User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

The Top 100 Most-Cited Articles on Nail Psoriasis: A Bibliometric Analysis

To the Editor:

Nail psoriasis is highly prevalent in patients with cutaneous psoriasis and also may present as an isolated finding. There is a strong association between nail psoriasis and development of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). However, publications on nail psoriasis are sparse compared with articles describing cutaneous psoriasis.1 Our objectives were to analyze the nail psoriasis literature for content, citations, and media attention.

The Web of Science database was searched for the term nail psoriasis on April 27, 2020, and publications by year, subject, and article type were compiled. Total and average yearly citations were calculated to create a list of the top 100 most-cited articles (eTable). First and last authors, sex, and Altmetric Attention Scores were then recorded. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was calculated to compare the relationship of Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific references and others on the list.

In our data set, the average total number of citations was 134.09 (range, 42–1617), with average yearly citations ranging from 2 to 108. Altmetric scores—measures of media attention of scholarly work—were available for 58 of 100 papers (58%), with an average score of 33.2 (range, 1–509).

Of the top 100 most-cited articles using the search term nail psoriasis, only 20% focused on nail psoriasis, with the remainder concentrating on psoriasis/PsA. Only 32% and 24% of first and last authors, respectively, were female. Fifty-two percent and 31% of the articles were published in dermatology and arthritis/rheumatology journals, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific and other articles in our data set (P=.7551).

For the nail psoriasis–specific articles, all 20 highlighted a lack of nail clinical trials, a positive association with PsA, and a correlation of increased cutaneous psoriasis body surface area with increased onychodystrophy likelihood.2 Three of 20 (15%) articles stated that nail psoriasis often is overlooked, despite the negative impact on quality of life,1 and emphasized the importance of patient compliance owing to the chronic nature of the disease. Only 1 of 20 (5%) articles focused on nail psoriasis treatments.3 There was no overlap between the 100 most-cited psoriasis articles from 1970 to 2012 and our top 100 articles on nail psoriasis.4

Treatment recommendations for nail psoriasis by consensus were published by a nail expert group in 2019.5 For 3 or fewer nails involved, suggested first-line treatment is intralesional matrix injections with triamcinolone acetonide. For more than 3 affected nails, systemic treatment with oral or biologic therapy is recommended.5 Although this article is likely to change clinical practice, it did not qualify for our list because it did not garner sufficient citations in the brief period between its publication date and our search (July 2019–April 2020).

This study is subject to several limitations. Only the Web of Science database was utilized, and only the term nail psoriasis was searched, potentially excluding relevant articles. Using total citations biases toward older articles.

Our bibliometric analysis highlights a lack of publications on nail psoriasis, with most articles focusing on psoriasis and PsA. This deficiency in highly cited nail psoriasis references is likely to be a barrier to physicians in managing patients with nail disease. There is a need for controlled clinical trials and better mechanisms to disseminate information on management of nail psoriasis to practicing physicians.

- Williamson L, Dalbeth N, Dockerty JL, et al. Extended report: nail disease in psoriatic arthritis—clinically important, potentially treatable and often overlooked. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:790-794. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh198

- Reich K. Approach to managing patients with nail psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(suppl 1):15-21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03364.x

- de Berker D. Management of nail psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:357-362. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00663.x

- Wu JJ, Choi YM, Marczynski W. The 100 most cited psoriasis articles in clinical dermatologic journals, 1970 to 2012. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:10-19.

- Rigopoulos D, Baran R, Chiheb S, et al. Recommendations for the definition, evaluation, and treatment of nail psoriasis in adult patients with no or mild skin psoriasis: a dermatologist and nail expert group consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:228-240. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.072

To the Editor:

Nail psoriasis is highly prevalent in patients with cutaneous psoriasis and also may present as an isolated finding. There is a strong association between nail psoriasis and development of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). However, publications on nail psoriasis are sparse compared with articles describing cutaneous psoriasis.1 Our objectives were to analyze the nail psoriasis literature for content, citations, and media attention.

The Web of Science database was searched for the term nail psoriasis on April 27, 2020, and publications by year, subject, and article type were compiled. Total and average yearly citations were calculated to create a list of the top 100 most-cited articles (eTable). First and last authors, sex, and Altmetric Attention Scores were then recorded. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was calculated to compare the relationship of Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific references and others on the list.

In our data set, the average total number of citations was 134.09 (range, 42–1617), with average yearly citations ranging from 2 to 108. Altmetric scores—measures of media attention of scholarly work—were available for 58 of 100 papers (58%), with an average score of 33.2 (range, 1–509).

Of the top 100 most-cited articles using the search term nail psoriasis, only 20% focused on nail psoriasis, with the remainder concentrating on psoriasis/PsA. Only 32% and 24% of first and last authors, respectively, were female. Fifty-two percent and 31% of the articles were published in dermatology and arthritis/rheumatology journals, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific and other articles in our data set (P=.7551).

For the nail psoriasis–specific articles, all 20 highlighted a lack of nail clinical trials, a positive association with PsA, and a correlation of increased cutaneous psoriasis body surface area with increased onychodystrophy likelihood.2 Three of 20 (15%) articles stated that nail psoriasis often is overlooked, despite the negative impact on quality of life,1 and emphasized the importance of patient compliance owing to the chronic nature of the disease. Only 1 of 20 (5%) articles focused on nail psoriasis treatments.3 There was no overlap between the 100 most-cited psoriasis articles from 1970 to 2012 and our top 100 articles on nail psoriasis.4

Treatment recommendations for nail psoriasis by consensus were published by a nail expert group in 2019.5 For 3 or fewer nails involved, suggested first-line treatment is intralesional matrix injections with triamcinolone acetonide. For more than 3 affected nails, systemic treatment with oral or biologic therapy is recommended.5 Although this article is likely to change clinical practice, it did not qualify for our list because it did not garner sufficient citations in the brief period between its publication date and our search (July 2019–April 2020).

This study is subject to several limitations. Only the Web of Science database was utilized, and only the term nail psoriasis was searched, potentially excluding relevant articles. Using total citations biases toward older articles.

Our bibliometric analysis highlights a lack of publications on nail psoriasis, with most articles focusing on psoriasis and PsA. This deficiency in highly cited nail psoriasis references is likely to be a barrier to physicians in managing patients with nail disease. There is a need for controlled clinical trials and better mechanisms to disseminate information on management of nail psoriasis to practicing physicians.

To the Editor:

Nail psoriasis is highly prevalent in patients with cutaneous psoriasis and also may present as an isolated finding. There is a strong association between nail psoriasis and development of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). However, publications on nail psoriasis are sparse compared with articles describing cutaneous psoriasis.1 Our objectives were to analyze the nail psoriasis literature for content, citations, and media attention.

The Web of Science database was searched for the term nail psoriasis on April 27, 2020, and publications by year, subject, and article type were compiled. Total and average yearly citations were calculated to create a list of the top 100 most-cited articles (eTable). First and last authors, sex, and Altmetric Attention Scores were then recorded. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was calculated to compare the relationship of Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific references and others on the list.

In our data set, the average total number of citations was 134.09 (range, 42–1617), with average yearly citations ranging from 2 to 108. Altmetric scores—measures of media attention of scholarly work—were available for 58 of 100 papers (58%), with an average score of 33.2 (range, 1–509).

Of the top 100 most-cited articles using the search term nail psoriasis, only 20% focused on nail psoriasis, with the remainder concentrating on psoriasis/PsA. Only 32% and 24% of first and last authors, respectively, were female. Fifty-two percent and 31% of the articles were published in dermatology and arthritis/rheumatology journals, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in Altmetric scores between nail psoriasis–specific and other articles in our data set (P=.7551).

For the nail psoriasis–specific articles, all 20 highlighted a lack of nail clinical trials, a positive association with PsA, and a correlation of increased cutaneous psoriasis body surface area with increased onychodystrophy likelihood.2 Three of 20 (15%) articles stated that nail psoriasis often is overlooked, despite the negative impact on quality of life,1 and emphasized the importance of patient compliance owing to the chronic nature of the disease. Only 1 of 20 (5%) articles focused on nail psoriasis treatments.3 There was no overlap between the 100 most-cited psoriasis articles from 1970 to 2012 and our top 100 articles on nail psoriasis.4

Treatment recommendations for nail psoriasis by consensus were published by a nail expert group in 2019.5 For 3 or fewer nails involved, suggested first-line treatment is intralesional matrix injections with triamcinolone acetonide. For more than 3 affected nails, systemic treatment with oral or biologic therapy is recommended.5 Although this article is likely to change clinical practice, it did not qualify for our list because it did not garner sufficient citations in the brief period between its publication date and our search (July 2019–April 2020).

This study is subject to several limitations. Only the Web of Science database was utilized, and only the term nail psoriasis was searched, potentially excluding relevant articles. Using total citations biases toward older articles.

Our bibliometric analysis highlights a lack of publications on nail psoriasis, with most articles focusing on psoriasis and PsA. This deficiency in highly cited nail psoriasis references is likely to be a barrier to physicians in managing patients with nail disease. There is a need for controlled clinical trials and better mechanisms to disseminate information on management of nail psoriasis to practicing physicians.

- Williamson L, Dalbeth N, Dockerty JL, et al. Extended report: nail disease in psoriatic arthritis—clinically important, potentially treatable and often overlooked. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:790-794. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh198

- Reich K. Approach to managing patients with nail psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(suppl 1):15-21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03364.x

- de Berker D. Management of nail psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:357-362. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00663.x

- Wu JJ, Choi YM, Marczynski W. The 100 most cited psoriasis articles in clinical dermatologic journals, 1970 to 2012. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:10-19.

- Rigopoulos D, Baran R, Chiheb S, et al. Recommendations for the definition, evaluation, and treatment of nail psoriasis in adult patients with no or mild skin psoriasis: a dermatologist and nail expert group consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:228-240. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.072

- Williamson L, Dalbeth N, Dockerty JL, et al. Extended report: nail disease in psoriatic arthritis—clinically important, potentially treatable and often overlooked. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:790-794. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh198

- Reich K. Approach to managing patients with nail psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(suppl 1):15-21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03364.x

- de Berker D. Management of nail psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:357-362. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00663.x

- Wu JJ, Choi YM, Marczynski W. The 100 most cited psoriasis articles in clinical dermatologic journals, 1970 to 2012. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:10-19.

- Rigopoulos D, Baran R, Chiheb S, et al. Recommendations for the definition, evaluation, and treatment of nail psoriasis in adult patients with no or mild skin psoriasis: a dermatologist and nail expert group consensus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:228-240. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.072

Reticular Rash on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

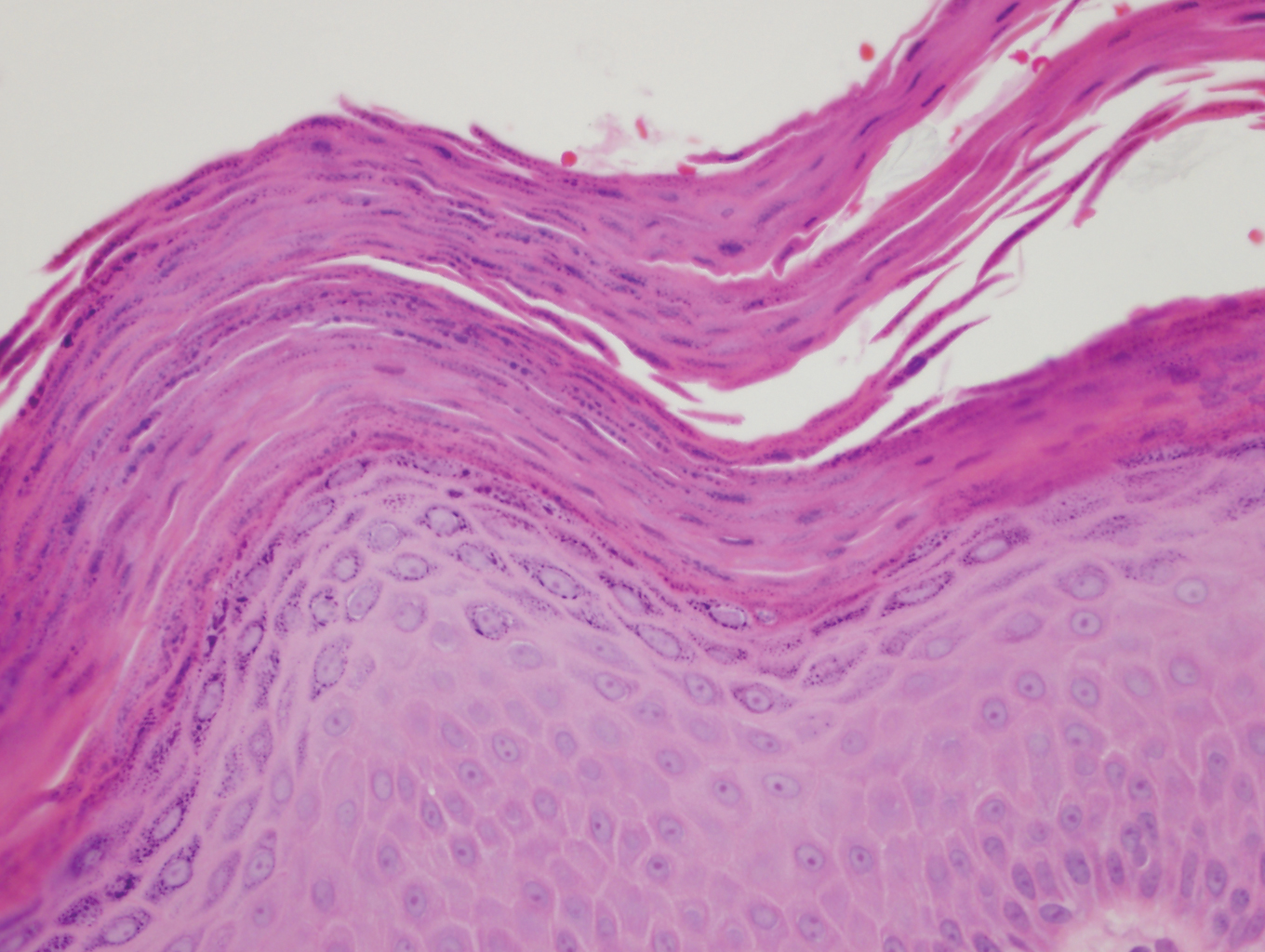

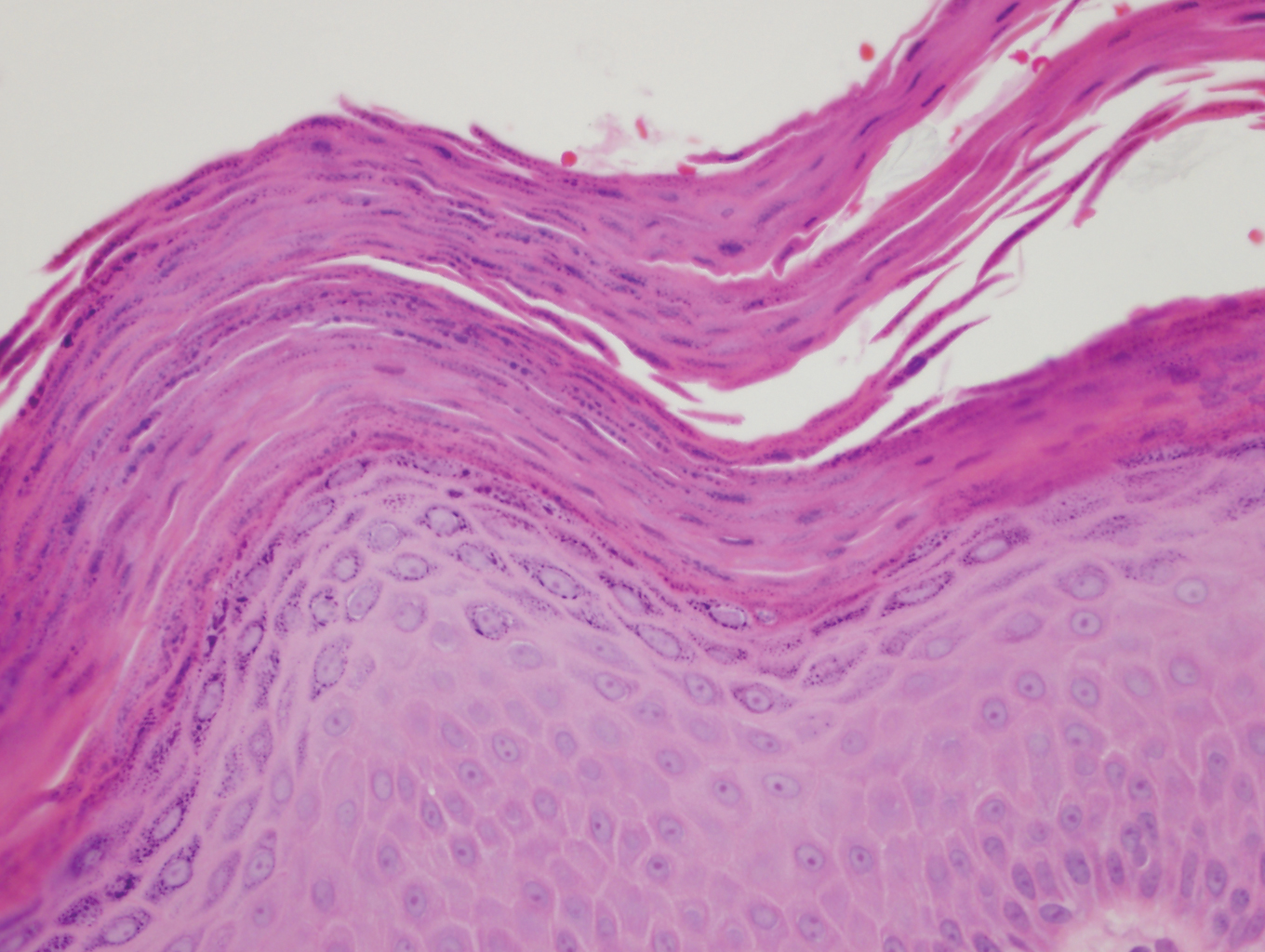

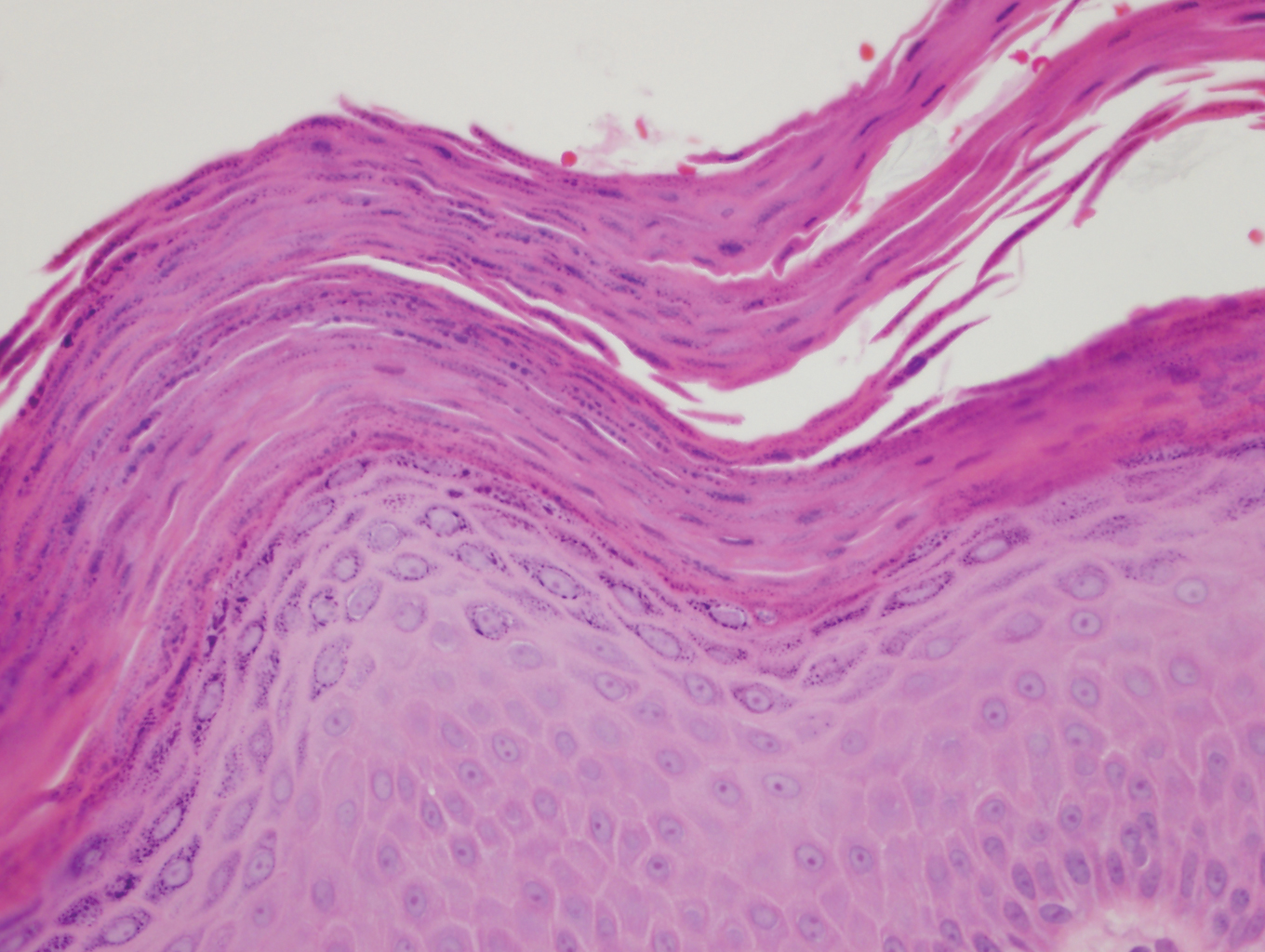

Based on the clinical findings and history, a diagnosis of erythema ab igne (EAI), a skin reaction to chronic infrared radiation exposure, was made. The name of this condition translates from Latin as “redness from fire”; other names include toasted skin syndrome and fire stains. The most common presentation is reticulated hyperpigmentation, erythema, and cutaneous atrophy, as well as possible crusting, scaling, or telangiectasia. The rash also typically presents in areas of heat exposure—from heated blankets, heating pads, or the use of infrared heaters or lamps.1,2 The patient usually will have pain and pruritus over the affected areas. The diagnosis of EAI largely is clinical and based on the patient’s history of exposure; it rarely requires biopsy and histologic analysis. However, some of the common histopathologic findings include hyperkeratosis, a hyperpigmented basal layer, hemosiderin deposits, prominent melanophages, basal cell degeneration, course collagen, and elastosis.2,3 These changes are common with UV radiation exposure and thermal damage. The primary treatment in all cases is to remove or reduce the source of infrared radiation. However, EAI has been reported to be successfully treated with removal of the insult as well as topical agents such as imiquimod and 5-fluorouracil.4 Possible complications include increased risk for malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma in the affected area.1

The possible differential for EAI includes livedo reticularis, livedo racemosa, cutis marmorata, and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. All of these conditions are related to dysfunction of the cutaneous vasculature that creates a reticular, mottled, reddish purple rash. When the livedo is reversible and idiopathic, it is referred to as livedo reticularis, but when it is generalized and permanent it is referred to as livedo racemosa. Livedo racemosa can be caused by a variety of conditions, including systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome.1 Physiologic livedo reticularis that is more transient and can be reversed by warming is referred to as cutis marmorata. Finally, cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita primarily is found in neonates, and although persistent, it usually improves with age. Erythema ab igne also is a type of livedo with a known heat exposure and localized distribution.

Our patient was educated on the etiology of the rash, specifically related to heating pad usage for multiple years, and the risk for cutaneous malignancy after longstanding EAI. It was recommended that she discontinue use of a heating pad on the affected areas to allow them to properly heal. If she found that heating pad usage was necessary, she was advised to limit use to 5 to 10 minutes with 2 to 3 hours in between applications. In addition, she was advised to apply petroleum jelly daily for assistance with wound healing as well as anti-itch sensitive lotion twice daily on the arms and back to alleviate some of the tingling pain. We explained that areas of hyperpigmentation may improve with time; however, areas of erythema/ atrophy may be long-lasting.

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2635.

- Dellavalle RP, Gillum P. Erythema ab igne following heating/cooling blanket use in the intensive care unit. Cutis. 2000;66:136-138.

- Finlayson GR, Sams WM Jr, Smith JG Jr. Erythema ab igne: a histopathological study. J Invest Dermatol. 1966;46:104-108.

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162:77-78.

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Based on the clinical findings and history, a diagnosis of erythema ab igne (EAI), a skin reaction to chronic infrared radiation exposure, was made. The name of this condition translates from Latin as “redness from fire”; other names include toasted skin syndrome and fire stains. The most common presentation is reticulated hyperpigmentation, erythema, and cutaneous atrophy, as well as possible crusting, scaling, or telangiectasia. The rash also typically presents in areas of heat exposure—from heated blankets, heating pads, or the use of infrared heaters or lamps.1,2 The patient usually will have pain and pruritus over the affected areas. The diagnosis of EAI largely is clinical and based on the patient’s history of exposure; it rarely requires biopsy and histologic analysis. However, some of the common histopathologic findings include hyperkeratosis, a hyperpigmented basal layer, hemosiderin deposits, prominent melanophages, basal cell degeneration, course collagen, and elastosis.2,3 These changes are common with UV radiation exposure and thermal damage. The primary treatment in all cases is to remove or reduce the source of infrared radiation. However, EAI has been reported to be successfully treated with removal of the insult as well as topical agents such as imiquimod and 5-fluorouracil.4 Possible complications include increased risk for malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma in the affected area.1

The possible differential for EAI includes livedo reticularis, livedo racemosa, cutis marmorata, and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. All of these conditions are related to dysfunction of the cutaneous vasculature that creates a reticular, mottled, reddish purple rash. When the livedo is reversible and idiopathic, it is referred to as livedo reticularis, but when it is generalized and permanent it is referred to as livedo racemosa. Livedo racemosa can be caused by a variety of conditions, including systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome.1 Physiologic livedo reticularis that is more transient and can be reversed by warming is referred to as cutis marmorata. Finally, cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita primarily is found in neonates, and although persistent, it usually improves with age. Erythema ab igne also is a type of livedo with a known heat exposure and localized distribution.

Our patient was educated on the etiology of the rash, specifically related to heating pad usage for multiple years, and the risk for cutaneous malignancy after longstanding EAI. It was recommended that she discontinue use of a heating pad on the affected areas to allow them to properly heal. If she found that heating pad usage was necessary, she was advised to limit use to 5 to 10 minutes with 2 to 3 hours in between applications. In addition, she was advised to apply petroleum jelly daily for assistance with wound healing as well as anti-itch sensitive lotion twice daily on the arms and back to alleviate some of the tingling pain. We explained that areas of hyperpigmentation may improve with time; however, areas of erythema/ atrophy may be long-lasting.

The Diagnosis: Erythema Ab Igne

Based on the clinical findings and history, a diagnosis of erythema ab igne (EAI), a skin reaction to chronic infrared radiation exposure, was made. The name of this condition translates from Latin as “redness from fire”; other names include toasted skin syndrome and fire stains. The most common presentation is reticulated hyperpigmentation, erythema, and cutaneous atrophy, as well as possible crusting, scaling, or telangiectasia. The rash also typically presents in areas of heat exposure—from heated blankets, heating pads, or the use of infrared heaters or lamps.1,2 The patient usually will have pain and pruritus over the affected areas. The diagnosis of EAI largely is clinical and based on the patient’s history of exposure; it rarely requires biopsy and histologic analysis. However, some of the common histopathologic findings include hyperkeratosis, a hyperpigmented basal layer, hemosiderin deposits, prominent melanophages, basal cell degeneration, course collagen, and elastosis.2,3 These changes are common with UV radiation exposure and thermal damage. The primary treatment in all cases is to remove or reduce the source of infrared radiation. However, EAI has been reported to be successfully treated with removal of the insult as well as topical agents such as imiquimod and 5-fluorouracil.4 Possible complications include increased risk for malignancies such as squamous cell carcinoma in the affected area.1

The possible differential for EAI includes livedo reticularis, livedo racemosa, cutis marmorata, and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. All of these conditions are related to dysfunction of the cutaneous vasculature that creates a reticular, mottled, reddish purple rash. When the livedo is reversible and idiopathic, it is referred to as livedo reticularis, but when it is generalized and permanent it is referred to as livedo racemosa. Livedo racemosa can be caused by a variety of conditions, including systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome.1 Physiologic livedo reticularis that is more transient and can be reversed by warming is referred to as cutis marmorata. Finally, cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita primarily is found in neonates, and although persistent, it usually improves with age. Erythema ab igne also is a type of livedo with a known heat exposure and localized distribution.

Our patient was educated on the etiology of the rash, specifically related to heating pad usage for multiple years, and the risk for cutaneous malignancy after longstanding EAI. It was recommended that she discontinue use of a heating pad on the affected areas to allow them to properly heal. If she found that heating pad usage was necessary, she was advised to limit use to 5 to 10 minutes with 2 to 3 hours in between applications. In addition, she was advised to apply petroleum jelly daily for assistance with wound healing as well as anti-itch sensitive lotion twice daily on the arms and back to alleviate some of the tingling pain. We explained that areas of hyperpigmentation may improve with time; however, areas of erythema/ atrophy may be long-lasting.

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2635.

- Dellavalle RP, Gillum P. Erythema ab igne following heating/cooling blanket use in the intensive care unit. Cutis. 2000;66:136-138.

- Finlayson GR, Sams WM Jr, Smith JG Jr. Erythema ab igne: a histopathological study. J Invest Dermatol. 1966;46:104-108.

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162:77-78.

- Aria AB, Chen L, Silapunt S. Erythema ab igne from heating pad use: a report of three clinical cases and a differential diagnosis. Cureus. 2018;10:E2635.

- Dellavalle RP, Gillum P. Erythema ab igne following heating/cooling blanket use in the intensive care unit. Cutis. 2000;66:136-138.

- Finlayson GR, Sams WM Jr, Smith JG Jr. Erythema ab igne: a histopathological study. J Invest Dermatol. 1966;46:104-108.

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162:77-78.

A 53-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic complex regional pain syndrome type 1, and chronic prescription opiate use presented to the hospital with a pruritic rash on the chest of 15 years’ duration that started a few weeks after a left shoulder repair. The patient was using fentanyl patches and acetaminophen with oxycodone as well as a heating pad for 20 to 22 hours per day for many years to help with her chronic pain. She also described similar lesions on the abdomen and back when she used the heating pad on those areas for weeks at a time. Vital signs were within normal limits. Physical examination revealed a lacy, reticular, eroded, well-demarcated rash on the chest along with areas of cracking. Laboratory evaluation did not reveal any abnormalities.

Use of Complementary Alternative Medicine and Supplementation for Skin Disease

Complementary alternative medicine (CAM) has been described by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine as “health care approaches that are not typically part of conventional medical care or that may have origins outside of usual Western practice.”1 Although this definition is broad, CAM encompasses therapies such as traditional Chinese medicine, herbal therapies, dietary supplements, and mind/body interventions. The use of CAM has grown, and according to a 2012 National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health survey, more than 30% of US adults and 12% of US children use health care approaches that are considered outside of conventional medical practice. In a survey study of US adults, at least 17.7% of respondents said they had taken a dietary supplement other than a vitamin or mineral in the last year.1 Data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey showed that the prevalence of adults with skin conditions using CAM was 84.5% compared to 38.3% in the general population.2 In addition, 8.15 million US patients with dermatologic conditions reported using CAM over a 5-year period.3 Complementary alternative medicine has emerged as an alternative or adjunct to standard treatments, making it important for dermatologists to understand the existing literature on these therapies. Herein, we review the current evidence-based literature that exists on CAM for the treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, and alopecia areata (AA).

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic, pruritic, inflammatory skin condition with considerable morbidity.4,5 The pathophysiology of AD is multifactorial and includes aspects of barrier dysfunction, IgE hypersensitivity, abnormal cell-mediated immune response, and environmental factors.6 Atopic dermatitis also is one of the most common inflammatory skin conditions in adults, affecting more than 7% of the US population and up to 20% of the total population in developed countries. Of those affected, 40% have moderate or severe symptoms that result in a substantial impact on quality of life.7 Despite advances in understanding disease pathology and treatment, a subset of patients opt to defer conventional treatments such as topical and systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, nonsteroidal immunomodulators, and biologics. Patients may seek alternative therapies when typical treatments fail or when the perceived side effects outweigh the benefits.5,8 The use of CAM has been well described in patients with AD; however, the existing evidence supporting its use along with its safety profile have not been thoroughly explored. Herein, we will discuss some of the most well-studied supplements for treatment of AD, including evening primrose oil (EPO), fish oil, and probiotics.5

Oral supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids commonly is reported in patients with AD.5,8 The idea that a fatty acid deficiency could lead to atopic skin conditions has been around since 1937, when it was suggested that patients with AD had lower levels of blood unsaturated fatty acids.9 Conflicting evidence regarding oral fatty acid ingestion and AD disease severity has emerged.10,11 One unsaturated fatty acid, γ-linolenic acid (GLA), has demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties and involvement in barrier repair.12 It is converted to dihomo-GLA in the body, which acts on cyclooxygenase enzymes to produce the inflammatory mediator prostaglandin E1. The production of GLA is mediated by the enzyme delta-6 desaturase in the metabolization of linoleic acid.12 However, it has been reported that in a subset of patients with AD, a malfunction of delta-6 desaturase may play a role in disease progression and result in lower baseline levels of GLA.10,12 Evening primrose oil and borage oil contain high amounts of GLA (8%–10% and 23%, respectively); thus, supplementation with these oils has been studied in AD.13

EPO for AD

Studies investigating EPO (Oenothera biennis) and its association with AD severity have shown mixed results. A Cochrane review reported that oral borage oil and EPO were not effective treatments for AD,14 while another larger randomized controlled trial (RCT) found no statistically significant improvement in AD symptoms.15 However, multiple smaller studies have found that clinical symptoms of AD, such as erythema, xerosis, pruritus, and total body surface area involved, did improve with oral EPO supplementation when compared to placebo, and the results were statistically significant (P=.04).16,17 One study looked at different dosages of EPO and found that groups ingesting both 160 mg and 320 mg daily experienced reductions in eczema area and severity index score, with greater improvement noted with the higher dosage.17 Side effects associated with oral EPO include an anticoagulant effect and transient gastrointestinal tract upset.8,14 There currently is not enough evidence or safety data to recommend this supplement to AD patients.

Although topical use of fatty acids with high concentrations of GLA, such as EPO and borage oil, have demonstrated improvement in subjective symptom severity, most studies have not reached statistical significance.10,11 One study used a 10% EPO cream for 2 weeks compared to placebo and found statistically significant improvement in patient-reported AD symptoms (P=.045). However, this study only included 10 participants, and therefore larger studies are necessary to confirm this result.18 Some RCTs have shown that topical coconut oil, sunflower seed oil, and sandalwood album oil improve AD symptom severity, but again, large controlled trials are needed.5 Unfortunately, many essential oils, including EPO, can cause a secondary allergic contact dermatitis and potentially worsen AD.19

Fish Oil for AD

Fish oil is a commonly used supplement for AD due to its high content of the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Omega-3 fatty acids exert anti-inflammatory effects by displacing arachidonic acid, a proinflammatory omega-6 fatty acid thought to increase IgE, as well as helper T cell (TH2) cytokines and prostaglandin E2.8,20 A 2012 Cochrane review found that, while some studies revealed mild improvement in AD symptoms with oral fish oil supplementation, these RCTs were of poor methodological quality.21 Multiple smaller studies have shown a decrease in pruritus, severity, and physician-rated clinical scores with fish oil use.5,8,20,22 One study with 145 participants reported that 6 g of fish oil once daily compared to isoenergetic corn oil for 16 weeks identified no statistically significant differences between the treatment groups.20 No adverse events were identified in any of the reported trials. Further studies should be conducted to assess the utility and dosing of fish oil supplements in AD patients.

Probiotics for AD

Probiotics consist of live microorganisms that enhance the microflora of the gastrointestinal tract.8,20 They have been shown to influence food digestion and also have demonstrated potential influence on the skin-gut axis.23 The theory that intestinal dysbiosis plays a role in AD pathogenesis has been investigated in multiple studies.23-25 The central premise is that low-fiber and high-fat Western diets lead to fundamental changes in the gut microbiome, resulting in fewer anti-inflammatory metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).23-25 These SCFAs are produced by microbes during the fermentation of dietary fiber and are known for their effect on epithelial barrier integrity and anti-inflammatory properties mediated through G protein–coupled receptor 43.25 Multiple studies have shown that the gut microbiome in patients with AD have higher proportions of Clostridium difficile, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus and lower levels of Bifidobacterium, Bacteroidetes, and Bacteroides species compared to healthy controls.26,27 Metagenomic analysis of fecal samples from patients with AD have shown a reduction of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii species when compared to controls, along with a decreased SCFA production, leading to the hypothesis that the gut microbiome may play a role in epithelial barrier disruption.28,29 Systematic reviews and smaller studies have found that oral probiotic use does lead to AD symptom improvement.8,30,31 A systematic review of 25 RCTs with 1599 participants found that supplementation with oral probiotics significantly decreased the SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) index in adults and children older than 1 year with AD but had no effect on infants younger than 1 year (P<.001). They also found that supplementation with diverse microbes or Lactobacillus species showed greater benefit than Bifidobacterium species alone.30 Another study analyzed the effect of oral Lactobacillus fermentum (1×109 CFU twice daily) in 53 children with AD vs placebo for 16 weeks. This study found a statically significant decrease in SCORAD index between oral probiotics and placebo, with 92% (n=24) of participants supplementing with probiotics having a lower SCORAD index than baseline compared to 63% (n=17) in the placebo group (P=.01).31 However, the use of probiotics for AD treatment has remained controversial. Two recent systematic reviews, including 39 RCTs of 2599 randomized patients, found that the use of currently available oral probiotics made little or no difference in patient-rated AD symptoms, investigator-rated AD symptoms, or quality of life.32,33 No adverse effects were observed in the included studies. Unfortunately, the individual RCTs included were heterogeneous, and future studies with standardized probiotic supplementation should be undertaken before probiotics can be routinely recommended.

The use of topical probiotics in AD also has recently emerged. Multiple studies have shown that patients with AD have higher levels of colonization with S aureus, which is associated with T-cell dysfunction, more severe allergic skin reactions, and disruptions in barrier function.34,35 Therefore, altering the skin microbiota through topical probiotics could theoretically reduce AD symptoms and flares. Multiple RCTs and smaller studies have shown that topical probiotics can alter the skin microbiota, improve erythema, and decrease scaling and pruritus in AD patients.35-38 One study used a heat-treated Lactobacillus johnsonii 0.3% lotion twice daily for 3 weeks vs placebo in patients with AD with positive S aureus skin cultures. The S aureus load decreased in patients using the topical probiotic lotion, which correlated with lower SCORAD index that was statistically significant compared to placebo (P=.012).36 More robust studies are needed to determine if topical probiotics should routinely be recommended in AD.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by pruritic, hyperkeratotic, scaly plaques.39,40 Keratinocyte hyperproliferation is central to psoriasis pathogenesis and is thought to be a T-cell–driven reaction to antigens or trauma in genetically predisposed individuals. Standard treatments for psoriasis currently include topical corticosteroids and anti-inflammatories, oral immunomodulatory therapy, biologic agents, and phototherapy.40 The use of CAM is highly prevalent among patients with psoriasis, with one study reporting that 51% (n=162) of psoriatic patients interviewed had used CAM.41 The most common reasons for CAM use included dissatisfaction with current treatment, adverse side effects of standard therapy, and patient-reported attempts at “trying everything to heal disease.”42 Herein, we will discuss some of the most frequently used supplements for treatment of psoriatic disease.39

Fish Oil for Psoriasis

One of the most common supplements used by patients with psoriasis is fish oil due to its purported anti-inflammatory qualities.20,39 The consensus on fish oil supplementation for psoriasis is mixed.43-45 Multiple RCTs have reported reductions in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) scores or symptomatic improvement with variable doses of fish oil.44,46 One RCT found that using EPA 1.8 g once daily and DHA 1.2 g once daily for 12 weeks resulted in significant improvement in pruritus, scaling, and erythema (P<.05).44 Another study reported a significant decrease in erythema (P=.02) and total body surface area affected (P=.0001) with EPA 3.6 g once daily and DHA 2.4 g once daily supplementation compared to olive oil supplementation for 15 weeks.46 Alternatively, multiple studies have failed to show statistically significant improvement in psoriatic symptoms with fish oil supplementation at variable doses and time frames (14–216 mg daily EPA, 9–80 mg daily DHA, from 2 weeks to 9 months).40,47,48 Fish oil may impart anticoagulant properties and should not be started without the guidance of a physician. Currently, there are no data to make specific recommendations on the use of fish oil as an adjunct psoriatic treatment.

Curcumin for Psoriasis

Another supplement routinely utilized in patients with psoriasis is curcumin,40,49,50 a yellow phytochemical that is a major component of the spice turmeric. Curcumin has been shown to inhibit certain proinflammatory cytokines including IL-17, IL-6, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor α and has been regarded as having immune-modulating, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties.40,50 Curcumin also has been reported to suppress phosphorylase kinase, an enzyme that has increased activity in psoriatic plaques that correlates with markers of psoriatic hyperproliferation.50,51 When applied topically, turmeric microgel 0.5% has been reported to decrease scaling, erythema, and psoriatic plaque thickness over the course of 9 weeks.50 In a nonrandomized trial with 10 participants, researchers found that phosphorylase kinase activity levels in psoriatic skin biopsies of patients applying topical curcumin 1% were lower than placebo and topical calcipotriol applied in combination. The lower phosphorylase kinase levels correlated with level of disease severity, and topical curcumin 1% showed a superior outcome when compared to topical calcipotriol.40,49 Although these preliminary results are interesting, there still are not enough data at this time to recommend topical curcumin as a treatment of psoriasis. No known adverse events have been reported with the use of topical curcumin to date.

Oral curcumin has poor oral bioavailability, and 40% to 90% of oral doses are excreted, making supplementation a challenge.40 In one RCT, oral curcumin 2 g daily (using a lecithin-based delivery system to increase bioavailability) was administered in combination with topical methylprednisolone aceponate 0.1%, resulting in significant improvement in psoriatic symptoms and lower IL-22 compared to placebo and topical methylprednisolone aceponate (P<.05).52 Other studies also have reported decreased PASI scores with oral curcumin supplementation.53,54 Adverse effects reported with oral curcumin included gastrointestinal tract upset and hot flashes.53 Although there is early evidence that may support the use of oral curcumin supplementation for psoriasis, more data are needed before recommending this therapy.

Indigo Naturalis for Psoriasis

Topical indigo naturalis (IN) also has been reported to improve psoriasis symptoms.39,53,55 The antipsoriatic effects are thought to occur through the active ingredient in IN (indirubin), which is responsible for inhibition of keratinocyte proliferation.40 One study reported that topical IN 1.4% containing indirubin 0.16% with a petroleum ointment vehicle applied to psoriatic plaques over 12 weeks resulted in a significant decrease in PASI scores from 18.9 at baseline to 6.3 after IN treatment (P<.001).56 Another study found that over 8 weeks, topical application of IN 2.83% containing indirubin 0.24% to psoriatic plaques vs petroleum jelly resulted in 56.3% (n=9) of the treatment group achieving PASI 75 compared to 0% in the placebo group (n=24).55 One deterrent in topical IN treatment is the dark blue pigment it contains; however, no other adverse outcomes were found with topical IN treatment.56 Larger clinical trials are necessary to further explore IN as a potential adjunct treatment in patients with mild psoriatic disease. When taken orally, IN has caused gastrointestinal tract disturbance and elevated liver enzyme levels.57

Herbal Toxicities

It is important to consider that oral supplements including curcumin and IN are widely available over-the-counter and online without oversight by the US Food and Drug Administration.40 Herbal supplements typically are compounded with other ingredients and have been associated with hepatotoxicity as well as drug-supplement interactions, including abnormal bleeding and clotting.58 There exists a lack of general surveillance data, making the true burden of herbal toxicities more difficult to accurately discern. Although some supplements have been associated with anti-inflammatory qualities and disease improvement, other herbal supplements have been shown to possess immunostimulatory characteristics. Herbal supplements such as spirulina, chlorella, Aphanizomenon flos-aquae, and echinacea have been shown to upregulate inflammatory pathways in a variety of autoimmune skin conditions.59

Probiotics for Psoriasis

Data on probiotic use in patients with psoriasis are limited.23 A distinct pattern of dysbiosis has been identified in psoriatic patients, as there is thought to be depletion of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium, lactobacilli, and F prausnitzii and increased colonization with pathogenic organisms such as Salmonella, E coli, Heliobacter, Campylobacter, and Alcaligenes in psoriasis patients.23,59,60 Early mouse studies have supported this hypothesis, as mice fed with Lactobacillus pentosus have developed milder forms of imiquimod-induced psoriasis compared to placebo,55 and mice receiving probiotic supplementation have lower levels of psoriasis-related proinflammatory markers such as TH17-associated cytokines.61 Another study in humans found that daily oral Bifidobacterium infantis supplementation for 8 weeks in psoriatic patients resulted in lower C-reactive protein and tumor necrosis factor α levels compared to placebo.62 Studies on the use of topical probiotics in psoriasis have been limited, and more research is needed to explore this relationship.38 At this time, no specific recommendations can be made on the use of probiotics in psoriatic patients.

Alopecia Areata

Alopecia areata is nonscarring hair loss that can affect the scalp, face, or body.63,64 The pathophysiology of AA involves the attack of the hair follicle matrix epithelium by inflammatory cells without hair follicle stem cell destruction. The precise events that precipitate these episodes are unknown, but triggers such as emotional or physical stress, vaccines, or viral infections have been reported.65 There is no cure for AA, and current treatments such as topical minoxidil and corticosteroids (topical, intralesional, or oral) vary widely in efficacy.64 Although Janus kinase inhibitors recently have shown promising results in the treatment of AA, the need for prolonged therapy may be frustrating to patients.66 Severity of AA also can vary, with 30% of patients experiencing extensive hair loss.67 The use of CAM has been widely reported in AA due to high levels of dissatisfaction with existing therapies.68 Herein, we discuss the most studied alternative treatments used in AA

Garlic and Onion for Alopecia

One alternative treatment that has shown promising initial results is application of topical garlic and onion extracts to affected areas.64,69,70 Both garlic and onion belong to the Allium genus and are high in sulfur and phenolic compounds.70 They have been reported to possess bactericidal and vasodilatory activity,71 and it has been hypothesized that onion and garlic extracts may induce therapeutic effects through induction of a mild contact dermatitis.70 One single-blinded, controlled trial using topical crude onion juice reported that 86.9% (n=20) of patients had full regrowth of hair compared to 13.3% (n=2) of patients treated with a tap water placebo at 8 weeks (P<.0001). This study also noted that patients using onion juice had a higher rate of erythema at application site; unfortunately, the study was small with only 38 patients.70 Another double-blind RCT using garlic gel 5% with betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% compared to betamethasone valerate cream alone found that after 3 months, patients in the garlic gel group had increased terminal hairs and smaller patch sizes compared to the betamethasone valerate cream group.69 More studies are needed to confirm these results.

Aromatherapy With Essential Oils for Alopecia

Another alternative treatment in AA that has demonstrated positive results is aromatherapy skin massage with essential oils to patches of alopecia.72 Although certain essential oils, such as tea tree oil, have been reported to have specific antibacterial or anti-inflammatory properties, essential oils have been reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis and should be used with caution.73,74 For example, tea tree oil is a well-known cause of allergic contact dermatitis, and positive patch testing has ranged from 0.1% to 3.5% in studies assessing topical tea tree oil 5% application.75 Overall, there have been nearly 80 essential oils implicated in contact dermatitis, with high-concentration products being one of the highest risk factors for an allergic contact reaction.76 One RCT compared daily scalp massage with essential oils (rosemary, lavender, thyme, and cedarwood in a carrier oil) to daily scalp massage with a placebo carrier oil in AA patients. The results showed that at 7 months of treatment, 44% (n=19) of the aromatherapy group showed improvement compared to 15% (n=6) in the control group.77 Another study used a similar group of essential oils (thyme, rosemary, atlas cedar, lavender, and EPO in a carrier oil) with daily scalp massage and reported similar improvement of AA symptoms compared to control; the investigators also reported irritation at application site in 1 patient.78 There currently are not enough data to recommend aromatherapy skin massage for the treatment of AA, and this practice may cause harm to the patient by induction of allergic contact dermatitis.

There have been a few studies to suggest that the use of total glucosides of peony with compound glycyrrhizin and oral Korean red ginseng may have beneficial effects on AA treatment, but efficacy and safety data are lacking, and these therapies should not be recommended without more information.64,79,80

Final Thoughts

Dermatologic patients frequently are opting for CAM,2 and although some therapies may show promising initial results, alternative medicines also can drive adverse events.19,30 The lack of oversight from the US Food and Drug Administration on the products leads to many unknowns for true health risks with over-the-counter CAM supplements.40 As the use of CAM becomes increasingly common among dermatologic patients, it is important for dermatologists to understand the benefits and risks, especially for commonly treated conditions. More data is needed before CAM can be routinely recommended.

- Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: what’s in a name? National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health website. Updated April 2021. Accessed April 25, 2021. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name

- Fuhrmann T, Smith N, Tausk F. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among adults with skin disease: updated results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:1000-1005.

- Landis ET, Davis SA, Feldman SR, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in dermatology in the United States. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:392-398.

- Solman L, Lloyd‐Lavery A, Grindlay DJC, et al. What’s new in atopic eczema? an analysis of systematic reviews published in 2016. part 1: treatment and prevention. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:363-369.

- Vieira BL, Lim NR, Lohman ME, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine for atopic dermatitis: an evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:557-581.

- David Boothe W, Tarbox JA, Tarbox MB. Atopic dermatitis: pathophysiology. In: Fortson EA, Feldman SR, Strowd LC, eds. Management of Atopic Dermatitis: Methods and Challenges. Springer International Publishing; 2017:21-37.

- Atopic dermatitis in America. Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America website. Accessed July 30, 2021. https://www.aafa.org/atopic-dermatitis-in-america

- Schlichte MJ, Vandersall A, Katta R. Diet and eczema: a review of dietary supplements for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:23-29.

- Brown WR, Hansen AE. Arachidonic and linolic acid of the serum in normal and eczematous human subjects. Proc Soc Exp Bio Med. 1937;36:113-117.

- Lee J, Bielory L. Complementary and alternative interventions in atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30:411-424.

- Ferreira MJ, Fiadeiro T, Silva M, et al. Topical γ-linolenic acid therapy in atopic dermatitis. Allergo J. 1998;7:213-216.

- Simon D, Eng PA, Borelli S, et al. Gamma-linolenic acid levels correlate with clinical efficacy of evening primrose oil in patients with atopic dermatitis. Adv Ther. 2014;31:180-188.

- Fan Y-Y, Chapkin RS. Importance of dietary γ-linolenic acid in human health and nutrition. J Nutr. 1998;128:1411-1414.

- Bamford JTM, Ray S, Musekiwa A, et al. Oral evening primrose oil and borage oil for eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD004416.

- Williams H. Evening primrose oil for atopic dermatitis. BMJ. 2003;327:2.

- Schalin-Karrila M, Mattila L, Jansen CT, et al. Evening primrose oil in the treatment of atopic eczema: effect on clinical status, plasma phospholipid fatty acids and circulating blood prostaglandins. Br J Dermatol. 1987;117:11-19.

- Chung BY, Park SY, Jung MJ, et al. Effect of evening primrose oil on Korean patients with mild atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical study. Ann Dermatol. 2018;30:409-416.

- Anstey A, Quigley M, Wilkinson JD. Topical evening primrose oil as treatment for atopic eczema. J Dermatolog Treat. 1990;1:199-201.

- de Groot AC, Schmidt E. Essential oils, part I: introduction. Dermatitis. 2016;27:39-42.

- Reynolds KA, Juhasz MLW, Mesinkovska NA. The role of oral vitamins and supplements in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1371-1376.

- Bath-Hextall FJ, Jenkinson C, Humphreys R, et al. Dietary supplements for established atopic eczema [published online February 15, 2012]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Accessed July 22, 2021. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005205.pub3

- Balic´ A, Vlašic´ D, Žužul K, et al. Omega-3 versus omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the prevention and treatment of inflammatory skin diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:741.

- Salem I, Ramser A, Isham N, et al. The gut microbiome as a major regulator of the gut-skin axis. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1459.

- Agrawal R, Wisniewski JA, Woodfolk JA. The role of regulatory T cells in atopic dermatitis. Pathogenesis Manage Atopic Dermatitis. 2011;41:112-124.

- Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461:1282-1286.

- Lee E, Lee S-Y, Kang M-J, et al. Clostridia in the gut and onset of atopic dermatitis via eosinophilic inflammation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:91-92.e1.

- Nylund L, Nermes M, Isolauri E, et al. Severity of atopic disease inversely correlates with intestinal microbiota diversity and butyrate-producing bacteria. Allergy. 2015;70:241-244.

- Kim H-J, Kim HY, Lee S-Y, et al. Clinical efficacy and mechanism of probiotics in allergic diseases. Korean J Pediatr. 2013;56:369-376.

- Song H, Yoo Y, Hwang J, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii subspecies-level dysbiosis in the human gut microbiome underlying atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:852-860.

- Kim S-O, Ah Y-M, Yu YM, et al. Effects of probiotics for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113:217-226.

- Weston S, Halbert A, Richmond P, et al. Effects of probiotics on atopic dermatitis: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:892-897.

- Huang R, Ning H, Shen M, et al. Probiotics for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:392.

- Makrgeorgou A, Leonardi-Bee J, Bath-Hextall FJ, et al. Probiotics for treating eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD006135.

- Knackstedt R, Knackstedt T, Gatherwright J. The role of topical probiotics in skin conditions: a systematic review of animal and human studies and implications for future therapies. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:15-21.

- Woo TE, Sibley CD. The emerging utility of the cutaneous microbiome in the treatment of acne and atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:222-228.

- Blanchet-Réthoré S, Bourdès V, Mercenier A, et al. Effect of a lotion containing the heat-treated probiotic strain Lactobacillus johnsonii NCC 533 on Staphylococcus aureus colonization in atopic dermatitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:249-257.

- Nakatsuji T, Hata TR, Tong Y, et al. Development of a human skin commensal microbe for bacteriotherapy of atopic dermatitis and use in a phase 1 randomized clinical trial. Nature Medicine. 2021;27:700-709.

- França K. Topical probiotics in dermatological therapy and skincare: a concise review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;11:71-77.

- Talbott W, Duffy N. Complementary and alternative medicine for psoriasis: what the dermatologist needs to know. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:147-165.

- Gamret AC, Price A, Fertig RM, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine therapies for psoriasis: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1330-1337.

- Fleischer AB, Feldman SR, Rapp SR, et al. Alternative therapies commonly used within a population of patients with psoriasis. Cutis. 1996;58:216-220.

- Ben-Arye E, Ziv M, Frenkel M, et al. Complementary medicine and psoriasis: linking the patient’s outlook with evidence-based medicine. Dermatology. 2003;207:302-307.

- Millsop JW, Bhatia BK, Debbaneh M, et al. Diet and psoriasis: part 3. role of nutritional supplements. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:561-569.

- Bittiner SB, Tucker WF, Cartwright I, et al. A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of fish oil in psoriasis. Lancet. 1988;1:378-380.

- Ford AR, Siegel M, Bagel J, et al. Dietary recommendations for adults with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: a Systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:934-950.

- Gupta AK, Ellis CN, Tellner DC, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of fish oil and low-dose UVB in the treatment of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:801-807.

- Kristensen S, Schmidt EB, Schlemmer A, et al. Beneficial effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on inflammation and analgesic use in psoriatic arthritis: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Rheumatol. 2018;47:27-36.

- Søyland E, Funk J, Rajka G, et al. Effect of dietary supplementation with very-long-chain n-3 fatty acids in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1812-1816.

- Heng MCY, Song MK, Harker J, et al. Drug-induced suppression of phosphorylase kinase activity correlates with resolution of psoriasis as assessed by clinical, histological and immunohistochemical parameters. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:937-949.

- Sarafian G, Afshar M, Mansouri P, et al. Topical turmeric microemulgel in the management of plaque psoriasis; a clinical evaluation. Iran J Pharm Res. 2015;14:865-876.

- Reddy S, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin is a non-competitive and selective inhibitor of phosphorylase kinase. FEBS Letters. 1994;341:19-22.

- Antiga E, Bonciolini V, Volpi W, et al. Oral curcumin (meriva) is effective as an adjuvant treatment and is able to reduce IL-22 serum levels in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:283634.

- Kurd SK, Smith N, VanVoorhees A, et al. Oral curcumin in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis vulgaris: a prospective clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:625-631.

- Carrion-Gutierrez M, Ramirez-Bosca A, Navarro-Lopez V, et al. Effects of Curcuma extract and visible light on adults with plaque psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:240-246.

- Cheng H-M, Wu Y-C, Wang Q, et al. Clinical efficacy and IL-17 targeting mechanism of indigo naturalis as a topical agent in moderate psoriasis. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17:439.

- Lin Y-K, Chang C-J, Chang Y-C, et al. Clinical assessment of patients with recalcitrant psoriasis in a randomized, observer-blind, vehicle-controlled trial using indigo naturalis. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1457-1464.

- Naganuma M, Sugimoto S, Suzuki H, et al. Adverse events in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with indigo naturalis: a Japanese nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:891-896.

- Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR. Review article: herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Alimentary Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:3-17.

- Bax CE, Chakka S, Concha JSS, et al. The effects of immunostimulatory herbal supplements on autoimmune skin diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1051-1058.

- Scher JU, Ubeda C, Artacho A, et al. Decreased bacterial diversity characterizes an altered gut microbiota in psoriatic arthritis and resembles dysbiosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:128-139.

- Chen Y-H, Wu C-S, Chao Y-H, et al. Lactobacillus pentosus GMNL-77 inhibits skin lesions in imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like mice. J Food Drug Anal. 2017;25:559-566.

- Groeger D, O’Mahony L, Murphy EF, et al. Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 modulates host inflammatory processes beyond the gut. Gut Microbes. 2013;4:325-339.

- Hosking A-M, Juhasz M, Atanaskova Mesinkovska N. Complementary and alternative treatments for alopecia: a comprehensive review. Skin Appendage Disord. 2019;5:72-89.

- Tkachenko E, Okhovat J-P, Manjaly P, et al. Complementary & alternative medicine for alopecia areata: a systematic review [published online December 20, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.027

- Lepe K, Zito PM. Alopecia areata. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Accessed July 22, 2021. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30725685/

- Ismail FF, Sinclair R. JAK inhibition in the treatment of alopecia areata—a promising new dawn? Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13:43-51. doi:10.1080/17512433.2020.1702878

- van den Biggelaar FJHM, Smolders J, Jansen JFA. Complementary and alternative medicine in alopecia areata. AM J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:11-20.

- Hussain ST, Mostaghimi A, Barr PJ, et al. Utilization of mental health resources and complementary and alternative therapies for alopecia areata: a U.S. survey. Int J Trichology. 2017;9:160-164.

- Hajheydari Z, Jamshidi M, Akbari J, et al. Combination of topical garlic gel and betamethasone valerate cream in the treatment of localized alopecia areata: a double-blind randomized controlled study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:29-32.

- Sharquie KE, Al-Obaidi HK. Onion juice (Allium cepa L.), a new topical treatment for alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2002;29:343-346.

- Burian JP, Sacramento LVS, Carlos IZ. Fungal infection control by garlic extracts (Allium sativum L.) and modulation of peritoneal macrophages activity in murine model of sporotrichosis. Braz J Biol. 2017;77:848-855.

- Hay IC, Jamieson M, Ormerod AD. Randomized trial of aromatherapy. successful treatment for alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1349-1352.

- Lakshmi C, Srinivas CR. Allergic contact dermatitis following aromatherapy with valiya narayana thailam—an ayurvedic oil presenting as exfoliative dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:297-298.

- Carson CF, Hammer KA, Riley TV. Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) oil: a review of antimicrobial and other medicinal properties. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:50-62.

- Groot AC de, Schmidt E. Tea tree oil: contact allergy and chemical composition. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:129-143.

- de Groot AC, Schmidt E. Essential oils, part I: introduction. dermatitis. 2016;27:39-42.

- Hay IC, Jamieson M, Ormerod AD. Randomized trial of aromatherapy. successful treatment for alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1349-1352.

- Ozmen I, Caliskan E, Arca E, et al. Efficacy of aromatherapy in the treatment of localized alopecia areata: a double-blind placebo controlled study. Gulhane Med J. 2015;57:233.

- Oh GN, Son SW. Efficacy of Korean red ginseng in the treatment of alopecia areata. J Ginseng Res. 2012;36:391-395.

- Yang D-Q, You L-P, Song P-H, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing total glucosides of paeony capsule and compound glycyrrhizin tablet for alopecia areata. Chin J Integr Med. 2012;18:621-625.

Complementary alternative medicine (CAM) has been described by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine as “health care approaches that are not typically part of conventional medical care or that may have origins outside of usual Western practice.”1 Although this definition is broad, CAM encompasses therapies such as traditional Chinese medicine, herbal therapies, dietary supplements, and mind/body interventions. The use of CAM has grown, and according to a 2012 National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health survey, more than 30% of US adults and 12% of US children use health care approaches that are considered outside of conventional medical practice. In a survey study of US adults, at least 17.7% of respondents said they had taken a dietary supplement other than a vitamin or mineral in the last year.1 Data from the 2007 National Health Interview Survey showed that the prevalence of adults with skin conditions using CAM was 84.5% compared to 38.3% in the general population.2 In addition, 8.15 million US patients with dermatologic conditions reported using CAM over a 5-year period.3 Complementary alternative medicine has emerged as an alternative or adjunct to standard treatments, making it important for dermatologists to understand the existing literature on these therapies. Herein, we review the current evidence-based literature that exists on CAM for the treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD), psoriasis, and alopecia areata (AA).

Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic, pruritic, inflammatory skin condition with considerable morbidity.4,5 The pathophysiology of AD is multifactorial and includes aspects of barrier dysfunction, IgE hypersensitivity, abnormal cell-mediated immune response, and environmental factors.6 Atopic dermatitis also is one of the most common inflammatory skin conditions in adults, affecting more than 7% of the US population and up to 20% of the total population in developed countries. Of those affected, 40% have moderate or severe symptoms that result in a substantial impact on quality of life.7 Despite advances in understanding disease pathology and treatment, a subset of patients opt to defer conventional treatments such as topical and systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, nonsteroidal immunomodulators, and biologics. Patients may seek alternative therapies when typical treatments fail or when the perceived side effects outweigh the benefits.5,8 The use of CAM has been well described in patients with AD; however, the existing evidence supporting its use along with its safety profile have not been thoroughly explored. Herein, we will discuss some of the most well-studied supplements for treatment of AD, including evening primrose oil (EPO), fish oil, and probiotics.5

Oral supplementation with polyunsaturated fatty acids commonly is reported in patients with AD.5,8 The idea that a fatty acid deficiency could lead to atopic skin conditions has been around since 1937, when it was suggested that patients with AD had lower levels of blood unsaturated fatty acids.9 Conflicting evidence regarding oral fatty acid ingestion and AD disease severity has emerged.10,11 One unsaturated fatty acid, γ-linolenic acid (GLA), has demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties and involvement in barrier repair.12 It is converted to dihomo-GLA in the body, which acts on cyclooxygenase enzymes to produce the inflammatory mediator prostaglandin E1. The production of GLA is mediated by the enzyme delta-6 desaturase in the metabolization of linoleic acid.12 However, it has been reported that in a subset of patients with AD, a malfunction of delta-6 desaturase may play a role in disease progression and result in lower baseline levels of GLA.10,12 Evening primrose oil and borage oil contain high amounts of GLA (8%–10% and 23%, respectively); thus, supplementation with these oils has been studied in AD.13

EPO for AD

Studies investigating EPO (Oenothera biennis) and its association with AD severity have shown mixed results. A Cochrane review reported that oral borage oil and EPO were not effective treatments for AD,14 while another larger randomized controlled trial (RCT) found no statistically significant improvement in AD symptoms.15 However, multiple smaller studies have found that clinical symptoms of AD, such as erythema, xerosis, pruritus, and total body surface area involved, did improve with oral EPO supplementation when compared to placebo, and the results were statistically significant (P=.04).16,17 One study looked at different dosages of EPO and found that groups ingesting both 160 mg and 320 mg daily experienced reductions in eczema area and severity index score, with greater improvement noted with the higher dosage.17 Side effects associated with oral EPO include an anticoagulant effect and transient gastrointestinal tract upset.8,14 There currently is not enough evidence or safety data to recommend this supplement to AD patients.

Although topical use of fatty acids with high concentrations of GLA, such as EPO and borage oil, have demonstrated improvement in subjective symptom severity, most studies have not reached statistical significance.10,11 One study used a 10% EPO cream for 2 weeks compared to placebo and found statistically significant improvement in patient-reported AD symptoms (P=.045). However, this study only included 10 participants, and therefore larger studies are necessary to confirm this result.18 Some RCTs have shown that topical coconut oil, sunflower seed oil, and sandalwood album oil improve AD symptom severity, but again, large controlled trials are needed.5 Unfortunately, many essential oils, including EPO, can cause a secondary allergic contact dermatitis and potentially worsen AD.19

Fish Oil for AD

Fish oil is a commonly used supplement for AD due to its high content of the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Omega-3 fatty acids exert anti-inflammatory effects by displacing arachidonic acid, a proinflammatory omega-6 fatty acid thought to increase IgE, as well as helper T cell (TH2) cytokines and prostaglandin E2.8,20 A 2012 Cochrane review found that, while some studies revealed mild improvement in AD symptoms with oral fish oil supplementation, these RCTs were of poor methodological quality.21 Multiple smaller studies have shown a decrease in pruritus, severity, and physician-rated clinical scores with fish oil use.5,8,20,22 One study with 145 participants reported that 6 g of fish oil once daily compared to isoenergetic corn oil for 16 weeks identified no statistically significant differences between the treatment groups.20 No adverse events were identified in any of the reported trials. Further studies should be conducted to assess the utility and dosing of fish oil supplements in AD patients.

Probiotics for AD

Probiotics consist of live microorganisms that enhance the microflora of the gastrointestinal tract.8,20 They have been shown to influence food digestion and also have demonstrated potential influence on the skin-gut axis.23 The theory that intestinal dysbiosis plays a role in AD pathogenesis has been investigated in multiple studies.23-25 The central premise is that low-fiber and high-fat Western diets lead to fundamental changes in the gut microbiome, resulting in fewer anti-inflammatory metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).23-25 These SCFAs are produced by microbes during the fermentation of dietary fiber and are known for their effect on epithelial barrier integrity and anti-inflammatory properties mediated through G protein–coupled receptor 43.25 Multiple studies have shown that the gut microbiome in patients with AD have higher proportions of Clostridium difficile, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus and lower levels of Bifidobacterium, Bacteroidetes, and Bacteroides species compared to healthy controls.26,27 Metagenomic analysis of fecal samples from patients with AD have shown a reduction of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii species when compared to controls, along with a decreased SCFA production, leading to the hypothesis that the gut microbiome may play a role in epithelial barrier disruption.28,29 Systematic reviews and smaller studies have found that oral probiotic use does lead to AD symptom improvement.8,30,31 A systematic review of 25 RCTs with 1599 participants found that supplementation with oral probiotics significantly decreased the SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis) index in adults and children older than 1 year with AD but had no effect on infants younger than 1 year (P<.001). They also found that supplementation with diverse microbes or Lactobacillus species showed greater benefit than Bifidobacterium species alone.30 Another study analyzed the effect of oral Lactobacillus fermentum (1×109 CFU twice daily) in 53 children with AD vs placebo for 16 weeks. This study found a statically significant decrease in SCORAD index between oral probiotics and placebo, with 92% (n=24) of participants supplementing with probiotics having a lower SCORAD index than baseline compared to 63% (n=17) in the placebo group (P=.01).31 However, the use of probiotics for AD treatment has remained controversial. Two recent systematic reviews, including 39 RCTs of 2599 randomized patients, found that the use of currently available oral probiotics made little or no difference in patient-rated AD symptoms, investigator-rated AD symptoms, or quality of life.32,33 No adverse effects were observed in the included studies. Unfortunately, the individual RCTs included were heterogeneous, and future studies with standardized probiotic supplementation should be undertaken before probiotics can be routinely recommended.

The use of topical probiotics in AD also has recently emerged. Multiple studies have shown that patients with AD have higher levels of colonization with S aureus, which is associated with T-cell dysfunction, more severe allergic skin reactions, and disruptions in barrier function.34,35 Therefore, altering the skin microbiota through topical probiotics could theoretically reduce AD symptoms and flares. Multiple RCTs and smaller studies have shown that topical probiotics can alter the skin microbiota, improve erythema, and decrease scaling and pruritus in AD patients.35-38 One study used a heat-treated Lactobacillus johnsonii 0.3% lotion twice daily for 3 weeks vs placebo in patients with AD with positive S aureus skin cultures. The S aureus load decreased in patients using the topical probiotic lotion, which correlated with lower SCORAD index that was statistically significant compared to placebo (P=.012).36 More robust studies are needed to determine if topical probiotics should routinely be recommended in AD.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by pruritic, hyperkeratotic, scaly plaques.39,40 Keratinocyte hyperproliferation is central to psoriasis pathogenesis and is thought to be a T-cell–driven reaction to antigens or trauma in genetically predisposed individuals. Standard treatments for psoriasis currently include topical corticosteroids and anti-inflammatories, oral immunomodulatory therapy, biologic agents, and phototherapy.40 The use of CAM is highly prevalent among patients with psoriasis, with one study reporting that 51% (n=162) of psoriatic patients interviewed had used CAM.41 The most common reasons for CAM use included dissatisfaction with current treatment, adverse side effects of standard therapy, and patient-reported attempts at “trying everything to heal disease.”42 Herein, we will discuss some of the most frequently used supplements for treatment of psoriatic disease.39

Fish Oil for Psoriasis

One of the most common supplements used by patients with psoriasis is fish oil due to its purported anti-inflammatory qualities.20,39 The consensus on fish oil supplementation for psoriasis is mixed.43-45 Multiple RCTs have reported reductions in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) scores or symptomatic improvement with variable doses of fish oil.44,46 One RCT found that using EPA 1.8 g once daily and DHA 1.2 g once daily for 12 weeks resulted in significant improvement in pruritus, scaling, and erythema (P<.05).44 Another study reported a significant decrease in erythema (P=.02) and total body surface area affected (P=.0001) with EPA 3.6 g once daily and DHA 2.4 g once daily supplementation compared to olive oil supplementation for 15 weeks.46 Alternatively, multiple studies have failed to show statistically significant improvement in psoriatic symptoms with fish oil supplementation at variable doses and time frames (14–216 mg daily EPA, 9–80 mg daily DHA, from 2 weeks to 9 months).40,47,48 Fish oil may impart anticoagulant properties and should not be started without the guidance of a physician. Currently, there are no data to make specific recommendations on the use of fish oil as an adjunct psoriatic treatment.

Curcumin for Psoriasis

Another supplement routinely utilized in patients with psoriasis is curcumin,40,49,50 a yellow phytochemical that is a major component of the spice turmeric. Curcumin has been shown to inhibit certain proinflammatory cytokines including IL-17, IL-6, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor α and has been regarded as having immune-modulating, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties.40,50 Curcumin also has been reported to suppress phosphorylase kinase, an enzyme that has increased activity in psoriatic plaques that correlates with markers of psoriatic hyperproliferation.50,51 When applied topically, turmeric microgel 0.5% has been reported to decrease scaling, erythema, and psoriatic plaque thickness over the course of 9 weeks.50 In a nonrandomized trial with 10 participants, researchers found that phosphorylase kinase activity levels in psoriatic skin biopsies of patients applying topical curcumin 1% were lower than placebo and topical calcipotriol applied in combination. The lower phosphorylase kinase levels correlated with level of disease severity, and topical curcumin 1% showed a superior outcome when compared to topical calcipotriol.40,49 Although these preliminary results are interesting, there still are not enough data at this time to recommend topical curcumin as a treatment of psoriasis. No known adverse events have been reported with the use of topical curcumin to date.