User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

What’s New in Topical Treatments for Psoriasis

In an era when we have access to a dizzying array of biologics for psoriasis treatment, it is easy to forget that topical therapies are still the bread and butter of treatment. For the majority of patients living with psoriasis, topical treatment is the only therapy they receive; indeed, a recent study examining a large national payer database found that 86% of psoriasis patients were managed with topical medications only.1 Thus, it is extremely important to understand how to optimize topical treatments, recognize pitfalls in management, and utilize newer agents that can been added to our treatment armamentarium for psoriasis.

In general, steroids have been the mainstay of topical treatment of psoriasis. Their broad anti-inflammatory activity works well against both the visible signs and symptoms of psoriasis as well as the underlying inflammatory milieu of the disease; however, these treatments are not without their downsides. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppression, especially in higher-potency topical steroids, is a serious concern that limits their use. In one study comparing lotion and cream formulations of clobetasol propionate, HPA axis suppression was seen in 80% (8/10) of adults in the lotion group and 30% (3/10) in the cream group after 4 weeks of treatment.2 These findings are not new; a 1987 study found that patients using less than 50 g of topical clobetasol per week, which is considered a low dose, could still exhibit HPA axis suppression.3 Severe HPA axis suppression may occur; one study of various topical steroids found some degree of HPA axis suppression in 38% (19/50) of patients, with a direct correlation with topical steroid potency.4 Additionally, cutaneous side effects such as striae formation, atrophy, and the possibility of tachyphylaxis must be considered. Various treatment regimens have been developed to limit topical steroid use, including steroid-sparing medications (eg, calcipotriene) used in conjunction with topical steroids, systemic treatments (eg, phototherapy) added on, or higher-potency topical steroids rotated with lower-potency steroids. Implementing other agents, such as topical retinoids or keratolytics, into the treatment regimen also is an important consideration in the overall approach to topical psoriasis therapy.

Notably, a number of newly approved topical treatments for psoriasis have emerged, and more are in the pipeline. When evaluating these agents, important considerations include safety, length of treatment course, and efficacy. Several of these agents hold promise for patients with psoriasis.

An alcohol-free, fixed-combination aerosol foam formulation of calcipotriene 0.005% and betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for plaque psoriasis in 2015. This agent was shown to be more efficacious than the same combination of active ingredients in an ointment formulation as well as either agent alone, with psoriasis area and severity index 75 response achieved in more than 50% of patients at week 4 of treatment.5 Notably, this product offers once-daily application with positive patient satisfaction scores.6 The novelty of this foam is in its ability to supersaturate the active ingredients on the surface of the skin with improved penetration and drug delivery.

A novel spray formulation of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% also has been developed and has been compared to augmented betamethasone dipropionate lotion. One benefit of this spray is that, based on the vasoconstriction test, the potency is similar to a mid-potency steroid while the efficacy is not significantly different from betamethasone dipropionate lotion, a class I steroid.7 Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression was similar following a 4-week treatment course compared to a 2-week course of the lotion formulation.8

The newest agent, halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01%, was approved for treatment of psoriasis in October 2018. Compared to halobetasol 0.05% cream or ointment, halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01% has one-fifth the concentration of the active ingredient with the same degree of success in efficacy scores.9 This reduction in drug concentration is possible because the proprietary lotion base allows for better drug delivery of the active ingredient. Importantly, HPA axis suppression was assessed over an 8-week period of use and no suppression was noted.9 Generic class I steroids should only be used for 2 weeks, which is the standard treatment period used in comparator trials; however, many patients will still have active lesions on their body after 2 weeks of treatment, and if using generic clobetasol or betamethasone dipropionate, the choice becomes whether to keep applying the medication and risk HPA axis suppression and cutaneous side effects or switch to a less effective treatment. However, some of the newer agents are indicated for 4 to 8 weeks of treatment.

Utilizing other classes of agents such as retinoids and keratolytics in our treatment armamentarium for psoriasis often is helpful. It has long been known that tazarotene can be combined with topical steroids for increased efficacy and limitation of the irritating effects of the retinoid.10 Similarly, keratolytics play a role in allowing a topically applied medication to penetrate deep enough to affect the underlying inflammation of psoriasis. Medications that include salicylic acid or urea may help to remove ostraceous scales from thick psoriasis lesions that would otherwise prevent delivery of topical steroids to achieve clinically meaningful results. For scalp psoriasis, there are salicylic acid solutions as well as newer agents such as a dimethicone-based topical product.11

Nonsteroidal topical anti-inflammatories also have been used off label for psoriasis treatment. These agents are especially useful in patients who were not successfully treated with calcipotriene or need adjunctive therapy. Although not extremely effective against plaque psoriasis, topical tacrolimus in particular seems to have a place in the treatment of inverse psoriasis where it can be utilized without concern for long-term side effects.12 Crisaborole ointment, a topical medication approved for treatment of atopic dermatitis, was studied in phase 2 trials, but development has not progressed for a psoriasis indication.13 It is reasonable to consider this medication in the same way that tacrolimus has been used, however, considering that the mechanism of action—phosphodiesterase type 4 inhibition—has successfully been implemented in an oral medication to treat psoriasis, apremilast.

There are numerous topical medications in the pipeline that are being developed to treat psoriasis. Of them, the most relevant is a fixed-dose combination of halobetasol propionate 0.01% and tazarotene 0.045% in a proprietary lotion vehicle. A decision from the US Food and Drug Administration is expected in the first quarter of 2019. This medication capitalizes on the aforementioned synergistic effects of tazarotene and a superpotent topical steroid to achieve improved efficacy. Similar to halobetasol lotion 0.01%, this product was evaluated over an 8-week period, and no HPA axis suppression was observed. Efficacy was significantly improved versus both placebo and either halobetasol or tazarotene alone.14

Overall, it is promising that after a long period of relative stagnancy, we have numerous new agents available and upcoming for the topical treatment of psoriasis. For the vast majority of patients, topical medications still represent the mainstay of treatment, and it is important that we have access to better, safer medications in this category.

- Murage MJ, Kern DM, Chang L, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with psoriasis using a large national payer database in the United States: a retrospective study [published online October 25, 2018]. J Med Econ. doi:10.1080/13696998.2018.1540424.

- Clobex [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2005.

- Ohman EM, Rogers S, Meenan FO, et al. Adrenal suppression following low-dose topical clobetasol propionate. J R Soc Med. 1987;80:422-424.

- Kerner M, Ishay A, Ziv M, et al. Evaluation of the pituitary-adrenal axis function in patients on topical steroid therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:215-216.

- Stein Gold L, Lebwohl M, Menter A, et al. Aerosol foam formulation of fixed combination calcipotriene plus betamethasone dipropionate is highly efficacious in patients with psoriasis vulgaris: pooled data from three randomized controlled studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:951-957.

- Paul C, Bang B, Lebwohl M. Fixed combination calcipotriol plus betamethasone dipropionate aerosol foam in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris: rationale for development and clinical profile. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18:115-121.

- Fowler JF Jr, Hebert AA, Sugarman J. DFD-01, a novel medium potency betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% emollient spray, demonstrates similar efficacy to augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% lotion for the treatment of moderate plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:154-162.

- Sidgiddi S, Pakunlu RI, Allenby K. Efficacy, safety, and potency of betamethasone dipropionate spray 0.05%: a treatment for adults with mildto-moderate plaque psoriasis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:14-22.

- Kerdel FA, Draelos ZD, Tyring SK, et al. A phase 2, multicenter, doubleblind, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical study to compare the safety and efficacy of a halobetasol propionate 0.01% lotion and halobetasol propionate 0.05% cream in the treatment of plaque psoriasis [published online November 5, 2018]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09 546634.2018.1523362.

- Lebwohl M, Poulin Y. Tazarotene in combination with topical corticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(4 pt 2):S139-S143.

- Hengge UR, Roschmann K, Candler H. Single-center, noninterventional clinical trial to assess the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of a dimeticone-based medical device in facilitating the removal of scales after topical application in patients with psoriasis corporis or psoriasis capitis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2017;7:41-49.

- Malecic N, Young H. Tacrolimus for the management of psoriasis: clinical utility and place in therapy. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2016;6:153-163.

- Nazarian R, Weinberg JM. AN-2728, a PDE4 inhibitor for the potential topical treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:1236-1242.

- Gold LS, Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination of halobetasol and tazarotene in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of 2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:287-293.

In an era when we have access to a dizzying array of biologics for psoriasis treatment, it is easy to forget that topical therapies are still the bread and butter of treatment. For the majority of patients living with psoriasis, topical treatment is the only therapy they receive; indeed, a recent study examining a large national payer database found that 86% of psoriasis patients were managed with topical medications only.1 Thus, it is extremely important to understand how to optimize topical treatments, recognize pitfalls in management, and utilize newer agents that can been added to our treatment armamentarium for psoriasis.

In general, steroids have been the mainstay of topical treatment of psoriasis. Their broad anti-inflammatory activity works well against both the visible signs and symptoms of psoriasis as well as the underlying inflammatory milieu of the disease; however, these treatments are not without their downsides. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppression, especially in higher-potency topical steroids, is a serious concern that limits their use. In one study comparing lotion and cream formulations of clobetasol propionate, HPA axis suppression was seen in 80% (8/10) of adults in the lotion group and 30% (3/10) in the cream group after 4 weeks of treatment.2 These findings are not new; a 1987 study found that patients using less than 50 g of topical clobetasol per week, which is considered a low dose, could still exhibit HPA axis suppression.3 Severe HPA axis suppression may occur; one study of various topical steroids found some degree of HPA axis suppression in 38% (19/50) of patients, with a direct correlation with topical steroid potency.4 Additionally, cutaneous side effects such as striae formation, atrophy, and the possibility of tachyphylaxis must be considered. Various treatment regimens have been developed to limit topical steroid use, including steroid-sparing medications (eg, calcipotriene) used in conjunction with topical steroids, systemic treatments (eg, phototherapy) added on, or higher-potency topical steroids rotated with lower-potency steroids. Implementing other agents, such as topical retinoids or keratolytics, into the treatment regimen also is an important consideration in the overall approach to topical psoriasis therapy.

Notably, a number of newly approved topical treatments for psoriasis have emerged, and more are in the pipeline. When evaluating these agents, important considerations include safety, length of treatment course, and efficacy. Several of these agents hold promise for patients with psoriasis.

An alcohol-free, fixed-combination aerosol foam formulation of calcipotriene 0.005% and betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for plaque psoriasis in 2015. This agent was shown to be more efficacious than the same combination of active ingredients in an ointment formulation as well as either agent alone, with psoriasis area and severity index 75 response achieved in more than 50% of patients at week 4 of treatment.5 Notably, this product offers once-daily application with positive patient satisfaction scores.6 The novelty of this foam is in its ability to supersaturate the active ingredients on the surface of the skin with improved penetration and drug delivery.

A novel spray formulation of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% also has been developed and has been compared to augmented betamethasone dipropionate lotion. One benefit of this spray is that, based on the vasoconstriction test, the potency is similar to a mid-potency steroid while the efficacy is not significantly different from betamethasone dipropionate lotion, a class I steroid.7 Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression was similar following a 4-week treatment course compared to a 2-week course of the lotion formulation.8

The newest agent, halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01%, was approved for treatment of psoriasis in October 2018. Compared to halobetasol 0.05% cream or ointment, halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01% has one-fifth the concentration of the active ingredient with the same degree of success in efficacy scores.9 This reduction in drug concentration is possible because the proprietary lotion base allows for better drug delivery of the active ingredient. Importantly, HPA axis suppression was assessed over an 8-week period of use and no suppression was noted.9 Generic class I steroids should only be used for 2 weeks, which is the standard treatment period used in comparator trials; however, many patients will still have active lesions on their body after 2 weeks of treatment, and if using generic clobetasol or betamethasone dipropionate, the choice becomes whether to keep applying the medication and risk HPA axis suppression and cutaneous side effects or switch to a less effective treatment. However, some of the newer agents are indicated for 4 to 8 weeks of treatment.

Utilizing other classes of agents such as retinoids and keratolytics in our treatment armamentarium for psoriasis often is helpful. It has long been known that tazarotene can be combined with topical steroids for increased efficacy and limitation of the irritating effects of the retinoid.10 Similarly, keratolytics play a role in allowing a topically applied medication to penetrate deep enough to affect the underlying inflammation of psoriasis. Medications that include salicylic acid or urea may help to remove ostraceous scales from thick psoriasis lesions that would otherwise prevent delivery of topical steroids to achieve clinically meaningful results. For scalp psoriasis, there are salicylic acid solutions as well as newer agents such as a dimethicone-based topical product.11

Nonsteroidal topical anti-inflammatories also have been used off label for psoriasis treatment. These agents are especially useful in patients who were not successfully treated with calcipotriene or need adjunctive therapy. Although not extremely effective against plaque psoriasis, topical tacrolimus in particular seems to have a place in the treatment of inverse psoriasis where it can be utilized without concern for long-term side effects.12 Crisaborole ointment, a topical medication approved for treatment of atopic dermatitis, was studied in phase 2 trials, but development has not progressed for a psoriasis indication.13 It is reasonable to consider this medication in the same way that tacrolimus has been used, however, considering that the mechanism of action—phosphodiesterase type 4 inhibition—has successfully been implemented in an oral medication to treat psoriasis, apremilast.

There are numerous topical medications in the pipeline that are being developed to treat psoriasis. Of them, the most relevant is a fixed-dose combination of halobetasol propionate 0.01% and tazarotene 0.045% in a proprietary lotion vehicle. A decision from the US Food and Drug Administration is expected in the first quarter of 2019. This medication capitalizes on the aforementioned synergistic effects of tazarotene and a superpotent topical steroid to achieve improved efficacy. Similar to halobetasol lotion 0.01%, this product was evaluated over an 8-week period, and no HPA axis suppression was observed. Efficacy was significantly improved versus both placebo and either halobetasol or tazarotene alone.14

Overall, it is promising that after a long period of relative stagnancy, we have numerous new agents available and upcoming for the topical treatment of psoriasis. For the vast majority of patients, topical medications still represent the mainstay of treatment, and it is important that we have access to better, safer medications in this category.

In an era when we have access to a dizzying array of biologics for psoriasis treatment, it is easy to forget that topical therapies are still the bread and butter of treatment. For the majority of patients living with psoriasis, topical treatment is the only therapy they receive; indeed, a recent study examining a large national payer database found that 86% of psoriasis patients were managed with topical medications only.1 Thus, it is extremely important to understand how to optimize topical treatments, recognize pitfalls in management, and utilize newer agents that can been added to our treatment armamentarium for psoriasis.

In general, steroids have been the mainstay of topical treatment of psoriasis. Their broad anti-inflammatory activity works well against both the visible signs and symptoms of psoriasis as well as the underlying inflammatory milieu of the disease; however, these treatments are not without their downsides. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppression, especially in higher-potency topical steroids, is a serious concern that limits their use. In one study comparing lotion and cream formulations of clobetasol propionate, HPA axis suppression was seen in 80% (8/10) of adults in the lotion group and 30% (3/10) in the cream group after 4 weeks of treatment.2 These findings are not new; a 1987 study found that patients using less than 50 g of topical clobetasol per week, which is considered a low dose, could still exhibit HPA axis suppression.3 Severe HPA axis suppression may occur; one study of various topical steroids found some degree of HPA axis suppression in 38% (19/50) of patients, with a direct correlation with topical steroid potency.4 Additionally, cutaneous side effects such as striae formation, atrophy, and the possibility of tachyphylaxis must be considered. Various treatment regimens have been developed to limit topical steroid use, including steroid-sparing medications (eg, calcipotriene) used in conjunction with topical steroids, systemic treatments (eg, phototherapy) added on, or higher-potency topical steroids rotated with lower-potency steroids. Implementing other agents, such as topical retinoids or keratolytics, into the treatment regimen also is an important consideration in the overall approach to topical psoriasis therapy.

Notably, a number of newly approved topical treatments for psoriasis have emerged, and more are in the pipeline. When evaluating these agents, important considerations include safety, length of treatment course, and efficacy. Several of these agents hold promise for patients with psoriasis.

An alcohol-free, fixed-combination aerosol foam formulation of calcipotriene 0.005% and betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for plaque psoriasis in 2015. This agent was shown to be more efficacious than the same combination of active ingredients in an ointment formulation as well as either agent alone, with psoriasis area and severity index 75 response achieved in more than 50% of patients at week 4 of treatment.5 Notably, this product offers once-daily application with positive patient satisfaction scores.6 The novelty of this foam is in its ability to supersaturate the active ingredients on the surface of the skin with improved penetration and drug delivery.

A novel spray formulation of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% also has been developed and has been compared to augmented betamethasone dipropionate lotion. One benefit of this spray is that, based on the vasoconstriction test, the potency is similar to a mid-potency steroid while the efficacy is not significantly different from betamethasone dipropionate lotion, a class I steroid.7 Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression was similar following a 4-week treatment course compared to a 2-week course of the lotion formulation.8

The newest agent, halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01%, was approved for treatment of psoriasis in October 2018. Compared to halobetasol 0.05% cream or ointment, halobetasol propionate lotion 0.01% has one-fifth the concentration of the active ingredient with the same degree of success in efficacy scores.9 This reduction in drug concentration is possible because the proprietary lotion base allows for better drug delivery of the active ingredient. Importantly, HPA axis suppression was assessed over an 8-week period of use and no suppression was noted.9 Generic class I steroids should only be used for 2 weeks, which is the standard treatment period used in comparator trials; however, many patients will still have active lesions on their body after 2 weeks of treatment, and if using generic clobetasol or betamethasone dipropionate, the choice becomes whether to keep applying the medication and risk HPA axis suppression and cutaneous side effects or switch to a less effective treatment. However, some of the newer agents are indicated for 4 to 8 weeks of treatment.

Utilizing other classes of agents such as retinoids and keratolytics in our treatment armamentarium for psoriasis often is helpful. It has long been known that tazarotene can be combined with topical steroids for increased efficacy and limitation of the irritating effects of the retinoid.10 Similarly, keratolytics play a role in allowing a topically applied medication to penetrate deep enough to affect the underlying inflammation of psoriasis. Medications that include salicylic acid or urea may help to remove ostraceous scales from thick psoriasis lesions that would otherwise prevent delivery of topical steroids to achieve clinically meaningful results. For scalp psoriasis, there are salicylic acid solutions as well as newer agents such as a dimethicone-based topical product.11

Nonsteroidal topical anti-inflammatories also have been used off label for psoriasis treatment. These agents are especially useful in patients who were not successfully treated with calcipotriene or need adjunctive therapy. Although not extremely effective against plaque psoriasis, topical tacrolimus in particular seems to have a place in the treatment of inverse psoriasis where it can be utilized without concern for long-term side effects.12 Crisaborole ointment, a topical medication approved for treatment of atopic dermatitis, was studied in phase 2 trials, but development has not progressed for a psoriasis indication.13 It is reasonable to consider this medication in the same way that tacrolimus has been used, however, considering that the mechanism of action—phosphodiesterase type 4 inhibition—has successfully been implemented in an oral medication to treat psoriasis, apremilast.

There are numerous topical medications in the pipeline that are being developed to treat psoriasis. Of them, the most relevant is a fixed-dose combination of halobetasol propionate 0.01% and tazarotene 0.045% in a proprietary lotion vehicle. A decision from the US Food and Drug Administration is expected in the first quarter of 2019. This medication capitalizes on the aforementioned synergistic effects of tazarotene and a superpotent topical steroid to achieve improved efficacy. Similar to halobetasol lotion 0.01%, this product was evaluated over an 8-week period, and no HPA axis suppression was observed. Efficacy was significantly improved versus both placebo and either halobetasol or tazarotene alone.14

Overall, it is promising that after a long period of relative stagnancy, we have numerous new agents available and upcoming for the topical treatment of psoriasis. For the vast majority of patients, topical medications still represent the mainstay of treatment, and it is important that we have access to better, safer medications in this category.

- Murage MJ, Kern DM, Chang L, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with psoriasis using a large national payer database in the United States: a retrospective study [published online October 25, 2018]. J Med Econ. doi:10.1080/13696998.2018.1540424.

- Clobex [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2005.

- Ohman EM, Rogers S, Meenan FO, et al. Adrenal suppression following low-dose topical clobetasol propionate. J R Soc Med. 1987;80:422-424.

- Kerner M, Ishay A, Ziv M, et al. Evaluation of the pituitary-adrenal axis function in patients on topical steroid therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:215-216.

- Stein Gold L, Lebwohl M, Menter A, et al. Aerosol foam formulation of fixed combination calcipotriene plus betamethasone dipropionate is highly efficacious in patients with psoriasis vulgaris: pooled data from three randomized controlled studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:951-957.

- Paul C, Bang B, Lebwohl M. Fixed combination calcipotriol plus betamethasone dipropionate aerosol foam in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris: rationale for development and clinical profile. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18:115-121.

- Fowler JF Jr, Hebert AA, Sugarman J. DFD-01, a novel medium potency betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% emollient spray, demonstrates similar efficacy to augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% lotion for the treatment of moderate plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:154-162.

- Sidgiddi S, Pakunlu RI, Allenby K. Efficacy, safety, and potency of betamethasone dipropionate spray 0.05%: a treatment for adults with mildto-moderate plaque psoriasis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:14-22.

- Kerdel FA, Draelos ZD, Tyring SK, et al. A phase 2, multicenter, doubleblind, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical study to compare the safety and efficacy of a halobetasol propionate 0.01% lotion and halobetasol propionate 0.05% cream in the treatment of plaque psoriasis [published online November 5, 2018]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09 546634.2018.1523362.

- Lebwohl M, Poulin Y. Tazarotene in combination with topical corticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(4 pt 2):S139-S143.

- Hengge UR, Roschmann K, Candler H. Single-center, noninterventional clinical trial to assess the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of a dimeticone-based medical device in facilitating the removal of scales after topical application in patients with psoriasis corporis or psoriasis capitis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2017;7:41-49.

- Malecic N, Young H. Tacrolimus for the management of psoriasis: clinical utility and place in therapy. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2016;6:153-163.

- Nazarian R, Weinberg JM. AN-2728, a PDE4 inhibitor for the potential topical treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:1236-1242.

- Gold LS, Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination of halobetasol and tazarotene in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of 2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:287-293.

- Murage MJ, Kern DM, Chang L, et al. Treatment patterns among patients with psoriasis using a large national payer database in the United States: a retrospective study [published online October 25, 2018]. J Med Econ. doi:10.1080/13696998.2018.1540424.

- Clobex [package insert]. Fort Worth, TX: Galderma Laboratories, LP; 2005.

- Ohman EM, Rogers S, Meenan FO, et al. Adrenal suppression following low-dose topical clobetasol propionate. J R Soc Med. 1987;80:422-424.

- Kerner M, Ishay A, Ziv M, et al. Evaluation of the pituitary-adrenal axis function in patients on topical steroid therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:215-216.

- Stein Gold L, Lebwohl M, Menter A, et al. Aerosol foam formulation of fixed combination calcipotriene plus betamethasone dipropionate is highly efficacious in patients with psoriasis vulgaris: pooled data from three randomized controlled studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:951-957.

- Paul C, Bang B, Lebwohl M. Fixed combination calcipotriol plus betamethasone dipropionate aerosol foam in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris: rationale for development and clinical profile. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2017;18:115-121.

- Fowler JF Jr, Hebert AA, Sugarman J. DFD-01, a novel medium potency betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% emollient spray, demonstrates similar efficacy to augmented betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% lotion for the treatment of moderate plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:154-162.

- Sidgiddi S, Pakunlu RI, Allenby K. Efficacy, safety, and potency of betamethasone dipropionate spray 0.05%: a treatment for adults with mildto-moderate plaque psoriasis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:14-22.

- Kerdel FA, Draelos ZD, Tyring SK, et al. A phase 2, multicenter, doubleblind, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical study to compare the safety and efficacy of a halobetasol propionate 0.01% lotion and halobetasol propionate 0.05% cream in the treatment of plaque psoriasis [published online November 5, 2018]. J Dermatolog Treat. doi:10.1080/09 546634.2018.1523362.

- Lebwohl M, Poulin Y. Tazarotene in combination with topical corticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(4 pt 2):S139-S143.

- Hengge UR, Roschmann K, Candler H. Single-center, noninterventional clinical trial to assess the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of a dimeticone-based medical device in facilitating the removal of scales after topical application in patients with psoriasis corporis or psoriasis capitis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2017;7:41-49.

- Malecic N, Young H. Tacrolimus for the management of psoriasis: clinical utility and place in therapy. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2016;6:153-163.

- Nazarian R, Weinberg JM. AN-2728, a PDE4 inhibitor for the potential topical treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:1236-1242.

- Gold LS, Lebwohl MG, Sugarman JL, et al. Safety and efficacy of a fixed combination of halobetasol and tazarotene in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results of 2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:287-293.

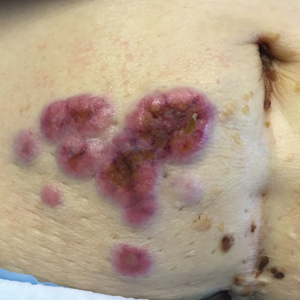

Erythematous Periumbilical Papules and Plaques

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

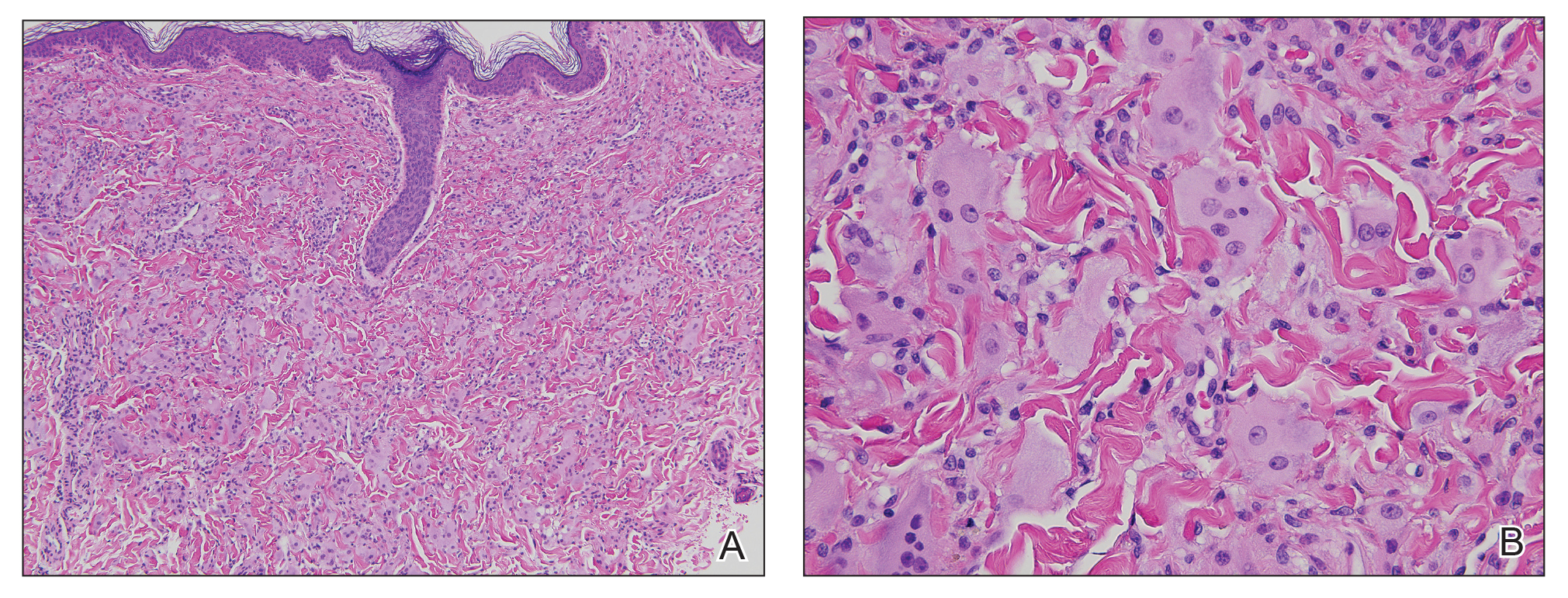

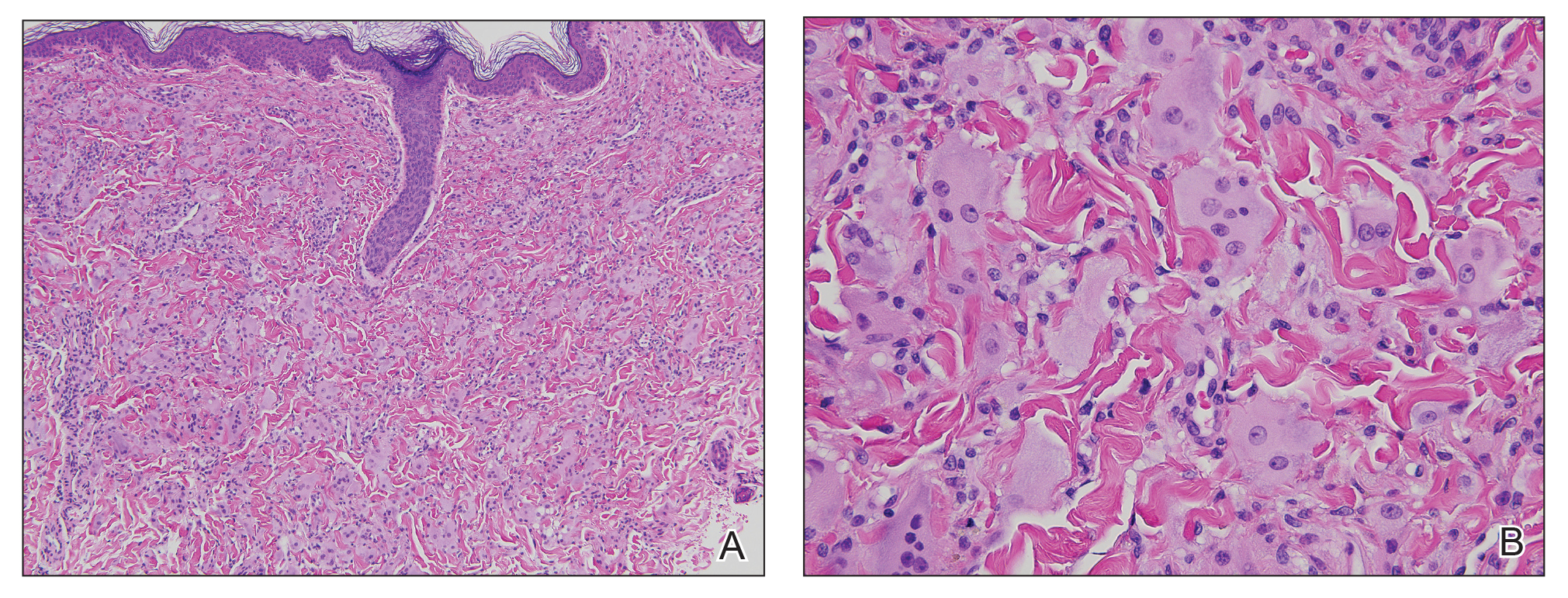

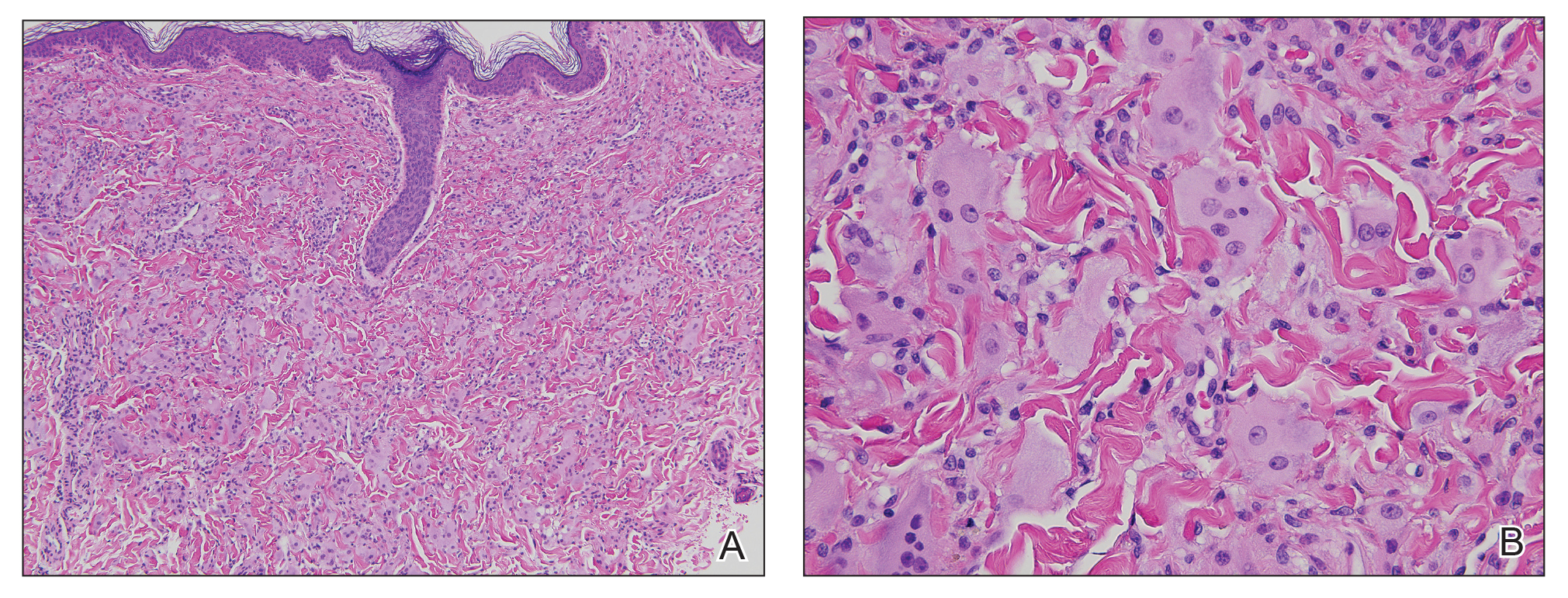

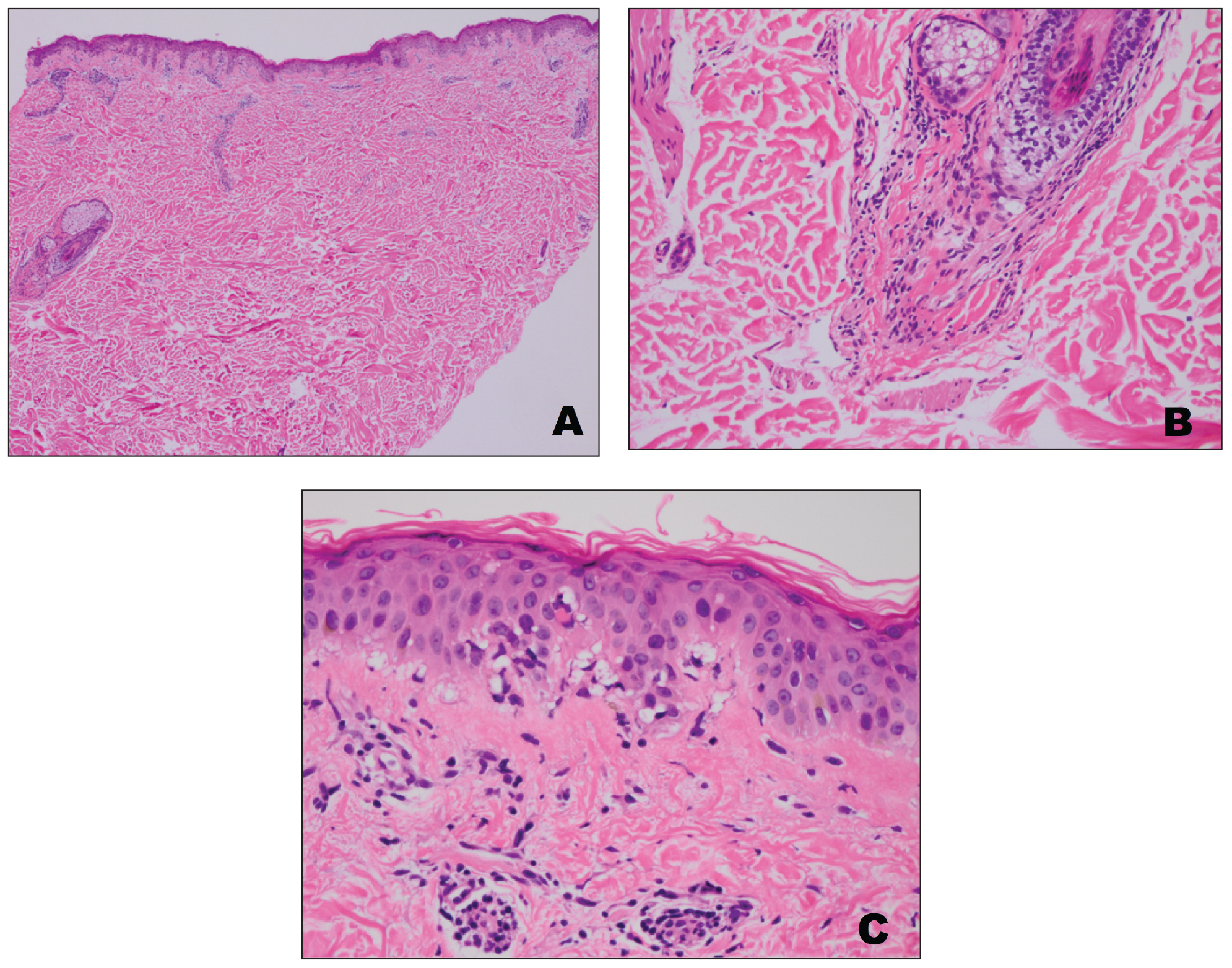

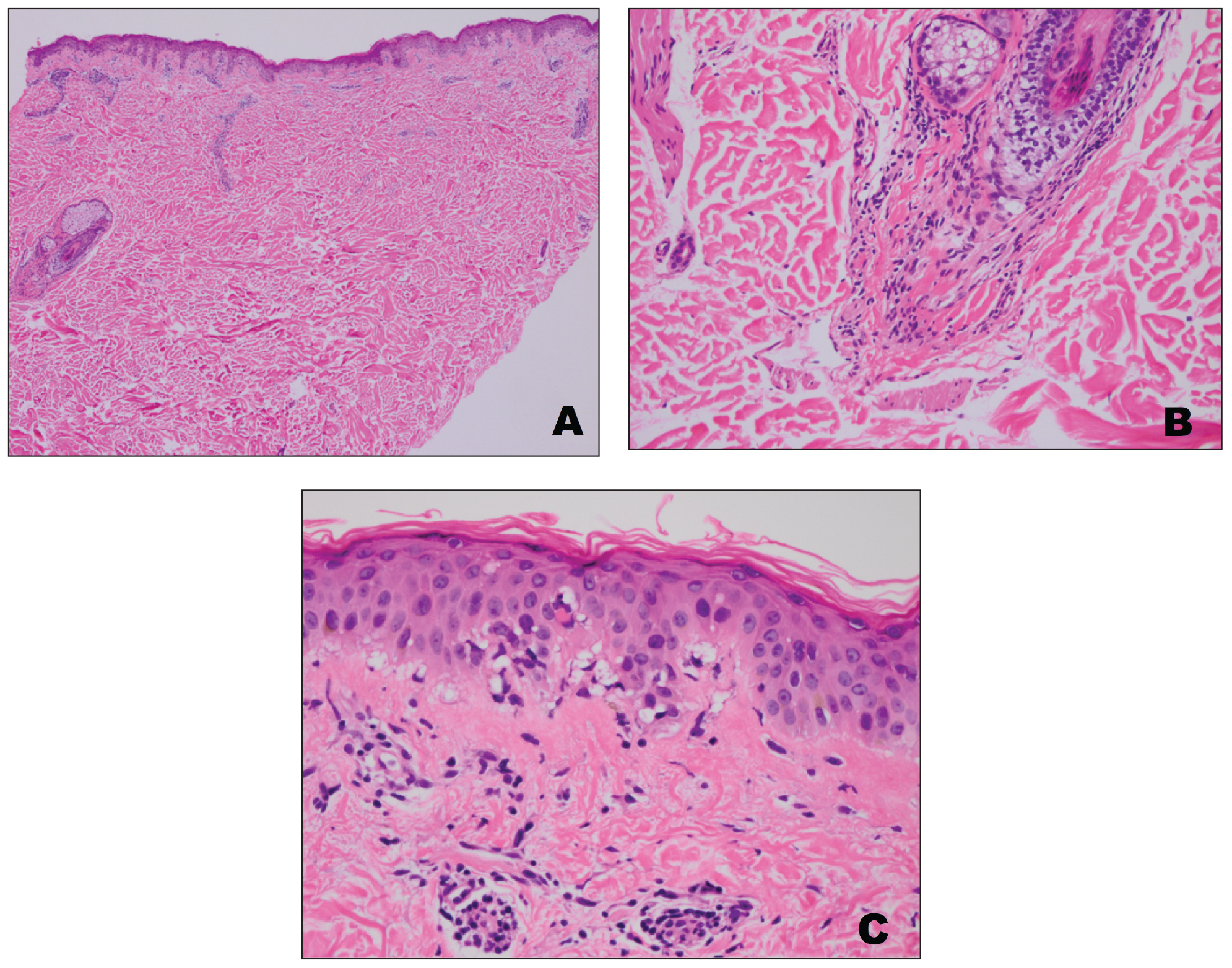

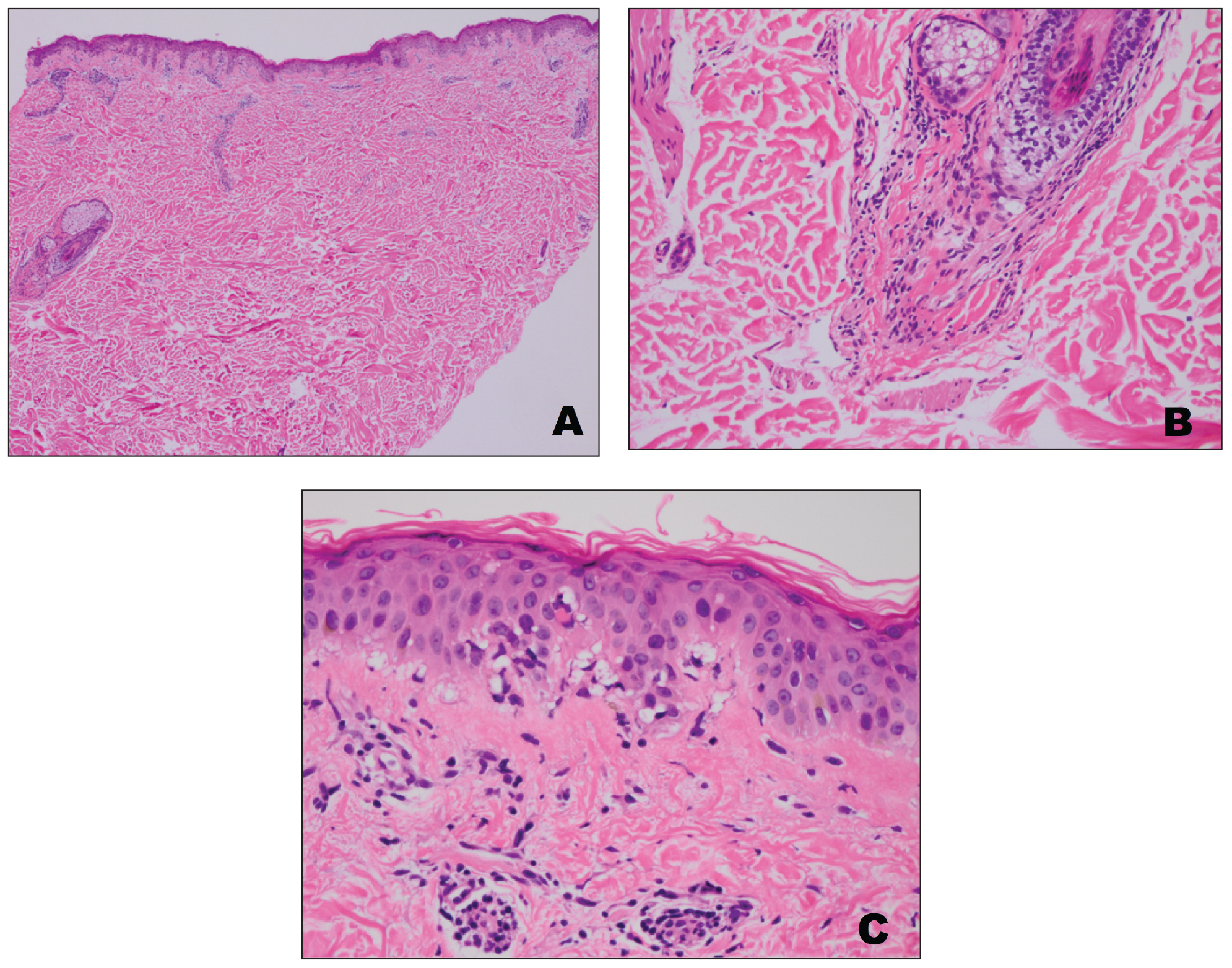

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

The Diagnosis: Metastatic Cancer

Further workup of patient 1 revealed an alkaline phosphatase level of 743 U/L (reference range, 30–120 U/L), total bilirubin level of 8.5 mg/dL (reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL), and a white blood cell count of 14,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated cancer of unknown primary site that had metastasized to the colon, liver, and lungs. There was suspicion for potential colon cancer as the primary disease; however, based on the cutaneous findings, a skin biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histology and immunohistochemistry revealed adenocarcinoma tumor cells positive for CDX2 (caudal type homeobox 2) and cytokeratin (CK) 7 with a subset positive for CK-20. The cells were negative for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 (GATA binding protein 3). Immunohistochemistry was most consistent with pancreatic cancer. During palliative percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage placement, a liver biopsy confirmed the skin biopsy results.

Further workup of patient 2 revealed a white blood cell count of 13,000/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL). Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed metastatic disease to the lungs with a suspicion for colon cancer as the primary site. Biopsy of the skin lesion revealed a mucin-producing adenocarcinoma, and immunohistochemistry was positive for keratin (AE1/AE3), CK-20, and CDX2, consistent with metastatic colon carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry of the biopsied skin lesion was nonreactive for CK-7. The patient had a colonoscopy that revealed a fungating, partially obstructing, circumferential large mass in the ascending colon.

Metastasis to the skin from visceral malignancies is not uncommon and may represent the first evidence of widespread disease, particularly in breast cancer or mucosal cancers of the head and neck.1 Cutaneous metastasis of colon cancer is uncommon and cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer is rare. Furthermore, nonumbilical sites are much more common than umbilical sites for cutaneous metastatic disease.2 Pancreatic cancer is estimated to be the origin of a cutaneous umbilical metastasis, frequently termed Sister Mary Joseph nodule, in 7% to 9% of cases; colon cancer is estimated to account for 13% to 15% of cases.3 Sister Mary Joseph nodule or sign refers to a nodule often bulging into the umbilicus, signifying metastasis from a

malignant cancer.

In a study of cutaneous metastases, 10% (42/420) of patients with metastatic disease had cutaneous metastasis; 0.48% (2/420) were due to pancreatic cancer and 4.3% (18/420) were due to colon cancer.4 In another review, 63 cases of cutaneous metastasis of pancreatic cancer were found, 43 of which were nonumbilical.2

On immunohistochemistry, CK-7 positivity is highly specific for pancreatic cancer.2 Cytokeratin 7 often is used in conjunction with CK-20 to differentiate various types of glandular tumors. CDX2 is a highly sensitive and specific marker for adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin.5 The negative estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, mammaglobin, gross cystic disease fluid protein, and GATA3 stains are useful in excluding breast cancer (patient 1 had history of breast cancer).

When cutaneous involvement is present in pancreatic cancer, the disease usually is widespread. Multiple studies have reported involvement of other organs with cutaneous metastasis at rates of 88.9%,6 90.3%,7 and 93.5%.2 However, early recognition of metastatic cancerous lesions can lead to earlier diagnosis and earlier palliative treatment, perhaps prolonging median survival time in patients. In a review of 63 patients with cutaneous metastatic pancreatic cancer, the authors found a median survival time of 5 months, with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination helping to improve survival time from a median of 3.0 to 8.3 months.2

The location of lesions and duration of disease in both patients was atypical for arthropod assault. Acyclovir-resistant herpes zoster rarely is reported outside of human immunodeficiency patients; in addition, there was a lack of clear dermatomal distribution. Although cutaneous Crohn disease can manifest as pink papules, it is rare and unlikely as a presenting symptom. Cutaneous sarcoidosis can take many different skin manifestations, and patients can have cutaneous involvement without systemic manifestation. In both patients, medical history was more indicative of metastatic cancer than the other options in the differential diagnosis.

Cutaneous metastasis from colon cancer and pancreatic cancer is rare, and the prognosis is poor in these cases; however, in the appropriate clinical scenario, especially in a patient with a history of cancer, sinister etiologies should be considered for firm red papules of the umbilicus. Skin biopsy coupled with immunohistochemical staining can assist in identifying the primary malignancy.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

- Schwartz RA. Cutaneous metastatic disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:161-165.

- Zhou HY, Wang XB, Gao F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic cancer: a case report and systematic review of the literature [published online October 10, 2014]. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:2654-2660.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph's nodule. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:410.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, et al. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immnohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310.

- Takeuchi H, Kawano T, Toda T, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a case report and a review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:275-277.

- Horino K, Hiraoka T, Kanemitsu K, et al. Subcutaneous metastases after curative resection for pancreatic carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 1999;19:406-408.

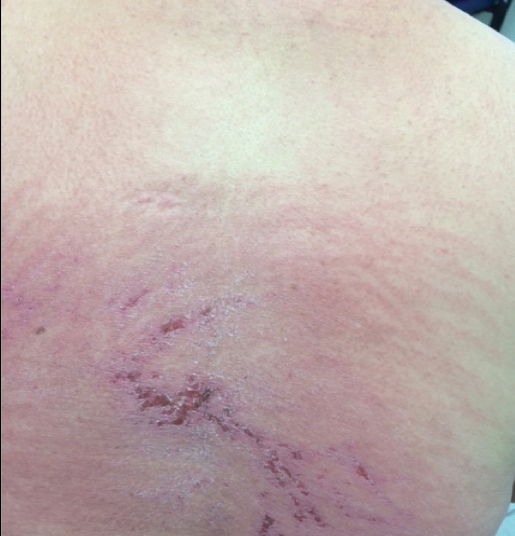

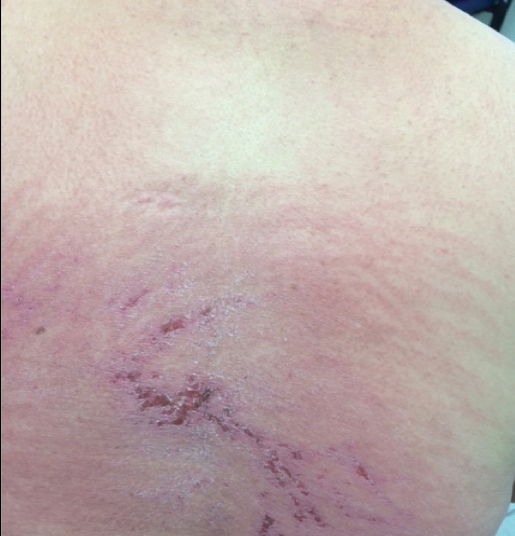

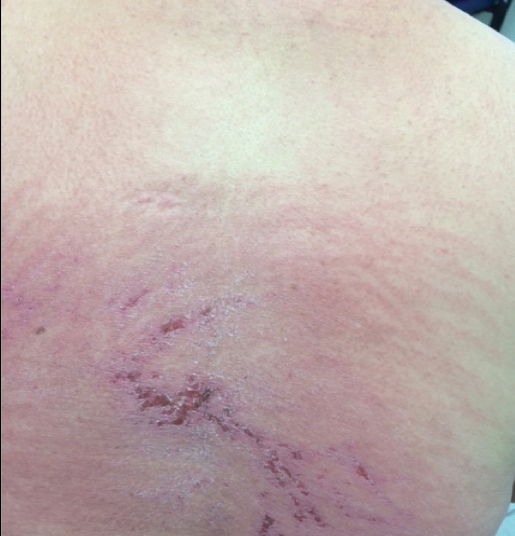

A 75-year-old woman (patient 1) with a history of localized invasive ductal breast cancer treated definitively with lumpectomy and radiation therapy more than a decade ago presented to the emergency department with jaundice, abdominal pain, weakness, and multiple periumbilical pink-red papules (top) of 2 weeks’ duration. Prior to presentation, the skin lesions did not improve with 10 days of acyclovir treatment prescribed by her primary care physician for presumed herpes zoster.

An 86-year-old man (patient 2) with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with ibrutinib presented to the emergency department with jaundice, abdominal pain, weakness, and multiple pink periumbilical papules (bottom) of 6 weeks’ duration. Prior to presentation, the skin lesions did not improve with 21 days of valacyclovir treatment prescribed by his oncologist for presumed herpes zoster.

The Dermatologist’s Role in Amputee Skin Care

Limb amputation is a major life-changing event that markedly affects a patient’s quality of life as well as his/her ability to participate in activities of daily living. The most prevalent causes for amputation include vascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, trauma, and cancer, respectively.1,2 For amputees, maintaining prosthetic use is a major physical and psychological undertaking that benefits from a multidisciplinary team approach. Although individuals with lower limb amputations are disproportionately impacted by skin disease due to the increased mechanical forces exerted over the lower limbs, patients with upper limb amputations also develop dermatologic conditions secondary to wearing prostheses.

Approximately 185,000 amputations occur each year in the United States.3 Although amputations resulting from peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus tend to occur in older individuals, amputations in younger patients usually occur from trauma.2 The US military has experienced increasing numbers of amputations from trauma due to the ongoing combat operations in the Middle East. Although improvements in body armor and tactical combat casualty care have reduced the number of preventable deaths, the number of casualties surviving with extremity injuries requiring amputation has increased.4,5 As of October 2017, 1705 US servicemembers underwent major limb amputations, with 1914 lower limb amputations and 302 upper limb amputations. These amputations mainly impacted men aged 21 to 29 years, but female servicemembers also were affected, and a small group of servicemembers had multiple amputations.6

One of the most common medical problems that amputees face during long-term care is skin disease, with approximately 75% of amputees using a lower limb prosthesis experiencing skin problems. In general, amputees experience nearly 65% more dermatologic concerns than the general population.7 In one study of 97 individuals with transfemoral amputations, some of the most common issues associated with socket prosthetics included heat and sweating in the prosthetic socket (72%) as well as sores and skin irritation from the socket (62%).8 Given the high incidence of skin disease on residual limbs, dermatologists are uniquely positioned to keep the amputee in his/her prosthesis and prevent prosthetic abandonment.

Complications Following Amputation

Although US military servicemembers who undergo amputations receive the very best prosthetic devices and rehabilitation resources, they still experience prosthesis abandonment.9 Despite the fact that prosthetic limbs and prosthesis technology have substantially improved over the last 2 decades, one study indicated that the high frequency of problems affecting tissue viability at residual limbs is due to the age-old problem of prosthetic fit.10 In patients with the most advanced prostheses, poor fit still results in mechanical damage to the skin, as the residual limb is exposed to unequal and shearing forces across the amputation site as well as high pressures that cause a vaso-occlusive effect.11,12 Issues with poor fit are especially important for more active patients, as they normally want to immediately return to their vigorous preinjury lifestyles. In these patients, even a properly fitting prosthetic may not be able to overcome the fact that the residual limb skin is not well suited for the mechanical forces generated by the prosthesis and the humid environment of the socket.1,13 Another complicating factor is the dynamic nature of the residual limb. Muscle atrophy, changes in gait, and weight gain or loss can lead to an ill-fitting prosthetic and subsequent skin breakdown.

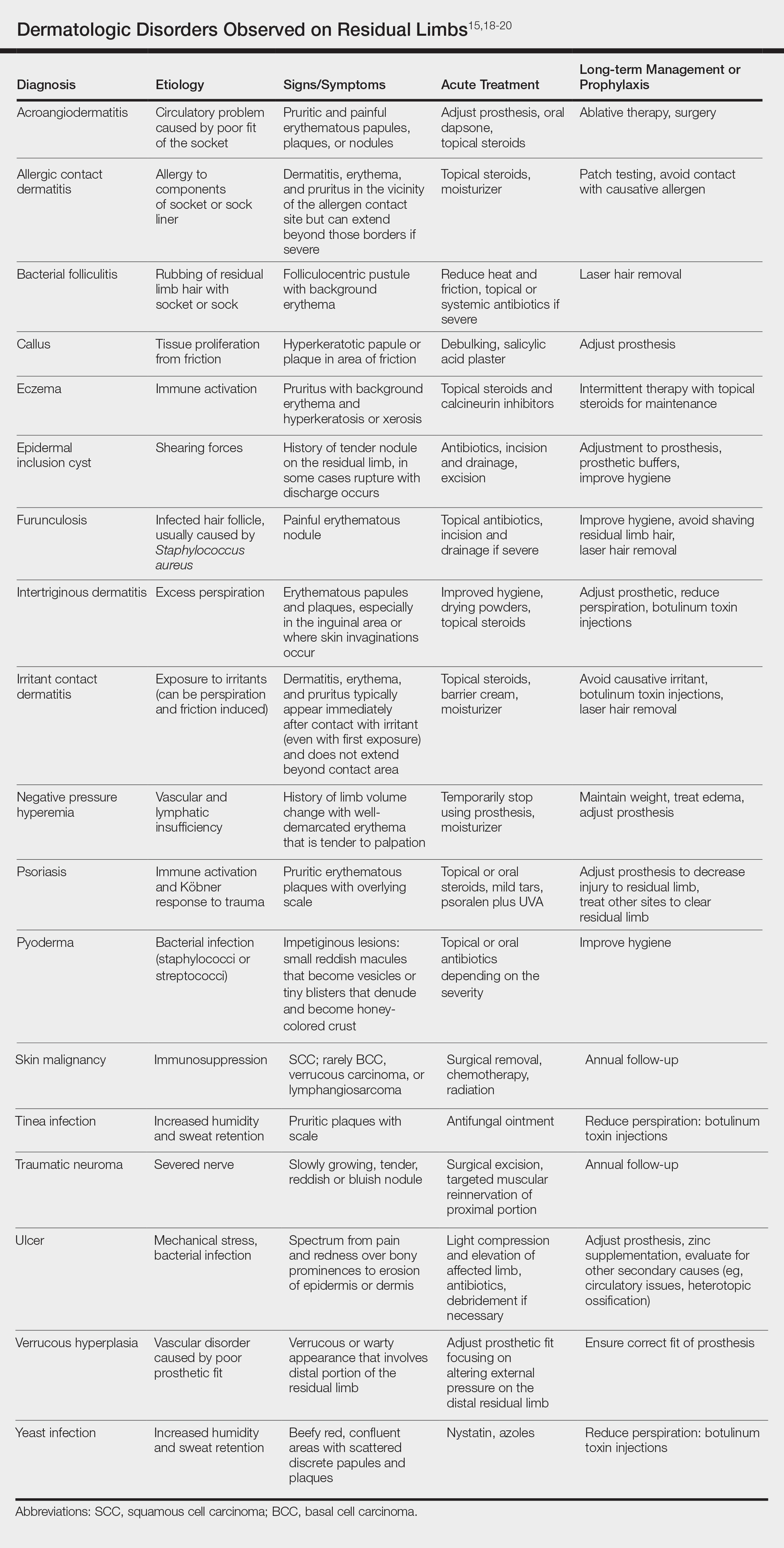

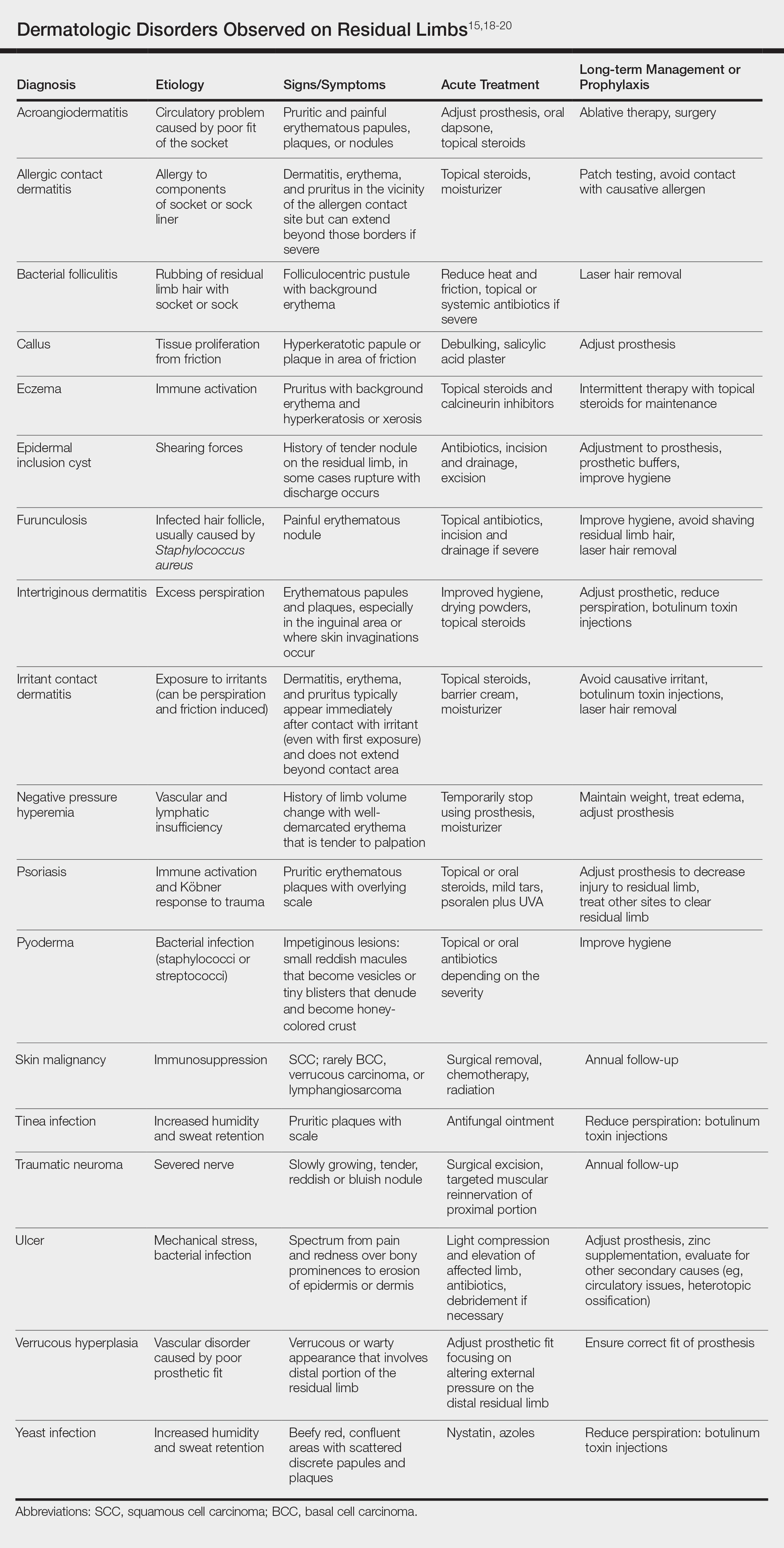

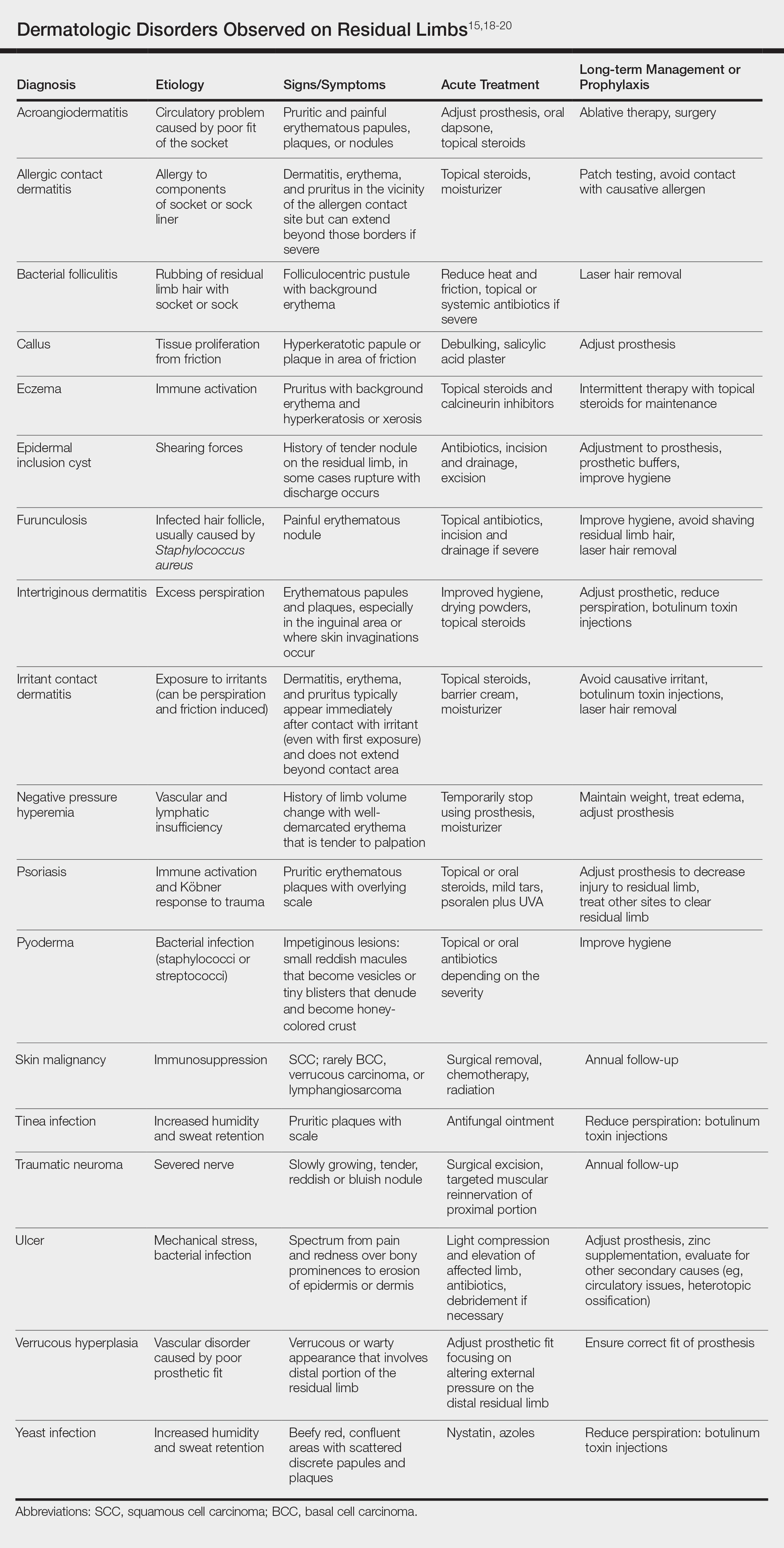

There are many case reports and review articles describing the skin problems in amputees.1,14-17 The Table summarizes these conditions and outlines treatment options for each.15,18-20

Most skin diseases on residual limbs are the result of mechanical skin breakdown, inflammation, infection, or combinations of these processes. Overall, amputees with diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease tend to have skin disease related to poor perfusion, whereas amputees who are active and healthy tend to have conditions related to mechanical stress.7,13,14,17,21,22 Bui et al17 reported ulcers, abscesses, and blisters as the most common skin conditions that occur at the site of residual limbs; however, other less common dermatologic disorders such as skin malignancies, verrucous hyperplasia and carcinoma, granulomatous cutaneous lesions, acroangiodermatitis, and bullous pemphigoid also are seen.23-26 Buikema and Meyerle15 hypothesize that these conditions, as well as the more common skin diseases, are partly from the amputation disrupting blood and lymphatic flow in the residual limb, which causes the site to act as an immunocompromised district that induces dysregulation of neuroimmune regulators.

It is important to note that skin disease on residual limbs is not just an acute problem. Long-term follow-up of 247 traumatic amputees from the Vietnam War showed that almost half of prosthesis users (48.2%) reported a skin problem in the preceding year, more than 38 years after the amputation. Additionally, one-quarter of these individuals experienced skin problems approximately 50% of the time, which unfortunately led to limited use or total abandonment of the prosthesis for the preceding year in 56% of the veterans surveyed.21

Other complications following amputation indirectly lead to skin problems. Heterotopic ossification, or the formation of bone at extraskeletal sites, has been observed in up to 65% of military amputees from recent operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.27,28 If symptomatic, heterotopic ossification can lead to poor prosthetic fit and subsequent skin breakdown. As a result, it has been reported that up to 40% of combat-related lower extremity amputations may require excision of heterotopic ossificiation.29

Amputation also can result in psychologic concerns that indirectly affect skin health. A systematic review by Mckechnie and John30 suggested that despite heterogeneity between studies, even using the lowest figures demonstrated the significance anxiety and depression play in the lives of traumatic amputees. If left untreated, these mental health issues can lead to poor residual limb hygiene and prosthetic maintenance due to reductions in the patient’s energy and motivation. Studies have shown that proper hygiene of residual limbs and silicone liners reduces associated skin problems.19,31

Role of the Dermatologist

Routine care and conservative management of amputee skin problems often are accomplished by prosthetists, primary care physicians, nurses, and physical therapists. In one study, more than 80% of the most common skin problems affecting amputees could be attributed to the prosthesis itself, which highlights the importance of the continued involvement of the prosthetist beyond the initial fitting period.13 However, when a skin problem becomes refractory to conservative management, referral to a dermatologist is prudent; therefore, the dermatologist is an integral member of the multidisciplinary team that provides care for amputees.

The dermatologist often is best positioned to diagnose skin diseases that result from wearing prostheses and is well versed in treatments for short-term and long-term management of skin disease on residual limbs. The dermatologist also can offer prophylactic treatments to decrease sweating and hair growth to prevent potential infections and subsequent skin breakdown. Additionally, proper education on self-care has been shown to decrease the amount of skin problems and increase functional status and quality of life for amputees.32,33 Dermatologists can assist with the patient education process as well as refer amputees to a useful resource from the Amputee Coalition website (www.amputee-coalition.org) to provide specific patient education on how to maintain skin on the residual limb to prevent skin disease.

Current Treatments and Future Directions

Skin disorders affecting residual limbs usually are conditions that dermatologists commonly encounter and are comfortable managing in general practice. Additionally, dermatologists routinely treat hyperhidrosis and conduct laser hair removal, both of which are effective prophylactic adjuncts for amputee skin health. There are a few treatments for reducing residual limb hyperhidrosis that are particularly useful. Although first-line treatment of residual limb hyperhidrosis often is topical aluminum chloride, it requires frequent application and often causes considerable skin irritation when applied to residual limbs. Alternatively, intradermal botulinum toxin has been shown to successfully reduce sweat production in individuals with residual limb hyperhidrosis and is well tolerated.34 A 2017 case report discussed the use of microwave thermal ablation of eccrine coils using a noninvasive 3-step hyperhidrosis treatment system on a bilateral below-the-knee amputee. The authors reported the patient tolerated the procedure well with decreased dermatitis and folliculitis, leading to his ability to wear a prosthetic for longer periods of time.35

Ablative fractional resurfacing with a CO2 laser is another key treatment modality central to amputees, more specifically to traumatic amputees. A CO2 laser can decrease skin tension and increase skin mobility associated with traumatic scars as well as decrease skin vulnerability to biofilms present in chronic wounds on residual limbs. It is believed that the pattern of injury caused by ablative fractional lasers disrupts biofilms and stimulates growth factor secretion and collagen remodeling through the concept of photomicrodebridement.36 The ablative fractional resurfacing approach to scar therapy and chronic wound debridement can result in less skin injury, allowing the amputee to continue rehabilitation and return more quickly to prosthetic use.37

One interesting area of research in amputee care involves the study of novel ways to increase the skin’s ability to adapt to mechanical stress and load bearing and accelerate wound healing on the residual limb. Multiple studies have identified collagen fibril enlargement as an important component of skin adaptation, and biomolecules such as decorin may enhance this process.38-40 The concept of increasing these biomolecules at the correct time during wound healing to strengthen the residual limb tissue currently is being studied.39

Another encouraging area of research is the involvement of fibroblasts in cutaneous wound healing and their role in determining the phenotype of residual limb skin in amputees. The clinical application of autologous fibroblasts is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for cosmetic use as a filler material and currently is under research for other applications, such as skin regeneration after surgery or manipulating skin characteristics to enhance the durability of residual limbs.41

Future preventative care of amputee skin may rely on tracking residual limb health before severe tissue injury occurs. For instance, Rink et al42 described an approach to monitor residual limb health using noninvasive imaging (eg, hyperspectral imaging, laser speckle imaging) and noninvasive probes that measure oxygenation, perfusion, skin barrier function, and skin hydration to the residual limb. Although these limb surveillance sensors would be employed by prosthetists, the dermatologist, as part of the multispecialty team, also could leverage the data for diagnosis and treatment considerations.

Final Thoughts

The dermatologist is an important member of the multidisciplinary team involved in the care of amputees. Skin disease is prevalent in amputees throughout their lives and often leads to abandonment of prostheses. Although current therapies and preventative treatments are for the most part successful, future research involving advanced technology to monitor skin health, increasing residual limb skin durability at the molecular level, and targeted laser therapies are promising. Through engagement and effective collaboration with the entire multidisciplinary team, dermatologists will have a considerable impact on amputee skin health.

- Dudek NL, Marks MB, Marshall SC, et al. Dermatologic conditions associated with use of a lower-extremity prosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:659-663.

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, et al. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:422-429.

- Kozak LJ. Ambulatory and Inpatient Procedures in the United States, 1995. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1998.

- Epstein RA, Heinemann AW, McFarland LV. Quality of life for veterans and servicemembers with major traumatic limb loss from Vietnam and OIF/OEF conflicts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:373-385.

- Dougherty AL, Mohrle CR, Galarneau MR, et al. Battlefield extremity injuries in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Injury. 2009;40:772-777.

- Farrokhi S, Perez K, Eskridge S, et al. Major deployment-related amputations of lower and upper limbs, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2017. MSMR. 2018;25:10-16.

- Highsmith MJ, Highsmith JT. Identifying and managing skin issues with lower-limb prosthetic use. Amputee Coalition website. https://www.amputee-coalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/.../skin_issues_lower.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2019.

- Hagberg K, Brånemark R. Consequences of non-vascular trans-femoral amputation: a survey of quality of life, prosthetic use and problems. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2001;25:186-194.

- Gajewski D, Granville R. The United States Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(10 spec no):S183-S187.

- Butler K, Bowen C, Hughes AM, et al. A systematic review of the key factors affecting tissue viability and rehabilitation outcomes of the residual limb in lower extremity traumatic amputees. J Tissue Viability. 2014;23:81-93.

- Mak AF, Zhang M, Boone DA. State-of-the-art research in lower-limb prosthetic biomechanics-socket interface: a review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38:161-174.

- Silver-Thorn MB, Steege JW. A review of prosthetic interface stress investigations. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1996;33:253-266.

- Dudek NL, Marks MB, Marshall SC. Skin problems in an amputee clinic. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:424-429.

- Meulenbelt HE, Geertzen JH, Dijkstra PU, et al. Skin problems in lower limb amputees: an overview by case reports. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:147-155.

- Buikema KE, Meyerle JH. Amputation stump: privileged harbor for infections, tumors, and immune disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:670-677.

- Highsmith JT, Highsmith MJ. Common skin pathology in LE prosthesis users. JAAPA. 2007;20:33-36, 47.

- Bui KM, Raugi GJ, Nguyen VQ, et al. Skin problems in individuals with lower-limb loss: literature review and proposed classification system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:1085-1090.

- Levy SW. Skin Problems of the Amputee. St. Louis, MO: Warren H. Green Inc; 1983.

- Levy SW, Allende MF, Barnes GH. Skin problems of the leg amputee. Arch Dermatol. 1962;85:65-81.

- Dumanian GA, Potter BK, Mioton LM, et al. Targeted muscle reinnervation treats neuroma and phantom pain in major limb amputees: a randomized clinical trial [published October 26, 2018]. Ann Surg. 2018. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003088.

- Yang NB, Garza LA, Foote CE, et al. High prevalence of stump dermatoses 38 years or more after amputation. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1283-1286.

- Meulenbelt HE, Geertzen JH, Jonkman MF, et al. Determinants of skin problems of the stump in lower-limb amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:74-81.

- Lin CH, Ma H, Chung MT, et al. Granulomatous cutaneous lesions associated with risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia in an amputated upper limb: risperidone-induced cutaneous granulomas. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:75-78.

- Schwartz RA, Bagley MP, Janniger CK, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of a leg amputation stump. Dermatology. 1991;182:193-195.

- Reilly GD, Boulton AJ, Harrington CI. Stump pemphigoid: a new complication of the amputee. Br Med J. 1983;287:875-876.

- Turan H, Bas¸kan EB, Adim SB, et al. Acroangiodermatitis in a below-knee amputation stump: correspondence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:560-561.

- Edwards DS, Kuhn KM, Potter BK, et al. Heterotopic ossification: a review of current understanding, treatment, and future. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30(suppl 3):S27-S30.

- Potter BK, Burns TC, Lacap AP, et al. Heterotopic ossification following traumatic and combat-related amputations: prevalence, risk factors, and preliminary results of excision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:476-486.

- Tintle SM, Shawen SB, Forsberg JA, et al. Reoperation after combat-related major lower extremity amputations. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:232-237.

- Mckechnie PS, John A. Anxiety and depression following traumatic limb amputation: a systematic review. Injury. 2014;45:1859-1866.

- Hachisuka K, Nakamura T, Ohmine S, et al. Hygiene problems of residual limb and silicone liners in transtibial amputees wearing the total surface bearing socket. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1286-1290.

- Pantera E, Pourtier-Piotte C, Bensoussan L, et al. Patient education after amputation: systematic review and experts’ opinions. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57:143-158.

- Blum C, Ehrler S, Isner ME. Assessment of therapeutic education in 135 lower limb amputees. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59:E161.

- Pasquina PF, Perry BN, Alphonso AL, et al. Residual limb hyperhidrosis and rimabotulinumtoxinB: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;97:659-664.e2.

- Mula KN, Winston J, Pace S, et al. Use of a microwave device for treatment of amputation residual limb hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:149-152.

- Shumaker PR, Kwan JM, Badiavas EV, et al. Rapid healing of scar-associated chronic wounds after ablative fractional resurfacing. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1289-1293.

- Anderson RR, Donelan MB, Hivnor C, et al. Laser treatment of traumatic scars with an emphasis on ablative fractional laser resurfacing: consensus report. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:187-193.

- Sanders JE, Mitchell SB, Wang YN, et al. An explant model for the investigation of skin adaptation to mechanical stress. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2002;49(12 pt 2):1626-1631.

- Wang YN, Sanders JE. How does skin adapt to repetitive mechanical stress to become load tolerant? Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:29-35.

- Sanders JE, Goldstein BS. Collagen fibril diameters increase and fibril densities decrease in skin subjected to repetitive compressive and shear stresses. J Biomech. 2001;34:1581-1587.

- Thangapazham R, Darling T, Meyerle J. Alteration of skin properties with autologous dermal fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:8407-8427.

- Rink CL, Wernke MM, Powell HM, et al. Standardized approach to quantitatively measure residual limb skin health in individuals with lower limb amputation. Adv Wound Care. 2017;6:225-232.

Limb amputation is a major life-changing event that markedly affects a patient’s quality of life as well as his/her ability to participate in activities of daily living. The most prevalent causes for amputation include vascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, trauma, and cancer, respectively.1,2 For amputees, maintaining prosthetic use is a major physical and psychological undertaking that benefits from a multidisciplinary team approach. Although individuals with lower limb amputations are disproportionately impacted by skin disease due to the increased mechanical forces exerted over the lower limbs, patients with upper limb amputations also develop dermatologic conditions secondary to wearing prostheses.

Approximately 185,000 amputations occur each year in the United States.3 Although amputations resulting from peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus tend to occur in older individuals, amputations in younger patients usually occur from trauma.2 The US military has experienced increasing numbers of amputations from trauma due to the ongoing combat operations in the Middle East. Although improvements in body armor and tactical combat casualty care have reduced the number of preventable deaths, the number of casualties surviving with extremity injuries requiring amputation has increased.4,5 As of October 2017, 1705 US servicemembers underwent major limb amputations, with 1914 lower limb amputations and 302 upper limb amputations. These amputations mainly impacted men aged 21 to 29 years, but female servicemembers also were affected, and a small group of servicemembers had multiple amputations.6

One of the most common medical problems that amputees face during long-term care is skin disease, with approximately 75% of amputees using a lower limb prosthesis experiencing skin problems. In general, amputees experience nearly 65% more dermatologic concerns than the general population.7 In one study of 97 individuals with transfemoral amputations, some of the most common issues associated with socket prosthetics included heat and sweating in the prosthetic socket (72%) as well as sores and skin irritation from the socket (62%).8 Given the high incidence of skin disease on residual limbs, dermatologists are uniquely positioned to keep the amputee in his/her prosthesis and prevent prosthetic abandonment.

Complications Following Amputation

Although US military servicemembers who undergo amputations receive the very best prosthetic devices and rehabilitation resources, they still experience prosthesis abandonment.9 Despite the fact that prosthetic limbs and prosthesis technology have substantially improved over the last 2 decades, one study indicated that the high frequency of problems affecting tissue viability at residual limbs is due to the age-old problem of prosthetic fit.10 In patients with the most advanced prostheses, poor fit still results in mechanical damage to the skin, as the residual limb is exposed to unequal and shearing forces across the amputation site as well as high pressures that cause a vaso-occlusive effect.11,12 Issues with poor fit are especially important for more active patients, as they normally want to immediately return to their vigorous preinjury lifestyles. In these patients, even a properly fitting prosthetic may not be able to overcome the fact that the residual limb skin is not well suited for the mechanical forces generated by the prosthesis and the humid environment of the socket.1,13 Another complicating factor is the dynamic nature of the residual limb. Muscle atrophy, changes in gait, and weight gain or loss can lead to an ill-fitting prosthetic and subsequent skin breakdown.

There are many case reports and review articles describing the skin problems in amputees.1,14-17 The Table summarizes these conditions and outlines treatment options for each.15,18-20

Most skin diseases on residual limbs are the result of mechanical skin breakdown, inflammation, infection, or combinations of these processes. Overall, amputees with diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease tend to have skin disease related to poor perfusion, whereas amputees who are active and healthy tend to have conditions related to mechanical stress.7,13,14,17,21,22 Bui et al17 reported ulcers, abscesses, and blisters as the most common skin conditions that occur at the site of residual limbs; however, other less common dermatologic disorders such as skin malignancies, verrucous hyperplasia and carcinoma, granulomatous cutaneous lesions, acroangiodermatitis, and bullous pemphigoid also are seen.23-26 Buikema and Meyerle15 hypothesize that these conditions, as well as the more common skin diseases, are partly from the amputation disrupting blood and lymphatic flow in the residual limb, which causes the site to act as an immunocompromised district that induces dysregulation of neuroimmune regulators.

It is important to note that skin disease on residual limbs is not just an acute problem. Long-term follow-up of 247 traumatic amputees from the Vietnam War showed that almost half of prosthesis users (48.2%) reported a skin problem in the preceding year, more than 38 years after the amputation. Additionally, one-quarter of these individuals experienced skin problems approximately 50% of the time, which unfortunately led to limited use or total abandonment of the prosthesis for the preceding year in 56% of the veterans surveyed.21

Other complications following amputation indirectly lead to skin problems. Heterotopic ossification, or the formation of bone at extraskeletal sites, has been observed in up to 65% of military amputees from recent operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.27,28 If symptomatic, heterotopic ossification can lead to poor prosthetic fit and subsequent skin breakdown. As a result, it has been reported that up to 40% of combat-related lower extremity amputations may require excision of heterotopic ossificiation.29

Amputation also can result in psychologic concerns that indirectly affect skin health. A systematic review by Mckechnie and John30 suggested that despite heterogeneity between studies, even using the lowest figures demonstrated the significance anxiety and depression play in the lives of traumatic amputees. If left untreated, these mental health issues can lead to poor residual limb hygiene and prosthetic maintenance due to reductions in the patient’s energy and motivation. Studies have shown that proper hygiene of residual limbs and silicone liners reduces associated skin problems.19,31

Role of the Dermatologist