User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Pigmented Pruritic Macules in the Genital Area

The Diagnosis: Pediculosis Pubis

Dermoscopy of the pubic hair demonstrated a louse clutching multiple shafts of hairs (Figure) as well as scattered nits, confirming the presence of Phthirus pubis and diagnosis of pediculosis pubis. The key clinical diagnostic feature in this case was severe itching of the pubic area, with visible nits present on pubic hairs. Itching and infestation also can involve other hair-bearing areas such as the chest, legs, and axillae. The patient was treated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the pubic area and chest. Symptoms and infestation were resolved at 1-week follow-up.

Pediculosis pubis is an infestation of pubic hairs by the pubic (crab) louse P pubis, which feeds on host blood. Other body areas covered with dense hair also may be involved; 60% of patients are infested in at least 2 different sites.1 Pediculosis pubis is most commonly sexually transmitted through direct contact.2 Worldwide prevalence has been estimated at approximately 2% of the adult population, and a survey of 817 US college students in 2009 indicated a lifetime prevalence of 1.3%.3 The prevalence is slightly higher in men, highest in men who have sex with men, and rare in individuals with shaved pubic hair.1 The most common symptom is pruritus of the genital area. Infested patients also may develop asymptomatic bluish gray macules (maculae ceruleae) secondary to hemosiderin deposition from louse bites.4

The diagnosis of pediculosis pubis is made by identification of P pubis, either by examination with the naked eye or confirmation with dermoscopy or microscopy. Although the 0.8- to 1.2-mm lice are visible to the naked eye, they can be difficult to see if not filled with blood, and nits on the hairs can be mistaken for white piedra (fungal infection of the hair shafts) or trichomycosis pubis (bacterial infection of the hair shafts).4 Scabies and tinea cruris do not present with attachments to the hairs. Scabies may present with papules and burrows and tinea cruris with scaly erythematous plaques. Small numbers of lice and nits may be missed by the naked eye or a traditional magnifying glass.5 The use of dermoscopy allows for fast and accurate identification of the characteristic lice and nits, even in these more challenging cases.5 Accurate diagnosis is important, as approximately 31% of infested patients have other concurrent sexually transmitted infections that warrant screening.6

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends first-line treatment with permethrin cream (1% or 5%) or pyrethrin with piperonyl butoxide applied to all affected areas and washed off after 10 minutes.7 Patients should be reevaluated after 1 week if symptoms persist and re-treated if lice are found on examination.7,8 Malathion lotion 0.5% (applied and washed off after 8-12 hours) or oral ivermectin (250 µg/kg, repeated after 2 weeks) may be used for alternative therapies or cases of permethrin or pyrethrin resistance.7 Ivermectin also is effective for involvement of eyelashes where topical insecticides should not be used.9 Sexual partners should be treated to prevent repeat transmission.7,8 Bedding and clothing can be decontaminated by machine wash on hot cycle or isolating from body contact for 72 hours.7 Patients also should be screened for other sexually transmitted infections, including human immunodeficiency virus.6

- Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Morrell DS. Infestations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1429-1430.

- Chosidow O. Scabies and pediculosis. Lancet. 2000;355:819-826.

- Anderson AL, Chaney E. Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis): history, biology and treatment vs. knowledge and beliefs of US college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:592-600.

- Ko CJ, Elston DM. Pediculosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:1-12; quiz 13-14.

- Chuh A, Lee A, Wong W, et al. Diagnosis of pediculosis pubis: a novel application of digital epiluminescence dermatoscopy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:837-838.

- Chapel TA, Katta T, Kuszmar T, et al. Pediculosis pubis in a clinic for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1979;6:257-260.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

- Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 3):S153-S159.

- Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Oral ivermectin therapy for phthiriasis palpebrum. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:134-135.

The Diagnosis: Pediculosis Pubis

Dermoscopy of the pubic hair demonstrated a louse clutching multiple shafts of hairs (Figure) as well as scattered nits, confirming the presence of Phthirus pubis and diagnosis of pediculosis pubis. The key clinical diagnostic feature in this case was severe itching of the pubic area, with visible nits present on pubic hairs. Itching and infestation also can involve other hair-bearing areas such as the chest, legs, and axillae. The patient was treated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the pubic area and chest. Symptoms and infestation were resolved at 1-week follow-up.

Pediculosis pubis is an infestation of pubic hairs by the pubic (crab) louse P pubis, which feeds on host blood. Other body areas covered with dense hair also may be involved; 60% of patients are infested in at least 2 different sites.1 Pediculosis pubis is most commonly sexually transmitted through direct contact.2 Worldwide prevalence has been estimated at approximately 2% of the adult population, and a survey of 817 US college students in 2009 indicated a lifetime prevalence of 1.3%.3 The prevalence is slightly higher in men, highest in men who have sex with men, and rare in individuals with shaved pubic hair.1 The most common symptom is pruritus of the genital area. Infested patients also may develop asymptomatic bluish gray macules (maculae ceruleae) secondary to hemosiderin deposition from louse bites.4

The diagnosis of pediculosis pubis is made by identification of P pubis, either by examination with the naked eye or confirmation with dermoscopy or microscopy. Although the 0.8- to 1.2-mm lice are visible to the naked eye, they can be difficult to see if not filled with blood, and nits on the hairs can be mistaken for white piedra (fungal infection of the hair shafts) or trichomycosis pubis (bacterial infection of the hair shafts).4 Scabies and tinea cruris do not present with attachments to the hairs. Scabies may present with papules and burrows and tinea cruris with scaly erythematous plaques. Small numbers of lice and nits may be missed by the naked eye or a traditional magnifying glass.5 The use of dermoscopy allows for fast and accurate identification of the characteristic lice and nits, even in these more challenging cases.5 Accurate diagnosis is important, as approximately 31% of infested patients have other concurrent sexually transmitted infections that warrant screening.6

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends first-line treatment with permethrin cream (1% or 5%) or pyrethrin with piperonyl butoxide applied to all affected areas and washed off after 10 minutes.7 Patients should be reevaluated after 1 week if symptoms persist and re-treated if lice are found on examination.7,8 Malathion lotion 0.5% (applied and washed off after 8-12 hours) or oral ivermectin (250 µg/kg, repeated after 2 weeks) may be used for alternative therapies or cases of permethrin or pyrethrin resistance.7 Ivermectin also is effective for involvement of eyelashes where topical insecticides should not be used.9 Sexual partners should be treated to prevent repeat transmission.7,8 Bedding and clothing can be decontaminated by machine wash on hot cycle or isolating from body contact for 72 hours.7 Patients also should be screened for other sexually transmitted infections, including human immunodeficiency virus.6

The Diagnosis: Pediculosis Pubis

Dermoscopy of the pubic hair demonstrated a louse clutching multiple shafts of hairs (Figure) as well as scattered nits, confirming the presence of Phthirus pubis and diagnosis of pediculosis pubis. The key clinical diagnostic feature in this case was severe itching of the pubic area, with visible nits present on pubic hairs. Itching and infestation also can involve other hair-bearing areas such as the chest, legs, and axillae. The patient was treated with permethrin cream 5% applied to the pubic area and chest. Symptoms and infestation were resolved at 1-week follow-up.

Pediculosis pubis is an infestation of pubic hairs by the pubic (crab) louse P pubis, which feeds on host blood. Other body areas covered with dense hair also may be involved; 60% of patients are infested in at least 2 different sites.1 Pediculosis pubis is most commonly sexually transmitted through direct contact.2 Worldwide prevalence has been estimated at approximately 2% of the adult population, and a survey of 817 US college students in 2009 indicated a lifetime prevalence of 1.3%.3 The prevalence is slightly higher in men, highest in men who have sex with men, and rare in individuals with shaved pubic hair.1 The most common symptom is pruritus of the genital area. Infested patients also may develop asymptomatic bluish gray macules (maculae ceruleae) secondary to hemosiderin deposition from louse bites.4

The diagnosis of pediculosis pubis is made by identification of P pubis, either by examination with the naked eye or confirmation with dermoscopy or microscopy. Although the 0.8- to 1.2-mm lice are visible to the naked eye, they can be difficult to see if not filled with blood, and nits on the hairs can be mistaken for white piedra (fungal infection of the hair shafts) or trichomycosis pubis (bacterial infection of the hair shafts).4 Scabies and tinea cruris do not present with attachments to the hairs. Scabies may present with papules and burrows and tinea cruris with scaly erythematous plaques. Small numbers of lice and nits may be missed by the naked eye or a traditional magnifying glass.5 The use of dermoscopy allows for fast and accurate identification of the characteristic lice and nits, even in these more challenging cases.5 Accurate diagnosis is important, as approximately 31% of infested patients have other concurrent sexually transmitted infections that warrant screening.6

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends first-line treatment with permethrin cream (1% or 5%) or pyrethrin with piperonyl butoxide applied to all affected areas and washed off after 10 minutes.7 Patients should be reevaluated after 1 week if symptoms persist and re-treated if lice are found on examination.7,8 Malathion lotion 0.5% (applied and washed off after 8-12 hours) or oral ivermectin (250 µg/kg, repeated after 2 weeks) may be used for alternative therapies or cases of permethrin or pyrethrin resistance.7 Ivermectin also is effective for involvement of eyelashes where topical insecticides should not be used.9 Sexual partners should be treated to prevent repeat transmission.7,8 Bedding and clothing can be decontaminated by machine wash on hot cycle or isolating from body contact for 72 hours.7 Patients also should be screened for other sexually transmitted infections, including human immunodeficiency virus.6

- Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Morrell DS. Infestations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1429-1430.

- Chosidow O. Scabies and pediculosis. Lancet. 2000;355:819-826.

- Anderson AL, Chaney E. Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis): history, biology and treatment vs. knowledge and beliefs of US college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:592-600.

- Ko CJ, Elston DM. Pediculosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:1-12; quiz 13-14.

- Chuh A, Lee A, Wong W, et al. Diagnosis of pediculosis pubis: a novel application of digital epiluminescence dermatoscopy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:837-838.

- Chapel TA, Katta T, Kuszmar T, et al. Pediculosis pubis in a clinic for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1979;6:257-260.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

- Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 3):S153-S159.

- Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Oral ivermectin therapy for phthiriasis palpebrum. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:134-135.

- Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Morrell DS. Infestations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1429-1430.

- Chosidow O. Scabies and pediculosis. Lancet. 2000;355:819-826.

- Anderson AL, Chaney E. Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis): history, biology and treatment vs. knowledge and beliefs of US college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:592-600.

- Ko CJ, Elston DM. Pediculosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:1-12; quiz 13-14.

- Chuh A, Lee A, Wong W, et al. Diagnosis of pediculosis pubis: a novel application of digital epiluminescence dermatoscopy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:837-838.

- Chapel TA, Katta T, Kuszmar T, et al. Pediculosis pubis in a clinic for treatment of sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 1979;6:257-260.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1-137.

- Leone PA. Scabies and pediculosis pubis: an update of treatment regimens and general review. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(suppl 3):S153-S159.

- Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Oral ivermectin therapy for phthiriasis palpebrum. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:134-135.

A 50-year-old man with a history of cerebrovascular accident presented with severe itching along the inguinal folds and over the chest of 2 months' duration. His last sexual encounter was 5 months prior. He had previously seen a primary care physician who told him he needed to clean the hair better. Examination of the genital area revealed pigmented macules and overlying particles among the pubic hair.

Innovations in Dermatology: Antibiotic Stewardship in Acne Therapy

Dermatology Residency Match: Data on Who Matched in 2018

Cross-contamination of Pathology Specimens: A Cautionary Tale

Cross-contamination of pathology specimens is a rare but nonnegligible source of potential morbidity in clinical practice. Contaminant tissue fragments, colloquially referred to as floaters, typically are readily identifiable based on obvious cytomorphologic differences, especially if the tissues arise from different organs; however, one cannot rely on such distinctions in a pathology laboratory dedicated to a single organ system (eg, dermatopathology). The inability to identify quickly and confidently the presence of a contaminant puts the patient at risk for misdiagnosis, which can lead to unnecessary morbidity or even mortality in the case of cancer misdiagnosis. Studies that have been conducted to estimate the incidence of this type of error have suggested an overall incidence rate between approximately 1% and 3%.1,2 Awareness of this phenomenon and careful scrutiny when the histopathologic evidence diverges considerably from the clinical impression is critical for minimizing the negative outcomes that could result from the presence of contaminant tissue. We present a case in which cross-contamination of a pathology specimen led to an initial erroneous diagnosis of an aggressive cutaneous melanoma in a patient with a benign adnexal neoplasm.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man was referred to the Pigmented Lesion and Melanoma Program at Stanford University Medical Center and Cancer Institute (Palo Alto, California) for evaluation and treatment of a presumed stage IIB melanoma on the right preauricular cheek based on a shave biopsy that had been performed (<1 month prior) by his local dermatology provider and subsequently read by an affiliated out-of-state dermatopathology laboratory. Per the clinical history that was gathered at the current presentation, neither the patient nor his wife had noticed the lesion prior to his dermatology provider pointing it out on the day of the biopsy. Additionally, he denied associated pain, bleeding, or ulceration. According to outside medical records, the referring dermatology provider described the lesion as a 4-mm pink pearly papule with telangiectasia favoring a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, and a diagnostic shave biopsy was performed. On presentation to our clinic, physical examination of the right preauricular cheek revealed a 4×3-mm depressed erythematous scar with no evidence of residual pigmentation or nodularity (Figure 1). There was no clinically appreciable regional lymphadenopathy.

The original dermatopathology report indicated an invasive melanoma with the following pathologic characteristics: superficial spreading type, Breslow depth of at least 2.16 mm, ulceration, and a mitotic index of 8 mitotic figures/mm2 with transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins. There was no evidence of regression, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or microsatellites. Interestingly, the report indicated that there also was a basaloid proliferation with features of cylindroma in the same pathology slide adjacent to the aggressive invasive melanoma that was described. Given the complexity of cases referred to our academic center, the standard of care includes internal dermatopathology review of all outside pathology specimens. This review proved critical to this patient’s care in light of the considerable divergence of the initial pathologic diagnosis and the reported clinical features of the lesion.

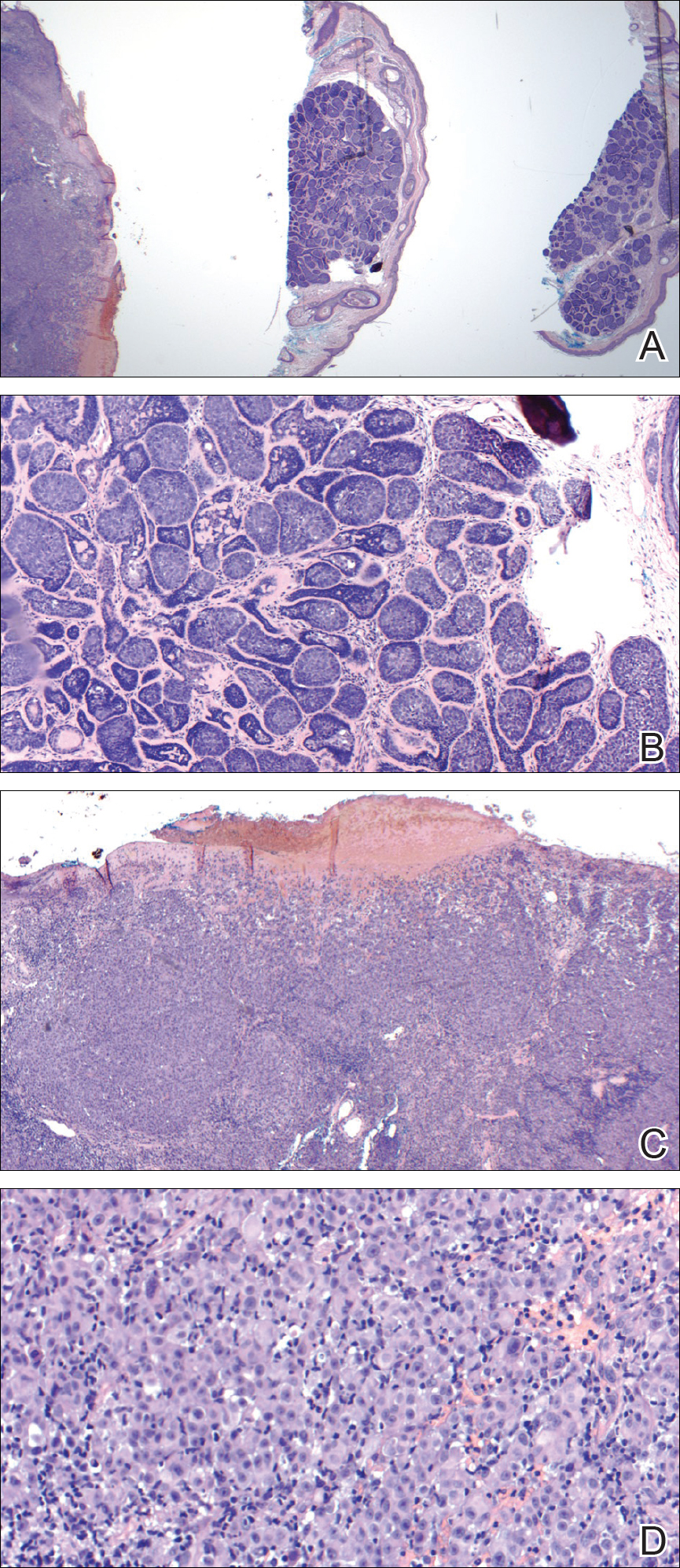

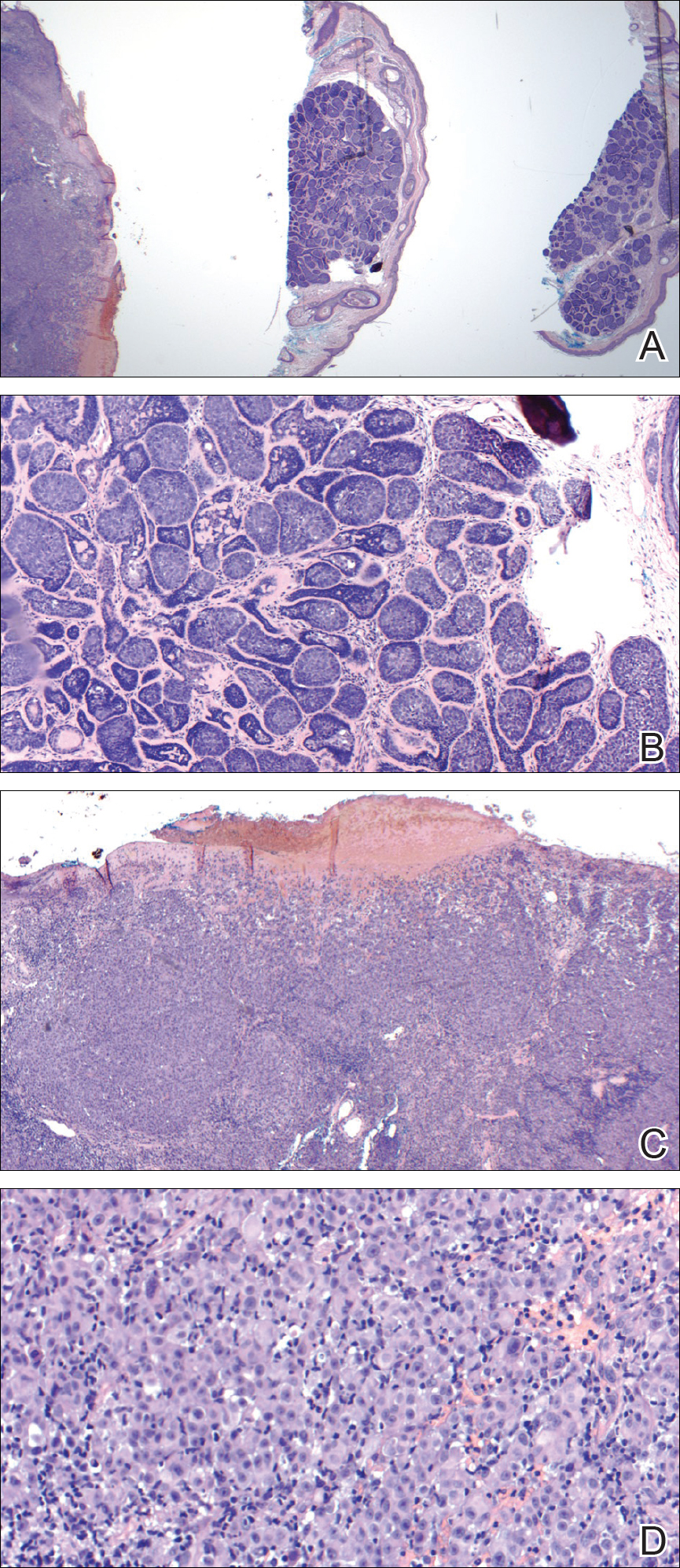

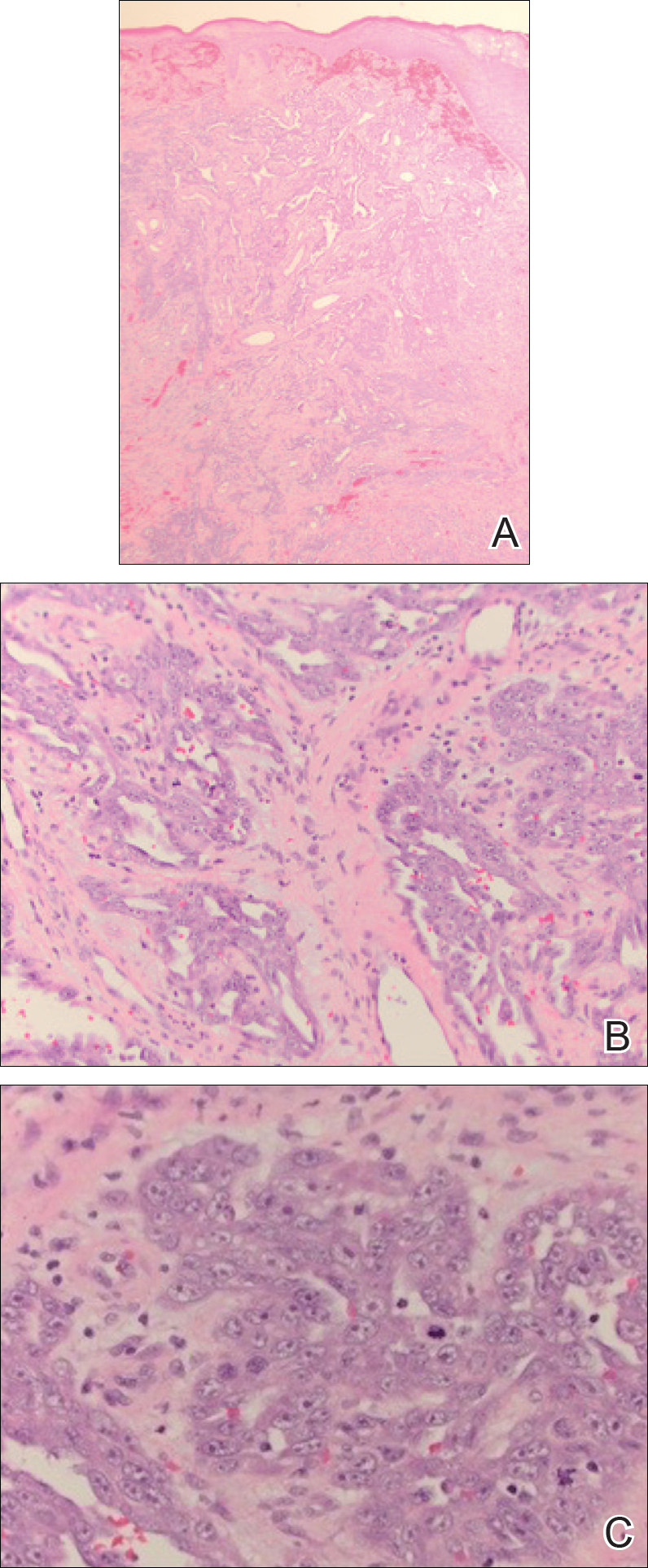

Internal review of the single pathology slide received from the referring provider showed a total of 4 sections, 3 of which are shown here (Figure 2A). Three sections, including the one not shown, were all consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma and showed no evidence of a melanocytic proliferation (Figure 2B). However, the fourth section demonstrated marked morphologic dissimilarity compared to the other 3 sections. This outlier section showed a thick cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 2.1 mm, ulceration, a mitotic rate of 12 mitotic figures/mm2, and broad transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins (Figures 2C and 2D). Correlation with the gross description of tissue processing on the original pathology report indicating that the specimen had been trisected raised suspicion that the fourth and very dissimilar section could be a contaminant from another source that was incorporated into our patient’s histologic sections during processing. Taken together, these discrepancies made the diagnosis of cylindroma alone far more likely than cutaneous melanoma, but we needed conclusive evidence given the dramatic difference in prognosis and management between a cylindroma and an aggressive cutaneous melanoma.

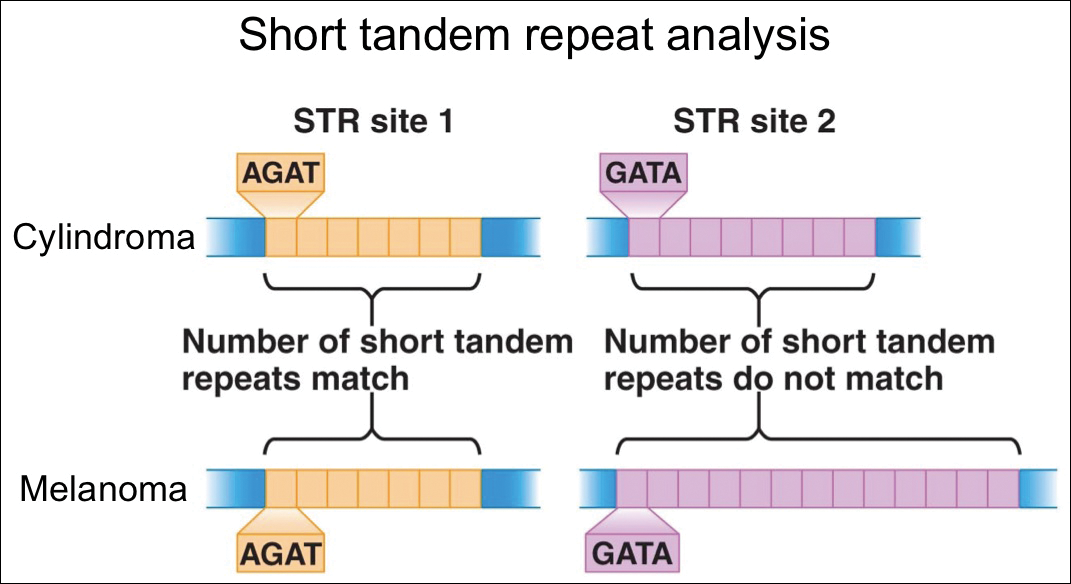

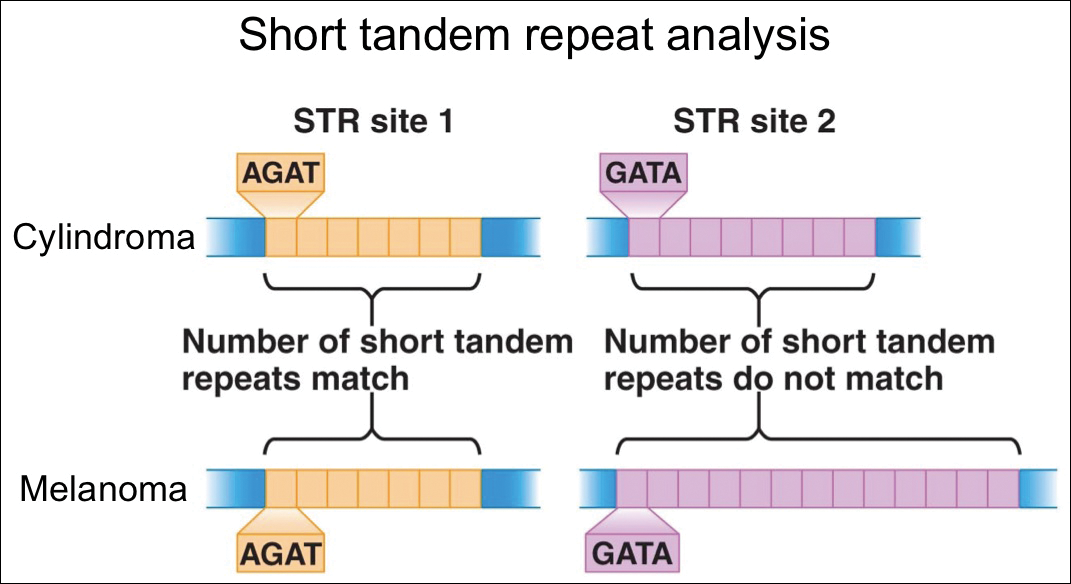

For further diagnostic clarification, we performed polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, a well-described forensic pathology technique, to determine if the melanoma and cylindroma specimens derived from different patients, as we hypothesized. This analysis revealed differences in all but one DNA locus tested between the cylindroma specimen and the melanoma specimen, confirming our hypothesis (Figure 3). Subsequent discussion of the case with staff from the dermatopathology laboratory that processed this specimen provided further support for our suspicion that the invasive melanoma specimen was part of a case processed prior to our patient’s benign lesion. Therefore, the wide local excision for treatment of the suspected melanoma fortunately was canceled, and the patient did not require further treatment of the benign cylindroma. The patient expressed relief and gratitude for this critical clarification and change in management.

Comment

Shah et al3 reported a similar case in which a benign granuloma of the lung masqueraded as a squamous cell carcinoma due to histopathologic contamination. Although few similar cases have been described in the literature, the risk posed by such contamination is remarkable, regardless of whether it occurs during specimen grossing, embedding, sectioning, or staining.1,4,5 This risk is amplified in facilities that process specimens originating predominantly from a single organ system or tissue type, as is often the case in dedicated dermatopathology laboratories. In this scenario, it is unlikely that one could use the presence of tissues from 2 different organ systems on a single slide as a way of easily recognizing the presence of a contaminant and rectifying the error. Additionally, the presence of malignant cells in the contaminant further complicates the problem and requires an investigation that can conclusively distinguish the contaminant from the patient’s actual tissue.

In our case, our dermatology and dermatopathology teams partnered with our molecular pathology team to find a solution. Polymorphic STR analysis via polymerase chain reaction amplification is a sensitive method employed commonly in forensic DNA laboratories for determining whether a sample submitted as evidence belongs to a given suspect.6 Although much more commonly used in forensics, STR analysis does have known roles in clinical medicine, such as chimerism testing after bone marrow or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.7 Given the relatively short period of time it takes along with the convenience of commercially available kits, a high discriminative ability, and well-validated interpretation procedures, STR analysis is an excellent method for determining if a given tissue sample came from a given patient, which is what was needed in our case.

The combined clinical, histopathologic, and molecular data in our case allowed for confident clarification of our patient’s diagnosis, sparing him the morbidity of wide local excision on the face, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and emotional distress associated with a diagnosis of aggressive cutaneous melanoma. Our case highlights the critical importance of internal review of pathology specimens in ensuring proper diagnosis and management and reminds us that, though rare, accidental contamination during processing of pathology specimens is a potential adverse event that must be considered, especially when a pathologic finding diverges considerably from what is anticipated based on the patient’s history and physical examination.

Acknowledgment

The authors express gratitude to the patient described herein who graciously provided permission for us to publish his case and clinical photography.

- Gephardt GN, Zarbo RJ. Extraneous tissue in surgical pathology: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 275 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1009-1014.

- Alam M, Shah AD, Ali S, et al. Floaters in Mohs micrographic surgery [published online June 27, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1317-1322.

- Shah PA, Prat MP, Hostler DC. Benign granuloma masquerading as squamous cell carcinoma due to a “floater.” Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(11, suppl 2):19-21.

- Platt E, Sommer P, McDonald L, et al. Tissue floaters and contaminants in the histology laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:973-978.

- Layfield LJ, Witt BL, Metzger KG, et al. Extraneous tissue: a potential source for diagnostic error in surgical pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:767-772.

- Butler JM. Forensic DNA testing. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011:1438-1450.

- Manasatienkij C, Ra-ngabpai C. Clinical application of forensic DNA analysis: a literature review. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:1357-1363.

Cross-contamination of pathology specimens is a rare but nonnegligible source of potential morbidity in clinical practice. Contaminant tissue fragments, colloquially referred to as floaters, typically are readily identifiable based on obvious cytomorphologic differences, especially if the tissues arise from different organs; however, one cannot rely on such distinctions in a pathology laboratory dedicated to a single organ system (eg, dermatopathology). The inability to identify quickly and confidently the presence of a contaminant puts the patient at risk for misdiagnosis, which can lead to unnecessary morbidity or even mortality in the case of cancer misdiagnosis. Studies that have been conducted to estimate the incidence of this type of error have suggested an overall incidence rate between approximately 1% and 3%.1,2 Awareness of this phenomenon and careful scrutiny when the histopathologic evidence diverges considerably from the clinical impression is critical for minimizing the negative outcomes that could result from the presence of contaminant tissue. We present a case in which cross-contamination of a pathology specimen led to an initial erroneous diagnosis of an aggressive cutaneous melanoma in a patient with a benign adnexal neoplasm.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man was referred to the Pigmented Lesion and Melanoma Program at Stanford University Medical Center and Cancer Institute (Palo Alto, California) for evaluation and treatment of a presumed stage IIB melanoma on the right preauricular cheek based on a shave biopsy that had been performed (<1 month prior) by his local dermatology provider and subsequently read by an affiliated out-of-state dermatopathology laboratory. Per the clinical history that was gathered at the current presentation, neither the patient nor his wife had noticed the lesion prior to his dermatology provider pointing it out on the day of the biopsy. Additionally, he denied associated pain, bleeding, or ulceration. According to outside medical records, the referring dermatology provider described the lesion as a 4-mm pink pearly papule with telangiectasia favoring a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, and a diagnostic shave biopsy was performed. On presentation to our clinic, physical examination of the right preauricular cheek revealed a 4×3-mm depressed erythematous scar with no evidence of residual pigmentation or nodularity (Figure 1). There was no clinically appreciable regional lymphadenopathy.

The original dermatopathology report indicated an invasive melanoma with the following pathologic characteristics: superficial spreading type, Breslow depth of at least 2.16 mm, ulceration, and a mitotic index of 8 mitotic figures/mm2 with transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins. There was no evidence of regression, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or microsatellites. Interestingly, the report indicated that there also was a basaloid proliferation with features of cylindroma in the same pathology slide adjacent to the aggressive invasive melanoma that was described. Given the complexity of cases referred to our academic center, the standard of care includes internal dermatopathology review of all outside pathology specimens. This review proved critical to this patient’s care in light of the considerable divergence of the initial pathologic diagnosis and the reported clinical features of the lesion.

Internal review of the single pathology slide received from the referring provider showed a total of 4 sections, 3 of which are shown here (Figure 2A). Three sections, including the one not shown, were all consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma and showed no evidence of a melanocytic proliferation (Figure 2B). However, the fourth section demonstrated marked morphologic dissimilarity compared to the other 3 sections. This outlier section showed a thick cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 2.1 mm, ulceration, a mitotic rate of 12 mitotic figures/mm2, and broad transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins (Figures 2C and 2D). Correlation with the gross description of tissue processing on the original pathology report indicating that the specimen had been trisected raised suspicion that the fourth and very dissimilar section could be a contaminant from another source that was incorporated into our patient’s histologic sections during processing. Taken together, these discrepancies made the diagnosis of cylindroma alone far more likely than cutaneous melanoma, but we needed conclusive evidence given the dramatic difference in prognosis and management between a cylindroma and an aggressive cutaneous melanoma.

For further diagnostic clarification, we performed polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, a well-described forensic pathology technique, to determine if the melanoma and cylindroma specimens derived from different patients, as we hypothesized. This analysis revealed differences in all but one DNA locus tested between the cylindroma specimen and the melanoma specimen, confirming our hypothesis (Figure 3). Subsequent discussion of the case with staff from the dermatopathology laboratory that processed this specimen provided further support for our suspicion that the invasive melanoma specimen was part of a case processed prior to our patient’s benign lesion. Therefore, the wide local excision for treatment of the suspected melanoma fortunately was canceled, and the patient did not require further treatment of the benign cylindroma. The patient expressed relief and gratitude for this critical clarification and change in management.

Comment

Shah et al3 reported a similar case in which a benign granuloma of the lung masqueraded as a squamous cell carcinoma due to histopathologic contamination. Although few similar cases have been described in the literature, the risk posed by such contamination is remarkable, regardless of whether it occurs during specimen grossing, embedding, sectioning, or staining.1,4,5 This risk is amplified in facilities that process specimens originating predominantly from a single organ system or tissue type, as is often the case in dedicated dermatopathology laboratories. In this scenario, it is unlikely that one could use the presence of tissues from 2 different organ systems on a single slide as a way of easily recognizing the presence of a contaminant and rectifying the error. Additionally, the presence of malignant cells in the contaminant further complicates the problem and requires an investigation that can conclusively distinguish the contaminant from the patient’s actual tissue.

In our case, our dermatology and dermatopathology teams partnered with our molecular pathology team to find a solution. Polymorphic STR analysis via polymerase chain reaction amplification is a sensitive method employed commonly in forensic DNA laboratories for determining whether a sample submitted as evidence belongs to a given suspect.6 Although much more commonly used in forensics, STR analysis does have known roles in clinical medicine, such as chimerism testing after bone marrow or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.7 Given the relatively short period of time it takes along with the convenience of commercially available kits, a high discriminative ability, and well-validated interpretation procedures, STR analysis is an excellent method for determining if a given tissue sample came from a given patient, which is what was needed in our case.

The combined clinical, histopathologic, and molecular data in our case allowed for confident clarification of our patient’s diagnosis, sparing him the morbidity of wide local excision on the face, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and emotional distress associated with a diagnosis of aggressive cutaneous melanoma. Our case highlights the critical importance of internal review of pathology specimens in ensuring proper diagnosis and management and reminds us that, though rare, accidental contamination during processing of pathology specimens is a potential adverse event that must be considered, especially when a pathologic finding diverges considerably from what is anticipated based on the patient’s history and physical examination.

Acknowledgment

The authors express gratitude to the patient described herein who graciously provided permission for us to publish his case and clinical photography.

Cross-contamination of pathology specimens is a rare but nonnegligible source of potential morbidity in clinical practice. Contaminant tissue fragments, colloquially referred to as floaters, typically are readily identifiable based on obvious cytomorphologic differences, especially if the tissues arise from different organs; however, one cannot rely on such distinctions in a pathology laboratory dedicated to a single organ system (eg, dermatopathology). The inability to identify quickly and confidently the presence of a contaminant puts the patient at risk for misdiagnosis, which can lead to unnecessary morbidity or even mortality in the case of cancer misdiagnosis. Studies that have been conducted to estimate the incidence of this type of error have suggested an overall incidence rate between approximately 1% and 3%.1,2 Awareness of this phenomenon and careful scrutiny when the histopathologic evidence diverges considerably from the clinical impression is critical for minimizing the negative outcomes that could result from the presence of contaminant tissue. We present a case in which cross-contamination of a pathology specimen led to an initial erroneous diagnosis of an aggressive cutaneous melanoma in a patient with a benign adnexal neoplasm.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man was referred to the Pigmented Lesion and Melanoma Program at Stanford University Medical Center and Cancer Institute (Palo Alto, California) for evaluation and treatment of a presumed stage IIB melanoma on the right preauricular cheek based on a shave biopsy that had been performed (<1 month prior) by his local dermatology provider and subsequently read by an affiliated out-of-state dermatopathology laboratory. Per the clinical history that was gathered at the current presentation, neither the patient nor his wife had noticed the lesion prior to his dermatology provider pointing it out on the day of the biopsy. Additionally, he denied associated pain, bleeding, or ulceration. According to outside medical records, the referring dermatology provider described the lesion as a 4-mm pink pearly papule with telangiectasia favoring a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, and a diagnostic shave biopsy was performed. On presentation to our clinic, physical examination of the right preauricular cheek revealed a 4×3-mm depressed erythematous scar with no evidence of residual pigmentation or nodularity (Figure 1). There was no clinically appreciable regional lymphadenopathy.

The original dermatopathology report indicated an invasive melanoma with the following pathologic characteristics: superficial spreading type, Breslow depth of at least 2.16 mm, ulceration, and a mitotic index of 8 mitotic figures/mm2 with transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins. There was no evidence of regression, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or microsatellites. Interestingly, the report indicated that there also was a basaloid proliferation with features of cylindroma in the same pathology slide adjacent to the aggressive invasive melanoma that was described. Given the complexity of cases referred to our academic center, the standard of care includes internal dermatopathology review of all outside pathology specimens. This review proved critical to this patient’s care in light of the considerable divergence of the initial pathologic diagnosis and the reported clinical features of the lesion.

Internal review of the single pathology slide received from the referring provider showed a total of 4 sections, 3 of which are shown here (Figure 2A). Three sections, including the one not shown, were all consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma and showed no evidence of a melanocytic proliferation (Figure 2B). However, the fourth section demonstrated marked morphologic dissimilarity compared to the other 3 sections. This outlier section showed a thick cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow depth of at least 2.1 mm, ulceration, a mitotic rate of 12 mitotic figures/mm2, and broad transection of the invasive component at the peripheral and deep margins (Figures 2C and 2D). Correlation with the gross description of tissue processing on the original pathology report indicating that the specimen had been trisected raised suspicion that the fourth and very dissimilar section could be a contaminant from another source that was incorporated into our patient’s histologic sections during processing. Taken together, these discrepancies made the diagnosis of cylindroma alone far more likely than cutaneous melanoma, but we needed conclusive evidence given the dramatic difference in prognosis and management between a cylindroma and an aggressive cutaneous melanoma.

For further diagnostic clarification, we performed polymorphic short tandem repeat (STR) analysis, a well-described forensic pathology technique, to determine if the melanoma and cylindroma specimens derived from different patients, as we hypothesized. This analysis revealed differences in all but one DNA locus tested between the cylindroma specimen and the melanoma specimen, confirming our hypothesis (Figure 3). Subsequent discussion of the case with staff from the dermatopathology laboratory that processed this specimen provided further support for our suspicion that the invasive melanoma specimen was part of a case processed prior to our patient’s benign lesion. Therefore, the wide local excision for treatment of the suspected melanoma fortunately was canceled, and the patient did not require further treatment of the benign cylindroma. The patient expressed relief and gratitude for this critical clarification and change in management.

Comment

Shah et al3 reported a similar case in which a benign granuloma of the lung masqueraded as a squamous cell carcinoma due to histopathologic contamination. Although few similar cases have been described in the literature, the risk posed by such contamination is remarkable, regardless of whether it occurs during specimen grossing, embedding, sectioning, or staining.1,4,5 This risk is amplified in facilities that process specimens originating predominantly from a single organ system or tissue type, as is often the case in dedicated dermatopathology laboratories. In this scenario, it is unlikely that one could use the presence of tissues from 2 different organ systems on a single slide as a way of easily recognizing the presence of a contaminant and rectifying the error. Additionally, the presence of malignant cells in the contaminant further complicates the problem and requires an investigation that can conclusively distinguish the contaminant from the patient’s actual tissue.

In our case, our dermatology and dermatopathology teams partnered with our molecular pathology team to find a solution. Polymorphic STR analysis via polymerase chain reaction amplification is a sensitive method employed commonly in forensic DNA laboratories for determining whether a sample submitted as evidence belongs to a given suspect.6 Although much more commonly used in forensics, STR analysis does have known roles in clinical medicine, such as chimerism testing after bone marrow or allogeneic stem cell transplantation.7 Given the relatively short period of time it takes along with the convenience of commercially available kits, a high discriminative ability, and well-validated interpretation procedures, STR analysis is an excellent method for determining if a given tissue sample came from a given patient, which is what was needed in our case.

The combined clinical, histopathologic, and molecular data in our case allowed for confident clarification of our patient’s diagnosis, sparing him the morbidity of wide local excision on the face, sentinel lymph node biopsy, and emotional distress associated with a diagnosis of aggressive cutaneous melanoma. Our case highlights the critical importance of internal review of pathology specimens in ensuring proper diagnosis and management and reminds us that, though rare, accidental contamination during processing of pathology specimens is a potential adverse event that must be considered, especially when a pathologic finding diverges considerably from what is anticipated based on the patient’s history and physical examination.

Acknowledgment

The authors express gratitude to the patient described herein who graciously provided permission for us to publish his case and clinical photography.

- Gephardt GN, Zarbo RJ. Extraneous tissue in surgical pathology: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 275 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1009-1014.

- Alam M, Shah AD, Ali S, et al. Floaters in Mohs micrographic surgery [published online June 27, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1317-1322.

- Shah PA, Prat MP, Hostler DC. Benign granuloma masquerading as squamous cell carcinoma due to a “floater.” Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(11, suppl 2):19-21.

- Platt E, Sommer P, McDonald L, et al. Tissue floaters and contaminants in the histology laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:973-978.

- Layfield LJ, Witt BL, Metzger KG, et al. Extraneous tissue: a potential source for diagnostic error in surgical pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:767-772.

- Butler JM. Forensic DNA testing. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011:1438-1450.

- Manasatienkij C, Ra-ngabpai C. Clinical application of forensic DNA analysis: a literature review. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:1357-1363.

- Gephardt GN, Zarbo RJ. Extraneous tissue in surgical pathology: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 275 laboratories. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1009-1014.

- Alam M, Shah AD, Ali S, et al. Floaters in Mohs micrographic surgery [published online June 27, 2013]. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1317-1322.

- Shah PA, Prat MP, Hostler DC. Benign granuloma masquerading as squamous cell carcinoma due to a “floater.” Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2017;76(11, suppl 2):19-21.

- Platt E, Sommer P, McDonald L, et al. Tissue floaters and contaminants in the histology laboratory. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:973-978.

- Layfield LJ, Witt BL, Metzger KG, et al. Extraneous tissue: a potential source for diagnostic error in surgical pathology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:767-772.

- Butler JM. Forensic DNA testing. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2011;2011:1438-1450.

- Manasatienkij C, Ra-ngabpai C. Clinical application of forensic DNA analysis: a literature review. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:1357-1363.

Resident Pearl

- Although cross-contamination of pathology specimens is rare, it does occur and can impact diagnosis and management if detected early.

Solitary Exophytic Plaque on the Left Groin

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

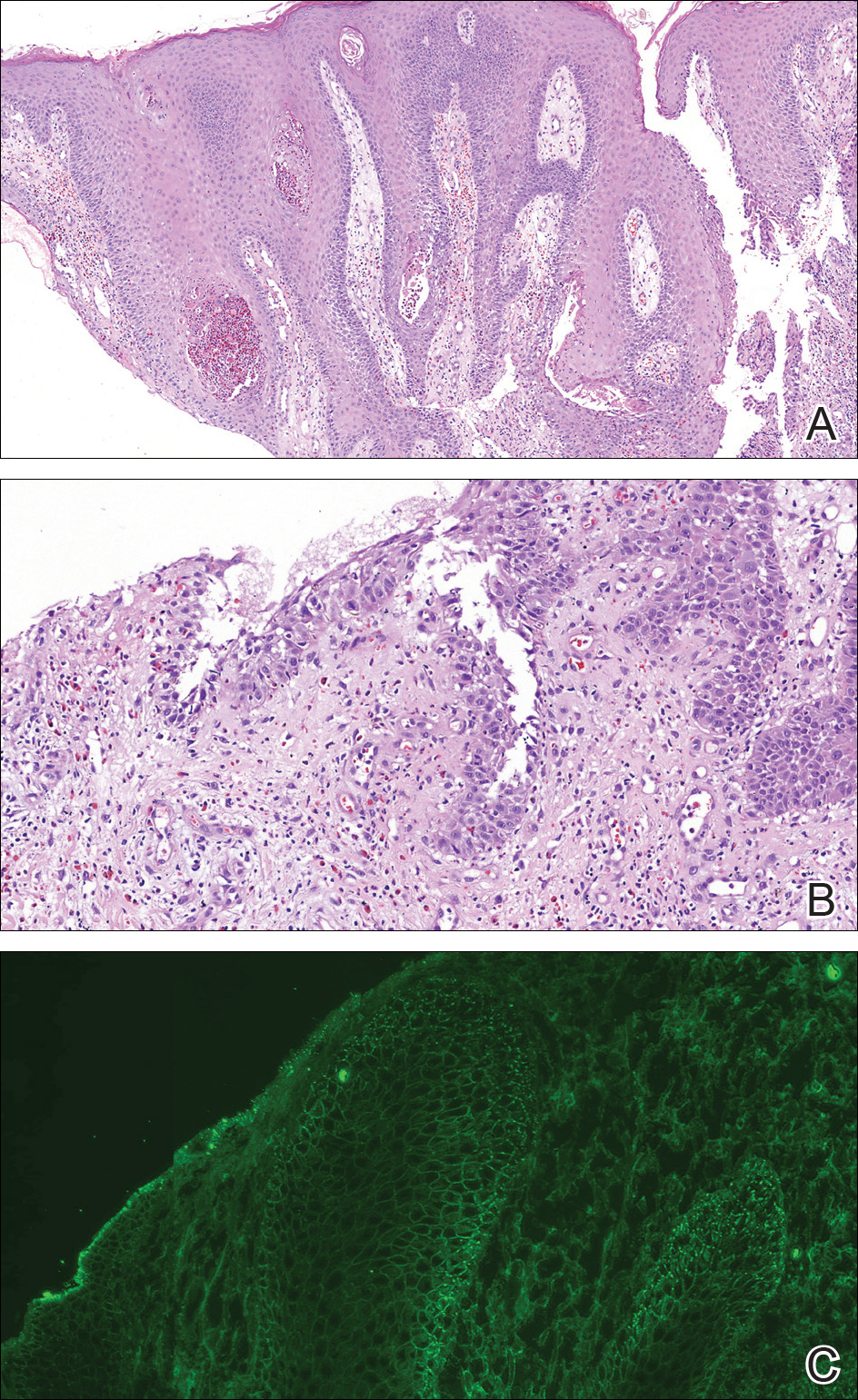

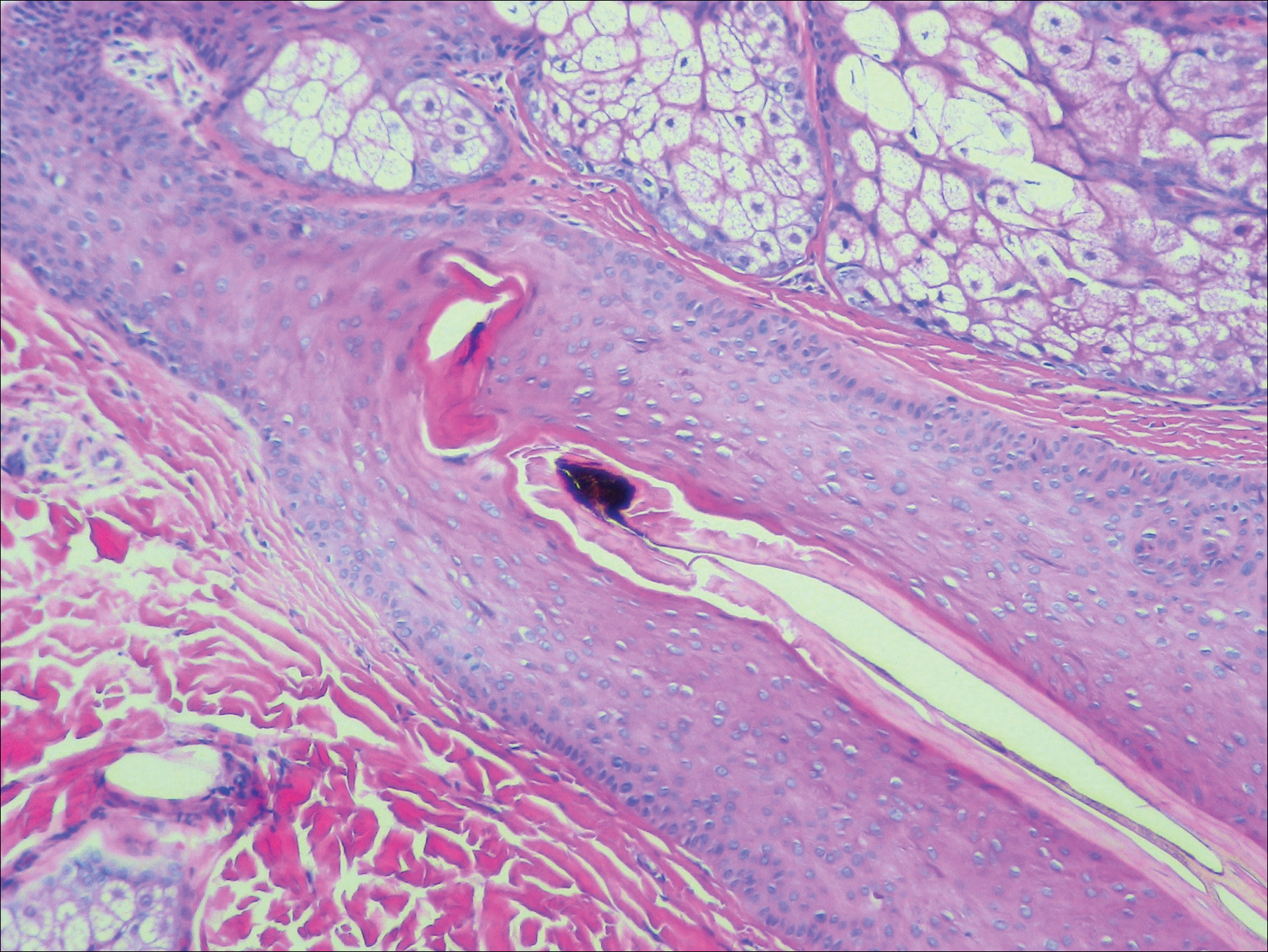

A punch biopsy was taken from the verrucous plaque, and microscopic examination demonstrated prominent epidermal hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses and a superficial dermatitis with abundant eosinophils (Figure 1A). Suprabasal acantholytic cleft formation was noted in a focal area (Figure 1B). Another punch biopsy was performed from the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence examination, which revealed intercellular deposits of IgG and C3 throughout the lower half of the epidermis (Figure 1C). Indirect immunofluorescence performed on monkey esophagus substrate showed circulating intercellular IgG antibodies in all the titers of up to 1/160 and an elevated level of IgG antidesmoglein 3 (anti-Dsg3) antibody (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index value, >200 RU/mL [reference range, <20 RU/mL]).

Because there was a solitary lesion, the decision was made to perform local treatment. One intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection (20 mg/mL) resulted in remarkable flattening of the lesion (Figure 2). Subsequently, treatment was continued with clobetasol propionate ointment 3 times weekly for 1 month. During a follow-up period of 2 years, no signs of local relapse or new lesions elsewhere were noted, and the patient continued to be on long-term longitudinal evaluation.

Pemphigus vegetans (PV) is an uncommon variant of pemphigus, typically manifesting with vegetating erosions and plaques localized to the intertriginous areas of the body. Local factors such as semiocclusion, maceration, and/or bacterial or fungal colonization have been hypothesized to account for the distinctive localization and vegetation of the lesions.1,2 Traditionally, 2 clinical subtypes of PV have been described: (1) Hallopeau type presenting with pustules that later evolve into vegetating plaques, and (2) Neumann type that initially manifests as vesicles and bullae with a more disseminated distribution, transforming into hypertrophic masses with erosions.1-5 However, this distinction may not always be clear, and patients with features of both forms have been reported.2,5

At present, our case would best be regarded as a localized form of PV presenting with a solitary lesion. It may progress to more disseminated disease or remain localized during its course; the literature contains reports exemplifying both possibilities. In a large retrospective study from Tunisia encompassing almost 3 decades, the majority of the patients initially presented with unifocal involvement; however, the disease eventually became multifocal in almost all patients during the study period, emphasizing the need for long-term follow-up.2 There also are reports of PV confined to a single anatomic site, such as the scalp, sole, or vulva, that remained localized for years.2,4,6,7 Involvement of the oral mucosa is an important finding of PV and the presenting concern in approximately three-quarters of patients.2 Interestingly, the oral mucosa was not involved in our patient despite the high titer of anti-Dsg3 antibody, which suggests the need for the presence of other factors for clinical expression of the disease.

Although PV is considered a vegetating clinicomorphologic variant of pemphigus vulgaris, PV is histopathologically distinguished from pemphigus vulgaris by the presence of epidermal hyperplasia and intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses. Importantly, the epidermis displays signs of exuberant proliferation such as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and/or papillomatosis of a varying degree.1,2,5 Of note, suprabasal acantholysis is usually overshadowed by the changes in PV and presents only focally, as in our patient. The most common autoantibody profile is IgG targeting Dsg3; however, a spectrum of other autoantibodies has been identified, such as IgG antidesmocollin 3, IgA anti-Dsg3, and IgG anti-Dsg1.8,9

The most important differential diagnosis of PV is pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. These 2 entities share many clinical and histopathological features; however, direct immunofluorescence is helpfulfor differentiation because it generally is negative in pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans.2,10 Furthermore, there is a well-established association between pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans and inflammatory bowel disorders, whereas PV has anecdotally been linked to malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and heroin abuse.1,2,10 Our patient was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus and denied weight loss or loss of appetite. For those cases of PV involving a single anatomic site, the differential diagnosis is broader and encompasses dermatoses such as verrucae, syphilitic chancre, condylomata lata, granuloma inguinale, herpes simplex virus infection, and Kaposi sarcoma.

Treatment of PV is similar to pemphigus vulgaris and consists of a combination of systemic corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents.1,5 On the other hand, more limited presentations of PV may be suitable for intralesional treatment with triamcinolone acetonide, thus avoiding potential adverse effects of systemic therapy.1,2 In our case with localized involvement, a favorable response was obtained with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, and we plan to utilize systemic corticosteroids if the disease becomes generalized during follow-up.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Zaraa I, Sellami A, Bouguerra C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans: a clinical, histological, immunopathological and prognostic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1160-1167.

- Madan V, August PJ. Exophytic plaques, blisters, and mouth ulcers. pemphigus vegetans (PV), Neumann type. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:715-720.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Monshi B, Marker M, Feichtinger H, et al. Pemphigus vegetans--immunopathological findings in a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:179-183.

- Jain VK, Dixit VB, Mohan H. Pemphigus vegetans in an unusual site. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:352-353.

- Wong KT, Wong KK. A case of acantholytic dermatosis of the vulva with features of pemphigus vegetans. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:453-456.

- Morizane S, Yamamoto T, Hisamatsu Y, et al. Pemphigus vegetans with IgG and IgA antidesmoglein 3 antibodies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1236-1237.

- Saruta H, Ishii N, Teye K, et al. Two cases of pemphigus vegetans with IgG anti-desmocollin 3 antibodies. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1209-1213.

- Mehravaran M, Kemény L, Husz S, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:266-269.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

A punch biopsy was taken from the verrucous plaque, and microscopic examination demonstrated prominent epidermal hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses and a superficial dermatitis with abundant eosinophils (Figure 1A). Suprabasal acantholytic cleft formation was noted in a focal area (Figure 1B). Another punch biopsy was performed from the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence examination, which revealed intercellular deposits of IgG and C3 throughout the lower half of the epidermis (Figure 1C). Indirect immunofluorescence performed on monkey esophagus substrate showed circulating intercellular IgG antibodies in all the titers of up to 1/160 and an elevated level of IgG antidesmoglein 3 (anti-Dsg3) antibody (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index value, >200 RU/mL [reference range, <20 RU/mL]).

Because there was a solitary lesion, the decision was made to perform local treatment. One intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection (20 mg/mL) resulted in remarkable flattening of the lesion (Figure 2). Subsequently, treatment was continued with clobetasol propionate ointment 3 times weekly for 1 month. During a follow-up period of 2 years, no signs of local relapse or new lesions elsewhere were noted, and the patient continued to be on long-term longitudinal evaluation.

Pemphigus vegetans (PV) is an uncommon variant of pemphigus, typically manifesting with vegetating erosions and plaques localized to the intertriginous areas of the body. Local factors such as semiocclusion, maceration, and/or bacterial or fungal colonization have been hypothesized to account for the distinctive localization and vegetation of the lesions.1,2 Traditionally, 2 clinical subtypes of PV have been described: (1) Hallopeau type presenting with pustules that later evolve into vegetating plaques, and (2) Neumann type that initially manifests as vesicles and bullae with a more disseminated distribution, transforming into hypertrophic masses with erosions.1-5 However, this distinction may not always be clear, and patients with features of both forms have been reported.2,5

At present, our case would best be regarded as a localized form of PV presenting with a solitary lesion. It may progress to more disseminated disease or remain localized during its course; the literature contains reports exemplifying both possibilities. In a large retrospective study from Tunisia encompassing almost 3 decades, the majority of the patients initially presented with unifocal involvement; however, the disease eventually became multifocal in almost all patients during the study period, emphasizing the need for long-term follow-up.2 There also are reports of PV confined to a single anatomic site, such as the scalp, sole, or vulva, that remained localized for years.2,4,6,7 Involvement of the oral mucosa is an important finding of PV and the presenting concern in approximately three-quarters of patients.2 Interestingly, the oral mucosa was not involved in our patient despite the high titer of anti-Dsg3 antibody, which suggests the need for the presence of other factors for clinical expression of the disease.

Although PV is considered a vegetating clinicomorphologic variant of pemphigus vulgaris, PV is histopathologically distinguished from pemphigus vulgaris by the presence of epidermal hyperplasia and intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses. Importantly, the epidermis displays signs of exuberant proliferation such as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and/or papillomatosis of a varying degree.1,2,5 Of note, suprabasal acantholysis is usually overshadowed by the changes in PV and presents only focally, as in our patient. The most common autoantibody profile is IgG targeting Dsg3; however, a spectrum of other autoantibodies has been identified, such as IgG antidesmocollin 3, IgA anti-Dsg3, and IgG anti-Dsg1.8,9

The most important differential diagnosis of PV is pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. These 2 entities share many clinical and histopathological features; however, direct immunofluorescence is helpfulfor differentiation because it generally is negative in pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans.2,10 Furthermore, there is a well-established association between pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans and inflammatory bowel disorders, whereas PV has anecdotally been linked to malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and heroin abuse.1,2,10 Our patient was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus and denied weight loss or loss of appetite. For those cases of PV involving a single anatomic site, the differential diagnosis is broader and encompasses dermatoses such as verrucae, syphilitic chancre, condylomata lata, granuloma inguinale, herpes simplex virus infection, and Kaposi sarcoma.

Treatment of PV is similar to pemphigus vulgaris and consists of a combination of systemic corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents.1,5 On the other hand, more limited presentations of PV may be suitable for intralesional treatment with triamcinolone acetonide, thus avoiding potential adverse effects of systemic therapy.1,2 In our case with localized involvement, a favorable response was obtained with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, and we plan to utilize systemic corticosteroids if the disease becomes generalized during follow-up.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

A punch biopsy was taken from the verrucous plaque, and microscopic examination demonstrated prominent epidermal hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses and a superficial dermatitis with abundant eosinophils (Figure 1A). Suprabasal acantholytic cleft formation was noted in a focal area (Figure 1B). Another punch biopsy was performed from the perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence examination, which revealed intercellular deposits of IgG and C3 throughout the lower half of the epidermis (Figure 1C). Indirect immunofluorescence performed on monkey esophagus substrate showed circulating intercellular IgG antibodies in all the titers of up to 1/160 and an elevated level of IgG antidesmoglein 3 (anti-Dsg3) antibody (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index value, >200 RU/mL [reference range, <20 RU/mL]).

Because there was a solitary lesion, the decision was made to perform local treatment. One intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection (20 mg/mL) resulted in remarkable flattening of the lesion (Figure 2). Subsequently, treatment was continued with clobetasol propionate ointment 3 times weekly for 1 month. During a follow-up period of 2 years, no signs of local relapse or new lesions elsewhere were noted, and the patient continued to be on long-term longitudinal evaluation.

Pemphigus vegetans (PV) is an uncommon variant of pemphigus, typically manifesting with vegetating erosions and plaques localized to the intertriginous areas of the body. Local factors such as semiocclusion, maceration, and/or bacterial or fungal colonization have been hypothesized to account for the distinctive localization and vegetation of the lesions.1,2 Traditionally, 2 clinical subtypes of PV have been described: (1) Hallopeau type presenting with pustules that later evolve into vegetating plaques, and (2) Neumann type that initially manifests as vesicles and bullae with a more disseminated distribution, transforming into hypertrophic masses with erosions.1-5 However, this distinction may not always be clear, and patients with features of both forms have been reported.2,5

At present, our case would best be regarded as a localized form of PV presenting with a solitary lesion. It may progress to more disseminated disease or remain localized during its course; the literature contains reports exemplifying both possibilities. In a large retrospective study from Tunisia encompassing almost 3 decades, the majority of the patients initially presented with unifocal involvement; however, the disease eventually became multifocal in almost all patients during the study period, emphasizing the need for long-term follow-up.2 There also are reports of PV confined to a single anatomic site, such as the scalp, sole, or vulva, that remained localized for years.2,4,6,7 Involvement of the oral mucosa is an important finding of PV and the presenting concern in approximately three-quarters of patients.2 Interestingly, the oral mucosa was not involved in our patient despite the high titer of anti-Dsg3 antibody, which suggests the need for the presence of other factors for clinical expression of the disease.

Although PV is considered a vegetating clinicomorphologic variant of pemphigus vulgaris, PV is histopathologically distinguished from pemphigus vulgaris by the presence of epidermal hyperplasia and intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses. Importantly, the epidermis displays signs of exuberant proliferation such as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and/or papillomatosis of a varying degree.1,2,5 Of note, suprabasal acantholysis is usually overshadowed by the changes in PV and presents only focally, as in our patient. The most common autoantibody profile is IgG targeting Dsg3; however, a spectrum of other autoantibodies has been identified, such as IgG antidesmocollin 3, IgA anti-Dsg3, and IgG anti-Dsg1.8,9

The most important differential diagnosis of PV is pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. These 2 entities share many clinical and histopathological features; however, direct immunofluorescence is helpfulfor differentiation because it generally is negative in pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans.2,10 Furthermore, there is a well-established association between pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans and inflammatory bowel disorders, whereas PV has anecdotally been linked to malignancy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, and heroin abuse.1,2,10 Our patient was seronegative for human immunodeficiency virus and denied weight loss or loss of appetite. For those cases of PV involving a single anatomic site, the differential diagnosis is broader and encompasses dermatoses such as verrucae, syphilitic chancre, condylomata lata, granuloma inguinale, herpes simplex virus infection, and Kaposi sarcoma.

Treatment of PV is similar to pemphigus vulgaris and consists of a combination of systemic corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents.1,5 On the other hand, more limited presentations of PV may be suitable for intralesional treatment with triamcinolone acetonide, thus avoiding potential adverse effects of systemic therapy.1,2 In our case with localized involvement, a favorable response was obtained with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide, and we plan to utilize systemic corticosteroids if the disease becomes generalized during follow-up.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Zaraa I, Sellami A, Bouguerra C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans: a clinical, histological, immunopathological and prognostic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1160-1167.

- Madan V, August PJ. Exophytic plaques, blisters, and mouth ulcers. pemphigus vegetans (PV), Neumann type. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:715-720.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Monshi B, Marker M, Feichtinger H, et al. Pemphigus vegetans--immunopathological findings in a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:179-183.

- Jain VK, Dixit VB, Mohan H. Pemphigus vegetans in an unusual site. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:352-353.

- Wong KT, Wong KK. A case of acantholytic dermatosis of the vulva with features of pemphigus vegetans. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:453-456.

- Morizane S, Yamamoto T, Hisamatsu Y, et al. Pemphigus vegetans with IgG and IgA antidesmoglein 3 antibodies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1236-1237.

- Saruta H, Ishii N, Teye K, et al. Two cases of pemphigus vegetans with IgG anti-desmocollin 3 antibodies. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1209-1213.

- Mehravaran M, Kemény L, Husz S, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:266-269.

- Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Caccavale S, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the folds (intertriginous areas). Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:471-476.

- Zaraa I, Sellami A, Bouguerra C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans: a clinical, histological, immunopathological and prognostic study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1160-1167.

- Madan V, August PJ. Exophytic plaques, blisters, and mouth ulcers. pemphigus vegetans (PV), Neumann type. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:715-720.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Monshi B, Marker M, Feichtinger H, et al. Pemphigus vegetans--immunopathological findings in a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:179-183.

- Jain VK, Dixit VB, Mohan H. Pemphigus vegetans in an unusual site. Int J Dermatol. 1989;28:352-353.

- Wong KT, Wong KK. A case of acantholytic dermatosis of the vulva with features of pemphigus vegetans. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:453-456.

- Morizane S, Yamamoto T, Hisamatsu Y, et al. Pemphigus vegetans with IgG and IgA antidesmoglein 3 antibodies. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1236-1237.

- Saruta H, Ishii N, Teye K, et al. Two cases of pemphigus vegetans with IgG anti-desmocollin 3 antibodies. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1209-1213.

- Mehravaran M, Kemény L, Husz S, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:266-269.

A 40-year-old otherwise healthy man presented with an exophytic plaque on the left groin of 1 month's duration. The lesion reportedly emerged as pustules that slowly expanded and coalesced. At an outside institution, cryotherapy was planned for a presumed diagnosis of condyloma acuminatum; however, the patient decided to get a second opinion. He denied recent intake of new drugs. Six months prior he had traveled to China and engaged in unprotected sexual intercourse. Physical examination revealed an approximately 4×2-cm exophytic plaque with a partially eroded and exudative surface on the left inguinal fold. Dermatologic examination, including the oral mucosa, was otherwise normal. Complete blood cell count and sexually transmitted disease panel were unremarkable.

Pediatric Skin Care: Survey of the Cutis Editorial Board

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on pediatric skin care. Here’s what we found.

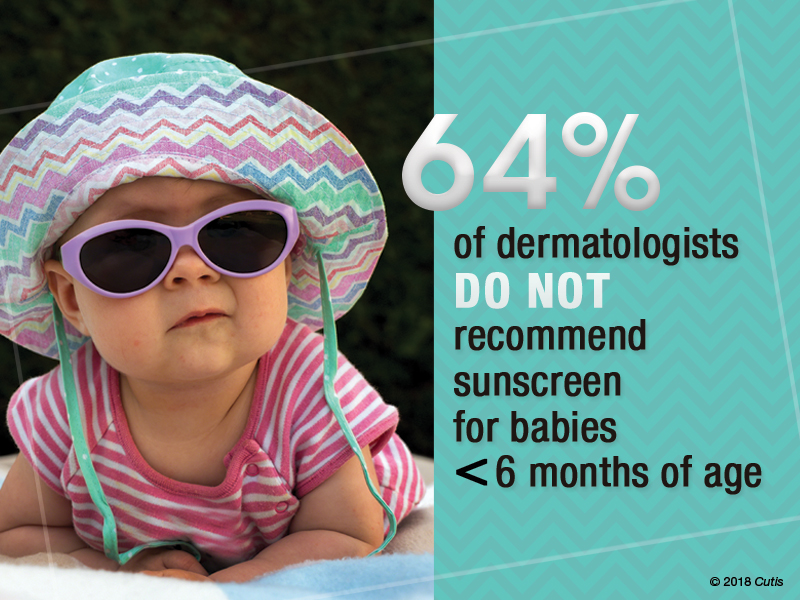

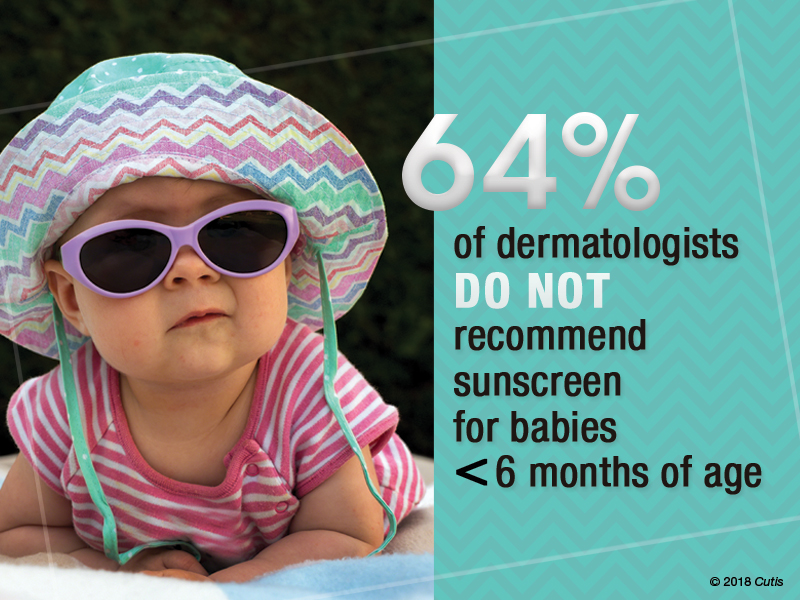

Do you recommend sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months?

More than half (64%) of dermatologists we surveyed do not recommend using sunscreens in babies younger than 6 months; they should stay out of the sun. They recommended sun-protective clothing, hats, and sunglasses in this age group.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Babies younger than 6 months are still developing barrier functionality and have a higher surface area to body weight ratio compared to older children and adults. There is decreased UV light barrier protection and increased risk for systemic drug absorption. Therefore, it is best to avoid sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months. Instead, I recommend avoiding sunlight during peak hours, keeping babies in the shade, and dressing them in sun-protective clothing and hats.

Next page: Bathing and eczema

What advice do you give parents/guardians on bathing for babies with eczema?

Two-thirds of dermatologists (68%) indicated that moisturizers should be applied after bathing babies with eczema. More than half (64%) suggested using fragrance-free cleansers. Results varied on the frequency of bathing; 32% said bathe once daily for short periods with warm water, and 41% suggested to reduce bathing to a few nights a week.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Dry skin is a characteristic feature of atopic dermatitis. We now know that skin barrier dysfunction, such as filaggrin deficiency, contributes to the pathophysiology in some patients. In addition, a paucity of stratum corneum and intercellular lipids increases transepidermal water loss. Therefore, emollients containing humectants to augment stratum corneum hydration and occludents to reduce evaporation are extremely helpful in maintenance treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Next page: Nonsteroidal agents

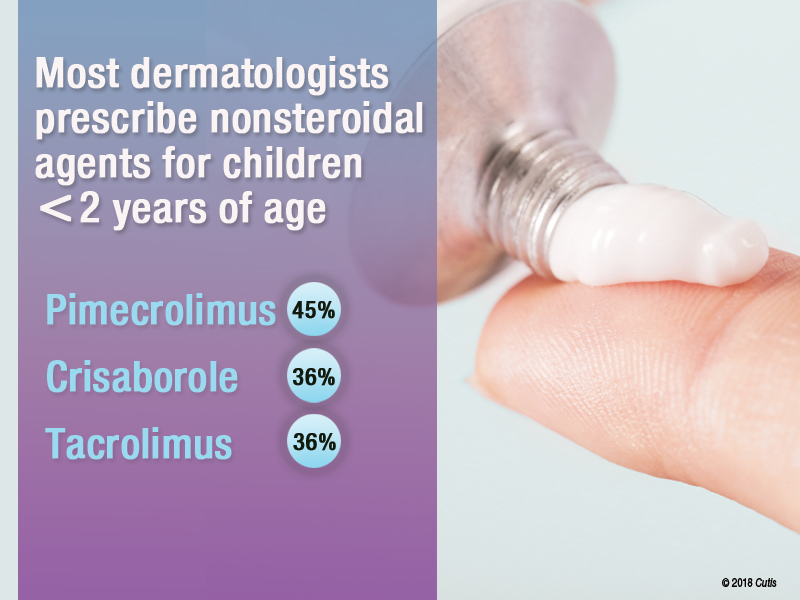

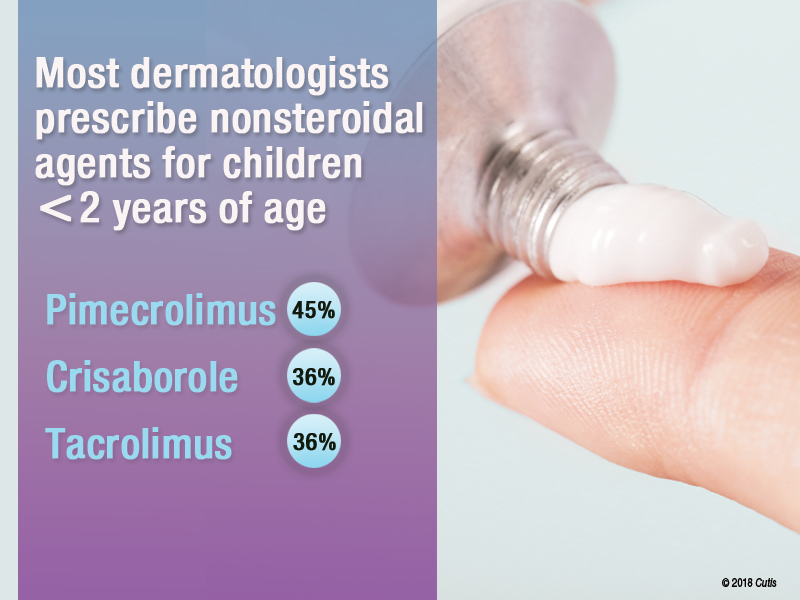

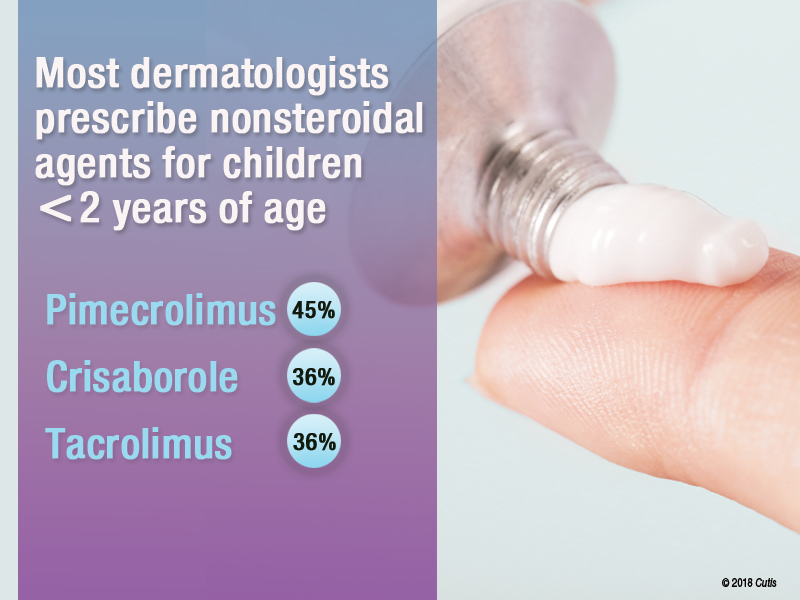

Do you prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years?

Almost two-thirds (64%) of dermatologists do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years.

If yes, which nonsteroidal agents do you prescribe for children?

Of those dermatologists who indicated that they do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years, almost half (45%) prescribe pimecrolimus, while 36% prescribe crisaborole or tacrolimus.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

We have limited options for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies for atopic dermatitis in children younger than 2 years. The risks of adverse effects also are higher in younger children compared to older children and adults, particularly hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal suppression with corticosteroids. Pimecrolimus was the most common nonsteroidal prescribed in this group. It should be noted that pimecrolimus is not FDA approved for use in children younger than 2 years; however, 2 phase 3 studies were conducted with 436 infants aged 3 months to 23 months and they demonstrated safety and efficacy.

Next page: Procedures in adolescents

Which procedures do you perform on adolescents?

Forty-one percent of dermatologists surveyed indicated that they do not perform procedures on adolescents. Of those that do, 32% use laser hair removal or chemical peels in adolescents, while only 23% each use light therapy for acne or onabotulinumtoxinA for hyperhidrosis. Pulsed dye laser use was reported in only 18% of dermatologists.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

The results of this survey are a reflection of the relatively recent trends in dermatology training. Now that there is board certification in pediatric dermatology, many dermatologists now refer to pediatric dermatologists for children who need or want procedures.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

Keep the regimen as simple as possible and make sure your skin care advice is culturally relevant.—Craig Burkhart, MD (Chapel Hill, North Carolina)

Please, avoid direct sun exposure as much as possible by wearing protective garments and finding shades in the outside.—Jisun Cha, MD (New Brunswick, New Jersey)

Good habits start early. Teach children how to care for their skin and they will carry that practice with them over the course of their lifetime, and hopefully pass it on.—James Q. Del Rosso, DO (Las Vegas, Nevada)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis Editorial Board Members within the United States from September 13, 2018, to October 4, 2018. A total of 22 usable responses were received.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on pediatric skin care. Here’s what we found.

Do you recommend sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months?

More than half (64%) of dermatologists we surveyed do not recommend using sunscreens in babies younger than 6 months; they should stay out of the sun. They recommended sun-protective clothing, hats, and sunglasses in this age group.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Babies younger than 6 months are still developing barrier functionality and have a higher surface area to body weight ratio compared to older children and adults. There is decreased UV light barrier protection and increased risk for systemic drug absorption. Therefore, it is best to avoid sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months. Instead, I recommend avoiding sunlight during peak hours, keeping babies in the shade, and dressing them in sun-protective clothing and hats.

Next page: Bathing and eczema

What advice do you give parents/guardians on bathing for babies with eczema?

Two-thirds of dermatologists (68%) indicated that moisturizers should be applied after bathing babies with eczema. More than half (64%) suggested using fragrance-free cleansers. Results varied on the frequency of bathing; 32% said bathe once daily for short periods with warm water, and 41% suggested to reduce bathing to a few nights a week.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Dry skin is a characteristic feature of atopic dermatitis. We now know that skin barrier dysfunction, such as filaggrin deficiency, contributes to the pathophysiology in some patients. In addition, a paucity of stratum corneum and intercellular lipids increases transepidermal water loss. Therefore, emollients containing humectants to augment stratum corneum hydration and occludents to reduce evaporation are extremely helpful in maintenance treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Next page: Nonsteroidal agents

Do you prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years?

Almost two-thirds (64%) of dermatologists do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years.

If yes, which nonsteroidal agents do you prescribe for children?

Of those dermatologists who indicated that they do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years, almost half (45%) prescribe pimecrolimus, while 36% prescribe crisaborole or tacrolimus.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

We have limited options for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies for atopic dermatitis in children younger than 2 years. The risks of adverse effects also are higher in younger children compared to older children and adults, particularly hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal suppression with corticosteroids. Pimecrolimus was the most common nonsteroidal prescribed in this group. It should be noted that pimecrolimus is not FDA approved for use in children younger than 2 years; however, 2 phase 3 studies were conducted with 436 infants aged 3 months to 23 months and they demonstrated safety and efficacy.

Next page: Procedures in adolescents

Which procedures do you perform on adolescents?

Forty-one percent of dermatologists surveyed indicated that they do not perform procedures on adolescents. Of those that do, 32% use laser hair removal or chemical peels in adolescents, while only 23% each use light therapy for acne or onabotulinumtoxinA for hyperhidrosis. Pulsed dye laser use was reported in only 18% of dermatologists.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

The results of this survey are a reflection of the relatively recent trends in dermatology training. Now that there is board certification in pediatric dermatology, many dermatologists now refer to pediatric dermatologists for children who need or want procedures.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

Keep the regimen as simple as possible and make sure your skin care advice is culturally relevant.—Craig Burkhart, MD (Chapel Hill, North Carolina)

Please, avoid direct sun exposure as much as possible by wearing protective garments and finding shades in the outside.—Jisun Cha, MD (New Brunswick, New Jersey)

Good habits start early. Teach children how to care for their skin and they will carry that practice with them over the course of their lifetime, and hopefully pass it on.—James Q. Del Rosso, DO (Las Vegas, Nevada)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis Editorial Board Members within the United States from September 13, 2018, to October 4, 2018. A total of 22 usable responses were received.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis Editorial Board answered 5 questions on pediatric skin care. Here’s what we found.

Do you recommend sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months?

More than half (64%) of dermatologists we surveyed do not recommend using sunscreens in babies younger than 6 months; they should stay out of the sun. They recommended sun-protective clothing, hats, and sunglasses in this age group.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Babies younger than 6 months are still developing barrier functionality and have a higher surface area to body weight ratio compared to older children and adults. There is decreased UV light barrier protection and increased risk for systemic drug absorption. Therefore, it is best to avoid sunscreen in babies younger than 6 months. Instead, I recommend avoiding sunlight during peak hours, keeping babies in the shade, and dressing them in sun-protective clothing and hats.

Next page: Bathing and eczema

What advice do you give parents/guardians on bathing for babies with eczema?

Two-thirds of dermatologists (68%) indicated that moisturizers should be applied after bathing babies with eczema. More than half (64%) suggested using fragrance-free cleansers. Results varied on the frequency of bathing; 32% said bathe once daily for short periods with warm water, and 41% suggested to reduce bathing to a few nights a week.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Dry skin is a characteristic feature of atopic dermatitis. We now know that skin barrier dysfunction, such as filaggrin deficiency, contributes to the pathophysiology in some patients. In addition, a paucity of stratum corneum and intercellular lipids increases transepidermal water loss. Therefore, emollients containing humectants to augment stratum corneum hydration and occludents to reduce evaporation are extremely helpful in maintenance treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Next page: Nonsteroidal agents

Do you prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years?

Almost two-thirds (64%) of dermatologists do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years.

If yes, which nonsteroidal agents do you prescribe for children?

Of those dermatologists who indicated that they do prescribe nonsteroidal agents for children younger than 2 years, almost half (45%) prescribe pimecrolimus, while 36% prescribe crisaborole or tacrolimus.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

We have limited options for US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved therapies for atopic dermatitis in children younger than 2 years. The risks of adverse effects also are higher in younger children compared to older children and adults, particularly hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal suppression with corticosteroids. Pimecrolimus was the most common nonsteroidal prescribed in this group. It should be noted that pimecrolimus is not FDA approved for use in children younger than 2 years; however, 2 phase 3 studies were conducted with 436 infants aged 3 months to 23 months and they demonstrated safety and efficacy.

Next page: Procedures in adolescents

Which procedures do you perform on adolescents?