User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

NORD Rare Action Network Issues Spring 2017 State Policy Legislative Tracker

NORD’s Rare Action Network (RAN) has released a state policy legislative tracker showing state-by-state legislation that is being tracked and where RAN is taking action on issues critical to the needs of patients and families affected by rare diseases.

NORD’s Rare Action Network (RAN) has released a state policy legislative tracker showing state-by-state legislation that is being tracked and where RAN is taking action on issues critical to the needs of patients and families affected by rare diseases.

NORD’s Rare Action Network (RAN) has released a state policy legislative tracker showing state-by-state legislation that is being tracked and where RAN is taking action on issues critical to the needs of patients and families affected by rare diseases.

NORD Issues RFPs for 2017 Research Grants for Study of Rare Diseases

US and international researchers are invited to apply for NORD research grants in the 2017 funding cycle. Seven grants are available at this time for study of the following five rare diseases: alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (ACD/MPV, appendix cancer and pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP), cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria and post-orgasmic illness syndrome (POIS).

June 23, 2017, is the deadline to submit an initial application. See full RFPs and download abstract templates on the NORD website. In addition, information is available about other research funding being offered by NORD member organizations.

US and international researchers are invited to apply for NORD research grants in the 2017 funding cycle. Seven grants are available at this time for study of the following five rare diseases: alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (ACD/MPV, appendix cancer and pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP), cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria and post-orgasmic illness syndrome (POIS).

June 23, 2017, is the deadline to submit an initial application. See full RFPs and download abstract templates on the NORD website. In addition, information is available about other research funding being offered by NORD member organizations.

US and international researchers are invited to apply for NORD research grants in the 2017 funding cycle. Seven grants are available at this time for study of the following five rare diseases: alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (ACD/MPV, appendix cancer and pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP), cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria and post-orgasmic illness syndrome (POIS).

June 23, 2017, is the deadline to submit an initial application. See full RFPs and download abstract templates on the NORD website. In addition, information is available about other research funding being offered by NORD member organizations.

Patient Advocacy Groups Oppose AHCA

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) and several other leading patient advocacy organizations have issued a joint statement opposing the American Health Care Act (AHCA). The patient advocates say the AHCA would:

- profoundly reduce health care coverage for millions of Americans

- weaken key consumer protections

- enable insurers to charge higher prices to those with pre-existing conditions and

- increase out-of-pocket costs for the sickest and oldest individuals

The organizations that joined together to issue the statement in addition NORD are: American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association, American Lung Association, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, March of Dimes, National MS Society, and WomenHeart: The National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease.

“As Congress considers this legislation,” the statement says, “we challenge lawmakers to remember their commitment to their constituents and the American people to protect lifesaving health care for millions of Americans, including those who struggle every day with chronic and other major health conditions. We stand ready to work with Congress toward a proposal that ensures all Americans have affordable access to the care they need.” Read the entire statement.

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) and several other leading patient advocacy organizations have issued a joint statement opposing the American Health Care Act (AHCA). The patient advocates say the AHCA would:

- profoundly reduce health care coverage for millions of Americans

- weaken key consumer protections

- enable insurers to charge higher prices to those with pre-existing conditions and

- increase out-of-pocket costs for the sickest and oldest individuals

The organizations that joined together to issue the statement in addition NORD are: American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association, American Lung Association, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, March of Dimes, National MS Society, and WomenHeart: The National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease.

“As Congress considers this legislation,” the statement says, “we challenge lawmakers to remember their commitment to their constituents and the American people to protect lifesaving health care for millions of Americans, including those who struggle every day with chronic and other major health conditions. We stand ready to work with Congress toward a proposal that ensures all Americans have affordable access to the care they need.” Read the entire statement.

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) and several other leading patient advocacy organizations have issued a joint statement opposing the American Health Care Act (AHCA). The patient advocates say the AHCA would:

- profoundly reduce health care coverage for millions of Americans

- weaken key consumer protections

- enable insurers to charge higher prices to those with pre-existing conditions and

- increase out-of-pocket costs for the sickest and oldest individuals

The organizations that joined together to issue the statement in addition NORD are: American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network, American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association, American Lung Association, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, March of Dimes, National MS Society, and WomenHeart: The National Coalition for Women with Heart Disease.

“As Congress considers this legislation,” the statement says, “we challenge lawmakers to remember their commitment to their constituents and the American people to protect lifesaving health care for millions of Americans, including those who struggle every day with chronic and other major health conditions. We stand ready to work with Congress toward a proposal that ensures all Americans have affordable access to the care they need.” Read the entire statement.

Product News: 05 2017

Dupixent

Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, announce US Food and Drug Administration approval of Dupixent (dupilumab) injection, a biologic

Renflexis

Samsung Bioepis Co, Ltd, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Renflexis (infliximab-abda) injection 100 mg, a biosimilar referencing infliximab. It is indicated in the United States for reducing signs and symptoms in patients with adult and pediatric Crohn disease, adult ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and adult plaque psoriasis. Renflexis will be marketed and distributed in the United States by Merck. For more information, visit www.samsungbioepis.com.

Replenix RetinolForte Treatment Serum

Topix Pharmaceuticals, Inc, introduces Replenix Retinol Forte Treatment Serum containing all- trans -retinol, which helps increase cell turnover to reduce the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles, im- prove skin texture and tone, and promote a collagen-rich appearance. The micropolymer delivery system stabilizes the retinol to protect and shield it from oxidation while on the skin. Its time-released delivery system creates a reservoir that continuously bathes the skin and minimizes irritation. It also contains green tea polyphenols to soothe and calm the skin, caffeine to diminish the appearance of redness, and hyaluronic acid to help skin retain moisture to replenish and repair skin barrier function. For more information, visit www.topixpharm.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Dupixent

Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, announce US Food and Drug Administration approval of Dupixent (dupilumab) injection, a biologic

Renflexis

Samsung Bioepis Co, Ltd, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Renflexis (infliximab-abda) injection 100 mg, a biosimilar referencing infliximab. It is indicated in the United States for reducing signs and symptoms in patients with adult and pediatric Crohn disease, adult ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and adult plaque psoriasis. Renflexis will be marketed and distributed in the United States by Merck. For more information, visit www.samsungbioepis.com.

Replenix RetinolForte Treatment Serum

Topix Pharmaceuticals, Inc, introduces Replenix Retinol Forte Treatment Serum containing all- trans -retinol, which helps increase cell turnover to reduce the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles, im- prove skin texture and tone, and promote a collagen-rich appearance. The micropolymer delivery system stabilizes the retinol to protect and shield it from oxidation while on the skin. Its time-released delivery system creates a reservoir that continuously bathes the skin and minimizes irritation. It also contains green tea polyphenols to soothe and calm the skin, caffeine to diminish the appearance of redness, and hyaluronic acid to help skin retain moisture to replenish and repair skin barrier function. For more information, visit www.topixpharm.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Dupixent

Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, announce US Food and Drug Administration approval of Dupixent (dupilumab) injection, a biologic

Renflexis

Samsung Bioepis Co, Ltd, announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Renflexis (infliximab-abda) injection 100 mg, a biosimilar referencing infliximab. It is indicated in the United States for reducing signs and symptoms in patients with adult and pediatric Crohn disease, adult ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and adult plaque psoriasis. Renflexis will be marketed and distributed in the United States by Merck. For more information, visit www.samsungbioepis.com.

Replenix RetinolForte Treatment Serum

Topix Pharmaceuticals, Inc, introduces Replenix Retinol Forte Treatment Serum containing all- trans -retinol, which helps increase cell turnover to reduce the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles, im- prove skin texture and tone, and promote a collagen-rich appearance. The micropolymer delivery system stabilizes the retinol to protect and shield it from oxidation while on the skin. Its time-released delivery system creates a reservoir that continuously bathes the skin and minimizes irritation. It also contains green tea polyphenols to soothe and calm the skin, caffeine to diminish the appearance of redness, and hyaluronic acid to help skin retain moisture to replenish and repair skin barrier function. For more information, visit www.topixpharm.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please email a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Transverse Melanonychia and Palmar Hyperpigmentation Secondary to Hydroxyurea Therapy

To the Editor:

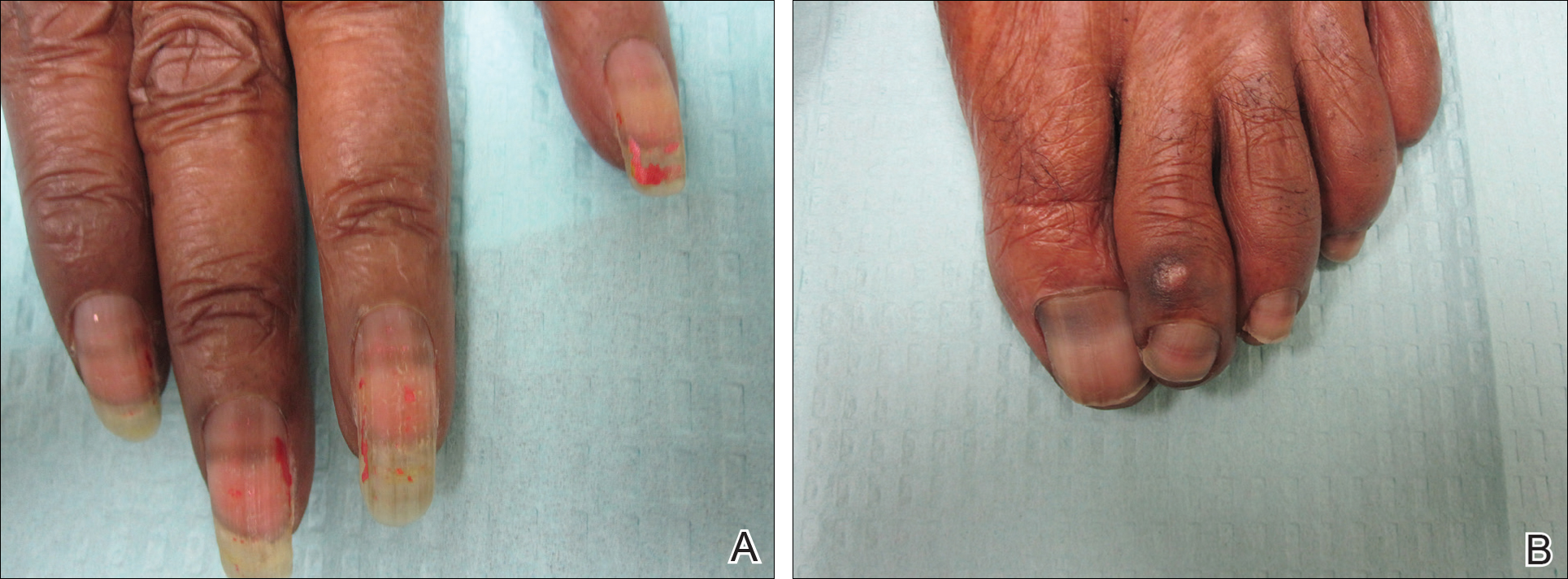

An 85-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, hypothyroidism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic myeloproliferative disorder presented to our clinic for evaluation of brown lesions on the hands and discoloration of the fingernails and toenails of 4 months’ duration. Six months prior to visiting our clinic she was admitted to the hospital for a pulmonary embolism. On admission she was noted to have a platelet count of more than 2 million/μL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/μL). She received urgent plasmapheresis and started hydroxyurea 500 mg twice daily, which she continued as an outpatient.

On physical examination at our clinic she had diffusely scattered red and brown macules on the bilateral palms and transverse hyperpigmented bands of various intensities on all fingernails and toenails (Figure). Her platelet count was 372,000/μL, white blood cell count was 5200/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), hemoglobin was 12.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), hematocrit was 39.0% (reference range, 41%–50%), and mean corpuscular volume was 87.5 fL per red cell (reference range, 80–96 fL per red cell).

The patient was diagnosed with hydroxyurea-induced nail hyperpigmentation and was counseled on the benign nature of the condition. Three months later her platelet count decreased to below 100,000/μL, and hydroxyurea was discontinued. She noticed considerable improvement in the lesions on the hands and nails with the cessation of hydroxyurea.

Hydroxyurea is a cytostatic agent that has been used for more than 40 years in the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders including chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and sickle cell anemia.1 It inhibits ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase and promotes cell death in the S phase of the cell cycle.1-3

Several adverse cutaneous reactions have been associated with hydroxyurea including increased pigmentation, hyperkeratosis, skin atrophy, xerosis, lichenoid eruptions, palmoplantar keratoderma, cutaneous vasculitis, alopecia, chronic leg ulcers, cutaneous carcinomas, and melanonychia.3,4

Hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia most often occurs after several months of therapy but has been reported to occur as early as 4 months and as late as 5 years after initiating the drug.1,4-6 The prevalence of melanonychia in the general population has been estimated at 1% and is thought to increase to approximately 4% in patients treated with hydroxyurea.1,2,6,7 The prevalence of affected individuals increases with age; it is more common in females as well as black and Hispanic patients.2

Multiple patterns of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia have been described, including longitudinal bands, transverse bands, and diffuse hyperpigmentation.1-3,6 By far the most common pattern described in the literature is longitudinal banding1-3,8; transverse bands are more rare. Although there are sporadic case reports linking the transverse bands with hydroxyurea, these bands occur more frequently with systemic chemotherapy such as doxorubicin and cyclosphosphamide.1,6

The exact pathogenesis of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia remains unclear, though it is thought to result from focal melanogenesis in the nail bed or matrix followed by deposition of melanin granules on the nail plate.5,8 When these melanocytes are activated, melanosomes filled with melanin are transferred to differentiating matrix cells, which migrate distally as they become nail plate oncocytes, resulting in a visible band of pigmentation in the nail plate.2 There also may be a genetic and photosensitivity component.1,2

Prior case series have described spontaneous remission of nail hyperpigmentation following discontinuation of hydroxyurea therapy.1 In many patients, however, the chronic nature of the myeloproliferative disorder and lack of alternative treatments make a therapeutic change difficult. Although the melanonychia itself is benign, it may precede the appearance of more serious mucocutaneous side effects, such as skin ulceration or development of cutaneous carcinomas, so careful monitoring should be performed.2

Our patient presented with melanonychia that was transverse, polydactylic, monochromic, stable in size and shape, and associated with palmar hyperpigmentation. Of note, the pigmentation remitted over time along with discontinuation of the drug. Although this presentation did not warrant a nail matrix biopsy, it should be noted that patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.2 Although transverse melanonychia most commonly is associated with other systemic chemotherapeutics, in the absence of such medications hydroxyurea was the likely culprit in our patient. The palmar hyperpigmentation, which has previously been reported with hydroxyurea use, further solidifies the diagnosis.

- Aste N, Futmo G, Contu F, et al. Nail pigmentation caused by hydroxyurea: report of 9 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:146-147.

- Murray N, Tapia P, Porcell J, et al. Acquired melanonychia in Chilean patients with essential thrombocythemia treated with hydroxyurea: a report of 7 clinical cases and review of the literature [published online February 7, 2013]. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:325246.

- Utas S. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:469-470.

- Saraceno R, Teoli M, Chimenti S. Hydroxyurea associated with concomitant occurrence of diffuse longitudinal melanonychia and multiple squamous cell carcinomas in an elderly subject. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1324-1329.

- Cohen AD, Hallel-Halevy D, Hatskelzon L, et al. Longitudinal melanonychia associated with hydroxyurea therapy in a patient with essential thrombocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 1999;13:137-139.

- Hernández-Martín A, Ros-Forteza S, de Unamuno P. Longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse nail hyperpigmentation induced by hydroxyurea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):333-334.

- Kwong Y. Hydroxyurea-induced nail pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:275-276.

- O’Branski E, Ware R, Prose N, et al. Skin and nail changes in children with sickle cell anemia receiving hydroxyurea therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:859-861.

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, hypothyroidism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic myeloproliferative disorder presented to our clinic for evaluation of brown lesions on the hands and discoloration of the fingernails and toenails of 4 months’ duration. Six months prior to visiting our clinic she was admitted to the hospital for a pulmonary embolism. On admission she was noted to have a platelet count of more than 2 million/μL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/μL). She received urgent plasmapheresis and started hydroxyurea 500 mg twice daily, which she continued as an outpatient.

On physical examination at our clinic she had diffusely scattered red and brown macules on the bilateral palms and transverse hyperpigmented bands of various intensities on all fingernails and toenails (Figure). Her platelet count was 372,000/μL, white blood cell count was 5200/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), hemoglobin was 12.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), hematocrit was 39.0% (reference range, 41%–50%), and mean corpuscular volume was 87.5 fL per red cell (reference range, 80–96 fL per red cell).

The patient was diagnosed with hydroxyurea-induced nail hyperpigmentation and was counseled on the benign nature of the condition. Three months later her platelet count decreased to below 100,000/μL, and hydroxyurea was discontinued. She noticed considerable improvement in the lesions on the hands and nails with the cessation of hydroxyurea.

Hydroxyurea is a cytostatic agent that has been used for more than 40 years in the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders including chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and sickle cell anemia.1 It inhibits ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase and promotes cell death in the S phase of the cell cycle.1-3

Several adverse cutaneous reactions have been associated with hydroxyurea including increased pigmentation, hyperkeratosis, skin atrophy, xerosis, lichenoid eruptions, palmoplantar keratoderma, cutaneous vasculitis, alopecia, chronic leg ulcers, cutaneous carcinomas, and melanonychia.3,4

Hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia most often occurs after several months of therapy but has been reported to occur as early as 4 months and as late as 5 years after initiating the drug.1,4-6 The prevalence of melanonychia in the general population has been estimated at 1% and is thought to increase to approximately 4% in patients treated with hydroxyurea.1,2,6,7 The prevalence of affected individuals increases with age; it is more common in females as well as black and Hispanic patients.2

Multiple patterns of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia have been described, including longitudinal bands, transverse bands, and diffuse hyperpigmentation.1-3,6 By far the most common pattern described in the literature is longitudinal banding1-3,8; transverse bands are more rare. Although there are sporadic case reports linking the transverse bands with hydroxyurea, these bands occur more frequently with systemic chemotherapy such as doxorubicin and cyclosphosphamide.1,6

The exact pathogenesis of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia remains unclear, though it is thought to result from focal melanogenesis in the nail bed or matrix followed by deposition of melanin granules on the nail plate.5,8 When these melanocytes are activated, melanosomes filled with melanin are transferred to differentiating matrix cells, which migrate distally as they become nail plate oncocytes, resulting in a visible band of pigmentation in the nail plate.2 There also may be a genetic and photosensitivity component.1,2

Prior case series have described spontaneous remission of nail hyperpigmentation following discontinuation of hydroxyurea therapy.1 In many patients, however, the chronic nature of the myeloproliferative disorder and lack of alternative treatments make a therapeutic change difficult. Although the melanonychia itself is benign, it may precede the appearance of more serious mucocutaneous side effects, such as skin ulceration or development of cutaneous carcinomas, so careful monitoring should be performed.2

Our patient presented with melanonychia that was transverse, polydactylic, monochromic, stable in size and shape, and associated with palmar hyperpigmentation. Of note, the pigmentation remitted over time along with discontinuation of the drug. Although this presentation did not warrant a nail matrix biopsy, it should be noted that patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.2 Although transverse melanonychia most commonly is associated with other systemic chemotherapeutics, in the absence of such medications hydroxyurea was the likely culprit in our patient. The palmar hyperpigmentation, which has previously been reported with hydroxyurea use, further solidifies the diagnosis.

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, stroke, hypothyroidism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic myeloproliferative disorder presented to our clinic for evaluation of brown lesions on the hands and discoloration of the fingernails and toenails of 4 months’ duration. Six months prior to visiting our clinic she was admitted to the hospital for a pulmonary embolism. On admission she was noted to have a platelet count of more than 2 million/μL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/μL). She received urgent plasmapheresis and started hydroxyurea 500 mg twice daily, which she continued as an outpatient.

On physical examination at our clinic she had diffusely scattered red and brown macules on the bilateral palms and transverse hyperpigmented bands of various intensities on all fingernails and toenails (Figure). Her platelet count was 372,000/μL, white blood cell count was 5200/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL), hemoglobin was 12.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), hematocrit was 39.0% (reference range, 41%–50%), and mean corpuscular volume was 87.5 fL per red cell (reference range, 80–96 fL per red cell).

The patient was diagnosed with hydroxyurea-induced nail hyperpigmentation and was counseled on the benign nature of the condition. Three months later her platelet count decreased to below 100,000/μL, and hydroxyurea was discontinued. She noticed considerable improvement in the lesions on the hands and nails with the cessation of hydroxyurea.

Hydroxyurea is a cytostatic agent that has been used for more than 40 years in the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders including chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and sickle cell anemia.1 It inhibits ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase and promotes cell death in the S phase of the cell cycle.1-3

Several adverse cutaneous reactions have been associated with hydroxyurea including increased pigmentation, hyperkeratosis, skin atrophy, xerosis, lichenoid eruptions, palmoplantar keratoderma, cutaneous vasculitis, alopecia, chronic leg ulcers, cutaneous carcinomas, and melanonychia.3,4

Hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia most often occurs after several months of therapy but has been reported to occur as early as 4 months and as late as 5 years after initiating the drug.1,4-6 The prevalence of melanonychia in the general population has been estimated at 1% and is thought to increase to approximately 4% in patients treated with hydroxyurea.1,2,6,7 The prevalence of affected individuals increases with age; it is more common in females as well as black and Hispanic patients.2

Multiple patterns of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia have been described, including longitudinal bands, transverse bands, and diffuse hyperpigmentation.1-3,6 By far the most common pattern described in the literature is longitudinal banding1-3,8; transverse bands are more rare. Although there are sporadic case reports linking the transverse bands with hydroxyurea, these bands occur more frequently with systemic chemotherapy such as doxorubicin and cyclosphosphamide.1,6

The exact pathogenesis of hydroxyurea-induced melanonychia remains unclear, though it is thought to result from focal melanogenesis in the nail bed or matrix followed by deposition of melanin granules on the nail plate.5,8 When these melanocytes are activated, melanosomes filled with melanin are transferred to differentiating matrix cells, which migrate distally as they become nail plate oncocytes, resulting in a visible band of pigmentation in the nail plate.2 There also may be a genetic and photosensitivity component.1,2

Prior case series have described spontaneous remission of nail hyperpigmentation following discontinuation of hydroxyurea therapy.1 In many patients, however, the chronic nature of the myeloproliferative disorder and lack of alternative treatments make a therapeutic change difficult. Although the melanonychia itself is benign, it may precede the appearance of more serious mucocutaneous side effects, such as skin ulceration or development of cutaneous carcinomas, so careful monitoring should be performed.2

Our patient presented with melanonychia that was transverse, polydactylic, monochromic, stable in size and shape, and associated with palmar hyperpigmentation. Of note, the pigmentation remitted over time along with discontinuation of the drug. Although this presentation did not warrant a nail matrix biopsy, it should be noted that patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.2 Although transverse melanonychia most commonly is associated with other systemic chemotherapeutics, in the absence of such medications hydroxyurea was the likely culprit in our patient. The palmar hyperpigmentation, which has previously been reported with hydroxyurea use, further solidifies the diagnosis.

- Aste N, Futmo G, Contu F, et al. Nail pigmentation caused by hydroxyurea: report of 9 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:146-147.

- Murray N, Tapia P, Porcell J, et al. Acquired melanonychia in Chilean patients with essential thrombocythemia treated with hydroxyurea: a report of 7 clinical cases and review of the literature [published online February 7, 2013]. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:325246.

- Utas S. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:469-470.

- Saraceno R, Teoli M, Chimenti S. Hydroxyurea associated with concomitant occurrence of diffuse longitudinal melanonychia and multiple squamous cell carcinomas in an elderly subject. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1324-1329.

- Cohen AD, Hallel-Halevy D, Hatskelzon L, et al. Longitudinal melanonychia associated with hydroxyurea therapy in a patient with essential thrombocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 1999;13:137-139.

- Hernández-Martín A, Ros-Forteza S, de Unamuno P. Longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse nail hyperpigmentation induced by hydroxyurea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):333-334.

- Kwong Y. Hydroxyurea-induced nail pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:275-276.

- O’Branski E, Ware R, Prose N, et al. Skin and nail changes in children with sickle cell anemia receiving hydroxyurea therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:859-861.

- Aste N, Futmo G, Contu F, et al. Nail pigmentation caused by hydroxyurea: report of 9 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:146-147.

- Murray N, Tapia P, Porcell J, et al. Acquired melanonychia in Chilean patients with essential thrombocythemia treated with hydroxyurea: a report of 7 clinical cases and review of the literature [published online February 7, 2013]. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:325246.

- Utas S. A case of hydroxyurea-induced longitudinal melanonychia. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:469-470.

- Saraceno R, Teoli M, Chimenti S. Hydroxyurea associated with concomitant occurrence of diffuse longitudinal melanonychia and multiple squamous cell carcinomas in an elderly subject. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1324-1329.

- Cohen AD, Hallel-Halevy D, Hatskelzon L, et al. Longitudinal melanonychia associated with hydroxyurea therapy in a patient with essential thrombocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 1999;13:137-139.

- Hernández-Martín A, Ros-Forteza S, de Unamuno P. Longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse nail hyperpigmentation induced by hydroxyurea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 2):333-334.

- Kwong Y. Hydroxyurea-induced nail pigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:275-276.

- O’Branski E, Ware R, Prose N, et al. Skin and nail changes in children with sickle cell anemia receiving hydroxyurea therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:859-861.

Practice Points

- Transverse melanonychia may result as a side effect of hydroxyurea.

- Discontinuation of hydroxyurea typically results in a resolution of symptoms. If the medication cannot be stopped, however, pigmentary changes may precede the development of severe mucocutaneous side effects and close monitoring is warranted.

- Patients with single nail melanonychia suspicious for melanoma should have a biopsy, even with concomitant use of hydroxyurea.

Enlarging Mass on the Lateral Neck

Branchial Cleft Cyst

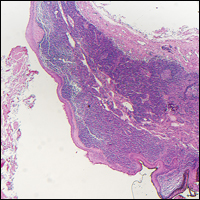

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

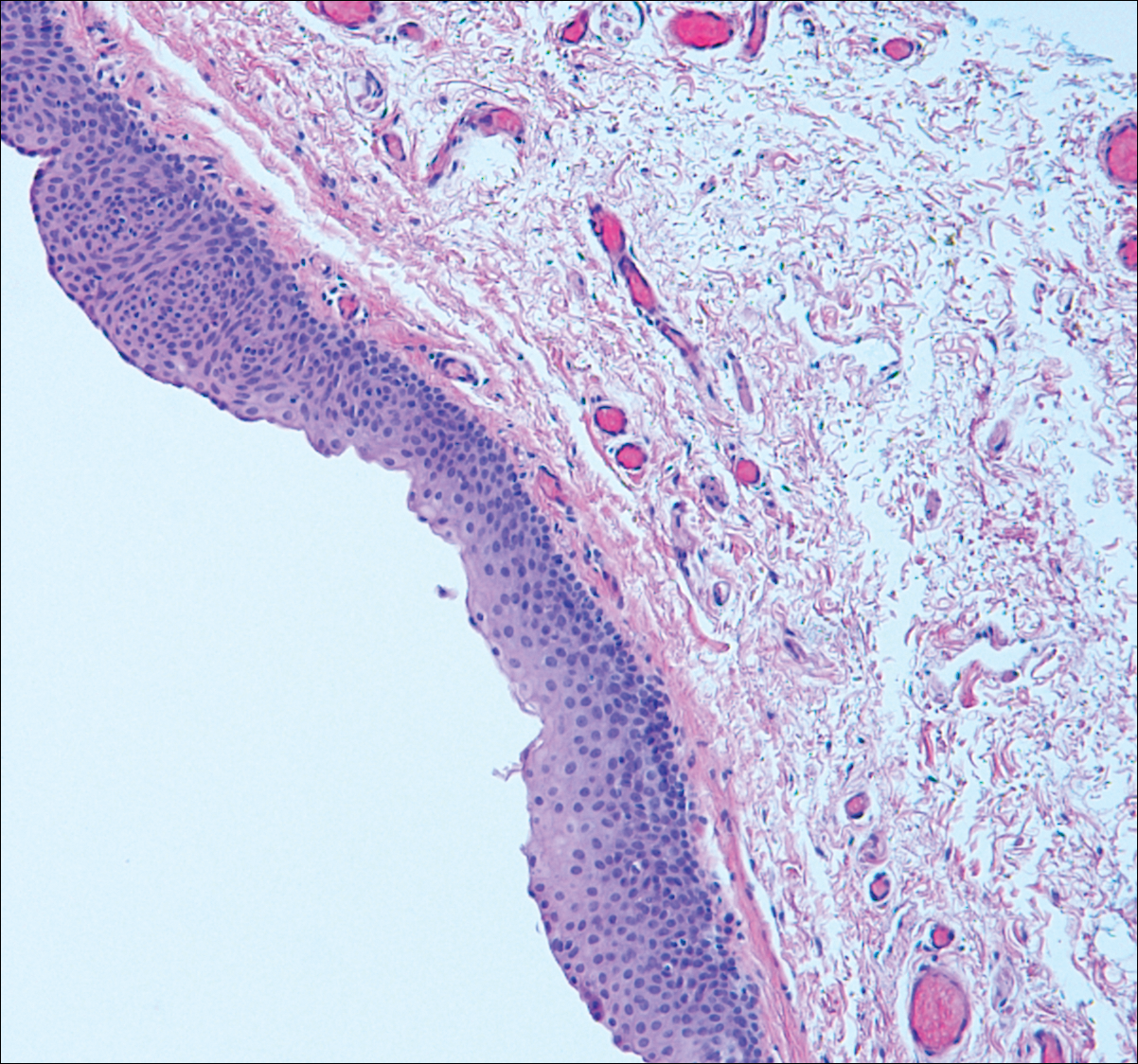

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

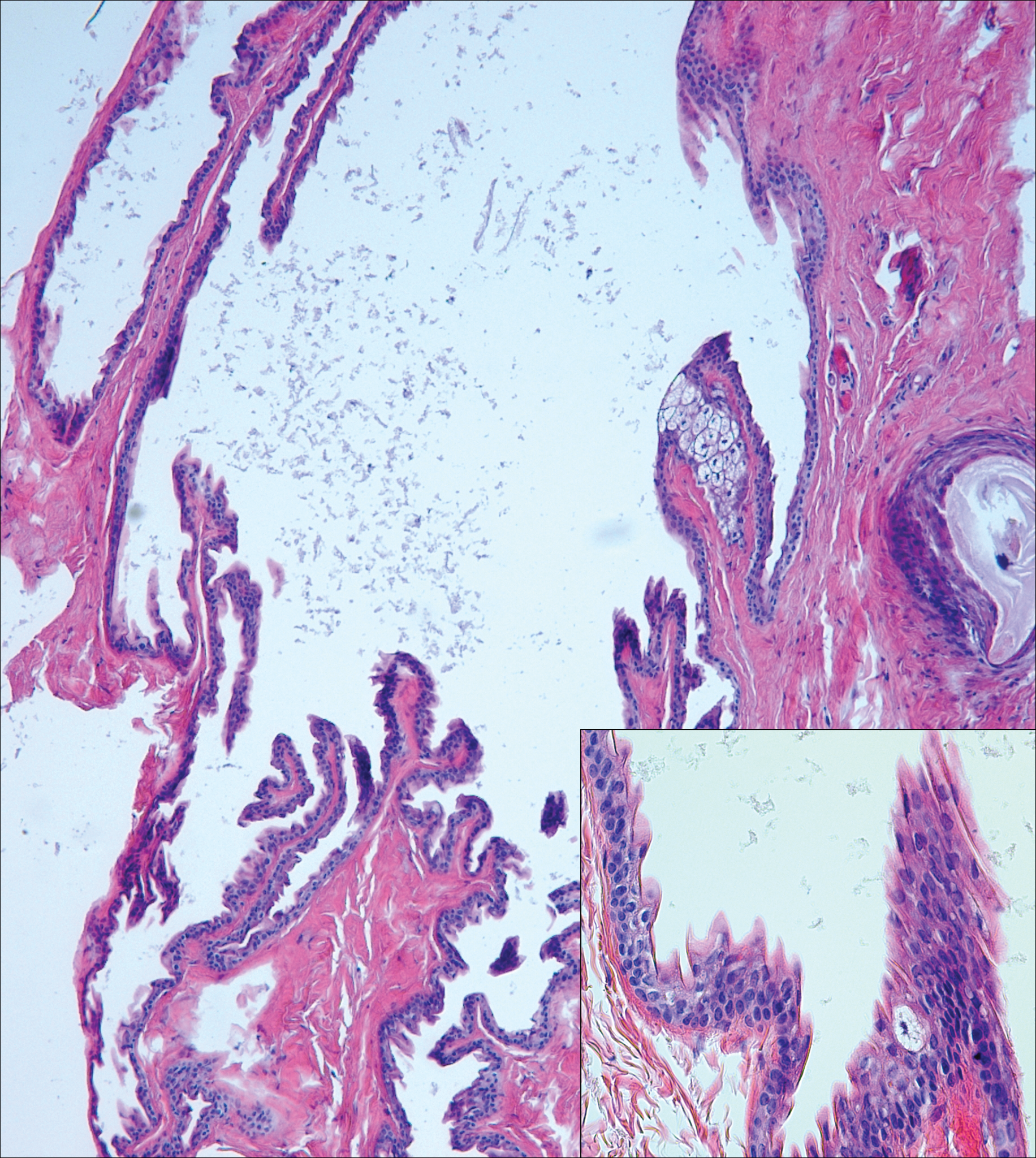

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

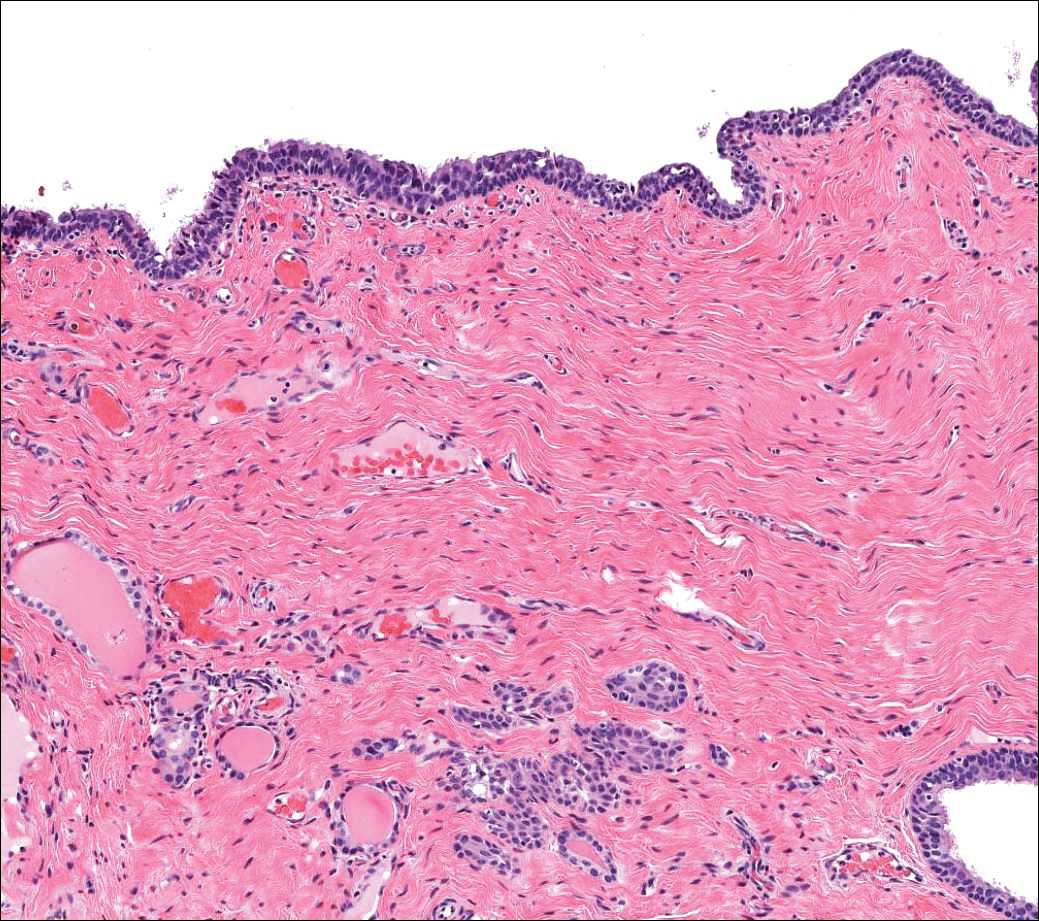

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

- Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, et al. Branchial cleft cyst: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:150.

- Stone MS. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1817-1828.

- Kirkham N, Aljefri K. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, et al, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:969-1024.

- Elston DM. Benign tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014:49-55.

- Hsu CG, Heller M, Johnston GS, et al. An unusual cause of airway compromise in the emergency department: mediastinal bronchogenic cyst [published online December 13, 2016]. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:E91-E93.

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

- Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, et al. Branchial cleft cyst: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:150.

- Stone MS. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1817-1828.

- Kirkham N, Aljefri K. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, et al, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:969-1024.

- Elston DM. Benign tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014:49-55.

- Hsu CG, Heller M, Johnston GS, et al. An unusual cause of airway compromise in the emergency department: mediastinal bronchogenic cyst [published online December 13, 2016]. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:E91-E93.

- Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, et al. Branchial cleft cyst: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:150.

- Stone MS. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1817-1828.

- Kirkham N, Aljefri K. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, et al, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:969-1024.

- Elston DM. Benign tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014:49-55.

- Hsu CG, Heller M, Johnston GS, et al. An unusual cause of airway compromise in the emergency department: mediastinal bronchogenic cyst [published online December 13, 2016]. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:E91-E93.

A 14-year-old adolescent boy presented with a nontender mass on the left lateral neck. The mass had been present since birth but had recently grown in size.

Diversity in Dermatology: A Society Devoted to Skin of Color

The US Census Bureau predicts that more than half of the country’s population will identify as a race other than non-Hispanic white by the year 2044.In 2014, the US population was 62.2% non-Hispanic white, and the projected figure for 2060 is 43.6%.1 However, most physicians currently are informed by research that is generalized from a study population of primarily white males.2 Disparities also exist among the physician population where black individuals and Latinos are underrepresented.3 These differences have inspired dermatologists to develop methods to address the need for parity among patients with skin of color. Both ethnic skin centers and the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) have been established since the turn of the millennium to improve disparities and prepare for the future. The efforts and impact of SOCS are widening since its inception and chronicle one approach to broadening the scope of the specialty of dermatology.

Established in 2004 by dermatologist Susan C. Taylor, MD (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), SOCS provides educational support to health care providers, the media, the legislature, third parties (eg, insurance organizations), and the general public on dermatologic health for patients with skin of color. The society is organized into committees that represent the multifaceted aspects of the organization. It also stimulates and endorses an increase in scientific knowledge through basic science and clinical, surgical, and cosmetic research.4

Scientific, research, mentorship, professional development, national and international outreach, patient education, and technology and media committees within SOCS, as well as a newly formed diversity in action task force, uphold the mission of the society. The scientific committee, one of the organization’s major committees, plans the annual symposium. The annual symposium, which immediately precedes the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, acts as a central educational symposium for dermatologists (both domestic and international), residents, students, and other scientists to present data on unique properties, statistics, and diseases associated with individuals with ethnic skin. New research, perspectives, and interests are shared with an audience of physicians, research fellows, residents, and students who are also the presenters of topics relevant to skin of color such as cutaneous T-cell lymphomas/mycosis fungoides in black individuals, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), pigmentary disorders in Brazilians, and many others. There is an emphasis on allowing learners to present their research in a comfortable and constructive setting, and these shorter talks are interspersed with experts who deliver cutting-edge lectures in their specialty area.4

Each year during the SOCS symposium, the SOCS Research Award is endowed to a dermatology resident, fellow, or young dermatologist within the first 8 years of postgraduate training. The research committee oversees the selection of the SOCS Research Award. Prior recipients of the award have explored topics such as genetic causes of keloid formation or CCCA, epigenetic changes in ethnic skin during skin aging, and development of a vitiligo-specific quality-of-life scale.4

Another key mission of SOCS is to foster the growth of younger dermatologists interested in skin of color via mentorships; SOCS has a mentorship committee dedicated to engaging in this effort. Dermatology residents or young dermatologists who are within 3 years of finishing residency can work with a SOCS-approved mentor to develop knowledge, skills, and networking in the skin of color realm. Research is encouraged, and 3 to 4 professional development meetings (both in person or online) help set objectives. The professional development committee also coordinates efforts to offer young dermatologists opportunities to work with experienced mentors and further partnerships with existing members.4

The national and international outreach committee acts as a liaison between organizations abroad and those based in the United States. The patient education committee strives to improve public knowledge about dermatologic diseases that affect individuals with skin of color. Ethnic patients often have poor access to medical information, and sometimes adequate medical information does not exist in the current searchable medical literature. The SOCS website (http://skinofcolorsociety.org/) offers an entire section on dermatology education with succinct, patient-friendly prose on diseases such as acne in skin of color, CCCA, eczema, melanoma, melasma, sun protection, tinea capitis, and more; the website also includes educational videos, blogs, and a central location for useful links to other dermatology organizations that may be of interest to both members and patients who use the site. Maintenance of the website and the SOCS media day fall under the purview of the technology and media committee. There have been 2 media days thus far that have given voice to sun safety and skin cancer in individuals with skin of color as well as hair health and cosmetic treatments for patients with pigmented skin. The content for the media days is provided by SOCS experts to national magazine editors and beauty bloggers to raise awareness about these issues and get the message to the public.4

The diversity in action task force is a new committee that is tasked with addressing training for individuals of diverse ethnicities and backgrounds for health care careers at every level, ranging from middle school to dermatology residency. Resources to help those applying to medical school and current medical students interested in dermatology as well as those applying for dermatology residency are being developed for students at all stages of their academic careers. The middle school to undergraduate educational levels will encompass general guidelines for success; the medical school level will focus on students taking the appropriate steps to enter dermatology residency. The task force also will act as a liaison through existing student groups, such as the Student National Medical Association, Minority Association of Premedical Students, Latino Medical Student Association, Dermatology Interest Group Association, and more to reach learners at critical stages in their academic development.4The society plays an important role in the educational process for dermatologists at all levels. Although this organization is critical in increasing knowledge of treatment of individuals with skin of color in research, clinical practice, and the public domain, the hope is that SOCS will continue to reach new members of the dermatology community. As a group that embraces the onus to improve skin of color education, the members of SOCS know that there is still much to do to increase awareness among the public as well as dermatology residents and dermatologists practicing in geographical regions that are not ethnically diverse. There are many reasons that both cultural competence and knowledge of skin of color in dermatology will be important as the United States becomes increasingly diverse, and SOCS is at the forefront of this effort. Looking to the future, the goals of SOCS really are the goals of dermatology, which are to continue to deliver the best care to all patients and to continue to improve our specialty with new techniques and medications for all patients who need care.

- Colby SL, Jennifer JO. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014.

- Oh SS, Galanter J, Thakur N, et al. Diversity in clinical and biomedical research: a promise yet to be fulfilled. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001918.

- Castillo-Page L. Diversity in the physician workforce facts & figures 2010. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2010. https://www.aamc.org/download/432976/data/factsandfigures2010.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2017.

- Our committees. Skin of Color Society website. http://skinofcolorsociety.org/about-socs/our-committees/. Accessed April 19, 2017.

The US Census Bureau predicts that more than half of the country’s population will identify as a race other than non-Hispanic white by the year 2044.In 2014, the US population was 62.2% non-Hispanic white, and the projected figure for 2060 is 43.6%.1 However, most physicians currently are informed by research that is generalized from a study population of primarily white males.2 Disparities also exist among the physician population where black individuals and Latinos are underrepresented.3 These differences have inspired dermatologists to develop methods to address the need for parity among patients with skin of color. Both ethnic skin centers and the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) have been established since the turn of the millennium to improve disparities and prepare for the future. The efforts and impact of SOCS are widening since its inception and chronicle one approach to broadening the scope of the specialty of dermatology.

Established in 2004 by dermatologist Susan C. Taylor, MD (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), SOCS provides educational support to health care providers, the media, the legislature, third parties (eg, insurance organizations), and the general public on dermatologic health for patients with skin of color. The society is organized into committees that represent the multifaceted aspects of the organization. It also stimulates and endorses an increase in scientific knowledge through basic science and clinical, surgical, and cosmetic research.4

Scientific, research, mentorship, professional development, national and international outreach, patient education, and technology and media committees within SOCS, as well as a newly formed diversity in action task force, uphold the mission of the society. The scientific committee, one of the organization’s major committees, plans the annual symposium. The annual symposium, which immediately precedes the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, acts as a central educational symposium for dermatologists (both domestic and international), residents, students, and other scientists to present data on unique properties, statistics, and diseases associated with individuals with ethnic skin. New research, perspectives, and interests are shared with an audience of physicians, research fellows, residents, and students who are also the presenters of topics relevant to skin of color such as cutaneous T-cell lymphomas/mycosis fungoides in black individuals, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), pigmentary disorders in Brazilians, and many others. There is an emphasis on allowing learners to present their research in a comfortable and constructive setting, and these shorter talks are interspersed with experts who deliver cutting-edge lectures in their specialty area.4

Each year during the SOCS symposium, the SOCS Research Award is endowed to a dermatology resident, fellow, or young dermatologist within the first 8 years of postgraduate training. The research committee oversees the selection of the SOCS Research Award. Prior recipients of the award have explored topics such as genetic causes of keloid formation or CCCA, epigenetic changes in ethnic skin during skin aging, and development of a vitiligo-specific quality-of-life scale.4

Another key mission of SOCS is to foster the growth of younger dermatologists interested in skin of color via mentorships; SOCS has a mentorship committee dedicated to engaging in this effort. Dermatology residents or young dermatologists who are within 3 years of finishing residency can work with a SOCS-approved mentor to develop knowledge, skills, and networking in the skin of color realm. Research is encouraged, and 3 to 4 professional development meetings (both in person or online) help set objectives. The professional development committee also coordinates efforts to offer young dermatologists opportunities to work with experienced mentors and further partnerships with existing members.4

The national and international outreach committee acts as a liaison between organizations abroad and those based in the United States. The patient education committee strives to improve public knowledge about dermatologic diseases that affect individuals with skin of color. Ethnic patients often have poor access to medical information, and sometimes adequate medical information does not exist in the current searchable medical literature. The SOCS website (http://skinofcolorsociety.org/) offers an entire section on dermatology education with succinct, patient-friendly prose on diseases such as acne in skin of color, CCCA, eczema, melanoma, melasma, sun protection, tinea capitis, and more; the website also includes educational videos, blogs, and a central location for useful links to other dermatology organizations that may be of interest to both members and patients who use the site. Maintenance of the website and the SOCS media day fall under the purview of the technology and media committee. There have been 2 media days thus far that have given voice to sun safety and skin cancer in individuals with skin of color as well as hair health and cosmetic treatments for patients with pigmented skin. The content for the media days is provided by SOCS experts to national magazine editors and beauty bloggers to raise awareness about these issues and get the message to the public.4

The diversity in action task force is a new committee that is tasked with addressing training for individuals of diverse ethnicities and backgrounds for health care careers at every level, ranging from middle school to dermatology residency. Resources to help those applying to medical school and current medical students interested in dermatology as well as those applying for dermatology residency are being developed for students at all stages of their academic careers. The middle school to undergraduate educational levels will encompass general guidelines for success; the medical school level will focus on students taking the appropriate steps to enter dermatology residency. The task force also will act as a liaison through existing student groups, such as the Student National Medical Association, Minority Association of Premedical Students, Latino Medical Student Association, Dermatology Interest Group Association, and more to reach learners at critical stages in their academic development.4The society plays an important role in the educational process for dermatologists at all levels. Although this organization is critical in increasing knowledge of treatment of individuals with skin of color in research, clinical practice, and the public domain, the hope is that SOCS will continue to reach new members of the dermatology community. As a group that embraces the onus to improve skin of color education, the members of SOCS know that there is still much to do to increase awareness among the public as well as dermatology residents and dermatologists practicing in geographical regions that are not ethnically diverse. There are many reasons that both cultural competence and knowledge of skin of color in dermatology will be important as the United States becomes increasingly diverse, and SOCS is at the forefront of this effort. Looking to the future, the goals of SOCS really are the goals of dermatology, which are to continue to deliver the best care to all patients and to continue to improve our specialty with new techniques and medications for all patients who need care.

The US Census Bureau predicts that more than half of the country’s population will identify as a race other than non-Hispanic white by the year 2044.In 2014, the US population was 62.2% non-Hispanic white, and the projected figure for 2060 is 43.6%.1 However, most physicians currently are informed by research that is generalized from a study population of primarily white males.2 Disparities also exist among the physician population where black individuals and Latinos are underrepresented.3 These differences have inspired dermatologists to develop methods to address the need for parity among patients with skin of color. Both ethnic skin centers and the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) have been established since the turn of the millennium to improve disparities and prepare for the future. The efforts and impact of SOCS are widening since its inception and chronicle one approach to broadening the scope of the specialty of dermatology.

Established in 2004 by dermatologist Susan C. Taylor, MD (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), SOCS provides educational support to health care providers, the media, the legislature, third parties (eg, insurance organizations), and the general public on dermatologic health for patients with skin of color. The society is organized into committees that represent the multifaceted aspects of the organization. It also stimulates and endorses an increase in scientific knowledge through basic science and clinical, surgical, and cosmetic research.4

Scientific, research, mentorship, professional development, national and international outreach, patient education, and technology and media committees within SOCS, as well as a newly formed diversity in action task force, uphold the mission of the society. The scientific committee, one of the organization’s major committees, plans the annual symposium. The annual symposium, which immediately precedes the Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, acts as a central educational symposium for dermatologists (both domestic and international), residents, students, and other scientists to present data on unique properties, statistics, and diseases associated with individuals with ethnic skin. New research, perspectives, and interests are shared with an audience of physicians, research fellows, residents, and students who are also the presenters of topics relevant to skin of color such as cutaneous T-cell lymphomas/mycosis fungoides in black individuals, central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), pigmentary disorders in Brazilians, and many others. There is an emphasis on allowing learners to present their research in a comfortable and constructive setting, and these shorter talks are interspersed with experts who deliver cutting-edge lectures in their specialty area.4

Each year during the SOCS symposium, the SOCS Research Award is endowed to a dermatology resident, fellow, or young dermatologist within the first 8 years of postgraduate training. The research committee oversees the selection of the SOCS Research Award. Prior recipients of the award have explored topics such as genetic causes of keloid formation or CCCA, epigenetic changes in ethnic skin during skin aging, and development of a vitiligo-specific quality-of-life scale.4

Another key mission of SOCS is to foster the growth of younger dermatologists interested in skin of color via mentorships; SOCS has a mentorship committee dedicated to engaging in this effort. Dermatology residents or young dermatologists who are within 3 years of finishing residency can work with a SOCS-approved mentor to develop knowledge, skills, and networking in the skin of color realm. Research is encouraged, and 3 to 4 professional development meetings (both in person or online) help set objectives. The professional development committee also coordinates efforts to offer young dermatologists opportunities to work with experienced mentors and further partnerships with existing members.4

The national and international outreach committee acts as a liaison between organizations abroad and those based in the United States. The patient education committee strives to improve public knowledge about dermatologic diseases that affect individuals with skin of color. Ethnic patients often have poor access to medical information, and sometimes adequate medical information does not exist in the current searchable medical literature. The SOCS website (http://skinofcolorsociety.org/) offers an entire section on dermatology education with succinct, patient-friendly prose on diseases such as acne in skin of color, CCCA, eczema, melanoma, melasma, sun protection, tinea capitis, and more; the website also includes educational videos, blogs, and a central location for useful links to other dermatology organizations that may be of interest to both members and patients who use the site. Maintenance of the website and the SOCS media day fall under the purview of the technology and media committee. There have been 2 media days thus far that have given voice to sun safety and skin cancer in individuals with skin of color as well as hair health and cosmetic treatments for patients with pigmented skin. The content for the media days is provided by SOCS experts to national magazine editors and beauty bloggers to raise awareness about these issues and get the message to the public.4

The diversity in action task force is a new committee that is tasked with addressing training for individuals of diverse ethnicities and backgrounds for health care careers at every level, ranging from middle school to dermatology residency. Resources to help those applying to medical school and current medical students interested in dermatology as well as those applying for dermatology residency are being developed for students at all stages of their academic careers. The middle school to undergraduate educational levels will encompass general guidelines for success; the medical school level will focus on students taking the appropriate steps to enter dermatology residency. The task force also will act as a liaison through existing student groups, such as the Student National Medical Association, Minority Association of Premedical Students, Latino Medical Student Association, Dermatology Interest Group Association, and more to reach learners at critical stages in their academic development.4The society plays an important role in the educational process for dermatologists at all levels. Although this organization is critical in increasing knowledge of treatment of individuals with skin of color in research, clinical practice, and the public domain, the hope is that SOCS will continue to reach new members of the dermatology community. As a group that embraces the onus to improve skin of color education, the members of SOCS know that there is still much to do to increase awareness among the public as well as dermatology residents and dermatologists practicing in geographical regions that are not ethnically diverse. There are many reasons that both cultural competence and knowledge of skin of color in dermatology will be important as the United States becomes increasingly diverse, and SOCS is at the forefront of this effort. Looking to the future, the goals of SOCS really are the goals of dermatology, which are to continue to deliver the best care to all patients and to continue to improve our specialty with new techniques and medications for all patients who need care.

- Colby SL, Jennifer JO. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014.

- Oh SS, Galanter J, Thakur N, et al. Diversity in clinical and biomedical research: a promise yet to be fulfilled. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001918.

- Castillo-Page L. Diversity in the physician workforce facts & figures 2010. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2010. https://www.aamc.org/download/432976/data/factsandfigures2010.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2017.

- Our committees. Skin of Color Society website. http://skinofcolorsociety.org/about-socs/our-committees/. Accessed April 19, 2017.

- Colby SL, Jennifer JO. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014.

- Oh SS, Galanter J, Thakur N, et al. Diversity in clinical and biomedical research: a promise yet to be fulfilled. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001918.

- Castillo-Page L. Diversity in the physician workforce facts & figures 2010. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2010. https://www.aamc.org/download/432976/data/factsandfigures2010.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2017.

- Our committees. Skin of Color Society website. http://skinofcolorsociety.org/about-socs/our-committees/. Accessed April 19, 2017.

Practice Points

- The mission of the Skin of Color Society (SOCS) is to improve education of young dermatologists relevant to skin of color patients.

- Educational resources on many different diseases important to patients with skin of color are available to patients and providers on the SOCS website.

Recalcitrant Solitary Erythematous Scaly Patch on the Foot

The Diagnosis: Pagetoid Reticulosis

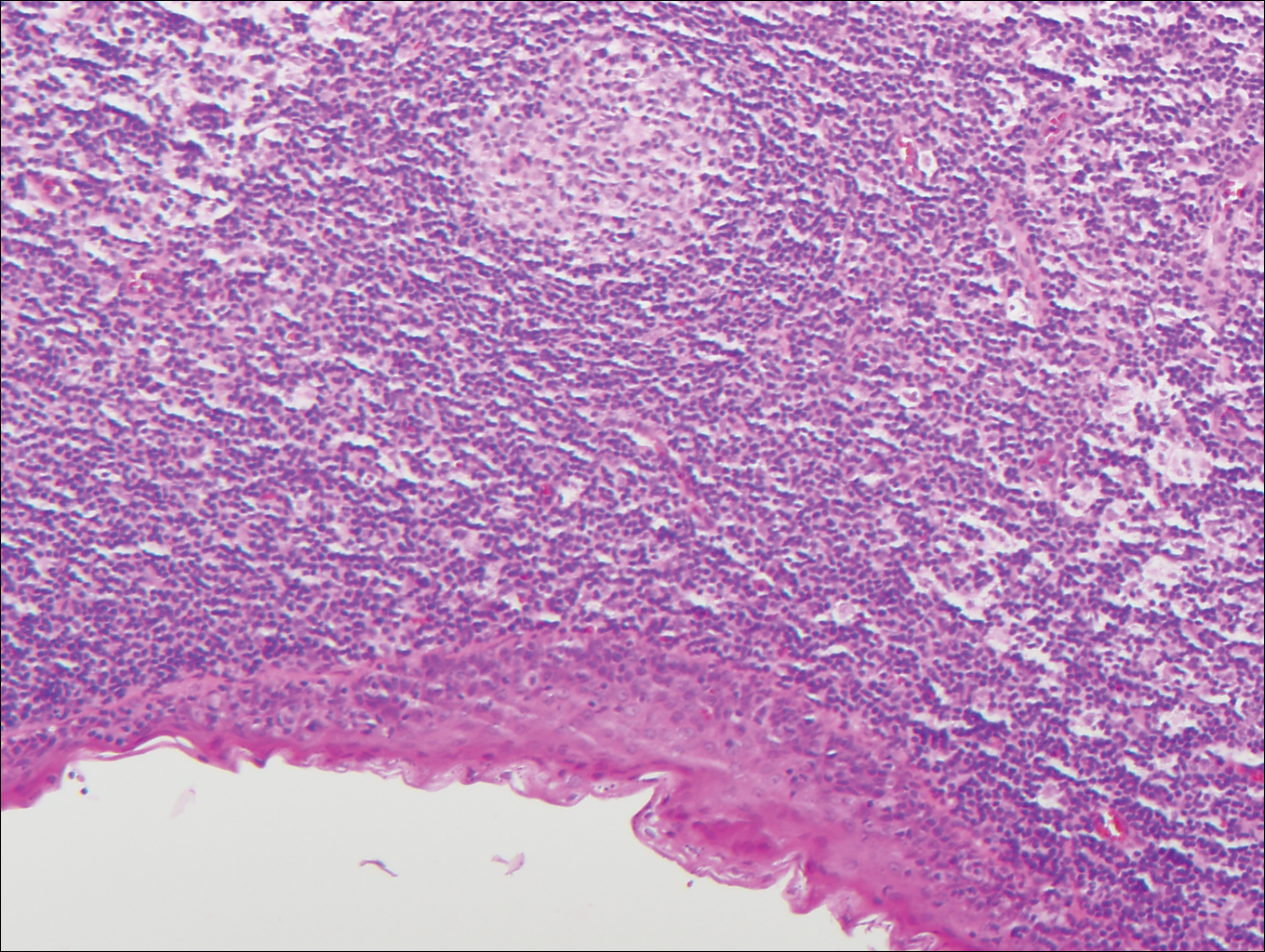

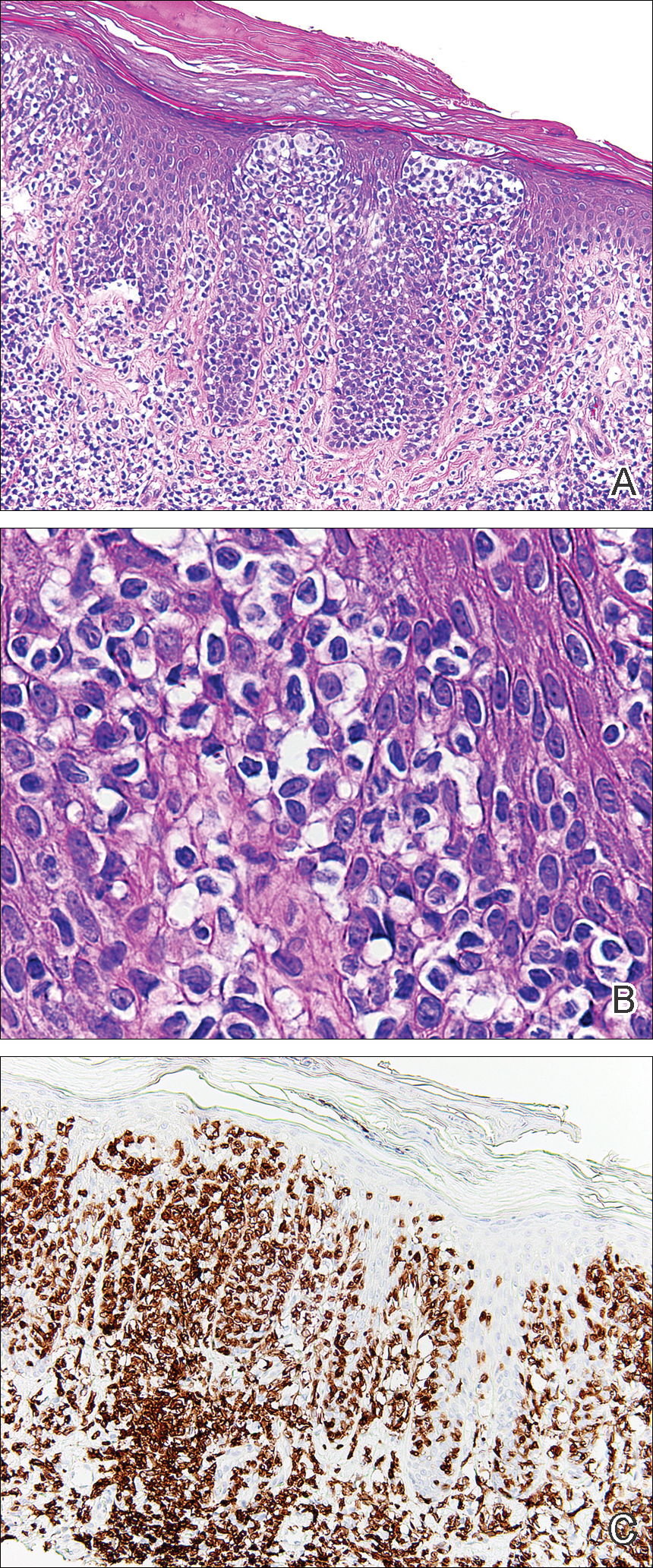

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dense infiltrate and psoriasiform pattern epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). There was conspicuous epidermotropism of moderately enlarged, hyperchromatic lymphocytes. Intraepidermal lymphocytes were slightly larger, darker, and more convoluted than those in the subjacent dermis (Figure, B). These cells exhibited CD3+ T-cell differentiation with an abnormal CD4-CD7-CD8- phenotype (Figure, C). The histopathologic finding of atypical epidermotropic T-cell infiltrate was compatible with a rare variant of mycosis fungoides known as pagetoid reticulosis (PR). After discussing the diagnosis and treatment options, the patient elected to begin with a conservative approach to therapy. We prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily under occlusion. At 1 month follow-up, the patient experienced marked improvement of the erythema and scaling of the lesion.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that has been categorized as an indolent localized variant of mycosis fungoides. This rare skin disorder was originally described by Woringer and Kolopp in 19391 and was further renamed in 1973 by Braun-Falco et al.2 At that time the term pagetoid reticulosis was introduced due to similarities in histopathologic findings seen in Paget disease of the nipple. Two variants of the disease have been described since then: the localized type and the disseminated type. The localized type, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease (WKD), typically presents as a persistent, sharply localized, scaly patch that slowly expands over several years. The lesion is classically located on the extensor surface of the hand or foot and often is asymptomatic. Due to the benign presentation, WKD can easily be confused with much more common diseases, such as psoriasis or fungal infections, resulting in a substantial delay in the diagnosis. The patient will often report a medical history notable for frequent office visits and numerous failed therapies. Even though it is exceedingly uncommon, these findings should prompt the practitioner to add WKD to their differential. The disseminated type of PR (also known as Ketron-Goodman disease) is characterized by diffuse cutaneous involvement, carries a much more progressive course, and often leads to a poor outcome.3 The histopathologic features of WKD and Ketron-Goodman disease are identical, and the 2 types are distinguished on clinical grounds alone.

Histopathologic features of PR are unique and often distinct in comparison to mycosis fungoides. Pagetoid reticulosis often is described as epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis, prominent acanthosis, and excessive epidermotropism of atypical lymphocytes scattered throughout the epidermis.3 The distinct pattern of epidermotropism seen in PR is the characteristic finding. Review of immunocytochemistry from reported cases has shown that CD marker expression of neoplastic T cells in PR can be variable in nature.4 Although it is known that immunophenotyping can be useful in diagnosing and distinguishing PR from other types of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, the clinical significance of the observed phenotypic variation remains a mystery. As of now, it appears to be prognostically irrelevant.5

There are numerous therapeutic options available for PR. Depending on the size and extent of the disease, surgical excision and radiotherapy may be an option and are the most effective.6 For patients who are not good candidates or opt out of these options, there are various pharmacotherapies that also have proven to work. Traditional therapies include topical corticosteroids, corticosteroid injections, and phototherapy. However, more recent trials with retinoids, such as alitretinoin or bexarotene, appear to offer a promising therapeutic approach.7

Pagetoid reticulosis is a true malignant lymphoma of T-cell lineage, but it typically carries an excellent prognosis. Rare cases have been reported to progress to disseminated lymphoma.8 Therefore, long-term follow-up for a patient diagnosed with PR is recommended.

- Woringer FR, Kolopp P. Lésion érythémato-squameuse polycyclique de l'avant-bras évoluantdepuis 6 ans chez un garçonnet de 13 ans. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1939;10:945-948.

- Braun-Falco O, Marghescu S, Wolff HH. Pagetoid reticulosis--Woringer-Kolopp's disease [in German]. Hautarzt. 1973;24:11-21.

- Haghighi B, Smoller BR, Leboit PE, et al. Pagetoid reticulosis (Woringer-Kolopp disease): an immunophenotypic, molecular, and clinicopathologic study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:502-510.

- Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Mourtzinos N, Puri PK, Wang G, et al. CD4/CD8 double negative pagetoid reticulosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:491-496.

- Lee J, Viakhireva N, Cesca C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Woringer-Kolopp disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:706-712.

- Schmitz L, Bierhoff E, Dirschka T. Alitretinoin: an effective treatment option for pagetoid reticulosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:1194-1195.

- Ioannides G, Engel MF, Rywlin AM. Woringer-Kolopp disease (pagetoid reticulosis). Am J Dermatopathol. 1983;5:153-158.

The Diagnosis: Pagetoid Reticulosis

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a dense infiltrate and psoriasiform pattern epidermal hyperplasia (Figure, A). There was conspicuous epidermotropism of moderately enlarged, hyperchromatic lymphocytes. Intraepidermal lymphocytes were slightly larger, darker, and more convoluted than those in the subjacent dermis (Figure, B). These cells exhibited CD3+ T-cell differentiation with an abnormal CD4-CD7-CD8- phenotype (Figure, C). The histopathologic finding of atypical epidermotropic T-cell infiltrate was compatible with a rare variant of mycosis fungoides known as pagetoid reticulosis (PR). After discussing the diagnosis and treatment options, the patient elected to begin with a conservative approach to therapy. We prescribed fluocinonide ointment 0.05% twice daily under occlusion. At 1 month follow-up, the patient experienced marked improvement of the erythema and scaling of the lesion.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that has been categorized as an indolent localized variant of mycosis fungoides. This rare skin disorder was originally described by Woringer and Kolopp in 19391 and was further renamed in 1973 by Braun-Falco et al.2 At that time the term pagetoid reticulosis was introduced due to similarities in histopathologic findings seen in Paget disease of the nipple. Two variants of the disease have been described since then: the localized type and the disseminated type. The localized type, also known as Woringer-Kolopp disease (WKD), typically presents as a persistent, sharply localized, scaly patch that slowly expands over several years. The lesion is classically located on the extensor surface of the hand or foot and often is asymptomatic. Due to the benign presentation, WKD can easily be confused with much more common diseases, such as psoriasis or fungal infections, resulting in a substantial delay in the diagnosis. The patient will often report a medical history notable for frequent office visits and numerous failed therapies. Even though it is exceedingly uncommon, these findings should prompt the practitioner to add WKD to their differential. The disseminated type of PR (also known as Ketron-Goodman disease) is characterized by diffuse cutaneous involvement, carries a much more progressive course, and often leads to a poor outcome.3 The histopathologic features of WKD and Ketron-Goodman disease are identical, and the 2 types are distinguished on clinical grounds alone.