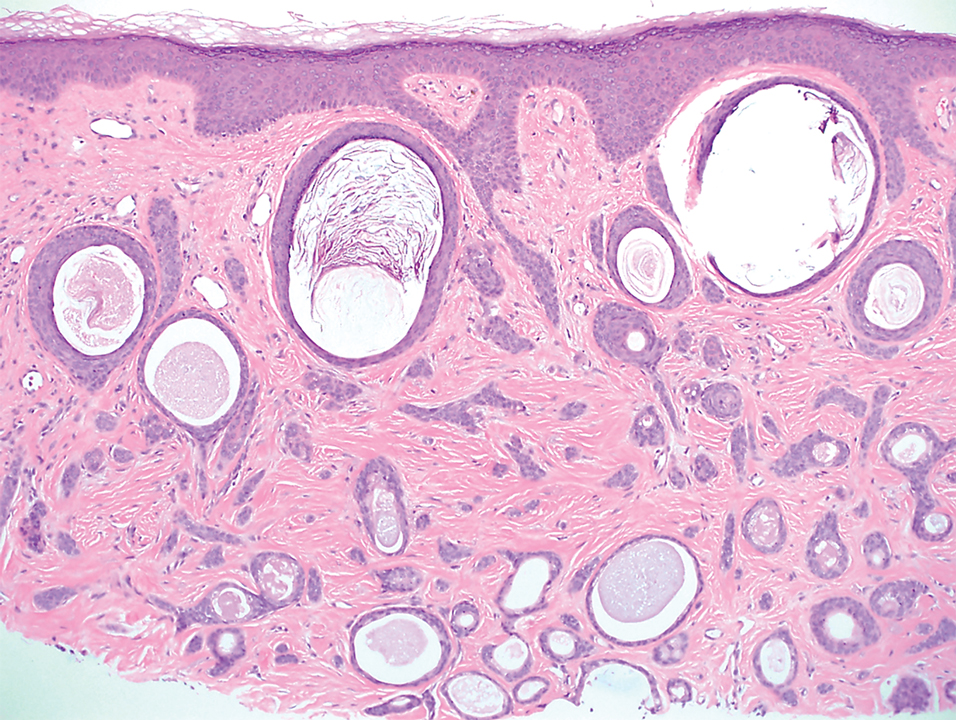

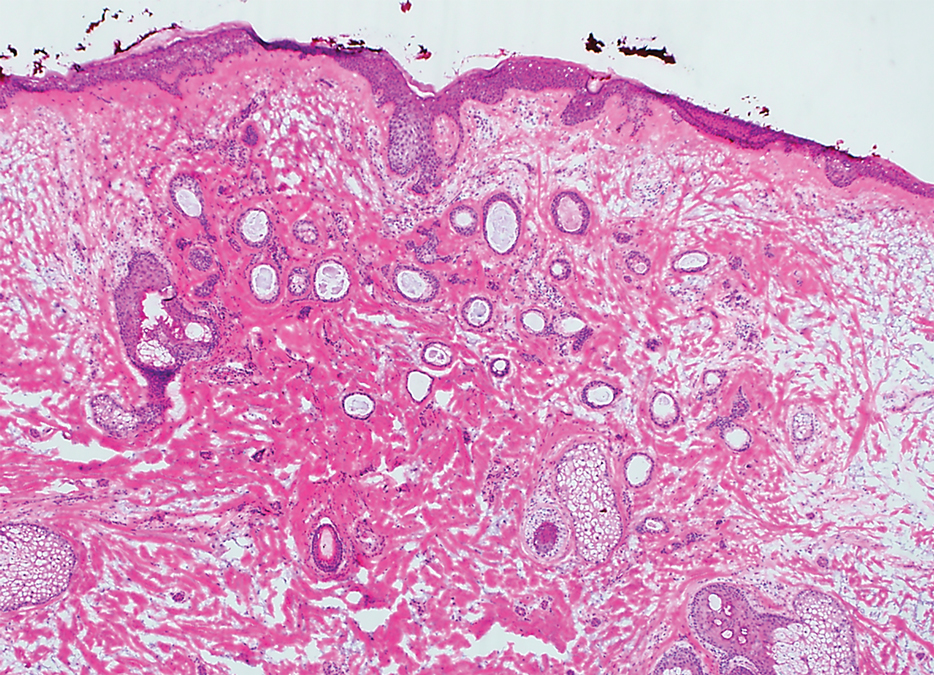

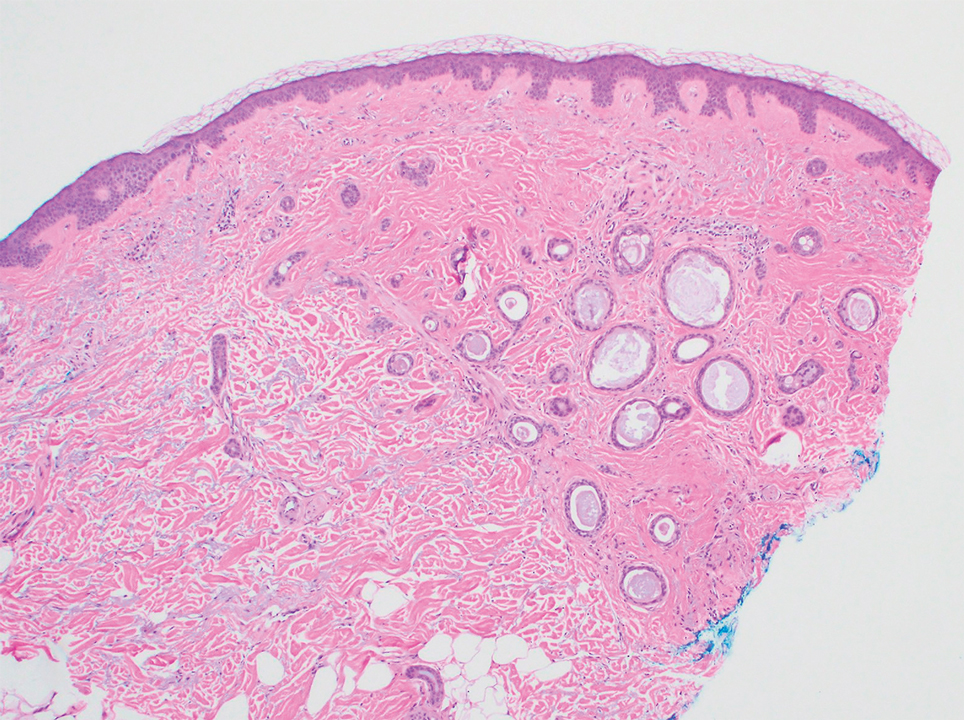

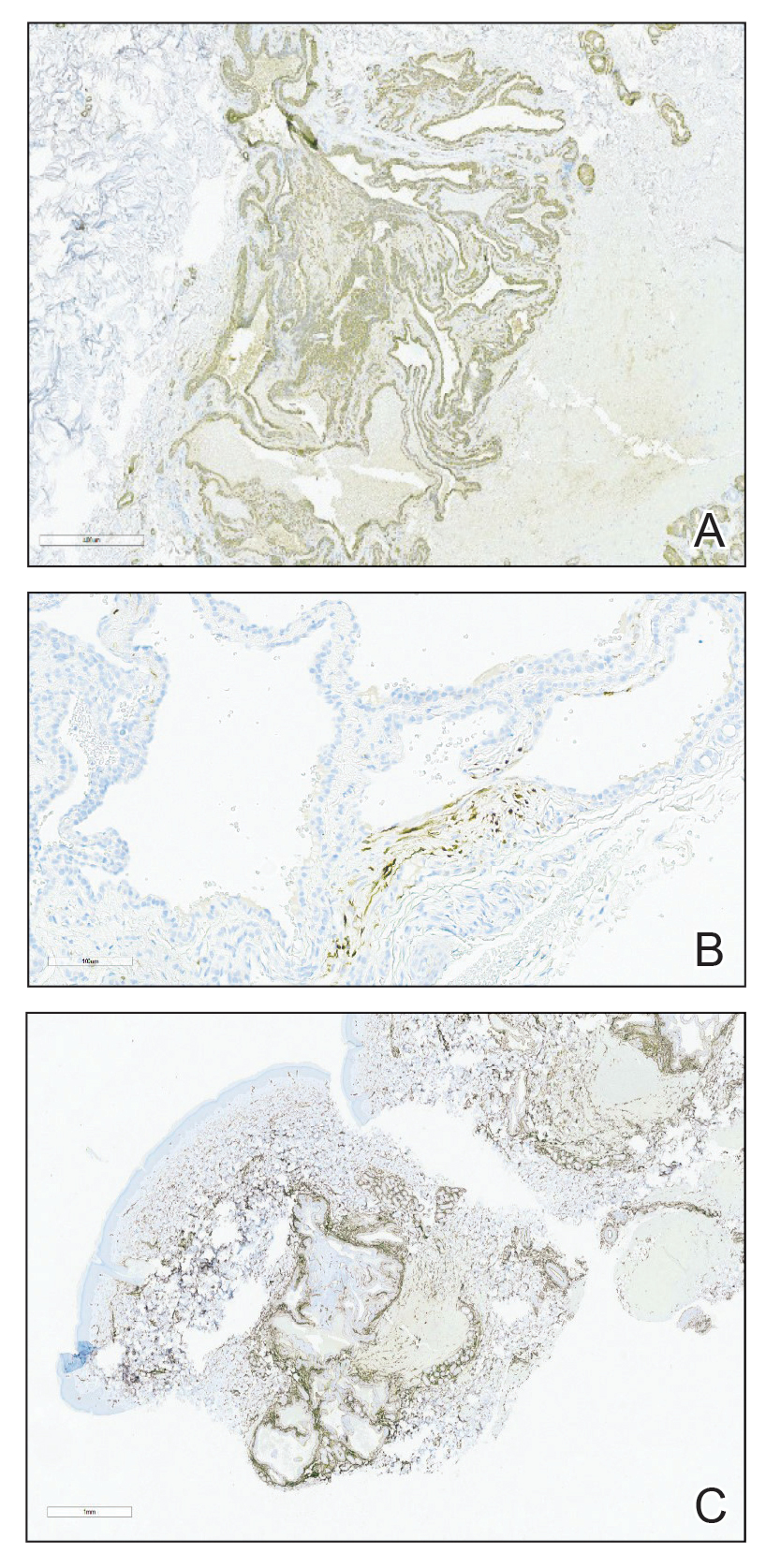

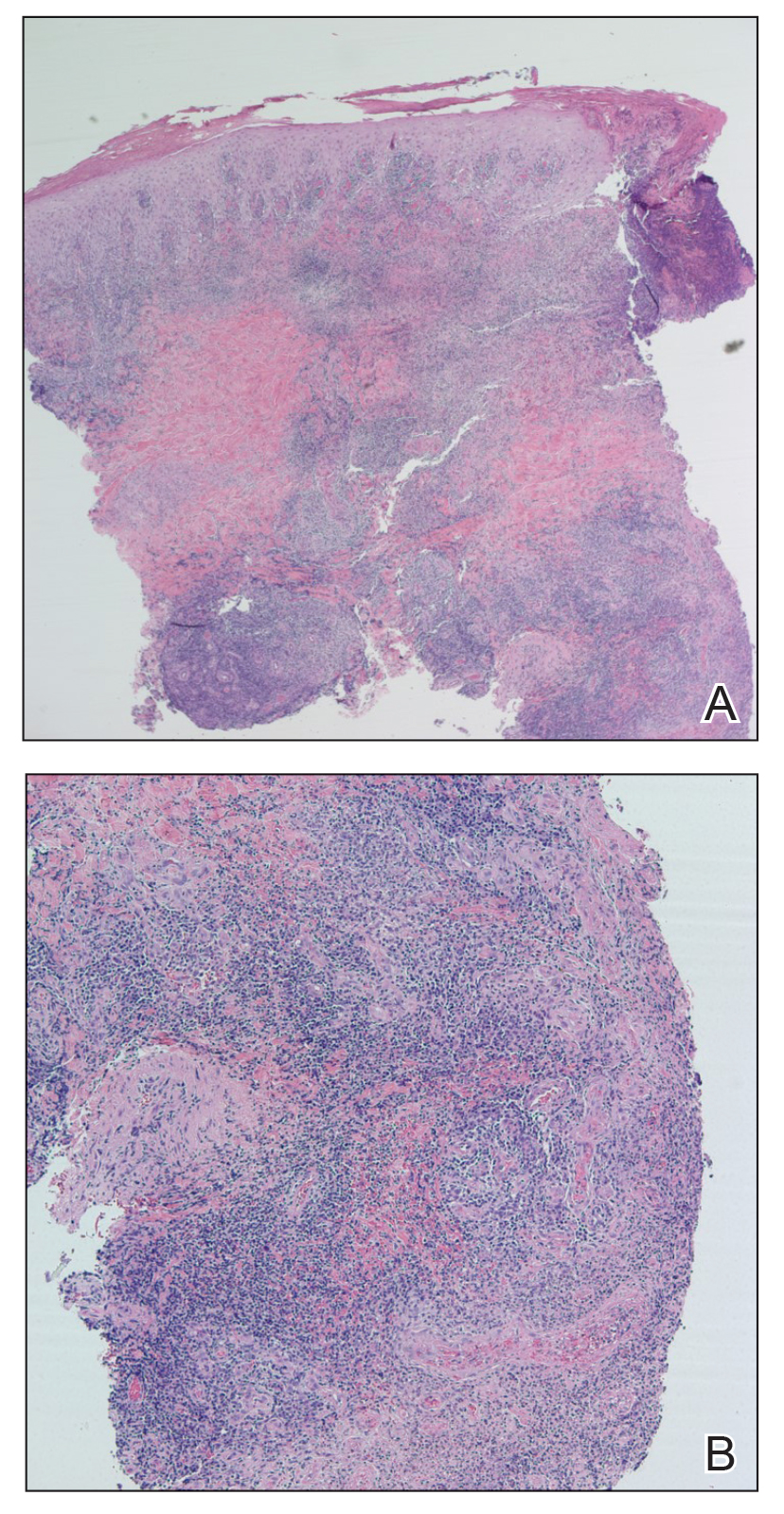

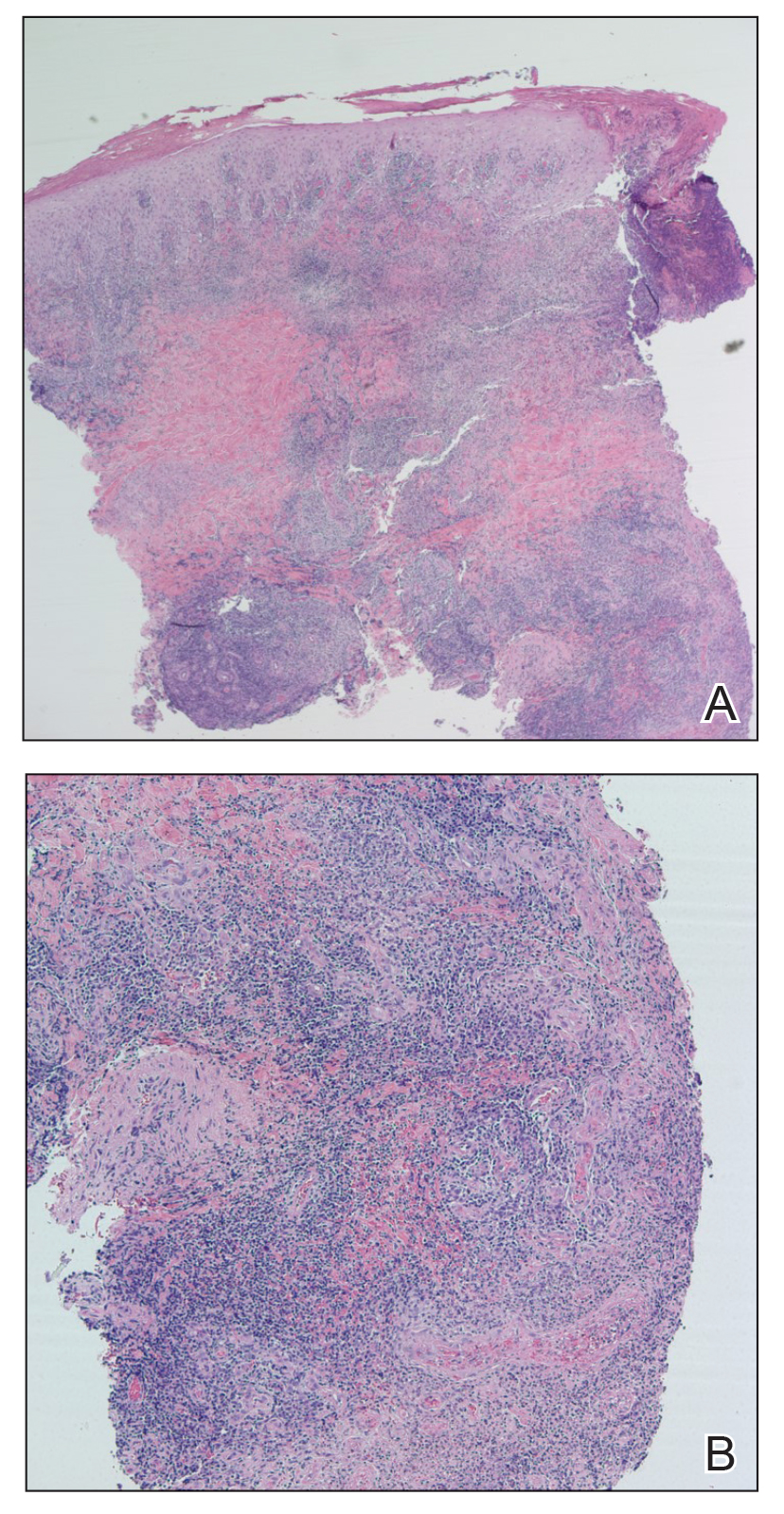

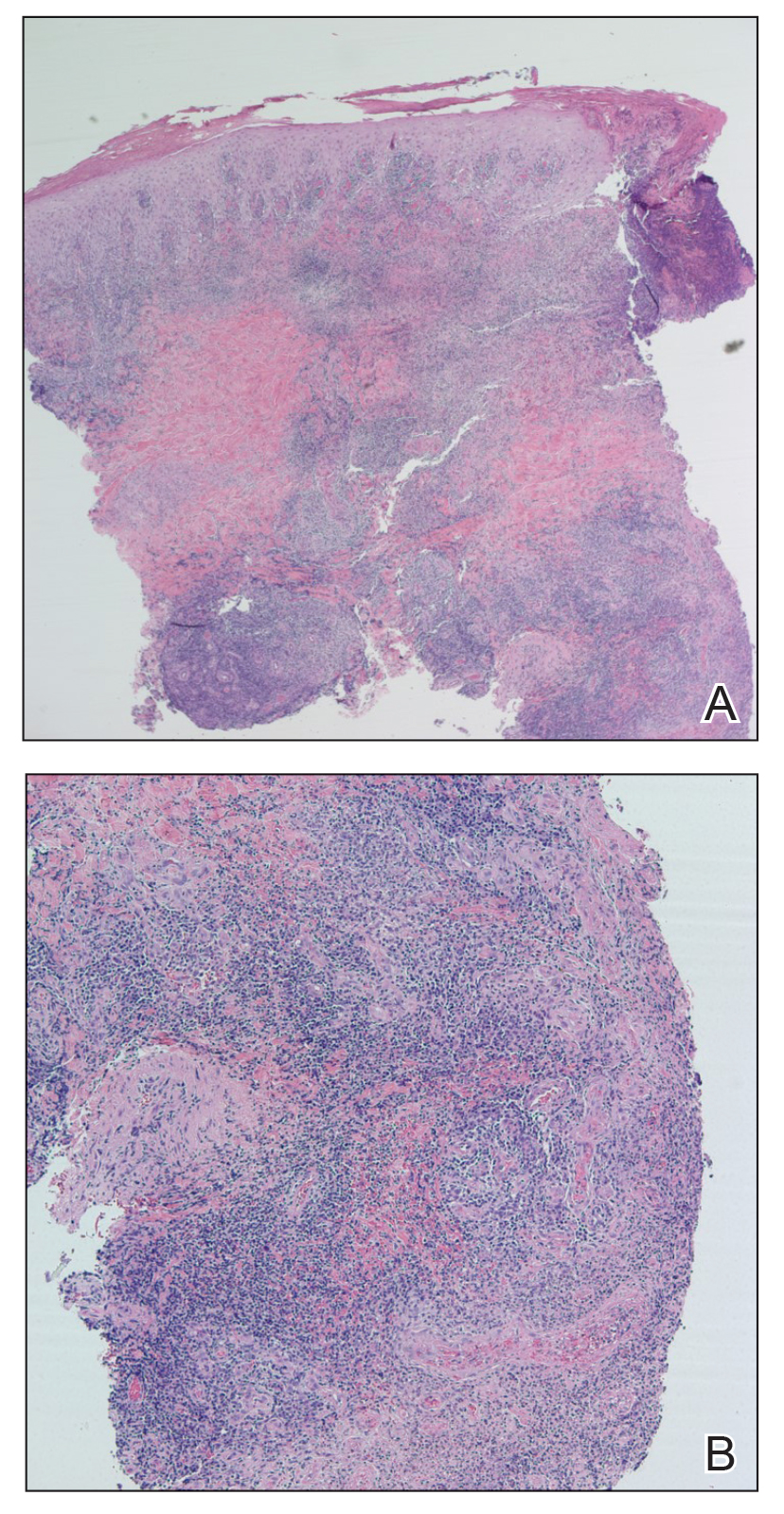

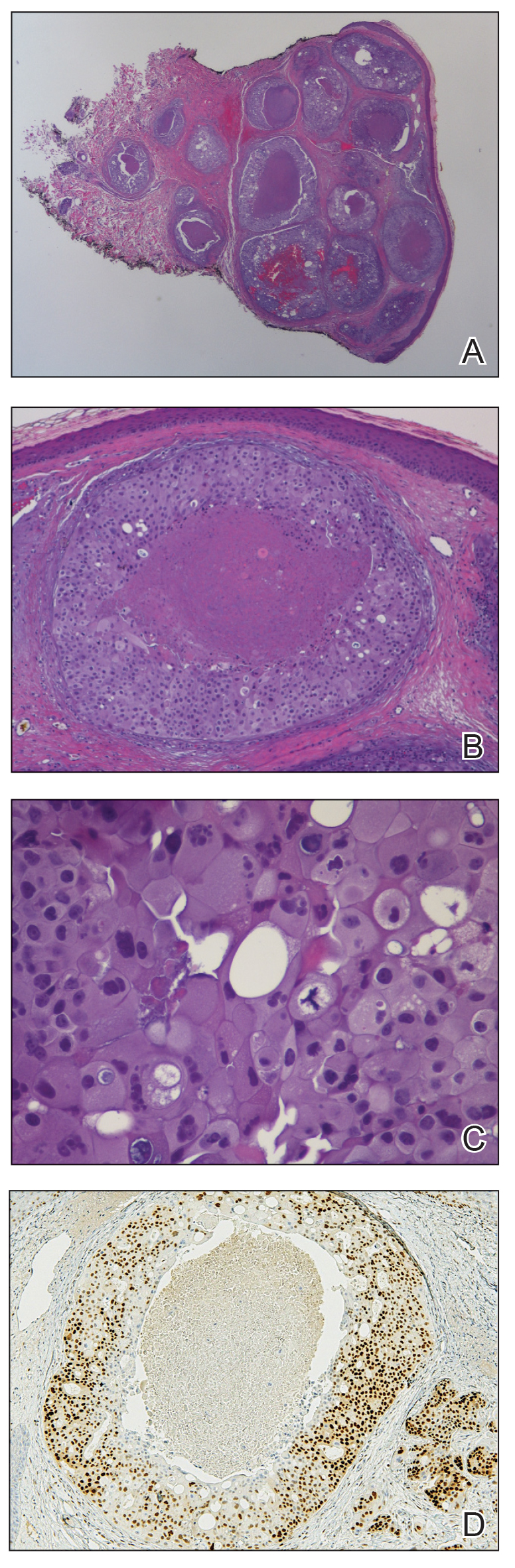

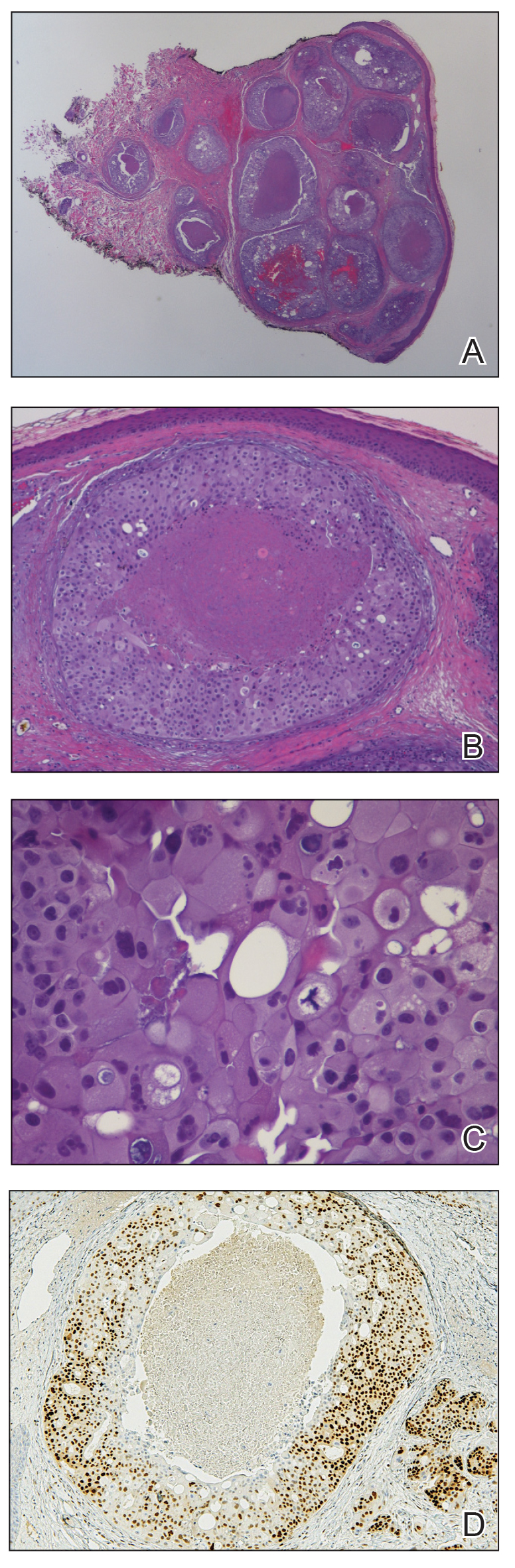

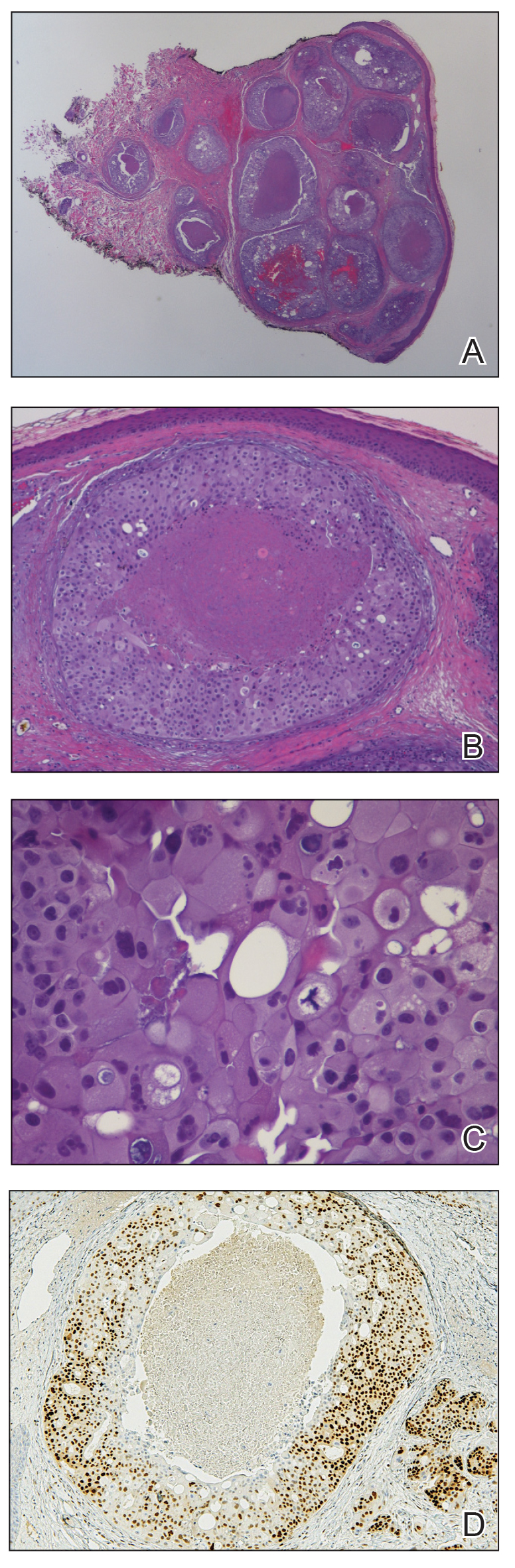

A punch biopsy demonstrated anastomosing fluidfilled spaces within the papillary and reticular dermal layers (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM)(formerly known as lymphangioma circumscriptum), a congenital vascular malformation composed of slow-flow lymphatic channels.1 The patient underwent serial excisions with improvement of the LM, though the treatment course was complicated by hypertrophic scar formation.

The classic clinical presentation of microcystic LM includes a crop of vesicles containing clear or hemorrhagic fluid with associated oozing or bleeding.2 When cutaneous lesions resembling microcystic LM develop in response to lymphatic damage and resulting stasis, such as from prior radiotherapy or surgery, the term lymphangiectasia is used to distinguish this entity from congenital microcystic LM.3

Microcystic LMs are histologically indistinguishable from macrocystic LMs; however, macrocystic LMs typically are clinically evident at birth as ill-defined subcutaneous masses.2,4-6 Dermatitis herpetiformis, a dermatologic manifestation of gluten sensitivity, causes intensely pruritic vesicles in a symmetric distribution on the elbows, knees, and buttocks. Histopathology shows neutrophilic microabscesses in the dermal papillae with subepidermal blistering. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates the deposition of IgA along the basement membrane with dermal papillae aggregates.6 The underlying dermis also may contain a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate rich in neutrophils. The vesicles of herpes zoster virus are painful and present in a dermatomal distribution. A viral cytopathic effect often is observed in keratinocytes, specifically with multinucleation, molding, and margination of chromatin material. The lesions are accompanied by variable lymphocytic inflammation and epithelial necrosis resulting in intraepidermal blistering.7 Extragenital lichen sclerosus presents as polygonal white papules merging to form plaques and may include hemorrhagic blisters in some instances. Histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolar interface changes, loss of elastic fibers, and hyalinization of the lamina propria with lymphocytic infiltrate.8

Endothelial cells in LM exhibit activating mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha gene, PIK3CA, which may lead to proliferation and overgrowth of the lymphatic vasculature, as well as increased production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate.9,10 Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) is expressed in the perivascular smooth muscle adjacent to lymphatic spaces in LMs but not in the their vasculature. 10 This pattern of PDE5 expression may cause perilesional vasculature to constrict, preventing lymphatic fluid from draining into the veins.11 It is theorized that the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil leads to relaxation of the vasculature adjacent to LMs, allowing the outflow of the accumulated lymphatic fluid and thus decompression.11-13

Management of LM should not only take into account the depth and location of involvement but also any associated symptoms or complications, such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or secondary infections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically has been considered the gold standard for determining the size and depth of involvement of the malformation.1,3,4 However, ultrasonography with Doppler flow may be considered an initial diagnostic and screening test, as it can distinguish between macrocystic and microcystic components and provide superior images of microcystic lesions, which are below the resolution capacity of MRI.4 Notably, our patient’s LM was undetectable on ultrasonography and was found to be largely superficial in nature on MRI.

Serial excision of the microcystic LM was conducted in our patient, but there currently is no consensus on optimal treatment of LM, and many treatment options are complicated by high recurrence rates or complications.5 Procedural approaches may include excision, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, sclerotherapy, or laser therapy, while pharmacologic approaches may include sildenafil for its inhibition of PDE5 or sirolimus (oral or topical) for its inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin.5,12-14 Because recurrence is highly likely, patients may require repeat treatments or a combination approach to therapy.1,5 The development of targeted therapies may lead to a shift in management of LMs in the future, as successful use of the PIK3CA inhibitor alpelisib recently has been reported to lead to clinical improvement of PIK3CA-related LMs, including in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes.15

- Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:353-374. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.069

- Alrashdan MS, Hammad HM, Alzumaili BAI, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the tongue: a case with marked hemorrhagic component. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:278-281. doi:10.1111/cup.13101

- Osborne GE, Chinn RJ, Francis ND, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the investigation of penile lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:467-468. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03695.x

- Davies D, Rogers M, Lam A, et al. Localized microcystic lymphatic malformations—ultrasound diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16: 423-429. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00110.x

- García-Montero P, Del Boz J, Baselga-Torres E, et al. Use of topical rapamycin in the treatment of superficial lymphatic malformations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:508-515. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.050

- Clarindo MV, Possebon AT, Soligo EM, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:865-875; quiz 876-877. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142966

- Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Histopathologic features of cutaneous herpes virus infections (herpes simplex, herpes varicella/zoster): a broad spectrum of presentations with common pseudolymphomatous aspects. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:50-58.

- Shiver M, Papasakelariou C, Brown JA, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus in a pediatric patient: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:383-385. doi:10.1111 /pde.12025

- Blesinger H, Kaulfuß S, Aung T, et al. PIK3CA mutations are specifically localized to lymphatic endothelial cells of lymphatic malformations [published online July 9, 2018]. PLoS One. 2018;13:E0200343. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200343

- Green JS, Prok L, Bruckner AL. Expression of phosphodiesterase-5 in lymphatic malformation tissue. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:455-456. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7002

- Swetman GL, Berk DR, Vasanawala SS, et al. Sildenafil for severe lymphatic malformations. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:384-386. doi:10.1056 /NEJMc1112482

- Tu JH, Tafoya E, Jeng M, et al. Long-term follow-up of lymphatic malformations in children treated with sildenafil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:559-565. doi:10.1111/pde.13237

- Maruani A, Tavernier E, Boccara O, et al. Sirolimus (rapamycin) for slow-flow malformations in children: the Observational-Phase Randomized Clinical PERFORMUS Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1289-1298. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3459

- Delestre F, Venot Q, Bayard C, et al. Alpelisib administration reduced lymphatic malformations in a mouse model and in patients. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabg0809. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed .abg0809

- Garreta Fontelles G, Pardo Pastor J, Grande Moreillo C. Alpelisib to treat CLOVES syndrome, a member of the PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome spectrum [published online February 21, 2022]. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:3891-3895. doi:10.1111/bcp.15270

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

A punch biopsy demonstrated anastomosing fluidfilled spaces within the papillary and reticular dermal layers (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM)(formerly known as lymphangioma circumscriptum), a congenital vascular malformation composed of slow-flow lymphatic channels.1 The patient underwent serial excisions with improvement of the LM, though the treatment course was complicated by hypertrophic scar formation.

The classic clinical presentation of microcystic LM includes a crop of vesicles containing clear or hemorrhagic fluid with associated oozing or bleeding.2 When cutaneous lesions resembling microcystic LM develop in response to lymphatic damage and resulting stasis, such as from prior radiotherapy or surgery, the term lymphangiectasia is used to distinguish this entity from congenital microcystic LM.3

Microcystic LMs are histologically indistinguishable from macrocystic LMs; however, macrocystic LMs typically are clinically evident at birth as ill-defined subcutaneous masses.2,4-6 Dermatitis herpetiformis, a dermatologic manifestation of gluten sensitivity, causes intensely pruritic vesicles in a symmetric distribution on the elbows, knees, and buttocks. Histopathology shows neutrophilic microabscesses in the dermal papillae with subepidermal blistering. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates the deposition of IgA along the basement membrane with dermal papillae aggregates.6 The underlying dermis also may contain a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate rich in neutrophils. The vesicles of herpes zoster virus are painful and present in a dermatomal distribution. A viral cytopathic effect often is observed in keratinocytes, specifically with multinucleation, molding, and margination of chromatin material. The lesions are accompanied by variable lymphocytic inflammation and epithelial necrosis resulting in intraepidermal blistering.7 Extragenital lichen sclerosus presents as polygonal white papules merging to form plaques and may include hemorrhagic blisters in some instances. Histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolar interface changes, loss of elastic fibers, and hyalinization of the lamina propria with lymphocytic infiltrate.8

Endothelial cells in LM exhibit activating mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha gene, PIK3CA, which may lead to proliferation and overgrowth of the lymphatic vasculature, as well as increased production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate.9,10 Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) is expressed in the perivascular smooth muscle adjacent to lymphatic spaces in LMs but not in the their vasculature. 10 This pattern of PDE5 expression may cause perilesional vasculature to constrict, preventing lymphatic fluid from draining into the veins.11 It is theorized that the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil leads to relaxation of the vasculature adjacent to LMs, allowing the outflow of the accumulated lymphatic fluid and thus decompression.11-13

Management of LM should not only take into account the depth and location of involvement but also any associated symptoms or complications, such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or secondary infections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically has been considered the gold standard for determining the size and depth of involvement of the malformation.1,3,4 However, ultrasonography with Doppler flow may be considered an initial diagnostic and screening test, as it can distinguish between macrocystic and microcystic components and provide superior images of microcystic lesions, which are below the resolution capacity of MRI.4 Notably, our patient’s LM was undetectable on ultrasonography and was found to be largely superficial in nature on MRI.

Serial excision of the microcystic LM was conducted in our patient, but there currently is no consensus on optimal treatment of LM, and many treatment options are complicated by high recurrence rates or complications.5 Procedural approaches may include excision, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, sclerotherapy, or laser therapy, while pharmacologic approaches may include sildenafil for its inhibition of PDE5 or sirolimus (oral or topical) for its inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin.5,12-14 Because recurrence is highly likely, patients may require repeat treatments or a combination approach to therapy.1,5 The development of targeted therapies may lead to a shift in management of LMs in the future, as successful use of the PIK3CA inhibitor alpelisib recently has been reported to lead to clinical improvement of PIK3CA-related LMs, including in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes.15

The Diagnosis: Microcystic Lymphatic Malformation

A punch biopsy demonstrated anastomosing fluidfilled spaces within the papillary and reticular dermal layers (Figure), confirming the diagnosis of microcystic lymphatic malformation (LM)(formerly known as lymphangioma circumscriptum), a congenital vascular malformation composed of slow-flow lymphatic channels.1 The patient underwent serial excisions with improvement of the LM, though the treatment course was complicated by hypertrophic scar formation.

The classic clinical presentation of microcystic LM includes a crop of vesicles containing clear or hemorrhagic fluid with associated oozing or bleeding.2 When cutaneous lesions resembling microcystic LM develop in response to lymphatic damage and resulting stasis, such as from prior radiotherapy or surgery, the term lymphangiectasia is used to distinguish this entity from congenital microcystic LM.3

Microcystic LMs are histologically indistinguishable from macrocystic LMs; however, macrocystic LMs typically are clinically evident at birth as ill-defined subcutaneous masses.2,4-6 Dermatitis herpetiformis, a dermatologic manifestation of gluten sensitivity, causes intensely pruritic vesicles in a symmetric distribution on the elbows, knees, and buttocks. Histopathology shows neutrophilic microabscesses in the dermal papillae with subepidermal blistering. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates the deposition of IgA along the basement membrane with dermal papillae aggregates.6 The underlying dermis also may contain a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate rich in neutrophils. The vesicles of herpes zoster virus are painful and present in a dermatomal distribution. A viral cytopathic effect often is observed in keratinocytes, specifically with multinucleation, molding, and margination of chromatin material. The lesions are accompanied by variable lymphocytic inflammation and epithelial necrosis resulting in intraepidermal blistering.7 Extragenital lichen sclerosus presents as polygonal white papules merging to form plaques and may include hemorrhagic blisters in some instances. Histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy with flattened rete ridges, vacuolar interface changes, loss of elastic fibers, and hyalinization of the lamina propria with lymphocytic infiltrate.8

Endothelial cells in LM exhibit activating mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha gene, PIK3CA, which may lead to proliferation and overgrowth of the lymphatic vasculature, as well as increased production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate.9,10 Phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) is expressed in the perivascular smooth muscle adjacent to lymphatic spaces in LMs but not in the their vasculature. 10 This pattern of PDE5 expression may cause perilesional vasculature to constrict, preventing lymphatic fluid from draining into the veins.11 It is theorized that the PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil leads to relaxation of the vasculature adjacent to LMs, allowing the outflow of the accumulated lymphatic fluid and thus decompression.11-13

Management of LM should not only take into account the depth and location of involvement but also any associated symptoms or complications, such as pruritus, pain, bleeding, or secondary infections. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically has been considered the gold standard for determining the size and depth of involvement of the malformation.1,3,4 However, ultrasonography with Doppler flow may be considered an initial diagnostic and screening test, as it can distinguish between macrocystic and microcystic components and provide superior images of microcystic lesions, which are below the resolution capacity of MRI.4 Notably, our patient’s LM was undetectable on ultrasonography and was found to be largely superficial in nature on MRI.

Serial excision of the microcystic LM was conducted in our patient, but there currently is no consensus on optimal treatment of LM, and many treatment options are complicated by high recurrence rates or complications.5 Procedural approaches may include excision, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, sclerotherapy, or laser therapy, while pharmacologic approaches may include sildenafil for its inhibition of PDE5 or sirolimus (oral or topical) for its inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin.5,12-14 Because recurrence is highly likely, patients may require repeat treatments or a combination approach to therapy.1,5 The development of targeted therapies may lead to a shift in management of LMs in the future, as successful use of the PIK3CA inhibitor alpelisib recently has been reported to lead to clinical improvement of PIK3CA-related LMs, including in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndromes.15

- Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:353-374. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.069

- Alrashdan MS, Hammad HM, Alzumaili BAI, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the tongue: a case with marked hemorrhagic component. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:278-281. doi:10.1111/cup.13101

- Osborne GE, Chinn RJ, Francis ND, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the investigation of penile lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:467-468. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03695.x

- Davies D, Rogers M, Lam A, et al. Localized microcystic lymphatic malformations—ultrasound diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16: 423-429. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00110.x

- García-Montero P, Del Boz J, Baselga-Torres E, et al. Use of topical rapamycin in the treatment of superficial lymphatic malformations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:508-515. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.050

- Clarindo MV, Possebon AT, Soligo EM, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:865-875; quiz 876-877. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142966

- Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Histopathologic features of cutaneous herpes virus infections (herpes simplex, herpes varicella/zoster): a broad spectrum of presentations with common pseudolymphomatous aspects. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:50-58.

- Shiver M, Papasakelariou C, Brown JA, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus in a pediatric patient: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:383-385. doi:10.1111 /pde.12025

- Blesinger H, Kaulfuß S, Aung T, et al. PIK3CA mutations are specifically localized to lymphatic endothelial cells of lymphatic malformations [published online July 9, 2018]. PLoS One. 2018;13:E0200343. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200343

- Green JS, Prok L, Bruckner AL. Expression of phosphodiesterase-5 in lymphatic malformation tissue. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:455-456. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7002

- Swetman GL, Berk DR, Vasanawala SS, et al. Sildenafil for severe lymphatic malformations. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:384-386. doi:10.1056 /NEJMc1112482

- Tu JH, Tafoya E, Jeng M, et al. Long-term follow-up of lymphatic malformations in children treated with sildenafil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:559-565. doi:10.1111/pde.13237

- Maruani A, Tavernier E, Boccara O, et al. Sirolimus (rapamycin) for slow-flow malformations in children: the Observational-Phase Randomized Clinical PERFORMUS Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1289-1298. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3459

- Delestre F, Venot Q, Bayard C, et al. Alpelisib administration reduced lymphatic malformations in a mouse model and in patients. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabg0809. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed .abg0809

- Garreta Fontelles G, Pardo Pastor J, Grande Moreillo C. Alpelisib to treat CLOVES syndrome, a member of the PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome spectrum [published online February 21, 2022]. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:3891-3895. doi:10.1111/bcp.15270

- Garzon MC, Huang JT, Enjolras O, et al. Vascular malformations: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:353-374. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.069

- Alrashdan MS, Hammad HM, Alzumaili BAI, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the tongue: a case with marked hemorrhagic component. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:278-281. doi:10.1111/cup.13101

- Osborne GE, Chinn RJ, Francis ND, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the investigation of penile lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:467-468. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03695.x

- Davies D, Rogers M, Lam A, et al. Localized microcystic lymphatic malformations—ultrasound diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16: 423-429. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00110.x

- García-Montero P, Del Boz J, Baselga-Torres E, et al. Use of topical rapamycin in the treatment of superficial lymphatic malformations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:508-515. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.050

- Clarindo MV, Possebon AT, Soligo EM, et al. Dermatitis herpetiformis: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:865-875; quiz 876-877. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142966

- Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Histopathologic features of cutaneous herpes virus infections (herpes simplex, herpes varicella/zoster): a broad spectrum of presentations with common pseudolymphomatous aspects. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:50-58.

- Shiver M, Papasakelariou C, Brown JA, et al. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus in a pediatric patient: a case report and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:383-385. doi:10.1111 /pde.12025

- Blesinger H, Kaulfuß S, Aung T, et al. PIK3CA mutations are specifically localized to lymphatic endothelial cells of lymphatic malformations [published online July 9, 2018]. PLoS One. 2018;13:E0200343. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200343

- Green JS, Prok L, Bruckner AL. Expression of phosphodiesterase-5 in lymphatic malformation tissue. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:455-456. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7002

- Swetman GL, Berk DR, Vasanawala SS, et al. Sildenafil for severe lymphatic malformations. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:384-386. doi:10.1056 /NEJMc1112482

- Tu JH, Tafoya E, Jeng M, et al. Long-term follow-up of lymphatic malformations in children treated with sildenafil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:559-565. doi:10.1111/pde.13237

- Maruani A, Tavernier E, Boccara O, et al. Sirolimus (rapamycin) for slow-flow malformations in children: the Observational-Phase Randomized Clinical PERFORMUS Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1289-1298. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.3459

- Delestre F, Venot Q, Bayard C, et al. Alpelisib administration reduced lymphatic malformations in a mouse model and in patients. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabg0809. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed .abg0809

- Garreta Fontelles G, Pardo Pastor J, Grande Moreillo C. Alpelisib to treat CLOVES syndrome, a member of the PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome spectrum [published online February 21, 2022]. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:3891-3895. doi:10.1111/bcp.15270

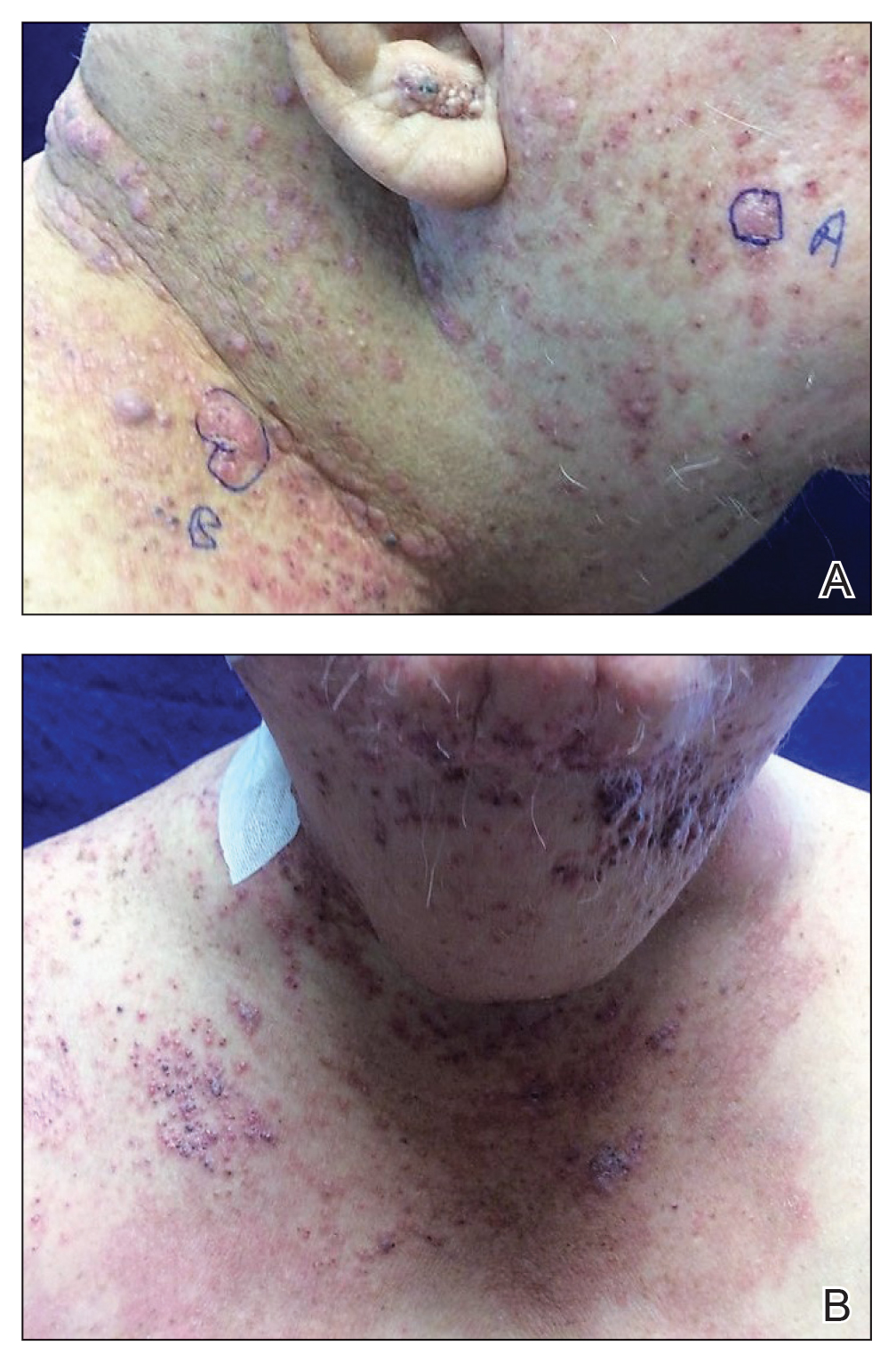

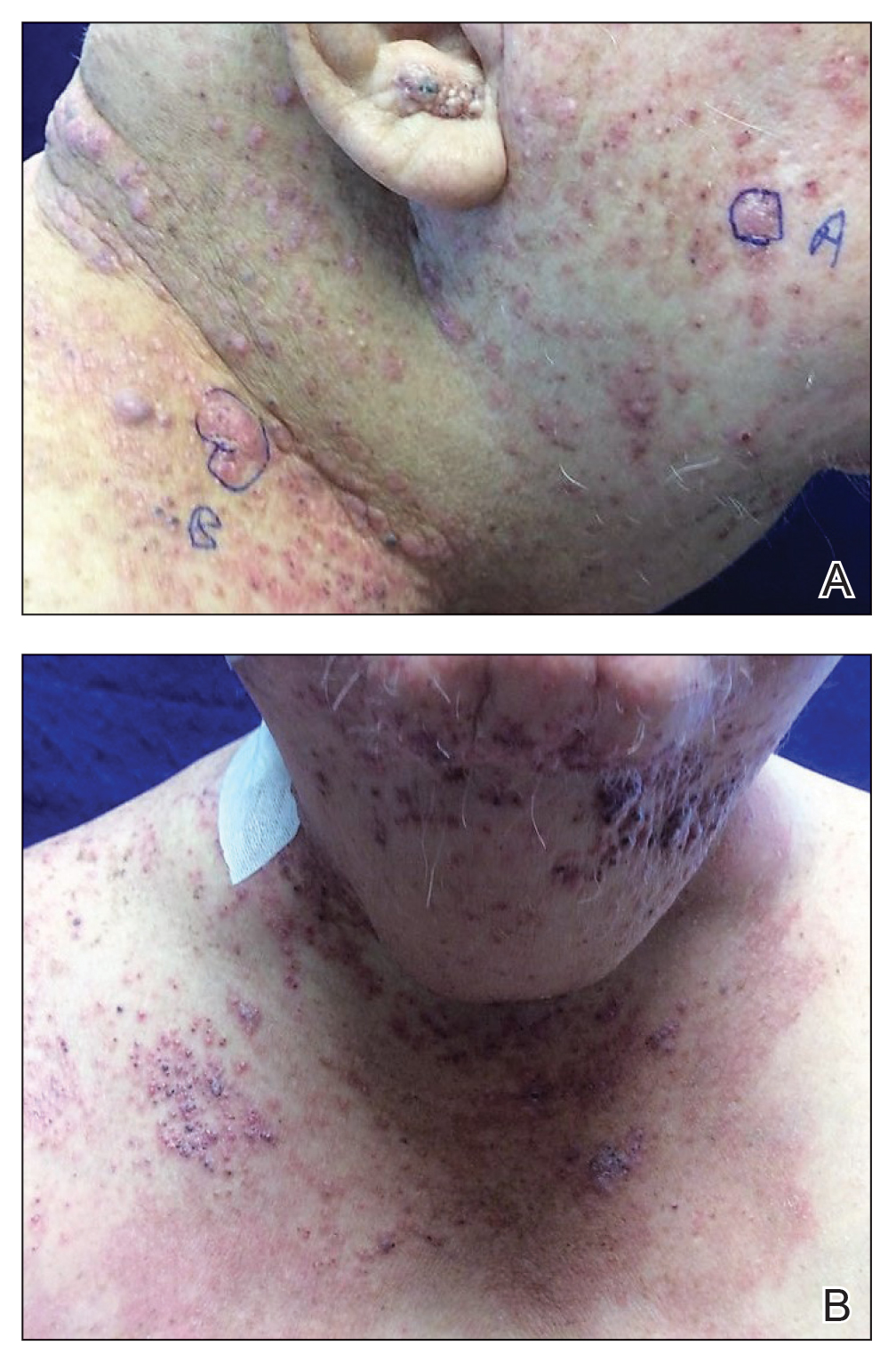

A 6-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash on the right side of the neck that was noted at birth as a small raised lesion but slowly increased over time in size and number of lesions. She reported pruritus and irritation, particularly when rubbed or scratched. There was no family history of similar skin abnormalities. Her medical history was notable for a left-sided cholesteatoma on tympanomastoidectomy. Physical examination revealed clustered vesicles on the right side of the neck with underlying erythema. The vesicles contained mostly clear fluid with a few focal areas of hemorrhagic fluid. Ultrasonography was unremarkable, and magnetic resonance imaging revealed superficial T2 hyperintense nonenhancing cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions overlying the right lateral neck with minimal extension into the superficial right supraclavicular soft tissues.

Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy With Ocular Involvement

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

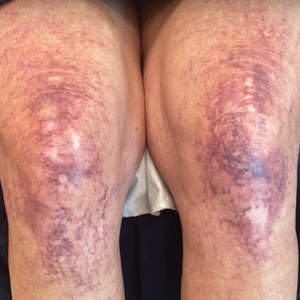

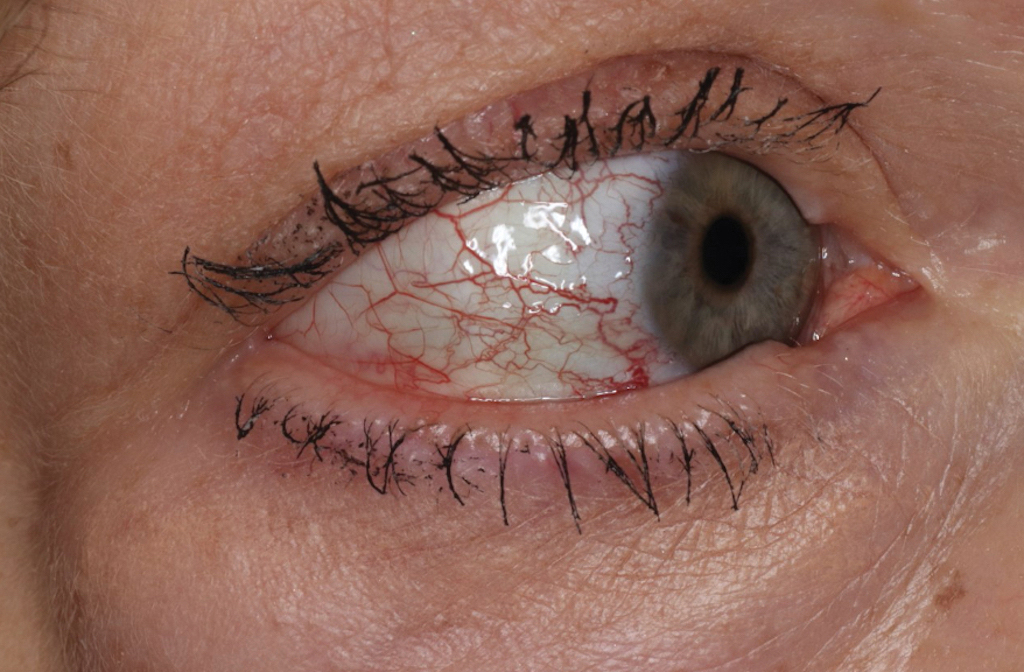

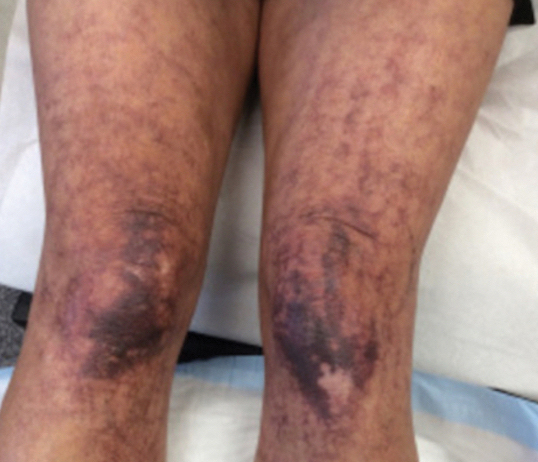

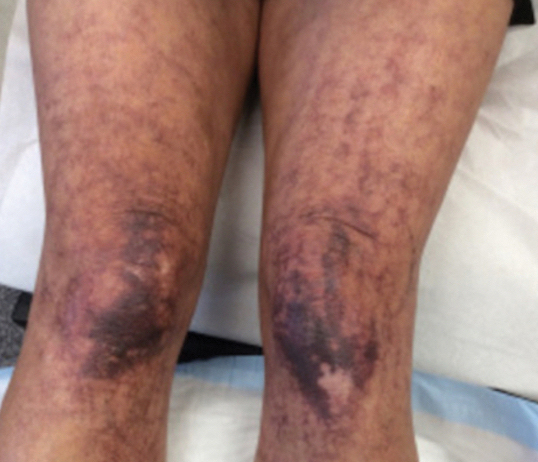

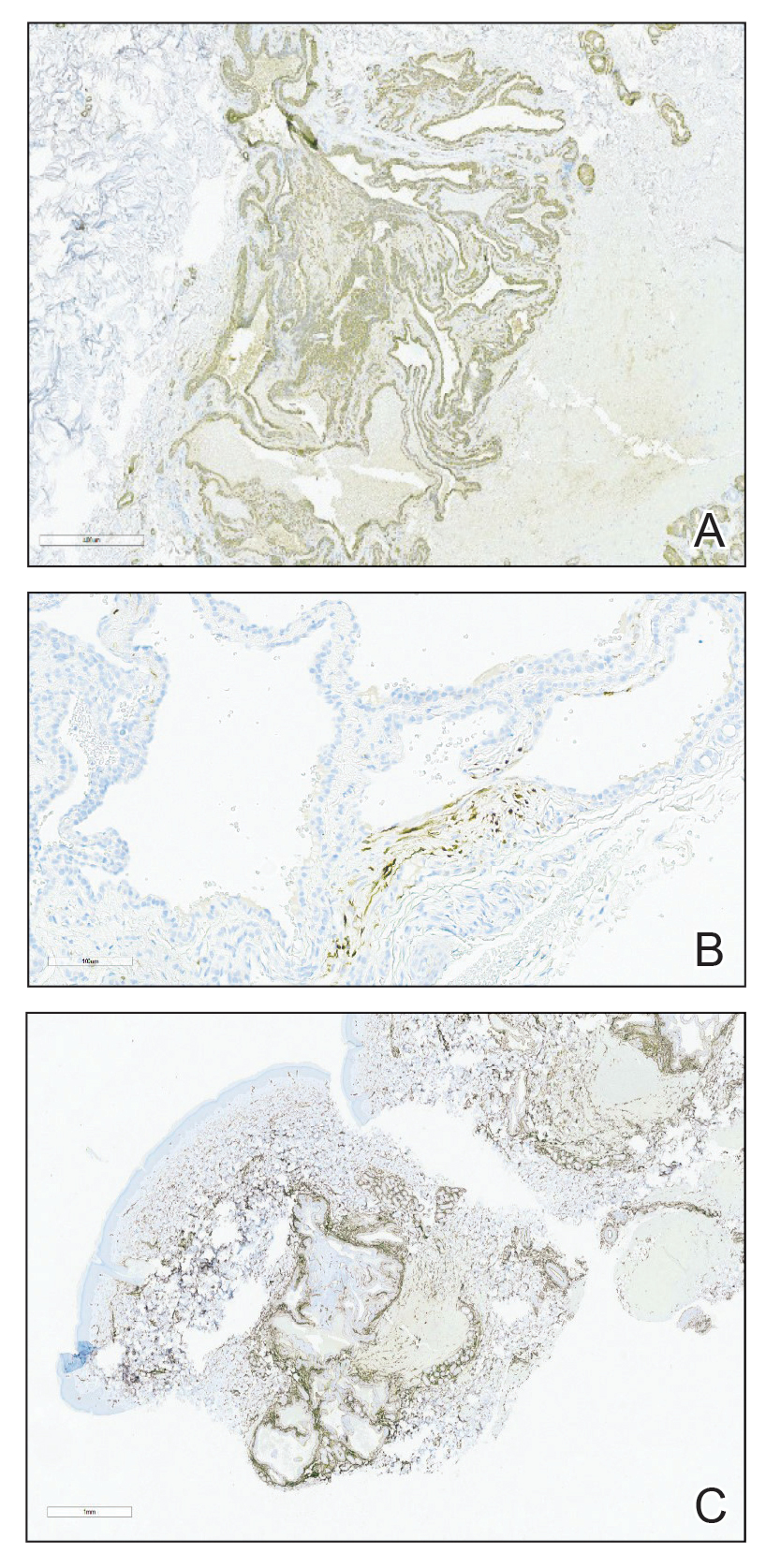

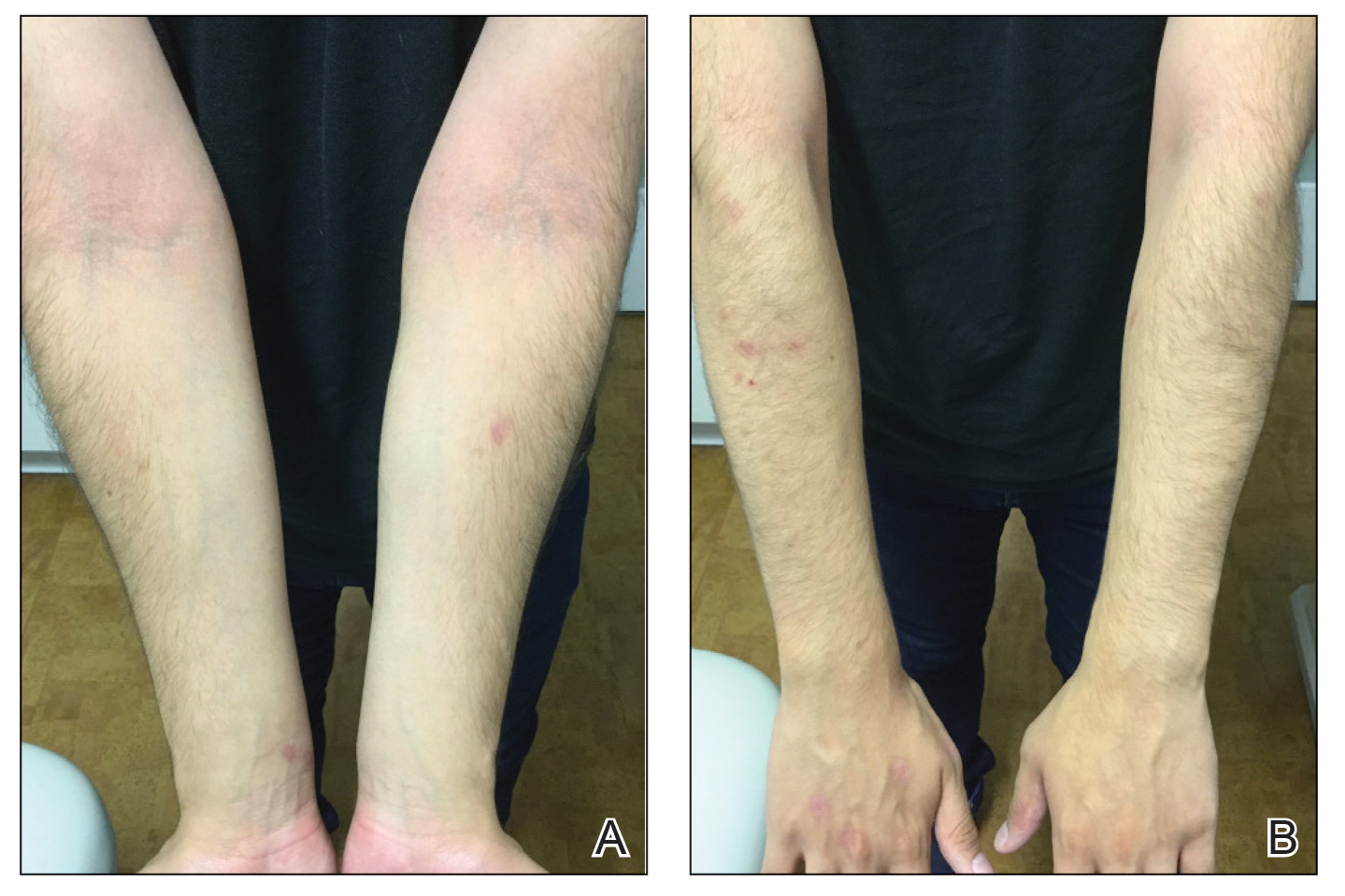

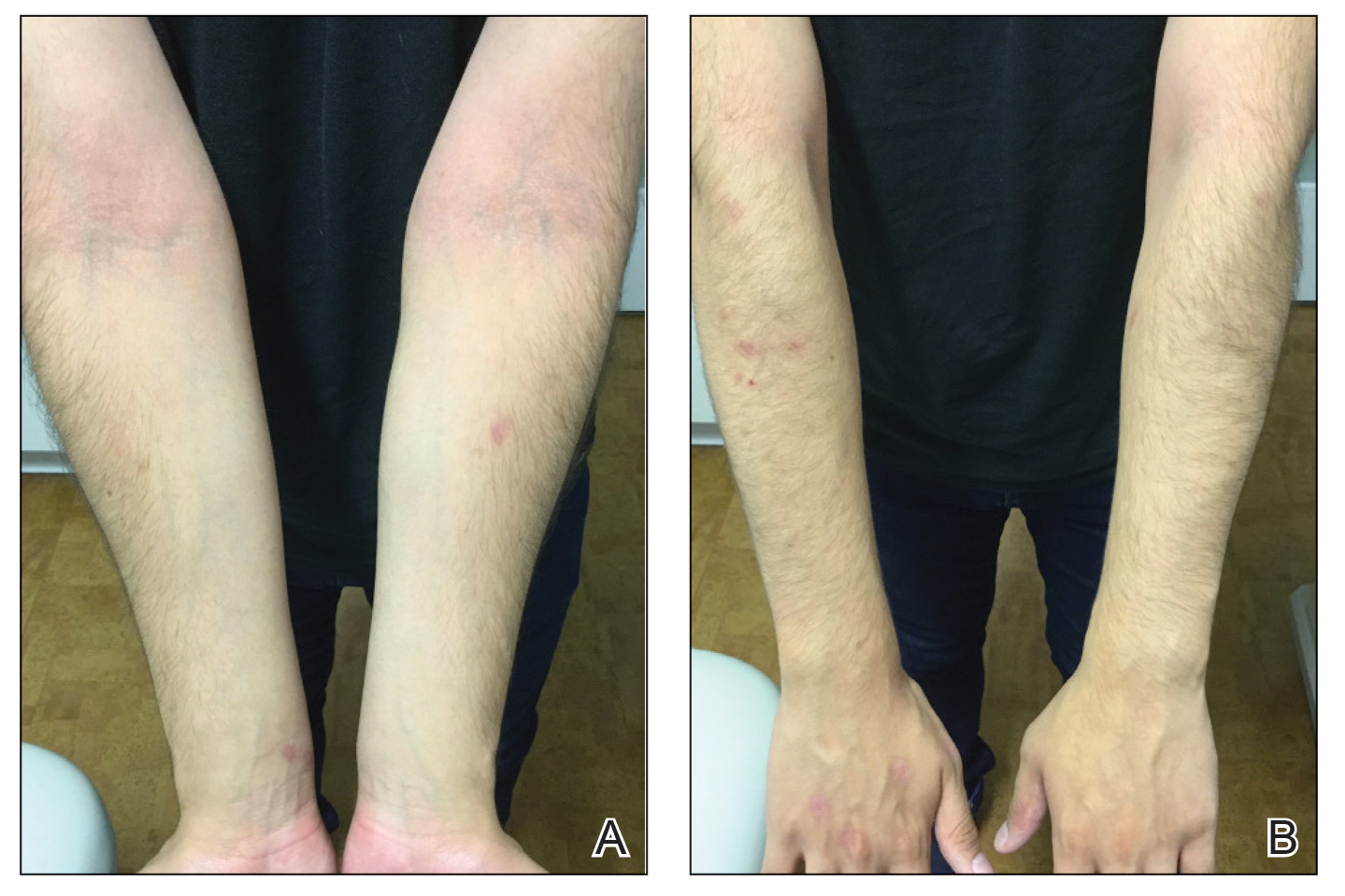

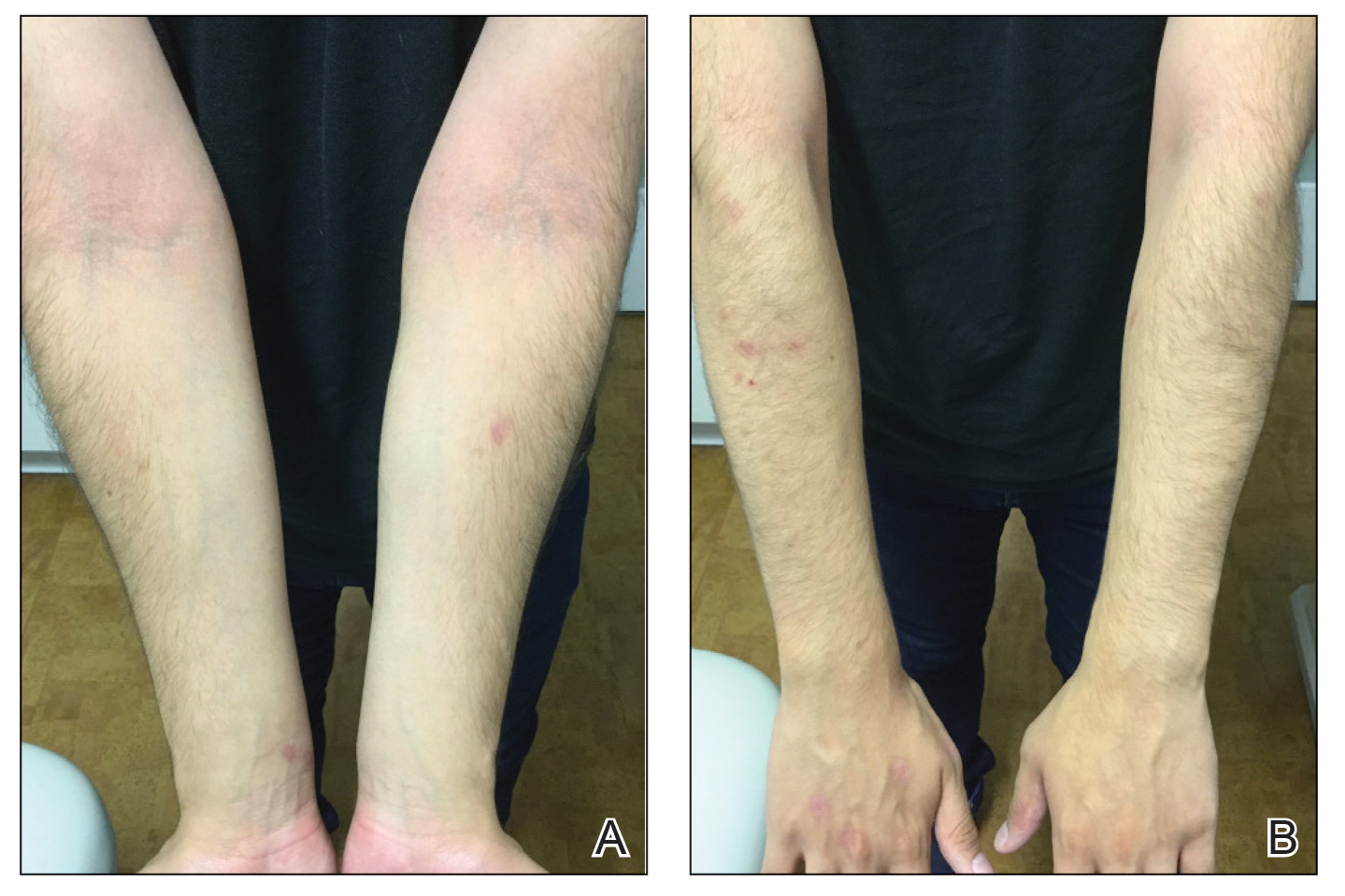

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

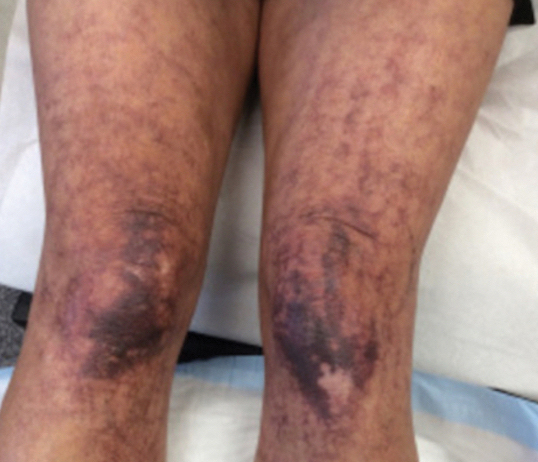

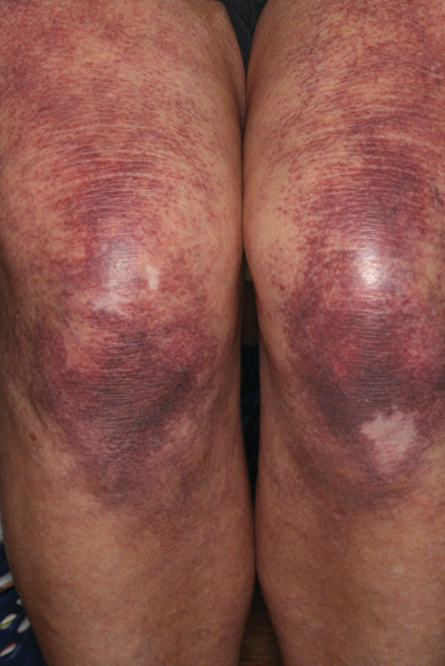

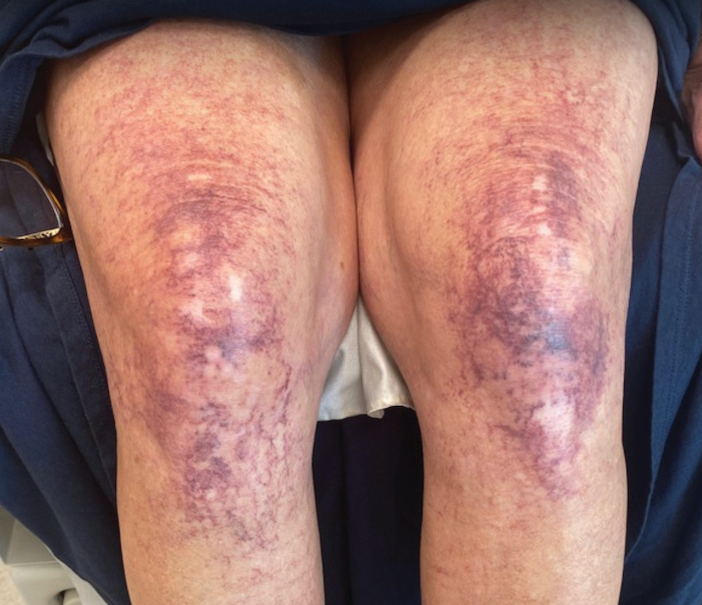

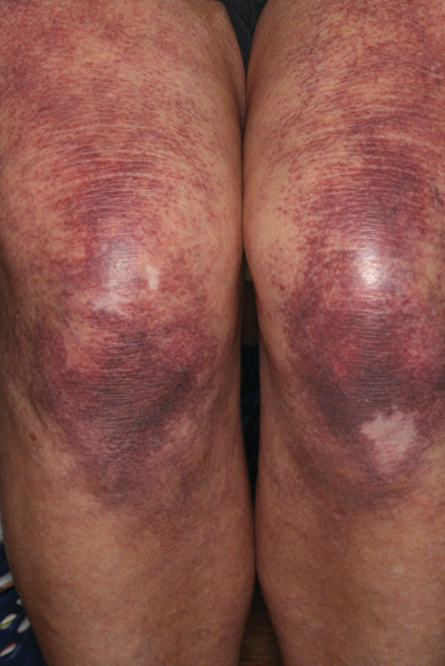

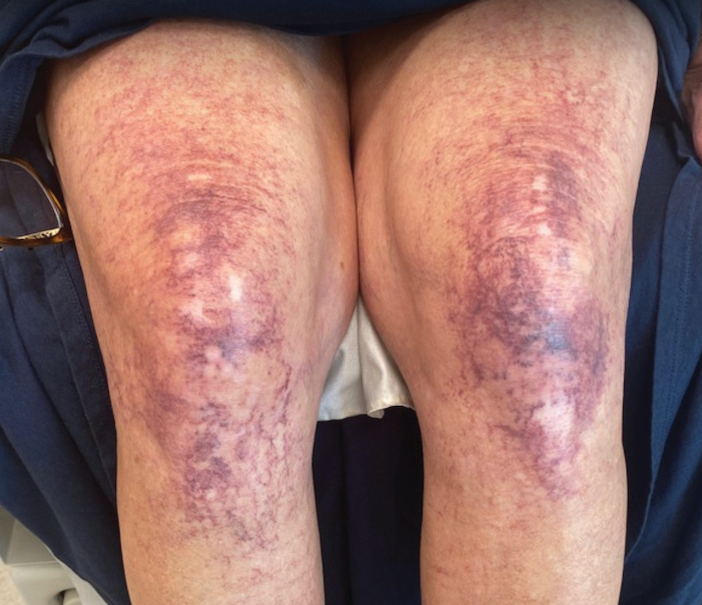

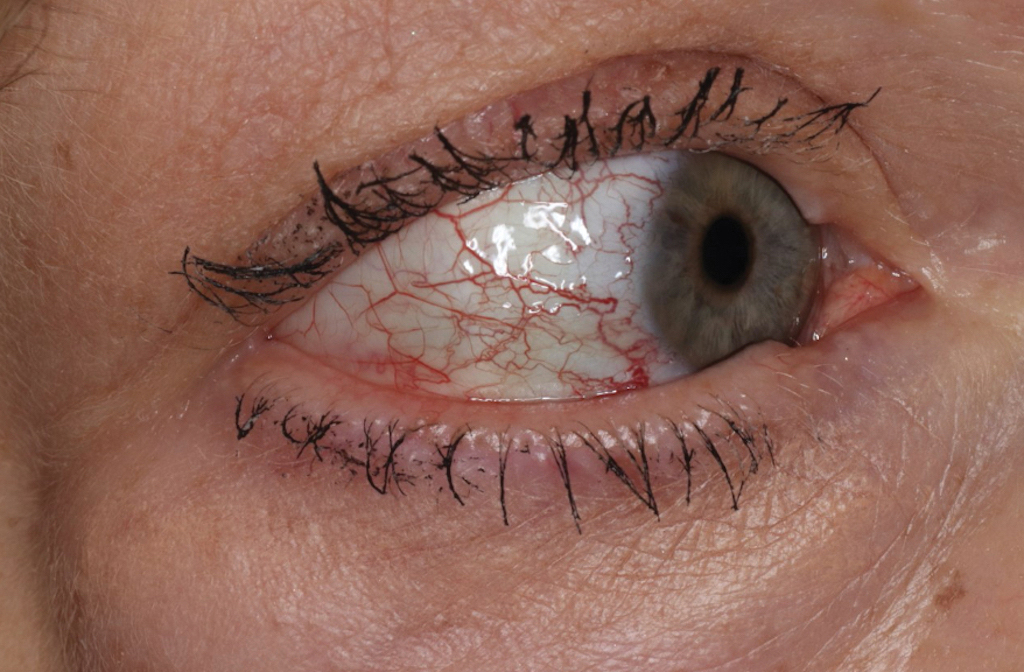

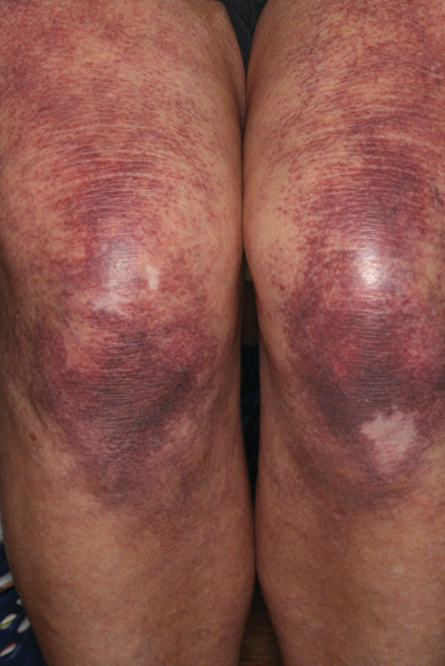

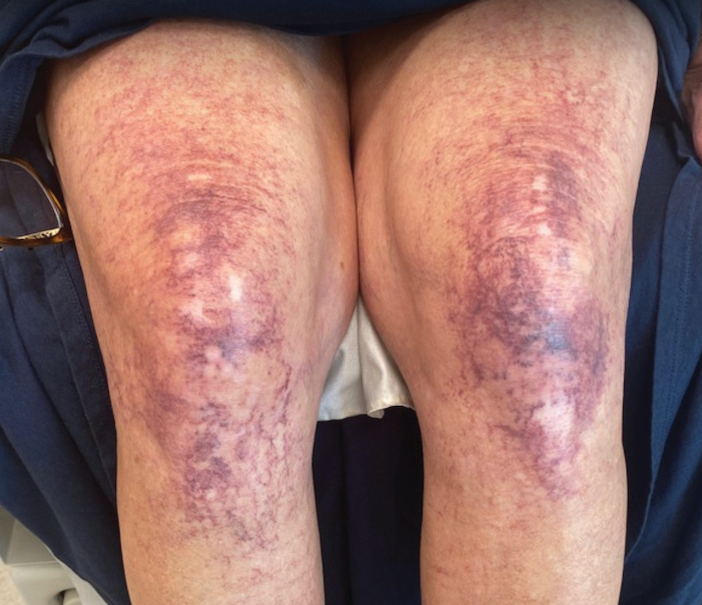

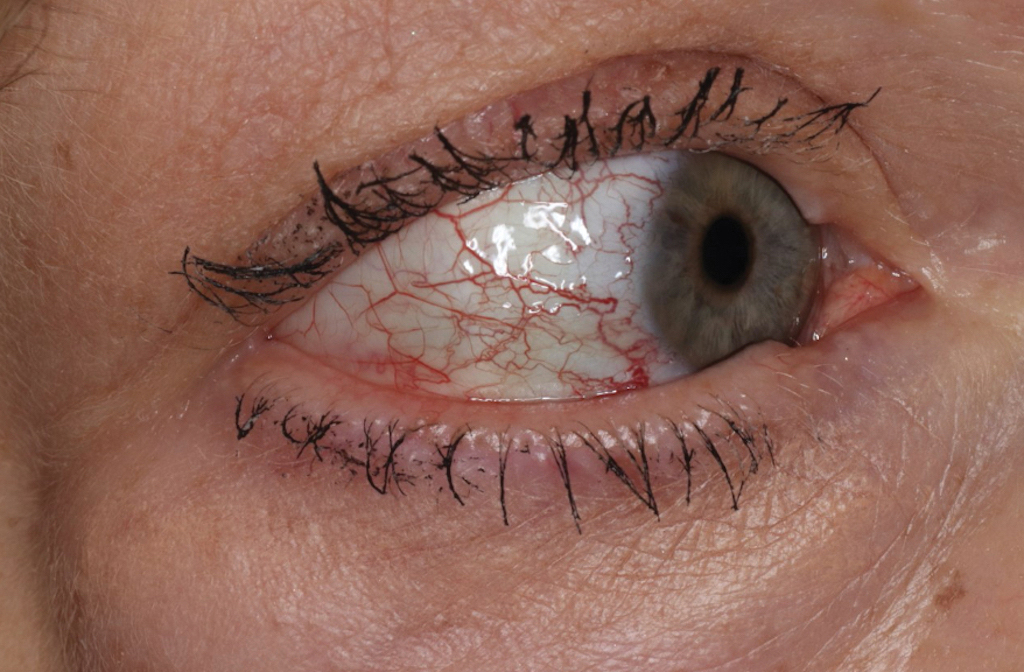

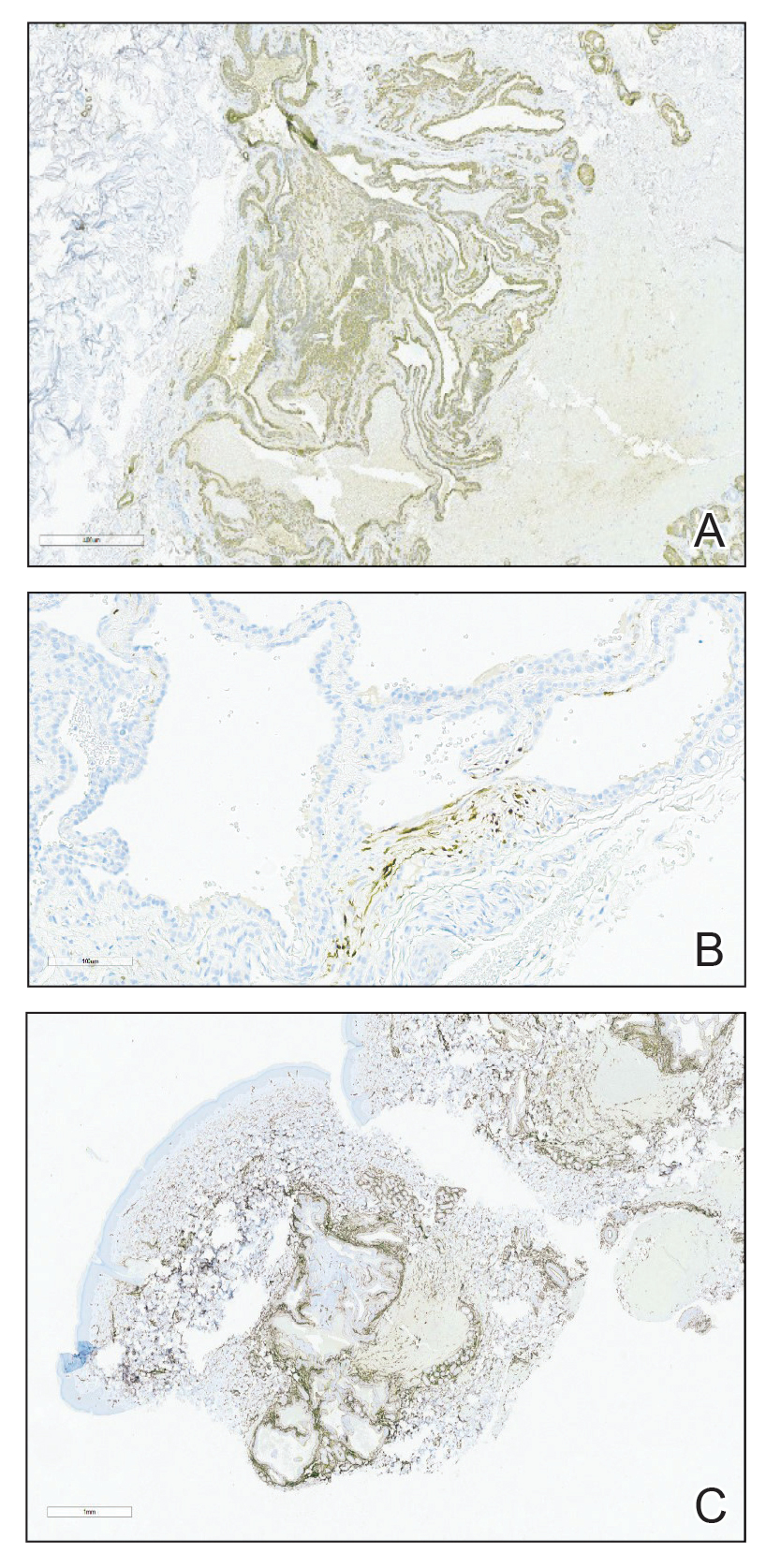

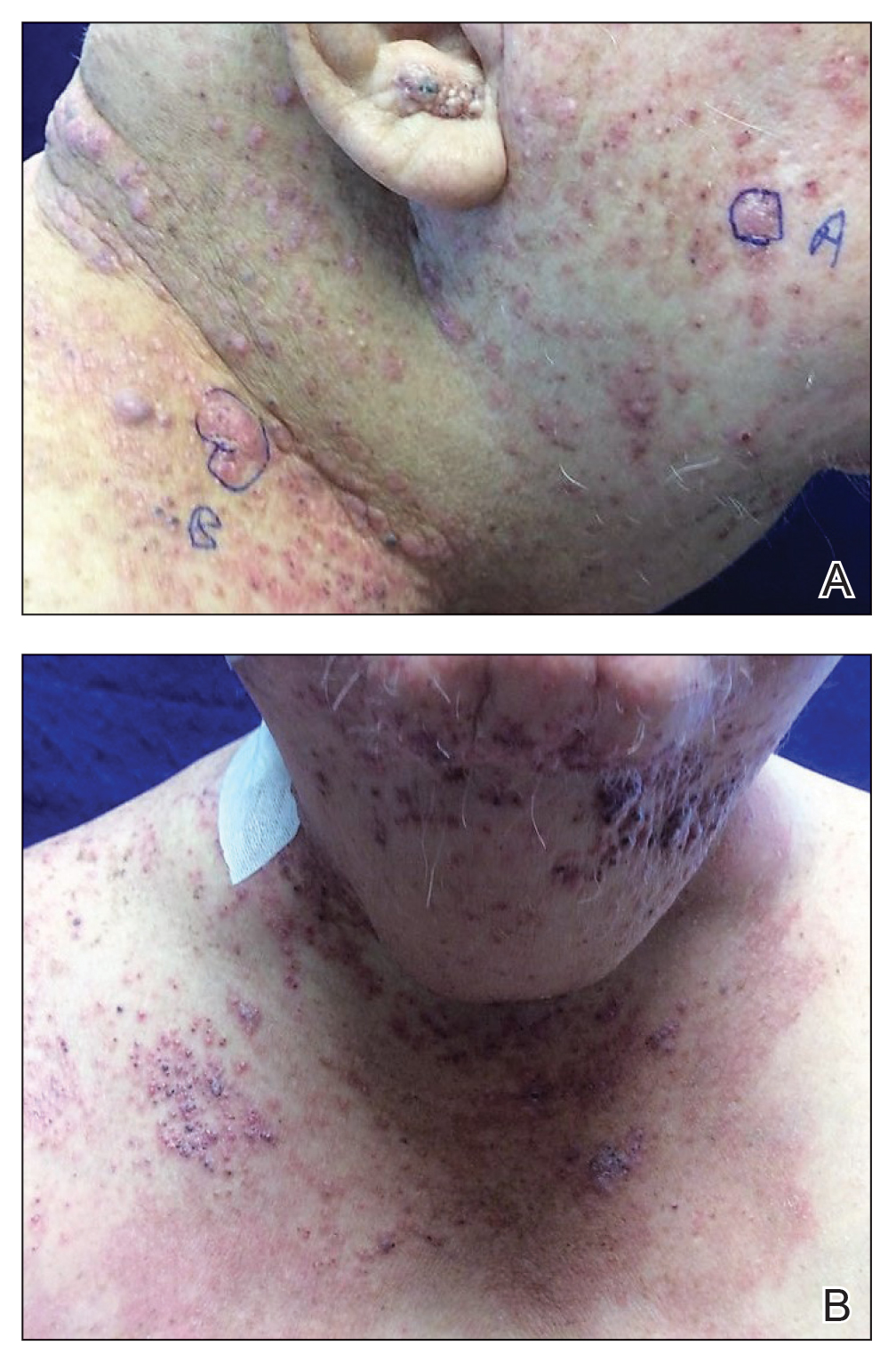

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

Practice Points

- Collagenous vasculopathy is an underrecognized entity.

- Although most patients exhibit only cutaneous disease, systemic involvement also should be assessed.

Skin in the Game: Inadequate Photoprotection Among Olympic Athletes

The XXXIII Olympic Summer Games will take place in Paris, France, from July 26 to August 11, 2024, and a variety of outdoor sporting events (eg, surfing, cycling, beach volleyball) will be included. Participation in the Olympic Games is a distinct honor for athletes selected to compete at the highest level in their sports.

Because of their training regimens and lifestyles, Olympic athletes face unique health risks. One such risk appears to be skin cancer, a substantial contributor to the global burden of disease. Taken together, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma account for 6.7 million cases of skin cancer worldwide. Squamous cell carcinoma and malignant skin melanoma were attributed to 1.2 million and 1.7 million life-years lost to disability, respectively.1

Olympic athletes are at increased risk for sunburn from UVA and UVB radiation, placing them at higher risk for both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers.2,3 Sweating increases skin photosensitivity, sportswear often offers inadequate sun protection, and sustained high-intensity exercise itself has an immunosuppressive effect. Athletes competing in skiing and snowboarding events also receive radiation reflected off snow and ice at high altitudes.3 In fact, skiing without sunscreen at 11,000-feet above sea level can induce sunburn after only 6 minutes of exposure.4 Moreover, sweat, water immersion, and friction can decrease the effectiveness of topical sunscreens.5

World-class athletes appear to be exposed to UV radiation to a substantially higher degree than the general public. In an analysis of 144 events at the 2020 XXXII Olympic Summer Games in Tokyo, Japan, the highest exposure assessments were for women’s tennis, men’s golf, and men’s road cycling.6 In a 2020 study (N=240), the rates of sunburn were as high as 76.7% among Olympic sailors, elite surfers, and windsurfers, with more than one-quarter of athletes reporting sunburn that lasted longer than 24 hours.7 An earlier study reported that professional cyclists were exposed to UV radiation during a single race that exceeded the personal exposure limit by 30 times.8

Regrettably, the high level of sun exposure experienced by elite athletes is compounded by their low rate of sunscreen use. In a 2020 survey of 95 Olympians and super sprint triathletes, approximately half rarely used sunscreen, with 1 in 5 athletes never using sunscreen during training.9 In another study of 246 elite athletes in surfing, windsurfing, and sailing, nearly half used inadequate sun protection and nearly one-quarter reported never using sunscreen.10 Surprisingly, as many as 90% of Olympic athletes and super sprint competitors understood the importance of using sunscreen.9

What can we learn from these findings?

First, elite athletes remain at high risk for skin cancer because of training regimens, occupational environmental hazards, and other requirements of their sport. Second, despite awareness of the risks of UV radiation exposure, Olympic athletes utilize inadequate photoprotection. Athletes with darker skin are still at risk for skin cancer, photoaging, and pigmentation disorders—indicating a need for photoprotective behaviors in athletes of all skin types.11

Therefore, efforts to promote adequate sunscreen use and understanding of the consequences of UV radiation may need to be prioritized earlier in athletes’ careers and implemented according to evidence-based guidelines. For example, the Stanford University Network for Sun Protection, Outreach, Research and Teamwork (Sunsport) provided information about skin cancer risk and prevention by educating student-athletes, coaches, and trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association in the United States. The Sunsport initiative led to a dramatic increase in sunscreen use by student-athletes as well as increased knowledge and discussion of skin cancer risk.12

- Zhang W, Zeng W, Jiang A, et al. Global, regional and national incidence, mortality and disability-adjusted life-years of skin cancers and trend analysis from 1990 to 2019: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Cancer Med. 2021;10:4905-4922. doi:10.1002/cam4.4046

- De Luca JF, Adams BB, Yosipovitch G. Skin manifestations of athletes competing in the summer Olympics: what a sports medicine physician should know. Sports Med. 2012;42:399-413. doi:10.2165/11599050-000000000-00000

- Moehrle M. Outdoor sports and skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:12-15. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.10.001

- Rigel DS, Rigel EG, Rigel AC. Effects of altitude and latitude on ambient UVB radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:114-116. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70542-6

- Harrison SC, Bergfeld WF. Ultraviolet light and skin cancer in athletes. Sports Health. 2009;1:335-340. doi:10.1177/19417381093338923

- Downs NJ, Axelsen T, Schouten P, et al. Biologically effective solar ultraviolet exposures and the potential skin cancer risk for individual gold medalists of the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympic Games. Temperature (Austin). 2019;7:89-108. doi:10.1080/23328940.2019.1581427

- De Castro-Maqueda G, Gutierrez-Manzanedo JV, Ponce-González JG, et al. Sun protection habits and sunburn in elite aquatics athletes: surfers, windsurfers and Olympic sailors. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35:312-320. doi:10.1007/s13187-018-1466-x

- Moehrle M, Heinrich L, Schmid A, et al. Extreme UV exposure of professional cyclists. Dermatology. 2000;201:44-45. doi:10.1159/000018428

- Buljan M, Kolic´ M, Šitum M, et al. Do athletes practicing outdoors know and care enough about the importance of photoprotection? Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2020;28:41-42.

- De Castro-Maqueda G, Gutierrez-Manzanedo JV, Lagares-Franco C. Sun exposure during water sports: do elite athletes adequately protect their skin against skin cancer? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:800. doi:10.3390/ijerph18020800

- Tsai J, Chien AL. Photoprotection for skin of color. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:195-205. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00670-z

- Ally MS, Swetter SM, Hirotsu KE, et al. Promoting sunscreen use and sun-protective practices in NCAA athletes: impact of SUNSPORT educational intervention for student-athletes, athletic trainers, and coaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:289-292.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.050

The XXXIII Olympic Summer Games will take place in Paris, France, from July 26 to August 11, 2024, and a variety of outdoor sporting events (eg, surfing, cycling, beach volleyball) will be included. Participation in the Olympic Games is a distinct honor for athletes selected to compete at the highest level in their sports.

Because of their training regimens and lifestyles, Olympic athletes face unique health risks. One such risk appears to be skin cancer, a substantial contributor to the global burden of disease. Taken together, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma account for 6.7 million cases of skin cancer worldwide. Squamous cell carcinoma and malignant skin melanoma were attributed to 1.2 million and 1.7 million life-years lost to disability, respectively.1

Olympic athletes are at increased risk for sunburn from UVA and UVB radiation, placing them at higher risk for both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers.2,3 Sweating increases skin photosensitivity, sportswear often offers inadequate sun protection, and sustained high-intensity exercise itself has an immunosuppressive effect. Athletes competing in skiing and snowboarding events also receive radiation reflected off snow and ice at high altitudes.3 In fact, skiing without sunscreen at 11,000-feet above sea level can induce sunburn after only 6 minutes of exposure.4 Moreover, sweat, water immersion, and friction can decrease the effectiveness of topical sunscreens.5

World-class athletes appear to be exposed to UV radiation to a substantially higher degree than the general public. In an analysis of 144 events at the 2020 XXXII Olympic Summer Games in Tokyo, Japan, the highest exposure assessments were for women’s tennis, men’s golf, and men’s road cycling.6 In a 2020 study (N=240), the rates of sunburn were as high as 76.7% among Olympic sailors, elite surfers, and windsurfers, with more than one-quarter of athletes reporting sunburn that lasted longer than 24 hours.7 An earlier study reported that professional cyclists were exposed to UV radiation during a single race that exceeded the personal exposure limit by 30 times.8

Regrettably, the high level of sun exposure experienced by elite athletes is compounded by their low rate of sunscreen use. In a 2020 survey of 95 Olympians and super sprint triathletes, approximately half rarely used sunscreen, with 1 in 5 athletes never using sunscreen during training.9 In another study of 246 elite athletes in surfing, windsurfing, and sailing, nearly half used inadequate sun protection and nearly one-quarter reported never using sunscreen.10 Surprisingly, as many as 90% of Olympic athletes and super sprint competitors understood the importance of using sunscreen.9

What can we learn from these findings?

First, elite athletes remain at high risk for skin cancer because of training regimens, occupational environmental hazards, and other requirements of their sport. Second, despite awareness of the risks of UV radiation exposure, Olympic athletes utilize inadequate photoprotection. Athletes with darker skin are still at risk for skin cancer, photoaging, and pigmentation disorders—indicating a need for photoprotective behaviors in athletes of all skin types.11

Therefore, efforts to promote adequate sunscreen use and understanding of the consequences of UV radiation may need to be prioritized earlier in athletes’ careers and implemented according to evidence-based guidelines. For example, the Stanford University Network for Sun Protection, Outreach, Research and Teamwork (Sunsport) provided information about skin cancer risk and prevention by educating student-athletes, coaches, and trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association in the United States. The Sunsport initiative led to a dramatic increase in sunscreen use by student-athletes as well as increased knowledge and discussion of skin cancer risk.12

The XXXIII Olympic Summer Games will take place in Paris, France, from July 26 to August 11, 2024, and a variety of outdoor sporting events (eg, surfing, cycling, beach volleyball) will be included. Participation in the Olympic Games is a distinct honor for athletes selected to compete at the highest level in their sports.

Because of their training regimens and lifestyles, Olympic athletes face unique health risks. One such risk appears to be skin cancer, a substantial contributor to the global burden of disease. Taken together, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma account for 6.7 million cases of skin cancer worldwide. Squamous cell carcinoma and malignant skin melanoma were attributed to 1.2 million and 1.7 million life-years lost to disability, respectively.1

Olympic athletes are at increased risk for sunburn from UVA and UVB radiation, placing them at higher risk for both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers.2,3 Sweating increases skin photosensitivity, sportswear often offers inadequate sun protection, and sustained high-intensity exercise itself has an immunosuppressive effect. Athletes competing in skiing and snowboarding events also receive radiation reflected off snow and ice at high altitudes.3 In fact, skiing without sunscreen at 11,000-feet above sea level can induce sunburn after only 6 minutes of exposure.4 Moreover, sweat, water immersion, and friction can decrease the effectiveness of topical sunscreens.5

World-class athletes appear to be exposed to UV radiation to a substantially higher degree than the general public. In an analysis of 144 events at the 2020 XXXII Olympic Summer Games in Tokyo, Japan, the highest exposure assessments were for women’s tennis, men’s golf, and men’s road cycling.6 In a 2020 study (N=240), the rates of sunburn were as high as 76.7% among Olympic sailors, elite surfers, and windsurfers, with more than one-quarter of athletes reporting sunburn that lasted longer than 24 hours.7 An earlier study reported that professional cyclists were exposed to UV radiation during a single race that exceeded the personal exposure limit by 30 times.8

Regrettably, the high level of sun exposure experienced by elite athletes is compounded by their low rate of sunscreen use. In a 2020 survey of 95 Olympians and super sprint triathletes, approximately half rarely used sunscreen, with 1 in 5 athletes never using sunscreen during training.9 In another study of 246 elite athletes in surfing, windsurfing, and sailing, nearly half used inadequate sun protection and nearly one-quarter reported never using sunscreen.10 Surprisingly, as many as 90% of Olympic athletes and super sprint competitors understood the importance of using sunscreen.9

What can we learn from these findings?

First, elite athletes remain at high risk for skin cancer because of training regimens, occupational environmental hazards, and other requirements of their sport. Second, despite awareness of the risks of UV radiation exposure, Olympic athletes utilize inadequate photoprotection. Athletes with darker skin are still at risk for skin cancer, photoaging, and pigmentation disorders—indicating a need for photoprotective behaviors in athletes of all skin types.11

Therefore, efforts to promote adequate sunscreen use and understanding of the consequences of UV radiation may need to be prioritized earlier in athletes’ careers and implemented according to evidence-based guidelines. For example, the Stanford University Network for Sun Protection, Outreach, Research and Teamwork (Sunsport) provided information about skin cancer risk and prevention by educating student-athletes, coaches, and trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association in the United States. The Sunsport initiative led to a dramatic increase in sunscreen use by student-athletes as well as increased knowledge and discussion of skin cancer risk.12

- Zhang W, Zeng W, Jiang A, et al. Global, regional and national incidence, mortality and disability-adjusted life-years of skin cancers and trend analysis from 1990 to 2019: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Cancer Med. 2021;10:4905-4922. doi:10.1002/cam4.4046

- De Luca JF, Adams BB, Yosipovitch G. Skin manifestations of athletes competing in the summer Olympics: what a sports medicine physician should know. Sports Med. 2012;42:399-413. doi:10.2165/11599050-000000000-00000

- Moehrle M. Outdoor sports and skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:12-15. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.10.001

- Rigel DS, Rigel EG, Rigel AC. Effects of altitude and latitude on ambient UVB radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:114-116. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70542-6

- Harrison SC, Bergfeld WF. Ultraviolet light and skin cancer in athletes. Sports Health. 2009;1:335-340. doi:10.1177/19417381093338923

- Downs NJ, Axelsen T, Schouten P, et al. Biologically effective solar ultraviolet exposures and the potential skin cancer risk for individual gold medalists of the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympic Games. Temperature (Austin). 2019;7:89-108. doi:10.1080/23328940.2019.1581427

- De Castro-Maqueda G, Gutierrez-Manzanedo JV, Ponce-González JG, et al. Sun protection habits and sunburn in elite aquatics athletes: surfers, windsurfers and Olympic sailors. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35:312-320. doi:10.1007/s13187-018-1466-x

- Moehrle M, Heinrich L, Schmid A, et al. Extreme UV exposure of professional cyclists. Dermatology. 2000;201:44-45. doi:10.1159/000018428

- Buljan M, Kolic´ M, Šitum M, et al. Do athletes practicing outdoors know and care enough about the importance of photoprotection? Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2020;28:41-42.

- De Castro-Maqueda G, Gutierrez-Manzanedo JV, Lagares-Franco C. Sun exposure during water sports: do elite athletes adequately protect their skin against skin cancer? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:800. doi:10.3390/ijerph18020800

- Tsai J, Chien AL. Photoprotection for skin of color. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:195-205. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00670-z

- Ally MS, Swetter SM, Hirotsu KE, et al. Promoting sunscreen use and sun-protective practices in NCAA athletes: impact of SUNSPORT educational intervention for student-athletes, athletic trainers, and coaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:289-292.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.050

- Zhang W, Zeng W, Jiang A, et al. Global, regional and national incidence, mortality and disability-adjusted life-years of skin cancers and trend analysis from 1990 to 2019: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Cancer Med. 2021;10:4905-4922. doi:10.1002/cam4.4046

- De Luca JF, Adams BB, Yosipovitch G. Skin manifestations of athletes competing in the summer Olympics: what a sports medicine physician should know. Sports Med. 2012;42:399-413. doi:10.2165/11599050-000000000-00000

- Moehrle M. Outdoor sports and skin cancer. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:12-15. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.10.001

- Rigel DS, Rigel EG, Rigel AC. Effects of altitude and latitude on ambient UVB radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:114-116. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70542-6

- Harrison SC, Bergfeld WF. Ultraviolet light and skin cancer in athletes. Sports Health. 2009;1:335-340. doi:10.1177/19417381093338923

- Downs NJ, Axelsen T, Schouten P, et al. Biologically effective solar ultraviolet exposures and the potential skin cancer risk for individual gold medalists of the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympic Games. Temperature (Austin). 2019;7:89-108. doi:10.1080/23328940.2019.1581427

- De Castro-Maqueda G, Gutierrez-Manzanedo JV, Ponce-González JG, et al. Sun protection habits and sunburn in elite aquatics athletes: surfers, windsurfers and Olympic sailors. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35:312-320. doi:10.1007/s13187-018-1466-x

- Moehrle M, Heinrich L, Schmid A, et al. Extreme UV exposure of professional cyclists. Dermatology. 2000;201:44-45. doi:10.1159/000018428

- Buljan M, Kolic´ M, Šitum M, et al. Do athletes practicing outdoors know and care enough about the importance of photoprotection? Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2020;28:41-42.

- De Castro-Maqueda G, Gutierrez-Manzanedo JV, Lagares-Franco C. Sun exposure during water sports: do elite athletes adequately protect their skin against skin cancer? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:800. doi:10.3390/ijerph18020800

- Tsai J, Chien AL. Photoprotection for skin of color. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:195-205. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00670-z

- Ally MS, Swetter SM, Hirotsu KE, et al. Promoting sunscreen use and sun-protective practices in NCAA athletes: impact of SUNSPORT educational intervention for student-athletes, athletic trainers, and coaches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:289-292.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.050

Practice Points

- Providers should further investigate how patients spend their time outside to assess cancer risk and appropriately guide patients.

- Many athletes typically train for hours outside; therefore, these patients should be educated on the importance of sunscreen reapplication and protective clothing.

The Clinical Diversity of Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder that affects individuals worldwide.1 Although AD previously was commonly described as a skin-limited disease of childhood characterized by eczema in the flexural folds and pruritus, our current understanding supports a more heterogeneous condition.2 We review the wide range of cutaneous presentations of AD with a focus on clinical and morphological presentations across diverse skin types—commonly referred to as skin of color (SOC).

Defining SOC in Relation to AD

The terms SOC, race, and ethnicity are used interchangeably, but their true meanings are distinct. Traditionally, race has been defined as a biological concept, grouping cohorts of individuals with a large degree of shared ancestry and genetic similarities,3 and ethnicity as a social construct, grouping individuals with common racial, national, tribal, religious, linguistic, or cultural backgrounds.4 In practice, both concepts can broadly be envisioned as mixed social, political, and economic constructs, as no one gene or biologic characteristic distinguishes one racial or ethnic group from another.5

The US Census Bureau recognizes 5 racial groupings: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.6 Hispanic or Latinx origin is considered an ethnicity. It is important to note the limitations of these labels, as they do not completely encapsulate the heterogeneity of the US population. Overgeneralization of racial and ethnic categories may dull or obscure true differences among populations.7

From an evolutionary perspective, skin pigmentation represents the product of 2 opposing clines produced by natural selection in response to both need for and protection from UV radiation across lattitudes.8 Defining SOC is not quite as simple. Skin of color often is equated with certain racial/ethnic groups, or even binary categories of Black vs non-Black or White vs non-White. Others may use the Fitzpatrick scale to discuss SOC, though this scale was originally created to measure the response of skin to UVA radiation exposure.9 The reality is that SOC is a complex term that cannot simply be defined by a certain group of skin tones, races, ethnicities, and/or Fitzpatrick skin types. With this in mind, SOC in the context of this article will often refer to non-White individuals based on the investigators’ terminology, but this definition is not all-encompassing.

Historically in medicine, racial/ethnic differences in outcomes have been equated to differences in biology/genetics without consideration of many external factors.10 The effects of racism, economic stability, health care access, environment, and education quality rarely are discussed, though they have a major impact on health and may better define associations with race or an SOC population. A discussion of the structural and social determinants of health contributing to disease outcomes should accompany any race-based guidelines to prevent inaccurately pathologizing race or SOC.10

Within the scope of AD, social determinants of health play an important role in contributing to disease morbidity. Environmental factors, including tobacco smoke, climate, pollutants, water hardness, und urban living, are related to AD prevalence and severity.11 Higher socioeconomic status is associated with increased AD rates,12 yet lower socioeconomic status is associated with more severe disease.13 Barriers to health care access and suboptimal care drive worse AD outcomes.14 Underrepresentation in clinical trials prevents the generalizability and safety of AD treatments.15 Disparities in these health determinants associated with AD likely are among the most important drivers of observed differences in disease presentation, severity, burden, and even prevalence—more so than genetics or ancestry alone16—yet this relationship is poorly understood and often presented as a consequence of race. It is critical to redefine the narrative when considering the heterogeneous presentations of AD in patients with SOC and acknowledge the limitations of current terminology when attempting to capture clinical diversity in AD, including in this review, where published findings often are limited by race-based analysis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of AD has been increasing over the last few decades, and rates vary by region. In the United States, the prevalence of childhood and adult AD is 13% and 7%, respectively.17,18 Globally, higher rates of pediatric AD are seen in Africa, Oceania, Southeast Asia (SEA), and Latin America compared to South Asia, Northern Europe, and Eastern Europe.19 The prevalence of AD varies widely within the same continent and country; for example, throughout Africa, prevalence was found to be anywhere between 4.7% and 23.3%.20