User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

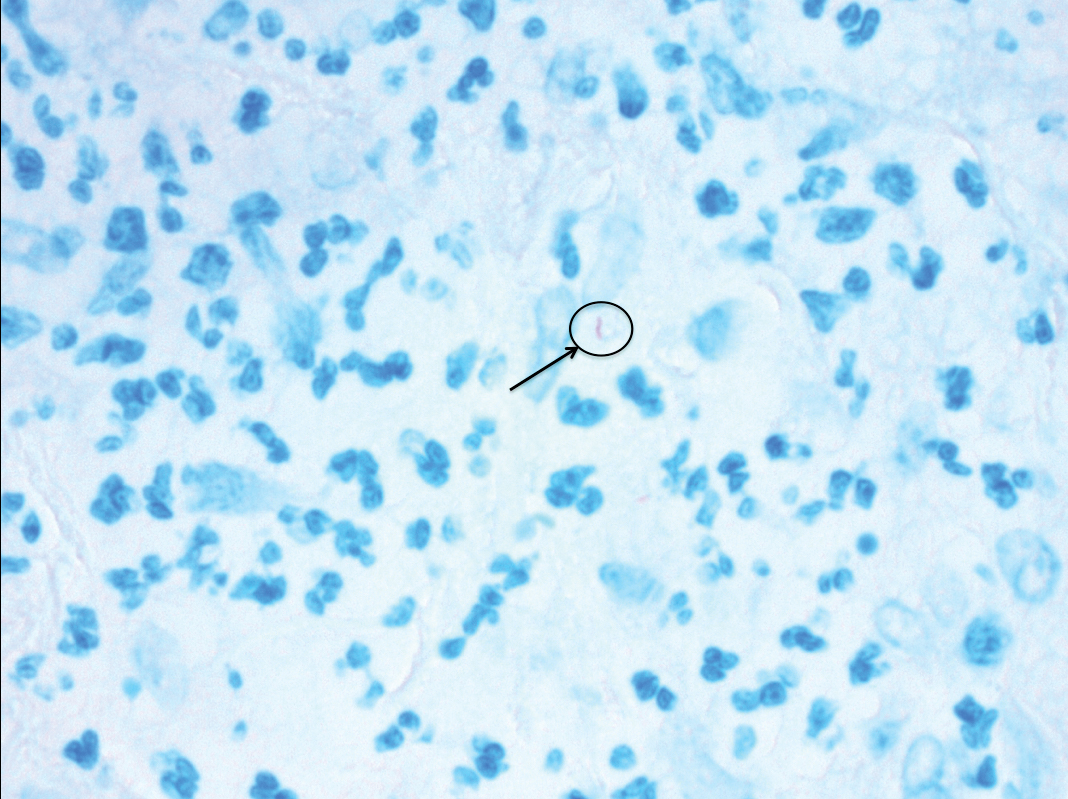

Pruritic Nodules on the Breast

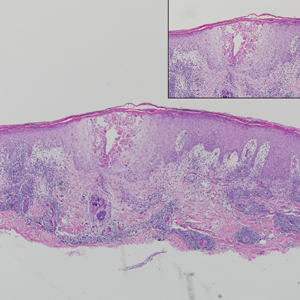

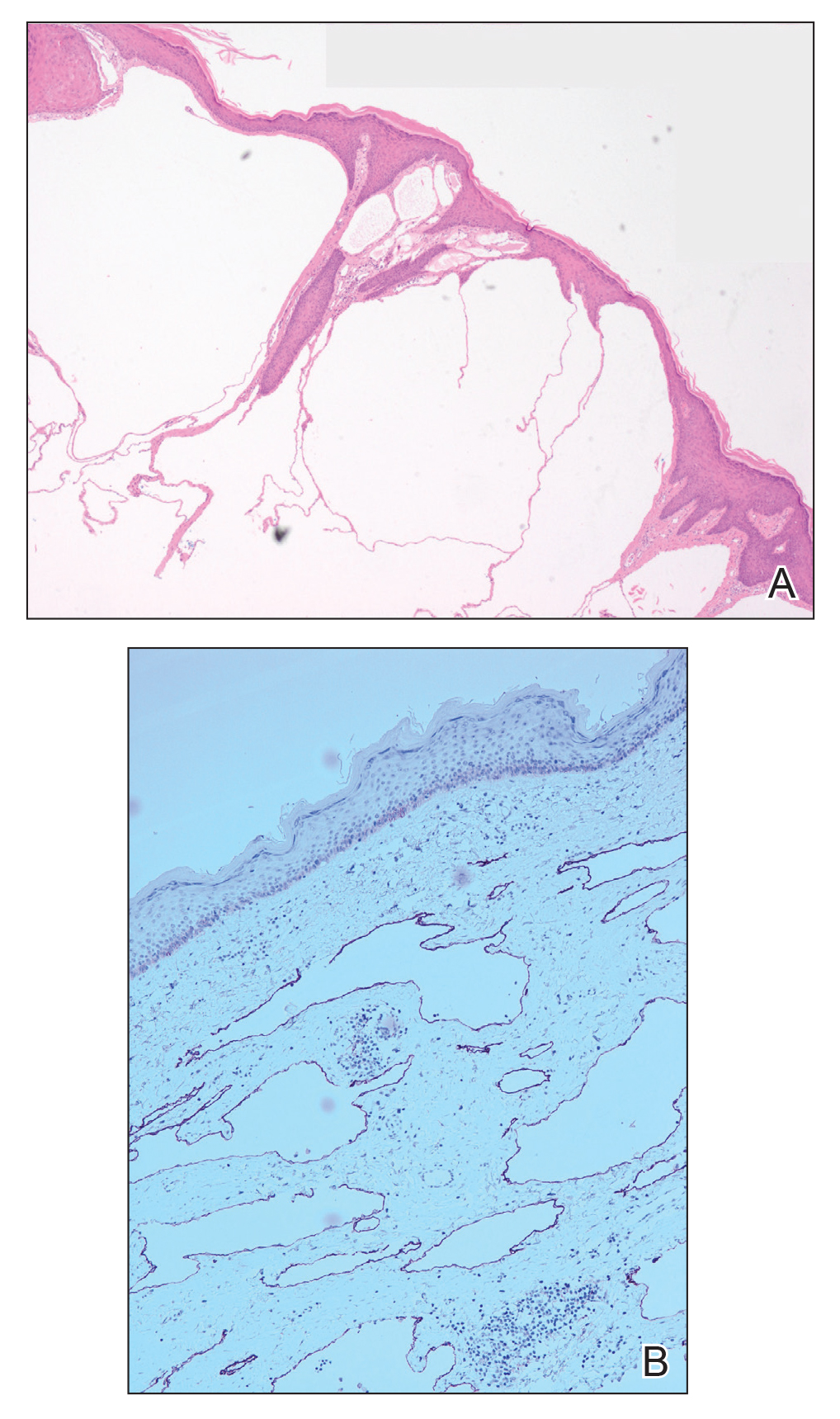

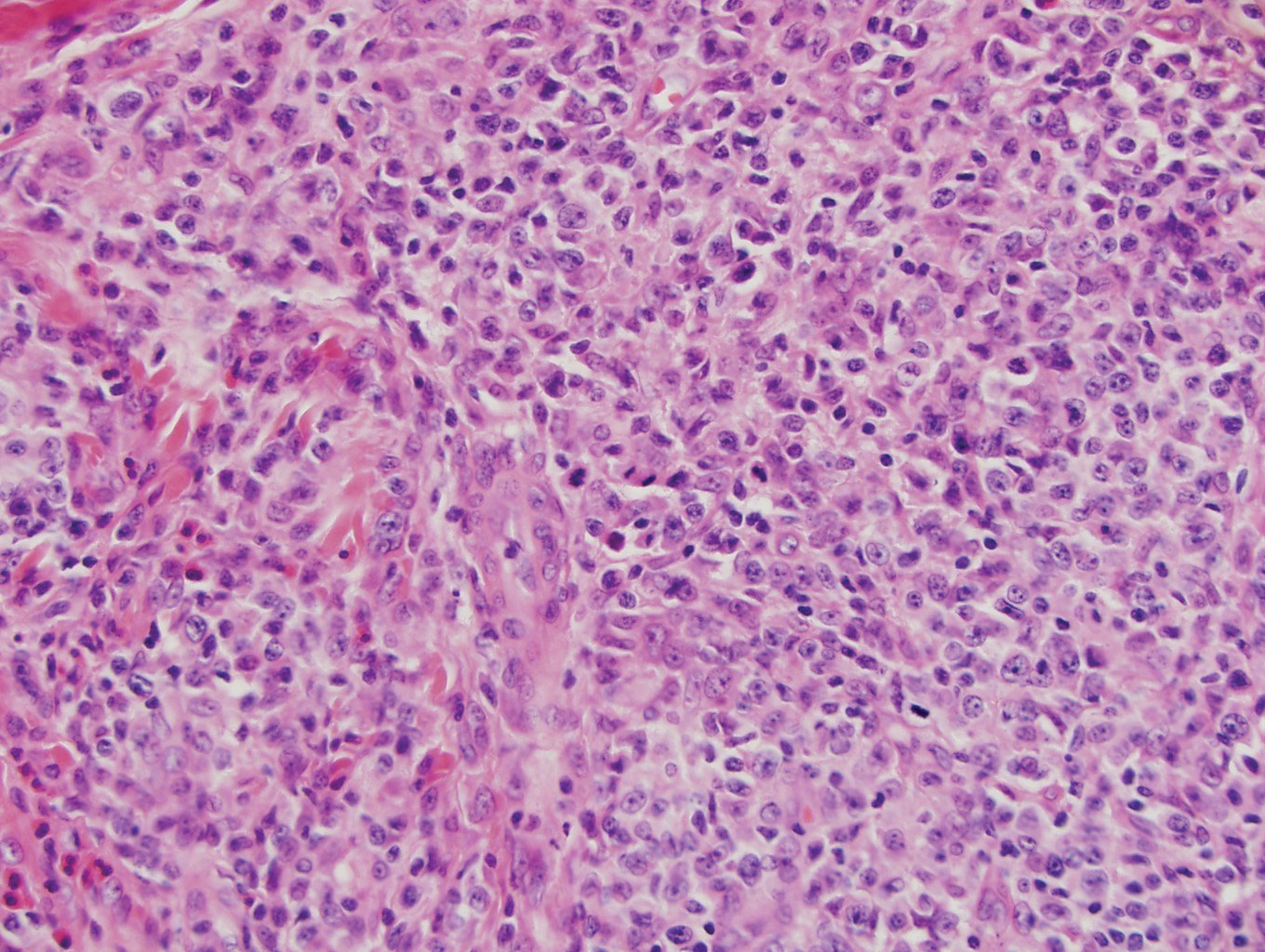

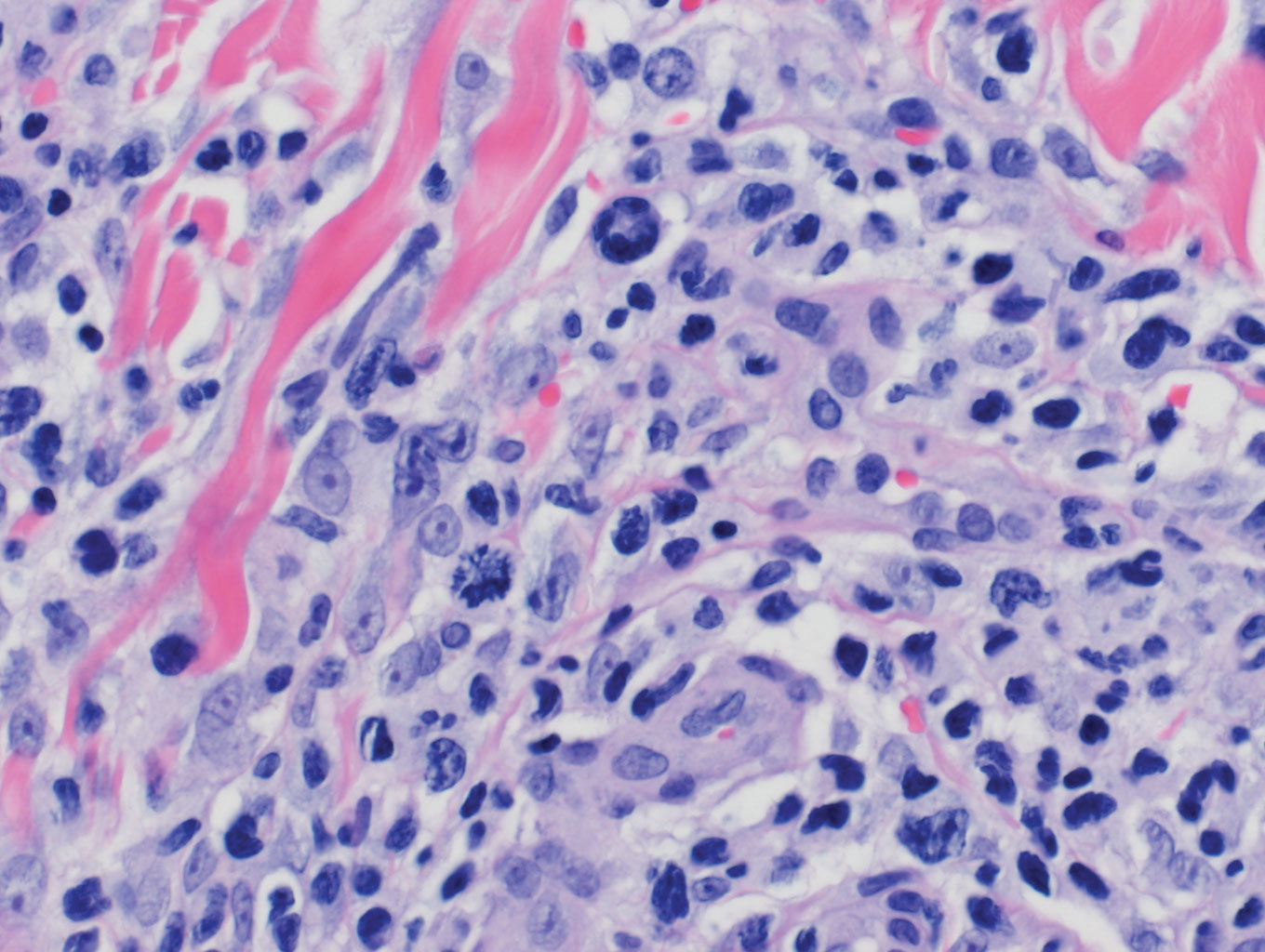

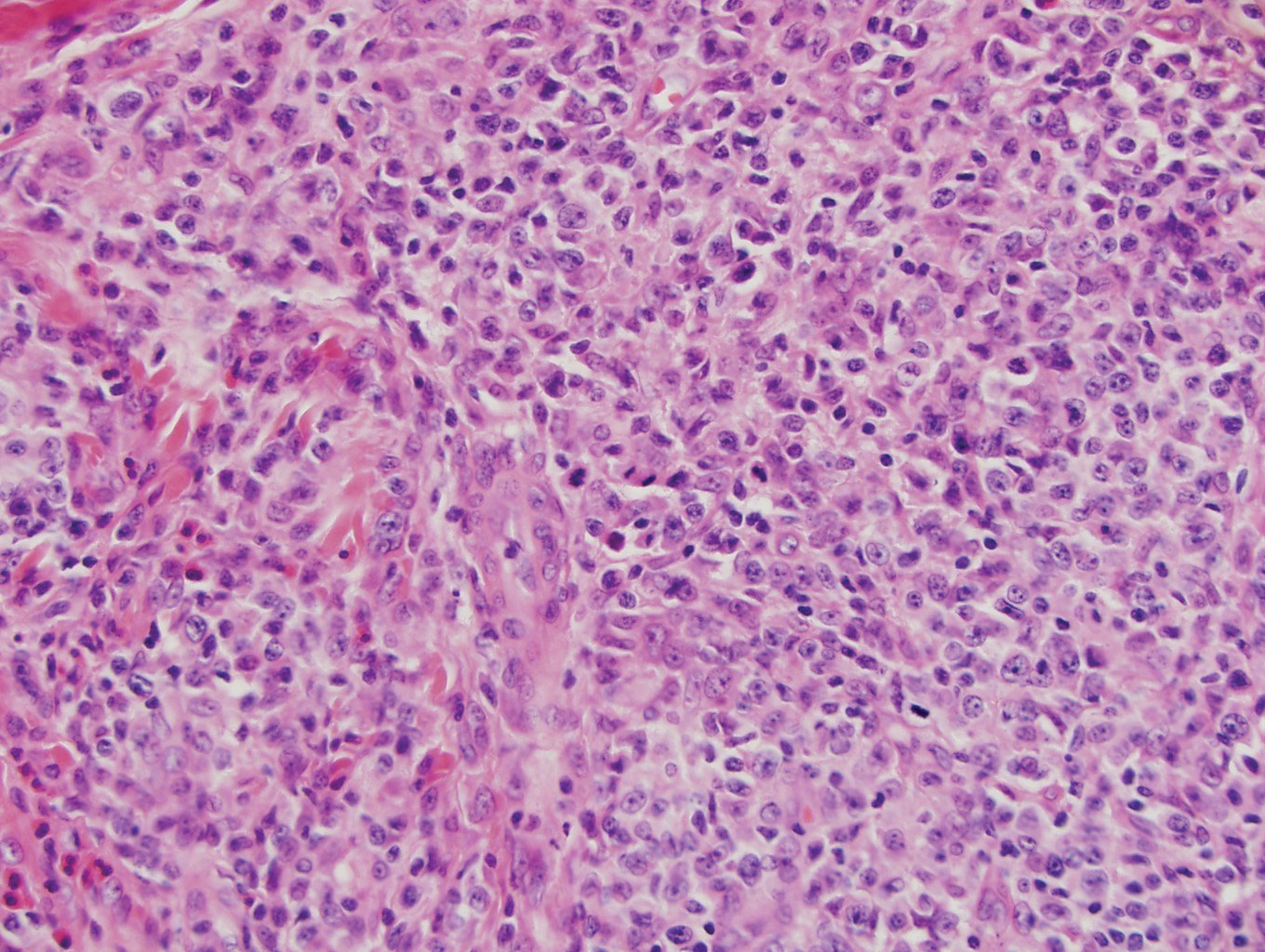

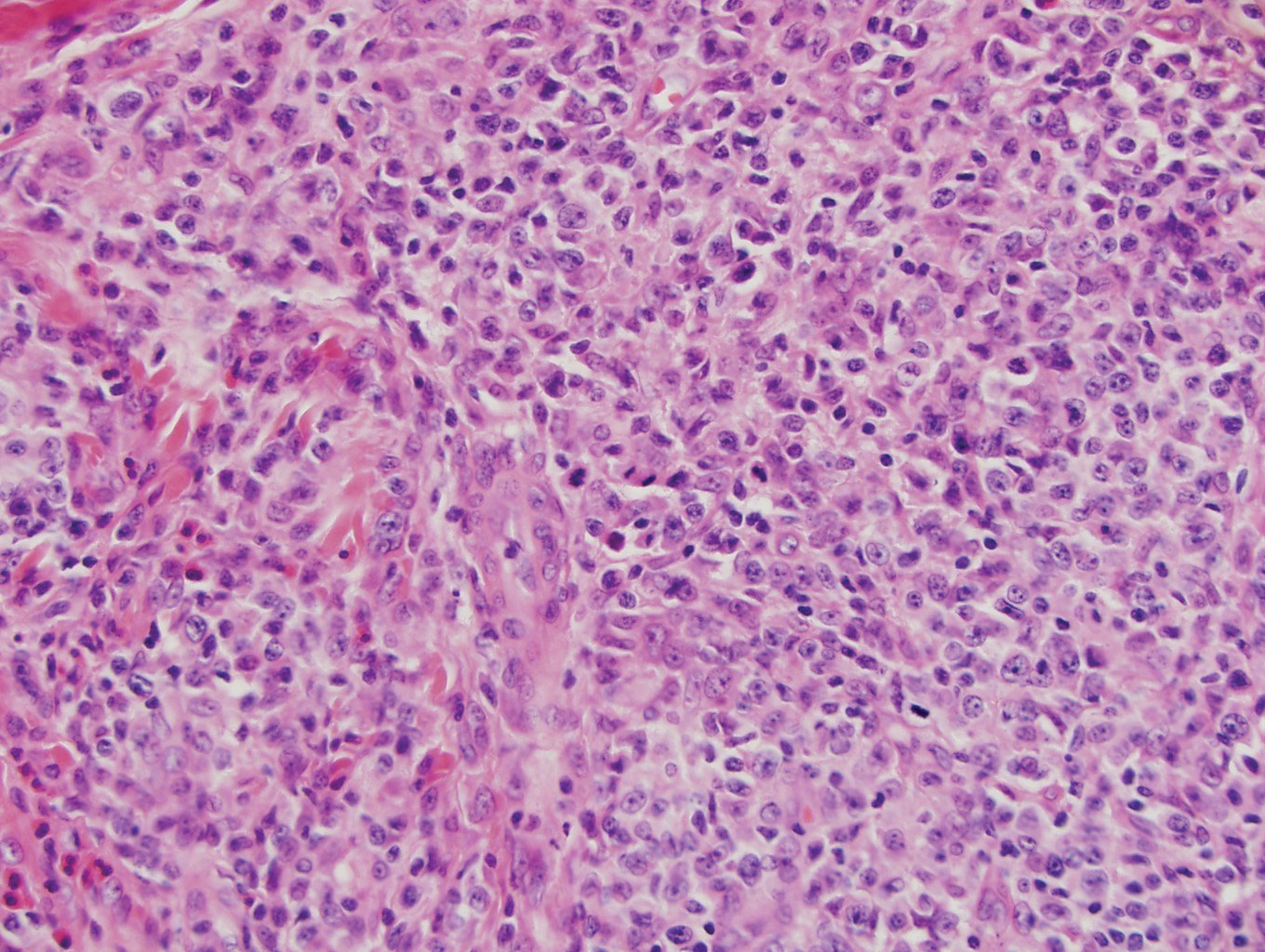

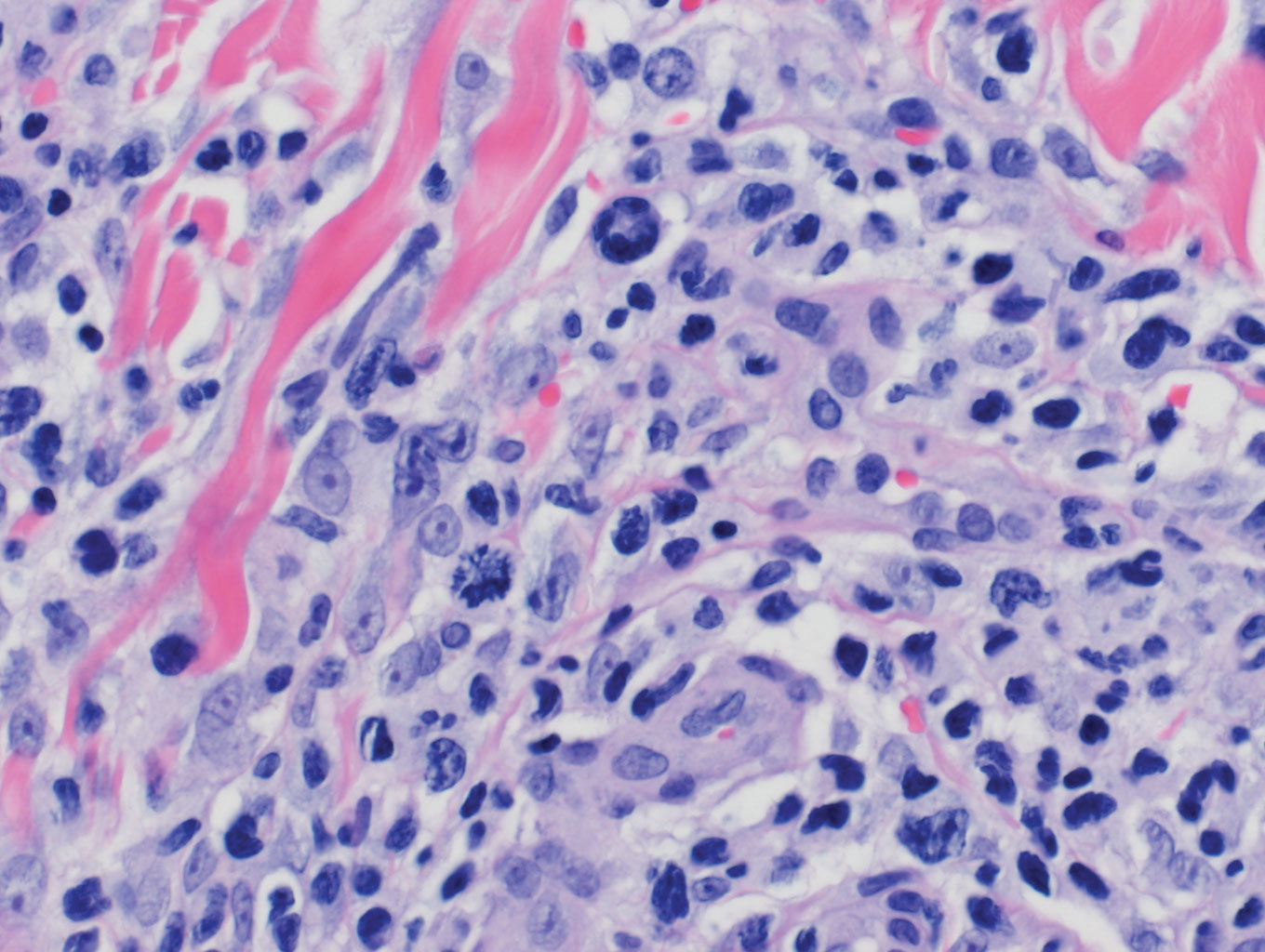

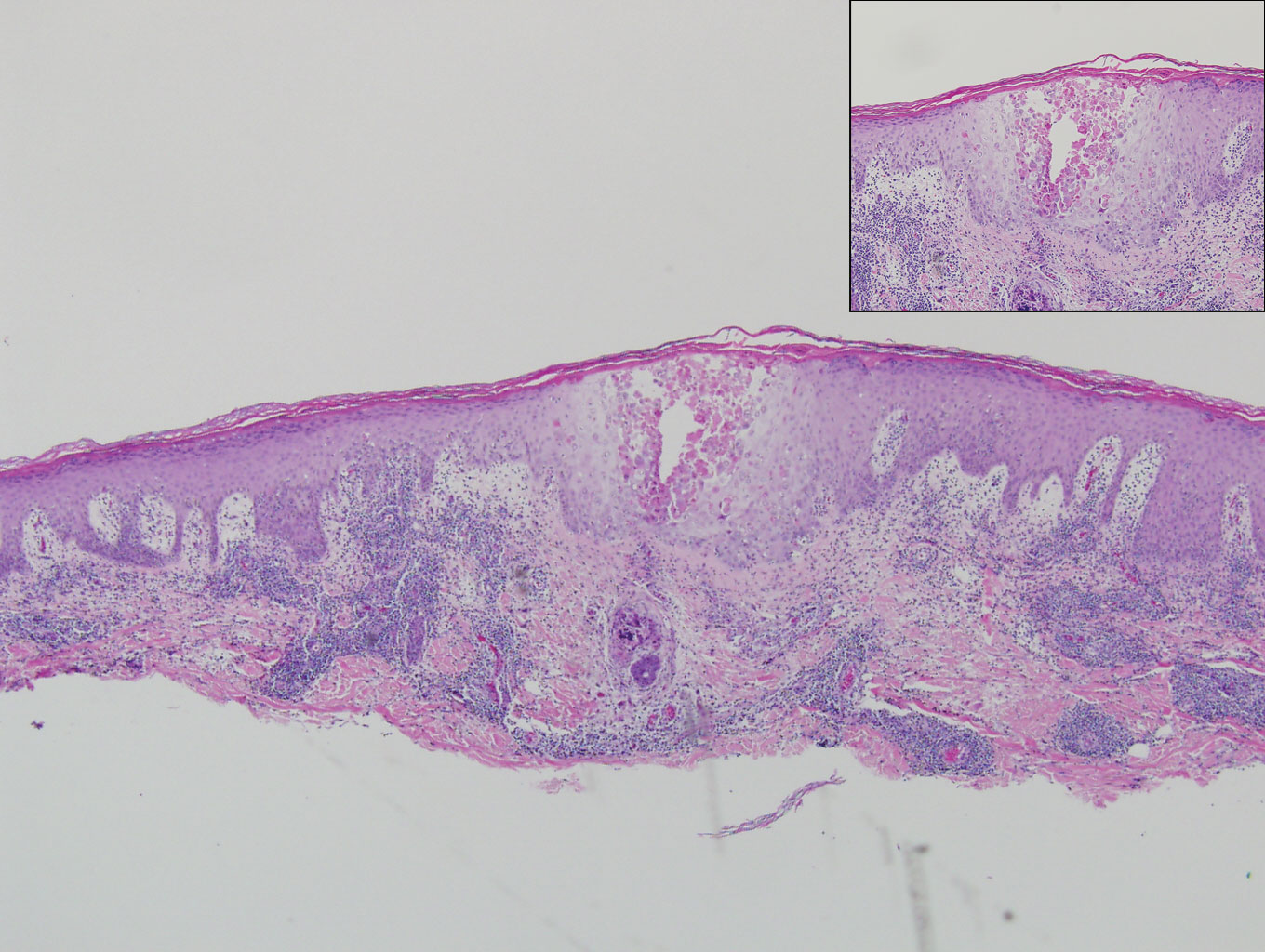

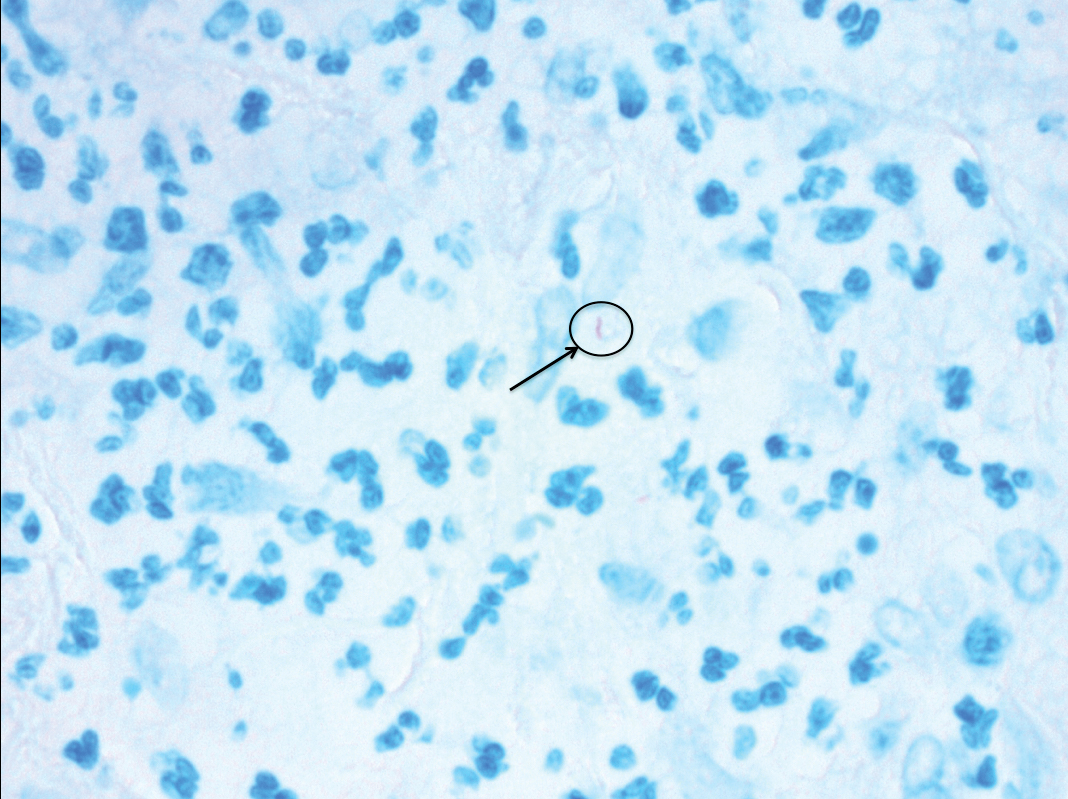

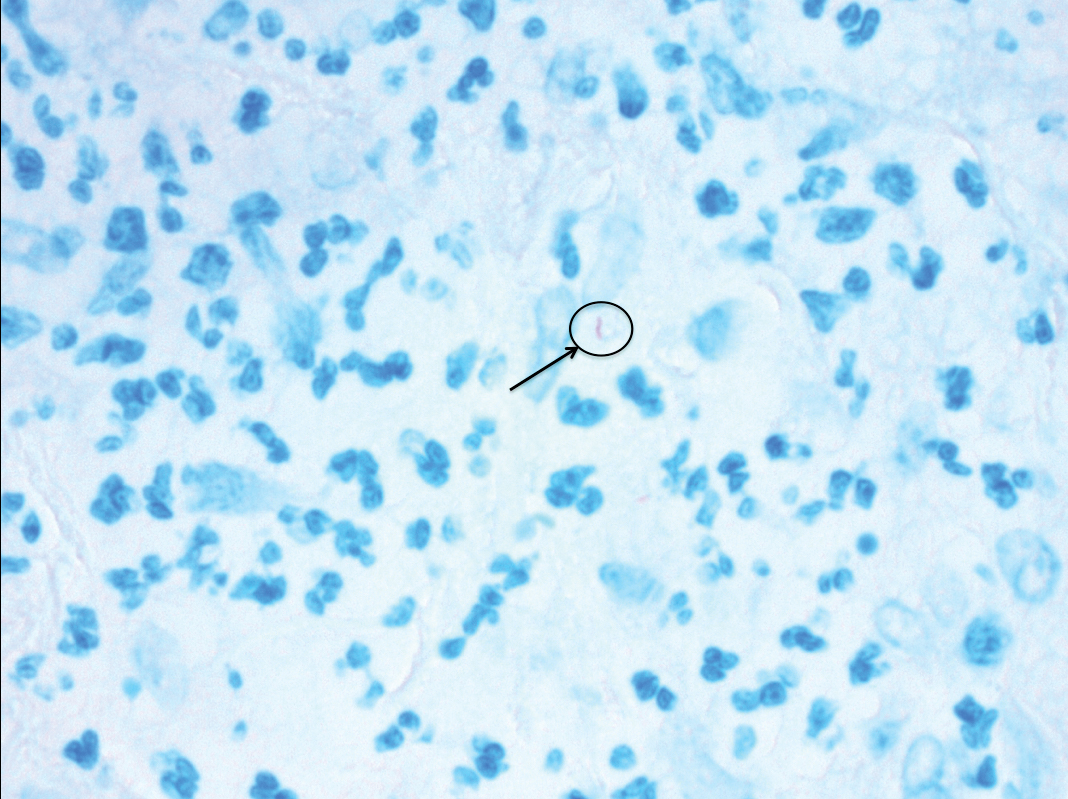

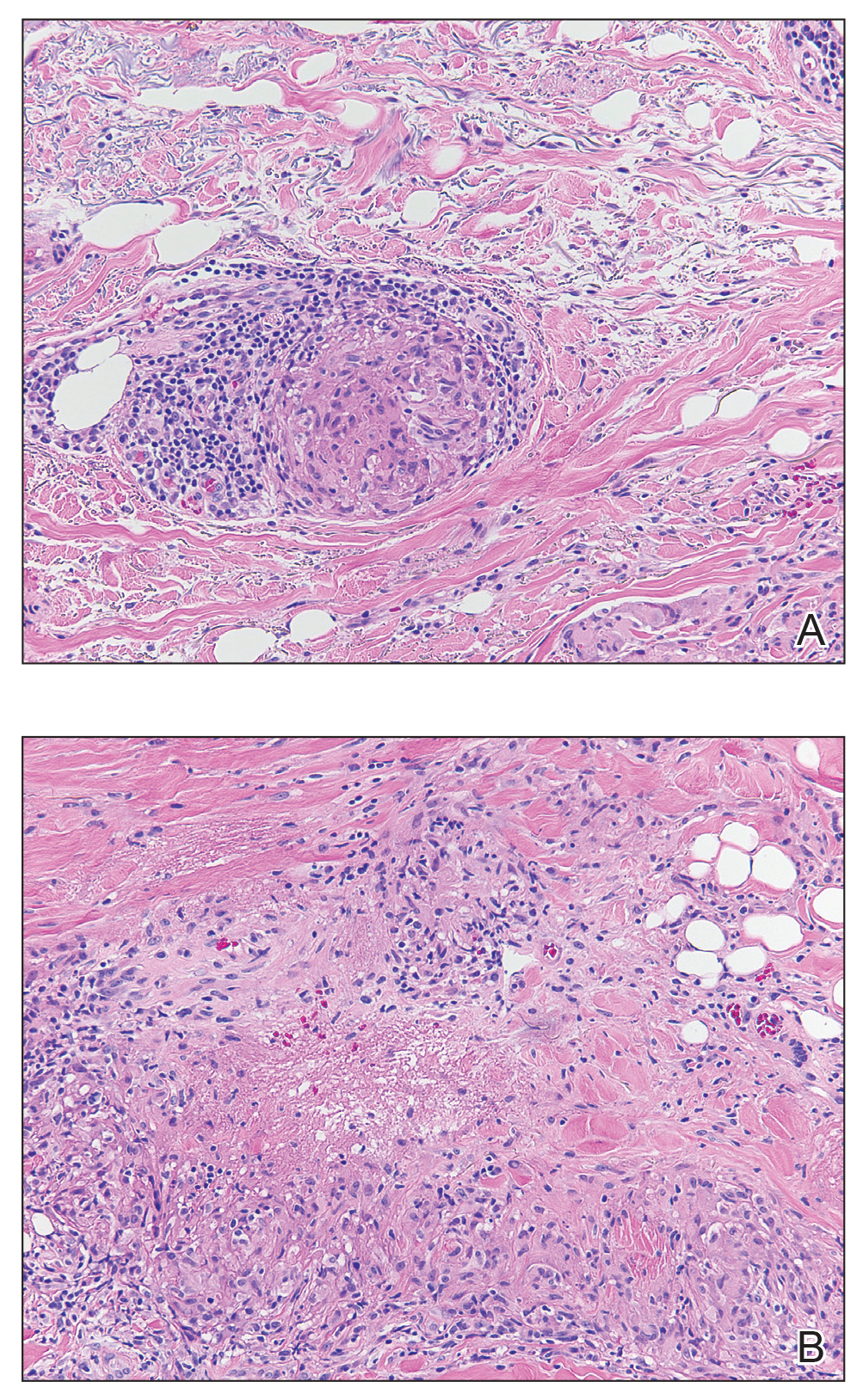

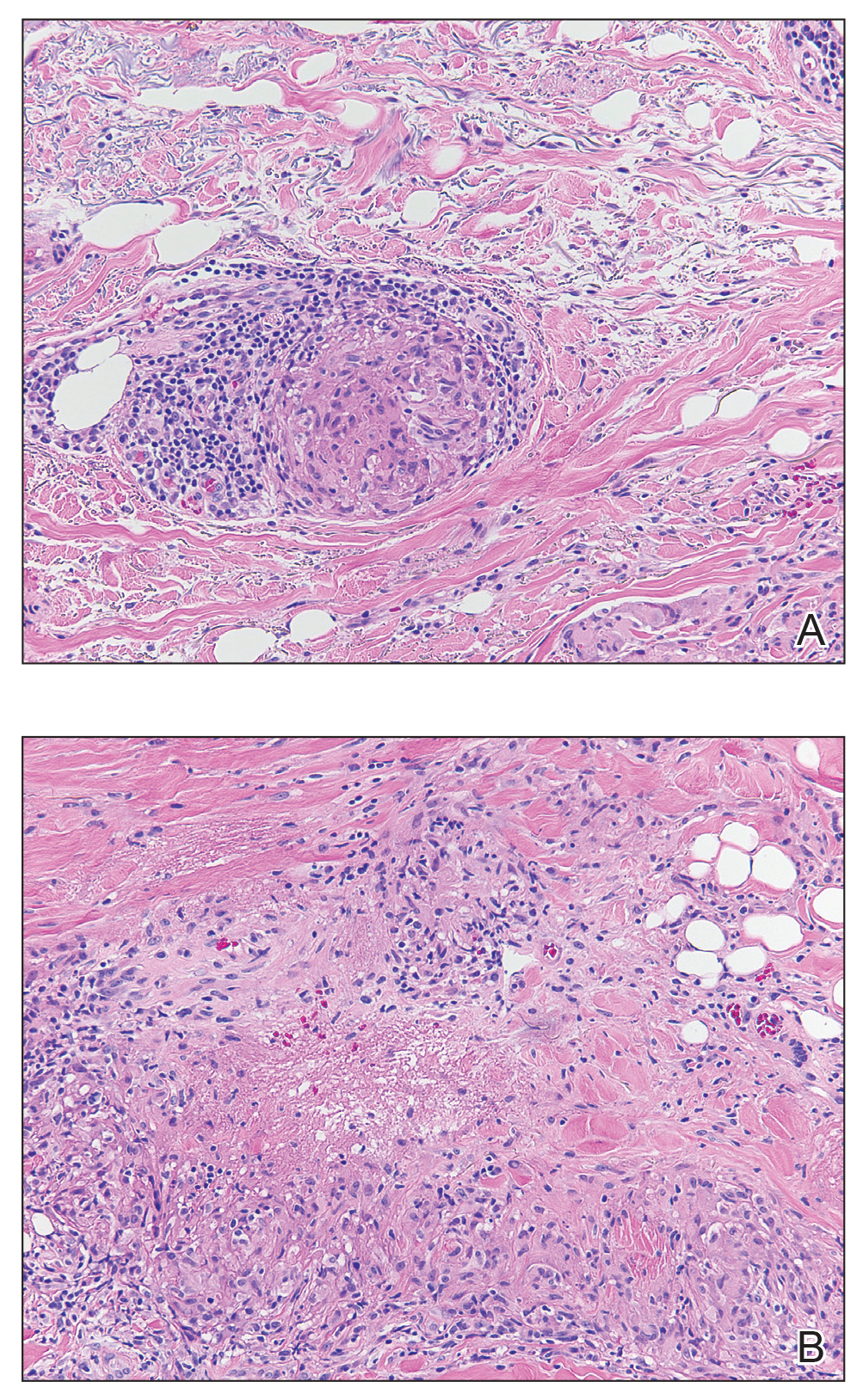

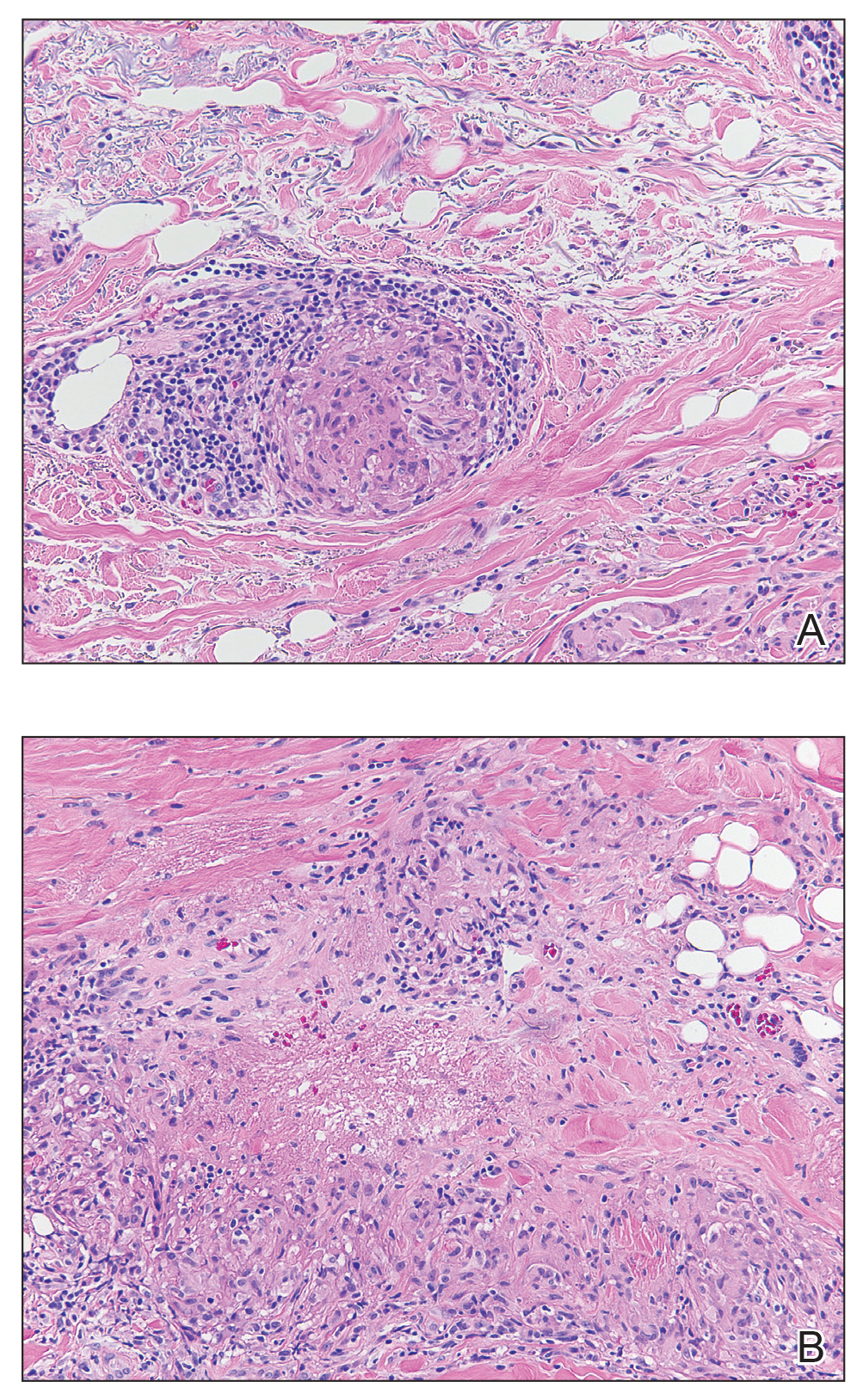

Microcystic lymphatic malformations, also known as lymphangioma circumscriptum, are rare hamartomatous lesions comprised of dilated lymphatic channels that can be both congenital and acquired.1 They often present as translucent or hemorrhagic vesicles of varying sizes that may contain lymphatic fluid and often can cluster together and appear verrucous (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis for microcystic lymphatic malformations commonly includes molluscum contagiosum, squamous cell carcinoma, verruca vulgaris, or condylomas, as well as atypical vascular lesions. They most often are found in children as congenital lesions but also may be acquired. Most acquired cases are due to chronic inflammatory and scarring processes that damage lymphatic structures, including surgery, radiation, infections, and even Crohn disease.2,3 Because the differential diagnosis is so broad and the disease can clinically mimic other common disease processes, biopsies often are performed to determine the diagnosis. On biopsy, pathologic examination revealed well-circumscribed nodular lesions with large lymphatic channels often in a background of connective tissue stroma. Increased eosinophilic material, including mast cells, also was seen (Figure 2A). On immunohistochemistry, staining showed D2-40 positivity (Figure 2B).

Damage to lymphatics from radiation and postsurgical excision of tumors are well-described causes of microcystic lymphatic malformations, as in our patient, with most instances in the literature occurring secondary to treatment of breast or cervical cancer.4-6 In these acquired cases, the pathogenesis is thought to be due to destruction and fibrosis at the layer of the reticular dermis, which causes lymphatic obstruction and subsequent dilation of superficial lymphatic channels.6

Microcystic lymphatic malformations can be difficult to distinguish from atypical vascular lesions, another common postradiation lesion. Both are benign well-circumscribed lesions that histologically do not extend into surrounding subcutaneous tissues and do not have multilayering of cells, mitosis, or hemorrhage.7 Although lymphatic lesions tend to form vesicles, atypical vascular lesions arising after radiation treatment present as erythematous or flesh-colored patches or papules. They also tend to be fairly superficial and often only involve the superficial to mid dermis. On histology they show thin-walled channels without erythrocytes that are lined by typical endothelial cells.7 Despite these differences, both clinically and histopathologically these lesions can appear similar to acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations. It is important to differentiate between these two entities, as atypical vascular lesions have a slightly higher rate of transformation into malignant tumors such as angiosarcomas.

Although angiosarcomas clinically may present as erythematous patches, plaques, or nodules similar to benign postradiation lesions, they tend to be more edematous than their benign counterparts.7,8 Two other clinical factors that can help determine if a postradiation lesion is benign or malignant are the size and time of onset of the lesion. Angiosarcomas tend to be much larger than benign postradiation lesions (median size, 7.5 cm) and tend to be more multifocal in nature.8,9 They also tend to arise on average 5 to 7 years after the initial radiation treatment, while benign lesions arise sooner.9

Small, asymptomatic, acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations can be followed clinically without treatment, but these lesions do not commonly regress spontaneously. Even when asymptomatic, many clinicians will opt for treatment to prevent secondary complications such as infections, drainage, and pain. Moreover, these lesions can have notable psychosocial impacts on patients due to poor cosmetic appearance. Unfortunately, there is no gold standard of treatment, and recurrence is common, even after treatment. Historically, surgical excision was the treatment of choice, but this option carries a high risk for scarring, invasiveness, and recurrence. Recurrence rates of up to 23.1% have been reported with decreased effectiveness of resection, particularly in areas of deeper involvement.10 For these deeper lesions, CO2 laser therapy is a promising evolving therapy. It can penetrate up to the mid dermis and seems to destroy the lymphatic channels between deep and surface lymphatics, preventing the cutaneous manifestations of the disease. It has the added benefit of minimal invasiveness and fewer side effects than complete excision, with most studies reporting hyperpigmentation and scarring as the most common side effects.11 Additional emerging therapies including sclerotherapy and isotretinoin have shown benefits in case studies. Sclerotherapy causes local tissue destruction and thrombosis leading to destruction of vessel lumens and fibrosis that halts disease progression and clears existing lesions.12 Oral therapy with isotretinoin appears to work by inhibiting certain cytokines and acting as an antiangiogenic factor.13 Given the rarity of microcystic lymphatic malformations, further research must be done to determine definitive treatment.

Acquired microcystic lymphatic malformation is an important sequela of radiation therapy and surgical excision of malignancy. Despite its striking clinical appearance, it is sometimes difficult to diagnose given its rarity. It is important that clinicians are able to recognize it clinically and understand common treatment options to prevent both the mental stigma and complications, including secondary infections, drainage, and pain.

- Whimster IW. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:473.

- Vlastos AT, Malpica A, Follen M. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:946-954.

- Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Burchette JL, et al. Acquired vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a comparison of 12 cases with Crohn’s associated lesions or radiation therapy induced tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:958-965.

- Kaya TI, Kokturk A, Polat A, et al. A case of cutaneous lymphangiectasis secondary to breast cancer treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:760-761.

- Ambrojo P, Cogolluda EF, Aguilar A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangiectases after therapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:57-59.

- Tasdelen I, Gokgoz S, Paksoy E, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasis after breast conservation treatment for breast cancer: report of a case. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:9.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process: a study from the French Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Ghaemmaghami F, Karimi Zarchi M, Mousavi A. Major labiaectomy as surgical management of vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: three cases and a review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:57-60.

- Savas J. Carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of microcystic lymphatic malformations (lymphangioma circumscriptum): a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1147-1157.

- Al Ghamdi KM, Mubki TF. Treatment of lymphangioma circumscriptum with sclerotherapy: an ignored effective remedy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:156-158.

- Ayhan E. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: good clinical response to isotretinoin therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E208-E209.

Microcystic lymphatic malformations, also known as lymphangioma circumscriptum, are rare hamartomatous lesions comprised of dilated lymphatic channels that can be both congenital and acquired.1 They often present as translucent or hemorrhagic vesicles of varying sizes that may contain lymphatic fluid and often can cluster together and appear verrucous (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis for microcystic lymphatic malformations commonly includes molluscum contagiosum, squamous cell carcinoma, verruca vulgaris, or condylomas, as well as atypical vascular lesions. They most often are found in children as congenital lesions but also may be acquired. Most acquired cases are due to chronic inflammatory and scarring processes that damage lymphatic structures, including surgery, radiation, infections, and even Crohn disease.2,3 Because the differential diagnosis is so broad and the disease can clinically mimic other common disease processes, biopsies often are performed to determine the diagnosis. On biopsy, pathologic examination revealed well-circumscribed nodular lesions with large lymphatic channels often in a background of connective tissue stroma. Increased eosinophilic material, including mast cells, also was seen (Figure 2A). On immunohistochemistry, staining showed D2-40 positivity (Figure 2B).

Damage to lymphatics from radiation and postsurgical excision of tumors are well-described causes of microcystic lymphatic malformations, as in our patient, with most instances in the literature occurring secondary to treatment of breast or cervical cancer.4-6 In these acquired cases, the pathogenesis is thought to be due to destruction and fibrosis at the layer of the reticular dermis, which causes lymphatic obstruction and subsequent dilation of superficial lymphatic channels.6

Microcystic lymphatic malformations can be difficult to distinguish from atypical vascular lesions, another common postradiation lesion. Both are benign well-circumscribed lesions that histologically do not extend into surrounding subcutaneous tissues and do not have multilayering of cells, mitosis, or hemorrhage.7 Although lymphatic lesions tend to form vesicles, atypical vascular lesions arising after radiation treatment present as erythematous or flesh-colored patches or papules. They also tend to be fairly superficial and often only involve the superficial to mid dermis. On histology they show thin-walled channels without erythrocytes that are lined by typical endothelial cells.7 Despite these differences, both clinically and histopathologically these lesions can appear similar to acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations. It is important to differentiate between these two entities, as atypical vascular lesions have a slightly higher rate of transformation into malignant tumors such as angiosarcomas.

Although angiosarcomas clinically may present as erythematous patches, plaques, or nodules similar to benign postradiation lesions, they tend to be more edematous than their benign counterparts.7,8 Two other clinical factors that can help determine if a postradiation lesion is benign or malignant are the size and time of onset of the lesion. Angiosarcomas tend to be much larger than benign postradiation lesions (median size, 7.5 cm) and tend to be more multifocal in nature.8,9 They also tend to arise on average 5 to 7 years after the initial radiation treatment, while benign lesions arise sooner.9

Small, asymptomatic, acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations can be followed clinically without treatment, but these lesions do not commonly regress spontaneously. Even when asymptomatic, many clinicians will opt for treatment to prevent secondary complications such as infections, drainage, and pain. Moreover, these lesions can have notable psychosocial impacts on patients due to poor cosmetic appearance. Unfortunately, there is no gold standard of treatment, and recurrence is common, even after treatment. Historically, surgical excision was the treatment of choice, but this option carries a high risk for scarring, invasiveness, and recurrence. Recurrence rates of up to 23.1% have been reported with decreased effectiveness of resection, particularly in areas of deeper involvement.10 For these deeper lesions, CO2 laser therapy is a promising evolving therapy. It can penetrate up to the mid dermis and seems to destroy the lymphatic channels between deep and surface lymphatics, preventing the cutaneous manifestations of the disease. It has the added benefit of minimal invasiveness and fewer side effects than complete excision, with most studies reporting hyperpigmentation and scarring as the most common side effects.11 Additional emerging therapies including sclerotherapy and isotretinoin have shown benefits in case studies. Sclerotherapy causes local tissue destruction and thrombosis leading to destruction of vessel lumens and fibrosis that halts disease progression and clears existing lesions.12 Oral therapy with isotretinoin appears to work by inhibiting certain cytokines and acting as an antiangiogenic factor.13 Given the rarity of microcystic lymphatic malformations, further research must be done to determine definitive treatment.

Acquired microcystic lymphatic malformation is an important sequela of radiation therapy and surgical excision of malignancy. Despite its striking clinical appearance, it is sometimes difficult to diagnose given its rarity. It is important that clinicians are able to recognize it clinically and understand common treatment options to prevent both the mental stigma and complications, including secondary infections, drainage, and pain.

Microcystic lymphatic malformations, also known as lymphangioma circumscriptum, are rare hamartomatous lesions comprised of dilated lymphatic channels that can be both congenital and acquired.1 They often present as translucent or hemorrhagic vesicles of varying sizes that may contain lymphatic fluid and often can cluster together and appear verrucous (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis for microcystic lymphatic malformations commonly includes molluscum contagiosum, squamous cell carcinoma, verruca vulgaris, or condylomas, as well as atypical vascular lesions. They most often are found in children as congenital lesions but also may be acquired. Most acquired cases are due to chronic inflammatory and scarring processes that damage lymphatic structures, including surgery, radiation, infections, and even Crohn disease.2,3 Because the differential diagnosis is so broad and the disease can clinically mimic other common disease processes, biopsies often are performed to determine the diagnosis. On biopsy, pathologic examination revealed well-circumscribed nodular lesions with large lymphatic channels often in a background of connective tissue stroma. Increased eosinophilic material, including mast cells, also was seen (Figure 2A). On immunohistochemistry, staining showed D2-40 positivity (Figure 2B).

Damage to lymphatics from radiation and postsurgical excision of tumors are well-described causes of microcystic lymphatic malformations, as in our patient, with most instances in the literature occurring secondary to treatment of breast or cervical cancer.4-6 In these acquired cases, the pathogenesis is thought to be due to destruction and fibrosis at the layer of the reticular dermis, which causes lymphatic obstruction and subsequent dilation of superficial lymphatic channels.6

Microcystic lymphatic malformations can be difficult to distinguish from atypical vascular lesions, another common postradiation lesion. Both are benign well-circumscribed lesions that histologically do not extend into surrounding subcutaneous tissues and do not have multilayering of cells, mitosis, or hemorrhage.7 Although lymphatic lesions tend to form vesicles, atypical vascular lesions arising after radiation treatment present as erythematous or flesh-colored patches or papules. They also tend to be fairly superficial and often only involve the superficial to mid dermis. On histology they show thin-walled channels without erythrocytes that are lined by typical endothelial cells.7 Despite these differences, both clinically and histopathologically these lesions can appear similar to acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations. It is important to differentiate between these two entities, as atypical vascular lesions have a slightly higher rate of transformation into malignant tumors such as angiosarcomas.

Although angiosarcomas clinically may present as erythematous patches, plaques, or nodules similar to benign postradiation lesions, they tend to be more edematous than their benign counterparts.7,8 Two other clinical factors that can help determine if a postradiation lesion is benign or malignant are the size and time of onset of the lesion. Angiosarcomas tend to be much larger than benign postradiation lesions (median size, 7.5 cm) and tend to be more multifocal in nature.8,9 They also tend to arise on average 5 to 7 years after the initial radiation treatment, while benign lesions arise sooner.9

Small, asymptomatic, acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations can be followed clinically without treatment, but these lesions do not commonly regress spontaneously. Even when asymptomatic, many clinicians will opt for treatment to prevent secondary complications such as infections, drainage, and pain. Moreover, these lesions can have notable psychosocial impacts on patients due to poor cosmetic appearance. Unfortunately, there is no gold standard of treatment, and recurrence is common, even after treatment. Historically, surgical excision was the treatment of choice, but this option carries a high risk for scarring, invasiveness, and recurrence. Recurrence rates of up to 23.1% have been reported with decreased effectiveness of resection, particularly in areas of deeper involvement.10 For these deeper lesions, CO2 laser therapy is a promising evolving therapy. It can penetrate up to the mid dermis and seems to destroy the lymphatic channels between deep and surface lymphatics, preventing the cutaneous manifestations of the disease. It has the added benefit of minimal invasiveness and fewer side effects than complete excision, with most studies reporting hyperpigmentation and scarring as the most common side effects.11 Additional emerging therapies including sclerotherapy and isotretinoin have shown benefits in case studies. Sclerotherapy causes local tissue destruction and thrombosis leading to destruction of vessel lumens and fibrosis that halts disease progression and clears existing lesions.12 Oral therapy with isotretinoin appears to work by inhibiting certain cytokines and acting as an antiangiogenic factor.13 Given the rarity of microcystic lymphatic malformations, further research must be done to determine definitive treatment.

Acquired microcystic lymphatic malformation is an important sequela of radiation therapy and surgical excision of malignancy. Despite its striking clinical appearance, it is sometimes difficult to diagnose given its rarity. It is important that clinicians are able to recognize it clinically and understand common treatment options to prevent both the mental stigma and complications, including secondary infections, drainage, and pain.

- Whimster IW. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:473.

- Vlastos AT, Malpica A, Follen M. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:946-954.

- Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Burchette JL, et al. Acquired vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a comparison of 12 cases with Crohn’s associated lesions or radiation therapy induced tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:958-965.

- Kaya TI, Kokturk A, Polat A, et al. A case of cutaneous lymphangiectasis secondary to breast cancer treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:760-761.

- Ambrojo P, Cogolluda EF, Aguilar A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangiectases after therapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:57-59.

- Tasdelen I, Gokgoz S, Paksoy E, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasis after breast conservation treatment for breast cancer: report of a case. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:9.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process: a study from the French Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Ghaemmaghami F, Karimi Zarchi M, Mousavi A. Major labiaectomy as surgical management of vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: three cases and a review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:57-60.

- Savas J. Carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of microcystic lymphatic malformations (lymphangioma circumscriptum): a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1147-1157.

- Al Ghamdi KM, Mubki TF. Treatment of lymphangioma circumscriptum with sclerotherapy: an ignored effective remedy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:156-158.

- Ayhan E. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: good clinical response to isotretinoin therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E208-E209.

- Whimster IW. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:473.

- Vlastos AT, Malpica A, Follen M. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:946-954.

- Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Burchette JL, et al. Acquired vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a comparison of 12 cases with Crohn’s associated lesions or radiation therapy induced tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:958-965.

- Kaya TI, Kokturk A, Polat A, et al. A case of cutaneous lymphangiectasis secondary to breast cancer treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:760-761.

- Ambrojo P, Cogolluda EF, Aguilar A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangiectases after therapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:57-59.

- Tasdelen I, Gokgoz S, Paksoy E, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasis after breast conservation treatment for breast cancer: report of a case. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:9.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process: a study from the French Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Ghaemmaghami F, Karimi Zarchi M, Mousavi A. Major labiaectomy as surgical management of vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: three cases and a review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:57-60.

- Savas J. Carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of microcystic lymphatic malformations (lymphangioma circumscriptum): a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1147-1157.

- Al Ghamdi KM, Mubki TF. Treatment of lymphangioma circumscriptum with sclerotherapy: an ignored effective remedy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:156-158.

- Ayhan E. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: good clinical response to isotretinoin therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E208-E209.

A 51-year-old woman with a history of bilateral breast cancer presented for evaluation of lesions on the underside of the right breast. She was first diagnosed with stage II cancer of the right breast that was subsequently treated with a mastectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy 7 years prior to presentation. One year later, she developed stage IIIC adenocarcinoma of the left breast and was treated with a modified radical mastectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy, and radiation. She had been followed closely by her oncologist with regular surveillance imaging (last at 7 months prior to presentation) that had all been negative for recurrent breast cancer. She presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of lesions on the underside of the right breast that were pruritic and occasionally painful with a burning quality. These lesions had recently begun to bleed when scratched but were not otherwise growing or spreading. On physical examination she was afebrile with stable vital signs. Skin examination was notable for numerous violaceous and translucent papules and nodules underneath the right breast and axilla overlying a well-healed mastectomy scar. No lymphadenopathy was present. Shave biopsies were performed and showed well-circumscribed nodular lesions with ectatic vascular channels separated by thin fibrous walls and filled with eosinophilic proteinaceous material and scattered red blood cells. Immunohistochemical staining also showed positivity for D2-40.

Supercharge Your On-Call Bag: 4 Must-Have Items for Dermatology Residents

It is no secret that a well-stocked on-call bag is one of the keys to providing inpatient care as a dermatology resident. Beyond the basic items that should never be left at home, there are some lesser-known tools that I have learned about from my book- and street-smart attendings and co-residents in the Department of Dermatology at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center (referred to here as Downstate). Here are our top 4 items to pack the next time you are on call. (Bonus: you will find them helpful in clinic, too.)

Item 1: WoundSeal Powder

The most valuable player in my on-call bag, WoundSeal Powder (Biolife) is an over-the-counter hemostatic agent that I learned about from Daniel M. Siegel, MD, MS, a Mohs surgeon at Downstate and former president of the American Academy of Dermatology. The powder consists of a hydrophilic polymer and potassium ferrate.1 When poured over a bleeding wound and pressed in place (eg, with a sterile cotton-tipped swab), the hydrophilic polymer absorbs plasma while the iron in potassium ferrate agglomerates blood solids. The result is a scablike seal that is safe to leave in place until the wound has healed.1

Since Dr. Siegel introduced WoundSeal to Downstate about a decade ago, it has become our department’s go-to hemostatic agent for most punch biopsies performed in the inpatient setting. In our experience, achieving hemostasis in the hospital usually is easier, safer, and faster with WoundSeal than suture. Furthermore, using WoundSeal eliminates the need for patients to follow up for suture removal. From a practical perspective, WoundSeal works best when the biopsy defect is positioned parallel to the ground so the powder can be poured directly over and into the defect. From a cosmetic perspective, we have found that WoundSeal and suture have similar outcomes when used for punch biopsies up to 4 mm in size on the trunk and extremities in both adult and pediatric patients. Working with other dermatology attendings such as Sharon A. Glick, MD; Eve Lowenstein, MD, PhD; and Jeannette Jakus, MD, MBA, I also have found WoundSeal helpful when taking care of suture-phobic children or patients with lesions that are less amenable to suture, such as an ulcer or indurated plaque.

Item 2: Purple Surgical Marker

Another tip I have learned from Drs. Siegel and Jakus: If you are ever in a bind for a topical antibacterial or antifungal agent, look no further than a sterile purple surgical marker. These markers are a surprising source of gentian violet, the same purple dye that is the basis of Gram staining and sold as an over-the-counter antiseptic in 1% to 2% concentrations. Purple surgical markers, on the other hand, are 2.5% to 10% gentian violet.2

Gentian violet has been shown to have antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antihelminthic, and antitrypanosomal properties, but its efficacy has been mostly demonstrated against Streptococcus, methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Candida.3 Given the dermatologic relevance of these organisms, gentian violet is a favorite among attendings at my residency program; it is not uncommon to remove a patient’s dressing and uncover an iatrogenically purple wound. Best of all, pediatric patients are invariably amused when they see someone drawing on their skin with a purple marker.

When using a sterile surgical marker to apply gentian violet to the skin, we use either the marker tip or the ink core, which Dr. Siegel taught me can be easily accessed by snapping most plastic markers in half.

Item 3: Handheld Blacklight

The Wood lamp is a useful tool in the diagnosis of various infectious diseases and pigmentary disorders,4 but it is not always practical to use when on call, as standard ones are relatively large and corded, so they must be plugged into an electric outlet to work. You can therefore imagine the gratitude I have for my co-residents Miriam Lieberman, MD; Jaime Alexander, MD; Nicole Weiler, MD; and Alessandra Haskin, MD, for introducing me to the most convenient Wood lamp: the handheld blacklight. For less than $10, this gadget combines the diagnostic power of UV light with the portability of a pocket-sized, battery-powered flashlight. You will never want to use another Wood lamp again.

Item 4: Normal Saline Flush

Normal saline can be used for more than storing specimens for frozen section or tissue culture; it also can substitute for Michel solution when storing specimens for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies. I learned this tip from Edward Heilman, MD, a dermatopathologist at Downstate. For the last 20 years, Dr. Heilman has been successfully storing DIF specimens in refrigerated normal saline for up to 24 hours when Michel solution is unavailable, after which the specimen is processed or transferred to Michel solution for further storage while being transported to an immunofluorescence laboratory.

In 2004, Vodegel et al5 formally studied this technique in 25 patients with autoimmune skin diseases such as pemphigus and pemphigoid. (Thanks to Dr. Lieberman for telling me about this study.) The experiment involved taking 4 punch biopsies from each patient and placing them in either normal saline at −80°C for 24 or 48 hours, room temperature Michel solution for 48 hours, or liquid nitrogen for up to 2 weeks before being processed for DIF and analyzed by a blinded interpreter. Interestingly, specimens stored in normal saline for 24 hours were the most diagnostic, with a conclusive diagnosis reached in 21 of 25 specimens (84%). This result was attributed to the statistically significant reduction (P<.01) in background fluorescence with normal saline compared to Michel solution and liquid nitrogen, which in turn allowed for easier detection of diagnostic immunoreactants. Similar to Dr. Heilman, the authors cautioned against placing DIF specimens in normal saline for more than 24 hours; in their experience, the risk for an artefactual split developing at the dermoepidermal junction increases with this practice.5

- Biolife. How WoundSeal works. WoundSeal website. http://woundseal.com/how-it-works. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Viscot Medical, LLC. Safety data sheet. http://www.viscot.com/download/MSDS%20Gentian%20Violet%20Ink.pdf. Published September 11, 2014. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Maley AM, Arbiser JL. Gentian violet: a 19th century drug re-emerges in the 21st century. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:775-780.

- Klatte JL, van der Beek N, Kemperman PM. 100 years of Wood’s lamp revised. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:842-847.

- Vodegel RM, de Jong MC, Meijer HJ, et al. Enhanced diagnostic immunofluorescence using biopsies transported in saline. BMC Dermatol. 2004;4:10.

It is no secret that a well-stocked on-call bag is one of the keys to providing inpatient care as a dermatology resident. Beyond the basic items that should never be left at home, there are some lesser-known tools that I have learned about from my book- and street-smart attendings and co-residents in the Department of Dermatology at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center (referred to here as Downstate). Here are our top 4 items to pack the next time you are on call. (Bonus: you will find them helpful in clinic, too.)

Item 1: WoundSeal Powder

The most valuable player in my on-call bag, WoundSeal Powder (Biolife) is an over-the-counter hemostatic agent that I learned about from Daniel M. Siegel, MD, MS, a Mohs surgeon at Downstate and former president of the American Academy of Dermatology. The powder consists of a hydrophilic polymer and potassium ferrate.1 When poured over a bleeding wound and pressed in place (eg, with a sterile cotton-tipped swab), the hydrophilic polymer absorbs plasma while the iron in potassium ferrate agglomerates blood solids. The result is a scablike seal that is safe to leave in place until the wound has healed.1

Since Dr. Siegel introduced WoundSeal to Downstate about a decade ago, it has become our department’s go-to hemostatic agent for most punch biopsies performed in the inpatient setting. In our experience, achieving hemostasis in the hospital usually is easier, safer, and faster with WoundSeal than suture. Furthermore, using WoundSeal eliminates the need for patients to follow up for suture removal. From a practical perspective, WoundSeal works best when the biopsy defect is positioned parallel to the ground so the powder can be poured directly over and into the defect. From a cosmetic perspective, we have found that WoundSeal and suture have similar outcomes when used for punch biopsies up to 4 mm in size on the trunk and extremities in both adult and pediatric patients. Working with other dermatology attendings such as Sharon A. Glick, MD; Eve Lowenstein, MD, PhD; and Jeannette Jakus, MD, MBA, I also have found WoundSeal helpful when taking care of suture-phobic children or patients with lesions that are less amenable to suture, such as an ulcer or indurated plaque.

Item 2: Purple Surgical Marker

Another tip I have learned from Drs. Siegel and Jakus: If you are ever in a bind for a topical antibacterial or antifungal agent, look no further than a sterile purple surgical marker. These markers are a surprising source of gentian violet, the same purple dye that is the basis of Gram staining and sold as an over-the-counter antiseptic in 1% to 2% concentrations. Purple surgical markers, on the other hand, are 2.5% to 10% gentian violet.2

Gentian violet has been shown to have antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antihelminthic, and antitrypanosomal properties, but its efficacy has been mostly demonstrated against Streptococcus, methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Candida.3 Given the dermatologic relevance of these organisms, gentian violet is a favorite among attendings at my residency program; it is not uncommon to remove a patient’s dressing and uncover an iatrogenically purple wound. Best of all, pediatric patients are invariably amused when they see someone drawing on their skin with a purple marker.

When using a sterile surgical marker to apply gentian violet to the skin, we use either the marker tip or the ink core, which Dr. Siegel taught me can be easily accessed by snapping most plastic markers in half.

Item 3: Handheld Blacklight

The Wood lamp is a useful tool in the diagnosis of various infectious diseases and pigmentary disorders,4 but it is not always practical to use when on call, as standard ones are relatively large and corded, so they must be plugged into an electric outlet to work. You can therefore imagine the gratitude I have for my co-residents Miriam Lieberman, MD; Jaime Alexander, MD; Nicole Weiler, MD; and Alessandra Haskin, MD, for introducing me to the most convenient Wood lamp: the handheld blacklight. For less than $10, this gadget combines the diagnostic power of UV light with the portability of a pocket-sized, battery-powered flashlight. You will never want to use another Wood lamp again.

Item 4: Normal Saline Flush

Normal saline can be used for more than storing specimens for frozen section or tissue culture; it also can substitute for Michel solution when storing specimens for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies. I learned this tip from Edward Heilman, MD, a dermatopathologist at Downstate. For the last 20 years, Dr. Heilman has been successfully storing DIF specimens in refrigerated normal saline for up to 24 hours when Michel solution is unavailable, after which the specimen is processed or transferred to Michel solution for further storage while being transported to an immunofluorescence laboratory.

In 2004, Vodegel et al5 formally studied this technique in 25 patients with autoimmune skin diseases such as pemphigus and pemphigoid. (Thanks to Dr. Lieberman for telling me about this study.) The experiment involved taking 4 punch biopsies from each patient and placing them in either normal saline at −80°C for 24 or 48 hours, room temperature Michel solution for 48 hours, or liquid nitrogen for up to 2 weeks before being processed for DIF and analyzed by a blinded interpreter. Interestingly, specimens stored in normal saline for 24 hours were the most diagnostic, with a conclusive diagnosis reached in 21 of 25 specimens (84%). This result was attributed to the statistically significant reduction (P<.01) in background fluorescence with normal saline compared to Michel solution and liquid nitrogen, which in turn allowed for easier detection of diagnostic immunoreactants. Similar to Dr. Heilman, the authors cautioned against placing DIF specimens in normal saline for more than 24 hours; in their experience, the risk for an artefactual split developing at the dermoepidermal junction increases with this practice.5

It is no secret that a well-stocked on-call bag is one of the keys to providing inpatient care as a dermatology resident. Beyond the basic items that should never be left at home, there are some lesser-known tools that I have learned about from my book- and street-smart attendings and co-residents in the Department of Dermatology at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center (referred to here as Downstate). Here are our top 4 items to pack the next time you are on call. (Bonus: you will find them helpful in clinic, too.)

Item 1: WoundSeal Powder

The most valuable player in my on-call bag, WoundSeal Powder (Biolife) is an over-the-counter hemostatic agent that I learned about from Daniel M. Siegel, MD, MS, a Mohs surgeon at Downstate and former president of the American Academy of Dermatology. The powder consists of a hydrophilic polymer and potassium ferrate.1 When poured over a bleeding wound and pressed in place (eg, with a sterile cotton-tipped swab), the hydrophilic polymer absorbs plasma while the iron in potassium ferrate agglomerates blood solids. The result is a scablike seal that is safe to leave in place until the wound has healed.1

Since Dr. Siegel introduced WoundSeal to Downstate about a decade ago, it has become our department’s go-to hemostatic agent for most punch biopsies performed in the inpatient setting. In our experience, achieving hemostasis in the hospital usually is easier, safer, and faster with WoundSeal than suture. Furthermore, using WoundSeal eliminates the need for patients to follow up for suture removal. From a practical perspective, WoundSeal works best when the biopsy defect is positioned parallel to the ground so the powder can be poured directly over and into the defect. From a cosmetic perspective, we have found that WoundSeal and suture have similar outcomes when used for punch biopsies up to 4 mm in size on the trunk and extremities in both adult and pediatric patients. Working with other dermatology attendings such as Sharon A. Glick, MD; Eve Lowenstein, MD, PhD; and Jeannette Jakus, MD, MBA, I also have found WoundSeal helpful when taking care of suture-phobic children or patients with lesions that are less amenable to suture, such as an ulcer or indurated plaque.

Item 2: Purple Surgical Marker

Another tip I have learned from Drs. Siegel and Jakus: If you are ever in a bind for a topical antibacterial or antifungal agent, look no further than a sterile purple surgical marker. These markers are a surprising source of gentian violet, the same purple dye that is the basis of Gram staining and sold as an over-the-counter antiseptic in 1% to 2% concentrations. Purple surgical markers, on the other hand, are 2.5% to 10% gentian violet.2

Gentian violet has been shown to have antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antihelminthic, and antitrypanosomal properties, but its efficacy has been mostly demonstrated against Streptococcus, methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Candida.3 Given the dermatologic relevance of these organisms, gentian violet is a favorite among attendings at my residency program; it is not uncommon to remove a patient’s dressing and uncover an iatrogenically purple wound. Best of all, pediatric patients are invariably amused when they see someone drawing on their skin with a purple marker.

When using a sterile surgical marker to apply gentian violet to the skin, we use either the marker tip or the ink core, which Dr. Siegel taught me can be easily accessed by snapping most plastic markers in half.

Item 3: Handheld Blacklight

The Wood lamp is a useful tool in the diagnosis of various infectious diseases and pigmentary disorders,4 but it is not always practical to use when on call, as standard ones are relatively large and corded, so they must be plugged into an electric outlet to work. You can therefore imagine the gratitude I have for my co-residents Miriam Lieberman, MD; Jaime Alexander, MD; Nicole Weiler, MD; and Alessandra Haskin, MD, for introducing me to the most convenient Wood lamp: the handheld blacklight. For less than $10, this gadget combines the diagnostic power of UV light with the portability of a pocket-sized, battery-powered flashlight. You will never want to use another Wood lamp again.

Item 4: Normal Saline Flush

Normal saline can be used for more than storing specimens for frozen section or tissue culture; it also can substitute for Michel solution when storing specimens for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies. I learned this tip from Edward Heilman, MD, a dermatopathologist at Downstate. For the last 20 years, Dr. Heilman has been successfully storing DIF specimens in refrigerated normal saline for up to 24 hours when Michel solution is unavailable, after which the specimen is processed or transferred to Michel solution for further storage while being transported to an immunofluorescence laboratory.

In 2004, Vodegel et al5 formally studied this technique in 25 patients with autoimmune skin diseases such as pemphigus and pemphigoid. (Thanks to Dr. Lieberman for telling me about this study.) The experiment involved taking 4 punch biopsies from each patient and placing them in either normal saline at −80°C for 24 or 48 hours, room temperature Michel solution for 48 hours, or liquid nitrogen for up to 2 weeks before being processed for DIF and analyzed by a blinded interpreter. Interestingly, specimens stored in normal saline for 24 hours were the most diagnostic, with a conclusive diagnosis reached in 21 of 25 specimens (84%). This result was attributed to the statistically significant reduction (P<.01) in background fluorescence with normal saline compared to Michel solution and liquid nitrogen, which in turn allowed for easier detection of diagnostic immunoreactants. Similar to Dr. Heilman, the authors cautioned against placing DIF specimens in normal saline for more than 24 hours; in their experience, the risk for an artefactual split developing at the dermoepidermal junction increases with this practice.5

- Biolife. How WoundSeal works. WoundSeal website. http://woundseal.com/how-it-works. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Viscot Medical, LLC. Safety data sheet. http://www.viscot.com/download/MSDS%20Gentian%20Violet%20Ink.pdf. Published September 11, 2014. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Maley AM, Arbiser JL. Gentian violet: a 19th century drug re-emerges in the 21st century. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:775-780.

- Klatte JL, van der Beek N, Kemperman PM. 100 years of Wood’s lamp revised. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:842-847.

- Vodegel RM, de Jong MC, Meijer HJ, et al. Enhanced diagnostic immunofluorescence using biopsies transported in saline. BMC Dermatol. 2004;4:10.

- Biolife. How WoundSeal works. WoundSeal website. http://woundseal.com/how-it-works. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Viscot Medical, LLC. Safety data sheet. http://www.viscot.com/download/MSDS%20Gentian%20Violet%20Ink.pdf. Published September 11, 2014. Accessed March 7, 2019.

- Maley AM, Arbiser JL. Gentian violet: a 19th century drug re-emerges in the 21st century. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:775-780.

- Klatte JL, van der Beek N, Kemperman PM. 100 years of Wood’s lamp revised. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:842-847.

- Vodegel RM, de Jong MC, Meijer HJ, et al. Enhanced diagnostic immunofluorescence using biopsies transported in saline. BMC Dermatol. 2004;4:10.

Resident Pearl

- The following unconventional items will come in handy the next time you are on call (or in clinic) and need an alternative to a suture, topical antimicrobial, Wood lamp, or Michel solution.

Concurrent Keratoacanthomas and Nonsarcoidal Granulomatous Reactions in New and Preexisting Tattoos

To the Editor:

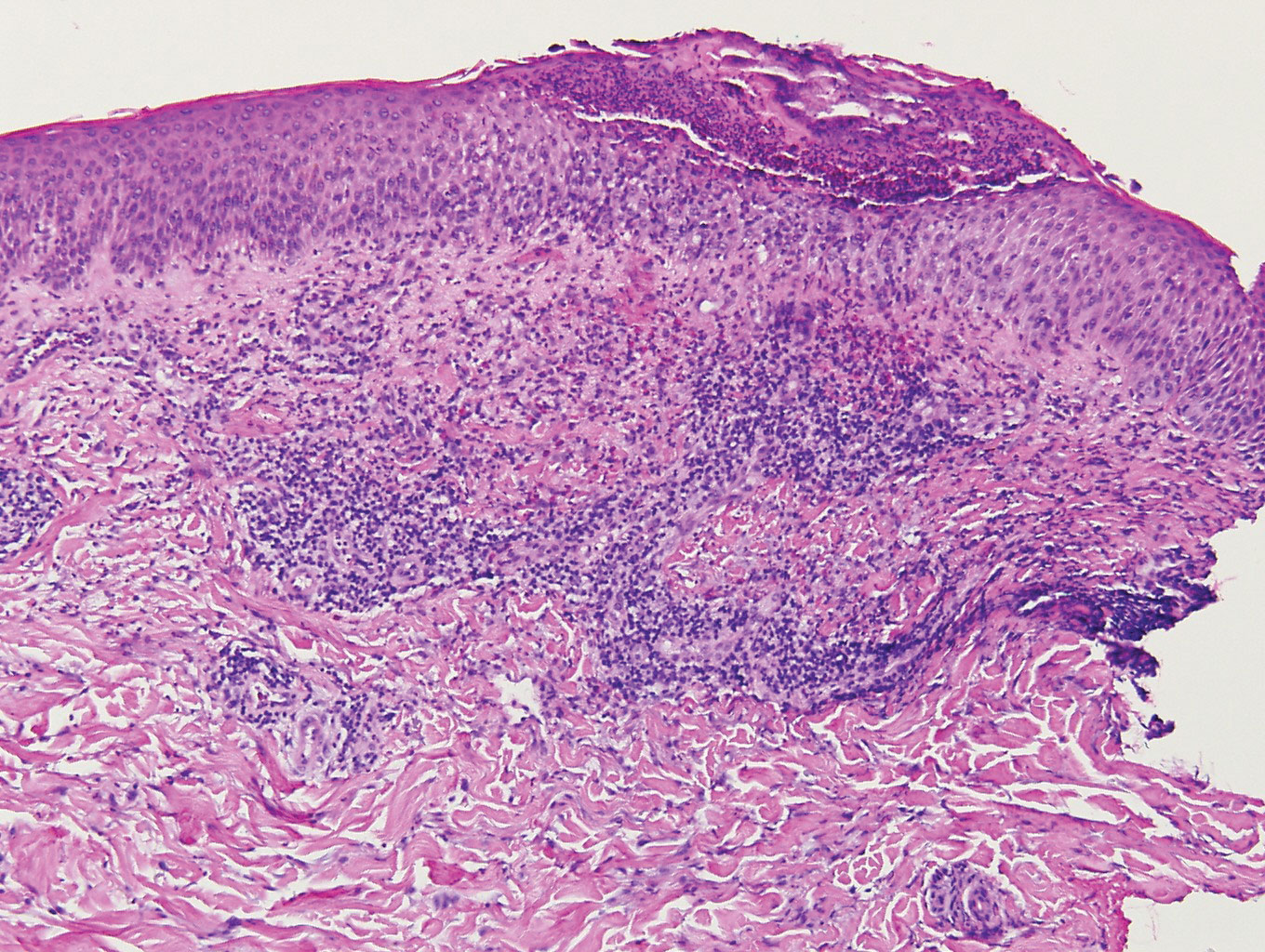

Cutaneous reactions to tattoos are common and histologically diverse. As outlined by Jacob,1 these reactions can be categorized into 4 main groups: inoculative/infective, hypersensitive, neoplastic, and coincidental. A thorough history and physical examination can aid in distinguishing the type of cutaneous reaction, but diagnosis often requires histopathologic clarification. We report the case of a patient who presented with painful indurated nodules within red ink areas of new and preexisting tattoos.

A 48-year-old woman with no prior medical conditions presented with tender pruritic nodules at the site of a new tattoo and within recently retouched tattoos of 5 months’ duration. The tattoos were done at an “organic” tattoo parlor 8 months prior to presentation. Simultaneously, the patient also developed induration and pain in 2 older tattoos that had been done 10 years prior and had not been retouched.

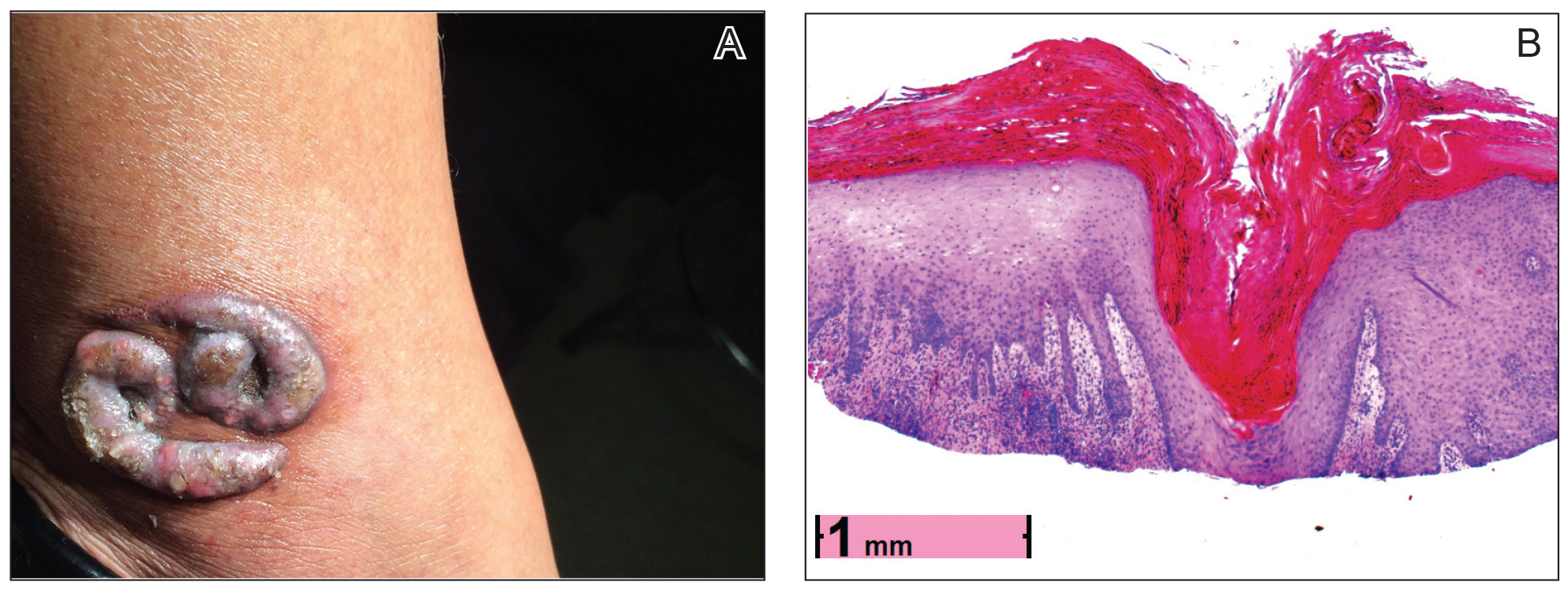

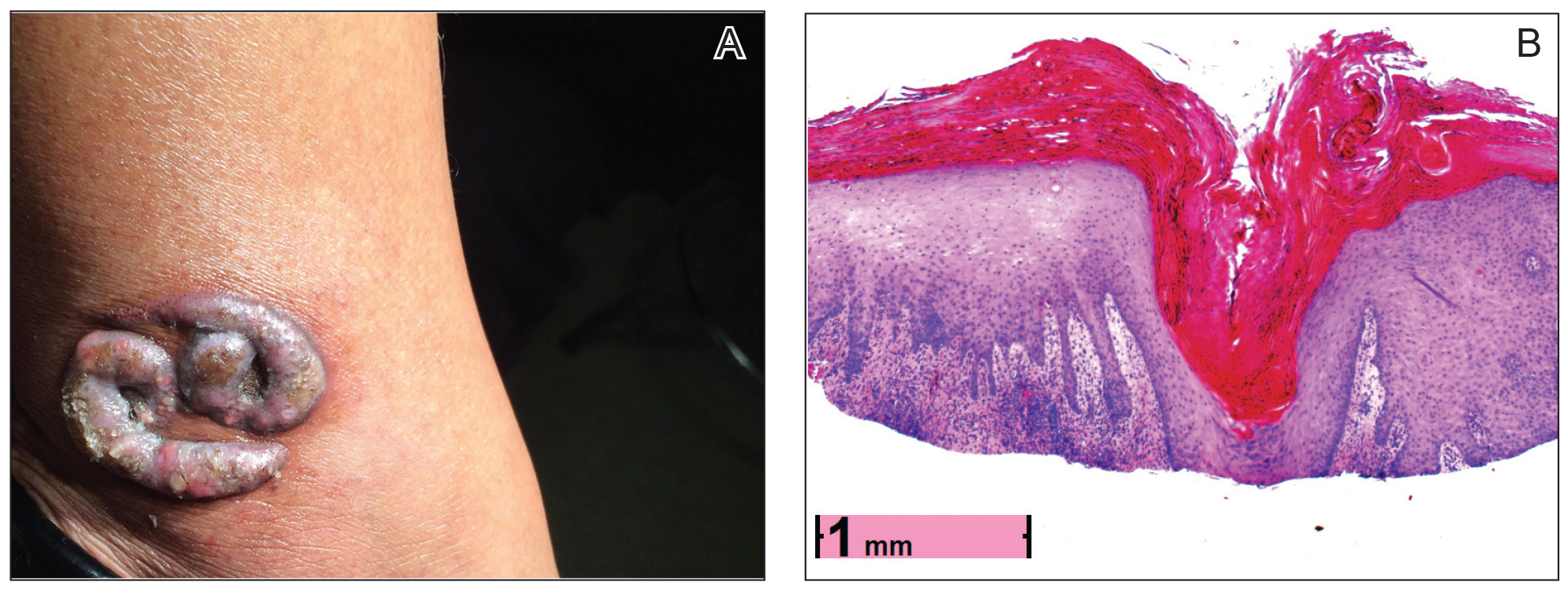

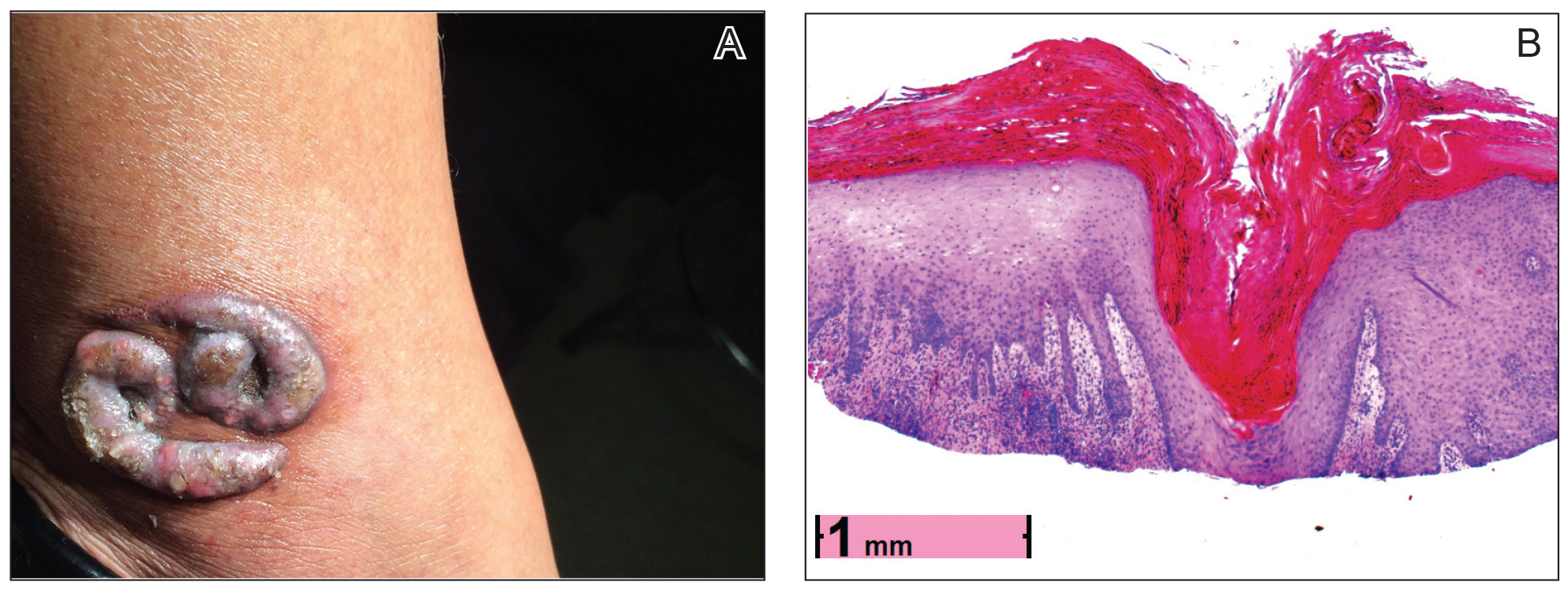

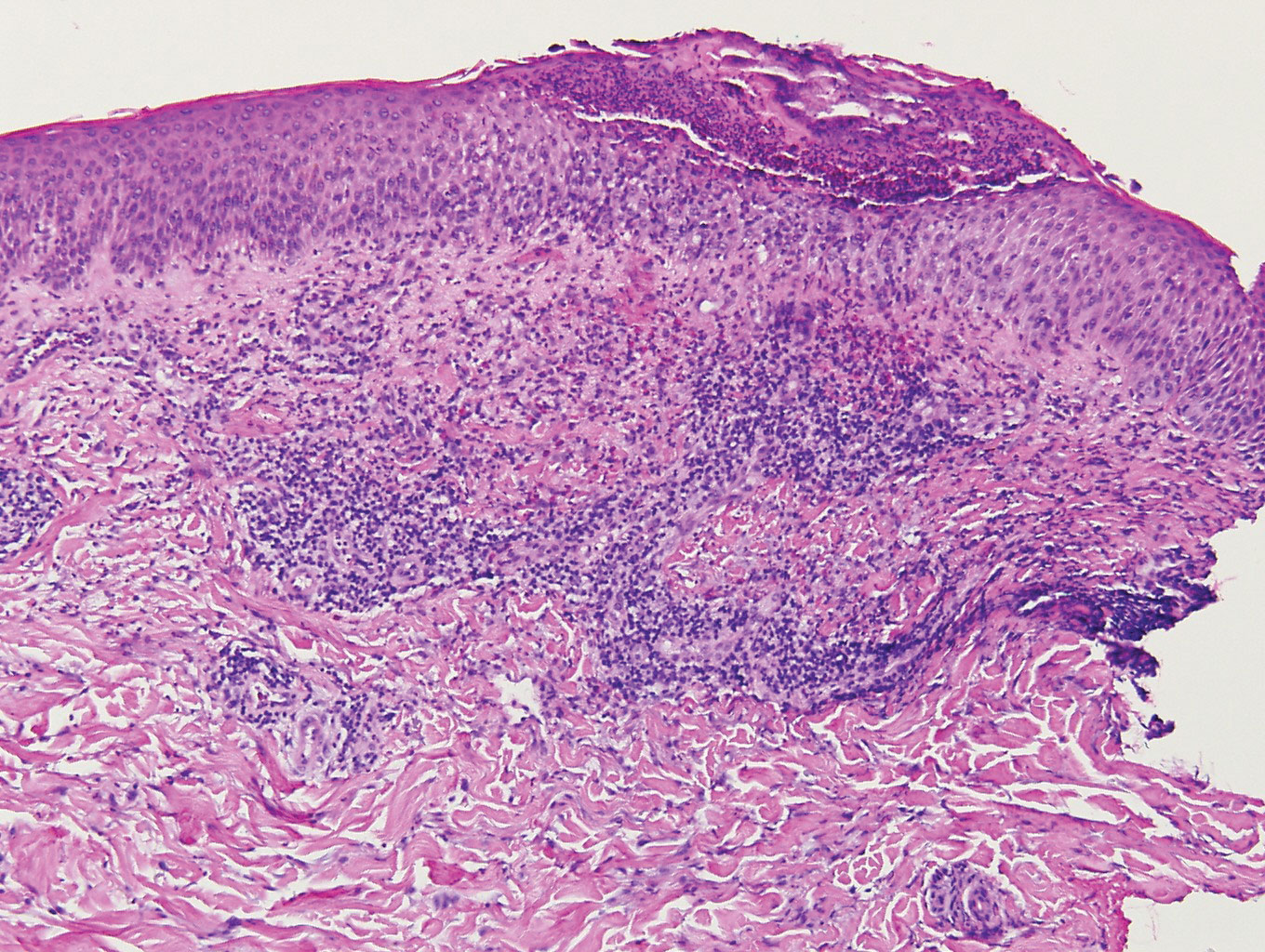

Physical examination revealed 2 smooth and serpiginous nodules nested perfectly within the new red tattoo on the left medial ankle (Figure 1A). Examination of the retouched tattoos on the dorsum of the right foot revealed 4 discrete nodules within the red, heart-shaped areas of the tattoos (Figure 2A). Additionally, the red-inked portions of an older tattoo on the left lateral calf that were outlined in red ink also were raised and indurated (Figure 3A), and a tattoo on the right volar wrist, also in red ink, was indurated and tender to palpation. The remainder of the physical examination was normal.

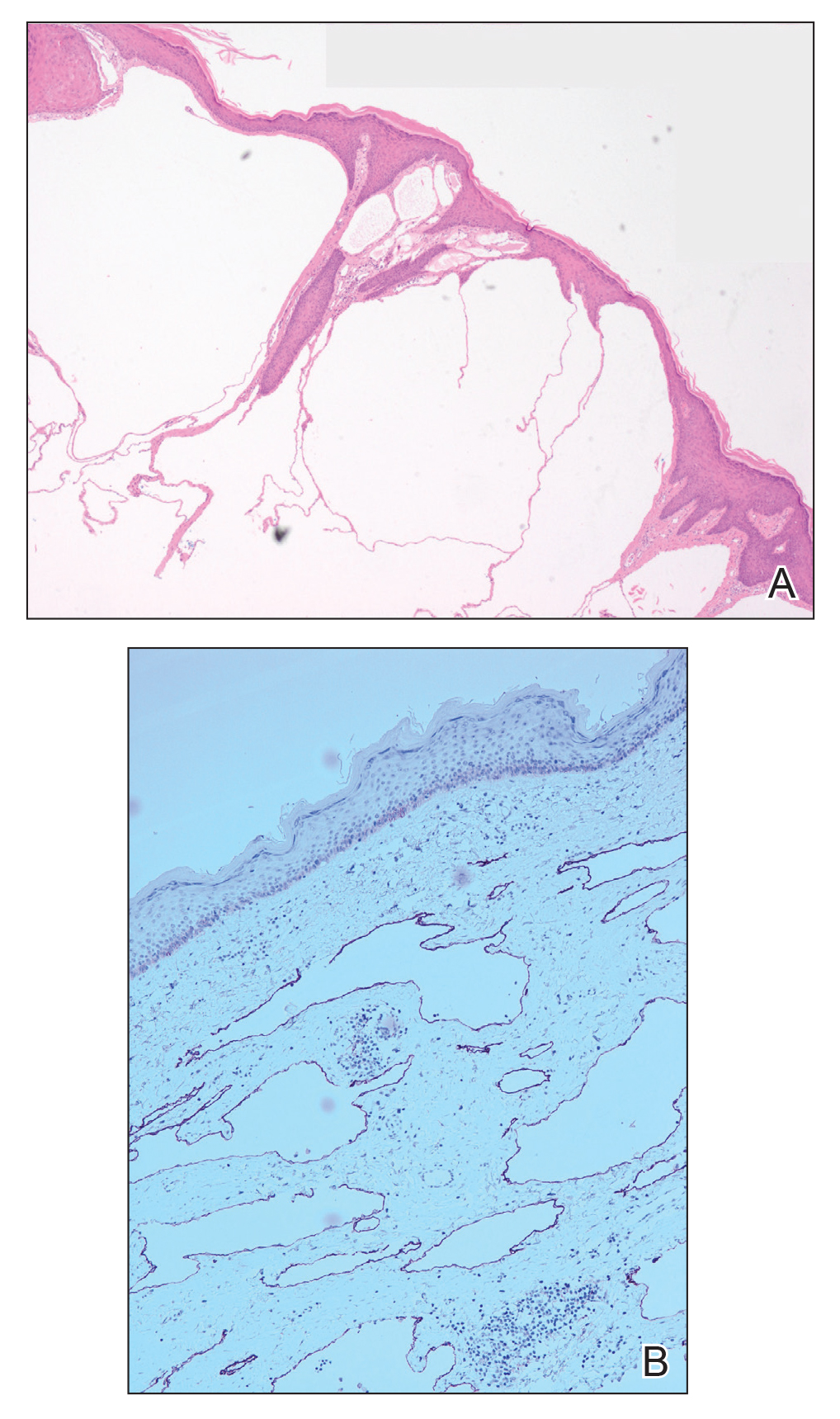

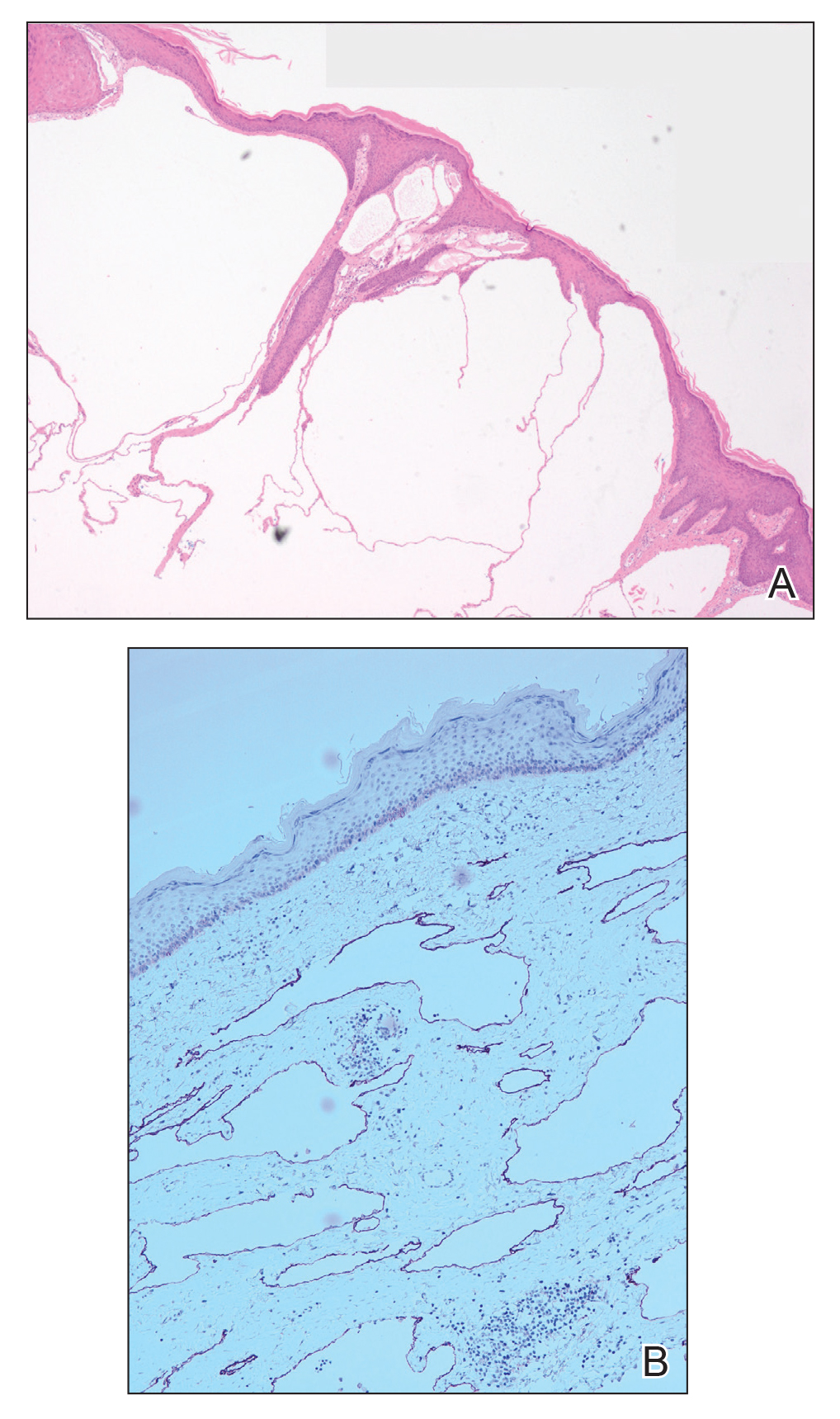

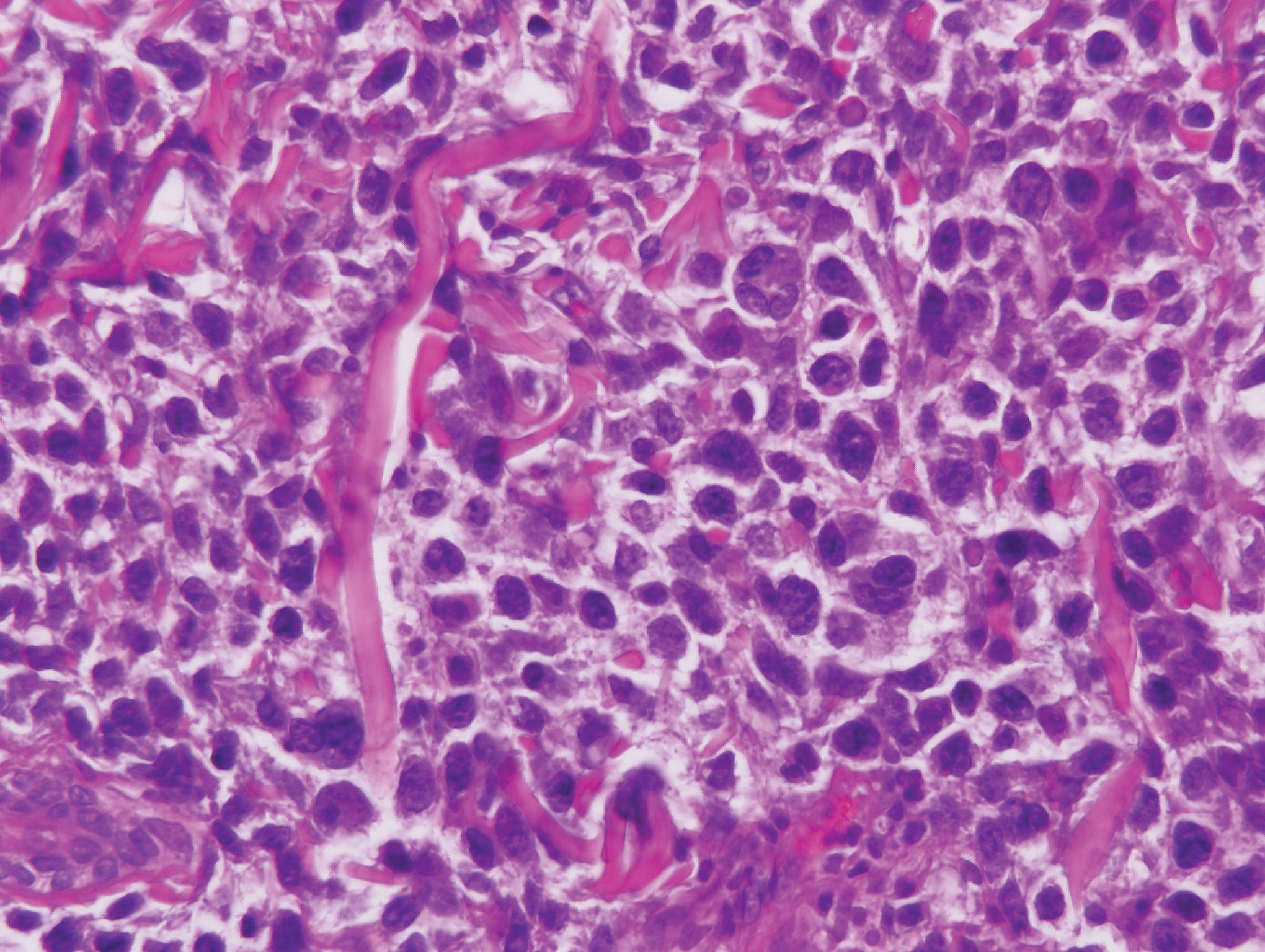

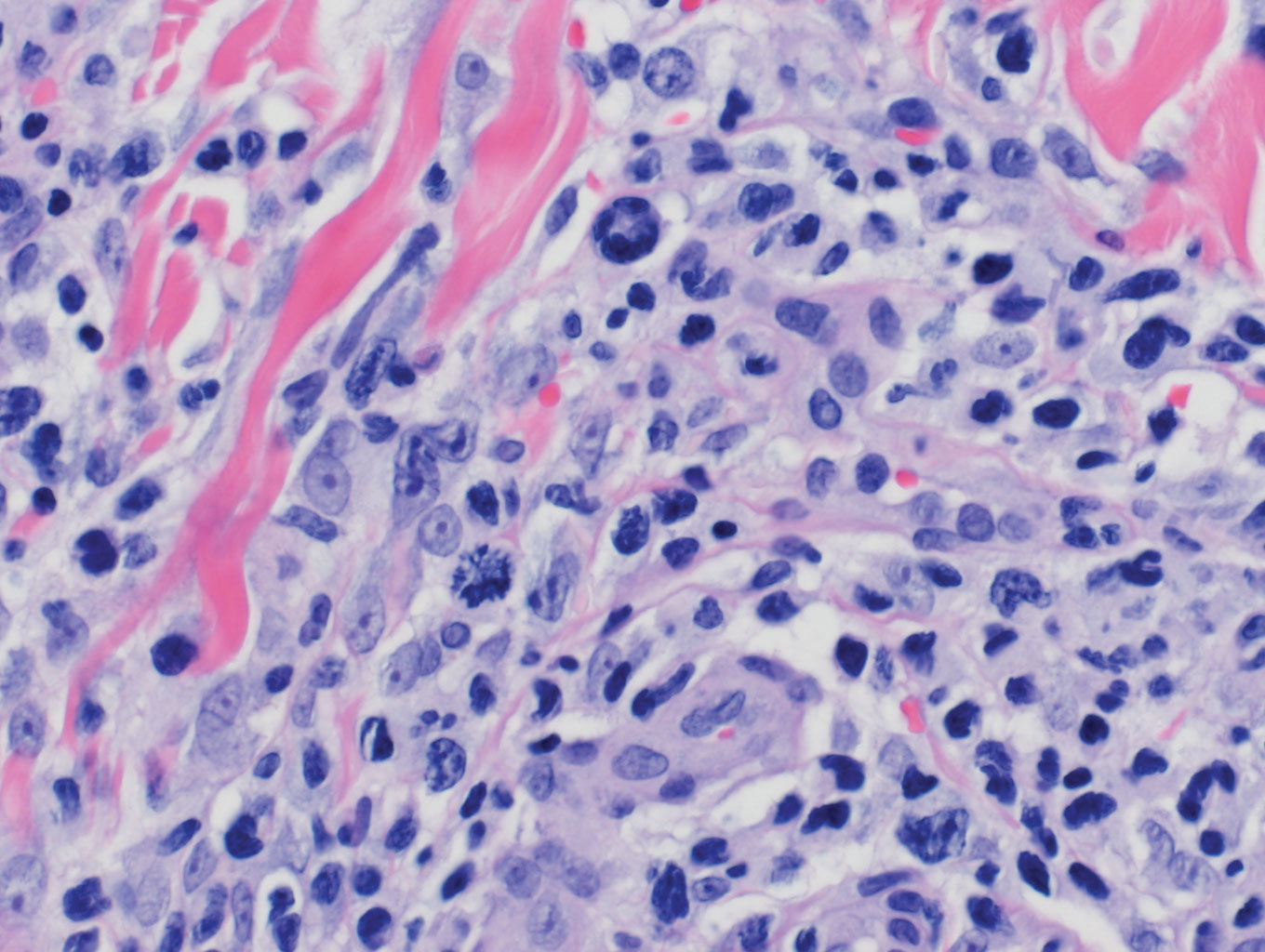

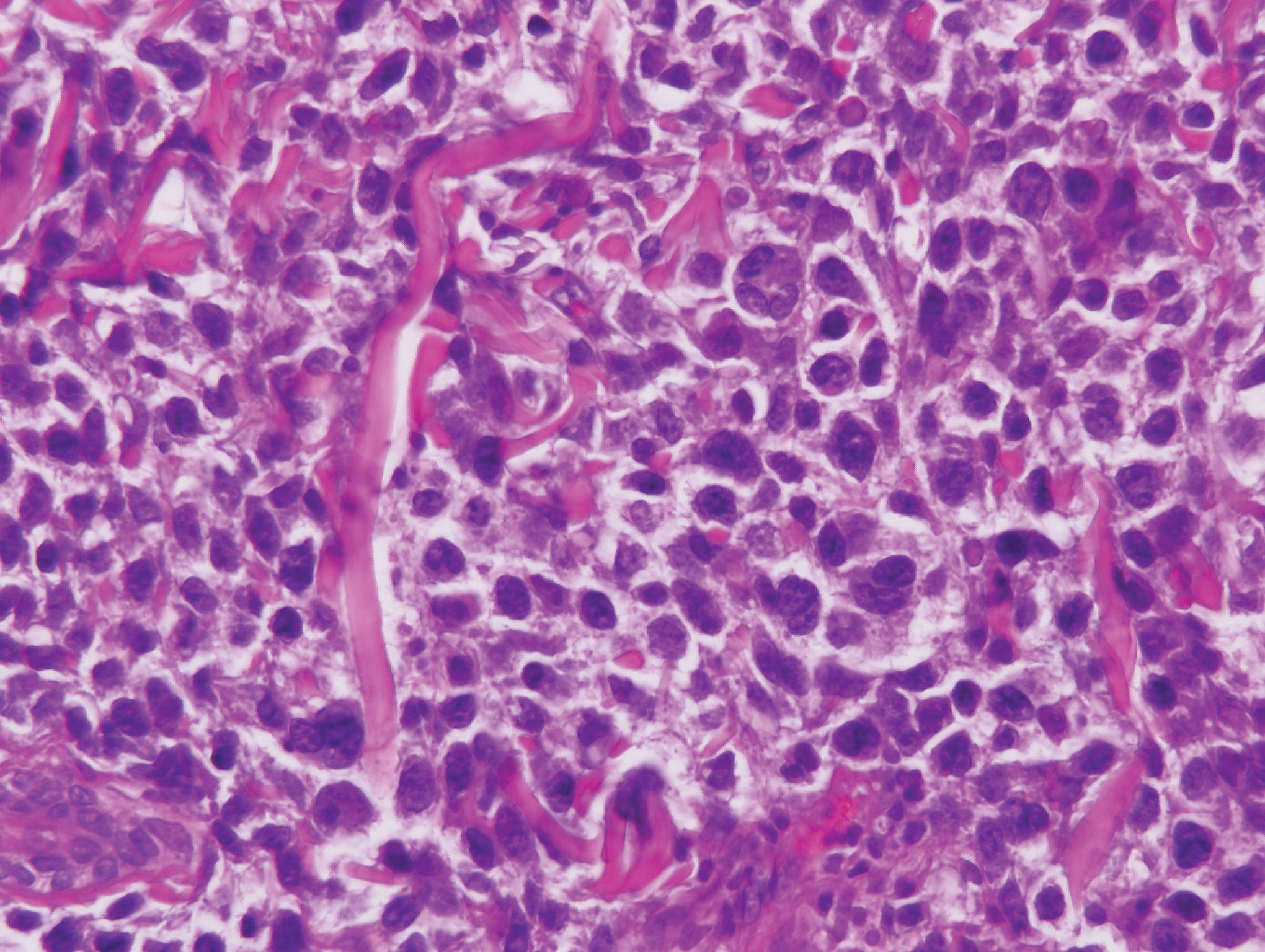

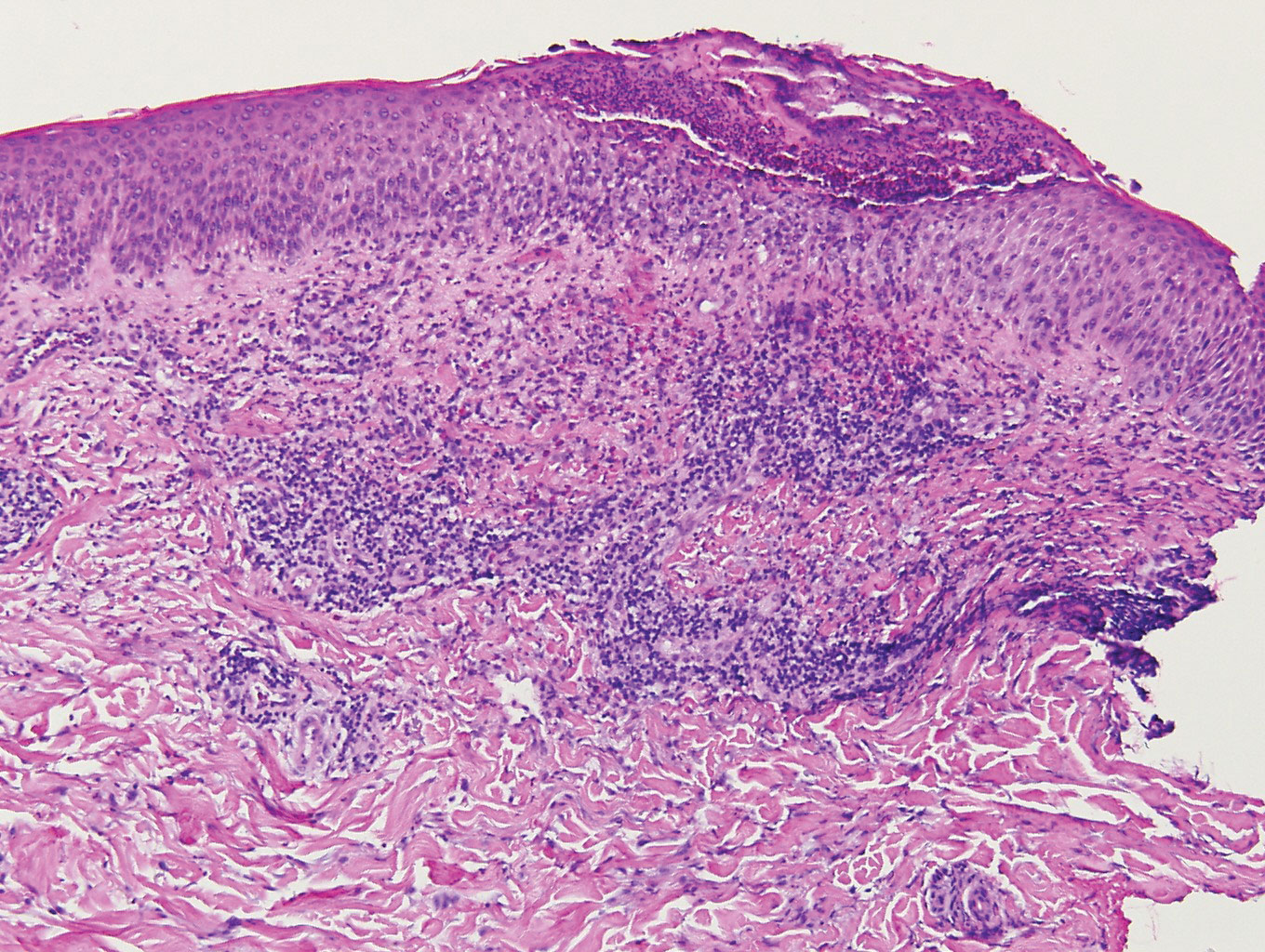

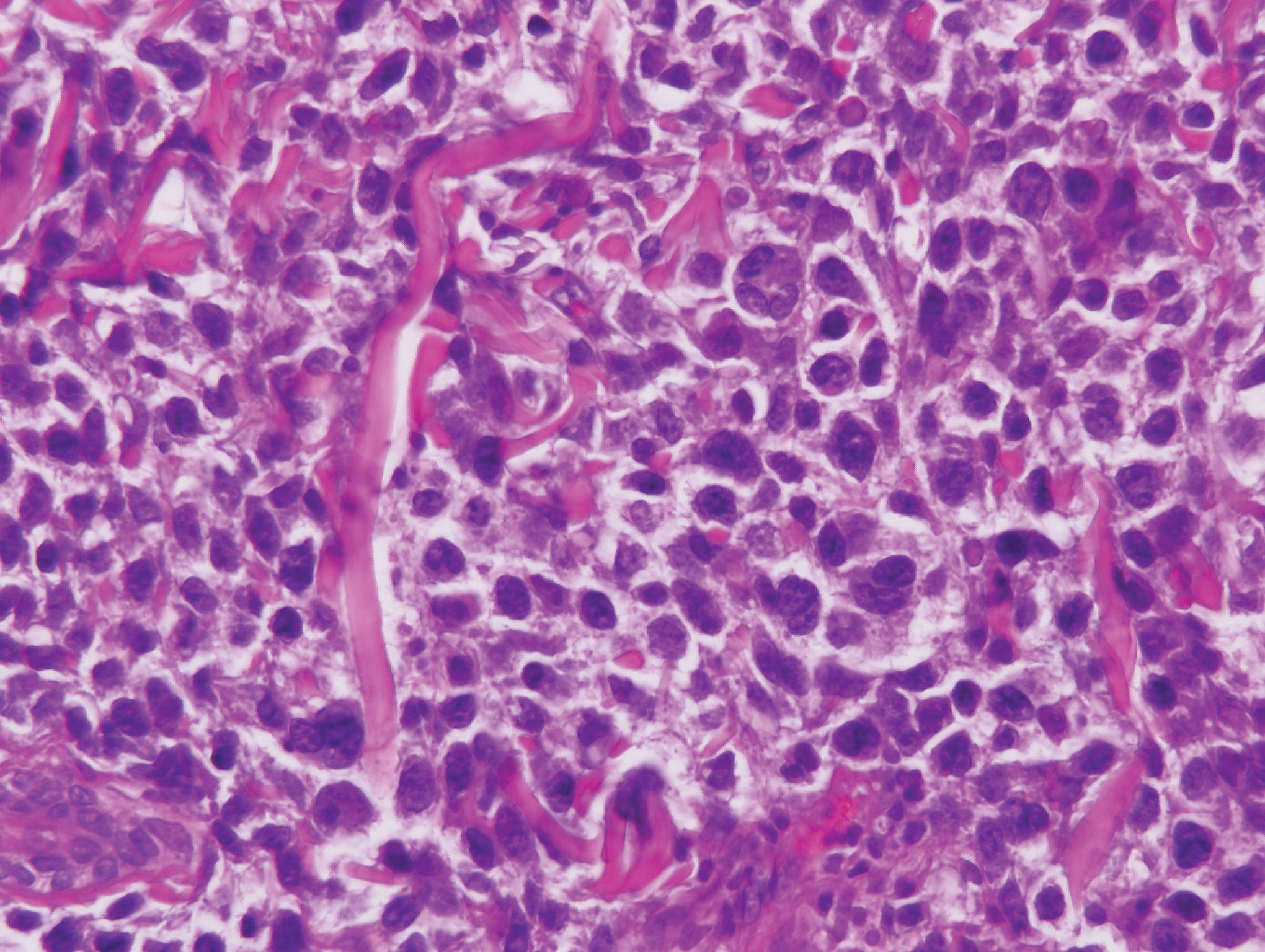

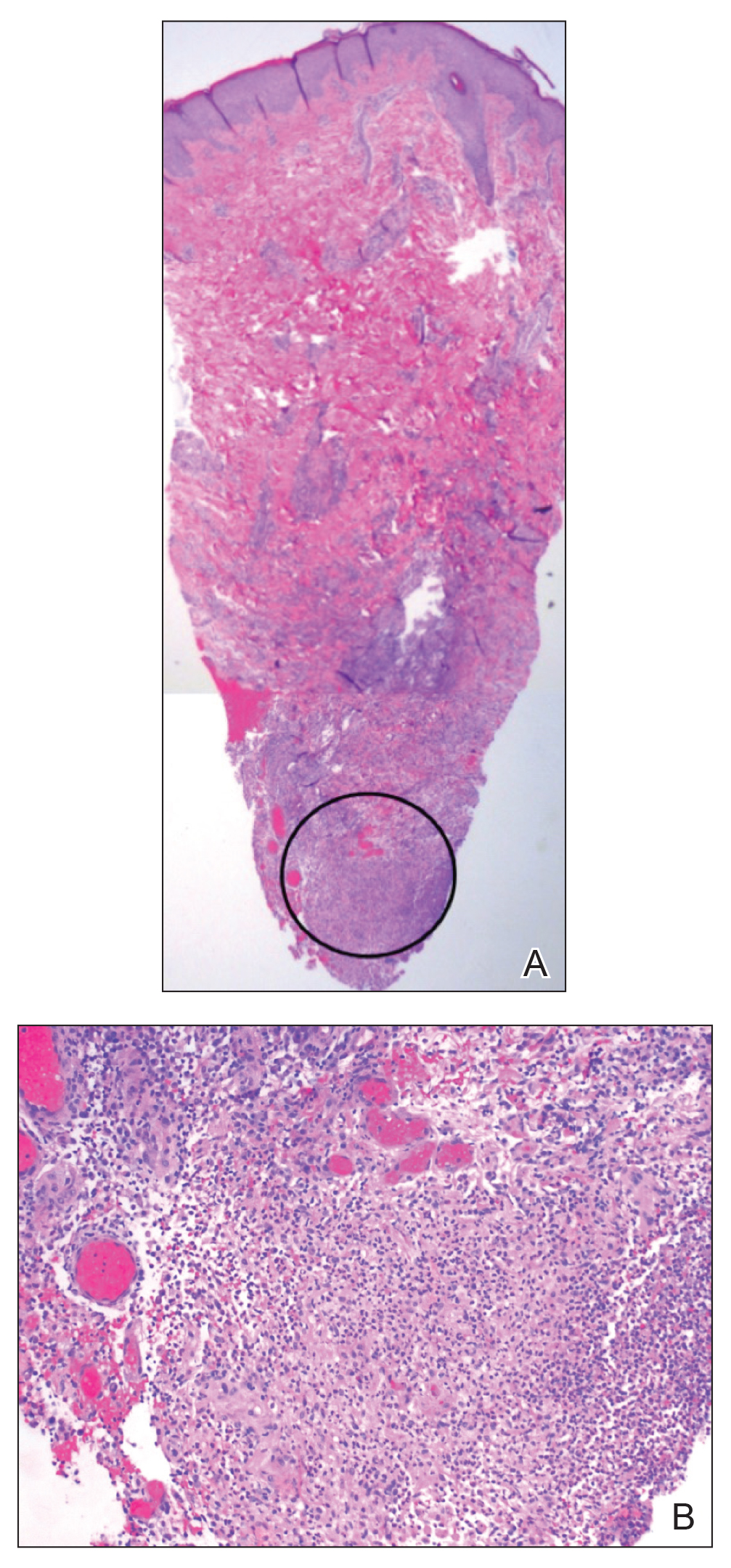

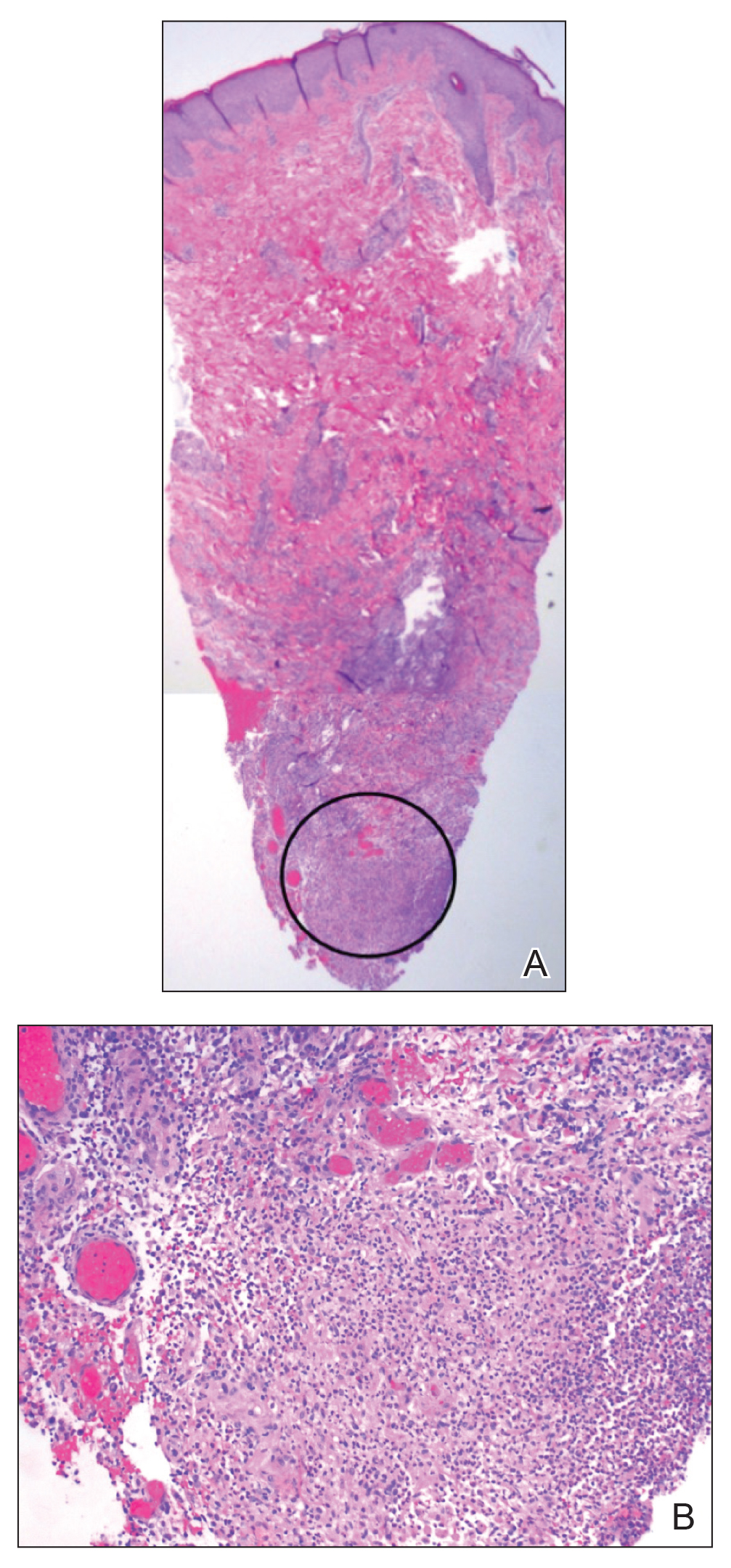

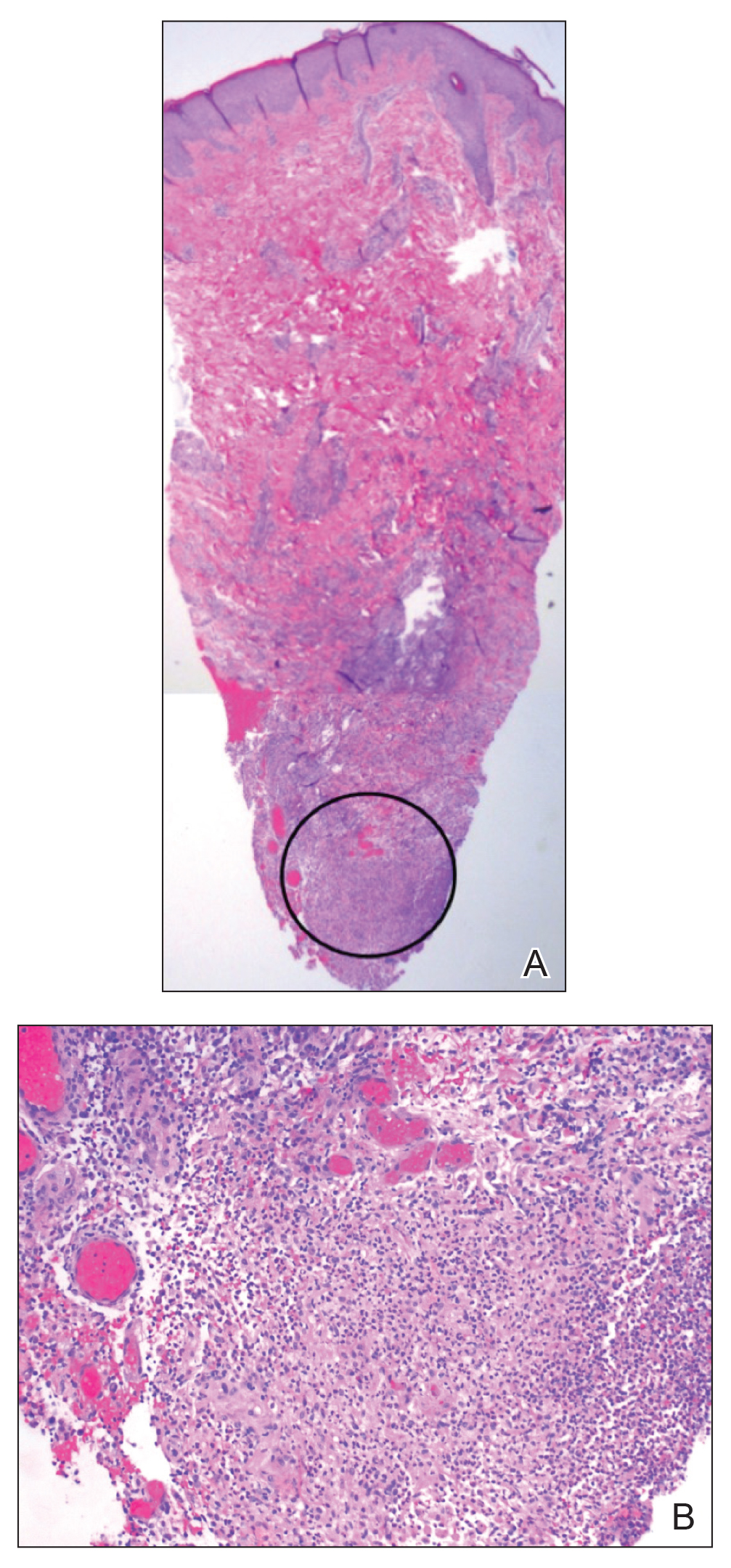

contiguous dilated follicular infundibula with atypical keratinocytes that had hyperchromatic nuclei, consistent with a keratoacanthoma, as well as a lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis above a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes (H&E, original magnification ×2.5 [original magnification ×6.2]).

The lesions continued to enlarge and become increasingly painful despite trials of fluticasone propionate cream 0.05%, clobetasol propionate gel 0.05%, a 7-day course of oral levofloxacin, and a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate. Ultimately, a shave biopsy from the new tattoo on the left medial ankle revealed an early keratoacanthoma (KA)(Figure 1B). Subsequent shave biopsies of the retouched tattoos on the dorsal foot and the preexisting tattoo on the calf revealed KAs and a granulomatous reaction, respectively (Figures 2B and 3B). The left ankle KA was treated with 2 injections of 5-fluorouracil without improvement. The patient ultimately underwent Mohs micrographic surgery of the left ankle KA and underwent total excision with skin graft.

The development of KAs within tattoos is a known but poorly understood phenomenon.2 Keratoacanthomas are common keratinizing, squamous cell lesions of follicular origin distinguished by their eruptive onset, rapid growth, and spontaneous involution. They typically present as solitary isolated nodules arising in sun-exposed areas of patients of either sex, with a predilection for individuals of Fitzpatrick skin types I and II and in areas of prior trauma or sun damage.3

Histologically, the proliferative phase is defined by keratin-filled invagination of the epidermis into the dermis, with areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and mitotic activity within the strands and nodules. A high degree of nuclear atypia underlines the diagnostic difficulty in distinguishing KAs from squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). A fully developed KA has less prominent cellular atypia and a characteristic buttressing lip of epithelium extending over the edges of an irregular, keratin-filled crater. In the final involution stage of KAs, granulation tissue and fibrosis predominate and apoptotic cells may be noted.4

The etiology of KAs remains controversial, but several factors have been correlated with their development, including UV light exposure, chemical carcinogenesis, genetic predisposition, viruses (namely human papillomavirus infection), immunosuppression, treatment with BRAF inhibitors, and trauma. Keratoacanthoma incidence also has been associated with chronic scarring diseases such as discoid lupus erythematous5 and lichen planus.6 Although solitary lesions are more typical, multiple generalized KAs can arise at once, as observed in generalized eruptive KA of Grzybowski, a rare condition, as well as in the multiple self-healing epitheliomas seen in Ferguson-Smith disease.

Because of the unusual histology of KAs and their tendency to spontaneously regress, it is not totally understood where they fall on the benign vs malignant spectrum. Some contest that KAs are benign and self-limited reactive proliferations, whereas others propose they are malignant variants of SCC.3,4,7,8 This debate is compounded by the difficulty in distinguishing KAs from SCC when specimen sampling is inadequate and given documentation that SCCs can develop within KAs over time.7 There also is some concern regarding the remote possibility of aggressive infiltration and even metastasis. One systematic review by Savage and Maize8 attempted to clarify the biologic behavior and malignant potential of KAs. Their review of 445 cases of KA with reported follow-up led to the conclusion that KAs exhibit a benign natural course with no reliable reports of death or metastasis. This finding was in stark contrast to 429 cases of SCC, of which 61 cases (14.2%) resulted in metastasis despite treatment.8

Our patient’s presentation was unique compared to others already reported in the literature because of the simultaneous development of nonsarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis within the older and nonretouched tattoos. Nonsarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis, which encompasses inflammatory skin diseases with histiocytes, is a reactive cutaneous proliferation that also has been reported to occur within tattoos.9,10 Granulomatous tattoo reactions can be further subdivided as foreign body type or sarcoidal type. Foreign body reactions are distinguished by the presence of pigment-containing multinucleated giant cells (as seen in our patient), whereas the sarcoidal type contains compact nodules of epithelioid histiocytes with few lymphocytes.4

The concurrent development of 2 clinically and histologically distinct entities suggests that a similar overlapping pathogenesis underlies each. One hypothesis is that the introduction of exogenous dyes may have instigated an inflammatory foreign body reaction, with the red ink acting as the unifying offender. The formation of granulomas in the preexisting tattoos is likely explained by an exaggerated immune response in the form of a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction triggered by reintroduction of the antigen—the red ink—in a presensitized host. Secondly, the parallel development of KAs within the new and retouched tattoos could be a result of the traumatic direct inoculation of the foreign material to which the body was presensitized and subsequent attempt by the skin to degrade and remove it.11

This case provides an example of the development of multiple KAs via a reactive process. Many other similar cases have been described in the literature, including case reports of KAs arising in areas of trauma such as thermal burns, vaccination sites, scars, skin grafts, arthropod bites, and tattoos.2-4,8 Together, the trauma and immune response may lead to localized inflammation and/or cellular hyperplasia, ultimately predisposing the individual to the development of dermoepidermal proliferation. Moreover, the exaggerated keratinocyte proliferation in KAs in response to trauma is reminiscent of the Köbner phenomenon. Other lesions that demonstrate köbnerization also have been reported to occur within new tattoos, including psoriasis, lichen planus, molluscum contagiosum, and verruca vulgaris.1,3

Although KAs are not always a consequence of trauma among humans, trauma-induced KA has been proven as a reliable phenomenon among animal models; an older study showed consistent KA development after animal skin was traumatized from the application of chemical carcinogens.12 Keratoacanthomas within areas of trauma seem to develop rapidly—within a week to a year after trauma—while the development of trauma-related nonmelanoma skin cancers appears to take longer, approximately 1 to 50 years later.13

More research is needed to clarify the pathophysiology of KAs and its precise relationship to trauma and immunology, but our case adds additional weight to the idea that some KAs are primarily reactive phenomena, sharing features of other reactive cutaneous proliferations such as foreign body granulomas.

- Jacob CI. Tattoo-associated dermatoses: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:962-965.

- Fraga GR, Prossick TA. Tattoo-associated keratoacanthomas: a series of 8 patients with 11 keratoacanthomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:85-90.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SL, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2005.

- Minicucci EM, Weber SA, Stolf HO, et al. Keratoacanthoma of the lower lip complicating discoid lupus erythematosus in a 14-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:329-330.

- Giesecke LM, Reid CM, James CL, et al. Giant keratoacanthoma arising in hypertrophic lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:267-269.

- Weedon DD, Malo J, Brooks D, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in keratoacanthoma: a neglected phenomenon in the elderly. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:423-426.

- Savage JA, Maize JC. Keratoacanthoma clinical behavior: a systematic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:422-429.

- Schwartz RA, Mathias CG, Miller CH, et al. Granulomatous reaction to purple tattoo pigment. Contact Derm. 1987;16:198-202.

- Bagley MP, Schwartz RA, Lambert WC. Hyperplastic reaction developing within a tattoo. granulomatous tattoo reaction, probably to mercuric sulfide (cinnabar). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1557, 1560-1561.

- Kluger N, Plantier F, Moguelet P, et al. Tattoos: natural history and histopathology of cutaneous reactions. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:146-154.

- Ghadially FN, Barton BW, Kerridge DF. The etiology of keratoacanthoma. Cancer. 1963;16:603-611.

- Kluger N, Koljonen V. Tattoos, inks, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e161-168.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous reactions to tattoos are common and histologically diverse. As outlined by Jacob,1 these reactions can be categorized into 4 main groups: inoculative/infective, hypersensitive, neoplastic, and coincidental. A thorough history and physical examination can aid in distinguishing the type of cutaneous reaction, but diagnosis often requires histopathologic clarification. We report the case of a patient who presented with painful indurated nodules within red ink areas of new and preexisting tattoos.

A 48-year-old woman with no prior medical conditions presented with tender pruritic nodules at the site of a new tattoo and within recently retouched tattoos of 5 months’ duration. The tattoos were done at an “organic” tattoo parlor 8 months prior to presentation. Simultaneously, the patient also developed induration and pain in 2 older tattoos that had been done 10 years prior and had not been retouched.

Physical examination revealed 2 smooth and serpiginous nodules nested perfectly within the new red tattoo on the left medial ankle (Figure 1A). Examination of the retouched tattoos on the dorsum of the right foot revealed 4 discrete nodules within the red, heart-shaped areas of the tattoos (Figure 2A). Additionally, the red-inked portions of an older tattoo on the left lateral calf that were outlined in red ink also were raised and indurated (Figure 3A), and a tattoo on the right volar wrist, also in red ink, was indurated and tender to palpation. The remainder of the physical examination was normal.

contiguous dilated follicular infundibula with atypical keratinocytes that had hyperchromatic nuclei, consistent with a keratoacanthoma, as well as a lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis above a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes (H&E, original magnification ×2.5 [original magnification ×6.2]).

The lesions continued to enlarge and become increasingly painful despite trials of fluticasone propionate cream 0.05%, clobetasol propionate gel 0.05%, a 7-day course of oral levofloxacin, and a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate. Ultimately, a shave biopsy from the new tattoo on the left medial ankle revealed an early keratoacanthoma (KA)(Figure 1B). Subsequent shave biopsies of the retouched tattoos on the dorsal foot and the preexisting tattoo on the calf revealed KAs and a granulomatous reaction, respectively (Figures 2B and 3B). The left ankle KA was treated with 2 injections of 5-fluorouracil without improvement. The patient ultimately underwent Mohs micrographic surgery of the left ankle KA and underwent total excision with skin graft.

The development of KAs within tattoos is a known but poorly understood phenomenon.2 Keratoacanthomas are common keratinizing, squamous cell lesions of follicular origin distinguished by their eruptive onset, rapid growth, and spontaneous involution. They typically present as solitary isolated nodules arising in sun-exposed areas of patients of either sex, with a predilection for individuals of Fitzpatrick skin types I and II and in areas of prior trauma or sun damage.3

Histologically, the proliferative phase is defined by keratin-filled invagination of the epidermis into the dermis, with areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and mitotic activity within the strands and nodules. A high degree of nuclear atypia underlines the diagnostic difficulty in distinguishing KAs from squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). A fully developed KA has less prominent cellular atypia and a characteristic buttressing lip of epithelium extending over the edges of an irregular, keratin-filled crater. In the final involution stage of KAs, granulation tissue and fibrosis predominate and apoptotic cells may be noted.4

The etiology of KAs remains controversial, but several factors have been correlated with their development, including UV light exposure, chemical carcinogenesis, genetic predisposition, viruses (namely human papillomavirus infection), immunosuppression, treatment with BRAF inhibitors, and trauma. Keratoacanthoma incidence also has been associated with chronic scarring diseases such as discoid lupus erythematous5 and lichen planus.6 Although solitary lesions are more typical, multiple generalized KAs can arise at once, as observed in generalized eruptive KA of Grzybowski, a rare condition, as well as in the multiple self-healing epitheliomas seen in Ferguson-Smith disease.

Because of the unusual histology of KAs and their tendency to spontaneously regress, it is not totally understood where they fall on the benign vs malignant spectrum. Some contest that KAs are benign and self-limited reactive proliferations, whereas others propose they are malignant variants of SCC.3,4,7,8 This debate is compounded by the difficulty in distinguishing KAs from SCC when specimen sampling is inadequate and given documentation that SCCs can develop within KAs over time.7 There also is some concern regarding the remote possibility of aggressive infiltration and even metastasis. One systematic review by Savage and Maize8 attempted to clarify the biologic behavior and malignant potential of KAs. Their review of 445 cases of KA with reported follow-up led to the conclusion that KAs exhibit a benign natural course with no reliable reports of death or metastasis. This finding was in stark contrast to 429 cases of SCC, of which 61 cases (14.2%) resulted in metastasis despite treatment.8

Our patient’s presentation was unique compared to others already reported in the literature because of the simultaneous development of nonsarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis within the older and nonretouched tattoos. Nonsarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis, which encompasses inflammatory skin diseases with histiocytes, is a reactive cutaneous proliferation that also has been reported to occur within tattoos.9,10 Granulomatous tattoo reactions can be further subdivided as foreign body type or sarcoidal type. Foreign body reactions are distinguished by the presence of pigment-containing multinucleated giant cells (as seen in our patient), whereas the sarcoidal type contains compact nodules of epithelioid histiocytes with few lymphocytes.4

The concurrent development of 2 clinically and histologically distinct entities suggests that a similar overlapping pathogenesis underlies each. One hypothesis is that the introduction of exogenous dyes may have instigated an inflammatory foreign body reaction, with the red ink acting as the unifying offender. The formation of granulomas in the preexisting tattoos is likely explained by an exaggerated immune response in the form of a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction triggered by reintroduction of the antigen—the red ink—in a presensitized host. Secondly, the parallel development of KAs within the new and retouched tattoos could be a result of the traumatic direct inoculation of the foreign material to which the body was presensitized and subsequent attempt by the skin to degrade and remove it.11

This case provides an example of the development of multiple KAs via a reactive process. Many other similar cases have been described in the literature, including case reports of KAs arising in areas of trauma such as thermal burns, vaccination sites, scars, skin grafts, arthropod bites, and tattoos.2-4,8 Together, the trauma and immune response may lead to localized inflammation and/or cellular hyperplasia, ultimately predisposing the individual to the development of dermoepidermal proliferation. Moreover, the exaggerated keratinocyte proliferation in KAs in response to trauma is reminiscent of the Köbner phenomenon. Other lesions that demonstrate köbnerization also have been reported to occur within new tattoos, including psoriasis, lichen planus, molluscum contagiosum, and verruca vulgaris.1,3

Although KAs are not always a consequence of trauma among humans, trauma-induced KA has been proven as a reliable phenomenon among animal models; an older study showed consistent KA development after animal skin was traumatized from the application of chemical carcinogens.12 Keratoacanthomas within areas of trauma seem to develop rapidly—within a week to a year after trauma—while the development of trauma-related nonmelanoma skin cancers appears to take longer, approximately 1 to 50 years later.13

More research is needed to clarify the pathophysiology of KAs and its precise relationship to trauma and immunology, but our case adds additional weight to the idea that some KAs are primarily reactive phenomena, sharing features of other reactive cutaneous proliferations such as foreign body granulomas.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous reactions to tattoos are common and histologically diverse. As outlined by Jacob,1 these reactions can be categorized into 4 main groups: inoculative/infective, hypersensitive, neoplastic, and coincidental. A thorough history and physical examination can aid in distinguishing the type of cutaneous reaction, but diagnosis often requires histopathologic clarification. We report the case of a patient who presented with painful indurated nodules within red ink areas of new and preexisting tattoos.

A 48-year-old woman with no prior medical conditions presented with tender pruritic nodules at the site of a new tattoo and within recently retouched tattoos of 5 months’ duration. The tattoos were done at an “organic” tattoo parlor 8 months prior to presentation. Simultaneously, the patient also developed induration and pain in 2 older tattoos that had been done 10 years prior and had not been retouched.

Physical examination revealed 2 smooth and serpiginous nodules nested perfectly within the new red tattoo on the left medial ankle (Figure 1A). Examination of the retouched tattoos on the dorsum of the right foot revealed 4 discrete nodules within the red, heart-shaped areas of the tattoos (Figure 2A). Additionally, the red-inked portions of an older tattoo on the left lateral calf that were outlined in red ink also were raised and indurated (Figure 3A), and a tattoo on the right volar wrist, also in red ink, was indurated and tender to palpation. The remainder of the physical examination was normal.

contiguous dilated follicular infundibula with atypical keratinocytes that had hyperchromatic nuclei, consistent with a keratoacanthoma, as well as a lymphocytic infiltrate in the dermis above a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes (H&E, original magnification ×2.5 [original magnification ×6.2]).

The lesions continued to enlarge and become increasingly painful despite trials of fluticasone propionate cream 0.05%, clobetasol propionate gel 0.05%, a 7-day course of oral levofloxacin, and a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate. Ultimately, a shave biopsy from the new tattoo on the left medial ankle revealed an early keratoacanthoma (KA)(Figure 1B). Subsequent shave biopsies of the retouched tattoos on the dorsal foot and the preexisting tattoo on the calf revealed KAs and a granulomatous reaction, respectively (Figures 2B and 3B). The left ankle KA was treated with 2 injections of 5-fluorouracil without improvement. The patient ultimately underwent Mohs micrographic surgery of the left ankle KA and underwent total excision with skin graft.

The development of KAs within tattoos is a known but poorly understood phenomenon.2 Keratoacanthomas are common keratinizing, squamous cell lesions of follicular origin distinguished by their eruptive onset, rapid growth, and spontaneous involution. They typically present as solitary isolated nodules arising in sun-exposed areas of patients of either sex, with a predilection for individuals of Fitzpatrick skin types I and II and in areas of prior trauma or sun damage.3

Histologically, the proliferative phase is defined by keratin-filled invagination of the epidermis into the dermis, with areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and mitotic activity within the strands and nodules. A high degree of nuclear atypia underlines the diagnostic difficulty in distinguishing KAs from squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). A fully developed KA has less prominent cellular atypia and a characteristic buttressing lip of epithelium extending over the edges of an irregular, keratin-filled crater. In the final involution stage of KAs, granulation tissue and fibrosis predominate and apoptotic cells may be noted.4

The etiology of KAs remains controversial, but several factors have been correlated with their development, including UV light exposure, chemical carcinogenesis, genetic predisposition, viruses (namely human papillomavirus infection), immunosuppression, treatment with BRAF inhibitors, and trauma. Keratoacanthoma incidence also has been associated with chronic scarring diseases such as discoid lupus erythematous5 and lichen planus.6 Although solitary lesions are more typical, multiple generalized KAs can arise at once, as observed in generalized eruptive KA of Grzybowski, a rare condition, as well as in the multiple self-healing epitheliomas seen in Ferguson-Smith disease.

Because of the unusual histology of KAs and their tendency to spontaneously regress, it is not totally understood where they fall on the benign vs malignant spectrum. Some contest that KAs are benign and self-limited reactive proliferations, whereas others propose they are malignant variants of SCC.3,4,7,8 This debate is compounded by the difficulty in distinguishing KAs from SCC when specimen sampling is inadequate and given documentation that SCCs can develop within KAs over time.7 There also is some concern regarding the remote possibility of aggressive infiltration and even metastasis. One systematic review by Savage and Maize8 attempted to clarify the biologic behavior and malignant potential of KAs. Their review of 445 cases of KA with reported follow-up led to the conclusion that KAs exhibit a benign natural course with no reliable reports of death or metastasis. This finding was in stark contrast to 429 cases of SCC, of which 61 cases (14.2%) resulted in metastasis despite treatment.8

Our patient’s presentation was unique compared to others already reported in the literature because of the simultaneous development of nonsarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis within the older and nonretouched tattoos. Nonsarcoidal granulomatous dermatitis, which encompasses inflammatory skin diseases with histiocytes, is a reactive cutaneous proliferation that also has been reported to occur within tattoos.9,10 Granulomatous tattoo reactions can be further subdivided as foreign body type or sarcoidal type. Foreign body reactions are distinguished by the presence of pigment-containing multinucleated giant cells (as seen in our patient), whereas the sarcoidal type contains compact nodules of epithelioid histiocytes with few lymphocytes.4

The concurrent development of 2 clinically and histologically distinct entities suggests that a similar overlapping pathogenesis underlies each. One hypothesis is that the introduction of exogenous dyes may have instigated an inflammatory foreign body reaction, with the red ink acting as the unifying offender. The formation of granulomas in the preexisting tattoos is likely explained by an exaggerated immune response in the form of a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction triggered by reintroduction of the antigen—the red ink—in a presensitized host. Secondly, the parallel development of KAs within the new and retouched tattoos could be a result of the traumatic direct inoculation of the foreign material to which the body was presensitized and subsequent attempt by the skin to degrade and remove it.11

This case provides an example of the development of multiple KAs via a reactive process. Many other similar cases have been described in the literature, including case reports of KAs arising in areas of trauma such as thermal burns, vaccination sites, scars, skin grafts, arthropod bites, and tattoos.2-4,8 Together, the trauma and immune response may lead to localized inflammation and/or cellular hyperplasia, ultimately predisposing the individual to the development of dermoepidermal proliferation. Moreover, the exaggerated keratinocyte proliferation in KAs in response to trauma is reminiscent of the Köbner phenomenon. Other lesions that demonstrate köbnerization also have been reported to occur within new tattoos, including psoriasis, lichen planus, molluscum contagiosum, and verruca vulgaris.1,3

Although KAs are not always a consequence of trauma among humans, trauma-induced KA has been proven as a reliable phenomenon among animal models; an older study showed consistent KA development after animal skin was traumatized from the application of chemical carcinogens.12 Keratoacanthomas within areas of trauma seem to develop rapidly—within a week to a year after trauma—while the development of trauma-related nonmelanoma skin cancers appears to take longer, approximately 1 to 50 years later.13

More research is needed to clarify the pathophysiology of KAs and its precise relationship to trauma and immunology, but our case adds additional weight to the idea that some KAs are primarily reactive phenomena, sharing features of other reactive cutaneous proliferations such as foreign body granulomas.

- Jacob CI. Tattoo-associated dermatoses: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:962-965.

- Fraga GR, Prossick TA. Tattoo-associated keratoacanthomas: a series of 8 patients with 11 keratoacanthomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:85-90.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SL, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2005.

- Minicucci EM, Weber SA, Stolf HO, et al. Keratoacanthoma of the lower lip complicating discoid lupus erythematosus in a 14-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:329-330.

- Giesecke LM, Reid CM, James CL, et al. Giant keratoacanthoma arising in hypertrophic lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:267-269.

- Weedon DD, Malo J, Brooks D, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in keratoacanthoma: a neglected phenomenon in the elderly. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:423-426.

- Savage JA, Maize JC. Keratoacanthoma clinical behavior: a systematic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:422-429.

- Schwartz RA, Mathias CG, Miller CH, et al. Granulomatous reaction to purple tattoo pigment. Contact Derm. 1987;16:198-202.

- Bagley MP, Schwartz RA, Lambert WC. Hyperplastic reaction developing within a tattoo. granulomatous tattoo reaction, probably to mercuric sulfide (cinnabar). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1557, 1560-1561.

- Kluger N, Plantier F, Moguelet P, et al. Tattoos: natural history and histopathology of cutaneous reactions. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:146-154.

- Ghadially FN, Barton BW, Kerridge DF. The etiology of keratoacanthoma. Cancer. 1963;16:603-611.

- Kluger N, Koljonen V. Tattoos, inks, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e161-168.

- Jacob CI. Tattoo-associated dermatoses: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:962-965.

- Fraga GR, Prossick TA. Tattoo-associated keratoacanthomas: a series of 8 patients with 11 keratoacanthomas. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:85-90.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SL, Gilchrest BA, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, et al, eds. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2005.

- Minicucci EM, Weber SA, Stolf HO, et al. Keratoacanthoma of the lower lip complicating discoid lupus erythematosus in a 14-year-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:329-330.

- Giesecke LM, Reid CM, James CL, et al. Giant keratoacanthoma arising in hypertrophic lichen planus. Australas J Dermatol. 2003;44:267-269.

- Weedon DD, Malo J, Brooks D, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in keratoacanthoma: a neglected phenomenon in the elderly. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:423-426.

- Savage JA, Maize JC. Keratoacanthoma clinical behavior: a systematic review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:422-429.

- Schwartz RA, Mathias CG, Miller CH, et al. Granulomatous reaction to purple tattoo pigment. Contact Derm. 1987;16:198-202.

- Bagley MP, Schwartz RA, Lambert WC. Hyperplastic reaction developing within a tattoo. granulomatous tattoo reaction, probably to mercuric sulfide (cinnabar). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1557, 1560-1561.

- Kluger N, Plantier F, Moguelet P, et al. Tattoos: natural history and histopathology of cutaneous reactions. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:146-154.

- Ghadially FN, Barton BW, Kerridge DF. The etiology of keratoacanthoma. Cancer. 1963;16:603-611.

- Kluger N, Koljonen V. Tattoos, inks, and cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e161-168.

Practice Points

- Keratoacanthomas (KAs) are common keratinizing, squamous cell lesions of follicular origin distinguished by their eruptive onset, rapid growth, and spontaneous involution.

- The etiology of KAs remains controversial, but several factors have been correlated with their development, including UV light exposure, chemical carcinogenesis, genetic predisposition, viruses (namely human papillomavirus infection), immunosuppression, scarring disorders, and trauma (including tattoos).

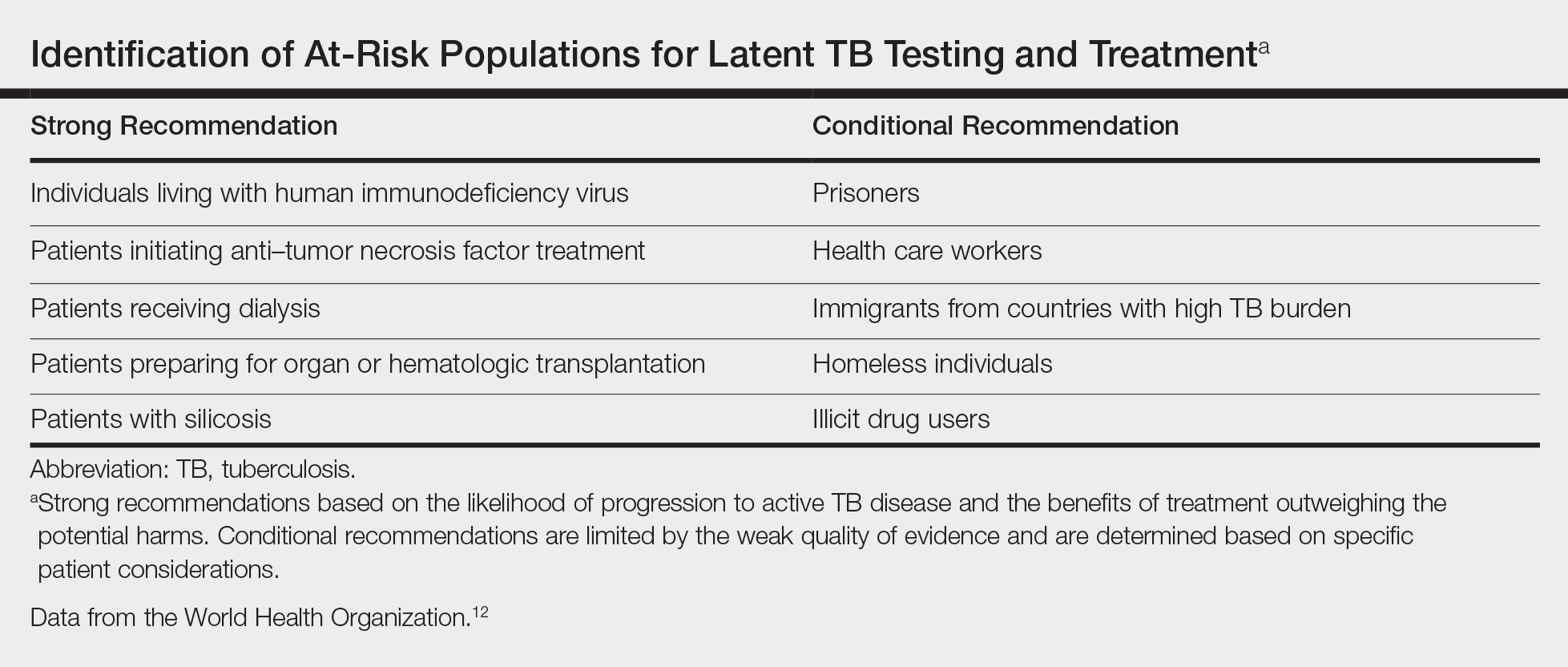

- Because of the unusual histology of KAs and their tendency to spontaneously regress, it is not totally understood where they fall on the benign vs malignant spectrum. Our case adds additional weight to the idea that some KAs are primarily reactive phenomena sharing features of other reactive cutaneous proliferations such as foreign body granulomas.