User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Business Education in Dermatology Residency: A Survey of Program Directors

Globally, the United States has the highest per-capita cost of health care; total costs are expected to account for approximately 20% of the nation’s gross domestic product by 2025.1 These rising costs have prompted residency programs and medical schools to incorporate business education into their curricula.2-5 Although medical training is demanding—with little room to add curricular components—these business-focused curricula have consistently received positive feedback from residents.5,6

In dermatology, more than 50% of residents opt to join a private practice upon graduation.7 In the United States, there also is an upward trend of practice acquisition and consolidation by private equity firms. Therefore, dermatology trainees are uniquely positioned to benefit from business education to make well-informed decisions about joining or starting a practice.Furthermore, whether in a private or academic setting, knowledge of foundational economics, business strategy, finance, marketing, and health care policy can equip dermatologists to more effectively advocate for local and national policies that benefit their patient population.7

We conducted a survey of dermatology program directors (PDs) to determine the availability of and perceptions regarding business education during residency training.

Materials and Methods

Institutional review board (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee) approval was obtained. The survey was distributed weekly during a 5-week period from July 2020 to August 2020 through the Research Electronic Data Capture survey application (www.project-redcap.org). Program director email addresses were obtained through the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) program list. A PD was included in the survey if they were employed by an accredited US osteopathic or allopathic program and their email address was provided in the ACGME program list or on their program’s faculty web page; a PD was excluded if an email address was not provided in the ACGME program list or on their program’s faculty web page.

The 8-part questionnaire was designed to assess the following characteristics: details about the respondent’s residency program (institutional affiliation, number of residents), the respondent’s professional background (number of years as a PD, business training experience), resources for business education provided by the program, the respondent’s opinion about business education for residents, and the respondent’s perception of the most important topics to include in a dermatology curriculum’s business education component, which included economics/finance, health care policy/government, management, marketing, negotiation, private equity involvement in health care, business strategy, supply chain/operations, and technology/product development. Responses were kept anonymous. Categorical and continuous variables were analyzed with medians and proportions.

Results

Of the 139 surveys distributed, 35 were completed and returned (response rate, 25.2%). Most programs were university-affiliated (71.4%) or community-affiliated (22.9%). The median number of residents was 12. The respondents had a median of 5 years’ experience in their role. Most respondents (65.7%) had no business training, although 20.0% had completed undergraduate business coursework, and 8.6% had attended formal seminars on business topics; 5.7% were self-taught on business topics.

Business Education Availability

Approximately half (51.4%) of programs offered business training to residents, primarily through seminars or lectures (94.4%) and take-home modules (16.7%). None of the programs offered a formal gap year during which residents could pursue a professional business degree. Most respondents thought business education during residency was important (82.8%) and that programs should implement more training (57.1%). When asked whether residents were competent to handle business aspects of dermatology upon graduation, most respondents disagreed somewhat (22.9%) or were neutral (40.0%).

Topics for Business Education

The most important topics identified for inclusion in a business curriculum were economics or finance (68.6%), management (68.6%), and health care policy or government (57.1%). Other identified topics included negotiation (40.0%), private equity involvement in health care (40.0%), strategy (11.4%), supply chain or operations (11.4%), marketing (2.9%), and technology (2.9%).

Comment

Residency programs and medical schools in the United States have started to integrate formal business training into their curricula; however, the state of business training in dermatology has not been characterized. Overall, this survey revealed largely positive perceptions about business education and identified a demand for more resources.

Whereas most PDs identified business education as important, only one half (51.4%) of the representative programs offered structured training. Notably, most PDs did not agree that graduating residents were competent to handle the business demands of dermatology practice. These responses highlight a gap in the demand and resources available for business training.

Identifying Curricular Resources

During an already demanding residency, additional curricular components need to be beneficial and worthwhile. To avoid significant disruption, business training could take place in the form of online lectures or take-home modules. Most programs represented in the survey responses had an academic affiliation and therefore commonly have access to an affiliated graduate business school and/or hospital administrators who have clinical and business training.

Community dermatologists who own or run their own practice also are uniquely positioned to provide residents with practical, dermatology-specific business education. Programs can utilize their institutional and local colleagues to aid in curricular design and implementation. In addition, a potential long-term solution to obtaining resources for business education is to coordinate with a national dermatology organization to create standardized modules that are available to all residency programs.

Key Curriculum Topics

Our survey identified the most important topics to include in a business curriculum for dermatology residents. Economics and finance, management, and health care policy would be valuable to a trainee regardless of whether they ultimately choose a career in academia or private practice. A thorough understanding of complex health care policy reinforces knowledge about insurance and regional and national regulations, which could ultimately benefit patient care. As an example, the American Academy of Dermatology outlines several advocacy priorities such as Medicare reimbursement policies, access to dermatologic care through public and private insurance, medication access and pricing, and preservation of private practice in the setting of market consolidation. Having a better understanding of health care policy and business could better equip dermatologists to lead these often business-driven advocacy efforts to ultimately improve patient care and advance the specialty.8

Limitations

There were notable limitations to this survey, primarily related to its design. With a 25% response rate, there was the potential for response and selection biases; therefore, these results might not be generalizable to all programs. In addition, views held by PDs might not be consistent with those of other members of the dermatology community; for example, surveying residents, other faculty members, and dermatologists in private practice would have provided a more comprehensive characterization of the topic.

Conclusion

This study assessed residency program directors’ perceptions of business education in dermatology training. There appears to be an imbalance between the perceived importance of such education and the resources that are available to provide it. More attention is needed to address this gap to ensure that dermatologists are prepared to manage a rapidly changing health care environment. Results of this survey should encourage efforts to establish (1) a standardized, dermatology-specific business curriculum and (2) a plan to make that curriculum accessible to trainees and other members of the dermatology community.

- Branning G, Vater M. Healthcare spending: plenty of blame to go around. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9:445-447.

- Bayard M, Peeples CR, Holt J, et al. An interactive approach to teaching practice management to family practice residents. Fam Med. 2003;35:622-624.

- Chan S. Management education during radiology residency: development of an educational practice. Acad Radiol. 2004;11:1308-1317.

- Ninan D, Patel D. Career and leadership education in anesthesia residency training. Cureus. 2018;10:e2546.

- Yu-Chin R. Teaching administration and management within psychiatric residency training. Acad Psychiatry. 2002;26:245-252.

- Winkelman JW, Brugnara C. Management training for pathology residents. II. experience with a focused curriculum. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101:564-568.

- Tan S, Seiger K, Renehan P, et al. Trends in private equity acquisition of dermatology practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1013-1021.

- Academy advocacy priorities. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 11, 2021. www.aad.org/member/advocacy/priorities

Globally, the United States has the highest per-capita cost of health care; total costs are expected to account for approximately 20% of the nation’s gross domestic product by 2025.1 These rising costs have prompted residency programs and medical schools to incorporate business education into their curricula.2-5 Although medical training is demanding—with little room to add curricular components—these business-focused curricula have consistently received positive feedback from residents.5,6

In dermatology, more than 50% of residents opt to join a private practice upon graduation.7 In the United States, there also is an upward trend of practice acquisition and consolidation by private equity firms. Therefore, dermatology trainees are uniquely positioned to benefit from business education to make well-informed decisions about joining or starting a practice.Furthermore, whether in a private or academic setting, knowledge of foundational economics, business strategy, finance, marketing, and health care policy can equip dermatologists to more effectively advocate for local and national policies that benefit their patient population.7

We conducted a survey of dermatology program directors (PDs) to determine the availability of and perceptions regarding business education during residency training.

Materials and Methods

Institutional review board (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee) approval was obtained. The survey was distributed weekly during a 5-week period from July 2020 to August 2020 through the Research Electronic Data Capture survey application (www.project-redcap.org). Program director email addresses were obtained through the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) program list. A PD was included in the survey if they were employed by an accredited US osteopathic or allopathic program and their email address was provided in the ACGME program list or on their program’s faculty web page; a PD was excluded if an email address was not provided in the ACGME program list or on their program’s faculty web page.

The 8-part questionnaire was designed to assess the following characteristics: details about the respondent’s residency program (institutional affiliation, number of residents), the respondent’s professional background (number of years as a PD, business training experience), resources for business education provided by the program, the respondent’s opinion about business education for residents, and the respondent’s perception of the most important topics to include in a dermatology curriculum’s business education component, which included economics/finance, health care policy/government, management, marketing, negotiation, private equity involvement in health care, business strategy, supply chain/operations, and technology/product development. Responses were kept anonymous. Categorical and continuous variables were analyzed with medians and proportions.

Results

Of the 139 surveys distributed, 35 were completed and returned (response rate, 25.2%). Most programs were university-affiliated (71.4%) or community-affiliated (22.9%). The median number of residents was 12. The respondents had a median of 5 years’ experience in their role. Most respondents (65.7%) had no business training, although 20.0% had completed undergraduate business coursework, and 8.6% had attended formal seminars on business topics; 5.7% were self-taught on business topics.

Business Education Availability

Approximately half (51.4%) of programs offered business training to residents, primarily through seminars or lectures (94.4%) and take-home modules (16.7%). None of the programs offered a formal gap year during which residents could pursue a professional business degree. Most respondents thought business education during residency was important (82.8%) and that programs should implement more training (57.1%). When asked whether residents were competent to handle business aspects of dermatology upon graduation, most respondents disagreed somewhat (22.9%) or were neutral (40.0%).

Topics for Business Education

The most important topics identified for inclusion in a business curriculum were economics or finance (68.6%), management (68.6%), and health care policy or government (57.1%). Other identified topics included negotiation (40.0%), private equity involvement in health care (40.0%), strategy (11.4%), supply chain or operations (11.4%), marketing (2.9%), and technology (2.9%).

Comment

Residency programs and medical schools in the United States have started to integrate formal business training into their curricula; however, the state of business training in dermatology has not been characterized. Overall, this survey revealed largely positive perceptions about business education and identified a demand for more resources.

Whereas most PDs identified business education as important, only one half (51.4%) of the representative programs offered structured training. Notably, most PDs did not agree that graduating residents were competent to handle the business demands of dermatology practice. These responses highlight a gap in the demand and resources available for business training.

Identifying Curricular Resources

During an already demanding residency, additional curricular components need to be beneficial and worthwhile. To avoid significant disruption, business training could take place in the form of online lectures or take-home modules. Most programs represented in the survey responses had an academic affiliation and therefore commonly have access to an affiliated graduate business school and/or hospital administrators who have clinical and business training.

Community dermatologists who own or run their own practice also are uniquely positioned to provide residents with practical, dermatology-specific business education. Programs can utilize their institutional and local colleagues to aid in curricular design and implementation. In addition, a potential long-term solution to obtaining resources for business education is to coordinate with a national dermatology organization to create standardized modules that are available to all residency programs.

Key Curriculum Topics

Our survey identified the most important topics to include in a business curriculum for dermatology residents. Economics and finance, management, and health care policy would be valuable to a trainee regardless of whether they ultimately choose a career in academia or private practice. A thorough understanding of complex health care policy reinforces knowledge about insurance and regional and national regulations, which could ultimately benefit patient care. As an example, the American Academy of Dermatology outlines several advocacy priorities such as Medicare reimbursement policies, access to dermatologic care through public and private insurance, medication access and pricing, and preservation of private practice in the setting of market consolidation. Having a better understanding of health care policy and business could better equip dermatologists to lead these often business-driven advocacy efforts to ultimately improve patient care and advance the specialty.8

Limitations

There were notable limitations to this survey, primarily related to its design. With a 25% response rate, there was the potential for response and selection biases; therefore, these results might not be generalizable to all programs. In addition, views held by PDs might not be consistent with those of other members of the dermatology community; for example, surveying residents, other faculty members, and dermatologists in private practice would have provided a more comprehensive characterization of the topic.

Conclusion

This study assessed residency program directors’ perceptions of business education in dermatology training. There appears to be an imbalance between the perceived importance of such education and the resources that are available to provide it. More attention is needed to address this gap to ensure that dermatologists are prepared to manage a rapidly changing health care environment. Results of this survey should encourage efforts to establish (1) a standardized, dermatology-specific business curriculum and (2) a plan to make that curriculum accessible to trainees and other members of the dermatology community.

Globally, the United States has the highest per-capita cost of health care; total costs are expected to account for approximately 20% of the nation’s gross domestic product by 2025.1 These rising costs have prompted residency programs and medical schools to incorporate business education into their curricula.2-5 Although medical training is demanding—with little room to add curricular components—these business-focused curricula have consistently received positive feedback from residents.5,6

In dermatology, more than 50% of residents opt to join a private practice upon graduation.7 In the United States, there also is an upward trend of practice acquisition and consolidation by private equity firms. Therefore, dermatology trainees are uniquely positioned to benefit from business education to make well-informed decisions about joining or starting a practice.Furthermore, whether in a private or academic setting, knowledge of foundational economics, business strategy, finance, marketing, and health care policy can equip dermatologists to more effectively advocate for local and national policies that benefit their patient population.7

We conducted a survey of dermatology program directors (PDs) to determine the availability of and perceptions regarding business education during residency training.

Materials and Methods

Institutional review board (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee) approval was obtained. The survey was distributed weekly during a 5-week period from July 2020 to August 2020 through the Research Electronic Data Capture survey application (www.project-redcap.org). Program director email addresses were obtained through the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) program list. A PD was included in the survey if they were employed by an accredited US osteopathic or allopathic program and their email address was provided in the ACGME program list or on their program’s faculty web page; a PD was excluded if an email address was not provided in the ACGME program list or on their program’s faculty web page.

The 8-part questionnaire was designed to assess the following characteristics: details about the respondent’s residency program (institutional affiliation, number of residents), the respondent’s professional background (number of years as a PD, business training experience), resources for business education provided by the program, the respondent’s opinion about business education for residents, and the respondent’s perception of the most important topics to include in a dermatology curriculum’s business education component, which included economics/finance, health care policy/government, management, marketing, negotiation, private equity involvement in health care, business strategy, supply chain/operations, and technology/product development. Responses were kept anonymous. Categorical and continuous variables were analyzed with medians and proportions.

Results

Of the 139 surveys distributed, 35 were completed and returned (response rate, 25.2%). Most programs were university-affiliated (71.4%) or community-affiliated (22.9%). The median number of residents was 12. The respondents had a median of 5 years’ experience in their role. Most respondents (65.7%) had no business training, although 20.0% had completed undergraduate business coursework, and 8.6% had attended formal seminars on business topics; 5.7% were self-taught on business topics.

Business Education Availability

Approximately half (51.4%) of programs offered business training to residents, primarily through seminars or lectures (94.4%) and take-home modules (16.7%). None of the programs offered a formal gap year during which residents could pursue a professional business degree. Most respondents thought business education during residency was important (82.8%) and that programs should implement more training (57.1%). When asked whether residents were competent to handle business aspects of dermatology upon graduation, most respondents disagreed somewhat (22.9%) or were neutral (40.0%).

Topics for Business Education

The most important topics identified for inclusion in a business curriculum were economics or finance (68.6%), management (68.6%), and health care policy or government (57.1%). Other identified topics included negotiation (40.0%), private equity involvement in health care (40.0%), strategy (11.4%), supply chain or operations (11.4%), marketing (2.9%), and technology (2.9%).

Comment

Residency programs and medical schools in the United States have started to integrate formal business training into their curricula; however, the state of business training in dermatology has not been characterized. Overall, this survey revealed largely positive perceptions about business education and identified a demand for more resources.

Whereas most PDs identified business education as important, only one half (51.4%) of the representative programs offered structured training. Notably, most PDs did not agree that graduating residents were competent to handle the business demands of dermatology practice. These responses highlight a gap in the demand and resources available for business training.

Identifying Curricular Resources

During an already demanding residency, additional curricular components need to be beneficial and worthwhile. To avoid significant disruption, business training could take place in the form of online lectures or take-home modules. Most programs represented in the survey responses had an academic affiliation and therefore commonly have access to an affiliated graduate business school and/or hospital administrators who have clinical and business training.

Community dermatologists who own or run their own practice also are uniquely positioned to provide residents with practical, dermatology-specific business education. Programs can utilize their institutional and local colleagues to aid in curricular design and implementation. In addition, a potential long-term solution to obtaining resources for business education is to coordinate with a national dermatology organization to create standardized modules that are available to all residency programs.

Key Curriculum Topics

Our survey identified the most important topics to include in a business curriculum for dermatology residents. Economics and finance, management, and health care policy would be valuable to a trainee regardless of whether they ultimately choose a career in academia or private practice. A thorough understanding of complex health care policy reinforces knowledge about insurance and regional and national regulations, which could ultimately benefit patient care. As an example, the American Academy of Dermatology outlines several advocacy priorities such as Medicare reimbursement policies, access to dermatologic care through public and private insurance, medication access and pricing, and preservation of private practice in the setting of market consolidation. Having a better understanding of health care policy and business could better equip dermatologists to lead these often business-driven advocacy efforts to ultimately improve patient care and advance the specialty.8

Limitations

There were notable limitations to this survey, primarily related to its design. With a 25% response rate, there was the potential for response and selection biases; therefore, these results might not be generalizable to all programs. In addition, views held by PDs might not be consistent with those of other members of the dermatology community; for example, surveying residents, other faculty members, and dermatologists in private practice would have provided a more comprehensive characterization of the topic.

Conclusion

This study assessed residency program directors’ perceptions of business education in dermatology training. There appears to be an imbalance between the perceived importance of such education and the resources that are available to provide it. More attention is needed to address this gap to ensure that dermatologists are prepared to manage a rapidly changing health care environment. Results of this survey should encourage efforts to establish (1) a standardized, dermatology-specific business curriculum and (2) a plan to make that curriculum accessible to trainees and other members of the dermatology community.

- Branning G, Vater M. Healthcare spending: plenty of blame to go around. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9:445-447.

- Bayard M, Peeples CR, Holt J, et al. An interactive approach to teaching practice management to family practice residents. Fam Med. 2003;35:622-624.

- Chan S. Management education during radiology residency: development of an educational practice. Acad Radiol. 2004;11:1308-1317.

- Ninan D, Patel D. Career and leadership education in anesthesia residency training. Cureus. 2018;10:e2546.

- Yu-Chin R. Teaching administration and management within psychiatric residency training. Acad Psychiatry. 2002;26:245-252.

- Winkelman JW, Brugnara C. Management training for pathology residents. II. experience with a focused curriculum. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101:564-568.

- Tan S, Seiger K, Renehan P, et al. Trends in private equity acquisition of dermatology practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1013-1021.

- Academy advocacy priorities. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 11, 2021. www.aad.org/member/advocacy/priorities

- Branning G, Vater M. Healthcare spending: plenty of blame to go around. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9:445-447.

- Bayard M, Peeples CR, Holt J, et al. An interactive approach to teaching practice management to family practice residents. Fam Med. 2003;35:622-624.

- Chan S. Management education during radiology residency: development of an educational practice. Acad Radiol. 2004;11:1308-1317.

- Ninan D, Patel D. Career and leadership education in anesthesia residency training. Cureus. 2018;10:e2546.

- Yu-Chin R. Teaching administration and management within psychiatric residency training. Acad Psychiatry. 2002;26:245-252.

- Winkelman JW, Brugnara C. Management training for pathology residents. II. experience with a focused curriculum. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101:564-568.

- Tan S, Seiger K, Renehan P, et al. Trends in private equity acquisition of dermatology practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1013-1021.

- Academy advocacy priorities. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 11, 2021. www.aad.org/member/advocacy/priorities

Practice Points

- In our survey of dermatology program directors, most felt inclusion of business education in residency training was important.

- Approximately half of the dermatology programs that responded to our survey offer business training to their residents.

- Economics and finance, management, and health care policy were the most important topics identified to include in a business curriculum for dermatology residents

Translating the 2019 AAD-NPF Guidelines of Care for Psoriasis With Attention to Comorbidities

Psoriasis is a chronic and relapsing systemic inflammatory disease that predisposes patients to a host of other conditions. It is believed that these widespread effects are due to chronic inflammation and cytokine activation, which affect multiple body processes and lead to the development of various comorbidities that need to be proactively managed.

In April 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released recommendation guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with an emphasis on common disease comorbidities, including psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease (CVD), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), metabolic syndrome, and mood disorders. Psychosocial wellness, mental health, and quality of life (QOL) measures in relation to psoriatic disease also were discussed.1

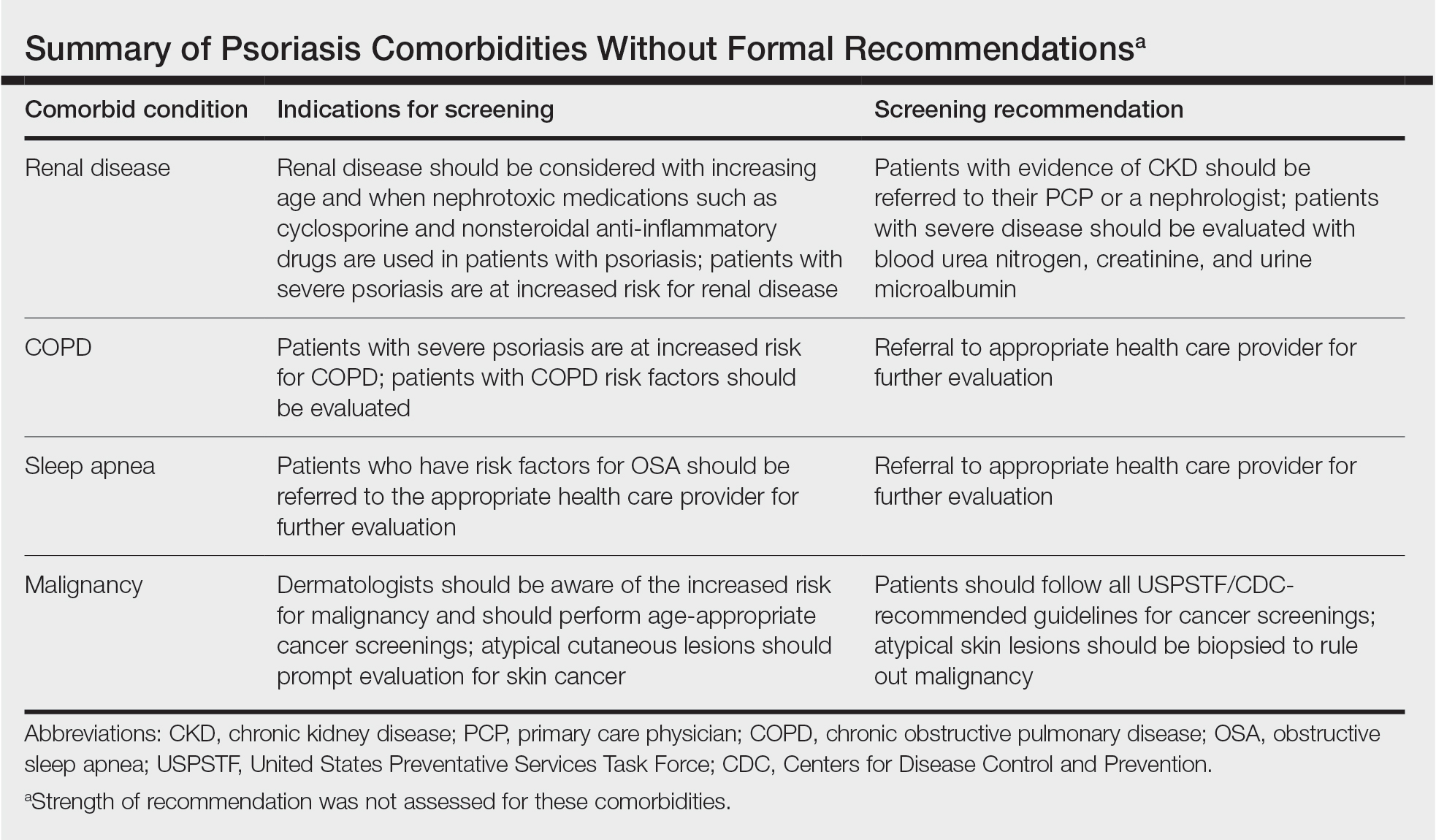

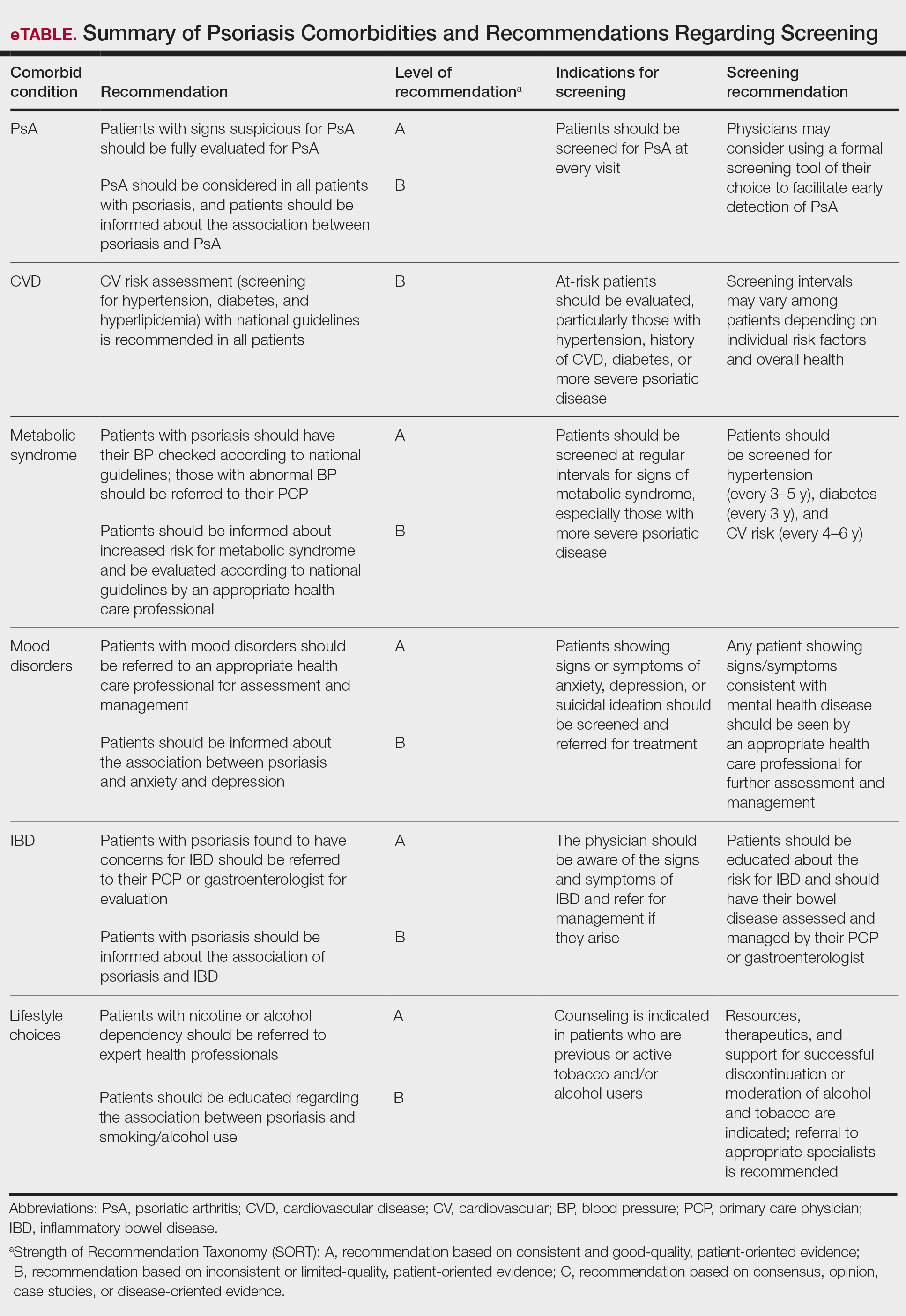

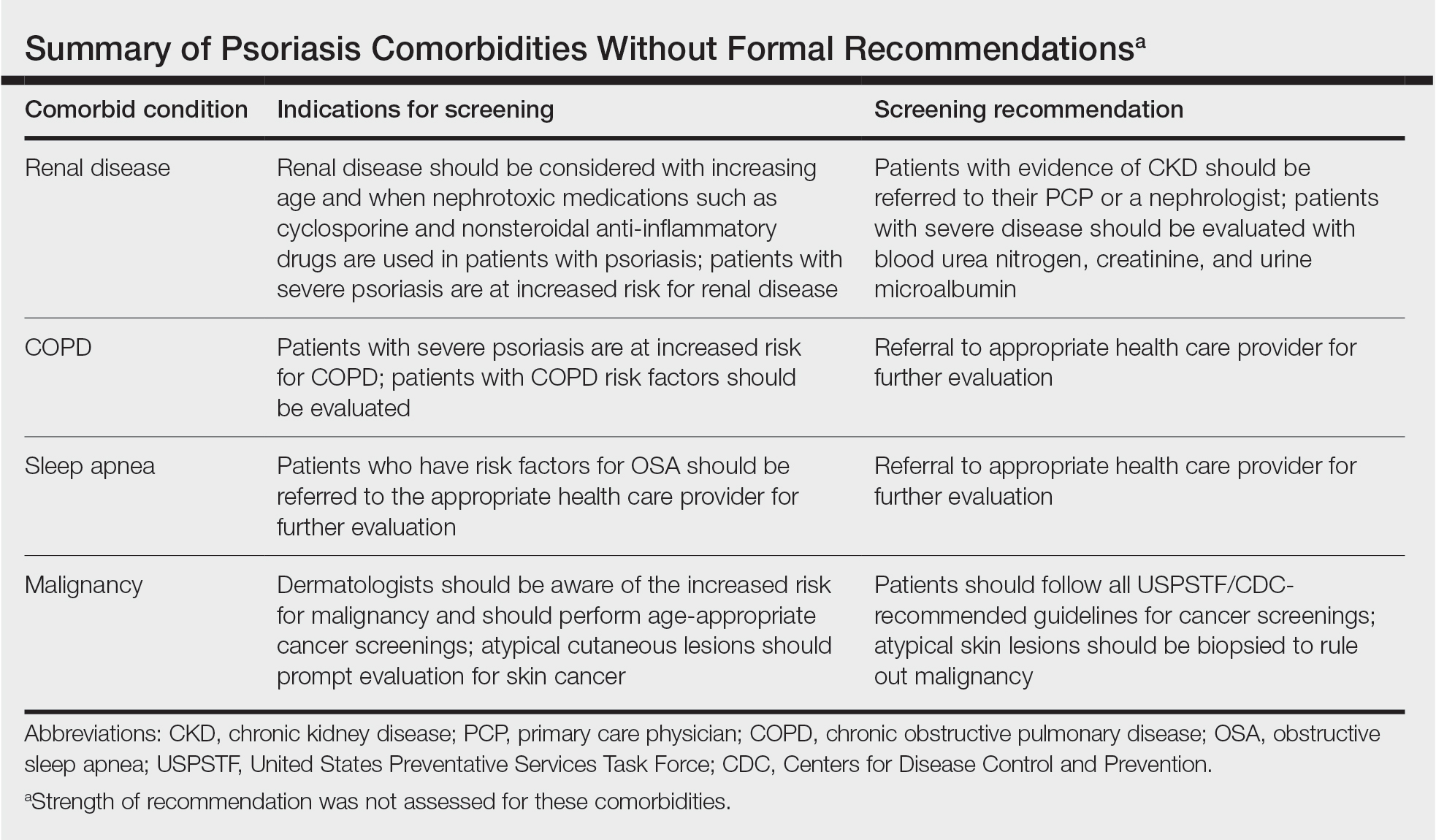

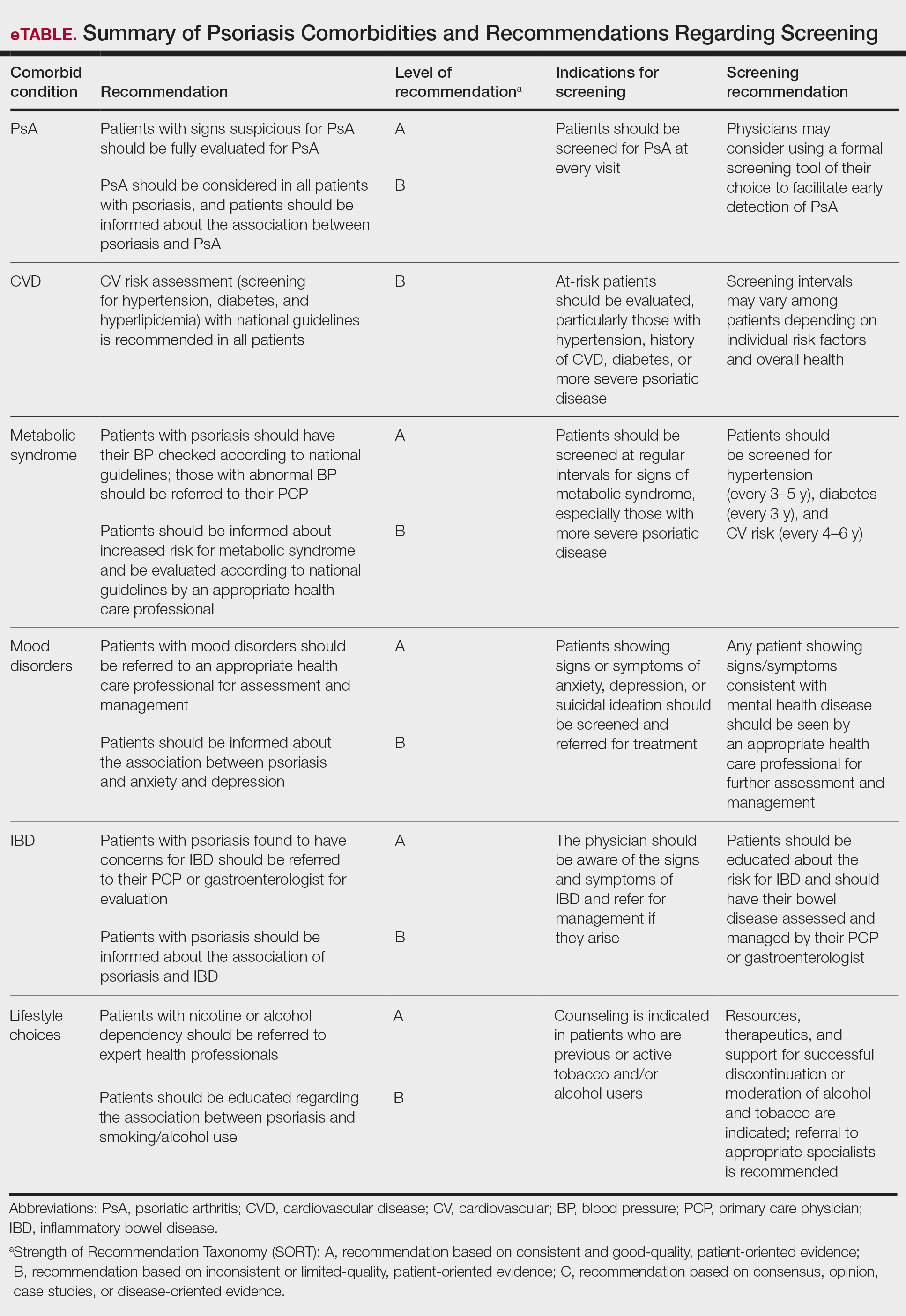

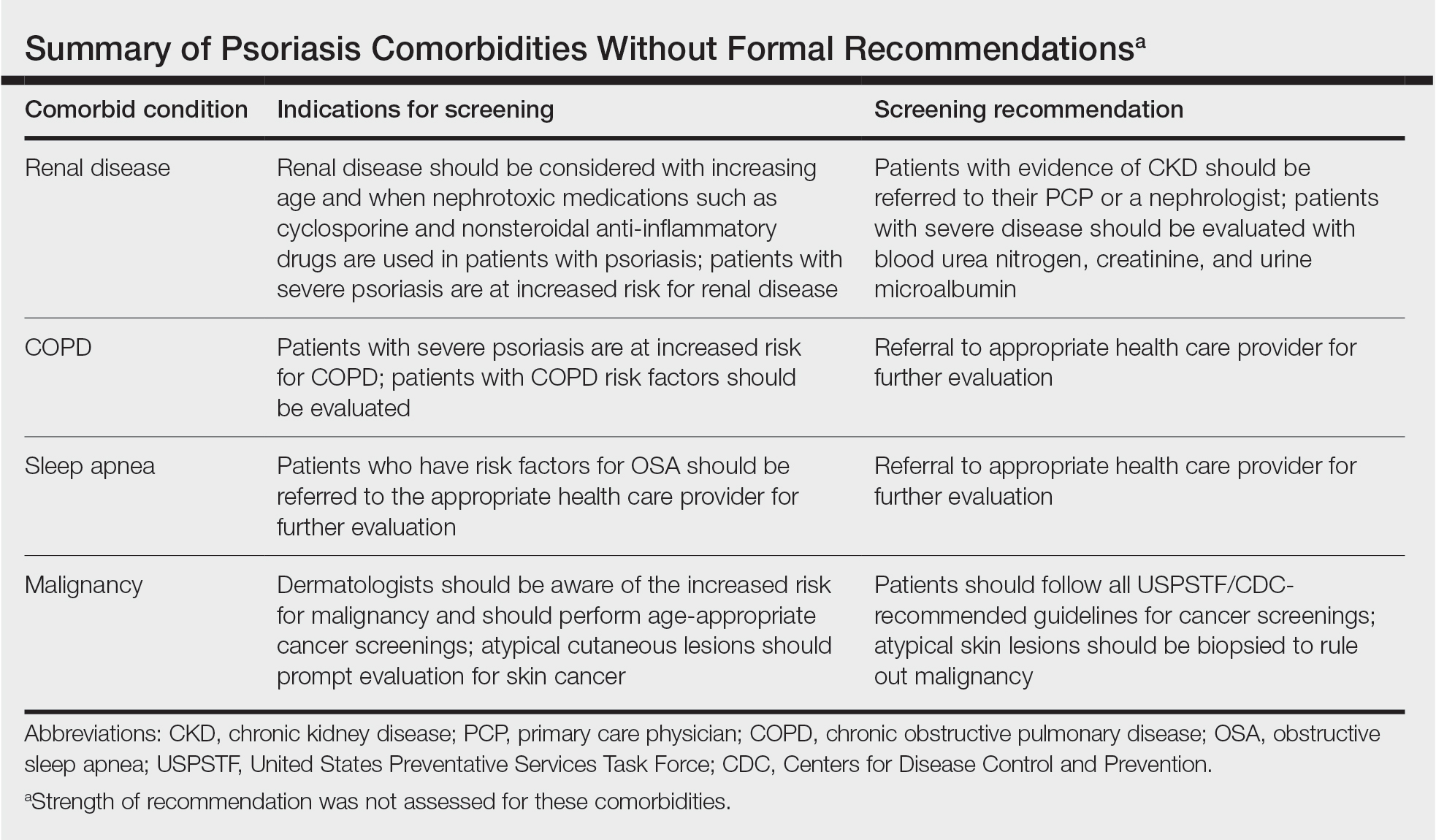

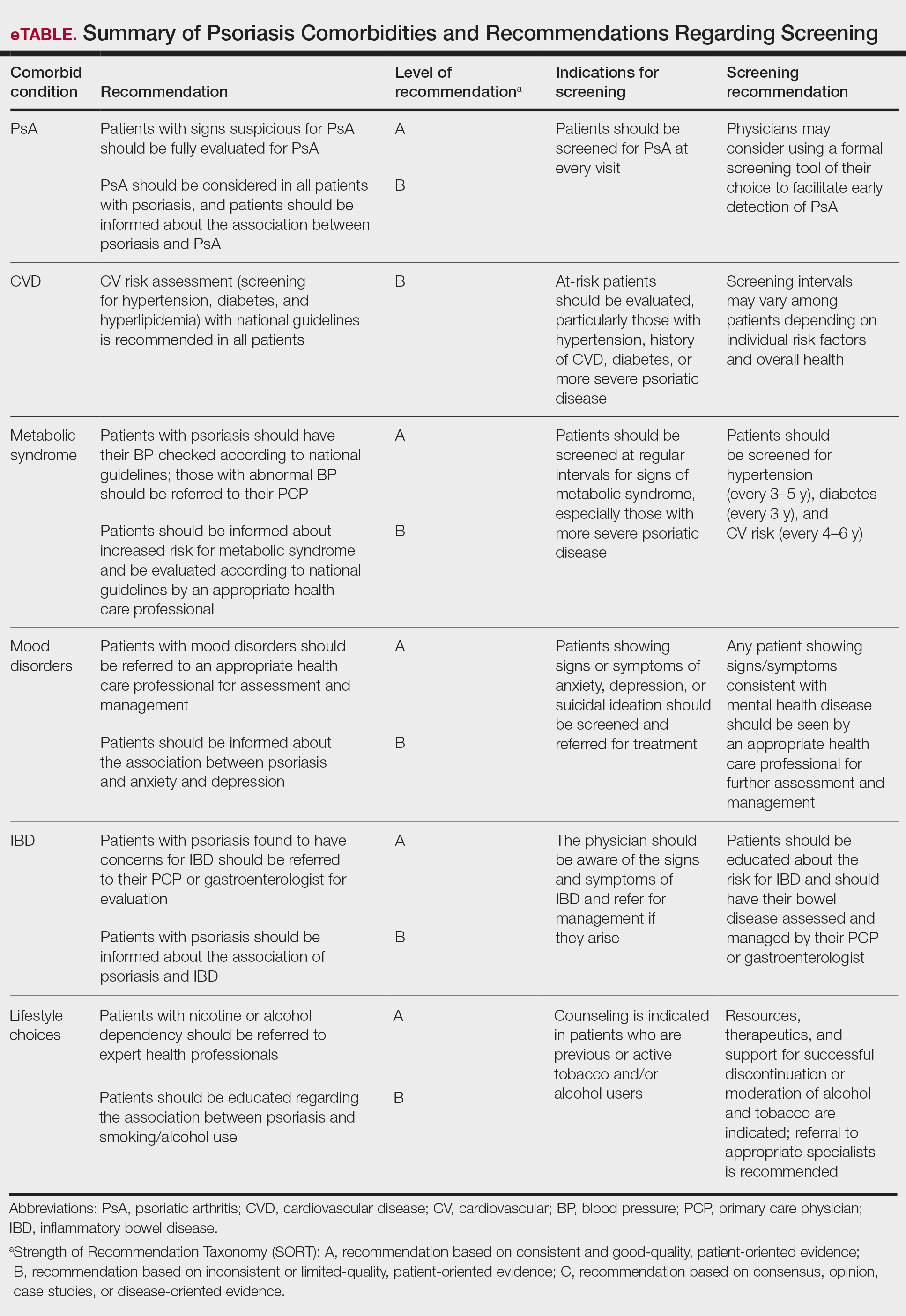

The AAD-NPF guidelines address current screening, monitoring, education, and treatment recommendations for the management of psoriatic comorbidities. The Table and eTable summarize the screening recommendations. These guidelines aim to assist dermatologists with comprehensive disease management by addressing potential extracutaneous manifestations of psoriasis in adults.

Screening and Risk Assessment

Patients with psoriasis should receive a thorough history and physical examination to assess disease severity and risk for potential comorbidities. Patients with greater disease severity—as measured by body surface area (BSA) involvement and type of therapy required—have a greater risk for other disease-related comorbidities, specifically metabolic syndrome, renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obstructive sleep apnea, uveitis, IBD, malignancy, and increased mortality.2 Because the likelihood of comorbidities is greatest with severe disease, more frequent monitoring is recommended for these patients.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Patients with psoriasis need to be evaluated for PsA at every visit. Patients presenting with signs and symptoms suspicious for PsA—joint swelling, peripheral joint involvement, and joint inflammation—warrant further evaluation and consultation. Early detection and treatment of PsA is essential for preventing unnecessary suffering and progressive joint destruction.3

There are several PsA screening questionnaires currently available, including the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation, Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen. No significant differences in sensitivity and specificity were found among these questionnaires when using the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis as the gold standard. All 3 questionnaires—the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation and the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool were developed for use in dermatology and rheumatology clinics, and the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen was developed for use in the primary care setting—were found to be effective in dermatology/rheumatology clinics and primary care clinics, respectively.3 False-positive results predominantly were seen in patients with degenerative joint disease or osteoarthritis. Dermatologists should conduct a thorough physical examination to distinguish PsA from degenerative joint disease. Imaging and laboratory tests to evaluate for signs of systemic inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) also can be helpful in distinguishing the 2 conditions; however, these metrics have not been shown to contribute to PsA diagnosis.1 Full rheumatologic consultation is warranted in challenging cases.

Cardiovascular Disease

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are recommended to screen patients for CVD risk factors using height, weight, blood pressure, blood glucose, hemoglobin A1C, lipid levels, abdominal circumference, and body mass index (BMI). Lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation, exercise, and dietary changes are encouraged to achieve and maintain a normal BMI.

Dermatologists also need to give special consideration to comorbidities when selecting medications and/or therapies for disease management. Patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for MI compared with patients using topical medications, phototherapy, and other oral agents.10 Additionally, patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events compared with patients treated with methotrexate or phototherapy.11,12

Metabolic Syndrome

Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. Patients with increased BSA involvement and

The association between psoriasis and weight loss has been analyzed in several studies. Weight loss, particularly in obese patients, has been shown to improve psoriasis severity, as measured by psoriasis area and severity index score and QOL measures.15 Another study found that gastric bypass was associated with a significant risk reduction in the development of psoriasis (P=.004) and the disease prognosis (P=.02 for severe psoriasis; P=.01 for PsA).16 Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their obesity status determined according to national guidelines. For patients with a BMI above 40 kg/m2 and standard weight-loss measures fail, bariatric surgery is recommended. Additionally, the impact of psoriasis medications on weight has been studied. Apremilast has been associated with weight loss, whereas etanercept and infliximab have been linked to weight gain.17,18

An association between psoriasis and hypertension also has been demonstrated by studies, especially among patients with severe disease. Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their blood pressure evaluated according to national guidelines, and those with a blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or higher should be referred to their PCP for assessment and treatment. Current evidence does not support restrictions on antihypertensive medications in patients with psoriasis. Physicians should be aware of the potential for cyclosporine to induce hypertension, which should be treated, specifically with amlodipine.19

Many studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and dyslipidemia, though the results are somewhat conflicting. In 2018, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology deemed psoriasis as an atherosclerotic CVD risk-enhancing condition, favoring early initiation of statin therapy. Because dyslipidemia plays a prominent role in atherosclerosis and CVD, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to undergo periodic screening with lipid tests (eg, fasting total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides).20 Patients with elevated fasting triglycerides or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol should be referred to their PCP for further management. Certain psoriasis medications also have been linked to dyslipidemia. Acitretin and cyclosporine are known to adversely affect lipid levels, so patients treated with either agent should undergo routine monitoring of serum lipid levels.

Psoriasis is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Because of the increased risk for diabetes in patients with severe disease, regular monitoring of fasting blood glucose and/or hemoglobin A1C levels in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis is recommended. Patients who meet criteria for prediabetes or diabetes should be referred to their PCP for further assessment and management.21,22

Mood Disorders

Psoriasis affects QOL and can have a major impact on patients’ interpersonal relationships. Studies have shown an association between psoriasis and mood disorders, specifically depression and anxiety. Unfortunately, patients with mood disorders are less likely to seek intervention for their skin disease, which poses a tremendous treatment barrier. Dermatologists should regularly monitor patients for psychiatric symptoms so that resources and treatments can be offered.

Certain psoriasis therapies have been shown to help alleviate associated depression and anxiety. Improvements in Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores were seen with etanercept.23 Adalimumab and ustekinumab showed improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index compared with placebo.24,25 Patients receiving Goeckerman treatment also had improvement in anxiety and depression scores compared with conventional therapy.26 Biologic medications had the largest impact on improving depression symptoms compared with conventional systemic therapy and phototherapy.27 The recommendations support use of biologics and the Goeckerman regimen for the concomitant treatment of mood disorders and psoriasis.

Renal Disease

Studies have supported an association between psoriasis and chronic kidney disease (CKD), independent of risk factors including vascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes. The prevalence of moderate to advanced CKD also has been found to be directly related to increasing BSA affected by psoriasis.28 Patients should receive testing of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and urine microalbumin levels to assess for occult renal disease. In addition, physicians should be cautious when prescribing nephrotoxic drugs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclosporine) and renally excreted agents (methotrexate and apremilast) because of the risk for underlying renal disease in patients with psoriasis. If newly acquired renal disease is suspected, physicians should withhold the offending agents. Patients with psoriasis with CKD are recommended to follow up with their PCP or nephrologist for evaluation and management.

Pulmonary Disease

Psoriasis also has an independent association with COPD. Patients with psoriasis have a higher likelihood of developing COPD (hazard ratio, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.42-3.89; P<.01) than controls.29 The prevalence of COPD also was found to correlate with psoriasis severity. Dermatologists should educate patients about the association between smoking and psoriasis as well as advise patients to discontinue smoking to reduce their risk for developing COPD and cancer.

Patients with psoriasis also are at an increased risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea should be considered in patients with risk factors including snoring, obesity, hypertension, or diabetes.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for developing IBD. The prevalence ratios of both Crohn disease (2.49) and ulcerative colitis (1.64) are increased in patients with psoriasis relative to patients without psoriasis.30 Physicians need to be aware of the association between psoriasis and IBD and the effect that their coexistence may have on treatment choice for patients.

Adalimumab and infliximab are approved for the treatment of IBD, and certolizumab and ustekinumab are approved for Crohn disease. Use of TNF inhibitors in patients with IBD may cause psoriasiform lesions to develop.31 Nonetheless, treatment should be individualized and psoriasiform lesions treated with standard psoriasis measures. Psoriasis patients with IBD are recommended to avoid IL-17–inhibitor therapy, given its potential to worsen IBD flares.

Malignancy

Psoriasis patients aged 0 to 79 years have a greater overall risk for malignancy compared with patients without psoriasis.32 Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for respiratory tract cancer, upper aerodigestive tract cancer, urinary tract cancer, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.33 A mild association exists between PsA and lymphoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), and lung cancer.34 More severe psoriasis is associated with greater risk for lymphoma and NMSC. Dermatologists are recommended to educate patients on their risk for certain malignancies and to refer patients to specialists upon suspicion of malignancy.

Risk for malignancy has been shown to be affected by psoriasis treatments. Patients treated with UVB have reduced overall cancer rates for all age groups (hazard ratio, 0.52; P=.3), while those treated with psoralen plus UVA have an increased incidence of

Lifestyle Choices and QOL

A crucial aspect of successful psoriasis management is patient education. The strongest recommendations support lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation and limitation of alcohol use. A tactful discussion regarding substance use, work productivity, interpersonal relationships, and sexual function can address substantial effects of psoriasis on QOL so that support and resources can be provided.

Final Thoughts

Management of psoriasis is multifaceted and involves screening, education, monitoring, and collaboration with PCPs and specialists. Regular follow-up with a dermatologist and PCP is strongly recommended for patients with psoriasis given the systemic nature of the disease. The 2019 AAD-NPF recommendations provide important information for dermatologists to coordinate care for complicated psoriasis cases, but clinical judgment is paramount when making medical decisions. The consideration of comorbidities is critical for developing a comprehensive treatment approach, and this approach will lead to better health outcomes and improved QOL for patients with psoriasis.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113.

- Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, Lewis JD, et al. The risk of mortality in patients with psoriasis: results from a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-1499.

- Coates LC, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:802-807.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3168-3209.

- Lerman JB, Joshi AA, Chaturvedi A, et al. Coronary plaque characterization in psoriasis reveals high-risk features that improve after treatment in a prospective observational study. Circulation. 2017;136:263-276.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and mortality in heart failure: a community study. Circulation. 2008;118:625-631.

- Russell SD, Saval MA, Robbins JL, et al. New York Heart Association functional class predicts exercise parameters in the current era. Am Heart J. 2009;158(4 suppl):S24-S30.

- Wu JJ, Poon K-YT, Channual JC, et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1244-1250.

- Wu JJ, Guerin A, Sundaram M, et al. Cardiovascular event risk assessment in psoriasis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors versus methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:81-90.

- Wu JJ, Sundaram M, Cloutier M, et al. The risk of cardiovascular events in psoriasis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors versus phototherapy: an observational cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:60-68.

- Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:403-414.

- Langan SM, Seminara NM, Shin DB, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study in the United Kingdom. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:556-562.

- Jensen P, Zachariae C, Christensen R, et al. Effect of weight loss on the severity of psoriasis: a randomized clinical study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:795-801.

- Egeberg A, Sørensen JA, Gislason GH, et al. Incidence and prognosis of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:344-349.

- Crowley J, Thaçi D, Joly P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of apremilast in patients with psoriasis: pooled safety analysis for ≥156 weeks from 2 phase 3, randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:310-317.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.052

- Gisondi P, Del Giglio M, Di Francesco V, et al. Weight loss improves the response of obese patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis to low-dose cyclosporine therapy: a randomized, controlled, investigator-blinded clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1242-1247.

- Leenen FHH, Coletta E, Davies RA. Prevention of renal dysfunction and hypertension by amlodipine after heart transplant. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:531-535.

- Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennet G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2014;129(suppl 2):S49-S73.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(suppl 1):S14-S80.

- Ratner RE, Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. An update on the diabetes prevention program. Endocr Pract. 2006;12(suppl 1):20-24.

- Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006;367:29-35.

- Kimball AB, Edson-Heredia E, Zhu B, et al. Understanding the relationship between pruritus severity and work productivity in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: sleep problems are a mediating factor. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:183-188.

- Langley RG, Tsai T-F, Flavin S, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate response to ustekinumab: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III NAVIGATE trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:114-123.

- Chern E, Yau D, Ho J-C, et al. Positive effect of modified Goeckerman regimen on quality of life and psychosocial distress in moderate and severe psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:447-451.

- Strober B, Gooderham M, de Jong EMGJ, et al. Depressive symptoms, depression, and the effect of biologic therapy among patients in Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:70-80.

- Wan J, Wang S, Haynes K, et al. Risk of moderate to advanced kidney disease in patients with psoriasis: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2013;347:f5961. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5961

- Chiang Y-Y, Lin H-W. Association between psoriasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based study in Taiwan. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:59-65.

- Cohen AD, Dreiher J, Birkenfeld S. Psoriasis associated with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:561-565.

- Denadai R, Teixeira FV, Saad-Hossne R. The onset of psoriasis during the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases with infliximab: should biological therapy be suspended? Arq Gastroenterol. 2012;49:172-176.

- Chen Y-J, Wu C-Y, Chen T-J, et al. The risk of cancer in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:84-91.

- Pouplard C, Brenaut E, Horreau C, et al. Risk of cancer in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(suppl 3):36-46.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Shin DB, Ogdie Beatty A, et al. The risk of cancer in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the health improvement network. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:282-290.

- Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, et al. Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23 458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn’s disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:517-524.

- Dommasch ED, Abuabara K, Shin DB, et al. The risk of infection and malignancy with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in adults with psoriatic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1035-1050.

- Gordon KB, Papp KA, Langley RG, et al. Long-term safety experience of ustekinumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis (part II of II): results from analyses of infections and malignancy from pooled phase II and III clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:742-751.

Psoriasis is a chronic and relapsing systemic inflammatory disease that predisposes patients to a host of other conditions. It is believed that these widespread effects are due to chronic inflammation and cytokine activation, which affect multiple body processes and lead to the development of various comorbidities that need to be proactively managed.

In April 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released recommendation guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with an emphasis on common disease comorbidities, including psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease (CVD), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), metabolic syndrome, and mood disorders. Psychosocial wellness, mental health, and quality of life (QOL) measures in relation to psoriatic disease also were discussed.1

The AAD-NPF guidelines address current screening, monitoring, education, and treatment recommendations for the management of psoriatic comorbidities. The Table and eTable summarize the screening recommendations. These guidelines aim to assist dermatologists with comprehensive disease management by addressing potential extracutaneous manifestations of psoriasis in adults.

Screening and Risk Assessment

Patients with psoriasis should receive a thorough history and physical examination to assess disease severity and risk for potential comorbidities. Patients with greater disease severity—as measured by body surface area (BSA) involvement and type of therapy required—have a greater risk for other disease-related comorbidities, specifically metabolic syndrome, renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obstructive sleep apnea, uveitis, IBD, malignancy, and increased mortality.2 Because the likelihood of comorbidities is greatest with severe disease, more frequent monitoring is recommended for these patients.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Patients with psoriasis need to be evaluated for PsA at every visit. Patients presenting with signs and symptoms suspicious for PsA—joint swelling, peripheral joint involvement, and joint inflammation—warrant further evaluation and consultation. Early detection and treatment of PsA is essential for preventing unnecessary suffering and progressive joint destruction.3

There are several PsA screening questionnaires currently available, including the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation, Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen. No significant differences in sensitivity and specificity were found among these questionnaires when using the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis as the gold standard. All 3 questionnaires—the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation and the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool were developed for use in dermatology and rheumatology clinics, and the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen was developed for use in the primary care setting—were found to be effective in dermatology/rheumatology clinics and primary care clinics, respectively.3 False-positive results predominantly were seen in patients with degenerative joint disease or osteoarthritis. Dermatologists should conduct a thorough physical examination to distinguish PsA from degenerative joint disease. Imaging and laboratory tests to evaluate for signs of systemic inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) also can be helpful in distinguishing the 2 conditions; however, these metrics have not been shown to contribute to PsA diagnosis.1 Full rheumatologic consultation is warranted in challenging cases.

Cardiovascular Disease

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are recommended to screen patients for CVD risk factors using height, weight, blood pressure, blood glucose, hemoglobin A1C, lipid levels, abdominal circumference, and body mass index (BMI). Lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation, exercise, and dietary changes are encouraged to achieve and maintain a normal BMI.

Dermatologists also need to give special consideration to comorbidities when selecting medications and/or therapies for disease management. Patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for MI compared with patients using topical medications, phototherapy, and other oral agents.10 Additionally, patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events compared with patients treated with methotrexate or phototherapy.11,12

Metabolic Syndrome

Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. Patients with increased BSA involvement and

The association between psoriasis and weight loss has been analyzed in several studies. Weight loss, particularly in obese patients, has been shown to improve psoriasis severity, as measured by psoriasis area and severity index score and QOL measures.15 Another study found that gastric bypass was associated with a significant risk reduction in the development of psoriasis (P=.004) and the disease prognosis (P=.02 for severe psoriasis; P=.01 for PsA).16 Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their obesity status determined according to national guidelines. For patients with a BMI above 40 kg/m2 and standard weight-loss measures fail, bariatric surgery is recommended. Additionally, the impact of psoriasis medications on weight has been studied. Apremilast has been associated with weight loss, whereas etanercept and infliximab have been linked to weight gain.17,18

An association between psoriasis and hypertension also has been demonstrated by studies, especially among patients with severe disease. Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their blood pressure evaluated according to national guidelines, and those with a blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or higher should be referred to their PCP for assessment and treatment. Current evidence does not support restrictions on antihypertensive medications in patients with psoriasis. Physicians should be aware of the potential for cyclosporine to induce hypertension, which should be treated, specifically with amlodipine.19

Many studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and dyslipidemia, though the results are somewhat conflicting. In 2018, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology deemed psoriasis as an atherosclerotic CVD risk-enhancing condition, favoring early initiation of statin therapy. Because dyslipidemia plays a prominent role in atherosclerosis and CVD, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to undergo periodic screening with lipid tests (eg, fasting total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides).20 Patients with elevated fasting triglycerides or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol should be referred to their PCP for further management. Certain psoriasis medications also have been linked to dyslipidemia. Acitretin and cyclosporine are known to adversely affect lipid levels, so patients treated with either agent should undergo routine monitoring of serum lipid levels.

Psoriasis is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Because of the increased risk for diabetes in patients with severe disease, regular monitoring of fasting blood glucose and/or hemoglobin A1C levels in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis is recommended. Patients who meet criteria for prediabetes or diabetes should be referred to their PCP for further assessment and management.21,22

Mood Disorders

Psoriasis affects QOL and can have a major impact on patients’ interpersonal relationships. Studies have shown an association between psoriasis and mood disorders, specifically depression and anxiety. Unfortunately, patients with mood disorders are less likely to seek intervention for their skin disease, which poses a tremendous treatment barrier. Dermatologists should regularly monitor patients for psychiatric symptoms so that resources and treatments can be offered.

Certain psoriasis therapies have been shown to help alleviate associated depression and anxiety. Improvements in Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores were seen with etanercept.23 Adalimumab and ustekinumab showed improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index compared with placebo.24,25 Patients receiving Goeckerman treatment also had improvement in anxiety and depression scores compared with conventional therapy.26 Biologic medications had the largest impact on improving depression symptoms compared with conventional systemic therapy and phototherapy.27 The recommendations support use of biologics and the Goeckerman regimen for the concomitant treatment of mood disorders and psoriasis.

Renal Disease

Studies have supported an association between psoriasis and chronic kidney disease (CKD), independent of risk factors including vascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes. The prevalence of moderate to advanced CKD also has been found to be directly related to increasing BSA affected by psoriasis.28 Patients should receive testing of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and urine microalbumin levels to assess for occult renal disease. In addition, physicians should be cautious when prescribing nephrotoxic drugs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclosporine) and renally excreted agents (methotrexate and apremilast) because of the risk for underlying renal disease in patients with psoriasis. If newly acquired renal disease is suspected, physicians should withhold the offending agents. Patients with psoriasis with CKD are recommended to follow up with their PCP or nephrologist for evaluation and management.

Pulmonary Disease

Psoriasis also has an independent association with COPD. Patients with psoriasis have a higher likelihood of developing COPD (hazard ratio, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.42-3.89; P<.01) than controls.29 The prevalence of COPD also was found to correlate with psoriasis severity. Dermatologists should educate patients about the association between smoking and psoriasis as well as advise patients to discontinue smoking to reduce their risk for developing COPD and cancer.

Patients with psoriasis also are at an increased risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea should be considered in patients with risk factors including snoring, obesity, hypertension, or diabetes.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for developing IBD. The prevalence ratios of both Crohn disease (2.49) and ulcerative colitis (1.64) are increased in patients with psoriasis relative to patients without psoriasis.30 Physicians need to be aware of the association between psoriasis and IBD and the effect that their coexistence may have on treatment choice for patients.

Adalimumab and infliximab are approved for the treatment of IBD, and certolizumab and ustekinumab are approved for Crohn disease. Use of TNF inhibitors in patients with IBD may cause psoriasiform lesions to develop.31 Nonetheless, treatment should be individualized and psoriasiform lesions treated with standard psoriasis measures. Psoriasis patients with IBD are recommended to avoid IL-17–inhibitor therapy, given its potential to worsen IBD flares.

Malignancy

Psoriasis patients aged 0 to 79 years have a greater overall risk for malignancy compared with patients without psoriasis.32 Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for respiratory tract cancer, upper aerodigestive tract cancer, urinary tract cancer, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.33 A mild association exists between PsA and lymphoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), and lung cancer.34 More severe psoriasis is associated with greater risk for lymphoma and NMSC. Dermatologists are recommended to educate patients on their risk for certain malignancies and to refer patients to specialists upon suspicion of malignancy.

Risk for malignancy has been shown to be affected by psoriasis treatments. Patients treated with UVB have reduced overall cancer rates for all age groups (hazard ratio, 0.52; P=.3), while those treated with psoralen plus UVA have an increased incidence of

Lifestyle Choices and QOL

A crucial aspect of successful psoriasis management is patient education. The strongest recommendations support lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation and limitation of alcohol use. A tactful discussion regarding substance use, work productivity, interpersonal relationships, and sexual function can address substantial effects of psoriasis on QOL so that support and resources can be provided.

Final Thoughts

Management of psoriasis is multifaceted and involves screening, education, monitoring, and collaboration with PCPs and specialists. Regular follow-up with a dermatologist and PCP is strongly recommended for patients with psoriasis given the systemic nature of the disease. The 2019 AAD-NPF recommendations provide important information for dermatologists to coordinate care for complicated psoriasis cases, but clinical judgment is paramount when making medical decisions. The consideration of comorbidities is critical for developing a comprehensive treatment approach, and this approach will lead to better health outcomes and improved QOL for patients with psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic and relapsing systemic inflammatory disease that predisposes patients to a host of other conditions. It is believed that these widespread effects are due to chronic inflammation and cytokine activation, which affect multiple body processes and lead to the development of various comorbidities that need to be proactively managed.

In April 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released recommendation guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with an emphasis on common disease comorbidities, including psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease (CVD), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), metabolic syndrome, and mood disorders. Psychosocial wellness, mental health, and quality of life (QOL) measures in relation to psoriatic disease also were discussed.1

The AAD-NPF guidelines address current screening, monitoring, education, and treatment recommendations for the management of psoriatic comorbidities. The Table and eTable summarize the screening recommendations. These guidelines aim to assist dermatologists with comprehensive disease management by addressing potential extracutaneous manifestations of psoriasis in adults.

Screening and Risk Assessment

Patients with psoriasis should receive a thorough history and physical examination to assess disease severity and risk for potential comorbidities. Patients with greater disease severity—as measured by body surface area (BSA) involvement and type of therapy required—have a greater risk for other disease-related comorbidities, specifically metabolic syndrome, renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obstructive sleep apnea, uveitis, IBD, malignancy, and increased mortality.2 Because the likelihood of comorbidities is greatest with severe disease, more frequent monitoring is recommended for these patients.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Patients with psoriasis need to be evaluated for PsA at every visit. Patients presenting with signs and symptoms suspicious for PsA—joint swelling, peripheral joint involvement, and joint inflammation—warrant further evaluation and consultation. Early detection and treatment of PsA is essential for preventing unnecessary suffering and progressive joint destruction.3

There are several PsA screening questionnaires currently available, including the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation, Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen. No significant differences in sensitivity and specificity were found among these questionnaires when using the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis as the gold standard. All 3 questionnaires—the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation and the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool were developed for use in dermatology and rheumatology clinics, and the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen was developed for use in the primary care setting—were found to be effective in dermatology/rheumatology clinics and primary care clinics, respectively.3 False-positive results predominantly were seen in patients with degenerative joint disease or osteoarthritis. Dermatologists should conduct a thorough physical examination to distinguish PsA from degenerative joint disease. Imaging and laboratory tests to evaluate for signs of systemic inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) also can be helpful in distinguishing the 2 conditions; however, these metrics have not been shown to contribute to PsA diagnosis.1 Full rheumatologic consultation is warranted in challenging cases.

Cardiovascular Disease

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are recommended to screen patients for CVD risk factors using height, weight, blood pressure, blood glucose, hemoglobin A1C, lipid levels, abdominal circumference, and body mass index (BMI). Lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation, exercise, and dietary changes are encouraged to achieve and maintain a normal BMI.

Dermatologists also need to give special consideration to comorbidities when selecting medications and/or therapies for disease management. Patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for MI compared with patients using topical medications, phototherapy, and other oral agents.10 Additionally, patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events compared with patients treated with methotrexate or phototherapy.11,12

Metabolic Syndrome

Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. Patients with increased BSA involvement and

The association between psoriasis and weight loss has been analyzed in several studies. Weight loss, particularly in obese patients, has been shown to improve psoriasis severity, as measured by psoriasis area and severity index score and QOL measures.15 Another study found that gastric bypass was associated with a significant risk reduction in the development of psoriasis (P=.004) and the disease prognosis (P=.02 for severe psoriasis; P=.01 for PsA).16 Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their obesity status determined according to national guidelines. For patients with a BMI above 40 kg/m2 and standard weight-loss measures fail, bariatric surgery is recommended. Additionally, the impact of psoriasis medications on weight has been studied. Apremilast has been associated with weight loss, whereas etanercept and infliximab have been linked to weight gain.17,18

An association between psoriasis and hypertension also has been demonstrated by studies, especially among patients with severe disease. Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their blood pressure evaluated according to national guidelines, and those with a blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or higher should be referred to their PCP for assessment and treatment. Current evidence does not support restrictions on antihypertensive medications in patients with psoriasis. Physicians should be aware of the potential for cyclosporine to induce hypertension, which should be treated, specifically with amlodipine.19

Many studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and dyslipidemia, though the results are somewhat conflicting. In 2018, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology deemed psoriasis as an atherosclerotic CVD risk-enhancing condition, favoring early initiation of statin therapy. Because dyslipidemia plays a prominent role in atherosclerosis and CVD, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to undergo periodic screening with lipid tests (eg, fasting total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides).20 Patients with elevated fasting triglycerides or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol should be referred to their PCP for further management. Certain psoriasis medications also have been linked to dyslipidemia. Acitretin and cyclosporine are known to adversely affect lipid levels, so patients treated with either agent should undergo routine monitoring of serum lipid levels.

Psoriasis is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Because of the increased risk for diabetes in patients with severe disease, regular monitoring of fasting blood glucose and/or hemoglobin A1C levels in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis is recommended. Patients who meet criteria for prediabetes or diabetes should be referred to their PCP for further assessment and management.21,22

Mood Disorders

Psoriasis affects QOL and can have a major impact on patients’ interpersonal relationships. Studies have shown an association between psoriasis and mood disorders, specifically depression and anxiety. Unfortunately, patients with mood disorders are less likely to seek intervention for their skin disease, which poses a tremendous treatment barrier. Dermatologists should regularly monitor patients for psychiatric symptoms so that resources and treatments can be offered.

Certain psoriasis therapies have been shown to help alleviate associated depression and anxiety. Improvements in Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores were seen with etanercept.23 Adalimumab and ustekinumab showed improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index compared with placebo.24,25 Patients receiving Goeckerman treatment also had improvement in anxiety and depression scores compared with conventional therapy.26 Biologic medications had the largest impact on improving depression symptoms compared with conventional systemic therapy and phototherapy.27 The recommendations support use of biologics and the Goeckerman regimen for the concomitant treatment of mood disorders and psoriasis.

Renal Disease

Studies have supported an association between psoriasis and chronic kidney disease (CKD), independent of risk factors including vascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes. The prevalence of moderate to advanced CKD also has been found to be directly related to increasing BSA affected by psoriasis.28 Patients should receive testing of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and urine microalbumin levels to assess for occult renal disease. In addition, physicians should be cautious when prescribing nephrotoxic drugs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclosporine) and renally excreted agents (methotrexate and apremilast) because of the risk for underlying renal disease in patients with psoriasis. If newly acquired renal disease is suspected, physicians should withhold the offending agents. Patients with psoriasis with CKD are recommended to follow up with their PCP or nephrologist for evaluation and management.

Pulmonary Disease

Psoriasis also has an independent association with COPD. Patients with psoriasis have a higher likelihood of developing COPD (hazard ratio, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.42-3.89; P<.01) than controls.29 The prevalence of COPD also was found to correlate with psoriasis severity. Dermatologists should educate patients about the association between smoking and psoriasis as well as advise patients to discontinue smoking to reduce their risk for developing COPD and cancer.

Patients with psoriasis also are at an increased risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea should be considered in patients with risk factors including snoring, obesity, hypertension, or diabetes.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for developing IBD. The prevalence ratios of both Crohn disease (2.49) and ulcerative colitis (1.64) are increased in patients with psoriasis relative to patients without psoriasis.30 Physicians need to be aware of the association between psoriasis and IBD and the effect that their coexistence may have on treatment choice for patients.

Adalimumab and infliximab are approved for the treatment of IBD, and certolizumab and ustekinumab are approved for Crohn disease. Use of TNF inhibitors in patients with IBD may cause psoriasiform lesions to develop.31 Nonetheless, treatment should be individualized and psoriasiform lesions treated with standard psoriasis measures. Psoriasis patients with IBD are recommended to avoid IL-17–inhibitor therapy, given its potential to worsen IBD flares.

Malignancy

Psoriasis patients aged 0 to 79 years have a greater overall risk for malignancy compared with patients without psoriasis.32 Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for respiratory tract cancer, upper aerodigestive tract cancer, urinary tract cancer, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.33 A mild association exists between PsA and lymphoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), and lung cancer.34 More severe psoriasis is associated with greater risk for lymphoma and NMSC. Dermatologists are recommended to educate patients on their risk for certain malignancies and to refer patients to specialists upon suspicion of malignancy.

Risk for malignancy has been shown to be affected by psoriasis treatments. Patients treated with UVB have reduced overall cancer rates for all age groups (hazard ratio, 0.52; P=.3), while those treated with psoralen plus UVA have an increased incidence of

Lifestyle Choices and QOL

A crucial aspect of successful psoriasis management is patient education. The strongest recommendations support lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation and limitation of alcohol use. A tactful discussion regarding substance use, work productivity, interpersonal relationships, and sexual function can address substantial effects of psoriasis on QOL so that support and resources can be provided.

Final Thoughts

Management of psoriasis is multifaceted and involves screening, education, monitoring, and collaboration with PCPs and specialists. Regular follow-up with a dermatologist and PCP is strongly recommended for patients with psoriasis given the systemic nature of the disease. The 2019 AAD-NPF recommendations provide important information for dermatologists to coordinate care for complicated psoriasis cases, but clinical judgment is paramount when making medical decisions. The consideration of comorbidities is critical for developing a comprehensive treatment approach, and this approach will lead to better health outcomes and improved QOL for patients with psoriasis.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113.

- Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, Lewis JD, et al. The risk of mortality in patients with psoriasis: results from a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-1499.

- Coates LC, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:802-807.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3168-3209.