User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Weighted Blankets May Help Reduce Preoperative Anxiety During Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Weighted Blankets May Help Reduce Preoperative Anxiety During Mohs Micrographic Surgery

To the Editor:

Patients with nonmelanoma skin cancers exhibit high quality-of-life satisfaction after treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or excision.1,2 However, perioperative anxiety in patients undergoing MMS is common, especially during the immediate preoperative period.3 Anxiety activates the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in physiologic changes such as tachycardia and hypertension.4,5 These sequelae may not only increase patient distress but also increase intraoperative bleeding, complication rates, and recovery times.4,5 Thus, the preoperative period represents a critical window for interventions aimed at reducing anxiety. Anxiety peaks during the perioperative period for a myriad of reasons, including anticipation of pain or potential complications. Enhancing patient comfort and well-being during the procedure may help reduce negative emotional sequelae, alleviate fear during procedures, and increase patient satisfaction.3

Weighted blankets (WBs) frequently are utilized in occupational and physical therapy as a deep pressure stimulation tool to alleviate anxiety by mimicking the experience of being massaged or swaddled.6 Deep pressure tools increase parasympathetic tone, help reduce anxiety, and provide a calming effect.7,8 Nonhospitalized individuals were more relaxed during mental health evaluations when using a WB, and deep pressure tools have frequently been used to calm individuals with autism spectrum disorders or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders.6 Furthermore, WBs have successfully been used to reduce anxiety in mental health care settings, as well as during chemotherapy infusions.6,9 The literature is sparse regarding the use of WB in the perioperative setting. Potential benefit has been demonstrated in the setting of dental cleanings and wisdom teeth extractions.7,8 In the current study, we investigated whether use of a WB could reduce preoperative anxiety in the setting of MMS.

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), and adult patients undergoing MMS to the head or neck were recruited to participate in a single-blind randomized controlled trial in the spring of 2023. Patients undergoing MMS on other areas of the body were excluded because the placement of the WB could interfere with the procedure. Other exclusion criteria included pregnancy, dementia, or current treatment with an anxiolytic medication.

Twenty-seven patients were included in the study, and informed consent was obtained. Patients were randomized to use a WB or standard hospital towel (control). The medical-grade WBs weighed 8.5 pounds, while the cotton hospital towels weighed less than 1 pound. The WBs were cleaned in between patients with standard germicidal disposable wipes.

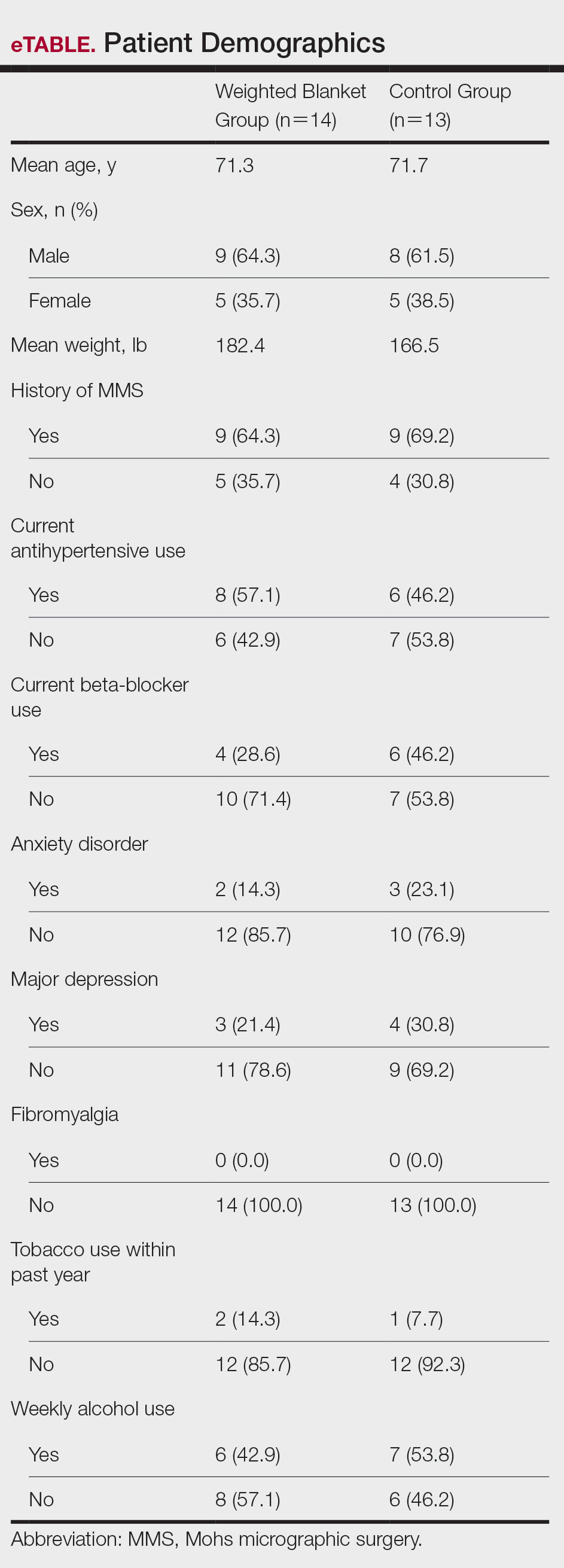

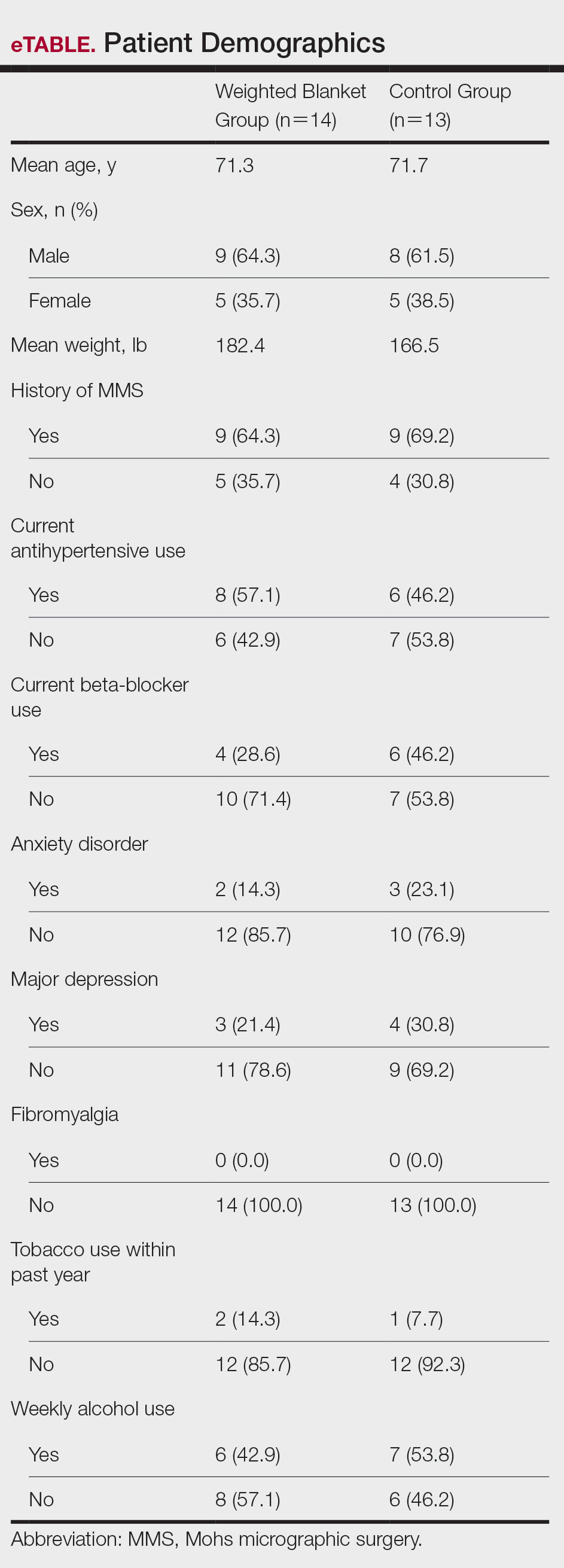

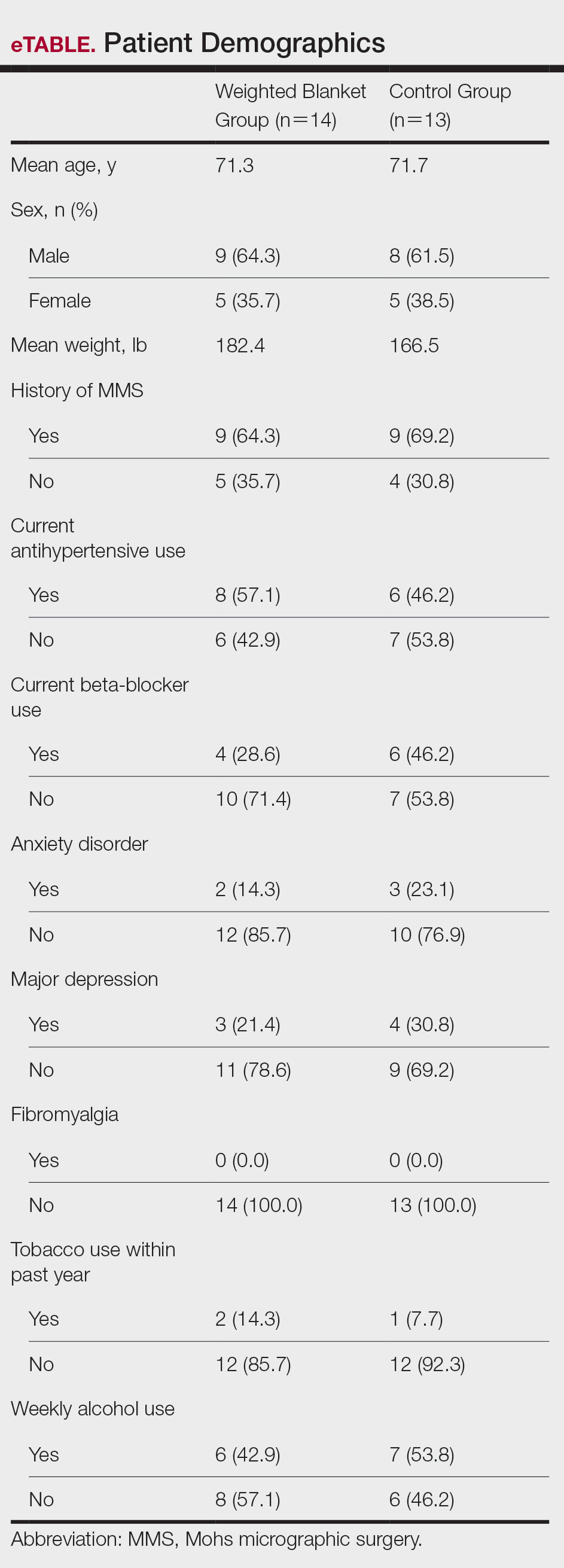

Patient data were collected from electronic medical records including age, sex, weight, history of prior MMS, and current use of antihypertensives and/or beta-blockers. Data also were collected on the presence of anxiety disorders, major depression, fibromyalgia, tobacco and alcohol use, hyperthyroidism, hyperhidrosis, cardiac arrhythmias (including atrial fibrillation), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral neuropathy, and menopausal symptoms.

During the procedure, anxiety was monitored using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Form Y-1, the visual analogue scale for anxiety (VAS-A), and vital signs including heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Vital signs were evaluated by nursing staff with the patient sitting up and the WB or hospital towel removed. Using these assessments, anxiety was measured at 3 different timepoints: upon arrival to the clinic (timepoint A), after the patient rested in a reclined beach-chair position with the WB or hospital towel placed over them for 10 minutes before administration of local anesthetic and starting the procedure (timepoint B), and after the first MMS stage was taken (timepoint C).

A power analysis was not completed due to a lack of previous studies on the use of WBs during MMS. Group means were analyzed using two-tailed t-tests and one-way analysis of variance. A P value of .05 indicated statistical significance.

Fourteen patients were randomized to the WB group and 13 were randomized to the control group. Patient demographics are outlined in the eTable. In the WB group, mean STAI scores progressively decreased at each timepoint (A: 15.3, B: 13.6, C: 12.7) and mean VAS-A scores followed a similar trend (A: 24.2, B: 19.3, C: 10.5). In the control group, the mean STAI scores remained stable at timepoints A and B (17.7) and then decreased at timepoint C (14.8). The mean VAS-A scores in the control group followed a similar pattern, remaining stable at timepoints A (22.9) and B (22.8) and then decreasing at timepoint C (14.4). These changes were not statistically significant.

Mean vital signs for both the WB and control groups were relatively stable across all timepoints, although they tended to decrease by timepoint C. In the WB group, mean heart rates were 69, 69, and 67 beats per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 136 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 68 mm Hg, and 66 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 20, 19, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. In the control group, mean heart rates were 70, 69, and 68 beats per minute across timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 133 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 74 mm Hg, and 68 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 19, 18, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. These changes were not statistically significant.

Our pilot study examined the effects of using a WB to alleviate preoperative anxiety during MMS. Our results suggest that WBs may modestly improve subjective anxiety immediately prior to undergoing MMS. Mean STAI and VAS-A scores decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B in the WB group vs the control group in which these scores remained stable. Although our study was not powered to determine statistical differences and significance was not reached, our results suggest a favorable trend in decreased anxiety scores. Our analysis was limited by a small sample size; therefore, additional larger-scale studies will be needed to confirm this trend.

Our results are broadly consistent with earlier studies that found improvement in physiologic proxies of anxiety with the use of WBs during chemotherapy infusions, dental procedures, and acute inpatient mental health hospitalizations.7-10 During periods of high anxiety, use of WBs shifts the autonomic nervous system from a sympathetic to a parasympathetic state, as demonstrated by increased high-frequency heart rate variability, a marker of parasympathetic activity.6,11 While the exact mechanism of how WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools affect high-frequency heart rate variability is unclear, one study showed that patients undergoing dental extractions were better equipped when using deep pressure stimulation tools to utilize calming techniques and regulate stress.12 The use of WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools may extend beyond the perioperative setting and also may be an effective tool for clinicians in other settings (eg, clinic visits, physical examinations).

In our study, all participants demonstrated the greatest reduction in anxiety at timepoint C after the first MMS stage, likely related to patients relaxing more after knowing what to expect from the surgery; this also may have been reflected somewhat in the slight downward trend noted in vital signs across both study groups. One concern regarding WB use in surgical settings is whether the added pressure could trigger unfavorable circulatory effects, such as elevated blood pressure. In our study, with the exception of diastolic blood pressure, vital signs appeared unaffected by the type of blanket used and remained relatively stable from timepoint A to timepoint B and decreased at timepoint C. Diastolic blood pressure in the WB group decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B, then decreased further from timepoint B to timepoint C. This mirrored the decreasing STAI score trend, compared to the control group who increased from timepoint A to timepoint B and reached a nadir at timepoint C. Consistent with prior WB studies, there were no adverse effects from WBs, including adverse impacts on vital signs.6,9

The original recruitment goal was not met due to staffing issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and subgroup analyses were deferred as a result of sample size limitations. It is possible that the WB intervention may have a larger impact on subpopulations more prone to perioperative anxiety (eg, patients undergoing MMS for the first time). However, the results of our pilot study suggest a beneficial effect from the use of WBs. While these preliminary data are promising, additional studies in the perioperative setting are needed to more accurately determine the clinical utility of WBs during MMS and other procedures.

- Eberle FC, Schippert W, Trilling B, et al. Cosmetic results of histographically controlled excision of non-melanoma skin cancer in the head and neck region. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:109-112. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0378.2005.04738.x

- Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1351-1357. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700740

- Kossintseva I, Zloty D. Determinants and timeline of perioperative anxiety in Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1029-1035. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000001152

- Pritchard MJ. Identifying and assessing anxiety in pre-operative patients. Nurs Stand. 2009;23:35-40. doi:10.7748/ns2009.08.23.51.35.c7222.

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:E20306. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020306

- Mullen B, Champagne T, Krishnamurty S, et al. Exploring the safety and therapeutic effects of deep pressure stimulation using a weighted blanket. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2008;24:65-89. doi:10.1300/ J004v24n01_05

- Chen HY, Yang H, Chi HJ, et al. Physiological effects of deep touch pressure on anxiety alleviation: the weighted blanket approach. J Med Biol Eng. 2013;33:463-470. doi:10.5405/jmbe.1043

- Chen HY, Yang H, Meng LF, et al. Effect of deep pressure input on parasympathetic system in patients with wisdom tooth surgery. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115:853-859. doi:10.1016 /j.jfma.2016.07.008

- Vinson J, Powers J, Mosesso K. Weighted blankets: anxiety reduction in adult patients receiving chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2020; 24:360-368. doi:10.1188/20.CJON.360-368

- Champagne T, Mullen B, Dickson D, et al. Evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the weighted blanket with adults during an inpatient mental health hospitalization. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2015;31:211-233. doi:10.1080/0164212X.2015.1066220

- Lane RD, McRae K, Reiman EM, et al. Neural correlates of heart rate variability during emotion. Neuroimage. 2009;44:213-222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.056

- Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum JW. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:3-18. doi: 10.1037 /0033-2909.130.1.3

To the Editor:

Patients with nonmelanoma skin cancers exhibit high quality-of-life satisfaction after treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or excision.1,2 However, perioperative anxiety in patients undergoing MMS is common, especially during the immediate preoperative period.3 Anxiety activates the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in physiologic changes such as tachycardia and hypertension.4,5 These sequelae may not only increase patient distress but also increase intraoperative bleeding, complication rates, and recovery times.4,5 Thus, the preoperative period represents a critical window for interventions aimed at reducing anxiety. Anxiety peaks during the perioperative period for a myriad of reasons, including anticipation of pain or potential complications. Enhancing patient comfort and well-being during the procedure may help reduce negative emotional sequelae, alleviate fear during procedures, and increase patient satisfaction.3

Weighted blankets (WBs) frequently are utilized in occupational and physical therapy as a deep pressure stimulation tool to alleviate anxiety by mimicking the experience of being massaged or swaddled.6 Deep pressure tools increase parasympathetic tone, help reduce anxiety, and provide a calming effect.7,8 Nonhospitalized individuals were more relaxed during mental health evaluations when using a WB, and deep pressure tools have frequently been used to calm individuals with autism spectrum disorders or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders.6 Furthermore, WBs have successfully been used to reduce anxiety in mental health care settings, as well as during chemotherapy infusions.6,9 The literature is sparse regarding the use of WB in the perioperative setting. Potential benefit has been demonstrated in the setting of dental cleanings and wisdom teeth extractions.7,8 In the current study, we investigated whether use of a WB could reduce preoperative anxiety in the setting of MMS.

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), and adult patients undergoing MMS to the head or neck were recruited to participate in a single-blind randomized controlled trial in the spring of 2023. Patients undergoing MMS on other areas of the body were excluded because the placement of the WB could interfere with the procedure. Other exclusion criteria included pregnancy, dementia, or current treatment with an anxiolytic medication.

Twenty-seven patients were included in the study, and informed consent was obtained. Patients were randomized to use a WB or standard hospital towel (control). The medical-grade WBs weighed 8.5 pounds, while the cotton hospital towels weighed less than 1 pound. The WBs were cleaned in between patients with standard germicidal disposable wipes.

Patient data were collected from electronic medical records including age, sex, weight, history of prior MMS, and current use of antihypertensives and/or beta-blockers. Data also were collected on the presence of anxiety disorders, major depression, fibromyalgia, tobacco and alcohol use, hyperthyroidism, hyperhidrosis, cardiac arrhythmias (including atrial fibrillation), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral neuropathy, and menopausal symptoms.

During the procedure, anxiety was monitored using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Form Y-1, the visual analogue scale for anxiety (VAS-A), and vital signs including heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Vital signs were evaluated by nursing staff with the patient sitting up and the WB or hospital towel removed. Using these assessments, anxiety was measured at 3 different timepoints: upon arrival to the clinic (timepoint A), after the patient rested in a reclined beach-chair position with the WB or hospital towel placed over them for 10 minutes before administration of local anesthetic and starting the procedure (timepoint B), and after the first MMS stage was taken (timepoint C).

A power analysis was not completed due to a lack of previous studies on the use of WBs during MMS. Group means were analyzed using two-tailed t-tests and one-way analysis of variance. A P value of .05 indicated statistical significance.

Fourteen patients were randomized to the WB group and 13 were randomized to the control group. Patient demographics are outlined in the eTable. In the WB group, mean STAI scores progressively decreased at each timepoint (A: 15.3, B: 13.6, C: 12.7) and mean VAS-A scores followed a similar trend (A: 24.2, B: 19.3, C: 10.5). In the control group, the mean STAI scores remained stable at timepoints A and B (17.7) and then decreased at timepoint C (14.8). The mean VAS-A scores in the control group followed a similar pattern, remaining stable at timepoints A (22.9) and B (22.8) and then decreasing at timepoint C (14.4). These changes were not statistically significant.

Mean vital signs for both the WB and control groups were relatively stable across all timepoints, although they tended to decrease by timepoint C. In the WB group, mean heart rates were 69, 69, and 67 beats per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 136 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 68 mm Hg, and 66 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 20, 19, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. In the control group, mean heart rates were 70, 69, and 68 beats per minute across timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 133 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 74 mm Hg, and 68 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 19, 18, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. These changes were not statistically significant.

Our pilot study examined the effects of using a WB to alleviate preoperative anxiety during MMS. Our results suggest that WBs may modestly improve subjective anxiety immediately prior to undergoing MMS. Mean STAI and VAS-A scores decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B in the WB group vs the control group in which these scores remained stable. Although our study was not powered to determine statistical differences and significance was not reached, our results suggest a favorable trend in decreased anxiety scores. Our analysis was limited by a small sample size; therefore, additional larger-scale studies will be needed to confirm this trend.

Our results are broadly consistent with earlier studies that found improvement in physiologic proxies of anxiety with the use of WBs during chemotherapy infusions, dental procedures, and acute inpatient mental health hospitalizations.7-10 During periods of high anxiety, use of WBs shifts the autonomic nervous system from a sympathetic to a parasympathetic state, as demonstrated by increased high-frequency heart rate variability, a marker of parasympathetic activity.6,11 While the exact mechanism of how WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools affect high-frequency heart rate variability is unclear, one study showed that patients undergoing dental extractions were better equipped when using deep pressure stimulation tools to utilize calming techniques and regulate stress.12 The use of WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools may extend beyond the perioperative setting and also may be an effective tool for clinicians in other settings (eg, clinic visits, physical examinations).

In our study, all participants demonstrated the greatest reduction in anxiety at timepoint C after the first MMS stage, likely related to patients relaxing more after knowing what to expect from the surgery; this also may have been reflected somewhat in the slight downward trend noted in vital signs across both study groups. One concern regarding WB use in surgical settings is whether the added pressure could trigger unfavorable circulatory effects, such as elevated blood pressure. In our study, with the exception of diastolic blood pressure, vital signs appeared unaffected by the type of blanket used and remained relatively stable from timepoint A to timepoint B and decreased at timepoint C. Diastolic blood pressure in the WB group decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B, then decreased further from timepoint B to timepoint C. This mirrored the decreasing STAI score trend, compared to the control group who increased from timepoint A to timepoint B and reached a nadir at timepoint C. Consistent with prior WB studies, there were no adverse effects from WBs, including adverse impacts on vital signs.6,9

The original recruitment goal was not met due to staffing issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and subgroup analyses were deferred as a result of sample size limitations. It is possible that the WB intervention may have a larger impact on subpopulations more prone to perioperative anxiety (eg, patients undergoing MMS for the first time). However, the results of our pilot study suggest a beneficial effect from the use of WBs. While these preliminary data are promising, additional studies in the perioperative setting are needed to more accurately determine the clinical utility of WBs during MMS and other procedures.

To the Editor:

Patients with nonmelanoma skin cancers exhibit high quality-of-life satisfaction after treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or excision.1,2 However, perioperative anxiety in patients undergoing MMS is common, especially during the immediate preoperative period.3 Anxiety activates the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in physiologic changes such as tachycardia and hypertension.4,5 These sequelae may not only increase patient distress but also increase intraoperative bleeding, complication rates, and recovery times.4,5 Thus, the preoperative period represents a critical window for interventions aimed at reducing anxiety. Anxiety peaks during the perioperative period for a myriad of reasons, including anticipation of pain or potential complications. Enhancing patient comfort and well-being during the procedure may help reduce negative emotional sequelae, alleviate fear during procedures, and increase patient satisfaction.3

Weighted blankets (WBs) frequently are utilized in occupational and physical therapy as a deep pressure stimulation tool to alleviate anxiety by mimicking the experience of being massaged or swaddled.6 Deep pressure tools increase parasympathetic tone, help reduce anxiety, and provide a calming effect.7,8 Nonhospitalized individuals were more relaxed during mental health evaluations when using a WB, and deep pressure tools have frequently been used to calm individuals with autism spectrum disorders or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders.6 Furthermore, WBs have successfully been used to reduce anxiety in mental health care settings, as well as during chemotherapy infusions.6,9 The literature is sparse regarding the use of WB in the perioperative setting. Potential benefit has been demonstrated in the setting of dental cleanings and wisdom teeth extractions.7,8 In the current study, we investigated whether use of a WB could reduce preoperative anxiety in the setting of MMS.

Institutional review board approval was obtained from the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, Virginia), and adult patients undergoing MMS to the head or neck were recruited to participate in a single-blind randomized controlled trial in the spring of 2023. Patients undergoing MMS on other areas of the body were excluded because the placement of the WB could interfere with the procedure. Other exclusion criteria included pregnancy, dementia, or current treatment with an anxiolytic medication.

Twenty-seven patients were included in the study, and informed consent was obtained. Patients were randomized to use a WB or standard hospital towel (control). The medical-grade WBs weighed 8.5 pounds, while the cotton hospital towels weighed less than 1 pound. The WBs were cleaned in between patients with standard germicidal disposable wipes.

Patient data were collected from electronic medical records including age, sex, weight, history of prior MMS, and current use of antihypertensives and/or beta-blockers. Data also were collected on the presence of anxiety disorders, major depression, fibromyalgia, tobacco and alcohol use, hyperthyroidism, hyperhidrosis, cardiac arrhythmias (including atrial fibrillation), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, peripheral neuropathy, and menopausal symptoms.

During the procedure, anxiety was monitored using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Form Y-1, the visual analogue scale for anxiety (VAS-A), and vital signs including heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. Vital signs were evaluated by nursing staff with the patient sitting up and the WB or hospital towel removed. Using these assessments, anxiety was measured at 3 different timepoints: upon arrival to the clinic (timepoint A), after the patient rested in a reclined beach-chair position with the WB or hospital towel placed over them for 10 minutes before administration of local anesthetic and starting the procedure (timepoint B), and after the first MMS stage was taken (timepoint C).

A power analysis was not completed due to a lack of previous studies on the use of WBs during MMS. Group means were analyzed using two-tailed t-tests and one-way analysis of variance. A P value of .05 indicated statistical significance.

Fourteen patients were randomized to the WB group and 13 were randomized to the control group. Patient demographics are outlined in the eTable. In the WB group, mean STAI scores progressively decreased at each timepoint (A: 15.3, B: 13.6, C: 12.7) and mean VAS-A scores followed a similar trend (A: 24.2, B: 19.3, C: 10.5). In the control group, the mean STAI scores remained stable at timepoints A and B (17.7) and then decreased at timepoint C (14.8). The mean VAS-A scores in the control group followed a similar pattern, remaining stable at timepoints A (22.9) and B (22.8) and then decreasing at timepoint C (14.4). These changes were not statistically significant.

Mean vital signs for both the WB and control groups were relatively stable across all timepoints, although they tended to decrease by timepoint C. In the WB group, mean heart rates were 69, 69, and 67 beats per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 136 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 68 mm Hg, and 66 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 20, 19, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. In the control group, mean heart rates were 70, 69, and 68 beats per minute across timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean systolic blood pressures were 137 mm Hg, 138 mm Hg, and 133 mm Hg and mean diastolic pressures were 71 mm Hg, 74 mm Hg, and 68 mm Hg at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. Mean respiratory rates were 19, 18, and 18 breaths per minute at timepoints A, B, and C, respectively. These changes were not statistically significant.

Our pilot study examined the effects of using a WB to alleviate preoperative anxiety during MMS. Our results suggest that WBs may modestly improve subjective anxiety immediately prior to undergoing MMS. Mean STAI and VAS-A scores decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B in the WB group vs the control group in which these scores remained stable. Although our study was not powered to determine statistical differences and significance was not reached, our results suggest a favorable trend in decreased anxiety scores. Our analysis was limited by a small sample size; therefore, additional larger-scale studies will be needed to confirm this trend.

Our results are broadly consistent with earlier studies that found improvement in physiologic proxies of anxiety with the use of WBs during chemotherapy infusions, dental procedures, and acute inpatient mental health hospitalizations.7-10 During periods of high anxiety, use of WBs shifts the autonomic nervous system from a sympathetic to a parasympathetic state, as demonstrated by increased high-frequency heart rate variability, a marker of parasympathetic activity.6,11 While the exact mechanism of how WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools affect high-frequency heart rate variability is unclear, one study showed that patients undergoing dental extractions were better equipped when using deep pressure stimulation tools to utilize calming techniques and regulate stress.12 The use of WBs and other deep pressure stimulation tools may extend beyond the perioperative setting and also may be an effective tool for clinicians in other settings (eg, clinic visits, physical examinations).

In our study, all participants demonstrated the greatest reduction in anxiety at timepoint C after the first MMS stage, likely related to patients relaxing more after knowing what to expect from the surgery; this also may have been reflected somewhat in the slight downward trend noted in vital signs across both study groups. One concern regarding WB use in surgical settings is whether the added pressure could trigger unfavorable circulatory effects, such as elevated blood pressure. In our study, with the exception of diastolic blood pressure, vital signs appeared unaffected by the type of blanket used and remained relatively stable from timepoint A to timepoint B and decreased at timepoint C. Diastolic blood pressure in the WB group decreased from timepoint A to timepoint B, then decreased further from timepoint B to timepoint C. This mirrored the decreasing STAI score trend, compared to the control group who increased from timepoint A to timepoint B and reached a nadir at timepoint C. Consistent with prior WB studies, there were no adverse effects from WBs, including adverse impacts on vital signs.6,9

The original recruitment goal was not met due to staffing issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and subgroup analyses were deferred as a result of sample size limitations. It is possible that the WB intervention may have a larger impact on subpopulations more prone to perioperative anxiety (eg, patients undergoing MMS for the first time). However, the results of our pilot study suggest a beneficial effect from the use of WBs. While these preliminary data are promising, additional studies in the perioperative setting are needed to more accurately determine the clinical utility of WBs during MMS and other procedures.

- Eberle FC, Schippert W, Trilling B, et al. Cosmetic results of histographically controlled excision of non-melanoma skin cancer in the head and neck region. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:109-112. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0378.2005.04738.x

- Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1351-1357. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700740

- Kossintseva I, Zloty D. Determinants and timeline of perioperative anxiety in Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1029-1035. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000001152

- Pritchard MJ. Identifying and assessing anxiety in pre-operative patients. Nurs Stand. 2009;23:35-40. doi:10.7748/ns2009.08.23.51.35.c7222.

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:E20306. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020306

- Mullen B, Champagne T, Krishnamurty S, et al. Exploring the safety and therapeutic effects of deep pressure stimulation using a weighted blanket. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2008;24:65-89. doi:10.1300/ J004v24n01_05

- Chen HY, Yang H, Chi HJ, et al. Physiological effects of deep touch pressure on anxiety alleviation: the weighted blanket approach. J Med Biol Eng. 2013;33:463-470. doi:10.5405/jmbe.1043

- Chen HY, Yang H, Meng LF, et al. Effect of deep pressure input on parasympathetic system in patients with wisdom tooth surgery. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115:853-859. doi:10.1016 /j.jfma.2016.07.008

- Vinson J, Powers J, Mosesso K. Weighted blankets: anxiety reduction in adult patients receiving chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2020; 24:360-368. doi:10.1188/20.CJON.360-368

- Champagne T, Mullen B, Dickson D, et al. Evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the weighted blanket with adults during an inpatient mental health hospitalization. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2015;31:211-233. doi:10.1080/0164212X.2015.1066220

- Lane RD, McRae K, Reiman EM, et al. Neural correlates of heart rate variability during emotion. Neuroimage. 2009;44:213-222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.056

- Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum JW. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:3-18. doi: 10.1037 /0033-2909.130.1.3

- Eberle FC, Schippert W, Trilling B, et al. Cosmetic results of histographically controlled excision of non-melanoma skin cancer in the head and neck region. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:109-112. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0378.2005.04738.x

- Chren MM, Sahay AP, Bertenthal DS, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes of treatments for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1351-1357. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700740

- Kossintseva I, Zloty D. Determinants and timeline of perioperative anxiety in Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1029-1035. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000001152

- Pritchard MJ. Identifying and assessing anxiety in pre-operative patients. Nurs Stand. 2009;23:35-40. doi:10.7748/ns2009.08.23.51.35.c7222.

- Mavros MN, Athanasiou S, Gkegkes ID, et al. Do psychological variables affect early surgical recovery? PLoS One. 2011;6:E20306. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020306

- Mullen B, Champagne T, Krishnamurty S, et al. Exploring the safety and therapeutic effects of deep pressure stimulation using a weighted blanket. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2008;24:65-89. doi:10.1300/ J004v24n01_05

- Chen HY, Yang H, Chi HJ, et al. Physiological effects of deep touch pressure on anxiety alleviation: the weighted blanket approach. J Med Biol Eng. 2013;33:463-470. doi:10.5405/jmbe.1043

- Chen HY, Yang H, Meng LF, et al. Effect of deep pressure input on parasympathetic system in patients with wisdom tooth surgery. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115:853-859. doi:10.1016 /j.jfma.2016.07.008

- Vinson J, Powers J, Mosesso K. Weighted blankets: anxiety reduction in adult patients receiving chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2020; 24:360-368. doi:10.1188/20.CJON.360-368

- Champagne T, Mullen B, Dickson D, et al. Evaluating the safety and effectiveness of the weighted blanket with adults during an inpatient mental health hospitalization. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2015;31:211-233. doi:10.1080/0164212X.2015.1066220

- Lane RD, McRae K, Reiman EM, et al. Neural correlates of heart rate variability during emotion. Neuroimage. 2009;44:213-222. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.056

- Moyer CA, Rounds J, Hannum JW. A meta-analysis of massage therapy research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:3-18. doi: 10.1037 /0033-2909.130.1.3

Weighted Blankets May Help Reduce Preoperative Anxiety During Mohs Micrographic Surgery

Weighted Blankets May Help Reduce Preoperative Anxiety During Mohs Micrographic Surgery

PRACTICE POINTS

- Preoperative anxiety in patients during Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) may increase intraoperative bleeding, complication rates, and recovery times.

- Using weighted blankets may reduce anxiety in patients undergoing MMS of the head and neck.

Dermatologic Implications of Glycemic Control Medications for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Dermatologic Implications of Glycemic Control Medications for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic disease characterized by uncontrolled hyperglycemia. Over the past few decades, its prevalence has steadily increased, now affecting approximately 10% of adults worldwide and ranking among the top 10 leading causes of death globally.1 The pathophysiology of T2DM involves persistent hyperglycemia that drives insulin resistance and a progressive decline in insulin production from the pancreas.2 Medical management of this condition aims to reduce blood glucose levels or enhance insulin production and sensitivity. Aside from lifestyle modifications, metformin is considered the first-line treatment for glycemic control according to the 2023 American Association of Clinical Endocrinology’s T2DM management algorithm.3 These updated guidelines stratify adjunct treatments by individualized glycemic targets and patient needs. For patients who are overweight or obese, glucagonlike peptide 1 (GLP-1) and dual GLP-1/ gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) agonists are the preferred adjunct or second-line treatments.3

In this review, we highlight the dermatologic adverse effects and potential therapeutic benefits of metformin as well as GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP agonists.

METFORMIN

Metformin is a biguanide agent used as a first-line treatment for T2DM because of its ability to reduce hepatic glucose production and increase peripheral tissue glucose uptake.4 In addition to its effects on glucose, metformin has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties via inhibition of the nuclear factor κB and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways, leading to decreased production of cytokines associated with T helper (Th) 1 and Th17 cell responses, such as IL-17, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α).5-7 These findings have spurred interest among clinicians in the potential use of metformin for inflammatory conditions, including dermatologic diseases such as psoriasis and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS).8

Adverse Effects

Metformin is administered orally and generally is well tolerated. The most common adverse effects include gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain.9 While cutaneous adverse effects are rare, multiple dermatologic adverse reactions to metformin have been reported,10,11 including leukocytoclastic vasculitis,11-13 fixed drug eruptions,14-17 drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome,18 and photosensitivity reactions.19 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis and DRESS syndrome typically develop within the first month following metformin initiation, while fixed drug eruption and photosensitivity reactions have more variable timing, occurring weeks to years after treatment initiation.12-19

Dermatologic Implications

Acanthosis Nigricans—Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is characterized by hyperpigmentation and velvety skin thickening, typically in intertriginous areas such as the back of the neck, axillae, and groin.20 It commonly is associated with insulin resistance and obesity.21-23 Treatments for AN primarily center around insulin sensitivity and weight loss,24,25 with some benefit observed from the use of keratolytic agents.26,27 Metformin may have utility in treating AN through its effects on insulin sensitivity and glycemic control. Multiple case reports have noted marked improvements in AN in patients with and without obesity with the addition of metformin to their existing treatment regimens in doses ranging from 500 mg to 1700 mg daily.28-30 However, an unblinded randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing the efficacy of metformin (500 mg 3 times daily) with rosiglitazone (4 mg/d), another T2DM medication, on AN neck lesions in patients who were overweight and obese found no significant effects in lesion severity and only modest improvements in skin texture in both groups at 12 weeks following treatment initiation.31 Another RCT comparing metformin (500 mg twice daily) with a twice-daily capsule containing α-lipoic acid, biotin, chromium polynicotinate, and zinc sulfate, showed significant (P<.001) improvements in AN neck lesions in both groups after 12 weeks.32 According to Sung et al,8 longer duration of therapy (>6 months), higher doses (1700–2000 mg), and lower baseline weight were associated with higher efficacy of metformin for treatment of AN. Overall, the use of metformin as an adjunct treatment for AN, particularly in patients with underlying hyperglycemia, is supported in the literature, but further studies are needed to clarify dosing, duration of therapy, and patient populations that will benefit most from adding metformin to their treatment regimens.

Hirsutism—Hirsutism, which is characterized by excessive hair growth in androgen-dependent areas, can be challenging to treat. Metformin has been shown to reduce circulating insulin, luteinizing hormone, androstenedione, and testosterone, thus improving underlying hyperandrogenism, particularly in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).33-35 Although single studies evaluating the efficacy of metformin for treatment of hirsutism in patients with PCOS have shown potential benefits,36-38 meta-analyses showed no significant effects of metformin compared to placebo or oral contraceptives and decreased benefits compared to spironolactone and flutamide.39 Given these findings showing that metformin was no more effective than placebo or other treatments, the current Endocrine Society guidelines recommend against the use of metformin for hirsutism.39,40 There may be a role for metformin as an adjuvant therapy in certain populations (eg, patients with comorbid T2DM), although further studies stratifying risk factors such as body mass index and age are needed.41

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa is a follicular occlusive disease characterized by recurrent inflamed nodules leading to chronic dermal abscesses, fibrosis, and sinus tract formation primarily in intertriginous areas such as the axillae and groin.42 Medical management depends on disease severity but usually involves antibiotic treatment with adjunct therapies such as oral contraceptives, antiandrogenic medications (eg, spironolactone), biologic medications, and metformin.42 Preclinical and clinical data suggest that metformin can impact HS through metabolic and immunomodulatory mechanisms.5,42 Like many chronic inflammatory disorders, HS is associated with metabolic syndrome.43,44 A study evaluating insulin secretion after oral glucose tolerance testing showed increased insulin levels in patients with HS compared to controls (P=.02), with 60% (6/10) of patients with HS meeting criteria for insulin resistance. In addition, serum insulin levels in insulin-resistant patients with HS correlated with increased lesional skin mTOR gene expression at 30 (r=.80) and 60 (r=1.00) minutes, and mTOR was found to be upregulated in lesional and extralesional skin in patients with HS compared to healthy controls (P<.01).45 Insulin activates mTOR signaling, which mediates cell growth and survival, among other processes.46 Thus, metformin’s ability to increase insulin sensitivity and inhibit mTOR signaling could be beneficial in the setting of HS. Additionally, insulin and insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) increase androgen signaling, a process that has been implicated in HS.47

Metformin also may impact HS through its effects on testosterone and other hormones.48 A study evaluating peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with HS showed reduced IL-17, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-6 levels in patients who were taking metformin (dose not reported) for longer than 6 months compared to patients who were not on metformin. Further analysis of ex vivo HS lesions cultured with metformin showed decreased IL-17, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-8 expression in tissue, suggesting an antiinflammatory role of metformin in HS.5

Although there are no known RCTs assessing the efficacy of metformin in HS, existing clinical data are supportive of the use of metformin for refractory HS.49 Following a case report describing a patient with T2DM and stable HS while on metformin,50 several cohort studies have assessed the efficacy of metformin for the treatment of HS. A prospective study evaluating the efficacy of metformin monotherapy (starting dose of 500 mg/d, titrated to 500 mg 3 times daily) in patients with and without T2DM with HS refractory to other therapies found clinical improvement in 72% (18/25) of patients using the Sartorius Hidradenitis Suppurativa Score, improving from a mean (SD) score of 34.40 (12.46) to 26.76 (11.22) at 12 weeks (P=.0055,) and 22.39 (11.30) at 24 weeks (P=.0001). Additionally, 64% (16/25) of patients showed improved quality of life as evaluated by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), which decreased from a mean (SD) score of 15.00 (4.96) to 10.08 (5.96)(P=.0017) at 12 weeks and 7.65 (7.12)(P=.000009) at 24 weeks on treatment.48 In a retrospective study of 53 patients with HS taking metformin started at 500 mg daily and increased to 500 mg twice daily after 2 weeks (when tolerated), 68% (36/53) showed some clinical response, with 19% (7/36) of those patients having achieved complete response to metformin monotherapy (defined as no active HS).51 Similarly, a retrospective study of pediatric patients with HS evaluating metformin (doses ranging from 500-2000 mg daily) as an adjunct therapy described a subset of patients with decreased frequency of HS flares with metformin.52 These studies emphasize the safety profile of metformin and support its current use as an adjunctive therapy for HS.

Acne Vulgaris—Acne vulgaris (AV) is a chronic inflammatory disorder affecting the pilosebaceous follicles.11 Similar to HS, AV has metabolic and hormonal influences that can be targeted by metformin.53 In AV, androgens lead to increased sebum production by binding to androgen receptors on sebocytes, which in turn attracts Cutibacterium acnes and promotes hyperkeratinization, inducing inflammation.54 Thus, the antiandrogenic effects of metformin may be beneficial for treatment of AV. Additionally, sebocytes express receptors for insulin and IGF-1, which can increase the size and number of sebocytes, as well as promote lipogenesis and inflammatory response, influencing sebum production.54 Serum levels for IGF-1 have been observed to be increased in patients with AV55 and reduced by metformin.56 A recent meta-analysis assessing the efficacy of metformin on AV indicated that 87% (13/15) of studies noted disease improvement on metformin, with 47% (7/15) of studies showing statistically significant (P<0.05) decreases in acne severity.57 Although most studies showed improvement, 47% (7/15) did not find significant differences between metformin and other interventions, indicating the availability of comparable treatment options. Overall, there has been a positive association between metformin use and acne improvement.57 However, it is important to note that most studies have focused on females with PCOS,57 and the main benefits of metformin in acne might be seen when managing comorbid conditions, particularly those associated with metabolic dysregulation and insulin resistance. Further studies are needed to determine the generalizability of prior results.

Psoriasis—Psoriasis is a chronic autoinflammatory disease characterized by epidermal hyperplasia with multiple cutaneous manifestations and potential for multiorgan involvement. Comorbid conditions include psoriatic arthritis, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease.58 Current treatment options depend on several factors (eg, disease severity, location of cutaneous lesions, comorbidities) and include topical, systemic, and phototherapy options, many of which target the immune system.58,59 A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs showed that metformin (500 mg/d or 1000 mg/d) was associated with significantly improved Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 75% reductions (odds ratio [OR], 22.02; 95% CI, 2.12-228.49; P=.01) and 75% reductions in erythema, scaling, and induration (OR, 9.12; 95% CI, 2.13-39.02; P=.003) compared to placebo.60 In addition, an RCT evaluating the efficacy of metformin (1000 mg/d) or pioglitazone (30 mg/d) for 12 weeks in patients with psoriasis with metabolic syndrome found significant improvements in PASI75 (P=.001) and erythema, scaling, and induration (P=.016) scores as well as in Physician Global Assessment scores (P=.012) compared to placebo and no differences compared to pioglitazone.61 While current psoriasis management guidelines do not include metformin, its use may be worth consideration as an adjunct therapy in patients with psoriasis and comorbidities such as T2DM and metabolic syndrome.59 Metformin’s potential benefits in psoriasis may lie outside its metabolic influences and occur secondary to its immunomodulatory effects, including targeting of the Th17 axis or cytokine-specific pathways such as TNF-α, which are known to be involved in psoriasis pathogenesis.58

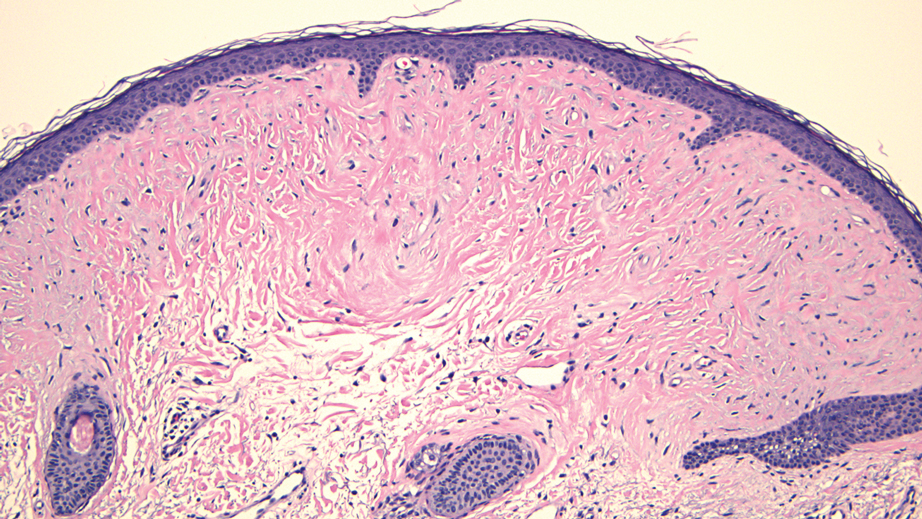

Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia—Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) is a form of scarring alopecia characterized by chronic inflammation leading to permanent loss of hair follicles on the crown of the scalp.62 Current treatments include topical and intralesional corticosteroids, as well as oral antibiotics. In addition, therapies including the antimalarial hydroxychloroquine and immunosuppressants mycophenolate and cyclosporine are used in refractory disease.63,64 A case report described 2 patients with hair regrowth after 4 and 6 months of treatment with topical metformin 10% compounded in a proprietary transdermal vehicle.65 The authors speculated that metformin’s effects on CCCA could be attributed to its known agonistic effects on the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway with subsequent reduction in inflammation-induced fibrosis.65,66 Microarray67 and proteomic68 analysis have shown that AMPK is known to be downregulated in CCCA , making it an interesting therapeutic target in this disease. A recent retrospective case series demonstrated that 67% (8/12) of patients with refractory CCCA had symptomatic improvement, and 50% (6/12) showed hair regrowth after 6 months of low-dose (500 mg/d) oral metformin treatment.62 In addition, metformin therapy showed antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects when comparing scalp biopsies before and after treatment. Results showed decreased expression of fibrosisrelated genes (matrix metalloproteinase 7, collagen type IV á 1 chain), and gene set variation analysis showing reduced Th17 (P=.04) and increased AMPK signaling (P=.02) gene set expression.62 These findings are consistent with previous studies describing the upregulation of AMPK66 and downregulation of Th176 following metformin treatment. The immunomodulatory effects of metformin could be attributed to AMPK-mediated mTOR and NF-κB downregulation,62 although more studies are needed to understand these mechanisms and further explore the use of metformin in CCCA.

Skin Cancer—Metformin also has been evaluated in the setting of skin malignancies, including melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma. Preclinical data suggest that metformin decreases cell viability in tumors through interactions with pathways involved in proinflammatory and prosurvival mechanisms such as NF-κB and mTOR.69,70 Additionally, given metformin’s inhibitory effects on oxidative phosphorylation, it has been postulated that it could be used to overcome treatment resistance driven by metabolic reprogramming.71,72 Most studies related to metformin and skin malignancies are still in preclinical stages; however, a meta-analysis of RCTs and cohort studies did not find significant associations between metformin use and skin cancer risk, although data trended toward a modest reduction in skin cancer among metformin users.73 A retrospective cohort study of melanoma in patients with T2DM taking metformin (250-2000 mg/d) found that the 5-year incidence of recurrence was lower in the metformin cohort compared to nonusers (43.8% vs 58.2%, respectively)(P=.002), and overall survival rates trended upward in the higher body mass index (>30) and melanoma stages 1 and 2 groups but did not reach statistical significance.74 In addition, a whole population casecontrol study in Iceland reported that metformin use at least 2 years before first-time basal cell carcinoma diagnosis was associated with a lower risk for disease (adjusted OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.61-0.83) with no significant dose-dependent differences; there were no notable effects on squamous cell carcinoma risk.75 Further preclinical and clinical data are needed to elucidate metformin’s effects on skin malignancies.

GLP-1 AND DUAL GLP-1/GIP AGONISTS

Glucagonlike peptide 1 and dual GLP-1/GIP agonists are emerging classes of medications currently approved as adjunct and second-line therapies for T2DM, particularly in patients who are overweight or obese as well as in those who are at risk for hypoglycemia.3 Currently approved GLP-1 agonists for T2DM include semaglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, and lixisenatide, while tirzepatide is the only approved dual GLP-1/GIP agonist. Activating GLP-1 and GIP receptors stimulates insulin secretion and decreases glucagon production by the pancreas, thereby reducing blood glucose levels. Additionally, some of these medications are approved for obesity given their effects in delayed gastric emptying and increased satiety, among other factors.

Over the past few years, multiple case reports have described the associations between GLP-1 agonist use and improvement of dermatologic conditions, particularly those associated with T2DM and obesity, including HS and psoriasis.76,77 The mechanisms through which this occurs are not fully elucidated, although basic science and clinical studies have shown that GLP-1 agonists have immunomodulatory effects by reducing proinflammatory cytokines and altering immune cell populations.77-80 The numerous ongoing clinical trials and research studies will help further elucidate their benefits in other disease settings.81

Adverse Reactions

Most GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP agonists are administered subcutaneously, and the most commonly reported cutaneous adverse effects are injection site reactions.82 Anaphylactic reactions to these medications also have been reported, although it is unclear if these were specific to the active ingredients or to injection excipients.83,84 A review of 33 cases of cutaneous reactions to GLP-1 agonists reported 11 (33%) dermal hypersensitivity reactions occurring as early as 4 weeks and as late as 3 years after treatment initiation. It also described 10 (30%) cases of eosinophilic panniculitis that developed within 3 weeks to 5 months of GLP-1 treatment, 3 (9%) cases of bullous pemphigoid that occurred within the first 2 months, 2 (6%) morbilliform drug eruptions that occurred within 5 weeks, 2 (6%) cases of angioedema that occurred 15 minutes to 2 weeks after treatment initiation, and 7 (21%) other isolated cutaneous reactions. Extended-release exenatide had the most reported reactions followed by liraglutide and subcutaneous semaglutide.85

In a different study, semaglutide use was most commonly associated with injection site reactions followed by alopecia, especially with oral administration. Unique cases of angioedema (2 days after injection), cutaneous hypersensitivity (within 10 months on treatment), bullous pemphigoid (within 2 months on treatment), eosinophilic fasciitis (within 2 weeks on treatment), and leukocytoclastic vasculitis (unclear timing), most of which resolved after discontinuation, also were reported.86 A recent case report linked semaglutide (0.5 mg/wk) to a case of drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus that developed within 3 months of treatment initiation and described systemic lupus erythematosus–like symptoms in a subset of patients using this medication, namely females older than 60 years, within the first month of treatment.87 Hyperhidrosis was listed as a common adverse event in exenatide clinical trials, and various cases of panniculitis with exenatide use have been reported.82,88 Alopecia, mainly attributed to accelerated telogen effluvium secondary to rapid weight loss, also has been reported, although hair loss is not officially listed as an adverse effect of GLP-1 agonists, and reports are highly variable.89 Also secondary to weight loss, facial changes including sunken eyes, development of wrinkles, sagging jowls around the neck and jaw, and a hollowed appearance, among others, are recognized as undesirable adverse effects.90 Mansour et al90 described the potential challenges and considerations to these rising concerns associated with GLP1-agonist use.

Dermatologic Implications

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Weight loss commonly is recommended as a lifestyle modification in the management of HS. Multiple reports have described clinical improvement of HS following weight loss with other medical interventions, such as dietary measures and bariatric surgery.91-94 Thus, it has been postulated that medically supported weight loss with GLP-1 agonists can help improve HS95; however, the data on the effectiveness of GLP-1 agonists on HS are still scarce and mostly have been reported in individual patients. One case report described a patient with improvements in their recalcitrant HS and DLQI score following weight loss on liraglutide (initial dose of 0.6 mg/d, titrated to 1.8 mg/d).76 In addition, a recent case report described improvements in HS and DLQI score following concomitant tirzepatide (initial dose of 2.5 mg/0.5 mL weekly, titrated to 7.5 mg/0.5 mL weekly) and infliximab treatment.96 The off-label use of these medications for HS is debated, and further studies regarding the benefits of GLP-1 agonists on HS still are needed.

Psoriasis—Similarly, several case reports have commented on the effects of GLP-1 agonists on psoriasis.97,98 An early study found GLP-1 receptors were expressed in psoriasis plaques but not in healthy skin and discussed that this could be due to immune infiltration in the plaques, providing a potential rationale for using anti-inflammatory GLP-1 agonists for psoriasis.99 Two prospective cohort studies observed improvements in PASI and DLQI scores in patients with psoriasis and T2DM after liraglutide treatment and noted important changes in immune cell populations.80,100 A recent RCT also found improvements in DLQI and PASI scores (P<.05) in patients with T2DM following liraglutide (1.8 mg/d) treatment, along with overall decreases in inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-23, IL-17, and TNF-α.77 However, another RCT in patients with obesity did not observe significant improvements in PASI and DLQI scores compared to placebo after 8 weeks of liraglutide (initial dose of 0.6 mg/d, titrated to 1.8 mg/d) treatment. 99 Although these results could have been influenced by the short length of treatment compared to other studies, which observed participants for more than 10 weeks, they highlight the need for tailored studies considering the different comorbidities to identify patients who could benefit the most from these therapies.

Alopecia—Although some studies have reported increased rates of alopecia following GLP-1 agonist treatment, others have speculated about the potential role of these medications in treating hair loss through improved insulin sensitivity and scalp blood flow.86,89 For example, a case report described a patient with improvement in androgenetic alopecia within 6 months of tirzepatide monotherapy at 2.5 mg weekly for the first 3 months followed by an increased dose of 5 mg weekly.101 The authors described the role of insulin in increasing dihydrotestosterone levels, which leads to miniaturization of the dermal papilla of hair follicles and argued that improvement of insulin resistance could benefit hair loss. Further studies can help elucidate the role of these medications on alopecia.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Standard T2DM treatments including metformin and GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP agonists exhibit metabolic, immunologic, and hormonal effects that should be explored in other disease contexts. We reviewed the current data on T2DM medications in dermatologic conditions to highlight the need for additional studies to better understand the role that these medications play across diverse patient populations. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a common comorbidity in dermatology patients, and understanding the multifactorial effects of these medications can help optimize treatment strategies, especially in patients with coexisting dermatologic and metabolic diseases.

- Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:88-98. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2017.151

- Ahmad E, Lim S, Lamptey R, et al. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2022;400: 1803-1820. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(22)01655-5

- Samson SL, Vellanki P, Blonde L, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Consensus Statement: comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2023 update. Endocr Pract. 2023;29:305-340. doi:10.1016/j.eprac.2023.02.001

- LaMoia TE, Shulman GI. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin action. Endocr Rev. 2021;42:77-96. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnaa023

- Petrasca A, Hambly R, Kearney N, et al. Metformin has antiinflammatory effects and induces immunometabolic reprogramming via multiple mechanisms in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2023;189:730-740. doi:10.1093/bjd/ljad305

- Duan W, Ding Y, Yu X, et al. Metformin mitigates autoimmune insulitis by inhibiting Th1 and Th17 responses while promoting Treg production. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11:2393-2402.

- Bharath LP, Nikolajczyk BS. The intersection of metformin and inflammation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021;320:C873-C879. doi:10.1152 /ajpcell.00604.2020

- Sung CT, Chao T, Lee A, et al. Oral metformin for treating dermatological diseases: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:713-720. doi:10.36849/jdd.2020.4874

- Feng J, Wang X, Ye X, et al. Mitochondria as an important target of metformin: the mechanism of action, toxic and side effects, and new therapeutic applications. Pharmacol Res. 2022;177:106114. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106114

- Klapholz L, Leitersdorf E, Weinrauch L. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis and pneumonitis induced by metformin. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:483. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6545.483

- Badr D, Kurban M, Abbas O. Metformin in dermatology: an overview. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1329-1335. doi:10.1111/jdv.12116

- Czarnowicki T, Ramot Y, Ingber A, et al. Metformin-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:61-63. doi:10.2165/11593230-000000000-00000

- Ben Salem C, Hmouda H, Slim R, et al. Rare case of metformininduced leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1685-1687. doi:10.1345/aph.1H155

- Abtahi-Naeini B, Momen T, Amiri R, et al. Metformin-induced generalized bullous fixed-drug eruption with a positive dechallengerechallenge test: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2023;2023:6353919. doi:10.1155/2023/6353919

- Al Masri D, Fleifel M, Hirbli K. Fixed drug eruption secondary to four anti-diabetic medications: an unusual case of polysensitivity. Cureus. 2021;13:E18599. doi:10.7759/cureus.18599

- Ramírez-Bellver JL, Lopez J, Macias E, et al. Metformin-induced generalized fixed drug eruption with cutaneous hemophagocytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:471-475. doi:10.1097/dad.0000000000000800

- Steber CJ, Perkins SL, Harris KB. Metformin-induced fixed-drug eruption confirmed by multiple exposures. Am J Case Rep. 2016;17:231-234. doi:10.12659/ajcr.896424

- Voore P, Odigwe C, Mirrakhimov AE, et al. DRESS syndrome following metformin administration: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Ther. 2016;23:E1970-E1973. doi:10.1097/mjt.0000000000000292

- Kastalli S, El Aïdli S, Chaabane A, et al. Photosensitivity induced by metformin: a report of 3 cases. Article in French. Tunis Med. 2009;87:703-705.

- Karadağ AS, You Y, Danarti R, et al. Acanthosis nigricans and the metabolic syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:48-53. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.09.008

- Kong AS, Williams RL, Smith M, et al. Acanthosis nigricans and diabetes risk factors: prevalence in young persons seen in southwestern US primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:202-208. doi:10.1370/afm.678

- Stuart CA, Gilkison CR, Smith MM, et al. Acanthosis nigricans as a risk factor for non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1998;37:73-79. doi:10.1177/000992289803700203

- Hud JA Jr, Cohen JB, Wagner JM, et al. Prevalence and significance of acanthosis nigricans in an adult obese population. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:941-944.

- Novotny R, Davis J, Butel J, et al. Effect of the Children’s Healthy Living Program on young child overweight, obesity, and acanthosis nigricans in the US-affiliated Pacific region: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:E183896. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3896

- Romo A, Benavides S. Treatment options in insulin resistance obesityrelated acanthosis nigricans. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1090-1094. doi:10.1345/aph.1K446

- Treesirichod A, Chaithirayanon S, Chaikul T, et al. The randomized trials of 10% urea cream and 0.025% tretinoin cream in the treatment of acanthosis nigricans. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:837-842. doi:10.108 0/09546634.2019.1708855

- Treesirichod A, Chaithirayanon S, Wongjitrat N. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of 0.1% adapalene gel and 0.025% tretinoin cream in the treatment of childhood acanthosis nigricans. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:330-334. doi:10.1111/pde.13799

- Hermanns-Lê T, Hermanns JF, Piérard GE. Juvenile acanthosis nigricans and insulin resistance. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:12-14. doi:10.1046 /j.1525-1470.2002.00013.x

- Walling HW, Messingham M, Myers LM, et al. Improvement of acanthosis nigricans on isotretinoin and metformin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2003;2:677-681.

- Giri D, Alsaffar H, Ramakrishnan R. Acanthosis nigricans and its response to metformin. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:e281-e282. doi:10.1111/pde.13206

- Bellot-Rojas P, Posadas-Sanchez R, Caracas-Portilla N, et al. Comparison of metformin versus rosiglitazone in patients with acanthosis nigricans: a pilot study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:884-889.

- Sett A, Pradhan S, Sancheti K, et al. Effectiveness and safety of metformin versus Canthex™ in patients with acanthosis nigricans: a randomized, double-blind controlled trial. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:115-121. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_417_17

- Genazzani AD, Battaglia C, Malavasi B, et al. Metformin administration modulates and restores luteinizing hormone spontaneous episodic secretion and ovarian function in nonobese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:114-119. doi:10.1016 /j.fertnstert.2003.05.020

- Kazerooni T, Dehghan-Kooshkghazi M. Effects of metformin therapy on hyperandrogenism in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2003;17:51-56.

- Kolodziejczyk B, Duleba AJ, Spaczynski RZ, et al. Metformin therapy decreases hyperandrogenism and hyperinsulinemia in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:1149-1154. doi:10.1016 /s0015-0282(00)00501-x

- Kelly CJ, Gordon D. The effect of metformin on hirsutism in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;147:217-221. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1470217

- Harborne L, Fleming R, Lyall H, et al. Metformin or antiandrogen in the treatment of hirsutism in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:4116-4123. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-030424

- Rezvanian H, Adibi N, Siavash M, et al. Increased insulin sensitivity by metformin enhances intense-pulsed-light-assisted hair removal in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Dermatology. 2009;218: 231-236. doi:10.1159/000187718

- Cosma M, Swiglo BA, Flynn DN, et al. Clinical review: insulin sensitizers for the treatment of hirsutism: a systematic review and metaanalyses of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1135-1142. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-2429

- Martin KA, Anderson RR, Chang RJ, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hirsutism in premenopausal women: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103:1233-1257.

- Fraison E, Kostova E, Moran LJ, et al. Metformin versus the combined oral contraceptive pill for hirsutism, acne, and menstrual pattern in polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;8:CD005552. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005552.pub3

- Hambly R, Kearney N, Hughes R, et al. Metformin treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: effect on metabolic parameters, inflammation, cardiovascular risk biomarkers, and immune mediators. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:6969. doi:10.3390/ijms24086969

- Gold DA, Reeder VJ, Mahan MG, et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:699-703. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.014

- Miller IM, Ellervik C, Vinding GR, et al. Association of metabolic syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150: 1273-1280. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.1165

- Monfrecola G, Balato A, Caiazzo G, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin, insulin resistance and hidradenitis suppurativa: a possible metabolic loop. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1631-1633. doi:10.1111/jdv.13233

- Yoon MS. The role of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in insulin signaling. Nutrients. 2017;9:1176. doi:10.3390/nu9111176

- Abu Rached N, Gambichler T, Dietrich JW, et al. The role of hormones in hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15250. doi:10.3390/ijms232315250

- Verdolini R, Clayton N, Smith A, et al. Metformin for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a little help along the way. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1101-1108. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04668.x

- Tsentemeidou A, Vakirlis E, Papadimitriou I, et al. Metformin in hidradenitis suppurativa: is it worth pursuing further? Skin Appendage Disord. 2023;9:187-190. doi:10.1159/000529359

- Arun B, Loffeld A. Long-standing hidradenitis suppurativa treated effectively with metformin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:920-921. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03121.x

- Jennings L, Hambly R, Hughes R, et al. Metformin use in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31:261-263. doi:10.1080/09546634 .2019.1592100

- Moussa C, Wadowski L, Price H, et al. Metformin as adjunctive therapy for pediatric patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1231-1234. doi:10.36849/jdd.2020.5447

- Cho M, Woo YR, Cho SH, et al. Metformin: a potential treatment for acne, hidradenitis suppurativa and rosacea. Acta Derm Venereol. 2023;103:adv18392. doi:10.2340/actadv.v103.18392

- Del Rosso JQ, Kircik L. The cutaneous effects of androgens and androgen-mediated sebum production and their pathophysiologic and therapeutic importance in acne vulgaris. J Dermatolog Treat. 2024;35:2298878. doi:10.1080/09546634.2023.2298878

- El-Tahlawi S, Ezzat Mohammad N, Mohamed El-Amir A, et al. Survivin and insulin-like growth factor-I: potential role in the pathogenesis of acne and post-acne scar. Scars Burn Heal. 2019;5:2059513118818031. doi:10.1177/2059513118818031

- Albalat W, Darwish H, Abd-Elaal WH, et al. The potential role of insulin-like growth factor 1 in acne vulgaris and its correlation with the clinical response before and after treatment with metformin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:6209-6214. doi:10.1111/jocd.15210

- Nguyen S, Nguyen ML, Roberts WS, et al. The efficacy of metformin as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of acne vulgaris: a systematic review. Cureus. 2024;16:E56246. doi:10.7759/cureus.56246

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994. doi:10.1016 /s0140-6736(14)61909-7

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058

- Huang Z, Li J, Chen H, et al. The efficacy of metformin for the treatment of psoriasis: a meta-analysis study. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2023;40:606-610. doi:10.5114/ada.2023.130524

- Singh S, Bhansali A. Randomized placebo control study of insulin sensitizers (metformin and pioglitazone) in psoriasis patients with metabolic syndrome (topical treatment cohort). BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:12. doi:10.1186 /s12895-016-0049-y

- Bao A, Qadri A, Gadre A, et al. Low-dose metformin and profibrotic signature in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;E243062. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.3062

- Lawson CN, Bakayoko A, Callender VD. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: challenges and treatments. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:389-405. doi:10.1016/j.det.2021.03.004

- Gathers RC, Lim HW. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: past, present, and future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:660-668. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2008.09.066

- Araoye EF, Thomas JAL, Aguh CU. Hair regrowth in 2 patients with recalcitrant central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia after use of topical metformin. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:106-108. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.12.008

- Foretz M, Guigas B, Bertrand L, et al. Metformin: from mechanisms of action to therapies. Cell Metab. 2014;20:953-966. doi:10.1016 /j.cmet.2014.09.018

- Aguh C, Dina Y, Talbot CC Jr, et al. Fibroproliferative genes are preferentially expressed in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:904-912.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1257

- Gadre A, Dyson T, Jedrych J, et al. Proteomic profiling of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia reveals role of humoral immune response pathway and metabolic dysregulation. JID Innov. 2024;4:100263. doi:10.1016/j.xjidi.2024.100263

- Chaudhary SC, Kurundkar D, Elmets CA, et al. Metformin, an antidiabetic agent reduces growth of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma by targeting mTOR signaling pathway. Photochem Photobiol. 2012;88:1149-1156. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.2012.01165.x

- Tomic T, Botton T, Cerezo M, et al. Metformin inhibits melanoma development through autophagy and apoptosis mechanisms. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e199. doi:10.1038/cddis.2011.86

- Mascaraque-Checa M, Gallego-Rentero M, Nicolás-Morala J, et al. Metformin overcomes metabolic reprogramming-induced resistance of skin squamous cell carcinoma to photodynamic therapy. Mol Metab. 2022;60:101496. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101496

- Mascaraque M, Delgado-Wicke P, Nuevo-Tapioles C, et al. Metformin as an adjuvant to photodynamic therapy in resistant basal cell carcinoma cells. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:668. doi:10.3390/cancers12030668

- Chang MS, Hartman RI, Xue J, et al. Risk of skin cancer associated with metformin use: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2021;14:77-84. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.Capr-20-0376

- Augustin RC, Huang Z, Ding F, et al. Metformin is associated with improved clinical outcomes in patients with melanoma: a retrospective, multi-institutional study. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1075823. doi:10.3389 /fonc.2023.1075823

- Adalsteinsson JA, Muzumdar S, Waldman R, et al. Metformin is associated with decreased risk of basal cell carcinoma: a whole-population casecontrol study from Iceland. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:56-61. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.042

- Jennings L, Nestor L, Molloy O, et al. The treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with the glucagon-like peptide-1 agonist liraglutide. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:858-859. doi:10.1111/bjd.15233

- Lin L, Xu X, Yu Y, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist liraglutide therapy for psoriasis patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized-controlled trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33: 1428-1434. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1826392

- Karacabeyli D, Lacaille D. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists in patients with inflammatory arthritis or psoriasis: a scoping review. J Clin Rheumatol. 2024;30:26-31. doi:10.1097/rhu.0000000000001949

- Yang J, Wang Z, Zhang X. GLP-1 receptor agonist impairs keratinocytes inflammatory signals by activating AMPK. Exp Mol Pathol. 2019;107: 124-128. doi:10.1016/j.yexmp.2019.01.014

- Buysschaert M, Baeck M, Preumont V, et al. Improvement of psoriasis during glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue therapy in type 2 diabetes is associated with decreasing dermal Υϛ T-cell number: a prospective case-series study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:155-161. doi:10.1111/bjd.12886

- Wilbon SS, Kolonin MG. GLP1 receptor agonists-effects beyond obesity and diabetes. Cells. 2023;13:65. doi:10.3390/cells13010065

- Filippatos TD, Panagiotopoulou TV, Elisaf MS. Adverse effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists. Rev Diabet Stud. 2014;11:202-230. doi:10.1900 /rds.2014.11.202

- He Z, Tabe AN, Rana S, et al. Tirzepatide-induced biphasic anaphylactic reaction: a case report. Cureus. 2023;15:e50112. doi:10.7759/cureus.50112

- Anthony MS, Aroda VR, Parlett LE, et al. Risk of anaphylaxis among new users of glp-1 receptor agonists: a cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2024;47:712-719. doi:10.2337/dc23-1911

- Salazar CE, Patil MK, Aihie O, et al. Rare cutaneous adverse reactions associated with GLP-1 agonists: a review of the published literature. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:248. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-02969-3

- Tran MM, Mirza FN, Lee AC, et al. Dermatologic findings associated with semaglutide use: a scoping review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:166-168. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.021

- Castellanos V, Workneh H, Malik A, et al. Semaglutide-induced lupus erythematosus with multiorgan involvement. Cureus. 2024;16:E55324. doi:10.7759/cureus.55324