User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Risk for Appendicitis, Cholecystitis, or Diverticulitis in Patients With Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

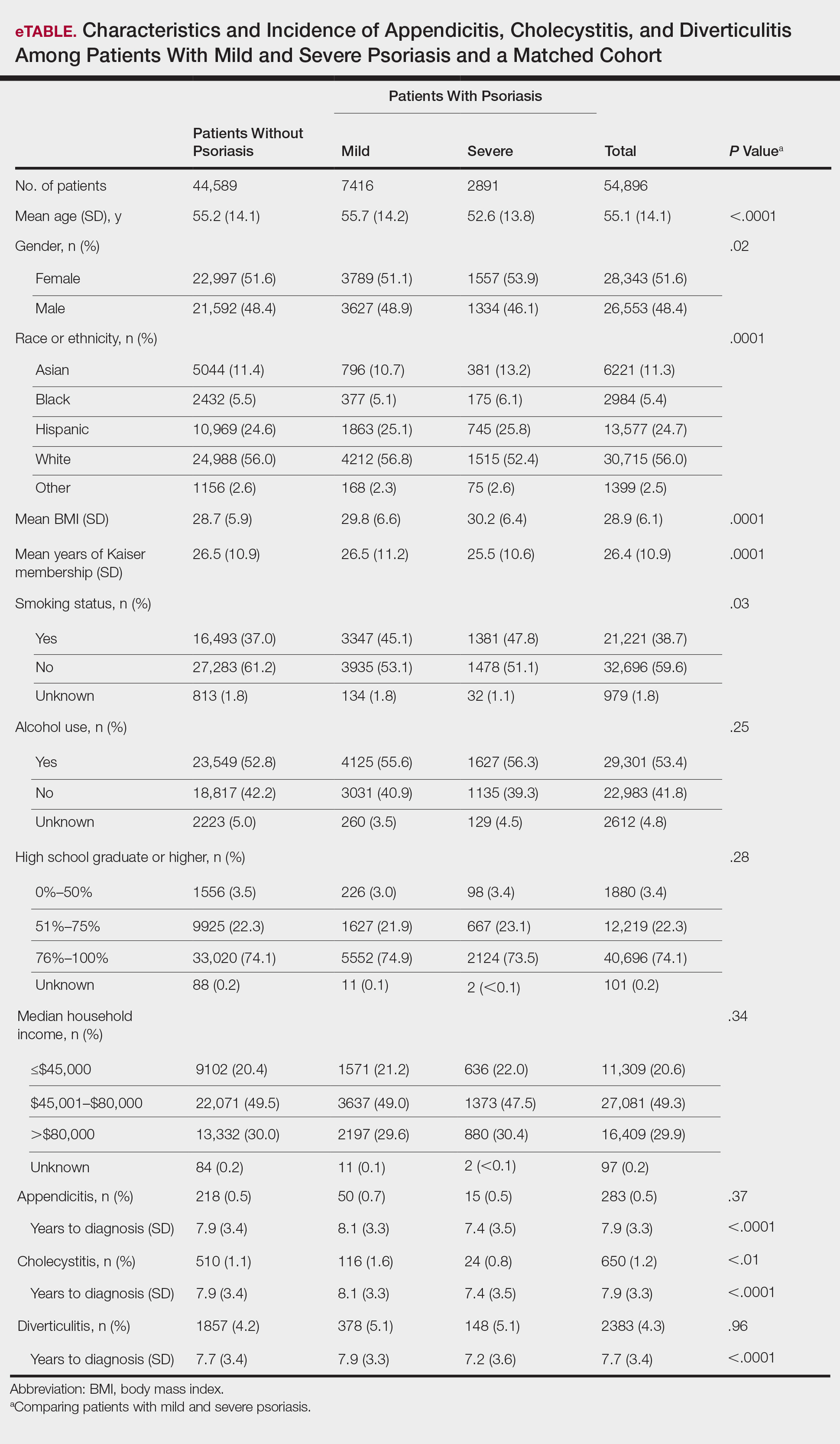

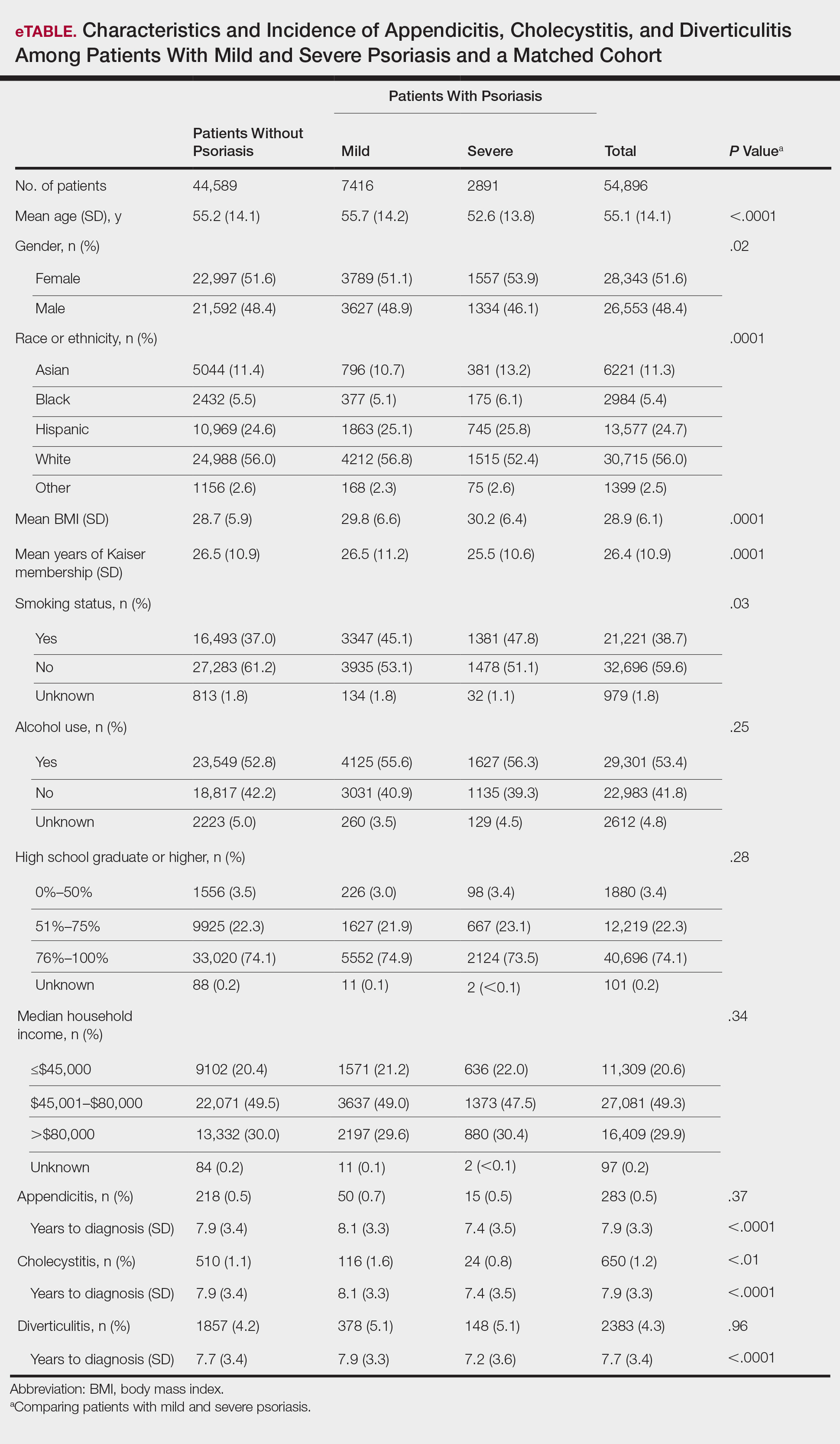

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

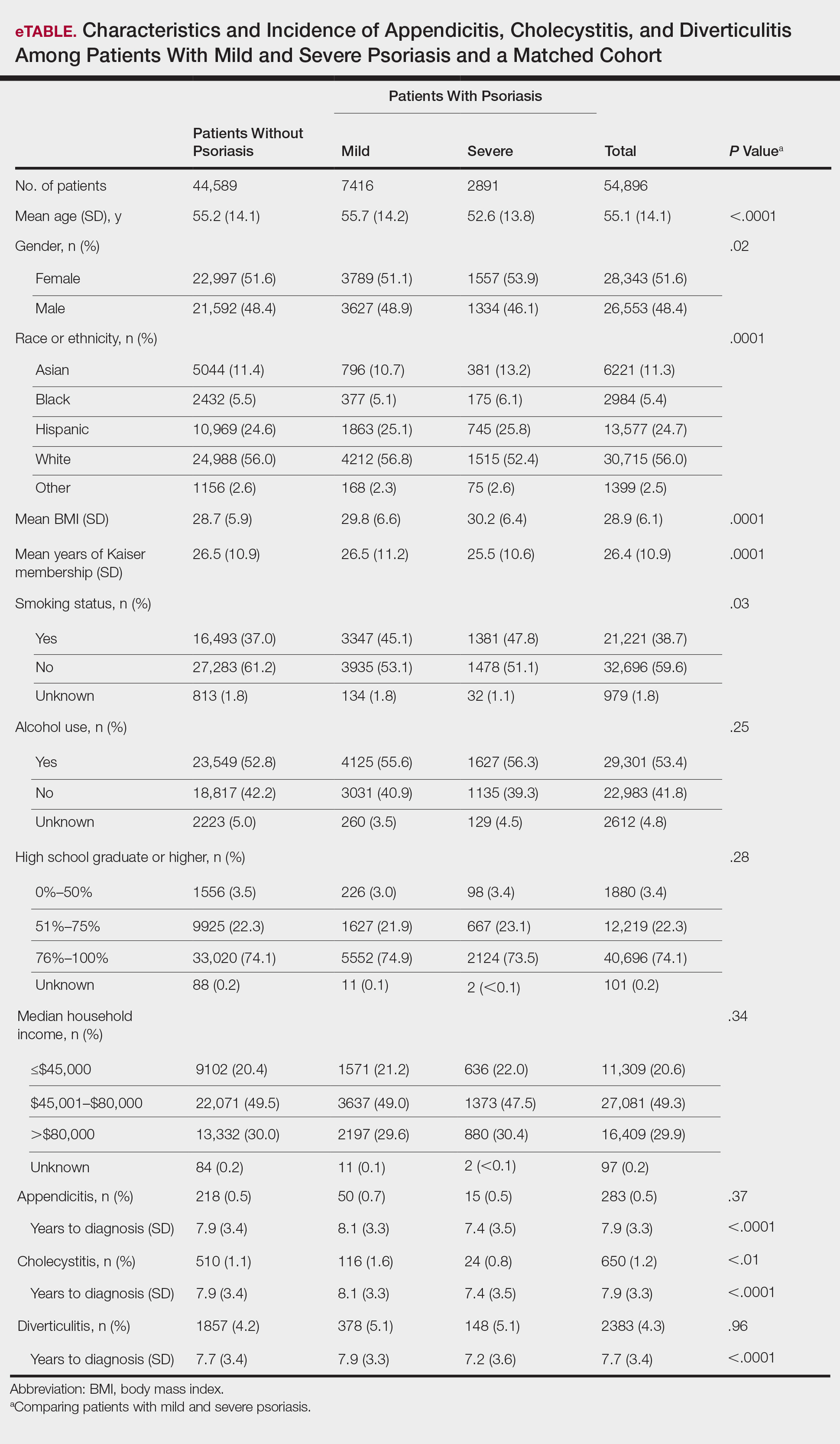

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

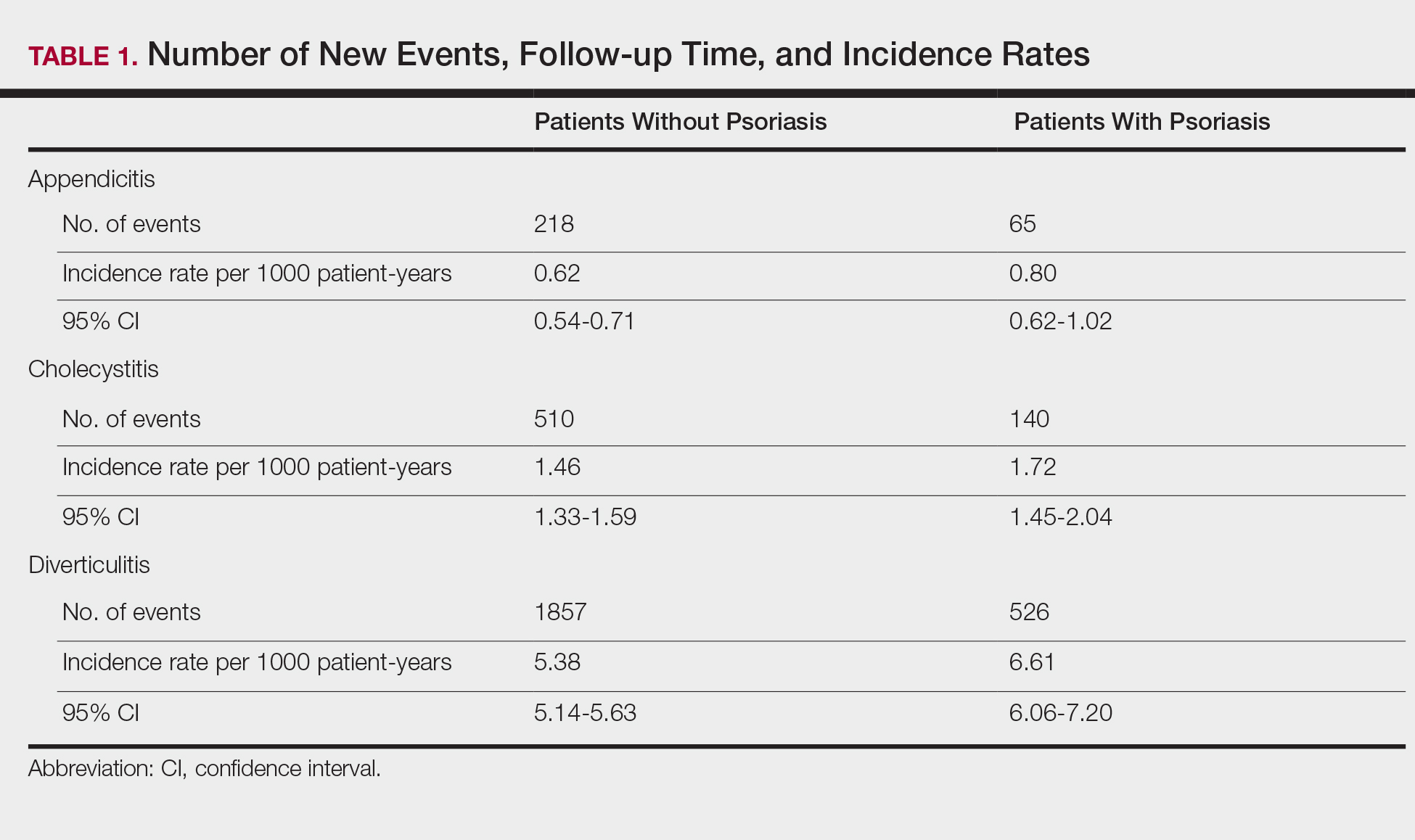

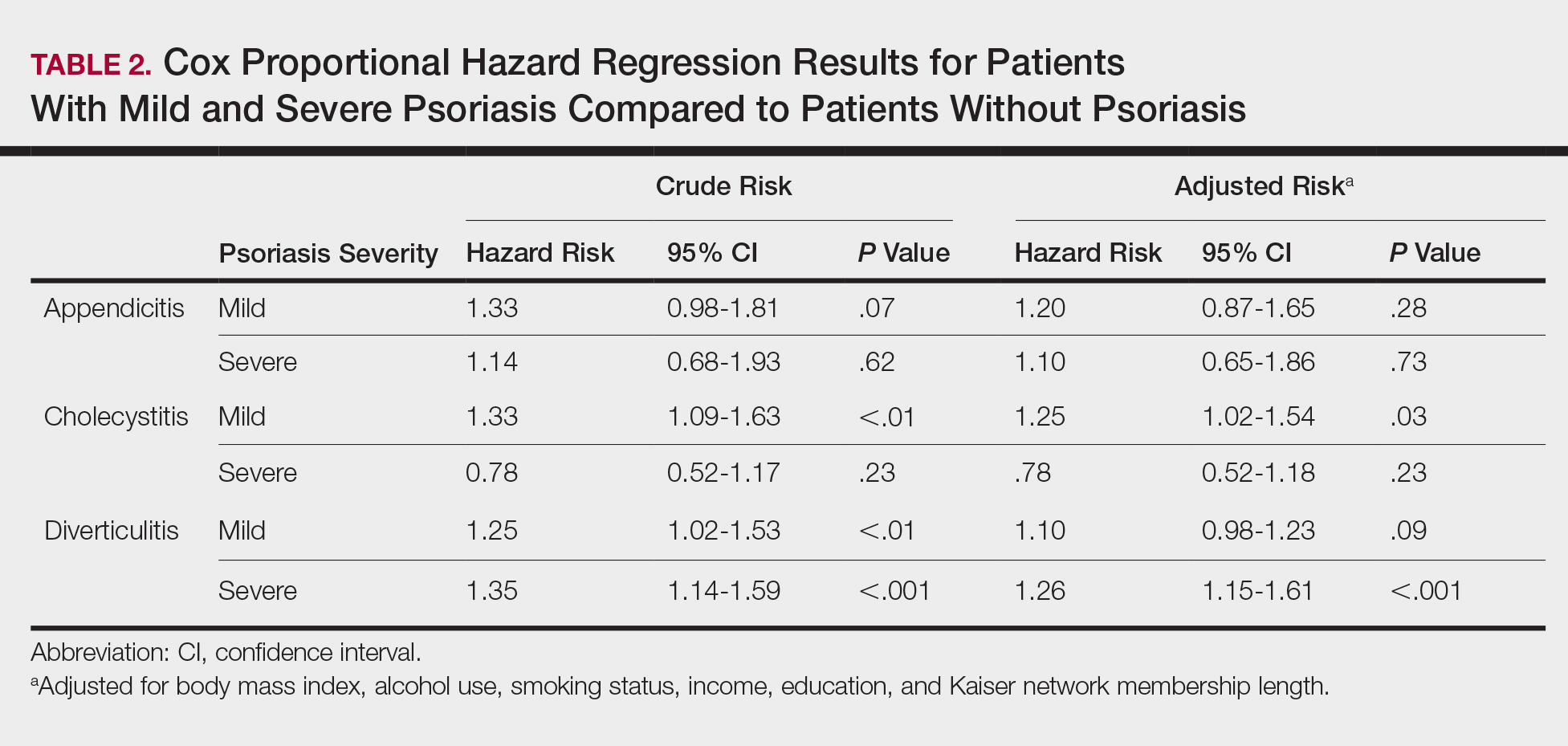

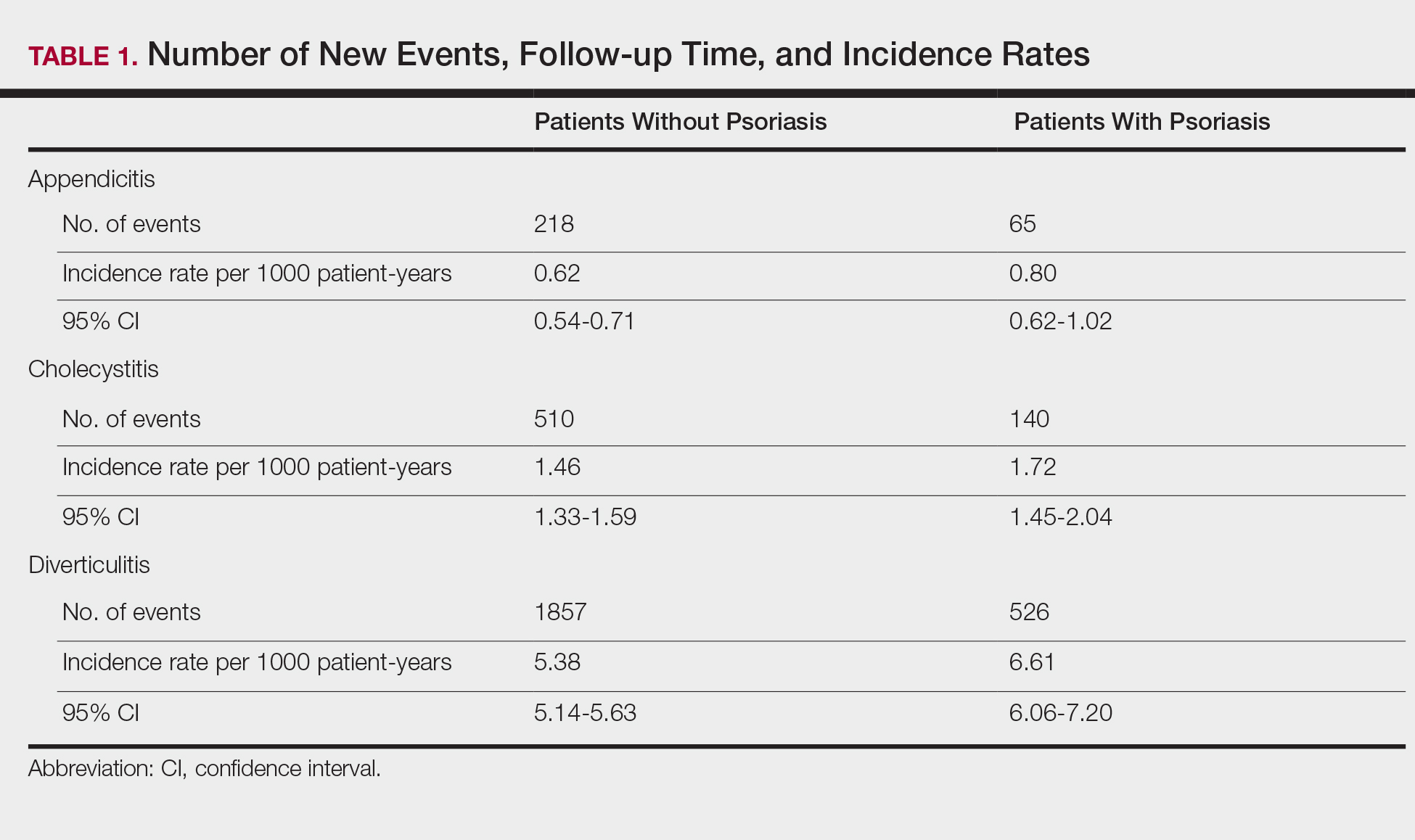

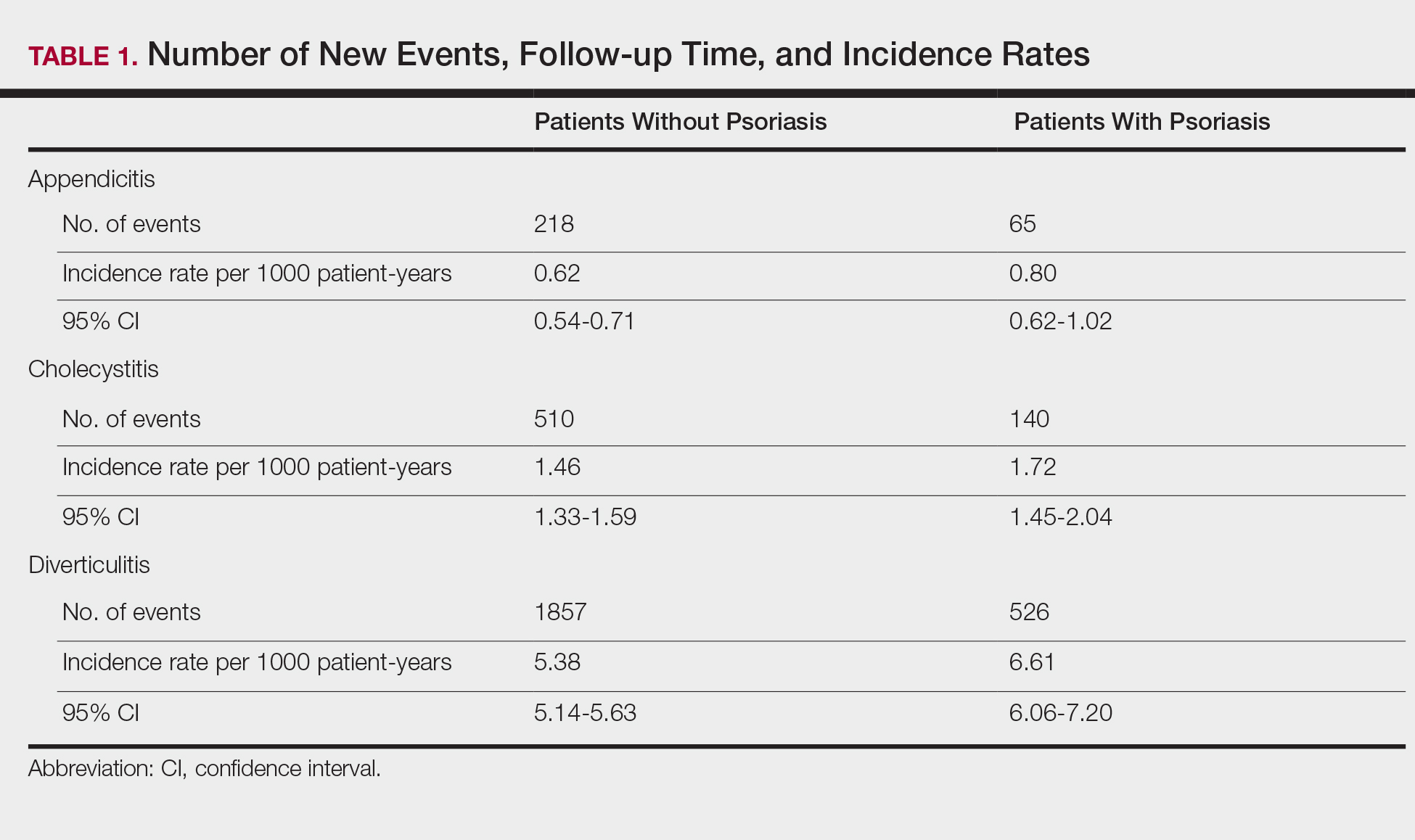

Appendicitis

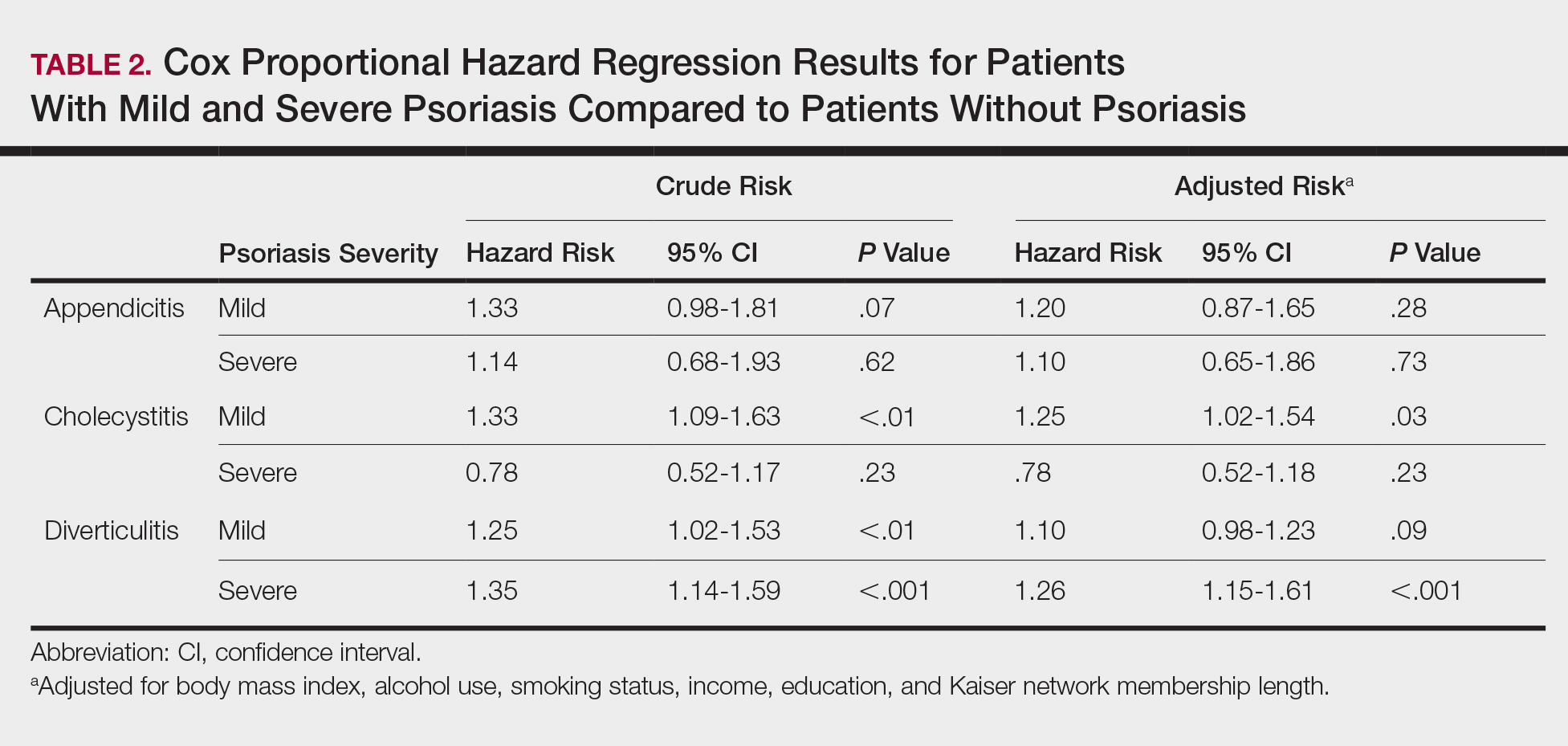

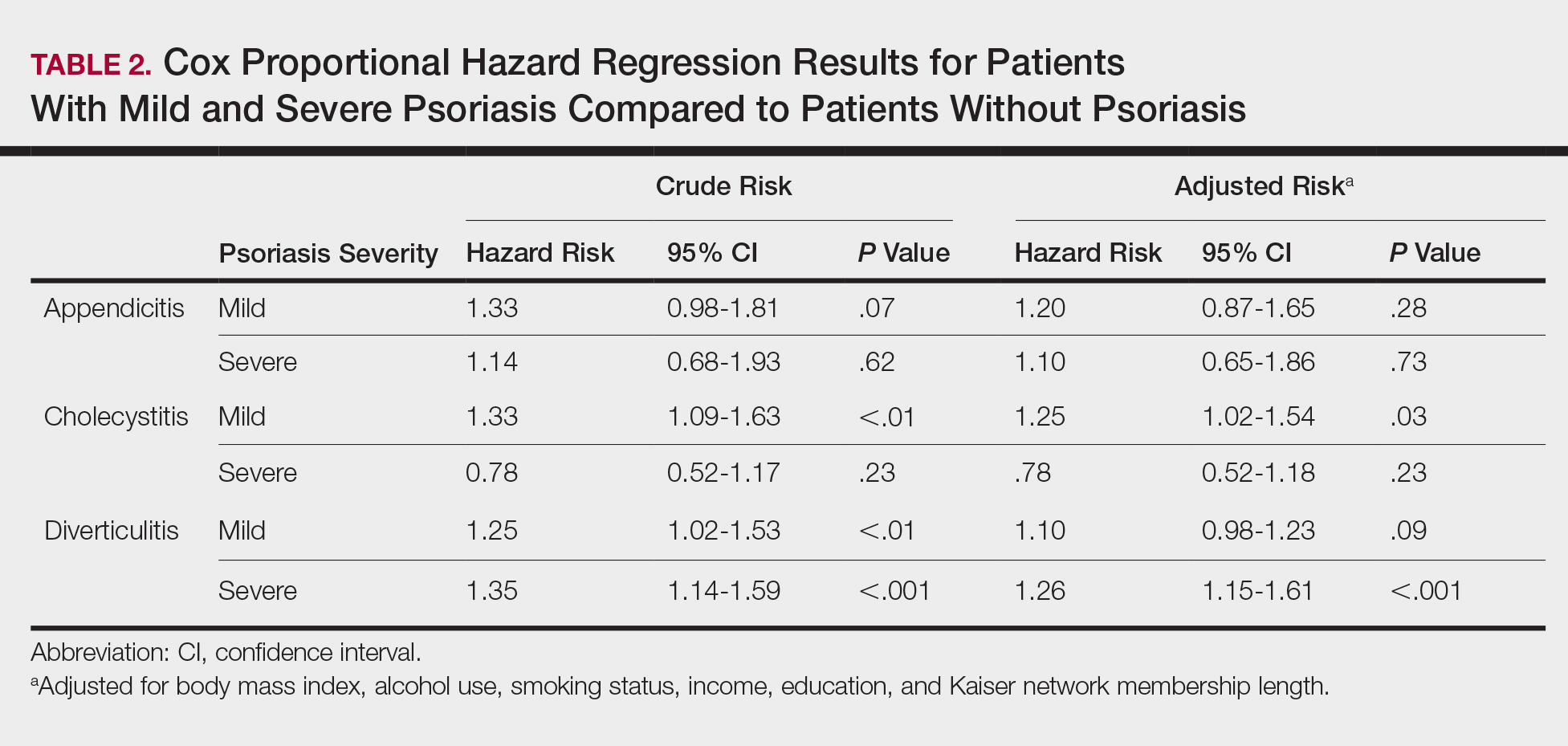

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

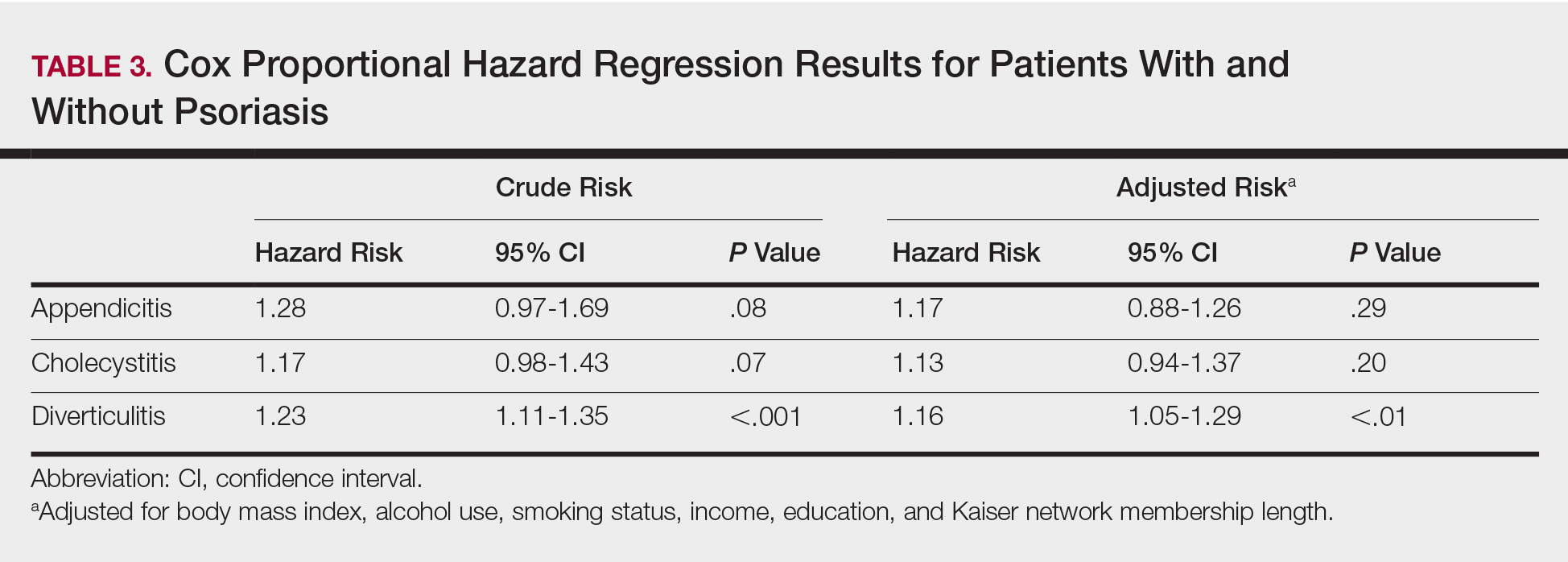

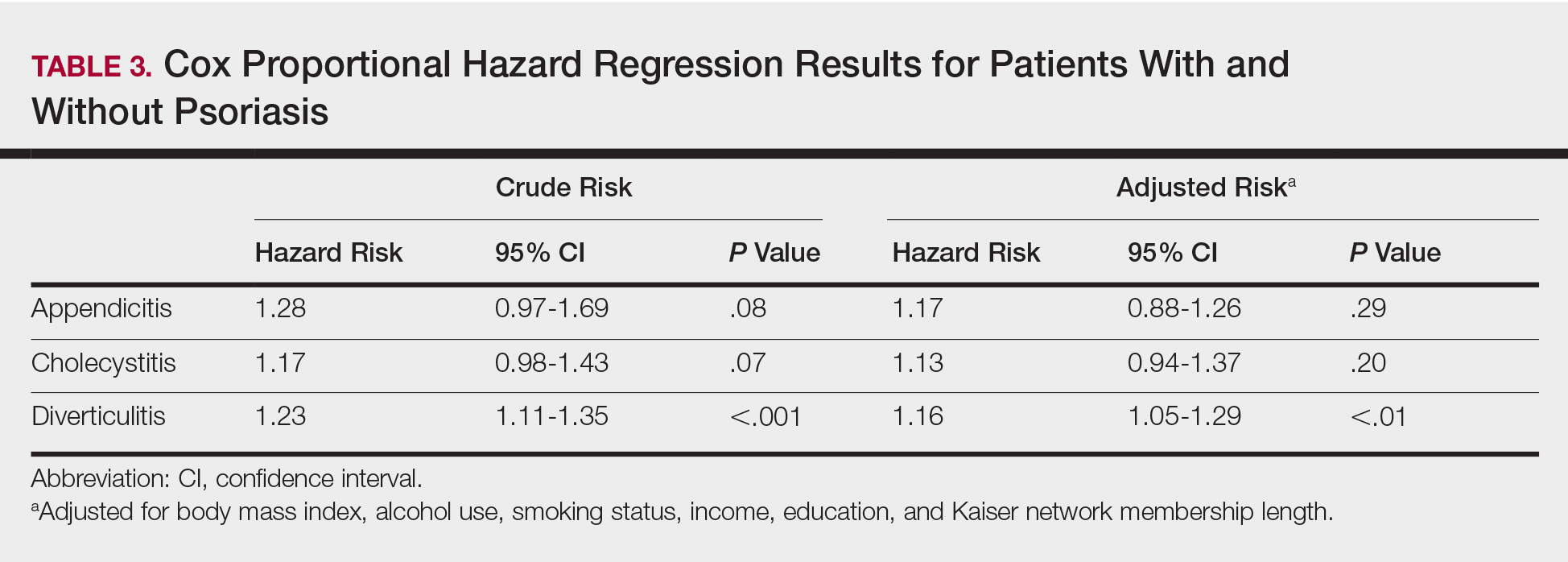

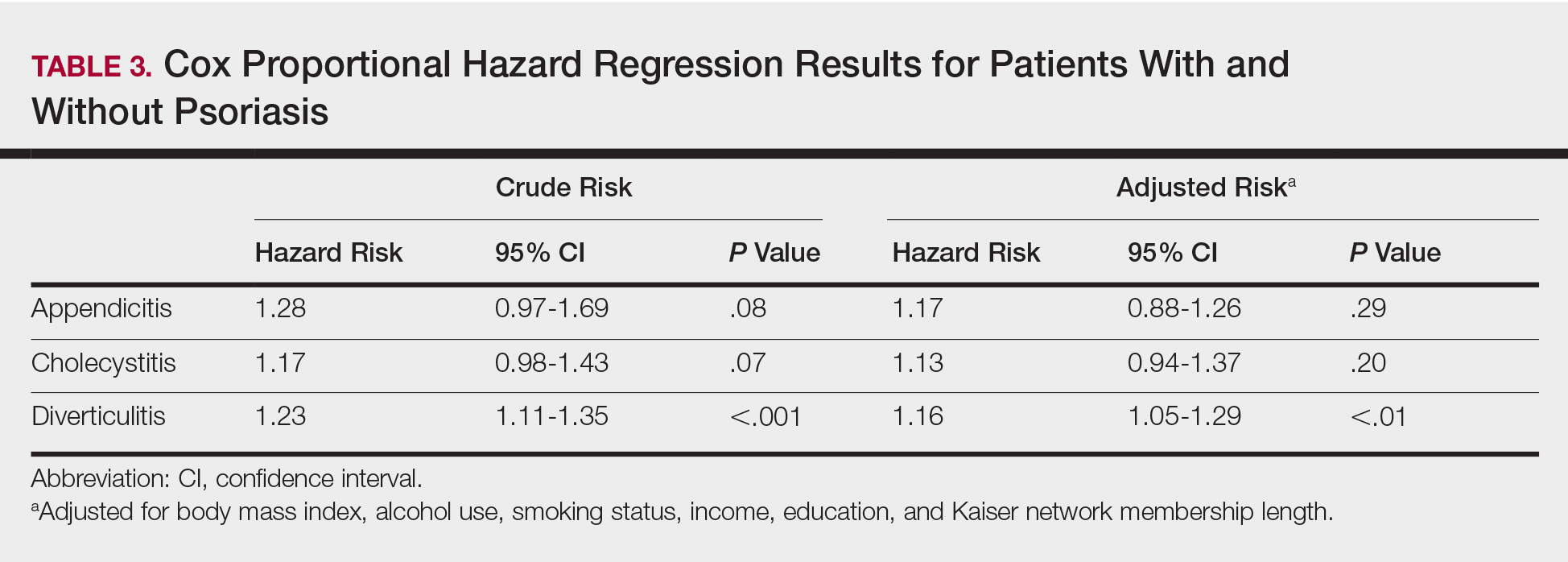

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.

- Smirnova SV, Barilo AA, Smolnikova MV. Hepatobiliary system diseases as the predictors of psoriasis progression [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2016:102-108.

- Bagel J, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with scalp involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:86-92.

- Foeldvari I, Krüger E, Schneider T. Acute, non-obstructive, sterile cholecystitis associated with etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:908-909.

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Appendicitis

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

Psoriasis is a chronic skin condition affecting approximately 2% to 3% of the population.1,2 Beyond cutaneous manifestations, psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory state that is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, including obesity,3,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus,5,6 hypertension,5 dyslipidemia,3,7 metabolic syndrome,7 atherosclerosis,8 peripheral vascular disease,9 coronary artery calcification,10 myocardial infarction,11-13 stroke,9,14 and cardiac death.15,16

Psoriasis also has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), possibly because of similar autoimmune mechanisms in the pathogenesis of both diseases.17,18 However, there is no literature regarding the risk for acute gastrointestinal pathologies such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis in patients with psoriasis.

The primary objective of this study was to examine if patients with psoriasis are at increased risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis compared to the general population. The secondary objective was to determine if patients with severe psoriasis (ie, patients treated with phototherapy or systemic therapy) are at a higher risk for these conditions compared to patients with mild psoriasis.

Methods

Patients and Tools

A descriptive, population-based cohort study design with controls from a matched cohort was used to ascertain the effect of psoriasis status on patients’ risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis. Our cohort was selected using administrative data from Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) during the study period (January 1, 2004, through December 31, 2016).

Kaiser Permanente Southern California is a large integrated health maintenance organization that includes approximately 4 million patients as of December 31, 2016, and includes roughly 20% of the region’s population. The geographic area served extends from Bakersfield in the lower California Central Valley to San Diego on the border with Mexico. Membership demographics, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity composition are representative of California.

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of psoriasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 696.1; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes L40.0, L40.4, L40.8, or L40.9) for at least 3 visits between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2016. Patients were not excluded if they also had a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis (ICD-9-CM code 696.0; ICD-10-CM code L40.5x). Patients also must have been continuously enrolled for at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date, which was defined as the date of the third psoriasis diagnosis.

Each patient with psoriasis was assigned to 1 of 2 cohorts: (1) severe psoriasis: patients who received UVB phototherapy, psoralen plus UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, acitretin, cyclosporine, apremilast, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, ustekinumab, efalizumab, alefacept, secukinumab, or ixekizumab during the study period; and (2) mild psoriasis: patients who had a diagnosis of psoriasis who did not receive one of these therapies during the study period.

Patients were excluded if they had a history of appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis at any time before the index date. Only patients older than 18 years were included.

Patients with psoriasis were frequency matched (1:5) with healthy patients, also from the KPSC network. Individuals were matched by age, sex, and ethnicity.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were described with means and SD for continuous variables as well as percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U Test for continuous variables were used to compare the patients’ characteristics by psoriasis status. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the risk for appendicitis, cholecystitis, or diverticulitis among patients with and without psoriasis and among patients with mild and severe psoriasis. Proportionality assumption was validated using Pearson product moment correlation between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log transformed time for each covariate.

Results were presented as crude (unadjusted) hazard ratios (HRs) and adjusted HRs, where confounding factors (ie, age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index [BMI], alcohol use, smoking status, income, education, and membership length) were adjusted. All tests were performed with SAS EG 5.1 and R software. P<.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are reported with the 95% confidence interval (CI), when appropriate.

Results

A total of 1,690,214 KPSC patients were eligible for the study; 10,307 (0.6%) met diagnostic and inclusion criteria for the psoriasis cohort. Patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher mean BMI (29.9 vs 28.7; P<.0001) as well as higher mean rates of alcohol use (56% vs 53%; P<.0001) and smoking (47% vs 38%; P<.01) compared to controls. Psoriasis patients had a shorter average duration of membership within the Kaiser network (P=.0001) compared to controls.

A total of 7416 patients met criteria for mild psoriasis and 2891 patients met criteria for severe psoriasis (eTable). Patients with severe psoriasis were significantly younger and had significantly higher mean BMI compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P<.0001 and P=.0001, respectively). No significant difference in rates of alcohol or tobacco use was detected among patients with mild and severe psoriasis.

Appendicitis

The prevalence of appendicitis was not significantly different between patients with and without psoriasis or between patients with mild and severe psoriasis, though the incidence rate was slightly higher among patients with psoriasis (0.80 per 1000 patient-years compared to 0.62 per 1000 patient-years among patients without psoriasis)(Table 1). However, there was not a significant difference in risk for appendicitis between healthy patients, patients with severe psoriasis, and patients with mild psoriasis after adjusting for potential confounding factors (Table 2). Interestingly, patients with severe psoriasis who had a diagnosis of appendicitis had a significantly shorter time to diagnosis of appendicitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001).

Cholecystitis

Psoriasis patients also did not have an increased prevalence of cholecystitis compared to healthy patients. However, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher prevalence of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis (P=.0038). Overall, patients with psoriasis had a slightly higher incidence rate (1.72 per 1000 patient-years) compared to healthy patients (1.46 per 1000 patient-years). Moreover, the time to diagnosis of cholecystitis was significantly shorter for patients with severe psoriasis than for patients with mild psoriasis (7.4 years vs 8.1 years; P<.0001). Mild psoriasis was associated with a significantly increased risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.09-1.63; P<.01) for cholecystitis compared to individuals without psoriasis in both the crude and adjusted models (Table 2). There was no difference between mild psoriasis patients and severe psoriasis patients in risk for cholecystitis.

Diverticulitis

Patients with psoriasis had a significantly greater prevalence of diverticulitis compared to the control cohort (5.1% vs 4.2%; P<.0001). There was no difference in prevalence between the severe psoriasis group and the mild psoriasis group (P=.96), but the time to diagnosis of diverticulitis was shorter in the severe psoriasis group than in the mild psoriasis group (7.2 years vs 7.9 years; P<.0001). Psoriasis patients had an incidence rate of diverticulitis of 6.61 per 1000 patient-years compared to 5.38 per 1000 patient-years in the control group. Psoriasis conferred a higher risk for diverticulitis in both the crude and adjusted models (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35 [P<.001] and HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.29; [P<.01], respectively)(Table 3); however, when stratified by disease severity, only patients with severe psoriasis were found to be at higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15-1.61; P<.001 for the adjusted model).

Comment

The objective of this study was to examine the background risks for specific gastrointestinal pathologies in a large cohort of patients with psoriasis compared to the general population. After adjusting for measured confounders, patients with severe psoriasis had a significantly higher risk of diverticulitis compared to the general population. Although more patients with severe psoriasis developed appendicitis or cholecystitis, the difference was not significant.

The pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticulitis has been thought to be related to increased intracolonic pressure and decreased dietary fiber intake, leading to formation of diverticula in the colon.19 Our study did not correct for differences in diet between the 2 groups, making it a possible confounding variable. Studies evaluating dietary habits of psoriatic patients have found that adult males with psoriasis might consume less fiber compared to healthy patients,20 and psoriasis patients also might consume less whole-grain fiber.21 Furthermore, fiber deficiency also might affect gut flora, causing low-grade chronic inflammation,18 which also has been supported by response to anti-inflammatory medications such as mesalazine.22 Given the autoimmune association between psoriasis and IBD, it is possible that psoriasis also might create an environment of chronic inflammation in the gut, predisposing patients with psoriasis to diverticulitis. However, further research is needed to better evaluate this possibility.

Our study also does not address any potential effects on outcomes of specific treatments for psoriasis. Brandl et al23 found that patients on immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases had longer hospital and intensive care unit stays, higher rates of emergency operations, and higher mortality while hospitalized. Because our results suggest that patients with severe psoriasis, who are therefore more likely to require treatment with an immunomodulator, are at higher risk for diverticulitis, these patients also might be at risk for poorer outcomes.

There is no literature evaluating the relationship between psoriasis and appendicitis. Our study found a slightly lower incidence rate compared to the national trend (9.38 per 10,000 patient-years in the United States in 2008) in both healthy patients and psoriasis patients.24 Of note, this statistic includes children, whereas our study did not, which might in part account for the lower rate. However, Cheluvappa et al25 hypothesized a relationship between appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy at a young age and protection against IBD. They also found that the mechanism for protection involves downregulation of the helper T cell (TH17) pathway,25 which also has been found to play a role in psoriasis pathogenesis.26,27 Although our results suggest that the risk for appendicitis is not increased for patients with psoriasis, further research might be able to determine if appendicitis and subsequent appendectomy also can offer protection against development of psoriasis.

We found that patients with severe psoriasis had a higher incidence rate of cholecystitis compared to patients with mild psoriasis. Egeberg et al28 found an increased risk for cholelithiasis among patients with psoriasis, which may contribute to a higher rate of cholecystitis. Although both acute and chronic cholecystitis were incorporated in this study, a Russian study found that chronic cholecystitis may be a predictor of progression of psoriasis.29 Moreover, patients with severe psoriasis had a shorter duration to diagnosis of cholecystitis than patients with mild psoriasis. It is possible that patients with severe psoriasis are in a state of greater chronic inflammation than those with mild psoriasis, and therefore, when combined with other risk factors for cholecystitis, may progress to disease more quickly. Alternatively, this finding could be treatment related, as there have been reported cases of cholecystitis related to etanercept use in patients treated for psoriasis and juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis.30,31 The relationship is not yet well defined, however, and further research is necessary to evaluate this association.

Study Strengths

Key strengths of this study include the large sample size and diversity of the patient population. Kaiser Permanente Southern California membership generally is representative of the broader community, making our results fairly generalizable to populations with health insurance. Use of a matched control cohort allows the results to be more specific to the disease of interest, and the population-based design minimizes bias.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Although the cohorts were categorized based on type of treatment received, exact therapies were not specified. As a retrospective study, it is difficult to control for potential confounding variables that are not included in the electronic medical record. The results of this study also demonstrated significantly shorter durations to diagnosis of all 3 conditions, indicating that surveillance bias may be present.

Conclusion

Patients with psoriasis may be at an increased risk for diverticulitis compared to patients without psoriasis, which could be due to the chronic inflammatory state induced by psoriasis. Therefore, it may be beneficial for clinicians to evaluate psoriasis patients for other risk factors for diverticulitis and subsequently provide counseling to these patients to minimize their risk for diverticulitis. Psoriasis patients do not appear to be at an increased risk for appendicitis or cholecystitis compared to controls; however, further research is needed for confirmation.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.

- Smirnova SV, Barilo AA, Smolnikova MV. Hepatobiliary system diseases as the predictors of psoriasis progression [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2016:102-108.

- Bagel J, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with scalp involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:86-92.

- Foeldvari I, Krüger E, Schneider T. Acute, non-obstructive, sterile cholecystitis associated with etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:908-909.

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385.

- Channual J, Wu JJ, Dann FJ. Effects of tumor necrosis factor-α blockade on metabolic syndrome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:61-73.

- Koebnick C, Black MH, Smith N, et al. The association of psoriasis and elevated blood lipids in overweight and obese children. J Pediatr. 2011;159:577-583.

- Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1527-1534.

- Qureshi AA, Choi HK, Setty AR, et al. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study of US female nurses. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:379-382.

- Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629-634.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- El-Mongy S, Fathy H, Abdelaziz A, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with chronic psoriasis: a potential association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:661-666.

- Prodanovich S, Kirsner RS, Kravetz JD, et al. Association of psoriasis with coronary artery, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular diseases and mortality. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:700-703.

- Ludwig RJ, Herzog C, Rostock A, et al. Psoriasis: a possible risk factor for development of coronary artery calcification. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:271-276.

- Kaye JA, Li L, Jick SS. Incidence of risk factors for myocardial infarction and other vascular diseases in patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:895-902.

- Kimball AB, Robinson D Jr, Wu Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors among psoriasis patients in two US healthcare databases, 2001-2002. Dermatology. 2008;217:27-37.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Mehta NN, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Patients with severe psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality: cohort study using the General Practice Research Database. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1000-1006.

- Abuabara K, Azfar RS, Shin DB, et al. Cause-specific mortality in patients with severe psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:586-592.

- Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:529-534.

- Wu JJ, Nguyen TU, Poon KY, et al. The association of psoriasis with autoimmune diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:924-930.

- Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38(5, suppl 1):S2-S7.

- Barrea L, Macchia PE, Tarantino G, et al. Nutrition: a key environmental dietary factor in clinical severity and cardio-metabolic risk in psoriatic male patients evaluated by 7-day food-frequency questionnaire. J Transl Med. 2015;13:303.

- Afifi L, Danesh MJ, Lee KM, et al. Dietary behaviors in psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from a U.S. National Survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2017;7:227-242.

- Matrana MR, Margolin DA. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of diverticular disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:141-146.

- Brandl A, Kratzer T, Kafka-Ritsch R, et al. Diverticulitis in immunosuppressed patients: a fatal outcome requiring a new approach? Can J Surg. 2016;59:254-261.

- Buckius MT, McGrath B, Monk J, et al. Changing epidemiology of acute appendicitis in the United States: study period 1993-2008. J Surg Res. 2012;175:185-190.

- Cheluvappa R, Luo AS, Grimm MC. T helper type 17 pathway suppression by appendicitis and appendectomy protects against colitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;175:316-322.

- Lynde CW, Poulin Y, Vender R, et al. Interleukin 17A: toward a new understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:141-150.

- Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005:2005;273-279.

- Egeberg A, Anderson YMF, Gislason GH, et al. Gallstone risk in adult patients with atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: possible effect of overweight and obesity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:627-631.

- Smirnova SV, Barilo AA, Smolnikova MV. Hepatobiliary system diseases as the predictors of psoriasis progression [in Russian]. Vestn Ross Akad Med Nauk. 2016:102-108.

- Bagel J, Lynde C, Tyring S, et al. Moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with scalp involvement: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:86-92.

- Foeldvari I, Krüger E, Schneider T. Acute, non-obstructive, sterile cholecystitis associated with etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of juvenile polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:908-909.

Practice Points

- Patients with psoriasis may have elevated risk of diverticulitis compared to healthy patients. However, psoriasis patients do not appear to have increased risk of appendicitis or cholecystitis.

- Clinicians treating psoriasis patients should consider assessing for other risk factors of diverticulitis at regular intervals.

Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman Disease

Case Report

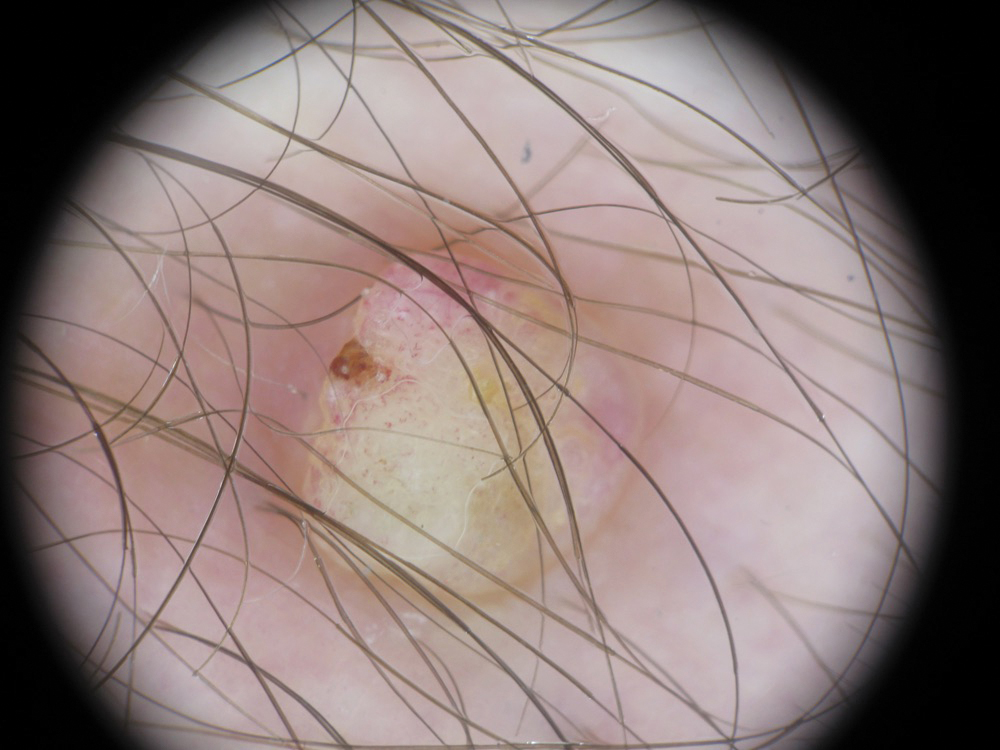

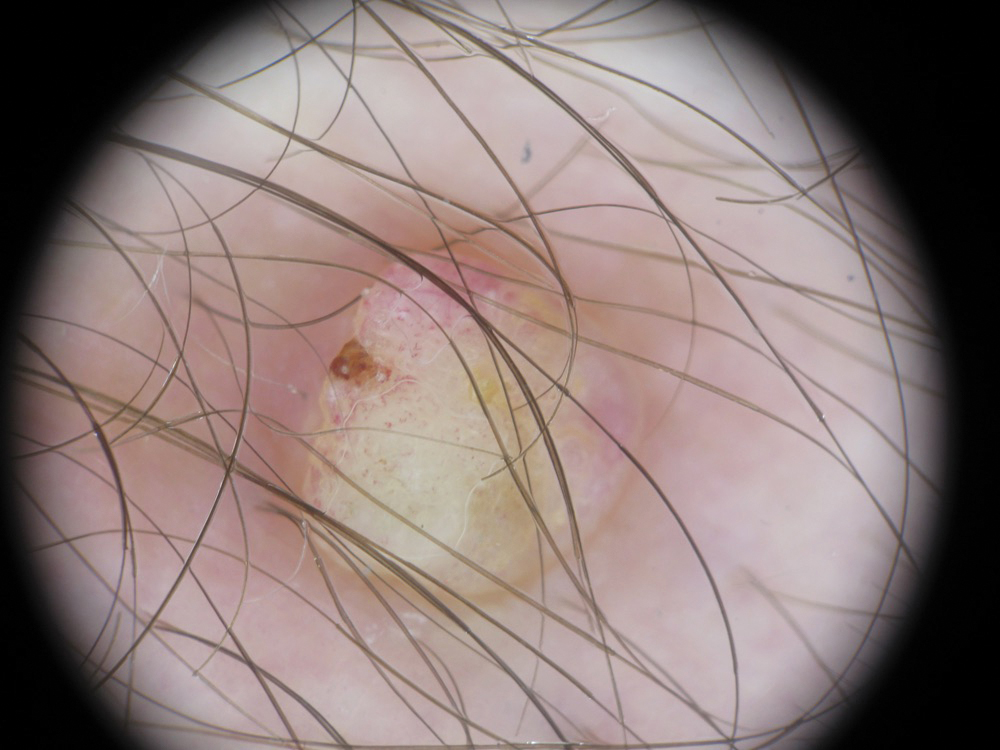

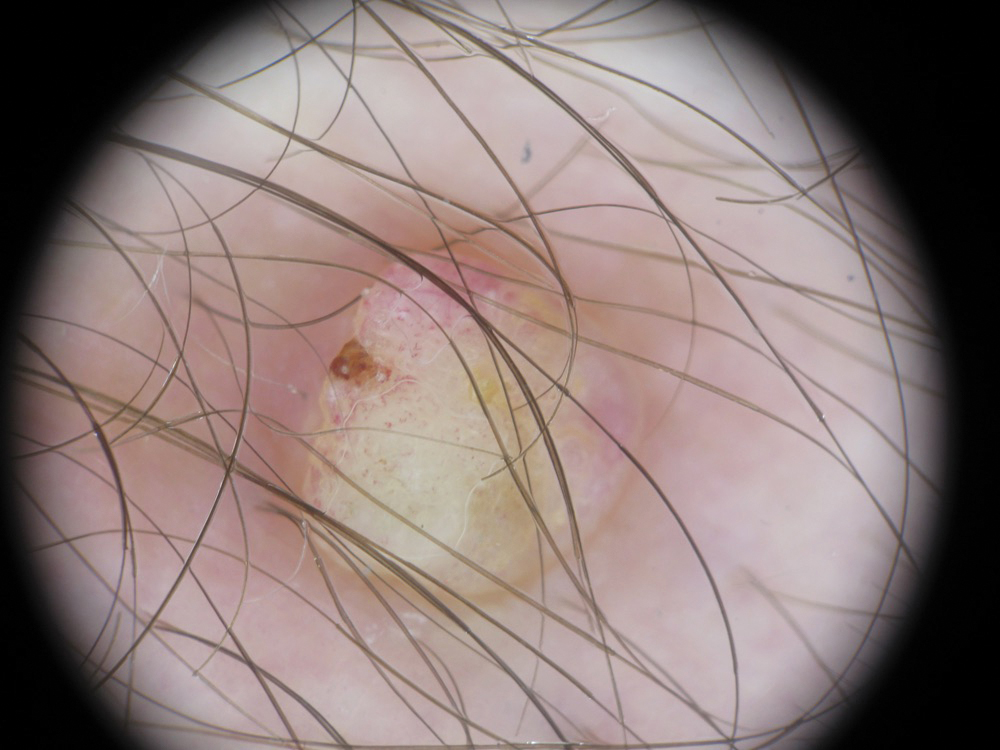

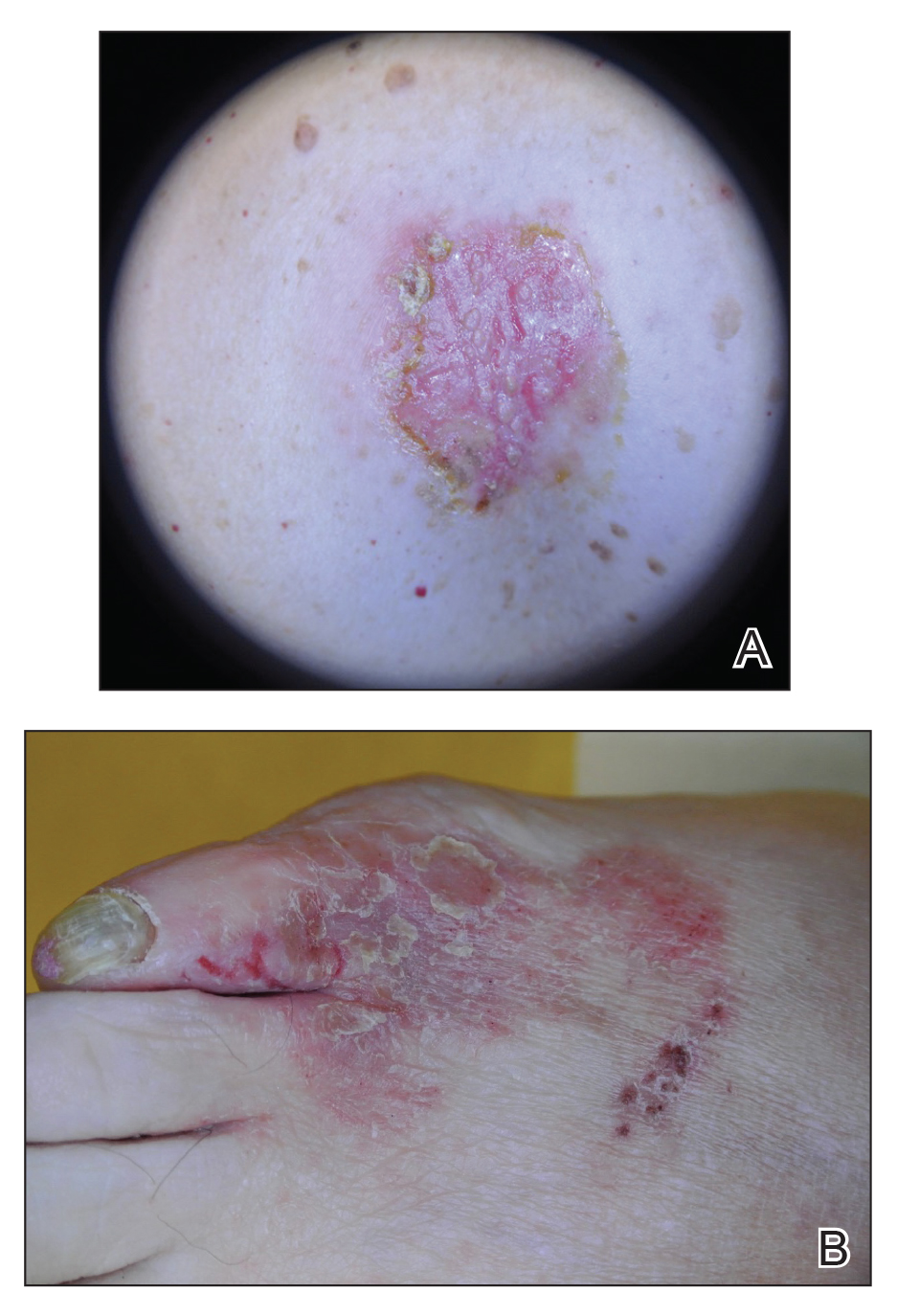

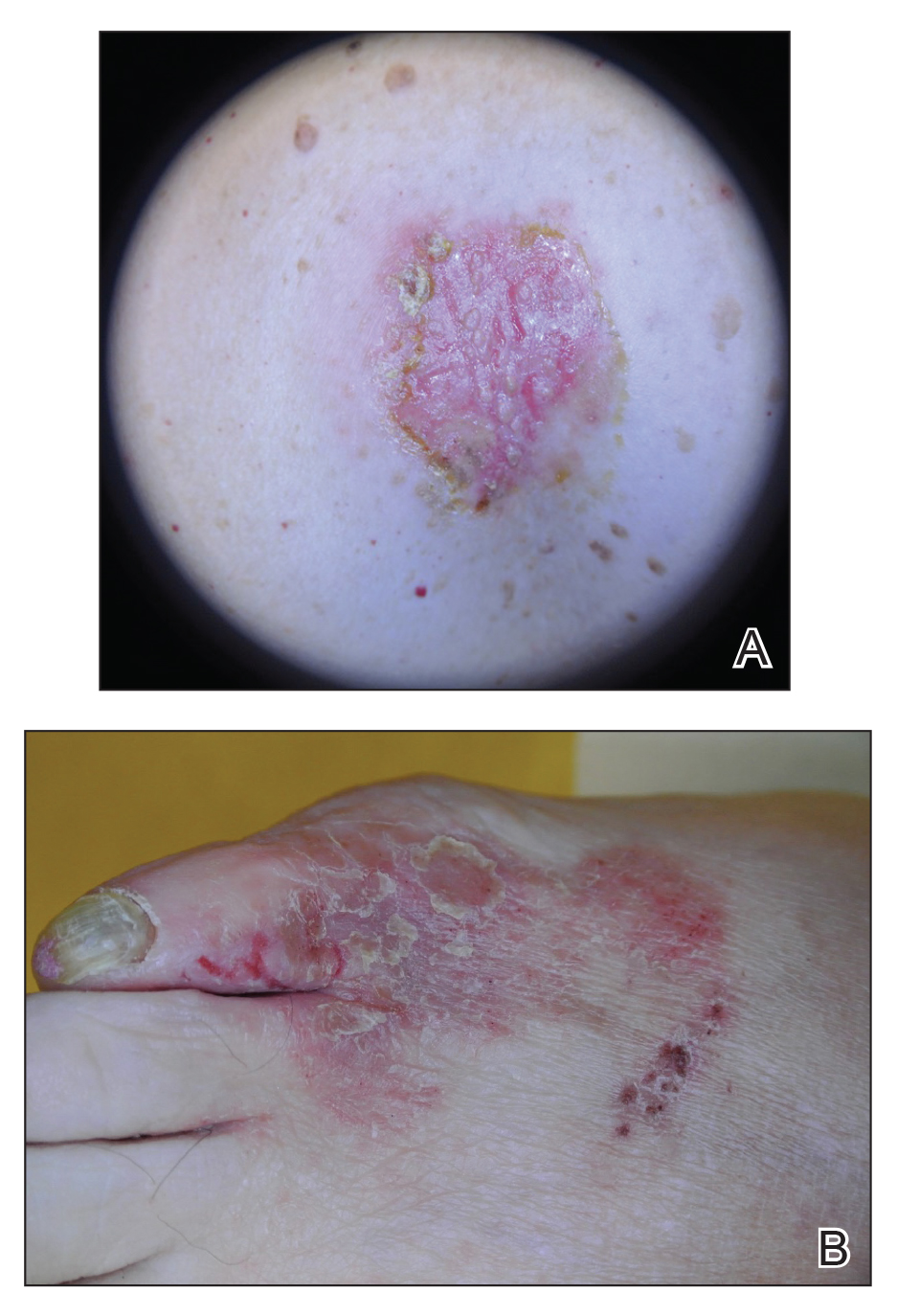

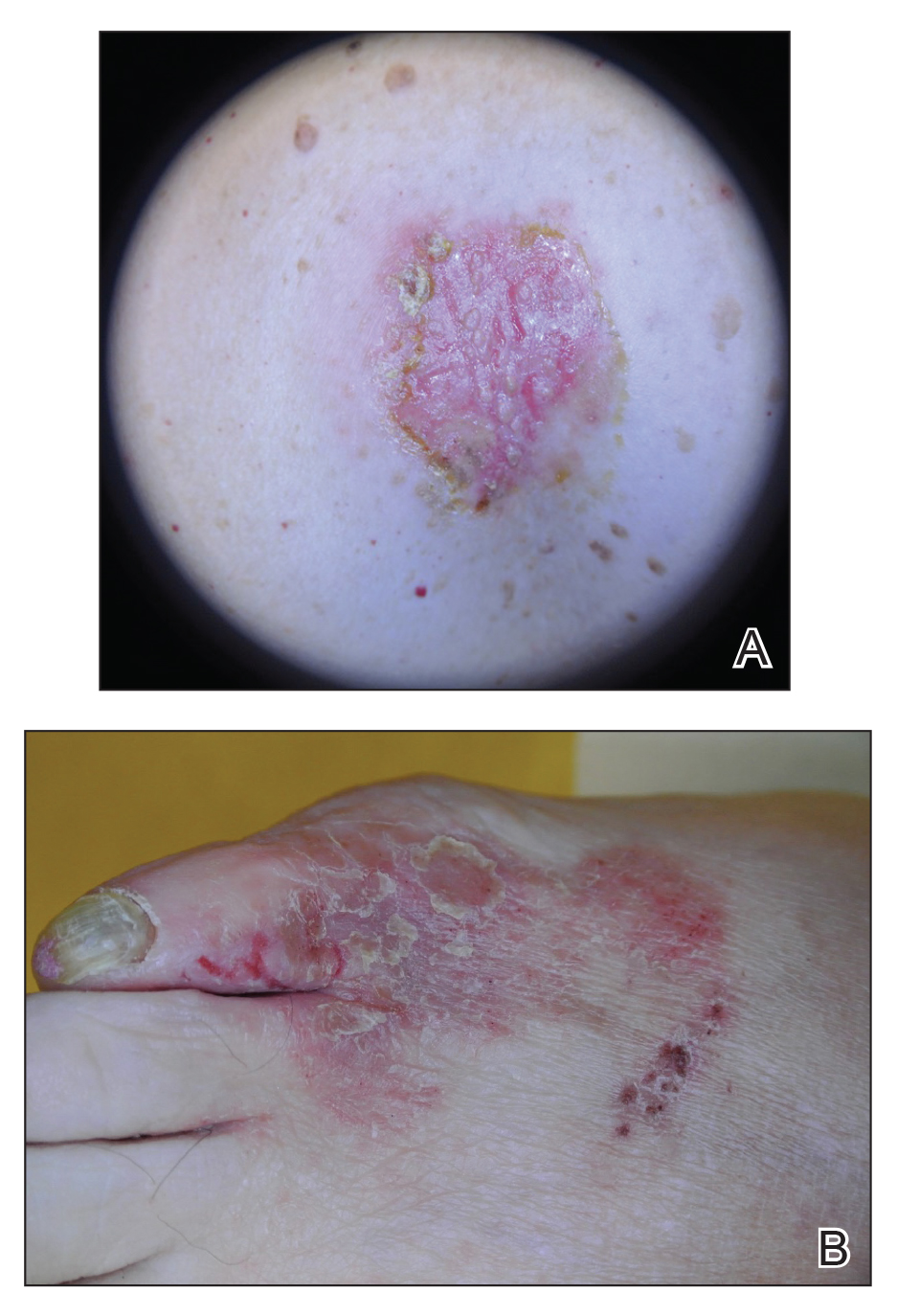

A 31-year-old black woman presented with a slow-spreading pruritic rash on the right thigh of 1 year’s duration. She had previously seen a dermatologist and was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% and mupirocin ointment 2% but declined a biopsy. Review of symptoms was negative for any constitutional symptoms. Family history included hypertension and eczema with a personal history of anxiety. Clinical examination revealed grouped flesh-colored to light pink papules and plaques within a hyperpigmented patch on the right medial thigh (Figure 1).

Histopathology

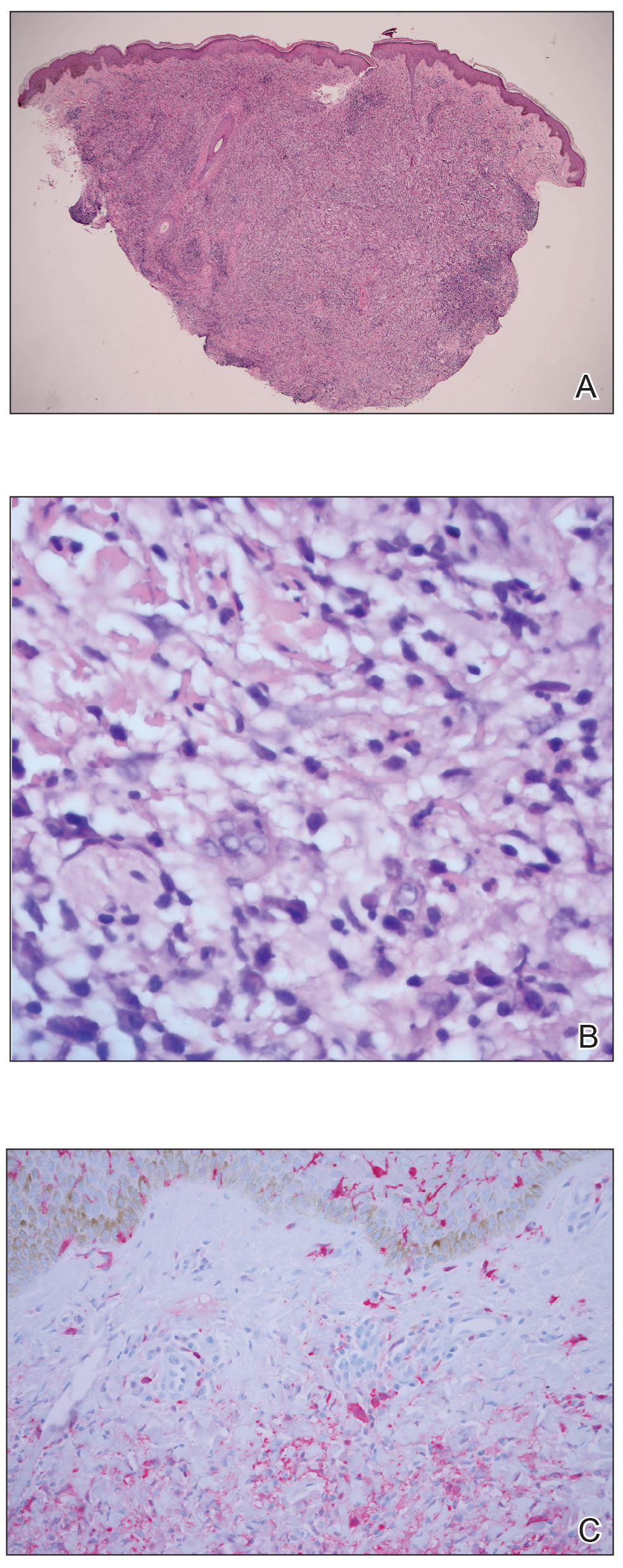

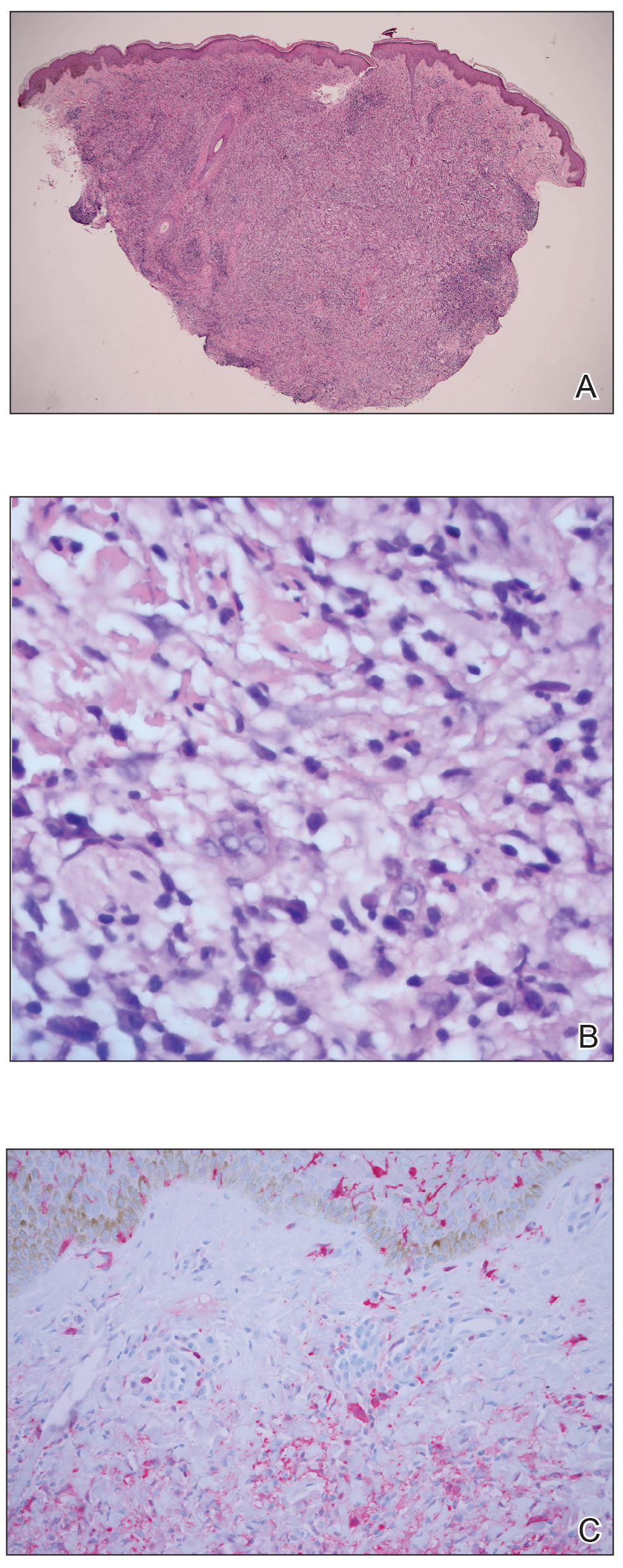

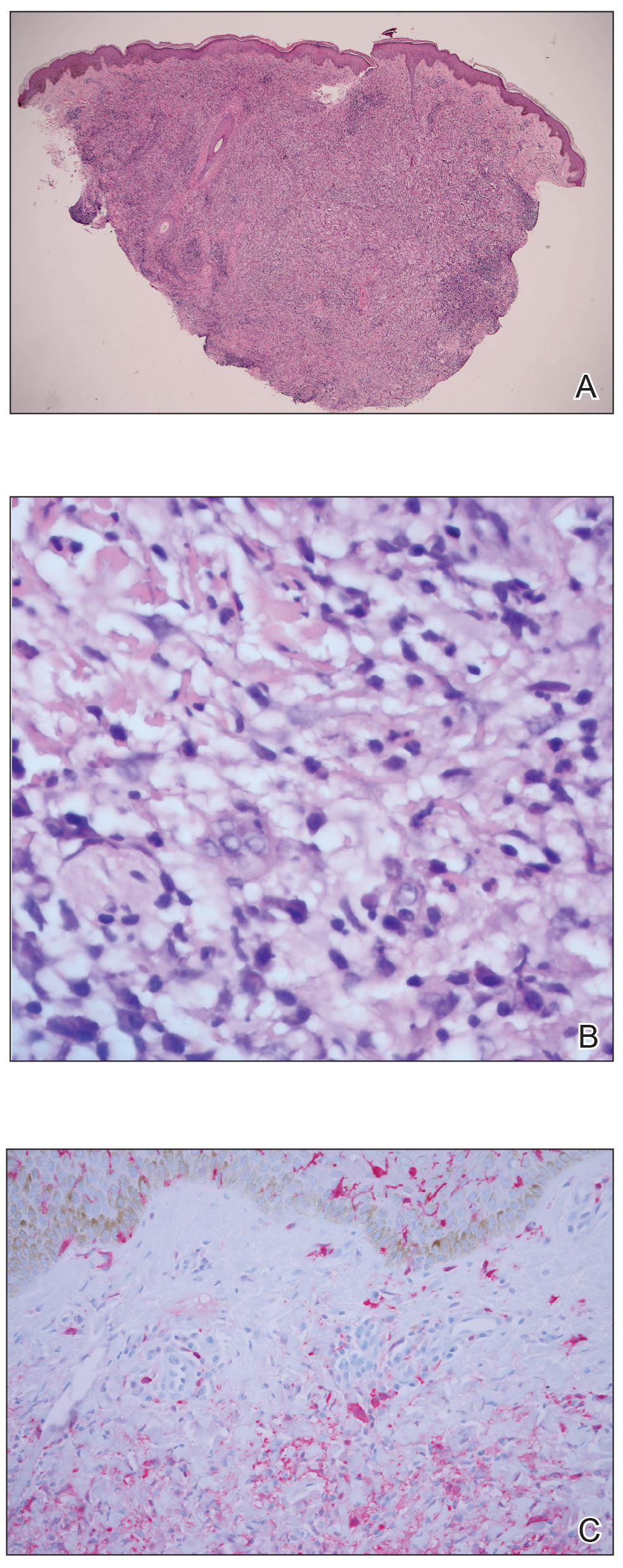

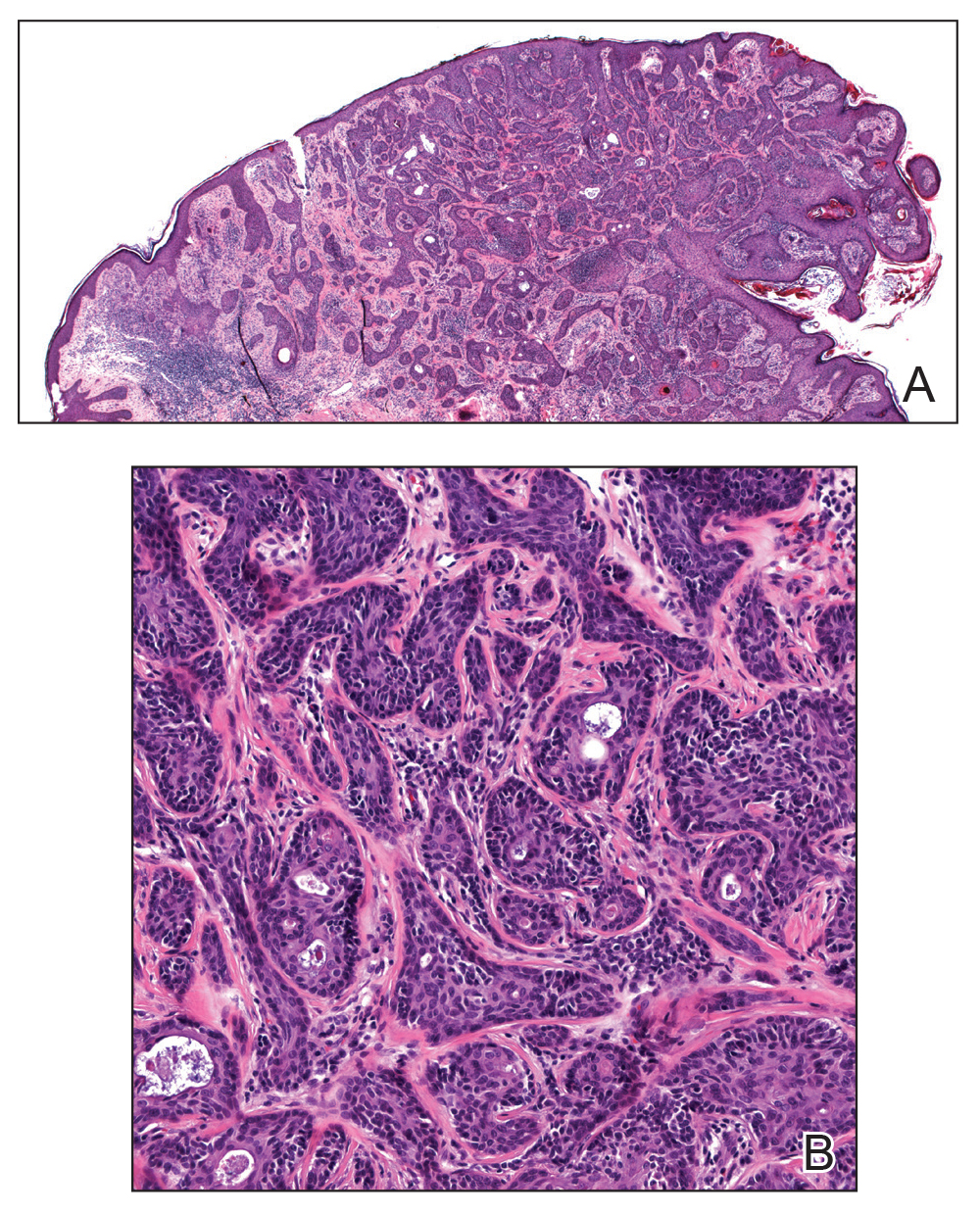

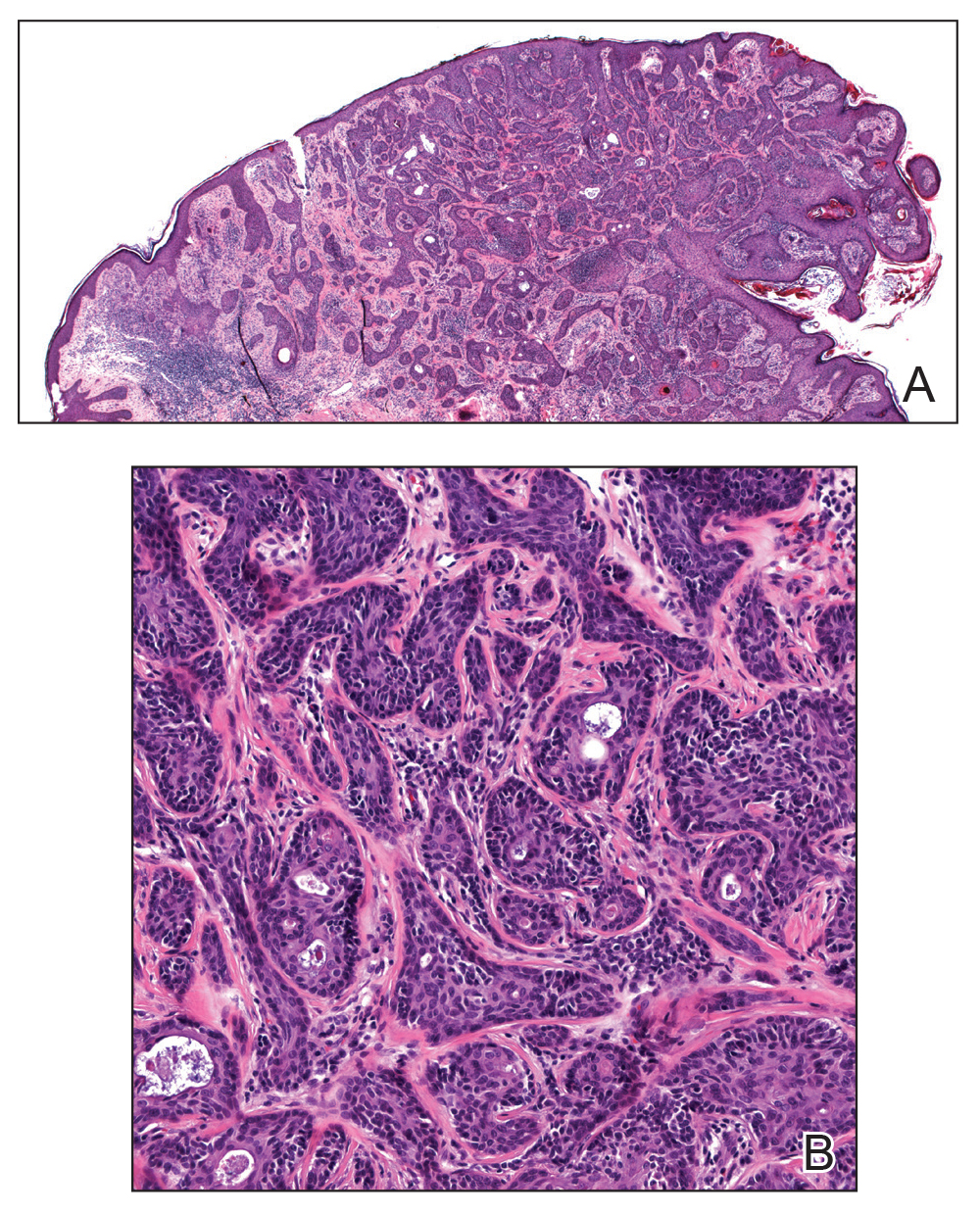

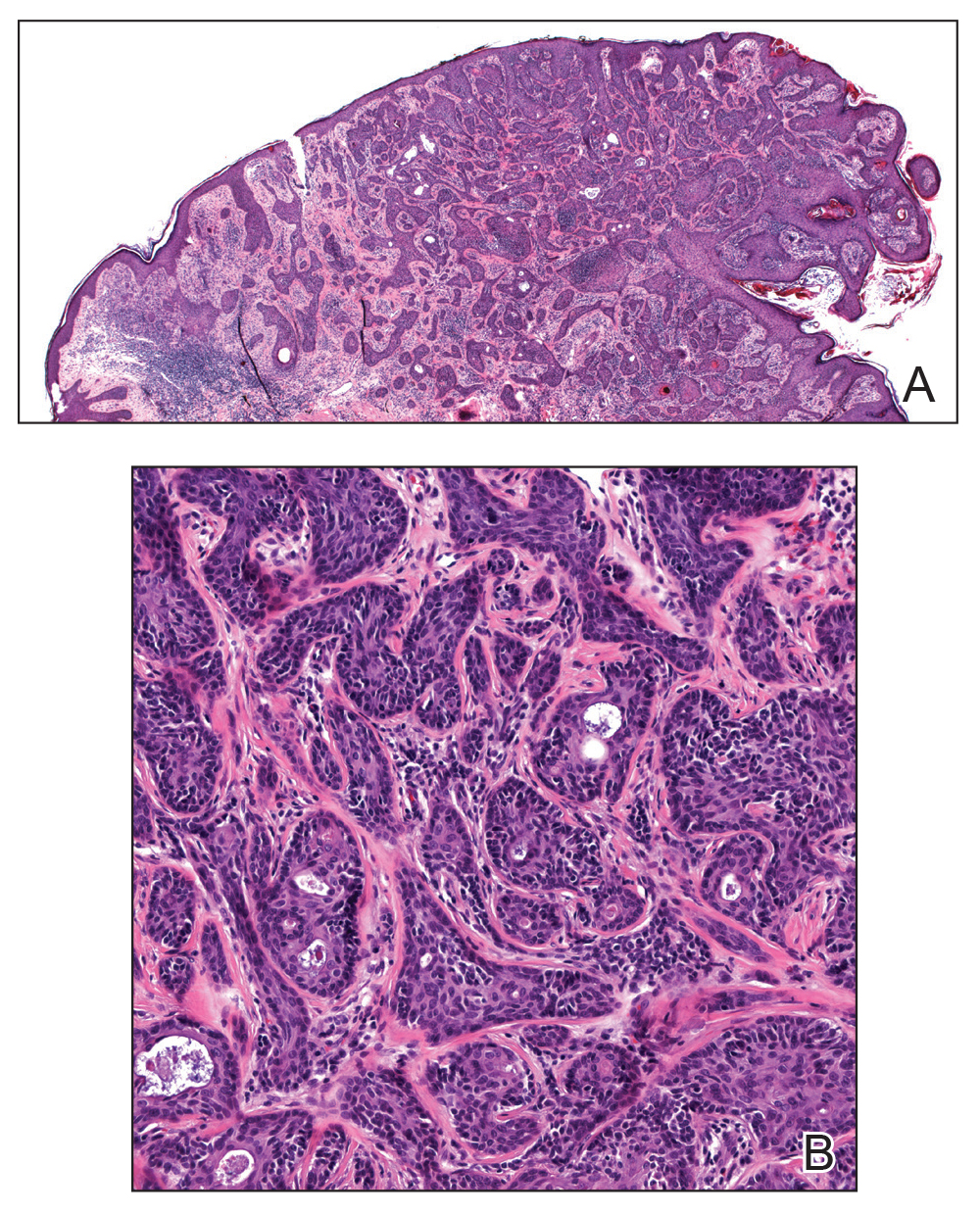

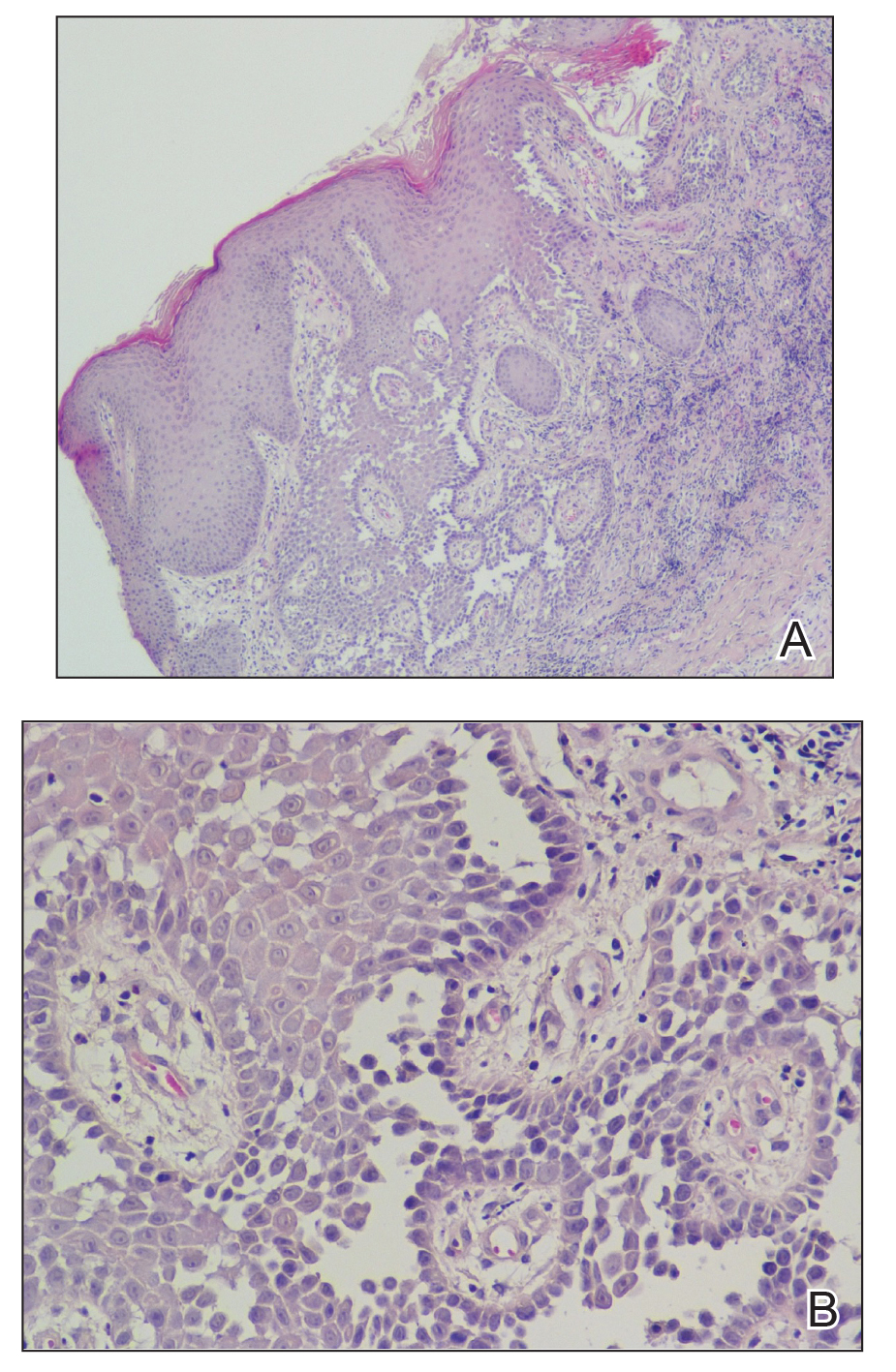

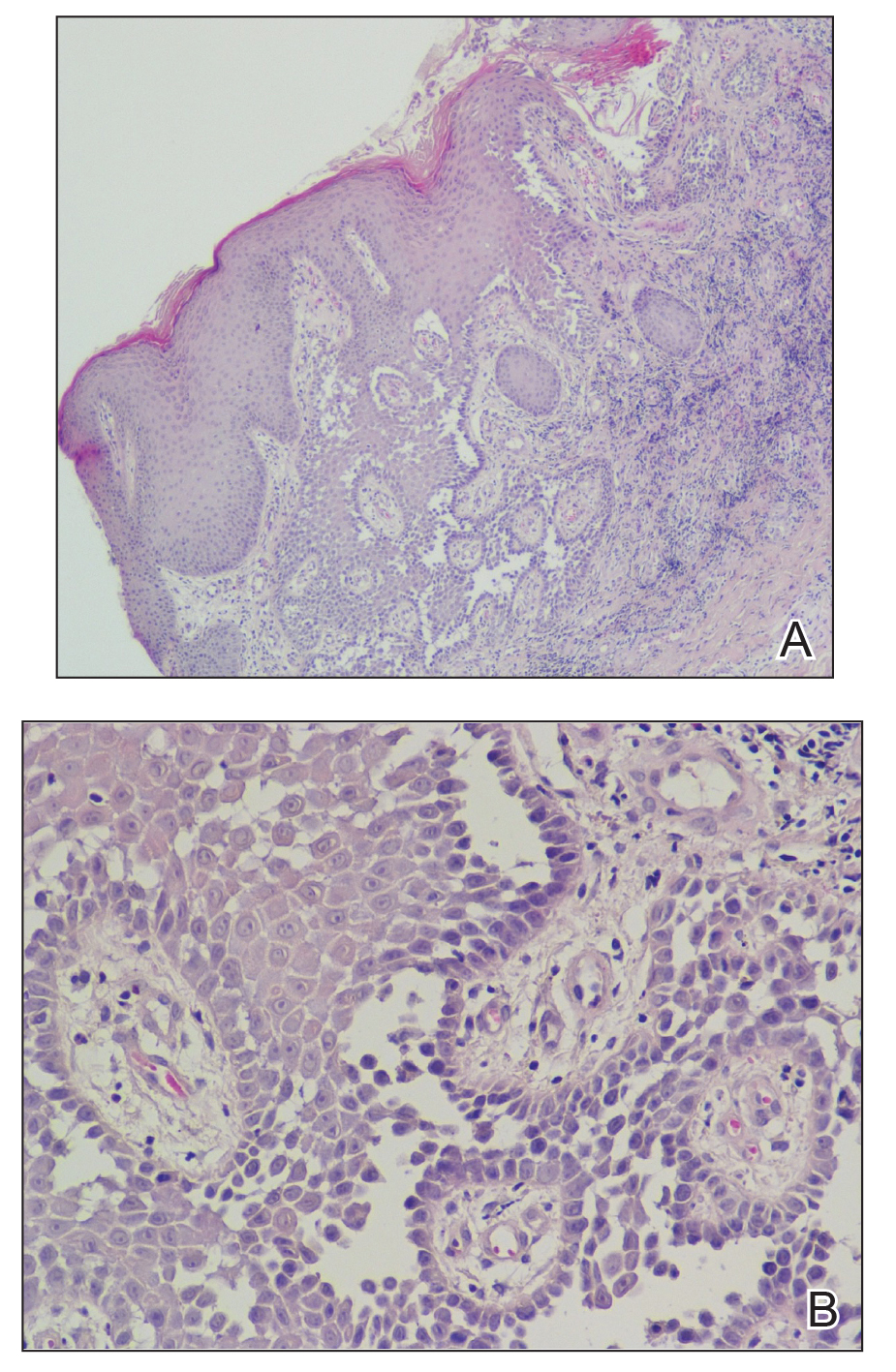

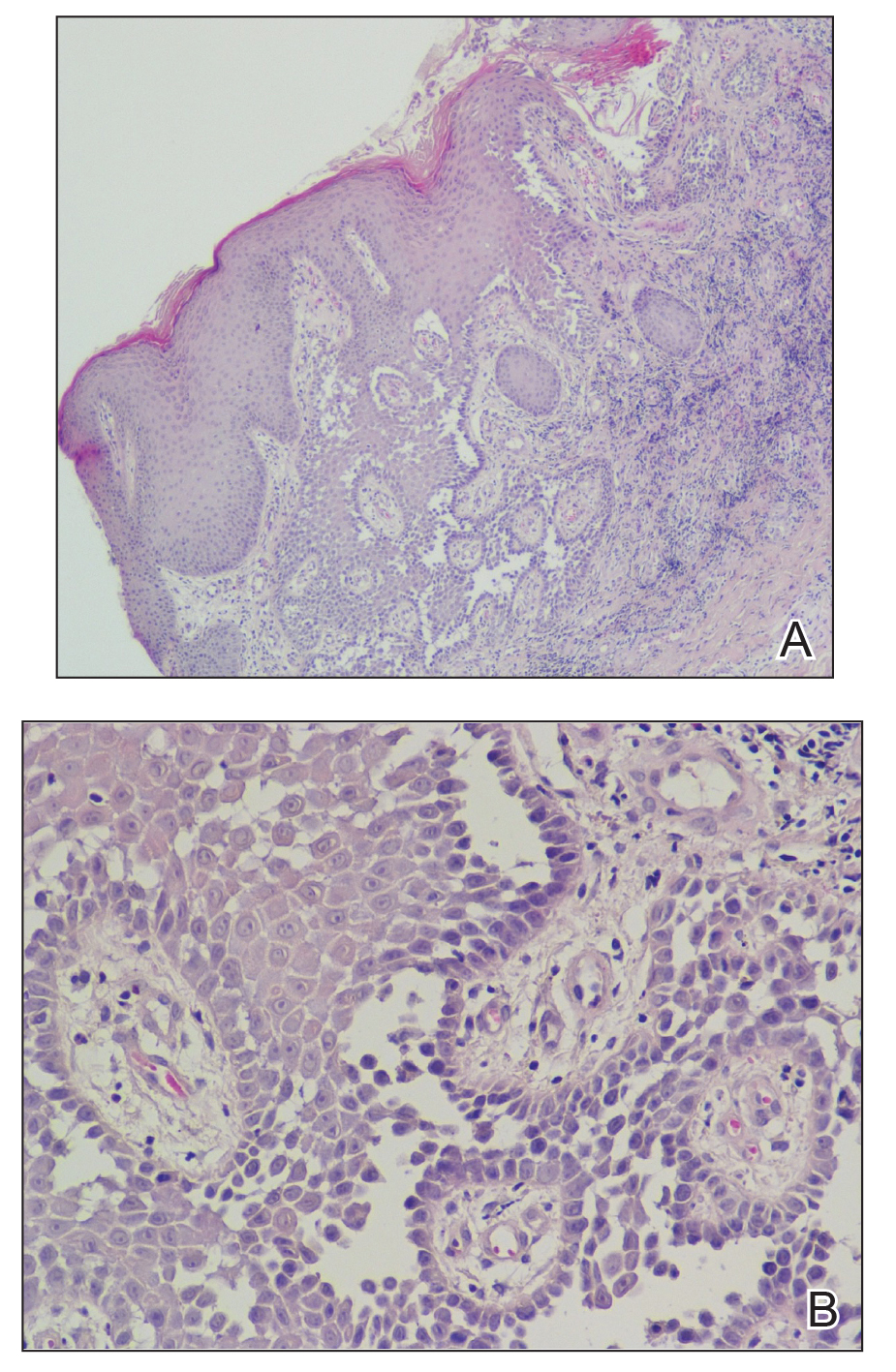

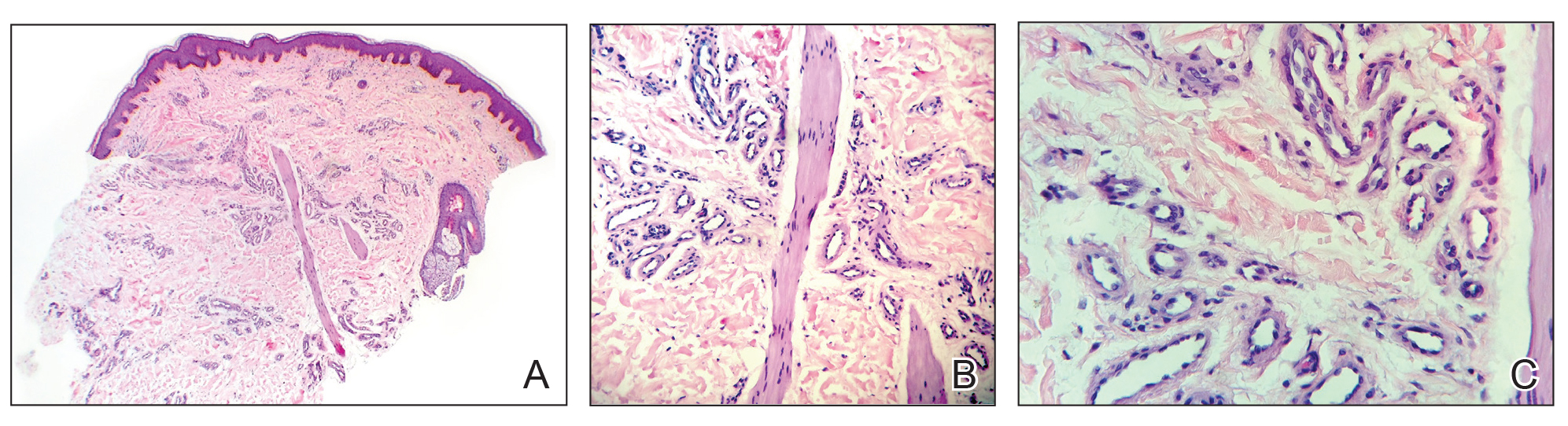

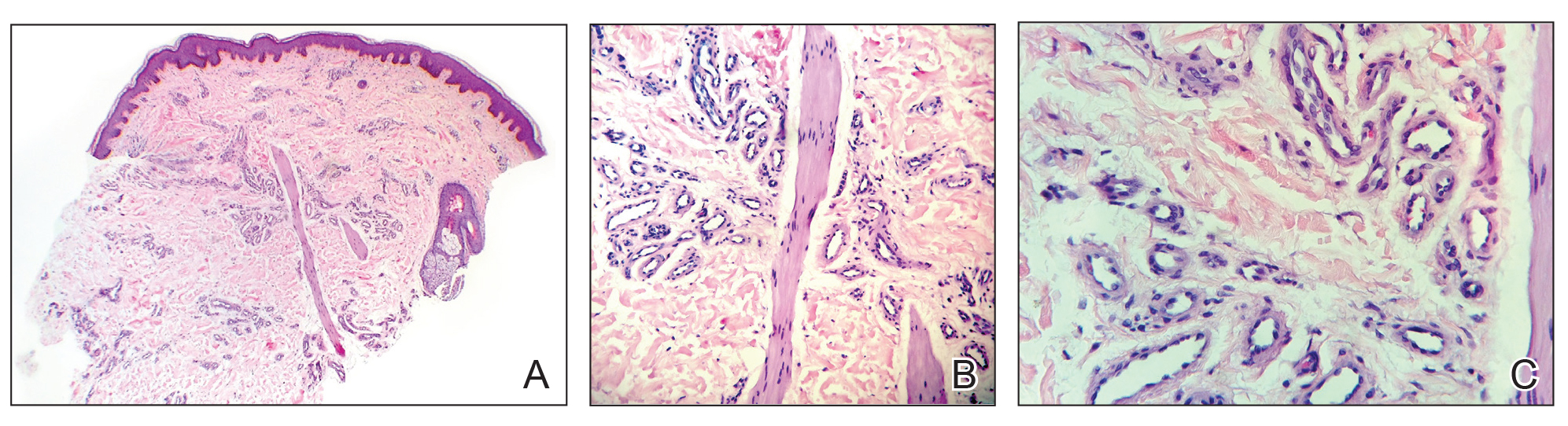

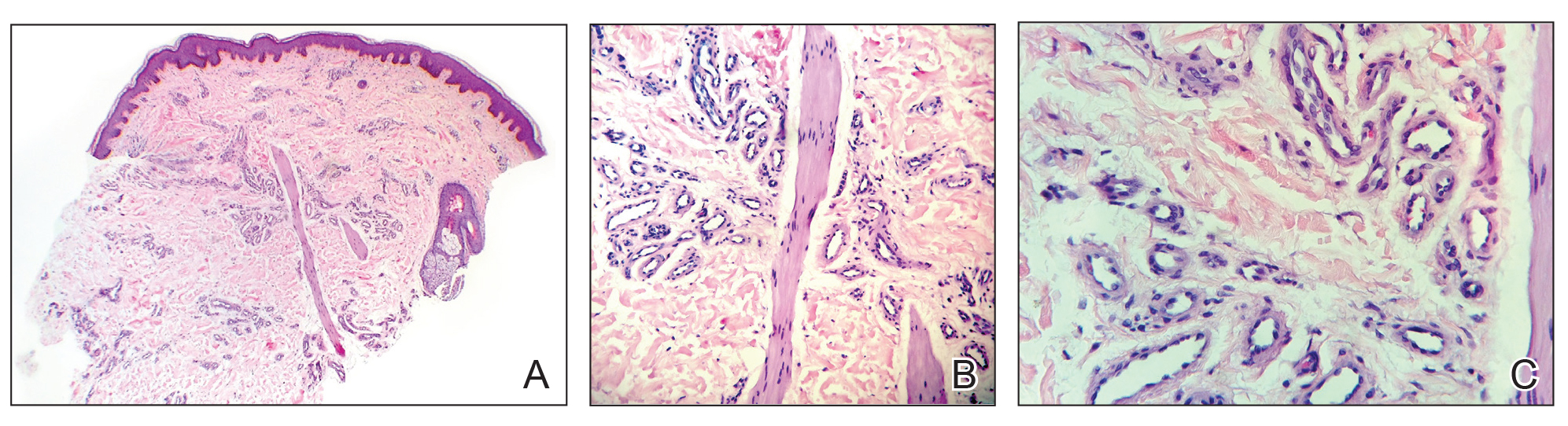

A punch biopsy was negative for fungal, bacterial, or acid-fast bacilli culture. Histopathologic evaluation demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of large histiocytes admixed with inflammatory cells composed predominantly of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The histiocytes within the inflammatory infiltrate had vesicular nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2A). Areas of emperipolesis were noted (Figure 2B). The large histiocytes stained positive for S-100 protein (Figure 2C) and negative for CD1a.

Course and Treatment

Laboratory studies revealed leukopenia. Prior to histopathologic results, empiric treatment was started with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. Once pathology confirmed the diagnosis of Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed and within normal limits. Due to the lack of systemic involvement, we diagnosed the rare form of purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD). In subsequent visits, treatment with oral prednisone (40 mg daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg daily for 1 week) and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (5 areas on the right medial thigh were injected with 1.0 mL of 10 mg/mL) was attempted with mild improvement, though the patient declined surgical excision.

Comment

Rosai-Dorfman disease (also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy) is a non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1 There are 2 main forms of RDD: one form that affects the lymph nodes and in certain cases the extranodal organs, and the other is purely CRDD. Cutaneous RDD is extremely rare and the etiology is unknown, though a number of viral and immune causes have been postulated. Cutaneous RDD presents as solitary or numerous papules, nodules, and/or plaques. Treatment options include steroids, methotrexate, dapsone, thalidomide, and isotretinoin, with varying efficacy reported.1

Extranodal forms occur in 43% of RDD cases, with the skin being the most common site.1 Other extranodal sites include the soft tissue, upper and lower respiratory tract, bones, genitourinary tract, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, orbits, testes, and rarely central nervous system involvement.2

Approximately 10% of RDD patients exhibit skin lesions, and in 3% it is contained solely in the skin.3 Pure CRDD was first documented in 1978 by Thawerani et al4 who presented the case of a 48-year-old man with a solitary nodule on the shoulder.

Cutaneous RDD and RDD may be distinct clinical entities. Cutaneous RDD has a later age of onset than RDD (median age, 43.5 years vs 20.6 years) and a female predominance (2:1 vs 1.4:1). It most commonly affects Asian and white individuals while the majority of patients with RDD are of African descent with rare reports in Asians.1

The etiology of CRDD remains unknown with hypotheses of viral and immune causes such as human herpesvirus 6, Epstein-Barr virus, and parvovirus B19. The polyclonal nature of the cell infiltrate and the clinical progression of RDD suggest a reactive process rather than a neoplastic disorder.1 Rosai-Dorfman disease has been hypothesized to be closely related to autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, an inherited disorder associated with defects in Fas-mediated apoptosis.5

Histologic findings in CRDD are similar to those in RDD, with a superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. A diffuse and nodular dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes exists in a background infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Foamy histiocytes may be seen in dermal lymphatics, and lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers also may be present. Emperipolesis, the presence of intact inflammatory cells within histiocytes, is common in CRDD. Less often, histiocytes may contain plasma cells, neutrophils, and red blood cells. Mitoses and nuclear atypia are rare. Cutaneous RDD histiocytes stain positive for S-100 protein, CD4, factor XIIIa, and CD68, and negative for CD1a. Birbeck granules are absent on electronic microscopy of CRDD tissue, eliminating Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1,3,5

The clinical diagnosis of CRDD is hard to confirm in the absence of lymphadenopathy. The lesions in CRDD may be solitary or numerous, usually presenting as papules, nodules, and/or plaques. More rarely, the lesions may present as pustules, acneform lesions, mimickers of vasculitis and panniculitis, macular erythema, large annular lesions resembling granuloma annulare, or even a breast mass.1,3 One case report with involvement of deep subcutaneous fat presented with flank swelling beneath papules and nodules.6

The most common site of lesions in CRDD is the face, with the eyelids and malar regions frequently involved, followed by the back, chest, thighs, flanks, and shoulders.1,5 Rarely, CRDD may be associated with other disorders, including bilateral uveitis, antinuclear antibody–positive lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, lymphoma, and human immunodeficiency virus.1

Numerous treatments have been attempted, yet the response often is poor. Because RDD is a benign and self-limiting disease, less aggressive therapeutic approaches should be used, if possible. Surgical excision of the lesions has been helpful in certain cases.6 Cryotherapy and local radiation, topical steroids, or laser treatment also have been found to improve the condition.1,7 For refractory cases, dapsone and thalidomide have been effective. Mixed results have been observed with isotretinoin and imatinib; some patients improved whereas others did not. Utikal et al8 described a patient with complete remission of CRDD after receiving imatinib therapy; however, a different study reported a patient with CRDD who was completely resistant to this treatment.9 One case presenting on the breast did not respond to topical steroids, acitretin, and thalidomide but later responded to methotrexate.10

Conclusion

Cutaneous RDD is an unusual clinical entity with varied lesions. Generally, CRDD follows a benign clinical course, with a possibility of spontaneous remission. Further studies are required to confidently classify the etiology and variance between both RDD and CRDD.

- Fang S, Chen AJ. Facial cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report and literature review [published online February 5, 2015]. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:1389-1392.

- Chen A, Fernedez A, Janik M, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB48.

- James WD, Berger T, Elston D, et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

- Thawerani H, Sanchez RL, Rosai J, et al. The cutaneous manifestations of sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:191-197.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012.

- Al Salamah SM, Abdullah M, Al Salamah RA, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease presenting as a flank swelling. Int J Health Sci. 2014;8:434-438.

- Khan A, Musbahi E, Suchak R, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease treated by surgical excision and a review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:AB259.

- Utikal J, Ugurel S, Kurzen H, et al. Imatinib as a treatment option forsystemic non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:736-740.

- Gebhardt C, Averbeck M, Paasch V, et al. A case of cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease refractory to imatinib therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:571-574.

- Nadal M, Kervarrec T, Machet MC, et al. Cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease located on the breast: rapid effectiveness of methotrexate after failure of topical corticosteroids, acitretin and thalidomide. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:758-759.

Case Report

A 31-year-old black woman presented with a slow-spreading pruritic rash on the right thigh of 1 year’s duration. She had previously seen a dermatologist and was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% and mupirocin ointment 2% but declined a biopsy. Review of symptoms was negative for any constitutional symptoms. Family history included hypertension and eczema with a personal history of anxiety. Clinical examination revealed grouped flesh-colored to light pink papules and plaques within a hyperpigmented patch on the right medial thigh (Figure 1).

Histopathology

A punch biopsy was negative for fungal, bacterial, or acid-fast bacilli culture. Histopathologic evaluation demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of large histiocytes admixed with inflammatory cells composed predominantly of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The histiocytes within the inflammatory infiltrate had vesicular nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2A). Areas of emperipolesis were noted (Figure 2B). The large histiocytes stained positive for S-100 protein (Figure 2C) and negative for CD1a.

Course and Treatment

Laboratory studies revealed leukopenia. Prior to histopathologic results, empiric treatment was started with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. Once pathology confirmed the diagnosis of Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed and within normal limits. Due to the lack of systemic involvement, we diagnosed the rare form of purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD). In subsequent visits, treatment with oral prednisone (40 mg daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg daily for 1 week) and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (5 areas on the right medial thigh were injected with 1.0 mL of 10 mg/mL) was attempted with mild improvement, though the patient declined surgical excision.

Comment

Rosai-Dorfman disease (also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy) is a non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1 There are 2 main forms of RDD: one form that affects the lymph nodes and in certain cases the extranodal organs, and the other is purely CRDD. Cutaneous RDD is extremely rare and the etiology is unknown, though a number of viral and immune causes have been postulated. Cutaneous RDD presents as solitary or numerous papules, nodules, and/or plaques. Treatment options include steroids, methotrexate, dapsone, thalidomide, and isotretinoin, with varying efficacy reported.1

Extranodal forms occur in 43% of RDD cases, with the skin being the most common site.1 Other extranodal sites include the soft tissue, upper and lower respiratory tract, bones, genitourinary tract, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, orbits, testes, and rarely central nervous system involvement.2

Approximately 10% of RDD patients exhibit skin lesions, and in 3% it is contained solely in the skin.3 Pure CRDD was first documented in 1978 by Thawerani et al4 who presented the case of a 48-year-old man with a solitary nodule on the shoulder.

Cutaneous RDD and RDD may be distinct clinical entities. Cutaneous RDD has a later age of onset than RDD (median age, 43.5 years vs 20.6 years) and a female predominance (2:1 vs 1.4:1). It most commonly affects Asian and white individuals while the majority of patients with RDD are of African descent with rare reports in Asians.1

The etiology of CRDD remains unknown with hypotheses of viral and immune causes such as human herpesvirus 6, Epstein-Barr virus, and parvovirus B19. The polyclonal nature of the cell infiltrate and the clinical progression of RDD suggest a reactive process rather than a neoplastic disorder.1 Rosai-Dorfman disease has been hypothesized to be closely related to autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, an inherited disorder associated with defects in Fas-mediated apoptosis.5

Histologic findings in CRDD are similar to those in RDD, with a superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. A diffuse and nodular dermal infiltrate of foamy histiocytes exists in a background infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Foamy histiocytes may be seen in dermal lymphatics, and lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers also may be present. Emperipolesis, the presence of intact inflammatory cells within histiocytes, is common in CRDD. Less often, histiocytes may contain plasma cells, neutrophils, and red blood cells. Mitoses and nuclear atypia are rare. Cutaneous RDD histiocytes stain positive for S-100 protein, CD4, factor XIIIa, and CD68, and negative for CD1a. Birbeck granules are absent on electronic microscopy of CRDD tissue, eliminating Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1,3,5

The clinical diagnosis of CRDD is hard to confirm in the absence of lymphadenopathy. The lesions in CRDD may be solitary or numerous, usually presenting as papules, nodules, and/or plaques. More rarely, the lesions may present as pustules, acneform lesions, mimickers of vasculitis and panniculitis, macular erythema, large annular lesions resembling granuloma annulare, or even a breast mass.1,3 One case report with involvement of deep subcutaneous fat presented with flank swelling beneath papules and nodules.6

The most common site of lesions in CRDD is the face, with the eyelids and malar regions frequently involved, followed by the back, chest, thighs, flanks, and shoulders.1,5 Rarely, CRDD may be associated with other disorders, including bilateral uveitis, antinuclear antibody–positive lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, hypothyroidism, lymphoma, and human immunodeficiency virus.1

Numerous treatments have been attempted, yet the response often is poor. Because RDD is a benign and self-limiting disease, less aggressive therapeutic approaches should be used, if possible. Surgical excision of the lesions has been helpful in certain cases.6 Cryotherapy and local radiation, topical steroids, or laser treatment also have been found to improve the condition.1,7 For refractory cases, dapsone and thalidomide have been effective. Mixed results have been observed with isotretinoin and imatinib; some patients improved whereas others did not. Utikal et al8 described a patient with complete remission of CRDD after receiving imatinib therapy; however, a different study reported a patient with CRDD who was completely resistant to this treatment.9 One case presenting on the breast did not respond to topical steroids, acitretin, and thalidomide but later responded to methotrexate.10

Conclusion

Cutaneous RDD is an unusual clinical entity with varied lesions. Generally, CRDD follows a benign clinical course, with a possibility of spontaneous remission. Further studies are required to confidently classify the etiology and variance between both RDD and CRDD.

Case Report

A 31-year-old black woman presented with a slow-spreading pruritic rash on the right thigh of 1 year’s duration. She had previously seen a dermatologist and was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% and mupirocin ointment 2% but declined a biopsy. Review of symptoms was negative for any constitutional symptoms. Family history included hypertension and eczema with a personal history of anxiety. Clinical examination revealed grouped flesh-colored to light pink papules and plaques within a hyperpigmented patch on the right medial thigh (Figure 1).

Histopathology

A punch biopsy was negative for fungal, bacterial, or acid-fast bacilli culture. Histopathologic evaluation demonstrated a dense dermal infiltrate of large histiocytes admixed with inflammatory cells composed predominantly of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The histiocytes within the inflammatory infiltrate had vesicular nuclei and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2A). Areas of emperipolesis were noted (Figure 2B). The large histiocytes stained positive for S-100 protein (Figure 2C) and negative for CD1a.

Course and Treatment

Laboratory studies revealed leukopenia. Prior to histopathologic results, empiric treatment was started with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. Once pathology confirmed the diagnosis of Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was performed and within normal limits. Due to the lack of systemic involvement, we diagnosed the rare form of purely cutaneous Rosai-Dorfman disease (CRDD). In subsequent visits, treatment with oral prednisone (40 mg daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg daily for 1 week) and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (5 areas on the right medial thigh were injected with 1.0 mL of 10 mg/mL) was attempted with mild improvement, though the patient declined surgical excision.

Comment

Rosai-Dorfman disease (also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy) is a non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis.1 There are 2 main forms of RDD: one form that affects the lymph nodes and in certain cases the extranodal organs, and the other is purely CRDD. Cutaneous RDD is extremely rare and the etiology is unknown, though a number of viral and immune causes have been postulated. Cutaneous RDD presents as solitary or numerous papules, nodules, and/or plaques. Treatment options include steroids, methotrexate, dapsone, thalidomide, and isotretinoin, with varying efficacy reported.1

Extranodal forms occur in 43% of RDD cases, with the skin being the most common site.1 Other extranodal sites include the soft tissue, upper and lower respiratory tract, bones, genitourinary tract, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, orbits, testes, and rarely central nervous system involvement.2

Approximately 10% of RDD patients exhibit skin lesions, and in 3% it is contained solely in the skin.3 Pure CRDD was first documented in 1978 by Thawerani et al4 who presented the case of a 48-year-old man with a solitary nodule on the shoulder.

Cutaneous RDD and RDD may be distinct clinical entities. Cutaneous RDD has a later age of onset than RDD (median age, 43.5 years vs 20.6 years) and a female predominance (2:1 vs 1.4:1). It most commonly affects Asian and white individuals while the majority of patients with RDD are of African descent with rare reports in Asians.1